Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

"'A BROTHER'S CHRISTMAS-BOX.'"

AND OTHER STORIES

BY

RUTH LAMB

AUTHOR OF "DEAR MISS MEG,"

"A WILFUL WARD," "HER OWN CHOICE,"

"ONLY A GIRL WIFE,"

ETC.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 BOUVERIE STREET, AND 65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

CONTENTS.

SIX MILESTONES: A CHRISTMAS MEMORY

ARTHUR DREAMING.

NOT a bit like Christmas.

Everybody said so to everybody else, and surely, what all agree about must be strictly true. The farmers' wives said it to each other, as they jogged to market with well-filled baskets, containing all sorts of home-fed Christmas cheer. The butcher said it to each customer in turn, as he lightly passed his keen-edged knife outside the yellow rind of his prime Christmas beef, to suggest where the actual incision should be made and the "cut" severed from the rest.

The grocer said it, as he handed over the parcels, so much larger than usual, because of the ingredients required for mince pies, spice bread, and plum pudding. The postman said it, as the wet dripped off his waterproof cape, and he handed letters with moist envelopes to outstretched hands, the owners of which kept well under cover, instead of presenting a smiling face and offering a pleasant greeting to Her Majesty's messenger.

Boys and girls in plenty, home from school and boiling over with long-suppressed energy, sat gloomily surveying the prospect, and feeling themselves defrauded. They understood Christmas to mean fun and frolic, notably such as a good, sharp frost brings with it. A Christmas with such weather seemed to have no real ring about it. Where was the good of getting stout nails inserted to roughen boot soles for sliding, of furbishing old or purchasing new skates, if the thin coat of ice on the pond had all disappeared, with no signs of renewal?

There had been a few flakes of feathery snow two days ago, but these had changed for sleet, and this for drizzle. The disgusted lads flung aside their skates; the girls, far better off under the circumstances, applied themselves to exclusively feminine occupations and secret preparations for the Christmas-tree.

One boy said, gloomily, that he had spent his time in watching the changes out of doors, and stated, for the benefit of his compeers, that these consisted of two varieties only, "squash and splash," —otherwise, as he condescended to explain, of constant drizzle, with a ground accompaniment of thick mud; and steady downpour, with an equally liberal supply of thin ditto.

The very horses, as they plodded wearily homeward through country lanes, dragging the wheels along deep ruts temporarily filled with mire, would have joined the human chorus if they could, and declared that such weather was "not a bit like Christmas."

Perhaps, if there was one individual who felt this more deeply than his neighbours, yet without saying it, the Rev. Arthur Worsley Glyn, curate of Little Cray, was the person. He did not say this, for two reasons; firstly, because he was alone, and pacing in somewhat melancholy fashion up and down his study; secondly—though this was really the stronger reason of the two—because he was not a man given to grumbling, either aloud or in his secret heart, about what could not be cured. I will leave him here whilst I tell his story as briefly as I can.

The Rev. Arthur, in his thirty years of life, had experienced some pretty rough travelling. His path thus far had been none of the smoothest, and the real hardship lay, not in the fact that difficulties had to be overcome, but in the knowledge that needless impediments had been placed in his way by the very hand which should rather have removed them.

It sometimes happens that the evil example of a parent is so overruled for good that the son shrinks with horror from the sin which has brought about domestic shipwreck; that having no earthly father to look up to, no paternal arm to lean upon or hand to guide, children seek more earnestly, and with a greater sense of need, the love of the Heavenly Father, the support of the everlasting arms. It had been so with Arthur Glyn, and from his very boyhood his mother and two young sisters had looked to him as the staff and comfort of their home, rather than to its nominal head.

Those who knew Worsley Glyn the elder marvelled that he could have a son like Arthur. They saw the man fritter away a fortune by all sorts of reckless expenditure, waste golden opportunities for want of exercising his undoubted talents, and lose a position which might have proved the stepping-stone to another fortune, from sheer indolence and self-indulgence.

Thus Worsley Glyn lost his self-respect, and went rapidly on the downward course, despite the efforts of loving hands which strove to stay him as he descended the social scale. The wife might cling to the arm on which in bygone days she was so proud to lean. Her feeble grasp was easily shaken off; her voice, half-choked with sobs, which implored him to stay in his home, was drowned by the invitations of boon companions. Mother and children had to struggle as best they might, lest they too should be dragged down by the reckless hand which ought to have upheld them and shielded them from every shock.

Himself a highly educated man, Worsley Glyn had resolved that Arthur, his first-born, should have every advantage that money could procure for him. The work of teaching and training was well begun; but whilst the boy's education was in progress, so great a change took place in the circumstances of the family that it could no longer be carried on in the same expensive manner.

"Never mind," said Arthur. "The Grammar School is open to me. I have no fear of failing to win a free scholarship there. With brains, health, and the determination to turn them to account, I shall do well enough at very little cost, so far as money goes."

So the earnest young student soon took his place at the Grammar School, and went onward and upward, until he went thence to Cambridge, the winner of two scholarships, which rendered him almost independent of help from his father.

Had Arthur needed assistance, it would not have been long forthcoming. Hard work and rigid economy, however, placed him beyond such need, and, when the young man's name stood high on the list of Wranglers, and a Fellowship followed, he began to think that now he might look joyfully forward and hope for a bright future. But with the thankful, congratulatory letters from home came also sad tidings of his father.

Money was gone, character forfeited; friends were becoming weary of helping, seeing that no opportunity was seized and utilized; no amount of pecuniary aid produced any permanent benefit, either to Worsley Glyn or his family. They pitied the gently nurtured lady whose fate was bound up with that of the reckless spendthrift. But people said, as it is quite natural they should say, that a wife cannot be separated from her husband; that if she could be aided without the benefit being shared by the worthless partner, helping hands should be outstretched in all directions.

This, however, could not be, so one friend fell off after another, and Mrs. Glyn was driven to tell her troubles to her son.

"You have always been my true comforter, Arthur," she wrote, "and often of late, I have been tempted to let you know how things have gone from bad to worse. But when your hopeful letters came, and I felt how necessary it was for my dear boy's mind to be clear from harassing thoughts, in order to ensure success after all these years of mental labour, I refrained from seeking relief for my own overburdened heart by telling what must grieve and trouble you. Now that your success is an accomplished fact, and your position a more assured one, you can better bear the tidings which I can no longer withhold. There is only One who knows what a trial it is to me to damp your well-earned triumph by bad news from home."

The tale which these words prefaced was sad enough. The father, Worsley Glyn, was doing nothing, and of income there was literally none. Those who had given him opportunities of retrieving his position, more for his family's sake than for his own, would trust him no longer. All available resources had been tried, and were exhausted. Of house debts there were few as yet; at Mr. Glyn's personal liabilities, his wife was afraid to hazard a guess. For herself, she said, she would rather starve than incur debts which she had no means to discharge.

Arthur knew that his mother had strained every nerve to give a thorough education to his young sisters, Hilda and Gertrude. Under her careful training they had grown-up into a lovely girlhood, tender, true, modest, refined, and well-informed, but in the way of accomplishments she could do little more. The services of good masters were needed in order to fit the girls for earning their bread as teachers, and such were too costly to be thought of for a moment.

Then there was another cause for anxiety. The life insurance which Mr. Glyn had been induced to effect in better days would fall through unless the premium were immediately paid. This was the more important as his health was beginning to fail, and the sum insured was the only semblance of a provision for mother and girls, as well as to meet Mr. Glyn's debts.

No wonder if the joyous light faded from Arthur's eyes, and the flush of gladness from his cheek, as he read his mother's letter. The long-hoped for, well-earned holiday must be given up. The sum hoarded and husbanded at the cost of much self-denial, in order to purchase change of scene and a brief rest to fit him the better for renewed labour, must be otherwise devoted.

It would pay the all-important insurance premium, and leave a very narrow margin for immediate necessities, and that was all.

Arthur Glyn was a brave young fellow. Not with the courage that makes a country ring with applause, because of some daring deed, entered upon, perhaps, in obedience to a momentary impulse, and with little thought of consequences. Yet many a hero in public life has proved himself a coward when called upon to exercise self-denial, or to battle with the petty cares and anxieties of daily life.

Ay, and many a simple-minded, true-hearted girl, who has taken a too heavy load on her young shoulders, and borne it, day after day, with head erect and smiling face, to save a still weaker back from being bowed, and a troubled mind from over-much sorrow, has shown a courage far beyond what is needed for a single act of valour, performed with the world looking on, and waiting to applaud its hero!

Arthur Glyn was an every-day hero, fighting his way by hairs' breadths, counting the cost of every step, and not shrinking from paying it to the full. Not that he came off conqueror in his own strength. What true hero ever did? Had he trusted to himself alone, he must have been worsted long before. But humbly seeking guidance and courage from above, the power was given him to work, to withstand, and to stand.

Here had come to him the tidings of fresh trouble, of a new burden to be borne. He asked himself, "Am I the person who should meet the one and bear the other?" He thought of the dear mother, grown grey and looking old before her time; of the girls, so young, fair, and, as yet, so dependent.

The matter did not require much consideration, and having once decided, Arthur Glyn was not the man to put off doing what conscience and duty declared to be right. So the premium was paid, and in the letter containing the money went a cheering message to Arthur's mother, and a promise that the greater portion of the income assured to him by the Fellowship should be dedicated to her use. As a tutor, he could earn enough in addition to supply his own wants, and he hoped to do yet more for those at home.

It is not to be supposed that the sacrifice cost Arthur no pang. He wanted the holiday as medicine for mind and body. He felt that he had earned it, and he knew that by but small efforts on the part of his father these greater struggles might have been spared, not to himself alone, but to those at home who were less fitted to endure hardship.

There were, however, two things for which Arthur Glyn was always remarkable: first, having made up his mind that a certain course was right, he took it, and at once; secondly, no human being ever heard him regret that he had done so, murmur at the cost to himself, or fret about what was inevitable.

Yet the sacrifice meant much. It was the darling wish of his heart to enter the ministry, and become a labourer in his Master's vineyard as early as possible. These home calls would compel him to use his talents first and foremost as a means of earning money, even bread for those at home.

"Ah, well!" thought he. "My Master has permitted the trouble to come, so it must be for good. There is work round and about the vineyard, if I cannot yet be admitted as a regular labourer. I can fight on my Captain's side, and 'endure hardness as a good soldier of Jesus Christ,' before I put on the uniform which is supposed to manifest me as such to the world at large."

Seven years have passed since Arthur Worsley Glyn made the mental resolve above recorded, and it has been bravely kept. He has worked hard and uncomplainingly, has cheered his mother, assisted to complete the education of his sisters, has stood by the death-bed of his father, penitent enough, but, alas! Repentance came too late to make any amends for all the trouble he had brought upon his family.

And, in order that no needless dishonour should be attached to his memory, the son had taken upon himself a weight of debt far exceeding the worst anticipations of those he left behind. Even with the insurance money to assist, Arthur was still heavily burdened. But though he might sometimes almost stagger under his load, he never swerved from the path which he had decided to be his path of duty.

He had been ordained about eighteen months. His beloved mother had been spared to see this, and to know that her girls would now be able to maintain themselves by their own exertions. She had only one anxiety, and whilst she grieved at the thought that Arthur had been obliged to deny himself so much, and for so long a time, she yet pleaded for the completion of the task he had taken upon himself.

"It has been uphill work for you, Arthur," she said. "But you have been the best of sons and brothers, and your life and words were made a blessing to your father in his last days. It seems almost wrong to ask you to persevere until all—"

"Hush, dear mother," said Arthur, tenderly; "do not add a word. I made a promise, and by God's help I will fulfil it. I will work until my father's debts are paid to the last farthing."

"Arthur, in God's Word there is a portrait drawn for us of the mother whose 'children shall rise up and call her blessed.' Surely it is no less joyous a picture when the mother can herself rise up, and say the same of her children. I thank God for His precious gifts in mine. Truly I can say of my son and daughters, they have been to me 'an heritage from the Lord.'"

"Mother, dear, if we children deserve such a name, it is to you we owe it—next to God. From our infancy you knelt with us at His footstool, and taught us that in Him alone could we find our Father, Saviour, and Sanctifier. You constantly pointed us to God's works as proofs of His almighty power, wisdom, glory, and greatness. In all things you strove to show us the wondrous love of our God, but most of all as manifested in the gift of His dear Son, to be our perfect Pattern in life, our all-sufficient Saviour by His death on the cross."

"You taught us not only to read the Bible, but to love it, and to go to its pages for guidance, for comfort, for a supply of every spiritual need, and to ask for the light of the Holy Spirit, that we might be made 'wise unto salvation.'"

"What is my greatest joy now? Is it not that in proclaiming the love of God in Christ Jesus, I proclaim what I believe and know by blessed experience?"

Arthur's face was fairly glowing with happiness as he spoke, and his mother's reflected the holy joy which stirred both hearts.

"I thank God that it is so, Arthur," said Mrs. Glyn. "My chief prayer for my children has ever been that those so dear to me should be dear to Him, for Christ's sake. May you be abundantly blessed in your ministry! But you will be. You have 'Christ in you, the hope of glory.' With Him you will surely have all things needful for soul and body."

The mother's words and the mother's blessing lingered in the memory of Arthur Glyn, and cheered him onward. But though Hilda and Gertrude were both in remunerative situations, and seven years of hard work had passed over Arthur's head, his task was not yet finished. His health had so far broken down, that a total change of scene and occupation became absolutely necessary.

He was compelled to give up teaching. His income would be very small during the coming year, for the Fellowship would be his but for three months longer, and he was now only curate of Little Cray, with a salary of a hundred and thirty pounds a year and a house. Further, after all the hard work and the self-denial of seven past years, more than three hundred pounds of debt still remained unpaid.

To the man of thirty, depending on his stipend as curate, it seemed as if his task were just beginning. At three-and-twenty, flushed with scholarly victories, with an assured income and unimpaired health, the greater work had been boldly undertaken. Now it was different. The sum still owing was but a remnant of the really important whole, yet it weighed the man down. Not that the load itself was so heavy comparatively, but the back was less strong, the spirits were less buoyant, and the health was somewhat impaired by severe mental labour. Not seriously. Arthur's constitution was sound; he only wanted rest to make him more vigorous than ever.

Still, after all that had been done and was yet to be accomplished, it can hardly be wondered at, if the curate's heart sank within him as he paced up and down his room, asking himself the question, "Shall I be able to fulfil my promise to my dead father, repeated to the dear mother on the last day of her life? Or shall I, after having accomplished so much, sink under the remainder?"

The thought had hardly shaped itself into a question when Arthur reproached himself for it. "Hitherto hath the Lord helped me," he thought. "I have trusted thus far; I will trust Him still."

LITTLE CRAY is one of the quaintest and quietest of English villages, but is only three miles from a large market town. It is made up, with two exceptions, of farmhouses and labourers' cottages. The latter, somewhat rude in construction, with thatched roofs and whitewashed walls, are picturesque to look upon, and exquisitely clean; a little bare-looking in winter, but in summer every cottage garden teems with old-fashioned flowers. Roses, honeysuckle, white-starred jasmine, canary and Virginia creepers, and the humbler nasturtium vie in throwing veils across the little porches, or spreading along the gables, or clambering over the thatch itself. And from amongst the trees that have stood for centuries the massive square tower of Little Cray Church can be seen for many a mile.

The rector, Mr. Worthington, does not reside in the village. Little Cray is the mother parish, but she has a daughter church much larger than herself, and vastly more fashionable. The place is near the coast, and what was once a cluster of fishermen's huts, has of late years developed into quite a fashionable watering-place. A large modern church has been built to meet the requirements thereof, and thither the rector has migrated to minister to a crowded congregation whilst the season lasts—at all times to a much more numerous one than is ever found within the ancient walls at Little Cray.

The new rectory house, with modern surroundings and comforts, is better suited to the needs of his family than the old dwelling in the village.

So this accounts for our curate's possession of a house to himself, and he is master of that ivy-covered domicile which peeps modestly out from among the trees near the old church tower.

I said he was master, but I am not quite sure of this. When he came to Little Cray, he was rather doubtful as to whether he should occupy the rectory or not. Certainly, he could not afford to furnish it, and there would be a difficulty about finding lodgings, as none had been required there within the memory of Little Cray's oldest inhabitant.

But the rector and his curate, though both young men, were old friends. The former was the elder, and he had been ordained and had married early. He was in Arthur's confidence as to the demands on his purse, and he thought he could solve the difficulty.

"There is a lot of furniture in the old house which I do not wish to remove, as we are having new in place of it. I should be grateful if you would allow it to stay. It suits this place and would not suit the new one. The house is just the spot for a brain-weary man to rest in—not good enough for you in any other respect, my dear fellow, and you will not stop here long. I can help you to make an arrangement which will be an immense accommodation to a worthy couple, and will, I think, just meet your views."

Whereupon Mr. Worthington introduced a comely matron, named Esther Morris, whose husband had obtained work in Little Cray, but could not find an empty cottage in which to locate his family. There were husband, wife, and two white-headed, sunburnt urchins, for whom it was guaranteed that they were "very bidable, knew manners, would not disturb the passon, and a look was enough to snub them."

Esther had been a servant at Little Cray Rectory before Mr. Worthington's time. It would be like coming home again if she were to keep house for the curate. Her household goods would furnish the part occupied by her family; those left by the rector, with Arthur's books and many pretty fancy articles made by the nimble fingers of his young sisters, would render the other portion all that he could desire.

The bargain was easily concluded. Mr. Glyn was to give house-room, firing, and lights to the Morris family, and Esther was to keep house and generally "do for" the curate, with occasional help, for which he was to pay. This agreement had been in force for six months, and now Christmas was coming, and with it Arthur Glyn hoped for the society of his younger sister, Gertrude. Hilda was passing the winter at Cannes with a delicate pupil, but Gertrude had sent a number of loving letters to tell him how she was reckoning on spending at least a month with dear old Arthur at Little Cray.

And the solitary young man, who had been living for others ever since he was able to think and act, was counting the hours until that happy one should arrive which would bring the sweet young face of his favourite to cheer his fireside.

But as he paced up and down the study on that dismal morning, on the shortest day, and one of the dreariest in all the year, his heart might well echo what bolder grumblers put into words, "It is not a bit like Christmas."

That open letter upon the study table replied, though mutely, "And I bring a message which will take the taste out of your Christmas dinner."

The letter was from Gertrude, and told a love tale—a very happy one. The lassie had won the affections of a good man, the uncle of her little pupils. He had wealth, position, high character, and must have sought the little damsel for herself alone, since all her dowry consisted in her fair young face, true heart, and well-cultivated mind. Better still, every one was agreeable, and so the girl's letter was full of sunshine and the shy happiness which wants to tell all its tale to the dear absent brother, but can hardly put it into words.

"He is to spend Christmas here, and they all want me to stay,"

wrote Gertrude. "Of course, I should like it, only I want you too,

dear Arthur. I cannot possibly be quite happy until you have seen him,

and told me that you, who stand in place of both father and mother, are

satisfied with my choice, and can ask God's blessing on it. You will

come to us, dear, if only on Christmas Eve. I am sure Mr. Worthington

will contrive to set you at liberty, and some time after the New Year

has begun I will join you at Little Cray. Only, if you cannot possibly

come, I will keep my promise, and spend Christmas at your village

parsonage. But do, please, try to join us here."

"The little gipsy!" exclaimed the Reverend Arthur, as he finished his, sister's letter. "To think of the child being engaged! But what nonsense I am talking to myself! She is two-and-twenty—a woman, and more, even, in the stern eye of the law—and can dispose of herself without let or hindrance from me—bless her! Not that I would hinder the bright little bird, or interfere with her choice of a mate. What an old fellow this letter makes me! I have left the girls such a long way behind that I can hardly realize how few years really lie between them and me!"

The curate paced up and down, pausing a moment to see the wet dripping and trickling from the eaves, the Christmas greenery of laurel, ivy, and holly shining like burnished metal under their washing, and to hear the melancholy coo of the pigeons as they crouched under the shelter of the overhanging roofs, and complained in a neighbourly way of there being "so much weather about."

Arthur's thoughts left his immediate surroundings. He knew Leonard Thorold, pretty Gertrude's fiancé, and could picture the little bright thing looking up to her tall lover as she nestled beside him, the dark eyes veiled with moisture, the half-shy yet all-trustful clasp on the strong arm that was to be her support through life. Half to himself, the brother murmured a prayer for her happiness, and then, sitting down, he wrote out his loving wishes, his hearty sympathy, his own unselfish resolution respecting the Christmas visit.

"It is impossible for me to leave Little Cray at this season," he

wrote. "It would not be right for me to suggest such a thing to Mr.

Worthington so, much as I should like to give my darling sister a

brother's kiss, and tell her, instead of writing it, how truly I

rejoice with her in this new-born happiness, I must be content to spend

my Christmas in old bachelor fashion. As to your coming to me! That is

equally impossible. A little cloaked and furred damsel, known to the

world as Gertrude Glyn, might be packed off by train, landed at the

station nearest to Little Cray, and thence conveyed in a borrowed trap

to the rectory. But if she were here in the body she would be absent in

spirit. Whilst I was talking to my little sister, she would be hearing

again that other voice which has so lately told its love tale, and

would answer Leonard whilst brother Arthur was speaking."

"No use, darling! I will not have the shell without the kernel,

and I love you far too well to wish for your presence under the

circumstances. Perhaps another Christmas we may—but no; I will not try

to look beyond your happy present. So good-bye, dear sister, and may

the joy which is now only in the bud bring glorious blossom in the

future. I believe you love wisely, for Leonard is a good man. May you

be to each other all that the great Creator willed when He gave man to

be the head of the woman, and the wife to be his true helpmeet!"

There were more messages, news of Hilda—all the little odds and ends of information which Arthur knew his sister would delight to receive from him. He told her how he was fussed, petted, and tyrannized over by Esther Morris, who interfered with his liberty of action in the choice of garments; of her solemn warnings on the subject of going out without a macintosh when there was only a microscopic shower falling, and her own evident sense of responsibility on the score of his health. Any and everything did he tell which could provoke his sister's mirth, and lead her to think how wonderfully well he was looked after, and how independent of other feminine presence.

Not one word about the sinking of heart; not a suggestion about his personal disappointment; no hint of the feeling with which he glanced at the cosy chair on the opposite side of the fireplace, in which he had reckoned on seeing his young sister. Only, when she came, that chair was to have been moved to the same side as his own, in order that hand might clasp hand, and loving pressure tell of mutual sympathy, as they exchanged confidences about the past year.

Let the little chair stand; no need to move it. The glossy head has found another resting-place; the taper fingers will be clasped by another hand than Arthur's!

And he might as well write to countermand that piano, carefully selected at the principal music shop in the market town before alluded to. It—the piano—had been almost recklessly hired for a month, that the little sister might miss no comfort, and that the brother, leaning back in his favourite chair, might listen as she sang hymn or song that the mother had loved in the old days, and taught to her children.

No need for the piano now.

And then, amidst the unspoken feelings of regret, came a reproachful thought. The brother, unselfish hitherto, was himself again, and shutting out the memory of his disappointment, blaming himself even for allowing it to intrude, he resolutely banished it, and kneeling down, thanked God for His goodness to the little sister, and prayed for her continued happiness in future years.

The dim light of that wintry day faded into darkness. The rain continued to patter outside, but the curate's fire, carefully replenished, gave a cheerful glow, and by it he sat dreaming just for once.

Not that he was given to day-dreams when there was work to be done, but just now rest was the truest economy, and as his mind was too busy to be altogether idle, dreaming was the employment which cost the least mental effort.

Gertrude was dispossessed from the little waiting chair, but as Arthur's dream progressed, he saw it occupied by another figure; a girl's also, younger than the sister by fully two years; taller, slighter, fairer than the little gipsy to whom he had been writing. He saw the delicate cheek, resting on a slender hand; the lovely violet eyes, full of feeling and tenderness; the abundant hair, drawn, but not tightly, from the fair forehead, and twisted in soft coils behind, innocent of frizzing-irons or fringes. All about the figure was sweet, feminine, and forming a delightful combination of girlish innocence and womanly goodness.

As Arthur saw the imaginary figure filling that place, the dream was bright enough to bring a little cry of gladness to his lips and a smile to his thoughtful face. He half-stretched out his arms as he rose involuntarily from his seat, but as he did so the vision faded, the chair became empty again.

A real face appeared in the doorway, and Esther Morris inquired if "master" called, for she thought she heard his voice. She brought the lighted lamp in her hand, thus anticipating a want that must shortly be attended to, and—only she did not know it—an extinguisher too, which shut out and put out the light of Arthur's dream.

"Better so," thought the curate, as he returned a civil, pleasant answer to Esther, and his thanks for the lamp, as if he had wished for either the one or the other. "If I have conquered the inclination to grieve after the real which is unattainable, no use for me to indulge in dreams, or fume if the vision is dissipated by the very substantial form of Esther Morris. If! but away with ifs!" And with no further self-indulgence than a single involuntary sigh after what might have been, the curate turned once more to his writing-table, and began to study his Christmas sermon.

YES, there were two of them; though in a tiny village there ought only to be one squire. Indeed, there was only one by right of ancient ownership and long family residence, and that was Mr. Spencer, of Cray Holm, who united in his own person the patronage of the living and the possession of all the broad acres which were included in Little Cray.

He had large estates elsewhere, in addition, was lord of the manor and everybody's landlord within a wide circle, but withal the kindest and most unassuming of men. He had a neighbourly greeting for young and old, the poor as well as the rich. He patted the heads of the youngsters who doffed caps or bobbed little curtseys at his approach, and had not an enemy in the world.

During the past year he had sustained a terrible loss. The partner of more than thirty years had died, and now the family at Cray Holm consisted only of the father, his old maiden sister, Adelaide, and a single fair daughter, just out of her teens. One son and an elder daughter were married, and lived elsewhere.

If you remember the figure that Arthur Glyn, the curate, saw in the little chair at his fireside, on that rainy December evening, you will not need a further description of the squire's daughter. Arthur's was but a twilight dream, which vanished at the sound of a voice. Anna Spencer was the living, breathing reality which had furnished the shadow for that vision.

She was not at the curate's fireside, but at the very moment when the dream took place, she and her father were pacing up and down the drawing-room at Cray Holm—she with her slender fingers clasped on his arm and clinging to him, as they walked together, to and fro, on the velvety carpet with noiseless footfall.

They talked softly, glancing now and then at the little old lady who was nodding by the fireside in the softest of chairs, whilst her brother and niece took the only exercise which the weather permitted.

Aunt Adelaide had complained that it was a sleepy sort of day "not a bit like Christmas," and had proved it by napping over her knitting. Anna had stolen out and forbidden the man to bring in lamps as yet, in order that the old lady might rest on till dinner-time; so only the ruddy firelight cast its gleams in and about the room.

A pretty, if somewhat sombre picture, made father and daughter—he a noble looking man of sixty, tall, well-built, erect, but with hair which had changed very fast from iron grey to silver within the last few months, since the death of his wife. Anna's fair face looked all the fairer, and her figure more slender, because of the soft black dress she wore.

Father and daughter had decided to have no family gathering at Cray Holm this Christmas. Each felt that it would be hard upon the little people to bring them to their grandfather's, and not provide for their enjoyment by gathering other children to make merry with them there.

"Poor darlings! I should love to see them all, but I could not bear fun and frolic, and pattering feet, and ringing laughter, just yet. They might all be here, but without her, Anna, Cray Holm would not look a bit like Christmas. Another year, please God, I shall have become more used to it. So we will be very quiet, dear—you, auntie, and I together. Stay—is there any lonely person who would be made the happier for joining our trio and turning it into a quartet,—one who would enjoy Christmas with us in our sober way, and help us to thank God for all the happy memories the past can furnish, and the glorious hopes born for us poor, sinful mortals with the birth of Christ, our Saviour?"

Mr. Spencer looked inquiringly at Anna. He had a motive in asking the question, and he watched a rising flush on her round cheek, which even the dim light sufficed to reveal. The girl turned off the question with a little quiet laugh, subdued for Aunt Adelaide's sake; and as she gave a half-frightened glance at the drowsy figure, then looked relieved to find that no harm had been done by the unintentional outbreak, she answered:

"There is Mr. Roger Ulyett, papa. Would he like to come, think you?"

Anna was young and loving. Somebody—we will not say who—had crept into the girl's warm heart, and would not be dislodged. She thought that no living being beside herself had the faintest guess as to the lodger that had established himself in that corner; but the loving heart gave a little flutter when her father asked his question. With a spirit of fun which even recent sorrow had not extinguished, the girl suggested "Mr. Roger Ulyett."

The rippling smile on her face broke out into a decided laugh, which made Aunt Adelaide stir upon her soft cushions. It did more. The ripple spread even to the face of Mr. Spencer himself, and he shook his head at Anna, who exulted in the success of her ruse and its effect on her father.

"I was not exactly thinking of Mr. Ulyett, Anna," replied he; "though, in spite of the way in which you have always persisted in laughing at him, he is a capital man; a gentleman, too, by birth, family, and education, for whom I have a true respect."

"And so have I, papa," replied Anna; "only I prefer to respect him at a little distance, as a rule, you know."

"He is your staunch and devoted admirer, Anna, though a hopeless one."

"That is just what I object to, papa."

"To his hopelessness, Anna?"

"No, papa; to his admiration. You know that."

"It is of a very harmless kind, my dear. I believe, when Roger Ulyett first came to the edge of Little Cray parish, built himself a grand house, filled it with costly furniture, and let the world know how fortune had favoured him by turning him into a millionaire before he was fifty, he also thought that money would buy everything. He knows better now, and has learned a great deal in his two years of residence."

Anna pursed her lips a little saucily, then answered—

"If you wish for Mr. Ulyett's presence on Christmas Day, papa, ask him, by all means; though I should think he will be spending it with one or other of the nephews and nieces of whose devoted attention he says so much."

"I happen to know that he is meaning to stay at Fairhill until the middle of January, at any rate. He has not invited any of his dutiful relatives, but intends to have the rector, Mrs. Worthington, and their children to dinner, and afterwards to give the cottagers of Little Cray and their youngsters such a treat and a Christmas-tree as they have never had or seen before. We could not have them here this time, and I meant to make up the loss in another way, and was considering how best to do it, when Mr. Ulyett told me his plan."

"'I do not wish to interfere with your old rights and privileges,' he said; 'but I know you cannot be in tune for this sort of thing yet. Let me do the Christmas business, just for this once, and you can give the youngsters a summer treat under the grand old trees in the park at Cray Holm. You see, my trees are not grown yet; yours are part of a grand heritage which only Time can give; money has to wait upon the old Reaper, after all. Besides, you know,' he continued, 'I must have some engagement to plead for not accepting the invitations I have received from nieces Georgiana, Amelia, Lucia, &c., and nephews too numerous to mention.'"

"I do dislike to hear Mr. Ulyett sneer in that way at his relatives. Just as though they were moved by nothing but mercenary motives in asking him. He shows that he mistrusts his own qualifications for winning their affection," said Anna, warmly.

"Not quite so, my dear. Roger Ulyett's kith and kin all turned their backs on him, because, seeing there were too many branches to the old family-tree for the soil to support, he betook himself to trade. They turned up their noses at him and it, when he accepted the invitation of a wealthy merchant, his godfather, to take a seat in his counting-house. Roger went, cared not a straw for being called a disgrace to the family; used his brains and his hands, too, wherever anything was found for either to do, and won a great fortune, whilst the brothers and sisters nursed their family pride in idleness, and consequent poverty. Do not fancy, Anna, that Roger Ulyett neglects the claims of kindred because he laughs now and then at their having discovered so many merits in the successful man, which were not perceptible in the youth who went out from among them to seek his fortune. I know that while he laughs, he also helps all of them who need it, in the most liberal fashion, and that his open-hearted kindness has won him the real esteem and affection of his relatives, who would fain make up for past slights."

"I am so glad to hear all this, papa. Indeed, I wish now that Mr. Ulyett could come on Christmas Day. His racy, shrewd talk might have amused you."

"To say the truth, my dear, I did ask him, and through doing so found out that he and Mr. Worthington had been laying their heads together, with the result aforesaid."

"That is just like you, papa," said Anna, "inviting guests, and saying nothing to me until they have either accepted or refused your invitation."

If the young speaker had a lingering hope that another invitation might have been given and accepted, she was mistaken; for Mr. Spencer meekly replied, "It was only the one, Anna, and Mr. Ulyett did not accept. Would you like to suggest another?"

There was Mr. Spencer throwing the responsibility on his daughter a second time. If he had only asked Arthur Glyn without leave, he need not have feared a scolding; as if he ever did fear one from such gentle lips!

Perhaps he guessed her thoughts, for he said, "Well, Anna, darling, there is only the curate, and surely Mr. Ulyett would not ask all the people from the new rectory, and neglect the solitary occupant of the old one."

"Mr. Glyn was expecting a sister, papa."

"True, my dear. I remember he told me so. Suppose, then, we ask the two to join us. He is a fine fellow, and a good man. He will talk to me without causing a jar on any tender string, and the young lady will be a little company for you and Aunt Adelaide, who has been sorrowfully remarking that she cannot believe this is the 21st of December, for it is 'not a bit like Christmas,' in-doors or out."

Anna did not wait for more to be said. She slipped quietly out of the room, and before Aunt Adelaide was finally roused by the second dinner-bell, the note of invitation was on its way to Little Cray Rectory, addressed in the clear writing of Anna Spencer. Guess, if you can, how the curate's brow smoothed, and the firelight seemed to dance again, as he read the kindly worded note, and felt that, in spite of drizzle and downpour—of the little sister's absence and his own loneliness—he could no longer look forward to the 25th of December with the thought that for him it would "not be a bit like Christmas."

Miss Spencer had not to wait long for a reply. In fact, the curate carried it himself. Despite the remonstrances of Esther Morris, who persisted that the weather was "not fit for a dog to go out in, much less a Christian and a passon," he donned stout boots and macintosh, and, heedless of rain overhead and mud below him, arrived at Cray Holm just when the little party had adjourned to the drawing-room after dinner.

Mr. Spencer rose and met him with words of welcome, adding that he was just wishing for a worthy opponent at chess; Aunt Adelaide thought Mr. Glyn very kind to venture out on such a night. And if Anna's words were few, her father put his own interpretation on her heightened colour, as she shook hands with Arthur, the last of the three. The father could scarcely forbear a smile as he mentally noted how quickly the invitation had been despatched to Mr. Glyn, and how prompt was the curate's response thereto.

Arthur said pleasant words to and made inquiry after the health of Aunt Adelaide, told Mr. Spencer he fearlessly accepted his challenge to the mimic battle, only he must first answer Miss Spencer's kind note verbally. This took some little time, for he had to tell that Gertrude was not coming to Little Cray, and to add the reason why.

Congratulations and inquiries followed, and Anna was not the least pleased to hear that the little dark-eyed governess was actually going to be the wife of a man whose position and means were similar to those of her own brother.

Mrs. Esther Morris had looked out after the curate as he started on his wet walk to the squire's, and had fervently wished that Mr. Glyn, "as kind a gentleman as ever trod on shoe leather, might not find sour grapes at Cray Holm." We shall see.

We must peep into the other great house, in which Mr. Roger Ulyett and Mr. Worthington are having a confidential chat. The rector has dined at Fairhill, and has arranged with his host all the details of the Christmas treat to the villagers.

We already know something of Mr. Ulyett, so we will not describe his gorgeous mansion or say much about its master. Mr. Spencer's portrait was sufficiently correct, so far as character goes, though few knew how much of good was hidden under brusque manners and a somewhat caustic mode of speech affected by the millionaire of Fairhill.

"By the way," said Mr. Worthington, "you will pardon my saying it, but Glyn seems to be rather left out in the cold. All the details of this Christmas festival have been settled without him."

"And far better so. He knows our plan, and has promised to look in and help to amuse the folk, if needful."

"Which will not be the case. You have devised a programme which will give Little Cray folk enough to talk of till Christmas comes again. But what is he going to do with himself at dinner-time? Surely he will not be left to spend that hour in solitude? I should have asked him, only we are all coming to you, and I thought—"

"I thought his sister was coming."

"She is not." And again the story of Arthur's letter and its contents is told, by a friend's tongue this time.

"Well, to say the truth, I did not want Glyn to be engaged to me, in case a more congenial invitation should reach him. I may be a disappointed man, you know," and the grimace which accompanied this remark made Mr. Worthington burst into a hearty laugh, "but I am no dog in the manger."

It was a favourite notion with Roger Ulyett to air his hopeless admiration of Miss Spencer in the presence of his sympathetic friend, Mr. Worthington.

Not that Roger Ulyett had ever made a formal proposal for the hand of Anna Spencer, for, as he told the rector, he was resolved to do nothing that would close the doors of Cray Holm against him. If he could not win the fair young mistress, he should like to see her and touch her hand as a faithful friend. "Men know they cannot reach the sun, but they like to bask in its warm rays," he said.

The rector laughed at this speech, and replied, "A truce to your joking. You know this sentimental talk is only meant in fun. You never had a serious thought of Anna Spencer."

"I never asked for her, for the excellent reason that she would have said 'No,' and would have been in the right to say it. But she is a gem of a girl, and if she only make a wise choice, Roger Ulyett will be the first to pray, 'May God bless her, and make her very happy with him ever after!'"

Mr. Worthington noted the unusually deep feeling with which Mr. Ulyett spoke. All the sharp, sarcastic ring had left his voice; the keen glance of his dark eyes softened into positive tenderness, and a phase of character rarely exhibited by him was laid bare to the rector's astonished gaze.

But his host only paused for an instant, and was his old self again.

"It takes a fairly wise man, Worthington, to find out that he is an old fool. Happily for me, I made the discovery, and took myself to task for it instead of indulging the world with a laugh at my expense. But, old cynic as people think me, I have a soft place in my heart. One article of faith with me is that 'true love ever desires first the happiness of the beloved object. It cannot be true or worthy of the name if its first aim is self-pleasing.'"

The rector nodded approvingly.

"You have got some other notion into your head about Anna Spencer," he said.

"I have. I believe that there is a man to whom she would not say 'No,' were he to ask the question I never dared to put into words. Not, mind you, that she would, even by a look, do aught to draw a man on for the sake of a petty triumph, or even betray her real feelings unsought. But I suppose certain feelings of one's own, make a looker-on clear-sighted. I have my opinion on the subject."

"More's the pity, for your words can only point to one individual. Poor fellow! His circumstances bind him to silence. He can never speak, let him feel what he may."

And Mr. Worthington was going to tell part of what he knew about Arthur Glyn's past and his quiet self-devotion, but Mr. Ulyett stopped him.

"I knew Worsley Glyn, his father. No need to tell me what a weight that young fellow's shoulders have had to carry from his very boyhood."

Then, turning the conversation, he went into some little details concerning a blanket distribution amongst the fishermen's wives at Cray Thorpe, and these lasted until the carriage came to take the rector home. I am afraid, when Arthur Glyn returned to his fireside at the same hour, his dream repeated itself, and even Esther's entrance with the bedroom candle did not put an end to it this time.

CHRISTMAS morning came, and the overladen postmen left greetings at the world's door, literally by the million. Arthur Glyn was not forgotten.

The little sister and her intended sent quite a budget of loving wishes, bright hopes—heartfelt regrets, too, that the dear brother could not be with them.

Hilda, far-away in the sunny South, had timed her letter so that Arthur might have it just at Christmas. There were more cards and letters still, and amongst the latter just one at which the curate looked distrustfully. He had been trying to make a few hearts more glad by his kindly thought, and when he expended a trifle for Esther and the white-headed urchins, had felt sorry that his slender purse and the claims upon it would let him do no more or better.

Arthur hoped that letter boded no evil. He did not know how he could bear it to-day; but he had been somewhat disturbed by a rather urgent appeal for the balance of one of his father's debts—the largest of those for which he had bound himself. The creditor was retiring from business, a prosperous man, and was not in need of immediate payment, but he wanted to straighten his books finally, and "could Mr. Glyn oblige him with the trifling balance?"

It was nearly a hundred pounds, and Arthur had not ten. The incident made him uneasy and down-hearted for the moment; but, like Hezekiah of old, he prayed, spreading his letter before the Lord.

The old Jewish king found comfort in his trouble; so did the young English clergyman. The one had a direct message in reply; the other had faith renewed and patience given to wait and see what way out would be made for him, in God's good time. He could say with a clear conscience—

"I have done what I could. My Master will require from me only in accordance with what He has given."

Yet surely, it is hardly to be wondered at, if the seal of that letter, with a London post-mark, and from an unknown correspondent, was the last which Arthur found courage to break. When he did so, an exclamation of surprise and astonishment broke from him. Day-dreams he had indulged in while sitting on that very spot, but the reality that met his sight had never been pictured in the wildest of them.

The envelope contained a number of Bank of England notes, new and crisp to the touch. He looked at the first: it was for a hundred pounds; the second, third—in short, the whole ten, were the same value! A thousand pounds was the sum contained in that suspicious-looking letter which he had shrunk from opening!

There was a large sheet of paper which covered the notes. Arthur snatched it eagerly. An inscription on the outer page, in printed letters, to him that the contents were "A Christmas-box for the Rev. Arthur Worsley Glyn."

But on the inner portion of the sheet were words which stirred the man's heart to its deepest fibre. Brave with Christian courage, he had thus far acted up to his resolution, and endured "hardness as a good soldier of Jesus Christ."

But the good-will of this unknown friend, made him weak, and he wept like a child.

We will read the words which so moved him over his shoulder, for the sheet lies open, and the curate is on his knees, with bowed head and clasped hands, as he thanks God for the wonderful answer which has come to the letter he had spread before his Divine Master.

"'Bear ye one another's burdens, and so fulfil the law of Christ.'"

"A brother in Christ claims the privilege of obeying this Divine

command, by lifting from your shoulders the burden so long and bravely

borne. He knows what you have accomplished, and of what mettle you

are made. Had health, strength, and fortune still favoured you, he

might have been contented to wait and see you rejoice over a task

accomplished without the helping hand of a human friend. He knows that

sometimes of late even the diminished load has proved too heavy. He has

pictured you on your knees before the Master you serve—a prayer-hearing

God. And he rejoices to think that the feeling which has prompted him

to send this free-will offering may be 'Our Father's' way of answering

His child's petition, for it pleases Him to work by feeble human hands."

"'Take, then, brother, and use what is here enclosed. It has cost the

sender no self-denial—he wishes it had, for the sake of Him in whose

name he offers it to you. It rejoices his heart to devote it to your

service. May yours be the lighter for receiving and using 'A brother's

Christmas-box.'"

Arthur read and re-read the letter, written in printing characters; but there was nothing to give him the slightest clue as to the sender—no mark on notes or paper; nothing on the envelope, except the postal impress, and London was a field far too wide to travel over in search of the unknown sender. Besides, Arthur had few acquaintances there, and none that he knew of anywhere who would be likely to send such a Christmas gift as this.

He thought once of Leonard Thorold, but soon dismissed that idea from his mind. His brother-in-law elect knew comparatively little of him.

Mr. Worthington? He was his true friend; but though his means were fairly good, they were not such as to render it likely that he would bestow so large a sum. Besides, the rector knew that it was more than treble the amount of the debts still owing.

He could not guess. Stay: there were two men in Little Cray that were rich enough, but should either do such a thing? Mr. Ulyett he dismissed from his mind at once. Mr. Spencer? Ana then a crimson flush covered the curate's too pale cheek. If he had indeed done this!

Off went Arthur into another dream, and in it, he said to himself, "If I stood now on the same ground that I did a few years ago, with college honours, my Fellowship, health, youth, strength, spirits, no debts or encumbrances, and a fair field to work in, I would not fear to try my fortune. But!"

And here, you see, was the drawback. The "if" and the "but" spoiled the vision; and then the first chime of the bells told Arthur that it was high time for him to turn his steps in the direction of the old square tower whence the sound came. As he walked thither, he almost made up his mind that Mr. Spencer was the sender of his letter and its contents.

"He is generous enough to do it—Christian enough to do it in such a spirit, and to accompany it with such a message," said he to himself.

Mr. Ulyett was in his pew, with the usual look of preternatural keenness on his face. Mr. Spencer's good countenance had, as was common to it now, a shade of sadness. No wonder, on that day. But it lighted up as he listened to the old message which the angels brought, and as he joined in the song, "Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good-will toward men."

I do not think the curate's previous preparation had much to do with his actual sermon that Christmas morning; but his hearers said that "young parson had never preached like that before, and that he could beat even Mr. Worthington all to nothing."

Perhaps Arthur's flock wondered most when, before the General Thanksgiving, the curate desired them to join him in thanking God for a special mercy vouchsafed to himself on that Christmas morning.

Then, when all was over, and Arthur walked home to Cray Holm with the Spencers, Anna looked at him in wonder, and even quiet Aunt Adelaide thought that Mr. Glyn seemed almost like a new man, he was so bright, and seemed so happy.

Quite contrary to expectation, there was another guest at Cray Holm that day—an old friend of Mr. Spencer's who had been called to the neighbourhood by urgent business, and who, finding that he could not well reach home for Christmas, had thrown himself upon the squire's hospitality. He had reached Cray Holm the night before, and was at church with the little party that morning. He spoke in warm terms of the curate's sermon, and, on the homeward way, asked his host many questions about Arthur Glyn's antecedents, the answers to which need not be repeated.

As to Arthur, he thought no Christmas Day had opened so brightly for him since he had enjoyed the happy season as a child, and in ignorance of the trials and responsibilities of riper years.

The guest, Mr. Mervyn, gave his arm with old-world courtesy to Aunt Adelaide, at the same time keeping pace with the squire, and chatting gaily about their mutual past.

Surely, under the circumstances, the younger pair acted discreetly in keeping at a little distance behind, so that the elders might talk without restraint! The sun shone out and spread a broad, if wintry smile over all the country round; the earth was crisp under foot, and the air keen enough to make people recall their former verdict, and say that "things looked a bit Christmas-like, after all."

Mr. Ulyett had waylaid the squire on his threshold before service, and made him promise that the little party from Cray Holm should look in at his large one at Fairhill. As Mr. Mervyn openly avowed his wish to go; Mr. Spencer would not disappoint his guest; dinner was fixed for an earlier hour; and it was settled unanimously that they would all go—even Aunt Adelaide.

Well might Arthur think that day just what Christmas should be, as he went into the dining-room with Anna, and took his place by her side for the meal.

Nobody could tell quite how it happened, but as the three gentlemen sat for a little while after dinner, the talk turned upon matrimony and the part that money ought to play in uniting or severing loving hearts. Mr. Mervyn seemed rather to deem it a drawback for a poor or even a rich man to marry "a lass wi' a tocher;" saying that he had always resolved never to wed a wife with money. He had been true to his determination, and had been rewarded by finding the richest of dowries in the dear wife herself.

Whereat the squire asserted that the man or woman possessing all the good qualities to make a perfect partner would neither be better nor worse for having the money, unless it were indispensable to their union.

"What does it matter which has it, provided either has enough to make marriage prudent?" he asked.

"Ah, but," returned Mr. Mervyn, "I could never be so beholden to a wife. If I had not possessed the means to offer such a home as I should like to see the woman I loved the mistress of, I should have borne my trial and held my peace."

"Then, sir," said the old squire, waxing warm, and standing erect as he spoke, "your love would have been worth little, and its strength but small, if money could have entered into such calculation with it, and pride strangled it altogether."

But he had hardly uttered the words ere he checked himself, and with a pleasant smile held out his hand to the old friend, who had risen, too, with a somewhat indignant manner, saying, "Forgive me, Mervyn, if I spoke too warmly. The question is but an abstract one, after all. I know: your true heart too well to doubt it. It happened that you could win your wife and keep your resolution. But had you loved a rich lassie, you would never have inflicted the cruel wrong of being silent about it, if you thought she had bestowed an honest heart upon you."

Mr. Mervyn laughed and clasped the squire's hand, and so linked, they passed out and into the drawing-room, the curate following, and greatly exercised in his mind by the discussion, in which he had taken no part but that of listener. He knew that Anna Spencer had half her dead mother's fortune, and that not a trifle, in her own right, and he had ever deemed this a barrier which his pride could not overleap.

There was a little interval of singing, and Aunt Adelaide dozed now and then, as old ladies will, and wakened with a start, to thank the young people for the music which had been unheard by her, and to declare that it was very pretty indeed.

The little party walked to Fairhill in the gloaming, and saw the children, and helped to distribute the gifts. And Mr. Spencer's face was like the weather—much more Christmas-like than could have been expected. His heart was far too warm, his nature too kindly, to be unsympathetic when he saw others happy. He tried to forget the cloud that had burst over his own hearth, and thanked God that there was so much of sunshine left for others and for him.

As to Mr. Ulyett! Nobody would have imagined that a caustic word had ever dropped from his lips, or that he could doubt the disinterestedness of any human being. He was the life and soul of the Christmas gathering. He was pulled about by small hands, and clung to, and made to act as a beast of burden. He looked so happy at being tyrannized over by a crowd of children, that everyone felt it was the greatest mistake for him to be an old bachelor.

Anna Spencer declared that she had quite fallen in love with Mr. Ulyett; which statement must, however, be received with caution. Girls will guess that had such a sentiment really existed, it would not have been publicly proclaimed.

All happy days must end. Before the guests departed, however, young and old sang a carol together, a few words of prayer were said, with thanks for the past year's good, while a blessing was asked for the new.

Then away through the lanes—and soon the moon looked down upon a sleeping village.

ARTHUR managed during the evening to tell his friend the rector about his mysterious Christmas-box. He showed him the letter, and asked Mr. Worthington if he could give him any clue to the sender of such a valuable gift. The look of genuine astonishment on his friend's face told even more than words. Mr. Worthington said, and truly, that he could not even hazard a guess as to the unknown donor.

"What should you do with the money, were you in my place?" he asked.

"Keep it, use it, and thank God for it."

"That was my first thought, but—"

"What else can you do? Depend on it, Glyn, your first thought was the right one. Look on this as God's gift, and use it as such, reverently and thankfully."

And Arthur took the advice and did so.

A month passed, and the curate was often the squire's invited guest at Cray Holm, and Anna's bright eyes seconded her father's welcome.

The curate began to wonder whether he ought to be so happy, or whether he should look upon that attractive fireside as dangerous ground, and flee whilst he had the power. He had no right to involve another in the pain of parting, and what other ending could there be? He recalled Mr. Spencer's words; he thought of the mysterious gift, and associated him with everything that was kind towards himself. Should he go to this good friend, tell him all that was in his heart, and abide by his decision?

He had about determined to do so, when a letter arrived from Mr. Mervyn. This gentleman had not forgotten the curate's Christmas sermon, and through his own influence had obtained the offer of a living for Arthur. It was of considerable value, but at a distance from Little Cray. With this letter in hand, he went to Mr. Spencer and told his twofold tale—the story of Mr. Mervyn's offer and of his own affection for Anna.

In answer to the latter, the squire opened the door of his daughter's pretty room, and told Arthur to repeat his story there; Anna's reply would serve for her father too, he said; and so he left them together.

I do not quite know how it is, that the very words used by wooers, and all the little tender accompaniments which wait upon an offer and its acceptance can be given in detail, unless a bird of the air does indeed carry the matter. The public are generally informed by us tale-tellers of everything done and every word said by our heroes and heroines when the crisis of their fate arrives. I will not be so communicative, though I could tell if I chose. Enough, that when the door of Anna's boudoir reopened she came out, led by Arthur, whose face sufficed to show Mr. Spencer what answer he had won. And as the girl threw her arms round her father's neck, and laid her bonny, blushing cheek on his shoulder, the squire clasped the young man's hand in his, and confirmed his daughter's gift.

"Only," he said, "I cannot spare her from Little Cray. If she does not reign under the old roof; she must have her new nest quite near it."

Matters were arranged in this wise: By dint of Mr. Mervyn's friendly efforts, the new and more valuable living was offered to Mr. Worthington, who, in consideration of his growing family, accepted the same. Arthur became rector, instead of curate, of Little Cray, and by the time the little sister's trousseau was ready, and her future home prepared by her expectant bridegroom, Miss Spencer was also ready to take her part in a double marriage ceremony, with Arthur.

When Arthur and his bride returned to Little Cray, after the usual tour, he on one occasion spoke to Mr. Spencer of the anonymous Christmas-box—

"I always felt that I had only one friend who would do a kind act so kindly. But for the encouragement then conveyed, I should never have dared to ask you for Anna," said he.

Then he discovered that Mr. Spencer had neither part nor lot in the matter, and had never even heard of it, until Arthur told his story. It was to Anna's feminine wit, that he was indebted for the discovery of the real sender.

"Had I known of it at the time, I should have guessed Mr. Roger Ulyett," she said. She was right. While many a one had misjudged that gentleman, and deemed him cynical and hard during his early residence at Little Cray, Anna had done justice to the true nobility of his character under all circumstances, except in his manifest devotion to herself. In after days, when Arthur's elder sister, Hilda, was Mrs. Roger Ulyett, and mistress of Fairhill, Roger was brought, not to own that he was the sender of that Christmas-box, but to say—

"If I had done such a thing, I should only have paid a very small instalment of the debt I owed your father. Had he taken advantage of a certain opening offered to him, I should not stand where I do to-day. He neglected his opportunities—I secured them; hence my fortune. It matters less now which of us got it, for it is all in the family."

SIX MILESTONES:

A CHRISTMAS MEMORY.

MANY men and women have days and seasons in their lives which stand out from all the rest, and mark its stages as the milestones bid us mark the distances we travel on the king's highway, and the guide-posts indicate a turn in a fresh direction.

I look back on such days and seasons, and I love to look, even though some of them bring sorrowful pictures before my mind's eye, or tell of actual bereavement—of hushed voices and empty chairs. For, thank God! the memories of mercies and blessings far outnumber those of a sorrowful sort. Indeed, He has shown me the exceeding preciousness of trial as a preparation for the enjoyment of happiness to follow, and which was held back for a little while, until I was fit to be trusted with it.

Thirty years is a large portion of even a long life, but as each Christmas is drawing near, I look back to the same season.

I was a homeless girl, just turned nineteen. I say "homeless," because there was no house in the whole wide world which I had the right to call home, no roof under which I could actually claim a shelter. I had neither father, mother, sister, nor brother, though three years before I had all these. How I lost them, one by one, and was left with no provision or property except two hundred pounds, the bequest of my great-aunt, I will not relate at length.

I had, however, one dowry which was better than houses or land, and was sure to be the best fitted to cheer me in my lonely condition, because it came to me as a direct gift from God. This was a bright and happy disposition, which inclined me to thankfulness rather than repining, and made me ever on the watch for some gleam of light, however dark might be the overhanging cloud.

I was nineteen when I found myself in the position I have described—namely, about to be homeless, and with an income of six pounds sterling per annum arising from the two hundred pounds in the Three per Cents.

I can hardly say, however, that this was my only heritage, for during my father's prosperous days, he had spent money freely enough on my education, and given me a good all-round training, which was likely to prove useful, and of which, I could not be deprived. Then he had left me an honoured name, and though, through unforeseen circumstances, he had no money or lands to leave his child, what he did leave sufficed to pay every claim, so that I could hold up my head and feel that his memory was free from the reproach of insolvency.

It had always been a matter alike of principle and of—shall I say, pride?—with him to owe no man anything. It lightened his last hours to know that no one would lose a penny through the trouble which had deprived him of everything in the shape of worldly goods.

I hope I cheered him too, for, when the curate had gone, he turned his dying eyes upon me, with a wealth of love and tenderness in the look, and said, "Lois, I never thought I should leave you penniless. I expected to enrich my children by what has beggared you, the last I have left. Can you forgive me?"

I turned a brave face towards him, choked back the sobs that wanted to make themselves heard, and said, "I am young and strong. Do not fear for me, father. If I could only keep you, I would work by your side, for you, or with you, and desire nothing better than to use such talents as God has bestowed upon me to gain a livelihood for us both. As to forgiving, do not name the word. What have I to forgive? You and my mother strove by every means that love could devise to make my life a happy one."

He smiled, and then, as if talking to himself, he said, "Yes, the child will have happy memories, and, thank God! No debt, no dishonour. He is faithful that promised to be a 'Father to the fatherless.' She may find earthly friends turn carelessly or coldly away, but that Friend will never forsake my Lois. But she is so young to be left alone."

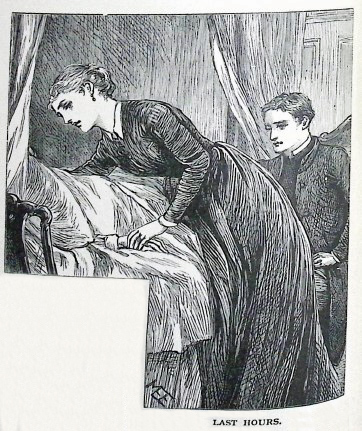

LAST HOURS.

I took up the subject in reply, though he had not addressed me directly.

"Not alone, father," I said. "What would be the worth of such promises as you have just called to mind, if I could not lay hold of them and get strength and comfort from them? I have no doubt, there will be rough places in my path, but what has God given me a brave heart and a bright spirit for? No doubt to fit me for what lies before me."

"True, my child. He bestows His gifts in proportion to the need of His children," he replied, and as my father spoke his face looked brighter still.

I would not give in whilst he lived and needed such ministry in word and work as I could render, so I stayed by him to the last. Then, when I could do no more for this well-loved parent, I went from the death-bed of my earthly father to the footstool of my Heavenly Father, and prayed for a renewal of the strength which I felt was fast breaking down.

I did not ask in vain, and when I rose from my knees it was with power to face my position and to begin my work.

It was on Christmas Day that the snow was cleared away round a newly made grave in Askerton Churchyard, and I stood on the strip of black bare ground thus uncovered, and saw all that remained of my father lowered to its last resting-place.

I was not quite alone. That would have been too terrible. My maternal uncle stood beside me, a kindly man, with not much depth of feeling or of purse. He had a large and expensive family, altogether out of proportion to his income, and knowing something of my present circumstances, had come to the funeral of his brother-in-law in fear and trembling—fear that the sight of my loneliness would be too much for his kindly nature to endure, and that he should be obliged to offer me a home in his already over-peopled dwelling; and trembling as to the reception I should meet with from his wife were I to accompany him thither.

He did offer to take me back with him, and was, I am sure, immensely relieved when, with grateful thanks, I firmly declined the invitation. Perhaps it may be thought I had little to thank him for, but indeed I had, because I knew his will to serve me exceeded his ability.

My uncle asked me a number of questions, which I was quite prepared to answer, and at every reply, his brow cleared. I could see that he had come to the funeral in doubt whether the expenses of it might not have to be met by himself. But I reassured him on this and every other point relating to money matters. There was absolutely nothing to be paid by any outsider.

Then my uncle turned to me. "About yourself, Lois. What are you going to do?"

I replied, as cheerfully as possible, "Pack up what belongs to me. This will soon be done."

He thought I was a strange girl, and he said, "You bear up wonderfully, Lois. It is hardly natural to see a girl like you coming from your father's funeral with dry eyes."

It was not natural. No one could be more sensible of this than myself, and when he said those words, looking straight in my face, I had hard work to steady my quivering lips and keep the tears from overflowing.

"Uncle James," I said, "it is the thought of my darling father that makes me both want to weep and keeps me from weeping. When I think of what I have lost, it is hard work indeed. He was so good."

I paused, and he looked pityingly down upon me, for he understood by my face and tone something of the struggle that was going on within, and of which before, he hardly guessed the existence.

"But," I continued, "think what it would have been for my father, ruined in means, broken in health, bereft of the true helpmeet of thirty years, and of his two eldest children, to begin a new struggle with the world. I turn my back upon the old, happy past, the very memory of which would break me down just now, and I say to myself, 'God knew best. He has reunited the two who loved each other so well on earth. He has given them back the children over whose graves they shed such bitter tears. What if I am left solitary?' I keep saying to myself, 'It is best so,' and this is why I will not weep, Uncle James."

"It is really wonderful, Lois, how a girl like you can argue the matter out in this way and keep so calm. Well, my dear, if you have quite made up your mind that you will not go back with me, I will try to catch the half-past two train. I think your aunt and the children hoped I might be home in time for dinner at five. Being Christmas Day, you know, they would all miss me. But before I start tell me where you go from here, and if you have money for present needs."

"Our old nurse, who married the lodge-keeper, will find me accommodation for a few days. I am willing to work, and hope soon to find some employment. As to money, I have this."

My face went very hot as I opened my purse. It held just half-a-sovereign, and about as much silver as made up a pound.

"And is this all? My poor child, I have not brought a great deal with me, but I can spare you a five-pound note; and mind, you must write for more when you want it. My sister's orphan daughter shall not be without a shilling to call her own."

I kissed my uncle's kind face, and thanked him, adding, "I shall pay this back, Uncle James. You have plenty of calls upon your purse without my adding to them. Will you please give me gold instead of the note?"

He did as I asked, deprecated the idea of repayment, and went away, I am sure, full of good-will and affection towards me, but not a little relieved to find that, God helping me, I meant to help myself.

I did sit down for a little while after my uncle left me, to indulge the grief which I had kept back whilst he was present. His allusion to all those who would be awaiting his coming, in order to gather round the Christmas dinner-table, was in such a strong contrast to my utter loneliness, that I was forced to let the waiting tears find a channel.

This little indulgence did me good, and I was even able to picture the welcome that my uncle would receive, and to fancy how the troop of children would be looking for him, and set up a glad shout when he came in sight; how clinging arms would surround his neck, and the youngest of all the flock would insist on being triumphantly carried, held by his father's strong grasp, shoulder-high into his mother's presence, and she would also be waiting with words of welcome.

Then my uncle would tell them about my poor father, and how he had left Lois so much better than he expected, and they would put the subject out of mind as a thing well got over, and begin to enjoy themselves as we had been used to do on bygone Christmas Days.

I did not think hardly of them as I drew this mental picture. My aunt was only akin by marriage, and of the large troop of cousins we knew but little personally.