Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

3

on the subject of

WORK IN THE BASKET

❦

Issued by the

Division of Military Aeronautics

U.S. Army

¶ A free translation of the French booklet “Instructions au sujet du Travail en Nacelle,” and an added discourse on Balloon Observations

WASHINGTON

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

AUGUST, 1918

In this pamphlet will be laid down the general principles and also the limitations which govern observation from balloons. Balloon observation includes more than actual artillery observation. (See “Employment of Balloons.”)

The details of cooperation between balloons and artillery are issued from time to time by the General Staff in the form of pamphlets. Whatever the system ordered at the time, there are certain principles which do not change.

In artillery observation it can not be emphasized too strongly that success depends both on—

1. The efficiency of the balloon observers, including an intimate knowledge of the ground within view.

2. An intimate knowledge by artillery commanders of the possibilities and limitations of balloon observation.

The limitations of balloon observation are—

1. Distance from the target.

2. Height of observer.

3. Visibility.

Distance from the target is inevitable, but can be lessened by advanced positions and winch tracks.4 During active operation it has sometimes been possible to approach balloons within 4,500 meters (4,921 yards) of the line.

The low height of the balloon compared with an aeroplane is a drawback, as it brings a question of dead ground and exaggerated perspective.

Visibility is the determining factor of the balloon’s usefulness. In very high winds, very misty or cloudy weather, observation is impossible, and owing to its stationary nature the balloon can not, by any special effort on the part of its observers, overcome unfavorable conditions in the same way as is possible in the case of aeroplane observation.

On the other hand, a balloon flying at a height of 1,500 meters (1,640 yards) and 7,000 meters (7,651 yards) from the line, under favorable weather conditions, combines in a marked degree many of the advantages of air and ground observation.

In the first place, glasses can be used. Secondly, the balloon observer can converse direct with the battery commander by telephone. Apart, therefore, from ease and certainty in reporting observations, the telephone system enables an elastic program of work to be drawn up and admits of personal conversation between the battery commander and the observer, often permitting mistakes or misunderstandings to be cleared up during shoot instead of afterwards.

Finally, owing to the continuous nature of his observation from the same spot, the balloon observer is able to learn his country in the greatest detail and can keep a close watch on suspected roads or areas of country.

5

The work of balloons is principally with the artillery, and close liaison between these two branches is indispensable if the best results are to be obtained. This close liaison should be promoted on the following lines:

(a) Balloon companies should each, as far as possible, be allotted specific artillery organizations. This facilitates telephone communication, prevents duplication of liaison work, and leads to a far more intimate and personal liaison than does any other method.

(b) Balloon observers must visit batteries frequently, and sometimes be attached for short periods. Shoots should be discussed, especially if unsuccessful. Observers should prepare and take with them when visiting batteries a list of targets which are clearly visible from the balloon and on which they can observe effectively. Similarly, artillery commanders should let balloon observers know of any further targets which they especially wish to engage, as work previously prepared on the ground saves time and gives better results.

(c) Artillery officers should visit the balloon and make ascents. They will thus become acquainted with the extent of view from the balloon and the ability and difficulties of the observers.

In view of the above, the work most suitable for balloons is as follows:

(a) Reporting modifications of enemy defensive organization; detecting movements of convoys and6 trains. Their importance and itineraries, locating infantry signals, and all other activities such as revealed by fires, smokes, dust, trails, etc.

(b) Spotting active hostile batteries and reporting hostile shelling. Reporting hostile shelling is a duty for which balloons are especially suitable, as they are favorably situated to observe both the flash of the gun and the fall of the shell. From this information it is possible to direct not only neutralizing fire on the hostile battery, but often also to establish the caliber of the guns and the arc of fire of the battery.

(a) Observing fire for destruction on all targets, counterbattery, or bombardment.

(b) Reporting fleeting targets and observing fire on them.

(c) Observing for registration fire.

(d) Observing fire on the enemy’s communications.

(e) Cooperation with aeroplanes.

7

[Translation of French document, “Instructions au sujet du Travail en Nacelle,” a publication of French G. Q. G., 1918, by Lieut. Kellogg.]

The rapidity and precision of the work in the basket depend not only on the natural gifts of the observer, but also very largely on his methods of work.

The object of the following instructions is to tell the student observers the general methods they should follow and to explain the use of these methods.

The principal operations which they must be able to execute rapidly are as follows:

1. Orientation and general reconnaissance of the terrain.

2. Spotting points on the ground seen on the map and points on the map seen on the ground.

3. Observation of fire.

This is the operation which the observer executes on his first ascension in a new sector; this is how it should be conducted.

1. Rapidly look over the terrain around the ascensional point in order to orient the map.

This is done by finding in some direction from the ascensional point a line giving an easily identified8 direction (a road, an edge of woods, etc.). Orient the map so as to make this line on the map parallel to the line on the ground.

The map can also be oriented by means of the compass.

2. Locate the horizontal projection of the balloon.

The observer may know already the winch position, but the balloon is carried off horizontally from the winch sometimes as much as 400 or 500 meters (436 to 545 yards). Thus it is essential not to confuse the winch position with the horizontal projection of the balloon. If this is done, errors will be made in the operations which we are going to discuss later, where we make use of this known point.

It is pretty hard to materialize definitely the vertical line passing through the basket. The effect of the wind and the movements of the balloon make it impossible to use a plumb line. The observer has to find his projection on the ground by leaning first from one side of the basket and then from the other in order to diminish the chances of error. An approximation of 25 or 50 meters is sufficiently accurate for the general reconnaissance which it is necessary to make.

3. Leaving the region beneath the balloon, acquaint yourself, step by step, with the most prominent points in different directions—masses of woods, villages, etc.

There are two methods—by the process of cheminement or tracing landmarks and by the process of direct alignment.

9

The process of “cheminement” or tracing consists in following outlines, such as roads, streams, or hedges, identifying as you go along details of the terrain which these lines pass through or near. On account of the deformations due to the effect of perspective and to the unevenness of the ground, and particularly on account of the deformation of angles, if it is a winding road, this method often leads to errors; it should be employed only in certain cases defined below:

The process of “direct alignment” consists of studying the terrain by following successive directions from the balloon position.

We call the “alignment” of a point the trace, on the terrain, of the vertical plane passing through this point and through the eye of the observer; in perspective vision, when the observer determines the point in question, this alignment would appear to him a vertical line. On the map it is nothing more than the straight line joining the point under consideration to the vertical projection of the balloon.

The method of alignment, then, consists in first identifying the most prominent points near the balloon and finding, by cheminement or tracing, the lines running from these points. A point found directly by cheminement should not be considered as definitely determined until its alignment has been verified.

This first reconnaissance is not to study the terrain in all its details, but only to fix in the memory a certain number of prominent points scattered throughout the sector in order to facilitate later work.

10

These points should be very distinct, visible to the naked eye, and of characteristic forms, so that there will be no danger of confusing them with others—masses of woods, important villages, etc. Roads with borders of trees, large paths for hauling supplies, when taken together, are very valuable for quickly finding others.

Generalities.—In all spotting operations, whether working from the map to the terrain or vice versa, the difficulty is due to the fact that the situation of the point has to be found on a two-dimension surface.

The best method of work will be, then, that which suppresses as quickly as possible one of these dimensions and to conduct the research on a straight line.

Any point can be placed on the terrain or on the map if you know the following elements:

1. Its “direction” or alignment.

2. Its situation on this alignment—that is, its “range.”

In oblique vision, a digression in direction is always much more apparent than a digression of the same size in range. Thus the direction of a point can be identified with more facility and precision than its range. For these reasons, the following methods consider two distinct phases in all spotting operations:

1. Investigation of direction.

2. Investigation of range.

11

The investigation in direction always comes first, as it is easier, and its result makes the investigation for range easier.

If it is a question of a very visible point (cross-roads, an isolated house, a corner of woods, etc.), the spotting can be done almost immediately, it was found in the general reconnaissance of the terrain, which was discussed in chapter 1.

If, on the contrary, the point under consideration is difficult to find (a piece of trench in a confused and cut-up region, a battery emplacement, etc.), we must have recourse to a precise method.

Join on the map the projection of the balloon and the center of the objective. Identify this direction on the terrain by finding on the alignment a prominent point. This line can be drawn in the basket. It is a good thing to draw the alignment on a vertical photograph of the objective also, in order to have a greater number of reference points than the map could give.

Identify on the map (or photo) two points, one situated over and one short of the objective. Narrow down this bracket step by step until the object is recognized.

12

As this investigation of the range is the more difficult, observers must be warned against certain methods which are to be absolutely avoided—

1. Never identify the range of a point by comparing it with that of a near-by point situated on a different alignment.

If these two points are not at exactly the same height, the deformations due to oblique vision can falsify their apparent relative range. The point farthest away can even seem nearer, and the nearest point farther away.

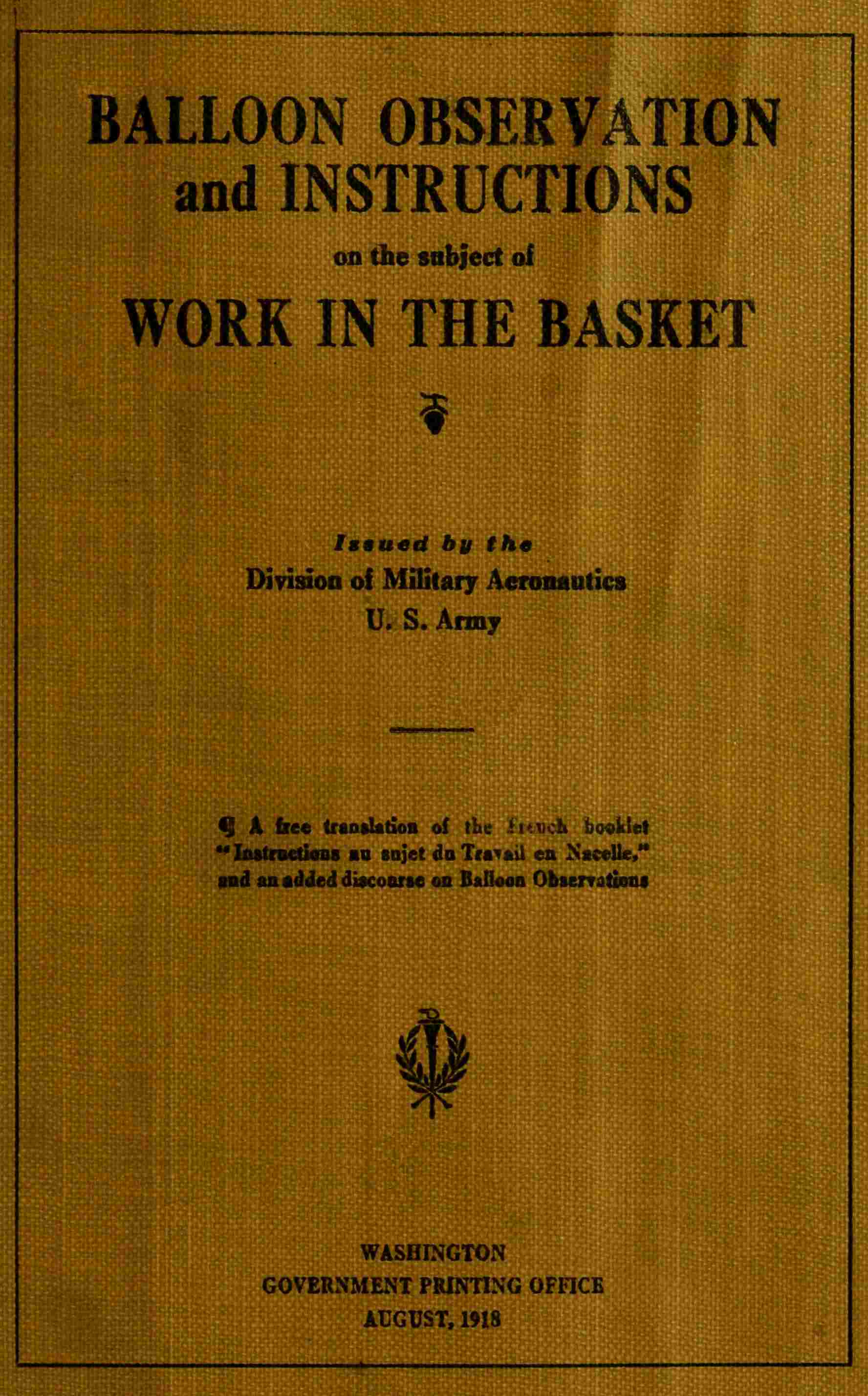

Fig. 1 Fig. 2

Example (fig. 1).—Suppose there are two trees, A and B, A being nearer the balloon and higher than B. It can happen that, in oblique vision (fig. 2), B having its image B´ and A its image A´, the depression of the image B´ is more than that of A´. In this case, the observer will be tempted to believe that the tree B is nearer him than the tree A.

2. All oblique alignment in investigating the range must be absolutely avoided.

Oblique alignment means a line connecting two points on the map and not passing through the horizontal projection of the balloon.

You might be tempted to use an alignment to find the range of an objective after having determined the direction. The process would consist in finding on the map two points so placed that the straight line between them passes through the objective, visualizing this line on the terrain, and placing the objective at the intersection of this visualized line and the direct alignment. This result, which would be accurate if the ground were absolutely flat, is made erroneous by the 14unevenness of the terrain. On account of this, the oblique alignment does not pass, in oblique vision, through the same points as its horizontal projection on the map.

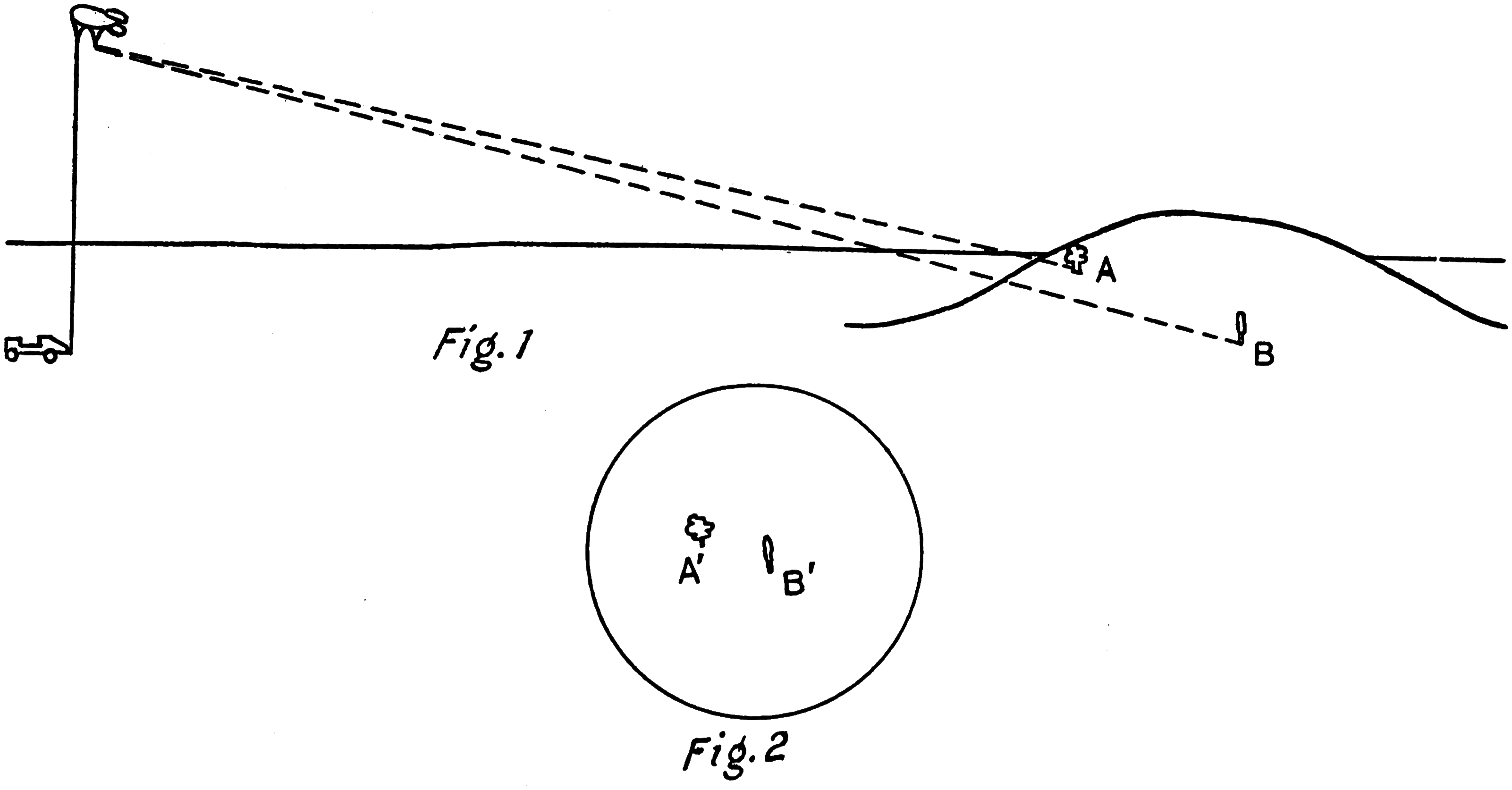

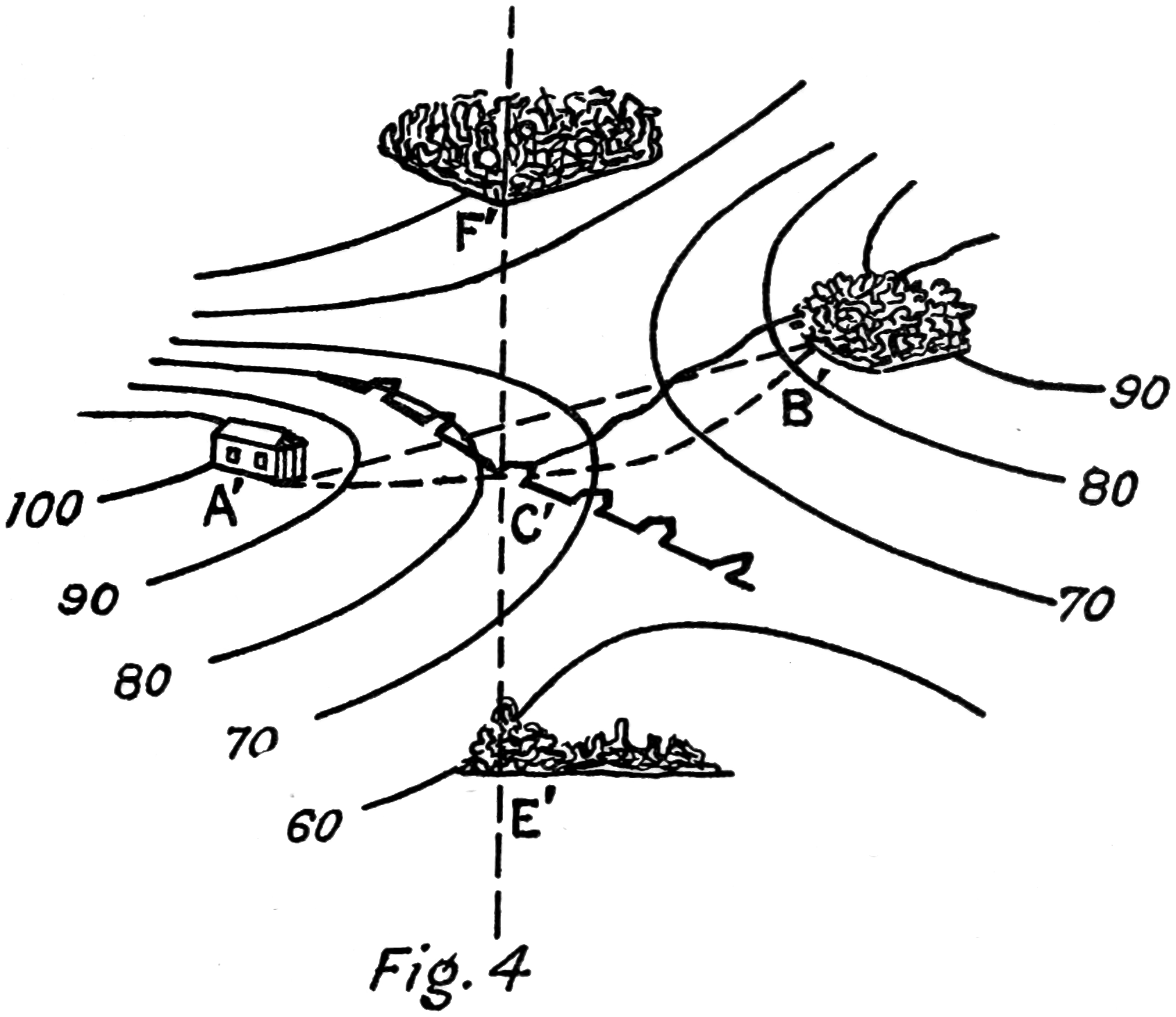

Example (fig. 3).—On the map C is the objective, A and B two points so situated that the line AB passes through C, and EF the direct alignment, or the line balloon objective. The line AB coincided on the terrain, with the trace of the vertical plane passing15 through A and B. In oblique vision (fig. 4) it is different. The line A′C′B′ is a curve which follows the irregularities of the ground, and the point C′ is not on the oblique alignment A′B′.

1. Determine first on the map the approximate region where the objective is seen.

A result which you can obtain very quickly, thanks to the points which you had found in your first reconnaissance of the terrain.

16

2. Investigation of direction.

This operation consists in determining the alignment of the objective. As this alignment is a straight line, you only have to know two points. One of them could be the horizontal projection of the balloon; but you must realize that this position is always changing a little, and it is hard to determine it with absolute precision. It is better to carry on the operation independent of this position, which means applying the following method:

Choose on the alignment of the center of the objective two points, one over and one short, and easily identifiable on the map. Draw with a pencil in the region of the objective the alignment thus obtained. These points should be, as far as possible, precise details of the terrain, such as a corner of woods, an angle of a house, a place where roads or trenches cross, an isolated tree, etc. When the alignment of the objective does not pass through any such points, the difficulty can be overcome by determining in what proportions it cuts a known element, such as an edge of woods or a hedge, provided this element is plainly perpendicular to the direction of observation.

This direction can be approximated to the extent of the thickness of the pencil mark. On its accuracy the final result depends. The difficulty lies in materializing the alignment—that is, the vertical line through the center of the objective—in order to lessen the chances for mistakes. Student observers should have frequent practice in this exercise.

17

When the point to be found is near the edge of the map it is sometimes necessary to take both reference points between the balloon and the objective; this should be avoided as much as possible, because it is apt to be less exact than when the objective is bracketed by its reference points.

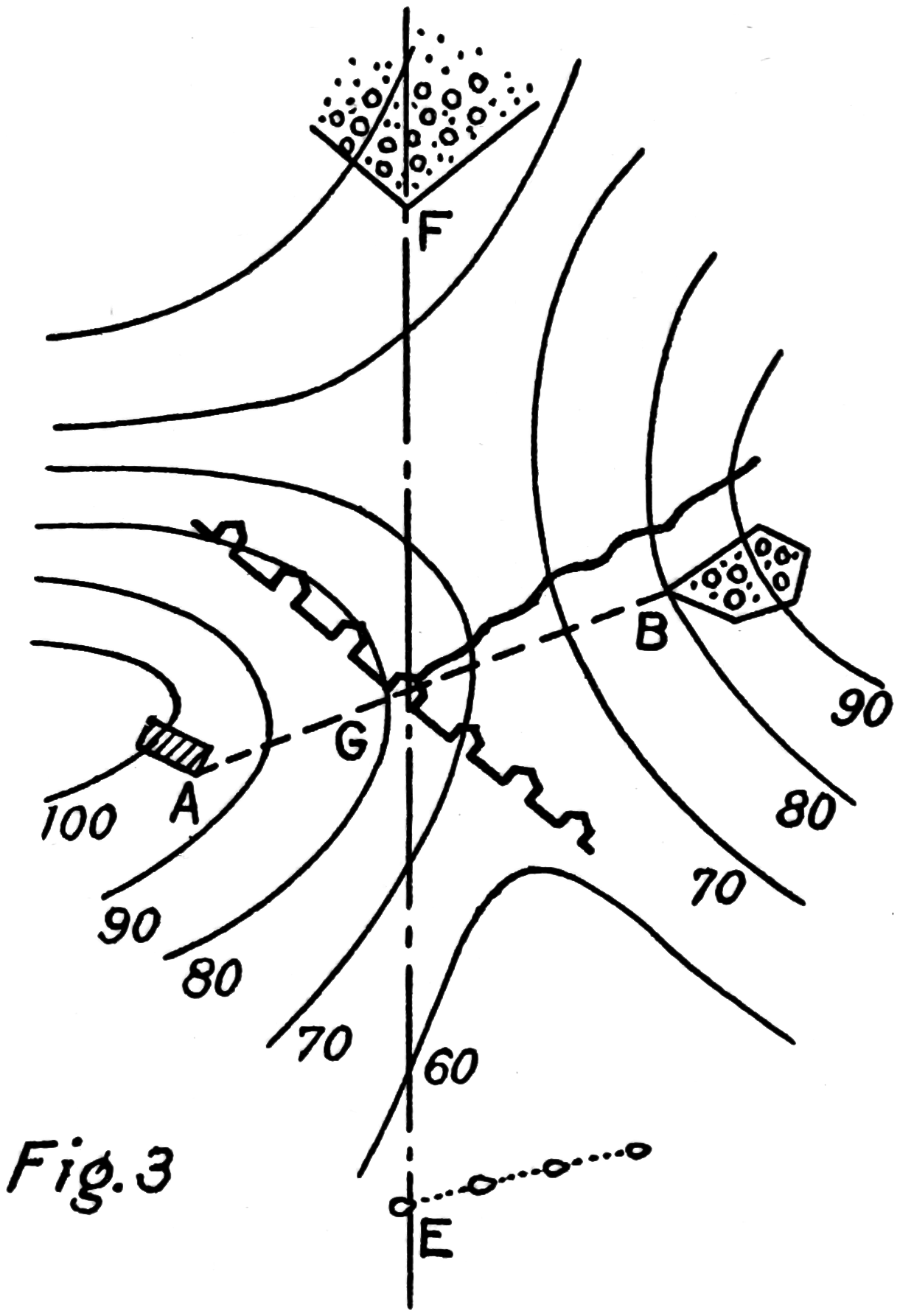

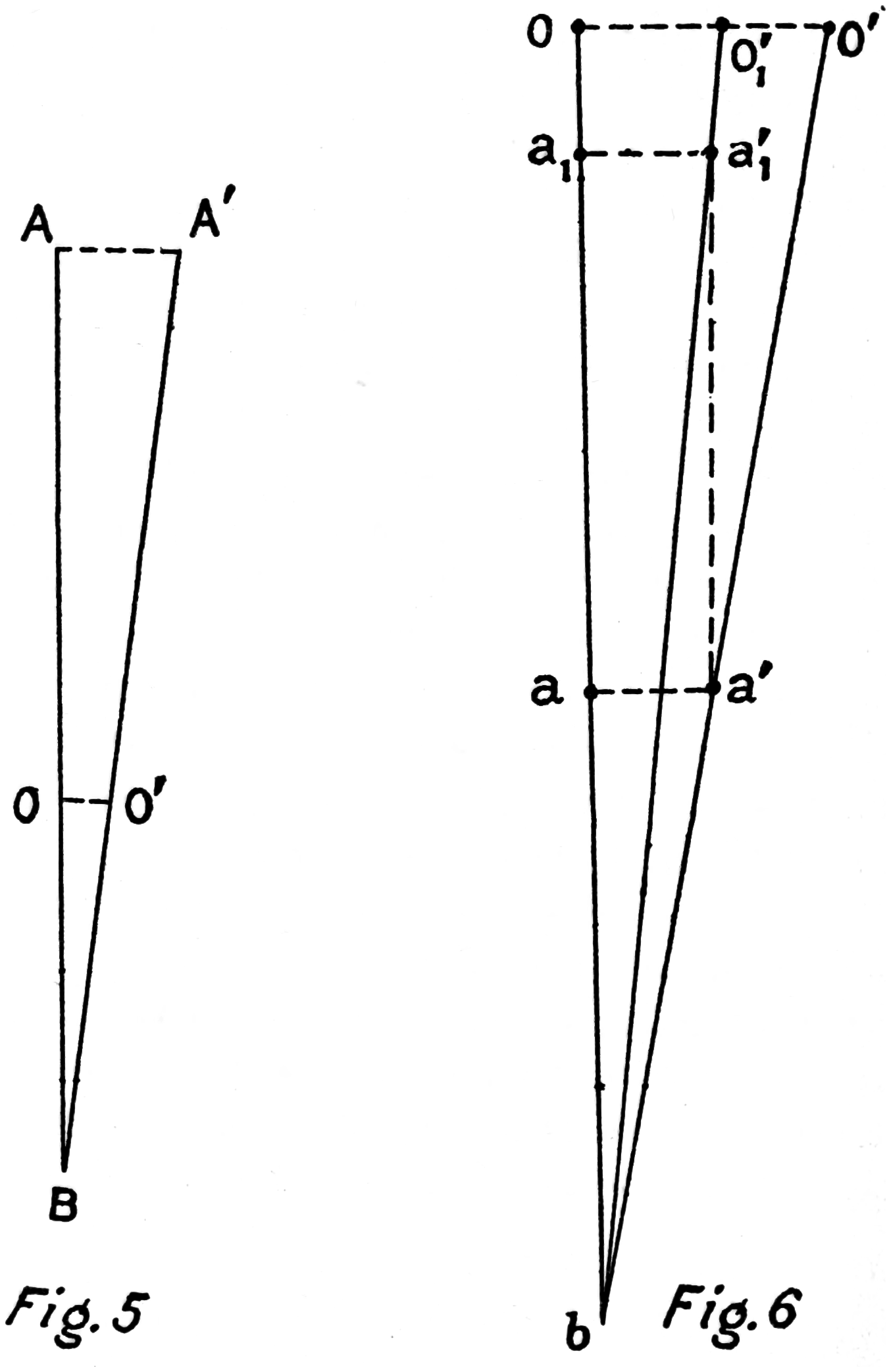

Thus (fig. 5), two reference points A and B determine the alignment AB, O, the objective, is situated at some point between A and B. An error AA′ in the spotting of one of these points leads to a smaller error in the position of the objective OO′—that is, smaller than AA′.

Fig. 5 Fig. 6

On the other hand, let both the reference points “a” and “b” (fig. 6) be situated short of the objective O, “a” being nearer the objective and “b” nearer to the balloon. An error aa′ in spotting “a” leads to an error OO′ in the objective greater than aa′. Notice that this error diminishes as “A” approaches O, thus “a” being as a₁, the error a₁a′₁ equal to aa′ leads to an error OO′₁, in the objective, less than OO′. We would thus obtain an analogous result if we would move the point “b” farther away.

Therefore, when you are obliged to take the two reference points between you and the objective, choose one as near the objective as possible and the other as near as possible to the balloon.

3. Investigation of range.

Identify details of the terrain situated over and short of the objective on the alignment. Narrow this bracket down step by step; situate the objective on the map according to its relative distance from the18 two nearest identifiable reference points, taking into account the deformations due to the laws of perspective and the relief of the ground.

If you have a vertical photograph of the region, trace the alignment on this photograph and make the investigation in range by the same means.

19

The dangers against which I warned you before in connection with the investigation of range apply in this case also, so it is unnecessary to repeat them.

When the two last identifiable reference points are some distance from each other, the situation of the objective has a possible error, of which you know the size according to the distance between the two reference points; it might be interesting to remember this in case different information is obtained on this objective from that obtained in the balloon.

This error can be considerably diminished if you use a vertical photograph; the investigation can then be carried on by the same method as on the map, with greater precision. In the case of a battery, particularly, it is for the observer to find the position of each piece.

In case, on account of dead ground or of a mask before the battery, the observer sees the flashes or the smoke without seeing the battery itself, he should mark the exact alignment in which the flashes or smoke are seen, and determine the bracket in range—that is, the reference points nearest the objective which are clearly over and short. This document compared with other information can facilitate the identification of the battery.

The observation of fire is essentially the following operation, repeated for each shot or salvo: Locating on the ground the position of one point, which is the20 point of burst, and announcing its situation in reference to another point, which is the target.

But it has been demonstrated that it is impossible, without using the map, to determine the error in range of one point relatively to another point not on the same alignment.

The operation must consist in:

1. Spotting on the map the point of burst.

2. Reading its position in reference to the target.

The observation of the burst—that is, the spotting of the point of impact—is the same whether the observation is direct or lateral.

Draw on the map, and copy if possible on a vertical photograph, the line balloon target (alignment of the center of the objective) and draw through this point a perpendicular to the alignment. In case the observation is lateral, draw also the line battery target and its perpendicular.

To draw the line balloon target, it is not necessary to know the horizontal projection of the balloon. It is enough to find on the ground a point situated directly on the alignment of the center of the objective.

When the shell bursts, take quickly an alignment and reference points in range of the point of burst; spot this point on the map or on the photograph; give its error in reference to the line battery-target, measuring it by the scale on the21 map or on the photograph. (It is well to put the graphic scale on the photos.)

The delicate part of the operation consists in seeing the shot at the moment of burst. One must try to spot the apex of the inverted cone formed by the burst, without paying any attention to the more or less considerable cloud of smoke which follows and which will cause mistakes if the burst was not seen immediately. The method of situating the point is the same as that described above.

For the direction, one reference point is enough, because one can consider the alignment of the point as practically parallel to the balloon-target. For the range, a rapid study of the terrain before the fire is sufficient to allow the observer to know the reference points by which he can guide himself. His eyes must never leave the point of burst until he has fixed well in his mind its situation in reference to appropriate reference points. Not to do this would lead to errors and to loss of time while he has to find the point again with his glasses to study it some more.

When the observation is direct, the direction of the burst is, of course, known as soon as it is seen. When the observation is lateral, it is well to remember that the line battery-target can not be materialized on the ground because it is in reality an oblique alignment, leading to the same errors which we have discussed. It follows all irregularities of the ground and, on account of this, can not be followed exactly in oblique vision.

22

Particularly around batteries, the ground is often very irregular. There may even be little spaces of dead ground, caused by hollows which the map does not always show. The above method, applied with the help of photographs, allows you to avoid errors resulting from the existence of these hidden parts.

1. Work sitting down, with the map on your knees and leaning against the edge of the basket.

This position is preferable to all others, because it allows the observer—

(a) To correct with his head and shoulders the movements of the basket.

(b) To have the map always before him. He can consult it at any moment, mark the necessary alignments without loss of time, use it as a desk for drawing or taking notes, or as a wind shield when looking at photographs.

The observer who works standing up must either pick up his map from the bottom of the basket every time he needs it, which is out of the question, or fasten it outside the basket; the latter solution is inadvisable, it necessitates working in the wind when the map is referred to, and every time the observer turns to look at his map he disturbs the equilibrium of the basket.

It is advisable to work standing up only on days when there is practically no wind, and the balloon is continually turning and never becomes oriented.

23

2. Have always within reach a flat rule, a pencil, and a duodecimeter rule.

To be able to trace an alignment on the map with precision, the rule must rest on a firm surface. This happens when the map is mounted on a drawing board; when it is mounted on a frame with rollers, the frame should have, between the two thicknesses of the map, a board level with the edges of the frame on which the rule can slide with its whole length on the map.

With a hard pencil, well sharpened, precise and neat alignments can be drawn.

The duodecimeter rule is for measuring distances on photographs and on the map; chiefly in observations of fire.

3. Hold the field glasses with both hands.

This advice, sometimes ignored by observers without expedience, has a great influence on the accuracy of information. When an observer holds the glasses in one hand, it is much more difficult for him to correct the movements caused by the balloon and to concentrate on a point. It is very important, therefore, to hold the glasses firmly with both hands, especially when you are making a delicate observation or when 25you wish to study an “objective” in detail.

24

Note 1.—All observations of rounds refer to the line battery target (b-t) and a line perpendicular to same passing through the target. Observations are given in meters right and left and whether the round is over or short. Indications as to deflection are given before those of range. Indications as to the amount of error precede those as to the sense of the error. Example, 50 meters “Right,” “over.” Owing to the dispersion of fire when adjusting fire for field artillery or howitzer, it is unnecessary and of little value to the battery to give the amount of the error in range except when asked for by the battery commander or when the error in range is abnormal (over 200 meters).

When the target is clearly visible and the effect of a round hitting a target is evident, the observation “Target” is reported. Unless the observer is certain of having seen the bursts “Unobserved” will be sent. If, however, after a few seconds smoke can be seen rising from trees, houses, etc., in proximity to the target, the observation “Unobserved, but smoke seen rising left and over,” may be given.

Note 2.—Observers must beware of being over-confident in their own powers of observation. True confidence only comes with experience, and this is best attained by making ascents with a trained observer26 when ranging a battery and checking one’s own observations with those given by him. An observation must never be given unless the observer is quite certain as to its correctness. It is essential to good results that the artillery may be able to rely absolutely on the observations sent down. The observer must watch the target but must avoid straining his eyes by putting up his glasses as soon as a round is fired. He should arrange for the chart room to inform him when a shell is about to fall. The latter must know the time of flight. Observers must learn to distinguish readily the bursts of different kinds of shells.

Note 3.—If the balloon-target line makes an angle with the battery-target line of more than 30° with field artillery and 20° with heavy, the balloon position will be given to the battery, and all observations will be given with reference to the balloon-target line and the battery will replot accordingly.