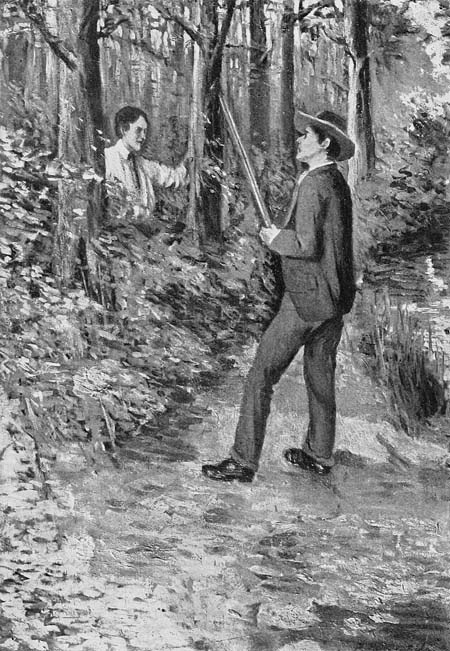

When Phil had taken hold of the sill, Chap gave him a lift

Page 140

The Young Master of

Hyson Hall

BY

Frank R. Stockton

Author of “Captain Chap,” “Rudder Grange,” etc.

With Illustrations by

VIRGINIA H. DAVISSON

and

CHARLES H. STEPHENS

PHILADELPHIA

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

1900

Copyright, 1882, by James Elverson.

Copyright, 1899, by J. B. Lippincott Company.

Electrotyped and Printed by J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia, U.S.A.

(By the Author)

This story was originally published in a paper for boys, under the title of “Philip Berkeley; or, the Master’s Gun.” It has recently been thoroughly revised, and a new title, which better expresses the import and purposes of the story, has been given to it upon this its first appearance in book form.

Those who may remember the story as it originally appeared will find that the master’s gun still exercises the same subtle influence over the fortunes of the Master of Hyson Hall as it did when it enjoyed the honor of a place in the title.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I.— | Old Bruden | 7 |

| II.— | In which Philip is very much Amazed | 15 |

| III.— | Old Bruden makes a Move | 22 |

| IV.— | In which Chap shoots a Little and plans a Great Deal | 32 |

| V.— | The Master’s Gun | 40 |

| VI.— | Arabian Blood | 50 |

| VII.— | What Jouncer put his Foot into | 55 |

| VIII.— | Chap enters the Fog | 64 |

| IX.— | Chap’s Iron Heel | 71 |

| X.— | In which a Story is told | 82 |

| XI.— | Philip is brought to a Halt | 91 |

| XII.— | Emile Touron | 99 |

| XIII.— | Old Bruden finds his Master | 110 |

| XIV.— | Phœnix sees his Duty and does it | 119 |

| XV.— | The Fire on the Thomas Wistar | 128 |

| XVI.— | Spatterdock Point | 137 |

| XVII.— | In which a Council is held | 148 |

| XVIII.— | Touron in the Field | 156 |

| XIX.— | Phil and Chap start on an Expedition | 167 |

| XX.— | “Zose Angel Bells” | 175 |

| XXI.— | On Separate Roads | 187 |

| XXII.— | In which there is a Good Deal of Fast Travelling | 196[viii] |

| XXIII.— | Mr. Godfrey Berkeley is heard from | 206 |

| XXIV.— | The Grocer’s Buggy Once More | 219 |

| XXV.— | Old Bruden makes an Impression | 225 |

| XXVI.— | Mr. Touron attends Personally to his Affairs | 233 |

| XXVII.— | The Lonely Sumach | 241 |

| XXVIII.— | The Return of the Runaway | 256 |

| XXIX.— | The One Fellow who was left yet | 266 |

| XXX.— | The Great Moment arrives | 276 |

| PAGE | |

| When Phil had taken hold of the sill, Chap gave him a lift | Frontispiece |

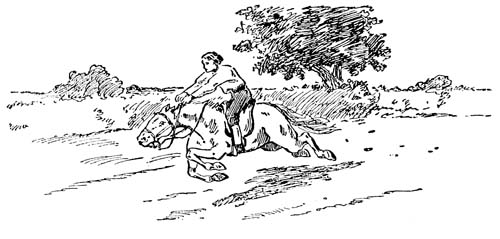

| Philip could not tell whether the horse’s hoofs struck the man or not | 56 |

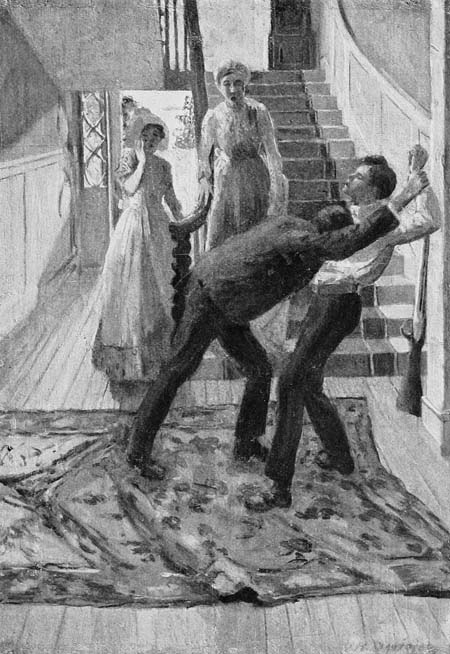

| He seemed intent upon pushing his antagonist backward | 117 |

| With a sickening feeling of fear he put Old Bruden back between the mattresses | 204 |

| “You had no right to look for me, sir, whoever you may be!” | 248 |

| A column of water rose from the river, together with a mass of mud and timbers | 282 |

[x]

THE YOUNG MASTER OF

HYSON HALL

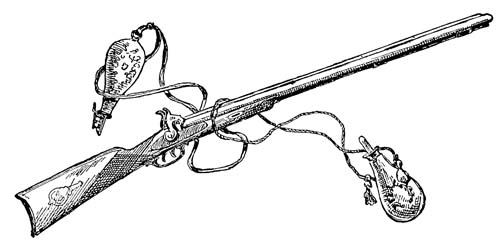

I may as well say at once that Old Bruden was the name of a double-barrelled shot-gun. It had originally belonged to a man by the name of Bruden, and by him had been traded for a cow to one of his neighbors.

From this person it had come, by purchase, into the possession of old Mr. Berkeley, of Hyson Hall, of whom I shall speak presently.

This double-barrelled shot-gun—which was now called by the name of its original owner—was not, at the time our story begins, a very valuable piece of property.

[8]The hammer of the left-hand barrel had a hitch in it, so that it could not always be depended upon to come down when the trigger was pulled. There was also a tradition that a piece of this left-hand barrel had been blown out by Mr. Bruden, who, by accident, had put a double load into it, and that a new piece had been welded in; but, as no mark of such gunsmithery could be found on the barrel, this story was generally disregarded, especially by the younger persons who occasionally used the weapon.

Hyson Hall, the residence of Godfrey Berkeley, the present owner of the gun, was a large, square house, standing about a quarter of a mile back from the Delaware River in Pennsylvania.

It had been built by Godfrey’s father, who was engaged, for the greater part of his life, in the Chinese tea-trade. When he retired from business he bought an estate of two hundred acres, on which he erected the great house, which he called Hyson Hall.

Old Mr. Berkeley was a very peculiar man, and his house was a peculiar house. The rooms were very large,—so spacious, indeed, and with such high ceilings, that it was sometimes almost impossible to warm them in winter.

The halls, stairways, and outer entrance were grand and imposing, and in some respects it looked[9] more like a public edifice than a private residence. The roof was flat, and was surrounded by a parapet, at various points upon which bells had been hung, in the Chinese fashion, which tinkled when the wind blew hard enough, and which probably reminded the old tea-merchant of the days and nights he had passed, when a younger man, in the land of the yellow-skinned Celestials.

But when his son, Godfrey Berkeley, came into possession of the house, he took down all the bells. He was an odd man himself, and could excuse a good deal of oddity, but these bells seemed ridiculous and absurd even to him.

At the time our story begins, the present owner of the property had not lived very long at Hyson Hall. It had been but three years since his father died, and during that time Godfrey Berkeley, then forty years old and a bachelor, devoted himself, as well as he knew how, to the management and improvement of the estate. He had been very much of a traveller ever since he was a boy, and he did not understand a great deal about farming or gardening, or the care of cows and beehives.

A wide pasture-field sloped up from the river to the bottom of the lawn, and there was an old-fashioned garden and some arable land behind the house; and Mr. Berkeley took a good deal of interest in looking after the operations of his small farm.

[10]Some of his neighbors, however, said that he was spending a great deal more money than he would ever get back again, and laughed a good deal at his notions about poultry-raising and improved fertilizers.

Nothing of this kind, however, disturbed the easy-going Godfrey. Sometimes he laughed at his mistakes, and sometimes he growled at them, but he asked for no advice, and took very little that was offered to him.

It is not likely, however, that Mr. Berkeley would have been satisfied at Hyson Hall had it not been for the company of Philip Berkeley, his only brother’s orphan son.

Philip was a boy about fifteen years old. He and his Uncle Godfrey were great friends, and there could be no doubt about Philip’s enjoyment of the life at Hyson Hall. During the greater part of the year he went to school in Boontown, a small town about three miles distant, riding there and back on a horse his uncle gave him; and during the long summer vacation there was plenty of rowing and fishing, and rambles with a gun through the Green Swamp, a wide extent of marshy forest-land, about a mile from the house.

There were neighbors not very far away, and some of these neighbors had boys; and so, sometimes with a companion or two of his own age, and[11] sometimes with his uncle, Philip’s days passed pleasantly enough.

Godfrey Berkeley had some very positive ideas about what a boy ought to do and ought to learn, but there was nothing of undue strictness or severity in his treatment of his nephew, whom he looked upon as his adopted son.

One pleasant evening in July, Godfrey Berkeley was stretched out upon a cane-seated lounge in the great hall, quietly smoking his after-supper pipe, when Philip came hurriedly tramping in.

“Uncle,” he said, “won’t you lend me Old Bruden to-morrow? Chap Webster and I want to go up the creek, and, if this weather lasts, perhaps we’ll camp out for a night, if you’ll let us have the little tent.”

Now, Philip had a gun of his own, but it was a small gun and a single-barrelled one; and as Chapman Webster, his best-loved friend, always carried a double-barrelled gun when they went out on their expeditions, Philip on such occasions generally borrowed Old Bruden.

To be sure, he seldom used the left-hand barrel, but it was always there if he needed it and chose to take the chances of the hammer coming down.

It might have been supposed that Mr. Godfrey Berkeley, who in former years had done so much travelling and hunting, would have had a better[12] fowling-piece than Old Bruden; but as he now often wandered all day with a gun upon his shoulder without firing a single shot, Old Bruden would have served him very well, even if neither hammer ever came down.

Philip’s requests were generally very reasonable, and his uncle seldom refused them, but this evening Mr. Berkeley seemed disturbed by the boy’s words.

For a few moments he said nothing, and then he took his pipe from his mouth and sat up.

“It seems curious, Phil,” he said, “that you should want Old Bruden to-morrow, and should be thinking of camping out. It’s really remarkable; you haven’t done such a thing for ever so long!”

“That’s because the weather hasn’t been good enough,” said Philip, “or else Chap Webster couldn’t go. But if you are going to use Old Bruden yourself, uncle, of course I don’t want it.”

“Oh, it isn’t that,” said Mr. Berkeley, laughing a little. “But I do not want you to take the gun to-morrow, especially on any long expedition.”

“Is anything the matter with it?” asked Phil, his eyes wide open. “Has it cracked anywhere?”

“I don’t know, indeed,” said Mr. Berkeley, “for it is so long since I fired Old Bruden that I can say very little about it. But I want you to understand,[13] my boy,” he said, more seriously, “that you should never use a gun unless you know for yourself that it is in good condition. You ought to be able to tell me whether or not there is anything the matter with Old Bruden.”

“Oh, I always look it over before I take it out,” said Phil. “But I thought you might just have found out something about the gun.”

“Not at all,” said Mr. Berkeley. “As far as I know, Old Bruden is exactly the same clumsy shot-gun that it was when I first bought it. But I don’t want you to go off with it to-morrow on any expedition with Chap Webster. I can’t give you my reasons for this now, but you shall know all about it to-morrow. That satisfies you, don’t it, my boy?”

“Oh, yes,” said Phil, trying to smile a little, though not feeling a bit like it.

His uncle’s discipline, whenever it was exercised at all, was of a military nature. He commanded, and Phil obeyed. The boy had learned to take a pride in that kind of soldierly obedience, about which his uncle talked so often, and it seldom bore very hard upon him.

He and Mr. Berkeley were generally of the same way of thinking, but to-night his disappointment was very hard to bear.

Several days before he had planned this expedition[14] with Chap Webster. They had had high anticipations in regard to it, and Phil did not suppose for a moment that his uncle would offer any objection to their plans. But he had objected, and there was an end to the whole affair.

Philip walked to the front door and gazed out over the moonlighted landscape.

“It will be a splendid day to-morrow,” he said to himself, “and as dry as a chip to-night, but all that amounts to nothing.”

And he turned on his heel and went into the house.

When Philip came down-stairs the next morning he found the breakfast ready, and Susan Corson, the housekeeper, standing in the middle of the dining-room, with a letter in her hand. Her countenance looked troubled, and as soon as the boy entered the room she said,—

“Mr. Berkeley isn’t about anywhere, and here is a letter for you which I found on the hall-table. I missed him a good while ago, because he is generally up so early, and I have been up to his room and looked through the whole house; and I blew the horn and sent the boy all over the place, but he isn’t to be found at all, and I believe he has gone off somewhere, and perhaps that letter tells you all about it.”

Before this speech was half over Philip had opened the letter and was reading it. It ran thus:

[16]

“When you read this letter, my dear Phil, I shall have run away—yes, actually cleared out and run away—from my good, kind nephew. It seems like turning things upside down for the man to run away and the boy to stay at home; but running away comes much more naturally to me than I hope it ever will to you, my very dear Philip. When about your age I began life by running away from home, and I have been doing the same thing at intervals ever since. The fact is, Phil, I have been so much of a rover, and a rambling life comes so natural to me, that I cannot any longer endure the monotonous days at Hyson Hall. It is true that I have enjoyed myself very much in the old house, and it is also true that I love you, Phil, and am delighted to be with you, and have you near me. But apart from the fact that I am tired of staying so long in one place, there are other reasons why I should go away for a time.

“And now, Phil, I want you, while I am gone, to take care of Hyson Hall and everything belonging to it. You know just how its affairs are going on, and, as you have kept my accounts for me almost from the first day you came to live with me, you know quite as much as I do about the house expenses and all that sort of thing. The next time you go to town you must take the enclosed note to Mr. Welford, my banker, and he will pay to you, from time to time, the amount I have been in the habit of drawing for regular house expenses. You see, Phil, I put a great deal of trust in you, but I don’t believe I could have a steward who would suit me better. Don’t spend any more money than you can help. Take good care of Jouncer, and keep everything as straight as you can. Of course, I don’t expect you to stay at home all the time and have no fun, but you can see now why I did not want you to take Old Bruden and go off on a[17] camping expedition on the very first day of your stewardship.

“And now, good-by, my boy. I expect to write to you again before very long, and I am quite sure that until I come back you will manage the old place just as well as you can; and if you do that, you will fully satisfy

“Your affectionate uncle,

“Godfrey Berkeley.”

As Philip stood on one side of the breakfast-table reading this letter, Susan Corson stood on the other, gazing steadfastly at him.

“Well,” said she, “where has he gone? and when is he coming back?”

“Those are two things he doesn’t mention,” said Philip. “And I haven’t any idea what it all means.”

“Well, what does he say?” asked Susan, a little sharply. “He surely must have told you something.”

Susan Corson was a middle-aged little woman, who thought a good deal of Mr. Godfrey Berkeley and a good deal of herself, and who had had, so far, no great objections to Philip, although, as a rule, she did not take any particular interest in boys.

“I will read you the letter,” said Philip.

And he read it to her from beginning to end, omitting here and there a passage relating to himself and his uncle’s trust in him.

[18]For a few minutes Susan did not say a word, and Philip also stood silent, looking down at the letter he held and thinking very hard.

“And while he is gone you are to be master here?” said the housekeeper.

“Yes,” said Philip; “that’s about the way to look at it.”

“Well, then,” said Susan, “there’s your breakfast.”

And she marched out of the room.

Philip sat down to the table, but he was still thinking so hard that he scarcely knew what he ate or drank. When he had about half finished his meal he heard a shout outside. He jumped up from the table and ran to the window. Standing in the roadway, in front of the house, he saw Chap Webster, who had just sent forth another shout. Phil ran out on the great stone porch.

“Hello, Chap!” he cried. “Come up here and wait till I have finished my breakfast.”

“Finished your breakfast!” exclaimed his companion. “Why, I thought we were going to make an early start! I didn’t half finish mine.”

“I’m sorry for that,” said Phil; “but just sit down here, and I’ll be out directly.”

If Philip had been the grown-up gentleman which he was sure to be if he lived long enough,[19] he would have asked his friend in to finish his breakfast with him; but he was a boy, and did not think of it.

There was nothing mean about him, however; he stopped eating before he was half done, so as not to keep Chap waiting.

Chap Webster was a long-legged boy, a little older than Philip. He had light hair, and what some of his friends called a buckwheat-cake face,—that is, it was very brown and a good deal freckled. He did not sit down at all, but stalked up and down the porch until Phil came out.

“Are you ready now?” he cried, as soon as the latter appeared at the hall door.

“No, I’m not ready,” said Phil; “and what is more, I am not going at all.”

Chap opened his mouth and eyes, and jammed his hands down into his trousers pockets.

“This is a pretty piece of business!” he exclaimed. “Here I’ve been up ever since sunrise getting my traps ready, and mother has put up a basket of provender, and everything is all ready for us to take up as we pass our house. I didn’t think you were that kind of fellow, Phil.”

“I didn’t think so myself,” said his companion; “but there’s no use of our shooting wild this way. Just you sit down and read that letter.”

Chap took a seat on a bench, and, leaning over,[20] with his elbows on his outspread knees, he carefully read Mr. Berkeley’s letter.

When he had finished it, and had turned over the sheet to see if there was anything more on the last page, he looked steadfastly at Phil, then whistled, and then lay back and laughed as if he would crack his sides.

Phil could see no cause for merriment, but the example was contagious, and he began to laugh, too.

“I always knew your uncle was a rare customer,” said Chap, at last; “but I never thought he’d be up to a thing like this. Why, Phil,” he cried, starting to his feet, “I’d rather be in your place than own a tug-boat!”

This was putting the matter very strongly, for to own a tug-boat, with which he could make a fortune by towing vessels up and down the river, was one of Chap Webster’s most earnest aspirations.

“Well, what would you do?” asked Philip.

“Do!” cried Chap, with sparkling eyes. “I’d do everything! I’d have all the fellows here. I’d give the biggest kind of picnics. I’d camp out, right here in front of the house. I’d put a mast in your uncle’s scow, and buy a sail for her. I’d dig up the old wreck, and I’d have fireworks every night. Do!” he added. “You’d soon see what I’d do!”

[21]“Yes,” said Philip, laughing, “and I’d soon see you stop doing, too. A pretty steward you’d make!”

“Phil,” said Chap, suddenly changing his manner, “how long do you think he’s going to stay away?”

“I don’t know any more about it than you do,” said Phil. “There’s his letter, and that’s all there is to go by.”

“Well, I’ll tell you what it is, Phil,” said Chap, very earnestly, “if your uncle stays away long enough, there are big things ahead. You know he said you were to have fun.”

Chap Webster did not stay very long at Hyson Hall.

“If the trip is to be given up,” he said to Phil, “I must go home and tell mother to take the things out of my basket. There’s no use letting them spoil, and the children might as well eat them. And, besides that, I’ve got a lot to think about. I tell you what it is, Phil, there’s a stack of responsibility about this thing.”

Phil could not help smiling as his long-legged friend strode rapidly away. There was certainly a great deal of responsibility attached to the new state of affairs, but why Chap need trouble his mind about it he could not imagine.

However, Chap was a great speculator in plans and projects, and took stock in such things whenever[23] he had a chance. As for Phil, he truly had a great deal to think about.

What should he do, and what should he do first?

He sat on the top of the broad stone steps that led up to the porch and thought the matter out. It was one of the most uncomfortable places he could have chosen, for the sun shone full in his face, and he was obliged to shield his eyes with his napkin, which he had forgotten to leave on the breakfast-table.

The establishment at Hyson Hall was not extensive, and Phil had been such a constant companion of his uncle, and had, under Mr. Berkeley’s direction, done so much of the daily management of the place, that, excepting the responsibility, there was nothing very novel in the duties of his trust.

A man and a boy were employed on the little farm, on which the only crop of any importance was a field of wheat. Until this was ready to cut there was nothing out of the way to be done on the farm. In the house the domestic force consisted of Susan Corson, who was the housekeeper and cook, a woman for general housework, and a half-grown girl named Jenny.

Phil very properly made up his mind that in regard to the general affairs of the establishment he would let them go on in the ordinary way until something unusual turned up.

[24]If he knew that his uncle intended to stay away for any considerable time, there were some plans that he thought he could carry out with considerable profit to the estate; but as he would not like to be interrupted in anything of the kind when it was half done, however sure he might feel that Mr. Berkeley would be well pleased with the result when all was finished, he concluded, for the present, to give up such projects.

There was enough for him to do, however, and there was no knowing what might turn up. There was only one particular injunction his uncle had laid upon him, and that was to take good care of Jouncer, and this was a matter he would attend to immediately.

And so, with one side of his head pretty well scorched, he jumped up, got his hat and ran down to the stables.

Jouncer was Mr. Godfrey Berkeley’s riding-horse, and whenever he went to town, or to visit any of his neighbors, he rode Jouncer.

This animal was considered by Phil and some of his boy friends to be a horse of great possibilities. It was believed, and some of the boys considered themselves good judges of such things, that he had Arabian blood in him, and that, if required, he could gallop with great swiftness and leap over the highest fences.

[25]Nothing positive, however, was known upon these points, for Mr. Berkeley did not care to make an animal exert itself unnecessarily, and always rode at a jog-trot.

Jouncer was found to be in comfortable circumstances, and as Phil looked at him as he was grazing in a little paddock back of the barn, he made up his mind that he would ride the noble beast, next day, to town, to see Mr. Welford.

He had never mounted Jouncer, except for very short rides on the place, and his own horse, Kit, could be brought up from the pasture just as well as not; but it seemed to him that in order to suitably represent his uncle, it would be the proper thing for him to ride his uncle’s horse.

Joel, the hired man, was full of eagerness to know all about Mr. Berkeley’s departure, of which he had already heard something in the house, and Phil satisfied him as well as he could, endeavoring besides to fully impress upon his mind the nature of the trust his uncle had imposed upon himself.

Joel thought it would have been much better if Mr. Berkeley had left the management of the place to him, but he was a cautious fellow and said nothing.

After dinner, which, by the way, Phil did not consider quite as good a meal as usual, he went[26] into the parlor to think over what he should say to Mr. Welford when he went to see him the next day.

The parlor was an immense room, very seldom used; but Phil thought it quiet and cool, and a very suitable place in which a person in his position might spend a little time after dinner.

He seated himself in a large arm-chair, but he had not cogitated more than two or three minutes before he heard a heavy step on the porch, and then a great knock at the door.

Susan was in the dining-room, and she hurried out to admit the visitor. As she approached the front door, Phil heard her exclaim, in tones of surprise,—

“Why, it’s Chap Webster!”

Phil was very much surprised, too, for this was the first time Chap had ever knocked at the front door. He generally announced his coming by a shout from some point outside of the house.

“Is the steward in?” asked Chap.

“The what?” cried Susan.

Phil laughed, and went to the parlor door.

“Come in here, Chap,” he said; “I’m in the parlor.”

Chap took off his hat, came in, and, after gazing around the spacious apartment for a moment, seated himself on a sofa.

[27]Susan Corson stopped a moment as she passed the door.

“In the parlor!” she ejaculated. “Upon—my—word!”

And then she walked severely down into the kitchen.

“Do you generally intend to sit in here?” asked Chap. “You never did when your uncle was at home.”

“I could have, if I had wanted to,” said Phil.

“And of course you want to now,” remarked his friend. “Some things make a great difference, don’t they?”

“Yes, I suppose they do,” said Phil.

“Now, I want to tell you, Phil!” cried Chap, with great animation. “I’ve been considering this matter all the morning, and I’ve come over to tell you what I’ve thought out. You can get eight-ounce cartridges of giant-powder at Boontown for twenty-five cents apiece. If I were you I’d buy five, and then we can go down and blow up the wreck the first night after we get them. It ought to be done at night, so that the flying timbers wouldn’t strike boats.”

Phil burst out laughing.

“You old humbug!” he cried. “Do you suppose that the first thing I am going to do is to blow up that ancient wreck?”

[28]“You might get thousands of dollars out of it!” exclaimed Chap; “and I guess your uncle would be glad of that.”

“Thousands of splinters!” exclaimed Phil. “But you needn’t think I’m going to do anything of that kind the minute I take charge of things here.”

“Take charge of things!” repeated Chap. “That sounds large and lofty. I suppose you feel like the lord of the manor. But I tell you what it is, my noble potentate, you mustn’t expect to look down too much on the neighboring barons.”

“It depends a good deal on the barons whether I do that or not,” said Phil.

“Now, look here,” said Chap, changing his tone; “if you won’t blow up the wreck, will you go after muskrats to-night? It’s a good moon, and I’ll bring my gun, and you can take Old Bruden.”

After having refused his friend so much, Phil could not decline so reasonable a proposition as this, and he consented to hunt muskrats that night.

It is true his uncle had not wished him to go on an expedition, but this would be on the river-bank, in front of the house.

Chap thereupon departed, and Phil was very glad to think of having a little sport that evening.[29] Muskrats were frequently found on the river-bank, and their skins were sometimes a source of a little private income to the boys, who could get twenty-five cents apiece for them in Boontown.

In the course of the afternoon Phil went up-stairs to the gun-room to get Old Bruden, in order to clean it, in readiness for the evening’s expedition. The gun-room was a small one on an upper floor, the walls of which were full of pegs and hooks for fowling-pieces, game-bags, and all the other accoutrements of the sportsman; but the room had never been furnished, as had been originally intended. With the exception of Old Bruden, his own little gun, and a few flasks and pouches, there had never been anything on the walls but pegs and hooks.

Old Mr. Berkeley had intended to be a sportsman, but before he could carry out his purpose had become too infirm to care about it.

Phil stepped up to the two pegs on which Old Bruden had always hung when not in use, but, to his utter amazement, the gun was not there.

He could not understand this at all. It had been one of his uncle’s most inflexible rules that neither of the guns were ever to be left about the house, but were always, when brought in, to be taken to this room and hung in their places.

Could it be possible his Uncle Godfrey had[30] taken Old Bruden with him? He presently came to the conclusion that this must be the case, and yet he could not imagine why in the world his uncle should want to take a gun with him. Was he going on a long tramp over the country?

Another thing surprised him. None of the shot-pouches or powder-flasks were missing. What was the good of a gun without ammunition?

But these questions were too puzzling for him, and he gave them up. He took his own little gun and went down-stairs. While he was cleaning it in the back-yard, Jenny came by from the barn with some eggs in her apron.

“Jenny,” said Phil, “did you see my uncle go away this morning?”

Jenny stopped, and, for a moment, was silent. Then she said,—

“I can’t tell you.”

“Oh, then,” exclaimed Phil, “of course you saw him! Did he take Old Bruden with him?”

“He didn’t tell me,” said Jenny, “not to tell that I saw him go, though I don’t believe he wanted me to tell. But he did tell me not to say how or when he went, and if I say he went with a gun, that would be telling how he went, wouldn’t it?”

“I suppose so,” said Phil. “I don’t want you to disobey any orders.”

[31]And Jenny passed on to the house.

After supper, Phil laid down on the cane-seated lounge in the hall to await for Chap. He did not expect him early, for the moon did not rise until after eight o’clock, and it was of no use going out at night after muskrats until that luminary had lighted up the river-bank. He was just dropping off into a little doze, when Jenny, coming from the kitchen, ran to the lounge.

“I haven’t a minute to stop,” she whispered, “for Susan sent me up-stairs to light the lamp in our room, and she is coming right after me. I’ve found out something. I can’t say anything about it now, but to-morrow I’ll tell you what it is, Master Phil.”

And away she ran.

Phil did not feel in the humor for guessing conundrums. He had had enough of that sort of thing for one day, and he stretched himself out again for another doze.

This time he dropped into a sleep, which lasted fifteen or twenty minutes, from which he was aroused by footsteps on the porch.

“Come in,” cried Phil, jumping up.

A person entered, but he was not Chapman Webster.

The person who entered the front door of Hyson Hall when Philip cried “Come in!” was a small, smooth-shaven man, wearing a high-crowned, black straw hat. There was a hanging-lamp burning in the hall, and as Phil sprang up to receive his visitor he could see his features distinctly, but he did not recognize him. He had never seen the man before.

“Is Mr. Berkeley in?” asked the visitor, taking off his hat.

“No, sir,” answered Philip, “he is not.”

“Can you tell me when he will be here? Do you expect him to-night?”

“No,” said Philip, “he will not be home to-night, and I can’t tell you just when he will return.”

[33]“That’s curious,” said the man. “I’d ’a’ thought he’d told you what time he’d be back.”

“Is there anything I can do for you?” asked Phil, not caring to pursue the previous subject any further.

“No,” said the man, “I don’t think there is. Is there any grown person about the house that I can speak to?”

This remark nettled Phil.

“No,” said he, “there is no grown person here. My uncle left me in charge of the place, and if you have anything to say, you can say it to me.”

“I hardly think I will,” said the man, putting on his hat. “I guess I’ll call again some time.”

“All right,” said Phil. And the person departed.

This visit perplexed Phil a good deal, and annoyed him also. If people did not intend to recognize him as general manager of Hyson Hall, there would be no use in his trying to go on with the business.

He wondered, too, who this man could be. He thought he knew everybody with whom his uncle ordinarily did business, but this man was a perfect stranger to him. He had been considering the matter but a short time when Chap arrived.

“Who is that old fellow out there talking to your Susan?” inquired Chap.

[34]“Talking to Susan!” cried Phil. “Why, I thought she was in bed long ago. And why should he be talking to her?”

And with this remark he started for the door.

“Oh, you needn’t go after him,” said Chap; “he left just as I came up. Who was he?”

Phil gave his friend no further satisfaction about the man with the black straw hat, except that he was a person who had come to see his uncle. He had no disposition to talk upon the subject.

“Well,” said Chap, “are we going after muskrats? Or has that little expedition been put off?”

“We’ll do that,” said Phil, taking his gun from a corner and putting on his hat. “Come along.”

Phil locked the front door and put the key in his pocket, and then the two boys, with their guns on their shoulders, walked over the lawn and the pasture-field to the river.

It was not, perhaps, altogether wise for Phil to leave the house that night, with nobody in it but a woman and a girl, but the man, Joel, lived with his mother in a small cottage just back of the garden, and Phil himself did not intend to go out of sight of the house.

The two boys had not walked very far before Chap stopped and exclaimed,—

“Why, Phil, what are you doing with that little pop-gun?”

[35]“Oh, this will do well enough to shoot all the muskrats we shall see,” said Phil.

“But, why didn’t you bring Old Bruden?” persisted Chap.

“Never you mind why I didn’t!” answered Phil, a little impatiently.

He was generally a good-humored fellow, but his mind had been greatly ruffled that day.

“My Lord High Steward,” said Chap, after they had walked a little way in silence, “I see what this thing is coming to. You are enveloping yourself in a cloud of mystery. That may be all very well for a fellow just starting off on a track which hasn’t been surveyed yet, and which is to go nobody knows where, and no rails laid, but if you don’t want me to thrust aside the cloud with my strong right arm, you’d better let me inside the fog, I tell you, my boy.”

“You’ve got a nice lot of metaphors tangled up there,” said Phil. “If you were to pick them out and hang them up to dry, in assorted sizes, a fellow might find out what you’re trying to say.”

The boys did not see many muskrats that evening. After a good deal of waiting and watching they shot two.

Chap proposed that they should go about half a mile farther down the river, where there were some low meadow-lands, protected by embankments,[36] and where there were generally a good many muskrats to be found.

These animals delight to burrow, and they sometimes made such extensive excavations into the embankments that these gave way, and the meadows were flooded when the tide came in.

“You know it’s doing a real service to Mr. Hamlin to shoot the muskrats down there,” said Chap.

Phil would have been very willing to do his neighbor a service, but he refused to go off his uncle’s place.

“Well, I will tell you what let’s do,” said Chap. “Let’s go down and look at the wreck. That is on your place, and I’ve never seen it by moonlight.”

“Very well,” said Phil, “we’ll go and look at it.”

The wreck, of which Chap Webster had made frequent mention, was the remains of a good-sized vessel, which was deeply embedded in the mud of the river, at one corner of the Hyson Hall estate.

At high tide it could not be seen at all, but when the tide was low a number of its forward ribs stuck up out of the mud.

It was generally believed, especially by the boys of the neighborhood, that this was the wreck of a[37] British sloop-of-war, which, in the time of the Revolution, had got into trouble down the river and had run up here for safety, but had afterwards been abandoned and sunk.

It was certain that the ship had come there when this part of the country was very thinly settled, for there was no one in the neighborhood who was able to give the exact facts in the case; but the story of the British war-vessel was a very good one, and was generally believed.

Chap Webster was one of a few persons who felt sure that there was a lot of British gold buried in this wreck.

“All war-vessels have to carry quantities of money,” he argued, “to pay off the crew and to do ever so many other things. And then, sometimes, they have prize-money aboard.”

The two boys walked out as far as the river-beach was firm enough to give them footing, and gazed at the wreck.

The tide was at its lowest ebb, and as much of the sunken vessel was visible as it was possible to see at any time.

The prospect was certainly not a hopeful one to any person who had an idea of raising the old wreck. A few ribs stuck up in a mournful way out of the watery mud, and that was all.

“Why, Chap,” said Phil, “we would have to[38] take out twenty scow-loads of mud before we could get at the fore-part of that vessel, and then we would not find anything worth having, anyway. All the valuables on board a ship are kept in the officers’ quarters, near the stern, and that is sunk in deep water.”

“Mud wouldn’t matter,” said the sanguine Chap. “We could blow all that out at once with the giant-powder.”

“And the people all over the county would think, the next morning, that it had been raining mud in the night,” said Phil.

“I don’t care what they’d think,” said Chap; “and I’m not at all sure about the treasure being always in the stern; but if it is there, and we could lower down a big, water-tight cartridge and explode it, we might loosen things so that they would float up.”

“Money wouldn’t float,” said Phil.

“Do you know, Phil Berkeley,” cried Chap, “that if I had a tug-boat, and could get a good hitch on to the sunken part of that ship, I believe I could pull it up and tow it into shallow water, where we could get at it?”

“If I wanted to get the sunken treasure, if there is any,” said Phil, “I wouldn’t like to have to wait until that time.”

“Do you mean,” said Chap, turning sharply[39] upon him, “that you think I am never going to have a tug-boat?”

“Oh, no!” said Phil, “I didn’t mean that. I only meant that I didn’t believe you could move that old wreck, or anything else that is as much a part of this continent as that is now.”

“Oh!” said Chap; “that’s it, is it?”

Then the two boys started for home, each carrying his muskrat by the tail.

The next morning Philip was sitting at the breakfast-table very much dissatisfied. He had had a poor breakfast, and he did not think that this should be. Susan need not cook as much as when there were two at the table, but certainly she might give him something good to eat. Even some eggs would have made matters different, and he had seen Jenny bringing in a lot the day before. He would have a talk with Susan on this subject, but first there were other things to be attended to. He must find Old Bruden.

“Jenny,” he said to the young girl who came in to clear away the breakfast things, “do you know anything about Old Bruden, my uncle’s double-barrelled shot-gun?”

Jenny came nearer to him, and said, in a low voice,—

[41]“If you wait five or six minutes she’ll be gone down to Joel’s house, then I’ve got something to tell you.”

Philip walked out on the porch. He remembered that Jenny had given him to understand, the evening before, that she had some sort of a mysterious communication to make, and now he supposed it was coming. He did not fancy such things at all. His own disposition, as well as his uncle’s teaching and example, made him averse to having controversies or confidences with servants. He did not object so much to Jenny, for, although she occupied a menial position, she belonged to a very respectable family, and he knew that his uncle expected her to go to school the next winter at Boontown.

For these and other reasons he was much more willing to hear Jenny’s story than to scold Susan about the breakfast, or to ask her what she knew of the man who came the night before. It was not very long before Jenny came out on the porch.

“Master Phil,” she said, “do you know that Susan was listening to all you said to the man last night? And when he went away she slipped down the back stairs and headed him off at the corner of the house. I looked out of our window, and I heard her tell him that the young boy he’d[42] been talking to had made a mistake when he said there was no grown person in the house, for she was there, and if he had any message to leave for Mr. Berkeley he might leave it with her. The man said he supposed she was grown, though she wasn’t very large; but he guessed he’d keep his messages and deliver them himself. And then Susan told him that there was no knowing when Mr. Berkeley would be back, and that she knew a great deal more about family affairs than that boy inside did. ‘Very well,’ said the man, ‘perhaps, when I come again, I’ll ask for you, if Mr. Berkeley isn’t here. What’s your name?’ And then she told him her name, and he went away.”

“You’d make a good reporter,” said Phil; “but I don’t think there is much in all that. It isn’t a nice thing, Jenny, to be listening out of windows to what people are saying.”

“That mayn’t be much,” said Jenny, not at all disconcerted; “but I can tell you something that is much. I can tell you where Old Bruden is.”

Phil suddenly became all animation. He had already ceased to care about the man with the black straw hat, but the whereabouts of Old Bruden was quite another affair.

“Where is it?” he asked, eagerly.

“It is up in our room, under Susan’s bed,” said Jenny.

[43]“How in the world did it get there?” asked Philip, in much surprise.

“She put it there herself, but what for I don’t know.”

“Go right up-stairs and get it,” said Phil.

And away ran Jenny.

She soon reappeared, carefully holding the gun out before her with both hands.

“Which end of it is loaded?” she said.

“Neither end, you goose,” replied Philip. “When there is a load in it, it is about the middle.”

“I don’t know anything about guns,” said Jenny. “I meant which side of it is loaded?”

“There isn’t any load in it now,” said Philip. “We always fire off the guns before we bring them in.”

And he drew out the ramrod and rattled it down one of the barrels.

“Why, there is a load in it!” he cried; “although there isn’t any cap on. I’d like to know what this means, and why Susan took Old Bruden, anyway. Just you take this gun and carry it carefully back up-stairs and put it where you found it. You needn’t be afraid of it, for it can’t go off; it isn’t capped. And then go to the kitchen, and as soon as Susan comes in tell her I want to see her.”

When Susan made her appearance in the hall,[44] where Philip was walking up and down, her countenance wore a very stern expression.

“Is anything the matter?” she said, shortly.

“Yes, there is a good deal the matter,” said Philip. “In the first place, do you know where my uncle’s double-barrelled gun is?”

To this question Susan made no immediate answer, but, with a cloth she held in her hand, she began to dust the hall-table.

“Haven’t you seen it?” repeated Philip.

“You’ve got a gun of your own,” said Susan, without turning around. “Isn’t that enough for you?”

“That is not the question. I want to know where Old Bruden is.”

“I don’t believe in boys having double-barrelled guns,” said Susan, “or any guns at all, for that matter.”

“It makes no difference to me what you believe or what you don’t believe,” said Philip, whose temper was gradually getting the better of him.

He remembered, however, his Uncle Godfrey’s frequently repeated precept, that a gentleman never quarrels with a servant, and restrained himself.

“Susan,” said he, “you know very well where that gun is, and I want you to get it and hang it on the pegs in the gun-room, where it belongs.”

[45]“You talk as if you were the master of everybody here,” said Susan.

“I am head of this house until my uncle comes back,” said Philip, “and I want you to understand it.”

“And suppose I don’t choose to understand it?” said Susan.

“Then I’ll get somebody who will!” retorted Philip, quickly.

The idea of getting any one to fill her place seemed so absurd to Susan that she could not help giving a little laugh.

“Is that all you have to say?” she asked.

“That is all,” said Philip; “but I wish you to remember it.”

Then Susan walked off to the kitchen. Phil had intended to speak to her in regard to the meals, but he forgot all about that.

This little contest was now over, and Philip did not know whether he had conquered or not. He was obliged to be content to wait and see what the result would be, and, in the mean time, there was a good deal for him to do.

He put his uncle’s letter to Mr. Welford in his pocket and went down to the stables.

If Joel had resisted his authority, or questioned his orders, it is likely there would have been a serious outbreak of temper; but Joel was a cautious[46] man, and, although he was a good deal surprised when Philip requested him to put the saddle and bridle on Jouncer, he immediately stopped the work he was doing and went to the paddock. At the gate, however, he stopped.

“If you’d rather have your own horse,” he said, “I can send Dick down to ketch him.”

“No, I’d rather have Jouncer this morning,” said Philip.

And Jouncer was saddled and bridled.

Philip had been gone about twenty minutes, when Susan came down to the stable-yard.

“And so he’s gone off on his uncle’s horse,” said she. “He’s getting high and mighty! He’s just been ordering me to take that gun and hang it on the pegs I got it from!”

“How did he know you had it?” asked Joel.

“He asked me where it was, and as I didn’t deny it, of course he knew I had it.”

“Why don’t you put it back?” said Joel. “You don’t want it.”

“I tell you what it is, Joel Burress!” said Susan; “you are a new-comer here, and you don’t understand things as I do!”

“I’ve been here two years,” said Joel.

“And I lived here eleven years with old Mr. Berkeley, and since then with Mr. Godfrey. Before that I lived five or six years with old[47] Abram Bruden. I know all about that gun. It used to hang over old Abram’s kitchen fireplace, and nobody ever took it down but himself. It was always called the Master’s gun, and if any of his sons, or anybody about the place, wanted to shoot they got some other gun, or went without. But when his son Charlie’s wife came there to be head of the house, and wanted a big yellow cow belonging to Silas Wingo, old Abram, who was getting a little weak in his mind anyway, and who hadn’t much money just then, traded off the gun to Silas for the cow. Silas Wingo was a man who would always a great deal rather shoot than milk. Now, just see what happened! In a precious little while after that gun left the house nobody ever thought of old Abram as being the master there. From that time till the day of his death he hardly ever had a word to say about his own affairs. And after a while Silas got hard up, and brought the gun round to old Mr. Berkeley, and sold it to him for twice as much as it was worth, I dare say. It wasn’t long after that before Silas was sold out of house and home; but his creditors let him live in a little house on his own farm, where he had been a pretty hard-headed master. Mr. Berkeley kept the gun as long as he lived, and was always head of his house, I can tell you. And so is Mr. Godfrey, too.”

[48]“I suppose you think,” said Joel, “that if young Phil has the gun he will be the real master now.”

“I don’t want no boys over me,” said Susan, curtly.

“Havin’ the gun don’t make any difference,” said Joel. “All the things you’ve told of could ’a’ happened if there’d never been a gun in the world.”

“It’s no use talking to me like that,” said Susan. “There’s something in these things. That gun is the Master’s gun, and always has been.”

“When do you really guess the head-master’ll come back?” asked Joel, very willing to change the subject.

“I don’t guess anything about it,” answered Susan.

“Perhaps he’s gone to see some of his relations,” remarked Joel.

“He hasn’t got many of them,” said the housekeeper. “His brother is dead, and this boy is the only child; and old Mr. Berkeley only had two sons and a daughter; and she married a Frenchman, and died somewhere out West. Godfrey was the youngest, but he got this place; though, whether the old man ever built houses for the others I don’t know.”

Joel laughed.

[49]“Then he hasn’t much of a family to visit, and perhaps he’ll be back all the sooner.”

“Humph!” said Susan. “He’s gone to see no relations.”

And she went back to the house.

Philip made up his mind that he would ride into town in a quiet and dignified way. To be sure, he would have been glad to find out what Jouncer was really made of, and whether or not, if he were put to his mettle, he would show any signs of that Arabian blood which some of the boys believed to be coursing in his veins. But he would do nothing of this kind to-day. He was going on a business errand, to see one of the principal men of Boontown, and he would ride his uncle’s horse as his uncle always rode him.

But Jouncer had not jogged along on the turnpike road more than a quarter of a mile before the sound of rapidly-approaching wheels was heard behind him.

“Hello, Phil!” cried the well-known voice of[51] Chap Webster. “I didn’t believe it at first, but it’s really true. Why, you are on Jouncer!”

Phil turned, and saw behind him a spring-wagon, drawn by a small gray horse, and driven by a short and very stout boy, by whose side sat Chap Webster.

“Hello, Phœnix!” said Phil. “Where are you going?”

“I am going to town after father,” said the stout boy.

This youth’s name was Phineas Poole, but his boy friends called him Phœnix, and by that name he was generally known.

“But what are you doing on Jouncer?” cried Chap.

“Well,” said Phil, with an air as if the matter was of slight importance, “I thought I’d ride him into town to-day. He ought to be exercised, you know.”

“Well, why don’t you exercise him?” said Chap, very earnestly. “If I was on his back I wouldn’t be crawlin’ along like that. If you ever want to find out whether he has got Arabian blood in him or not, now’s your chance.”

“What would you do?” asked Phil.

“Do!” cried Chap. “Why, I’d put him across that ditch, and over that fence, and I’d clip it in a bee-line straight across the fields to town!”

[52]“Clip both your legs off,” said Phil, “and break his neck! I’m not going to make such a fool of myself the first day I ride my uncle’s horse.”

“Upon my word!” said Chap, in a desponding voice; then addressing himself to Phœnix, he said, “I do believe that Phil Berkeley is nothing but a humdrumist, after all! And to think of his opportunities! Come, Phœnix, touch up Selim, and let’s get along to town. It will be time enough to go at this rate when we take to riding cows.”

Selim was a resolute little horse, who, when he was touched up, generally did his best, and so, the moment he felt the whip, he put his head down as low as he could get it, and began to work his sturdy legs with as much rapidity as if a heavy head of steam had just been let on to the engine which moved his machinery, and the spring-wagon passed rapidly by Jouncer and went rattling ahead.

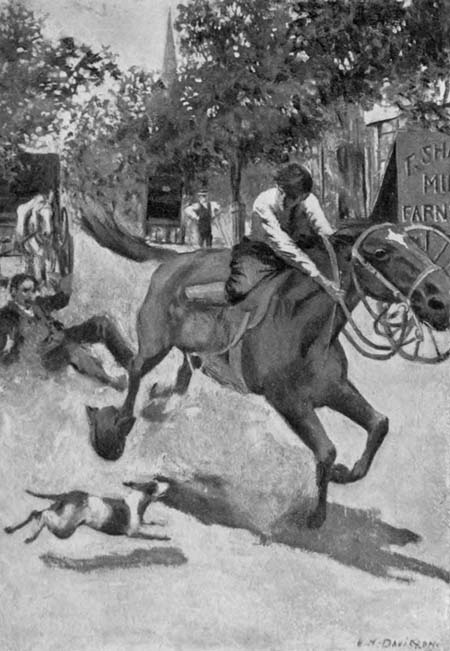

Now, Phil was a boy of spirit, and did not like this treatment at all. Without a moment’s hesitation he jammed his heels into Jouncer’s sides and urged him forward. Jouncer, too, was a horse of spirit, and never fancied being passed on the road, often giving his master considerable trouble on such occasions, and it is likely, therefore, even if he had not felt Philip’s heels, that he would have made haste to overtake that spring-wagon, and[53] now, having a double motive, he struck into a gallop, and soon caught up with the vehicle.

“Hi!” shouted Chap, in great excitement, turning around, and half standing up as he spoke; “don’t let him pass us! Whip up Selim! That Jouncer can’t beat us into town! Good-by, Phil!”

When Selim felt the whip again—and it came down a good deal harder this time—he put on more steam, and as he had been trotting as fast as he could before, he now began to run. After him came Jouncer, clattering furiously on the hard turnpike.

“It is ridiculous,” thought Phil, “for a little horse like that, with a wagon and two boys behind him, to keep ahead of Jouncer and me,” and with his heels and a little riding-cane he carried, he began to urge his horse to greater speed.

Jouncer’s blood, whatever kind it was, now began to boil, and he soon needed no urging. Turning a little to the left, he galloped so vigorously that it seemed that he must quickly pass the wagon. But Selim was a stanch little horse, and could run at a high speed,—for a short distance, at any rate,—and the wagon behind him seemed to be a matter he did not consider at all. He clattered bravely on, and still kept the lead, Chap shouting wildly, and Phœnix bringing down the whip every now and then with a resolute whang.

[54]A loaded hay-wagon was now seen ahead, and it was with some difficulty that the stout Phœnix turned his horse so as to pass on one side without a collision.

Jouncer passed on the other side, and when the rider and the drivers came in sight of each other again, Jouncer was ahead, and after that he kept the lead, galloping as madly as if he were carrying the news to Aix.

The boys in the wagon, for a short time, pushed on after him at their best speed, but soon perceiving that they could not catch up with Jouncer, and that they were beaten in the race, they pulled up their panting and dripping little horse, and let him walk the rest of the way to town.

Philip, as soon as he saw that he had won in the trial of speed, began to pull up Jouncer, but he did no more than begin, for he found the undertaking too much for him. Arabian blood seemed to give a hardness to the jaw, a stiffness to the neck, and a power of leaping and bounding to the body of a horse which he had never dreamed of. He could not stop Jouncer at all, and so went dashing along the turnpike until he thundered wildly into the main street of the town, which, as it was market-day, was pretty well thronged with vehicles and people.

Jouncer’s hoofs made such a clatter on the hard pavements of the main street of Boontown that the people had time to scatter to the right and left, while the horse guided himself clear of the wagons and buggies.

Philip had no power to stop or to turn him. All he could do was to stick on, which he did right well.

Everybody saw that it was a runaway. The boys shouted, and some of the women screamed, and one negro man ran out into the street to stop the horse, but his courage failed him as Jouncer approached, and he let him pass.

The wildly galloping horse had passed more than half through the town, when a man who was about to cross the street suddenly heard or saw the rapidly-approaching animal, and gave a[56] quick start backward. His heels slipped or struck something, and he fell sprawling on his back, a bundle he carried rolling one way and his hat another.

Jouncer passed quite close to him as he lay upon the ground, but Philip could not tell whether the horse’s hoofs struck the man or not.

He turned his head to look back, but just at this moment Jouncer went round a corner, and, rushing along a side street, was soon out in the open country.

When he found himself on an uneven and dusty road, the horse seemed to lose his taste for galloping, and very soon slackened his pace. He then moderated the boiling of his Arabian blood to such a degree that his rider was enabled to pull him in, and finally to stop him.

Philip dismounted, and as he stood by the roadside, with the bridle in his hand, he could not help feeling glad that neither his uncle nor Joel were there at that moment to see Jouncer.

It was a very hot day, and the noble animal looked as if he had taken a Russian steam-bath, and had had a little too much of it. His sides were heaving, he was puffing hard, and every hair was dripping, but the queerest thing about him was a black straw hat, through the crown of which he had thrust one of his hind feet, and which was now stuck fast above his fetlock.

Philip could not tell whether the horse’s hoofs struck the man or not

[57]Philip made the horse lift his foot, and he pulled off the hat. Then he exclaimed,—

“I’ve seen this hat before, and I am sure I never saw but one of the kind. I remember now. It belonged to the man who came to see uncle last night. I hope I haven’t hurt him, whoever he is.”

Much troubled in his mind, Philip took the hat in one hand and Jouncer’s bridle in the other, and led the horse slowly back to town. He would have first rubbed him down, but he had nothing to do it with.

Not caring, after his John Gilpin ride, to re-enter the main thoroughfare of the town, he went along a side street until he reached a shady spot, not very far from Mr. Welford’s office.

Jouncer was beginning to dry off by this time, and, having tied him to a tree, Philip walked up the main street. He first went to the store where his uncle generally bought groceries and other supplies, and going up to Mr. McNeal,—one of the partners, with whom he was acquainted,—he asked him if he had heard that anybody had been hurt by a runaway horse a short time before.

Mr. McNeal had not heard of any accident of the kind, and rather guessed if anything of that sort had occurred he would have known of it, for people had been coming to the store pretty steadily all the morning.

[58]Philip then told him about the runaway and the man who had tumbled down, and concluded by asking him if he might leave that hat there to be called for.

“Very well,” said Mr. McNeal, taking the hat. “I’ll hang it up in a safe place; but it strikes me that the owner of this had better buy a new one.”

“It isn’t hurt much,” said Phil. “I looked at it carefully. The top of the crown can easily be sewed on, and it is pretty fine straw, you see.”

“Yes,” said the other, “it has been a good hat, but I don’t think I ever saw another like it, though I’ve sold a good many hats myself. After all, if the man who wore it likes this kind of hat, I guess he’ll want this one back again, for he’s not apt to get another like it—at least, in this town. It must belong to a stranger, for nobody here wears such a thing.”

The hat was then put away, and Philip, having borrowed half a sheet of paper, wrote thereon a notice to the effect that any one having lost a black straw hat might get it by applying at the store of Henderson & McNeal, and describing the article.

He then went round to the post-office, near by, and stuck up this notice by the side of the main door, in company with a great many other notices of cows and horses for sale, articles lost, and matters of that nature. After this he went to see Mr. Welford.

[59]The banker was a quiet, middle-aged man, who knew Philip very well, the boy having frequently visited his office to attend to business for his uncle. He read Mr. Godfrey Berkeley’s note.

“It is very strange,” he remarked,—“very strange! Didn’t he tell you when he was coming back?”

“No, sir,” answered Philip; “but I thought he might have said something about it in your note.”

“Not a word,” said Mr. Welford. “And I am very sorry, indeed, that I did not know that he was going away at this time. It might have prevented a good deal of trouble. But there is nothing to be done now but to carry out his instructions. You can draw the money you need in the manner he mentions here, and, of course, you will be as economical as you can in your expenditures. I hope he won’t be gone very long; but, in the mean time, we must get on the best we can.”

He looked at Philip a moment, and then he said,—

“You are a young fellow to have charge of a house and farm, though I suppose your uncle knew what he was about. How did you come to town?”

This question was asked as a sort of finishing remark to the conversation, and the banker picked up some papers which lay on his desk.

“I rode in,” said Philip, “on uncle’s horse.”

[60]Mr. Welford turned suddenly, as if the thought had just struck him.

“Was that you,” he said, “who went tearing up the street a while ago?”

“Yes, sir,” said Philip. “The horse ran away with me.”

“I thought your uncle’s horse was a very gentle beast? At least he always seemed so to me.”

“He is gentle, as a general thing,” said Philip; “but the fact is, I had a little race on the road, and that got his blood up.”

“Oh!” said Mr. Welford.

And then Philip took his leave.

“I am sorry he’s that kind of boy,” said the banker to himself, as he took up his papers again. “I hope Godfrey Berkeley will not stay away long.”

As Philip went to get his horse he found a man holding him by the bridle.

“Do you know,” said the man, “that there’s a fine of five dollars for tying a horse to a tree in this town?”

Philip’s heart went right down into his boots.

“No, sir,” he said; “I didn’t know it at all.”

“Well, there is,” said the other; “and, as I had to wait for a customer who’s going to meet me here, I untied the horse and held him. I thought I might save somebody five dollars, before a town[61] constable came along. There’s only two of them, to be sure, but they’re as likely to be in one place as another.”

Phil’s heart came out of his boots with a bound.

“I’m very much obliged to you, sir,” he said. “I didn’t know anything about that law.”

The man was a tall and rather coarsely dressed person, wearing a linen coat and high boots, into which his trousers were thrust.

As Phil looked up at him, he saw that he had a very pleasant and kindly countenance.

“You’ve ridden your horse pretty hard,” said the man. “He looks as if you had been salting him down. Did you come in town for a doctor?”

“No,” said Phil.

And then he explained how Jouncer had happened to travel so fast.

“If you want to race a horse,” said the other,— “that is, if you do such things at all,—you ought to wait for cooler weather. It is pretty hard on a beast to make him run on a day like this.”

“But I didn’t make him do much of it,” said Phil. “He did almost all the hard running on his own account.”

“I tell you what it is,” said the man, with a smile, “when a horse has a human bein’ on his back, nearly all the brains of that party is to be found under the rider’s hat; and if them brains[62] ain’t put to good use there’s always a pretty fair chance of trouble.”

Phil agreed that this was so, and, mounting Jouncer, he bade the man good-by and rode homeward.

When about half a mile out of town he overtook a boy walking in a foot-path by the side of the turnpike.

“Hello, Phœnix!” cried Phil; “what are you doing here?”

“Going home,” said Phœnix.

“But why are you walking?” asked Phil, as he rode slowly by the side of his sturdy friend.

“Well,” said Phœnix, “the old man was awful mad when he saw Selim. Chap and I did think of driving the horse into the river, so that he’d get wet even all over; but then there wasn’t any good reason for giving him a wash, and Chap and I thought it might hurt him to drive him in when he was so hot.”

“It would have killed him, sure!” exclaimed Phil.

“That’s what Chap and I thought,” said Phœnix, “and we didn’t do it.”

“So your father was mad, was he?” said Phil.

“Mad is no word for it,” replied his friend. “He just blazed; and when he got through he told me that, as I had had such an extra good[63] time riding into town, I might walk home. Chap wanted to walk with me, but he wouldn’t let him. But I tell you one thing, I’d a great sight rather walk home than ride with the old man to-day.”

“I’ll take you up behind me,” said Phil, “if you say so. I don’t believe Jouncer will mind it.”

“Much obliged,” said Phœnix, taking off his hat and wiping the perspiration from his heated forehead, “but I guess I won’t. I rather like walking, especially on a fine day like this.”

“A blazing fine day,” said Phil, laughing; “but if I can’t do anything for you I’ll push on, or I’ll be late for dinner.”

That afternoon Phil went up into the gun-room to see if Susan had obeyed his orders in regard to putting Old Bruden back into its proper place, but the gun was not there.

He was a good deal annoyed at this, for he did not want to have any further dispute with the housekeeper; but he comforted himself by thinking that perhaps she had not yet been up-stairs, and that she would replace the gun that night when she went to her room.

But the next morning, when he visited the gun-room, Old Bruden was not to be seen.

Things now looked very gloomy to our young friend. He did not like quarrelling, and hard words, whether given or taken, were equally unpleasant to him; and yet he plainly saw that if his authority was to be worth anything that he[65] must have a conflict with the housekeeper, which would be pretty sure to be a tough one.

He had already suggested an improvement in his meals, which had been received by Susan in a very contemptuous way.

While he was trying to make up his mind as to what course he would take to bring the housekeeper to a proper sense of his position, he saw Chap Webster coming up to the house. It was evident from his friend’s countenance that he had a plan on his mind.

“Hello, Phil!” cried Chap, “I’ll tell you a splendid thing for this afternoon. We’ll take our guns and go over to the Green Swamp. We are pretty sure to get a shot at something,—big blacksnakes, perhaps, and I want one to stuff,—and then we may find the lonely sumach.”

Among the boy-beliefs of that neighborhood was one that in or about the centre of the Green Swamp there stood a large and poisonous sumach-tree, which, like the direful upas of Java, dealt out death to all who ventured beneath its shade.

Next to owning a tug-boat and blowing up the old wreck, Chap’s dearest desire was to find this tree. Not that he wished to venture beneath its shade, but he wished to see it, and to go just under its outer twigs, so that if he began to feel sick or faint, he would be pretty sure that he[66] would die should he go all the way under, and that this was actually a poisonous sumach-tree, just as good as a real upas.

“Chap,” said Phil, “you are always going in for something watery. I believe that in a former state of existence you were a stork.”

“That may be,” said Chap; “and I’m a pretty long-legged bird yet. But what do you say to the swamp? I expect it has dried up a good deal this hot weather, and if we are careful in stepping from one hummock of grass to another, perhaps we won’t get into the mud and water. But you must carry Old Bruden this time, for we may have to take two or three shots at a blacksnake, and long shots, too.”

Phil had begun to cheer up under the influence of Chap’s animation, but his spirits now fell again. He was silent for a moment, and then he said,—

“Chap, let’s go down under the old chestnut-tree and have a talk. I want to tell you something.”

He had resolved to take his friend into his confidence. This sort of thing was too much for one boy to bear alone.

“Any time in pleasant weather, till the burrs begin to stiffen, I don’t mind sitting under a chestnut-tree,” said Chap, as he took his seat beside Phil, beneath the great tree at the bottom of[67] the lawn, “but after that I prefer some other kind of shade. Now, what have you got to tell?”

Thereupon Phil related the facts of Susan’s insubordination and the various other out-of-way events that had happened lately.

“It is just what I told you, Phil,” said Chap. “You are in a regular cloud. But now that you have let me into the fog, we will go to work and scatter it like a hurricane. I tell you it is a regular rebellion that’s rising up here, and it’s got to be crushed out in the bud!”

“Nipped, you mean,” Philip suggested.

“Nipped, frozen, squashed! anything, so that we get our iron heel on it! I go in for throttling her, and holding her head under water until she blubbers!”

“Who? Susan?” asked Phil.

“Well, not exactly Susan,” said Chap, “but the whole spirit of rebellion. I’d begin with the housekeeper. She should be reduced to submission or crumbled into ashes. And as for Joel, if he cuts up rough when you want Jouncer again, as you say you think he may, I’d come down on him like a clap of thunder at the very first sign of mutiny. And the man who came here on a secret mission, I’d settle him. I’d ride into town and get his hat if he hasn’t called for it yet, and I’d put up a notice that he must come here, to this[68] house, for his hat; and when he came I’d make him divulge his reasons for wearing such a hat, and tell where he got it; and he should never cross that threshold till he laid bare the object of his midnight visit.”

“It wasn’t midnight,” said Phil.

“Well, then, whatever time of night it was. And I’ll tell you another thing. I don’t altogether like the way Mr. Welford acted. From what you say, I don’t think he came up to the mark as lively as he should have done. I’d keep my eye on him, too.”

“You wouldn’t do anything to Mr. Hamlin who lives beyond the meadows, would you?” said Phil.

“Why, no!” exclaimed Chap, looking around in surprise. “What has he got to do with it?”

“Oh, nothing,” said Phil. “I only supposed you might think it mean to leave him out of the general vengeance. But I tell you, Chap, you’re too lofty and tremendous, with your thunder-claps and your iron heel. These people don’t need anything like that.”

“Don’t you believe a word of it!” exclaimed Chap. “It isn’t the big, savage hen-hawks that give the most trouble and are hard to get rid of. It’s the potato-bugs. That’s where your iron heel comes in. If you don’t scrunch this thing in the[69] egg it will get ahead of you. You may just rest certain of that.”

“Well, let’s scrunch,” said Phil. “How would you begin?”

“I can’t say just exactly what I’d do first,” answered Chap; “but suppose we divide things. I’ll take Susan and you take Joel, and then I’ll take the man with the black straw hat, and you can have Mr. Welford.”

“You are choosing the heavy end of the load,” said Phil.

“That suits me,” said Chap. “I like to give a good lift when I get well under a thing with some heft in it.”

Phil did not fancy the idea of his friend undertaking to reduce Susan to proper submission; but, as Chap seemed fairly aching for the job, and as he had been such a frequent visitor to the house, and, being a very social boy, was really more intimate with Susan than Philip himself was, the latter finally consented that Chap’s arrangements should be carried out.

“But don’t come down too heavy at first,” said Phil. “I don’t want her annihilated—only reformed.”

“All right!” said Chap. “I’ll start in as mild as a pot of bonny-clabber.”

“Chap,” cried Phil, as a happy idea struck him,[70] “you come here and stay for a few days. Your folks will let you, I know.”

“Boy,” cried Chap, springing to his feet, “you are beginning to show signs of life! I’ll go and ask them.”

And away he went, like a pair of compasses going mad.

It was not thought strange in the Webster family that Philip Berkeley, being left alone in the great house where he lived, should want one of his boy friends to stay with him for a time during his uncle’s absence; and, as Chap was not particularly needed at home, permission was given him to go and visit Philip for a few days.

The strictest injunctions, however, were laid upon him to behave himself in as quiet and orderly a way as if Mr. Godfrey Berkeley were at home.

“Orderly?” said Chap to himself, as he put a few clothes into a very large valise. “I should think so! Why, I’m going there to establish order!”

When Chap entered Hyson Hall that afternoon, with his big valise, he met the housekeeper at the door.

“How do you do, Susan?” he said, with his most radiant expression of countenance.

Susan nodded as she looked, in surprise, at the valise.

“What have you got in that?” she asked.

“My dress suit,” said Chap, blandly; “or, at least, it mostly holds the suit I dress in at night. I’ve come to stay with you for a while, Susan,” he added, with as sweet a smile as he could call up.

“Stay awhile!” she exclaimed.

“Yes,” said Chap. “Poor Phil is so lonely! My folks were glad enough to let me come.”

“I should think so,” cried Susan, getting very[72] dark in the face; “and do they suppose I’m going to cook and slave for two boys?”

“Oh, you needn’t slave at all, Susan!” said Chap, almost tenderly. “All you have to do is to cook a little more than twice as much as you do for Phil, and I’m content.”

“Did he ask you to come? That Philip?” said Susan.

“Oh, yes, indeed!” said Chap. “You don’t suppose that I’d go about visiting houses, for a week at a time, without being asked? And now, which is to be my room? I can carry my baggage up there myself.”

“You can sleep where you choose,” said Susan, “in the cellar, the parlor, or the top of the house. This goes ahead of anything yet!”

And off she marched.

Phil was not in the house when Chap arrived; but when he came in, and his visitor told him of his interview with the housekeeper, he laughed heartily.

“Why, Chap,” he said, “you did begin mild, sure enough. I didn’t think you could be as dulcet as that.”

“Oh, yes,” said Chap, “that is the way to do it. I pulled on my heaviest woollen sock over my iron heel. But the heel is there, my boy,—it’s there.”

[73]“Not a very original simile,” remarked Phil.

“It’ll do for the country,” said Chap, “and a velvet glove is very different from a woollen sock, if you happen to have cold feet.”

Chap easily gave up the expedition to the cedar swamp that day, as it was agreed that the blacksnakes and the lonely sumach would probably wait until proper possession of Old Bruden could be regained, and the rest of the day was chiefly spent in laying out plans for future operations.

Susan took no steps to prepare a sleeping apartment for the visitor, but she gave the boys a very good supper, for, despite her anger, she did not want Chap Webster to go home and tell his family that she did not know how to keep house.

By Phil’s directions, however, Jenny prepared a room for Chap, and the next morning operations were begun to put down all rebellion, actual or expected.

Phil did not forget, however, that he had the business of the house and farm to attend to, and to this he resolved each day to give the first place. After breakfast, therefore, he informed Chap that he intended to ride over to a neighbor’s farm to see about some oats which had been bought before his uncle’s departure, but which had not yet been delivered.

“You can come along, if you like,” said Phil.[74] “Kit has been turned out to grass, but I can have him caught.”

“That means you are going to ride Jouncer?” said Chap.

“Yes, I intend to ride him,” Phil replied.

“Good boy!” cried Chap. “You’ll kill two birds with one stone. You’ll see about the oats, and you’ll have a chance to open fire on Joel, if he shows symptoms of revolt. As for me, I don’t think I’ll go with you. I’d rather stay home and see if I can’t get Old Bruden. I have your lordship’s permission to do that, haven’t I? I couldn’t go ahead, you know, without authority.”

“All right,” said Phil, “provided Susan delivers it up in a proper manner. That is the point, you know,—she is to give it up. I don’t want to get the gun in any underhanded way.”

“Exactly,” said Chap. “The laying down of the sword, or rather the hanging up of the gun, is what we are aiming at. You need not be afraid of me. I go in for high-handed—high-minded, I mean—warfare.”

Phil laughed, and, telling Chap to keep a sharp lookout on his own defences, left him alone with his warlike ideas.

Joel had been pretty grum and cross when Philip returned from his ride to town the day before, saying repeatedly that the horse had never[75] been used in that way since Mr. Berkeley bought him. Phil explained how the thing had happened, but this did not make it appear in any better light in Joel’s eyes. Phil left him currying the horse and growling steadily.

Our young friend, therefore, was not surprised this morning when he told Joel that he wanted to ride Jouncer over to the Trumbull Farm, to see a dark cloud spread over that individual’s countenance.

“You don’t want to take that horse out again, do you?” he asked, sharply.

“Yes,” said Philip, “I intend to take him out again. He ought to be used, and I don’t propose to let him run away with me this time.”

“He’ll do it, if he’s a mind to,” said Joel.

“No, he won’t,” replied Phil. “I know him better now, and I won’t let him get a start on me, as he did yesterday. Uncle left especial directions that I was to take good care of Jouncer, and one way to take care of him is to ride him and not let him get fat and lazy.”

“No danger of his gettin’ fat,” said Joel, “with your style of ridin’.”

“Joel,” said Phil, his face flushing a little, “I don’t want to talk any more about this. I am going to ride Jouncer this morning, and if you don’t choose to saddle him I’ll do it myself.”

[76]“Oh, you’re master,” said Joel, “and if you say so the thing has got to be done, I s’pose; and if the horse is rode to death, that’s your lookout; but I guess I’m responsible for the saddlin’ and bridlin’ and feedin’, ain’t I?”

“Certainly,” said Phil.

“Then I’ll attend to them things myself,” remarked Joel, as he went into the stable.