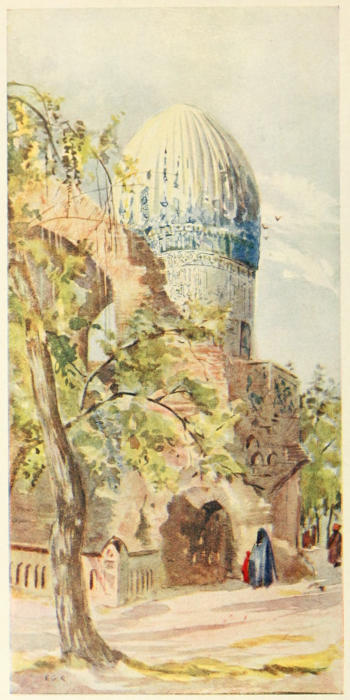

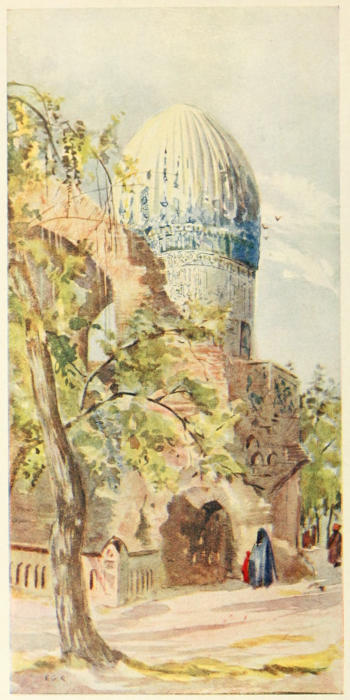

TAMERLANE’S TOMB

TAMERLANE’S TOMB

THE FACE OF

MANCHURIA

KOREA

& RUSSIAN

TURKESTAN

WRITTEN AND ILLUSTRATED WITH

XXIV PLATES BY E. G. KEMP, F.R.S.G.S.

AUTHOR OF “THE FACE OF CHINA”

NEW YORK

DUFFIELD & COMPANY

1911

All rights reserved

Less than three years ago I made a journey with a friend, Miss MacDougall, across the Chinese Empire from north-east to south-west, and while my interests in the changes going on there was intensified, a profound anxiety took possession of my mind as to the effect these changes would produce in the national life. The European and other Powers who had wrangled over the possibility of commercial and political advantages to be obtained from the Chinese Government (after the Boxer troubles) have withdrawn to a certain extent, but like snarling dogs dragged from their prey, they still keep covetous eyes upon it, and both Russia and Japan continue steadily but silently to strengthen their hold upon its borders. These borders are Manchuria and Korea, and it is in this direction that fresh developments must be expected. I read all the available literature bearing on the subject, but so rapidly had the changes occurred that books were already out of date, and they failed to make me see the country as it now is.

As an instance of this, let me quote Whigham’s (correspondent to the Morning Post) “Manchuria and Korea,” published in 1904.[1] “One cannot seriously[x] believe that Japan would ever invade Manchuria, unless, indeed, she be caught by the madness with which the gods first visit those whom they wish to destroy; but if ever her army did occupy Moukden she would only find another Moscow in the ancient capital of the Manchus, and when all is said and done what would be the use? She could never hope to hold the Liao valley for ever against Russia; Great Britain might just as well try to hold Normandy again against France.... The conclusion is that as far as Manchuria is concerned, Russia is even now more or less invulnerable,” &c. &c. This was published the year the Russo-Japanese war took place.

Taking heart of grace by the kind reception of my former book on China, I determined to visit Manchuria and Korea, and to try and describe them by pen and brush as I had described the Face of China. My former fellow-traveller was willing and eager to repeat our wanderings, so we set out on February 1st of this year, 1910, via the Trans-Siberian Railway. Much has been written by various travellers about this part of the journey, but the questions that I wanted answered are mostly ignored by them. Baedeker is wholly inadequate. I begin therefore my tale from the point where we crossed the border into Manchuria, so as to give more continuity to the narrative and avoid repetition. On our return journey across Siberia I give details which may possibly be of service to those who intend travelling on that line, and also the general information about the condition of the country at the[xi] present time, which I have gathered from reliable sources since my return.

When we started for our four months’ tour we had no intention of extending it to Turkestan, but finding that a railway line connected it with the one on which we were travelling, and that it could be reached in three days from Samara on the Trans-Siberian line, we decided to include it in our programme and so vary the journey home. It proved to be of extraordinary artistic interest, not to mention its historical importance both as the centre of Moslem learning and of Russian experiments in civilizing Central Asia. Russia looks with a jealous eye upon the traveller, and a special permit has to be obtained in order to travel through Turkestan, even on the railway line. Not only is it necessary to apply for this through the British Embassy at St. Petersburg, but several weeks elapse before a notification can be received that the Russian Government graciously permits the traveller to cross Turkestan. We were informed also that when all these formalities had been duly observed, the traveller was still liable to be stopped by the police on the ground that they (the police) had not received official notice of the traveller’s coming, and in that case he would be ordered to return by the way he came. Despite this discouraging information we determined to try our luck, and in due course received a “note verbale” from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at St. Petersburg, addressed to the British Embassy, permitting us to visit Tashkent, Samarkand,[xii] and Bokhara. In point of fact our difficulty proved to be not that of getting in, but that of getting out of Russian territory, as will be seen later on.

Despite the difficulties, Russian Turkestan is well worth visiting, and had the scope of this book permitted, I should like to have added further illustrations of Samarkand. All the illustrations suffer from lack of time, and the earlier ones from the inclemency of the weather, but they are an attempt to show as accurately as possible what the countries and people are like, and especially to give correct colouring, in this way supplementing the photographs with which many previous works on these countries have been illustrated.

We were warned before undertaking the journey that great dangers would lie in our path. I should indeed regret depriving the arm-chair critic of the pleasure of threatening us with tigers, brigands, Hun Hutzes, and the lowest class of Japanese ruffian, or of his special satisfaction in shaking his head over the follies of those who run into unnecessary danger; but in the interest of other travellers I must confess that we met none of these things, though doubtless it would have added to the piquancy of the narrative to have done so. The only striped beasts we saw in the forests were chipmunks, and the only people who were to be feared were the monks in a certain Buddhist monastery.

I cannot omit a word of thanks to the many missionaries who helped to make our journey such a[xiii] pleasant one, and without whose kindly aid we should have missed a large part of its interest. The Medical Mission work of the Irish and Scotch Presbyterians in Manchuria, and the various branches of work of American and Australian Presbyterians in Korea have been briefly described in this book, but their profound value can only be appreciated by those who have come in personal contact with them. In the troublous times of the last decade they have proved their worth, and I only hope that the ominous cloud still overhanging the land may be dispersed and a time of prosperous growth succeed the trials which they have triumphantly endured.

As I write these words the June number World’s Work falls into my hands, and I read what Japanese writers have to say upon the Manchurian question. Adachi Kinnosuke points out that, despite the immense financial strain of the war with Russia, Japan has trebled her army and strengthened her navy to an equal extent during the few years that have elapsed since that struggle, which cost her the lives of 300,000 men. The reason which he assigns for these military preparations is the necessity of being able to face China. At the close of the Russo-Japanese war Baron Komura tried to induce the Chinese Government to open Manchuria to Japanese colonists, but as Manchuria is imperatively needed by China for her own surplus population, which are pouring into it daily by thousands in the early spring, it was only natural that she should resent the proposal, and refuse to grant the desired[xiv] permission. Hence the present attitude of Japan. “If you do not allow our people to colonise Manchuria peacefully, there is only one thing for us to do: to enter it anyhow.” Yet the density of population in Japan at the present time is considerably less than that of Great Britain, of Belgium, of Holland, of Saxony, of Alsace Lorraine, of Hesse, of Baden; not to mention other non-European countries. The new Russo-Japanese Alliance is concerned mainly with their railways, and Japan insists on China relinquishing her project of a railway into Mongolia. Now it is an open secret that Russia is to have a railway direct from Irkutsk to Peking—the inference is obvious. The situation is an interesting one; but I have neither the knowledge nor the impertinence requisite for prophesying the course of events. My object will be attained if I can in any way succeed in describing the condition of affairs at the present moment.

The latest step in advance is the annexation of Korea, the highroad into Manchuria.

August 26, 1910.

| Preface | vij | |

| PART I The Face of Manchuria |

||

| I. | Hulan | 3 |

| II. | Moukden | 11 |

| III. | Hsin Muntun | 34 |

| IV. | Liao Yang | 42 |

| V. | A Visit to the Thousand Peaks | 51 |

| VI. | From Moukden to Korea | 58 |

| XIV. | Ashiho | 141 |

| (For narrative purposes included in Part II.) | ||

| PART II The Face of Korea |

||

| VII. | Pyöng Yang | 67 |

| VIII. | Sunday at Pyöng Yang | 74[xvi] |

| IX. | The History of Roman Catholicism in Korea | 84 |

| X. | Seoul | 93 |

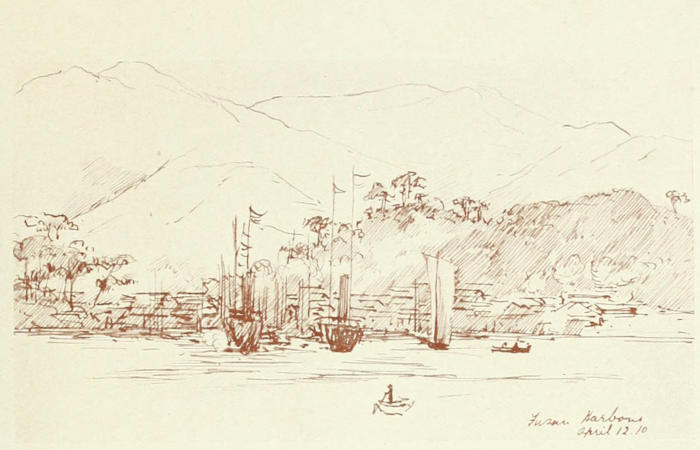

| XI. | Fusan | 107 |

| XII. | The Diamond Mountains | 113 |

| XIII. | Seoul to Dalny | 134 |

| XIV. | Ashiho | 141 |

| PART III The Face of Russian Turkestan |

||

| XV. | Through Siberia | 151 |

| XVI. | Into Turkestan | 171 |

| XVII. | Tashkent | 178 |

| XVIII. | The Home of Tamerlane | 188 |

| XIX. | Samarkand | 201 |

| XX. | Bokhara | 220 |

| XXI. | Through the Caucasus | 230 |

| Index | 241 | |

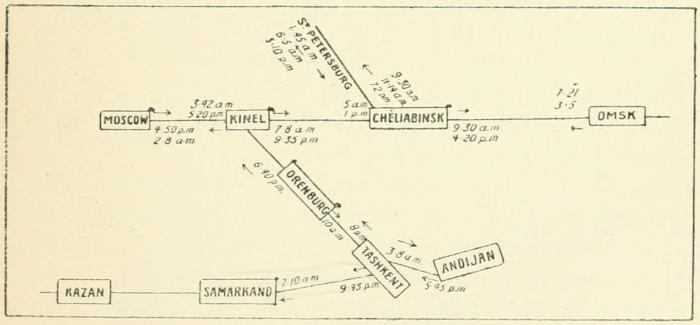

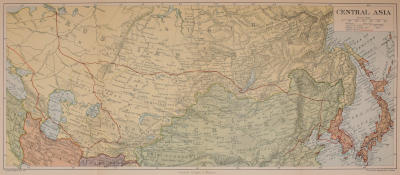

| Map | To face page 248 | |

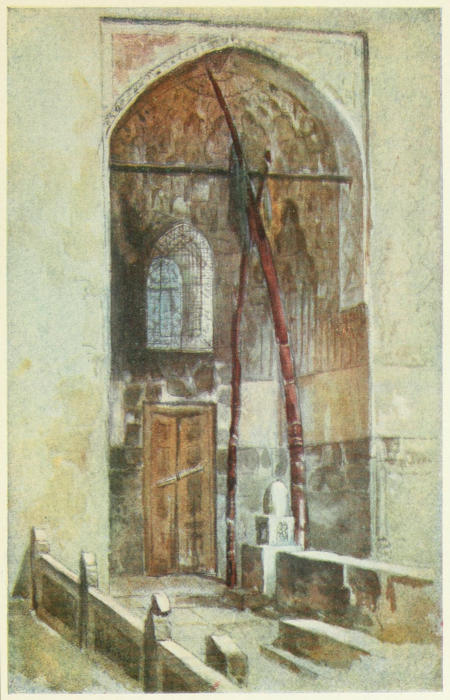

| Tamerlane’s Tomb | Frontispiece |

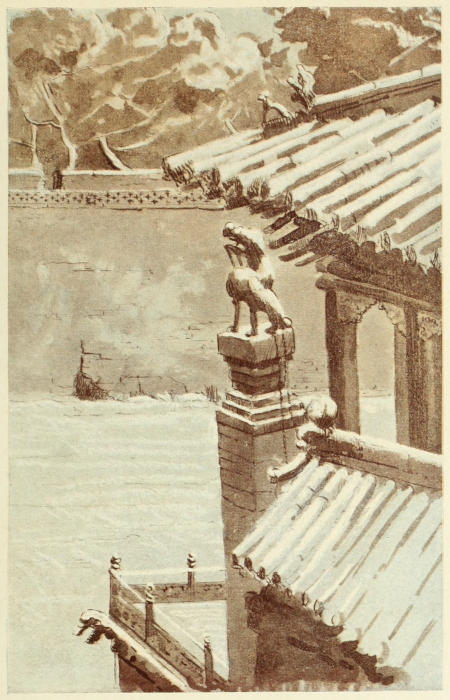

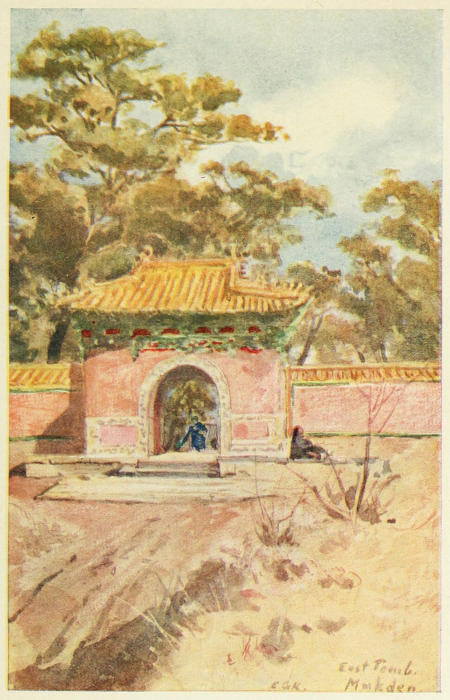

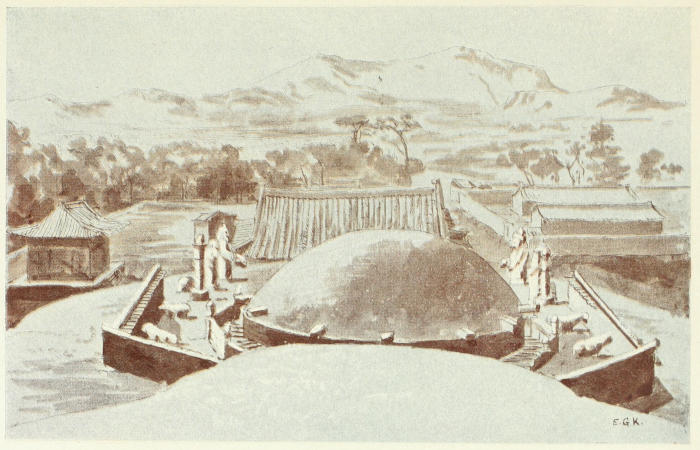

| Foo Ling Tomb | To face page 12 |

| Imperial Tomb, Moukden | 28 |

| Manchu Ladies’ Greeting | 36 |

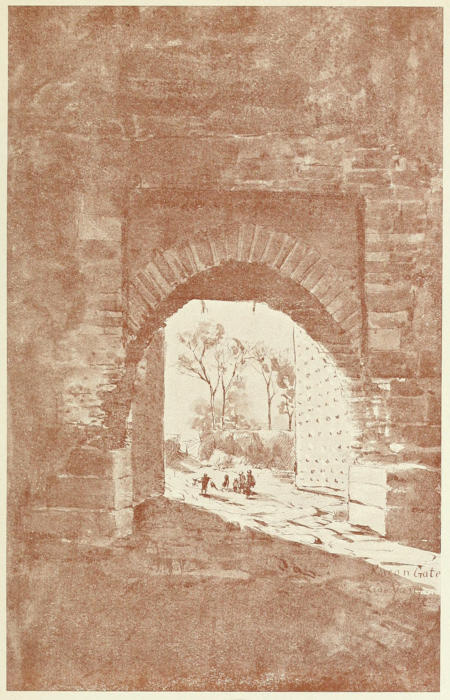

| Korean Gate, Liao Yang | 42 |

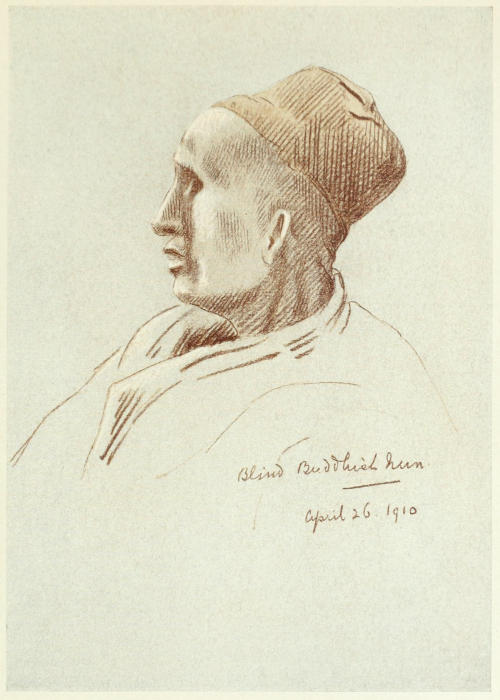

| Blind Buddhist Nun | 49 |

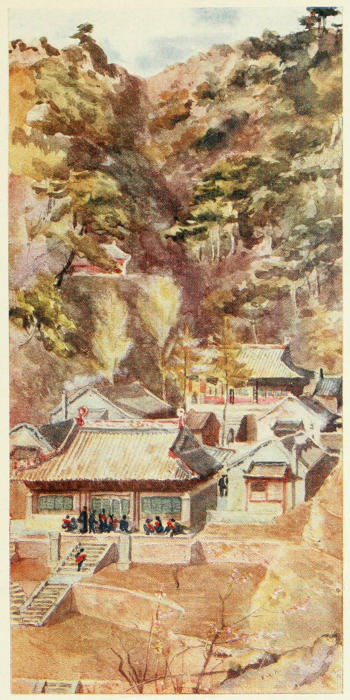

| Buddhist Monastery | 53 |

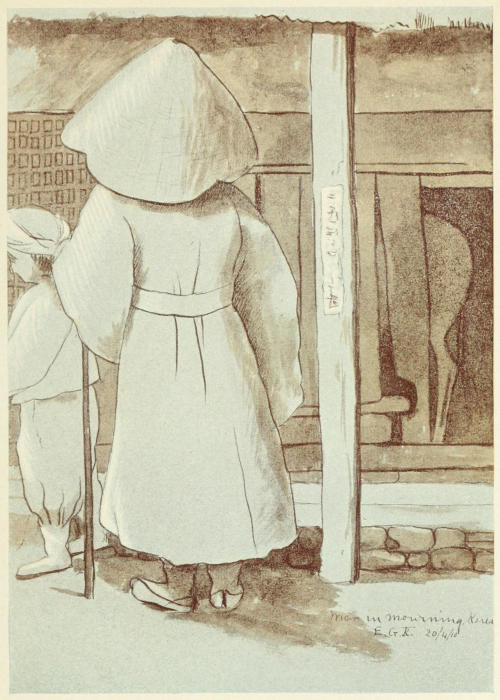

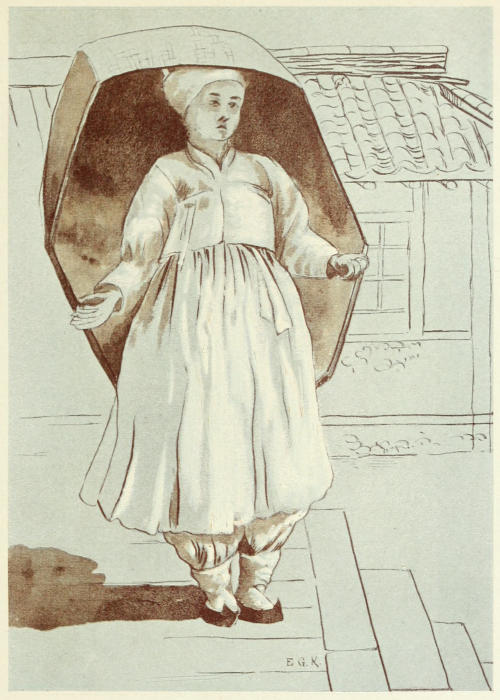

| Korean in Mourning | 69 |

| Coy Korean Maiden | 76 |

| Korean Woman | 94 |

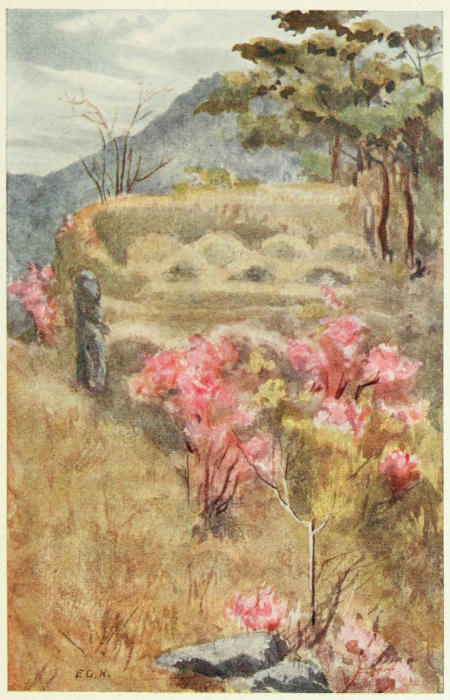

| Empress’s Tomb | 102 |

| Korean Graves | 103 |

| (A) Fusan; (B) Korean Village | 108 |

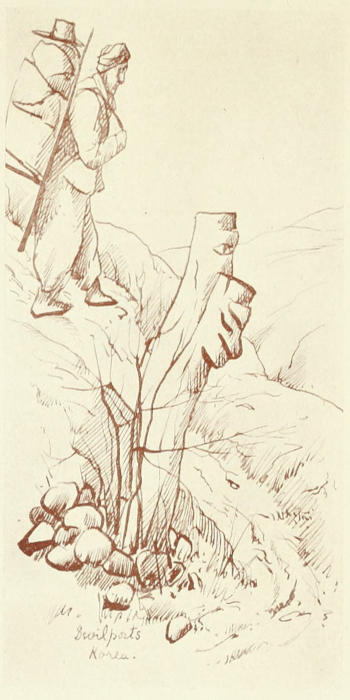

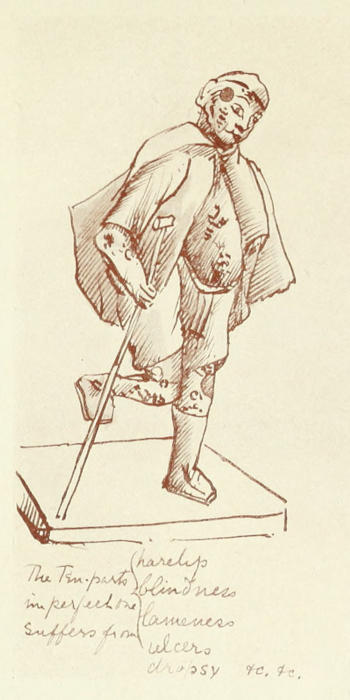

| (A) Devil Posts; (B) “Ten Parts Imperfect One” | 118 |

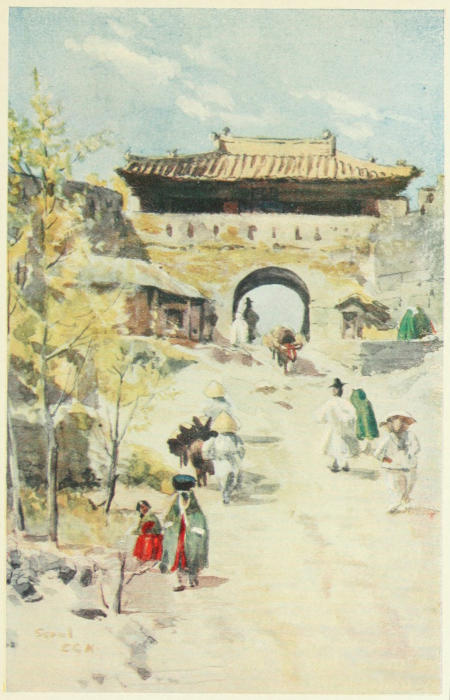

| North Gate, Seoul | 131 |

| Mohammedan Mosque | 145 |

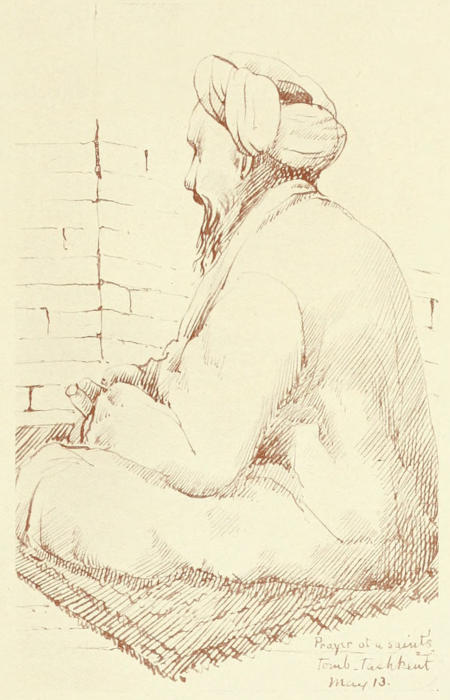

| Prayer at a Saint’s Tomb | 184 |

| Tamerlane’s Tomb (Interior) | 190 |

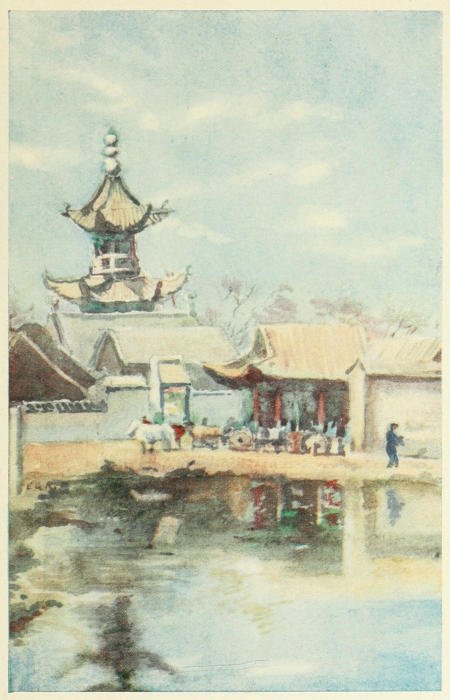

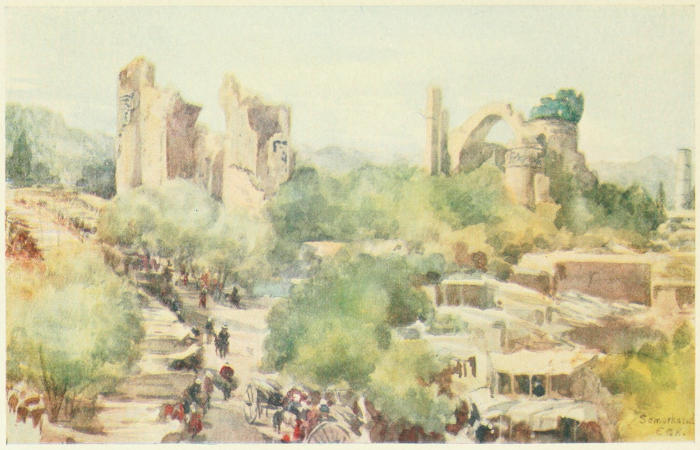

| Samarkand | 211 |

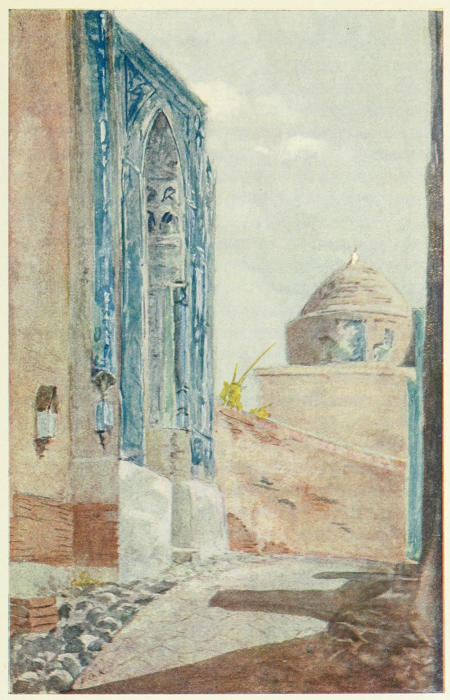

| Hazréti Shah Zindeh | 215 |

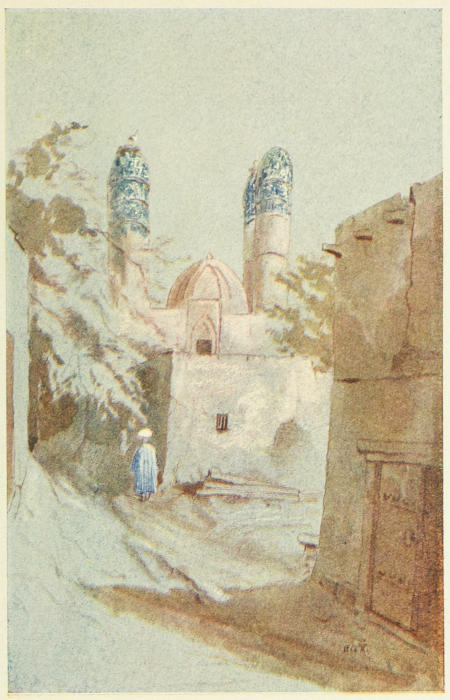

| Mosque at Bokhara | 226 |

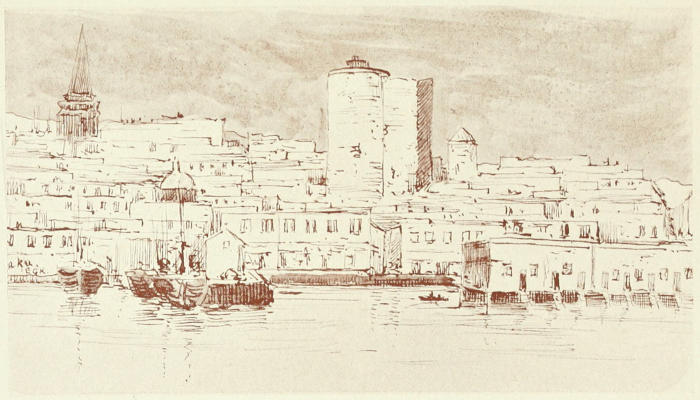

| Baku | 231 |

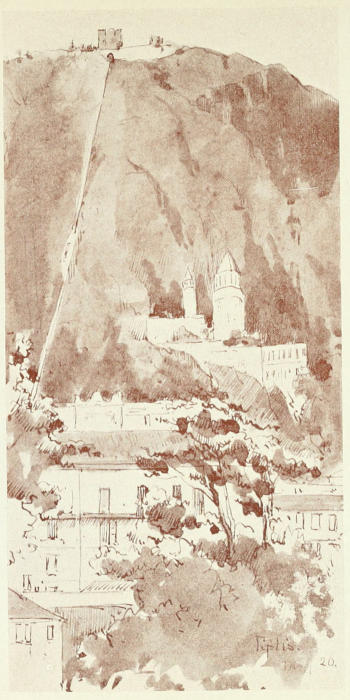

| (A) Tiflis; (B) A Persian | 233 |

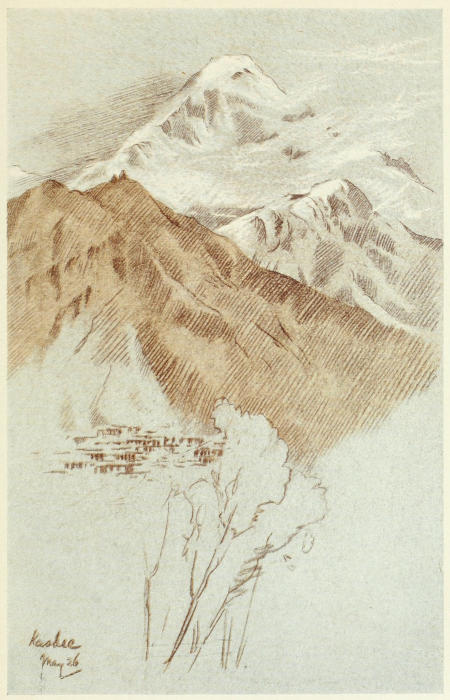

| Mount Kasbec | 236 |

There is always a thrill of expectation for the genuine traveller on crossing the frontier into an unknown country, which even the sight of the custom-house fails to dispel. In the case of Manchuria we were fortunate enough to escape the custom-house altogether, as having no registered luggage we only received a perfunctory visit from the politest of officials in our railway carriage at about 11 P.M. While all the rest of the travellers had to turn out and spend an hour or more in an offensive-smelling office, we comfortably went to bed and awoke next morning to find a glorious, dazzling sun shining on the snowy plain between Manchuria (town) and our terminus, Kharbin. The railway station is in the Russian town, which has been built up round it, and still looks painfully new: it lies on the banks of the great Sungari River, at the junction of the Trans-Siberian line with the line to Moukden and Peking. After a night’s rest in the Russian hotel we started[4] for Hulan, a Chinese town about sixteen miles to the north of Kharbin.

No Chinese vehicle is allowed in the Russian quarter, so we were obliged to take a droshky to the Chinese town, about a half mile distant, where our belongings were transferred to the sleigh, which was the only possible vehicle for crossing the open country. It was of a most primitive description, a sort of raft on runners, with a little straw on it covered with a rug. Our luggage was somewhat insecurely corded on, and we seated ourselves in the midst of it, only too soon to become acutely aware of the extraordinary number of corners which it possessed. Between the shafts, which consisted of two sapling birches denuded of their branches, was a shaggy pony, and another little pony ran alongside to give what further assistance he could, both animals having a miscellaneous harness of bits of old cord, which looked incapable of enduring any strain, though the event proved quite the contrary. We passed through the old town, which was gay with New Year decorations, the doors all bright with tutelary deities, freshly pasted up. Already the streets were filled with traffic, heavily-laden waggons of corn drawn by teams varying from four to eight, stacks of straw on rafts, fitted with runners similar to those of the one we were on, and all the various equipages likely to be found in such a nondescript place. The drollest of all was a little wooden house on runners, with a tall chimney, which we supposed to be on its way to some other permanent position. This, however, proved to be the[5] bus plying daily between Kharbin and Hulan, the place of our destination. It contained eleven passengers inside, and a stove. Outside was a heap of bedding on a wooden box tied on a narrow ledge at the back, upon which lounged another passenger.

It was desperately cold and almost impossible to keep one’s extremities warm, but the Chinese cope successfully with this difficulty. Nearly every one wears ear muffs (some of them beautifully embroidered and fur-lined), or big turned-up collars as high as their heads, or caps coming over the ears, and at the other extremity large felt boots. Passing through the busy town we plunged down into the river-bed of the Sungari, a most perilous descent, as the sledges slither away and sometimes turn completely round, unless the driver dexterously contrives to push them into a convenient rut. We passed one heavy cart that had turned completely on to its side, while yet another was being dug out of a rut with a pickaxe. The ponies show their mettle, and though they have the worst of tempers, and not infrequently give a sudden bite to the passers-by, they work with a will to drag their often too heavy loads over the difficult ground. We passed the landing-stage, whence in summer the steamers ply daily up to Hulan.

After struggling up the farther bank we passed over a bumpy plain for several hours, with various incidents to mark the road. Our umbrellas soon disappeared, then a collision sent a basket flying. Sometimes we were in imminent peril as some passing vehicle would[6] skid violently; once I thought escape was impossible, as a large cart crashed into our side, missing my arm by a hair’s-breadth, but we strove—I hope not unsuccessfully—to imitate the Chinese imperturbability of appearance. During one of our halts for repairs we were overtaken by the above-mentioned bus, and, behold! there was the Chinaman still on the back of it, trying to take a nap. We passed and repassed the vehicle, and he was always in the act of trying to sleep in some different attitude, but apparently never succeeding—the only Chinaman I have ever met who failed to sleep in any attitude whatever!

These plains are very fertile, and as soon as spring comes there is a steady stream of workers to be seen arriving from China proper, especially from the province of Shantung, to which they return when the harvest is ended. Many come to accumulate enough money during eight or nine years to buy land and bring their families up to live here. In fact we met some emigrants already arriving with all their scanty possessions. The Chinese Government is now waking up to the importance of colonisation on the borders of the empire, in order to check the sure and steady pressure of the Russians from without.

As we approached Hulan we came to another river to be crossed, but not nearly so large a one as the Sungari. Few foreigners come to such an out-of-the-way corner of the empire, so people came hurrying out to see us, calling to one another, “Come and see the shaggy women!” “These shaggy women[7] are tip-top!” The expression “shaggy” seems to have been first applied to the Russians, who wear their hair somewhat loose and long, but it is now the common designation for foreigners of all nationalities.

We travelled slowly, though occasionally our little ponies would break into a trot; then the driver would leap into the air, fold his legs beneath him and alight seated cross-legged on the cart, with a solid thud, like some gigantic frog. Hulan is quite a Chinese town, and indeed Manchuria is rapidly becoming populated with the Chinese, for whom its fertile plains offer an excellent home. The old Manchu towns are in a decadent condition, and can only hope for a fresh lease of life by new blood being introduced from the south. No wonder the Japanese cast covetous eyes on the land where crops produce an increase of 100 per cent. The crops are mainly wheat and beans, both of which are being largely exported to Britain. Great quantities of oil are obtained from the beans, and the refuse is made into large flat cakes, nearly as big as cart wheels, which form excellent fuel. The price of beans in the north is three times as great as it was a year ago, and the people in Manchuria are on the whole more prosperous than elsewhere in the Chinese Empire.

On Sunday morning we attended service in the Mission Hall, and received a warm welcome from the people, to whom we were formally presented at the conclusion of the service. The Mission is still in its infancy, but promises well, and when the medical[8] side is started will make more rapid progress. The next day “the faithful of Hulan” sent us gifts of cakes, and asked when we were leaving, that they might speed us on our way. We left too early, however, to go and thank them in person, as we had a four hours’ sleigh ride in order to catch the express at Kharbin, which only goes twice a week direct to Moukden. Unfortunately we had mistaken the day, and we doubly regretted that we had not waited to return the courtesies shown to us.

The first section of the railway line running southwards is still in the hands of Russia, and one’s attention is continually arrested by the large numbers of soldiers who are kept all along the line to guard it. Kwan-cheng-tze is the terminus of the Russian line: it is not quite half-way from Kharbin to Moukden. The Japanese call their station at Kwan-cheng-tze Changchun, which is rather puzzling to the traveller who is unaware that the place boasts two names. All passengers have to change trains here.

We had a leisurely journey across the plains, and arrived at Kwan-cheng-tze about 8.30, our halting-place for the night. It boasts a brand new Japanese hotel just opposite the station, which was radiantly clean and fresh, such a contrast to the Russian one at Kharbin. There was no lack of attention, for the Chinese boys flew to do our bidding, and fetched us tea unbidden. In the morning we started at 8.30 on the Japanese section of the line. The cars are long open corridor ones, and kept admirably clean, but one[9] misses the privacy so dear to the Englishman. All day long we slowly wended our way southward, stopping at many stations of a mushroom growth: it requires no imagination to fancy yourself back in Europe as far as the houses are concerned, but the people are quite out of keeping with them. The train had a sonorous bell attached to the engine, absolutely like that of a church, which heralded our approach to the stations. At almost every station there is a little house where hot water is to be obtained; the moment the train stops out dash numbers of Chinese, carrying their teapots, which they get replenished. We had no need to bestir ourselves, as the conductor was most attentive and kept us well supplied. The trains always have Japanese military officials on board, who usually go only short stages, being replaced by others whenever they get out. The trains are very crowded, and in the third class they are packed like monkeys in cages: some of the carriages have three shelves one above the other, on which the passengers lie, and as they are lighted at the top by a single dim candle, at night the top man certainly has the best of it.

At 6 P.M. we steamed into Moukden punctual to the minute, and found a deafening crowd ready to lay hold of the passengers. We were greeted by a man possessing a few words of English, and able to understand where we wanted to go, so we were glad to entrust ourselves to his care. He even satisfied any curiosity we might have had as to the personal[10] appearance of our host, whose main feature, judging from the description, was a huge moustache. The drive was thrilling, and the five miles were none too long; it was the New Year festival, and all sorts of things were to be seen in the thronged streets. Brilliant moonlight illuminated the city from above, and lanterns and fireworks lit it up intermittently from within. A short drive brought us near a thoroughly Burmese dagoba of old times, and then through a horrible iron archway of the worst type of modern times. Farther on we passed through the gloomy gateway in the big city wall, and found an almost impenetrable throng of sightseers. Our driver had no longer a chance of pointing out interesting buildings, and giving us details of his faith, &c., with which he had varied the earlier part of the drive, for he was obliged to keep up a monotonous shout of “hech! hech! hech!” only varied by what sounded like “hurry on, hurry on!” a much needed injunction to his steed. After about an hour’s drive we reached the group of Mission buildings, hospitals, schools, and dwelling-houses situated on the river bank, which is radiant with lotus blossom in the summer-time. But I must not begin describing the charms of Moukden at the end of a chapter: it demands one to itself. As the relation of Manchuria to China is but little known, it may be of interest to the reader to have the brief account which forms the beginning of the next chapter, but after this warning it is easy for those who are not interested to skip the next four pages.

The story of the rise of the Manchu dynasty is like a romance, and no parallel to it is to be found in the pages of history. In the middle of the sixteenth century there was no Manchu Empire, and the Manchus themselves were wild, uncultured barbarians without any written language, living in caves which they hollowed in the earth, and engaged in constant warfare with other tribes living like themselves in the northern part of that country which we call Manchuria, the central and southern part being inhabited by the Chinese. In the year 1559 Noorhachu was born, with the prospect of becoming ruler over six little hamlets; by the year 1616 he had conquered all the adjacent tribes and founded the Manchu kingdom, receiving from the “great Ministers” the title of Ying Ming—“brave and illustrious.” Noorhachu’s military conquests and singular political sagacity alarmed the Chinese, whose frequent attacks and whose murder of his father and grandfather had roused his deep-seated enmity. He prepared an army of picked men, and drew up a paper of “seven hates,” addressed to the Emperor of China.[12] Instead of despatching it to the Emperor, he addressed it to Heaven, burning the document with full sacrificial rites, after which he started his campaign (1617) by attacking the Chinese in the territory east of Moukden. In the midst of this campaign he was recalled to his capital, Hingking, by the news that a Chinese army of 200,000 men was approaching. On reaching Moukden this force divided into four armies of equal size: they were all in turn defeated by the smaller forces of Noorhachu within the space of five days, the number of killed being computed at 45,000. After one month’s rest he led his victorious troops to the conquest of Moukden and Liao Yang, and at the latter place he built a palace for himself and made it the seat of government.

Noorhachu, or as he was afterwards styled, Taidsoo = the Great Ancestor, was far-sighted enough to recognise that his only means of holding the large territory which he had won was by wise and good administration, and in this he was successful. In 1625 he retired to Moukden and made it his capital; in the following year he died there, after an unsuccessful campaign against the Chinese. They were led by a determined general who brought (for the first time) “terrific western cannon” against him, which had been cast by Jesuit missionaries.

FOO LING TOMB, MOUKDEN

Noorhachu was buried in the Foo Ling tomb, east of Moukden, a fitting resting-place for the great founder of the Manchu dynasty. It was during his son’s reign that the Manchu dynasty was firmly placed[13] upon the throne of China in the person of Noorhachu’s grandson, a boy of five years old (1644). His father had been summoned by the Chinese to aid them against several hordes of rebels who had devastated the empire, and he sent a powerful army led by his brother. The Manchus, after defeating the rebel army, marched on Peking, where Li Dsuchung, the most noted rebel leader, had entrenched himself, and where the last of the Ming Emperors had in consequence committed suicide. Li Dsuchung had indeed proclaimed himself Emperor in his stead, but after a reign of one day he fled from the city at the approach of the Manchus, was pursued by them, and severely defeated. The Manchu general at once sent for his nephew—the ninth son of the reigning monarch, a child of five years old—and placed him upon the throne, himself acting as Regent. The new Emperor received the title of Ta-tsing, or “Great Pure”—the name of the present dynasty. The Regent was an able ruler, and soon succeeded in dispersing the rebels and restoring order throughout the empire. At the end of six months comparative peace had been established, and the Regent issued a proclamation that all who submitted to the new rule would enjoy the same rank, position, and emoluments, as they had done under the Ming dynasty.[2] He ordered sacrifices to be offered at the Ming tombs, and that a tomb should be erected[14] for the last of them, where sacrifices should also be offered. He postponed the enforcement of the humiliating law requiring change of dress, the shaving of the head, and wearing of the queue and Manchu cap, and he promised those who complained of the neglect of etiquette and music among officials, that proper attention should be given to this matter as soon as war was at an end. It is an interesting fact that the Manchus should afterwards have so completely succeeded in imposing their dress on the Chinaman, the wearing of the queue becoming universal; but equally interesting is it to observe that the women never could be made to adopt it. The Manchu woman’s dress is to this day quite different from the Chinese, from its wonderful wing-like head-dress down to its large shoes. The Chinese woman refused to unbind her feet, and was in consequence never admitted within the precincts of the palace at Peking. In fact it may be stated that whereas it is impossible to distinguish between a Chinaman and a Manchu, there is no part of a Chinese woman’s dress which is quite the same as a Manchu’s. The latter have different styles of arranging their hair from the spreadeagle style, so commonly seen in Peking, to the curious one shown in the sketch (see next chapter), and also wear different kinds of shoes—some with a heel attached to the centre of the sole, others with a flat white sole some two inches thick.

The foregoing historical details are mainly drawn from Dr. Ross’s book, “The Manchus, or the Reigning Dynasty of China.” The uniqueness of the story lies[15] in the fact that when the Manchus conquered China they were merely a horde of savages attacking a highly educated people, infinitely their superiors in number and resources. They not only conquered them, but for centuries they imposed their yoke upon them, always hated, yet always obeyed. As the centuries elapsed the Manchus grew weaker in their own country, and never fused with the conquered race. In China proper they still live apart; walled Manchu cities may be found within many walled Chinese cities; and it is only last year that the stringent rule forbidding Manchu women to marry Chinese husbands has been rescinded. It needs no explanation to see why the opposite rule held with regard to Manchu men marrying Chinese wives, who, ipso facto, lost their nationality.

I have tried to show in the foregoing pages how the Manchus won their position in China, and also how the southern part of Manchuria, including Moukden, was originally Chinese. Those who wish to wrest it from China are seeking to take an integral part of the empire. No one who visits Moukden can fail to see that it is a thoroughly Chinese city, with its magnificent walls and gateways, and the big drum tower and bell, like the one at Peking. Alas for the modern utilitarian spirit! Already they are beginning to pull down the fine old gateways, and to replace the inimitable shop fronts with shabby imitations of European ones.

It was cold weather when we walked through[16] those fascinating streets, and in the fish shops we saw quantities of frozen as well as dried comestibles. Game was plentiful and cheap, and the frozen deer had quite a life-like appearance, standing waiting for a customer. In one street nothing but boots was being sold, and the fact was evident from afar, for outside the shops were hung gaily painted effigies of boots, some two feet in length. Above some shops were dragons, over others tigers, or the phœnix, or lotus blossoms all painted in every colour of the rainbow, and hanging from them signboards bearing the name of the shopkeepers. The cash shops have almost a screen of strings of gigantic cash dependent from the eaves. The curio shops still contain things to charm the soul of the artist, though every day sees their treasures diminishing, to be replaced by modern imitations. The glorious jade that used to be obtainable is scarcely to be found, and the bronzes have mostly been carried off to the West; still one hopes for the best, and carries off a few things, which if not so old as they boast to be, have at least an air of antiquity and some noble suggestion of the glory of the art of the Ming dynasty.

Our first expedition at Moukden was naturally to the Foo Ling tombs to see where the great founder of the Manchu dynasty lies buried. It is disappointing to be unable to gain information as to the date of the tomb, but no doubt the Manchus adopted the architecture and arts of China at an early stage of their conquest.

It was by no means a promising morning when we set out, but our time was limited, and we had persuaded the doctor to take an unwonted holiday from his strenuous labours, so delay was impossible. Where no guide-books are obtainable, it is doubly valuable to have kind friends willing to place their knowledge at your disposal, and doctors are skilful at smoothing other things as well as pillows; in fact I can give no better advice to travellers than to try and secure the help of the medical missionary—the busier the better—as a guide to all that is best worth seeing in the foreign field. Dr. Young had kindly procured for us the requisite permit to visit the tombs, which can only be obtained through the British Consul. We set out in a weird glass chariot, quite suggestive of Cinderella’s coach; it had windows the whole way round, and was lined with mouse-coloured plush, not to mention a fine mirror opposite to us. We had a retainer standing on a step behind, who spent all his time jumping on and off, as he required to lead the horse round every corner and over every obstacle in the road. Passing outside the city we saw an endless stretch of graves beyond graves; then we came to a beautiful park-like place where lilies of the valley grow thickly in the spring—but alas! people are digging them up so ruthlessly, that it is to be feared there will soon be none left. The trees seemed to grow finer and finer as we neared the tombs. The wall surrounding them has been damaged by its occupation during the war, when the Japanese troops took[18] possession and were attacked by the Russians: the wall is riddled by bullets, but it is astonishing how comparatively little damage had been done. The gateway is beautifully decorated with green tiles, and there are handsome large green medallions set in the Venetian red wall. Inside is a fine avenue of hoary trees leading to the main avenue, in which are some curious stone animals; these are so familiar to us by photos and by the description of other travellers, that it is unnecessary for me to attempt it. They form but a detail of the fine effect which is created by the lofty buildings among the trees, enclosed within a high wall. The colouring of the building—mellowed by time—is superb, and as we saw it under the fast falling snow, was most impressive.

Some difficulty attended our entrance despite the permit, but the doctor’s tact overcame it, and once inside they were most civil to us, and became quite interested when I began to sketch. The actual grave of Noorhachu, or Taidsoo, the grandfather of the first Manchu Emperor of China (Ching dynasty 1644), is a lofty mound at the far end of the enclosure, and surrounded by a wall of its own. The entrance by which the ruling Emperor approaches the tomb is very fine, a handsomely carved marble pailow surrounded by trees, and as we looked at the whole group of buildings from the top of the wall, along which there is an excellent walk, they form a most impressive sight. The trees are full of mistletoe, but of a different species from ours; it has either yellow[19] or scarlet berries, and in some trees we saw both varieties.

There are many interesting monuments in Moukden, but I venture to think this is the finest of all. The design is copied from the Ming tombs near Peking, and it is said that it was originally planned to carry away the stone animals from the former in order to use them for the Moukden tombs. This design was frustrated, however, for a descendant of the Mings accidentally heard of it, whereupon he at once went and mutilated all the stone beasts, knocking off the ear of one and the beard from another, and thereby rendering them useless. While this explanation is merely a tradition, the fact remains. The Ming tombs, forty miles north of Peking, are designed on a much larger scale than the Moukden ones, and cover a distance of several miles in length, as compared with acres in the case of the latter. In my opinion this detracts considerably from the effect, as only one detail can be properly seen at a time; first the fine marble pailow of five gateways, then at varying distances other gateways (very dilapidated), then a square tower containing a stone tablet on a tortoise, then a dromos of stone animals and warriors facing one another, with a considerable space between each couple, so that the sixteen couples extend over a space nearly a mile in length. Between them and the tombs is a considerably greater distance, and whereas the above-mentioned memorials are all in a straight line, the thirteen tombs are arranged in a fan[20] shape at the base of the hills which enclose the end of the valley.

These Peking tombs date back to the time of the Ming dynasty, which ended in 1644, and the Moukden tombs are considerably later. Their whole design is taken direct from the former, and there is no attempt to introduce any Manchu characteristics. The reason for this is obvious; the Manchus were emerging from a state of barbarism, and possessed no architecture worthy of the name.

After the tombs the most interesting building at Moukden is the palace, for which also an order has to be obtained through the Consul. We visited it twice.

This palace is thoroughly Chinese in appearance (I failed to ascertain its date, but it is at least some centuries old), with its gorgeous golden roofs and Venetian red walls. The façades are decorated with coloured tiles of great beauty and infinite variety of detail: they challenge comparison with some of the majolica most highly prized in Europe. Under the wide eaves there are finely carved dragons, stretching their sinuous length from end to end. The buildings are ranged court beyond court, with a fine staircase leading to the innermost one at the back. But the main object of the visitor is to see the priceless treasures locked up in its rooms, for they contain the most valuable possessions of the Chinese throne. Unfortunately, when admittance has been obtained, it is not easy to see the treasures, for they are carefully wrapped up in cases, or stacked in hopeless confusion in cupboards,[21] and are taken out one by one and laid on a table for the visitor to see them, and then put away again. First we were shown imperial robes, studded with pearls and jewels, then jade-mounted swords. Jade is considered by the Chinese to be the most precious of all stones, and it is one of the hardest to cut. “It was first brought to England from Spanish America by Sir Walter Raleigh,” says Bushnell (“Chinese Art,” p. 134), and he derived the word “jade” from the Spanish piedra de hijade—“stone of the loins.” Vessels of jade are always used in the Chinese Imperial ritual worship, and must be of various colours, according to the particular ceremonial in which they are employed.

After showing us these things the officials began to lose their distrust, and invited us to come inside the enclosure and peer into the dark cupboards, whence we picked out things that looked particularly attractive, but found that the waning light prevented our doing justice to the opportunity.

It was on our second visit that we were shown the much more valuable collection of bronzes and porcelain, the door to which could only be unlocked after prolonged effort, and in the presence of special officials. Other visitors besides ourselves were anxious to enter, but a special permit was required, and they were sent away disappointed. The porcelain was piled in endless heaps in glass cases, which probably remained unopened for decades, and there was no attempt at classification. The beauty of colour and design could be[22] but imperfectly realised, as sets of bowls or dishes were all piled in one another, so as to occupy the least possible space, and there was but little variety in proportion to the large quantity of china displayed. A visit to the British Museum gives a much better conception of this form of Chinese art. It was much the same case with the bronzes, and it was even more difficult to see them than the china. There was one fine example of the “gold splash,” which is so well represented at the South Kensington Museum in Mr. Behren’s collection. To my great disappointment there was little variety of design. It is to be hoped that the Chinese may be sufficiently imbued by the modern spirit to make them copy (to a certain extent) the arrangement of our museums, so that the art treasures contained in the palace may be more accessible to visitors. Outside the palace were the curious fences known as “deer’s horns,” which are also to be seen at the great tombs and outside official buildings. They are long pieces of wood set at right angles to one another as closely as possible, and running through a long heavy beam. The lower ends of the cross pieces are heavy, and are set into the ground, the upper ones taper to a point: altogether the “deer’s horns” form a strong, though simple, barrier. They are usually painted red.

After seeing the palace we visited the fine church, built by the native Christians after the destruction of the former one by the Boxers in 1800. It seats several hundred people, and has a native pastor. It may[23] interest readers to know that among the State papers found during the Russian occupation of Moukden was a description of the destruction of the property of the Christians. This was written in Manchu, which is quite different from Chinese writing, and bound in imperial yellow silk, enclosed in a yellow silk box and sent to Peking. There it was countersigned by the late Emperor and late Dowager Empress, and sent back to Moukden to be placed in the State archives. Could any more conclusive proof be found that the Boxer outrages were sanctioned by the Court at Peking? We were privileged to see this interesting historical document.

At the time of the Boxers all the missionaries in Manchuria were obliged to flee, some without time to take even necessary clothing with them. One of the most popular doctors learnt afterwards that the robbers in a certain village had planned to carry him off in order to save him from the Boxers! It is impossible to overestimate the influence of the medical missionary, and no mission field has been more favoured in this respect than Manchuria. The medical mission work was started at Moukden in 1882 by Dr. Christie, who has steadily built up the work there, and whose new hospital is the model for what such institutions should be. Despite the prejudices of the people, the work has steadily grown. The renown of the foreign doctor has spread for hundreds of miles, and the message which is nearest to his heart has been carried into remote villages in the Long White Mountains by[24] patients who return from the hospital not only cured, but also imbued with the missionary spirit which has brought a new life to them. The respect which is felt for this work is shown in no way more clearly than in the fact that when the hospital was obliged to be left for ten months during the war between China and Japan, the buildings with their contents were left absolutely unharmed.

Not so fortunate, however, was the hospital during the Boxer time, for all the buildings were destroyed by fire, and when they might have been rebuilt, another desolating war swept over the country. The missionaries had returned and had their hands more than full, for Moukden was the refuge to which crowds of destitute Chinese were driven. No less than seventeen refuges, containing some 10,000 people, were under the care of the missionaries, for the officials thankfully recognised their efforts and cooperated with them, doing similar work themselves. There were as many as four hospitals being carried on at the same time, for not only were there numbers of wounded, but epidemics of smallpox and fever spread among the refugees.

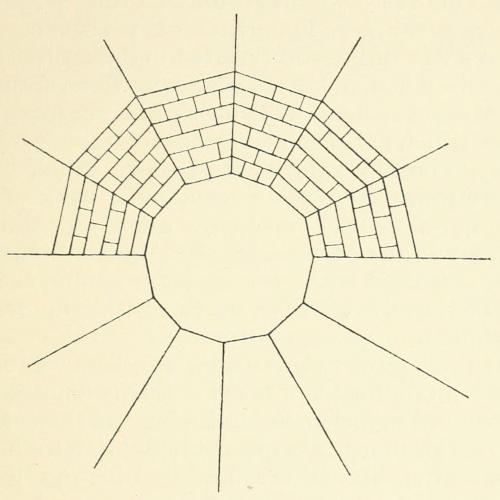

When at last the time came for building the new hospital, the money granted as an indemnity for the destruction of the former ones by the Boxers was wholly inadequate, for the price of everything was more than quadrupled. The Chinese were not slow to show their sense of indebtedness for the unstinted labours on their behalf, and the new buildings, owing[25] to their generosity, were built on a larger scale than before. The Japanese, too, came forward with most generous aid, in return for the work that had been done for their wounded during the war. Marshal Oyama sent a donation of about £100 for the Red Cross work, and ordered all the wood required for the buildings to be sent up by rail, free of charge, from Newchwang. This was of the greatest importance, as there was no seasoned wood to be obtained in Moukden, and it meant a saving of several hundred pounds. The Viceroy sent a gift of over £600, to which he added another £150 when he opened the new hospital. Another friend carted all the bricks and tiles; a director of the Chinese railway ordered all the requisite Portland cement and floor tiles to be brought up free of charge from Tang Shan to Hsin Muntun, and others helped in various ways. No wonder the hospital is such a splendid success, when it has such workers and such friends! It has several wings radiating out from a long central corridor, with a fine operating theatre at the end. There is an X-ray apparatus and other special furnishings.[3] There are outbuildings for students, &c., a laboratory and class-rooms, besides the preaching hall, where service goes on daily.

But what, it may be asked, is the staff for this large[26] work? The surprising answer is one man; only last year has a second been appointed, to give a part of his time to assisting Dr. Christie. He has, of course, trained Chinese assistants to help him in the work, and very efficient some of them are, and two Chinese hospital evangelists, who follow up the cases, but the bulk of the work falls on himself. What would our doctors at home think of having to perform ten operations in a day, after handing over nine minor ones to the assistants? But that was the case the day we visited the hospital. It accommodates 110 patients, and the beds do not lack occupants. The attendance of out-patients is frequently 200 or 300 per morning, so that the attendance for the year is very large, last year numbering over 26,000. After the recent visit of the Naval Commission returning from Europe, a request came for medical aid for 200 men with badly frost-bitten ears, as the soldiers are not allowed to wear ear-muffs when on parade. It is not etiquette to wear ear-muffs or spectacles when speaking to any one, and the curious custom is now coming into fashion of touching the glasses instead of removing them. The hospital is a free one, but poor as are many of the patients, few of the in-patients leave without giving an offering, and many out-patients do the same. Some of the beds are supported from home, and it only requires £5 per annum to support one.

It will be seen from these figures how requisite it is to have a larger staff, and to undertake (what is now[27] being planned) a training college for the Chinese. The late Viceroy promised a yearly sum of about £420 for this purpose, but as he has been replaced by an anti-foreign Viceroy, it was feared that his promise would not be ratified by his successor. Despite the further fact that the new buildings are not yet begun, when the matter was placed before him he promised to consider it, and shortly afterwards sent word that the sum had been duly placed in the bank to the credit of the mission. The college will be a union one of the Irish Presbyterians and the United Free Church of Scotland, and may draw students also from the Danish Lutheran stations, the only other missionary society working in Manchuria. As there are now some 40,000 Christians there will be no difficulty in finding students, though it will not be entirely confined to Christians.

The course will be a thorough one, extending over five years after the preliminary examination, and diplomas will be given. The estimated cost of the new buildings and equipment is £2500, and two houses for professors £1500. An excellent site has already been obtained through the generosity of the Chinese, which is close to the hospital.

I have described at some length the medical mission here, and yet have done scant justice to it; of the women’s work a word must also be said. There are two fully qualified women doctors, and their hospital, with accommodation for seventy patients, is so crowded, that a new wing is now being added. They do a[28] large amount of work in the people’s homes, as many of the ladies are not to be reached otherwise, also they do work as far as time allows in the district round Moukden. When it is known that the doctor is coming, patients crowd to see her; and one realises a little the magnitude of the work when one chances to see the missionary come back utterly worn out by a two days’ visitation, having interviewed over 900 patients in that short space of time.

Women’s work in Moukden is not merely medical, but also educational. Besides the training of Bible women there is an excellent girls’ boarding school, for which new buildings (badly needed) are in course of erection. Great excitement was caused in the little community by the girls being taken, for the first time in their lives, to see an exhibition. It is rather disappointing to the traveller who thinks he is going to the genuine Far East to find it invaded by industrial exhibitions and school excursions, but alas, such is the prosaic fact.

We devoted a day to visiting the imperial tombs on the north of the city, and although it was the end of March, we suffered intensely from the cold, and had not the advantage of going in a glass coach as we did on the occasion of visiting the eastern tombs. The road was too rough, and even the solid droshky built in Odessa, and drawn by two sturdy beasts, was severely tested by the frightful ruts into which we were frequently plunged. The Russian driver was a capital, good-tempered fellow, and never hesitated to[29] drive through a quagmire or up a bank into a ploughed field when necessity compelled. After three hours’ driving we approached a fine bluff crowned with pine-trees, among which gleamed the golden roofs of the tombs, so we knew that our destination was at hand.

IMPERIAL TOMB, MOUKDEN

“Deer’s horns” palisades enclosed the wood at the base of the cliff, and we turned up a gully to the left of it. The road soon became very steep, and we left the carriage to climb up on foot. The view of the entrance gate among the trees as seen in the accompanying sketch, was peculiarly striking after the long drive over the dun-coloured plain, for as yet there was no sign of spring. Passing through the gateway we soon came to the lofty façade of the main enclosure, and a surly old guardian of the place came to challenge our entry. We produced the permit, which we had obtained through the Consul, and were kept a long time waiting before we were allowed to enter, but there was plenty to interest us in the scene. It was a sort of square, with the dwellings of the officials on either side, and at the lower end a small temple facing the plain below, down to which were long flights of steps, and then a steep paved incline the same width as the steps and with balustrades at the sides. Lofty pine-trees surrounded the place, and scattered amongst them at the bottom were stone animals and figures. At a short distance from the steps was the State entrance gateway, but that was closed. One could imagine how fine the effect would be to see a gorgeous royal[30] procession enter the gateway from the plain, cross the short level space under the avenue of pine-trees, and mount the long ascent to the towering, golden-roofed temples behind which the imperial tomb stands. The colouring in the brilliant sunlight looked very rich as it gleamed among the dark pine-trees.

Before leaving, we asked the man who had showed us round if we could have some hot water for tea, but he said there was none, so we took our things outside, and sat down to sketch and lunch. At first I could not think what was the matter, for the paint seemed thoroughly intractable; then it suddenly dawned on me that no sooner was a wet wash laid on the paper than it froze. Yet this was the last week of March, and midday, with the sun shining full on us. Sketching generally seems to be done under difficulties, and this trip more so than ever. It will be understood how doubly welcome was the sight of our guide returning to say that he had got hot water for us, and he took away our teapot and filled it, for all Chinese understand the right making of tea. As we were drinking it shortly afterwards, a pitiable figure came creeping up the hill, evidently suffering acutely from asthma. When we offered him a cup of hot tea a look of intense gratitude shone in his eyes, and when he had drunk it, still speechless, he drew himself up and made a European military salute, then passed slowly on to the gateway.

As we returned to the city we agreed that no one should fail to visit the tombs who comes to Moukden.[31] It is of course tiresome to have to get permits, and takes a little time, but there is nothing within the city that is half so picturesque as these two groups of tombs, to each of which a whole day should be devoted. Some inscriptions at the Foo Ling tomb, we were told, are quite unique, but the heavy snow when we were there prevented our doing justice to the fine details of architecture.

There is an unpromising-looking hotel at Moukden called the Astor House, but Americans who stayed there assured us it was quite comfortable, and every one passing through Moukden ought certainly to stop and see it, especially in view of its being so rapidly modernised. The old temples seem to be in a state of utter disrepair, and the most interesting one, the Fox Temple, will soon cease to exist. The worship of the fox is very common in Manchuria, and is especially incumbent upon officials, all Mandarins being supposed to do it, as the fox is the keeper of the seals of office. Doolittle, in his “Social Life of the Chinese,” says: “There is in connection with some of the principal civil yamens a small two-storied building devoted to the worship of his Majesty, Master Reynard. There is no image or picture of a fox to be worshipped, but simply an imaginary fox somewhere. Incense, candles, and wine are placed upon a table in the room of the second storey of this building, and before this table the Mandarin kneels down and bows his head in the customary manner, as an act of reverence to Reynard, the keeper of his seals of office. This[32] sacrifice, it is affirmed, is never performed by deputy. The Chinese believe the official seal of the Mandarin, after he has arrived at his yamen, to be in the keeping of the fox. They assert with great earnestness, and apparent sincerity, that if the Mandarin did not worship the fox on his arrival at his residence, his seal of office would shortly disappear in some inexplicable way, or some singular and strange calamity would certainly befall him or his yamen.”

We visited the Temple of Hell, where all sorts of horrible penalties are vividly depicted in stucco, and these are more terrible as indicating what Chinese punishments have been, than in suggesting what may be expected in the future world. The temples seem to be little frequented by the people, and it is only on certain occasions that the people flock to them. The ancestral tablets in his own home have the main part of a Chinaman’s devotions.

On our second visit to Moukden we had rather a rickety droshky, and were amused to see the way the driver arranged the luggage. The Chinese never make any difficulty about the quantity, for fear by so doing of losing a fare. The man therefore entirely filled his footboard with luggage, and seated himself on it with a large bag of bedding on his lap. We had not gone far when a wheel rolled off into the gutter, and we waited some time for it to be put on again, the luggage meanwhile being deposited in the road. The job was not satisfactorily managed, for we had to go very, very slowly, and have the wheel continually hammered on.[33] It began to rain, and in order to put up the hood most of the luggage had to be piled on the top of ourselves, and we found it, to say the least, both hot and heavy. At last our driver gave up in despair, and by means of signs made us understand that he would go and fetch another vehicle. When he returned with a cart the transfer was soon made, and our driver with great secrecy explained that he had bargained with the carter to take us to our destination for a certain sum. The difficulty then arose as to how we were to pay him, for we only possessed Japanese and Pekingese money, which he eyed with distrust, and declined to accept. We gave him, however, a rather liberal fare, and pointed to him to take it to a big shop, opposite which we were standing. There he was reassured as to its value, and came back smiling; he thrust his head into the cart with a final rejoinder to us only to pay the right fare to the carter, evidently feeling that we were liable to spend our money too lavishly.

From Moukden we made a flying visit to Peking and into Shansi, but as that does not come within the scope of this book, I shall take up my narrative from the point where we re-entered Manchuria on our return by the South Manchurian Railway. We were astonished to see the hundreds of emigrants going north: every train was packed with them. There was an accident on the line, a young lad of twenty having his leg badly crushed by the train preceding ours. First aid was rendered by the officials, who are trained to give it, and by means of a chunk of coal and some cord the bleeding was stopped, the ligature being so tight as completely to stop the circulation. The lad was put on a big sort of door and placed in the luggage van of our train, and the conductor came round as soon as we had started again to see if a doctor was aboard to give further aid. Our party provided one, and there were all necessary requisites in the shape of bandages, splints, permanganate of potash, &c., in the surgery at the junction farther up the line, so that the patient was made as comfortable as possible when he arrived there, and a message[35] was telegraphed to the medical mission at Hsin Muntun, which happened to be both his and also our destination. On arrival the doctor and assistants were waiting, and the young man was carried away at once to the hospital. Amputation was necessary, but the lad would not at first agree to it; however, just as we had finished dinner a message came to say that his friends had been summoned, and that both they and he were willing for the operation to take place, so no time was lost in performing it.

Next morning we visited him in the hospital, and found him looking quite comfortable, and not at all pale even.

In the early days of the railway there were countless accidents; people would drop things on to the line, and then creep under the train to pick them out, or step in front of it just as it was starting. We were surprised to find blue glass windows in many of the trains, but the explanation of that was, that being unaccustomed to glass, people were continually putting their heads through them as long as they were uncoloured! Even now the trains all approach and leave the stations extraordinarily slowly, and there is a great bell ringing in order to warn people off the line. Of course there are no overhead or underground passages for crossing the line, so that it makes accidents almost inevitable. They are taken with the usual Chinese stolid imperturbability.

Hsin Muntun is an interesting little town not far distant from Moukden, which we visited in order to[36] see the admirable mission work carried on there by members of the Irish Presbyterian Mission, having received a cordial invitation from one of the staff whom we happened to meet on the railway as we travelled south. The Irish and Scotch Presbyterians may be said to have federated in Manchuria, and work together with hearty goodwill. Though Hsin Muntun offered no striking characteristics, I had the good fortune to make sketches of the women there, with their curious head-dress, similar to that worn throughout the country.

In the women’s hospital were two widows, acting as assistants; they donned their best garments for my benefit, and may be seen in the accompanying sketch, saluting one another in the Manchu style. The Manchus always wear the hair dressed over a metal framework, either as in the sketch, or like a wide flat bow, and with both styles of head-dress a large bunch of artificial flowers is worn, and gold ornaments in addition. In winter a cap is worn out of doors, with fur round it, and embroidered strings hanging down behind, not to mention ear-muffs, an imperative necessity where the cold is so intense. We found that in the women’s hospital they decided to have the bulk of the accommodation in the shape of heated khangs, as in the homes of the people; these are brick platforms, used instead of bedsteads: they are greatly preferred by the patients. It may not be so sanitary, but the people feel much more at home on the khang, and as physical health is not the main object of medical mission work,[37] it is obvious that due regard must be paid to the likings or prejudices of the people among whom the missionary is working. The cost of medical mission work is heavy, and we were touched by the efforts to utilise to the utmost the money which had been sent from home for the buildings. The funds had not been sufficient to provide for a porch or front door, so a mat shed had been erected till the requisite money should be forthcoming. Efficiency does not depend on these things, but workers would be much encouraged if their supporters were more numerous, or more generous.

MANCHU LADIES’ GREETING

The men’s hospital is larger, and is complete—very simple, but thoroughly practical, and attracting patients from all the country round. Our visit took place at rather a slack time of year, and it was undergoing a New Year’s cleaning, as that is the occasion when all patients, if possible, return to their own homes. After visiting both the men’s and the women’s hospitals we went to the girls’ school, and met with a great surprise. Three years ago the school was not in existence, and when the children first came, mostly from Christian homes in neighbouring villages, they were absolutely ignorant of reading and writing. Now we saw them examined in geography, arithmetic, algebra, singing, and drilling. There are about fifty boarders: they are under the charge of a Chinese matron, with four senior girls as monitors to help her. These girls were examined last term along with the boys, who had been studying many years.[38] The best girl pupil obtained an average of 84 per cent. marks, coming out ahead of the boys in arithmetic, Scripture, and algebra. She got 100 per cent. for arithmetic, 95 for an essay, 96 for Chinese classics (memorised), and 85 for explaining the Chinese classics. The children’s sums were as neat and the figures as well written as one could wish to see, their maps excellent, and they answered the questions in geography on all parts of the world, pointing out the places on the charts on the wall. I am forced to admit that the examination in geography was more painful to us than to the examined, for we were required, without book or map, to ask questions on Australasia and South America, parts of the world with which I was sadly unfamiliar. We happened to go back into the schoolroom after school had been dismissed, and found a child who had not been able to point out on the map the way from Shanghai to England now receiving a lesson on it from the monitor. The Irish master told us the girls are “tigers” for work, and far keener than the boys, to whom education has always been open. We went into the courtyard to watch them drill, and here again we were struck with the success of the monitress, who had learnt the exercises from a book, with merely an explanation from the foreign teacher when she failed to understand it. The singing is entirely taught on the sol-fa system, and the children have already learnt to sing creditably simple part music. They are nearly all Chinese, but apparently there is little appreciable[39] difference between the intellectual ability of Chinese and Manchus. Morning school closed with two or three short prayers by the girls, and the repetition of the Lord’s Prayer: they always dismiss themselves. The education is free, but the children’s food is provided by the parents: they looked thoroughly well and happy, and comparatively clean, and none are allowed to have bound feet. They have a large measure of freedom, except that they are not allowed outside the large compound. The money for the building came in a way as unexpected as welcome. The missionary received word that an official desired him to come to the railway station to see him on his way through Hsin Muntun, and when they met, the official presented him with a cheque for 3000 taels in aid of the excellent educational work that he was doing. This enabled him to start building the girls’ school, of which he had to be not only the founder, but also the architect. In the same way the doctor had to design his house and hospitals, and superintend the building of them; no doubt the labour is far greater for a man without architectural training; otherwise the buildings seem to be quite as well done as the majority of houses, and at considerably smaller cost.

Leaving Hsin Muntun we started for Moukden, where the Chinese stationmaster had been asked to give us assistance in changing stations, so that we might not miss the train. He spoke a little English, and sent a man with us to look after our luggage in one cart, while we went in another. The road was[40] indescribable, for a thaw had set in, and oceans of mud added to the horrors of the way, emitting a stench which had lost nothing by six months’ frost. We were flung to and fro in the cart, and it seemed an endless drive. On arrival we rejoiced to see that the clock had not yet struck, though it was just approaching the hour for the train to start. As this was the Japanese line (the one which extends from Dalny to Kwan Chengtze), we had to get our money changed into Japanese yen before we could buy tickets, and were then told there was no train for three and a half hours. As our friends had sent to the station at Hsin Muntun to inquire, and been told that this train was running, we felt rather provoked, but found the explanation in the fact that it only ran three times a week, and this was not the right day. A pleasant little fellow took us to a comfortable waiting-room, and fetched us a kettle of hot water to make tea, but no sooner had we done this than another official came and turned us out in order to prepare a meal for a Japanese family, and we had to retire to a miserable little office. The Japanese line is well managed and clean: the Chinese attendant comes round at intervals with his feather brush, and is ready to provide you with hot water whenever you want it, and comes to brush you down before you leave the train. We were thankful to betake ourselves to the train as soon as it came in, although there was still an hour before it was due to start for Liao Yang. The journey is only thirty miles, but the ordinary trains take nearly three hours, and[41] one finds it rather slow and monotonous. When one thinks, however, of the pre-railway days, when you might not infrequently take the same length of time to do three miles, thanks to the ocean of mud which constitutes a road as soon as the spring thaw sets in, ten miles an hour seems wild speed.

Liao Yang was the ancient capital of the Liao Tong province of Southern Manchuria, and it is the most beautiful of Manchurian cities, for within the walls are orchards of plum, cherry, apricot, and pear, which look radiantly lovely against the sombre background of the walls. Originally it was not Manchu but Chinese, as I have pointed out on page 15. The Manchus tried to gain possession of it, but, failing in the attempt, they built a city for themselves on the other side of the river, which is called the New Liao Yang. In addition to the four usual gateways into the city—north, south, east, and west—there is one which is quite different in appearance, called the Korean Gate, through which the Korean envoys used to pass when bringing tribute. Through it there is a lovely view on to the river, with low-lying hills in the distance: the sketch is looking not out of the city, but inwards. Just within the gate is a dusty sort of waste place at the foot of the wall, frequented by scavenger dogs, and you may see, as we did, a wisp of straw in which a dead baby has been wrapped and cast out, for the Chinese do[43] not bury them, in the hopes that the ill-luck caused by the death of the child may be averted.[4] To this day the cart may be seen going round Peking to collect the little corpses, just like a scavenger’s cart.

KOREAN GATE, LIAO YANG

Just outside the Korean Gate we saw a cadet corps marching along in good style, with drums beating, and creating just as much interest as a similar one does at home. These city walls were in existence before the Manchu dynasty came (in 1644), and yet the bricks look as new in most parts as if they had just been built, and it is only where the Russians made breaches in them that they are at all ruinous; we found this to our cost when we wanted to climb down them after seeing the view. The dust had accumulated somewhat on the outer side, so we climbed up with comparatively little difficulty, and were well rewarded by the glorious panorama illuminated by the rays of the setting sun. The Liao River runs just outside the east wall, and the fields and distant hills wore the lovely golden colour of an Egyptian scene. Just below us the ferry-boat was conveying passengers, carts, mules, cows, donkeys, &c., from one shore to the other, and we watched a carter first getting his cart up the steep bank and then returning[44] to carry his fare, an old lady, up the bank on his back. A recalcitrant cow had to be hauled aboard by a cord tied to its front leg and by its bridle, but most of the animals seemed quite accustomed to the job. After watching them awhile we turned southward to where a range of hills bounded the horizon, ending with a peak loftier than the rest, and known by the Japanese as “Kuropatkin’s eye.” This ridge was held by the Russians during the war, and for six months previous to the battle of Liao Yang they were busy making defences between the hills and the city. The trenches and barbed wire entanglements were admirably executed, and it cost seven days of hard fighting before the Japanese were able to enter the city. Point after point was taken and retaken; the Russian ranks were mowed down like standing corn, and the Japanese displayed an equal courage, so that during those seven days the loss of the two armies was reckoned at 25,000 men left dead on the field. The Japanese general sat in a temple some miles away from the scene of action, directing the operations, but with the information coming steadily in from all points by telephone. He had pushed forward, leaving no means of retreat, and by the end of the battle he was at the end of his resources, victorious, but unable to follow up the victory. In England few people realised the tremendous struggle that was going on, and the magnificent prowess of the two nations. The Russian soldier mournfully asked, “Why do we come out here to fight?” but he fought valiantly[45] all the same. Eighteen months ago Kitchener sent a party of forty young officers from India to visit these battlefields, with Japanese lecturers to instruct them daily, while they sat taking notes on the hill-sides overlooking the plain. There was always one Japanese soldier present, who had taken part in the action, to describe his own personal experiences, which must have added a vivid touch to the technical details. The Japanese travelled lightly, and, fortunately for them, the standing crops rendered cavalry practically useless. The principal crop is millet, which grows fifteen feet in height, and the Russians crushed it down by means of improvised rollers drawn by horses. In the Japanese army everything is utilised, and is as compact as possible. A general was seen lost in study one day, and he explained that he had found a use for the little boxes in which the rations were carried and for the paper in them, but he could not think what to do with the string! During a plague of rats in the north the Japanese all provided themselves with ear-muffs, which they manufactured out of the rat skins.

One of the interesting sights at Liao Yang is the Fox Temple, which stands on a little hill, and is reached by a fine flight of steps. The worship of the fox is a purely indigenous form of worship in China; but it is mixed up with the other religions, and fox shrines may be seen in Buddhist or Taoist temples.

In the principal building was a Buddha, before which worshippers were offering cakes and incense,[46] and there was also a large bag of paper money on the altar. In an adjoining shrine were three large figures of the fox family, dressed as officials, with literary badges on the front of their robes. The old priest came in to remove some of the offerings for his midday meal, and on inquiry said he had often seen the fox come in, and that it was white. In one of the side doors is a hole, just like those to be seen for cats in old French castles, through which the fox is supposed to enter.

As we returned from the walls we watched a man flying a wonderful centipede kite, some sixty feet in length. The head was that of a dragon, with wide open jaws, and a red tongue; its eyes rotated in their sockets with a whirring sound, and it was painted gold, and pink, and blue. The sections of the body were round discs of green and pink paper on a light bamboo framework, with a stick about four feet long protruding on each side, and a tuft of feathers at the ends to represent the legs of the beast. This kite is a graceful object serpentining in the sky, and when at a considerable height, a messenger kite was sent up to it, which discharged a shower of crackers (?) on its arrival and then sped swiftly down the string again, having accomplished its errand. These kites sometimes require as many as six men to hold them, and a very strong cord is necessary.

Passing along the street we came to an interesting medicine stall, where four bears’ paws and some stags’ antlers were the most prominent goods. The latter[47] are in great request when they are in velvet, and hunters dig pits for the deer in the eastern mountains of Manchuria. Sometimes the hunter is robbed of his prey by the wily bear, who finds the antlers a tasty morsel, and gnaws them off before the hunter comes round to visit the pit. As medicine the antlers are dried and ground into powder. Other medicines on the stall were eagles’ claws, deers’ hoofs, and dried centipedes, about four inches long, attached to bits of bamboo. We bought one of these, and inquired what disease it is used for; “wind in the stomach,” was the reply.

All diseases in China seem to have their root in an evil temper, and it is not uncommon for patients so afflicted to come for medicinal treatment to the dispensary. The prescription of one of the lady doctors is as follows: “Go into a room alone, take a mouthful of mixture (a nice pleasant one), and hold it in the mouth twenty minutes before swallowing.” This remedy has excellent effects, and may be used in England with equal efficacy.

We were so charmed with the city of Liao Yang, that it required small persuasion to induce us to return there a month later in order to visit the neighbouring mountains of Chang Shan (a thousand peaks), and I shall let the account of it follow the present chapter. It was the last week in April, and all the fruit-trees and the elms were bursting into blossom and leaf, as we walked from the station outside the gate to the mission premises within it, embowered among orchards, and[48] the scent of lilac filling the air. The mission gardens were beginning to show signs of the loveliness which has won them a well-deserved reputation among travellers, and we returned like old friends to our former quarters. Life on the mission field soon cements friendship, and medical mission work must appeal even to the stubbornest heart. We had already visited the two hospitals, models of practical, unostentatious usefulness, with the excellent native staff trained by Dr. Westwater, whose name is a household word in the land. To him was due the fact that the town was saved from the horrors of bombardment by the Russian troops, and one has but to walk through the streets of Liao Yang with him to see how universal is the respect in which he is held.

There are various temples of different religions in Liao Yang, and we visited the Temple of Hell, where are depicted all the horrors of future punishment, than which nothing could be more ghastly than the Chinese conception. The grotesqueness of their realistic execution in coloured plaster fortunately took away some of the gruesomeness, and in one of the side shrines we found the extraordinary figure of the popular deity, called the “Ten Parts Imperfect One.” The sketch in Chapter XII. hardly does justice to the hideousness of the figure, which represents the main woes to which flesh is heir in China—lameness, blindness, dropsy, harelip, boils, &c. &c., and to this deity the people come to pray in all cases of sickness.

BLIND BUDDHIST NUN

We also visited a picturesque Buddhist shrine,[49] where an old blind nun lives, the owner of much property, and of the orchards adjacent to the mission property. We found her seated on the khang immediately behind the figure of the Buddha, where she has spent many, many years in meditation. She welcomed us with cordiality, and made us sit down beside her, while she entered into a long and intimate conversation with our host, whom she had not met for some years. The nun had a remarkable head, closely shaven, of course, under her black cap, and looked more like a man than a woman. She told us that she became blind when she was only six years old, and now she was seventy-nine. She felt our hands with the subtle, searching touch of the blind, and had not a little to say on them; we much regretted our ignorance of Chinese, as our feminine curiosity to know what she said was left ungratified. The conversation then turned on the great problems of life, both this life and the next, but she seemed entirely ignorant of Buddhist philosophy, and took refuge in futile platitudes; as regards the future she said, “We die, and there is nothing more.” It is disappointing to find how utterly ignorant they are of anything beyond the externals of their religion. The Taoist monks, on the contrary, boast many men of learning, and have more conception of real religion. I understand this is also the case in other parts of the Chinese Empire.

In contrast with the various temples nothing more charming could be found than the simple beauty of[50] the mission church. It is always difficult to arrange for parts of a building to be screened off without spoiling the effect of it as a whole; at the present time this is still considered necessary in China, so that the men and women may be separated from one another, also they have separate entrances. In the Liao Yang church the difficulty was ingeniously conquered by making the transept the women’s part, and diminishing the space of the nave where it joins the transept, by erecting a smaller arch on either side containing a screen. The pulpit, being in the centre, commands the whole building. This church was designed by an architect specially sent out by the mission committee, and it is of no small importance that such buildings should be carefully designed to be in harmony with the architecture of the country, and not to seem European. At the great World Missionary Conference at Edinburgh, stress was laid by speakers from all lands on the growing desire of native Christians to have their own national churches. To this end every detail must be studied; not only must religion be taught them in their own language, but the churches in which they worship must have a homelike feeling, so that nothing may suggest to them that Christianity is a foreign religion. When all is said and done it came from the East and not from the West, so that its externals at least should have as little Western colouring as possible.