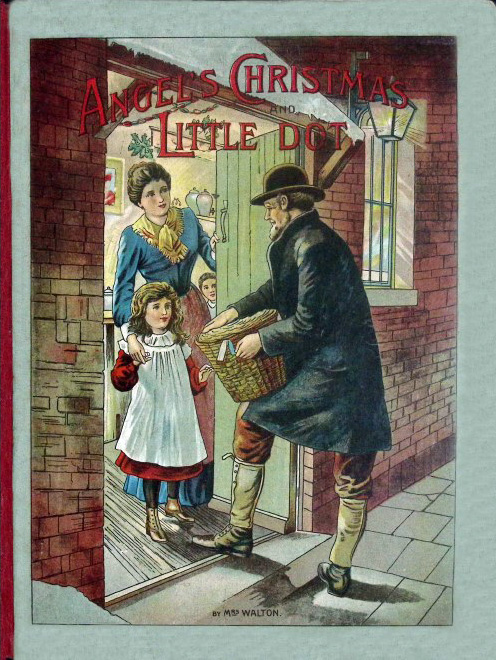

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

"HERE'S WRITING AT THE BEGINNING, MOTHER;

WHAT DOES IT SAY?"

AND

BY

MRS. O. F. WALTON

AUTHOR OF

"THE MYSTERIOUS HOUSE," "PEEP BEHIND THE SCENES,"

"CHRISTIE, THE KING'S SERVANT," "WINTER'S FOLLY," ETC.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 BOUVERIE STREET AND 65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

CONTENTS

CHAPTER III. LITTLE ELLIE'S SISTER

CHAPTER IV. THE LOUD KNOCK IN PLEASANT PLACE

CHAPTER VI. THE GREAT BIRTHDAY

CHAPTER I. OLD SOLOMON'S VISITOR

CHAPTER IV. LILIAN AND HER WORDS

CHAPTER V. DOT'S BUSY THOUGHTS

CHAPTER VII. THE LITTLE WHITE STONE

CHAPTER VIII. THE FADING DAISY

CHAPTER IX. OLD SOLOMON'S HOPE

THE WINGLESS ANGEL

FROM morning till night, poor Mrs. Blyth was hard at work with her great mangle.

It was a very dismal room; no one could call it anything else. The window was very small, several of the panes patched together with pieces of brown paper, and the dust and the spiders had been very busy trying how much sunshine they could keep from coming into the gloomy little room.

Yet one could hardly blame poor Mrs. Blyth very much, for she had a hard life and plenty to do. A drunken husband, a mangle, and five children! No wonder that she had not time to look after the spiders!

The mangle filled up at least half of the room, and from early morning till late at night it was going backwards and forwards, almost without stopping. When Mrs. Blyth was making dinner ready, Angel turned; and when Angel was eating her dinner with her little brothers and sisters, Mrs. Blyth turned again. And in this way the mangle was almost always going; and old Mrs. Sawyer, lying on her bed next door, would quite have missed the noise it made rolling backwards and forwards, which acted as a kind of lullaby to her the whole week long.

Little Angel was standing by the door with a large clothes-basket in her arms, waiting for it to be filled. She was the eldest of the five children, and she was not quite seven years old. She was very small, and her little figure was a good deal bent with turning the heavy mangle. She had to stand on a stool to turn it, and it made her back ache. But that did not matter,—the mangle must be turned, or they would have no dinner to-morrow.

And now the clothes must be carried home; and they were a very heavy load.

"Is all these for Mrs. Douglas, mother?" said little Angel, when the flannels, and dusters, and towels, and stockings were all piled carefully into the basket.

"Yes, child; there's just six and a half dozen. Now mind you don't spill any of them."

Little Angel tried to lift the great basket, but it was more than she could manage; the blood rushed into her little pale face with the effort.

"Tim will help you," said her mother. "Go and call him; I'll give him a slice of treacle and bread, if he'll come."

Tim, who was a neighbour's little boy, agreed to the bargain, and the two children started together.

On they toiled through the wet and muddy streets, almost without speaking, until little Angel paused before a large house in one of the grander streets of that small town.

"Who lives here?" said Tim, as he glanced up at the bow windows and at the great door with pillars on each side of it.

"This is where we're going," said Angel. "These are Mrs. Douglas's clothes. Help me to carry them in."

So the children went by a long passage to the back door.

They rang twice before any one came to open it; and then the cook came to the door with a very red face, and with very white hands, for she was in the midst of baking.

"You'll have to wait a minute or two," she said; "come inside and put your basket down; it's Miss Ellie's birthday, and I'm very busy. I'll take them out of the basket when these cakes are done."

The two children stood on the mat by the kitchen door, and looked around them. There was a large fire, and the cook was taking a number of little cakes from the oven shelf. They were curious little cakes, of all shapes and sizes. Some were round, some square, some diamond-shaped: some were like birds, some like fishes, some like leaves.

The children peered curiously at them as the cook arranged them on tiny plates, not larger than the inside of Angel's little hand. She was in the midst of doing this when the kitchen door opened, and a little girl ran in. She was much younger than Angel, and she was dressed in a white frock and blue sash. In her arms was a beautiful doll, more beautiful than any doll Angel had ever seen except in a toy-shop window.

The little girl ran quickly into the kitchen; but when she saw the children she looked shyly at them, and crept up to cook's side.

"Now, Miss Ellie," said cook, "are you come to look at your cakes?" and she lifted the little girl upon a stool, that she might stand by and watch what she was doing.

"Are all these for my birthday?" said the child.

"Yes, every one of them," said cook.

"Oh, what a great many! Aren't there a great many, cook?"

"Yes; but I suppose there's plenty of little folks to eat them," said cook, laughing.

"Oh yes," said the child; "there's me, and Alice, and Fanny, and Jemmy; and then there's Nellie Rogers and Joe Rogers, and little Eva; and there's Charlie and Willie Campbell. And then there are all my dollies: they must come to my birthday tea, mustn't they, cook?"

"Oh, of course," said cook; "it would never do to leave them out. Is that a new one, Miss Ellie?"

"Yes; Uncle Harry gave her to me for a birthday present. Isn't she nice? She has curls, cook!"

"Oh, she is a beauty!" said cook. "What's her name?"

"I don't know," said the child; "I can't think what would be the nicest name. What would you call her if she was your dolly, cook?"

"Oh, Emma, or Sarah, or Jane, or something of that sort," said cook, laughing.

"I don't think those are very pretty names," said the little girl; "I would like her to have quite a new name, that I never heard before."

"Well, we must think about it," said cook. "I must go and take the clothes out now, and let these children go."

"Who is that little girl, cook," whispered the child.

"She has brought the clothes from the mangle: her mother mangles them."

"What is her name, cook?" whispered Ellie again.

"I don't know, Miss Ellie; you'd better ask her," said cook.

"You ask her, please, cook," whispered the child again.

So cook turned to the children, and asked them what were their names.

"He's Tim, ma'am," said the little girl, pointing at the boy, standing shyly with his finger in his mouth; "and I'm Angel."

"Oh, cook!" whispered little Ellie, "please, please let me see her wings. Are they tucked up under her shawl? Oh, please do let me see them!"

But the cook did nothing but laugh.

"However did you come by such an outlandish name?" she said, turning to little Angel.

"Please, ma'am, it's Angel for short," said the child.

"And what is it for long?"

"It's Angelina, please, ma'am, for long. My mother read it in a penny number before she was married; and Angelina lived in a palace, please, ma'am, and had gold shoes and a carriage with six horses, my mother said."

"Well, to be sure!" said cook. "And so she gave you that heathenish name, when you haven't got gold shoes, nor a carriage, nor six horses. Well, to be sure!"

"Oh, cook!" said little Ellie, "I think it's a beautiful name: the angels live in heaven."

"She doesn't live there, poor little soul!" said cook compassionately; "I'll be bound it's anything but heaven where she lives. Her father drinks, and her mother has five of them."

"Cook," whispered the child again, "would she like one of my birthday cakes?"

"I should think so," said cook. "Should we give her one?"

And, to Angel's great astonishment, she found herself the sole owner and possessor of a pastry bird, a fish, a star, and a heart; while little Tim was made equally rich.

The children were almost too pleased to say "Thank you!"

"There, now! The basket's ready," said cook; "and here's the money for your mother."

Angel and Tim took up the basket, and turned to go.

"Good-bye, little Angel," said the child shyly; "I do wish you had some wings."

"Cook, don't you think Angelina would be a pretty name for my dolly?" they heard her saying as they went down the steps.

"Ay, it was nice in there!" said Tim, as they walked homewards in the dirty, dismal, muddy streets. "I wish I had a birthday."

"Did you ever have one?" asked Angel; "I never did."

"Yes, one," said Tim; "only once, and that was a long, long time ago."

"What is a birthday?" said Angel.

"It's a nice sort of a day!" said Tim, "When everybody's good to you, and gives you things. One day mother let me have a birthday."

"And what was it like?" said little Angel.

"Oh, the kitchen was swept all clean and tidy, and mother never scolded me once all day, and she made a cake for tea that had lots of currants in it—not just one in each slice, like the cake we have on Sundays. And father gave me a penny and a packet of goodies for my very own! That's the only birthday I ever had. Mother says she hasn't any time for birthdays now."

"I wonder if I shall ever have a birthday," said little Angel with a sigh, as she went in to turn the mangle once more.

WHO KNOCKS?

THE mangle went on, backwards and forwards, until very late that night. Little Angel's arms and back ached terribly when the work was finished and she and her mother crept close to the flickering fire.

"Now go to bed, Angel," said her mother.

"Oh, mother, please let me stop a little longer with you. Are you going to sit up?"

"Yes, I must wait till he comes," said the mother wearily, glancing at the large clock which was ticking solemnly in the corner of the little kitchen. "Oh dear, oh dear! what a lot of trouble there is in the world!"

"Mother," said little Angel suddenly, "did you ever have a birthday?"

Mrs. Blyth did not answer at first, but bent lower over the fire. Little Angel fancied she was crying.

"Yes," she said at last, "when I was a little girl, and my father was alive. I wish I was a little girl now."

"Was it so very nice having a birthday, mother?"

"It was very nice having a father," said Mrs. Blyth. "Ay, and he was a good father too; he was a real good man, was your grandfather, Angel."

"What did you do on your birthday, mother?" asked the child.

"Oh, it was a real happy day. My mother made a plum-pudding for us, and my father took us all to the park for a walk after tea. And then, he used always to give me a present. I have one of them yet."

"Where is it, mother?" said little Angel; "do let me see it."

"Oh, it's up on that shelf," said her mother, pointing to some little shelves at the top of the kitchen. "It's a shame to let it lie there when I promised him to read it every day. But what can a woman do that's got a drunken husband, five children, and a mangle?" she said, more to herself than to the child.

"Please let me look at your birthday present, mother," said little Angel again.

Mrs. Blyth stood upon one of the broken chairs, and took down from the shelf an old and shabby book. The cover was half off, and it was thickly coated with dust. One of the spiders had been busy in its neighbourhood, and had fastened one end of a large cobweb to its cover.

She wiped it with her dirty apron, and handed it to the child; then she sat down again, and bent over the fire.

"Here's writing at the beginning, mother," said Angel; "what does it say?"

Mrs. Blyth took the book, and a tear fell on the soiled leaves of the Bible as she opened it.

"Given to Emily Brownlow by her dear Father on her birthday, with the hope that she will remember her promise."

"And what was the promise, mother!"

"That I would read it, child," said her mother shortly.

"But you never do read it, mother."

"No, it's a shame," said her mother; "I must begin."

"Read me just one little bit before I go to bed," said Angel, sitting on the stool at her mother's feet.

Mrs. Blyth turned over the leaves, and in a mechanical way began to read the first verse on which her eye fell.

"'Behold, I stand at the door and knock: if any man hear My voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with Me.'"

"Who is knocking, mother?" asked Angel.

"It means Jesus Christ, I think," said her mother. "'Behold, I stand at the door and knock.' I expect it means Jesus. I learnt a hymn at the Sunday school about it. I went to the Sunday school when my father was alive. I remember it began—"

"Behold a Stranger at the door,

He gently knocks—has knocked before;"

"and then—I can't remember what came next—something about using no other friend so ill."

"I never heard Him knock," said Angel; "does He come when I'm in bed at night?"

"No," said her mother; "I don't think it's that door He knocks at. I don't rightly know what it means."

"Read it again, please, mother."

So Mrs. Blyth read the text again.

"I hope He won't come in to-night," said little Angel, when she had finished.

"Why not, child?" asked her mother.

"Because we've got nothing for supper to-night, only those crusts Billy and Tommy left at tea. I'm afraid He wouldn't like those."

"Oh, it doesn't mean He's really coming to supper," said the mother; "I wish I could remember what it does mean. But it's lots of years since I read it. My father died when I was only ten, and nobody never took any trouble with me afterwards."

Little Angel was very sleepy now, so her mother took her upstairs, and put her into the bed with her little brothers and sisters, and then she sat down on a chair beside her, and buried her face in her hands. Recollections of a father's love and of a father's teaching were coming into that poor, ignorant mind. Imperfect, childish recollections they were, and yet quite distinct enough to make her sigh for what had been and for what might have been.

And so she sat, this poor wife, as the clock ticked on and the children slept. Then, after long hours of waiting, came a great noise at the door, and she rose, trembling, to open it.

Little Angel started from her sleep, and, sitting up in bed, called out, "Mother, He's come; I heard Him knock."

"Yes," said her mother, who was lighting the candle, "I'm going to let him in."

"Oh, please let me go down and see Him."

"No, nonsense, child," said her mother; "your father's sure to be in drink. I'll get him quickly to bed."

"Oh, dear!" said little Angel, in a disappointed voice, as she lay down, "I thought it was Jesus knocking at the door!"

LITTLE ELLIE'S SISTER

THE next week there were more clothes to be taken home to Mrs. Douglas's. It was not a heavy load this time, and little Angel went alone. She was passing under one of the bow windows on her way to the passage leading to the kitchen door, when she heard a loud tapping on the pane. She looked up, and there was little Ellie nodding to her, and kissing her hand, and holding up the new doll for her to see.

And when cook opened the kitchen door, and Angel came in with the clothes, little Ellie was just coming in at the other door.

"Please, cook," said the child, "Mabel wants to see the little Angel."

"Bless us!" said cook, laughing. "I'd clean forgot about the child's name. I couldn't think what angel it was at first. You take her, Miss Ellie."

"Please, come," said the little girl; and she held out her tiny hand for Angel to take.

Little Angel had never seen such a beautiful house. They went up a long easy staircase, very different from the one Angel climbed at night when she went to bed. They passed a splendid window, with pretty coloured glass in it, which threw all sorts of lovely colours on the stairs. And the carpet was so soft that Angel could not hear the sound of her own feet.

At the top of the staircase was a long passage, with doors at both sides of it. Ellie opened one of these, and led Angel into a pretty little sitting-room. A bright fire was burning in the grate, and by the side of the fire was a sofa. On this sofa Angel saw a young lady lying, with a very sweet and gentle face. She looked very ill and tired, Angel thought, and had such a kind face that she could not feel afraid of her.

"This is the little Angel, Mabel," said little Ellie, as she took her by the hand to her sister's couch.

"Bring a stool for her to sit on, Ellie. I'm very glad to see you, little Angel."

"Yes; but, Mabel, cook says she hasn't any wings, and she doesn't think she lives in heaven. She says it's only her name."

"Yes," said her sister; "I understand. But some day, I hope she will live in heaven. Do you think you will, little Angel?"

"I hope so, please, ma'am," said Angel.

"But, if you are ever to live in heaven with the Lord Jesus, you must learn to love Him now," said the young lady.

"Is that the door He knocks at?" said Angel, starting from her seat, as a sudden thought seized her.

"What do you mean, little Angel?"

"The door with the great pillars on each side of it, and the brass bell and knocker; is it there He knocks every night?"

"I don't quite understand what you mean," said Mabel gently. "Can you tell me a little more about it?"

"My mother read it in the Bible last night, and it said He knocked at a door and wanted to come in, and mother said she didn't think it meant our door."

"Is this what you mean?" said the young lady. She took up a little Bible which lay beside her, and read aloud: "'Behold, I stand at the door, and knock.'"

"Yes, that's it," said Angel; "and my mother said she had clean forgot what it meant; but she thought it meant Jesus."

"Yes; your mother was quite right, little Angel; it is Jesus who is knocking at the door."

"Then it is this door with the pillars," said the child.

"No, not this door," said the young lady; "it means a door that belongs to you, little Angel. It is not a door that you can see or touch; it is the door of little Angel's heart. Jesus calls it a door, to show you what He means. He wants to come into your heart. He wants you to love Him, and to give your own little self to Him. This is what it means, little Angel."

The child looked as if she did not quite understand.

"Do you love your mother, little Angel?" asked the young lady.

"Oh yes, please, ma'am; very much."

"Then your mother is inside your heart. You love her with your heart, don't you?"

"Oh yes, please, ma'am; she does everything for me, does mother."

"But Jesus loves you better than your mother does; and He has done a great deal more for you than she has."

"Has He?" said little Angel simply.

"Yes, indeed He has. Do you know, He lived in heaven, where everything is beautiful and happy, and He left His home there and came to live down here. He lived a very sorrowful life. He was a poor man, little Angel. He had no home of His own, but went about from place to place, often very tired, and hungry, and faint. And people were very unkind to Him; they laughed at Him and hated Him, and threw stones at Him, and hunted Him from place to place; and at last, little Angel, He was nailed on a cross of wood, and they put a crown of thorns on His head."

"Oh yes, please, ma'am; mother has a picture of that. Jesus is on a cross, and some soldiers laughing at Him; it's in a book on the drawers-top that my father bought at a sale."

"Yes," said the young lady; "that was how He died; oh, such a cruel, painful death! And, little Angel, it was all for you!"

"All for me!" said the child.

"Yes, little Angel, all for you. For, if Jesus had not died, you could never, never have gone to heaven. Shall I tell you why?"

"Yes, please, ma'am," said the child.

"You could never have gone to heaven, because no one can go there who has done any wrong; only good and holy people can go there; all who have done anything wrong must be punished for it. And, little Angel, have you ever done anything wrong?"

"Yes," said little Angel, hanging down her head; "yes, please, ma'am, I have."

"Then you could never go to heaven, for God must punish sin. But Jesus is God, and He came and led that sorrowful life, and then died that dreadful death, that He might be punished instead of you—instead of you, little Angel. And now He says, 'I wonder if little Angel will love Me for dying for her? I will knock at the door of her heart, and see if she will let Me in, and love Me for what I have done for her, and be My little child!'"

Angel opened her eyes very wide, and looked earnestly at the young lady as she spoke.

"How old are you, little Angel?" she asked.

"Going on seven, ma'am," said Angel promptly.

"Then He has been waiting for you for years. Knocking—knocking, and you have never let Him in!"

"That's a long time!" said Angel.

"Yes; and still He does not give up knocking. He is waiting still; waiting for you to love Him; waiting for you to let Him in."

"He must be very tired," said Angel; "I wish I knew how to let Him in."

The young lady did not answer at once; she covered her face with her hand for a minute, and was quite still.

Then she said, "Little Angel, I have been praying to Him to help me to show you how to let Him into your heart. But I think, after all, the best way will be for you to ask Him yourself. Will you ask Him now?"

"I don't know how," said Angel; "I don't know what to say."

"When you pray, little Angel, you should talk to Jesus just as you are talking to me, and ask for just what you want. Kneel down by me, and I will help you."

Little Ellie, who had been listening in silence all this time, knelt down too, whilst her sister prayed.

"O Lord Jesus, show little Angel how to open the door of her heart to Thee! Grant that she may let Thee in, and not keep Thee waiting any longer. Oh, may she indeed be saved by Thee, and love Thee with all her heart, for all that Thou hast done for her! Amen."

"And now, little Angel," said Mabel, when the children rose from their knees, "when you get home you must ask Him yourself, and remember He ever listens to every word that you say."

Angel had a great deal to think of as she walked home that morning with her empty basket. She was very quiet all day as she was looking after the children and turning the mangle—so quiet that her mother asked her if she were ill. But Angel said, No, she was quite well, and turned the mangle quietly again. But when the other children were in bed, and she and her mother were alone, Angel said:

"Mother, do you know how old you are?"

"Dear me, let me see," said her mother. "I was just nineteen when I got married to your father. I know I was just nineteen then, because I remember my old aunt said, 'You're young enough, my lass, not twenty yet. You'd better not be in a hurry.' Well, I was nineteen then, and, let me see, I believe we've been married eight years next month. Nineteen and eight, what's that? Count it on your fingers, Angel."

"Twenty-seven, mother," said little Angel, when she had carefully counted it twice over. "Twenty-seven years old! Then Jesus has been knocking at your door twenty-seven years! What a long time!"

"Oh, you're after that again, are you?" said her mother. "I wish I could remember what it means."

"Miss Douglas told me," said Angel; and she repeated, as well as she could, the conversation in the little sitting-room.

"Well, to be sure," said the mother, "it's very wonderful to think He waits so long; I'm afraid I've been very bad to Him."

"Won't you let Him in to-night, mother?"

"Oh, child! I'm too busy," she said; "there's so much to do. There's the children, and your father, and the mangle to look after, and always dinner to cook, and things to clear away, and such lots of clothes to wash, and your father's shirts to iron. I've no time to be good, Angel."

"But Miss Douglas said if you don't let Him into your heart and love Him, you won't ever live with Him and the angels in heaven."

"Ah, well!" said the mother. "I suppose not; but there's lots of time yet. When baby gets a bit older, and Tom goes to school, I shall have a bit more time; and then, Angel, I can sit still a bit and think about it."

"Only, perhaps, as He's been knocking twenty-seven years," said Angel, "it's such a very long time, He may get tired of waiting, and walk away."

"Oh no! I hope not," said her mother; and she got up and bustled about the room, and sent Angel off to bed. She hoped the child would forget about it before morning.

But when she went upstairs, after a few minutes, to see if Angel was in bed, she found her kneeling in her nightgown before the window. There was no light in the room, but the blind was up, and the moonlight was streaming on the child's fair hair and clasped hands.

"She looks like one of the little angels in heaven," said the mother to herself.

Angel had not heard her mother come upstairs, so Mrs. Blyth stood quietly on the last step, and listened to Angel's little prayer.

"Oh, Jesus, please come in to-night! Oh it was very bad to keep You outside when You did all that for me! Oh, Jesus, please don't knock any longer, but just walk into my heart, and please never go away again? Amen."

And then Angel crept into bed, and her mother wiped her eyes, and came in and kissed her.

THE LOUD KNOCK IN PLEASANT PLACE

"MOTHER! mother!" said little Angel, in the middle of the night, creeping over to the bed where her father and mother were asleep. "Mother, mother, there's a loud knock at our door!"

"Bless you, child," said the mother, "you're dreaming. Your father's been in long since. Go to bed again."

"No, mother, listen; there it is again."

This time Mrs. Blyth heard it, and even Mr. Blyth opened his eyes, and said, "What's that?"

Some one was knocking at the door as loudly as he could. Mrs. Blyth put on some clothes, lighted a candle, and went down stairs to see what it was.

When she came back her face was very white indeed. "Oh, Angel," she said, "it's Tim; his mother's dead! She went to bed quite well, and then Mr. Carter woke and heard her groaning, and she was dead in two minutes—before he could call anybody."

"Oh, mother," said little Angel, trembling, "how dreadful! She was washing all day yesterday, and I saw her put the shutters up just before I came to bed."

"Yes," said Mrs. Blyth; "I'm sure it's made me feel quite sick. I must go over and help them a bit, poor things."

Angel could not sleep any more that night. She lay awake thinking of poor Tim, who had no mother, and wondering if Mrs. Carter were in heaven with the angels. When her mother came back it was time to get up. Mrs. Blyth had been crying very much, and she went about her work almost without uttering a word.

But when she and Angel were turning the mangle, she said—

"Angel, do you remember what you said when you waked me last night? You said, 'Mother, there's a loud knock at our door.' I've never got those words out of my head since. All the time I was laying out poor Mrs. Carter I heard you, saying, 'There's a loud knock at our door, mother.' And when Mr. Carter told the doctor how well she had been all yesterday, and the doctor said, 'Yes, it's very sudden, very sudden indeed,' I heard you saying again, 'There's a loud knock at our door, mother.' And now, even when I'm turning the mangle, it seems to be saying those same words over and over again."

"Yes," she said, after a minute or two, "it's of no use me saying, 'I'm too busy, I can't let Him in just yet.' Death won't take that excuse when he knocks at the door."

That was a very dull day. Angel peeped out of the window, and saw the closed house opposite, and the darkened room upstairs where poor Mrs. Carter was lying. And then the man came to measure her for her coffin, and then Mr. Carter and his poor little motherless children came into Mrs. Blyth's house to get their dinner, and Mr. Carter cried all the time, and would hardly eat anything.

It was a very dismal day.

But after tea, as Angel was washing up the tea things, and her mother was folding the clothes for the mangle, an unusual sound was heard in the narrow court where they lived. It was the sound of singing—several voices singing.

In a moment, all in Pleasant Place had opened their doors or their windows and were looking out. They saw a young man standing in the middle of the court, and a little knot of people round him, with open books in their hands.

"What is it, mother?" asked little Angel, as Mrs. Blyth came into the room.

"That's young Mr. Douglas, Miss Douglas's brother," said her mother, in a whisper. "I've often seen him there when I've been to take the clothes home; he's one of the ministers here."

"Why, mother," said the child, as she listened to the singing, "they are singing your hymn—the hymn you learnt in the Sunday School."

"No," said her mother, "it isn't my hymn, but it's very like it."

"Knocking, knocking! Who is there?

Waiting, waiting, oh, how fair!

'Tis a Pilgrim, strange and kingly,

Never such was seen before;

Oh! My soul, for such a wonder,

Wilt thou not undo the door?"

"Eighteen doors in this court," said the young minister, looking round on the people, who were all peeping out at him. "Eighteen doors, and every one of them open!"

"Listen to-night to the story of a door—a closed door!"

"Here is a closed door, and some one standing outside it. He knocks at the door; He calls out to the one inside; then He waits, He listens. There is no sound within; no one comes to open the door."

"He knocks again; He calls again; He listens again. No one comes."

"Will He walk again? No, He waits still; He knocks once more; He calls again; He listens again. No answer."

"Surely the door must be bolted and barred so fast inside that it cannot be opened, or perhaps the owner of the house is out, or asleep, or deaf, and does not hear the knocking."

"But look a little longer. Some more people come up to the door and knock, and as soon as ever they knock they are admitted. They are let in, and the door is shut in the face of Him who has waited so long."

"Many times in the day that door is opened to all kinds of people; but it is always closed in the face of the One who still stands outside."

"Does He weary of standing there? No; night comes, but He goes on knocking, goes on calling, goes on listening for any answer from within."

"Who is He? Is He a beggar come to ask for money?"

"No, He is no beggar; for if you look you will see that His hands are full of presents for the one inside the house."

"Is He a rent collector come to demand that which is due to Him? No; for although the house really belongs to Him, He demands nothing, He only pleads for an entrance."

"Is He an enemy to the one inside? No; He is, on the contrary, his best friend, the One to whom he owes everything."

"What a strange thing that He is kept outside!"

"Is it a strange thing?" said the minister, looking earnestly at all the people. "Is it a strange thing? Then get up at once and let Him in, for it is at your door He is knocking."

"My door!" you say. "My door! What do you mean? No one is knocking at my door."

"No one? Oh, my friends! Did you hear no knock this morning at your door—your heart's door. When the neighbours came in and told you that one in that house, whom you had seen well and strong a few hours before, was now in eternity—oh, my friends! Was it not a knock?"

"Did not the Lord Jesus, your best Friend, knock then? Did He not call as well as knock? Did you not hear Him saying, 'Are you ready to die? Oh, let Me in before it is too late!'"

"That was a very loud knock, my friends; but it is not the only time He has knocked. Day after day, week after week, year after year, ever since you were little children, He has been knocking and waiting, and knocking and waiting for you to let Him in. That night when you were so ill, and the doctor told you that you might never get better, was He not knocking then?"

"And when your child died, and you stood by its open grave, was He not knocking then?"

"And these are only the great, startling knocks; there are many others which you do not hear—there is too much noise and bustle inside the house for their sound to reach you. Yet never a day passes that He does not knock in some way or other."

"But oh! Take care, for the day is coming—who can say how soon? When there will be a last knock, a last call; and then He will turn and walk away from the door, never to return."

"Oh, my friends! Why do you keep Him waiting outside? You let all others in. Your pleasures, your companions, your work,—all these knock at the door, and are let in at once. But you have no room for Christ."

"But oh! Remember, if there is no room for Christ in your heart, there will be no room for you in Christ's heaven."

"My friend, He is knocking now; it may be His last knock. He is calling now; it may be His last call."

"'Oh, let Me in.'" He cries, "'and I will make you happy; I am bringing you forgiveness, and peace, and joy, and rest, and all that you need. Oh, let Me in before it is too late! I have waited so patiently and so long, and still I wait. Will you not, even this night, undo the door?'"

When the little service was over the people went back into their houses, and Angel and her mother went on with their work. And as Angel wiped the cups and saucers, she sang softly to herself the chorus of the hymn—

"Oh! My soul, for such a wonder,

Wilt thou not undo the door?"

"Yes, I will!" said her mother suddenly, bursting into tears; "I will undo the door; I will keep Him waiting no longer."

ANGEL'S BIRTHDAY

IT was a bright, sunny morning, some weeks after that little service was held in Pleasant Place.

The sunbeams were streaming in at Mrs. Blyth's window, for the cobwebs and spiders had some time ago received notice to quit, and the dust had all been cleared away, and found no chance of returning.

Mrs. Blyth was a different woman. Her troubles and trials remained, and she had just as much to do, and just as many children to look after, but she herself was quite different. She had opened the door of her heart, and the Lord Jesus had come in. And He had brought sunshine with Him into that dark and ignorant heart. Life, instead of being a burden and a weariness, was now full of interest to Mrs. Blyth, because she was trying to do every little thing to please Jesus, who had done so much for her. Whether she was washing the children, or cleaning the house, or turning the mangle, she tried to do it all to please Him. She remembered that He was looking at her, and that He would be pleased if she did it well. It was wonderful how that thought helped her, and how it made the work easy and pleasant.

So, through the bright, clean window, the morning sunbeams were streaming on little Angel's head. Her mother was standing by her side, watching her as she lay asleep, and waiting for her to awake.

As soon as ever Angel opened her eyes, her mother said—

"Little Angel, do you know what to-day is?"

"No, mother," said Angel, rubbing her eyes, and sitting up in bed.

"It's your birthday, Angel; it is indeed!" said her mother. "I hunted it out in your grandmother's old Bible. It's the day you were born, just seven years ago!"

"And am I really going to have a birthday, mother?" said Angel, in a very astonished voice.

"Yes, a real good birthday," said her mother; "so get up and come downstairs, before any of it is gone."

Angel was not long in putting on her clothes and coming down. She found the table put quite ready for breakfast, with a clean tablecloth, and the mugs and plates set in order for her and her little brothers and sisters; and in a little jar in the middle of the table was a beautiful bunch of flowers. Real country flowers they were, evidently gathered from some pleasant cottage garden far away. There were stocks and mignonette, and southernwood, and sweetbrier, and a number of other flowers, the names of which neither Angel nor her mother knew.

"Oh mother, mother," said little Angel, "what a beautiful nosegay!"

"It's for you, Angel," said her mother: "for your birthday. I got it at the early market. My father always gave me a posy on my birthday."

"Oh, mother," said little Angel, "is it really for me?"

But that was not all, for by the side of Angel's plate she found a parcel. It was tied up in brown paper, and there was a thick piece of string round it, fastened tightly in so many knots that it took Angel a long time to open it. Her little hands quite shook with excitement when at last she took off the cover and looked inside. It was a little book, in a plain black binding.

"Oh, mother," said Angel, "what is it? Is it for my birthday?"

"Yes," said her mother; "look at the writing at the beginning. I'll read it to you."

It was very uneven writing, and very much blotted, for Mrs. Blyth was only a poor scholar; but little Angel did not notice this—it seemed very wonderful to her to be able to write at all.

Now, what was written in the little book was this:

"Given to little Angel by her dear mother; and she hopes she will promise to read it, and will keep her promise better than I did."

"But I can't read, mother," said Angel.

"No; but you must learn," said her mother. "I mean that you shall go to school regular now, Angel. Why, you're seven years old to-day!"

Poor little Angel's head was nearly turned; it was such a wonderful thing to have a birthday.

But the wonders of the day were not over yet; for when, after breakfast, Angel asked for the clothes to mangle, her mother said: "They're all done Angel; I'm just going to take them home. I've done a lot these three nights when you was in bed, that we might have a bit of a holiday to-day."

"A holiday, mother!" said Angel. "Oh, how nice! No mangling all day!"

"No mangling all day," repeated the mother, as if the thought were as pleasant to her as to Angel.

But the wonders of the day were not yet over.

"Angel," said her mother, as they were washing the children, "did you ever see the sea?"

"No, mother," said Angel; "but Tim has; he went last Easter Monday with his uncle."

"Well," said her mother, "if it doesn't rain, you shall see it to-day."

"Oh, mother!" was all that little Angel could say. And who do you think is going to take you, child? "I don't know, mother."

"Why, Angel, your father is. He came in last night as soon as you'd gone to bed. He sat down in that arm-chair by the fire, and he said, 'Dear me! how comfortable things is just now at home! If they was always like this, I wouldn't stop out of an evening.'"

"So I said, 'If God helps me, John, they always shall be like this, and a deal better, too, when the children gets a bit bigger.' And your father stopped at home and read his newspaper, Angel, and then we had a bit of supper together. It was like when we was first married, child; and as we ate our supper, Angel, I said, 'It's Angel's birthday to-morrow, John.' And your father said, 'Is it? Why, to-morrow's Saturday. Let's all go to the sea together;' and he took quite a handful of shillings out of his pocket. 'Here's enough to pay,' he said. 'Have them all ready at dinner-time, and we'll go by the one-o'clock train.'"

"Oh, mother," said little Angel, "it is so nice to have a birthday!"

True to his promise, John Blyth came home at dinner-time, with the shillings still in his pocket. His mates had tried hard to persuade him to turn into the Blue Dragon on his way home, but he told them he had an engagement, and had no time to stay.

What a happy afternoon that was!

Angel had never been in a train before, and her father took her on his knee, pointing out to her the houses, and trees, and fields, and sheep, and cows, and horses, as they went by. And then they arrived at the sea, and oh! What a great, wonderful sea it seemed to Angel! She and her little brothers and sisters made houses in the sand, and took off their shoes and stockings and waded in the water, and picked up quite a basketful of all kinds of beautiful shells; whilst her father and mother sat, with the baby, under the shadow of the cliffs and watched them.

And then they all came home together to tea, and her father never went out again that night, but sat with them by the fire, and told Angel stories till it was time to go to bed.

"Oh, mother," said Angel again, a sleepy head on the pillow, "it is nice to have a birthday!"

THE GREAT BIRTHDAY

THE bells were ringing merrily from the tower of the old church close to Pleasant Place.

The street near the church was full of people bustling to and fro, going in and out of the different shops, and hurrying along as if none of them had any time to lose. The shops were unusually gay and tempting, for it was Christmas Eve. Even Pleasant Place looked a little less dull than usual. There were sprigs of holly in some of the windows, and most of the houses were a little cleaner and brighter than usual.

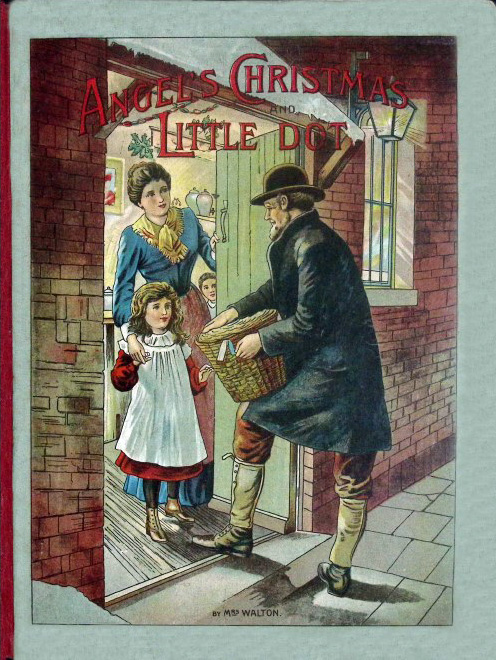

Angel and her mother had been very busy all day. They had just finished their mangling, and had put all the clothes out of the way for Christmas Day, when they heard a knock at the door, and Angel went to open it.

"It's a basket, mother," she said. "It can't be for us."

The man who had brought the basket laughed.

"It's for an Angel!" he said. "Have you got any of that article in here? Here's the direction I was to bring it to—'Little Angel, No. 9, Pleasant Place.'"

"Then, please, it's for me," said Angel.

"For you!" said the man. "Well, to be sure! So you are the angel, are you? All right, here's your basket!" And he was gone before they could ask more.

The basket was opened with some difficulty, for it was tightly tied up, and then Angel and her mother put out the contents on the table amidst many exclamations.

There was first a plum-pudding, then a number of oranges and apples, then a large cake, and then a pretty Christmas card, with a picture of a robin hopping about in the snow, and these words printed on it, "A Happy Christmas to you all."

"Where can they all have come from?" said little Angel, as one good thing after another came out of the basket. At the very bottom of the basket they found a tiny note.

"This will tell us about it," said Mrs. Blyth. "Why, it's directed to you, Angel!"

So Angel's mother sat down, stirred the fire, spelt it carefully out, and read it aloud by the firelight.

"MY DEAR LITTLE ANGEL,"

"I send you a few little things for Christmas

Day. I hope you will have a very happy day. Do not

forget whose Birthday it is. Your friend,"

"MABEL DOUGLAS."

"Whose birthday is it, mother?" asked little Angel.

"The Lord Jesus Christ's," said her mother reverently. "Did I never tell you that, little Angel? It's the day we think about Him being born a little baby at Bethlehem."

"SO YOU ARE THE ANGEL, ARE YOU? HERE'S YOUR BASKET."

Angel was sitting on her stool in front of the fire thinking, and it was some time before she spoke again. Then she said suddenly, "What are you going to give Him, mother?"

"Give who, Angel?"

"What are you going to give the Lord Jesus for His birthday?"

"Oh, I don't know," said her mother. "I don't see how we can give Him anything."

"No," said little Angel sadly; "I've only got one penny,—that wouldn't buy anything good enough. I would have liked to give Him something on His birthday; He did such a lot for us."

"We can try to please Him, Angel," said her mother, "and do everything that we think He would like."

"Yes," said little Angel, "we must try all day long."

That was a very happy Christmas Day for Angel and for her mother.

"This is the Lord Jesus' birthday," was Angel's first thought when she awoke in the morning; and all through the day she was asking herself this question, "What would Jesus like?" And whatever she thought He would like that she tried to do.

Angel's father was at home to dinner, and was very kind to her all day. He had not been seen inside a public-house since Angel's birthday. It was a very good little Christmas dinner. As they were eating it, Mr. Blyth said:

"Emily, have you seen those bills on the wall at the top of the court?"

Angel's mother said, "No; I have not been out to-day."

"There's to be a meeting to-night in that little schoolroom just a bit of way down the street. That new young minister's going to speak; and it says on the bills it will all be over in half an hour. I've a good mind to go and hear what he's got to say. Will you come with me?"

"Yes, that I will," said Mrs. Blyth, with tears in her eyes. She had not been inside a place of worship with her husband since the first year they were married.

"Can't Angel come too?" said her father, as he looked at her earnest little face.

"Not very well," said Mrs. Blyth; "we can't all go. Some one must stop with baby and the children."

When Angel's large plum-pudding was put on the table, a sudden thought seized her. "Mother," she whispered, "don't you think Jesus would like poor old Mrs. Sawyer to have a bit of it?"

"Yes," said Mrs. Blyth, "I'll cut her a slice, and one for Annie too, poor girl. Will you take them in?"

So Angel went next door with her two slices of plum-pudding. She found Mrs. Sawyer and her niece Annie just beginning their dinner. There was nothing on the table but some tea, and a loaf of bread with a few currants in it, so Angel felt very glad she had brought the pudding. She was sure Jesus would be pleased they should have it; and she thought it would make Him glad on His birthday to see how Mrs. Sawyer and Annie smiled when they saw what she had brought them.

"Are you going to this meeting to-night?" said Annie, as Angel turned to go.

"No, I'm not going," said Angel; "but father and mother are. I must mind the children."

"I'll tell you what," said Annie; "if you'll bring them in here, I'll mind them. I can't leave aunt, and they'll be a bit of company for her."

And so it came to pass that Pleasant Place beheld the wonderful sight of Mr. and Mrs. Blyth and Angel all going together to the little meeting in the schoolroom.

A good many Pleasant Place people were there; and they looked round in astonishment as Mr. Blyth came in, for they thought him about the most unlikely man in the whole court to be there. And his wife and little Angel, as they sat beside him, prayed very earnestly that he might get a blessing.

Mr. Douglas's text was a very strange one for Christmas Day—at least, so many of the people thought when he gave it out. It had only four words, so that even little Angel could remember it quite well—

"GIVE ME THINE HEART."

"Suppose," said the minister, "it was my birthday, and every one in my house was keeping it. They all had a holiday and went out into the country, and there was a very good dinner, which they all very much enjoyed, and altogether it was a very pleasant day to them indeed."

"But suppose that I, whose birthday it was, was quite left out of it. No one gave me a single present; no one even spoke to me; no one took the slightest notice of me. In fact, all day long I was quite forgotten; I never once came into their thoughts."

"Nay, more. Not only did they do nothing whatever to give me pleasure, but they seemed all day long to take a delight in doing the very things which they knew grieved me and pained me, and were distressing to me."

"Surely, my friends, that would be a strange way of keeping my birthday; surely I should feel very hurt by such conduct; surely it would be a perfect sham to pretend to be keeping my birthday, and yet not take the slightest notice of me, except to annoy and wound me! My friends," said the minister, "this afternoon I took a walk. In the course of my walk I saw a number of people who pretended to be keeping a birthday. And yet what were a great many of them doing? They were eating and drinking and enjoying themselves, and having a merry time of it."

"But I noticed that the One whose birthday it was, was quite forgotten: they had not given Him one single present all day long they had never once spoken to Him; all day long He had never been in their thoughts; all day long He had been completely and entirely passed by and forgotten."

"Nor was this all. I saw some who seemed to be taking a pleasure in doing the very things He does not like, the very things which offend and grieve Him—drinking and quarrelling, and taking His holy name in vain."

"And yet all these, my friends, pretended to be keeping the Lord Jesus Christ's birthday!"

"But, I trust, by seeing you here to-night, that you have not been amongst their number. I would therefore only put to you this one question—"

"The Lord Jesus Christ's birthday! Have you made Him a present to-day?"

"A present!" you say. "What can I give Him? He is the King of kings and Lord of lords. What have I that is fit for a present to a king?"

"Give Him what He asks for, my friends. He says to you to-night, 'Give Me thine heart.'"

"That is the birthday present He is looking for. Will you hold it back?"

"Oh, think of what we are commemorating to-day. Think how He left His glory, and came to be a poor, helpless babe for you; think, my friends, of all His wonderful love to you. And then I would ask you, Can you refuse Him what He asks? Can you say—"

"Lord, I cannot give Thee my heart. I will give it to the world, to pleasure, to sin, to Satan, but not to Thee,—no, not to Thee. I have no birthday present for Thee to-night?"

"Oh, will you not rather say—"

"'Lord, here is my heart; I bring it to Thee; take it for Thine own.

Cleanse it in Thy blood; make it fit to be Thine'"?

"Will you not this night lay at your King's feet the only birthday present you can give Him—the only one He asks for—your heart?"

"Mother," said little Angel, as they walked home, "we can give Him a present, after all."

It was her father who answered her.

"Yes, Angel," he said, in a husky voice; "and we mustn't let Christmas Day pass before we have done it."

And that night amongst the angels in heaven there was joy—joy over one sinner who repented of the evil of his way, and laid at his Lord's feet a birthday present, even his heart.

There was joy amongst the angels in heaven; and a little Angel on earth shared in their joy.

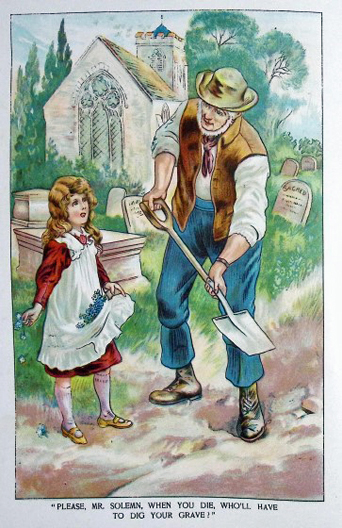

"PLEASE, MR. SOLEMN, WHEN YOU DIE,

WHO'LL HAVE TO DIG YOUR GRAVE?"

OLD SOLOMON'S VISITOR

IT was a bright morning in spring, and the cemetery on the outskirts of the town looked more peaceful, if possible, than it usually did. The dew was still on the grass, for it was not yet nine o'clock. The violets and snowdrops on little children's graves were peeping above the soil, and speaking of the resurrection. The robins were singing their sweetest songs on the top of mossy gravestones—happy in the stillness of the place. And the sunbeams were busy everywhere, sunning the flowers, lighting up the dewdrops, and making everything glad and pleasant. Some of them even found their way into the deep grave in which Solomon Whitaker, the old grave-digger, was working, and they made it a little less dismal, and not quite so dark.

Not that old Whitaker thought it either dismal or dark. He had been a grave-digger nearly all his life, so he looked upon grave-digging as his vocation, and thought it, on the whole, more pleasant employment than that of most of his neighbours.

It was very quiet in the cemetery at all times, but especially in the early morning; and the old man was not a little startled by hearing a very small voice speaking to him from the top of the grave.

"What are you doing down there, old man?" said the little voice.

The grave-digger looked up quickly, and there, far above him, and peeping cautiously into the grave, was a child in a clean white pinafore, and with a quantity of dark brown hair hanging over her shoulders.

"Whoever in the world are you?" was his first question.

His voice sounded very awful, coming as it did out of the deep grave, and the child ran away, and disappeared as suddenly as she had come.

Solomon looked up several times afterwards as he threw up fresh spadefuls of earth, but for some time he saw no more of his little visitor. But she was not far away; she was hiding behind a high tombstone, and in a few minutes she took courage, and went again to the top of the grave. This time she did not speak, but stood with her finger in her mouth, looking shyly down upon him, as her long brown hair blew wildly about in the breeze.

Solomon thought he had never seen such a pretty little thing. He had had a little girl once, and though she had been dead more than thirty years, he had not quite forgotten her.

"What do they call you, my little dear?" said he, as gently as his husky old voice would let him say it.

"Dot," said the child, nodding her head at him from the top of the grave.

"That's a very funny name," said Solomon. "I can't think on that I ever heard it afore."

"Dot isn't my real name; they call me Ruth in my father's big Bible on our parlour table."

"That's got nothing to do with Dot as I can see," said the grave-digger musingly.

"No," she said, shaking her long brown hair out of her eyes; "it's 'cause I'm such a little dot of a thing that they call me Dot."

"Oh, that's it, is it?" said Solomon; and then he went into a deep meditation on names, and called to mind some strange ones which he read on the old churchyard gravestones.

When Solomon was in one of his "reverdies," as his old wife used to call them when she was alive, he seldom took much notice of what was going on around him, and he had almost forgotten the little girl, when she said suddenly, in a half-frightened voice—

"I wonder what they call you, old man?"

"Solomon," said the grave-digger; "Mr. Solomon Whitaker—that's my name."

"Then, please, Mr. Solemn, what are you doing down there?"

"I'm digging a grave," said Solomon.

"What's it for, please, Mr. Solemn?" asked the child.

"Why, to bury folks in, of course," said the old man.

Little Dot retreated several steps when she heard this, as if she were afraid Mr. Solomon might want to bury her. When he looked up again there was only a corner of her white pinafore in sight. But as he went on quietly with his work, and took no notice of her, Dot thought she might venture near again, for she wanted to ask Mr. Solomon another question.

"Please," she began, "who are you going to put in that there hole?"

"It's a man as fell down dead last week. He was a hard-working fellow, that he was," said the grave-digger; for he always liked to give people a good word when digging their graves.

Dot now seemed satisfied; and, on her side, told the old man that she had come to live in one of the small cottages near the cemetery gates, and that they used to be "ever so far off" in the country.

Then she ran away to another part of the cemetery, and old Solomon shaded his eyes with his hand to watch her out of sight.

DOT'S DAISIES

DOT'S mother had lived all her life in a remote part of Yorkshire, far away from church or chapel or any kind of school. But her husband had been born and brought up in a town, and country life did not suit him. And so, when Dot was about five years old, he returned to his native place, and took one of the cottages close to the cemetery, in order that his little girl might still have some green grass on which to run about, and might still see a few spring flowers.

The cemetery was some way out of the town; and Dot's mother, having had but little education herself, did not think it at all necessary that Dot, at her tender age, should go to school, and therefore the little girl was allowed to spend most of her time in the cemetery, with which she was very well pleased. She liked to run round the gravestones, and climb over the grassy mounds, and watch the robins hopping from tree to tree.

But Dot's favourite place was by old Solomon's side. She went about with him from one part of the cemetery to another, and he liked to feel her tiny hand in his. She took a great interest, too, in the graves he was digging. She watched him shaping them neatly and making them tidy, as he called it, until she began, as she fancied, to understand grave-digging nearly as well as he did. But she sometimes puzzled the old man by her questions, for Dot always wanted to know everything about what she saw.

"Mr. Solemn," she said one day, "shall you make me a little grave when I die?"

"Yes," he said, "I suppose I shall, little woman."

Dot thought this over for a long time.

"I don't want to go into a grave," she said; "it doesn't look nice."

"No," said the grave-digger, "you needn't be frightened; you won't have to go just yet. Why, you're ever such a little mite of a thing!"

"Please, Mr. Solemn, when you die, who'll have to dig your grave, please?"

"I don't know," said Solomon uneasily; "they'll have to get a new digger, I suppose."

"Maybe you'd better dig one ready when you've a bit of time, Mr. Solemn."

But though Solomon was very fond of digging other people's graves—for he was so much used to it that it had become quite a pleasure to him—he had no wish to dig his own, nor did he like thinking about it, though Dot seemed as if she would not let him forget it.

Another day, when he was working in a distant part of the cemetery, she asked him—

"Whereabouts will they bury you, Mr. Solemn?"

And when they were standing over a newly made grave, and Solomon was admiring his work, she said—

"I hope they will make your grave neat, Mr. Solemn."

But though these questions and remarks made old Whitaker very uneasy—for he had a sort of uncomfortable feeling in his heart when he thought of the day when his grave-digging would come to an end—still, for all that, he liked little Dot, and he would have missed the child much if anything had kept her from his side. She took such an interest in his graves, too, and watched them growing deeper and deeper with as much pleasure as he did himself. And, whether we be rich or poor, high or low, interest in our work generally wins our hearts. And by and by Dot found herself a way, as she thought, of helping old Solomon to make his graves look nice.

He was working one day at the bottom of a grave, and Dot was sitting on the grass at a little distance. He thought she was busy with her doll, for she had not been talking to him for a long time, and he gave a jump as he suddenly felt something patting on his head, and heard Dot's merry little laugh at the top of the grave. She had filled her pinafore with daisies, and thrown them upon him in the deep grave.

"Whatever in the world is that for?" said the old man, good-naturedly, as he shook the flowers off his head.

"It's to make it pretty," said Dot. "It'll make it white and soft, you know, Mr. Solemn."

Solomon submitted very patiently; and from that time the child always gathered daisies to scatter at the bottom of Solomon's graves, till he began to look upon it as a necessary finish to his work. He often thought Dot was like a daisy herself, so fresh and bright she was. He wondered at himself when he reckoned how much he loved her. For his own little girl had been dead so many years; and it was so long now since he had dug his old wife's grave, that Solomon had almost forgotten how to love. He had had no one since to care for him, and he had cared for no one.

But little Dot had crept into his old heart unawares.

THE LITTLE GRAVE

OLD Solomon was digging a grave one day in a very quiet corner of the cemetery. Dot was with him, as usual, prattling away in her pretty childish way.

"It's a tidy grave, is this," remarked the old man, as he smoothed the sides with his spade; "nice and dry too; it'll do me credit."

"It's a very little one," said Dot.

"Yes, it's like to be little when it's for a little girl; you wouldn't want a very big grave, Dot."

"No," said Dot; "but you would want a good big one, wouldn't you, Mr. Solemn?"

The mention of his own grave always made Solomon go into one of his "reverdies." But he was recalled by Dot's asking quickly—

"Mr. Solemn, is she a very little girl?"

"Yes," said the old man; "maybe about your size, Dot. Her pa came about the grave. I was in the office when he called, 'and,' said he, 'I want a nice quiet little corner, for it is for my little girl.'"

"Did he look sorry?" said Dot.

"Yes," he said; "folks mostly do look sorry when they come about graves."

Dot had never watched the digging of a grave with so much interest as she did that of this little girl. She never left Solomon's side, not even to play with her doll. She was very quiet, too, as she stood with her large eyes wide open, watching all his movements. He wondered what had come over her, and he looked up several times rather anxiously as he threw up the spadefuls of earth.

"Mr. Solemn," she said, when he had finished, "when will they put the little girl in?"

"To-morrow morning," said the old man, "somewhere about eleven."

Dot nodded her head, and made up her mind she would be in this corner of the cemetery at eleven o'clock.

When Solomon came back from his dinner, and went to take a last look at the little grave, he found the bottom of it covered with white daisies which Dot had thrown in.

"She has made it pretty, bless her!" he murmured.

Dot crept behind the bushes near the chapel the next day, to watch the little girl's funeral arrive. She saw the small coffin taken from the hearse, and carried on in front. Then she watched the people get out of the carriages, and a lady and gentleman, whom she felt sure were the little girl's father and mother, walked on first. The lady had her handkerchief to her eyes, and Dot could see that she was crying. After her walked two little girls, and they were crying also.

There were a few other people at the funeral, but Dot did not care to look at them; she wanted to see what became of the little girl's coffin, which had just been carried into the chapel. She waited patiently till they brought it out, and then she followed the mournful procession at a little distance, till they reached the corner of the cemetery where Solomon had dug the grave.

Solomon was there, standing by the grave, when the bearers came up with the coffin. Dot could see him quite well, and she could see the minister standing at the end of the grave, and all the people in a circle round it. She did not like to go very near, but she could hear the minister reading something in a very solemn voice, and then the coffin was let down into the grave. The little girl's mamma cried very much, and Dot cried too, she felt so sorry for her.

When the service was over, they all looked into the grave, and then they walked away. Dot ran up as soon as they were gone, and, taking hold of Solomon's hand, she peeped into the grave. The little coffin was at the bottom, and some of Dot's daisies were lying round it.

"Is the little girl inside there?" said Dot in an awestruck voice.

"Yes," said Solomon, "she's in there, poor thing. I'll have to fill it up now."

"Isn't it very dark?" said Dot.

"Isn't what dark?"

"In there," said Dot. "Isn't it very dark and cold for the poor little girl?"

"Oh, I don't know that," said Solomon. "I don't suppose folks feels cold when they are dead; anyhow, we must cover her up warm."

But poor Dot's heart was very full; and, sitting on the grass beside the little girl's grave, she began to cry and sob as if her heart would break.

"Don't cry, Dot," said the old man; "maybe the little girl knows nothing about it—maybe she's asleep like."

But Dot's tears only flowed the faster. For she felt sure if the little girl were asleep, and knew nothing about it, as old Solomon said, she would be waking up some day, and then how dreadful it would be for her.

"Come, Dot," said Solomon at last, "I must fill it up."

Then Dot jumped up hastily. "Please, Mr. Solemn, wait one minute," she cried, as she disappeared amongst the bushes.

"Whatever is she up to now?" said the old grave-digger.

She soon came back with her pinafore full of daisies. She had been gathering them all the morning, and had hid them in a shady place under the trees. Then, with a little sob, she threw them into the deep grave, and watched them fall on the little coffin. After this she watched Solomon finish his work, and did not go home till the little girl's grave was made, as old Solomon said, "all right and comfortable."

LILIAN AND HER WORDS

DOT took a very great interest in "her little girl's grave," as she called it. She was up early the next morning; and as soon as her mother had washed her, and given her her breakfast, she ran to the quiet corner in the cemetery to look at the new-made grave. It looked very bare, Dot thought, and she ran away to gather a number of daisies to spread upon the top of it. She covered it as well as she could with them, and she patted the sides of the grave with her little hands, to make it more smooth and tidy. Dot wondered if the little girl knew what she was doing, and if it made her any happier to know there were daisies above her.

She thought she would ask Solomon; so when she had finished she went in search of him. He was not far away, and she begged him to come and look at what she had done to her little girl's grave. He took hold of Dot's hand, and she led him to the place.

"See, Mr. Solemn," she said, "haven't I made my little girl pretty?"

"Aye," he answered; "you have found a many daisies, Dot."

"But, Mr. Solemn," asked Dot anxiously, "do you think she knows?"

"Why, Dot, I don't know—maybe she does," he said, for he did not like to disappoint her.

"Mr. Solemn, shall I put you some daisies at the top of your grave?" said Dot, as they walked away.

Solomon made no answer. Dot had reminded him so often of his own grave, that he had sometimes begun to think about it, and to wonder how long it would be before it would have to be made. He had a vague idea that when he was buried, he would not come to an end.

He had heard of heaven and of hell; and though he had never thought much about either of them, he had a kind of feeling that some day he must go to one or other. Hell, he had heard, was for bad people, and heaven for good ones; and though Solomon tried to persuade himself that he belonged to the latter class, he could not quite come to that opinion. There was something in his heart which told him all was not right with him, and made the subject an unpleasant one. He wished Dot would let it drop, and not talk to him any more about it; and then he went into a reverie about Dot, and Dot's daisies, and all her pretty ways.

It was the afternoon of the same day, and Dot was sitting beside her little girl's grave, trying to make the daisies look more pretty by putting some leaves among them, when she heard footsteps crossing the broad gravel path. She jumped up, and peeped behind the trees to see who was coming. It was the lady and gentleman whom she had seen at the funeral, and they were coming to look at their little grave. Dot felt very shy, but she could not run away without meeting them, so she hid behind a hawthorn bush at the other side.

The little girl's papa and mamma came close to the grave, and Dot was so near that, as they knelt down beside it, she could hear a great deal of what they were saying. The lady was crying very much, and for some time she did not speak. But the gentleman said—

"I wonder who has put those flowers here, my dear; how very pretty they are!"

"Yes," said the lady, through her tears; "and the grave was full of them yesterday."

"How pleased our little girl would have been!" said he. "She was so fond of daisies! Who can have done it?"

Little Dot heard all this from her hiding-place, and she felt very pleased that she had made her little girl's grave so pretty.

The lady cried a great deal as she sat by the grave; but just before they left, Dot heard the gentleman say—

"Don't cry, dearest; remember what our little Lilian said the night before she died."

"Yes," said the lady, "I will not forget."

And she dried her eyes, and Dot thought she tried to smile as she looked up at the blue sky. Then she took a bunch of white violets which she had brought with her, and put them in the middle of the grave, but she did not move any of Dot's daisies, at which she looked very lovingly and tenderly.

As soon as they were gone, Dot came out from behind the hawthorn bush. She went up to her little girl's grave, and kneeling on the grass beside it she smelt the white violets and stroked them with her tiny hand. They made it look so much nicer, she thought; but she felt very glad that the lady had liked her daisies. She would gather some fresh ones to-morrow.

Dot walked home very slowly. She had so much to think over. She knew her little girl's name now, and that she was fond of daisies. She would not forget that. Dot felt very sorry for the poor lady; she wished she could tell her so. And then she began to wonder what it was that her little girl had said the night before she died. It must be something nice, Dot thought, to make the lady wipe her eyes and try to smile. Perhaps the little girl had said she did not mind being put into the dark hole. Dot thought it could hardly be that, for she felt sure she would mind it very much indeed. Dot was sure she would be very frightened if she had to die, and old Solomon had to dig a grave for her. No, it could not be that which Lilian had said. Perhaps Solomon was right, and the little girl was asleep. If so, Dot hoped it would be a long, long time before she woke up again.

Solomon had left his work, or Dot would have told him about what she had seen. But it was tea-time now, and she must go home. Her mother was standing at the door looking out for her, and she called to the child to be quick and come in to tea.

Dot found her father at home, and they began their meal. But little Dot was so quiet, and sat so still, that her father asked her what was the matter. Then she thought she would ask him what she wanted to know, for he was very kind to her, and generally tried to answer her questions.

So Dot told him about her little girl's grave, and what the lady and gentleman had talked about, and she asked what he thought the little girl had said, which had made her mother stop crying.

But Dot's father could not tell her. And when Dot said she was sure she would not like to be put in a hole like that, her father only laughed, and told her not to trouble her little head about it: she was too young to think of such things.

"But my little girl was only just about as big as me," said Dot, "'cause Mr. Solemn told me so."

That was an argument which her father could not answer, so he told Dot to be quick over her supper, and get to bed. And when she was asleep, he said to his wife that he did not think the cemetery was a good place for his little girl to play in—it made her gloomy. But Dot's mother said it was better than the street, and Dot was too light-hearted to be dull long.

And whilst they were talking little Dot was dreaming of Lilian, and of what she had said the night before she died.

DOT'S BUSY THOUGHTS

A DAY or two after, as Dot was putting fresh daisies on the little grave, she felt a hand on her shoulder, and looking up she saw her little girl's mamma. She had come up very quietly, and Dot was so intent on what she was doing that she had not heard her. It was too late to run away; but the lady's face was so kind and loving that the child could not be afraid. She took hold of Dot's little hand, and sat down beside her, and then she said very gently—

"Is this the little girl who gathered the daisies?"

"Yes," said Dot shyly, "it was me."

The lady seemed very pleased, and she asked Dot what her name was, and where she lived. Then she said—

"Dot, what was it made you bring these pretty flowers here?"

"Please," said the child, "it was 'cause Mr. Solemn said she was ever such a little girl—maybe about as big as me."

"Who is Mr. Solemn?" asked the lady.

"IS THIS THE LITTLE GIRL WHO GATHERED THE DAISIES?"

"It's an old man—him as digs the graves; he made my little girl's grave," said Dot, under her breath, "and he filled it up and all."

The tears came into the lady's eyes, and she stooped down and kissed the child.

Dot was beginning to feel quite at home with the little girl's mamma, and she stroked the lady's soft glove with her tiny hand.

They sat quite still for some time. Dot never moved, and the lady had almost forgotten her—she was thinking of her own little girl. The tears began to run down her cheeks, though she tried to keep them back, and some of them fell upon Dot as she sat at her feet.

"I was thinking of my little girl," said the lady, as Dot looked sorrowfully up to her face.

"Please," said Dot, "I wonder what your little girl said to you the night before she died?" She thought perhaps it might comfort the lady to think of it, as it had done so the other day.

The lady looked very surprised when Dot said this, as she had had no idea that the little girl was near when she was talking to her husband.

"How did you know, Dot?" she asked.

"Please, I couldn't help it," said little Dot; "I was putting the daisies."

"Yes?" said the lady, and she waited for the child to go on.

"And I ran in there," said Dot, nodding at the hawthorn bush. "I heard you—and, please, don't be angry."

"I am not angry," said the lady.

Dot looked in her face, and saw she was gazing at her with a very sweet smile.

"Then, please," said little Dot, "I would like very much to know what the little girl said."

"I will tell you, Dot," said the lady. "Come and sit on my knee."

There was a flat tombstone close by, on which they sat whilst the girl's mamma talked to Dot. She found it very hard to speak about her child, it was so short a time since she had died. But she tried her very best, for the sake of the little girl who had covered the grave with daisies.

"Lilian was only ill a very short time," said the lady; "a week before she died she was running about and playing—just as you have been doing to-day, Dot. But she took a bad cold, and soon the doctor told me my little girl must die."

"Oh," said Dot, with a little sob, "I am so sorry for the poor little girl!"

"Lilian wasn't afraid to die, Dot," said the lady.

"Wasn't she?" said Dot. "I should be frightened ever so much—but maybe she'd never seen Mr. Solemn bury anybody; maybe she didn't know she had to go into that dark hole."

"Listen, Dot," said the lady, "and I will tell you what my little girl said the night before she died."

"'Mamma,' she said, 'don't let Violet and Ethel think that I'm down deep in the cemetery; but take them out, and show them the blue sky and all the white clouds, and tell them, Little sister Lilian's up there with Jesus.' Violet and Ethel are my other little girls, Dot."

"Yes," said Dot, in a whisper; "I saw them at the funeral."

"That is what my little girl said, which made me stop crying the other day."

Dot looked very puzzled. There was a great deal that she wanted to think over and to ask Solomon about.

The lady was obliged to go home, for it was getting late. She kissed the child before she went, and said she hoped Dot would see her little girl one day, above the blue sky.

Dot could not make out what the lady meant, nor what her little girl had meant the night before she died. She wanted very much to hear more about her, and she hoped the lady would soon come again.

"Mr. Solemn," said Dot the next day, as she was in her usual place on the top of one of Solomon's graves, "didn't you say that my little girl was in that long box?"

"Yes," said Solomon—"yes, Dot, I said so, I believe."

"But my little girl's mamma says she isn't in there, Mr. Solemn, and my little girl said so the night before she died."

"Where is she, then?" said Solomon.

"She's somewhere up there," said Dot, pointing with her finger to the blue sky.

"Oh, in heaven," said Solomon. "Yes, Dot, I suppose she is in heaven."

"How did she get there?" said Dot. "I want to know all about it, Mr. Solemn."

"Oh, I don't know," said the old man. "Good folks always go to heaven."

"Shall you go to heaven, Mr. Solemn, when you die?"

"I hope I shall, Dot, I'm sure," said the old man. "But there, run away a little; I want to tidy round a bit."

Now, Solomon had very often "tidied round," as he called it, without sending little Dot away; but he did not want her to ask him any more questions, and he hoped she would forget it before she came back.

But Dot had not forgotten. She had not even been playing; she had been sitting on an old tombstone, thinking about what Solomon had said. And as soon as he had finished the grave she ran up to him.

"Mr. Solemn," she said, "did she get out in the night?"

"Who get out?" said the old man, in a very puzzled voice.

"My little girl, Mr. Solemn. Did she get out that night, after you covered her up, you know?"

"No," said Solomon, "she couldn't get out—how could she?"

"Then she's in there yet," said little Dot very sorrowfully.

"Yes, she's there, safe enough," said the grave-digger; "it's the last home of man, is the grave, Dot."

"But, Mr. Solemn, you said she was in heaven," Dot went on, in a very mournful little voice.

Solomon did not know how to answer her; indeed it was very puzzling to himself. He wished he could think what to say to Dot; but nothing would come to him, so he gave up the attempt, and tried to think of something else.

But Dot's busy little mind was not satisfied. The little girl's mamma must be right; and she had said she hoped Dot would see Lilian above the blue sky. Dot wondered how she would get up above the sky.