[Pg i]

[Pg iii]

BY

EDMUND G. GARDNER, M.A.

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

681 Fifth Avenue

[Pg iv]

Copyright, 1923

By E. P. Dutton & Company

All Rights Reserved

PRINTED IN THE UNITED

STATES OF AMERICA

[Pg v]

TO

PHILIP H. WICKSTEED

A SMALL TRIBUTE

OF

DEEP AFFECTION AND HIGH ESTEEM

[Pg vii]

[Pg vi]

I would ask the reader to take the present volume, not as a new book on Dante, but merely as a revision of the Primer which was first published in 1900. It has been as far as possible brought up to date, the chief modifications being naturally in the sections devoted to the poet’s life and Opere minori, and in the bibliographical appendix; but the work remains substantially the same. Were I now to write a new Dante Primer, after the interval of nearly a quarter of a century, I should be disposed to attach considerably less importance to the allegorical meaning of the Divina Commedia, and to emphasise, more than I have here done, the aspect of Dante as the symbol and national hero of Italy.

E. G. G.

London, July, 1923.

[Pg viii]

N.B.—The “Sexcentenary Dante” (the testo critico published under the auspices of the Società Dantesca Italiana) adopts a slightly different numbering of the chapters, or paragraphs, of the Vita Nuova and the second treatise of the Convivio from that presented by the “Oxford Dante” and the “Temple Classics.” I have kept to the latter (which is indicated in brackets in the testo critico). Similarly, I have followed the numbering of the Epistolae in Dr. Toynbee’s edition and the “Oxford Dante” (also given in brackets in the testo critico). In the section on the lyrical poetry, Rime refers to the testo critico as edited by Professor Barbi, O. to the new Oxford edition revised by Dr. Toynbee. In the closing passage of the Letter to a Florentine friend, I have followed the reading retained by Dr. Toynbee. I have frequently availed myself of Dr. Wicksteed’s translation of the Letters and Monarchia, of Mr. A. G. F. Howell’s version of the De Vulgari Eloquentia, and occasionally of Carlyle’s rendering of the Inferno. Every student of Dante must inevitably owe much to others; but, in this new edition of my Primer, I would express my indebtedness in particular to the writings of Dr. Paget Toynbee, Dr. Philip H. Wicksteed, the late Ernesto Giacomo Parodi, and Prof. Michele Barbi.

⁂ To the Bibliographical Appendix should be added: A. Fiammazzo, Il commento dantesco di Graziolo de’ Bambaglioli (Savona, 1915), and P. Revelli, L’Italia nella Divina Commedia (Milan, 1923).

[Pg ix]

| CHAPTER I | |

| Dante in his Times— | |

| I. The End of the Middle Ages.—II. Dante’s Childhood and Adolescence.—III. After the Death of Beatrice.—IV. Dante’s Political Life.—V. First Period of Exile.—VI. The Invasion of Henry VII.—VII. Last Period of Exile.—VIII. Dante’s Works and First Interpreters | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Dante’s Minor Italian Works— | |

| I. The Vita Nuova.—II. The Rime.—III. The Convivio | 67 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Dante’s Latin Works— | |

| I. The De Vulgari Eloquentia.—II. The Monarchia.—III. The Epistolae.—IV. The Eclogae.—V. The Quaestio de Aqua et Terra | 102 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The “Divina Commedia”— | |

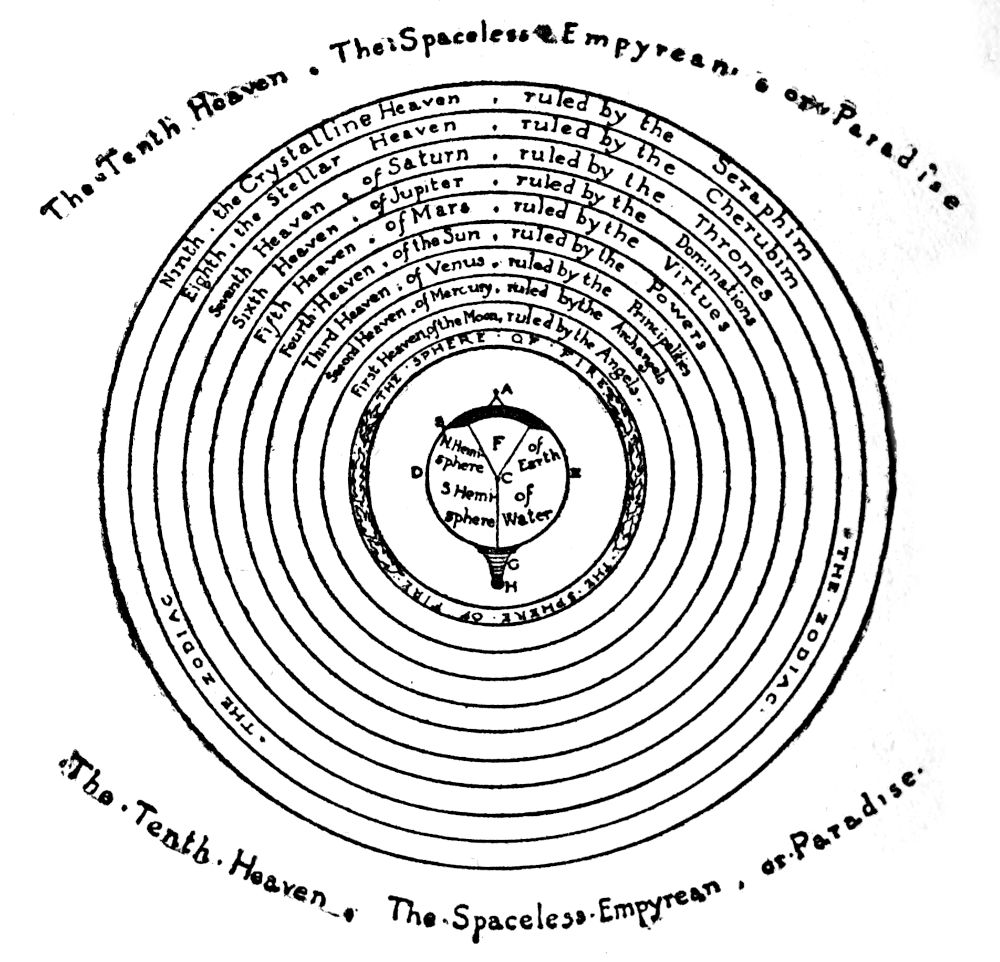

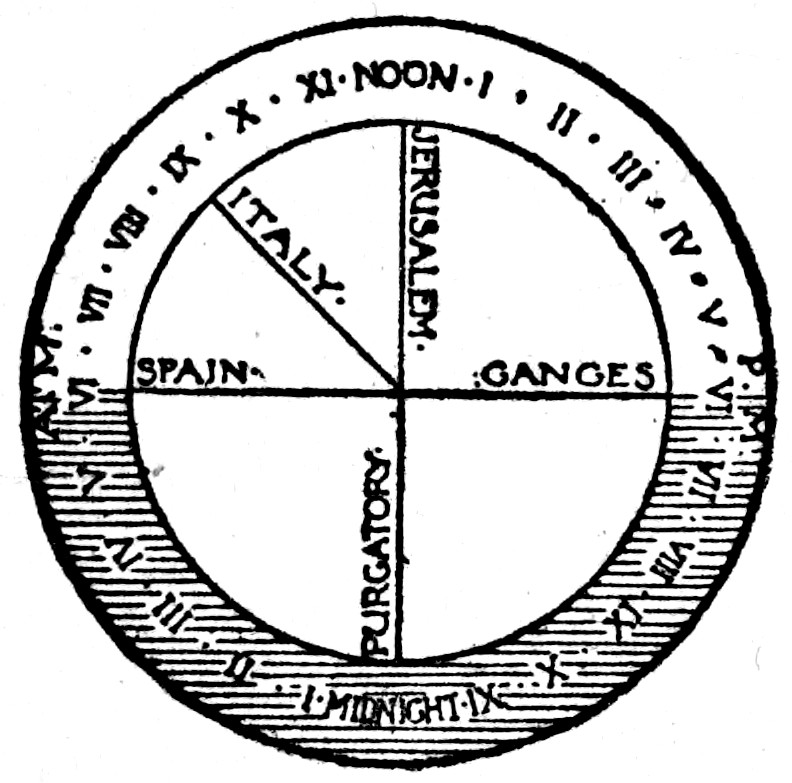

| I. Introductory.—II. The Inferno.—III. The Purgatorio.—IV. The Paradiso | 136 |

| Bibliographical Appendix | 223 |

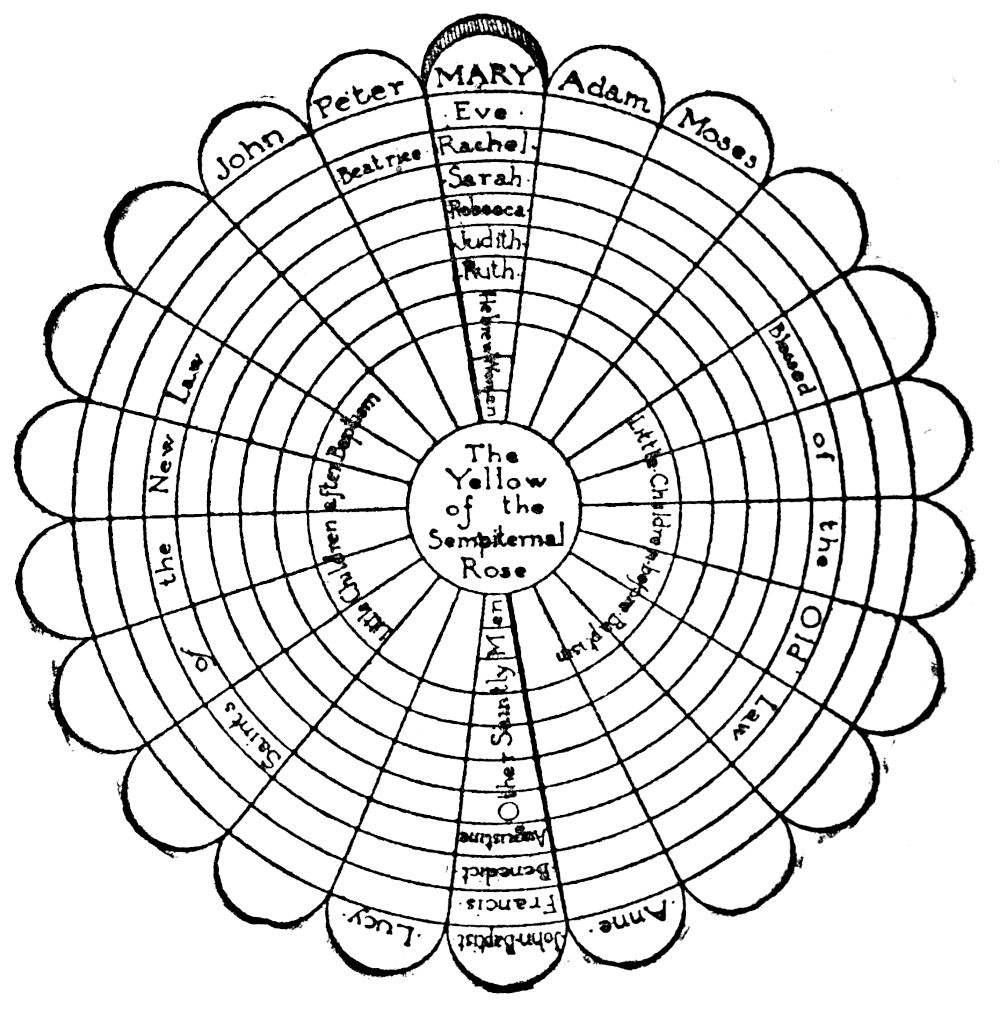

| Diagrams and Tables | 233 |

| Index | 249 |

[Pg 1]

DANTE

From Gregory VII. to Frederick II.—The twelfth and thirteenth centuries cover the last and more familiar portion of the Middle Ages. They are the period of chivalry, of the crusades and of romance, when the Neo-Latin languages bore fruit in the prose and poetry of France, the lyrics of the Provençal troubadours, and the earliest vernacular literature of Italy; the period which saw the development of Gothic architecture, the rise of scholastic philosophy, the institution of the Franciscan and Dominican orders, the recovery by western Europe of the works of Aristotle, the elevation of Catholic theology into a systematic harmony of reason and revelation under the influence of the christianised Aristotelianism of Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas. The vernacular literature of Italy developed comparatively late, and (until the time of Aquinas and Bonaventura) her part in the scholastic movement was secondary to that of France, but she had led[Pg 2] the way in the revival of the study of Roman law and jurisprudence, which centred at Bologna, where the great Irnerius taught at the beginning of the twelfth century. It was thus that the first European university, studium generale, came into being, and Bologna boasts the proud title alma mater studiorum.

There are two predominant political factors in Italy which appear at the end of the twelfth century, and hold the field up to the time of Dante’s birth. Out of the war of investitures between Pope and Emperor, the struggle which we associate mainly with the name of Hildebrand (Gregory VII.), emerged the Italian city-states, the free communes of northern and central Italy, whose development culminated in the heroic resistance offered by the first Lombard League to the mightiest of mediaeval German Caesars, Frederick I. (Barbarossa), which won the battle of Legnano (1176) and obtained the peace of Constance (1183). In the south, the Normans—conquering Apulia and Calabria, delivering Sicily from the Saracens—consolidated their rule into a feudal monarchy, making their capital Palermo one of the most splendid cities of the mediaeval world. The third and last of these Norman kings of Sicily, William II. (Par. xx. 61-66), died in 1189. The son of Barbarossa, Henry VI., claimed the kingdom in the right of his wife Constance (Par. iii. 115-120), and established the Suabian dynasty on the throne. His son, Frederick II.,[Pg 3] continued the cultured traditions of the Norman kings; but the union in his person of the kingdom of Sicily with the Empire led to a continuous struggle with the Italian communes and the Papacy, which embittered his closing years until his death in 1250. The reign of Frederick II. is the period of the Guelf and Ghibelline factions, and the beginning of the rise of tyrants in the Italian cities, tyrants of whom the most terrible example was Ezzelino da Romano (Inf. xii. 110).

The Battle of Benevento.—The policy of Frederick II. was continued by his son Manfred (crowned King of Sicily in 1258), against whom Pope Clement IV., claiming the right to dispose of the kingdom as a fief of the Church, summoned Charles of Anjou, the brother of St. Louis of France. Charles entered Italy (Purg. xx. 67), encountered and defeated Manfred on the plains of Grandella near Benevento, in February 1266, and the papal legate refused the rites of Christian burial to the fallen king (Purg. iii. 124-132). This battle of Benevento marks an epoch in Italian history. It ended for the time the struggle between the Roman Pontiffs and the German Caesars; it initiated the new strife between the Papacy and the royal house of France. Henceforth the old ideal significance of “Guelf” and “Ghibelline,” as denoting adherents of Church and Empire respectively, becomes lost in the local conflicts of each Italian district and city. The imperial power was at an end in Italy; but the Popes, by calling[Pg 4] in this new foreign aid, had prepared the way for the humiliation of Pope Boniface at Anagni and the corruption of Avignon. The fall of the silver eagle from Manfred’s helmet before the golden lilies on Charles’s standard may be taken as symbolical. The preponderance in Italian politics had passed back from Germany to France; the influence of the house of Capet was substituted for the overthrown authority of the Emperor (Purg. xx. 43, 44). Three weeks after the battle Charles entered Naples in triumph, King of Apulia and Sicily; an Angevin dynasty was established upon the throne of the most potent state of Italy.

Art and Letters.—This political transformation was profoundly felt in Italian literature. A new courtly poetry, that of the so-called “Sicilian School,” had come into being in the south, partly based on Provençal models, in the first quarter of the thirteenth century. Its poets—mainly Sicilians and Apulians, but with recruits from other parts of the peninsula—had almost given to Italy a literary language. “The Sicilian vernacular,” writes Dante in his De Vulgari Eloquentia, “seems to have gained for itself a renown beyond the others; for whatever Italians produce in poetry is called Sicilian, and we find that many native poets have sung weightily.” This he ascribes to the fostering influence of the imperial rule of the house of Suabia: “Those illustrious heroes, Frederick Caesar and his well-begotten son Manfred, showing their nobility and rectitude[Pg 5] of soul, as long as fortune lasted, followed human things, disdaining the bestial; wherefore the noble in heart and endowed with graces strove to cleave to the majesty of such great princes; so that, in their time, whatever the excellent among Italians attempted first appeared at the court of these great sovereigns. And, because the royal throne was Sicily, it came about that whatever our predecessors produced in the vernacular is called Sicilian” (V. E. i. 12). The house of Anjou made Naples their capital, and treated Sicily as a conquered province. After Benevento the literary centre of Italy shifted from Palermo and the royal court of the south to Bologna and the republican cities of Tuscany. Guittone d’Arezzo (Purg. xxvi. 124-126) founded a school of Tuscan poets, extending the field of Italian lyrical poetry to political and ethical themes as well as love (which had been the sole subject of the Sicilian School). The beginnings of Italian literary prose had already appeared at Bologna, with the first vernacular models for composition of the rhetoricians, the masters of the ars dictandi. Here, within the next eight years, St. Thomas Aquinas published the first and second parts of the Summa Theologica; and the poetry of the first great singer of modern Italy, Guido Guinizelli (Purg. xxvi. 91-114), rose to spiritual heights undreamed of in the older schools, in his canzone on Love and true nobility: Al cor gentil ripara sempre Amore; “To the gentle heart doth Love ever repair.” And, in the[Pg 6] sphere of the plastic arts, these were the years that saw the last triumphs of Niccolò Pisano, “the Father of Sculpture to Italy,” and the earliest masterpieces of Cimabue, the teacher of Giotto (Purg. xi. 94-96), the shepherd boy who came from the fields to free Italian painting from Byzantine fetters, and who “developed an artistic language which was the true expression of the Italian national character.”

Birth and Family.—Dante Alighieri, in its Latin form Alagherii, was born at Florence in 1265, probably in the latter part of May, some nine months before the battle of Benevento. His father, Alighiero di Bellincione di Alighiero, came of an ancient and honourable family of that section of the city named from the Porta San Piero. Although Guelfs, the Alighieri were probably of the same stock as the Elisei, decadent nobles of supposed Roman descent, who took the Ghibelline side in the days of Frederick II., when the city was first involved in these factions after the murder of young Buondelmonte in her “last peace” in 1215 (Par. xvi. 136-147). Among the warriors of the Cross, in the Heaven of Mars, Dante meets his great-great-grandfather Cacciaguida. Born probably in 1091, Cacciaguida married a wife from the valley of the Po, a member of one or other of the families afterwards known as the Aldighieri or Alighieri at Ferrara, Parma, and Bologna, was[Pg 7] knighted by Conrad III., and died in battle against the infidels in the disastrous second crusade (Par. xv. 137-148). None of Cacciaguida’s descendants had attained to any distinction in the Republic. Brunetto di Bellincione, Dante’s uncle, probably fought for the Guelfs at Montaperti in 1260, where he may have been one of those in charge of the carroccio, the battle-car which accompanied the army. Besides Cacciaguida and his son Alaghiero, or Alighiero, the first to bear the name, who is said by his father to be still in the purgatorial terrace of the proud (Par. xv. 91-96), the only other member of the family introduced into the Divina Commedia is Geri del Bello, a grandson of the elder Alighiero and cousin of Dante’s father, a sower of discord and a murderer (Inf. xxix. 13-36), whose violent and well-deserved death had not yet been avenged.

The Florentine Republic.—As far as Florence was concerned, the real strife of Guelfs and Ghibellines was a struggle for supremacy, first without and then within the city, of a democracy of merchants and traders, with a military aristocracy of partly Teutonic descent, who were gradually being deprived of their territorial and feudal sway, which they had held nominally from the Emperor in the contado, the country districts of Tuscany included in the continually extending Florentine commune. Although the party names were first introduced into Florence in 1215, the struggle had virtually begun after the death of[Pg 8] the great Countess Matilda in 1115; and had resulted in a regular and constitutional advance of the power of the people, interrupted by a few intervals. It was in one of these intervals that Dante was born. The popular government (Primo Popolo), which had been established shortly before the death of Frederick II. in 1250, and worked victoriously for ten years, had been overthrown in 1260 at the disastrous battle of Montaperti, “the havoc and the great slaughter, which dyed the Arbia red” (Inf. x. 85, 86). The patriotism of Farinata degli Uberti saved Florence from total destruction, but all the leading Guelf families were driven out, and the government remained in the power of a despotic Ghibelline aristocracy, under Manfred’s vicar, Count Guido Novello, supported by German mercenaries. After the fall of Manfred, an attempt was made to effect a peace between the Ghibellines and the people; but a revolution on St. Martin’s Day, November 11th, 1266, led to the expulsion of Guido Novello and his forces, and the formation of a provisional democratic government. In January 1267 the banished Guelfs—many of whom had fought under the papal banner at Benevento—returned; on Easter Day French troops entered Florence, the Ghibellines fled, the Guelfs made Charles of Anjou suzerain of the city, and accepted his vicar as podestà. The government was reorganised, with a new institution, the Parte Guelfa, to secure the Guelf predominance in the Republic.

[Pg 9]

The defeat of young Conradin, grandson of Frederick II., at Tagliacozzo in 1268, followed by his judicial murder (Purg. xx. 68), confirmed the triumph of the Guelfs and the power of Charles in Italy. In Florence the future conflict lay between the new Guelf aristocracy and the burghers and people, between the Grandi and the Popolani; the magnates in their palaces and towers, associated into societies and groups of families, surrounding themselves with retainers and swordsmen, but always divided among themselves; and the people, soon to become “very fierce and hot in lordship,” as Villani says, artisans and traders ready to rush out from stalls and workshops to follow the standards of their Arts or Guilds in defence of liberty. In the year after the House of Suabia ended with Conradin upon the scaffold, the Florentines took partial vengeance for Montaperti at the battle of Colle di Valdelsa (Purg. xiii. 115-120), where the Sienese were routed and Provenzano Salvani (Purg. xi. 109-114) killed. It is said to have been Provenzano Salvani who, in the great Ghibelline council at Empoli, had proposed that Florence should be destroyed.

Dante’s Boyhood.—It is not clear how Dante came to be born in Florence, since he gives us to understand (Inf. x. 46-50) that his family were fiercely adverse to the Ghibellines and would naturally have been in exile until the close of 1266. Probably his father, of whom scarcely anything is known, took no prominent part in politics and had[Pg 10] been allowed to remain in the city. Besides the houses in the Piazza San Martino, he possessed two farms and some land in the country. Dante’s mother, Bella (perhaps an abbreviation of Gabriella), is believed to have been Alighiero’s first wife, and to have died soon after the poet’s birth. Her family is not known, though it has been suggested that she may have been the daughter of Durante di Scolaio degli Abati, a Guelf noble. Alighiero married again, Lapa di Chiarissimo Cialuffi, the daughter of a prominent Guelf popolano; by this second marriage he had a son, Francesco, and a daughter, Tana (Gaetana), who married Lapo Riccomanni. Another daughter, whose name is not known, married Leone Poggi; it is not quite certain whether her mother was Bella or Lapa. Dante never mentions his mother nor his father, whom he also lost in boyhood, in any of his works (excepting such indirect references as Inf. viii. 45, and Conv. i. 13); but, in the Vita Nuova, a “young and gentle lady, who was united to me by very near kindred,” appears watching by the poet in his illness. In the loveliest of his early lyrics she is described as

which Rossetti renders:

This lady was, perhaps, one of these two sisters; and it is tempting to infer from Dante’s words[Pg 11] that a tender affection existed between him and her. It was from Dante’s nephew, Andrea Poggi, that Boccaccio obtained some of his information concerning the poet, and it would be pleasant to think that Andrea’s mother is the heroine of this canzone (V. N. xxiii.); but there are chronological difficulties in the identification.

Sources.—Our sources for Dante’s biography, in addition to his own works, are primarily a short chapter in the Chronicle of his neighbour Giovanni Villani, the epoch-making work of Boccaccio, Filippo Villani’s unimportant sketch at the end of the fourteenth and the brief but reliable life by Leonardo Bruni at the beginning of the fifteenth century. In addition we have some scanty hints given by the early commentators on the Divina Commedia, and a few documents, including the consulte or reports of the deliberations of the various councils of the Florentine Republic. Boccaccio’s work has come down to us in two forms: the Vita di Dante (or Trattatello in laude di Dante) and the so-called Compendio (itself in two redactions, the Primo and Secondo Compendio); the researches of Michele Barbi have finally established that both are authentic, the Compendio being the author’s own later revision. The tendency of recent scholarship has in a considerable measure rehabilitated the once discredited authority of Boccaccio, and rejected the excessive scepticism represented in the nineteenth century by Bartoli and Scartazzini.

[Pg 12]

Beatrice.—Although Leonardo Bruni rebukes Boccaccio, “our Boccaccio that most sweet and pleasant man,” for having lingered so long over Dante’s love affairs, still the story of the poet’s first love remains the one salient fact of his youth and early manhood. We may surmise from the Vita Nuova that at the end of his eighteenth year, presumably in May 1283, Dante became enamoured of the glorious lady of his mind, Beatrice, who had first appeared to him as a child in her ninth year, nine years before. It is not quite certain whether Beatrice was her real name or one beneath which Dante conceals her identity; assuredly she was “Beatrice,” the giver of blessing, to him and through him to all lovers of the noblest and fairest things in literature. Tradition, following Boccaccio, has identified her with Bice, the daughter of Folco Portinari, a wealthy Florentine who founded the hospital of S. Maria Nuova, and died in 1289 (cf. V. N. xxii.). Folco’s daughter is shown by her father’s will to have been the wife of Simone dei Bardi, a rich and noble banker. This has been confirmed by the discovery that, while the printed commentary of Dante’s son Pietro upon the Commedia hardly suggests that Beatrice was a real woman at all, there exists a fuller and later recension by Pietro of his own work which contains a distinct statement that the lady raised to fame in his father’s poem was in very fact Bice Portinari. Nevertheless, there are still found critics who see in Beatrice not a real[Pg 13] woman, but a mystically exalted ideal of womanhood or a merely allegorical figure; while Scartazzini at one time maintained that the woman Dante loved was an unknown Florentine maiden, who would have been his wife but for her untimely death. This can hardly be deduced from the Vita Nuova; in its noblest passages the woman of Dante’s worship is scarcely regarded as an object that can be possessed; death has not robbed him of an expected beatitude, but all the world of an earthly miracle. But, although it was in the fullest correspondence with mediaeval ideals and fashions that chivalrous love and devotion should be directed by preference to a married woman, the love of Dante for Beatrice was something at once more real and more exalted than the artificial passion of the troubadours; a true romantic love that linked heaven to earth, and was a revelation for the whole course of life.

Poetry, Friendship, Study.—Already, at the age of eighteen, Dante was a poet: “I had already seen for myself the art of saying words in rhyme” (V. N. iii.). It was on the occasion of what we take as the real beginning of his love that he wrote the opening sonnet of the Vita Nuova, in which he demands an explanation of a dream from “all the faithful of Love.” The new poet was at once recognised. Among the many answers came a sonnet from the most famous Italian lyrist then living, Guido Cavalcanti, henceforth to be the first of Dante’s friends: “And this was, as it[Pg 14] were, the beginning of the friendship between him and me, when he knew that I was he who had sent that sonnet to him” (cf. Inf. x. 60). In the same year, 1283, Dante’s name first occurs in a document concerning some business transactions as his late father’s heir.

There are no external events recorded in Dante’s life between 1283 and 1289. Boccaccio represents him as devoted to study. He certainly owed much to the paternal advice of the old rhetorician and statesman, Brunetto Latini, who had been secretary of the commune and, until his death in 1294, was one of the most influential citizens in the state: “For in my memory is fixed, and now goes to my heart, the dear, kind, paternal image of you, when in the world, from time to time, you taught me how man makes himself eternal” (Inf. xv. 82). Of his growing maturity in art, the lyrics of the Vita Nuova bear witness; the prose narrative shows that he had studied the Latin poets as well as the new singers of Provence and Italy, had already dipped into scholastic philosophy, and was not unacquainted with Aristotle. At the same time, Leonardo Bruni was obviously right in describing Dante as not severing himself from the world, but excelling in every youthful exercise; and it would seem from the Vita Nuova that, in spite of his supreme devotion for Beatrice, there were other Florentine damsels who moved his heart for a time. Dante speaks of “one who, according to the degrees of friendship, is my[Pg 15] friend immediately after the first,” and than whom there was no one nearer in kinship to Beatrice (V. N. xxxiii.). Those who identify Dante’s Beatrice with the daughter of Messer Folco suppose that this second friend was one of her three brothers, probably Manetto Portinari, to whom a sonnet of Guido’s may have been addressed. Casella the musician, and Lapo Gianni the poet, are mentioned with affection in the Purgatorio (Canto ii.), and in one of Dante’s sonnets respectively; Lippo de’ Bardi, evidently like Casella a musician, and a certain Meuccio likewise appear as friends in other of his earliest lyrics. Cino da Pistoia, like Cavalcanti, seems to have answered Dante’s dream; their friendship was perhaps at present mainly confined to exchanging poems. Boccaccio and Benvenuto da Imola speak of an early visit of Dante’s to the universities of Bologna and Padua, and there is some evidence for thinking that he was at Bologna some time not later than 1287. He may possibly have served in some cavalry expedition to check the harrying parties of Aretines in 1288; for, when the great battle of the following year was fought, it found Dante “no novice in arms,” as a fragment of one of his lost letters puts it, non fanciullo nell’ armi.

Popular Government.—Twenty years had now passed since the victory of Colle di Valdelsa in 1269. Great changes had taken place in the meanwhile. The estrangement between Charles of Anjou and the Popes, Gregory X. and Nicholas[Pg 16] III., the attempts of these latter to weaken the king’s power by reconciling the Florentine Guelfs with the Ghibelline exiles, and the dissensions among the Guelf magnates themselves within the city, had led, in 1280, to the peace arranged by Cardinal Latino Frangipani. A government was set up of fourteen buonuomini, magnates and popolani, eight Guelfs and six Ghibellines. But the city remained strenuously Guelf. Nicholas III. had deprived King Charles of the offices of Senator of Rome and Vicar Imperial and had allowed Rudolph of Hapsburg to establish a vicar in Tuscany (Inf. xix. 99). In 1282 came the Vespers of Palermo (Par. viii. 75). The Sicilians rose, massacred Charles’s adherents, and received as their king Peter of Aragon, the husband of Manfred’s daughter Constance (Purg. iii. 143). The hitherto united kingdom of Sicily, which had been the heritage of the imperial Suabians from the Norman heroes of the house of Hauteville, was thus divided between a French and a Spanish line of kings (Par. xx. 63); the former at Naples as kings of “Sicily and Jerusalem,” the latter in the island as kings of “Trinacria.” Charles was henceforth too much occupied in war with the Sicilians and Aragonese to interfere in the internal affairs of Tuscany. In the June of this year a peaceful revolution took place in Florence. Instead of the fourteen buonuomini, the government was put into the hands of the Priors of the Arts or Guilds, who, associated with the Captain, were henceforth[Pg 17] recognised as the chief magistrates of the Republic, composing the Signoria, during the two months for which they were elected to hold office. Their number, originally three, was raised to six; both grandi and popolani were at first eligible, provided the former left their order by enrolling themselves in one of the Guilds. A thorough organisation of these Guilds, the Arti maggiori (which were mainly engaged in wholesale commerce, exportation and importation, and the mercantile relations of Florence with foreign countries) and Arti minori (which carried on the retail traffic and internal trade of the city), secured the administration in the hands of the trading classes.

Thus was established the democratic constitution of the state in which Dante was afterwards to play his part. There was the central administration of the six Priors, one for each sesto of the city, with the council of a hundred “good men of the people without whose deliberation no great thing or expenditure could be done” (Villani, vii. 16). The executive was composed of the Captain of the People and the Podestà, both Italian nobles from other states, holding office for six months, each with his two councils, a special and a general council, the general council of the Podestà being the general council of the Commune. The great Guilds had their own council (Consiglio delle Capitudini delle Arti), and their consuls or rectors, while specially associated with the two councils of the Captain, were sometimes admitted to[Pg 18] those of the Podestà; the nobles were excluded from all these councils, excepting the special council of the Podestà and the general council of the Commune. But, while the central government of the Republic was thus entirely popular, the magnates still retained control over the captains of the Guelf Society, with their two councils, and exerted considerable influence upon the Podestà, always one of their own order and an alien, in whose councils they still sat. The Podestà, however, was now little more than a chief justice; “the Priors, with the Captain of the People, had to determine the great and weighty matters of the commonwealth, and to summon and conduct councils and make regulations” (Villani).

Battle of Campaldino.—A period of prosperity and victory followed for Florence. The crushing defeat inflicted upon Pisa by Genoa at the great naval battle of Meloria in 1284 was much to her advantage; as was also, perhaps, the decline of the Angevin power after the victory of Peter of Aragon’s fleet (Purg. xx. 79). Charles II., the “cripple of Jerusalem,” who succeeded his father as king of Naples, was a less formidable suzerain. On June 11th, 1289, the Tuscan Ghibellines were utterly defeated by the Florentines and their allies at the battle of Campaldino. According to Leonardo Bruni—and there seems no adequate reason for rejecting his testimony—Dante was present, “fighting valiantly on horseback in the front rank,” apparently among the 150 who volunteered[Pg 19] or were chosen as feditori, amongst whom was Vieri de’ Cerchi, who was later to acquire a more dubious reputation in politics. Bruni states that in a letter Dante draws a plan of the fight; and he quotes what seems to be a fragment of another letter, written later, where Dante speaks of “the battle of Campaldino, in which the Ghibelline party was almost utterly destroyed and undone; where I found myself no novice in arms, and where I had much fear, and in the end very great gladness, by reason of the varying chances of that battle.”

Dante probably took part in the subsequent events of the campaign; the wasting of the Aretine territory, the unsuccessful attack upon Arezzo, the surrender of the Pisan fortress of Caprona. “Thus once I saw the footmen, who marched out under treaty from Caprona, fear at seeing themselves among so many enemies” (Inf. xxi. 94-96). There appears to be a direct reference to his personal experiences of the campaign in the opening of Inferno xxii.: “I have seen ere now horsemen moving camp and beginning the assault, and holding their muster, and at times retiring to escape; coursers have I seen upon your land, O Aretines! and seen the march of foragers, the shock of tournaments and race of jousts, now with trumpets and now with bells, with drums and castle signals.” He has sung of Campaldino in peculiarly pathetic strains in Canto V. of the Purgatorio. On the lower slopes of the Mountain of[Pg 20] Purgation wanders the soul of Buonconte da Montefeltro, who led the Aretine cavalry, and whose body was never found; mortally wounded and forsaken by all, he had died gasping out the name of Mary, and his Giovanna had forgotten even to pray for his soul.

Death of Beatrice.—In the following year, 1290, Beatrice died: “The Lord of justice called this most gentle one to glory under the banner of that blessed queen Mary virgin, whose name was in very great reverence in the words of this blessed Beatrice” (V. N. xxix.). Although Dante complicates the date by a reference to “the usage of Arabia,” she appears to have died on the evening of June 8th;[1] and the poet lifts up his voice with the prophet: “How doth the city sit solitary that was full of people! How is she become as a widow, she that was great among the nations!”

Philosophic Refuge.—It is not easy to get a very definite idea of Dante’s private life during the next ten years. With the completion of the Vita Nuova, shortly after Beatrice’s death, an epoch closes in his life, as in his work. From the Convivio it would appear that in his sorrow Dante took refuge in the study of the De Consolatione Philosophiae of Boëthius and Cicero’s De Amicitia; that he frequented “the schools of the religious[Pg 21] and the disputations of philosophers,” where he became deeply enamoured of Philosophy. Cino da Pistoia addressed to him an exceedingly beautiful canzone, consoling him for the loss of Beatrice, bidding him take comfort in the contemplation of her glory among the saints and angels of Paradise, where she is praying to God for her lover’s peace. This poem is quoted years later by Dante himself in the second book of the De Vulgari Eloquentia (ii. 6), where he couples it with his own canzone—

“Love that in my mind discourses to me,” with which Casella consoles the penitent spirits upon the shore of Purgatory: “The amorous chant which was wont to quiet all my desires.”

Aberrations.—It would seem, however, that neither the memory of Beatrice nor his philosophical devotion kept Dante from falling into what he afterwards came to regard as a morally unworthy life. Tanto giù cadde, “so low he fell” (Purg. xxx. 136). It is almost impossible to hold, as Witte and Scartazzini would have us do, that the poignant reproaches which Beatrice addresses to Dante, when he meets her on Lethe’s banks, are connected mainly with intellectual errors, with culpable neglect of Theology or speculative wanderings from revealed truth, for there are but scanty, if any, traces of this in the poet’s writings at any period of his career. The dark wood in which he wandered, led by the world and the flesh,[Pg 22] was that of sensual passion and moral aberration for a while from the light of reason and the virtue which is the “ordering of love.”

Friendship with Forese Donati.—Dante was evidently intimate with the great Donati family, whose houses were in the same district of the city. Corso di Simone Donati, a turbulent and ambitious spirit, had done heroically at Campaldino, and was now intent upon having his own way in the state. A close and familiar friendship united Dante with Corso’s brother Forese, a sensual man of pleasure. Six sonnets interchanged between these two friends, though now only in part intelligible, do little credit to either. “If thou recall to mind,” Dante says to Forese in the sixth terrace of Purgatory, “what thou wast with me and I was with thee, the present memory will still be grievous” (Purg. xxiii, 115). Forese died in July 1296; the author of the Ottimo Commento, who wrote about 1334, and professes to have known the divine poet, tells us that Dante induced his friend when on his death-bed to repent and receive the last sacraments. Another sonnet of Dante’s shows him in friendly correspondence with Brunetto (Betto) Brunelleschi, a noble who later played a sinister part in the factions and, like Corso Donati, met a violent death.

Loves, Marriage, and Debts.—Several very striking canzoni, written for a lady whom Dante represents under various stony images, and whose name may possibly have been Pietra, are frequently[Pg 23] assigned to this period of the poet’s life, but may perhaps have been written in the early days of his exile. From other lyrics and sonnets we dimly discern that several women may have crossed Dante’s life now and later, of whom nothing can be known. Dante married Gemma di Manetto Donati, a distant kinswoman of Corso and Forese. In the Paradiso (xvi. 119) he refers with complacency to his wife’s ancestor, Ubertino Donati, Manetto’s great-grandfather, whose family pride scorned any alliance with the Adimari. According to Boccaccio, the marriage took place some time after the death of Beatrice, and it was certainly not later than 1297; but there is documentary evidence that Gemma’s dowry was settled in 1277, which points to an early betrothal. The union has generally been supposed—on somewhat inadequate grounds—to have been an unhappy one. Gemma bore Dante two sons, Jacopo and Pietro, and either one or two daughters. Boccaccio’s statement, that she did not share the poet’s exile, is usually accepted; she was living in Florence after his death, and died there after 1332.[2] During the following years, between 1297 and[Pg 24] 1300, Dante was contracting debts (Durante di Scolaio degli Abati and Manetto Donati being among his sureties), which altogether amounted to a very large sum, but which were cleared off from the poet’s estate after his death.

Election of Boniface VIII.—Upon the abdication of Celestine V., Cardinal Benedetto Gaetani was made Pope on Christmas Eve 1294, under the title of Boniface VIII. (Inf. xix. 52-57), an event ominous for Florence and for Dante. Although canonised by the Church, there is little doubt that St. Celestine is the first soul met by Dante in the vestibule of Hell: Colui che fece per viltà il gran rifiuto (Inf. iii. 58-60), “He who made from cowardice the great renunciation.”

Giano della Bella.—Florence had just confirmed the democratic character of her constitution by the reforms of Giano della Bella, a noble who had identified himself with the popular cause (Par. xvi. 132). By the Ordinances of Justice in 1293 stringent provisions were enacted against the nobles, who since Campaldino had grown increasingly aggressive towards the people and factious against each other. They were henceforth more rigorously excluded from the Priorate and Council of the Hundred, as also from the councils of the Captain and Capitudini; severe penalties were exacted for offences against popolani; and, in order that these ordinances should be[Pg 25] carried out, a new magistrate, the Gonfaloniere di Guistizia or Standard-bearer of Justice, was added to the Signoria to hold office like the Priors for two months in rotation from the different districts of the city. Thus was completed the secondo popolo, the second democratic constitution of Florence. The third of these standard-bearers was Dino Compagni, the chronicler. Giano della Bella was meditating the continuation of his work by depriving the captains of the Guelf Society of their power and resources, when a riot, in which Corso Donati played a prominent part, caused his overthrow in March 1295. By his fall the government remained in the hands of the rich burghers, being practically an oligarchy of merchants and bankers.

First Steps in Political Life.—In this same year 1295, the first year of the pontificate of Boniface VIII., Dante entered political life. Although of noble descent, the Alighieri do not seem to have ranked as magnates. By a modification in the Ordinances of Justice in July 1295, citizens, without actually exercising an “art,” were admitted to office provided they had matriculated and were not knights, if not more than two persons in their family had held knighthood within the last twenty years. Dante now (or perhaps a little later) enrolled his name in the matricola of the Art of Physicians and Apothecaries, which included painters and booksellers. For the six months from November 1st, 1295, to April 30th, 1296,[Pg 26] he was a member of the Special Council of the Captain. On December 14th, as one of the savi or specially summoned counsellors, he gave his opinion (consuluit) in the Council of the Capitudini of the Arts on the procedure to be adopted for the election of the new Signoria. On January 23rd, 1296, the Pope inaugurated his aggressive policy towards the Republic by addressing a bull to the Podestà, Captain, Ancients, Priors and Rectors of the Arts, to the Council and the Commune of Florence (purposely ignoring the new office of Gonfaloniere). After denouncing in unmeasured terms the wickedness of that “rock of scandal,” Giano della Bella, and extolling the prudence of the Florentines in expelling him, the Pope, hearing that certain persons are striving to obtain his recall, utterly forbids anything of the kind without special licence from the Holy See, under penalty of excommunication and interdict. The Pope further protests his great and special affection for Florence, amongst the cities devoted to God and the Apostolic See. “I love France so well,” says Shakespeare’s King Henry, “that I will not part with a village of it; I will have it all mine.”

Although Boccaccio, and others in his steps, have somewhat exaggerated Dante’s influence in the politics of the Republic, there can be no doubt that he soon came to take a decided attitude in direct opposition to all lawlessness, and in resistance to any external interference in Florentine matters, whether from Rome, Naples, or France.[Pg 27] The eldest son of Charles II., Carlo Martello, whom Dante had “loved much and with good cause” (Par. viii. 55) during his visit to Florence in the spring of 1294, had died in the following year; and his father was harassing the Florentines for money to carry on the Sicilian war. Dante, on leaving the Council of the Captain, had been elected to the Council of the Hundred, in which, on June 5th, 1296, he spoke in support of various proposals, including one on the embellishment of the cathedral and baptistery by the removal of the old hospital, and another undertaking not to receive men under ban of the Commune of Pistoia in the city and contado of Florence. In the previous May, in consequence of internal factions, Pistoia had given Florence control of the city, with power to send a podestà and a captain every six months. After this we do not hear of Dante again until May 7th, 1300, when he acted as ambassador to San Gemignano to announce that a parliament was to be held for the purpose of electing a captain for the Guelf League of Tuscany, and to invite the Commune to send representatives. But already the storm cloud which loomed on the horizon had burst upon the city on May Day 1300.

Blacks and Whites.—The new division of parties in Florence became associated with the feud between two noble families, the Donati and the Cerchi, headed respectively by two of the heroes of Campaldino, Corso Donati and Vieri de’ Cerchi. The names Neri and Bianchi, Black[Pg 28] Guelfs and White Guelfs, by which the two factions became known, seem to have been derived from a similar division in Pistoia, the ringleaders of which, being banished to Florence, embittered the quarrels already in progress in the ruling city. But the roots of the trouble went deeper and were political, connected with the discontent of both magnates and popolo minuto under the hegemony of the Greater Arts. The Bianchi were opposed to a costly policy of expansion; the Neri, who had wider international and mercantile connections, looked beyond the affairs of the Commune, and favoured intimate relations with the Angevin sovereigns of Naples and the Pope. To the Bianchi adhered those nobles who had matriculated in the Arts, the more moderate spirits among the burghers, the remains of the party of Giano della Bella who supported the Ordinances of Justice in a modified form. While the Bianchi drew closer to the constitutional government, the strength of the Neri lay in the councils of the Guelf Society and the influence of the aristocratic bankers. Guido Cavalcanti (who, even after the modification of the Ordinances, would have been excluded from office) was allied with the Cerchi, but probably less influenced by political considerations than by his personal hostility towards Messer Corso, who was in high favour with the Pope. Florence was now indeed “disposed for woeful ruin” (Purg. xxiv. 81), but there had been a “long[Pg 29] contention” (Inf. vi. 64) before the parties came to bloodshed.

The Jubilee.—On February 22nd, 1300, Pope Boniface issued the bull proclaiming the first papal jubilee. It began with the previous Christmas Day and lasted through the year 1300. Amongst the throngs of pilgrims from all parts of the world to Rome were Giovanni Villani and, probably, Dante (Inf. xviii. 29). This visit to Rome inspired Villani to undertake his great chronicle; and it is the epoch to which Dante assigns the vision which is the subject of the Divina Commedia (Purg. ii. 98). The Pope, however, had his eyes on Florence, and had apparently resolved to make Tuscany a part of the Papal States. Possibly he had already opened negotiations with the Neri through his agents and bankers, the Spini. A plot against the state on the part of three Florentines in the service of the Pope was discovered to the Signoria, and sentence passed against the offenders on April 18th.[3] Boniface wrote to the Bishop of Florence, on April 24th, 1300, demanding from the Commune that the sentences should be annulled and the accusers sent to him. The Priors having refused compliance and denied his jurisdiction in the matter, the Pope issued a second bull, declaring that he had no intention of derogating from the jurisdiction[Pg 30] or liberty of Florence, which he intended to increase; but asserting the absolute supremacy of the Roman Pontiff both in spiritual and temporal things over all peoples and kingdoms, and demanding again, with threats of vengeance spiritual and temporal, that the sentences against his adherents should be annulled, that the three accusers with six of the most violent against his authority should appear before him, and that the officers of the Republic should send representatives to answer for their conduct. This was on May 15th, but, two days earlier, the Pope had written to the Duke of Saxony, and sent the Bishop of Ancona to Germany, to demand from Albert of Austria the renunciation absolutely to the Holy See of all rights claimed by the Emperors in Tuscany.

Dante’s Priorate.—But in the meantime bloodshed had taken place in Florence. On May 1st the two factions came to blows in the Piazza di Santa Trinita; and on May 4th full powers had been given to the Priors to defend the liberty of the Commune and People of Florence against dangers from within and without (which had evidently irritated the Pope). The whole city was now divided; magnates and burghers alike became bitter partisans of one or other faction. The Pope, who had previously made a vain attempt to reconcile Vieri de’ Cerchi with the Donati, sent the Franciscan Cardinal Matteo d’Acquasparta as legate and peacemaker to Florence, in the interests of the captains of the Guelf Society and the Neri,[Pg 31] who accused the Signoria of Ghibelline tendencies. The Cardinal arrived in June. From June 15th to August 14th Dante was one of the six Priors by election. “All my misfortunes,” he says in the letter quoted by Leonardo Bruni, “had their cause and origin in my ill-omened election to the Priorate; of which Priorate, though by prudence I was not worthy, still by faith and age I was not unworthy.” We know too little of the facts to be able to comment upon this cryptic utterance. On the first day of office (June 15th), the sentence passed in the previous April against the three Florentines in the papal service was formally consigned to Dante and his colleagues—Lapo Gianni (probably the same person as his poet friend of that name) acting as notary. There were disturbances in the city. On St. John’s Eve an assault was made upon the Consuls of the Arts by certain magnates of the Neri, and their opponents threatened to take up arms. The Priors, perhaps on Dante’s motion, exiled (or, more accurately, put under bounds outside the territory of the Republic) some prominent members of both factions, including Corso Donati and Guido Cavalcanti. The Neri attempted to resist, expecting aid from the Cardinal and from Lucca; the Bianchi obeyed. Negotiations continued between the Signoria and the Cardinal, Dante and his colleagues resisting the papal demands without coming to a formal rupture.

The Bianchi in Power.—The succeeding Signoria[Pg 32] was less prudent. The banished Bianchi were allowed to return just after Dante had left office (as he himself states in a lost letter seen by Leonardo Bruni), on the plea of the illness of Guido Cavalcanti, who had contracted malaria at Sarzana, and died at Florence in the last days of August. At the end of September a complete rupture ensued with Cardinal Matteo d’Acquasparta, who broke off negotiations and retired to Bologna, leaving the city under an interdict. Corso Donati had broken bounds and gone to the Pope, who, towards the close of 1300, nominated Charles of Valois, brother of Philip the Fair, captain-general of the papal states, and summoned him to Italy to aid Charles of Naples against Frederick of Aragon in Sicily and reduce the “rebels” of Tuscany to submission.

We meet the name of Dante on several occasions among the consulte of the Florentine Republic during 1301. It is probable that he was one of the savi called to council on March 15th, and that he opposed the granting of a subsidy in money which the King of Naples had demanded for the Sicilian war and which was made by the Council of the Hundred.[4] On April 14th he was among the savi in the Council of the Capitudini for the election of the new Signoria, of which Palmieri Altoviti was the leading spirit. On April 28th Dante was appointed officialis et superestans, in[Pg 33] connection with the works in the street of San Procolo, possibly with the object of more readily bringing up troops from the country. During the priorate of Palmieri Altoviti (April 15th to June 14th), a conspiracy was discovered, hatched at a meeting of the Neri in the church of S. Trinita, to overthrow the government and invite the Pope to send Charles of Valois to Florence. In consequence a number of Neri were banished and their possessions confiscated, a fresh sentence being passed against Corso Donati. The Bianchi were all potent in Florence; and, in May 1301, they procured the expulsion of the Neri from Pistoia (ruthlessly carried out by the Florentine captain, Andrea Gherardini), which was the beginning of the end (Inf. xxiv. 143): “Pistoia first is thinned of Neri; then Florence renovates folk and rule.”

The Coming of Charles of Valois.—The government still shrank from directly opposing the Pope, who, by letter from Cardinal Matteo d’Acquasparta, demanded the continuation of the service of a hundred horsemen. On June 19th, 1301, in a united meeting of the Councils of the Hundred, of the Captain, and of the Capitudini, and again in the Council of the Hundred apart, Dante spoke against compliance, urging “quod de servitio faciendo domini Papae nihil fiat”—with the result that the matter was postponed. In the united Councils of the Hundred, the Captain, the Podestà, and the Capitudini, on September 13th, he pleaded for the preservation of the Ordinances[Pg 34] of Justice (a sign that the State was regarded as in peril). On this occasion all the twenty-one arts were represented, which we may connect with Leonardo Bruni’s statement that Dante had advised the Priors to strengthen themselves with the support of the “moltitudine del popolo.” On September 20th, in the Council of the Captain, he supported a request of the ambassadors of the Commune of Bologna (then allied with the Bianchi) for free passage for their importation of grain. On September 28th, again in the Council of the Captain, he defended a certain Neri di Gherardino Diedati (whose father was destined to share the poet’s fate) from an injust charge. This is the last recorded time that Dantes Alagherii consuluit in Florence. Already Charles of Valois was on his way, preparing to “joust with the lance of Judas” (Purg. xx. 70-78). On November 1st, after giving solemn pledges to the Signoria (Dino Compagni being one of the Priors), Charles with 1200 horsemen entered Florence without opposition.

Leonardo Bruni asserts that Dante was absent at Rome on an embassy to the Pope when the latter’s “peacemaker” entered Florence. It would appear that the Florentine government had requested the allied Commune of Bologna to send an embassy to Boniface, simultaneously with an embassy from Siena with which were associated three ambassadors from Florence: Maso di Ruggierino Minerbetti, Corazza da Signa, and Dante[Pg 35] Alighieri. Their purpose was to make their own terms with the Pontiff in order to avert the intervention of Charles. The mission set out at the beginning of October; but one of the Bolognese ambassadors, Ubaldino Malavolti, having business of his own with the Florentine government, delayed the others so long that they did not arrive in time.[5] Boccaccio asserts that, when the Bianchi proposed to send Dante on such an embassy, he answered somewhat arrogantly: “If I go, who stays? and if I stay, who goes?” According to Dino Compagni, Boniface sent two of the Florentines—Maso Minerbetti and Corazza da Signa—back to Florence to demand submission to his will, but detained Dante at his court. The fact of Dante taking part in such an embassy is confirmed by the author of the Ottimo Commento, as also by an anonymous commentator on the canzone of the Tre donne, and, though seriously questioned by many Dante scholars, it is now generally accepted as historical. The other two ambassadors returned almost simultaneously with the arrival of the French prince. Yielding to necessity and trusting to his solemn oath, the Signoria, in a parliament held in S. Maria Novella, gave Charles authority to pacify the city; which he set about doing by restoring the Neri to power. Corso[Pg 36] Donati with his allies entered Florence in arms, to plunder and massacre at their pleasure, the last Signoria of the Bianchi being compelled to resign on November 7th (cf. Purg. vi. 143, 144). A second effort by the Cardinal Matteo from the Pope to reconcile the two factions was resisted by Charles and the Neri; and the work of proscription began. The new Podestà, Cante de’ Gabrielli da Gubbio, passed sentence after sentence against the ruined Bianchi. Finally, at the beginning of April, their chiefs were betrayed into a real or pretended conspiracy against Charles, and driven out with their followers and adherents, both nobles and burghers, six hundred in number; their houses were destroyed, and their goods confiscated, themselves sentenced as rebels. On April 4th, 1302, Charles left Florence, covered with disgrace and full of plunder, leaving the government entirely in the hands of the Neri. “Having cast forth the greatest part of the flowers from thy bosom, O Florence,” writes Dante in the De Vulgari Eloquentia, “the second Totila went fruitlessly to Sicily” (V. E. ii. 6).

Sentences against Dante.—The first sentence against Dante is dated January 27th, 1302, and includes four other names. Gherardino Diedati, formerly Prior, is accused of taking bribes for the release of a prisoner, and has not appeared when summoned. Palmieri Altoviti (who had taken the lead in putting down the conspiracy hatched in Santa Trinita), Dante Alighieri, Lippo Becchi[Pg 37] (one of the denouncers of Boniface’s agents in 1300), and Orlanduccio Orlandi are accused of “barratry,” fraud and corrupt practices, unlawful gains and extortions and the like, in office and out of office; of having corruptly and fraudulently used the money and resources of the Commune against the Supreme Pontiff, and to resist the coming of Messer Carlo, or against the pacific state of Florence and the Guelf Party; of having caused the expulsion of the Neri from Pistoia, and severed that city from Florence and the Church. Since they have contumaciously absented themselves, when summoned to appear before the Podestà’s court, they are held to have confessed their guilt, and sentenced to pay a heavy fine and restore what they have extorted. If not paid in three days, all their goods shall be confiscated; even if they pay, they are exiled for two years and perpetually excluded as falsifiers and barrators, tamquam falsarii et barattarii, from holding any office or benefice under the Commune of Florence. On March 10th, a further sentence condemns these five with ten others to be burned to death, if any of them at any time shall come into the power of the Commune. In this latter sentence there is no mention of any political offence, but only of malversation and contumacy. None of Dante’s six colleagues in the Signoria are included in either sentence; but in the second appear the names of Lapo Salterelli, who had headed the opposition to Boniface in the spring of 1300, but whom the poet[Pg 38] judges sternly (cf. Par. xv. 128), and Andrea Gherardini, who had been Florentine captain at Pistoia.

There can be little doubt that, in spite of the wording of these two sentences, Dante’s real offence was his opposition to the policy of Pope Boniface. In the De Volgari Eloquentia (i. 6) he declares that he is suffering exile unjustly because of his love for Florence. All his early biographers bear testimony to his absolute innocence of the charge of malversation and barratry; it has been left to modern commentators to question it. In the letter to a Florentine friend, Dante speaks of his innocence manifest to all, innocentia manifesta quibuslibet, as though in direct answer to the fama publica referente of the Podestà’s sentence. His likening himself to Hippolytus is a no less emphatic protestation of innocence: “As Hippolytus departed from Athens, by reason of his pitiless and treacherous stepmother, so from Florence needs must thou depart. This is willed, this is already being sought, and soon will it be done for him who thinks it, there where Christ is put to sale each day” (Par. xvii. 46-51). “I hold my exile as an honour”:

he says in his canzone of the Tre donne. Had Dante completed the Convivio, he would probably have furnished us with a complete apologia in the fourteenth treatise, where he intended to comment[Pg 39] upon this canzone and discuss Justice. “Justice,” he says in Conv. i. 12, “is so lovable that, as the philosopher says in the fifth of the Ethics, even her enemies love her, such as thieves and robbers; and therefore we see that her contrary, which is injustice, is especially hated (as is treachery, ingratitude, falseness, theft, rapine, deceit, and their like). The which are such inhuman sins that, to defend himself from the infamy of these, it is conceded by long usance that a man may speak of himself, and may declare himself to be faithful and loyal. Of this virtue I shall speak more fully in the fourteenth treatise.”

“Since it was the pleasure of the citizens of the most beautiful and most famous daughter of Rome, Florence, to cast me forth from her sweet bosom (in which I was born and nourished up to the summit of my life, and in which, with her goodwill, I desire with all my heart to rest my wearied mind and to end the time given me), I have gone through almost all the parts to which this language extends, a pilgrim, almost a beggar, showing against my will the wound of fortune, which is wont unjustly to be ofttimes reputed to the wounded.”

In these words (Conv. i. 3), Dante sums up the earlier portion of his exile. There are few lines of poetry more noble in pathos, more dignified in reticence, than those which he has put into the[Pg 40] mouth of Cacciaguida (Par. xvii. 55-60): “Thou shalt leave everything beloved most dearly, and this is that arrow which the bow of exile first shoots. Thou shalt test how savours of salt another’s bread, and how hard the ascending and descending by another’s stairs.”

Early Days of Exile.—The terms of the first sentence against Dante seem to imply that, if he had returned to Florence, he fled from the city before January 27th, 1302. We do not know where he went. Boccaccio, apparently from a misunderstanding of Par. xvii. 70, says Verona; if we suppose it to have been Siena, this would explain Leonardo Bruni’s account of Dante’s first hearing particulars of his ruin at the latter city. The sentence against Messer Vieri de’ Cerchi, with the other leaders, is dated April 5th in the terrible Libro del Chiodo, the black book of the Guelf Party. Arezzo, Forlì, Siena, Bologna, were the chief resorts of the exiled Bianchi; in Bologna they seem for some time to have been especially welcome. Dante first joined them in a meeting held at Gargonza, where they are said by Bruni to have made the poet one of their twelve councillors, and to have fixed their headquarters at Arezzo. For a short time Dante made common cause with them, but found their society extremely uncongenial (Par. xvii. 61-66). On June 8th, 1302, there is documentary evidence of his presence with some others in the choir of San Godenzo at the foot of the Apennines, where the Bianchi allied[Pg 41] with the Ghibelline Ubaldini to make war upon Florence. The fact of this meeting having been held in Florentine territory and followed by several cavalry raids induced a fresh sentence in July from the new Podestà, Gherardino da Gambara of Brescia, in which, however, Dante is not mentioned.

Failure of the Bianchi.—A heavy blow was inflicted upon the exiles by the treachery of Carlino di Pazzi (Inf. xxxii. 69), who surrendered the castle of Piantravigne in Valdarno to the Neri, when many Bianchi were slain or taken. The cruelty of the Romagnole, Count Fulcieri da Calboli, the next Podestà of Florence from January to September 1303, towards such of the unfortunate Bianchi as fell into his hands has received its meed of infamy in Purg. xiv. 58-66. It is perhaps noteworthy (as bearing upon the date of Dante’s separation from his fellow-exiles) that the poet’s name does not appear among the Bianchi who, under the leadership of the Ghibelline captain, Scarpetta degli Ordelaffi of Forlì, signed an agreement with their allies in Bologna on June 18th in this year; but this may merely imply that he did not go to Bologna. He was possibly associated with Scarpetta at Forlì about this time. These renewed attempts to recover the state by force of arms resulted only in the disastrous defeat of Pulicciano in Mugello.

Death of Boniface VIII.—In this same year Sciarra Colonna and William of Nogaret, in the[Pg 42] name of Philip the Fair, seized Boniface VIII. at Anagni, and treated the old Pontiff with such barbarity that he died in a few days, October 11th, 1303. The seizure had been arranged by the infamous Musciatto Franzesi, who had been instrumental in the bringing of Charles of Valois to Florence. “I see the golden lilies enter Alagna,” cries Hugh Capet in the Purgatorio; “and in His vicar Christ made captive. I see Him mocked a second time. I see renewed the vinegar and gall, and Him slain between thieves that live” (Purg. xx. 86-90).

Benedict XI.—In succession to Boniface, Nicholas of Treviso, the master-general of the Dominicans, a man of humble birth and of saintly life, was made Pope on October 22nd, 1303, as Benedict XI. He at once devoted himself to healing the wounds of Italy, and sent to Florence as peacemaker the Dominican Cardinal, Niccolò da Prato, who was of Ghibelline origin. The peacemaker arrived in March 1304, and was received with great honour. Representatives of the Bianchi and Ghibellines came to the city at his invitation; and, when May opened, there was an attempt to revive the traditional festivities which had ended on that fatal May Day of 1300. But a terrible disaster on the Ponte alla Carraia cast an ominous gloom over the city, and the Neri treacherously forced the Cardinal to leave. Hardly had he gone when, on June 10th, fighting broke out in the streets, and a fire, purposely started by the Neri, devastated[Pg 43] Florence. On July 7th Pope Benedict died, perhaps poisoned, at Perugia; and, seeing this last hope taken from them, the irreconcilable portion of the Bianchi, led by Baschiera della Tosa, aided by the Ghibellines of Tuscany under Tolosato degli Uberti, with allies from Bologna and Arezzo, made a valiant attempt to surprise Florence on July 20th from Lastra. Baschiera, with about a thousand horsemen, captured a part of the suburbs, and drew up his force near San Marco, “with white standards displayed, and garlands of olives, with drawn swords, crying peace” (Compagni). Through his impetuosity and not awaiting the coming of Tolosato, this enterprise ended in utter disaster, and with its failure the last hopes of the Bianchi were dashed to the ground.

Separation from the Bianchi and Wanderings in Exile.—After the defeat of Lastra, Bruni represents Dante as going from Arezzo to Verona, utterly humbled. We learn from the Paradiso (xvii. 61-69) that, estranged from his fellow-exiles who had turned violently against him, he had been compelled to form a party to himself. It is held by some scholars that he had broken away from them in the previous year, and that, towards the end of 1303, he had found his first refuge at Verona in “the courtesy of the great Lombard,” Bartolommeo della Scala, at whose court he now first saw his young brother, afterwards famous as Can Grande, and already in boyhood showing sparks of future greatness (ibid. 70-78). Others[Pg 44] would identify il gran Lombardo with Bartolommeo’s brother and successor, Albuino della Scala, who ruled in Verona from March 1304 until October 1311, and associated Can Grande with him as the commander of his troops. There is no certain documentary evidence of Dante’s movements between June 1302 and October 1306. It is not improbable that, in 1304 or 1305, he stayed some time at Bologna. The first book of the De Vulgari Eloquentia seems in many respects to bear witness to this stay at Bologna, where the exiles were still welcome; a certain kindliness towards the Bolognese, very different from his treatment of them later in the Divina Commedia, is apparent, together with a peculiar acquaintance with their dialect. But on March 1st, 1306, the Bolognese made a pact with the Neri, after which they expelled the Florentine exiles, ordering that no Bianchi or Ghibellines should be found in Bolognese territory on pain of death. Dante perhaps went to Padua from Bologna, and, though the supposed documentary proof of his residence in Padua on August 27th, 1306, cannot be accepted without reserve, it is tempting to accept the statement of Benvenuto da Imola that the poet was entertained by Giotto when the painter was engaged upon the frescoes of the Madonna dell’ Arena. In October, Dante was in Lunigiana, a guest of the Malaspina, that honoured race adorned with the glory of purse and sword (Purg. viii. 121-139). Here, according to Boccaccio, he[Pg 45] recovered from Florence some manuscript which he had left behind him in his flight; possibly what he afterwards rewrote as the first seven cantos of the Inferno. On October 6th he acted as ambassador and nuncio of the Marquis Franceschino Malaspina in establishing peace between his house and the Bishop of Luni. This is the last certain trace of Dante’s feet in Italy for nearly five years. There is a strangely beautiful canzone of his which may have been written at this time. Love has seized upon the poet in the midst of the Alps (i.e. Apennines): “In the valley of the river by whose side thou hast ever power upon me”; “Thou goest, my mountain song; perchance shalt see Florence, my city, that bars me out of herself, void of love and nude of pity; if thou dost enter in, go saying: Now my maker can no more make war upon you; there, whence I come, such a chain binds him that, even if your cruelty relax, he has no liberty to return hither.”[6]

Dante had probably, as Bruni tells us, been abstaining from any hostile action towards Florence, and hoping to be recalled by the government spontaneously. There are traces of this state of mind in the Convivio (i. 3). It would be about[Pg 46] this time that he wrote in vain the letter mentioned by Bruni, but now lost, Popule mee quid feci tibi.

Clement V.—Death of Corso Donati.—In the meantime Clement V., a Gascon, and formerly Archbishop of Bordeaux, had been elected Pope. “From westward there shall come a lawless shepherd of uglier deeds” than even Boniface VIII., writes Dante in Inferno xix. He translated the Papal Court from Rome to Avignon, and thus in 1305 initiated the Babylonian captivity of the Popes, which lasted for more than seventy years, “to the great damage of all Christendom, but especially of Rome” (Platina). Scandalous as was his subservience to the French king, and utterly unworthy of the Papacy as he showed himself, it must be admitted that Clement made serious efforts to relieve the persecuted Bianchi and Ghibellines—efforts which were cut short by the surrender of Pistoia in 1306 and the incompetence of his legate, the Cardinal Napoleone Orsini. In October 1308, Corso Donati came to the violent end mentioned as a prophecy in Purg. xxiv.; suspected, with good reason, of aiming at the lordship of Florence with the aid of the Ghibelline captain, Uguccione della Faggiuola, whose daughter he had married, he was denounced as a traitor and killed in his flight from the city.

Dante Possibly at Paris.—Villani tells us that Dante, after exile, went to the Studio at Bologna, and then to Paris and to many parts of the world. The visit to Paris is also affirmed by Boccaccio,[Pg 47] and it is not impossible that Dante went thither, between 1307 and 1309, by way of the Riviera and Provence. A highly improbable legend of his presence at Oxford is based upon an ambiguous line in a poetical epistle from Boccaccio to Petrarch and the later testimony of Giovanni da Serravalle at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Dante’s stay in Paris has been seriously questioned, and still remains uncertain. The University of Paris was then the first in the world in theology and scholastic philosophy. Boccaccio tells us that the disputations which Dante sustained there were regarded as most marvellous triumphs of scholastic subtlety. According to Giovanni da Serravalle (who has, however, placed his Parisian experiences too early), Dante was forced to return before taking the doctorate of theology, for which he had already fulfilled the preliminaries. He may have stayed in Paris until 1310, when tremendous events put an end to his studies and imperatively summoned him back to Italy.

“Lo, now is the acceptable time wherein arise the signs of consolation and peace. For a new day is breaking from the east, showing forth the dawn which already is dispersing the darkness of our long calamity; and already the eastern breezes begin to blow, the face of heaven glows red, and confirms the hopes of the nations with a[Pg 48] caressing calm. And we too shall see the looked-for joy, we who have kept vigil through the long night in the desert” (Epist. v. 1).

Election of Henry VII.—On May 1st, 1308, Albert of Austria, who, by his neglect of Italy, had suffered the garden of the Empire to be desert, was assassinated by his nephew (Purg. vi. 97-105). In November, with the concurrence of the Pope and in opposition to the royal house of France, Henry of Luxemburg was elected Emperor. In January 1309 he was crowned at Aix as Henry VII.; in May 1310 he announced to the Italian cities his intention of coming to Rome for the imperial crown. Here was a true King of the Romans and successor of Caesar, such as the Italians had not recognised since the death of Frederick II. (Conv. iv. 3). The saddle was no longer empty; Italy had once more a king and Rome a spouse. It is in the glory of this imperial sunrise that Dante appears again, and, in the letter just quoted to the Princes and Peoples of Italy, his voice is heard, hailing the advent of this new Moses, this most clement Henry, divus Augustus Caesar, who is hastening to the nuptials, illuminated in the rays of the Apostolic benediction. The letter seems to have been written after the beginning of September, when the Pope issued an encyclical on Henry’s behalf, and before the latter part of October 1310, when the Emperor arrived in Italy. According to the fifteenth-century historian, Flavio Biondo, Dante was at[Pg 49] this time at Forlì with Scarpetta degli Ordelaffi. In January 1311 Henry took the iron crown (or its substitute) at Milan. Dante, sometime before the end of March, paid his homage to the Emperor (Epist. vii. 2): “I saw thee, as beseems Imperial Majesty, most benignant, and heard thee most clement, when that my hands handled thy feet and my lips paid their debt. Then did my spirit exult in thee, and I spoke silently with myself: ‘Behold the Lamb of God. Behold Him who hath taken away the sins of the world.’”

National Policy of Florence.—The Emperor himself shared the golden dream of the Italian idealists, and, believing in the possibility of the union of Church and Empire in a peaceful Italy healed of her wounds, addressed himself ardently to his impossible task, forcing cities to take back their exiles, patching up old quarrels. Opposed to him arises the less sympathetic figure of King Robert of Naples, who, having succeeded his father, Charles II., in May 1309, was preparing—though still for a while negotiating on his own account with Henry—to head the Guelf opposition. While others temporised, Florence openly defied the Emperor, insulted his envoys, and refused to send ambassadors to his coronation. While the Emperor put his imperial vicars into Italian cities, as though he were another Frederick Barbarossa, the Florentines drew closer their alliance with Robert, formed a confederation of Guelf cities, and aided with money and men all who[Pg 50] made head against the German King. In spite of the bitter language used by Dante in his letters, modern historians have naturally recognised in this one of the most glorious chapters in the history of the Republic. “Florence,” writes Pasquale Villari, “called on the Guelf cities, and all seeking to preserve freedom and escape foreign tyranny, to join in an Italian confederation, with herself at its head. This is, indeed, the moment in which the small merchant republic initiates a truly national policy, and becomes a great Italian power. So, in the medieval shape of a feudal and universal Empire, on the one hand, and in that of a municipal confederation on the other, a gleam of the national idea first began to appear, though still in the far distance and veiled in clouds.”

Letters and Fresh Sentence.—On March 31st, 1311, from “the boundaries of Tuscany under the source of the Arno,” and on April 17th, from “Tuscany under the source of the Arno,” Dante addressed two terrible letters to “the most wicked Florentines within,” and to “the most sacred triumphant and only lord, Henry by divine providence King of the Romans, ever Augustus.” In the former he reasserts the rights and sanctity of the Empire, and, whilst hurling the fiercest invective upon the Florentine government, foretells their utter destruction and warns them of their inability to withstand the might of the Emperor. In the latter he rebukes the “minister of God and son of the Church and promoter of Roman glory”[Pg 51] for his delay in Lombardy, and urges him on against Florence, “the sick sheep that infects all the flock of the Lord with her contagion.” Let him lay her low and Israel will be delivered. “Then shall our heritage, the taking away of which we weep without ceasing, be restored to us again; and even as we now groan, remembering the holy Jerusalem, exiles in Babylon, so then, citizens breathing again in peace, we shall look back in our joy upon the miseries of confusion.” These letters were evidently written from the Casentino, where Dante had gone probably on an imperial mission to one or other of the Conti Guidi. He was perhaps staying at the castle of Poppi, and there is a tradition that the Florentine government sent agents to arrest him there. Probably in consequence of these letters, a new condemnation was pronounced against him; on September 2nd, 1311, Dante is included in the long list of exiles who, in the “reform” of Baldo d’Aguglione, are to be excepted from amnesty and for ever excluded from Florence.

Failure of the Emperor.—But in the meantime Brescia, “the lioness of Italy,” who had offered as heroic a resistance to Henry VII. as she was to do five centuries later to the Austrians of Haynau, had been forced to surrender; and the Emperor had at last moved southwards to Genoa and thence to Pisa, from which parties of imperialists ravaged the Florentine territory. From Genoa, on December 24th, 1311, he issued a decree[Pg 52] placing Florence under the ban of the Empire, and declaring the Florentine exiles under his special protection. Dante (with Palmieri Altoviti and other exiles) was probably at Pisa in the early spring of 1312, and it may well have been there that Petrarch—then a little boy in his eighth year—saw his great predecessor. Rome itself was partly held by the troops of King Robert and the Florentines; with difficulty was Henry crowned by the Pope’s legates in the Church of St. John Lateran on June 29th, 1312. From September 19th to October 31st Henry besieged Florence, himself ill with fever. “Do ye trust in any defence girt by your contemptible rampart?” Dante had written to the Florentines: “What shall it avail to have girt you with a rampart and to have fortified yourselves with outworks and battlements, when, terrible in gold, that eagle shall swoop down on you which, soaring now over the Pyrenees, now over Caucasus, now over Atlas, ever strengthened by the support of the soldiery of heaven, looked down of old upon vast oceans in its flight?” But the golden eagle did not venture upon an assault. Wasting the country as it went, the imperial army retreated. Early in 1313 the Florentines gave the signory of their city to King Robert for five years, while the Emperor from Pisa placed the king under the ban of the Empire, and declared him a public enemy. The Pope himself had deserted the imperial cause, and was fulminating excommunication if Henry[Pg 53] invaded Robert’s kingdom (cf. Par. xvii. 82; xxx. 144), when the Emperor, moving from Pisa with reinforcements from Germany and Sicily, died on the march towards Naples at Buonconvento, near Siena, on August 24th, 1313. Dante had not accompanied the imperialists against Florence; he yet retained so much reverence for his fatherland, as Bruni writes, apparently from some lost letter of the poet’s. We do not know where he was when the fatal news reached him. Cino da Pistoia and Sennuccio del Bene broke out into elegiac canzoni on the dead hero; Dante was silent, and waited till he could more worthily write the apotheosis of his alto Arrigo in the Empyrean (Par. xxx. 133-138).