A STORY FOR GIRLS

BOOKS BY ADELE E. THOMPSON.

The Brave Heart Series.

Five Volumes. Illustrated. Each $1.25.

BETTY SELDON, PATRIOT,

A Girl’s Part in the Revolution.

BRAVE HEART ELIZABETH,

A Story of the Ohio Frontier.

A LASSIE OF THE ISLES,

A Story of the Old and New Worlds.

POLLY OF THE PINES,

A Patriot Girl of the Carolinas.

AMERICAN PATTY,

A Story of 1812.

BECK’S FORTUNE,

A Story of School and Seminary Life.

Illustrated by Louis Meynell. $1.25.

NOBODY’S ROSE,

Or The Girlhood of Rose Shannon.

Illustrated by A. G. Learned. Price, Net $1.00. Postpaid $1.12.

LOTHROP, LEE & SHEPARD CO., BOSTON.

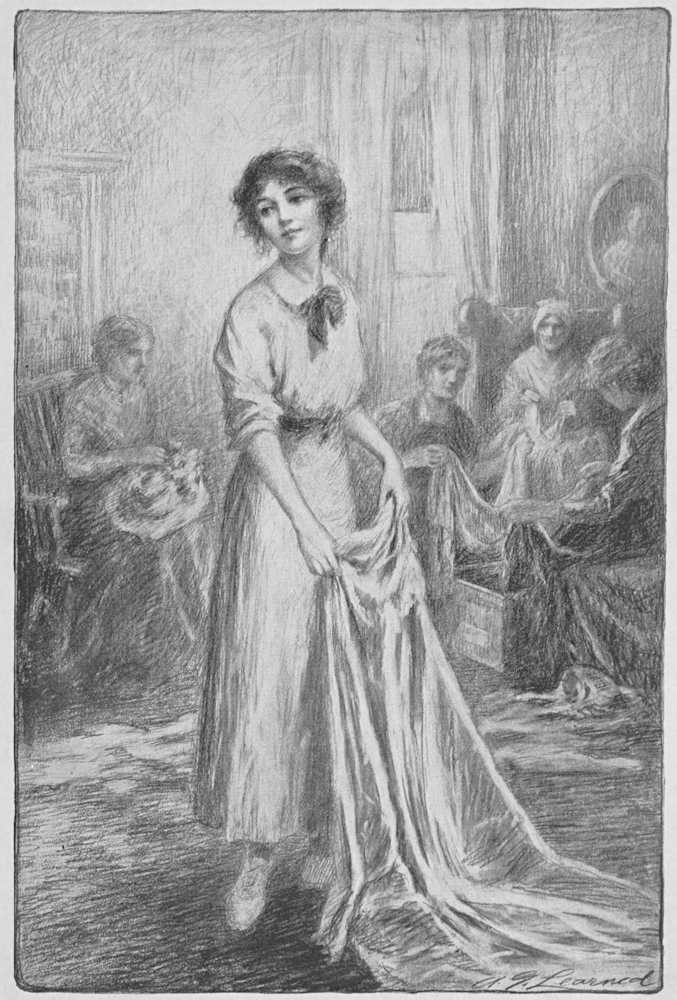

“Now I’m Rose, I’m nobody’s Rose!”—Page 270.

NOBODY’S ROSE

OR

The Girlhood of Rose Shannon

BY

ADELE E. THOMPSON

ILLUSTRATED BY A. G. LEARNED

BOSTON

LOTHROP, LEE & SHEPARD CO.

Copyright, 1912, by Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co.

Published, August, 1912

All Rights Reserved

Nobody’s Rose

NORWOOD PRESS

BERWICK & SMITH CO.

NORWOOD, MASS.

U. S. A.

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| How Posey Came Adrift | 11 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| An Exposure | 30 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The New Home | 42 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The New Life | 54 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Picnic | 71 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Storm Breaks | 85 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| A Desperate Resolve | 93 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| A New Acquaintance | 108 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Two Happy Travelers | 123 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Ben’s Story | 135 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| A Storm, and a Shelter | 147 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| A Parting of Ways | 162 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| A Door Opens | 173 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Posey Becomes Rose | 185 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| At the Fifields’ | 195 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| Under a Cloud | 206 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| Sunshine Again | 219 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| Great-Uncle Samuel | 236 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| Rose Finds a Resting-Place | 247 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| Paying Debts | 257 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| The Box from Great-Aunt Sarah | 266 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| Quiet Days | 275 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| A Visit from an Old Friend | 284 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| And College Next | 294 |

| “Now I’m Rose, I’m nobody’s Rose!” (Page 270) | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

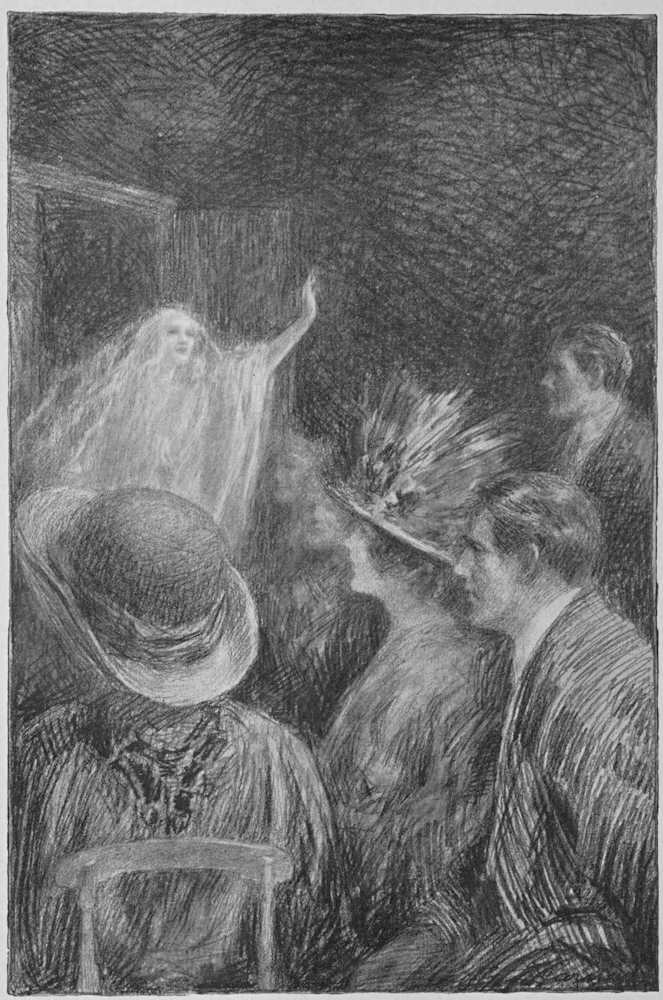

| Out of the door of the cabinet a white, shadowy little figure had lightly floated | 32 |

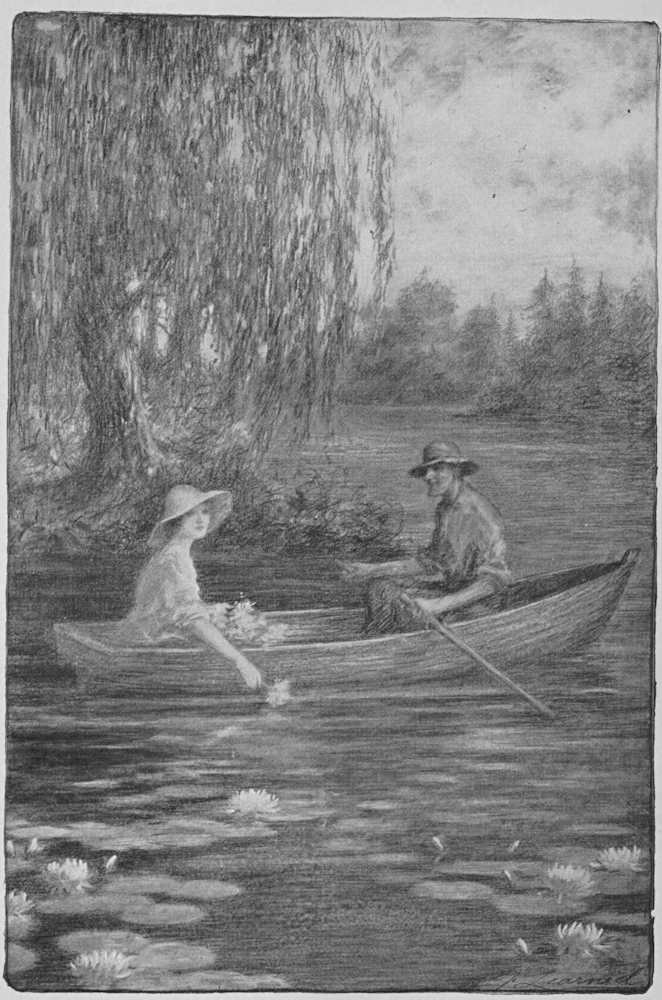

| It was an hour that Posey never forgot | 76 |

| “When I get a farm I shall need somebody to keep the house” | 144 |

| “Here is a clue to Rose’s family” | 216 |

| “Clear Jarvis and no mistake” | 238 |

[Pg 11]

NOBODY’S ROSE

Out in the open country the day was dull and grey, with low-hanging clouds and occasional drops of slow-falling rain, but in the city the clouds of smoke hung still lower than those of the sky, and the dropping soot-flakes made black the moisture gathered on the roofs of the houses, the leaves of the trees, and the sidewalks trodden by many feet.

It was on a city street, one where the smoke-clouds from the tall chimneys trailed low and the soot fell in its largest flakes, that ever and again a sound asserted itself above the beat of hurrying feet. The sound was not loud, only a little girl sobbing softly to herself as she shrank with her head on her arm at one side of an open stairway; and the words that she repeated over and over to herself, “What shall I do? Where shall I[Pg 12] go?” were less in the nature of questions than a lamentation. But children tearful, loudly, even vociferously tearful, were in that vicinity so frequent that people passed and repassed the child without giving to her thought or heed.

For the street was one more populous than select, and while the tall red brick houses that bordered it had once aspired to something of the aristocratic, they were now hopelessly sunken to the tenement stage; while the neighboring region leading through the sandy open square of the Haymarket, where loads of hay always stood awaiting purchasers, down the long steep hill to the river, with its crowded shipping and its border of great lumber yards, shops, and factories, had never made pretense to anything except poverty of the most open and unattractive kind. In summer the whole region fairly swarmed with the overflowing inmates of the overcrowded houses. Children were everywhere, in large part barefooted, ragged, and so dirty that they might easily have been taken for an outgrowth of the sandheaps in which they burrowed and buried themselves when tired of[Pg 13] the delights of the street. To see them there, in utter indifference to the constant passing of heavily loaded teams sometimes prompted the inquiry as to how many were daily killed? But though, on occasion, they were dragged from under the very horses’ hoofs by the untidy women whose shrill voices were so often heard sounding from open doors and windows, few were the accidents to either life or limb.

The not distant city market house increased the crowds, especially at certain hours of the day, as also the street venders and itinerants who contributed their full share to the noise and confusion. Hook-nosed old men, with bags over their shoulders, and shrill cries of “P-a-p-e-r r-a-g-s” abounded; the organ-grinder with his monkey was a frequent figure, with the invariable crowd of youngsters at his heels; the maimed and the blind, wearing placards appealing to the public sympathy and extending tin cups for contributions, were to be found on the corners; the scissors-grinder’s bell was a common sound, as were the sonorous offers of “Glassputin.” Here was a man loudly and monotonously[Pg 14] appealing to the credulity of the public, and soliciting patronage for his wonderful fortune-telling birds, a little company of dingy and forlorn-looking canaries, who by the selection of sundry envelopes were supposed to reveal the past, present, and future. There, another man exhibited a row of plates with heavy weights attached, and extolled the wonderful merits of his cement for mending crockery, while the sellers of small wares, combs, pocketbooks, letter-paper, cheap jewelry, and the like, added their calls to the rest.

A few of the houses still retained a dingy scrap of yard, where thin and trampled grass blades made an effort to grow, but the most part had been built out to the street and converted into cheap restaurants, cheap clothing shops, cheap furniture shops, and the class of establishments that are cheap indeed, especially as regards the character of their wares.

In such a confusion of people and sounds it is not strange that a small girl crying to herself would attract so little attention that even the big, fat policeman on that beat passed her a number of times before he noticed[Pg 15] her, and then did not stop, as he saw that she was well dressed. At last, as she still remained crouched down in a dejected little heap, he stopped, moved as much by the thought of a little girl in his own home as from a sense of duty, with the inquiry, “Here, Sis, what’s the matter with you?”

She started up at the brusque but not unkindly tone, and lifting from her sheltering arm a round and dimpled face, with wide grey eyes, now swollen and disfigured with tears, answered brokenly and in a half-frightened voice, for the policeman stood to her as the terror rather than the guardian of the law, “Oh, I don’t know what to do! I don’t know where to go!”

“You don’t, eh? Well, it seems to me you are a pretty big girl to get lost; where do you live?”

“I don’t live anywhere,” with a fresh sob.

“That’s rather queer, not to live anywhere,” and he looked at her a trifle more sternly. “What’s your name, if you have any?”

“Posey Sharpe.”

“Oh, indeed,” and he glanced at the stairway[Pg 16] before him, where a small black sign with gilt lettering on the step just above her head read,

“Madam Atheldena Sharpe,

“CLAIRVOYANT.”

“So that was your mother, was it, who raised all that row here last night?”

“No, she wasn’t my mother, but I lived with her.”

“If she wasn’t, how comes it your name is the same?”

“It isn’t, really, only I’ve lived with her so long that people called me that. She said I was her niece, but I wasn’t any relation at all.”

He looked at the sign again, “Madam Sharpe. Well,” with a chuckle at his own witticism, “she wasn’t sharp enough to keep from being exposed. And you were the spirit child, I suppose?”

Posey nodded, a very dejected-looking spirit she seemed at that moment.

“Well, when she took herself off so suddenly why didn’t you go with her?”

“I ran up under the roof and hid, and I[Pg 17] didn’t know till this morning that she had gone.”

“I see; and was she so good to you, and did you think so much of her that you are taking on this way?”

Posey hesitated a moment. “She might have been better, and she might have been worse,” she answered with a candor of simplicity. “But I haven’t anybody else to live with, and I didn’t think she’d use me so.”

“I see; it was rather rough.” There was sympathy in his tone, and even in the way he tapped his knee with his polished club.

“And,” continued Posey, “this morning the man who owns the place came and he was awfully mad and cross. He said Madam Sharpe owed him for rent, and that she had hurt the reputation of the building, and he told me to put my things in my trunk, and he shoved it out into the hall and told me to clear out, and he locked the door so I couldn’t go in again. And I haven’t had any dinner, nor I haven’t a cent of money, nor anywhere to go, and I don’t know what’ll become of me,” and she wrung her hands with another burst of tears.

[Pg 18]

Here was the cause of her misery—the semblance of home, care, and protection, poor though it was, had been suddenly stricken away, leaving her a helpless, solitary estray, a bit of flotsam at the mercy of the world’s buffeting currents. Nor was her misery softened by even the dubious bliss of ignorance that most children enjoy as to the sterner realities of life, for already in her eleven years she had learned only too well what poverty implies, and how sad a thing it is to be friendless and homeless.

Poor little Posey, with her soft eyes, dimpled mouth, and rosy face, she seemed made for sunshine and caresses. Scant indeed, however, had been her measure of either. Her earliest remembrance had been of a home of two rooms in a tenement, a poor place, from which her father was often absent, and sometimes returned with an unsteady step; but a home which held the greatest earthly gift, a loving, tender mother. She was a pale, sweet, sad-faced young mother, who shed many tears, and lavished on her little daughter all the wealth of love the heart can bestow on its one treasure. But as time went by she[Pg 19] grew thinner and paler, the flush on her cheek deeper, and her cough sharper, more frequent, till even Posey, with a child’s apprehension, would throw her little arms around her neck, with a vague fear of what she could not have told herself. Then came a time when her mother could not rise from her bed; and at last, when Posey was six years old, the thread of life that had been so long failing suddenly snapped.

When the mother realized that the end was at hand she called her child to her and kissed her again and again. “Darling,” she said, holding her to her as though mother-love would prove itself stronger than even death, “Mamma is going away, going to leave you.”

“Where are you going to, Mamma?”

“God wants me to come to Him, to heaven.”

“Oh, don’t go!” and Posey clung to her, frightened both by her look and tone. “Don’t leave me, take me with you if you go.”

“Mamma cannot, dear, though she would, oh, so gladly. But I want you to listen now, and though you are only a little girl, never, never forget what I am saying. Be good,[Pg 20] wherever you are try to be good, always tell the truth, always be honest, and every night say the prayer I have taught you; remember that mamma has gone to heaven and will wait for you; and above all remember, remember always, that God loves you and will take care of you.”

“Do you know where my husband is?” she asked a little later of the neighboring woman who was caring for her.

“No, but I can try and find him.” In her own mind she thought it would be no difficult task.

“It’s no matter,” was the weary answer of the wife, who had sadly learned long before that her husband’s presence was slight cause for happiness. “Tell him good-by for me, and to send a letter he will find in my workbox to my mother; so she will know that I asked her forgiveness before I died. And I want her, as I know she will for my sake, to take my child.”

Her voice that had been growing weaker and weaker failed as she whispered the last word. A slight coughing-fit followed, there were a few fluttering breaths, and the nurse[Pg 21] who had been holding her hand laid it softly down.

“Oh, what is the matter with my mamma?” cried Posey in a frightened tone. “What makes her look so white; and lie so still? Mamma, Mamma, speak to me, do!”

But the ear that had always listened to her slightest call, would hear her no more. And the woman lifting kindly in her arms the now motherless child, terror-stricken and sobbing, though too young to understand the great loss and sorrow that had come to her, carried her gently from the room.

When the absent husband at last came home and was told his wife’s last message he listened to it moodily. “I don’t know any great reason she had to ask her mother’s forgiveness, just because she married me,” he said. “I’m not the worst man in the world, by a long way, if her mother did make such a fuss about it. And as for letting her have Posey to bring up and set against me, I’ll do nothing of the kind. I can take care of my own child, and I shall do it.”

A natural and praiseworthy sentiment, this last, had he been a sober, industrious man,[Pg 22] but unfortunately for himself and all connected with him he was neither. As a consequence, in the days that followed his little girl suffered much from neglect, and often from privation. Sometimes he feasted her on candy and sweetmeats till she was almost sick, and again, and more often, he left her to fare as best she might, and go hungry unless some neighbor fed her, while many were the nights she lay awake trembling in the darkness in her little bed, afraid of the dark, and almost more afraid of hearing the unsteady steps that would announce a drunken father.

But when her mother had been dead less than a year, there was a disturbance one evening in a near-by saloon. Revolvers were used, and one man, present but not involved in the quarrel, was fatally wounded. Posey never saw her father again. Taken to a hospital, public charity cared for him in his last hours and laid him in his grave. When they came to tell his child of his death they found her playing merrily with a doll she had made for herself of a rolled-up apron and a little shoulder-shawl.

[Pg 23]

It was hardly to be expected that she would comprehend her loss. For that matter, she hardly knew that she had met with one, and Mrs. Malone, across the hall, was decidedly of the opinion that she had not. For her mother she had grieved long and passionately; that her father was gone made but slight impression. She had received from him so little of affection that she did not miss its absence, and as to kindness and care, she had as much from the neighbors.

For a time she was passed from one to another of these, sharing the proverbial charity of the poor, minding babies, running errands, and doing such little tasks as her years and strength permitted. There was a kind-hearted reluctance among these humble friends to handing her over to public charity. A remembrance of her mother’s wish for her still lingered, and Mrs. Malone even tried to find the letter she had spoken of, but no doubt her husband had destroyed it. There was occasional talk of an effort to find this grandmother, but Posey knew nothing of her whereabouts, every one else was equally ignorant, and it never went beyond the talk.

[Pg 24]

It was at this time that Posey came under the notice of Madam Atheldena Sharpe, a lady who was making her wits provide her support, and who was quick to see how a pretty and easily taught child might be a help towards that end. To her taking possession of Posey there was no one to object. None of the few people she knew felt able to assume the burden of her support. To most of them the clairvoyant with her showy manners and fine-sounding phrases seemed a very imposing person, and Posey was counted a fortunate child to have found such a protector.

So Posey entered on the second phase of her life, bearing with her pitifully few mementos of her vanished home—a china dog her father had bought her in an unwontedly generous mood, a book of children’s poems, out of which her mother had read to her and taught her to read, a locket that had belonged to her mother, and her pocket Bible.

It was but a short time till new attractions were added to “Madam’s” séances—mysterious bells rang, an equally mysterious tambourine was tinkled; and presently out of a cabinet, that now made part of the furnishing[Pg 25] of the room, appeared what was understood to be a spirit materialized, an ethereal-looking little figure in the dim light, with long golden hair and floating white draperies.

As to the question of right or wrong in all this the child gave little thought. At first she had been too young and the various details had been but so many tasks; then as she grew older and began to realize the humbug behind that needed such constant and careful guarding from discovery, she was inclined to laugh at people for being so easily duped. But in the main it was to her simply a means of living, the way in which their bread and butter came.

For the ignorance of most children as to the value of money, or its need in daily life had with Posey been early and sadly dispelled. Better than many an older person she understood not only its necessity but how to make the most of it. From behind some door or curtain she would watch the people as they came to consult the clairvoyant, or gathered for a séance, as eagerly as the “Madam” herself; she knew exactly what each would add to the family purse, and so[Pg 26] could tell pretty well in advance if the next day’s dinner would be scanty or plenty, and whether the medium would be pleasant or the contrary. For though not destitute of kindly impulses her mood was apt to vary in large measure with her success.

In their changing life Posey was soon far from the city where she had lived, and finding her of even more value than she had expected Madam Sharpe gave to the child her own name, and took all possible pains to efface all remembrance of her earlier life, at the same time impressing on her the fact of her homeless and friendless condition, and that but for her kindness she would be a little beggar on the street; so that, as was her intention, Posey grew into the belief that Madam Atheldena Sharpe was all that stood between her and absolute distress, and with that picture constantly before her she yielded the more readily to that lady’s frequent exactions and petulance.

That she might become still more valuable, she was sent to school whenever their stay in a place permitted, though seldom was that long enough for the forming of friendships.[Pg 27] Indeed Madam Sharpe did not encourage such, for though singularly trusty, still she was always afraid that to other children Posey might be tempted to betray some jealously guarded secrets. For this reason, fortunately for her, Posey was never allowed the freedom of the streets, or the acquaintance of the children among whom she was thrown.

As soon as she grew old enough the “Madam” made her useful in domestic matters. She was taught to sweep and dust the rooms, to go to market, to prepare their simple meals, and to attend to most of the “light housekeeping” which best suited Madam Sharpe’s finances and business. In the evenings if people enough came to form a “circle” she had her part to take in the “manifestations,” which was to her only another of her daily tasks, and when ended she was quickly and gladly in bed and asleep.

So Posey’s life was by no means an idle one. She had enough to do to fill the most of her time, and for the rest, though often she was lonely and longed for companionship, still she had been accustomed from a little[Pg 28] child to amusing herself and so had acquired numberless resources to that end. Perhaps the most important result of this way of life was the distinctness in which it kept her mother’s memory, which might have faded had existence for her been happier or less monotonous. Facts and events grew blurred and indistinct, but her mother remained as vivid as a living presence.

No doubt with time imagination added its share till the remembrance grew into her ideal of all that was true and pure and lovely, as it was her greatest solace and comfort. Her words, except those last ones fixed by the solemnity of death, she did not so much remember, but the tenor of her mother’s teachings, her influence, her personality, were indelibly stamped on her mind. In every grief her first impulsive thought was, “Oh, my mamma!” as though even that mute appeal was a consolation; while the reflection, “Would Mamma like to have me?” influenced her actions more than the actual presence of many a living mother. Never a night did she omit to kneel and repeat the prayer she had learned at her knee. Though she had long[Pg 29] known them all by heart, she never grew tired of the book of child’s poems out of which her mother had read to her. Often of an evening sitting alone and lonely, out of her vague and fragmentary memories she would try to recall the songs she had sung and the stories she had told her; and many a night when the day had been hard in her small world did she cry herself to sleep with the yearning plaint on her lips, “I do so want to see my mamma!” All this had the effect of keeping her strangely pure, and through the atmosphere of sordid deceit, if not worse, that surrounded her she walked as if guided and led by the mother-hand so long still and folded.

[Pg 30]

This phase of her life continued till Posey was nearly twelve. At first in the spirit-manifestations she had simply followed the clairvoyant’s directions, but as she became older she not only learned to make herself up for the occasions, but to introduce little variations of her own, which added not a little to the interest and popularity of the séances. Gradually, too, she came to take a certain personal pride in her rôle, of amusement at her own cleverness, and of elation at the sensation she created. As for the moral question, that held no place; she was simply a little actress playing well her part, with an under thought of the profits.

In the earlier days when the “Madam” had both to dress her, and teach her every detail, she had only been able to appear in one “manifestation,” but now she could manage several, and frequently appeared in succession[Pg 31] as an Indian princess, a French girl, and “little Nellie of the Golden Hair.” For the French girl, “Madam” had her take French lessons so that her replies could be in that language, and on occasions when all the “influences” were favorable she would sing very softly and sadly a little French song, accompanying herself on a “materialized” guitar.

For a long time she never ventured outside the cabinet, but gaining boldness with practice she at last came into the room, hovering near the circle gathered round the table, and answering any question put her by the clairvoyant, who at such times was always in a trance.

Madam Sharpe was greatly elated by all this, and to her fancy new, brilliant, and profitable successes seemed opening before her. Alas, in this very increase of popularity, and with it of public attention, lay her undoing, as it drew to her séances not only the easily credulous, and the sincere believers, but the doubting skeptics whose purpose was investigation.

So it came one evening that several young men of the latter class, including a newspaper[Pg 32] reporter, were present, and after the lights had been turned low and dim, and the thrill of hushed expectancy had settled over the waiting circle, and out of the slowly opening door of the cabinet a white, shadowy little figure had lightly floated, and as the “spirit” passed near the newspaper reporter he adroitly threw a pinch of snuff in its face.

A sneeze followed, a most decidedly human sneeze. Quick as thought he seized it in a strong grasp, while another of the “investigators” as quickly turned the gas high and bright, and then and there was revealed to that astounded circle a plump, round-faced, very flesh-and-blood little girl, with the white powder partly rubbed off her rosy face, her wig of long, floating, yellow hair awry, and her white gauze dress crumpled and torn; frightened, angry, and stoutly struggling to escape. As soon as she saw that exposure had come Madam Sharpe hastily made her escape, and a moment later Posey managed to free herself from the hand of her captor and darted from the room.

Out of the door of the cabinet a white, shadowy little figure had lightly floated.—Page 32.

But evidence enough remained: the cabinet, that through a sliding panel opened into [Pg 33]an adjoining room, the guitar, the wigs, the costumes of the different “materializations.”

A storm of indignation naturally followed these discoveries, a storm so loud as to arouse the attention of all in the vicinity, and to bring a policeman to the scene. An angry but fruitless search was made for the clairvoyant, who was near enough to hear the threats expressed as she cowered in her place of retreat.

A much duller comprehension than hers would have realized that her career in that city was ended. Reporters, as she well knew, would catch it up, and the morning papers spread the news of her exposure far and wide, even should she escape the arrest she had heard threatened on the ugly charge of obtaining money under false pretenses. While the crowd was still surging through her rooms, she had decided that the sooner she was away the better; and as soon as the neighborhood regaining quiet had sunk into slumber, she secured, as hastily and secretly as possible, the removal of her few personal effects, and, thanks to the express speed of[Pg 34] the railroad, was many miles distant when morning dawned.

Angry though she was at Posey, the innocent cause of the trouble, yet had the latter been at hand she would have taken her in her flight. But Posey up in the attic, to which she had fled and from which she had not dared to venture, had fallen asleep on a soft heap of rubbish, and Madam Atheldena Sharpe, now as ever thoroughly selfish, abandoned with hardly a thought the child who had so long shared her fortunes. And when with the morning Posey, waking, crept cautiously down, her tumbled finery looking tawdry enough in the daylight, it was to find only empty, disordered rooms, from which the clairvoyant and all belonging to her had vanished.

So for the second time, and with an increased keenness of apprehension of all it implied, Posey was again thrown on the world. And now, for the first time, in the person of the fat, good-natured policeman, Society, that great factor of civilization, became aware of her existence, took her under its charge, and in due time placed her in the “Children’s[Pg 35] Refuge,” an institution where the city was already providing for some two or three hundred similar waifs and strays.

This was a new, strange home indeed, and at the same time a statelier one than she had ever known—the tall brick building, with its great wings, one the boys’ and the other the girls’ department, stretching on either side. While accustomed as she had been all her life to a haphazard, makeshift existence, the exquisite neatness, the perfect order, and the regular system at first equally amazed and depressed. Posey had brought with her a somewhat varied store of accomplishments, but as she looked at the long rows of girls, with their neat uniforms of blue dresses and checked aprons, and noticed the clock-work regularity of their daily life she felt that she had much, very much, to learn.

The Refuge was not an institution where appalling cruelties are hidden under the surface of smoothness. The children were as well clothed, well fed, well taught, and well cared for as is possible where such gathered numbers make separate mothering almost impossible. As a necessity, system, regularity,[Pg 36] was the rule; from the rising in the morning till the retiring at night the ringing of the great bell ordered all; eating, play, work, study, was at its monition. And if any tried rebellion, as Posey at the first sometimes felt inclined to do, it was speedily to find that they but bruised themselves against the strong force which controlled the whole.

Into this routine Posey soon settled; she had her little white bed in one of the rows of the long dormitory, her desk in the schoolroom, her place in the work-room, where at certain hours in the day the girls worked at making paper boxes; and her group of friends in the playground. After the lonely isolation of most of her previous life it was a great change, this becoming one in such a multitude. But hardest of all for her was it to become used to the pressure of discipline, not severe but constant, the feeling that she was never free from the watchful, overlooking eye.

In almost every respect she was much better off here than when in the hands of Madam Sharpe, but though never alone, as in the old days, she was often as lonely as when she sat secluded in the kitchen-bedroom of the clairvoyant,[Pg 37] lonely for the love, the tenderness, that her child heart had longed for so long and so vainly.

After all that Posey had had to do when with the “Madam” it was not hard for her to learn to make paper boxes quickly and well. In the schoolroom, too, she was soon able to take a place near the head of her class, something that gave her not a little pride. Rewards were not offered to the scholars, but one day a reward came to her that she never forgot, and that had not a little influence in shaping her future. It was at the close of a session when she had acquitted herself with even more than her usual credit, and Miss Grey, the teacher, in passing her desk as she was putting her books in order, stopped with a pleasant smile and said, “Posey, I am very glad to see you so ambitious in your studies; if you will study and try I think you can one day make a teacher.”

It was to Posey a new idea, and the stirring of her first real ambition. Was it possible that she could become a teacher like Miss Grey, and have pupils who should in like manner admire her, and, best of all, make a[Pg 38] place and earn a living for herself? Her heart thrilled, first with the idea, and again with the determination that it should be possible. And Miss Grey, busy with her many pupils and manifold duties, went her way unconscious of the ray of promise she had given, a ray that should shine as a day-star of hope through many a long day. For that matter, she had no idea of the feeling she had inspired in Posey’s heart, how she watched, admired, and imitated her, absorbed her ideas, was influenced by her opinions, and when she finally left, for a home of her own, missed her.

With all the teachers and matrons Posey was in the main a favorite. But for the study of individual character there was scant time; when she was good, little attention was paid to her, when she was naughty she received the punishment she had incurred. For while Posey possessed a certain intrepid strength of purpose that carried her over many a hard place, as well as in her work and lessons, these were coupled with an impulsiveness of action and warmth of temper that often brought her into temporary disgrace.

[Pg 39]

Still, on the whole, the year and a half she passed at the Refuge was as happy as any she had spent since her mother’s death. But one day a summons came for her to the Superintendent’s office, where sat a stout lady, with a face of hard, mottled red flesh, one whom she had noticed a little while before making the rounds of the rooms.

“Yes,” she said, regarding Posey with a fixed gaze of her beady black eyes, “I think I will try this one. I’ll take her home with me and keep her for a while, anyway. No, I don’t care to ask her any questions. I wouldn’t know much more if I did, and I can find out enough in short order. So hurry and get yourself ready,” to Posey, “for I’ve no time to lose.” And when Posey heard this she hardly knew whether she ought to be glad or sorry.

The Refuge did not let its charges go out without providing as far as possible for their welfare and future. As Mrs. Hagood had furnished ample references as to her capability for such a charge; and as she further promised to give Posey good care, moral instruction, and the advantage of the school in[Pg 40] her village, the Refuge authorities felt that in this case they had amply done their duty. So in a very short time Posey’s few belongings were packed, the parting words said, and in company with Mrs. Hagood she had passed and left behind the tall wrought-iron gates of the Refuge.

To live in the country had always been to Posey a dream of delight, though her knowledge of the country was limited to fleeting views from car windows. She had, too, a faint memory of stories her mother had once told her of the happiness of a childhood spent among orchards and meadows; and with all these in mind she had often looked at the dusty trees bordering the stone-paved streets, and the swift-flowing streams that filled the gutters after a rain, trying to cheat imagination into the belief that they were real brooks and genuine woods.

So now when Mrs. Hagood told her that her new home was to be in a little country village her heart beat high with anticipation, and she decided that she was glad she was going. On their way to the train in the street cars they skirted the Haymarket, and Posey[Pg 41] looked out with mingled feelings at the tall brick building, the scene of her memorable misadventure. Not that she had any desire to return to Madam Sharpe. With a child’s quick intuition for shams, the clairvoyant’s manifold deceptions had inspired her with anything but a profound respect, nor had she by any means forgotten the cruelty of her desertion. Besides, was she not now going into the beautiful country, to be as free as a bird among the birds and flowers?

[Pg 42]

Before Posey hardly had time to realize the change, the city with its crowded houses and busy streets, its smoke and confusion, its glitter of wealth, its grime of poverty, was left behind, and she was seated by the side of Mrs. Hagood in the cars on her way to her new home, something over an hour’s ride distant.

Though yet early in March it was a sunny, spring-like day. Under the bland air the snow had almost disappeared from the brown fields, and only lingered in occasional patches of white in hollows and along sheltering fences. The willows by brookside ways were showing their early catkins, while the woods, distinct against the tender blue of the spring sky, by their reddening tinge told that life was already stirring in the leaf-buds, so soon to unfold.

In some of the woods that the train sped[Pg 43] through, Posey caught glimpses of smoke curling up from small, weather-worn buildings, while from the trees around them hung buckets, some painted a bright red, others of shining tin; she could even now and then hear from the open car window a musical drip, drip, which the more increased her wonder.

“What are all those pails hanging to the trees for?” she finally asked. “And what is the sound just as though water was dropping?”

“Goodness alive, didn’t you ever see a sugar bush opened before?” inquired Mrs. Hagood. “That’s where they are making maple sugar and syrup; those are maple trees, and what you hear is the sap running; it’s been a good sap day, too.”

This explanation did not make the matter very clear to Posey, but what Mrs. Hagood meant was that the warmth of the spring day had caused a rapid upward flow of the sap, or juice of the tree, which had been stored in the roots through the winter; and by making incisions in the tree this sap, which is sweetest in the maple, is caught and boiled into syrup or sugar.

[Pg 44]

For all the outward attractions, Posey had already given some very earnest and anxious looks at Mrs. Hagood, with whom her home was now to be for an indefinite time. Child as she was, she quickly felt that there was nothing of the flimsy, the pretentious, about that lady. The substantial was stamped on every feature, and though her shawl was handsomer and her black silk dress of finer quality than she had ever seen Miss Grey wear, she was conscious that Mrs. Hagood lacked something the little teacher possessed—the essential quality that made the latter the true lady.

But the time had been short, or so it seemed, for the much there was to think and see, when Mrs. Hagood gathered up her numerous packages, and Posey found herself hurried out on the platform of a wayside station. Truly she was in the country. A few scattered farmhouses were in sight in the distance, but the little station stood between the far-reaching railroad tracks and the muddy country road wholly apart and alone. No one but themselves had alighted, and they were the sole occupants of the building, not[Pg 45] even a station-master appearing in sight. “Is this a village?” Posey asked as she looked around in wide-eyed surprise.

“Mercy, no, child, the village is two miles from here.”

“And what a queer depot,” added Posey. “I never was in one before where there weren’t lots of people.”

“People in the country have to stay at home and work,” was the short reply. Posey had already noticed that Mrs. Hagood had a way of clipping her words off short as though she had no time to waste on them.

“When they do go,” she added, “they mostly take the morning train, as I did, and come back later. This train never stops here unless it has passengers to let off, or some one flags it to get on.”

As she talked they had walked around the narrow platform to the opposite side of the station, and Mrs. Hagood, shading her eyes with her hand, for the afternoon sun was now low and level, looked down the road with the remark, “I should like to know where Elnathan Hagood is. I told him to be here in time to meet this train.”

[Pg 46]

Naturally Posey felt a degree of curiosity as to the family she was about to enter, and with Mrs. Hagood’s words came the reflection, “So, then, she has a boy. I hope I shall like him.”

A few moments later an open buggy drawn by a stout, sleek bay horse came in sight over the nearest hill, whose occupant Posey saw as it drew near was a small, middle-aged man, with a pleasant face, mild blue eyes, and a fringe of thin brown beard, touched with grey, under his chin.

“I thought, Elnathan,” was Mrs. Hagood’s greeting as he drew up to the platform, “that I told you to be here by train-time.”

As Elnathan Hagood climbed slowly out over the muddy wheel, there was apparent a slight stoop to his shoulders, and droop to his hat-brim, and a certain subtle but none the less palpable air of one who had long been subjected to a slightly repressive, not to say depressing influence. “Wal, now, Almiry,” he remarked with the manner of a man to whom the apologetic had become habitual, “I did lay out to be here on time, but the roads[Pg 47] hev thawed so since morning that it took me longer than I’d calc’lated on.”

His wife gave a sniff of contempt. “I only hope I sha’n’t catch my death o’ cold waitin’ here in this raw wind, clear tired out as I be, too. But now you are here at last, see if you can put these things in, and not be all the afternoon about it, either.”

“I see you did get a little girl,” with a nod and kindly smile at Posey, who stood a little apart.

“Yes,” rejoined Mrs. Hagood tartly, “I said I was goin’ to, and when I plan to do a thing I carry it out as I planned it, and when I planned it.

“I know,” she continued, regarding Posey as though she had been a wooden image, or something equally destitute of hearing, to say nothing of feeling, “that it’s a big risk to take one of those street children; you never know what tricks they have, or what they may turn out to be. This one isn’t very big, but she looks healthy, an’ I see she was spry, an’ I guess I’ll be able to make her earn as much as her salt, anyway.”

Posey’s cheeks flamed hotly, and she was[Pg 48] on the point of an indignant protest that she had never been a street child in her life, when she caught a slight shake of the head from Mr. Hagood. Then Mrs. Hagood turned away to direct her husband as he folded a horse-blanket to form a seat for Posey, at the same time enveloping herself in a large, black, shiny waterproof cloak, to protect her from the mud, and tying a thick brown veil over her bonnet to serve the same purpose.

When all was ready, Mr. Hagood lifted Posey into the buggy, with another friendly smile that went warm to her heart, and as soon as the various packages with which she had returned laden, were settled to Mrs. Hagood’s satisfaction they were on their way. But they had not driven far when leaning across Posey, who was seated between them, Mrs. Hagood snatched the reins from her husband’s hands, exclaiming, “Elnathan Hagood, give me those lines, an’ see if I can’t drive without gettin’ into every mudhole we come to.”

Mr. Hagood yielded without a word. The first thought of their wide-eyed young companion was of wonder that he should do so.[Pg 49] In her heart she felt that if she were a man she would not, but as she furtively glanced from him to his wife, it was with the instinctive feeling that protest or opposition on his part would be useless.

On account of the muddy clay road their progress was but slow, but accustomed only to city sights, and for so long to the seclusion of the Refuge, Posey enjoyed every step of the way. The pleasant farmhouses they passed, set in their wide, deep yards; the barns with cattle standing around, chewing placid cuds and looking at them with large soft eyes; the full and rushing brooks that came darting out of the fields with a swirl to rush across the road into the fields again; the bits of woods, shadowy and quiet; the soft brown of the rolling fields; the fresh spring air, the wide outlook, the very novelty and strangeness of it all. And to her it seemed quite too soon that climbing the long hill they entered the village of Horsham, whose white church spire had for some time been looking down on them.

Horsham, like most country villages, consisted of a central cluster of stores and shops,[Pg 50] from which radiated a scattering company of comfortable homes, and all surrounded and over-arched with imbosoming trees. Presently the sleek bay horse turned into the yard of one of the most cosy of these, trim with white paint and green blinds. At the first glance Posey saw that everything about the place was faultlessly neat and tidy; and also that on the opposite side of the drive, near the street but in the same yard, was another and smaller building bearing above its door a sign,

ELNATHAN HAGOOD. WAGONS REPAIRED.

She had little time to look around, however, for Mrs. Hagood, unlocking a side door, led the way into a large, comfortable kitchen. Hastily divesting herself of her outer wraps, she opened the door to a bedroom off from it, which was only long enough for the bed, and wide enough to admit at the side of the bed a washstand and a chair.

“Here, Posey,” she said, “is your room. You will find it clean and tidy, and I shall expect you to keep it so. Now take off your things and hang them on those nails behind[Pg 51] the door, and put on one of your gingham aprons, that you wore at the Refuge, to keep your dress clean. Then take that pail on the corner table to the spring at the end of the yard and fill it with water. Mind that you don’t slop it over you, or spill any on the floor as you bring it in, either. Then fill the teakettle and put it on to boil, and go out in the woodhouse and get seven potatoes out of the basketful on a bench by the door. Wash them in the tin basin that hangs up over the sink and put them in the oven to bake.” Here Mrs. Hagood added some more wood to that which had burned low in the stove, opened the draughts and set it to burning briskly. “By the time you have done that I will have my dress changed and be back to show you where to get the things to set the table.”

Posey had proceeded as far as the filling of the teakettle when Mr. Hagood entered and after a glance around the room as if to assure himself that they were alone drew from his pocket a handful of apples. “They’re russets,” he said in a cautious voice, holding them out to her. “They’ve[Pg 52] just got meller an’ I thought mebby you’d like to keep ’em in your room an’ eat one when you felt like it.” And Posey gratefully accepted the good-will offering, and the suggestive hint implied with it.

After supper she washed up the dishes under Mrs. Hagood’s supervision, and when that was done and the lamp lighted gladly sat down, for she was decidedly tired after the unwonted events and excitement of the day. Unless company came, the kitchen was also the living-room, for Mrs. Hagood said it was good enough for them, and saved the dirt and wear of carpets in the front rooms. So Mr. Hagood drew up to the table with his spectacles and weekly paper and was soon absorbed in the latter, while Mrs. Hagood brought out a blue and white sock, partly finished, which she attacked vigorously.

Noticing with a glance of disapproval Posey’s folded hands she asked, “What did you do evenings at the Refuge?”

“We studied part of the evening, and then we read, or one of the teachers read to us, and sometimes we sang, or played quiet games.”

[Pg 53]

“Well,” with emphasis, “I think they had better been teaching poor children who will always have to work for their living, something of some use. Do you know how to knit?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Then I will set up a stocking of cotton yarn for you to-morrow and show you how. When I was your age I knit all my own stockings, and always had knitting to catch up when I’d nothing else to do. Girls then didn’t sit with their hands idle much, I can tell you,” and her knitting needles clicked loud and fast.

Thus was Posey introduced to her new home. And that night as she sat in her tiny room, in a frame of mind it must be confessed somewhat depressed by the formidable personality of Mrs. Hagood, she ate one of the russet apples, which she had hidden in a drawer in the stand, and felt cheered and comforted by the spirit of kindly sympathy it represented, together with its mute assurance that in the household she would find at least one friend.

[Pg 54]

The next morning Posey was awakened by the voice of Mrs. Hagood at her door, “Come, Posey; time to get up, and be spry about it, too.”

The clock was just striking six as she came out of her room, but the kitchen was already warm and Mrs. Hagood in a loose calico wrapper was busy about the breakfast.

“I don’t want you to dawdle in bed,” was her salutation. “I’m stirring myself mornings and I want folks about me to stir, too. Hurry and wash you, then take this dish and go down cellar for some cucumber pickles. They are in that row on the left hand side, the third jar. Now mind and remember, for I don’t want to keep telling things over to you.”

As she returned with the pickles Mr. Hagood came in with a pail of foaming milk, and Posey, who in her household experience had[Pg 55] been accustomed to see milk measured by the pint, or more often the half-pint, gave a little cry of wonder and delight.

“I want ter know?” and Mr. Hagood’s thin, kindly face wrinkled from mouth to eyes in a smile. “Never saw so much milk as this at once before. Why I get this pail full every night and morning, and I calc’late Brindle’ll do still better when she gets out to grass.” As he spoke he had strained out a cupful of the fresh, warm milk and handed it to Posey, saying, “Drink that now, an’ see if it don’t taste good.”

“What are you doing, Elnathan?” demanded Mrs. Hagood, who was skillfully turning some eggs she was frying.

“Wal, now, Almiry, I’m just givin’ the child what she never had before in her life, a drink o’ fresh, warm milk. I thought, Almiry,” with an accent of mild reproof, “you’d like her to have what milk she wanted to drink.”

“You know as well as anybody,” was her tart retort, “that I never scrimped anybody or anything around me yet of victuals; Posey can have all the milk she wants to drink with[Pg 56] her breakfast, but there’s no use for her to be stoppin’ her work and spendin’ time to drink it now, or you to be lettin’ the cream rise on the milk before it’s strained, to watch her.”

Breakfast out of the way Mrs. Hagood said, “Now, Posey, you may go out and feed the chickens. You will find a bag of shelled corn on the granary floor; give them the basin that stands on a barrel beside it twice full.”

It was a command that Posey gladly obeyed, but she wondered that the flock of eager fluttering chickens, who crowded around her, and flew up into the granary door, seemed so indifferent to the breakfast she scattered for them. “Go and eat,” she vainly urged, “go!”

Posey had on occasion seen city hens, poor, dirty, bedraggled fowls, but these were so different, plump and snowy, bright of eye, and sleek of plumage, that it was a pleasure to linger among them. But Mrs. Hagood’s voice soon sounded from the door, “Posey, is it going to take you all the forenoon to feed those hens?”

A little later as Posey was washing the[Pg 57] breakfast dishes, taking great pains to follow all of Mrs. Hagood’s many directions, for she truly wished to please, she heard that lady calling her, and dropping the wiping-towel ran out into the yard to see what was wanted.

“How came all those beans here on the ground?” Mrs. Hagood demanded sharply, pointing as she spoke to the white kernels scattered around.

“Why,” replied Posey in surprise, “that is what I fed the chickens as you told me.”

“‘As I told you!’ A likely story that I would tell you to feed the hens beans. Don’t you know enough to know beans from corn?”

“No, I don’t,” retorted Posey hotly. “And why should I? I never was in the country before in my life, and I don’t know anything about corn, except green corn, or beans, either.”

“Shut right up,” exclaimed Mrs. Hagood sternly. “I won’t put up with any impudence, and I want you to make up your mind to that. Now look here,” holding up a handful of yellow kernels, “this is corn; remember it, and if you make such a blunder[Pg 58] again I’ll help you to remember with a whip.”

Posey turned slowly and with a swelling heart re-entered the house. She had meant no harm, the two bags had sat side by side, the mistake had been wholly accidental, and under other circumstances she would have been sorry enough, but now with the sense of injustice burning at her heart she said to herself, “Cross old thing, I don’t care if I did spill her old beans, not one bit.”

So Posey’s life with Mrs. Hagood began, and had the latter been an agreeable person to live with it might have been a pleasant life; she was comfortably clothed, she had an abundance of wholesome food, and the work expected of her was in no way beyond her strength. But Mrs. Hagood always so managed that when one task was ended another was ready to take its place. With her it was one continuous grind from morning till night; that the child required a share of pleasure and recreation was an idea she would have scouted. She worked all the time, she would have said, why was it any worse for Posey? Besides, this was a poor child who would always[Pg 59] have to earn her living and the sooner she realized it the better.

So the stocking was set up, and Posey inducted into the mysteries of knitting. For other spare moments there were towels to hem and sheets to turn, and when everything else failed to fill all the available time there was always on hand a huge basket of carpet rags to be cut, sewed, and wound.

With it all she was one of those women who never dream of bestowing praise: if the work were ever so well done, and Posey was at times fired with the ambition to see how well she could do, never a word of commendation followed; if on the contrary, there was any failure, and Mrs. Hagood’s eyes were always alert for faults, there was always the word of sharp reproof. Then Posey would solace herself with the reflection that she couldn’t suit her if she tried, and she wasn’t going to try any more, and she hoped she wouldn’t be suited, “so there!”

Often and often as Posey sat in the open doorway in the long summer afternoons, the distant woods beyond the village beckoning with their green shade and the basket of endless[Pg 60] carpet rags at her side, did she wish herself back within the pent-up walls of the Refuge; for there when her appointed task was done she could enjoy some free time, while here was no escape from the atmosphere of repression, fault-finding, and petty irritation, to say nothing of the absence of all love and sympathy, or even interest.

Mrs. Hagood would have said that all she was doing was for Posey’s interest, but it is exceedingly doubtful if Almira Hagood ever viewed anything or any one in a light separate from her own interest. With a sublime self-confidence in her own ideas and opinions, she would unhesitatingly have crushed a stronger opposition to her will; how much the more anything so insignificant as the wishes and feelings of a little charity girl! One, too, whom she had taken solely that she might have her work, and whose highest good therefore was to be useful, as her highest aim and desire ought to be to do the work she assigned her quickly and well; while, unfortunately for both, Posey’s mind was often filled with a host of other and widely differing wishes and desires.

[Pg 61]

Had kindly Mr. Hagood been an active factor in the domestic economy, her life would have been very different; but he was only a passive factor, so passive, in fact, as to be seldom considered, and least of all by his wife. From the first Posey had regarded Mr. Hagood in the light of a fellow sufferer, with the present advantage of his little shop to escape to, where with his work as a plea he managed to spend not only most of his days but many of his evenings, and where he could enjoy the pleasure of his pipe and dog, both forbidden the house, and a frequent chance visitor. For Mrs. Hagood so frowned upon his making one of the nightly group at the village store and post-office that, social as he was by nature, he seldom ventured on the enjoyment.

Still if this was his present advantage, he would always, so Posey reflected, have to live with Mrs. Hagood, while some glad day she would be old enough to leave, and then never need see her again unless she chose, which she didn’t much think would ever happen.

An amiable, easy-going man, Elnathan Hagood, it was said, at the time of his marriage[Pg 62] had inclined to ways slightly convivial. But his wife speedily changed all that, and by the sheer force of her superior will had set and kept his feet in a straight path. By nature “handy” with tools the shop had been her idea, where she started him as surgeon to the various disabled vehicles of Horsham; while she, in the meantime, having taken charge of his modest patrimony, proceeded to put it out to usury, in a literal as well as figurative sense.

In all the country round no one knew how to drive a sharp bargain, and for that matter a hard one, better than Almira Hagood; and woe to the luckless debtor who expected mercy at her hands. With these qualities but few really liked Mrs. Hagood; she was too dominant, positive, selfish, and avaricious to win many friends, or to care much for friendship. At the same time, and for all that her methods were now and then a shade questionable, there were many who admired her thrift, energy, business shrewdness, and practical ability, and took a certain pride in her success as in some sort reflecting credit on her home village.

[Pg 63]

It is almost needless to say that in the twenty years or more she had managed the property it had greatly increased in value, and at this time included outlying farms, village property, bank stock, mortgages, and sundry other investments. In regard to this she never thought of consulting her husband, and if he ever ventured on a suggestion as a rule passed it over without the slightest regard. The word “we” was one seldom heard from her lips. It was always “my horse,” “my cow”; she referred to the time when “I built my barn,” or “when I bought my farm,” with a complete ignoring of any partner in the firm matrimonial. Indeed, whatever the light in which she regarded Elnathan Hagood personally, for his ability and opinions she did not disguise her contempt, and any attempt to assert himself was quickly and vigorously suppressed; and the common opinion as to his condition was voiced by an old companion, “I tell you, she keeps his nose clus to the grindstun.”

It was then not strange that for the most part he went about with the subdued and apologetic air of one aware of his own insignificance.[Pg 64] Sometimes, for his kindly nature held an especially tender place for children, he attempted to expostulate in Posey’s behalf; but his mild, “Now, Almiry, I wouldn’t,” or “Almiry, you know children will be children,” made matters no better for Posey, and only brought a storm about his own head.

Weakness held no part in Mrs. Hagood; “capable” was the term that truly fitted her; at the same time there was no more tenderness in her nature than in her well-polished cook-stove. A timid, sensitive child would have wilted, pined, and perhaps have died in her atmosphere; but Posey was not more sensitive than the average healthy, hungry child, and was even more than usually high-spirited and fearless. Her affections—meagerly as they had been fed—were warm, her impulses generous, and her nature one to whom love and kindness might have proved controlling forces where threats and violence failed. Such being the case, her life with Mrs. Hagood could hardly fail to intensify all her faults of temperament; the more so as the almost daily outraging of her sense of justice[Pg 65] led to a feeling of resentment that from its frequency became well-nigh constant.

There were also occasions when this rose to an especial high-water mark. One such was the event of a Sunday School picnic to a little lake distant some half-hour’s ride on the cars. An event that all the younger members of the school had looked forward to with eager anticipations, and Posey perhaps most of all, for a picnic was something she had never known. But when the time came Mrs. Hagood flatly refused her permission to attend.

“I’m not going to throw away forty cents to go, and if I wouldn’t for myself I don’t know why I should for you,” she had said. “Crystal Lake! I want to know! Nobody ever thought of calling it anything but Wilson’s Pond when I was a girl, or of its being any great sight. But now it’s Crystal Lake folks must all run to see it, and I don’t suppose it’s anything more than it was before.”

“Almiry,” ventured Mr. Hagood in his most persuasive tone, with a glance at Posey’s drooping head, “ef you’ll let her go I’ll pay the fare.”

[Pg 66]

“Really, Elnathan Hagood,” turning on him with withering sarcasm, “seems to me you have grown suddenly rich. If you have more money than you know what to do with you may go over to the store and get me ten pounds of sugar, and a couple of pounds of raisins. I want them right away. As for Posey, I’ve said once she couldn’t go and that settles it. I don’t believe in picnics, anyway; they’re just an excuse for people to spend time and money; Posey hasn’t been good for anything since they began to talk of this one, and if she was to go she’d wear out her shoes, and tear her dress, and come home so used up she wouldn’t be good for anything for a week to come. It’s all nonsense, and she’s enough sight better off right here.”

So with a swelling heart Posey saw the others gathering for the start. “Why, Posey, aren’t you ready?” called one of her classmates over the fence as she was sweeping off the walk.

“No, I can’t go,” she answered with the curtness of despair.

“Won’t Mrs. Hagood let you?”

[Pg 67]

Posey shook her head; it was an occasion where words were insignificant.

“Well, I just think she’s a horrid, mean old thing,” cried the indignant and friendly sympathizer.

“Who’s that is a ‘mean old thing’?” demanded Mrs. Hagood, who at that moment suddenly appeared around the corner of the house.

“No-nobody,” stammered the little girl, all the more frightened because of her guilty consciousness.

“Oh,” blandly remarked that lady, “it was my mistake then; I thought I heard you saying that somebody was,” and with a grim smile she turned away, adding as she did so, “Posey, you have swept that walk long enough, come in now and wash the dishes.”

It is to be feared that Mrs. Hagood found Posey anything but efficient help that day, for the bitter rebellion in her heart found outward expression in careless, sullen indifference. She slopped water on the floor, jammed the wood into the stove, and slammed the dishes with a violence that threatened their destruction. And when Mrs. Hagood sharply[Pg 68] demanded what she was thinking of, she muttered a reply in a tone that brought her a shake, with the admonition to be careful, if she knew what was good for herself.

After the morning’s work was finished Posey was sent out to pick currants for jelly; and a little later Mr. Hagood might have been seen slipping, with all the caution of a criminal, along behind the screening grapevine trellis towards the end of the garden where were the currant bushes, and half hidden among them Posey shedding hot and bitter tears over her task.

“I’m real sorry you couldn’t go, Posey,” he said in a voice lowered as if fearful it might reach the keen ears of his wife, “for I know how you’d been a-lottin’ on it; but Mrs. Hagood knows what’s best fer you.”

Loyalty was a strong element in Elnathan Hagood’s nature. Whatever his private thought might be, not a complaining word of her had he ever been heard to utter. And child though she was, Posey instinctively recognized and respected this feeling, but now carried away by her disappointment and grief she exclaimed passionately, “I don’t know[Pg 69] whether she does or not! At any rate I don’t believe she ever was a little girl in her life.”

“Well, you know the real trouble is,” explained Mr. Hagood, “that she never had any little girl of her own.” For it was one of his favorite theories that a child, especially a little daughter, would have softened all the asperity of that somewhat flinty nature, rendering it at once sweet and tender.

“Besides,” he continued, “a picnic isn’t anything really so wonderful. I wouldn’t give a single cent to go to one myself; though to be sure I’m gettin’ oldish and a bit stiff for swingin’, and rowin’ on the lake, and racin’ through the woods, an’ all that sort of thing I used to enjoy so when I was your age.”

He checked himself with the sudden realization that this was hardly the way to impress upon her what undesirable affairs picnics were, and busied himself in extracting a paper parcel from his coat pocket. “Now don’t cry any more,” he urged; “see here, I’ve brought you some nuts and candy.”

“Oh, Mr. Hagood,” cried Posey impulsively jumping up and throwing her arms around[Pg 70] his neck, to his great astonishment, and hardly less confusion, “you are the very best man in all the world!”

“Well, now, Honey,” his wrinkled face flushing with pleasure at the caress, to him something so unwonted and unexpected, and giving her hand an awkward stroke by way of return, “you be a good girl and mebby you and I will go somewhere and have a picnic by ourselves some day. I’ll see if I can’t fix it.”

Then Mr. Hagood, in the same stealthy manner with which he had come, returned to his shop. And Posey behind the currant bushes forgot to breathe out threatenings and slaughter against Mrs. Hagood, as she munched her candy, so much the sweeter for the sympathy that had accompanied it, and found herself more cheered than an hour before she would have believed it possible she ever could be again.

[Pg 71]

“Elnathan, I’m out of flour; you must go to mill to-day,” said Mrs. Hagood one morning a little later.

Mr. Hagood had been anticipating this direction, but he answered with a guileless air, “Must you have it to-day? Joe Hatch is a hurryin’ about his wagon.”

“Yes, I can’t bake again till I have some more flour; and I guess Joe Hatch can wait.”

“You couldn’t go?”

“Me? The idea; no, my time’s worth too much to spend a good share of the day going to mill. There was a payment due yesterday on that money I lent Dawson, and if he doesn’t come this morning I shall go around and see him.”

Mr. Hagood paused in the door with a reflective manner, “I don’t know, Almira, but ’twould be a good idea to take Posey along and show her the way; old Jim’s that gentle[Pg 72] she could drive him well enough, an’ ’twould be dreadful handy sometimes if I could send her to mill when I’m pushed with work. She’s quick to learn anything.”

“Quick enough when she wants to be. But why don’t you send her to-day? You can tell her the way; she could hardly miss it.”

“Y-e-s, but it’s kind of ticklish gettin’ down the hill there at the mill, I’d want to show her about that myself. But it’s just as you say.”

Mrs. Hagood hesitated, but the thought that if Posey could take his place in going to mill Mr. Hagood could be at work decided the matter. “Well, take her then,” she said; “she’s in the garden picking peas; call her in and tell her to get ready.”

Just before he was ready to start, Mr. Hagood came in, “There’s never no knowin’ how many will be ahead of me, or how long I’ll have to wait my turn; the last time I got pretty nigh famished, so I wish you’d put up a bite o’ lunch in case I have to wait again, as I’m likely to.”

Then with the bag of wheat in the back of the stout buggy, the basket of lunch under the seat, and Rover, the old dog, capering[Pg 73] around them, they set off, between meadows where the sun of the July morning had not yet dried the dewy freshness from the grass, and cornfields, the ribbon leaves of whose green rows waved and rustled in the light breeze. When they were well outside the village Rover came to the side of the buggy and looked up with expectant eyes. “Almiry says there ain’t no sense in lettin’ a dog ride,” Mr. Hagood remarked apologetically, “an’ I s’pose she’s right. But Rover does enjoy it so much that when I’m alone I generally let him. Come up, old fellow! There,” as the dog bounded into the buggy, “sit up now like a gentleman.” And Rover lifting his head, lolled out his tongue, and looked first at one and then the other with an air of deep content.

It was a five-mile drive, but it seemed short to Posey, though easy-going Jim took his own gait, and once when Mr. Hagood saw on a converging road another wagon piled with bags he held his own horse back until he saw they had the right of way, which in this case assured him a wait of two or three hours at least.

[Pg 74]

At last the mill was reached, with the wide, smooth pond spreading above it, whose water tumbling over the dam hurried foam-flecked away through a deep, rocky gorge, made still more shadowy by the hemlocks that lined it, on whose very verge stood the tall old mill. “You think it’s a pretty place?” as Posey gave a little cry of delight as the shining water came in view. “Well, I do myself, for a fact. But look now ef I ever send you alone,” and Posey watched as he wound down the short but steep descent to the mill door, through which she looked with wide, curious eyes.

“And you never saw a grist mill afore? Well, come right in an’ see one now,” and Posey followed Mr. Hagood and the miller who had shouldered their bag of wheat inside, where belts and bands were whirring, and great hoppers slowly turning as they fed the grain to the crushing stones. The noise and clatter drowned the miller’s voice but she understood his good-natured smile and beckoning finger as he opened little doors here and there and she caught glimpses of the wheat on its way to be cleansed from impurities,[Pg 75] of the flour passing through its silken bolting sieve, of a flowing brown stream of bran, and a white cataract of swiftly falling flour: the flour that whitened the miller’s coat and cap, and lay as a covering over the floor, and powdered all the beams and ledges of the mill, and swayed with the wind in cobweb veils and festoons from the high rafters. And mingled with all was the steady, insistent sound of the falling water just outside, the power that gave force and motion to it all.

“We’ll have quite a spell to wait,” remarked Mr. Hagood, motioning Posey to the door so that his voice could be heard, “there’s two big grists ahead of us; how’d you like to go out on the pond? There’s a boat under the willows at the end of the dam.”

Like it? Of course she would, and in a few moments she was dipping her fingers in the clear water as Mr. Hagood rowed the little boat toward the upper end of the pond where lily pads were floating on the placid surface with here and there a blossom opening waxy-white petals. It was an hour that Posey never forgot, the soft blue sky above, the[Pg 76] gentle motion of the boat, the lake-like water that rippled away from the oars, and the lily blossoms with their golden hearts.

“Well, now, Posey,” said Mr. Hagood, as they drew in to shore at last, “must be about noon by the shadders, an’ rowin’s kinder hungry work, so I guess we may as well have our lunch.”

For this they chose a spot down close to the stream below the fall, on a great rock that jutted out, covered with a green carpet of softest moss, and shaded by the drooping hemlocks that found their foothold in the ledges above. Here Posey spread out the contents of the well-filled basket, for Mrs. Hagood’s provision was always an ample one, the slices of bread and butter, the thin pink shavings of dried beef, the pickles, the doughnuts and cookies, while Mr. Hagood added as his contribution a couple of big golden oranges.

“I’m so glad we had to wait!” observed Posey as she munched her bread and butter.

It was an hour that Posey never forgot.—Page 75.

“This isn’t much of a wait,” answered Mr. Hagood. “When I was a boy an’ used to go to mill with my grist in a bag on the [Pg 77]horse behind me, like as not I’d have to wait till the next day. An’ before that when it was a hundred miles to the nearest mill father used to be gone a week at least.”

“I guess he didn’t go very often,” hazarded Posey.

“Not very, especially as there wasn’t anything but blazed trees for roads to go by. In them early pioneer days when folks first began to come here to Ohio it was a pretty serious question how to get meal and flour; sometimes they’d shave it off, an’ sometimes grind it in a coffee mill. I’ve heard Aunt Sally Bliss tell that once she nailed the door of an old tin lantern to a board and grated corn enough for Johnny-cake for her family; while quite a few did like my father; he hollowed out a place in the top of a stump, worked off a stone till it had a handle for a pestle, then put the wheat or corn, a little at a time, in the hollow and pounded it till it was fine enough to use.”

“That must have been ever so much work.”

“Yes, there was plenty of hard work those days, but the people had real good times after all. Sometimes I think better’n we have[Pg 78] now,” he added as he slowly peeled his orange.

“Not any better than to-day,” protested Posey.

“An’ have you enjoyed it?” a smile brightening his face, as the miller came to the mill door and waved his whitened hand in token that the flour was ready and they rose to leave, “Has it been like a picnic?”

“A picnic, yes,” a sudden comprehension coming to her what he had meant it for. “Dear Mr. Hagood, it’s been so good of you, and it is the loveliest day I ever had in all my life.”

So it will be seen that even under Mrs. Hagood’s rule Posey’s life was not all shadow, the less so that Mr. Hagood touched by her pleasure managed with gentle guile and under one pretext and another to secure her for a companion now and then. Outings which it would be hard to tell which enjoyed the more, Posey for herself or Mr. Hagood for her. Occasionally, too, some matter of business would call Mrs. Hagood away for the afternoon, when she would take her towels to hem or carpet rags to sew, as the case[Pg 79] might be, out to the little shop with its mingled odors of fresh lumber, paint, and varnish, where Mr. Hagood hummed old tunes and whistled softly to himself as he worked. And where seated on a rheumatic buggy seat in one corner, with the shaggy head of Rover resting on her knee, in watching Mr. Hagood at his work, and listening to his favorite old-time stories she would find real if unexciting enjoyment.

Then again during the season of raspberries and blackberries many were the delightful hours Posey spent berrying in the “back pasture.” A field this, only a little remote from the village, but hidden from it by a bit of intervening woods, and so shut away from all outward, disturbing sight or sound that with its peaceful stillness and sunny, wind-swept solitude, it seemed as genuine a bit of nature as though the subduing hand of man had never been laid upon it, and one which the city-bred child fairly revelled in.

A big, stony, thin-soiled field was the “back pasture,” affording hardly grass enough for the two or three cows which fed there, hence held in slight esteem by its owner and suffered[Pg 80] to lapse into an almost unchecked growth of briars and undergrowth, with here and there a thicket of young and fast-growing trees, a spot where wild growths ran riot, where bittersweet hung its clusters, and the wild grape tangled its strong and leafy meshes; a spot, too, that the birds knew, where they nested and sang, for the most part unmolested and unafraid.

But the crowning charm of the place to Posey was the chattering brook that with many a curve and bend, as if seeking excuse to linger, ran in a little hollow through the centre of the pasture. A clear, sparkling little stream, gurgling and hurrying through the sunlit spaces, loitering in the shadows of the willows whose green fingers bent down to meet its current, with shallow places where one could wade or cross on stepping-stones, and deep pools where minnows loved to gather and hide them under the trailing grasses of the banks.

This was Posey’s first acquaintance with a brook and for her it had not only charm but almost personality; she talked to it as she would to a companion, beside it she felt a[Pg 81] certain sense of companionship, and no matter how often she might come, always she greeted the sight of the stream with the same delight.

For her these were truly halcyon days, and most fervently did she wish that berries ripened the year round. As it was, being both quick of eyes and nimble of fingers, Mrs. Hagood permitted her to come nearly as often as she chose while they were in season. So many a summer morning was thus spent, for the best picking was to the earliest comer, and where it often happened, an addition to her own content if not to the contents of her basket, she met other children of the village bent on a similar errand.

And always whatever of the hard or unpleasant the days might hold, every week brought its Sunday, when the interminable hemming and patch-work and carpet rags, with the other more distasteful of the week-day duties were laid aside for one day. Mrs. Hagood was not herself greatly given to church-going, but she considered it an eminently respectable habit and saw to it that the family credit was duly upheld by Mr.[Pg 82] Hagood and Posey. In her own mind Posey held the Sundays when Mrs. Hagood stayed at home as by far the most enjoyable. For then Mr. Hagood could pass her surreptitious stems of caraway seed, with an occasional peppermint drop; moreover, he could drop into a gentle doze, and she could venture to move now and then without fear of a sharp nudge from Mrs. Hagood’s vigorous elbow.

There, too, was the Sunday School, where she could sit with a row of other girls, exchange furtive remarks between the teacher’s questions, compare library books, or loiter for little chats on the homeward way.

Then in the long summer Sunday afternoons she could lie on the grass under the shading maples and read the same library books; or perhaps, what was still better, while Mrs. Hagood dozed in her favorite rocker, she, Mr. Hagood and Rover, who made the third in this trio of friends, would stroll away together, beyond the village, across the open, sunny, breeze-swept fields, past ripening grain and meadow, along fence-rows where alders spread their umbels of lace-like blossoms, and later the golden rod tossed the[Pg 83] plumes of its yellow-crested army. These fence-rows that were in very truth the “squirrels’ highway,” on which the sight every now and then of one skurrying along with bright eyes and bushy tail saucily waving defiance, would set Rover nearly wild with excitement, to the great amusement of his companions.

“Poor old Rover!” was the way Posey commonly spoke of her dumb friend. But there was certainly no occasion for the first adjective, for Mrs. Hagood could truly boast that nothing around her suffered for the lack of enough to eat; and as a reward for his canine faithfulness she even went so far as to give him a discarded mat on which he might lie in the woodhouse. But whine he ever so pitifully, he was not allowed to cross beyond that threshold and join the family circle, a privilege his social dog nature did so crave. And all his tail-wagging and mute appeals were equally without avail to draw from his mistress the caressing touch or word his dog soul so evidently and ardently longed for.