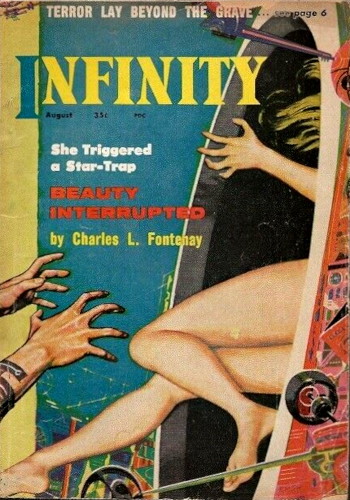

By CHARLES L. FONTENAY

Illustrated by ED EMSH

The Earthmen were selfish; they obviously wanted

to hold the people of Orcti back. But no planet

has a monopoly on science—or the ability to spy!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Infinity August 1958.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Birkala looked through the iron fence and his eyes were yellow with envy and a kind of hatred. The Earthman, Erik, was in the garden, painting on a large canvas and chatting amiably with Spira, Birkala's sister.

"The Earthmen have everything and they give us nothing," said Birkala to his companion, Direka.

Direka nodded and grinned stupidly. Direka was simple in the head, and he always agreed with everything Birkala said. Direka was hunchbacked, also, and it pleased Birkala to compare his own straight, youthful body to the crooked form of Direka. Altogether, Direka was a most satisfactory companion.

"The Earthmen live for centuries, but our life-span is that of a mayfly, and they do nothing about it," said Birkala bitterly. "The Earthmen flash from world to world in an instant, but we must use antiquated rockets and be confined to our own system of planets."

Direka nodded again.

"The Earthmen are greedy," he agreed sagely.

"I am going to talk with the Earthmen," said Birkala, and added cruelly: "You must leave me, Direka. Your crooked body would hurt the Earthmen's sensitive eyes."

"Yes, I shall go so you may talk with the Earthman," assented Direka and moved away sadly down the street.

Birkala watched him go, and smiled ruefully. He did not really like to hurt Direka, but if he made Direka think the Earthman was repelled at the sight of him, perhaps Direka would engender his own hatred of Erik, instead of merely echoing Birkala's emotions.

Birkala stepped to the open gate and entered the garden. It was a more beautiful garden than even the greatest artists of the world Orcti could arrange, for into Erik's planning had gone the aesthetic tradition of many millennia. The green sun that swam in Orcti's violet sky shone down on foliage and grasses of orange and brown and rust, and so carefully were things placed that even the great silver-and-blue lina flowers did not blare their supremacy over lesser plants, as in most Orcti gardens. They blended with the statuary and foliage, with the walks and the pools, tamely contributing their beauty to the balanced picture of peace and quietude.

Erik looked up from his easel as Birkala approached. He was a blond man of noble face and bearing, looking to be Birkala's own age. Yet this Earthman had lived and traveled the stars before Birkala's great grandfather was conceived in the womb.

Spira sat nude on the edge of a fountain pool, one knee bent and one hand dipped gracefully in the sparkling water. She sat patiently and kept her wide golden eyes fixed on Erik's face, but recognized Birkala's approach with a faint smile. The sunlight glinted from her yellow-green hair and burnt orange skin.

Birkala stood at Erik's shoulder, his feet apart and his hands clasped behind him, and studied the unfinished painting critically. With a sure, light brush, Erik had captured the innocence of a young woman seated by a fountain. The style was so simple as to be almost calligraphic, yet a few lines and spots of paint portrayed to the eye the long curve of Spira's thigh, the tilt of her breasts, the candor and loveliness of her face.

Birkala's eyes dropped from the canvas to Erik's seated figure, and his expression altered from unwilling admiration to defiant scorn. The Earthman's short-sleeved smock was agape and exposed Erik's perfectly muscled body to the warm sunshine.

"Why are Earthmen so obsessed with nudity?" demanded Birkala. Birkala himself wore loose trousers, shiny boots with curled toes, a shirt with flowing sleeves, a scarf about his throat. Beneath this was under-clothing.

"We are not obsessed with nudity, Birkala," replied Erik gently. "The human body is natural and it is beautiful. We see nothing shameful about it, and we wear clothing only when needed for protection against the elements."

"That is all right for you to say. It would be all right for me to believe. But can you say a hunched body like Direka's is beautiful?"

"Not to unsympathetic eyes, perhaps. Poor Direka! But there will be a day when on Orcti, as on Earth, no one is born with a deformed body."

Birkala sat down on a rock, crushing a bunch of purple minita flowers beside it.

"Always in the future," he said bitterly. "Always promises, in the dim, distant future. You Earthmen know many things and have many things that you promise us, but why must these promises always be for our grandchildren's grandchildren?"

"We found you in mud huts, and now you live in clean cities," reproved Erik, beginning to wipe his brushes clean. "We found you driving oxen, and now you ride spaceships to the other planets of your system."

"Your lives are centuries long, and ours are three-score and ten," countered Birkala. "It is true we have spaceships, but you step into a beam transmitter and cross the galaxy in seconds."

"That is because you are not ready," replied Erik mildly.

Birkala sat silent, his anger building up in him. Spira, seeing that Erik was finished with painting for the moment, arose in a graceful flow of motion and came to them. She stood beside Erik, one hand on his shoulder, and studied the canvas without speaking.

"You're the only Earthman on all Orcti," Birkala began again. "Since I was a child I've heard of Erik, the Earthman who lives in the garden in the heart of the city. Since I was a child I've heard that Erik, the Earthman, watches over us like a noble god. Why do you really stay on Orcti, Erik? To prevent us from progressing too swiftly and challenging the position of Earth?"

"Why do you carp at Erik?" demanded Spira, and there was a note of anger to her soft voice. "Erik has always been a friend to us, Birkala."

"Ah, yes, and especially a friend to pretty little Spira," replied Birkala with deep irony. "She is my sister, Erik. Should I be honored that the great Earthman takes my sister as a mistress?"

Spira flushed, for the term "mistress" was not a respectable one on Orcti.

"I love Spira, like a daughter and a wife at once," said Erik. "I think you know that, Birkala. No one was happier than you when she came to me. I do not marry her because I am forbidden to be bound by the laws of Orcti, but I shall cherish her all of her life."

"Yes. I know the schedule. And then another young woman shall grace the garden of the always-young Earthman. How nice for the Earthman!"

"Why are you so savage today, Birkala?" asked Spira, genuinely puzzled. "I know that you have been restless for a long time, but we knew as children that other women had been in my place long before I was born."

"Birkala is angry because he is a good scientist," explained Erik with an understanding smile. "Birkala thought yesterday that he had discovered the principle on which the beam transmitter is based, and I showed him that his theory is wrong. He is angry with himself for having been mistaken."

Birkala spat into the fountain.

"I am not so sure I was wrong," he retorted. "I think it could be that you tried to direct me away from my theory because you don't want me to find the truth."

He turned and strode from the garden, frowning, his face hot.

Turning right from the garden gate along the street, he passed in front of Erik's house, which was flush with the sidewalk. As he did so, he was surprised to see the door ajar and Direka sitting in it.

Direka evidently had been waiting for Birkala to appear. He rose quickly, almost stumbling down the steps, and gestured eagerly at Birkala.

"Come quickly, Birkala!" he chattered. "I have found a way into the part of the Earthman's house which is forbidden!"

Birkala hesitated, then followed the crooked little man into Erik's house.

Erik kept his house open. It was never locked, and Birkala had never heard that anyone had had the temerity to try to rob or harm the mysterious Earthman. Anyone could walk in or out, but few did without invitations, for the people of Orcti held Erik in awe.

But the rear portion of the house was without windows or doors. It was not too apparent from the outside, but Birkala had been in Erik's house many times and had discovered long ago that there was a large section of it closed and inaccessible.

As fast as his short legs could move, Direka led Birkala through the simply furnished house. Birkala followed easily, and smiled. Direka was like a monkey; he was not bright, but he was clever and eager.

In Erik's bedroom, Direka stopped, panting, and pointed triumphantly at the rear wall. There was a great crack in it, near Erik's bed. A section of the wall was a secret door, and it had been left ajar.

"Good fortune!" breathed Birkala, his eyes sparkling. "I have wondered for a long time what was behind that wall."

He pushed the door wider and went through the opening, Direka crowding at his heels. It was very dark, the only light coming through the crack from the bedroom. Birkala could see nothing.

He felt about the walls for a switch, without success.

"I wonder how one turns on the light in here?" he said to Direka.

At the word "light", light sprang into being all around them. It was a soft, indirect illumination which appeared to have no source and cast no shadow.

They were in a sort of corridor which paralleled the wall through which they had just come. On the opposite wall of this hallway were banks of dials and charts and switches, and in the center of this opposite wall was an open doorway.

Cautiously, Birkala and Direka moved down the corridor and peered through the open door. It gave entrance to a square room, which was lighted with the same sort of illumination as the hall.

There was nothing in the room. There were just four walls, a ceiling and a floor. There was no furniture. There were no windows and there was no other door.

"A strange thing!" muttered Birkala. "Erik does not retire to this place, for he is always around the house. I have walked into his bedroom and found him asleep. What is the purpose of this room?"

"Perhaps a dungeon," darkly suggested Direka, who was a devotee of adventure pictures at the theaters.

Birkala backed away from the door and studied the array of dials and switches. As Erik had said, Birkala was a good scientist. Birkala was thoroughly familiar with the nervous and intestinal workings of spaceships. He had made several trips to other planets in Orcti's system, and had made several contributions of his own to the science of rocketry and astrogation.

He whistled softly between his teeth.

"We've found it, Direka!" he exclaimed to his companion. "This is the beam transmitter that Erik has kept hidden so carefully. This is the control panel, and the room undoubtedly is the transmitter itself."

Direka looked puzzled, then brightened.

"Now we can go to Earth? Yes, Birkala?" he chirped.

Birkala inspected the control panel carefully. The charts were star-charts, etched on metal under glass. Below each was a series of dials, and Birkala deduced that these dials set the coordinates on the charts, establishing the destination. He recognized the configurations of the heavens from Orcti.

"Yes, Direka, I think we could," he said. "But then the Earthmen would know we had been meddling. If we should go, we should go here, I think."

He stabbed a finger at one of the charts, at a star on the outer edge of the inhabited portion of the galaxy.

"The inhabited planet in this system is no more advanced than Orcti," he said. "If I could go there, I could perhaps evade discovery by the Earthman there. But we certainly shall not risk going anywhere until I learn more about the operation of this machine."

Birkala was too good a scientist not to realize that grave danger was involved in tinkering with an unfamiliar machine. But he was too ardent a scientist and his obsession with the beam transmitter was too strong for him not to risk danger to himself willingly.

"Direka, you go out into the house, and if you see either Erik or Spira approaching, warn me quickly," he commanded. "I must study this machine."

Direka slipped out through the opening, and Birkala turned back to the control panel. As experienced as he was with machinery and technical matters, he nevertheless expected to be baffled by this product of Earth's advanced science.

But the controls were surprisingly simple. There were the destination coordinates, and Birkala was able to read enough of the square, blocky Earth writing to discern the designations for off and on beside what was apparently the control lever. There were some power—or volume—or perhaps distance—controls about which he was not sure; the best thing to do about them was not to touch them.

There were no controls in the room itself, so Birkala deduced that one set the coordinates for one's destination, switched on the machine and then walked into the room. The room probably acted as both sender and receiver, and after a time lapse the sending apparatus perhaps switched off automatically so that the room could receive again.

He pushed aside the chill, disturbing speculation about the controls of unknown purpose. He set the coordinates firmly for the star system Denragi, and pushed the switch to the on position.

At first Birkala thought the power source to the machine must be disconnected. There was no throbbing, no hum, no indication that it had been activated. Yes, there was one: a bright red spark showed square on the destination he had set by the coordinates. Denragi shone of its own light on the control panel.

Encouraged, he stepped to the door of the empty room.

Birkala recoiled, appalled.

He could not see into the room. The luminescence was gone. The room was absolutely dark.

Yet the darkness was more than the absence of light. It was more, even, than the utter jet-blackness of intergalactic space. It was an active blackness, a presence of blackness, and it filled the room to the very edge of the door, untouched by the normal light from the hallway.

The most frightening thing about it was that he felt an impulse to move into the room, a strong pull into the room, into the blackness. As he instinctively resisted, the pull grew stronger.

And then Birkala was terrified. For the pull was so strong that he could not step back away from the yawning door.

In a semi-daze, he fought with his mind, for the force was not a physical one. He fought, and he felt his control slipping.

There came a commotion from the bedroom behind him, the sound of upraised voices. There was Direka's agonized chatter, a shrill protest, and the firm angry voice of a woman.

He was able to turn his head slightly to see Spira come through the opening into the hallway.

Birkala could not speak. He tried to warn Spira back with his strained, stinging eyes. But, unclothed as she had been at the fountain, she walked purposefully to him.

"Birkala, you know Erik does not wish you tampering with these forbidden things!" she chided, and laid a restraining hand on his shoulder.

At her touch, the powerful attractive force drained from Birkala in a rush. Released, he staggered back and fell against the opposite wall of the corridor.

But Spira was yanked into the black room like a filing to a magnet, and vanished utterly.

When Spira left him to go into the house, Erik sat for a few moments, studying his unfinished canvas critically. Now, an arc of pure orange there, a trace of subdued green there....

A disturbing current intruded from the outer fringes of his mind, that still undeveloped realm of precognition. There was something ... something was to happen ... to Spira!

He rose in haste, and strode swiftly into the house.

He encountered the hunchback sneaking from the direction of the bedroom. At sight of him, Direka broke into an awkward trot toward the front door. There was something in his face that made Erik speed his steps.

The hidden panel to the back of the house was open. Erik burst through it.

The transmitter was on, and its electrical aura hovered ominously around the door of the transmission room. In the hallway across from that door, Birkala was struggling to his feet.

Erik seized Birkala in time to prevent him from hurling himself into the blackness of the activated room.

"Spira!" gasped Birkala. "She was pulled in there!"

With the strength of a giant, Erik hurled Birkala the length of the corridor.

"Get out!" he roared. "Quickly!"

Erik plunged into the holocaust of hostile blackness.

The room was endless, infinite. It was all space and all beyond space, and there was no light there for human eyes to see.

There was an alien presence in this nothingness, a vampire presence that clutched a pathetic, limp figure light-years away, and reached out toward Erik with its hungry essence.

Erik stood straight in the midst of nothing, his head thrown back, his yellow hair lifting on the wind that blows between the galaxies. The questing essence touched him and explored him, blindly unaware of humanity's challenge to its elemental insistence.

Erik let his mind expand beyond him in a flexing of sure strength. Erik forced his mind from him in a blaze of anger. Erik attacked with his mind, magnificent in its unchained and immeasurable power.

The alien force receded, it dwindled, it diminished. It melted before the strength of Erik's mind, that was a burning, pulsating power like light, and yet was not light. The vampire essence slowly, reluctantly, relinquished its distant, doll-like victim and retired in pain beyond the edges of the galaxies.

In a room that was a room once more, in a room that was yet dark but lighted to him by the cold fire of his brain, Erik strode to a corner and lifted the crumpled, unconscious figure of Spira in his arms. Carrying her tenderly, he left the terrible room.

The corridor was empty. Birkala was no longer there.

Erik pulled down the control switch, and the blackness that had sprung up behind him in the transmission room faded into the harmless air of Orcti.

Bearing Spira, Erik strode through the house and out into the garden.

Birkala was pacing back and forth near the easel, his face working in his agitation. Erik approached him, and laid Spira gently on the soft grass before him. She lay still, the rise and fall of her breasts the only indication that she lived.

"Is she all right?" choked Birkala, kneeling at her side in an agony of remorse.

"She is not harmed physically," said Erik, and Birkala gasped with relief. Erik added: "But you must see the rest of your answer."

He leaned over her and called softly:

"Spira!"

As though awakening from a spell, Spira opened her golden eyes. They fixed themselves on Erik's sorrowful face, and they widened. She smiled.

But, with growing horror, Birkala realized it was not the smile of Spira, the sister of his childhood. It carried no message of recognition nor of intelligence. It was the pitiful smile of mindlessness.

She gurgled.

Erik helped her to sit up, and she stared about her wonderingly.

"You have looked on me as an alien, Birkala," he said sternly, "but we are of the same humanity. The mother of your race, too, was Earth. But while the far-flung children of Earth had to start as pioneers to build the cultures of their varied worlds, the men of Earth forged ahead through the millennia in their climb toward whatever estate may one day be the goal of mankind.

"We of Earth who come to your worlds are watchers to help you avoid some of the pitfalls we know may divert you from that same path we have trod, and destroy you. When you think of me as a man, Birkala, you think of me as one who knows the secret of long life and has a physical science in advance of your own. But the difference is far more: there are thresholds beyond the physical which you cannot comprehend, and beyond these thresholds the man of Earth has gone and explored and moves ever outward."

"I know this must be true," murmured Birkala brokenly, stroking his sister's yellow-green hair. "I wronged you, Erik."

"No, you wronged yourself, Birkala, and your people. Because you stand at the pinnacle of your own science, you thought you could step forward into ours. Because the words 'beam transmitter' signify technology to you, you would not understand that no physical means of transportation could transcend the limiting speed of light. You could not understand that this thing called, in your language, a beam transmitter, reaches out into unguessed dimensions.

"Birkala, the reason Earth has not given you the beam transmitter is not that it is beyond your technological capabilities. It is that you have not developed in mind and heart to the point where you can cope with the awful perils of those dimensions, dangers that even we do not understand fully. As the people of Orcti are impelled to cover their bodies with clothing, so are they incapable of facing such things with their naked minds. You could have destroyed your entire world, instead of just your sister."

There were tears in Birkala's eyes.

"And is she, then, destroyed?" he asked in a low voice.

"She must go home with you," said Erik. "I cannot help her. Slowly she may recover some of her own personality, and years from now she may be again part of the woman she was. But Spira is the price you have paid for your temerity, and she will always be there to remind you of that."

Shaking his head, Birkala arose and urged the girl to her feet. Erik helped him dress her in the clothing she had worn when she came to the garden, the saucy skirt and shirt of the women of Orcti. Taking her by the hand, Birkala started to lead her carefully away.

"Wait, Birkala," said Erik.

He took the canvas from his easel and handed it to Birkala.

"It is yours and you must keep it," he said sadly. "It is like Spira. It is beauty interrupted before it could fulfill its promise."