By DAVID ELY

Illustrated by ADKINS

For Sampson to destroy the Philistines, he had to

bring their very temple crashing to the ground.

But for Dr. Browl to destroy the culture-mongers,

he needed merely a monstrous easel.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories March 1962.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The old man's tour of the art museums was quite an amusing spectacle. Indeed, it became a standing joke among those polite and cultivated gentlemen whose chief function in life is to obtain and display great paintings. They were accustomed to dealing with eccentric members of the public—but never had they witnessed anything to match the ludicrous performance of old Dr. Browl! (Of course, they carefully concealed their mirth, for Dr. Browl was far too rich to be laughed at openly; and after all, he might decide some day to honor the museums with bequests from the fortune he had amassed with his remarkable inventions in the field of optics, which had earned him the sobriquet, the Wizard of Light.)

Dr. Browl was a copyist. He had his easel, his brushes and his paints. He had a little smock, too, and a beret that perched on his bald dome. But he had not the slightest resemblance to any of the other earnest amateurs who sat dutifully daubing their canvases in imitation of the masterpieces that hung before them. No, Dr. Browl was different!

He would arrive at a museum in princely fashion, in an enormous black limousine. Two liveried servants would lug in his easel, another would carry his encased palette, and Dr. Browl himself would hobble in on the arm of a nurse. Then he would sit down grumpily in a folding chair while the easel was being set up by his servants, and glare around at the little crowd that always gathered to watch him.

The easel itself was remarkable. It was a monument in wood and brass and steel, and as massive as an upright piano. It was equipped, moreover, with one of Dr. Browl's own inventions, a bank of mysterious lamps that gave off no visible light, but which presumably bathed each picture he sought to copy in a special radiance seen by him alone, through a great pair of black-lensed spectacles he clapped on his nose.

His painting technique was even more bizarre. Dr. Browl would fairly fling the colors from palette to canvas, his little claw-hands darting back and forth with demonic speed. Faster and faster his jerky movements would become, until it seemed that the only remaining step in hastiness would be to hurl the palette itself against the canvas. His copies, naturally, were gross caricatures, and his only accomplishments the spoilage of innocent canvas and good paint.

At this feverish pace, he would copy one masterpiece after another. Often he would manage to work his way through an entire collection in a single day. He required only two weeks, for example, to make a complete round of the Louvre, with its many thousands of paintings, neglecting to copy not a single one. His energy and industry were without parallel. Within the space of two years, his pellmell progress had carried him through every significant art repository in the Western world.

Dr. Browl's fanatic devotion to painting seemed beyond explanation. Some said it was merely a lamentable aberration. Others suggested the existence of a guilt complex, for it was rumored that the old man had once burned his own small art collection in a fit of senile rage. But Dr. Browl seemed far from being guilt-ridden. From time to time, as his servants would shift the heavy easel to a new location, he would lower his black spectacles and briefly eye the amused by-standers. A strange look, the old man had. Ironical, and contemptuous, too; but more than that, for there would sometimes be a devilish gleam of mockery there that suggested some wild, wicked humor. The people were snickering at him, were they? Well, it would seem that he was barely able to contain his own laughter at them!

It was in the spring of 196- that Dr. Browl completed his remarkable tour of museums and galleries. The first series of incidents, however, did not occur until slightly more than a year later.

One bright June morning, a van stopped in front of the offices of the London art dealers, Bouser & Baillie. Two workmen delivered a large flat crate which proved to contain Manet's famous "Boy With Drum," recently returned to its owner, the Countess Palumbo, from an exhibit at the National Gallery. But Bouser & Baillie found no note attached to explain why the Countess had sent it. Was it to be loaned to another exhibit, was it to be sold, or was it simply to be cleaned?

Perforce, Bouser & Baillie telephoned their client at her Norfolk estate, and with suitable apologies, requested instructions. The Countess was annoyed. What was this nonsense about "Boy With Drum"? She had no intention of exhibiting it or selling it or having it cleaned, and in fact, had not sent it at all. The picture was hanging right in her drawing-room at that very moment, in its accustomed place. "Boy With Drum" indeed! She hung up sharply. Bouser & Baillie looked at each other and then at the canvas in question. Incredible—and yet it was the "Boy With Drum"! Or was it? They approached it warily for a closer look.

Meanwhile, that same morning, another van had parked outside the offices of a similarly distinguished firm of art dealers, Sack, Bonesteel & Woodward. The deliverymen struggled in with a burden quite like the one deposited at Bouser & Baillie, obtained their receipt, and departed.

The crate contained nothing less than Manet's "Boy With Drum." Sack gasped. Bonesteel grunted. Woodward carefully inspected the empty crate for a note, but found none. Had the picture been delivered to them by error? It did not seem so, for their corporate name was plainly stencilled on the crate. Sack gave Bonesteel a significant look. The masterpiece, they knew, was part of the Palumbo collection. Could it be that the Countess had chosen this dramatic gesture to indicate her desire to let them handle her considerable business? After much consultation, Woodward was nominated to make the call, which was effected not five minutes after the Countess had angrily hung up on Bouser & Baillie. Another "Boy With Drum"? She flew into a rage and screamed out a variety of Central European epithets, then flung her telephone receiver the full length of its coiled elastic cord, so that as she stomped furiously out of the room, the receiver crept cautiously back toward its table, while poor Woodward, in London, sat transfixed, staring foolishly at his two worried partners and at the mute painting beyond.

The following morning, Bouser & Baillie telephoned the leading British authenticator of art objects, Dr. A. B. T. Joll, and politely requested him to visit their offices to have a look at a picture which seemed to be an extremely skillful forgery of "Boy With Drum." It was so skillful, Bouser & Baillie admitted, that it had them baffled. Dr. Joll, foreseeing a plump little fee, readily agreed, and promised to bring his full kit of instruments. Nothing pleased him more than the prospect of detecting a good, sound job of forgery. He had once been termed by the press "the Sherlock Holmes of the art world," which privately delighted him; unfortunately, there had yet appeared no artistic equivalent of Professor Moriarty to provide him with a serious challenge.

He went down to Bouser & Baillie that very morning, and after spending two full hours sniffing and poking the canvas, and making several tests with his own portable super-speed electro-chemical laboratory apparatus, he turned calmly to face the partners, and announced:

"Gentlemen, this is no forgery. It is the original."

Bouser & Baillie were thunderstruck. They did not doubt Dr. Joll's judgment (and with reason, for the expert had never once been wrong); rather, they were horrified by the inescapable conclusion. If this were the original, then the Countess had bought a fake—and had bought it on the strength of Bouser & Baillie's advice! They sank into adjacent chairs and sat trembling in silence.

Dr. Joll, meanwhile, examined his watch, found it was nearly time for lunch, and called his office to see if any important messages had been left in his absence. No messages, his secretary reported, but Mr. Bonesteel of Sack, Bonesteel & Woodward had just stepped in on what he said was a most urgent matter. Would Dr. Joll care to speak to him? "Put him on," said Dr. Joll, with Holmesian dispatch.

But he was soon disappointed. "Look here, Mr. Bonesteel," he interrupted, "I'm afraid I can save you the trouble. It so happens, coincidentally, that I've just finished examining the original.... Yes, right here at Bouser & Baillie. The original 'Boy With Drum'.... No doubt about it, sir, you have a fake."

Bonesteel was persistent, however, and so Dr. Joll at length reluctantly agreed to stop by for a look after lunch.

His mood underwent a transformation after he had made a cursory inspection of Sack, Bonesteel & Woodward's "Boy With Drum." He frowned, he polished his spectacles, he cleared his throat, and he reached for his kit. One hour grew to two, to three. At last, Dr. Joll stepped back, haggard and shaken, feeling much the same, perhaps, as had Holmes himself, when he tottered on the brink of the Reichenbach Fall in the grip of the criminal genius. A nasty doubt flashed through Joll's mind. Had he been hoaxed by the two firms? Had Bouser & Baillie rushed the original up to Sack, Bonesteel & Woodward while he had been at lunch? That would be preposterous—and yet the alternative was no less confounding.

He telephoned at once to Bouser & Baillie. Within the hour, the two partners appeared at the offices of the rival firm, carrying their "Boy With Drum" between them. Joll set the two paintings side by side and went grimly to work. It was quite late at night when he finished.

"There is only one explanation, gentlemen," he told the five dealers. "Only one. Manet painted two identical versions of 'Boy With Drum'!"

Not until the next morning did the distraught dealers attempt to trace the source of the two mysterious deliveries. In each case, however, their efforts were frustrated. The delivery firms had duly responded to pick-up calls from unexceptional addresses (one in Kensington, the other near Paddington), and had been paid on the spot by husky young men who had been waiting with their crates at the curbside. It developed further that these young men had not actually been occupants of the addresses in question.

The most stunning blow of all, however, came the following afternoon, when Bouser & Baillie mustered sufficient courage to escort Dr. Joll to Norfolk, to break the difficult news to the Countess. The news proved to be even more difficult than the three gentlemen had imagined, for Dr. Joll's examination of the lady's "Boy With Drum" confirmed that it, too, was the original; or rather, that it was now but one of three originals. Other experts were hastily consulted, and their opinions supported that of Joll. Had Manet been seized by a fit of madness which had compelled him thus to repeat himself, not once but twice? Whatever the motive, his performance was undoubtedly the most brilliant technical tour-de-force in art history, for the three canvases were identical, down to the last detail seen under the most powerful microscope.

Manet's fiendish skill did not impress the Countess. She felt that the painter had deliberately outraged her, and she wished that he were still living, so that she might have the opportunity of snubbing him. That being impossible, she determined to snub his work. "Sell it at once!" she ordered Bouser & Baillie. "You told me last year you could get me half again what I paid for it. Then do so now! In fact," she added, to show the selflessness of her grudge against Manet, "I don't care if there's no profit at all—just sell it!"

"Ah, um—" Bouser began. But he found himself unable to speak. Baillie tried, too, with no greater success. How could they make it clear to this dangerous female that the existence of two other originals had placed the marketability of her own in grave jeopardy? There was doubt, indeed, whether any buyer could now be found—at any price. And more than that, if she chose to donate the canvas outright to a museum, would the museum be likely to accept?

While the two partners stood thus uncomfortably searching their minds for some way of phrasing these unpleasant truths, a delivery van back in London was edging into a parking space in front of the firm of John Pickering & Sons, art dealers. Within the van was a crate, and within the crate was a painting.

It was the fourth original "Boy With Drum."

Before the art world had time to digest the incredible evidence of the four identical Manets, the second series of incidents took place.

This time the locale was Rome, and the painting involved was Holbein's famous portrait of the Duke of Kent, one of the ornaments of the Pellagrini Gallery. At half-past ten on a Monday morning, a truck arrived at the rear of the building to deliver a large crate. There was no clue on the exterior of the crate as to its origin or contents, but Gallery officials, assuming that their curiosity would be satisfied by some document tacked within, signed the delivery receipt and had the crate lugged to a store-room. Opening it, they found no such document, only what appeared to be a marvelously clever imitation of their precious Holbein.

They chuckled merrily at the joke. Then one of them remarked innocently that it reminded him of the remarkable Manet duplications which were currently vexing the English. At once a pall of doubt settled over the group. Another Manet case? Utter nonsense! But that afternoon, the Roman counterpart of Dr. Joll was quietly called in to examine the strange gift. Professor Rienzo was not as swift as his English colleague, and was still inspecting the supposed forgery the next morning, when a different truck arrived with another portrait of the Duke of Kent, just like the first.

Indeed, it was also just like the one that hung so proudly in the Gallery itself—at least that was Professor Rienzo's firm opinion, enunciated the following day at a special meeting of the Gallery's directors. "I stake my reputation on it!" Rienzo declared. "You have now three Holbein Kents, identically the same!"

But Rienzo was wrong. There were not three Kents, but four, for another one had just arrived. The next day, the fifth appeared, and thus, on the day after that, the entire staff of the Gallery waited in a delirium of expectation for Holbein Kent VI. They were not disappointed.

Where had the canvases come from? But, like the London dealers, the Pellagrini Gallery officials were unable to find out. They could follow the trail back only as far as some young man on a street-corner, or in a hotel lobby, or again, at some sidewalk cafe, each time waiting calmly with his crate for the appearance of the summoned truck—then vanishing.

In their agitation, the custodians of the multiple Holbein considered trying to hush up the affair, but they had barely broached the topic when the mysterious donor rendered further discussion useless. Holbein Kent VII was duly delivered—not to the Gallery, however, but to the art editor of one of Rome's great newspapers. The story was out in the open.

In the following weeks, the tempo quickened. No longer were there isolated incidents, first in one city and then in another. The plague of original masterpieces became epidemic.

Item: Every art dealer in Vienna received, on the same day, twenty-five different paintings by Picasso, Braque, and Matisse. Each was subsequently established as being fully authentic, to the consternation of those museums and private collectors in a dozen countries who had acquired, at enormous cost, the originals.

Item: The Tate Gallery in London was notified by the confused headmaster of a private school near Bath that one thousand copies of a celebrated Van Gogh had been delivered to him, apparently in error. At least, he said, they seemed to be copies. He had recalled that the Tate owned the original. Perhaps the shipment had been intended for the Gallery? The Tate officials grimly agreed that it probably had.

Item: One morning, the base of one exterior wall of the Louvre was found to be solidly lined with the "Mona Lisa." There were hundreds of them, side by side, smiling enigmatically out across the Seine, and each, naturally, was as genuine as the single one inside the great palace.

What was perhaps the most serious case occurred in New York. Directors of a famous art museum were notified one day in a letter from a law firm that a wealthy gentleman, recently deceased, had willed to the museum his entire collection of paintings. Would the directors care to appear at such-and-such an address the following day to inspect the offered canvases? The directors wrote a polite acknowledgment and the next day dispatched one of their junior members to the address given. Presumably the donor had left them an attic-full of junk, but still there might be something worthwhile there.

The junior member telephoned his colleagues at once. They hastened to the spot. The collection was most remarkable. It covered every wall of every room in an otherwise vacant five-story building, and the directors could hardly call any of it junk, for it duplicated with the most appalling exactitude the entire contents of their own museum. Every last painting was reproduced there, and as if that were not enough, inspection of the basement revealed that for each canvas displayed in the rooms above, a precise duplicate existed in storage.

The directors were aghast. It was Manet and Holbein all over again, but on a scale beyond all imagining. To make matters worse, someone had impudently tipped off the press, and there was a crowd of reporters and photographers, not to mention a number of curiosity-seekers who had wandered in from the street. One of the directors telephoned the museum and ordered it closed immediately, but of course that could not prevent the instant collapse of the values of the museum's collection.

Once more, investigation proved fruitless. The law firm indignantly denied authorship of the letter. Someone evidently had purloined the stationery. The dead man, too, was a fraud, having never existed, and as for the person who had rented the building, the real estate agent could recall only that it was a young man named Smith, who had paid in advance weeks earlier, and had not been seen since.

By this time, the entire art world was in a state of nervous collapse. Dozens of masterworks had been rendered worthless by their sheer profusion. Others joined the list every day. Collectors sought frantically to sell—but no one would buy. Even those paintings as yet untouched by the blight could not be sold, for what buyer could be sure that a hundred identical canvases would not quickly turn up elsewhere? Dealers' offices were closed, museum doors were shut—and most horrible of all, artists were ceasing to paint.

In desperation, the leading museums and galleries pooled funds to hire private detectives. Weeks passed, and the flow of originals continued, but the detectives failed to produce a single positive lead—except for one, and it was so fantastic that the art impresarios angrily rejected it.

One shipment of masterpieces had been traced, through an intricate system of straw parties and other devices, back to the New York apartment of Dr. Cyrus E. Browl. Could the Wizard of Light be the mass-production virtuoso? Ridiculous! Several of the museum directors remembered his fumbling attempts to copy their treasures. It had been pathetic—the old man had been clumsier than the rawest novice, and besides, his eyes were so weak now, he could hardly see across a room!

But one of the art experts was suddenly struck by the memory of that huge easel and the peculiar array of lightless lamps, and hastened off to pay Dr. Browl a visit. He quickly returned, looking much older, and in an unsteady voice made a report:

"I've seen Dr. Browl—and I've seen it."

"Seen what?"

The dealer's cheeks quivered. "The thing. The thing that does it!"

The art experts all stared at the speaker. "Then he is the one?" someone asked.

"Yes. And he is willing to see us tomorrow afternoon...."

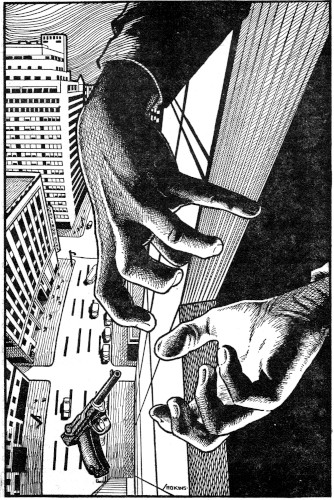

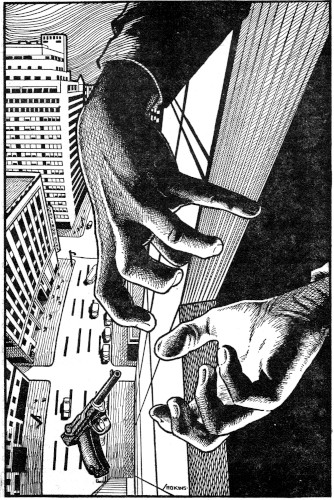

The Wizard of Light occupied the four topmost floors of a mid-town apartment building. Most of that space was used for his laboratories (the city having granted him special permission), from which had issued many important inventions, although none in the last few years.

Dr. Browl received his uneasy guests in a huge room whose far wall, opposite the main entranceway, was composed entirely of glass. It was, in fact, a gigantic window, which afforded a splendid view of the city.

The art dealers and exhibitors were hardly in a frame of mind to appreciate the scene, however, as they filed into the room and at their host's direction, seated themselves on chairs and sofas arranged in rows off to one side.

"All here?" asked the Wizard, searching the apprehensive faces before him with his uncertain old eyes. Someone muttered in the affirmative, and the Wizard broke into a high-pitched cackling. It confirmed the worst fears of his visitors. They were dealing with a demented genius who would be beyond the persuasions of reason.

"Now I'll get out my little toy," the Wizard declared cheerfully. He hobbled past them to one of the room's several doors, opened it, and pulled forth his easel, which had been mounted on little tires so that feeble as he was, he could maneuver it around quite easily.

"Looks like a fancy easel, doesn't it, eh?" he chortled, wheeling it out in front of his audience. "Well, it is an easel, but it's more than just an easel! It's a camera, my friends. Not an ordinary camera—oh, no! It's a three-dimensional molecular camera!" He laughed so hard that he was forced to lean against his bulky creation for support.

When he had recovered, he went on more calmly: "I won't confuse you with the technical details, gentlemen. You would hardly understand them anyway. Let me merely assure you that this camera contains a high-speed electronic scanning device which accurately records in its memory the precise structure of each molecule of matter within its range." With this, the Wizard pressed a button and the front part of the easel, which happened to be trained on the main entranceway, began to purr.

"You recorded the paintings you were pretending to copy!" one of the dealers blurted out.

"Precisely," rejoined the Wizard. "But of course that is just half the story. To record is not to reproduce. Yet my invention is capable of both tasks." He punched another button. The machine stopped purring, and instead, its rear section began to vibrate. "Reproduction!" cried the Wizard, excitedly. "The memorized particles now begin to be duplicated by means of a cybernetic reactor, which with infinite speed and skill, dips into a little reservoir of atomic raw materials, so to speak, and fashions from them the requisite molecules! Thus I produce not merely copies of your vaunted masterpieces, but the masterpieces themselves—complete to the last fragment of aged wood frame and cracked canvas!"

"Of course," he added more soberly, "there are a few problems still to be solved. The reproduction is not instantaneous, but takes several minutes to solidify. And then, too," he went on, as if musing to himself, "there is the unfortunate circumstance that my pictures will dissolve within a few months, reverting to their elemental state."

He perceived that his last remark had greatly heartened his listeners, and snapped at them angrily:

"Don't get your hopes up, gentlemen! I shall perfect it, never fear! And in the meantime, I can keep on producing!"

One of the curators spoke: "Why do you want to ruin us?"

"It should be obvious," the Wizard declared. "My object is not to destroy you, but art. Art falsifies nature in general, and light values in particular. It is the curse of mankind. Years ago I decided to eliminate it. But how? The answer, my friends, was not long in coming. I determined to destroy art by rendering it commercially worthless—which, needless to say, I am well on the way to accomplishing!—for I know that in this world, nothing can survive the loss of monetary value!"

The visitors trembled in their chairs. If any proof were lacking of the old man's dementia, his wild statement had supplied it. And was his lunacy, they wondered, to mean the end of their fees and their stipends, and, incidentally, of painting itself? What could they do to thwart the old fiend? Chuck him out the window, possibly, along with his infernal machine.

But the window seemed to be fogged. A peculiar little cloud was whirling in front of it, right behind the molecular camera. They stared at it, greatly puzzled.

The Wizard mistook the object of their scrutiny and embraced his invention protectively. "You want to destroy it, do you?" he cried. "Stay where you are!" He pulled a small revolver from his pocket and brandished it threateningly, meanwhile tugging at the machine, to roll it away.

It was then that Fate intervened, as if the potential irony were too great to be resisted. The cloud behind the camera began to take on a recognizable shape. It became a scientifically exact depiction of the entranceway, in fact, for the Wizard, in his excitement, had neglected to turn off his machine, and it had dutifully gone about its business. True, the representation of the entranceway had not quite solidified, but it was firm enough to obscure the plate-glass window behind it, and so when the weak-eyed Wizard hastily pulled his great camera toward the nearest exit, his confusion was understandable.

There was a loud noise of splintering as the old gentleman propelled his invention through the window, and a cry of vexation as he followed it.

By the time the art experts reached street-level, sixteen stories below, there was little left to be seen. The molecular camera was a mere tangle of wires and metal, yet it still hummed erratically on for a time, and before the astonished eyes of the gathering crowd, it belched out its final and greatest creation—a magnificent melange of all periods and styles, a triumphant distillation of man's artistic genius through the ages, marred only by the unfortunate representation, in one corner, of a human nose in juxtaposition with the thumb of an upraised hand whose fingers were indelicately spread. However, this minor annoyance was blocked out, and the masterpiece was exhibited in the leading galleries of the civilized world, until, like the machine's other productions, it crumbled and fell into dust.

THE END