By JOHN SILLETTO

Illustrated by RICHARD KLUGA

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. He exists, if

nowhere else, on one particular planet, where there are

a Daddy and a Mommy and 137 Kids. It's a very very happy

place—until somebody asks the quite obvious question....

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Infinity October 1958.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER I

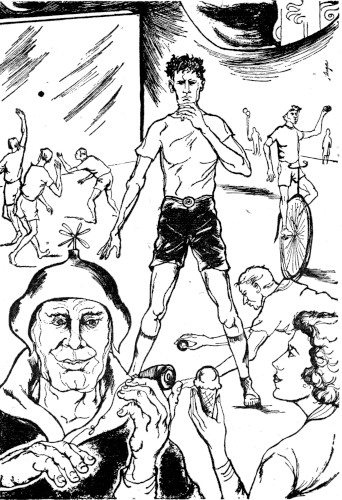

He was about thirty-eight years old, Earth-scale, with a sprinkling of premature gray in his thick hair. His stride as he came toward the desk had a youthful bounce, but his eyes were a little less bright than I was accustomed to here in Fairyland. His brows were pulled slightly inward, and he wasn't smiling.

"Hi, Mike-One," I said.

"Good morning, Daddy." Very formal, and solemn. A bad sign, I thought.

I gave him a big reassuring grin and waved him into a chair. "This is a pleasant surprise, Mike-One. I hardly ever have a caller during Ice Cream Recess."

He squirmed in the chair, looking down at his feet. "I—I could come back later, Daddy."

"No, no," I said hastily, "that's all right. A feller must have something pretty important on his mind to bring him all the way up to Daddy's office at Ice Cream time."

Mike-One fidgeted. He tugged at a lock of hair and began to twist it. "Well...."

"Come on," I cajoled. "What's it all about? That's what Daddy's here for, you know—to listen to your troubles!"

He scuffed his feet around on the floor. Then he took out a handkerchief and blew his nose. "Well ... see, I got a buddy—well, he ain't really my best buddy, or even second best. Sometimes we play chess together. Or checkers, only he thinks checkers is silly."

I cleared my throat and smiled patiently, waiting for him to come to the point. When he didn't go on I said, "What's his name?"

"Uh ... Adam."

"Adam-Two, or -Three?"

"-Two."

I nodded. "Okay, go on."

"He talks crazy, an' he's always wonderin' about things. I never seen a kid to wonder so much. An' he's only twenty-three."

I nodded again. "And now he's got you to wonderin' about something and you want Daddy to straighten you out. Right?"

"Uh-huh."

"Okay," I said, "shoot!"

He sniffed and scuffed his feet and scrooched around in the chair some more. Then suddenly he opened his eyes wide and looked me square in the face and blurted: "Is there really a Santa Claus?"

The grin I was wearing froze on my face. It seemed I'd been waiting twenty years for one of the Kids to ask me that question. Daddy, is there a Santa Claus? A loaded question, loaded and fused and capable of blasting the Fairyland Experiment into space-dust.

Mike-One was waiting for an answer, I had to deal with the crisis of the moment and worry about implications later.

I stood up and walked around the desk and put my hands on his shoulders. "Mike," I said, "how many Christmases can you remember?"

"Gee, Daddy, I don't know. Lots and lots."

"Let's see, now. You're thirty-eight, and Christmas comes twice a year, so that's two times thirty-eight—seventy-six Christmases. Of course, you can't remember all of them. But of the ones you remember, did you ever not see Santa Claus, Mike?"

"No, Daddy. I always saw him."

"Well then, why come asking me if there is such a person when you know there is because you see him all the time?"

Mike-One looked more uncomfortable than ever. "Well, Adam-Two says he don't think there is a Cold Side of Number One Sun. He thinks it's hot all the way around, an' if that's so then Santa Claus couldn't live there. He says he thinks Santa Claus is just pretend an' that you or somebody from the Council of Uncles dresses up that way at Christmastime."

I scowled. How the devil had Adam-Two managed to figure that one out?

"Listen, Mike," I said. "You trust your Daddy, don't you?"

"Golly. Course I do!"

"All right, then. There is a Santa Claus, Mike-One. He's as real as you or me or the pink clouds or the green rain.... He's as real as Fairyland itself. So just don't pay any more attention to Adam-Two and his crazy notions. Okay?"

He grinned and stood up, blinking his eyes to hold back the tears. "Th-thank you, Daddy!"

I clapped him on the back. "You're welcome, pal. Now if you hurry, you just might get back down in time for a dish of ice cream!"

When the indicator over the elevator door told me that Mike-One had been safely deposited at the bottom of Daddy's Tower, I walked across the circular office to the windows facing the Compound.

Ice Cream Recess was about over and the Kids were straggling out in all directions from the peppermint-striped Ice Cream and Candy Factory just to the right of the Midway entrance. Except for the few whose turn it was to learn "something new" in Mommy's school room, they were on their own from now until Lunchtime. It was Free-Play period.

From my hundred-foot high vantage point, I watched them go; walking, running, skipping or hopping toward their favorite play spots. They had their choice of the slides and swings in the Playground, the swimming pool, tennis courts, ball diamond, gridiron, golf course, bowling alley and skating rinks—and of course, the rides on the Midway.

I watched them go, and my heart thumped a little faster. My gang, I thought.... Not really mine, of course, except from the standpoint of responsibility, but I couldn't have loved them more if I'd sired each and every one of them. And Mommy (sometimes I almost forgot her name was Ruth) felt the same way. It was a funny thing, this paternal feeling—even a little weird, if I stopped to remember that a baker's dozen of them were actually older than I. But a child is still a child, whatever his chronological age may be, and the inhabitants of Fairyland were children in every sense except the physical.

It was a big job, being Daddy to so many kids—but one that had set lightly on my shoulders, so far. They were a wonderful gang, healthy and happy. Really happy. And I couldn't think of a single place in the Universe where you'd find another hundred and thirty-seven human beings about whom you could make that statement.

A wonderful gang ... all sizes and shapes and personalities, ranging in physical age from five to forty-three. Mental age ... well, that was another story. After years of research and experimentation, we'd settled on eight as the optimum of mental development. And so, there wasn't a Kid in Fairyland mentally older than eight years....

Or was there?

Mike-One's confused story of his friend Adam-Two re-echoed in my head. He says he don't think there is a Cold Side of Number One Sun. He thinks it's hot all the way around. He says he thinks Santa Claus is just pretend....

Something was wrong. Something big and important and dangerous, and I didn't know what I was going to do about it. Adam-Two, unlike some of the older Kids, had been born in Fairyland. There wasn't one single solitary thing in his life history to account for this sudden, terrifying curiosity and insight. Nothing. Not even pre-natal influence, if there is such a thing.

I wondered if Ruth had noticed anything strange about him. If so, she'd never mentioned it.

I decided I'd better have a Daddy-and-son chat with young Adam right away.

I walked through the Midway in the warm, twin-star sunshine, waving and shouting back at the Kids on the rides who shrieked "Hi, Daddy!" as they caught sight of me. Nobody had seen Adam-Two, so I escaped after a brief roller coaster ride ("Aw, come on Daddy, just once!") with a trio of husky thirty-year-olds who called themselves the "Three Bears."

Adam-Two wasn't at the Playground either, nor the Swimming Pool, nor the Tennis Courts. I decided he must be in the Recreation Hall, so I headed in that direction, taking a short cut through Pretty Park at the north end of the Midway. The park was a big place, stretching east and west from the Baseball Diamond to the Pony Stables at the edge of Camping Woods, and northward as far as the Golf Course.

This was my favorite spot in Fairyland. I always came here when I wanted to relax, or think something through without any interruptions. It had once been an oasis on this otherwise barren desert planet, and was therefore the logical site for the Fairyland Compound. An underground spring in the center of the park was our main water supply. The clear, cold fluid bubbled out of the rocks to form a lovely lake which was perhaps fifty yards across at the widest part. The lakeshore was ringed with tall, unearthly palm-like trees—strange and beautiful.

I found Adam-Two there beside the lake, sitting on a rock with his shoes and socks off, dangling his bare feet in the cold water and gazing upward into the swaying tree-tops.

"Hi, Adam-Two!"

"Hello." He didn't seem either surprised or glad to see me.

He was above average height, well over six feet, and exceptionally thin. Physically awkward, too, I remembered. He invariably struck out on the Ball Diamond, invariably sliced into the rough on the Golf Course. His hair was dark and curly and he had a nervous way of ruffling it with his fingers, so that it was always in disarray.

But the most unusual thing about him was his eyes. They were ice-blue, set deep back under a high, ridged forehead. They stared out at you with a kind of ruthless, unblinking intensity that made you uncomfortable, and I wondered why I'd never noticed those eyes before. It was like looking at a stranger, though I'd known him since he was little more than a baby.

I sat down alongside him on the rock. "Whatcha doin'?"

He didn't answer for awhile. His bare feet made white froth in the water. At last he said, "Thinking."

I waited, but apparently he wasn't going to elaborate. "I hear tell you've been doing some of your thinkin' out loud," I said quietly.

No answer.

"It's all right to think," I went on. "That's good for us. But a feller ought to be careful about sounding off to the other Kids about somethin' maybe he don't know anything about."

Still no answer. He kept lashing the water with his feet. His indifference and lack of attention were beginning to annoy me, and I was annoyed at myself for being annoyed with him and for beating around the bush with him.

"What makes the trees grow?"

His query was so sudden and unexpected that it caught me off guard. That made me more annoyed than ever.

"You're supposed to have learned that from Mommy in school," I said curtly.

Another long pause. "She says the fairies touch the trees and flowers with their magic wands. She says that's what makes them grow."

"That's right."

"I don't believe in fairies," he said, matter-of-factly.

I scowled fiercely at him. "Oh, you don't, eh? First it's Santa Claus, now the fairies. The next thing we know you'll stop believing in Mommies and Daddies!"

He looked up into the tree-tops again. "I think the sun has something to do with it," he went on, as though I hadn't said a word. "They seem to be sort of reaching for the sun, as if the sun gave them life...."

His eyes met mine—cold and intensely blue and very frank. "Why don't you tell me the truth?"

I stood up, fighting to control my rising anger. "Are you calling your Daddy a liar?" I shouted.

"I only asked a simple question."

"All right." I was regaining a little of my composure, but it was evident that I needed more time to think this through. "Let's just forget it for now.... Let's go over to the Rec Hall and have a game of chess, shall we?" Adam was Chess Champ of Fairyland.

Splash-splash-splash. His feet fluttered wildly in the water again. "I can't," he said. Splash-splash-splash.

I raised my eyebrows. "Why not?"

"I'm not through thinking."

What he needs is a spanking, I thought grimly. But spankings were outlawed in Fairyland. They were old-fashioned, and conducive to the generation of neuroses. I'd never considered the regulation as a handicap—until now.

"Okay, feller," I said, with exaggerated calm, "but just let me hear one more report—just one, mind you—about you telling the Kids there's no Santa Claus, or no fairies, and you'll be on the No Ice Cream List for a month!"

Splash-splash-splash. "I get tired of ice cream every day."

I stalked away, not trusting myself to speak.

That night after the Kids were bedded down in the dormitories, Mommy and I stretched out in our lounge-chairs to watch the video-cast from Earth. The news was dull, the kind that reminds you history repeats itself, and so what?

The Martian colony was complaining about taxes and threatening to secede; the campaign for Galaxy Manager was in full swing and the network was allotting equal mud-slinging and empty-promise time to each Party; the Solar Congress had doubled the defense budget for next year; and an unconfirmed report had been received that an unidentified space ship had landed on the dark side of Earth's moon. I yawned and switched off the set.

"Why the hell does anybody want to live on Earth?" I said.

Ruth smiled at me, a sympathetic wifely smile. She'd been watching me all evening and she knew something wasn't right. "What's the matter, Harry?"

I sighed. "Tell me about Adam-Two."

"Oh, Him."

"Yeah. Him."

She looked a little embarrassed. "I didn't suppose you knew. Did he tell you?"

Now I was confused. "Did he tell me what?"

She stood up suddenly. "Stop sparring with me, Harry. Did he tell you or not?"

"Tell me what?" I almost shouted it this time.

"That he ... he asked me to play House with him."

"Ruth!"

She laughed, a little shakily. "Don't get hysterical, Daddy. I didn't do it."

I slumped in my seat. "That's encouraging."

"What d'you suppose is the matter with him, Harry?"

"I was about to ask you the same thing," I said. "I never thought of him as being much different from the rest. A little more shy, maybe, and a little less exuberant on the physical side. Not enough to worry about, though.... How's he in school?"

She frowned. "He's in the fifth year of third grade now. An above-average student, and very inquisitive. And kind of shy, like you said. I always thought he was well-adjusted, although I don't think he ever plays House with the same girl twice. I just never thought of him as a problem, until today. That—that question!"

"Yeah," I said wryly, "he seems to be full of questions." I told her about my visit from Mike-One and the chat with Adam. "Well, Mommy," I said, "it looks like after all these years it's finally happening...."

"What's finally happening, Daddy?"

I sighed. "One of our Kids is growing up."

CHAPTER II

I suppose it was partly my fault that the Adam-Two business very nearly got out of hand during the next few days. In the first place, I was at a loss to know what to do about him, and in the second place I was sweating day and night over the blankety-blanked Annual Report for the Council of Uncles, who were due to arrive the following week. I hated paper work, with the result that I usually got caught short and had to compress a whole year's work into the space of a few days.

The Council of Uncles, of course, wasn't really any such thing. The title was just a nickname for the benefit of the Kids. Officially, they were the Inter-Galactic Inspection Council of the Solar Committee for Sociological Research. The purpose of the Committee was to find out what people need to be happy, and the purpose of the Inspection Council was to check around and see who was happy and who wasn't.

Some two hundred years ago, society had reached a kind of static condition in the realm of scientific development. For the first time in seven thousand years of civilization, Man was faced with almost total leisure. And to his great surprise, he found himself no nearer happiness than when he started. And so a crusade had begun; Man decided at last to turn his knack for research and development inward upon himself. Scientists began to ponder and experiment with the questions that had plagued philosophers for ages.

The coming of Automation had relieved men from the burden of working for a living, and left them with a choice between cultural pursuits and pure recreation. Which should it be? A good deal of rivalry, some friendly and some otherwise, existed between the proponents of the two major schools of thought. The intellectuals were dubbed "Highbrows," the pleasure-boys were known as "Happy Hooligans."

Mankind, the Highbrows contended, was still undergoing a kind of evolution—a gradual transition from a purely physical or animal existence to a purely mental or intellectual state. The machines had released him from physical bondage—as they had been intended to do—so that he might rise at last above his animal beginnings. Man could now rise to undreamed-of cultural heights, or he could sink into the depths of sensual degradation. The choice was up to him, but if he chose the latter Nature might very well not permit him to survive.

Fiddle-de-dee, said the Hooligans. The trouble with Man was that he has always insisted on pretending to be something he isn't, always seeking some deep meaning and significance in life instead of relaxing and enjoying it. Excessive doses of education and culture merely serve to compound this felony, magnify his inferiority complex, and make him thoroughly unhappy. Teach people how to enjoy themselves instead of how to be miserable, they cried.

Fairyland was a sort of sociological laboratory for the Happy Hooligans—a colossal, costly experiment that had been going on for some forty-five years. It was designed to test the theory that most of the misery in the world stems from the fact that kids are allowed to grow up, to abandon their childhood dreams, to quit having fun. They learn that there really isn't any Santa Claus, and they never quite recover from the shock.

So far, the experiment appeared to be a successful one. Fairyland Kids were happy kids, and they all believe in Santa Claus.

All but one....

On day-one of that ill-starred week, the merry-go-round on the Midway broke down. Investigation disclosed that Adam-Two had found my tool kit and had disassembled the remote-control drive mechanism to "find out what makes it go."

He was placed on half-rations of Ice Cream for a period of ten days.

On day-two, Adam was discovered late at night, after Taps, in the washroom of the boys dorm swearing in applicants for a "Question and Answer Club." When questioned as to the purpose of this so-called club, he refused to answer. His charter members, however, confessed eagerly. The Club was to dream up among themselves a Question of the Week. Questions were to be presented weekly to Mommy and Daddy and unless satisfactory answers were forthcoming, the club members would refuse to eat. The first Question of the Week was: Why are there two kinds of Kids; boys and girls?

Adam-Two was placed on No-Dessert-at-Dinner for a period of one week.

On day-five, Adam was missing from his bed at Taps. He had not registered to spend the night playing House in one of the cottages in Pretty Park either, so I set out to find him.

It took me an hour and a half, but I finally located him on the far side of the Golf Course. He was attacking the Great Wall of Fairyland. The Great Wall, over a hundred feet high, surrounded the entire Compound. It was encased in a pseudo-gravity field with a repellent force of -3g and you could no more approach the Great Wall than you could fly.

I watched in stunned amazement as Adam-Two, the Kid who despised football, time after time took a running start, lowered his head and charged at the wall like a varsity tackler, only to be thrown for a five-yard loss.

When I gathered he had no intention of giving up until he dropped from exhaustion, I walked over to where the G-field had thrown him after his last lunge. "Adam, what are you trying to do?"

He stood up, breathing heavily, and brushed himself off. "I ... wanted to see ... what was on the ... other side."

"There's nothing nice over there," I said. "It's a bad place. Fairyland is a much nicer place to be."

"I wanted to see for myself." His voice was as devoid of emotion as his face. "Why can't I get near the wall? What is it that throws me back?"

"The fairies have cast a spell on the wall," I said. "A magic spell, because they don't want us to go to the bad place. They want us to stay in Fairyland where we're happy."

Abruptly, Adam started off across the Golf Course toward the dormitory. "Okay," he said quietly. "Okay ... Daddy."

Adam-Two was placed on Limited Midway Privileges for a period of four days.

All of which gave me an uneasy and alien feeling of helplessness. My self-confidence, based on twenty years' experience with the Kids of Fairyland and before that five years' experience as a Space Scoutmaster on Earth, was visibly shaken.

Adam wasn't just being ornery, the way most any kid is likely to be at times. If it had been just that, the loss of privileges would have remedied the situation. Neither was he actually malicious. He obviously wasn't out to harm anyone, he was simply curious. Curious in a way that was distinctly unhealthy for the rest of Fairyland. He was growing up, and I didn't know how to cope with him.

So I wrote him up in the Annual Report.

CHAPTER III

It was a big day in Fairyland whenever the Council of Uncles came. Bigger in a way than either Christmas or Circus Time, because they came twice a year and the Council of Uncles only once.

I'd adjusted the controls of the Weather Generators the night before so that Arrival Day dawned warm and clear. The Kids were all dressed in Sunday-best and the festival flags were flying from the tops of all the buildings. Across the side of Daddy's Tower that faced the desert and spaceport, a gay, multi-colored banner constructed by the third-graders proclaimed: WELCOME UNCLES!

The Kids were gathered in the courtyard at the foot of the Tower, their eyes scanning the green sky for the first glimpse of the Uncles' spaceship. Up in the Tower at the radar console, I picked up a blip at about three hundred kilomiles. I interrogated, and the target trace blinked in the proper code sequence.

I turned on the kiddiecom system and announced that we had just received a message from the Cold Side of Number One Sun. The sound of cheering drifted up from the courtyard.

"The Uncles will be here in ten minutes," I said. "Mommy, will you lead us in a rehearsal of the 'Welcome Song,' please?"

I stood by the window, listening to the vast sound of a hundred and thirty-seven voices, each trying to outdo the other in amplitude and sincerity.

It was discordant, it was childish—it was even ludicrous—but I loved it. I loved it without quite understanding it, and it made me feel happy yet sad at the same time....

I took the elevator down to the loading platform and drove the monorail car out to the spaceport, which was ten miles from Fairyland—across the arid, lifeless desert. We'd built the dock close enough for easy access yet far enough away so that the awesome sight of a spaceship landing or blasting off wouldn't generate too much curiosity in the Kids. It was a link with the Outside World, a world that had no reality for them and for that reason could not stand too close an inspection.

The Earth ship was snuggling comfortably into the dock as I climbed out of the car. I ran across the landing platform and pressed the control switch that lowered the gangway against the ship's hatch.

Boswell, the Council Chairman, was first down the gangway. He was short, fat without being flabby, and completely bald except for a fringe of white fuzz around the back of his head and over his ears. He had an oversized nose, and bright blue eyes that twinkled perpetually. The Kids called him Uncle Chub.

"Well well well, Harry. You look fine. Fine. Good to see you. How's it going?"

"Fine, sir. Just fine."

His three colleagues followed close on his heels. I shook hands with each of them. Two of them I'd known as long as I had Boswell, ever since I'd become the Third Daddy of Fairyland.

There was old Eaker, lean and tall and solemn, with never much to say. The Kids called him Uncle Thin. ("Good to see you, Harry. How are you doing?") Then there was Hopkins, about my age and therefore younger than either Boswell or Eaker. A nice, medium guy, Hopkins—medium build, medium gray hair, medium voice, affable without being garrulous, intelligent without being stuffy. The Kids called him Uncle Hoppy. ("Hi, Dad. How's the gang?")

The fourth Councilman was a stranger. Boswell introduced him as William Pettigrew. He was slightly built, fidgety, shrill-voiced and weasel-faced. His mouth was fixed in a perpetual smirk, and I formed a dislike for him—immediate and intense. I wondered what the Kids would call him, and a suggestion immediately came to mind: Uncle Jerk.

"Can't say as I approve of this place at all," said Pettigrew as we climbed aboard the mono-car. "Matter of fact, I strongly disapprove."

"Well, sir," I said, trying not to gnash my teeth, "I don't quite see how you can be certain until you've seen it."

"Principle. Matter of principle."

I didn't answer. Hoppy caught my eye and winked.

A rousing cheer came from the Kids down in the courtyard as we climbed out of the car. Then I heard the brief, plaintive whimper of Mommy's pitch-pipe and once again the "Welcome Song" reverberated throughout Fairyland. The Uncles waved down at the Kids, with the exception of Pettigrew, who fidgeted until the song was finished. As we descended in the lift, he said: "This place must cost the taxpayers a tidy sum."

"As a matter of fact, we're almost self-sustaining," I said. "A few tons of reactor fuel per annum is all we require to—"

"Don't humor him, Harry," said Boswell. "Let him read the Report."

Pettigrew glared, but except for an inaudible mutter he took Boswell's squelch without comment. I was wondering what significance might be hidden in this addition of a fourth Uncle to the Council, but I finally shrugged it off. Earthside politics bored the hell out of me.

Mommy was waiting to greet us as we stepped out of the elevator and Uncle Chub gave her a big hug. "How's the First Lady of the Galaxy?" he said, and she brightened as though it were a spontaneous compliment she was hearing for the first time instead of the twentieth.

Then the Kids broke ranks and milled around us, squealing and laughing and firing questions about Santa Claus. Being new, Pettigrew received a good deal of attention. "Who are you?" "What's your Uncle-name?" "Do you live with Santy Claus or with the fairies?" "How cold is the cold side of Number One Sun?" "Do you like merry-go-rounds better than rolly-coasters?"

The pelting of this verbal barrage sent him spinning like a crippled spaceship and I wedged myself through the ring of Kids to rescue him. "Come on, gang! Break it up!"

Pettigrew gave me a look of wide-eyed terror. "They're insane," he whispered. "Look at them! They're adults, but they act like—like—"

"Like children," I said. "That's what they are, Mr. Pettigrew. I thought the other Councilors had explained—"

"They did. But I never thought—well, I mean this is awful!"

I grinned, "You'll get used to it."

"Whole thing is ludicrous. Ludicrous!" He waved an all-encompassing hand that included the Kids, Fairyland, its basic concept, and me.

I was getting more disenchanted with this character all the time. "Now just a minute, you—"

A strong hand closed over my arm and I looked around into the grinning face of Hoppy. "Let's get the program started, eh?" he said.

The next three hours were a hodge-podge of well-rehearsed chaos. The Council had to inspect everything so they could return a first-hand report to the Solar Committee for Sociological Research, and on the other hand all the Kids had to show off for the Uncles.

The first stop on the agenda was the Arts & Crafts Building where we exhibited the drawings and clay animals and models and beadwork and a thousand-and-one other items the Kids had made with their own hands. From there we adjourned to the school where Ruth had displayed a few samples of the work of each class.

"We only have one teacher," I explained to Pettigrew, "because each class meets for just an hour a day. We stagger the classes, kindergarten through third grade. The Kids spend an average of five years in each grade, including kindergarten."

"Ridiculous!"

"There's nothing ridiculous about it," I said, patiently, "for the simple reason that they're not in any hurry."

"Hmph. Well, I am. Let's get on with it."

From the school the procession migrated to the Recreation Hall. We visited the game room for demonstrations by Checker Champ Mike-One and Chess Champ Adam-Two, then witnessed exhibitions at the Bowling Alley, Basketball Court, and the Ice and Roller Rinks. I explained to Pettigrew that each Kid was Champ of something. There were enough categories for everybody, and nobody was allowed to be Champ of more than one thing at a time. Uncle Petty mumbled something I didn't catch.

We skirted the Midway and took a tour of the Pretty Park. Here at last was something Pettigrew could accept; he almost smiled as he saw the huge flower beds raised by the Botany Team. But the almost-smile disappeared as we explained to him the purpose of the little cottages nestled among the trees. His eyes bugged and his face became quite red, and his voice failed him so that he could only sputter.

"We only retard the mind," I explained, "not the body. Playing House is just another recreational activity, like riding the merry-go-round or playing golf. The Kids enjoy it, but they don't make a big thing out of it. We treat the whole subject quite casually, and frankly."

I'll say this for Pettigrew, he had spunk. He swallowed his moral indignation, squared his thin shoulders, took a deep breath and managed to find his voice. But it failed him again on the word "pregnancy."

"We allow that to occur only rarely," I said. "We're building to a static population of a hundred and forty. At the current rate of one Dolly per year, in three more years we'll—"

"One what per year?"

"Dolly." I caught Hoppy's muffled snort behind me and managed to hold down the size of my grin. "The Kids call it 'making a Dolly.' It's a rare treat and the girls look forward to it."

When the danger of apoplexy had subsided, Mr. Pettigrew choked, "This—this is ... monstrous! Monstrous!" And, having found the right word, he savored it: "Monstrous."

There were too many kids around to pursue the discussion. Little pitchers, I thought. I was especially concerned about Adam-Two, who had been lurking as close to the group of Uncles as possible, soaking in every word like a damp sponge. Twice I whispered to Ruth to decoy him out of earshot, but she was too busy to keep an eye on him all the time. She'd no sooner turn her back than he'd edge up through the crowd again, a look of fierce curiosity on his thin face.

From the Pretty Park we made our way to the Golf Course, the Football and Baseball Fields, then the Tennis Courts and Swimming Pool. Demonstrations were given at each stop, with much shouting and applause. After the final demonstration by the Diving Champ, we made a tour of the dormitories. Pettigrew went through a minor tantrum again when the Dolly Team showed him through the small Maternity Ward in the girls' dorm.

At last we filed into the Auditorium for the Happy Show. The Kids who weren't Champs of some game or craft were all in the Happy Show. We watched, listened, and applauded for the Song Champ, the Somersault Champ, the Dancing Champ, the Yo-yo Champ, and many more. The piece-de-resistance was a playlet entitled "The Uncles' Visit," where three of the boys imitated Uncles Chub, Hoppy, and Thin. (We hadn't been expecting Uncle Petty, so he wasn't in it. Probably just was as well, I thought.) It was a riot.

After the show, lollipops were passed out to everybody and it was Free Time until lunch. Mommy stayed below to keep an eye on things and I herded the Uncles up to the conference room in the Tower.

Uncle Chub Boswell rapped the meeting to order. He paid me the standard compliment about how healthy and happy the Kids looked and what a fine job Ruth and I were doing here, then asked me to read the Annual Report.

Before I could get my papers in order, Pettigrew piped, "Mr. Chairman, I'd like to ask a few pertinent questions."

"All right, Petty. Make it brief."

"Thank you. I should like to ask—er, what was your name again?"

"Barnaby," I said. "Harry Barnaby. Just call me Daddy."

He glared my grin into oblivion. "Mr. Barnaby, I would like you to explain to me the purpose of this installation."

For some reason, the tone of his voice on the word "installation" infuriated me. "What the devil are you driving at?" I snapped.

There was a faint suggestion of a sneer on his pasty little face. "I'm interested in ascertaining, Mr. Barnaby, just how you justify the continued conduction of this perpetual circus and picnic for the mentally retarded, at tremendous expense to the taxpayers."

I felt an almost irresistible urge to lean across the conference table and hit him in the mouth. I turned to Boswell and said, "Chub, I think you'd better get this pip-squeak out of here."

Boswell glowered at Pettigrew. "Petty, I told you to watch your lip."

"I don't have to take that kind of talk from you, Boswell!"

"Yes you do, as long as I'm Chairman of this committee!"

"Don't be surprised if we have a new Chairman shortly after we return to Earth," said Mr. Pettigrew smugly.

Boswell grinned at me. "Mr. Pettigrew figgers he's got influence, Harry. He has a second cousin on the Senate Committee of the Galactic Council. Figgers he'll have me sacked and make himself Chairman. He ain't been a bureaucrat long enough to appreciate the red-tape involved in that kind of caper."

I laughed, and managed to look at Pettigrew without wanting to hit him. "I don't mind questions," I said, "as long as they're put to me in a civil manner.

"I'll tell you, Mr. Pettigrew, what the purpose of this 'installation' is. We're trying to find out how to make people happy. And we think we've got the answer. Don't let them find out that there's no Santa Claus, that everybody dies, that it doesn't always pay to be good. Don't let them know that sex is dirty, childbirth is painful, and not everybody can be a champion. Don't let them find out what a stupid, sordid, ugly, ridiculous place the world is. In short, Mr. Pettigrew, don't let them grow up!"

"Nonsense!"

"Nonsense, Mr. Pettigrew? You saw them. You saw how they live. You saw their faces and heard them laugh. Judge for yourself."

Pettigrew scowled at me. "Am I to understand, Mr. Barnaby, that you seriously propose that this quaint little ... er ... experiment be adopted as a way of life, for everybody?"

"Why not?" I was warming to my subject now, and I leaned across the table toward him. "Why not? We've had seven thousand years of civilization. We spent the first six thousand learning more and more subtle and complex reasons for hating one another and the last thousand in developing more elaborate and fiendish ways of destroying one another. And out of our so-called scientific advancement, accidentally, has come a thing called automation. The age of the laborer and breadwinner is past. What are we going to do, Mr. Pettigrew? Let man use his leisure time to discover even more effective ways of destroying himself ... or let him live in a Fairyland?"

Uncle Petty turned his head slowly, letting his gaze travel around the room as if he were seeking moral support. He started to say something, then shook his head.

"Think of it," I went on, "a whole world full of happy kids! And a new kind of aristocracy—the Daddies and Mommies. They and their children would be trained to supervise, to keep an eye on things, just as Ruth and I do here. The Kids could be trained to do what little maintenance the machines require—"

"You're insane!" Pettigrew exploded. "That's it! You're crazier than the rest of them out there. You—"

I don't know whether or not I really intended to hit him, or how things might have turned out if I had. Luckily, Boswell jumped to his feet and pulled me back as I made a lunge across the table. "Take it easy, Harry," he said quietly. Then he turned to Pettigrew. "Petty, we've had enough out of you for today. Open your mouth again and I'll lock you in the ship till we're ready to leave!"

Pettigrew slid lower in his chair and after a brief mumbling was silent. I apologized to Boswell for losing my temper. "Forget it, Harry," he chuckled. "Wanted to hit 'im myself lots of times.... Well, let's have the Report, eh?"

The bulk of the Annual Report consisted of a lot of dry statistics about the hydroponics crop, the weight and height and emotional ratings of the Kids, reports on certain educational and recreational experiments, and so on. The problem of Adam-Two was the last item on the agenda, and as I read it they perked up their ears and stopped yawning.

"... and in light of these developments, the under-signed recommends that Adam-Two be transported to Earth and given a normal education so that he may be assimilated into the society."

I stood for a moment, holding the papers in my hand, looking from one to the other of that quartet of blank, silent faces.

Finally, Boswell cleared his throat. "Harry, let me get this straight. You think this ... what's his name? Adam-Two. You actually think he's—ah—growing up?"

I nodded. "There isn't a doubt in my mind, and Ruth agrees."

"And you think we oughta take him back to Earth with us?"

"Sure, I do. I think that's the only solution, don't you?"

Eaker coughed discreetly. "I'm afraid it isn't any solution at all."

"What would we do with him?" Hoppy wanted to know.

"Look," I said, "the kid is a misfit. He doesn't belong here. He belongs on Earth where he can get an education and maybe a chance to ... to make something of himself."

Boswell cleared his throat again. "Seems like he'd be a worse misfit on Earth than he is here, Harry."

"He would not!" I snapped. "He's a sharp kid. He'd adapt himself in no time."

Eaker spoke up again. "It seems to me we're overlooking an important point here, gentlemen. Isn't Fairyland supposed to be a sort of testing ground for a particular sociological theory? It seems to me we'd be defeating our purpose if we removed this lad just because he doesn't seem to fit. If the world is to be converted to a Fairyland, there'll be more Adam-Two's from time to time. What's to be done with them?"

"Nuts!" I said. "It's not the same problem, and you know it. If the whole world were like this place, Fairyland would be the only reality there was. Guys like Adam would have to accept it.... Why don't you just admit that you don't want to be bothered with this?"

Boswell rapped for order. "Gentlemen, there's no need to waste any more time with this.... Now Harry, you know we've got no real jurisdiction in this. We're just advisory. The Kids are all wards of the Solar State and if you want to appeal for help through official channels, we'll be glad to initiate a request for you when we get back to Earth."

I realized now that I might as well have saved my breath. It was the old bureaucratic buck-pass. For twenty years, the Uncles' visit had been merely an annual ritual—and they intended to keep it that way. They had a nice, soft touch and they weren't going to let anything spoil it. Sure, they'd initiate a report ... and by the time it filtered through the spiral nebula of red-tape, Adam and I would both have died of old age.

I gathered up my papers. "Just forget it," I said sourly. "If there's no further business, let's adjourn for lunch and I'll take you back to the ship."

At the spaceport we shook hands and Hoppy hung back after the others had gone up the gangway. He put his hand on my shoulder. "I'm sorry about this Adam thing, Harry."

"Forget it."

"I know how you feel, and I wish we could help. But you know how it is...."

"Sure. I know how it is."

"The Administration's all wound up in the Rearmament Program. Doubling the size of the space fleet. Everybody's edgy, wondering whether there's going to be war with the Centauri crowd. Hardly anyone remembers there is such a place as Fairyland. If we go back and kick up a fuss, no telling what might happen. Most of the Government budget is earmarked for defense. We might all find ourselves among the unemployed."

I looked at him for a long time, until his eyes couldn't meet mine any more. "Hoppy," I said quietly, "how long has it been since they stopped thinking of Fairyland as a practical possibility?"

He shrugged, still not looking at me. "I don't know, Harry. Twelve, maybe fifteen years, I suppose. There aren't many Happy Hooligans around any more—at least they aren't working at it. They're all getting rich off the defense effort."

"So they're just letting us drift along out here because it's easier than disbanding the thing and trying to rehabilitate the Kids. That right?"

He nodded. "That's about it."

I took a deep breath, and shook my head. "Why, Hoppy? Why?"

"Oh, hell!" he blurted. "Let's face it, Harry. The whole idea just isn't practical. It would never work."

"Never work!" I shouted. "It's been working for forty years!"

"Sure, sure—it works here. On an isolated desert planet a billion miles from Earth, it works fine. But you can't remake the whole world into a Fairyland, Harry. You just can't do it!"

There was a sinking, sickening feeling in my guts. "Okay, Hoppy. Okay.... Blast off."

He stood looking at me for a moment, then turned and hurried up the gangway.

Just as he reached the hatch, two figures emerged suddenly from the ship. One wore the uniform of a Space Fleet astro-navigator. The other was Adam-Two.

I ran up the gangway in time to hear the navigator telling Hoppy, "I found him in the forward chart room."

"Adam!" I yelled. "What are you up to now?"

"I wanted to go along," he said. "I wanted to see if they were really going to the cold side of Number One Sun."

I grabbed his arm and hustled him down to the mono-car. We slid clear of the dock and about half a mile away I stopped the car to watch them blast off.

Adam's eyes were wide with wonderment. "What makes it go?"

"Rocket motors," I said absently. I watched the ship, now just a mote disappearing in the twilight sky. And I thought, There goes the tag end of a twenty-year dream.

That was all it had ever been; I knew that now. Just a dream, and a stupid one at that. I'd deluded myself even more than the Kids.

"What's a rocket motor?"

I looked at Adam. "What? What did you say?"

"I said, what's a rocket motor?"

"Who said anything about rocket motors?"

"You did. I asked you what makes it go and you said, rocket motors."

I frowned. "Forget it. Magic makes it go. Santa Claus magic."

"Okay, Daddy. Sure."

Something about his tone made me look sharply at him. He was grinning at me; a cynical, adult-type grin. Yesterday it would have made me furious. Today, for some crazy reason, it made me burst out laughing. I laughed for quite a long time, and then as suddenly as it began, it was over. I rumpled his hair and started the car.

"Adam," I said, "take a tip from your Daddy. Stop trying to find out about things. Hang onto your dreams. Dreams are happy things, and truth is sometimes pretty ugly...."

CHAPTER IV

That night after Taps I told Ruth about the Council meeting and about my chat with Hoppy at the ship. She came and sat beside me and, in the age-old manner of a loyal wife, assured me that everything was going to be all right.

I stood up and began prowling around the room. "It's not all right. The plain and simple truth is that we've thrown away twenty years on this pipe dream. All for nothing!"

"You don't mean that, Harry. Not for nothing."

"The hell I don't! Remember how skeptical we were when we first heard about this place? Then old Hogarth, Daddy-Two, came to see us. Remember how we fell for it? We were going to be doing something important! We were the vanguard of a world revolution—the greatest thing since the invention of people. A great sociological advancement.... What a laugh! Fairyland is nothing but a—an orphan home! And mark my words, sooner or later they're going to come and close the place down!"

Ruth patted the seat beside her. "Harry, come back and sit down."

I scowled at her. But I sat.

"Harry," she said, "I'm just a woman. I don't know much about world revolutions or sociology. But I know one thing. No matter what happens, these twenty years haven't been wasted. We've been happy, Harry. And so have the Kids."

"I wonder.... Are they happy, Ruth? Do we even know what happiness is?"

She smiled. "Darling, please don't go abstract on me. I know they're happy."

"And what about Adam?"

She shook her head. "I suppose he's not. But the percentage is still pretty high, don't you think? You said Fairyland is nothing more than an orphan home, and maybe you're right. I guess I never really thought of it any other way."

I stared at the woman who had been my wife for twenty-three years as if I'd never seen her before. "You mean you never, not even at the beginning, believed in the idea of Fairyland?"

"I just didn't think much about it, Harry. I believed in the Kids, that's all. I figured that our job was to look after them and keep them happy and well. We've done that job, and I think it's a pretty fine achievement. I'm proud—for both of us!"

"Thanks," I said dully. "You know, Mommy, I'd almost forgotten...."

"Almost forgotten what, Daddy?"

I laughed shortly. "What it feels like to find out there's no Santa Claus!"

In the two-week interval between Uncles' Day and Christmas-Two, the air in Fairyland became super-charged with a kind of hushed expectancy, and of course everybody was being extra-special good in the manner of kids everywhere during Santa's Season. The holiday spirit should have been contagious, but this season I wasn't having any. My pet theory and private dream had been scuttled, so I sulked around feeling sorry for myself.

Even Adam-Two was a model of juvenile deportment. Never late for meals, always washed behind his ears, and—best of all—he stopped asking embarrassing questions. This sudden change probably would have made me suspicious if I'd been thinking clearly. As it was, I merely felt grateful. And of course Mommy was too busy helping the girls make popcorn and candy to concern herself with such things.

On Christmas Eve, I turned the weather machines to Snow—a category specially reserved for our two Christmases—and the big, soft white flakes came drifting lazily down into Fairyland. The lights were out in all the buildings, the Kids were asleep, and our two moons were bright and full. Ruth and I stood silently on the front porch, watching the snow and the moonlight.

"Harry...."

"Mm?"

"Do you still think these twenty years were wasted?"

I slipped an arm around her waist. "It isn't fair to ask me that on a night like this.... But if they were, I'm glad we wasted them together."

She leaned over and kissed my cheek. "Thank you, Daddy. Merry Christmas."

"Merry Christmas, Mommy."

Next morning, I donned my pillow-stuffed Santa uniform and itchy white whiskers and stood with Mommy on the Auditorium stage, beaming into a bright sea of expectant faces.

"Merry Christmas, everybody. Mer-r-r-y Christmas! Ho-ho-ho-ho-ho!"

"Merry Christmas, Santa Claus!" came the answering chorus.

"Did you all manage to bust up your toys from last Christmas?"

"Ye-e-e-s!"

"Good!" I boomed. "Ho-ho-ho! Can't get new ones unless we bust up the old ones, you know!"

We all sang "Christmas in Fairyland," and then it was Present Passing Time. Santa's Space Sled was behind me, chock full of toys. I reached back and pulled out a package.

"Julia-Three!"

"Here I am, Santy!" She came running down the aisle, a lovely blonde of about twenty-five, curls flying.

"Have you been a good girl, Julia-Three?"

"Yes, Santy."

"And you wanted a new dolly?"

She nodded emphatically.

"You broke your dolly from last Christmas?"

"Yes, Santy."

"Fine."

She took her present and went skipping off the far side of the stage.

Everything went smoothly for perhaps half an hour and the sled was about half empty when I snagged a small, flat package marked "Adam-Two."

He strolled down the aisle and up onto the stage. His eyes were bright—a little too bright—and there was just the hint of a smile on his thin face.

"Well, well, Adam-Two! Have you been a good boy?"

"Not very."

I gave him a fierce Santa Claus frown. "Well, now, that's too bad. But old Santa's glad that you're honest about it.... By the way, you didn't send old Santy a letter, did you?"

"No. I didn't think I'd get a present because I wasn't good. Anyway, I didn't know what I wanted." He was staring fixedly at my beard.

"Well, suppose we give you a present anyway, and you try very hard to be good between now and next Christmas, eh? Ho-ho-ho-ho!"

We'd gotten him a set of chess men. He took the package without looking at it. "Where's Daddy?" he asked suddenly.

It was so unexpected, so matter-of-fact, that it caught me off balance. The Kids were always too excited on Christmas morning to worry about where Daddy might be.

"Well, sir ... ho-ho-ho ... ah, Daddy was kinda sleepy this morning, so he thought he'd rest up a bit and let Mommy and Santa Claus look after things—Merry Christmas, Adam-Two! Now, let's see who's next—"

I turned to pull another package from the sled, and Adam took one quick step forward, grabbed my beard and yanked hard! It came away in his hands, and there I stood with my naked Daddy-face exposed to all the Kids.

The silence was immediate, and deadly.

Then I heard Adam's sudden, sharp intake of breath that was almost like a sob. I glanced at him for just an instant, but in that instant I glimpsed the terrible disappointment he must have felt. It was all there, in his eyes and in his face. He hadn't wanted that beard to come off. He'd wanted Santa Claus to be real....

He turned away from me and faced the Kids, holding that phony beard high over his head. "You see!" he shrilled. "It's just like I said! There really isn't any Santa Claus. He's just—just make-believe, like the fairies and—and—" His voice broke and he threw the beard down, jumped off the stage and ran toward the exit.

Ruth called to him. "Adam! Come back here at once!"

"Let him go, Mommy." I looked ruefully out at our stunned and silent audience. "We've got something more important to do first."

I stepped forward and pulled off my Santa Claus hat. For a long moment I just stood there, trying to decide what to say. Even if I'd had my speech rehearsed, I don't think I could have talked around the lump in my throat.

I couldn't shake the feeling that somehow I had failed them. It was a feeling that went much deeper than my inability to cope with Adam-Two and his problem. It was a real, deep-down hollow feeling that stemmed from my conviction, ever since the Uncles' visit, that the whole idea of Fairyland was a mistake. I wanted to talk to each and every one of them, alone. I wanted to tell them, "It's going to be all right. Mommy and Daddy love you and will always look after you, so you mustn't worry."

And so I stood there on the stage in my ridiculous, padded Santa suit, and somehow managed a smile. "Kids," I said, "Daddy's sure sorry, but you see Santa Claus just couldn't make it today. He—his spaceship broke down—like our merry-go-round, remember? So Santa asked Daddy to sort of ... to pretend—"

Down in the front row, nine-year old Molly-Five suddenly began to sob. Two rows behind her, thirteen-year old Mary-Three took up the cry. Then across the aisle from Mary, another girl wailed, "I want Santa Claus!" In the back of the Auditorium, fifteen-year-old Johnny-Four shouted, "We hate you! You're a mean old Daddy!"

And there in the aisle, pointing an accusing finger at me, was thirty-eight-year old Mike-One, who brought his Santa-problem to me—was it only three weeks ago? Mike-One, his arm extended, his chin trembling, yelling: "You lied to me! You lied, lied, lied!"

It took the better part of an hour to restore a semblance of order. When the first shock was over and the hysterical, contagious tears had subsided a little, Mommy and I managed to convince the Kids, at least most of them, that Santa was alive and well, that he was very sorry he couldn't make it, but if they'd be good and not fuss about it they'd all get something extra special next Christmas. Just for good measure, we doubled the Ice Cream Ration for the next two weeks.

When it was over, I went looking for Adam-Two.

I was boiling mad, and I knew I ought to wait until I cooled off before having it out with him. But after what he'd pulled today, I didn't dare trust him out of my sight that long. I knew that my anger was irrational, but the knowledge didn't help much.

I found him behind the Picnic Grounds, throwing snowballs at the Great Wall. He was using the force field like a billiard cushion to bank his shots back in toward the trees.

He saw me coming and waited quietly, idly tossing a snowball from one hand to the other. For a moment I thought he might be going to heave it at me. But then he looked down at it, as if it were something he'd outgrown, and tossed it indifferently aside.

The expression on his face was not one of defiance, or arrogance—but neither was it that of a boy who was sorry he'd been naughty. I guess it was a sort of waiting look.

"Well, son," I said, surprised that my anger had suddenly evaporated, "you sure messed things up, didn't you?"

"I guess I did, all right."

"You're not sorry?"

"I had to find out."

I nodded. "And you figure you did find out, is that it?"

"Yes."

"You wouldn't believe me if I told you that Santa just couldn't get here—that he asked me to pretend to be him so the Kids wouldn't be disappointed?"

He shook his head. "No, I wouldn't believe it."

For a moment the anger boiled up in me again and I wanted to grab him and shake him. I had a crazy notion that if I shook him hard enough I could shake him back into the mold, and make him once again just a Kid in Fairyland. Then everything would be all right....

I bent over and made a snowball and heaved it at the Wall, to give my hands something to do. My throw was too straight and the force field kicked it back at us. We both ducked as it whizzed over our heads, then grinned at each other.

"Come on over to Mommy and Daddy's House," I said. "I want to talk to you."

We trudged along through the three-inch snow, down the path between the Circus Grounds and the dormitories. The Kids were drifting back from lunch, and I noticed the noise level was considerably lower than on any other Christmas I could remember. They hadn't completely recovered yet, and they probably wouldn't for a long time. I didn't know what to do about it except to sweat it out.

Ruth greeted us at the door. "Hello, Adam," she said. "Come on in."

"You're not angry with me?"

She shook her head. "We know you couldn't help yourself, don't we, Daddy?"

"I guess so," I said drily.

We went into the living room and I waved Adam to a seat. I stretched out in my favorite chair-lounge, feeling suddenly very old and very tired. Adam sat forward in his chair, watching me with that waiting look—defiant yet shy, courageous, yet a little afraid, resigned and yet hopeful....

"Adam," I said at last, "what are you trying to prove? What is it you want?"

He wet his lips and lowered his eyes for a moment. Then his gaze met mine without flinching. "It's like I told you once before," he said quietly. "I just want to know the truth, the real truth about everything!"

I got to my feet and began to slowly pace the floor. I paused in front of Ruth's chair and looked down at her. She caught my hand, gave it a squeeze and nodded.

I turned back to Adam. "You won't like it," I said.

"Maybe not. But I gotta know. I just gotta!"

"Not 'gotta'," Ruth corrected automatically. "'Have to'."

"I have to know."

I paced three more laps, still hesitating. I felt like a surgeon, trying to decide whether or not to operate when it's a toss-up whether the operation will kill the patient or cure him.

"All right, Adam," I said wearily. "You win. But you have to promise me something. Promise me that you'll never say anything to the other Kids about what I'm going to tell you."

Now it was his turn to weigh a decision, and I could feel the battle going on behind those crystal-clear eyes. His innate honesty, battling with his insatiable curiosity. He considered for perhaps a full minute, then he nodded. "Okay. I don't think it's right not to tell Kids the truth—but I promise."

"Cross your heart?"

"Cross my heart."

I took a deep breath, signalled Ruth to make some coffee, and began.

"You were right about Santa Claus, Adam. He's just make-believe, and so are the fairies. Santa Claus was invented by Mommies and Daddies to represent the spirit of Christmas for kids too little to understand its real meaning. People on Earth still observe the holiday, although they've gradually forgotten what it really stands for. I'll explain that part to you later."

"What's Earth, Daddy?"

"Earth is where everybody lived before there were any spaceships. It's a big place, and some of it's nice and some of it not so nice. The people live in houses, something like this one, and the ones in a house are called families. There's a Mommy and a Daddy for each family, and their kids live in the house with them."

"Where do the kids come from?"

"From the Mommy. It's the same as what we call 'making a Dolly'."

"Oh."

I talked for six hours, until I was so hoarse my voice was cracking on every other word. He took it all in stride, injecting a question here and there, absorbing it all like an unemotional sponge. But when I began to talk about war, he became a little upset. I explained how it had begun as individual struggles for survival or supremacy in the days of the cavemen, how it had evolved along with society into struggles between families and tribes, then nations, and now—between planets.

"But why do they kill each other, Daddy? That doesn't prove anything."

I laughed. "Son, if I could answer that one, I'd be Daddy Number One of the whole universe!"

We finally packed Adam off to bed in the spare room, after promising him we'd talk some more the next night. I'd shown him my library and told him he could come and read any time he liked, though of course he mustn't take any books out of the house where the Kids might see them.

Ruth and I stood on the front porch for awhile in the moonlight, gazing out over our once-peaceful little world.

"Harry, what will become of him?"

"I don't know.... He'll have to decide for himself. He became a man tonight, you know. I'd like him to stay, but I imagine he'll want to go to Earth. He's got a mind that just won't stop. The best thing we can do is try to teach him the things he'll need to survive in that cock-eyed world, and turn him loose. It's no good trying to hang onto your kids once they're grown up, Mommy."

She shivered a little and moved closer to me. "I suppose you're right. I think I know now why mothers hate to see their children grow up."

I put my arm around her and gave her an affectionate squeeze. "He'll be all right.... You know, in a way I'm almost glad this happened. Maybe—just maybe—Adam has given us the answer. Maybe the thing to do is not to keep them Kids all their lives, but to let them grow up more slowly, in their own time instead of to some prescribed formula. The world has kept getting more complicated all the time, and a kid just can't grow up in it as easily as before."

When we were in bed, just before I put out the light, I said, "I guess I can answer your question now, Mommy. I don't still think these twenty years were wasted. If I had it to do over again, I'd still want to be Daddy of Fairyland."

CHAPTER V

The next morning at breakfast time I went upstairs and knocked on the door of Adam's room. He called to me to come in and I opened the door then stopped, one foot over the threshold.

Across the room, admiring his bewhiskered face in the mirror, was Santa Claus!

"Ho-ho-ho!" he boomed, in a perfect imitation of my own Santa-voice. "Merry Christmas, Daddy!" He tugged at the beard and there was the grinning face of Adam-Two. "I found it in the closet," he said. "Do I look the part?"

I laughed. "For a minute I thought you were the real thing."

He looked away. "I—I guess you know I'll want to go to Earth to live."

I nodded. "It will be pretty rough at first. You realize that?"

"Yes, I expect it will.... Daddy, I'm sorry I messed up Christmas for the Kids yesterday. I'd kind of like to make up for it by playing Santa for them today. Will you stand by me in case some smarty-pants tries to snatch my beard off?"

I grinned at him, but I didn't say anything because I discovered there was a strange kind of lump in my throat.

"I was thinking, too," he went on, "that maybe I could come back with the supply ship each Christmas and—and do the same thing, if you'd like me to."

I cleared my throat. "That—that would be fine, Adam."

He hesitated again, then blurted, "It isn't right, you know. Fairyland, I mean. It isn't fair to kids not to let them grow up. And it isn't the answer to all the things you told me are wrong about the world."

"I know, Adam. I know."

"Sooner or later they'll realize that, on Earth."

"I think they already have," I said.

He scratched his chin under the beard. "Then some day they might decide to close Fairyland, mightn't they? So I was thinking, maybe each Christmastime you and Mommy could choose two or three of the older Kids and sort of get them ready for the world. The way you did me. Then I could take them back to Earth with me, and help them get started. You could tell the other Kids they went to live with Santa Claus."

I stared at him in amazement. This—this Kid, I couldn't think of him any other way—yesterday had been little more than a juvenile delinquent. Today he was a mature, thinking adult who in a few sparse words had provided the answer to the question that had been gnawing at me for two weeks: what was to become of Fairyland?

I felt the way a father must feel when he suddenly realizes his boy has grown up, and has turned out all right. Kind of proud, and more than a little grateful.

I gripped Adam's hand. "Son, you've got yourself a deal! Come along and let's surprise the Kids!"

We went down the stairs arm in arm, and I called to Ruth: "Hey, Mommy! Guess what. There really is a Santa Claus, after all!"