(Larger)

Early

Explorers of

Plymouth Harbor

1525–1619

by

Henry F. Howe

Published jointly by

Plimoth Plantation, Inc.

and the Pilgrim Society

Plymouth, 1953

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of the illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them. Full-size, higher-resolution versions of the illustrations may be seen by clicking (Larger) below them.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

(Larger)

by

Henry F. Howe

Published jointly by

Plimoth Plantation, Inc.

and the Pilgrim Society

Plymouth, 1953

Copyright by Plimoth Plantation, Inc., and the Pilgrim Society, 1953

Henry F. Howe is author of Prologue to New England, New York, 1943, and Salt Rivers of the Massachusetts Shore, New York, 1951, both published by Rinehart & Co., Inc. Much of the material here presented is condensed from these volumes.

The cover decoration, which is reproduced from the London 1614 translation of Bartholomew Pitiscus, Trigonometry: or the doctrine of triangles, shows not only early seventeenth century ships but seamen using a cross-staff and casting a lead.

Printed in offset by The Meriden Gravure Company, Meriden, Connecticut

Composition by The Anthoensen Press, Portland, Maine

3

Visitors to Plymouth are often amazed to learn that the Mayflower was not the first vessel to drop anchor in Plymouth Harbor. The “stern and rock-bound coast” of Massachusetts was in fact explored by more than twenty recorded expeditions before the arrival of the Pilgrims. At least six of these sailed into Plymouth Harbor. Plymouth appeared on five good maps of the Massachusetts coast by 1616, one of them a detailed map of Plymouth Harbor itself, made by Samuel de Champlain in 1605. The Harbor had been successively called Whitson Bay, the Port du Cap St. Louis, and Cranes Bay by English, French and Dutch explorers, but the name Plimouth, bestowed on it by Captain John Smith in 1614, was the one the Pilgrims perpetuated.

The Pilgrim voyage was the successful culmination of a century of maritime efforts along the New England coast by Spanish explorers, Portuguese fishermen, French and Dutch fur traders, and Elizabethan English “sea dogs.” All the western ports of Europe seethed with ambitious shipmasters in search of opportunities for profit in commerce or fishing, free-booting, the slave trade, warfare or piracy. Some, like Henry Hudson, visited New England primarily as geographers looking for a Northwest Passage through North America. A few were probing out possibilities for a colonial beachhead in the New World. One of these, led by French Jesuits, had, like the Pilgrims, a religious motive. Three or four others attempted New England colonies, but failed. Only the Pilgrims succeeded in hanging on, through the inevitable preliminary disasters of the first year or two, to found a permanent colony.

4

Indians of Massachusetts probably first saw Europeans during the four Vinland voyages of Leif Ericsson and his successors between 1003 and 1015 A.D. There is good reason to suppose that these voyages touched the shores of Cape Cod and the islands about Martha’s Vineyard, but no direct evidence connects them with Plymouth Harbor. Continuous contact with Europeans did not begin until nearly five hundred years later when John Cabot’s second Newfoundland voyage coasted North America southward to the Carolinas in 1498. The Portuguese nobleman, Miguel Cortereal, a castaway on a voyage of exploration, may have lived among the Indians at the head of Narragansett Bay from 1502 until 1511. Certainly these Indians, the ancestors of Massasoit, were visited in 1524 by Giovanni da Verrazano, whose French expedition spent two weeks in Narragansett Bay in that year. Verrazano wrote that he was met by about twenty dugout canoes filled with eager people, dressed in embroidered deerskins and necklaces. The women wore ornaments of copper on their heads and in their ears, and painted their faces. These Indians were delighted to trade furs for bright bits of colored glass. They lived in circular houses “ten or twelve paces in circumference, made of logs split in halves, covered with roofs of straw, nicely put on.” From the description, these people were no doubt the Wampanoags, who a hundred years later were such friendly allies to the Pilgrims at Plymouth, only thirty miles away.

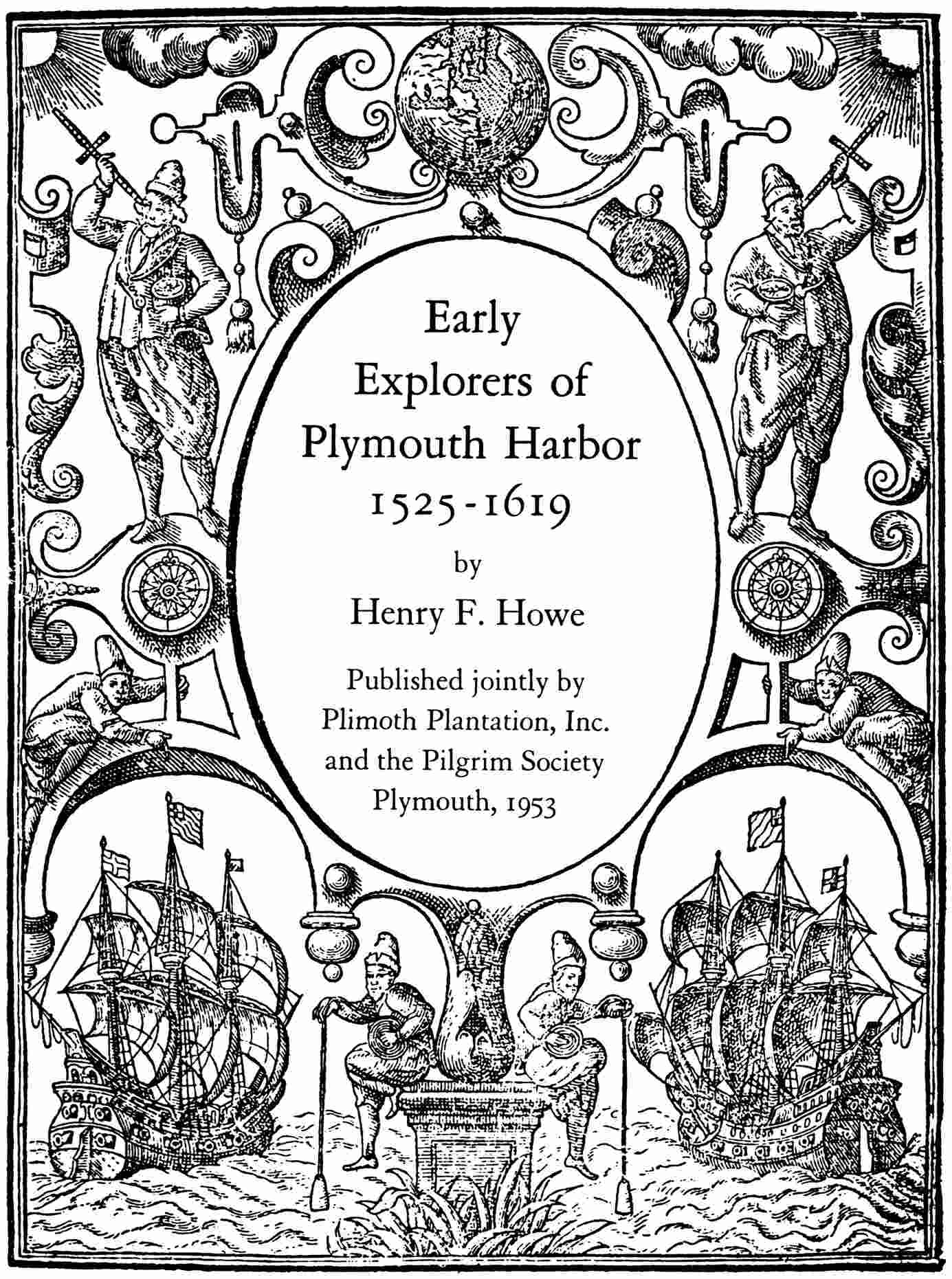

Verrazano did not enter Massachusetts Bay. But in the spring of 1525 a Spaniard, Estevan Gomez, cruised for two months on the New England coast. While he left no narrative of his voyage, “Tierra de Estevan Gomez” appeared immediately5 on Spanish maps of the period, notably that of Ribero, 1529. An indentation of the bay shore behind his “Cabo de Arenas” sufficiently suggests Plymouth Harbor and Cape Cod Bay to make one speculate whether this is not in fact the first record of a visit to Plymouth, ninety-five years before the landing of the Pilgrims. What has been interpreted as Boston Harbor on this Ribero map bears the name “Bay of St. Christoval,” but the indentation that suggests Plymouth remains nameless. It seems likely that Estevan Gomez was the discoverer of Plymouth in 1525.

After these first Massachusetts discoveries, there follows a period of seventy-five years of documentary obscurity so far as Massachusetts is concerned. Maritime activities about Newfoundland, the St. Lawrence River, and Nova Scotia steadily grew. Cartier founded, and then had to abandon, his French colony at Quebec. Jehan Allefonsce, one of his shipmasters, was blown southward from the Newfoundland banks in 1542, into “a great bay in latitude 42°,” but Massachusetts Bay is not mentioned during the rest of the century. Both French and English built up an increasing fur trade on the Maine coast, especially about the Penobscot and in the Bay of Fundy. Fishermen from all the maritime nations of Europe crowded in increasing numbers to the Newfoundland banks, carrying back apparently inexhaustible supplies of codfish to feed Catholic Europe in the season of Lent. By 1578 as many as 350 fishing vessels were making the transatlantic voyage, usually twice each year. Since fishermen and fur traders rarely left written records, we can only assume that with the increased volume of shipping, some of these vessels found their way to Massachusetts shores. But we have no documentary evidence of their visits.

(Larger)

TIERA DE AYLLON

TIERA DE ESTEVA GOMEZ

TIERA NOVA: DE CORTEREAI

Map of the North American Coast, a portion of the World Map made by Diego Ribero in 1529, showing the results of the explorations of Estevan Gomez in 1525

Reproduced from the Map Collection, Yale University Library

Inevitably the tremendous growth of all this free-lance commercial shipping, in the fur trade and fisheries, must lead to attempts to organize it either into colonial administrations under government control, or business companies privately financed. Everyone could see that permanent bases were needed in the New World. International quarrels and actual piracy were already appearing in the Newfoundland fisheries. Sir Humphrey Gilbert determined to make Newfoundland an English colony. But in 1583 his well-organized expedition came to grief by shipwreck. His half brother, Sir Walter Raleigh, renewed the attempt, this time at Roanoke in the Carolinas, but was unable to maintain the colony’s supply, once it was established. The project failed. But the idea was right, and men in England like Raleigh and Richard Hakluyt, the historian of English voyages, kept preaching the necessity of overseas colonies. Similar ideas were growing in the western ports of France.

The turn of the century marked the beginning of a concerted campaign on the part of both France and England to establish plantations in New England. The first move was made by a group of free-lance English merchants who in 1602 sent out Bartholomew Gosnold on a commercial voyage with thirty-two men in the bark Concord. Its objective was twofold, to get sassafras (a medication thought to be “of sovereigne vertue for the French poxe”) and to establish an outpost somewhere in the area described by Verrazano seventy-five years before. Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s son Bartholomew was among the company. After brief landings on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, the expedition built a hut on the islet in the pond on Cuttyhunk Island in Buzzards Bay, there traded with the Indians, cut a cargo of sassafras root and cedarwood,8 and after a minor altercation with the natives pulled up stakes and sailed back to England with two enthusiastic narratives of the country and its commodities.

Less than nine months later, and obviously because of the success of the Gosnold voyage, a new expedition of two vessels, Speedwell and Discoverer, with forty-four men and boys, sailed to Massachusetts from Bristol under command of Martin Pring, a Devonshire skipper. This voyage was instigated by Richard Hakluyt, together with some merchants of Bristol. Robert Salterne, pilot of the Gosnold voyage, was assistant to Pring. Deliberately avoiding the long sail around Cape Cod, Pring entered Massachusetts Bay, coasted its North Shore looking for sassafras, and finding none, sailed across to “a certaine Bay, which we called Whitson Bay.” It had a “pleasant Hill thereunto adjoyning,” and a “Haven winding in compasse like the Shell of a Snaile,” with twenty fathoms at the entrance, and seven fathoms at the land-locked anchorage. Here was a “sufficient quantitie of Sassafras.” This was Plymouth Harbor in 1603.

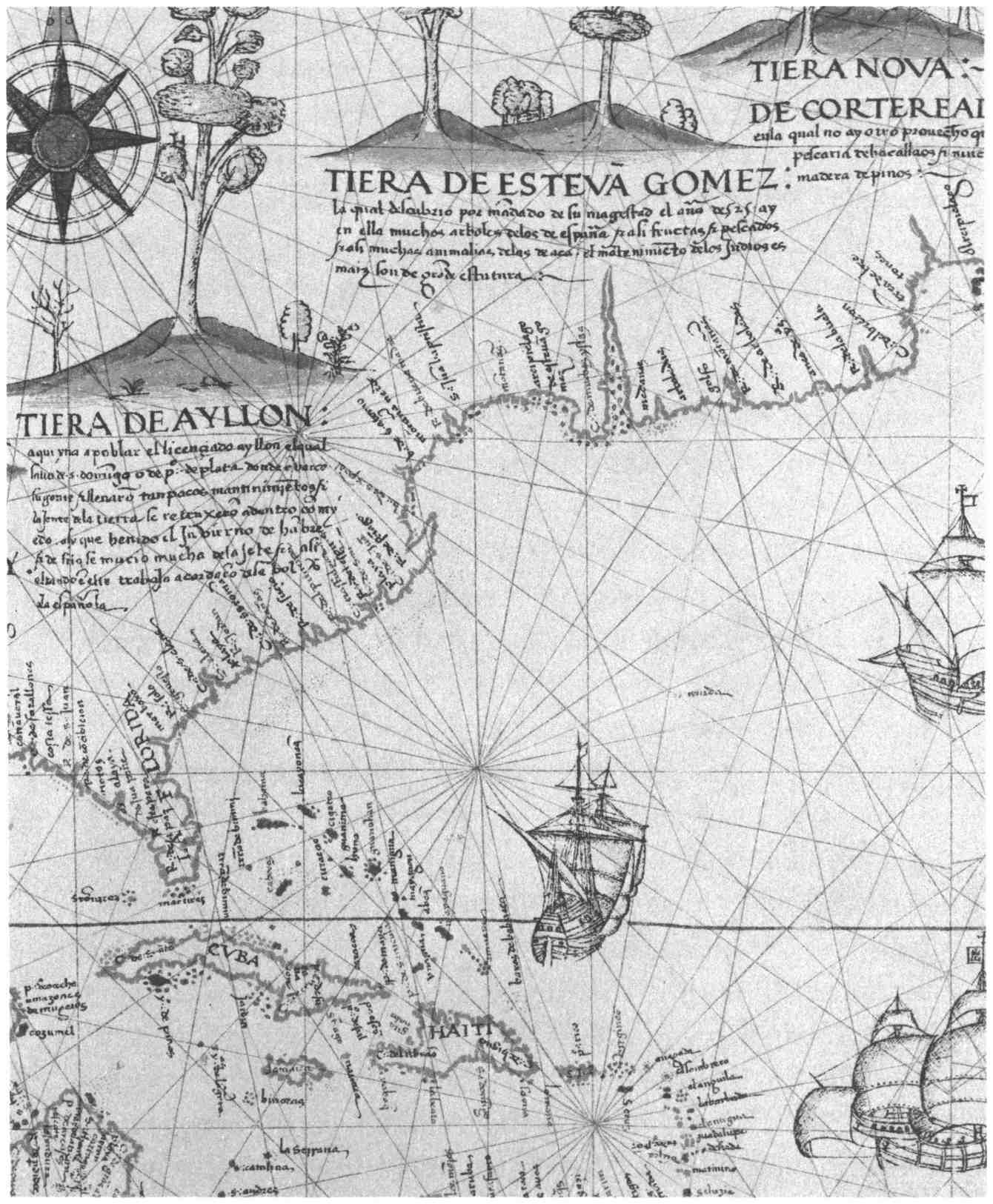

Ashore, Pring’s men built a “small baricado” or watchtower and kept it manned with sentinels while the crew worked in the woods. They also took ashore with them two great mastiff dogs, of whom the Indians were mortally afraid. Indians appeared in considerable numbers, “at one time one hundred and twentie at once.” One of the crew delighted the natives by playing a guitar and they sang and “danced twentie in a ring” about him and gave him gifts of tobacco, tobacco pipes, snakeskin girdles and “Fawnes skinnes.” They had black and yellow bows, and prettily decorated quivers of rushes filled with long feathered arrows. They used birch-bark canoes “where of we brought one to Bristoll.” Their gardens were9 planted with tobacco, pumpkins, cucumbers and corn. The men wore breech clouts, and feathers in their knotted hair; the women “Aprons of Leather skins before them down to the knees, and a Bears skinne like an Irish Mantle over one shoulder.”

(Larger)

Martin Pring’s men ashore with a mastiff, Plymouth Harbor, 1603

Reproduced from J. P. Abelin, De Wytheroemde Voyagien der Engelsen (Leiden, 1727) in the Boston Athenæum

For the story of the latter days of their seven weeks’ stay at Plymouth, we can scarcely do better than read Pring’s narrative in the original: “By the end of July we had laded our small Barke called the Discoverer with as much Sassafras as we thought sufficient, and sent her home into England before, to give some speedie contentment to the Adventurers; who arrived safely in Kingrode about a fortnight before us. After10 their departure we so bestirred ourselves, that our shippe also had gotten in her lading, during which time there fell out this accident. On a day about noone tide while our men which used to cut down Sassafras in the woods were asleep, as they used to do for two houres in the heat of the day, there came down about seven score Savages armed with their Bowes and Arrowes, and environed our House or Barricado, wherein were foure of our men alone with their Muskets to keepe Centinell, whom they sought to have come down unto them, which they utterly refused, and stood upon their guard. Our Master like-wise being very careful and circumspect, having not past two with him in the shippe, put the same in the best defence he could, lest they should have invaded the same, and caused a piece of great Ordnance to bee shot off to give terrour to the Indians, and warning to our men which were fast asleepe in the woods: at the noyse of which peece they ... betooke them to their weapons, and with their Mastives, great Foole with an halfe Pike in his mouth, drew down to their ship; whom when the Indians beheld afarre off with the Mastive which they most feared, in dissembling manner they turned all to a jest and sport and departed away in friendly manner, yet not long after, even the day before our departure, they set fire on the woods where wee wrought, which wee did behold to burne for a mile space, and the very same day that wee weighed Anchor, they came down to the shore in greater number, to wit, very neere two hundred by our estimation, and some of them came in theire Boates to our ship, and would have had us come in againe, but we sent them back, and would none of their entertainment.” One would love to know more than is provided in Martin Pring’s brief narrative in order to estimate fairly whether the English had given11 provocation to the Indians for this threatened attack at Plymouth. The only hint of provocation is the taking of a canoe back to England.

Had Plymouth been populated by two hundred Indians in 1620 it seems unlikely that the Pilgrims could have survived. The English adventurers transferred their explorations to the coast of Maine, where in 1605 George Waymouth, and in 1606 Martin Pring, made investigations preparatory to the major colonization attempt of the English Plymouth Company at Sagadahoc, the mouth of the Kennebec River. This colony failed after a year through a breakdown in leadership. For our purposes it is significant that the English sent no further explorations into Massachusetts waters for eight years after the voyages of Gosnold and Martin Pring. It looks as though the enmity of the Massachusetts Indians dissuaded English merchants from further plans to set up a colony in that region.

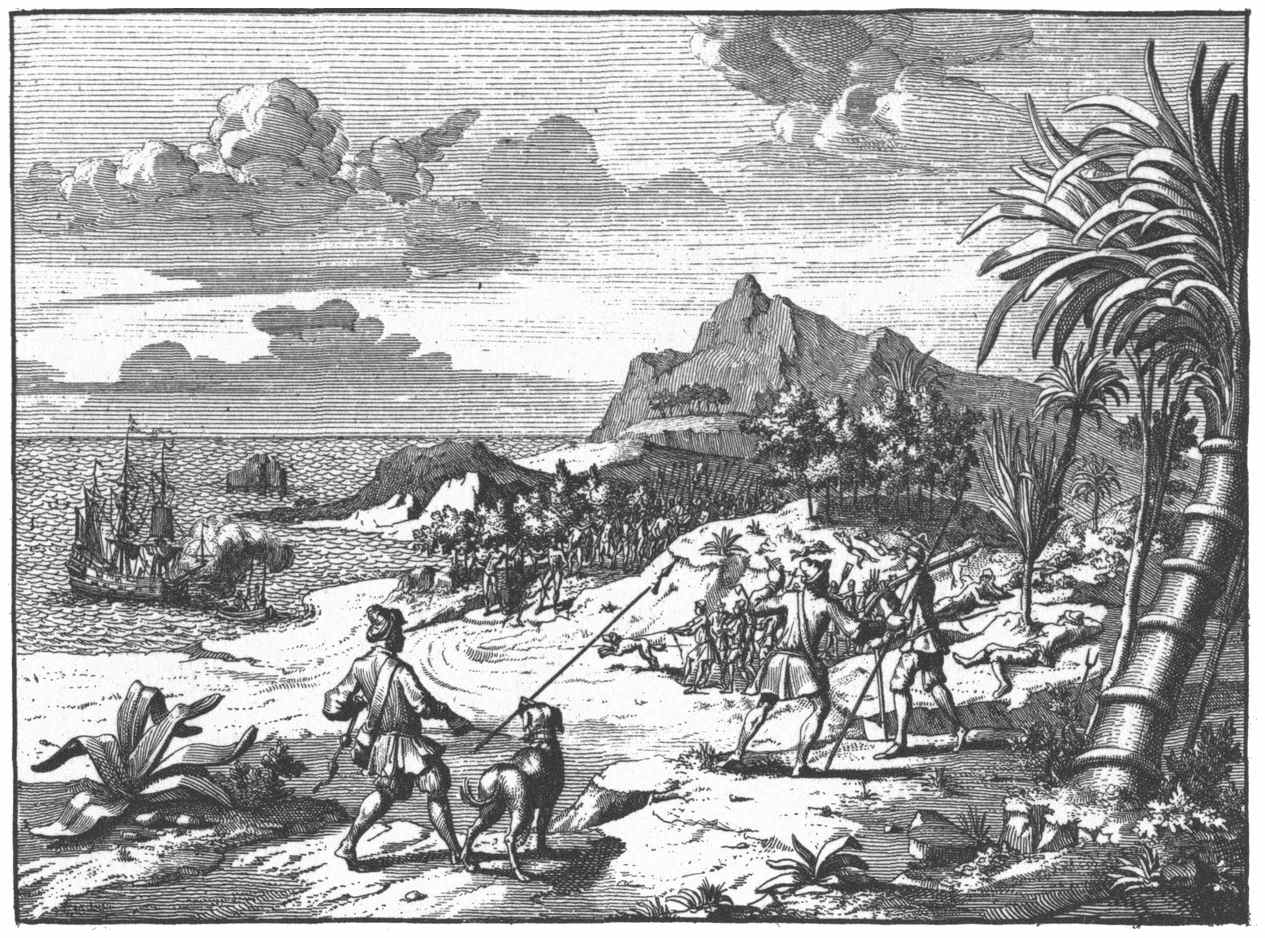

Plymouth’s next visitor was that great French explorer and empire builder, the founder of Canada, Samuel de Champlain. A group of French merchants organized by the governor of Dieppe, that old French port which had been sending fishermen to America for more than a century, succeeded in 1603 in getting from Henri IV a commission to found a colony. After spending the summer of 1603 exploring the St. Lawrence, the leaders decided that a more southern climate was desirable. Accordingly in 1604, De Monts and Pont-Grave, with Samuel de Champlain as geographer and chronicler of the expedition, explored the Bay of Fundy and founded a colony on Dochet Island in Passamaquoddy Bay. Half the colonists died during the first winter, and the colony was moved across the Bay to a better site at what is now Annapolis, Nova Scotia. Meantime Champlain spent the summers of 1605 and 1606 exploring the New England coast, familiarizing himself with all the shores as far south as Woods Hole in Massachusetts. He wrote a splendid account of these expeditions, which is still good reading; and for the first time produced a good map of the Massachusetts coast, with detail maps of Gloucester, Plymouth, Eastham and Chatham harbors.

12

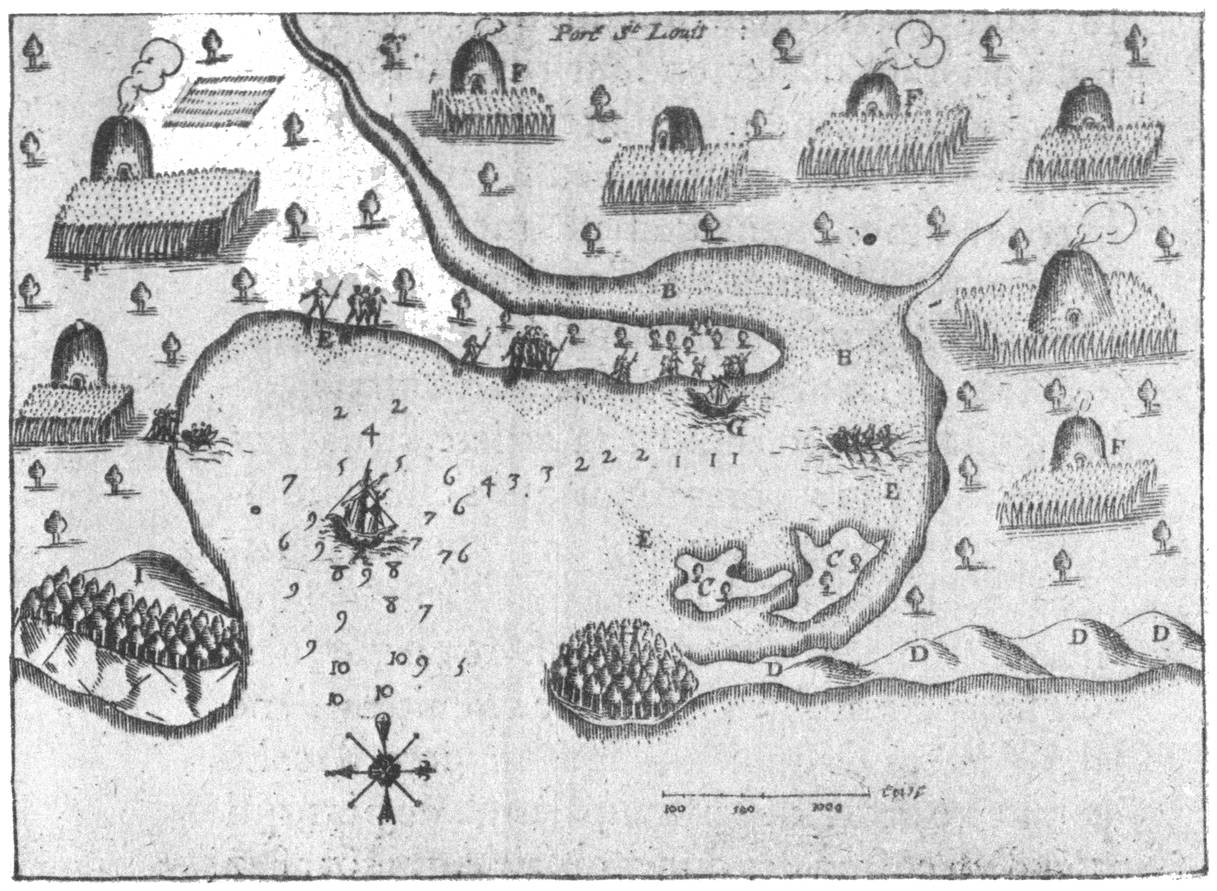

(Larger)

Champlain’s Map of Plymouth Harbor, 1605

Legends on Champlain’s Map of Port St. Louis with comments

A. SHOWS THE PLACE WHERE VESSELS ANCHOR

The figures show the fathoms of water. The depths are now much less than those indicated on the map, and the difference may represent an actual change.

B. THE CHANNEL

C. TWO ISLANDS

Clarks Island, a low swell of upland occupied by farms, and Saquish Head, likewise low upland occupied by a few buildings and some bushes.

D. SAND DUNES

The long line of dune beaches, collectively called Duxbury Beach, connecting Brant and Gurnet points.

E. SHOALS

A prominent feature of this part of Plymouth Harbor and of Duxbury Bay. As Champlain states, they are largely bare at low tide.

F. WIGWAMS WHERE THE INDIANS CULTIVATE THE LAND

A number are situated on the slope where now stands the historic city of Plymouth founded by the Pilgrim Fathers fifteen years after this visit of Champlain.

G. THE SPOT WHERE WE RAN OUR PINNACE AGROUND

Browns Bank, still an impediment to the navigation of the harbor. Apparently it was while their pinnace was aground that Champlain landed on the north end of Long Beach, where he sketched this map.

H. A KIND OF ISLAND COVERED WITH TREES, AND CONNECTED WITH THE SAND DUNES

The Gurnet, a low-swelling upland island, ending in a low bluff; it is largely bare of trees and occupied by a group of buildings belonging to the light station. It was thickly wooded when the Pilgrim Fathers settled here in 1620. Slafter’s contention that this was Saquish Head he later abandoned.

I. A FAIRLY HIGH PROMONTORY, WHICH IS VISIBLE FROM FOUR TO FIVE LEAGUES OUT TO SEA

Manomet Hill, 360 feet in height, a plateau ridge cut to an abrupt bluff where it reaches the sea, thus forming a conspicuous landmark.

14

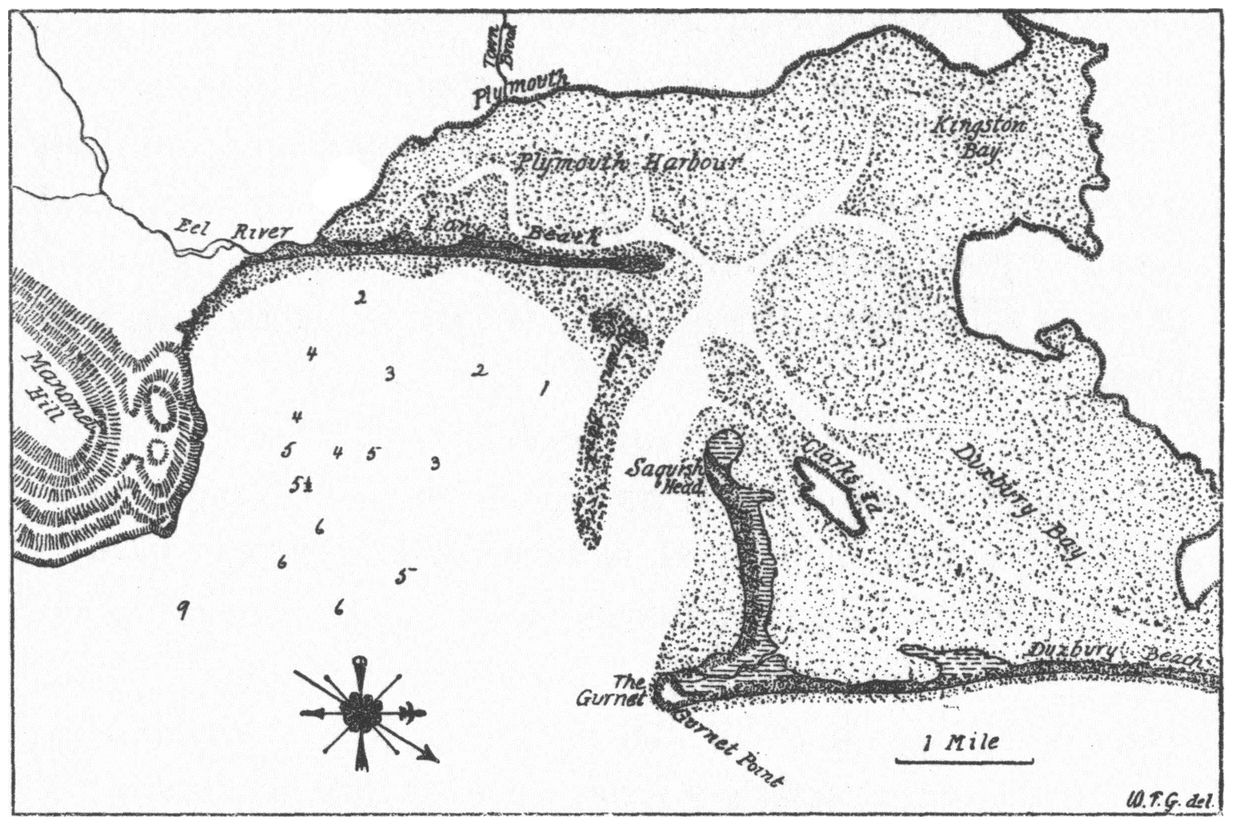

(Larger)

Map of Plymouth Harbor, Massachusetts, adapted from a modern chart for comparison with Champlain’s map of Port St. Louis, to which it is adjusted as nearly as possible in scale, extent, and meridian

Reproduced from the Champlain Society edition of The Works of Samuel de Champlain, plate LXXIV. The compass is Champlain’s, which is supposed to be set to the magnetic meridian, but the true north is shown by the arrow.

Champlain’s Plymouth visit occurred in 1605, two years after Pring’s expedition. He had spent several days in Gloucester Harbor and a night in Boston Harbor, where he had watched the building of a dugout canoe by the Indians. Coming down the South Shore, his bark grounded on one of the numerous ledges that dot that portion of Massachusetts Bay. “If we had not speedily got it off, it would have overturned in the sea, since the tide was falling all around, and there were five or six fathoms of water. But God preserved us and we anchored” near a cape, which perhaps was Brant Rock. “There came to us fifteen or sixteen canoes of savages. In some of them there were fifteen or sixteen, who began to manifest great signs of joy, and made various harangues, which we could not in the least understand. Sieur de Monts sent three or four in our canoe, not only to get water but to see their chief, whose name was Honabetha.—Those whom we had sent to them brought us some little squashes as big as the fist which we ate as a salad like cucumbers, and which we found very good—We saw here a great many little houses scattered over the fields where they plant their Indian corn.”

The expedition now sailed southward into Plymouth Harbor. “The next day [July 18] we doubled Cap St. Louis, so named by Sieur de Monts, a land rather low, and in latitude 42° 45’. The same day we sailed two leagues along a sandy15 coast as we passed along which we saw a great many cabins and gardens. The wind being contrary, we entered a little bay [Plymouth] to await a time favorable for proceeding. There came to us two or three canoes, which had just been fishing for cod and other fish, which are found there in large numbers. These they catch with hooks made of a piece of wood, to which they attach a bone in the shape of a spear, and fasten it very securely. The whole thing has a fang-shape, and the line attached to it is made out of the bark of a tree. They gave me one of their hooks, which I took as a curiosity. In it the bone was fastened on by hemp, like that in France, as it seemed to me. And they told me that they gathered this plant without being obliged to cultivate it; and indicated that it grew to the height of four or five feet. This canoe went back on shore to give notice to their fellow inhabitants, who caused columns of smoke to rise on our account. We saw eighteen or twenty savages, who came to the shore and began to dance.” Was this a reminiscence of dancing to the guitar for Pring’s sailor, perhaps? “Our canoe landed in order to give them some bagatelles, at which they were greatly pleased. Some of them came to us and begged us to go to their river. We weighed anchor to do so, but were unable to enter on account of the small amount of water, it being low tide, and were accordingly obliged to anchor at the mouth. I went ashore where I saw many others who received us very cordially. I made also an examination of the river, but saw only an arm of water extending a short distance inland, where the land is only in part cleared up. Running into this is merely a brook not deep enough for boats except at full tide. The circuit of the Bay is about a league. On one side of the entrance to this Bay there is a point which is almost an island, covered with wood, principally18 pines, and adjoins sand banks which are very extensive. On the other side the land is high. There are two islets in this bay, which are not seen until one has entered and around which it is almost dry at low tide. This place is very conspicuous from the sea, for the coast is very low excepting the cape at the entrance to the bay. We named it Port du Cap St. Louis, distant two leagues from the above cape and ten from the Island Cape [Gloucester]. It is in about the same latitude as Cap St. Louis.”

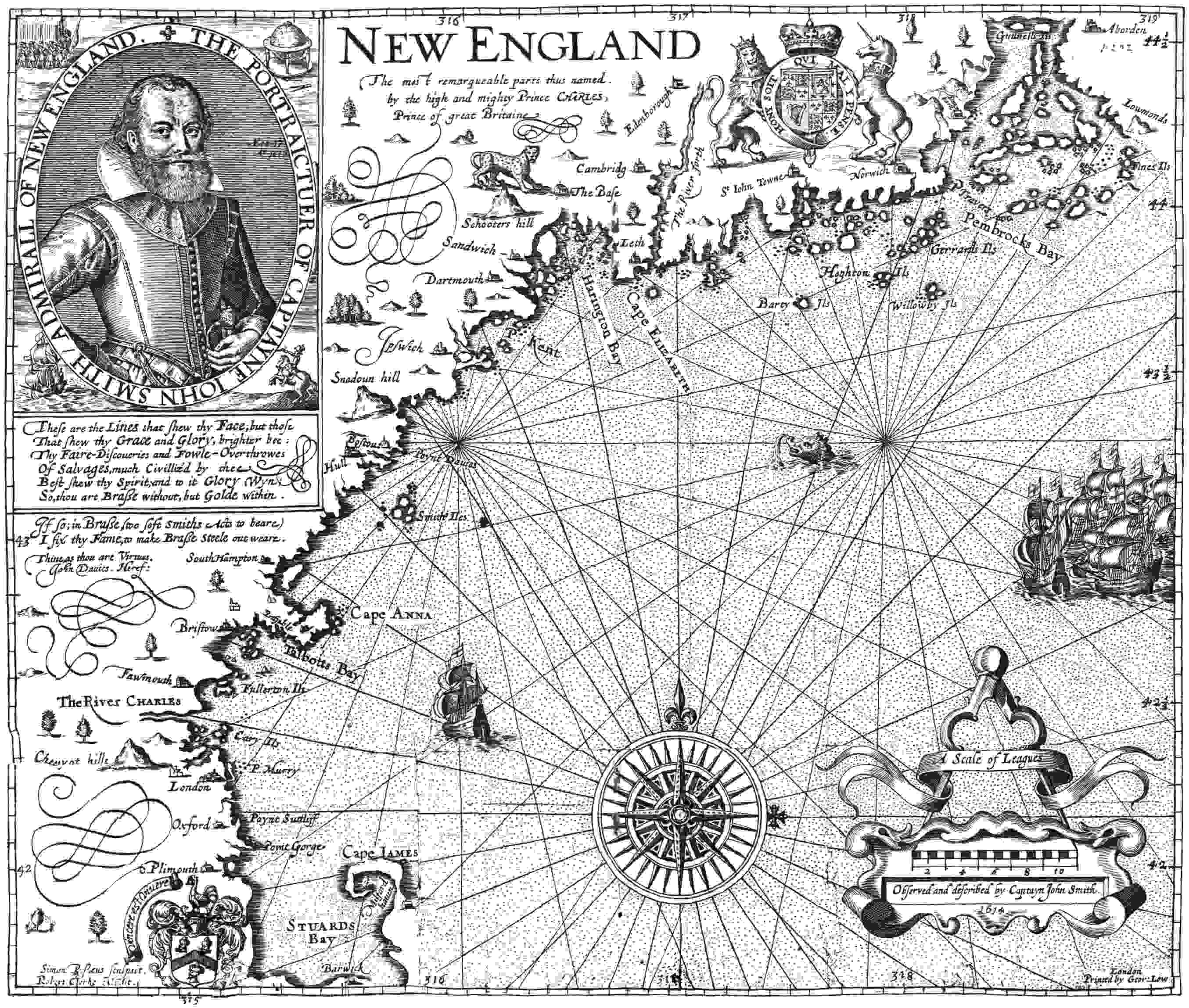

(Larger)

New England

CAPTAIN JOHN SMITH’S MAP OF NEW ENGLAND, 1614

Reproduced from the Pequot Collection, Yale University Library

Champlain’s map of Plymouth Harbor, which is reproduced herewith, was a quick sketch which he drew from the end of Long Beach after his vessel went aground there, probably during the afternoon of their arrival. Since the expedition stayed in Plymouth Harbor only over one night, too much accuracy of detail must not be expected of it. Saquish Head is represented as an island, and no distinction is made between Eel River and Town Brook. Plymouth Harbor has probably shoaled a good deal since the early seventeenth century, since it would now be impossible to find a seven-fathom anchorage anywhere except immediately around Duxbury Pier Light; yet Champlain’s anchorage in the middle of Plymouth Bay is so designated. Martin Pring had even described a landlocked anchorage in seven fathoms. The chief value of Champlain’s little map, aside from confirming the locality, is its evidences of very extensive Indian houses and cornfields occupying much of the slopes above the shore all the way around from the Eel River area through Plymouth and Kingston to the shores of Duxbury Bay.

The expedition left Plymouth on July 19 and sailed around the shores of Cape Cod Bay before rounding the Cape and arriving the next day at Nauset Harbor in Eastham. During19 several days’ stay there, a French sailor was killed by the Indians in a scuffle over a kettle. The following year, when Champlain returned to Cape Cod, a more serious disaster occurred. Four hundred Indians at Chatham ambushed and massacred five Frenchmen in a dawn raid, then returned and disinterred their bodies after burial. The French took vengeance by coolly slaughtering half a dozen Indians a few days later. But, like the English adventurers, the French then abandoned Massachusetts and never returned. Champlain reported that in all his travels he had found no place better for settlement than Nova Scotia. Two years later, changes of plans in France transferred him to Quebec, where he spent the remainder of his career laying the foundations of French Canada along the St. Lawrence. Massachusetts Indians had again rebuffed the threat of European penetration.

We have already noted that while Champlain was in Massachusetts, George Waymouth and Martin Pring had been exploring Maine. The coördination of these exploratory voyages was largely the work of Sir Ferdinando Gorges, a diligent organizer of New England colonial preparations. In 1606 the administrative architecture of the English colonial movement in America was built. King James gave charters to two companies, the London Company and the Plymouth Company, providing for settlements respectively in what came to be known as “Southern” and “Northern” Virginia. The successful colony at Jamestown was founded by the London Company in 1607. The coincident attempt by the Plymouth Company, organized by Gorges, and the Popham and Gilbert families, to found a colony on the Kennebec River in Maine failed after a year’s trial. This Sagadahoc Colony failure was a blow to New England colonization, the effects of20 which lasted for a generation, since the impression of New England as a subarctic area, impractical for settlement, remained in English minds for many years. It needs to be emphasized, however, that despite this setback to English hopes, the loss of fortunes invested in the enterprise, and the breakdown of the Plymouth Company produced by this failure, the enterprise had come much nearer to success than Humphrey Gilbert’s attempted colony in Newfoundland. Much was learned about techniques of living in the new country, getting along with Indians, and the need for continuous replacement and supply. These ventures were hazardous: they required courage, teamwork, strong leadership, and personnel of heroic wisdom and tenacity.

After the Sagadahoc failure, the pattern of English activity on the New England coast reverted for five years to the former state of occasional trading and fishing voyages. The only events that touched even remotely on Plymouth history were Cape Cod visits of three men from different areas of activity. In 1609 Henry Hudson landed briefly on Cape Cod on his way from Maine to his explorations of the Hudson River which led to the Dutch claims in that region. Samuel Argall from Virginia in 1610 likewise saw Cape Cod on a voyage designed to supplement Jamestown’s failing food supplies with New England codfish. And in 1611 Captain Edward Harlow, sent on an exploring voyage to the Cape Cod region by the Earl of Southampton, seems to have had five skirmishes with Indians on Cape Cod and the Vineyard. Harlow’s vessel was attacked by canoes while at anchor, and lost a long boat being towed astern to the Indians, who thereupon beached her, filled her with sand and successfully prevented the English from retaking her. Harlow returned to England21 with little except five captured natives. Among them was Epenow, an Indian whose treachery later accounted for the death of Captain Thomas Dermer.

In 1613 the French fur-trading activities on the Bay of Fundy were supplemented by an ambitious project to establish a Jesuit missionary colony in that region. But this second French attempt to colonize Maine was nipped in the bud after only a few weeks by Sir Samuel Argall’s armed cruiser, sent from Virginia for the purpose. This ended the threat of France as a colonial power in New England except for occasional incursions into eastern Maine.

The year 1614 opened with a visitor to Plymouth from a new quarter. Dutch fur traders, following in the wake of Henry Hudson’s 1609 discoveries, were already at work in the Hudson River. Two of them, Adrian Block and Hendrick Christiansen, were about to weigh anchor from Manhattan and depart for the Netherlands with a cargo of furs in the fall of 1613 when one of their ships caught fire and burned to the water’s edge. Both crews therefore stayed over the winter on Manhattan Island, and there built a new “yacht,” the Onrust, which they felt must be given a shakedown cruise before attempting the Atlantic crossing. Block therefore sailed her eastward, the first passage of Long Island Sound by a European, and explored the Connecticut shore and rivers, Narragansett Bay and the Cape Cod region, to all of which he laid claim for the Dutch as “Nieu Nederlant.” Contemporary Dutch accounts offer us little of interest about the Massachusetts phases of this voyage except some sailing directions in Massachusetts Bay that suggest that Adrian Block sailed from a place called Pye Bay, usually identified with Salem, to the Lizard on the English Channel. But the Figurative Map22 which he published in 1616 as a part of his report to the States General of the Netherlands contains many additional details to which Dutch names are applied, including a wholly unmistakable outline of Plymouth Harbor, here called Cranes Bay. From this it seems obvious that Block did visit Plymouth in the spring of 1614, and may be considered as yet another of its explorers. It would be interesting to know whether any of the Leyden Pilgrims, living in the Netherlands for four years after the map’s publication, ever saw it before setting out for the New World. In view of the controversy over whether the Pilgrims were indeed headed for the Hudson River, it is interesting to note that this map of Adrian Block’s would have been the most accurate one available to them as a guide to the New York region, yet there is nothing in the Pilgrim chronicles to suggest that they had it with them on the Mayflower.

Also in 1614 there came sailing into Plymouth Harbor a man whose map and writings were used by the Pilgrims, though he said that they refused his advice and his leadership. Captain John Smith would like to have been the founder of New England, but had to be content to be its Hakluyt. He named New England, and “Plimouth,” and Massachusetts, and the Charles River and Cape Ann—at least he was the first to publish these names. He produced the best known map of New England of that early period. He spent the last seventeen years of his life writing the history of New England voyages and pamphleteering for its settlement. Yet a succession of misfortunes prevented him from ever revisiting the coast for which he developed such enthusiasm during his three months’ voyage in 1614. Smith had already been governor of Virginia and had experience in what it took to plant a successful23 colony. His writings had unquestionably a strong influence on the Massachusetts colonial undertakings, particularly since he was not afraid of Indians and since he recognized the difference between the bleak coast of Maine and the relatively better-situated Massachusetts area as a site for colonial development.

John Smith arrived at Monhegan Island in Maine in April, 1614, with two vessels. In the smaller of these he spent his time exploring and mapping the coast from the Penobscot to Cape Cod, much as Champlain had done nine years earlier. Thomas Hunt in the larger vessel remained at Monhegan, fishing. Reaching “the Countrie of the Massachusetts, which is the Paradise of all those parts,” Smith entered Boston Harbor. “For heere are many Iles all planted with corne: groves, mulberries, salvage gardens, and good harbours: the coast is for the most part high clayie, sandie cliffs. The Sea Coast as you passe, shews you all along large corne fields and great troupes of well proportioned people; but the French, having remained heere neere six weeks left nothing for us.” At Cohasset he wrote: “We found the people in those parts verie kinde, but in their furie no lesse valiant. For upon a quarrell we had with one of them, hee onely with three others, crossed the harbor of Quonahassit to certaine rocks whereby wee must passe; and there let flie their arrowes for our shot, till we were out of danger,—yet one of them was slaine, and another shot through his thigh.” His description of Plymouth, which was variously known as Patuxet or Accomack, immediately follows the Cohasset episode quoted above: “Then come you to Accomack, an excellent good harbor, good land, and no want of anything except industrious people. After much kindnesse, upon a small occasion, wee fought also with fortie or24 fiftie of those; though some were hurt, and some were slaine; yet within an hour after they became friends.” In another passage he adds, “we tooke six or seven of their Canowes which towards the evening they ransomed for Bever skinnes.” Apparently Smith supplied a motive for the resumption of friendship, knowing that the Indians could be bought off. This was the kind of Indian policy Myles Standish used at times; in fact there is a certain resemblance between the two men. In any case Smith left for England with a cargo of beaver, and the Indians of Plymouth got back their canoes.

But the next visitor to Plymouth, still in 1614, did not leave as good an impression. With Smith departed for England, Thomas Hunt appeared in Plymouth Harbor in Smith’s larger vessel. Not content with a hold full of Monhegan codfish, Hunt now kidnaped twenty or more Plymouth natives, stowed them below decks, and sailed away to Spain, where he sold them into slavery at Malaga, “for £20 to a man.” This was a typical seaman’s private venture, or side bet to the profits of the codfish cargo. John Smith wrote that “this wilde act kept him [Hunt] ever after from any more emploiment in those parts.” Samuel Purchas termed Hunt’s “Savage hunting of Savages a new and Devillish Project.” One can imagine what bitterness grew toward the English among Massachusetts Indians after this demonstration of European barbarism.

The quirks of history are at times worthy of the most fantastic fiction. Thomas Hunt’s universally condemned crime happened to produce one result which proved of great advantage to the Pilgrims. Among the twenty wretched Plymouth natives whom Hunt sold at the “Straights of Gibralter” was an Indian named Squanto. Then began a five-year European education which trained Squanto for his irreplaceable services25 to the Pilgrims as their interpreter. Squanto was rescued by good Spanish friars, “that so they might nurture [him] in the Popish religion.” In some unknown manner he reached England and continued his education for several years in the household of one John Slany, an officer of the Newfoundland Company. His subsequent travels will appear in our discussion of Thomas Dermer’s voyage in 1619. It is sufficient at this point to note that perhaps the greatest blessing ever bestowed upon the Pilgrim Fathers was the gift of a treacherous English shipmaster, a Spanish Catholic friar, and an English merchant adventurer.

Things were going badly in another area of Massachusetts during that eventful year of 1614. As though the expeditions of Block, Smith, and Hunt were not sufficient for one year, Nicholas Hobson now made his appearance at Martha’s Vineyard. Sent out by Sir Ferdinando Gorges in an attempt to establish a fur-trading post in that region, Hobson was using the Indian, Epenow, captured by Harlow’s expedition in 1611, as his pilot through the shoals of Nantucket Sound. Epenow cleverly contrived his escape, and a full-scale battle ensued. “Divers of the Indians were then slain by the English, and the Master of the English vessel and several of the Company wounded by the Indians.” Hobson’s party “returned to England, bringing nothing back with them, but the News of their bad Success, and that there was a War broke out between the English and the Indians.” Increase Mather later remarked that “Hunt’s forementioned Scandal, had caused the Indians to contract such a mortal Hatred against all Men of the English Nation, that it was no small Difficulty to settle anywhere within their Territoryes.”

It was at this point in history that another strange series of26 events took place, of much more far-reaching significance. With English expeditions defeated and sent back to England empty-handed, with an Indian war “broke out,” fate, or Providence, or whatever you call that destiny which seems at times to intercede for civilization in its remorseless quest for progress, now took a hand. Some European disease, to which the natives had no resistance and the Europeans complete immunity, swept the coasts of Massachusetts clear of Indians. Suddenly it appeared in all the river villages along the Mystic, the Charles, the Neponset, the North River, and at Plymouth. No one knows what it was—whether chicken pox or measles or scarlet fever. The Indians believed it was the product of a curse leveled at them by one of the last survivors of a French crew wrecked on Boston Harbor’s Peddock’s Island in 1615. By analogy with what later happened to other primitive races in the Americas and the Pacific islands, it was probably one of the children’s diseases. The Indians died in thousands. A population of a hundred thousand shrank to five thousand in the area from Gloucester to New Bedford. “They died on heapes,” Thomas Morton wrote, “and the living that were able to shift for themselves would runne away and let them dy and let there Carkases ly above the ground without buriall.... And the bones and skulls upon the severall places of their habitations made such a spectacle after my comming into those parts that as I travailed in that Forrest, nere the Massachusetts, it seemed to mee a new-found Golgotha.”

Overnight the Indian war had vanished. Overnight the coast from Saco Bay in Maine to Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island lay wide open to European settlements. The cleared fields along the rivers and salt marshes grew up to weeds,27 ready for the spade of the English planter. For twenty miles inland the land was cleared of the Indian menace in precisely the area where they had been most agricultural, in what John Smith had called the “Paradise of all those parts.” The choicest sites for plantations, at the river mouths and along the tidal reaches of Boston Bay, Salem, Gloucester, and Plymouth, were stripped of opposition. Beaver, deer, and codfish multiplied unhindered. Smith’s description of Plymouth, “good harbor, good land and no want of anything but industrious people,” was now doubly true of the whole mainland shore of Massachusetts Bay.

These conditions were confirmed by Captain Thomas Dermer in 1619. Dermer had been associated with John Smith and Ferdinando Gorges in an attempted New England voyage in 1615, and was probably familiar with the coast. He was in Newfoundland in 1618 and there became acquainted with Squanto, who had been living in the household of John Slany in England. Squanto’s European stay was now completed, and someone had brought him out to Newfoundland. Dermer appreciated how valuable he might prove to be in a trading voyage to Massachusetts, and secured permission from Governor John Mason of Newfoundland, and also from Sir Ferdinando Gorges, to use him as a pilot for a Massachusetts voyage.

Arrived in Massachusetts Bay, Dermer wrote: “I passed alongst the coast where I found some ancient Plantations, not long since populous now utterly void, in other places a remnant remaines but not free of sickenesse. Their disease the Plague for wee might perceive the sores of some that had escaped, who describe the spots of such as usually die.” Reaching Plymouth, which, we remember, was Squanto’s home, he28 goes on: “When I arrived at my Savages native Country (finding all dead) I travelled alongst a daies journey Westward, to a place called Nummastaquyt [Nemasket or Middleboro], where finding Inhabitants I dispatched a messenger a dayes journey further west to Poconokit, which bordereth on the sea; whence came to see me two Kings; attended with a guard of fiftie armed men, who being well satisfied with that my Savage and I discoursed unto them—gave me content in whatsoever I demanded.” At Poconokit he “redeemed a Frenchman, and afterwards another at Mastachusit,” victims of shipwreck three years before. What a chronicle these two castaways might have added to Massachusetts history had their memoirs been preserved!

Squanto now found himself the only survivor of those two hundred or more natives of Plymouth whom Martin Pring and Champlain and John Smith had encountered. We note that he brought the Englishmen of Dermer’s party into friendly association with the sachems of Poconokit, which was Massasoit’s village at the mouth of the Taunton River. This was the first friendly contact with Massachusetts Indians in five years, the first since the criminal barbarity of Thomas Hunt had aroused the enmity of the natives in 1614. We can read between the lines what a reconciliation the homecoming of Squanto, himself a victim of that barbarous kidnaping, must have produced among the Wampanoags. For Dermer freed Squanto later, in 1619, and he found his way back to Massasoit before the arrival of the Pilgrims. Whether Sir Ferdinando Gorges or Dermer himself was responsible for this peacemaking gesture, we have no way of knowing, but it seems to have cemented again a long-standing peace between the English and the Wampanoags, which was worth a29 whole battalion of soldiers to the safety of New Plymouth. Captain Thomas Dermer, who probably never heard of the Pilgrims, thus brought them peace. The Indian war was ended.

It is therefore the more tragic that Dermer died of Indian arrow wounds the next year after a battle with Epenow of Martha’s Vineyard, an Indian captive who had not made peace with the English. Had Epenow, instead of Squanto, lived at Plymouth, history might have run quite differently. Captain Thomas Dermer may be considered the first of the Plymouth martyrs, who lost his life after saving a New Plymouth that did not yet exist, though the Mayflower was on its way when he died.

It is a strange commentary on the justice of history that the men who had spent their lives on New England colonization had almost no share in the first successful plantation in Massachusetts. We have seen what an outpouring of futile struggle men like Gorges and Smith and Dermer had expended on the failures that set the stage for the Pilgrims. It was now to fall to the lot of a group of English exiles, who had lived twelve years in the Netherlands, to arrive by accident in Massachusetts at the precise moment when the merchant adventurers, whom they despised, had succeeded in producing the conditions for success. The Pilgrim legend is well founded, in the tribute it pays to the forthright courage and persistence of the forefathers, but it ignores their utter dependence on the maritime renaissance of England as the foundation on which their success rested. The line of succession stemming from the exploits of Drake and Hawkins and the ships that sank the Armada carried directly on into the efforts of Gosnold, Pring, Gorges, Smith, Hobson, and Dermer to set the stage30 for Plymouth. The fur trade and the fisheries by which New Plymouth finally paid off its creditors had been painstakingly developed by many hazardous years of experiment by small shipowners of Bristol and Plymouth and other smaller havens in the west of England. Faith in New England ventures, so nearly destroyed by the Sagadahoc failure, had been kept alive and sedulously cultivated by a little group of earnest men around Gorges and John Smith, so that money could be available to finance even the risky trading voyages necessary to keep a foothold on the coast. We have seen how recently peace had been made with the Indians.

The Pilgrims ascribed all these blessings to acts of Providence in their behalf. But Providence has a way of fulfilling its aims through the acts of determined men. Any visitor to Plymouth who reveres the Pilgrims should also honor those representatives of the glorious maritime energies of the Old World whose discoveries and explorations prepared the way for permanent settlement. To them also applies the phrase which Bradford used of the Plymouth colonists:

“They were set as stepping-stones for others who came after.”

Punctuation, hyphenation, and spelling were made consistent when a predominant preference was found in the original book; otherwise they were not changed.

Simple typographical errors were corrected; unbalanced quotation marks were remedied when the change was obvious, and otherwise left unbalanced.

Illustrations in this eBook have been positioned between paragraphs and outside quotations.