By ROBERT F. YOUNG

Illustrated by SUMMERS

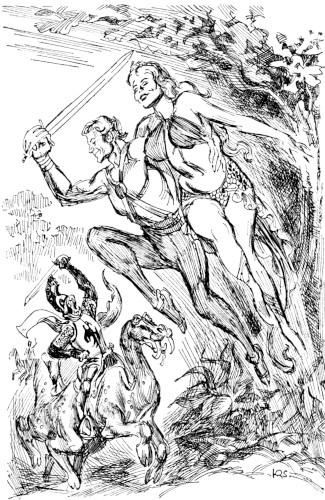

The Tarks were attacking, the bosomy princess

was clinging to him in terror, and Harold Smith

realized he was at the end of his plot-line.

What a dilemma! And what an opportunity!!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories July 1962.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

For the most part, all Harold Worthington Smith's Martian stories ever netted him were standard rejection slips, but every now and then one or another of the editors to whom he submitted them would pen him a brief note to the effect that his writing indicated an unusually vivid imagination. However, they invariably added, his dialogue was stilted, his heroines were dimensionally impossible, and his stories were wish-fulfillment reveries in a Burroughs vein—unredeemed, unfortunately, by Burroughs' high-flown puritanical idealism.

Harold agreed with them wholeheartedly on point no. 1. Thanks to his ability to achieve total identification with his protagonists, he did have an unusually vivid imagination. Take this very minute, for instance: His main character—Thon Carther the Earthman—was standing on the ocher moss of the Martian dead-sea bottom beside the big-breasted blond princess whom he had rescued from Tarkia some two thousand words ago, fearlessly awaiting the oncoming horde of Tarks. But it wasn't really Thon Carther who was standing there, it was Harold Worthington Smith—a tall, tanned and handsome Harold Worthington Smith, to be sure, but Harold Worthington Smith just the same.

On points no. 2 and 3, however—be it said forthwith—he did not agree. He had, moreover, written to the editors in question and said so. A Burroughs influence, he had said, was an essential ingredient in the makeup of any science-fiction writer, and he was reasonably certain that he didn't exhibit one any more than half a dozen other scribes he could name. And as for his heroines being dimensionally impossible, such an attitude merely betrayed an inherent geocentricism: simply because 46-21-46 females didn't exist on Earth was no reason to take it for granted that they didn't exist on Mars. (He discreetly avoided any reference to point no. 4: there were times when he wondered about his dialogue himself.)

It was a warm afternoon in August. His wife had gone to visit her sister, giving him temporary respite from her nagging, and there was no sound in the apartment except the steady hum of the electric fan and the sporadic clacking of the ancient typewriter. Altogether it was one of those rare moments when it was possible for his imagination to take over completely. It was, in fact, though he was not yet aware of it, the climactic moment in his career as a creative writer.

The Tark horde was rapidly closing in, and Thon Carther/Harold Worthington Smith decided it was high time he drew his sword. Clackety-clack-clack. The blond princess, who hailed from the triple cities of Hydrogen and whose name was Thejah Doris, moved closer to him, and her golden shoulder brushed his sinewy arm. A tingling phalanx of thrills charged up and down his backbone. Clack-clackety-clack. Clack!

"Fear not, my princess," he said. "This noble sword has tasted the blood of many a Tark and is keen for the taste of the blood of many more!"

"My chieftain," she breathed, moving even closer.

He hefted the big sword, and the rays of the declining sun danced brightly on its burnished surface. For all its size, it was as light as a yardstick in his big brown masculine hand. The foremost Tark rider was very close now. Startlingly close, Thon-Smith realized with a start—and startlingly realistic. The malevolent green features stood out with dismaying clarity, and the tusks of the elongated eyeteeth gleamed with terrifying vividness.

Wildly Thon-Smith felt for his typewriter. Next he felt for his desk. Finally he looked around him for the familiar walls of the apartment. They, too, had disappeared. A shudder shot through his tall, tanned body. Something awful had happened.

Something even more awful was going to happen if he didn't do something and do it soon, for the Tarks, looming building-tall astride their six-legged mounts, were almost upon them. He remembered the plot just in time, and seizing Thejah Doris around her slender waist, he gave a mighty leap that carried them—thanks to the tenuous Martian gravity—over the entire green horde to a resilient section of the dead-sea bottom a hundred feet behind the rearmost rider. It was, he reflected, somewhat of a deus ex machina stratagem now that he came to think of it; but now was no time to be hyper-critical.

The Tark horde had become a milling mass of chlorophyllic bodies, white tusks and squealing mounts. The warriors in the front ranks had tele-reined their toats before those in the middle ranks had wised up to what had happened, and those in the rear ranks still hadn't wised up. Chaos reigned. Thon-Smith was not slow to take advantage of the situation which he had so fortuitously provided. He was still upset over his missing typewriter, his missing desk, and his missing apartment, not to mention his missing civilization, but there would be time for reconnaissance later. Right now there was the little matter of Escape to be taken care of.

Briefly he referred to his mental synopsis of the plot. Oh, yes, there was an atmosphere boat hidden in the mound of desiccated algae before which his leap had conveniently terminated. (Another deus ex machina stratagem, he thought with annoyance; but again he reminded himself that now was no time to be quibbling over the literary aspects of the situation.)

"Come, my princess," he said, taking Thejah Doris' arm.

"Lead on, my chieftain!"

The atmosphere boat was there, just as he had visualized it. After uncovering it, they boarded its narrow deck, and soon they were rising into the darkening sky, once again thwarting the Tarks, who had reorganized their ranks and were charging with redoubled ferocity toward the mound.

Thejah Doris lay down beside him on the comfortable pilot's couch. "At last we are alone!" she breathed in her Martian-Hungarian accent.

Reconnaissance could wait, Thon-Smith decided quickly. There were worse fates after all than writing oneself so completely into one's stories that one could not extricate oneself. "My princess," he said, directing the prow of the atmosphere boat toward the littoral of an ancient continent and slipping his arm beneath her bare shoulders.

Immediately there came a frenzied scratching from the small forward cabin, and before he could even gain his feet a great eight-legged creature with multi-fanged, slavering jaws leaped upon him and began caressing his face with its long tongue. His faithful Droola! He winced. He'd forgotten all about his faithful watchdog. But a plot was a plot, and like any other scheme of things you had to go along with it. "Droola," he said. "Good old faithful Droola!"

Presently the nearer moon appeared and began its hurtling journey across the night sky. Stars winked into cold clean brightness. The atmosphere boat reached the mainland, floated over shadow-filled ravines and moon-kissed hilltops. The argent ribbon of a canal showed in the distance.

Thon-Smith's heartbeat quickened as he thought of the next sequence. He could hardly wait till the canal was beneath them, till the time came to guide the boat down to the argent sward that bordered the farther bank. He stepped lightly down to the soft turf and lifted Thejah Doris down beside him. He answered her questioning eyes: "A swim will refresh us, my princess. It will sharpen our senses and re-double our chances of eluding our persistent pursuers."

"But I cannot swim, my chieftain."

The externals did not call for a leer at this point; nevertheless, he had a hard time averting one. "Fear not, my princess," he said. "I, Thon Carther, will instruct you."

They walked together to the bank and stood there hand in hand. Behind them, Droola leaped from the deck and went romping up and down the esplanade. The nearer moon was high in the sky now, and the farther moon was just beginning to show above the hills. "First," Thon-Smith said, "we must remove our accouterments. They will weigh us down in the water and make movement well nigh impossible."

"All of them, my chieftain?"

"Yes, my princess, all of them."

She raised her hand to the gossamer thread that held her Martian equivalent of a halter in place. Abruptly the muffled thunder of padded toat hooves sounded in the distance.

Her hand dropped like a stone. "The Tarks!" she cried. "Oh, my chieftain, the mortal enemies of my people are close upon our heels!"

He choked back his disappointment. How could he have forgotten? He, the author, the creator! "Quickly," he said, seizing her arm. "Into the atmosphere boat. The canal will not stop them!"

By the time they gained the deck the foremost rank of the Tark horde had reached the opposite bank. The green warriors did not pause for so much as a second, but goaded their mounts into the water. Once in the canal, Tark and toat became as one, and the horde took on the aspect of a school of gigantic green porpoises, leaping in and out of the water with incredible swiftness, reaching the other bank in a matter of minutes. But by then Thon-Smith and Thejah Doris were rising once again into the night sky. The romping Droola discovered their departure just in time, and with a mighty leap managed to gain the after deck and scramble to safety.

As soon as the craft gained sufficient altitude Thon-Smith threw it into fast-flight and aligned the prow with the canal bank. The cool night air became a cold wind and the countryside blurred beneath them. He maintained the speed till he was sure their pursuers could no longer overtake them, then he cut down to slowflight and returned his attention to Thejah Doris.

She was lying on her side, gazing at him admiringly. Again he slipped his arm beneath her shoulders, but he had no sooner done so when Droola, still shivering from the wind of fast-flight, bounded forward and snuggled between them.

The interruption was essential to the story's word count, but just the same it was frustrating. Even Thejah Doris looked put out, though she didn't say anything. Instead, she turned and reclined upon her back, hands clasped behind her head, and let the two moons vie with one another to do justice to her charms. It was an interesting contest to watch, and soon Thon-Smith became engrossed. He became so engrossed, in fact, that he failed to see the tower till it was too late.

It was a tall tower—remarkably tall when you considered the altitude of the atmosphere boat. He yanked the tiller savagely, but their momentum was too great, and a moment later the bow crumpled against stone. The deck tilted abruptly, and he barely managed to grab Thejah Doris before she tumbled over the low rail, and it was all he could do to maintain his balance till the rapidly sinking craft came opposite the dark aperture of a window. He leaped lightly to the sill, his Martian princess in his arms, and stepped into the musty gloom of a lofty chamber.

The faithful Droola was not so fortunate. It essayed the leap, but missed the sill by a good two feet. (He'd been planning on getting rid of Droola for a long time.) Dutifully he listened for the sound of the faithful body striking the ground, but when, an appropriate time later, the sound came, he could not summon the emotional response which the plot called for. All he could manage was a sort of vague contrition which was immediately negated by the realization that at last he and Thejah Doris were really alone.

She had discovered tapers on the dusty shelves that lined one wall of the chamber, and now she lit three of them and set them upon the rough wooden table that stood in the middle of the stone floor. "There is nothing to fear, my chieftain," she said. "This is one of the deserted locktowers once maintained by the ancient Mii when Mars was young and great barges plied her blue canals. Above us is the control room itself, from which the mighty locks, now rusted and fallen to ruin, were manipulated by the ancient Miian tenders. Now the towers stand silent and forlorn, the havens of occasional wandering bards who find the lofty rooms and empty echoing stairways conducive to their search for the ever-elusive Muse."

He stared at her. It was, he had to admit, rather incongruous phraseology to be issuing from the lips of a blonde who, for all her royal blood, still looked more like a burlesque queen than she did a princess. Well, no matter. "You look lovely by candlelight," he said.

"You are very gallant, my chieftain."

She lit another candle and went over and placed it in a wall niche beside an ancient sleeping couch. She turned and faced him. "At last we are alone."

He started toward her, arms outstretched. Simultaneously the thunder of padded toat hooves sounded in the distance.

"The Tarks!" Thejah Doris cried, eluding him and running to the window. "They've seen our light! Oh, my chieftain, the mortal enemies of my people threaten us once again!"

"Oh, for Pete's sake!" Thon-Smith said, throwing up his hands. "No wonder my stories get bounced!"

Resignedly he went over and joined her at the window. Sure enough, the Tark horde was back in the running again. Wearily he explored his mind for the next sequence. All he could find were the words, END OF PART ONE. That was when he remembered that he'd been trying his hand at a serial and had neglected to plot it beyond the first installment.

"Oh, my chieftain, what are we going to do?"

He did not answer. He was thinking—thinking furiously. If a writer could write himself so completely into a story that he became physically involved in it, was there any reason why he couldn't extricate himself by writing a factual account of his real life?

It was worth a try. The alternative was to plot Installment Two, and somehow he didn't feel quite up to it. Installment One had been rather an enervating experience.

Abruptly another thought struck him: Why a factual account?

He remembered his dingy little apartment, his dilapidated typewriter, his collection of rejection slips, his nagging, flat-chested wife—Suddenly he looked at Thejah Doris standing beside him with heaving breast, anxiously watching the relentless approach of the Tarks.

Why a factual account indeed!

He concentrated. When he had the plot firmly fixed in his mind he sat down at the table to write. A momentary crises arose. There was no paper, no pen, not even a pencil. Then he remembered what Thejah Doris had said about the wandering bards, and he began searching for a drawer. Even Martian poets needed something to write on. Presently he found one and pulled it out. Sure enough, it contained several sheets of parchment-like paper, a long quill pen and a small vial of black fluid.

The thunder of padded toat hooves was growing louder by the minute. "Oh, my chieftain, what are we going to do!" Thejah Doris cried again.

"We're going to swap serials," Thon-Smith said, and began to write.

It was a fine bright morning. Harold Worthington Smith awoke late and lay for a while watching the robins flitting among the branches of the box elder outside his bedroom window. Then he got up and slipped leisurely into his lounging robe. Yawning, he stepped across the hall to his study. Below him in the kitchen his wife was humming happily, and he could smell coffee perking, wheatcakes frying and sausage sizzling.

He entered his study and walked over to the desk. He sat down. There were three long thin letters lying beside his solid gold typewriter where his wife had placed them. He opened them nonchalantly. The first one was from The Edgar Rice Burroughs Reader and contained a check for $750.00, the second was from Dead-Sea Bottom Stories and contained a check for $2500.00, and the third was from Red Planet Stories and contained a check for $5000.00.

The phone rang. He picked it up. "HWS speaking."

"Good morning, sir. This is Parker, of Mammalian Blonde Stories. Regarding that last piece you were kind enough to let us have a look at, would $10,000.00 be—"

"Sorry," Harold Worthington Smith said, "I never discuss business matters before breakfast. Call me back later."

Click.

"Harold," his wife called from the foot of the stairs, "there's an editor outside."

"Another one?"

"Yes. Shall I let him in?"

"I suppose so. Tell him I'll try to give him a minute while I'm having my coffee."

He stacked the checks neatly and placed them on the large pile of checks to the right of the gold typewriter. He made a mental note to try to make the bank today. Checks were a nuisance when you let too many of them accumulate. He threw the three long thin envelopes into the wastebasket marked "Long Thin Envelopes." It was full again, he noticed. He could have sworn he'd just emptied it a day or two ago.

His wife came running up the stairs. "Harold, two more editors just drove up! Shall I let them in, too?"

"You might as well," Harold Worthington Smith said. "If you don't, they'll just hang around the door all day and make a nuisance of themselves." He looked at her critically. She'd come through remarkably well. If anything she was even better stacked than she'd been before. "Tell them I'll be down presently, princess. And put some clothes on. For now," he added.

After she had gone he looked the study over carefully. When he was sure that no traces of his previous reality were present he descended slowly and majestically to the hall where the three editors humbly awaited him.

THE END