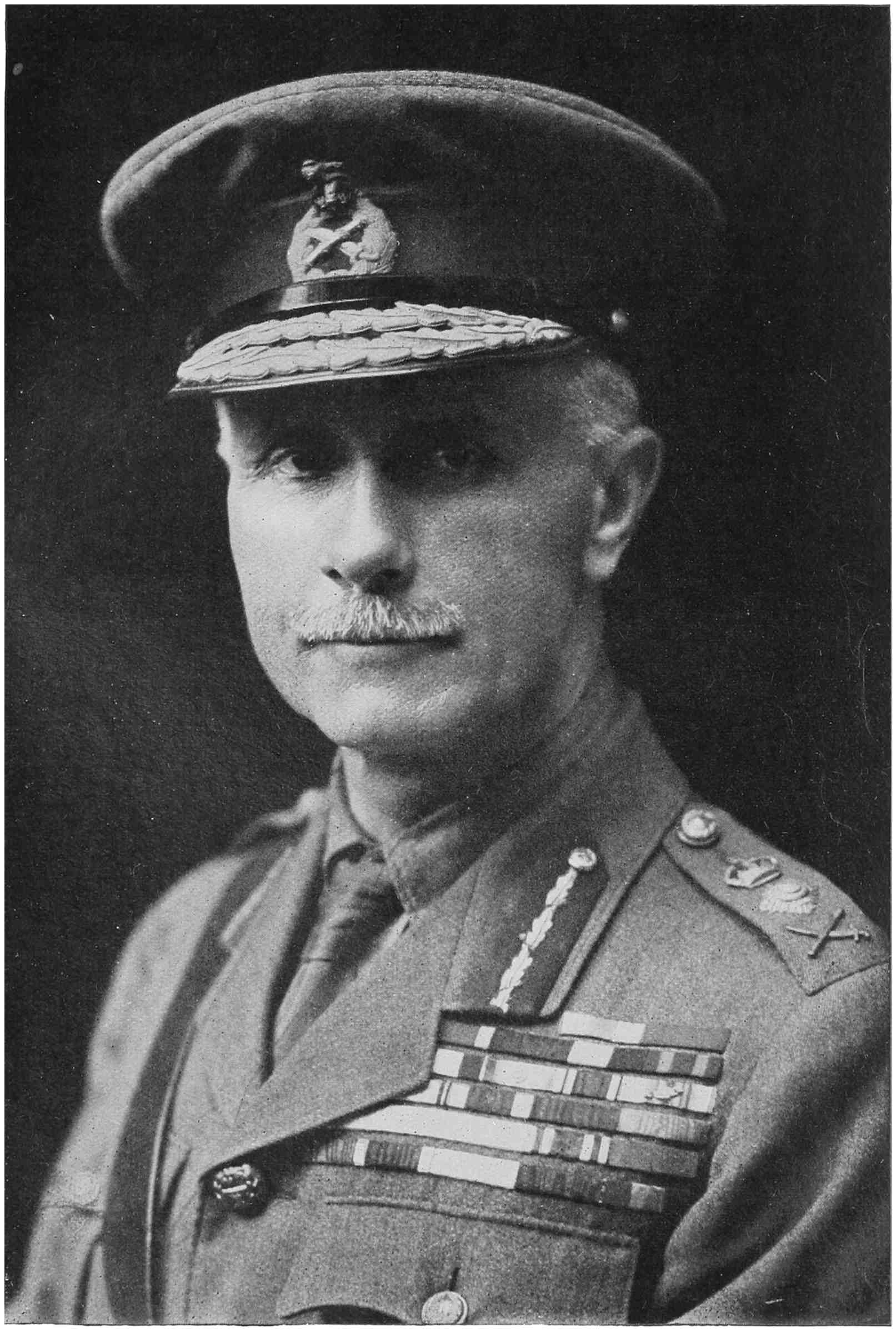

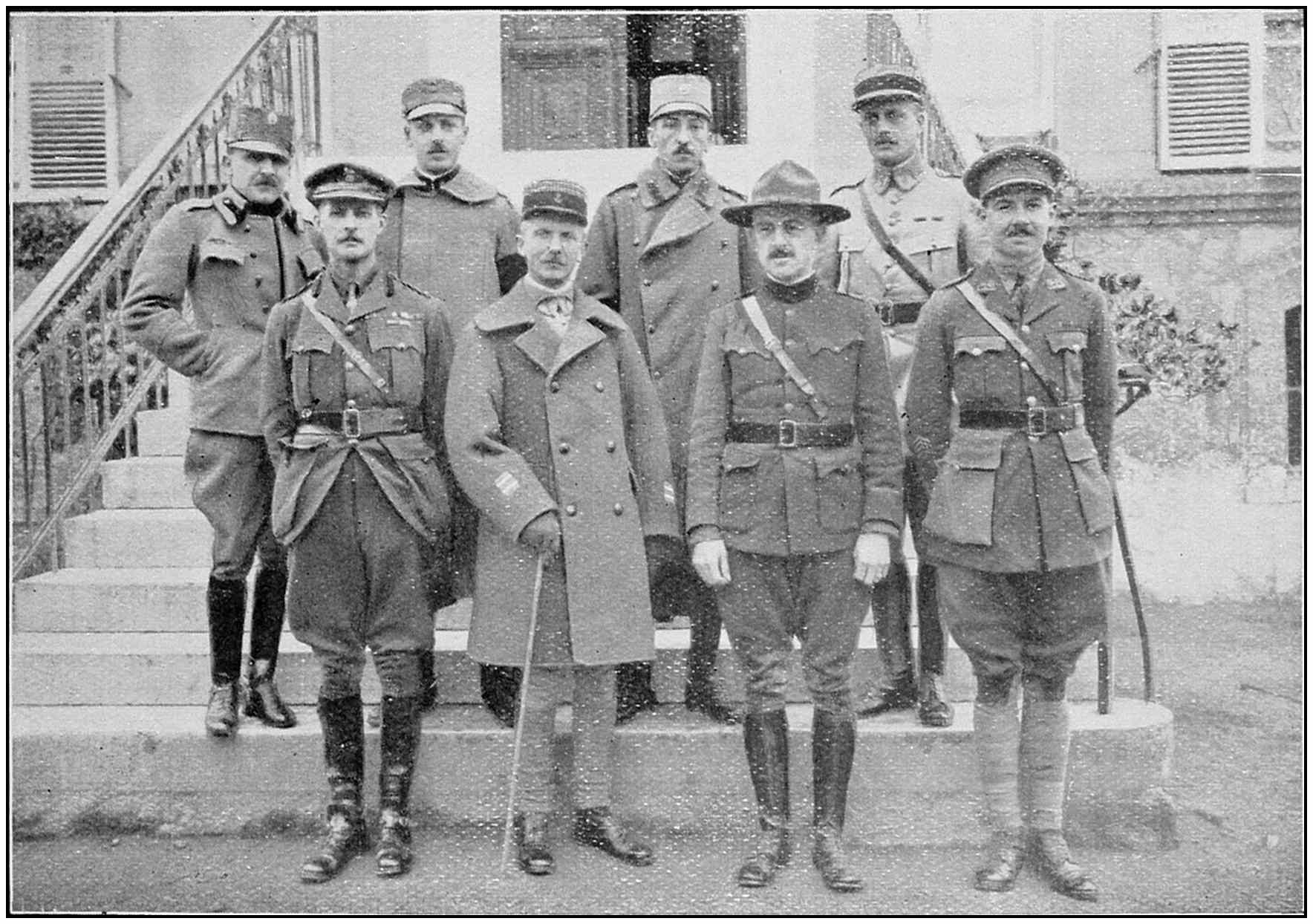

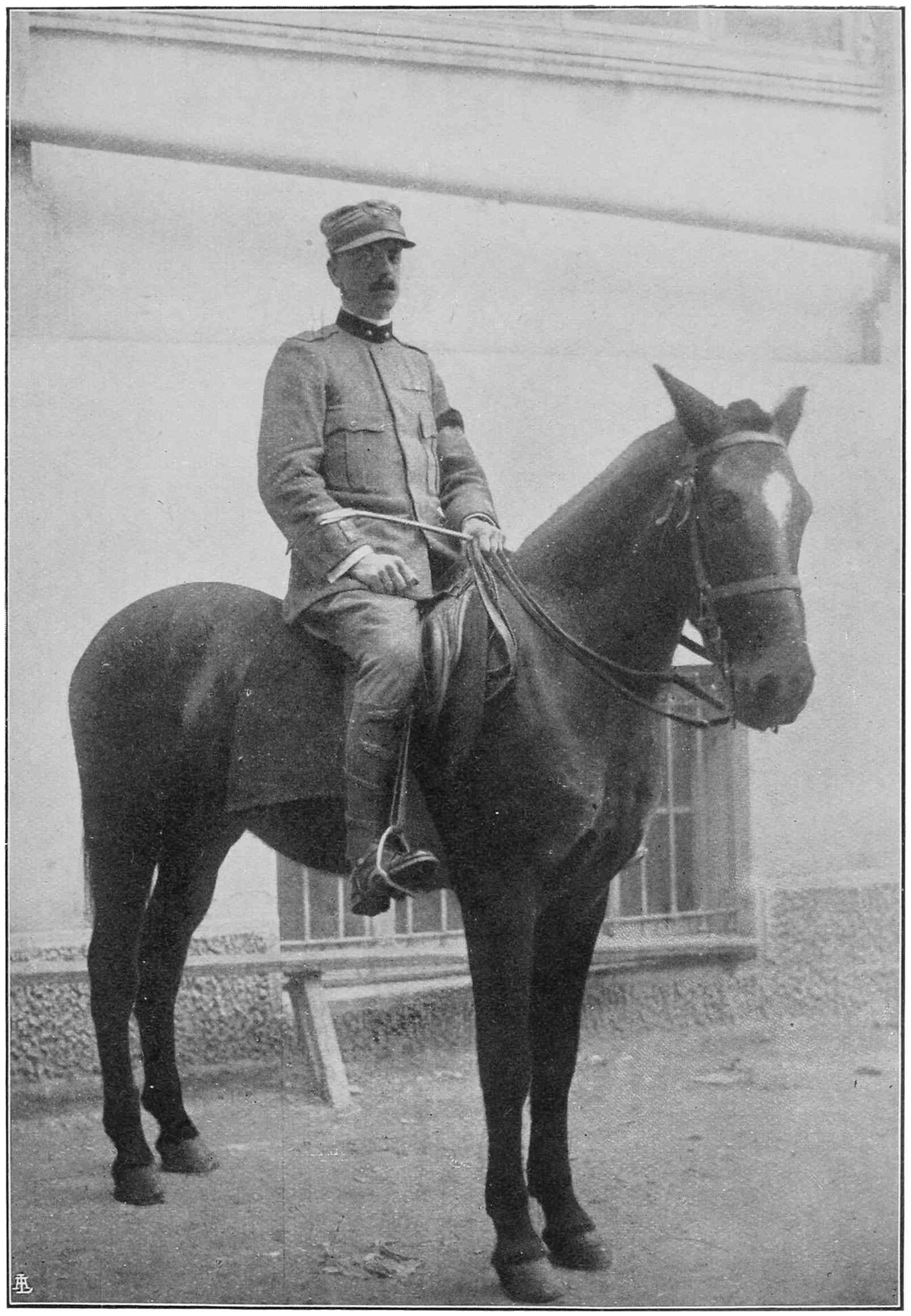

GENERAL SIR G. F. MILNE.

Frontispiece.

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

Cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain. It combines the original cover with the original title page.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF

GIROLAMO SAVONAROLA

By Professor Pasquale Villari

Translated by Linda Villari

Illustrated. Cloth, 8s. 6d. net

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF

NICCOLO MACHIAVELLI

By Professor Pasquale Villari

Translated by Linda Villari

Illustrated. Cloth, 8s. 6d. net

T. FISHER UNWIN LTD LONDON

GENERAL SIR G. F. MILNE.

Frontispiece.

THE MACEDONIAN

CAMPAIGN By LUIGI

VILLARI With Illustrations and Maps

T. FISHER UNWIN LTD

LONDON: ADELPHI TERRACE

First published in English 1922

(All rights reserved)

5

The operations of the Allied forces, and in particular those of the Italian contingent in Macedonia, are less well known than those of almost any other of the many campaigns into which the World War is subdivided. There have already been several published accounts of it in English and French, but these works have dealt almost exclusively with the action of the British or French contingent, and are mostly of a polemical or journalistic character; very little has been written about the other Allied forces, or about the campaign as a whole. Owing to the position which I held for two years as Italian liaison officer with the various Allied Commands in the East, I have been able to collect a good deal of unpublished material on the subject, and I felt that it might be useful to give a consecutive account of these events, correcting many inaccuracies which have been spread about. The book was written originally in Italian, and dealt in particular detail with the operations of the Italian expeditionary force. In the present English edition I have omitted certain details concerning the Italian force, which were of less interest for a non-Italian public, while I have added some further material of a general character, which I only obtained since the Italian edition was written.

The published authoritative and reliable sources for the history of the Macedonian campaign are very few. A bibliography is appended. Besides my own notes6 and recollections of the events, set down day by day, and the records of various conversations which I had with the chief actors in the Balkan war drama, I must acknowledge the valuable assistance afforded to me by various Italian and foreign officers and officials. My especial thanks are due to the following:

General Petitti di Roreto, for information on the events of the early period of the campaign;

General Ernesto Mombelli, who supplied me with a great deal of useful information and advice on the latter period;

Colonel Vitale, under whom I worked for some time, and who first instructed me in the duties of a liaison officer;

Colonel Fenoglietto, who kindly provided a part of the photographs reproduced in the book;

Commendatore Fracassetti, director of the Museo del Risorgimento in Rome, who kindly placed a large number of photographs at my disposal, authorizing me to make use of them;

Captain Harold Goad, British liaison officer with the Italian force from soon after its landing at Salonica until it was broken up in the summer of 1919, who supplied me with many details concerning the topography of the Italian area of the Macedonian front, which he knew stone by stone, and his notes and recollections of many political and military episodes. Few men have done such admirable and disinterested work in favour of good relations between Britain and Italy, both during and after the war, as this officer, who was most deservedly decorated with the Italian silver medal for valour in the field.

L. V.

7

| PAGE | ||

| PREFATORY NOTE | 5 | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | INTRODUCTION—REASONS FOR THE MACEDONIAN CAMPAIGN AND FOR THE PARTICIPATION OF ITALY. POLITICAL INTRIGUES AND FIRST MILITARY OPERATIONS | 11 |

| II. | OPERATIONS IN THE SUMMER AND AUTUMN OF 1916 | 36 |

| III. | THE COMMAND OF THE ALLIED ARMIES IN THE ORIENT. THE FRENCH TROOPS | 56 |

| IV. | THE BRITISH SALONICA FORCE | 68 |

| V. | THE SERBIANS | 85 |

| VI. | THE ITALIAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE | 96 |

| VII. | OPERATIONS IN THE WINTER AND SPRING OF 1917 | 118 |

| VIII. | GREEK AFFAIRS | 137 |

| IX. | SALONICA AND THE WAY THITHER | 157 |

| X. | IRRITATION AGAINST GENERAL SARRAIL | 171 |

| XI. | FROM THE SALONICA FIRE TO THE RECALL OF SARRAIL | 179 |

| XII. | GENERAL GUILLAUMAT | 191 |

| XIII. | MARKING TIME. ARRIVAL OF GENERAL FRANCHET D’ESPÉREY | 199 |

| XIV. | ON THE EVE OF THE OFFENSIVE | 2118 |

| XV. | THE BATTLE OF THE BALKANS | 225 |

| XVI. | FINAL OPERATIONS | 255 |

| APPENDIX A. LETTER FROM VOIVOD MICHICH TO GENERAL PETITTI DI RORETO CONCERNING THE FIGHTING ON HILL 1050 IN FEBRUARY 1917 | 271 | |

| APPENDIX B. LOSSES OF THE BELLIGERENTS DURING THE MACEDONIAN CAMPAIGN | 272 | |

| APPENDIX C. GENERAL FRANCHET D’ESPÉREY’S TELEGRAM TO THE FRENCH GOVERNMENT CONCERNING THE ARMISTICE NEGOTIATIONS WITH BULGARIA | 273 | |

| APPENDIX D. ARMISTICE BETWEEN THE ALLIES AND BULGARIA, SIGNED AT SALONICA ON SEPTEMBER 29, 1918 | 274 | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 277 | |

| INDEX | 279 | |

9

| GENERAL SIR. G. F. MILNE Frontispiece | |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

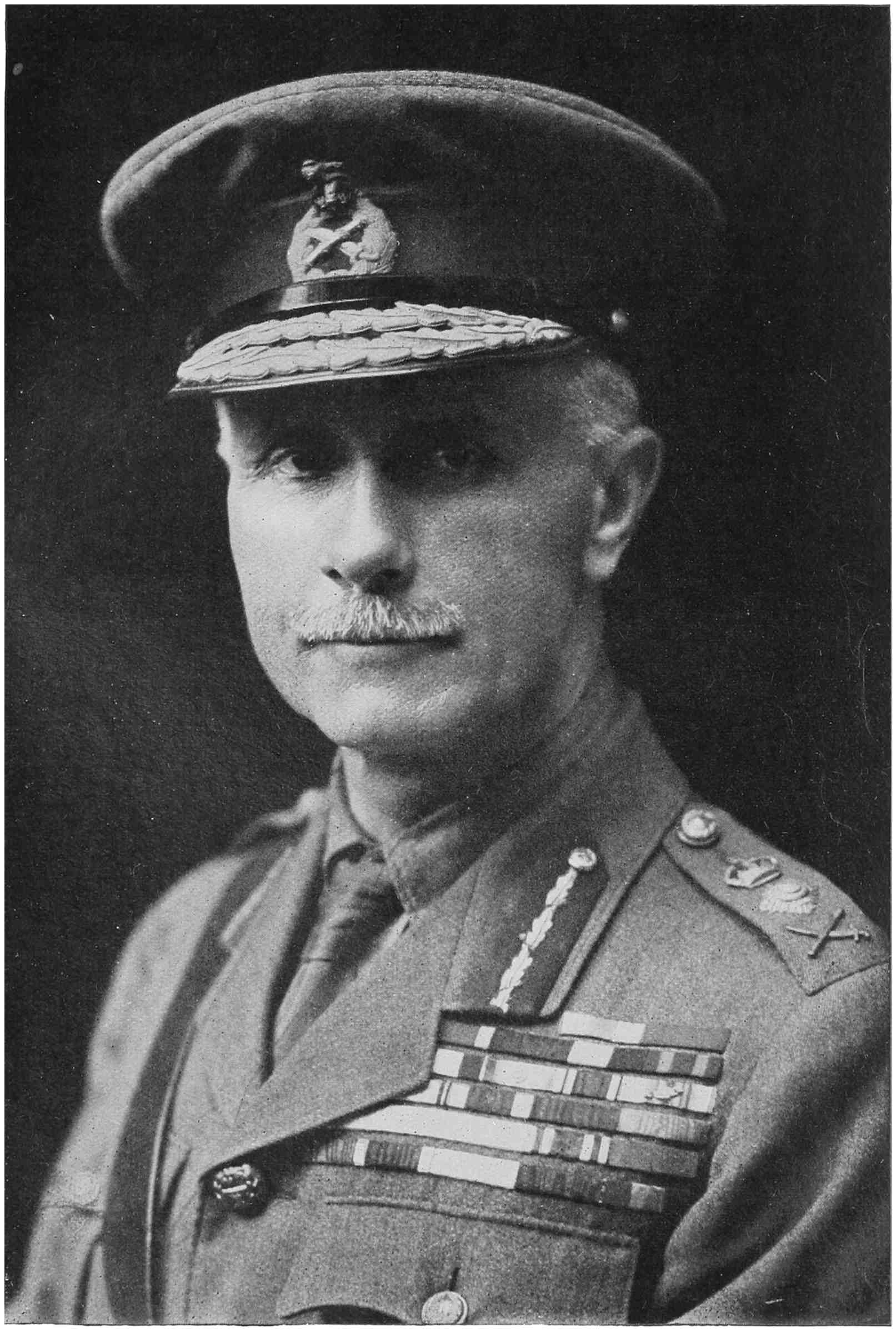

| GENERAL ERNESTO MOMBELLI, COMMANDER OF THE ITALIAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE IN MACEDONIA | 10 |

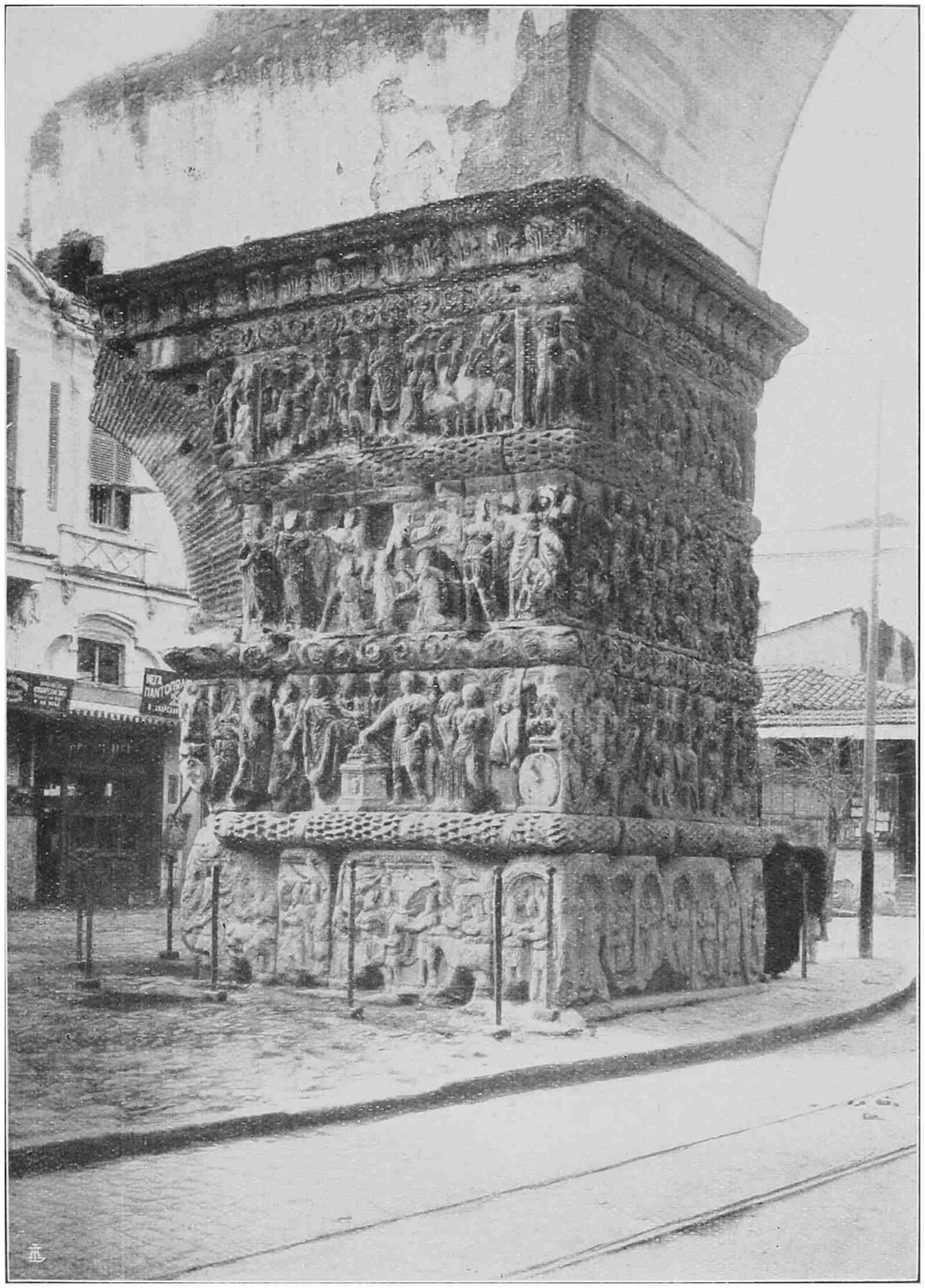

| ARCH OF GALERUS, SALONICA | 20 |

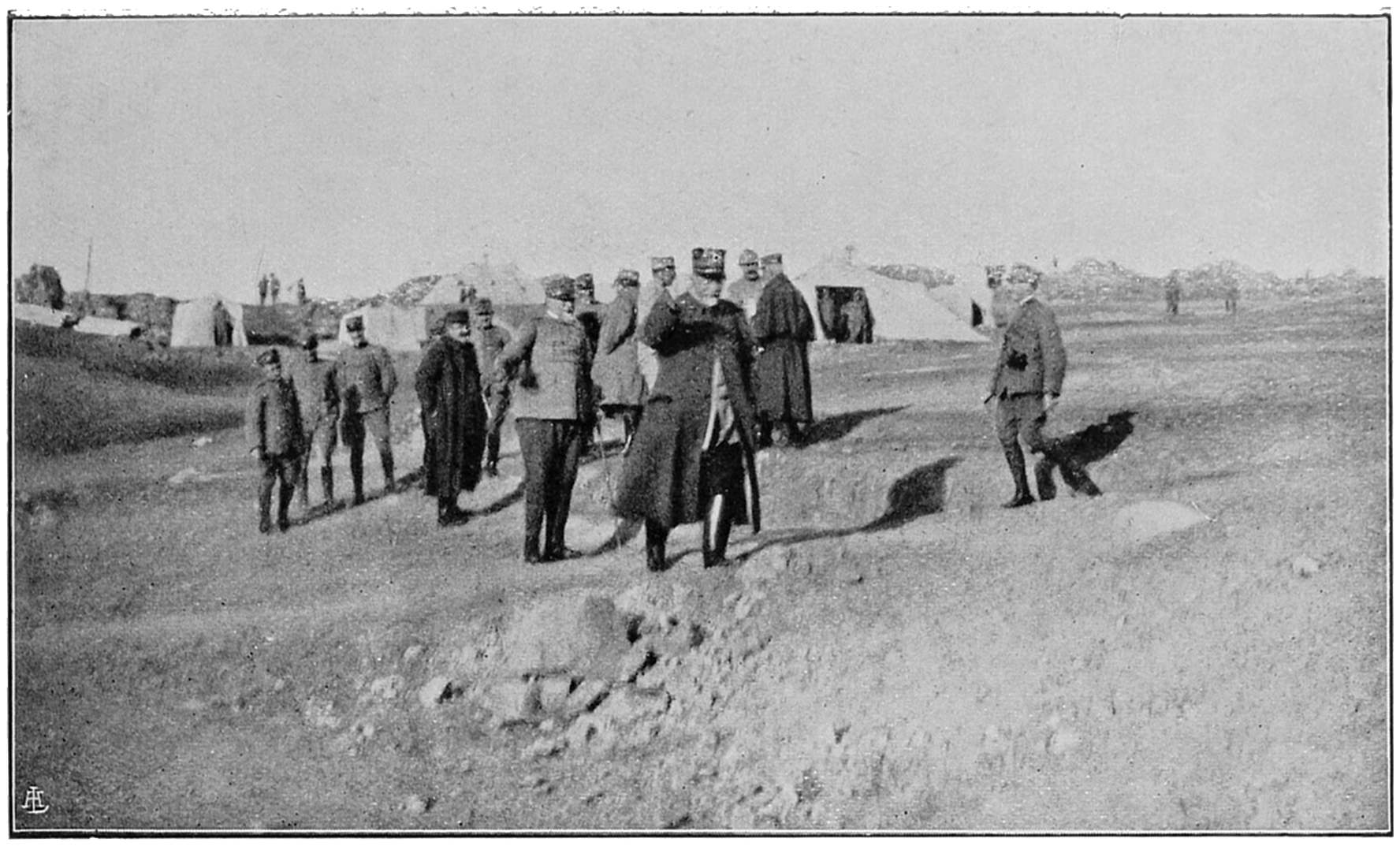

| GENERAL LEBLOIS BIDDING FAREWELL TO GENERAL PETITTI AT TEPAVCI | 38 |

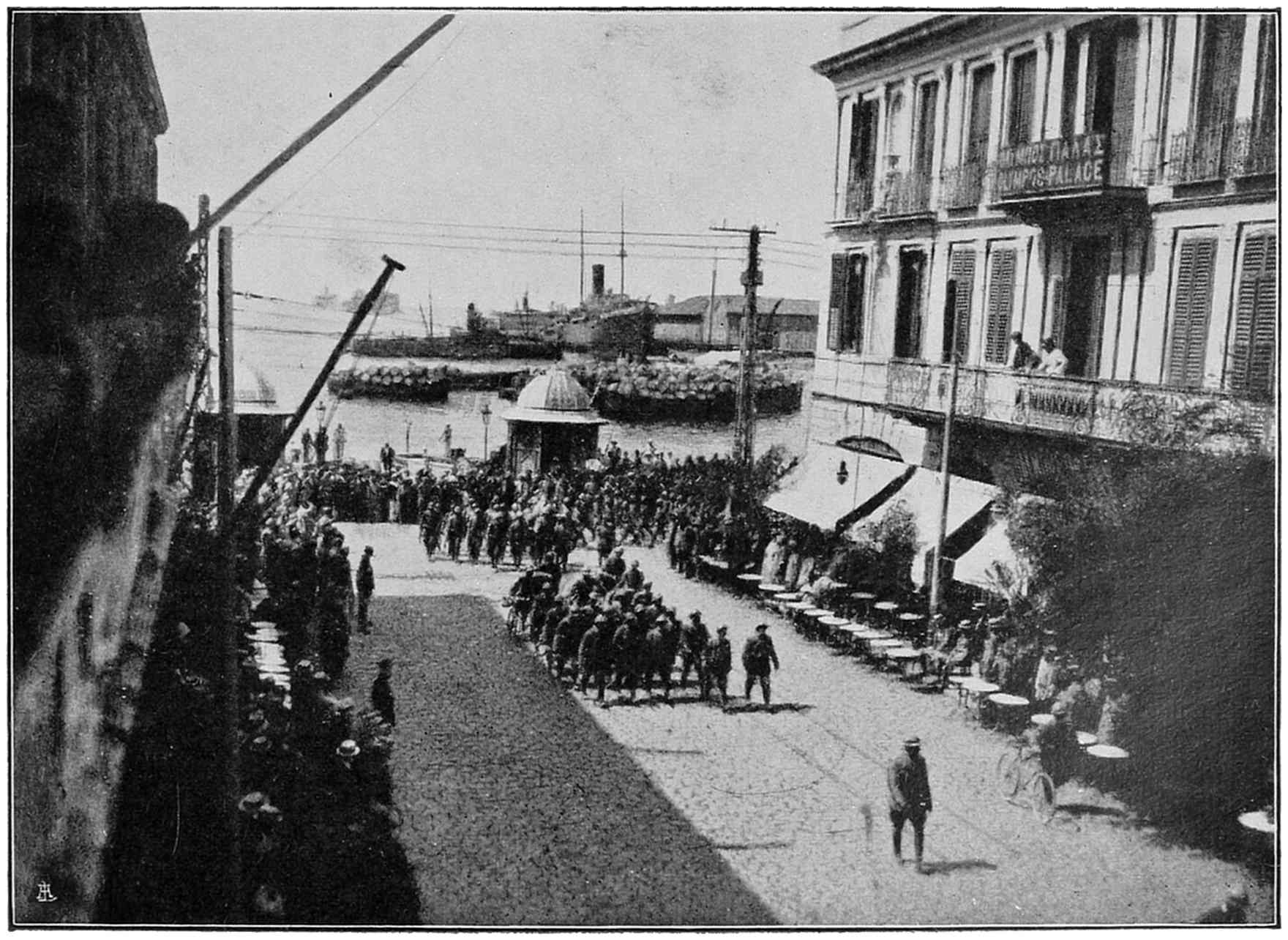

| LANDING OF ITALIAN TROOPS AT SALONICA | 38 |

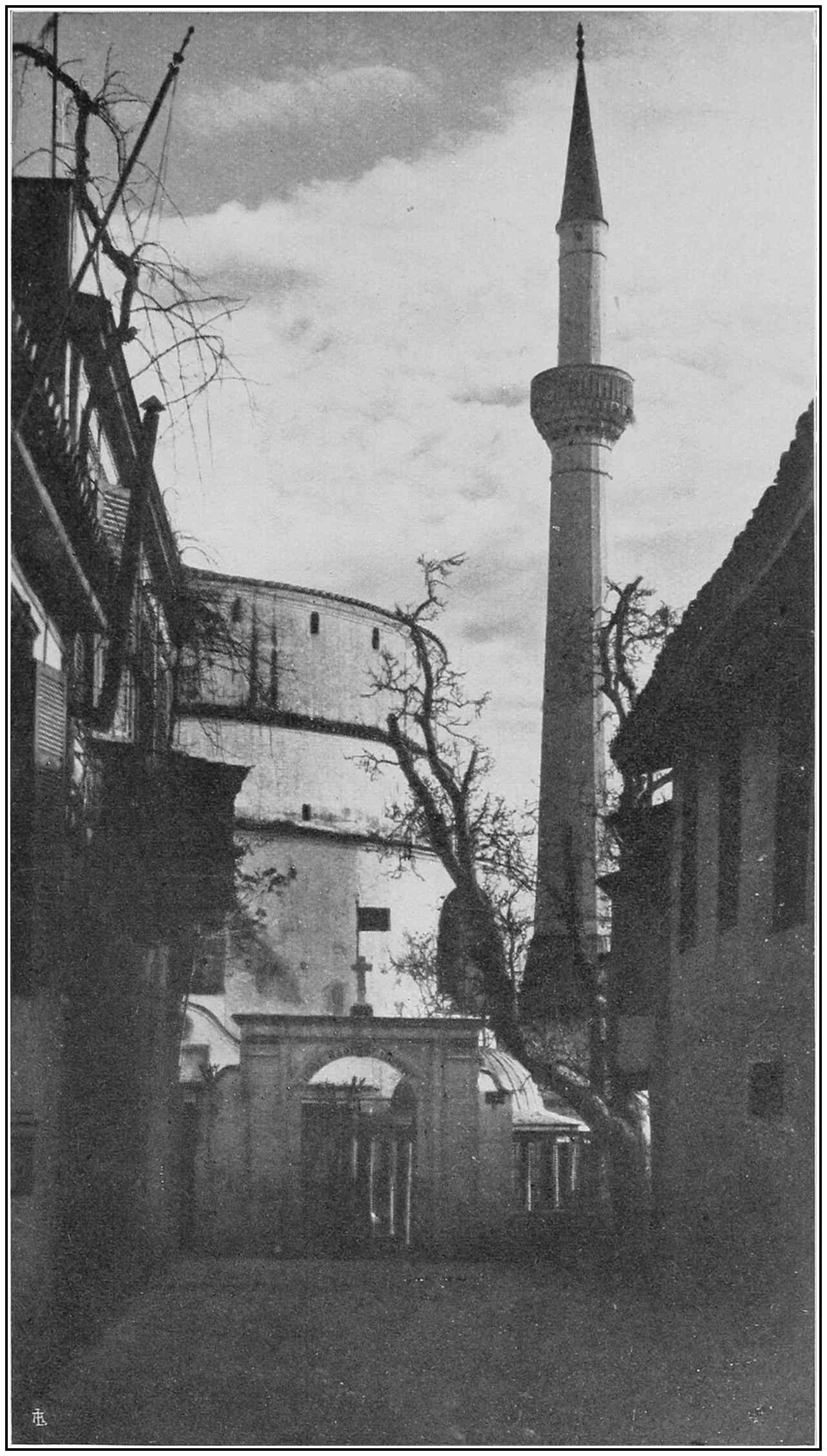

| CHURCH OF ST. GEORGE, SALONICA | 58 |

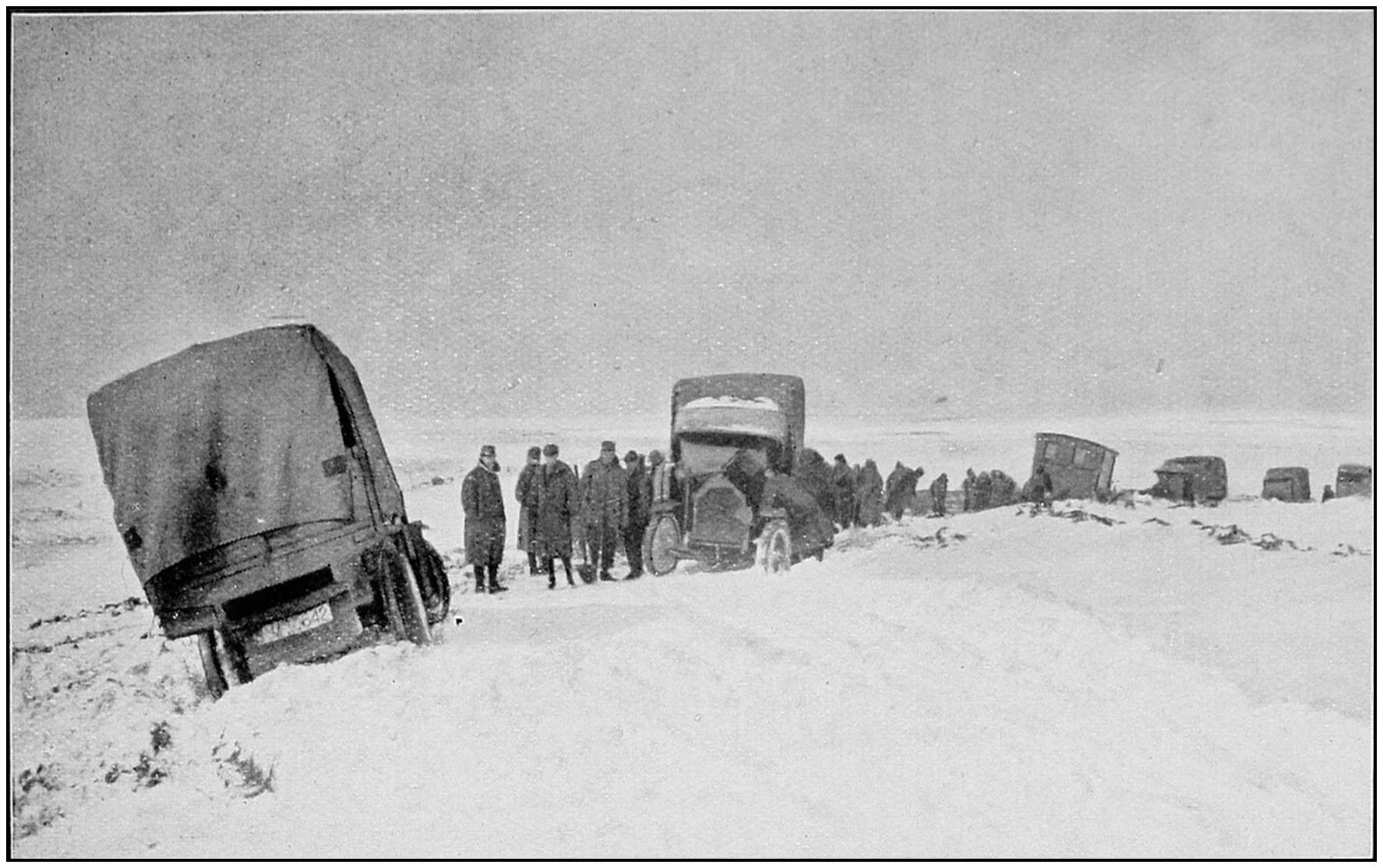

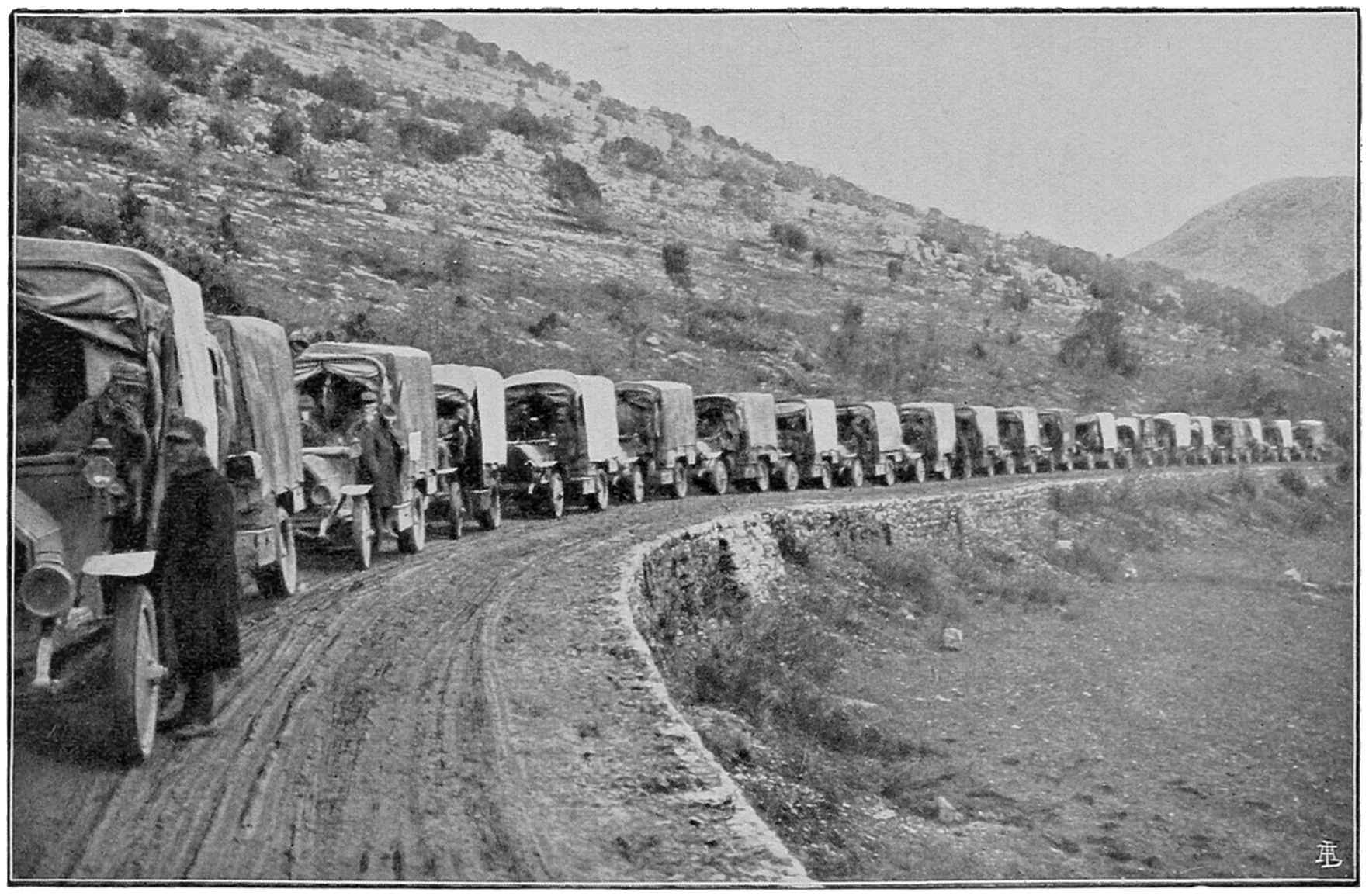

| TRANSPORT IN WINTER | 62 |

| THE ALLIED LIAISON OFFICERS AT G.H.Q., SALONICA | 62 |

| THE AUTHOR | 76 |

| GENERAL MOMBELLI INAUGURATING A SCHOOL FOR SERB CHILDREN BUILT BY ITALIAN SOLDIERS AT BROD | 88 |

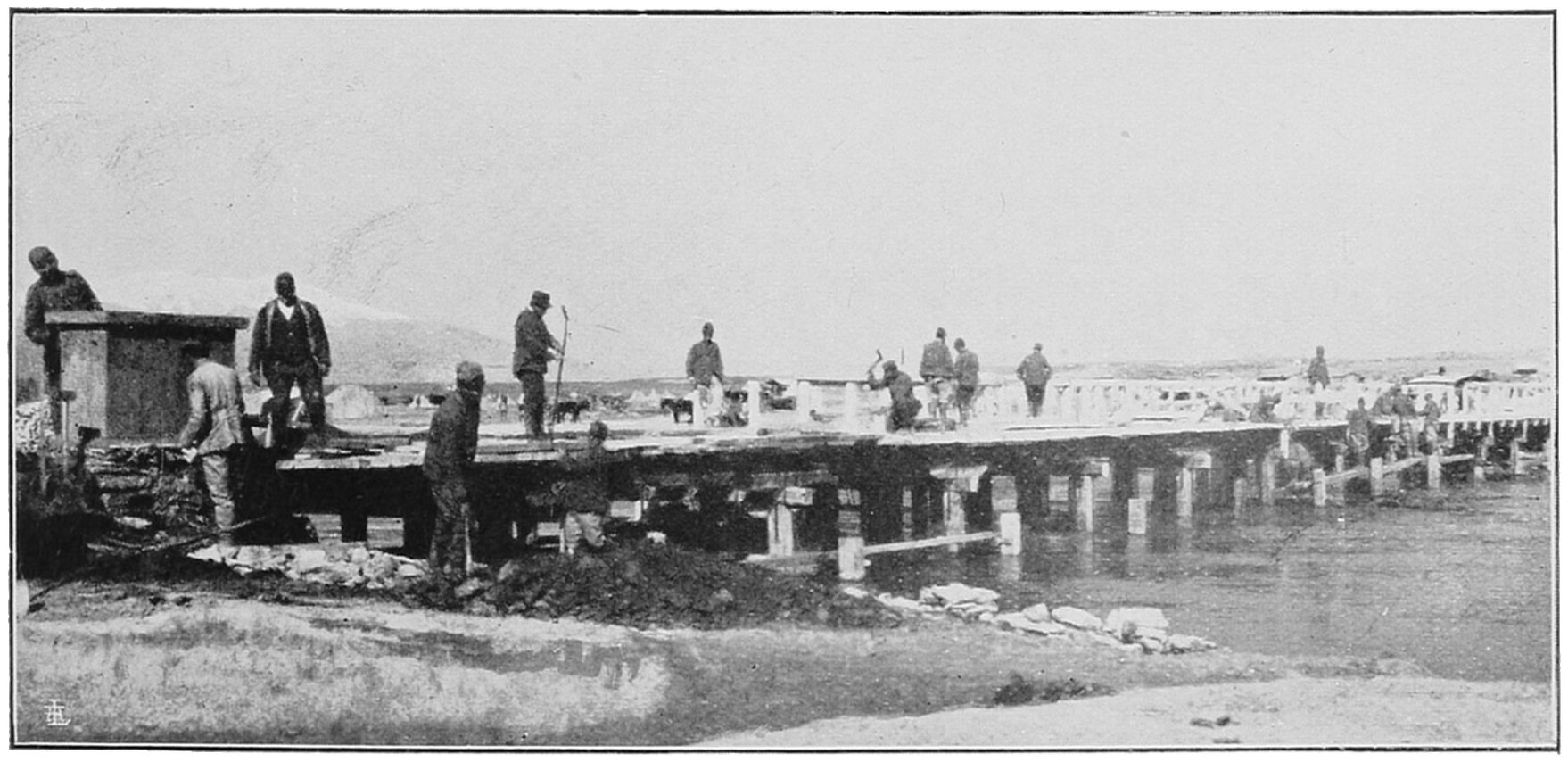

| ITALIAN BRIDGE OVER THE CERNA AT BROD | 88 |

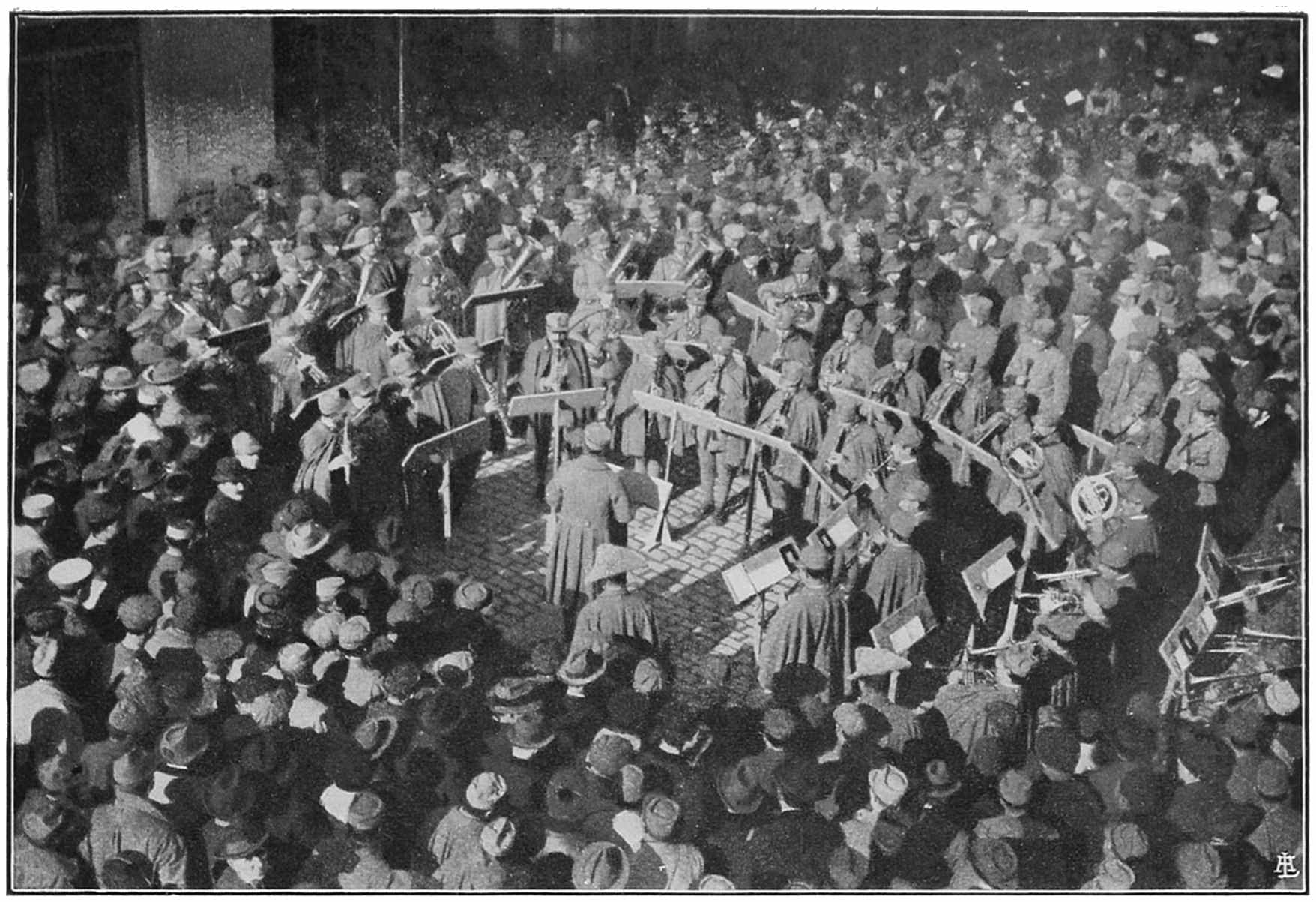

| THE BAND OF THE 35TH DIVISION PLAYING IN THE PLACE DE LA LIBERTÉ AT SALONICA | 102 |

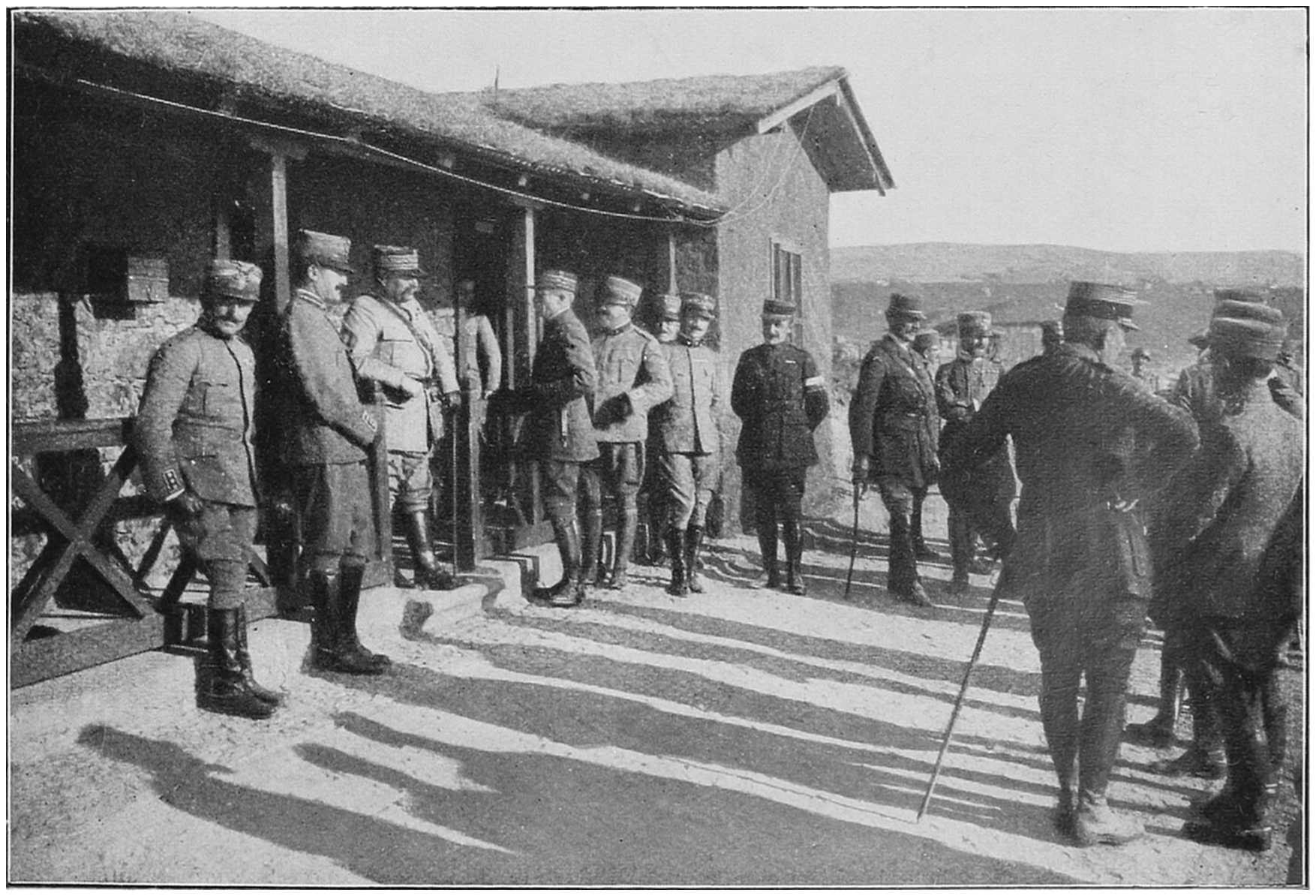

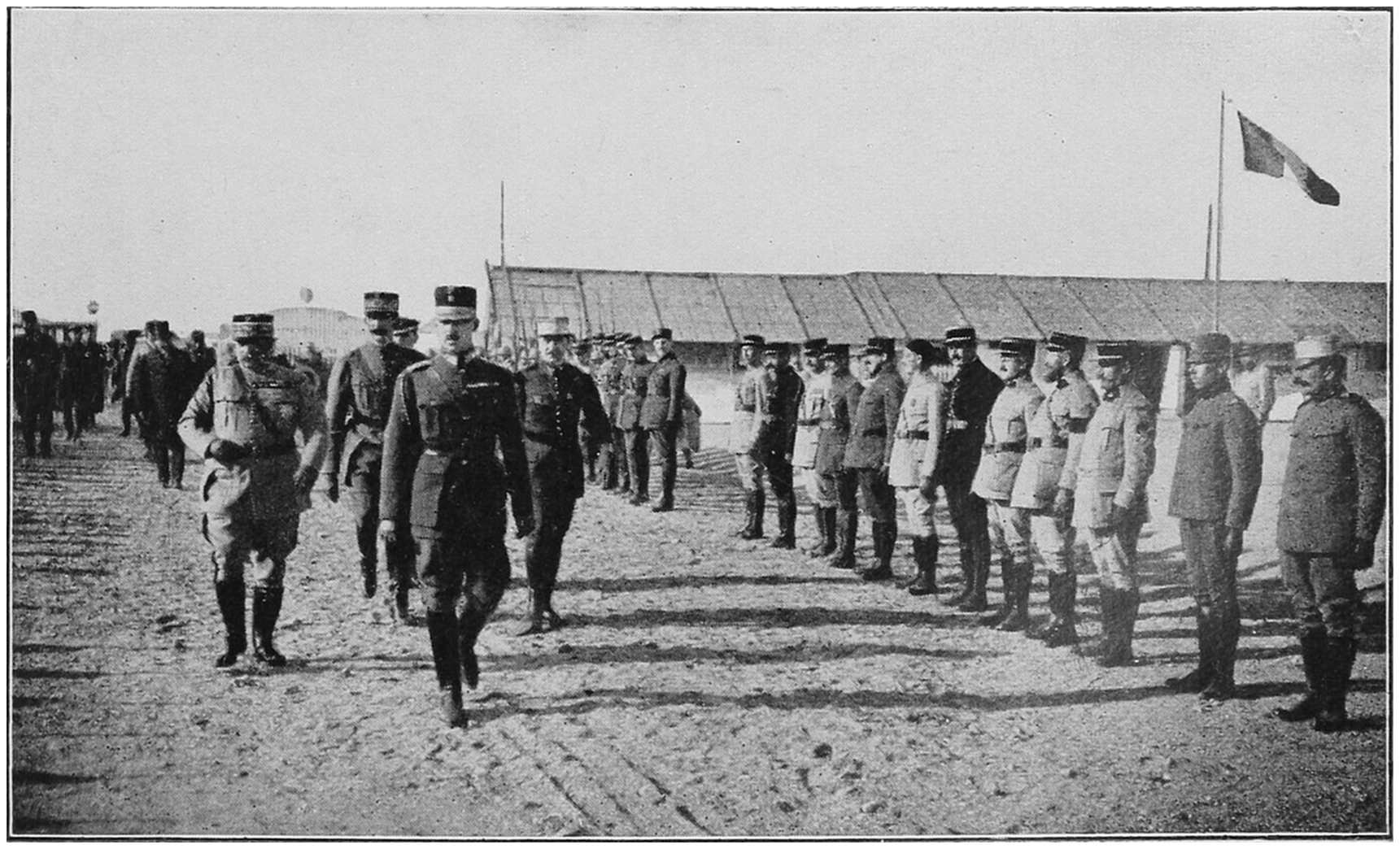

| GENERAL GUILLAUMAT VISITS GENERAL MOMBELLI AT TEPAVCI | 102 |

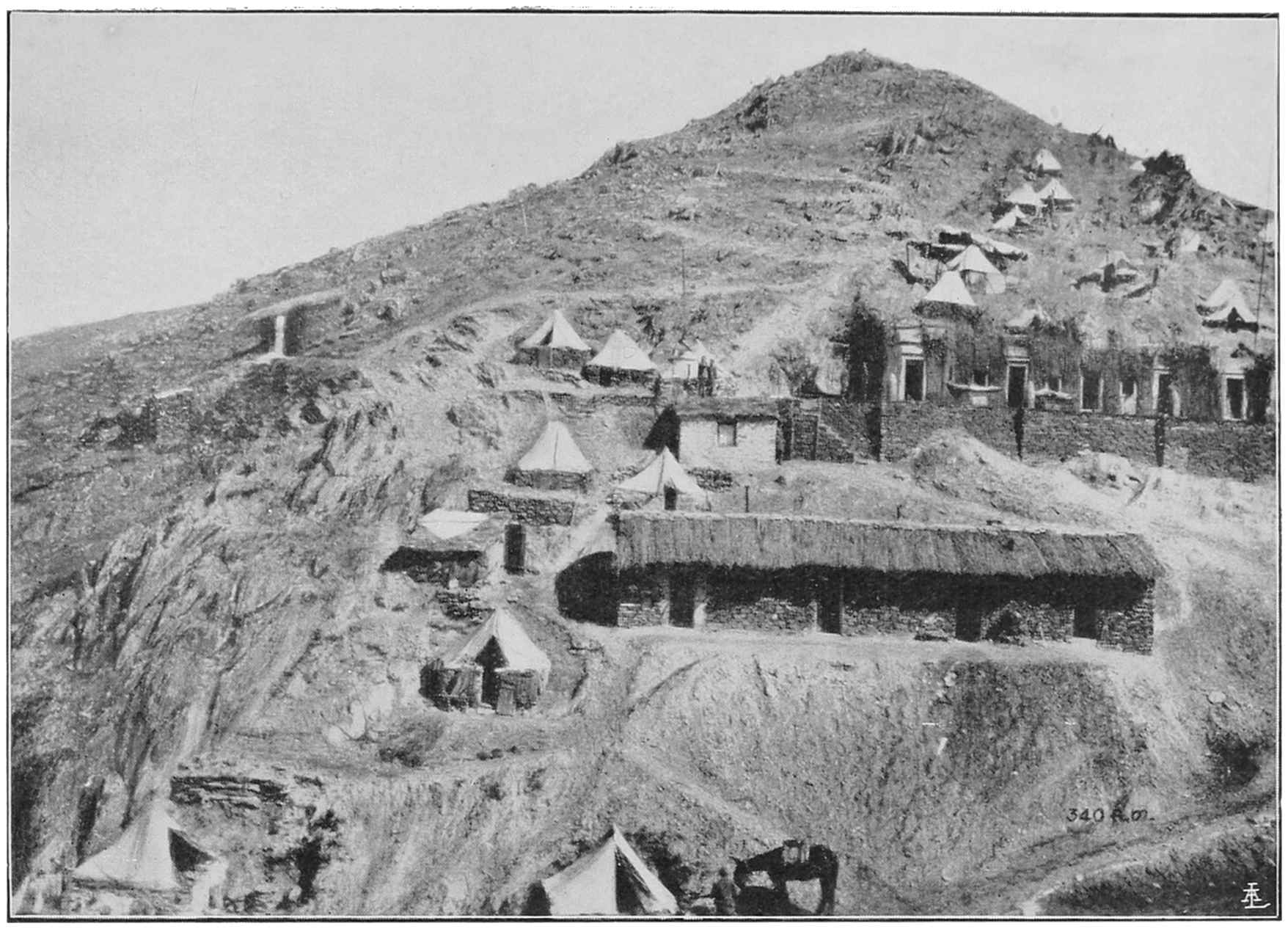

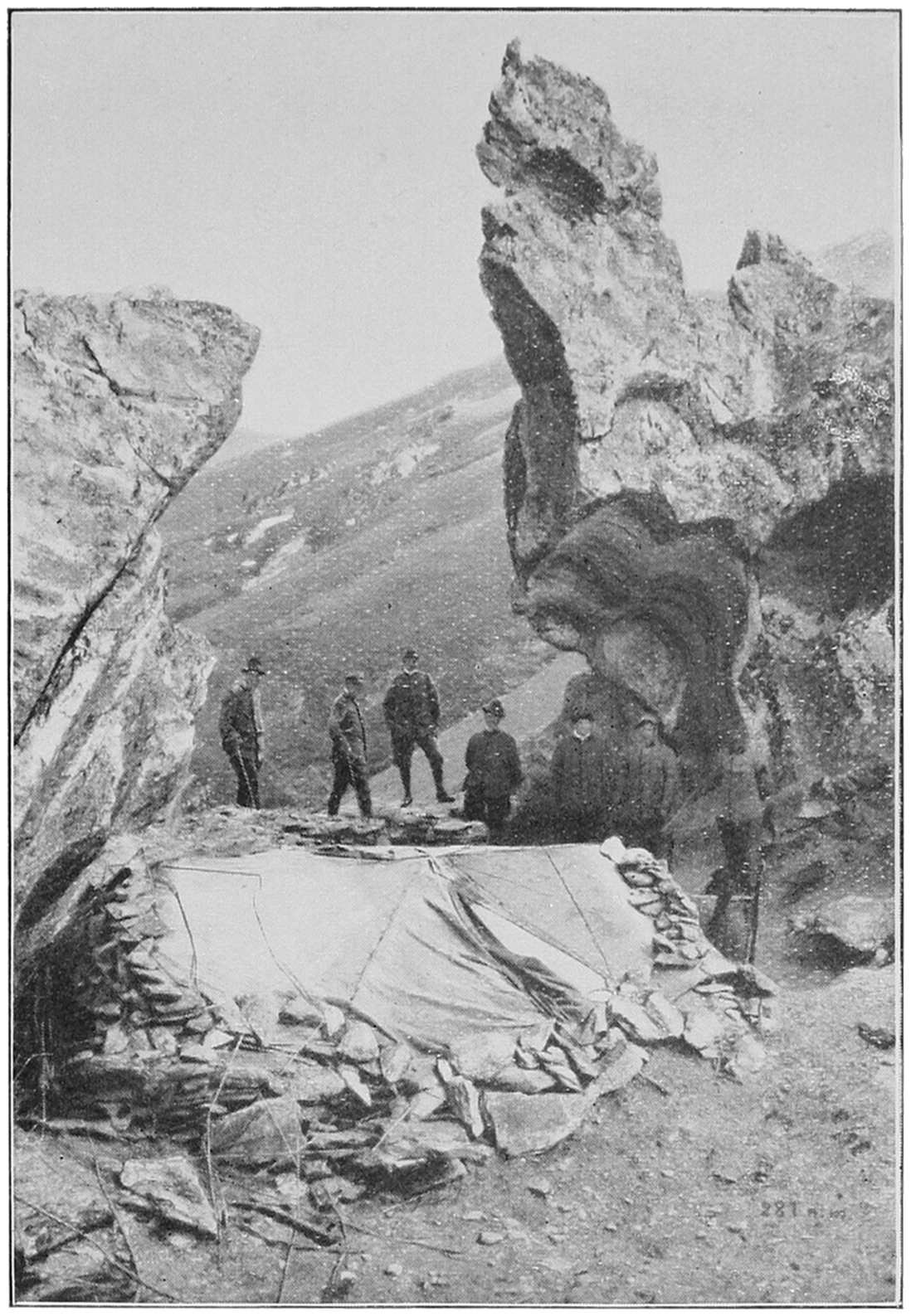

| CAMP NEAR THE PARALOVO MONASTERY | 122 |

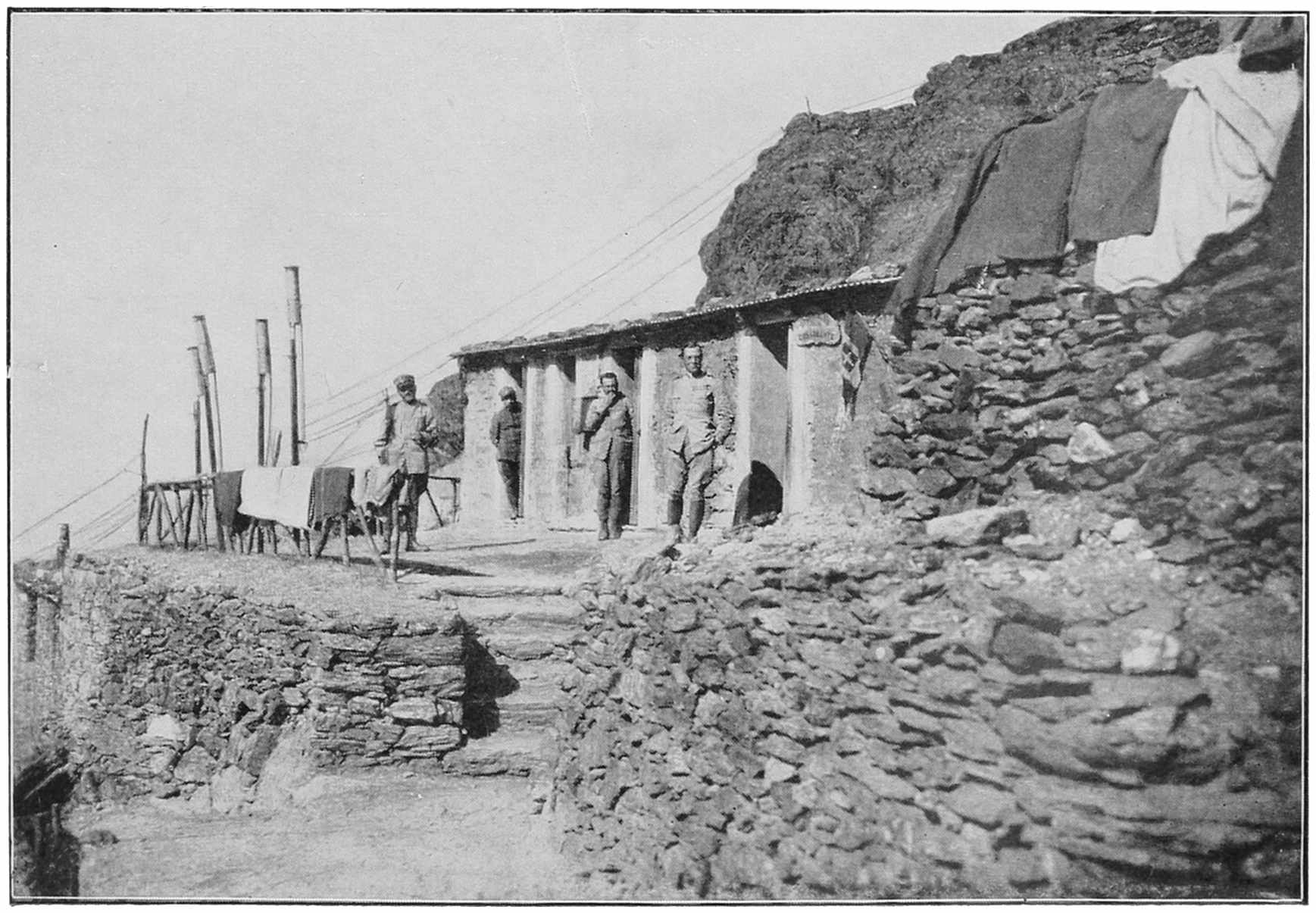

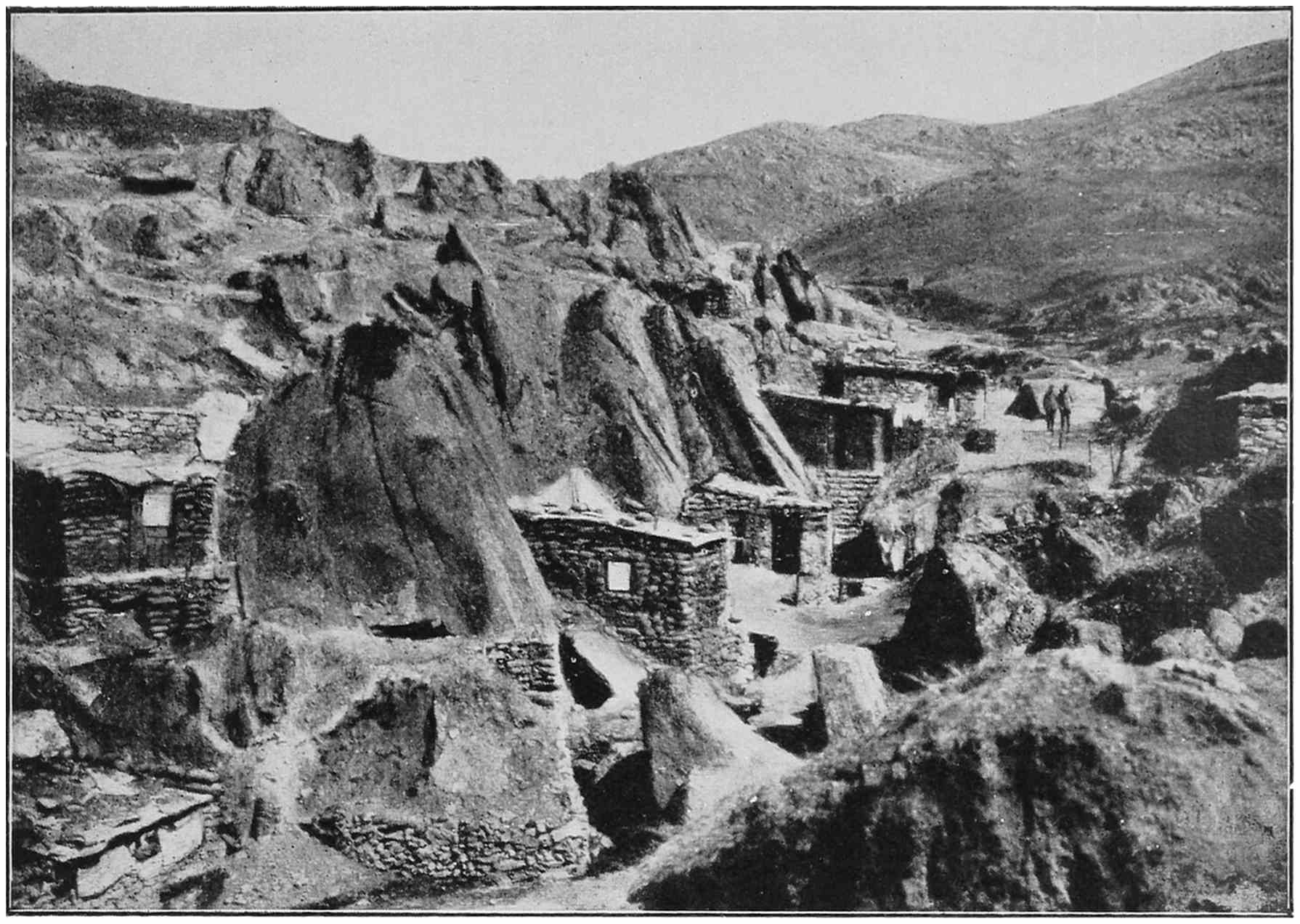

| H.Q. OF AN INFANTRY REGIMENT ON HILL 1050 | 122 |

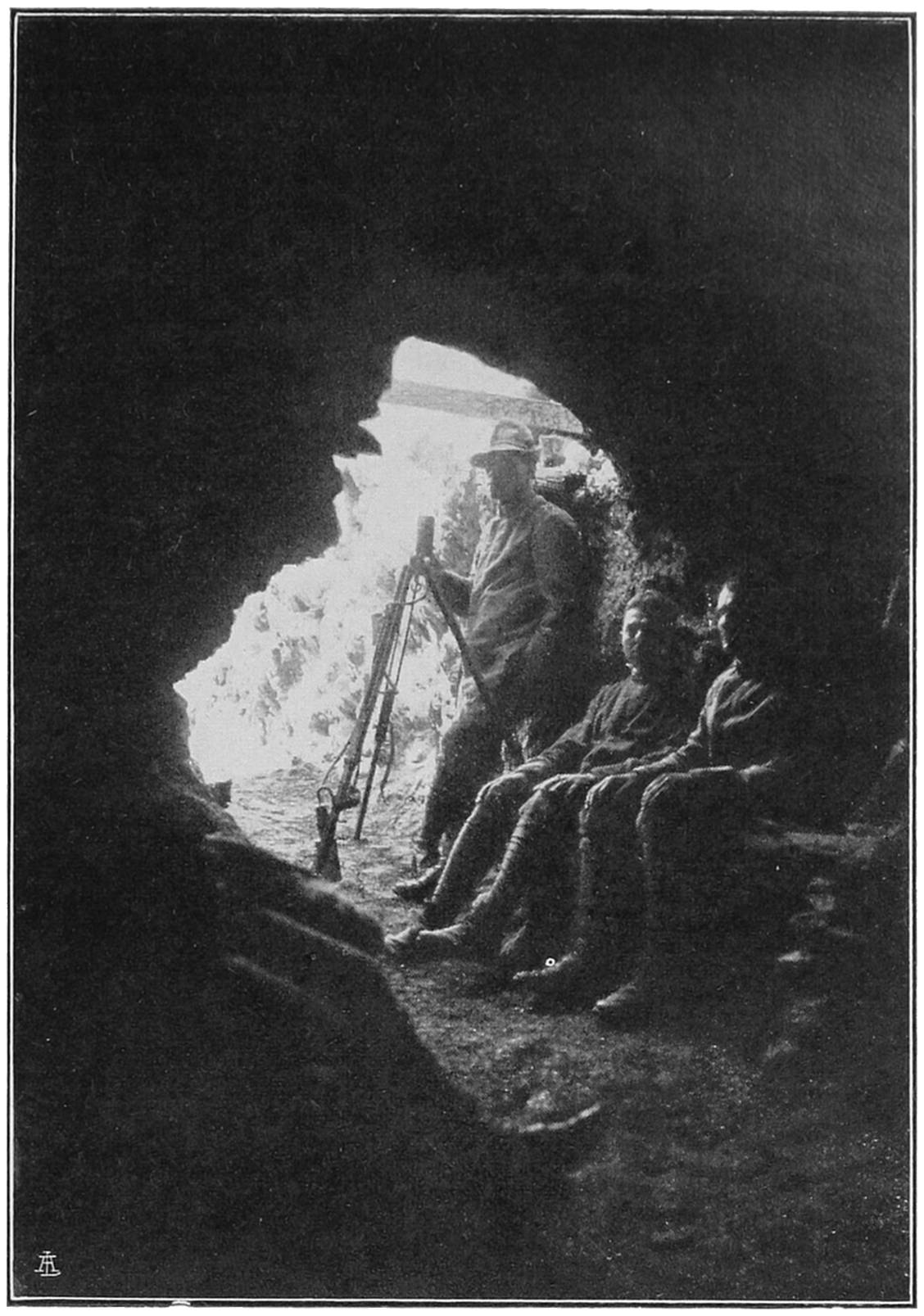

| HELIOGRAPH IN A CAVERN ON HILL 1050 | 126 |

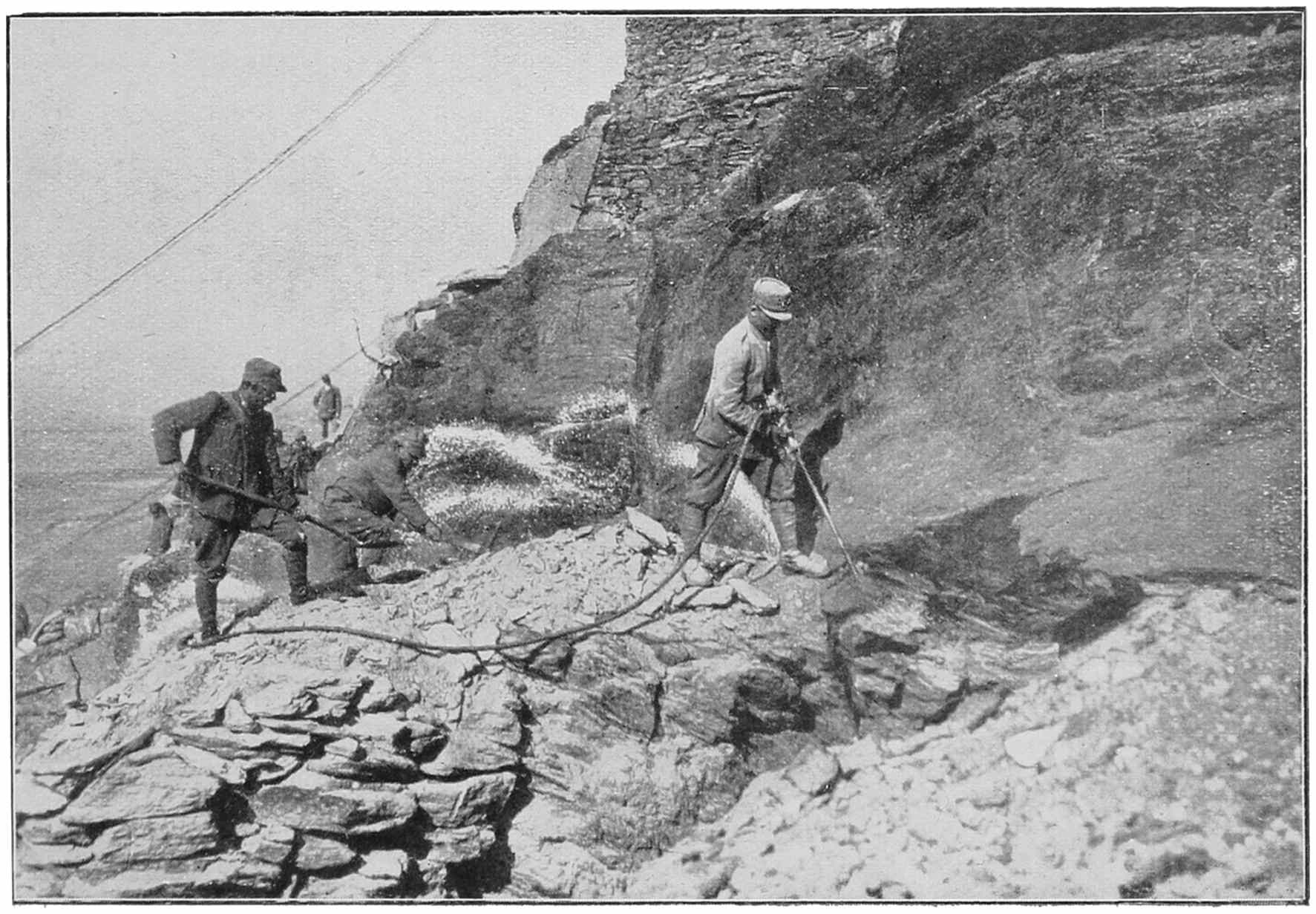

| ROCK-PERFORATING MACHINE ON HILL 1050 | 126 |

| CAMP UNDER THE PITON BRÛLÉ | 134 |

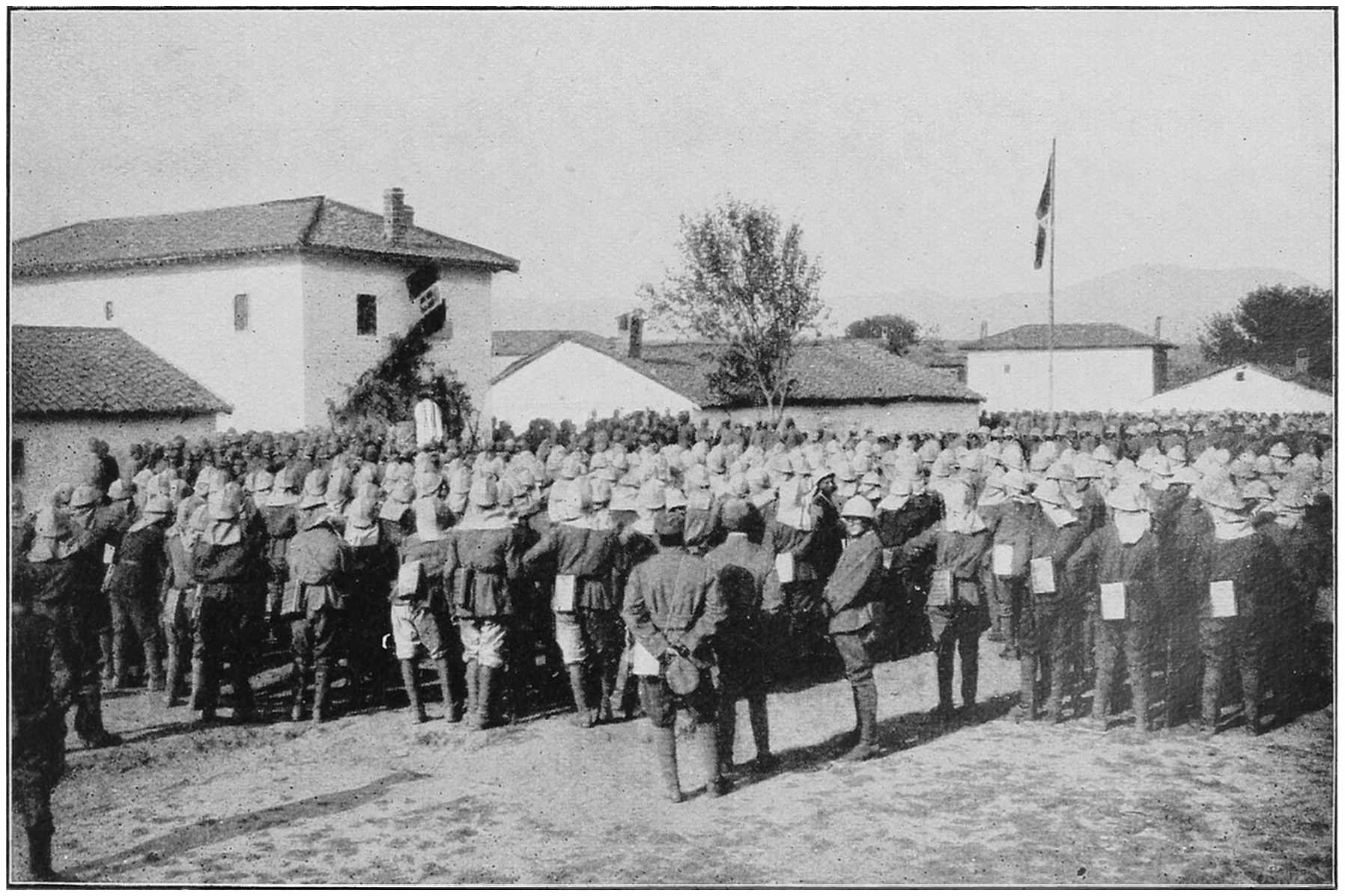

| ITALIAN NATIONAL FESTIVAL (THE STATUTO) AT SAKULEVO. HIGH MASS | 134 |

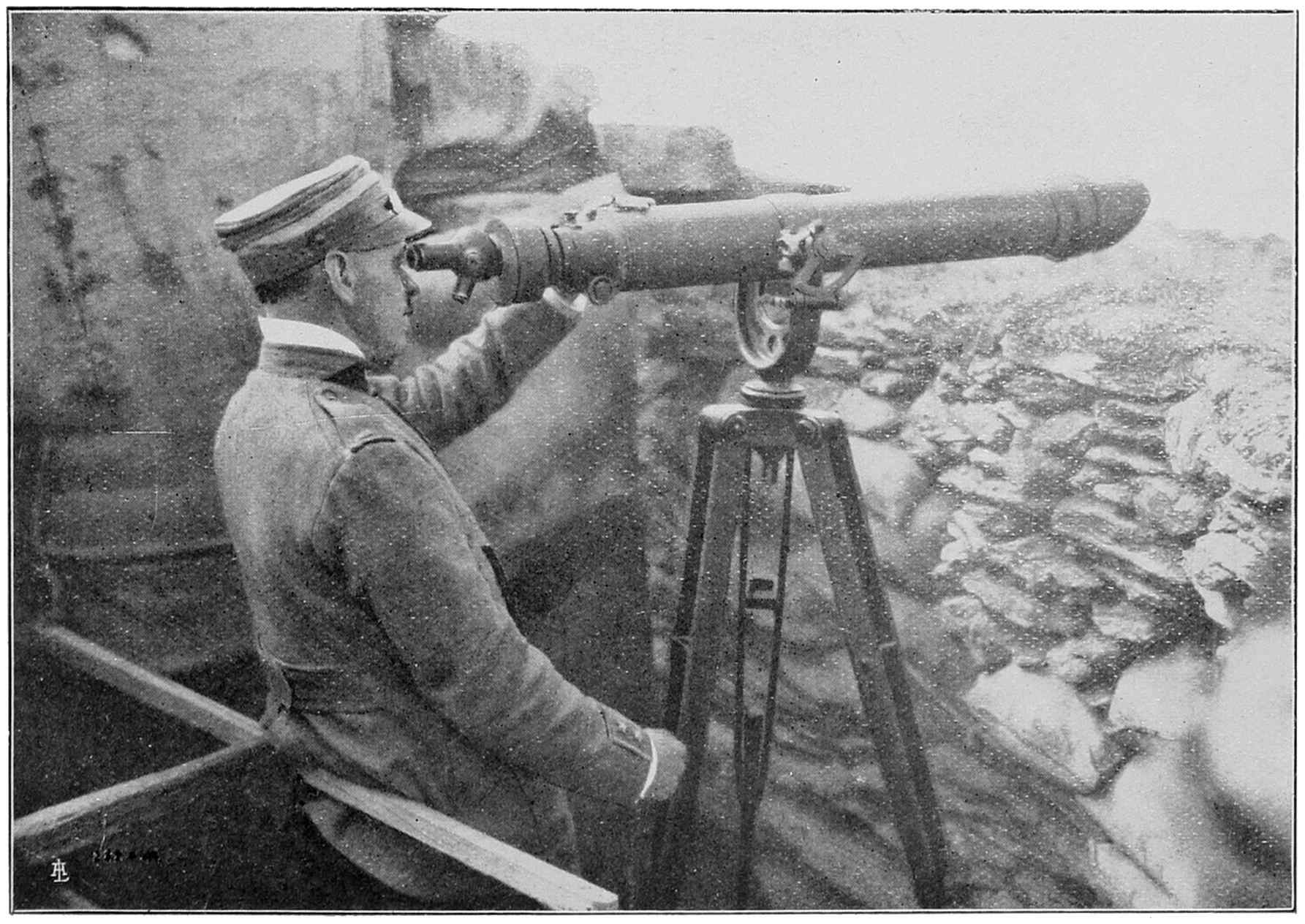

| HILL 1075: ARTILLERY CAMP | 140 |

| ARTILLERY O.P. | 140 |

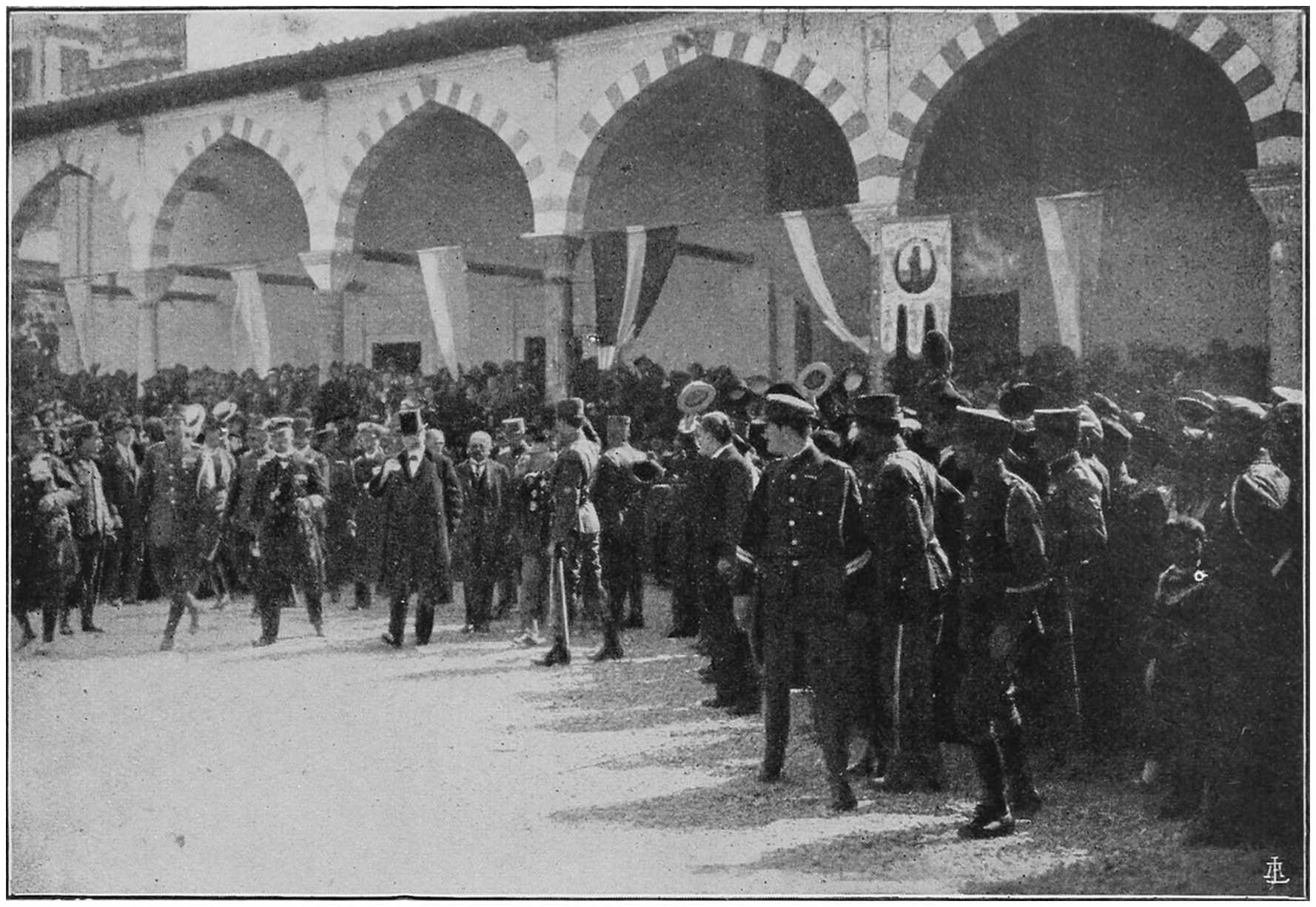

| THE GREEK NATIONAL FESTIVAL ON APRIL 7, 1917: M. VENIZELOS LEAVING THE CHURCH OF S. SOPHIA, SALONICA | 15810 |

| KING ALEXANDER OF GREECE VISITS A FRENCH CAMP | 158 |

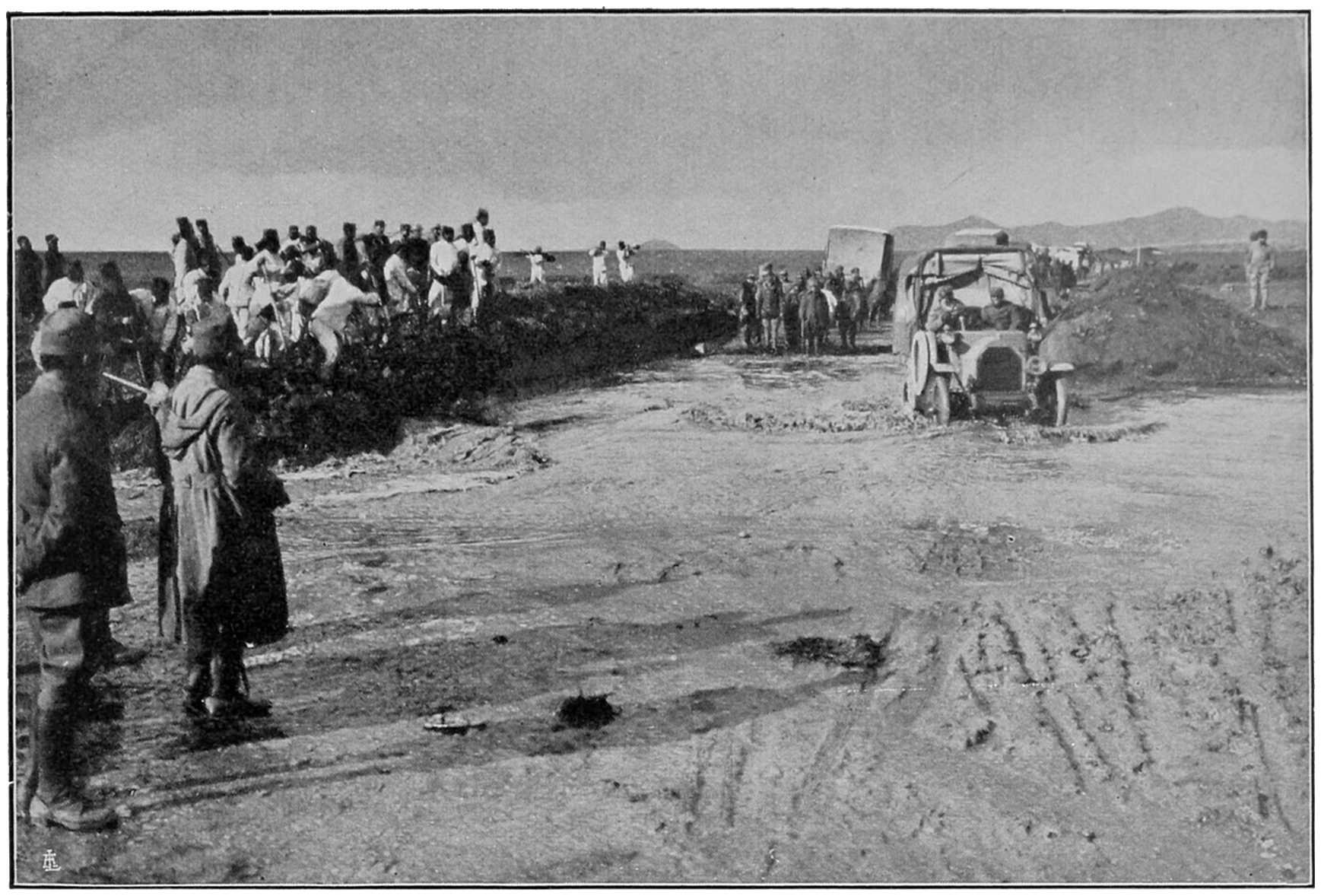

| A FLOODED ROAD | 172 |

| LEAVE PARTY FROM MACEDONIA ON THE SANTI QUARANTA ROAD (Photograph by Lieut. Landini.) |

172 |

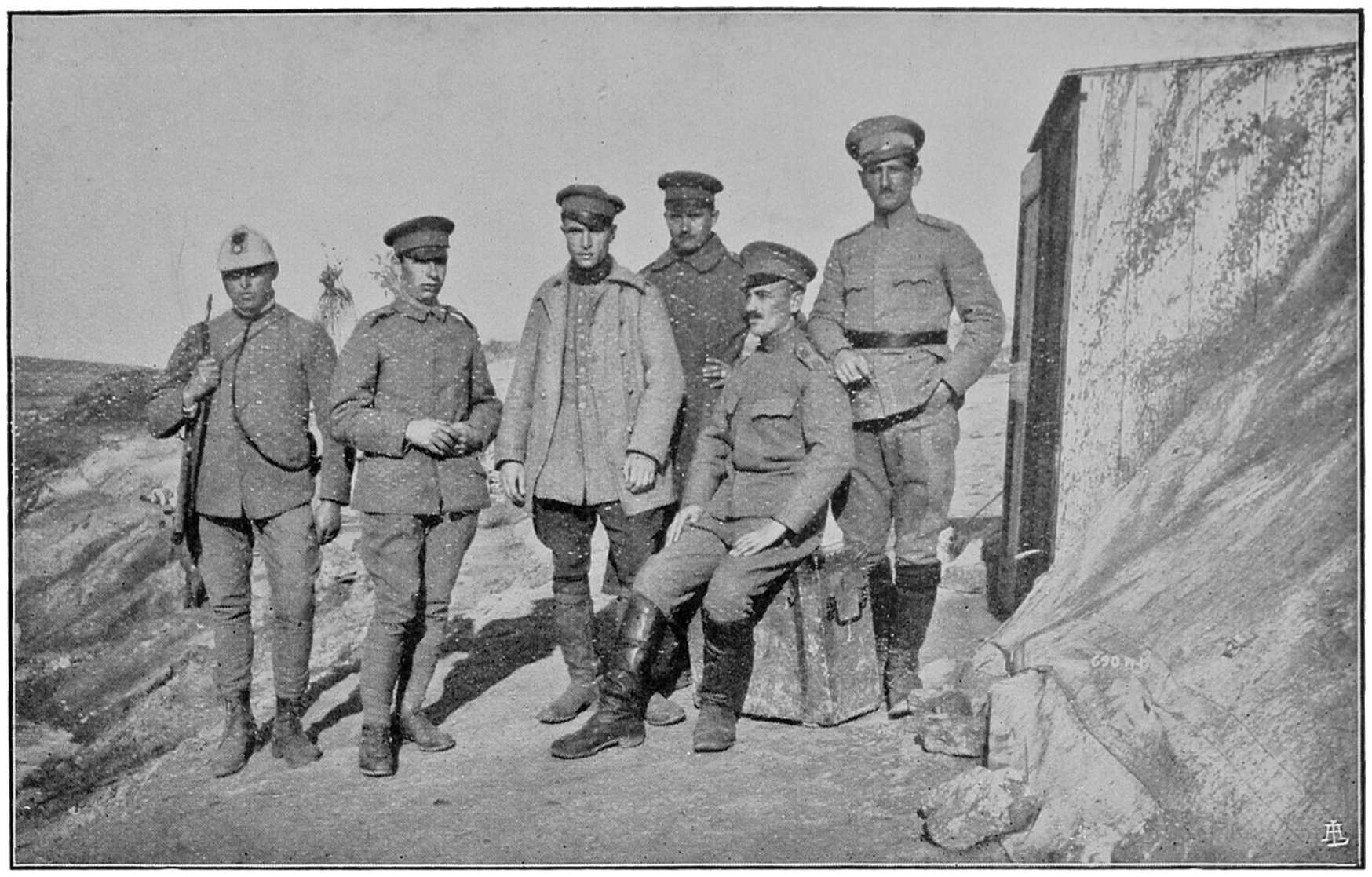

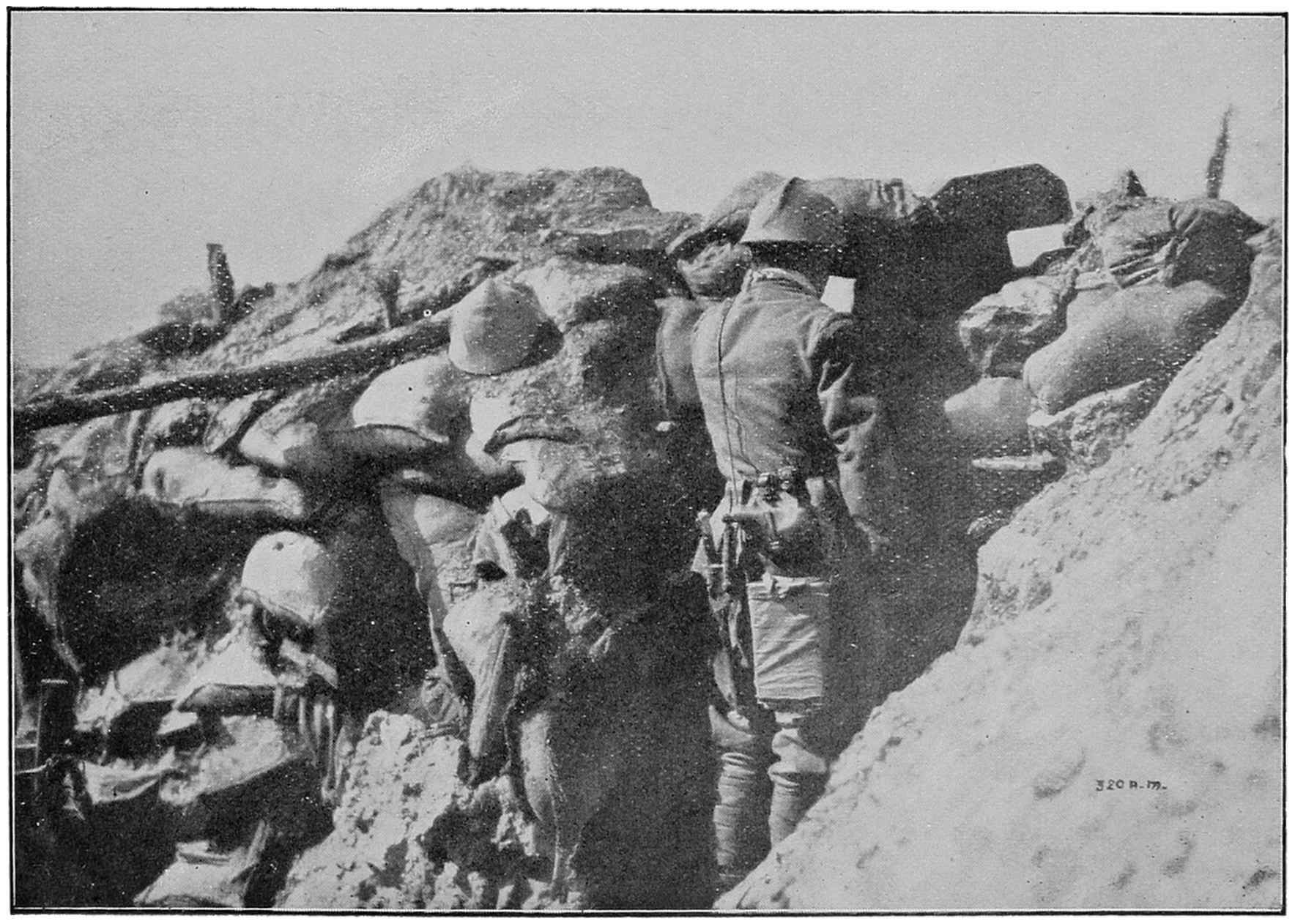

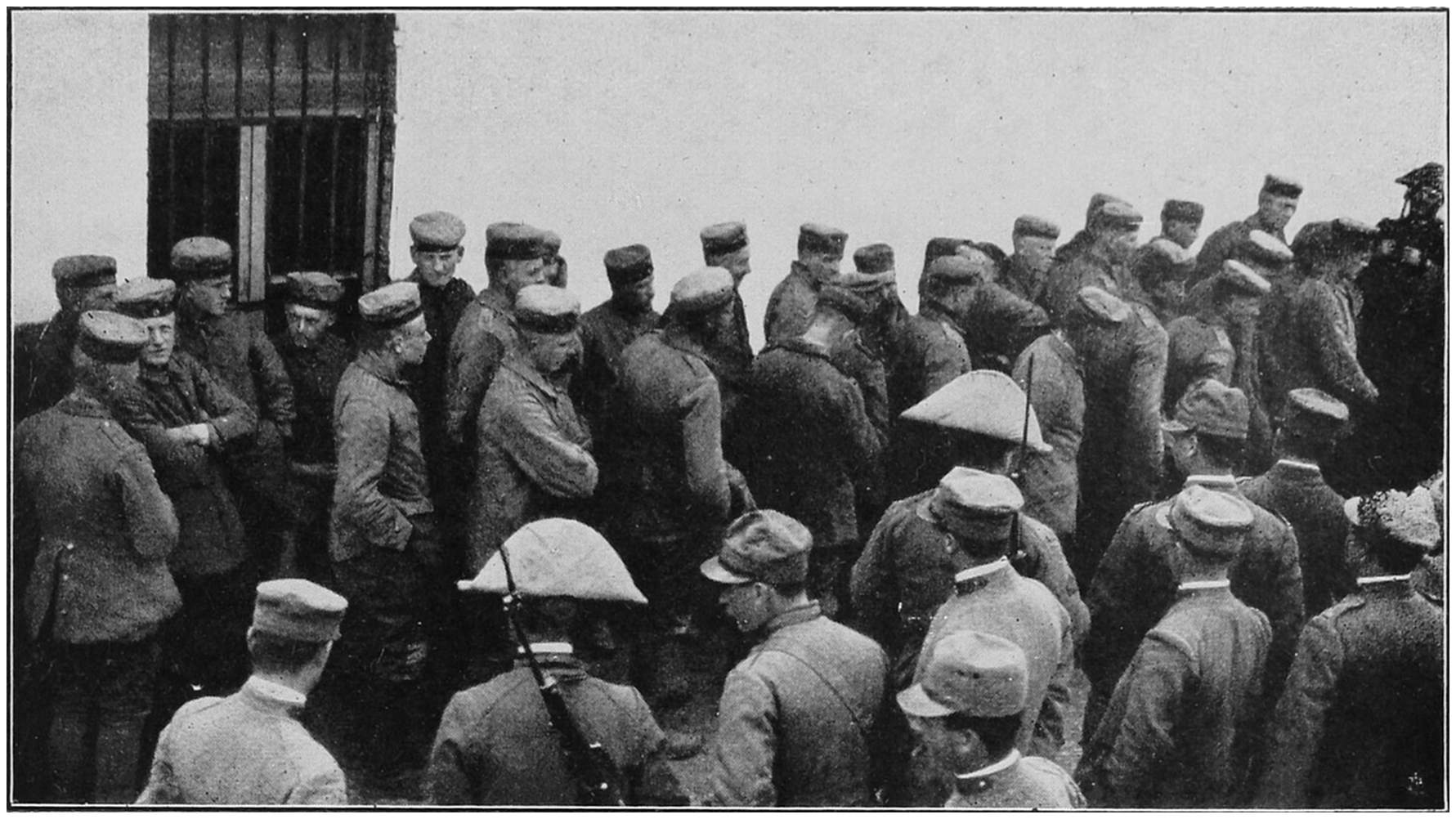

| BULGARIAN PRISONERS | 180 |

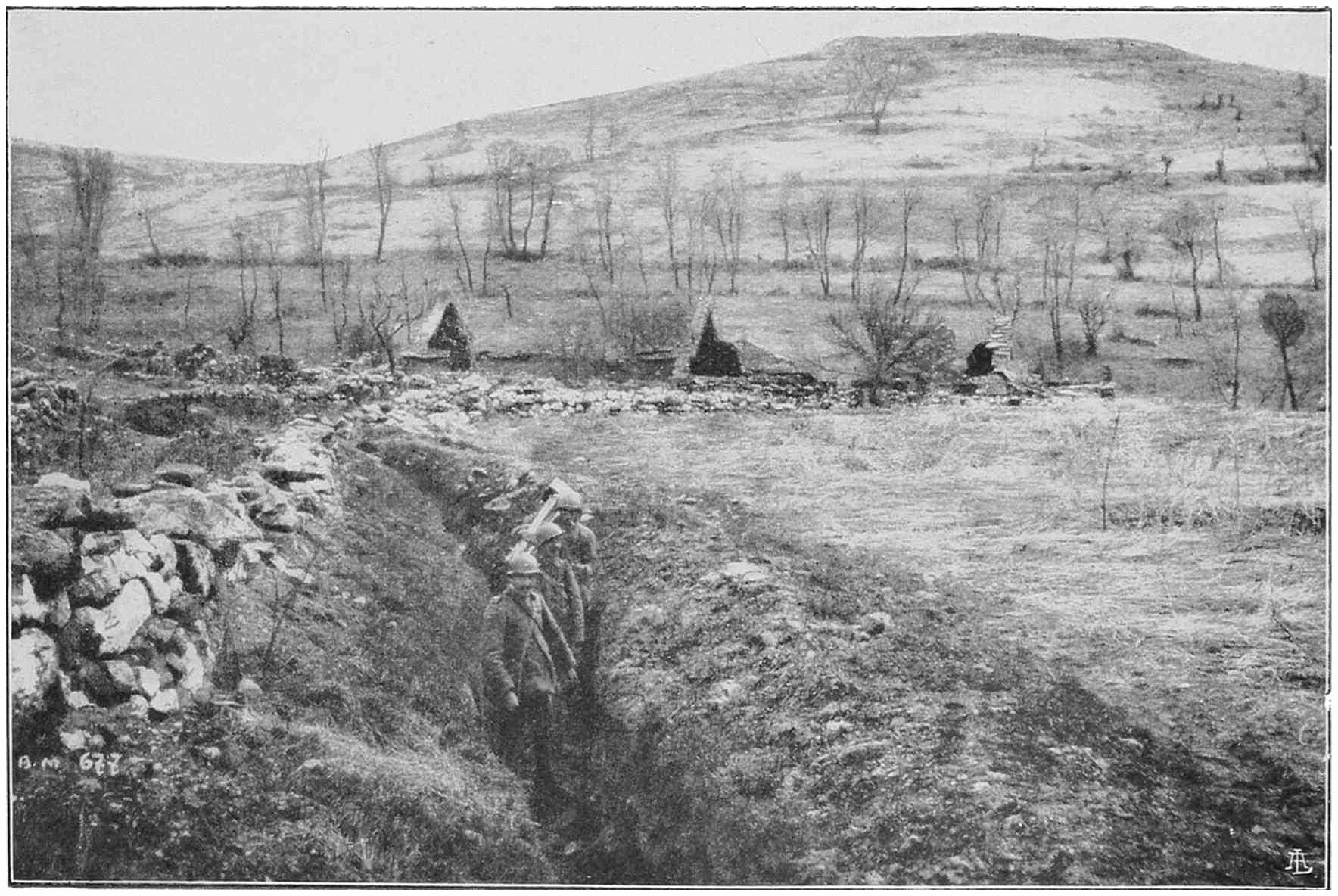

| IN THE “CASTELLETTO” TRENCHES | 180 |

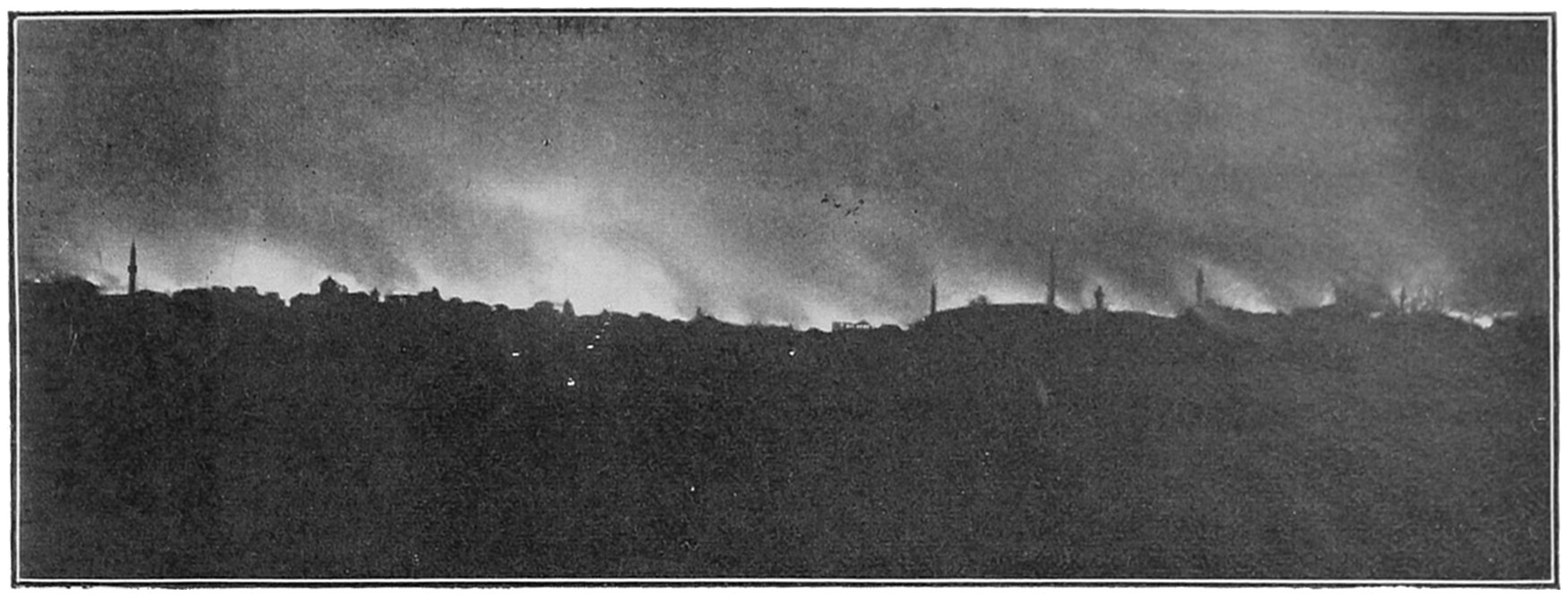

| THE SALONICA FIRE, NIGHT FROM AUGUST 18 TO 19, 1917 | 192 |

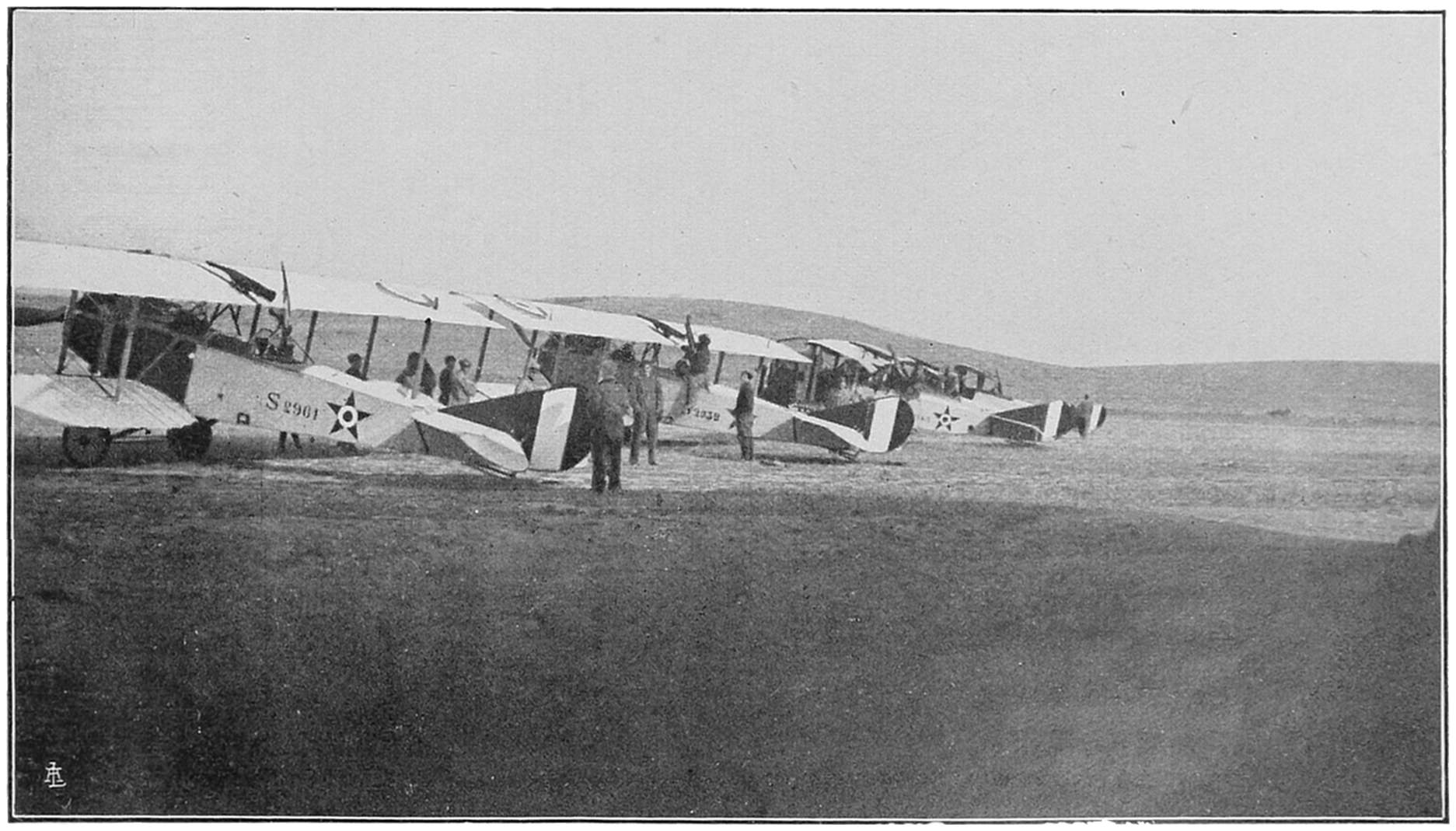

| CAMP OF THE 111TH FLIGHT: ITALIAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE | 192 |

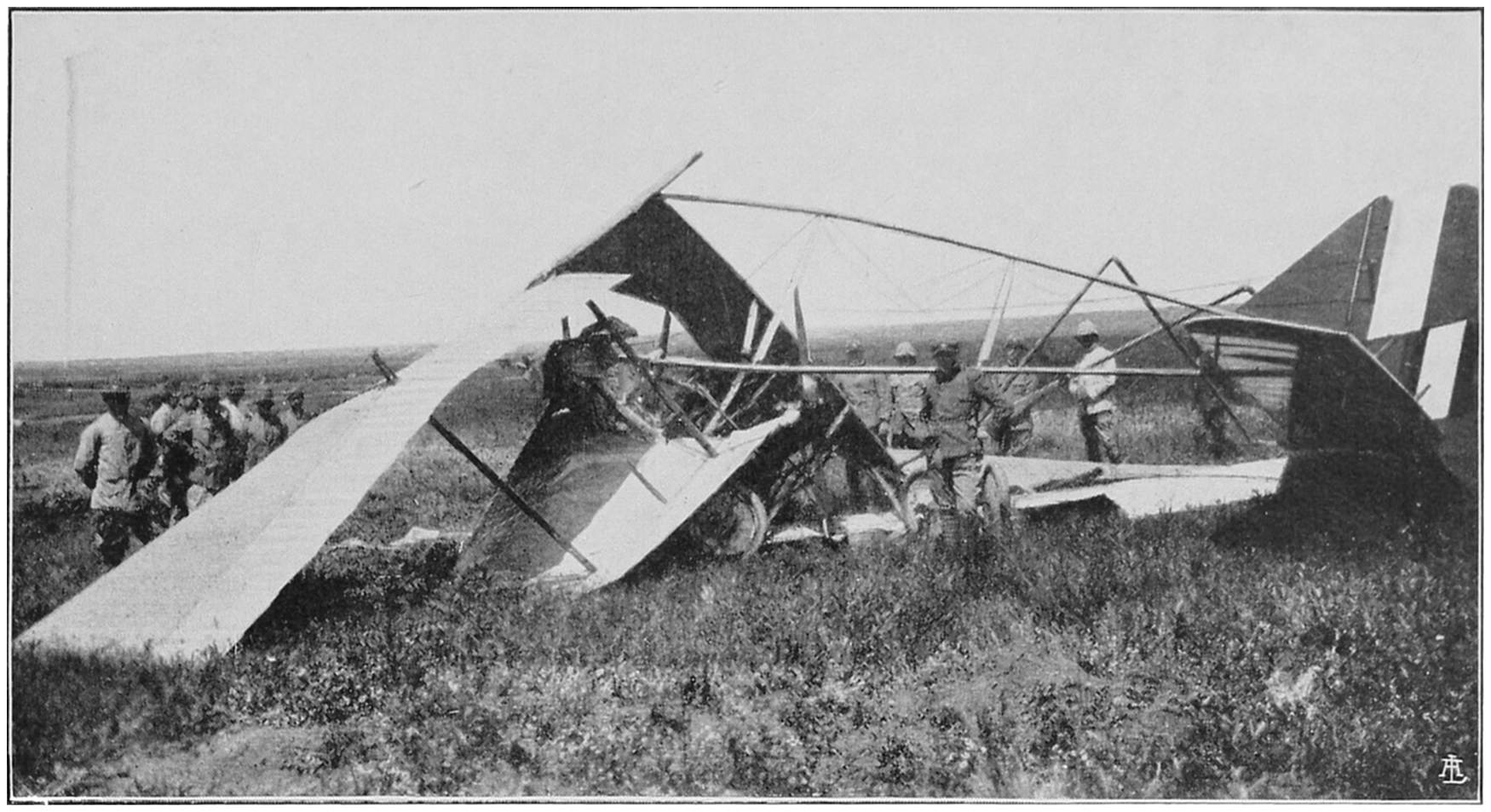

| CRASHED ITALIAN AEROPLANE | 246 |

| COMMUNICATION TRENCHES IN THE MEGLENTZI VALLEY | 246 |

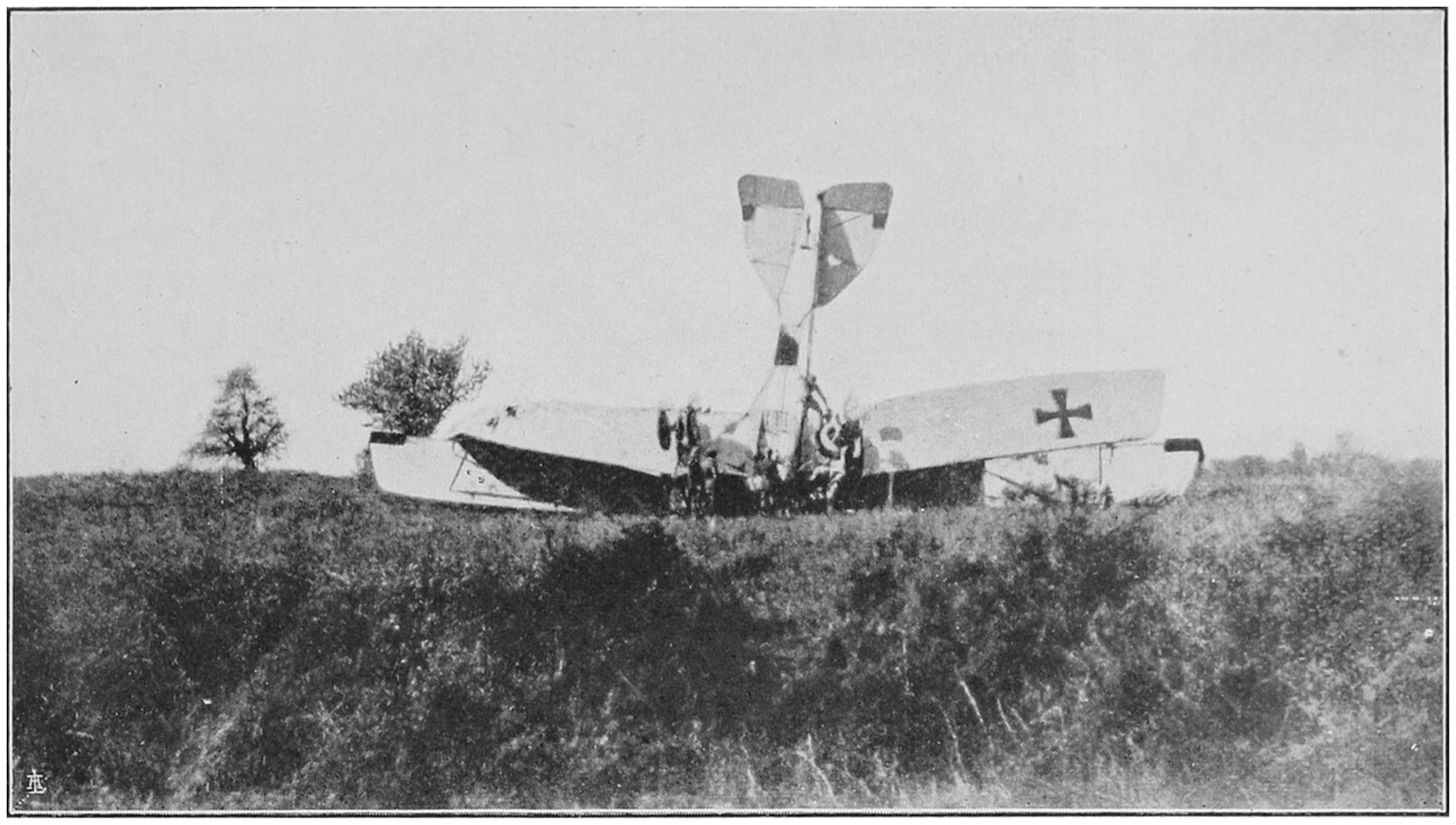

| CRASHED GERMAN AEROPLANE | 250 |

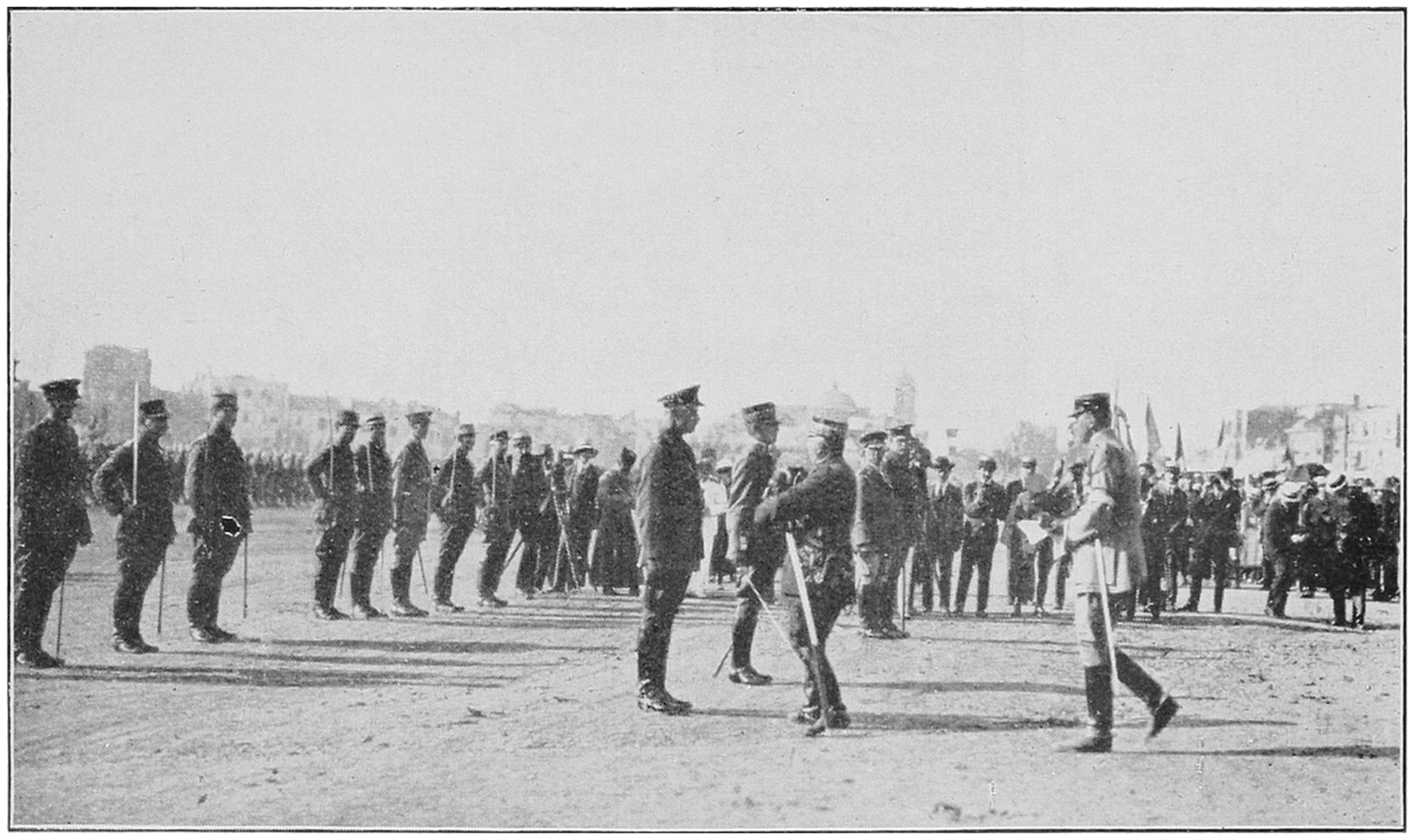

| GENERAL FRANCHET D’ESPÉREY DECORATING GENERALS MILNE AND MOMBELLI | 250 |

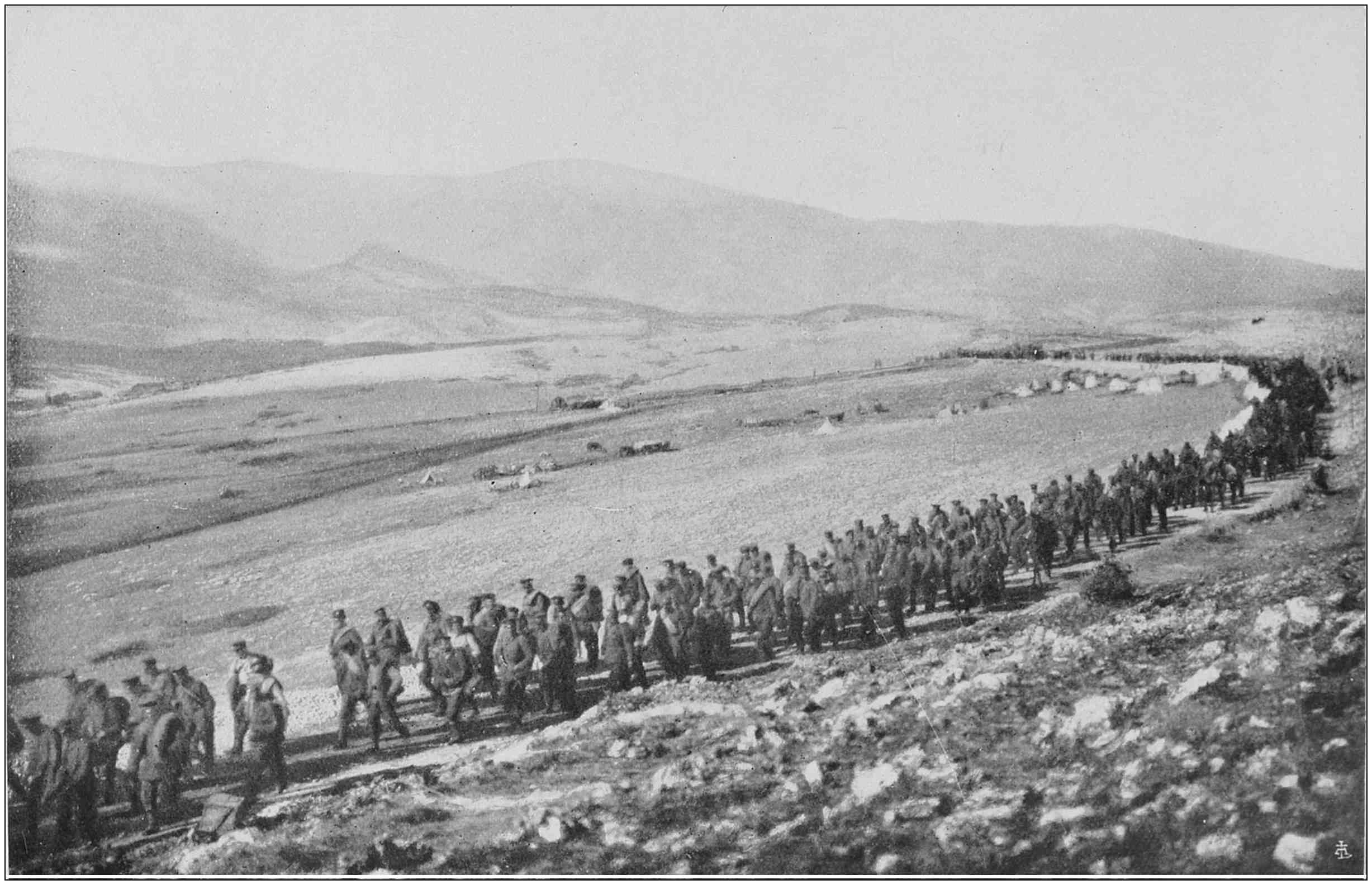

| AFTER THE VICTORY: ENEMY PRISONERS | 256 |

| GERMAN PRISONERS CAPTURED BY THE ITALIANS ON HILL 1050 | 262 |

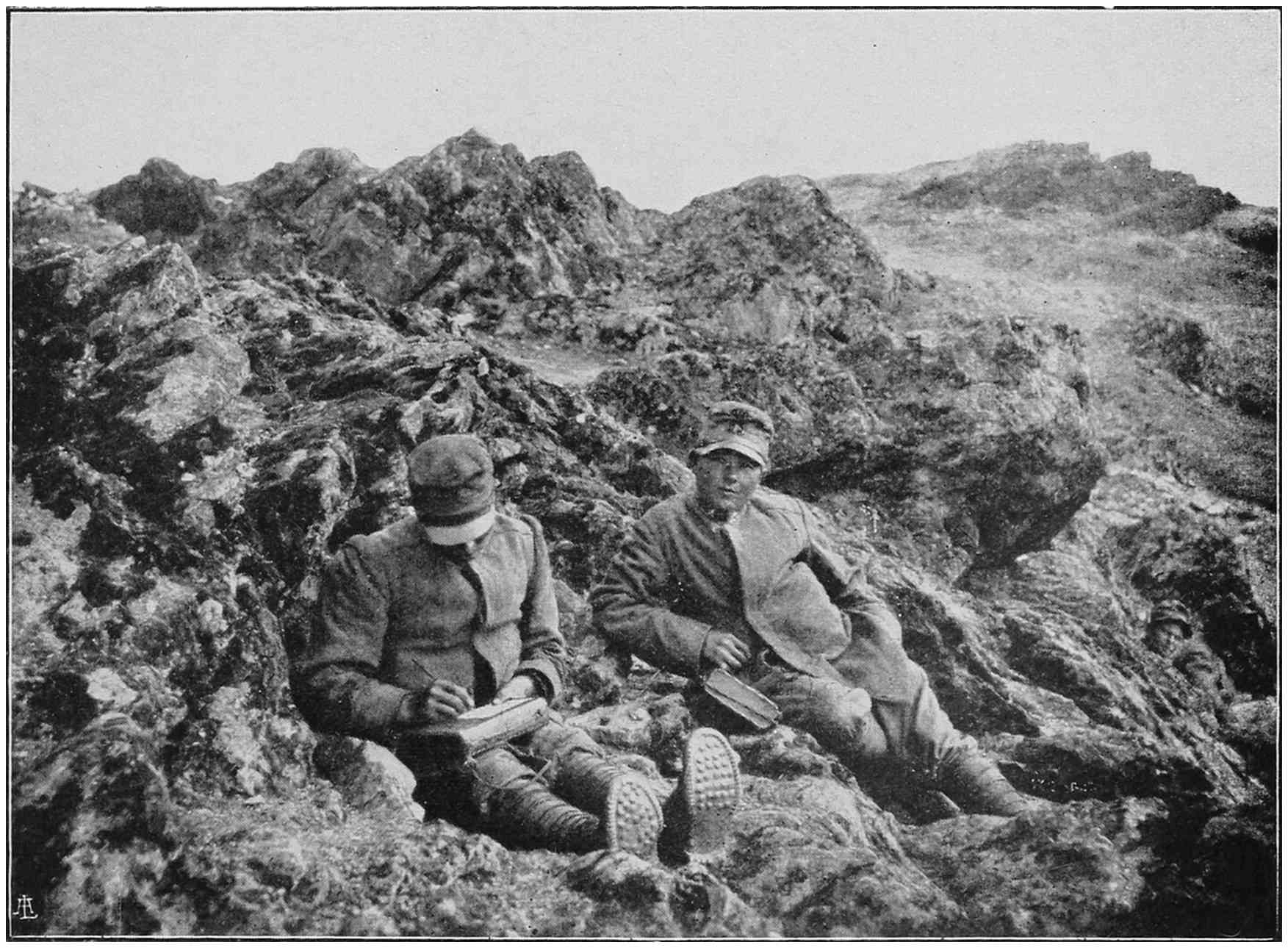

| HILL 1050: HOURS OF REST | 262 |

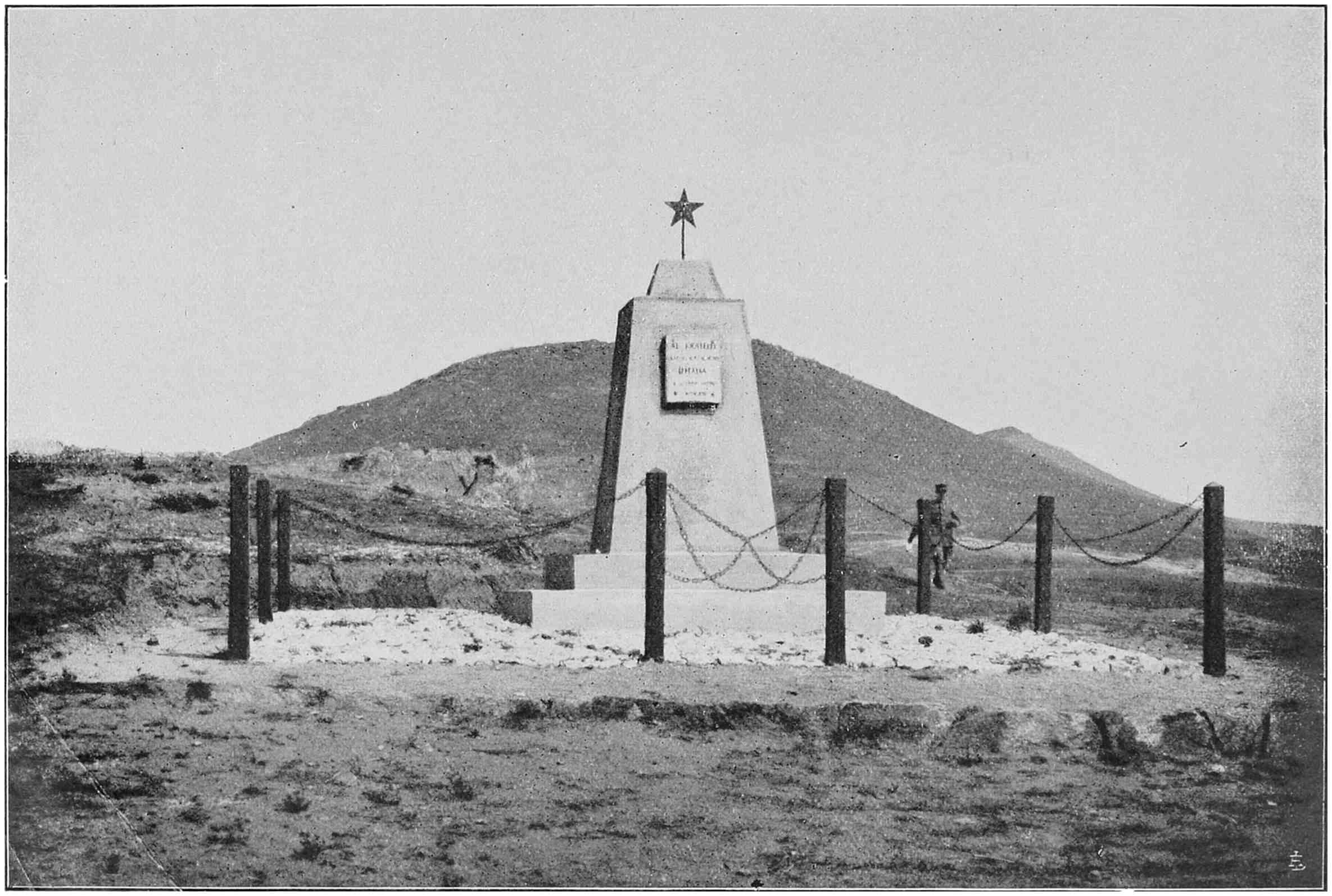

| MONUMENT TO THE FALLEN OF THE 161ST ITALIAN REGIMENT ON VRATA HILL | 264 |

| MAPS | |

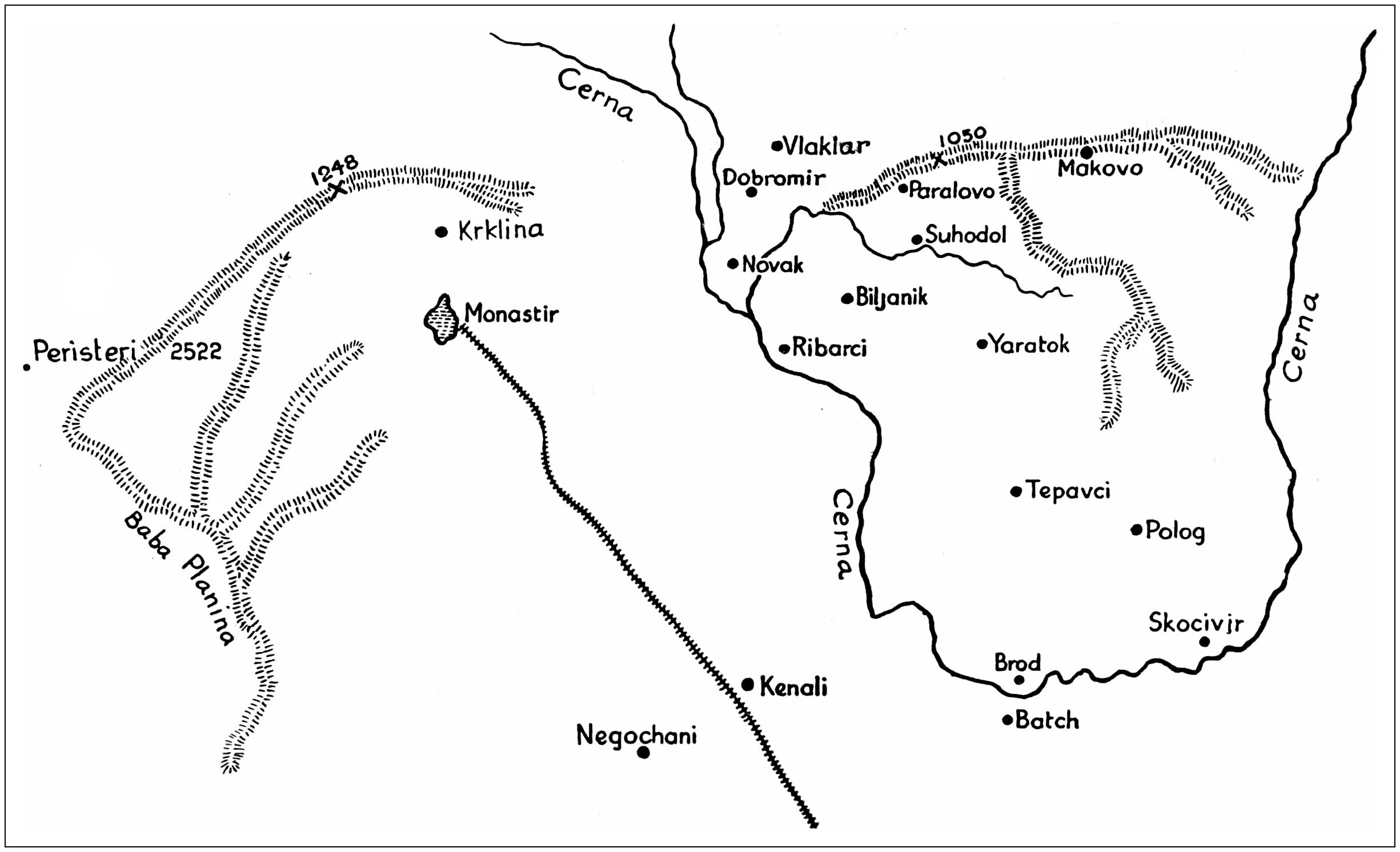

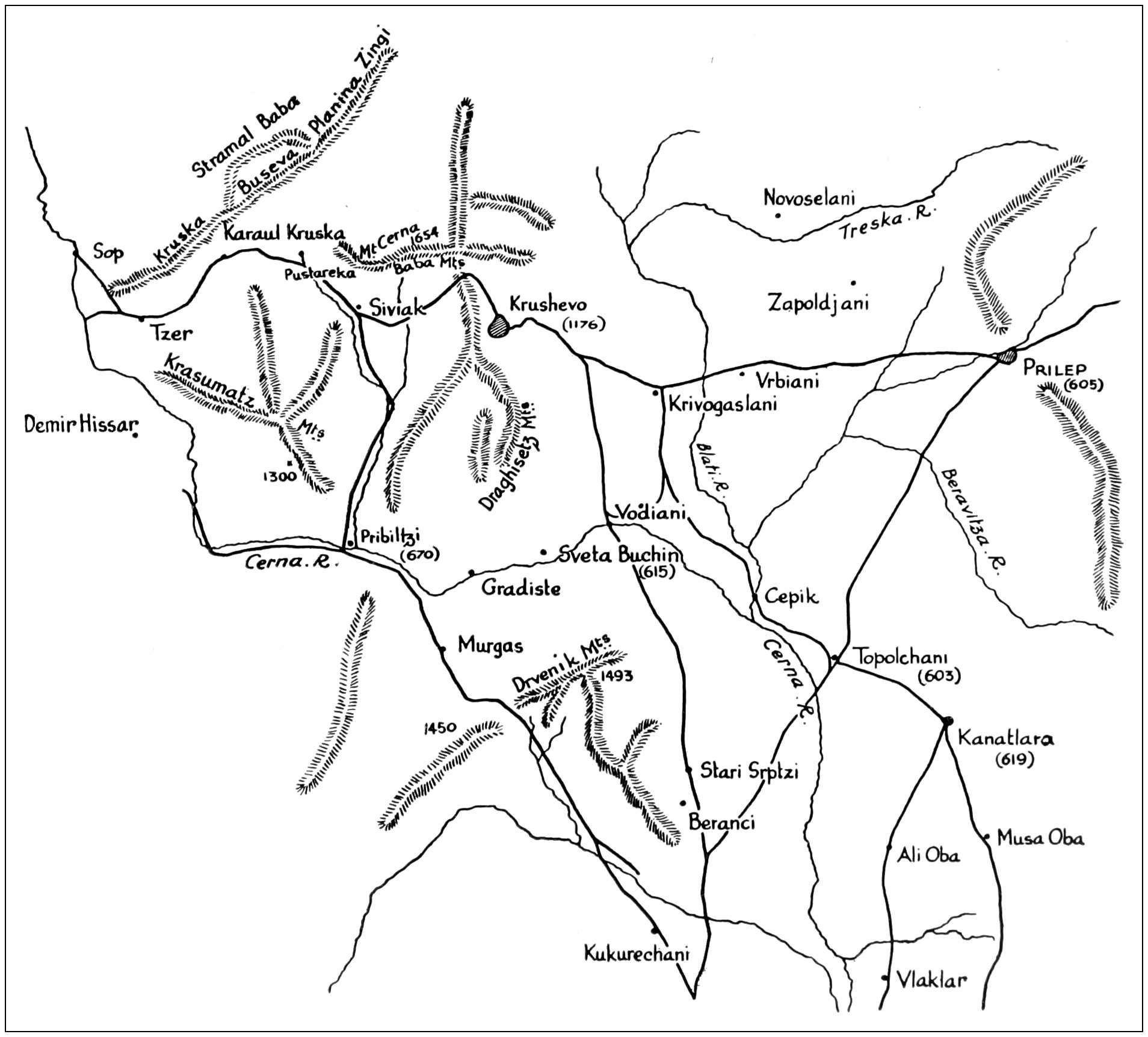

| AREA OF THE ITALIAN FORCE | 104 |

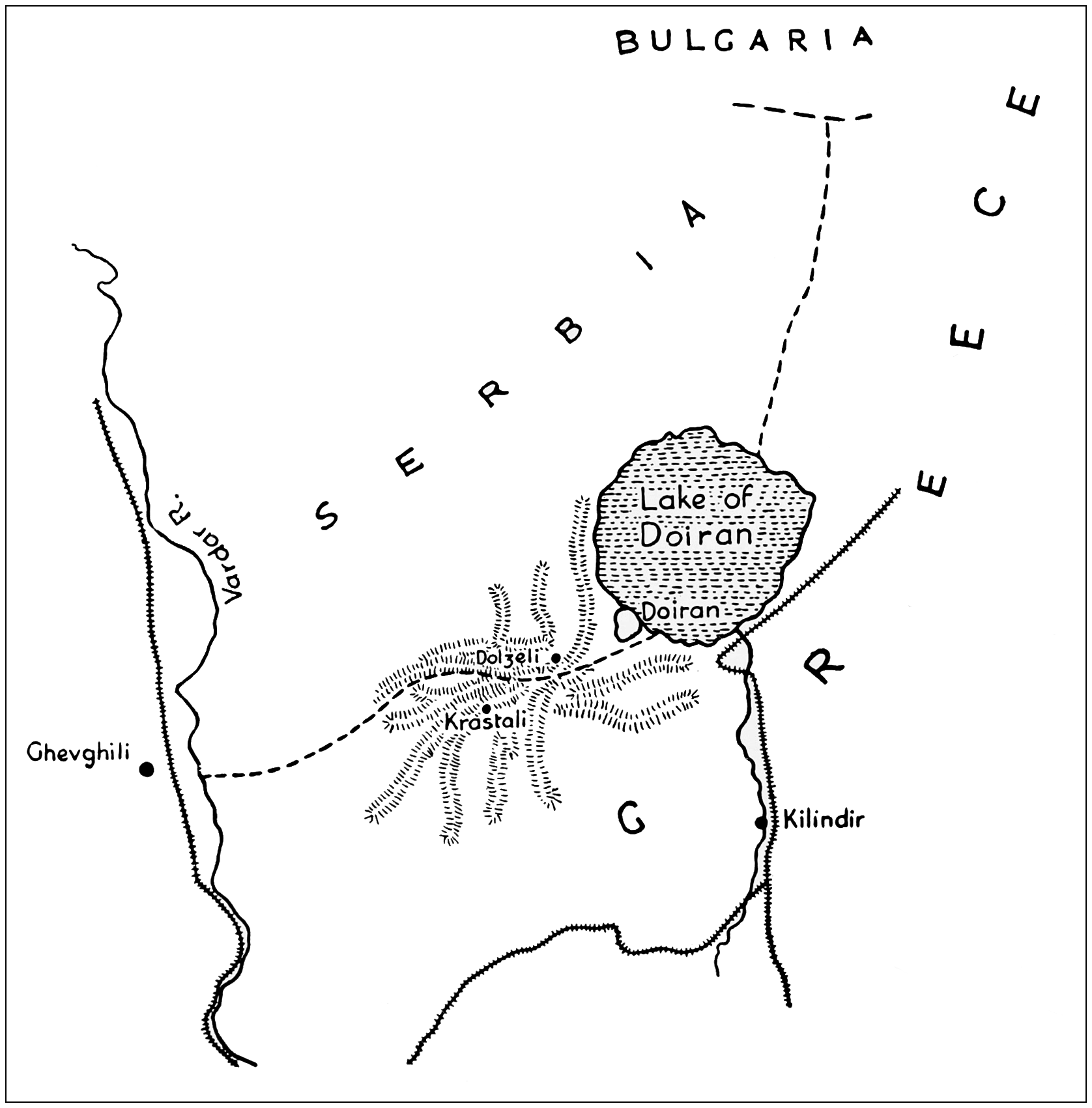

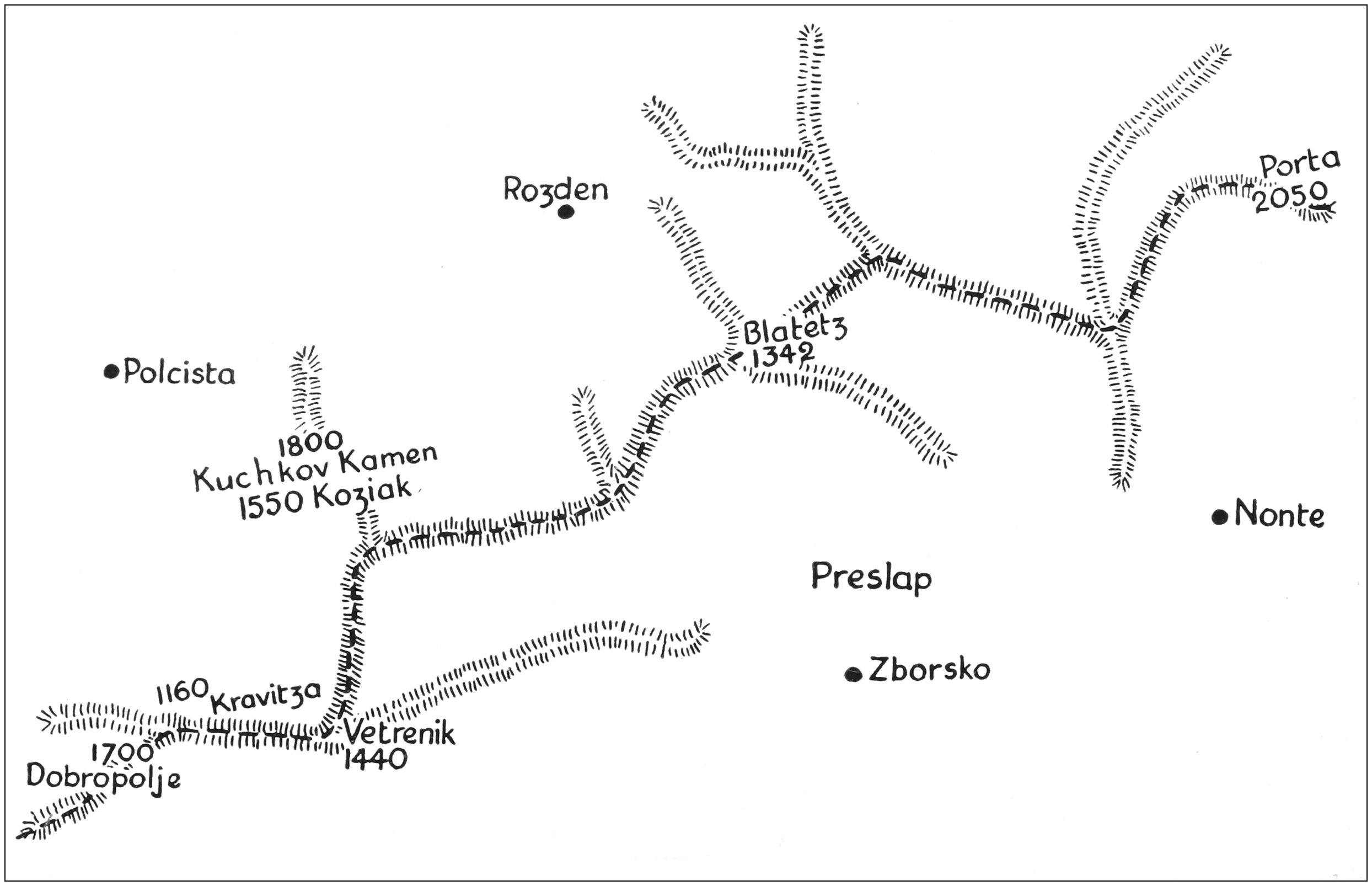

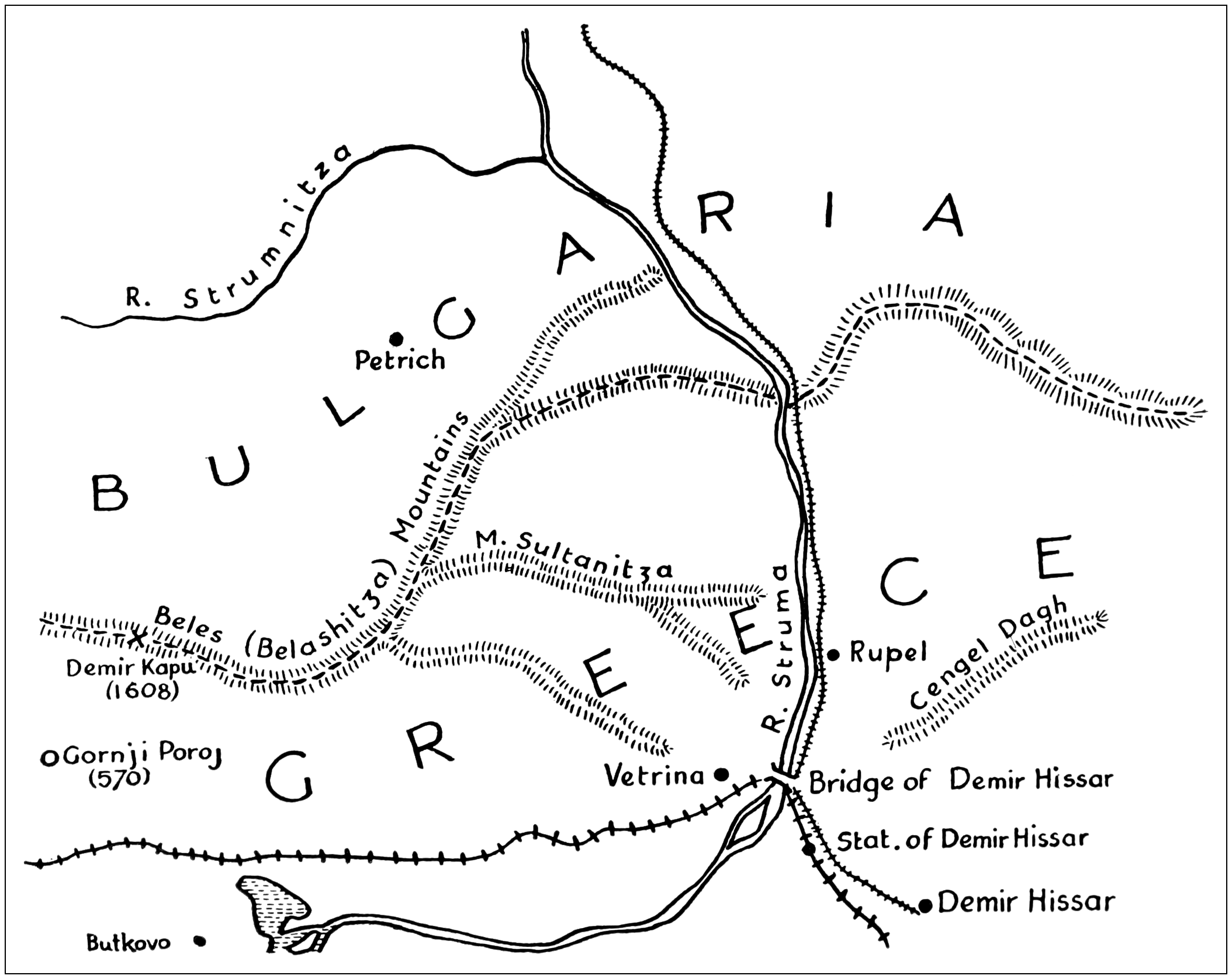

| AREA OF THE BRITISH XII CORPS | 129 |

| AREA OF THE FRANCO-SERB GROUP | 213 |

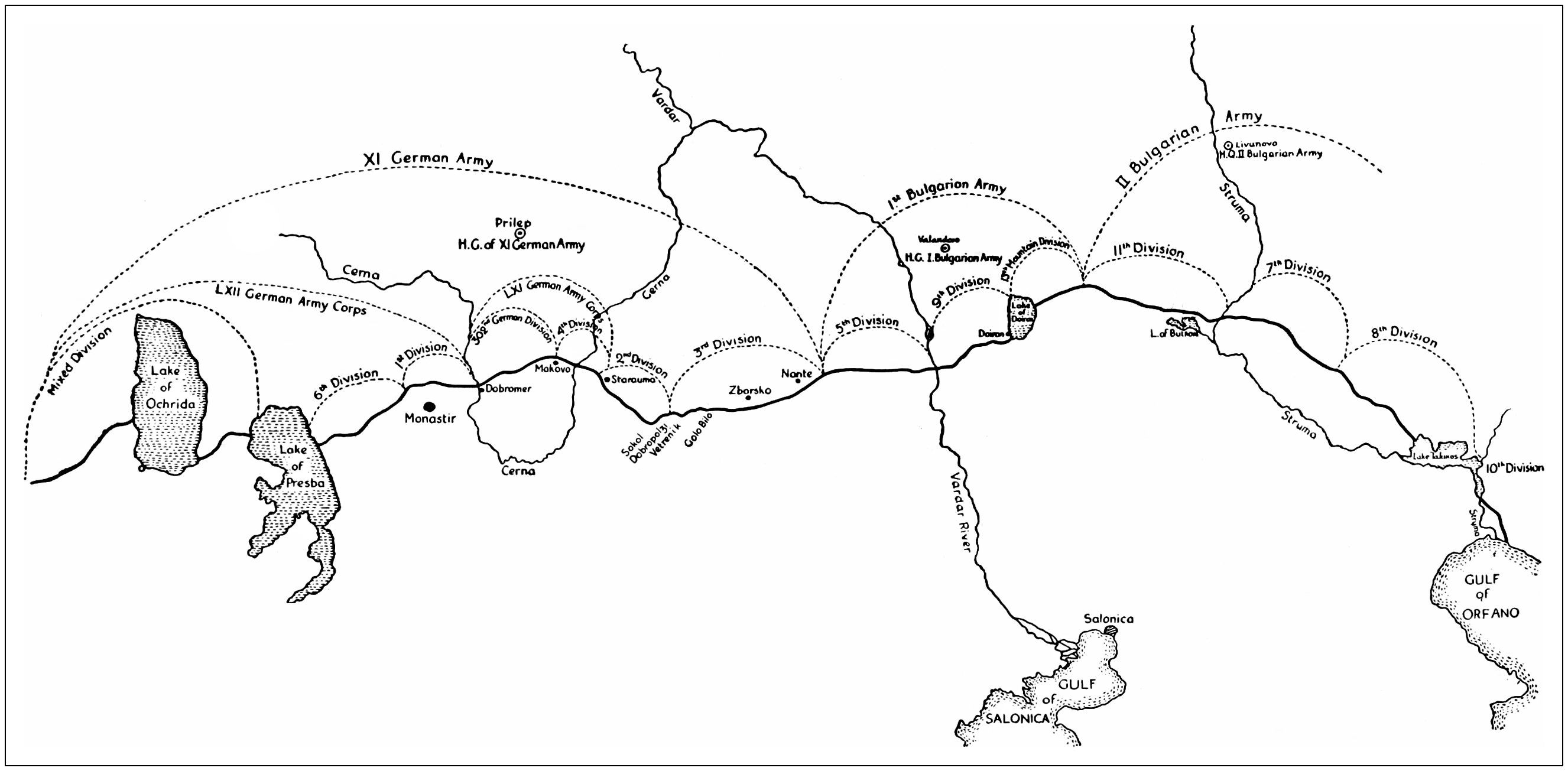

| ENEMY ORDER OF BATTLE, SEPTEMBER 15, 1918 | 227 |

| THE PRILEP-KRUSHEVO AREA | 236 |

| GRÆCO-BULGARIAN FRONTIER | 242 |

GENERAL ERNESTO MOMBELLI, COMMANDER OF THE ITALIAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE IN MACEDONIA.

To face p. 10.

The great victory of our army on the Italian front with which the war came to an end made the Italian public almost forget the deeds achieved by Italian troops on other fronts, and particularly in Macedonia. This has happened not only in Italy; even France and Britain, who had far larger contingents in Macedonia than ours, do not seem to have appreciated at their full value the operations in that area. There was a whole school of strategists, professional and amateur, competent and incompetent, known as the “Westerners,” who desired that every effort should be concentrated exclusively on the French and Italian fronts, and that the operations on the various Eastern fronts should be neglected or even abandoned altogether. Until the Balkan offensive of September 1918, that front, in the opinion of the great majority of the public and even in that of many political and military circles, was of small importance; according to the pure “Westerners,” the Salonica expedition was an error in its very origin, and a useless dispersion of troops who might have been more usefully employed elsewhere. There were even those who maintained the necessity of withdrawing the troops already sent to the East, and others who, although they did not go quite so far, were opposed to any increase of the forces in Macedonia, and even objected to their being provided with the necessary reinforcements and materials.

12

In support of this view it must be admitted that the Salonica expedition absorbed a vast quantity of tonnage, at a moment when tonnage in all the Entente countries was dangerously scarce, and when the voyage between England, France, Italy and Macedonia was extremely risky on account of submarines. It is also true that for about three years that expedition produced no tangible results; so much so that the Germans called it with ironical satisfaction their largest concentration camp, “an enemy army, prisoner of itself.”

Yet it was with the victorious offensive of September, 1918, that the Entente struck the first knock-down blow at the Central Powers and produced the first real breach in the enemy barrier which helped the armies in France and Italy to achieve final victory. Even Marshal von Ludendorff, in his memoirs, recognized the enormous importance of the Allied victory in the Balkans. Until September 15th, 1918, in fact, the enemy’s line of chief resistance from the North Sea to the Swiss frontier, from the Stelvio to the mouth of the Piave, from the Voyussa to the Struma, was intact. When the Balkan front collapsed, the whole of the rest of the enemy front in the West as in the East was threatened by a vast encircling movement, the moral effect of which was not less serious than its material consequences.

But it was not only at the moment of the victorious offensive that the Eastern expedition justified itself. Even in the preceding period of long and enervating suspense, the presence of the Allied armies in Macedonia had an importance which was far from indifferent with regard to the general economy of the war. Owing to causes which we shall subsequently examine, the Army of the Orient1 had not been able to carry out the task originally assigned to it of bringing aid to invaded Serbia and saving her from her extreme ruin, and it was therefore believed that that army had no longer any raison d’être. The truth, however, is very different, because for months and years it mounted guard in the Balkans, preventing the Central Empires13 from reaching Salonica and invading Old Greece,2 where they might have established innumerable new submarine bases and thus dominated the whole of the Eastern Mediterranean. This would have rendered any traffic with Egypt and consequently with India and Australia practically impossible, that is to say, with some of the most important sources of supply for the whole of the Entente and particularly for Italy. If the Army of the Orient was enmeshed amidst the marshes and arid rocks of Macedonia, on the other hand that Army nailed down the whole of the Bulgarian Army, consisting of close on three-quarters of a million men,3 amply provided with artillery both Bulgarian and German, throughout the whole of the war, and for a time certain German and Turkish divisions as well, forces which might themselves have been employed elsewhere. Incidentally, the operations in Albania against the Austrians could not have been maintained without the support of the Army of the Orient on its right.

In Italy, perhaps more than elsewhere, the advantages of the Macedonian expedition were doubted, and in many political and military circles, as well as among the mass of the public, the current of opinion was opposed to any Italian participation in the operations of that sector. Even when Italian participation had been decided upon, and the Italian expeditionary force was actually in Macedonia, it was not always possible for it to obtain all that it needed, and the command had to struggle hard to obtain the indispensable minimum of reinforcements and materials. Even among the officers of that force, many considered Italian intervention in the East useless and even harmful. Various reasons contributed to this opinion. In the first place, the fact that Italy’s war aims were at the gates of Italy and not in the Balkans influenced public feeling in general. Secondly, the fact that our expeditionary force was in a subordinate position seemed14 to many to be derogatory to Italian dignity; a feeling which may be compared with the one that the war with Austria was in a certain sense apart from the general World War. This attitude, which lasted to the end, has been very injurious to our interests in the Balkans and elsewhere, and those among us who really felt the inter-Allied character of the war have had to struggle without ceasing both to convince our dissident compatriots of their error, and to prove to the Allies that those who maintained the purely Italian character of the war only represented a part of Italian public opinion, and that part not the best informed.

Yet Italy’s participation in the Eastern expedition was inevitable. Independently of boundary questions of a general character, it was not possible that Italy should remain absent from that area, which subsequent events have proved to be extremely important. Even before the war we had great political and economic interests in the Balkans, interests in part destroyed and in part menaced by the Austrians and Germans in the course of the campaign; it was absolutely necessary that we ourselves should participate in reconstructing them, instead of leaving this work entirely to others. Further, in the new settlement which the war would create in the Near East, fresh interests and new currents of trade were bound to be created. For this reason too it was necessary that Italy by her presence should participate directly in shaping this new settlement. We complain now that our interests in the East are not sufficiently recognized and respected, but how could we have claimed recognition and respect for them if we had had no share at all in the Macedonian campaign? Above all, what would have been our prestige among the Balkan peoples if the latter had seen the victorious troops of France, Britain, Serbia and even Greece marching past, and not those of Italy? Our victory in Italy would not have sufficed to affirm our position among the Balkan peoples if they had not seen us take part in the victory won in their own homelands. It would indeed have been better if our participation had been far greater and our expeditionary force on a far larger scale.

15

The vicissitudes of the Army of the Orient are much less known than those of all the other armies in the World War, and in particular those of the Italian expeditionary force are largely ignored by the public, even in Italy. Many believe that it was merely a modest contingent, because it was called the “35th Infantry Division,” whereas in reality its strength was superior to that of an army corps; and considering the conditions of the area where it was fighting, its importance was equal to that of an army. It is with the object of making known to the public a little more of the actions of that fine unit and the debt of gratitude which the country owes to its officers and men for their long and arduous struggle, conducted in one of the most pestilent climates in Europe amid great hardship, and the increase of Italy’s prestige obtained by their merit, that I have undertaken to write these pages.

When the World War broke out, Austria immediately commenced an offensive against Serbia, and the Entente Powers could not at first send assistance to the latter on account of her geographical situation, as she was surrounded on all sides by enemy or neutral States, except to the south-west, but communications through Montenegro were extremely difficult, and by that route only a few volunteers penetrated into Serbia. Supplies and armies could arrive by way of Salonica, but always in the face of serious difficulties, both on account of the obstruction offered by Greece, whose neutrality was not benevolent, and of the attempts made by Bulgarian bands, with or without the approval of the Sofia Government, which was also neutral but still less benevolent, to cut the Vardar railway. The Serbians, however, had proved themselves in the first months of the war capable of defending their country, and they inflicted serious defeats on the Austrians, first at Tzer, in the loop formed by the Save and the Danube, in September, 1914, and later on in the winter at Valievo, where the hostile army, after having occupied Belgrade and penetrated into the heart of Serbia, was beaten and put to flight, leaving thousands of prisoners and vast booty in the hands of the Serbians.

16

Nevertheless the Serbians were in urgent need of assistance. Their food situation was still very grave, their supply of arms and munitions quite inadequate, and a terrible epidemic of spotted typhus was raging throughout the country. But in addition to material obstacles, the very psychology of the people rendered it difficult to assist them. In the spring of 1915, when the intervention of Italy was certain, the Serbs had a chance of inflicting a new and perhaps decisive defeat on the Austrians by co-operating with us. France, Great Britain, and Russia then brought strong pressure to bear on the Serbian Government to induce it to launch an offensive in the direction of Agram at the moment when the Italians were about to attack on the Isonzo. The Government agreed, and submitted a plan of operations to the Allies, which was approved, but just when it should have been put into execution, the Serbian Army did not move; as a result of fresh pressure on the part of the Allies the Government again promised to attack, but again did nothing. Finally, when this pressure was renewed for the third time, reinforced, it is said, by a personal letter from the Tsar, Belgrade replied at the last moment that it had decided not to attack in the direction of Croatia, because it wished to carry out another plan against Bulgaria, who was still neutral! The reasons for this sudden change in the decisions of the Serbian Government must be sought in the influence of the secret societies which permeate the whole political life of the country, and especially the army. The most important of these societies was the notorious “Black Hand,” to which many of the regicide officers belonged. Although the Government itself was apparently favourable to the action proposed by the Entente, which offered great possibilities of success, inasmuch as the Austrians had only a small body of troops in Croatia, it was not strong enough to resist the influence of the secret societies, who placed their veto on any action in co-operation with Italy.4 The full details of this affair are not17 quite clear, but one thing is certain, and that is that owing to Serbia’s inaction Austria was able to withdraw five out of the six divisions which were left on the Save and send them to the Italian front. At that period of the war the Serbian front was considered in the Austrian Army almost as a rest camp.

In the autumn of 1915 the Serbian débâcle took place, caused chiefly by the Bulgarian attack. The intervention of Turkey on the side of the Central Empires had rendered Bulgaria’s position extremely difficult, but that was not the chief reason of the latter’s intervention. Bulgaria had remained profoundly dissatisfied with the results of the Peace of Bucarest (1913), which brought the Turko-Balkan War to an end and deprived her of a great part of the fruits of her victory against the Turks. The fault was to a large extent her own, because she had attacked her ex-Allies, Serbia and Greece, and had been completely defeated by them; she then lost not only the whole of Macedonia, to conquer which she had entered the war, but also Eastern Thrace, with Adrianople and Kirk-Kilisse, which were reoccupied by the Turks when the Bulgarian Army had been beaten by the Serbs and Greeks, and a part of Dobrugia which had belonged to her since the creation of the Bulgarian State in 1878, and had been annexed by Roumania, who had intervened in the war at the last moment. This left a bitter feeling of spite in the soul of the Bulgarians, and sowed the seeds of a future war of revenge.

This violent irritation against the Serbs, Greeks and Roumanians was not the only cause which threw the Bulgarians into the arms of the Central Empires, and of their former mortal enemies, the Turks. Their main aspiration—almost their only one since the creation of the Bulgarian State—has been Macedonia. The Dobrugia and Thrace are of comparatively small interest to them, whereas Macedonia, on the contrary, is the bourne of all their desires. In Thrace and in the Dobrugia the population is very mixed, and the Bulgarians, in spite of the statistics drawn up by the Sofia Government, are a minority, and the non-Bulgarian elements of the population—Turks,18 Greeks, Roumanians—are racially entirely different. In Macedonia, on the other hand, at least in Central and Northern Macedonia, the great majority is Slav, and the Bulgarians consider it Bulgarian. In reality the population is racially and linguistically something between Serbian and Bulgarian, and the predominance of Serbian or Bulgarian sentiments varies according to the proximity of the frontier of one or other of these States, the activity of their respective propagandists, and the greater or less prestige and strength of the two Governments. I will not quote statistics which, being drawn up by Balkan writers, have a doubtful value and no scientific basis, but it is certain that the Bulgarian peoples are convinced that if Macedonia were annexed to Bulgaria, in a few years the population would become wholly Bulgarian, so that the State would find itself with a considerable increase of inhabitants—not aliens who cannot be assimilated, such as Greeks, Roumanians or Turks, whose territories can only be Bulgarized by massacre or deportation en masse, but of a race which is already very closely akin to the Bulgarian race. Further, in Macedonia there are several cities closely connected with the most ancient and sacred historical traditions of the Bulgarian peoples, such as Monastir and Ochrida. The latter was indeed for a time the capital of the Bulgarian Empire and for many centuries the see of the Bulgarian patriarchate. Bulgarian propaganda had always been much more active and more able than that of the Serbians under the Turkish régime, a propaganda based on excellent schools and assassinations, and, as until the wars of 1912–13, the Bulgarians appeared to be the most solid, and from a military point of view the strongest of the Balkan States, Bulgaria exercised a powerful force of attraction over the Macedonians. In consequence of this propaganda and of Turkish persecutions, a large number of active and intelligent Macedonians migrated into Bulgaria, where they occupied many important positions in the country. A large part of the political men, diplomats, consuls, high officials, professors, school-masters, officers and merchants in Bulgaria are Macedonians, and they have long dominated the internal and19 foreign policy of the country, directing it naturally towards Macedonia. On the whole, Bulgarian feeling predominates over Serbian or Greek feeling throughout almost the whole of Macedonia.

During the Turko-Balkan War, the Bulgarians had conquered a large part of Macedonia and Thrace, and their legitimate aspirations might thus have been satisfied, but, owing to the mad ambition of their Government, or rather of a small number of ambitious officers, they attempted to obtain a great deal more, and threw themselves without reflecting into the foolhardy enterprise which was the second Balkan War. The unfortunate result of that campaign made them lose the whole of their conquests, with the exception of Western Thrace and the districts of Strumitza and Djumaya forming part of Macedonia. They retained, it is true, the port of Dede-Agatch and the railway connecting it with the rest of Bulgaria, passing through a strip of Turkish territory (Sufli—Demotika—Adrianople—Mustafa Pasha). But if they were justly prevented from obtaining satisfaction for these exaggerated ambitions, they were on the other hand deprived of territories to which on national grounds they had some legitimate claims. The Serbian authorities in Macedonia, while maintaining that that country was purely Serbian, showed by their policy that they considered the population preponderantly Bulgarian, inasmuch as they instituted a system of such extreme and rigorous terrorism as is only explicable on the ground that they were ruling over a conquered territory, whose inhabitants were hostile to them, and must be kept down by force.

The Bulgarian aspiration to regain Macedonia was by no means eliminated by the unfortunate outcome of the second Balkan War. On the contrary, it was strengthened and embittered, and when the World War broke out Bulgaria regarded it merely from the point of view of a possible readjustment of the Macedonian frontier in her own favour. I have been told that the Bulgarian Prime Minister, when a British diplomat went to see him a short time before Bulgaria entered the war, pointed to a map of the Balkans on the wall and said: “We care little about the British,20 Germans, French, Russians, Italians or Austrians; our only thought is Macedonia; whichever of the two groups of Powers will enable us to conquer it will have our alliance.” I do not know if this anecdote is true, but in any case it represents crudely but accurately Bulgarian mentality. The Governments of the Entente understood this state of feeling, but their situation was embarrassing and delicate. They tried to convince Serbia of the necessity of handing over Macedonia, or at least part of it, to Bulgaria, promising her compensation elsewhere. But they did not care to insist too much, because Serbia was an ally, and the compensation offered to her was in territories still retained by the enemy, whereas Bulgaria was a neutral, but a short while ago Serbia’s enemy, who was attempting a sort of blackmail, and who hitherto made use of comitadji bands, or at least gave them a free hand, to blow up the bridges on the Vardar, Serbia’s only line of supply. Serbia would not hear of this proposal, and in fact intended, as we have seen, to attack Bulgaria before the latter came to a decision; but the Entente, and particularly the Tsar of Russia, naturally dissuaded them from such action, which would have been little different from that committed by the Germans in invading Belgium. Certainly Serbia would have been wiser had she shown herself more conciliatory towards Bulgaria; if she had done so, she would have avoided the catastrophe of 1915 and the three terrible years of German-Bulgarian slavery. But the Serbians, we must not forget, are a Balkan people. They have no high political sense nor broad views, and probably even on this occasion the secret societies, with their insatiable and megalomaniac ambitions, brought pressure to bear on the Government to induce it to reject any idea of compromise. However this may be, Serbia did not give way, and the diplomacy of the Entente could do nothing.

ARCH OF GALERUS, SALONICA.

To face p. 20.

The Entente counted much on the sympathy for Russia, which it believed to be very widespread among the Bulgarians, but that sympathy carried no weight in the decisions of the Sofia Government. The Bulgarians, like other Balkan peoples, are vindictive for all offences suffered, and understand gratitude largely in the sense of anticipation of benefits to come. In the case of Russia, moreover, their gratitude towards her for having freed them from the Ottoman yoke had been much weakened by the foolish, overbearing and intriguing conduct of the Russian officials in Bulgaria after 1878. The Bulgarians quickly forgot the thousands of Russians who had fallen at Plevna for Bulgarian liberty, but they retained a lively recollection of the persecutions and brutality of Generals Kaulbars and Ernroth, and of their satellites who misgoverned the country for many years; of Russia’s illicit interference in their internal affairs at the time of Prince Alexander of Battenberg; and of the fact that Russia abandoned Bulgaria when she was attacked without warning or provocation by Serbia in 1885. By the summer of 1915 the Bulgarians had come to the conclusion that the Central Empires were stronger than the Entente, and that the former therefore offered them a better chance of reconquering Macedonia than the latter. On September 10th, 1915, a general mobilization was ordered in Bulgaria, and on the 29th Bulgarian troops attacked Serbia at Kadibogaz, without a formal declaration of war.

Bulgarian intervention had, however, already been decided upon for some time. Bulgaria had obtained a loan from Germany which tied her hand and foot, and, further, after protracted negotiations promoted by Germany, she had concluded on September 6th an agreement with Turkey, whereby the latter granted her a rectification of the frontiers, so that the railway between Dede-Agatch and the rest of Bulgaria should pass wholly through Bulgarian territory. There were two immediate consequences of Bulgarian intervention. The first was that Turkey could now receive supplies from Germany with greater facility because there was only a small strip of Serbian territory to be invaded so as to establish communications by way of the Danube, and it was very soon occupied. The second consequence, which was a result of the first, was that the situation of the Allies on the Dardanelles became far more critical. The British Command knew that the arrival of powerful German artillery at Gallipoli was imminent, and that as soon as it was in22 position the situation of the Allied expeditionary force would become very precarious. The fact that Bulgaria was now an ally of the Central Powers greatly facilitated the sending of this artillery, and it was on the eve of its arrival that the evacuation of the blood-stained peninsula was decided upon.

Germany, after the various Austrian defeats in Serbia, determined to take the command of a new punitive expedition herself, and in view of the co-operation of Bulgaria she had concentrated a powerful Austro-German army, amply supplied with artillery, including guns of the heaviest calibre, in South Hungary under the command of the German Field-Marshal von Mackensen. The invasion of Serbia was carried out by the Austrians and Germans from the north and also from the west (from Bosnia), and by the Bulgarian Army from the east and south-east. The Serbians fought heroically, opposing a desperate resistance on three fronts, and at one moment it seemed as if they might miraculously succeed; perhaps indeed they might have saved themselves, or at least avoided the extreme disaster, if they had only followed the advice of the Allies. But although it soon became known that a new and more formidable attempt was about to be made by the enemy to crush Serbia definitely, the Serbs refused to create a modern defensive system of trenches and wire entanglements, which in a mountainous territory such as that of Serbia would at least have held up the invaders for a considerable time. To the suggestions made by the Allies that these methods be adopted, the Serbs replied with typical Balkan vaingloriousness: “Wire entanglements and trenches are all very well for the Germans and Austrians, for the French, Italians, British or Russians, but we have no use for them; we fight in the open and drive out the enemy.” Their victories over the Austrians had made them lose their heads and forget that these victories were not due solely to their own courage but also, to a considerable extent, to the serious strategical and tactical errors of the Austrian commanders, from General Potiorek downwards, errors which were not repeated by Marshal von Mackensen. The new invasion carried out by23 the formidable Austro-German Army to which we have referred, and there came also the stab in the back on the part of the Bulgarians.

The enemy had 12 German and Austrian divisions advancing up the Morava valley, and 7 Bulgarian divisions (divisions of 6 regiments each, many of whose regiments were of 4 battalions), which pushed forward in the direction of the Nish-Uskub railway. Altogether these forces comprised 341 battalions, of which 111 were German, 53 Austro-Hungarian, and 177 Bulgarian; against these forces the Serbs could only oppose 194 battalions—116 against the Austrians and Germans, and 78 against the Bulgarians. They were, moreover, exhausted by the long struggle, and reduced to about half their organic strength. Serbia had been deprived of her lines of supply via the Morava and Toplitza valleys by the enemy invasion. The only hope for her army was to establish a connexion with the relieving forces which the Allies were preparing to send up from Salonica. On October 17th the railway was cut at Vrania, thus interrupting communications with Salonica; on the 27th Veles and Uskub were occupied.

As soon as the preparations for a new enemy invasion of Serbia were known, the Entente decided to send an expeditionary force to Salonica and at the same time decided, as we have seen, to withdraw the Dardanelles force.5 This decision was taken at the end of September, and on the 29th a mission, comprised of one British and two French officers departed from Mudros for Salonica with very vague orders. On reaching their destination, they set to work to prepare for the disembarkation of the troops, but they found themselves faced with the most insidious obstruction on the part of the Greek authorities. The Athens Government, of which M. Venizelos was president, had given its unwilling consent to the landing of the Allies, but the civil officials and the military commanders on the spot did everything to interfere with their operations. The first Allied contingents were British and French troops from the Dardanelles. They were elements24 of the 10th British Division commanded by General Sir Bryan Mahon, who for some time commanded all the British troops in Macedonia, and of the 156th French Division commanded by General Bailloud. The landing began on October 5th, and in a short time the 2 divisions were complete, although reduced in strength by sickness and losses to very weak effectives. Later, the 57th French Division arrived. On October 12th General Sarrail arrived at Salonica as Commander of all the French troops in the Orient. For a considerable time nothing was decided as to the relations between the different commands in Macedonia, and although the rank of Commander-in-Chief had been conferred on General Sarrail, the British Commander, and later also the Serbian Commander, insisted on maintaining their own autonomy. It was not until June 23, 1916, that an agreement was concluded on this matter between the French and British General Staffs, but even this was somewhat vague. “The question of the Command,” this document states, “is regulated by the following formula: Instructions concerning the initial offensive as well as the line of conduct necessary for the further development of operations will be established by mutual agreement between the French and British Commands. It is thus understood that the Commander of the British forces will give the Commander of the French forces assistance and co-operation in proportion to the effectives and equipment of the troops under his orders. He will be responsible, however, to the British Government for the employment of his forces. The Commander of the French forces will consult with the Commander of the British forces as to the manner in which the latter shall be employed; with this reserve, he will have as Commander-in-Chief authority to establish the duties and objectives to be attained, the area of action, and the date for the commencement of operations.”6 It is easy to see that the authority of General Sarrail over the British Commander was quite illusory. His orders might be discussed, and they were. Field-Marshal French had said clearly to the British Commander in Macedonia: “You will never be25 in a subordinate position,” and in fact every time that Sarrail sought to make use of the British or even French troops, temporarily placed under British Command, he had to conduct negotiations as if it were a political act. We shall see subsequently why it was that he never succeeded in imposing his authority, but the fact certainly did not contribute to the success of the operations in the Near East.

Day by day fresh troops and fresh material arrived at Salonica, but the ill-will of the Greek authorities rendered everything difficult. The buildings which the Allies needed were always found to have been already requisitioned by the Greeks, so that the French and British had to encamp on Zeitenlik, a spot at 5 km. to the north of Salonica, at that time, before the drainage works afterwards carried out by the Allies, infected with malaria. In the purchase of foodstuffs and material every sort of difficulty was encountered. Worse still, every movement of the Allies was spied upon by and communicated to the enemy, either indirectly via Athens by the Greek authorities, or directly by the German, Austrian, Bulgarian and Turkish Consuls, who continued to reside in Salonica. The situation was absolutely preposterous—an Entente army operating in a neutral country which was friendly to the enemy.

On November 17th, 1915, the Anglo-French troops were about 120,000, of whom two-thirds were French, and on the 20th a fresh British division arrived, but they were still far from the 300,000 men deemed necessary for operations on a large scale. There was another greater danger which was anything but indifferent. The Greek Army, comprised about 240,000 men, of whom half were in Macedonia, and if its military value was not very formidable, it might have, in alliance with the enemy, represented a serious menace to the Entente.

The initial objective of the Allies was to bring assistance to the Serbs who were retreating before the Austro-German and Bulgarian invasion. This assistance was to have taken the form of an advance up the Vardar Valley towards Uskub or towards Monastir. As soon as the troops were landed at Salonica they were immediately pushed forward towards the front, the British to the east of the Vardar26 and the French to the west. On October 20th the French reached Krivolak on the Vardar and occupied the whole peninsula formed by that river and the Cerna, while the British were to the north of lake of Doiran, on the Kosturino Pass on the Beles Mountains, whence it is possible to descend into Bulgaria. The Serbs were being driven ever further south, but a detachment of their army was holding Monastir. If they had followed the advice of the Allies and had retreated towards them, perhaps a part of the army might have been saved; but, attracted by the mirage of an outlet on the Adriatic, or for some other motive, they insisted on deviating towards the west, thus undertaking that retreat across Albania which was to prove one of the most terrible tragedies of the whole war. Before the invasion the Serbian Army comprised 400,000 men, when it reached Albania it was reduced to 150,000, with some tens of thousands of Austrian prisoners; the rest had died of hunger and suffering. This miserable remnant was saved by the assistance of the Allies, and particularly of the Italians, as we shall see further on. The retreat through Albania rendered the situation of the Anglo-French on the middle Vardar untenable. When the French learnt that the Bulgarians had occupied the Babuna Pass between Veles and Monastir at the beginning of November, they tried to break the enemy front on the left bank of the Cerna in the hope of reaching the Serbs to the north-west of that pass. For fifteen days (November 5–19th) a fierce struggle went on between the French and the Bulgarians, in which our Allies showed all their admirable military qualities. The Bulgarians counter-attacked on the Cerna and were repulsed with heavy losses, but as the bulk of the Serbian Army had retreated towards Albania and the French had been unable to capture the dominating position of Mount Arkhangel (west of Gradsko on the Vardar), the offensive passed definitely to the Bulgarians. On the 2nd, General Sarrail ordered a general retreat from Krivolak on Salonica. Even this operation was anything but easy. It was necessary to withdraw 3 divisions (the 122nd had been recently added to the 156th and 57th) and an enormous quantity of material along the Vardar Valley over a single-track27 railway and without decent carriage roads, in a season when the rains converted the whole country into a vast muddy swamp. It must be admitted that General Sarrail conducted this retreat in good order. The Bulgarians were attacking from the north towards Krivolak and from the west on the Cerna, while from the east they were attacking the British at Kosturino, while irregular bands were trying to capture convoys along the Vardar, and enemy artillery from the Beles range dominated the railway. Added to this there was rain, snow and cold.

There were two plans of retreat, which may be described as the maximum and the minimum. The first consisted in withdrawing to the entrenched camp at Salonica, the other in resisting on an intermediate position between the Krivolak-Cerna line and Salonica along the Greek frontier. The first had the advantage of considerably shortening the line to be defended, and of bringing it nearer to the base: but on the other hand, besides adversely affecting the prestige of the Allies, it would have left the road from Macedonia and Albania into Old Greece open to the enemy, thus renewing and reinforcing German pressure on King Constantine in favour of Greek intervention on the side of the Central Empires. In that case Salonica, and with it the whole of the Allied Armies, would have been irreparably lost. Consequently the second plan was adopted.

The French retreat was carried out by echelons. First the detachments on the left of the Cerna were withdrawn to the right bank and the bridge at Vozartzi destroyed. Then a concentration took place at Krivolak, which was the rail-head, and the troops retreated in four stages. The Bulgarian attacks near the Cerna having been repulsed, the French reached Demir-Kapu without difficulty. They passed through the narrow gorge by night, while the rearguard covered the retreat. The Bulgarians tried to out-flank the French, advancing by mountain paths on the Marianska Planina so as to fall on them when emerging from the gorge, but their attempt failed. On December 7th the bridge and tunnel at Strumitza were blown up. On the 8th, although exhausted by the interminable march, the French repulsed still other enemy attacks. The great28 depots at Ghevgheli were evacuated, and on the 10th, as the Bulgarians were attacking along the river, the convoys had to continue their retreat over the mountains. The two African march regiments counter-attacked with great vigour, and on the 11th, the depots having been burnt and the railway and the bridge destroyed, all the troops withdrew beyond the Greek frontier.

The British (10th Division), who occupied the area between the Vardar, the Lake of Doiran and the Kosturino Pass, were not attacked until the end of November, but on December 6th the Germans and Bulgarians attacked and the British commenced their withdrawal. On the 12th they too had crossed the Greek frontier between Ghevgheli and Doiran, and the enemy did not advance farther for the time being.

The enemy had by now occupied the whole of Serbia, including Monastir, which had been evacuated on December 5th, the Serbian garrison having withdrawn to Salonica, but for political reasons they did not wish to cross the Greek frontier, as they considered the Greece of King Constantine (Venizelos having fallen) a benevolent neutral. This gave the Allies breathing space and time to reinforce themselves. On December 3rd, the French Government ordered General Sarrail to create an entrenched camp at Salonica. The area from Topshin to Dogandzi and Daudli was entrusted to the French, that from Daudli to the sea, passing along the Lakes of Langaza and Besik and through the Rendina gorge, to the British. The former had their usual 3 divisions, the British five (22nd, 28th, 26th, 10th, and in addition the 27th without artillery in reserve at Salonica). Within two months the first positions were created with three lines of resistance and a barbed wire entanglement 10 metres broad defended by 30 heavy batteries. These defences had been made according to all the latest scientific rules of war, and had the advantage of not having been constructed under the pressure of the enemy, as was the case with the great entrenched camps in France. Of the three lines of defence, the first and second were in excellent condition, whereas the third was merely sketched. The works were in groups of three,29 so that the two more advanced ones were dominated by the one in the rear. They were united to each other by communication trenches, which could also be used as firing trenches. Beyond the entrenched camp the Allies occupied advanced positions, the French as far as Sorovich, and later (March 21st, 1916) Florina, and farther east along the railway between Kilkish and Kilindir; the British towards the Lake Doiran.

Allies and enemies now stopped along the line which they were to occupy without important change for several months. The enemy lines passed to the south of Kenali (on the railway between Florina and Monastir) along the ridge of Mount Kaimakchalan and thence along the mountains to Lake Doiran. Beyond the lake they ascended on to the crest of the Beles mountains, following the Græco-Bulgarian frontier of 1913. The enemy attack was expected from week to week, but it did not come, and in the meanwhile the Allies continued to receive reinforcements (French and British) and material, and they were able to strengthen their defences and improve their situation.

In all there were at the beginning of 1916 a little less than 100,000 French troops, about as many British and a few thousand Serbs, altogether about 200,000 men to defend the entrenched camp, forming an arc of a circle of 120 kilometres, in addition to the advanced positions. There were 358 French and 350 British guns, but the heaviest French guns were only long 155 mm. and the heaviest British were of 6 in. General Sarrail had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Armies in the Orient. The British Army, in May, 1916, was commanded by Lieutenant-General George (now Sir George) Milne, under the superior command, although in a limited measure, of General Sarrail. The enemy forces amounted to about 280,000 men.

The results of these operations, although disaster had been avoided, cannot be regarded as brilliant, nor were they of such character as to raise the prestige of General Sarrail with the Allies, nor of the Allies in general with the enemy States and those who were still neutral. A well-executed30 retreat without heavy losses in men or material may be a fine operation from a technical point of view, but it does not arouse enthusiasm. On the other hand, the relative conditions of the two armies amounted to a situation of stalemate from which it would not be easy to emerge. General Lord Kitchener, who had come to inspect the Macedonian Army in December 1915, had actually proposed the withdrawal of the expedition, which appeared to him as to many other experts a useless dispersion of forces, and the Governments were in doubt as to whether or not it were advisable to carry out this suggestion. But in the course of 1916 the Allies received a new reinforcement, in the shape of the revived Serbian Army, which was destined to exercise a considerable political and military influence on the future vicissitudes of the Oriental campaign.

The disastrous retreat through Albania in which the Serbian Army had lost nearly all its artillery and more than half its effectives, took refuge in Corfu, save a few detachments which were sent to Bizerta. In Corfu the exhausted and worn-out soldiers rested, were re-equipped with everything and thoroughly reorganized. As soon as they began to recover from their terrible experiences they wished to go to Macedonia to take part in the Allied operations. They began to reach Salonica in the spring of 1916, and at the end of April there were about 15,000 of them, besides the detachment formed of the men who had escaped from Monastir. At the end of June they amounted to 120,000 and in July to 152,000. They were divided into three armies, each comprising two divisions: I Army (Morava and Vardar Division); II (Shumadia and Timok) and III (Drina and Danube), in addition to the cavalry division and the volunteer corps, with 72 machine-gun sections. The artillery was supplied to a great extent by the French, except for a few guns saved in the retreat, to which some others captured from the enemy were afterwards added. They had 6 groups of 75 mm., 6 of 80 mm. mountain batteries (afterwards replaced by 65 mm. quick-firing guns), 6 groups of Krupp 70 mm. or Schneider 75 mm. mountain guns, 6 groups of 120 mm. howitzers, 6 batteries of 58 mm.31 trench guns. Scattered about the mountains along the border between Macedonia and Albania and in Macedonia there were irregular Serbian comitadji bands estimated, in July 1916, at about 5,000 men, who broke up and reformed according to circumstances, now attempting a raid, now hiding among the mountains. Other bands continued to exist in Old Serbia, and in fact they rose in revolt in the winter of 1916–17, causing serious anxiety to the enemy; the movement, however, was ruthlessly repressed.

But the situation of the Allies continued to be made extremely difficult by the conduct of the Greek authorities who, although officially neutral, were in reality most unfriendly. They had created a regular system of espionage in favour of the Central Empires, headed by Colonel Messalas, who sent reports of every variation in the strength and distribution of the Allied troops to the Ministry of War at Athens and to the King and Queen, whence they reached the German G.H.Q. The Consuls of the enemy States were naturally extremely active in this work of espionage and the Allied G.H.Q., owing to its peculiar situation, and not wishing to come to a regular breach with Greece, either because it was feared that she might definitely go over to the enemy or in the hope of inducing her to join the Entente, had its hands tied. When, however, in consequence of information supplied by enemy agents, German aeroplanes bombed the city, causing considerable damage, and killing a number of people, General Sarrail declared that he would henceforth consider the area occupied by the Allies as a war zone, and on the night of December 30th Franco-British patrols arrested the four enemy consuls and seized their archives, whence they obtained valuable information concerning enemy spies. A British detachment had on its own account arrested the German Consul at Drama in the train near Serres, in spite of violent rhodomontades and protests of the Greek officers in the same compartment.

Graver anxiety was caused by the Greek Army. At the end of 1915, its distribution was as follows: The I and II Corps were in Old Greece, except the artillery, which32 was between Salonica and Vassilika; the III Corps was echeloned between Salonica, Yenidje-Vardar, Verria, Ekshisu, Banitza and Florina; the IV between Serres and Drama, and the V between Langaza and Guvesne. In theory the Greek troops were to guard the frontier, preventing the Germans and Bulgarians from violating it, but none of the Allies had the slightest confidence that they would have offered any resistance to an attempt at invasion, even if they did not actively co-operate in it. Further, Greek officers and officials conducted an active and lucrative contraband in favour of the “hereditary enemy.” The British writer, G. Ward Price, notes that it is remarkable how instinctively the soldiers of the various Allied Armies—the most heterogeneous collection of characters, types and standards of conduct—were agreed in hating the Greeks at that time.7

The Allies now began to bring pressure to bear on the Greek Government in order that the Greek Army should be withdrawn from Macedonia and demobilized. On January 28th an Anglo-French detachment, with the co-operation of warships, among which was the Italian cruiser Piemonte, occupied the forts of Karaburun, south-east of Salonica, the port of which is dominated by them, and expelled the Greek garrison. On the night of January 31st-February 1st, a German Zeppelin bombarded Salonica; it was afterwards brought down and destroyed near the mouth of the Vardar, and at the same time luminous signals were seen coming from the city. General Sarrail, who since January 15th had assumed the control of the police, the railways and the telegraph, seized the occasion to proclaim the state of siege. The chief of the French Sûreté and the British A.P.M. proceeded little by little to cleanse the town of suspicious elements, and there was good need of it. In the meanwhile the Greek troops slowly and unwillingly began to evacuate Macedonia. On May 23rd, 1916, the Germano-Bulgar Army, on the pretext that the Allies were carrying out threatening movements in the Serres area, crossed the Greek frontier and demanded the evacuation of Fort Rupel dominating33 the narrow defile through which the Struma opens its way to the east Macedonian plain and flows down to the sea. The Commander of the garrison made a feeble protest, fired a few shots to salve his conscience, and asked for instructions from Athens. These were to the effect that he should hand over the fort with all its material, which he did with enthusiasm. In conformity with analogous instructions, the whole of the IV Corps, distributed through the Serres area and commanded by Colonel Hadzopoulos, surrendered to the Bulgarians and Germans, except 2,500 men of the Serres Division who, with their Commander, Colonel Christodoulos, refused to submit to this dishonour and managed to escape to the island of Thasos, whence in September they were transported to Salonica and formed the nucleus of the future Venizelist army.

The conduct of the Greek Government is explained by some retrospective history. M. Venizelos, although convinced of the erroneous policy pursued by King Constantine, hesitated to promote an open rebellion against him, also because he saw much weakness and indecision among the Allies. The King had dissolved the Chamber in June 1915, and whereas in that Parliament, which had been elected by 750,000 voters, the majority was in favour of Venizelos, in the new Chamber, elected by only 200,000 voters in December in an illegal manner under Government pressure and threats, the majority was hostile to him. But independently of these illegalities, Greek public opinion was to a great extent opposed to the policy of Venizelos, who desired the intervention of Greece in favour of the Entente, not only in order to meet Greece’s obligations of honour towards Serbia, but also in the higher interests of Greece herself. Facts have proved that he was right, but in 1915 the policy of Constantine might well have been deemed the more prudent. Serbia was, like Belgium, invaded and devastated; Bulgaria and Turkey allied to Germany and Austria; one half of Albania occupied by the Austrians and the other half by the Italians—the latter undesired neighbours of Greece—and German terrorist propaganda, which in Italy had failed so miserably, in Greece achieved the success of fear.34 “Should we throw ourselves into this conflict and run the risk of seeing our country invaded and devastated?” the Greeks asked themselves, and most of them came to the conclusion that it was better to remain neutral and to make money through war trade; from the point of view of their immediate interests, they were not altogether wrong. It is not true, however, that the whole population was pro-German. The King and the Queen (sister of the Emperor William) were pro-Germans, and so also were nearly the whole of the General Staff, and the majority of the generals and field officers educated in Germany or at least trained according to German methods. The masses were indifferent to the respective moral merits of the two groups of belligerents, and did not want war, and as Constantine would have found it extremely difficult to make war in open alliance with the Central Empires, he tried to help them by remaining neutral. In the popular mind Venizelos consequently came to be synonymous with intervention and Constantine with peace; the people preferred peace. Further, as the army was still mobilized there was a good deal of discontent, and the people regarded Venizelos as responsible for this state of things. Another reason in favour of neutrality was that if Greece had intervened she would have found herself in alliance with Italy, against whom she was much irritated owing to the question of the Dodecannese and Southern Albania. Finally, she had reason to believe that the Allies had offered a considerable part of Macedonia to Bulgaria in September 1915, in the vain hope of obtaining the latter’s intervention against the Central Powers. In the meanwhile, Venizelos was awaiting the moment for action. For all these reasons, the surrender of Rupel and of the IV Army Corps did not arouse that reaction which was expected, and which in other circumstances would certainly have occurred. King Constantine had received as a reward for his policy a loan from the Central Empires of 75 million drachmæ, while at the same time he was trying to negotiate another for 125 millions from the Allies. In spite of the declaration of the Prime Minister, M. Skouloudis, in the Chamber, there was a general belief throughout the Allied countries, as even M. Coronillas, Greek Minister in Rome, and his35 colleague in Paris, M. Caclamanos admitted, that the Government of King Constantine had concluded an agreement with Thrace, Germany and Bulgaria.8 The treachery of Rupel and the 4th Corps produced very unfavourable results for the Allies. The whole of Eastern Macedonia fell into the hands of the enemy without a blow having been struck. Demir-Hissar, Serres, Drama, Kavalla were occupied by the Bulgarians, and the fighting line was brought to the course of the Struma from Rupel to the sea, and although these towns might have been retaken without great difficulty, they were dominated by very strong positions on the mountains behind them, which were immediately fortified. For this reason, Great Britain, France and Russia renewed their demands on the Government at Athens in order that all the remaining Greek troops be withdrawn into Greece, the army demobilized, and the anti-Constitutional Government abolished.9 It will be noted that in all the affairs of Greece it was always these three Governments who acted, and not the Entente as a whole. This was due to the fact that, owing to the London Convention of May 7, 1832, these three Powers were declared the protectors of the Greek Kingdom and of its Constitution. The evacuation of Macedonia was carried out slowly, as was also the demobilization. What remained of the Greek Army was nearly all concentrated in the Peloponnese, where it could be easily watched and prevented from returning towards Macedonia. But the Royal Government did everything in its power to avoid fulfilling its engagements, and while the demobilization was being carried out, leagues of Epistrates (Reservists) were being formed. These associations, organized by officers devoted to King Constantine, constituted a new element hostile to the Entente. Then also, the Government tried to maintain armed forces in Northern Greece by strengthening the gendarmerie and creating hidden deposits of arms. Although the importance of these attempts were much exaggerated, they nevertheless caused some anxiety to the Allied Armies in Macedonia.

36

I have already set forth the reasons wherefore I consider that Italy’s participation in the Macedonian expedition was opportune, and indeed indispensable. Our Government was finally convinced of this necessity, but accepted it somewhat unwillingly, both for political and military reasons; consequently our participation was ever maintained within modest proportions. In accordance with the terms of the agreement concluded between ourselves and our Allies, Italy undertook, in the summer of 1916, to participate in the Macedonian expedition with a division, which, however, was only to be provided with mountain artillery; the field and heavy artillery attached to our contingent was to be supplied by the French Army. There were then some good reasons for not endowing these troops too generously with artillery; the Italian Army in general was inadequately provided with guns, and during the Austrian offensive from the Trentino in the spring of that year it had lost many batteries, especially of medium and heavy calibre. These reasons, however, did not continue to exist in the later phases of the campaign, but nevertheless our expeditionary force in the Balkans was never provided with artillery of its own, except with the above-mentioned mountain batteries, a fact which was to cause us considerable difficulties in the future.

Our contingent consisted of the 35th Infantry Division, a name destined to occupy a high place in the roll of honour of the Italian Army, although it has been hitherto less well known than that of many other units. To this division many other detachments had been added which37 properly belong to an army corps or even an army. Originally, it had consisted of the Sicilia Brigade (61st and 62nd Infantry Regiments)10 and the Cagliari Brigade (63rd and 64th), several machine-gun companies, a squadron of the Lucca Light Cavalry (16th Regiment), eight mountain batteries of four 65 mm. guns each, various companies of engineers, transport and other services, etc. The division had achieved an honourable record on the Alpine front, where it had suffered heavy losses; but before coming out to the East it had been reorganized, brought up to full strength, and admirably equipped. The command of the force had been entrusted to General Petitti di Roreto, a very distinguished and gallant officer, and an excellent organizer; his Chief of the Staff was Colonel Garbasso.

The first Italian detachments reached Salonica on August 11, 1916. The fine appearance, smart equipment, and the vigorous and martial aspect of the men in their grey-green uniforms and steel helmets, marching along the quay under the brilliant summer sun, created an excellent impression. Representatives of the various Allied armies were there to receive them, with the band of the Zouaves. The numerous and patriotic Italian colony, which had seen the troops of almost all the other Allied armies arrive—there was even a Russian contingent which had come over from France—was in a paroxysm of excitement when at last it saw the Italian troops and admired the battle flags of our fine regiments fluttering in the breeze. It was not only to strengthen the Allied front in the Orient that it was advisable to send an Italian contingent, but also to affirm Italian prestige among the Balkan peoples, a duty which the 35th Division fulfilled no less well than it accomplished its purely military tasks.

Our expeditionary force was at first destined to take part in an action on the Macedonian front, in co-operation with the Russian and Roumanian offensive, Roumania’s38 intervention being already decided. But the total strength of all the Allied forces in Macedonia was insufficient for an operation on a large scale, and by the time the Italians had landed this scheme was hardly thought of any longer. General Petitti was to take orders directly from the Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Armies in the Orient (General Sarrail), as regards the tactical employment of his troops, but he alone was responsible for all the details of their employment, and it was agreed that the Italian division should not be split up.

The Italians had not come to the Balkans to stop in Salonica, and General Petitti was anxious to be sent to the front at once. He was at first entrusted with the Krusha Balkan sector, east of Lake Doiran and opposite the Beles mountains, a formidable and imposing rock barrier strongly held by the Bulgars. A month after the landing of the first detachment the bulk of the division was already at the front. This area, which had been first held by the 57th French Division, was not then very active, but we had a front of 48 km. to hold with only two brigades; there were no defences to speak of, and everything had to be created anew. In the short time which we occupied it we completely transformed it. Many lines of trenches were dug, wire entanglements laid down, works of all kinds constructed, and, in addition, the whole area was provided by us with a complete network of roads.

LANDING OF ITALIAN TROOPS AT SALONICA.

To face p. 38.

At first we were in liaison with the British on our right and the French on our left; besides occupying the Krusha Balkan positions, we also relieved the French in certain advanced positions in the valley between the former range and the Beles. General Petitti from the first disapproved of this distribution, because the aforesaid advanced positions were isolated and so far from the main body of his forces that they could not receive assistance in case of a sudden attack, nor be protected by artillery, being beyond the range of our guns. General Sarrail insisted on those positions being maintained, but the Italian Commander repeatedly requested to be authorized to evacuate them, all the more so as they represented39 no military advantage. They were held by a battalion of the 62nd Regiment, of which one company was at Gornji Poroj, a large village at the foot of the Beles range, and the others at other points in the valley. Finally, on September 17th, he received instructions to evacuate them, and he immediately gave the necessary orders. On the day fixed for the withdrawal Gornji Poroj was suddenly attacked by overwhelming Bulgarian forces, but it should be noted that the attack had been provoked by us in order to give support to another attack which the British were carrying out elsewhere. The Gornji Poroj Company (the 6th),11 was faced by a battalion and a half of Bulgars, and had orders to resist at all costs so as to protect the withdrawal of the other three companies, and it carried out its task with great gallantry. The Bulgarian barrage fire prevented the arrival of reinforcements, and the company was soon entirely surrounded. It continued to hold out throughout the afternoon and night, and it was not until 36 hours after the commencement of the engagement, when its ammunition had given out, that the gallant survivors ended their resistance with a charge. The battalion commander continued to hear in the far distance the cries “Savoia!” and “Viva l’Italia!” without being able to send assistance. Some 180 men failed to answer the roll call. The 8th Company, which had remained at Poroj Station, some distance from the village, to collect stragglers, was also attacked and almost surrounded by superior hostile forces, but managed to effect its withdrawal during the night.

General Petitti soon had occasion to be dissatisfied with the conduct of General Sarrail towards the Italians. As I have said, we had a French division (the 16th Colonial) on our left. On September 26th the Italian Command learned from General Gérome, without any warning from G.H.Q., that a part of that division was being withdrawn, as well as certain other detachments on the lines of communication which were expected to act as reinforcements for our troops. Thus the Italians found themselves with their left flank in the air and not a single40 battalion in support nearer than Salonica, whereas they had 6 Bulgarian regiments directly in front of them and a whole division on their flank. General Sarrail even wanted them to extend their line towards the left so as to relieve the departing troops. General Petitti addressed an energetic protest to General Sarrail against such conduct, refused to extend his front, and referred the matter to the Italian Supreme Command. The protest proved effective, and a British brigade relieved the departing French.

We now found ourselves with the British on our left as well as on our right. From the very first our relations with the British Army had always been of the friendliest nature. This complete collaboration between the armies of the two Allied countries was afterwards intensified on the Italian front, but I do not think that the feeling was anywhere more intimate or cordial than in Macedonia, and this in spite of the insinuations of General Sarrail to General Petitti. During the two years in which the Italians fought on the Macedonian front there was never the slightest conflict or disagreement between ourselves and the British, which is more, I venture to think, than can be said for any other two armies on that front.

Knowledge of the incidents with the Italians reached the French G.H.Q. and General Sarrail received a reprimand from his superiors in consequence. On October 2nd he came to our H.Q. at Karamudi with the Prince Regent of Serbia and two French parliamentary commissioners, and after the usual exchange of compliments, he complained to General Petitti that he had caused him (Sarrail) to be reproved by Marshal Joffre. General Petitti replied that he had merely communicated to the Italian Comando Supremo the protest which he had sent to General Sarrail himself. The latter showed him Joffre’s telegram, in which it was stated that he had failed to maintain a spirit of camaraderie with Petitti; General Petitti then showed him the text of his own telegram to the Comando Supremo, whereupon General Sarrail, addressing himself to the Prince Regent of Serbia41 and the two deputies, said: “From the cordial manner in which General Petitti has received us, you will gather by what a friendly spirit of camaraderie we are united, and how a trifling incident has been magnified.” This explained the reason why Sarrail had induced the Prince Regent of Serbia and the two French political men to accompany him to Karamudli.

Our troops suffered a great deal from malaria, their area being one of the unhealthiest in the country. The broad valley between the Krusha Balkan and the Beles ranges, which had once been thickly populated and well cultivated, was now a desert; having been abandoned for two years, it constituted a terrible hotbed of malarial fever. The shores of the lakes of Doiran and Butkova, at the two ends of the valley, are marshy, and muddy watercourses flow sluggishly down, widening the fen zone. The troops in the lower positions near the plain were the worst sufferers, and a large part of the malaria cases in the Cerna loop in 1917 and 1918 were in reality relapses from the Krusha Balkan period.

During the spring of 1916 the Germans and Bulgars had been busy preparing for an offensive on a large scale against the Allies. The 11th Bulgarian Division, composed of Macedonian troops, who were not too trustworthy and provided a number of deserters, was dissolved. The Monastir front was strengthened with units drawn from the Dobrugia and Eastern Macedonia. In the spring there were 3 Bulgarian divisions between Strumitza and Xanthi, 3 in the Dobrugia and 5 in the Monastir area, in addition to 2 German divisions, and in July we have the following distribution of forces; 3 divisions and 1 cavalry brigade in the Dobrugia, 2 brigades and some other units on the Struma, 2 Bulgarian and 1 German division (the only one left in Macedonia) on the Vardar, all these forces being detailed for the attack on the entrenched camp at Salonica. In the Monastir plain there was a mobile reserve for attack consisting of two infantry divisions and 3 cavalry brigades. In all, 8 Bulgarian infantry and 1 cavalry division, 1 German division, and 1 or 2 Turkish divisions. The plan consists42 of a rapid offensive on the two wings, with the object of cutting the Allies’ retreat towards Greece or Albania,12 so as to oblige General Sarrail to fight a siege battle and perhaps to capitulate. Since the retreat along the Vardar down to the summer of 1916 Sarrail had had orders to remain on the defensive, but now that the alliance with Roumania had been concluded, the Entente Powers contemplated, as we have seen, an operation in Macedonia to give support to the Roumanian Army and perhaps effect a junction with it. Roumania declared war on August 28th, but she had asked that the Army of the Orient should attack ten days before. It was, on the contrary, the enemy who was the first to attack.

General Sarrail was now “Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Armies in the Orient,” and his command was known as the Commandement des Armées Alliées, abbreviated “C.A.A.” The French troops under his orders were grouped together under the name of Armée française d’Orient (commonly called the “A.F.O.”), and then commanded by General Cordonnier. It was the latter who conducted the operations of the summer and autumn of 1916.

On August 17th the Bulgarians crossed the Greek frontier at two points, advancing eastward to the mouth of the Struma and westward towards Lake Ostrovo, which they reached on the 23rd. Soon after they occupied Florina and Banitza, obliging the Serbs, who were holding that area, to fall back on Ekshisu and Sorovich.

Against the enemy the Allies disposed of the following forces: rather less than 200,000 French and British, 120,000 Serbs, 10,000 Russians (who had arrived in July) and 30,000 Italians. The French artillery amounted to 346 guns, the British to 370, the Serbian to 284, ours to 32. The machine guns were a little over 1,300, the cavalry about 3300 sabres. In all 360,000 men, but in reality43 the strengths were much reduced owing to malaria and the difficulties of communications, so that barely half of that number was available.

The enemy had one great advantage as compared with the Allies—the real and effective unity of command. While the greater part of the enemy forces were Bulgarian the chief command was German, and it was exercised without question. The Allies on the other hand only resigned themselves to the unity of command—that of General Sarrail—in July, 1916, and even then most unwillingly. The other Allied commanders had no confidence in Sarrail’s military qualities, and above all distrusted him for his taste for petty political intrigue. Consequently he could never exercise that absolute authority which is an indispensable condition for success.

Our expeditionary force took orders from General Sarrail, but when any question of great importance arose, such as the change of sector of the division or of a part of it, the extension of its front, etc., the consent of the Italian Comando Supremo was necessary. All this of course interfered with the development of the operations, and General Sarrail complains about his situation in that connexion very bitterly in his memoirs, but it was due to his own defects as recognized by all.

The Bulgarian advance in the Monastir area at one moment made the situation of the Allies appear really critical, because if the enemy had succeeded in breaking through the line on the mountains north of Vodena there would have been nothing more to stop them from descending to the plain and consequently penetrating into Greece, and the Allies would have had to remain besieged within the entrenched camp of Salonica. But the further they advanced the more they became exhausted, whereas while the Serbs fell back they were more and more strongly reinforced. The critical point was the Lake of Ostrovo; on August 22nd the Serb left repulsed five successive attacks on the heights west of the lake between the Kayalar plain and the Rudnik basin, and was subsequently reinforced by a part of the 156th French division. The Allies immediately launched their44 counter-offensive, which was also designed to assist the Roumanians, then just commencing hostilities.

On August 25th an Anglo-French incident occurred, neither the first nor the last. General Cordonnier had requested General Sarrail that the French Division on the Vardar, then at the disposal of the British, should be placed under his own orders for the imminent operations towards Monastir. General Sarrail not having authority to give orders to General Milne, merely passed on the request to him; but General Milne would not agree to the departure of more than one French regiment. At the same time General Cordonnier, having placed some French batteries at the disposal of the Serbs, at their own request, sent a French general to the Serbian Army as “artillery commander.” This aroused vigorous protests at the Serbian G.H.Q. in Salonica, and the French artillery general had to be satisfied with the title of “adviser.”