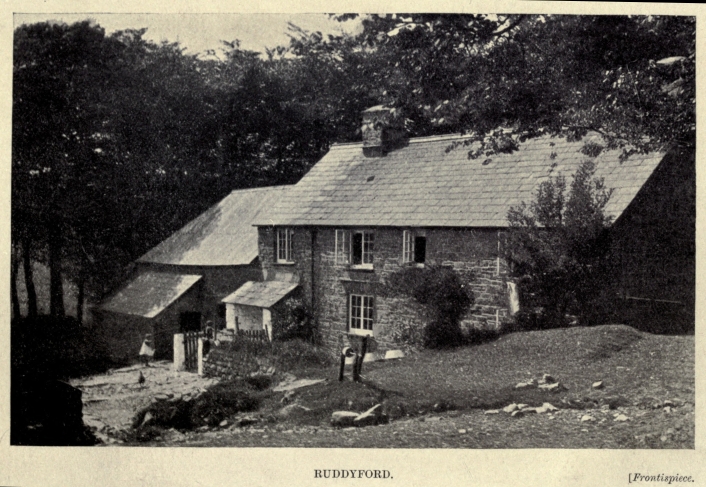

RUDDYFORD.

BY

EDEN PHILLPOTTS

LONDON

CHAPMAN AND HALL, LTD.

1907

RICHARD CLAY & SONS, LIMITED,

BREAD STREET HILL, E.C., AND

BUNGAY, SUFFOLK.

CONTENTS

BOOK I

CHAP.

I. THE MAN ON THE CAIRN

II. RUDDYFORD

III. A THEATRE OF FAILURE

IV. SYMPATHY

V. THE KEEPER OF THE CASTLE

VI. WATTERN OKE

VII. PLAIN SPEAKING

VIII. A REPRIMAND

IX. THE COMMITTEE MEETS

X. 'DARLING BLUE-EYES!'

XI. SUSAN BEINGS THE NEWS

XII. THE PRICE OF SARAH JANE

BOOK II

I. FIRST BLOOD TO BRENDON

II. THE GATES OF THE MORNING

III. PROGRESS IN IDEAS

IV. SATURDAY NIGHT

V. VISIT TO A HERMIT

VI. AWAKENING OF WOODROW

VII. IN COMMITTEE

VIII. ADVENT

IX. A HUNGRY MAN

X. KIT'S STEPS

XI. TROUBLE AT AMICOMBE HILL

XII. THE HERMIT PASSES

XIII. BURSTING OF THE SPRINGS

XIV. A LUNAR RAINBOW

BOOK III

I. BRENDON STOPS AT RUDDYFORD

II. AFTER CHAPEL

III. JARRATT BECOMES A FATHER

IV. THE FARMER COMES HOME

V. THE FRUIT OF FAITH

VI. PHILIP FALLS

VII. A CHRISTIAN CONVERT

VIII. THE LOAN

IX. THE MEMORY OF MR. HUGGINS

X. FAREWELL

XI. THE DOLLS

XII. THE MOCK BURIAL

XIII. ANOTHER EFFIGY

XIV. THE LONELY ALTARS

XV. SET OF MOON

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

RUDDYFORD (Frontispiece)

THE CAIRNS ON WHITE HILL

THE OLD PEAT WORKS

TAVY CLEEVE

LYDFORD CASTLE

LYDFORD

DUNNAGOAT COT

GREAT LINKS

KIT'S STEPS

RUDDYFORD

BENEATH GREAT LINKS

THE WHIRLWIND

Fifty years ago a wild and stormy sky spread above the gorges of Lyd, and the vale was flooded in silver mist, dazzling by contrast with the darkness round about. Great welter of vapour, here radiant, here gloomy, obscured the sinking sun; but whence he shone, vans of wet light fell through the tumultuous clouds, and touched into sudden, humid, and luminous brilliancy the forests and hills beneath.

A high wind raged along the sky and roared over the grave-crowned bosom of White Hill on Northern Dartmoor. Before it, like an autumn leaf, one solitary soul appeared to be blown. Beheld from afar, he presented an elongated spot driven between earth and air; but viewed more closely, the man revealed unusual stature and great physical strength. The storm was not thrusting him before it; accident merely willed that the wind and he should be fellow-travellers.

Grey cairns of the stone heroes of old lie together on the crest of White Hill, and the man now climbed one of these heaps of granite, and stood there, and gazed upon an immense vision outspread easterly against oncoming night. It was as though the hours of darkness, tramping lowly in the sun's wake, had thrown before them pioneers of cloud. Two ranges of jagged tors swept across the skyline and rose, grey and shadowy, against the purple of the air. Already their pinnacles were dissolved into gloom, and from Great Links, the warden of the range, right and left to lower elevations, the fog banks rolled and crept along under the naked shoulders of the hills. Over this huge amphitheatre the man's eyes passed; then, where Ger Tor lifts its crags above Tavy, another spirit was manifest, and evidences of humanity became apparent upon the fringes of the Moor. Here trivial detail threaded the confines of inviolate space; walls stretched hither and thither; a scatter of white dots showed where the sheep roamed; and, at valley-bottom, a mile under the barrows of White Hill, folded in peace, with its crofts and arable land about it, lay a homestead. Rounded clumps of beech and sycamore concealed the dwelling; the farm itself stood at the apex of a triangle, whose base widened out into fertile regions southerly. Meadows, very verdant after hay harvest, extended here, and about the invisible house stood ricks, out-buildings, that glimmered cold as water under corrugated iron roofs, and a glaucous patch of garden green, where flourished half an acre of cabbage. One field had geese upon it; in another, two horses grazed. A leat drawn from Tavy wound into the domains of the farm, and a second rivulet fell out of the Moor beside it. Cows were being driven into the yard. An earth-coloured man tended them, and a black and white speck raced violently about in their rear. A dog's faint barking might be heard upon the hill when the wind lulled.

The contrast between the ambient desolation and this sequestered abode of human life impressed itself upon the spectator's slow mind. Again he ranged the ring of hills with his eyes; then lowered them to Ruddyford Farm. Despite the turmoil of the hour and the hum and roar of the wind; despite the savage glories of a silver sunset westerly and the bleak and leaden aspect of the east; despite the rain that now touched his nape coldly and flogged the forgotten tomb on which he stood; this man's heart was warm, and he smiled into the comfortable valley and nodded his head with appreciation.

The rain and the wind had been his companions from childhood; the sunshine and the seasons belonged to him as environment of daily life. He minded the manifestations of nature as little as the ponies that now scampered past him in a whinnying drove; he was young and as yet knew no pain; he regarded the advent of winter without fear, and welcomed the equinox of autumn as indifferently as the first frost or the spring rain. These things only concerned him when they bore upon husbandry and the business of life.

Now, like a map rolled out before his eyes, lay the man's new home and extended the theatre of his future days. Upon this great stage he would move henceforth, pursue hope, fulfil destiny, and perchance win the things that he desired to win.

The accidents of wind and storm surrounding this introduction did not influence the newcomer or affect his mind. Intensity and rare powers of faith belonged to him; but imagination was little indicated in his character. His interest now poured out upon the cultivated earth spread below, and had his actual future habitation been visible instead of hidden, it had not attracted him. That behind the sycamores there stood a roof-tree henceforth to shield his head, mattered nothing; that within its walls were now congregated his future master and companions, did not impress itself upon his thoughts. He was occupied with the fertile acres, now fading into night, and with the cattle that pastured round about upon the Moor. Familiar with the face of the earth seen afar off, he calculated to a few tons what hay had recently been saved here, appreciated certain evidences of prosperity, as revealed by the aspect and position of the fields; noted with satisfaction the marks of agricultural wisdom; frowned at signs that argued other views than his own.

He pictured himself at work, longed to be at it, yearned for outlets to his great, natural energies and vigorous bent of mind. Death had thrown him into the market of men, and, after three months' idleness, he found a new task, on a part of the Moor remote from his former labours. But the familiar aspects of the waste attracted him irresistibly. He rejoiced to return, to feel the heath under his feet, and see the manner of his future toil clearly written under his eyes. It seemed to him that Ruddyford, with its garden, tenements, and outlying fields, was but an unfinished thing waiting for his sure hand to complete. He would strengthen the walls, widen the borders, heighten the welfare of this farm. No glance backward into the glories of the sunset did he give, for he was young. The peace of Lydford's woodland glades and the lush, low lands beneath, drew no desire from him. Villages, hamlets, and the gregarious life of them, attracted him not at all. The sky to live under, a roof to sleep under, Dartmoor to work upon: these were the things that he found precious at this season. And Fate had granted them all.

Clouds touched his face coldly; the nightly mists swept down and concealed the hills and valleys spread between. For a moment Ruddyford peeped, like a picture, from a frame of cobweb colour. Then it was hidden by sheets of rain.

The man leapt off the grave of that other man, whose ashes in the morning of days had here been buried. So long had he stood motionless that it seemed as though a statue, set up to some vanished hero, grew suddenly incarnate, and, animated by the spirit of the mighty dead, now hastened from this uplifted loneliness down into the highways of life.

A fierce torrent scourged the hill as the traveller hurried from it. He was drenched before he reached the farmhouse door. A dog ran out and growled and showed its teeth at him. Then, in answer to his knock, an old man came slowly down the stone-paved passage.

"Ah, you'll be Mr. Daniel Brendon, no doubt? Your box was fetched up from Mary Tavy this marning. You catched that scat o' rain, I'm afraid. Come in an' welcome, an' I'll show you where you'm to lie."

A feature of Devon are those cultivated peninsulas of land that thrust forward up the surrounding coombs and point into Dartmoor's bosom. The foothills of this great tableland are fledged with forests and rich with fertile earth; but here and there, greatly daring, the farms have fought upward and reclaimed a little of the actual desolation.

Ruddyford was driven like a wedge into that stony wilderness beneath the Moor's north-western ramparts. White Hill sheltered it from the west; the flank of Ger Tor sloped easterly; to the south flowed Tavy through fertile tilth, grey hamlets, and green woods. Only northward was little immediate shelter; and upon the north Daniel Brendon opened his eyes when dawned the first day of his new life.

His chamber window showed him the glitter of a soaking world spread under grey of dawn. His little room was sparsely furnished, and the whitewashed walls were naked. He dressed, prayed, then turned to a wooden box and unpacked his few possessions. He stowed his clothes in a yellow chest-of-drawers with white china handles; his desk he put in the window, on a deep sill, the breadth of the wall. His boots and a pair of felt slippers he placed in a row. Some pictures remained. One represented his father and mother, both six years dead. The photograph was smeared with yellow, but the stain had missed the faces. An old, dogged man, in his Sunday black, sat in a chair and stared stolidly at the beholder; beside him stood a thin, tall woman of anxious eyes and gentle mouth. The face of the man explained the expression of his wife. This picture Daniel hung up on a nail; and beside it he placed another—the portrait of his only sister. There had been but two of them. His sister resembled her mother, and was married to a small tradesman at Plymouth. Her health caused Daniel uneasiness, for it was indifferent. Lastly, from the bottom of his box, he took an illuminated text, and set it over the head of his bed. His father had given it to him.

"The fear of the Lord is the beginning of Wisdom."

Daniel often reflected that at least he might claim the beginning of wisdom, for greatly he feared.

Outwardly Brendon was well made, and handsome on a mighty scale. If he ever gloried it was in his strength. He stood four inches over six feet, yet, until another was placed beside him, did not appear very tall, by reason of his just proportions. He was a brown man with small, triangular whiskers and a moustache that he cut straight across his lip, like a tooth-brush. The cropped hair on his face spoilt it, for the features were finely moulded, and, in repose, revealed something of the large, soulless, physical beauty of a Greek statue of youth. His mind, after the manner of huge men, moved slowly. His eyes were of the character of a dog's: large, brown, innocent, and trustful, yet capable of flashing into passionate wrath or smouldering with emotion.

A noise, that Daniel made in hammering up his text, brought somebody to the door. It was the man who had welcomed him overnight, and he entered the newcomer's private chamber without ceremony.

"Hold on, my son!" he said. "You'll wake master, then us shall all have a very unrestful day. Mr. Woodrow be a poor sleeper, like his faither afore him, and mustn't be roused till half after seven. He bides in the room below this, so I hope as you'll always go about so gentle of a morning as your gert bulk will let 'e."

"So I will then," said Daniel. "'Tis lucky I've been moving wi'out my boots. I tread that heavy, Mr. Prout."

Old John Prout looked with admiration and some envy at the young man.

"'Tis a great gift of Providence to have such a fine body and such power of arm. But things be pretty evenly divided, when you've wit to see all round 'em. You'll have to go afoot all your life; no horse will ever carry you."

Daniel laughed.

"Nought but a cart-horse, for sartain. But my own legs be very good to travel upon."

"Without a doubt—now; wait till you'm up my age. Then the miles get dreadful long if you've got to trust to your feet. I've my own pony here, and I should be no more use than the dead branch of a tree without him."

The withered but hard old man looked round Daniel's room. He had lived all his life at Ruddyford; he was a bachelor, and devoted his life to his master. Reynold Woodrow, the present farmer's father, Prout had obeyed, but secretly disliked. Hilary Woodrow, the living owner of Ruddyford, he worshipped with devoutness and profoundly admired. The man could do no wrong in his servant's eyes.

Now John regarded Daniel's text, where it shone with tarnished crimson and gold.

"You'm a religious man, then?"

"I hope so."

"Well, why not? For my part, I like to see the chaps go to church or chapel of a Sunday. Master don't go, but he's no objection to it. He'd so soon have a Roman as a Plymouth Brother, so long as they stood to work weekdays and earned their money. 'Tis a tidy tramp to worship, however."

"Why, Lydford ban't above four miles."

"That's the distance. As for me, I don't say I'm not right with God, for I hope that I am. But, touching outward observances, I don't follow 'em. More do Mr. Woodrow, though a better man never had a bad cough."

"I'd fear to face a day's work until I'd gone on my knees," declared Brendon, without self-consciousness.

"Ah! at my time of life, us bow the heart rather than the knee—specially if the rheumatics be harboured at that joint, as in my case. But a very fine text for a bed-head, 'The fear of the Lord is the beginning of Wisdom.' And I'll tell you another thing. The love of the Lord is the end of it. That ban't in the Bible, yet a living word as my life have taught me. I go my even way and ban't particular about prayer, nor worship, nor none of that. And as for the bread and wine, I haven't touched 'em for a score of years; yet I love the Lord an' trust Him, for all the world like a babby trusts its mother's breast for breakfast. 'Tis an awful simple religion."

"Simple enough to lose your salvation, I should reckon. If you believe, you did ought to tremble. 'Tis for God A'mighty to love you, not for you to love Him so loud, and yet do nought to show it. No prayers, no sacrament, no worship—what's that but to be a heathen man—begging your pardon?"

"You'll see different if you stop along of us. 'Tis a good working faith that breeds my peace of mind and master's. My fault is that I'm too easy with you chaps. Even the dogs know what a soft old silly I be."

Brendon considered this confession, and it brought him to a subject now upon his mind.

"What's my job exactly? How do I stand? I'd hoped to have a bit of authority myself here, along of my good papers."

"Farmer will tell 'e all about that after his breakfast. The things[1] will be your job, I suppose. But he'll explain himself. He's made of kindness, yet no common sort of man. Them as know him would go through fire an' water for him. However, 'tis an art to know him, and only comes with patience."

[1] Things. Cattle. A moor-man always speaks of 'things' when he means flocks and herds.

"Not married?"

"No, nor like to be. He offered hisself to a cat-hearted minx down to Peter Tavy; and she took him; and 'twas all settled. Then there comed along, a cousin of hers, who has a linen-draper's shop near London, and be damned if she didn't change her mind! It set Hilary Woodrow against women, as well it might. There's only one female in this house, and you can hardly say she's a woman. Merely a voice and a pair of eyes and a pair of hands, and a few bones tied up in a petticoat. My sister, Tabitha—as good a soul as ever fretted a houseful of males. 'Bachelors' Hall' they call this place down to Lydford. And so 'tis, for only the ploughman, Joe Tapson, have ever been married; and he'll tell you plainly, without false feeling, that the day that made him a widow-man, was the first he ever thanked his God for."

A thin voice came up the stairs.

"John—breaksis!"

"Come to breakfast," said Mr. Prout. "Then I'll walk around the place with 'e, afore the master be ready."

So dull was the dawn, that firelight shone in the polished surfaces of the kitchen, and its genial glow made the morning chill and lifeless by contrast.

Three men already sat at the table, and John Prout took the head of it. The newcomer was listened to with courtesy, and his extraordinary size won him open admiration.

"A good big un's the best that woman breeds," said the widower, Tapson. He was himself a man somewhat undersized. He had but one eye, a wrinkled brown skin, and a little goat-beard; but the rest of his face was shaved clean once a week—on Sunday morning.

"No tender spot?" he asked. "So often you gert whackers have a soft place somewhere that brings you down to the level of common men when it comes to work. 'Tis the heart gets tired most often, along wi' the power o' pumping the blood to the frame."

"No weak spot that I know about, thank God," said Daniel.

"Us'll have to get up a wraslin' bout betwixt you and the 'Infant,'" declared another labourer, called Agg. He was a red man of average size, with a pleasant and simple countenance.

"The 'Infant's' a chap to Lydford," he explained. "He was at a shop up in London, but got home-sick an' come back to the country. Very near so large as you be."

"I know about him," answered Brendon. "'Tis William Churchward, the schoolmaster's son. There's a bit more of him below the waist than what there is of me; but I'm a lot harder and I stand two inch taller."

"You could throw him across the river," said Joe Tapson.

There came a knock at the door while breakfast progressed, and a girl appeared. She was a wild-looking, rough-haired little thing of sixteen. She entered with great self-possession, took off her sunbonnet, shook her black hair out of her eyes, and set down a large round bundle in a red handkerchief.

The men laughed; Miss Prout's voice rose to its highest cadences, and her thin shape swayed with indignation.

"Again, Susan! Twice in two months. 'Tis beyond belief, and a disgrace to the family!"

"Well, Aunt Tab, who wouldn't? Last night Aunt Hepsy didn't give me no supper, because I dropped the salt-cellar in the apple-tart—a thing anybody might do. And I'm leery as a hawk, so I am."

"There's no patience in you," grumbled Mr. Prout's sister. "Why for can't you understand the nature of your Aunt Hepsy, and make due allowances for it? Such a trollop as you—such a fuzzy-poll, down-at-heels maid—be the very one to drive her daft. 'Twas a Christian act to take you—friendless orphan that you be; but as to service—how you think you'll ever rise to it, I can't say."

Susan's uncle had given her some breakfast, and she ate heartily, and showed herself quite at home.

"Aunt Hepsy's always a bit kinder after I've runned away, however," exclaimed the girl; "that is, after she've told me what she thinks about me."

Daniel Brendon observed Susan closely, for she sat on a kitchen form beside him at Mr. Prout's right hand. A neat little budding shape she had, and small brown hands, like a monkey's.

Presently she looked up at him inquiringly.

"This here's Mr. Brendon," explained Agg. Then he turned to Daniel.

"The maiden be Mr. Prout's niece, you must know. She's with the family of Weekes to Lydford, learning to get clever for sarvice. But she'm always running away—ban't you, Susan? Here's the mustard to your bacon, my dear."

"I run away when I'm that pushed," explained Susan, with her mouth full. "'Tis a lesson to 'em. I wouldn't run from Uncle Weekes, for a kinder man never lives; but Aunt Hepsy's different."

"For that matter, I dare say Phil Weekes would be jolly glad to run along with you sometimes, if he could," said Tapson. But the remark annoyed Miss Prout, and she reproved him sharply.

"You'll do better to mind your own affairs, Joe. Ban't no business of yours to talk rude about other people's families; an' I'll thank you not to do so. No man ever had a better wife than Philip Weekes have got; which I say, though she is my own flesh and blood; and 'tis a very improper thing all you men siding with this here silly little toad; and you ought to stop it, John, as well you know."

"So I ought," admitted Mr. Prout. "Now, up an' away. And, after dinner, I be going into Lydford, so you can come back along wi' me, Susan."

"Let me bide one day," pleaded the girl. "Then I can help Aunt Tab wi' the washing."

"Right well you know the time to come here, you cunning wench!" said her aunt. "Some of these days, Susie, Hephzibah Weekes won't take 'e back at all. Her patience ban't her first virtue, as you ought to know by this time."

"So I do. But her power of keeping money in her pocket be. She'll always take me back, because I'm the only maiden as she'll ever get for nought. She says I ought to pay her!"

"So you ought, if you could. Didn't you go to her after your mother died, wi'out a smurry to your back? There's no gratitude in girls nowadays. Well, you can bide till to-morrow; and, so soon as you've done, you'd best to light wash-house fire, while I clear up."

Brendon walked round Ruddyford presently with the head man, and saw much to admire and not a little to regret. He longed to be at work that he might reveal his modern principles and knowledge; but Mr. Prout was not much impressed by Daniel's opinions, and showed a stout, conservative spirit.

"You'm a great man for new-fangled notions, I see," he remarked. "Well, you must tell master 'bout it. For my part, I've made up my mind on most questions of farming by now, and can't change no more. But he'll hear you. Trust him for that. He hears us all with wonderful large patience for a young man of his age. I'm glad you like the place. 'Tis a funny old sort of a spot, but I wouldn't go nowheres else for a hat of money."

At ten o'clock Hilary Woodrow came into the kitchen, where his new man was waiting for him.

"Morning, Tabitha,' said the farmer. Then he turned to Brendon.

"Come this way, please. We'll talk in the air."

They walked together beside the great patch of cabbage that Daniel had marked from the hills.

"Your character was very good, and I'm glad to have you here," began the farmer.

He indicated the work he expected, and the general rules, hours and regulations of Ruddyford, while Daniel listened in silence.

Hilary Woodrow was a thin man of medium height and rather refined appearance. His colour was dark and his face clearly cut, with small, delicate features. His voice was gentle, and an air of lassitude sat upon him, as though life already tended to weariness. His age was thirty-five, but he looked rather more, and a touch of grey already appeared about the sides of his head. To Daniel he appeared a very fragile being, and yet his clear, cold voice and his choice of words impressed the labourer, though he knew not why. Brendon felt that his master possessed a master's power. He found himself touching his forelock instinctively, when the other stopped sometimes and looked him straight in the face.

This secret of strength was built upon dual foundations. Woodrow possessed a strong will, and he had enjoyed an unusual education. His father and mother, fired by ambition for their only child, had sent him to Tavistock Grammar School. Thence he went to London to read law, but neither the place nor the profession suited him. He learnt much, but gladly returned to Dartmoor when his father died suddenly and left his mother alone. At her husband's death, Hester Woodrow's dreams for the boy instantly crumbled, and she was well content that her son should succeed Reynold Woodrow and remain beside her. Hilary's health offered another reason, for London had done him little good in respect of that. He was a sensual man.

The large events of his life numbered few. First came experience of the metropolis; and since one must wither a while in cities before the full, far-reaching message of nature can be read, his years in London largely helped to teach young Woodrow the meaning and the blessing of his home. Then fell a father's death; and it awoke him to experience of grief and the weight of responsibility. Following upon these enlightenments came love. He was accepted, and jilted after the wedding-day had been named. Lastly, just before his thirtieth birthday, his mother died and left him alone in the world, for he had no near relations. Ruddyford was a freehold farm, and now Hilary Woodrow owned it. On his mother's death he had felt disposed to throw up all and travel. But he found himself uneasy in mind and body if long absent from the high grounds of the Moor; and finally he determined to spend his days as his father had done before him.

Much did the Prouts desire a mistress at Ruddyford for the comfort of everybody concerned there; but Hilary, after his reverse, held aloof from women. Indeed, his life was very solitary for so young a man. He did not make friends, and, among his equals, was cold and reserved. He felt a little nervous of his health, and showed a sensitiveness to weather that puzzled the folk who are superior to that weakness.

Thus he stood, at the limits of youth, and gazed ahead without much enthusiasm or interest. He found great pleasure in books and in riding. He did not smoke, and drank but little. His heart was kind, and he performed good deeds, if they were easy to perform. His mind was of a sceptic bent, but he prided himself justly on a generous tolerance. Most men liked him and wished that they knew him better; but he was a character more likely to be understood by women than men.

Daniel Brendon listened to his duties, and found himself disappointed. No special department awaited him; no control was destined to be placed in his hands. He had come to help with the rough and varied work of the farm. It was expected of him to turn his hand to anything and everything; to take his daily task from John Prout, and to stand on the same footing as the other labourers.

"Mr. Prout said something about the beasts," he explained, slowly. "'Twas my hope, master, as you'd put a bit of trust in me, seeing my papers."

"I put trust in everybody. You'll never find a more trustful man. It's a secret of farming to trust—when you can."

"But I had the handling of a power of things at Postbridge."

"So you will have with me."

"A man an' a boy under my orders, too."

Woodrow laughed.

"I see. You'll only have three dogs under your orders here."

"Not that I want——"

"Yes, you do—we all do. You'll get power enough, Brendon, if 'tis in you. Power comes out of ourselves. Go ahead and do your work. Perhaps, six months hence, you'll be so powerful that we shall have to part company—eh?"

"I know my job very well."

"Of course you do. I shouldn't want you otherwise. If your will is as strong as your legs and arms, you ought to have a farm of your own before long. How old are you?"

"Twenty-five, master."

"I'd give Ruddyford twice over to have your limbs."

"They are so good as yours, while you pay for 'em."

"Go ahead, then. Take a tramp round before dinner, and see what you think of those heifers up the hill. I've had an offer for them, but don't feel quite satisfied. Tell me what you reckon they are worth—taking the whole five-and-twenty together."

In two minutes Daniel was away with a couple of sheepdogs after him. He reflected on this, his first piece of work, and it pleased him. He was an accurate judge of stock and knew that he could estimate very closely the value of the heifers.

With his thoughts for company Brendon strode upon an errand to the high Moor. He had been at Ruddyford a fortnight, and liked the people, but his master troubled him, for he did not understand Mr. Woodrow's attitude. The farmer's silence puzzled Daniel more than hard words had done. His consolation was that a like reticence and apparent indifference were displayed to all.

Now Brendon climbed aloft to the lonely bosom of Amicombe Hill. He breasted the eastern shoulder of Great Links, and then stood a moment, startled by the strangeness of the scene before him. This field of industry had already passed into the catalogue of man's failures upon Dartmoor, and ruin marked the spot. Round about, as though torn by giant ploughs, the shaggy slope of the hill was seamed and ripped with long lines of darkness. A broken wall or two rose here and there, and radiating amid the desolation of bog and mire, old tramways ran red. In the midst of these morasses stood the peat works, like a mass of simmering, molten metal poured out upon the Moor and left to rust there. Low stone buildings with rotten roofs, gleaming corrugated iron still white, black walls, broken chimneys, and scattered debris of stone and steel huddled here in mournful decay. Everywhere cracked wheels, broken trolleys, twisted tram-lines, and dilapidated plant, sank into wreck and rot amid the growing things. Like a sea the waste billowed round about and began to swallow and smother this futile enterprise. Leaks and cracks gaped everywhere. Raw mountains of peat slowly grew green again under heath and grass and the wild sorrel. Here were miles of rusty wire in huge red tangles, that looked as though the lightning had played at cat's-cradle with them; here washes of dim and dingy green swept the hills; here flat liverworts and tumid fungus ate the woodwork like cancers; here beds of emerald sphagnum swallowed the old peat-knives and spades. Sections of the peat laid bare showed a gradual change in quality, from the tough and fibrous integument of heather-root and grass, to a pure cake, growing heavier and darker, until, two yards from the surface, it was inky black and soft as butter. From six to ten feet of this fuel spread in a layer of many million tons over the granite bones of Amicombe Hill. Immense quantities were already removed, but the enterprise failed utterly, and the great hill, where so much of sanguine toil had been expended, still stretched under the sky with little more than scratches on its face.

Brendon approached this cemetery of hope, to find a ghost there. The buildings, dwarfed by distance, soon towered above him as he reached them, and he found that they contained huge chambers internally blackened by the peat, yet illuminated by shafts of outer light that pierced into them. Through broken windows and gaping walls day came, and revealed immense, silent wheels, and bars thrust out of hollows, and deep pits. Great pipes stretched from darkness into darkness again; drums and tanks and forges stood up about him; mysterious apertures sundered the walls and gaped in the floors; strange implements appeared; stacks of peat-cake rose, piled orderly; broken bricks, silent machinery, hillocks of rubbish and dirt, heaps of metal and balks of timber loomed together from a dusky twilight, and choked these stricken and shadowy halls.

Dead silence reigned here to Daniel's ears, fresh from the songs of the wind on the Moor. But, as his eyes grew accustomed to the velvety darkness and fitful illumination of these earth-stained chambers, so his ears also were presently tuned to the peace of the place. Then, through the stillness, there came a sound, like some great creature breathing in sleep. It was too regular for the wind, too loud for any life. It panted steadily, and the noise appeared to come from beneath the listener's feet.

Daniel lifted his voice, and it thundered and clanged about him, like a sudden explosion. A dozen echoes wakened, and he guessed that no such volume of sound had rolled through these iron-vaulted chambers since the machinery ceased.

"Be you here, Mr. Friend?" he shouted, and all the stagnant air rang.

No answering voice reached him; but the stertorous breathing ceased, and presently came the fall of slow feet. A head rose out of the earth; then it emerged, and a body and legs followed.

"Come down below, will 'e? I can't leave my work," said the apparition; then it sank again, and Brendon followed it down a flight of wooden steps. One cracked under his weight.

"Mind what you'm doing," called back the leader. "They'm rotten as touchwood in places."

Below was a forge, which Daniel had heard panting, and beside it stood retorts and various rough chemical appliances. The operator returned to his bellows and a great ray of hot, red light flashed and waned, flashed and waned.

Like some ancient alchemist amid his alembics, the older man now appeared, and his countenance lent aid to the simile, for it was bearded and harsh and bright of eye. Gregory Friend might have been sixty, and looked almost aged under these conditions. His natural colour was fair, but a life in the atmosphere of the great fuel-beds had stained his visible parts to redness. His very beard, folk said, was dyed darker than nature. He stood there, a strange man of fanatic spirit; and his eyes showed it. They burnt with unconquerable hope; they indicated a being to whom some sort of faith must be the breath of life. It remained for Daniel to discover the articles of that faith; and they were not far to seek.

"I be come from Ruddyford," said the labourer. "Master wants four journeys o' peat, and I was to say that the carts will be up Tuesday."

Friend nodded.

"'Tis ready; and a thousand journeys for that matter. Look here. The Company have sent these samples from Wales. What do 'e think of 'em?"

"I ban't skilled in peat," said Daniel. "It seems all right."

"Not to my eye. Peat be sent up to me from Scotland and Wales and Ireland; and I try it with my tools here. But 'tis trash—all trash—alongside our peat. There's less tar to it, an' less gas to it, an' less power o' heat to it. Do 'e see these?"

The expert handed Daniel a number of little, heavy, black cakes, as hard as a brick.

"You've made 'em, I suppose?"

"'Tis Amicombe peat—the best in the world. Better than coal, you might almost say. We dry and we powder; then we build the cakes an' put 'em in thicky press till they are squeezed as hard as stone. There's your fuel! 'Twill smelt iron in the furnace! What other fashion o' peat but ours can do it? None as ever I heard tell about. Look at this here tar. What other peat will give you such stuff? None—none but Amicombe Hill. Millions of tons waiting—thousands of pounds of good money lying here under this heath—waiting."

"And 'twill have to wait, seemingly."

"That's the point. People think the Company's dead. But it ban't dead. I've seen the whole history. I was among the first they took on. I helped from the beginning. It ban't dead, only in low water. They may start again—they must. 'Tis madness to stop now."

"You believe in it?"

"I'd stake my last shilling in it. For that matter, I have done so. Company owes me fifty pounds less three, this very minute. But if the wise ones have their way, I'll get five hundred for my fifty yet."

Mr. Friend's fire had sunk low; into the darkness from above shot one ray of daylight, blue by contrast with the gloom of the laboratory.

"Come an' have a look at the engine," said the caretaker. "'Tis near twenty year since steam was up; and I've given such watchful heed to it that us might be running again in a week—but for a plate here and there that's eaten away."

Brendon had wit to perceive that Mr. Friend's perspective was distorted in this matter. As one who lives intimately with a companion, and cleaves too close to mark the truth of Time's sure carving on a loved face, so this enthusiast quite failed to appreciate the real state of the peat works, or their absolute and utter ruination.

The Company indeed lingered, but any likelihood of reconstruction was remote. From time to time engineers appeared upon the scene, made suggestions, and revived Gregory Friend; but nought came of these visits: everything remained stationary save the hand of Nature.

Daniel praised a fifteen-horse-power engine, which the guardian of this desolation kept oiled and clean; he heard the peat expert's story, and discovered that, while Friend's belief in man had long since perished, his belief in Amicombe Hill and its hoarded possibilities was boundless and unshaken. This shaggy monster, heather-clad, with unctuous black fen rolling ten feet thick over its granite ribs, was his God. He worshipped it, ministered to it, played high priest to it. They walked together presently over the shining ridges where black pools lay and chocolate-coloured cuttings shone, fringed with the pink bog-heather. Mr. Friend thrust his fingers into the peat and reviewed a thousand great scads, where they stood upright, propped together to dry. In Gregory's eyes, as they wandered upon that scene forlorn, were the reverence of a worshipper and the pride of a parent.

"They've never yet proved it," he said. "But I have. Not an acre of these miles but I've tested. 'Tis all good, right through."

"But master was talking a bit ago, and he said that your peat-cake be more expensive than coals, when all's said."

"He's wrong, then. Ton per ton you could have the pressed cake for a thought less than coal—if they'd only listen to me. But there 'tis; they'm stiff-necked, and send down empty fools instead of practical people. They talk folly and pocket their cash and go; and nothing comes of it; and I be left to wait till they hear me. A sensible man will happen along presently. Until then, the place is in my hands. Only I and the God that made this here hill, know what be in it. China clay, mind you, as well! I've showed it to 'em. I've put it under their noses, but they won't hearken."

"D'you live up here?"

"I do—across to Dunnagoat Cottage. Us'll go back that way and I'll give 'e a drink."

Friend washed his hands in a pool. Then he returned to the works, extinguished his lamp and fire, locked the outer door of the great chambers, and set off southward beside Brendon.

He learnt the newcomer's name, remarked on his size, and then returned to peat. But Daniel was weary of the subject and strove to change it.

"You'm lonely up here, I reckon, an' not another house for miles," he said.

"I keep up here and bide honest," answered Friend. "If you go down-along among the rogues, your honesty wears away, an' you never know it have gone, till somebody stands up to your face and tells you so. I've seen young men slide from it without ever meaning to. As to being lonely, I've got my darter and my work. I go to Lydford once a week for letters. But a town drives me mad—all the noise and business and silly talk."

They tramped over coarse fen, spattered with ling and the ragged white tufts of the cotton grass. Upon the waste shone cheerful light, where the blades of rough moor herbage began to perish from their tips and burn orange-red. Through the midst ran a pathway on which the gravel of granite glittered. Pools extended round about, and beneath them the infant Rattle-brook, newcome from her cradle under Hunter Tor, purred southward to Tavy.

The men followed this stream, and so approached a solitary grey cottage that stood nakedly in the very heart of the wilderness. Stark space surrounded it. At first sight it looked no more than a boulder, larger than common, that had been hurled hither from the neighbouring hill at some seismic convulsion of olden days. But, unlike the stones around it, this lump of lifted granite was hollow, had windows pierced in its lowly chambers, and a hearth upon its floor. It seemed a thing lifted by some sleight of power unknown, for it rose here utterly unexpected and, as it appeared, without purpose. No trace was left of the means by which it came. Not a wall, not a bank or alignment encircled it; no enclosure of any kind approached it; no outer rampart fenced it from the desolation. Heather-clad ridges of peat ran to the very threshold; rough natural clitters of rock tumbled to its walls; door and windows opened upon primal chaos, rolling and rising, sinking and falling in leagues on every side. Heavy morasses stretched to north and east; westward rose Dunnagoat Tor, that gave a name to the cot, and past the entrance Rattle-brook rippled noisily. Away, whence morning came, the great hogged back of Cut Hill swelled skyward, and the towers and battlements of Fur Tor arose; while southerly, brown, featureless, interminable undulations drifted along the horizon and faded upon air, or climbed to the far distant crags and precipices of Great Mis.

The door of Gregory Friend's home faced west; and now it framed a woman.

Sarah Jane Friend's eyes opened wide to see so mighty a stranger approaching with her father. But he was of their own class, for his raiment proclaimed him. Therefore the woman left the doorstep and walked a little way to meet them.

Of purest Saxon type was she. One might have guessed that some strain of blood from the Heptarchy had been handed onward through the centuries, unalloyed with any Celtic or Norman addition. So did not the aboriginal Danmonii look; for the women who herded in the old granite lodges aforetime and logged the stoneman's babies in a wolf-skin were swarthy and small. Sarah Jane stood five feet ten, and was fair of face. Her hair shone of the palest gold that a woman's hair can be; her skin was white. Only the summer suns and the wind from the ocean warmed it to clear redness. When winter came again and the light was low, her face grew pale once more. But pallid it was not. Health shone in her radiant blue eyes and on her lips. She revealed great riches of natural beauty, but they were displayed to no artificial advantage, and her generous breast and stately hips went uncontrolled. She was clad in a dirty print gown, over which, for apron, hung an old sack with "Amicombe Peat Works" stamped in faded black letters across it. Her sleeves were rolled up; her hair was wild about her nape.

Mr. Friend had found Daniel to his taste, for a steadfast listener always cheered him and made him amiable.

"This be Mr. Daniel Brendon," he said. "He'm working to Ruddyford, and comes up with a message. Give us a drink o' cider."

Sarah nodded, cast a swift glance at the labourer, and returned to her house.

"Won't come in—I be in such a muck o' dirt," declared Dan; but the other insisted.

"Peat ban't dirt," he said. "'Tis sweet, wholesome stuff, an' good anywhere."

They sat at a deal table presently, and Gregory's daughter brought two large stone-ware mugs decorated with black trees on a blue ground. She poured out their cider and spoke to the visitor.

"How do 'e like it down-along then, mister?"

"Very nice, thank you kindly," he answered, looking into her eyes and wondering at the colour of them.

"John Prout's a good old chap," she said.

"So he is, then. Never met a better."

"How his sister can keep all you men in order I don't know, I'm sure."

"She's a very patient creature. Here's luck, Mr. Friend."

He turned to the peat-master and lifted his mug. Gregory thanked him.

"You'm an understanding chap, seemingly; though they'm rare in the rising generation. What's your work to Ruddyford?"

Dan's face fell.

"To be plain with you, not all I could wish. Master 'pears to think a man of my inches can't be no good in the head. He puts nought but heavy work upon me—not that I mind that, for I can do what it takes two others to do—to say it without boasting, being built so. But I'm an understanding man, as you be good enough to allow, and I'd hoped that he'd have seen it, too, and let me have authority here an' there."

"Of course," said Sarah Jane. "If you can do two men's work, you ought to have the ordering of people."

"But a big arm be nought nowadays, along o' steam power," he explained. "I haven't a word against Tapson, or Agg, or yet Lethbridge: they'm very good fellows all. But, if I may say so without being thought ill of, they'm simple men, and want a better man to watch 'em. Now such as they would bide here, for instance, and talk the minute-hand round the clock—from no badness in them, but just empty minds."

He rose and prepared to go.

"Your parts will come to be knowed, if you're skilled in 'em and bide your time," said Mr. Friend; "though if you balance patience against the shortness of life, 'tis often a question whether some among us don't push patience too far. I've been patient too long for one; but that's because I can't be nothing else. I've told 'em the great truth—God knows. But ban't my part to lead. I must obey. Yet, knowing what I know about Amicombe Hill, 'tis hard to wait. Sometimes I think the Promised Land ban't for me at all."

"I should hope the Promised Land was for all of us," ventured Daniel.

"That Land—yes. I mean yonder hill, bursting with fatness."

He waved up the valley in the direction of the peat works.

They came to the door and Sarah spoke again.

"I should think Mr. Woodrow wouldn't stand in your way. He rode up to see father last year, and was a very kindly man, though rather sorrowful-looking."

"He is a kindly man," said Brendon, "and a good master, which we all allow. But he'm only half alive, so to say. At least, the other half of him be hidden from us. He'm not one of us, along of his education. A great reader of books and a great secret thinker."

"I'm sure he'll come to know your vartues, if he's such a clever man as all that," said Sarah Jane frankly.

The compliment took Daniel's breath away. He laughed foolishly.

"'Tis terrible kind of you to say so, and I thank you very much for them words," he answered.

The father eyed them, and saw Mr. Brendon's neck and cheeks grow red. The young men often revealed these phenomena before his daughter's good wishes. She was amiable and generous-hearted. Her exceedingly sequestered life might have made some women shy; but to her it lent a candour and unconventional singleness of mind, that rendered more sophisticated spirits uneasy. The doors of her nature were thrown open; she almost thought aloud. Numerous suitors courted her in consequence, and a clown or two had erred before Sarah Jane, because they imagined that her good-natured interest in their affairs must be significant and special. Brendon, however, was not the man to make any such mistake. He departed, impressed and flattered at her sympathy; yet his mind did not dwell upon that. He sought rather to think a picture of her young face, and strove to find a just simile for her hair. He decided that it was the colour of kerning corn, when first the green fades and the milky grain begins to feel the kiss of summer.

A man cried to him before he had gone more than a hundred yards from Dunnagoat Cottage, and, rather gladly, he retraced his steps. But Sarah Jane had disappeared, and Mr. Friend was alone. Gregory advanced to meet him as he returned.

"I like you," said the elder. "You'm serious-minded and might wish to hear more about the truth of peat. What do you do of a Sunday?"

"I go to church mornings; then there's a few odd bits o' work; but I've nought between three o'clock and supper."

"Next Sunday, if the day's fine, I'm going over to Wattern Oke."

"I know the hill."

"You can meet me an' my darter there an' have a tell, if you mind to."

"I'm sure nothing would please me better, Mr. Friend—'tis a very great act of kindness to propose it."

Gregory nodded and said no more, while Brendon, gratified by the invitation, went his way.

He had no thought for the immensity of the earth vision now rolling under his feet. His eye turned inward to regard impressions recently registered by memory. Friend's strange, peat-smeared face, his shining beard, and wild eyes; Sarah Jane's neck and shoulders and straight back; her hands that held the cider-jug; her voice, so kindly—these things quite filled the man's slow brain.

Of a devout intensity under religious influence, Brendon's strenuous nature developed less favourably beneath pressure of mundane affairs. He could be passionate and he could be harsh. He found it uncommonly difficult to forgive injury, and sometimes sulked before imaginary injustice. He was somewhat sensitive and given to brooding. He knew his own good qualities, but while too modest to push them, felt secret sense of wrong when others failed to discover them swiftly. Like all men, he delighted to be taken at his own valuation; but though his humility would not publish that valuation, yet, when his cause was not advanced, he resented it and made a grievance of neglect.

It was early at present to predict his future at Ruddyford. The place proceeded automatically. Nobody was ambitious of power, or of work; each did his toll of toil, and all were friends. Nominally Mr. Prout ruled; in reality the little commonwealth had no head under the master. In time of rare disputes John Prout laid down the law and none questioned him. Few difficulties arose, for Woodrow paid well and kept the farm in a state of culture unusually high. A very rare standard of comfort prevailed, and neighbours always held that Hilary Woodrow was rather an amateur, or gentleman-farmer, than one who lived by his labours and worked for bread. But none could say of him that he neglected his business. He knew the possibilities of Ruddyford, spent only upon the land what it was worth, and devoted the greater part of his money and care to raising of sheep and cattle.

Brendon strode down the great side of Hare Tor, then suddenly perceiving that he was walking out of his way, turned right-handed. The wind blew up rain roughly from the south, and separate cloud-banks slunk along the hills, as though they hastened to some place of secret meeting. Daniel passed down among them, and was within a hundred yards of the farm, when Prout, on a grey pony, met him.

"You've seed Friend and told him about the peat?" he asked.

"Ess; 'twill be ready—'tis ready now, for that matter."

"A curious human be Greg Friend," commented Mr. Prout. "Peat! Why, he's made of peat—body and bones—just the same as me an' you be made of earth. He thinks peat, and dreams peat, and talks peat—the wonder is he don't eat peat!"

John Prout lived alone in a cottage thirty yards from the main building of Ruddyford. It contained four rooms, of which he only occupied two. Now and again Tabitha insisted upon tidying up for him, but he dreaded her visitations, and avoided them as much as possible.

Brendon stopped at his door, and John spoke again before he alighted.

"Not but what Friend isn't a very good sort of man. The peat's a bee in his bonnet, yet never an honester or straighter chap walked among us. He looks to Amicombe Hill to make everybody's fortune presently."

"He calls it the Promised Land," said Daniel.

"He do—poor fellow! He's out there. It don't promise nothing and won't yield nothing. They bogs have swallowed a long sight more solid money than anybody will ever dig up out of 'em again; and 'twould be well for Greg's peace of mind if he could see it; but he won't. He goes messing about with his bottles and bellows, and gets gas and tar out of the stuff, and makes such a fuss, as though he'd found diamonds; but 'tis all one. Peat's good, but coal's better, and God A'mighty meant it to be. You can't turn peat into coal, or hurry up nature. She won't be hurried, and there's an end of it."

"He've got a fine darter, seemingly."

Mr. Prout laughed.

"Ah! you met her—eh? Yes, she's a proper maiden—a regular wonder in her way—so open, and clear-minded as a bird. Never yet heard a girl speak so frank—'tis like a child more than what you'd expect from a grown-up woman. But ban't she lovely in her Sunday frill-de-dills! I was up over last spring, and drinked a dish of tea with 'em. Lucky the chap as gets her—bachelor though I am, I say it."

"Be she tokened?"

"A good few's after her, I believe; but there's only one in the running. I mean Jarratt Weekes to Lydford—the castle keeper there."

"I know the man—why, he's old!"

"Doan't you say that. 'Tis hard thing for my ears to hear. If he's old at forty, what be I at sixty-five? I won't let nobody say I'm old, Daniel!"

"Old for her, I mean. There must be best part of twenty year between 'em."

"It often works very well an' keeps down the family."

"Can't fancy her along with that man."

"She won't ax your leave, my son. But her father's rather of your mind, I fancy. Gregory never did like Jarratt Weekes—nor any of the Weekes breed, for that matter. Jarratt was spoiled as a child. He'm the only son of his parents, and more hard than soft—just as you would expect the child of Hepsy Weekes to be. She's stamped herself upon him."

"Us'll be late for dinner if us talk any more; though what you tell me is very interesting," answered Brendon.

The former glories of Lydford have long since vanished away; yet once it was among the most ancient of Devon boroughs, and stood only second to Exeter in credit and renown. Before the Norman Conquest Lydford flourished as a fortified town; when, "for largeness in lands and liberties" no western centre of civilization might compare with it. But hither came the bloody Danes by way of Tavistock, to consume with fire and sword, and raze this Saxon stronghold to the ground. From these blows the borough recovered, and upon the ruins of the settlement arose a mediæval town wherein, for certain centuries, there reigned a measure of prosperity. The late Norman castle belonged to the twelfth century. It was a true "keep" and a stout border fortress. Within its walls were held the Courts, beneath its floors were hidden the dungeon, of the Stannaries. From the Commonwealth until two hundred years ago, the castle lay in ruins; then a partial restoration overtook it; Manor and Borough Courts were held there; prisoners again languished within its walls. But when Prince Town rose, at the heart of Dartmoor's central wastes, all seats of local authority were moved thither; Lydford Castle fell back into final neglect, and the story of many centuries was ended.

To-day this survival of ancient pride and power lies gaunt, ruined, hideous, and, in unvenerable age, still squats and scowls four-square to all the winds that blow. From its ugly window-holes to its tattered crown there is no beautiful thing about it, save the tapestry of nature that sucks life from its bones and helps to hide them. Grass and ferns, hawkweed, sweet yarrow, toadflax, and fragrant wormwood thrive within its rents and crevices; seedling ash and elder find foothold in the deep embrasures; ivy mantles the masonry and conceals its meanness. The place sulks, like an untamable and unlovely beast dying. It reflects to the imagination the dolours and agonies of forlorn wretches—innocent and guilty—who have pined and perished within its dungeons. Now these subterranean dens, stripped to the light, are crumbling between the thumb and forefinger of Time; their gloomy corners glimmer green with moss and tongues of fern and moisture oozing; briars drape the walls from which hung staples; wood strawberries, like rubies, glitter among the riven stones. Windows and a door still gape in the thickness of the walls; and above, where once were floors, low entrances open upon air. In the midst extends a square of grass; aloft, a spectator may climb to the decayed stump of the ruin, and survey Lydford's present humility; her church, dwarfed largely by the bulk of the castle; her single row of little dwellings; the dimpled land of orchards and meadows round about her; and the wide amphitheatre of Dartmoor towering semi-circular to the East.

Fifty years ago, as now, the village straggled away from the feet of the castle under roofs of grey thatch and tar-pitched slate. Many of the cottages had little gardens before them, and one dwelling, larger than the rest, stood with a bright, rosy-washed face, low windows and low brow of grey thatch, behind luxuriance of autumn flowers. To the door of it there led a blue slate path, and on either side smiled red phloxes, bell-flowers, tiger-lilies with scarlet, black-spattered chalices, and pansies of many shades. A little golden yew, clipped into a pyramid, stood on one side of the door; upon the other sat a man peeling potatoes.

Philip Weekes was short and square and round in the back. His black beard, cut close to the chin, began to turn white; his hair was also grizzled. His cheeks were red and round; his large grey eyes had a wistful expression, as of eyes that ached with hope of a sight long delayed. His voice, but seldom heard, was mournful in its cadence. Now Mr. Weekes dropped his last potato into a pail of water; then he picked up the pail, and a second, that contained the peelings. With these he went to the rear of his house. It was necessary to go out through the front gate, and as he did so a friend stopped him.

"Nice weather, schoolmaster," he said in his mild tones. "Very seasonable indeed. And I observe your son up at the ruin with a party every time I pass. He must be doing well, Mr. Weekes."

"Nothing to complain about, I believe; but Jarratt—to say it friendly—is terrible close. I don't know what he's worth, Mr. Churchward."

"I expect your good lady does, however."

The father nodded.

"Very likely. I ban't in all their councils."

The schoolmaster—a tall, stout man, with a pedagogic manner and some reputation for knowledge—made no comment upon this speech, but discreetly pursued his way. He stopped at the Castle Inn, however, for the half-pint of ale he always allowed himself after morning school. The little public-house stood almost under the castle walls; and beyond it rose a bower of ancient trees, through which appeared the crocketed turrets of St. Petrock's. Adam Churchward was a widower and enjoyed high esteem at Lydford. People thought more of him than the vicar, because though of lesser learning, he displayed it to better advantage and denied himself to none. He was self-conscious under his large and heavy manner, but he concealed the fact, and nobody knew the uneasiness that often sat behind his white shirt-front and black tie, when accident threatened the foundations of his fame.

As he emptied potato peelings into a barrel, there came to the master of this flowery garden a wild and untidy brown maid, easily to be recognized as the runaway Susan.

"Pleace, Uncle Phil, aunt says if you've done them 'taters she'd like 'em to see the fire, if us be going to have dinner come presently."

"They'm done," he said. "I be bringing of 'em."

A voice like a guinea-hen's came through the open door.

"Now, master, if you've finished looking at the sky, I'll thank you to fetch a dollop o' peat. An' be them fowls killed yet? You know what Mrs. Swain said last Saturday? Yours be the bestest fowls as ever come into Plymouth Market, Hephzibah,' she said. 'I'd go miles for such poultry; an' you sell 'em too cheap most times; but if your husband would only kill 'em a thought sooner, to improve their softness——' 'He shall do it, ma'am,' I said; but well I knowed all the time I might so soon speak to a pig in his sty as you—such a lazy rogue you be."

"I'll kill 'em after dinner—plenty of time."

"'Plenty of time'! Always your wicked, loafing way. Put off—put off—where's that gal? Go an' sweep the best bedroom, Susan. 'Plenty of time.' You'll come to eternity presently—with nothing to show for it. Then, when they ax what you've been doing with your time, you'll cut a pretty cheap figure, Philip Weekes."

Her husband exhibited a startling indifference to this attack; but it was the indifference that an artilleryman displays to the roar and thunder of ordnance. His wife talked all day long—often half the night also; and her language was invariably hyperbolic and sensational. Nobody ever took her tragic diction seriously, least of all her husband. His position in the home circle was long since defined. He did a great deal of women's work, suffered immense indignities with philosophic indifference, and brightened into some semblance of content and satisfaction once a week. This was upon Saturday nights, when his partner invariably slept at Plymouth. Her husband and she were hucksters; but since, among its other disabilities, Lydford was denied the comfort of a market, they had to seek farther for customers, and it was to Plymouth that they took their produce.

Every Friday Mr. Weekes harnessed his pony and drove a little cart from Lydford into Bridgetstowe, through certain hamlets. He paid a succession of visits, and collected from the folk good store of eggs, butter, rabbits, ducks, honey, apples and other fruit, according to the season. His own contributions to the store were poultry and cream. He had one cow, and kept a strain of large Indian game fowls which were noted amongst the customers of Mrs. Weekes. On Saturday the market woman was driven to Lydford Station with her stores, and after a busy day in Plymouth, she slept with a married niece there, and returned to her home again on the following morning.

This programme had continued for nearly forty years. On rare occasions Philip Weekes himself went to market; but, as his wife declared, "master was not a good salesman," and she never let him take her place at the stall if she could help it.

Hephzibah was a little, lean woman, with white, wild locks sticking out round her head, like a silver aureole that had been drawn through a bramble-bush. She had bright pink cheeks, a long upper lip, a hard mouth with very few teeth left therein, and eyes that feared nothing and dropped before nothing. She was proud of herself and her house. She had a mania for sweeping her carpets; and if at any moment Susan was discovered at rest, her aunt instantly despatched her to the broom. After a good market Hephzibah was busier than ever, and drove her niece and her husband hither and thither before her, like leaves in a gale of wind; if the market had been bad, the strain became terrific, and Susan generally found it necessary, to run away. Mr. Weekes could not thus escape; but he bowed under the tempest, anticipated his wife's commands to the best of his power, and contrived to be much in the company of his Indian game fowls. After each week of tragical clacking and frantic sweeping Saturday came, and the peace of the grave descended upon Mr. Weekes. During Saturday he would not even suffer Susan to open her mouth.

"'Pon Saturdays give me silence," he said. "The ear wants rest, like any other member."

While his wife's shrill tongue echoed about her corner of the market-place and lured customers from far, he sat at home in a profound reverie and soaked in silence. By eventide he felt greatly refreshed, and generally spent an hour or two at the Castle Inn—a practice forbidden to him on other days.

"Go," said Mrs. Weekes; "go this instant moment, afore dinner, an' kill the properest brace you can catch. If you won't work, you shan't eat, and that's common-sense and Bible both. Mrs. Swain said——"

Her husband nodded, felt that his penknife was in his pocket, and went out. The poultry-run stood close at hand at the top of Philip's solitary field. Sacks were nailed along the bottom of the gate, to keep safe the chicks, and a large fowl-house filled one corner. As the master entered, a hundred handsome birds, with shining plumage of cinnamon and ebony, ran and swooped round him in hope. But he had brought death, not dinner. A gallows stood in a corner, and soon two fine fowls hung from it by their long yellow legs and fulfilled destiny. Then Mr. Weekes girt an apron about him, took the corpses into a shed, spread a cloth for the feathers, sat down upon a milking-stool and began to pluck them.

Meantime the other occupant of his home had returned to dinner. Jarratt Weekes, the huckster's son, came back from his morning's work at the castle and called to his mother to hasten the meal.

"There's quite a lot of people about to-day," he said, "and a party of a dozen be coming up at three o'clock to look over the ruin."

"Then you must make hay while the sun shines," declared Mrs. Weekes.

Hephzibah's only child had now reached the age of forty, and the understanding between them was very close and intimate. Reticent to all else, he found his mother so much of his own way of thinking, that from her he had no secrets. She admired his thrift, and held his penuriousness a virtue. Despite her garrulity, Mrs. Weekes could keep close counsel where it suited her to do so; and neither her son's affairs nor her own ever made matter for speech. They enjoyed an inner compact from which even the head of the house was excluded. Jarratt Weekes despised his father, and failed to note the older man's virtues. The castle-keeper himself could boast a personable exterior; but he was mean, and his countenance, though not unhandsome, betrayed it. He loved money for itself, and had saved ever since he was a boy. His clean-shorn, strongly featured face was spoiled by the eyes. They were bright and very keen, but too close together. He looked all his years by reason of a system of netted lines that were stamped over his forehead, upon his cheeks and round the corners of his lips. He lent money, ran sheep upon Dartmoor, and was busy in many small ways that helped his pocket. He paid his mother five shillings a week for board and lodging; and she tried almost every day of her life to make him give seven-and-six, yet secretly admired him for refusing to do so. He was of medium height, and in figure not unlike his father, but still straight in the back and of upright bearing.

Jarratt sat down at the kitchen table, while his mother made ready a meal for him. The room was empty, and overhead sounded the regular stroke of Susan's broom.

"Glad you're alone," he said, "for I wanted to talk a moment. I saw Sarah Jane to Bridgetstowe yesterday. She'd come down with a message from her father. Sunday week she's going to take her dinner with us. Then I shall ax her."

Mrs. Weekes nodded, and for a moment her tongue was silent. She looked at her son, and a shadow of something akin to emotion swept over her high-coloured cheeks and bold eyes.

"What a change 'twill be! I suppose you'll take the house to the corner? Mrs. Routleigh can't hold out over Christmas."

"Yes, I shall take it. But there's Sarah Jane to be managed first."

"Not much trouble there. She ban't a fool. She'll jump at you."

"You're not often wrong; but I'm doubtful. Sarah's not like other girls. She don't care for comfort and luxury."

"Give her the chance! She's young yet. They all like comfort, and they all want a husband. Quite right too."

"She can have her pick of twenty husbands—such a rare piece as her."

"Them pretty ones all think that; an' they often come to grief over it. They put off choosing year after year till suddenly they find 'emselves wrong side of thirty, and the flat chits, that was childern yesterday, grown up into wife-old maidens. Then they run about after the men they used to despise. But the men be looking for something younger by that time. You men—the years betwixt thirty to forty don't hit you; and what you lose in juice an' comeliness, you make up at the bank. But ban't so with us. There's no interest on good looks—all the other way. These things I've told Sarah Jane myself; so be sure she knows 'em. You'm a thought old for her: that's my only fear."

"Would you go at it like a bull at a gate, or wind round it? She knows well enough what I feel. Why, I gived her a brooch that cost five shillings and sixpence come her last birthday."

"Dash at her! She's the sort that must be stormed. Don't dwell over-much on the advantages, because she's too young to prize 'em. Catch fire an' blaze like a young 'un. They like it best that way. Don't take 'no' for an answer. 'Twas a dash that caught me; though you'd never think it to see your father now-a-days."

He listened respectfully.

"I'm not the dashing sort, however."

"No, you ban't. Still, that's the best way with she. Many a woman's been surprised into saying 'yes.' Do anything but write it. Sarah Jane wouldn't stand writing. For that matter, 'tis a question if she can read penmanship. An ignorant girl along of her bringing up."

"Good at figures, however; for Gregory Friend told me so."

"What does he know about figures? Still, 'tis very much in her favour if true."

Mrs. Weekes now went to the window and looked out of it. Down the street stood an ivy-covered cottage where two ways met. Beside it men were working in the road.

"The water-leat will run through your back orchard, won't it?"

"Yes; I'd counted upon that. The new leat goes from one side to t'other. 'Twill be a great source of strength and improve the value of the property."

"The sooner you buy the better then—afore Widow Routleigh understands—eh?"

He hesitated a moment, then confessed.

"I have bought," he said.

"Well done you! Why didn't you tell me?"

"I was going to. But keep silent as the pit about it. Only me, an' her, and her lawyer knows. As a matter of fact, I bought before the leat got near the place. I knowed 'twas coming; they never thought of it."

"You'm a wonder!"

She looked at the house destined for her son and his bride.

"You won't be far off—that's to the good. You an' me must always be close cronies, Jar. Who else have I got?"

"No fear of that."

She went to the oven, put a stew upon the table, and lifted her voice to the accustomed penetrating note.

"Dinner! Dinner! Come, master! Us can't bide about all afternoon for you. Susan, get down house, will 'e, an' let me see the dustpan. I know what your sweeping be like—only too well."

Mr. Weekes received a volume of reproaches as he entered five minutes later, and took his place at the head of the table.

"I've been plucking fowls, an' had to wash," he said.

"Then I hope to God you chose the right ones. Mrs. Swain will have 'em the same size to a hair. If they come to table a thought uneven, her pleasure's spoilt. And the best customer I've got in the Three Towns. But what do you care...? Susan, you dirty imp, can't you... Tchut! If your parents don't turn in their graves, it ban't no fault of yours...!"

So she played chorus to the banquet. How Mrs. Weekes ever found time to eat none knew.

When Daniel Brendon stepped out of the world into church, a change came upon his spirit, and he had the power of absorbing himself in religious fervour. He lived under the permanent sense of a divine presence, and when life prospered with him and nothing hurt or angered him, the labourer's mind was cheered by the companionship of his Maker. Only if overtaken by a dark mood, or conscious of wrong-doing, did he feel solitary. The experience was rare, yet he faced it without self-delusion, and assured himself that when God forsook his heart, the fault was his own.

In a temper amiable and at peace he kept the Sunday appointment with Gregory Friend. During morning worship he had heard a sermon that comforted his disquiet, and served for a time to mask from his sight the ambitions proper to his nature. He had been told to do with his might the thing that his hand found to do; he had been warned against casting his desires in too large a mould; he had heard of the dignity of patience.

Brendon's mind was therefore contented, and as he strode through the evening of the year's work and marked the sun turn westward over a mighty pageant of autumn, he felt resignation brooding within him. Nature, for once, chimed with the things of his soul and blazoned a commentary upon the cherished dogmas of his faith.

He stood where the little Rattle leapt to Tavy, flung a last loop of light, and, laughing to the end of her short life, poured her crystal into a greater sister's bosom. Sinuously, by many falls, they glided together under the crags and battlements of the Cleeve; and the September sun beat straight into that nest of rivers, to touch each lesser rill that threaded glittering downward and hung like a silver rope over shelf of stone, or in some channel cut by ancient floods. Their ways were marked by verdure; by sphagnum, in sheets of emerald or rose, orange or palest lemon; by dark rushes, stiffly springing, and by the happiness of secret flowers. Heath and grey, granite shone together; a smooth, green coomb stretched beside water's meet, but beyond it all was confusion of steep hills and stony precipices. Over their bosoms the breath of autumn hung in misty fire, while strange, poised boulders crouched upon them threateningly and sparkled in the sun. Haze of blue brake-fern shimmered here and burnt at points to sudden gold, where death had already touched it. Light streamed down, mingling with the air, until all things were transfigured and the darkest shadows abounded in warm tones. The ling still shone, and its familiar, fleeting mantle of pale amethyst answered the brilliance of the sky with radiant flower-light that refreshed the jewels of the late furze by splendour of contrast. The unclouded firmament lent its proper glory to this vale. Even under the sun's throne air was made visible, and hung like a transparent curtain over the world—a curtain less than cloud and more than clarity. It obscured nothing, yet informed the great hills and distant, sunk horizon with its own azure magic; it transfused the far-off undulations of the earth, and so wrought upon leagues of sun-warmed ether that they washed away material details and particulars. There remained only huge generality of light aloft, and delicate, vague delineation of opal and of pearl in the valleys beneath.

The rivers, spattered with rocks and wholly unshadowed, ran together in a skein of molten gold. Behind the murmuring hills they vanished westerly; and though these waters gleamed with the highest light under the sky, yet even in the dazzling force of sheer sunshine, flung direct upon their liquid mirrors, were degrees of brilliance—from the pure and steady sheen of pools, through splendour of broken waters, up to blinding flashes of foam, where the sun met a million simultaneous bubbles and stamped the tiny, blazing image of himself upon each.

Sunshine indeed poured out upon all created things. It lighted the majesty of the hills and flamed above each granite tower and heather ridge; it brightened the coats of the wandering herds and shone upon little rough calves and foals that crept beside their mothers; it touched the solitary heron's pinion, as he flapped heavily to his haunt; and forgot not the wonder of Vanessa's wings, nor the snake on the stone, nor the lizard in the herbage. Each diurnal life was glorified by the splendour of day; and when there fell presently a cloud-shadow, like a bridge across the Cleeve, it heightened the surrounding brilliance and, passing, made the light more admirable. Upward, like the music from a golden shell, came Tavy's immemorial song; and it echoed most musical on the ear of him who, crowning this vision with conscious intelligence, could dimly apprehend some part of what he saw.

Daniel seated himself on rocks overlooking the Cleeve. His massive body felt the sun's heat strike through it; and now he stared unblinking upward, and now scanned the glen upon his right. That way, round, featureless hills climbed one behind the other, until they rose to a distant gap upon the northern horizon where stood Dunnagoat cot against the sky. Low tors broke out of the hills about it, and upon their summits, like graven images, the cattle stood in motionless groups, according to their wont on days of great heat.

Brendon rose presently, stretched himself, and, seen far off, appeared to be saluting the sun. Then he turned to the hills and passed a little way along them. His eye had marked two specks, a mile distant, and as they approached they grew into a man and woman.

Gregory Friend, with his daughter, met Daniel beside a green barrow. He shook hands and remarked on the splendour of the hour. The peat-man had put off his enthusiasm with his working clothes. He wore black and appeared somewhat bored and listless, for the week-days only found him worshipping.

"He hates Sabbaths," explained Sarah. "To keep off his business be a great trouble to him; but he says as we must mark the day outwardly as well as inwardly. So he dons his black, an' twiddles his thumbs, an' looks up the valley to the works, but holds away from 'em."

She wore a crude blue dress that chimed with nothing in nature and fitted ill. Brendon, however, admired it exceedingly.

"'Tis very nice 'pon top of Wattern Oke, if you care to come so far," he said.

They returned to the place where Daniel had sat.

"I'll spread my coat for 'e, so as you shan't soil thicky lovely gown," he suggested to Sarah Jane.

"No call to do that, thank you. I'll sit 'pon this stone. I'm glad you like the dress. I put it on for you to see. My word, 'tis summer come back again to-day!"

The labourer was fluttered, but could think of nothing to say. Both men smoked their pipes, and Friend began to thrust his stick into the earth. They spoke of general subjects, then Daniel remembered a remark that the other had made upon their first meeting. He had no desire to hear more concerning peat; but his heart told him that the theme must at least give one of the party pleasure, and therefore he led to it. Moreover, he felt a strong desire to please Gregory, yet scarcely knew his reason.

"You was going to give me a little of your large knowledge 'bout Amicombe Hill, master," he said, after an interval of silence.

Mr. Friend's somewhat lethargic attitude instantly changed. He sat up briskly and his eyes brightened.