Day & Haghe, Lithrs to the Queen

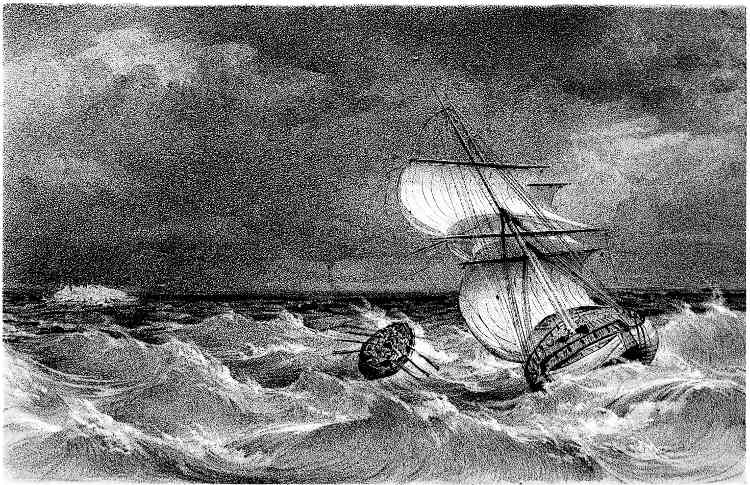

SHIPWRECK NEAR THE ISLAND OF RHODES

London, Henry Colburn, Gt. Marlborough St., 1846.

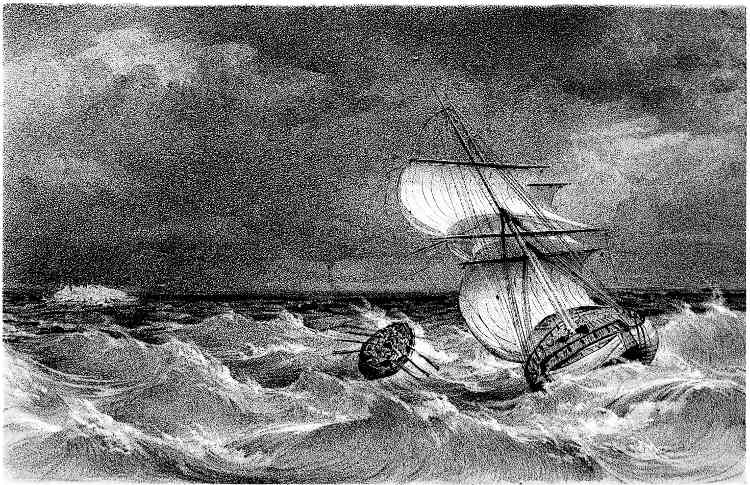

Day & Haghe, Lithrs to the Queen

SHIPWRECK NEAR THE ISLAND OF RHODES

London, Henry Colburn, Gt. Marlborough St., 1846.

FORMING THE COMPLETION

OF

HER MEMOIRS.

NARRATED BY

HER PHYSICIAN.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

HENRY COLBURN, PUBLISHER,

GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET.

1846.

Frederick Shoberl, Junior, Printer to His Royal Highness Prince Albert, 51, Rupert Street, Haymarket, London.

TO

JOHN SCOTT, ESQ., M.D.

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, AND FELLOW OF THE ROYAL

COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS OF LONDON,

A GENTLEMAN AT ONCE EMINENT FOR HIS EXTENSIVE

ACQUAINTANCE WITH ORIENTAL LANGUAGES,

AND FOR HIS CLASSICAL KNOWLEDGE,

THESE VOLUMES ARE INSCRIBED,

BY HIS OBLIGED FRIEND,

THE AUTHOR.

[v]

The Travels now presented to the public are intended to complete the Memoirs of Lady Hester Stanhope; and the author trusts that the interest excited by his former work—shown by the rapid sale of an extensive first edition, and the demand for a second—will be manifested equally for this. Indeed, he cannot doubt that the reader will be anxious to learn by what steps an unprotected woman progressively gained so marked an ascendency in a strange land, the language and the usages of which were altogether contrary to her own, whereby the attempt became so much the more difficult. As, then, the Memoirs embraced a period of about fifteen years, in which the author endeavoured to trace the causes that led to the “decline and fall” of her ladyship’s somewhat visionary empire in the East, the Travels[vi] will now take up her history from the time she quitted England, and, by a faithful narrative of her extraordinary adventures, show the rise and growth of her Oriental greatness.

A distinct line may at once be drawn between this and other books of peregrinations in the East. The reader will here find no antiquarian research, no new views of the political relations of sects and parties: but these Travels exhibit what others do not—a heroine who marches at the head of Arab tribes through the Syrian desert; who calls governors of cities to her aid, whilst she excavates the earth in search of hidden treasures; who sends generals with their troops to carry fire and sword into the fearful passes of a mountainous country, to avenge the death of a murdered traveller; and who then goes, defenceless and unprotected, a sojourner amidst the people on whom these chastisements had fallen.

This work embraces a period reaching from the thirty-sixth to the forty-third year of Lady Hester’s life. It fills up an interval so far important, as connecting her residence with Mr. Pitt and the occurrences which marked the last fifteen years of her existence; and enables those, who may be disposed to blame or applaud her conduct, to speak at least upon[vii] certain grounds: and, though her enemies may find eccentricities enough to satisfy their inclination to ridicule her, her friends will dwell with pleasure on such of her actions as must, in the eyes of unbiassed persons, excite praise; whilst the undoubted marks of a superior mind, which, every now and then, show themselves, will bring into evidence the talents and energy which she inherited from her ancestor, the great Lord Chatham.

Some apology may seem necessary for the paucity of incidents in the first six or eight chapters. Twice had the author to lament the loss of what is most precious to a traveller, supposing him to have noted down from day to day the occurrences of his route. Up to the early part of the year 1812 the narrative is compiled from letters, written to friends in England, and from notes fortunately preserved. All that is subsequent to May, 1812, is copied from a journal kept unbroken for four or five years, during an intercourse which afforded the same facilities for observation as he enjoyed in preparing his former work.

On the criticisms which were passed on that work, the “Memoirs of Lady Hester Stanhope,” he feels bound, in justification of himself, to make a few observations. Unacquainted with the motives which[viii] actuated the writers of them, the public will, perhaps, when these are explained, entertain a different opinion from what, otherwise, it might be led to do.

Mr. Pitt, during his long administration, was surrounded by many coadjutors, who were raised by his patronage and favour to high places in the government. His generous nature led him to tolerate in some of them a line of conduct based on principles and motives less pure than his own. These men, in becoming the channel of advancement to others of an inferior class, created a host of followers, who thought it, and, where they survive, may think it still, a party duty to support the reputation of those persons to whom they owed their advancement. Mr. Pitt’s niece and companion, Lady Hester, endowed with a finer discrimination of character than her uncle, and enabled from her position as a bystander to take a just measure of the abilities and motives of those who seemed to be acting with him, could scarcely bear with the stupidity of some, the duplicity of others, and the baseness of almost all. Gifted by nature with a most retentive memory, so as to be able to compare men’s actions and assertions from time to time, just in her appreciation of their designs, fearless of their anger and a match for their ridicule, disclaiming all compromise with insincerity[ix] and vice, she aimed with an unerring hand the shafts of her disdain at all those whose vices and perfidy called forth her execration.

What then must have been the rage of these persons, who, finding their patrons unmasked in conversations related with strict fidelity, had no resource left them, but, where the narration was unimpeachable, to malign the narrator! All this is well understood by the higher classes of society in England: they may read the critic’s vituperation, but they know why he is enraged, and they leave out his observations in the estimate which they form of the author’s claim to their attention: but the mass of the public, who are less in the secret, pity the author, or perhaps even join in the ridicule against him.

Let those, therefore, who are open to conviction, correct their judgment and be undeceived. Let them be persuaded that, although the adherents of a Heliogabalus, of a versatile, or an insincere minister, a pompous Lord, or an intriguing Duchess, may for a time be successful in their abuse, truth at length will prevail, and the indignation of a noble-minded, upright, and virtuous woman, become matter of history.

Among a host of critics, the Memoirs have been[x] pronounced by some of another class as devoid of artistic excellence. The author’s total abnegation of self, and his steady adherence to the rule he had laid down of shadowing the background on which he stood, in order to throw greater light on the more prominent figure in front, seems to have availed him nothing! Surely these critics might have had the sense to perceive that the author, if he had been so disposed, could have given to himself a much more flattering costume, and have arrayed himself in a garb of Eastern glitter as imposing as the most vivid fancy could desire. What was to prevent him from describing his familiar visits to the great people of the country, and the intercourse which he enjoyed with many of them—from recounting his pleasant adventures with lords and princes—from enumerating the ambassadorial gaieties of Constantinople, the frivolities of Smyrna, Cairo, and other cities, in which he bore his share—or from colouring incidents calculated to impose on the reader, too far removed from the scene of action to be able to decide what degree of credit was to be given to them? But it was not the author’s purpose to divert attention from the heroine of his story; and in all the adventures which the reader may peruse in the following pages, he wishes his[xi] own share in them to be lost sight of, excepting where his presence is necessary for making the description complete.

One word more remains to be added as to the credit which is to be attached to what Lady Hester Stanhope says of herself and others. The author of this narrative can conscientiously affirm that, after an intimate knowledge of her ladyship’s character for upwards of thirty years, he was always impressed with the highest respect for her veracity. Indeed, her courage was of too lofty a nature ever to allow her to condescend to utter a falsehood.

May 1, 1846.

| VOL. I. | |

|---|---|

| Shipwreck near the Island of Rhodes (see p. 99) | Frontispiece. |

| Giorgio Dallegio, page to Lady Hester (see p. 131) | xx |

| A Drùze Aakel | 334 |

| Drûze Women | 345 |

| VOL. II | |

| Lady Hester Stanhope’s Arrival at Palmyra (see p. 130) | Frontispiece. |

| Village of Yabrud | 42 |

| Bridge over the Orontes | 47 |

| Calat El Medyk | 236 |

| Convent of Mar Elias | 309 |

| Interior of a Syrian Cottage | 313 |

| A Greek Monk | 333 |

| Interior of a Greek Sepulchre | 340 |

| Various Sarcophagi hewn out of rocks | 346 |

| Meshmushy | 375 |

| Costume of the Drûzes | 377 |

| Geser Behannyn | 381 |

| VOL. III. | |

| Portrait of the Author in his Bedouin Dress | Frontispiece. |

| Ras el Ayn, Bâlbec | 21 |

| Statue found at Gebayl, and presented to Lady Hester Stanhope by the Prince of the Drûzes, now in the possession of the Earl of Lonsdale | 73 |

| Princess of Wales’s Tent | 127 |

| Statue found at Ascalon | 162 |

| Palace of the Shayhh Beshýr at Muktara | 319 |

| English Consul’s House, at Larnaka | 363 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

| Departure from England—Danger of Shipwreck—Gibraltar—Malta—City of La Valetta—Public Edifices—General aspect of the Island—Commerce—Character of the Inhabitants—Island of Goza—Mansion of the Governor at San Antonio occupied by Lady Hester Stanhope—English Visitors—Lady Hester resolves on an Eastern Tour | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Zante—Earthquakes—Patras—The Marquis of Sligo joins Lady Hester’s party—Corinth—Visit of the Bey’s harým to Lady Hester—Indiscreet curiosity—Women of the East—Isthmus of Corinth—Kencri—The Piræus | 22 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Athens—Residence there—Accommodations—Researches of Lord Sligo—Embarkation for Constantinople—Sunium—Temple of Minerva—Zea—The Hellespont—Greek Sailors in a gale of wind—Erakli—Constantinople | 38 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Procession of the Sultan to the Mosque—A Dinner party—Therapia—Visiters there—Lady Hester seeks permission to reside in France—Turbulence of the Janissaries—Pera—Visit to Hafez Aly—Captain Pasha—Mahometan patients attended by the Author—Princess Morousi—Disagreeable climate of Constantinople—Return Lord Sligo to Malta | 50 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Author goes to Brusa—Situation of the city—Baths—Surrounding country—Residence at Brusa—Lady Hester mistaken for a youth—Women of Brusa—Return of the Author to Constantinople—Sudden death of Mr. Alexander, Lady Hester’s banker—Departure from Brusa—Residence at Bebec—Provisions—Excursion to the village of Belgrade—Throwing the Girýd—Fast of Ramadàn—Lady Hester resolves to winter in Egypt—Presents to the Author for professional attentions | 73 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Departure from Constantinople—Prince’s Islands—Scio—Drunken Turk—Rhodes—Storm—The ship springs a leak—Servants dismayed—Land seen—The ship founders—Escape of the passengers to a rock—The sailors proceed to the Island of Rhodes—They return—The crew mutiny—The passengers gain the Island; and reach a hamlet—Our distressed situation—The Author departs for the town of Rhodes—Hassan Bey refuses assistance—The houses—Lady Hester ill of a fever—Lindo—Its port—The Archon Petraki—Reports that the party were lost—Lady Hester arrives at Rhodes—Town—Why Lady Hester chose the Turkish dress—Posting in Turkey—Mustafa | 95 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Author sets out for Smyrna—Etienne—Port of Marmora—Arabkui—Oolah—Moolah—Aharkui—Ancient temple—Capu Rash—Sarcophagi—Chinny Su—River Meander—Ferry—Guzel Issar—Frank doctor—Ruins of Magnesia—Chapan Oglu’s officers—Baynder—Civility of the governor—Pressing a horse—Smyrna—Visit to the consul—Purchases—Renegado Welchman—Mustafa lays a plan to rob the Author—Departure for Rhodes—Eleusis—Scio—Stancho—Cavo Crio, the ancient Cidus—Ruins—Wall—Temple—Theatre—Stadium—Rhodes—New dresses—Servants cabal—Georgio Dallegio—Town of Rhodes—Embarkation in the Salsette frigate—Harbour of Marmora—Arrival at Alexandria | 112 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Reception at Alexandria—Inhabitants—Commerce—Fortifications—Battle of Abukír—Administration of Justice—Servants—Climate—Asses—Ruins of Old Alexandria—Lake Madiah—Passage boats—The boat with the Author and his party pursued and the passengers made prisoners—Their liberation—Bay of Abukír—Lake Edko—Porters—Rosetta—House of Signor Petrucci—Fleas and musquitoes—The town of Rosetta and environs—Sedentary habits of the Turks—Abu Mandur—Exportation of corn—Mashes, a kind of barge—Voyage up the Nile—Banks of the river—Rich soil—Villages—First sight of the Pyramids—Bulák—Cairo—Pasha and his suite—Lodgings—Lady Hester’s attire—Her visit to the Pasha—Mameluke riding—Horse-market—Opening of a mummy—French Mamelukes—Mr. Wynne—Dancing Women—The Pyramids—Narrow escape from drowning | 135 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Author returns to Alexandria, in company with Mr. Wynne and Mr. McNamara—Proceeds to Rosetta—Coast of the Delta—Deserted hamlet—Brackish water—Misery of the Peasantry—Mouth of Lake Brulos—Dews of Egypt pernicious—Brulos—Melons—Egyptian encampment—Quail-snares—Arrival at Damietta—Honours paid by the Pasha at Cairo to Lady Hester—Description of Damietta—Rice mills—Large oxen—Salt tanks—Papyrus—Literary Society—Abûna Saba—Lady Hester arrives at Damietta—Tents and baggage—Servants—Fleas, &c.—Departure from Damietta—El Usby—Sameness of scenery in Egypt—Naked children—Increase of the Delta denied—Martello towers—Iachimo hired—We sail for Syria—List of the party—French Mamelukes—Wages of servants in the Levant—Arrival at Jaffa—Customs in seaports—Costume of Egyptian women | 167 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Loss of journals—Difficulties in learning Eastern languages—Signor Damiani; his simplicity—Porters—Residence at the Franciscan convent—Lady Hester’s dress—Not distinguishable from a Turk—Description of Jaffa—Buildings—Environs of Jaffa—Orchards—Mohammed Aga: his revenues: his expenditure—Pilgrims: their sufferings—Object of their pilgrimage—Departure for Jerusalem—Mr. Pearce leaves the party—Peasants reaping—Ramlah—Its monastery—Locusts—Lyd—Departure from Ramlah—Sober exhortation of a drunken priest—Mountains of Judæa—Abu Ghosh—Supper—Guards—Selim’s apprehensions—Cold—Brothers’s prophecy—Jerusalem—Lady Hester’s lodgings—Dragomans—Visit to the governor—Kengi Ahmed—Emir Bey; his history—Holy Sepulchre—Mount Calvary—Visit to the Jews’ quarter—Bethlehem—Monastery—Bethlehemites reputed to be robbers—Horses—Accident to Mr. B.—Mufti’s dinner—Memorable places | 188 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Departure from Jerusalem—Arabian characters of horses not to be trusted—Ramlah—Demand of the governor to inspect Lady Hester’s firmâns—Alarm of Selim, the Mameluke—Illness of Mr. Pearce at Jaffa—Janissary dismissed—Departure from Ramlah—Politic conduct of Dragomans—River Awgy—Harým—Inhabitants of Galilee—Scorpions, and other venomous reptiles—Um Khaled—Marble columns—Illness of Yusef the guide—Mountaineers of Gebel Khalýl and Nablûs—Cæsarea—Remains of the ancient city—Obstacles to exploring them—Ma el Zerky—Tontûra—Women carrying water—Beauty of the road—Aatlyt—Mount Carmel—Häifa—Carmelite convent—River Mkutta, the Kishon of Scripture—Arrival at Acre | 221 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Increased illness of Yusef—Servants leave—Visit to Mâlem Haym, minister of the pasha—His history—Description of Acre—Visit to the pasha—Hospitality of M. Catafago—Disposal of time—Excursion to Nazareth—Franciscan convent—Residence and family of M. Catafago—Villages and lands farmed out by him—The Convent library—Arrival of Shaykh Ibrahim (Burckhardt), the celebrated traveller—Visit to the plain of Esdraëlon—Fûly—Battle of Fûly—Departure of Shaykh Ibrahim for Egypt—Excursion to Segery—Visit to the Shaykh—Bargain for a horse—Accident to Lady Hester | 251 |

GIORGIO DALLEGIO, PAGE TO LADY HESTER STANHOPE.

[1]

TRAVELS

OF

LADY HESTER STANHOPE.

Departure from England—Danger of Shipwreck—Gibraltar—Malta—City of La Valetta—Public Edifices—General aspect of the Island—Commerce—Character of the Inhabitants—Island of Goza—Mansion of the Governor at San Antonio occupied by Lady Hester Stanhope—English Visitors—Lady Hester resolves on an Eastern Tour.

The writer of this narrative had just completed his studies in medicine, when he was engaged, through the recommendation of an eminent anatomist and surgeon, to attend Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope, in the capacity of her physician, on a voyage to Sicily; in which island it was her intention to reside two or three years, for the benefit of her health, that had[2] suffered greatly from family afflictions.[1] Her ladyship was accompanied by her half-brother, the Honourable James Hamilton Stanhope, and his friend, Mr. Nassau Sutton.

On the 10th of February, 1810, we embarked at Portsmouth, on board the Jason frigate, commanded by the Hon. James King, having under convoy a fleet of transports and merchant vessels bound for Gibraltar. Our voyage was an alternation of calms and gales. We were seven days in reaching the Land’s End; then, having passed Cape Finisterre and Cape St. Vincent, we were overtaken, on the 6th of March, by a violent gale of wind, which dispersed the convoy, and drove us so far to leeward that we found ourselves on the shoals of Trafalgar.

It was for some hours uncertain whether we should not have to encounter the horrors of shipwreck, on that very shore where so many brave sailors perished after the battle which derives its name from these shoals: but, on the following morning, by dint of beating to windward, under a pressure of sail, in a most tremendous sea, we weathered the land, and gained the Straits of Gibraltar, through which we ran.

We anchored in the Bay of Tetuan, at the back of the promontory of Ceuta, facing Gibraltar, on the[3] African coast. Mount Atlas, the scene of so many of the fables of antiquity, was visible from this point; but its form was far from corresponding with the shape pictured by my imagination, presenting rather the appearance of a chain of mountains than of one single mount.

The wind abated the next day, when we weighed anchor, and entered the Bay of Gibraltar. As we approached the rock, we were struck with the grandeur and singularity of its appearance. Lady Hester and her brother were received at the Convent, the residence of the lieutenant-governor, Lieut. Gen. Campbell. Mr. Sutton and myself had apartments assigned to us in a house adjoining the Convent, where we occasionally partook of the hospitality of Colonel M’Coomb, of the Corsican Rangers, although we dined and lived principally at the Governor’s palace.

I visited the fortifications in company with the Lieutenant-Governor and Captain Stanhope.

As I had never before sailed to a latitude so southern as Gibraltar, I was much struck with the difference of temperature into which we were now transported. There were flowers in bloom, shrubs in leaf, and other appearances of an early spring; and I hastened, the morning after our arrival, to enjoy the luxury of bathing in the sea. These feelings of pleasure at the change of climate were, however, greatly abated by the attacks to which we were daily and nightly exposed from the musquitoes, which entirely destroyed our rest.[4] How impartial has Nature been in all her dealings! Go where you will, if you sum up the amount of good and evil, every country will be found to have about an equal portion of both; and, in many cases, where Providence has seemed to be more beneficent than was equitable, a little fly will strike the balance.

The French, about this time, had overrun almost the whole of Spain, and parties of their cavalry had approached within three miles of the fortifications of Gibraltar. Our excursions, therefore, beyond the isthmus were exceedingly limited, and the only neighbouring places I saw were St. Roque and Algeziras. Numbers of Spanish fugitives flocked in every day. Those who bore arms were sent to Cadiz, and the rest remained in security at Ceuta, a possession of the Spanish on the African side of the Straits, ceded about this time to the English.

The Marquis of Sligo and Mr. Bruce,[2] both of whom afterwards joined Lady Hester’s party, were also at Gibraltar. These gentlemen, with several other Englishmen and many Spanish noblemen and officers, who, with their families, had taken refuge here, constituted the society at the Lieutenant-Governor’s house.

Gibraltar seemed to me to be a place where no one[5] would live but from necessity. Provisions and the necessaries of life of all kinds were exceedingly dear. The meat was poor and lean; vegetables were scarce; and servants, from the plenty of bad wine, were always drunk. Out-door amusements on a rock, where half the accessible places are to be reached by steps only, or where a start of a horse would plunge his rider over a precipice, must be, of course, but few; although, to horsemen, the neutral ground, which is an isthmus of sand joining the rock to Spain, affords an agreeable level for equestrian exercise.

Soon after our arrival at Gibraltar, Captain Stanhope, Lady Hester’s brother, received an order to join his regiment, the 1st Foot Guards, at Cadiz; and Mr. Sutton departed for Minorca, whither his affairs led him. Her ladyship, for whom a garrison town had no charms, was anxious to pursue her voyage. Her state of health rendered the civilities, with which she was overwhelmed, irksome to her; so that she readily availed herself of an offer made by Captain Whitby,[3] of the Cerberus frigate, to take her passage with him to Malta: and, on the 7th of April, we sailed out of the bay, after a double risk, first of the boat’s being swamped in getting on board, and then of the frigate’s falling on a rock, by missing stays, in going out. We put into Port Mahon on our way,[6] and arrived at Malta on the 21st of April, after a passage of fifteen days.

Few cities are more striking at first sight than La Valetta, the capital of Malta. It happened to be Easter day; and the ringing of bells and firing of crackers and guns, as we entered the harbour, about ten in the morning, together with the varied appearance of English, Moorish, and Greek ships, with their different flags mingled in a most agreeable confusion, and reflected from a green water, transparent to the bottom, at the foot of stupendous fortifications, altogether rendered it one of the most cheerful and animating sights we had ever beheld.

Lady Hester was expected at Malta, and the Governor and some other persons of note invited her to take up her residence at their houses. She accepted the invitation of Mr. Fernandez, the Deputy Commissary-General. We landed in the afternoon. In walking through the streets, I found myself surrounded by buildings, different in style from any that I had yet seen, and jostled by a race of people, sufficiently strange to attract my attention strongly. I now felt that I was fairly out of England; which, while in Gibraltar, where the population is so largely made up of English, and where the English language is so generally spoken, I never could persuade myself to be the case.

The residence of Mr. Fernandez was a large house, formerly the inn[4] or hotel of the French knights: each[7] nation, as it would appear, having had a separate palace to lodge in. The sleeping rooms were old-fashioned and gloomy, with windows like embrasures, almost twenty feet apart.

Malta contains two principal cities and twenty-two villages, or casals, as they are called. The old city, Civita Vecchia, was the only one at the time the knights took possession of the island. It is still called by the natives El Medina (the Arabic word for the city.). It has no edifices worthy of notice but the palace of the grand-master and the cathedral, in which are some paintings by Matthias Preti. Its greatest curiosity is the catacombs. They are very extensive, and contain what may be called excavated streets in all directions. From these branch off corridors, wherein are formed apartments containing tombs or sepulchres without number. These catacombs have likewise served as asylums for individuals who fled from religious persecution, and for the inhabitants generally, whenever piratical descents were made on the island.

The modern city, Valetta, was founded in 1566; and, by the enthusiasm of the islanders, who voluntarily aided in the works, it was finished in 1571. It is entirely built of the calcareous stone of the rock on which it stands. A piece of ground was given to each of the nations (or languages, as it was usual to style them) for their respective habitations or inns. The streets are built at right angles, and paved with[8] flat square stones, and the houses are spacious, lofty, and with regular fronts, most of them having a balcony projecting over the street. The object of the architect seems to have been, besides beauty and strength, to gain shade and coolness. Hence the walls of the houses are generally from six to twelve feet thick, and the floors always of stone:[5] the doors are folding, and the windows down to the ground. In every house of the principal inhabitants, in the summer, there is a suite of rooms thrown open. Thus, by having five or six rooms in a line, great coolness, and, if required, a current of air is obtained, the value of which can be sufficiently appreciated by those only who live in very hot countries. In most of the dwellings, the ground floor is used for warehouses and shops; and the family resides on the first floor, the bed-rooms and sitting-rooms being all on the same level. Every house has a cistern, into which rain-water runs from the roof. These roofs, formed of an excellent cement, are flat. Besides the private[9] cisterns, there are public reservoirs, and also a fountain, the source of which is at the village of Diar Chandal, twelve or thirteen miles from La Valetta whither the water is conveyed by a subterranean aqueduct.

The public edifices most worthy of notice are the Palace of the Grand Master, the Hotels or Inns of the different languages, the Conservatory, the Treasury, the University, the Town Hall, the Palace of Justice, the Hospital, and the Barracks, all built with great simplicity. Indeed, La Valetta is much more striking from the arrangement of the general mass of buildings than from the details of any particular one.

The palace, once the residence of the Grand Master of the Knights of St. John, is a magnificent edifice, in its general appearance somewhat like Somerset House. It contains many splendid rooms and saloons, hung with tapestry and damask; and there is a spacious hall, the walls of which are curiously painted in commemoration of the naval victories of the Christian knights over the Moslems. The grand staircase is of remarkably easy ascent. In one part of the Conservatory is the Library: in 1790, it had 60,000 volumes, although founded so lately as 1760: its rapid increase was owing to a law, whereby the books of every knight, at his decease, wherever he might be, were to be sent to Malta. Adjoining to the library is a museum, which contains many interesting objects.

The Hospital is a spacious edifice, open for the[10] sick and wounded of all countries. The knights were formerly bound to attend them, and the utensils employed were almost all of silver, but of quite plain workmanship; so that it might be seen that cleanliness, not ostentation, was the purpose for which they were made.

The Church of St. John is a building, the imposing grandeur of which, when I first saw it, made a strong impression upon me. It consists of an immense nave, from which branch off, right and left, small chapels, each adorned with richly sculptured altars, beautified with everything that superstition can collect. The roof is arched, and painted in fresco by Matthias Preti, the Calabrian. The walls are also decorated with paintings by him and other masters: and the pavement is one uninterrupted piece of mosaic of coloured marbles. Some idea of its effect may be formed by imagining the pictures in the gallery of the Louvre at Paris to be taken from their frames, sewed together, and the spectator to be walking on them. The subjects are less lively, certainly; because, in St. John’s church, each mosaic picture covers the tomb of some Maltese knight, and consequently death and his emblems form the principal features in it; but they are not the less beautiful. The church of St. John was built by the Grand-Master, La Cassière: its riches were, before their spoliation by the French, immense, from the donations made every five years by the master and priors of the order, and by the piety of individuals.[11] The carved ornaments were all gilt with sequin gold by the liberality of the Grand-Master, Coloner.

There is a pleasure garden, called the Boschetto, nearly south-west of La Valetta, which is the only place in the island that has trees of any size: they are arranged in symmetrical forms; and there are several avenues and arbours of orange-trees, interspersed with cedars. This garden is situate in a deep valley, where springs communicate a refreshing coolness to the atmosphere.

The general appearance of the island of Malta is the most unpromising for agriculture that can be conceived. Nowhere is the face of nature so uninviting. A surface of stone has, however, by the effect of industry, been powdered over with a soil, the general depth of which is said to be from six inches to a foot: yet, on this scanty bed, grow lemon, orange, pomegranate, fig, and other fruit-trees, besides corn, cotton, lichen, kali, &c., in the greatest luxuriance. The vines spread wherever they are trained, and the oranges acquire the richest flavour.

Cotton is much cultivated in Malta. That which I saw most frequently was of a cinnamon colour when raw, and not like the white common cotton. Corn is said to yield from 16 to 60 for 1. The fruits are of exquisite flavour. Flowers are very fine, and I could not help fancying the roses more fragrant than in my own country. Malta honey is highly esteemed; but always remains in a liquid state.

[12]

The commerce of Malta consists in the exportation of oranges and lemons, potash, lichen, orange-flower water, preserved apricots, pomegranates, honey, seeds of vegetables, and Maltese stone. The Maltese likewise export fillagree-work, in which the native artists excel; also clocks and boilers. They import corn, cloth, fuel, wine, brandy, &c. Ice brought from Sicily is likewise an article of great consumption. The profits of their exports would not have been sufficient to defray even the cost of the quantity of corn imported: but, to meet this, they had, during the existence of the Order, the prizes made at sea, whereas now they have the consumption of provisions for victualling ships and a flourishing commerce.

The Maltese are very expert and daring seamen. In their speronaras, which are boats without a deck, about thirty feet long, they are to be seen in all parts of the Mediterranean; and, like the sailors of the Kentish and Sussex coast, as their principal occupation is smuggling, they cannot always wait to choose their weather to put to sea in.

Since the English had been in possession of the island, commerce had flourished to a prodigious extent, as was demonstrated by the fleets of merchantmen constantly floating in the spacious harbours, and by the splendid equipages and sumptuous entertainments of the merchants, who were living in a style of luxury suitable to princes.

Nor can I refrain from saying a few words on the almost regal entertainments which the governor at[13] this time gave. His palace, well fitted for the display of a court, with its spacious halls and vast saloons, was often the scene of banquets and festivities, which I scarcely can hope to see again. The English, shut out from the continent, resorted principally to the Mediterranean. Malta, when we arrived there, was full of English and Neapolitan nobility, and the officers of the fleet and of the garrison, vying in their showy dresses with the foreign costumes intermixed with them, formed a striking picture. Dinners of fifty or sixty covers were of every day’s occurrence at the Governor’s palace, and the singular usage of a high table, as in college-halls at the Universities, was not uncommon at suppers after balls. On one occasion, it fell to my lot to hand a lady of rank into the supper-room, and, taking a seat by her side, I found myself directly opposite to the governor, separated by the breadth and not the length of the table, with the Duchess of Pienne on his right hand, Lady Hester on his left, and a string of Lords and Ladies and Counts and Countesses on either hand. But Lady Hester had then recently quitted England, and she had not yet begun her tirades against “doctors and tutors,” nor possibly would have dared openly to intimate the aristocratic superiority of rank over professional claims, as she did afterwards: so she was delighted to see me enjoy myself, and pleased at the attentions which the General showed me, in common with his other guests.

[14]

The Maltese have never mixed with the nations which have held them in subjection. Their original character, therefore, remains unchanged, and their physiognomy indicates an African origin. Their hair is curly; they have flattish noses, and turned-up lips, and their colour and language are nearly the same as those of the people of the Barbary States. It is a lingo of Italian grafted on Arabic. They are said to be active, faithful, economical, courageous, and good sailors; but they are Africans for passion, jealousy, vindictiveness, and thieving, being likewise very mercenary. Their superstition in religious matters is proverbial. By many English, however, who had resided among them for some time, the Maltese were pronounced to be ferocious, ignorant, lazy, passionate, revengeful, and, if married, jealous beyond conception.

Of their superstition an example occurred just before our arrival, in the brutal manner in which they treated a British officer of the 14th regiment of foot, who, whether purposely or unintentionally, offended them by passing through the line of a procession on horseback, for which supposed insult to their religion they dragged him from his horse, and nearly tore him in pieces. I cannot, however, forbear to observe that the lower orders did not appear to deserve the charge of laziness; for the men were slim in their persons, quick in their intellects, and of inconceivable activity. They are remarkably sober in their[15] diet: an onion or an anchovy, with dry bread, will serve them for a meal. No people are more attached to their country than the Maltese to their barren rock.

The upper classes of the inhabitants dress like the French: but the common people wear a dress resembling that which is given to Figaro in the opera, with this difference, that they have trousers instead of tight breeches.

The women are small, and have beautiful hands and feet. When they go out, they wear a black silk shawl, which covers their head and half the face, and is very gracefully wrapped about their bodies; beneath this is a coloured upper petticoat, and a corset or stomacher. They are fond to excess of gold ornaments, which they estimate by value more than taste: and their ears, necks, and arms are set off with rings, chains, and bracelets. They wear shoe-buckles of gold or silver. Although very brown, they are often handsome—I think generally so: and when I say that they are in figure like English maid-servants, I do not mean to disparage them by such a comparison, but rather to mark the plumpness of their flesh and the roundness of their limbs. Children, until they are six or seven years old, are seen rolling naked in the filth of the streets.

The repasts of the Maltese are plentiful: they dine at twelve and sup in the evening. When an entertainment is given, it is common to have three complete courses, and from five to ten different sorts of wine.[16] They rise from table after dinner, taking coffee and liqueurs, like the French. Both rich and poor indulge themselves with a siesta after dinner, generally until half-past two or three o’clock. During this time, the shops are shut; and, to judge by the stillness which reigns in town and country from twelve to three o’clock, one would suppose that the island was deserted. About half-past two the shops are re-opened; as evening comes on, the population appears out of doors, and all is gaiety and life.

There are some antient remains on the island, as the ruins of Ghorghenti; of Hagior Khan; of a Greek house at Casal Zorrick; and of a supposed temple of Hercules.

Goza, a smaller island, separated by a channel, four miles broad, from Malta, has some tracts of pasture land on it, and supplies Malta with cattle and fruit. There are some Cyclopean remains on this island worthy of inspection. It has also an alabaster quarry near the village of Zeberg, and a convent of Capuchin friars, about half a mile from which is a grotto of neat workmanship hollowed out of the rock.

I was told that, in sailing round this small island, several remarkable appearances are presented by its cliffs, which have some curious caves in their sides. For two or three miles, they rise quite perpendicular to the height of from 130 to 160 feet: yet so daring are the inhabitants, that, for the sake of birds’ eggs or of fishing, they will venture down their sides, stepping[17] from crag to crag, where, to an inexperienced eye, it would appear utterly impossible to find footing.

About five miles from La Valetta there was a country residence of the Governor’s, called the palace of St. Antonio, in a village of the same name. On our first arrival in the island, it was occupied by Lord and Lady Bute: but, on their departure for England, on the 28th of May, General Oakes,[6] who showed on all occasions great attention to Lady Hester, politely offered it for her residence; we therefore quitted the hospitable roof of Mr. Fernandez, and betook ourselves thither on the 1st of June.

This palace is a large irregular edifice, with a beggarly exterior, rendered more ugly by a quadrangular steeple, which looks like a belfry. It is constructed of the soft stone of the island, with stone floors, and with ceilings and walls painted in fresco. The walls were hung with some tolerable pictures. The entrance to it is by an avenue of orange trees, the appearance of which, though richer, is much less imposing than the lofty oaks and elms forming the avenues of our own country. About half way down the avenue, which is two hundred and fifty yards long, the road turns abruptly on the left into the courtyard of the palace: this is spacious, and covered with vines to the right and left. At the end of it two doors lead, one into the house and the other into the garden.

[18]

The house contains some handsome and spacious rooms, but the absence of carpeting and matting, rendered necessary by the heat of the climate, gave an air of nakedness displeasing to the eye of an Englishman. I always felt as if sitting in a stone kitchen. It was in the garden that a proper estimate might be formed of the magnificence of the mansion, which might vie, in horticultural beauties, with many of the first gardens in Europe. In its plan it was not unlike the orangerie at Versailles; but at Versailles, no care could ever give to the orange, pomegranate, and lemon trees, half the vigour they showed here. The walks were lined with myrtle hedges, ten feet high; and there was a terrace with a colonnade, where the vines twined their branches in wonderful profusion in every direction in which they were trained. There were five hedges also of double oleander; and, as a proof of the luxuriance of the growth of plants, the marshmallow, if left in the soil, grew to the height of a filbert-tree.

The Governor, General Oakes, strove, in every way in his power, to render Lady Hester’s stay at Malta agreeable to her. He visited her daily at the palace of St. Antonio, and we were his constant guests at the dinners and parties at his own residence.

At the beginning of July, in this year, an earthquake was felt by several inhabitants of Malta. I should presume that habit renders persons quicker at feeling these slight shocks; for, during many years[19] that I was up the Mediterranean, I was present when shocks were felt, but never perceived them myself.

On the 29th of July, Mr. Adair and Mr. Hobhouse, returning from Constantinople, landed at Malta, and, after performing a short quarantine, were entertained at the Governor’s. Many British travellers had visited Malta in the course of this year: for, besides those of whom mention has already been made, there were several noblemen, as also Mr. Thomas Sheridan, whose brilliant vivacity was not yet diminished by the incipient malady under which he finally sunk, Mr. Drummond, Mr. Fiott,[7] and Mr. B.; the last of whom, when he learned that Lady Hester’s brother had been called away by his duties as a soldier, undertook to escort her in the perilous journey which she had resolved to make through European and Asiatic Turkey.

Lady H. Stanhope had begun to grow tired of Malta. The thermometer generally stood as high as 85° Fahrenheit in the afternoon, and the excessive heat had produced some disagreeable effects on her constitution, so that she often complained of sickness of stomach, feverish thirst, and loss of appetite; and was tormented with many other painful sensations which the summer months commonly produce in those, who, for the first time, visit hot countries.

Sicily was at that time threatened with a descent[20] from the coast of Calabria; where Murat, the new King of Naples, was in person urging on the necessary preparations. Several English and Sicilian families had hastily quitted the island to take refuge in Malta, and many fears were entertained as to the probable issue of the enterprise. At all events, the impending storm presented no temptations to Lady Hester to go thither, and she accordingly changed her destination for the only part of Europe which was now open to the English, namely, Turkey.

I have said that Mr. B. had undertaken to escort Lady Hester into Greece. Her ladyship had brought out with her an English maid, named Ann Fry, and a valet, named François, a native of Coblentz.

Lady Hester had been fortunate enough, on two former occasions, to obtain a king’s ship to convey her from place to place: but it was vain to hope that one could now be spared, when every vessel on the station was so much needed to scour the Straits of Messina, and to prevent the threatened landing in Sicily. Accordingly, she resolved on hiring a merchant-vessel; and an American brig, bound for Smyrna, was almost engaged, when it happened that the Belle Poule frigate of 38 guns, commanded by Captain C. Brisbane, came into Malta from Corfu, to which island she was to return; and the captain very politely offered to convey her ladyship and her party to one of the Ionian Islands.

On the second of August, we embarked in the Belle[21] Poule, and arrived at the cruizing station, off Corfu, on the third day. We passed Corfu, Little and Great Cephalonia, and Fano, and on the 8th anchored in the bay of Zante.

[22]

Zante—Earthquakes—Patras—The Marquis of Sligo joins Lady Hester’s party—Corinth—Visit of the Bey’s harým to Lady Hester—Indiscreet curiosity—Women of the East—Isthmus of Corinth—Kencri—The Piræus.

A British ship of war is at all times a noble and interesting spectacle, but, in the Mediterranean, she becomes a beautiful one also. For a week together the sea was scarcely rougher than the bosom of a lake; and the white dresses and straw hats of the sailors, the cleanness of the decks, and the awning over our heads, combined with the serenity of the weather, gave to our voyage the appearance of a party of pleasure.

The view was truly enchanting, when, doubling the north-east point of the island of Zante, we of a sudden discovered the bay and surrounding country. At the foot of mountains which are seen on the right hand, stand the white houses of the chief town, extending for a mile and a half. Immediately behind, and elevated above them, olive-trees, cypresses, and vineyards,[23] meet the eye as it ascends: and the picture is crowned by the castle which commands the town beneath it. From the bottom of the bay a fertile plain extends four or five miles inland, bounded in the distance by blue hills. On the left, a high mountain, the ancient Etatus, corresponding with that on the opposite shore, rises conically from its promontory, and, like the other, exhibits at different heights white villas, olive woods, vineyards, and arid patches of soil, left apparently neglected, or else inaccessible to the plough of the husbandman.

Captain Brisbane went on shore the same evening; and the next morning Mr. Foresti, the English consul, and an aide-de-camp from Major-General Oswald, who was Commander-in-Chief of the Ionian Islands, came on board: soon after which we landed, and residences were assigned to us in the town. The civility and attention of Lady Hester’s host may be judged of from the fact that, every morning, as soon as she was visible, he waited on her, in full dress, to inquire if the arrangements of the house, from day to day, were such as she approved.

When seen from the castle, from which almost the whole circuit of the island can be taken in at one view, its features were not less delightful than those I have before described. Hence it has obtained the name of “the Golden Island,” “the Flower of the Levant,” &c. It is composed of two chains of mountains to the north and south, with a spacious vale between[24] them. Looking down upon this vale, instead of meadows of herbage and fields of corn, is beheld a luxuriant garden of all the productions of warm climates. It is here that the currants grow which are in such request in England. It was the vintage time at our arrival, and I saw the process of drying them. The vines which produce them grow no higher than gooseberry-bushes, and are not sticked. The currants, when gathered, are spread in the open fields, on spots smoothed for the purpose, near the vines, where they lie in square layers about an inch thick, until they become shrivelled and blackened by the sun, and assume the appearance which they have when they reach us, a change which is effected in a few days. They are shovelled up into sacks, and deposited in roomy places called seraglios, where they are kept for about three years, and are then fit for exportation and use. Undried, these grapes are about as large again as an English currant, and in taste exceedingly luscious. They are exclusively the production of this island, with the exception of those grown in the Morea. Currants, with dried olives and olive oil, are the staple commodities of Zante.

The fertility of this happy spot seemed inexhaustible, if a judgment might be formed from the cheapness of its productions. Half a dozen lemons cost only a halfpenny, and grapes, peaches, and other fruits were to be had almost for plucking. Turkeys were sold at one shilling each: geese, poultry, &c., in proportion.[25] The wines of the island, like those of Cephalonia, seemed to us to have little flavour: and it is said that, to make them keep, the skins, jars, or casks in which they are put, are smeared over with rosin. This is the case also up the Archipelago; and custom alone can reconcile a stranger to the taste, which at length becomes just tolerable.

Of the native Zanteots such as I saw may be described in a few words. The women paint their faces excessively, particularly with white round the mouth: they take great pride in long hair, and make the greatest possible display of it. Among the higher classes, the unmarried females are kept much shut up in rooms with blinds to the windows, and are often betrothed without being seen by their future husbands. Among the lower and middle orders there must be a greater freedom of conduct, since many young creatures of considerable beauty were pointed out to me as having attached themselves to English officers without the sanction of the Church; whilst assassination, which formerly followed almost inevitably an illicit connection, if discovered, from the hand of some of the relatives of the female, was now rarely heard of.

Zante was, at this time, garrisoned by the 35th regiment of infantry: it is a defensible place, owing to the strong castle above the town. There was an Albanian regiment quartered in it, under the command of Major (afterwards General) Church. Zante[26] is proverbial for the frequency of earthquakes. The Zanteots declare that they experience them every week; we were there a fortnight and felt none. But the fissures in the walls of almost every house bore sufficient testimony to the severity of one which shook the island at the end of July; in consequence of which some of the inhabitants were so much alarmed that they slept for some time in tents, and many of the English officers were among the number. It happened just after midnight. Those who spoke of it to me described it as beginning somewhat like the trembling that agitates a house in London when a carriage passes it rapidly. The shocks lasted for half a minute, and were repeated several times. Wine glasses danced off the table on which they were standing, and the houses and walls seemed almost to reel: yet, when all was over, nothing was to be seen but here and there a ceiling peeled off, and irregular cracks through the stone walls. Many ludicrous situations arose from the terror in which persons left their beds; as few had time or inclination to stop to put on their clothes before they ran out into the streets.

Captain Brisbane made no stay at Zante, but sailed to rejoin his squadron. General Oswald displayed much courtesy in his attentions to Lady Hester during the fortnight she was on the island; and, when she thought proper to depart, he furnished her with a government transport, in which we left Zante for Patras on the 23rd of August. A felucca was hired to accompany us, into which it was proposed[27] to disembark at Patras, in case (which was probable) the Turkish governor of the castle at the entrance of the Gulf of Lepanto should refuse admission to an English vessel. We landed at Patras on the following evening. Mr. Strani, the English consul, gave us a most hospitable reception in his own house.

A valley, about a mile in width, runs from the shore of the Gulf of Lepanto to a chain of mountains. The valley is covered with vineyards and olive-trees: and, at the verge of it, near the foot of the hills, stands Patras, the ancient Patra. The houses, built of mud, are despicable without and comfortless within. Here and there I observed a mosque. Melancholy indeed was the change from the fine streets of La Valetta to the mud habitations of Patras! Still I felt that I was in Greece, and the language and appearance of the inhabitants had something magical in it. My bosom beat with emotion as I now trod, for the first time, the soil of a people, in studying whose language and habits the chief part of fifteen years of my early life had been—I still think wisely—expended.

Mr. B. and myself, having some leisure here, resolved to try the hot bath. We were exceedingly overpowered by the heat, and experienced the feelings common I believe to all those who enter a hamám for the first time, namely, a sense of suffocation so great as to alarm ourselves and the bather. But those who overcome this first impression never fail to like the process better on each succeeding experiment.

[28]

We found at Patras an English woman married to a Greek sailor, and through her means her husband recommended himself to Lady Hester’s notice as a servant, and he was hired to accompany us to Athens.

Our two German servants had a quarrel when at this place, and sallied forth to fight with sabres. François had served in the Austrian, French, and English armies. As they were exceedingly vociferous, many persons assembled as spectators, and prevented their coming to blows.

The Marquis of Sligo had been cruizing some months in the Mediterranean Sea, in his yacht, a commodious vessel of considerable burden. He was at this time on a visit to Veli, pasha of the Morea, who resided at Tripolizza;[8] but no sooner did he hear of Lady Hester’s arrival at Zante, than he remanded his vessel to Malta, and hastened towards Patras to meet her. Mr. B. had written to him from Patras, and the letter found him at Corinth; where he took a boat, and arrived on the evening of the 27th, just as we were on the point of embarking in a felucca for Corinth, and he immediately joined Lady Hester’s[29] party. We set sail by night; and, passing the spot where once stood a temple of Neptune, we entered the Gulf of Lepanto or of Corinth. We proceeded up the gulf, landing to take our meals; for here the delightful bowers, formed by nature of myrtle, oleander, laurel, arbutus, and other shrubs, invite one to live in the open air. By night we slept on deck; the cabin, with a tilted awning toward the stem, being reserved for her ladyship, who suffered much from the heat.

We arrived at Corinth on the 7th of September. It blew so fresh on our reaching the landing-place, that we had much difficulty in getting on shore. Corinth is at some little distance from the strand. Here we made a stay of three days. The weather was so hot that Lord Sligo and myself suspended our beds in an arbour formed by vines, and there slept. Corinth is a miserable town, and has not much to interest the traveller in actual remains of edifices, although its desolate and altered state appeals very forcibly to his recollections. A fragment only of one Doric temple remains, affording no specimen of that order of architecture which derives its name from the city. One might question the existence even of a city of such celebrity, if there were not here and there some traces and fragments of buildings, which just satisfy doubt but not curiosity. Corinth is surrounded by marshes, which render it most unwholesome; and the plague was said to depopulate it frequently.[30] I paid a visit to the son of the bey, or governor: he received me very civilly, gave me a pipe and coffee, and permitted me to view his apartments: he begged some Peruvian bark of me, which he seemed to hold in great estimation.

The bey himself, an elderly man, sent his harým, consisting of his wife and about a dozen young females, her slaves, to visit Lady Hester. Lord Sligo, Mr. B., and myself, were sitting with her ladyship at the time; but it was intimated to us by the interpreter, that women could not enter whilst men were present. On an occasion so tempting, none but the over-fastidious will blame us for resolving to hide ourselves in an adjoining room, and obtain, through the crevices of the wainscot, a sight of these beauties of Corinth: for we naturally supposed that a man whose will was law throughout the province would have selected only beautiful females as the companions of his leisure hours.

As soon as we had retired, the ladies were introduced, and by the engaging manner with which Lady Hester welcomed them, they became in a few moments quite familiar with her. They unveiled their faces, threw off their ferigees,[9] and placed themselves on the sofa, in attitudes apparently negligent, although of studied grace, as best fitting to display their figures, their jewels, and the long tresses that contrasted with the dazzling clearness (for I will not say whiteness) of[31] their complexions. The conversation was carried on by signs and gestures; and, naturally inquisitive as females in all countries are on matters of dress, they began to examine Lady Hester’s, and to compare it with their own. Unconscious that the eyes of men were watching them, their naked feet, and sometimes their bosoms, Βαθυκολπαι, from the nature of a Turkish dress, were exposed. At length we relieved Lady Hester from the unpleasant situation in which she found herself unintentionally placed, both on our part and hers, by a half smothered laugh, which acted like an electric shock on the Moslem ladies; for, resuming their veils and ferigees in dismay, they suppressed their gaiety at once, and made earnest signs to know what the noise was. Our position was critical: for so surely as we had been discovered would the bey have endeavoured to do us some mischief. Her ladyship saw by their seriousness how much they were offended; she persisted in affirming it was nothing, and succeeded in pacifying them; but they very soon afterwards went away, and no doubt agreed that it would be best to hush up their suspicions, lest the bey’s jealousy might be excited to their own detriment.

I will here anticipate the course of my narrative, and put down a few observations about Turkish women, which are the result of seven years’ residence among them; observations, too, made under advantageous circumstances, from the frequent occasion I had to pay visits to harýms, in my capacity of physician.

[32]

A female in the Levant generally arrives at puberty about the age of twelve years, and is seldom married later than fifteen; often at twelve or thirteen, or even earlier. It is a mistake to suppose that Mahometans consider what the French call embonpoint as an essential quality of beauty: their taste I believe to be the same with that of men of other nations, who have given the matter a thought; and rounded limbs and a plumpness which conceals the bones, are with them, and I conceive elsewhere, the requisites for a perfect form.

From the fortieth day after birth, when the mother makes her appearance abroad, children in the East are carried to the bath, and continue, weekly, to frequent it for the rest of their lives. This custom, it is supposed, enervates their frames, renders the muscles flaccid, and prematurely brings on old age: but I differ entirely from those who assert this; convinced as I am that a woman of thirty-five in the East is in as good preservation as a woman of the same period of life in England or France. To say nothing of the antient Greeks and Romans, from whom we have the finest models of female beauty, and who made as frequent use of the bath as Turks now-a-days do, I would assert that travellers have been deceived by appearances; and, forgetting for the moment that no artificial means are used in the East to conceal the wearing effects of child-bearing, and the natural decay of the female frame, they have imagined that they saw no where the same graceful form which distinguishes[33] their own fair countrywomen, without considering how far that form may be owing to artificial means and expedients. On this point I will only make one other observation, namely, that I have seen a native lady of Damascus, the mother of seven children, whom I had considered in her own country as already shapeless, display, on her arrival in London, by the aid of a mantuamaker, a shape which was the envy of one sex and the admiration of the other.

It is for softness of skin and inodorous sweetness that the women of the East are without rivals. Depilation is used to its utmost extent; and the strigil and frequent ablutions give their bodies as much purity as is consistent with human nature. Does it not imply a commendable cleanliness of person, when an eastern coquette would think no more of winding off a skein of silk on her toes than on her hands, and has no idea that it is possible for the latter to be less agreeable to the touch or any other sense than the former?

The Turkish women stain their hair (if not naturally black or dark brown) with henna powder, made by pulverising the dried leaf of a shrub[10] which imparts a golden brown or auburn colour. But the unprejudiced eye will see nothing more unnatural in this than in the white powder formerly so much used in England and France for the same purpose. One cannot say so much for the straitness which they give to their hair, studiously shunning ringlets and curls; and there seem to[34] be no examples of it in antiquity. Of the custom which they have of giving a black rim to the eyelids I speak confidently in commendation; for no eyes are so brilliant as those which Nature has so set; examples of which, though rare, are not wanting among us.

The Turks, in their notions of grace, exclude all angular lines. Hence their women seldom walk or sit stiffly upright. The sofa is their throne, and the drooping-headed flower,[11] not the straight reed, is their model.

I now return to the course of my narrative. On the Isthmus of Corinth, towards the Ægean Sea, there is a small port, called Kenkri; there, a two-masted vessel, rigged like a bombard, was hired to convey us to Athens; and, on the evening of the fourth day, we embarked. Kenkri is eight miles from Corinth; and, as we crossed the Isthmus on post-horses, I shall describe the nature of our cavalcade. Persons of consideration, when travelling in Turkey, procure from the Pasha of the province, or the nearest governor, an order, by which post-horses are to be furnished to them—I believe gratis, if the order were complied with to the letter. Such an order as this the Marquis of Sligo had obtained at Tripolizza. The horses are used indifferently for riding or for luggage, and each person is provided with his own saddle. Lord Sligo had with him a Tartar, two Albanians (presented to him by Veli Pasha) superbly[35] dressed in the costume of their country, with silver-stocked pistols and silver-hilted yatagans; a dragoman, or interpreter; a Turkish cook; an artist, to paint views and costumes; besides three English servants in livery, and one out of livery. These, with himself, made up eleven persons. Lady Hester and Mr. B., with their retinue, made up eleven more; forming a cavalcade with myself and servant, of twenty-five persons, all the males of which were armed with a sabre and pistols.

In this manner we crossed the Isthmus, and, embarking, lay all night in the harbour. Kenkri (the ancient Cenchræa) has little left of its pristine splendour. There were a few broken columns lying about, and part of the pier of the harbour still remained. At daybreak on the 12th of September, we weighed anchor. The wind was fair, the day delightful, and by twelve o’clock we were at the entrance of the Piræus.

The master of the vessel was a man of fine stature, of noble mien, and of a prepossessing countenance. From beneath his red skull-cap, his curling hair behind formed a bush, somewhat like a bishop’s wig; for the Greeks of certain districts shave the forehead and crown, and leave the hair behind of its natural length. He had with him a son, about twelve years old, whom Lady Hester would have taken to attend upon her, could the captain have been induced to part with him.

[36]

The fame of Lord Byron’s exploit in swimming across the Hellespont, from Sestos to Abydos, in imitation of Leander, had already reached us, and, just as we were passing the molehead, we saw a man jump from it into the sea, whom Lord Sligo recognized to be Lord Byron himself, and, haling him, bade him hasten to dress and to come and join us.

Just before arriving at the Piræus is Caluri, formerly the island of Salamis, close to which the fleet of Xerxes was beaten by the Greeks. It seemed that in the strait between Salamis and another island called Psyttalia, where the battle raged the fiercest, there would be scarcely room for a seventy-four gun ship to wear; hence we may infer the small size of the ships of those days, and the Piræus, which contained the whole Athenian fleet, is hardly more spacious than the two harbours of Ramsgate. Its entrance is exceedingly narrow, but having, I was told, a depth of six or seven fathoms.

We sailed in, and anchored before a mean building at the bottom of the port, which served as a custom-house. There happened to be on the strand about a dozen horses, which had brought down part of the freight of a polacca lying at the quay to load. These were forcibly seized by our Tartar, and, laden with our baggage, sent off to the town, which is six miles inland. Lord Sligo himself set off on one of the horses of Lord Byron, who had now joined us, to send down conveyances for Lady Hester and the rest of us.

[37]

While we were waiting on the shore, we had leisure to survey what was around us. The country immediately adjoining the port seemed bare and without verdure. Some remains of the quays, which once bordered the Piræus, lay scattered at the water’s edge, and a few ill-constructed boats, made fast by rush hawsers, showed how low the navy of Athens had declined. There were some Turkish women sitting on the bank, covered in every part excepting their eyes, who immediately walked away when we attempted to approach them. We were ignorant of the customs of the country, and Mr. B. made signs to them to stop, which excited greatly the anger of some Turks who were standing near us.

The horses arrived in about two hours. As we quitted the Piræus, the aspect of the country became more pleasing. Gentle slopes and hills, rising and sinking with a pleasing wavy line, gave a tranquillity and repose to the scenery which few can understand who have not felt it in those countries.

While musing on the goodly prospect around me, on temples and demi-gods, on the Parthenon and Socrates, the cool Ilyssus and the shades of Academus, my reflections were interrupted by the loud smack of a whip, applied by Aly the Tartar to the back of a poor Greek, accompanied by a louder oath, which at once dissipated my vision, and brought me back to the reality of things around me.

[38]

Athens—Residence there—Accommodations—Researches of Lord Sligo—Embarkation for Constantinople—Sunium—Temple of Minerva—Zea—The Hellespont—Greek Sailors in a gale of wind—Erakli—Constantinople.

It was evening before we entered Athens. Preparations had been made for our coming, and a house was cleared of its tenants expressly for Lady Hester. Mr. B. and myself were lodged in a house which Lord Sligo had occupied some time previous to our reaching Greece. It had been tenanted by other English travellers, and the owners, who let it, were so far acquainted with Englishmen’s wants, as to have procured some chairs and a table, furniture then seldom found in a room in Turkey.

I employed the first day in making my apartment tidy. I found my bed-room to be a whitewashed chamber, having an unglazed window, with a shutter, which excluded light and let in the wind. There were large crevices in the floor, through which the dust and rubbish were swept, not by a long-handled broom, for I never saw one throughout Turkey, but by a hand-broom. Upon these materials my servant had to[39] go to work to make me a chamber. A mat was spread upon the floor, as being the coolest covering to the gaping chinks; my camp-bed was laid on boards, supported by two trestles; a piece of white linen formed a curtain to the window, and, my musquito net being suspended upon cross pieces of twine, I found myself almost as comfortable as if I had been lying upon an English fourpost bedstead. Lord Sligo and Mr. B., who seemed to despise luxuries in proportion as they had the means of enjoying them, made their beds on the floor, and all the servants slept in the open air. But, in this climate, to sleep under the cope of heaven is no cause of complaint; for, during the voyage from Patras to Corinth, all of us, as said above, excepting Lady Hester, lay on deck. It was now six months since I had seen a drop of rain, and, I might almost say a cloud; indeed, the serenity and dryness of the weather had been such, that prayers (we were told) had been offered up at Athens by the Christians for rain, accompanied by the novel expedient of penning a flock of sheep in the porch of the church, whose plaintive bleatings, it was supposed, would give greater effect to the petitions of the people, and move the pity of Heaven.

The house occupied by Lady Hester was spacious and handsome, having a courtyard, a bath, and other requisites for comfort and quiet. None of the windows of the house had casements, and, to ensure greater warmth, it was necessary to nail up some of them with old carpets, mats, &c. Her ladyship was a great contriver[40] of comfort, and I have often known her transform a naked room, with holes in the walls, floors, and doors, into a snug apartment. The janissary sat at her gate, on a raised wooden couch, something like a kitchen table with a railed back to it, which is generally to be seen at the doorways of most great persons in European Turkey, and upon which the master of the house will often place himself, to smoke his pipe, and to breathe the morning and evening air. The janissary acted as porter and guard.

I observed one morning that Aly, this janissary, had his feet swathed in old rags: on inquiring what was the matter, he pretended that they were covered on account of the cold; but I learned in the course of the day that he had been bastinadoed on the soles at the governor’s, for riotous behaviour at a tavern.

It was many days before we were settled, and very many more before we had surveyed the numerous beauties of architecture and statuary which are yet left in this celebrated city. Our time passed most delightfully. The mornings were spent in examining the remains of ancient edifices, in rides, and in excursions into the environs; the evenings in the society of a few clever artists, who, enamoured of the spot, seemed wedded to it for the rest of their days. Of these, M. Lusieri and M. Fauvel are very generally known by their drawings. Fauvel was living in a small house on the site of the ancient agora. There were likewise many English and some other foreigners[41] at this time at Athens. Among the English I may name Lord Plymouth, Messieurs Gordon, Hunt, and Haygarth. Two British merchants, Mr. John Galt,[12] and Mr. Struthers, passed through the place on their way to Constantinople. Of foreigners, there were gentlemen who have since distinguished themselves in their respective careers.

I had not been a day in Athens before I was beset with the sick, maimed, halt, and blind, importuning me for advice and medicine. St. Paul had not more patients than I, but how different our means of cure! I, however, did what I could for all, and obtained admission to several Turkish and Greek houses in my professional capacity.

Lord Sligo had, on a previous visit to Athens, carried on several excavations among the ruins, and he renewed them on his return thither. One of those was on the Theban road, about two hundred yards from the city wall, where he employed a dozen men; another was on the side of the Acropolis; others were in other parts, and all were attended with some success. His researches brought to light several tombs. He found, at different times, some beautiful vases, gold ornaments, lacrymatories, lamps, and other objects, generally buried with the ancient Greeks. He bought, likewise, many bas-reliefs, coins, and other antiquities, all of which now compose part of his valuable cabinet at Westport Place, in Ireland.

[42]

An English gentleman named Watson, coming from Janina, fell ill on his way, and died just as he reached Athens. He was buried in the Temple of Theseus; and, as there was no memorial to testify where his body lay and his death was yet recent and the circumstances known, Lord Sligo, to whom they were told, with that sympathy for the misfortunes of others which was so natural to him, immediately took the necessary steps for placing a marble slab with an epitaph over his grave. But no slab could be found fitting for the purpose, and there were no workmen in all Athens capable of cutting the inscription.

Lord Sligo and Mr. B. made an excursion to Delphos, but, on account of my professional avocations, I could not accompany them any farther than Thebes, whence I returned the following day, with a guide only, over unfrequented mountains.

Lord Byron made one of the small society which collected every evening at Lady Hester’s: he had been the college friend of Lord Sligo and Mr. B. It was strange enough, however, that on the third or fourth day after our arrival, he alleged pressing business at Patras, in the Morea, and left us, but returned some days before our departure from Athens, when I saw him frequently. Lady Hester’s opinion of him has appeared in another publication. What struck me as singular in his behaviour was his mode of entering a room; he would wheel round from chair to chair, until he reached the one where he proposed[43] sitting, as if anxious to conceal his lameness as much as possible. He consulted me for the indisposition of a young Greek, about whom he seemed much interested.

After having remained at Athens one month and four days, we were informed that a Greek polacca, a ship of nearly two hundred tons burden, was about to sail from the Piræus to Constantinople, with a cargo of wheat, part of the revenue of the Kislar Aga, to whom Athens belongs as a fief. As an opportunity like this might not very speedily offer again, it was resolved, now that we had seen whatever the place contained worthy of curiosity, to take our passage in her, which was agreed for at five hundred piasters, a sum equal to £25. The cabin, after having been whitewashed to kill the vermin, was set apart for Lady Hester; the servants occupied the hold, which was full of wheat, to within two feet and a half of the deck; and Lord S., Mr. B., and myself, slept in the open air, although the nights were beginning to be cold.

We embarked on the 16th of October, and, on the first day, sailed down the gulf of Ægina. The wind freshened so much as to induce the captain to cast anchor under the promontory of Sunium, where Theseus dedicated a temple to Minerva. The promontory is called by European mariners Capo de’ Colonni. We lay here the whole of the 17th, the storm still continuing, and we landed to see the ruins[44] of the temple, the columns of which still attract the admiration of the traveller.

In a little nook at the foot of the promontory lay a small Greek boat, bound from Athens to Zea. She was hauled up on the shore, and the crew, with a passenger or two, were sitting round a fire in a cave in the rock. One was a female, and I recognized in her a very pretty-faced woman, whom I had seen in the cell of a holy friar in Athens, when, on one occasion, I had paid him a visit in the evening, somewhat after the accustomed hour. Around the temple, and covering the adjacent mountains, was a forest of stunted firs; and, in the wantonness of idlers, which sometimes leads to a great deal of mischief, we threw some firebrands among the brushwood, with the intention of setting fire to the forest, and of scaring the wolves, which were said to be very numerous hereabouts; but, fortunately, the rain that had fallen prevented the conflagration.

We quitted the promontory on the 18th, and in a few hours reached Zea, and entered the port to pass the night. The servants, from some trifling cause, had quarrelled with the crew; and matters had become so serious, that we slept on our arms, we being only sixteen in number, and they twenty. There are no bounds to the restlessness and cupidity of Greeks. In the present instance, whilst, on the one hand, the crew were cheating and robbing the servants, the captain, on the other, was scheming and contriving[45] how he could obtain more passengers, in spite of the agreement he had made with us.

On the 19th, in the morning, no fewer than twenty persons came alongside, whom he wished to take on board; but we threatened to quit the vessel, and not to pay him anything—which menace had the desired effect, and they returned to the shore.

Those islands of the Cyclades which we saw had a barren appearance, exhibiting neither verdure nor trees. Zea is of the number. The town stands on the top of a conical mountain, which occupies the centre of the island. I landed, and procured a mule, which carried me up to it. I was entertained with coffee, preserves, and a pipe, at the house of Mr. Pangolo, the British agent, and I procured a few coins from some of the inhabitants.

On the 22nd we quitted Zea, and passed Negropont and Mytelene. The weather was unusually fine. Dolphins gambolled round our prow, and light airs filled our cotton sails. On the 24th we were abreast of the Troad, and entered the Hellespont at twelve o’clock.

When we had passed the two castles which guard the entrance, lovely indeed were the prospects that opened upon us, in each of the two quarters of the world! On the side of Europe the scenery was bolder than on the opposite; but the softness of the Asiatic shore was too attractive to lose by the comparison, and its warm and languishing features accorded[46] with the enervating character which we imagine to be so fatal to the energies of its natives. As we advanced, every spot on each side of us revived the recollections of some classic story. It was here that Xerxes lashed the waves—it was there that Leander braved them: now we looked for the corpse of the too adventurous lover; and now we thought we saw the eddies writhing under the scourge of the vain and baffled despot. We saw, also, where the battle of Ægos Potamos was fought.

On the 24th, in the evening, passing Gallipoli, we entered the sea of Marmora. On the 25th, we were becalmed within three miles of the island that gives its name to the sea.

At night the wind blew strongly, and our situation by degrees became extremely perilous. My cot was slung athwart the deck from the mizen-mast to the quarter-railing, which, landsman-like, (in spite of the representation of the Greek captain) I had fancied to be the best way; when, after having been a short time in bed, the heeling of the vessel became so great that I was constantly thrown to the foot of my cot, and was, at last, compelled to get out and dress myself, as the sailors wanted all the facility which could be afforded them for working the ship.