Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

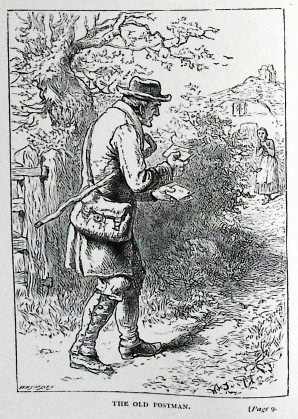

THE OLD POSTMAN.

BY

EGLANTON THORNE

Author of "It's All Real True," "The Old Worcester Jug,"

"The Two Crowns," etc.

London

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

56, PATERNOSTER ROW, AND 65, ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

VI. SUFFERING FOR CONSCIENCE SAKE

XIV. JERRY'S FAITH HAS ITS REWARD

AS MANY AS TOUCHED HIM

LOOKING FOR A LETTER.

"OH dear! I do wish the postman would make haste and come," said Ellen Mansfield to herself, as she stood at the farmyard gate, looking eagerly up the narrow lane into which it opened.

It was a bright July morning, and the sun was pouring its warm rays on her fair hair and rosy cheeks, as she waited bareheaded in the open air, having no fear of the effects of such exposure to its influence. She was so absorbed in her watch for the country letter-carrier, who was never very punctual to his time, as to give heed to naught besides. Wolf, the old sheep-dog, crept close to her side, and put his nose into her hand, but his mute expression of affection met with no response. The chickens gathered round her, and chirped in vain, with the hope of attracting her attention, and being rewarded with some bread-crumbs or grains of corn, such as she often bestowed on them.

Ellen's thoughts were all of the letter which she hoped would arrive that morning. But presently, she was roused by the sound of her mother's voice calling to her from within the house—

"Ellen, Ellen, where are you? I want you directly!"

Ellen looked annoyed, and her lip pouted.

"How tiresome!" she muttered to herself.

And instead of hastening to obey the summons, she went a few steps down the lane, so that the thick hedge might hide her from her mother's view, in case she came to the door to look for her.

Ellen was a tall, well-grown girl, about sixteen years of age, with a bright, intelligent face, having the fresh complexion and clear blue eyes which only country girls can boast. She was strong and active, and her mother naturally expected much help from this daughter, the eldest child of a family of ten. But Ellen hated house-work, and thought it a hardship that she should be expected to undertake such tasks, and was always glad when, as now, she managed to elude her mother's vigilance and enjoy some minutes of idleness.

The minutes were many this morning, for the postman did not come any the quicker because she was waiting for him. And her conscience told her more than once that she ought to return to the house, yet still she lingered. At last, she caught sight of the old man coming slowly down the lane, sorting some letters in his hand as he came.

"Oh dear! Why can't he walk a little faster?" thought Ellen, impatiently. "He moves like a snail. I am sure one of those letters must be from Aunt Matilda."

There was a house on the other side of the lane for which the postman was bound before he came to Ellen's home. Ellen watched him go in at the gate, and waited anxiously for his reappearance. But when he came out again, there were no letters in his hand.

"He must have one for us," said Ellen to herself; and she hurried forward to meet him.

"No letter for you this morning," he said, in reply to her questioning glance.

"No letter?" repeated Ellen, in dismay. "Are you quite sure? Have you not made a mistake?"

"No, indeed; I don't make mistakes so easily," he replied, smiling at the notion. "Bring you one to-morrow, perhaps."

So saying, he passed on his way, leaving Ellen overwhelmed with disappointment. She had counted so on the arrival of this letter, and had felt so sure that it would come, that she scarcely knew how to bear the delay.

The idea of waiting another whole day, only perhaps to be again disappointed, was disheartening. She stood still where she was, for she felt little inclination now to set about the domestic tasks which should have been commenced earlier.

As she stood idly leaning against the hedge, her face wearing a most discontented expression, the sound of approaching steps fell on her ear. A young man was walking quickly down the lane, looking about him with the air of one unacquainted with the locality, and in search of some particular place. Ellen observed him with curiosity, for he was to her a stranger, and the appearance of a stranger in that rural neighbourhood was a rare event. His demeanour was different from that of any of the country folk thereabout. He was dressed in a black suit, which showed a spotless shirt-front set off by a little black tie, and wore a "wide-awake" hat. His was a pleasant, honest face, with a kindliness of expression which conquered Ellen's usual shyness, as, to her surprise, he stopped short on seeing her, and addressed to her a question:

"Will you kindly tell me if this is the way to Farmer Holroyd's?"

"Yes, sir," replied Ellen. "But you must turn to the left when you get to the bottom of the lane, and take the path across the fields, which you will see. That will take you direct to the house."

"Thank you, thank you," said the stranger, standing still, however, and looking about him with an observant eye. "Do you live in that house?"

"Yes, sir," answered Ellen.

"Will you tell your parents, for perhaps they may not have heard of it, that there will be preaching this evening in Farmer Holroyd's barn at seven o'clock, and that I shall be very happy to see them there, if they are able to be present—and you also, if you can accompany them," he added, kindly.

"Thank you, sir," said Ellen, with some hesitation. "I'll tell them. But father and mother are mostly too busy to go anywhere."

"Are they? I'm sorry for that. But you are not too busy, I suppose?"

Ellen coloured, for she knew she must appear to him an idler. She felt no desire to attend the meeting in Farmer Holroyd's barn, yet was at a loss for an excuse for not doing so.

"No," she said, in answer to his remark. "But I do not know that I shall be able to come."

Her manner plainly said, "I do not care to come"; and so he understood it.

"I shall be glad to see you there, if you can manage it," he said, gently. "I should be sorry to think that your heart is indifferent to Him who is your best friend. Do not, I pray you, make the great mistake of finding time and inclination for everything save the 'one thing needful.'"

With these words he turned away, and Ellen, feeling rather disconcerted, and ashamed at having wasted so much of her morning, hastened back to the house.

"Where have you been all this time, Ellen?" asked her mother, who was engaged in hushing the baby to sleep. "I have been calling you for the last quarter of an hour. It is too bad of you to get out of the way when you know there is so much to be done. Here it is past nine o'clock, and the beds are not made nor the breakfast things washed. What have you been about?"

Mrs. Mansfield, a pale, anxious-looking woman, spoke in low, querulous accents, as though she did not expect her remonstrances to have much effect.

"I have been watching for the postman, mother," replied Ellen. "But he brought no letter. I can't think why Aunt Matilda does not write."

"She would need to think awhile before she answered my letter," returned her mother. "She is not one to do things in a hurry. I could have told you there would be no letter this morning. You'd much better have been about your work than loitering at the gate."

Ellen gave her head an impatient toss at this rebuke, and began, with much unnecessary bustle and clatter, to wash the cups and saucers which had been used for the morning meal.

"Where is Lucy?" she asked, presently.

"Upstairs, giving Jerry his breakfast," her mother answered; adding with a sigh, "The poor lad has had a bad night, and is sadly this morning."

Ellen said nothing, but her mother's words awakened within her some self-reproach, for in her eagerness to get the letter she had forgotten the wants of her favourite brother, to whom she generally attended.

She worked busily for some time, in the vain hope of making up for lost time, and the breakfast things were soon washed and replaced on the dresser. She did not forget to tell her mother of the stranger she had seen, and of the meeting to be held that evening in Farmer Holroyd's barn.

"Ah!" remarked Mrs. Mansfield. "It's all very well for those who have nothing else to do to go to those meetings, but it wouldn't do for me to think of it."

Yet she sighed as she spoke, for she remembered that in her young days she had attended such services with delight. And the recollection induced her to add, "You can go if you like, Ellen."

But Ellen was not sure that she would like to go.

JERRY'S TRIAL.

WHEN Ellen went upstairs to make the beds, she went first of all to a little room at the head of the stairs, known as Jerry's room. She lifted the latch with a careful hand, and entered with a light step.

The young sufferer she feared to disturb was not asleep, however, but greeted her with the words:

"Oh, Ellen! at last! I began to think you were not coming to see me this morning."

"Oh, Jerry, you know I should not fail to come," replied Ellen, as she kissed her little brother, all the dearer on account of the affliction which made him a helpless invalid.

It was sad to look upon Jerry's tiny, wasted face, almost as white as the pillow upon which it rested, and wearing such a pathetic expression of suffering. The blue veins so plainly visible on his temples, the dark circles beneath the sad eyes, the tremulous movement of the mouth, all bore witness to the pain he had so frequently to endure. Yet the smile with which he welcomed his sister was very sweet, and his tones more cheerful than one could have expected.

He lay on a low couch drawn close to the open window, through which he could gaze at the green meadows and orchards which surrounded the house, and watch the cows going to and fro at milking-time, or the haymakers at their work, and catch many of the pleasant sights and sounds which a farm affords. It was a relief to him to be able thus to look upon the outer world, for he was seldom well enough to leave his couch, and there was little hope that he would ever move about like other children.

All had been done that could be done to alleviate the sadness of his life, and, in spite of its rough, uneven floor and sloping ceilings, his little room was a pleasant place. Any pictures that found their way to the house were nailed upon the walls to gladden Jerry's eyes. The rose-tree which grew luxuriantly outside was carefully trained about the window, that Jerry might enjoy the perfume of its blossoms. And a jar of flowers invariably stood beside his bed whenever there were any to be had.

Such books as the home could boast were always to be found in Jerry's room, for he was a great reader. And ever since the day, more than three years ago, when, in his seventh year, a sudden fall from the hay-loft had wrought terrible mischief to his spine, books had been his loved companions.

Not so dear, however, as his brothers and sisters, Ellen, Tom, and Lucy, older than himself, and the little ones that followed, who ever received a warm welcome from him, if he were well enough to see them.

Sometimes, however, on his bad days, when the paroxysms of pain were agonising, he could endure the presence of no one save his mother, whose sympathy was so true and tried.

Books were not the only means of diversion which Jerry possessed. When his head ached with reading, he could amuse himself with straw-plaiting. In the part of England in which the Mansfields lived, poor people used to devote their leisure to this employment, and found it remunerative. But of late years, for sundry reasons, this trade has declined, and although Jerry plaited many a yard of straw, he earned very little by it. That little, however, was acceptable, and supplied him with many comforts which he must otherwise have lacked. For Joseph Mansfield's family was longer than his purse, and he could not afford to keep any of his children in idleness.

He paid a heavy rent for the few acres of land which he farmed, and was frequently in arrears with it. When a bad season came, or any of the cattle died, his face grew long, and he talked about ruin, whilst his wife looked more pale and worried than ever.

The elder children knew that their parents expected them to work for themselves as soon as they were old enough to do so, and Ellen was especially anxious to be earning her own living. There was no need for her to leave home in search of employment, had she been willing to perform the work that lay to hand, for the management of the house and dairy, and the care of so many little ones, with all the washing and mending their clothes required, was more than Mrs. Mansfield could accomplish unaided.

But, as we have said, Ellen disliked these household tasks, and always gave her assistance grudgingly. Being handy with her needle, she had set her heart on becoming a dressmaker. And, after trying long to dissuade her from this purpose, her mother had, in compliance with her wishes, written to her aunt, who was a dressmaker at Charmouth, a large seaport about thirty miles distant from Ellen's home, to ask her to take her niece as an apprentice. It was the answer to this letter that Ellen was so eagerly expecting.

"What has kept you so long this morning, Nell?" her little brother inquired as she seated herself by his side.

"Nothing particular, Jerry. I wasted my time in watching for the postman. All in vain, however, for he brought no letter from Aunt Matilda."

Jerry's face clouded at these words.

"I can't bear to think of your going away from home, Nelly," he said.

"I shall be sorry to leave you all, but very glad for other reasons to go," replied Ellen.

"I can't think what mother will do without you," said Jerry. "She will miss you dreadfully. She is busy enough as it is, but she will have to work harder than ever when you are gone."

Ellen coloured, and bit her lip in momentary annoyance. She did not like to be reminded of such considerations as Jerry's words suggested.

"There is Lucy to help mother," she said.

"Oh yes. Lucy can do a good deal, I know," returned Jerry. "But not all that you can, I should think."

"I hope I shall get a holiday sometimes, and come home to see you all," remarked Ellen, anxious to change the conversation. "And when I've learnt my trade, Jerry, I'll settle somewhere near here, and you shall come and live with me. I'll take such good care of you, and buy you lots of books."

Jerry smiled rather sadly, and shook his head. "I'm afraid that will never be, Nelly. Sometimes I think I shall have to lie in this room the whole of my life; and, oh, I do begin to feel so tired of it!"

"I daresay you do," said his sister, tenderly, "and you feel worse than usual this morning after your bad night. But you'll be better in an hour or two's time, dear."

Jerry sighed deeply, and, hoping to divert his thoughts, Ellen began to tell him about the stranger who was to preach that evening in Farmer Holroyd's barn.

"Oh dear! How I wish I could go and hear him," he exclaimed.

"I wish you could," said Ellen, thinking with sorrow how impossible it was for him to do so.

"Shall you go, Nelly?" he asked.

"I don't know," answered Ellen.

"Oh, Ellen! I wish you would go," he said, "for then you would be able to tell me what he said. You can't think how I long to know about some things."

"What things, Jerry?" asked Ellen, in surprise.

"The things that I read of in the Bible, Nelly, about the Lord Jesus, and how He healed poor sick people. I often wonder if there was any one in the crowds that came to Him as helpless as I."

"There was the man with the palsy," suggested Ellen.

"Yes, he could not move any better than I can," the boy replied. "His friends carried him on his bed to Jesus. Oh, Nelly! how I wish Jesus were on the earth now, for then perhaps He would make me whole. Though I might not be able to get to Him, after all."

"We would carry you to Him, if we possibly could, Jerry," said his sister.

"Yes, I know you would," he replied, with a smile; "but it's of no use thinking of it. Yet when I feel so weary of lying here, I do wish I might be made whole as those people were. I suppose God could make me well now if He liked—couldn't He, Nelly? Do you think, if I prayed very hard to Him, He would?"

"I don't know," replied Ellen doubtfully; "but I think I should try if I were you, Jerry."

The boy lay silent for a while, his contracted brow showing that he was engaged in earnest thought.

Presently, he roused himself and said, "You will go to-night, Nelly?"

"Yes, Jerry," Ellen replied.

"And you will tell me all about it when you come back?"

"Yes, I'll be sure to, Jerry."

THE GREAT PHYSICIAN.

ELLEN was as good as her word. In spite of her disinclination to go to the meeting, she left home a little before seven, and slowly made her way to Farmer Holroyd's barn. She was exceedingly fond of her little brother Jerry, and would have done anything even more disagreeable to her feelings to procure him gratification.

The air was so fresh and sweet on this July evening, and the way through the fields so pleasant, that Ellen did not feel disposed to hurry herself. She climbed to the top of a hedge to gather some dog-roses that grew there, then spying some wild strawberries on the other side, clambered down to refresh herself with them. She lost so much time thus, that when she reached the barn, she found that the service had already commenced, and every seat was taken except those in close proximity to the little table at which the preacher was stationed, a position which she would gladly have avoided.

There was no help for it, however, and she had to push her way to the vacant place through the midst of the little congregation, who were heartily singing the hymn with which the service opened.

Such meetings as this were welcomed by not a few in that country district, which lay several miles from any church, and whose scattered inhabitants depended entirely for religious instruction on the occasional visit of an evangelist such as the one about to address them. At a brief notice, many persons would gather together in a barn or cottage to hear the Word, some cheerfully coming a considerable distance for the purpose.

Ellen felt the preacher's eye rest upon her with a glance of recognition as she seated herself but a few feet in front of him. She had seldom been to such a meeting before, for Mrs. Mansfield, although brought up in a Christian home, had suffered the cares of this life to render her indifferent to all that concerned the eternal life beyond, and had allowed her family to grow up almost in ignorance of that Saviour who is peculiarly the friend of the poor and heavy laden.

Sundays passed much as other days in their home, and the Bible would have been unread had it not been for Jerry, who, having exhausted the contents of all the other books, took to reading it. And found so much therein to interest and soothe him, and at the same time so much to excite wonder, that he never tired of it, and was continually proposing to his mother questions concerning its truths which she found hard to answer.

In the hope of being able to understand his thoughts, and sympathise with them, she had lately begun to read the Scriptures again herself, and the sacred words awoke the echoes of a Christian father's voice, long since silenced by death, and stirred within her contrition and shame. She inwardly longed to accompany Ellen, and listen once more to the word of truth; but if she did so, who would attend to the dairy, or look after the baby, or soothe Jerry, if he had one of his bad attacks of pain? No, the busy mother's place was at home, and He who had laid these burdens upon her would not suffer them to hinder her approach unto Himself, but would draw nigh to her and help her to bear them, if she would only let Him.

Ellen thought of Jerry when the preacher announced his text, for it was Mark's graphic statement concerning the Saviour:

"As many as touched Him were made whole."

She prepared herself to listen attentively, and soon became so interested in the speaker's words, that she could not help doing so. She felt sorry when he ceased, and would gladly have listened to him longer. She was pleased to see that he had with him a number of little books and tracts, which he began to distribute to the people at the close of the service, for she knew how glad Jerry would be to have one.

As she went forward to take a book from his hand, the preacher smiled kindly upon Ellen, and said, "I am glad you were able to come after all. Remember, 'As many as touched Him were made whole.'"

He was not able to say more, for the people were gathering about him to receive tracts, but the words made a lasting impression on Ellen's mind.

Half an hour later, she was seated beside her little brother's bed, doing her best to give him an account of the address to which she had listened. It was surprising how difficult she found it to remember the preacher's words, although they had interested her so much. When she had repeated the text she was silent for a while, trying to put into shape the vague notions which were all her mind had retained.

"'As many as touched Him were made whole,'" repeated Jerry. "Tell me all he said about it, Ellen."

"I will tell you all I can remember," replied his sister. "I forget exactly how he began, but I know he said how eagerly those who had sick friends brought them to Jesus, for then I thought of you, Jerry. They brought them and laid them in the streets, that they might touch the hem of His garment; and those who touched merely the border of the long, flowing robe He wore were made whole."

"Yes, I know that," returned Jerry, who had got hold of his mother's Bible and found the passage; "it says so here. What else did he say? Did he say whether Christ will make people whole now?"

"Yes; he said Jesus is the same now as He was in the days when He lived on the earth. He called Him the Great Physician, and that means a doctor, you know, Jerry. But I am not sure that He heals people in the way you mean," she hastened to add, as she caught the eager glance her brother cast upon her.

"I scarcely know how to explain it to you, but the preacher said it was sin that caused all the sickness and sorrow that there is in the world. Before Adam and Eve sinned, pain was not known. He said sin was worse than any bodily disease—far more terrible even than the leprosy, which is described in the Bible, and of which he spoke a good deal. Oh dear, I wish I could remember better. He said we were all infected with it, and were not able to cure ourselves, but Christ could heal us, and if we only touched Him by faith, He would make us whole. He spoke as if we were all dreadful sinners, and I fancied he looked at me in particular; yet I am sure I am no worse than other girls. I don't steal, or tell lies, or use bad words, so I really don't see that I am so very wicked."

"But didn't he say anything about Jesus curing people's bodies?" asked poor Jerry, anxiously.

"No, dear; it was all about the soul, and how we were to be saved from sin. He said we must go in faith to Jesus, just as the poor woman did who touched Him in the crowd, or the blind man who cried to Him as He came out of Jericho. What we all wanted, he said, was to have our sins forgiven; and only Jesus can forgive sins."

"Yes," observed Jerry, who was well acquainted with the gospel narrative, "Jesus used to forgive the sins of those whom He cured. Do you think I am very wicked, Nelly?"

Tears were in the boy's eyes, and his sister stooped down and kissed him fondly as she answered, "No, that I am sure you are not, Jerry."

"And yet I must be," returned Jerry, "if it is sin that causes suffering, as you say the preacher said."

Ellen looked perplexed. "I am afraid I have not told it you rightly, Jerry, for I know he said we ought not to say of any one that because he was greatly afflicted, therefore he was a great sinner. If we did so, we should be like the Pharisees, who considered the man who was born blind a sinner. Don't you trouble yourself about that, dear. I am sure you are not very sinful."

Jerry sighed. "Is there nothing else you can tell me, Nelly?" he asked, after a pause.

Ellen tried to think of something that might comfort him. "I remember the preacher said that, whatever might be our sins and sorrows, they could not be beyond Christ's power to heal. Just as He could cure all manner of diseases when on earth, so now He can relieve all our wants, and help us in all our distresses."

"Did he say that?" asked Jerry eagerly.

"Yes, I think I have repeated his words correctly," replied his sister.

The boy's face took a more hopeful expression as he continued to turn over the leaves of the Bible which he held in his hand. After a while, however, he ceased to do so, and Ellen, bending over him, saw that he had fallen asleep with his finger resting on the passage which tells how as many as touched the Saviour were made whole.

LEAVING HOME.

THE next morning brought the longed-for letter, which was entirely to Ellen's satisfaction.

Her aunt was willing to teach her dressmaking, and, being in immediate need of another assistant, would be glad for Ellen to come to her with as little delay as possible.

Ellen busied herself with her preparations, and amid the bustle and excitement of the few days that intervened before her departure, the serious thoughts awakened in her mind by the preaching to which she had listened were driven away. Her time was so fully occupied, that her visits to Jerry's room were necessarily brief and hurried, and the conversation narrated in the preceding chapter was not renewed.

Yet Jerry had not forgotten it. His thoughts constantly dwelt on Him who made whole all who touched Him, and he read with deeper interest than before, the records of His blessed life. Many a prayer breathed from that couch of suffering reached the ear of the Great Physician, who sent an answer of peace to the heart of the sick child.

Not for physical health alone did Jerry make petition. The words repeated to him by his sister had revealed a deeper, more deadly malady than that which deprived his limbs of strength and caused him such pain. Jerry no longer doubted his sinfulness. Searching his heart by the light of God's Word, he discovered its hidden evil, and with the knowledge of sin came a longing for deliverance, which caused him to pray as earnestly for health of soul as for health of body. He knew that Jesus could forgive sins and he doubted not His willingness; so, touching by faith the Almighty Saviour, he received the blessing, and experienced a joyful assurance that his sins had been forgiven him for His name's sake.

"Jesus has forgiven my sins, Nelly," he whispered to his sister, on the morning of her departure, when she came to bid him good-bye. "And I believe that He will make me well yet, if I wait patiently. You know how long He kept that woman waiting who cried out to Him to heal her daughter. And yet, He healed her after all. So I hope He will make me whole, if I keep on asking Him. He has said to me, 'Be of good cheer, thy sins are forgiven thee'; soon, perhaps, I shall hear Him say, 'Arise and walk.'"

"I am sure I hope so, dear Jerry," said Ellen, wondering at her little brother's faith.

"I don't seem to mind lying here now," said Jerry. "I feel so much happier than I did, and everything seems bright about me. Not but what I am very sorry you are going to leave us, Ellen," he hastened to add, throwing his arms affectionately about his sister's neck.

"Dear Jerry, I cannot bear to say good-bye to you," exclaimed Ellen, with emotion. "But I will write to you as often as ever I can, and tell you all that I think you will like to hear. And you'll be sure to write to me, won't you, when you feel well enough?"

"Yes, I'll try to write, Nelly; but you know I'm not much of a hand at that sort of thing."

"Never mind what a scribble it is; I'll make it out somehow, never fear. I shall be only too glad to see your writing, whatever it looks like."

They would have said much more to each other, but Mrs. Mansfield's voice was now heard from below, bidding Ellen make haste, or she would not get to the distant station in time for the train. The brother and sister fondly but silently embraced, for both felt a choking sensation that made words almost impossible. And then Ellen tore herself away and ran downstairs. The light cart stood at the door with her small trunk already placed in it, and her father was waiting to drive her to the station.

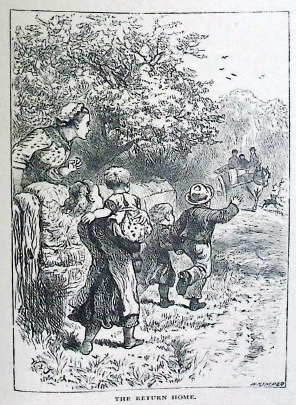

Now that the moment of departure had come, Ellen found that it was more trying to leave her home than she had anticipated. She fairly broke down and cried heartily as she kissed her little brothers and sisters, and received her mother's last anxious injunctions with respect to her health and conduct. Willy had gathered a huge bunch of flowers for his sister as a parting gift, and little Johnny a few strawberries, and all had so much to say that Ellen would certainly have missed her train had she stayed to listen to them. Her father was obliged hastily to cut short the farewells, place her in the cart, and drive off without any more ado.

Ellen felt sad as she drove away, waving her hand to her brothers and sisters clustered at the gate, and her mother, who stood at the door with the baby in her arms. But she soon ceased to cry, and began to take a cheerful view of the separation. Her mind was busy with thoughts of the pleasant future which she imagined lay before her as they drove through the country lanes, between fields of ripening corn, or meadows still covered with sweet-scented hay.

"Good-bye, my lass," said her father, kissing her affectionately, as she sat in a third-class carriage, with her ticket for Charmouth in her hand. "Be a good girl, and try to please your aunt. Your father will be right glad to see you whenever you can come home."

The whistle sounded, and Ellen waved a last good-bye to her father as the train glided out of the station. She was off at last, as she had so often longed to be, going away from the irksome duties and restraints of a home which was after all, dearer to her than she had hitherto imagined, to new scenes and fresh employment, which she believed would prove less distasteful.

She was nearly two hours getting to Charmouth, although it was no great distance, for the train jogged along in a leisurely sort of way, stopping at all the little country stations, whose officials never seem to hurry themselves to secure its speedy departure. And, besides, she had to wait half an hour at a junction on the way. The morning had been bright and sunshiny when she started, but as she went along, she observed dark clouds gathering in the sky, and when she reached Charmouth it was raining heavily.

She had expected that her aunt would either come herself or send some one to meet her; but, to her dismay, when she alighted from the train, she found there was no one there. She stood alone on the platform amidst the bustle and confusion created by the arrival of the train, and which was so bewildering to one accustomed to the quietude of country life, and wondered what she had better do. She watched her fellow-travellers as they hurriedly collected their luggage, and, some in conveyances, some on foot, took their departure from the station.

Then, she timidly made inquiries of an old porter, whose honest countenance inspired her with trust, and who told her that the street in which her aunt lived, was not very far off, and if she could wait till after the arrival of the express, he would undertake to show her the way, and carry her trunk thither.

To this proposal, Ellen was glad to agree. And after waiting till the express had come snorting into the station and deposited its passengers, and they had all satisfactorily obtained their luggage and departed, the old man shouldered Ellen's trunk, and led the way along wet, sloppy streets, which had a cheerless look to a stranger's eye. The rain fell fast, and Ellen's print gown was wet through, and she felt chilled both outwardly and inwardly before she reached her aunt's house.

"Number 13, this is the place," said the porter. And Ellen was further assured of the fact by seeing in the window, which prominently displayed an open fashion-book, backed by some mantles and children's dresses, a card, on which was printed in ornamental letters,—

"Miss Mansfield, dress and mantle maker."

The man gave a loud rap at the door, which was opened by a girl about Ellen's age, smartly yet untidily dressed, who stared rudely at her as she invited her to enter.

"If that's Ellen, tell her not to give the porter more than sixpence," cried a shrill voice from the top of the stairs.

But Ellen had already ungrudgingly given the man the shilling he asked.

"Tell Ellen to take off her boots before she comes upstairs," cried the shrill voice again.

An injunction which Ellen was glad to obey, for her feet were damp.

"My! You are wet," remarked the girl who had admitted her, smiling as she spoke, as though she found the fact amusing.

When Ellen had removed her muddy boots, she followed the other girl upstairs to the work-room, in which her aunt was seated, engaged in putting the finishing touches to a silk mantle, and at the same time vigorously scolding her companion, a young girl, with pale, thin face, and large dark eyes. It was many years since Ellen had seen her aunt, for, although she did not live so very far from her brother's home, Miss Mansfield was generally too busy to be able to pay him a visit.

Ellen looked at her timidly and anxiously as she entered the work-room. Miss Mansfield was a tall, thin woman, with sallow complexion, sharp features, a quick, observant glance, which nothing escaped, and an equally active tongue. In the work-room, her tones were high, and her manner marked by considerable asperity. But when addressing her employers, her voice was soft and insinuating, and her bearing graciousness itself. A tyrant to those about her, she could be obsequious without measure to any one whose favour she was anxious to win.

"So you've got here at last, then," she exclaimed as Ellen entered, speaking quickly, in spite of the pins which she held between her thin lips, and on account of which it doubtless was, that she gave Ellen no kiss of welcome such as a niece had a right to expect. "I suppose you did not think to be met, did you? I thought you were old enough to find your way here alone, and I am too busy to afford to waste any time, I can tell you. I hope you did not give that porter more than sixpence?"

"I had given him the shilling before you spoke, ma'am," replied Ellen.

"Then, my dear, you should not have done so. You should never give that sort of people what they ask. They'll be sure to cheat you, if they can. When you've lived in town a while, you'll know better, I trust, than to let yourself be imposed on so easily. This is the first time you've been from home, isn't it?"

"Yes, ma'am," replied Ellen timidly, with difficulty keeping back the tears which were ready to fall.

"Why, what a tall girl you are, to be sure!" continued her aunt, taking a pin from the front of her dress, which was so studded with needles and pins as to give her the appearance of an animated pincushion. "Goodness me! How wet your dress is! It looks like a soaked rag, and it was clean on this morning, I daresay—wasn't it? I thought so," she continued, as Ellen answered in the affirmative. "I hope you have not brought many such dresses, for they'll be of no use to you here. Anything so light as that, is not fit for town wear. You want something that will not require washing every week, and that won't spoil with a drop of rain. Well, you'd better go and take it off now, and then, I daresay you'll like a cup of tea. Julia, show Ellen where she is to sleep, and don't stop there chattering, but come back to your work directly. By the bye, I hope you left them all well at home?"

"Yes, thank you; all are well except Jerry," Ellen replied, in a faint voice, as she quitted the room, and followed her guide to a little room at the top of the house, very barely furnished, and having, to her eyes, accustomed to the purity of country surroundings, a dingy appearance.

Left to herself here, Ellen sank down on the little bed, and gave vent to the feelings of disappointment and discomfort produced by her aunt's cold, brusque reception in a flood of tears.

IN THE WORK-ROOM.

ELLEN found her new life very different in reality from what it had appeared in anticipation.

Dressmaking did not prove so agreeable an occupation as she had expected to find it, and before she had been more than a week at Charmouth, she was painfully conscious of home-sickness.

Her aunt's quick, sharp ways frightened her, and the fear of offending rendered her so timid and nervous, that she made more mistakes than she would otherwise have done. She wondered how her companions in the work-room could take their mistress's frequent scoldings so coolly as they appeared to do. But they had grown accustomed to her voluble expressions of displeasure, and knew that she often appeared more angry than she really was.

Exceedingly quick-tempered, Miss Mansfield had a kind heart, in spite of her sharp speech and abrupt manner. She meant to treat her niece well, for she was pleased with her appearance and liked her needlework, although she often found fault with it. She would have been astonished could she have known with what dread and dislike her bearing had from the first inspired Ellen. From force of habit, it had become a part of her nature to scold, and she had no idea how disagreeable this practice was to those about her.

Ellen found the long hours of sewing, with her aunt's keen eyes constantly on the watch to detect the least diminution of energy, quite as tedious as the hours spent in assisting her mother at home. Occasionally she was sent out on errands; but, unaccustomed to town life, she made so many blunders, that she was not often thus employed. Once she got into sore disgrace by telling a lady to whom she carried an expensive mantle, which had been ordered, and who consulted her on the subject, that it did not suit her.

The consequence was, the mantle was returned to be re-made, greatly to Miss Mansfield's annoyance, who vented her displeasure most severely upon the well-meaning cause of it.

Ellen's fellow-workers differed much in character and demeanour. Julia Coleman was a shrewd, talkative girl, who could work well if she liked, but tried Miss Mansfield's patience greatly by her lazy, careless ways. She was quick in excusing her own shortcomings, however, and by deceit and untruth would try to shield herself from blame. Ellen was inclined to like her, for she was bright and lively, and anxious to make friends with the new-comer.

Mary Nelson was several years older than the other girls, having already served her apprenticeship, and being retained in Miss Mansfield's employ because her assistance was of such value. She was a very quiet girl, and seldom spoke unless addressed. She would stitch away as diligently when Miss Mansfield was out of the room as in her presence. Her health was delicate, and sometimes she became faint from bending over her work too long. Ellen felt sorry for her at such times, and was profuse in her expressions of sympathy and offers of assistance. Mary was grateful for her kindness, and tried to show that she was so. A friendly feeling sprang up between the two girls, although they said little to each other.

Miss Mansfield did not like much talking to go on in the work-room, and when she was present, her voice was generally the only one heard. Certainly that more than compensated for the silence of the others.

As Julia and Mary did not live in the house, and were always glad to hurry home as soon as they could get permission to do so, Ellen had little opportunity for unrestrained intercourse with them, except when anything occurred to take her aunt from home.

She was obliged to go out on business one evening, and left the girls some work to finish before they went home. They worked pretty diligently, for they were anxious to get their task finished, but as they worked Julia chatted freely.

"What do you do with yourself on Sundays, Ellen?" she asked. "Don't you find it very dull here?"

"Yes, rather," Ellen admitted. "But I don't get up till late in the morning, for aunt is never in a hurry on Sundays. Then I generally write a long letter home, and in the evening, I go to church with aunt; so the time passes quickly. I like it better than sewing all the day."

"I daresay you do," returned Julia. "But, for all that, it is hard that you should not have some pleasure on the only holiday you get. I wish you could come with me for a walk next Sunday afternoon. I would take you about, and show you more of the town than you have yet seen."

"Thank you," replied Ellen. "I should like to take a walk with you, if aunt would let me, but I know it is of no use to ask her. For the other Sunday I asked her if I might take a little stroll by myself, and she answered me so crossly, and said it was 'not seemly for young girls to be gadding about the streets alone.'"

"Well, I must say I don't envy you, Ellen, being shut up the whole of the day with that old cross-patch," Julia said, with a laugh.

"No, I don't like it at all," rejoined Ellen discontentedly. "I get dreadfully tired of being always indoors. At home, I never used to stay in the house for more than an hour at a time, but here I can scarcely ever get out."

"I wonder if you would like to go with me to my Bible-class?" said Mary Nelson, looking up from her work. "I should think your aunt would have no objection to that."

"What is a Bible-class like?" asked Ellen. "I have never been to one."

"And if you take my advice you never will!" exclaimed Julia. "You will find it a great deal slower than staying at home, I can tell you."

"I don't find it so," said Mary. "I would not miss going on any account. Our teacher is such a pleasant young lady, and so kind and good to us all, that we love her dearly. She makes the lessons most interesting."

Julia smiled scornfully, and gave her head a significant toss.

Ellen thought she would like to go with Mary to her class, yet somehow she felt ashamed to say so before Julia. But the recollection of her brother Jerry, and his love for the Word of God, gave her courage, and she said firmly,—

"I should like to go with you next Sunday, Mary, if aunt will let me."

"Very well; that is agreed," answered Mary, with a smile. "I shall be very pleased to have your company."

Julia gave expression to her contempt for this arrangement by indulging in a low whistle, and Ellen felt that she had fallen in her fellow-apprentice's estimation.

SUFFERING FOR CONSCIENCE SAKE.

MISS MANSFIELD was quite willing that Ellen should go with Mary to the Bible-class. During the time the latter had been in her employ, she had worked so steadily and faithfully that Miss Mansfield felt the utmost confidence in her, and had no fear of her leading Ellen into mischief.

Accordingly, the next Sunday afternoon, Mary called for Ellen, and the two set off together for the school at which the class was held. It took them about twenty minutes to reach it, and as the afternoon was bright, Ellen thoroughly enjoyed the walk thither. She felt rather shy and awkward as she entered the class-room, where about a dozen girls were seated, awaiting the arrival of their teacher. But they greeted the new-comer kindly, and she soon felt at ease with them.

Presently Miss Graham, their teacher, came in, and Ellen felt drawn to her directly she looked at her pleasant face, with its sweet smile and soft, loving blue eyes. She gave Ellen a kind welcome to the class, and expressed the hope that she would be willing and able to attend regularly.

"Have you not a Bible?" Miss Graham asked, seeing that Ellen was about to look over with Mary.

"No, ma'am, I have not one of my own," replied Ellen, colouring as she spoke.

"Then I will give you one, so that you may not say that any longer," said Miss Graham pleasantly, opening a drawer in the table at which she was seated, and taking from it a neat little black Bible, in which she proceeded to write Ellen's name.

Ellen was very pleased to receive this gift, and longed to show it to Jerry, whose admiration, she knew, it would be sure to call forth.

She was interested in the lesson that followed, and went away at the close of the class, carrying her Bible in her hand, resolved to read it frequently, that she might become able to answer Miss Graham's questions as readily as Mary and some other of the girls had done.

Every Sunday for the next few weeks, she went with Mary to the class, although Julia laughed at her for doing so. She used to write Jerry many a letter containing an account of the lessons Miss Graham had given at the class.

These letters were eagerly read by the poor sick lad, and the passages of Scripture to which reference was made, examined. He was somewhat better than he had been when Ellen left home. The attacks of pain were less frequent, and his spirits bright and hopeful. His faith in the Lord Jesus, though simple and childlike, was strong, and he often spoke confidently of the time, which he believed would soon come, when the Lord would make him whole.

His letters to his sister—curious documents, written in a large, sprawling hand—contained many allusions to this hope. And from the cheering accounts of his improved health, which she received, not from himself alone, but also from her mother, Ellen was encouraged to hope that it might not prove deceptive.

One of the truths impressed upon her mind by Miss Graham's instruction, was the value and importance of prayer. And every day she prayed fervently that her little brother might be restored to health.

She had yet to learn her own need of spiritual health, and the preciousness of Christ as a Saviour from sin.

As winter approached, Miss Mansfield was overwhelmed with work, and stitch as fast as they might, she and her assistants were scarcely able to get it all done. It would have been well, if Miss Mansfield had had the good sense to refrain from undertaking more than it was in her power to accomplish. But she never liked to refuse work, and would frequently promise to execute an order by a given time when she knew it was quite impossible for her to do so.

She did not spare herself, but worked the hardest of all. Her needle was seldom laid aside till after midnight, yet she was often plying it again before daylight. She suffered from such excessive application, and became so impatient and irritable, that Ellen was quite afraid to address her. The least mistake was sure to be most severely censured.

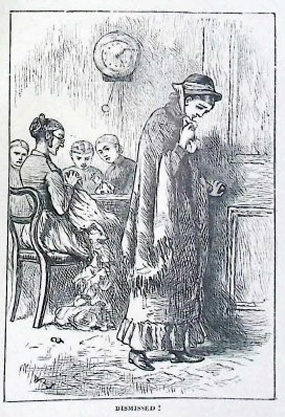

"It's of no use making a fuss about it," exclaimed Miss Mansfield, one Saturday evening, when the girls were bending over their work with pale, weary faces, for it was past their usual hour of dismissal. "These dresses must be got out of hand. You will have to come for a couple of hours to-morrow, Mary, and help me finish them off."

Mary looked up in astonishment, not unmixed with fear. She grew red for a moment, but the colour quickly faded from her face, leaving it paler than before.

"Come to-morrow, Miss Mansfield?" she repeated questioningly, as if she doubted the hearing of her ears.

"Yes, to-morrow; do I not speak plainly enough?" replied Miss Mansfield, with impatience.

"I cannot come on Sunday, Miss Mansfield," said Mary firmly, though her voice betrayed agitation.

"And why not, pray?" asked her employer, sharply.

"Because I think it would be wrong to do such work on the Lord's day," answered Mary.

"Do you think I should ask you to do it, if it were wrong?" returned the dressmaker, angrily. "But I suppose I don't know what is right. You are one of those Pharisees who set themselves up for being better than everybody else. Of course, it is wrong to work upon Sundays as a rule, but this is a case of necessity. And I only want you to come for two hours in the morning. You'd be able to go to your Bible-class in the afternoon, and to church in the evening. What harm could there be in that, just for once?"

"I am very sorry, ma'am," replied Mary, "but I can't think it would be right to do so."

"You'd better say you would rather not oblige me. That would be nearer the truth, I expect," returned Miss Mansfield. "But I won't put up with such hypocritical ways. If you don't choose to help me to-morrow, you need not trouble yourself to come here again."

"Oh, pray do not say that!" exclaimed Mary, imploringly.

"I do say it, and I mean it too," retorted Miss Mansfield, who had worked herself up into a passion. "So now you understand, and can act accordingly. If you don't come to-morrow, you shan't come on Monday. Now which will you do?"

"Indeed, ma'am, I can't come to-morrow," replied Mary, in great distress. "I will work extra hours next week, or do anything I can to oblige you, but I cannot sew on Sunday."

"Very well, then, that is enough," said Miss Mansfield, white with anger. "Now you may put on your things and go home. And remember, I do not wish to see you here again, unless you think better of your refusal to comply with my wishes. Here is your week's wages."

Mary's tears fell fast as she prepared to obey this unkind command. With trembling hands, she slowly put on her bonnet and shawl, and turned to take her leave. She paused for a moment at the door, and cast a beseeching glance of distress at her stern employer.

DISMISSED!

But Miss Mansfield had taken up her work, and was apparently stitching away too earnestly to be conscious of her appealing look.

"Good-night, ma'am," said Mary, in a broken voice.

Miss Mansfield's needle suddenly snapped in two, and she uttered an impatient exclamation, but took no notice of Mary's words. And, sorely troubled, the poor girl went slowly downstairs and out of the house.

DREARY DAYS.

IF Miss Mansfield expected that Mary would change her mind, and come to work on the following morning, she was disappointed. She managed to finish the dresses unaided, but resented no less bitterly Mary's refusal to help her.

Much to Ellen's vexation, she was told not to go to the Bible-class, as her aunt did not wish her to hold any further intercourse with Mary Nelson. It was a great disappointment, for she had come to look forward with pleasure to her Sunday afternoons, and was so attached to her kind teacher that she could not bear the thought of missing her lessons. She was sorry also to be separated from Mary, who had shown herself in many ways a kind friend. The days that followed were dismal enough.

Miss Mansfield's temper was worse than ever, and it was impossible to give her satisfaction. For several weeks, Ellen was obliged to remain away from her class, and during that time saw nothing of Mary. At last, however, she obtained her aunt's permission to go to it once more. Miss Mansfield consented, because she was anxious to hear something of Mary Nelson. She had expected that Mary would be sure to come, sooner or later, and beg to be taken into her employ again; but as the days passed on, and nothing was heard of her, Miss Mansfield grew anxious to know whether she had found work elsewhere.

Like most hasty-tempered individuals, Miss Mansfield had forgotten in what strong terms she had expressed her displeasure with her assistant, and wondered that Mary should have made no attempt to persuade her to pardon the offence given. She greatly missed Mary's skilful needle, and at that busy season, found it no easy matter to supply her place. But her pride would not suffer her to recall the girl, after having so summarily dismissed her, or she would gladly have done so.

Ellen set off for the Bible-class with the hope of meeting Mary there. She was surprised to find her absent, and still more so when at the close, Miss Graham said to her, "Can you tell me anything of Mary Nelson, Ellen? She has not been to the class for two Sundays."

"No, miss; I have seen nothing of her for the last month," was Ellen's reply.

"Does she not work for your aunt?" inquired Miss Graham, in astonishment.

"No, not now," replied Ellen, colouring as she spoke. "My aunt dismissed her."

Miss Graham seemed much surprised to hear this, but asked no questions as to the circumstances under which Mary had been dismissed.

"I have not seen you here for some weeks," she said. "I began to fear you had ceased to take an interest in the class."

"Oh, no!" Ellen assured her. "It was not that. I have been very sorry to stay away, but my aunt did not wish me to come."

"Indeed! I am sorry for that," replied her teacher. "Have you come with her permission this afternoon?"

"Yes, Miss Graham."

"Then I hope she will let you come again next Sunday. I must try to see Mary Nelson this week, for her absence makes me anxious. I trust she is not ill, but she is usually so regular in her attendance that I am sure she would not stay away for any trivial cause."

Ellen felt anxious also, as she remembered how white and ill Mary had looked on the Saturday evening when she had gone away in such distress.

"Did you see Mary Nelson at the class?" Miss Mansfield inquired, in her most abrupt manner, of her niece when she returned.

"No; she was not there," replied Ellen.

Miss Mansfield looked surprised.

"Indeed! I thought she was always to be found there, and wouldn't be absent on any account. But I daresay she is not such a saint after all as she used to make herself out to be."

"Miss Graham said she thought Mary must be ill," observed Ellen, "because she had not been to the class for two Sundays, and she scarcely ever stays away."

Miss Mansfield felt uncomfortable.

She was conscious that she had been too hard upon Mary, who deserved better treatment at her hands, after having worked so faithfully for her during several years.

She knew what delicate health the girl had always had, and feared that she was ill. She almost resolved that she would try to see Mary on the following day, and assist her, if she were ill. And if she found her out of work, offer to take her again into her employ.

But with the fresh demands on her time and attention which Monday morning brought, much to her after regret, this half-formed resolution was forgotten.

A LONELY SUFFERER.

MISS GRAHAM did not forget her intention of visiting Mary and discovering the reason of her absence from the Bible-class.

Early in the week, she directed her steps to the narrow street in an obscure quarter of the town where Mary occupied a small room over a greengrocer's shop.

"Is Mary Nelson within?" Miss Graham inquired of an untidy-looking woman, with a face expressive of indolent good-humour, who stood behind the counter of the close little shop, redolent of many odours, that of onions being the most perceptible.

"Yes, miss, she's within certainly, for she can't leave her bed: she's very bad indeed."

"Oh! I am grieved to hear that," exclaimed Miss Graham. "I feared she must be ill. May I go up to her room?"

"Yes, if you please, miss. I'm sure she'll be very thankful to see you, for she's in great trouble, poor girl."

Anxious as the woman's words rendered Miss Graham, she was little prepared to find Mary so ill as she was. Of delicate constitution, and highly susceptible of cold, Mary had been unable to throw off a chill taken on a wet day which had been passed in going about from one place to another in search of employment, and severe inflammation of the lungs was the result. That she was most seriously ill, Miss Graham could not doubt as she looked upon her white, strangely-altered countenance, and met the excited gaze of those usually calm eyes.

"Oh! Miss Graham, is it you?" exclaimed the girl, in a hoarse whisper. "How kind of you to come! I am so glad to see you!"

"My dear girl, I am grieved to find you so ill," said her teacher, with difficulty concealing the alarm Mary's appearance caused her. "How long have you been thus?"

"I have been in bed nearly a week," replied Mary. "I tried to keep up as long as I could, and I was obliged to go out to see about getting work; but I gave in at last. The pain at my side has been dreadful."

"It is a pity that you did not give in sooner, I think," said Miss Graham. "But now, let me see what I can do for you. Being a doctor's daughter, I ought to have some notion how to treat sick folk. Have you had no advice?"

"Mrs. Jones got me some cough mixture at the chemist's, and some stuff to rub on my chest," replied Mary; "but they don't seem to have done me any good."

"When I go home, Mary, I will ask my father to come and look at you," said Miss Graham, as she gently raised the pillow and placed the sick girl in a more easy position. "He will be able to give you something to relieve you, I trust."

"You are very kind," murmured poor Mary, as she held her teacher's hand tightly in her own wasted one, and looked up into her face with eyes full of love. "You are very kind, Miss Graham, but I don't think it will be of any use for him to come."

"Why, have you such a poor opinion of his skill?" said her friend, trying to speak lightly, though her heart was heavy enough.

"No, you know I do not mean that," said Mary, speaking with difficulty. "But I feel so Ill, and I do not think that I shall ever be any better. Something seems to tell me that I shall not be here long. And I am not sorry that it should be so, for I feel weary of life."

"It is not strange that you should feel so," replied Miss Graham. "We are all apt to get sad and depressed when we are ill. But I hope you will soon be better, and live to see many and happy days, if it be God's will. But whatever may be the issue of this illness, I trust you know Him who is our best Friend, in life or death. Can you feel that the arms of His love are about you?"

A faint smile passed over Mary's face as she answered, "Yes, I have long trusted and loved Him. I often have wished to tell you so, but I did not like. I have been a poor Christian, so faithless and cowardly; but I don't know what I should have done all these years without Jesus. You don't know what a dreary life it is to sit sewing all day long, till one's side aches, and one feels ill all over. I used to think sometimes that if the ladies who wore the pretty dresses knew what it cost us poor girls to make them, they wouldn't care about them so much. Well, I don't think I shall ever make any more. You know Miss Mansfield would not let me work for her any longer, because I could not consent to work on Sunday. It has been such a trouble to me, for no one else would take me on, and my money is almost gone. Indeed, I could not pay Mrs. Jones my rent last week, but she was kind enough to say it did not matter till I was well again."

"Do not trouble about that, dear Mary," said Miss Graham gently. "It shall be made right."

"Thank you; you are so good to me. Before you came I was feeling so lonely and miserable, I thought it seemed as if God had forgotten me. But He hadn't, you see, for He sent you to comfort me."

"God never forgets His children, nor forsakes them in trouble," observed her teacher, adding, as she noticed the girl's excited appearance, "Now, I cannot let you talk any longer; you must keep quiet, or I shall be obliged to leave you."

"Oh, do not say that!" pleaded Mary, "For I have so much to tell you. I want to thank you for all your kindness to me at the Bible-class. You can't think what a comfort and help your lessons have been to me. If I am never at the class again, will you say good-bye to all the girls for me? And will you give my love to Ellen Mansfield and Julia Coleman, with whom I used to work, and say how much I hope they will both have Jesus for their Friend? You might give Julia my Bible; I don't think she has one of her own. I often longed to speak to them of the Saviour, yet I was afraid. But I feel so happy in His love now, that I could speak to any one of Him."

"Dear Mary, I hope yet to see you restored to health," said Miss Graham. "But should it please God to take you to Himself, I will carry out your wishes. Now do not exhaust yourself by speaking more."

But in vain, she tried to enforce silence.

Mary's usual timidity was gone. And although she drew every breath with difficulty, and could scarcely raise her voice above a whisper, she spoke with an eager rapidity, which was symptomatic of the fever which consumed her.

Fearing that her presence would prove too exciting if she stayed longer, Miss Graham thought it best to take her leave, promising to return in a short time, accompanied, if possible, by her father.

AN ALARMING INCIDENT.

IN the evening of the same day, Ellen and Julia were alone in the work-room, Miss Mansfield having gone out to take an order. She had not neglected to leave the girls plenty to do in her absence; but Julia, being in an idle mood, soon dropped her work, and began to amuse herself by inspecting the various articles of attire, some almost finished, others but just commenced, with which the apartment was littered.

Ellen was trying hard to get her task finished by Miss Mansfield's return, although she could not help having her attention somewhat distracted by her companion's proceedings, especially when she began to deck herself in one of the garments, an action which would have provoked Miss Mansfield's severest displeasure had she known of it. After a time, however, Julia wearied of this diversion, and bethought her of another.

"Did you see the muslins that were sent for that wedding order, Ellen?" she asked.

"I did not look at them," Ellen replied. "Aunt unpacked them herself, and placed them in the show-room. The ladies are coming to see them to-morrow, I believe."

"I say, Ellen, I vote you and I have a look at them now," exclaimed Julia.

"Oh, no, we must not do that," returned Ellen. "And indeed we cannot, for aunt always locks up the show-room before she goes out."

"Of course she does," said Julia, "but she does not take the key with her."

"How do you know that?" asked Ellen, in surprise.

"Because I happened to see her put it in here," replied Julia, opening a drawer as she spoke, and displaying the key to Ellen's astonished eyes. "Now, come along, Ellen; let's make a voyage of discovery."

"Oh, Julia! We had better not go downstairs," remonstrated Ellen. "Aunt may return at any moment, and she would be so angry if she found us there."

"Nonsense! She won't be here for another hour, I'm quite certain," answered Julia. "I want to see those dresses, if you don't, Ellen; so I shall go down."

So saying, Julia proceeded to light a candle which stood at hand.

"Oh, what would aunt say if she could see you?" exclaimed Ellen. "You know she never lets any one but herself go into that room with a candle."

"Well, she won't see me," observed Julia, coolly, "and I can carry a candle as well as she can. Really, Ellen, you are looking quite frightened. What simple things you country girls are!"

There was nothing annoyed Ellen so much as to be thus taunted with being a country girl. It was foolish of her to mind it, but she did. She coloured as Julia spoke, and exclaimed pettishly, "I am sure I am not at all frightened, so you are mistaken for once in your opinion of country girls."

"Then you should not act as if you were," retorted Julia. "Come along with me, and look at those muslins, if you are not afraid."

Ellen hesitated, and felt unwilling to go, but the fear of Julia's ridicule overcame her better judgment, and she followed her downstairs.

The girls entered the front room, which was reserved for the reception of customers, and where were displayed sundry patterns, trimmings, and dress materials. On the chintz-covered sofa lay several pieces of delicate muslin, whose beauty called forth strong expressions of admiration from Julia as she bent down to examine them, holding the candle so dangerously close as to excite Ellen's fears.

"Do be careful how you hold that candle, Julia!" she exclaimed.

But Julia seemed desirous to frighten Ellen as much as possible, for the only effect of her remonstrance was that the candle was held more carelessly than before. Julia was holding it thus, when they were suddenly startled by Miss Mansfield's loud knock at the door. Both jumped at the sound, and in her fright, the candle fell from Julia's hand on to the heap of muslins. Instantly the gauzy material took fire, and the flame rapidly mounting caught Ellen's apron, and in a moment, she was in flames.

"Oh, Julia! Help me! Help me!" she screamed, in her terror.

But, much alarmed, Julia lost all presence of mind, and rushed out of the room, shrieking, "Fire! Fire!"

She ran to the front door, at which Miss Mansfield was loudly knocking.

The current of air which entered the house as she opened the door fanned the flames which enveloped Ellen, and but for her aunt's prompt succour, she might have been burned to death.

With admirable coolness, deciding in a moment what was to be done, Miss Mansfield pulled off the thick woollen shawl which she wore, and wrapped it tightly round her niece, thus smothering the flames. With the help of some water hastily fetched from the kitchen adjoining, the fire was soon extinguished. Meanwhile, Julia remained at the door wringing her hands, and telling every one who passed that the house was on fire. The consequence was, an alarm was raised, and a crowd of persons, increasing at every moment, gathered in front of the house. A fire engine would have been summoned by some of the more enterprising, had not Miss Mansfield suddenly appeared at the door, and shortly and sharply assured them that there was no need, since the fire was quite out.

"If some one would fetch a doctor, it would be more to the purpose," she added.

Scarcely had she spoken, when the sound of wheels was heard, and most providentially, as it proved, Dr. Graham's carriage bowled into the street. In a moment, its progress was arrested, and the services of the doctor enlisted on behalf of the sufferer.

With cheerful alacrity, Dr. Graham alighted from his carriage and entered Miss Mansfield's house. He found her bending over her niece's unconscious form, endeavouring, as gently as she could, though her hands were little accustomed to such offices, to remove her scorched garments and discover the extent to which she was injured. He came to her aid with his more skilful hands, and, after a careful examination, pronounced that the poor girl, though badly burnt, was in no danger.

Still, he foresaw that she would suffer great pain when restored to consciousness. Her burns must be carefully dressed, and would require constant attention for some time. He therefore advised Miss Mansfield to have her niece at once removed to a neighbouring hospital, where everything would be at hand that her state rendered necessary, and she would have better nursing than she could possibly have in her aunt's house.

Dr. Graham kindly offered to convey her thither in his carriage without any delay, and himself make arrangements for her benefit and superintend the dressing of her burns.

Miss Mansfield hesitated a little before she agreed to his kind proposal.

"I should not like to have it said that I turned my niece away from my house to the hospital when she was so bad," she remarked.

"None but the ignorant and foolish would misunderstand your motives and blame you for so doing," replied Dr. Graham. "In the hospital, your niece will have the best advice and most skilful treatment. It would be difficult for you, occupied as you are, to provide for her wants and give her the attention she will require here."

Miss Mansfield was sensible enough to see the wisdom of the doctor's advice. She therefore made no further objection to his plan, but busied herself in carrying out his directions, and assisted to carry Ellen to the carriage. Still in a state of insensibility, she was lifted into the brougham and borne to the hospital. Here the good doctor was indefatigable in his efforts on her behalf, and did not leave till he saw her restored to consciousness, with her wounds comfortably dressed.

Her aunt remained with her to as late an hour as the rules of the hospital would permit, and then, not without many tears from Ellen, took her departure.

A CONVERSATION.

WHILST her father was thus attending to Ellen, Miss Graham was anxiously awaiting his return home. He had left her at Mary's bedside, whither he had accompanied her. She had waited to see the patient fall into a deep sleep under the influence of the draught her father had prescribed before she left her. She quite expected to find him within when she re-entered her home, and was surprised at his absence, and still more so when an hour passed and yet he did not come.

"I cannot think what can be keeping papa," she remarked to her cousin, who was visiting her.

"Oh, he has probably been called to see some new patient," replied her companion, a pretty young lady, very fashionably dressed. "There's no accounting for a doctor's movements. Nor for a dressmaker's either, I'm thinking; they hardly ever keep their word. Mrs. Brown promised me my dress to-day, but she has not yet sent it. It is so tiresome, for I wanted particularly to wear it to-morrow."

"Why, you only ordered it on Friday," remarked Miss Graham. "I should not think she could possibly make it in so short a time."

"No, I did not give her very long, certainly," replied the young lady. "But I told her I must have it to-day, and she promised me I should. What is the matter, Theresa? Why do you look so grave? Are you meditating giving me a lecture on my extravagance?"

"It would not be of much use, I fear," returned her cousin, with a smile. "Your words made me think of the young girl to whom I took my father this evening. She used to work for a dressmaker, but lost her situation because she would not consent to work on Sunday. It was a great trouble to her, poor girl. She could not get any one else to employ her, and going about from place to place, in all sorts of weather, she caught a severe cold, which terminated in this illness: from which I much fear she will never recover."

"Poor girl! How very sad!" observed her companion. "But why should my words remind you of her? You don't suppose, I hope, that I should wish to make any one work on Sunday?"

"I don't think any lady would be so selfish as to wish it, if the question were put to her," replied Miss Graham. "But when so many insist upon having their orders executed with all speed, the dressmaker feels forced to make time somehow, and is tempted to encroach upon the only day of rest that her apprentices can ever enjoy."

"But what is one to do? One must be properly dressed," returned the young lady, glancing complacently at her elegant attire. "Excuse me, Cousin Theresa, but you can't expect every one to be so indifferent to dress as yourself, or to adopt your Quaker-like simplicity."

"Nay, you need not apologise," replied her cousin, with perfect good temper. "I feel flattered by your remark, for, excepting the poke bonnet, I rather admire the style adopted by Quaker ladies. But surely one can be properly dressed without requiring a new dress for every occasion, especially if it can only be obtained at the cost of suffering to others. In such a case we ought, I think, for the sake of our poorer sisters, to deny ourselves the gratification of appearing in the latest fashion."

"But surely we help them by giving them plenty of employment. A liberal expenditure in dress must be good for trade."

"Not necessarily," replied Miss Graham. "It has been proved often enough that the extravagance of the rich can only exert a baneful influence upon the condition of the poor. The habits of the upper classes are imitated by those beneath them, and inexpressible sin and misery are often the result. If ladies were more considerate towards those they employ, and more anxious to influence them aright, young workwomen would not be exposed to the terrible temptations by which many are overcome."

Miss Graham would have said more, for the subject was one on which she had thought and felt much, and she was moreover well acquainted with the circumstances of the class for which she pleaded, but she was here interrupted by the entrance of her father.

"Oh, papa, what has detained you so long?" she inquired.

In a few words, he described to her what had occurred at Miss Mansfield's, and the aid he had rendered the sufferer.

Miss Graham's sympathy was warmly excited on Ellen's behalf, and whilst rapidly questioning her father with regard to the particulars of the occurrence, she forgot for a while the sad condition of her other scholar. But presently, remembering her, she inquired anxiously, "What did you think of Mary Nelson, papa?"

Dr. Graham shook his head, and grew grave.

"She is very ill, Theresa," he replied.

"But she may recover? You do not give up hope?" asked his daughter, alarmed at his manner.

"Whilst there is life, there is always hope, my dear," was her father's reply.

Miss Graham asked no further for she knew but too well what those words meant.

IN THE HOSPITAL.

LEFT to herself in a strange place, with none but strangers near, and suffering such pain as she had never known before, Ellen felt very unhappy. The long ward, with its double row of small white beds, seemed dreary to her, and she longed to be in her own dear home, tended by her mother's hands, and cheered by her father's loving words.

The nurse who waited upon her was most kind, and did her best to comfort the poor girl. But she could not understand the thoughts which troubled the sufferer's mind, and made her situation so unendurable. The knowledge that this suffering was the result of her own wilfulness and folly added to her pain. If only she had had the courage to resist Julia's persuasions, and act rightly, this trouble would not have befallen her.

How it would distress her mother to receive a letter from Aunt Matilda telling her of what had occurred! And Jerry! How sorry Jerry would be! Ellen could picture the dismay the news would cause in her home. And the thought that all this might have been prevented if she had but acted wisely, was not reassuring.

Night approached, and stillness and repose pervaded the ward. Most of its occupants slept through the night, but there were a few whose maladies deprived them of rest. Ellen was one of these. Her burns smarted so sorely that sleep was out of the question, and as the night wore on her agitation of mind increased.

She began to fear that she might not recover. She had heard of persons dying from the effect of burns—what if she should die?

Oh, how the thought of death alarmed her! What a terrible sense of her sinfulness and unworthiness it awakened! How different her past conduct, which had been so easily excused, looked in the light cast upon it by that thought! She remembered how of late she had neglected reading her Bible, and had been glad to banish from her mind the serious thoughts that had been aroused by Miss Graham's earnest teaching. How she had suffered herself to be persuaded by Julia into doing much that she knew to be wrong, and had even uttered words which were not true. Oh, how the recollection now troubled her!

The pangs of conscience were sharper than her bodily pains.

The fear of dying all unprepared as she was, threw her into an agony. She longed for the presence of some friend to whom she might confide all that troubled her, and who could give her comfort. If only Miss Graham were there!

Ellen raised herself on her elbow, and from her bed in the corner looked down the long, dimly-lighted ward. Was there any one there so wicked and miserable as herself? she wondered.

The night nurse was seated at some distance from Ellen's bed, but she heard her move, and came at once to her.

"Can't you sleep, my dear?" she asked, kindly. "Is the pain very bad?"

"Yes, very, and my head aches, and I am so thirsty," complained Ellen.

The nurse held a glass of toast-water to her lips; then shook up the pillow, and placed her in a more easy position.

"There, now you will sleep, I think," she said, as she left her side.

But no, there was no rest for that weary, conscience-stricken spirit. The same thoughts revolved in her mind, the same fears distressed her. The King of Terrors, like a grim enemy, confronted her, and she saw not the Prince of Life, who has despoiled him of his power.

But in the midst of her distress, there floated across her mind words heard some time before and forgotten. What recalled them she knew not. Doubtless the Holy Spirit prompted their recollection.

"'As many as touched Him were made whole.'"

Long had the words slumbered in her memory; now they awoke, and gave their message to the heart that so sorely needed it.

She recalled the occasion when she had first heard them. The scene in Farmer Holroyd's barn presented itself to her mental vision. Again she saw the earnest young preacher, and the eagerly-listening people. She remembered the nature of the discourse then uttered; the graphic description of the leprosy of sin, and the misery and death to which it would lead. Ah, she understood it all now, as she did not then. The leprosy was cleaving to her flesh; she felt its contamination, but no remedy could she command. Yet what did the words say—those words which she recollected the preacher had bidden her remember?

"'As many as touched Him were made whole.'"

She had heard Christ proclaimed as the Great Physician, she had spoken of Him as such to her brother, but had all the while been unconscious of her own need of His healing touch. But now, how precious was the truth that Christ could make her whole! But would He? Was there any doubt of His willingness to pardon and cleanse?