U. S. DEPARTMENT OF

AGRICULTURE

FARMERS’ BULLETIN No. 1327

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

To meet the requests continually received for information on the care of canaries in sickness and health, this bulletin has been compiled from numerous sources, including personal experiences and observations of the author. It is intended for all who are interested in canaries.

This bulletin is a revision of and supersedes Farmers’ Bulletin 770.

Washington, D. C.

Issued May, 1923.

[Pg 1]

CANARIES: THEIR CARE AND MANAGEMENT.

By Alexander Wetmore, Assistant Biologist, Division of Biological Investigations, Bureau of Biological Survey.

| Page. | ||

| Introduction | 1 | |

| History | 2 | |

| Varieties | 3 | |

| Cages | 5 | |

| Care of cages | 7 | |

| Indoor and outdoor aviaries | 8 | |

| Food | 9 | |

| Bathing | 10 | |

| Molt | 11 | |

| Color feeding | 12 | |

| Breeding | 13 | |

| Sex and age | 15 | |

| Vermin | 16 | |

| Care of feet and bill | 17 | |

| Diseases and injuries | 17 | |

| Broken limbs | 18 | |

| Loss of feathers about head | 18 | |

| Respiratory troubles | 19 | |

| Intestinal complaints | 19 | |

| Bibliography | 20 | |

Among the birds kept for household pets none is more common or better known than the canary. So simple are its requirements in the way of food and care that it needs little attention, and because of its pleasing songs and interesting habits it is a universal favorite. Readily adaptable to cage life, canaries display little of the fear shown by wild birds in captivity, and the ease with which they may be induced to nest and rear young adds to their popularity.

Canaries have been domesticated for several hundred years and, though more common in western Europe and the United States than elsewhere, have been carried over practically the entire civilized world. In England and Germany there are hundreds of canary breeders and many avicultural societies. Several periodicals dealing solely with cage birds are published there, and in the larger cities bird exhibitions are held annually. Similar activities in the United States, while of younger growth, are making considerable progress.

During the 10-year period prior to 1915 more than 3,250,000 canaries were imported into the United States, mainly from Germany and England. With the continuance of the World War the number brought in decreased steadily, until it fell from an average of more than 1,000 birds per day in 1914 to about 10,000 for the year 1918. Importations from Germany practically ceased, and comparatively few birds were to be obtained from England, so that dealers were forced to look to the Orient, mainly to China, for the small number secured. This depression continued until 1920, but with return to more normal conditions in 1921, about 70,000 were imported, and in 1922 more than 150,000, largely from the former sources in Europe as well as the Orient.

Canaries seem to thrive in any climate where not exposed to too severe weather conditions, and in spite of the long period they have[Pg 2] been protected and held in captivity they are capable of enduring a surprising degree of cold when hardened to it. In England it is not unusual to find them in outdoor aviaries throughout the year, and in the comparatively mild climate of California they thrive under these conditions. They seem able to establish themselves again in a wild state under favorable circumstances. A brood of domestic canaries released in 1909 on Midway Island, a sandy islet in the Hawaiian group, had increased by 1914 until it was estimated that it numbered about 1,000.

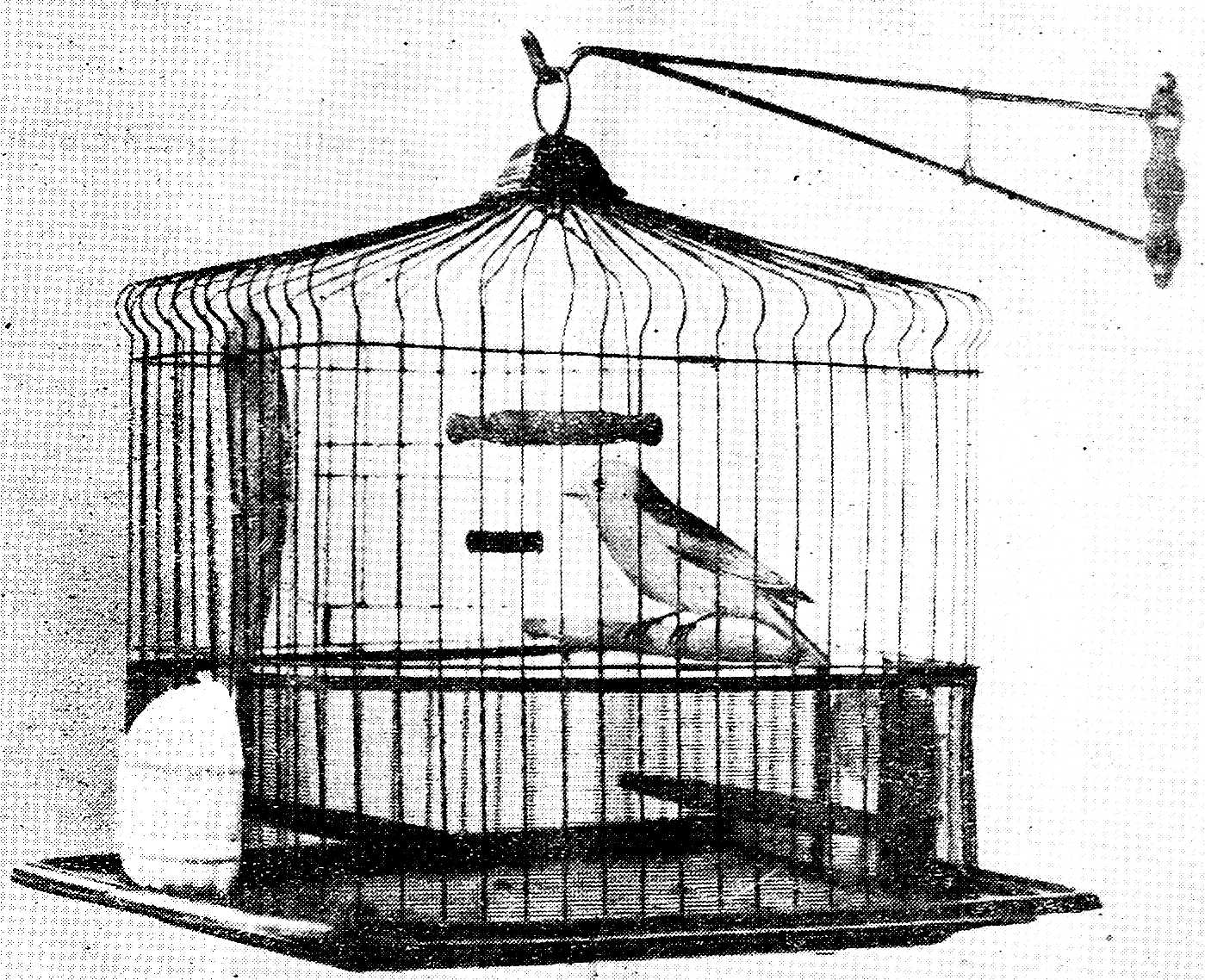

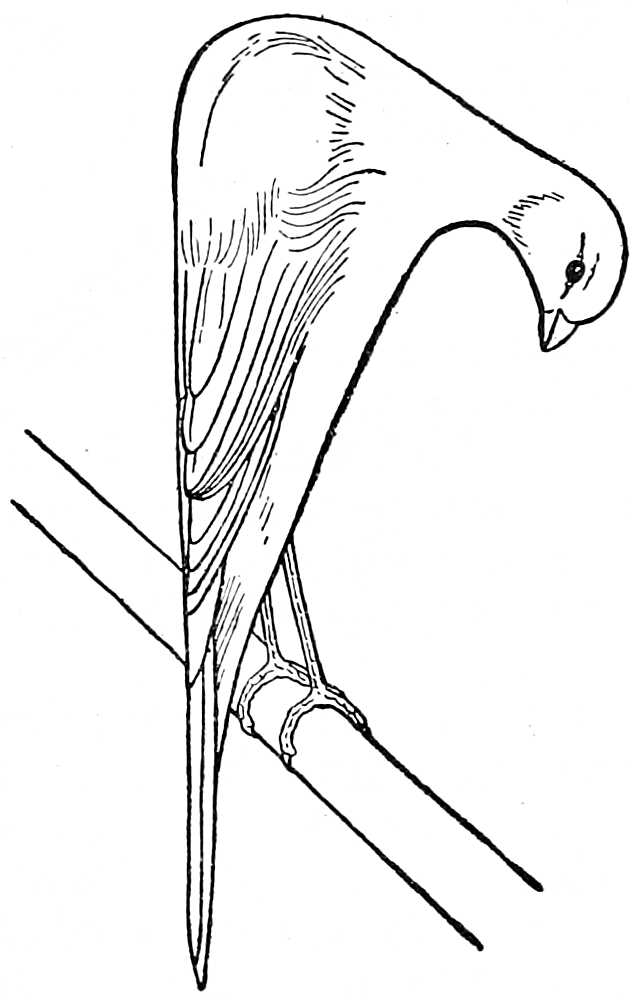

The origin of the canary as a cage bird is as obscure as is the early history of other domesticated animals. It seems probable that captive canaries were first secured from the Canary Islands, a group with which they have long been popularly associated. There are in the Old World, however, two closely allied forms from which the domesticated canary may have come. One of these, the bird now recognized as the “wild canary,” is found in the Canary Islands (with the exception of the islands of Fuerteventura and Lanzarote), Madeira, and the Azores. This form is illustrated in Figure 1. The other form, the serin finch,[1] ranges through southern Europe and northern Africa, extending eastward into Palestine and Asia Minor. In a wild state these two forms are very similar in color and to a novice are hardly distinguishable.

Fig. 1.—Wild canary.

If, as is supposed, the original supply of canaries came from the Canary Islands, it may be considered doubtful that the stock thus secured has furnished the ancestors of all our canaries. The slight differences in color between the serin finch and the canary would probably have passed unnoticed by early ornithologists and bird lovers. With bird catching a widespread practice in middle and southern Europe, the serin would often be made captive and be accepted without question as a canary. In this way serins and wild canaries may have been interbred until all distinguishable differences were lost.

The original canary, whether serin or true wild canary, in its native haunt was much different in color from its modern pure-bred descendant. The back of the wild bird is, in general, gray, tinged with olive-green, especially on the rump, with dark shaft streaks on[Pg 3] the feathers. Underneath it is yellowish, streaked on sides and flanks with dusky. Wild canaries from the Canary Islands, the Azores, and Madeira differ from the Continental serins in being slightly grayer with less of yellowish green in the plumage above. In addition, the rump is duller yellow and the bill is distinctly larger. All the wild birds have the feet and legs (tarsi) horn brown, the upper half of the bill dark brown or horn color, and the lower half paler.

Both of the wild varieties inhabit vineyards, thickets, and more open country where bordered by trees. At times, during fall and winter, great flocks are found together. The birds feed upon various seeds and occasionally eat figs or other small fruits in season. In a wild state they nest early in spring and again later, rearing two broods. The nest, made of plant stems and grasses and lined with hair and plant downs, is placed in bushes or low trees. The eggs are clear green in color, spotted and clouded with deep wine red and reddish brown. From three to five eggs are deposited.

[1] The scientific name of the serin is Serinus serinus serinus. The wild canary is known as Serinus s. canarius. Both were first described by Linnaeus.

Variation among domesticated canaries began early, as Hernandez, in 1587, speaks of the canary as wholly yellow in color save for the tips of the wings. The various forms have had their origin in distinct geographic areas, and though some are almost extinct at present, all at one time or another have had a devoted following of fanciers. At present at least 14 distinct strains, with a large number of varieties, are known.

The common canary is reared primarily for its song, and from it probably came the roller, or song canary, a great favorite in Germany and, more recently, in England and the United States. In rearing song canaries attempt is made to produce males with clear, soft, pleasing songs with long rolls or trills, and no attention whatever is paid to other characters. These birds, therefore, may be nondescript as regards color and appearance, and in mating care is taken only to secure males that are good singers and females from good stock.

The young birds when fledged are put in rooms with males noted for their soft song, and here, through imitation, they develop their own vocal powers. Careful watch is kept over them, and any bird that develops harsh notes is removed at once to prevent his corrupting the purity of tone in the song of his brothers. A mechanical instrument known as a bird organ, that produces liquid trills, is frequently utilized in training, usually when the adult birds are silent during molt. Ordinarily the room where song canaries are being trained is darkened, and frequently the cages containing the young birds are screened with cloth to lessen a tendency to objectionable loudness of song. In six months or less, their education completed, these songsters may be sold or in their turn utilized in training others still younger. It is common to teach these birds some simple strain or air, through its constant repetition by whistling or by means of an instrument. Well-trained birds are popular pets and frequently bring high prices.

[Pg 4]

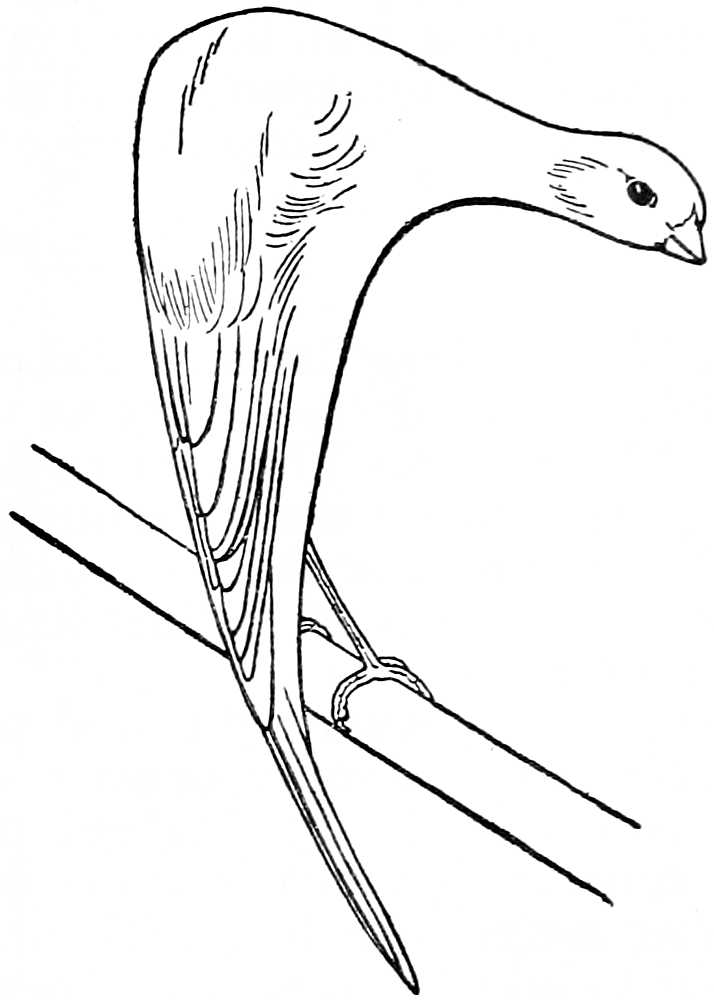

In the class of exhibition birds, perhaps none is more striking than the Belgian canary, pictured in Figure 2. Formerly known as the “king of the fancy,” it was reared extensively in Belgium, but of late years its popularity has been on the decline, so that as late as 1911 it was said that few pure-bred Belgians were to be found. The typical Belgian canary is a large bird with a small head, long, slender neck, large shoulders, and a long, tapering body. It is primarily a bird of “position.” When assuming the peculiar and desired attitude the bird throws its shoulders up and brings the head down well below their level; the back and tail form a perpendicular line and the feet are held close together.

Another bird of position is the Scotch fancy canary, illustrated in Figure 3. This variety resembles the Belgian, but when in position throws the tail in under the perch until its outline in profile is almost a semicircle.

Fig. 2.—Belgian fancy canary.

Fig. 3.—Scotch fancy canary.

Another well-marked variety is the cinnamon canary, one of the earliest forms to appear, but one whose origin is wholly unknown. Its true color is a dun or dull brown that has been likened to cinnamon. In exhibition birds the color is usually intensified by color feeding (see p. 14). The cinnamon canary is peculiar also in possessing red or pink eyes, a character that denotes cinnamon blood even in a yellow or buff bird. The cinnamon inheritance is transmitted only by the male; young reared from a cinnamon mother and a male of any other form lacking cinnamon blood never show signs of their cinnamon parentage.

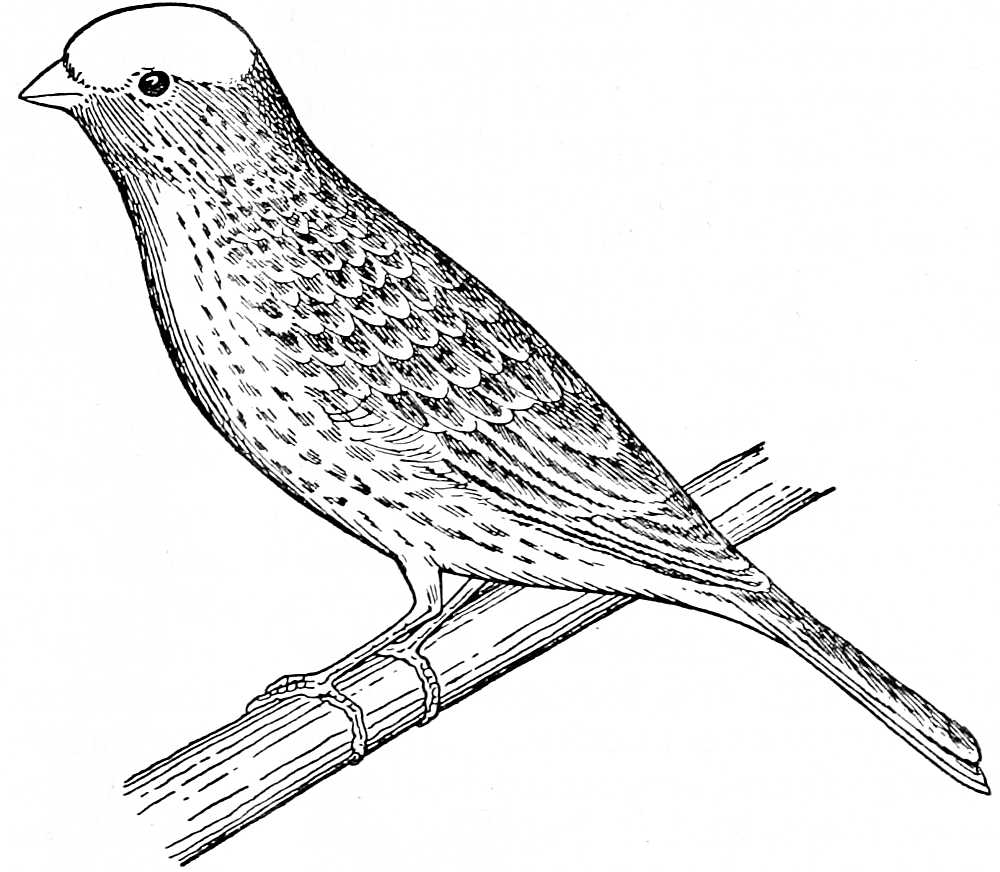

Among the old-established varieties that now are in decadence none is more striking than the lizard canary. Lizard canaries are known as “gold” or “silver,” according as the body color is yellow or silvery gray. The wings and tail are black and the back is spangled with numerous somewhat triangular black spots. The crown in pure-bred birds is unspotted and light in color, as shown in Figure 4.

[Pg 5]

Fig. 4.—Lizard canary.

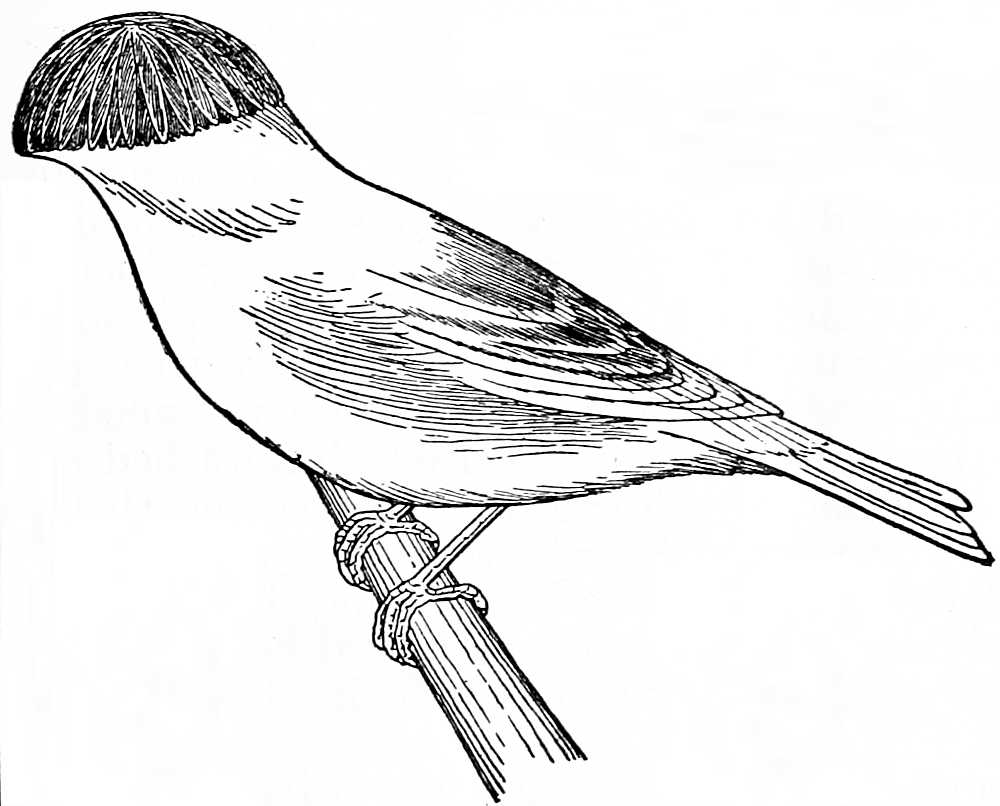

The crested canary, pictured in Figure 5, is another unusual form, with a long crest that extends down around the head below the level of the eyes. Another, the frill or Dutch frill canary, is a large bird with long curling feathers. The Lancashire is the largest of known varieties of the canary, standing head and shoulders above all others. These “giant” canaries may be crested or smooth headed. Other forms that may be mentioned are the Border Fancy, a small bird; and the Norwich, or Norwich plain-head, from which come many of the common canaries.

Fig. 5.—Crested canary.

It must not be supposed that the varieties of canaries enumerated above cover the entire field. For each of the main forms there are almost endless groups or divisions that have been developed on color peculiarities. To obtain pure-bred birds requires constant care and supervision, and with any slackness of method hosts of mongrels appear. Interbreeding between various forms, even though they differ widely in color, results in reversion to the original type, which was a spotted or striped greenish bird, certain proof of the common origin of all.

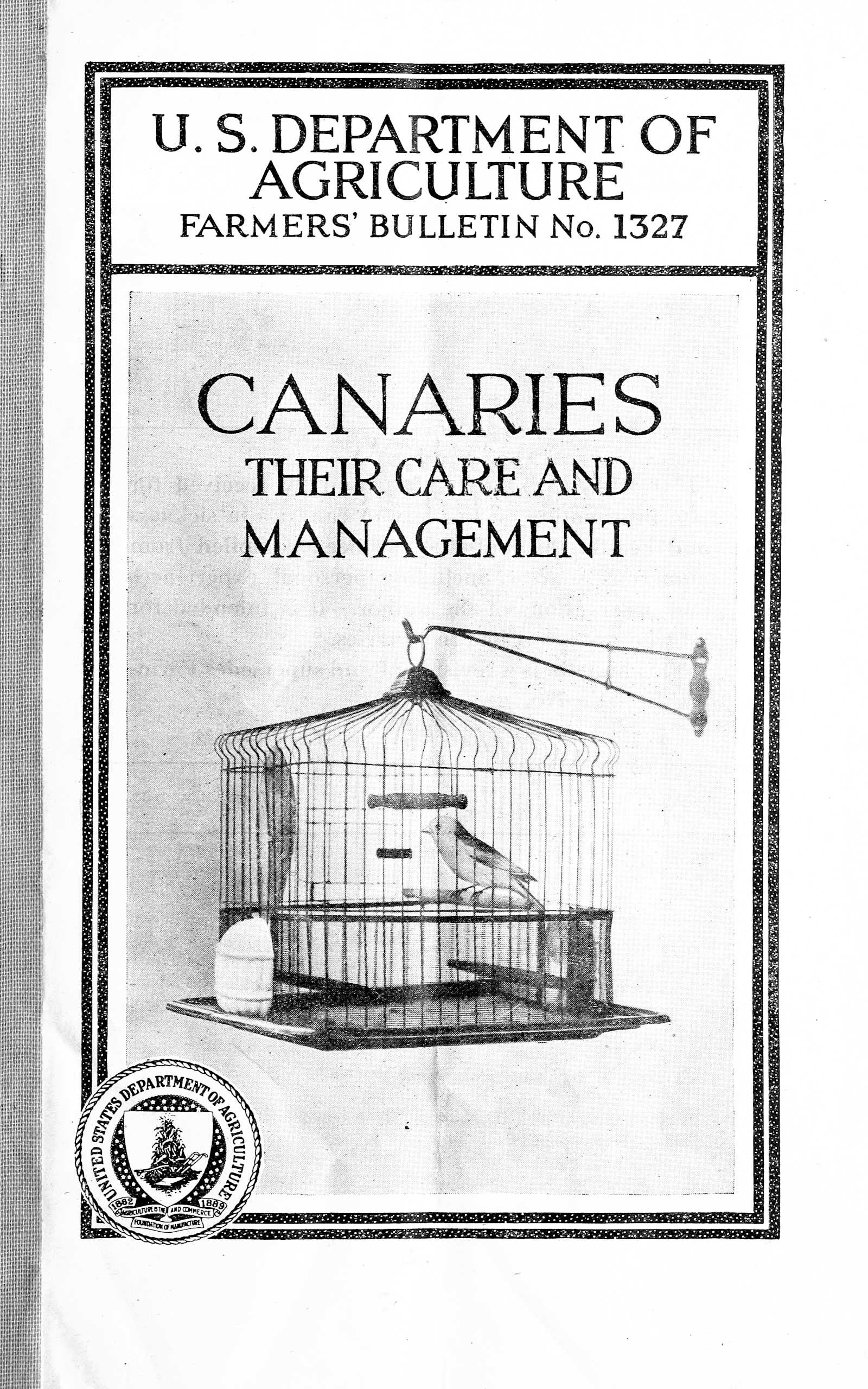

When choosing cages in which to keep canaries, the primary consideration should be the comfort of the birds, and this should not be sacrificed to any desire for ornate appearance. There are several types on the market, any of which may serve. So far as shape is concerned, a square cage is best, as it affords more room for exercise than one that is round.

[Pg 6]

For one bird, the cage should not be less than 9½ inches long, 6½ inches wide, and 9 inches high. A larger size is to be preferred. The ordinary cages obtained from dealers in this country are made of wire and are open on all sides. Each is fitted with receptacles for food and water, usually at opposite ends. A fine-mesh wire screen may be bought from the dealer and fastened around the lower half of the cage to prevent the scattering of seeds and seed hulls. A common substitute for this is a simple muslin bag, held in place by a drawstring fastening tightly about the middle of the cage.

In a cage of ordinary size three perches are sufficient. One may be placed at either end at a distance that will allow easy access to the food and water receptacles, and the third elevated above the middle of the cage at its center. Another convenient arrangement is to run one perch lengthwise of the cage, in such way that the bird may reach the feeding receptacles from it, and to place the two other perches transversely above it near either end. A bird confined in small quarters is dependent for exercise on hopping about from perch to perch, and this arrangement will give the maximum freedom of movement. In larger cages four perches may be advisable. These should not be placed so that they interfere with the free movement of the bird, and for reasons of cleanliness one perch should not be directly above another. In small wire cages, if the swing perch usually found suspended in the center is removed, the bird will have more room, and in hopping back and forth will not be continually striking head or wings. In larger cages this perch may remain. Perches should be large enough for the toes of the bird to grasp them readily and encircle them for three-fourths of their circumference. If they are too small they cramp the foot, while if too large they may cause malformed toes or claws, especially in young birds. Perches should be elliptical in shape, about three-eighths of an inch in the long diameter, which should be horizontal. If those furnished with the cage do not meet these requirements, others may be made from soft wood without much trouble.

Cages in which canaries are to breed must be large and roomy in comparison with those intended for single occupants. An English authority gives the standard size for breeding cages as 22 inches long, 12 inches wide, and 16 inches high. Several types of open breeding cages made of wire may be obtained, or a box with a removable wire front may be made. If it is planned to use wooden cages for several seasons they should be enameled or whitewashed inside to permit thorough cleaning. Such cages should be smooth inside and any with cracked or warped boards should be avoided, as crevices may harbor dirt or mites. Though cages may be made of wire screen this is not advised, as cages so constructed become very dirty, and there is danger that birds may catch their claws in the wire and become injured.

Where numbers of canaries are kept box cages with wire fronts are convenient, as they may be placed in racks one above another or arranged on a series of shelves along the wall of the bird room. They are provided with a sand tray three-fourths of an inch deep that slides in and out from the front and facilitates cleaning. Perches for these cages may be adjusted in the following manner: One end is notched and the other has a brad driven in it filed to a sharp point. The sharpened brad is pressed against the back of the cage and a[Pg 7] wire on the front is slipped into the notch. If made the right length the pressure of the wire will hold the perch in position.

For shipping birds the small wicker cages in which canaries come to dealers are best. These are fitted with deep, narrow-necked food and water receptacles that do not readily spill, so that there is a minimum of waste during the journey. A small packet or sack of seed should be tied to the outside of the cage in order that the bird’s supply may be replenished en route.

Though canaries when acclimated can endure a great degree of cold without discomfort, they are susceptible to sudden changes in temperature, and cold drafts may soon prove fatal. This should be borne in mind in choosing a place for the cage. Direct exposure to a strong draft of cold air must always be avoided. A cage may be placed on a small shelf along the wall or suspended from a bracket attached to the wall or window casing. Swinging brackets are inexpensive and are convenient for use when it is impracticable to fasten hooks in the ceiling. When one or two canaries are kept as pets, it is usual to suspend their cages before a window, where the birds may enjoy light and sunshine, a good practice where the window is kept closed during cool or stormy weather and the joints are tight. It may be necessary to line the edges of the window frame and the junction of the upper and lower halves of the window with weather stripping to prevent drafts, and it is best to suspend the cage so that it will hang opposite or below the junction of the two halves of the window frame. The room must remain at a fairly even temperature day and night, and in cold weather it is well to cover the cage with a towel or other light cloth at night. A cage should never be suspended directly above a radiator, and it is best to avoid keeping birds in small kitchens, as the fluctuations in heat are perhaps more marked there than in any other part of the house. Exposure to damp air may prove fatal, another reason for avoiding the steam-laden air of small kitchens.

Wherever placed, the cage must be kept scrupulously clean if the canary is to remain in good health and free from vermin. The supply of water should be renewed daily, and the seed cup replenished at least every other day. The receptacles for these necessities should be cleaned and washed carefully at short intervals. Cages that have removable bases should have the tray in the bottom covered with several thicknesses of paper, or the heavy coarse-grained sandpaper, known as gravel paper, that may be secured from dealers in cage-bird supplies, may be used. This should be renewed whenever the cage is cleaned, and in addition the pan should be washed in hot water from time to time. Lime on the perches may be removed by means of a scraper made of a bit of tin fastened to a wire or tacked at right angles to a stick small enough to pass easily between the wires of the cage. Cages with bottom attached should be provided with a sand tray that slides in and out through a slot in the front. This serves to catch droppings, seed hulls, and other waste, and may be easily pulled out, cleaned, and refilled with fresh sand.

[Pg 8]

Those who keep birds for pleasure, and who do not care to breed them for exhibition or to maintain any particular standard, may receive much enjoyment from aviaries in which numbers of canaries are kept in one inclosure. The size of the aviary or bird room will be governed wholly by circumstances, as it may range from an entire room to a small screened inclosure or part of a conservatory. A room large enough for the owner to enter without unduly frightening the occupants makes an ideal indoor aviary, and where space permits it may be fitted up without great expense. The floor should be covered to the depth of half an inch to an inch with clean sand or sawdust. Small evergreen trees planted in large pots furnish suitable decorations, and may be replaced from time to time as they are destroyed by the inmates of the aviary. A branching dead tree and one or two limbs nailed across corners at suitable heights furnish more artistic perches than straight rods. In addition, pegs 4 or 5 inches long may be driven or nailed to the walls to furnish resting places.

Seed should be supplied in self-regulating hoppers, preferably attached to the wall, and water given in self-feeding fountain containers. These become less dirty than open dishes placed on the floor. Sand must be furnished in a box or dish where it is not used on the floor. Soft foods and green foods may be supplied on little shelves or a small table. At the proper season nesting boxes may be hung on the walls, and nesting material supplied in racks or in open-mesh bags hung to some support. A shallow pan of water may be kept constantly on the floor or, better, may be inserted for an hour each day for bathing. A screened flying cage may be built on the outside of a window and the birds admitted to it in pleasant weather. Perches, if of natural wood, should have smooth bark or should be peeled, as crevices often harbor mites. Plants and other decorations should not be placed so near the wall that birds may be trapped behind them.

Aviaries constructed out of doors, like bird rooms, may be made simple or elaborate, large or small, according to circumstances. Where there is sufficient ground available a small frame structure may be built and covered with strong galvanized wire screen of small-sized mesh. Part, at least, of the roof should be covered as a protection against stormy weather, and two sides should be boarded up to afford protection from cold winds. Where the winter climate is severe it is necessary to build a closed addition with board or cement floor and a connecting door, in which the birds may be protected during the cold season. Canaries when acclimatized, however, can withstand moderately cold weather as well as native birds.

The open portion of the aviary should have a board or cement base sunk to a depth of 8 to 10 inches around the bottom to prevent entrance of rats, mice, or larger animals. If a fence with an overhang at the top is not constructed to keep out animals, it is best to make the screen walls double by nailing screen wire to both sides of the wooden frame, so that birds clinging to the wire may not be injured by cats or dogs. Where space does not permit an elaborate structure a lean-to may be built against another wall to make an inclosure large enough for a number of birds. Where needed, the[Pg 9] sides of the aviary may be fitted with windows that can be put in place in winter. The entrance to the outdoor aviary should be through a small porch or anteroom that need be merely large enough to permit entrance through an outside door, with a second door leading into the aviary itself. The outside door should be closed before the inner one is opened, so that none of the birds can escape.

The fittings of the outdoor aviary may be adapted from those described for the indoor bird room. With an earth floor it is possible to grow evergreen and deciduous shrubs for shelter and ornament. Where space permits a hedge of privet along the open side of the aviary furnishes a shelter in which birds delight to nest. To avoid overheating in hot weather shade should be provided for part of the structure.

In aviaries birds pair more or less at random. To avoid constant bickering or even serious fighting in the breeding season it is usual to regulate the number of males so that the females outnumber them two to one.

The food requirements of canaries are simple. Canary seed to which have been added rape seed and a little hemp is a staple diet that persons who keep only a few birds usually purchase ready mixed. Canary seed alone does not furnish a balanced food, but forms a good combination with hemp and summer rape. Much of the rape seed in prepared seed sold in cartons is of a species that even wild birds do not eat, as it is pungent and bitter in flavor, but all relish the mild taste of true summer rape. Seed is given in little cups that are fastened between the wires of the cage.

In addition to a seed supply lettuce or a bit of apple should be placed between the wires of the cage frequently. And those properly situated may, in season, vary this menu by the addition of chickweed, dandelion heads, thistle and plantain seeds, and the fruiting heads and tender leaves of senecio and shepherd’s purse. Watercress, wild oats, knot grass, and other grasses are relished, especially in spring and early in summer.

Bread moistened in scalded milk, given cold at intervals, is beneficial. Soft foods must not be made too wet. With bread, enough liquid to soften the food but not to run or render it a paste is sufficient. Supplies of moist foods must be kept strictly fresh and clean or sickness may result. Special dishes, known as food holders, or slides that slip through the wires of the cage are often used in giving softened bread and similar supplies. Cuttle bone should always be available.

When canaries do not seem to thrive it is well to crack open a few of the seeds to make certain that empty husks alone are not being fed. Hemp, while a valuable addition to the diet, should not be given in excess, as it is fattening and may make birds so lethargic that they cease to sing, or in exceptional cases may even cause death. When canaries cease to sing from the effects of overfeeding it is well to supply some of the stimulating foods known as song restorers, or other prepared foods that may be obtained from dealers.

During the time of molt a few linseeds added to the seed supply are believed to give gloss and sheen to the new feathers. Linseeds should be given in small quantity, as they are injurious if eaten in[Pg 10] excess. Meal worms fed occasionally are beneficial for birds that are not thriving. A craving for animal food may be satisfied by bits of raw steak, but it is not well to continue feeding raw meat for any length of time, as it may cause a foul odor about the cage. Delicate birds may be fed canary, rape, and hemp seed soaked in cold water for 24 hours, rinsed, and then drained. Maw seed (poppy seed) is favored by English canary fanciers as a stimulant, but its use must be guarded, as it may be poisonous to other animals, including man.

During the breeding season egg food must be given daily as soon as the birds are paired. This is prepared by mincing an entire hard-boiled egg or passing it through a sieve, and adding to it an equal quantity of bread or unsalted cracker crumbs. This may be given to unmated birds as well at intervals of a week or so. When female canaries begin to incubate, egg food may be fed every three or four days or even less frequently. Addition of brown sugar in small quantity to the egg food is supposed to prevent egg-binding in young females. When the young hatch, egg food should be supplied at once. Some recommend that the yolk of a hard-boiled egg be given alone for the first day. Bread crumbs are added to this daily until on the third day egg food as ordinarily prepared is supplied. Attempt should be made to regulate the supply of egg food or other soft food so that it will be eaten without waste. The actual quantity will vary in individual cases. The usual seed supply should be present, no matter what other food is given. Egg food must be given until the young are fully grown and able to crack seed for themselves. Cracked seed may be fed to lighten the labor of the parents, but it is well to eliminate hemp from such a supply, as the hull of hemp seed contains a poisonous substance that occasionally kills young birds. Drinking water should be available to canaries at all times.

Under normal conditions most birds probably bathe daily, and canaries in captivity should be allowed the same opportunity. In open wire cages in common use for singing birds the base is removed and the cage placed over a small dish containing water. In open-front cages in which the bottom is not detachable small bath cages which fasten at the open door are used. These are only a few inches wide but serve to hold a dish for water. Many birds are notional in bathing and at times ignore the offered bath. Usually the process of cleaning the cage and renewing the seed and water will excite in them a desire for bathing, and often when a bath is not provided the bird will do its best to perform its ablutions in the small supply of water in the drinking cup. When individual birds obstinately refuse to enter the water, if enough clean sand to cover the bottom is placed in the dish they bathe more readily. After the bath the water may be drained carefully and the sand left to dry in the dish for use another time.

Birds brought into strange quarters may refuse to bathe for the first few days. When water is offered they either ignore it or sitting on a perch go through the motions of bathing and drying, fluttering wings and tail with a great whirring of feathers. The bath[Pg 11] should be offered whenever the cage is cleaned, and if left alone the birds will act normally after a few days.

Small china or earthenware dishes that are not too deep make good bathing pans. When a bird becomes accustomed to one dish it will usually refuse to bathe in another of different shape or color. In winter the water should be warmed until tepid. Even in warm weather very cold water is not advisable. If the room, ordinarily warm, becomes cold temporarily, birds should not be allowed to bathe. With the plumage wet and bedraggled there is increased susceptibility to cold drafts. During molt the bath should be given not more than twice each week. If the bird is molting on color food, one bath each week is sufficient. The female canary should not be allowed to bathe from the time the eggs hatch until the young are 3 or 4 days old.

Canaries renew their covering of feathers once each year. In adults this molt occurs late in summer, and the first sign of it may be the presence of a wing or tail feather on the bottom of the cage. These large feathers are shed in pairs, so that one from either wing or from either side of the tail is dropped at approximately the same time. Never in ordinary circumstances does the canary have the wing and tail entirely devoid of large feathers. This provision is of no particular significance in a cage bird, but enables wild birds to maintain their powers of flight. The bodily covering is renewed piecemeal as well, so that except about the head there is normally no extensive area wholly devoid of feathers at any time. Some birds drop a few of the body feathers all through the year, a symptom that need cause no anxiety.

With breeding birds the molt usually comes immediately after the breeding season and may begin as early as the latter part of July. Normally it comes during August, and on the average should be at its height in September. Young birds molt the juvenal body plumage after leaving the nest, but retain the first growth of wing and tail feathers for a year. In healthy birds the entire molt requires about two months.

Canaries usually need no special care during molt. Though in an abnormal bodily state at this time, healthy individuals will come through the period in good condition. Birds are somewhat dull and stupid when molting and should be disturbed as little as possible. Bathing may be permitted once or twice each week, but if birds do not wish to bathe they should not be sprayed with water. It is well to add egg food or moistened bread to the ordinary fare once or twice each week during molt. For ailing birds a very slight quantity of sulphur may be added to the egg food, or a weak saffron tea given instead of pure drinking water. A few linseeds in the seed supply give a gloss and sheen to the new feathers not otherwise obtainable.

When canaries fail to molt at the proper season molt may sometimes be induced by covering the cage with a dark cloth and placing it in a warm protected place where the bird will not be disturbed.

Old birds or those weak in physical vigor often fail to renew their entire feather covering, a condition for which little remedy may be offered. Usually this incomplete molt is a sign of extreme age or[Pg 12] breakdown, though if the bird lives, a supply of nutritious, easily assimilated food and careful protection during the next molt may result in improvement.

A great change in temperature or a sudden chill may check the progress of molt and occasionally cause serious trouble. If a bird shows signs of distress, it should be placed at once in a warm, protected place. Ten drops of sweet spirits of niter and a few shreds of saffron added to the drinking water are beneficial.

That the color of canaries may be deepened or intensified by certain foods given during the molt is well known and has attracted much interest. Turmeric, marigold flowers, saffron, cochineal, annatto, mustard seed, and other agents rich in natural color are often used for this purpose, ordinarily in combination with red pepper as a base. For a long time methods of preparing and feeding color foods were kept secret, but now they are outlined in many manuals on canary feeding.

In selecting canaries for experiments in color feeding preference should be given to strong, vigorous, male birds. During digestion and assimilation the concentrated food used puts more or less of a strain upon the system, and birds that are old or constitutionally weak may not thrive, or may even succumb under the treatment. Color food may be given young canaries at the age of 7 or 8 weeks to produce a deep color at their first molt. Birds with color that is naturally full and rich should be selected. Those having greenish markings or those descended from a male parent well marked with green are preferable. Pale birds seldom color well.

A standard color food may be prepared as follows: To the ordinary egg food (one hard-boiled egg chopped fine with an equal bulk of bread crumbs or unsalted cracker crumbs) add a teaspoonful of ground sweet red pepper. Mix until the food shows an even reddish tint throughout. Care should be taken to see that the supply of ground sweet pepper used is fresh and clean and that it is not artificially colored. Each bird to be experimented upon should receive one small teaspoonful of the prepared food daily. The quantity of pepper in the mixture is increased gradually, until two heaping teaspoonfuls are used. Addition of a little brown sugar and a few drops of pure olive oil is beneficial, and a small quantity of hot red pepper gives a better flavor. The food should be prepared fresh each day, and in mixing allowance must be made for variation in the size of eggs used.

Some breeders increase the proportion of sweet red pepper until 4 teaspoonfuls are added to the usual quantity of egg food. Half a teaspoonful of this concentrated food is allowed each bird. This method may be used during a short, quick molt. The usual supply of seed must be kept in the cage, for canaries can not subsist on the color food alone.

Those who do not care to use such an elaborate preparation in color feeding may substitute pieces of the common sweet red peppers sold in fresh vegetable markets for the bits of lettuce ordinarily given as green food. Canaries eat these readily, and from the effect of this food eaten during molt become noticeably deeper and richer in color.

[Pg 13]

Color feeding to be successful must be started as soon as the canaries are ready to molt, and feeding must be continued until no more pin feathers can be found anywhere on the body when the feathers are carefully blown aside. The color food actually supplies an enriched color element that otherwise is lacking. Until the artificial color is firmly fixed in the matured feather it fades easily when exposed to strong light. The birds chosen for color feeding should be kept in a dim light away from the windows and with the cages shaded. Open-front cages are easily provided with a screen of paper or cloth, but care must be taken to leave space for ventilation. Direct sunlight must be avoided. Bathing must not be permitted more often than once a week, and the birds should be disturbed as little as possible.

Should a bird refuse the color food, the seed supply may be removed for a short time morning and evening and the color food substituted. Usually in a day or two the stimulating food will be eaten eagerly. Linseeds should be given (as during the regular molt) to impart a gloss to the new feathers. With proper care there will be little trouble in producing fine, healthy birds with rich, highly colored plumage. The enhanced color lasts only during the continuance of the growth of feathers, and if color feeding is not resorted to at the next molt the canary will again be plain.

The breeding season for canaries begins properly in March. Though birds often show signs of its approach as early as January, it is better, because of the effect of changing weather conditions upon callow young, to postpone nesting activities until later, if possible. Some canary fanciers keep canaries paired throughout the year, but the more common practice is to separate the sexes except when breeding. The beginning of the mating season is marked by ringing, vigorous song among male birds, accompanied by much restless activity. Females, indifferent until now, respond with loud call notes, flit their wings, and otherwise evince their interest. Birds may be paired without these preliminary signs, but usually this tends only to lengthen the breeding season without material benefit. The instinct to breed may be stimulated when necessary by the addition of egg food and green stuff to the diet.

Canaries in captivity are polygamous when opportunity offers, and many breeders place two or even three females with each male. Others, however, keep canaries in pairs, as they are more readily handled, and when the young are hatched the male is able to assist in caring for them. Where two females are kept with one male the birds should be placed in a cage divided by slides into three compartments. The male is placed in the middle, and a female on either side. During half the day the male is thrown with one female and during the remainder with the other. This arrangement necessitates the use of three sets of seed and water cups in each cage. When the females begin to incubate the male is removed or excluded from both.

A cage suitable for one pair of canaries should be equipped with a sliding wire partition. The male and the female are placed one in either compartment and the two left to make acquaintance. The male will begin to feed the female through the wires in a day or two,[Pg 14] or perhaps at once, and when this is observed the slide may be withdrawn and the birds kept together. If a cage is used that has no slide, there is usually some bickering between the birds at first, but birds are rarely found that do not in the end agree. A cage thus used without a slide should be new to both birds, in order that neither may resent the presence of an intruder in a cage which it has been accustomed to consider its own.

Soon after pairing the female will be seen carrying feathers in her bill or searching about the bottom of the cage. If a little nesting material is given her she will be content to arrange and rearrange it for a few days. As soon as she shows serious intention of building, enough material for actual nest construction may be supplied. If a considerable quantity is furnished at first it is merely wasted. The material may be held in a small wire rack suspended on the outside of the cage or placed inside. Bits of string, cotton, slender blades of dried grass, dried moss, cow’s hair, or other soft material will serve well. No long strings or long hairs should be given, as these may cause trouble later by entangling the feet and legs of mother and young. Everything furnished should be clean and free from dust. Some canaries are expert nest builders, while others construct a slovenly structure that barely serves to contain the eggs. Some fanciers prefer to construct nests for their birds, and with certain birds this is necessary as some females may refuse to build.

Canaries build in anything that offers support. A nest box of wood, or, better, an earthenware nest pan, may be fastened to the side or back of the cage midway between the two perches. The rush or willow nests sold by many dealers, while serviceable, may harbor vermin. The earthenware nest pan is best, as when the breeding season is over it is readily cleaned and put away for another year. Failing this, a box 1¼ inches or more deep made of thin wood may be used. The nest box or pan should have a lining or bottom covering of felt. This may be pasted in the earthenware pan, and may be soaked loose without trouble when it is desired to renew it. The nest receptacle, of whatever description, should be suspended an inch above the level of the perches. This prevents the young from leaving the nest too soon. The receptacle should not be near enough to the top of the cage to interfere with the movements of the occupants. If the nest is not too near the perches the male is not so likely to be obtrusive during incubation.

The first egg will be deposited from a week to a month after the birds are paired. Normally it is laid in about two weeks. The number of eggs in a sitting may vary from three to six, with four or five as the usual number. The eggs should be removed as soon as laid. This may be done readily with a teaspoon, with care not to injure the delicate shells. They should be kept in a cool place, slightly embedded in fine corn meal or bran or cared for in some other manner that does not allow them to roll about or touch each other. On the evening of the day on which the third egg is laid all may be returned to the nest.

Removing the eggs and then replacing them postpones incubation and development in those first laid and makes the time of hatching more even. The normal period of incubation is 14 days.

Egg binding sometimes causes trouble and may be dealt with as follows: The vent may be oiled carefully with a drop or two of[Pg 15] warmed castor oil and the bird returned to the cage. If the egg is not deposited within half an hour the canary should be held for a few minutes with the vent over the steam of hot water. A good method is to fill a narrow-necked jar or bottle with hot water and cover the mouth of the receptacle with cheese cloth; the female is then held carefully for a minute or two in the rising steam. Often the egg will drop at once and be caught in the cheesecloth, or it may be deposited in the normal manner after the bird is returned to the cage.

The male canary is ordinarily a model husband and parent, giving no trouble, but if he should annoy the female during incubation or attempt to injure the young he should be removed at once. It is the natural instinct of an incubating bird to conceal itself as much as possible, and though canaries are tame, this tendency should be recognized and respected. This does not mean that they are to be neglected. Each breeding cage should be equipped with a sand tray which should be cleaned at least every other day. In no other way can it be hoped to rear numbers of birds successfully. Except for this necessary care and the provision of food, water, and bathing facilities, the birds should be bothered as little as possible.

Sometimes trouble is caused by inability of the young to free themselves from the shell or egg membrane, a condition for which there is usually no remedy at the time. With succeeding settings the difficulty may be obviated by sprinkling the eggs slightly with water each evening. Some breeders when the young canaries are 8 days old place them in a new nest, a practice that may be necessary when the old nest is infested with parasites. In such instances a little insect powder should be sprinkled over the body before the young birds are placed in their new quarters.

The young birds leave the nest when 20 to 30 days old. They may be left with the parents as long as they are fed and should never be removed entirely until it is found that they are able to crack the seeds upon which they must feed. It is advisable to continue the use of egg food for a time and gradually to decrease the amount given to get the birds accustomed to a diet of seed alone.

Canaries often rear two or three broods a season and the female may be ready to breed again when the young are three weeks old. It is only necessary to provide a second nest and nesting material and let her proceed. The care of the young will then devolve on the male. Nesting material should be provided at once or the female may pluck the feathers from her growing young. If this can not be stopped the young should be placed in a small nursery cage suspended from the side of the breeding cage in a manner that will allow feeding between the wires. When the young are finally removed they must not be placed with birds older and stronger for a time. They should be watched carefully the first day, and if any one does not feed it must be returned to the parents at once. Though most of the losses among canaries come at this time, with care in food and cleanliness there should be little trouble.

To determine sex and age in living canaries is difficult and is to be attempted only by one who has had long experience as a canary[Pg 16] fancier. The external characters denoting sex are not easily described. In nearly all cases a male may be recognized by his proficiency as a songster, but occasionally female birds also possess a clear, full song. When in breeding condition the sex may be determined readily by examining the vent. In males it is protuberant, while in females it does not project below the level of the abdomen. By daily observation the canary breeder is generally able to distinguish the sexes through slight differences in carriage and mannerisms not apparent to one not familiar with them.

In judging age the feet offer the only characters easily seen, but even these can not always be relied upon. Birds a year old or less usually have the skin and scales covering the feet and tarsi smooth and of fine texture. In older birds they appear coarser and roughened. Very old birds usually have had the claws trimmed until they appear blunt or rounded rather than sharp and pointed (see p. 19).

Canaries have lived many years when cared for regularly. Dr. C. W. Richmond, Associate Curator of Birds in the United States National Museum, relates that two birds, hatched in the same brood and kept entirely separated after they left the nest, lived 18 years, dying within a few weeks of each other. Another case is on record in which a canary was known to be at least 34 years old when it died, and even this advanced age may have been exceeded. Usually with advancing years birds molt irregularly or lose part of the feathers entirely. Often their eyesight is impaired. It is said that canaries that have not been paired live much longer than those allowed to breed.

Canaries are affected by two forms of external parasites. The larger of these, a bird louse[2] known usually as the gray louse, is an insect with a slender, elongate body and a large head armed with strong jaws. This pest feeds upon the feather structure of the bird’s outer covering, and though it does not suck the blood of its host, its sharp claws irritate the skin and cause discomfort to the bird. The eggs of the gray louse are attached to the feathers by a gum and are not easily removed. The young insects resemble the adults and in a few weeks after hatching are fully grown. They are best combated by blowing insect powder (pyrethrum) into the plumage of the affected bird with a small bellows or blower. This treatment should be repeated two or three times at intervals of a week to insure the destruction of any young lice hatching in the meantime.

The other parasite of canaries is a small mite,[3] a minute spiderlike creature that when fully grown is barely visible to the unaided eye. Its natural color is whitish, but nearly always it is filled with blood sucked from the body of the unfortunate bird harboring it, so that it appears bright red. These mites are nocturnal, and except in cases of severe infestation are seldom found upon the body of their host during the day. They are often found in the slits at the ends of the perches or in the round piece of metal forming the support at the top of the ordinary wire cage. In wooden cages they hide in cracks, nail holes, or crevices, and their presence is betrayed upon close examination by minute white spottings. If unnoticed, they multiply rapidly[Pg 17] and sap the strength of the bird by sucking its blood. When their presence is suspected a little coal oil, or kerosene, applied freely to the cage with a brush may be sufficient to kill the pests. Or the bird may be removed temporarily and the cage cleaned thoroughly with a solution of 1 ounce of commercial carbolic acid in a gallon of water, applied with a small brush, taking care to reach all crevices. In severe infestations it may be necessary to immerse the cage for several minutes in water that is boiling hot. Insect powder may be used as for the gray louse.

Where facilities for frequent bathing are offered and the cage is kept clean, there is usually little trouble with either mites or bird lice. When a bird is sick and neglects its customary bathing, cleaning, and preening, it is surprising to see how rapidly these pests multiply. With care, however, they may be completely eradicated, though fresh outbreaks are likely to occur when new birds are obtained. In wooden cages cracks in the boards that have harbored mites may be closed with glue to prevent a return of the pests.

[2] Docophorns communis Nitzsch. Order Mallophaga.

[3] Dermanyssus avium De Geer, closely allied to the chicken mite D. gallinae De Geer.

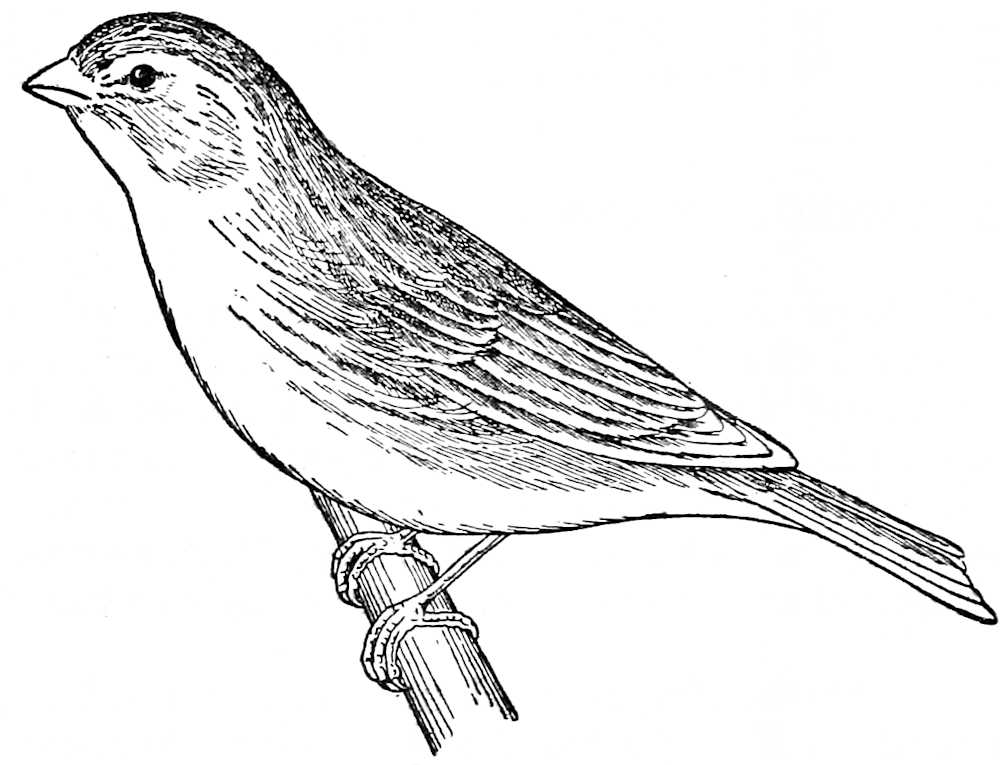

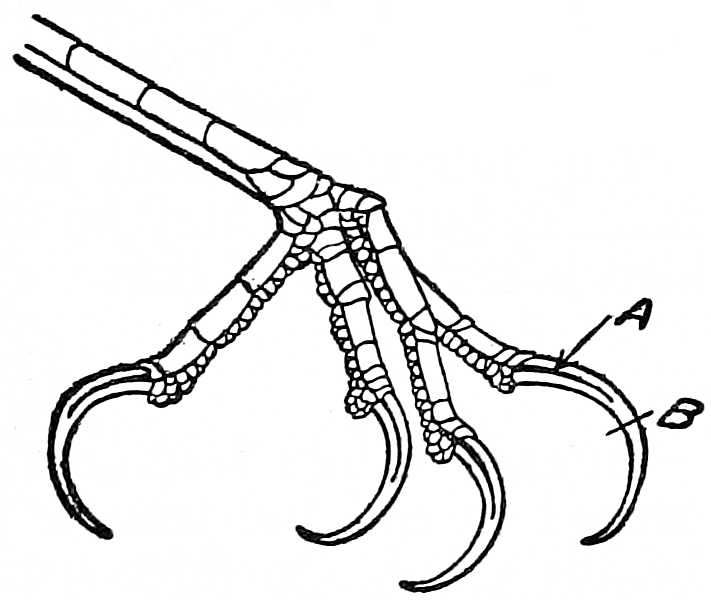

As a canary grows old it will be noticed that its claws become long and catch on the perches and wires as it hops about the cage. In a state of nature the activities of the bird as it moves about on the ground or among twigs and limbs keep the claws properly worn down. Confined in a cage the canary is less active, and while the claws have the same rate of growth they are here subject to much less abrasion. It is necessary, therefore, to trim them with a pair of sharp scissors every few months. It is important to watch the condition of the claws carefully, as by catching they may cause a broken leg. In each claw a slender blood vessel extends well down toward the tip. This is indicated in Figure 6 by the letter A, and may be seen on close examination through the transparent sheath of the bird’s claw. In trimming cut well beyond this canal (at the point B in the figure) and take special care not to break the leg while handling the bird.

Fig. 6.—Diagram of foot of canary with overgrown claws. A, Terminal blood vessel; B, point at which claw may be trimmed without injury.

In cage birds the horny covering of the bill, as well as the claws, sometimes becomes distorted through growth without sufficient wear. The tips of the mandibles may be pared down with a sharp knife, but care must be taken not to cut deep enough to reach the quick.

With ordinary care in cleanliness, freedom from cold damp drafts, and a well-regulated food supply, canaries are subject to few ills. In fact, most of their troubles may be traced to some untoward circumstance in handling them. Their diseases are very little understood and correct diagnosis is difficult, and though much has been written regarding them this has served mainly to reveal general ignorance on the subject. Present knowledge does not warrant an exhaustive[Pg 18] account of diseases, but in the following notes information is given on the more usual complaints of canaries.

When canaries become sick the first care should be to see that the diet is proper and to examine into the general sanitary conditions under which the birds are living. If canaries are confined in company with others, sick birds must be removed at once to a separate cage, since their companions will continually peck and worry them. Where numbers of canaries are kept, as a precaution to prevent spread of contagious or infectious diseases ailing birds should be removed from the bird room. It is always well to move a sick bird to a warm place. Heat and protection from drafts work wonders with ailing canaries and often are sufficient alone to restore them to health.

When medicine is necessary it is best to administer it in the drinking water. If this can not be done it may be given directly in the bill by means of a quill or a medicine dropper. In administering medicines it must be remembered that a canary is small and that a single drop in most cases is a large dose. Indiscriminate dosing of birds with various remedies is to be avoided.

The few instructions that follow are not to be regarded as infallible, but they may be of assistance in simple ailments. When a bird is seriously ill there is usually little chance of its recovery.

In case of bad fractures or injuries it is perhaps best for all concerned to end the trouble by killing the bird. If a valuable bird breaks a leg, a slender splint of wood wrapped in a slight wisp of cotton and held by a bandage may be applied with care. This support must not be touched for two or three weeks, but then it may be removed entirely. When the break occurs in the lower leg (tarsus) a small quill makes a simple support. The quill is split and cut down until it fits snugly around the part affected. It is then padded inside with a few shreds of cotton and tied carefully in place with silk thread.

Broken wings should be allowed to heal without outside interference. All high perches should be removed from the cage, and food and water made easily accessible. A bird with a broken wing must be kept as quiet as possible in order that the fracture may heal.

Baldness is sometimes occasioned by mites or bird lice and may be treated best by removing the cause. Loss of feathers about the head, however, may indicate old age or general debility. At the natural time of molt the growth of feathers on the bare spots may be aided by warmth and a well-regulated diet. In addition to the usual food, twice a week give a little bread moistened with milk which has been dusted with a mixture of two parts of sulphur to one of potassium chlorate. At the same intervals rub a little carbolized petrolatum on the bare places. Baldness is said to arise at times, particularly in spring, through failure to provide the canary with lettuce, apple, or other green food. In such cases improvement may be made by supplying this need.

[Pg 19]

The fact that canaries are injured by cold drafts can not be too strongly emphasized, and it may be said that a large proportion of their common ailments come from such exposure. In many cases exposure is followed by congestion in the intestinal region, and death ensues in a very short time. In ordinary colds there is difficulty in breathing and some liquid discharge from the nose. Frequently this is accompanied by coughing. A bird thus affected should be kept in a warm room free from all drafts and protected from irritating dust, vapor, or tobacco smoke. The symptoms are increased as the cold progresses and becomes acute, and the bird sits with feathers puffed out, seeming really ill. Breathing is difficult and rapid. If there is enough catarrhal secretion partly to block the respiratory passages a slight bluish tint is noticed beneath the transparent sheath of the bill. As a remedy, place in the drinking cup 1 ounce of water to which have been added 20 drops of sirup of tolu, 10 of sweet spirits of niter, and 10 of glycerin.

Pneumonia in cage birds often follows exposure and is nearly always fatal. The symptoms, rapid and difficult breathing with little catarrhal discharge, appear suddenly. The bird becomes very weak at once and usually dies in from two to seven days. Little can be done beyond sheltering the bird, as noted above, and providing an easily assimilated food, as egg food and bread moistened in milk.

Asthma is a chronic affection, in which there is difficulty in expiration of air in breathing. In severe cases a contraction of the abdominal muscles is evident in forcing the air from the lungs. Asthma is more in evidence at night, and often birds apparently free from it during the day will wheeze when at rest. There is practically nothing that can be done for it. Sometimes a semblance of asthma is caused by indigestion from overeating. Fanciers consider asthma hereditary and do not recommend birds so affected for breeding purposes.

Intestinal troubles in canaries arise in most cases from the food or water supply and are avoided by cleanliness and proper care. Dirty water cups with foul water, decayed or soured fresh or soft foods, or a poor seed supply lead inevitably to trouble. Should the canary contract diarrhea, remove all green and soft foods from the cage for a time and give only the normal seed supply. As a remedy, add a small quantity of Epsom salts to the drinking water for a day. If there is no improvement, feed the bird a bit of moist bread, with the surface covered lightly with bismuth (subnitrate), or place an ounce of water in the drinking cup, to which have been added three or four drops of tincture of opium. For constipation, the addition of lettuce, apple, chickweed, or other green food to the regular menu is usually sufficient; if not, a pinch of Epsom salts may be added to the drinking water. The quantity of the purgative should be enough to impart a faintly saline taste to the solution. Castor oil is not a good corrective remedy for small birds.

[Pg 20]

Occasionally birds in confinement “go light,” or waste away until they are far below their normal standard of plumpness, without marked symptoms of disease. In such cases change the seed supply, making sure that the seed is fresh and wholesome, and vary the diet with green foods, and with bread softened with milk. It is also beneficial to change the location of the cage; if possible, place the cage where it will receive the sun for a few hours each day, except in the heat of midsummer. Make sure that the canary is not infested with mites.

When worms are present, as sometimes happens, small fragments of these internal parasites may be seen in the droppings when the cage is cleaned. As a remedy, place in the drinking cup 8 or 10 drops of tincture of gentian in an ounce of water. This may be given for two days, and, in addition, two drops of olive oil may be administered in the bill by means of a medicine dropper.

For more serious complaints than those enumerated it will be well, if possible, for the amateur to seek the advice of some person with experience in handling cage birds.

For the benefit of those who may wish further information on the care of canaries a short list of standard works on the subject is appended. (None of these is available for free distribution by the United States Department of Agriculture.)[4]

Battye, H. W.

Yorkshire Canaries, How to Breed, Manage, and Exhibit. 80 pp., ill. F. Carl, 154 Fleet St., London, E. C.

Boaler, G. H.

Seeds, Foods, and Wild Plants for Cage Birds. 97 pp., ill. F. Carl, 154 Fleet St., London, E. C.

Brunskill, E.

Canary Culture for Amateurs. F. Carl, 154 Fleet St., London, E. C.

Church, T. A.

The Roller; Concerning Its Health, Habits, Feeding, etc. 223 pp., ill. Stuyvesant Press, New York, N. Y.

Crandall, L. S.

Pets; Their History and Care. Ill. H. Holt & Co., New York, N. Y.

——

Pets and How to Care for Them. Ill. Pub. by New York Zoological Park, New York, N. Y.

Creswell, W. G.

The Hygiene of Bird Keeping. F. Carl, 154 Fleet St., London, E. C.

House, C. A.

Canary Manual. 130 pp., ill. F. Carl, 154 Fleet St., London, E. C.

——

Norwich Canaries. 48 pp., ill. F. Carl, 154 Fleet St, London, E. C.

Lewer, S. H.

Canaries, Hybrids, and British Birds in Cage and Aviary. 424 pp., 26 pls. (color), and other ills. Waverly Book Co., 7 and 8 Old Bailey, London, E. C.

Norman, H.

[Pg 21]

Aviaries, Bird Rooms, and Cages. F. Carl, 154 Fleet St., London, E. C.

Page, W. T.

Foreign Birds for Beginners. 60 pp., ill. F. Carl, 154 Fleet St., London, E. C.

Ramsden, J. W.

The Colour Feeding of Canaries and Other Birds. F. Carl, 154 Fleet St., London, E. C.

St. John, C.

Our Canaries: A Thoroughly Practical and Comprehensive Guide to the Successful Keeping, Breeding, and Exhibiting of Every Known Variety of the Domesticated Canary. 32 pls. (color) and many ills. Pub. in 16 parts, 1910-11. F. Carl, 154 Fleet St., London, E. C.

Verrill, A. H.

Pets for Pleasure and Profit. 359 pp., 152 ills. 1915. Charles Scribners’ Sons, New York, N. Y.

Avicultural Magazine. Pub. for the Avicultural Society, by Stephen Austin & Sons, 5 Fore St., Hertford, England.

Cage Birds and Bird World. Pub. weekly by F. Carl, 154 Fleet St., London, E. C.

Roller Canary. Pub. monthly at 2144 Sacramento St., San Francisco, Calif.

[Pg 22]

[4] Addresses of dealers in cage birds and cage-bird supplies may be obtained on application to the Biological Survey, U. S. Department of Agriculture.

| Secretary of Agriculture | Henry C. Wallace. | |

| Assistant Secretary | C. W. Pugsley. | |

| Director of Scientific Work | E. D. Ball. | |

| Director of Regulatory Work | ——. | |

| Weather Bureau | Charles F. Marvin, Chief. | |

| Bureau of Agricultural Economics | Henry C. Taylor, Chief. | |

| Bureau of Animal Industry | John R. Mohler, Chief. | |

| Bureau of Plant Industry | William A. Taylor, Chief. | |

| Forest Service | W. B. Greeley, Chief. | |

| Bureau of Chemistry | Walter G. Campbell, Acting Chief. | |

| Bureau of Soils | Milton Whitney, Chief. | |

| Bureau of Entomology | L. O. Howard, Chief. | |

| Bureau of Biological Survey | E. W. Nelson, Chief. | |

| Bureau of Public Roads | Thomas H. MacDonald, Chief. | |

| Fixed Nitrogen Research Laboratory | F. G. Cottrell, Director. | |

| Division of Accounts and Disbursements | A. Zappone, Chief. | |

| Division of Publications | Edwin C. Powell, Acting Chief. | |

| Library | Claribel R. Barnett, Librarian. | |

| States Relations Service | A. C. True, Director. | |

| Federal Horticultural Board | C. L. Marlatt, Chairman. | |

| Insecticide and Fungicide Board | J. K. Haywood, Chairman. | |

| Packers and Stockyards Administration | Chester Morrill, Assistant to the Secretary. | |

| Grain Future Trading Act Administration | ||

| Office of the Solicitor | R. W. Williams, Solicitor. |

This bulletin is a contribution from the—

| Bureau of Biological Survey | E. W. Nelson, Chief. |

| Division of Food Habits Research | W. L. McAtee, in Charge. |

ADDITIONAL COPIES

OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE PROCURED FROM

THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON, D. C.

AT

5 CENTS PER COPY

PURCHASER AGREES NOT TO RESELL OR DISTRIBUTE THIS

COPY FOR PROFIT.—PUB. RES. 57, APPROVED MAY 11, 1922