RARE DAYS IN JAPAN

[From an old poem composed by the Mikado Gomei, who died A. D. 641.]

BY

GEORGE TRUMBULL LADD, LL. D.

Author of “In Korea with Marquis Ito,”

“Knowledge, Life, and Reality,”

“Philosophy of Conduct,”

etc., etc.

ILLUSTRATED

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

BOMBAY, AND CALCUTTA

1910

Copyright, 1910, By

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

Published, September, 1910

By many friends, both in this country and in the Far East, the question has often been asked me: “Why do you not write a book about Japan?” Whatever answer to this question à propos of each particular occasion, may have been given, there have been two reasons which have made me decline the temptation hitherto. Of the innumerable books, having for their main subject, “The Land of the Rising Sun,” which have appeared during the last forty years, a small but sufficient number have described with a fair accuracy and reasonable sympathy, certain aspects of the country, its people, their past history, and recent development. To correct even, much more to counteract, the influence of the far greater number which, if the wish of the world of readers is to know the truth, might well never have been written, is a thankless and a hopeless task for any one author to essay.

A yet more intimate and personal consideration, however, has prevented me up to the present time from complying with these friendly requests. Many of the experiences, of special interest to myself, and[x] perhaps most likely to be specially interesting and instructive to the public, have been so intimate and personal, that to disclose them frankly would have seemed like a breach of courtesy, if not of confidence. The highly favoured guest feels a sort of honourable reserve about speaking of the personality and household of his host. He does not go away after weeks spent at another’s table, to describe the dishes, the silver and other furnishings, and the food.

What I have told in this book of some of the many rare and notably happy, and, I hope, useful days, which have fallen to my good fortune at some time during my three visits to Japan, has not, I trust, transgressed the limits of friendly truth on the one hand, or of a friendly reserve on the other. And if the narrative should give to any of my countrymen a better comprehension of the best side of this ambitious, and on the whole admirable and lovable people, and a small share in the pleasure which the experiences narrated have given to the author, he will be much more than amply rewarded.

George Trumbull Ladd.

New Haven, June, 1910.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Visiting the Imperial Diet | 1 |

| II | Down the Katsura-gawa | 25 |

| III | Climbing Asama-yama | 46 |

| IV | The Summer-School at Hakoné | 74 |

| V | Japanese Audiences | 99 |

| VI | Gardens and Garden Parties | 126 |

| VII | At the Theatre | 156 |

| VIII | The Nō, or Japanese Miracle-Play | 190 |

| IX | Ikegami and Japanese Buddhism | 217 |

| X | Hikoné and Its Patriot Martyr | 248 |

| XI | Hiro-Mura, the House of “A Living God” | 281 |

| XII | Court Functions and Imperial Audiences | 314 |

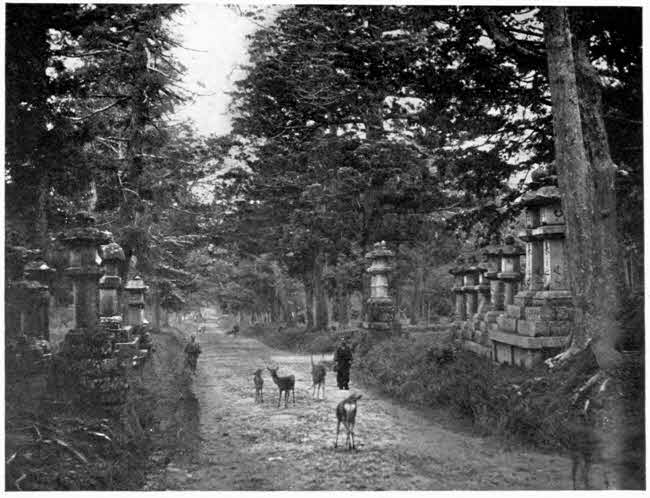

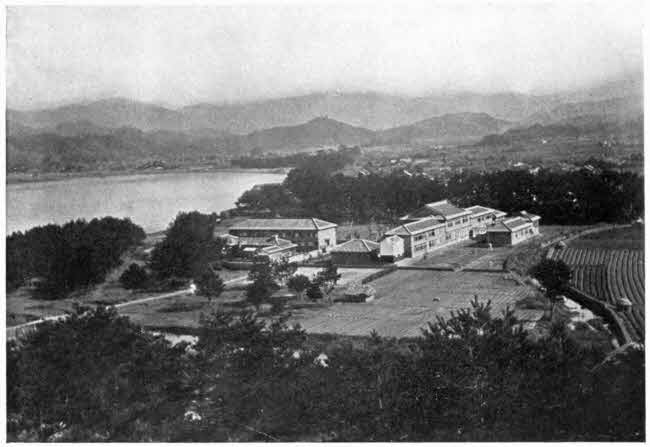

| Country Scenes and Country Customs | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

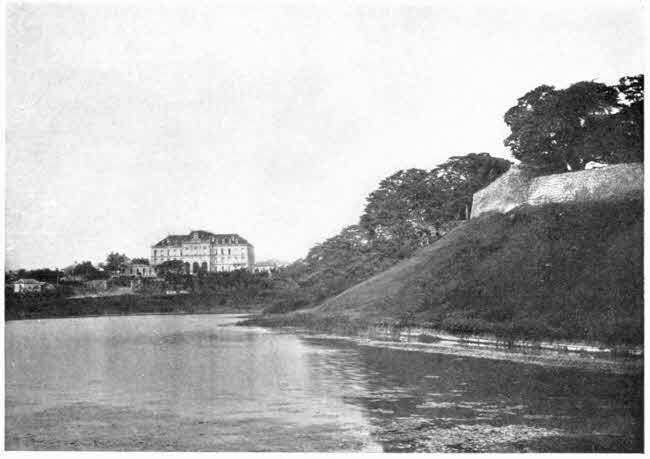

| “The Picturesque Moat and Ancient Wall” | 18 |

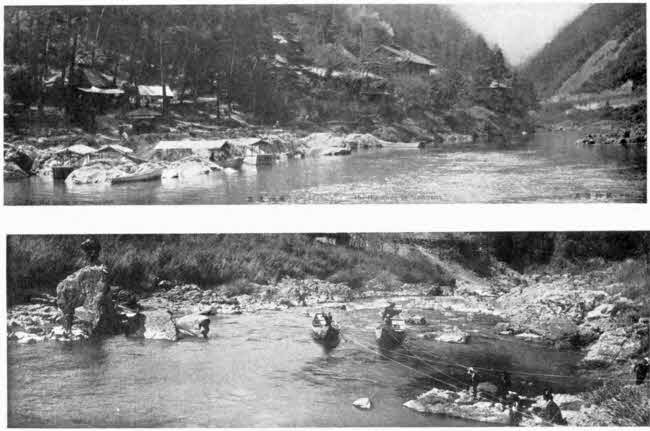

| “The Charm of the Scenery Along the Banks” | 32 |

| “To Tend These Trees Became a Privilege” | 38 |

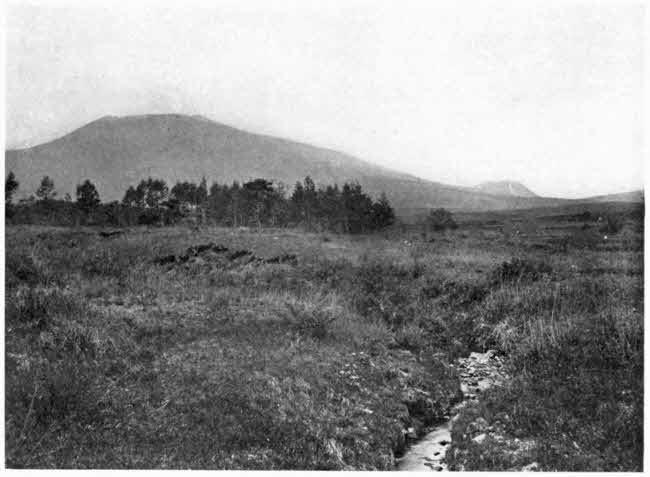

| “The Villages Have Never Been Rebuilt” | 56 |

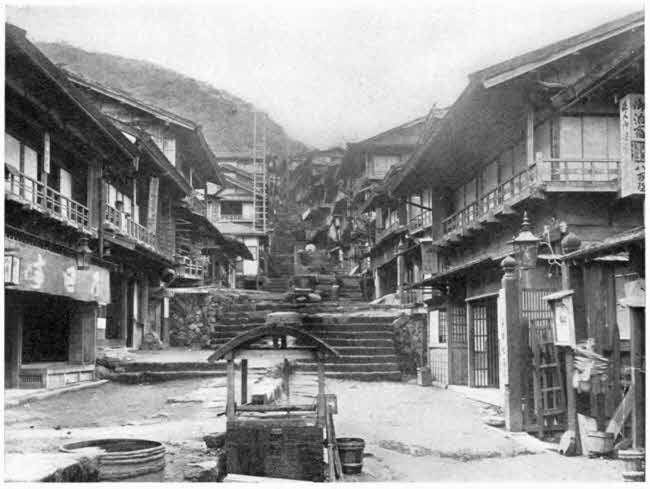

| “For Centuries Lovers Have Met About the Old Well” | 72 |

| “Dark and Solemn and Stately Cryptomerias” | 78 |

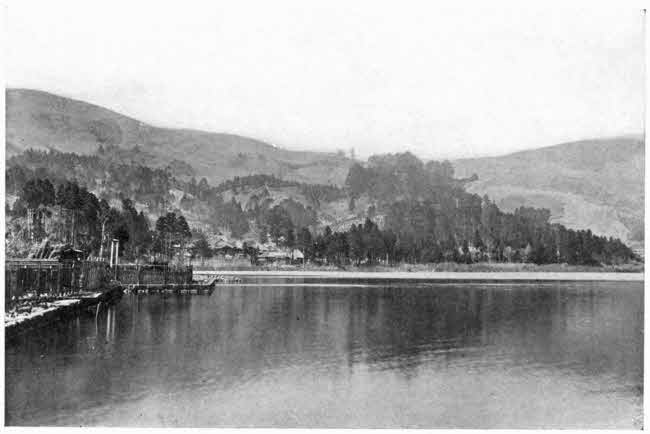

| “Ashi-no-Umi, which is, being Interpreted, ‘The Sea of Reeds’” | 84 |

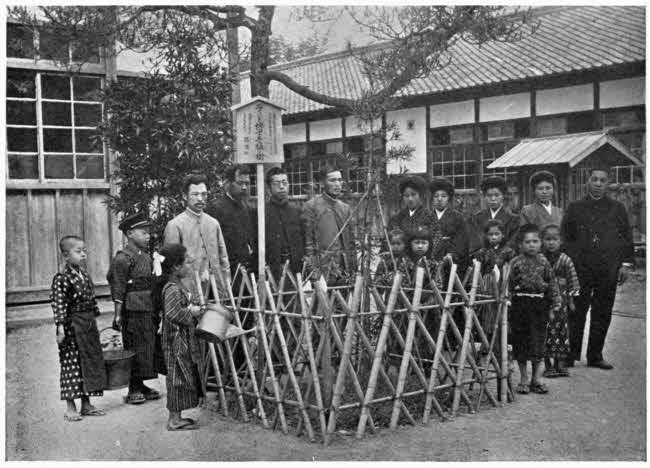

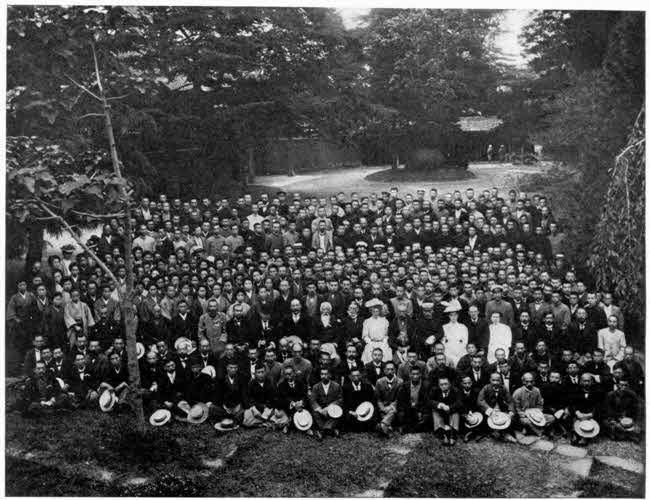

| “Class and Teacher Always Had to be Photographed” | 108 |

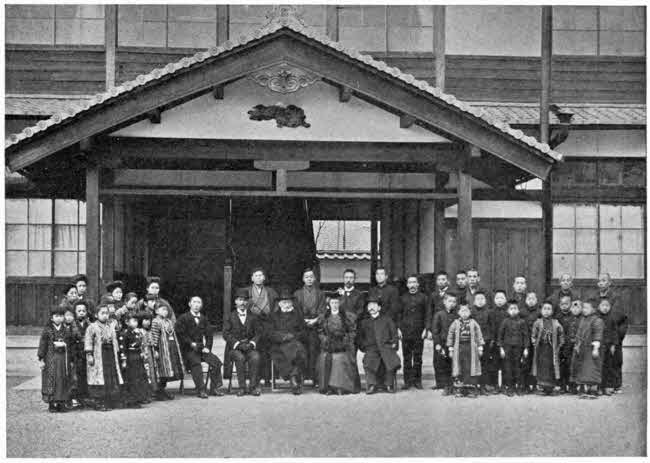

| “The Bearing of the Boys and Girls is Serious, Respectful and Affectionate” | 118 |

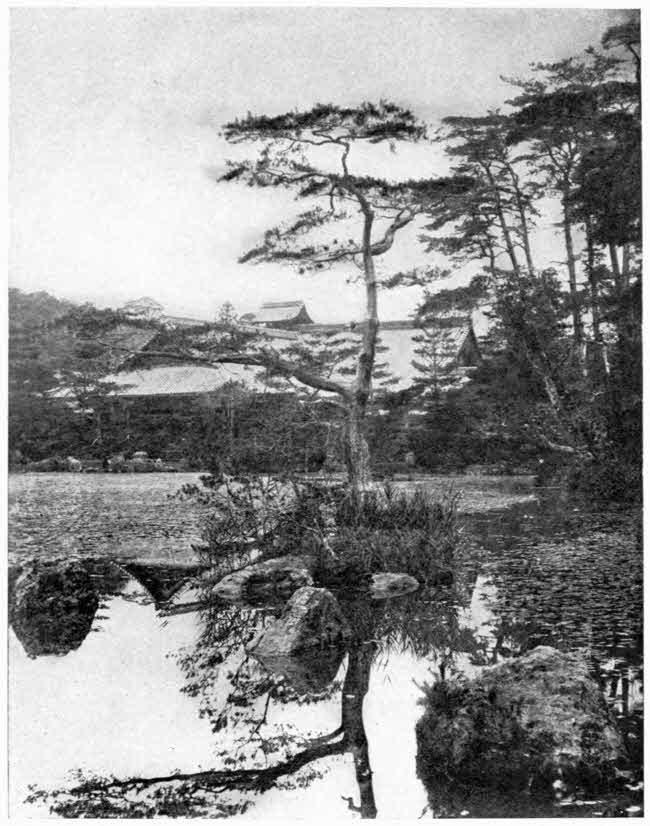

| “It is Nature Combed and Trimmed” | 130 |

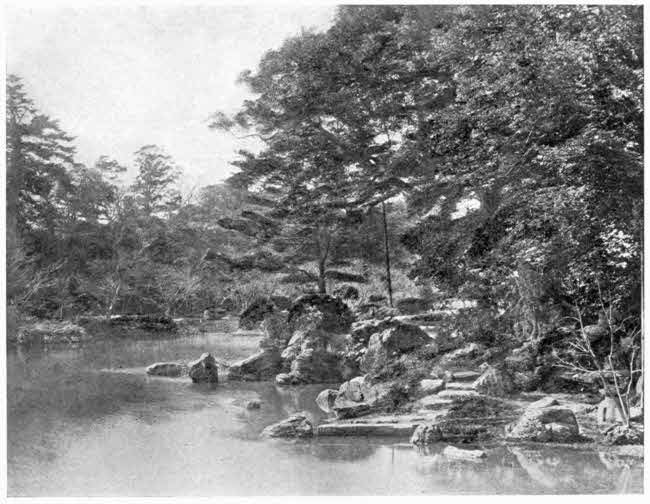

| “Winding Paths Over Rude Moss-covered Stepping-Stones” | 142 |

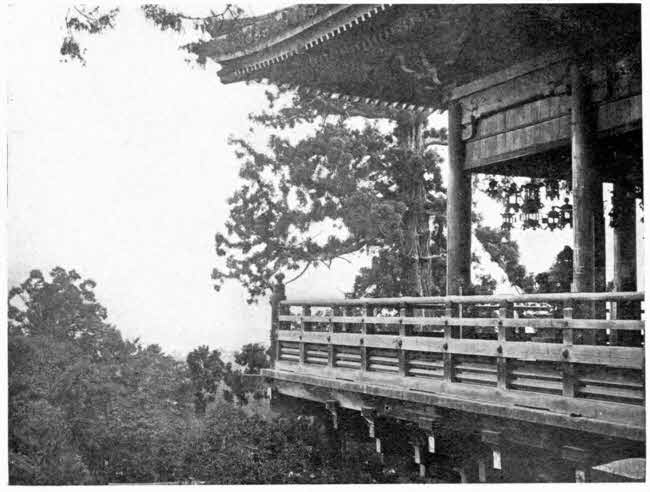

| “The Worship of Nature in the Open Air” | 152 |

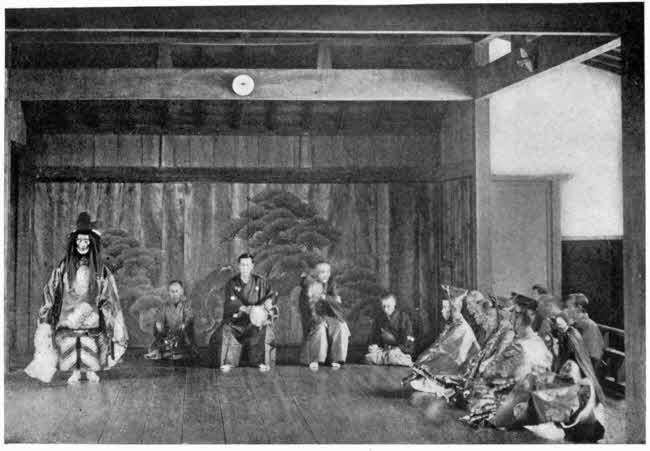

| “In One Corner of the Stage Sits the Chorus” | 194 |

| “Leading Actors in the Dramas of that Day” | 208 |

| “Leading Actors in the Dramas of that Day” | 212[xiv] |

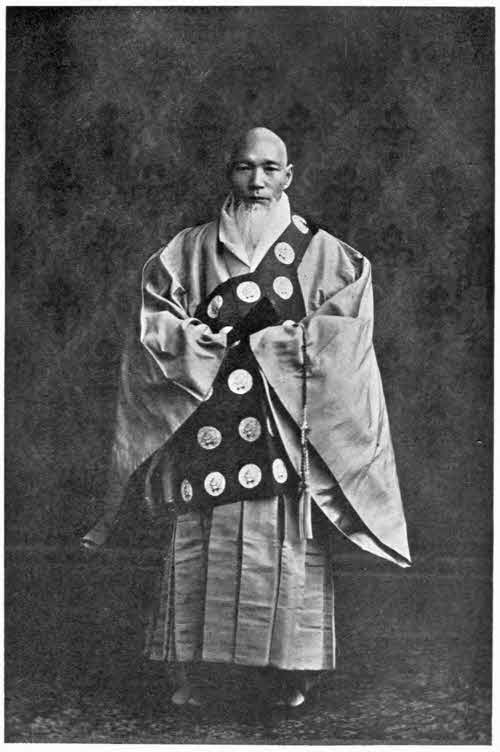

| “The Chief Abbot Came in to Greet Us” | 226 |

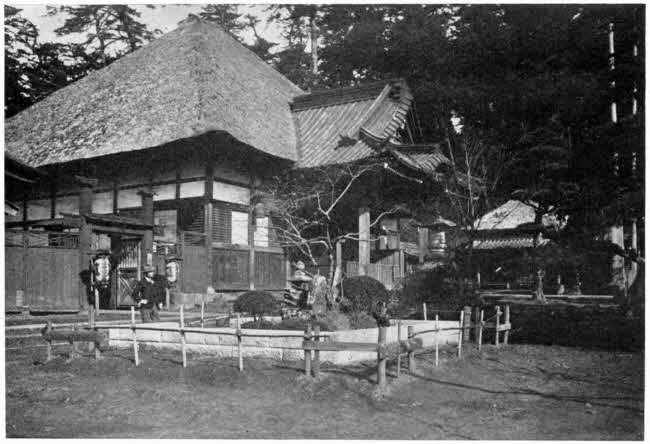

| “Where Nichiren Spent His Last Days” | 234 |

| “Picturesquely Seated on a Wooded Hill” | 250 |

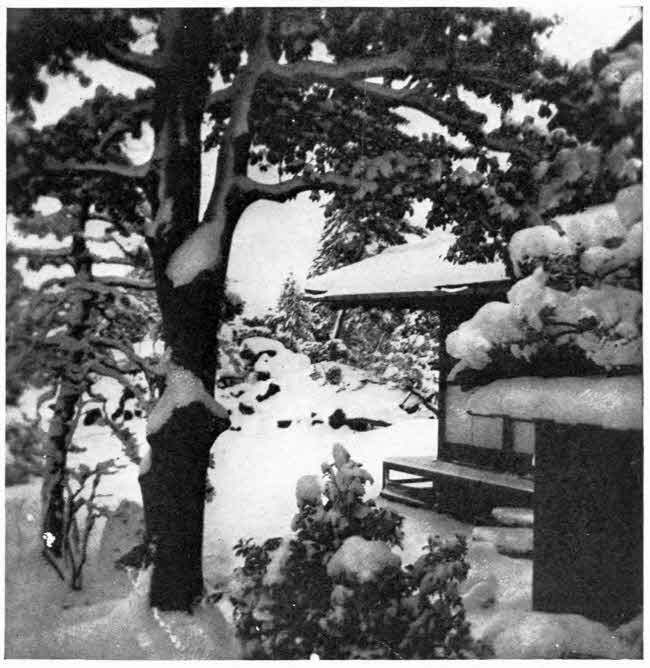

| “All Covered with Fresh-Fallen Snow” | 276 |

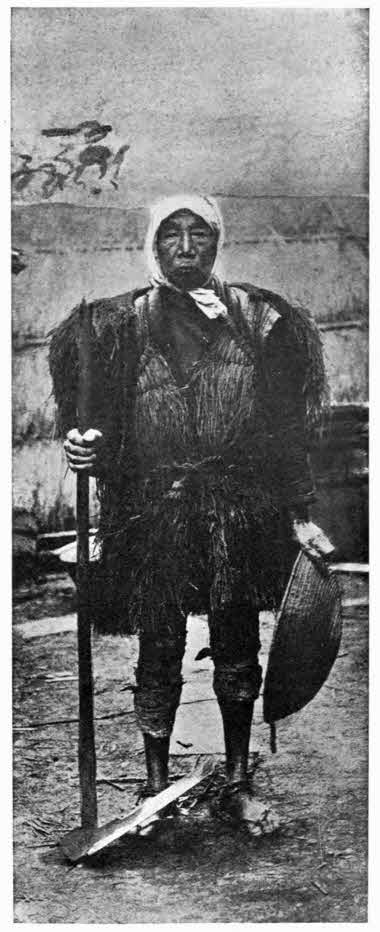

| “Peasants Were Going to and from Their Work” | 294 |

| “You can not Mock the Conviction of Millions” | 302 |

| “The Beautiful Grounds in Full Sight of the Bay” | 308 |

| “They Took Part in Out-Door Sports” | 320 |

The utter strangeness of feeling which came over me when, in May of 1892, I first landed in Japan, will never be repeated by any experience of travel in the future amidst other scenes, no matter how wholly new they may chance to be. Between Vancouver, so like one of our own Western towns, and the Land of the Rising Sun, nature provided nothing to prepare the mind for a distinctly different type of landscape and of civilisation. There was only the monotonous watery waste of the Northern Pacific, and the equally monotonous roll of the Empress of China, as she mounted one side and slid down the other, of its long-sweeping billows. There was indeed good company on board the ship. For besides the amusement afforded by the “correspondent of a Press Syndicate,” who boasted openly of the high price at which he was valued, but who prepared his first letter on “What I saw in China,” from the ship’s library, and then mailed it immediately on arrival at the post-office in Yokohama, there were several honest folk who had lived for years in the Far East.[2] Each of these had one or more intelligent opinions to impart to an inquirer really desirous of learning the truth. Even the lesson from the ignorance and duplicity of this moulder of public opinion through the American press was not wholly without its value as a warning and a guide in future observations of Japan and the Japanese. The social atmosphere of the ship was, however, not at all Oriental. For dress, meals, hours, conversation, and games, were all in Western style. Even with Doctor Sato, the most distinguished of the Japanese passengers, who was returning from seven years of study with the celebrated German bacteriologist, Professor Koch, I could converse only in a European language.

The night of Friday, May 27, 1892, was pitchy dark, and the rain fell in such torrents as the Captain said he had seldom or never seen outside the tropics. This officer did not think it safe to leave the bridge during the entire night, and was several times on the point of stopping the ship. But the downpour of the night left everything absolutely clear; and when the day dawned, Fujiyama, the “incomparable mountain,” could be seen from the bridge at the distance of more than one-hundred and thirty miles. In the many views which I have since had of Fuji, from many different points of view, I have never[3] seen the head and entire bulk of the sacred mountain stand out as it did for us on that first vision, now nearly twenty years ago.

The other first sights of Japan were then essentially the same as those which greet the traveller of to-day. The naked bodies of the fishermen, shining like polished copper in the sunlight; the wonderful colours of the sea; the hills terraced higher up for various kinds of grain and lower down for rice; the brown thatched huts in the villages along the shores of the Bay; and, finally, the busy and brilliant harbour of Yokohama,—all these sights have scarcely changed at all. But the rush of rival launches, the scramble of the sampans, the frantic clawing with boat-hooks, which sometimes reached sides that were made of flesh instead of wood, and the hauling of the Chinese steerage passengers to places where they did not wish to go, have since been much better brought under the control of law. The experience of landing as a novice in Japan is at present, therefore, less picturesque and exciting; but it is much more comfortable and safe.

The arrival of the Empress of China some hours earlier than her advertised time had deceived the friends who were to meet me; and so I had to make my way alone to a hotel in Tokyo. But notes despatched[4] by messengers to two of them—one a native and since a distinguished member of the Diet, and the other an American and a classmate at Andover, within two hours quite relieved my feelings of strangeness and friendlessness; and never since those hours have such feelings returned while sojourning among a people whom I have learned to admire so much and love so well.

It had been my expectation to start by next morning’s train for the ancient capital of Kyoto, where I was to give a course of lectures in the missionary College of Doshisha. But in the evening it was proposed that I should delay my starting for a single day longer, and visit the Imperial Diet, which had only a few days before, amidst no little political excitement, begun its sittings. I gladly consented; since it was likely to prove a rare and rarely instructive experience to observe for myself, in the company of friends who could interpret both customs and language, this early attempt at constitutional government on the part of a people who had been for so many centuries previously under a strictly monarchical system, and excluded until very recently from all the world’s progress in the practice of the more popular forms of self-government. The second session of the First Diet, which began to sit on November 29, 1890,[5] had been brought to a sudden termination on the twenty-fifth of December, 1891, by an Imperial order. This order implied that the First Diet had made something of a “mess” of their attempts at constitutional government. The “extraordinary general election” which had been carried out on the fifteenth of February, 1892, had been everywhere rather stormy and in some places even bloody. But the new Diet had come together again and were once more to be permitted to try their hand at law-making under the terms of the Constitution which his Imperial Majesty had been most “graciously pleased to grant” to His people. The memory of the impressions made by the observations of this visit is rendered much more vivid and even a matter for astonishment, when these impressions are compared with the recent history of the sad failures and exceedingly small successes of the Russian Duma. So sharply marked and even enormous a contrast seems, in my judgment, about equally due to differences in the two peoples and differences in the two Emperors. Another fact also must be taken into the account of any attempt at comparison. The aristocracy of Russia, who form the entourage and councillors of the Tsar are quite too frequently corrupt and without any genuine patriotism or regard for the good of the people;[6] while the statesmen of Japan, whom the Emperor has freely made his most trusted advisers, for numbers, patriotism, courage, sagacity, and unselfishness, have probably not had their equals anywhere else in the history of the modern world.

The Japanese friends who undertook to provide tickets of admission to the House of Peers were unsuccessful in their application. It was easier for the foreign friend to obtain written permission for the Lower House. It was necessary, then, to set forth with the promise of having only half of our coveted opportunity, but with the secret hope that some stroke of good luck might make possible the fulfilment of the other half. And this, so far as I was concerned, happily came true.

As our party were entering the door of the House of Representatives, I was startled by the cry of “soshi” and the rush toward us of two or three of the Parliamentary police officers, who proceeded to divest the meekest and most peaceable of its members, the Reverend Mr. H——, of the very harmless small walking-stick which he was carrying in his hand. It should be explained that, according to Professor Chamberlain, since 1888 there had sprung up a class of rowdy youths, called soshi in Japanese—“juvenile agitators who have taken all politics to[7] be their province, who obtrude their views and their presence on ministers of state, and waylaid—bludgeon and knife in hand—those whose opinions on matters of public interest happen to differ from their own. They are, in a strangely modernised disguise, the representatives of the wandering swashbucklers or rōnin of the old régime.”

After his cane had been put in guard, and a salutary rebuke administered to my clerical friend for his seeming disregard of the regulations providing for the freedom from this kind of “influence” which was guaranteed to the law-makers of the New Japan, we were allowed to go upon our way. Curiously enough, however, the very first thing, after the opening, which came before the House, explained more clearly why what seemed such an extraordinary fuss had been made over so insignificant a trifle. For one of the representatives rose to complain that only the day before a member of the Liberal party had been set upon and badly cut with knives by soshi supposed to belong to the Government party. The complaint was intended to be made more effective and bitter by the added remark that the Speaker of the House had been known to be very polite, in this and in all cases where a similar ill-turn had been done to one of his own party, to send around to[8] the residence of the sufferer messages of condolence and of inquiry after the state of his health. In the numerous reverse cases, however, the politeness of this officer of the whole House had not appeared equally adequate to the occasions afforded by the “roughs” of the anti-Government party. To this sarcastic sally the Speaker, with perfect good temper, made a quiet reply; and at once the entire body broke out into laughter, and the matter was forthwith dropped from attention. On my asking for an interpretation of this mirth-provoking remark, it was given to me as follows: “The members of the Speaker’s party had always taken pains to inform him of their injuries, and so he had known just where to distribute such favours; but if the members of the opposite party would let him know when they were suffering in the same manner, he would be at least equally happy to extend the same courtesies to them.”

It will assist to a better appreciation of what I saw on this occasion, of the personnel and procedure of the Japanese House of Representatives, if some account is given of its present constitution; this differs from that of 1892 only in the fact that it is somewhat more popular now than it was then. The House is composed of members returned by male Japanese subjects of not less than twenty-five years[9] of age and paying a direct tax of not less than ten yen. There are two kinds of members; those returned by incorporated cities containing not less than 30,000 inhabitants, and those by people residing in other districts. The incorporated cities form independent electoral districts; and larger cities containing more than 100,000 inhabitants are allowed to return one member for every 130,000 people. The other districts send one member at the rate of approximately every 130,000 people; each prefecture being regarded as one electoral district. Election is carried on by open ballot, one vote for each man; and a general election is to take place every four years, supposing the House sits through these four years without suffering a dissolution in the interval. The qualifications for a seat in the House are simple for all classes of candidates. Every Japanese subject who has attained the age of not less than thirty years is eligible;—only those who are mentally defective or have been deprived of civil rights being disqualified. The property qualification which was at first enforced for candidates was abolished in 1900 by an Amendment to the Law of Election.

I am sure that no unprejudiced observer of the body of men who composed the Japanese House of[10] Representatives in the Spring of 1892, could have failed to be greatly impressed with a certain air of somewhat undisciplined vigour and as yet unskilled but promising business-like quality. The first odd detail to be noticed was a polished black tablet standing on the desk of each member and inscribed with the Japanese character for his number. Thus they undertook to avoid that dislike to having one’s own name ill used, in which all men share but which is particularly offensive among Oriental peoples. For instead of referring to one another as “the gentleman from Arkansas,” etc., they made reference to one another as “number so or so.” How could anything be more strictly impersonal than sarcasm, or criticism, or even abuse, directed against a number that happens only temporarily to be connected with one’s Self!

It was my good fortune to light upon a time when the business of the day was most interesting and suggestive of the temper and intentions of these new experimenters in popular legislation; and, as well, of the hold they already supposed themselves to possess on the purse-strings of the General Government. What was my surprise to find that this power was, to all appearances, far more effective and frankly exercised by the Japanese Diet than has for a long[11] time been the case with our own House of Congress. For here there was little chance for secret and illicit influences brought to bear upon Committees on Appropriations; or for secure jobbery or log-rolling or lobbying with particular legislators.

The business of the day was the passing upon requests for supplementary grants from the different Departments of the General Government. It was conducted in the following perfectly open and intelligible way: The Vice-Minister of each Department was allowed so many minutes in which he was expected to explain the exact purpose for which the money was wanted; and to tell precisely in yen how much would be required for that purpose and for that purpose only. The request having been read, the Vice-Minister then retired, and fifteen minutes, not more, were allowed for a speech from some member of the opposition. The Speaker, or—to use the more appropriate Japanese title—President of the House, was at that time Mr. T. Hoshi, who had qualified as a barrister in London, and who in personal appearance bore a somewhat striking resemblance to the late President Harper of Chicago University. He seemed to preside with commendable tact and dignity.

As I look backward upon that session of the Imperial[12] Japanese Diet, there is one item of business which it transacted that fills me with astonishment. The request of the Department of Education for money to rebuild the school-houses which had been destroyed by the terrible earthquake of the preceding winter was immediately granted. Similar requests from the Department of Justice, which wished to rebuild the wrecked court-houses, and from the Department of Communications, for funds to restore the post-offices, also met with a favourable reception. But when the Government asked an appropriation for the Department of the Navy, with which to found iron-works, so that they might be prepared to repair their own war-ships, the request was almost as promptly denied! To be sure, the alleged ground of the denial was that the plans of the Government were not yet sufficiently matured.

At this juncture Mr. Kojiro Matsukata, the third son of Japan’s great financier, Marquis Matsukata, came into the gallery where we were sitting and offered to take me into the House of Peers. But before I follow him there let me recall another courtesy from this same Japanese friend, which came fifteen years later; and which, by suggesting contrasts with the action of the Diet in 1892, will emphasise in a picturesque way the great and rapid changes[13] which have since then taken place in Japan. On the morning of February 19, 1907, Mr. Matsukata, who is now president of the ship-building company at Kawasaki, near Kobe, showed me over the yards. This plant is situated for the most part on made ground; and it required four years and a half to find firm bottom at an expense of more than yen 1,000,000. The capital of the company is now more than yen 10,000,000. All over the works the din of 9,000 workmen made conversation nearly impossible. But when we had returned to his office, a quiet chat with the host over the inevitable but always grateful cups of tea, elicited these among other interesting incidents. Above the master’s desk hung the photograph of a group which included Admiral Togo; and still higher up, above the photograph, a motto in the Admiral’s own hand-writing, executed on one of his visits to the works—he having been summoned by the Emperor for consultation during the Russo-Japanese war. On my asking for a translation of the motto, I was told that it read simply: “Keep the Peace.” Just two days before the battle of the Sea of Japan, Mr. Matsukata had a telegraphic message from Togo, which came “out of the blue,” so to say, and which read in this significant way: “After a thousand different thoughts, now one fixed[14] purpose.” In the centre of another group-photograph of smaller size, sat the celebrated Russian General, Kuropatkin. This picture was taken on the occasion of his visit to the ship-yards some years before. Mr. Matsukata became at that time well acquainted with Kuropatkin, and described him to me as a kindly and simple-minded gentleman of the type of an English squire. He was very fond of fishing; but like my friend, the Russian General Y——, he appeared to have an almost passionate abhorrence of war. He once said to my host: “Why do you build war ships; why not build only merchant ships; that is much better?” To this it was replied: “Why do you carry your sword? Throw away the sword and I will stop building war ships.” And, indeed, in most modern wars, it is not the men who must do the fighting or the people who must pay the bills, that are chiefly responsible for their initiation; it is the selfish promoters of schemes for the plunder of other nations, the cowardly politicians, and perhaps above all, the unscrupulous press, which are chiefly responsible for the horrors of war. Through all modern history, since men ceased to be frankly barbarian in their treatment of other peoples and races, it has been commercial greed, and its subsidised agents among the makers of laws and[15] of public feeling, which have chiefly been guilty for the waste of treasure and life among civilised peoples.

But let us leave the noise of the Kawasaki Dock Yards, where in 1907 Russian ships were repairing, Chinese gun-boats and torpedo and other boats for Siam were building, and merchant and war ships for the home country were in various stages of new construction or repair; and let us return to the quiet of the House of Peers when I visited it in May of 1892. After a short time spent in one of the retiring rooms, which are assigned according to the rank of the members—Marquis Matsukata being then Premier—we were admitted to the gallery of the Foreign Ambassadors, from which there is a particularly good view of the entire Upper House.

The Japanese House of Peers is composed of four classes of members. These are (1) Princes of the Blood; (2) Peers, such as the Princes and Marquises, who sit by virtue of their right, when they reach the age of twenty-five, and Counts, Viscounts, and Barons, who are elected to represent their own respective classes; (3) men of erudition who are nominated by the Emperor for their distinguished services to the state; and (4) representatives of the highest tax-payers, who are elected from among[16] themselves, and only one from each prefecture. Each of the three inferior orders can return not more than one-fifth of the total number of peers; and the total of the non-titled members must not be greater than that of the titled members. It is thus made obvious that the Japanese House of Peers is essentially an aristocratic body; and yet that it represents all the most important interests of the country in some good degree—whatever may be thought of the proportion of representation assigned to each interest. The care that science and scholarship shall have at least some worthy representation in the national counsels and legislation is well worthy of imitation by the United States. And when to this provision we add the facts, that a Minister of Education takes rank with the other Ministers, that the Professors in the Imperial Universities have court rank by virtue of their services, and that the permanent President of the Imperial Teacher’s Association is a Baron and a member of the House of Peers, we may well begin to doubt whether the recognition accorded to the value of education in relation to the national life, and to the dignity and worth of the teacher’s office, is in this country so superior to that of other nations, after all.

The appearance of the Chamber occupied by the[17] Peers was somewhat more luxurious than that of the Lower House; although it was then, and still is, quite unimposing as compared with buildings used for legislative purposes in this country and in Europe. Indeed, everywhere in Tokyo, the ugly German architecture of the Government buildings contrasts strikingly with the picturesque moat and ancient walls of the Imperial grounds. More elaborate decoration, and the platform above which an ascent by a few steps led to the throne from which His Majesty opens Parliament, were the only claims of the Upper Chamber to distinction. The personnel of the members seemed to me on the whole less vigorous than that of the Lower House. This was in part due to the sprinkling of youthful marquises, who, as has already been explained, take their seats by hereditary right at the age of twenty-five. In marked contrast with them was the grim old General T——, a member of the Commission which visited the United States in 1871, who asserted himself by asking a question and then going on to make a speech, in spite of the taunts of two or three of the younger members. The manner of voting in the Upper House was particularly interesting; as the roll was called, each member mounted the platform and deposited either a white or a blue card in a black[18] lacquer box which stood in front of the President of the Chamber.

Here the business of the day was important on account of the precedent which it was likely to establish. A Viscount member had been promoted to a Count, and the question had arisen whether his seat should be declared vacant. The report of the committee which disqualified him from sitting as a Count was voted upon and adopted. Then came up the case of two Counts who were claimants for the same seat. The vote for these rival candidates had stood 30 to 31; but one voter among the majority had been declared disqualified; because, having held a Viscount’s seat, on being promoted to a Count, he had attempted to vote as a Count. All this, while of importance as precedents determining the future constitution of the House of Peers, had not at all the same wide-reaching significance as the signs in the Lower House of the beginnings in Japan of that struggle which is still going on all over the world between the demands of the Central Government for money and the legislative body which votes the appropriations to meet these demands.

It was under very different circumstances that I witnessed a quite dissimilar scene, when in December of 1906 my next visit was paid to the Imperial Diet[19] of Japan. This occasion was the opening of the Diet by the Emperor in person. Now, while my court rank gave me the right to request an official invitation to the ceremony, the nature of the ceremony itself required that all who attended should come in full dress and wearing their decorations, if they were the possessors of decorations at all. It was also required that all visitors should be in their respective waiting-rooms for a full hour before the ceremony began. None might enter the House later than ten o’clock, although His Majesty did not leave the palace until half-past this hour. This waiting, however, gave a not undesirable opportunity to make some new acquaintance, or to have a chat with two or three old friends. But besides the members of the various diplomatic corps and a French Count, who appeared to be a visitor at his nation’s Embassy, there were no other foreigners in the waiting-room to which I was directed on arrival.

During the hour spent in waiting, however, I had a most interesting conversation with Baron R——, an attaché of the German Embassy, who seemed a very clever and sensible young gentleman. The excitement over the recent action of the San Francisco School Board was then at its extreme height; and on discussing with him an “open letter” which I[20] had just published, explaining in behalf of my Japanese friends the relation in which this action, with some of the questions which it raised, stood to our national constitution, I found him thoroughly acquainted with the historical and the political bearings of the whole difficult subject. I could not avoid a regretful sigh over the doubt whether one-half of our own representatives, or even of our foreign service, were so well informed on the nature of our constitution and its history as was this German diplomat. However this may be, certain it is that a higher grade of culture is eminently desirable in both the legislative and diplomatic classes of our public service. In the same connection the Baron gave it as his opinion that Japan had produced in this generation a nobler and more knightly type of individual manhood than can be found in any country in Europe. Such a verdict can, of course, never acquire any higher trustworthiness than an individual’s opinion. But if we ask ourselves, “Where in the world is another city of 45,000 inhabitants to be found, which has produced in this generation six generals who are the equals of Field Marshall Oyama, Admiral Togo, and Generals Oku, Count Nodzu, and the two Saigos?” I imagine the answer would be exceedingly hard to find. Perhaps the truth is, as one of my[21] best informed Japanese friends once quaintly said: “In America you have a few big, bad men, and a good many small good men; but in Japan we have a few big, good men and a good many small bad men.” At any rate, the six “big men,” whose names have just been mentioned, were about fifty years ago living and playing as boys together in an area so small that the houses and yards of their parents, and all the space intervening, might have been covered by a ten-acre lot.

As soon as His Majesty had arrived, all those who had been waiting were conducted to their proper chambers in the gallery of the Peer’s House, where I found myself seated with Japanese only, and between those of a higher rank on the right and of a lower rank on the left. The members of both Houses of the Diet were standing on the floor below;—those from the Lower House on the left and facing the throne, and those from the House of Peers on the right. The former were dressed, with some exceptions, in evening-dress, and the latter in court uniform with gold epaulets on their shoulders. All the spectators in the galleries were in court dress. On the right of the platform, from which steps led up to the throne, stood a group of some fifteen or twenty court officials. At about five minutes past[22] eleven an equal number of such personages came into the Chamber by the opposite door of the platform and arranged themselves so as to form a passage through the midst of them for the Emperor. Not more than five minutes later His Majesty entered, and ascending to the throne, sat down for a moment; but almost immediately rose and received from the hand of Marquis Saionji, the Prime Minister, the address from the throne inscribed on a parchment scroll. This he then read, or rather intoned, in a remarkably clear but soft and musical voice. The entire address occupied not more than three minutes in the reading. After it was finished, Prince Tokugawa, President of the Peers, went up from the floor of the House to the platform, and then to a place before the throne; here he received the scroll from the Emperor’s hand. After which he backed down to the floor again, went directly in front of His Majesty and made a final bow. The Emperor himself immediately descended from the throne and made his exit from the platform by the door at which he had entered, followed by all the courtiers.

All were enjoined to remain in their places until the Emperor had left the House; the audience then dispersed without further regard to order or to precedence.[23] So simple and brief was this impressive ceremony!

Nearly all over the civilised world, at the present time, there seems to be a growing distrust of government by legislative bodies as at present constituted and an increasing doubt as to the final fate of this form of government. The distrust and doubt are chiefly due to the fact that the legislators seem so largely under the control of the struggle which is everywhere going on between the now privileged classes, in their efforts to retain their inherited or acquired advantages, and the socially lower or less prosperous classes, in their efforts to wrest away these advantages and to secure what they—whether rightly or wrongly—regard as equal rights and equal opportunities with their more favoured and prosperous fellows. It is not strange, in view of this so nearly universal fact, that any inquiry as to the past and present success of legislation under constitutional government in Japan, should receive such various and conflicting answers both from intelligent natives and from observant foreigners. There can be no doubt among those who know the inside of Japanese politics that the success of this sort which has hitherto been attained in Japan has been in large measure due to the wise and firm but gracious conduct[24] of the Emperor himself; and to that small group of “elder statesmen” and other councillors whom he has trusted and supported so faithfully. But no few men, however wise and great, could have achieved by themselves what has actually been accomplished in the last half-century of the Empire’s history. Great credit must then be given to hundreds and thousands of lesser heroes; and indeed the events of this history cannot be accounted for without admitting that the genius of the race, accentuated by their long period of seclusion, is the dominant factor. The one fault, which most threatens the cause of parliamentary and constitutional government of Japan, is a certain inability, hitherto inherent, to avoid the evils of an extreme partisanship and to learn that art of practical compromises which has made the Anglo-Saxon race so successful hitherto in constitutional and popular government.

[25]

At four o’clock in the morning of the second day after my visit to the Imperial Diet in the Spring of 1892, I arrived at the station of Kyoto,—for more than a thousand years the capital of Japan. Here the unbroken line of heavenly descended Mikados lived and held their court; but most of the time in only nominal rule, while a succession of Daimyos, military captains, and Shoguns, seized and held the real power of government. Here also are the finest temples and factories for the various kinds of native art-work; and here is where the relics of the magnificence, combined with simplicity, of the court life during Japan’s feudal ages may best be seen and studied by privileged inquirers. It was fortunate, then, that my first introduction to interior views of Japanese life and Japanese character was had in the ancient rather than in the much more thoroughly modernised Capital City of Tokyo.

At that time, the journey between the two capitals required some five or six hours longer than is now necessary. The fact that there were then no sleeping-cars,[26] together with my interest in watching my fellow travellers, had prevented my getting any sleep the night before. When, therefore, I had been escorted to the home of my host and forthwith informed that within two hours a delegation of students would visit me, for the double purpose of extending a welcome and of giving instructions as to the topics on which they wished to be lectured to, I made bold to go to bed and leave word that I should be glad to see them if they would return about noon. At the appointed hour this first meeting with Japanese students face to face, in their native land, came off. It was conducted with an appropriately polite solemnity by both parties. An elaborate interchange of greetings and compliments began the interview; and then the future speaker listened attentively and patiently, while the delegation from a portion of his future audience recited the subjects about which they deemed it best for him to speak. The reply was to the effect that the subjects for the course of lectures had already been selected and carefully prepared: the program, therefore, could not be altered; but some of the topics coincided closely with the program suggested by the Committee; and a series of conversations would accompany the lectures, at which the topics not provided for in the[27] course of lectures could be brought up for discussion in the form of question and answer.

This experience and others somewhat similar, which followed with sufficient rapidity, early taught me a valuable lesson for all subsequent intercourse with the Japanese—young and old, and irrespective of distinctions of classes. With full right, and on a basis of history and racial characteristics, they do not gratefully tolerate being looked down upon, or even condescended to, by foreigners. But they respect, as we Anglo-Saxons do, the person who deals with them in manly frankness, and on terms of manly equality. And they admire and practice more than we do, the proper mixture of quietness and politeness in manner with courage and firmness at the heart (suaviter in modo, fortiter in re). In his admirable volumes on the Russo-Japanese war, General Ian Hamilton tells the story of how he asked some of the Japanese military authorities, What they considered the most essential quality for a great field-marshal or general in conducting a battle; and how the reply was these simple words: “Du calme.” The private soldier—although not in accordance with his best service of the cause—may indulge in the wild excitement which Lieutenant Sakurai’s “Human Bullets” depicts in such horribly[28] graphic manner; but not so the officer in command of the field. He must keep the cool head and the unperturbed heart, with its steady pulse-beat, if he is going to fight successfully an up-hill battle.

After only two days of lecturing at Doshisha, the institution founded by Neesima, the unveiling of whose portrait has lately been celebrated at Amherst College where he graduated some thirty years ago, the weekly holiday arrived; and with it the time for an excursion down the rapids of the Katsura-gawa, which was to give me the first views of country scenes and country customs in Japan. The day was as bright and beautiful as a day in early June can possibly be. Nowhere else in the world, where I have been, are one’s pleasant impressions and happiness in country excursions more completely dependent upon the weather than in the Land of the “Rising Sun.” Although this sun is of the kind which “smites you by day” in the Summer months, you can easily guard against its smiting by use of pith hat and umbrella; but you cannot so readily defend your spirits against the depressing effect of day after day of cloud and down-pour or drizzle of rain.

The starting at half-past seven o’clock made necessary an early rising and an early breakfast; but this is custom and no hardship in the Summer time of[29] Japan. Indeed it has often seemed to me that the Japanese in the cities at this time of the year do not go to bed at all. The insufficiency of sleep is probably one chief reason for the prevalence of nervous disorders among this class of the population. It is somewhat compensated for, however, by the wonderful ability of the coolies, which they possess in common with Orientals generally, of falling asleep and waking up, like the opening and shutting of a jack-knife.

It is not quite possible for the most gifted master of the descriptive style to depict the charm of the first jinrikisha ride out into the country surrounding Kyoto. At least, the charm experienced by me on the occasion of this excursion will never be forgotten. The excellent road; the durable and handsome stone bridges; the continuous gardens and frequent villages; the perpetual stir along the highway, with the multitude of jinrikishas and two-wheeled carts,—some drawn by men and boys, and some by bulls, mostly black,—or of foot-passengers, coming into the city on business or going into the country bent on pleasure;—all these made the entire journey exceedingly lively and interesting. Further out, in the more solitary places, were the terraces covered with verdure and flowers, the hills carpeted with what[30] looked like large and luxurious ferns, but which really was “mountain grass,” and the water-falls; but perhaps most beautiful of all, the bamboo groves, whose slender trunks and delicate foliage threw a matchless chiaroscuro upon the brilliantly coloured ground below. Here was indeed a genuine chiaroscuro; for the parts in shadow had “the clearness and warmth of those in light, and those in light the depth and softness of those in shadow.”

What might have been a ridiculous or even a dangerous adventure met us at the mouth of the long tunnel which the work of the government has substituted for the ancient mountain pass. For, as we reached the spot and were about to enter its mouth, strange noises issuing from within made us pause to investigate their cause. On peering into the darkness, we were able to make out that a full-grown male of the domestic bovine species had broken the straw rope by which two coolies were leading him, and was charging toward our end of the tunnel with all the bellowing and antic fury which is wont to characterise this animal under similar circumstances. It did not seem that the issue of an encounter between us in jinrikishas and the bull, in so narrow a passage with high and roofed-over stone walls on either side, would be to our advantage. We therefore[31] laid aside our dignity, got down from our jinrikishas, and squeezed both ourselves and them as closely as possible against the side of the cut at the end of the tunnel. Fortunately we had not long to wait in this position of rather uncertain security. For either the sight of us, barring his passage, or some trick of his own brain, induced the infuriated animal to turn about and make his exit at the other end of the tunnel; and after waiting long enough to place a sufficient distance between the two parties, we continued our journey without further adventure.

On reaching Hozu, the village where the boat was to be taken for the rapids, we found that President Kozaki and one of his teachers were waiting for us. Some one-hundred and twenty boys of the Preparatory School, who had risen in the night and walked out to Hozu, had started down the rapids several hours before. The boat in waiting for our party was of the style considered safest and most manageable by the experienced boatmen, who during the previous fifteen years had piloted thousands of persons down the Katsura-gawa, at all stages of its waters, with a loss of only five lives. The boat was very broad for its length, low, and light; with its bottom only slightly curved, fore and aft, and toward both sides. So thin were the boards between[32] the passengers and the swift, boiling waters, that one could feel them bend like paper as we shot over the waves. We sat upon blankets laid on the bottom of the boat. There were four boatmen;—one steersman with a long oar, in the stern, two oarsmen on the same side, toward the bank of the river, in the middle of the boat, and one man with a pole, in the bow. Once only during thirteen miles of rapids between Hozu and Arashi-yama did the boat strike a rock, from which it bounded off lightly;—the sole result being a somewhat sharp interchange of opinion as to who was to blame, between the steersman and the other boatmen.

The excitement of the ride did not in any respect interfere with a constant and increasing admiration of the charm of the scenery along the banks of the river. The canyon of the stream and the surrounding hills were equally beautiful. The nearer banks were adorned with bamboo groves, the attractiveness of whose delicately contrasted or blended light and shadows has already been referred to; and at this season, great clumps of azaleas—scarlet, pink, and crimson—made spots of brilliant colouring upon the sober background of moss and fern and soil and rock.

The average trip down the rapids of the Katsura-gawa[33] occupies two hours. But the favourable stage of the water, helped out by the skilful management of the craft on this occasion, brought us to the landing place at Arashi-yama in scarcely more than an hour and a half. Our entire course may be described in the guide-book style as follows: “Of the numerous small rapids and races, the following are a few of the most exciting:—Koya no taki, or ‘Hut Rapids,’ a long race terminating in a pretty rapid, the passage being narrow between artificially constructed embankments of rock; Takase, or ‘High Rapids’; Shishi no Kuchi, or ‘The Lion’s Mouth’; and Tonase-daki ‘the last on the descent, where the river rushes between numerous rocks and islets.’”

Arashi-yama, made picturesque by its hills everywhere covered with pine trees, its plantations of cherry trees which are said to have been brought from Yoshino in the thirteenth century by the Emperor Kameyama, and its justly celebrated maple groves, was an appropriately beautiful spot for the termination of our excursion. After taking luncheon in one of its tea-houses,—my first meal, squatted on the mats, in Japanese style,—my host and I left the rest of the party and went back to his home in the city by jinrikishas. On the way we stopped at one of those oldest, smallest, and most obscure of[34] ancient temples, which so often in Japan are overlooked by the tourist, but which not infrequently are of all others best worth the visiting. Here the mild-mannered, sincere old priest opened everything freely to our inspection, lighted the tapers and replenished the incense sticks; and even allowed us the very unusual privilege of handling the sacred things about the idols. Finally, putting a paper-covering over his mouth, and after much prayer, he approached on his knees the “holy of holies,” drew aside the gilt screens and showed us the inner shrine; and he then took out the shoes belonging to the god and let us handle and admire them.

From his point of view, the pious custodian of the sacred relics was indulging in an altogether justifiable pride. For the temple of Uzumasa is one of the oldest in Japan. It was founded in A. D. 604, by Shōtoku Taishi, the Japanese Constantine, who consecrated it to Buddhist gods whose images had been brought from Korea. Although the original buildings were burned some centuries ago, the relics and specimens of the most ancient art were fortunately saved. Nowhere else in the whole country, except at Nara or Hōryūji—and there only to those who are favoured with special privileges by the Government—can such a multitude of these things be seen[35] and studied. The antiquarian interest in them is just now enhanced by the fact that many of them, although called Japanese, were really made either in Korea or else under the instruction of Korean teachers. It is one of the shiftings of human history which has now placed upon the Japanese the responsibility of instructing in every kind of modern art their former teachers.

The accessories and incidents of my second excursion to the rapids of the Katsura-gawa were of a totally different order. The day was in early March of 1907, bright and beautiful, but somewhat cool for such a venture. At the Nijo station—for one could now reach the upper rapids by rail—my wife and I met President Harada and one of the lady teachers of Doshisha, and two of the Professors of the Imperial University. Passes and a present of envelopes containing a number of pretty picture cards, from the Manager of the Kyoto Railway Company, were waiting for the party. The ride to the village of Kameoka was pleasant, although even the earliest of the plum blossoms had not yet appeared to beautify the landscape.

I had been anticipating a day of complete freedom for recreation; but the Christian pastor of the village, who had kindly arranged for our boat, had[36] with equal kindness of intention toward his parish, betrayed our coming; and the inevitable under such circumstances happened. The usual committee of Mayor, representatives of the schools and others, were at the station to welcome us. “Could I not visit the Primary School and say a few words—just show myself, indeed—to the children who were all waiting eager with expectation?” Of course, Yes: for how could so reasonable a request, so politely proffered, be reasonably and politely denied? Besides, the children were encouraged to plant and care for trees about the school-buildings; and it was greatly desired that I should plant one to commemorate our visit. Of course, again, Yes. Soon, then, a long row of jinrikishas, holding both hosts and guests, was being hurried over the mile or more separating the station from the nearest school-building. On drawing near we found some 500 or 600 children—first the boys and then the girls—ranged along on either side of the roadway; and between them, all bowing as they are carefully trained to do in Japanese style and waving flags of both countries, we passed, until we were discharged at the door of the large school-house hall.

After luncheon was finished, I assisted at the planting of two small fir-trees just in front of the[37] building, by dropping into the hole the first two or three mattocks full of earth. We were then conducted to the play-ground near by, where the whole school was drawn up in the form of a hollow square. Here, from one end of the square, I spoke to the children for not more than ten minutes, and President Harada interpreted; after which the head-master made a characteristically poetical response by way of thanks,—saying that the memory of the visit and the impression of the words spoken would be evergreen, like the tree which had been planted, and expressing the wish that the future long lives of both their guests might be symbolised by the life of the tree. To tend these trees became a privilege for which the pupils of the school have since kept up a friendly rivalry.

The excursionists were quite naturally desirous of getting off promptly upon the postponed pleasure trip; but this was not even yet easily to be done. For now followed the request to visit two schools of the higher grade and make a short talk to the pupils in them. I compromised on the condition that the two should be gathered into the same assembly; and this was cheerfully, and for the Japanese, promptly done. The combined audience made about three-hundred of each sex—older boys and girls—standing close[38] together, one on one side and the other on the other side of the room, in soldier-like ranks, facing the speaker with curious and eager eyes, but with most exemplary behaviour. Again I spoke for ten minutes; after which followed the interpretation and the address of thanks and of promise to remember and put into practice the speaker’s injunctions.

At the termination of this ceremony, I said—I fear a little abruptly—“Arigato” (“Thank you”) and “Sayonara” (“Good-bye”) and started to go. But I was brought to a halt by the suggestive, “Dozo, chotto” (“In a moment, please”) and then asked to give the boys of the school a chance to precede us to the river bank on foot, from which they wished to see us off and to bid us a Japanese good-bye. And who that knows what a Japanese “good-bye,” when genuine and hearty, really is, would not give more than a single little moment, at almost any juncture, to be the recipient of one? The boys, thereupon, filed out in good military fashion; and after giving them a fair start, we took our jinrikishas again and were carried to the river’s bank. It was still some little time before the boat was ready; and then the party, seated on the blankets and secured against the cold by a covering of rugs, accompanied by the pastor and one of the[39] teachers as an escort, started down the river. Several hundred yards below our starting point, the three-hundred school boys stood in single file along the bank, and continued to “banzai” in their best style until a turn in the river hid them from our sight.

I have dwelt at such length on this seemingly trivial incident, because I should be glad to give an adequate impression of the influence of the lower grades of the public schools of Japan in inculcating lessons of order and politeness upon the children of the nation; and in this way preparing them for fitting in well with the existing social order and for obedience to the sovereign authority of the Emperor, of their parents, and in general of their elders. The common impression that Japanese babies are born so little nervous or so good-natured that they never cry, is indeed far enough from the truth. They do cry, as all healthy babies should, when hurt or when grieved; or, with particular vehemence, when mad. They are almost without exception injudiciously indulged by their parents, their nurses, and in truth by everybody else. But from the time the boy or girl begins to attend school, an astonishing change takes place. How far this change is due to the influence of the teacher’s instruction and example, and how[40] far to the spirit and practice of the older pupils, it is perhaps not easy to say. But, in school, both sexes are immediately placed under a close-fitting system of physical and intellectual drill. Thus the pride and ambition of all are called out by the effort to succeed and to excel. The Imperial rescripts, the wise sayings and noble achievements of ancient sages and heroes, the arousement of that spirit which is called “Bushidō” or “Yamato-Damashii,” the appeal to the pride and love of country, and instruction in ethics—as the Japanese understand ethics—prolonged from the kindergarten to the University;—all these means are employed in the public system of education with the intention of producing citizens serviceable to the State. They are all needed in the effort of the Government to control the ferment of new ideas and the pressure of the new forces which are shaping the future commercial, political, and social life of the nation, perhaps too rapidly for its own good.

For the interested and sympathetic teacher of children there are no more delightful experiences than may be had by visiting and observing the primary grades of the public schools of Japan. I have had the pleasure of speaking to several thousands of their pupils. At the summons, the boys would come filing[41] in on one side, and the girls on the other side, of the large assembly room with which every well-appointed school-house is now being provided; and as quietly as drilled and veteran soldiers they would form themselves into a compacted phalanx of the large style of ancient Macedonia. Six hundred pairs of bright black eyes are then gazing steadily and unflinchingly, but with a quiet and engaging respectfulness, into the eyes of the speaker. And if his experience is like my own, he will never see the slightest sign of inattention, impatience, or disorder, on the part of a single one of his childish auditors. Further, as to the effect of this upon the older boys when out of school: Although I have been in a considerable number of places, both in the cities and in the country places of Japan, I have never seen two Japanese boys quarrelling or even behaving rudely toward each other so far as their language was concerned. The second item of “advice” in the “Imperial Rescript to the Army and Navy,” which precedes even the exhortation—“It is incumbent on soldiers to be brave and courageous”—reads as follows: “Soldiers must be polite in their behaviour and ways. In the army and navy, there are hierarchical ranks from the Marshal to the private or bluejacket which bind together the whole for purposes[42] of command, and there are the gradations of seniority within the same rank. The junior must obey the senior; the inferior must take orders from the superior, who transmits them to Our direct command; and inferior and junior officers and men must pay respect to their superiors and seniors, even though they be not their direct superiors and seniors. Superiors must never be haughty and proud toward those of lower rank, and severity of discipline must be reserved for exceptional cases. In all other cases superiors must treat those beneath them with kindness and especial clemency, so that all men may unite as one man in the service of the country. If you do not observe courtesy of behaviour, if inferiors treat their superiors with disrespect, or superiors their inferiors with harshness, if, in a word, the harmonious relations between superiors and inferiors be lost, you will be not only playing havoc with the army, but committing serious crimes against the country.”

The success in blending courage with courtesy, bravery with politeness, which this way of disciplining the youth of the country may attain, and actually has attained in Japan, is a complete refutation of the silly notion—so common, alas! in Anglo-Saxon and Christian lands, that haughtiness in “superiors” and insolence in “inferiors,” together with the[43] readiness to fight one’s fellows with fists, swords, or pistols, is a necessary part of a soldier’s preparation for the most successful resistance to the enemies of one’s country. It is difficult to conceive of more impressive lessons regarding the effects produced by different systems of education upon different racial characteristics than that afforded by the following two incidents. For some weeks in the Autumn of 1899 I occupied a house in Tokyo, from the rooms of which nearly everything going on in one of the large public schools of the city could be either overheard or overlooked. But not once did a harsh word or a loud cry reach our ears, or a rude and impolite action our eyes. But during a residence of a fortnight in similar proximity to one of the best Christian colleges of India, there was scarcely an hour of the school day when some seemingly serious uproar was not in evidence in the room beneath our window. And it was not an uncommon thing to observe both pupil and teacher standing on their feet and vociferously “sassing” each other,—with one or more of the other pupils occasionally chiming in. More suggestive of vital differences, however, is another experience of mine. Toward the close of the Russo-Japanese war a Japanese pupil, a Buddhist priest, who had fought in the Chino-Japanese war[44] and had been decorated for his bravery, had been called out into the “reserves.” A letter received from him while his regiment was still waiting to be ordered to the front, after telling how he had left the school for “temple-boys,” which he had founded on his return from his studies in this country, and of which he was the Dean, added these pregnant words: “Pray for us, that we may have success and victory.” Now it so happened that almost the same mail which brought this letter, carried to another member of my family a letter from a Christian Hindū, who had come to this country for theological study. In this letter, too, there was an appeal to our pious sympathy; but it took the following form: “Pray for me, that I may be able to bear the cold.” Surely, Great Britain need not fear an uprising of the “intellectuals” in India, so long as its babus are educated in such manner as to foster so unenduring character, however gifted in philosophical speculation and eloquence of speech.

The system of education now established in Japan, both in its Universities and in its public schools, has still many weaknesses and deficiencies, and some glaring faults. Nor are Japanese boys, especially when they have grown older and become more wise in their own eyes, always agreeable to their teachers,[45] or easy to manage and to instruct. But of all this we may perhaps conclude to speak at another time. This at any rate is certain: There are few memories in the life-time of at least one American teacher, which he more gladly recalls, and more delights to cherish, than those which signalise his many meetings with the school children of Japan: and among them all, not the least pleasant is that of the three hundred boys of Kameoka, standing in a row upon the banks of the Katsura-gawa and shouting their “banzais” to the departing boat.

And, indeed, having already described with sufficient fulness how one runs the rapids, admires the banks, perhaps visits a shrine or a tea-house on the way, and arrives in safety to find refreshment and rest at Arashi-yama, there is nothing more worth saying to be said on the subject.

[46]

Between a series of addresses which I had been giving in his church, in early July of 1892, in Tokyo, and the opening of work at the summer-school at Hakoné, Mr. T. Yokoi and I planned an excursion of a few days to the mountainous region in the interior northward of the Capital City. The addresses had been on topics in philosophy—chiefly the Philosophy of Religion. The weather proved as uncomfortable and debilitating as Japanese summer weather can easily be. In spite of this, however, about two hundred and fifty men, with few exceptions from the student classes, had been constant in attendance and interest to the very end; and I was asking myself where else in the world under similar discouraging circumstances, such an audience for such a subject could readily be secured.

The evening before we were to set out upon our trip, I was given a dinner in the apartments of one of the temples in the suburbs of Tokyo. The whole entertainment was characteristic of old-fashioned Japanese ideals of the most refined hospitality; a[47] brief description of what took place may therefore help to correct any impression that the posturing of geisha girls and the drinking of quantities of hot saké is the only way in which the cultivated gentlemen of Japan know how to amuse themselves. As the principal feature of entertainment on this occasion, an artist of local reputation, who worked with water-colours, had been called to the assistance of the hosts; and we all spent a most pleasant and instructive hour or two, seated on the mats around him and watching the skill of his art in rapid designing and executing. The kakemonos thus produced were then presented to the principal guest as souvenirs of the occasion. The artistic skill of this old gentleman was not indeed equal to his enthusiasm. But on later visits to Japan I have enjoyed the benefits of both observation and possession, in instances where the art exhibited has been of a much higher order. For example, at a dinner given by my Japanese publishers to Mrs. Ladd and me, we witnessed what has since seemed to both of us a most astonishing feat of cultivated æsthetical dexterity. The son of one of the more celebrated artists of Japan at that time (1899), himself a workman of much more than local reputation, had after some hesitation been secured to give an exhibition of his skill at free-hand drawing[48] in water-colours. When two or three designs of his own suggestion had been executed, in not more than ten minutes each, the artist asked to have the subjects for the other designs suggested for him. Among these suggestions, he was requested to paint a lotus; and this was his answer to the request. Selecting a brush somewhat more than two inches in width, he wet three sections of its edge with as many different colours, and then with one sweep of hand and wrist, and without removing the brush from the paper, he drew the complete cup of a large lotus—its curved outlines clearly defined and beautifully shaped, and the shading of the inside of the cup made faithful to nature by the unequal pressure of the brush as it glided over the surface of the paper.

After the dinner, which followed upon the display of the painter’s skill, and which was served by the temple servants, the entire party divided into groups or pairs and strolled in the moonlight through the gardens which lay behind the temple buildings. The topic of talk introduced by the Japanese friend with whom I was paired off carried our thought back to the quiet and peaceful life lived in this same garden by the monks in ancient days; and not by the monks only, but also by the daimyos and generals who were glad, after the fretful time of youth was over, to[49] spend their later and latest days in leisurely contemplation. In general, in the “Old Japan,” the father of the family was tempted to exercise his right of retiring from active life before the age of fifty, and of laying off upon the eldest son the duty of supporting the family and even of paying the debts which the father might have contracted. But it was, and still is, a partial compensation for this custom of seeking early relief from service, that the Japanese, and the Oriental world generally, recognise and honour better than we are apt to do, the need of every human soul to a certain amount of rest, recreation, and time for meditation.

The entertainment over, and the uneaten portion of each guest’s food neatly boxed and placed under the seat of his jinrikisha for distribution among his servants on the home-coming, I was taken back to my lodgings through streets as brilliantly lighted as lanterns and coal-oil lamps can well do, and crowded with a populace of both sexes and all ages who were spending the greater part of the night in the celebration of a local religious festival. The necessity of sitting up still later in order to write letters for the mail which left by the steamer next day, and of rising at four o’clock in the morning, to take an early train from a distant station, did not afford the best[50] physical preparation for the hardships which were to be endured during the two or three days following.

It was on applying for a ticket to Yokogawa, which was as far toward the foot of Asama-yama from Tokyo as the railway could take one in those days, that I experienced the only bit of annoying interference with my movements which I have ever met with, when travelling in Japan. But this was in the days of passports and strict governmental regulations for the conduct of foreigners and of natives in their treatment of foreigners. These regulations required that all tourists who wished to visit places beyond ten ri, or about twenty-four and a half miles, distant from some treaty-port, must obtain passports from the Japanese Government by application through the diplomatic representative of the country to which they belonged. The purpose of the proposed tour must be expressly stated; and it must be one of these two purposes,—either “for scientific information” or “for the benefit of the health.” The exact route over which it was proposed to travel must also be stated, and the length of time for which the permission was desired. Applications for more than three months were likely to be refused. It was, further, the duty of every keeper of an inn or tea-house where a foreign traveller wished to pass the night, to[51] take up the passport and hand it over to the local police for inspection and for safe keeping until the departure of his guest. The strictness of the compliance with these regulations, however, differed in different places; and nowhere did they serve to destroy or greatly to restrict the kindness and hospitable feelings of the common people. For example, I recall the pathetic story of a missionary, who had lost his way, and having become so exhausted that he felt he could not take another step, applied for shelter during the night in the hut of a peasant family. The man did not dare to break the law which forbade him to harbour the foreign stranger; but he offered, and actually undertook to carry on his back the tired missionary, to the nearest place where he could obtain legal entertainment!

Some weeks before, after a visit in company with a missionary friend and his family to the Shintō temples at Ise, we had all turned aside for a night of rest at the charming sea-side resort of Futami. The other members of the family felt quite at their ease, for they were armed with their passports for the summer vacation; not so, however, the gentleman who was the family’s head and guardian and my interpreter. For he was without the necessary legal permission to pass the night away from home;[52] while the day’s journey of thirty miles in a basha without springs made the prospect of a return journey that same night anything but desirable to contemplate. But the issue was happy; for the large number of passports furnished by the entire party and duly made over to the police by our host seemed to prove a sufficient covering for us all. And we had come off victorious in another battle with legal restrictions,—a battle royal between the maids, who at the risk of suffocation to human beings, insisted on obeying the law by shutting tight the amado, or wooden sliding doors which formed the outside of our sleeping apartments, and the human beings, who rather than be suffocated, were willing to break the law; since, at best, a modicum of uneasy sleep was to be obtained only in this way. But such petty annoyances are now forgotten; and nowhere else in the world is travel freer and more of kindly pains taken by all classes to make it comfortable and interesting, than in the Japan of the present day.

The policeman at the station being in time satisfied with the legitimacy of the foreigner’s purpose to get where he could ascend Asama-yama, both for purposes of scientific information and for his health, my friend and I took the train for Yokogawa. The railway journey was without incident or special interest.[53] At that date there was a break of about seven miles in the Nakasendō, or “Central Mountain Road,”—the grading and tunnelling being far from complete between Yokohawa and Karuizawa, from which point we intended to make the ascent of the mountain. Although the Nakasendō seems to have been originally constructed early in the eighth century, since it traverses mountainous and sparsely cultivated districts, remote from populous centres, good accommodations for travellers were at that time (1892) not to be had. At present, Karuizawa is one of the principal summer resorts of all this part of Japan; and several thousands of visitors congregate there annually. Travel by jinrikisha up this mountain pass was then difficult and expensive, and we wished to save both strength and time for our walk of the following day. We had, therefore, only the tram as a remaining choice. In the nearly twelve miles of tram-way there were scarcely twenty rods of straight track; and the ascent to be made amounted to some 2,000 feet in all. Yet the miserable horses which drew the small car were whipped into a run almost the entire way. The car itself resembled a diminutive den for wild beasts, such as menageries use in their street parades, although far less commodious or elegant. It was designed to hold[54] twelve passengers; but this complement could possibly be got in, only if the passengers were uniformly of small size and submitted to the tightest kind of packing. By sitting up as straight as I could, and sandwiching my legs in between the legs of the Japanese fellow-traveller on the opposite side, it was barely possible to bring my thigh bones within the limits of the width allowed by the car. Plainly this vehicle was not planned to accommodate the man of foreign dimensions. As we swayed around the perpetually recurring curves of the narrow track, it was rather difficult to avoid slight feelings of nervousness; and these were not completely allayed by being assured that accidents did not happen so very often; nor, more especially, by the sight of a horse and cart which had plunged off the roadway to the valley forty or more feet below, where the animal lay dying and surrounded by a little crowd of those calm and inactive spectators who, in Japan, are so accustomed to regard all similar events as shikata-ga-nai (or things which cannot be helped). We arrived, however, at Shin (or New) Karuizawa, somewhat jumbled and bruised, but in safety; and here we at once took jinrikishas for the older place of the same name.

Asama-yama is the largest now continuously active[55] volcano in Japan. Its last great and very destructive eruption was in the summer of 1783, when a vast stream of lava destroyed a considerable extent of primeval forest and buried several villages, especially on the north side of the mountain. Over most of this area the villages have never been rebuilt. Even the plain across which we rode between the two Karuizawas, and which lies to the southeast, is composed of volcanic ash and scoriæ; and since 1892, stones of considerable size have often been thrown into the yards of the villas inhabited by the summer visitors in this region. Yet more recently, there have been exhibitions of the tremendous destructive forces which are only biding their time within the concealed depths of this most strenuous of Japan’s volcanos. On the south side of the mountain rise two steep rocky walls, some distance apart, the outer one being lower and partly covered with vegetation. It is thought by geologists that these are the remains of two successive concentric craters; and therefore that the present cone is the third of Asama-yama’s vent-holes for its ever-active inner forces.

It had been our intention to follow what the guide-book described as the “best plan” for making the ascent of the volcano; and this was to take horses from the old village of Karuizawa, where it[56] was said foreign saddles might be procured, ride to Ko-Asama, and then walk up by a path of cinders, described as steep but good and solid, and plainly marked at intervals by small cairns. First inquiry, however, did not succeed in getting any trace of suitable horses, not to mention the highly desirable equipment of “foreign saddles.” After taking a late and scanty luncheon in a tea-house which for Japan, even in the most remote country places, seemed unusually dirty and disreputable, we went out in further search of the equipment for the climb of the next day. On emerging from the tea-house, right opposite its door, we came upon a gentleman in a jinrikisha, who was a traveller from America—a much rarer sight in those parts twenty years ago than at the present time. Salutations and inquiries as to “Where from” and “What about,” were quickly interchanged as a matter of course. It turned out that we were making the acquaintance of the father of one of the Canadian missionaries, who was visiting his son and who was at that very instant on his way to the station to take train to Komoro, a village some fourteen miles over the pass, from which that night a party of ten or twelve were planning to ascend Asama-yama by moonlight. Permission was asked and cordially[57] given for us to become members of this party; and the gentleman in the jinrikisha then went on his way as rapidly as the rather decrepit vehicle and its runner could convey him.

As for us, all our energies were now bent on catching that train; for it was the last one of the day and it was certain that our plans could not easily be carried out from the point of starting where we then were. Our belongings were hastily thrust into the bags and a hurry call issued for jinrikishas to take us to the station. But our new acquaintance had gone off in the only jinrikisha available in the whole village of Karuizawa. What was to be done? A sturdy old woman volunteered her assistance; and some of the luggage having been mounted on a frame on her back, we grabbed the remainder and started upon a sort of dog-trot across the ashy plain which separated the tea-house by more than a mile and a half from the railway station. As we came in sight of the train, the variety of signals deemed necessary to announce by orderly stages the approach of so important an event gave notice to both eyes and ears that it was proposing soon to start down the mountain pass; and if it once got fairly started, the nature of the grade would make it more difficult either to stop or to overtake it. My[58] friend, therefore, ran forward gesticulating and calling out; while I assisted the old woman with the burdens and gave her wages and tips without greatly slackening our pace. The railway trains of that earlier period, especially in country places, were more accommodating than is possible with the largely increased traffic of to-day; and the addition of two to the complement of passengers was more important than it would be at present. And so we arrived, breathless but well pleased, and were introduced to several ladies in the compartment, who belonged to the party which proposed to make the ascension together.

The route from Karuizawa to Komoro is a part of what is considered by the guide-book of that period, “on the whole the most picturesque railway route in Japan.” The first half is, indeed, comparatively uninteresting; but when the road begins to wind around the southern slope of Asama-yama, the character of the scenery changes rapidly. Here is the water-shed where all the drainage of the great mountain pours down through deep gullies into rivers which flow either northward into the Sea of Japan or southward into the Pacific. From the height of the road-bed, the traveller looks down upon paddy-fields lying far below. The mountain[59] itself changes its apparent shape and its colouring. The flat top of the cone lengthens out; it now becomes evident that Asama is not isolated, but is the last and highest of a range of mountains. The pinkish brown colouring of the sides assumes a blackish hue; and chasms rough with indurated lava break up into segments which follow the regularity of the slopes on which they lie.

Komoro, the village at which we arrived just as the daylight was giving out, was formerly the seat of a daimyo; but it has now turned the picturesque castle-grounds which overhang the river into a public garden. It boasted of considerable industries in the form of the manufacture of saddlery, vehicles, and tools and agricultural implements. But its citizens I found at that time more rude, inhospitable, and uncivilised than those I have ever since encountered anywhere else in Japan. Our first application for entertainment at an inn was gruffly refused; but we were taken in by another host, whom we afterwards found to have all the silly dishonest tricks by which the worst class of inn-keepers used formerly to impose upon foreigners.