[1]

Hyphenations have been standardised.

Changes made are noted at the end of the book.

THE AUTHOR.

OR

Through the Emerald Isle With

an Aeroplane.

BY

ALEXANDER CORKEY

AUTHOR OF

“The Victory of Allan Rutledge—A Tale of the Middle West.”

WITH AN INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER

SHOWING THE

BRIGHT FUTURE OF IRELAND

BY

HON. WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN.

Published by Shockley Bros. & Cook, Oskaloosa, Iowa.

Published in London, England, by Richard J. James, Publisher,

London House Yard, St. Paul’s, E. C.

DEDICATED

TO

MESSRS. WILBUR AND ORVILLE WRIGHT,

INVENTORS OF THE AEROPLANE AND CONQUERORS

OF THE AIR

COPYRIGHT, 1910, BY ALEXANDER CORKEY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

[7]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| INTRODUCTORY BY HON. W. J. BRYAN | 13 | |

| I. | THE BEGINNING OF MY AEROPLANE TRIP THROUGH IRELAND | 18 |

| II. | FLYING OVER KILLARNEY IN AN AIRSHIP | 26 |

| III. | OUR EXPERIENCES IN COUNTY KERRY | 33 |

| IV. | A THRILLING VISIT IN CONNEMARA | 39 |

| V. | ALMOST A DISASTER | 45 |

| VI. | FROM WESTPOINT TO ENNISKILLEN | 49 |

| VII. | A DAY IN ENNISKILLEN | 55 |

| VIII. | CIRCLING OVER LONDONDERRY IN AN AEROPLANE | 60 |

| IX. | ALIGHTING AT THE GIANT’S CAUSEWAY | 67 |

| X. | OUR REST ON THE ANTRIM COAST | 73 |

| XI. | A FLIGHT IN AN AEROPLANE WITH AN IRISH GIRL | 80 |

| XII. | OVER AND AROUND BELFAST | 87 |

| XIII. | ALIGHTING IN DROGHEDA | 93 |

| XIV. | WITH FRIENDS IN DUBLIN | 98 |

| XV. | GUESTS IN AN IRISH HOME | 104 |

| XVI. | AROUND THE CAPITAL CITY OF IRELAND | 111 |

| XVII. | WICKLOW, THE GARDEN OF IRELAND | 115 |

| XVIII. | BACK AGAIN TO CORK | 123 |

| XIX. | OUR LAST DAY IN IRELAND. SEEING TIPPERARY | 127 |

| FRONTISPIECE, | The Author |

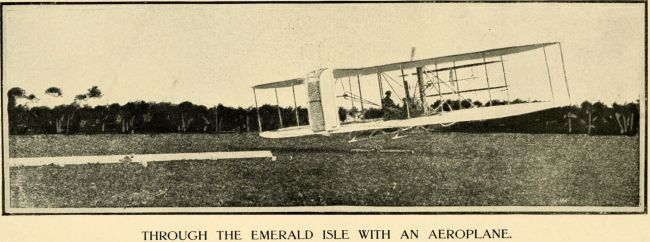

| THROUGH THE EMERALD ISLE WITH AN AEROPLANE, | Opposite Page 24 |

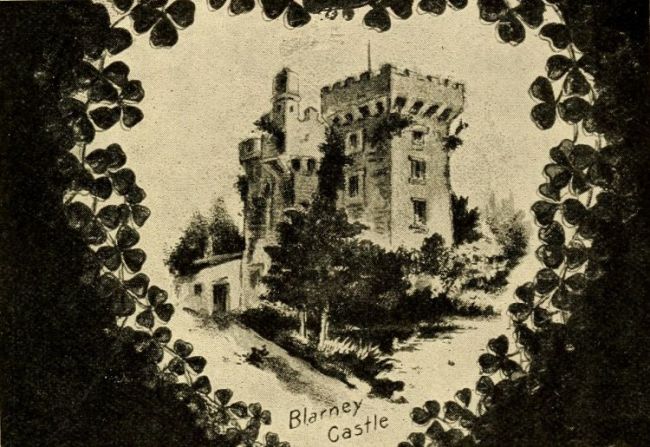

| BLARNEY CASTLE, | Opposite Page 32 |

| AN IRISH CABIN, | Opposite Page 40 |

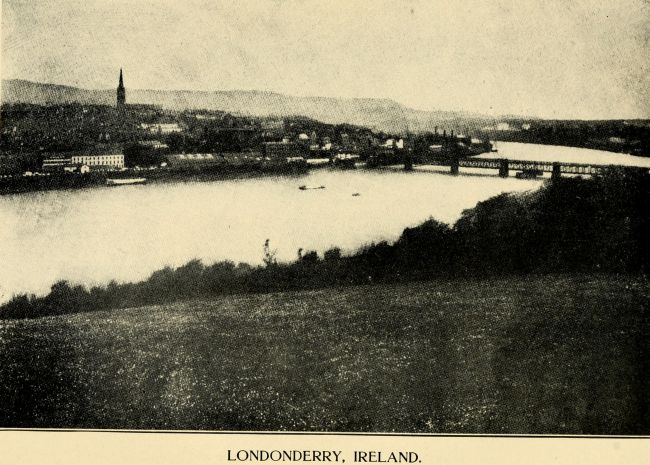

| LONDONDERRY, IRELAND, | Opposite Page 60 |

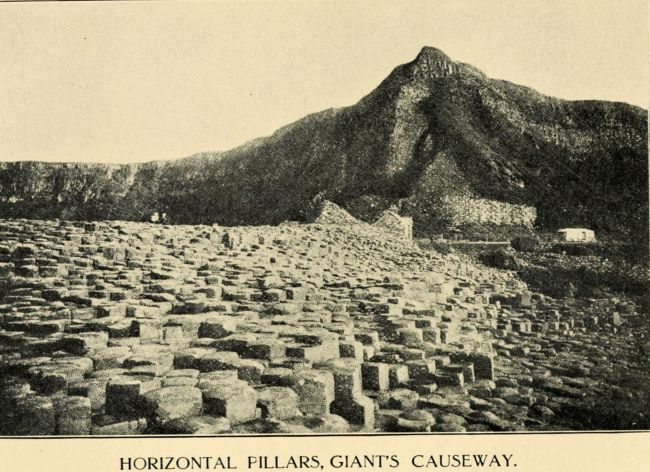

| GIANT’S CAUSEWAY, | Opposite Page 74 |

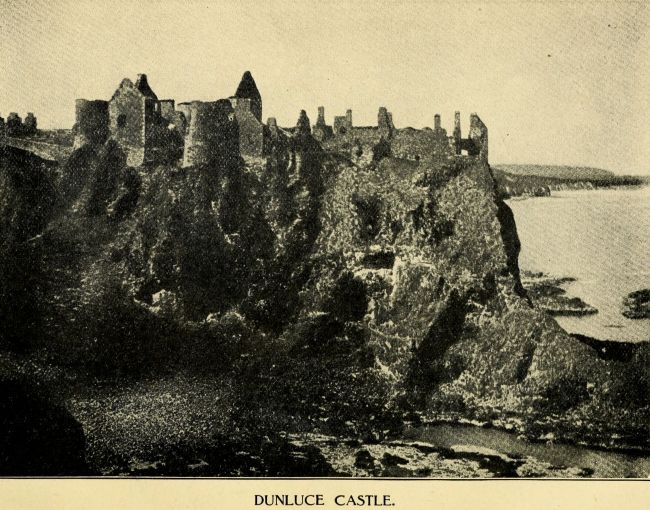

| DUNLUCE CASTLE, | Opposite Page 82 |

| AN IRISH JAUNTING CAR, | Opposite Page 96 |

| AN IRISH VILLAGE, | Opposite Page 120 |

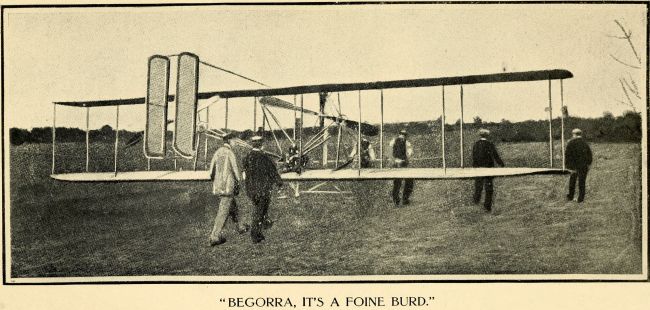

| “BEGORRA, IT’S A FOINE BURD,” | Opposite Page 132 |

Preface

The aeroplane is man’s latest invention. Through it man has become lord of the air. The steamship and steam engine had already given him victory over sea and land. Now he is complete master of the situation.

One of the most delightful uses of the aeroplane is in sightseeing. Aerial tourist travel will soon become popular, as a bird’s-eye view of a country is the most satisfactory of all.

For several reasons, however, many will be unable to enjoy this latest luxury, traveling IN THE BODY, but WITH THE MIND everyone who desires can enjoy in the following pages, an aeroplane trip through Ireland, fairest of all lands.

This mental excursion in the aeroplane has obvious advantages over a like physical experience, as every aeronaut will cheerfully acknowledge. Future aerial travelers over Erin will be able to witness to the truthfulness of this bird’s-eye view of Ireland, and I trust the historical allusions will add to the interest of our survey of the island’s lovely scenes. The visits to Irish homes, and the glimpses of Irish character will also, I am sure, be enjoyed.

I wish to thank Hon. William Jennings Bryan for the Introductory Chapter, in which, from the viewpoint of a practical statesman, he shows the bright future of the Emerald Isle. The full account of this famous visit of his to Ireland was published in the Commoner, which owns the copyright.

THE AUTHOR.

[13]

Introductory Chapter

SHOWING THE BRIGHT FUTURE OF IRELAND

BY

HON. WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN

My visit to Ireland was too brief to enable me to look into the condition of the tenants in the various parts of the island, but by the courtesy of the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Mr. Timothy Harrington, and Mr. John Dillon, both members of Parliament, I met a number of the prominent representatives of Ireland in national politics.

It is true that home rule has not yet been secured, but the contest for home rule has focused attention upon the industrial and political condition of Erin, and a number of remedial measures have been adopted.

First, the tenant was given title to his improvements and then the amount of the rent was judicially determined. More recently the authorities have been building cottages for the rural laborers. Over 15,000 of these cottages have already been erected and arrangements are being made for some 19,000 more. These are much more comfortable than the former dwellings, and much safer from a sanitary point of view. The recent Land Purchase Act, which went into effect on[14] November first, (1903), seems likely to exert a very great influence upon the condition of the people. According to its terms the Government is to buy the land from the landlord and sell it to the tenants.

As the Government can borrow money at a lower rate than the ordinary borrower, it is able to give the tenant much better terms than he gets from his present landlord, and at the same time purchase the land of the landlord at a price that is equitable. The landlords are showing a disposition to comply with the spirit of the law, although some of them are attempting to get a larger price for their land than it was worth prior to the passage of the law.

The purpose of the law is to remove from politics the landlord question, which has been a delicate one to deal with. Most of the larger estates were given to the ancestors of the present holders, and many of the owners live in England and collect their rents through a local agent. The new law makes the Government the landlord; and the tenant, by paying a certain annual sum for 63 years, becomes the owner of the fee. He has the privilege of paying all, or any part, at any time, and can dispose of his interest.

The settlement which is now being effected not only removes the friction which has existed between the tenant and the landlord, but puts the tenant in a position where he can appeal to the Government with reasonable certainty of redress in case unforeseen circumstances make his lot harder than at present anticipated.

[15]

The assurance that he will become the owner of the fee will give to the Irish farmer an ambition that has heretofore been wanting, for he will be able to save without fear of an increase in the rent.

Not only is the land question in process of settlement, but there has been at the same time other improvements which make for the permanent progress of the people. There is a constant increase in educational facilities, and a large number of co-operative banks have been established. Agricultural societies have been formed for the improvement of crops and stock, and the trend is distinctly upward. The Irish leaders have not obtained all that they labored for—there is much to be secured before their work is complete, but when the history of Ireland is written, the leaders now living will be able to regard with justifiable pride the results of their devotion and sacrifice and their names will be added to the long list of Irish patriots and statesmen.

In Dublin I paid my respects to Lord Dudley, Lieutenant Governor of Ireland, whose residence, the Viceregal Lodge, is in Phoenix Park, and found him so genial and affable a host that I am led to hope that in his administration of the executive branch of the Government he will make the same attempt at just treatment that parliament has made in the enactment of the recent land measures.

Dublin is a very substantial looking city and much more ancient in appearance than Belfast, the latter reminding[16] one more of an enterprising American city. We did not have a chance to visit any of the industries of Dublin, and only a linen factory and a shipyard in Belfast, but as the linen factory, The York Street Linen Mills, was one of the largest in Ireland, and the shipyard, Harland and Wolff’s, the largest in the world, they gave some idea of the industrial possibilities of the island.

Queenstown, Ireland, the first town to greet the tourist when he reaches Northern Europe and the last to bid him farewell when he departs, is a quaint and interesting old place. Here the returning traveller has a chance to spend any change which he has left, for blackthorn canes and shillelaghs, “Robert Emmett” and “Harp of Erin” handkerchiefs and lace collars are offered in abundance. At Queenstown one can hear the Irish brogue in all its richness and, if he takes a little jaunt about the town, he can enjoy the humor for which the Irish are famed.

To one accustomed to the farms of the Mississippi and the Missouri valleys, the little farms of Ireland seem contracted indeed, but what they lack in size they make up in thoroughness of cultivation. The farm houses are not large, but from the railroad train they looked neat and well kept.

There is a general desire among the leaders of thought in Ireland to check the emigration from that country. They feel that Ireland, under fair conditions,[17] can support a much larger population than she now has. Ireland, they say, has been drained of many of its most enterprising and vigorous sons and daughters. It is hardly probable that the steps already taken will entirely check the movement towards the United States, but there is no doubt that the inhabitants of Ireland and their friends across the water contemplate the future With Brighter Hopes and Anticipations than they have for a century.

[18]

BEGINNING OF MY AEROPLANE TRIP THROUGH IRELAND

It all happened in this way. Early last summer I was travelling through Ohio and came to the prosperous city of Dayton. While spending a few days visiting in this enterprising city, a friend met me, and proposed to call on the Wright Brothers, who had won wide fame as the men who knew how to fly.

I was rather skeptical about a man contesting the atmosphere with the fowls of the air. I had a private opinion that Mother Earth was meant for man, and that the nearer he kept to it the better. I went to see these aeronauts with a prejudice against the flying business.

We soon found the airship factory, and we were introduced to Mr. Wilbur Wright. He greeted us very cordially, and even took us around his factory, showing us an aeroplane and explaining its workings. I was astonished at the simplicity of the airship and was impressed with the enthusiasm of the successful young aeronaut. I began to thaw out. I asked a lot of questions. Before half an hour had passed by I was a convert to the flying business, and made up my mind that Mr. Wright was a “bird.” He had discovered not only how to fly, but also, which is more important, how to light.

[19]

That was the beginning of my interest in aeroplanes. I do not expect that anything wonderful would have come out of my Dayton experience had I not journeyed the next week to New York State to visit an old-time friend, Mr. Mike Connor. Naturally, I began to display my new-found knowledge about aeronautics on the first opportunity. To my great surprise I found that Mr. Connor was also an enthusiastic aeroplanist. I found he knew all about flying. When I expressed wonder at his knowledge of this recent art of cleaving the heaven’s blue, he told me he had been studying the matter for a long time. He said he could get few of his friends to take any stock in this latest victory of man over nature, and he was delighted to find me a sympathetic listener to his descriptions of the coming uses of flying machines.

Looking carefully around the room, as if to see that no unfriendly ear could hear, he finally confessed to me in a stage whisper:

“I have an aeroplane of my own. I bought it two months ago, and I can now fly with it beautifully.”

“Good,” I cried, “let me see it.”

He at once took me out to the shed where he kept the “bird.” I looked it over with intense interest, which pleased my good friend, Mike, (as I must call him) very much. It was a Wright aeroplane, about the same size as the one Mr. Wilbur Wright had shown me at Dayton. The two main planes, like the top and bottom of a[20] street car, were 40 feet long and 7 feet wide. The distance between the upper and lower planes was 6 feet. These planes were covered with a stout cloth, like tent cloth. There were two small horizontal planes in front, controlled by levers, by which the aeroplane was raised or lowered at will when it was in the air. At the rear there was also a double set of planes, vertically placed, to assist in turning the airship, just as a helm turns a ship in the water. Motion was generated by two large propellers, seven feet long, made of spruce wood, which ran in opposite directions. Power was furnished by a compact, 25-horse power motor, which Mike, whom I knew to be an expert with gasoline engines, said was one of the best he ever handled.

“Just as reliable as steam,” he assured me, when I spoke of the unreliability of the ordinary motor.

Mike explained to me how to start, how to rise and descend, and how to turn in the air.

I asked him why he had not let me know about this new treasure before, and he told me his friends to whom he had spoken about it had treated him so coldly, that he had ceased to mention the matter, but he had quietly been practicing with his machine until now he was able to fly anywhere. There was a large meadow back of his house, surrounded by thick groves, and in this secluded spot he had spent weeks perfecting himself in the art of flying.

As it was too late that day for a flight he promised[21] to take me on my first jaunt among the clouds next morning.

I had known Mike Connor since he was a boy. His father had left him a lot of money, but he was not the usual wild kind of heir. He looked after his estate closely, but, having a heap of time on his hands, he was always ready for a diversion. When the bicycles first came out, he had two or three of the finest makes. He was the very first in his neighborhood to purchase an automobile, and he soon became an expert with his motor car. Accordingly, I was not surprised to know that he had so soon mastered the use of the aeroplane.

When we came back to the house he asked me suddenly:

“Jack, what are you going to do this summer?”

“I have been planning,” I replied, “to take a run across the fish pond and visit old Ireland again.”

“Good,” he fairly shouted.

I looked at him a little curiously, wondering why he was so interested in my visit to the Emerald Isle.

“Let us go together,” he continued enthusiastically, “and take the aeroplane.”

This was certainly a novel proposition, and I laughed so heartily at the idea of flying through Ireland that Mike got impatient.

“Don’t you think we can do it?” he asked.

“Let us wait till morning,” I answered evasively, “and we will see about it.” Mike’s face fell, and I[22] could see he thought I was not a thorough convert to the aeroplane art.

There is something of the Scotchman about me, and I wanted to know a little more about the “bird” business before I started on a vacation trip with wings. An Irish bog would not be a bad place for an aeronaut to alight in case he had to descend unceremoniously, but I didn’t want to spoil a nice outing in Ireland by breaking my neck trying to fly.

The next morning we were up with the birds and soon had the aeroplane all ready for a flight. The Wright aeroplane ascends from a “starting rail,” which is merely a stout board turned up on end.

The meadow was an ideal place to fly. It was an immense level field, about half a mile long, and quarter of a mile broad. I had all confidence in Mike and had no reason to believe he meant to destroy me, but I was just a little shaky as I climbed up into the second seat over the motor.

Mike vaulted easily into his seat, started the motor, and in a few seconds we were off. I can never describe the excitement of the next ten minutes. We rose to the height of about 80 feet, and then sailed rapidly round and round the field. The sensation of flying was something entirely new. I was exhilarated, charmed, delighted. After I became a little used to it I was able to observe the field below, which glided under us with marvelous speed.

[23]

After ten minutes of this thrilling experience Mike decided to land, as he did not wish to try my nerves too severely the first time. The landing was perfect. Mike shut off the motor at a height of 70 feet, and the aeroplane came gliding down like a big bird. I could not tell just when we came to earth, so gently did the airship alight. It glided along on its runners for a short distance and then came quietly to a stop.

I stepped out on the grass like a man in a dream.

“How did you like it?” asked Mike.

For answer I fairly hugged him. He was pleased and asked at once about a trip through Ireland.

“It would be grand,” I exclaimed, “let us go.”

We had several other flights together and we were both confident that we could have a glorious time in the Emerald Isle with an airship.

We soon completed our arrangements. The aeroplane was taken to pieces and carefully packed. Each box was marked “Queenstown.”

In three weeks’ time we were ready to start. We booked on the Lusitania, and, as the boxes, in which our aeroplane was stored, were taken on board as baggage, we landed in five days at Queenstown, airship and all.

I had crossed the Atlantic several times before, but this voyage was the most exciting of all. We sat on deck and talked of our plans when we landed. Mike was sure of his ability to fly a day at a time, and so we outlined a strenuous program. I was well acquainted[24] with Ireland, and I had marked our stopping places as we would fly through the island.

Sometimes fear of failure would take possession of my mind. The whole thing was so novel. Such a thing as flying round a country on a sightseeing trip had never been attempted. I was fearful I had been rash.

A talk with Mike always sent these fears to the winds. He had no fears whatever.

As Mike was to have the chief share in piloting our airship, I decided to take generous notes and prepare a full account of the places we visited and our most exciting experiences as we flew over the green fields of Erin. From these notes I have prepared for the world the account of our trip which is found in the following chapters.

We had not breathed a word about our plans to anyone on board during our voyage across the Atlantic, and when we landed at Queenstown we quietly sent on our “baggage” to Cork, and followed ourselves that evening. We had planned to begin our flight from Cork. We expected to fly around the island in a couple of days and then visit some attractive places one by one. We were compelled to change this plan, as we shall see.

After a good night’s rest at the Imperial Hotel in Cork, we “assembled,” as aeronauts say, the various parts of our airship the next morning on a level field just outside the city.

We avoided the public as much as possible, and the few people who came around found us non-committal, and wondered what we were doing.

THROUGH THE EMERALD ISLE WITH AN AEROPLANE.

[25]

In the evening when we were left alone, about nine o’clock, (it is still quite light at this time in Ireland during July) we made a short trial ascent. Our first flight beneath the kindly Irish skies was a complete success. Everything was working beautifully.

Well satisfied with our first day’s work we returned to our hotel for the night. Our plan was to fly the first day as far as the Giant’s Causeway, going up the West side of the island. On the second day we expected to return to Cork and make trips here and there after that.

We had another good night’s rest, and rose with the sun, or rather a little before it. We found our aeroplane in the field as we left it, and after carefully examining every part, Mike said:

“All right, Jack. Let us start.”

I climbed up on my seat. Mike started the motor. The machine began to move along the starting rail, and rose like a bird. When we had gone up to about the height of 200 feet we circled around over Cork. In the dawning light we could see the strange tower of the Church of Saint Mary Shandon, St. Patrick’s Street, and the beautiful Cathedral of St. Finbar’s. I could also distinguish Queen’s College.

Turning in a northwestern direction, Mike said to me:

“Now we’re off.”

We were speeding through the air towards Killarney.

[26]

FLYING OVER KILLARNEY IN AN AIRSHIP

It was just 4:30 by my watch as we started from Cork on that eventful 11th day of July. There was good daylight, but the city was still wrapped in its slumbers.

It was a beautiful summer morning and our spirits rose with the aeroplane. We began the strangest trip through Ireland that was ever made by man. I can never forget the sight of the green fields of County Cork that morning. It was a scene of peaceful loveliness.

The first place of interest we passed over was Blarney Castle, which is only five miles from Cork. We swept directly over the famous ruin, and I had a strange feeling as I looked down on the far-famed fortress from my aerial seat. As I had been at Blarney Castle before I was able to locate that part of the wall where the Blarney Stone is seen. I tried to point it out to Mike, but, before I could get the place described, we had flown over it. We learned that to describe anything like that on the aeroplane you have to look as far ahead as possible. I had no idea the country around Blarney was so beautiful until I had a good bird’s eve view of it. I was convinced that we would see all the scenic beauties of Ireland from our aeroplane as they had never been seen before.

[27]

The distance from Cork to Killarney is 50 miles as the crow flies, and as we were now traveling like crows we measured distances as they did. We could see the River Lee at our left as it meandered through the neat farms and little fields of the Cork farmers. The pleasant-looking cottages fairly flew beneath us. We were surprised to see so much of County Cork under cultivation, as we expected to see it all in grazing land. I found out later that under the beneficent new Land Laws most of these small farmers now own their own farms, and that this part of Ireland is prospering.

It was a perfect picture that met our gaze as we looked around. The small fields were divided with thick hedges, or stone walls, sometimes with a wall of earth. Groves were frequent. Here and there a lordly mansion peered out at us through the trees.

Quite a distance to our left we could see Macroom, where the railroad from Cork ends. It looked so quiet and still in that region that morning that I was reminded that there was a tradition that the gentle Quaker, William Penn, was born there. Penn’s father had a seat at Macroom, but I think the young William gave his first cry in London. At least, I once saw the font in a London church in which he was immersed as a tiny infant.

“Now for the mountains,” said Mike, as the Kerry hills drew near. Their peaks loomed up before us big as the Himalayas. Mike began to raise the airship higher and higher.

[28]

Right here I want to confess that often throughout the whole trip in this aeroplane with Mike I had shaky feelings that were a little unpleasant. Once in a while in imagination I could see myself tumbling over and over to the ground, like a wounded bird. Nor were my fears altogether groundless, as we shall see. If Mike had any such apprehensions he never said a word to me about it. I rather think he was so busily engaged constantly with the operation of the aeroplane that he had little time to think of anything else. I had much better chance to see the country than he did, but I also had more time on my hands during which I could conjure up all kinds of disasters. I well remember that, as we rose to a dizzy height, in order to clear the Kerry Mountains, I had almost a nervous attack. For a moment I shut my eyes and heartily wished I was on the earth again. If I could have gotten safely to land just then, I am afraid that all the gold in Ophir would not have tempted me to fly again. I was roused by a cry from Mike.

“Look,” he fairly shouted, “isn’t that grand?”

I opened my eyes quickly and saw Mike, with his face all aglow, gazing on a high peak which we soon recognized as Mount Mangerton.

It towered far above us, high as we were, for this peak is over 2,700 feet high. Soon the Devil’s Punchbowl, another high mountain peak, with a flat top, came into view. This mountain, which is over 2,600 feet[29] high, is easily recognized. Formerly it was a volcano, but long ago burnt itself out. The crater is now filled with clear, cold spring water, which is piped to the village of Killarney. It is surely an Irishism to call this beautiful water from this huge natural reservoir the “devil’s punch.”

We were looking so intently on these great hills that we crossed the crest of the divide before we were aware. All at once Mike startled me again.

“In the name of all that is great, look there,” he exclaimed.

Never can I forget the sight that lay before us as I lowered my eyes and caught my first glimpse of the Vale of Killarney. The panorama was one of surpassing loveliness. There was no fear whatever in my heart now. All was wonder, admiration, delight. The three Killarney Lakes lay embosomed among the towering hills. The Lakes are fully eleven miles long and at one place two and a half miles broad. Magnificent forests fringe them on every side, and over sixty wooded islands float in the charmed waters. Just ahead of us was Muckross Abbey. This ancient Abbey was founded in 1440 by the McCarthys, and is a notable ruin. The walls and tower are in good condition. We could see the ivy glisten in the morning light from the top of the tower, and I caught a passing glimpse of the gigantic yew tree, nearly fourteen feet in circumference, which every visitor to Muckross Abbey will remember.

[30]

“Hurrah for old Ireland,” cried Mike, as we glided down to within 150 feet of the waters of the Upper Lake. We soon rose again to about 300 feet above the water, as this gave us the best view, and at this altitude we sailed triumphantly along the entire course of the Lakes.

Here we first noticed the effect that an aeroplane had on the ordinary denizens of the earth. It was now 6:00 o’clock, and some early risers among the tourists at Killarney were enjoying the marvels of a Killarney morning along the banks. We could hear their excited exclamations as they caught sight of us, but we flew on majestically.

We soon passed the two smaller Lakes, which are joined by short narrow streams, and discerned Ross Castle clothing itself with all the glories of a morning of sunshine as it has done, every time it has had a chance, for 600 years. I say “every time it has had a chance” advisedly, for all who are acquainted with Killarney weather know that this fine ruin is often compelled to clothe itself with morning mists and rain.

Ross Castle was on our right and, beyond it, we could see Kenmare House, the home of the Earl of Kenmare, who owns Killarney. It is situated in the midst of a lovely park, with beautiful gardens, covering fully 1900 acres of woodland and lawn. However, as Mike and I sailed past it in our airship we would not have exchanged places with the Earl himself. Beyond Kenmare[31] House we could see Killarney village straggling along amongst the trees. We were now crossing the Lower Lake, which is the largest, being nearly six miles long. We turned to our left and gazed with awe at the towering peaks which enclose this scene of beauty. The shifting of the light among the hills was glorious. Looking over our shoulders to the left we caught sight of Carntual, over 3,400 feet high, the highest mountain in Ireland. Altogether there are six prominent peaks, and as they rise from the level they make a majestic scene. We passed directly over the Innisfallen island. This large and beautiful island in the Lower Lake covers twenty-one acres and from above it looked like “a beautiful miniature of a beautiful country.” We could see the famous ruins of Innisfallen Abbey on the island. This Abbey was founded in 600 by St. Finian, and it is one of the oldest ecclesiastical ruins in Erin. The Irish poet, Thomas Moore, has immortalized this little Island in his ode:

“Sweet Innisfallen, fare thee well.”

After passing Innisfallen we discussed our further route. Mike wanted to circle over the Lakes again, but I objected. I wanted to carry away the remembrance of Killarney as I had seen it for the first time from an aeroplane. I was afraid a second look would take away some of the charm. Mike also wanted to go up the Gap of Dunloe, but I also objected to this, as I wished to hurry on direct to the North of Ireland that day. We compromised[32] by agreeing to turn around at the north end of the lakes, and make a circle over the north part of Lower Lake, while we took our last look at Killarney’s Vale.

When we had finally turned our backs on the glorious scene and Mike started north over the high plains, I repeated softly:

Mike roused me rudely from my dreams by remarking:

“These two angels haven’t folded their wings from the looks of things. See how the ground flies past.”

I laughed good-naturedly and gradually woke up from the spell of the beauteous Lakes of Killarney.

I pulled out my watch. It was 6:20. A short time later we caught sight of the railroad between Killarney and Tralee and followed it about 100 feet above the tracks.

Blarney Castle

[33]

OUR EXPERIENCES IN COUNTY KERRY

As we winged our way above the railroad ties we rested after the excitement of Killarney. We were now in the heart of Kerry. This part of Ireland is not as prosperous as some other parts. The land is hilly and rocky. Fences are generally made of stone. The little cottages are also built of stone, thatched with straw. We could see the stack of peats beside them to be used as fuel, and the little potato patch which furnished food. Blue smoke was beginning to curl in the air from some of these cabins, telling us that rural Ireland was awakening for another day of life, such as it is.

Of all the sensations that ever visited Ireland, we surely were the greatest in modern times. We were much amused to see the different ways in which our appearance in the air was greeted. Sometimes the children (plentiful throughout all Ireland) would be playing in front of the cabin. As they heard the noise of our motor we could see them stop their play and gaze at us in amazement, and then, with a yell, all would dive at once for the door of their home. The mother, generally with a baby in her arms, would appear quickly. Sometimes the woman would shriek, like the children, and run inside again. At other times we noticed the women[34] get down on their knees, as in prayer. Once or twice, the woman ran out and waved her arms at us, as though in greeting. The men generally looked stolidly at us in mute amazement.

We had an exciting time when passing a morning train coming from Tralee. We could see it smoking in the distance, and to avoid a collision, as Mike said, we turned the aeroplane about 100 feet to the right side of the track. The engineer caught sight of us first, and signalled us with a number of toots on his whistle. The tooting brought the passengers to the windows and soon heads were sticking out along the side of the train from one end to the other. They waved their hats, handkerchiefs, umbrellas, newspapers, and I saw one old gentleman vigorously shaking a book at us. I took out my handkerchief and waved it in return. The engineer kept tooting his whistle until he was far past us.

We watched the little Kerry cows, which looked carefully for any stray vegetation to be found in the Kerry uplands, for we had heard that the Kerry cow never looks up, for fear it would lose a bite. Certainly none looked up at us. Cows and men have a serious time of it in Kerry, forcing a churlish soil for daily food. Many of the men in Kerry spend part of the year in England working there, while the wives and children look after the cabbage and potato patches. We saw pigs and goats, and a few sheep around some of the cottages.

The English Government has a Board, called the[35] Congested Districts’ Board, which is at present doing excellent work in assisting the people of Kerry and others of these hilly western counties. This board aids in migration to other parts of Ireland, if it is found necessary, and also assists in developing the country as far as is possible. Breeds of stock are improved through its help, and industries, such as rug-making, lace-making and basket-making, are encouraged. This Board has also been useful in developing the fisheries industry on the west coast by constructing landing places and equipping boats for the fishermen.

As the morning advanced, and the entire population had aroused itself we were kept in a state of continual amusement by the excitement we caused, as we whizzed across the solitary moors. I felt real sympathy with Bridget, who, as she walked from the wedding altar on Pat’s arm, whispered to him:

“If we could only stand and see ourselves now, wouldn’t it be hivin, Pat?” I felt if we could only see ourselves from the ground and hear the comments of the natives our bliss would have been full.

We passed Tralee at 6:35. This is a pretty town situated on Tralee Bay. There are many beautiful residences in its neighborhood. Lord Kirchener was born here.

We were 200 feet in the air when we swept at full speed over the closely built houses of the town. We could see a few people stirring on the streets and they[36] looked up at us in wonder, but did not make any manifestation. Evidently they knew what an aeroplane was.

After passing Tralee we kept close to the coast, and soon saw the wide mouth of the river Shannon ahead of us. This is Ireland’s largest river, 220 miles long, pouring itself into the sea North of County Kerry. The Kerry coast is rather bleak and it was with a feeling of relief that we rushed across the wide mouth of the Shannon into County Clare.

Here our motor gave its first trouble. As we were crossing the Shannon it alarmed me by beginning to “knock” (as motorists say) and Mike told me the sparker was not working properly. We had planned to make our first landing at Kilkee on the coast of Clare, and, as this was not far distant, Mike kept on at full speed along the coast. The coast scenery here is rugged and grand. Kilkee is situated at the head of a little bay, called Moore’s Bay. When we reached this bay Mike sped clear out over its waters, to my amazement, and then turned up the bay to Kilkee.

Coming up the bay we could see much excitement on the shore near the town. People were running down to the shore from all directions. Mike circled over the town, about 300 feet in the air, and then came down on a level stretch of coast beside the village.

Kilkee is over 100 miles from Cork, as the crow, or aeroplane, flies. We landed exactly at 8:00 o’clock. As I stepped from my seat, I felt stiff and lame, but a little[37] exercise straightened me out. Mike busied himself at once with the motor. He began unscrewing the spark plugs and overhauling the whole engine.

Meanwhile the crowd kept gathering until, I suppose, in ten minutes, the entire town was standing around us open-mouthed. The boys in the crowd closed in on us at once and began asking all sorts of questions. When we told them we were from America the buzz of excitement grew louder, as they thought at first that we had crossed the Atlantic, since we came directly from the sea. Mike, at last, explained that we had only come from Cork that morning. This was wonderful enough to them and we heard all kinds of exclamations. “The Saints preserve us,” said one good lady, with a shawl wrapped around her head, “what’s the world coming to?”

“Begorra,” said a genuine Irishman, “I never thought they could make a crow out of a man.”

Some volunteered the information that they had sons, or brothers, in America, and it was not long until the crowd and us were on familiar terms. We hired two honest-looking fellows to watch the aeroplane, and keep the boys off from it, while we went down the straggling street of the town, looking for a place to get some refreshments.

A man, whom one of the bystanders assured us was “the bist man in town,” took us in charge and escorted us to his own home. His good wife, a kindly, middle-aged[38] Irish woman of the middle class, soon had a cup of hot tea and some “scones” ready for us. This was our first taste of Irish hospitality and it astonished us.

We found our host a most companionable man. When we explained our plans about an aeroplane trip all around Ireland, he said:

“You Americans can do anything.”

Our host accompanied us back to the airship where there was still the same wondering crowd. The two watchmen were busy keeping the little lads away from the machine. They helped Mike arrange the starting rail, and Mike and I took our seats.

Our guards cleared the way. Mike started the motor, and shouted “Good-bye.”

“Bye-bye,” shouted the crowd, in the heartiest way.

“Come back again,” shouted our host.

At this a little boy piped up, to the amusement of us all:

Amid cheers we arose lightly from the earth, and were soon speeding once more up the Clare coast towards Galway. We left Kilkee at 9:00 o’clock.

[39]

A THRILLING VISIT TO CONNEMARA

I had read of the grandeur of the Irish seacoast in County Clare, and I asked Mike to keep as close to the sea as he could. He obeyed me only too well, half of the time being over the ocean.

The rugged cliffs grew more and more picturesque as we neared Hag’s Head. After passing over this promontory, the famous Moher Cliffs came into view. These are sheer precipices, fully 600 feet high, and, as seen from the ocean, they present a magnificent appearance. In passing these cliffs our aeroplane was about 500 feet above the sea, and about 100 feet out from land, so that we saw them to the best advantage. These cliffs stretch along the coast for five or six miles. From the Moher Cliffs we turned landward, in a northeastly direction, as we wished to pass over the city of Galway, and enter the Connemara country from the shores of Lake Corrib.

The Clare farms seemed somewhat better than those of Kerry, but not much. We saw many one-room cabins. For many miles we flew about 60 feet over Clare, and I observed the country with interest. Clare and Galway are the present centers of unrest in Ireland. There is where “cattle-driving” is practised most. Fences[40] are destroyed and large herds of cattle, belonging to some landlord, are scattered over the country roads, The cause of “cattle-driving” is the enmity of the peasants toward the landlords who turn their estates into vast grazing farms, thus depriving the peasants of any soil to cultivate.

The Government has tried to have the landlords sell out their estates to these landless ones, but some refuse to do so, and there is no compulsory legislation at present in the matter of landlords selling to tenants.

As these landlords do not live in Ireland and have little interest in Irish people the Government is now seeking remedial legislation which will compel the landlord to sell his estate. Absentee landlordism has been Ireland’s historic curse for centuries. As one Irishman expressed it: “Ireland has been overrun with absentee landlords.”

For many years the English Government sought merely to repress the outbreaks of the dissatisfied Irish. Now, an honest attempt is being made to cure the cause of the discontent, and this accounts for these Land Laws, which have proved of such benefit already to the Emerald Isle.

Absentee landlords are hard to intimidate by popular outbreaks. On one occasion the angry tenants threatened to shoot the steward of a particularly obnoxious landlord, and the steward wrote about it to his master in England. The brave Englishman promptly replied: “Tell the tenants that no threat to shoot you will terrify me.”

Irish Cabin

The humble cot beneath the Mountain side.

[41]

We reached Galway Bay shortly after ten o’clock and fifteen minutes later we were circling over the ancient city of Galway. Galway has been called a Dutch city, and its architecture, as we looked down on it, did seem more varied than the usual plain style of Irish buildings.

We created great excitement as we circled over the city at a height of 150 feet. The motor was acting a little erratic occasionally, and I wanted Mike to alight, but he disliked facing the curious crowds.

“There are lots of bogs in County Galway,” he said laughingly. “We will light easy on one of them if the motor stops.”

The river, connecting Lough Corrib and Galway Bay, divides the city into two parts, connected by several bridges. Crowds rushed out on the bridges as they saw us fly overhead. We could hear them cheering and some one fired off a pistol. This frightened Mike and he started toward Lough Corrib, like a wild duck which had been bombarded by a hunter.

I saw a fine old church in Galway, and I easily recognized Queen’s College. It is a noble Gothic building.

This is one of the three “godless” Colleges, established in Ireland by Queen Victoria early in her reign. They are called “godless” by the Irish because they have[42] no specific religious instruction in their curriculum. The other Queen’s Colleges are located at Belfast and Cork.

We were now speeding over Lough Corrib, a large fresh-water lake, where there is excellent fishing. Mike is a keen fisherman and his teeth watered as I told him of Lough Corrib’s reputation amongst the disciples of Isaac Walton.

A few miles from Galway we turned west into the heart of the far-famed Connemara country. As we swept over this part of Ireland we could see why Connemara is so celebrated. It makes a splendid panorama. There are literally hundreds of little lakes, there is grand mountain scenery, there are the heather and peat lands in abundance.

We were glad to fly over it, however, rather than live there, for the monotony and barren soil repel a man with an active mind and a good stomach.

Men were scarce, but we saw some, mostly at work in the peat lands. We caught sight of some Connemara women also, with red skirts, and Mike said he thought they were shoeless.

We went through the pass of Kylemore, called the “Gem of Connemara.” Two lofty peaks rise on each side, and, in order to avoid land currents, we had to rise to a height of 500 feet in going through.

I was astonished to see in this out-of-the-way place a magnificent country home. It was surrounded with[43] an immense garden, and the walks and drives were beautified with flaming red fuchsia hedges.

I hastily referred to my little guide book, and found it was Kylemore Castle, and that an American lady lived there. She was formerly Miss Helena Zimmerman, of Cincinnati, Ohio, but she fell from grace and is now known as the Duchess of Manchester. She must have some pangs of conscience about it, for no live American girl would live in this solitary region unless as an act of penance for her sins.

We passed close enough to Clifden, the extreme western point in Ireland, to see Clifden Castle, and also the Marconi Station. Marconi found a resting place at Clifden for the weary wireless messages after their long flight across the Atlantic, and he has a large Station here. He also found a resting place at Clifden for his weary heart, as he married Miss O’Brien, a beauty of Western Ireland.

We could hear plainly the sending of a wireless message. It was like a bombardment, report following report, like the discharge of artillery. Passing west of the Twelve Pins, a striking group of mountains, we entered County Mayo along the seacoast. Skirting Mount Muilrea, 2,685 feet high, we turned northeast to Croagh Patrick.

If Ireland’s mountains were pressed out, the area of the island would be doubled. County Mayo resembles[44] County Clare, and the stone cabins, little fields, and winding roads, are all distinctly Irish.

We were now used to the excitement caused everywhere as we whirred over the astonished peasants. One Irishman in County Mayo amused us hugely. He must have had ears like an Indian’s, for he heard our motor while we were fully a mile behind him. Turning suddenly, he gave our aeroplane one long look, and then, dropping his bundle on the road, he started to run like a hare, as if to make his escape. It may have been his conscience that troubled him. Mike lowered the aeroplane until we were not more than 25 feet above him, as we shot directly over his head. Just as we passed above him he let out an unearthly shriek.

Perhaps it was a retributive act of justice, but, at any rate, a few moments later we were a good deal more scared than the Irishman.

[45]

ALMOST A DISASTER

My hand trembles as I recall Croagh Patrick, and our flight over it. This mountain is fully 2,500 feet high, and rises abruptly from the shores of Clew Bay. In many ways it was the most attractive mountain to me in all Ireland. There is a flat plain, with some ruins, on the top of it, and in former times it was a place of great sanctity.

Saint Patrick, after whom the mountain is named, made several pilgrimages to its summit, and here St. Patrick exercised magic power for Ireland’s welfare. Here is the record in the historian’s own words:

“St. Patrick brought together here all the demons, toads, serpents, and other venomous creatures in Ireland and imprisoned them in a deep ravine on the sea front of the mountain, known as Lugnademon (the pit of the demons) as fast as they came in answer to his summons, and kept them safely there until he was ready to destroy them. Then, standing on the summit of the Croagh, St. Patrick, with a bell in hand, cursed them and expelled them from Ireland for ever. And every time he rang the bell thousands of toads, adders, snakes, reptiles and other noisome things went down, tumbling neck and heels after each other, and were swallowed up for ever in the sea.”

[46]

As we neared Croagh Patrick I bravely asked Mike to sail over its flat top, and see this sacred spot. Mike was ready to do it in a minute. He pulled the levers and we began to ascend, while still over two miles distant from the mountain. Higher and higher we went when we reached an altitude of 2,000 feet, I could feel my heart begin to thump.

Timing himself with an accuracy, which astonished me, Mike sailed over the top of Croagh Patrick about 30 feet above the flat plain. He circled around once and we passed close beside the ruin of the ancient chapel. There is also a large Celtic Cross standing upright on the summit.

I was so glad to have old Mother Earth so near once more, that I suggested that we land. Mike was going to bring the aeroplane down when he remembered that there was no way to rig up a starting rail on the top of Croagh Patrick, and so we kept on in our flight. A minute afterwards I was sorry we did not alight, anyhow.

After his second circle around the flat plain, which is half a mile square, Mike started east, and in a couple of minutes the earth was 2,500 feet below us. The suddenness of the appearance of this vast abyss between us and land seemed even to unnerve Mike for a moment. I almost collapsed.

Then Mike did a foolish thing. He imagined he could glide down from this height, and he shut off the[47] motor. We glided swiftly some 300 feet, and then I could feel the aeroplane begin to sink under us. What happened I do not just know. The first intimation I had of real danger was Mike’s face as he quickly turned to start the motor. I could hear the big propellers whiz behind me. In starting the motor, Mike released a lever for an instant. As we were descending with lightning speed this was almost the cause of a fatal disaster. The aeroplane began to rock violently, and I was almost thrown from my seat. The accident to Orville Wright and Lieutenant Selfridge at Washington the year before flashed before my mind. I wondered if Mike could regain control of the machine. I caught the sides of my seat and braced myself against the foot-rail. Even then I had difficulty in holding on. I glanced at Mike. His face was pale. His eyes shone. Every muscle and nerve was tense. He was like a rider on a runaway horse, determined to assert his mastery. His self-control was perfect.

In spite of Mike’s coolness I am surprised we escaped. As the aeroplane kept sinking and rocking like a ship in a storm, I closed my eyes and resigned myself to my fate. I was aroused by Mike’s voice.

“A close call, Jack, old boy,” he said affectionately. I could see that there were tears in his eyes. He was thinking of me and of my escape. Brave Mike. I wanted to hug him right there. I looked around and saw we were about 500 feet above ground, the aeroplane gliding smoothly through the air.

[48]

It was fortunate for us there was no breeze to speak of. All that morning, except for a little while on the seacoast, the wind gave us no trouble.

I was glad to see Westpoint a few miles ahead, as we had planned to stop there for a lunch, and to replenish our supply of gasoline, or petrol, as they call it in Ireland.

One good thing came out of our Croagh Patrick experience. I began to help Mike in operating the aeroplane. I took entire charge of the motor, which I could reach more readily than he could, at any rate. This left him free to manage the levers. He was the captain and gave all orders, but I started and stopped the motor the rest of our trip.

I found this of advantage to me, especially after the rapid descent from Croagh Patrick, as it gave me something to do, and, when not engaged watching the scenery, or consulting my map or guide-book, I could busy myself with the motor.

We had other exciting incidents, but this division of labor assisted us in keeping the aeroplane completely under our control—as long as the motor worked.

[49]

FROM WESTPOINT TO ENNISKILLEN

Mike made an excellent landing in an open space in a beautiful park beside Westpoint. A small crowd soon gathered around us when we lit, but Mike and I paid little attention to them. I stepped out on the ground and looked at my watch. It was one o’clock. We had been in the air four hours. Mike felt the strain of this long aerial journey also, but not so much as I did. He was more accustomed to aeroplaning.

Our motor had been acting well, on the whole. It was a new style motor, without carburetor, and I had been suspicious of it, but it surpassed any motor I had ever seen in reliability.

We had just finished stretching out our tired limbs when a middle-aged man, with a kindly, honest face, but an important air, came hurrying along the driveway of the park in our direction.

We heard several in the crowd exclaim: “The Keeper, the Keeper.” The new comer looked at us in astonishment and then he inspected our aeroplane. Then he looked at us again, and exclaimed: “By the Powers.”

We did not know what kind of a salutation this might be, but Mike told what we were doing and why we had alighted in the Park.

[50]

The “Keeper,” as they called him, at once became friendly and introduced himself as the Steward of the Marquis of Sligo, in whose park we had alighted and whose mansion was close at hand. The Steward resided at the mansion, as the Marquis did not spend much time on his Irish estate.

He invited us to come up to the mansion, which invitation we gladly accepted. Following the Steward, we soon arrived at the stately home of the Marquis of Sligo, who owns the greater part of this section of Ireland. He is an absentee landlord, but he comes to Westpoint occasionally, and he treats his tenants liberally, for an Irish landlord. The large park around his mansion is open to all Westporters. We noticed, from the signs, that automobiles were not allowed to enter the park, but aeroplanes were not excluded, at least, not yet.

The Steward served us a good lunch, and sent a boy with a pony-cart to town to get the petrol. The Sligo Mansion is luxuriously furnished, and Mike and I felt like royal travellers.

The Steward’s kindness was explained when he began to talk about America. He had two brothers in the New World, and told us that tens of thousands of Irishmen from County Mayo and County Galway had left Ireland for America in the past twenty years.

Westport is the most westerly town in Ireland, and is only 1,600 miles from Nova Scotia. At one time it[51] was proposed to run a line of steamers from here to America, but the project fell through.

We would like to have spent a day or two around Westport, but we still thought we could reach the Giant’s Causeway that evening, although I was beginning to think that Antrim was quite a long ways off.

The Steward showed us around the gardens and grounds, and even offered to drive us over the town, but we were anxious to get started in the air again and we declined. It was 2:00 o’clock when we had the starting rail in place and had everything in readiness for another flight.

An immense crowd had gathered around the aeroplane. They made few remarks, evidently restrained by the presence of the steward, for whom they showed much respect. One or two did volunteer an Irish farewell.

“Ah, then,” said one old woman, “it’s not often we have the blessing of such fine company, good luck to your honors, and God send you safe back again.”

“Good-bye,” said a good-natured Son of Erin, with the map of Ireland all over his face. “Good-bye, and I hope ye can kape on your feet until you land agin.”

“God bless you, sors,” said the Steward, “and keep you safe and bring you back.”

One gets used to hearing the name of Deity in Ireland, but it does not shock you. The Irish use God’s name familiarly, but reverently; not lightly, as in[52] France; or vulgarly, as so often in America. No one calls on God to damn you in Ireland. God is appealed to for blessing.

“Good-bye,” Mike and I shouted, as we rose in the air. The crowd broke out in cheers, as we sailed away toward County Sligo.

We crossed several lakes and much enjoyed the rest of our flight over County Mayo, but it is not a desirable part of Ireland in which to till the soil. We passed over a pretty little town on a railroad, called Castlebar. We entered County Sligo near Swinford.

Just after entering County Sligo, Mike said to me:

“Where’s our sunshine?”

I looked around. The entire sky was overcast. We were having the usual experience with the Irish weather, which some one has said is as changeable as the Irish character. Smiles and tears come at a moment’s notice.

The clouds soon got to work and it began to drizzle. Passing over Sligo we could see the farms improve, and when we reached County Leitrim, which we entered near Lake Allen, we could see a marked improvement. The soil was fertile, the farms and houses were larger, and there was a general air of prosperity apparent.

Our aeroplane whizzed through the misty, rainy atmosphere, like an ocean liner through a fog, but as the upper plane got soaked through, it began to leak down on us, and the water-logged planes made the machine[53] more difficult to control. Mike told me that the airship was not built for Irish weather, but he afterwards remedied this defect, as we shall see.

When we reached County Fermanagh we began to realize Ireland’s agricultural possibilities. Ulster is a different world from Connaught. The landscape is rolling, covered with cultivated farms. The houses are often two-storied, slated, and neatly kept. There are large barns and every appearance of prosperity. The picture presented to us in Ulster was not so romantic as in Connemara, but it is more like living. In many parts of Connaught a crow would need to have its rations along, but there are signs of plenty in Ulster. We could well understand why the Irish did not altogether approve of the grim Oliver’s dictum: “To Connaught with every Irishman.”

The inhabitants of the North of Ireland are also different from the Irish of the West. They are largely Protestant in religion and of Scotch descent. Their forefathers were brought to Ireland by James I., in the early part of the 17th century. Several of the English rulers had a good deal to do with the history of Ireland. Henry VIII., Queen Elizabeth, Oliver Cromwell, and James I., had extensive real estate dealings in the Emerald Isle in years gone by, and when they had completed their bargains the map of Ireland was altered and the feelings of many of the Irish were badly lacerated. It has taken centuries for these wounded feelings to heal.

[54]

It was after four o’clock when we sighted the chimneys of Enniskillen. This prosperous town is built on Lake Erne, or Lough Erne, as the natives call it. Lough Erne is another of Ireland’s large fresh-water lakes. Enniskillen is famous as the city which, like Londonderry endured victoriously a siege in 1689, the year of the commotion between James II. and William III. Its defenders manifested the greatest bravery. The banners captured at the Battle of the Boyne, where William III. defeated James II., hang in Enniskillen’s Town Hall.

Tired and wet, I seconded heartily Mike’s suggestion that we spend the night here. I felt that I could not fly another mile. We came down rather abruptly in a field near town. The water-soaked aeroplane had become hard to control, and we narrowly missed a big hawthorn hedge. A farm house was near by, and the farmer came running to us, followed by a little crowd of children of all ages. After explanations, we turned the aeroplane over to him for the night, and trudged into town. Walking seemed pleasant to us both, as we had been flying for a whole day. In spite of the misty rain, we enjoyed every step of our mile walk to the Royal Hotel. We had a good Irish supper, or “tea,” as they called it, and soon afterwards we retired for the night.

The day ended perhaps a little ingloriously, but we were well content.

[55]

A DAY IN ENNISKILLEN

When we woke up late the next morning the sun was shining in at the windows. We congratulated ourselves on having escaped the bad weather of the previous evening, and we expected to again enjoy the sight of Ireland’s green fields lit up with sunshine.

When I arose I felt quite stiff and sore, and I saw Mike moved around with more than his usual precision. The prolonged flight of the previous day had wearied us considerably. Some aeronauts may wonder we could make such a long flight, but straight, cross-country aeroplaning differs much from circling a mile track. The aeroplane is not so comfortable as a dirigible balloon, and a flight like Count Zeppelin’s recent cross-country trip in Europe would be quite strenuous in the heavier-than-air machines at present. But a journey of 300 or 400 miles a day, with proper stops, does not call for any extraordinary endurance.

As we came down stairs to breakfast we heard a band out on the street and we noticed an air of excitement on every hand. We thought, at first, that we were the occasion of the evident agitation, but a waiter soon showed us that there were greater things, even, than aeroplanists in Ireland on that day.

[56]

“It’s a foine Twelfth of July,” he said to us.

“What about the Twelfth of July?” asked Mike.

The waiter stared at him, until Mike went on:

“What’s going on here today?”

Then the waiter, seeing we were ignorant Americans explained to us how they celebrated the victory of the Boyne every Twelfth of July, and how the celebration that day was to be the biggest ever held. Then I remembered how the great day in the North of Ireland is the Twelfth of July, just as the Seventeenth of March is the great day in the rest of Ireland. However, St. Patrick’s Day is now generally observed in some way not only in Ireland, but in all the world.

“Mike,” said I, “let us stay in Enniskillen today and celebrate.”

“We’ll stay and rest,” said Mike, “and see what they do here on the ‘glorious Twelfth’, as our waiter calls it.”

After breakfast we went out on the streets, and found them filling up with a holiday crowd. I was reminded of a celebration of July Fourth in America. Excursion trains coming in from different points in the surrounding territory added to the crowd every hour. These excursion parties brought with them in every case one or two fife bands, and occasionally a brass band. These bands played popular airs to the great delight of the crowd. All these numerous bands, and the immense crowd of Irishmen and Irish women, gathered in a large field beside Enniskillen. It was a scene of the greatest[57] enthusiasm. Bands in different parts of the field were playing different airs. All was hub-bub and excitement. There were stands all around where all kinds of drinks were sold. Already several plainly showed that they had been drinking a liquid much stronger than lemonade. Lads and lasses were walking around, jostling, crowding and laughing. It was a good-natured crowd, as there was no counter-demonstration of any kind, as happens sometimes in other parts of Ireland, I understand. The differences between the Roman Catholic and Protestant are very acute in the Emerald Isle for several reasons. Often the two sides have bitter disputes. In this controversy, as in all else, the inevitable humor of the Irish sometimes crops out. The famous Father O’Leary had a polemical contest with the Protestant Bishop of Cloyne. The Bishop, in a pamphlet, inveighed with great acrimony against the doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church, and particularly against purgatory.

Father O’Leary, in his reply, slyly observed, “that, much as the Bishop disliked purgatory, he might go farther and fare worse.”

When Dean Swift was at Carlow, he found the Episcopal Church badly dilapidated. “Why don’t you give it to the Catholics?” said the caustic Dean. “You know they would repair it and you could take it from them afterwards.” It is not theology alone that separates Catholics and Protestants in Ireland. The real estate deals of the English Kings and Queens have something to do with it.

[58]

We enjoyed immensely our day in Enniskillen. We saw a typical North of Ireland crowd, heard an Irish orator declaim against “the foes of Ireland,” listened to Irish bands, and shared in the enthusiasm of the occasion. There was an excursion steamer running on Lough Erne and in the afternoon we had a delightful boat ride. In the evening, while at supper, we had a sample of real Irish wit. There was a large sign in the dining room with this notice: “Strangers are requested not to give any money to the waiters, as attention is charged for in the bill.”

Our waiter saw Mike reading this sign, and remarked to him:

“Oh, Mister, sure that doesn’t concern you at all. We’re not makin’ a stranger o’ you, sor.”

We laughed heartily, and told him we never felt more at home in our lives. “Tips” are as necessary in Ireland, even when traveling with an aeroplane, as raincoats.

We had been informed that we would find wretched hotels in Ireland, but the Imperial Hotel at Cork and the Royal Hotel at Enniskillen, are excellent hotels, and, as a rule, we found the hotel accommodations satisfactory. In the evening, before dark, we sauntered forth, and Mike went into a “shop,” as they call stores in Erin, and bought out their entire supply of light oil-cloth. Taking this with us, we went out to see our aeroplane. In the excitement of July Twelfth, the news of our strange craft evidently did not spread very wide, and we[59] were very glad to escape notoriety in Enniskillen. We found the airship just as we left it the previous night. The farmer wondered what had become of us. Mike got some tacks and a hammer, and covered the upper plane entirely with oil-cloth.

“Even an airship needs a rain-coat in this country,” said Mike to the farmer.

“But, sor,” said the farmer, “it’s such a gentle rain we have here.”

The oil-cloth was quite a good idea on the part of Mike. It gave us both a big umbrella during the rest of our trip, and the sudden showers were not so disagreeable.

The next morning we started at 5:00 o’clock, and after rewarding our farmer friend for his care of the aeroplane, we ascended into the Irish atmosphere again. After circling over Enniskillen, we turned North, and, leaving Lough Erne far to the West, we sped, like a gigantic eagle, towards Tyrone.

[60]

CIRCLING OVER LONDONDERRY IN AN AEROPLANE

We were almost an hour in reaching Omagh, the county seat of County Tyrone. As we flew over the city we were surprised to see how new-looking it was in appearance, as it is one of Ireland’s oldest towns. I learned later that the old town had been destroyed some two hundred years ago, and that Omagh of today is comparatively modern. It is a neat and prosperous city, with streets, some of them very steep, running in every direction. A beautiful Cathedral adorns the hillside, and an old barracks, now used as a police station, is an imposing structure. There are several large Presbyterian churches which show every sign of progress and prosperity. There were only a few people on the streets when we winged our way across the city at 6:00 o’clock. These stared up at us and we could see them running to the high places to keep us in sight. The farms in County Tyrone looked large compared with the microscopic farms of Connaught and Kerry, but they looked very small to an American. The macadamized roads are models in the way they are kept up, but they are narrow and winding. When the wagon roads cross a railroad, there is never a grade crossing. Generally the wagon road runs over the railroad, but occasionally dips under it.

LONDONDERRY, IRELAND.

[61]

We had another exciting experience with an early train from Omagh to Derry. We caught up with this train at Newtonstewart, a picturesque little place. The engineer saw us, and, like his fellow-Irishman in County Kerry, he tooted his whistle in our honor. We flew alongside the train for several miles, about 100 feet from the side of the track, and 30 feet high in the air. As the race continued, every passenger grew more and more excited. They cheered and shouted. Mike, with both his hands on his levers, could only look down and grin, but I was able to wave my handkerchief and cap. The engineer gave one long, farewell toot, as he stopped at a station, while we flew on our way.

At Strabane, a good-sized town, some twenty miles from Londonderry, we created wild excitement. A number of people were around the station, as we whizzed past, just about 20 feet in the air, directly over the railroad tracks. We rose to a height of 75 feet just after passing the station, and we could hear their loud cheering, as we rose like a bird. The river Foyle formed at Strabane by the junction of the rivers Finn and Mourne, flows from Strabane to Derry (as Londonderry is called by the natives) a wide and noble stream.

Mike turned the aeroplane directly over the river after we left Strabane, and we flew above it for many miles. This Foyle Valley is a rich agricultural country, and I could see the crops of oats, flax, turnips, and[62] potatoes, growing in luxuriance in the fertile little fields. About half way between Strabane and Derry our motor gave us the first serious trouble. While we were sailing along over the river, all at once it stopped, like a balky horse.

“Start the motor, Jack,” Mike yelled, thinking I had shut her off.

“It stopped itself,” I answered.

“Gee-whitaker,” said Mike, and I could see him tug at the levers in order to turn the airship towards the shore and bring it safely to the ground. Fortunately we were quite high in the air, fully 200 feet, and we were only a short distance from the east bank of the river. In a few seconds Mike had brought us down safely, a few yards from the river’s edge, on the flat embankment. Mike soon remedied the trouble—a screw had loosened. How to get started again was now our problem, as we needed some kind of starting rail. Some men around a group of houses a short distance away, saw us, and came running with all speed. They stared and gaped at us without saying a word. Mike spoke to one of them, and explaining our trouble, asked him to get a long stout board, to use as a starting rail. The rustic ran back to the cottages, and soon returned with a good board, which Mike soon turned into a starting rail. Meanwhile, his companions began to make remarks, in true Irish style, about the aeroplane.

[63]

“Isn’t that a new way to ‘hoof it’?” said a fellow with an Irish cast of countenance.

“Let us get one, and then we can fly to America,” said one of the youngest of them, a lad about eighteen years of age. The young fellows in rural Ireland all look upon America as the Eldorado of the world.

One of them said to me: “I should think, sor, your air-boat would be lonesome in Ireland.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because,” said Erin’s son, “it’s the only one in the whole country, sor.”

“Come back again, sors,” one of them shouted as we arose from the earth to continue our journey. We noticed this is a familiar parting phrase in Erin.

It was seven o’clock when we saw the smoke of Derry. In spite of our recent mishaps, Mike steered right into the middle of the Foyle, as we came close to the city. At Derry the river is spanned by a fine iron bridge. As we passed over this bridge, about twenty feet above it, we frightened a passing horse into a runaway, and attracted the attention of a crowd of laborers, who were crossing the bridge. Speeding on down the Foyle, we saw below us the masts and funnels of a number of ships, for Derry is an important seaport. Along the docks crowds of working men greeted us with shouts, and some of the steamers sent us a scream of whistles. I was much interested in old Derry. I had visited it often before, and, when we reached the end of the docks, I asked Mike to circle clear around the city.[64] We rose to a height of 300 feet, and the famous city lay under us, like a picture. We could see the historic walls which enclosed the ancient city, about a mile in circumference, and still adorned with many antique cannon. The well-remembered siege of Derry happened in 1689, when James II. besieged the city for 105 days, and the gallant defenders were reduced to the greatest extremities. To make matters worse, Colonel Lundy, who commanded the garrison, turned traitor, and opened negotiations with the besiegers. His treachery was discovered, and he made his escape in disguise. Rev. Geo. Walker, one of the heroes of the siege, has been remembered with a fine monument, built on one of the bastions of the wall. On this monument, every December 18th, an effigy of the traitor, Lundy, is burned amid great cheering by the descendants of the old defenders of Derry. Derry Cathedral has interesting relics of this famous siege, but it is not a noteworthy building from an architectural viewpoint.

Derry is now quite an educational centre. Foyle College is a prosperous institution with a pleasant location, overlooking the river. Magee College, a Presbyterian institution, is beautifully located on a high hill north of the city. The architecture of the building is stately, and this seat of learning is an important part of modern Derry. A large number of the Irish Presbyterian ministers are educated here.

We could see the large shirt factories, which bring[65] much wealth, and lots of women into Derry. Most of the employees are women.

The town on the east side of the Foyle is called Waterside. There is a high bluff, just south of Waterside, which is covered with villas owned by prosperous Derrymen. We passed over a large military barracks at the north end of Waterside. Evidently, some of the officers in the barracks had been watching our flight around the city, and they were ready for us. As we swept over the barrack square, three large guns were suddenly discharged, in our honor, we suppose. Mike was so astonished at the sudden reports that he unconsciously pulled a lever, making the aeroplane veer sharply so that it began to rock. He had it under control again in a moment, but we could hear the cheering of the red-coated soldiers, as they noticed our maneuvers.

We sailed on, sorry to leave the historic Maiden City (as Derry is proudly called because it was never captured.) Shortly after passing the barracks, we turned east, sailing over a number of delightful country homes. Two miles east of Derry we passed over the lovely valley of the Faughan river. This beautiful spot was one of the finest scenes we found in the whole north of Ireland. It was a valley filled with peace, quietness and sunshine that morning. We went as far east as Dungiven, a small country town about the centre of County Derry. Many modern mansions adorn the countryside, and the fertile soil well repays its careful cultivation.

[66]

“Look at the rain,” said Mike, as we turned north from Dungiven.

And raining it was. While I was gazing down on Derry’s green fields and lovely rivers, the clouds were hastily gathering overhead, and threatening all kinds of things. Soon the rain was pattering down upon our aeroplane, but it fell harmlessly on our rain-coated airship. It was only a shower, but while it lasted the rain came down in a hurry. As an Irishman would put it, some of the drops were “as big as a shilling or eighteen pence.” In a little while the sudden tempest had spent itself, and the sun was shining as though nothing had happened.

We followed a small stream, called the Roe, to Limavady, which we reached a little after eight o’clock. We had planned to stop here for some refreshments for ourselves, and our faithful “bird,” and Mike was delighted to see a large level field near the town, where he made a good descent, alighting without a jar. In five minutes, people were running towards us in all directions. We had circled the little town before alighting, and had aroused everybody. They crowded around us as at Kilkee, and soon began asking all kinds of questions. We satisfied them as best we could, hired a watchman to guard the aeroplane, and, accompanied by a motley following, we walked into Limavady.

[67]

ALIGHTING AT THE GIANT’S CAUSEWAY

We ascended from Limavady at 8:30. We were once more cheered to the echo as we left the earth. After leaving Limavady, we came to a low range of hills, and Mike had to use his raising levers freely as we climbed their sides. We saw the familiar heather and peat, and even the little cabins, much the same as we saw in County Mayo. At the top of the hills we had a magnificent view. We could see Coleraine clearly, nestling beside the Bann river, and, away in the distance, we saw again the sea. The surrounding country was like a panorama. We glided swiftly down the mountain side, and flew around the quaint old town of Coleraine. Scotch-Irishmen live in Coleraine, and it has the reputation of having the best bakers in the whole island. Mike and I did not condescend to test this, although it was perhaps as well for us not to alight there, for Coleraine is famous for something besides bread. Fine old Coleraine whisky is known throughout the length and breadth of Ireland. A Donegal clergyman, on hearing of a sermon against drink, said: “Sure, I am forever at them about it. It’s the bad stuff they take that does the mischief. I have told them from the altar that I never touched a drop myself but the best Coleraine.”

[68]

Sky-pilots, whether spiritual or atmospheric, have to leave whisky alone nowadays, so, in spite of its fame, we merely circled over the city. Coleraine is known for many centuries in Irish history. St. Patrick built a church here. Columba visited it in 590. Later on the salmon fishing in the river Bann, which flowed through the city, made Coleraine a place of some commercial importance. Like Derry and Enniskillen, Coleraine was besieged in 1689 by the troops of James II., and the garrison was compelled to evacuate the town, and retreat to Derry.

After passing over Coleraine, we came to the seacoast again at Portstewart. I could see the row of houses along the quay, in one of which Lever used to live. Lever’s home was in Dublin, but he spent a year as a dispensary doctor at Portstewart, and did some writing here. A stiff breeze was blowing along the coast, and Mike was kept busy handling the airship. Leaving Portstewart, we went along the rough coast to Portrush. This was formerly a dreaded coast, many a brave ship going to pieces on the rocks. Portrush is the fashionable watering place of the North of Ireland, and it is crowded with visitors during July and August. The town is built on a ridge that projects into the sea. The strands are beautiful. The ridge on which the town is built ends in a hill, called Ramore hill, which is a favorite promenade. We could see the bathers swimming in the surf, as we skimmed along the strand towards the White Rocks. These are cliffs of a strange white formation.[69] A little beyond the White Rocks Mike slowed up, and passed around the picturesque ruins of Dunluce Castle. This ancient ruin crowns a high cliff, and, before men could fly, was a difficult place to reach. Right in front of us we could see the headlands above the Giant’s Causeway. I did not very much enjoy my sail from Dunluce to those headlands. After leaving the Castle, Mike turned directly out to sea, instead of following the coast, and crossed a bay of a few miles to the Causeway. I remembered our experience over the river Foyle, and I did not altogether appreciate Mike’s daring. I was really relieved as we rose over the great cliff that over-hangs the Causeway, and circled around with the earth under us. We were both delighted to reach the Northern end of the Island. It was not quite ten o’clock when we arrived.