PUBLISHED BY

VERMONT MAPLE SUGAR MAKERS’

ASSOCIATION

PURE

VERMONT

| Maple Sugar |

|

Maple Syrup |

Home of the Sugar Maple

History of the Maple Sugar Industry from the Indian Down

to the Present Time.

How Made and How to Procure That Which is Pure and Free

From Adulterations.

Recipes for its Use in Cooking and Making Candies, Etc.

PUBLISHED BY THE

VERMONT MAPLE SUGAR MAKERS’ ASSOCIATION,

December, 1912.

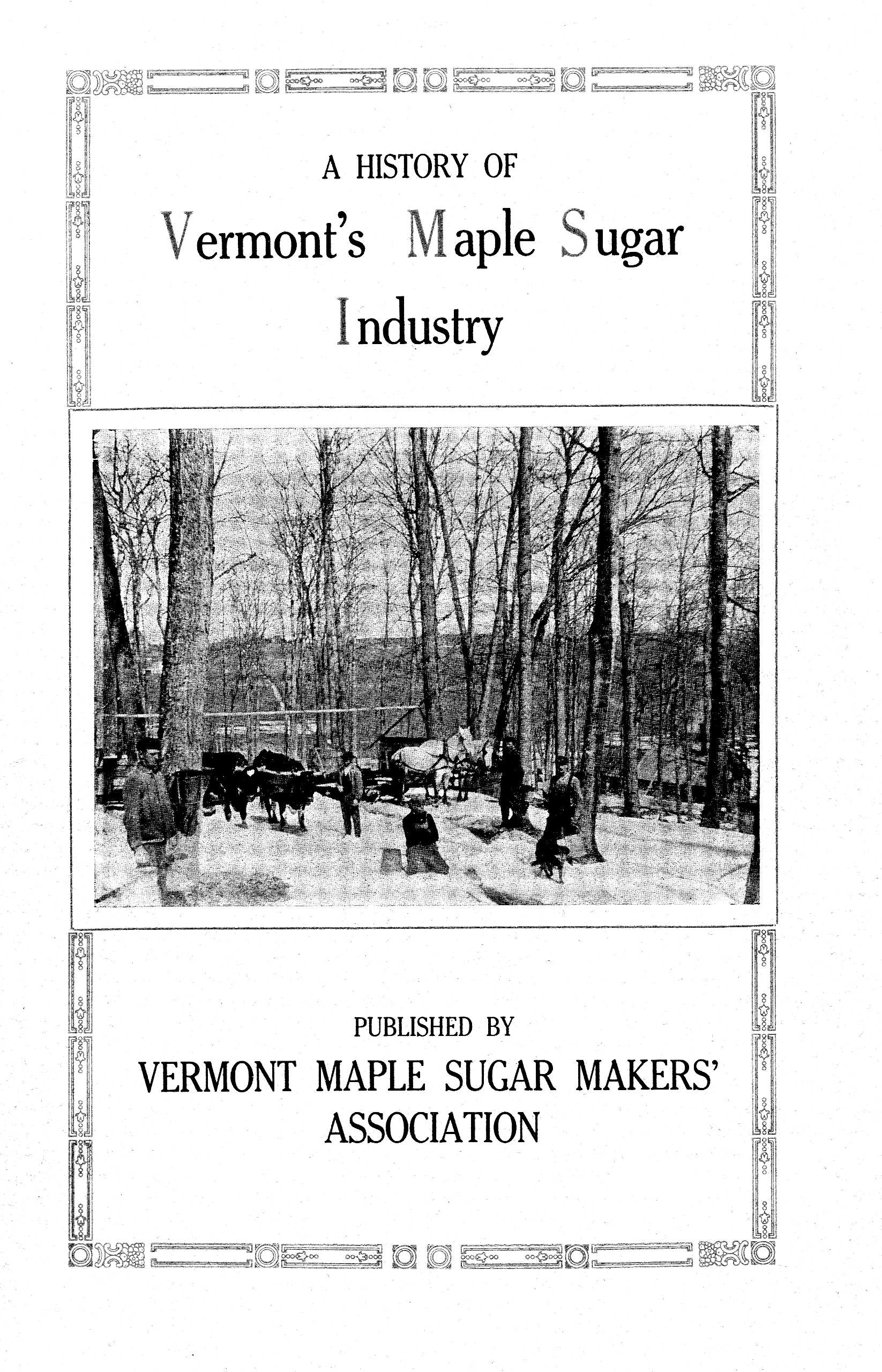

A SUGAR MAPLE TREE 125 YEARS OLD, GROWING IN OPEN GROUND.

[Pg 3]

To the Green Mountain State belongs the honor of furnishing the Maple its safest refuge and best home. Here it grows in all its beauty and luxury of foliage. Here too, as the frosts of fall settle upon our maple forests has the painters tried to copy and place upon canvas the picture as the glossy green leaves turn to red and gold. Once it reigned supreme as King of the forests of Vermont. Thousands of acres once occupied by the sugar maple have been cleared for agriculture, and the maple like the dusky warrier has gradually been driven back to the hills.

Sugar maples have been transplanted to some extent in France, Germany, Austria and England, with a view to adding sugar making to their many lines of industries, but without satisfactory results.

Of all the trees of the forest the maple was the most valuable to the early settlers. Its wood furnished the best fuel for their greedy fireplaces. Also in the early days a considerable income was derived from the burning of charcoal, and the maple made the best of material for this. But even more than for all these purposes it lost its life in the manufacture of potash. Not alone was the settlers’ great iron kettles used for boiling down the sap of the maple into sugar, but were principally used for boiling down the lye leached from wood ashes into potash thus deriving a large income, although it resulted in the same old story of killing the goose that laid the golden egg. But alas! Not alone did the people of years gone by destroy and lay waste our maple groves. The maple worm for several years stripped our trees of their foliage, and bid fair to make sugaring a thing of the past. But worst of all at the present time are the veneer mills, which pay large prices for maple logs. And unless some means be found to induce the farmer to spare his maple grove, the maple Sugar industry of Vermont, like the Indian Brave who roamed at will beneath their shade will have passed from among us.

Well may we cherish this grand old tree and be proud of sending forth to the world an article which in its purity and delicacy of flavor is unsurpassed by any sweetness otherwise produced.

[Pg 4]

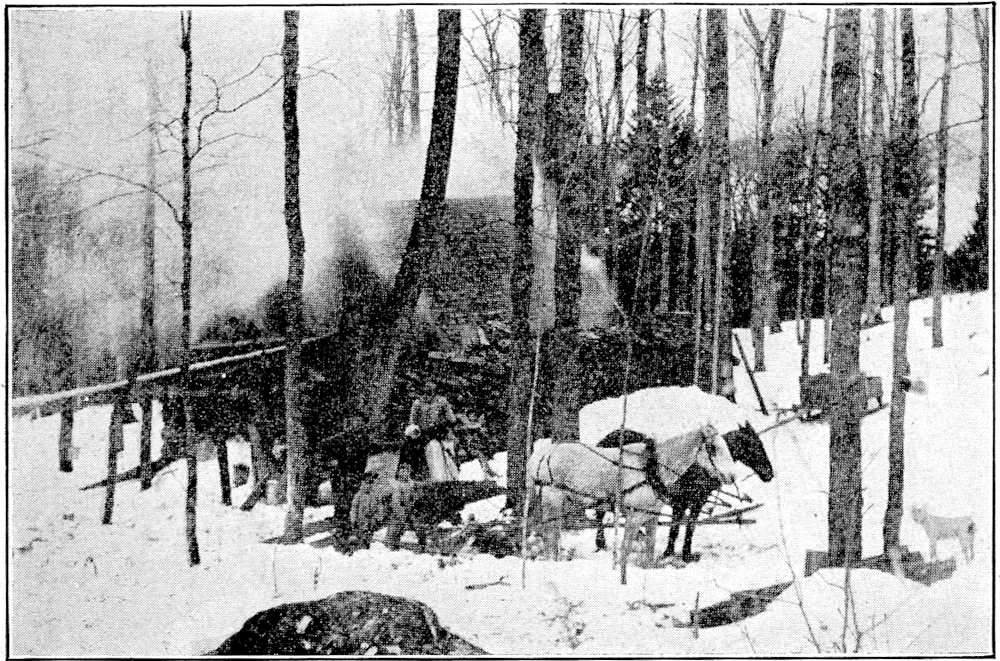

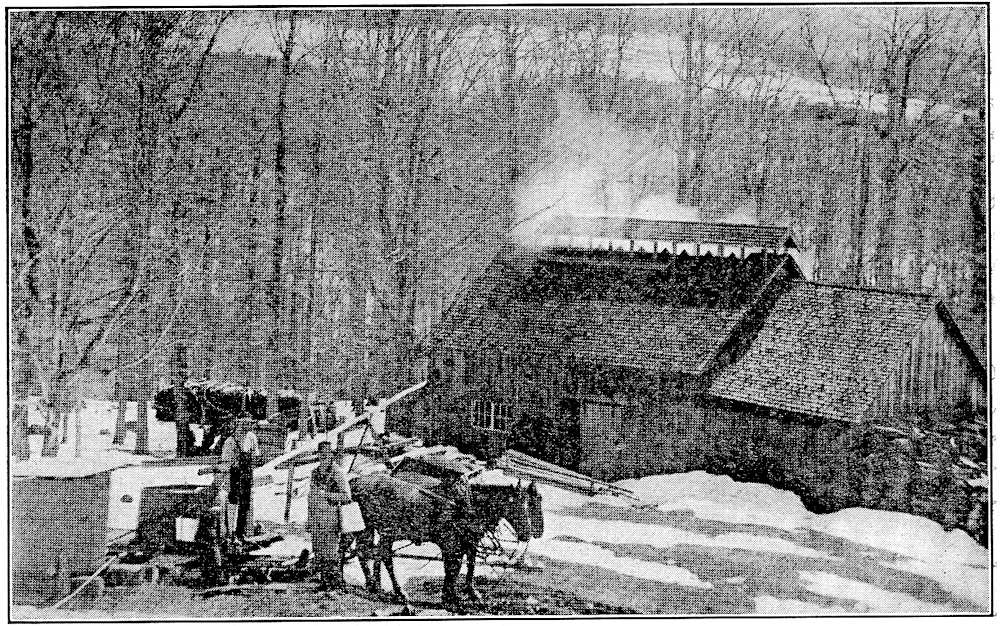

GATHERING MAPLE SAP WITH OXEN AFTER A SNOW STORM.

[Pg 5]

Vermont has an enviable world wide reputation for the production of two things: men and maple sugar. The noble record of the former as given to us in history and also records of the present day are known to all. But that the latter also has a history of much interest is little known.

Along with the maize and tobacco, maple sugar had its origin among the Indians. For time unknown before the white man came to this continent the aborigines drew the sap of the maple tree and distilled therefrom a sweet syrup. The various tribes of Canada, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan all knew of this art. Where ever the white people came in contact with the Indians in a region where the maple tree grew they found them making this delicious sweet, and it was from them the white man learned the process.

The probable way in which the Indians discovered this art is contained in one of their Legends, as given by Rowland E. Robinson in the Atlantic Monthly:

“While Woksis, the mighty hunter was out one day in search of game, his diligent squaw Moqua busied herself embroidering him some moccasins. For the evening meal of her lord she boiled some moose meat in the sweet water from a maple tree just by the wigwam. Becoming interested in her work, she forgot the moose meat, and the sweet water boiled away to a thick brown syrup.”

“When Woksis returned he found such a dainty morsel ready for his supper, as he had never before tasted. The great chief eagerly devoured the viand, licked the kettle clean and then went out and told his tribe that Kose-Kus-beh, a heaven sent instructor, had taught Moqua how to make a delicious food by boiling the juice of the maple. And the discovery soon became known among all the Indians.” To get the sap the Indians with their tomahawks cut a long slanting gash in the tree, below the lower end of this gash a notch was cut to hold a chip along which the sap would flow. The sap was caught in birch bark dishes and boiled in earthen kettles. The small quantity of dark syrup thus produced was the Indians only supply of sugar. Imagine ourselves limited in this necessity of life to a little taste each spring, and we can think what a delicacy their maple sugar must have been to the Indian. We fondly anticipate the coming of this season of the year, either for pleasure or profit. How long these anticipations have existed in the hearts of men we know not, but we do know that long before the foot of white man touched the virgin soil of New England, long before the woodman’s axe echoed among our hills and valleys, the dusky race, who freely roamed the primeval forest gathered the maple sap in the primative way. It is not improbable that the young braves and dusky maidens of the tribe, had sugar parties, ate sugar upon snow and became sweet with each as do the boys and girls at sugar parties today.

[Pg 6]

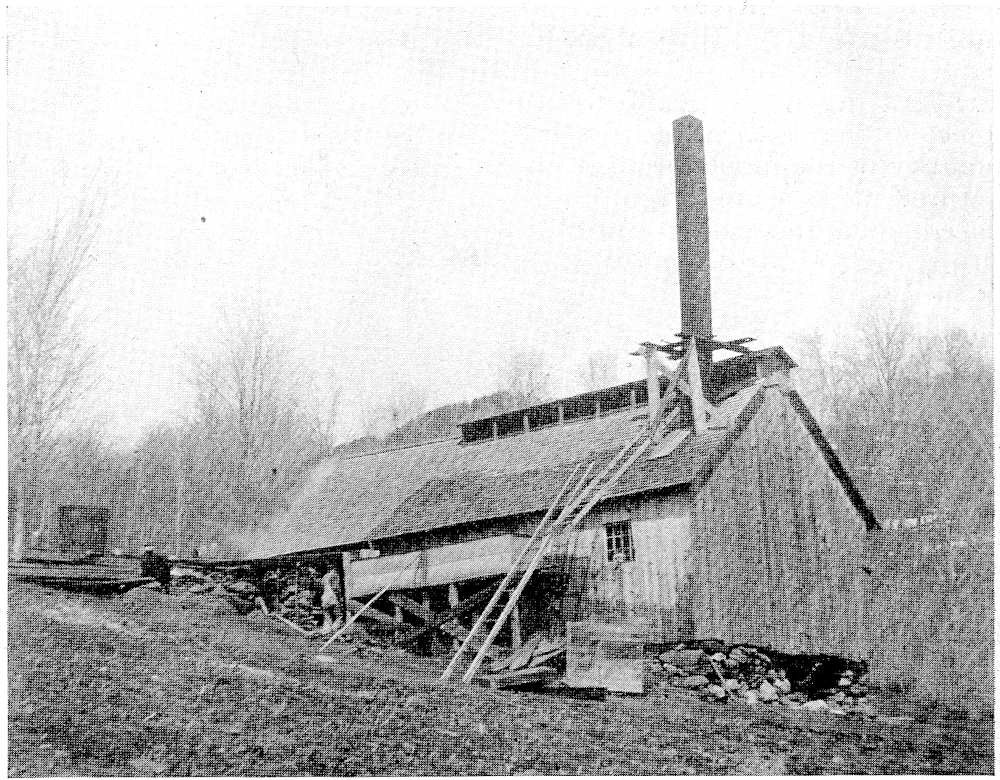

THE PRIMATIVE METHOD, OF BOILING MAPLE SAP.

[Pg 7]

The first white people to make maple sugar were the Canadians. The manufacture of maple sugar in Vermont dates back to a very early day; the first settlers like their neighbors in Canada first learned the art of making it from the Indian, who they observed notching the trees in the springtime.

For a hundred years or more the methods of production remained without material change, save the substitution of iron or copper kettles for vessels of clay or bark, and the use of better utensils. The sugar was made merely for home use; cane sugar was a luxury and often unobtainable by the pioneer farmer at any cost.

The trees were tapped with axes in the Indian way, the sap caught in wooden troughs and gathered to some central place in buckets, carried on the shoulders with a sap yoke; and if the snow was deep, snow shoes were used to travel on; the boiling was done in large iron kettles swung upon a pole in the open woods in some hollow sheltered from the wind, with no protection from the sun, rain or snow, and the numerous impurities of charcoal, ashes and leaves.

Although this was greatly in advance of the primative methods of sugar making by the Indians, the product thus secured was dark in color, strong in flavor, not altogether the flavor of the maple, and quite variable in quality. This method with slight improvements and modifications was principally used in the state until within the past 50 years; since that time great improvements have been made. But the boys and girls of today can scarcely realize the conditions incident to the sugar season even 40 or 50 years ago, nor can they fully realize the pleasures which this season brought to the young people of those times, more especially the boys. In those days it was no small matter to get ready for sugaring. Each wooden hoop on the buckets must be tightened, with new hoops to replace the broken ones. It required several days to soak the buckets and make them hold the sap. The kettle, holders and buckets must then be taken to the sugar orchard.

The boiling place must be shovelled out, and perhaps new posts set for the lug pole on which to hang the kettles. Then the big back logs must be hauled and some wood cut to start the boiling. A few new sap spouts were needed each year, and these were made from green sumac trees of proper size, and whittled to fit the auger hole; the small pith being burned out with a redhot iron. With the inch or three-fourths inch auger, one man could tap about 50 trees in a day if he did not bore more than three inches deep, which was the rule. If a new sap yoke was needed, a small basswood tree of right size was cut, and the proper length for a yoke, halved, dug out to fit the neck and shoulders, and the ends shaved to right dimensions. To make “the yoke easy and the burden light” required a good fitting sap yoke.

Thus it will be seen that in the days gone by much work, and some ingenuity were needed to get ready for sugaring. In those days the sugar season called for hard work from the men and boys also who were always required to do their part in gathering the nearby[Pg 8] sap and tending the fires. But there were two sources of intense enjoyment for the boys which largely compensated for the tired legs in carrying the sap, and burnt faces and hands in tending fires.

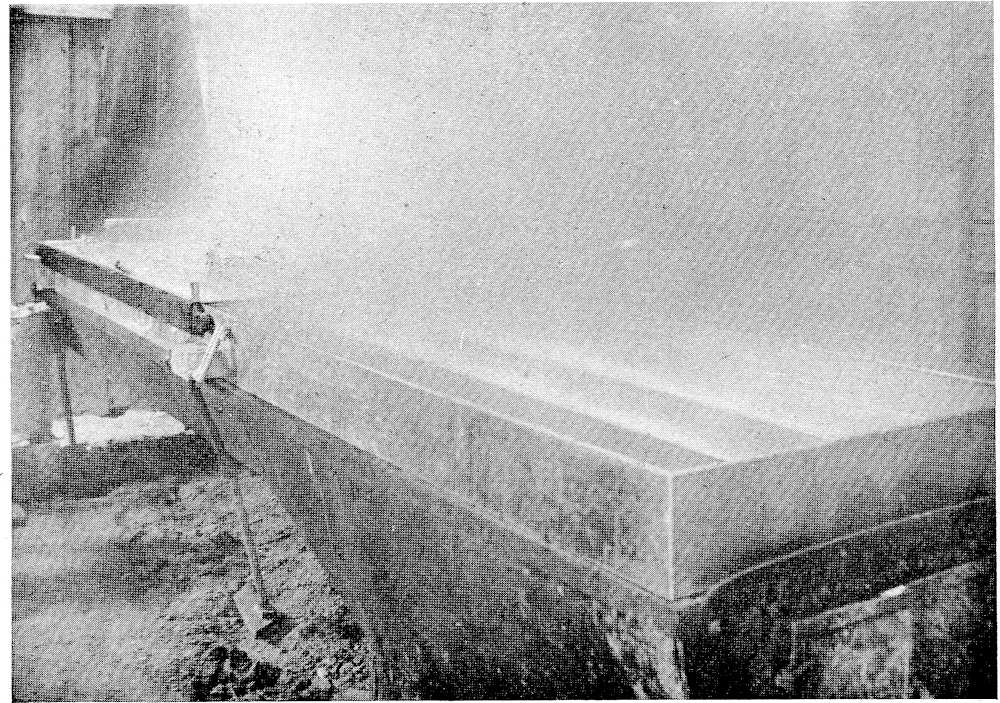

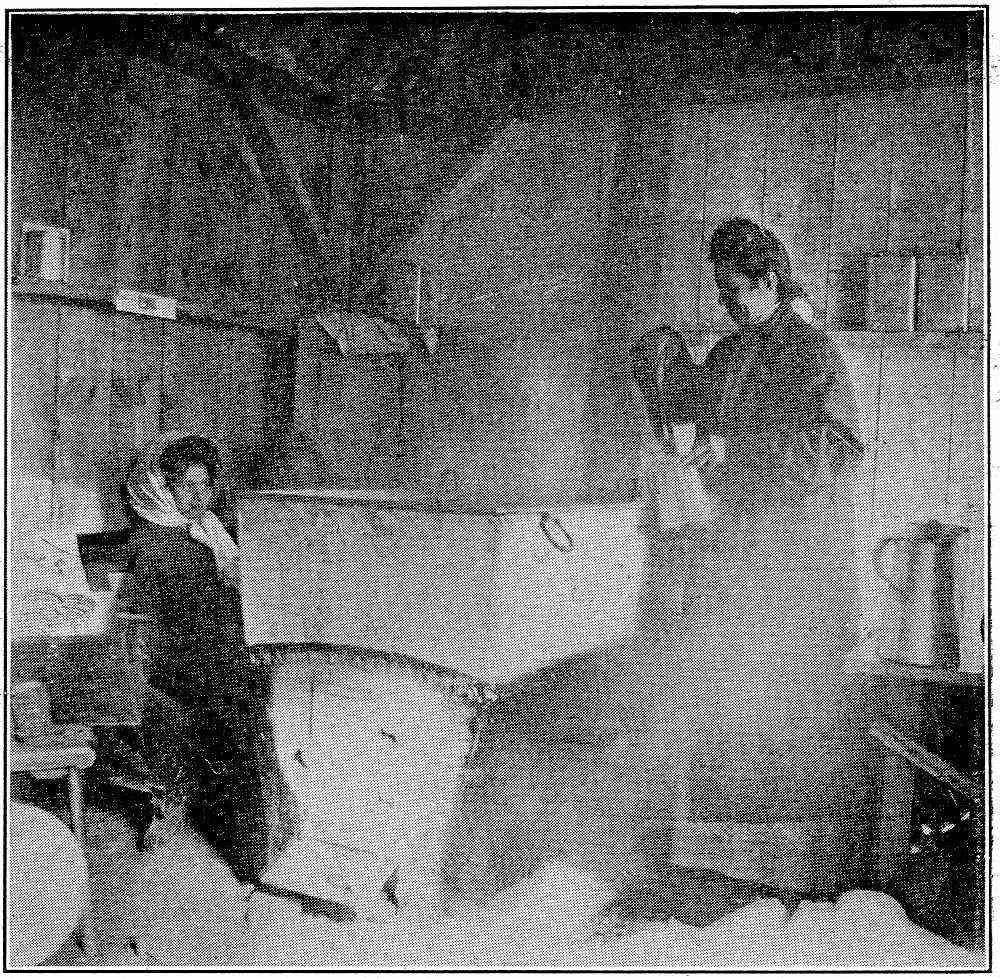

SUGAR HOUSE INTERIOR. BOILING SAP WITH PANS AND HEATER; NOW SLIGHTLY OUT OF DATE.

These were sugaring off times, one of which came any day towards night, when the sap was gathered in, and father gave permission to take some of the sweetest boiling from the big syrup kettle, and sugar off in the little four quart kettle, which mother would kindly let us take to the boiling place for that purpose. Some live coals were raked from the big fire and the little kettle with its precious sweet was placed thereon, and carefully watched until the sugar would blow through a twig loop or lay on snow. The sugar was very dark and often contained bits of charcoal that had fallen into the big kettles in boiling, but that did not matter; it was sweet and the feast always a delightful one. The other occasion was, in a measure, a sort of state performance and generally occurred at the close of a good run of sap, with fifteen or twenty buckets of syrup on hand. Early in the morning the biggest kettle was taken from the boiling place, carefully washed and set on three large stones. It was then filled about two-thirds full of syrup and a fire started. When milk warm, six or eight quarts of milk, with half a dozen well beaten eggs were added to the syrup to “cleanse it.” Just before boiling was the skimming time, when a pailful or more of dark thick scum would be taken from the top of the syrup. About noon the boys, and oftentimes the girls also would gather around the kettle to see it boil and taste the sweet as it slowly thickened to sugar; but not until about two o’clock in the[Pg 9] afternoon would it be thick enough to lay on snow. In sugaring off with the little kettle we did not always have as much sugar as we wanted, but when the big kettle was on, we ate grained or waxed sugar, and hot sugar and doughnuts, until we wanted no more. Only those who have had these experiences can realize the intense enjoyments of the sugar seasons of the years gone by.

MODERN SAP EVAPORATOR IN OPERATION.

Within the past 40 or 50 years, great improvements have been made along the line of sugar implements; first the crude sugar shed was built and the kettles were incased in an arch; then came the large smooth bottom pans which were considered the height of perfection. But the ever restless Yankee was not content with this. First came the heater which heated the sap before it went into the pans; next the crude form of evaporator, with wooden sides and corrugations running across the pans but no opening beneath. Then the evaporator of the present day of which there are many kinds, all of which are good and capable of converting from twenty-five to a hundred gallons of sap into syrup in an hour; this will be explained later.

The bit of small size has taken the place of the axe, tapping iron and large auger. The tin bucket with covers have placed in the background the old troughs and wooden buckets. The team and lines of piping have lightened the burden of the man with a sap yoke and snow shoes, and instead of boiling out of doors or in the old shed a comfortable, convenient plank floor sugar house is now used. Thus[Pg 10] we see the change which has taken place along the different lines of the industry. It has worked itself into a trade or science and men make a study of it. Therefore instead of the dark colored article containing numerous flavors, the present product with the modern methods is light in color, flavored only with the aroma of the maple, and the fine qualities possessed by this article has already won for itself a reputation far beyond the limits of our state. It has already passed the point of being considered a necessity and its use is now limited to those who can afford it as a luxury; even the poorest quality the price per pound will purchase several pounds of cane sugar for home use. Thus the poor farmer cannot use it except as a delicacy. The total product of maple sugar in the United States as stated in our census is about 50,000,000 pounds. Of this Vermont is credited with about one-fourth of the entire output. We do not wish to be misunderstood; all the pure maple sugar is not of this fine quality; only the best grade which is a small percent of the amount manufactured is entitled to the high prices received. The small quantity of the so-called first class goods have led the producers to grade their product, so that we have the first, second and third grades with prices to compare with the quality; the reason of these numerous grades are several. First, the chemical changes which take place with the sap being exposed to the weather, the advance of the season and last but not least, the many sugar makers who do not take the care they should and who do not have the suitable machines and utensils for making a No. 1 article.

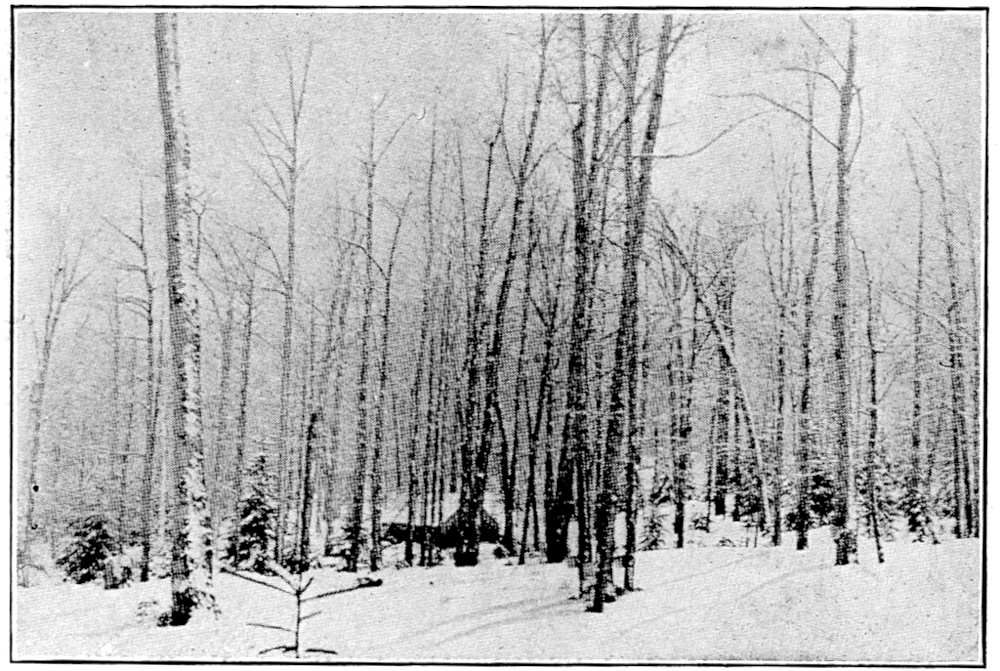

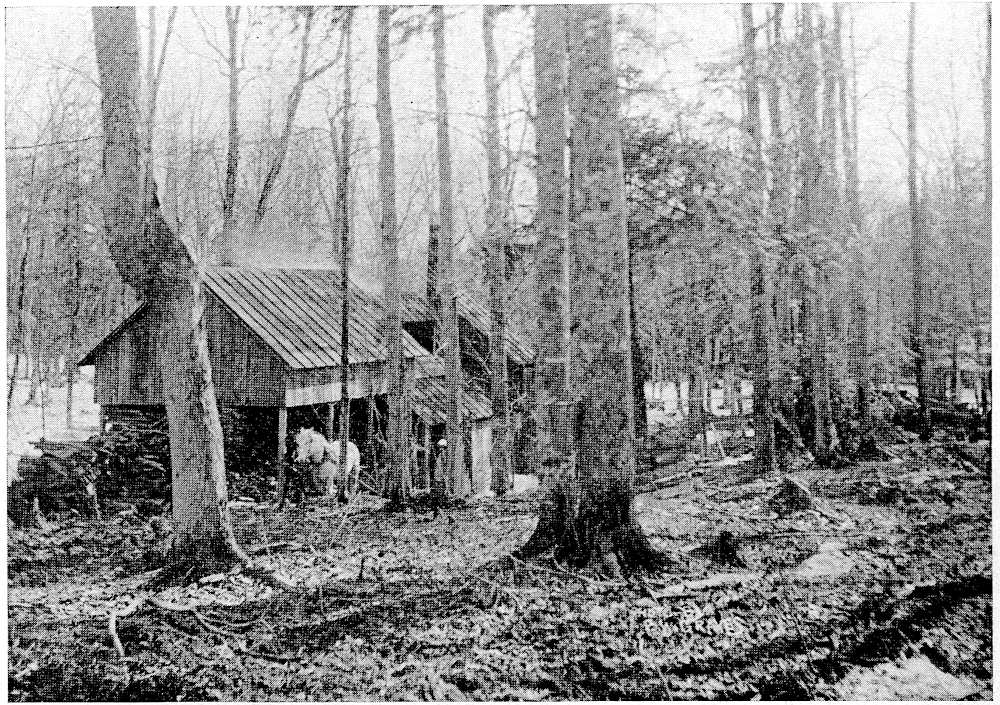

MAPLE SUGAR CAMP EARLY IN THE SEASON; GROUND COVERED WITH SNOW.

The ever increasing demand for pure, genuine, first class maple goods at a high price as compared to other sugars has led to the[Pg 11] making and placing upon the market numerous imitations of our maple product, in which the poorer grade of maple sugar is used as a flavoring. These goods often bear fraudulent labels in which it is represented that they were manufactured in Vermont, though with the exception of a few pounds used as flavoring, the stuff manufactured of glucose and other compounds, never saw a maple tree in Vermont or any other state.

This is the article placed upon the market in January and February, marked “Vermont New Maple Sugar”. You may ask, how may we get this best grade of maple sugar and be sure of its purity and quality. By corresponding with any member of the Vermont Maple Sugar Makers’ Association, whose names appear at the back of this booklet. Get your goods direct from the producers.

If Vermont is noted as being the home of any industry, that industry is the production of maple sugar and syrup, and in this booklet we will tell you something of the process of manufacture and of whom you can procure this delicious luxury in all its purity.

The producer must first have a grove of maple trees of the sugar maple variety. These groves Vermont has in abundance. They are on the hillside and in the valley; yet a grove of sugar maples that can be utilized for sugar making cannot be produced in a few years, as the tree is comparatively of slow growth and lives to a good old age. Not many trees are used for sugar making until they are 40 years old, and have a diameter of a foot or more. These are called second growth. Then there are others, two, three or even four feet in diameter; sturdy old trees that have withstood the storms of many winters. Some of the trees used for sugar making purposes have been growing since the Pilgrim Fathers landed in 1620.

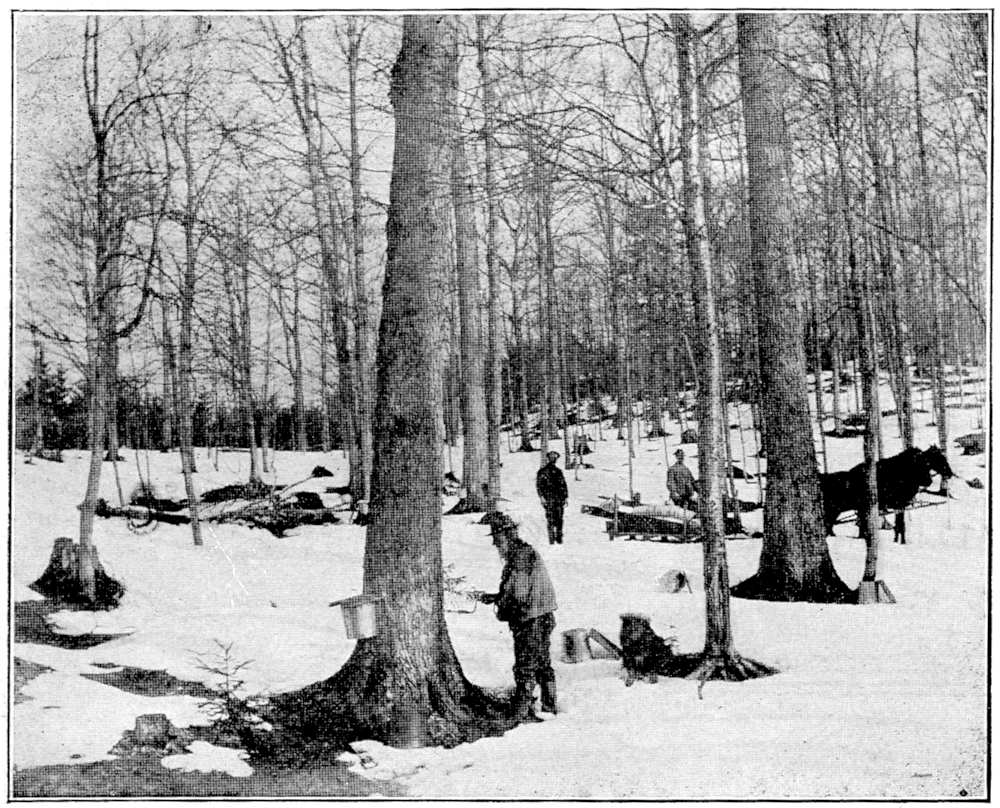

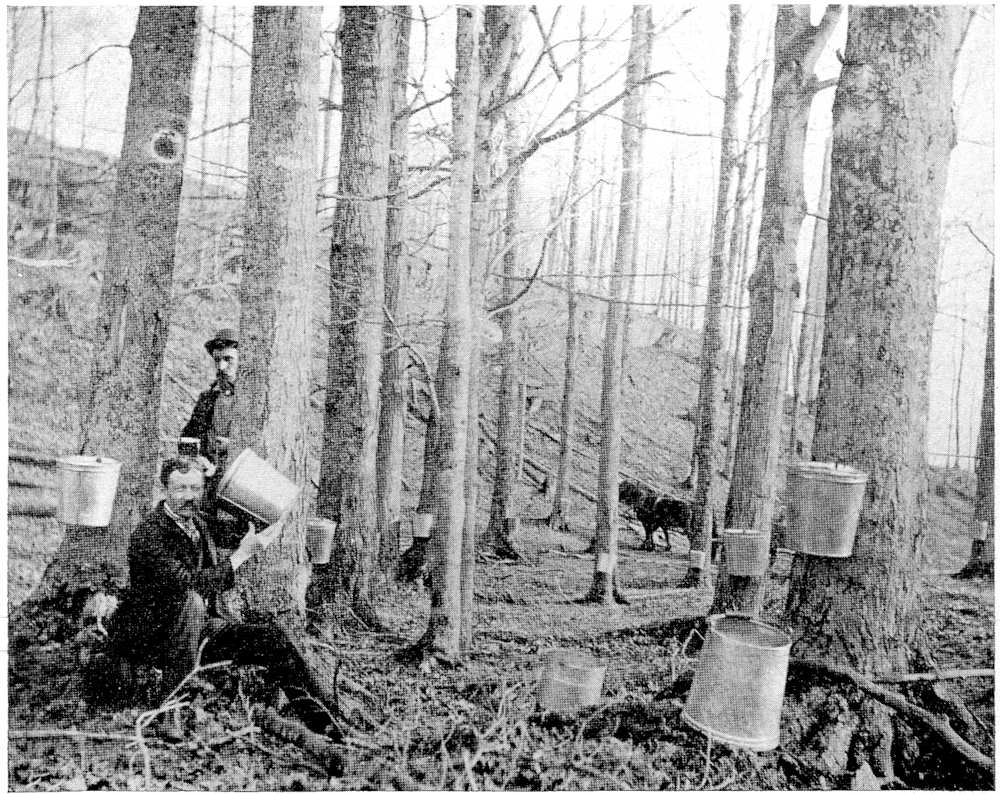

Along in March of each year, the farmer begins to watch the weather for signs of spring and conditions favorable to a flow of sap. It can only be obtained for a period of a few weeks in the spring, and on certain days when the weather conditions are favorable. Snow usually lays on the ground when the sugarmaker begins his operations in the sugar camp. The first step is to break roads in the soft and thawing snow, so that the teams can get about and gather the sap. This breaking roads is often no light task as the snow oftentimes has icy crusts beneath the surface. After the oxen or horses have been over the road several times and they have become somewhat passable, the buckets are distributed one or two to a tree and the sugar maker goes about his grove tapping them by boring a hole with a bit three-eighths to one-half inch in diameter and two or three feet from the ground as the snow will permit; in this hole he drives a spout that conveys the sap to the bucket, and on which the bucket usually hangs.

[Pg 12]

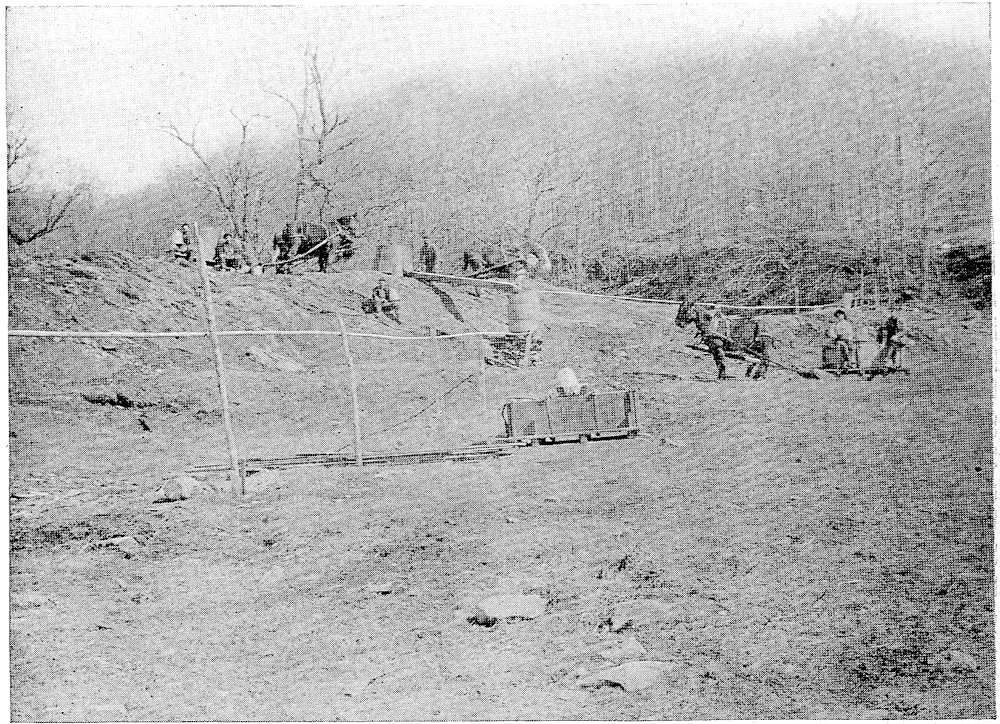

TAPPING THE GROVE.

When the sugar maker has finished tapping his trees he is ready for a flow of sap. Sometimes it comes at once and then again the weather may turn suddenly cold and for a week or ten days there is nothing doing in the sugar camp; meantime he can get his boiling apparatus in readiness and perhaps get a little more wood.

But spring will come sooner or later and there is bound to be a rush of sap. Then comes the busy time in the camp; the men and boys gather the sap with oxen and horses. This is usually done with a tank holding from 20 to 40 pails on a sled and drawn to the sugar house and stored in tanks from which in turn it flows to the boiling pan or evaporator; the flow from the storage tank being regulated by feeders which keeps the boiling sap in the evaporator constantly at the same level. The sap as it boils passes from one compartment to another becoming more dense and sweeter until it reaches the syruping off pan, where it is drawn off in the form of syrup. The right density can be determined by a thermometer or the skilled operator can tell by the way the syrup “leather aprons” from the edge of the dipper. If the thermometer is used a temperature of 219° F. will give a syrup that will weigh eleven pounds to the gallon net. It must be remembered, however, that the thermometers are graduated at the sea level, and as the altitude increases a lower temperature will give the same result on account of the reduced air pressure. An allowance of 1° for every 500 feet rise has been found to be about right; thus at an altitude of 1,000 feet a boiling temperature of 217°F. will give the 11 pounds syrup. Syrup is not however usually brought to the required density in the evaporating pan but is drawn off a little less than 11 pounds net,[Pg 13] and brought to a uniform standard in larger quantities than would be possible in the evaporating pan. The fire under the boiling sap should be quick and hot, as the sooner it is reduced to syrup after it runs from the tree the better the product. As the sap begins to boil a scum of bubbles rises to the top, which must be constantly removed with a skimmer, and the man who tends the fires, skims the sap and draws off the syrup has a busy job.

When the sap has been reduced to syrup having a density of about 11 pounds to the gallon, the niter or malate of lime, sometimes called sugar sand, which is held in solution in the sap and which crystalizes or precipitates at this stage of evaporation, can be separated from the syrup. This is accomplished in two or more ways; some strain it through felt while hot and leave the syrup free of niter; others let stand in buckets or tanks until cold; then turn or draw off the clear amber syrup leaving the malate of lime at the bottom.

Nothing has as yet been said about sugaring off, but this is a process by itself and comes after we get the syrup. Anyone who has maple syrup can sugar off, as the saying is, or convert the syrup to sugar by boiling it.

In the sugar camp the sugaring off is usually done in a deep pan on a separate arch, as the boiling sugar has a tendency to boil over unless constantly watched. The size of the pan depends on the form of product to be made. If the sugar is to be put in tin pails or wood tubs it can be handled in lots of 100 pounds or more; this would require a pan 12 inches high, 2 feet wide and 4 feet long. For shipping long distances or to hot climates the sugar should be cooked down to a density of 240° to 245°F. Great care is necessary however, not to burn or scorch the sugar when cooked to so high a temperature. For ordinary purposes if the sugar is to be used soon after it is made a temperature of 235° to 238° is high enough.

When making small cakes it is better to have two or more smaller pans and have the batches of sugar done at different intervals as the color and grain of the cake sugar depend largely on the amount of stirring it gets while hot and the sooner it is stirred after it is done the better. When the sugar gets so thick that it will barely pour it is run into moulds where it soon hardens and is ready to be wrapped in waxed paper, packed in boxes and sent to market.

There is another form of sugar, and no sugar party is complete without it, that is sugar on snow or ice. Boil the syrup down a little past 230°, cool it and put on snow with the spoon. When cooled, the waxed sugar eaten with an occasional plain doughnut and now and then a pickle is a pleasure long to be remembered and a banquet fit for a King.

To be sure and get the pure goods, order direct from the producer or from the Vermont Maple Sugar Makers’ Market, Randolph, Vt., where maple goods can be procured at any season of the year.

This market is the outgrowth of and closely connected with the Vermont Maple Sugar Makers’ Association.

The addresses of producers will be found at the back part of this booklet.

[Pg 14]

Will Carleton in Everywhere.

[Pg 16]

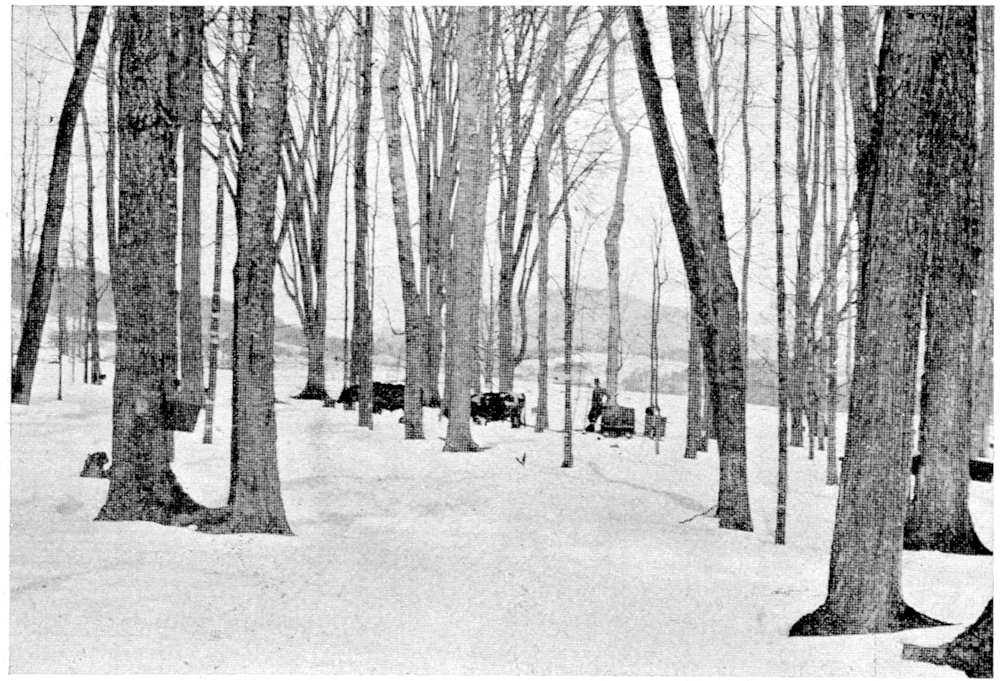

MAPLE GROVE IN SOUTHEASTERN VERMONT. ASCUTNEY MOUNTAIN IN THE DISTANCE.

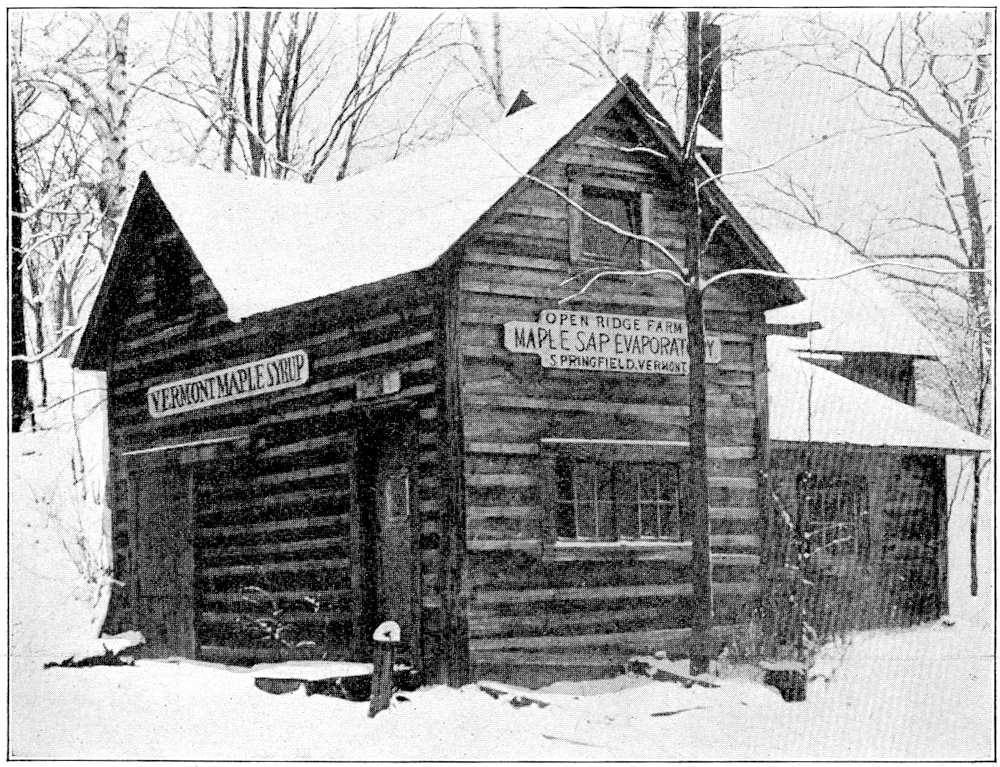

E. Wellman Barnard, Open Ridge, Springfield, Vt.

When Vermonters congregate at some special social function when responses are expected concerning the state and its products, the speakers may be relied on to advance at least the claim of excellence for the men it sends to other states and countries to become noted factors in the land of their adoption; for its gracious women; for its pure bred Morgan horses and its far famed maple sweets. These claims are in a great measure valid and the inborn pride that vouches for them is pardonable, for of the first it is only necessary to consult municipal, state and national Blue Books to find corroborative evidence; the second are known the world around in art and song and story. The supple Morgan, elastic to the tread of his native hills, with arching neck and prancing feet, an ear for martial music, and an intelligence too often of a higher degree than his master, has enlivened the trotting and road stock of the country. It is of the last product and the environment of its manufacture we will treat. Vermont has become as justly celebrated for its fine flavored maple products, as for the silky fibre of its merino wool. For the climate and soil contribute to that end as much as do the soils and climate of Cuba and Sumatra to the delicate aroma of smoking tobacco, and it is[Pg 17] safe to say that nowhere in the known world do these exact conditions occur to such a great degree as in the section which comprises upper New England and some portions of New York and Canada. There is probably no crop dependent upon the elements, so sensitive to and actuated by meteorological conditions as this, from the day the bud of the maple bursts forth a tiny leaf in May or June to the day of sap flowing in the March or April following. The summer’s heat is quite as essential as the winter cold, for the former makes the starchy growth to the tree that the latter converts into sugar, and while the sugar maker is blistering in his hay field in mid-summer or putting up the fires to keep out 30° below zero temperature when winter shuts him in, he knows the right forces are at work in nature’s laboratory to produce his sugar crop, and is so patient in his discontent. The sugar season may commence early in March or it may be delayed until April, all again “depends on the weather.” The old time saying “When ye ancient moon of April shall glow so shall ye maple sap in abundance flow,” often holds good, but when it sometimes happens there are two last quarters of a moon in April the sugar maker can take his choice as to which he will close the harvest.

THE CAMP AFTER A SUGAR SNOW.

As the sun advances northward from its long southern sojourn and the north and south winds lock and interlock for supremacy, the frost and fury line gradually recedes and the more direct actinic[Pg 18] rays of the sun thaws out the hard frozen timber, the crows hold their annual matrimonial pow-wow for pairing; blue birds come and a snow crust often forms at night hard enough to hold a man if not a team. It is then the sugar maker begins to think of his annual effort.

All up-to-date plants have substantial buildings, running water and heaters for washing; use galvanized iron tanks for gathering and storage; galvanized iron or tin buckets and sap spouts and also one of the more modern evaporators. This often represents a cash outlay quite sufficient to handle some business in town and is in use only two or three weeks in the year, the rest of the time being idle unless the owner includes the making of cider apple jellies in the fall and provides himself with a copper evaporator for the purpose.

If the sugar maker has been wise he has erected his sugar house along side a bank or declivity at least 30 feet high and easy of approach so that he can handle all the sap by gravity from the gathering tank downward to the straining tank and on to the holding tanks and then into the evaporator; each being well below the other. He uses an iron arch and stack which he keeps well coated with asphalt varnish to prevent rust and in case the draft of his arch is not good uses a Fenn rotary chimney top on his stack. Of course he has an ample supply of wood fuel that has been provided a year or more in advance under an adjoining shed so that it may be very dry for a quick fire is one of the main factors of rapid evaporation so necessary for good product, and another quite as important is that the evaporator room be built for it, with a space of about 5 feet all around it, and the walls sealed close to make a hot air draft upward. He does not need to kill the goose that lays the golden egg by providing sound rock maple wood. Any timber will do if dry; old dry pine stumps are the ne plus ultra and hemlock boughs, a good second.

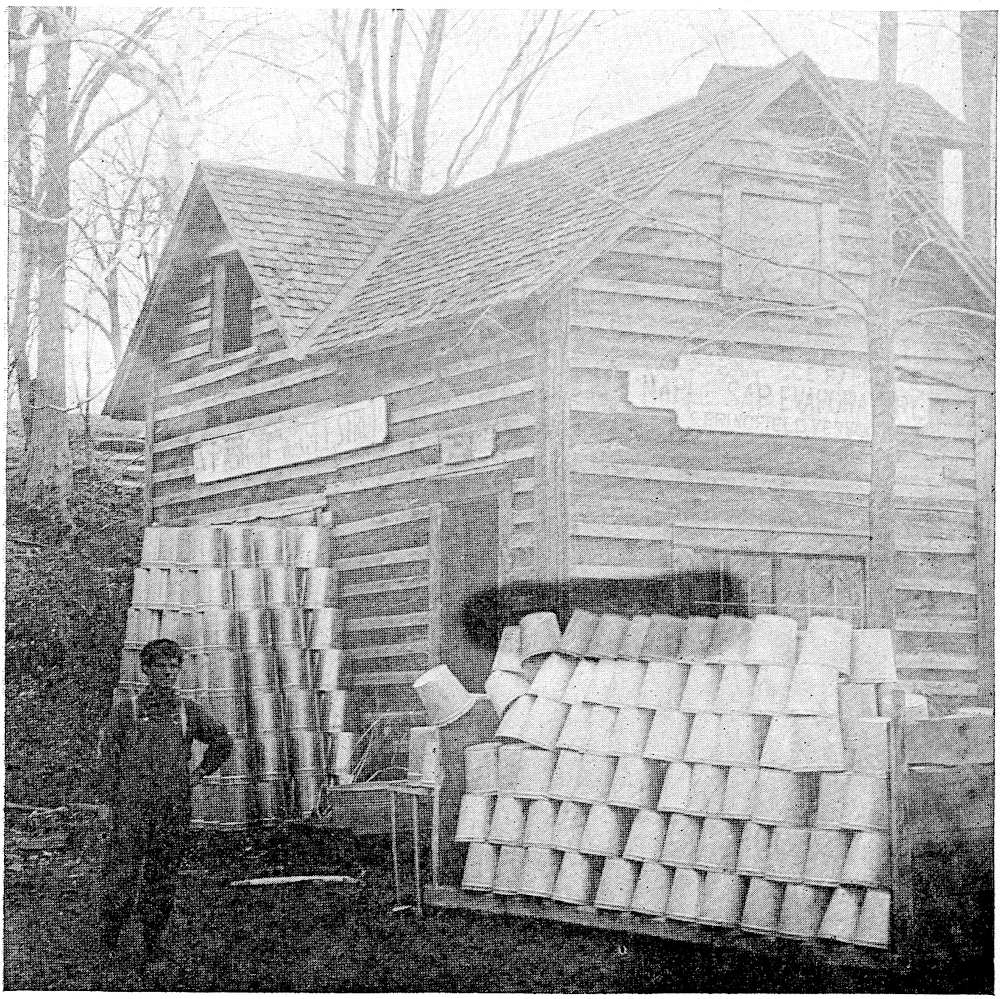

AT THE CLOSE OF THE SEASON; BUCKETS DRYING IN THE SUN.

The competent sugar maker has thoroughly cleansed all his apparatus when he put it up at the end of the season before, but many things will need a new scald. The buckets however, and spouts are usually ready for business if properly stored after a little dusting at short notice and this is most important and often saves the first run of sap, and here let me add, the competent sugar maker must be as alert and use as much care and forethought as the competent hay maker, who cures hay rather than “handles it”. Afterthought does not count at sugaring except for the next season, but then again scatter brains has poor memory. Our city cousin whom we gladly greet in our homes in the “good old summer time” has lost some of the joys of the round of the country season if he has not been on hand on the morning of some fine spicy day when through the brilliant mirror-like atmosphere Mount Washington looks like the Jungfrau, standing aloft in the grand circle of the green and granite mountains of New England so reminiscent of Switzerland, and robin red breast is back to his old home sending forth cheery notes of greeting to go along with the sugar maker and his big load of buckets to the sugar bush, over a road that has been shoveled or plowed or broken through the deep snows on a thawy day ready for the event and in the early[Pg 19] morn, while the snow crust will hold up and with plenty of helpers the buckets, perhaps a thousand or more, are hung. The men who tap the trees with the wide swing bit stock and 7-16 bit, but have the experience and adeptness to quickly select new growth timber in the old tapped tree and also to secure an upright resting place for the bucket. The spout men must never chaffer the tree into the inner bark and must not injure the spout when driving it securely in. The bucket should be properly placed and kept so at all future gatherings of sap. There is some discussion pro and con as to the convenience and necessity of covers, but they save lots of trouble in stormy weather and save much good sap that otherwise would be wasted. The coming bucket will be a large one, holding more then 20 quarts, perfectly covered, well flared for ice expansion and compression, concaved on one side to fit the tree and having in the bottom a flat, sap tight, easily worked faucet that will discharge quickly all the sap into the gathering pails without disturbing the bucket. Inventors[Pg 20] take notice. Our city friend may take a hand at gathering and note the necessity of getting the sap from tree to evaporator quickly and holding it in as low temperature as possible to prevent acids inherent to the tree circulation getting in adverse chemical action and detrimenting the product. It is a good plan to have good, clean chunks of ice on hand to keep in storage tanks although at times it will not be required because of the low temperature prevailing. The ideal sugar weather is 25° at night and 55° during the day with damp northerly winds.

Now as the sap has commenced running our guest will soon realize that the whole proposition and output depends strictly on the weather conditions. A shift of the wind; a change in temperature or humidity and especially a change of barometer pressure, which is the actual force behind a rapid flow of sap, may turn a big sap day into a complete fiasco and perhaps the often reoccurrence, a whole season, and thus the competent sugar maker with his $30 per month and board “help” and $4.00 per day teams may be quite out of pocket at the end of the season for no cause of his own, even though he obtain $1.50 per gallon for his canned syrup; but then he may charge all this up in his profit and loss account along with his products of milk and cream for the city contractor often backing up the latter with a mortgage on his farm the grain, help and imposed conditions account that the mill may go around by day and year.

MAPLE GROVE IN EARLY SPRING.

Has it ever occurred to the city consumer that the modern dairy building and apparatus so glibly demanded will cost from $3,000 to $5,000 according to locality, for a herd of 25 cows often more than the whole farm does sell for at auction after such improvement has been added. And this holds good as to the sugar output; $1,000 goes a short way for a 2,500 tree establishment and it is the many full buckets that count against short runs, rather than a smaller number with less initial expense. Moreover it should be borne in mind by the town consumer that the farm price demanded has never been exorbitant[Pg 21] for any product and that for at least a quarter of a century has ruled so dangerously low that no other business or calling that did not have its habitation and crude food products included in the output would have stood up to it for a season; but then, there is the middleman who is often a needless or exaggerated adjunct that in many lines has become an avaricious parasite to legitimate business—but that is another story and our city friends can help us solve that after they have canvassed the situation by actual contact, and with benefit to themselves.

By Dr. Harvey W. Wiley.

(From the Government Bulletin.)

Maple sugar was made by the early settlers as an article of food, the West Indian cane sugar being costly and difficult to transport inland. The commonest kind of “muscovado,” however, was preferred to maple sugar, if it could be obtained. With the increased supply of cane sugar there is little doubt that maple sugar would have almost ceased to be a commodity on the market but for its peculiar flavor, which, while objectionable for general purposes, created a special demand. Thus, while the cheaper and unflavored cane product has almost displaced maple sugar as an article of food, the demand for maple syrup and sugar as luxuries and flavoring materials not only keeps the industry alive, but calls for a continually increasing supply.

It would naturally be supposed that this growth in demand would have been followed by a corresponding increase in production. Such, however, is not the case; while the demand for maple sugar and syrup is continually increasing, the production has been more or less stationary for twenty years. The explanation lies in the fact that, at the very lowest estimate, seven-eighths of the product sold today is a spurious article, which is only in part maple sugar, or is manufactured entirely from foreign materials.

When maple sugar began to come into general demand, the market fell naturally into the hands of the wholesale dealers. The farmers were unorganized, and, as a rule, out of touch with the consumers. Consequently the sugar, made in the early spring, when the farmer was most in need of ready money, was generally either sold to the country store at a low price, or exchanged for cane sugar, pound for pound, irrespective of general market conditions. It was then bought again by the “mixers” and used to flavor a body of glucose or cane sugar six or ten times as great, making a product which was marketed as “pure maple sugar.” The mixers preferred to buy a dark, inferior sugar, because it would go further in the mixture. If the season was bad they bought less, but at almost the same price, and increased the proportion of the adulterant. Thus a shortage in the maple sugar crop[Pg 22] has no effect whatever on the general supply. It is also true that while the trade in maple sugar has been steadily growing, the production from the trees has remained stationary. The mixer controls the situation, with the effect of lowering the profits of the farmer, preventing a compensatory increase in price when the crop is short, and retarding progress in the industry by the demand for a low-grade tub sugar.

MAPLE SUGAR CAMP IN ONE OF THE

LARGEST GROVES IN NORTHERN VERMONT.

(Continuation of this picture on opposite page.)

But there has always been a certain amount of trade in pure maple sugar and syrup. A part of the city and town population comes from the country, where they have known the genuine article, and they have generally been able to supply their wants by dealing directly with the producers. The progressive and well-to-do sugar maker has also worked in this field. Of course there are farmers and others who, having pride and capacity, do their utmost to produce the best goods and market them in the most advantageous manner. Such sugar makers are unwilling to sell their high-grade goods to the mixers at a low price, but make every effort to reach a steady market of regular customers.

In the effort to make such a market more general, several maple sugar makers’ associations have come into existence. That of Vermont is the most notable. The annual meetings of this society have done much to stimulate improved methods, as well as to build up a legitimate trade. The association has established a central market,[Pg 23] has adopted a registered trade-mark, and guarantees absolute purity. Its trade, through advertising and other business methods, has reached good proportions. But there is only a very small part of the business, even at the present time, which is not in the hands of the mixers.

MAPLE SUGAR CAMP IN ONE OF THE

LARGEST GROVES IN NORTHERN VERMONT.

The following quotations are from the testimony of Mr. Madden before the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, Fifty-seventh Congress, pages 85 and following:

Mr. Madden. I would like to speak to you a moment in regard to maple syrup. That is a subject that will undoubtedly interest you all. We are in a very peculiar position in regard to maple syrup. We do not believe it is right that a syrup composed of maple syrup made from either the sap of the maple tree or from maple sugar and mixed with glucose should be sold as a maple syrup; but we do believe that a maple syrup made from syrup of the maple sugar and mixed with cane-sugar syrup or refined-sugar syrup, I will say—because beet and cane sugar are the same after they have been through boneblack—we do believe that should be sold for maple syrup, and I will tell you why. In the first place, the amount of sap of maple syrup—that is, syrup that is made from boiling the sap of the maple tree without converting it into sugar—is so limited that it would not, in my judgment, supply more than 5 percent of the demand for maple syrup in the United States.

Now, when maple sap is boiled into sugar—and I want to say before I go further that the reason that the amount of sap syrup[Pg 24] is so limited is because it is hard to keep it from fermentation, and the season is so short in which the sap runs that it is difficult to manufacture, to boil enough in the camps to supply the demand; consequently a large proportion of the sap in the States where maple sugar is made is boiled into maple sugar. Now, we have found by experience—not by chemical analysis, but by experience—that the maple sugar made from the sap of the maple tree in Ohio is not so strong as the maple sugar made from the sap of the maple tree in Vermont, and that the maple sugar made from the sap of the maple tree in Vermont is not so strong in flavor as that which is made in Canada, in Quebec Province, because it seems the colder the climate, the stronger in flavor the maple sap is.

Now, we buy these various sugars and reduce them to a liquor to make maple syrup, and I will give you my word, gentlemen, if we take a Canadian sugar, which is the highest priced maple sugar we have, it being worth at the present time twelve cents a pound, while Vermont is worth only eight cents a pound—I give you my word that if we make a liquor by melting that Canadian maple sugar, without the addition of sugar to reduce the strength of the flavor, it is so strong you could not use it.

Mr. Coombs. What do you mean by strong?

Mr. Madden. Strong in flavor.

Mr. Coombs. You mean it is positive?

Mr. Madden. The flavor is so positive; yes, sir.

Mr. Coombs. And it is sweet?

Mr. Madden. Sweet, yes; but if you put it on a hot cake you would say right away, “Take it away; I won’t have such stuff,” and you would ordinarily say that it was glucose. You would be wrong, but that is what you would say.

Now the Vermont sugar is not so strong, and it does not require so much cane sugar to reduce that to a flavor comparing with the natural maple syrup obtained from the sap itself; and I tell you that we can take maple sugar and reduce it, blending it with cane sugar—and by that I mean take ordinary cut-loaf sugar, for instance, and melt it—and we can take this syrup that is made by melting the maple sugar and blend it with the white syrup, and we can produce a maple syrup that is in flavor strong enough and yet delicate enough to satisfy the appetite, and that, in my judgment, is better than the sap syrup made from the maple tree for a great majority of the people.

As an illustration, although we get $11.50 per dozen gallons for a sap maple syrup that is boiled from the sap of the maple tree and the character of the maple syrup that I have just described, about 95 percent of our business is on the syrup that is made from the maple sugar and the cane sugar rather than on the syrup made from the sap itself. Now, if we have to take this maple syrup and brand it as cane sugar, or have any such restrictions, we can not sell it. Now, what are we going to do? We do not believe in frauds any more than you do. We think just as much of our reputation as you do of yours; but we do not want to be held responsible for conditions that we have not built up.

[Pg 25]

INTERIOR OF MODERN EQUIPPED MAPLE SUGAR CAMP.

Mr. Coombs. It seems to me your whole argument has illustrated that everybody who buys these things knows he is not buying the pure article.

Mr. Richardson. It is either that or you are deceiving them, one or the other.

Mr. Madden. Well, I will answer another phase of that question.

Now, it is commonly assumed, I think, that these blends, mixtures, substitutes, and what some of our theoretical gentlemen call commercial frauds, are done for the purpose of palming off on the people something that is cheap or inferior at a high price. Right there is where the mistake is made. The profits on that class of goods are less to us than on the higher class and more expensive goods, because competition forces these lower-class commodities down to such an extent that they pay us less profit than any other.

We could not take a maple sugar and mix it with cane sugar and obtain the price for pure maple-sugar syrup unless it had the quality, unless it cost so much. In other words, in speaking of maple syrup—and here is the part of this I forgot to speak of—if you take maple sugar and reduce it to the liquor, as we call it, and had to sell it without the addition of any reducing sugar or white syrup—not glucose, but pure cane or beet sugar—if you have to sell it without doing that, it would be so expensive as to be prohibitory, because with Canadian maple sugar worth twelve cents a pound today, it taking eight pounds of it to make a gallon of syrup, you would have a price of nearly a[Pg 26] dollar a gallon for your liquor as a first cost, without the cost of package. * * *

The above quotations will illustrate sufficiently well the processes of manufacturers and dealers in adulterating maple syrup. It is evident from this testimony that if the pure article be obtained when purchased at random it is by accident rather than by intention. Whatever may be the condition of the products when they leave the manufacturers in Vermont, New York, Ohio, or Canada, it is evident that all that part which goes into general commerce is subject to extensive adulterations. Only that part which enters domestic commerce, that is sold directly by the manufacturer to the consumer, can be considered above suspicion.

It is evident from the above résumé of the subject that the adulteration of maple syrup is practiced to an enormous extent. As stated by one of the witnesses, it is doubtful if more than 5 percent of the amount sold in this country is the genuine article. It is evident that the makers of the genuine article are forced into competition with these extensive adulterations, thus lowering the legitimate price. Every grove of maple trees in the United States would be worth a great deal more to its owner if the state and national laws should be so framed as to eradicate this great evil. Such laws would permit the sale of these mixed goods under their proper names, and thus protect both the manufacturer and consumer.

With a steadily growing demand for maple syrup, which today is almost entirely supplied by the mixer, the producers of pure syrup can hope to control the trade only through organization. The difference between the pure and the adulterated product is so marked that there would be little question as to choice, with the genuine sugar known to the popular trade. A large number of the consumers hardly know pure maple syrup when they taste it, and as so great a part of that on the market is spurious, they have little chance to learn. Under such a condition the market can be gained for the pure product only by means of united action. An example of such action is the present Vermont Sugar Growers’ Association.

The situation is very similar to that which has already been successfully met, in the case of certain other farm products, by organized cooperation of producers. Sometimes, as in Germany and Canada, this has been initiated and substantially aided by government action; sometimes, as in Ireland and England, it has been carried through entirely by private enterprise. Some years ago Canadian dairy products formed but an insignificant proportion of the exports of these articles to Great Britain. Now, through the efforts of the Canadian government to foster intelligent and honest methods of production, an English market has been secured for the Canadian output. The Irish Agricultural Organization Society has gone far toward bringing about an economic regeneration of the island, and in Germany rural prosperity has been vastly increased by the same methods. In all these cases the principal purposes aimed at have been[Pg 27] the improvement of methods of production, and furnishing a guaranty of purity to consumers.

In the case of maple sugar producers the first necessity is a market for high grade, unadulterated sugar and syrup. This they should be able to secure without much difficulty through responsible association, which can guarantee the quality of all the product bearing its name or stamp. * * *

Maple sap is a nearly colorless liquid composed of water, sugar and various mineral substances, such as lime, potash, magnesia, and iron; it also contains some organic matter in the form of vegetable acids. The peculiar flavor of maple sugar comes, not from the sugar, but from some one or a combination of all the other substances contained in the sap.

The amount of sugar in the sap of the average sugar maple tree varies greatly, the percentage changing in each tree as the season progresses. Careful experiments have shown that the sap contains on an average about 3 percent of sugar. The maximum is reported at 10.2 percent, which was found in a small flow of sap from a sugar maple near the end of a season, during which the tree averaged 5.01 percent.

The sap season throughout the maple sugar belt of the United States generally begins about the middle of March and continues until the third week in April but it varies very widely with a late or an early spring. Sugar making has begun as early as February 22 and as late as the first week in April. The season lasts on an average about four weeks. The longest run on record included forty-three days, and the shortest eight days.

LARGE MAPLE SUGAR CAMP IN CENTRAL VERMONT.

[Pg 28]

Was organized at Morrisville, Vermont, January, 1893. The object of this association is to improve the quality and increase the quantity of the maple product of the state, and to protect the manufacturer and consumer from the many fraudulent preparations that are placed upon the markets of this country as pure maple sugar and syrup, and to inform the general public where the genuine article can be procured. The members of this association consist of the best manufacturers of maple sugar and syrup in the state, and their names and post-office address may be found in this work, and any dealer or consumer ordering sugar or syrup from them will be sure to get that which is pure and free from adulteration.

The association owns and issues a protected label to its members upon their agreement, filed with the secretary, that they will only use it upon packages containing pure maple sugar or syrup, of standard quality, of their own manufacture, a copy of which label will be found in this work, and a purchaser of a package covered by this label may be assured of its purity. The improper or unauthorized use of this label or any adulteration of the products covered by the same will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law by the association.

While it is true that the sugar product of the state has improved greatly within the past few years, it is also true that there is considerable of the product at the present time that does not show the improvements that have been noted. It is one of the rules of the Vermont Maple Sugar Makers’ Association that no member shall use the label of the association on goods of an inferior quality, and a member who does so use it is liable to be expelled from its membership; therefore, it is well to insist upon packages bearing this label, and customers are requested to report to the secretary of the society any case of receiving poor goods bearing this label. While it is the first object of the association to improve the quality of maple products, and increase the quantity now produced, which can easily be doubled, it recognizes as of the utmost importance that it should place before the consumers the knowledge which shall enable them to secure pure goods instead of an imitation product.

The fact that there is more of the spurious than of the genuine sold at the present time shows that there is chance for abundant work in that direction, and the officers of the association will always be glad to aid customers in placing their orders when requested so to do, as far as practicable, a medium of information between producer and customer in which it is hoped that each will receive an advantage.

Maple goods as put up in Vermont, are in three general classes. 1. The syrup or maple honey is put up and sealed in air-tight tin[Pg 29] cans or in glass, the usual form being the gallon tin can either round or oblong and the syrup in these cans should weigh eleven pounds net to the gallon or about eleven and three-fourths pounds including can. Pure syrup varies to quite an extent in color. The first run of sap usually produces syrup of a lighter color than is produced later in the season. The color also depends upon the method used in collecting the sap and boiling it and, other things being equal, the less time that is allowed between the production of the sap and its conversion into syrup or sugar the whiter will be the product. Were it possible to convert sap to sugar without any lapse of time or exposure to the air the product would be perfectly white. There has been a suspicion among people who are familiar with Vermont maple products of the last generation that the present goods were not pure because so much whiter than formerly, but the change is due entirely to the improved and more rapid methods of manufacture.

WELL LOCATED MAPLE SUGAR CAMP IN SOUTHEASTERN VERMONT.

There is practically no adulteration of maple sugar in Vermont. The state has a stringent law on the subject and the maple sugar makers of the state will tolerate no infringement of its provisions, so that the customer can feel great security in ordering sugar or syrup of producers or dealers in the state, and can feel absolute security in[Pg 30] ordering these goods of any of the members of the Vermont Maple Sugar Makers’ Association, bearing the label of the association. The name and post-office address of all the members of the association will be found in this booklet.

Sugar. To keep maple sugar in a warm climate, store in as cool and dry a place as possible. If in tin and tightly covered it will mould and ferment on top. To prevent this the best method is to take off the covers and paste over the top of the can a piece of strong manila paper. This will also serve to keep out the ants. Tubs with covers are not as liable to ferment, but is it well to treat them in the same manner.

Syrup. Syrup should be put in air-tight packages and kept so until used. If the syrup is received packed in sawdust the best method is to leave it in the original package and store in a dark cool place, until needed for use, and if it is put up in glass be very careful to keep it from the light. If for any reason the syrup should begin to ferment, which will be known in the case of tin packages by a bulging of the head of the can called “swelled-head” it should be borne in mind that it is not necessarily spoiled as would be the case with fruit, but by heating it to a boiling temperature the fermentation can be arrested and the original flavor, to a great extent, restored. And in this connection it may be said that either syrup or sugar, which has been kept for some time, will be greatly improved in flavor by the same treatment.

NEAR THE CLOSE OF THE MAPLE SUGAR SEASON.

[Pg 31]

Helen M. Winslow, in Harper’s Bazaar.

[Pg 32]

Vermont has a Pure Food and Drug law which strictly prohibits the adulteration and misbranding of food products including maple sugar and syrup. (Public Statutes of Vermont, sections 5466 to 5494 inclusive.)

Purchasers of maple products made in Vermont may rest assured that they are as represented, and made from the sap of the maple tree and nothing else. The maple sugar and syrup produced in Vermont is not only pure but it has a delicacy of flavor and aroma not found in the same product made in other localities. This fine flavor is the result of the soil and climatic conditions to be found in the State.

Be in readiness to get the first run.

Have all utensils thoroughly cleansed and scalded.

Employ none but competent and experienced men to tap your trees.

Cut away the rough bark, only, before tapping, leaving bark sufficiently thick to hold the spout firmly to prevent leaking.

The finest flavor and lightest color will be obtained by shallow tapping.

Gather often, boil at once. Every delay in the process of evaporating sap will injure more or less the quality of the sugar.

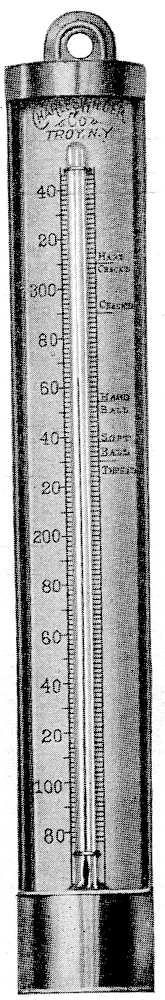

Always strain your sap. Use felt strainers for syrup. Boil down to 11 pounds per gallon; test by a correct thermometer, and can hot to prevent crystalizing in bottom of the can.

Give full gallon measure and ship only standard goods to your best trade.

Use a reliable thermometer. It is as indispensable in the sugar house as in the dairy.

Use tin or painted buckets and the best improved metallic spout.

The bucket cover has come to stay. Use them, they will save their cost in one season.

Join your State Maple Sugar Makers’ Association, and attend the convention.

Do not think that you know it all, for maple sugar making is a science about which you may learn something every season if you are observing.

[Pg 33]

LARGE MAPLE SUGAR CAMP IN NORTHERN VERMONT.

One quart of bread dough when it is moulded for the last raising, mould in a cup of maple sugar, ¼ teaspoonful of soda, 1 tablespoon of butter. Let it rise and mould again and cut out, rise and bake. These are very nice.

One egg, ½ cup maple sugar, 3 teaspoons of baking powder in flour enough to make a rather stiff batter, ⅓ cup of butter, 1 cup milk. Bake in hot gem pans in a hot oven.

One egg, ½ cup each of milk and cream, 2 teaspoons baking powder, 3 teaspoons granulated maple sugar, add flour till about as thick as griddle cakes.

Three eggs, 1 tablespoonful sweet cream, ½ teaspoonful salt, 2 cups of sweet milk, 2 teaspoonfuls baking powder, about 4 cups of flour. Mix the baking powder thoroughly with the flour, add the flour to the milk, add the salt, then the eggs well beaten. Fry in hot lard. Serve hot, with warm maple sap syrup.

[Pg 34]

Pare and core some good tart apples, put them in a shallow earthen dish; fill the center where the core has been taken out with granulated maple sugar, add water to cover bottom of dish. Bake in a moderate oven until soft, basting often with the syrup.

For one pie: ¾ cup of lard, 3 or 4 good sour apples which have been pared and sliced; 1½ cups flour, ½ teaspoonful salt, 1 cup maple sugar. Mix the lard, flour and salt thoroughly, add just enough cold water to work it lightly together; the less you handle pie crust the better it is—just enough to get it into shape to roll. Roll and put on plate, spread the apple and add the sugar. Bake in a moderate oven.

One layer of wheat bread sliced thin, 1 layer of sliced apples, put on another layer of bread and apples and so on alternately until the dish is full; flavor with lemon, pour over all two teaspoons water; cover and bake one-half hour. To be eaten with maple syrup.

1 pint flour, 1 teaspoonful cream of tartar, ½ teaspoon of soda, milk enough to make a little thinner than biscuit, add 1 pint of berries; boil 1 hour.

The sauce (served hot): 1 cup of maple sugar, ⅔ of cup of hot water, 1 tablespoonful of flour, butter size of an egg.

Let come to a boil, then pour it over a well beaten egg, stirring the egg. Flavor.

One-half cup of butter, ½ cup of milk, ½ teaspoon soda, whites of 5 eggs, 1 cup of maple sugar, 2 cups of flour, 1 teaspoon cream of tartar. Beat the butter to a cream, then gradually add the sugar and stir until light and creamy, then add the milk, then the whites of eggs which have been beaten to stiff froth, last the flour in which the soda and cream of tartar have been thoroughly mixed. Bake in three layers in a quick oven. To be frosted with maple sugar frosting.

One cup maple sugar, 2 cups of flour, 1 cup of chopped raisins, 3 teaspoonfuls of baking powder, ½ cup of sweet milk, 2 eggs, 1 cup of chopped English walnuts.

Beat the butter to a cream, add the sugar gradually, and when light add the eggs well beaten, then the milk, and last the flour in which the baking powder has been thoroughly mixed. Mix this quickly and add the nuts and raisins. Bake in rather deep sheets in a moderate oven about 35 minutes.

Yolks of 4 eggs, ½ cup of butter, 1 teaspoonful of soda, 1½ cups flour, ½ cup of maple molasses, ½ cup sour cream, spices of all kinds.

For the light part: Whites of 4 eggs beaten to a froth, ½ cup of butter, ½ teaspoon of cream tartar, ½ cup of flour, 1 cup of white sugar, 2 tablespoons of sweet milk, in which dissolve ½ teaspoon of soda.

One cup thinly sliced sweet apples cooked until transparent (in one cup maple sugar, and water to make a good syrup); when cool, add 1 cup dry maple sugar, 2 eggs, 1 heaping teaspoonful mixed spices, ½ cup of butter, ½ cup cream, 1 teaspoonful soda, flour till the spoon will stand in the middle without falling.

[Pg 35]

One quart of milk, 3 cups of flour, ½ teaspoonful of salt, 2 eggs, 3 teaspoonfuls of baking powder.

Mix the baking powder thoroughly with the flour, add the flour to the milk, add the salt then the eggs, well beaten. Fry on a hot griddle in large cakes. Butter and spread with maple sugar in layers until you have a plate four or five inches high. Cut in pie shape and serve hot.

One cup of maple sugar, 1 egg, ½ teaspoonful of salt, 1 cup sour cream, 1½ cup of flour, 1 teaspoonful soda.

Add the soda to the cream; when it foams add the egg well beaten; next, the sugar and salt, last the flour. Bake in a quick oven.

One cup sugar, 1 cup each of butter and sour milk, 1 cup of chopped raisins, nutmeg and cinnamon, 1 egg, 1 teaspoonful soda, 2 cups flour, 2 cups butter, 4 eggs, 2 cups maple sugar, 1 cup maple syrup, 1 cup sweet milk, 1 teaspoon soda, 1 teaspoon all kinds of spices, 1 pound raisins, 1 pound currants, ½ pound citron, nearly 6 cups of flour.

One-half cup maple sugar, ½ cup granulated sugar, ½ cup of water. Boil until it will hair from a spoon. Stir briskly into the beaten white of an egg. Beat until cool enough to spread.

1. Two cups maple sugar, 1 cup sour cream, 1 teaspoonful soda, flour enough to make a stiff paste, 1 cup butter, 2 eggs, 2 tablespoonfuls ginger.

Roll thin and bake quick.

2. One cup maple molasses, 1 teaspoonful each of soda and ginger, ⅔ cup butter, mix hard and roll thin.

Two cups of maple syrup, 1 cup of sweet milk, flour enough to roll—about 5 cups, 1 cup of butter, 2 teaspoonfuls of baking powder. 4 eggs.

Beat the sugar and butter to a cream, add the eggs well beaten, add the milk, next the flour in which the baking powder has been well mixed. Roll and cut in any form to suit the taste. Bake in a moderate oven.

One cup of maple syrup, 2 cups of flour, ½ teaspoonful salt, 1 teaspoonful soda, 1 cup of sour cream, 1 egg, 1 teaspoonful ginger.

Add the soda to the cream; when it foams add the egg well beaten, then the maple syrup, salt and ginger; last add the flour. Bake in a quick oven.

One pound maple sugar, 1 pint of water, boil ten minutes, skim and cool.

One quart cream, 2 cups maple sugar, 2 eggs, 1 pint of milk, ½ cup of flour, scant.

Let the milk come to a boil. Beat one cup of sugar, flour and eggs until the mixture is light and creamy, then stir into the boiling milk; cook until the flour is thoroughly cooked. Set away to cool. When cold whip the cream, add the other cup of sugar and turn into the cooked mixture and freeze.

[Pg 36]

One quart of chopped beef, ½ pound of suet, 1 cup of butter, 1 pint of molasses, 2 quarts of chopped apples, 2 cups of raisins, 2 pounds of maple sugar, 1 tablespoonful each of cloves, allspice and cinnamon.

Boil slowly in 2 quarts of sweet cider two or three hours, being careful not to let it burn.

Seven pounds fruit, 1 pint best maple or cider vinegar, 1 tablespoonful ground cinnamon, 3 pounds of maple sugar, 1 teaspoonful ground cloves, 1 teaspoonful ground allspice. Boil until the fruit is tender. This is excellent for plums, pears, peaches or cucumbers.

For preparing maple sugar for eating on snow, either sugar or syrup may be used, but the syrup if obtainable, is best. Boil the syrup until, when dropped on snow, it remains on the surface and becomes waxy, then spread it upon the surface of the snow or a block of ice. If the sugar is used, add a little water and melt it, being careful not to burn, and treat in the same manner as the syrup. This will be found, as every sugar maker knows, one of the most delicious treats obtainable.

Place together in the kettle, 2 pounds of maple sugar, 1 pound of brown sugar, ½ pound of glucose and 1 pint of water, and stir until the mixture is dissolved. Boil until the taffy will snap when tested in cold water, then pour it upon a buttered dish or slab to cool. The candy may be checked off in squares, or, if preferred, it may be pulled until white.

Three cups sugar, 1 cup syrup, ½ cup water. When it comes to a boil put in one large spoonful of vinegar ¼ teaspoonful of cream of tartar, 1 lump of butter the size of a walnut. Boil until brittle when dropped into cold water. Pull until light and dry.

Two cups maple honey, 1 cup sugar, ¼ teaspoonful soda, lump of butter half as big as an egg. Boil until brittle when dropped in water, and then take off and cool on plates. When cold, pull and cut up.

Two cups maple sugar, ½ cup of water, 1 tablespoonful vinegar. Boil until it will be crumpy when dropped in cold water. Turn on buttered plates; when cool enough, pull and cut into sticks.

No. 1. Place in a batter bowl the whites of two eggs and two cups of the best maple syrup. Whip these together with an egg-beater or fork, and then throw in enough XXX confectioners’ sugar to thicken sufficiently to mould into shapes. Coat with either chocolate or plain cream.

No. 2. Mix two pounds of maple sugar, a fourth of a teaspoonful of cream of tartar and a cup of water, and boil until a little of the syrup will form a “soft ball” when tried in water. Set it away in the kettle until almost cold, and then work it with the paddle until it becomes creamy or cloudy, when pour immediately into a shallow tin pan. When cold, turn the pan upside down, when the cream will drop out. Divide into blocks.

[Pg 37]

A REFRESHING DRINK.

Two cups of maple sugar, one-half cup of cream. Let it boil until it hairs then stir in one cup of nuts, butternuts preferable.

Pour into buttered tins and when nearly cold cut in squares.

Two cups of white sugar. One cup of maple sugar, two-thirds cup of sweet milk. Cook twelve minutes after it begins to boil. Remove from the stove and add a piece of butter size of a walnut and 1 cup of walnut meats. Stir until it thickens then pour into a buttered tin. When nearly cold cut in squares.

Two pint bowls maple sugar, 1 pint bowl white sugar, 1 pint bowl of water, two or three tablespoons whipped cream, one large coffee cup butternuts. Place kettle with the sugar and water in it on back of the stove until sugar is dissolved then draw forward and boil until the soft ball stage is reached (being careful not to stir the sugar after it commences to boil). Remove to a cool place until nearly cold before stirring. When partly grained add whipped cream, turn into tins and set in a cool place to harden.

Nice maple sugar with sufficient water to dissolve it, 1 tablespoonful of vinegar to 2 pounds of sugar, and butter size of walnut. Boil until very hard when tried in water. Pour immediately into a buttered pan in which the nuts have been placed. Cut into sticks before cold.

[Pg 38]

Measure a cup and a half each of coffee and maple sugar, one cupful of cream, and a fourth of a small teaspoonful of cream of tartar, and boil the cream and sugar together, adding the cream of tartar, wet with a little cream, as soon as the syrup reaches the boiling point. Cook until a drop of syrup, lifted out on the point of a skewer and dropped into very cold water, may be rolled into a soft, creamy ball between the fingers. Care must be taken to stir the syrup incessantly, and also that the bottom of the pan or kettle does not come into direct contact with the fire, as the cream is very apt to scorch. When done, remove from the fire, flavor, and pour on a slab, sprinkled with a very little water. When cold, cream the candy as directed for fondant, and as soon as perfectly smooth, form into a sheet half an inch thick, using the rolling pin. Let it remain on the slab a few hours, when divide into strips and wrap in parafin paper.

Place in the kettle a scanty cupful of new maple molasses and a tablespoonful of butter, and, when boiling add a grated cocoanut. Cook over a slow fire, stirring until done. As soon as the hot candy will harden when dropped into cold water, pour it out upon a well buttered slab; and when hardened sufficiently cut it into squares and wrap in parafin paper.

Take three cupfuls of dry maple sugar, a cupful of vinegar and water in equal parts (one-third vinegar and two-thirds water may be used if the vinegar is very strong) and a piece of butter the size of a walnut. Boil the sugar, water and vinegar together until half done, then add the butter, stirring only enough to incorporate the butter thoroughly, and boil until done. Drop a little of the candy now and then into cold water and test by pulling it apart; if it snaps it is done and must be immediately poured upon a buttered dish to cool. Flavor with a little vanilla extract poured upon the top. When the taffy has cooled sufficiently to handle, it may be pulled, cut into short lengths and placed on buttered dishes or parafin paper.

Take a tablespoonful of butter, three of water and one cupful of maple sugar; boil until it is ready to candy and then add three quarts of nicely popped corn. Stir briskly until the mixture is evenly distributed over the corn. Keep up the stirring until it cools when each kernel will be separately coated. Close and undivided attention may be necessary to the success of this kind of candy. Nuts are delicious prepared by this method.

To a quart of water add a small single handful of hoarhound herbs and boil for about half an hour. Strain and press all the liquor from the herbs. Place on the fire and add to this liquid three pounds of maple sugar. When it boils add half a teaspoonful of cream of tartar. Test, and when it reaches the “hard crack” or 290 degrees, add a piece of butter as large as a hulled walnut. When the butter is dissolved, pour the whole mass on a marble slab or onto a greased platter. When almost cold mark into squares with a knife.

Two cups of maple molasses, 2 teaspoonfuls of butter, 1 cup of maple sugar, ½ cup of water.

Boil all together until done,—be careful not to stir while cooking. When done, pull.

[Pg 39]

A. A. CARLETON, President.

H. B. CHAPIN, Secretary.

HOMER W. VAIL, Treasurer.

P. B. B. NORTHROP, Auditor.

[Pg 40]

| President, A. A. CARLETON | West Newbury |

| Secretary, H. B. CHAPIN | Middlesex |

| First Vice-President, C. E. MARTIN | Rochester |

| Second Vice-President, W. E. YORK | West Lincoln |

| Treasurer, HOMER W. VAIL | Randolph |

| Auditor, P. B. B. NORTHROP | Sheldon |

MEMBERS.

Abbott, Walter, Marshfield.

Allbee, G. H., East Hardwick.

Ames, S. E., Rockburn, P. Q.

Badger, C. A., East Montpelier.

Badger, Jennie E., East Montpelier.

Barnard, E. Wellman, Springfield.

Barnett, R. E., West Newbury.

Bellmore, William, Northfield.

Benton, John, Lincoln.

Bigelow, F. M., Essex.

Blanchard, F. W., Ascutneyville.

Bristol, E. J., Vergennes.

Brock, John B., West Newbury.

Bronson, B. G., East Hardwick.

Cady, H. H., Cambridge.

Carleton, A. A., West Newbury.

Carleton, G. W., Bradford.

Carter, W. E., Rutland.

Chase, Perry, East Fairfield.

Chamberlin, R. S., West Newbury.

Chapin, H. B., Middlesex.

Chapin, Mrs. M. E., Middlesex.

Clark, C. C., West Lincoln.

Clough, G. L., Pike, N. H., R. F. D. No. 1.

Collins, E. B., Hyde Park.

Colvin, C. H., Danby.

Colvin, Mrs. C. H., Danby.

Colvin, N. E., Danby.

Cooke, J. B. & Son, Greensboro.

Dillingham, Hon. W. P., Montpelier.

Daniels, Sam, Hardwick.

Durant, John, West Newbury.

Fay, E. B., East Hardwick.

Forty, H. S., Berkshire Center.

Foster, Charles, Cabot.

Foster, H. S., North Calais.

Gillfillan, W. N. & Son, South Ryegate.

Gorton, E. O., Starksboro.

Grimm, G. H., Rutland.

Grimm, J. H., Montreal, P. Q.

Harrington, T. E., Windham.

Harvey, N. C. & C. E., Rochester.

Hastings, Cyrus, Corinth.

Hayes, Mrs. A. L., Strafford.

Hayes, J. R., Strafford.

Hewes, C. E., So. Londonderry.

Hewins, H. W., Thetford Center.

Hewitt, Bristol, R. F. D. No. 1.

Hill, S. W., Bristol, R. F. D. No. 3.

Holden, John C., N. Clarendon.

Holden, W. W., Northfield.

Hooper, E. J., E. Fairfield.

Hoyt, B. F. Lancaster, N. H., R. F. D. No. 3.

Hubbell, M. L., Enosburg Falls.[Pg 41]

Jackson, A. E., Greensboro.

Jackson, O. H., Westford.

Jenne, A. M., Richford, R. F. D. No. 1.

Kneeland, D. A. Waitsfield.

Ladd, A. A. Richford, R. F. D. No. 1.

Ladd, N. P., Richford, R. F. D. No. 2.

Leader Evaporator Co., Burlington.

Lilley, J. O., Plainfield.

Martin, C. E., Rochester.

Martin, R. J., Rochester.

McMahon, C. L., Stowe.

Metcalf, Homer J., Underhill.

Miles, McMahon & Son, Stowe.

Morrell, Walter, Middlesex.

Morse, Ira E., Cambridge.

Morse, L. B., Norwich.

Northrop, K. E., Sheldon.

Northrop, P. B. B., Sheldon.

Ormsbee, C. O., Montpelier.

Osgood, L. K., Rutland.

Orvis, C. M. Bristol, R. F. D. No. 3.

Patterson, W. H., Fairfield.

Perry, Dolphus, Fairfield.

Perry, Walter J., Cabot.

Pike, J. Burton, Marshfield.

Prindle, Guy, St. Albans, R. F. D. No. 4.

Prindle, Martin, St. Albans, R. F. D. No. 4.

Ritchie, F. M., Boltonville.

Ridlon, M. H., W. Rutland, R. F. D. No. 2.

Rogers, B. O., West Newbury.

Rogers, Eldon, Rupert.

Rowell, B. R., Corinth, R. F. D. No. 1.

Russell, Frank L., Shrewsbury.

Salmon, A., West Glover.

Salmon, N. K., West Glover.

Soule, Geo. H., Fairfield.

Smith, E. W., Richford, R. F. D. No. 2.

Spear, J. P., West Newbury.

Spear, V. I., Randolph.

Strafford, West Rutland, R. F. D. No. 2.

Story, C. J. & Son, Morrisville.

Swan, P. B., Montgomery.

Tabor, H. S., Montpelier.

Tanner, Geo. F., Springfield.

Trefren, William, Bradford, R. F. D. No. 1.

Tuller, A. A. Warren.

Tuxbury, A. J., So. Ryegate, R. F. D. No. 1.

Tuxbury, W. H., West Newbury.

Tyler, J. B. C., West Newbury.

Walbridge, E. P., Cabot.

Welch Bros., Maple Co., Burlington.

Whitcombe, R. O., Plainfield.

Whitney, Alex H., Tunbridge.

Whiting, H. W., 276 W. 126th St., New York City.

Wilber, Frank, Rochester.

Wilder, L. O., Middlesex.

York, Wm. E., West Lincoln.

[Pg 42]

“A Sweet Little Story”

The Vermont Maple Sugar Maker’s Association was born in January, 1894. G. H. Grimm, at that convention, made the first display of high grade Maple Sugar and Syrup, winning first prize, then and there after, for years in succession, until Sugar Makers became sufficiently interested to make exhibits worthy of the industry.

Thereafter, the Grimm exhibits were wholly confined to utensils for producing a high grade quality of maple sweets. Grimm utensils won the highest awards of the Association in 1894, 1895, 1896, 1897, 1898, 1899, 1901, 1904 and 1905. In the three years omitted, Grimm exhibits were not in competition.

The Grimm Evaporator and Grimm Sap Spout is more extensively used by up-to-date Sugar Makers than any other make. More Grimm Evaporators are annually sold than the combined output of all competitors. I will forfeit $500.00 if this statement is not absolutely true. Competitors are invited to investigate, order books are at their disposal. The Grimm Spout has benefited the Sugar Maker and the Maple tree, more than any other article in the Sugar Bush. If you desire first quality, the Grimm Evaporator is in a class by itself. Ask those who have used it for nearly thirty years. Addresses can be had for the asking.

The Grimm Evaporator is made with or without Syphons, and with the latest improvements, no other evaporator can evaporate sap faster nor make as good a quality of product as the Improved Grimm Evaporator.

G. H. GRIMM,

Rutland, Vt.

ORDERS FOR MAPLE SYRUP AND SUGAR, MADE WITH

GRIMM UTENSILS, ARE SOLICITED FROM CONSUMERS.

[Pg 43]

PURE MAPLE SUGAR

MADE BY

Vermont

Vermont

Maple Sugar

Makers’

Association

Members of Vermont Maple

Sugar Makers’ Association have

the right to use this label only

upon packages containing pure

maple products.

The above is an exact reproduction of the label of the Vermont Maple Sugar Makers’ Association; 100 of which are furnished free of charge, if requested, with name and address printed on them, to each member on receipt of $1.00 for membership fee. Additional labels at 35 cents per 100.

H. B. CHAPIN, Secretary.

[Pg 44]

|

|

|

Use “WILDER” GUARANTEED ACCURATE THERMOMETERS and be assured of Correct Temperatures. Endorsed by leading Confectioners and Maple Sugar Manufacturers everywhere. |

| Nos. 684-688 | No. 870 | Nos. 860-862 |

Home Candy Makers’ Thermometer.

Write for our

Catalog, or procure

through your

Dealer.

Manufactured by

| CHAS. WILDER CO. | EST. 1860 |

TROY, N. Y. |

[Pg 45]

Page’s Perfected

Poultry Food

THE KIND THAT MAKES HENS LAY

Remember, we handle BEEF SCRAPS, GRANULATED BONE, ALFALFA MEAL, GRIT, OYSTER SHELLS, CHARCOAL, ETC., and during the freezing weather we sell GREEN CUT BONE AND MEAT.

If you want anything in our line, write us.

CARROLL S. PAGE

HYDE PARK,

VERMONT

Pure Vermont Maple Sugar

and Syrup

Special attention to filling orders for consumers. We guarantee full weight and measure and satisfaction to our customers. Price list on application.

Vermont Maple Sugar Makers’ Market

RANDOLPH, VERMONT

[Pg 46]

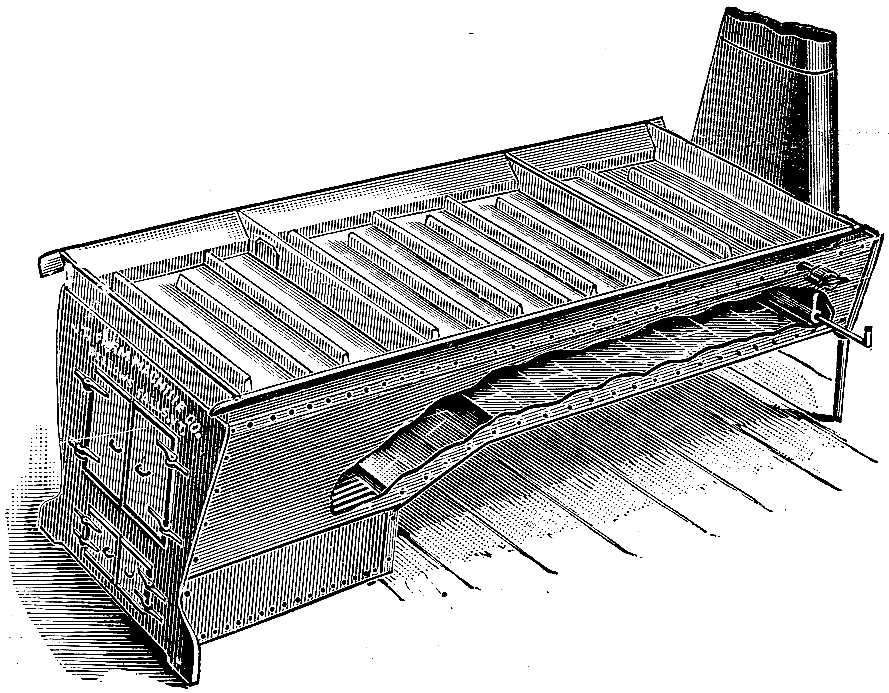

Williams Bellows Falls Evaporators

are commonly admitted superior to every other appliance for evaporating maple sap. Best maple sugar makers throughout the state and country prefer the Williams Bellows Falls Evaporator for these superior features:

1st.—Simplicity. There is a free flow of sap from end to end. No need of siphons. They are easy to tend, easy to handle and cannot burn the bottom if left with a fire in the arch.

2nd.—Durability. These evaporators are made of galvanized iron, tin plate or copper, tin plated. The material is the highest quality obtainable, and the evaporator will keep its shape with long service. “It is almost impossible to wear them out.”

3rd.—Double Heating Surface. The crimps, which run crosswise, are pressed from the same sheet metal as the bottom. As they are open underneath, they not only prevent the heat passing up the chimney, but give double the heating surface of other pans.

4th.—Cost. Heating surface considered, the Williams is the cheapest evaporator made. Our catalogue gives the price of any size evaporator as well as of all other sugar makers supplies.

We can give you high quality goods, at reasonable prices. Try us.

VERMONT FARM MACHINE CO.

Bellows Falls, Vt.

[Pg 47]

THE MONARCH

SUGAR TOOLS

A Maple Sugar Outfit That’s

Worth While.

TRIED, TESTED, PROVEN by a Multitude of Vermont’s

BEST SUGAR MAKERS for Twenty Years.

As good as the Monarch Line. If the past has been, the 1913 is the peer of them all, and represents the greatest advance ever yet made in an equipment of this kind. Simple to operate. Easy to handle, rapid evaporation, choicest quality of production, and the greatest labor and fuel saver yet designed.

The Monarch is the winner at the Fairs but better still the winner in the Sugar Bush, and is a prime favorite with the good producers as the rapidly increasing business proves.

If not using a Monarch get in touch with Headquarters,

TRUE & BLANCHARD CO., Sole Mfrs.

F. L. TRUE, Rutland, Vt.

F. L. PATTERSON, New York,

Selling Agents.

[Pg 48]

Capital City Press

One of the Best Equipped

Plants in New England

Good Service at Right Prices

LET US ESTIMATE

ON YOUR NEXT JOB

Capital City Press

Montpelier,

Vermont