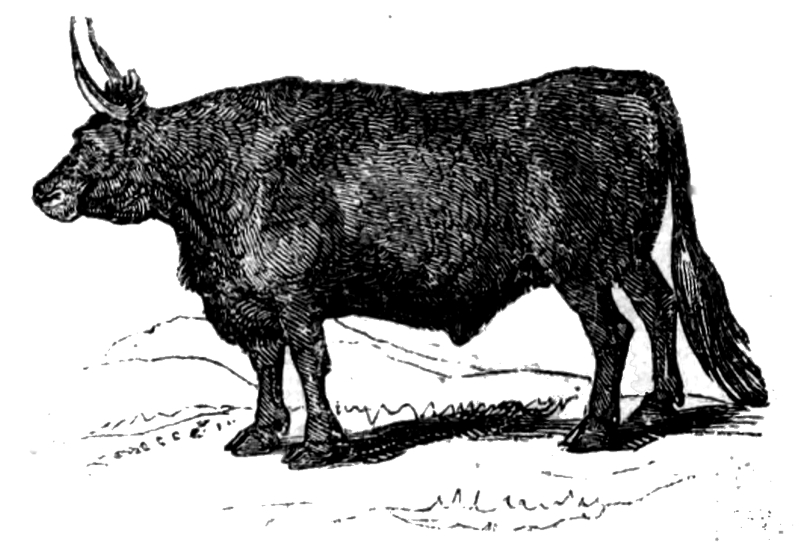

THE KYLOE OX.

| Page | |

| The Kyloe Ox | 7 |

| The Horse | 8 |

| The Race Horse | 12 |

| The Cart Horse | 16 |

| The Mule | 20 |

| The Ass | 24 |

| The Bull | 28 |

| The Cow | 32 |

| The Ram | 36 |

| The Sheep | 40 |

| The Goat | 44 |

| The Stag | 48 |

| The Fallow Deer | 52 |

| The Roebuck | 56 |

| The Boar | 60 |

| The Sow | 64 |

| The Domestic Cat | 68 |

| The Wild Cat | 72 |

| The Weasel | 76 |

| The Martin | 80 |

| The Ferret | 84 |

| The Polecat | 88 |

| The Badger | 92 |

| 6The Fox | 96 |

| The Wolf | 100 |

| The Shepherd’s Dog | 104 |

| The Bulldog | 108 |

| The Newfoundland dog | 112 |

| The Greyhound | 116 |

| The Foxhound | 120 |

| The Harrier | 124 |

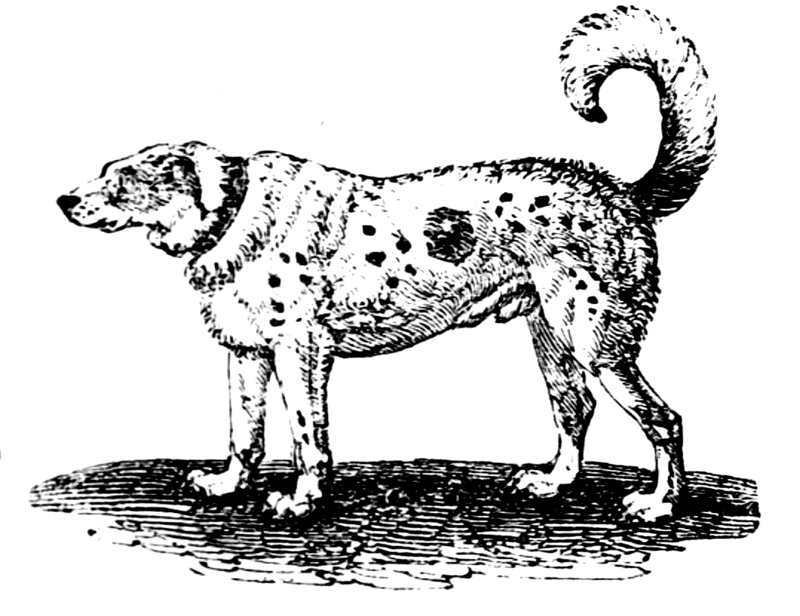

| The Pointer | 128 |

| The Spaniel | 132 |

| The Terrier | 136 |

| The Hare | 140 |

| The Rabbit | 144 |

| The Squirrel | 148 |

| The Dormouse | 152 |

| The Rat | 156 |

| The Water Rat | 160 |

| The Mouse | 164 |

| The Mole | 168 |

| The Hedgehog | 172 |

| The Bat | 176 |

| The Guinea Pig | 180 |

| The Otter | 184 |

| The Ichneumon | 188 |

This most useful animal is a native of Scotland, and is said to have derived its name from having crossed the kyles, or ferries, which abound in the Highlands.

The Kyloe Ox is of a black colour, and has a very thick hide, and a great deal of hair. Its horns are large and long. Its flesh is the finest kind of beef: and there is scarcely a single part of the Ox that cannot be made use of. The hide is made into leather, the gristles are made into glue, the horns into knife-handles, drinking-cups, &c. and the bones are a substitute for ivory.

This noble animal is found in almost every part of the world. In Arabia and Africa are wild horses, which wander about in herds; and in South America many thousands are seen in one drove.

The horse is used for riding, and is then guided by the rein. He is used for drawing carriages, carts, and waggons, for ploughing, and also for war. Hunting seems to be enjoyed as much by the horse as by his rider: and in the race he shows great eagerness to be the foremost.

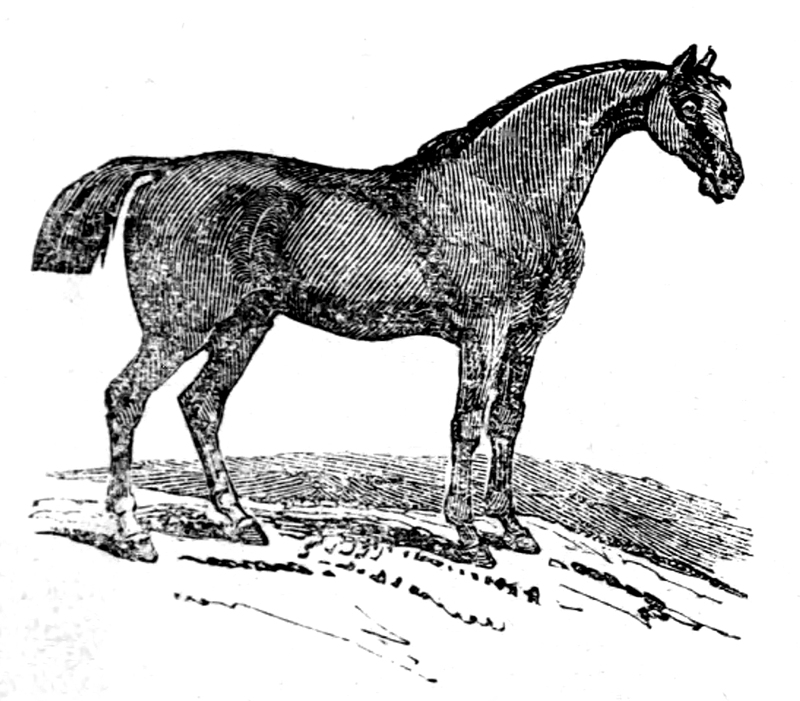

THE HORSE.

When kindly used, the horse is very fond both of his feeder and of his rider. He has a very good memory. 9A gentleman once rode a young horse thirty miles from his home to see his friend. The horse had never been in that part of the country before, and the road was hard to find: after asking the way of many persons whom he met, the gentleman at last got to his friend’s house. Two years afterwards he had again to go the same journey, and it became quite dark, long before he could get to the place. “Well,” said he, “here I am, far from any house, and I know not an inch of the road, and I can hardly see my horse’s head. I have heard much of the memory of the horse; it is my only hope now, go on;” so saying, he threw the reins on his horse’s neck, and in half an hour he was safe at his friend’s gate.

The horse is found in high perfection in Arabia. To the people of that country they are as dear as their own children; and by constantly living in the same tent with their owner and his family, they become very familiar and gentle. They are not used to the spur, but the least touch with the foot sets them in motion. They form the principal riches of many of the Arab tribes, who use them both for plunder and for the chase.

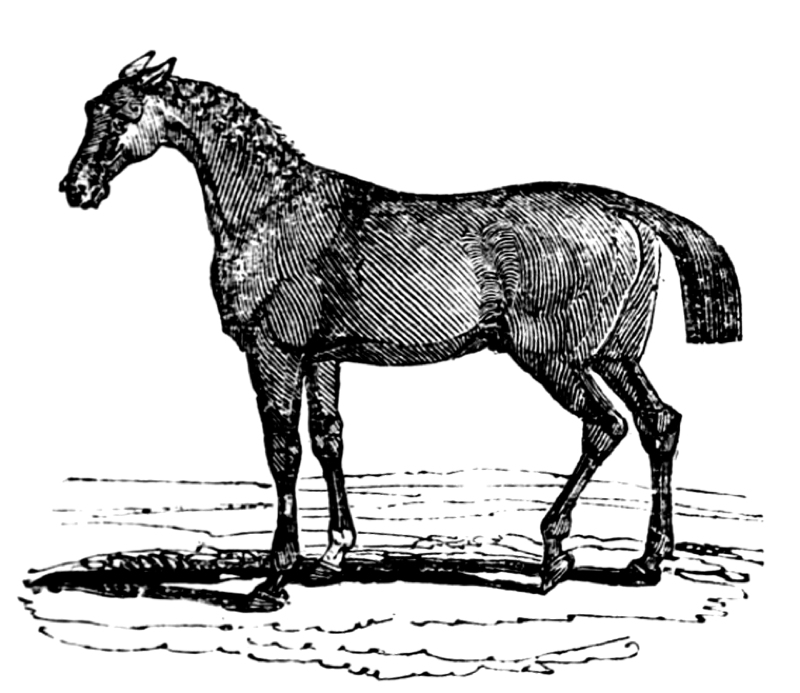

THE RACE HORSE.

Of one of these people a touching story is told. The whole stock of a poor Arabian of the desert was a mare, and he consented to sell her to a French merchant for a very 13large sum of money. At length with only a miserable rag to cover his body he brought his noble courser to the house of the buyer. Having dismounted, he looked first at the gold and then at the mare, and heaving a deep sigh, he exclaimed, “To whom is it that I am going to give thee up? To Frenchmen, who will tie thee close, who will beat thee, who will render thee miserable! Return with me my beauty! my jewel! and rejoice the hearts of my children!” Having said this he sprang on her back, and was out of sight in a moment. Still, for a continuance of great exertion, the English Race Horse is said to be superior to the Arabian, and for fleetness, he will yield to none. A Race Horse will go at the rate of a mile in less than two minutes.

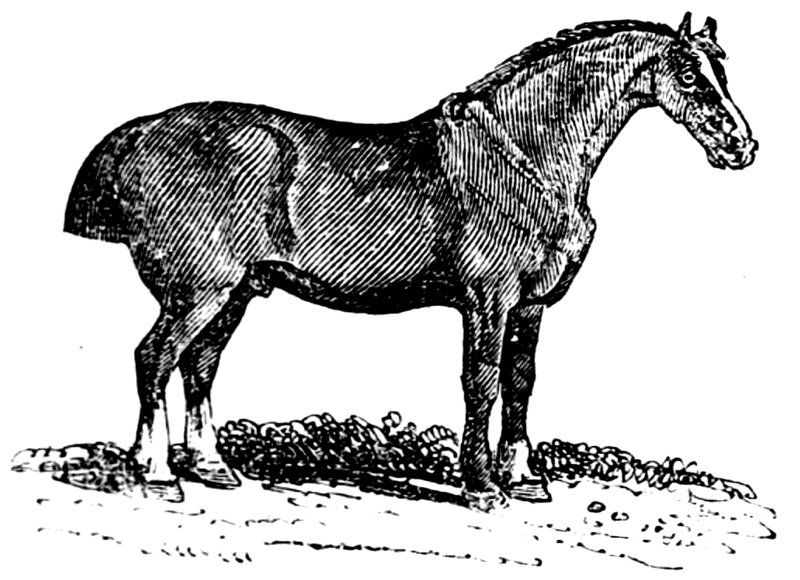

THE CART HORSE.

Till of late years, Pack-Horses were employed in the northern parts of England, to carry goods and parcels. In their journeys over barren moors, they strictly observed the line of order and regularity they were first taught to keep. The leading horse, always chosen for his steadiness and sagacity, being furnished with bells, gave notice to the rest, which followed the sound, though sometimes at a distance. Some years ago, one of them who had been long used to follow his leader, was from accident or fatigue, put into an inferior rank; when, as if sensible of his disgrace, he by the greatest exertion 17recovered his usual station, but on arriving at the inn-yard, he dropped down dead!

These horses are not now seen; the old English Road Horse is strong and active, and capable of enduring great hardship; and though the form of the common Cart Horse is heavy, and his motion slow, he is extremely useful, and is employed in a great many ways. In London there have been instances of a single horse drawing, for a short space, so great a weight as three tons.

THE MULE.

The common Mule sometimes lives to the age of thirty years. It is very useful in carrying burdens, particularly in very mountainous places, where horses are not so sure-footed. People of the first quality in Spain are drawn by Mules. Their going down the mountains of the Alps is very wonderful. They place their fore feet as if they were stopping themselves; they then put their hinder feet together, but a little forward, as if they were about to lie down. In this way, having taken a look over the road, they slide down with great swiftness. In the mean time, all the rider has to do is, to 21keep himself fast on the saddle without checking the rein; for the least motion is sufficient to disorder the equal balance of the animal, in which case both would certainly be dashed to pieces. In their swiftest motion, when they seem to have lost all government of themselves, they follow exactly the different windings of the road, as if they had settled in their minds which way they were to go.

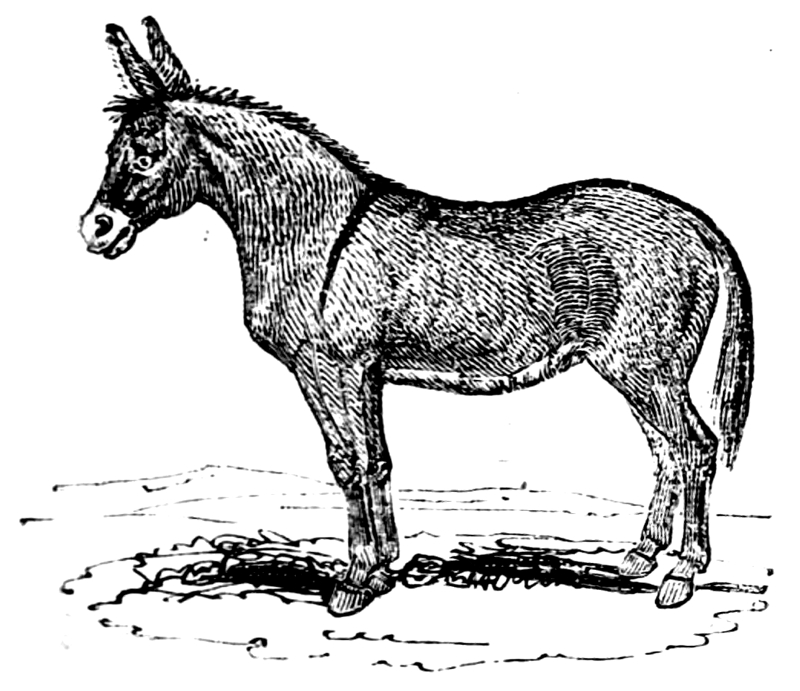

The Ass has to endure the hardest labour, and is contented with the coarsest food. The statement that Asses are stubborn animals is not true, it arises from ill usage, and not from any defect in their temper.

THE ASS.

An old man, who a few years ago sold vegetables in London, used in his employment an Ass, which conveyed his baskets from door to door. He frequently gave the poor creature a handful of hay, or a piece of coarse bread, or some greens, by way of refreshment and reward. The old man had no need of any stick for the animal, indeed he seldom had to lift up his hand to drive it on. This kind 25treatment being one day observed, he was asked whether his beast was not apt to be stubborn. “Ah! master (he replied), it is of no use to be cruel; and as for stubbornness I cannot complain, for he is ready to do any thing, and to go any where. I bred him myself. He is sometimes skittish and playful, and once ran away from me; there were then more than fifty people after him, attempting in vain to stop him, yet after all he turned back of his own accord, and never stopped till he ran his head kindly into my bosom.”

The Bull equals the horse in size, though he is not quite so high; his form is more bulky, and he is stronger made about the neck and head.

THE BULL.

Bull-baiting is a very cruel sport; this mode of killing Bulls is derived from one kind of ancient hunting, very like the Spanish bull-fights of the present day. On notice being given that a wild Bull would be slain on a certain day, the inhabitants of the neighbourhood assembled, sometimes to the number of a hundred horsemen, and four or five hundred foot, all armed with guns or other weapons. Those on foot stood upon the walls or got into trees, while the 29horsemen rode off a Bull from the rest of the herd, until he stood at bay, when they dismounted and fired. At some of these huntings twenty or thirty shots have been fired before the animal was killed. This dangerous sport is now but little practised. There is scarcely any part of the Ox that is not of some use to mankind. Boxes, combs, knife-handles, and drinking vessels, are made of the horns. Glue is made of the sinews, gristles, and the finer pieces of cuttings and parings of the hides, boiled in water till they become jelly-like, and the parts sufficiently dissolved, and then dried. The bone is a cheap substitute, in many instances, for ivory. And the thinnest of the calves-skins are made into vellum.

THE COW.

The Cow is the most important animal of the farmer’s stock. Being equally capable of enduring heat and cold. It is an inhabitant of the frozen, as well as of the most scorching climates. There are a great variety of kinds; and they are all of a very humble and gentle disposition. The climate and pastures of Great Britain are well adapted to the nature of this animal; and we are indebted to the variety and abundance of our wholesome vegetables, for the number and excellence of our cattle, which range over our hills, and enliven our plains—a source of wealth and boast to this happy country. 33Not having the upper fore-teeth, the Cow prefers the high and rich grass in pastures, to the short and more delicate herbage generally selected by the horse. For this reason, where the grass is rather high and flourishing in our pastures than large and full, the Cow thrives well; and there is no part of Europe in which this animal grows larger, gives more milk, or fattens sooner. The quantity of milk given by Cows is various; some give only about six quarts in a day, whilst others give from fifteen to twenty.

THE RAM.

Sheep are very useful animals: they are quiet and harmless. They tremble at the voice of the shepherd, or at the barking of his dog; but, on the great hills where they run about at liberty, away from the shepherd, they shew more courage. Sometimes a Ram or Wether will boldly attack a single dog, and often come off victorious; but when the danger is more alarming, they collect the strength of the whole flock. On such occasions they draw up in a complete body, placing the female and the young in the middle, while the males take the foremost ranks, keeping close by each other. Thus an armed front is 37formed on all sides that cannot easily be attacked without danger of destruction to the dog. In this manner they wait with firmness the approach of the enemy, nor does their courage fail them in the moment of attack: for, when the dog advances within a few yards of the line, the Rams dart upon him with such force as to lay him dead at their feet, unless he save himself in time by flight.

THE SHEEP.

Sheep supply us both with food and clothing: and the wool alone affords, in some countries, an amazing source of industry and wealth. They are harmless animals, and, in general, very shy and timid. The Sheep in the high mountains of Wales are very wild, and do not collect into large flocks, but graze in parties of from eight to a dozen. One is always placed at a distance from the rest, to give notice of the approach of danger. When he observes a stranger advancing, he allows him to approach as near, perhaps, as eighty or a hundred yards, but keeps a watchful eye upon his motions; if 41the stranger shows a design of coming closer, he alarms the rest of the flock by a loud hiss or whistle, twice or thrice repeated, when the whole party instantly scour away with great speed, to the most inaccessible parts of the mountains. No country produces finer Sheep than Great Britain. Of these the Sheep that are bred in Lincolnshire and the northern parts, are the largest and bear the most wool. In other parts of England they are generally smaller; and in the mountainous parts of Wales and Scotland they are very small.

THE GOAT.

Although very shy and timid in a wild state, goats are easily trained as domestic animals, being very sensible of kind treatment. The disposition of this creature is, however, extremely unsettled, as is shewn by the irregularity of all his actions. He walks, stops short, runs, leaps, approaches or retires, shews and conceals himself, or flies off, as if induced by mere whim, and without any other cause than what arises from the strange vivacity of his temper. Goats love to feed on the tops of hills, and prefer the very elevated and rugged parts of mountains, finding sufficient food in the most heathy 45and barren grounds. They are so active as to leap with ease and the utmost security, among the most dreadful precipices; and even when two of them are yoked together, they will, as it were by mutual consent, take the most hazardous leaps together, and exert their efforts in such a united manner as generally to get through the danger unhurt. In mountainous countries they are of great service to mankind; the flesh of the old ones being salted as winter provision, and the milk being used in many places for making cheese. These animals require but little care and attention, and easily provide for themselves proper and sufficient food.

This is the most beautiful animal of the Deer kind. The elegance of his form, the lightness of his motions, the flexibility of his limbs, his bold branching horns, which are yearly renewed, his grandeur, strength and swiftness, give him a decided rank over every other inhabitant of the forest. The age of the Stag is known by its horns: he begins to shed them about the end of February or the beginning of March: each year they become larger.

THE STAG.

The usual colour of the Stag, in England, is red; in other countries it is commonly brown or yellow. His eye is extremely beautiful, soft and sparkling: his hearing is quick; 49and his sense of smell very strong. When listening, he raises his head, erects his ears, and seems attentive to every noise, which he can hear at a great distance. When he approaches a thicket, he stops to look round him on all sides; if he perceives nothing to alarm him, he moves slowly forward; but on the least appearance of danger, he flies off with the rapidity of the wind. He appears to listen with great delight to the sound of the shepherd’s pipe, which is sometimes made use of to ensnare him to his destruction.

These animals live together in herds, which sometimes divide into two parties, and maintain obstinate battles for the possession of a favourite part of the park: each one having its leader, which is always the oldest and strongest of the flock. They attack in regular order of battle; they fight with courage, and mutually defend each other.

THE FALLOW DEER.

The chief difference between the Stag and the Fallow deer, seems to be in the size and form of their horns; the latter are much smaller than those of the former. The Fallow deer is easily tamed, feeds on a variety of things which the stag refuses, 53and preserves its condition nearly the same throughout the year, although its flesh, called venison, is considered much finer at particular seasons. We have in England two varieties of the Fallow deer, which are said to be of foreign origin: the beautiful spotted kind were brought from Bengal in India. These animals, with some variation, are found in almost every country of Europe. Those of Spain are as large as stags, but darker; their necks are also more slender; and their tails, which are longer than those of ours, are black above, and white beneath.

The form of the Roebuck is elegant, and its motions light and easy. It bounds seemingly without much effort, and runs with great swiftness. When hunted, it tries to evade its pursuers by the most curious methods: it often returns upon its former steps, till, by various windings, it entirely misleads the hounds. This cunning animal then, by a sudden spring, bounds to one side; and, lying close down upon its belly, lets the hounds pass by, without offering to stir.

THE ROEBUCK.

The Roe was at one time common in many parts of England and Wales; but at present it is to be 57found only in the Highlands of Scotland. It is the smallest of all the Deer kind, being only three feet four inches long, and rather more than two feet in height: the horns are from eight to nine inches long, upright, round, and divided into three branches; the body is covered with long hair. When the female has young, and they are in danger, she hides them in a thicket; and, to preserve them, offers herself to be chased. Numbers of fawns are taken alive from their dams by the peasants, and many are worried by dogs, foxes, and other enemies; so that the beautiful Roe is becoming daily more scarce.

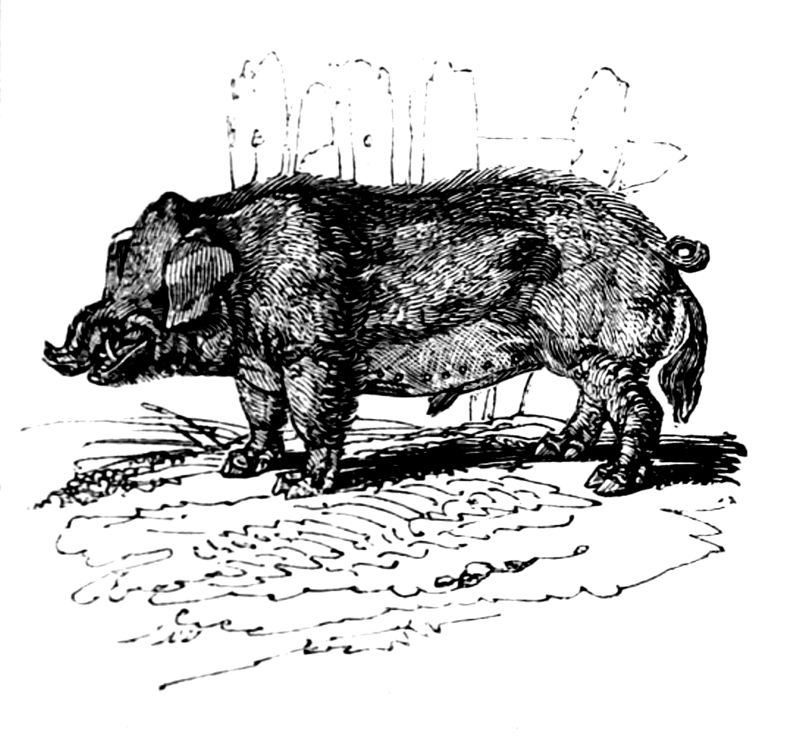

The Boar is naturally stupid, inactive, and drowsy. It is very restless at a change of the weather: and during high winds it runs about with great violence, screaming loudly at the same time. It is thought to foresee the approach of bad weather. Before a storm comes on it may be seen carrying straw to its sty, for the purpose of making itself a bed.

THE BOAR.

The form of the Boar is very clumsy. Its neck is strong, its snout is long and hard, and made for turning up the earth for roots of various kinds, of which it is very fond. It has likewise a quick sense of smelling. 61The flesh of the Hog is of great use, and makes an elegant, as well as almost a constant article for the table. It takes salt better than any other kind of meat, and can be kept longer. It is of great importance in ships’ stores, as it forms the principal food during long voyages.

THE SOW.

The Sow is, generally speaking, a harmless and inoffensive creature. Its food consists of a variety of things that would otherwise be wasted; the refuse of the field, the garden, the barn, or the kitchen, afford them a very good meal. These animals select with great sagacity and niceness the plants they prefer, and are never poisoned like some others by mistaking one plant for another. Selfish, obstinate, and greedy as many think them, no animal, it is said, has greater feeling for those of its own kind. They have been known to gather round a dog that teased them, and kill him on the spot. If a male and female 65are put in a sty together when young, the female will not eat her food for some time if her companion is removed from her.

Many things shew that they are not quite so stupid as some are inclined to believe. We have had exhibitions of their ingenuity, which have attracted great attention and astonishment. And it is stated as a remarkable fact, that a gamekeeper actually broke in a New Forest Sow to find game nearly as well as a pointer.

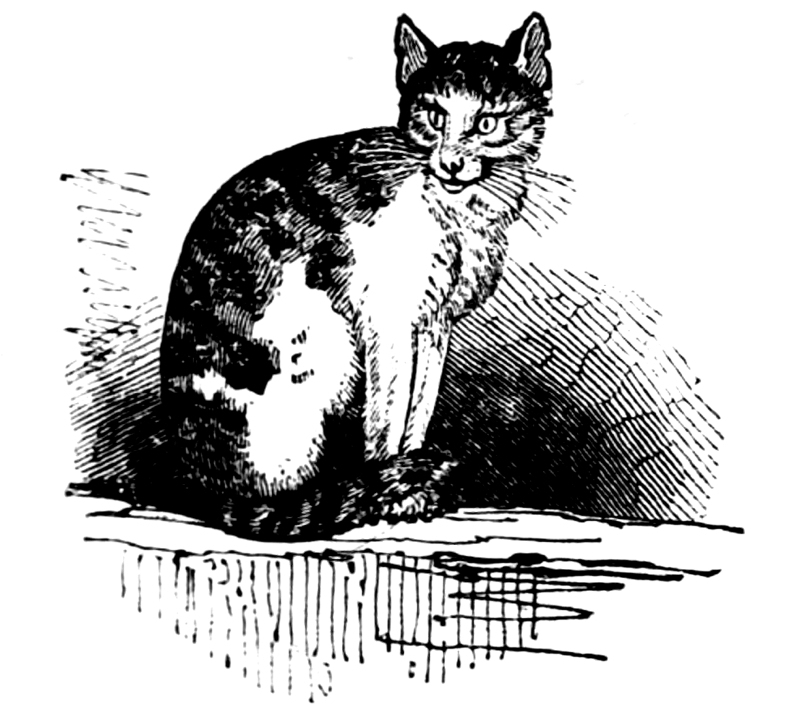

The Tame Cat may be found in almost all countries, and it differs but little from the wild cat except in the brightness of its colours. It is very useful in our houses in catching the rats and mice.

THE TAME CAT.

Of all animals when young, there is none more prettily playful and amusing than the Kitten, and little children are mostly very fond of them; but it generally changes its disposition as it grows older. From being naturally ravenous, it learns in time to disguise its appetite, and to seize the favourable moment for plunder. Sly and artful, it has learned to conceal its intentions till 69it can put them in force: and whenever the opportunity occurs, it directly seizes upon whatever it finds, flies off with it, and remains at a distance till it thinks its offence is forgotten. Instances of the fidelity of Cats, however, are not so rare as some would have us imagine. A French traveller had an Angora Cat, a native of Egypt, which kept by his side in his solitary moments; she often interrupted him in his meditations by affectionate caresses, and in his absence sought and called for him with great inquietude.

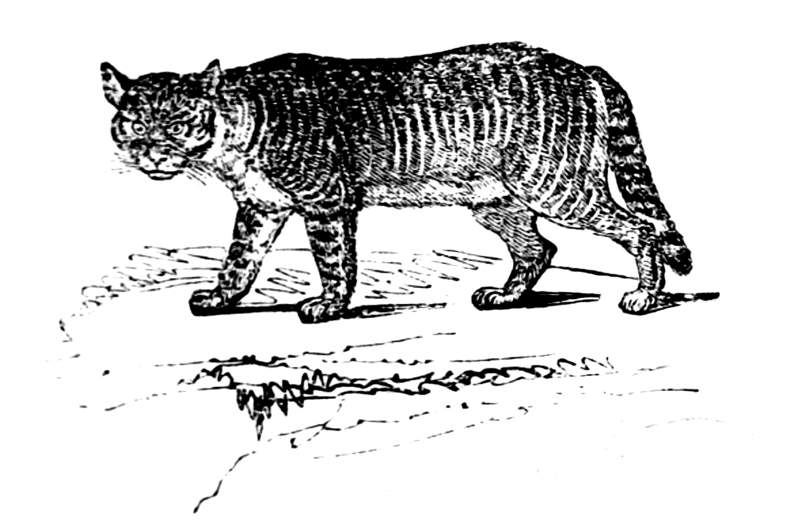

THE WILD CAT.

The hair of the Wild Cat is soft and fine, and of a pale yellow colour, mixed with grey; a dusky-coloured line runs along the back, from its head to its tail; the tail is thick, and marked with bars of black and white. It is larger and stronger than the tame Cat, and its fur much longer. It inhabits the most hilly and woody parts of this island, lives in trees, and hunts for birds and small animals, such as rabbits, hares, rats, mice, moles, &c.; and it is also very destructive among poultry. The Cat seems to possess something like an additional sense, by means of its whiskers. These whiskers consist 73not only of long hairs on the upper lips, but also of four or five others standing up from each eyebrow, and also two or three on each cheek; all of which, when the animal erects them, make, with their extremities, so many points in the compass of a circle as to be at least equal in extent to their own bodies. With this assistance, it is supposed it can at once discover whether any hole or space is large enough to admit the body, which to those living in a wild state is of the greatest consequence; and to the domestic Cat of great service.

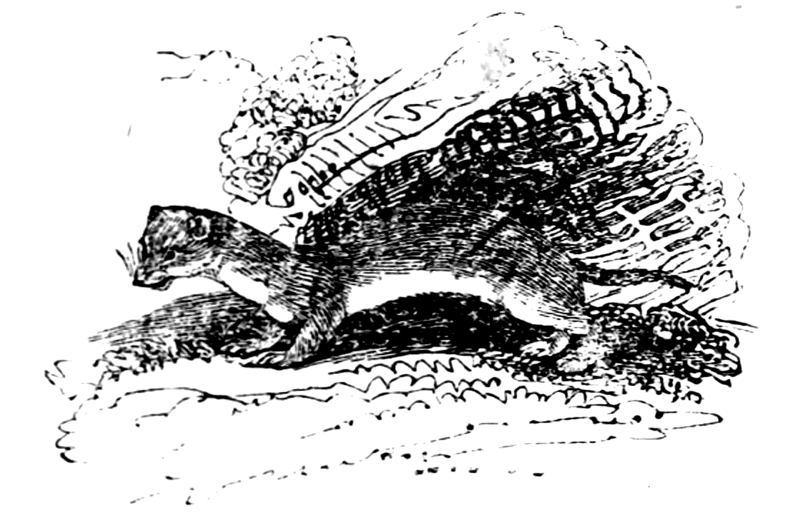

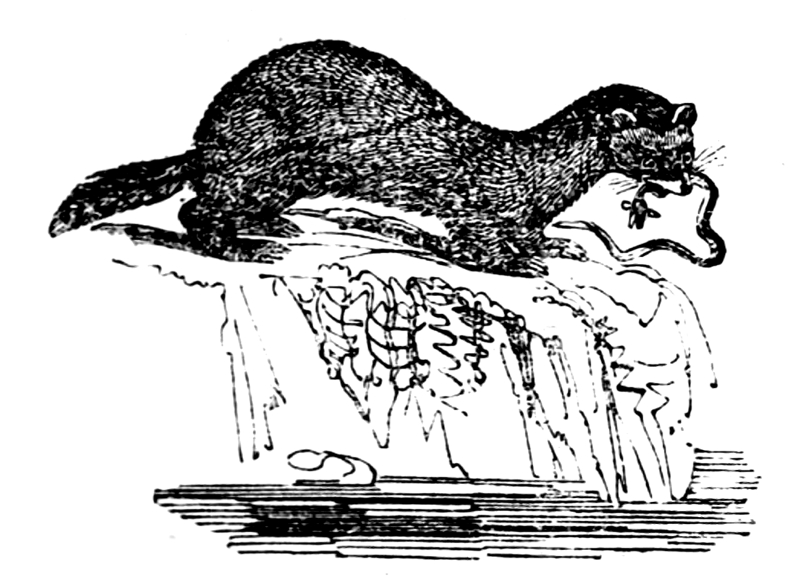

The length of this animal does not exceed seven inches: its height is two inches and a half. The most usual colour of the Weasel is a pale reddish brown on the back, sides, and legs; the throat and belly are white. This animal is very common, and well known in this country; it is destructive to young birds, poultry, and rabbits, and is a keen devourer of eggs. It will follow a young hare, which becomes so terrified as to give itself up to it without resistance, making at the same time the most piteous outcries.

THE WEASEL.

The Weasel is very useful to the farmer. During the winter it frequents 77his barns and granaries, which it clears of rats and mice; it is a more deadly enemy to them than even the Cat; for being more active and slender it pursues them into their holes, and kills them quickly. Though the Weasel is a wild little animal, there are instances to prove, that it is capable of being made quite tame. They have been taught to lick the hand from which they receive their food, and even to follow their master.

THE MARTIN.

The Martin lives chiefly in the pine-tree forests of North America. The principal difference between the Pine-Weasel and the Martin is in the colour. The breast of the former is yellow; the colour of the body much darker; and the fur in general, greatly superior in fineness, beauty, and value. The Martin is about eighteen inches long; the tail is ten inches long, and full of hair, especially towards the end, which is thick and bushy; the ears are broad, round and open; the body is covered with a thick fur, of a dark brown colour: the head is brown, mixed with red; the throat and breast are 81white; the feet are broad, and covered on the under side with a thick fur; the claws are white, large, and sharp, well adapted for climbing trees, where it mostly lives. The skin has a very nice scent; its fur is valuable, and highly prized. When taken young, it is easily tamed, and becomes very playful and good-humoured, but is not to be depended upon. It readily takes advantage of the first opportunity to regain its liberty, and retire to the woods. The food of the Martin consists of rats, mice, poultry, game, birds, and grain, and it is also extremely fond of honey.

THE FERRET.

This little creature is a native of Africa, and is only known to us in a domestic state. It is unable to bear a cold climate, and cannot live without great care and shelter. It is usually kept in a box, with wool, of which it makes itself a warm bed. It sleeps a great part of the day; and the moment it awakes, it seems eager for its food, which is commonly bread and milk. The length of the Ferret is about fourteen inches; the tail is five inches long; its nose is sharper than that of the Weasel, its ears are round, and its eyes red and fiery: the colour of the whole body is a very pale yellow. When employed to clear the rabbit warren, 85it must be muzzled, that it may not kill the rabbits in their holes, but only oblige them to come out, that the warrener may catch them in his nets. If the Ferret be suffered to go in without a muzzle, or should free himself from it whilst in the hole, there is great danger of losing it: for, after satisfying itself with blood, it falls asleep, and it is then almost impossible to get at it. The most usual method is by digging it out, or smoking the hole. If these do not succeed, it continues during the summer among the rabbit holes, and lives upon the prey it finds there; but is sure to perish in the winter.

THE POLECAT.

The Polecat is not afraid of mankind, but approaches our dwellings with confidence, mounts to their roofs, and often lives in barns, hay-lofts, or other places that are much frequented. From thence he prowls about under the shadow of night, to attack the poultry. He is very active, and runs fast. While running, his belly seems to touch the ground; but in preparing to jump, he arches his back very much, by means of which the force of his spring is greatly increased. The Polecat, during summer, lives in woods, or about rabbit-warrens. Here, if he cannot find a hole ready made that suits him, he 89forms a retreat for himself, in the ground, about two yards in length, which he contrives, if he can, to end among the roots of some large tree. From thence he often comes forth and destroys game and rabbits. These animals are also very fond of honey; and in winter when the bees are weakened by the coldness of the season, they have been known to attack the hives and to devour their contents very eagerly.

THE BADGER.

This animal is a native of Europe, but is known to live in warm countries. It is found, without any variety, in Spain, France, Italy, Germany, Britain, Poland, and Sweden. The usual length of the Badger is somewhat above two feet, and the tail is about six inches long; its eyes are small, and are placed in a black stripe which begins behind the ears, and runs towards the nose; the throat and legs are black; the back, sides, and tail, are of a dirty grey, mixed with black; the legs and feet are very short, strong, and thick; each foot has five toes; those on the fore feet are armed with strong claws, well adapted for digging.

93Although furnished with powerful weapons of offence, and having besides strength to use them with great effect, it is very harmless and inoffensive; and unless attacked, employs them only for its support. The Badger retires to the most secret places, where it digs its hole, and forms its dwelling under ground. Its food consists chiefly of roots, fruits, grass, insects, and frogs. Few creatures defend themselves better, or bite with greater keenness, than the Badger. On that account it has been often baited with dogs trained for the purpose; but, happily, little is now heard of this very cruel sport. The Badger is a very sleepy animal. It keeps its hole during the day, and feeds only in the night.

THE FOX.

The Fox is a native of almost every quarter of the globe; and is of so wild and savage a nature that it is said to be impossible fully to tame him: when partially so, he is very playful; but will on the least offence, bite those with whom he is most familiar. He possesses more cunning than any other beast of prey. This quality he shows in his mode of providing for himself a place of security, where he retires from pressing dangers, and brings up his young; and his craftiness is also discovered by his schemes to catch lambs, geese, hens, and all kinds of small birds.

When he can conveniently do so, 97the Fox fixes his abode on the border of a wood, in the neighbourhood of some farm or village. He listens to the crowing of the cocks, or the cries of the poultry. He scents them at a distance; he chooses his time with judgment; and conceals his road, as well as his design. He slips forward with caution, sometimes even trailing his body; and seldom misses his booty. If he can leap the wall, or creep in beneath the gate, he ravages the court-yard, puts all to death, and retires with his prey. He hunts the young hares in the plains; and seizes the old ones in their seats. The eye of the Fox is of a lively hazel colour, and very expressive.

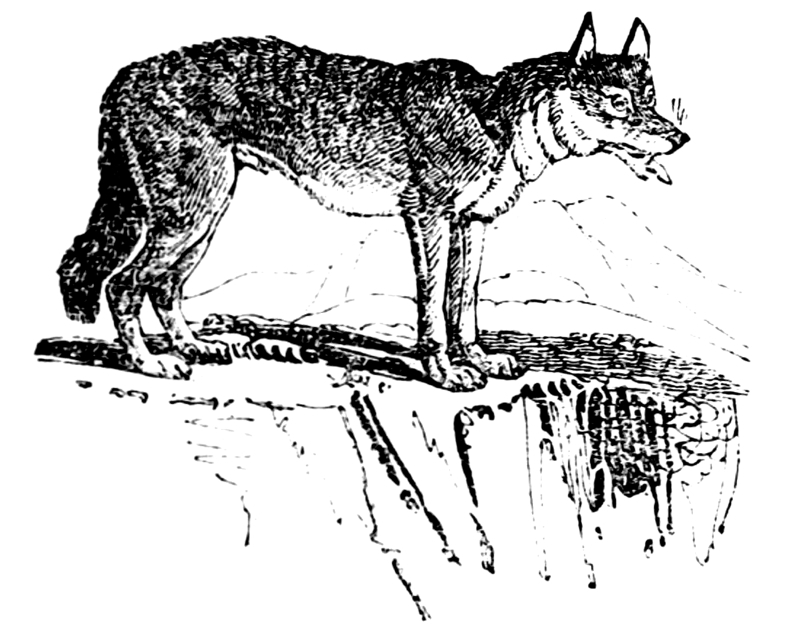

These animals are natives of almost all the temperate and cold countries of the globe; and were formerly so numerous in this island, that King Edgar, about a thousand years ago, changed the punishments for some offences, into a demand of a certain number of Wolves’ tongues from each criminal; and once converted a heavy and oppressive tax on one of the Welsh princes, into a yearly tribute of three hundred Wolves’ heads. Some hundred years after, these animals increased to such a degree, that great rewards were given for destroying them.

THE WOLF.

The Wolf is very savage indeed 101when it is hungry. It then braves every danger, and even attacks those animals that are protected by man. Man himself, upon these occasions, frequently falls a victim to its power; and it is said, that when Wolves have once tasted human blood, they always give it the preference. The Wolf has great strength, especially in the muscles of his neck and jaw: he can carry a sheep in his mouth, and easily run off with it in that manner. His bite is cruel and deadly, and keener as it meets with no opposition: but when opposed, he is cautious and careful, and seldom fights but from necessity. Sometimes whole droves of them join in the cruel work of destruction.

THE SHEPHERD’S DOG.

This useful animal, ever faithful to his charge, reigns at the head of the flock, where he is better heard, and more attended to, than even the Shepherd himself. In the few remaining large tracts of land which are appropriated to the feeding of Sheep, this dog is of the utmost importance. Large flocks range over extensive tracts of land, seemingly without controul: their only guide being the Shepherd, attended by his Dog, the constant companion of his toil. It receives his commands, and is always prompt to execute them; it is the watchful guardian of the flock, prevents straying, keeps them together, and conducts them from 105one pasture to another: it will not suffer strange sheep to mix with them, but carefully keeps off every intruder. In driving a number of sheep to any distant part, a well-trained Dog never fails to confine them to the road; he watches every avenue that leads from it, where he takes his stand, to prevent them from going out of the way. He pursues the stragglers if any escape, and forces them into order, without doing them the least injury. If the Shepherd be at any time absent he depends upon his Dog to keep them together; and as soon as he gives the well-known signal, this faithful creature conducts them to his master, though at a great distance.

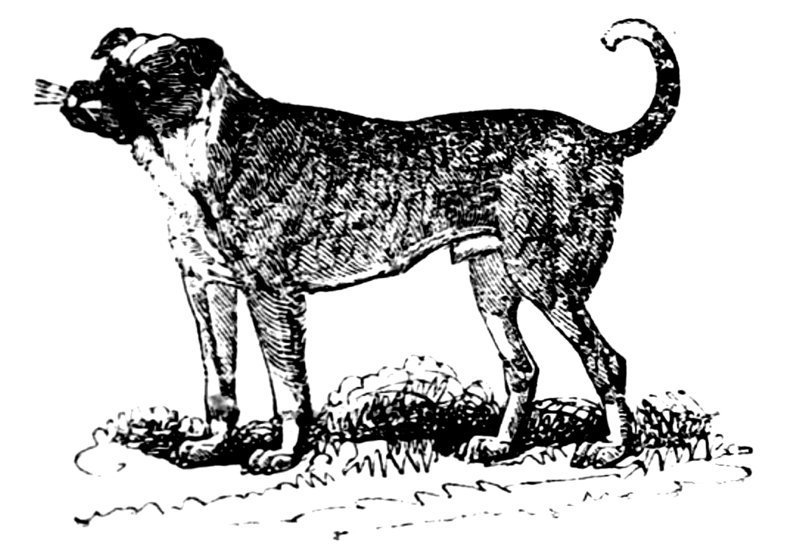

THE BULLDOG.

When little children meet any dogs they should take care not to tease them, more particularly the Bulldog, for when that dog is completely roused it is the fiercest of its kind, and is probably the most courageous creature in the world. It is low in stature, but very strong. Its nose is short; and the under jaw projects beyond the upper, which makes it look very fierce. Its courage in attacking the bull is well known; its fury in seizing and its obstinacy in keeping its hold, are truly astonishing. It always aims at the front, and generally fastens upon the lip, the tongue, the eye, or some part of 109the face; where it hangs in spite of every effort of the bull to get away from it.

Many stories are told us of this most cruel sport; but of late years the inhuman custom of baiting the bull has been almost entirely laid aside, and there are now few Dogs of this kind to be seen. The great danger of the Bulldog is, he always makes his attack without barking.

This breed of Dogs was originally brought from the country of which they bear the name, where their great strength and sagacity render them extremely useful to the settlers on those coasts, who use them in bringing down wood from the forests to the sea side. Three or four of them yoked to a sledge, will draw two or three hundred weight of wood piled upon it, for several miles, with great ease: they are not attended by a driver, nor any person to guide them; but after having delivered their loading, they return immediately to the woods, where they are accustomed to be fed.

THE NEWFOUNDLAND DOG.

During a severe storm in the winter 113of 1789, a ship, belonging to Newcastle, was lost near Yarmouth; and a Newfoundland Dog alone escaped to the shore, bringing in his mouth the captain’s pocket-book. He landed amidst a number of people, several of whom tried in vain to take it from him. The sagacious animal, as if sensible of the importance of the charge which in all probability was delivered to him by his perishing master, at length leapt fawningly against the breast of a man, who had attracted his notice among the crowd, and delivered the book to him. The Dog immediately returned to the place where he had landed, and watched with great attention every thing that came from the wrecked vessel, and tried to bring it to shore.

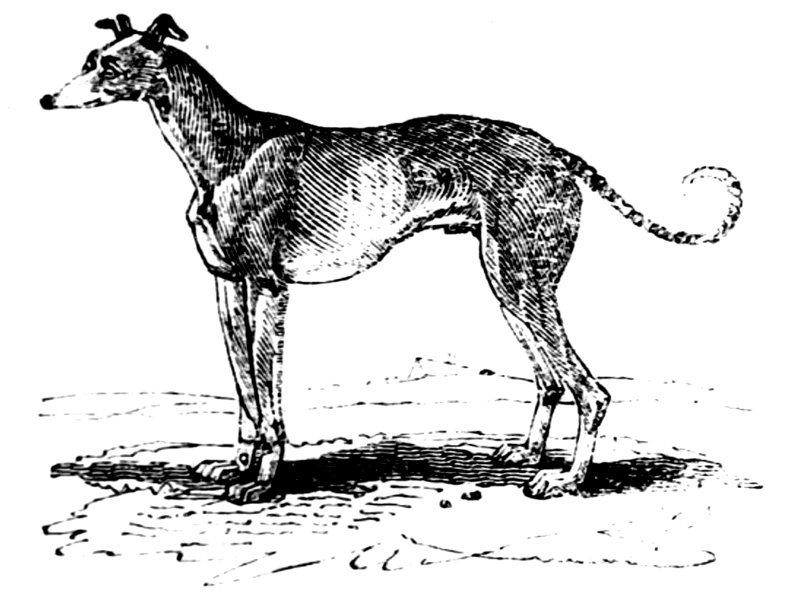

THE GREYHOUND.

The Greyhound is the fleetest of all dogs, and can outrun every animal of the chase; but as it wants the faculty of scenting, it follows only by the eye. It was formerly held in such estimation, as to be considered the peculiar companion of gentlemen; and by the forest laws of King Canute, about a thousand years ago, it was enacted, that no person under that degree should presume to keep a Greyhound. It was supposed to be the Irish Greyhound, rendered thinner and more delicate by the difference of climate and of culture. The Irish Greyhound is the largest of the dog kind, and its appearance 117the most beautiful and majestic. It is only to be found in Ireland, where it was formerly of great use in clearing the country of wolves. It is now extremely rare, and is kept more for show than for use, being equally unserviceable for hunting the stag, the fox, or the hare. These dogs are about three feet high, generally of a white or cinnamon colour, and in make resemble a Greyhound. Their aspect is mild, their disposition gentle and peaceable, and their strength so great, that in combat the mastiff or bulldog is far from being equal to them. They commonly seize their antagonists by the back, and shake them to death, which their great size generally enables them to do with ease.

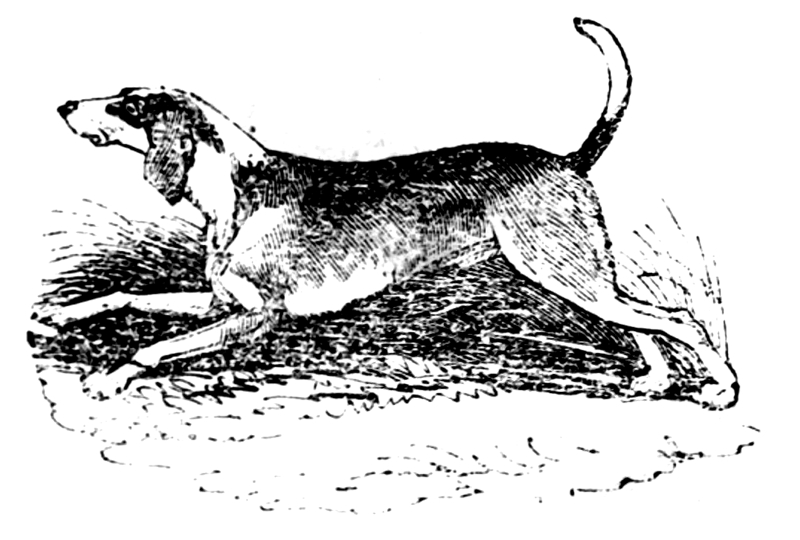

THE FOXHOUND.

The Foxhounds generally preferred are tall, light-made, but strong, and possessed of great courage, speed, and activity. No country in Europe can boast of Dogs of this kind, of equal swiftness, strength, or agility, to those of Great Britain, where the utmost attention is paid to their training. The climate also seems congenial to their nature; for it has been said that when Hounds of English breed have been sent into France, or other countries, they in some degree lose those admirable qualities for which they were once so remarkable. In England attachment to the chase has been considered a trait in the national character; from 121the care and attention which have been given to the rearing of Dogs and Horses, it is no matter of surprise that this country should excel all others in that diversion.

Many years since a very large stag was turned out of Wingfield Park, in the county of Westmorland, and was pursued by the Hounds, till, by fatigue or accident the whole pack was thrown out, except two favourite Dogs which continued the chase the greater part of the day. The stag returned to the park from whence he set out; and, as his last effort, leapt the wall, and immediately expired. One of the Hounds pursued him thither; but, being unable to get over, laid down and died: the other dog was found dead at a little distance.

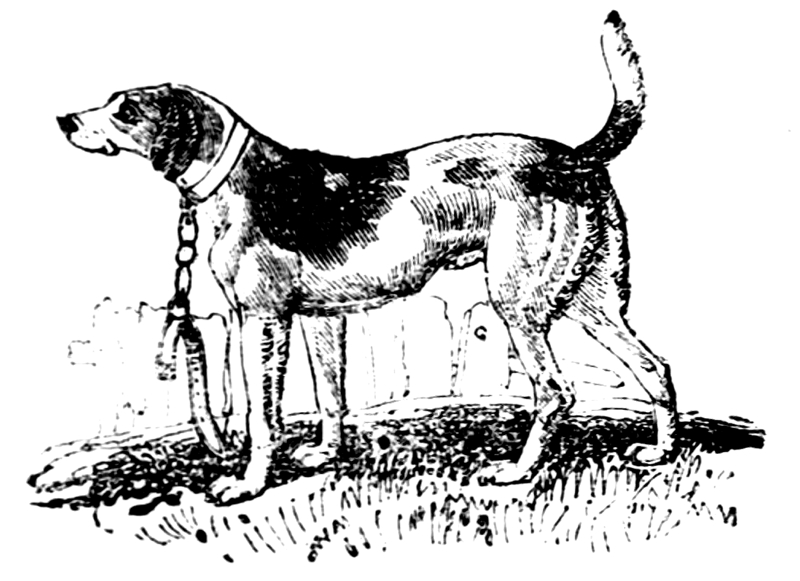

THE HARRIER.

These Dogs are kept for the business of the chase. They pursue the hare with the greatest eagerness, hardly giving her time to breathe. The most eager sportsmen find it sufficient exercise to keep in with their speed. There is a kind of Dog between this and the large Terrier, which forms a strong, active, and hardy Hound, used in hunting the otter. It is rough, wire-haired, thick-quartered, long-eared, and thin-shouldered. There is reason to suppose, that the Beagle and the Harrier must have been introduced into Great Britain after the Romans became masters of the island a thousand years ago, as, before that time the 125Britons were occupied in clearing their extensive forests of the various wild beasts, such as wild boars, bears and wolves, with which they then abounded; and for that purpose larger and stronger dogs than the Harrier or the Beagle would be required.

In the New Forest, in 1810, a person, in getting over a stile observed there was blood upon it; he knew that deer had been killed, and sheep stolen. He obtained a bloodhound. The dog being brought to the spot and led to the scent followed in it, and at length came to a heap of furze, belonging to a cottager. The woman of the house attempted to drive away the dog, but was prevented. On removing the faggots a hole was found containing the body of a sheep and a quantity of salted meat.

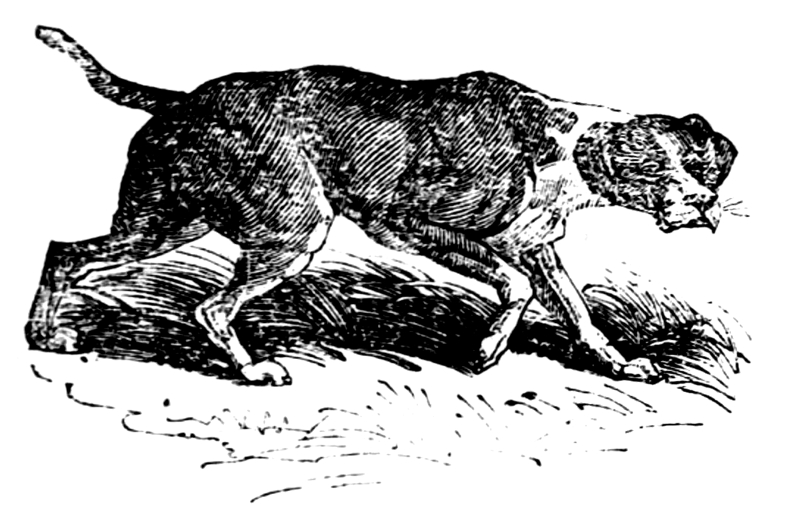

THE POINTER.

This dog is highly esteemed for its use in the pursuit of game. It is remarkable for the quickness with which it receives instruction. It may be said to be almost self-taught; whilst the old English dog requires the greatest care and attention in breaking and training to the sport. The Spanish Pointer, however, is not so durable and hardy, nor so able to undergo the fatigues of an extensive sport. It is chiefly employed in finding partridges, and pheasants, either for the gun or the net. It is said that an English nobleman, Robert Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, in the days of King 129Edward VI. was the first who broke a setting-dog to the net. We are often astonished at the senses of the higher quadrupeds, such as the dog and the horse, by which man employs them for his use. The senses most called into action in the dog are those of smell and hearing. Accordingly the fox-hound can tell the scent of the fox he is pursuing from one that may cross his path; the spaniel or terrier will track his master by his scent through a crowded city; the watch-dog barks when no one else hears a foot fall. This is partly natural and partly attained by exercise and attention.

THE SPANIEL.

This kind of dog is of great value, from the readiness with which it receives instruction, the quickness with which it obeys commands, and its great docility and strong attachment to its master. Of this one striking proof may be given. Old Daniel, the gamekeeper to the Rev. Mr. Corsellis, had reared a Spaniel named Dash, which became his constant attendant both by night and day. Wherever the gamekeeper appeared, Dash was never far distant. When the gamekeeper died, little Dash would not quit the body, but laid upon the bed by its side. After his master was buried, this faithful 133dog would frequently visit the room where he breathed his last, and would remain there for hours. From thence, for fourteen days he constantly visited the grave, at the end of which time he died.

Perhaps the most remarkable instance of attachment is that of the little dog who crept within the clothes of Mary Queen of Scots just previous to her execution, and could not afterward be separated from the corpse but by force.

The Terrier is a very hardy dog, and is of much service to us, as he is an exceeding great enemy to rats and most other vermin: he has very great courage, and will even attack the badger, nor does he seem to care for the desperate wounds he often receives when fighting with it. He is more particularly useful, on account of having such a very acute scent.

THE TERRIER.

There are two varieties of this dog, the one has got very short legs, a long back, and is commonly of a black or yellowish colour mingled with white; the other is of a more sprightly appearance, with a much shorter 137body, and the colour of this species is a reddish-brown or black.

When gentlemen go out a hunting, they generally take one of these dogs to accompany their hounds, for they are very expert in forcing foxes and other game from their coverts; and their scent being so very quick, they often cause a great deal of amusement.

This animal not possessing any means of self defence is furnished by Providence with a high degree of fear. It is attentive to every alarm, and is furnished with very long ears, which are tube-like, and catch the most remote sounds. The eyes are so prominent, as to enable the animal to see both before and behind. The Hare feeds in the evening, and sleeps during the day, and, as he mostly lies on the ground, he has the feet protected, both above and below, with a thick covering of hair. In a moonlight evening many of these creatures may sometimes be seen starting together, leaping about and 141pursuing each other; but the least noise alarms them, and they then scamper off each in a different direction. Their pace is a kind of gallop, or quick succession of leaps; and they are very swift, particularly in ascending hills. In winter they generally choose a form exposed to the south, and in summer they change this for one looking to the north: in both cases, they have the instinct of commonly fixing on a place where the objects around them are nearly of the colour of their bodies.

THE RABBIT.

The Rabbit abounds in Great Britain, where its skin forms a very considerable article in the manufactory of hats. Although the Hare and the Rabbit are so like each other, nature has placed a strong barrier between them, in their feeling of mutual aversion. Besides this, there is a wide difference in their habits and pursuits: the rabbit lives in holes in the earth, where it brings forth its young, and retires from the approach of danger; whilst the Hare prefers the open fields, and trusts to its speed for safety. The female makes a bed of down for her young, which she pulls off her own coat. She never leaves them, but when pressed with 145hunger, and returns as soon as that is supplied. During the time she tends them, she carefully conceals them from the male, lest he should devour them; and often covers up the mouth of the hole, that her retreat may not be discovered. The tame Rabbit is of various colours, and is somewhat larger than the wild Rabbit; but its flesh is not so good, being softer and more insipid. Its food is generally cabbage leaves, colewort, blades of corn, sourdock, and other moist plants; but sweet short hay, and a little clean oats, make the best diet.

THE SQUIRREL.

This beautiful little creature is of a bright brown colour, inclined to red; the breast and belly are white; the ears are ornamented with long tufts of hair; the eyes are large, black, and lively; the fore teeth strong and sharp; and the fore legs are curiously furnished with long stiff hairs, which project on each side like whiskers. When it eats, it sits upright, and uses its fore feet as hands to convey food to its mouth. It is equally admired for its neatness and elegance of form, as for its liveliness and activity. Its disposition is gentle and harmless. Though naturally wild, and very timid, it is easily taught to receive with freedom the most familiar 149caresses from the hand that feeds it. It usually lives in woods, and makes its nest of moss or dry leaves in the hollow of trees. It seldom descends upon the ground, but leaps from tree to tree with great agility. Its food consists of fruits, almonds, nuts, and acorns; of which it collects great stores for winter provision, and secures them carefully near its nest. In the summer it feeds on buds and young shoots, and is very fond of the cones or apples of the fur and pine trees. The tail of the Squirrel is its greatest ornament, and serves as a defence from the cold, being large enough to cover the whole body; it likewise assists it in leaping from one tree to another.

This animal is very much like the common mouse. Its colour is a tawny red, the throat white, the tail tufted. When it is thirsty it does not lap, but dips its fore feet, with the toes bent, into the water, and drinks from them. In the summer this curious little creature is very industrious, laying up its provision for the winter, which consists of nuts, beans, and acorns. As soon as the cold weather approaches, it rolls itself up into a ball, with its tail curled over its head between its ears, and continues in that state till the warm weather comes again.

THE DORMOUSE.

Dormice build their nests either 153in the hollows of trees, or near the bottom of thick shrubs, and line them with moss, soft birchens, and dried leaves. Conscious of the length of time they have to pass in their solitary cells, they are very choice of the materials they make use of.

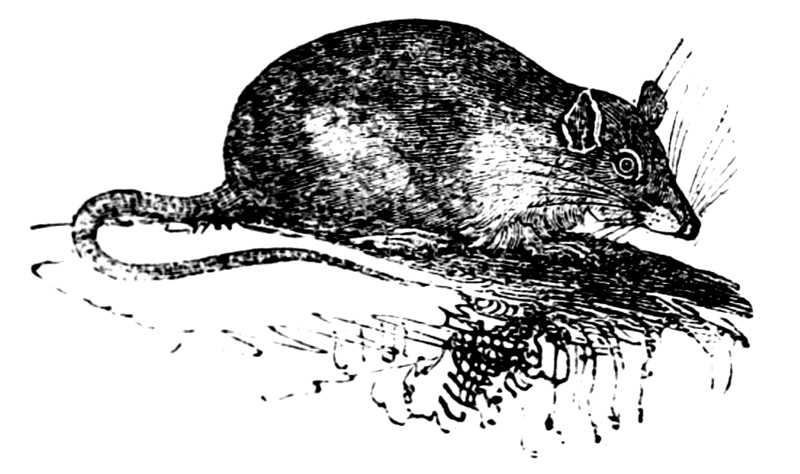

THE RAT.

There are two kinds known in this country—the Black Rat, which was formerly universal, but is now very rarely seen, having been almost all destroyed by the large brown kind, generally distinguished by the name of the Norway Rat. This formidable invader is now found throughout the country, from whence every method has been tried in vain to expel it. It is about nine inches long; of a light brown colour, the throat and under part of a dirty white inclining to grey; its feet are naked, and of a pale flesh colour; and the tail is as long as the body. It is a very bold little animal, and when closely pursued, will turn and fasten on its assailant. 157Its bite is keen, and the wound it inflicts is painful, and difficult to heal, owing to the form of its teeth, which are long, sharp, and irregular. It is a very singular fact in the history of these animals, that the skins of such as have been devoured in their holes, (and they frequently feed upon each other,) have been found curiously turned inside out; every part being completely turned, even to the ends of the toes. How the operation is performed, it would be difficult to discover; but it appears to be effected by some peculiar mode of eating out the contents. Besides the numbers that perish in this unnatural way, they have many fierce and terrible enemies that take every opportunity to destroy them.

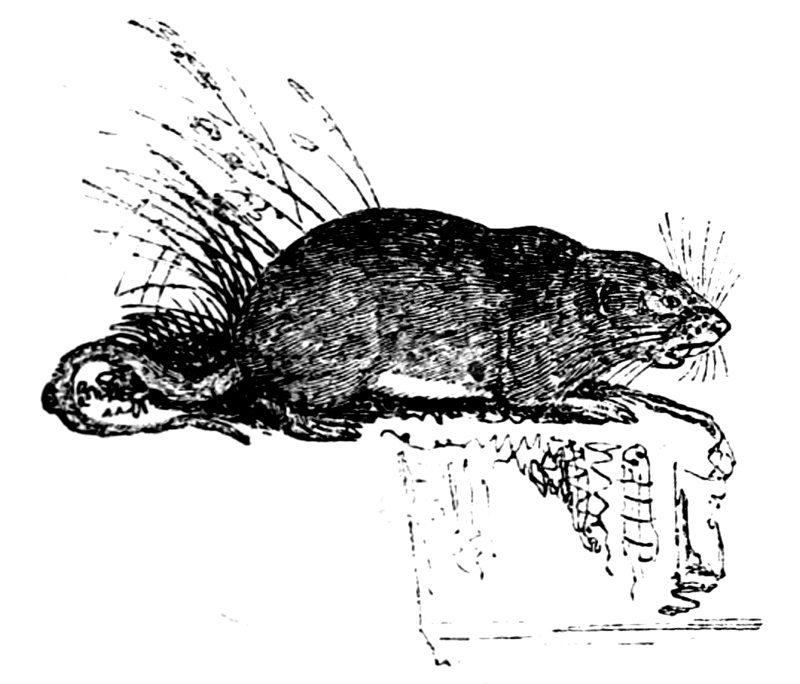

THE WATER RAT.

The Water Rat is somewhat smaller than the common brown Rat; its head and nose are thicker; its eyes are small; its ears short, scarcely appearing through the hair; its teeth are large, strong and yellow. In an old one, the lower front teeth measure somewhat more than half an inch in length. The hair on its head and body is thicker and longer than that of the common Rat, and chiefly of a dark brown colour, mixed with red; the belly is grey; the tail five inches long, covered with short black hairs, and the tip of the tail is white. The Water Rat generally frequents the sides of rivers, ponds, and ditches, where it burrows, and 161forms its nest. It feeds on frogs, small fish, and spawn; swims and dives remarkably fast; and can continue a long time under water.

The Musk Rat somewhat resembles the one just described. The eyes are large; the ears short, rounded, and covered both inside and outside with hair. Its fur is soft, glossy, and of a reddish-brown colour; and beneath this is a much finer fur or thick down, which is very useful in the manufacture of hats. The tail is flattened and covered with scales.

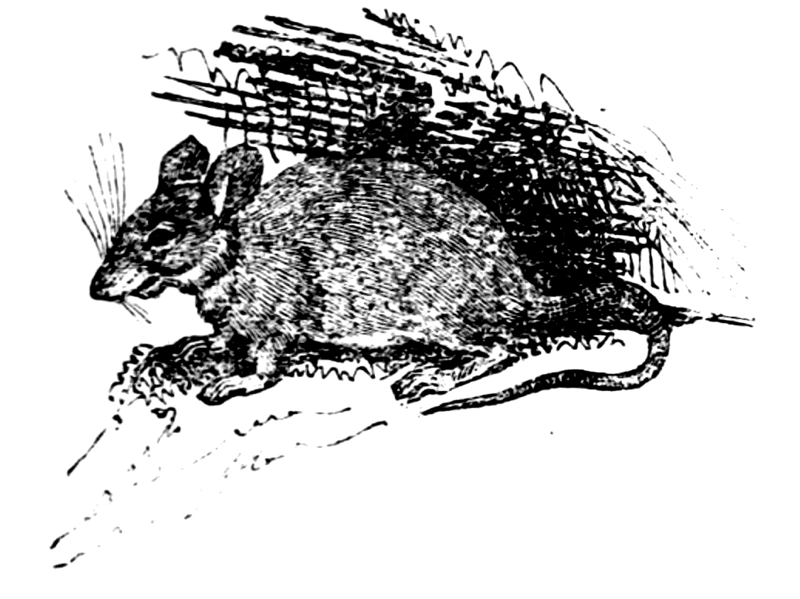

THE MOUSE.

This little creature we all know, because it eats our cheese, and tries all the good things in the larder, we keep a cat to catch it: yet it is very pretty. It hides itself in the walls and under the floors; and in these places it sometimes lays up a considerable store of provision for future subsistence. Its food is various; and, as it is able to pass through a very small hole, there are few places secure from its approach. It seems a constant attendant on man, and is to be found only near his dwelling. Its sight and hearing are extremely acute: and as soon as it observes the least motion, or hears the slightest noise, it listens attentively, 165sitting erect on its hinder feet; and, if the alarm continues, it runs in haste to its retreat. But if it be gradually encouraged, and nourishment and security are offered, it will, by degrees, lose those fears. An instance is related of a Mouse that made its appearance every day at the table of its benefactor, and there waited until it had received its usual portion of food, which it devoured, and then ran away. Some few of this species are of a pure white colour; but whether they be a permanent kind, or only an accidental variety, cannot well be determined.

THE MOLE.

This animal is mostly found in grounds where the soil is loose and soft, and affords the greatest quantity of worms and insects, on which it feeds. Destined to seek its food under the surface of the earth, it is wonderfully adapted by the all-wise Author of Nature, to its peculiar mode of living. It enjoys the sense of hearing and smelling in a very eminent degree: but is almost void of sight. To an animal of such habits, a larger degree of sight would be attended with great inconvenience, as well as be liable to continual injuries. Its eyes are extremely small, and completely hid in the fur. The form of this creature’s body, and particularly 169the construction of its fore feet, are admirably adapted to the purpose of making its way in the earth, which it does with wonderful ease: these feet are quite naked, very broad, with large palms, almost like a hand: there are five toes on each, with strong nails at the end. The hind feet are very small, with five slender toes and a small thumb on the inside. Whenever surprised on the surface of the ground, the mole disappears in an instant.

THE HEDGEHOG.

The Hedgehog generally resides in small thickets and hedges; lives on fruits, worms, beetles, and all kinds of insects; it conceals itself in the day, and feeds only during the night. This animal is provided by nature with a prickly armour, which defends it from the attacks of all the smaller beasts of prey. When alarmed, it immediately collects itself into the form of a ball, and presents on all sides a surface covered with sharp points, which few animals are hardy enough to engage. The more it is harassed, the closer it rolls itself. There are few dogs that will venture to attack the Hedgehog. This little 173animal has been so far domesticated as to learn to turn a spit by means of a small wheel in which it is placed; it likewise answered to its name. In the winter, it wraps itself up in a warm nest, made of moss, dried grass, and leaves; and sleeps out the greater part of that season. It is frequently found so completely encircled with herbage that it resembles a ball of dried leaves.

This curious animal appears at first sight to be a bird, but it has nothing in common with them, but the power of raising itself into the air. The common species of this animal is about the size of a mouse, or nearly two inches and a half in length: the wings are in fact an extension of the skin all round the body; it is stretched on every side when the animal flies, by the four inner toes of the fore feet, which are very long.

THE BAT.

The body of the Bat is covered with a short fur, of a mouse colour, tinged with red; the eyes are very small, and the ears like those of a mouse.

177The Bat appears early in the summer, and begins its flight towards evening. It feeds upon gnats, moths, and almost all insects. This animal sleeps away the greater part of its time, never venturing abroad by day-light, nor yet in wet weather.

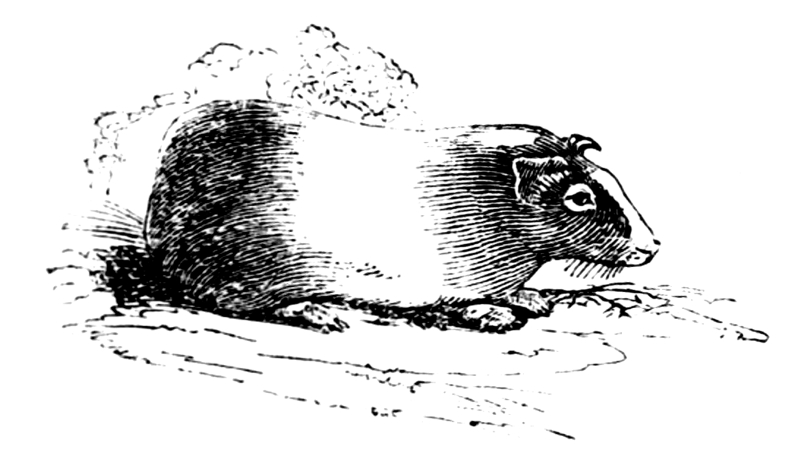

THE GUINEA PIG.

This curious little animal, which is sometimes called the Restless Cavy, is a native of Brazil, but many of them are kept in a domestic state in various countries. It is of the rabbit kind, and resembles that animal very much in its appearance and habits. It is not quite so large as the rabbit, and is marked with white, black, and orange colours. It has not got any tail, which makes it look very curious. It is a very neat animal, and spends much of its time in cleaning the fur of its companions. It never seems to form any attachment, and will suffer its young to be taken away and destroyed, without 181making any resistance. If any of their young ones chance to get dirtied the female takes such a dislike to them, that she will never let them come near her again.

Guinea Pigs will sometimes scratch and kick each other till they are covered with blood.

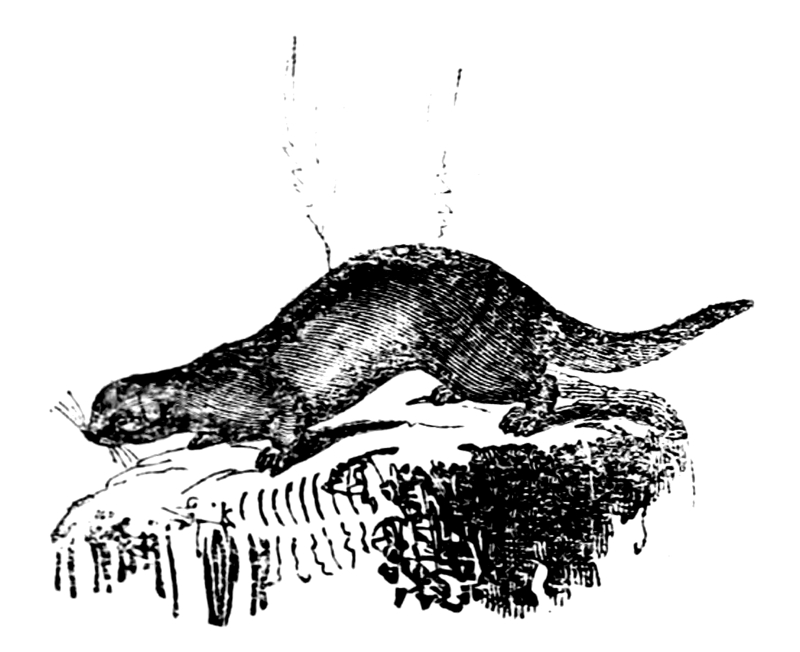

THE OTTER.

These animals are, in general, rather more than three feet long from the point of their nose to the tip of their tail. Their legs are very short, but they are strong and muscular. The colour of their body is mostly of a deep brown.

Otters live chiefly on the banks of rivers or brooks. They make the entrance to their burrows under water, and work upwards, forming several lodges, that they may have a retreat in case of high floods; they end by making a small hole for the purpose of admitting air, but they take care that this hole shall come out in the midst of some thick bush, 185so that they may not be discovered. They are easily tamed, and are kept by many fishermen, being found of great service. The fishermen send them into the water, and they will often drive the fish into their nets, and sometimes bring out the larger ones in their mouths.

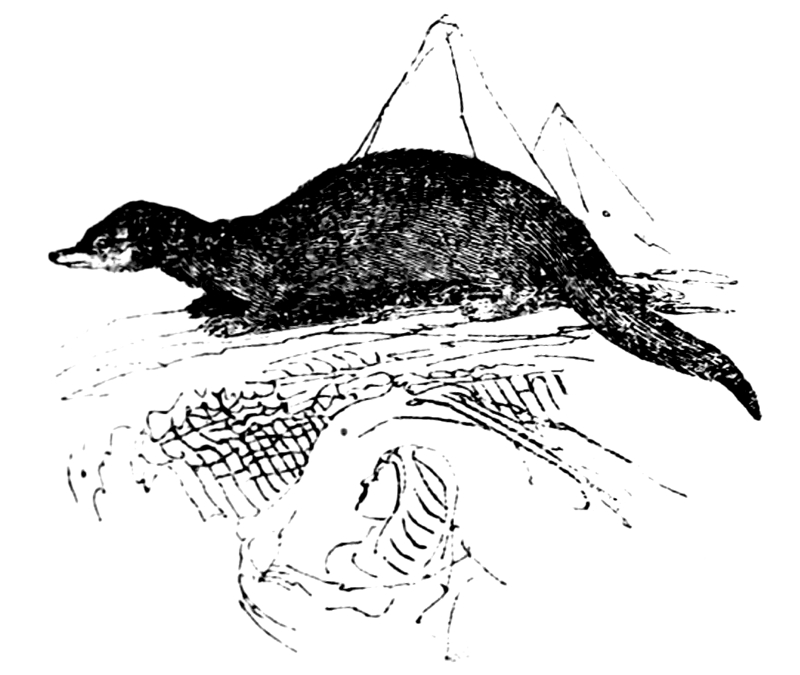

This curious little animal is a native of Egypt, Barbary, and the Cape of Good Hope. It is, in general, about the size of a common cat, but rather longer in its body, and shorter in its legs. Its colour is a pale reddish grey. It is sometimes streaked with a variety of colours, in the same manner as a domestic cat. While eating, it sits upright, and uses its fore feet like hands.

THE ICHNEUMON.

This animal is the boldest and most useful of the weasel kind. It is of very great service in Egypt, and indeed is almost worshipped there, for it destroys a great quantity of the eggs of the crocodile, and will even 189attack the crocodile itself. Rats, mice, birds, serpents, and lizards become its prey; and it will even seize the most poisonous reptiles, and if bitten by them, it is said to be able to cure itself by the use of some herb. The Egyptians esteem it so much, that they keep it in their houses, as we do the cat.