TRANSCRIBER'S NOTES

In the plain text version Italic text is denoted by _underscores_. Small Caps are represented in UPPER CASE. The sign ^ represents a superscript; thus e^ represents the lower case letter “e” written immediately above the level of the previous character.

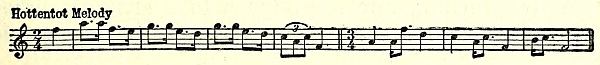

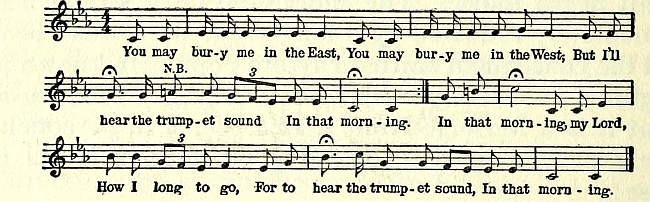

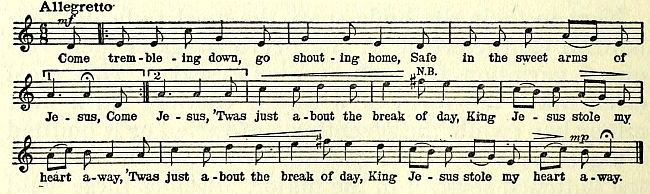

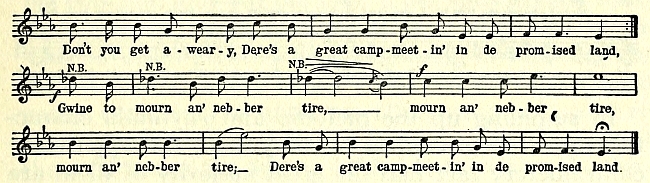

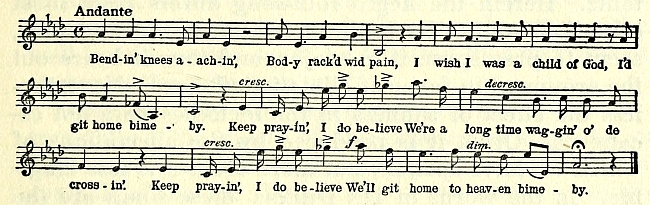

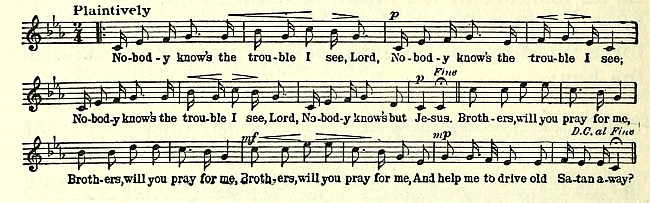

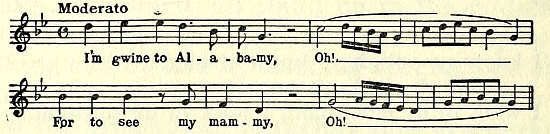

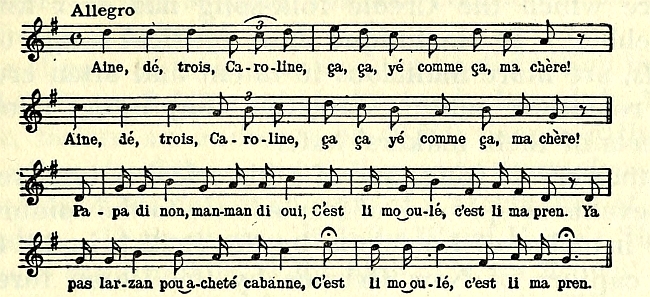

The musical files for the musical examples discussed in the book have been provided by Jude Eylander. Those examples can be heard by clicking on the [Listen] tab. This is only possible in the HTML version of the book. The scores that appear in the original book have been included as “jpg” images.

In some cases the scores that were used to generate the music files differ slightly from the original scores. Those differences are due to modifications that were made by the Music Transcriber during the process of creating the musical archives in order to make the music play accurately on modern musical transcribing programs. These scores are included as PNG images, and can be seen by clicking on the [PNG] tag in the HTML version of the book.

Obvious punctuation and other printing errors have been corrected.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

THE ART OF MUSIC

A Comprehensive Library of Information

for Music Lovers and Musicians

Editor-in-Chief

DANIEL GREGORY MASON

Columbia University

Associate Editors

EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL

Harvard University Past Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin

Managing Editor

CÉSAR SAERCHINGER

Modern Music Society of New York

In Fourteen Volumes

Profusely Illustrated

NEW YORK

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC

Edward Alexander MacDowell

After a photo from life

THE ART OF MUSIC: VOLUME FOUR

Music in America

Department Editors:

ARTHUR FARWELL

AND

W. DERMOT DARBY

Introduction by

ARTHUR FARWELL

Associate Editor 'Musical America'

Formerly Lecturer on Music, Cornell University, and

Supervisor of Municipal Concerts, City of New York

NEW YORK

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC

[Pg vi]

Copyright, 1915, by

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc.

[All Rights Reserved]

[Pg vii]

MUSIC IN AMERICA

Prophecy, not history, is the most truly important concern of music in America. What a new world, with new processes and new ideals, will do with the tractable and still unformed art of music; what will arise from the contact of this art with our unprecedented democracy—these are the questions of deepest import in our musical life in the United States. The past has consisted chiefly of a tasting of the musical art and traditions of the old world. The present is divided between imitation of the old and searching for the new, both in quality and application. The fruitage of our national musical life is still for the future. Intense as are the activities of the present, they are still merely the preparation of the soil for a future growth the nature and extent of which we can only guess at to-day. The stream of musical evolution in America, in the present transitional period, is rapidly overflowing its wonted banks, and passing the boundaries of the traditional musical world. The many are striving to obtain that which has been the exclusive possession of the few, and in this endeavor are not only extending, but also actually transforming the art. The paramount issues change with the passing of the seasons. One imported European sensation gives way to another. The problem of the true basis of American music dissolves overnight, and gives way to the problem [Pg viii] of the specific evaluation of individual composers, whatsoever their tendency. The questions of the narrow concert world dwindle before the greater question of a broad musical administration for the people. We stand, in fact, in a state of chaos with respect of musical activities and ideals, and only the clearest thinkers are able to catch the truer and larger drift of the national evolution, or effectively direct it. Too many persons are ready to suppose that the issues of music in America lie wholly within the scope of purely musical considerations, and that they do not depend, as is actually the case in certain important respects, upon the nature of the national ideals and tendencies. The national need will condition the supply, and the more truly and deeply a national need is fulfilled, the more vital will be the result. For this reason it is important that the general national condition with respect of music be carefully studied, and that misconceptions and theories be relinquished in favor of a knowledge of facts.

If now we set out to glance over the circumstances which have eventually brought about the present condition of music in America, we find that this history, taken in its largest outlines, has a threefold aspect, the features of which may be roughly termed appreciation, creation, and administration. The degree in which the new world has grasped and understood the facts of musical development in the old must constitute a chief factor in any consideration of its musical evolution, and this subject will naturally include a reference to musical culture in America. The second general division of the subject relates to American composers and the creative musical output of the nation. The matter of the appreciation of this output will best be touched upon in connection with this aspect of the subject. With the question of administration we approach a phase of the subject which has of late assumed momentous [Pg ix] proportions, touching directly, as it does, the great question of the relation of music to the people—the reaction of democracy to the art of music. The divisions of Appreciation and Administration are, of course, very closely related, and some chapters, such as that on Education, embody both aspects in almost equal degree. Hence the line cannot be very sharply drawn. Our sequence of chapters, while emphasizing the three aspects here set forth, has therefore been arranged with a view to presenting as continuous a story as possible. The chapters reviewing the creative activities of American composers have accordingly been placed together at the end of the volume.

We can not deeply consider the matter of the appreciation of the musical art of the old world by the new, without coming to the realization that it is complete. This, it must be recognized, is a matter which does not ultimately depend upon the numerical extent of the appreciators, but upon the quality of appreciation existing within the nation. Were this not so, we could not affirm the existence of a complete appreciation of its musical art by any nation of the world. In the broad sense in which we must necessarily speak in dealing only with the major facts of civilization and evolution, we may say that German musical art is appreciated by the German nation, even if only here or there someone is found who understands precisely the principles of Beethoven's form, or Wagner's harmony. In the practical progress of the world it is general acceptance and use, together with a sufficient artistic appreciation, technical and otherwise, on the part of certain individuals, which constitutes national appreciation of art. The knowledge and action of such preëminent individuals qualify the appreciative life of the nation. The evolution of the world to-day resides in the evolution of the progressive thought of individuals. Such thought outdistances the slower[Pg x] mental operations of the mass, which is nevertheless drawn along into ever new sets of changing conditions, through the modern development of the means of communication and the corresponding rapidity of both material and spiritual advance.

Such conditions of appreciation exist in a signal manner in the America of to-day. It is the simplest and most obvious of facts that there is a general acceptance and use of European musical art, old and new, throughout the 'musical world' of America. The relation of that 'musical world' to the whole population will be considered later. It is equally obvious to the qualified observer that no point of European musical art is without its thorough-going students and appreciators, and ardent conservators, in America. From Bach and Haydn, nay, from the Gregorian chant, the Greek enharmonic, the Oriental scale, down through every intermediate period and personality to the present day of Stravinsky and Schönberg, every phase of musical history and life has its students and its champions in the new world. America has, in truth, summed up the musical life of the ages and reflects it daily in the multitudinous activities of her musical world. The quality of American appreciation has one advantage of the greatest significance over that of any other land, in that it is without national or racial prejudice. Being without history or unity, with respect of race, the American people are without a racial folk-song, and hence are bound by no ancient racial sympathy or habit to a particular fundamental conception of the character of music. German music, French, Russian, Bohemian, Scandinavian, Italian—all are accepted with equal eagerness and sympathy. In America the world's music falls on fresh ears, with the result that a catholicity of taste prevails such as is to be found in no other land, and with the further result that a unique and broadly inclusive national impression of musical[Pg xi] character in general has been gained. This in turn is leading to a national creative musical output which, if it has not converged upon any one distinctive national character, is, on the other hand, wholly free from dependence upon the traditional character of the music of any other nation, and could have been produced by no other nation.

The upshot of the status of American appreciation of musical art is that, although the work of more extensively familiarizing the population with the world's music must continue, the evolution, broadly, of America as an appreciative nation has been fulfilled, and it can from now on find no true musical progress except as a creative nation. Not only has it studied, at home and abroad, all that the outside world has produced, but it has now thoroughly studied the various phases of aboriginal music which exist upon its own soil. The national life has passed beyond its school days and entered the period where it has no alternative but to face judgment as a musically productive nation with legitimate pretensions to maturity.

In view of the intense musical interest and eagerness of the American people, of the vigorous and very rapidly expanding development of musical life in the United States since the Civil War, and the enormous sums which the nation spends annually for musical education, both at home and abroad, it would be irrational to expect anything less than the results above indicated. Musical education, which has played so vast a part in this development, shares, nevertheless, the general chaotic condition of American musical life. The absence of a National Academy of Music leaves the country still without any official standard of musical education, although high ideals and thorough courses are maintained in the music departments of the larger universities. There are several independent musical academies and conservatories of high standing,[Pg xii] with a sufficiently broad and well ordered curriculum, and an unnumbered mass of nondescript music schools innocent of all normal standards. The same scale, from the highest excellence to downright charlatanism, is to be found in the field of private instruction, and one of the greatest educational problems which the nation faces is to bring some element of standardization into this field. This is a matter for state action, and in several states a movement is well under way for the licensing of music teachers. The development of music in the public schools, well grounded in the early part of the last century, has of late years been pushed with vigor and intelligence, and has led to unprecedented studies in the adaptation of music to the child, as well as to the composition of a great quantity of new and appropriate children's songs of excellent quality. The chief difficulty with national musical progress through the public schools lies in the fact that such a minute proportion of public school scholars go to high school and college, most of them losing all contact with musical education before reaching an age when their interest in it can be firmly established. This circumstance is now happily being continually more widely met from extra-educational quarters, in the present movement for music for the people through various channels to be referred to later. Professional educators are inclined to lay too much stress on school education as a means of developing appreciation in the mass, forgetting that the time must come when the chief musical training of the people, with respect of their ultimate enjoyment of music, must consist in a general public hearing of music of the highest order.

In centres of highly refined musical culture, America, from East to West, is not lacking. An aristocracy of musical appreciation has followed upon the establishment of symphonic and chamber music organizations in a number of cities. This culture is, however, almost[Pg xiii] exclusively devoted to the maintenance of traditional European standards, and is inclined to take slight cognizance of the native and democratic developments in which the true national progress of the present lies. The presence of such a culture in America is therefore not altogether an unmixed blessing; in fact it may lead to certain results of positive evil. The presence of retrospective hyper-refinement in a nation at a time when rugged creative strength, even if crude in its artistic results, should be manifested, may be harmful in its effect upon normal creative progress, especially when, with the backing of wealth, the press, and the academy, it arrogates to itself the possession of the true vision of artistic standards.

If, then, the tide of musical appreciation in America has reached a normal level, in accordance with the general civilization of the world of to-day, if the appreciative era, purely as such, is past, the creative epoch has only fairly begun. America, in musical composition, already reckons a historical sequence approaching to a classical, a romantic and an ultra-modern period, exhibiting the strange spectacle of most of the founders of the first period living to see the flowering of the last, during their active lifetime. In fact, some of the pioneers have actively engaged in fostering the issues of all three epochs. The truth of this curious condition is that this triple-aspected development of the past fifty years can not in reality be said to represent even the beginning of the actual creative epoch of the nation. As the child is said to pass through phases corresponding to the entire ancient history of the race, so this chapter in American music represents the rapid passage of the youthful America through the previous history of the art; it has represented the desire to catch up with the world at large. Even if some works of lasting value have been produced, as is undoubtedly the case, this period has in[Pg xiv] actuality represented a mere reflex of European musical civilization, a surface agitation, to be followed by an authentic and original national productivity along the lines of its own needs and ideals.

So irregular and tumultuous have been the conditions of musical development in America, that early influences have been of relatively small qualitative importance in determining the ultimate issues of American music. There are but two such early influences of importance to record, and one of these has become wholly negligible with relation to our independent art of music, finding its only resultant effect in the church music of America. This, attributable in the first instance to the Netherland school of the Renaissance, appeared as the early English contrapuntal school of Purcell, becoming associated with the music of the Protestant Church in England, and finally becoming diluted to the productions of the school of Billings and Hopkinson in America. American hymnology undoubtedly owes its character to this evolutionary sequence, although in the end American church music has become inundated with the German influence in its more sentimental aspects, and presents in general a profound degeneration too momentous for discussion in the present brief review. The one great original influence acknowledged by the nation, in its musically creative life, is the mighty German tradition of the epoch of Beethoven. It is significant and fortuitous that America was colonized, musically, at the time when the influence of that tradition was paramount in the world. It was the emigrating German music teacher, in every city and town of the United States, who implanted the fundamental conception of musical art in American civilization. Accepted and consulted everywhere, he determined the character of music in America in the period of reconstruction and educational expansion after the Civil War. His influence[Pg xv] was solidified by the character of symphonic and choral enterprise, and by that of the performances of German musical artists touring in America. The Italian was the accredited opera singer and nothing more; the German was the teacher.

In the subsequent course of developments, two matters have militated against the ultimate domination of the German influence in American composition. One is the extensive change which has since occurred in the racial nature of the population. Continued immigration from all lands has eventually produced a population too diverse to accept and perpetuate, as its dominant musical character, the tradition of any one nation, however musically great. The other is the amazing musical awakening of all Europe since the epoch of Beethoven, and especially since Wagner, and the consequent deluge of modern music from various nations which has poured in upon American musical life. In view of the infinity of newly revealed possibilities, the American composer has been unwilling to continue to reflect merely the one tradition with which his nation was formerly acquainted, in howsoever high honor that tradition was held. It is to be said, however, that the substantial character of German formal musical construction has exerted, as it should, a permanent influence upon the American attitude toward composition, and one which is certain to operate beneficially upon the creative musical life of the nation. The American point of departure has been one not so much of technical system and ideals generally, as of temperament.

A third matter qualifying this emancipation of American music is the unearthing of the mass of aboriginal folk music peculiar to America, particularly that of the Indian and the negro. This has had a far more significant and widespread influence upon composers in America than critics in general have been willing[Pg xvi] to admit, and many of the strongest works now appearing in this country acknowledge an influence from these sources.

The 'American folk-song' discussion arose after what has been termed the classical period of American music, of which J. K. Paine may be considered the founder, and during the period in which the romantic influence, culminating in the work of MacDowell, was beginning to yield to the influence of the ultra-moderns. The factors which broke the exclusive German domination in America were, on one hand, the following up on this side of the water of the musical individuality gained by other European nations, and, on the other hand, the movement for the development of aboriginal folk-song in America. To these causes, some may add a spontaneous climatic influence, but of this there has as yet been no material demonstration.

The gist of the folk-song discussion was the question as to whether the basis of a characteristic national American musical art was to be found in the music of the negroes or Indians. This discussion arose after Antonin Dvořák's proclamation of such a possibility during his sojourn in America in the years 1892-95, and rose to its height several years after the foundation in 1901, by the writer, of The Wa-Wan Press, a movement for the attainment of a greater freedom in American music along both modern European and American aboriginal lines. As in all such matters, the question was answered by the degree and quality of creativeness in the works brought forward in exemplification of the principle. Good works on Indian or negro themes have lived, and bad ones have died. It soon became plainly evident that there was no popular prejudice against music drawing upon the characteristics of these native aboriginal sources; on the contrary, much interest was evinced, as has frequently been shown by the attitude of audiences listening to[Pg xvii] such works and by the popularity which certain of them have attained. The subject has also been made one for special study by numerous musical clubs throughout the country. What was asked was merely that the result should be good music. The influence of Indian and negro music upon American composition has thus spontaneously come to be recognized as a national and acceptable one, and the reflection of it by American composers to-day arouses scarcely a murmur of comment. That only a certain proportion of composers in America would respond to these influences was soon perceived, and with the readiness of the people to accept this kind of work, it became merely a question of the proportion of American musical art which should exhibit these tendencies. There appears to be no diminution of the tendency of many composers to draw upon these apparently inexhaustible aboriginal sources, and with the constant advance of creative musical art in America, and with its eagerness to press to a conclusion every available phase of music susceptible of development, there is every reason to believe that this influence, now generally recognized, will lead to a very considerable mass of achievement of a high character. America is too diverse in its sympathies and ideals to acknowledge any one national or racial influence as paramount in its musical art, but absolute creative freedom is essential to its national character.

Upon the original German influence, which has been rapidly modified in America by the work of Wagner and Strauss, there has followed chiefly the influence of modern France. Many American composers have lent themselves with avidity to the assimilation of the new technical resources revealed by Debussy and his colleagues, with excellent results so long as they considered these merely as accretions to their previous resource, but in general with equal failure where they have thought to create in the spirit of the French idiom.[Pg xviii] The directness of Russian musical expression has made its appeal to American composers, though its influence upon the color of American music has been inconsiderable in comparison with the French. The one cumulative effect of the many influences, from within and without, which have qualified the nature of American music, especially during the last two decades, has been to wrench it free from the uninspiring and nationally inappropriate character which it had acquired as the result of its original exclusive early German influence, without, it is to be noted, leading it into imitative subservience to the particular character of the musical art of any other nation. In other words, America has gained its creative musical freedom, even if still too new to that condition to manifest its ultimate results. With this widened horizon, the true creative epoch of American music has only now begun. The handful of American composers of serious ideals and noteworthy ability who could be named a few years ago has increased to scores, and new names appear in such rapid succession that the fairly definite knowledge which America had of its chief composers of the 'classical' and 'romantic' epochs can give only the feeblest conception of the present condition of composition in America. The best of the newer work shows a loftiness of ideals, a breadth of outlook, a definiteness of purpose, a freshness of color, a sense of the beautiful and an esprit which argue strongly for the future honor of American music. The chief danger which threatens the American composer is the tendency to accept and conform to the standards of the centres of conventional and fashionable musical culture, especially in unsubstantial modern aspects, and to fail to study out the real nature and musical needs of the American people. Such a tendency naturally lingers with the lingering domination of Europe over the standards and the machinery of American musical life. Conformity means representation[Pg xix] and a certain sort of acclaim for the composer; nonconformity means severance from the usual and conventional centres and institutions of musical culture. Critical approbation does not mean the response of the people; the composers most highly acclaimed by the critics can by no means be said to have come closest to touching the national heart. The attitude of the world of musical 'culture' in America is still cold toward the native producer; this narrow American 'culture' world pays for the maintenance of fashionable foreign standards, and resents any interference with this course. Concert singers are seldom heard in American songs worthy of their artistry, and orchestral conductors seldom give, on their own initiative, successful native orchestral works, an isolated performance of which has been arduously procured elsewhere.

With the people generally, however, the matter is quite otherwise. The people of the nation have never shown a disposition to receive otherwise than cordially the work of their own composers. From Stephen Foster, through the ranks of popular music composers, to MacDowell, to many song composers of the present, and latterly to the composers of music for popular festivals and pageants—wherever the composer has gone directly to the people and served their needs, whether in the sphere of lesser or greater ideals, he has found a ready welcome and a hearty response. The pathway of true creativity, of healthy growth and achievement for the composer in America to-day, lies in abandoning the competition with European sensationalists and ultra-modernists in the narrow arena of the concert halls of 'culture', and turning to the fulfilment of national needs in the broadest and deepest sense.

The accomplishment of this matter is linked with the third and last general division of our main subject,[Pg xx] the question of administration. As a natural consequence of events in American musical history, dating from the earliest days, there has arisen the so-called 'musical world' of America to-day, the well-defined national system of concert, recital and operatic life. This system arose normally to supply the new world with the products of the highly developed musical art of the old, and in such a capacity it has admirably served its purpose. In the course of time, however, and with the increasing wealth and musical culture of America, the harvest to be reaped by the commercial exploitation of foreign artists has not remained unperceived by a country not naturally backward in the perception of commercial advantage. It is quite natural that those who took into their hands the management of these affairs should seek the greatest profit which they could be made to yield. This, it will readily be seen, was not to come from the broad development of a given locality, which would involve education and a departure from the centres of wealth, but from the exploitation of the narrow circle of wealth and culture which existed in every community of importance. Thus a great circuit was established throughout the country, by which a process of skimming the cream from as many communities as possible was set in operation, in the presentation of famous foreign artists to what has been allowed to pass as the American public. Thus a system established originally as a service to the people has finally degenerated to the condition of a commercial enterprise which is utterly without regard to the broader interests of the people. The true condition of affairs is made evident to-day by the fact that when a resident of any moderate-sized prosperous American city starts to inaugurate some local musical enterprise for the benefit of the whole community, and calling for the entire community's support, he learns that the concert and recital life of his city, its 'musical[Pg xxi] world,' reaches and is supported by but from three to five per cent. of the entire population. The other ninety-five to ninety-seven per cent. find the regular musical events beyond their means, as well as beyond the facts of their culture, though in the latter respect America is now rapidly learning that the enjoyment of the best music is far less dependent upon special education than has commonly been supposed.

Meanwhile, by phonograph and player-piano, by newspaper and magazine, by high-class municipal concerts and occasional chance glimpses into the world of greater musical possibilities, the mass of the people have begun to become awakened to the existence of the larger musical world which they do not see and the larger musical life which they do not share, and to crave participation in it. Finally, therefore, we have the spectacle of an American 'musical world' which is no longer true to American conditions and which does not serve the people. In short, we have finally come face to face with the problem of the reaction of musical art and democracy.

With this question the nation has of late begun to deal in no half-hearted or uncertain manner. In fact, the national response to this situation involves the greatest American musical movement of the day. In its earlier phase the question asked was: Will the people, under democracy, rise to the accepted standards of musical culture? A negative answer to this question has been generally entertained, and among cultured people it has been commonly supposed that democracy would drag down the standards of musical culture. That a wholly new and multifold phase of musical life would arise to meet the requirements of a civilization such as that of America seems to have been earlier suspected or foreseen only by a few thinking students of conditions, who recognized the fact that the exact meeting of the mass, as it became more enlightened, with[Pg xxii] the conditions of traditional musical culture was not the solution which was to be expected or even desired. The plain fact was that the people at large were not enjoying the benefits, the pleasure, recreation, or inspiration, as the case might be, of all that the world prizes as music in any of its forms above that of popular songs and dances. Neither the educational system, on the one hand, nor the cultural system, on the other, provided them with it. One merely gave a little elementary training of the most primitive sort, and for a short time, to children, and the other did not reach beyond the extremely restricted sphere of culture and wealth. A movement was needed which should bring music in all of its forms directly to the masses of the people, and in the nation-wide campaign for what may be termed 'music for the people' such a movement has arisen. Experiments on every hand have shown that the people have needed only to be brought in contact with the higher forms of music, under advantageous conditions, to rise spontaneously to the enjoyment of it. The movement, in its activities, has assumed no particular form, but has taken a variety of forms according to the possibilities of local conditions. The 'Forest Festival,' or 'Midsummer High Jinks,' of the Bohemian Club in San Francisco, while not open to the general public, has nevertheless shown the potent appeal of outdoor musical dramatic festivals to a large number of persons not commonly in touch with musical life. Municipal concerts on a scale not hitherto attempted, such as those in Central Park, New York, presenting not band, but orchestral concerts of the world's greatest music, have met with an astonishing and enthusiastic response on the part of the masses who have hitherto had no opportunity of hearing anything above the popular music of the streets, the dance halls, and the 'movies.' The musical phase of the social centre movement has assumed vast and national[Pg xxiii] proportions, making use of the public school halls for concerts and recitals for thousands of persons who were previously without musical opportunities. Certain towns, such as Bethlehem, Pa., Lindsburg, Kans., and the towns of the 'Litchfield County Choral Union,' Conn., have established choral enterprises which include in the choruses practically the entire population. In two years the custom of Christmas trees with music, free to the people, has become almost a national movement. The 'community chorus,' such as that established in Rochester, N. Y., with a membership of nearly one thousand drawn from the people at large, and singing in the public parks and school halls, should prove a desirable form of people's musical enterprise in many places. Standard symphony orchestras in various cities are branching out extensively in the direction of giving concerts involving the highest order of music to the people at popular prices, and in some cities the organization of symphony orchestras for popular price concerts is threatening the existence of the regular orchestra. And well-nigh surpassing in significance most other phases of the general movement, and certainly in their popular inclusiveness, are the pageants or 'community dramas' with music, which are now constituting a feature of community life throughout the country.

If, then, the appreciative epoch along the older lines, is concluded in America, it may be said that the nation is coming to a new appreciation of music, as a whole, in its relation to humanity. The new movement will call forth new and larger efforts on the part of American composers, who, with their present thorough assimilation of the various musical influences of the world, will lead the nation into a new and mature creative epoch.

Arthur Farwell.

August, 1914.

[Pg xxiv]

[Pg xxv]

CONTENTS OF VOLUME FOUR

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction by Arthur Farwell | vii | |

| Part I. Appreciation | ||

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | Our English Inheritance | 1 |

| The foundation of American musical culture—State of English musical culture in the seventeenth century—The Virginia colonists—The Puritans in England and in America; New England psalmody. |

||

| II. | Beginnings of Musical Culture in America | 22 |

| The foundations of American music—New England's musical awakening; early publications of psalm-tunes; reform of church singing—Early concerts in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, the South—The American attitude toward music—The beginnings of American music: Hopkinson; Lyon; Billings and their contemporaries. |

||

| III. | Early Concert Life | 55 |

| Sources of information—Boston Concerts of the eighteenth century; New England outside of Boston—Concerts Concerts in Philadelphia; open-air concerts—Concert in New York—life of the South; Charleston, Baltimore, etc.; Conclusion. |

||

| Part II. Organization | ||

| IV. | Early Musical Organizations | 84 |

| Origin of musical societies—The South; The St. Cecilia of Charleston; Philadelphia and New York in the eighteenth century—The Euterpean Society; the New York Choral Society; Sacred Music Society; other New York Societies—New Society of Boston; other societies in Boston and elsewhere. |

||

| V. | The Beginnings of Opera | 104 |

| Scantiness of theatrical performances in America; Charleston and Tony Aston; New York, Philadelphia and elsewhere—The Revolution and after; rivalry between New York and Philadelphia—The New Orleans opera. |

||

| VI. | Opera in the United States. Part I: New York | 117 |

| The New York opera as a factor of musical culture—Manuel García and his troupe; da Ponte's dream—The vicissitudes of the Italian Opera House; Palmo's attempt at 'democratic' opera—The beginnings of 'social' opera: the Academy of Music, German opera, Maretzek to Strakosch—The early years of the Metropolitan—The Grau régime—Conried; Hammerstein; Gatti-Casazza; Opera in English—The Century Opera Company. |

||

| VII. | Opera in the United States. Part II | 158 |

| San Francisco's operatic experiences—New Orleans and its opera house—Philadelphia; influence of New Orleans, New York, etc.; The Academy of Music—Chicago's early operatic history; the Chicago-Philadelphia company; Boston—Comic opera in New York and elsewhere. |

||

| VIII. | Instrumental Organizations in the United States | 181 |

| The New York Philharmonic Society and other New York orchestras—Orchestral organizations in Boston—The Theodore Thomas orchestra of Chicago—Orchestral music in Cincinnati—The Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra—Orchestral music in the West; the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra—Chamber music ensembles—Visiting orchestras. |

||

| IX. | Choral Organizations and Music Festivals | 206 |

| The Handel and Haydn and other Boston societies—Choral organizations in New York, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere—Cincinnati, Milwaukee, St. Louis, Chicago and the Far West—Music festivals. |

||

| X. | Musical Education in America | 230 |

| Early singing teachers and schools—Music societies in colleges—Introduction of music into the public schools—Juvenile music—Conservatories—Musical courses in colleges and universities—Community music—Present state of public school music—Municipal music. |

||

| Part III. Creation | ||

| XI. | The Folk-Element in American Music | 277 |

| Nationalism in music—Sources of American folk-song; classification of folk-songs—General characteristics of the negro folk-song—The negro folk-song and its makers—Other American folk-songs—The negro minstrel tunes; Stephen Foster, etc.—Patriotic and national songs. |

||

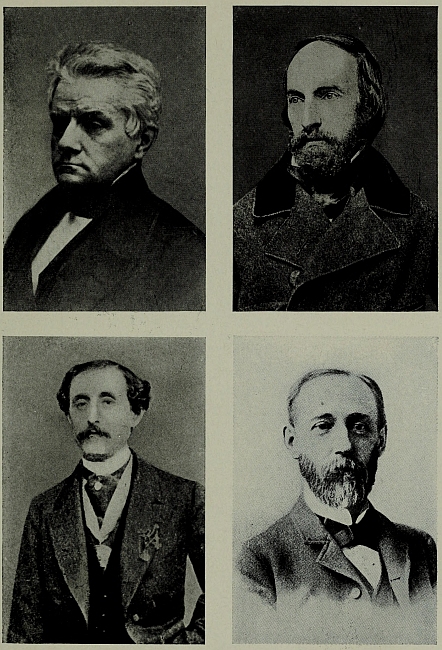

| XII. | The Classic Period of American Composition | 331 |

| Pioneers in American Composition: Fry, Emery, Gottschalk—The Boston group of 'classicists': Chadwick, Foote, Parker, and others—Other exponents of the 'Classical': William Mason, Dudley Buck, Arthur Whiting, and others—The lyricists: Ethelbert Nevin; American song-writers—Composers of church music. |

||

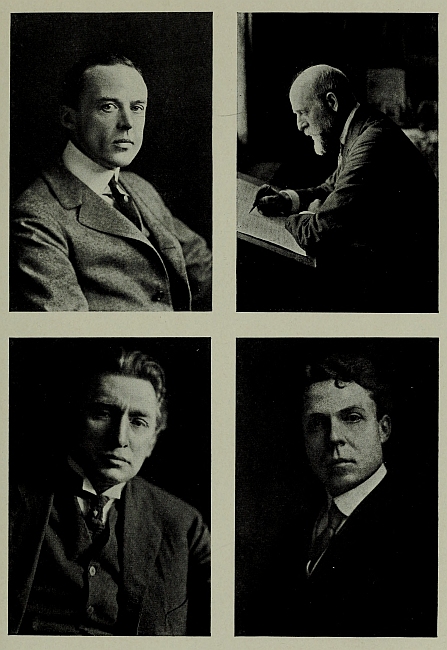

| XIII. | Romanticists and Neo-Classicists | 360 |

| Influences and conditions of the period—Edward MacDowell—Edgar Stillman-Kelley—Arne Oldberg; Henry Hadley; F. S. Converse—E. R. Kroeger; Rubin Goldmark; Howard Brockway; Homer N. Bartlett—Daniel Gregory Mason; David Stanley Smith; Edward Burlingame Hill—The younger men: Philip Greeley Clapp; Arthur Bergh; Joseph Henius; Carl Busch—The San Francisco Group; Miscellany—Women Composers. |

||

| XIV. | Nationalists, Eclectics and Ultra-Moderns | 407 |

| The new spirit and its various manifestations—Henry F. Gilbert, Arthur Farwell, Harvey W. Loomis—Frederic Ayres, Arthur Shepherd, Noble Kreider, Benjamin Lambord—Campbell-Tipton; Arthur Nevin; C. W. Cadman; J. A. Carpenter; T. C. Whitmer—W. H. Humiston, John Powell, Blair Fairchild, Maurice Arnold—Sidney Homer; Clough-Leighter and others—Charles M. Loeffler and other Americans of foreign birth or residence. |

||

| XV. | The Lighter Vein | 451 |

| Sources of American popular music—Its past and present phases—American comic opera: Reginald de Koven; Victor Herbert; John Philip Sousa; other writers of light opera—The decline of light opera and the present state of theatrical music. |

||

| Literature | 465 | |

| Index | 469 |

[Pg xxvi]

[Pg xxvii]

[Pg xxix]

[Pg xxx]

MUSIC IN AMERICA

[Pg 1]

The foundation of American musical culture—State of English musical culture in the seventeenth century—The Virginia colonists—The Puritans in England and in America; New England psalmody.

Whatever else the American music-lover may be, he is decidedly not chauvinistic. Deprecatingly he is wont to speak of native artistic accomplishment, and, however much he may be disposed to vaunt the stellar achievements of our few great opera houses and orchestras, he is content to draw a veil of modest silence over that part of our musical history which precedes the advent of those de luxe organizations. Hence it is, perhaps, that the searchlight of the historian has played but fitfully upon the early musical life of America—for, although popular interest may not inspire the writing of history, it is not without its influence on the publication thereof. Possibly the musical life of pre-Revolutionary America has had little to do with shaping the ultimate artistic destinies of the nation, yet it formed the matrix into which our subsequent musical culture has been embedded and as such it is of both interest and importance to those who would follow a phase of our national development, as yet regrettably neglected.

It is a peculiar tendency of the American historian to lay the foundation of our national history squarely on the Rock of Plymouth. A solid foundation, truly, but not a very broad one. The predominant influence of New England in the industrial and commercial development of the United States can hardly be gainsaid.[Pg 2] That its influences on the country's æsthetic development have been equally predominant is questionable. More especially in musical matters are we inclined to call it into dispute. If we might judge from American popular music, we should be disposed to infer that such influences as may have been active in the shaping of it came chiefly from the South. Nor is popular music a negligible criterion in this respect, for in it have always lain the germs of truly national art. Of course, our knowledge of the state of musical culture in the early colonies does not enable us to say definitely and dogmatically just where and how American musical development first began. It will probably appear eventually that the early musical life of the colonies has had very little to do with our musical culture of to-day. But, purely as a matter of historic justice, it might be pointed out that unqualified statements, such as the assertion of Ritter that 'the first steps of American musical development may be traced back to the first establishment of English Puritan colonies in New England,' are, to say the least, somewhat premature.[1]

A consideration of music among the Indians is not germane to our present purpose. As far as we are [Pg 3]concerned Indian music is an exotic, and it is only of recent years that American composers have turned to it in a conscious search for national color which is, perhaps, the first real symptom of aspiration toward characteristically national expression. From the point of view of musical history the development of American music must be considered as beginning among the first white settlers on these shores, and it may be said at once that those beginnings, like Guy of Warwick's death, are still 'wrop in mystery.' Regarding musical life in the colonies before the year 1700 our information is so slight as to be negligible. For almost a century preceding that year white men—many of them men of culture—had been settled in America.[2] That these men completely forgot the art in which so many of them found pleasure, and in which at least a few of them must have possessed some skill, is a supposition too absurd to be seriously entertained. As to the nature and proportions of their musical activities we have no exact evidence and, in default of such, it is necessary for us to dip a little into comparative history.

In England the curtain of the seventeenth century rose on a country that as yet knew not cropped heads nor Geneva cloaks nor steeple-crowned hats nor the snuffling drone of Hop-on-High-Bomby mournfully mouthing the sinfulness of the flesh and the menace of the wrath to come. England still deserved its old-time appellation of 'merrie.' It still ate and drank, sang and swore, bussed and wantoned blithely, lustily, as befitted a country with a full purse, a sound constitution, and a healthy indifference to the disturbing subtleties of theology and metaphysics. It was a robust, Falstaffian England, still unregenerate, still addicted to sack and loose company, but with a mind as clearly [Pg 4]keen as a Sheffield blade and a heart as soft and impressionable as its own Devonshire butter—'pitiful-hearted butter that melted at the sweet tale of the sun.' In short, a normal, vigorous, able-bodied, human country, not yet soured by the virus of an acidulated Puritanism, nor devitalized by the distemper of a cultivated licentiousness; a country in whose fertile soil the seeds of art might well germinate and flourish apace. And, as a matter of fact, English music, like English drama and poetry, was then approaching the culmination of its golden age. In Italy, Palestrina had just died; Peri and Monteverdi were shaping the beginnings of opera; the madrigal, the mystery, the morality and the masque were the prevailing media of secular musico-literary expression, while popular instrumental music was represented by Pavans, Galliards, Allmains, Courantes, and other courtly-sounding forms. The stern, strict god of polyphony was already stooping to flirt with the light and wayward muse of the people, making the first tentative advances toward a union from which was destined to spring a seductively human art. Never since has England stood so high musically among the nations of Europe. Never since has she produced composers who so closely rivalled the greatest of their contemporaries. There was William Byrd 'a Father of Musicke,' as the Cheque-book of the Chapel Royal has it—one of the most learned contrapuntists of his time and unequalled by any of his contemporaries in compositions for the virginals. There was John Dowland, 'whose heavenly touch upon the lute doth ravish human sense.' There was Orlando Gibbons, one of the greatest composers of his period, who was then in the beginning of his distinguished career. These, and many other English composers of scarcely lesser note, were as highly honored abroad as they were at home. Their influence on the development of German music has been admitted even by German[Pg 5] critics.[3] In England the madrigal flourished then as it did nowhere else in Europe and reached a degree of perfection hitherto unattained even by the best madrigalists of Italy and the Netherlands. What Peri and Monteverdi were doing successfully in Italy in the pseudo-Grecian music-drama, the English were attempting to do, more characteristically though less successfully, in the masque. Some of the most famous of English popular songs—like 'The Bailiff's Daughter of Islington,' 'The Three Ravens,' and 'Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes'—have come down to us from that period. Indeed, the musical vitality of the England of that time was truly remarkable, and thousands of madrigals, motets, anthems, ayres, and ballets remain as eloquent witnesses to its teeming fecundity. English instrumentalists were then rated the best in Europe and were as commonly employed in the courts of Germany as German instrumentalists are now employed in the restaurants of London.

Nor was this noteworthy musical activity confined to the small class of professional musicians. If we may believe Morley,[4] and read aright the references of Shakespeare and other contemporary writers, music was sedulously practised by all classes in England, from the sovereign to the beggar. Queen Elizabeth, we find, played excellently on the virginals and the poliphant, though it does not appear that her dour successor took very kindly to such exercises. It seems to have been a matter of course that every well-reared girl should sing at sight and play acceptably on the virginals, the flute, and the cittern. Sight-reading—alas for our degenerate days—was apparently a universal accomplishment, at least among people of the better classes. After viols were introduced, every gentleman's [Pg 6]house contained a chest of them and the chance visitor was expected to take his part at sight in the impromptu concerts which were a favorite form of social diversion. 'Tinkers sang catches,' says Chappell, 'milkmaids sang ballads; carters whistled; each trade, and even the beggars had their special songs; the bass-viol hung in the drawing-room for the amusement of waiting visitors; and the lute, cittern, and virginals, for the amusement of waiting customers, were the necessary furniture of the barber-shop. They had music at dinner; music at supper; music at weddings; music at funerals; music at night, music at dawn; music at work; music at play.'

From this intensely musical England came the band of colonists who landed at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. About half of them were 'gentlemen' and the remainder were soldiers and servants. The proportion of gentlemen—'unruly gallants,' as Capt. John Smith calls them—was less in later emigrations, though it was always comparatively high. Many soldiers came, and some convicts and young vagrants picked up in the streets of London were sent out as servants. Starvation, disease, and the attacks of Indians left very few survivors among those who came to Virginia during the first ten years. Afterward the population grew very rapidly and contained, on the whole, representative elements of all classes in England, with a comparatively large proportion of the upper classes. In 1619, as we learn from a statement of John Rolfe, quoted in John Smith's 'Generali Historie,' the first negro slaves were introduced into Virginia. A description in the 'Briefe Declaration' shows Virginia about two years later as a country already in the enjoyment of peace[Pg 7] and prosperity. 'The plenty of these times,' says the writer, 'unlike the old days of death and confusion, was such that every man gave free entertainment to friends and strangers.' About that time land was laid out for a free school at Charles City and for a university and college at Henrico, but the project was not then carried through. As yet, however, there was not any pressing demand for public educational advantages, as the proportion of children was still very small. Later years saw a great increase in the population, both native and English born. During the Civil War there was a large exodus from England of cavaliers, as well as merchants, yeomen, and other substantial people, who found the troubles at home little to their taste or profit. There must have been little to distinguish the Virginia society about the middle of the seventeenth century from English society of the same period. The colonists lived well; they were prosperous; they had good, substantial houses equipped with good, substantial English furniture; they entertained with open-handed freedom and generosity. 'The Virginia planter,' says George Park Fisher, 'was essentially a transplanted Englishman in tastes and convictions and imitated the social amenities and culture of the mother country. Thus in time was formed a society distinguished for its refinement, executive ability and generous hospitality for which the Ancient Dominion is proverbial.'[5]

The population of Virginia always remained largely rural, but nevertheless there was social life aplenty. Education was mainly in the hands of the clergy, who, as a rule, were Englishmen of culture. But steps toward public education were taken at a very early period. The attempt of 1621 failed, as we have noticed, but in 1635—three years before John Harvard made his [Pg 8]bequest—Benjamin Syms left an endowment for a free school in Virginia. This, to quote a recent writer, 'was the first legacy by a resident of the American plantations for the promotion of education.' Another free school was established in 1655 by Captain Henry King, and two in 1659 by Thomas Eaton and Captain William Whittingdon. In 1670, according to a report from Sir William Berkeley to the Commissioners of Foreign Plantations, the population of Virginia consisted of 40,000 persons, of whom 2,000 were negro slaves and 5,000 white servants. The 2,000 negro slaves probably included a number of mulattoes, for even then there must have been traffic between white men and negro women, as we may infer from the law which gave to a child the status of its mother. The remainder of the population was almost exclusively English. What we have said of Virginia in the seventeenth century applies also in a general way to Maryland and Carolina, both as to population and conditions, though the Huguenot emigration to Carolina in 1685 made a decided difference in the character of the population there subsequent to that date.

This brief incursion into general history has been made, not to prove anything, but to bring forward a few facts which may be found suggestive. The Southern colonists during the seventeenth century were predominantly English people of the first and second generations. They were fairly representative of contemporary English society, though the proportion of 'gentlemen' was higher among them than at home. They came, as we have seen, from a country where music was practised enthusiastically by all classes. It is preposterous to think that in the new country they discarded their musical tastes like a worn-out garment. There is no reason why they should have done so. After the first years of famine and turmoil and death they were comparatively peaceful and prosperous. There were[Pg 9] among them, it is true, a certain number of stern-faced Puritans, melancholy preachers of the sinfulness of pleasure; but on the whole the attitude of the Southern colonists toward life was that of the gay, gallant, laughter-loving cavaliers. There is little doubt that these same gallant gentlemen kept up in the colonies that devotion to the joyeuse science for which they had been famed since the days of Cœur de Lion. In the announcements of the early concerts at Charleston in the first half of the eighteenth century we find that the orchestra was often composed in part of neighboring gentlemen, who were good enough to lend their services for the occasion, or sometimes that certain gentlemen, of their courtesy, obliged with instrumental or vocal selections. Whence we may infer that the custom of keeping a chest of viols in his house for the use of his family and his guests, so generally observed by the English gentleman at the beginning of the seventeenth century, was still honored by the colonial gentleman at the beginning of the eighteenth.

The cultured colonists followed English fashions very closely in all things, and the music they played was doubtless the music in vogue in London drawing-rooms and concert halls. The humble colonists, presumably, were less concerned with the mode, and sang and played the old English tunes which they and their fathers and their grandfathers had brought across the sea. American historians have taken for granted, with a good deal of smug complacency, that there was no real musical life among these people. The assumption seems to be based—if it has any basis—on the fact that the population of the South was preëminently rural. But that there was little urban life does not mean that there was little community life. On the contrary, life in the South was much more intimately gregarious than is usual in towns and cities, and it is in hospitable social gatherings rather than in stiff-backed attendance[Pg 10] at concerts and operas that the musical soul of a people finds real expression. Furthermore, the Southern colonists had a communal consciousness, as we may see from their early essays in public education, and it is probable that this consciousness expressed itself in other ways of which we have no evidence. The churches brought them together, also, perhaps for social as well as religious gatherings. It is, indeed, a plausible surmise that musical reunions of some sort, apart from purely private entertainments, were not unknown to them.

The music of the colonial proletariat was English, that of the gentlefolk largely so. Among the common people this music may have undergone some alteration in the course of time, and certain gifted ones among them may have made original music of their own. We can conceive that the gentlefolk occasionally occupied themselves with musical composition, and some of their efforts, perchance, percolated through the classes and became the property of all the people. We cannot say, but it is possible; it is even probable. If English music did not undergo a change in Virginia and Maryland and Carolina, we can be sure that it altered somewhat in the hands of the pioneers who carried it to Kentucky, to Missouri, to Texas. One hears in the Southwest many quaint, characteristic old songs and tunes of unmistakably English origin. We can safely assume that by the time they reached Missouri and Texas from England they had absorbed quite a little local color.

Nor must we forget that the music of the American negroes is the music of the English colonists strained through the African temperament; or perhaps we should say the African temperament strained through the music of the English colonists. In any case, Afro-American music is a blend, and the mixing, we may suppose, began with the beginning of slavery in the[Pg 11] Southern colonies. The negro slaves were an ignorant, impressionable people set down in the middle of a white civilization from which they naturally and immediately began to absorb the things that were appreciable to their senses. The most easily appreciable, perhaps, of these things was music, and such music as the negroes heard among the white people they absorbed and, to some extent, assimilated.[6]

Just how much all this has to do with American music we cannot say, any more than we can say just what is American music. National music, we take it, is the composite musical inheritance of a people, molded and colored by their composite characteristics, inherited and acquired. And the music of the South is undoubtedly part of the musical inheritance of the American people. How much of that inheritance we have rejected and how much retained will not appear until some historian arises with enough scholarship to analyze our musical heritage in detail; with enough genius in research to trace its elements to their sources; and with enough patriotic enthusiasm to lend him patience for the task. In the meantime, surface conditions fail to justify the arbitrary ruling out of the South as an utterly negligible factor in our musical development.

In approaching the history of the New England Puritans one is in danger of making serious mistakes, due to temperamental prejudices and to a misconception of the Puritan attitude toward life. The term Puritan itself is more or less indeterminate, covering all sorts and conditions of men with a wide diversity [Pg 12]of views on things spiritual and temporal.[7] There is a very general impression, totally unsupported by historic evidence, that the Puritans frowned intolerantly on every worldly diversion, including music. Many of the zealots did, it is true—in every movement there are extremists—and the general trend of thought was influenced somewhat by their thunderous denunciations of all appearance of frivolity. In such circumstances the average human being, uncertain how far he may safely go, is inclined to avoid the vicinity of danger and seek the haven of a strictly negative attitude toward everything about which may hang the very slightest suspicion of impropriety. We have many instances in history of this same tendency. The early Christians, taking Christ's warning against the world and the flesh in its most extreme literalness, adopted a course for avoiding hell and gaining heaven which, if consistently followed, would soon have left the world barren of any beings from whom the population either of heaven or of hell might be recruited. We are apt, however, to exaggerate the self-denying habits of the Puritans. On many points of conduct and dogma they were fiercely and uncompromisingly intolerant. Their Sabbath observance was strict to the point of absurdity. But in general they were not disposed to deprive the world of innocent pleasure.

The New England Puritans were more or less of a piece with their English brethren, and we have every evidence that the latter tolerated music, even cultivated it with assiduity. Milton's love of music is well known.[8] John Bunyan, a typical lower-class Puritan, speaks of it frequently and appreciatively in the 'Pilgrim's[Pg 13] Progress.' 'That musicke in itself is lawfull, usefull and commendable,' says Prynne in his 'Histrio-mastix,' 'no man, no Christian dares deny, since the Scriptures, Fathers and generally all Christian, all Pagan Authors extant do with one consent averre it.' Even the anonymous author of the 'Short Treatise against Stage-Playes' (1625) admits that 'musicke is a cheerful recreation to the minde that hath been blunted with serious meditations.' Not only Cromwell, but many other Parliamentary officers, including Hutchinson, Humphrey, and Taylor, were sincere devotees of the art. Colonel Hutchinson, one of the regicides, 'had a great love to music,' according to the 'Memoirs' of his wife, and often diverted himself with a viol, 'on which he played masterly; he had an exact ear and judgment in other music.' In the retinue of Balustrode Whitelocke, who was sent by Cromwell as ambassador to Queen Christina of Sweden in 1653, were two persons included 'chiefly for music,' besides two trumpeters. Whitelocke himself was 'in his younger days a master and composer of music.' On one occasion, during his stay at the Swedish court, the queen's musicians 'played many lessons of English composition,' and on another occasion, after the ambassador's party had played for her, Christina declared that 'she never heard so good a concert of music and of English songs; and desired Whitelocke, at his return to England, to procure her some.'

Ecclesiastical music was indeed vigorously suppressed, but solely for reasons touching the propriety of its employment in the worship of God. Outside the churches the Puritans showed no particular objection to the art. In fact, the practice of music was common enough among them, if we are to believe the statement of Solomon Eccles, a professional musician, who was successively a Presbyterian, an Independent, a Baptist, and an Antinomian, and always found it easy to make[Pg 14] a living by his profession. Notwithstanding the ban on theatres, public operatic performances were inaugurated in London in 1656 and were continued without interference. The publishing of music flourished under the Commonwealth as it never did before in England, and large collections of Ayres, Dialogues, and other pieces remain to us from that period. Such activity in music publishing could have been stimulated only by a corresponding demand, and a demand for printed music could not have co-existed with a neglect of musical practice.[9]

However, we must not jump to the conclusion that the American Puritans were as freely inclined to the practice of music as their brethren across the sea. As a matter of fact, they had no musical life whatsoever. There are some points in the psychology and condition of the New England colonists which may help to explain this seeming anomaly. A large proportion of the people of England were Puritans merely because it was not safe or convenient for them to be anything else, and they changed their moral and theological complexions just as soon as a change in fashion rendered the transformation desirable. Many of the most prominent members of the Parliamentary party were drawn into the movement more through political ambition or democratic ideals than for religious reasons. Cromwell's famous 'Trust in God and keep your powder dry' might well express the mental attitude of more than a few of them. Even among the religious leaders were a goodly number whose only desire was to reform what they considered the ritualistic abuses in the English church of their time and who had not the slightest ambition to suppress the harmless pleasures of life or the ordinary manifestations of human instincts. The New England Puritans, on the other hand, were a select[Pg 15] group of people who were driven across an inhospitable ocean to the barren shores of a strange land by the indomitable zeal of their convictions, the stern intractability of their consciences and the adamantine obstinacy of their independence. They were not Puritans merely in externals; they were Puritans to the core. Their view of life was uncompromisingly serious. The world was not to them a place for dalliance; it was a place for work, for the earnest sowing of seeds that might bring forth a harvest of grace and godliness, a harvest worthy to be garnered by the Master into His eternal storehouse. So, however kindly they may have looked upon music, they could not conscientiously have allowed it to engage much of their attention. They could with consistence postpone the gratification of their musical tastes to the next world, where, for all eternity, the practice of music would be their chief occupation. Besides, the life of the first settlers in New England was not such as to encourage any indulgence in unnecessary relaxation. What with the stubborn barrenness of the soil, the ferocity of the Indians, and the extreme inclemency of the climate, they had little opportunity for the cultivation of those gentler arts toward which by taste and temperament they were not, in any case, very strongly inclined.

And, indeed, from such information as we are able to gather on the subject, it would appear that the practice of music, even in its simplest forms, was practically unknown to the New England Puritans before the end of the seventeenth century, though some of the Leyden colonists, according to Winslow, were 'very expert in music.' Out of the forty-odd psalm tunes in use among the Pilgrims only five were generally known to New England congregations a generation later, and, even of these five, no congregation could ever perform one with any approach to unanimity. 'In the latter part of the seventeenth and the commencement of the eighteenth[Pg 16] centuries,' says Hood, 'the congregations throughout New England were rarely able to sing more than three or four tunes. The knowledge and use of notes, too, had so long been neglected that the few melodies sung became corrupted until no two individuals sang them alike.' The Rev. Thomas Symmes, in an essay published in 1723, tells us that 'in our congregations we us'd frequently to have some people singing a note or two after the next had done. And you commonly strike the notes not together, but one after another, one being half-way thro' the second note, before his neighbor had done with the first. This is just as melodious to a well-tuned musical ear as Æsop was beautiful to a curious eye.' 'It's strange,' he comments further on, 'that people that are so set against stated forms of prayer should be so fond of singing half a dozen tunes, nay one tune from Sabbath to Sabbath; till everybody nauseates it, that has any relish of singing.' In fact, the reverend gentleman confesses that if anything could drive him to Quakerism or Popery it would be the style of singing in vogue among his co-religionists. John Eliot, son of the Indian apostle, in an essay published in 1725, says that 'often at lectures, and especially at ordinations, where people of many congregations met together, their ways of singing are so different that 'tis not easy to know what tune is sung, and in reality there is none. 'Tis rather jumble and confusion. Altho' they all doubtless intend some tune or other, and, it may be, the same, yet they differ almost as much as if, everyone sung a different tune.' The effect must have been delightful. Samuel Sewall, who was precentor of his church for twenty-four years, makes the following plaintive entry in his diary for February 6, 1715: 'This day I set Windsor tune, and the people at the second going over into Oxford, do what I could.' Under date of February 23, 1718, he writes: 'I set York tune, and the congregation went out of it into St.[Pg 17] David's in the very 2nd going over. They did the same three weeks be.' Certainly the vocal efforts of the New England saints must have been excruciating when they moved the Reverend Thomas Walter to declare that the singing of his congregation 'sounded like five hundred different tunes roared out at the same time.' It is almost unbelievable that people of intelligence, as most of the early New Englanders were, should be so utterly callous to ear-splitting discords of that kind, but the testimony of their own pastors puts the matter beyond doubt.

Now much of this extraordinary chaos in the congregational singing of the seventeenth century New England colonists was probably due to the prevailing doubt as to whether singing was, after all, quite proper to the worship of God. Until well into the eighteenth century the propriety of singing psalms in church was a subject of heated controversy. John Cotton published a tract in defense of the custom in 1647 ('Singing of Psalms a Gospel Ordinance'), and, as late as 1723, a number of clergymen published a tract called 'Cases of Conscience about Singing Psalms, briefly considered and resolved,' in which we find the proposition: 'Whether you do believe that singing Psalms, Hymns and Spiritual Songs is an external part of Divine Worship, to be observed in and by the assembly of God's people on the Lord's Days, as well as on other occasional meetings of the Saints, for the worshipping of God....' Those who had taken singing in church as a matter of course, and had made of it such a cacophantic horror as is described by Eliot, Walter, and others, characteristically championed their own style of singing, which they called 'the old way,' and zealously opposed any attempt to sing by rule as a step toward Popery.

But, apart from all differences of opinion upon church singing as such, no people who were in the[Pg 18] habit of practising music, even in the most elementary way, could make such a hopeless mess of ensemble singing in unison, when the tunes were so old and familiar and the number of them so limited. Ensemble singing by a mixed gathering of untrained people is likely to be pretty bad in any case, but even among a heterogeneous and untutored crowd there are always a number whose accuracy of ear and intonation suffices to keep the others more or less close to the melody—especially when it is a familiar one. Among New England colonists, however, the ability to sing must have been about as common as the ability to dance on the tight rope. The Rev. Thomas Symmes assures us that he was present 'in a congregation, when singing was for a whole Sabbath omitted, for want of a man able to lead the assembly in singing.' Certainly the good people of that congregation on the whole must not have counted singing among their diversions—if they had any. We have no ground for stating flatly that the New Englanders of the seventeenth century absolutely abstained from singing on all occasions; but if they did sing it was in a most primitive and haphazard fashion.

Instrumental music certainly was taboo to them. As far as we know there was not a musical instrument in New England before the year 1700. If there was, it has shown remarkable ingenuity in escaping detection. Before leaving this world for a better one, the New England colonist was meticulously careful in making out a full and exact inventory of his material possessions. He told in painful detail just how many pots and pans, bolsters, pillows, tables and chairs he had been blessed with and in just what condition he bequeathed them to posterity. Nothing detachable in the house was too small nor of too little value to escape his conscientious enumeration. But of musical instruments the testamentary literature of New England contains[Pg 19] no mention. The first suggestion we find of the existence of such a thing is a laconic reference in the diary of the Rev. Joseph Green under date of May 29, 1711: 'I was at Mr. Thomas Brattle's, heard ye organs and saw strange things in a microscope.' We have no means of knowing, unfortunately, what were the musical qualities of Mr. Thomas Brattle's 'organs'; perhaps they were as strange as the things the reverend diarist saw in the microscope. Anyhow, as far as we can discover, they were unique in New England. Perhaps they were the same that Mr. Brattle bequeathed to the Brattle Square Church of Boston in 1713. The congregation of the church did not 'think it proper to use the same in the public worship of God,' and the instrument was consequently given to King's Chapel, where it was introduced in the services, to the consternation, anger and disgust of Dr. Cotton Mather and the greater part of the population of New England. This organ is still preserved for the benefit of the curious, and, though its musical possibilities apparently were limited, it at least marked a precedent which, as we shall see in a later chapter, was followed by good results.

It has been mentioned that most of the New England congregations, at the end of the seventeenth century, knew not more than five psalm-tunes. Those, it is assumed, were the psalms called 'Old Hundred,' 'York,' 'Hackney,' 'Windsor,' and 'Martyrs.' The early Pilgrims, presumably, were more eclectic. They used the volume of tunes compiled by the Rev. Henry Ainsworth, of Amsterdam. The version of Sternhold and Hopkins was used in Ipswich and perhaps elsewhere. In 1640 both the Ainsworth and the Sternhold and Hopkins versions were generally superseded by the 'Bay Psalm Book,' though Ainsworth's psalter was retained by the churches of Salem and Plymouth for some time longer. The 'Bay Psalm Book' was compiled by a number of Colonial clergymen, including Rev. Thomas[Pg 20] Weld, Rev. John Eliot, of Roxbury, and Rev. Richard Mather, of Dorchester. It is interesting chiefly as containing some of the quaintest verses ever written. Thus:

'And sayd he would them waste; had not

Moses stood (whom he chose)

'fore him i' the breach: to turn his wrath

lest that he should waste those.'

and again:

'Like as the heart panting doth bray

after the water-brooks,

even in such wise, O God, my soule

after Thee panting looks.'

The settings of the tunes in the New England psalm-books were those of Playford and Ravenscroft, but, as we have seen, the congregations habitually introduced original harmonizations of their own. The general method of singing those psalms was known as 'lining out.' That is to say, the minister or deacon first sang each line, to give the key, and the congregation followed his lead—more or less. The results of this system were often ludicrous. For instance, there is the well-known example, cited by Hood, where the deacon declares cryptically:

'The Lord will come and he will not,'

and follows this up with the perplexing injunction:

'Be silent, but speak out.'

Owing to the efforts of John Cotton and other cultured clergymen the people as a whole soon came to accept singing as proper to divine service, but many decades passed before they could be persuaded that the cultivation of the voice or the use of any outward[Pg 21] means to acquire skillfulness in singing was decent or godly. Not to the outward voice, they argued, but to the voice of the heart did God lend ear; and, though their singing was verily as the bellowing of the bulls of Bashan, it mattered not except to the ears of their neighbors, who, in truth, must have been sufficiently calloused to the discord of harsh sounds. This peculiar attitude lasted until well into the eighteenth century. Even as late as 1723 the 'Cases of Conscience,' to which we have referred, contained such questions as:

'Whether you do believe that singing in the worship of God ought to be done skillfully?' and 'whether you do believe that skillfulness in singing may ordinarily be gained in the use of outward means by the blessing of God?' By the efforts of enlightened clergymen like Mather, Symmes, Dwight, Eliot, Walter, and Stoddard the people of New England were finally brought to a realization of the fact that their praise would be just as acceptable to God if offered on the key; but their conversion was a slow and painful process. Two decades of the eighteenth century had passed before they began to pay any attention to the cultivation of church music, and, as we shall see in the next chapter, this awakening interest coincided with the first faint stirrings of a general musical life in the Puritan colonies.

W. D. D.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] The sentence quoted opens Frederic Louis Ritter's 'Music in America.' In the next sentence the author admits the prior arrival of the Cavaliers on these shores, but hastens to add that they exercised very little influence on American musical development. 'It is a curious historical fact,' he says, 'that earnest interest in musical matters was first taken by the psalm-singing Puritans.' It is curious. We quote further: 'From the crude form of a barbarously sung, simple psalmody there rose a musical culture in the United States which now excites the admiration of the art-lover, and at the same time justifies the expectation and hope of a realization, at some future epoch, of an American school of music.' Quantum sufficit. Louis C. Elson, in his 'History of American Music,' also tells us that 'the true beginnings of American music ... must be sought in ... the rigid, narrow, and often commonplace psalm-singing of New England.' If these things be so, well may the American composer exclaim in the words of the immortal Sly 'Now, Lord be thanked for my good amends!'

[2] We are leaving out of consideration the Spanish settlement of Florida as well as the French settlement of Quebec, and have in mind only those early colonies which formed the nucleus of the United States.

[3] See Max Seiffert in Vierteljahrschrift für Musikwissenschaft, 1891.

[4] Thomas Morley, 'A Plain and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke,' 1597.

[5] 'The Colonial Era,' in the American History Series, New York, 1892-1902.

[6] See Chapter XI for a further treatment of negro music.

[7] Strictly speaking the Pilgrims who came from Leyden to Plymouth were not Puritans. They were Separatists, and their movement antedated the Puritan movement per se. It would be highly inconvenient, however, in a work of this character to draw constant distinctions between Pilgrims and Puritans and we shall consequently speak of them in general as one.

[8] Cf. Sigmund Spaeth: 'Milton's Knowledge of Music,' New York, 1913.

[9] For a full statement of the Puritan case in respect to music, see Henry Davey: 'History of English Music,' Chap. VII. London, 1895.

[Pg 22]