*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CELTIC SCOTLAND: A HISTORY OF ANCIENT ALBAN, VOLUME 2 (OF 3) ***

Footnotes were numbered beginning afresh with each chapter. They have

been resequenced across the entire text for uniqueness. On occasion,

notes are cross-referenced by number. These references have

been changed as well.

Footnotes have been collected at the end of each chapter, and are

linked for ease of reference.

Links have been provided for the several references

to Volume I and III of this series in the Project Gutenberg repository.

We suggest that these be opened in a new tab or window.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

Printed by Thomas and Archibald Constable

FOR

DAVID DOUGLAS, EDINBURGH

| LONDON |

HAMILTON, ADAMS, AND CO. |

| CAMBRIDGE |

MACMILLAN AND BOWES. |

| GLASGOW |

JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS |

II

CELTIC SCOTLAND:

A HISTORY OF

Ancient Alban

BY

WILLIAM F. SKENE, D.C.L., LL.D.

HISTORIOGRAPHER-ROYAL FOR SCOTLAND.

Volume II.

CHURCH AND CULTURE.

SECOND EDITION.

EDINBURGH: DAVID DOUGLAS

1887

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

This volume being now likewise out of print, it has

been thought right to issue a new edition.

The Author has for this purpose carefully revised

the text, and made such corrections and alterations

as appeared to be demanded. These, however, he

was glad to find are few in number and unimportant

in character.

Edinburgh, 27 Inverleith Row,

2nd May 1887.

vi

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION.

The volume now published contains the second of

the three books into which the history of Scotland

during the Celtic period has been divided, and, like

the first volume, forms a substantive work in itself.

It deals entirely with the history of the old Celtic

Church, and its influence on the culture of the

people. The early ecclesiastical history of Scotland

is a subject beset with even greater difficulties than

those which affect its early civil history. It shares

with the latter that perversion of its history which

has been caused by the artificial system elaborated

by our oldest historians. The fictitious antiquity

given by it to the settlements of the Scots is

accompanied by a supposed introduction of Christianity

at an earlier period, equally devoid of historic

foundation; and this supposed early Christian

Church has given rise to what may be called the

Culdean controversy, by which the true history has

been further obscured. It is a disadvantage which

affects the history of all churches, that it is almost

inevitably viewed through the medium of the ecclesiastical

prepossessions of the historian. This has

been peculiarly the case with the history of the

viiearly church in Scotland, which has become the

battle-field on which Catholic and Protestant, Episcopalian

and Presbyterian, have contended for their

respective tenets; and this evil is greatly aggravated

when the basis of the controversy consists of such

a strange mixture of fact and fable as that which

characterises the history of the early Scottish

Church, as it is usually represented.

People are tired, however, of this incessant repetition

by church historians of the same one-sided

arguments, and partial statement of authorities

adduced to assimilate the early Celtic Church, in

its doctrine and constitution, to one or other of the

great ecclesiastical parties of the modern church.

They want to know what sort of a church this early

Celtic Church really was, irrespective of all ecclesiastical

bias, and this the Author has attempted to

show in the following volume. He has endeavoured

simply to tell the tale of the early Celtic Church, as

he finds it recorded in the oldest and most authentic

sources of information. With this view he has

treated of the history of the church mainly in its

external aspect, and has been unable to touch, to

any great extent, upon its doctrinal history, or to

attempt to exhibit its theological characteristics.

The discussion of these questions must still be left

to the polemical historians. From the works of

these writers the Author has thus derived little

assistance; but his task has been greatly aided by

another class of writers, who have brought to bear

upon the different branches of the subject that

viiisound judgment, extensive research, and critical

acumen, which are requisite to extricate the true

history of the early church from the fictitious and

controversial matter with which it has been

encumbered.

The first to bring these qualities to bear upon

the subject was undoubtedly the late Dr. Joseph

Robertson, in a very remarkable essay which

appeared in the Quarterly Review in 1849, under

the title of ‘Scottish Abbeys and Cathedrals’ (vol.

lxxxv. p. 103); and this was followed by a valuable

essay ‘On the Scholastic Offices in the Scottish

Church in the twelfth and thirteenth Centuries,’

printed in 1852 in the Miscellany of the Spalding

Club (vol. v. p. 56). But, in 1857, there appeared

by far the most important work bearing upon the

history of the early Scottish Church. This was the

edition of Adamnan’s Life of St. Columba, by the

Rev. Dr. Reeves, now Dean of Armagh, printed for

the Irish Archæological Society and the Bannatyne

Club. This work is a perfect model of an exhaustive

treatment of its subject, and exercised at once an

influence upon the study of Scottish church history,

the importance of which cannot be over-estimated.

It was followed, in 1864, by a work of the same

author on The Culdees of the British Islands as they

appear in History, in which he has brought

together almost all the evidence we possess with

regard to their history. In the same year the

late Bishop of Brechin commenced his useful labours

in this department of history by publishing the

ixMissal of Arbuthnot, with a valuable preface. And

in 1866 the late Dr. Joseph Robertson produced his

last and most important work, viz., the Statuta

Ecclesiæ Scoticanæ, which he edited for the Bannatyne

Club, in two volumes, the first of which consists

of an elaborate introduction by himself. It is cause

of much regret that this accurate and acute historian

had not lived to devote his great abilities

and extensive research to a complete history of the

church, which would have rendered the present

attempt unnecessary.

Dr. John Stuart, who had already, in his great

work on the Sculptured Stones of Scotland, made

one of the most important contributions to the

elucidation of Scottish antiquities which we possess,

edited in 1868 the Charters of the Priory of the

Isle of May for the Society of Antiquaries, with a

valuable preface; and in 1869 we are indebted to

him for an admirable edition of the Book of Deer,

printed for the Spalding Club, to which he has prefixed

an elaborate preface. Chapters IV. and V. of

this preface on Celtic polity and on the early Scottish

Church are essays of singular ability, and full of

acute and valuable suggestive matter.

In 1872 the late Bishop of Brechin published his

‘Kalendars of Scottish Saints, with personal notices

of those of Alba, Laudonia, and Strathclyde: an

attempt to fix the districts of their several missions

and the churches where they were chiefly had in

remembrance.’ It is a very useful compilation, and

may be referred to for the churches dedicated to the

xvarious founders of the early churches mentioned in

this work. It is only necessary to add that in 1874

Dr. Reeves’s valuable edition of Adamnan’s Life of

St. Columba was, with his consent, published in the

series of Scottish Historians, with a translation of

the Life by the late Bishop of Brechin; and that in

the same year there appeared in the same series an

edition by him of the Lives of St. Ninian and St.

Kentigern, with translations, introduction, and

notes.

Such is a short view of what has already been

done for the history of the early Celtic Church of

Scotland by historians of this class. The author of

the present work is fully conscious of the imperfect

manner in which he has executed the task he set

before himself; but, without claiming to possess the

same qualities in an equal degree, he has at least

endeavoured to perform it in the same spirit, and

takes this opportunity of acknowledging the extent

to which he has freely availed himself of their

labours. He has especially to acknowledge the

valuable aid given him by W. Maunsell Hennessey,

Esq., of the Public Record Office, Dublin, in

enabling him to enrich his work with a translation

of the Old Irish Life of St. Columba, by that

eminent Irish scholar, which will be found in the

appendix; and he has also to thank John Taylor

Brown, Esq., and Felix Skene, Esq., for a careful

revision of the proof-sheets of this work.

Edinburgh, 27 Inverleith Row,

14th April 1877.

xi

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

BOOK II.

CHURCH AND CULTURE.

CHAPTER I.

THE CHURCHES IN THE WEST.

| |

PAGE |

| Early notices of the British Church |

1 |

| Church of Saint Ninian |

2 |

| Mission of Saint Columbanus to Gaul |

6 |

| Controversy regarding Easter |

7 |

| Three orders of Saints in the early Irish Church; Secular, Monastic, and Eremitical |

12 |

| The Church of Saint Patrick |

14 |

| Collegiate Churches of Seven Bishops |

24 |

| Church of the Southern Picts |

26 |

| Early Dalriadic Church |

33 |

| Church south of the Firths of Forth and Clyde |

35 |

| Apostasy of early Churches |

39 |

CHAPTER II.

THE MONASTIC CHURCH IN IRELAND.

| The second order of Catholic Presbyters |

41 |

| The entire Church monastic. Relative position of Bishops and Presbyters |

42 |

| The Presbyter-abbot |

44 |

| Monastic character of the Church derived from Gaul |

45 |

| xiiMonachism reached the Irish Church through two different channels |

45 |

| First channel through the monastery of Candida Casa, or Whithern, in Galloway |

46 |

| Second channel through Bretagne and Wales |

49 |

| The school of Clonard |

50 |

| The Twelve Apostles of Ireland |

51 |

| Saint Columba one of the twelve |

52 |

| A.D. 545. Founds the monastery of Derry |

53 |

| A.D. 558. Foundation of Bangor |

55 |

| The primitive Irish monastery |

57 |

| The Monastic family |

61 |

| Island monasteries |

62 |

| Monasteries were Christian colonies |

63 |

| Privilege of sanctuary |

65 |

| Law of succession to the abbacy |

66 |

| The right of the church from the tribe |

71 |

| The right of the tribe from the church |

72 |

| Influence of the church |

73 |

| Monasteries were seminaries of instruction |

75 |

| Early churches founded in the Western Isles |

76 |

| Mission of Saint Columba to Britain |

78 |

CHAPTER III.

THE MONASTIC CHURCH IN IONA.

| A.D. 563. St. Columba crosses from Ireland to Britain with twelve followers |

85 |

| Founds a monastery in Iona |

88 |

| Description of the island |

88 |

| Character of the Columban Church |

93 |

| Site of the original wooden monastery |

95 |

| Constitution of the monastery |

101 |

| St. Columba’s labours among the Picts |

104 |

| A.D. 565. Converts King Brude |

105 |

| Character of the paganism of the Scots and Picts |

108 |

| Proceedings of St. Columba in converting the northern Picts |

119 |

| A.D. 574. St. Columba inaugurates King Aidan and attends the assembly of Drumceatt |

122 |

xiiiCHAPTER IV.

THE FAMILY OF IONA.

| What St. Columba had accomplished in twelve years; and meaning of the expression ‘Family of Iona’ |

127 |

| Monasteries founded by him in the islands |

128 |

| Monasteries founded during his life by others in the islands |

133 |

| Monasteries founded by Columba and others among the northern Picts |

134 |

| A.D. 584-597. Monasteries founded by Columba among the southern Picts |

135 |

| Visit of Saint Columba to Ireland |

138 |

| Last day of his life |

138 |

| Character of Saint Columba |

143 |

| Primacy of Iona and successors of St. Columba |

148 |

| A.D. 597-599. Baithene, son of Brendan |

149 |

| A.D. 599-605. Laisren, son of Feradhach |

150 |

| A.D. 605-623. Fergna Brit, son of Failbhe |

151 |

| A.D. 623-652. Segine, son of Fiachna |

154 |

| A.D. 634. Extension of Columban Church to Northumbria |

154 |

| A.D. 634. Church of the southern Scots of Ireland conforms to Rome |

159 |

| A.D. 652-657. Suibhne, son of Cuirtri |

163 |

| A.D. 657-669. Cummene Ailbhe, son of Ernan |

163 |

| A.D. 664. Termination of the Columban Church in Northumbria |

164 |

| A.D. 669-679. Failbhe, son of Pipan |

168 |

| A.D. 673. Foundation of church of Applecross by Maelrubha |

169 |

| A.D. 679-704. Adamnan, son of Ronan |

170 |

| A.D. 686. First mission to Northumbria |

170 |

| Adamnan repairs the monastery of Iona |

171 |

| A.D. 688. Second mission to Northumbria |

172 |

| A.D. 692. Synod of Tara. The northern Scots, with the exception of the Columban monasteries, conform to Rome |

173 |

| A.D. 704-717. Schism at Iona after the death of Adamnan |

175 |

| A.D. 717. Expulsion of the Columban monks from the kingdom of the Picts |

177 |

xivCHAPTER V.

THE CHURCHES OF CUMBRIA AND LOTHIAN.

| A.D. 573. Battle of Ardderyd. Rydderch Hael becomes king of Strathclyde |

179 |

| Oldest account of birth of Kentigern |

180 |

| Jocelyn’s account of his birth |

181 |

| Anachronism in connecting St. Servanus with St. Kentigern |

184 |

| Earlier notices of Kentigern |

185 |

| Kentigern driven to Wales |

186 |

| Kentigern founds the monastery of Llanelwy in Wales |

188 |

| A.D. 573. Rydderch Hael becomes king of Cumbria and recalls Kentigern |

190 |

| Kentigern fixes his see first at Hoddam |

191 |

| Mission of Kentigern in Galloway, Alban, and Orkneys |

192 |

| Meeting of Kentigern and Columba |

194 |

| Death of Kentigern |

196 |

| A.D. 627. Conversion of the Angles to Christianity |

198 |

| The Monasteries in Lothian |

200 |

| Saint Cudberct or Cuthbert |

201 |

| Irish Life of St. Cuthbert |

203 |

| A.D. 651-661. Cudberct’s life in the monastery of Melrose |

206 |

| A.D. 661. Cudberct becomes prior of Melrose |

208 |

| A.D. 664. Cudberct goes to Lindisfarne |

209 |

| A.D. 669-678. St. Wilfrid, bishop over all the dominions of King Osuiu, and founds church of Hexham, which he dedicates to St. Andrew |

210 |

| A.D. 670. Cudberct withdraws to the Farne island |

211 |

| A.D. 684. Cudberct becomes bishop of Lindisfarne |

213 |

| A.D. 686. Cudberct resigns the bishopric and retires to Farne island |

214 |

| A.D. 687. Death of Cudberct |

214 |

| A.D. 698. Relics of Cudberct enshrined |

218 |

| A.D. 688. Strathclyde Britons conform to Rome |

219 |

| A.D. 705-709. Wilfrid founds chapels at Hexham, dedicated to St. Michael and St. Mary |

220 |

| A.D. 709-731. Relics of St. Andrew brought to Hexham by Acca |

222 |

| xvMonastery of Balthere at Tyninghame |

223 |

| Anglic bishopric of Whithern, founded about A.D. 730, and comes to an end about A.D. 803 |

224 |

CHAPTER VI.

THE SECULAR CLERGY AND THE CULDEES.

| No appearance of the name of Culdee till after the expulsion of Columban monks |

226 |

| Monastic Church affected by two opposite influences |

227 |

| First by secular clergy |

227 |

| Legend of Bonifacius |

229 |

| Legend of Fergusianus |

232 |

| Churches dedicated to St. Peter |

233 |

| Second influence: the Anchoretical life |

233 |

| Anchorites called Deicolæ or God-worshippers |

237 |

| Anchorites called the people of God |

239 |

| A.D. 747. Order of Secular Canons instituted |

241 |

| Deicolæ brought under canonical rule |

242 |

| Deicolæ in the Saxon Church |

243 |

| Anchoretical life in Ireland and Scotland |

245 |

| Anchorites called Deoraidh De, or God’s pilgrims |

247 |

| The third order of Irish Saints—Eremitical |

248 |

| Deicolæ termed in Ireland Ceile De |

250 |

| Deicolæ and Ceile De show the same characteristics |

252 |

| Ceile De brought under the canonical rule |

254 |

| Ceile De called Keledei in Scotland, and first appear in territory of the southern Picts |

255 |

| Legend of St. Servanus |

255 |

| Servanus introduces Keledei, who are hermits |

258 |

| Keledei of Glasgow, who were solitary clerics |

259 |

| Legends connected with the foundation of St. Andrews |

261 |

| Older legend belongs to foundation of monastery in sixth century |

266 |

| Columban monasteries among the Picts fell into the hands of laymen |

268 |

| Second legend belongs to later foundation, to which relics of St. Andrew were brought |

271 |

| xviKeledei of St. Andrews originally hermits |

275 |

| Canonical rule brought into Scotland, and Keledei become canons |

275 |

| Conclusion as to origin of the Culdees |

276 |

CHAPTER VII.

THE COÄRBS OF COLUMCILLE.

| A.D. 717-772. Schism still exists in Iona |

278 |

| Two parties with rival abbots |

279 |

| Two missionaries, St. Modan and St. Ronan, in connection with Roman party |

282 |

| A.D. 726. An Anchorite becomes abbot of Iona |

283 |

| The term Comhorba or Coärb applied to abbots of Columban monasteries |

285 |

| A.D. 772-801. Breasal, son of Seghine, sole abbot of Iona |

288 |

| A.D. 794. First appearance of Danish pirates, and Iona repeatedly ravaged by them |

290 |

| A.D. 801-802. Connachtach, abbot of Iona |

290 |

| A.D. 802-814. Cellach, son of Congal, abbot of Iona |

291 |

| A.D. 802-807. Remains of St. Columba enshrined |

292 |

| A.D. 814-831. Diarmaid, abbot of Iona |

297 |

| Monastery rebuilt with stone |

297 |

| Shrine of St. Columba placed in stone monastery |

300 |

| A.D. 825. Martyrdom of St. Blathmac protecting the shrine |

300 |

| A.D. 831-854. Innrechtach ua Finachta, abbot of Iona |

306 |

| A.D. 850-865. Tuathal, son of Artguso, first bishop of Fortrenn and abbot of Dunkeld |

307 |

| Cellach, son of Aillelo, abbot of Kildare and of Iona |

307 |

| A.D. 865-908. Primacy transferred to Abernethy, where three elections of bishops take place |

310 |

| Legend of St. Adrian |

311 |

| A.D. 878. Shrine and relics of St. Columba taken to Ireland |

317 |

CHAPTER VIII.

THE SCOTTISH CHURCH.

| A.D. 878-889. First appearance of the name ‘The Scottish Church’ when freed from servitude under Pictish law |

320 |

| xviiA.D. 908. Primacy transferred to St. Andrews. Cellach first bishop of Alban |

323 |

| A.D. 921. Introduction of canonical rule of the Culdees |

324 |

| Fothad, son of Bran, second bishop of Alban |

327 |

| A.D. 955-963. Malisius bishop of Alban |

329 |

| A.D. 963-970. Maelbrigde bishop of Alban |

330 |

| A.D. 970-995. Cellach, son of Ferdalaig, bishop of Alban |

331 |

| Iona ravaged by Danes; shrine of St. Columba transferred to Down |

332 |

| A.D. 1025-1028. Alwynus bishop of Alban |

336 |

| Lay abbots of Dunkeld |

337 |

| Hereditary succession in benefices |

338 |

| Church offices held by laymen, and retained by their heirs |

338 |

| A.D. 1028-1055. Maelduin bishop of Alban |

343 |

| A.D. 1055-1059. Tuthald bishop of Alban |

344 |

| A.D. 1059-1093. Fothad last bishop of Alban |

344 |

| Character of Queen Margaret, and her reforms in the church |

344 |

| Anchorites at this time |

351 |

| Queen Margaret rebuilds the monastery of Iona |

352 |

| A.D. 1093-1107. After death of Fothad no bishop for fourteen years |

354 |

| Keledei of St. Andrews |

356 |

| The Cele De of Iona |

360 |

CHAPTER IX.

EXTINCTION OF THE OLD CELTIC CHURCH IN SCOTLAND.

| Causes which brought the Celtic Church to an end |

365 |

| A.D. 1093-1107. See of St. Andrews remains vacant, and churches founded in Lothian only |

366 |

| A.D. 1107. Turgot appointed bishop of St. Andrews, and the sees of Moray and Dunkeld created |

368 |

| Establishment of the bishopric of Moray |

368 |

| Establishment of the bishopric of Dunkeld |

370 |

| Rights of Keledei pass to St. Andrews |

372 |

| Canons-regular introduced into Scotland |

374 |

| Diocese of Glasgow restored by Earl David |

375 |

| Bishoprics and monasteries founded by King David |

376 |

| Establishment of bishopric of Ross |

377 |

| xviiiEstablishment of bishopric of Aberdeen |

378 |

| Monasteries of Deer and Turriff |

380 |

| Establishment of bishopric of Caithness |

382 |

| The communities of Keledei superseded by regular canons |

384 |

| Suppression of Keledei of St. Andrews |

384 |

| Suppression of Keledei of Lochleven |

388 |

| Suppression of Keledei of Monimusk |

389 |

| Monastic orders of Church of Rome introduced |

392 |

| Columban abbacies or Abthens in possession of lay abbots |

393 |

| Establishment of bishoprics of Dunblane and Brechin |

395 |

| Bishoprics of Brechin and Dunblane formed from old see of Abernethy |

397 |

| Suppression of Keledei of Abernethy |

398 |

| Failure of Celtic Church of Brechin |

400 |

| Failure of Celtic Church in bishopric of Dunblane |

402 |

| Failure of Celtic Church in Bishopric of Dunkeld |

405 |

| Formation of diocese of Argyll or Lismore |

408 |

| Condition of Columban Church of Kilmun |

410 |

| Condition of Columban Church of Applecross |

411 |

| State of Celtic monastery of Iona |

412 |

| A.D. 1203. Foundation of Benedictine abbey and nunnery at Iona, and disappearance of Celtic community |

415 |

| Remains of old Celtic Church |

417 |

CHAPTER X.

LEARNING AND LANGUAGE.

| Character of the Irish Monastic Church for learning |

419 |

| Resorted to by foreign students |

420 |

| Iona as a school of learning |

421 |

| Literature of the Monastic Church |

422 |

| The Scribhnidh, or scribes in the monasteries |

423 |

| The Book of Armagh |

423 |

| Hagiology of the Irish Church |

425 |

| Analysis of the Lives of St. Patrick |

427 |

| Lives of St. Bridget |

443 |

| Hagiology of the Scottish Church |

444 |

| Bearing of the Church on the education of the people |

444 |

| The Ferleiginn, or lector |

444 |

| The Scolocs |

446 |

| xixInfluence of the Church on literature and language |

448 |

| Art of writing introduced |

448 |

| Spoken dialects of Irish |

450 |

| Peculiarities of Irish dialects |

451 |

| Written Irish |

452 |

| Scotch Gaelic |

453 |

| Origin of Scotch Gaelic |

454 |

| A written language introduced by Scottish monks |

457 |

| Gaelic termed Scottish, and Lowland Scotch, English |

459 |

| A.D. 1478-1560. Period of neglected education and no learning |

461 |

| After 1520 Scotch Gaelic called Irish, and the name Scotch passes over to Lowland Scotch |

462 |

| After Reformation Scotch Gaelic becomes a written language |

463 |

| APPENDIX. |

| I. |

| The old Irish Life of St. Columba; being a discourse on his Life and Character delivered to the Brethren on his Festival. Translated from the original Irish text by W. Maunsell Hennessey, Esq., M.R.I.A. |

467 |

| II. |

| The Rule of St. Columba |

508 |

| III. |

| Catalogue of Religious Houses at the end of the Chronicle of Henry of Silgrave, c. A.D. 1272, so far as it relates to Scotland |

509 |

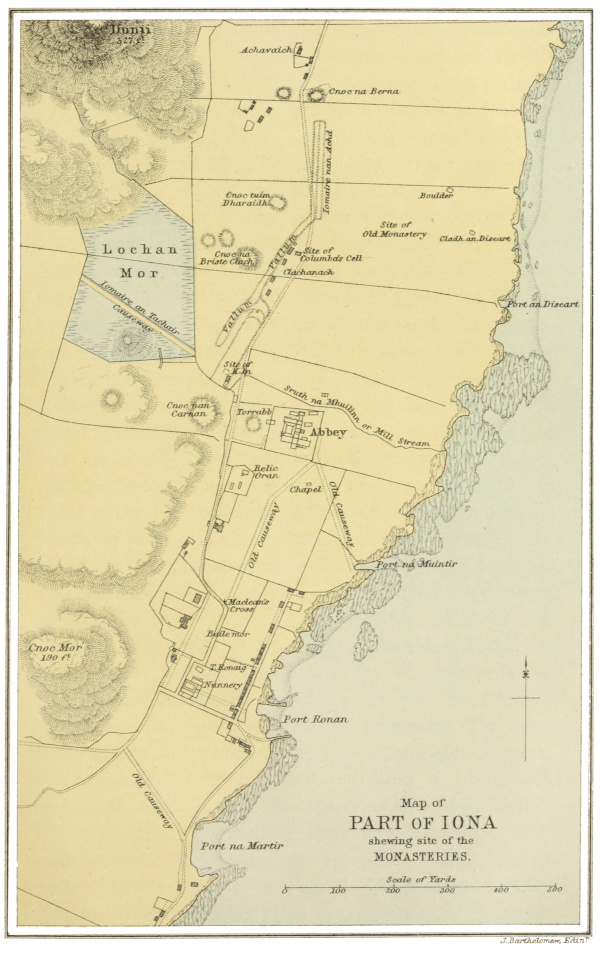

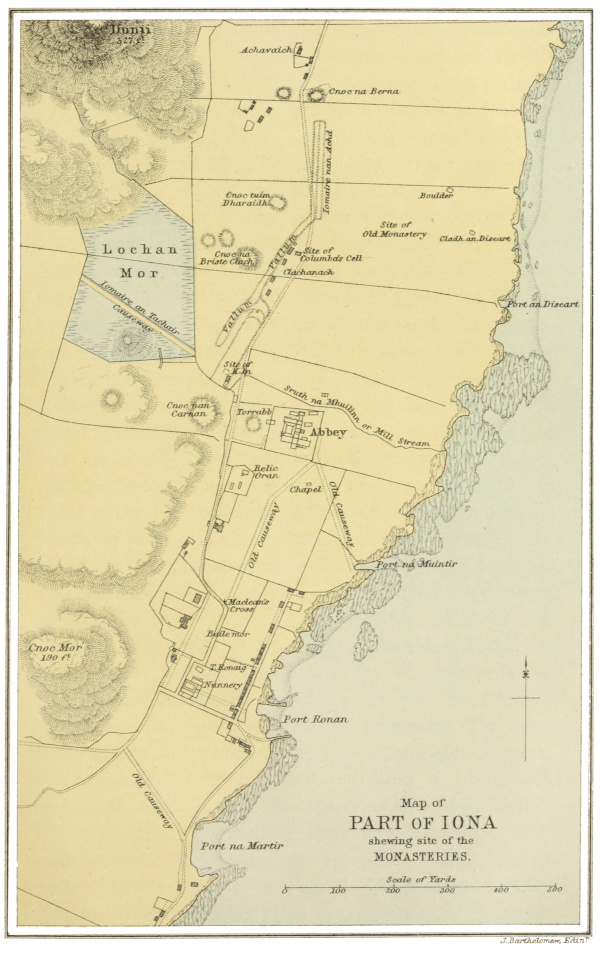

| Map of Iona, showing site of the monasteries |

to face page |

100 |

| Map illustrating history of the Monastic Church prior to eighth century |

” |

178 |

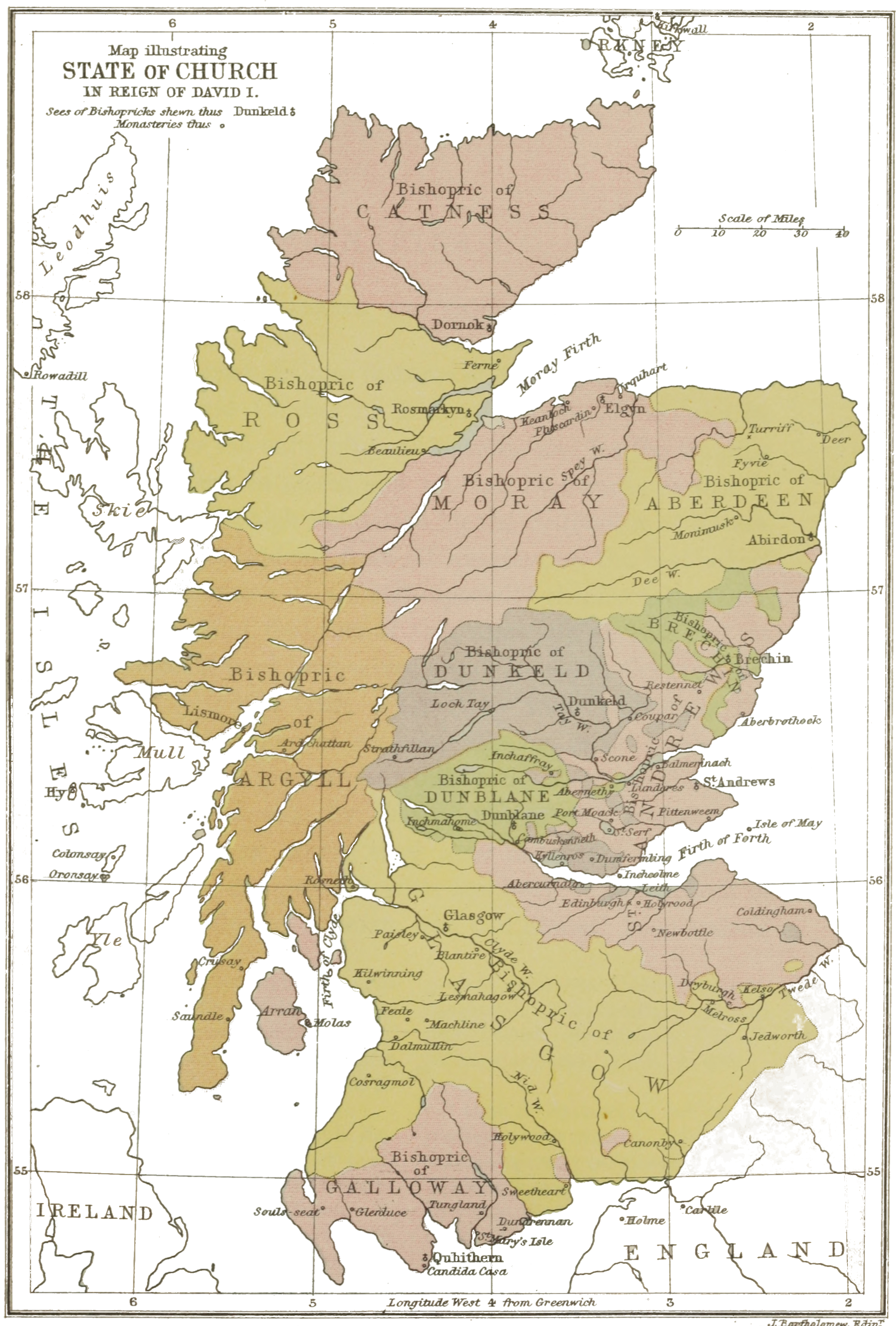

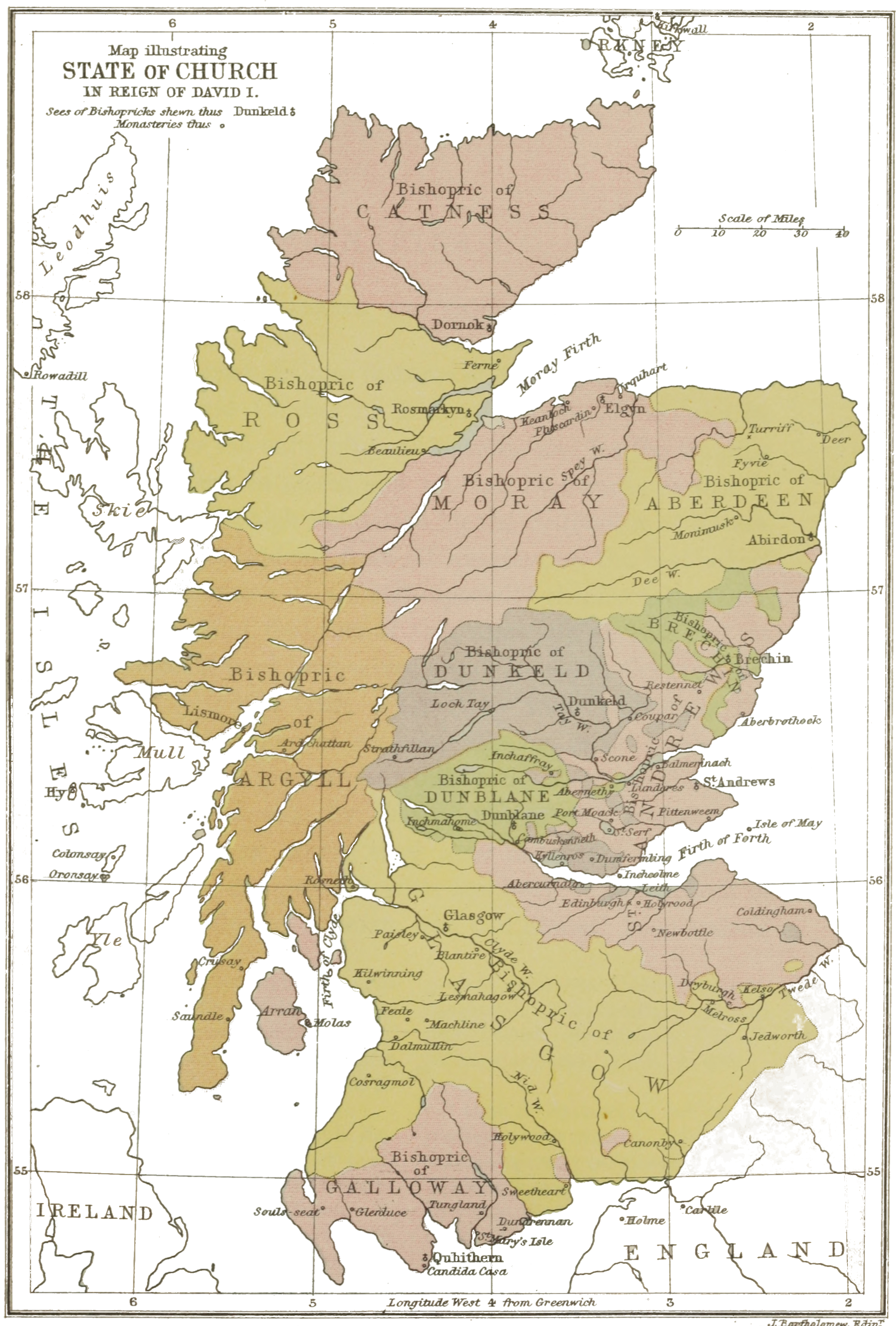

| Map illustrating state of the Church in the reign of David I. |

” |

418 |

1

BOOK II.

CHURCH AND CULTURE.

CHAPTER I.

THE CHURCHES IN THE WEST.

Early notices of the British Church.

In endeavouring to form a just conception of the history and

characteristics of the early Celtic Churches of the British

Isles, it is necessary at the very outset to discriminate

between three consecutive periods, which are strongly contrasted.

The first is that period which preceded the withdrawal

of the Roman troops from Britain and the termination

of the civil government of the Roman province there

in the beginning of the fifth century; the second, the period

of isolation which followed, when the invasion of the Roman

provinces in Gaul and Britain by the Barbarians interposed

a barrier of paganism between the churches of Britain and

the Continent, and for the time cut off all communication

between them; and the third, that which followed the

renewal of that intercourse, when they again came into contact

in the end of the sixth century.

During the Roman occupation of Britain the Christian

religion had unquestionably made its way under their

auspices into the island, and the Roman province in Britain

was, in this respect, no exception to the other provinces of

the empire. It can hardly be doubted that, as early as the

second century of their occupation, a Christian Church had

been established within its limits, and there were even

2reports that it had penetrated to regions beyond it. It is

unnecessary for the purpose of this work, and it would be

out of place here, to enter into any inquiry as to the actual

period and history of the introduction of the Christian

Church into the British province, a subject which has been

fully discussed by other writers.[1] Our more immediate

concern is with the churches founded beyond its limits,

among those tribes termed by the Roman writers Barbarians,

in opposition to the provincial Britons. Suffice it to say

that during the Roman occupation the Christian Church in

Britain was a part of the Church of the empire. It was

more immediately connected with that of Gaul, but it

acknowledged Rome as its head, from whom its mission was

considered to be derived, and it presented no features of

difference from the Roman Church in the other western

provinces.

Church of Saint Ninian.

Towards the end of the Roman occupation the Christian

Church seems to have penetrated in two directions beyond

the limits of the province, but in other respects to have

possessed the same character. During that troublous time

when the province was assailed by the barbarians on the

north and west, and its actual boundary had been drawn

back from its nominal limits, a Christian Church was established

in the district extending along the north shore of

the Solway Firth, where Ptolemy had placed the tribe of

the Novantæ, its principal seat being at one of their towns

situated on the west side of Wigtown Bay, and termed by him

‘Leukopibia.’ The fact is reported by Bede as one well

known to have taken place. The missionary was Ninian, a

bishop of the nation of the Britons, who had been trained at

3Rome in the doctrine and discipline of the western Church,

and who built at Leukopibia a church of stone, which was

vulgarly called Candida Casa, and dedicated to St. Martin of

Tours.[2] This is the earliest account we have of him, and

shows very plainly both his relation to Rome as the source

of his mission and his connection with the Church of

Gaul. It is probable that Ailred of Rievaulx, in his Life

of Ninian, written in the twelfth century, but derived from

older materials, repeats a true fact when he says that

Ninian heard of the death of Martin while he was erecting

this church; and this fixes the date of its foundation at the

year 397. From Bede’s statement we learn that the object

of his mission seems to have been the conversion of the

Pictish nation, with the view probably of arresting, or at

least mitigating, their attacks upon the provincial Britons.

He founded his church of Candida Casa among the people

occupying the district on the north side of the Solway Firth,

extending from the Nith to the Irish Channel, who afterwards

appear as the Picts of Galloway; and we are told that

through his preaching the Southern Picts, extending as far

north as the great mountain range of the Grampians, abandoned

their idolatrous worship and received the true faith.

While the Christian Church had thus been extended into

the southern province of the Pictish nation, it appears to

have by this time penetrated also to the Scots of Ireland.

If the old Irish Life of Ninian can be trusted, he is said to

have left Britain and spent the last years of his life in

Ireland, where he founded a church in Leinster called Cluain

Conaire, and it is certain that he was commemorated there

on the 16th of September under the name of Monenn.[3] The

4date of Ninian’s death is not recorded. It has been almost

uniformly stated by modern writers to have taken place on

the 16th September in the year 432, and has been given

by some on the authority of Bede, by others on that of

Ailred; but no such date is to be found in either writer, and

this supposed year of his death rests upon no authority

whatever.

The Roman dominion in Britain came to an end in 410,

when the troops were withdrawn from the province and the

provincial cities left to protect themselves. Roman Britain

thus ceased, to all intents and purposes, to form part of the

empire; her intercourse with the Continent was almost entirely

cut off by the incursions of the barbarian tribes into

Roman Gaul; and, with the exception of a few contemporary

notices of the Church during some years after the termination

of the Roman dominion, all is silence for a century and a

half, till it is broken in the succeeding century by the

querulous voice of Gildas. The few facts which we learn

from contemporary sources are these: that in the year 429

the churches of Britain had been corrupted by the ‘Pelagian

Agricola, son of the Pelagian bishop Severianus,’ who had

introduced the Pelagian heresy among them to some

extent;[4] that the orthodox clergy communicated the

fact to the Gallican bishops, by whom a synod was held,

when it was resolved to send Germanus bishop of Auxerre,

and Lupus bishop of Troyes, to Britain; and that, at the instance

of Palladius the deacon, Germanus received a mission

from Celestine, bishop of Rome, to bring back to the

Catholic faith the Britons tainted with this heresy.[5] Two

5years after, in 431, according to the same chronicler, Pope

Celestine ordained Palladius a bishop, and sent him to the

Christian Scots of Ireland as their first bishop; and thus,

‘having ordained a bishop to the Scots, while he endeavoured

to preserve Roman Britain as Catholic, he made the barbarian

island Christian,’[6] in this sense at least that he had formed

into a regular church those of its inhabitants who had already

become Christian. Whether the Christian religion had been

introduced into Ireland by the preaching of Ninian, or whether

it had existed there from even an earlier period, there are now

no materials to indicate;[7] but the mission of Palladius seems

to imply that Ninian was at this time dead.

Such are the few facts which we have from contemporary

sources at this time; and all other accounts which we possess

of the church among the barbarians are derived from

tradition or legend, which will be dealt with in its proper

place. These few isolated statements show us a church in

Roman Britain, which had been extended, in one direction,

into the districts north of the Roman wall, till arrested by

the great mountain barrier separating the northern from the

southern Picts, and, in another, to the island of Ireland, then

the only country inhabited by the people called Scots. We

find it in close connection with the Gallican Church, and

regarding the Patriarch of Rome as the head of the Western

6Church and the source of ecclesiastical authority and mission.

With the exception of the temporary prevalence of the

Pelagian heresy in Britain, we can discover no trace of any

divergence between them in doctrine or practice.[8] There now

follows a long period of utter darkness, during which all

connection with the Continent was broken off; and we learn

nothing further regarding the churches beyond the western

limits of the empire, till the church of the extreme west

came into contact with that of Gaul towards the end of the

sixth century.

Mission of Saint Columbanus to Gaul.

In the year 590 the ecclesiastical world in Gaul, in which

the Franks and Burgundians were already settled, was

startled by the sudden appearance of a small band of missionaries

on her shores. They were thirteen in number—a

leader with twelve followers. Their outward appearance was

strange and striking. They were clothed in a garment of

coarse texture made of wool, and of the natural colour of the

material, under which was a white tunic. They were tonsured,

but in a different manner from the Gaulish ecclesiastics.

Their heads were shaved in front from ear to ear, the anterior

half of the head being made bare, while their hair flowed

down naturally and unchecked from the back of the head.

They had each a pilgrim’s staff, a leathern water-bottle and

a wallet, and a case containing some relics. They spoke

among themselves a foreign language, resembling in sound

the dialect of Armorica, but they conversed readily in Latin

with those who understood that language.[9] When asked

7who they were and whence they came, they replied,—‘We

are Irish, dwelling at the very ends of the earth. We be

men who receive naught beyond the doctrine of the evangelists

and apostles. The Catholic faith, as it was first delivered by

the successors of the holy apostles, is still maintained among

us with unchanged fidelity;’ and their leader gave the

following account of himself,—‘I am a Scottish pilgrim, and

my speech and actions correspond to my name, which is in

Hebrew Jonah, in Greek Peristera, and in Latin Columba,

a dove.’[10] In this guise they appeared before the people,

addressing them everywhere with the whole power of their

native eloquence. Some learned the language of the country.

The rest employed an interpreter when they preached before

the laity. To ecclesiastics they spoke the common language

of the Latin Church. Their leader, Columbanus, was a man

of commanding presence and powerful eloquence, and endowed

with a determination of character and intensity of purpose

which influenced, either favourably or the reverse, every

one with whom he came in contact. From the kings he soon

obtained permission to settle in their territories and to erect

monasteries; and two monastic establishments soon arose

within the recesses of the Vosges mountains, which now

divide Alsace from France—those of Luxeuil and Fontaines,

to which the youth of the country flocked in numbers for

instruction, or for training as monks.

Controversy regarding Easter.

They had not been long established there when the

Gaulish clergy became aware that in the new monasteries

the festival of Easter was occasionally celebrated on a

different Sunday from that observed by the Roman Church,

8there being occasionally an interval of a week between the

two, and sometimes even the violent discrepancy of an entire

month. This arose from a difference in the mode of calculating

the Sunday on which Easter ought to fall, both in

regard to the week within which it ought to be celebrated

and the cycle of years by which the month was to be determined.

By the law of Moses the passover was to be slain

on the fourteenth day of the first month of the year, in the

evening (Exod. xii. 2, 3, 6), and the children of Israel were

further directed to eat unleavened bread seven days:—‘In

the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month, at even,

ye shall eat unleavened bread, until the one-and-twentieth

day of the month’ (Ib. xii. 18). It was further declared that

the month in which the fourteenth day or the full moon fell

first after the vernal equinox was to be their first month.

In applying this rule to the Christian Easter, the Eastern

Church, in the main, adopted it literally, and celebrated

Easter on the same day as the Jewish Passover, on whatever

day of the week it might fall. The Western Church, however,

held that, as our Saviour had risen from the dead on

the first day of the week after the Passover, the festival of

Easter should be celebrated on the Sunday between the

fourteenth and the twentieth day of the moon on the first

month of the Jewish lunar year. In order to bring the lunar

date into connection with the solar year so as to fix the day

of the month on which Easter was to be kept, various cycles

were framed by the Church; till at length the Easter cycle

of nineteen years was introduced at Alexandria by Anatolius,

bishop of Laodicea, in 270, by which Easter was celebrated

on the Sunday falling on the fourteenth day of the moon, or

between that day and the twentieth on a cycle of nineteen

years. In the Western Church, however, the time for

celebrating Easter was calculated on a cycle of eighty-four

years, which was improved by Sulpicius Severus in 410, and

continued to be used till 457, when a longer cycle of 532

9years was introduced by Victorius of Aquitaine, based upon

the cycle of nineteen years; and in the year 525 the

computation was finally fixed by Dionysius Exiguus on the

cycle of nineteen years. By this time it was likewise held

that, as the Passover was slain on the evening of the fourteenth

day of the moon, according to the Jewish system of

reckoning the days from evening to evening, the fifteenth,

and not the fourteenth, ought to be considered as the first

day of unleavened bread, and consequently Easter ought to

fall on the Sunday between the fifteenth and twenty-first

days of the moon; and by a canon of the fourth council of

Orleans, held in the year 541, it was directed that the Easter

festival should be observed by all at the same time, according

to the tables of Victorius.[11]

These changes in the mode of computation in the

Western Church took place after the connection between

Britain and the rest of the empire had ceased, and when the

British Churches were left in a state of isolation. They

therefore still retained the older mode of computation, which

had been once common to the whole Western Church; and

thus it came that when Columbanus went on his mission

to Gaul he found the continental Churches celebrating the

festival of Easter on the Sunday between the fifteenth and

twenty-first days of the moon, calculated on the cycle of

nineteen years, while the British and Irish Churches

celebrated the same festival on the Sunday between the

fourteenth and twentieth days of the moon, calculated

according to the cycle of eighty-four years; the difference

in the days of the moon causing an occasional divergence of

a week, and that of the cycles a possible divergence of a

month.[12] The prelates of Gaul seem to have eagerly caught

10at a ground upon which they could charge these strange

missionaries, who had taken such a hold upon the country,

with following practices at variance with the universal

Church, and thus pursuing a schismatical course. A council

was summoned for the purpose of considering what steps

they ought to take with regard to these strangers; but

Columbanus, though probably included in the summons,

contented himself by sending a letter, which is still extant,

addressed to ‘our holy lords and fathers or brethren in

Christ, the bishops, presbyters, and other orders of Holy

Church,’[13] in which he vindicates the mode of keeping

Easter which he had received from his fathers, according to

the cycle of eighty-four years, refers to Anatolius as having

been commended by Eusebius and St. Jerome, and denounces

the change made by Victorius as an innovation. He claimed

his right to follow the course derived from his fathers, and

remonstrated with them for endeavouring to trouble him on

such a point. What the result of this synod was we do not

know; but it was followed by an appeal by Columbanus to

the Pope himself. To Columbanus Rome was still the

traditional Rome of the fourth and fifth centuries. Since

then the Irish Church had not come into contact with her,

and inherited the same feelings of regard and deference with

which the early church had regarded her before the period of

their isolation, and while she was still to them the acknowledged

head of the churches in the western provinces of the

Roman empire. In this letter, which also is extant, he

11addressed Boniface IV. as ‘the holy lord and[14] Apostolic

Father in Christ, the Pope.’ He tells him that he had long

desired to visit in spirit and confer ‘with those who preside

in the apostolic chair, the most beloved prelates over all the

faithful, the most revered fathers by right of apostolic honour.’

He vindicates the doctrine of his church as no way differing

from that of other orthodox churches, but claims to be regarded

‘as still in his fatherland, and not bound to accept

the rules of these Gauls; but as placed in the wilderness and,

offending no one, to abide by the rules of his seniors;’ and

he appeals to ‘the judgment of the 150 fathers of the Council

of Constantinople, who judged that the churches of God

established among the Barbarians should live according to

the laws taught them by their fathers.’ This was the second

œcumenical council held at Constantinople in the year 381.

The second canon directs that the bishops belonging to each

diocese shall not interfere with churches beyond its bounds.

It then regulates the jurisdiction of the great patriarchates,

and concludes by declaring that the churches of God among

the Barbarian people—that is, beyond the bounds of the

Roman empire—shall be regulated by the customs of their

fathers.[15] The position which Columbanus took up was

substantially this—‘Your jurisdiction as Bishop of Rome

does not extend beyond the limits of the Roman empire. I

am a missionary from a church of God among the Barbarians,

and, though temporarily within the limits of your territorial

jurisdiction, and bound to regard you with respect and

deference, I claim the right to follow the customs of my

own church handed down to us by our fathers.’

It is unnecessary for our purpose to enter further into

the life and doings of Columbanus. They have been referred

to here at the very outset, because it was by his mission that

the churches of the extreme west were again, for the first

12time, brought into contact with the Roman Church; and he

has left behind him authentic writings which present to us at

once the points of contrast between the two churches, and

the relation they bore to each other, and thus afford us a fixed

point from which to start in our examination of the early

history and peculiar characteristics of these Celtic churches

during the dark period of their isolation, when all intercourse

with the Continent was cut off.

Three Orders of Saints in early Irish Church; Secular, Monastic, and Eremitical.

There are two ancient documents, both belonging to the

eighth century, which afford us, at the outset, a view of the

characteristic features of the early Irish Church. One is a

‘Catalogue of the Saints of Ireland according to their

different periods,’ in which they are arranged in three classes

corresponding to three periods of the church;[16] and the other

is the Litany of Angus the Culdee, in which he invokes the

saints of the early church in different groups.[17] The

Catalogue of the Saints proceeds thus:—‘The first order of

Catholic saints was in the time of Patricius; and then they

were all bishops, famous and holy and full of the Holy

Ghost; 350 in number, founders of churches. They had one

head, Christ, and one chief, Patricius; they observed one

mass,[18] one celebration, one tonsure from ear to ear. They

celebrated one Easter, on the fourteenth moon after the

vernal equinox, and what was excommunicated by one

church, all excommunicated. They rejected not the services

and society of women,’ or as another MS. has it, ‘they

excluded from the churches neither laymen nor women;

because, founded on the rock Christ, they feared not the

blast of temptation. This order of saints continued for four

13reigns.[19] All these bishops were sprung from the Romans,

and Franks, and Britons, and Scots. The second order was

of Catholic Presbyters. For in this order there were few

bishops and many presbyters, in number three hundred.

They had one head, our Lord; they celebrated different

masses,[20] and had different rules, one Easter on the fourteenth

moon after the equinox, one tonsure from ear to ear;

they refused the services of women, separating them from

the monasteries. This order has hitherto lasted for four

reigns.[21] They received a mass from Bishop David, and

Gillas and Docus, the Britons.[22] The third order of Saints

was of this sort. They were holy presbyters, and a few

bishops; one hundred in number; who dwelt in desert

places, and lived on herbs and water, and the alms; they

shunned private property,’ or, as the other MS. has it, ‘they

despised all earthly things, and wholly avoided all whispering

and backbiting; they had different rules and masses, and

different tonsures, for some had the coronal and others the

hair (behind); and a different Paschal festival. For some

celebrated the Resurrection on the fourteenth moon, or on

the sixteenth with hard intentions. These lived during four

reigns, and continued to that great mortality’[23] in the year

666. This document presents us with a short picture of the

church prior to the year 666, and it is hardly possible to

mistake its leading characteristic features during each of the

three periods. In the first period we find churches and a

secular clergy. In the second, the churches are superseded

by monasteries, and we find a regular or monastic clergy;

and in the third, we see an eremitical clergy living in

14solitary places. But while this seems to indicate, and may

to some extent have arisen from, a deepening asceticism—the

clergy passing from a life under the ordinary canonical

law of the church, through the discipline and strict rule of

monastic observances, to a solitary life of privation and self-denial

in what was called the Desert—there were probably

causes connected both with the social state of the wild people

among whom they exercised their clerical functions and with

the result of their labours, which led to the church being

reconstructed from time to time on a different basis, and

thus presenting a different outward aspect. The distinction

in order between the bishop and the presbyter, however,

seems to have been preserved throughout, though their relation

to each other, in respect to numbers and jurisdiction, varied

at different periods.

The Church of Saint Patrick.

The first order of Saints representing the Church during

the first period had Christ for their head, and St. Patrick for

their leader or chief. They claimed therefore to be peculiarly

the Church of Saint Patrick. And here we are struck at the

outset by the fact that there is no mention whatever of the

mission of Palladius; and if we turn to the few notices of

the early Irish Church in contemporary writers of other

countries, we find the equally striking contrast that, while

they record the mission of Palladius, they make no mention

of Patrick. The life of Patrick, as usually told and accepted

in history, is derived in the main from his acts, as contained

in Lives of the Saint compiled at different times ranging

from the eighth to the twelfth century. Seven of these

lives were published by Colgan in his Trias Thaumaturga,

and he has attempted to assign fixed dates to those which

are anonymous; but it is obvious that they are, to a large

extent, composed of legendary and traditional matter. The

Book of Armagh, which was compiled about the year 807,[24]

15presents us with two older narratives. One was compiled by

Muirchu Maccumachtheni, or the son of Cogitosus, at the

suggestion of Aedh, bishop of Sletty, who died in 698; the

other by Tirechan, who is believed to be the author of the

Catalogue of the Saints. Both, therefore, belong to the same

period. Muirchu’s life is imperfect, as we only possess a

short summary of the first part;[25] and we can gather from it

that Patrick had gone to Rome to prepare for his mission, but

went no farther than Gaul, as he there met the disciples of

Palladius, at a place called Ebmoria, who reported the death

of Palladius, who, having failed in his mission, had died on

his return to Rome in the territory of the Britons; and that

Patrick then received the episcopal degree from Matho the

holy king and bishop, and proceeded on his mission to

Ireland.[26] Tirechan’s account is more precise. He says,

‘In the xiii. year of Theodosius the emperor, Patricius the

bishop was sent by Bishop Celestine, Pope of Rome, for the

instruction of the Irish; which Celestine was the forty-second

bishop of the apostolic see of the city of Rome after

Peter. Palladius the Bishop was the first sent, who is

otherwise called Patricius, and suffered martyrdom among

the Scots, as the ancient saints relate. Then the second

Patricius was sent by an angel of God, named Victor, and

by Pope Celestine, by whose means all Ireland believed,

and who baptized almost all the inhabitants.’[27] This account

of his mission also appears in all the Irish Annals, and is

16apparently taken from the older chronicle of Marianus

Scotus, who died in the year 1084, and who gives it thus:—‘In

the eighth year of Theodosius, Bassus and Antiochus

being consuls, Palladius, being ordained by Pope Celestine,

was sent as first bishop to the Scots believing in Christ.

After him St. Patricius, a Briton by birth, was consecrated

by St. Celestine the Pope, and sent to the archiepiscopate of

Ireland. There during sixty years, preaching with signs and

miracles, he converted the whole island of Ireland to the

faith.’[28] As Pope Celestine died in July 432, this supposed

mission of Patrick must have taken place within a year at

least of that of Palladius; and while Probus records the

latter alone, without any hint of its sudden termination, we

are asked to believe that it had proved at once unsuccessful,

and that Palladius having either suffered martyrdom or died

within the year, a second mission, headed by Patrick, was sent

either directly by or during the life of Pope Celestine. If

this be so, if it be true that the mission of Palladius effected

nothing and came to an end either by his martyrdom or

flight within a year, and that Patrick’s mission, which

succeeded it, was followed by the conversion of the whole

island, it seems strange that nothing should have been known

on the Continent at the time of this great event, and that it

should be noticed by no contemporary author. Not a single

writer prior to the eighth century mentions it; and even

Bede, who quotes the passage in Probus recording the

mission of Palladius, and mentions those of Ninian and

Columba, is silent as to that of Patrick. Columbanus, and

the other missionaries from Ireland who followed him, seem

to have told their foreign disciples nothing about him, and

in the writings of the former which have been preserved,—in

his letters to the Popes and the Gaulish clergy, and in

his sermons to his monks,—the name of Patrick, the great

founder of his church, never appears. We should be

17tempted to conclude, as many have done, that the account

of Patrick and of his mission was entirely mythical, and that

neither the one nor the other had any real existence, were

it not that, when we turn to the writings of two of the contemporaries

of Columbanus at home, we do find an occasional

mention of Patrick at a sufficiently early date to leave no

reasonable doubt of his existence, and that two documents

are attributed to him which may fairly be accepted as

genuine. The oldest authentic notice of Patrick occurs in a

letter which is still extant, written by Cummian to Segienus,

abbot of Iona, in the year 634, regarding the proper time for

keeping Easter. In it he refers to the cycle ‘introduced

into use by our pope, Saint Patricius;’[29] and Adamnan,

writing in the end of the seventh century, in the second

preface to his Life of Columba mentions ‘Maucta, a pilgrim

from Britain, a holy man, a disciple of Saint Patricius the

bishop.’[30] These early notices, though few in number, seem

sufficient to prove his existence; but if we are to receive

as genuine documents his Confession and the Epistle to

Coroticus, as undoubtedly we ought, they not only afford

conclusive evidence of his own existence and the reality of

his mission, but give us his own account of the leading

particulars of his life.[31] The information he gives us may

be shortly stated thus:—Patricius was born of Christian

parents and belonged to a Christian people; for he ‘was the

son of Calpornius a deacon, son of the late Potitus a presbyter,

who lived in the village of Bannavem of Tabernia, where he

had a small farm.’[32] He was of gentle birth, his father

being also a ‘decurio,’ that is, one of the council or magistracy

18of a Roman provincial town.[33] He lived at this little farm

when, in his sixteenth year, he was taken captive and brought

to Hibernia or Ireland with many thousands; and he adds,

‘as we deserved, for we had forsaken God, and had not kept

his commandments, and were disobedient to our priests, who

admonished us for our salvation.’ He remained six years in

slavery in Ireland, where he was employed tending sheep;

and then he escaped in a ship, the sailors of which were

pagans, and after three days reached land, and for twenty-eight

days journeyed through a desert. He was again taken

captive, and remained two months with these people, when

on the sixtieth night he was delivered from their hands. A

few years after he was with his parents, or relations, in the

Roman province of Britain,[34] when he resolved, in consequence

of a vision, to leave his native country and his

kindred, and go to Ireland as a missionary to preach the

gospel, which, he says, he was able to accomplish after

several years.

Saint Patrick’s narrative of his early life conveys the

impression that he was a simple youth, of an earnest and

enthusiastic temperament, who, in the solitude of his

captivity in Ireland, had communed with his own spirit and

been brought under a deep sense of religion; and, when

again restored to his native country and his home, had

brooded over the desire which strong religious conviction

creates in many a youth to devote himself to missionary

labour, till he became persuaded that he had received a

divine call. If he was taken captive in his sixteenth year

and remained six years in captivity, he was twenty-two

when he escaped, and was probably now between twenty-five

and thirty years old. He had early been made

19a deacon,[35] and must at this time have gone to Ireland

probably in priest’s orders; for he tells us that he had

lived and preached among the Irish from his youth up,

and given the faith to the people among whom he dwelt.[36]

At the age of forty-five he was consecrated a bishop,

and in his epistle to Coroticus he designates himself

‘Patricius, a sinner and unlearned, but appointed a bishop

in Ireland.’[37]

It is clear from Patrick’s own account of himself that he

was a citizen of the Roman province in Britain;[38] that his

family had been Christian for at least two generations, and

belonged to the aristocracy of a Roman provincial town, and

that the district of Tabernia, in which it was situated, was

exposed to the incursions of the Scots; that he had laboured

among the Irish as a missionary for at least fifteen, if not

twenty, years before he was consecrated a bishop, and it was

only latterly that his labours were crowned with much

success. His Confession appears to have been written

towards the end of his life, as he concludes it by saying that

it was written in Ireland, and that this was his confession

20before he died;[39] and his epistle was written to Coroticus

while the Franks were still pagan—that is, before their

conversion in the year 496. In his Confession he tells us

that through his ministry clerics had been ordained for this

people newly come to the faith, and that in Hiberio or

Ireland ‘those who never had the knowledge of God, and

had hitherto only worshipped unclean idols, have lately

become the people of the Lord, and are called the sons of

God. The sons of the Scoti and the daughters of princes

are seen to be monks and virgins of Christ.’[40] In the

epistle to Coroticus he addresses his ‘beloved brethren and

children whom he had begotten in such numbers to Christ.’[41]

It is, however, remarkable that he does not in either document

make the slightest allusion to Palladius or his mission,

and this leads certainly to the inference that it had failed

and had never become an efficient and operative episcopal

mission in the country. Patrick’s episcopate must certainly

have followed that of Palladius, and that possibly at no

great distance of time; and if he was then forty-five years

of age, this would throw his sixteenth year, when he was

taken captive, to the first decade of the century, when the

Roman province was exposed to the incursions of the Scots,

and thus he must have himself already laboured as a missionary

among the Irish people, to whom Palladius was sent

as their first bishop.

Such is the account which Patrick gives of himself inhimself in

these documents, which we accept as undoubtedly genuine;

and we shall see how, at a later period, this simple narrative

21became incrusted with a mass of traditional, legendary, and

fictitious matter, which had gradually accumulated in the

minds of the people, and was brought into shape and added

from time to time to the story of Saint Patrick’s life and

labours by each successive biographer.

Patrick states in his Confession simply that he ordained

clerics, but we are told in the Catalogue of the Saints that

‘they were all bishops, famous and holy, and full of the Holy

Ghost, 350 in number, founders of churches;’ and this is

confirmed by Angus the Culdee, in his Litany, where he invokes

‘seven times fifty holy bishops, with three hundred

priests, whom Patraic ordained,’ and quotes the verse—

‘Seven times fifty holy cleric bishops

[42]The saint ordained,

With three hundred pure presbyters

[43]Upon whom he conferred orders.’

Upwards of one half of his clergy seem, therefore, to

have been bishops, and he appears to have placed a bishop,

consecrated by himself, in each church which he founded.

The difference in order between bishop and presbyter is here

fully recognised; and there was nothing in this very inconsistent

with the state of the primitive church before it

became a territorial church, and its hierarchical arrangements

and jurisdiction were adapted to and modelled upon the

civil government of the Roman empire.[44] In the earlier period

of the Christian Church there was, besides the chief bishop

in each city, whose consecration required the action of at least

three bishops, an order of ‘Chorepiscopi,’ or country bishops,[45]

22who were consecrated by the chief bishop; and the relative

proportion of bishops and presbyters was very different from

what it afterwards became. We find in the Apostolical

Constitutions in the ordinances of the church of Alexandria

that ‘if there should be a place having a few faithful men in

it, before the multitude increase, who shall be able to make

a dedication to pious uses for the bishop to the extent of

twelve men, let them write to the churches round about the

place, in which the multitude of believers are established.

If the bishop whom they shall appoint hath attended to the

knowledge and patience of the love of God, with those with

him, let him ordain two presbyters when he hath examined

them, or rather three;’[46] and we are told that in Asia Minor

alone there were upwards of four hundred bishops.[47] Such

a church as this could not have been very unlike the Irish

Church at this period—the relative proportion of bishops

and presbyters much the same; and Patrick seems to have

adapted it to the state of society among the people who were

the objects of his mission. Their social system was one based

upon the tribe, and it consisted of a congeries of small septs

united together by no very close tie. Anything like a territorial

church, with a central jurisdiction, was hardly possible

among them. Patrick tells us nothing of the mode in which

he was consecrated a bishop; but the expression in his

epistle to Coroticus, that he was constituted the bishop in

Ireland, seems to imply that he regarded himself as chief

bishop for the whole people. He founded churches wherever

he could obtain a grant from the chief of the sept, and appears

to have placed in each Tuath or tribe a bishop, ordained by

himself, who may have had one or more presbyters with him.

It was, in short, a congregational and tribal episcopacy, united

by a federal rather than a territorial tie under regular

jurisdiction; and this is implied by the statement that ‘what

23was excommunicated by one church was excommunicated by

all.’ During Patrick’s life, he no doubt exercised a superintendence

over the whole; but we do not see any trace of

the metropolitan jurisdiction of the church of Armagh over

the rest.

‘All these bishops,’ we are told in the Catalogue of the

Saints, ‘were sprung from the Romans, and Franks, and

Britons, and Scots.’ By the Romans and Britons probably

those are meant who belonged to the Roman province in

Britain, and followed Patrick in his mission; by the Franks

those who came from Gaul appear to be intended; and

whenever it was possible, he no doubt appointed a native

Scot, and one of the tribe among whom he founded a

church, to be its bishop. The extent to which the foreign

element entered into the clergy of his church may be

learnt from the Litany of Angus, who invokes ‘the Romans

in Achudh Galma, in Hy Echach; the Romans in Letar

Erca; the Romans and Cairsech, daughter of Brocan, in

Cill Achudh Dallrach; Cuan, a Roman, in Achill; the

Romans in Cluan Caincumni; and the Romans with

Aedan in Cluan Dartada; the Gauls in Saillidu; the Gauls

in Magh Salach; and the Gauls in Achudh Ginain; the

Saxons in Rigar; and the Saxons in Cluan Muicceda;

fifty men of the Britons with Monan, in Lann Leire.’

And, in another tract by Angus the Culdee on the Mothers

of the Saints, he has, ‘Dina, daughter of the king of the

Saxons, was the mother of the ten sons of Bracan, king of

Britain, son of Bracha Meoc: viz. St. Mogoroc of Struthuir;

St. Mochonoc, the pilgrim of Kil Mucraisse and of Gelinnia in

the region of Delbhna Eathra; Dirad of Eadardr uim; Duban

of Rinndubhain alithir; Carenn of Killchairinne; Carpre,

the pilgrim of Killchairpre; Isiol Farannain; Iust in Slemna

of Alban; Elloc of Kill Moelloc, near Lochgarman; Pian

of Killphiain in Ossory; Coeman, the pilgrim of Kill Choeman,

in the region of Gesille and elsewhere. She was also

24mother of Mobeoc of Gleanngeirg, for he was a son of

Brachan, son of Bracha Meoc.’[48]

The first order, too, ‘rejected not the services and society

of women,’ or, according to another MS., ‘they excluded from

their churches neither laymen nor women,’ which indicates

their character as secular clergy, in contradistinction to those

under a monastic rule. ‘They celebrated Easter on the fourteenth

moon after the vernal equinox,’ that is, as we have seen

elsewhere, from the fourteenth to the twenty-first day of the

moon; and there appears to have been no difference in this

respect between them and the Church of Rome prior to the

year 457. Their clergy were tonsured; but at this time there

were in the Church various forms of tonsure, and the first form,

‘from ear to ear,’ that is, having the hair removed from the

fore part of the head and leaving it to grow behind the ears, was

also practised in Gaul, from whence it was probably derived.[49]

Although Patrick alludes to the great numbers he converted,

there does not seem to have been anything like a

national adoption of Christianity. It is remarkable enough

that the Ardri or chief king of Ireland appears to have remained

pagan during the entire period of his mission, and it

was not till the year 513 that a Christian monarch ruled in

Tara. Neither did the arrangement by which isolated bishops

were placed in each sept or tribe whose chief or petty king

had been converted prove well calculated to disseminate

Christianity through the whole tribe, and to leaven the entire

people with its influence.

Collegiate Churches of Seven Bishops.

This appears to have led, towards the end of his life, to

the adoption of a very peculiar sort of Collegiate Church.

It consisted in a group of seven bishops placed together in

one church; and they were brought closer to the tribal

25system based on the family which prevailed in Ireland, by

these bishops being usually seven brothers selected from one

family in the tribe. We see the germs of something of the

kind in Tirechan’s Annotations, where it is said that towards

the end of his career ‘Patrick passed the Shannon three times,

and completed seven years in the western quarter, and came

from the plain of Tochuir to Dulo Ocheni, and founded seven

churches there.’ And again, ‘The seven sons of Doath—that

is Cluain, Findglais and Imsruth, Culcais, Deruthmar,

Culcais and Cennlocho—faithfully made offerings to God and

Saint Patrick.’[50] But Angus the Culdee in his Litany gives

us a list of no fewer than one hundred and fifty-three groups

of seven bishops in the same church, all of whom he invokes.

A few of these we can identify sufficiently to show that they

usually consisted of seven brothers living together in one

church, and that they belong to this period. For instance,

he invokes ‘the seven bishops of Tulach na’n Epscop,’ or

Tulach of the Bishops; and we find in the old Irish Life of

St. Bridget, who died in 525, that on one occasion at Tealagh,

in the west of Leinster, ‘pious nobles, i.e. seven bishops, were

her guests.’[51] Again he invokes ‘the seven bishops of Drom

Arbelaig;’ and in the Irish Calendar on 15th January we

have ‘seven bishops, sons of Finn, alias Fincrettan of Druimairbealagh.’

Again he invokes ‘the seven bishops in

Tamhnach;’ and in the Calendars on 21st July we have this

notice: ‘The seven bishops of Tamhnach Buadha, and we find

seven bishops, the sons of one father, and their names and

history among the race of Fiacha Suighdhe, son of Feidhlimidh

Reachtmhar, son of Tuathal Teachtmhar.’ Again he

invokes ‘the seven bishops of Cluan Emain;’ and we are

told in the Life of Saint Forannan that, after the Council of

Drumceatt Columba was met by a large concourse of

ecclesiastics, among whom the descendants of Cennaine, the

26aunt of St. Bridget, are alone enumerated, and among these

are ‘the seven bishops of Cluain-Hemain,’ now Clonown, near

Athlone, and they are represented in the Genealogy of the

Saints in the Book of Lecan as seven brethren, the sons of

the same mother.[52] Such appear to be in the main the

characteristics of the early Irish Church in this the first period

of its history; and we must now turn to Scotland to see to

what extent they are reflected there.

Church of the southern Picts.

The dark interval of a century between the death of

Ninian and the coming of Columba when we find ourselves

treading on firm ground, is thus filled up by Fordun:—

‘In A.D. 430 Pope Celestinus sent Saint Palladius into

Scotia, as the first bishop therein. It is therefore fitting that

the Scots should diligently keep his festival and church commemorations,

for by his word and example he with anxious

care taught their nation—that of the Scots to wit—the

orthodox faith, although they had for a long time previously

believed in Christ. Before his arrival, the Scots had, as

teachers of the faith and administrators of the Sacraments,

priests only or monks, following the rite of the primitive

church. So he arrived in Scotland with a great company of

clergy in the eleventh year of the reign of King Eugenius,

and the king freely gave him a place of abode where he

wanted one. Moreover, Palladius had as his fellow-worker

in preaching and administering the Sacraments a most holy

man, Servanus; who was ordained bishop and created by

Palladius his coadjutor—one worthy of him in all respects—in

order to teach the people the orthodox faith, and with

anxious care perfect the work of the Gospel; for Palladius

was not equal to discharging alone the pastoral duties over

so great a nation.’ And again: ‘The holy bishop Terrananus

likewise was a disciple of the blessed Palladius, who was his

godfather and his fostering teacher and furtherer in all the

27rudiments of letters and of the faith.’[53] This statement has

been substantially accepted as history by all historians of

the Church in Scotland; but when we examine the grounds

on which it rests, we shall see reason to doubt whether

Palladius ever was in Scotland, and to place Servanus at a

much later period. Terrananus alone appears to have any

real claim to belong to this period.

The only real information we possess as to the acts of

Palladius, in addition to the short notice of his mission given

us by the contemporary chronicler Prosper of Aquitaine, is

derived from the Lives of St. Patrick; and we shall see how

this statement of Palladius’ missionary labours in Scotland

grew out of these lives, combined with the fictitious character

of the early history of Scotland as it is represented by Fordun.

The oldest Lives of Patrick are those in the Book of Armagh;

and Tirechan, whose annotations contain our first notices of

his life, states that Palladius ‘suffered martyrdom among

the Scots’—that is, the Irish—‘as the ancient saints relate.’[54]

Muirchu, whose Life was compiled soon after, says, after

narrating his mission to Ireland, ‘Neither did those rude and

savage people readily receive his doctrine, nor did he wish

to pass his time in a land not his own; but returning hence

to him who sent him, having begun his passage the first

tide, little of his journey being accomplished, he died in the

territory of the Britons.’Britons.’[55] The next notice we have of him

is in the Life attributed to Mark the Anchorite which belongs

to the beginning of the ninth century, and is added to the

Historia Britonum of Nennius. Here Palladius is not allowed

to land in Ireland at all, ‘but tempests and signs from God

prevented his landing, for no one can receive anything on

earth except it be given him from above. Returning, therefore,

28from Ireland to Britain, Palladius died in the land of the

Picts.’[56] Probus, who had the Book of Armagh before him,

and embodies many passages of Muirchu’s Life in his own

narrative, repeats his account of Palladius, but substitutes

for the expression ‘in the territory of the Britons’ that of ‘in

the territory of the Picts.’[57] The Life termed by Colgan the

third follows that of Muirchu, and states that ‘he returned

to go to Rome, and died in the region of the Britons.’[58]

Another Life makes Palladius land in Ireland and found

three churches there; but ‘seeing that he could not do much

good there, wishing to return to Rome, he migrated to the

Lord in the region of the Picts. Others, however, say that

he was crowned with martyrdom in Ireland,’[59] alluding in

the latter part to the statement of Tirechan. The Tripartite