July the 1st. 1749.

At day break we got up, and rowed a good while before we got to the place where we

left the true road. The country which we passed was the poorest and most disagreeable

imaginable. We saw nothing but a row of amazing high mountains covered with woods,

steep and dirty on their sides; so that we found it difficult to get to a dry place,

in order to land and boil our dinner. In many places the ground, which was very smooth,

was under water, and looked like the sides of our Swedish morasses which are intended to be drained; for this reason the Dutch in Albany call these parts the Drowned Lands.1 Some of [2]the mountains run from S. S. W. to N. N. E. and when they come to the river, they

form perpendicular shores, and are full of stones of different magnitudes. The river

runs for the distance of some miles together from south to north.

The wind blew north all day, and made it very hard work for us to get forwards, though

we all rowed as hard as we could, for our provisions were eaten to-day at breakfast.

The river was frequently an English mile and more broad, then it became narrow again, and so on alternately; but upon

the whole it kept a good breadth, and was surrounded on both sides by high mountains.

About six o’clock in the evening, we arrived at a point of land, about twelve English miles from Fort St. Frederic. Behind this point the river is converted into a spacious bay; and as the wind still

kept blowing pretty strong from the north, it was impossible for us to get forwards,

since we were extremely weak. We were therefore obliged to pass the night here, in

spite of the remonstrances of our hungry stomachs.

It is to be attributed to the peculiar grace of God towards us that we met the above

mentioned Frenchmen on our journey, [3]and that they gave us leave to take one of their bark boats. It seldom happens once

in three years, that the French go this road to Albany; for they commonly pass over the lake St. Sacrement, or, as the English call it, lake George, which is the nearer and better road, and every body wondered why they took this

troublesome one. If we had not got their large strong boat, and been obliged to keep

that which we had made, we would in all probability have been very ill off; for to

venture upon the great bay during the least wind with so wretched a vessel, would

have been a great piece of temerity, and we should have been in danger of being starved

if we had waited for a calm. For being without fire-arms, and these deserts having

but few quadrupeds, we must have subsisted upon frogs and snakes, which, (especially

the latter) abound in these parts. I can never think of this journey, without reverently

acknowledging the peculiar care and providence of the merciful Creator.

July the 2d. Early this morning we set out on our journey again, it being moonshine and

calm, and we feared lest the wind should change and become unfavourable to us if we

stopped any longer. We all rowed as hard as possible, and happily arrived about eight

in the morning at Fort [4]St. Frederic, which the English call Crown Point. Monsieur Lusignan, the governor, received us very politely. He was about fifty years old, well acquainted

with polite literature, and had made several journies into this country, by which

he had acquired an exact knowledge of several things relative to its state.

I was informed that during the whole of this summer, a continual drought had been

here, and that they had not had any rain since last spring. The excessive heat had

retarded the growth of plants; and on all dry hills the grass, and a vast number of

plants, were quite dried up; the small trees, which grew near rocks, heated by the

sun, had withered leaves, and the corn in the fields bore a very wretched aspect.

The wheat had not yet eared, nor were the pease in blossoms. The ground was full of

wide and deep cracks, in which the little snakes retired and hid themselves when pursued,

as into an impregnable asylum.

The country hereabout, it is said, contains vast forests of firs of the white, black,

and red kind, which had been formerly still more extensive. One of the chief reasons

of their decrease are, the numerous fires which happen every year in the woods, through

the carelessness of the Indians, who frequently [5]make great fires when they are hunting, which spread over the fir woods when every

thing is dry.

Great efforts are made here for the advancement of Natural History, and there are few places in the world where such good regulations are made for this

useful purpose, all which is chiefly owing to the care and zeal of a single person.

From hence it appears, how well a useful science is received and set off, when the

leading men of a country are its patrons. The governor of the fort, was pleased to

shew me a long paper, which the then governor-general of Canada, the Marquis la Galissonniere had sent him. It was the same marquis, who some years after, as a French admiral, engaged the English fleet under admiral Byng, the consequence of which was the conquest of Minorca. In this writing, a number of trees and plants are mentioned, which grow in North-America, and deserve to be collected and cultivated on account of their useful qualities.

Some of them are described, among which, is the Polygala Senega, or Rattle Snake-root; and with several of them the places where they grow are mentioned. It is further

requested that all kinds of seeds and roots be gathered here; and, to assist such

an undertaking, a method of preserving [6]the gathered seeds and roots, is prescribed, so that they may grow, and be sent to

Paris. Specimens of all kinds of minerals are required; and all the places in the French settlements are mentioned, where any useful or remarkable stone, earth, or ore has

been found. There is likewise a manner of making observations and collections of curiosities

in the animal kingdom. To these requests it is added, to enquire and get information,

in every possible manner, to what purpose and in what manner the Indians employ certain plants and other productions of nature, as medicines, or in any other

case. This useful paper was drawn up by order of the marquis la Galissonniere, by Mr. Gaulthier, the royal physician at Quebec, and afterwards corrected and improved by the marquis’s own hand. He had several

copies made of it, which he sent to all the officers in the forts, and likewise to

other learned men who travelled in the country. At the end of the writing is an injunction

to the officers, to let the governor-general know, which of the common soldiers had

used the greatest diligence in the discovery and collection of plants and other natural

curiosities, that he might be able to promote them, when an opportunity occurred,

to places adapted [7]to their respective capacities, or to reward them in any other manner. I found that

the people of distinction, in general here, had a much greater taste for natural history

and other parts of literature, than in the English colonies, where it was every body’s sole care and employment to scrape a fortune

together, and where the sciences were held in universal contempt.2 It was still [8]complained of here, that those who studied natural history, did not sufficiently enquire

into the medicinal use of the plants of Canada.

The French, who are born in France, are said to enjoy a better health in Canada than in their native country, and to attain to a greater age, than the French born in Canada. I was likewise assured that the European Frenchmen can do more work, and perform more journies in winter, without prejudice to their

health, than those born in this country. The intermitting fever which attacks the

Europeans on their arrival in Pensylvania, and which as it were makes the climate familiar to them,3 is not known here, and the people are as well after their arrival as before. The

English have frequently observed, that those who are born in America of European parents, can never bear sea-voyages, and go to the different parts of South America, as well as those born in Europe. The French born in Canada have the same constitutions; and when any of them go to the West-India islands, such as Martinique, Domingo, &c. and make some stay there, they commonly fall sick and die soon after: those

[9]who fall ill there seldom recover, unless they are brought back to Canada. On the contrary, those who go from France to those islands can more easily bear the climate, and attain a great age there,

which I heard confirmed in many parts of Canada.

July the 5th. Whilst we were at dinner, we several times heard a repeated disagreeable

outcry, at some distance from the fort, in the river Woodcreek: Mr. Lusignan, the governor, told us this cry was no good omen, because he could conclude from

it that the Indians, whom we escaped near fort Anne, had completed their design of revenging the death of one of their brethren upon

the English, and that their shouts shewed that they had killed an Englishman. As soon as I came to the window, I saw their boat, with a long pole at one end,

on the extremity of which they had put a bloody skull. As soon as they were landed,

we heard that they, being six in number, had continued their journey (from the place

where we had marks of their passing the night), till they had got within the English boundaries, where they found a man and his son employed in mowing the corn. They

crept on towards this man, and shot him dead upon the spot. This happened near the

very village, where the English, two years [10]before, killed the brother of one of these Indians, who were then gone out to attack them. According to their custom they cut off the

skull of the dead man, and took it with them, together with his clothes and his son,

who was about nine years old. As soon as they came within a mile of fort St. Frederic, they put the skull on a pole, in the fore part of the boat, and shouted, as a sign

of their success. They were dressed in shirts, as usual, but some of them had put

on the dead man’s clothes; one his coat, the other his breeches, another his hat,

&c. Their faces were painted with vermillion, with which their shirts were marked

across the shoulders. Most of them had great rings in their ears, which seemed to

be a great inconvenience to them, as they were obliged to hold them when they leaped,

or did any thing which required a violent motion. Some of them had girdles of the

skins of Rattle-snakes, with the rattles on them; the son of the murdered man had nothing but his shirt,

breeches and cap, and the Indians had marked his shoulders with red. When they got on shore, they took hold of the

pole on which the skull was put, and danced and sung at the same time. Their view

in taking the boy, was to carry him to [11]their habitations, to educate him instead of their dead brother, and afterwards to

marry him to one of their relations. Notwithstanding they had perpetrated this act

of violence in time of peace, contrary to the command of the governor in Montreal, and to the advice of the governor of St. Frederic, yet the latter could not at present deny them provisions, and whatever they wanted

for their journey, because he did not think it adviseable to exasperate them; but

when they came to Montreal, the governor called them to account for this action, and took the boy from them,

whom he afterwards sent to his relations: Mr. Lusignan asked them, what they would have done to me and my companions, if they had met us

in the desert? They replied, that as it was their chief intention to take their revenge

on the Englishmen in the village where their brother was killed, they would have let us alone; but

it much depended on the humour they were in, just at the time when we first came to

their sight. However, the commander and all the Frenchmen said, that what had happened to me was infinitely safer and better.

Some years ago a skeleton of an amazing great animal had been found in that part of

[12]Canada, where the Illinois live. One of the lieutenants in the fort assured me, that he had seen it. The Indians, who were there, had found it in a swamp. They were surprised at the sight of it,

and when they were asked, what they thought it was? They answered that it must be

the skeleton of the chief or father of all the beavers. It was of a prodigious bulk,

and had thick white teeth, about ten inches long. It was looked upon as the skeleton

of an elephant. The lieutenant assured me that the figure of the whole snout was yet

to be seen, though it was half mouldered. He added, that he had not observed, that

any of the bones were taken away, but thought the skeleton lay quite perfect there.

I have heard people talk of this monstrous skeleton in several other parts of Canada4.

Bears are plentiful hereabouts, and they kept a young one, about three months old,

at the fort. He had perfectly the same shape, and qualities, as our common bears in

Europe, except the ears, which seemed to be longer in proportion, and the hairs which were

stiffer; his colour was deep [13]brown, almost black. He played and wrestled every day with one of the dogs. A vast

number of bear-skins are annually exported to France from Canada. The Indians prepare an oil from bear’s grease, with which in summer they daub their face, hands,

and all naked parts of their body, to secure them from the bite of the gnats. With

this oil they likewise frequently smear the body, when they are excessively cold,

tired with labour, hurt, and in other cases. They believe it softens the skin, and

makes the body pliant, and is very serviceable to old age.

The common Dandelion (Leontodon Taraxacum, Linn.) grows in abundance on the pastures and roads between the fields, and was now

in flower. In spring when the young leaves begin to come up, the French dig up the plants, take their roots5, wash them, cut them, and prepare them as a common sallad; but they have a bitter

taste. It is not usual here to make use of the leaves for eating.

July the 6th. The soldiers, which had been paid off after the war, had built houses round

the fort, on the grounds allotted [14]to them; but most of these habitations were no more than wretched cottages, no better

than those in the most wreched places of Sweden; with that difference, however, that their inhabitants here were rarely oppressed

by hunger, and could eat good and pure wheat bread. The huts which they had erected

consisted of boards, standing perpendicularly close to each other. The roofs were

of wood too. The crevices were stopped up with clay, to keep the room warm. The floor

was commonly clay, or a black limestone, which is common here. The hearth was built

of the same stone, except the place were the fire was to ly, which was made of grey

sandstones, which for the greatest part consist of particles of quartz. In some hearths,

the stones quite close to the fire-place were limestones; however, I was assured that

there was no danger of fire, especially if the stones, which were most exposed to

the heat, were of a large size. They had no glass in their windows.

July the 8th. The Galium tinctorium is called Tisavojaune rouge by the French throughout all Canada, and abounds in the woods round this place, growing in a moist but fine soil. The

roots of this plant are employed by the Indians in dying the quills of the American porcupines red, which they [15]put into several pieces of their work; and air, sun, or water seldom change this colour.

The French women in Canada sometimes dye their clothes red with these roots, which are but small, like those

of Galium luteum, or yellow bedstraw.

The horses are left out of doors during the winter, and find their food in the woods,

living upon nothing but dry plants, which are very abundant; however they do not fall

off by this food, but look very fine and plump in spring.

July the 9th. The skeleton of a whale was found some French miles from Quebec, and one French mile from the river St. Lawrence, in a place where no flowing water comes to at present. This skeleton has been of

a very considerable size, and the governor of the fort said, he had spoke with several

people who had seen it.

July the 10th. The boats which are here made use of, are of three kinds. 1. Bark-boats, made of the bark of trees, and of ribs of wood. 2. Canoes, consisting of a single piece of wood, hollowed out, which I have already described

before6. They are here made of the white fir, and of different sizes. They are not brought

[16]forward by rowing, but by paddling; by which method not half the strength can be applied;

which is made use of in rowing; and a single man might, I think, row as fast as two

of them could paddle. 3. The third kind of boats are Bateaux. They are always made very large here, and employed for large cargoes. They are flat

bottomed, and the bottom is made of the red, but more commonly of the white oak, which

resists better, when it runs against a stone, than other wood. The sides are made

of the white fir, because oak would make the Bateau too heavy. They make plenty of tar and pitch here.

The soldiery enjoy such advantages here, as they are not allowed in every part of

the world. Those who formed the garrison of this place, had a very plentiful allowance

from their government. They get everyday a pound and a half of wheat bread, which

is almost more than they can eat. They likewise get pease, bacon, and salt meat in

plenty. Sometimes they kill oxen and other cattle, the flesh of which is distributed

among the soldiers. All the officers kept cows, at the expence of the king, and the

milk they gave was more than sufficient to supply them. The soldiers had each a small

garden without the fort, which [17]they were allowed, to attend, and plant in it whatever they liked, and some of them

had built summer-houses in them, and planted all kind of pot-herbs. The governor told

me, that it was a general custom to allow the soldiers a spot of ground for kitchen-gardens,

at such of the French forts hereabouts as were not situated near great towns, from

whence they could be supplied with greens. In time of peace the soldiers have very

little trouble with being upon guard at the fort; and as the lake close by is full

of fish, and the woods abound with birds and animals, those amongst them who choose

to be diligent, may live extremely well, and very grand in regard to food. Each soldier

got a new coat every two years; but annually, a waistcoat, cap, hat, breeches, cravat,

two pair of stockings, two pair of shoes, and as much wood as he had occasion for

in winter. They likewise got five sols7 a piece every day; which is augmented to thirty sols when they have any particular

labour for the king. When this is considered, it is not surprising to find the men

are very fresh, well fed, strong and lively here. When a soldier falls sick he is

brought to the hospital, where the king [18]provides him with a bed, food, medicines, and people to take care of, and serve him.

When some of them asked leave to be absent for a day or two, to go abroad, it was

generally granted them, if circumstances would permit, and they enjoyed as usual their

share of provisions and money, but were obliged to get some of their comrades to mount

the guard for them as often as it came to their turns, for which they gave them an

equivalent. The governor and officers were duly honoured by the soldiers; however,

the soldiers and officers often spoke together as comrades, without any ceremonies,

and with a very becoming freedom. The soldiers who are sent hither from France, commonly serve till they are forty or fifty years old, after which they are dismissed

and allowed to settle upon, and cultivate a piece of ground. But if they have agreed

on their arrival to serve no longer than a certain number of years, they are dismissed

at the expiration of their term. Those who are born here, commonly agree to serve

the crown during six, eight, or ten years; after which they are dismissed, and set

up for farmers in the country. The king presents each dismissed soldier with a piece

of land, being commonly [19]40 arpens8 long and but three broad, if the soil be of equal goodness throughout; but they get

somewhat more, if it be a worse ground9. As soon as a soldier settles to cultivate such a piece of land, he is at first assisted

by the king, who supplies himself, his wife and children, with provisions, during

the three or four first years. The king likewise gives him a cow, and the most necessary

instruments for agriculture. Some soldiers are sent to assist him in building a house,

for which the king pays them. These are great helps to a poor man, who begins to keep

house, and it seems that in a country where the troops are so highly distinguished

by the royal favour, the king cannot be at a loss for soldiers. For the better cultivation

and population of Canada, a plan has been proposed some years ago, for sending 300 men over from France every year, by which means the [20]old soldiers may always be dismissed, marry, and settle in the country. The land which

was allotted to the soldiers about this place, was very good, consisting throughout

of a deep mould, mixed with clay.

July the 11th. The harrows which they make use of here are made entirely of wood, and

of a triangular form. The ploughs seemed to be less convenient. The wheels upon which

the plough-beam is placed, are as thick as the wheels of a cart, and all the wood-work

is so clumsily made that it requires a horse to draw the plough along a smooth field.

Rock-stones of different sorts lay scattered on the fields. Some were from three to

five feet high, and about three feet broad. They were pretty much alike in regard

to the kind of the stone, however, I observed three different species in them.

1. Some consisted of a quartz, whose colour resembled sugar candy, and which was mixed

with a black small grained glimmer, a black horn-stone, and a few minute grains of

a brown spar. The quartz was most abundant in the mixture; the glimmer was likewise

in great quantity, but the spar was inconsiderable. The several kinds of stones were

well mixed, and though the eye could distinguish them, yet no instrument [21]could separate them. The stone was very hard and compact, and the grains of quartz

looked very fine.

2. Some pieces consisted of grey particles of quartz, black glimmer, and horn-stone,

together with a few particles of spar, which made a very close, hard, and compact

mixture, only differing from the former in colour.

3. A few of the stones consisted of a mixture of white quartz and black glimmer, to

which some red grains of quartz were added. The spar (quartz) was most predominant

in this mixture, and the glimmer appeared in large flakes. This stone was not so well

mixed as the former, and was by far not so hard and so compact, being easily pounded.

The mountains on which fort St. Frederic is built, as likewise those on which the above kinds of stone are found, consisted

generally of a deep black lime-stone, lying in lamellæ as slates do, and it might

be called a kind of slates, which can be turned into quicklime by fire10. This lime-stone is quite black in the inside, and, when broken, appears to be of

an exceeding [22]fine texture. There are some grains of a dark spar scattered in it, which, together

with some other inequalities, form veins in it. The strata which ly uppermost in the

mountains consist of a grey lime-stone, which is seemingly no more than a variety

of the preceding. The black lime-stone is constantly found filled with petrefactions

of all kinds, and chiefly the following:

Pectinites, or petrefied Ostreæ Pectines. These petrefied shells were more abundant than any others that have been found here,

and sometimes whole strata are met with, consisting merely of a quantity of shells

of this sort, grown together. They are generally small, never exceeding an inch and

a half in length. They are found in two different states of petrefaction; one shews

always the impressions of the elevated and hollow surfaces of the shells, without

any vestige of the shells themselves. In the other appears the real shell sticking

in the stone, and by its light colour is easily distinguishable from the stone. Both

these kinds are plentiful in the stone; however, the impressions are more in number

than the real shells. Some of the shells are very elevated, especially in the middle,

where they form as it were a hump; others again [23]are depressed in the middle; but in most of them the outward surface is remarkably

elevated. The furrows always run longitudinally, or from the top, diverging to the

margin.

Petrefied Cornua Ammonis. These are likewise frequently found, but not equal to the former in number: like

the pectinitæ, they are found really petrefied, and in impressions; amongst them were some petrefied

snails. Some of these Cornua Ammonis were remarkably big, and I do not remember seeing their equals, for they measured

above two feet in diameter.

Different kinds of corals could be plainly seen in, and separated from, the stone

in which they lay. Some were white and ramose, or Lithophytes; others were starry corals, or Madrepores; the latter were rather scarce.

I must give the name of Stone-balls to a kind of stones foreign to me, which are found in great plenty in some of the

rock-stones. They were globular, one half of them projecting generally above the rock,

and the other remaining in it. They consist of nearly parallel fibres, which arise

from the bottom as from a center, and spread over the surface of the ball and have

a grey colour. The outside of the balls is smooth, [24]but has a number of small pores, which externally appear to be covered with a pale

grey crust. They are from an inch to an inch and a half in diameter.

Amongst some other kinds of sand, which are found on the shores of lake Champlain, two were very peculiar, and commonly lay in the same place; the one was black, and

the other reddish brown, or granite coloured.

The black sand always lies uppermost, consists of very fine grains, which, when examined

by a microscope, appear to have a dark blue colour, like that of a smooth iron, not

attacked by rust. Some grains are roundish, but most of them angular, with shining

surfaces; and they sparkle when the sun shines. All the grains of this sand without

exception are attracted by the magnet. Amongst these black or deep blue grains, they

meet with a few grains of a red or garnet coloured sand, which is the same with the

red sand which lies immediately under it, and which I shall now describe. This red

or garnet coloured sand is very fine, but not so fine as the black sand. Its grains

not only participate of the colour of garnets, but they are really nothing but pounded

garnets. Some grains are round, others angulated; all shine and [25]are semipellucid; but the magnet has no effect on them, and they do not sparkle so

much in sunshine. This red sand is seldom found very pure, it being commonly mixed

with a white sand, consisting of particles of quartz. The black and red sand is not

found in every part of the shore, but only in a few places, in the order before mentioned.

The uppermost or black sand lay about a quarter of an inch deep; when it was carefully

taken off, the sand under it became of a deeper red the deeper it lay, and its depth

was commonly greater than that of the former. When this was carefully taken away,

the white sand of quartz appeared mixed very much at top with the red sand, but growing

purer the deeper it lay. This white sand was above four inches deep, had round grains,

which made it entirely like a pearl sand. Below this was a pale grey angulated quartz

sand. In some places the garnet coloured sand lay uppermost, and this grey angulated

one immediately under it, without a grain of either the black or the white sand.

I cannot determine the origin of the black or steel-coloured sand, for it was not

known here whether there were iron mines in the neighbourhood or not. But I am rather

inclined to believe they may be found [26]in these parts, as they are common in different parts of Canada, and as this sand is found on the shores of almost all the lakes, and rivers in Canada, though not in equal quantities. The red or garnet coloured sand has its origin hereabouts;

for though the rocks near fort St. Frederic contained no garnets, yet there are stones of different sizes on the shores, quite

different from the stones which form those rocks; these stones are very full of grains

of garnets, and when pounded there is no perceptible difference between them and the

red sand. In the more northerly parts of Canada, or below Quebec, the mountains themselves contain a great number of garnets. The garnet-coloured

sand is very common on the shores of the river St. Lawrence. I shall leave out several observations which I made upon the minerals hereabouts,

as uninteresting to most of my readers.

The Apocynum androsæmifolium grows in abundance on hills covered with trees, and is in full flower about this

time; the French call it Herbe à la puce. When the stalk is cut or tore, a white milky juice comes out. The French attribute the same qualities to this plant, which the poison-tree, or Rhus vernix, has in the English colonies; that its poison is noxious to some [27]persons, and harmless to others. The milky juice, when spread upon the hands and body,

has no bad effect on some persons; whereas others cannot come near it without being

blistered. I saw a soldier whose hands were blistered all over, merely by plucking

the plant, in order to shew it me; and it is said its exhalations affect some people,

when they come within reach of them. It is generally allowed here, that the lactescent

juice of this plant, when spread on any part of the human body not only swells the

part, but frequently corrodes the skin; at least there are few examples of persons

on whom it had no effect. As for my part, it has never hurt me, though in presence

of several people I touched the plant, and rubbed my hands with the juice till they

were white all over; and I have often rubbed the plant in my hands till it was quite

crushed, without feeling the least inconvenience, or change on my hand. The cattle

never touch this plant.

July the 12th. Burdock, or Arctium Lappa, grows in several places about the fort; and the governor told me, that its tender

shoots are eaten in spring as raddishes, after the exterior peel is taken off.

The Sison Canadense abounds in the [28]woods of all North-America. The French call it cerfeuil sauvage, and make use of it in spring, in green soups, like chervil. It is universally praised

here as a wholesome, antiscorbutic plant, and as one of the best which can be had

here in spring.

The Asclepias Syriaca, or, as the French call it, le Cotonier, grows abundant in the country, on the sides of hills which ly near rivers and other

situations, as well in a dry and open place in the woods, as in a rich, loose soil.

When the stalk is cut or broken it emits a lactescent juice, and for this reason the

plant is reckoned in some degree poisonous. The French in Canada nevertheless use its tender shoots in spring, preparing them like asparagus; and

the use of them is not attended with any bad consequences, as the slender shoots have

not yet had time to suck up any thing poisonous. Its flowers are very odoriferous,

and, when in season, they fill the woods with their fragrant exhalations, and make

it agreeable to travel in them; especially in the evening. The French in Canada make a sugar of the flowers, which for that purpose are gathered in the morning,

when they are covered all over with dew. This dew is expressed, and by boiling yields

a very good brown, palatable [29]sugar. The pods of this plant when ripe contain a kind of wool, which encloses the

seed, and resembles cotton, from whence the plant has got its French name. The poor collect it, and fill their beds, especially their children’s, with

it instead of feathers. This plant flowers in Canada at the end of June and beginning of July, and the seeds are ripe in the middle of September. The horses never eat of this plant.

July the 16th. This morning I crossed lake Champlain to the high mountain on its western side, in order to examine the plants and other

curiosities there. From the top of the rocks, at a little distance from fort St. Frederic, a row of very high mountains appear on the western shore of lake Champlain, extending from south to north; and on the eastern side of this lake is another chain

of high mountains, running in the same direction. Those on the eastern side are not

close to the lake, being about ten or twelve miles from it; and the country between

it and them is low and flat, and covered with woods, which likewise clothe the mountains,

except in such places, as the fires, which destroy the forests here, have reached

them and burnt them down. These mountains have generally steep sides, but sometimes

they are found gradually [30]sloping. We crossed the lake in a canoe, which could only contain three persons, and

as soon as we landed we walked from the shore to the top of the mountains. Their sides

are very steep, and covered with a mould, and some great rock-stones lay on them.

All the mountains are covered with trees; but in some places the forests have been

destroyed by fire. After a great deal of trouble we reached the top of one of the

mountains, which was covered with a dusty mould. It was none of the highest; and some

of those which were at a greater distance were much higher, but we had no time to

go to them; for the wind encreased, and our boat was but a little one. We found no

curious plants, or any thing remarkable here.

When we returned to the shore we found the wind risen to such a height, that we did

not venture to cross the lake in our boat, and for that reason I left the fellow to

bring it back, as soon as the wind subsided, and walked round the bay, which was a

walk of about seven English miles. I was followed by my servant, and for want of a road, we kept close to the

shore where we passed over mountains and sharp stones; through thick forests and deep

marshes, all which were known to be inhabited by [31]numberless rattle-snakes, of which we happily saw none at all. The shore is very full

of stones in some places, and covered with large angulated rock-stones, which are

sometimes roundish, and their edges as it were worn off. Now and then we met with

a small sandy spot, covered with grey, but chiefly with the fine red sand which I

have before mentioned; and the black iron sand likewise occurred sometimes. We found

stones of a red glimmer of a fine texture, on the mountains. Sometimes these mountains

with the trees on them stood perpendicular with the water-side, but in some places

the shore was marshy.

I saw a number of petrefied Cornua Ammonis in one place, near the shore, among a number of stones and rocks. The rocks consist

of a grey limestone, which is a variety of the black one, and lies in strata, as that

does. Some of them contain a number of petrefactions, with and without shells; and

in one place we found prodigious large Cornua Ammonis, about twenty inches in breadth. In some places the water had wore off the stone,

but could not have the same effect on the petrefactions, which lay elevated above,

and in a manner glued on the stones.

[32]

The mountains near the shore are amazingly high and large, consisting of a compact

grey rock-stone, which does not ly in strata as the lime-stone, and the chief of whose

constituent parts are a grey quartz, and a dark glimmer. This rock-stone reached down

to the water, in places where the mountains flood close to the shore; but where they

were at some distance from it, they were supplied by strata of grey and black lime-stone,

which reached to the water side, and which I never have seen covered with the grey

rocks.

The Zizania aquatica grows in mud, and in the most rapid parts of brooks, and is in full bloom about this

time.

July the 17th. The distempers which rage among the Indians are rheumatisms and pleurisies, which arise from their being obliged frequently to ly in moist parts of the woods

at night; from the sudden changes of heat and cold, to which the air is exposed here;

and from their being frequently loaded with too great a quantity of strong liquor,

in which case they commonly ly down naked in the open air, without any regard to the

season, or the weather. These distempers, especially the pleurisies, are likewise

very common among the French here; and the governor told me [33]he had once had a very violent fit of the latter, and that Dr. Sarrasin had cured him in the following manner, which has been found to succeed best here.

He gave him sudorifics, which were to operate between eight and ten hours; he was

then bled, and the sudorifics repeated; he was bled again, and that effectually cured

him.

Dr. Sarrasin was the royal physician at Quebec, and a correspondent of the royal academy of sciences at Paris. He was possessed of great knowledge in the practice of physic, anatomy, and other

sciences, and very agreeable in his behaviour. He died at Quebec, of a malignant fever, which had been brought to that place by a ship, and with which

he was infected at an hospital, where he visited the sick. He left a son, who likewise

studied physic, and went to France to make himself more perfect in the practical part of it, but he died there.

The intermitting fevers sometimes come amongst the people here, and the venereal disease

is common here. The Indians are likewise infected with it; and many of them have had it, and some still have

it; but they likewise are perfectly possessed of the art of curing it. There are examples

of Frenchmen and Indians, infected all over the body with this disease, who have been radically [34]and perfectly cured by the Indians, within five or six months. The French have not been able to find this remedy out; though they know that the Indians employ no mercury, but that their chief remedies are roots, which are unknown to

the French. I have afterwards heard what these plants were, and given an account of them at

large to the royal Swedish academy of sciences11.

We are very well acquainted in Sweden with the pain caused by the Tæniæ, or a kind of worms. They are less abundant in the British North-American colonies; but in Canada they are very frequent. Some of these worms, which have been evacuated by a person,

have been several yards long. It is not known, whether the Indians are afflicted with them, or not. No particular remedies against them are known here,

and no one can give an account from whence they come, though the eating of some fruits

contributes, as is conjectured, to create them.

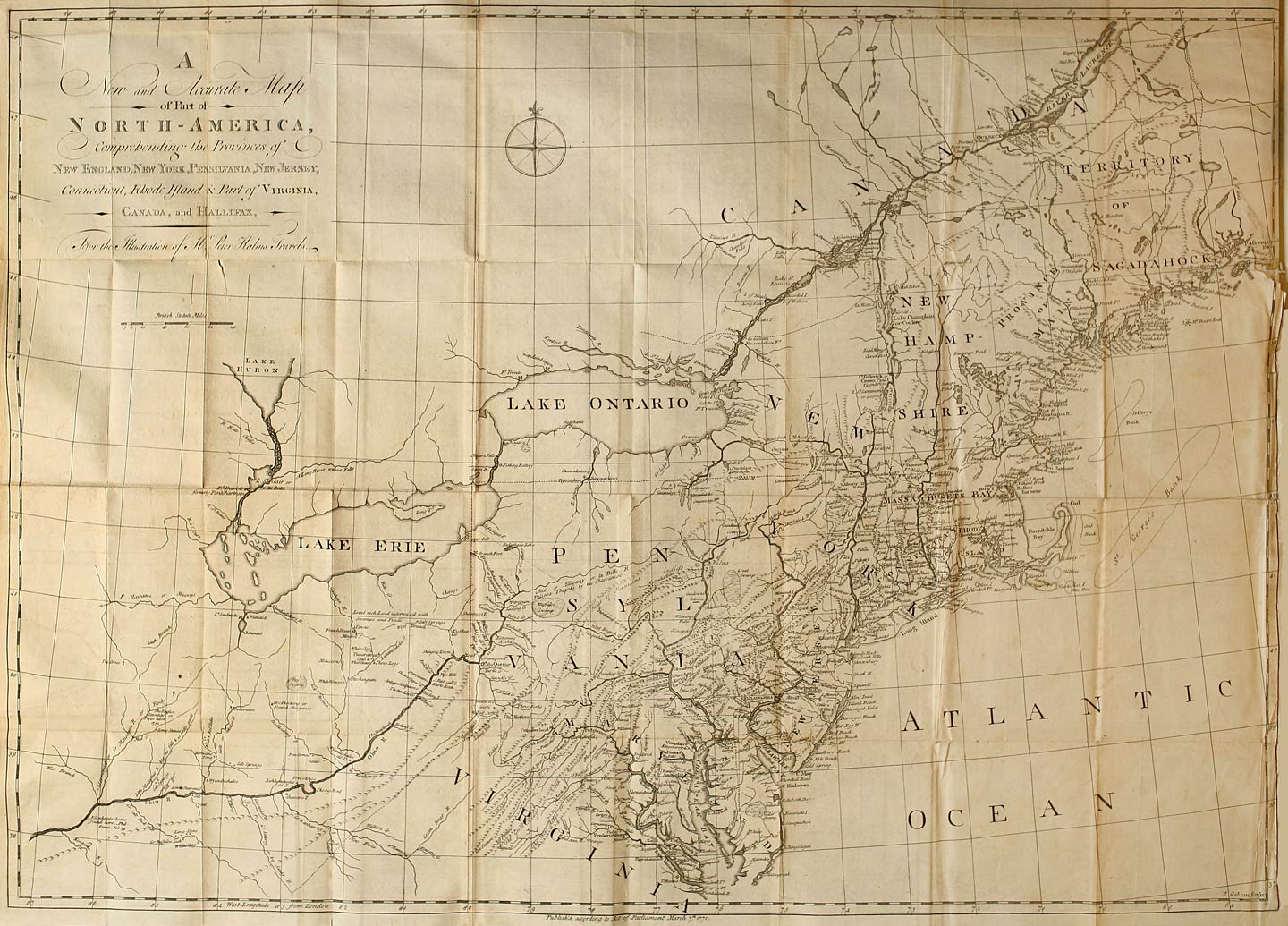

July the 19th. Fort St. Frederic is a fortification, on the southern extremity of lake Champlain, situated on a neck of land, between that lake and the river, which arises [35]from the union of the river Woodcreek, and lake St. Sacrement. The breadth of this river is here about a good musket shot. The English call this fortress Crownpoint, but its French name is derived from the French secretary of state, Frederic Maurepas, in whose hands the direction and management of the French court of admiralty was, at the time of the erection of this fort: for it is to be

observed, that the government of Canada is subject to the court of admiralty in France, and the governor-general is always chosen out of that court. As most of the places

in Canada bear the names of saints, custom has made it necessary to prefix the word Saint to the name of the fortress. The fort is built on a rock, consisting of black lime-slates,

as aforesaid; it is nearly quadrangular, has high and thick walls, made of the same

lime-stone, of which there is a quarry about half a mile from the fort. On the eastern

part of the fort, is a high tower, which is proof against bombshells, provided with

very thick and substantial walls, and well stored with cannon, from the bottom almost

to the very top; and the governor lives in the tower. In the terre-plein of the fort

is a well built little church, and houses of stone for the officers and soldiers.

There are sharp rocks [36]on all sides towards the land, beyond a cannon-shot from the fort, but among them

are some which are as high as the walls of the fort, and very near them.

The soil about fort St. Frederic is said to be very fertile, on both sides of the river; and before the last war a

great many French families, especially old soldiers, have settled there; but the king obliged them

to go into Canada, or to settle close to the fort, and to ly in it at night. A great number of them

returned at this time, and it was thought that about forty or fifty families would

go to settle here this autumn. Within one or two musket-shots to the east of the fort,

is a wind-mill, built of stone with very thick walls, and most of the flour which

is wanted to supply the fort is ground here. This wind-mill is so contrived, as to

serve the purpose of a redoubt, and at the top of it are five or six small pieces

of cannon. During the last war, there was a number of soldiers quartered in this mill,

because they could from thence look a great way up the river, and observe whether

the English boats approached; which could not be done from the fort itself, and which was a matter

of great consequence, as the English might (if this guard had not been placed here) have gone in their little [37]boats close under the western shore of the river, and then the hills would have prevented

their being seen from the fort. Therefore the fort ought to have been built on the

spot where the mill stands, and all those who come to see it, are immediately struck

with the absurdity of its situation. If it had been erected in the place of the mill,

it would have commanded the river, and prevented the approach of the enemy; and a

small ditch cut through the loose limestone, from the river (which comes out of the

lake St. Sacrement) to lake Champlain, would have surrounded the fort with flowing water, because it would have been situated

on the extremity of the neck of land. In that case the fort would always have been

sufficiently supplied with fresh water, and at a distance from the high rocks, which

surround it in its present situation. We prepared to-day to leave this place, having

waited during some days for the arrival of the yacht, which plies constantly all summer

between the forts St. John12 and St. Frederic: during our stay here, we had received many favours. The governor of the fort, Mr.

Lusignan, a man of learning and of great [38]politeness, heaped obligations upon us, and treated us with as much civility as if

we had been his relations. I had the honor of eating at his table during my stay here,

and my servant was allowed to eat with his. We had our rooms, &c. to ourselves, and

at our departure the governor supplied us with ample provisions for our journey to

fort St. John. In short, he did us more favours than we could have expected from our own countrymen,

and the officers were likewise particularly obliging to us.

About eleven o’clock in the morning we set out, with a fair wind. On both sides of

the lake are high chains of mountains; with the difference which I have before observed,

that on the eastern shore, is a low piece of ground covered with a forest, extending

between twelve and eighteen English miles, after which the mountains begin; and the country behind them belongs to New England. This chain consists of high mountains, which are to be considered as the boundaries

between the French and English possessions in these parts of North America. On the western shore of the lake, the mountains reach quite to the water side. The

lake at first is but a French mile broad, but always encreases afterwards. The country is inhabited [39]within a French mile of the fort, but after that, it is covered with a thick forest. At the distance

of about ten French miles from fort St. Frederic, the lake is four such miles broad, and we perceive some islands in it. The captain

of the yacht said there were about sixty islands in that lake, of which some were

of a considerable size. He assured me that the lake was in most parts so deep, that

a line of two hundred yards could not fathom it; and close to the shore, where a chain

of mountains generally runs across the country, it frequently has a depth of eighty

fathoms. Fourteen French miles from fort St. Frederic we saw four large islands in the lake, which is here about six French miles broad. This day the sky was cloudy, and the clouds, which were very low, seemed

to surround several high mountains, near the lake, with a fog; and from many mountains

the fog rose, as the smoke of a charcoal-kiln. Now and then we saw a little river

which fell into the lake: the country behind the high mountains, on the western side

of the lake, is, as I am told, covered for many miles together with a tall forest,

intersected by many rivers and brooks, with marshes and small lakes, and very fit

to be inhabited. The shores are [40]sometimes rocky, and sometimes sandy here. Towards night the mountains decreased gradually;

the lake is very clear, and we observed neither rocks nor shallows in it. Late at

night the wind abated, and we anchored close to the shore, and spent one night here.

July the 20th. This morning we proceeded with a fair wind. The place where we passed the

night, was above half way to fort St. John; for the distance of that place from fort St. Frederic, across lake Champlain is computed to be forty-one French miles; that lake is here about six English miles in breadth. The mountains were now out of sight, and the country low, plain,

and covered with trees. The shores were sandy, and the lake appeared now from four

to six miles broad. It was really broader, but the islands made it appear narrower.

We often saw Indians in bark-boats, close to the shore, which was however not inhabited; for the Indians came here only to catch sturgeons, wherewith this lake abounds, and which we often

saw leaping up into the air. These Indians lead a very singular life: At one time of the year they live upon the small store

of maize, beans, and melons, which they have planted; during another period, or about

this time, [41]their food is fish, without bread or any other meat; and another season, they eat

nothing but stags, roes, beavers, &c. which they shoot in the woods, and rivers. They,

however, enjoy long life, perfect health, and are more able to undergo hardships than

other people. They sing and dance, are joyful, and always content; and would not,

for a great deal, exchange their manner of life for that which is preferred in Europe.

When we were yet ten French miles from fort St. John, we law some houses on the western side of the lake, in which the French had lived before the last war, and which they then abandoned, as it was by no means

safe: they now returned to them again. These were the first houses and settlements

which we saw after we had left those about fort St. Frederic.

There formerly was a wooden fort, or redoubt, on the eastern side of the lake, near

the water-side; and the place where it stood was shewn me, which at present is quite

overgrown with trees. The French built it to prevent the incursions of the Indians, over this lake; and I was assured that many Frenchmen had been slain in these places. At the same time they told me, that they reckon four

women to one [42]man in Canada, because annually several Frenchmen are killed on their expeditions, which they undertake for the sake of trading with

the Indians.

A windmill, built of stone, stands on the east side of the lake on a projecting piece

of ground. Some Frenchmen have lived near it; but they left it when the war broke out, and are not yet come

back to it. From this mill to fort St. John they reckon eight French miles. The English, with their Indians, have burnt the houses here several times, but the mill remained unhurt.

The yacht which we went in to St. John was the first that was built here, and employed on lake Champlain, for formerly they made use of bateaux to send provisions over the lake. The Captain of the yacht was a Frenchman, born in this country; he had built it, and taken the soundings of the lake, in order

to find out the true road, between fort St. John and fort St. Frederic. Opposite the windmill the lake is about three fathoms deep, but it grows more and

more shallow, the nearer it comes to fort St. John.

We now perceived houses on the shore again. The captain had otter-skins in the cabin,

which were perfectly the same, in [43]colour and species, with the European ones. Otters are said to be very abundant in Canada.

Seal-skins are here made use of to cover boxes and trunks, and they often make portmantles of

them in Canada. The common people had their tobacco-pouches made of the same skins. The seals here

are entirely the same with the Swedish or European one, which are grey with black spots. They are said to be plentiful in the mouth

of the river St. Lawrence, below Quebec, and go up that river as far as its water is salt. They have not been found in any

of the great lakes of Canada. The French call them Loups marins.13

The French, in their colonies, spend much more time in prayer and external worship, than the

English, and Dutch settlers in the British colonies. The latter have neither morning nor evening prayer in their ships and yachts,

and no difference is made between Sunday and other days. They never, or very seldom,

say grace at dinner. On the contrary, the French here have prayers every morning and night on board their shipping, and on Sundays

they pray more than commonly: they regularly say grace at their meals; and every one

of [44]them says prayers in private as soon as he gets up. At fort St. Frederic all the soldiers assembled together for morning and evening prayers. The only fault

was, that most of the prayers were read in Latin, which a great part of the people do not understand. Below the aforementioned wind-mill,

the breadth of the lake is about a musket-shot, and it looks more like a river than

a lake. The country on both sides is low and flat, and covered with woods. We saw

at first a few scattered cottages along the shore; but a little further, the country

is inhabited without interruption. The lake is here from six to ten foot deep, and

forms several islands. During the whole course of this voyage, the situation of the

lake was always directly from S. S. W. to N. N. E.

In some parts of Canada are great tracts of land belonging to single persons; from these lands, pieces, of

forty Arpens long, and four wide, are allotted to each discharged soldier, who intends to settle

here; but after his household is established, he is obliged to pay the owner of the lands six French Francs annually.

The lake was now so shallow in several places, that we were obliged to trace the way

for the yacht, by sounding the depth [45]with branches of trees. In other places opposite, it was sometimes two fathom deep.

In the evening, about sun set, we arrived at fort St. Jean, or St. John, having had a continual change of rain, sun-shine, wind, and calm, all the afternoon.

July the 21st. St. John is a wooden fort, which the French built in 1748, on the western shore of the mouth of lake Champlain, close to the water-side. It was intended to cover the country round about it, which

they were then going to people, and to serve as a magazine for provisions and ammunition,

which were usually sent from Montreal to fort St. Frederic; because they may go in yachts from hence to the last mentioned place, which is impossible

lower down, as about two gun-shot further, there is a shallow full of stones, and

very rapid water in the river, over which they can only pass in bateaux, or flat vessels. Formerly fort Chamblan, which lies four French miles lower, was the magazine of provisions; but as they were forced first to send

them hither in bateaux, and then from hence in yachts, and the road to fort Chamblan from Montreal being by land, and much round about, this fort was erected. It has a low situation,

and lies [46]in a sandy soil, and the country about it is likewise low, flat; and covered with

woods. The fort is quadrangular, and includes the space of one arpent square. In each of the two corners which look towards the lake is a wooden building,

four stories high, the lower part of which is of stone to the height of about a fathom

and a half. In these buildings which are polyangular, are holes for cannon and lesser fire-arms.

In each of the two other corners towards the country, is only a little wooden house,

two stories high. These buildings are intended for the habitations of the soldiers,

and for the better defence of the place; between these houses, there are poles, two

fathoms and a half high, sharpened at the top, and driven into the ground close to

one another. They are made of the Thuya tree, which is here reckoned the best wood for keeping from putrefaction, and is

much preferable to fir in that point. Lower down the palisades were double, one row

within the other. For the convenience of the soldiers, a broad elevated pavement,

of more than two yards in height, is made in the inside of the fort all along the

palisades, with a balustrade. On this pavement the soldiers stand and fire through

the holes upon the enemy, without being exposed to [47]their fire. In the last year, 1748, two hundred men were in garrison here; but at

this time there were only a governor, a commissary, a baker, and six soldiers to take

care of the fort and buildings, and to superintend the provisions which are carried

to this place. The person who now commanded at the fort, was the Chevalier de Gannes, a very agreeable gentleman, and brother-in-law to Mr. Lusignan, the governor of fort St. Frederic. The ground about the fort, on both sides of the water, is rich and has a very good

soil; but it is still without inhabitants, though it is talked of, that it should

get some as soon as possible.

The French in all Canada call the gnats Marangoins, which name, it is said, they have borrowed from the Indians. These insects are in such prodigious numbers in the woods round fort St. John, that it would have been more properly called fort de Marangoins. The marshes and the low situation of the country, together with the extent of the

woods, contribute greatly to their multiplying so much; and when the woods will be

cut down, the water drained, and the country cultivated, they probably will decrease

in number, and vanish at last, as they have done in other places.

[48]

The Rattle Snake, according to the unanimous accounts of the French, is never seen in this neighbourhood, nor further north near Montreal and Quebec; and the mountains which surround fort St. Frederic, are the most northerly part on this side, where they have been seen. Of all the

snakes which are found in Canada to the north of these mountains, none is poisonous enough to do any great harm to

a man; and all without exception run away when they see a man. My remarks on the nature

and properties of the rattle-snake, I have communicated to the royal Swedish academy of sciences,14 and thither I refer my readers.

July the 22d. This evening some people arrived with horses from Prairie, in order to fetch us. The governor had sent for them at my desire, because there

were not yet any horses near fort St. John, the place being only a year old, and the people had not had time to settle near

it. Those who led the horses, brought letters to the governor from the governor-general

of Canada, the Marquis la Galissonniere, dated at Quebec the fifteenth of this month, and from the vice-governor of Montreal, the Baron [49]de Longueil, dated the twenty-first of the same month. They mentioned that I had been particularly

recommended by the French court, and that the governor should supply me with every thing I wanted, and forward

my journey; and at the same time the governor received two little casks of wine for

me, which they thought would relieve me on my journey. At night we drank the kings

of France and Sweden’s health, under a salute from the cannon of the fort, and the health of the governor-general

and others.

July the 23d. This morning we set out on our journey to Prairie, from whence we intended to proceed to Montreal; the distance of Prairie from fort St. John, by land, is reckoned six French miles, and from thence to Montreal two lieues (leagues) and a half, by the river St. Lawrence. At first we kept along the shore, so that we had on our right the Riviere de St. Jean (St. John’s river). This is the name of the mouth of the lake Champlain, which falls into the river St. Lawrence, and is sometimes called Riviere de Champlain (Champlain river.) After we had travelled about a French mile, we turned to the left from the shore. The country was always low, woody, and

pretty wet, though it was [50]in the midst of summer; so that we found it difficult to get forward. But it is to

be observed that fort St. John was only built last summer, when this road was first made, and consequently it could

not yet have acquired a proper degree of solidity. Two hundred and sixty men were

three months at work, in making this road; for which they were fed at the expence

of the government, and each received thirty sols every day; and I was told that they

would again resume the work next autumn. The country hereabouts is low and woody,

and of course the residence of millions of gnats and flies, which were very troublesome

to us. After we had gone about three French miles, we came out of the woods, and the ground seemed to have been formerly a marsh,

which was now dried up. From hence we had a pretty good prospect on all sides. On

our right hand at a great distance we saw two high mountains, rising remarkably above

the rest; and they were not far from fort Champlain. We could likewise from hence see the high mountain which lies near Montreal; and our road went on nearly in a straight line. Soon after, we got again upon wet

and low grounds, and after that into a wood which consisted chiefly of [51]the fir with leaves which have a silvery underside.15 We found the soil which we passed over to-day, very fine and rich, and when the woods will be cleared and the ground cultivated,

it will probably prove very fertile. There are no rocks, and hardly any stones near

the road.

About four French miles from fort St. John, the country makes quite another appearance. It is all cultivated, and a continual

variety of fields with excellent wheat, pease, and oats, presented itself to our view;

but we saw no other kinds of corn. The farms stood scattered, and each of them was

surrounded by its corn fields, and meadows; the houses are built of wood and very

small. Instead of moss, which cannot be got here, they employ clay for stopping up

the crevices in the walls. The roofs are made very much sloping, and covered with

straw. The soil is good, flat, and divided by several rivulets; and only in a few

places there are some little hills. The prospect is very fine from this part of the

road, and as far as I could see the country, it was cultivated; all the fields were

covered with corn, and they generally use summer-wheat here. The ground is [52]still very fertile, so that there is no occasion for leaving it ly as fallow. The

forests are pretty much cleared, and it is to be feared that there will be a time,

when wood will become very scarce. Such was the appearance of the country quite up

to Prairie, and the river St. Lawrence, which last we had now always in sight; and, in a word this country was, in my opinion

the finest of North-America, which I had hitherto seen.

About dinner-time we arrived at Prairie, which is situated on a little rising ground near the river St. Lawrence. We staid here this day, because I intended to visit the places in this neighbourhood,

before I went on.

Prairie de la Magdelene is a small village on the eastern side of the river St. Lawrence, about two French miles and a half from Montreal, which place lies N. W. from hence, on the other side of the river. All the country

round Prairie is quite flat, and has hardly any risings. On all sides are large corn-fields, meadows,

and pastures. On the western side, the river St. Lawrence passes by, and has here a breadth of a French mile and a half, if not more. Most of the houses in Prairie are built of timber, with sloping wooden roofs, and the crevices in [53]the walls are stopped up with clay. There are some little buildings of stone, chiefly

of the black lime-stone, or of pieces of rock-stone, in which latter the enchasement

of the doors and windows was made of the black lime-stone. In the midst of the village

is a pretty church of stone, with a steeple at the west end of it, furnished with

bells. Before the door is a cross, together with ladders, tongs, hammers, nails, &c.

which are to represent all the instruments made use of at the crucifixion of our Saviour,

and perhaps many others besides them. The village is surrounded with palisades, from

four yards to five high, put up formerly as a barrier against the incursions of the

Indians. Without these palisades are several little kitchen and pleasure gardens, but very

few fruit-trees in them. The rising grounds along the river, are very inconsiderable

here. In this place there was a priest, and a captain, who assumed the name of governor.

The corn-fields round the place are extensive, and sown with summer-wheat; but rye,

barley and maize are never seen. To the south-west of this place is a great fall in

the river St. Lawrence, and the noise which it causes, may be plainly heard here. When the water in spring

encreases in the river, [54]on account of the ice which then begins to dissolve, it sometimes happens to rise

so high as to overflow a great part of the fields, and, instead of fertilizing them

as the river Nile fertilizes the Egyptian fields by its inundations, it does them much damage, by carrying a number of grasses

and plants on them, the seeds of which spread the worst kind of weeds, and ruin the

fields. These inundations oblige the people to take their cattle a great way off,

because the water covers a great tract of land; but happily it never stays on it above

two or three days. The cause of these inundations is generally owing to the stopping

of ice in some part of the river.

The Zizania aquatica, or Folle Avoine grows plentiful in the rivulet, or brook, which flows somewhat below Prairie.

July the 24th. This morning I went from Prairie in a bateau to Montreal, upon the river St. Lawrence. The river is very rapid, but not very deep near Prairie, so that the yacht cannot go higher than Montreal, except in spring with the high water, when they can come up to Prairie, but no further. The town of Montreal may be seen at Prairie, and all the way down to it. On our arrival, there we found a crowd of people at

that gate of the town, where we [55]were to pass through. They were very desirous of seeing us, because they were informed

that some Swedes were to come to town; people of whom they had heard something, but whom they had

never seen; and we were assured by every body, that we were the first Swedes that ever came to Montreal. As soon as we were landed, the governor of the town sent a captain to me, who desired

I would follow him to the governor’s house, where he introduced me to him. The Baron

Longueuil was as yet vice-governor, but he daily expected his promotion from France. He received me more civilly and generously than I can well describe, and shewed

me letters from the governor-general at Quebec, the Marquis de la Galissonniere, which mentioned that he had received orders from the French court to supply me with whatever I should want, as I was to travel in this country

at the expence of his most Christian majesty. In short governor Longueuil loaded me with greater favours than I could expect or even imagine, both during my

present stay and on my return from Quebec.

The difference between the manners and customs of the French in Montreal and Canada, and those of the English in the American colonies, is as great as that between [56]the manners of those two nations in Europe. The women in general are handsome here; they are well bred, and virtuous with an

innocent and becoming freedom. They dress out very fine on Sundays; and though on

the other days they do not take much pains with other parts of their dress, yet they

are very fond of adorning their heads, the hair of which is always curled and powdered,

and ornamented with glittering bodkins and aigrettes. Every day but Sunday, they wear

a little neat jacket, and a short petticoat which hardly reaches half the leg, and

in this particular they seem to imitate the Indian women. The heels of their shoes are high, and very narrow, and it is surprizing how

they walk on them. In their knowledge of œconomy, they greatly surpass the English women in the plantations, who indeed have taken the liberty of throwing all the burthen

of housekeeping upon their husbands, and sit in their chairs all day with folded arms.16 The women in Canada on the contrary do not spare themselves, especially among the common [57]people, where they are always in the fields, meadows, stables, &c. and do not dislike

any work whatsoever. However, they seem rather remiss in regard to the cleaning of

the utensils, and apartments; for sometimes the floors, both in the town and country,

were hardly cleaned once in six months, which is a disagreeable sight to one who comes

from amongst the Dutch and English, where the constant scouring and scrubbing of the floors, is reckoned as important

as the exercise of religion itself. To prevent the thick dust, which is thus left

on the floor, from being noxious to the health, the women wet it several times a day,

which renders it more consistent; repeating the aspersion as often as the dust is

dry and rises again. Upon the whole, however, they are not averse to the taking a

part in all the business of housekeeping; and I have with pleasure seen the daughters

of the better sort of people, and of the governor himself, not too finely dressed,

and going into kitchens and cellars, to look that every thing be done as it ought.

The men are extremely civil, and take their hats off to every person indifferently

whom they meet in the streets. It is customary to return a visit the day after you

have received one; though one should have some scores to pay in one day.

[58]

I have been told by some among the French, who had gone a beaver-hunting with the Indians to the northern parts of Canada, that the animals, whose skins they endeavour to get, and which are there in great

plenty, are beavers, wild cats, or lynxs, and martens. These animals are the more

valued, the further they are caught to the north, for their skins have better hair,

and look better than those which are taken more southward, and they became gradually

better or worse, the more they are northward or southward.

White Patridges17 is the name which the French in Canada give to a kind of birds, abounding during winter near Hudson’s Bay, and which are undoubtedly our Ptarmigans, or Snow-hens (Tetrao Lagopus). They are very plentiful at the time of a great frost, and when a considerable quantity

of snow happens to fall. They are described to me as having rough white feet, and

being white all over, except three or four black feathers in the tail; and they are

reckoned very fine eating. From Edward’s Natural History of Birds (pag. 72.) it appears, that the ptarmigans are common

about Hudson’s Bay18.

[59]

Hares are likewise said to be plentiful near Hudson’s Bay, and they are abundant even in Canada, where I have often seen, and found them perfectly corresponding with our Swedish hares. In summer they have a brownish grey, and in winter a snowy white colour, as

with us19.

Mechanics, such as architecture, cabinet-work, turning, and the like, were not yet

so forward here as they ought to be; and the English, in that particular, out do the French. The chief cause of this is, that scarce any other people than dismissed soldiers

come to settle here, who have not had any opportunity of learning a mechanical trade,

but have sometimes accidentally, and through necessity been obliged to it. There are

however some, who have a good notion of mechanics, and I saw a person here, who made

very good clocks, and watches, though he had had but very little instruction.

July the 27th. The common house-flies have but been observed in this country about one

hundred and fifty years ago, as I have been assured by several persons in this town,

and in Quebec. All the Indians assert the same thing, and are of opinion that the [60]common flies first came over here, with the Europeans and their ships, which were stranded on this coast. I shall not dispute this; however,

I know, that whilst I was in the desarts between Saratoga and Crownpoint, or fort St. Frederic, and sat down to rest or to eat, a number of our common flies always came, and settled

on me. It is therefore dubious, whether they have not been longer in America than the term above mentioned, or whether they have been imported from Europe. On the other hand, it may be urged that the flies were left in those desarts at the

time when fort Anne was yet in a good condition, and when the English often travelled there and back again; not to mention that several Europeans, both before and after that time, had travelled through those places, and carried

the flies with them, which were attracted by their provisions.

Wild Cattle are abundant in the southern parts of Canada, and have been there since times immemorial. They are plentiful in those parts, particularly

where the Illinois Indians live, which are nearly in the same latitude with Philadelphia; but further to the north they are seldom observed. I saw the skin of a wild ox to-day;

it was as big as one of the largest ox hides in Europe, [61]but had better hair. The hair is dark brown, like that on a brown bear-skin. That

which is close to the skin, is as soft as wool. This hide was not very thick; and

in general they do not reckon them so valuable as bear-skins in France. In winter they are spread on the floors, to keep the feet warm. Some of these wild

cattle, as I am told, have a long and fine wool, as good, if not better, than sheep

wool. They make stockings, cloth, gloves, and other pieces of worsted work of it,

which look as well as if they were made of the best sheep wool; and the Indians employ it for several uses. The flesh equals the best beef in goodness and fatness.

Sometimes the hides are thick, and may be made use of as cow-hides are in Europe. The wild cattle in general are said to be stronger and bigger, than European cattle, and of a brown red colour. Their horns are but short, though very thick close

to the head. These and several other qualities, which they have in common with, and

in greater perfection than the tame cattle, have induced some to endeavour to tame

them; by which means they would obtain the advantages arising from their goodness

of hair, and, on account of their great strength, be able to employ them [62]successfully in agriculture. With this view some have repeatedly got young wild calves,

and brought them up in Quebec, and other places, among the tame cattle; but they commonly died in three or four

years time; and though they have seen people every day, yet they have always retained

a natural ferocity. They have constantly been very shy, pricked up their ears at the

sight of a man, and trembled, or run about; so that the art of taming them has not

hitherto been found out. Some have been of opinion, that these cattle cannot well

bear the cold; as they never go north of the place I mentioned, though the summers

be very hot, even in those northern parts. They think that, when the country about

the Illinois will be better peopled, it will be more easy to tame these cattle, and that afterwards

they might more easily be used to the northerly climates20. The Indians and French in Canada, make use of the horns of these creatures to put gun-powder in. I have briefly mentioned

the wild cattle in the former parts of this journey21.

[63]

The peace, which was concluded between France and England, was proclaimed this day. The soldiers were under arms; the artillery on the walls

was fired off, and some salutes were given by the small fire-arms. All night some

fireworks were exhibited, and the whole town was illuminated. All the streets were

crowded with people, till late at night. The governor invited me to supper, and to

partake of the joy of the inhabitants. There were present a number of officers, and

persons of distinction; and the festival concluded with the greatest joy.

July the 28th. This morning I accompanied the governor, baron Longueuil, and his family, to a little island called Magdelene, which is his own property. It lies in the river St. Lawrence, directly opposite to the town, on the eastern side. The governor had here a very

neat house, though it was not very large, a fine extensive garden, and a court-yard.

The river passes between the town and this island, and is very rapid. Near the town

it is deep enough for yachts; but towards the island it grows more shallow, so that

they are obliged to push the boats forwards with poles. There was a mill on the island,

turned by the mere force of the stream, without an additional mill-dam.

[64]

The smooth sumach, or Rhus glabra, grows in great plenty here. I have no where seen it so tall as in this place, where

it had sometimes the height of eight yards, and a proportionable thickness.

Sassafras is planted here; for it is never found wild in these parts, fort Anne being the most northerly place where I have found it wild. Those shrubs which were

on the island, had been planted many years ago; however, they were but small shrubs,

from two to three feet high, and scarce so much. The reason is, because the stem is

killed every winter, almost down to the very root, and must produce new shoots every

spring, as I have found from my own observations here; and so it appeared to be near

the forts Anne, Nicholson, and Oswego. It will therefore be in vain to attempt to plant sassafras in a very cold climate.

The red Mulberry-trees (Morus rubra, Linn.) are likewise planted here. I saw four or five of them about five yards high,

which the governor told me, had been twenty years in this place, and were brought

from more southerly parts, since they do not grow wild near Montreal. The most northerly place, where I have found it growing spontaneously, is about

twenty English miles north of Albany, as I have [65]been assured by the country people, who live in that place, and who at the same time

informed me, that it was very scarce in the woods. When I came to Saratoga, I enquired whether any of these mulberry-trees had been found in that neighbourhood?

but every body told me, that they were never seen in those parts, but that the before

mentioned place, twenty miles above Albany, is the most northern one where they grow. Those mulberry-trees, which were planted

on this island, succeed very well, though they are placed in a poor soil. Their foliage

is large and thick, but they did not bear any fruits this year. However, I was informed

that they can bear a considerable degree of cold.

The Waterbeech was planted here in a shady place, and was grown to a great height. All the French hereabouts call it Cotonier22. It is never found wild near the river St. Lawrence; nor north of fort St. Frederic, where it is now very scarce.

The red Cedar is called Cedre rouge by the French, and it was likewise planted in the governor’s garden, whither it had been brought