UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME:

J. M. SYNGE

By P. P. Howe

HENRY JAMES

By Ford Madox Hueffer

HENRIK IBSEN

By R. Ellis Roberts

THOMAS HARDY

By Lascelles Abercrombie

BERNARD SHAW

By P. P. Howe

WALTER PATER

By Edward Thomas

WALT WHITMAN

By Basil de Sélincourt

SAMUEL BUTLER

By Gilbert Cannan

A. C. SWINBURNE

By Edward Thomas

GEORGE GISSING

By Frank Swinnerton

RUDYARD KIPLING

By Cyril Falls

WILLIAM MORRIS

By John Drinkwater

ROBERT BRIDGES

By F. E. Brett Young

MAURICE MAETERLINCK

By Una Taylor

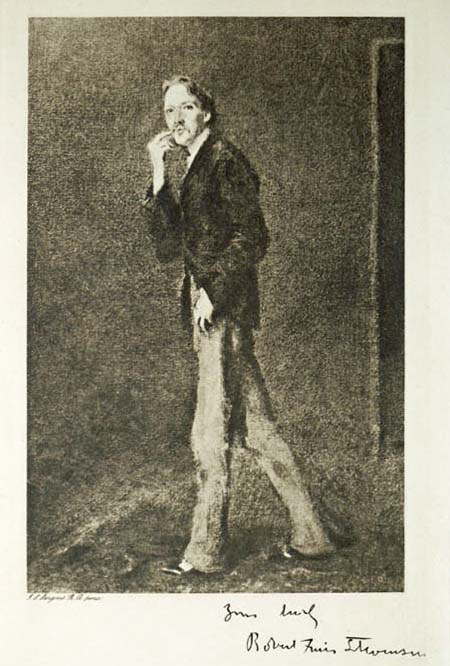

Yours truly

Robert Louis Stevenson

R. L. STEVENSON

A CRITICAL STUDY

BY

FRANK SWINNERTON

LONDON

MARTIN SECKER

NUMBER FIVE JOHN STREET

ADELPHI

MCMXIV

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

THE MERRY HEART

THE YOUNG IDEA

THE CASEMENT

THE HAPPY FAMILY

ON THE STAIRCASE

GEORGE GISSING:

A CRITICAL STUDY

The Sargent portrait of Stevenson which forms the frontispiece to this volume has been included by permission of Mr. Lloyd Osbourne, to whom the publisher wishes to express his acknowledgments and thanks.

TO

DOUGLAS GRAY

IN MALICE

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | BIOGRAPHICAL | 9 |

| II. | JUVENILIA | 36 |

| III. | TRAVEL BOOKS | 42 |

| IV. | ESSAYS | 62 |

| V. | POEMS | 90 |

| VI. | PLAYS | 102 |

| VII. | SHORT STORIES | 116 |

| VIII. | NOVELS AND ROMANCES | 143 |

| IX. | CONCLUSION | 185 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 211 | |

[8]

As the purpose of this book is entirely critical, and as there already exist several works dealing extensively with the life of Stevenson, the present biographical section is intentionally summary. Its object is merely to sketch in outline the principal events of Stevenson’s life, in order that what follows may require no passages of biographical elucidation. Stevenson was a writer of many sorts of stories, essays, poems; and in all this diversity he was at no time preoccupied with one particular form of art. In considering each form separately, as I purpose doing, it has been necessary to group into single divisions work written at greatly different times and in greatly differing conditions. In Mr. Graham Balfour’s “Life,” and very remarkably in Sir Sidney Colvin’s able commentaries upon Stevenson’s letters, may be found information at first hand which I could only give by acts of piracy. To those[10] works, therefore, I refer the reader who wishes to follow in chronological detail the growth of Stevenson’s talent. They are, indeed, essential to all who are primarily interested in Stevenson the man. Here, the attempt will be made only to summarise the events of his days, and to estimate the ultimate value of his work in various departments of letters. This book is not a biography; it is not an “appreciation”; it is simply a critical study.

Stevenson was born on November 13, 1850; and he died, almost exactly forty-four years later, on December 3, 1894. His first literary work, undertaken at the age of six, was an essay upon the history of Moses. This he dictated to his mother, and was rewarded for it by the gift of a Bible picture book. It is from the date of that triumph that Stevenson’s desire to be a writer must be calculated. A history of Joseph followed, and later on, apparently at the age of nine, he again dictated an account of certain travels in Perth. His first published work was a pamphlet on The Pentland Rising, written (but full of quotations) at the age of sixteen. His first “regular or paid contribution to periodical literature” was the essay called Roads (now[11] included in Essays of Travel), which was written when the author was between twenty-two and twenty-three. The first actual book to be published was An Inland Voyage (1878), written when Stevenson was twenty-seven; but all the essays which ultimately formed the volumes entitled Virginibus Puerisque (1881) and Familiar Studies of Men and Books (1882) are the product of 1874 and onwards. These, indicated very roughly, are the beginnings of his literary career. Of course there were many other contributary facts which led to his turning author; and there is probably no writer whose childhood is so fully “documented” as Stevenson’s. He claimed to be one of those who do not forget their own lives, and, in accordance with his practice, he has supplied us with numerous essays in which we may trace his growth and his experiences. That he was an only child and a delicate one we all know; so, too, we know that his grandfather was that Robert Stevenson who built the Bell Rock lighthouse. In the few chapters contributed by Robert Louis to A Family of Engineers we shall find an account, some of it fanciful, but some of it also perfectly accurate, of the Stevenson family and of Robert Stevenson, the grandfather, in particular. In Memories and Portraits is included a sketch of[12] Thomas Stevenson, the father of Robert Louis; and in Mr. Balfour’s “Life” there is ample information for those who wish to study the influences of heredity.

For our own purpose it may be interesting to note three points in this connection. As a boy, and even as a youth, Stevenson was expected by his father to be an engineer and to carry on the family tradition. His early training therefore brought him much to the sea, with rather special facilities for appreciating the more active relations of man to the sea. The second point is that the Stevensons had always been, true to their Scots instincts, very strict religious disciplinarians (Robert Stevenson the elder is very illuminating on this); but that they were also very shrewd and determined men of action. Finally, another grandfather of Robert Louis, this time on the Balfour side, was in fact a clergyman. Stevenson significantly admits that he may have inherited from this grandfather the love of sermonising, which is as noticeable in An Inland Voyage and in Virginibus Puerisque as it is in his latest non-fictional work. We cannot forget that his contribution to festivities marking the anniversary of his marriage was upon one occasion a sermon on St. Jacob’s Oil, delivered from a pulpit carried as part-cargo[13] by the “Janet Nichol.” From his mother, too, he is said to have inherited that constitutional delicacy which made him subject throughout his life to periods of serious illness, and which eventually led to his early death.

There was one other influence upon his childhood which must not be neglected as long as the pendulum of thought association swings steadily from heredity to environment. That influence was the influence exercised by his nurse, Alison Cunningham. It is admitted to have been enormous, and I am not sure that it is desirable to repeat in this place what is so much common knowledge. But it is perhaps worth while to emphasise the fact that, while Alison Cunningham was not only a devoted nurse, night and day, to the delicate child, she actually was in many ways responsible for the peculiar bent of Stevenson’s mind. She it was who read to him, who declaimed to him, the sounds of fine words which he loved so well in after life. The meaning of the words he sometimes did not grasp; the sounds—so admirable, it would seem, was her delivery—were his deep delight. Not only that: she introduced him thus early to the Covenanting writers upon whom he claimed to have based his sense of style; and, however lightly we may regard his various affirmations as to the[14] source of his “style,” and as to the principles upon which we might expect to find it based, the sense of style, which is quite another thing, was almost certainly awakened in him by these means. Sense of style, I think, is a much greater point in Stevenson’s equipment than the actual “style.” The style varies; the sense of style is constant, as it must be in any writer who is not a Freeman. Alison Cunningham, being herself possessed of this sense, or of the savour of words, impressed it upon “her boy”; and the result we may see. All Stevenson’s subsequent “learning” was so much exercise: no man learns how to write solely by observation and imitation.

From being a lonely and delicate child spinning fancies and hearing stirring words and stories and sermons in the nursery, Stevenson became a lonely and delicate child in many places. One of them was the Manse at Colinton, the home of his clerical grandfather. Another was the house in Heriot Row, Edinburgh, where he played with his brilliant cousin R. A. M. Stevenson. R. A. M. was not his only cousin—there were many others; but the personality of R. A. M. is such that one could wish to know the whole of it, so attractive are the references in Stevenson’s essays and letters, and in Mr. Balfour’s biography.[15] I imagine, although I cannot be sure, that it was with R. A. M. that Stevenson played at producing plays on toy-stages. We shall see later how impossible he found it, when he came to consider the drama as a literary field, to shake off the influence of Skelt’s drama; but anybody who has played with toy-stages will respond to the enthusiasm discovered in A Penny Plain and Twopence Coloured, and will sympathise with the delight which Stevenson must later have felt on being able to revive in Mr. Lloyd Osbourne’s company the old Skeltian joys.

School followed in due course, the attendances broken by sickness and possibly by the incurable idleness which one supposes to have been due to lassitude rather than to mischief. Mr. Balfour details the components of Stevenson’s education, from Latin and French and German, to bathing and dancing. Football is also mentioned, while riding seems to have developed into a sort of reckless horsemanship. When he was eleven or twelve Stevenson came first to London, and went with his father to Homburg. Later he went twice with Mrs. Stevenson to Mentone, travelling, besides, on the first occasion, through Italy, and returning by way of Germany and the Rhine. It is, however, remarkable that he does not seem[16] to have retained much memory of so interesting an experience; a fact which would suggest that, although he was able at this time to store for future use ample impressions of his own feelings and his own habits, he had not yet awakened to any very lively or precise observation of the external world. That observation began with the determination to write, and Stevenson then lost no opportunity of setting down exactly his impressions of things seen.

In 1867—that is, after the publication, and after the withdrawal, of The Pentland Rising—Stevenson began his training as a civil engineer, working for a Science degree at Edinburgh University. One may learn something of his experience there from Memories and Portraits and even from The Memoir of Fleeming Jenkin. It was now that he met Charles Baxter (the letters to whom are the jolliest and apparently most candid of any he wrote), James Walter Ferrier, Sir Walter Simpson (the real hero of An Inland Voyage), and Fleeming Jenkin, whose wife mistook Stevenson for a poet. Here, too, he joined the “Speculative Society,” of which presently he became an unimportant president. Moreover, the friendships formed at the University led to the foundation of a mysterious society of six members, called the L.J.R. (signifying Liberty, Justice, Reverence),[17] which has been the occasion of much comment on account of the secrecy with which the meaning of the initials has been guarded.

It was while he was at the University that his desire to write became acute. By his own account, he went everywhere with two little books, one to read, and one to write in. He read a great deal, talked a great deal, made friends, and charmed everybody very much. In 1868, 1869, and 1870 he spent some time on the West Coast of Scotland, watching the work which was being carried on by his father’s firm at Anstruther, Wick, and finally at Earraid (an island introduced into Catriona and The Merry Men). In 1871 he received from the Scottish Society of Arts a silver medal for a paper (A New Form of Intermittent Light for Lighthouses); and two years later another paper, On the Thermal Influence of Forests, was communicated to the Royal Society of Edinburgh. But it was in 1871 that Stevenson gave up, and induced his father most unwillingly to give up, the plans hitherto regarded as definite for his future career. He could not become a civil engineer; but determined that he must make his way by letters. A compromise was effected, by the terms of which he read for the Bar; and he passed his preliminary examination in 1872.

[18]

In 1873 Stevenson, then in great distress because of religious differences with his father, made the acquaintance of Mrs. Sitwell (now Lady Colvin) and, through her, of Sidney Colvin himself. The importance of these two friendships could hardly be over-estimated. Mrs. Sitwell gave readily and generously the sympathy of which Stevenson was so much in need; and Mr. Colvin (as he then was) proved to be, not only a friend, but a guide and a most influential champion. It was through Mr. Colvin that Stevenson made his real start as a professional writer, for Mr. Colvin was a writer and the friend of writers, a critic and the friend of—editors. Stevenson’s plans for removal to London were made, and to London he came; but he was then so prostrated with nervous exhaustion, with danger of serious complications, that he was sent to the Riviera for the winter. Mr. Colvin joined him at Mentone, and introduced him to Andrew Lang. Thereafter, Stevenson went to Paris; and it was not until the end of April, 1874, that he returned to Edinburgh, apparently so far recovered that he could enjoy, three months later, a long yachting excursion on the West[19] Coast. Further study followed, and at length Stevenson was in 1875 called to the Scottish Bar, having been elected previously, through Mr. Colvin’s kindly agency, a member of the Savile Club. Membership of the Savile led to the beginning of his association with Leslie Stephen, and to his introduction to the then editors of “The Academy” and “The Saturday Review.” In this period of his life occurred the journey described in An Inland Voyage, and his highly important “discovery” of W. E. Henley in an Edinburgh hospital.

Finally, it is important to remember that in these full years, 1874-1879, Stevenson spent a considerable amount of time in France, where he stayed as a rule either in Paris or in the neighbourhood of Fontainebleau, most frequently at Barbizon. Details of his life in France are to be found in The Wrecker, in the essay called Forest Notes in Essays of Travel, and in that on Fontainebleau in Across the Plains. He was writing fairly steadily, and he was getting his work published without embarrassing difficulty, from Ordered South in 1874 to Travels with a Donkey in 1879. And it was in Grez in 1876 that he made the acquaintance of Mrs. Osbourne, an American lady separated from her husband. The meeting was in fact the turning-point in his career:[20] even Travels with a Donkey, as he admitted in a letter to his cousin, R. A. M. Stevenson, contains “lots of mere protestations to F.” When Mrs. Osbourne returned to America in 1878 she sought and obtained a divorce from her husband. Stevenson heard of her intention, and heard also that she was ill. He was filled with the idea of marrying Mrs. Osbourne, and was determined to put his character to the test of so long and arduous a journey for the purpose, with the inevitable strain which his purpose involved. With perhaps a final exhibition of quite youthful affectation, and a serious misconception of his parents’ attitude to himself and to the desirability of such a marriage, Stevenson took parental opposition for granted. Nevertheless, it is a proof of considerable, if unnecessary, courage, that he followed Mrs. Osbourne to California by a sort of emigrant ship and an American emigrant train. His experiences on the journey are veraciously recorded in The Amateur Emigrant and Across the Plains.

The rough, miserable journey, and the exhaustion consequent upon the undertaking of so long and difficult an expedition, brought Stevenson’s vitality very low; so that, after much strain, much miscellaneous literary work, and many self-imposed privations, he fell[21] seriously ill at San Francisco towards the end of 1879. Only careful nursing, and a genial cable from his father, promising an annual sum of £250, restored health and spirits; and on May 19, 1880, he was married to Mrs. Osbourne. Their life at Silverado has already been described in The Silverado Squatters; it was followed by a return to Europe, a succession of journeys from Scotland to Davos, Barbizon, Paris, and St. Germain; and a further series back again to Pitlochry and Braemar. At the last-named place Treasure Island was begun, and nineteen chapters of the book were written: here, too, we gather, the first poems for A Child’s Garden of Verses laid the foundations of that book. Again, owing to bad weather in Scotland, it was found necessary to resort to Davos, where the Stevensons lived in a châlet, and where the works of the Davos Press saw the light. After a winter so spent, Stevenson was pronounced well enough to resume normal life, and he returned accordingly to England and Scotland. But before long it was necessary to go to the South of France, and after various misfortunes he settled at length at Hyères. Here he wrote The Silverado Squatters and resumed work on Prince Otto, a work long before planned as both novel and play.

Further illness succeeded, until it was found[22] possible to settle at Bournemouth, in the house called Skerryvore; and in Bournemouth Stevenson spent a comparatively long time (from 1884 to 1887). Here he made new friendships and revived old ones. Now were published A Child’s Garden, Prince Otto, The Dynamiter, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Kidnapped; and now, in 1887, occurred the death of Stevenson’s father, of whom a sketch is given in Memories and Portraits.

The relations of father and son were obviously peculiar. Thomas Stevenson was strict in the matter of faith—more strict than those of this day can perhaps understand—and it is evident that this strictness provoked conflict between Robert Louis and his father. By the letters to Mrs. Sitwell we gather that the differences greatly troubled Robert Louis; but it seems very clear on the other hand that wherever the elder Stevenson’s character is actively illustrated in Mr. Balfour’s “Life,” or in Stevenson’s letters, the instance is one of kindness and consideration. Mr. Charles Baxter recalls the dreadful expression of his friend when the first draft of propositions for the L.J.R. fell into Thomas Stevenson’s hands; and no doubt there is much that is personal in such stories as Weir, The Wrecker, and John Nicholson, in which the relations of fathers[23] and sons are studied. That Thomas loved and admired his son seems certain; but it must be supposed that his own austerity was not always tolerable to a nature less austere and sensitive to the charge of levity.

Almost immediately after the death of his father, Stevenson left England finally. He went first to New York, and then to Saranac (in the Adirondacks), where the climate was said to be beneficial to those suffering from lung trouble. Here he began The Master of Ballantrae while Mr. Lloyd Osbourne was busy on The Wrong Box; and, when summer was returning, the whole party removed, first to New Jersey, and then to the schooner “Casco,” in which they travelled to the Marquesas. In the next three years they wandered much among the groups of islands in the South Seas. The Master of Ballantrae was finished in a house, or rather, in a pavilion, at Waikiki, a short distance from Honolulu. It was after finishing that book that Stevenson made further journeys, until at last, by means of a trading schooner called “The Equator,” the Stevensons all went to Samoa, where they settled in Apia. Here Robert Louis bought land, and built a home; and here, during the last years of his life, he lived in greater continuous health—broken though it was[24] with occasional periods of illness more or less serious—than he had enjoyed for a number of years.

At Apia he was active, both physically and in the way of authorship: his exile, trying though it must at times have been, involved health and happiness; and his loyal friends and his increasingly numerous admirers kept him, as far as they were able to do, from the dire neglect into which the thousands of miles’ distance from home might suggest that he would inevitably fall. I say his loyal friends, rather than many, because Mrs. Stevenson particularly declares that Stevenson had few intimate friends. Well-wishers and admirers he had; but there is noticeable in the majority of those letters so ably collected and edited by Sir Sidney Colvin a lack of the genuine give and take of true intimacy. Information concerning himself and his doings, which suggests the use of his friends as tests or sounding-boards, forms the staple of such letters. I am told that many intimate letters are not included—for reasons which are perfectly clear and good; but the truth is that it is only in the letters to Baxter that there is any sense of great ease. Even the letters to Sir Sidney Colvin,[25] full, clear, friendly as they are, suggest impenetrable reserves and an intense respect for the man to whom they were written. They suggest that Stevenson very much wanted Sir Sidney to go on admiring, liking, and believing in him; but they are not letters showing any deep understanding or taking-for-granted of understanding. Candour, of course, there is; a jocularity natural to Stevenson; a reliance upon the integrity and goodwill of his correspondent; a complete gratitude. All we miss is the little tick of feeling which would give ease to the whole series of letters. They might all have been written for other eyes. When one says that, one dismisses the complete spontaneity of the letters in what may seem to be an arbitrary fashion. But one is not, after all, surprised that Stevenson should have made the request that a selection of his letters should be published.

Of friends, then, there must be few, because Mrs. Stevenson is obviously in a better position than anybody else to judge upon this point. She says that, contrary to the general impression, Stevenson had few really intimate friends, because his nature was deeply reserved. From that we may infer that, like other vain men, who, however, are purged by their vanity rather than destroyed by it, he told much[26] about himself without finally, as the phrase is, “giving himself away.” His high spirits, his “bursts of confidence,” his gay jocularity—all these things, part of the man’s irrepressible vanity, were health to him: they enabled him to keep light in a system which might have developed, through physical delicacy, in the direction of morbidity. That he was naturally cold, in the sense that he kept his face always towards his friends, I am prepared to believe: if he had not done that he perhaps would have lost their respect, since personal charm is a fragile base for friendship. By his own family at Vailima he was accused of being “secretive,” as Mrs. Strong records in “Memories of Vailima.” And Stevenson, it must be remembered, was a Scotsman, with a great fund of melancholy. Quite clearly, Henley, his friend for years and his collaborator, never understood him. Henley deplored the later Stevenson, and loved the Louis (or rather, the Lewis) he had known in early days. He loved, that is, the charming person who had discovered him, and with whom he had talked and plotted and bragged. He did not love the man who seems to have turned from him. The cause of their estrangement I do not know. I imagine that they thought differently of the merits of the plays, that Henley pressed[27] Stevenson at a time when Stevenson felt himself to be drawing away from Henley and passing into a rather delightful isolation, and that when Henley clung to their old comradeship with characteristic vehemence, Stevenson felt suddenly bored with so loud an ally. That may be sheer nonsense: I only infer it. Whatever the cause, Stevenson seems to me always a little patronising to Henley, and Henley’s attack in the “Pall Mall Magazine” (December, 1901) suggests as well as envy the blunt bewilderment of a man forsaken. Henley, of course, knew that he lacked the inventive power of Stevenson; and he knew that his power to feel was more intense than Stevenson’s. That in itself makes a sufficient explanation of the quarrel: literary friends must not be rivals, or their critical faculty will overrun into spleen at any injudicious comparisons.

Besides Henley, there is R. A. M. Stevenson, a fascinating figure; but imperfectly shown in the “Letters.” There is Sir Sidney Colvin, best and truest of friends. There is Charles Baxter, the recipient of the letters which seem to me the jolliest Stevenson wrote—a man of much joviality, I am told, and a very loyal worker on his friend’s behalf. For the rest, they are friends in a general sense:[28] not intimates, but men whose good opinion Stevenson was proud to have earned: friends in the wide (but not the most subtle) scheme of friendship which makes for social ease and confidence and interest. Baxter and R. A. M. Stevenson were survivors of early intimacies. Mrs. Sitwell and Sir Sidney Colvin belonged to a later time, a time of stress, but a time also of growth. The others, whom we thus objectionably lump together in a single questionable word, were the warm, kind acquaintances of manhood. It is useless to demand intimacy in these cases, and I should not have laboured the point if it had not been suggested that Stevenson was one of those who had a genius for friendship. He was always, I imagine, cordial, friendly, charming to these friends; but his letters (unless we suppose Sir Sidney Colvin to have edited more freely than we should ordinarily suspect) do not seem to have much to say about his correspondents, and it is not perhaps very unreasonable to think that his own work and his own character were the basis of the exchange of letters. Stevenson no doubt liked these friends; but I am disposed to question whether he was very much interested in them. I think Stevenson generally inspired more affection than he was accustomed to give in return.

[29]

We must remember, in thus speaking of Stevenson’s friendships, that he was a Scotsman, that he had been really a lonely child and boy, accustomed to a degree of solitude, that he was an egoist (as, presumably, all writers are egoists), and that his personal charm is unquestioned. Men who met him for the first time were fascinated by his vivacity, his fresh play of expression, his manner; and Stevenson, of course, as was only natural, responded instantly to their admiration. He was carried away in talk, and in talk walked with his new friends until they, forced as they were by other engagements to leave him, gained from such a vivid ripple of comment an impression of something alive and mercurial, something like the wonderful run of quicksilver, in a companion so inexhaustibly vivacious. It was the nervous brilliance of Stevenson which attracted men often of greater real ability; he possessed a quality which they felt to be foreign, almost dazzling. So Stevenson, leaving them, strung to a height of exhilaration by his own excited verbosity, would go upon his way, also attracted by his happy feelings and his happy phrases. In[30] such a case the man of charm has two alternatives: he can suppress his ebullience for the purpose of learning or giving; or he can recognise the excitement and, supposing it to be lyricism, can, if I may use that word (as I have above used the word “verbosity”) without any evil meaning being attached to it, exploit his charm. Stevenson, I believe, exploited his charm. It is often so exploited; the temptation to exploit it is sometimes irresistible. The kind thing, the attractive thing, the charming thing—this is the thing to say and do, rather than the honest thing. Instinctively a girl learns the better side of her face, the particular irresistible turn of her head, the perfect cadence of voice. So does the man who has this personal charm. So, too, does he realise instinctively the value of the external details of friendship. In only one point does the knowledge of such externals fail. The kind thing makes friends (in the sense of cordial strangers); but it does not make anything more subtle than cordial strangeness; and it does not seem to me that anybody really ever knew Stevenson very well. He told them much about himself, gaily; and they knew he was charming. I do not suggest any duplicity on his part. He was perfectly real in his vivacity, but it was nervous vivacity,[31] an excitement that led, when it relaxed, or was relaxed, to exhaustion, possibly even to tears, just as we know that Stevenson could be carried by his own fooling to the verge of hysteria. So it was that Stevenson became a figure to himself, as well as to his friends; by his desire to continue the pleasant impression already created, he did tend to see himself objectively (just as he is said to have made the gestures he was describing in his work, and even to have gone running to a mirror to see the expression the imagined person in his book was wearing). In his early books that is plain; in Lay Morals we may feel that he is all the time in the pulpit, leaning over, and talking very earnestly, very gently, very persuasively, and with extraordinary self-consciousness, to a congregation that is quite clearly charmed by his personality. Above all, very persuasively; and above even his persuasiveness, the deprecating sense of charm, the use of personal anecdote to give the sermon an authentic air of confession.

The nervous, vivid buoyancy of his characteristic manner was a part of his lack of health. He was, it is known, rarely in actual pain; and it is very often the case that delicate persons have this nervous exuberance of temperament, which has almost the show of[32] vitality. It has the show; but when the person is no longer before us, our memory is a vague, fond dream of something intangible—what we call, elusive. We talk of elusive charm when we cannot remember a single thing that has aroused in us the impression of having been charmed. Exactly in that way was Stevenson remembered by those he met—as a vivid butterfly is remembered; something indescribably strange and curious, not to be caught and held, for its brilliant and wayward fluttering. The charm was the thing that attracted men kinder, more staid, more truly genial, wiser than himself; it excused the meagre philosophisings and it excused some of those rather selfish and thoughtless actions which Mr. Balfour says nobody dreamed of resenting. The same charm we shall find in most of Stevenson’s work, until it grows stale in St. Ives. We shall speak of its literary aspects later. At this moment we are dealing exclusively with his manner. I want to show that Stevenson’s ill-health was not the ill-health which makes a man peevish through constant pain. It was, in fact, extreme delicacy, rather than ill-health; and the reaction from delicacy of physical health (or, in reality, the consequence of this delicacy) was this peculiar nervous[33] brilliancy of manner which I have described. It is often mistaken by writers on Stevenson for courage; but this is an unimaginative conception resulting from the notion that he was constantly in pain, and that he deliberately willed to be cheerful and gay. Nobody who deliberately wills to be cheerful ever succeeds in being more than drolly unconvincing. Stevenson had courage which was otherwise illustrated: this cheerfulness, this “funning” was the natural consequence of nervous excitability, which, as I have said, often appears as though it was vitality, as though it must be of more substance than we know it really is. It is like the colour in an invalid’s cheek, like the invalid’s energy, like the invalid’s bright eyes: it is due to the stimulus of excitement. Stevenson, alone, had his flat moments of dull mood and tired vanity; Stevenson, in company, thrilled with the life which his friends regarded as his inimitable and unquestionable personal charm.

You are thus to imagine a nervously-moving man, tall, very dark, very thin; his hair generally worn long; his eyes, large, dark, and bright, unusually wide apart; his face long, markedly boned. His dress, with velvet jacket, is bizarre; his whole manner is restless; his hands, skeleton-thin, constantly flickering with[34] every change of pose. His grace of movement, his extraordinary play of expression, are everywhere commented upon by those who essay verbal portraiture; and all agree that the photographs in existence reproduce only the dead features which expression changed each instant. Stevenson, it seems, varied his position suddenly and frequently—moving from hearth-rug to chair, from chair, again, to table, walking quickly and brushing his moustache as we may see in Sargent’s brilliant impression. Nervousness was in every movement, every gesture; and the figure of Stevenson seems to be recalled, by many of those who attempt the description, as invariably in motion, the face alive with interest and expression, while the man all the time talked, like “young Mr. Harry Fielding, who pours out everything he has in his heart, and is, in effect, as brilliant, as engaging, and as arresting a talker as Colonel Esmond has known.”

I give the portrait for what it may be worth. No doubt it does not represent the Stevenson of Samoa; perhaps it does not represent the real Stevenson at all. It is Stevenson as one may imagine him, and as another may find it impossible to imagine him. There is room, surely, for a variety of portraits, as for the inevitable variety of critical estimates; and if[35] the estimates hitherto have all followed a particular line of pleasant comment, at least the portraits one sees and reads are all portraits of diverse Stevensons made dull or trivial or engrossing according to the opportunities and skill of the delineator. I offer my portrait, in this and in succeeding chapters, in good faith: more, it would be impossible for me to claim.

Before we come to the main divisions of Stevenson’s work it may be as well to consider briefly those few early works which, to the majority of readers, were first made known by their inclusion in the Edinburgh Edition. It is unfortunately impossible to recover the original essay upon Moses, or the earliest romances; so that we are presented first with The Pentland Rising, published as a pamphlet when Stevenson was sixteen. This is conscientious and fully-documented work, written too close to authorities to have much flexibility or personal interest; but it is not strikingly immature. Daniel Defoe, Burnet, Fuller’s “History of the Holy Warre,” and a surprising number of other writers upon the period are successively quoted with good effect; and it is amusing to note the references to “A Cloud of Witnesses,” which appears to have been a favourite with Alison Cunningham. This pamphlet is decidedly the outcome of Alison[37] Cunningham’s teaching, full as it is of the authentic manner of the Covenanters, which Stevenson was presently to imitate to the admiration of all the world.

Many readers of Stevenson must have regarded with eyes of marvel the two serious papers, the gravity of which is perfect, dealing with the Thermal Influence of Forests, and with a new form of Intermittent Light. I have no ability to determine the scientific value of these papers; and as literary works they have less interest than most of the other instances of Juvenilia. They are illustrated with diagrams, and they possess coherence and lucidity. In any work these two qualities are important, and we shall find that clearness is a quality which Stevenson never lost. He always succeeded in being clear, in escaping the obscure sayings of the philosopher or the enthusiast. That is to say, he was a writer. He was a writer in those two scientific papers, no less than in Virginibus Puerisque or Prince Otto. When obscurity is so easy, clearness is a distinguished virtue; and if Stevenson sometimes errs to the extent of robbing his work of thickets and dim frightening darknesses, that is also because he was a writer, and because he preferred to be a writer.

There follow a number of shorter pieces,[38] some of them the fruit of his University days of practising; some later, so that they include the papers on Roads and Forest Notes which are mentioned in the next chapter. These sometimes show obvious immaturity, but they also show more than anything else could do the real doggedness with which Stevenson pursued his aim of learning to write. They show him, at least, forming his sentences with careful attention to rhythm and to sound—not yet elaborate, not yet so “kneaded” as his manner was in a little while to be. It is here sometimes thin, as is the subject-matter. In one sketch, The Wreath of Immortelles, we may catch a glimpse of the method of opening an essay which Stevenson developed later; but, on the other hand, in the Forest Notes (possibly more mature work) there is really excellent treatment of good and interesting matter. Three “criticisms” have point. One, of Lord Lytton’s “Fables in Slang,” is fairly conventional; the second, on Salvini’s Macbeth, was the one condemned by Fleeming Jenkin because it showed Stevenson thinking more about himself than about Salvini; the third is a very delightful little paper on Bagster’s illustrated edition of “The Pilgrim’s Progress.”

All these short pieces are of interest because they show the growth of Stevenson as a writer.[39] They are the more interesting because at the same time they illustrate the way in which Stevenson gradually made his work take on the impress of his personality. All young work lacks character, as young hand-writing does, and as young style does; and all young essay-work in particular appears sometimes rather tepid and even silly when the author tries to interest us in his “ego.” Stevenson from the first saw himself as the central object in his essay: it is amusing to watch how soon he begins to make himself count as an effective central object. At first the personality is thin: it has not carried. Later it develops with the development of style: the use of words becomes firmer, and with that firmness comes greater confidence, greater ease, in the projection of the author’s self. It is perhaps not until we reach the familiar essays that we find Stevenson fully master of himself, for literary purposes; but the growth provides matter for rather ingenious study.

In that volume of the collected editions which contains these early essays it is customary to include the works issued by the Davos Press; and Mr. Lloyd Osbourne (at the age of twelve the proprietor of the Davos[40] Press) has also discovered a wholly amusing account of an important military campaign conducted in an attic at Davos by himself and Stevenson as opposed commanders of tin soldiers. The game, which had of course inexhaustible interest, has also, as described by Mr. Osbourne, its intricacies for the lay mind; but Stevenson’s account of this particular campaign, written by means of official reports, rumours, newspapers yellow and otherwise, offers no difficulty. It is an excellent piece of pretence. The Davos Press, which provided the world with unique works by Stevenson and by Mr. Osbourne, illustrated with original woodcuts, belongs, as does the war-game, to the time spent in the châlet at Davos shortly after Stevenson’s marriage. It shows how easily he could enjoy elaborate games (as most men do enjoy them, if they are not deterred by self-importance or preoccupation with matters more strictly commercial); and the relationship with Mr. Osbourne seems to have been as frank and lively as anybody could desire.

I have mentioned these matters out of their due place because they seem to me to have a value as contributing to certain suggestions which I shall make later. By his marriage, Stevenson gained not only a very devoted[41] wife but a very intimate boy-friend, the kind of friend he very likely had long wanted. There was almost twenty years’ difference between them; but that, I think, made the friendship more suited to Stevenson’s nature. By means of this difference he could indulge in that very conscious make-belief for which his nature craved—a detached make-belief, which enabled him to enjoy the play both in fact and as a spectator, to make up for Mr. Osbourne’s admitted superiority in marksmanship by the subtilty of his own military devices; finally, to enjoy the quite personal pleasure of placing upon record, with plans and military terms, in the best journalistic style, accounts of his military achievements. The art of gloating innocently over his own power to gloat; the power to delight consciously in his own delight at being able to play—these, I believe, are naturally Scots pleasures, and profoundly Stevensonian pleasures. I hope that no reader will deny Stevenson the right to such enjoyments, for Stevenson’s not very complex nature is really bound up in them. If we take from him the satisfaction of seeing himself in every conceivable posture, we take from him a vanity which permeates his whole life-work, and which, properly regarded, is harmless to offend our taste.

“One of the pleasantest things in the world,” says Hazlitt, “is going on a journey; but I like to go alone.” In his earliest days of manhood, Stevenson also formed the habit of going alone; and in his own essay upon Walking Tours he very circumstantially endorses Hazlitt’s view, for reasons into which we need not enter here. We may find an indication of his habit even so early as the fragment, included in Essays of Travel, which describes a journey from Cockermouth to Keswick. Other papers, of various dates, show that, either from choice or from necessity, he often did tramp solitary; but it is worth noting that only in the walk through the Cevennes and in his journey to America did Stevenson ever travel alone for any length of time. His other, and on the whole more important, travel-books are the descriptions of journeys taken in company.

[43]Furthermore, in the early essay which we have just noted he rather ostentatiously proclaims his practice in writing accounts of his tours. He says, “I cannot describe a thing that is before me at the moment, or that has been before me only a little while before; I must allow my recollections to get thoroughly strained free from all chaff till nothing be except the pure gold.” Apart from the surprising alchemy of the declaration, this disability is wholly to his credit; but Stevenson found, of course, that when he planned to record a journey of some duration, in a form more or less chronological, he must preserve a sense of fabric in his book by keeping a daily diary of experiences. That is why, in his earliest book of travel, An Inland Voyage, he mentions “writing-up” his diary at the end of each day; and it explains also the frequent references in later books to such an evening occupation. As Stevenson admitted in Cockermouth and Keswick, the process of incubation might in the long run be unreasonably prolonged; and perhaps it is true that experience taught him very early that in the professional writer thrift is a virtue. It was, if so, a lesson that he never forgot.

Although the fragment on Keswick to which I have referred is clearly a juvenile piece of[44] work, it is highly entertaining as a small piece of autobiography. On its own account the essay is rather pragmatical and anecdotal, after the manner of an afternoon sermon, and it gives as yet small evidence that the writer has any highly developed sense of accurate and significant observation. But to the reader who cares to go below its superficial interest, there is other material. Not without value are the boyish allusions to his pipe, to his whisky-and-soda, and to his importance in the smoking-room of the hotel. These are all typical, and interesting. What, however, is clear on the question of mere literary talent, is Stevenson’s ability to spin something out of himself. He must be talking; and, if he has nothing of much moment to say, there must follow some apt reflection, or a “tale of an old Scots minister.”

Would that the ability, a very dangerous ability, had been shed as soon as were some of Stevenson’s juvenile theories about the art of writing! This particular ability remains very noticeably in his first full-size travel-book, An Inland Voyage, along with another trait—his abnormal consciousness of his own appearance in the eyes of other people. Stevenson was always interested in that aspect of his personality: he could not forget for a moment[45] that his costume, his face, his manner, all carried some impression to the beholder. It was a part of his nature that he should see children upon the river bank, not merely as children, but as an audience, a congregation of speculating souls busy wondering about him, likening him among themselves to some particular figure, interested in him. Nobody, I think, had ever failed to be interested in him.

An Inland Voyage, on the whole, is a poor book. It records a canoeing expedition made with a friend; and it is full of Puritanical obtuseness and a strained vanity which interferes with the main narrative. Setting out from Antwerp, the two friends paddled, often in the rain, and sometimes—as in the case of Stevenson’s arrest, and his dangerous accident with the fallen tree across the swollen Oise—in dire straits. They travelled on the Sambre and down the Oise by Origny and Moy, Noyon, Compiègne, and Précy; but the weather was bad, and there were trying difficulties about lodgings; and Stevenson’s account reads as though he had been chilled through and through, and as though he needed nothing so[46] much as his home. Almost invariably, in this book, his little spurts of epigram and apophthegm suggest low spirits as well as a sort of cautious experimentalism; and the book, which apparently was very handsomely received by the Press on its publication, is eked out with matter which, beneath the nervous delicacy of Stevenson’s practising style, is raw and sometimes banale. In no other travel-book is there shown such obvious effort. What emerges from An Inland Voyage is the charmingly natural behaviour on several occasions of Stevenson’s companion, a proof even thus early of the author’s ability to be aware of these traits in his friends which, on the printed page, convey to the reader an impression of the person so lightly sketched. This, however, is an exiguous interest in a book supposed to be a picturesque work of travel and topography.

Very much superior is the Sternian Travels with a Donkey. Here there is much greater lightness of touch, and a really admirable sense of observation is revealed. Some of the descriptions of things seen are written with indescribable delicacy, as are the character sketches. Just so are some of the descriptions of places contained in the series of letters to Mrs. Sitwell. In Travels with a Donkey for[47] the first time the reader actually makes a third with Stevenson and the endearing Modestine upon their journey, travelling with them and sharing the sensations of the human pedestrian. If we resent certain intolerable affectations—such as the pretentious and penurious fancy of placing money by the roadside in payment for lodgings in the open air—that resentment may be partly due to the fact that we are not told the amount of the payment, as well, of course, as to the fact that we suspect the author’s motive in detailing his charities. Stevenson seems, in fact, to be asking for commendation of a fantastic generosity without giving us sufficient evidence to evoke any feeling of conviction. We see him here, not so much obeying a happy impulse as observing himself in the light of his own esteem; and that is hardly a pleasant sight to the onlooker. To counterbalance such lapses—which, very likely, are regarded by lovers of Stevenson as no lapses at all, but as delightful exhalations of personality, as glimpses of his character which they are enabled to enjoy only through this very innocent vanity which we have noted,—there are a thousand graceful touches, fit to remind us that Travels with a Donkey is a much better book than An Inland Voyage, and, in fact, the best of his travel-books until we reach that[48] delightfully modest one which is too little known—The Silverado Squatters. The Donkey is the first in which the charming side of his personality really “gets going,” and it will always remain a pretty and effective sketch of a journey taken in wayward weather, with good spirits, a shrewd and observant eye, and, what is also to the point, a commendable courage.

The Amateur Emigrant and Across the Plains, two long records which, although published separately, are practically a single work, for all their difference from that book are a drop to the executive level of An Inland Voyage. Here again Stevenson was affected by the discomforts of his lonely travelling, and no doubt by his poor health. Both records are for the most part superficial and crabbed. The descriptions of travelling-companions are conscientious, but they have, as Stevenson’s earliest admirers were the first to remark, no imagination or genuine moulding: the accounts are a good deal like uninspired letters home. If one thinks what Stevenson, in happy circumstances, might have made of the tale of his journey, one realises how lifeless are the descriptions given. They have no sense of actual contact; they have lost grip in losing charm, and might have been written[49] by somebody with far less of an eye to the significance of the passing scene. Stevenson claimed to have been aware of the prosaic character of the records, and, indeed, in one letter to Sir Sidney Colvin he said, “It bored me hellishly to write; well, it’s going to bore others to read; that’s only fair.” So perhaps it is not worth while to analyse such confessedly inferior works. Only once in The Amateur Emigrant—in the anecdote of two men who lodged perilously in New York—does Stevenson’s boyish love of the picturesquely terrible bring a note of tense reality to the writing. In its own way the account of the two men looking from their bedroom, through the frame of a seeming picture, into another room where three men are crouching in darkness, is a little masterpiece of horror. It belongs to his romances rather than to his travel-books; but it is the passage that stands out most distinctly from the two which are under notice at the moment. No other scene in either The Amateur Emigrant or Across the Plains compares with it for interest or value.

Following upon his tedious journey to America, and the hardships and illness which,[50] before his marriage, brought him nearly to his grave, Stevenson went to the mountains for health. The Silverado Squatters was written-up later, and, from Stevenson’s letters of that time, it seems to have been condemned as uncharacteristic. But it may have been that, as I think was the case, Stevenson’s voyage to America and his marriage considerably affected his outlook. For one thing he really had come into contact with hard inconvenience and loneliness, with a self-inflicted exile from his family (and a hostility to his marriage on their part which existed more in his imagination than in fact), which matured him. Those of us who never take these voyages out into the unknown, who sit tight and think comfortably of such things as emigrant trains, cannot realise with what sudden effect the stubborn impact of realities can work upon those who actually venture forth. One small instance will show something of the experience Stevenson gained. On the voyage he met emigrants who were leaving Scotland because there was nothing else for them to do, because to stay meant “to starve.” Coming to these men, and hearing from them something of the lives they had left, he touched a new aspect of life which, in spite of his runnings to-and-fro[51] in Edinburgh and elsewhere, he had never appreciated. He writes, in The Amateur Emigrant:

I had heard vaguely of these reverses; of whole streets of houses standing deserted by the Tyne, the cellar-doors broken and removed for firewood; of homeless men loitering at the street-corners of Glasgow with their chests beside them; of closed factories, useless strikes, and starving girls. But I had never taken them home to me or represented these distresses livingly to my imagination.

And when, in Across the Plains, he tells how his emigrant train, going in one direction, crowded, was met by another, also crowded, returning, must that not have reacted upon his mind? My own impression, which of course is based upon nothing more than the apparent change in Stevenson’s manner of writing, is that The Silverado Squatters, as we now have it, very much altered from the condemned first drafts, represents the emergence of a new Stevenson, who, in The Amateur Emigrant and Across the Plains, had been overweighted by the material realities he had in bad health encountered, and who, in consequence, had failed to make those accounts vivid. The Silverado Squatters has more substance than[52] its predecessors. It is much more free, it is almost entirely free, from affectation. The style is less full of trope, and may be considered therefore, by some readers, as the less individual. But the matter and manner are more strictly united than hitherto. We are not interrupted by such trivial explosions of sententiousness as “We must all set our pocket-watches by the clock of Fate,” and in the degree in which the matter entirely “fills-out” the manner the book is so far remarkable. It is not generally regarded as convenient to say that Stevenson’s matter was often thin, and his style a mere ruffle and scent to draw off the more frigid kind of reader; yet when we come to work so able and so unpretentious as The Silverado Squatters, in which Stevenson is honestly trying to show what he saw and knew (instead of trying to show the effect of his address upon a strange community) we do seem to feel that what has gone before has been less immediately the natural work of the writer, and more the fancy sketch of the writer’s own sense of his picturesque figure. In one aspect, in its lack of vivacity, The Silverado Squatters may compare to disadvantage with earlier work; it may seem, and indeed is ordinarily condemned as, less pungent, and less elastic; but that[53] could only be to those who miss the fact that Stevenson’s pungency and elasticity were the consequence of the unwearying revision to which most of his work was subjected. He was never a quick worker, never one of those careless writers whose ear approves while the pen is in motion. He had a fine ear, but not essentially a quick ear; he was not what is sometimes called a “natural” writer, but with devoted labour went again and again through what he had written, revising it until his fastidiousness was relieved. This way of working, while it served to allay what he called the “heat of composition”—a heat which some readers find very grateful in other, less painstaking writers—has patent virtues. It is likely to make work more polished and more finely balanced. Nevertheless, it probably has the effect of reducing the vigour and resilience of a style. However that may be, it is a method making great demands upon a writer’s deep conscientiousness; and it is not the purpose of this book to extol the rapid method or the quick ear. All we may do at this moment is to suggest that Stevenson, having done well in practising year after year the craft of the writer, had now turned very deliberately and honourably in the first year of his marriage to that other side of the[54] writer’s craft, the sober description, free from the amateur’s experimentalism, of the real world as he saw it. Even so, it is a world made smooth by his temperament—his love of smoothness, which one may see exemplified in his declared love of simple landscape—and by his matured dexterity in manipulating sentences. It is a world seen, not with rich vitality, but with the friendly interest of one in a fair haven, whose imagination is not fierce enough to be a torture to him. Stevenson heard, saw, and really felt his surroundings; his descriptions of sudden beauties here at Silverado, as later in Samoa, have the quiet religious character which distinguished all his truest intuitions of beauty. Not his the ecstatic oneness with the lovely things of Nature which makes Keats the purest exponent of what Keats himself called “that delicate snail’s-horn perception of beauty”: Stevenson’s ecstasy had to be stirred by excitement; he had not the poet’s open-handed out-running to the emotion of place. But his sense of the remoteness of the squatters of Silverado, his early-morning peeps into the wonders of colour and aspect in a strange corner of the earth, his shrewd understanding of sullen human nature, are made clear to the reader by plain expression. The book is self-conscious[55] in a good sense; not, as has often hitherto been the case, in a bad one.

If we notice such a change of attitude in The Silverado Squatters, we shall find it even more fully revealed in the volume of his letters for an American magazine which appeared under the title of In the South Seas. Some of the letters were withheld, as too tedious; even now, the book is frankly called dull by many staunch admirers of Stevenson. To others, however, it must surely appear otherwise. It is, in effect, a sort of glorified log; but a log of real enterprise and adventure in a marvellous part of the world. Stevenson heroically tried to penetrate to the heart of the South Seas. He was caught up by the islands and their people, and was bent upon making them known to those who lived afar. In the political intrigues so honestly described in his letters, Stevenson may, indeed, appear to throw away the importance of his own genius; but the sacrifice is made in obedience to his deepest convictions of right. He still sees himself as the point of focus; but we do not resent that when we find ourselves so clearly in his train. Even while his friends were urging him to give up the Samoan[56] politics which threatened to become the King Charles’s head of his correspondence, he continued to live amid the difficulties from which he felt that he could not in honour withdraw. And although the Samoan period had its fluctuations of talent, it was, upon the whole, the time when his boyish love of game took on a keener zest of earnest and made him indeed a man. The period marks a further decline in the more strictly romantic nature of his work, as we may later on be able to discuss in comparing St. Ives with earlier and more triumphant experiments in that field; but it opens the path for the sober realism (if that word may here be used without sinister connotation) of the torso known as Weir of Hermiston, a fragment in which it is usual to find the greatest promise of all. This is all of a piece with the increasing purpose of Stevenson’s way in life. It is a good sign when a professional author forsakes romance in favour of reality; for romance may be conjured for bread-and-butter, while reality withstands the most persuasive cajollery. Stevenson was the professional author in his collaborations, and in such work as St. Ives; but in In the South Seas as in Weir he is writing truth for the love of truth, than which there can be no more noble kind of authorship.

[57]

In San Francisco, as we have seen, Stevenson chartered a schooner-yacht, and went to the South Seas in pursuit of health. On board ship he was always happy; and he made more than one cruise, in different ships, among the Gilbert, Paumotuan, and Marquesan groups of islands. He also stayed for periods of varying length in the three groups of islands, became familiar with the manners of the natives, realised their distinctions, and made many new friends among them. His mind was entirely occupied with them; he saw everything he could, and learned everything he could, his shrewd Scots habit of inquiry filling him with a satisfied sense of labour. A big book, proving beyond doubt the entire peculiarity of the South Sea islands and their islanders, was planning in his mind; a book which would soundly establish his reputation as something other than a literary man and a teller of tales. In the South Seas, as I have already mentioned, was found dull by friendly critics; yet it is full of observation and of feeling. It is the wisest of the travel-books, and the most genuine, for Stevenson has put picturesqueness behind him for what it is—the hall-mark of the second-rate writer; and[58] he has risen to a height of understanding which adds to his stature. There is, in the portrait of Tembinok’, a simplicity which is impressive: throughout, there is a simple exposition of a fascinating subject, a kind of life remote from our experience, a civilisation strict and dignified, minds and habits interesting in themselves and by contrast with our own. The book may not be the epitome of the South Seas for which the chapters were planned as rough notes; other writers may have known more than Stevenson knew of the actual life of the islands. It is true that he frequented kings’ palaces, and that his acquaintance with common native life was very largely a matter of observation caught up in passing, or by hearsay, or by the contemplation of public gatherings. That is true. What we, as readers endeavouring patiently to trace the growth of Stevenson’s knowledge, must, however, remember above all things, is that the book is really a finer and a more distinguished work than An Inland Voyage or Travels with a Donkey. It has not the grimaces of the first, or the pleasing delicacy of the second. It is a better book than The Amateur Emigrant and Across the Plains. It is fuller and richer than The Silverado Squatters. What, then, do we ask of a book of travel? Is it that we may see[59] the author goading his donkey, or putting money by the wayside for his night’s lodging; or is it that we may see what he has seen? With Stevenson, the trouble is, I suppose, that, having thought of him always as a dilettante, his admirers cannot reconcile themselves to his wish to be a real traveller and a real historian. Perhaps they recognise that he had not the necessary equipment? Rather, it is very likely that, being largely uncreative themselves, they had planned for Stevenson a future different from the one into which gradually he drifted. All creative writers have such friends. We may say, perhaps, that a man who was not Stevenson could have written In the South Seas, though I believe that is not the case. But if we put the books slowly in order we shall almost certainly find that while Travels with a Donkey is a pretty favourite, with airs and graces, and a rather imaginary figure charmingly posed as its chief attraction, In the South Seas is the work of the same writer, grown less affected, more intent upon seeing things as they are, and less intent upon being seen in their midst. There is the problem. If a travel-book is an exploitation of the traveller’s self, we can be charmed with it: let us not, therefore, because we find less charm in In the South Seas, find[60] the later book dull. Stevenson is duller because he is older: the bloom is going: he is not equal intellectually to the task he has set himself. But there is a greater sincerity in the later travel-books, an honest looking upon the world. It is surely better to look straight with clear eyes than to dress life up in a bundle of tropes and go singing up the pasteboard mountain. Stevenson’s admirers want the song upon the mountain, because they want to continue the legend that he never grew up. They want him to be the little boy with a fine night of stars in his eyes and a pack upon his back, singing cheerily that it is better to travel hopefully than to arrive. That is why Stevenson’s best work is, relatively speaking, neglected in favour of work that tarnishes with the passing of youth. And it is all because of the insatiable desire of mediocrity for the picturesque. We must be surprised and startled, and have our senses titillated by savours and perfumes; we must have the strange and the new; we must have a fashion to follow and to forget. Stevenson has been a fashionable traveller, and his sober maturity is too dull; he has lost his charm. Well, we must make a new fashion. Interest in a figure must give place to interest in the work. If the work no longer interests, then[61] our worship of Stevenson is founded upon a shadow, is founded, let us say, upon the applause of his friends, who sought in his work the fascination they found in his person.

There have been some English essayists whose writing is so packed with thought that it is almost difficult to follow the thought in its condensation. Such was Bacon, whose essays were by way of being “assays,” written so tightly that each little sentence was the compression of the author’s furthest belief upon that aspect of his subject, and so that to modern students the reading of Bacon’s essays resembles the reading of a whole volume printed in Diamond type. There have been English essayists whose essays are clear-cut refinements of truth more superficial or more simple. Such was Addison, who wrote with a deliberate and flowing elegance, and whose essays Stevenson found himself unable to read. There have been such essayists as Hazlitt, the shrewd sincerity of whose perceptions is expressed with so much appropriateness that his essays are examples of what essays should be. There has never been[63] in England a critic or an essayist of quite the same calibre as Hazlitt. It was of Hazlitt that Stevenson wrote, in words so true that they summarily arrest by their significance the reader who does not expect to find in Walking Tours so vital an appraisement: “Though we are mighty fine fellows nowadays, we cannot write like Hazlitt.” And, in succession, for there would be no purpose in continuing the list for its own sake, there have been essayists who, intentionally resting their work upon style and upon the charm of personality, have in a thousand ways diversified their ordinary experience, and so have been enabled to disclose as many new aspects and delights to the reader. Such an essayist was Lamb. Hazlitt, I think, was the last of the great English essayists, because Hazlitt sought truth continuously and found his incomparable manner in the disinterested love of precision to truth. But Lamb is the favourite; and Lamb is the English writer of whom most readers think first when the word “essay” is mentioned. That is because Lamb brought to its highest pitch that personal and idiosyncratic sort of excursion among memories which has created the modern essay, and which has severed it from the older traditions of both Bacon and Addison. It is to the school of[64] Lamb, in that one sense, that Stevenson belonged. He did not “write for antiquity,” as Lamb did; he did not write deliberately in the antique vein or in what Andrew Lang called “elderly English”; but he wrote, with conscious and anxious literary finish, essays which had as their object the conveyance in an alluring manner of his own predilections. He quite early made his personality what Henley more exactly supposed that it only afterwards became—a marketable commodity—as all writers of strong or acquired personality are bound to do.

Since Stevenson there have been few essayists of classic rank, largely because the essay has lost ground, and because interest in “pure” literature has been confined to work of established position (by which is meant the work of defunct writers). There has been Arthur Symons, of whose following of Pater as an epicure of sensation we have heard so much that the original quality of his fine work—both in criticism and in the essay—has been obscured. There has been an imitator of Stevenson, an invalid lady using the pseudonym “Michael Fairless”; and there have been Mr. Max Beerbohm, Mr. E. V. Lucas, Mr. Belloc, Mr. Chesterton, Mr. Street, Mr. A. C. Benson, and Mr. Filson Young. These writers have all[65] been of the “personal” school, frankly accepting the essay as the most personal form in literature, and impressing upon their work the particular personal qualities which they enjoy. Some of them have been more robust than others, some less distinguished; but all of them are known to us (in relation to their essays) as writers of personality rather than as writers of abstract excellence. An essay upon the art of the essay, tracing its development, examining its purpose, and distinguishing between its exponents, might be a very fascinating work. Such an essay is manifestly out of place here; but it is noteworthy that, apart from the distinguished writers whose names I have given, nearly all the minor writers (that is, nearly all those whose names I have not mentioned) who have produced essays since the death of Stevenson, or who are nowadays producing genteel essays, have been deeply under his influence. It is further noteworthy that most of those who have been so powerfully influenced have been women.

From the grimly earnest abstracts of knowledge contributed by Bacon to the art of the essay, to the dilettante survey of a few fancies,[66] or memories, or aspects of common truth which ordinarily composed a single essay by Stevenson, is a far cry. But Stevenson, as I have said, belonged to the kind of essayist of whom in England Charles Lamb is most representative, and of whom Montaigne was most probably his more direct model—the writer who conveyed information about his personal tastes and friends and ancient practices in a form made prepossessing by a flavoured style. To those traits, in Stevenson’s case, was added a strong didactic strain, as much marked in his early essays as in the later ones; and it is this strain which differentiates Stevenson’s work from that of Lamb and Montaigne. Montaigne’s essays are the delicious vintage of a ripe mind both credulous and sceptical, grown old enough to examine with great candour and curiousness the details of its own vagaries: many of Stevenson’s most characteristic essays are the work of his youth, as they proclaim by the substitution of the pseudo-candour of vanity for the difficult candour of Montaigne’s shrewd naïveté. He was thirty or thirty-one when the collection entitled Virginibus Puerisque was published. A year later there followed Familiar Studies of Men and Books. He was only thirty-seven (Montaigne was thirty-eight when he “retired” from active life and began[67] to produce his essays) when his third collection, Memories and Portraits, obviously more sedate and less open to the charge of literary affectation, completed the familiar trilogy. Although Across the Plains did not appear until 1892, many of the essays which help to form that book had earlier received periodical publication (the dated essays range from 1878 to 1888); while some of the papers posthumously collected in The Art of Writing belong to 1881. So it is not unfair to say that the bulk of Stevenson’s essays were composed before he reached the age of thirty-five; and thirty-five, although it is an age by which many writers have achieved fame, is not quite the age by which personality is so much matured as to yield readily to condensation. Therefore we must not look, in Stevenson’s essays, for the judgments of maturity, although we may find in Virginibus Puerisque a rather middle-aged inexperience. We must rather seek the significance of these essays in the degree in which they reveal consciously the graces and the faultless negligé of an attractive temperament. We may look to find at its highest point the illustration of those principles of style which Stevenson endeavoured to formulate in one very careful essay upon the subject (to the chagrin, I seem to remember, at the time of its[68] republication, of so many critics who misunderstood the aim of the essay). And we shall assuredly find exhibited the power Stevenson possessed of quoting happily from other writers. Quotation with effect is a matter of great skill; and Stevenson, although his reading was peculiar rather than wide, drew from this very fact much of the inimitable effect obtained by references so apt.

One note which we shall find persistently struck and re-struck in Stevenson’s essays is the memory of childhood. From Child’s Play to The Lantern-Bearers we are confronted by a mass of material regarding one childhood, by which is supported a series of generalisations about all children and their early years. So we proceed to youth, to the story of A College Magazine; and so to Ordered South. Then we return again to An Old Scotch Gardener and The Manse, where again that single childhood, so well-stored with memories, provides the picture. Now it is one thing for Stevenson to re-vivify his own childhood, for that is a very legitimate satisfaction which nobody would deny him; but it is another thing for Stevenson, from that single experience and with no other apparent observation or inquiry, to[69] generalise about all children. While he tells us what he did, in what books and adventures and happenings he found his delight, we may read with amusement. When, upon the other hand, he says, “children are thus or thus,” it is open to any candid reader to disagree with Stevenson. Whether it is that he has set the example, or whether it is that he merely exemplifies the practice, I cannot say; but Stevenson is one of those very numerous people who talk wisely and shrewdly about children in the bulk without seeming to know anything about them. These wiseacres alternately under-rate and make too ingenious the intelligence and the calculations of childhood, so that children in their hands seem to become either sentimental barbarians or callous schemers, but are never, in the main, children at all. Stevenson has a few excellent words upon children: he admirably says, “It is the grown people who make the nursery stories; all the children do, is jealously to preserve the text”: but I am sorry to say that, upon the whole, I can find little else that is of value in his general observations.

It is open to anybody to reconstruct a single real childhood from Stevenson’s essays, and no doubt that is a matter of considerable interest, as anything which enables us to understand a[70] man is of value. Curiously enough, however, Stevenson’s essays upon the habits and notions of children seem to suggest a great deal too much thought about play, and too little actual play. They seem to show him, as a little boy, so precocious and lacking in heart, that he is watching himself play rather than playing. It is not the preliminary planning of play that delights children, not the academic invention of games and deceits; it is the immediate and enjoyable act of play. Our author shows us a rather elderly child who, in deceiving himself, has savoured not so much the game as the supreme cleverness of his own self-deception. That, to any person who truly remembers the state of childhood, may be accepted as a perfectly legitimate recollection; and it is so far coherent. That his own habit should be, in these essays, extended to all other children whatsoever—in fact, to “children”—is to make all children delicate little Scots boys, greatly loved, very self-conscious, and, in the long run, rather tiresome, as lonely, delicate little boys incline to become towards the end of the day. Unfortunately the readers of Stevenson’s essays about little boys have mostly been little girls; and they are not themselves children, but grown-up people who are looking back at their own childhood[71] through the falsifying medium of culture and indulgent, dishonest memory. Culture, in dwelling upon interpretations and upon purposes, and in seeing childhood always through the refraction of consequence, destroys interest in play itself; and if play is once called in question it very quickly becomes tedious rigmarole.

Stevenson’s essays must thus be divided into two parts, the first descriptive, the second generalised. The first division, sometimes delightful, is also sometimes sophisticated, and sometimes is exaggerative of the originality of certain examples of play. The second is about as questionable as any writing on children has ever been, because it is based too strictly upon expanded recollections of a single abnormal model. You do not, by such means, obtain good generalisations.

Something of the same objection might be urged against Stevenson’s rather unpleasant descriptions of adolescence. These again are not typical. Stevenson himself was the only youth he ever knew—he never had the detachment to examine disinterestedly the qualities of any person but himself—and we might gain from his descriptions an impression of youth which[72] actually will not bear the stereoscopic test to which we are bound to submit all generalisations. To read the essays with the ingenuous mind of youth is to feel wisdom, grown old and immaculate, passing from author to reader. It is to marvel at this debonair philosopher, who finds himself never in a quandary, and who has the strategies of childhood and of youth balanced in his extended hand. It is to proceed from childhood to youth, and from youth to the married state; and our adviser describes to us in turn, with astonishing confidence, the simplified relations, which otherwise we might have supposed so intricate, of the lover, the husband, and the wife. Nothing comes amiss to him: love, jealousy, the blind bow-boy, truth of intercourse—these and many other aspects of married life are discoursed upon with grace and the wistful sagaciousness of a decayed inexperience. But when we consider the various arguments, and when we bring the essays Virginibus Puerisque back to their starting-point, we shall find that they rest upon the boyish discovery that marriages occur between unlikely persons. Stevenson has not been able to resist the desire to institute an inquiry into the reasons. He cannot suppose that these persons love one another; and yet why else should they marry? Well, he is[73] writing an essay, and not a sociological study, so that—as the result of his inquiry—we must not expect to receive a very distinct contribution to our knowledge. We may prepare only to be edified, to be, perhaps, greatly amused by a young man who may at least shock us, or stir us, if he is unable to show this fruitful source of comedy in action. We are even, possibly, alert to render our author the compliment of preliminary enjoyment, before we have come to his inquiry. What Stevenson has to tell us about marriage, however, is a commonplace; even if it is a commonplace dressed and flavoured. It is that “marriage is a field of battle—not a bed of roses”; and it is that “to marry is to domesticate the Recording Angel.” “Alas!” as Stevenson says of another matter, “If that were all!”