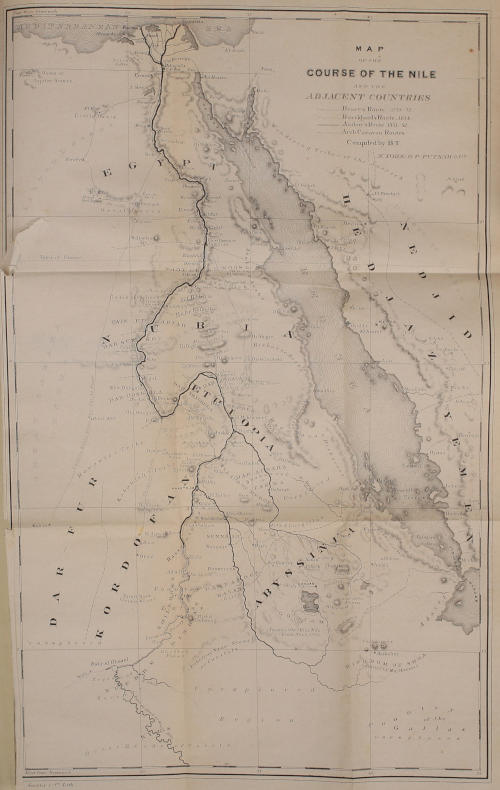

ABA, VILLAGE OF THE SHILLOOK NEGROES.

ABA, VILLAGE OF THE SHILLOOK NEGROES.

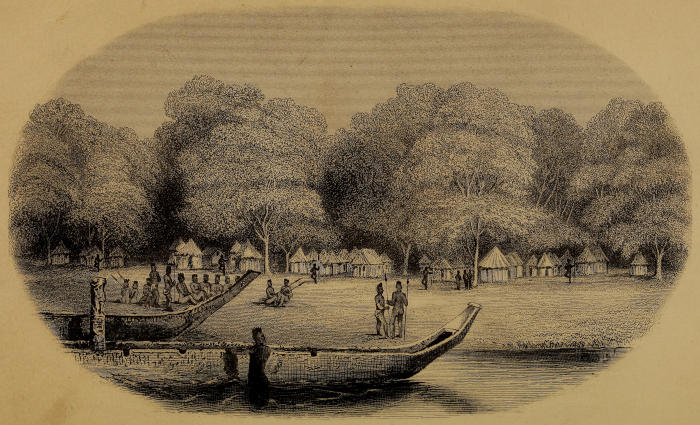

CENTRAL AFRICA

BAYARD TAYLOR.

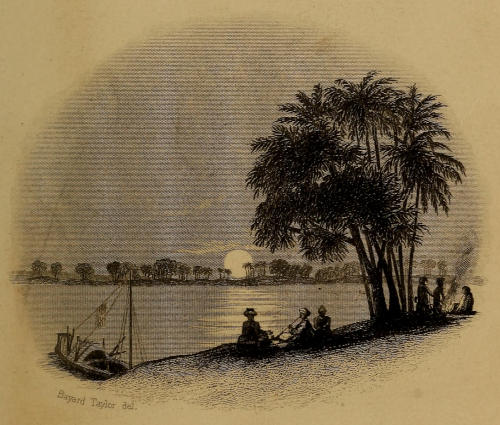

The Ethiopian Nile. Bayard Taylor del.

New-York: G. P. Putnam.

A

JOURNEY TO CENTRAL AFRICA;

OR,

LIFE AND LANDSCAPES FROM EGYPT

TO THE NEGRO KINGDOMS OF

THE WHITE NILE.

By BAYARD TAYLOR.

WITH A MAP AND ILLUSTRATIONS BY THE AUTHOR.

NEW YORK:

G. P. PUTNAM AND SON, 661 Broadway,

Opposite Bond Street.

1869.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1854, by

G. P. PUTNAM & CO.,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern

District of New York.

RIVERSIDE, CAMBRIDGE:

PRINTED BY H. O. HOUGHTON AND COMPANY.

Dedicated to

A. B.

OF SAXE-COBURG-GOTHA,

BY

HIS FELLOW-TRAVELLER IN EGYPT.

B. T.

There is an old Italian proverb, which says a man has lived to no purpose, unless he has either built a house, begotten a son, or written a book. As I have already complied more than once with the latter of these requisitions, I must seek to justify the present repetition thereof, on other grounds. My reasons for offering this volume to the public are, simply, that there is room for it. It is the record of a journey which led me, for the most part, over fresh fields, by paths which comparatively few had trodden before me. Although I cannot hope to add much to the general stock of information concerning Central Africa, I may serve, at least, as an additional witness, to confirm or illustrate the evidence of others. Hence, the preparation of this work has appeared to me rather in the light[2] of a duty than a diversion, and I have endeavored to impart as much instruction as amusement to the reader. While seeking to give correct pictures of the rich, adventurous life into which I was thrown, I have resisted the temptation to yield myself up to its more subtle and poetic aspects. My aim has been to furnish a faithful narrative of my own experience, believing that none of those embellishments which the imagination so readily furnishes, can equal the charm of the unadorned truth.

There are a few words of further explanation which I wish to say. The journey was undertaken solely for the purpose of restoring a frame exhausted by severe mental labor. A previous experience of a tropical climate convinced me that I should best accomplish my object by a visit to Egypt, and as I had a whole winter before me, I determined to penetrate as far into the interior of Africa as the time would allow, attracted less by the historical and geographical interest of those regions than by the desire to participate in their free, vigorous, semi-barbaric life. If it had been my intention, as some of my friends supposed, to search for the undiscovered sources of the White Nile, I should not have turned back, until the aim was accomplished or all means had failed.

I am aware that, by including in this work my journey through Egypt, I have gone over much ground[3] which is already familiar. Egypt, however, was the vestibule through which I passed to Ethiopia and the kingdoms beyond, and I have not been able to omit my impressions of that country without detracting from the completeness of the narrative. This book is the record of a single journey, which, both in its character and in the circumstances that suggested and accompanied it, occupies a separate place in my memory. Its performance was one uninterrupted enjoyment, for, whatever the privations to which it exposed me, they were neutralized by the physical delight of restored health and by a happy confidence in the successful issue of the journey, which never forsook me. It is therefore but just to say, that the pictures I have drawn may seem over-bright to others who may hereafter follow me; and I should warn all such that they must expect to encounter many troubles and annoyances.

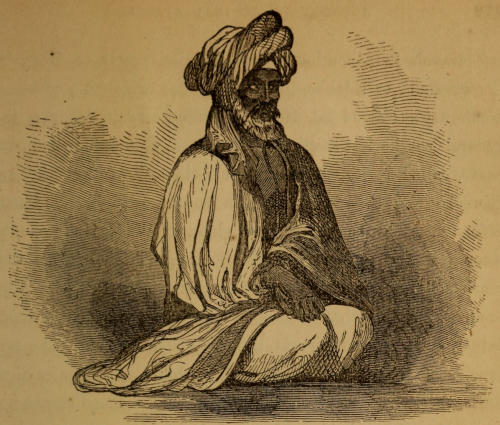

Although I have described somewhat minutely the antiquities of Nubia and Ethiopia which I visited, and have not been insensible to the interest which every traveller in Egypt must feel in the remains of her ancient art, I have aimed at giving representations of the living races which inhabit those countries rather than the old ones which have passed away. I have taken it for granted that the reader will feel more interested—as I was—in a live Arab, than a dead[4] Pharaoh. I am indebted wholly to the works of Champollion, Wilkinson and Lepsius for whatever allusions I have made to the age and character of the Egyptian ruins.

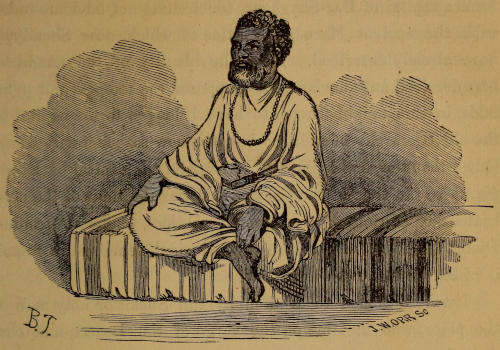

B. T.

New York, July, 1854.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Arrival at Alexandria—The Landing—My First Oriental Bath—The City—Preparations for Departure, | 13 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

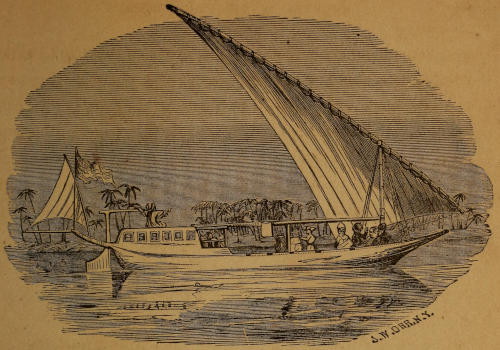

| Departure—The Kangia—The Egyptian Climate—The Mahmoudieh Canal—Entrance into the Nile—Pleasures of the Journey—Studying Arabic—Sight of the Pyramids—The Barrage—Approach to Cairo, | 21 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Entrance—The Ezbekiyeh—Saracenic Houses—Donkeys—The Bazaars—The Streets—Processions—View from the Citadel—Mosque of Mohammed Ali—The Road to Suez—The Island of Rhoda, | 34 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Necessity of Leaving Immediately—Engaging a Boat—The Dragomen—Achmet el Saïdi—Funds—Information—Procuring an Outfit—Preparing for the Desert—The Lucky Day—Exertions to Leave—Off, | 46 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Howling Dervishes—A Chicken Factory—Ride to the Pyramids—Quarrel with the Arabs—The Ascent—View from the Summit—Backsheesh—Effect of Pyramid-climbing—The Sphinx—Playing the Cadi—We obtain Justice—Visit to Sakkara and the Mummy Pits—The Exhumation of Memphis—Interview with M. Mariette—Account of his Discoveries—Statue of Remeses II.—Return to the Nile, | 55[6] |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Leaving the Pyramids—A Calm and a Breeze—A Coptic Visit—Minyeh—The Grottoes of Beni-Hassan—Doum Palms and Crocodiles—Djebel Aboufayda—Entrance into Upper Egypt—Diversions of the Boatmen—Siout—Its Tombs—A Landscape—A Bath, | 71 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

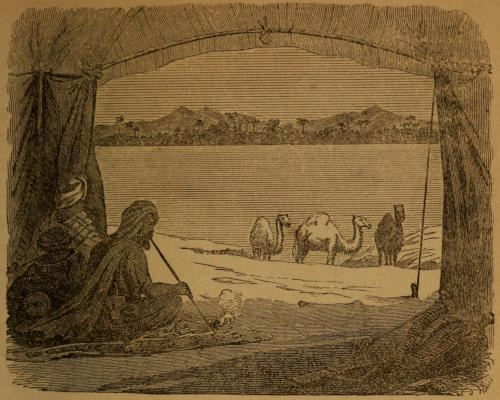

| Independence of Nile Life—The Dahabiyeh—Our Servants—Our Residence—Our Manner of Living—The Climate—The Natives—Costume—Our Sunset Repose—My Friend—A Sensuous Life Defended, | 85 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Calm—Mountains and Tombs—A Night Adventure in Ekhmin—Character of the Boatmen—Fair Wind—Pilgrims—Egyptian Agriculture—Sugar and Cotton—Grain—Sheep—Arrival at Kenneh—A Landscape—The Temple of Dendera—First Impressions of Egyptian Art—Portrait of Cleopatra—A Happy Meeting—We approach Thebes, | 98 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Arrival at Thebes—Ground-Plan of the Remains—We Cross to the Western Bank—Guides—The Temple of Goorneh—Valley of the Kings’ Tombs—Belzoni’s Tomb—The Races of Men—Vandalism of Antiquarians—Bruce’s Tomb—Memnon—The Grandfather of Sesostris—The Head of Amunoph—The Colossi of the Plain—Memnonian Music—The Statue of Rameses—The Memnonium—Beauty of Egyptian Art—More Scrambles among the Tombs—The Bats of the Assasseef—Medeenet Abou—Sculptured Histories—The Great Court of the Temple—We return to Luxor, | 113 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Dancing Girls of Egypt—A Night Scene in Luxor—The Orange-Blossom and the Apple-Blossom—The Beautiful Bemba—The Dance—Performance of the Apple-Blossom—The Temple of Luxor—A Mohammedan School—Gallop to Karnak—View of the Ruins—The Great Hall of Pillars—Bedouin Diversions—A Night Ride—Karnak under the Full Moon—Farewell to Thebes, | 131 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The Temple of Hermontis—Esneh and its Temple—The Governor—El Kab by Torch-light—The Temple of Edfou—The Quarries of Djebel Silsileh—Ombos—Approach to Nubia—Change in the Scenery and Inhabitants—A Mirage—Arrival at Assouan, | 145 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| An Official Visit—Achmet’s Dexterity—The Island of Elephantine—Nubian Children—Trip to Philæ—Linant Bey—The Island of Philæ—Sculptures—The Negro Race—Breakfast[7] in a Ptolemaic Temple—The Island of Biggeh—Backsheesh—The Cataract—The Granite Quarries of Assouan—The Travellers separate, | 152 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Solitary Travel—Scenery of the Nubian Nile—Agriculture—The Inhabitants—Arrival at Korosko—The Governor—The Tent Pitched—Shekh Abou-Mohammed—Bargaining for Camels—A Drove of Giraffes—Visits—Preparations for the Desert—My Last Evening on the Nile, | 162 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

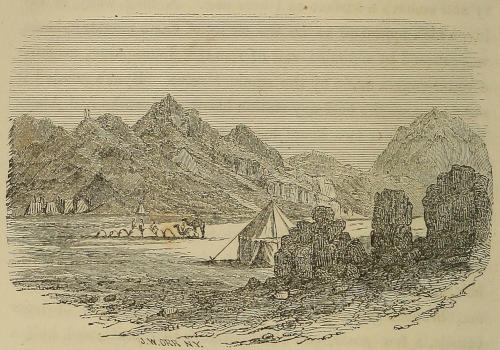

| The Curve of the Nile—Routes across the Desert—Our Caravan starts—Riding on a Dromedary—The Guide and Camel-drivers—Hair-dressing—El Biban—Scenery—Dead Camels—An Unexpected Visit—The Guide makes my Grave—The River without Water—Characteristics of the Mirage—Desert Life—The Sun—The Desert Air—Infernal Scenery—The Wells of Mûrr-hàt—Christmas—Mountain Chains—Meeting Caravans—Plains of Gravel—The Story of Joseph—Djebel Mokràt—The Last Day in the Desert—We see the Nile again, | 171 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| A Draught of Water—Abou-Hammed—The Island of Mokràt—Ethiopian Scenery—The People—An Ababdeh Apollo—Encampment on the Nile—Tomb of an Englishman—Eesa’s Wedding—A White Arab—The Last Day of the Year—Abou-Hashym—Incidents—Loss of my Thermometer—The Valley of Wild Asses—The Eleventh Cataract—Approach to Berber—Vultures—Eyoub Outwitted—We reach El Mekheyref—The Caravan Broken up, | 198 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| A Wedding—My Reception by the Military Governor—Achmet—The Bridegroom—A Guard—I am an American Bey—Kèff—The Bey’s Visit—The Civil Governor—About the Navy—The Priest’s Visit—Riding in State—The Dongolese Stallion—A Merchant’s House—The Town—Dinner at the Governor’s—The Pains of Royalty—A Salute to the American Flag—Departure, | 206 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Fortunate Travel—The America—Ethiopian Scenery—The Atbara River—Damer—A Melon Patch—Agriculture—The Inhabitants—Change of Scenery—The First Hippopotamus—Crocodiles—Effect of My Map—The Raïs and Sailors—Arabs in Ethiopia—Ornamental Scars—Beshir—The Slave Bakhita—We Approach Meroë, | 219 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Arrival at Bedjerowiyeh—The Ruins of Meroë—Walk Across the Plain—The Pyramids—Character of their Masonry—The Tower and Vault—Finding of the Treasure—The Second Group—More Ruins—Site of the City—Number of the Pyramids—The Antiquity of Meroë—Ethiopian and Egyptian Civilization—The Caucasian Race—Reflections, | 229[8] |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The Landscapes of Ethiopia—My Evenings beside the Nile—Experiences of the Arabian Nights—The Story of the Sultana Zobeide and the Wood-cutter—Character of the Arabian Tales—Religion, | 238 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Arrival at Shendy—Appearance of the Town—Shendy in Former Days—We Touch at El Metemma—The Nile beyond Shendy—Flesh Diet vs. Vegetables—We Escape Shipwreck—A Walk on Shore—The Rapids of Derreira—Djebel Gerri—The Twelfth Cataract—Night in the Mountain Gorge—Crocodiles—A Drink of Mareesa—My Birth-Day—Fair Wind—Approach to Khartoum—The Junction of the Two Niles—Appearance of the City—We Drop Anchor, | 258 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| The American Flag—A Rencontre—Search for a House—The Austrian Consular Agent—Description of his Residence—The Garden—The Menagerie—Barbaric Pomp and State—Picturesque Character of the Society of Khartoum—Foundation and Growth of the City—Its Appearance—The Population—Unhealthiness of the Climate—Assembly of Ethiopian Chieftains—Visit of Two Shekhs—Dinner and Fireworks, | 270 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Visit to the Catholic Mission—Dr. Knoblecher, the Apostolic Vicar—Moussa Bey—Visit to Lattif Pasha—Reception—The Pasha’s Palace—Lions—We Dine with the Pasha—Ceremonies upon the Occasion—Music—The Guests—The Franks in Khartoum—Dr. Péney—Visit to the Sultana Nasra—An Ethiopian Dinner—Character of the Sultana, | 280 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Recent Explorations of Soudân—Limit of the Tropical Rains—The Conquest of Ethiopia—Countries Tributary to Egypt—The District of Takka—Expedition of Moussa Bey—The Atbara River—The Abyssinian Frontier—Christian Ruins of Abou-Haràss—The Kingdom of Sennaar—Kordofan—Dar-Fūr—The Princess of Dar-Fūr in Khartoum—Her Visit to Dr. Reitz—The Unknown Countries of Central Africa, | 297 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Excursions around Khartoum—A Race into the Desert—Euphorbia Forest—The Banks of the Blue Nile—A Saint’s Grave—The Confluence of the Two Niles—Magnitude of the Nile—Comparative Size of the Rivers—Their Names—Desire to penetrate further into Africa—Attractions of the White Nile—Engage the Boat John Ledyard—Former Restrictions against exploring the River—Visit to the Pasha—Despotic Hospitality—Achmet’s Misgivings—We set sail, | 309[9] |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Departure from Khartoum—We enter the White Nile—Mirage and Landscape—The Consul returns—Progress—Loss of the Flag—Scenery of the Shores—Territory of the Hassaniyehs—Curious Conjugal Custom—Multitudes of Water Fowls—Increased Richness of Vegetation—Apes—Sunset on the White Nile—We reach the Kingdom of the Shillook Negroes, | 320 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

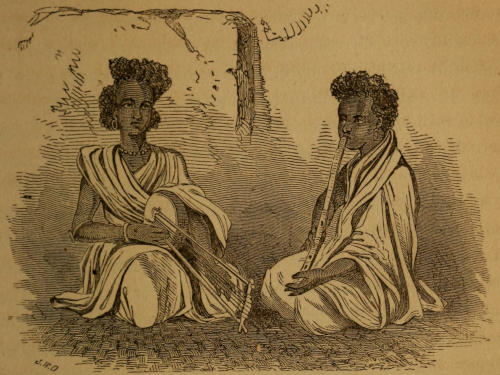

| Morning—Magnificence of the Island Scenery—Birds and Hippopotami—Flight of the Natives—The Island of Aba—Signs of Population—A Band of Warriors—The Shekh and the Sultan—A Treaty of Peace—The Robe of Honor—Suspicions—We walk to the Village—Appearance of the Shillooks—The Village—The Sultan gives Audience—Women and Children—Ornaments of the Natives—My Watch—A Jar of Honey—Suspicion and Alarm—The Shillook and the Sultan’s Black Wife—Character of the Shillooks—The Land of the Lotus—Population of the Shillook Kingdom—The Turning Point—A View from the Mast-Head, | 329 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Explorations of the White Nile—Dr. Knoblecher’s Voyage in 1849-50—The Lands of the Shillooks and Dinkas—Intercourse with the Natives—Wild Elephants and Giraffes—The Sobat River—The Country of Marshes—The Gazelle Lake—The Nuehrs—Interview with the Chief of the Kyks—The Zhir Country—Land of the Baris—The Rapids Surmounted—Arrival at Logwek, in Lat. 4° 10′ North—Panorama from Mt. Logwek—Sources of the White Nile—Character of the Bari Nation—Return of the Expedition—Fascination of the Nile, | 345 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| We leave the Islands of the Shillooks—Tropical Jungles—A Whim and its Consequences—Lairs of Wild Beasts—Arrival among the Hassaniyehs—A Village—The Woman and the Sultan—A Dance of Salutation—My Arab Sailor—A Swarthy Cleopatra—Salutation of the Saint—Miraculous Fishing—Night View of a Hassaniyeh Village—Wad Shèllayeh—A Shekh’s Residence—An Ebony Cherub—The Cook Attempts Suicide—Evening Landscape—The Natives and their Cattle—A Boyish Governor—We reach Khartoum at Midnight, | 356 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| The Departure of Abd-el Kader Bey—An Illuminated Picture—The Breakfast on the Island—Horsemanship—The Pasha’s Stories—Departure of Lattif Effendi’s Expedition—A Night on the Sand—Abou-Sin, and his Shukoree Warriors—Change in the Climate—Intense Heat and its Effects—Preparations for Returning—A Money Transaction—Farewell Visits—A Dinner with Royal Guests—Jolly King Dyaab—A Shillook Dance—Reconciliation—Taking Leave of my Pets, | 372[10] |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| The Commerce of Soudân—Avenues of Trade—The Merchants—Character of the Imports—Speculation—The Gum Trade of Kordofan—The Ivory Trade—Abuses of the Government—The Traffic in Slaves—Prices of Slaves—Their Treatment, | 384 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Farewell Breakfast—Departure from Khartoum—Parting with Dr. Reitz—A Prediction and its Fulfilment—Dreary Appearance of the Country—Lions—Burying-Grounds—The Natives—My Kababish Guide, Mohammed—Character of the Arabs—Habits of Deception—My Dromedary—Mutton and Mareesa—A Soudân Ditty—The Rowyàn—Akaba Gerri—Heat and Scenery—An Altercation with the Guide—A Mishap—A Landscape—Tedious Approach to El Metemma—Appearance of the Town—Preparations for the Desert—Meeting Old Acquaintances, | 392 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Entering the Desert—Character of the Scenery—Wells—Fear of the Arabs—The Laloom Tree—Effect of the Hot Wind—Mohammed overtakes us—Arab Endurance—An unpleasant Bedfellow—Comedy of the Crows—Gazelles—We encounter a Sand-storm—The Mountain of Thirst—The Wells of Djeekdud—A Mountain Pass—Desert Intoxication—Scenery of the Table-land—Bir Khannik—The Kababish Arabs—Gazelles again—Ruins of an Ancient Coptic Monastery—Distant View of the Nile Valley—Djebel Berkel—We come into Port, | 406 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Our whereabouts—Shekh Mohammed Abd e’-Djebàl—My residence at Abdôm—Crossing the River—A Superb Landscape—The Town of Merawe—Ride to Djebel Berkel—The Temples of Napata—Ascent of the Mountain—Ethiopian Panorama—Lost and Found—The Pyramids—The Governor of Merawe—A Scene in the Divan—The Shekh and I—The Governor Dines with me—Ruins of the City of Napata—A Talk about Religions—Engaging Camels for Wadi-Halfa—The Shekh’s Parting Blessing, | 421 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Appearance of the Country—Korti—The Town of Ambukol—The Caravan reorganized—A Fiery Ride—We reach Edabbe—An Illuminated Landscape—A Torment—Nubian Agriculture—Old Dongola—The Palace-Mosque of the Nubian Kings—A Panorama of Desolation—The Old City—Nubian Gratitude—Another Sand-Storm—A Dreary Journey—The Approach to Handak—A House of Doubtful Character—The Inmates—Journey to El Ordee (New Dongola)—Khoorshid Bey—Appearance of the Town, | 438 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| We start for Wadi-Halfa—The Plague of Black Gnats—Mohammed’s Coffin—The Island of Argo—Market-Day—Scenery of the Nile—Entering Dar El-Màhass—Ruined[11] Fortresses—The Camel-Men—A Rocky Chaos—Fakir Bender—The Akaba of Màhass—Camp in the Wilderness—The Charm of Desolation—The Nile again—Pilgrims from Dar-Fūr—The Struggle of the Nile—An Arcadian Landscape—The Temple of Soleb—Dar Sukkôt—The Land of Dates—The Island of Sai—A Sea of Sand—Camp by the River—A Hyena Barbecue, | 457 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| The Batn El-Hadjar, or Belly of Stone—Ancient Granite Quarries—The Village of Dal—A Ruined Fortress—A Wilderness of Stones—The Hot Springs of Ukmé—A Windy Night—A Dreary Day in the Desert—The Shekh’s Camel Fails—Descent to Samneh—The Temple and Cataract—Meersheh—The Sale of Abou-Sin—We Emerge from the Belly of Stone—A Kababish Caravan—The Rock of Abou-Seer—View of the Second Cataract—We reach Wadi-Halfa—Selling my Dromedaries—Farewell to Abou-Sin—Thanksgiving on the Ferry-boat—Parting with the Camel-men, | 471 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| Wadi Haifa—A Boat for Assouan—We Embark on the Nile Again—An Egyptian Dream—The Temples of Abou-Simbel—The Smaller Temple—The Colossi of Remeses II.—Vulgarity of Travellers—Entering the Great Temple—My Impressions—Character of Abou-Simbel—The Smaller Chambers—The Races of Men—Remeses and the Captive Kings—Departure, | 486 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| I Lose my Sunshine, and Regain it—Nubian Scenery—Derr—The Temple of Amada—Mysterious Rappings—Familiar Scenes—Halt at Korosko—Escape from Shipwreck—The Temple of Sebooa—Chasing other Boats—Temple of Djerf Hossayn—A Backsheesh Experiment—Kalabshee—Temple of Dabôd—We reach the Egyptian Frontier, | 495 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| Assouan—A Boat for Cairo—English Tourists—A Head-wind—Ophthalmia—Esneh—A Mummied Princess—Ali Effendi’s Stories—A Donkey Afrite—Arrival at Luxor—The Egyptian Autumn—A Day at Thebes—Songs of the Sailors—Ali leaves me—Ride to Dendera—Head-winds again—Visit to Tahtah—The House of Rufaā Bey, | 506 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| Siout in Harvest-time—A kind Englishwoman—A Slight Experience of Hasheesh—The Calm—Rapid Progress down the Nile—The Last Day of the Voyage—Arrival at Cairo—Tourists preparing for the Desert—Parting with Achmet—Conclusion, | 517 |

Arrival at Alexandria—The Landing—My First Oriental Bath—The City—Preparations for Departure.

I left Smyrna in the Lloyd steamer, Conte Stürmer, on the first day of November, 1851. We passed the blue Sporadic Isles—Cos, and Rhodes, and Karpathos—and crossing the breadth of the Eastern Mediterranean, favored all the way by unruffled seas, and skies of perfect azure, made the pharos of Alexandria on the evening of the 3d. The entrance to the harbor is a narrow and difficult passage through reefs, and no vessel dares to attempt it at night, but with the first streak of dawn we were boarded by an Egyptian pilot, and the rising sun lighted up for us the white walls of the city, the windmills of the Ras el-Tin, or Cape of Figs, and the low yellow sand-hills in which I recognized Africa—for they were prophetic of the desert behind them.

We entered the old harbor between the island of Pharos and the main land (now connected by a peninsular strip, on which the Frank quarter is built), soon after sunrise.[14] The water swarmed with boats before the anchor dropped, and the Egyptian health officer had no sooner departed than we were boarded by a crowd of dragomen, hotel runners, and boatmen. A squinting Arab, who wore a white dress and red sash, accosted me in Italian, offering to conduct me to the Oriental Hotel. A German and a Smyrniote, whose acquaintance I had made during the voyage, joined me in accepting his services, and we were speedily boated ashore. We landed on a pile of stones, not far from a mean-looking edifice called the Custom-House. Many friends were there to welcome us, and I shall never forget the eagerness with which they dragged us ashore, and the zeal with which they pommelled one another in their generous efforts to take charge of our effects. True, we could have wished that their faces had been better washed, their baggy trousers less ragged and their red caps less greasy, and we were perhaps ungrateful in allowing our Arab to rate them soundly and cuff the ears of the more obstreperous, before our trunks and carpet-bags could be portioned among them. At the Custom-House we were visited by two dark gentlemen, in turbans and black flowing robes, who passed our baggage without scrutiny, gently whispering in our ears, “backsheesh,”—a word which we then heard for the first time, but which was to be the key-note of much of our future experience. The procession of porters was then set in motion, and we passed through several streets of whitewashed two story houses, to the great square of the Frank quarter, which opened before us warm and brilliant in the morning sunshine.

The principal hotels and consulates front on this square The architecture is Italian, with here and there a dash of Saracenic,[15] in the windows and doorways, especially in new buildings. A small obelisk of alabaster, a present from Mohammed Ali, stands in the centre, on a pedestal which was meant for a fountain, but has no water. All this I noted, as well as a crowd of donkeys and donkey-boys, and a string of laden camels, on our way to the hotel, which we found to be a long and not particularly clean edifice, on the northern side of the square. The English and French steamers had just arrived, and no rooms were to be had until after the departure of the afternoon boat for Cairo. Our dragoman, who called himself Ibrahim, suggested a bath as the most agreeable means of passing the intermediate time.

The clear sky, the temperature (like that of a mild July day at home), and the novel interest of the groups in the streets, were sufficient to compensate for any annoyance: but when we reached the square of the French Church, and saw a garden of palm-trees waving their coronals of glittering leaves every thing else was forgotten. My German friend, who had never seen palms, except as starveling exotics in Sorrento and Smyrna, lifted his hands in rapture, and even I, who had heard tens of thousands rustle in the hot winds of the Tropics, felt my heart leap as if their beauty were equally new to my eyes. For no amount of experience can deprive the traveller of that happy feeling of novelty which marks his first day on the soil of a new continent. I gave myself up wholly to its inebriation. Et ego in Africâ, was the sum of my thoughts, and I neither saw nor cared to know the fact (which we discovered in due time), that our friend Ibrahim was an arrant knave.

The bath to which he conducted us was pronounced to be[16] the finest in Alexandria, the most superb in all the Orient, but it did not at all accord with our ideas of Eastern luxury. Moreover, the bath-keeper was his intimate friend, and would bathe us as no Christians were ever bathed before. One fact Ibrahim kept to himself, which was, that his intimate friend and he shared the spoils of our inexperience. We were conducted to a one-story building, of very unprepossessing exterior. As we entered the low, vaulted entrance, my ears were saluted with a dolorous, groaning sound, which I at first conjectured to proceed from the persons undergoing the operation, but which I afterward ascertained was made by a wheel turned by a buffalo, employed in raising water from the well. In a sort of basement hall, smelling of soap-suds, and with a large tank of dirty water in the centre, we were received by the bath-keeper, who showed us into a room containing three low divans with pillows. Here we disrobed, and Ibrahim, who had procured a quantity of napkins, enveloped our heads in turbans and swathed our loins in a simple Adamite garment. Heavy wooden clogs were attached to our feet, and an animated bronze statue led the way through gloomy passages, sometimes hot and steamy, sometimes cold and soapy, and redolent of any thing but the spicy odors of Araby the Blest, to a small vaulted chamber, lighted by a few apertures in the ceiling. The moist heat was almost suffocating; hot water flowed over the stone floor, and the stone benches we sat upon were somewhat cooler than kitchen stoves. The bronze individual left us, and very soon, sweating at every pore, we began to think of the three Hebrews in the furnace. Our comfort was not increased by the groaning sound which we still heard, and by seeing, through a hole in the door, five or six naked[17] figures lying motionless along the edge of a steaming vat, in the outer room.

Presently our statue returned with a pair of coarse hair-gloves on his hands. He snatched off our turbans, and then, seizing one of my friends by the shoulder as if he had been a sheep, began a sort of rasping operation upon his back. This process, varied occasionally by a dash of scalding water, was extended to each of our three bodies, and we were then suffered to rest awhile. A course of soap-suds followed, which was softer and more pleasant in its effect, except when he took us by the hair, and holding back our heads, scrubbed our faces most lustily, as if there were no such things as eyes, noses and mouths. By this time we had reached such a salamandrine temperature that the final operation of a dozen pailfuls of hot water poured over the head, was really delightful. After a plunge in a seething tank, we were led back to our chamber and enveloped in loose muslin robes. Turbans were bound on our heads and we lay on the divans to recover from the languor of the bath. The change produced by our new costume was astonishing. The stout German became a Turkish mollah, the young Smyrniote a picturesque Persian, and I—I scarcely know what, but, as my friends assured me, a much better Moslem than Frank. Cups of black coffee, and pipes of inferior tobacco completed the process, and in spite of the lack of cleanliness and superabundance of fleas, we went forth lighter in body, and filled with a calm content which nothing seemed able to disturb.

After a late breakfast at the hotel, we sallied out for a survey of the city. The door was beleaguered by the donkeys and their attendant drivers, who hailed us in all languages at[18] once. “Venez, Monsieur!” “Take a ride, sir; here is a good donkey!” “Schœner Esel!” “Prendete il mio burrico!”—and you are made the vortex of a whirlpool of donkeys. The one-eyed donkey-boys fight, the donkeys kick, and there is no rest till you have bestridden one of the little beasts. The driver then gives his tail a twist and his rump a thwack, and you are carried off in triumph. The animal is so small that you seem the more silly of the two, when you have mounted, but after he has carried you for an hour in a rapid gallop, you recover your dignity in your respect for him.

The spotless blue of the sky and the delicious elasticity of the air were truly intoxicating, as we galloped between gardens of date-trees, laden with ripe fruit, to the city gate, and through it into a broad road, fringed with acacias, leading to the Mahmoudieh canal. But to the south, on a rise of dry, sandy soil, stood the Pillar of Diocletian—not of Pompey, whose name it bears. It is a simple column, ninety-eight feet in height, but the shaft is a single block of red granite, and stands superbly against the background of such a sky and such a sea. It is the only relic of the ancient Alexandria worthy of its fame, but you could not wish for one more imposing and eloquent. The glowing white houses of the town, the minarets, the palms and the acacias fill the landscape, but it stands apart from them, in the sand, and looks only to the sea and the desert.

In the evening we took donkeys again and rode out of the town to a café on the banks of the canal. A sunset of burning rose and orange sank over the desert behind Pompey’s Pillar, and the balmiest of breezes stole towards us from the sea, through palm gardens. A Swiss gentleman, M. de Gonzenbach,[19] whose kindness I shall always gratefully remember, accompanied us. As we sat under the acacias, sipping the black Turkish coffee, the steamer for Cairo passed, disturbing the serenity of the air with its foul smoke, and marring the delicious repose of the landscape in such wise, that we vowed we would have nothing to do with steam so long as we voyaged on the Nile. Our donkey-drivers patiently held the bridles of our long-eared chargers till we were ready to return. It was dark, and not seeing at first my attendant, a little one-eyed imp, I called at random: “Abdallah!” This, it happened, was actually his name, and he came trotting up, holding the stirrup ready for me to mount. The quickness with which these young Arabs pick up languages, is truly astonishing. “Come vi chiamate?” (what’s your name?) I asked of Abdallah, as we rode homeward. The words were new to him, but I finally made him understand their meaning, whereupon he put his knowledge into practice by asking me: “Come vi chiamate?” “Abbas Pasha,” I replied. “Oh, well,” was his prompt rejoinder, “if you are Abbas Pasha, then I am Seyd Pasha.” The next morning he was at the door with his donkey, which I fully intended to mount, but became entangled in a wilderness of donkeys, out of which Ibrahim extricated me by hoisting me on another animal. As I rode away, I caught a glimpse of the little fellow, crying lustily over his disappointment.

We three chance companions fraternized so agreeably that we determined to hire a boat for Cairo, in preference to waiting for the next steamer. We accordingly rode over to the Mahmoudieh Canal, accompanied by Ibrahim, to inspect the barks. Like all dragomen, Ibrahim had his private preferences, and[20] conducted us on board a boat belonging to a friend of his, a grizzly raïs, or captain. The craft was a small kangia, with a large lateen sail at the bow and a little one at the stern. It was not very new, but looked clean, and the raïs demanded three hundred piastres for the voyage. The piastre is the current coin of the East. Its value is fluctuating, and always higher in Egypt than in Syria and Turkey, but may be assumed at about five cents, or twenty to the American dollar. Before closing the bargain, we asked the advice of M. de Gonzenbach, who immediately despatched his Egyptian servant and engaged a boat at two hundred and twenty-five piastres. Every thing was to be in readiness for our departure on the following evening.

Departure—The Kangia—The Egyptian Climate—The Mahmoudieh Canal—Entrance Into the Nile—Pleasures of the Journey—Studying Arabic—Sight of the Pyramids—The Barrage—Approach to Cairo.

We paid a most exorbitant bill at the Oriental Hotel, and started on donkey-back for our boat, at sunset. Our preparations for the voyage consisted of bread, rice, coffee, sugar, butter and a few other comestibles; an earthen furnace and charcoal; pots and stew-pans, plates, knives and forks, wooden spoons, coffee-cups and water-jars; three large mats of cane-leaves, for bedding; and for luxuries, a few bottles of claret, and a gazelle-skin stuffed with choice Latakieh tobacco. We were prudent enough to take a supper with us from the hotel, and not trust to our own cooking the first night on board.

We waited till dark on the banks of the Canal before our baggage appeared. There is a Custom-House on all sides of Alexandria, and goods going out must pay as well as goods coming in. The gate was closed, and nothing less than the silver oil of a dollar greased its hinges sufficiently for our cart to pass through. But what was our surprise on reaching the boat, to find the same kangia and the same grizzly raïs, who had previously demanded three hundred piastres. He seemed no less[22] astonished than we, for the bargain had been made by a third party, and I believe he bore us a grudge during the rest of the voyage. The contract placed the boat at our disposition; so we went on board immediately, bade adieu to the kind friends who had accompanied us, and were rowed down the Canal in the full glow of African moonlight.

Some account of our vessel and crew will not be out of place here. The boat was about thirty-five feet in length, with a short upright mast in the bow, supporting a lateen sail fifty feet long. Against the mast stood a square wooden box, lined with clay, which served as a fireplace for cooking. The middle boards of the deck were loose and allowed entrance to the hold, where our baggage was stowed. The sailors also lifted them and sat on the cross-beams, with their feet on the shallow keel, when they used the oars. The cabin, which occupied the stern of the boat, was built above and below the deck, so that after stepping down into it we could stand upright. The first compartment contained two broad benches, with a smaller chamber in the rear, allowing just enough room, in all, for three persons to sleep. We spread our mats on the boards, placed carpet-bags for pillows (first taking out the books), and our beds were made. Ibrahim slept on the deck, against the cabin-door.

Our raïs, or captain, was an old Arab, with a black, wrinkled face, a grizzly beard and a tattered blue robe. There were five sailors—one with crooked eyes, one with a moustache, two copper-colored Fellahs, and one tall Nubian, black as the Egyptian darkness. The three latter were our favorites, and more cheerful and faithful creatures I never saw. One of the Fellahs sang nasal love-songs the whole day long, and was always[23] foremost in the everlasting refrain of “haylee-sah!” and “ya salaam!” with which the Egyptian sailors row and tow and pole their boats against the current. Before we left the boat we had acquired a kind of affection for these three men, while the raïs, with his grim face and croaking voice, grew more repulsive every day.

We spread a mat on the deck, lighted our lantern and sat down to supper, while a gentle north wind slowly carried our boat along through shadows of palms and clear spaces of moonlight. Ibrahim filled the shebooks, and for four hours we sat in the open air, which seemed to grow sweeter and purer with every breath we inhaled. We were a triad—the sacred number—and it would have been difficult to find another triad so harmonious and yet differing so strongly in its parts. One was a Landwirth from Saxe-Coburg, a man of forty-five, tall, yet portly in person, and accustomed to the most comfortable living and the best society in Germany. Another was a Smyrniote merchant, a young man of thirty, to whom all parts of Europe were familiar, who spoke eight languages, and who within four months had visited Ispahan and the Caucasus. Of the third it behooves me not to speak, save that he was from the New World, and that he differed entirely from his friends in stature, features, station in life, and every thing else but mutual goodfellowship. “Ah,” said the German in the fulness of his heart, as we basked in the moonlight, “what a heavenly air! what beautiful palms! and this wonderful repose in all Nature, which I never felt before!” “It is better than the gardens of Ispahan,” added the Smyrniote. Nor did I deceive them when I said that for many months past I had known no mood of mind so peaceful and grateful.

We rose somewhat stiff from our hard beds, but a cup of coffee and the fresh morning air restored the amenity of the voyage. The banks of the Canal are flat and dull, and the country through which we passed, after leaving the marshy brink of Lake Mareotis, was in many places still too wet from the recent inundation to be ploughed for the winter crops. It is a dead level of rich black loam, and produces rice, maize, sugar-cane and millet. Here and there the sand has blown over it, and large spaces are given up to a sort of coarse, wiry grass. The villages are miserable collections of mud huts, but the date-palms which shadow them and the strings of camels that slowly pass to and fro, render even their unsightliness picturesque. In two or three places we passed mud machines, driven by steam, for the purpose of cleaning the Canal. Ropes were stretched across the channel on both sides, and a large number of trading boats were obliged to halt, although the wind was very favorable. The barrier was withdrawn for us Franks, and the courteous engineer touched his tarboosh in reply to our salutations, as we shot through.

Towards noon we stopped at a village, and the Asian went ashore with Ibrahim to buy provisions, while the European walked ahead with his fowling-piece, to shoot wild ducks for dinner. The American stayed on board and studied an Arabic vocabulary. Presently Ibrahim appeared with two fowls, two pigeons, a pot of milk and a dozen eggs. The Asian set about preparing breakfast, and showed himself so skilful that our bark soon exhaled the most savory odors. When we picked up our European he had only two hawks to offer us, but we gave him in return a breakfast which he declared perfect. We ate on deck, seated on a mat; a pleasant wind filled our sails,[25] and myriads of swallows circled and twittered over our heads in the cloudless air. The calm, contemplative state produced by the coffee and pipes which Ibrahim brought us, lasted the whole afternoon, and the villages, the cane-fields, the Moslem oratories, the wide level of the Delta and the distant mounds of forgotten cities, passed before our eyes like the pictures of a dream. Only one of these pictures marred the serenity of our minds. It was an Arab burying-ground, on the banks of the Canal—a collection of heaps of mud, baked in the sun. At the head and foot of one of the most recent, sat two women—paid mourners—who howled and sobbed, in long, piteous, despairing cries, which were most painful to hear. I should never have imagined that any thing but the keenest grief could teach such heart-breaking sounds.

When I climbed the bank at sunset, for a walk, the minarets of Atfeh, on the Nile, were visible. Two rows of acacias, planted along the Canal, formed a pleasant arcade, through which we sailed, to the muddy excrescences of the town. The locks were closed for the night, and we were obliged to halt, which gave us an opportunity of witnessing an Arabic marriage procession. The noise of two wooden drums and a sort of fife announced the approach of the bride, who, attended by her relatives, came down the bank from the mud-ovens above. She was closely veiled, but the Arabs crowded around to get a peep at her face. No sooner had the three Franks approached, than she was doubly guarded and hurried off to the house of her intended husband. Some time afterwards I ascended the bank to have a nearer view of the miserable hovels, but was received with such outcries and menacing gestures, that I made a slow and dignified retreat. We visited, however, the house of the[26] bridegroom’s father, where twenty or thirty Arabs, seated on the ground, were singing an epithalamium, to which they kept time by clapping their hands.

Next morning, while our raïs was getting his permit to pass the locks (for which four official signatures and a fee of thirty piastres are necessary), we visited the bazaar, and purchased long tubes of jasmine-wood for our pipes, and vegetables for our kitchen. On all such occasions we detailed Seyd, the tall Nubian, whose ebony face shone resplendent under a snow-white turban, to be our attendant. The stately gravity with which he walked behind us, carrying bread and vegetables, was worthy the pipe-bearer of a Sultan. By this time we had installed the Asian as cook, and he very cheerfully undertook the service. We soon discovered that the skill of Ibrahim extended no further than to the making of a pilaff and the preparation of coffee. Moreover his habits and appearance were not calculated to make us relish his handiwork. The naïveté with which he took the wash-basin to make soup in, and wiped our knives and forks on his own baggy pantaloons, would have been very amusing if we had not been interested parties. The Asian was one day crumbling some loaf sugar with a hammer, when Ibrahim, who had been watching him, suddenly exclaimed in a tone of mingled pity and contempt, “that’s not the way!” Thereupon he took up some of the lumps, and wrapped them in one corner of his long white shirt, which he thrust into his mouth, and after crushing the sugar between his teeth, emptied it into the bowl with an air of triumph.

A whole squadron of boats was waiting at the locks, but with Frankish impudence, we pushed through them, and took our place in the front rank. The sun was intensely hot, and[27] we sweated and broiled for a full hour, in the midst of a horrible tumult of Arabs, before the clumsy officers closed the last gate on us and let us float forth on the Nile. It is the western, or Canopic branch of the river which flows past Atfeh. It is not broader than the Hudson at Albany, but was more muddy and slimy from its recent overflow than the Mississippi at New Orleans. Its water is no less sweet and wholesome than that of the latter river. After leaving the monotonous banks of the Canal, the aspect of its shores, fringed with groves of palm, was unspeakably cheerful and inspiring. On the opposite side, the slender white minarets of Fooah, once a rich manufacturing town, sparkled in the noonday sun. A fresh north wind from the Mediterranean slowly pressed our boat against the strong current, while the heavily-laden merchant vessels followed in our wake, their two immense lateen sails expanded like the wings of the Arabian roc. We drank to the glory of old Father Nile in a cup of his own brown current, and then called Ibrahim to replenish the empty shebooks. Those who object to tobacco under the form of cigars, or are nauseated by the fumes of a German meerschaum, should be told that the Turkish pipe, filled with Latakieh, is quite another thing. The aroma, which you inhale through a long jasmine tube, topped with a soft amber mouth-piece, is as fragrant as roses and refreshing as ripe dates. I have no doubt that the atmosphere of celestial musk and amber which surrounded Mahomet, according to the Persian Chronicles, was none other than genuine Latakieh, at twenty piastres the oka. One thing is certain, that without the capacity to smoke a shebook, no one can taste the true flavor of the Orient.

An hour or two after sunset the wind fell, and for the rest[28] of the night our men tracked the boat slowly forward, singing cheerily as they tugged at the long tow-rope. The Asian spread on the deck his Albanian capote, the European his ample travelling cloak, and the representatives of three Continents, travelling in the fourth, lay on their backs enjoying the moonlight, the palms, and more than all, the perfect silence and repose. With every day of our journey I felt more deeply and gratefully this sense of rest. Under such a glorious sky, no disturbance seemed possible. It was of little consequence whether the boat went forward or backward, whether we struck on a sand-bar or ploughed the water under a full head of wind; every thing was right. My conscience made me no reproach for such a lazy life. In America we live too fast and work too hard, I thought: shall I not know what Rest is, once before I die? The European said to me naïvely, one day: “I am a little surprised, but very glad, that no one of us has yet spoken of European politics.” Europe! I had forgotten that such a land existed: and as for America, it seemed very dim and distant.

Sometimes I varied this repose by trying to pick up the language. Wilkinson’s Vocabulary and Capt. Hayes’s Grammar did me great service, and after I had tried a number of words with Ibrahim, to get the pronunciation, I made bolder essays. One day when the sailors were engaged in a most vociferous discussion, I broke upon them with: “What is all this noise about? stop instantly!” The effect was instantaneous; the men were silent, and Seyd, turning up his eyes in wonder, cried out: “Wallah! the Howadji talks Arabic!” The two copper-faced Fellahs thought it very amusing, and every new word I learned sufficed to set them laughing for half[29] an hour. I called out to a fisherman, seated on the bank: “O Fisherman, have you any fish?” and he held up a string of them and made answer: “O Howadji, I have.” This solemn form of address, which is universal in Arabic, makes the language very piquant to a student.

During our second night on the river, we passed the site of ancient Saïs, one of the most renowned of Egyptian cities, which has left nothing but a few shapeless mounds. The country was in many places still wet from the inundation, which was the largest that had occurred for many years. The Fellahs were ploughing for wheat, with a single buffalo geared to a sharp pole, which scratched up the soil to the depth of three inches. Fields of maize and sugar-cane were frequent, and I noticed also some plantations of tobacco, millet, and a species of lupin, which is cultivated for its beans. The only vegetables we found for sale in the villages, were onions, leeks and tomatoes. Milk, butter and eggs are abundant and very good, but the cheese of the country is detestable. The habitations resemble ant-hills, rather than human dwellings, and the villages are dépôts of filth and vermin, on the most magnificent scale. Our boat was fortunately free from the latter, except a few cockroaches. Except the palm and acacia, without which a Nile journey would lose half its attractions, I saw few trees. Here and there stood a group of superb plane-trees, and the banana sometimes appeared in the gardens, but there is nothing of that marvellous luxuriance and variety of vegetation which is elsewhere exhibited in the neighborhood of the Tropics.

On the evening of the third day we reached the town of Nadir, and, as there was no wind, went ashore for an hour or two. There was a café on the bank—a mud house, with two[30] windows, adorned with wooden frames, carved in the Moorish style. A divan, built of clay and whitewashed, extended along one side of the room, and on this we seated ourselves cross-legged, while the host prepared the little coffee-cups and filled the pipes. Through the open door we saw the Nile, gleaming broadly under the full moon, and in the distance, two tall palm-trees stood clearly against the sky. Our boatmen, whom we had treated to booza, the Egyptian beer, sat before us, and joined in the chorus of a song, which was sung to entertain us. The performers were three women, and a man who played a coarse reed flute. One of the women had a tambourine, another a small wooden drum, and the third kept time by slapping the closed fingers of the right hand on the palm of the left. The song, which had a wild, rude harmony that pleased me, was followed by a dance, executed by one of the women. It was very similar to the fandango, as danced by the natives of the Isthmus of Panama, and was more lascivious than graceful. The women, however, were of the lowest class, and their performances were adapted to the taste of the boatmen and camel-drivers, by whom they are patronized.

The next day the yellow hills of the Libyan Desert, which in some places press the arable land of the Delta even to the brink of the Nile, appeared in the west. The sand appeared to be steadily advancing towards the river, and near Werdan had already buried a grove of acacias as high as their first branches. The tops were green and flourishing above the deluge, but another year or two would overwhelm them completely. We had a thick fog during the night, and the following day was exceedingly hot though the air was transparent as crystal. Our three faces were already of the color of new[31] bronze, which was burned into the skin by the reflection from the water. While my friends were enjoying their usual afternoon repose, a secret presentiment made me climb to the roof of our cabin. I had not sat there long, before I descried two faint blue triangles on the horizon, far to the south. I rudely broke in upon their indolence with a shout of “the Pyramids!” which Seyd echoed with “El-hàram Faraoon!” I was as much impressed with the view as I expected to be, but I completely nullified the European’s emotion by translating to him Thackeray’s description of his first sight of those renowned monuments.

The same evening we reached the northern point of the Delta, where we were obliged to remain all night, as the wind was not sufficiently strong to allow us to pass the Barrage. Singularly enough, this immense work, which is among the greatest undertakings of modern times, is scarcely heard of out of Egypt. It is nothing less than a damming of the Nile, which is to have the effect of producing two inundations a year, and doubling the crops throughout the Delta. Here, where the flood divides itself into two main branches, which find separate mouths at Damietta and Rosetta, an immense dam has not only been projected, but is far advanced toward completion. Each branch will be spanned by sixty-two arches, besides a central gateway ninety feet in breadth, and flanked by lofty stone towers. The point of the Delta, between the two dams, is protected by a curtain of solid masonry, and the abutments which it joins are fortified by towers sixty or seventy feet in height. The piers have curved breakwaters on the upper side, while the opposite parapet of the arches rises high above them, so that the dam consists of three successive terraces,[32] and presents itself like a wedge, against the force of such an immense body of water. The material is brick, faced with stone. When complete, it is intended to close the side-arches during low water, leaving only the central gateway open. By this means sufficient water will be gained to fill all the irrigating canals, while a new channel, cut through the centre of the Delta, will render productive a vast tract of fertile land. The project is a grand one, and the only obstacle to its success is the light, porous character of the alluvial soil on which the piers are founded. The undertaking was planned and commenced by M. Linant, and has since been continued by other engineers.

The Egyptian boatmen have reason to complain of the Barrage. The main force of the river is poured through the narrow space wherein the piers have not yet been sunk, which cannot be passed without a strong north wind. Forty or fifty boats were lying along the shore, waiting the favorable moment. We obtained permission from the engineer to attach our boat to a large government barge, which was to be drawn up by a stationary windlass. As we put off, the wind freshened, and we were slowly urged against the current to the main rapid, where we were obliged to hold on to our big friend. Behind us the river was white with sails—craft of all kinds, pushed up by the wind, dragged down by the water, striking against each other, entangling their long sails and crowding into the narrow passage, amid shouts, cries and a bewildering profusion of Arabic gutturals. For half an hour, the scene was most exciting, but thanks to the windlass, we reached smoother water, and sailed off gayly for Cairo.

The true Nile expanded before us, nearly two miles in[33] width. To the south, the three Pyramids of Gizeh loomed up like isolated mountain-peaks on the verge of the Desert. On the right hand the Mokattam Hills lay red and bare in the sunshine, and ere long, over the distant gardens of Shoobra, we caught sight of the Citadel of Cairo, and the minarets of the mosque of Sultan Hassan. The north wind was faithful: at three o’clock we were anchored in Boulak, paid our raïs, gave the crew a backsheesh, for which they kissed our hands with many exclamations of “taïb!” (good!) and set out for Cairo.

Entrance—The Ezbekiyeh—Saracenic Houses—Donkeys—The Bazaars—The Streets—Processions—View from the Citadel—Mosque of Mohammed Ali—The Road to Suez—The Island of Rhoda.

Our approach to and entrance into Cairo was the illuminated frontispiece to the volume of my Eastern life. From the Nile we had already seen the mosque of Sultan Hassan, the white domes, and long, pencil-like minarets of the new mosque of Mohammed Ali, and the massive masonry of the Citadel, crowning a projecting spur of the Mokattam Hills, which touches the city on the eastern side. But when, mounted on ambling donkeys, we followed the laden baggage-horses through the streets of Boulak, and entered the broad, shaded highway leading through gardens, grain-fields and groves of palm and banana, to the gate of the Ezbekiyeh—the great square of Cairo—the scene, which, at a distance, had been dimmed and softened by the filmy screen of the Egyptian air, now became so gay, picturesque and animated, so full of life and motion and color, that my dreams of the East were at once displaced by the vivid reality. The donkey-riding multitudes who passed continually to and fro, were wholly unlike[35] the crowds of Smyrna and Alexandria, where the growing influence of European dress and customs is already visible. Here, every thing still exhaled the rich aroma of the Orient as it had been wafted to me from the Thousand and One Nights, the Persian poets and the Arab chroniclers. I forgot that I still wore a Frank dress, and found myself wondering at the temerity of the few Europeans we met. I looked without surprise on the long processions of donkeys carrying water-skins, the heavily-laden camels, the women with white masks on their faces and black bags around their bodies, the stolid Nubian slaves, the grave Abyssinians, and all the other various characters that passed and repassed us. But because they were so familiar, they were none the less interesting, for all had been acquaintances, when, like Tennyson, “true Mussulman was I, and sworn,” under the reign of the good Haroun Al-Raschid.

We entered the Ezbekiyeh, which is wholly overgrown with majestic acacias and plane-trees, and thickets of aromatic flowering shrubs. It is in the Frank quarter of the city, and was first laid out and planted by order of Mohammed Ali. All the principal hotels front upon it, and light, thatched cafés fill the space under the plane-trees, where the beau monde of Cairo promenade every Sunday evening. Nothing of the old City of the Caliphs, except a few tall minarets, can be seen from this quarter, but the bowery luxuriance of the foliage is all that the eye demands, and over the plain white walls, on every side, the palms—single, or in friendly groups—lift their feathery crowns. After installing our household gods in the chambers of the quiet and comfortable Hotel d’Europe, we went out to enjoy the sweet evening air in front of one of the cafés. I[36] tried for the first time the narghileh, or Persian water-pipe. The soft, velvety leaves of the tobacco of Shiraz are burned in a small cup, the tube of which enters a glass vase, half filled with rose-scented water. From the top of this vase issues a flexible tube, several feet in length, with a mouth-piece of wood or amber. At each inspiration, the smoke is drawn downward and rises through the water with a pleasant bubbling sound. It is deprived of all the essential oil of the weed, and is exceedingly mild, cool and fragrant. But instead of being puffed out of the mouth in whiffs, it is breathed full into the lungs and out again, like the common air. This is not so difficult a matter as might be supposed; the sensation is pleasant and slightly exhilarating, and is not injurious to the lungs when moderately indulged in.

The Turkish quarter of Cairo still retains the picturesque Saracenic architecture of the times of the Caliphs. The houses are mostly three stories in height, each story projecting over the other, and the plain stone walls are either whitewashed or striped with horizontal red bars, in a manner which would be absurd under a northern sky, but which is here singularly harmonious and agreeable. The only signs of sculpture are occasional doorways with richly carved arches, or the light marble gallery surrounding a fountained court. I saw a few of these in retired parts of the city. The traveller, however, has an exhaustless source of delight in the wooden balconies inclosing the upper windows. The extraordinary lightness, grace and delicate fragility of their workmanship, rendered still more striking by contrast with the naked solidity of the walls to which they cling, gave me a new idea of the skill and fancy of the Saracenic architects. The wood seems rather woven in[37] the loom, than cut with the saw and chisel. Through these lattices of fine net-work, with borders worked in lace-like patterns, and sometimes topped with slender turrets and pinnacles, the wives of the Cairene merchants sit and watch the crowds passing softly to and fro in the twilight of the bazaars, themselves unseen. It needed no effort of the imagination to people the fairy watch-towers under which we rode daily, with forms as beautiful as those which live in the voluptuous melodies of Hafiz.

To see Cairo thoroughly, one must first accustom himself to the ways of those long-eared cabs, without the use of which I would advise no one to trust himself in the bazaars. Donkey-riding is universal, and no one thinks of going beyond the Frank quarter on foot. If he does, he must submit to be followed by not less than six donkeys with their drivers. A friend of mine, who was attended by such a cavalcade for two hours, was obliged to yield at last, and made no second attempt. When we first appeared in the gateway of our hotel, equipped for an excursion, the rush of men and animals was so great, that we were forced to retreat until our servant and the porter whipped us a path through the yelling and braying mob. After one or two trials, I found an intelligent Arab boy, named Kish, who, for five piastres a day, furnished strong and ambitious donkeys, which he kept ready at the door from morning till night. The other drivers respected Kish’s privilege, and thenceforth I had no trouble. The donkeys are so small that my feet nearly touched the ground, but there is no end to their strength and endurance. Their gait, whether a pace or a gallop, is so easy and light that fatigue is impossible. The drivers take great pride in having high-cushioned red saddles, and[38] in hanging bits of jingling brass to the bridles. They keep their donkeys close shorn, and frequently beautify them by painting them various colors. The first animal I rode had legs barred like a zebra’s, and my friend’s rejoiced in purple flanks and a yellow belly. The drivers run behind them with a short stick, punching them from time to time, or giving them a sharp pinch on the rump. Very few of them own their donkeys, and I understood their pertinacity when I learned that they frequently received a beating on returning home in the evening empty-handed.

The passage of the bazaars seems at first quite as hazardous on donkey-back as on foot, but it is the difference between knocking somebody down and being knocked down yourself, and one naturally prefers the former alternative. There is no use in attempting to guide the donkey, for he won’t be guided. The driver shouts behind, and you are dashed at full speed into a confusion of other donkeys, camels, horses, carts, water-carriers and footmen. In vain you cry out: “Bess!” (enough!) “Piano!” and other desperate adjurations; the driver’s only reply is: “Let the bridle hang loose!” You dodge your head under a camel-load of planks; your leg brushes the wheel of a dust-cart; you strike a fat Turk plump in the back; you miraculously escape upsetting a fruit-stand; you scatter a company of spectral, white-masked women, and at last reach some more quiet street, with the sensation of a man who has stormed a battery. At first this sort of riding made me very nervous, but finally I let the donkey go his own way, and took a curious interest in seeing how near a chance I ran of striking or being struck. Sometimes there seemed no hope of avoiding a violent collision, but by a series of the most remarkable dodges he generally[39] carried me through in safety. The cries of the driver, running behind, gave me no little amusement: “The Howadji comes! Take care on the right hand! take care on the left hand! O man, take care! O maiden, take care! O boy, get out of the way! The Howadji comes!” Kish had strong lungs and his donkey would let nothing pass him, and so, wherever we went, we contributed our full share to the universal noise and confusion.

Cairo is the cleanest of all oriental cities. The regulations established by Mohammed Ali are strictly carried out. Each man is obliged to sweep before his own door, and the dirt is carried away in carts every morning. Besides this, the streets are watered several times a day, and are nearly always cool and free from dust. The constant evaporation of the water, however, is said to be injurious to the eyes of the inhabitants, though in other respects the city is healthy. The quantity of sore-eyed, cross-eyed, one-eyed, and totally blind persons one meets every where, is surprising. There are some beggars, mostly old or deformed, but by no means so abundant or impertinent as in the Italian cities. A number of shabby policemen, in blue frock-coats and white pantaloons, parade the principal thoroughfares, but I never saw their services called into requisition. The soldiers, who wear a European dress of white cotton, are by far the most awkward and unpicturesque class. Even the Fellah, whose single brown garment hangs loose from his shoulders to his knees, has an air of dignity compared with these Frankish caricatures. The genuine Egyptian costume, which bears considerable resemblance to the Greek, and especially the Hydriote, is simple and graceful. The colors are dark—principally brown, blue, green and violet—relieved by a[40] heavy silk sash of some gay pattern, and by the red slippers and tarboosh. But, as in Turkey, the Pashas and Beys, and many of the minor officers of the civil departments have adopted the Frank dress, retaining only the tarboosh,—a change which is by no means becoming to them. I went into an Egyptian barber-shop one day, to have my hair shorn, and enjoyed the preparatory pipe and coffee in company with two individuals, whom I supposed to be French or Italians of the vulgar order, until the barber combed out the long locks on the top of their head, by which Mussulmen expect to be lifted up into Paradise. When they had gone, the man informed me that one was Khalim Pasha, one of the grandsons of Mohammed Ali, and the other a Bey, of considerable notoriety. The Egyptians certainly do not gain any thing by adopting a costume which, in this climate, is neither so convenient nor so agreeable as their own.

Besides the animated life of the bazaars, which I had an opportunity of seeing, in making my outfit for the winter’s journey, I rarely went out without witnessing some incident or ceremony illustrative of Egyptian character and customs. One morning I encountered a stately procession, with music and banners, accompanying a venerable personage, with a green turban on his head and a long white beard flowing over his breast. This, as Kish assured me, was the Shereef of Mecca. He was attended by officers in the richest Turkish and Egyptian costumes, mounted on splendid Arabian steeds, who were almost hidden under their broad housings of green and crimson velvet, embroidered with gold. The people on all sides, as he passed, laid their hands on their breasts and bowed low, which he answered by slowly lifting his hand. It was a simple motion, but nothing could have been more calm and majestic.

On another occasion, I met a bridal procession in the streets of Boulak. Three musicians, playing on piercing flutes, headed the march, followed by the parents of the bride, who, surrounded by her maids, walked under a crimson canopy. She was shrouded from head to foot in a red robe, over which a gilded diadem was fastened around her head. A large crowd of friends and relatives closed the procession, close behind which followed another, of very different character. The chief actors were four boys, of five or six years old, on their way to be circumcised. Each was mounted on a handsome horse, and wore the gala garments of a full-grown man, in which their little bodies were entirely lost. The proud parents marched by their sides, supporting them, and occasionally holding to their lips bottles of milk and sherbet. One was a jet black Nubian, who seemed particularly delighted with his situation, and grinned on all sides as he passed along. This procession was headed by a buffoon, who carried a laugh with him which opened a ready passage through the crowd. A man followed balancing on his chin a long pole crowned with a bunch of flowers. He came to me for backsheesh. His success brought me two swordsmen out of the procession, who cut at each other with scimitars and caught the blows on their shields. The coolness, swiftness and skill with which they parried the strokes was really admirable, and the concluding flourish was a masterpiece. One of them, striking with the full sweep of his arm, aimed directly at the face of the other, as if to divide his head into two parts; but without making a pause, the glittering weapon turned, and sliced the air within half an inch of his eyes. The man neither winked nor moved a muscle of his face, but after the scimitar had passed, dashed it up with his shield, which he then reversed,[42] and dropping on one knee, held to me for backsheesh. After these came a camel, with a tuft of ostrich feathers on his head and a boy on his back, who pounded vigorously on two wooden drums with one hand, while he stretched the other down to me for backsheesh. Luckily the little candidates for circumcision were too busily engaged with their milk bottles and sugar-plums, to join in the universal cry.

I had little time to devote to the sights of Cairo, and was obliged to omit the excursions to the Petrified Forest, to Heliopolis and Old Cairo, until my return. Besides the city itself, which was always full of interest, I saw little else except the Citadel and the Island of Rhoda. We took the early morning for our ride to the former place, and were fortunate enough to find our view of the Nile-plain unobscured by the mists customary at this season. The morning light is most favorable to the landscape, which lies wholly to the westward. The shadows of the Citadel and the crests of the Mokattam Hills then lie broad and cool over the city, but do not touch its minarets, which glitter in the air like shafts of white and rosy flame. The populace is up and stirring, and you can hear the cries of the donkeymen and water-carriers from under the sycamores and acacias that shade the road to Boulak. Over the rich palm-gardens, the blue streak of the river and the plain beyond, you see the phantoms of two pyramids in the haze which still curtains the Libyan Desert. Northward, beyond the parks and palaces of Shoobra, the Nile stretches his two great arms toward the sea, dotted, far into the distance, with sails that flash in the sun. From no other point, and at no other time, is Cairo so grand and beautiful.

Within the walls of the Citadel is the Bir Youssef—Joseph’s[43] Well—as it is called by the Arabs, not from the virtuous Hebrew, but from Sultan Saladin, who dug it out and put it in operation. The well itself dates from the old Egyptian time, but was filled with sand and entirely lost for many centuries. It consists of an upper and lower shaft, cut through the solid rock, to the depth of two hundred and sixty feet. A winding gallery, lighted from the shaft, extends to the bottom of the first division, where, in a chamber cut in the rock, a mule turns the large wheel which brings up a continual string of buckets from the fountain below. The water is poured into a spacious basin, and carried thence to the top by another string of buckets set in motion at the surface. Attended by two Arabs with torches, we made the descent of the first shaft and took a drink of the fresh, cool fluid. This well, and the spot where the Mameluke Emin Bey jumped his horse over the wall and escaped the massacre of his comrades, are the only interesting historical points about the Citadel; and the new mosque of Mohammed Ali, which overlooks the city from the most projecting platform of the fortifications, is the only part which has any claim to architectural beauty. Although it has been in process of erection for many years, this mosque is not nearly completed internally. The exterior is finished, and its large, white, depressed dome, flanked by minarets so tall and reed-like that they seem ready to bend with every breeze, is the first signal of Cairo to travellers coming up or down the Nile. The interior walls are lined throughout with oriental alabaster, stained with the orange flush of Egyptian sunsets, and the three domes blaze with elaborate arabesques of green, blue, crimson and gold. In a temporary chamber, fitted up in one corner, rests the coffin of Mohammed Ali, covered[44] with a heavy velvet pall, and under the marble arches before it, a company of priests, squatted on the green carpet covering the floor, bow their heads continually and recite prayers or fragments of the Koran.

Before descending into the city, I rode a little way into the Desert to the tombs of the Caliphs, on the road to Suez. They consist mostly of stone canopies raised on pillars, with mosques or oratories attached to them, exhibiting considerable variety in their design, but are more curious than impressive. The track in the sand made by the pilgrims to Mecca and the overland passengers to Suez, had far more real interest in my eyes. The pilgrims are fewer, and the passengers more numerous, with each successive year. English-built omnibuses, whirled along by galloping post-horses, scatter the sand, and in the midst of the herbless Desert, the travellers regale themselves with beef-steak and ale, and growl if the accustomed Cheshire is found wanting. At this rate, how long will it be before there is a telegraph-station in Mecca, and the operator explodes with his wire a cannon on the Citadel of Cairo, to announce that the prayers on Mount Arafat have commenced?

The Island of Rhoda, which I visited on a soft, golden afternoon, is but a reminiscence of what it was a few years ago. Since Ibrahim Pasha’s death it has been wholly neglected, and though we found a few gardeners at work, digging up the sodden flower-beds and clipping the rank myrtle hedges, they only served to make the neglect more palpable. During the recent inundation, the Nile had risen to within a few inches of covering the whole island, and the soil was still soft and clammy. Nearly all the growths of the tropics are nurtured here; the coffee, the Indian fig, the mango, and other[45] trees alternate with the palm, orange, acacia, and the yellow mimosa, whose blossoms make the isle fragrant. I gathered a bunch of roses and jasmine-flowers from the unpruned vines. In the centre of the garden is an artificial grotto lined with shells, many of which have been broken off and carried away by ridiculous tourists. There is no limit to human silliness, as I have wisely concluded, after seeing Pompey’s Pillar disfigured by “Isaac Jones” (or some equally classic name), in capitals of black paint, a yard long, and finding “Jenny Lind” equally prominent on the topmost stone of the great Pyramid (Of course, the enthusiastic artist chiselled his own name beside hers.) A mallet and chisel are often to be found in the outfits of English and American travellers, and to judge from the frequency of certain names, and the pains bestowed upon their inscription, the owners must have spent the most of their time in Upper Egypt, in leaving records of their vulgar vanity.

Necessity of Leaving Immediately—Engaging a Boat—The Dragomen—Achmet el Saïdi—Funds—Information—Procuring an Outfit—Preparing for the Desert—The Lucky Day—Exertions to Leave—Off!

I devoted but little time to seeing Cairo, for the travelling season had arrived, and a speedy departure from Cairo was absolutely necessary. The trip to Khartoum occupies at least two months and it is not safe to remain there later than the first of March, on account of the heat and the rainy season, which is very unhealthy for strangers. Dr. Knoblecher, the Catholic Apostolic Vicar for Central Africa, had left about a month previous, on his expedition to the sources of the White Nile. I therefore went zealously to work, and in five days my preparations were nearly completed. I prevailed upon the European of our triad, who had intended proceeding no further than Cairo, to join me for the voyage to Assouan, on the Nubian frontier, and our first care was to engage a good dahabiyeh, or Nile-boat. This arrangement gave me great joy, for nowhere is a congenial comrade so desirable as on the Nile. My friend appreciated the river, and without the prospect of seeing Thebes, Ombos and Philæ, would have cheerfully borne all the inconveniences and delays of the journey, for the Nile’s[47] sake alone. Commend me to such a man, for of the hundreds of tourists who visit the East, there are few such! On my arrival, I had found that the rumors I had heard on the road respecting the number of travellers and the rise in the price of boats, were partially true. Not more than a dozen boats had left for Upper Egypt, but the price had been raised in anticipation. The ship carpenters and painters were busily employed all along the shore at Boulak, in renovating the old barks or building new ones, and the Beys and Pashas who owned the craft were anticipating a good harvest. Some travellers paid forty-five pounds a month for their vessels, but I found little difficulty in getting a large and convenient boat, for two persons, at twenty pounds a month. This price, it should be understood, includes the services of ten men, who find their own provisions, and only receive a gratuity in case of good behavior. The American Consul, Mr. Kahil, had kindly obtained for me the promise of a bark from Ismaïl Pasha, before our arrival—a superb vessel, furnished with beds, tables, chairs and divans, in a very handsome style—which was offered at thirty pounds a month, but it was much larger than we needed. In the course of my inspection of the fleet of barks at Boulak, I found several which might be had at fifteen, and seventeen pounds a month, but they were old, inconvenient, and full of vermin. Our boat, which I named the Cleopatra, had been newly cleansed and painted, and contained, besides a spacious cabin, with beds and divans, a sort of portico on the outside, with cushioned seats, where we proposed to sit during the balmy twilights, and smoke our shebooks.

Without a tolerable knowledge of Arabic, a dragoman is indispensable. The few phrases I had picked up, on the way[48] from Alexandria, availed me little, and would have been useless in Nubia, where either the Berberi language, or a different Arabic dialect is spoken; and I therefore engaged a dragoman for the journey. This class of persons always swarm in Cairo, and I had not been there a day before I was visited by half a dozen, who were anxious to make the trip to Khartoum. How they knew I was going there, I cannot imagine; but I found that they knew the plans of every traveller in Cairo as well. I endeavored to find one who had already made the journey, but of all who presented themselves, only two had been farther than the second Cataract. One of these was a Nubian, who had made a trip with the Sennaar merchants, as far as Shendy, in Ethiopia; but he had a sinister, treacherous face, and I refused him at once. The other was an old man, named Suleyman Ali, who had been for three years a servant of Champollion, whose certificate of his faithfulness and honesty he produced.

He had been three years in Sennaar, and in addition to Italian, (the only Frank tongue he knew), spoke several Ethiopian dialects. He was a fine, venerable figure, with an honest face, and I had almost decided to take him, when I learned that he was in feeble health and would scarcely be able to endure the hardships of the journey. I finally made choice of a dark Egyptian, born in the valley of Thebes. He was called Achmet el Saïdi, or Achmet of Upper Egypt, and when a boy had been for several years a servant in the house of the English Consul at Alexandria. He spoke English fluently, as well as a little Italian and Turkish. I was first attracted to him by his bold, manly face, and finding that his recommendations were excellent, and that he had sufficient spirit, courage and address[49] to serve us both in case of peril, I engaged him, notwithstanding he had never travelled beyond Wadi Halfa (the Second Cataract). I judged, however, that I was quite as familiar with the geography of Central Africa as any dragoman I could procure, and that, in any case, I should find it best to form my own plans and choose my own paths. How far I was justified in my choice, will appear in the course of the narrative.