A RECORD, IN THE MAKING

THE ISLAND OF STONE MONEY

UAP OF THE CAROLINES

A RECORD, IN THE MAKING

UAP

OF

THE CAROLINES

By

WILLIAM HENRY FURNESS, 3RD, M.D., F.R.G.S.

AUTHOR OF

“HOME-LIFE OF THE BORNEO HEAD-HUNTERS”

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

BY THE AUTHOR

PHILADELPHIA & LONDON

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

1910

Copyright, 1910

By J. B. Lippincott Company

Published September, 1910

Printed by J. B. Lippincott Company

The Washington Square Press, Philadelphia, U. S. A.

IN MEMORIAM

23 JUNE, 1909

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Introductory | 11 |

| II | Native Houses | 21 |

| III | Bachelors’ Houses | 36 |

| IV | Costume and Adornments | 56 |

| V | Songs and Incantations | 69 |

| VI | Dance and Posture Songs | 82 |

| VII | Money and Currency | 92 |

| VIII | Uap Friendships | 107 |

| IX | Religion | 142 |

| X | Perception of Colour | 155 |

| XI | Tattooing | 157 |

| XII | Burial Rites | 162 |

| Uap Grammar | 180 | |

| Vocabulary | 199 |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

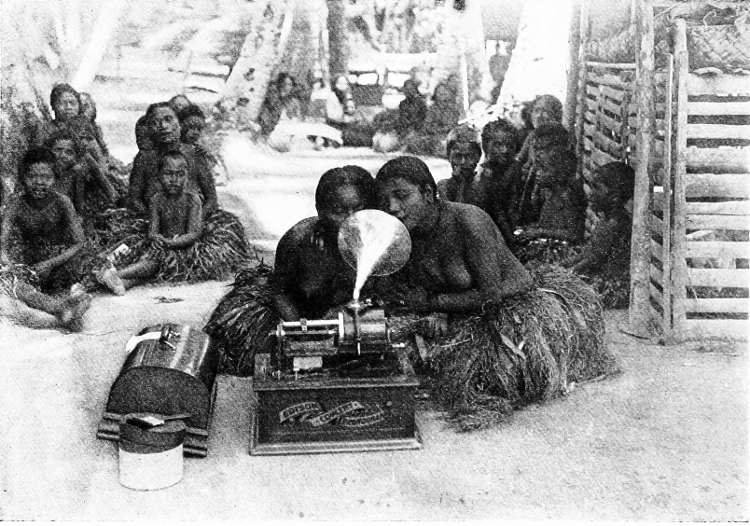

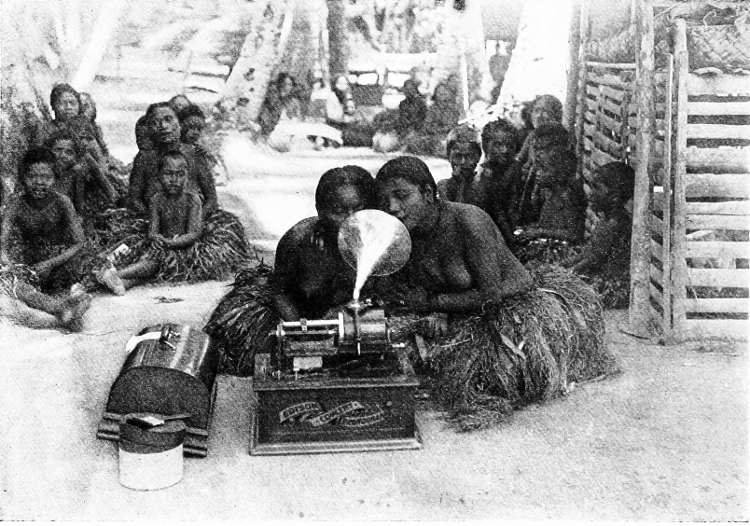

| A Record, in the Making | Frontispiece |

| A Native Residence | 22 |

| A Rich Man’s House | 24 |

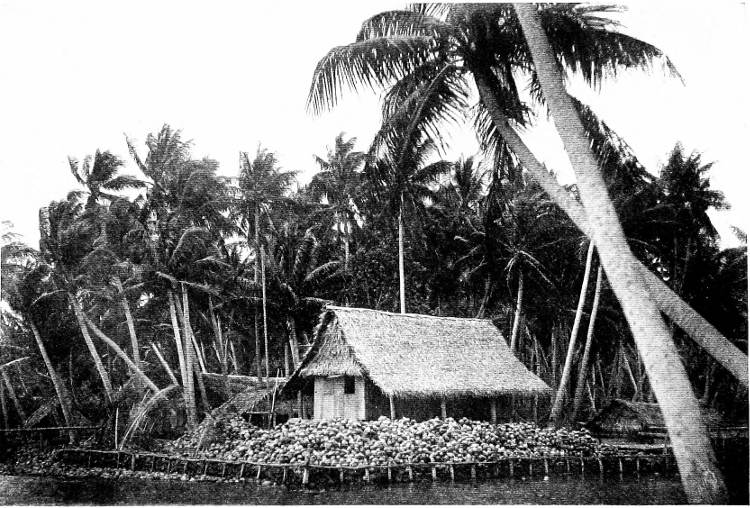

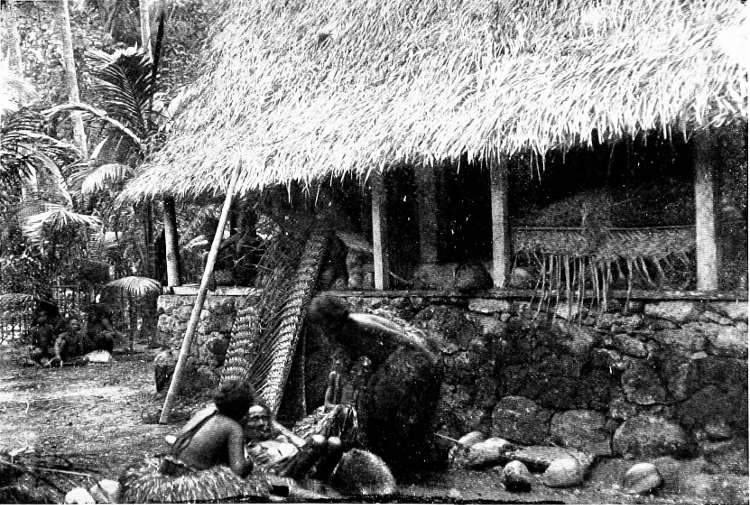

| House of a Copra Trader | 26 |

| A Native-Made Path | 30 |

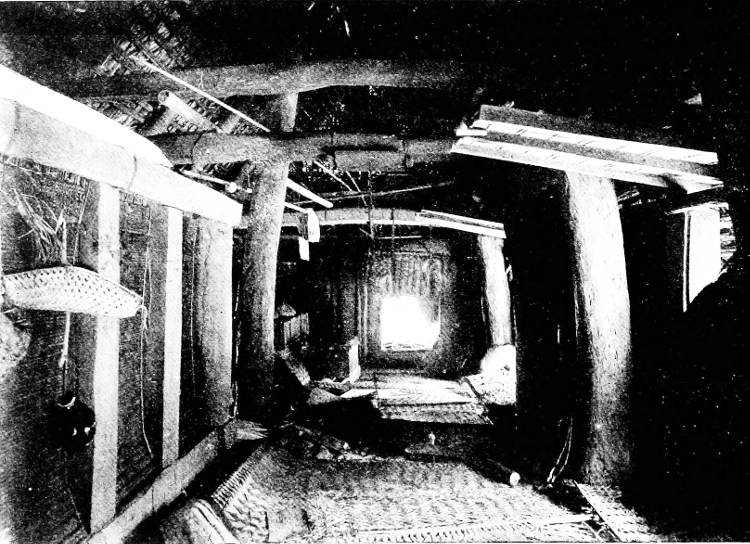

| A “Pabai,” or Men’s Club-House | 36 |

| Return From a Fishing Cruise on the Open Sea | 40 |

| A “Failu” | 44 |

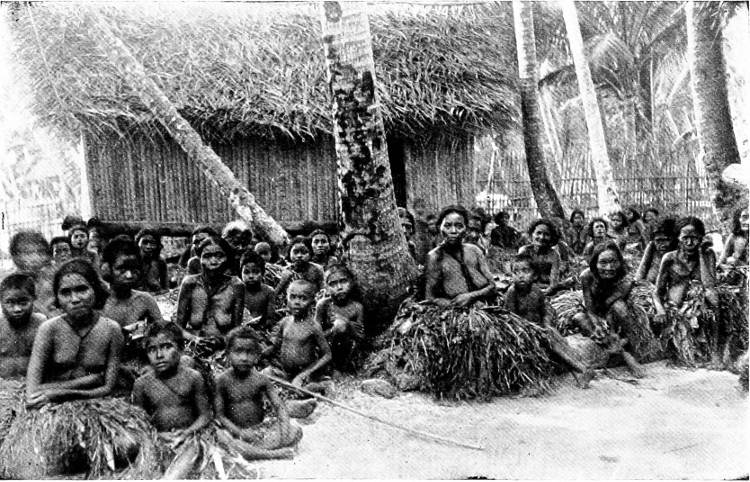

| Man and Wife of “Pimlingai,” or Slave Class | 48 |

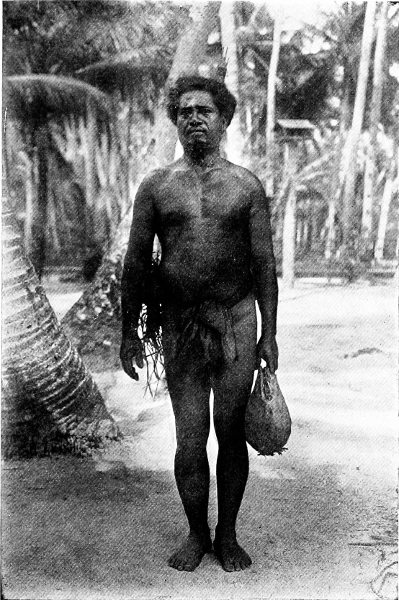

| Lemet, a Mispil | 52 |

| Waigong, a Boy of Sixteen or Seventeen | 56 |

| Full Dress of a High-Class Damsel | 60 |

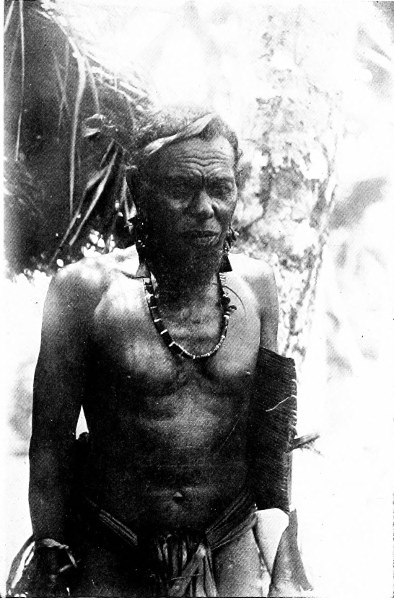

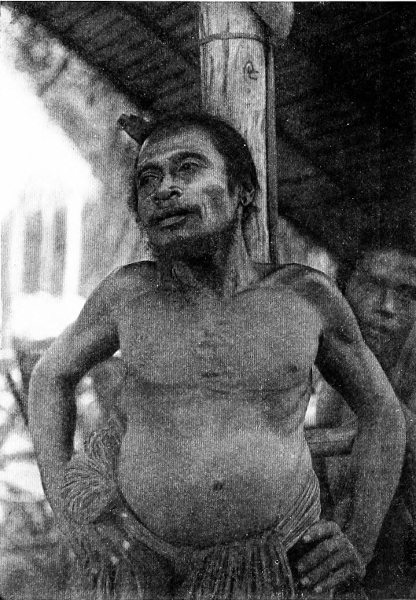

| Inifel, a Turbulent Chief | 64 |

| A Phonographic Matinée | 72 |

| Four Damsels Who Sang into the Phonograph | 74 |

| Lian, Chief of Dulukan | 76 |

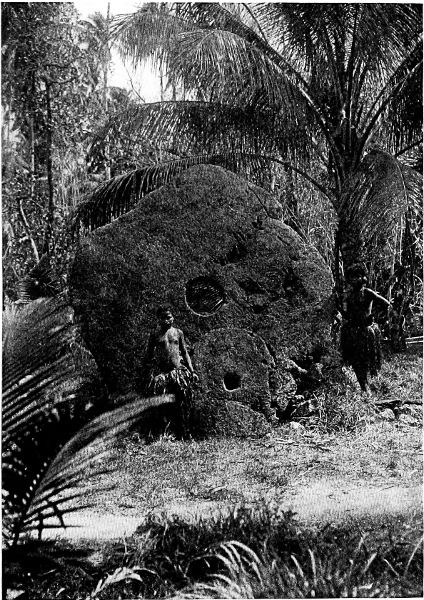

| The Largest “Fei” on the Island | 92 |

| Stone Money Belonging to the “Failu” | 96 |

| “Gagai,” or Cat’s Cradle | 108 |

| Kakofel, the Daughter of Lian | 110 |

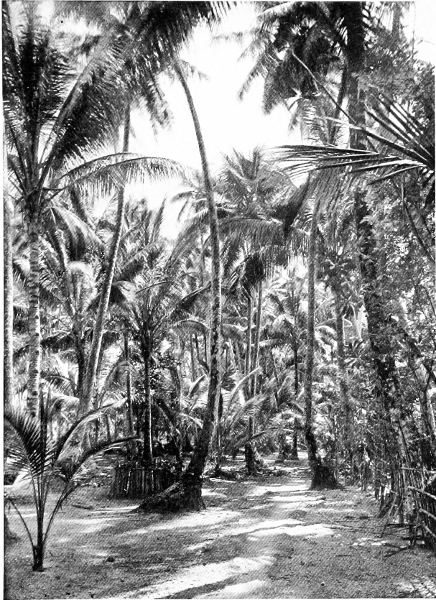

| Coconut Grove | 114 |

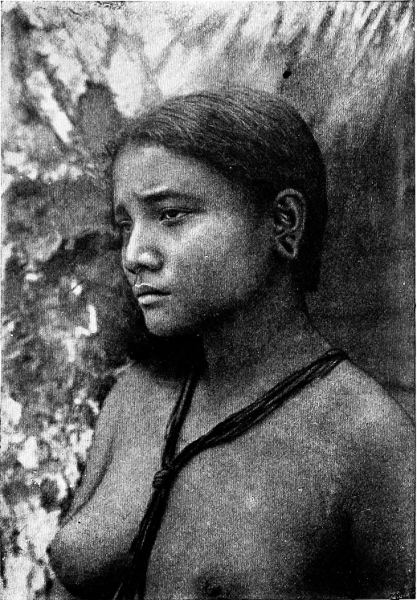

| Migiul, a Mispil | 124 |

| Fatumak | 126 |

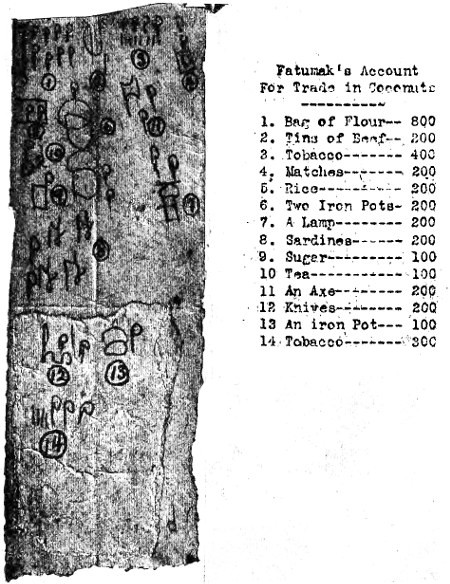

| Fatumak’s Account for Coconuts Rendered | 138 |

| The Mode of Carrying Babies | 154 |

| The Tattooing of the Men of Fashion | 158 |

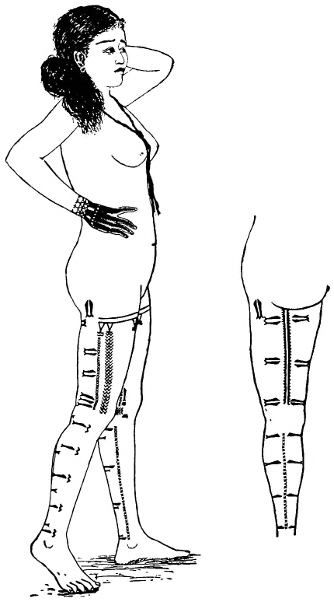

| Tattooing | 159 |

| Usual Tattoo Marks of a Mispil | 160 |

| Funeral Gifts of Stone Money and Pearl Shells | 166 |

| Gyeiga Placing Two Pearl Shells on Her Father’s Corpse | 168 |

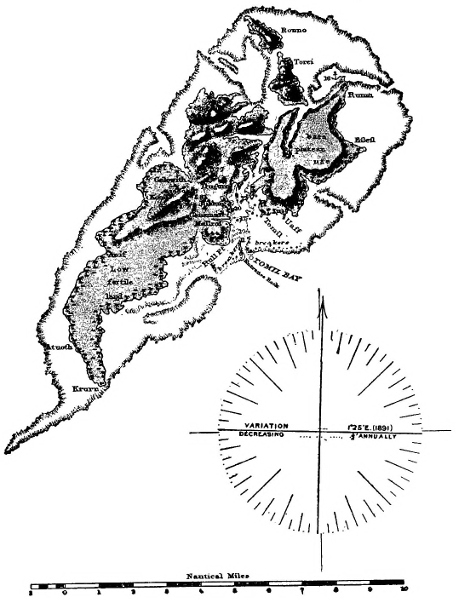

| Map | 273 |

[11]

THE

ISLAND OF STONE MONEY

Although old-time Pacific whalers and missionaries, both of them, let us hope, from kindly motives of rendering the islanders happy, introduced two unfortunate attendants of western civilization—alcohol and diversity of faiths—nevertheless the natives of The Caroline Islands have retained the greater part of their original primitive beliefs, and recently, under admirable German rule, have perforce abandoned alcohol. Wherefore they are become an exceedingly pleasant and gentle folk to visit; this is especially true of the natives of the island of Uap or Yap, the most westerly of the group. Like all other primitive people (it hurts one’s feelings to call them savages or even uncivilized,—one is too broad[12] and the other too narrow) they are shy at first, either through mistrust or awe, but, let acquaintance and confidence be once established, and they are good company and benignantly ready to tolerate, even to foster condescendingly, the incomprehensible peculiarities and demented foibles of the white-faced visitor.

When I visited The Caroline Islands in 1903, there was but one small steamer, of a German trading company, which, about five times a year, links these little worlds with our great one, and the people which it brings from the uttermost horizon must seem to the natives quite as wonderful as beings from Mars might seem to us; we at least can discern the little point of light from which our Martian visitors might come, and can appreciate the size and distance of another world, but to the man of Uap, whose whole world in length and breadth is but a day’s walk, the little steamboat emerges from an invisible spot, out of the very ocean.

[13]

After a whole month of tossing and rolling and endless pitching on the tiny, 500-ton steamer, Oceana, plying between Sydney and The Marshall and Caroline Islands and Hong-Kong, we were within one night’s sail of the little island of Uap,—a mere dot on our school maps. Here I intended to remain for nearly two months and await the return trip of the steamer. The five short stops which the steamer had made at other enchanting, alluring islands had been veritable hors-d’œuvres to whet the appetite, and while drinking in the beauty of my last sunset from the deck of the copra-laden little steamer, with the sea the colour of liquid rose leaves and the sky shaded off in all tints of yellow, orange, green, blue, mauve, and rose-color, I was thrilled by the thought that I was soon to enjoy again the earthy perfume of damp groves of palm, the pungent odor of rancid coconut oil, and the scent of fires of sappy wood, whereof all combined compose the peculiar atmosphere of the palm-thatched houses of Pacific Islanders. I expected to be awakened on the following[14] morning by the sudden change from tossing on the open sea to the smooth gliding of the vessel through the waters of the calm lagoon, and with that delicious smell of land and of lush vegetation. Instead of this, however, in the gray of dawn, I was instantly aroused by the clang of the captain’s signal to the engine room, ringing first “stop” and then “full speed astern.” I jumped from my berth to the deck and looked into a thick, impenetrable fog that utterly hemmed us in. From every side an ominous roar of breakers rose above the thump of the engines. The fog lifted; there were the reefs and breakers distant not a hundred and fifty feet dead ahead of us; then down came the fog and off we backed, only to find that the reefs encircled us completely. Even before the glow on the light and fleecy clouds which formed the ineffable beauty of the sunset had faded, heavy clouds had arisen; by midnight the sky was inky black with no star to guide our course. The captain thus fell a victim to the strong, variable currents, characteristic of these[15] waters, which are indeed but one of the many varieties of thorns which hedge these Sleeping Beauties of the ocean; these had been responsible for our being hurried on much faster than the log could show, and here we were almost on top of the reef, two hours ahead of time, with the land hidden behind an impenetrable veil.

Our situation was like a fever-dream, wherein vague but fatal dangers threaten, and, strain as we may, we are unable to open our eyes. The fog had been like a great eyelid, raised and lowered just long enough to give us one fleeting glimpse, and no more, of fatal peril, while the thunder and hissing swish of the breakers were like the deadly warnings of a rattlesnake before it strikes. Then, of a sudden, again the dense fog lifted completely, and the land seemed verily to rise out of the sea, and we found ourselves directly in front of the very entrance to the harbour with the channel of deep-blue water almost running out to meet us. Five minutes more of fog and we should have been pounding helplessly on the reefs[16] with the garden gates impenetrably closed.

I mention this only to give the hint that were the gates wider open and less dangerously ajar, “trade’s unfeeling train” would have long ago wholly overrun these imprisoned little lands and dispossessed the aboriginal “swain.”

Yap, or rather Uāāp, with a prolonged broad ā, the pronunciation invariably used by the natives, means, in their old language, I was told, “the Land,” which, I suppose, exactly meant to the aborigines—the whole world. Uap is, as I have said before, the westernmost of The Caroline group, and lies about nine degrees north of the equator. It is not an atoll, but the result of volcanic upheaval; it is encircled, nevertheless, by coral reefs from three to five miles wide, and has, at about the middle of the southwestern coast, a good harbour in Tomil Bay.

To recall very briefly the general history of this group of islands: They have been known to the civilized world since 1527, when they were discovered by the Portuguese; a hundred[17] and fifty years later they were annexed by Spain and named in honour of Carolus II. At the close of the Spanish-American war the whole group was purchased from Spain by Germany for the sum of $3,300,000, and since then under judicious and enlightened government has steadily improved in productiveness.

The natives of Uap, in number from five to six thousand, are of that perplexing type known generally as Micronesian, which covers a multitude of conjectures. The natives of each island have certain characteristics of form and features which make relationship to natives of other islands or groups of islands a possibility; but, on the other hand, there are such differences in language, in customs, in manner of living, that it is well-nigh impossible to state, with any degree of certainty, what or whence is the parent stock or predominant race. By way of generalization merely, and not as deciding the question, let me say that the people of Uap are of the Malayan type,—a light coffee-coloured skin; hair black[18] and inclined to wave or curl, not crinkly, like the Melanesian and African; eyes very dark brown, almost black; cheek bones rather high and noses inclined to be hooked, but not prominent. In this last feature they resemble other Polynesians and the Melanesians of New Guinea and The Solomon Islands. They are not as tall nor, on an average, as strongly built as the natives of Samoa, Fiji, or Tahiti. Since the sale of intoxicants and gunpowder has been prohibited, except to the trustworthy chiefs, they are gentle, docile, and lazy; formerly, under the very lax rule of Spain they were exceedingly troublesome and frequently made raids upon the Spanish and German traders, and were continuously at internecine war.

Personal details are generally uninteresting; it therefore suffices to say that I was received most kindly by the little colony of white people who live upon the island, consisting of the resident doctor, then acting as Governor; the postmaster; the manager—an American—of[19] The Jaluit Trading Company; and four Spanish and German copra traders.

I was most hospitably entertained by Herr Friedlander, one of these copra traders, and, in point of residence, the oldest white trader on the island. With a courteous friendliness for which I shall be always grateful, he invited me to lodge with him at his little copra station in Dulukan, where I could be all the time in close touch with the natives; not only was he always ready to act as my interpreter, but was also at every turn unwearied in his kindness and devotion. I had expected and hoped to share the home life in the houses of the natives, as I had done in Borneo, but the village life and the home life of the people of Uap differ so widely from those of the Borneans that I found it would be better by far to stay in Herr Friedlander’s comfortable little pile-built house and visit the natives, or get them to visit me.

As soon as the Oceana had discharged her cargo and departed on her way to Hong-Kong, we set our sail of matting in Friedlander’s[20] native-built copra barge, which was fairly loaded to the gunwales with my luggage and photographic outfit, and glided through green aisles of mangrove and over the glassy blue and green water of the lagoon to the southern end of the island where lies the delightful, scattered little village of Dulukan.

[21]

The island is divided into districts, more or less defined, which are the remnants of former days when these districts marked the division into hostile tribes; but now, under one government, these separate districts are but little regarded as tribal divisions, and within them the houses are scattered indiscriminately in small groups. Such a thing as a village street or even a road between rows of dwellings nowhere exists; there is, therefore, nothing of what we would call village life, when

The large “bachelor houses,” to be sure, are adequate meeting places for the men, but the poor neglected women have no common ground where the heart-easing and nutritious gossip of the day may be exchanged. In the coconut groves, which form a broad band[22] along the coast all round the island, each house is surrounded by a neatly-swept clearing, and this little lawn, if that can be called a lawn which is devoid of grass, is brightened here and there by variegated crotons, suggestive of the neatness of the Uap housewife, and affording an attractive playground of chequered shade under the lofty palms. The houses are always built upon a platform, about two and a half to three feet high, of masses of coralline rock, which look like huge pieces of pumice stone; when first taken from the water this soft lime-like rock lends itself admirably to being smoothed and fashioned with the primitive implements of the natives. The platform is made level on top by filling in with rubble and earth or with a covering of large flat stones. This loosely built foundation is, I suppose, to serve the same purpose as the high piles whereon tropical houses are usually built, namely, to keep the floor, which is also the domestic bed, as high and dry as possible above the level of the ground, which at times is deluged with rain in the usual tropical abundance.[23] Well constructed houses have a broad and long foundation platform, whereon is built a second stage just large enough to be covered by the house; the lower and larger then serves as a broad uncovered veranda round at least three sides of the building. The cornerposts for the framework are embedded in the upper dais of stone so that the occasional typhoons which sweep the island and level even the coconut palms may not carry away the whole structure. Every beam and stanchion is mortised to its fellow and bound with innumerable lashings of twine made from the fibre of coconut husks; not a nail is used and scarcely a peg.

A NATIVE RESIDENCE

In the little yards or clearings about the houses and on the larger broad platform of stones whereon the houses are built, all that there is of village life goes on; here guests are received and entertained, councils of the wise held, and news passed round. It is decidedly bad manners for any visitor to enter a house, except by special invitation, no matter how intimate a friend he may be. Very often, to[24] add to comfort, upright stones are imbedded in the lower platform to serve as back rests when sessions of the councils happen to be prolonged or the orator prosy. A matting of bamboo grass, or else panels of interwoven fronds of the coconut palm form the side walls of the house; security and secrecy, it must be remembered, are hardly necessary in such small communities, where all are acquaintances, and every article of household use or of luxury is almost as well known to everybody as to the actual owner; stolen goods are not marketable and thefts are quite rare, except, of course, of coconuts that happen to fall unexpectedly and temptingly from a neighbour’s tree.

The interior of the house is neither bright nor cheerful; it is not strange, therefore, that there is but little indoor life. The eaves of the palm-thatched roof overhang so far that they almost touch the level of the floor and all the light and air come through the doorway, or through one or two panels in the wall which are occasionally raised like shutters and [25]held by a wooden hook suspended from the rafters.

A RICH MAN’S HOUSE. ON THE RIGHT IS A FINE WHITE “FEI,” AND, HANGING FROM THE RAFTER IN FRONT OF THE DOOR, A BANANA FIBRE MAT

How any dust at all can collect on a small island in mid-Pacific is a mystery; nevertheless, every article in a Uap house is coated deep with cobwebs and fine dust. This is also the case, however, in the houses of all Pacific Islanders that I have ever visited, and is possibly due to absence of chimneys and abundance of smoke.

There is always in private houses in Uap an inner room or corner, screened off from the common room, where the owners of the house sleep at night. This little sleeping-room is totally dark except for what little light may filter through the walls or under the eaves. There is, of course, no second story to the houses, except a general storage place under the rafters, on top of the cross beams, where any article, not in daily use, such as a leaky canoe, a ragged fish net, a broken spear, etc., is tucked away.

I have groped my way through many a Uap house, of course with the full permission of[26] the owner, rummaging in every dark corner in search of articles of ethnological interest, but only once or twice was my search rewarded. The owners did not seem to object in the slightest degree to my curiosity, and after giving me liberty to poke and pry to my heart’s content, they stood by smiling and good-naturedly answering my questions as to the names and uses of everything. They knew well enough that I should not find what they considered their really valuable possessions, which were probably hidden away in the darkness of the inner chamber, and were sure moreover that whatever I found that I wanted would be paid for by many a stick of “trade” tobacco.

It was near a scattered collection of houses such as these that, on a cloudless afternoon in February, I landed at Friedlander’s charming little copra station. He is married to a native of Guam, a convert to the Roman Catholic faith, but not to the western method of living and style of house; so [27]Friedlander has built for her a home to her liking, bare of all furniture, except mats on the floor, and with an open hearth for cooking and for the comforting circulation of smoke throughout the house, or rather room; here she lives “shut up in measureless content” with her select circle of native friends, together with a sprinkling of elderly relatives, which seems to be an inevitable household element in the Orient.

HOUSE OF A COPRA TRADER

My host and I, however, put up at his own little house built within the same compound, on piles six feet high and furnished with two comfortable cot-beds, tables, and chairs. The whole house is about twenty feet long by ten wide and constructed as openly as possible, with roof and walls of palm-leaf thatch, for coolness’ sake. This is also his office where he transacts business, such as the purchase of coconuts or the payment for the manufacturing of copra. Copra, by the way, is made by cutting out the meat of ripe coconuts and placing it on screens to dry in the sun. When thus dried, it is exported to Europe, where the oil[28] is expressed and used in the manufacture of fine soaps.

After my luggage had been carried up from the little jetty of rough, spongy, coral blocks to the house, about twenty feet away, and while Friedlander was busy with his group of natives, settling accounts for coconuts delivered during his absence, and with unpacking his boxes of new articles of trade, I strolled forth to take a preliminary survey of my field, provided with a note-book wherein were certain useful phrases in the Uap tongue which I was anxious to put to the test.

The compound about Friedlander’s several houses was quite deserted; everybody had gathered about the master to watch the unpacking and drink in with open ears and gaping mouths every syllable that fell from his lips; and, of course, to ask innumerable irrelevant questions. The declining sun cast long bands of orange light between the gray and mossy-green trunks of the palms, and the sandy earth of the well-swept little compound was rippling with the flickering shadows of[29] the over-arching coconut fronds. There was no song nor twitter of birds; the only sound was the murmur of voices from the crowd within the house, and from a little inlet beside the deserted husking sheds came a rhythmical swish of innumerable coconut husks floating there in an almost solid mass. I turned out of the bamboo wicket gate eager for exploration, and, feeling very much

I became suddenly aware, however, of the drollest, coffee-coloured, curly-headed, little seven-year-old girl gazing at me with solemn black eyes, awestruck and spellbound. The expression of those wide open eyes, framed all round in long black lashes, was awe, fear, and curiosity mingled; her hands, prettily and delicately shaped, not overly clean, were pressed one upon the other on her little bare chest as if to quell the thumpings of fright, and, whether from astonishment or by nature, her glossy black curls stood up in short spirals all over her head. She was such a typical, little, wild[30] gingerbread baby, that I could not avoid stopping at once to scrutinize her as earnestly as she scrutinized me. Although she was the only one of her kind in sight, she stood her ground bravely and betrayed nervousness only in the slight digging of her little stubby brown toes in the sand as if she were preparing a good foothold for a precipitate dash. As I looked down upon her, the bunchy little skirt of dried brown grasses and strips of pandanus leaves, her sole garment, gave her the appearance of a little brown imp just rising out of the ground. I thought I detected a slight turning movement in those nervous little feet, so for fear of frightening her into the headlong dash, I looked as benignant, unconcerned, and unsurprised as I could, and turned down the path outside the fence toward the first house in sight. With no particular objective point I followed one of the wide, native-built paths constructed of sand, finely-broken shells, and decomposed coral, and, inasmuch as they dry off almost instantly after a heavy shower, they are excellently devised for rainy [31]seasons. These footpaths (there is not a cart in the community) extend from one end of the island to the other and branch off toward all the principal settlements; many of the smaller branches are, however, constructed with no great care and consist merely of a narrow paving of rough coral and stone, well adapted for tough bare feet, but not for stiff, slippery, leather soles.

A NATIVE-MADE PATH

The road past Friedlander’s Station at Dulukan is one of the main thoroughfares and well kept up; down this I turned, with the long vista before me of gray, sun-flecked road, overarched by the cloistered fronds and bordered by the slanting stems of coconut palms, with here and there spots of bright color from variegated crotons and dracænas. I was lost in admiration of the beauty of it all and was still thinking of my first encounter with an island-born elf, when I heard the patter of tiny feet behind me, and turning, saw again the little jungle baby trotting close after me. Curiosity had spurred on her valour to conquer discretion, and now she stood close beside[32] me, and, with a sidelong glance, smiled coyly and inquiringly, showing a row of white baby teeth set rather far apart. I too smiled in return at the droll little figure, and, not having my Uap Ollendorf at my tongue’s end, I said in English “Come along, little elf, and take a walk.” The spell was broken; I became to her a human being with articulate speech, and not a green-eyed demon. At once there issued forth in a childish little treble a stream of higgledy-piggledy words, and then she wistfully waited for a reply. The Uap vernacular failed me, so I simply shook my head despairingly. Then I heard her say distinctly one of my note-book phrases, Mini fithing am igur? “What’s your name?” This I could answer and she tried hard to repeat the name I gave; after several ineffectual struggles, she looked up consolingly, and patting her chest with her outspread hand, and nodding her head each time to emphasize it, she reiterated “Pooguroo, Pooguroo, Pooguroo,” clearly intimating that this was her own name. Here then was all the formal introduction[33] necessary, so we two sauntered down the path together, she keeping up a constant chatter and patter, while pointing toward houses here and there in the open grove of palms. I think she was telling me the name of every house-owner in the neighbourhood and the whole of his family history and also his wife’s, but I was restricted to “Oh’s” and “Ah’s” and grunting assents; but all distinction of race or age vanished and here I gained my first little friend, staunch and true, among the people of Uap. I never found out who she was, further than that she was Pooguroo; she was always on hand when anything was astir, and always proved a fearless little friend among the children; but who her parents were, or where her home, I never knew. Adoption, or rather exchange of children at an early age, is so common that it is a wise father that knows his own child. To the mind of the Uap parents children are not like toothbrushes whereof every one prefers his own; they are more or less public property as soon as they[34] are able to run about from house to house. They cannot without extraordinary exertion fall off the island, and, like little guinea-pigs, they can find food anywhere; their clothing grows by every roadside, and any shelter, or no shelter, is good enough for the night. They cannot starve, there are no wild beasts or snakes to harm them, and should they tear their clothes, nature mends them, leaving only a scar to show the patch; what matters it if they sleep under the high, star-powdered ceiling of their foster mother’s nursery, or curled up on mats beneath their father’s thatch? There is no implication here that parents are not fond of their children; on the contrary, they love them so much that they see their own children in all children. It is the ease of life and its surroundings which have atrophied the emotion of parental love. Has not “too light winning made the prize light?” When a father has merely to say to his wife and children “Go out and shake your breakfast off the trees” or, “Go to the thicket and gather your clothes,” to him the struggle for[35] existence is meaningless, and, without a struggle, the prizes of life, which include a wife and family, are held in light esteem. Parental love, by being extended to all children, becomes diluted and shallow. Is it not here then, in an untutored tropic island, that the realization is to be found of the Spartan ideal? Somebody’s children are always about the houses and to the fore in all excitements, and never did I see them roughly handled or harshly treated. As soon as they are old enough they must win their own way, and, if boys, at a very early age, they make the pabai or failu—the man’s house—their home by night and day, sharing the cooked food of their elders, or living on raw coconuts, and chewing betel incessantly.

[36]

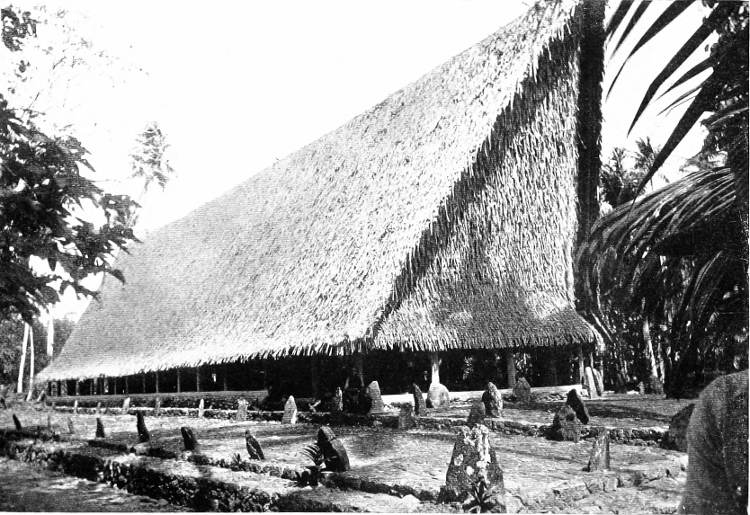

One of the most noteworthy features of Uap life are the large houses known as failu, when situated on the coast, and pabai, when built inland beyond the belt of coconut groves. These houses are found in all Uap villages, and pertain exclusively to the men, be they married or single; herein councils are held, and the affairs of the community are discussed, free from all intervention of women; and here, too, men and boys entertain themselves with song and dance, in which, under the plea that it would not be decorous for women to join, a desire may be detected to escape feminine criticism. A failu or pabai is frequently years in building; the men do not wait, however for its final completion and ceremonial opening before occupying it, but often make it their home even should no more than the framework and roof be finished. Every post, every beam is selected with extremest[37] care, so that all its natural curves and angles may be used without further shaping. No nails, and, indeed, very few pegs are used to hold the beams together; each beam is attached to another by mortising, and then literally thousands of yards of cord, made from the fibre of coconut husks, are used to bind the joints. The lashings of this brown kaya cord furnish excellent opportunities for ornamentation; wherefore, with tropical lavishness and Oriental contempt for the expenditure of time, the main posts, for four or five feet below the cross beams, are often bound with cords interlaced into beautiful basket patterns and complicated knots; where the slanting supports of the thatched roof meet the side walls there is a continuous, graceful band of interwoven cords, where each knot has its own peculiar designation and invariable position.

A “PABAI,” OR MEN’S CLUB-HOUSE

When, after years of fitful labor, one of these club-houses is finally complete, a feast is spread and dances are performed in front of the structure, to which all, including even the[38] women, for the nonce, are invited; the house is then and there given a name, and new fire is started in the fireplace by means of the fire drill, the most primitive method of obtaining fire known in Uap. Thereafter this failu or pabai belongs exclusively to the men, and no women, with but one exception, dare set foot within its precincts.

During the fishing season every fisherman, while plying his craft, lies under a most strict taboo. Wherefore, one very important use of the failu, or “house on the shore,” possibly its primitive cause, is to provide a place of seclusion for the tabooed fishermen during their intervals of rest. After three or four days and nights of hard work in boats on the open sea outside the lagoon, the fishermen return to the failu to distribute their haul of fish and to repair damages to their boats and nets. Whether the sea has been calm or stormy, they are always an exhausted crew; their meat and drink have consisted almost exclusively of coconuts, and their quarters have been extremely cramped in the long,[39] narrow, out-rigger canoes. Not for these poor wretches, however, are the refreshing comforts of home when, weary and worn, they return to recuperate; an inexorable, rigorous taboo enshrouds them until the last hour of the six or eight weeks of the fishing season. During their brief seasons of needful rest, not a fishermen dare leave the failu or, under any pretext whatsoever, visit his own house; he must not so much as look on the face of woman (with one exception) be she his own, or another’s, mother, wife or daughter. If the heedless fisherman steal but a glance, flying fish will infallibly bore out his eyes at night. They may not even join in song or dance with the other men of the failu in the evening, but must keep strictly and silently apart; nor may their stay-at-home companions mingle with them; and, worst of all, until the fishing season is over and past, they can have none of a fisherman’s prerogative of endlessly expatiating on the unprecedented size and weight of the fish that they have missed,—tantum religio potuit suadere malorum.

[40]

It is truly impressive to see large fishing canoes come in after a cruise; they carry twenty or more men, and have often experienced extremely rough weather for craft which, according to our ideas, are so unwieldy, and unstable. In their management they can be paralleled only by the vessel provided by the “Bellman” in the “Hunting of the Snark,” where at times it was not at all out of the ordinary for the bow to get mixed up with the rudder. Inasmuch as the whole balance of the boat depends upon the out-rigger, it would never do, of course, to have the large, heavy sail, bearing the weight of the wind, on the opposite side of the boat; consequently, when sailing up in the wind, where tacking is necessary, instead of putting about or jibing, the crew assemble and, lifting the mast with all the rigging, carry it bodily from the bow to the stern, where it is stepped anew; the stern then becomes the bow, and the man at the helm has to scramble quickly to the other end of the boat to find out which way he is going. Of course, such a liberty never can [41]be taken with the mast and rigging under any other than a very mild breeze; consequently, in rough weather there is nothing for it but to keep on one course until the wind abates, or else take in all sail and drift. Herein lies one of the causes which accounts, I think, for the mixture of inhabitants throughout Polynesia and Micronesia; canoes full of helpless fishermen have been known to drift from The Gilbert and Marshall Islands a thousand miles or more; from the very centre of The Carolines down to the northern coast of New Guinea and The Solomons. Is it any wonder then that the return of a canoe full of friends, fathers, and husbands, who, for the common good, have ventured forth on the vasty deep, far beyond the sight of their little world, should be hailed, as it always is by the simple islanders, with emotions almost akin to awe? Even to us it seems little short of a miracle, when we reflect that this return is effected without compass or sextant. It is not strange, therefore, that the lives of these venturers should be hedged about with peculiar laws and[42] mysterious restrictions, as if they were beings apart from the common herd, and superior.

RETURN FROM A FISHING CRUISE ON THE OPEN SEA

A canoe is usually sighted long before it turns into the entrance to the lagoon, and then the members of the failu stand or squat on the stone platform at the seaward end of the house and quietly watch the slow approach of their daring comrades. When they are within a half a mile or so of the shore where the water is shoal and thickly sown with many protruding treacherous boulders,—the remains of ancient fish-weirs,—the mast with its sail of matting is unstepped and stowed; the canoe is then guided on its tortuous way with poles and paddles. The approach is slow and silent; there is no shouting, no outward excitement; it has all the solemnity of a religious ceremony; the waiting crowd on the shore is hushed or converses in subdued whispers; the great, unwieldy canoe moves slowly onward with all the dignity of a majestic ocean liner coming into port. As soon as the bow touches the shore, the fishermen at once disembark and silently march up into the failu, leaving[43] two members of the crew to protect with matting the painted figureheads of conventionalized frigate birds, at the bow and stern; and, after unloading the fish, to take the canoe to its mooring nearby.

I once went into a failu immediately after the fishermen had returned; the whole interior aspect of the house was changed; more than two-thirds of the floor was partitioned off into little stalls or pens made of matting of green coconut fronds with the leaves interwoven. The sides of the little pens were just high enough to permit the occupants when sitting down to look over and see what was going on; if they wished to be unseen, they had only to lie down. Possibly, these partitions are not so much for seclusion as to prevent any one from stepping over the legs of the sleeping fishermen, a terribly ill-omened accident, and sure to bring misfortune on the sleeper. The other members of the failu were gathered together at the inland end of the house, and were either at their usual trifling occupations, or mending fine cast-nets, or fashioning from[44] a section of bamboo a box for powdered lime, that indispensable adjunct to betel chewing; some young dandies, or oofoof, as they are termed, were grouped about a little heap of glowing embers, which they had raked together for cheerfulness’ sake, and, also, to save the expense of innumerable matches for their cigarettes; they were humming in unison one of their unintelligible and unmusical songs. It was probably either etiquette or taboo, but no one seemed to be paying any attention to the fishermen, who seemed to be, in fact, absolutely ignored ever since their arrival. These poor, tired men were each installed, and the whole floor looked like a gigantic wasp’s nest, with every cell-cap off, and demure grubs just sticking their heads out. After all their hard, self-sacrificing work at sea to provide food for the community, they are literally imprisoned till the time arrives for them to sail again; they are not allowed to go further inland than the inland side of the house, and if their mothers, wives, or daughters bring any gift, or wish to talk to them, [45]the women must stand down near the shore, with their backs turned toward the house; then the men may go out and speak to them, or, with their backs turned to them, receive what has been brought, and return at once to their prison.

A “FAILU”; THE DIVISIONS ON EITHER SIDE ARE SLEEPING QUARTERS

The fish are displayed on the stone platform in front of the house, or on stands of bamboo or palm, and are then apportioned to the families of the fishermen, or to purchasers from the district. Payment is made in shell money or in the stone money-wheels peculiar to Uap. A feature of this barter, which speaks much for the ingrained honesty of these people, is that the money is deposited on the ground near the failu, possibly several days before the fishermen return; no one ever attempts to steal it, or lay false claim to it; there it remains, untouched and safe, until the owner receives the fish. The strings of pearl-shell money and the stone wheels received in payment for the fish, become the property of the failu, and are expended for such purposes only as will benefit the whole house, namely, the purchase[46] of new canoes, rigging, nets, etc., or else reserved to pay the heavy indemnity which must invariably be paid for the theft of a new mistress, or mispil.

The custom of having one mistress common to all the members of the failu, is merely a form of polyandry, which reveals in a striking degree a noteworthy characteristic of the men of Uap, namely, a complete freedom from the emotion of jealousy. In every failu and pabai there lives a young woman, or sometimes two young women, who are the companions without preference to all the men of the house; I was assured repeatedly, moreover, that this possession of a wife in common never awakens any jealous animosity among themselves in the breasts of the numerous husbands. A mispil must always be stolen by force or cunning, from a district at some distance from that wherein her captors reside. After she has been fairly, or unfairly, captured and installed in her new home, she loses no shade of respect among her own people; on the contrary, have not her beauty and her worth received the[47] highest proof of her exalted perfection, in the devotion, not of one, but of a whole community of lovers? Unlike a prophet, it is in her own country and among her own kith and kin that she is held in honour. But in the community where she is an alien, her social rank is gone. None of the matrons in the district of her failu, who live at home with their husbands and children, will have any social intercourse with her. By the men, whether in her failu or out of it, the mispil is invariably treated with every consideration and respect; no unseemly actions may take place in her presence, and all coarse language is scrupulously avoided when she is within hearing; nevertheless, owing to her station, she is permitted to hear and see the songs and dances, from which other women are barred.

If, by chance, a preference of one lover over another become observable, no blame whatever is attached to her, but the favourite is quietly told that, in the opinion of the whole house, he must retire, or possibly leave the failu for a while and live with friends in another district.

[48]

The mispil’s food, and her luxuries, such as tobacco and betel nut, are supplied by the men, and she is never required to work in the taro fields, as are the wives and daughters of the district. At quite a distance, in the bush behind the failu, a little house is built for her sole use when she wishes to be secluded; here she occupies her time in making new skirts for herself of leaves, and during her sojourn in her little home, known as tapal, the men sedulously place her food near by, but dare not so much as take one step within the enclosure around her house.

The men of the failu treat their mispils with far more respect and devotion than is generally shown by the men outside to the wives of their own household. The mispils are absolutely faithful to the men of their failu or pabai, regarding themselves as unquestionable property, having been sought and captured at the risk of men’s lives, and paid for withal in costly pieces of stone money.

They are by no means kept as prisoners; as soon as the excitement over their capture has [49]abated in their own village, they are at full liberty to return home and visit their family and friends, and they always return willingly and voluntarily to the failu.

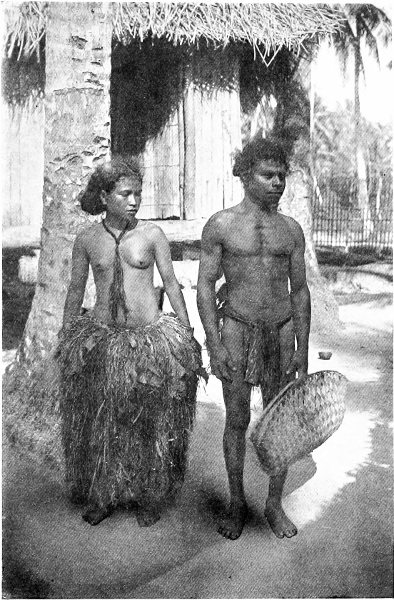

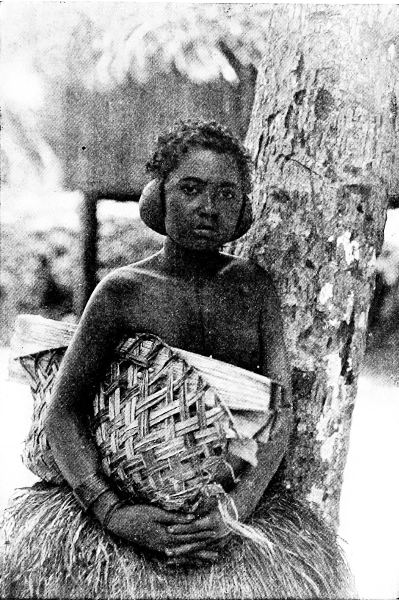

MAN AND WIFE OF THE “PIMLINGAI,” OR SLAVE CLASS

In ancient times,—which were probably no further removed than the last generation, history in these islands does not usually date much further back than the memory of the oldest inhabitant,—when there were many districts at constant war with each other and the high-born nobles were divided into two tribes, the ulun-pagel and the bultreh-e-pilun, the capture of a mispil was always accompanied by bloodshed and enduring feuds; but, nowadays, since abstinence from alcohol has cooled their brains, and they all regard themselves as really one people (with the exception of the tribe of slaves known as Pimlingai), the seizure of a young girl to fill the office of mispil is reduced to little more than a commonplace burglary; nay, it is almost always furtively prearranged with the chief of the district, inasmuch as it is to him that the parents appeal for redress. If certain captors,—or shall we[50] say burglars,—have already made choice of a victim from his district as their future mispil, it might be difficult, if not impossible, for him to prevent them from carrying out their design, but, inasmuch as he is fully assured that they are prepared to pay a good round sum in shell money and stone money by way of indemnity, he contrives, nowadays, by means of this bribe to salve the wounds of a disrupted family and dispel all thoughts of a bloody retaliation. Nevertheless, the whole proceeding is still carried out with the greatest possible secrecy and stealth.

With Friedlander’s help, as interpreter, I elicited from an intelligent young fellow named Gamiau, the following account of the capture of Lemet, the mispil of Dulukan. Gamiau, the leader of the party, was a quiet, serious, young fellow, about eighteen or twenty years old; foremost in dance and song, and, consequently, admired by his companions for the fertility of his poetic and acrobatic resources. He was not tall, but well built, with a skin as smooth as velvet, which seemed to[51] stretch tightly over the muscles underneath like a brown kid glove. He was sitting cross-legged on the floor of our little house one evening when no one else was present, and, taking intermittent puffs at his cigarette of “Niggerhead” tobacco rolled in a fragment of palm-leaf, gave us this somewhat disjointed account of the theft of a mispil.

“Lemet, our mispil, is a daughter of Pagel of Libenau, who is a brother of the chief of Bugol in the Rul district. We had not decided upon her or any other girl before we started out, but we had heard that the girls of Bugol were all pretty.

“About twenty of us from the failu of Dulukan stocked a canoe with all sorts of trade and set out for Bugol; we knew that the chief there would help us if we took plenty of presents to him, so we put in a good stock of reng [a species of turmeric used as an ornamental dye], several strings of flat pearl shells, and one large and very high priced fei [stone money]. When we reached Bugol, we separated, so that no one should suspect that we[52] were after a girl, and, having given our presents to the chief, we waited there two months and a half enjoying ourselves, but all the time on a furtive look-out for a mispil for our failu, but we could not make a choice.

“Then word came to us that we had better go to Rul, a short distance away, so that no one would suspect our plans; in this place we waited eighteen days until word came again to us from the chief of Bugol that he had selected a girl for us, and we were to move across the bay to Tomil, and build a house in the mangroves by the shore and wait till his messengers came. So we went, and, after a night and a day, two Bugol men came. Early, early in the morning, before daylight, six of us and the two Bugol men paddled very noiselessly over to Libenau. We left the canoe and four of our men in it near the shore, and I,—Gamiau,—and Fatufal and the Bugol men went ashore. Without speaking a word, the Bugols led us through the underbrush and finally pointed out the house, and whispered that we would find the girl asleep all by herself [53]in a little hut at the end of her father’s house. We crept up very, very softly, peeped in, and there we saw her, sound asleep, stretched out on her mat with nothing over her. Then we jumped in suddenly and one of us held her arms, and the other kept his hand tight over her mouth so that she could not cry out, and, just as she was, we carried her back to the canoe and paddled quickly down to Aff where the other men were waiting. When we got there, one of us stole a skirt from a house nearby, for she had no clothes. On the way home we stopped at Rul and gave two beautiful shells to the Chief, because Rul is really the head of the whole district. The girl cried a little, and seemed very sad while she was in the canoe, but now, after two months, she is as happy as can be and has never once attempted to leave us.”

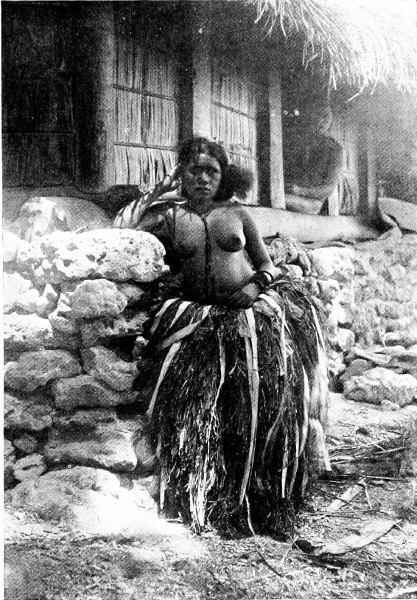

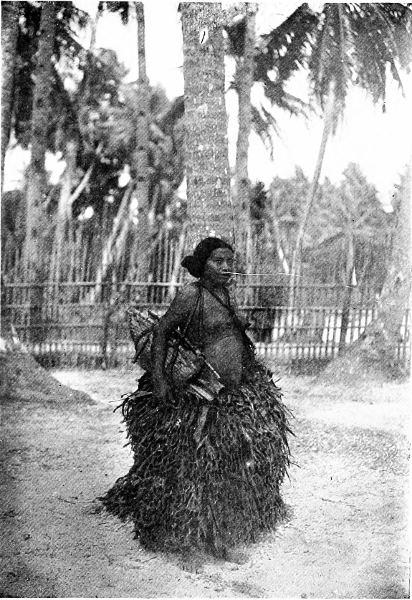

LEMET. A “MISPIL”

Haec fabula docet that the example set by young Lochinvar has still its genial modifications in Uap, and that, although the Bugol bride may not be so compliant as the Netherby, yet the stealing of a mispil is not now an[54] exploit wholly devoid of romance, nor of a spice of danger. A haunting suspicion will obtrude, however, that the girl had been privately “coached” by the chief, and that her family had been paid her equivalent in several good shells and were discreet enough to keep out of the way, and make the course of love run as smooth as possible. Be it added that the members of the failu who venture on these expeditions are always thereafter admired as heroes.

In dress the mispil is in no wise distinguished from other women, except by tattoo marks on her hands and legs. In this tattooing there seems to be, however, no set pattern, and the designs are not so elaborate as lasting, and, since it is not the custom for any other women to be thus ornamented, I found it occasionally possible to decipher on hands and legs of highly respectable, albeit wrinkled and shrivelled, old grandmothers, a former chapter in their history when to them all the world was young and they were the cynosure of every eye in a failu. This is explained by the[55] fact that should a mispil prove enceinte, the duty devolves on one of the men of the failu to take her as his wife, build a house for her, and bring up his own separate family. Here again, the remarkable scheme of social relations and of morality, by which these people live, renders such a compulsory marriage perfectly adjustable and by no means a disgrace. The wife of my excellent friend, Lian, the Chief of Dulukan, showed the ineffaceable and unmistakable tell-tale tattoo on her hands and legs, and both he and she held their social heads very high in the community.

Verily, it does seem that even in austere eyes this feature of the failu loses half its immorality in losing all its grossness.

[56]

There is apparently no formal initiation into a failu; when very young the boys wander in and out of it continually; and, if they please, may even sleep there; thus they gradually glide into an accepted fellowship, and, when about ten or eleven years old, may join the men as associates in the adult dances. At about this same age the young boys are known as petir, and may wear but one loin-cloth (or none at all). The next promotion is two loin-cloths, the second longer than the first little scrap, and more elaborately interlaced; they are now known as pagul. The adult man is called pumawn, and wears, first, a loin-cloth; then over this a long rope of thin strips of pandanus leaves and grasses known as kavurr; next, to add a touch of color, a bunch of the same material, stained red, is tucked in at the side and so looped that it hangs down in front over the loin-cloth.

[57]

The badge of a freeman, distinguishing him at once from a slave, is an ornamental comb in the knot of hair on the top of his head. One of the Ulun-pagel, the aristocratic tribe, assured me in the most emphatic terms that he would instantly attempt to kill a Pimlingai or “slave” should he meet one wearing such a comb. This comb, albeit of no great intrinsic value, is, therefore, the essential feature of male attire. It is made merely of fifteen or twenty narrow strips of bamboo, about eight inches long, sharpened at one end, with shorter, slightly wedge-shaped pieces inserted between each strip four or five inches from the sharpened ends, whereby the teeth of the comb are kept apart; the upper ends are now bound together with ornamental lashings of coconut fibre. A simple form, but nevertheless deemed foppishly elegant, is that wherein the strips of bamboo are fastened together with a peg run through at about the middle; the strips are then slid past each other like the ribs of a fan; these broad, unpointed, upper ends lend themselves admirably to such decoration[58] as the insertion of bright leaves of croton, tufts of cotton, strips of pandanus, etc. In one of my first attempts at photographing with a cinematograph camera, many yards of the narrow film, which, when undeveloped looks like stiff yellow ribbon, were spoiled; with exasperation, and, I fear, imprecations, I cut this worthless film ruthlessly from the little sprocket wheels which carry it through the camera, and tossed it away. No princely gift could I have devised which would have been received with more exuberant delight than these worthless strips of film; to Uap eyes they happened to be just of the most fascinating shade of yellow, and to the Uap nostril they possessed a peculiar and ravishing perfume; and as a supreme grace they vibrated like serpents when inserted in combs and caught by the breeze; in a trice every head was wreathed with coils like Medusa’s and every face was radiant with smiles.

WAIGONG, A BOY OF SIXTEEN OR SEVENTEEN

Other male ornaments consist of earrings, necklaces, bracelets, and armlets. Mutilations[59] of nose or of lips are not in fashion; earlobes, however, being appendages not ornamental and by no means useful, are always, the world over, responsive to improvement at the behest of beauty. They are not neglected in Uap. Both boys and girls have the earlobes pierced and stretched at an early age,—at about the tenth or twelfth year,—but this mutilation is never stretched to the extent that it is in the island of Ruk (in the central Carolines), nor as it is in Borneo, where the lobe is so elongated that it becomes a mere loop of skin drooping below the shoulders. The Uap men and women are satisfied with a simple hole through the lobe, about three-fourths of an inch in diameter, just about large enough for the insertion of bright leaves or flowers or a tuft of cotton. After an incision is made with a piece of sharpened coconut shell, a roll of leaves of a plant, which they call maluek,[1] is at once inserted. This leaf, and this leaf only, must be used; to it[60] is ascribed peculiar properties both of stretching and healing; it must be first warmed over the fire, then soaked and softened in coconut oil, rolled up tightly and pushed through the wound. As soon as this plug becomes loose, it is renewed, and an additional leaf added until the hole is of sufficient size and is healed. The boys grin and bear the suffering without any protection for their poor swollen and inflamed ears, which, after the fourth or fifth day, certainly look exceedingly painful; but the girls are allowed to wear protectors made of the halves of a coconut shell, held in place by strings attached to the upper edges, passing over the head, and strings from the lower edges, tied under the chin. These shells are stained a bright yellow with a turmeric, already mentioned, known as reng. Another and a smaller hole, just about large enough for the stem of a flower is often made in the rim of the ear a little above the larger hole in the lobe; this is designed for no particular ornament, but merely supplements the larger one when the latter is completely filled with [61]earrings and bouquets; a white and yellow flower of Frangipanni, or the spray of a delicate little orchid, growing on coconut trees, greatly enhances the charm when waving above red and green crotons and a pendant of pink shell. Women do not in general affect manufactured earrings; they cling more to natural effects of leaves and flowers. The men’s ear ornaments consist of short loops of small glass beads, whereto is attached a piece of pink or white shell usually cut in a triangular shape, with each edge about an inch in length; this is pendant from the loop of beads about three inches below the ear. The triangular shape is, in general, obligatory, inasmuch as the shell from which it is cut has this one sole patch of rosy pink near the umbo. This shell is exceedingly rare on the shores of Uap; consequently, these pink pendants are highly valued and owned only by the wealthy families who part with them reluctantly, and only at an exorbitant price. Other pendants of less value are made from any fine white shell, or of tortoise-shell; any[62] man may wear these who has patience enough to scrape the shells to the proper shape. Still another variety of ear ornament is a piece of thin tortoise-shell, about a third of an inch wide, bent into the shape of a U; this is hooked in the lobe of the ear, and from the outer open ends are suspended little strings of beads. In default of other ornament the men will insert anything with gay colors; my cinematograph film, whenever I happened to discard it, was sure to be seen for the next two or three days either fluttering from combs or passed through loops and coiled about the ears.

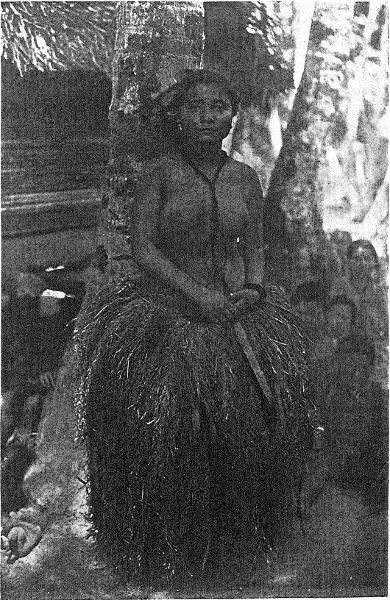

FULL DRESS OF A HIGH-CLASS DAMSEL

Ordinary necklaces, worn by all the common folk, are made of thin discs of coconut shell or tortoise-shell, about a quarter of an inch in diameter, and strung closely and tightly together, interspersed at intervals with similar discs of white shell, so that they make a flexible cord which coils like a collar rather tightly about the neck.

One of the most highly prized possessions of the men is, however, a necklace of beads[63] made of the same rose-coloured shell whereof they make their ear pendants. In each shell of superior quality there is of the pink or red portion only enough to make one good bead about an inch and a half long by half an inch wide and an eighth of an inch thick; such a bead is usually strung in the middle of the necklace among others graded off from it in size, on both sides, merging into oblong pieces about half an inch long, of the same breadth and thickness as the bead in the centre; then, finally, follow discs about one sixteenth of an inch thick. One day, a chief, named Inifel, with a suite of followers from his district of Magachpa, at the northern end of the island, paid us a visit; for an old man, his features bore as treacherous and malevolent a stamp as ever I saw; he scowled at everything and everybody from under his shaggy grizzled eyebrows, with a piercing gleam at once suspicious and sinister; he was magnificent in adornment, however, with a thauei,—a red-shell necklace,—of surpassing splendour, composed throughout of exquisite[64] red shell beads of the very largest size, except where, at intervals of every seven or eight red beads, there followed one of pure white. So satanic were his looks that I did not dare even to hint at the purchase of so gorgeous a prize, lest he should propose my soul, or my shadow, by some devilish contract, as the price. These strings of shell beads are usually about three feet long, and hang far down on the chest. Beyond question they are exceedingly beautiful, especially when set off by the dark, burnished livery of a tawny skin.

INIFEL, A TURBULENT CHIEF; ON HIS LEFT ARM IS A LARGE WHITE BRACELET, MADE FROM A CONCH SHELL; ABOUT HIS NECK A HIGHLY VALUABLE NECKLACE

A report of these red shell ornaments had reached me by rumour before I came to Uap, and I had been assured that it was utterly impossible to buy one; hence it was, naturally of course, the one thing I set my heart on possessing; wherefore I caused it to be widely known that I was prepared to pay a good round price for a red necklace, and I begged old Ronoboi, one of my first acquaintances among the nobility, not only a Chief, but also a powerful soothsayer, or mach-mach, to strain every nerve to procure one for me. He [65]shook his grave head dubiously, saying he would try, but had no hope whatever of success. Later, I saw some thaueis that were truly excellent, but the owners would not listen to a syllable of sale, and seemed even to doubt that a white man existed with wealth enough to purchase a perfect one. After several rebuffs in my attempts to buy these enviable “jewels” from wearers who looked otherwise impecunious enough, I found out that these necklaces were actually loaned, at interest, and were not the disposable property of the wearer, who, for work or services performed, was privileged to strut about, thus adorned, for a certain number of days, with that delicious glow around the heart, whether civilised or savage, which the consciousness of being well-dressed invariably bestows. In fact, the thauei, in Uap, is a medium of exchange, and is not often parted with outright, but loaned out; the interest on the loan is to be paid for in labour. After three weeks of eager and zealous endeavour, I succeeded at last in obtaining a very inferior string of merely round[66] discs, but I had to pay for it the staggering sum of thirty marks ($7.50); when the owner delivered it to me, he exclaimed, “There now, you have the price of a murder; offer that to a man and tell him whom you want killed, and it’s done!” Not until the very day I left the island did I get a really fine thauei; after almost tearful pleadings on my part, old Ronoboi, possibly by a good deal of hook and probably by a good deal more crook, persuaded one of his subjects and eke believers in the awful mysteries of mach-mach, to part with a prized heirloom, which the dear old chief and wizard solemnly and secretly brought to me. I gave him a double handful of silver mark pieces; this seemed to hush effectually the “still, small voice;” furthermore, can a king do wrong? and the necklace is mine!

The only other ornaments that the men wear are armlets and bracelets of shell or of tortoise-shell. These are made simply by cutting a narrow section from the base of one of the large conical sea-shells and breaking out all the inner whorls; the ring thus formed[67] is then slipped over the arm and worn above the elbow or wrist. I noticed none that was carved or decorated; they were merely smoothed and polished. The tortoise-shell bracelets are plain, broad bands which, after softening in hot water, are bent around the wrists, where they fit tightly, leaving the ends about three fourths of an inch apart, so that they may be sprung off the arm, and need not be slipped over the hand. These tortoise-shell ornaments are usually engraved with a few parallel lines running round them.

One peculiar shell bracelet, much affected by old men, is made of a large, white conical sea-shell, whereof the base and all the interior spirals have been cut away; this is worn like a cuff on the wrist with the big end upward. It seems incredible that they can get their hands through so small an opening, but in some way they do squeeze them through. One of my particular friends, Fatumak by name, of whom I shall speak later, told me that, once upon a time, a man from Goror, at the southernmost point of the island, tried to go[68] up to the land of departed spirits,—Falraman,—but he never reached his destination, although he saw many marvelous things, and brought back to the Chiefs extraordinary novelties; among them, these shell cuffs, and chickens.

[69]

That I might obtain permanent records of their songs and incantations, I carried with me a large-sized phonograph, with all needful appliances. With much relish I anticipated the consternation of the natives when they saw and heard a box whence issued a living human voice and music played by all sorts of instruments.

In order to introduce them to it with due paralysing effect, I made a selection of band music and several songs in English; with these I intended to charm them before requesting them to speak or sing into that embarrassing, expressionless metal horn. Experience had taught me, however, the impossibility of foretelling the fashion in which untutored minds will accept such miracles, and I was not altogether unprepared to have their bewilderment find expression in a shower of well-directed coconuts at the first bars of[70] “Lead kindly light” or other soothing, peaceful hymns. But what was my unexpected amazement and infinite chagrin, when the audience I had gathered displayed not the faintest interest in the performance beyond the sight of the revolution of the little wax cylinder. A living, human voice, singing a sweet English love-song, and issuing from a brass horn attached to a machine, was, to them, not half as awesome as the whirling wheels and the buzz of clock-work; some of the audience actually turned away in indifference, if not in disgust, and went off to resume their work of husking coconuts.

Completely crestfallen, I ventured to ask one man when the tune was finished what he thought of it; “An all right sort of tom-tom” was his careless and patronizing reply. (Tom-tom is an adopted word which they apply to cheap musical boxes,—in fact to any variety of musical instrument,—introduced many years ago by whalers and copra traders.) Friedlander himself was astounded at their mortifying indifference, and[71] suggested very justly that it was probably because the words meant nothing to them, and that the phonograph was to them only another form of hurdy-gurdy. A human voice uttering incomprehensible sounds had to them no more meaning than the beating of a tin pan.

Cast down, but not utterly discouraged, I tried a second song by a melodious female voice, but this fell just as absolutely flat as the former. As a final and desperate resource, I put on a blank roll and the recording needle, and then induced one of the youths to speak a few native words into the horn, and immediately ground off a reproduction of his very words. The effect was magical! The audience forgot to breathe in awed silence! Their eyes dilated! Their jaws fell! And they began repeating after the instrument the words of their very own language, in the boy’s very own voice, now issuing from the bottom of the horn! Was the boy himself imprisoned there? For five or six seconds after the voice ceased, they remained silent, looking from one to another, and then—then they burst into peals[72] and peals of screaming laughter, clamourously and vehemently imploring me to repeat it. Of course I complied. The coconut huskers dropped their work and hurried back helter-skelter, to hear a little machine that after only a minute’s acquaintance could talk as well as they could themselves! The conquest was complete! Thereafter I had no difficulty whatsoever in finding volunteers to sing or repeat set speeches. The miracle of a “tom-tom that talked and sung” was assured, and its success unbounded!

A PHONOGRAPHIC MATINÉE

At my first and second exhibition men alone happened to be present. A request then came to me from the women, through Friedlander’s wife, that I should give them an exhibition, to which, as they were shy, no men should be admitted. Accordingly, kind-hearted Friedlander had one of his copra storehouses cleared,—it was a little house on low piles, with walls and floor of bamboo slats, about twenty feet long and ten feet wide. At one end I set up my phonograph, and the audience duly gathered in bunches and bundles,—I use [73]the words advisedly, so enormous and expansive are the skirts of dried grasses and leaves. The hall was filled to overflowing. But in a house of bamboo the walls and floor have many a chink, and I think I may truly say there was no single crevice without its outside ear. I tried the same experiment with the women as with the men, and first of all I gave them an English song; and precisely the same result followed; the performance emphatically bored them, and they conversed with each other and pointed to the different parts of the machine as if the entertainment was yet to begin. But the native song, that I gave them next, awed them into silence in a trice; with dilated eyes they scrutinised me wonderingly, before, behind and on every side, to see that there was no living man concealed who was the real singer. The silence, however, lasted but a minute, and was then broken by shouts of delighted laughter, and thereupon followed such a commotion and eager shifting of places to get a nearer view of the mystery, that I really expected every minute that the whole audience,[74] myself included, would crash through the frail floor to the ground below. The rows of jet black teeth on a broad grin from ear to ear, seemed to darken the room. During the intermission, while I was putting on another record, cigarettes burned hard and fast to brace up the nerves for another thrill. After two or three men’s songs, I asked for a song from the women; they were reluctant and very shy, but finally they induced two young girls to sing a duet, which they said is wont to be sung at funerals, setting forth the good qualities of the deceased and the intense grief of the survivors. It must have been the identical tune that the original “old cow died on,” so monotonous, so lugubrious, so discordant was it. Evidently the débutantes had not assisted at many funerals; they frequently made awkward pauses and looked around despairingly until kind friends prompted them loudly. It did not turn out to be a good record, but it served to interest the women intensely, and render them anxious to hear their own voices as others hear them.

FOUR DAMSELS WHO SANG INTO THE PHONOGRAPH

[75]

Thereafter the fame of the tom-tom-ni-non,—the “talking tom-tom,”—spread all over the island. I think that eventually I must have been visited by every human being in Uap, from babies in arms to hoary age,—everything that could creep, walk, or hobble. From far and near there came crowds so insistent that almost every day I had to give a session in the morning for the men, and a select session for the women in the afternoon, but I no longer crowded them into the little copra house; open air exhibitions were perfectly satisfactory.

It was intensely interesting to watch their expression as they recognised the words of a familiar song, or speech, and knew the speaker’s voice. There was one particular chant, sung for me by three men from the adjacent failu, which Lian, the chief, cautioned me not to play for the women; it was quite as well they should not hear it. Pleased with this unexpected display of refinement, I assured him at once that I would do my best to comply with his request. At that early stage of my knowledge of their song-language[76] the songs were all so much alike, and the tunes so completely indistinguishable one from another, that one afternoon, in my innocency, before I was aware, the forbidden song was droning away on the phonograph, and I was awakened to my oversight by the “nods and becks and wreathèd smiles” of the women before me; but I had gone too far to retreat. I glanced up and saw Lian at a little distance off, standing in the doorway of our house. He was both smiling and scowling, but from his position at one side he was watching keenly the women’s faces while they were listening to that mysterious song. There were also a few other men standing further off behind the rows of women who were sitting cross-legged on the ground. The women’s eyes danced with merriment and, as soon as the song was recognized, a suppressed giggle went round the audience and they turned to one another with up-lifted brows and wide open eyes, with a sort of “did-you-ever!—no-I-never” expression; it evidently diverted them, so I submitted to fate. Lian still stood watching, and I saw [77]his lips repeating each word; then came several bars of the song which gave forth nothing but a low humming, with plaintive cadences. The women all cast their eyes on the ground, laughing, but ashamed to laugh. Lian gave a foolish, sickly smile and, shaking his head weakly, retreated into the obscurity of the house; the men in the background could not suppress two or three loud guffaws, and then, stooping down to hide their embarrassment, busied themselves at once with splitting the husks of some coconuts.

LIAN, CHIEF OF DULUKAN

I had, indeed, quite innocently proved a marplot, and suffered the women to hear one of the secret songs of the failu. The combined questioning of Friedlander and myself failed to elicit its meaning, or why the men should have been so particularly anxious to keep it from the women’s ears. We never could get any further explanation than that it was “merely one of the songs sung only in the failu.”

An odd feature of all their songs and incantations is that they are not in the modern[78] Uap language at all, nor in a language used by the people in any other island. They say it is the primitive language of Palalagab, the ancient name of Uap, and they use these words when they compose a new song. It is, however, impossible to extract any meaning, or, rather, any literal meaning out of these mere strings of words; they translated them for us into modern Uap, but this yielded merely a collection of what seemed to be absolutely disconnected and irrelevant statements. They usually began with an appeal for attention, such as “Hear what we have been doing;” “Listen to what we are saying,” or “Open your ears to hear;” then follow immediately one after another, such sentences as “Brave men, all the same as devils, make a mach-mach for good weather at sea”—“When we go in a canoe and see a bird, we say we are near to land, when we see a fish, we say we are near to land”—“Listen to what we young boys dreamt about”—“We all got in a canoe;” etc.

These are the sentences of a song which Tomak, a high-class man, sang into the phonograph[79] and then told us proudly that he himself composed it, but he could give us no more than the above sentences translated into modern Uap, and he was unable to say what meaning he intended to convey. This same incomprehensible language is, of course, a heaven-sent boon to the mach-mach men; luckily nobody, not even themselves, can tell what they are talking about.[2]

Powerful spells may be purchased and learned from the mach-mach men for large sums; at times they are heirlooms and pass on from father to son or younger brother. Since they must all be transmitted by word of mouth, is it surprising that they should become at last mere nondescript jargon? It is not, however, beyond possibility that the wizards understand these random sentiments and disjointed sentences; they are experts[80] at reading between lines, and what to us is the merest platitude, becomes in their ears a lyric overflowing with sentiment. Nay, is it not even so with the Japanese whom we have lately learned to admire in the arts of peace as well as of war, and especially in Painting, Poetry’s twin sister? There flits across my memory the following Japanese “Poem” consisting of these three lines and no more:

To a Japanese this is all sufficient to conjure up a picture of two lovers sundered by cruel fate, each happy in the thought that both are gazing at the same moon and longing for the moon’s mirror to reflect an image of the beloved face, while the “Delightful” at the close has all the convincing emphasis of the “Assuredly” in the Koran.

Indeed it is not straining probability too far to suggest that a Uap song, which was thus translated for me:—

[81]

may, to the languishing Uap youths or lovelorn maids express all the tenderness of Lover’s

In both songs we have a limitless expanse of seas, and eternal fidelity (how full is the image of a “burr” with its side glance of annoying persistence!). It is in the last line, however, that the Uap song bears the palm, and rises to a height of self-knowledge rarely attained by poets, of all men, and beyond all praise in its open confession of what is patent to all.

Let no one hereafter cast a slur on Uap poetry,—least of all those who admire Emily Dickinson, that belated Uap poetess, who would have been hailed as a Sappho had she been born under the palms of The Carolines.

[82]

I was extremely desirous of taking a moving picture of one of their dances, and, accordingly, promised the natives of our district that if they would perform a really good, genuine dance, and hold it outside of the failu, in the bright light of day, they should have all the tobacco they could smoke for many days and a lavish feast of their favourite tinned meats, sardines, salmon, boned chicken, etc., all to be had in Friedlander’s Emporium. But little did I dream at what expense I was to get my wish. There are two affiliated failus, both within a hundred yards of Friedlander’s house, and, the nights being almost as light as day under the full moon, rehearsals for the dance and song took place in the cool night outside the failu, and lasted far on toward dawn. It took at least a week of rehearsals, and I am afraid poor Friedlander deeply anathematised the unmelodious, howling, explosive[83] nights I was responsible for, at peaceful Dulukan. The singers punctuate the end of each verse or stanza with a loud clap produced by bending the left arm at the elbow, and holding it across the chest, then the right hand with the fingers and thumb held together and the palm bent so that it is cup-shaped, is clapped down sharply over the bend of the left arm, and produces, when skilfully done, a report nearly as loud as a pistol. When this is performed simultaneously by thirty or forty men and boys, it wakes the echoes, and everything else that is trying to get a wink of sleep.

At last the momentous day for the dance dawned, and I urgently begged the performers to be ready before noon so that I could get the best possible light under the thick palm trees. By eight o’clock in the morning they were all busy and bustling near the failu, donning their costumes and having head-dresses renovated and elaborated; and I adjusted my five-hundred feet of film ready for an exceptional show; my camera was all set up to begin at a[84] moment’s notice. Ten o’clock came, and they were still busy. The day wore on to eleven o’clock; still came the threadbare answer that they were not nearly ready, but would surely be fully decked out by noon, or a little after.

Noon found them still as excited as bees about to swarm and preparing long strips of pandanus leaves or of the bast of Hibiscus for their costumes, collecting white chicken-feathers, bits of cotton wool or pieces of paper for their combs, and practising the steps of their dance. The hours came and passed; one o’clock; two o’clock; three o’clock; and not until near five o’clock in the afternoon did they pronounce themselves ready.

I had refrained from bothering them with too many requests to hurry; it would have been not only absolutely useless, but I desired to be sure that they were really completely satisfied with themselves and would therefore enter into the spirit of the dance with animation, and not with that resigned mien implying “of course, since you insist.”

At last they filed out from behind the failu[85] and burst in all their glory upon my aching sight; they had been fully nine hours most busily and incessantly dressing and I could not, after the closest scrutiny, detect that they had done anything more than dab on their foreheads and cheeks a few streaks of white paint with the lime from their betel baskets, and decorate their combs with streamers of pandanus leaves and yellow stained paper, and tie bands of narrow palm fronds round both knees and their right elbows (only the right elbows, so as not to interfere with the punctuation). They walked with exultant pride and supreme self-consciousness to the front of the failu where there was a good open space, and there sat down cross-legged in one long straight line, the little boys, or petir, at one end; the youths, or pagul, in the middle; and the proficient adults, or pumawn, at the other end; all arranged according to size and age.

These dances, or rather posture-songs, are to the natives like theatrical performances or grand opera; the rumour of this performance had spread near and far, and for several[86] hours an audience of a hundred or more men, women, and children had waited patiently and expectantly, smoking innumerable cigarettes and chewing many a pound of betel nut.

Out of consideration for the “ladies” the first number on the programme was, paradoxical as it may seem, a sitting-down dance or “tsuru.” This song-dance is the only one that is considered proper for the women to witness and hear. As well as I could make out, it is a dramatic narration of adventures of heroes in canoes at sea, or dramatic legends of the Kan or devils who control the lives of men. While the men sing in unison, with the higher voices of the boys in accord making it slightly harmonious, they wave their arms about, sometimes as though rowing with paddles, sometimes as though repelling foes, but most of the time merely accompanying the cadences of the song with graceful, waving motions of the wrists; no weapons, neither sword, spear, nor shield, were used.

This posture-dance belongs to the same class as those to be seen in Japan, Anam, Siam, the[87] Malay States, and Java. The dancers do not move from their sitting position; every now and then they make a loud clap, on the bend of their elbows with the palms of their hands, and apparently the stanza is finished. Several times they seemed merely to take a rest between songs and, without rising, begin another; possibly it was only another verse or chapter of the same narrative; I had no one to interpret or explain it to me.