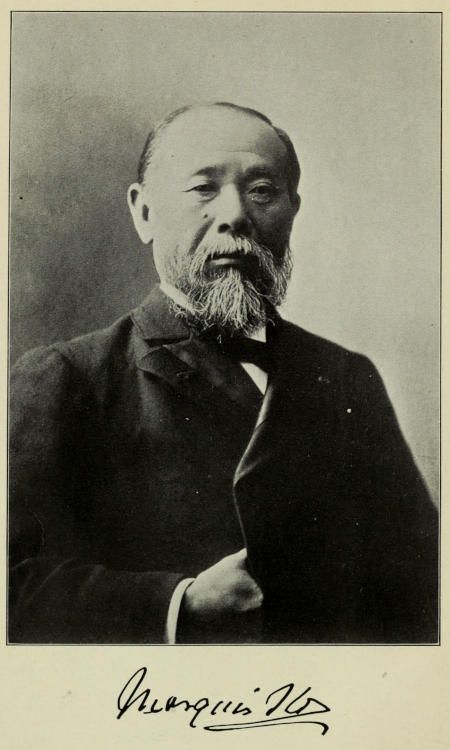

Marquis Ito

Marquis Ito

IN KOREA

WITH

MARQUIS ITO

Part I

A NARRATIVE OF PERSONAL EXPERIENCES

Part II

A CRITICAL AND HISTORICAL INQUIRY

BY

GEORGE TRUMBULL LADD, LL.D.

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

NEW YORK: 1908

Copyright, 1908, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published February, 1908

TO THE

DEAR COMPANION

OF ITS EXPERIENCES AND THE

READY SCRIBE OF MUCH OF ITS MANUSCRIPT

THIS BOOK IS GRATEFULLY

AND AFFECTIONATELY

DEDICATED

The contents and purposes of this volume may be conveniently classified under three heads; for here are statements of fact, expressions of opinion, and certain ventures into the realm of conjecture. The statements of fact are, almost without exception, made on grounds of personal observation, or on the authority of the most competent and trustworthy first-hand witnesses. For the earlier periods of the history of the relations, friendly or hostile, between Japan and Korea, these authorities are indeed no longer living, and they cannot be subjected to cross-questioning. But the choice between the truth they told and the mistakes and falsehoods of a contradictory character is in most cases not difficult to make. For events of the present generation the reader will find the statements of the witnesses quoted, and of the documents cited, to be in general unimpeachable. I believe, then, that what is claimed to be truth of fact in this book is as nearly exact and worthy of implicit confidence as it is ordinarily given to human beings to be in matters pertaining to the history of human affairs.

In expressing my own opinions as to the truth or untruth of certain contentions, and as to the merit or demerit of certain transactions, I have uniformly tried to base these opinions upon the fullest obtainable knowledge of the facts. In some cases the judgments at which I have been compelled to arrive contradict those which have been and still are widely current; in some cases they can scarcely fail to be interpreted as an impeachment of other writers who have had either a[x] narrator’s interest only in the same events or even a more substantial concernment. I have no wish to deny the apologetic character of this book. But at every point the charge of being swerved from the truth by prejudice may be met with these replies: First, very unusual opportunities were afforded the author for ascertaining the truth; and, second, in almost every case where the evidence brought forward seems insufficient there is much more of the same sort of evidence already in his possession, and still more to be had for the asking. But in these days one must limit the size of such undertakings. Few readers wish to wade through a long stretch of shoals in order to reach the firm ground of historical verity.

As to the ventures at conjecture which are sparingly put forth, let them be rated at their seeming worth, after the facts have been carefully studied and the opinions weighed, which have called out these ventures. They are confessedly only entitled to a claim for a certain degree, higher or lower, of probability. The status of all things in the Far East—and for the matter of that, all over the civilized world—is just now so unstable and loaded with uncertainties that no human insight can penetrate to the centre of the forces at work, and no human foresight can look far into the future.

The division of the book into two parts may seem at first sight to injure its unity. Such a division has for its result, as a matter of course, a somewhat abrupt change in the character of the material employed and in the style of its handling. The First Part is a narrative of personal observations and experiences. It gives the results, however, of a serious study of a complicated situation; and it pronounces more or less confident judgments upon a number of subordinate questions involved in the general problem of establishing satisfactory relations between two nations which are inseparably bound together—physically, socially, politically—whether for the[xi] weal or for the woe of both. In the Second Part the attempt is made to submit these judgments to the tests of history. But what is history? Of no other civilized country than Korea is the truth of the cynical saying more obvious that much of what has been written as history is lies, and that most of real history is unwritten. All of which has tended to make the writer duly appreciate the unspeakable advantage of having access to authentic information which, for diplomatic and other sufficient reasons, has not hitherto been made public.

The underlying literary and logical unity which binds together the two seemingly diverse Parts of the one book is made clear by stating in general terms the problem upon which it aims to throw light. This problem concerns the relations to be established between Japan and Korea—a question which has for centuries been proposed in various imperative and even affective ways to both these nations. It is also a question which has several times disturbed greatly the entire Orient, and the recent phases of which have come near to upsetting the expectations and more deliberate plans of the entire civilized world. To lay the foundations, under greatly and suddenly changed conditions, of a satisfactory and permanent peace, one of the greatest statesmen of the Orient is giving—with all his mind and heart—the later years of his eventful life. I hope that this book may make its readers know somewhat better what the problem has been and is; and what Prince Ito, as Japanese Resident-General in Korea, is trying to accomplish for its solution.

It remains for the Preface only to acknowledge the author’s obligations. These are so special to one person—namely, Mr. D. W. Stevens, who has been for some time official “Adviser to the Korean Council of State and Counsellor to the Resident-General”—that without his generous and painstaking assistance in varied ways the Second Part of the book[xii] could never have appeared in its present form. It is hoped that this general acknowledgment will serve to cover many cases where Mr. Stevens’ name is not especially mentioned in connection with the text. Grateful acknowledgment is also made to Mr. Furuya, the private secretary of the Resident-General, for his painstaking translation from the original Japanese or Chinese official documents; to Mr. M. Zumoto, editor of the Seoul Press, for varied information on many subjects; and to Dr. George Heber Jones for facts and suggestions imparted in conversation and embodied in writings of his. My obligations to the Resident-General himself, for the perfectly untrammelled and unprejudiced opportunity, with its complete freedom to ask all manner of questions, which his invitation afforded, are, I trust, sufficiently emphasized in the title of the book. Other debts to writers upon any part of the field are acknowledged in their proper connections.

George Trumbull Ladd.

Hayama, Japan, September, 1907.

| CONTENTS OF PART I | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Invitation | 1 |

| II. | First Glimpses of Korea | 15 |

| III. | Life in Seoul | 37 |

| IV. | Life in Seoul (Continued) | 65 |

| V. | The Visit To Pyeng-yang | 90 |

| VI. | Chemulpo and Other Places | 112 |

| VII. | The Departure | 139 |

| VIII. | Personal Reminiscences and Impressions | 148 |

| CONTENTS OF PART II | ||

| IX. | The Problem: Historical | 179 |

| X. | The Problem: Historical (Continued) | 222 |

| XI. | The Compact | 252 |

| XII. | Rulers and People | 280 |

| XIII. | Resources and Finance | 300[xiv] |

| XIV. | Education and the Public Justice | 326 |

| XV. | Foreigners and Foreign Relations | 352 |

| XVI. | Wrongs: Real and Fancied | 367 |

| XVII. | Missions and Missionaries | 388 |

| XVIII. | July, 1907, and After | 414 |

| XIX. | The Solution of the Problem | 444 |

| Portrait of Marquis Ito | Frontispiece |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

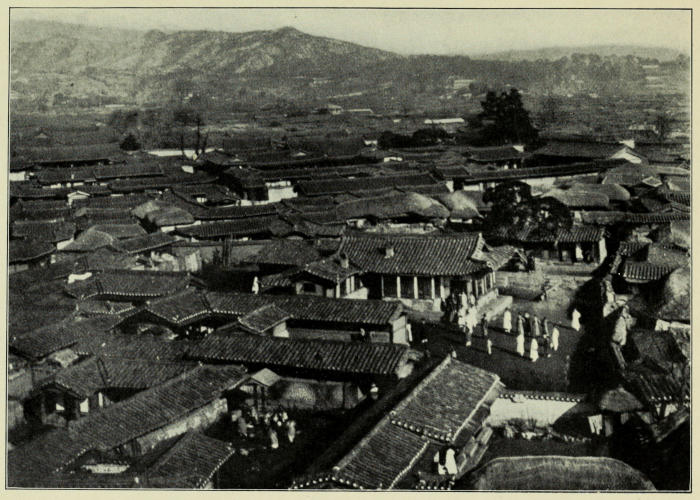

| Bird’s-Eye View of the Capital City | 22 |

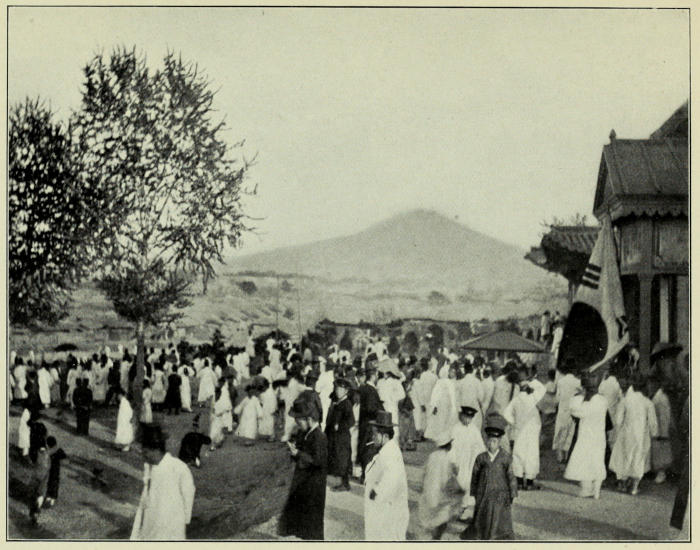

| Going to the Lecture at Independence Hall | 52 |

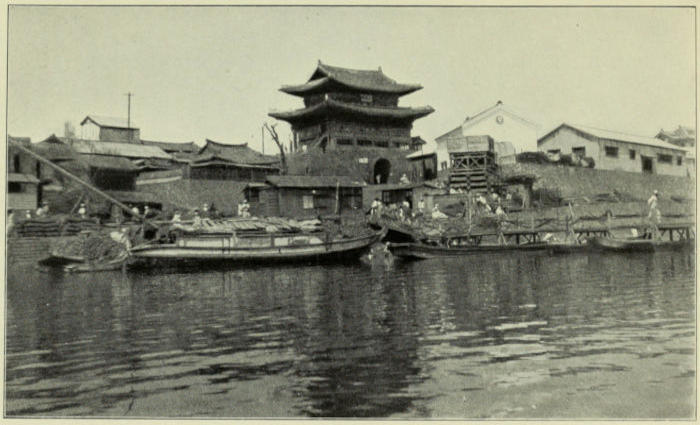

| Water-gate at Pyeng-yang | 100 |

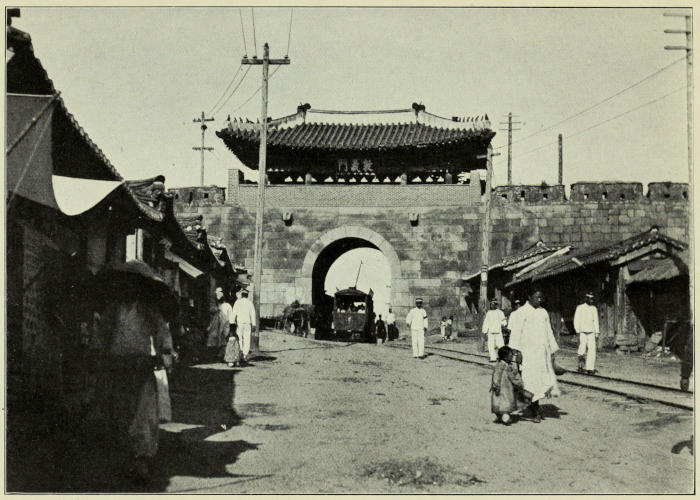

| West Gate or “Gate of Generous Righteousness” | 132 |

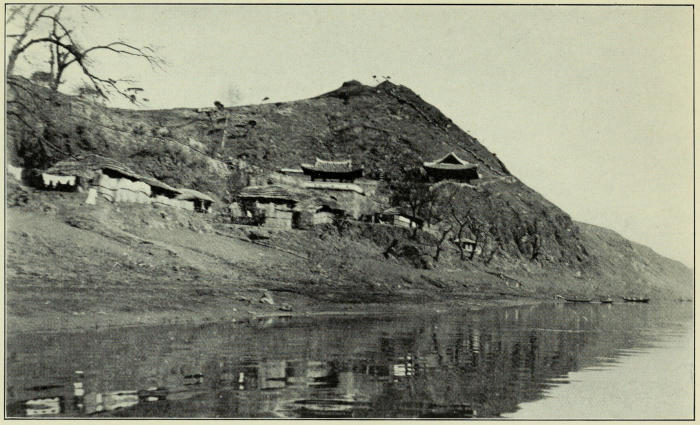

| Peony Point at Pyeng-yang | 184 |

| The Tong-Kwan Tai-Kwol Palace | 206 |

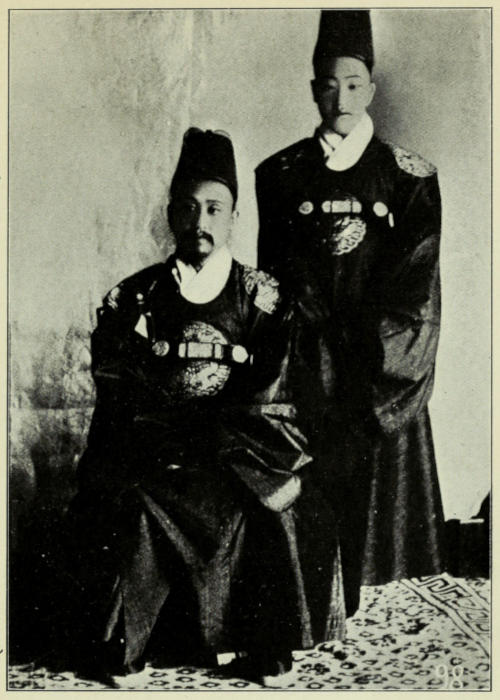

| The Ex-Emperor and Present Emperor | 284 |

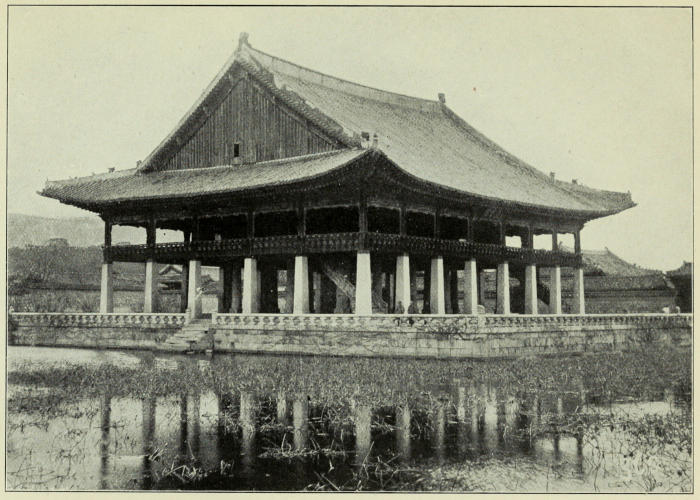

| The Hall of Congratulations | 306 |

| Street Scene in Seoul | 330 |

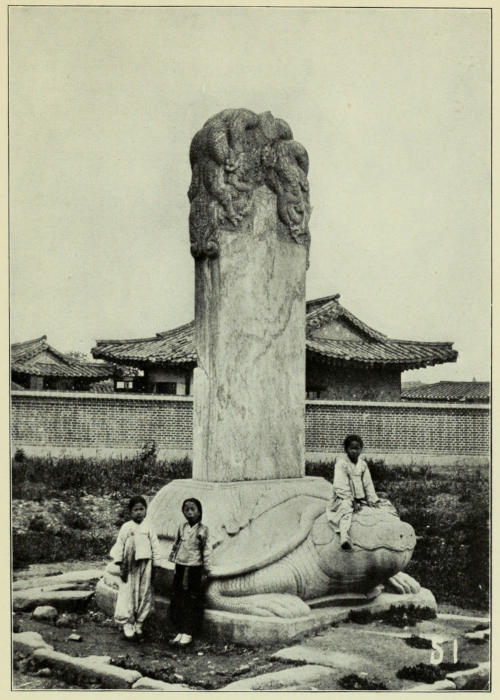

| The Stone-Turtle Monument | 384 |

| Funeral Procession in Seoul | 408 |

It was in early August of 1906 that I left New Haven for a third visit to Japan. Travelling by the way of the Great Lakes through Duluth and St. Paul, after a stay of two weeks in Seattle, we took the Japanese ship Aki Maru for Yokohama, where we arrived just before the port was closed for the night of September 20. Since this ship was making its first trip after being released from transport service in conveying the Japanese troops home from Manchuria, and was manned by officers who had personal experiences of the war to narrate, the voyage was one of uncommon interest. Captain Yagi had been in command of the transport ship Kinshu Maru when it was sunk by the Russians, off the northeastern coast of Korea. He had then been carried to Vladivostok, and subsequently to Russia, where he remained in prison until the end of the war. Among the various narratives to which I listened with interest were the two following; they are repeated here because they illustrate the code of honor whose spirit so generally pervaded the army and navy of Japan during their contest with their formidable enemy. It is in reliance on the triumph of this code that those who know the nation best are hopeful of its ability to overcome the difficulties[2] which are being encountered in the effort to establish a condition favorable to safety, peace, and prosperity by a Japanese Protectorate over Korea.

At Vladivostok the American Consul pressed upon Captain Yagi a sum of money sufficient to provide a more suitable supply of food during his journey by rail to Russia. This kindly offer was respectfully declined on the sentimental ground that, as an officer of Japan, he could not honorably receive from a stranger a loan which it was altogether likely he would never be able to repay. But when still further urged, although he continued to decline the money, he begged only the Consul’s card, “lest he might himself forget the name or die,” and so his Government would be unable to acknowledge the kindness shown to one of its officers. The card was given, sent to Tokyo, and—as the Captain supposed—the Consul was “thanked officially.” The first officer, an Englishman, who had been in the service of Japan on the Aki Maru, while it was used for transporting troops to Manchuria and prisoners on its return, told this equally significant story. His ship had brought to Japan as prisoner the Russian officer second in command at the battle of Nan-san. Having been wounded in the foot, the Russian was, after his capture, carried for a long distance by Japanese soldiers, to whom, when they reached the hospital tent, he offered a $20 gold-piece. But they all refused to receive money from a wounded foe. “If it had been Russian soldiers,” said this officer of his own countrymen, “they would not only have taken this money but would have gone through my pockets besides.”

Before leaving home only two official invitations had been received, namely, to lecture on Education before the teachers in the Tokyo branch of the Imperial Educational Society; and to give a course in the Imperial University of Kyoto, on a topic which it was afterward decided should be the “Philosophy of Religion.” This university was to open in the following[3] autumn a Department of Philosophy (such a forward movement having been delayed by the war with Russia). Almost immediately on our arrival, a multitude of requests for courses of lectures and public addresses came to the committee in charge of the arrangements, with the result that the six months from October 1, 1906, to April 1, 1907, were crowded full of interesting and enjoyable work. In the intervals of work, however, there was opportunity left for much valuable social intercourse and for meeting with men like Togo, Oyama, Noghi, and others in military and business, as well as educational circles, whose names and deeds are well known all over the civilized world. But it is not the narrative of these six months which is before us at the present time, although doubtless they had a somewhat important influence in securing the opportunity and providing the preparation for the subsequent visit to Korea.

The thought of seeing something of the “Hermit Kingdom” (a title, by the way, which is no longer appropriate) had been in our minds before leaving America, only as a somewhat remote possibility. Not long after our arrival in Japan the hint was several times given by an intimate friend, who is also in the confidence of Marquis Ito, that the latter intended, on his return in mid-winter from Seoul, to invite us to be his guests in his Korean residence. It was not, however, until the afternoon of December 5 that the invitation was first received. This was at the garden-party given by Marquis Nabeshima on his sixty-first birthday. It should be explained that every Japanese is born under one of the twelve signs—corresponding to our signs of the Zodiac. When five of these periods have been completed the total of sixty years corresponds with the end of six periods of ten years each—a reckoning which is, I believe, of Chinese origin. The fortunate man, therefore, may be said to begin life over again; and presents such as are ordinarily appropriate only to childhood[4] are entirely in order on such a festal occasion. While walking in the beautiful garden, which is of Japanese style but much modified by Italian ideals, the private secretary of Marquis Ito, Mr. Furuya, came to us and announced that his chief, who had recently returned from Seoul to Japan, was near and wished to see me. After an exchange of friendly greetings almost immediately the Marquis said: “I am expecting to see you in my own land, which is now Korea”; and when I jestingly asked, “But is it safe to be in Korea?” (implying some fear of a Russian invasion under his protectorate) he shook his fist playfully in the air and answered: “But I will protect you.” To this he added, pointing to his sword: “You see, I am half-military now.” The significance of the last remark will be the better understood when it is remembered that from the days of his young manhood to the present hour, Ito has always stood for the peaceful policy and the cultivation of friendly relations between Japan and all the rest of the world. For this reason he has never been the favorite of the military party; and he is to-day opposed in his administration of Korean affairs by those who would apply to them the mailed hand of punishment and suppression rather than hold out the friendly but firm hand of guidance and help.

Even after this interview the real purpose of the invitation to visit Korea was not evident. A week later, however, it was disclosed by a visit from Mr. Yamada of the Japan Times, who came from Marquis Ito to present his request more fully and to arrange for a subsequent extended conference upon the subject. I was then informed, in a general way, how it was thought by the Resident-General I might be of help to him and to Japan in solving the difficult problem of furthering for the Koreans themselves the benefits which the existing relations of the two countries made it desirable for both to secure. Complaints of various sorts were constantly being made, not only against individual Japanese,[5] but also against the Japanese administration, as unjust and oppressive to the Koreans, and as selfish and exclusive toward other foreigners than its own countrymen. Especially had such complaints of late been propagated by American missionaries, either directly by letters and newspaper articles, or more indirectly by tales told to travellers who, since they were only passing a few days in Korea, had neither desire nor opportunity to investigate their accuracy. In this way, exaggerations and falsehoods were spread abroad as freely as one-sided or half-truths. In the office of Resident-General the Marquis greatly desired to be absolutely just and fair, and to prevent the mistakes, so harmful both to Korea and to Japan, which followed the Japanese occupation of Korea at the close of the Chino-Japan war. But it was difficult, and in most cases impossible, for him even to find out what the complaints were; they came to the public ear in America and England before he was able to get any indication of their existence even. And when his attention was called to them in this roundabout fashion, further difficulties, almost insuperable, intervened between him and the authors of these complaints; for in most cases it turned out that the foreign plaintiffs had no first-hand information regarding the truth of the Korean stories. They would not themselves take the pains to investigate the complaints, much less would they go to the trouble to bring the attention of the Resident-General to the matters complained of in order that he might use his magisterial authority to remedy them. In respect to these, and certain other difficulties, Marquis Ito thought that I might assist his administration if I would spend some time upon the ground as his guest.

The nature of this invitation put upon me the responsibility of answering two questions which were by no means altogether easy of solution; and on which it was, from their very nature, impossible to get much trustworthy advice. The[6] first of these concerned my own fitness for so delicate and difficult but altogether unaccustomed work. The second raised the doubt whether I could in this way be more useful to Japan and to humanity than by carrying out the original plan of spending the spring months lecturing in Kiushu. After consulting with the few friends to whom I could properly mention the subject, and reflecting that the judgment of His Imperial Majesty, with whom Marquis Ito would doubtless confer, as well as of the Resident-General himself, might fairly be considered conclusive, I accepted the invitation; but it was with mingled feelings of pleasure and of somewhat painful hesitation as to how I should be able to succeed.

The illness of Marquis Ito which, though not serious, compelled him to retire from the exciting life of the capital city to the seaside, and then to the hills, prevented my meeting him before I left Tokyo for Kyoto to fulfil my engagements in the latter city. But, by correspondence with a friend, I was kept informed of the Marquis’ plans for his return to Korea, and thus could govern my engagements so as to be in the vicinity of some point on his route thither, at which the meeting with him might take place.

The expected conference followed immediately after our return from one of the most delightful of the many gratifying experiences which came to us during our year in Japan. We had taken a trip to the village of Hiro Mura, where formerly lived Hamaguchi Goryo, the benevolent patron of his village, whose act of self-sacrifice in burning his rice straw in order to guide the bewildered villagers to a place of safety when they were being overwhelmed by a tidal wave in the darkness of midnight, has been made the theme of one of Lafcadio Hearn’s interesting tales. Mr. Hearn, it appears, had never visited the locality; and, indeed, we were assured that we were the first foreigners who had ever been seen in the village streets. A former pupil of mine is at the head of a flourishing[7] school patronized by the Hamaguchi family; and having accepted his invitation, in the name of the entire region, to visit them and speak to the school and to the teachers of the Prefecture, the cordial greeting, hospitable entertainment, and the surpassingly beautiful scenery, afforded a rich reward for the three or four days of time required. For, as to the scenery, not the drive around the Bay of Naples or along the Bosphorus excels in natural beauty the jinrikisha ride that surmounts the cliffs, or clings to their sides, above the bay of Shimidzu (“Clear Water”); while for a certain picturesqueness of human interest it surpasses them both. On the way back to Wakayama—for Hiro Mura is more than twenty miles from the nearest railway station—three men to each jinrikisha, running with scarcely a pause and at a rate that would have gained credit for any horse as a fairly good roadster, brought us to the well-situated tea-house at Waka-no-ura. For centuries the most celebrated of Japanese poets have sung the praises of the scenery of this region—the boats with the women gathering seaweed at low tide, the fishermen in the offing, the storks standing on one leg in the water or flying above the rushes of the salt marsh. Here we were met for tiffin by the Governor of the Prefecture and the mayor of the city, and immediately after escorted to the city hall of Wakayama, where an audience of some eight hundred, officials and teachers, had already assembled. While in the waiting-room of this hall, a telegram from Mr. Yokoi was handed to me, announcing that Marquis Ito had already left Oiso and would reach Kyoto that very evening and arrange to see me the next day.

It was now necessary to change the plan of sight-seeing in the interesting castle-town of Wakayama for an immediate return to Kyoto. Thus we were taken directly from the Hall to the railway station and, on reaching Osaka, hurried across the city in time to catch an evening train; an hour[8] later we found our boys waiting, with their jinrikishas, at the station in Kyoto. From the hotel in Kyoto I sent word at once to Marquis Ito of our arrival and placed myself at his command for the long-deferred interview. The messenger brought back an invitation for luncheon at one o’clock of the next day.

When we reached the “Kyoto Hotel,” at the time appointed we were ushered into the room where Marquis Ito, his aide-de-camp, General Murata, his attending physician, his secretary, and four guests besides ourselves, were already gathered. After leaving the luncheon table, we had scarcely entered the parlor when the Marquis’ secretary said: “The Marquis would like to see you in his room.” I followed to the private parlor, from which the two servants, who were laughing and chatting before the open fire, were dismissed by a wave of the hand, and pointing me to a chair and seating himself, the Marquis began immediately upon the matters for conference about which the interview had been arranged.

His Excellency spoke very slowly but with great distinctness and earnestness; this is, indeed, his habitual manner of speech whether using English or his native language. The manner of speech is characteristic of the mental habit, and the established principles of action. In the very first place he wished it to be made clear that he had no detailed directions, or even suggestions, to offer. I was to feel quite independent as to my plans and movements in co-operating with him to raise out of their present, and indeed historical, low condition the unfortunate Koreans. In all matters affecting the home policy of his government as Resident-General, he was now a Korean himself; he was primarily interested in the welfare, educationally and economically, of these thirteen or fourteen millions of wretched people who had been so long and so badly misgoverned. In their wish to remain independent he sympathized with them. The wish was natural and proper;[9] indeed, one would be compelled to think less highly of them, if they did not have and show this wish. As to foreign relations, and as to those Koreans who were plotting with foreigners against the Japanese, his attitude was of necessity entirely different. He was against these selfish intrigues; he was pledged to this attitude of opposition by loyalty to his own Emperor, to his own country, and, indeed, to the best good fortune for Korea itself. Japan was henceforth bound to protect herself and the Koreans against the evil influence and domination of foreign nations who cared only to exploit the country in their own selfish interests or to the injury of the Japanese. When his own countrymen took part in such selfish schemes, he was against them, too.

Again and again did the Resident-General affirm that the helping of Korea was on his conscience and on his heart; that he cared nothing for criticism or opposition, if only he could bring about this desirable result of good to the Koreans themselves. He then went on to say that diplomatic negotiations between Japan and both Russia and France were so far advanced that a virtual entente cordiale had already been reached. Treaties, formally concluded, would soon, he hoped and believed, secure definite terms for the continuance of peaceful relations. Japan had already received from Russia proposals for such a permanent arrangement; the reply of Japan was so near a rapprochement to the proposals of Russia as to encourage the judgment that actual agreement on the terms of a treaty could not be far away. The situation, indeed, was now such that Russia had invited Japan to make counter proposals. The present Foreign Minister of Russia the Marquis regarded as one of his most trusted friends; the Russian Minister was ready, in the name of the Czar, to affirm his Government’s willingness to abandon the aggressive policy toward Korea and Manchuria, in case Japan would, on her part, pledge herself to be content with her present[10] possessions. The status quo was, then, to be the basis of the new treaties. Great Britain, as Japan’s ally, was not only ready for this, but was approaching Russia with a view to a settlement of the questions in controversy between the two nations, in regard to Persia, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, where they had common interests. France would, as a nation on good terms with both Great Britain and Russia, and as herself the friend of peace, gladly agree. He was, then, hopeful that in the near future a permanent basis of peace for the whole Orient might be secured by concurrence of the four great nations most immediately interested.

To these disclosures of his plans and hopes, so frankly and fully made as to excite my surprise, Marquis Ito then added the wish that I should at this time, or subsequently while on the ground, ask of him any questions whatever, information on which might guide in forming a correct judgment as to the situation there, or assist in the effort toward the improvement educationally, industrially, or morally, of the Koreans themselves. In reply I expressed my satisfaction at the confidences which His Excellency had given me, and my hearty sympathy with his plans for the peaceful development of Korea. Nothing, it seemed to me, could be more important in the interests of humanity than to have the strife of foreign nations for a selfish supremacy in the Far East come to a speedy end. But the perfect freedom of inquiry and action allowed to me was in some sort an embarrassment. It would have been easier to have had a definite work assigned, and a definite method prescribed. However, I should do the best that my inexperience in such matters made possible, in order to justify his favorable judgment.

It was my intention at first to prepare for the work in Korea by much reading of books. But the professional and social demands made upon both time and strength, to the very last hour of our stay in Japan, prevented the carrying out of[11] this intention. When, later on, it became possible to read what had previously been published, I discovered that the deprivation was no hindrance, but perhaps a positive advantage, to the end of success in my task. A story of recent experiences of Korean intrigue which had already been reported to me in detail was of more practical value than the reading of many learned treatises. The story was as follows: Among the several representatives of American Christian and benevolent enterprises who have recently visited that country, for the size of his audiences and the warmth of his greeting, one had been particularly distinguished. At his first public address, some four thousand persons, men and boys (for the Korean women are never seen at such gatherings) had attempted to crowd into “Independence Hall.” Of these, however, nine-tenths came with the vague feeling that it is somehow for the political interest of Koreans to seem friendly to citizens of foreign Christian countries—especially of the United States—in order to secure help for themselves in an appeal to interfere with the Japanese administration. In this case the speaker was at first supposed to have great political influence. But the audience, seeing that the subjects of address were religious rather than political, fell off greatly on the second occasion. Meanwhile, some of the Korean officials, in order to win credit for themselves for procuring the audience, had falsely reported that the Korean Emperor wished to see this distinguished representative from America. But when they learned that application for the audience had been duly made, through the proper Japanese official, they came around again and, with many salaams and circuitous approaches, expressed the regrets of His Majesty that, being indisposed, he was unable to grant the audience which had been applied for. At the very time of this second falsehood, the proper official was in the act of making out the permit to enter the palace. The audience came off. And while the American[12] guest was in the waiting-room, the Minister of the Household, watching his chance to escape observation, with his hand upon his heart, appealed to the distinguished American for his nation’s sympathy against the oppression of the Japanese. During the two months of my own experience with the ways of the Koreans, all this, and much more of the same sort, was abundantly and frequently illustrated. And, indeed, no small portion of the recent movement toward Christianity is more a political than a religious affair. But of this I shall speak in detail later on.

It was the understanding with Marquis Ito at the interview in Kyoto that he should have me informed at Nagasaki, at some time between March 20th and 24th, when he desired us to come to Seoul; and that arrangements should then be made for meeting our Japanese escort at Shimonoseki. On returning to the hotel parlor the Marquis apologized to Mrs. Ladd for keeping her husband away so long, and remarked, playfully, that the diplomatic part of the conference was not to be communicated even to her, until its expectations had become matters of history.

Three days later we started for Nagasaki, where I was to spend somewhat more than a week lecturing to the teachers of the Prefecture, and to the pupils of the Higher Commercial School. As we crossed the straits to Moji, the sun rose gloriously over the mountains and set the sea, the shore, and the ships in the two harbors aglow with its vitalizing fire. The police officer assigned to guard his country’s guests, pointed out to us the battleship waiting to take the Resident-General to his difficult and unappreciated work in Korea; and nearer the other side of the channel we noted with pleasure the Aki Maru, on which six months before we had crossed the Northern Pacific.

It had been in my plans, even before reaching Japan, to spend a month or two in Kiushu, a part of the Empire which[13] is in some respects most interesting, and which I had never visited before. And, indeed, in reliance on a telegram from Tokyo which read: “Fix your own date, telegraph Zumoto” (the gentleman who was to accompany us from Shimonoseki), “Seoul,” arrangements had already been completed for lectures at Fukuoka, and had been begun for a short course also at Kumamoto. But the very next day after these instructions had been followed, a telegram came from Mr. Zumoto himself, who was already waiting at Shimonoseki to accompany us to Seoul, inquiring when we could start, and adding that “the Marquis hoped it would be at once.” All engagements besides the one at Nagasaki were therefore promptly cancelled. On the evening of March 24th, Mr. Akai, who had been our kindly escort in behalf of the friends at Nagasaki, put us into the hands of our escort to Korea, at the station in Moji.

Since the steamer for Fusan did not start until the following evening, we had the daylight hours to renew our acquaintance with Shimonoseki. The historical connections which this region has had with our distinguished host made the time here all the more vividly interesting. At this place, as an obscure young man, Ito had risked his life in the interests of progress by way of peace; and here, too, as the Commissioner of his Emperor, the now celebrated Marquis had concluded the treaty with China through her Commissioner, Li Hung Chang. But what need be said about the story of these enterprises belongs more properly with the biography of the man. At about 8.30 o’clock in the evening of March 25th the harbor launch, with the chief of the harbor police in charge, conveyed the party to the ship Iki Maru. The evening was lovely; bright moonlight, mild breeze, and moderate temperature. After tea, at about eleven, we “turned in” to pass a comfortable night in a well-warmed and well-ventilated cabin.

I have dwelt with what might otherwise seem unnecessary detail upon my invitation to Korea, because it throws needed light upon the nature and opportunity of this visit, as well as upon the character of the man who gave the invitation, and of the administration of which he is the guiding mind and the inspiring spirit. I was to be entirely independent, absolutely free from all orders or even suggestions, to form an opinion as to the sincerity and wisdom of the present Japanese administration, as to the character and needs of the Korean public, and as to the Korean Court. The fullest confidential information on all points was to be freely put at my disposal; but the purpose of the visit was to be in full accord with that of the Residency-General—namely, to help the Koreans, and to convince all reasonable foreigners of the intention to deal justly with them. Suggestions as to any possible improvements were earnestly requested. For I hesitate to say that His Excellency, with a sincerity which could not be doubted, asked that I should advise him whenever I thought best. So far as this understanding properly extends, the unmerited title of “Unofficial Adviser to the Resident-General,” bestowed by some of the foreign and native papers, was not wholly misplaced. But the term is more creditable to the sincerity of Marquis Ito than to my own fitness for any such title. “Adviser,” in any strictly official or political meaning of the term, is a word altogether inappropriate to describe our relations at any time.

It was soon after seven on the morning of Tuesday, March 26, 1907, that we had our first sight of Chosen, “The Land of Morning Calm.” The day was superb, fully bearing out the high praise which is almost universally bestowed upon the Korean weather in Spring—the sunshine bright and genial, the air clear and stimulating like wine. Tsushima, the island which for centuries has acted as a sort of bridge between the two countries, was fading in the distance on our port stern. The wardens of Tsushima, under the Tokugawa Shogunate and, as well, much earlier, had a sort of monopoly of the trade with southern Korea. From Tsushima, several centuries ago, came the trees which make conspicuous the one thickly wooded hill in Fusan, now the only public park in the whole country. In front rose the coast; its mountains denuded of trees and rather unsightly when seen nearer at hand, but at a distance, under such a sky, strikingly beautiful for their varied richness of strong coloring. The town of Fusan, as we approached it, had a comfortable look, with its Japanese buildings, many of them obviously new, nestled about the pine-covered hill which has already been noticed as its public park.

From the steamer’s deck our companion pointed out the eminence on which, according to the narrative written by a contemporary in Chinese (the book has never been translated and copies of the original are rare), the Korean Governor[16] of the District, when hunting in the early morning more than three centuries ago, looked out to sea and to his amazement saw myriads of foreign-looking boats filled with armed men approaching the bay. It was the army sent by Hideyoshi for the invasion of the peninsula. The Korean magistrate hastened to his official residence in the town, but scarcely had he arrived when the Japanese forces were upon him and had taken possession of everything. In twenty-one days the invaders were in Seoul. But according to the universal custom of the country when invaded, from whatever quarter and by whomsoever, the cowardly court—a motley horde of king, concubines, eunuchs, sorcerers, and idle officials—had fled; then a Korean mob burned and sacked the deserted palace and did what well could be done toward desolating the city. For seven years the Japanese held Southern Korea, even after their navy had been destroyed, so as to make it impossible to transport reinforcements sufficient to meet the combined forces of the Chinese and the Koreans. It was the fear of a similar experience which, centuries later, made them so careful first to incapacitate the Russian navy as a matter of supreme importance. On another low hill to the right, our attention was directed to the remnants of one of the forts built at the time by the invading Japanese; and further inland, the train ran near to traces of the wall which they erected for the defence of their last hold upon the conquered country. Even then “the people hated them with a hatred which is the legacy of centuries; but could not allege anything against them, admitting that they paid for all they got, molested no one, and were seldom seen outside the yamen gates.”

On the wharf at Fusan there were waiting to welcome us the local Resident, the manager of the Fusan-Seoul Railway, and other Japanese officials—all fine-looking men with an alert air and gentlemanly bearing. The official launch conveyed[17] us to the landing near the railway station, which is now some distance up the bay, but which will soon be brought down to the new wharf that is in process of building, in such good time that we had an hour and a half to spend before leaving for Seoul. Most of this time was improved in visiting a Korean school on the hillside just above. We were not, however, to see this educational institution at work, but only the empty school-rooms and several of the Korean and Japanese teachers. For the one hundred and seventy children of this school, clothed in holiday garments of various shades in green, pink, carmine, purple, yellow, and a few in white or black, were just starting for the station to give a “send-off” to Prince Eui Wha. This Prince is the second living son of the Korean Emperor and, in the event of the death or declared incapacity of the Crown Prince, the legitimate heir to the throne. There was much blowing of small trumpets and many unsuccessful attempts on the part of the teachers to get and keep the line in order, as the brilliantly colored procession moved down the hill.

The teachers who remained behind showed me courteously over the school-rooms and interpreted the “curriculum” of the school which had been posted for my benefit in one of the rooms. I give it below as a good example of the kind of instruction which is afforded in the best of the primary grades of the Korean school system as fostered by the Japanese:

1st Class—Ages, 7-9 years, inclusive:

Chinese classics; morals; penmanship; gymnastics.

2d Class—Ages, 10-11 years, inclusive:

Chinese classics; national literature; penmanship; Korean history; gymnastics.

3d Class—Ages, 12-13 years, inclusive:

Chinese classics; arithmetic; composition; national and universal history; gymnastics.

4th Class—Ages, 14-15 years, inclusive:

Chinese classics; arithmetic; composition; Japanese language; universal history; gymnastics.

5th Class—Ages, 16 years and over:

English; Japanese; geography; national and universal history; Korean law; international law.

It will appear that this scheme of education is based upon a Chinese model, largely modified to meet modern requirements and, in the upper classes, designed to fit those who are able to continue in school for the lower grades of the Korean official appointments.

On returning to the station we found the children in line on one side of the road and on the other a row of Korean men, some in clean and some in dirty-white clothing, waiting for the coming of the Prince. The difference between the mildly disorderly and unenthusiastic behavior of the Korean crowd and the precise and alert enthusiasm of the Japanese on similar occasions was significant. The Japanese policemen treated all the people, especially the children, with conspicuous gentleness. The Prince, who arrived at last in a jinrikisha and took the reserved carriage just back of the one reserved for us, had a languid and somewhat blasé air; but he bowed politely and removed his hat for an instant as he passed by.

Before the train left the station a number of the principal civil officers of Japanese Fusan appeared to bid us a good journey; and so we entered Korea as we had left Japan, reminded that we were among friends and should feel at home. Indeed, at every important station the cards of the leading officials, who had been informed of the arrival of his guests from the office of the Resident-General at Seoul, were handed in; and this was followed by hand-shaking and the interchange of salutations.

The country through which the train passed during the entire day was very monotonous—or perhaps “repetitious” is the better descriptive word. Each mile, while in itself interesting and possessed of a certain beauty due to the rich coloring of the denuded rock of the mountains and of the sand of the valleys, which are deprived of their natural green covering by the neglect to bar out the summer floods, was very like every other of the nearly three hundred miles between Fusan and Seoul. Here, as everywhere in Korea, there was an almost complete absence of any special interests, either natural or human, such as crowd the hills and valleys of Japan. Of roads there appeared to be nothing worthy of the name—only rough and tortuous paths, in parts difficult for the Korean pony or even for the pedestrian to traverse. No considerable evidences of any other industry than the unenlightened and unimproved native forms of agriculture were visible on purely Korean territory. But at Taiden—about 170 miles from Fusan and 106 from Seoul—where the car of the Prince was switched off, and where he remained overnight in order that he might arrive at the Capital in the daylight, something better appeared. This city is situated on a mountainous plateau and is surrounded by extensive rice-fields, some of which, we were told, belong to the son of Marquis Nabeshima, to Count Kabayama, and to other Japanese. In spots, the number of which is increasing, all over Southern Korea, Japanese small farmers are giving object-lessons in improved agriculture; and grouped around all the stations of the railway, the neat houses and tidy gardens of the same immigrants are teaching the natives to aspire after better homes. Our escort believes that the process of amalgamation, which has already begun, will in time settle all race differences, at least in this part of the country.

At ten o’clock our train arrived at the South-Gate station[20] of Seoul, where we were met by General Murata, Marquis Ito’s aide-de-camp, Mr. Miura, the Seoul Resident, Mr. Ichihara, manager of the Japanese banks established in Korea, a friend of years’ standing, and others, both gentlemen and ladies. The dimly lighted streets through which the jinrikishas passed afforded no glimpses, even, into the character of the city where were to be spent somewhat more than two exceedingly interesting and rather exciting months. But less than an hour later we were lodged in comfortable quarters at Miss Sontag’s house, and were having a first experience of the almost alarming stillness of a Korean night. Even in the midst of a multitude of more than two hundred thousand souls, the occasional bark of a dog and the unceasing rat-tat of the ironing-sticks of some diligent housewife, getting her lord’s clothing of a dazzling whiteness for next day’s parade, are the only sounds that are sure to strike the ear and soothe to sleep brains which must be prevented from working on things inward, if they sleep soundly at all. But this is the place to speak in well-merited praise of the unwearied kindness and generosity of our hostess. Miss Sontag not only makes the physical comforts of those visiting Seoul, who are fortunate enough to be her guests, far different from what they could be without her friendly help, but is also able to afford much insight into Korean customs, of which her experience has been most intimate and intelligently derived.

With the morning light of March 27th began first observations of the physical conditions and more obvious social peculiarities of Seoul—the place which has been fitly styled “an encyclopædia of most of the features of Korean so-called city life.” It is impossible to describe Seoul, however, in any such fashion as to satisfy the conflicting opinions of all—whether transient foreign observer or old-time resident. The former will base his estimate upon the particular aspects[21] or incidents concerning which his missionary or diplomatic friend has given him presumably, but by no means always actually, trustworthy information; or upon what his own uninstructed eye and untrained ear may happen to see and hear; while the more permanent indweller in Seoul is pretty sure to conceive of it, and of its inhabitants, according to the success or the failure of his schemes for promoting his own commercial, political, or religious interests. This difference is apt to become emphatic, whenever any of the patent relations of the two peoples chiefly interested, the Koreans and the Japanese, are directly or even more remotely concerned. The point of view taken for comparison also determines much. Approached from Peking or from any one of scores of places in China, Seoul seems no filthier than the visitor’s accustomed surroundings have been. But he who comes from Old or New England, or from Japan, will observe many things, greatly to his disgust. The missionary who compares his own method in conducting a prayer-meeting with that pursued by the guard in clearing the way at the railway station, or with that to which the policeman or the jinrikisha-runner on the street is compelled by the crowd of idle and stately stepping pedestrians, will doubtless complain of the rudeness shown to the Koreans by the invading Japanese. And if he is disposed to overlook the conduct of the roughs in San Francisco, or to minimize the accounts of the behavior of American soldiers in the Philippines, or has forgotten his own experiences at the Brooklyn Bridge, he may send home letters deprecating the inferior civilization of the Far East. On the other hand, he who knows the practice of Korean robbers, official and unofficial, toward their own countrymen, or who recalls the sight of a Korean mob tearing their victim limb from limb, or who credits the reports of the unutterable cruelties that have for centuries gone on behind the palace walls, will, of course, take a widely divergent point[22] of view. But let us—laying aside prejudice—glance at the externals of the capital city of Korea, as they appeared during the months of April and May, 1907.

The word Seoul,[1] coined by the Shilla Kingdom in Southeastern Korea and originally pronounced So-ra-pul, means “national capital”; and Hanyang (“Sun of the Han”), the real name of the present capital, is only one of a succession of “Seouls,” of which Song-do and Pyeng-yang were the most notable. To the imagination of the ignorant populace of Korea, who can have no conception of what real civic beauty and decency are in these modern days, and who are accustomed to express themselves with Oriental hyperbole, Hanyang is the “Observation of all Nations,” “the King’s city in the clouds,” “a city that spirits regard and ghosts conceal”; and to be hailed as the “Coiled Dragon and the Crouching Tiger.” When the town came down from the mountain retreat of Puk Han (to be described later) and spread over the plain in order to utilize the Han River, it took the river’s name; but it was only some five hundred and twenty years ago made “Seoul” by the founder of the present dynasty selecting it as his capital city.

The situation of the chief city of modern Korea becomes more and more impressive and, in every important respect, satisfactory, the greater the frequency of one’s reflective observation from any one of numerous favorable points of view. There is no natural reason why, under the governmental reforms and material improvements which are now being put into effect, Seoul should not become as healthy, prosperous, and beautiful a place of residence as can be shown anywhere in the Far East. While its lower level is only some 120 feet above tide-water, and within easy reach of the sea by[23] the river, the city is, with the exception of the side which opens toward and stretches down to this waterway, completely surrounded by mountains. On the north these guardian peaks rise to the height of 2,500 feet, from the tops of which magnificent views can be obtained, not only of the town nestled at their feet but of the surrounding land and of the ocean, far away. It is not necessary, however, to climb so high in order to discover the geographical peculiarities of Seoul. “To secure the best view of the city and its surroundings,” says Dr. Jones, “one should ascend the lower slopes of Nam-san” (a mountain almost wholly within the walls) “on a bright sunny day in Spring. Taking a position on one of the many spurs jutting out from this mountain a really notable scene greets the eye. The stone screen of mountains enclosing the city begins at the left, with Signal Peak distinguished by a lone pine-tree on its top. In former years there was a beacon fire-station here, which formed one of the termini of the long line of fire-stations that in pre-telegraph days signalled to the authorities the weal or woe of the people.”

Bird’s-Eye View of the Capital City.

Attention should again be called—at least for all lovers of natural beauty—to the intensity and changeable character of the colors of the surrounding mountains and hills, and of the city enclosed by them in its plain, or in places where a few houses, mostly foreign, climb their sides. These colors are often very intense; but they change in a remarkable way, according to the brilliancy and direction of the sunlight, and the varying mixtures of sunshine and shadow. From such a point of view, the city itself, which is for the most part mean and filthy when seen from the streets, appears as a sort of grayish carpet, with dark-green spots made by the pines, for the plain beneath one’s feet. As has already been indicated, the hillsides, both within and around the walls, are uninhabited. They are devoted—and thus wasted—to the[24] mounds that cover the long-forgotten dead. By calculation, upon a basis of counting, it is estimated that one of these burial grounds in the vicinity of Seoul has no fewer than 750,000 of these graves. It is neither reverence nor any other worthy feeling, however, which is the chief factor in fostering a custom so expensive of comfort to the living; it is superstitious fear, akin to that spirit-worship, which is largely devil-worship, and which is really the only effective religion of the non-Christian Korean people. Foreign residents upon the hillsides find it difficult to keep their Korean servants during the night, so dominated are they by their fear. In this respect, as well as others, there is an important difference between so-called ancestor-worship, as in Korea, and ancestor-worship in Japan.

The most obvious thing of interest in Seoul is the city wall. Its construction was begun early in 1396, four years after the present dynasty came to the throne; it was finished in about nine months by the forced labor of men aggregating in number 198,000. According to the legendary account, the course of the wall was marked out by a Buddhist monk, who had the help of a miraculous fall of snow that indicated the line which should be taken in order to avoid a dangerous mixture of the “tiger” influence and the “dragon” influence. To this day the Koreans, like the Chinese, whose pernicious domination they have followed in this as in many other respects, are firm believers in geomancy. The fact is, however, that the wall surrounding Seoul wanders, without any assignable reason, some twelve miles, as recent surveys have settled the long dispute about its length, over hills and along valleys, enclosing a vast amount of uninhabitable as well as inhabited space. It is built of partially dressed stone, with large blocks laid lengthwise at the base, and the superstructure formed of layers of smaller stone—the whole surmounted by battlements about five feet high and pierced with loop-holes for archery[25] adapted to the varying distances of an approaching foe. In height it ranges from twenty to forty feet; it is banked by an embankment of earth from twelve to fifteen feet thick. Various attempts have been made at patching up this decaying structure, but it can never have had the solidity and impregnability against attack by the methods of mediæval warfare which were given to fortifications of the same era in Japan. Moreover, the Korean defenders of the wall customarily ran away as the foe approached; and this the Japanese seldom or never did. Thus Seoul was easily captured by the warriors of Hideyoshi in 1592, and nearly a half century later by a Manchu invading army. The wall is, of course, useless for purposes of defence against modern warfare; and its continuance in existence, at least in large part, depends upon the length of time during which the sentiment of pride triumphs over more utilitarian considerations.

It is the Gates of Seoul which emphasize the visitor’s interest in the city wall and which give most of character to its picturesque features. In themselves, they are mere “tunnels pierced in the wall”; but they are rendered architecturally interesting by the wide-spreading eaves and graceful curvature and, in some cases, striking ornamentation of their roofs. They are, in all, eight in number, one of which is the “concealed.” They bear the names of the points of the compass—South, Little West, West, Northwest, East, Little East, and East Water; this is not, however, because they face true to these points, but because in the main they form the principal avenues of communication between the inside of the wall and the outlying regions situated in these general directions. Each of the gates has, besides, another name characterized by the customary Korean hyperbole. There are, for example, the “Gate of Exalted Ceremony,” the “Gate of Effulgent Righteousness” (or, in two other cases, different kinds of righteousness), the “Gate of Brilliant Splendor,” etc. But[26] in and out of these gates, for one-half of a thousand years, far more of corruption, cruelty, and darkness, has crept, or trailed, or strutted, than of the qualities fitly called by their high-sounding names. It was over them that the late “lamented queen” festooned more than a score of heads freshly taken from her political enemies in order to signify to the Tai-won-kun that she retained control of His Majesty, in spite of the fact that his father had obtained permission to re-enter the city through that same gateway. But why disturb our admiration of a point of structural interest by recalling one of the long list of doings in and around Seoul, no less distinctive of the character of its government? In those older days, when the Great Bell of the city rang the curfew, the gates were at once locked for the night; and any inquirer may hear from missionaries and travellers how they have climbed the wall in order not to sleep outside—thus incurring the death penalty, which was not, however, at all likely to be enforced upon the protected foreigner. The gates themselves, and the devices for locking them, are very similar to those so frequently met with as the relics of mediæval Europe. But the clay manikins (or Son-o-gong) which sit astride the ridges of the roof, are designed to warn and ward off all evil spirits that may attempt to enter the city. The old-fashioned guards, with their dreadful array of big knives and swords, have now given place to the modern policeman, whose principal duty is to keep the gateway clear for traffic. This service is needed, for it is said that no fewer than 20,000 foot-passengers, besides a stream of laden ponies and bullocks, and a tolerably frequent schedule of electric cars, sometimes pass through the South Gate in a single day. And the Koreans in the streets are a slow-moving, stubborn, and stupid crowd.

To the ordinary traveller, after the first strangeness of its more obvious aspects is over, not much remains of particular interest in the capital city of Korea. Of fine buildings, of[27] museums, picture-galleries, temples, theatres, parks, and public gardens, there is little or nothing to compare with any European or Japanese city of the same size. There is, however, here as everywhere in the peninsula, no little of antiquarian and historical interest which awaits the researches of those trained and enthusiastic in such pursuits. Of those sights which the city of Seoul within the walls can show, there are three principal classes—the so-called palaces, the shrines, and the monuments. Even these are interesting, not for their intrinsic grandeur or beauty, but chiefly for their connection with the legends or historical incidents of the country.

To quote again from the articles of Dr. Jones: “The Koreans apply the term Kung or palace to all residences of royalty, and to them Seoul is a city of palaces, for there are eighteen Kung of varying sizes and degrees of importance in and about the city.” Among the eighteen, however, “there are several which are to-day a name and nothing more.” Of these minor palaces the most interesting is that called the “Special South Palace,” which was erected nearly five hundred years ago by one of the kings for his favorite daughter and her consort. But the latter made it such a “veritable den of infamy” that it was abandoned as a house haunted by evil spirits and unsafe for habitation. The mixture of fawning malice and hypocritical servility characteristic of Korean officialdom was at one time humorously exhibited in a way to deceive even the Chinese; for when the Mings were overthrown by the Manchus, the hated envoys of the latter were assigned to this House, “for their entertainment and as a covert derogation to their dignity.” Thus, too, with the so-called “Mulberry Palace,” known by the Koreans as the “Palace of Splendid Happiness.” It was erected by the tyrant Lord Kwanghai who was here dethroned, and from here sent into exile, where he died a prisoner. From it also his successor was driven out by the usurping “Three Days,[28] King.” It was in this palace, also, that the King Suk-jong, having surprised his favorite concubine in practising magic rites to accomplish the death of the Queen whom she had already caused to be divorced and banished, turned upon the concubine herself, sentenced her to drink poison, and when she in revenge mutilated the Crown Prince, had her torn in pieces. Its present name is derived from one of the many fruitless experiments which the present Government of Korea, left to itself, is constantly making. The “mulberry” plantation remains only as a name to adorn, or degrade, the ruins of the palace. But if any visitor to Seoul thinks that such violence, lust, and thriftlessness, must of necessity belong to the ancient history of Korea, let him learn his mistake. Were the firm, strong hand of the Japanese Resident-General withdrawn, there is not one of these horrid deeds which might not be reproduced at any hour.

These are not, however, the “Major Palaces,” through which the foreign visitor is usually conducted, after having obtained a permit from the proper authorities. The palace, known to the Koreans as the Kyung-pok, or “Palace of Beautiful Blessing,” and to foreigners as the “Summer Palace,” dates from 1394, and was occupied by the present Emperor until 1896. Nowhere else have I seen so large a space (it is estimated that the principal enclosure containing only the buildings deemed necessary for his Korean Majesty’s comfort, contains one hundred acres, besides which there are other enclosures running up the slopes of the mountains and designed for defence) strewn over with desolated and half-ruined barbaric splendor. The main Gateway, through whose central arch no other person than His Majesty and his bearers may pass, is an impressive structure and is still in fairly good repair. It is guarded by stone effigies of the Hai-tai, or mythical sea-monsters, who are prepared to spout water against the mysterious influences[29] stored in the “fire mountain,” some ten miles away to the southward. They are therefore called “Fire Dogs.” Once inside the enclosure, one is presented with a melancholy picture of neglect, swiftly oncoming decay, and advancing ruin. All this is the more melancholy, because the present palace buildings are only about fifty years old, were erected by the Prince-parent of the present Emperor, almost to the financial ruin of the country, and were abandoned only after the assassination of the Queen, October 8, 1895.

Amidst this crowded waste where formerly three thousand persons lived in attendance upon the separate establishments for the King, Queen, Crown Prince, and the Dowagers, there are only two buildings which, architecturally considered, are worthy of note. One of these is the old “Audience Hall.” Its columns, although many are cracked for a considerable part of their length, and none of them ever possessed anything like the beauty or finish of the noble wooden pillars of the Nishi Hongwanji in Kyoto (which, however, they resemble in style and effect), seem to have been made of entire stately trees. There are really no galleries, but the appearance is that of a two-galleried hall. The strong colors of red, black, green, and blue, with which the carved and panelled ceiling is decorated, in a manner similar to that of the castles in the Tokugawa period in Japan, seem to find their way through one’s upturned eyes to the base of the brain. In some of its structural features this Audience Hall resembles the audience halls of the Muhammadan monarchs in Northern India more than anything to be found in Japan. This is especially true of the high platform on which the throne was placed. The decoration central over it, and that central in the ceiling of the whole hall, is golden dragons, with clouds and flames, in bas-reliefs; it is in an excellent state of preservation.

The other really fine building in the entire collection is the[30] so-called “Hall of Congratulations,” whose upper floor is supported by forty-eight granite monoliths—six rows of eight each in a row. These pillars are about sixteen feet high and three feet square. The lotus pond surrounding the building is oblong and faced with masonry; while miniature islands rise here and there above the surface of the water. This Hall was intended for state social functions of the out-of-door character.

By going still further back of the sleeping apartments of the King, which consisted of nine rooms arranged in a square, so that the eight surrounding the central room could guard it from intrusion or attack, we come in front of the wall behind whose screen are the apartments in one of which the brilliant and attractive but cruel Queen met her own most tragic and cruel death. All are now forbidden to enter there. But some twelve years before, our escort had seen the dark bloodstains on the floor—perhaps hers, perhaps those of her chamberlain who met his death in trying to protect his queen. And one has only to look a little way over to the right in order to see the now peaceful pine-grove where her body was dragged and burned. Such was the deed which terminated the royal habitation of another, and this the most splendid, of the palaces of Seoul!

It is the grounds, rather than the buildings, of the East Palace, especially when the azaleas and cherry bushes and apricot-trees are in full bloom, which constitute its beauty. Here the diplomatic corps and the other invited guests of the Emperor are accustomed to have picnics and afternoon teas. The apartments, which were united into one so-called palace in the reign of Suk-jong (1694-1720) appear to be most distinctively Korean and are unlike any other buildings which I have ever seen. The rooms are small and rambling; and the screens between them are decorated with those geometrical patterns which are so ancient and so nearly universal[31] wherever architecture has reached a certain stage of development. The ceilings are low and devoid of decoration, but are made pleasing by being everywhere “beamed-over.” This palace, too, has not escaped its history of violence and its bath of blood. Here it was that, in 1884, the party of Progressives, headed by Mr. Kim Ok-kiun, tried to enforce reforms by capturing the person of the King. But the conservative party of Koreans, helped by eight hundred Chinese soldiers under the leadership of the Major Yuan, who afterward became Li Hung Chang’s successor, and is even to-day cutting an important figure in the complicated politics of China, finally drove out the Progressives and the one hundred and forty Japanese who were defending them.

Little else of the mildly exciting “sights” of Seoul remains besides the Great Bell and the Marble Pagoda. The former bears witness to an art in which the Koreans once excelled, but which is now, like all the other arts, either lost or neglected. At Nikko, it will be remembered, there is a Korean bell which was presented to one of the Japanese Shoguns. Setting aside all legends as to the time and incidents of its manufacture and hanging, a recently deciphered inscription on its own side tells the date as 1469 and gives the names of the prominent men connected with the undertaking. The report of a Chinese envoy of 1489, who says of the bell, “It calls all men to rest, to rise, to work, to play,” taken in conjunction with the fact that, to avoid the troubles of faction and violence, men were forbidden on the streets after dark, probably gave rise to the report that women only were allowed to go abroad at night. And this is believed by natives and travellers until the present hour. But the bell, which once rung to open and close the massive city gates, now rings only to tell of midnight and midday. And, although it is about eight feet in diameter and ten feet high, it is no great sight as looked at by peeking through the bars of its surrounding[32] cage. It does, however, like many other things else in Seoul, bear witness to the life of the past and the changes of the present.

The marble pagoda is at the same time the most notable existing monument of Buddhism in Korea and the most interesting art-object in Seoul. It came, however, from abroad; tradition connects its gift with a Mongol princess who, after the death of Kublai Khan, came to Korea in 1310 to become the queen-consort of King Chung-sun. It was brought in a junk from China and at first erected in the grounds of a temple in the little town of Hanyang—the predecessor of Seoul on the same site; for the capital of the present dynasty was not then built. The temple grounds were beautified in its honor; roads were constructed leading to it; and a bridge was built over a stream running near by. But the Korean inevitable happened to it—the fate meted out to all that shows signs of order, industry, or art, when not of immediate selfish interest to the rulers of Korea. The roads, encroached upon by surrounding hovels, became foul and narrow alleys; a squatter built his straw-thatched hut about it; and the stream became the main sewer of the city, which is cleaned only by the downpour of the summer rains. Thus, as says our chronicler: “The gift to Korea of one of the mighty Mongol Khans, whose arms had literally shaken the world, became the impedimenta of a Korean coolie’s backyard, sixteen by twenty feet square!” What wonder, however, in a land where court officials and palace hangers-on do not hesitate to-day to steal the screens, and other presents from foreign monarchs and plutocrats, out from under His Majesty’s very eyes.[2]

The pagoda itself, which has now been cleared from the clutter of huts and made the central object in Seoul’s first attempt at the beginnings of a public park, deserves a brief description. It is of white marble, much stained by time, war, and neglect, and was originally thirteen stories in height; although only ten of these are now standing, while the upper three have been removed and rest beside it on the ground. The base and first six stories have twenty sides; the remainder are squares. Each story is symmetrically diminished in size; some have galleries with curved eaves and upturned corners. The ornamentation is exceedingly complicated and abstruse in its symbolism and suggestiveness. There are sculptured upon the flat surfaces processions of tigers, dragons, men on foot and on horseback, teachers discoursing in groves, pictures taken from the traditional life of Buddha, and various bas-reliefs of different Buddhas. The lower stories are composed of several blocks of carved stone, but the smaller and upper stories are monoliths.

Near the pagoda stands the Tortoise Tablet, a very ancient structure; the tablet is said originally to have been brought from the Southern Kingdom of Scilla, and erected upon the ledge of granite which outcropped in this place, after the rock had itself been carved into the shape of a tortoise. It was designed to memorialize the building of a temple which dates back to the eleventh century A. D. The tablet is probably more than one thousand years old.

Within the small enclosure surrounding these relics, Mr. Megata, the Japanese financial adviser to the Korean Government, is trying to encourage the public spirit of the natives and entertain the resident foreigners by providing band concerts on Saturday afternoons. Thus this spot also offers a study in epitome of the history, present changes, and future prospects of the capital city of Korea.

Of the few shrines which the royal prohibition of Buddhism[34] and the low and decaying interest in all religious conceptions rising above the level of spirit-worship—and this mostly devil-worship—have allowed to remain in Seoul, the only ones of any particular importance are the Imperial Ancestral Shrines and the so-called “Temple to Heaven.” But even the guests of Marquis Ito did not think it wise to ask for permission to visit these shrines, or to exhibit any more curiosity respecting them than to glance by the guard, through the open doors of the gateway, while passing along the street. As to the New Palace, which is a stone building of modified Doric architecture, and is so far finished externally that it can be seen to have decided claims to beauty, if only the superstitions of the monarch and of his counsellors among the blind-men and the sorcerers had permitted it to be well placed—this was ever before our eyes from the windows of Miss Sontag’s house. And what was seen of the buildings occupied at the time of our visit by His Majesty and the Court, so far as it is worth a word, will be described in another place.

The Seoul seen from the surrounding mountain-sides, and the Seoul of so-called palaces, is not the city in which the people live. Apart from a few of its inhabitants—such as the missionaries, certain foreign business men and diplomatic agents, together with a small number of native officials who have acquired a taste for foreign ways—the Seoul of the people is disgustingly filthy and abjectly squalid. It is, indeed, not so filthy and miserable, and lacking in all the comforts and decencies of respectable Western life, as it was a generation, or even a few years ago. Several of the streets have now been—not only occasionally when the King was going a “processioning” through them, but habitually and to the benefit of the populace—cleared of their encroachments of squatter hovels, huts, and booths. The gutters along the sides of these streets do not quite so much as formerly disturb the eyes and nostrils of the pedestrian, especially if he walks[35] in the middle of the thoroughfare; their use for vile purposes is not so much in evidence as was the case before any of the natives had even a glimmering sense of decency about such matters. In spite of the increased business activity of the city there is not to-day quite the same stream of white-robed saunterers, stately in gait but low in character, to give a semi-holiday aspect to the “Broadways” of Seoul; for electric cars transport the multitudes back and forth in several directions. Besides, there is the neat, attractive Japanese quarter. Here, according to my observation, the Koreans themselves were doing more sight-seeing and more trading than in their own quarters; for here the cheaper products of the new and hitherto unknown world are skilfully displayed. But otherwise and elsewhere in the city, the same unsanitary conditions and indecent habits, in all respects, prevail. The narrow, winding alleys are flanked with shallow, open ditches, that are not only the drains and sewers but the latrines of the dwellers in the low earth-walled houses on either side. Cowardly and lean dogs, naked children, and rows of men squatting and sucking their long pipes or lying flat upon the ground, crowd and obstruct these alleys. And from them the wide-spreading Korean roofs cut off the purifying and enlivening sunlight. Many of the most wretched and unsanitary of these hovels squat under the shadow of the stately city wall. May its stones sometime be used to build a better and healthier city!

There are, however, yet more notable changes and improvements than those already accomplished, which seem destined surely and speedily to follow. A water-supply, for which the surveys and contracts have already been completed and for which, during our visit, the pipes were beginning to be laid, will not only diminish the dangers that lurk in the cans of the professional water-carriers and in the private wells, but will assist the summer rains in their formidable[36] task of washing clean the open sewers. More of these foul, winding alleys, and huddles of hovels, will be abolished. The increase in the interests of life, and the enjoyment of the rewards of protected industry, will diminish the drunkenness and gluttony, varied by enforced periods of starvation, which now distress the people. The new hospital and medical school—the former of which will immediately relieve much suffering and the latter of which will perform the yet more important service of educating a native medical class—are among the most cherished projects of the Resident-General. And when to these more essential matters there is added the cultivation of the native love of nature and taste for flowers, it is not an extravagant hope to picture Seoul as becoming, in many respects, a not undesirable place for residence, before many years are past. Even now, with the spring covering of bloom from plum, apricot, apple, and cherry, and with the profusion of flowering shrubs which adorns the valleys and the mountain-sides, one feels inclined to overlook, at least for the months of April and May, the foul sights of the gutters and the surrounding hovels. But all this was, as it were, only background and theatre for the work I wished to do and the observations I wished to make.

After accepting Marquis Ito’s formal invitation to attempt a special kind of service in Korea, the first problem to be solved concerned the choice of ways for approaching that service. Its solution was by no means obvious. In Japan there were more of urgent requests for public addresses and lectures of various kinds than could possibly be accepted. And everywhere that the speaker went, influential and large organizations of an educational and public character, to whose support the governors, of the Kens and the mayors of the cities were officially committed, could be relied upon to make all necessary arrangements and to carry the arrangements through effectively. More important still, there was the most eager interest in the subjects upon which the prospective audiences wished to be addressed, and the attitude of an open mind and even of warm personal attachment toward “the friend of Japan.” In Korea, however, all the influences would be of precisely the opposite character—indifference, deficiencies, hindrances, if not active opposition, so far as the native attitude was concerned. In Korea there were no educational associations; and, outside of a very small circle in a few cities, there was little or no interest in education. The local magistrates were, almost without exception, devoted to “squeezes” rather than to the increase of intelligence and the moral improvement of their districts. The teachers of the few existing schools were, in general, without[38] any modern culture; they were even without the most rudimentary ideas on the subjects of pedagogy, ethics, and religion. Only in a small number of places were there any halls that could accommodate an audience, should one be gathered by an appeal to curiosity and to the Korean thirst for “look-see”; while to be known as a “friend of Japan” and a guest of Marquis Ito was to erect an almost insuperable obstacle in the way of reaching the ears of the Korean upper and middle classes, to say nothing of convincing their minds or touching their hearts. Addressing the lower classes on any scholastic topic was impossible. Through what organ, then, could a stranger help the Resident-General in his benevolent plans for the welfare of the people of Korea?