James Grey Jackson.

Engraved by E. Scriven (Historical Engraver to H.R.H. the

Prince Regent.)

from an Aquatinta profile by Mrs.

Read.

Published Augst. 12th. 1811. by G. & W. Nicol. Pall Mall.

Large-size versions of illustrations are available by clicking them.

AN

ACCOUNT

OF

THE EMPIRE OF

MAROCCO,

&c. &c.

James Grey Jackson.

Engraved by E. Scriven (Historical Engraver to H.R.H. the

Prince Regent.)

from an Aquatinta profile by Mrs.

Read.

Published Augst. 12th. 1811. by G. & W. Nicol. Pall Mall.

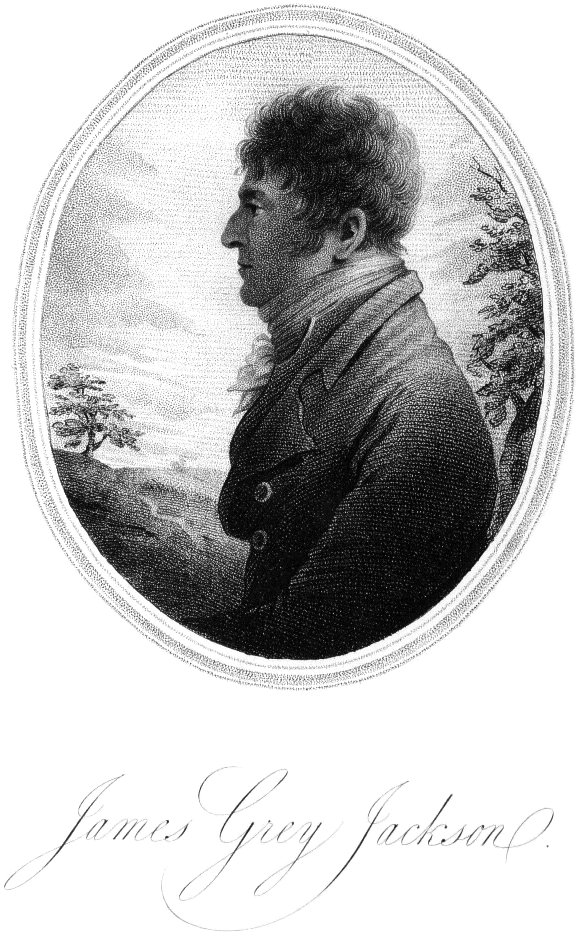

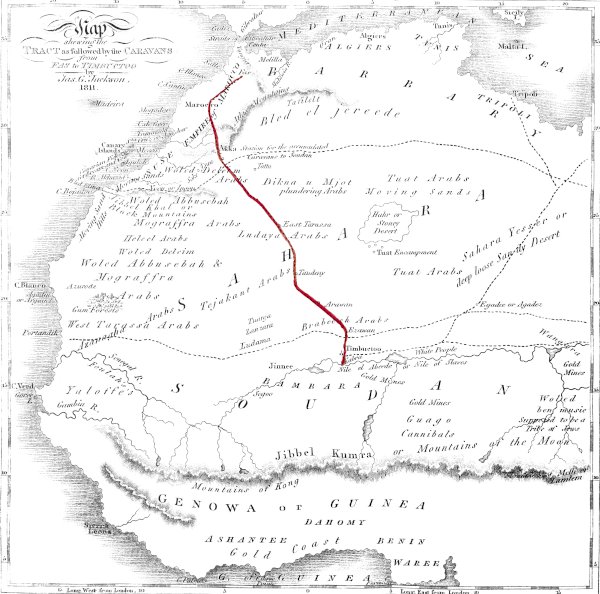

An

Accurate Map

of

West Barbary,

Including

Suse and Tafilelt,

forming the Dominions of the present

Emperor of Marocco,

Containing

several Towns, & Districts never

inserted in any former Map,

By

James Grey Jackson 1811.

| London Published Augst. 30th. 1811. by G. & W. Nicoll Pall Mall. | S. T. Neele. sc. Strand. |

AND THE

DISTRICTS OF SUSE AND TAFILELT;

COMPILED

FROM

MISCELLANEOUS OBSERVATIONS MADE DURING A LONG

RESIDENCE IN,

AND VARIOUS JOURNIES THROUGH, THESE COUNTRIES.

TO WHICH IS ADDED AN

ACCOUNT OF

SHIPWRECKS ON THE WESTERN COAST OF AFRICA,

AND AN

INTERESTING

ACCOUNT OF

TIMBUCTOO,

THE GREAT EMPORIUM OF CENTRAL AFRICA.

BY JAMES GREY JACKSON, ESQ.

ILLUSTRATED WITH IMPROVED MAPS AND NEW ENGRAVINGS.

SECOND EDITION,

CORRECTED, NEWLY ARRANGED, AND

CONSIDERABLY ENLARGED.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THE

AUTHOR,

BY W. BULMER AND CO.

CLEVELAND-ROW, ST. JAMES’S;

AND SOLD BY G. AND W. NICOL, BOOKSELLERS TO HIS MAJESTY,

PALL-MALL.

1811.

TO

HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS

GEORGE,

PRINCE OF

WALES,

&c. &c. &c. &c.

THIS ACCOUNT

OF

THE EMPIRE OF

MAROCCO,

IS,

WITH PERMISSION,

RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED,

BY

HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS’S

MOST OBEDIENT,

MOST HUMBLE, AND MOST DEVOTED SERVANT,

THE AUTHOR.

Bloomsbury-square,

May 30, 1809.

The very favourable manner in which the first Edition of this Account of Marocco was received by the Public, and the flattering terms in which it was spoken of by the most eminent Critical Journals of the day,[1] afford me now an opportunity, in presenting a second Edition to the world, of thus publicly returning my most grateful acknowledgments, and at the same time of enlarging and improving the work, and thereby rendering it still more worthy of public approbation: this I have been enabled to do from my own original notes, many of which were forgotten or overlooked in the first arrangement of the book.

The new matter now submitted to the Public, consists principally in a fuller account of the revenues of the state, several additions on various other subjects, as the natural history of the country, its inhabitants, and their modes of life, administration of justice, treatment of children, and education of youth; some further observations on the plague, and the diseases incident to the inhabitants; a comparison between the ancient language of the Canary Islands and that of the Shelluhs of South Atlas; Mr. Betton’s philanthropic Will and patriotic intentions, manifested in his liberal bequest to emancipate British seamen from captivity; cautions to navigators; laws, manufactures, and customs of Timbuctoo; and, for the amusement of the Arabic scholar, three Letters are introduced, with their translations, to enable him to compare the Arabic of Africa with that of Asia. Finally, there is scarcely a page that has not received some additional matter or improvement.

Indeed I have been anxious to discuss every subject that could in[iv] any manner tend to illustrate the actual state of the Empire of Marocco, being confident that the more these subjects are discussed among us, the more they will merit our attention: and that, if ever the interior of Africa is to be explored by Europeans, if ever we are to reach the grand object of our research, the Emporium of Central Africa (Timbuctoo), Marocco is the most eligible point to set out from. But it is indispensably necessary that we should first overcome our own prejudices and misconceptions respecting this country; we should first secure to ourselves all those advantages which would result from an active and uninterrupted commercial intercourse with the principal Sea Ports of the Western Coast; and when these objects shall have been accomplished, the rest will readily follow.

In the first Edition I promised that, should my labours meet with approbation, I would publish the political history of Marocco: this I had written, and intended as a second part to this Edition (indeed three sheets of it were printed); but considering that the subject has been before discussed, and being unwilling to trouble the public with intelligence not altogether new, I have thought it expedient to suppress it.

It is not probable that I shall do any thing more to this work, I therefore now dismiss it as perfect as I can render it. The greater part of it, I repeat, is the fruit of my own knowledge and experience; and I have never spoken on the authority of others, but when I have had opportunities of investigating the sources of their intelligence, and when I have had every reason to believe their information correct.[2]

J. G. JACKSON.

Burton Street,

Sept. 30th, 1811.

FOOTNOTES:

[1]Edinburgh Review, No. 28. Critical Review, Aug. 1809. London Review, August 1809. Anti-jacobin Review, Aug. and Sept. 1809. &c. &c.

[2]Since this book first appeared, the Proceedings of the Society for promoting the Discovery of the interior Parts of Africa have been published in two volumes octavo. In the second volume are two letters from me to Sir Joseph Banks, wherein I observe the following errors of the press, which I take the liberty here to correct: P. 366, for zahaht, read rahaht; p. 373, for Alshærrah, read Emsharrah; p. 376, for Ait Elkoh, read Ait Ebkoh; for Idantenan, r. Idautenan; for Kitrivæ, read Kitiwa; and for Alsigina, read Emsegina.

The following sheets have been compiled from various notes and observations made during a residence of sixteen years in different parts of the Empire of Marocco, in the successive reigns of Cidi Mohammed ben Abdallah ben Ismael, Muley Yezzid, Muley el Hesham, and Muley Soliman ben Mohammed; and which were originally intended merely as memoranda for my own use; but shortly after my last arrival in England, I had the honour to converse with a distinguished Nobleman[3] on the subject of African knowledge, and from his Lordship’s suggestions I first determined to submit to the public such information as a long intercourse with the natives of Barbary, as well in a political as a commercial capacity, and a thorough knowledge of the languages of North Africa had enabled me to obtain.

It was justly observed by Mr. Matra, our late consul at Marocco, that “there are more books written on Barbary than on any other country, and yet there is no country with which we are so little acquainted.” The cause of this is to be found in the superficial knowledge which the authors of such books[vi] possessed respecting this part of the world; having been generally men who came suddenly into the country, and travelled through it without knowing any thing either of the manners, character, customs, or language of the people. Indeed, the greater part of the compositions respecting North Africa, are narratives of journies of Ambassadors, &c. to the Emperor’s court, generally for the purpose of redeeming captives, compiled by some person attached to the embassy, who, however faithfully he may relate what passes under his own eye, is, nevertheless from his situation, and usual short stay, unable to collect any satisfactory information respecting the country in general, and what he does collect, is too often from some illiterate interpreter, ever jealous of affording information to Europeans even on the most trifling subjects.

Leo Africanus is, with very few exceptions, perhaps the only author who has depicted the country in its true light; and although he has committed some errors, chiefly geographical, yet Marmol, as well as many moderns, have servilely copied him. There is some original matter contained in a book, entitled, “A Journey to Mequinez, on the occasion of Commodore Stuart’s Embassy, &c. &c.” London, 1725. Lemprière’s Marocco contains an interesting description of the Horem, or the Seraglio; but the rest of his account has many errors; the map appears to be copied chiefly from Chenier, some of whose orthographical[vii] errors he has adopted. The work of the last mentioned author is the best I have seen,[4] and this is to be attributed to his having resided in the country several years; and though his ridiculous pride did not allow him to associate generally with the Moors, yet a partial knowledge of their language, and his natural penetration and judgment, enabled him to make many useful observations derived from experience.[5]

It must be obvious to every one, that a considerable portion of time and study is requisite to obtain a thorough acquaintance with the moral and political character of any nation, but particularly with one which differs in every respect from our own, as does that of Marocco; he, therefore, who would be thoroughly acquainted with that country, must reside in it for a length of time; he must possess opportunities of penetrating into the councils of the State, as well as of studying the genius of the people; he must view them in war and in peace; in public and in domestic life; note their military skill, and their commercial[viii] system; and finally, and above all, he must have an accurate and practical knowledge of their language, in order to cut off one otherwise universal source of error, misconception, and misrepresentation.

Certainly no country has of late occupied so much attention as Africa, and the exertions of the African Association to explore the interior of this interesting quarter of the globe, do them the highest credit; and if their emissaries have not always been successful, or obtained information only of minor importance compared with the great object of their researches, it is to be attributed to their want of a sufficient knowledge of the nature of the country, and the character and prejudices of its inhabitants, without which, science to a traveller in these regions, is comparatively of little value. When we consider the disadvantages under which Mr. Parke laboured in this respect, and that he travelled in an European dress, it is really astonishing that that gentleman should have penetrated so far as he did, in his first mission; and we are not so much surprised at the perils he endured, as that he should have returned in safety to his native country. Had he previously resided a short time in Barbary, and obtained there a tolerable proficiency in the African Arabic, and with the customs adopted the dress of the country, what might we not have expected from his perseverance and enterprising spirit? Whatever plans future travellers may adopt, I would recommend to them to lay aside[ix] the dress of Europe; for, besides its being a badge of Christianity wherever he goes, it inevitably exposes him to danger; and it is so indecent in the eyes of the Arabs and Moors, that a man with no other clothing than a piece of linen round his middle, would excite in them less indignation.

Mr. Horneman, in the above respects, certainly set out with a more probable chance of success; though I much fear the expectations which he raised will never be fulfilled. From his Journal, indeed, he appears to have been of far too sanguine a disposition, and to have relied too much on the fair professions of his African fellow-travellers, an instance of which occurs in his letter from Mourzouk, where he says, “Under protection of two great Shereefs I have the best hopes of success in my undertaking.” Here the hopes of success originate in the very cause that would induce a man versed in the character and springs of action of the Africans, to despair of success. It was the promises of these people that led Major Houghton to his ruin; and the fair representations made by some of them to the first emissaries of the African Association have been proved to be false by the difficulties and dangers which their successors have had to encounter, in attempting to penetrate to Timbuctoo. The Shereefs are very plausible people; many of them possess uncommon suavity of manners, which is too apt to throw the confiding European off his guard, and make him the victim of[x] their artful designs; as to their information, it is not to be depended on; they will say every thing to mislead, an instance of which will be presently mentioned in the case of Mr. Parke. In another place Mr. Horneman says, “In respect to my astronomical instruments, I shall take special care never to be discovered in the act of observation; should these instruments, however, attract notice, the answer is ready, they are articles of sale, nor is there fear I should be deprived of them whilst master of my price.” Nothing can evince greater ignorance of the people than this; indeed I am surprised Mr. Horneman could entertain such an idea. The mode of travelling in Africa will prevent the possibility of his availing himself of these precautions; there is no cafilah, or caravan of itinerant merchants and traders in that country, which does not contain some person who has either been to sea, or has seen nautical instruments, and knows their use. That they are articles for sale would indeed sound very well for a person going through Europe, but there are no purchasers for such things in Africa; besides, no people under heaven are more jealous, or suspicious of every thing which they do not comprehend, than the Africans. The description of them by Sallust holds at this day, and is perhaps a better drawn character of the modern African (although it alludes to their ancestors) than any description which has hitherto been given of this extraordinary[xi] people. These ignorant, barbarous savages, as we call them, are much more sagacious, and possess much better intellects, than we have yet been aware of.

The error above alluded to, into which Mr. Parke was led by a Shereef, was in regard to the distance from Marocco through Sueerah, or Mogodor, to Wedinoon, which he makes twenty days,[6] when it is in reality but ten, as I have repeatedly travelled the distance; viz. Marocco to Sueerah, or Mogodor, three days; to Agadeer, or Santa Cruz, three; to Wedinoon four. There is also another error in the same gentleman’s book, which it is proper to notice; he says, Saheel signifies the north country; nothing but an ignorance of Arabic could have thus misled him; Saheel in that language signifying nothing more than an extensive plain; thus the extensive plains south-east of the river Suse are called Saheel; the low country near El Waladia is called Saheel; and if an Arab were to pass over Salisbury Plain, he would term it Saheel. In these few notices respecting the travels of two of the hitherto most successful emissaries of the African Association, I have no other object in view than to point out errors which may mislead those who follow them, and I therefore hope, that they will be favourably received by that respectable body, and by the authors themselves, should they happily return to this country. I had[xii] written several remarks on Mr. Horneman’s Journal, which I intended to give in an appendix, but as they might create ill-will, and involve me in useless controversy, I have suppressed them.

With regard to the following Work, it has been my endeavour throughout, to give the reader a clear account of the present state of the Empire of Marocco, and of its commercial relations with the interior, as well as with Europe: on the latter some readers may perhaps think I have enlarged too much, but it was my wish to be particular, on that subject, and to shew the advantages which this country might, and ought to derive from an extensive trade with Barbary. In other respects, I have been as concise as possible, introducing little or nothing of what has been satisfactorily detailed by late writers on the same subject. In the Map of Marocco, I have given the encampments of the various tribes of Arabs, and omitted such towns and villages as are found in modern maps, but which now no longer exist. The track of the caravans through the Desert to Timbuctoo, is, together with the account of that city and the adjacent country, given from sources of information which I had every reason to believe correct. The engravings are from drawings made on the spot by myself; but from the extreme jealousy of the natives, particularly those of the interior provinces, and the consequent difficulty of taking[xiii] views without being discovered, trifling inaccuracies may have been committed in some of them. Some apology ought perhaps to be made for my language; but any defect, in this respect, will, I trust be excused, when it is recollected that a plain relation of facts, and not an elegant composition, was all I had in view. Some readers, probably may express surprise, that I have said nothing of the political history of the country; but this I have reserved for a future publication should the present one meet with the approbation of the public.

FOOTNOTES:

[3]The Right Hon. the Earl of Moira.

[4]There is a small volume translated from the French of the Abbé Poiret, entitled, Travels through Barbary in a series of letters, written from the Ancient Numidia, in the years 1785 and 1786, which contains many judicious observations. The Abbé was doubtless a man of penetration, and understood the character of the people whom he described.

[5]There is an interesting and, I believe, a very faithful account of an embassy from Queen Elizabeth to Muley Abd El Melk, Emperor of Marocco in 1577, in the Gentleman’s Mag. September 1810, page 219, in which the reader may correct the following errors of the press: for Elchies, r. Alkaids; for lintals, r. quintals.

[6]See Parke’s Travels, 4to. edit. page 141.

| Page | ||

| 1. | Map of the Empire of Marocco to face the title | |

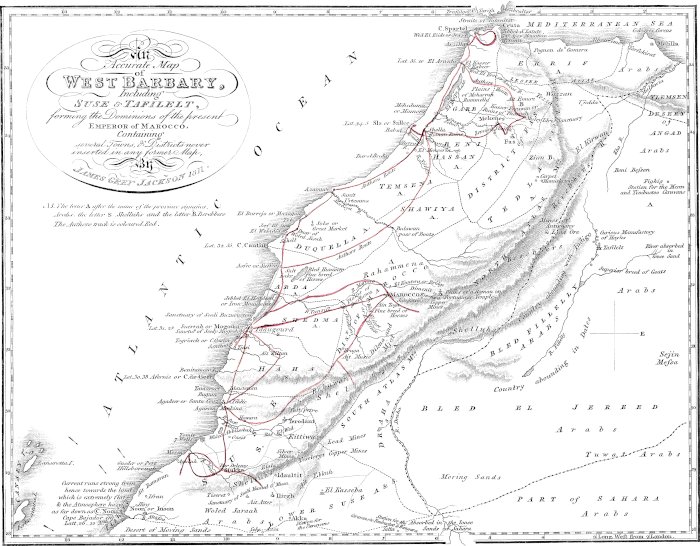

| 2. | View of the Atlas as seen from the Terraces at Mogodor | 10 |

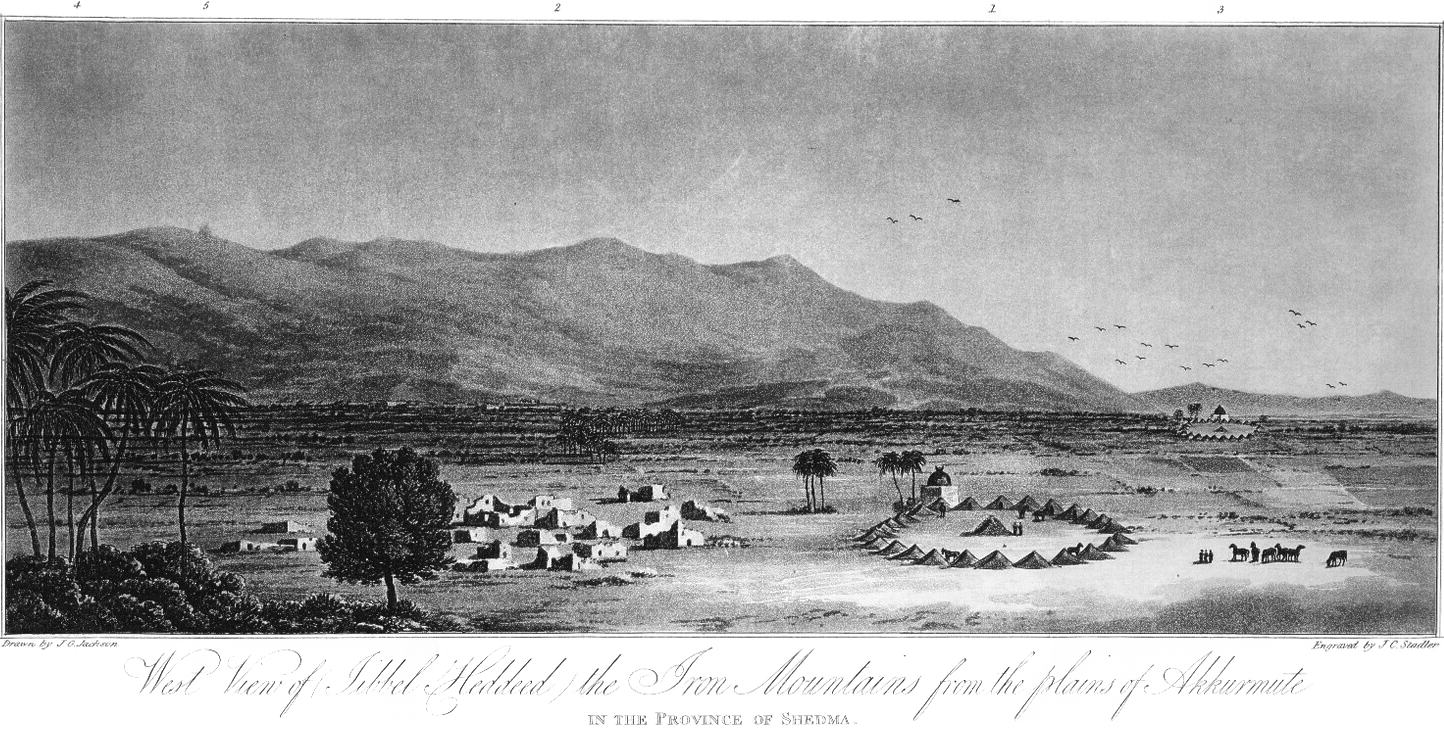

| 3. | View of the Plains of Akkurmute and Jibbel Heddid | 46 |

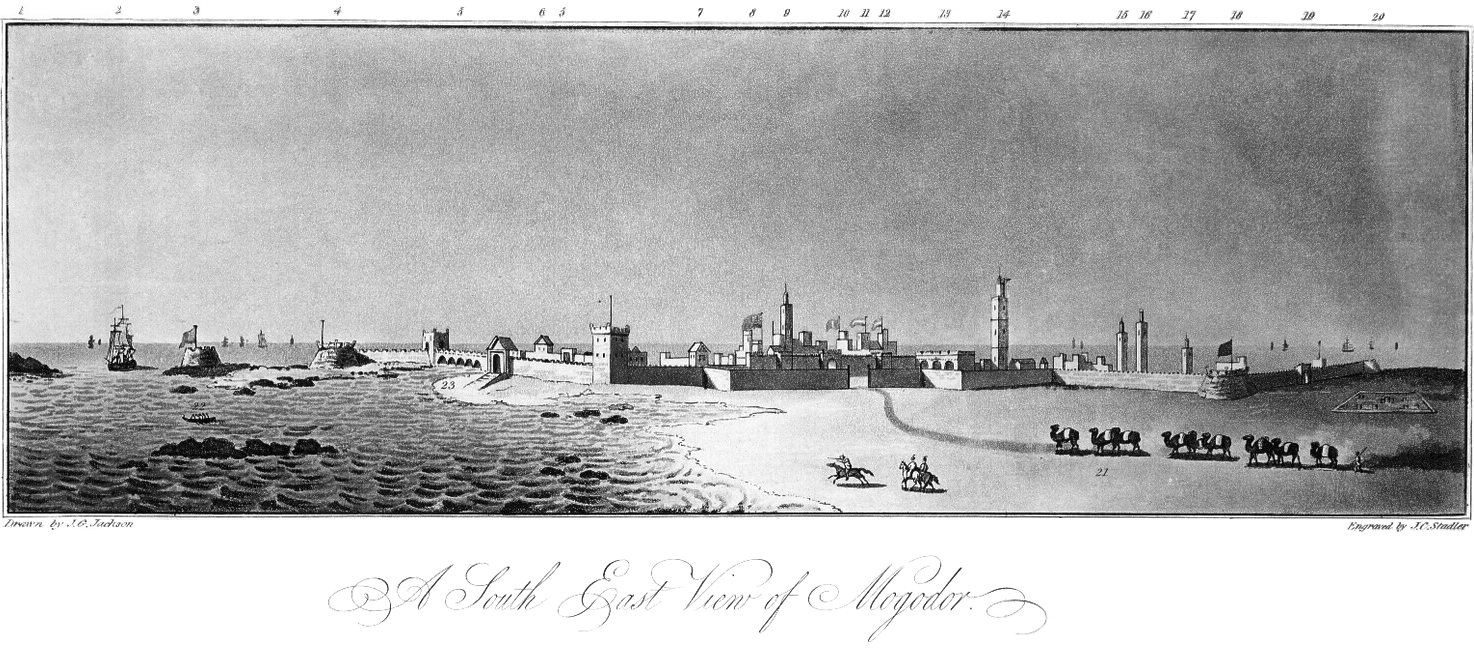

| 4. | View of Mogodor | 47 |

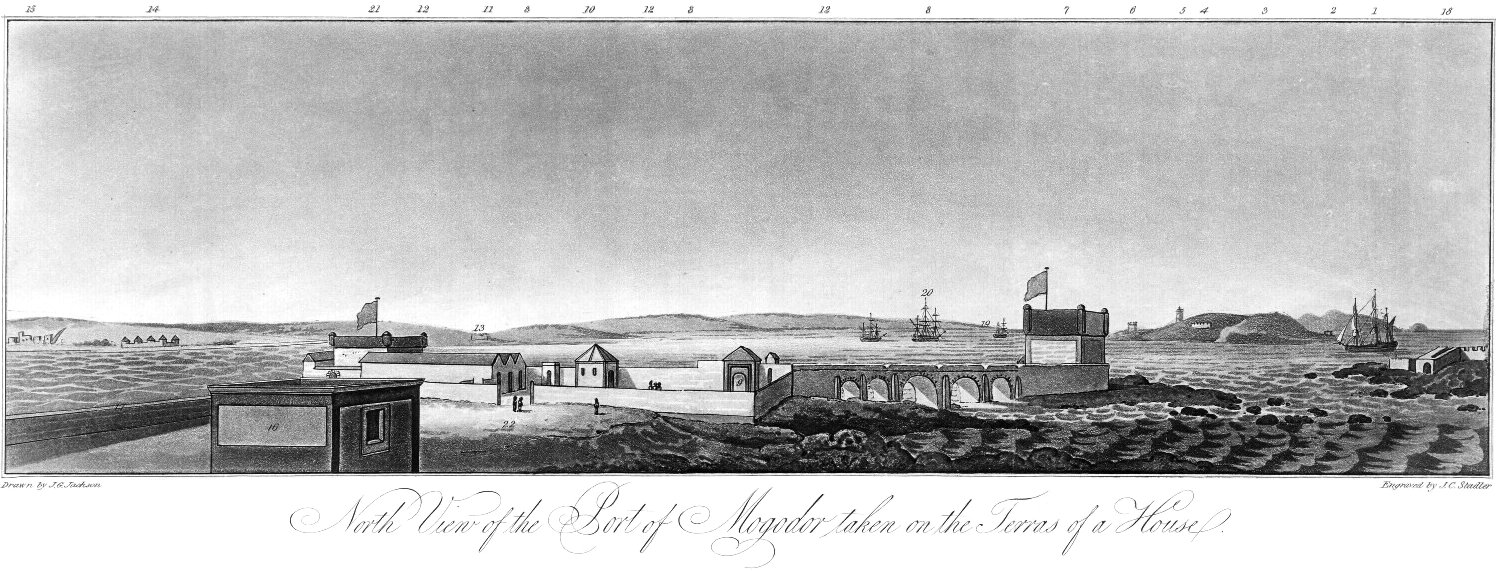

| 5. | View of the Port and Entrance of ditto | 48 |

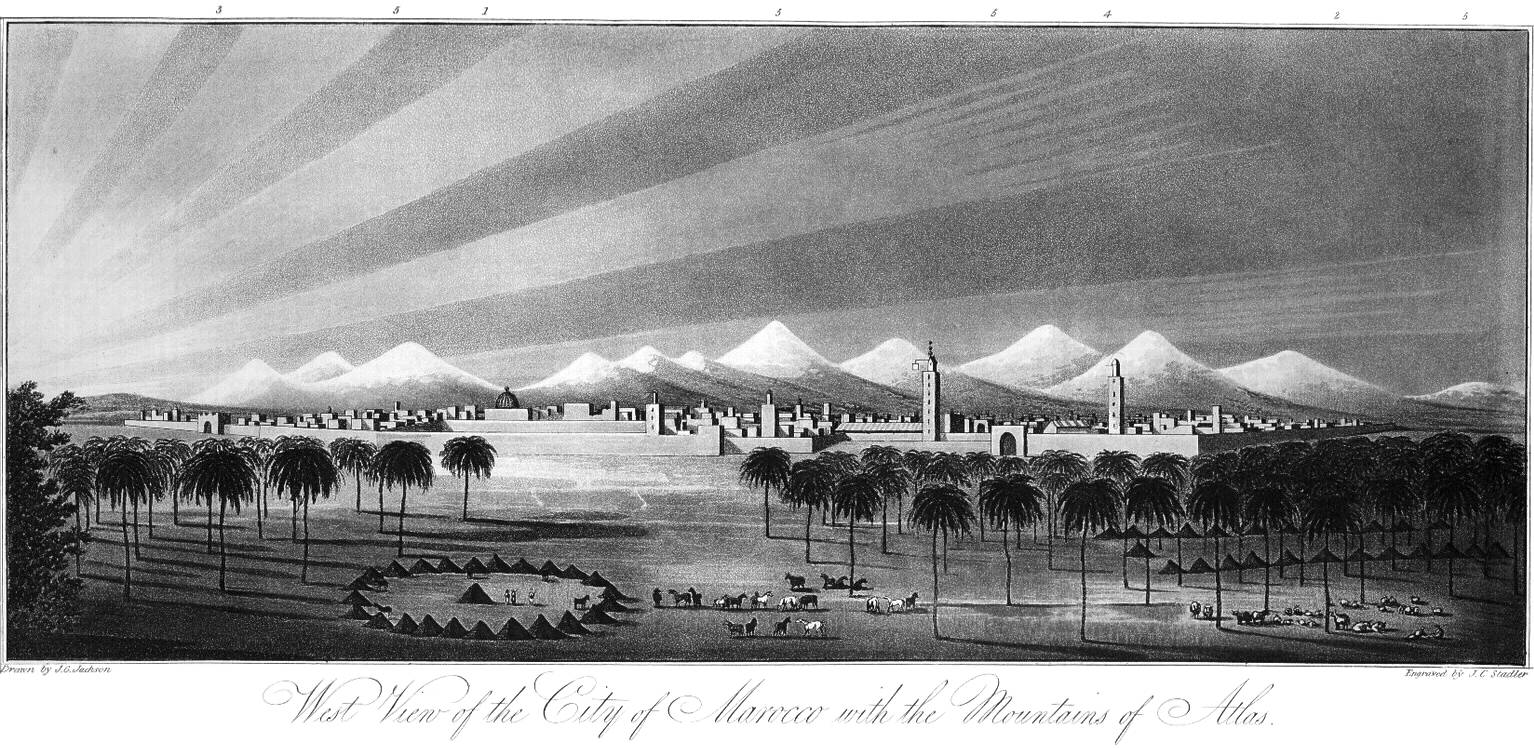

| 6. | View of the City of Marocco and Atlas Mountains | 57 |

| 7. | Camelion | 99 |

| 8. | Locust | 103 |

| 9. | Buskah | 109 |

| 10. | El Efah | 110 |

| 11. | Euphorbium Plant | 134 |

| 12. | Feshook ditto | 136 |

| 13. | Dibben Feshook | 136 |

| 14. | Map, shewing the track of the Caravans across Sahara | 282 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Page. | |

| Geographical Divisions of the Empire of Marocco | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Rivers, Mountains, and Climate of Marocco | 4 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Description of the different Provinces — their Soil, Culture, and Produce | 13 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Population of the Empire of Marocco. — Account of its Sea-ports, Cities, and Inland Towns | 25 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Zoology | 74 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Metallic, Mineral, and Vegetable Productions | 126 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Description of the Inhabitants of West Barbary — their Dress — Religious Ceremonies and Opinions — their Character — Manners and Customs — Diseases — Funerals — Etiquette of the Court — Sources of Revenue | 140 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Some Account of a peculiar species of Plague, which depopulated West Barbary in 1799, and 1800, and to the effects of which the Author was an eye-witness | 171 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Some Observations on the Mohammedan Religion | 196 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Languages of Africa — Various Dialects of the Arabic Language — Difference between the Berebber and Shelluh Languages — Specimen of the Mandinga[xvi] — Comparison of the Shelluh Language with that of Siwah, and also with that of the Canary Islands, and Similitude of Customs | 209 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| General Commerce of Marocco — Annual Exports and Imports of the Port of Mogodor — Importance and Advantages of a Trade with the Empire of Marocco — Cause of its Decline — Present State of our Relations with the Barbary Powers | 234 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Shipwrecks on the Western Coast of Africa about Wedinoon and Sahara — State of the British and other Captives whilst in possession of the Saharawans, or roving Arabs of the Desert — Suggestion of the Author for the Alleviation of their Sufferings — Mode of their Redemption | 269 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Commercial Relations of the Empire of Marocco with Timbuctoo, and other Districts of Soudan — Route of the Caravans to and from Soudan — Of the City of Timbuctoo — The productive Gold Mines in its Vicinage — Of the navigable Intercourse between Jinnie and Timbuctoo; and from the latter to Cairo in Egypt: the whole being collected from the most authentic and corroborating testimonies of the Guides of the Caravans, Itinerant Merchants of Soudan, and other creditable sources of Intelligence | 282 |

AN ACCOUNT

OF

THE EMPIRE OF

MAROCCO,

&c. &c.

Geographical Divisions of the Empire of Marocco.

The empire of Marocco,[7] including Tafilelt,[8] is bounded on the north by the Mediterranean sea; on the east by Tlemsen,[9] the Desert of Angad, Sejin Messa,[10] and Bled-el-jerrêde;[11] on the south by Sahara (or the Great Desert); and on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. It may be divided into four grand divisions.

1st, The northern division, which contains the provinces of Erreef,[12] El Garb, Benihassen, Temsena, Shawia, Tedla, and the district of Fas;[13] these are inhabited by Arabs of various tribes, living in tents, whose original stock inhabit Sahara; to[2] which may be added the various tribes of Berebbers, inhabiting the mountains of Atlas,[14] and the intermedial plains, of which the chief clans or Kabyles are the Girwan, Ait Imure, Zian,[15] Gibbellah, and Zimurh-Shelluh.

The principal towns of this division are, Fas (old and new city, called by the Arabs Fas Jeddede and Fas el Balie), Mekinas, or Mequinas, Tetuan, Tangier, Arzilla, El Araiche, Sla, or Salée, Rabat, Al Kassar, Fedalla, Dar-el-beida, and the Sanctuary of Muley Dris Zerone, where the Mohammedan religion was first planted in West Barbary.

2d, The central division; which contains the provinces of Dukella or Duquella, Abda, Shedma, Haha, and the district of Marocco.[16] The chief towns being Marocco, Fruga, Azamore, Mazagan, Tet, Al Waladia, Asfie, or Saffee, Sueerah, or Mogodor.[17]

3d, The southern division; containing the provinces of Draha and Suse; which latter is inhabited by many powerful tribes or Kabyles, the chief of which are Howara, Emsekina, Exima, Idautenan, Idaultit, Ait-Atter, Wedinoon, Kitiwa, Ait-Bamaran, Messa, and Shtuka; of these Howara, Wedinoon, and[3] half of Ait-Bamaran are Arabs; the others are Shelluhs. The principal towns of this division are Terodant, Agadeer,[18] or Santa Cruz, Inoon, or Noon, Ifran, or Ufran, Akka, Tatta, Messa, and Dar-Delemie.

4th, The eastern division, which lies to the east of the Atlas, and is called Tafilelt; it was formerly a separate kingdom. A river of the same name passes through this territory, on the banks of which the present Emperor’s father, Sidi Mohammed ben Abdallah, built a magnificent palace. There are many other adjacent buildings and houses inhabited by sherreefs, or Mohammedan princes of the present dynasty, with their respective establishments.[19]

FOOTNOTES:

[7]Marakusha in the original Arabic; and called by the Spaniards Marruecos.

[8]Commonly called Tafilet.

[9]In many maps called Tremecin.

[10]Commonly called Sigelmessa.

[11]Commonly called Biledulgerid.

[12]It is through this province that the chain of mountains called the Lesser Atlas passes, viz. from Tangier to Bona, in the Kingdom of Algiers.

[13]Commonly called Fez.

[14]The Atlas mountains are called in Arabic Jibbel Attils, i.e. the mountains of snow; hence, probably, the word Atlas.

[15]Zian is a warlike tribe; it lately opposed an imperial army of upwards of thirty thousand men. This Kabyle is defended from attacks by rugged and almost inaccessible passes.

[16]By the negligence of authors Marocco has been called Morocco, as Mohammed or Muhammed has been transformed to Mahommed, and Mohammedan to Mahommedan.

[17]Sueerah is the proper name; Europeans have called it Mogodor, from a saint who was buried a mile from the town, called Sidy Mogodool, which last word, from oral tradition, has been corrupted to Mogador, and sometimes to Mogadore.

[18]Agadeer is the Arabian name, Guertguessem the ancient African name, and Santa Cruz is the Portugueze appellation.

[19]The modern Arabs divide Northern Africa into three grand divisions: the first extends from the Equator to the Nile el Abeede, or river of Nigritia, and is called Soudan, which is an African word indicative of black, the inhabitants being of that colour: the second extends from the river of Soudan to Bled-el-jerrêde, and is denominated Sahara, from the aridity and flatness of the land: the third division comprises Bled-el-jerrêde, the maritime states of Barbary, Egypt, and Abyssinia. Some authors have affirmed that Bled-el-jerrêde signifies the Country of Dates; others, that it signifies the Country of Locusts; dates certainly abound there; but the name does not imply dates. Jerâad is the Arabic for locusts; but it is a different word from Jerrêde, which signifies dry.

Rivers, Mountains, and Climate of Marocco.

The following are the principal rivers in the empire of Marocco:

The Muluwia, which separates the empire from Angad and Tlemsen, rises at the foot of the Atlas, and, passing through the desert of Angad, discharges itself into the Mediterranean about thirty miles S.E. of Mellilla. This is a deep and impetuous stream, impassable in (Liali) the period between the 20th of December and 30th of January inclusive, or the forty shortest days, as computed by the old style; in summer it is not only fordable, but often quite dry, and is called from that circumstance El Bahar billa ma, or, a sea without water.

El Kose, or Luccos, at El Araiche, so called from its arched windings, El Kose signifying in the Arabic of the western Arabs an arch. Ships of 100 or 150 tons may enter this river at high water; it abounds in the fish called shebbel: it is never fordable, but ferries are constantly crossing with horses, camels, passengers and their baggage, &c.

The Baht rises in the Atlas, and partly loses itself in the swamps and lakes of the province of El Garb; the other branch probably falls into the river Seboo.

The Seboo is the largest river in West Barbary; it rises in a piece of water situated in the midst of a forest, near the foot of Atlas, eastward of the cities of Fas and Mequinas, and winding[5] through the plains, passes within six miles of Fas. Another stream, proceeding from the south of Fas, passes through the city, and discharges itself into this river: this stream is of so much value to the Fasees, from supplying the town with water, that it is called (Wed el Juhor) the river of pearls. Some auxiliary streams proceeding from the territory of Tezza fall into the Seboo in Liali (the period before mentioned). This river is impassable except in boats, or on rafts. At Meheduma, or Mamora, where it enters the ocean, it is a large, deep, and navigable stream; but the port being evacuated, foreign commerce is annihilated, and little shipping has been admitted since the Portugueze quitted the place. This river abounds more than any other in that rich and delicate fish called shebbel. If there were any encouragement to industry in this country, corn might be conveyed up the Seboo to Fas at a very low charge, whereas it is now transported to that populous city on camels, the expense of the hire of which often exceeds the original cost of the grain.

The Bu Regreg.—This river rises in one of the mountains of Atlas, and proceeding through the woods and valleys of the territory of Fas, traverses the plains of the province of Beni Hassen, and discharges itself into the ocean between the towns of Salée and Rabat, the former being on the northern, the latter on the southern bank: here some of the Emperor’s sloops of war, which are denominated by his subjects frigates, are laid up for the winter. This river is never fordable, but ferries are constantly passing to and fro.

The Morbeya also rises in the Atlas mountains, and dividing the territory of Fas from the province of Tedla, passes through a part of Shawia, and afterwards separates that province and[6] Temsena from Duquella; dividing that part of the empire west of Atlas into two divisions. There was a bridge over this river at a short distance from the pass called Bulawan, built by Muley Bel Hassen, a prince of the Mareen family; at this pass the river is crossed on rafts of rushes and reeds, and on others consisting of inflated goat skins. Westward of this pass, the river meanders through the plains, and enters the ocean at the port of Azamor. The Morbeya abounds in the fish called shebbel, the season for which is in the spring. This river not being at any time fordable, horses and travellers, together with their baggage, are transported across by ferries.

The Tensift.[20]—This river rises in the Atlas, east of Marocco, and passing about five miles north of that city, it proceeds through the territory of Marocco, Rahamena, and nearly divides the two maritime provinces of Shedma and Abda, discharging itself into the ocean about sixteen miles south of the town of Saffy. This river receives in its course some tributary streams issuing from Atlas, the principal of which is the Wed Niffis, which, flowing from the south, enters it, after taking a northerly course through the plains of Marocco or Sheshawa. The Tensift is an impetuous stream during the Liali, but in summer it is fordable in several places; and at the ferry near the mouth of the river, at low water, reaches as high as the stirrups. In many places it is extremely deep, and dangerous to cross without a guide; about six miles from Marocco, a[7] bridge crosses it, which was erected by Muley El Mansor; it is very strong but flat, with many arches. One of the Kings of Marocco attempted to destroy this bridge, to prevent the passage of an hostile army, but the cement was so hard that men with pick-axes were employed several days before they could sever the stones; and they had not time to effect its destruction, before the army passed. The shebbel of the Tensift is much esteemed, as is also the water, which is extremely salubrious, and aids considerably the powers of digestion, which, from the intense heat of the climate, are often weakened and relaxed. This river is supposed to be the Phut of Ptolemy; on the northern bank, where it falls into the ocean, is to be perceived the ruins of an ancient town, probably the Asama of that Geographer.

There is a small stream two miles south of Mogodor, from whence that town is supplied with water; and about twelve or fourteen miles more to the south, we reach

The River Tidsi, which discharges itself into the ocean a few miles south of Tegrewelt, or Cape Ossem, where the ancient city of Tidsi formerly stood. Passing to the south in the plains at the foot of that branch of Atlas which forms Afarnie, or the lofty Cape de Geer,[21] we meet

The River Benitamer, which, with the before mentioned branch of Atlas, divides the provinces of Haha and Suse.

[8]Farther to the south is another river called

Wed Tamaract; and about sixteen or seventeen miles south of that place, and about six south of Agadeer, or Santa Cruz,[22] the majestic

River Suse discharges itself into the ocean. This fine river rises at Ras-el-Wed, at the foot of Atlas, about thirty miles from the city of Terodant. The (fulahs) cultivators of land, and the gardeners of Suse have drained off this river so much in its passage through the plains of Howara and Exima, that it is fordable at its mouth at low water in the summer, so that camels and other animals are enabled to cross it with burthens on their backs: at its mouth is a bar of sand which at low water almost separates it from the ocean. The banks of this river are inundated in winter, but in summer are variegated with Indian corn, wheat, barley, pasture lands, beautiful gardens, and productive orchards. Either this river, or that of Messa, must have been the Una of Ptolomy, which is placed in lat. 28° 30′ N. We may presume that the Suse was anciently navigable as far as Terodant, as there are still in the walls of the castle of[9] that city immense large iron rings, such as we see in maritime towns in Europe, for the purpose of mooring ships.

Draha.—The river of this name flows from the north-east of Atlas to the south, and passing through the province of Draha, it disappears in the absorbing sands of Sahara. A great part of the country through which it passes being a saline earth, its waters have a brackish taste, like most of the rivers proceeding from Atlas, which take their course eastward. It is small in summer, but impetuous and impassable in winter, or at least during Liali. It is not improbable that this river formerly continued its course westward, discharging itself into the ocean at Wednoon, and called by the ancients Darodus; but it often happens in Africa, particularly on the confines of any desert country, that the course of rivers is not only changed by the moveable hills of dry sand, but sometimes absorbed altogether, as is now the case with the Draha, after its entrance into the Desert.

River of Messa, called Wed Messa, flows from Atlas; it is, as before observed, a separate stream from the river Suse, and is drained off by the (fulah) cultivators or farmers during its passage. It was navigated by the Portugueze before they abandoned this place for the New World. Leo Africanus has committed another error (which has been copied by modern writers,[23] in calling the river of Messa the river Suse,[24] which I ascertained to be quite a different stream when I was at Messa, and thirty miles distant from the former, though they both flow from E. to W. A bar of sand separates this river entirely at[10] low water from the ocean, but at flood tide it is not fordable. Between the mouth of the river Messa and that of Suse, is a road-stead called Tomée; the country is inhabited by the Woled Abbusebah Arabs, who informed me, when I went there, during the interregnum, with the (Khalif) Vice-regent Mohammed ben Delemy, by order of the (Sherreef) Prince, that British and other vessels often took in water there: it is called by the Arabs (Sebah biure) the place of seven wells, of which wells three only remain, and these we found to contain excellent water. After inspecting the place, and the nature of the road-stead, we returned to the Vice-regent’s castle in Shtuka. Concerning this remarkable sea-port it would be inexpedient at present to disclose more.

River Akassa.—This river is navigable to Noon, above which it becomes a small stream, fordable in various places; it has been called by some Wed Noon, i.e. the river of Noon, but the proper name is Wed Akassa; the word Wedinoon is applied to the adjacent territory.

The Mountains of West and South Barbary are the Atlas and its various branches, which receive different names, according to the provinces in which they are situated. The greater Atlas, or main chain of these mountains, extends from (Jibbel d’Zatute) Ape’s Hill to Shtuka and Ait Bamaran, in Lower Suse, passing about thirty miles eastward of the city of Marocco, where they are immensely high, and covered with snow throughout the year. On a clear day, this part of the Atlas appears at Mogodor, a distance of about a hundred and forty miles, in the form of a saddle; and is visible at sea, several leagues off the coast. These mountains are extremely fertile in many places,[11] and produce excellent fruits; having the advantage of various climates, according to the ascent towards the snow, which, contrasted with the verdure beneath, has a singular and picturesque effect.

Plate 2.

| Drawn by J. G. Jackson. | Engraved J. C. Stadler. |

A Distant View of the Atlas Mountains East of

the City of Marocco

as they appear from Mogodor on a clear morning

before the rising Sun

taken from the Terras of the British Vice Consuls

House.

| 1 | Mosque of Seedy Usif. | 3 | Genoese Consuls Tower. |

| 2 | Atlas Mountains, distant 140 Miles. | 4 | Sand Hills. |

London Published June 4. 1811. by W. & G. Nicholl Pall Mall.

In many places the mountains are uninhabited, and form immense chasms, as if they had been rent asunder by some convulsion of nature; this is the case throughout the ridge that intersects the plains which separate Marocco from Terodant. In this part is a narrow pass, called Bebawan, having a chain of mountains on one side, ascending almost perpendicularly; and on the other side, a precipice as steep as Dover Cliff, but more than ten times the heighth. When the army which I accompanied to Marocco crossed this defile, they were obliged to pass rank and file, the cavalry dismounted: two mules missed their step, and were precipitated into the abyss: the path was not more than fifteen inches wide, cut out of a rock of marble, in some parts extremely smooth and slippery, in others rugged.

In the branches of the Atlas east of Marocco, are mines of copper; and those which pass through the province of Suse produce, besides copper, iron, lead, silver, sulphur, and salt-petre: there are also mines of gold, mixed with antimony and lead ore. The inhabitants of the upper region of Atlas, together with their herds (which would otherwise perish in the snow), live four months of the year in excavations in the mountains; viz. from November to February, inclusive.

The climate of Marocco is healthy and invigorating; from March to September the atmosphere is scarcely ever charged with clouds; and even in the rainy season, viz. from September till March, there is seldom a day wherein the sun is not seen at[12] some interval. The heat is cooled by sea-breezes during the former period; in the interior, however, the heat is intense. The rainy season, which begins about October, ends in March; but if it continue longer, it is generally accompanied with contagious fevers. The trade winds (which begin to blow about March, and continue till September or October) are sometimes so violent, as to effect the nerves and limbs of the natives who inhabit the coast. The inhabitants are robust; and some live to a great age. The Shelluhs, or inhabitants of the mountains of Atlas, south of Marocco, are, however, a meagre people, which proceeds, in a great measure, from their abstemious diet, seldom indulging in animal food, and living for the most part on barley gruel, bread, and honey: the Arabs, the Moors, and the Berebbers, on the contrary, live in a hospitable manner, and eat more nutritious food, though they prefer the farinaceous kind.

FOOTNOTES:

[20]This river is vulgarly called Wed Marakosh, or the river of Marocco, because it passes through the district of that name; but the proper name is Wed Tensift, or the river Tensift; and this is the name given it by Leo Africanus (Book IX.), the only author who has hitherto spelt the word correctly; he has however committed a considerable error in affirming that it discharges itself into the ocean at Saffy.

[21]A Shelluh name, expressive of a quick wind, because there is always wind at this Cape; but ships should be extremely careful not to approach it, in going down the coast; not but that the water is very deep, as the Cape rises almost perpendicularly from the ocean, but because the land is so extremely high that those ships which approach within a league of it, are almost always becalmed on the south side of it, and are in consequence three days in getting down to Agadeer, whilst other vessels which keep more to the west, reach that port in a few hours. This Cape is a western branch of the Atlas.

[22]Leo Africanus, who undoubtedly has given us the best description of Africa, commits an error, however, in describing this river. “The great river of Sus, flowing out of the mountains of Atlas, that separate the two provinces of Hea and Sus (Haha and Suse) in sunder, runneth southward among the said mountains, stretching unto the fields of the foresaid region, and from thence tending westward unto a place called Guartguessen,[a] where it dischargeth itself into the main ocean.” See 9th book of Leo Africanus. The Cape de Geer was formerly the separation of the provinces of Haha and Suse, but now the river of Tamaract may be called the boundary, which is fifteen miles to the northward of the mouth of the river Suse; and Guartguessen, or Agadeer, or Santa Cruz, is six miles north of the river Suse. Had I not resided three years at Santa Cruz, in sight of the river Suse, which I have repeatedly forded in various parts, I should not have presumed to dispute Leo’s assertion.

[a]The ancient name of Agadeer or Santa Cruz in Leo’s time.

[23]Vide Brooks’s Gazeteer, 12th edition, title Messa.

[24]Through the three small towns of Messa runneth a certain great river called Sus. Vide Leo Africanus, 2d book, title Town of Messa.

Description of the different Provinces, their Soil, Culture, and Produce.

In describing the soil and produce of this extensive empire, we will proceed through the various provinces, beginning with the northern, called

This province extending along the shore of the Mediterranean sea, produces corn and cattle in abundance; that part of it contiguous to Tetuan produces the most delicious oranges in the world; also figs, grapes, melons, apricots, plums, strawberries, apples, pears, pomgranates, citrons, lemons, limes, and the refreshing fruit of the opuntia, or prickly pear, called by the Arabs (Kermuse Ensarrah) Christian fig. This fruit was probably first brought into the country from the Canary Islands, as it abounds in Suse, and is called by the Shelluhs of South Atlas, (Takanarite) the Canary fruit. A ridge of mountains passes from Tangier, along this province to the eastward, as far as Bona, in Algiers; these mountains are called Jibbel Erreef by the natives, and the Lesser Atlas by Europeans.

The next province is called El Garb[25] (g guttural.) It is of the[14] same nature with that already described; from the port of El Araiche, eastward, as far as the foot of Atlas, is a fine champaign country, extremely abundant in wheat and barley: here are the extensive plains of Emsharrah Rumellah, famous for the camp of Muley Ismael, great grandfather of the present Emperor Soliman, where he retained his army of Bukarrie Blacks to the amount of one hundred thousand horse. This army possessed the finest horses in the empire. The remains of the habitations are still discernible. There is a forest eastward of El Araiche of considerable extent, consisting chiefly of oak, with some cork, and other valuable large trees; more to the southward and eastward, we discover a forest of cork only, the trees of which are as large as full grown oaks. From Mequinas to Muley Idris Zerone, the renowned sanctuary at the foot of Atlas, east of the city of Mequinas, the country is flat, with gentle hills occasionally, and inhabited by the tribe of Ait Imure, a Kabyle which dwells in straggling tents, and a warlike tribe of Berebbers. The Emperor Seedy Mohammed, father to the reigning Emperor Soliman, used to denominate the Ait Imure the English of Barbary.[26]

The country between Fas and Mequinas, and from thence to Salée, is of the same description as the foregoing; a rich champaign, abounding prodigiously in corn, and inhabited altogether by Arabs, with the exception, however, of the Zimur’h Shelluh, another Kabyle of Berebbers. In short, the whole northern[27] division of this empire is an uninterrupted corn field; a rich black, and sometimes red soil, without stones or clay, with scarcely any wood upon it (the forests before mentioned, and the olive plantations and gardens about the cities of Fas and Mequinas excepted), but incalculably productive. The inhabitants do not use dung, but reap the corn high from the ground, and burn the stubble, the ashes of which serve as manure. During this period of the year, viz. August, enormous clouds of smoke are seen mounting the declivities of hills and mountains, penetrating without resistance the woods, and leaving nothing behind but black ashes and cinders: these fires heat the atmosphere considerably, as they continue burning during two months. In sowing, the husbandmen throw the grain on the ground, and afterwards plough it in. Oats they make no use of: beans, peas, caravances, and Indian corn, are cultivated occasionally in lands adjacent to rivers: the fruits are similar to those before described, and are in great abundance, oranges being sold at a ducket or a dollar a thousand, at Tetuan, Salée, and some other places; grapes, melons, and figs of various kinds, and other fruits, are proportionally abundant. Cotton of a superior quality is grown in the environs of Salée and Rabat,[16] also hemp. The tobacco called Mequinasi, so much esteemed for making snuff, is the produce of the province of Benihassen, as well as the country adjacent to the city of Mequinas.

These are most productive in corn; the crop of one year would be sufficient for the consumption of the whole empire, provided all the ground capable of producing wheat and barley were to be sown. These fine provinces abound in horses and horned cattle; their flocks are numerous, and the horses of Abda are of the most select breed in the country. The cavalry of Temsena is the best appointed of the empire, excepting the black troops of the Emperor, called Abeed Seedy Bukarrie.

Two falls of rain in Abda are sufficient to bring to maturity a good crop of wheat; nor does the soil require more. The water-melons of Duquella are of a prodigious size, and indeed everything thrives in this prolific province: horses, horned cattle, the flocks, nay even the dogs and cats, all appear in good condition. The inhabitants are, for the most part, a laborious and trading people, and great speculators: they grow tobacco for the markets of Soudan and Timbuctoo. Nearly midway between Saffee and Marocco is a large salt lake, from which many camels are daily loaded with salt for the interior.

The province of Shedma produces wheat and barley; its fruits are not so rich as those of the north, or of Suse; it abounds however in cattle. Of goats it furnishes annually an incalculable number, the skins of which form a principal article of exportation from the port of Mogodor; and such is the animosity[17] and opposition often among the merchants there, that they have sometimes given as much for the skin, as the animal itself was sold for. Honey, wax, and tobacco are produced in this province, the two former in great abundance; also gum arabic, called by the Arabs Alk Tolh, but of an inferior quality to that of the Marocco district.

Haha is a country of great extent, interspersed with mountains and valleys, hills and dales, and inhabited by twelve Kabyles of Shelluhs. This is the first province, from the shores of the Mediterranean, in which villages and walled habitations are met with, scattered through the country; the before mentioned provinces (with the exception of the sea-port towns and the cities of Fas, Mequinas, Marocco, and Muley Idris Zerone) being altogether inhabited by Arabs living in tents. The houses of Haha are built of stone, each having a tower, and are erected on elevated situations, forming a pleasing view to the traveller. Here we find forests of the argan tree, which produces olives, from the kernel of which the Shelluhs express an oil,[28] much superior to butter for frying fish; it is also employed economically for lamps, a pint of it burning nearly as long as double the quantity of olive or sallad oil. Wax, gum-sandrac and arabic, almonds, bitter and sweet, and oil of olives, are the productions of this picturesque province, besides grapes, water-melons, citrons, pomgranates, oranges, lemons, limes, pears, apricots, and other fruits. Barley is more abundant than wheat.[18] The Shelluhs of Haha are physiognomically distinguishable (by a person who has resided any time among them) from the Arabs of the plains, from the Moors of the towns, and from the Berebbers of North Atlas, and even from the Shelluhs of Suse, though in their language, manners, and mode of living they resemble the latter. The mountains of Haha produce the famous wood called Arar, which is proof against rot or the worm. Some beams of this wood taken down from the roof of my dwelling-house at Agadeer, which had been up fifty years, were found perfectly sound, and free from decay.

We now come to Suse, the most extensive, and, excepting grain, the richest province of the empire. The olive, the almond, the date, the orange, the grape, and all the other fruits produced in the northern provinces abound here, particularly about the city of Terodant (the capital of Suse, formerly a kingdom), Ras-el-Wed, and in the mountains of Edautenan.[29] The grapes of Edautenan are exquisitely rich. Indigo grows wild in all the low lands, and is of a vivid blue; but the natives do not perfectly understand the preparation of it for the purpose of dying.

Suse contains many warlike tribes, among which are Howara, Woled Abbusebah, and Ait Bamaran; these are Arabs;—[19] Shtuka, Elala, Edaultit, Ait Atter, Kitiwa, Msegina, and Idautenan, who are Shelluhs.

There is not, perhaps, a finer climate in the world than that of Suse, generally, if we except the disagreable season of the hot winds. It is said, however, and it is a phenomenon, that at Akka rain never falls; it is extremely hot there in the months of June, July, and August; about the beginning of September the (Shume) hot wind from Sahara blows with violence during three, seven, fourteen, or twenty-one days.[30] One year, however, whilst I resided at (Agadeer) Santa Cruz, it blew twenty-eight days; but this was an extraordinary instance.[31] The heat is so extreme during the prevalence of the Shume, that it is not possible to walk out; the ground burns the feet; and the terraced roofs of the houses are frequently peeled off by the parching heat of the wind, which resembles that which proceeds from the mouth of an oven: at this time clothes are oppressive. These violent winds introduce the rainy season.

The (Lukseb) sugar-cane grows spontaneously about Terodant. Cotton, indigo, gum, and various kinds of medicinal herbs are produced here. The stick liquorice is so abundant that it is called (Ark Suse) the root of Suse. The olive plantations in different parts of Suse are extensive, and extremely productive; about Ras-el-Wed and Terodant a traveller may proceed two days through these plantations, which form an uninterrupted[20] shade impenetrable to the rays of the sun; the same may be said of the plantations of the almond, which also abound in this province. Of corn they sow sufficient only for their own annual consumption; and although the whole country might be made one continued vineyard, yet they plant but few vines; for wine being prohibited, they require no more grapes than they can consume themselves, or dispose of in the natural state. The Jews, however, make a little wine and brandy from the grape, as well as from the raisin. The date, which here begins to produce a luxurious fruit, is found in perfection on the confines of the Desert in Lower Suse. At Akka and Tatta the palm or date-tree is very small, but extremely productive; and although the fruit be not made an article of trade, as at Tafilelt, it is exquisitely flavoured, and possesses various qualities. The most esteemed kind of date is the Butube, the next is the Buskrie.

Suse produces more almonds and oil of olives than all the other provinces collectively. (Gum Amarad) a red gum partaking of the intermediate quality between the (tolh gum) gum arabic and the Aurwar, or Alk Soudan Senegal gum, is first found in this province. Wax is produced in great abundance; also gum euphorbium, gum sandrac, wild thyme, worm-seed, orriss root, orchillo weed, and coloquinth. Antimony, salt-petre of a superior quality, copper, and silver, are found here; the two latter in abundance about Elala, and in Shtuka.

Draha and Tafilelt produce a superior breed of goats, and a great abundance of dates: the countries situated near the banks of the rivers of Draha and Tafilelt have several plantations of[21] Indian corn, rice, and indigo. There are upwards of thirty sorts of dates in this part of Bled-el-jerrêde;[32] the best and most esteemed is that called Butube, which is seldom brought to Europe, as it will not keep so long as the Admoh date, the kind imported into England, but considered by the natives of Tafilelt so inferior, that it is given only to the cattle; it is of a very indigestive quality: when a Filelly[33] Arab has eaten too many dates, and finds them oppressive, he has recourse to dried fish, which, it is said, counteracts their ill effects. This fruit forms the principal food of the inhabitants of Bled-el-jerrêde, of which Tafilelt is a part; the produce of one plantation near the imperial palace[34] at Tafilelt sold some few years past for five thousand dollars, although they are so abundant there that a camel load, or three quintals, is sold for two dollars. The face of the country from the Ruins of Pharoah to the palace of Tafilelt is as follows:

Tafilelt is eight (erhellat[35] de lowd) days journey on horseback from the Ruins of Pharoah; proceeding eastward from these ruins, the traveller immediately ascends the lofty Atlas, and on the third day, about sun-set, reaches the plains on the other side; the remaining five days journey is through a wide extended plain totally destitute of vegetation, and on which[22] rain never falls; the soil is a whitish clay, impregnated with salt, which when moistened resembles soap. A river, which rises in the Atlas, passes through this vast plain from the south-west to the north-east; at Tafilelt it is described to be as wide as the Morbeya at Azamor in West Barbary, that is, about the width of the Thames at Putney; the water of this river receives a brackish taste, by passing through the saline plains: after running a course of fifteen erhellat,[36] or four hundred and fifty miles, it is absorbed in the desert of Angad. It has several (l’uksebbat) castles of terrace wall on its banks, inhabited by the (Sherreefs) princes of the reigning family of Marocco. Latterly wheat and barley have been cultivated near the river and the castles. The food of the inhabitants, who are Arabs, consists, for the most part (as already observed), in dates; their principal meal is after sun-set, the heat being so intolerable as not to suffer them to eat any thing substantial while the sun is above the horizon.

There is another river, inferior to the one before mentioned, which rises in the plains north of Tafilelt, and flowing in a southerly direction, is absorbed in the great desert, of Sahara: the water of this river is so very brackish, as to be unfit for culinary purposes; it is of a colour similar to chalk and water, but if left to stand in a vessel during the night it becomes clear by the morning, though it is still too salt to drink. These extensive plains abound every where in water, which is found at the depth of two cubits,[37] but so brackish as to be palatable only to those who have been long accustomed to the use of it.

[23]The people have among themselves a strict sense of honour; a robbery has scarcely been known in the memory of the oldest man, though they use no locks or bars. Commercial transactions being for the most part in the way of barter or exchange, they need but little specie: gold dust is the circulating medium in all transactions of magnitude. They live in the simple patriarchal manner of the Arabs, differing from them only in having walled habitations, which are invariably near the river.

It is intensely hot here, during a great part of the year, the (Shume) wind from Sahara blowing tempestuously in July, August, and September, carrying with it particles of earth and sand, which are very pernicious to the eyes, and produce ophthalmia.

A considerable trade is carried on from this place to Timbuctoo, Houssa, and Jinnie, south of Sahara, and to Marocco, Fas, Suse, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. Indigo abounds here, but from the indolence of the cultivators it is of an inferior quality. There are mines of antimony and lead ore: the Elkahol Filelly,[38] so much used by the Arabs and African women to give a softness to the eyes, and to blacken the eye-brows, is the produce of this country. The common dress of the inhabitants consists of a loose shirt of blue cotton, with a shawl or belt round the waist.

An Akkabah, or accumulated caravan, goes annually from hence to Timbuctoo.

Woollen hayks[39] for garments are manufactured here of a curious texture, extremely light and fine, called El Haik Filelly.

[24]If we except the habitations and castles near the river, the population of the plains is very inconsiderable: a few tents of the Arabs whose original stock inhabit Sahara, are occasionally discovered, which serve to break the uniformity of the unvaried horizon. A person who imagines a vast plain, bounded by an even horizon, similar to the sea out of sight of land, will have an accurate idea of this country.

The goats of Tafilelt are uncommonly large: there is a breed of them preserved by the Emperor of Marocco on the island of Mogodor.

FOOTNOTES:

[25]This is the westernmost province of Marocco northward, as its name denotes, El Garb signifying the West. There is a tradition among the Arabians, that it was originally united to Trafalgar and Gibraltar, shutting up the Mediterranean sea, the waters from which passed into the western ocean by a subterraneous passage; and at this day they call Trafalgar Traf-el-garb, i.e. the piece or part of El Garb; and Gibraltar Jibbel-traf, i.e. the mountain of the piece, or part of El Garb.

[26]The ignorance of the Mohammedans in geography, added to their vanity, induces them to imagine that the empire of Marocco is nearly as large as all Europe, and they accordingly ascribe to the inhabitants of the various provinces the character of some European nation: thus the warlike Ait Imure are compared to the English, the people of Duquella to the Spaniards, and those of Shawia to the Russians.

[28]This oil possesses a powerful smell, which is extracted from it by boiling with it an onion and the crumb of a loaf; without this preparation it is said to possess qualities productive of leprous affection.

[29]North of Santa Cruz, and south-east of Cape de Geer, are several lofty inaccessible mountains, proceeding from the main chain of Atlas, which form some intermediate plains, inhabited by a bold and warlike race of Shelluhs, denominated Edautenan. On account of certain essential services afforded by this people to Muley Ismael, or some ancient Emperor of Marocco, they are free from all imposts and taxes, a privilege which is confirmed to them, whenever a new Emperor ascends the throne of Marocco. They wear their hair long behind, but shaved, or short, before; they have an interesting and warlike appearance.

[30]If it blow more than three days, it is expected to continue seven; and if it exceed seven, it is said to continue fourteen, and so on. During the years that I was in the country, it never blew at Mogodor more than three or seven.

[31]The Bashaw then informed me that he had never before known it to continue more than twenty-one days, and he was a man of seventy, and a native of Suse.

[32]Bled-el-jerrêde is the country situated between the maritime states of Barbary and Sahara, or the Desert.

[33]Filelly is the term given to the natives of Tafilelt, as Drahawie is to those of Draha.

[34]The father of the present Sultan Soliman built a magnificent palace on the banks of the river of Tafilelt, which bounds his dominions to the eastward; the pillars are of marble, and were many of them transported across the Atlas, having been collected from the (Ukser Farawan) Ruins of Pharoah, near to the sanctuary of Muley Dris Zerone, west of Atlas.

[35]A horse erhella (or day’s journey) is thirty-five miles English.

[36]An ordinary erhella is thirty English miles.

[37]A cubit is twenty-one inches.

[38]Elkahol Filelly signifies lead ore of Tafilelt.

[39]The hayk of the Arabs is a plain piece of cloth, of wool, cotton, or silk, and is thrown over their under dress, somewhat similar to the Roman toga.

Population of the Empire of Marocco. — Account of its Sea-ports, Cities, and Towns.

Various and contradictory statements have been made by travellers, of the population of this country. From all the accounts which I have been able to collect on the subject, and from authentic information, extracted from the Imperial Register, of the inhabitants of each province, I think the following as correct a statement as can possibly be made:

| Inhabitants. | ||

|---|---|---|

| The city of | Marocco | 270,000 |

| Fas, old and new city | 380,000 | |

| Mequinas | 110,000 | |

| Muley Dris Zerone | 12,000 | |

| Tetuan | 16,000 | |

| Tangier | 6,000 | |

| Arzilla | 1,000 | |

| El Araiche | 3,000 | |

| Mamora | 300 | |

| Salée | 18,000 | |

| Rabat | 25,000 | |

| Total | 841,300 | |

| [26]Brought over | 841,300 | |

| El Mensoria, Fedalla, and El Kasser Kabeer | 1,000 | |

| Dar el Beida | 1,000 | |

| Azamor | 1,000 | |

| Mazagan, Tet, and El Woladia | 3,000 | |

| Saffy, or Asfee | 12,000 | |

| Mogodor, or Sueerah | 10,000 | |

| Santa Cruz, or Agadeer | 300 | |

| Terodant | 25,000 | |

| Messa | 1,000 | |

| Total population of the towns | 895,600 | |

| The Province of | Erreef | 200,000 |

| El Garb | 200,000 | |

| Benihassen | 300,000 | |

| Tedla | 450,000 | |

| District of | Fas, exclusive of the cities or towns | 1,280,000 |

| Duquella | 966,000 | |

| Temsena and Shawia | 1,160,000 | |

| Abda | 500,000 | |

| Shedma | 550,000 | |

| District of | Marocco | 1,250,000 |

| Haha | 708,000 | |

| Draha | 350,000 | |

| Carried forward | 7,914,000 | |

| [27]Brought forward, | 7,914,000 | |

| Suse, viz. | ||

| Benitamer, | 11,000 | |

| Idautenan, | 10,000 | |

| Msegina | 87,000 | |

| Exima, | 11,000 | |

| Howara | 80,000 | |

| Kitiwa | 50,000 | |

| Shtuka | 380,000 | |

| Ait Bamaran | 300,000 | |

| Wedinoon | 200,000 | |

| Ras el Wed | 80,000 | |

| Elala | 25,000 | |

| Seedi Hamed O Musa sanctuary and district | 20,000 | |

| Akka, and territory | 10,000 | |

| Tatta, and ditto | 10,000 | |

| Ufran, or Ifran | 10,000 | |

| Ilirgh | 10,000 | |

| Messa, and territory | 10,000 | |

| Teeselerst | 25,000 | |

| The district of Agadeer, or Santa Cruz including Tildi, Taddert, and Tamaract | 1,000 | |

| Woled Busebbah, the part of that Kabyle, which now inhabits Suse | 1,000 | |

| Ait Atter | 360,000 | |

| Idaultit, | 400,000 | |

| Carried over | 10,005,000 | |

| [28]Brought over | 10,005,000 | |

| Inferior Kabyles, forming other parts of Suse, not specified | 336,000 | |

| 10,341,000 | ||

| Total. | ||

| The tribes of the Berebbers of North Atlas altogether | 3,000,000 | |

| District of Tafilelt | 650,000 | |

| Provinces of the Marocco Empire, West of Atlas | 10,341,000 | |

| Inland cities, towns, and ports | 895,600 | |

| Total population of the whole empire, including Tafilelt | 14,886,600 | |

Persons who have travelled through the country, unacquainted with the mode of living of the inhabitants, may, probably, consider the above as an exaggerated statement: but it should be understood, that a stranger, in such cases, sees little of the population, as the various douars of Arabs are at a considerable distance from the roads, from which they always retire, to avoid the visits of travellers, whom they are compelled, by the laws of hospitality, to furnish with necessary provisions for three days, without receiving any pecuniary remuneration; of this fact travellers, in general, have not been apprised, and have, in consequence, formed calculations which represent the population very inferior to what it actually is.

[29]The western coast of Marocco is defended with numerous rocks, level with the surface of the water, which extend along the shore in various parts, from the Streights of Gibraltar to Agadeer: we find, however, occasionally, in the intermediate places, an extensive beach, where the water is shallow, and the surf runs high. The empire of Marocco is separated from Algiers by the river Muluwia, which falls into the Mediterranean sea, in long. W. from London, 1° 30′.

The sea-ports of this empire have but a limited commerce with foreign nations: and are consequently neither very extensive nor populous.

Proceeding along the coast of the Mediterranean, we come to the town of Melilla, (the ancient Ryssadirium,) called by the Arabs Melilia, in possession of the Spaniards, who have a garrison here; the country, in its vicinity, abounds with wax and honey, which latter is equal to that of Minorca, and when kept a year, is nearly as hard and white as loaf sugar. The Goths, in whose possession Melilla was when the Arabs invaded the country, abandoned it; and the latter, after retaining it some years, forsook it to dwell in their tents. The Spaniards took possession of it about the beginning of the 15th century. It was besieged by Seedy Mohammed ben Abdallah, Emperor of Marocco, in the year 1774, but without effect.

The next town worthy of notice is Bedis de Gomaira, situated between two mountains, at the bottom of which there was anciently a city called Bedis, supposed to have been founded by the Carthaginians. The Arabs call it Belis, and some Europeans, by a corruption of the word, Velis, the name given it in most of our maps and charts. In the neighbourhood of this place[30] are forests of excellent timber, with which the Moors, before the Spaniards obtained possession of it, built fishing-vessels.

Proceeding from hence westward, we discover the river Busega, near Tetuan, or Tetawan, as it is called by the Arabs, where some of the Emperor’s gallies occasionally winter. About four miles inland from the roadstead, stands the town of Tetuan, in the province of El Garb: this town is built on the declivity of a rocky hill, but is neither large nor strong: its walls are built of mud and mortar, framed in wooden cases, and beaten down with mallets. The inhabitants are rich from commerce, receiving from Spain and Gibraltar dollars, German linens, and cloths, also British manufactures, for which they barter wax, skins, leather, raisins, almonds, olives, oranges, honey, &c. It is inhabited by Moors and Jews, who, for the most part, speak a corrupt Spanish, in which language their commercial negociations are transacted. The environs of Tetuan abound in gardens of the most delicious fruits; here are grown the finest oranges in the world, and they are in great abundance; the adjacent country abounds also in vineyards, the grapes of which are exquisite, and in great variety. From the raisins and figs the Jews distil an ardent spirit (called Mahaya), which, when a year old, is similar to the Irish usquebah, and they prefer it to European brandy or rum, because it does not (as they pretend) heat the blood: they drink immoderately of this spirit, and generally take a glass of it before eating.

Tetuan was founded, according to report, by the Africans, and was a populous town at the time the Moors were driven out of Spain. It was the place of residence for many of the consuls of the European powers, till the year 1770, when an Englishman[31] having shot or wounded a Moor, all the Europeans were ordered to quit the place, and the Emperor Seedy Mohammed declared, he would never suffer an European to settle there again. It is remarkable, that in this declaration he literally kept his word.

This port carried on a considerable trade in provisions with Gibraltar, as vessels are obliged to come here in preference to Tangier, whenever the wind is in the west, and does not permit them to make the latter place; at this time ships may lie in security, and our fleets often water and victual here, as did that of the immortal Nelson, previous to his victory in Aboukeer Bay.[40]

We next come to Cibta, or Ceuta, as it is called by Europeans; it is situated near (Jibbel d’Zatute) Ape’s Mountain, called by the ancients Abyla, one of the pillars of Hercules.

The town of Ceuta is probably of Carthaginian origin; the Romans colonized it; it afterwards became the metropolis of the places which the Goths held in Hispania Transfretana; was next occupied by the Arabs; and, in 1415, taken by the Portugueze; it is now in the possession of Spain. It is celebrated for the strength of its fortifications, its advantageous situation at the entrance of the Mediterranean, being the nearest point to Europe. It is situated on a rising ground, at the foot of the mountain; near it stands the mountain with seven summits, called by the Arabs Sebat Jibbel, and by the ancients, Septem Fratres. If the Emperor Yezzed had succeeded in taking Ceuta, which he twice besieged about the close of the last century,[32] without success, his intention was to harass the trade of the European nations, by fitting out gallies and rovers, for the purpose of capturing and carrying the merchant ships into Tangier, Tetuan, and Ceuta, as they passed through the Streights; but the place is capable, on the land side, of resisting every attack that may be made upon it by the Mohammedans, unless they were aided by some European naval force.

The whole coast from hence to Tangier, the next town we come to, is rugged, and interspersed with projecting cliffs. Tangier, anciently called Tinjis, and Tingia, and now, by the Arabs, Tinjiah, is situated at the western mouth of the Streights, and a day’s journey distant from Tetuan. This town was first possessed by the Romans, next by the Goths, and was given up by Count Julian to the Mohammedans. It was taken in the 15th century by the crown of Portugal, which gave it, in 1662, as part of the dowry of the princess Catherine of Portugal, upon her marriage to Charles the Second of England. The English, however, finding the expenses of keeping it to exceed the advantages derived from the possession of it, abandoned it in 1684, after destroying the mole and fortifications. It still retains some batteries in good condition, facing the bay, at the bottom of which is a river, and the remains of the bridge of Old Tangier; but the sand has so accumulated at the mouth of this river, that the bridge, had it stood, would have been now useless.

Tangier is favourable to Moorish piracy, even without the possession of Ceuta, being the narrowest part of the Streights; but it will never become a commercial town, having but few productions in its vicinage. The Spaniards here ship eggs, fowls, vegetables, and some fruits; but the chief exports are cattle and[33] edible vegetables, which are carried to Gibraltar for the supply of the garrison: this supply is allowed by the Emperor, not perhaps from any predilection towards us (although he apparently prefers the English to any other European power), but because it was a grant from his great grandfather Muley Ismael, whose successors have not infringed on the ordinances of their renowned ancestor, the Mohammedans having a great respect for the deeds of their forefathers.

Westward of Tangier is Cape Spartel, the headland which divides the Streights from the western ocean; after doubling this Cape, at the distance of 15 miles, stands the little town of Arzilla, called by the Carthaginians Zilia, and by the Romans, who had a garrison here, Julia Traducta; it belonged afterwards to the Goths, and latterly to the Mohammedans. Alphonso of Portugal took it in 1741; but about the end of the 16th century, it was abandoned by the Portuguese, and again fell into the hands of the Moors. A river discharges itself at this place into the ocean; but there is no trade carried on.

Proceeding down the coast southward, we discover, at the distance of 33 miles, the town of El Araiche, standing on the river El Kos. El Araice, whence its name is derived, signifies, in the Arabic, flower, or pleasure gardens.[41] This was formerly a town of some commerce; remains of the commercial houses, which appear to have been large and spacious, still exist. The adjacent country is very fine and productive, and furnishes corn, wax, and oil, the two former in abundance; it also contains woods of full-grown trees, fit for ship building. The river El Kos has a bar of sand at its entrance, but is sufficiently deep[34] to admit ships of 100 tons. The gardens of the Hesperides have been supposed to have been situated here.

El Araiche was fortified about the end of the 16th century by Muley ben Nassar; in 1610 it was given up to Spain, and in 1689 retaken by Muley Ismael. There is an excellent market-place in the town: the castle, which commands the entrance of the road, is in good repair, and the guns well mounted, an uncommon thing in this country: and it is further strengthened by several batteries on the banks of the river. The French entered the river in 1765, but by a feint of the Moors, they were induced to go too far up, when they were surrounded by superior numbers, and fell victims to their own impetuosity.

Some foreign commerce was carried on here by the nations of Europe so late as the year 1780, when the Emperor Seedy Mohammed, for some reason unavowed, caused it to be evacuated, and ordered the Europeans to quit it; some of whom went to Mogodor, and others to Europe.

The larger vessels of the Emperor, which, however, are but small, when compared to our ships of the line, generally winter in a cove on the north side of the river, where there are magazines of naval stores, sufficient for the equipment of such force. The soil is sandy, and too loose to admit of the erection of stocks for ship building. The road is not secure in winter, when the winds blow from the south and west, but from April to September inclusive, it is a safe anchorage. El Araiche stands in 35° 11′ N. lat.

Proceeding southward from El Araiche, we reach Maheduma (or Mamora, as it is called by Europeans), distant sixty-five miles. This town is situated on an eminence, close to the river, near the southern banks; it is a poor neglected place, the[35] ferrymen and the inhabitants of which subsist by fishing for (Shebbel) a species of salmon, of which they take an incredible quantity, for the supply of the interior, as well as the neighbouring country, from the autumn till the spring.

The country hereabouts is a continued plain, in which are three fresh-water lakes, one of which is 20 miles in length. This country was formerly populous, but the incalculable number of musquitos, gnats, nippers, and other annoying insects, have obliged the inhabitants to quit the place. These lakes abound in eels, which are taken and salted for preservation and sale; ducks and all kinds of water-fowl also abound on them. Skiffs made of the fan palm and of rushes, about seven feet long and two broad, are used by the fisherman, who guides them with a pole, and pierces the eels with a lance, or long dart, when he sees them in the water, which is not deep. There are a few insulated spots in the largest lake, on which are (Zawiat) sanctuaries, inhabited by the Maraboots, who are held in veneration by the inhabitants of the plains. The plains and valleys are delightfully pleasant in the months of March and April; but in June, July, and August, when musquitos are so indescribably troublesome, they are parched up. On an eminence, at the southern extremity towards the river Seboo, is a sanctuary and asylum for travellers, annexed to which are several gardens and plantations of olives and almonds. The sand bank at the mouth of the Seboo has partially disappeared, and perhaps a little nautical skill might make the river navigable with safety to ships of 200 tons burden.

Travelling to the south from Meheduma, at the distance of sixteen miles we reach Slâa, or Salée, on the northern bank of the river, which is formed by the junction of the streams of the[36] Buregreg and Wieroo; the river at Salée was formerly capable of receiving large vessels; when going thence, however, a few years since, to Mogodor, the vessel which conveyed me, being about 150 tons burden, struck three times on the bar; and as the sand continues to accumulate, it is likely that in another century there will be a separation from the ocean at ebb tide, as is the case in some of the rivers of Haha and Suse already mentioned.

Salée is encompassed by a strong wall, about thirty-five feet high and three feet thick, on the top of which are battlements flanked with towers of considerable strength. At the south-west corner of the town there is a battery of twenty-four pieces of cannon, which commands the entrance of the Buregreg. To the north of the town, in the plains, are the remains of many gardens, and the ruins of a town, built by Muley Ismael for his (Abeed Seedy Bukaree) black troops. When I visited Salée, I was conducted to the subterraneous apartment, where the Europeans were formerly confined, who had the misfortune to fall into the hands of these miscreants:[42] it is a miserable dungeon, though spacious. The streets of Salée, like those of all old towns in this country, are narrow; and the Kasseria, or department for shops and buying and selling, as well as many of the streets, have a canopy which extends across from house to house, which is expedient to the comfort of the people, protecting them from the fierce effulgence of the meridian sun. Salée stands in 34° 2′ N. lat.