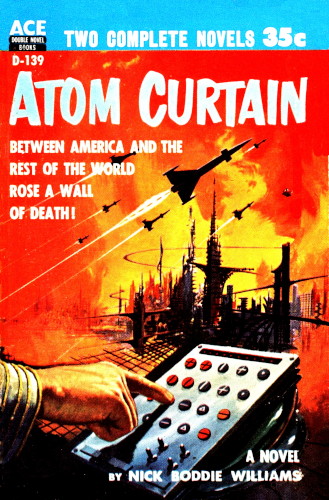

By NICK BODDIE WILLIAMS

ACE BOOKS, INC.

23 West 47th Street, New York 36, N. Y.

Copyright, 1956, by Nick Boddie Williams

All Rights Reserved

Printed in U.S.A.

[Transcriber's Note: Extensive research did not uncover any

evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

HE BROKE THE BARRIER TO A CONTINENT IN EXILE!

For two hundred and seventy years America had been totally cut off from the rest of the world by an impenetrable wall of raging atomic fury. To the frightened countries of the Old World, what had once been the greatest of all powers was now the most fearful of all mysteries.

No man ached to know what lay behind that frightful barrier more than Emmett O'Hara, restless air-sentinel of the International Patrol—whose American ancestors had been stranded in Britain the day the Atom Curtain was raised.

Then, on December 20, in the year 2230, while on routine patrol, O'Hara did the impossible. He broke through the barrier—and lived! But the full story of O'Hara's discoveries and adventures in Atomic America is so utterly breath-taking that readers are sure to rate it a classic of modern science-fiction.

Nick Boddie Williams says he hit on the idea of writing THE ATOM CURTAIN "while debating with an editorial writer what might possibly happen to nations behind the Iron Curtain, and how much more likely all of it would be to happen if the Curtain were Atomic, rather than Iron. It's about the same line of thinking that led Doyle to write The Lost World, or any number of men to dwell upon cut-off places. But of course I couldn't write about Eurasia, for I've never been there. It was written at the time we were debating the setting up of a fixed line far out from our shores (the Taft plan, the Hoover idea), which became, a little luridly, the approximate line of my Atomic Curtain. A good many philosophical ideas got mixed up in what was essentially an adventure story, but I can't be accused of following any one line, except perhaps Darwin's." Williams, who works on the Los Angeles Times, considers himself a newspaperman rather than a writer. Nevertheless he has had stories published in Colliers, Saturday Evening Post, Woman's Home Companion, and others.

PART ONE

Now at last I must make this accusation and disclose the truth.

I make it with the hard realization of the dangers that are inherent for us all. I make it knowing that these risks have terrified those whom we chose to govern us, and I make it only because their terror has paralyzed their minds. And you and I—the world as we know it—cannot wait any longer.

We must not underestimate these risks. We take the chance of losing everything that mankind has accomplished in the tens of thousands of years since our first ancestor shed his tail and rose erect and walked in the full consciousness that he, alone of all God's creatures, had a soul.

But it is a risk we must take. We must take it now, while there is still time, or we condemn our world—the countless billions of Europe and Asia and Africa—forever to our chronic agonies of hunger and disease, which I now know are needless.

Between what we stand to lose and what it is possible to achieve, if we act wisely and in time, there is a middle course which means freedom from starvation and pestilence. The truth is that we need fear only our greed. If we can content ourselves with enough, and not insist upon too much, if we act with iron resolution in this immediate future, we can revivify our static history. The facts as I know them convince me of this, and more to the point, they have convinced far abler minds, although not those of the World Council of Nations, which in the final analysis means the Twelve Old Men of Geneva. It is their minds which you and I must now convince. Or we must set the Twelve Old Men aside.

And so I am compelled before the bar of public opinion to accuse these Twelve Old Men. It was they alone, acting in secrecy, who ordered that the sensational O'Hara Report be buried deep within the archives of the International Patrol at Geneva, never—they thought—to be made public. They have buried the Report and they have attempted to blot out even the vague rumor that it did exist. Those few who actually read it, the officials at Croydon Airport here in London who first received it and sent it sealed upon its way to Geneva, have been transferred to the more remote corners of the earth, never two of them together and none of them knowing where the other is. Not more than a fraction of the upper hierarchy in government has even heard of the Report and that fraction has gone and will continue to go to extreme lengths to prevent inquiries concerning it. It is the greatest hush-hush document of all time.

But within hours of its receipt at Croydon, I, Arthur Blair, obtained a first-hand summary of the Report. For reasons which will become obvious I was ordered by my paper, the Observer, to obtain the text of it, and for reasons which were even more imperative to me I sought to do it. I went at once to Croydon, where I was rewarded only by blank and noncommittal stares, as if I were inquiring after the secrets of the fourth dimension or the precise geographical location of the lost continent of Mu.

I did not resent that attitude. I had expected it. But what I did not anticipate was the reaction of the Twelve Old Men. I was in Paris, on my way to Geneva, before I realized how far they meant to go to silence me. The warning was delivered by a small, clean-shaven little man in a business suit who called while I was absent from my hotel room. When I returned, he smilingly assured me that he had no interest in me—the condition of my luggage proved him a liar—and in the next breath told me that my chance of leaving Paris alive, if my direction was Geneva, was less than zero.

The little man in the business suit impressed me. A more oblique approach and possibly some short cuts were indicated. In consequence I went from Paris quite openly to the resort of Trieste. I spent three weeks there, as obviously "resorting" as I could, until the night I chose for departing aboard a chartered fishing boat that landed me eventually at Salonika.

An old acquaintance of mine at Salonika, an incurable romantic, suspecting me of extraordinary journalism—a missing blonde, perhaps—provided me with what I asked, a private plane for the Prefecture of Turkey.

That plane was shot down two minutes after leaving Salonika. I happened not to be aboard it, although my labeled luggage was. I had the satisfaction of reading an account of my accidental death in the Istanbul press when I arrived there two days later.

I felt certain that I had thrown off any pursuit and that I could now proceed safely direct to Geneva. You may imagine my concern when my host in Istanbul, who knew me only by a pen name I had used obscurely years before, offered me my morning coffee and then sipped his own, and immediately keeled over.

A charge of murdering my host was subsequently filed against me. That charge is outstanding today. I do not doubt the evidence is there to convict me, manufactured evidence, were I located and returned to the Prefecture of Turkey.

But I have no intention of being located until the world knows what I have to tell. I had no such intention from the moment I saw my host's complexion changing to that ugly blue that goes with cyanic poisoning. And before the spittle upon his writhing lips was dry—it was intended that they should have been my lips—I had disappeared again.

All this scrambling is a personal matter, an adventure I suppose, of no importance save to those who befriended me. Some of them are dead and beyond the dangerously long arm of the World Council's Bureau of Security. Some of them are not dead or aware that they ran the risk of death, for I did not share the purpose of my frantic journey home. Yet I cannot—I dare not—trace any further the slow zigzagging pattern by which I returned to London.

My journey was a failure. I did not get the text of the O'Hara Report. I am never going to get it, for the august authority which decreed my persecution has consigned it to oblivion. That authority was unquestionably the Twelve Old Men.

Yes, theirs must be this terrible responsibility. Theirs alone must be the blame if future generations of our world are doomed so needlessly to subhuman levels. It is they who have decided—unless we can break through the lethargy of hypercautious minds—that in this year of A.D. 2230, more than two hundred and eighty-five years after the first splitting of the atom, the Sahara must still remain the Sahara, a vast wasteland capable of feeding all our starving and multiplying billions were only water made available. It is they who decree by their conspiracy of silence that the deserts of Australia and Arabia and China are as parched today, and the tundras of Siberia as utterly fruitless, as they were in the years before the miracle of Los Alamos. It is they, these dread-chilled Twelve Old Men, who are insisting that the Western Hemisphere, which at one time seemed destined to redeem us all from want, must remain for further centuries a whispered mystery behind its impenetrable Atomic Curtain.

Why are they doing this to us? Why were they so determined that I must be silenced? Are they brutal men, incapable of understanding how our billions suffer? No, the answers are not so simple. Their minds grope vague through the twilight world of doubt and fear, for they do not trust us—by their very natures they cannot trust us—to guide ourselves according to the facts laid down in the O'Hara Report.

But I insist that the people must know these facts. The people must get the truth—as I got the truth—from Emmett O'Hara himself.

Yes, I got the truth from Emmett O'Hara himself, soon after he filed at Croydon the text of his astonishing Report. That is why my life is at forfeit—not that the Twelve Old Men are sure I know, but they suspect it. They are capable at least of decision in one respect, they will do anything to preserve the status quo. But they are panicked at the possibilities that Emmett O'Hara has brought back to us. They cannot bring themselves, these doubting old men, to believe that he is acting in the interests of both our world and that which lies behind the Atomic Curtain, the fabled Western Hemisphere. And they will never accept, unless we force them—and there is almost no time left to do it now—the offer that O'Hara brought to us.

That offer will come to us formally, and we will have to act on it at once, at any moment in these next few days. And I pledge you this, that if we accept, our world begins to live again. And theirs.

I wish for your peace of mind that I could tell you precisely what has happened to O'Hara and that magnificent creature whom he introduced to me as his wife. And she was his wife, I think. Certainly she was his woman, bound to him by all the custom of that strange society from which she came. And if O'Hara had the time, in the brief interval between the filing of his Report and his abrupt and traceless disappearance, I would like to think that he further complied with the laws under which he was born and reared, although I know it would not have mattered to anyone except myself—O'Hara would not have cared. And she would not have given a snap of her exquisite and completely capable fingers. What could possibly have seemed of value in our conventions to those two? When you know what they knew—or at least what O'Hara knew—when you have experienced the nadir of disillusion and the zenith of human living, what could seem of essential value except the savor of the next moment's breath?

As I say, O'Hara vanished. He filed this Report of his in London at four o'clock on the afternoon of his return, which was the day after Christmas. He immediately went to his old flat in Bloomsbury from which he telephoned to me at the Observer, and at six o'clock I dined with him. By eight o'clock I had heard from him the substance of his Report. It was then that I met his wife, if wife she was.

At eight-fifteen I left them, and went immediately to the Observer, where for two hours I was in conference with the Editorial Director, Edgar Soames, who told me that the story could not be published without the complete documentation of the text. The Observer, as Soames pointed out, had its reputation as a journal of fact to remember and not even the paramount importance of my story could be permitted to override that.

Very well, documentation. I returned to O'Hara's flat in Bloomsbury by eleven o'clock. O'Hara was not there, or was that splendid red-haired creature who—well, they were gone, and their few belongings were gone, and the flat itself, so I was told repeatedly by the manager of the properties, had not been occupied at all for the past three years. Surely I was mistaken—O'Hara? Never heard of an Emmett O'Hara!

No, the manager had never heard of an Emmett O'Hara. And neither, I soon discovered, had anyone else. He seemed to be a delusion I had suffered. I had spent those two hours listening to his amazing Report, and there had never been such an O'Hara in the International Patrol and the letters that I had earlier received from him had never been written. Or they were forgeries, perhaps—yellow journalism!

Someone had moved very swiftly. But whether it was O'Hara himself, or whether it was the Bureau of Security, I could not determine. It is essential for me—and the rest of us—in this hour of imminent crisis to rely upon faith in his indomitable skill and courage, and to believe he managed his escape. Although he had had his luck twice over.

That was a phrase that O'Hara used himself. "I have had my luck twice over," he told me, and then he laughed, that deep roar of mirth that I remembered from our school days together.

"Twice over?" I answered. "A thousand times, I should say."

"I don't mean this business I've been telling you," O'Hara said. "Or rather, not the hazard of death. Although," he smiled, "there is the hazard of death in this part of it too. Will you come into the next room, I want you to see Nedra."

"Nedra?"

"Yes," he said. "Nedra. You didn't think I'd leave her there?"

I stared at him. "Is this in your Report?"

"Certainly not. It is a private matter. But the boys at Croydon saw her when we landed there. I remember their surprise—more surprised even, I suppose, than when I wirelessed that I was coming in, and that knocked them flat. Are you coming with me?"

"Yes."

"Then get behind me," he cautioned. "And hand me that gadget."

It was a length of intricately carved wood, about four feet long, tapering toward one end and worn smooth by the palms of many hands. O'Hara took it, tossed it into the air and caught it expertly by the smaller end, a trick that must have taken practice. "Very useful," he said, "if living is important—though I'm not too sure that it is. We live too long, most of us, and at last we begin to think that living is an end in itself. And so we want it easier and easier, with never a thought that it can become too easy."

"You haven't found it easy lately, have you, O'Hara?"

"Not until I landed at Croydon," he replied. "But that was four hours ago and it's gotten boring." He gripped the club of carved wood tightly. "Now, open that door—"

So it had gotten boring, had it? Within three hours O'Hara had vanished, both he and Nedra, as if they had never existed. I should have known that I was not going to get documentation for any such articles in the Observer. I must have been bemused by my real joy at seeing O'Hara again after supposing that he was lost forever. Then, too, the impact of what he had told me had blunted my sense of the realities of life. For the moment I saw it all only as a tremendous story—a story particularly tremendous to O'Hara and myself because of our mutual origin.

For we were children together, went to school together, were inseparable until he chose for his career the thankless if adventurous life of a pilot in the International Patrol. I cannot say that I chose my own career—I drifted into it, as so many journalists do, trying my hand first at this and that and gradually retreating into the job of writing about what others, with more spirit or greater advantage, were doing in this world.

Yet it never occurred to me in those early days that the biggest job that I would undertake would be writing about O'Hara. Nor to him, I am sure. Adventure—yes, he had expected adventure, but not of the sort to interest anyone except himself and possibly his surviving relatives. The doubtful thrills of supersonic speed, the sensation of flirting with death from atomic poisoning, the constant prospect of plunging through the polar icecap at better than two thousand miles an hour—these, perhaps, O'Hara anticipated as the ultimate possibilities of his career in the Patrol. And then, always, he would be closest to the riddle that since his childhood had absorbed him, flying his charted course along the outer fringes of that dense wall of radiation that enclosed like the half of a glass globe the Western Hemisphere—the Atomic Curtain.

Neither of these were careers a native of the Prefecture of Britain would have selected, but the truth is that they were among the best open to us. Our two families had come together to England in that great migration from North America which immediately preceded the establishment of the Atomic Curtain. I remember O'Hara, then not quite eighteen years old, questioning his father one night when I was visiting him, as I often did, for he was my idol in those days, much bigger than I and much bolder. I had never dared to ask these things.

"Why did our people leave America?" he asked. "It was their country, wasn't it?"

"Yes, their country," his father answered solemnly, for that word—country—still had a peculiarly religious sound to it, however outmoded it had now become. "But they—your ancestor and those who agreed with him—believed that what America was going to do was wrong."

"Excuse me, sir, I don't see why it was," O'Hara said. "If the Americans—the Yanks"—and how he loved that word—"didn't like the rest of the world, why shouldn't they have cut themselves off from it?"

"I'm sorry, Emmett, you're too immature to understand," his father answered.

"Isn't that the answer that men give when they themselves do not understand?" O'Hara persisted, and I held my breath.

But his father considered that, as he always considered anything O'Hara said—they were people of logic, people of the exploring turn of mind. At last he said, "Yes, that is true. I've never really understood why they did it. When I was your age, I asked my father these same questions. It seemed unfair that we should have given up what I had so often heard was a considerable position in that world—in North America—to come to this crowded hemisphere as emigrants, as a suspected people, second class by birth and law, and solely in obedience to the dictates of an ideal. But your grandfather himself was a little vague upon these points—after all, he did not remember the trip, he had only heard of it, how his people had been forced to give up all possessions, to begin life anew in a country already too poor to support its own citizens."

"You mention an ideal, sir," O'Hara said. "What is it?"

"It was that this was one world, or should have been one world, not irrevocably halved by the Atomic Curtain. It was that if Providence had wished them separate worlds, It would have made them so."

"Then it was a mistaken ideal," O'Hara said, "for if Providence had intended this to be one world, it would be now."

His father smiled. "That's enough, my young philosopher. To bed with you!"

And so we went to bed, but not to sleep, for O'Hara was excited by the conversation. He lay flat upon the counterpane, his cheekbones pressed against the butts of his palms and his dark eyes restless, seeming lighted by the intense curiosity of his young mind, talking on and on for hours, long after I was drowsy.

"It's always been like that," he told me. "Down through the countless centuries of time—when a people have made a bad decision and have lost everything by it, they have described their motive as obedience to an ideal. Remember your American history?"

"How could I remember it?" I asked. "Nobody teaches that."

"They used to teach it. And they still have the books at Oxford. Great reading, too—the Revolution, the Civil War, the three World Wars. You'd be astonished how often that theme recurs in them—obedience to an ideal. Yes, I suppose it's true, those of us who left the Western Hemisphere before the Atomic Curtain blamed it on an ideal. And I'd bet it's equally true that those who stayed, knowing that they would forever be isolated from the world that you and I know, invoked the same apology—an ideal guided them. Eternal peace, freedom from want and from fear—"

A clock was striking somewhere in the house. It was one o'clock. I shivered without knowing why.

"And did they find it, I wonder?" O'Hara's voice resumed. "What has happened to the Americans in these two hundred and seventy years since they launched the Atomic Curtain? And what would have happened to the rest of us—to Europe and Asia and Africa—if they had not launched it? For they were a wonderful people, wonderful improvisers, wonderfully inventive. Oh, I don't mean the little things that we have here, electric lights, the radio—but the big things, the sublime things that changed history—or seemed about to change it. The atomic bomb of Los Alamos, the hydrogen bomb of Bikini and the tests at Yucca Flats, those alone were leading the world into new, strange paths, glorious paths for the scientific mind, and all the world was following them swiftly. All of us were to have the blessings along with the horrors of atomic fission, until—"

"I know that much," I said. "Until the Third World War."

O'Hara smiled queerly. "So you do read some?"

"I read a great deal," I retorted. "Contemporary things, the important things, not long-forgotten books of useless American history."

"But you remember, don't you, why the Third World War stopped?"

"Oh, yes. It was thorium."

"Thorium," he whispered. "Yes, that was it—thorium. The greatest of their improvisations! For when they devised the techniques for the fission of thorium, so infinitely more plentiful in supply than uranium, no combination of powers that lacked the formulae could longer challenge them. They wrote the peace that they wanted with those formulae. And that peace forbade atomic fission for the rest of the world. No nation dared touch it, no scientist anywhere, except in America, dared to experiment with it, knowing that the slightest radiation detectable by Washington's scintillometers might bring within the next half hour obliteration, complete obliteration.

"And actually, that was the conquest of the world. Yet they chose instead of ruling their conquered world to erect around and above the Western Hemisphere that vast umbrella of radioactivity, the Atomic Curtain. And the two continents of North and South America were lost behind it as utterly as if they had been swallowed in the seas that girt their shores."

"Even with their thorium, they must have been afraid," I said.

O'Hara scoffed at me. "Of what? Maybe of themselves, maybe of their own power, but certainly of nothing else. They could have destroyed the other nations of the world, and the others were so well aware of it that they have not since risked the science of fission, still dreading the rain of warheads that might come screeching through the Atomic Curtain. Even today, although a century and a half has passed, we're still so obsessed with that dread that we maintain the International Patrol, ceaselessly flying the outer fringe of radiation in the stupid hope that if that rain of warheads comes, we shall have a warning of it. But what good would a warning do? A few minutes to pray, perhaps. For there's no defense and so it is a stupid, useless dread, made terrible because beyond the Curtain all is mystery to us, something that we no longer understand—"

"And cannot help," I pointed out.

But O'Hara did not hear me. "That's it," he cried. "The Mystery! The greatest of all powers, unknown to us, a terra incognita. I'm surprised that we, dreading them so much and knowing nothing of their mind, do not worship them, for dread and ignorance and mystery are the requisites for a god. A race of gods!"

"They may be all of that," I said. "I rather like the notion that I am descended from a race of gods. Inflates my ego, which can bear a little of it. Can't I go to sleep now?"

"Not even a race of gods could possibly keep you from that," O'Hara said, and he put out the light.

It was a fixation. What he had said was true enough—for later on I did get around to those long-forgotten useless books that gathered cobwebs in a cluttered Oxford subcellar—but for most of us, scrabbling like insects to earn a living for ourselves, the two lost continents of the Western Hemisphere were not much more important than the rings of Saturn—a phenomenon that did not drastically affect the price of eggs. We knew, of course, that the World Council kept its International Patrol circling as near the Atomic Curtain as its aircraft dared to go, but that was a problem for the Twelve Old Men of Geneva, much as the gradually extending icecaps of the two poles were their problem. Theirs and O'Hara's—and the Sunday supplements.

The point is, we had lived with the vague knowledge of the Atomic Curtain all our lives, and the whole thing was too fantastic either to understand or to matter to the average run of us. It was like the toadstools of our forests—they were quite poisonous, but so long as we did not have to touch them, we ignored them. I remember a passage from one of those books I finally unearthed at Oxford—a curious thing, possibly a fake, and yet dressed out in the most pompous language, purporting to be the considered opinion of some distinguished man of science at what apparently was a famous university, a place called Harvard, and confirming a suspicion that life was possible on Mars. Yet nowhere in the American histories of that year, nor in any of the contemporary American publications, could I find any evidence of general alarm about it. So there was life on Mars. Presumably no one bought extra ammunition for his gun, nor hoarded food, nor drank himself to death, nor went to church more arduously because of any such remote impracticality. Who was going to Mars? And who—to bring this analogy down into our times—except the pilots of the International Patrol meant to venture toward the well-defined and fortunately distant zones contaminated by the Atomic Curtain?

Yet I must admit that something of O'Hara's fascination for it crept contagiously into the letters that came back to me from those far-flung and frigid bases out of which he flew for the Patrol. There was news in them, too, although I did not always recognize it.

The first of these letters reached me within a month after I squeaked onto the staff of the Observer. O'Hara had by then completed his basic indoctrination with the International Patrol and was serving his initial hitch in the least desirable of the Patrol's assignments, with nothing behind him but the Antarctic seas and the vast polar cap, not a city worth the name closer than Hobart, in Tasmania, completely across the Antarctic Circle from his base.

It must have been dull work, flying from the Falkland Islands to South Shetland, deafened by roaring jets and blinded by the frightful gales that swirled around Cape Horn, and for variety he had the constant ticking of his scintillometer telling him how closely he was approaching the southern boundary of the Atomic Curtain, quite narrow there, encompassing the Cape itself and the wild seas immediately beyond.

Dull work? I remember O'Hara's first letter: "The black sky meets the blacker water upon a horizon even more intensely black, a horizon that is a ribbon of mourning constantly below the level of my eyesight, as if these were dead seas and dead heavens. But the coloration is deceptive, for they are not dead. The howling violence that must have been the planet's birthing wail still echoes here, the raging winds that must have screeched throughout infinity when Earth ripped loose from the Sun—and beyond, ten miles ahead of me, perhaps, the Wall of Death invisibly stands shimmering.

"One second's miscalculation at the speed I fly and I'd be into it. Freezing one instant, roasted to the bone the next. How thick is that wall? The guess that we credit oftenest is twelve miles. A scant twelve miles of radioactivity, and I could fly that far in the time it would take you to snap shut the fingers of your hand—perhaps my craft on its momentum would plunge through. I think it would. I think I could aim it for the southern tip of South America, and by the time that you could walk across the editorial room there at the Observer in London, I would have smashed across the Atomic Curtain and landed on that coast that once was Patagonia. Isn't that a challenge? A terrific challenge, to be the first within two hundred and seventy years to reach the two lost continents! But it has the undeniable drawback that I would be dead, and so could not gloat like stout Balboa on a peak in Darien.

"I saw the Curtain doing its merry routine one day last week. I was flying quite low, not a hundred feet above the surface of the sea, making a customary check upon the water's radioactivity. We do this every flight, to check upon the contamination of the water, which usually is quite constant, flowing out from below the Curtain a distance of fifty miles but decreasing in activity with an almost mathematical precision. Yet when there is a really powerful gale blowing southward or westward from the Curtain, from the tip of what once was called Chile or Argentina, both now encompassed by the Curtain, the surface currents sometimes are reversed from the Cape—the fabled Cape Horn of early mariners—and the contamination flows much further toward the Antarctic before it diffuses.

"Of course our base in the Falklands is mildly contaminated, all these fringe areas are, and all of us have a touch of the atomic sickness, just as those living in the tropics have malaria. You know what it's like—nausea sometimes, and always diarrhea, a tendency toward bleeding gums and conjunctivitis and—well, yes, dammit, falling hair, baldness. I shall resemble the egg of the great auk in another ten years of this. Sounds terrible. Actually, though, these are only tendencies, for we do not expose ourselves beyond the lowest background counts upon our scintillometers. We're taking no chances—this is a Patrol, not a combat unit, for there's nothing to combat. Nothing, nothing but that invisible curtain, at a fixed latitude and a fixed longitude for every foot of its tens of thousands of miles, with only the variances of the surface contamination that I mentioned. Which brings me back to what I meant to tell you.

"I was patrolling one hundred feet above the ocean's surface when I saw ahead of me, not quite to that black ribbon of a horizon I have described, a strange dark object, apparently floating on the sea. Immediately I changed course toward it, but when I had reached the absolute limit of radioactivity that we are permitted the dark object was still ten or more miles ahead of me.

"It must have been, at that instant, extremely close to the Curtain itself. If it was not within it! Yet it was plowing toward me through heavy seas, the first moving object I had ever seen in this sector.

"I was forced to turn back. Within the fraction of a second I had lost it. But barring a gale, I had sufficient fuel for some minutes' cruising. I made a tight arc and approached again. The object was still there, and still approaching.

"I'm sure that had my squadron commander been spying upon me, he would have grounded me for life. For in the next ten minutes I flew perhaps a hundred oval patterns, approaching the object, retreating from contamination, then reapproaching, again and again, trying to keep in contact with it until it got close enough for inspection. By that time my fuel could not be further safely expended, and I wirelessed back to our Falklands base with my report, then continued on to South Shetland.

"A snowstorm screamed down on me minutes before I landed and I came in blind. Had I spent another five minutes at those oval patterns I would not have made it. Frightened me a little. I suppose I can become too damned enamored of that mystery out there.

"But delay your literary fancies a minute. There is a sequel—for we flew double patrols throughout the following week. The dark object was not sighted again upon the surface of the sea—the blizzard, I presume, obscured its week of passage. Then just yesterday a Patrol craft over South Orkney Island picked up a disturbing buzz upon its scintillometer. There should have been no such extreme contamination that far south and west of the Curtain. We threw a dozen craft into the sector within half an hour, and finally, wrecked on the craggy shores of Coronation Island, we found our dark object.

"It was hot, very hot—too dangerous to examine closely. We put an amphibian down alongside Coronation and they worked for several hours with telescopic cameras. The pictures have just been developed here. And I really did have something!

"What we've got, as nearly as we can determine from rather grainy prints, is a kind of ship, fashioned of undressed logs, a very crude and unseaworthy vessel I am sure, but also with the virtue of being unsinkable. There is a cabin of sorts amidships of it with some sheets of a shining material, similar to asbestos, tacked onto it. And close to that, extremely blurred upon our prints, are three black objects that we have decided must be men. That is, they must have been men once, before they drifted into the Atomic Curtain. They are charcoal now, but the pattern of arms and legs, however distorted in their horrible death, shows distinctly. Three men upon a boat of logs, from where?

"The Sandwich Islands, possibly. It would represent a tremendous voyage, thousands of miles through the worst of weather, but where else could men come from in these desolate seas?

"Unless you want to go along with me in the most improbable of fantasies—unless they came from behind the Atomic Curtain! From the Western Hemisphere, from the Lost Continents! Too absurd, of course. We know the level that their civilization had achieved. They would not now be using boats so crudely built of logs, and most assuredly, if they did build it, they would not sail it into their Atomic Curtain. No—purely fantasy, and yet I like it. I would give my next promotion to go aboard that vessel! But I am not yet prepared to give my life, which it would cost me. Ten years from now, possibly, when the contamination has abated, if it does abate—jot that down, remember it—ten years from now, on Coronation Island in the Antarctic, there still may be the wreckage of a boat that can reveal to us what Man behind the Atomic Curtain nowadays is like!

"Ah, well—"

Yes, there was news in that letter, but I mistook it instead for a bit of a feature, and did quite nicely with it in a little piece that must have given old Jules Verne a turn or two within his grave. Improbabilia—the pseudoscientific flare. Good reading for small boys on rainy Saturdays!

O'Hara was back in London two years later, on his way to Stockholm for reassignment. I picked him up at his flat in Bloomsbury. He wore by then the three gold bars and half-globe of a lieutenancy, and in his brilliant blue uniform he seemed more than ever to me a man set apart, for not many Patrol pilots and none like O'Hara were walking the streets of London, so far removed from their duty routes. He had put on weight, a good deal of it, yet he had managed somehow to absorb it compactly—six feet three and a good two hundred and thirty pounds, his dark face burned and weathered, only less dark than a Polynesian, and his thick, clustered hair jet black—for his prediction had not come true, he was no auk's egg.

"What happened?" I asked him. "The atomic sickness?"

We were lunching together at Swall's, where the roast is excellent, and O'Hara finished his before he answered me. "I'd forgotten that," he said at last. "You get over it. I suppose you build up a tolerance for it. The first year is a little rough—you can spot a cadet immediately by his red-rimmed eyes and the unhealthy color that comes through windburn pallidly, like an underglow of yellow. And this although they're never bucking more than .165 milliroentgens an hour. Then all at once, within a month's time, you're over the hump and it goes away and you're safe enough at .225—you're safe enough, that is, for short periods of time, and unless you're a damned fool and ram yourself into the Curtain. You don't tolerate that—though you never realize it. For you don't have time. You're cinders rather instantly."

"You lose cadets?"

"A percentage—a definite percentage—three out of ten. They simply cannot seem to learn that all of this has been estimated exactly and that there is no margin for error. The Curtain is constant, and the pattern of your flight must be constant, barring the variations caused by gales, for which there is a single rule—get the hell down south before your craft is slammed into the Curtain. We had a new man last summer, though—"

He paused, his shoulders hunching forward and his eyes seeing beyond me, beyond Swall's, back into the Antarctic. His fingers tapped three times, slowly, upon the table.

"Yes?" I said.

O'Hara jumped. It seemed incredible, but he did exactly that, he jumped, as if I had screamed out at him.

"Excuse me," he said, and laughed quickly. "Lost myself for a moment. Because we've never known precisely what it was. A mistake in his readings, certainly. He must have been confused, which can and does occur when inexperienced men are making those long overwater hops. Perhaps their vision blurs. And possibly—well, we ought not to get that type, they should screen them out, but there's considerable pressure for replacements, losing 30 per cent. If a candidate can pass the twenty-twenty test he's taken, but there should be a sharp downgrading on fatigue and on emotional reaction."

"Surely they get emotion ratings?"

"Yes—up to a point. But it's still not selective enough. It wasn't in Anstruther's case."

"The new man you mentioned?"

"Yes. He was in my squadron basing on the Falklands. Nice lad, well set up, an angel face—blond with blue eyes. Well educated, too, and rather religious. He had intended going into the ministry until this Patrol bug got him. I liked the boy—reminded me a great deal of myself when I first got out there. You know—eager, imaginative. I think that was the trouble—too imaginative. On that last flight of his, a pattern he'd flown a dozen times by then, down to South Shetland, it happened that I was catching his calls at our wireless hut. That's no part of my job but I was disturbed about him. Only a hunch, or was it more than that? I suspect that I knew, out of my own experience I knew, how he felt about those hops and I should have cashiered him. But I didn't do it—you hate to do it, you've got no reason that makes sense, you'd look hysterical putting it into a report, for the boys in medical had given him the go-ahead. And so I was listening to his calls, that feeling of my guilt just dormant, just across the border line from actually wirelessing him to swing away from the Curtain while he could—to turn back."

O'Hara's fingers made those three rapid taps upon the table once more. Then he continued:

"It was all so routine. I keep insisting to myself that I had no warning whatever—it was all completely routine. A series of latitude and longitude readings, the constant repetition of his milliroentgen count, quite safe. He was keeping his distance from the Curtain and had worked his way to the latitude of the Cape, the point beyond which there's no extraordinary danger, for the Curtain ends about there and the rest of it is simply overwater flying to the South Shetland base. I was beginning to relax. I was telling myself that men with premonitions are the spiritual cousins of water dousers and the little gents who peer myopically at crystal balls. And then all at once the droning of Anstruther's voice broke off.

"That could happen any time. And yet the silence slapped me. It was like that exactly, a cold slap in my face. Not over four seconds of complete silence. Then Anstruther's voice came back again and it was a scream.

"But not terror. I want to emphasize that it was not terror. The boy simply cracked. Excitement. But a shocking excitement to me, jubilation. As if he were cheering his crew to victory—a shattering vibration in the wireless and these words: 'It's gone! It's gone! There's no count. I can't find it—it's gone—the Curtain—'

"And then nothing. Never another word. Never a trace of him or the craft."

"And you think—?"

"No, we don't," O'Hara said. "We speculate, but there is no basis for thinking anything. Not the slightest clue, not the shred of a fact. Flying at better than a thousand miles an hour he could have done anything, once he'd lost control of himself like that. The bottom of the sea."

"Or rammed against the Curtain?"

"Yes. Quite probably."

"And through it?"

"You're remembering one of those silly letters I wrote you when I first got out there. I don't know—there's no evidence. But I should think his craft would atomize, I don't think he'd get through it. Whatever it was, Anstruther simply lost his bearings—his readings definitely establish that he was not near the Curtain when he cracked, his last actual reading in milliroentgens was well within his safety limit—and then, when his mind blew up, he misinterpreted what his instruments were showing. And that killed him. Somehow, and it doesn't really matter how, that killed him. Have we time for pudding? I'm off for Stockholm at three-ten."

I did not go to Croydon to see him off. They are not keen on that in the Patrol. Farewells, I imagine, are depressing, although it would not have depressed O'Hara. Nothing was very likely to depress him for long, even Anstruther's fate. Cadets came and went, and if their officers took to heart too much that unfortunate 30 per cent there were always the sanitary rules of the Twelve Old Men of Geneva, who had conceived out of their latent if stupid fear the organization of the globular operations of the Patrol. Those who became morose simply were pensioned off. Utilized, as they expressed it—they were utilized, used up, discarded. But in style and comfort, like old race horses.

A year passed before O'Hara wrote that he had got his captaincy. He was based then on Wrangell Island, one hundred miles from where the Curtain swerves toward the outmost top of Siberia, crossing the Anadyr Mountains to enclose the lost passage to the Indies, Bering Strait.

"Think how they searched for it," he wrote, speaking of the Strait. "The ancient Norse king, Bloodyaxe, hunting whale and walrus through the moving ice as far toward the east as Novaya Zembla on this Siberian coast, Sebastian Cabot in the time of Henry VIII seeking the northern sealane to Cathay—or have you dug this far yet in your histories? And John Rut of Plymouth and Hugh Willoughby who perished with his men on the Kola Peninsula, and old Barents the invincible, and Henrik Hudson driven back westward by the polar ice and so forced to explore the continent that's long since lost again, Hudson Bay and Hudson River, and dying with his young son finally while drifting in a small boat in the seas that he had opened up; until in 1728 old Vitus Bering working for the great Czar Peter pushed eastward from Okhotsk and ascertained at last the Strait—yes, history, my boy, the grand epic of the Northeast Passage, hundreds dying valiantly, and now their work forever lost, their passage closed by the impenetrable Curtain.

"Time telescopes up here. Within a day I can be above the Anadyr Gulf, the eastern reaches of the Bering Sea and not six hundred miles from where our ancestors launched rockets to obliterate the port of Vladivostok in the Third World War—the great base that was in Alaska, at Nome—I can be over the Anadyr Gulf at dawn, cross the Anadyr Mountains to our base at Wrangell and before my fuel's gone land at Bear Island, guarding the Kolyma River that flows northeast from Siberia. Refueling, I can hit New Siberia Island or our Lena River operations base at Barkin, take off with more fuel for the Yenisei, touch at Franz Josef Land, tag up in Ice Fjord in the Spitzbergens, drop down to Stockholm and be with you for roast beef at Swall's by night—provided ground crews nowhere along the line are dogging it. From the stamping grounds of Vitus Bering, year 1728, to Swall's in London, year 2230—within a day's flying. And so, what's time?

"But that's a fat route I've outlined for you—that's the easy stuff, the points we'd like to be flying between. For actually after the Curtain passes the longitude of Wrangell it curves much closer to where we presume we'd find the North American continent, south of the pole on the far side from us, crossing the vast seaborne ice sheets in its path toward the northern tip of Greenland. And for anything like an effective patrol we must fly deep isosceles triangles toward it from our land bases strung across the top of Europe and Asia. We cannot fly for long close to the Curtain in the Arctic—we must fly toward it and then back, a series of exploratory fingers extended out to it, which is tougher than our Antarctic patrols. Over water—which means ice—and out of sight of land almost entirely. Navigation problems. Adds to the strain—there now, the nasty word! Must not say that.

"But I've seen more of Northern Europe and Siberia in the last twelve months than all the expeditions of the czars and Muscovite Bolsheviks explored in their thousand years. The debris of their two cultures lies scattered across the top of this vast Eurasian land mass, with immense glassy pockets where their cities once stood, the scars of the Third World War. And through the air that we are flying that first cloud of rockets came from the continent of North America, leveling all Russia down to the latitude of Moscow before the ultimatum and the surrender. A creeping barrage of rockets, and I've seen the evidence that it spared nothing, neither cities nor forests nor ice floes nor the barren tundras. It's all down there below us when we're flying, the record of that last war, the really Great war that shattered the political pattern of Europe and Asia and forced the eventual formation of the World Council of Nations and the division of the earth outside the Curtain into its system of prefects, bearing their old and now quite meaningless national names.

"Yes, here in the frozen north was the earth remolded into the system we now know, before the Western Hemisphere retreated finally behind the Curtain.

"And so to us of the Patrol time seems to telescope. The past is with us. We are, in truth, the guardians of the past, for if there is a future—which means change—it lies beyond the Curtain, among the peoples of the Western Hemisphere, who alone now possess the knowledge that could rear and maintain this Wall of Death. Or is it actually, for them, a Wall of Life? What are they doing there in those lost continents? What wonders have they now achieved in their two hundred and seventy years of isolated and unimpeded progress? And what remains as the grand adventure for the rest of us unless it is the penetration—?

"Ah, you see, I am very close to utilized. And that nasty word creeps through my mind again, the word we must not whisper among ourselves in the Patrol—strain! Soon, I do not doubt, I shall be back forever in London, washed up much as poor Anstruther was washed up, a victim of proximity to the Curtain. Prepare a pleasant little snuggery for me."

But O'Hara was not coming back to London as soon as he pretended to anticipate. I have included these letters from him here only to indicate the acuteness of his mind, how very close he often was to the scientific truths while he rambled on in his most extravagant mood. But this is not a scientific paper—my aim is political, and in particular it is economic, if anyone nowadays distinguishes between the two. My aim is Truth and the revelation of it, as I got it from Emmett O'Hara on that evening of his return, a few days more than one year after he disappeared while flying on patrol out of his base on Wrangell Island.

Two days before Christmas, December 23, 2228, I heard that O'Hara had vanished. His father telephoned me as soon as they got the cable, asking if it were possible for me, through the Observer, to obtain further information. I was able to learn a few details, but there wasn't much to learn.

O'Hara had left the International Patrol's base at Wrangell on a routine long-distance flight toward the Curtain at 12:15 P.M., December 20th. His flight pattern called for him to proceed to the seventieth degree of latitude and to fly along it until his scintillometer recorded .250 milliroentgens an hour, which was the maximum permissible even for a veteran. He was then to pivot westward, proceeding for three hundred miles along the Curtain's fringe, then turn back toward Wrangell and arrive by 1 P.M., the slow time because he would be taking readings constantly and must keep his craft well throttled to do it. He took off with an excessive fuel load, for his rank as a captain permitted him to make any necessary extensions of his flight, subject to confirmation of the change by wireless.

O'Hara did reach the seventieth degree of latitude and did reach the Curtain fringe. That much he reported in radiocasts made at intervals of three minutes. Then, soon after he began the 300-mile leg of his flight along the Curtain, according to Colonel Alfred Tournant, base commander at Wrangell, O'Hara reported a sudden gale, with violent southward winds and electrical disturbance, but nothing that his craft should not have been able to penetrate. Then, at 12:34, according to Colonel Tournant, O'Hara's voice came in:

"O'Hara, Flight Twelve, Latitude 74, Longitude 163, Milliroentgens .255—a little close to it, eh? Miles per hour 897 and retarding—there's a gigantic thunderhead piling up and I—Tournant? You listening? I don't like this—lightning's too thick—Tournant? Request permission to change course instantly! Milliroentgens .268—I'm heading north toward the Pole. Miles per hour 1004—but I'm not—getting away—"

A blast of static drowned his voice.

And that was all.

That was really all the details there were about O'Hara's vanishing. Within a dozen words he was talking jestingly and then calling Tournant in sudden alarm. And changing course. And then those final words: "—but I'm not—getting away—"

On the tenth of March Colonel Tournant arrived unexpectedly in London and the Observer sent me to interview him. He'd had a splendid record with the Patrol and was considered the coming man in it, quite probably its next Vice Marshal. The Observer did not need to send me—nothing in London except the Bureau of Security itself could have kept me from seeing him. He received me in his rooms at Claridge's, and after we shook hands, he indicated a well-laden liquor cabinet.

"You should find something there you like," he said. "Let me help you. You—ah—you knew Captain O'Hara?"

"From childhood," I replied. "My best and perhaps my only friend."

Colonel Tournant smiled quickly. He was a small and dapper man—what I should have considered the raw material for a martinet—thickly mustached, brown-eyed, and with the dark tan of most men in the Patrol, a very nervous, brittle manner, a pacer. "Yes, you'd think that," he said. "O'Hara gave everyone that impression. I can tell from the way you speak, though—you're also an émigré, aren't you? Descended from O'Hara's Yanks? Some of the words you and he use, some of the inflections. He was my best friend, too, though not from childhood. How old do you suppose I am?"

The question startled me. There seemed to be no connection. "Forty-five," I guessed.

He flicked his fingers through his hair. "Gray enough for it," he said, his smile a little forced. "It happens that I'm thirty-two, six years older than O'Hara was. And here I am in London for my terminal—I'm utilized."

"You're utilized! But we supposed—"

"I know," he snapped. "You supposed that you were interviewing the next Vice Marshal of the Patrol. The truth is I'm finished. At thirty-two, I'm finished."

"That's news with an upper-case N," I pointed out. "Am I permitted to disclose it?"

"Why not? It's no disgrace." He shrugged. "I asked for it. I've lost my stomach for the work. If it got O'Hara, I know damn well I'm too old for it. For if ever there was a pilot whom I considered superior, who would not—well, disintegrate—it was O'Hara. He had everything to qualify him for the work, coolness and brains, resourcefulness, an utter lack of fear. Yet the Curtain got him."

"The Curtain? Excuse me, Colonel, I understood it was that thunderhead. He said in that last radiocast of his that he could not get away—"

"Don't be an ass," Tournant snapped. "O'Hara knew weather. Besides, I personally flew one hundred hours in the sector of his final call and there was no wreckage. I flew that much! And I sent four squadrons into it. We'd have found the feather of an albatross had it been there. Thunderhead be damned. The Curtain got O'Hara—do you recall the sequence of readings in his final radiocast? Milliroentgens .255 and then again in seconds milliroentgens .268—notice that jump? In seconds, mind you! And within those seconds he believed that he was turning toward the Pole, which meant away from the Curtain. Do you want to know what took place? His mind disintegrated. The best of minds—the most stable of minds, and O'Hara certainly had that—can take so much of that constant strain and then without warning it happens." He stared at me pugnaciously, then he snapped his fingers. "Like that, my scribbling friend, the mind blinks out and that's an end of your pilot. No, thanks. I've had enough. I shall cultivate roses—tea roses. And when I die, they'll not need to handle my body with tongs. Have another drink?"

I considered my empty glass a moment and then I said, "Yes, for a toast. To O'Hara."

We drank it together.

And that drink set the stage, I like to think, as completely as it could be set for the day after Christmas, December 26th, 2229. For what nicer thing can a man do for a lost friend than to embalm his memory in the best of Scotch? Yes, the stage was set, but it so happened that on the twenty-sixth of December I was writing about quite another stage—I was doing my annual squib on the glories of Peter Pan, the timeless pageant of the season, and how Jill Ferguson best typified the centuries-old tradition of the ageless boy. I had got as far as the second paragraph, and was beginning to feel the spirit of the thing, when the telephone on my desk at the Observer began ringing. I picked it up.

"Caught in the purple prose again," a voice came over the wire. "You're writing about the pageants, aren't you?"

"Is it any of your business?" I snapped.

"I'm making it my business."

"Are you, indeed? Just who the devil are you?"

"My name is O'Hara. Emmett O'Hara."

"That's a very rotten joke."

"Yes, isn't it? But I do want to see you. I've just gotten in from Cairo after four days' flying and I need a drink and Nedra doesn't drink and I hate to drink alone. I've opened up my flat in Bloomsbury. How fast can you make it?"

I pressed my face within my hands. Then, listening for the sound of the voice, I said, "O'Hara?"

"Do you realize you're wasting time and I haven't much to waste?" he said. "I want to see you. Now shake it up, old boy, I've poured for you—"

"O'Hara, is it really you?"

"Can you make it by six?"

"But it's—"

"I know—impossible. But can you do it?"

When I knocked, he opened the door. He stood there casually, grinning at me as if I had just come back from an errand to the corner grocer's. The collar of his brilliant blue uniform was open at the throat. The three bars and half-globe were missing. His jet-black hair was tousled carelessly.

"Well, come in," he said and pulled me into the sitting room of the flat. "I've got us something for supper. Here, drink this up."

"O'Hara!" I cried.

And he laughed. "I'm glad to see you, too." He gripped my shoulder and then thrust a glass into my hand. "Drink it up. That's good. The principle of the funnel."

"But where—? Colonel Tournant told me—"

"Now, here's another, though you may nurse it longer if you wish," O'Hara said, and filled my glass. "The supper will keep, it's tinned stuff anyway. Colonel Tournant told you, eh? I'll give him the shock of his life. Aren't you going to sit down?"

"Not until you tell me where you've been?"

"Really," he said, "you'd better sit down. Because it so happens that I am going to tell you. That's the chair for you. Attend to your drink. And while you're doing that, I'll take you back for a moment to the 74th degree of latitude and the 163rd degree of longitude, one year ago plus four days."

He raised his glass. When he put it down it was empty.

"If you saw Tournant, you know that much," he said. "But I don't think he could have told you what I found there."

"The sudden gale?" I asked. "The thunderhead—"

A cry came from the room beyond us. A strange, low cry, mournful, somehow distressing, very sad, as if someone were lonely beyond the point of bearing, and I confess I leaped up and turned toward O'Hara.

"Now, that's a deceiving noise," he said, perfectly calm. "You think it sounds heartbroken, don't you? I assure you, it isn't. I'll get around to that in time, but not if you keep fidgeting. Yes, it was that sudden gale—"

I managed to remember where we'd been. O'Hara was talking very rapidly.

"Remember that I wrote you our Wrangell base is not too far from where the continents of Asia and North America once joined, where Bering Strait broke through. It's a weather factory, storms are put together there. Winds often swirl well beyond hurricane force, howling in all that icy desolation as if there were the slightest sense to it, for there's nothing at all to terrify." He was leaning forward now, recalling it. "On that day I wasn't terrified. I didn't like it but I'd beaten winds as bad as that. So I kept on the course laid out for my patrol that day, holding my speed around nine hundred miles an hour and sticking to an arc that gave me milliroentgen readings of .250 an hour. Not too close to the Curtain for an old hand at it."

He paused to fill his glass. He glanced just once toward the room beyond, then back to me. "You know, I'd never taken chances with the Curtain. I'd seen it's effect, and I'd never really gotten over losing Anstruther. I want to make it clear that I was not taking chances—I was flying it safely, accurately, giving myself the full margin. The gale was bothersome but the flight was going perfectly. Nothing unusual. Around 12:30 I began plowing through an electrical field, sheet lightning, vast livid flashes, but it wasn't until two minutes later, 12:32 P.M., that I first saw the thunderhead.

"One glance was all I had—time to report it on my radiocast—and instantly the thing was blowing up. It seemed to erupt, caught in an updraft, and belched blackly high above me in enormous toppling billows, the Arctic's unleashed fury roaring with a thousand forked, flaming tongues.

"My scintillometer's buzzing caught my ear. It was up to .268. I was veering straight for the Curtain. I swung at once, heading toward the Pole, due north away from the Curtain, and shot my speed above one thousand miles an hour, but the thunderhead seemed now to be collapsing on me and I could not accelerate swiftly enough to get from underneath. I could not break loose. I knew that within an instant I was going to be in the vortex of that swirling mass of wind and shrieking fire. Then it exploded.

"I remember that distinctly—it exploded into flame. And it blacked me out.

"I came out of concussion slowly—seconds, probably, but I seemed to be dragging myself back into consciousness. My craft was 500 feet above the ice. And there was no thunderhead. The wind was strong, around 120 miles an hour, but my speed was stabilized at 1125 miles per hour, and my milliroentgen count was .320. Very dangerous. And worse, my craft was headed south again. I swung it back toward the Pole.

"That should have cut my MR count. But within seconds the scintillometer was jumping up to .325, then .350. I was approaching the Curtain, and while headed due north!

"I turned back south. The MR count was dropping instantly. It didn't make sense. It was not possible, because I'd been between the Pole and the Curtain when I had blacked out. It was then that I made an automatic check on my position. Latitude 73—I'd gotten far off course during the time I'd been blacked out. Longitude 136—I checked that again. But that was it. The longitude was 136 degrees."

O'Hara knew exactly where that position placed him. But he did precisely what any laboratory technician would have done—he repeated his experiment, trying to find an error in his calculations. There was none and he knew it. He knew, even before that final check, that he had got through the Atomic Curtain.

Somehow, he had got past the wall of death that had cut off the Western Hemisphere for almost two hundred and seventy years. He now was flying above the ice field that abutted the upper reaches of the North American continent.

He glanced at his fuel gauge, and then turning south he set his motors at their maximum cruising speed. If he was trapped within the Western Hemisphere, the terra incognita that had fascinated him since he was old enough to read, he knew that he must fly as far below the desolation of the Arctic as his craft would go. And then—

"Then we shall see," O'Hara told himself. "Yes, we shall see—at last."

PART TWO

When he at last convinced himself that he had got through the Atomic Curtain, O'Hara said, his first feeling was a wild and utterly unreasoning elation.

"I've done it!" he kept repeating to himself, much as if he had booted home a twenty-to-one shot at the races at Aintree. "I've actually done it—the first man in two hundred and seventy years to smash through. Now we shall see!"

But that exuberance did not long continue. For here he was, presumably in the Western Hemisphere, the cradle of the future, a terra incognita since that Third World War, and it seemed no different from the polar regions that he had been flying for the International Patrol. No different at all—the limitless gray reaches of the sky, the same vast twisted sheets of polar ice pierced only at great intervals by craggy, barren peaks—the islands of the Beaufort Sea, above the northern coast of Canada.

O'Hara was cruising at two thousand miles an hour. His fuel gauges indicated that he might keep going for three thousand miles, depending on his altitude. It was necessary, he knew, to get above forty thousand feet and to stay there for his best distance, and he had to have distance toward the south—for the storms of December would have driven snow deep along the lost continent of North America. He was not equipped for any lengthy existence in snow. His craft had the Patrol's usual paraphernalia—an inflatable boat, a signal pistol, a .38 automatic with six clips of ammunition, emergency water supply, emergency rations, the items considered indispensable when a rescue team could be expected to begin search soon after he failed to report to his base at Wrangell Island. But now, south of the Curtain, no rescue team was coming. None could get through. In consequence, his life depended on getting below the wasteland of the Arctic.

These things, O'Hara said, ticked automatically through his mind in those first few minutes after he realized that he had got through the Curtain—these, and the overwhelming importance of the fact itself, that the Curtain could be pierced. He had, of course, no idea how the thing had been achieved. It had happened while he was unconscious, but as he reasoned it, his craft must have spun from north to south and then rammed through. Nor had he any data on the milliroentgen count of the Curtain itself—he had no idea of the contamination to which he had been exposed. He realized that at this moment he should have been a charred mass of carbon, like the bodies of those men on Coronation Island, in the Antarctic, after their vessel of logs had drifted into the Curtain.

But the indisputable fact remained that he was not carbonized. He could only accept it and take whatever precautions seemed most likely to keep him alive, which now, at this moment, seemed to call for flying south.

Within minutes he was crossing a coastline, and following the bed of a frozen river that pointed roughly south. Far toward his right—the west—the saw-toothed stubs of mountains poked their glittering ice-sheathed peaks up from the continent, and O'Hara was remembering the maps he'd studied as a boy. That way, the west, must be Alaska. Again he checked his position in latitude and longitude, then deciding that the river course below him must be the Mackenzie, reaching down past Great Bear Lake in Canada toward Great Slave Lake. And somewhere distant past the snow-packed tundras toward the east would be the land-locked gulf of Hudson Bay.

"Remember," O'Hara said, "I wrote that time telescopes in the Patrol? It was telescoping for me now—I was back again with old Hendrik Hudson, though thank God not in quite the same kind of boat. I was opening up the West again, seeing the amazing continent, the wonders that I'd seen before only as dotted lines and red-and-blue ink sworls on long-forgotten maps. And in five minutes—the five since I had passed the Curtain—I was exploring more of this tremendous northland than old Hendrik ever dreamed of."

Wonders, yes—but wonders unfortunately very like those of the land mass of Siberia, and so no different from what he'd known before he smashed through the Curtain. O'Hara felt somehow as if the myths of the Lost Continent had let him down. Until he noticed the recording of his scintillometer.

It had dropped only to .305 milliroentgens an hour. That was high—dangerously high according to the flying regulations of the Patrol, yet it had been much higher further north, toward the Curtain. He could only hope that with his progress south the count would gradually decline. Then it occurred to him that radioactive water might be running underneath the ice of the Mackenzie, draining southward from the Curtain, and he swerved hard toward the east, leaving the river bed some hundred miles behind before he made another reading. The milliroentgen count, rather than dropping, had risen to .325 an hour. And simultaneously O'Hara's memory dredged up a curious fact—the Mackenzie flowed toward the north. It could not possibly be contaminated from the Curtain.

O'Hara now turned again toward the west, crossing the Mackenzie and heading for a tremendous region of ice-capped peaks, their vast flanks swathed with the silver sheen of the greatest glaciers he had ever seen—the northern reaches of the Rockies, he concluded, the neckbones of the spinal column of the continent.

In this race westward, his milliroentgen count was sliding steadily, until, above the mountain chain itself, the count seemed stabilized at last at .285. Yet when he pushed beyond, toward the western coast—the Pacific—the count immediately began to jump again. He made the indicated correction in his flight, adhering to the southeast curvature of the mountain chain, and concluding that he had discovered a corridor of lesser contamination, its base upon the Curtain in the north, and its two flanks, on the eastern and western sides of the mountains, strongly radioactive.

He had now been below the Curtain—below, that is, the northern ellipse of the Curtain, for it was known to enclose the Atlantic and Pacific coasts as well—for thirty minutes, boring steadily south despite the zigzag pattern of his exploration, and the character of the terrain was changing, not less mountainous but with some indications of a seasonal variation in the snow pack, for oftener now the bare rock precipices and peaks showed through, and beyond the upraised spine of the Rockies, toward the distant shimmering deep blue of the Pacific, the snow itself had taken on a stippled appearance—immense forests, O'Hara concluded, blanketed but shaping the white countours upon them. And farther still, merging into the rim of the ocean's curve, lay a varying band of dark brown and black and vivid green, presumably a thickly forested shore, completely free of snow. O'Hara made a quick calculation based on his known altitude and an approximation of the distance to the horizon. The result astonished him. The forest belt extended inland for three hundred miles.

Yet the flight was becoming monotonous to the point of lulling him. The letdown that followed his discovery that the upper reaches of the continent were so remarkably similar to Siberia had increased, and with the passage of time he felt his eyelids inexorably closing. There was nothing to it. The dreaded continent was a fable made mysterious only by distorted memories of its history. It was, after all, a hoax—an empty shell, and he was penetrating deep—

His next thought jerked him erect in the cockpit of his craft. Suppose it was in fact an empty shell? Suppose there was nothing in this immensity behind the Curtain, the land which had been his fathers' fathers, but these ice-choked rivers and frozen tundras and forests and these tortured and interlocking mountain chains? Suppose it was dead—without life?

And it well might be. O'Hara himself had been exposed steadily now for the better part of an hour to a degree of contamination that the International Patrol considered beyond dangerous, and in his flights to the east and west he had plunged through belts exceeding .300 milliroentgens an hour. Was it not probably that these Americans in establishing their Atomic Curtain had simultaneously contaminated their two continents beyond endurance? The suicide of a race?

In an instant of panic, O'Hara swung in a tight arc to the north. He had, he felt, only the one chance to escape—a dash at maximum speed back to the Curtain and through it.

But, as instantly, he discarded that. Whatever it was that had got him through the Curtain in the first place could not be expected to work twice. He was convinced that it had been a kind of providential accident, something to do with that splitting blast of electrical power in the thunderhead, and he was here, within this Western Hemisphere, inescapably cut off.

His reason, too, came quickly to his rescue. These mountains and the far slope toward the Pacific Coast were smothered in their forests. And trees were life—biological life. If there was plant life there would be germination, bacteria—surely animal bacteria, surely animal life at however low a scale. Though perhaps not men.

Perhaps not men! Then this was indeed the grand adventure. He headed south again.

All these speculations and the resultant skittering about, as O'Hara said, had eaten into his flying time and he had not made the progress that he had anticipated, yet it was not quite two o'clock, not ninety minutes after he had crashed through the Curtain, when O'Hara saw a compelling flash of light upon his right. It was the first time that he had been conscious of the increasing clarity of the sun, no longer so obscured by clouds or ice fogs. O'Hara spiraled down toward a wide plateau, ringed with a lesser inner range of mountains.

The flash, he discovered, was reflected from a rectangular object, rather like a huge jewel, set into the face of a tall pile of masonry that reached some thirty stories high, a single needle rising from the snow-clad plain. Losing altitude fast, very nearly making of it a power dive, O'Hara pulled out of it level with the tower—for that was what it proved to be, a giant tower of stone and metal, expertly fashioned, a glittering and soaring pinnacle unlike anything that he had ever seen.

The flash was a reflection from the gemlike surface, which apparently was glass. The upper story seemed to be a kind of solarium, with six facets so arranged that they caught the sun constantly. The stories below it lacked openings of any sort, and O'Hara concluded that if in fact the tower had once been used for offices or dwellings those who lived there had relied entirely upon indirect lighting.

He was convinced that it was deserted now. There was a complete deadness to it, a stone and metal tower rising abruptly from a snow-blanketed plain, long abandoned, long forgotten. And descending lower, he could make out the geometric patterns of low structures and broad avenues, but with a skeletal emptiness about them, the roofs collapsed, the walls themselves in many places having toppled into the general ruin. A dead city, certainly, yet once it must have been a metropolis, culminating in its strange, massive tower before it died.

"Forgotten names from forgotten histories came back to me," he said. "The northwest coast—not Vancouver? Not Seattle? No, for both of them had been upon the coast itself. Spokane, then? Or possibly some city that had flourished after the establishment of the Curtain? But it did not matter, the place was dead, with the anonymity of the dead. A graveyard of a civilization that had been the mightiest on earth. Yet the proof that this civilization actually had existed—that it was no myth—was enormously stimulating to me. It was my second big moment."

The tower and the ruined city had taken his attention from the business of flying. Now suddenly he was startled by the rapid-fire of his scintillometer. It was recording .400 milliroentgens an hour—unendurable!

"The dead," said O'Hara, "were reaching out for me. They wanted me, an alien probing through the skies above their tomb. And I felt their hostility, as if a shower of warheads had come roaring up. The contamination was as murderous as any warheads would have been."

The tautness of his steep climb skyward and sharp swerve back toward the spinal cord of the continent precluded any further observations. He was now acutely alarmed. He expected at any moment to discover upon his body the raw violence of radioactive burns, he anticipated bleeding and there was at the hinges of his jaws a definite sensation of nausea. Yet moments passed without development of these symptoms. The nausea abated. He was not stricken yet, or if he was, the effects were not yet obvious. And this raised possibilities of conditioning to the contamination that had never been explored—that no one, in the world he knew, had dared to explore. It might yet prove to be that man could exist in these extremes of radioactivity.

Large mottled patches now were appearing between the pale blue-white stretches of endless snow. The mountain peaks and the high plateaus still presented their heavily drifted appearance, but in the deeper valleys an occasional ice-free river twisted, seeking its outlet either toward the east or west—the east, O'Hara remembered, would lead to the intricate arterial system that would at last merge into the Mississippi River, the continental sewer that dumped its burden of silt and debris into the swampland delta of—what was it? Louisiana? The whole once-familiar pattern of maps he had intensely studied as a child now was coming back vividly—the two mountain systems, Appalachian and Rockies, the great valley of the Mississippi, the Atlantic and Pacific coastlands, the spider web of fabulous cities, names like New York and Washington, Chicago and Kansas City, Los Angeles and San Francisco, and somewhere in these Rockies which he was now following were—or had been—Salt Lake City and Denver.

There was a definite excitement in these names that for O'Hara rolled back the drab present to that glittering past, when the word tomorrow had meant more than a repetition of today.

O'Hara felt positive now that he had established a second major fact. For almost two hours he had been flying these forbidden skies, yet no patrol—save the atomic radiation of the dead city—had so far challenged him. It was inconceivable that any important civilization could exist upon the northernmost of the two Lost Continents without patrolling its skies, and consequently, if a civilization did exist, it must have shifted to the south, leaving these wastes. But for some minutes past, he had observed a peculiar series of geometric designs, resembling the drawings of ancient Cretan labyrinths, far below him on the frozen surface. He now was approaching another of these, extending for miles upon the floor of a wide valley, and very cautiously, with his eyes constantly flicking back to his scintillometer, he began to descend toward it, diving.

As rapidly, his milliroentgen count began to climb, reaching .290 within the first five thousand feet of descent, then to .300 when his altitude was down to 30,000 and jumping very sharply at 24,000 feet to .325. The strange labyrinth was much too hot for inspection. But the regularity of its form seemed proof that it was man-made, and that decided O'Hara. He continued down until his altimeter registered 5,000 feet.

The labyrinth's pattern was precise. It was composed of an almost infinite number of thick parallel lines, joined at the ends, so that it actually resembled an endless pipe, though various segments of it were colored in a multiplicity of pastel shades—a vast farm of pipes, reaching for miles across the valley's floor, its purpose not apparent to O'Hara. His milliroentgen count now was approaching .400, and again he made that steep climb back to 40,000 feet.

These pipe farms soon were visible in every major valley, and further toward the east, upon the great slope of the plains toward the Mississippi, they were everywhere like the squares of a continental checkerboard, in some places partly obscured by snow drifts and in others lying exposed to the sun's brilliance.