CAMION CARTOONS

![[Logo]](images/titlepage.jpg)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

![[Logo]](images/titlepage.jpg)

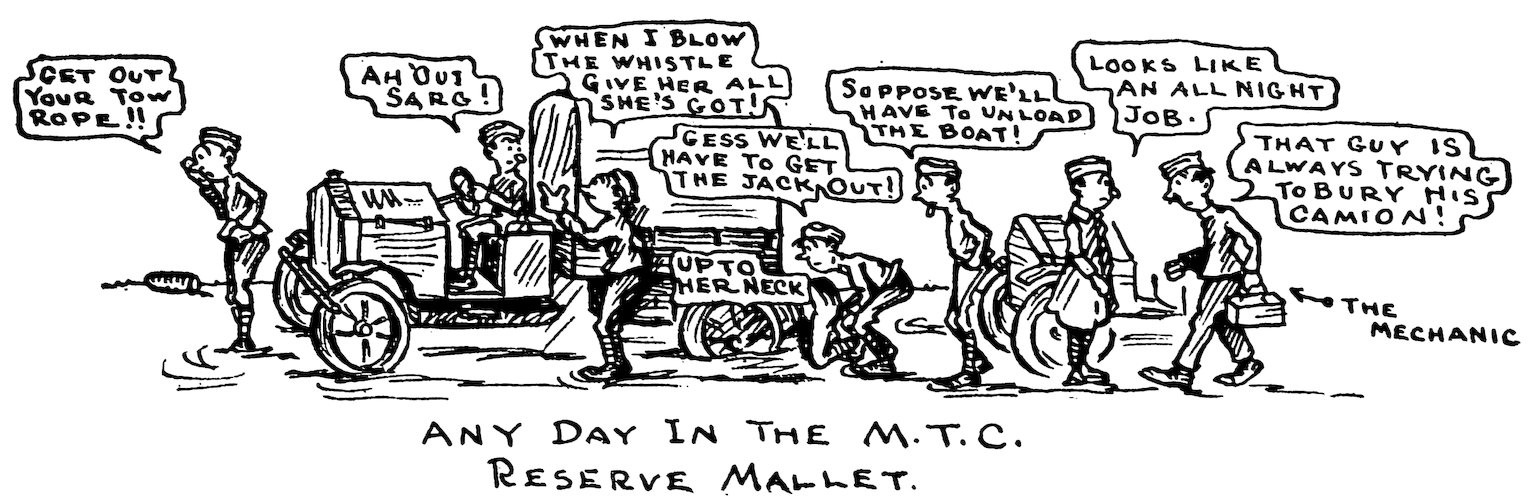

The writer of these letters and maker of these drawings went overseas with the first Technology unit; landed in France on the Fourth of July, 1917; began his service as a member of the Reserve Mallet, and was mustered into the American Army on October 1, 1917. In preparing the letters and cartoons for the press, it was thought best to begin where rumors of impending German surrender first appear in the correspondence, thus confining the humorously illustrated story to the last weeks of the war. Mr. Day wrote his letters with no intention or expectation of having them published; that is entirely the work of his friends, who believe that vihis impromptu sketches will be found to furnish ample justification for the existence of this book.

Mr. Day served in the Reserve Mallet, a camion unit to whose spirit and efficiency Stars and Stripes has paid the following unaffected and authentic tribute:

“In a summer when again and again the historic phrase ‘Franco-American troops’ makes its appearance in the communiqués, the distinction of being the complete amalgam of the two armies belongs to the flying squadron of emergency transportation, that trundling troop of trucks, that charging company of camions, the Mallet Reserve.

“This organization consists of 700 five-ton trucks—American trucks driven over French roads, driven now by French now by American drivers, officered by French and American viiofficers, carrying French and American troops, French and American ammunition.

“The Mallet Reserve is so named because its commanding officer is Major Mallet of the French Cavalry, and is called a Reserve because it is attached to no Army Corps, but rather is held in reserve for emergency duty whenever a crisis in the war brings a crisis in transportation.

“This means that the interminable line of camions bearing the Mallet mark will invariably appear wherever things are hottest, that the trucks and their drivers know no rest from one year’s end to the other.

“Thus you saw them along the roads up Cambrai way last fall. When French troops were rushed into the gap that opened during the German drive of March, Mallet trucks carried them, and they were Mallet trucks which bore northward the French soldiers who viiimade their sudden and startling appearance among the British in Flanders during the April fighting. The American troops and ammunition that were moved with a rush to the lines of the Chateau-Thierry front were transported, many of them, in the home grown camions of the Mallet Reserve.

“The trucks themselves, if you examine them, tell many a story of transport under shell-fire, tell of machine gunners borne to the very rim of the battle so that gunners need only drop from the camion, run down a field and start firing.”

When this book went to press, Mr. Day was still in service, with the American Army of Occupation.

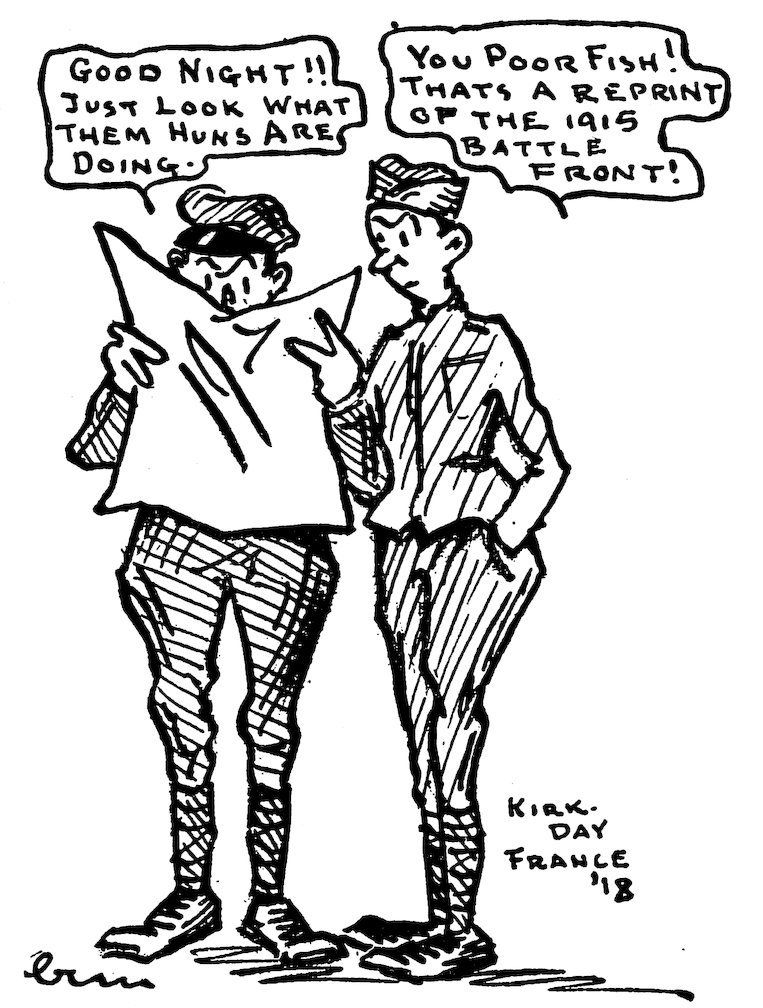

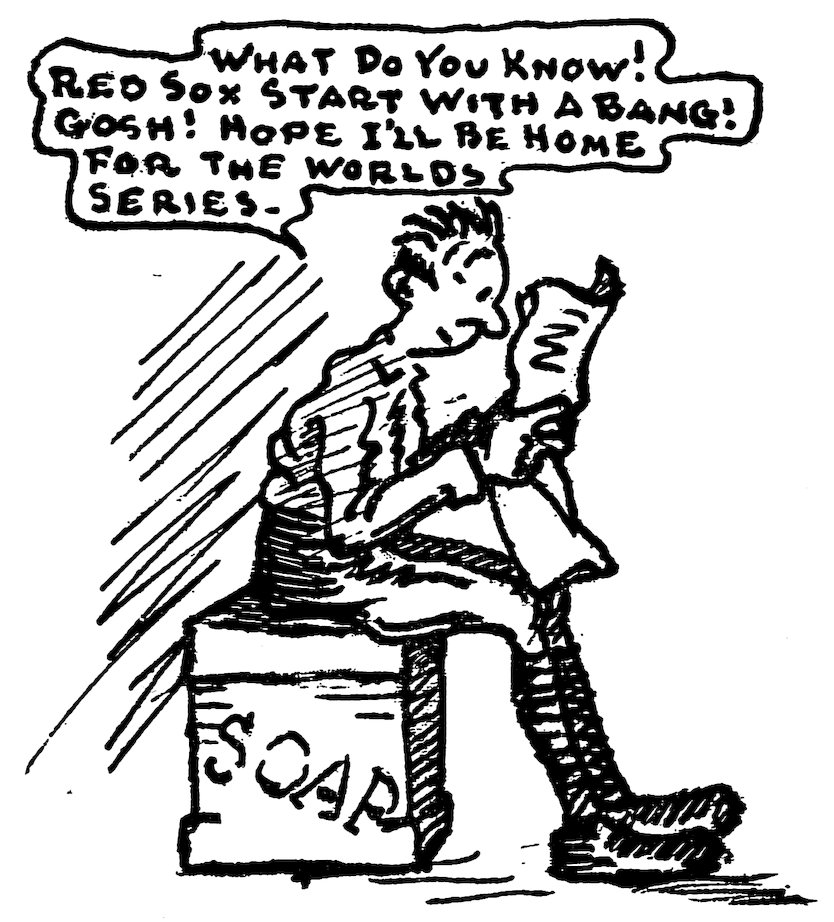

Today the war ended!—at least, one of the buck privates read it so. He got hold of a French newspaper, and caused some excitement until one of the boys, who could read the Lingo, commandeered the sheet. At any rate, the Huns are beginning to squeal. Just wait until a few Boche villages begin to get theirs, and peace notes will begin to come over....

Well! I arrived back in camp again after some jumping about France. We got away from Aix without any trouble, but from then on we began to wonder if we would get 2back into camp for Christmas. The trains over here hate to get anywhere.

It was night when we arrived in Paris, late as usual, and so dark we had to hang on to each other to keep from getting lost. Having been there before, I was elected guide, and I got the gang to the Provost Marshal O. K., where we got our passes stamped, and then I left them for the University Union. Coming back from permission, I was not loaded down with money, but did have enough to see me through one night. The Union was crowded, but I found a place at a nearby hotel—a dandy room on the ground floor, which rather surprised me. During the bombing season, ground floor rooms are the first to be taken.

4The next afternoon I went, with a lieutenant I had met at the Union, to take a look at Napoleon’s tomb. We walked over—the lieutenant’s pocketbook must have been as flat as mine. I will never regret going, and I shall never forget the thrill I got when standing in the doorway of the chapel and seeing that golden light flooding the cross.

That golden light, that living cross, and the pale blue-gray rays falling from the side windows, made me feel miles from any one.

The tomb itself was covered with sandbags. I remember going to the tomb when I was here with you, before the war; but how I could have forgotten that inspiring sight is beyond me.

There was no more time for sightseeing, as I could not take a chance on missing my train.

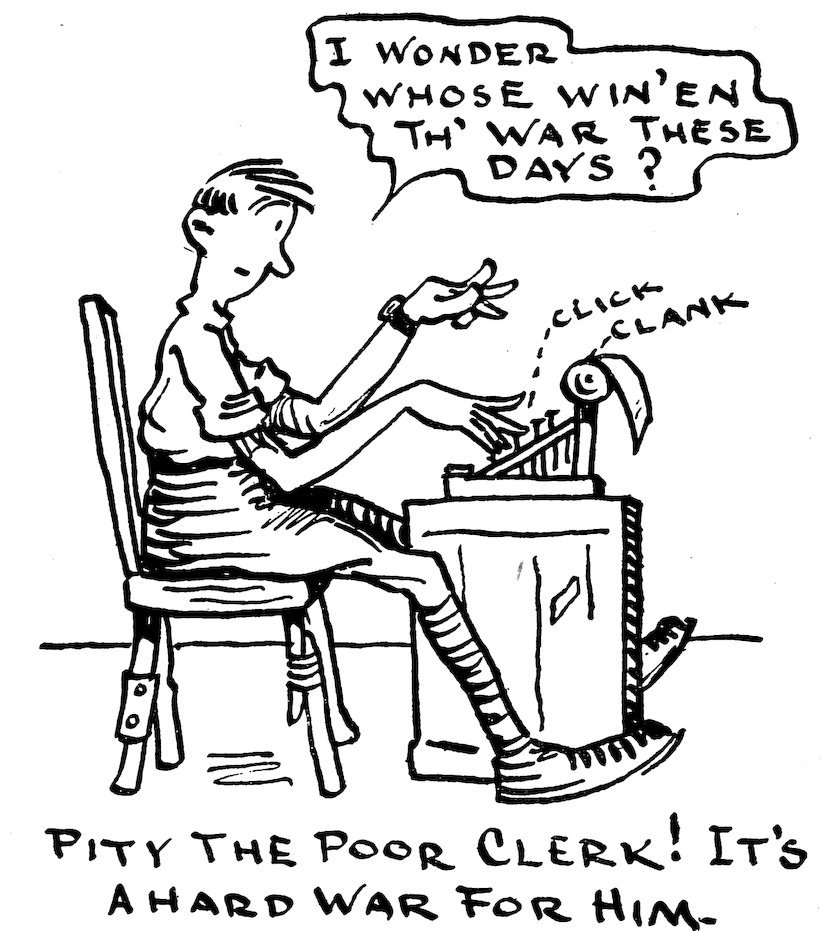

6Since my return I have heard the news that our company clerk is leaving, and that I am to take on his job as well as have charge of the mess. It will be pretty nice in the winter, but I hate inside work and would much rather ride a camion.

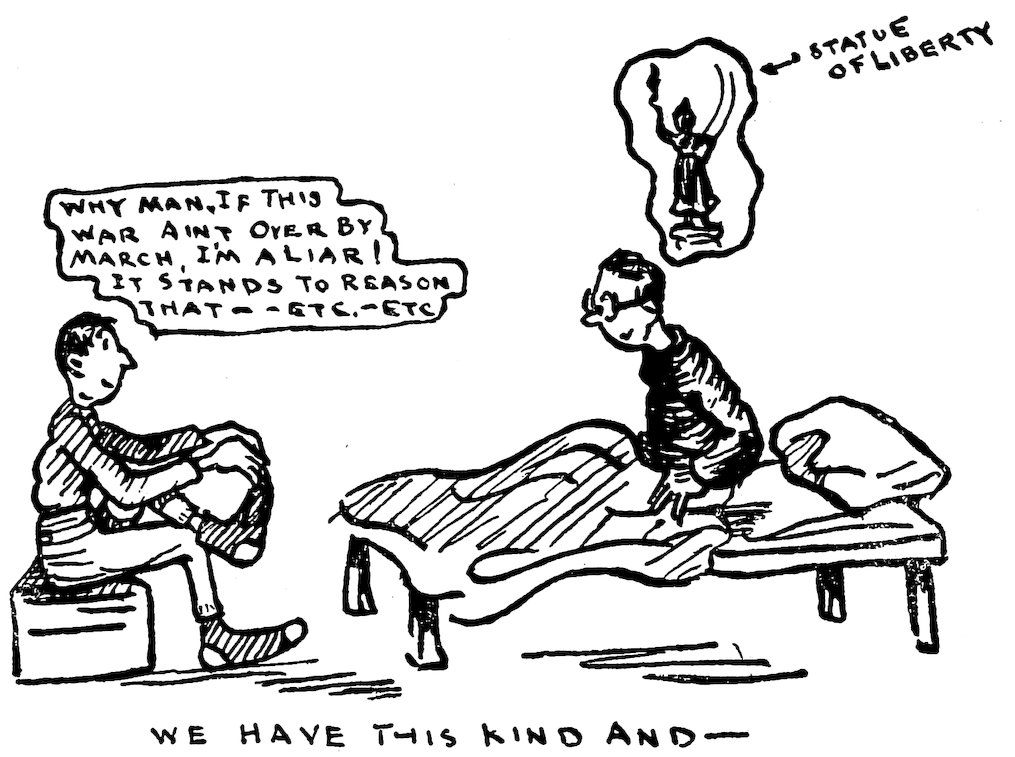

Today has been another rumor day. Those coming back from convois sure have one hot line from the front. “William the Hun” has agreed, and the Boche have stacked arms and are doing the goose-step back to Germany. Would that it were true! Still, the way the Huns are going now, they haven’t time to goose-step, it’s more of a fox-trot.

I’m enclosing one ticket good for a visit from Santa Claus. Tell him to pack the cigarettes and gum with care. Don’t chase around to get stuff to fill the box—just pack it full of cigarettes and send it along. Don’t put in a Christmas card, it takes up room.

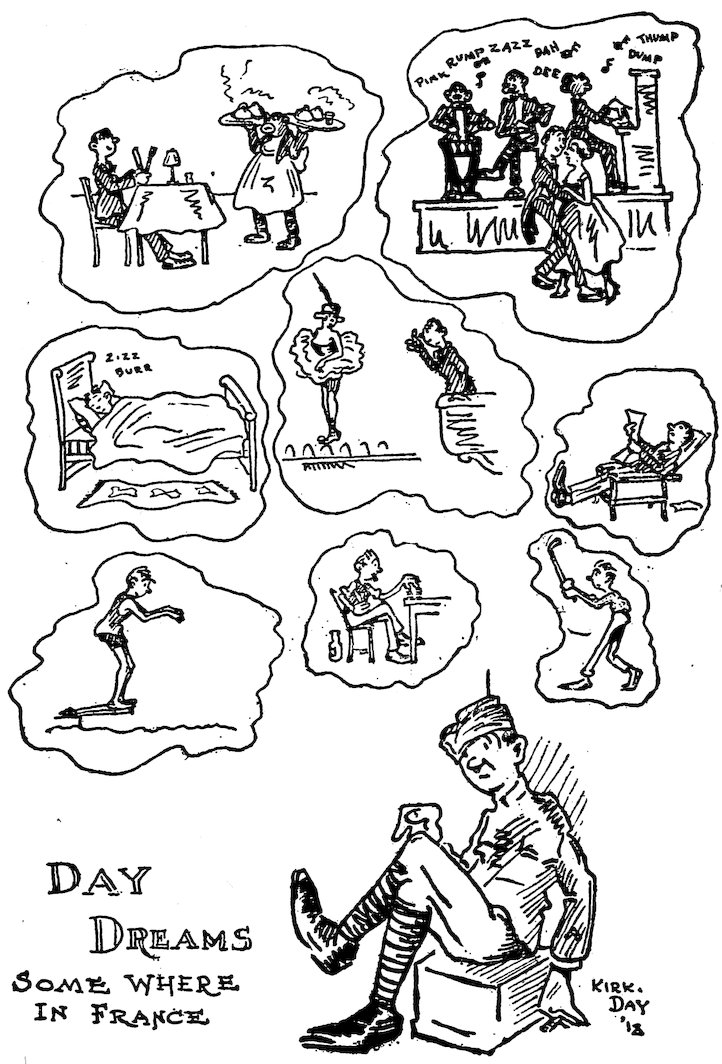

Once upon a time I went to church and they sang a song about “Rest, rest, for the weary.” When I get home, I’m going to climb into bed and let them sing me to sleep with that song. Weary! Sleep! I could make a hibernating bear look as though it had insomnia.

Did I ever write a letter in which I didn’t say “We have moved.” If so it must have been when little apples were made. We have moved! The way the Huns are going backwards, my next letter should be headed “Somewhere in Germany.” This move has been one for the better in regard to quarters. The Germans didn’t do much hating in this village. No doubt they didn’t have time. At any rate the houses are standing on their own feet and the roofs are pretty much all together.

12Germany is down and out. Everywhere you notice and see it. The French are rubbing the defeat in. Before this wonderful drive you never saw a light anywhere. Now everywhere you see them. Autos go by with their head lights thumbing their noses. In the woods, in the field, in houses, and barracks, there is no attempt to conceal lights.

I have just finished up with the “Flu.” Believe me, eight days with it is enough for me and I don’t want to see it again. Feel about as useful as a pair of pajamas in the army. The Flu hit me when I wasn’t looking and got me down before I knew what struck me. They took me over to the camp infirmary and put me to bed. When you are once in bed you have no desire to leave. If you do get up you find that your legs are no longer mates, and refuse to work together.

16Just now I’m back in my old room wondering what it has all been about. I slept most of the time at the infirmary and had some fine dreams. Pushing logs about and driving over cliffs in camions were my favorites. Once in a while I would dream that I was at home again, but every time I was to see you they would make me crank up my camion and go somewhere else. I hope some day I’ll be able to dream without having a camion enter into it. I still don’t feel much like sitting down to any kind of a meal. The first shave I had since I was taken was yesterday. It nearly killed me, and I left my moustache on until my arm gets a little stronger. The camp is shy a barber or I would have let someone else do the job. If we don’t get a barber soon I’m going to start braiding my hair....

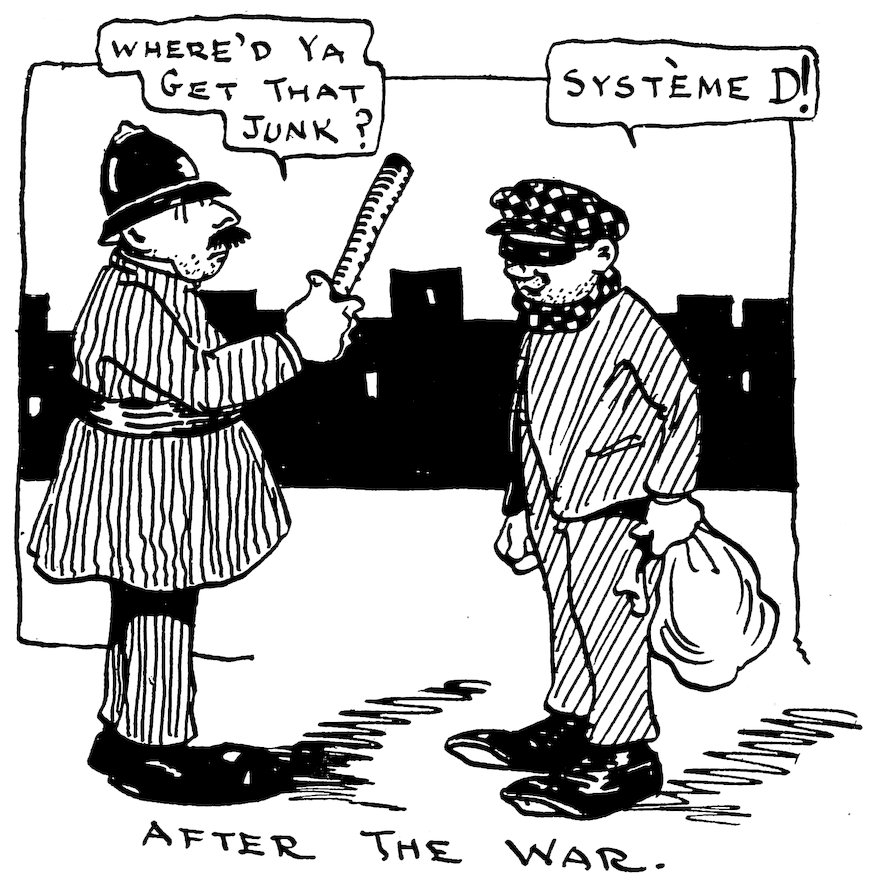

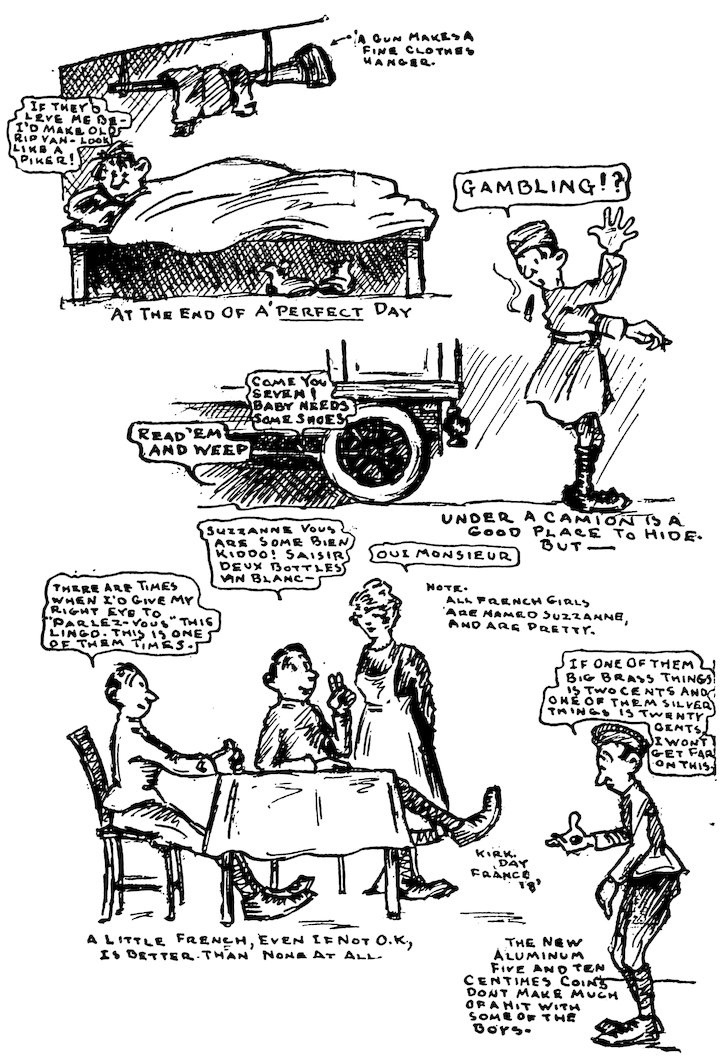

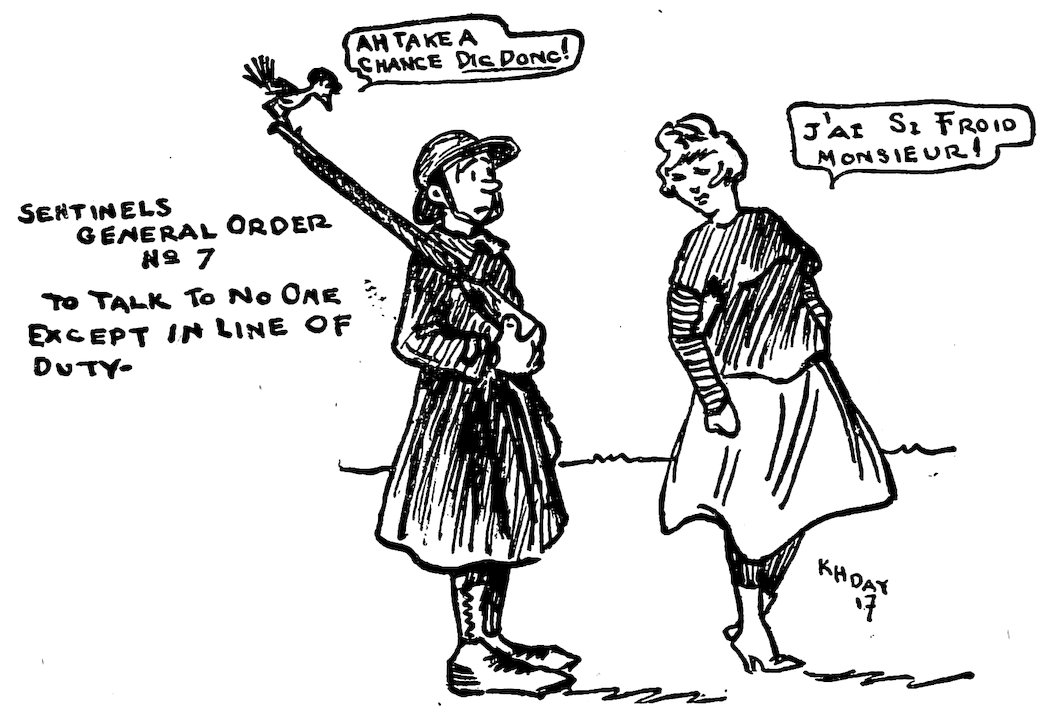

18Over here nothing is ever stolen, swiped or pinched. It is always “Système D.” As I understand it there are three right ways of getting things in the French army. Either by Système A, B, or C. If you can’t get what you want through these three channels, you “Système D” it. All sorts of things from coal to pianos have been obtained through this “let not your left hand see what your right is doing” method. Some one said that by the end of the war we would all be first class crooks. There may be more truth than poetry in that. At any rate it’s a safe bet that we won’t starve to death while the war is going on. You would think that “Gott Mit Uns” was made in the United States instead of Germany, if you were to look at the belts. I thought, until I went on permission, that only the boys in the Reserve Mallet wore the Hun belt. As far as I’ve seen practically every “Yank” has and wears one of these belts. Fully as many pants in the United States Army in France are held up by “Gott Mit Uns” as are held up by the regulation belt.

Isn’t the news wonderful! One of the boys drifted in with a French newspaper and translated the armistice terms laid down to Austria. The Allies certainly left out the silver platter when they handed them over. Wouldn’t I like to be there when the Hun comes running out with the white flag to call on General Foch. We are all saying, “When we move let’s take a trip to Austria.” It may be a case like the fellow who said, “Why learn French when we will be talking German in Berlin soon.” Only it will be Vienna if we should roll to Austria. Just think of their being eighty minutes from Berlin by air. Soon the aviation report will be, “So many tons of bombs dropped on ‘Unter den Linden.’” Won’t the Huns yell!

22One of the boys that has come in since I started this letter has just gone out to get a bottle of wine so that we can celebrate the glorious reports. If we start in celebrating all such news, it will be—“Vin tous les jours.” Italy showed that she had a punch in each hand. Sad news from the front—“No wine.” Some one else must have decided to celebrate....

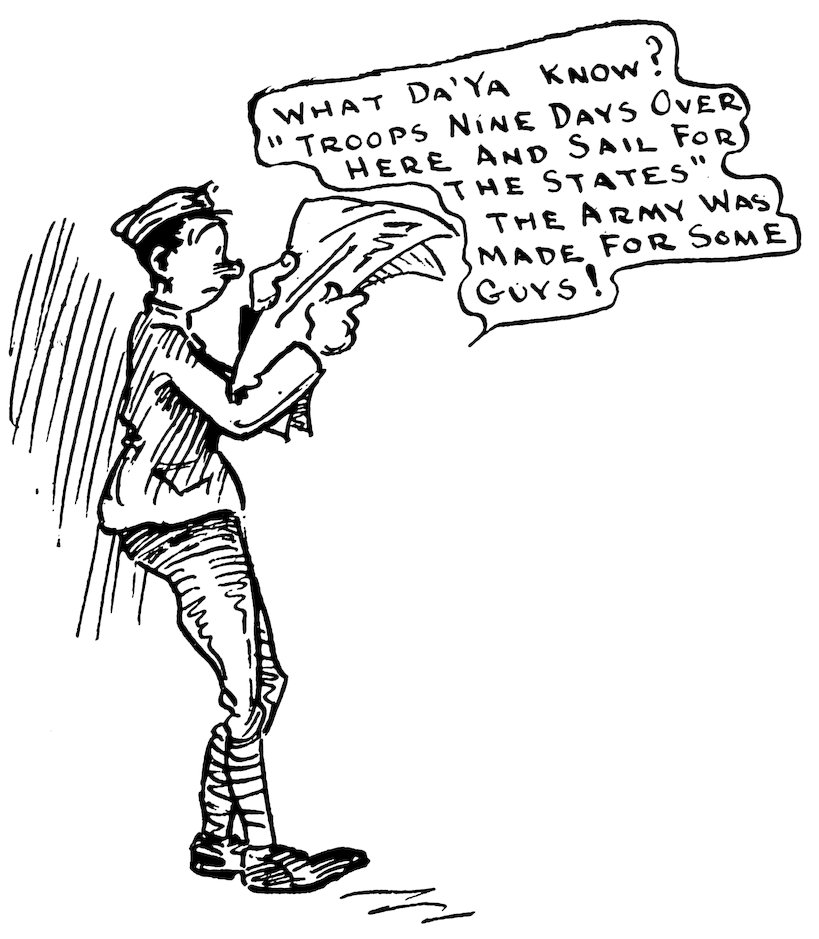

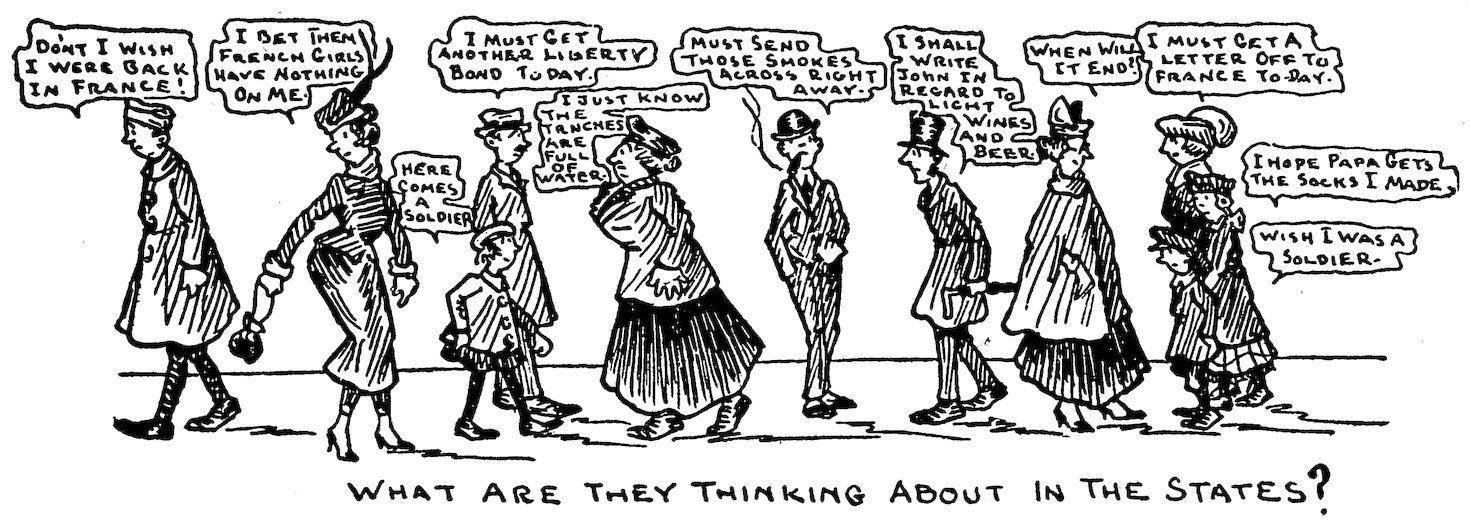

All the talk these days is, “When I get home.” I’ve heard what every man is going to eat, wear, and do, when he gets to the other side. Each one has his own taste in regard to food. In the clothing line, anything but a uniform is popular. As for doing—I am afraid the wheels of progress are not going to move very fast. All the boys are going to just sit or sleep.

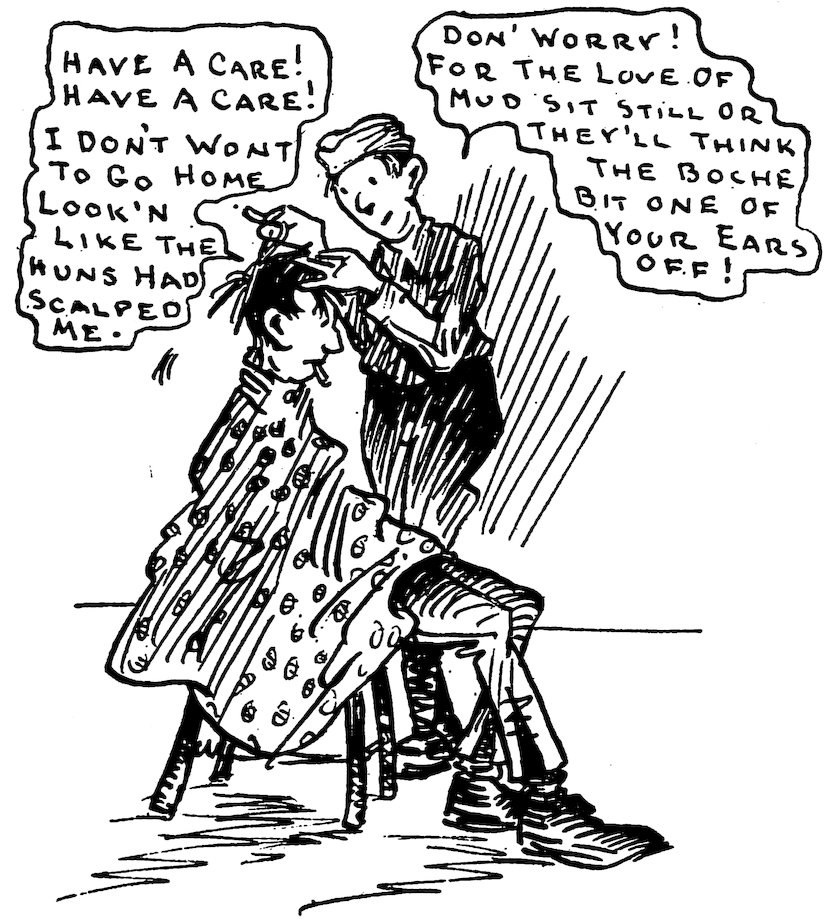

24There is now a barber in town—A French one. Although I need a hair cut pretty badly, I think I’ll stay away. From the work he has done on a few of the boys, I have come to the conclusion that I can do as good a job myself. Over here a bald headed man has the advantage. Nothing doing with the clippers, however, once was enough for me with a convict head....

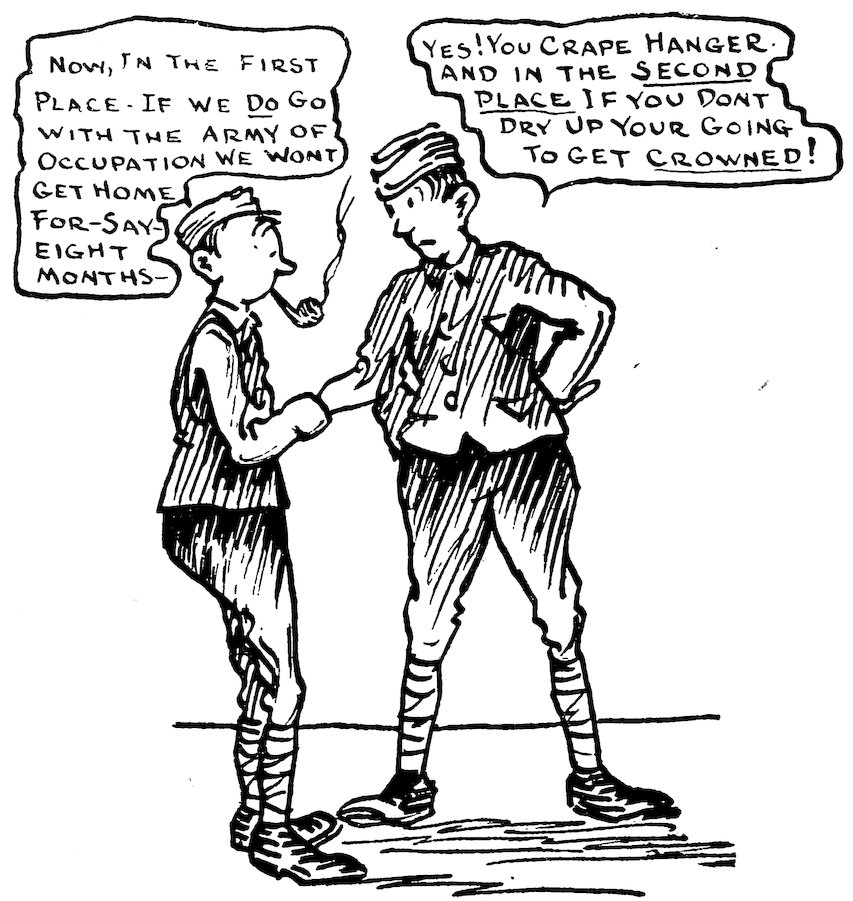

The latest in regard to what becomes of us after peace is declared, is that we will be with the Army of Occupation. That doesn’t sound at all good. It is a good thing that hearing is not believing in most cases or I would be on pins and needles all the time.

The night before last there was wild excitement in camp. All afternoon we had been hearing the latest news from the front, and the war was finished at least every five minutes. That night one of the boys returned from the mission and said that a Lieutenant told him that there was no doubt about it, Germany had thrown up the sponge. I wasn’t there, being asleep in bed at the time, but they woke me up and told me between—hics—that the war was over. The piano in one company’s house was playing all the war music that was ever written and the air rang with cheers, popping of corks, songs, and whatnot. It wasn’t long before our door was banged open. We were paged and told that the war was fini, and to come out and join the party. I’m afraid they didn’t get much of a response from us, both of us being pretty tired. Some day they won’t be crying wolf and we are going to miss out on the party. The Frenchmen are just about crazy, and who can blame them? When the end comes, and it’s coming sooner than any of us realize, you in the States will get the all over feeling long before we do. Things will go on for us camion drivers just about as they are going now, and not until both feet are planted on the other side of the pond will the guerre be really finished for us.

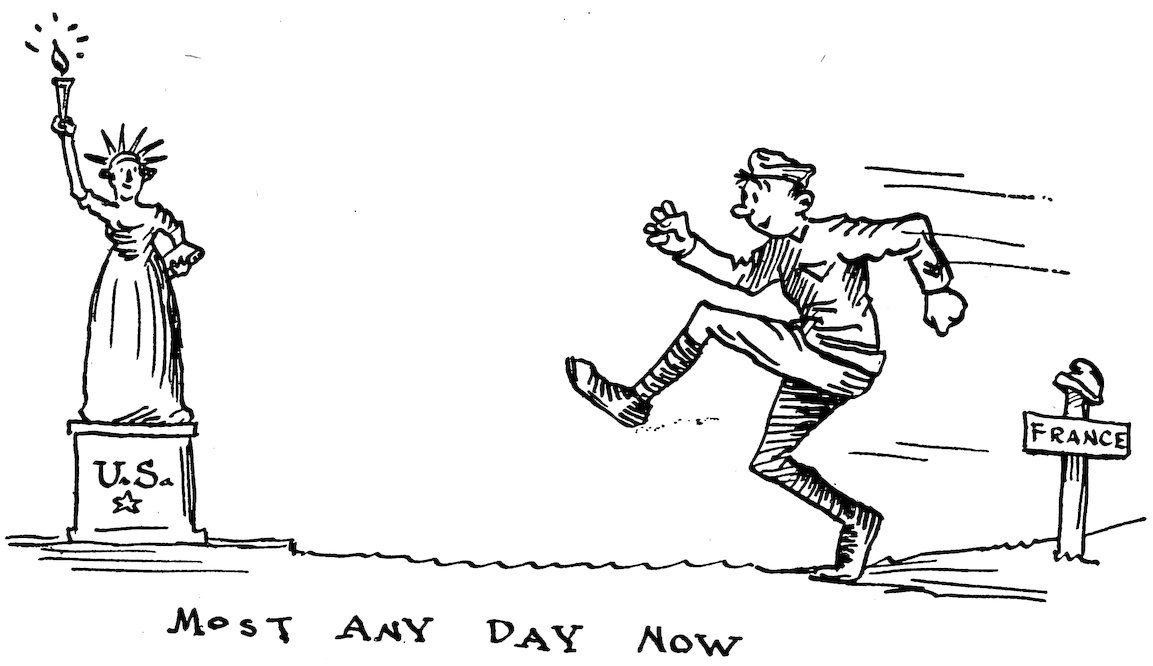

Am I awake or is it a dream. It doesn’t seem possible that the war is OVER. When it was brought home to me that the armistice had been signed, it left me not dancing with joy but numb. It didn’t seem possible and now, two hours after, I’m just beginning to cheer. Think of the millions that are made happy these days, and think of those whose boys will never return. Just about two weeks ago the lieutenant I had in C Co. was killed. He was a fraternity brother of mine, and one of the finest fellows I have ever had the pleasure of knowing. I am glad that I have had the privilege of being one in the great Army of Right. My only regret is that I could not have come over about three years sooner.

32I remember when I first got here, early in July, 1917, how we looked forward to the day when America would have its army in the field. There was no question in our minds about their showing something. When they did get in they showed something all right, they showed more than something. It was a case of “The best is none too good.”

We have moved along twice since I last wrote. To look at the signs in this place you would think you were in Germany. German names for streets and German signs everywhere. This isn’t the first of that kind that we have struck, but it was more so than the others. We are in a huge farmhouse that used to be for Hun officers only. Its roof hasn’t a hole and we haven’t a broken pane of glass in our windows. We have the best room yet, and a fireplace that could take a tree, roots and all. The Boche turned a nearby farm into a bath house and it is a wonder. Showers beaucoup and tiled bath rooms with enameled tubs. They moved so fast that there isn’t much damage done. They did leave their trade mark though. There is a chateau that looks perfectly O. K. from the outside, but inside it is a total loss. They planted a mine and wrecked it. Mines are planted all over the road. Yesterday afternoon two went off. The last blew our windows open.

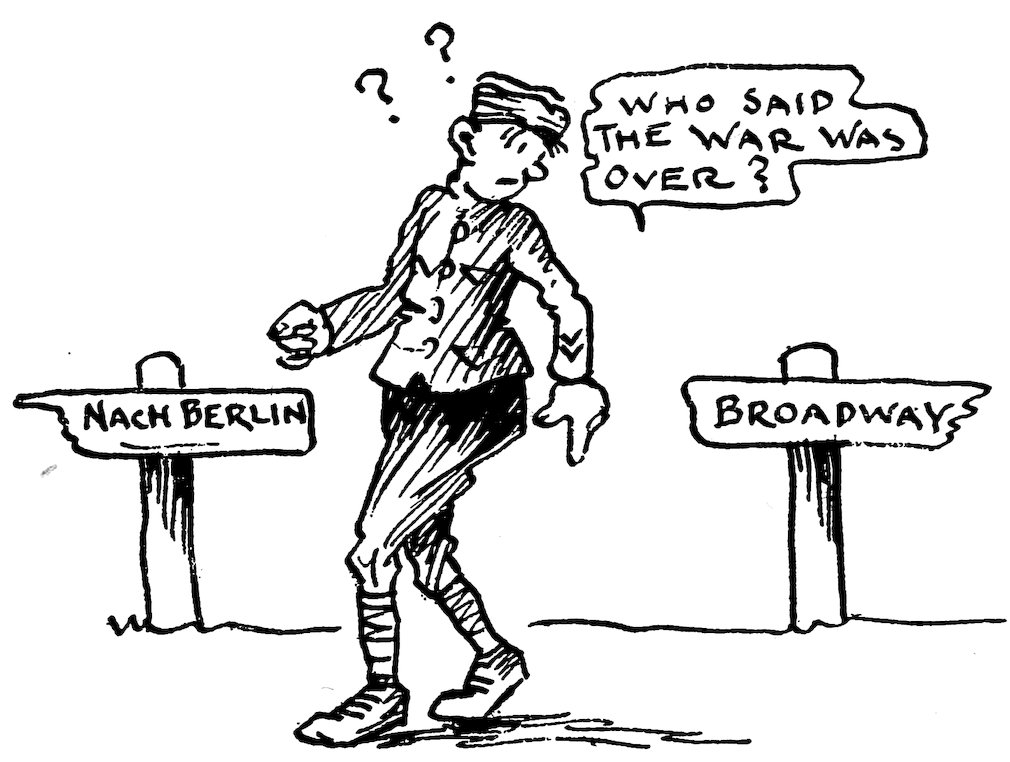

34Understand we are on our way to Somewhere in Germany.

We will be on the move, I expect, for some time now so my letters may be few and far between. Will try and keep them coming through.

Wars may come and wars may go, but we go on forever. Believe me! when we heard that the armistice had been signed, you would have thought we had all gone suddenly crazy. It took some time, I’ll admit, for the good news to sink in—but when it did—Oh boy!

We are now on the way towards Germany. It is almost a certainty that we will travel along with one of the French armies of occupation; carrying Ravitaillement (grub for man and beast) to them. Talk about moving, ever since the last shell was fired, that’s all we have been doing. You would think we were a checker game. I can’t say we were tickled to death at the “Army of Occupation” news as we expected to be on our way towards the States within a couple of months.

They say that a tug boat, or some kind of a water animal, is going to brave the dangers and carry mail across to the folks at home. I am therefore stealing a few moments from my soldierly duties to throw a bit of ink. I’d much rather take the place of this letter and let them ferry me across instead, but as we are elected to be a part of the clean-up squad, it can’t be done.

It is sad but true, but we are a part of one of the French armies of occupation and are now “Nach Berlin.” We are making the grade by the instalment plan—stop here today and move on tomorrow. Our job is carrying “Ravitaillement,” and we are just as busy now as we were during the days of shot, shell, and bomb. Just as busy, but it’s a great deal more tiresome without any excitement.

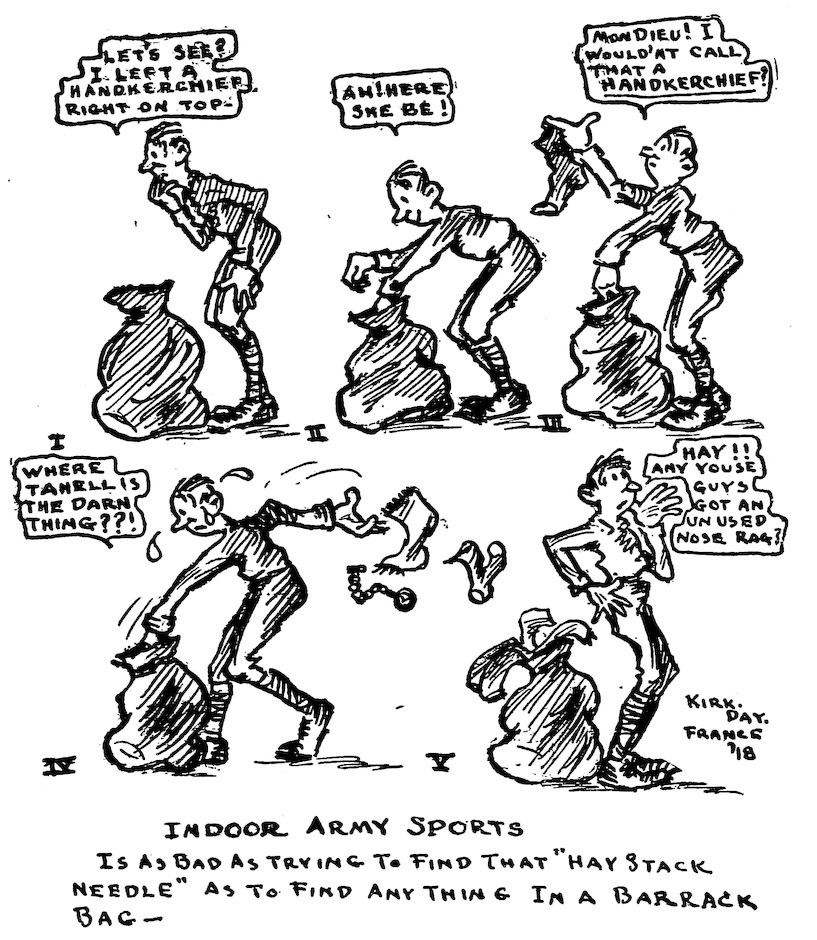

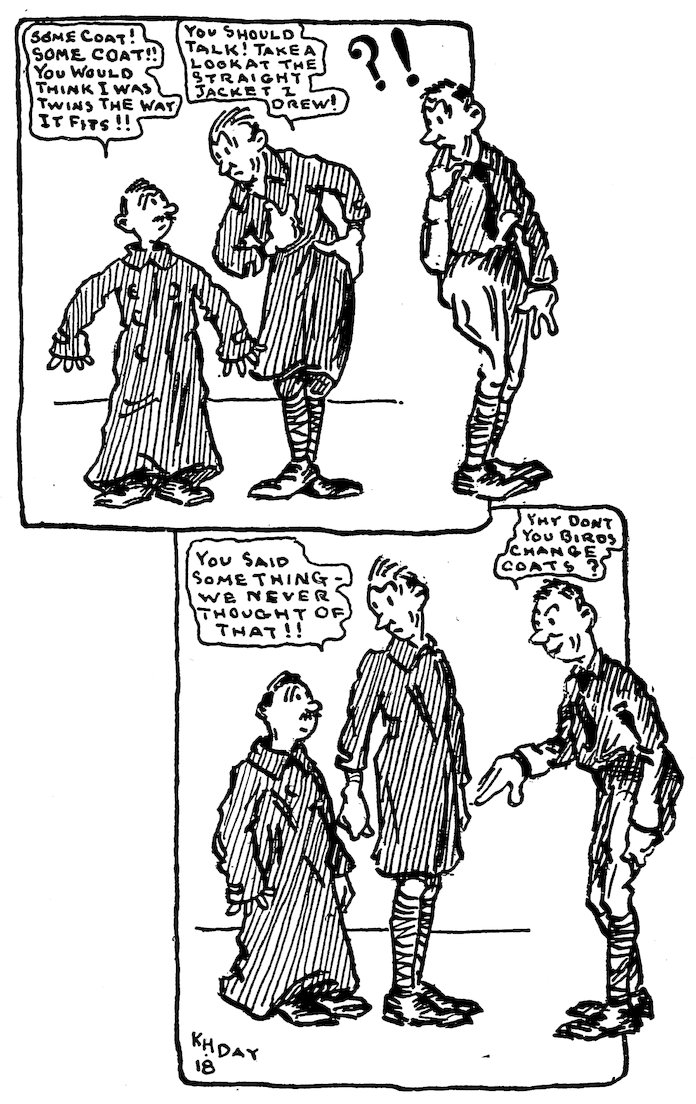

40That is, it’s more tiresome for the drivers and some sergeants. The clerk’s duties are just the same, although I have been told that I’m to take over the mess and supply sergeant’s jobs along with what I am already doing, which is nothing at all. Guess they decided I was wearing out too many chairs, and drawing too many pictures for a “Soldat deuxième classe.” There was enough yelling with the old mess sergeant and I can see a battle royal ahead of me when I begin to dish up the chow. As for getting clothes, it can’t be done. Some of the men are running around in pants held together with wire, pins, and string.

It is going to be a cold winter, and I hope that those at the other end get a little pep and begin to unwind Mr. Red Tape.

42All day troops have been passing here, going up; part of the army that we are attached to, so I wouldn’t be surprised if we were on the go again soon.

Have seen thousands of returning prisoners, refugees full of spirit, but so pinched and hungry looking, clothed in rags and even in the uniform of the Boche soldier. We fed some at our kitchen one night and they were starved.

In the town I sent my last letter from, the son of the people whose house we had taken over dropped in to look the place over. It was the first time in four years that he had seen his parents’ home. His mother, sixty-four, and his father, sixty-eight, were carried off by the Huns in February. They were expected back almost any day and he wanted to see what there was left. The house was in perfect condition and there were a few sticks of furniture about, but the Boche had taken the meat and left nothing but the bone. His parents were more fortunate than many, having a home with a roof, but even then it’s pretty tough for two old people to return to their home and find it stripped of the things they loved.

44From the shooting around here one would think that the war was still going on. Almost every one that has a gun is out banging away, and once in a while a mine will go off and shake the house. The Italians stationed here got hold of some rockets, and every night they dot the sky with red and green lights. Every day is a Fourth of July, but not a “safe and sane” one.

The Italians were life savers in that they had a portable barber shop, first time we have run into a good barber shop in a long time. One of the boys in our company took a hand at the game, but after trying his luck on a few heads, the bottom fell out of his business.

46The camions are just about on their last legs. It is to be expected, as they are rolled “tous les jours” and they are not in the camp long enough for the drivers to work on them. Out of our eighteen cars we have about ten that are able to roll. If they keep on going, there won’t be anything left to drive and they will have to send us home.

The American army has forgotten for so long that we, in the Reserve Mallet, are a part of them, we don’t expect them to think of us suddenly in this stage of the game.

Permissions are still going on and no one seems in any hurry to get back. Those who were in Paris at the time of the signing of the armistice have wild tales to tell.

The lid is off, at last we can come out of the trenches and go over the top in our letters. Old Man Censor has had his whiskers cut and we can throw the ink from bottle to paper without a worry.

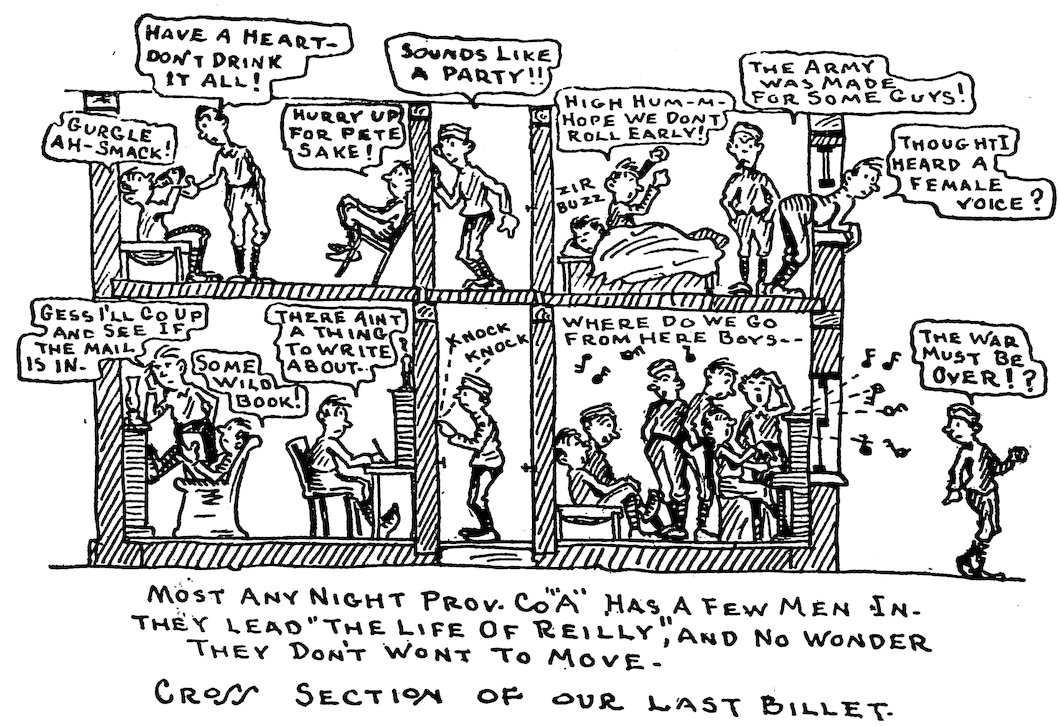

As you know, I jumped from the minor league (American Field Service) into the major (U. S. Army) on October 1st, 1917. After taking the leap we were sent to Soissons (Aisne) which was to be our home for some little time. Soissons was some town! The Boche had been there before us, but had left a great part of the city standing. With its hotels, cafés, tea rooms, stores, and bath house, we led the life of Riley.

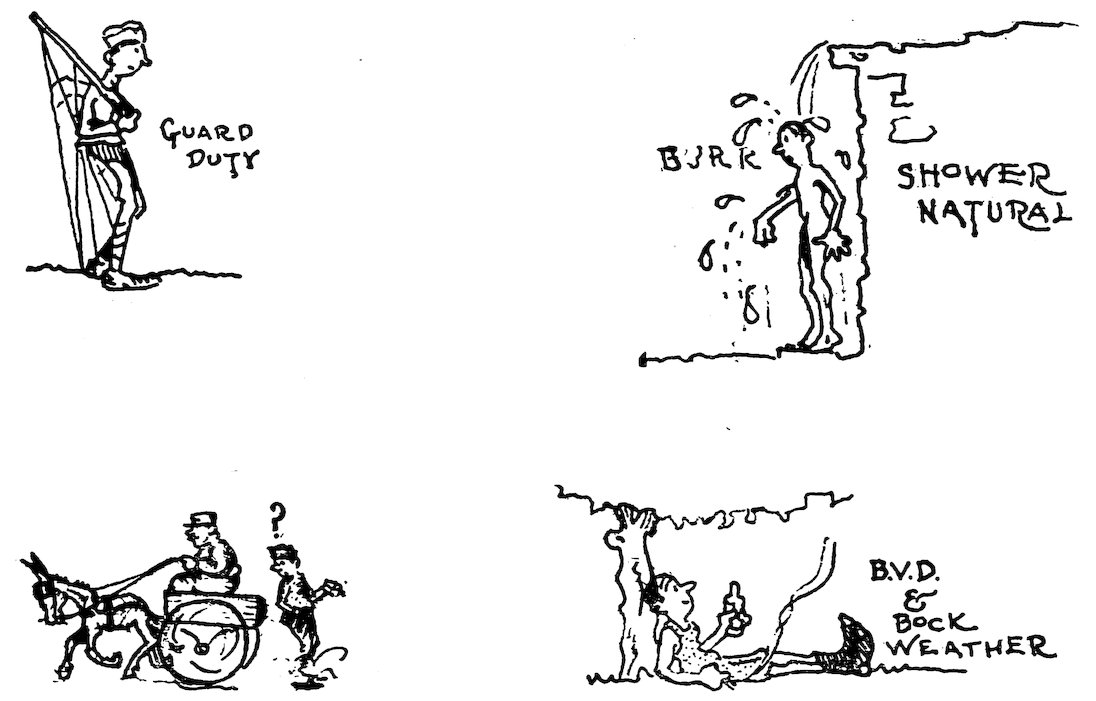

50Our camp lay just on the edge of the city on the bank of the Aisne river, and in the camp I had my first lesson in ditch digging, kitchen policing, drilling, rock breaking, and a few other like things.

Things went along pretty smooth for us until March 21, when there came the grand finale as far as Soissons was concerned. Up to that date we had had a few air raids, which would start the twins barking and us running for abris. The twins were a pair of “seventy-fives” in a field right behind camp.

On March 21 things began to pick up. All the morning I had been hauling rock and more rock, and along towards noon I was tired, dirty, and didn’t much care if school kept or not. I walked into our barracks and started some water boiling to remove my rock hauling makeup (as far as I know, that water is still boiling). Was lying on my bunk when the word came that we were to pack up our stuff and be ready to move at any moment. It was like a bolt out of a clear sky. “Be ready to move,” and we thought we were settled for the rest of the war!

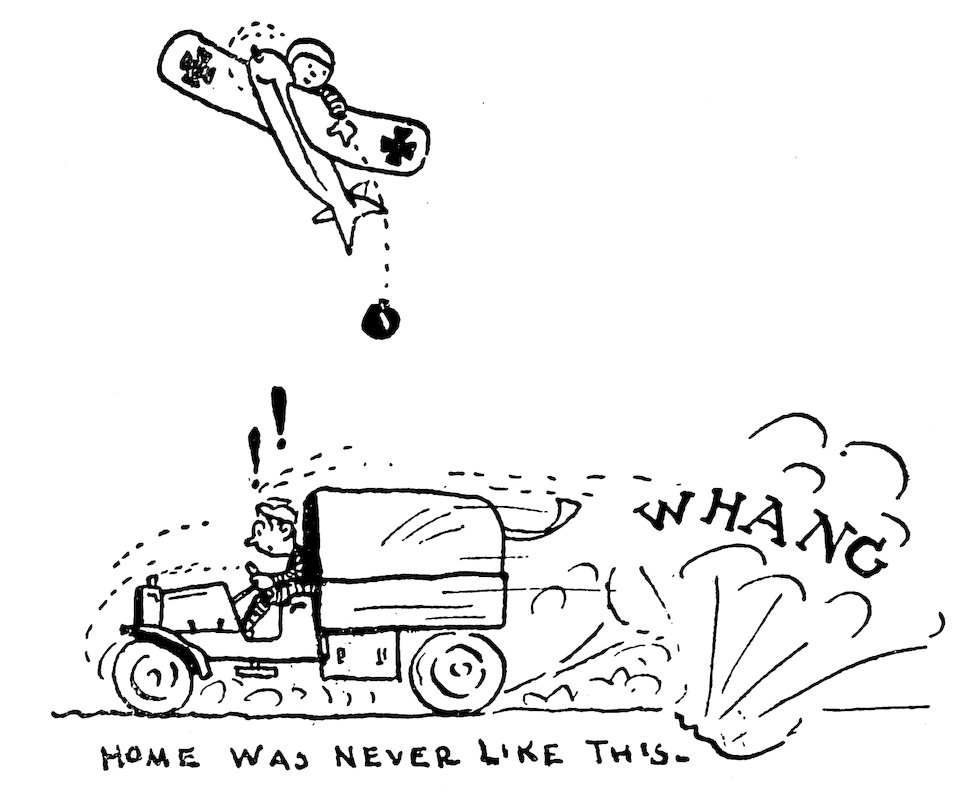

52It did not take long to roll up my blankets, to dump my stuff into my barracks bag, and to lug it all down to my truck. Started to roll my blankets after I got them to the camion, when there came a whistle, a bang, and a shower of dirt, stones, and twigs. A shell had landed on the other side of the river. Before I had time to collect my thoughts there came another whistle. This time I was under the truck ahead of the bang,—more dirt, rocks, and twigs. No wonder they were moving camp! There was a bridge dead ahead of me, about forty yards away. These two shells had just missed the end furthest from me, and I could see that if the bridge was the attraction I didn’t want to stick around. My blankets were still unrolled and I started at them again. Another whistle, another dive, and this time a regular downpour. This shell had landed on my side of the river just off the bridge. Right on its heels came another, and this one saw my exit. I started for camp on the run, but didn’t get far before there came a bang. The concussion floored me and when I picked myself together, saw a bunch of the boys gathered around something under a tree that had been hit.

54The something was one of the boys wounded, in the leg. Why no one else was wounded, or no one killed, is a miracle, as that shell hit where every one seemed to be. No doubt hitting so high up the éclat was thrown over our head. The boy who was wounded is now in the States. His leg is now O. K., but he will always be lame.

56That noon while at lunch two more shells landed in the river, side of the dining room. It seemed as though they were following us. Later on when we turned the trucks around and ran them by camp away from the bridge, the shells began to land up at that end. That night, however, the Huns raised their guns and began to send the shells over our heads towards the railway station. All that night we would hear the whistle of the shells passing over head and the bang in the distance of their landing.

The next day we moved out of Soissons onto the “Route de Paris.” We were just outside the city and all night and most of the day it was bang, bang, bang. The Huns certainly were throwing the shells into the city, and it didn’t make you feel “in the pink,” when you had to go into it for water, and to the storehouse and railway station for supplies. All the time we were there it was “beaucoup” work. We carried a great many troops from one front to another and miles of shells. In fact it was work from then on.

58After a short stay here we carried on to Villa Helon, which is about two kilometers from Longpont. This town was a gem and it certainly was tough when we had to leave. The day we left, May 28, I believe, the town roads were crowded with incoming and outgoing troops.

We moved at about midnight and the Huns gave us a farewell in the shape of a bombing. The French were setting up their famous seventy-five guns in the rear of the chateau as we pulled out. That wonderful chateau is now, no doubt, a heap of ruins.

Refugees were everywhere. Wagons loaded with their goods, people on foot, in carts, on bicycles, all moving towards Paris, crowded the roads.

60From Villa Helon we pushed on to Barcy, stopping over night a couple of times at some towns. Barcy lies just outside the city of Meaux and is right where France turned the Germans back in 1914.

While in this town we carried shell after shell to those points where the heaviest fighting was going on. It was at Chateau-Thierry that we first saw the American troops in number.

What a changed Chateau-Thierry it was when the Boche were driven out! It wasn’t as badly shot up as I expected to find it, but it certainly had been mauled.

62From Barcy we moved to Hardivillers. This small town lies between Breteuil and Crèvecœur-le-Grand, not far from Amiens. In the latter place and beyond, we saw our first of the British. It was in and around Amiens that bombs were the thickest. The country was so open that a night convoi was always an invitation for a bomb. Between Moreuil and Hangest they took twelve shots at us without a hit. That same night, however, they got another section and wounded a couple of men and killed another.

Our next stop was Bus, the town of no roofs and German dugouts, with the nearby woods that sported the German huts. Bus is between Montdidier and Roye. The former city is the worst shot up of any that I have seen. It lies on the top of a hill and is just blown to dust. Not a wall or a tree standing. One could live in Roye without a great deal of rebuilding, but there are only walls left. Ham wasn’t shot up, but burned. While at Bus my permission came through and I left the bunch not knowing where I would find them when I came back.

64Port-à-Binson was where I found them. No doubt you read how the Germans tried to get into Épernay on account of its being a centre for supplies. Port-à-Binson is not far from Épernay, lying on the bank of the river Marne. Here it was I took up the duties of clerk—something I’ll always remember.

When we moved again it was to Jonchery, between Fismes and Rheims. While in the Field Service I had often gone through Fismes; you wouldn’t know it now, ruins is no name for it. From there we rolled on to Malmaison. Here we got the news that the armistice had been signed. Since leaving that town, we have stopped over night in a few other villages until we struck here.

66This account is more or less a bunch of names. I haven’t said much about the work, which has been carrying shells most of the time. Nor have I given much dope on some of the excitement that we have seen. Believe me, we have had a little excitement in the way of bombs, and once in a while, shells.

I wrote about the Boche and their camouflaged plans. That took place at Chézy aux Orxois between Chateau-Thierry and Mareuil sur Ourcq. On that day we were carrying shells and my car being the last had the fusees. You can see that underneath my car was no place at all to use as an abris.

I’m enclosing a bit of German propaganda, some of the bunk that they used to drop from planes. They certainly must have been in a pipe dream if they expected any one to fall for that stuff. Their minds work in a queer way.

68One of the men who used to work in the atelier when we had French workmen, came in to see us the other day. He had just got back from his permission and from seeing his wife and son who had been prisoners. The Huns had cut the forefinger from each of his wife’s hands. That was mild compared with some of the other things that they did.

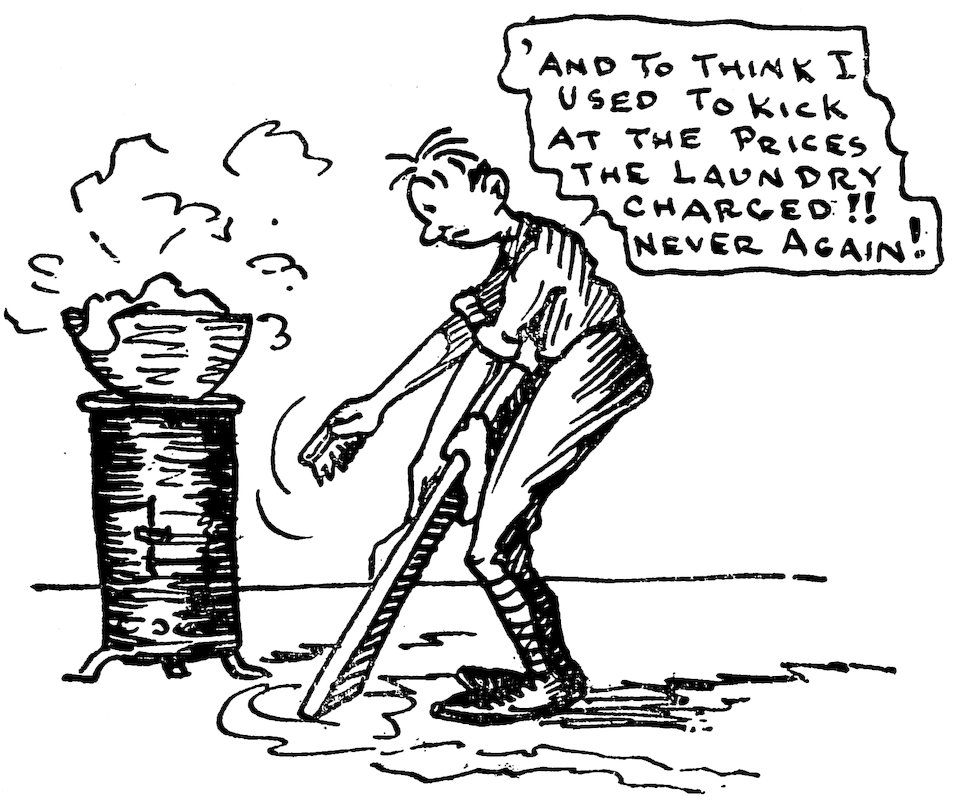

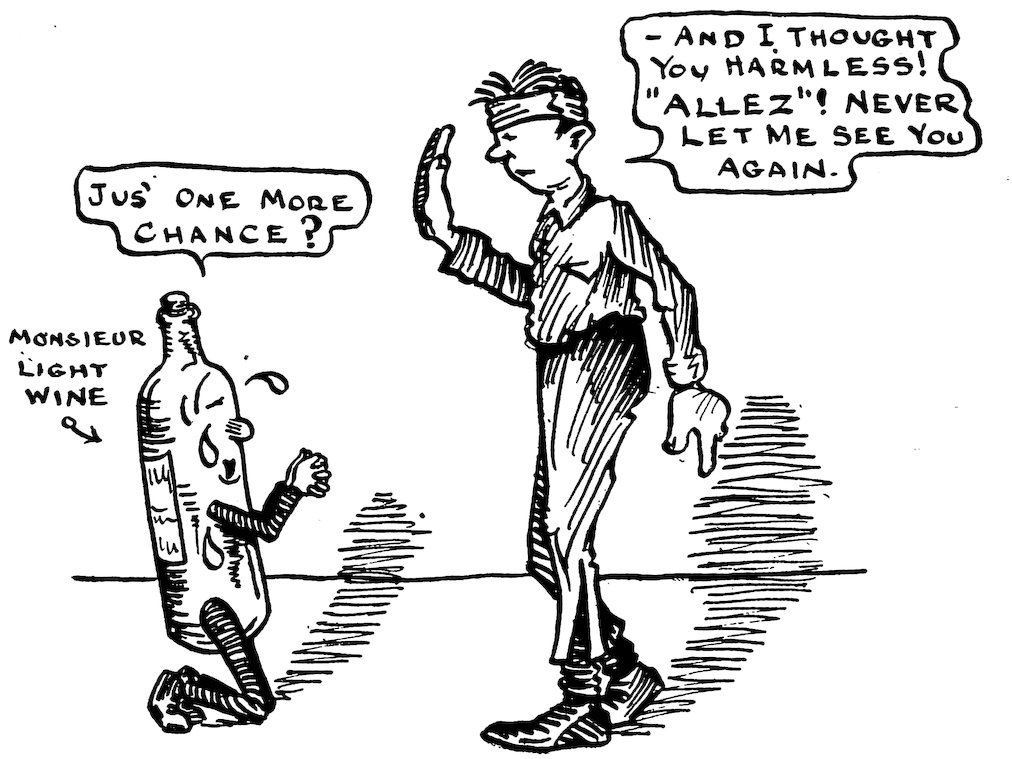

The other night we staged a party. The result is my drawing of Monsieur Light Wine. Never again.

Rumors are flying about. The latest is that all men will return to their original companies. That’s all right, but what becomes of the Field Service men? If it’s all the same to those higher up, I’ll take home.

Winter has at last taken the padlock off. The rain that has been falling for the last few days, has now turned to snow and the temperature has moved from its suite half way up to one near the ground floor. Rubber boots and an over coat are very much in style these days—also a red nose.

We are now taking the count in the village of Boulzicourt near the cities of Mézières and Charleville. Sedan is also quite close by. The day before yesterday I took a trip to Charleville: object, a bath. Managed to catch a ride on a truck going over.

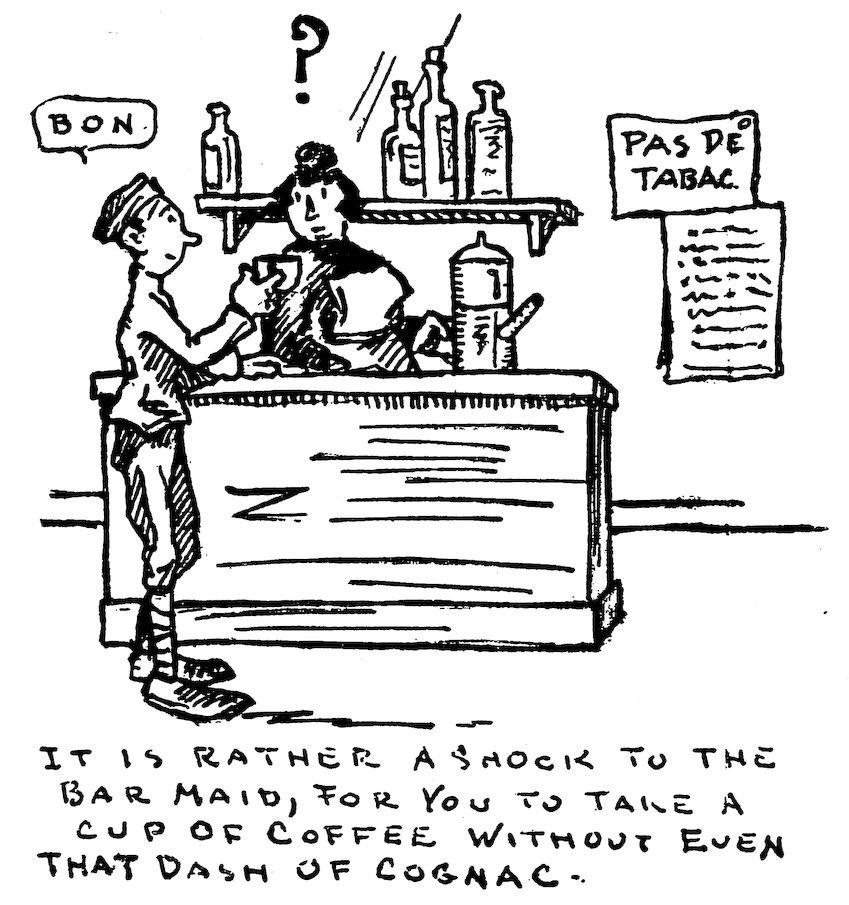

72After the bath, met a couple of the boys and we hustled around to get things fixed up for supper. None of the cafés or restaurants have started in to serve meals so we went into the market and got some steak and potatoes. The prices are sky high, but one has to eat. These we took around to a small café and had them cooked up. The steak was tough, but the “cuisinier” had cooked it in a most delicious way — with Pinard. The potatoes as usual were French Fried. We had brought along our own wine or we would have been out of luck.

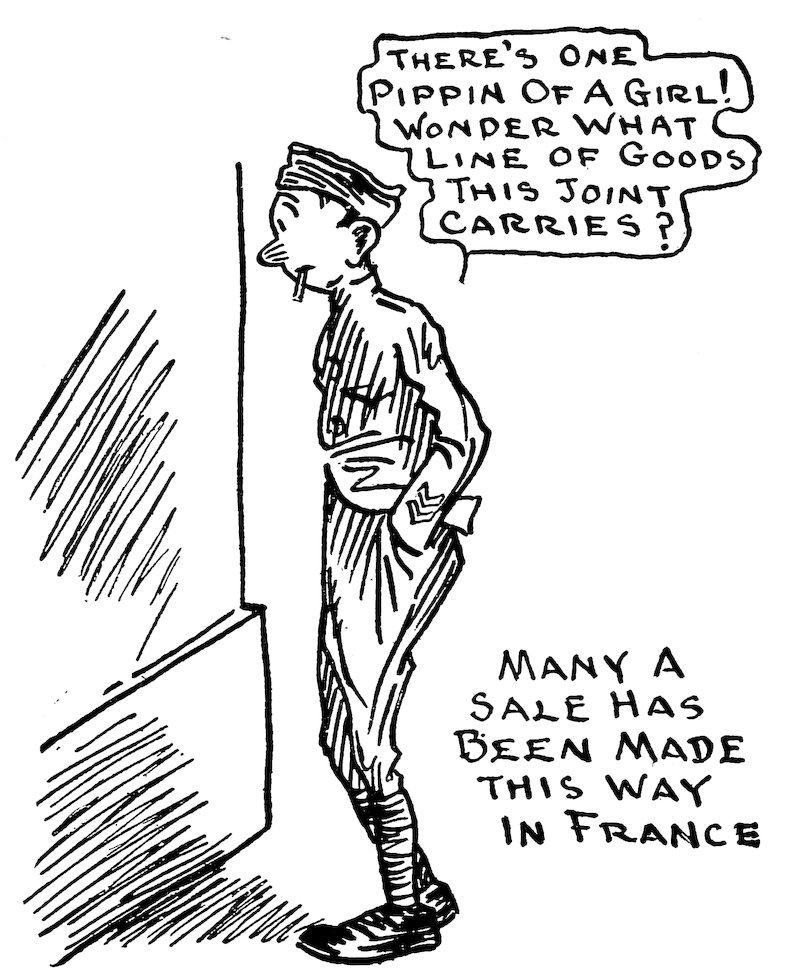

After supper we drifted around to a dance hall. It was crowded, about ten men to one girl, so we didn’t try our luck at the French dancing. All they do is whirl—always in one way and they never reverse. Once in awhile you see someone trying to do the old turkey trot. After sticking around a short while, we started home. No ride this time—no luck at all, so we burnt up the road for the ten kilom’s.

74Yesterday I was over to Sedan. It was raining so hard that I didn’t do much chasing around. Of the two cities Charleville is the more picturesque with its long sloping roofs and its quaint old fashioned French appearance. Sedan looks more modern, more like the States.

The day we moved, five of us got left behind. That is there wasn’t enough room in the remaining camion—the others had pulled out and we thought they were waiting somewhere down the line. The first stop we knew was to be at Boulzicourt, so we started out on foot. All of us were dressed pretty warmly, as we had expected to hold down the front end of a camion. It was raining and soon our overcoats were weighing close to a ton. Up the line about three miles, I discovered that two letters for one of the boys had been forgotten in the shuffle. It was up to me to go back and one of the boys said he’d come along. Back we went and rescued the mail. We got under way again and this time had the luck to jump an ambulance that was going straight through. It was going, it didn’t even hit the high spots. About half way we passed the other three birds riding the back end of a truck. We pulled into Boulzicourt and discovered that the camion had moved on to a place called Flize, which is on the way to Sedan.

78A camion came bowling along so we hopped aboard. Of course it was going to the wrong village, but we didn’t worry—one can always catch a ride. At Mézières the truck pulled up and we jumped off. It was still raining and we weren’t what you would call dry. Hungry and not a thing could be had in the way of food. Nothing in the shops, but we did manage to get coffee. Along towards night, we ran into a Frenchman that set us up to one fine supper with wine and rum. About that time we decided we might as well be setting out for the camp. It was raining great guns and was so dark that we gave it up as a bad job. Instead we got a room over a café. The woman who ran the place came over on the ark. She had remained during the years that the Boche held the town, and, as a consequence kept running in German with her French—something that happens quite frequently in these parts. Our room was a wonder. The bed boasted seven mattresses; reminded me of the fairy story of how to tell a real princess—when a bunch of Janes claimed the crown and to test them out they put them to bed on a stack of mattresses. Underneath was a pea. The fake ones slept like a log, but she of the purple couldn’t sleep at all and, in the morning, she was black and blue from the lump raised by the pea. We either are not of the purple or there was nothing under the mattresses, for we certainly tore off the sleep. Just before we turned in there was an awful banging on Madame’s door, and yells in French, German, and Sanscrit I guess. She had locked herself in. We went out and discovered the key sticking into the lock of her door. We gave it a turn, but the door stayed shut. We gave it a couple of more turns, and tried other combinations—still the door refused to open. In the meantime the old girl was yelling “nicht’s” and “ja’s” and French cuss words. We expected the whole town to show up. Finally Bill had the brilliant idea of seeing how our door worked. We went over to try it out and in fooling with it the door knob came out in my hand. I went over, stuck it into Madame’s door and “Voilà” the caged bird was free. In the morning we set out for Flize.

82It was still raining and we didn’t get a ride. We walked and walked and no sign of camp. My coat was soaked through, my rubber boots were raising the devil with my feet, and my labors had given me a turkish bath. We pulled into Flize, with nothing like a camp in sight. While we were deciding whether to wait around for a ride to Sedan, where the Mission was, or to look for quarters, one of our trucks came panting along. The camp was at Boulzicourt. They had come over near Flize, had stayed two hours, and had gone to Boulzicourt. A staff car came flying along, we got a ride and here we are.

This town is quite large. Our quarters are very comfortable. We are billeted in a French house. Four of us have a front room, and if the sun ever comes out, we should get our share of it. Our fireplace is working all the time and we are kept busy getting wood to keep the home fire burning.

84Madame had us in for coffee the other afternoon. She was here while the Huns held the town. Naturally she has no love for them. What they couldn’t steal they took, and she’s just about left high and dry. Her son was captured at Verdun, but is now home.

The town hasn’t come back to life yet. When it does there are enough cafés to feed and drink us all. Two dance halls with these player pianos are open. Ten centimes sets the music going. They have a total of nine tunes among which is the Merry Widow—you can see how up to date the music is. At nights these places are crowded with the French troops and Italian road workers. All told I’ve seen three girls, all at once, in these places.

86Yesterday my Christmas box showed up. The cigarettes came at the right moment, as for three days I’d been using a corn cob. The “Y” had run out of smokes, and they hardly ever visit us nowadays. The knife was a wonder—too good to use.

The other day some of our trucks hauled champagne. They came through here and stopped for supper, and then went on. They left a few cases behind, so water isn’t very popular just now.

There is a chance of our getting back inside of a year—just a chance. Hate to think of another winter over here. Guess by the time I get back there won’t be anything going on in the states, the war will be a dead issue then.

Of course we had a big feed. The army didn’t come across with any extras, but by scouring the country for miles around our company, and all the companies for that matter, had some meal served up. Here’s our line up—celery soup, roast beef, mashed potatoes, macaroni with cheese and tomatoes, a salad, cake, prune pie, celery, and cocoa. Besides the Red Cross sent cigarettes, candy, and crackers.

![[Artilery shell]](images/i_097.jpg)

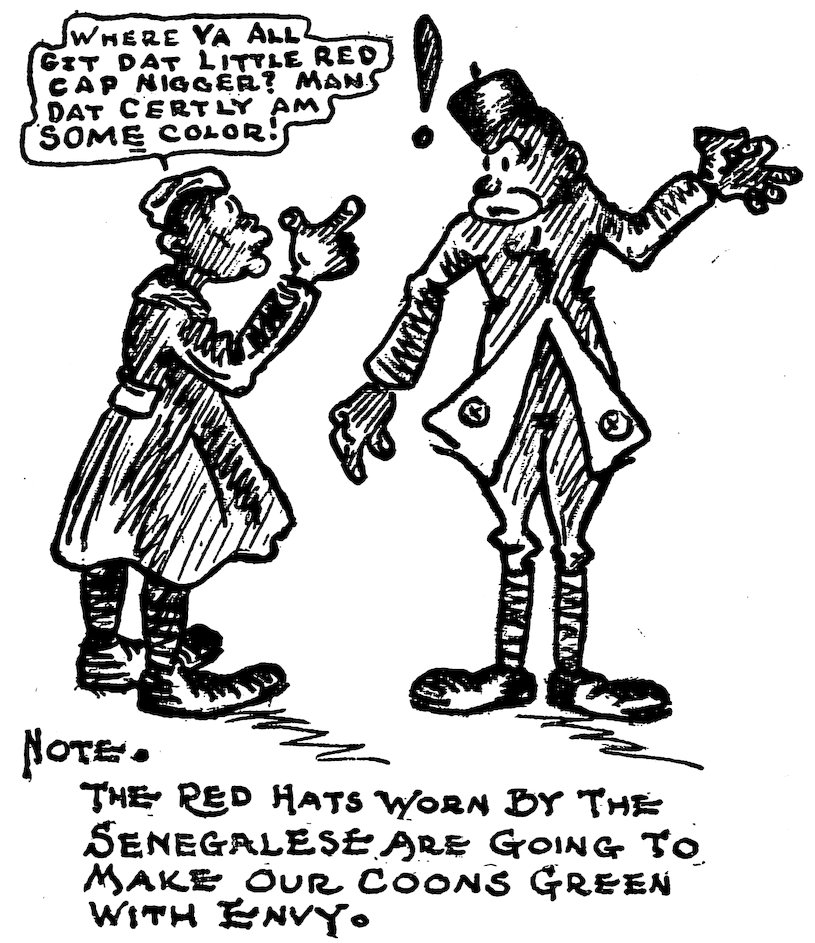

90In the afternoon we took a ride by camion to Sedan where the “Y” was putting on some kind of a show for us. After much cheering, and not missing a single bump we arrived and found that the show was going on—movies were being run off—French movies, a nice long drawn out thing in six or seven parts on Nero, his love affairs, his fiddle, and Rome. I for one wasn’t at all mad when they cut the picture short and started in on some live stuff. After a Lieutenant got a couple of stories off his chest, the ball started. Some real American coons from a near by outfit were the live stuff. They sang by fours, threes, and twos, and when they got tired of that they gave us some A No. 1 clog dancing. Believe me! they could sure shuffle their feet. The “Y” had decked them out in some paper caps which added to the hilarity. They were the whole show and it was worth the trip to see them.

The “Y” also were there with the Christmas tree. We rang the bell for chocolate, cigarettes, a cigar, and cookies.

92The other day I went over to Charleville again. Ran into a place that had real pies—chocolate and apple. Also had cakes. The prices were near the top, but we bought a few notwithstanding. The girl behind the counter could have sold us ice at the North Pole—she was a peach. Two of us told the boys to break away and we would show them something better—and we did. There was a girl in a small café that we had discovered on our last trip. We took the boys along in and they agreed that she was the class. Here we ate the pies and cakes and the girl behind the bar came in for a share. It was a good thing that we were riding in the Ford and not walking, or we would never have got back to camp. Those pies went fine but we ate more than our share I’m afraid.

Last night and today it snowed again—just enough for snow balls. This afternoon we were throwing them with the French kids. They can peg them as well as our boys, but I guess they forget how to use their wing when they get older.

94There are two kids that drop into the office three times a day for their cigarette allowance. The oldest is sixteen and the youngest thirteen. I made the mistake of giving them one the first day and they now take it as a matter of course. Guess I’ll start them to work sweeping out the place on their next visit. That may break them of the habit—like offering a tramp work when he asks for food.

I don’t know if it will work, however, as there are a couple who hang out at our kitchen. They lug all the water, and do all the odd jobs. They are a great help to the K. P.’s—in fact our kitchen police, since these kids came along, live the life of Riley and as for the kids, they eat to their hearts’ content.

96Saw Les. Herrick yesterday. He’s looking fine. We went over the feed we had last Christmas night—it was a wonder. One of the boys reminded me that last Christmas eve we were pulled out of bed eleven times on account of air raids. The Boche did their best to put one over on us, but we fooled them. I’ll never forget those raids. First you would hear the guns barking in the distance. Then the bark would get nearer and nearer. Next the twins would let out their war cry. Finally the Lieut. would stick his head in the door with the words, “I want every man to go to the abri at once.” Then would be the hunt in the dark for shoes, tin derby, gas mask, and coat. Then a few bombs. Then the dash for the abri. Then the standing around wondering how long it was going to last. Then another bark from the twins. Then a few more bombs. Then the dying away buzz of the planes. Then the grand return, only to do it all over again a few minutes later. It was a great life. The Field Service sent a wallet to us for a Christmas present. On the inside there is printed in gold letters “Dernier Noël de la Guerre en France.” Translated literally that means, “It is more blessed to give than to receive.” Understand that they were also going to give us some kind of a medal but they weren’t finished in time and that later on they will come through.

98So another Christmas came and another Christmas passed in France. It was a pretty good Christmas at that, but if it’s all the same to all those concerned I’ll take my next at home.

We have slid into the New Year almost without knowing it. We did, however, have a small celebration New Year’s Eve; but as there was no ringing of bells or tooting of horns at midnight, we had nothing to remind us just what this party was all about.

The night before last the French troops in town put on a show. Stage, scenery, and orchestra were very much there, even a spotlight. The acts were mostly singing ones; sad songs, glad songs, and every old kind of a song were dished up. There were also a couple of monologues thrown in for good luck. They talked so fast that I wasn’t able to get what they were all about, but from the laughs and cheers they must have been not only good but spicy. To wind things up, there was a one-act play. There were two women parts, both taken by French soldiers. They were right there with the looks and form divine. I was able to follow the play and as they say at home, it was rather broad.

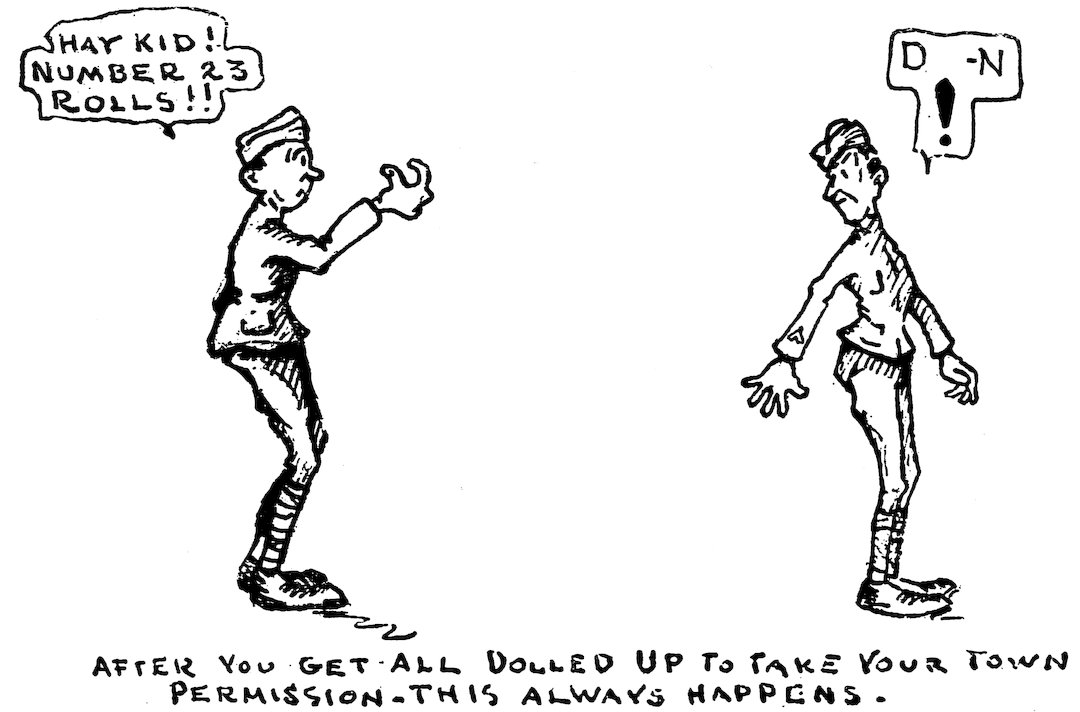

102Today was qualification card day. An officer sits at a table with a card, that has more questions on it than a questionnaire and shoots question after question at you. You are asked everything, from who your favorite actress is to how old is Ann. One question was, “What branch of the service would you choose, if you had to do it all over again?” Guess everyone answered that question the same: “Anything but this.” After all was said and done, it was still a question of when we would get home.

104Went over to Charleville the other day. Same old reason—to get a bath. The bath house was closed, however, there being no water. Going over you came pretty close to collecting on my insurance. We got a ride on a truck, the driver of which would be a wonder as a tank jockey. After missing a few pedestrians, he ended up by trying to do a Brodie off a bridge. Some German prisoners were ahead of us on the bridge, pushing a field range along. There was a space left about big enough for a baby carriage to squeeze by, and “dauntless Harry,” seeing an opening, tried to see if his truck would fit said opening. It didn’t, and the first thing we knew the camion had crashed through the railing and the front wheels were dangling in space. The drop wasn’t a great distance, but if we had taken the fall no doubt we would have been found with the camion resting on the back of our necks.

This week has been full of ’most everything from M. P’s. to Colonels.

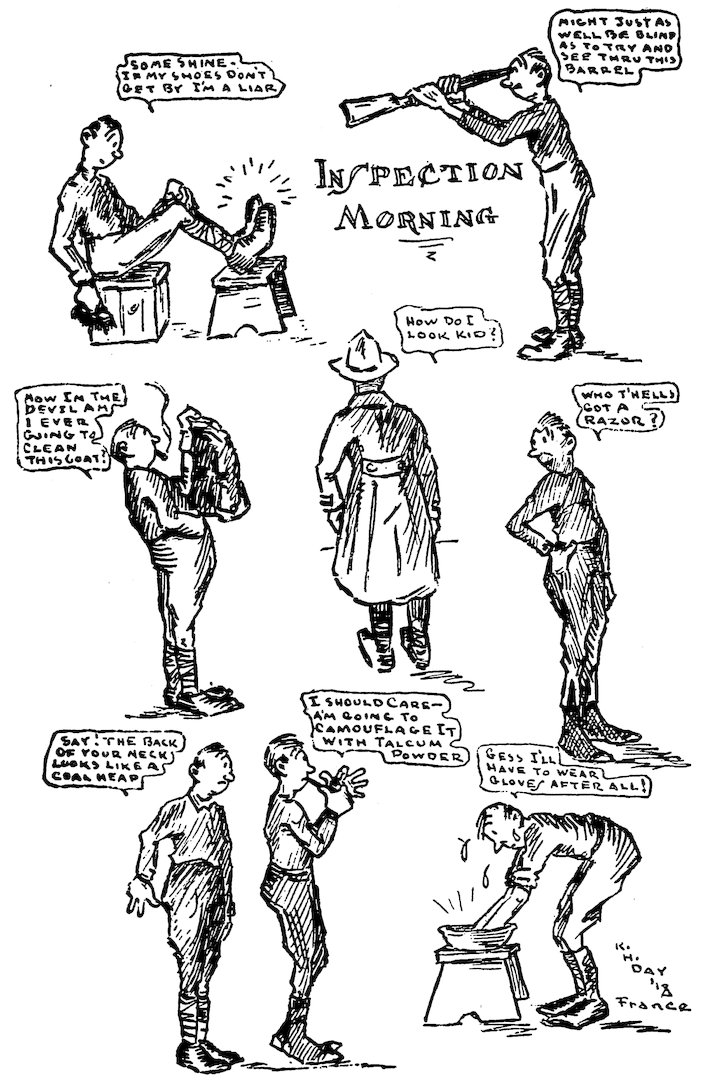

Today the Inspector-General gave us the once over, only he isn’t a General, just a Colonel. You never saw such a scrubbing, brushing, and general cleaning up, as went on. Our quarters looked like a livery stable when we started in, but at the finish the Board of Health would have presented us with a blue ribbon. Clothes were folded up and placed on bunks, shoes shined to a white heat, faces washed and shaved, nails cleaned, and guns dusted off. At two o’clock the curtain went up. Down to the field we marched where we were to be looked over and to look over. We were all curious to see just what kind of an army bird an Inspector-General was. Judging from majors and colonels we had seen, we expected someone who would scare us out of seven years of life when he asked a question. However, this colonel was O. K. and for once an inspection was almost a pleasure. After being given the up and down we marched back to camp where we fell out to stand by our beds for a barracks inspection. We stood by our beds, on which were laid out all our A. E. F. possessions. Being in the company office, and being company clerk, I expected to have all sorts of questions fired at me in regard to service records, reports, and all that goes to make the life of a clerk anything but a joy. However, I didn’t have to open my mouth.

110The inspector said that the French had spoken very highly of us and our work. In fact the French M. T. C. have said that their American Groupes have done more work, rolled more cars, and kept their camions in better conditions than any French section. That if the French had had the camions that we did, the cars would have been in the junk pile long ago.

Our Groupe commander received the Croix de Guerre last Sunday. He says it’s for the work done by his men at the front when they hauled tanks. It was at the time when Lieutenant Edwards was killed.

I’ve been to Luxembourg. Our Lieutenant gave us his permission and Ford to make the trip. Last Saturday at noon we started out. We got to Luxembourg at seven and three of us went into a hotel to get rooms and see about supper. The other two went out on a hunt for a garage. We got the rooms (you never saw such beds), arranged for supper, and then went out to the corner to wait for the return of the jitney jockeys. We had no sooner started waiting than two M. P.’s (military police) gave us the glad hand. Wanted to know what we were doing and if we had passes.

112We told them we were waiting for two boys who had gone to stable a flivver and that our pass was with them. That didn’t seem to please the M. P.’s. (They are always hard to please.) They wanted to know just what our business in Luxembourg was and just what kind of a pass we had. We told them we were in Luxembourg for pleasure only, and that our pass was a red auto pass signed by Major Mallet and countersigned by our Lieutenant. That answer didn’t make the M. P.’s feel any more friendly. Instead they told us in no polite terms to come with them. We went!

114The three of us were marched to the city hall where our names, number, and A. E. F. address was taken, everything but finger prints. The room where this third degree took place was no doubt the club room of the Luxembourg police, as three or four of them were scattered about the scenery. (Their uniform is good enough for any general, if brass buttons count.) After getting our pedigree, an M. P. picked up a very businesslike looking key and invited us to come with him. We went. We were taken to a six by four cell which was already inhabited by two other law breakers. Just about this time we woke up to the fact that we were arrested and questions came thick and fast. The questions didn’t get us anywhere, so we asked to see an A. P. M. officer. There wasn’t any but at twelve o’clock we could see the sergeant of the guard in another jail. Good night! One hundred and fifty kilometers—to be pinched!

116All the time we were wondering what had become of the other two. In about an hour we heard the door out front open and then heard voices in the club room. It was they! The pass was no good, to be good it needed only a General’s scrawl. The gate opened and in they came.

At twelve o’clock we were pulled out and lined up with the rest of that night’s haul. About twenty of us, I should say. We were then marched to the other side of the river to the railroad station. Through the waiting room and upstairs we were taken. A very heavy door was opened and we were pushed into a room. In this room were gathered the round-up from all the smaller jails. There were about fifty of us, and the room was overflowing. No chairs, bunks or pictures, just a dirty floor and a blank wall. The gathering was a rummage sale.

![[Taking a photograph]](images/i_125.jpg)

118About six o’clock the corporal of the guard came in. He looked the room over and asked where the five men were who had the French pass. We spoke up and were told to come with him. We went and were told that our pass was no good, that we could go but would have to leave town at once.

Luxembourg, from what I saw of it, is a wonderful city. Street cars, electric lights, cafés, hotels, stores and at least one good-looking girl, were a few of the things we saw.

No doubt you have noticed that each division has some sort of shoulder insignia. Ours is a yellow trumpet on a green background. It is the coat of arms of the Mallet Reserve. If ever you see on the left sleeve right where it joins the shoulder the yellow trumpet on the green background, you will know that the Mallet Reserve is on its way.