1. New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

2. Certain hyphenation and spelling variations are retained as in original which is sourced by bibliographic references.

3. Footnotes were moved to the end of the book.

4. Illustrations were moved from middle to end of the paragraph.

[i]

SIR JOHN LUBBOCK’S

HUNDRED BOOKS

[ii]

Reprinted

by permission of George Bell and Sons

from “Bohn’s

Standard Library”

for “Sir John Lubbock’s Hundred Books.”

[iii]

Sir John Lubbock’s Hundred Books

THE GREAT INDIAN EPICS

THE STORIES OF THE

RAMAYANA

AND THE

MAHABHARATA

BY

JOHN CAMPBELL OMAN

PROFESSOR OF NATURAL SCIENCE IN THE GOVERNMENT COLLEGE LAHORE

AUTHOR OF “INDIAN LIFE RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL” ETC.

WITH NOTES APPENDICES AND ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW EDITION REVISED

London and New York

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS

LIMITED

[iv]

CHISWICK PRESS:—CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

[v]

The Indian Epics are precious relics of the spring-time of Eastern thought, revealing a new and singularly fascinating world, which differs very remarkably from that depicted in the epic poetry of Western lands. But although these epics are extremely interesting, and although they are accessible in English translations, more or less complete, they are such voluminous works that their mere bulk is enough to repel the ordinary English reader, and even the student, in these days of feverish occupation.

I may, no doubt, be justly reminded that every Indian History, written within recent years, contains abstracts of the two epics; but these abstracts, I would observe, are skeletons rather than miniatures of the poems; they are the dry bones, on which the historians try to support a fabric of historical inferences or conjectures, and they are necessarily deficient in the mythological, romantic and social elements so important to a proper comprehension of the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata.” Besides, when the structures are so colossal, so composite and in many respects so beautiful, there can be no harm in having yet another view of them, taken probably from a new standpoint.

[vi]

In Europe the Homeric poems are very extensively studied in the original Greek; they are productions of very moderate size in comparison with the Indian Epics; many and excellent translations of them, in both prose and verse, are always issuing from the press; and yet condensed epitomes of the “Iliad” and “Odyssey” are welcomed by the reading public, by whom also prose versions of the poetical narratives of even English poets—as Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare and Browning—are favourably received.

Such being the case, I make no apology for the appearance of this little volume, in which I have not only tried to reproduce faithfully, in a strictly limited space, the main incidents and more striking features of those gigantic and wonderful creations of the ancient bards of India—the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata”—but also to direct attention to the abiding influence of those works upon the habits and conceptions of the modern Hindu.

As they are often very incorrectly cited in support of views for which there is no authority whatever in their multitudinous verses, it has been my especial aim to give as accurate a presentment as possible of the Indian Epics, taken as a whole; so that a fair and just idea—neither too high nor too low—of their varied contents and their intellectual level might be formed by the readers of this volume, be they Europeans or Indians. And from what I have recently learned, I have good ground for believing that both classes of readers will, after perusal of this little book, be in a position to see the erroneous character of many ideas in regard to life in ancient India which are current in their respective circles.

[vii]

Where, for any reason, I have especially desired that an event recorded, or an opinion expressed, in the epics should be reproduced without the possibility of misrepresentation on my part, I have thought it best to quote verbatim the translations of them made by Hindu scholars; although, unfortunately, their versions are by no means elegant, and, indeed, often quite the reverse. But as they, no doubt, reflect the structure and texture of the poems in a way that no more free or polished English rendering could possibly do, I fancy the citations I have made will not be unwelcome to most readers.

My book is divided into two distinct parts dealing separately with the “Ramayana” and the “Mahabharata,” and at the end of each part I have given, in the form of an Appendix, one or two of the more striking legendary episodes lavishly scattered through these famous epics, and which, though not essential for the comprehension of the main story, are too beautiful or important to be omitted. Of these episodes I should say that they are the best-known portions of the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata,” having been told and retold in all the leading Indian vernaculars, and having, most of them, been brought before the European world in both prose and verse.

[viii]

A General Introduction to the two poems, and a concluding chapter, containing remarks and inferences based on the materials supplied to the reader in Parts I. and II., complete the scheme of this little volume, which, I trust, will be found to be something more than a mere epitome of the great Sanskrit epics; for, in its preparation, I have had the advantage of considerable local knowledge and an intimate acquaintance with the people of Aryavarta.

J. C. O.

[ix]

| Section | Part / Chapter | Page |

| General Introduction | 1 | |

| PART I.—THE RAMAYANA | ||

| CHAPTER I | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 15 | |

| CHAPTER II | ||

| The Story of Rama’s Adventures | 19 | |

| [x]CHAPTER III | ||

| The Ram Lila or Play of Rama | 75 | |

| APPENDIX | ||

| The Story of the Descent of Ganga | 87 | |

| Notes | 91 | |

| PART II.—THE MAHABHARATA | ||

| CHAPTER I | Introductory Remarks | 95 |

| CHAPTER II | The Story of the Great War | 101 |

| CHAPTER III | The Sacred Land | 197 |

| APPENDIX | ||

| (1) The Bhagavatgita or Divine Song | 207 | |

| (2) The Churning of the Ocean | 219 | |

| (3) Nala and Damayanti | 225 | |

| Notes | 237 | |

| Concluding Remarks | 241 | |

| FOOTNOTES | ||

[xi]

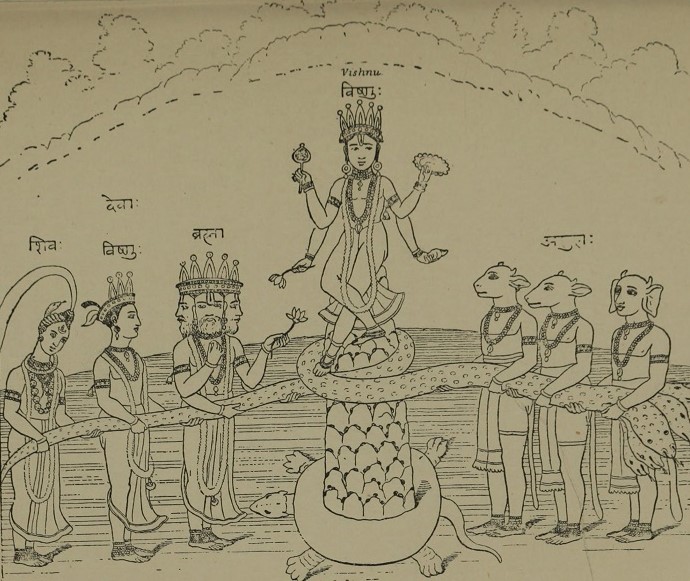

| Illustration | Page | |

| The Abduction of Sita. (From an illustrated Urdu Version) |

face | 50 |

| Hanuman and the Vanars Rejoicing at the Restoration of Sita. (Reduced from Moor’s “Hindu Pantheon”) | face | 70 |

| Men with Knives and Skewers passed through their Flesh.(From a Photograph) | face | 76 |

| “The Terrible Demon King of Lanka and his no less Formidable Brother.” (From a Photograph) | face | 80 |

| The Temple and Bathing Ghâts on the Sacred Lake at Kurukshetra.(From a Photograph) | face | 200 |

| The Churning of the Ocean. (Reduced from Moor’s “Hindu Pantheon”) | face | 220 |

[1]

Foremost amongst the many valuable relics of the old-world literature of India stand the two famous epics, the “Ramayana” and the “Mahabharata,” which are loved with an untiring love by the Hindus, for they have kept alive, through many a dreary century, the memory of the ancient heroes of the land, whose names are still borne by the patient husbandman and the proud chief.[1] These great poems have a special claim to the attention even of foreigners, if considered simply as representative illustrations of the genius of a most interesting people, their importance being enhanced by the fact that they are, to this day, accepted as entirely and literally true by some two hundred millions of the inhabitants of India. And they have the further recommendation of being rich in varied attractions, even when regarded merely as the ideal and unsubstantial creations of Oriental imagination.

Both the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata” are very lengthy works which, taken together, would make up not less than about five and twenty printed volumes[2] of ordinary size. They embrace detailed histories of wars and adventures and many a story that the Western World would now call a mere fairy tale, to be listened to by children with wide-eyed attention. But interwoven with the narrative of events and legendary romances is a great bulk of philosophical, theological, and ethical materials, covering probably the whole field of later Indian speculation. Indeed, the epics are a storehouse of Brahmanical instruction in the arts of politics and government; in cosmogony and religion; in mythology and mysticism; in ritualism and the conduct of daily life. They abound in dialogues wherein the subtle wisdom of the East is well displayed, and brim-over with stories and anecdotes intended to point some moral, to afford consolation in trouble, or to inculcate a useful lesson. To epitomize all this satisfactorily would be quite impossible; but what I have given in this little volume will, I hope, be sufficient to show the nature and structure of the epics, the characteristics that distinguish them as essentially Indian productions, and the light they throw upon the condition of India and the state of Hindu society at the time the several portions were written, or, at any rate, collected together. The narrative, brief though it be, will reflect the more abiding features of Indian national life, revealing some unfamiliar ideas and strange customs. Even within the narrow limits of the reduced picture here presented, the reader will get something more than a glimpse of those famous Eastern sages, whose half-comprehended story has furnished the Theosophists of our own day with the queer notion of their extraordinary Mahatmas; he will learn somewhat of the wisdom and pretensions of those sages, and will not fail to note that the belief in divine incarnations was firmly rooted in India in very early times. He will incidentally acquire a knowledge of all the fundamental[3] religious ideas of the Hindus and of the highest developments of their philosophy; he will also become familiar with some primitive customs which have left unmistakable traces in the institutions of modern social life in the East as well as in the West; and will, perhaps, be able to track to their origin some strange conceptions which are floating about the intellectual atmosphere of our time.

Woven out of the old-time sagas of a remarkable people, “the ancient Aryans of India, in many respects the most wonderful race that ever lived on Earth,”[2] the Sanskrit epics must have a permanent interest for educated people in every land; while all Indian studies must have an attraction for those who desire to watch, with intelligent appreciation, the wonderfully interesting transformations in religion and manners, which contact with Western civilization is producing in the ancient and populous land of the Hindus. Not less interesting will such studies be to those who are able to note the curious, though as yet slight, reaction of Hindu thought upon modern European ideas in certain directions; as, for example, in the rise of Theosophy, in the sentimental tendency manifested in some quarters towards asceticism, Buddhism and Pantheism; in the approval by a small class in Europe of the cremation of the dead, and in the growing fascination of such doctrines as those of metempsychosis and Karma.

Although it is difficult for the Englishman of the nineteenth century to understand the intellectual attitude of modern India in respect to the wild legends of its youth, it may help towards a comprehension of this point if one reflects that had not Christianity superseded the original religions of Northern Europe, had the Eddas and Sagas, with their weird tales of[4] wonder and mystery, continued to be authoritative scripture in Britain, the religious faith of England might now have been somewhat on a par with that of India to-day—an extraordinary medley of the wildest legends and deepest philosophy. It is a subject for wonder how the gods of the ancestors of the English people have entirely faded from popular recollection in Britain, how Sagas and Eddas have been completely forgotten, leaving only a substratum of old superstitions about witchcraft, omens, etc. (once religious beliefs), amongst the more backward of the populace. How many Englishmen ever think, how many of them even know, anything about Thor or Odin and the bloody sacrifices (often human sacrifices)[3] with which those deities were honoured? How many realize that the worship of these gods and the rites referred to had a footing in some parts of Europe as recently as eight hundred years ago?[4]

The almost complete extinction of the ancestral beliefs of the European nations is a striking fact to which the religious history of India presents no parallel. In Europe the great wall of Judaic Christianity—too often cemented with blood—has been reared, in colossal dimensions, between the past and the present, cutting off all communication between the indigenous faiths and modern speculative philosophy of the Western nations; while diverting the affectionate interest of the devout from local to foreign shrines.

No barrier of nearly similar proportions has ever been raised in India. Islam, it is true, has planted its towers in many parts of the country and has, to some restricted extent, blocked the old highways of thought, causing a certain estrangement between the old and new world of ideas; but the severance between[5] the past and the present has nowhere been as complete as in Europe, for many an Indian Muslim, though professing monotheism, still lingers upon the threshold of the old Hindu temples, and still, in times of trouble, will stealthily invoke the aid of the national deities, who are not yet dead and buried like those of the Vikings. Hence it may be asserted of the vast majority of the Indian people that their vision extends reverentially backward, through an uninterrupted vista, to the gods and heroes of their remote ancestors.

And who were those remote ancestors, those Aryan invaders of India in the gray dawn of human history? We have had two answers to that question. A few years ago the philologists assured us, very positively, that the Aryans were a vigorous primitive race whose home was in central Asia and who had sent successive waves of emigration and conquest westwards, right across the continent of Europe, to be arrested in their onward march only by the wide waters of the Atlantic. We were also assured, by these learned investigators into the mysteries of words and languages, that one horde of Asiatic Aryans, instead of following the usual westward course adopted by their brethren, had turned their thoughts towards the sunnier climes of the South, and, scaling the northwestern barrier of India, had conquered the aborigines and settled in the great Indo-Gangetic plain at the foot of the Himalayas. These conclusions find a place in all our text-books of Indian or European history. The schoolboy, who has read his Hunter’s brief history[5] of India, knows well that “the forefathers of the Greek and the Roman, of the English and the Hindu, dwelt together in Central Asia, spoke the same tongue, worshipped the same gods,” and[6] that “the history of ancient Europe is the story of the Aryan settlements around the shores of the Mediterranean.” However, these conclusions have recently undergone revision and radical modification. Within the last decade a theory, which originated in England with Dr. Latham and which met with contemptuous disregard when first propounded, has been revived by certain German savants and scientists.[6] Supported by the latest results of craniological and anthropological investigation, Latham’s theory, in a modified form, has, under the erudite advocacy of Dr. Schrader and Karl Penka, gained all but universal acceptance. The theory now in favour, which is founded more on inferences from racial than linguistic peculiarities, differs from the one referred to above in a very important respect. The home of the Aryans, instead of being found in Central Asia, is traced to Europe, so that the Aryan invaders of India, many centuries before Christ, were men of European descent who pushed their way eastward and gradually extended their dominion first over Iran and subsequently over Northern India, having scaled the snowclad Himalayas, literally in search of “fresh fields and pastures new.” When they reached India, after a long sojourn in Eastern countries, they were a mixed European and Asiatic race, with probably a large share of Turanian blood,[7] speaking a language of Aryan origin.[8] A strong, warlike, aggressive race, these Aryans won[7] for themselves a dominant position in ancient India, and have left to this day the unmistakable traces of their language in many of the vernaculars of the land.

The decision of the question of the origin of the Aryans and the locality of their primitive home is not one of purely antiquarian interest, it is one of national importance, as anyone will be prepared to admit who knows, and can recall to mind, the effect upon the educated Hindus of the announcement that their own ancestors had been the irresistible subjugators of Europe. Whether the Norman conquerors of England were of Celtic or, as the late Professor Freeman insisted, of Teutonic stock, is not unimportant to the Englishman for the true comprehension of his national history and not without some influence even in practical politics; but of far greater moment will it be for the Hindu whether he learn to regard the Aryans of old as an Asiatic or a European race, cradled on the “Roof of the World” or in the flats of the Don.

Although all Hindus look upon the Aryan heroes of the Indian epics as the ancestors of their race, and fondly pride themselves in their mighty deeds, the claim, in the case of the vast majority, is, of course, untenable; since the great bulk of the Indian population has no real title to Aryan descent. Yet Rama and Arjuna are truly Indian creations, enshrined in the sacred literature of the land. And the pride and faith of the Hindus in these demigods has, perhaps, sustained their spirits and elevated their characters, through the vicissitudes of many a century since the heroic age of India.

What genuine facts, or real events, may underlie the poetical narratives of the authors of the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata” will never be known. The details naïvely introduced are often such as to leave[8] an irresistible impression that there is a substratum of substantial truth serving as a foundation for the fantastic and airy structure reared by the poets, and we now and then recognize, for instance in their despairing fatefulness, a distant echo of ideas which have travelled with the Aryan race to the Northern Seas. But the too fertile imagination of the Indian poets, their supreme contempt for details and utter disregard of topographical accuracy, leave little hope of our ever getting any satisfactory history out of the Sanskrit epics, or even of our establishing an identity in regard to localities and details of construction such as has been traced, in our own day, by Schliemann, between the buried citadel of Hissarlik on the Hellespont and vanished Ilion. For those who do not share these opinions there is a wide and deep field for industrious research; but I confess that I am somewhat indifferent regarding the extremely doubtful history or the very fanciful allegory that may be laboriously extracted from the Indian epics by ingenious historians and mythologists. Indeed I would protest against these grand epics being treated as history, for then they must be judged by the canons of historical composition and would be shorn of their highest merits. They are poems not history, they are the romantic legends and living aspirations of a people, not the sober annals of their social and political life.

Like the other great poems created by the genius of the past, the Indian epics have a value quite independent of either the history or the allegory which they enshrine. They appeal to our predilection for the marvellous and our love of the beautiful, while affording us striking pictures of the manners of a bygone age, which, for many reasons, we would not willingly lose.

Being religious books, the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata” are, more or less, known to the Hindus;[9] but it is a noteworthy fact that even educated Indians are but little acquainted with the details of these poems, although both epics have been translated into the leading vernaculars of the country and also into English. I have known educated young men, with more faith in their ancient books than knowledge of their contents, warmly deny the possibility of certain narratives having a place in these books, because, to their somewhat Europeanized ideas, they seemed too far-fetched to be probable. The more striking incidents are, however, familiar to every Hindu, for Brahmans wander all over the country, reciting the sacred poems to the people. They gather an audience of both sexes and all ages and read to them from the venerable Sanskrit, rendering the verses of the dead language of the Aryan invaders of India into the living speech of their hearers. Sometimes the Brahmans read and expound vernacular translations of these poems of Valmiki and Vyasa. Often-times these recitations are accompanied with much ceremony and dignified with a display of religious formalities.[9] Day after day the people congregate to listen, with rapt attention, to the old national stories, and the moral lessons drawn from them, for their instruction, by the Pandits. To this day a considerable proportion of the people of India order much of their lives upon the models supplied by their venerable epics, which have,[10] moreover, mainly inspired such plastic and pictorial work as the Indian people have produced; being for the Hindu artist what the beautiful creations of Greek fancy, or the weird myths of the Middle Ages, have been for his European brother.

Impressed with the importance of some knowledge of the Indian epics on the part of everyone directly or indirectly interested in the life and opinions of the strange and highly intellectual Hindu race, which has preserved its marked individuality of character through so many centuries of foreign domination, I have written, for the benefit of those, whether Europeans or Indians, who may be acquainted with the English language, the brief epitomes of them contained in the following pages; deriving my materials not from the original Sanskrit poems, which are sealed books to me, but from the translations, more or less complete and literal, of these voluminous works, which have been given to the world by both European and Indian scholars. On all occasions where religious opinions or theological doctrines are concerned I have given the preference to the translations of native scholars, as I know that Indian Sanskritists have a happy contempt for Western interpretations of their sacred books, and it seemed very desirable, in such a case, to let the Hindus speak for themselves. Besides, I am of opinion that the English versions of the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata,” now being given to the world by Indian scholars, have a unique value, which later translations will, in all probability, not possess. The present translators are orthodox Hindus possessing a competent knowledge of English, and their aim has been to produce English versions of their sacred poems, as understood and accepted by themselves and by the orthodox Indian world to-day, their renderings, no doubt, reflecting the traditional interpretation handed down from past times. Hereafter we shall have more[11] learned translations, in which European ideas will do duty for Indian ones, and the old poems will be interpreted up to our own standard of science and philosophy. In wild legends we shall discover subtle allegories veiling sober history, in license and poetry we shall find deep religious mysteries, and in archaic notions shall recognize, with admiration, the structure of modern philosophy. Something of this has already come about, and that the rest is not far-off is evident; for we have only recently been told, that “in the shlokas of the ‘Ramayana’ and ‘Mahabharata’ we have many important historical truths relating to the ancient colonization of the Indian continent by conquering invaders ... all designedly concealed in the priestly phraseology of the Brahman, but with such exactitude of method, nicety of expression and particularity of detail, as to render the whole capable of being transformed into a sober, intelligible and probable history of the political revolutions that took place over the extent of India during ages antecedent to the records of authentic history, by anyone who will take the trouble to read the Sanskrit aright through the veil of allegory covering it.”[10]

While regretting my shortcomings in respect to the language of the bards who composed the Sanskrit epics, since I am thereby cut off from appreciating the beauty of their versification and the felicities of expression which no translation can possibly preserve, I derive consolation from the reflection, that with sufficiently accurate translations at hand—similar to our English versions of the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures—a knowledge of Sanskrit is certainly not essential for the production of a work with the moderate pretensions of this little volume.[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS

Once every year, at the great festival known as the Dasahra, the story of the famous Hindu epic, the “Ramayana,” is, throughout Northern India, recalled to popular memory, by a great out-door dramatic representation of the principal and crowning events in the life of the hero, Rama. The “Ramayana” is not merely a popular story, it is an inspired poem, every detail of which is, in the belief of the great majority of the Indian people, strictly true. Although composed at least nineteen centuries ago, it still lives enshrined in the hearts of the children of Aryavarta and is as familiar to them to-day as it has been to their ancestors for fifty generations. Pious pilgrims even now retrace, step by step, the wanderings, as well as the triumphal progress, of Rama, from his birth-place in Oudh to the distant island of Ceylon. Millions believe in the efficacy of his name alone to insure them safety and salvation. For these reasons the poem is of especial value and interest to anyone desirous of understanding the people of India; affording, as it does, an insight into the thoughts and feelings of the bard or bards who composed it and of a race of men who, through[16] two thousand eventful years, have not grown weary of it.

In the following chapters I shall first give a brief summary of the leading events narrated in the “Ramayana” and then proceed to link, as it were, the past with the present, by describing the annual play as I have often witnessed it in Northern India.

The “Ramayana,” written in the Sanskrit language, embraces an account of the birth and adventures of Rama. The whole poem, which is divided into seven books or sections, contains about fifty thousand lines and occupies five goodly volumes in Mr. Ralph Griffith’s metrical translation,[11] which is, to a certain extent, an abridged version. To Valmiki is attributed the authorship of this famous epic, and a pretty story is told of the manner in which he came to write it. A renowned ascetic, a sort of celestial being, named Narada, had related to Valmiki the main incidents of the adventurous life of Rama, and had deeply interested that sage in the history of the hero and his companions. Pondering the events described by Narada, Valmiki went to the river to bathe. Close at hand two beautiful herons, in happy unconsciousness of danger, were disporting themselves on the wooded bank of the stream, when suddenly one of the innocent pair was laid prostrate by the arrow of an unseen fowler. The other bird, afflicted with grief, fluttered timidly about her dead mate, uttering sore cries of distress. Touched to the heart by her plaintive sorrow, Valmiki gave expression to his feelings of irritation and sympathy in words which, to his own surprise, had assumed a rhythmic measure and were capable of being chanted with an instrumental accompaniment. Presently, Brahma himself, the Creator of all, visited the sage in [17] his hermitage, but Valmiki’s mind was so much occupied with the little tragedy at the river-side, that he unconsciously gave utterance to the verses he had extemporized on the occasion. Brahma, smiling, informed the hermit that the verses had come to his lips in order that he might compose the delightful and instructive story of Rama in that particular measure or shloka. Assuring Valmiki that all the details of the stirring tale would be revealed to him, the Supreme Being directed the sage to compose the great epic, which should endure as long as the mountains and seas exist upon this earth. How Valmiki acquired a knowledge of all the details of the story is worth remembering, as being peculiarly Indian in its conception.

“Sitting himself facing the east on a cushion of Kusa grass, and sipping water according to the ordinance, he addressed himself to the contemplation of the subject through Yoga.[12] And, by virtue of his Yoga powers, he clearly observed before him Rama and Lakshmana, and Sita, and Dasahratha, together with his wives, in his kingdom, laughing and talking and acting and bearing themselves as in real life.”[13] [18]

[19]

THE STORY

The story of the “Ramayana,” in brief outline, is as follows:

In the ancient land of Kosala, watered by the River Surayu, stood the famous Ayodhya,[14] a fortified and impregnable city of matchless beauty, and resplendent with burnished gold, where everyone was virtuous, beautiful, rich and happy. Wide streets traversed this city in every direction, lined with elegant shops and stately palaces glittering all over with gems. There was no lack of food in Ayodhya, for “it abounded in paddy and rice, and its water was as sweet as the juice of the sugar-cane.” Gardens, mango-groves and “theatres for females” were to be found everywhere. Dulcet music from Venas and Panavas resounding on all sides, bore evidence to the taste of the people. Learned and virtuous Brahmans, skilled in sacrificial rites, formed a considerable proportion of the population; which also included a crowd of eulogists and “troops of courtesans.” The pride of ancient families supported a large number of genealogists. Hosts of skilled artisans of every kind contributed to the conveniences and elegancies of life, while an army[20] of doughty warriors protected this magnificent and opulent city from its envious foes. Over this wonderful and prosperous capital of a flourishing kingdom, ruled King Dasahratha, a man some sixty thousand years of age, gifted with every virtue and blessed beyond most mortals. But, as if to prove that human happiness can never exist unalloyed with sorrow, even he had one serious cause for grief; he was childless, although he had three wives and seven hundred and fifty concubines.[15] Acting upon the advice of the priests, the Maharajah determined to offer, with all the complicated but necessary rites, the sacrifice of a horse, as a means of prevailing upon the gods to bless his house with offspring. The accomplishment of such a sacrifice was no easy matter, or to be lightly undertaken, even by a mighty monarch like Dasahratha, since it was an essential condition of success that the sacrifice should be conducted without error or omission in the minutest details of the ritual of an intricate ceremony, extending over three days. Not only would any flaw in the proceedings render the sacrifice nugatory, but it was to be feared that learned demons (Brahma-Rakshasas), ever maliciously on the look-out for shortcomings in the sacrifices attempted by men, might cause the destruction of the unfortunate performer of an imperfect sacrifice of such momentous importance. However, the sacrifice was actually performed on a magnificent scale and most satisfactorily, with the assistance of an army of artisans, astrologers, dancers, conductors of theatres, and persons learned in the ceremonial law. Birds, beasts, reptiles, and aquatic animals were sacrificed by the priests on this auspicious[21] occasion, but the sacred horse itself was despatched, with three strokes, by the hand of Kauçalya, Dasahratha’s queen. When the ceremonies had been conducted to a successful close, Dasahratha showed his piety and generosity by making a free gift of the whole earth to the officiating priests; but they were content to restore the magnificent present, modestly accepting in its stead fabulous quantities of gold and silver and innumerable cows.

The gods, Gandharvas and Siddhas, propitiated by the offerings profusely made to them, assembled, each one for his share,[16] and Dasahratha was promised four sons.[17] While these events were transpiring, a ten-headed Rakshasa named Ravana was making himself the terror of gods and men, under the protection of a boon bestowed upon him by the Creator (Brahma), that neither god nor demon should be able to deprive him of his life. This boon had been obtained by the Rakshasa as the reward of long and painful austerities.[18]

[22]

The hierarchy of minor gods, in their own interest and for the sake of the saints who were constantly being disturbed in their devotions by this Ravana and his fellows, appealed to the Supreme Deity to find some remedy for the evil. Brahma, after reflecting on the matter, replied—

“One only way I find

To stay this fiend of evil mind.

He prayed me once his life to guard

From demon, God and heavenly bard,

And spirits of the earth and air,

And I consenting heard his prayer.

But the proud giant in his scorn,

Recked not of man of woman born,

None else may take his life away

But only man the fiend may slay.”

—Griffith.

On receiving this reply the gods petitioned Vishnu to divide himself into four parts and to appear on earth, incarnate as the promised sons of Dasahratha, and thus, in human form, to rid the world of Ravana. Vishnu consented. He proceeded to the earth and appeared amidst the sacrificial flames of Dasahratha’s offering, in an assumed form “of matchless splendour, strength and size”—black, with a red face, and shaggy hair—apparelled in crimson robes, and adorned with celestial ornaments, holding in his hands a vase of gold, containing heavenly nectar, which he handed to the king, with instructions to make his three queens[23] partake of the sacred draught, in order that they might be blessed with sons.

Dasahratha distributed the nectar amongst his wives, though not in equal proportions. In due time the promised sons were born, viz., Rama, Lakshmana, Bharata and Satrughna. Rama possessed the larger share of the divine nature and decidedly excelled his brothers in prowess. To him, especially, was allotted the task of destroying Ravana. And countless hosts of monkeys and bears were begotten by the gods, at Brahma’s[19] suggestion, to aid him in his work.

Whilst yet a mere stripling, Rama was appealed to by the sage Vishwamitra to destroy certain demons who interrupted the religious rites of the hermits.

The boy was only sixteen years of age, and Dasahratha, naturally solicitous for his safety, declined to let him go to fight the dreadful brood of demons, who had an evil reputation for cruelty and ferocity; but the mighty ascetic waxed so wrath at this refusal of his request, that “the entire earth began to tremble and the gods even were inspired with awe.” Vasishta, the king’s spiritual adviser, who had unbounded confidence in Vishwamitra’s power to protect the prince from all harm, strongly advised compliance with the ascetic’s request, and Dasahratha was prevailed upon to allow Rama and Lakshmana to leave Ayodhya with Vishwamitra.

The incidents of the journey reveal a very primitive state of society. The princes and their guide were all of them on foot, apparently quite unattended by servants and unprovided with even the most ordinary necessaries of life. When they reached the River Surayu,[20] Vishwamitra communicated certain mantras[24] or spells to Rama, by the knowledge of which he would be protected from fatigue and fever[21] and from the possibility of being surprised by the Rakshasas against whom he was going to wage war.

The land through which our travellers journeyed was sparsely inhabited. A goodly portion of it seems to have been covered with woods, more or less pleasant, abounding in the hermitages of ascetics, some of whom had been carrying on their austerities for thousands of years. Beside these pleasant woods there were vast, trackless forests, infested by ferocious beasts and grim Rakshasas, and it was not long before the might of the semi-divine stripling, Rama, was tried against one of these terrible creatures, Tarika by name, an ogress of dreadful power, whom Rama undertook to destroy “in the interests of Brahmans, kine and celestials.” When the ascetic and the two princes arrived in the dark forest where the dreaded Tarika ruled supreme, Rama twanged his bowstring loudly, as a haughty challenge to this redoubtable giantess. Incensed at the audacious sound of the bowstring, Tarika uttered terrible roars and rushed out to attack the presumptuous prince. The ascetic raised a defiant roar in response. That was his entire contribution to the combat in which Rama and his adversary were immediately involved, Lakshmana taking part in it also. This, the first conflict in which Rama was engaged, may be taken as a type of all his subsequent battles. Raising clouds of dust, Tarika, “by help of illusion,” poured a shower of huge stones upon the brothers, but these ponderous missiles were met and arrested in mid-air by a volley of arrows. The battle raged fiercely, but the brothers succeeded with their shafts in depriving Tarika of her hands, her[25] nose and her ears. Thus disabled and disfigured, Tarika changed her shape[22] and even concealed herself from view, while still continuing the fight with unabated fury; but Rama, guided by sound alone, assailed his invisible foe with such effect that he eventually laid her dead at his feet, to the joy of Vishwamitra and the relief of the denizens of the great forest over which she had terrorized.

After this successful combat, the ascetic, Vishwamitra, conferred on Rama a gift of strange weapons, which even the celestials were incapable of wielding. How very different the magic weapons received by Rama were from those familiar to the sons of men, will be apparent from the poet’s statement that the weapons themselves made their appearance spontaneously before Rama, “and with clasped hands, they, well-pleased, addressed Rama thus: These, O highly generous one, are thy servants, O Raghava. Whatever thou wishest, good betide thee, shall by all means be accomplished by us.”

Such wonderful and efficient weapons, endowed with a consciousness and individuality of their own, needed, however, to be kept under strict control, lest in their over-zeal or excitement they might effect undesigned and irreparable mischief. The sage accordingly communicated to Rama the various mantras or spells by which they might, on critical occasions, be restrained and regulated in their operations.

In their woodland wanderings amongst the hermitages the brothers and their guide came across many sages whose laborious austerities were constantly being hindered by wicked, flesh-eating Rakshasas. Indeed the world, outside the cities and villages,—which[26] it would seem were very few and far between,—as pictured by Valmiki, is a very strange one, mostly peopled by two sets of beings, hermits striving after supernatural power through the practice of austerities, and demons bent on frustrating their endeavours by unseasonable interruptions of their rites, or impious pollution of their sacrifices. Sometimes, as in the case of Ravana, the demons themselves would practise austerities for the attainment of power.

Very prominent figures in the poem are the great ascetics, like Vishwamitra himself, who, a Kshatriya by caste and a king by lineage, had obtained, through dire austerities prolonged over thousands of years, the exalted rank and power of Brahmanhood. A single example of his self-inflicted hardships and the consequences resulting therefrom may not be out of place. He once restrained his breath for a thousand years, when vapours began to issue from his head, “and at this the three worlds became afflicted with fear.” Like most of his order, he was a very proud and irate personage, ready, upon very slight provocation, to utter a terrible and not-to-be-escaped-from curse.[23] Once, in a fit of rage against the celestials, Vishwamitra created entire systems of stars and even threatened, in his fury, to create another India by “the process of his self-earned asceticism.”

The life led by the princely brothers in their pedestrian wanderings with this mighty sage was simplicity itself. They performed their religious rites regularly, adoring the rising sun, the blazing fire or the flowing river, as the case might be. Their sojourn in the forests was enlivened by pleasant communion[27] with the hermits to whose kind hospitality they were usually indebted for a night’s lodging, if such it can be called, and a simple fare of milk and fruits. Vishwamitra added interest to their journeyings by satisfying the curiosity of the brothers in regard to the history of the several places they visited. Here, as he informed them, the god Rudra had performed his austerities—for even the gods were not above the necessity and ambition of ascetic practices—and blasted the impious Kama into nothingness with a breath. There, the great god Vishnu of mighty asceticism, worshipped of all the deities, dwelt during hundreds of Yugas, for the purpose of carrying on his austerities and practising yoga.[24] At one time Vishwamitra would relate the history of the origin of Ganga and of her descent upon the earth, as the mighty and purifying Ganges, chief of rivers. At another time he would himself listen complacently, along with his princely companions, to the history of his own wonderful asceticism and marvellous performances, as the wise Satananda related it for the special edification of Rama.

So passed away the time in the forests, not altogether peacefully, however, for the object of the journey would not have been fulfilled without sundry fierce and entirely successful encounters with the Rakshasas, those fiendish interrupters of sacrifice and persistent enemies of the anchorites. Eventually the wanderers came to the kingdom of Mithila, whose king, Janaka,[25] had a lovely daughter to bestow upon the worthy and fortunate man who should bend a certain formidable[28] bow which had belonged to Siva and which he had once threatened to use in the destruction of the gods.

Janaka’s daughter, the famous Sita, whose matrimonial future was thus connected with Siva’s bow, was of superhuman origin, having sprung from the earth in a mysterious manner; for, while Janaka was ploughing the ground in the course of a child-conferring sacrifice, the lovely maiden had, by the favour of the gods, come to him out of the furrow.

Allured by the fame of Sita’s beauty, suitor after suitor had come to Mithila and tried that tough bow of Siva’s, but without success; and Rama’s curiosity was awakened about both the mighty weapon and the maiden fair.

Having been introduced by Vishwamitra to the King of Mithila, Rama was allowed to essay his strength against the huge bow, and huge it was indeed, for it had to be carried on an eight-wheeled cart which “was with difficulty drawn along by five thousand stalwart persons of well-developed frames.” To Rama, however, the bending of this gigantic bow was an easy matter, and he not only bent but broke it too, at which event all present, overwhelmed by the noise, rolled head over heels, with the exception of Vishwamitra, the “king and the two Raghavas.” The lovely and much-coveted prize was Rama’s of course. Arrangements for the wedding were carried out in grand style. Dasahratha and his two other sons were invited to Mithila and brides were found, in the family of Janaka, for all the four brothers. Upon a daïs covered with a canopy, and decked with flowers, the happy brides and bridegrooms were placed, attended by the king and the priests of the two families. Water-pots, golden ladles, censers, and conches, together with platters containing rice, butter, curds and other things for the Hom sacrifice, were also arranged for use on the platform. The sacrificial fire was lighted,[29] the appropriate mantras repeated, and the four bridegrooms led their brides first round the fire, and then round the king and the priests. At this stage of the proceedings showers of celestial flowers rained down upon the happy couples, now united in the bonds of matrimony.[26] After these marriages the return to Ayodhya was accomplished with rejoicings and in great state; but Vishwamitra took his solitary way to the Northern Mountains.

As the years went by and Rama was grown to man’s estate he was endowed with every princely virtue; the people idolized him, and his father, desirous of retiring from the cares of government, determined to place him upon the throne. But, although apparently simple of execution, this arrangement was beset with difficulties. Rama was the son of the Rajah’s eldest and principal wife; but Bharata was the son of his favourite wife, the slender-waisted Kaikeyi. The suffrages of the people and Dasahratha’s own wishes were entirely in favour of Rama, but, apparently unwilling to face the grief or opposition of his darling Kaikeyi, the king took advantage of Bharata’s absence on a visit to a distant court to carry out the rather sudden preparations for Rama’s installation as Yuva-Rajah, hoping, it would seem, to keep Kaikeyi in complete ignorance of what was being done. The whole city, however, was in a state of bustle and excitement at the approaching event. The streets were being washed and watered, flag-staffs were being erected on every side, gay bunting was floating about and garlands of flowers adorned the houses. Musicians played in the highways and in the temples, and, notwithstanding the seclusion of the women’s apartments, it was impossible to conceal from[30] the inmates of the zenana what was going on in the great world outside. A deformed and cunning slave-girl, named Manthara, found out and revealed the whole plot to Bharata’s mother. At first Kaikeyi received the intelligence with pleasure, for Rama was dear to everybody; but the slave-girl so worked upon her feelings of envy and jealousy, by artfully picturing to her the very inferior position she would hold in the world’s estimation, the painful slights she would have to endure and the humiliation she would have to suffer, once Kauçalya’s son was raised to the throne, that in a passion of rage and grief, she threw away her ornaments and, with dishevelled hair, flew to the “chamber of sorrow” and flung herself down upon the floor, weeping bitterly. Here the old king found her “like a sky enveloped in darkness with the stars hid” and had to endure the angry reproaches of his disconsolate favourite. Acting upon a suggestion of the deformed slave-girl, the queen reminded her husband of a promise made by him long previously, that he would grant her any two requests she might make. She now demanded the fulfilment of the royal promise, her two requests being that Rama should be sent away into banishment in the forests for a period of fourteen years and that her own son Bharata should be elevated to the dignity of Yuva-Rajah. On these terms, and on these only, would the offended and ambitious Kaikeyi be reconciled to her uxorious lord. If these conditions were refused she was resolved to rid the king of her hated presence. Dasahratha, poor old man, was overwhelmed by this unexpected crisis. He fell at his wife’s feet, he explained that preparations for Rama’s installation had already commenced, he besought her not to expose him to ridicule and contempt, he coaxed and flattered her, alluding to her lovely eyes and shapely hips, he extolled Rama’s affectionate devotion to herself. He next heaped bitter reproaches upon Kaikeyi’s unreasonable[31] pride and finally swooned away in despair. But she was firm in her purpose and would not be shaken by anything, kind or unkind, that this “lord of earth” could say to her. The royal word she knew was sacred, and had to be kept at any cost.

As soon as it came to be known what a strange and unforeseen turn events had taken, the female apartments were the scene of loud lamentations, and the entire city was plunged in mourning. Rama, of expansive and coppery eyes,[27] long-armed, dark blue like a lotus, a mighty bowman of matchless strength, with the gait of a mad elephant, brave, truthful, humble-minded, respectful and generous to Brahmans, and having his passions under complete control, was the idol of the zenana, the court, and the populace. The thought of his unmerited banishment to the forests was intolerable to everyone. But he himself, with exemplary filial devotion, prepared to go into exile at once, without a murmur. The poet devotes considerable space to a minute description of the sorrow experienced by the prominent characters in the story on account of Rama’s banishment. Each one indulges in a lengthy lamentation, picturing the privations and sufferings of the ill-fated trio, and nearly everyone protests that it will be impossible to live without Rama. With affectionate regard for Sita’s comfort, and loving apprehension for her safety, Rama resolved to leave her behind with his mother; but no argument, no inducement, could prevail upon the devoted wife to be parted from her beloved husband. What were the terrors of the forest to her, what the discomfort of the wilderness, when shared with Rama? Racked with sorrow at the proposed separation, Sita burst into a flood of[32] tears and became almost insensible with grief. At the sight of her tribulation Rama, overcome with emotion, threw his arms about his dear wife and agreed to take her with him, come what may.

Lakshmana, with devoted loyalty, would also accompany his brother into exile.

Kaikeyi, apprehensive of delays, hurried on their preparations, and herself, unblushingly, provided them with the bark dresses worn by ascetics. The two brothers donned their new vestments in the king’s presence.

“But Sita, in her silks arrayed,

Threw glances, trembling and afraid,

On the bark coat she had to wear

Like a shy doe that eyes the snare.

Ashamed and weeping for distress

From the queen’s hand she took the dress.

The fair one, by her husband’s side,

Who matched heaven’s minstrel monarch, cried:

‘How bind they on their woodland dress,

Those hermits of the wilderness?’

There stood the pride of Janak’s race

Perplexed, with sad appealing face,

One coat the lady’s fingers grasped,

One round her neck she feebly clasped,

But failed again, again, confused

By the wild garb she ne’er had used.

Then quickly hastening Rama, pride

Of all who cherish virtue, tied

The rough bark mantle on her, o’er

The silken raiment that she wore.

Then the sad women when they saw

Rama the choice bark round her draw,

Rained water from each tender eye

And cried aloud with bitter cry.”[28]

—Griffith.

[33]

After giving away vast treasures to the Brahmans the ill-fated trio took a pathetic leave of the now miserable old king, of Kauçalya who mourned like a cow deprived of her calf, of Sumitra the mother of Lakshmana, and of their “other three hundred and fifty mothers.” With an exalted sense of filial duty the exiles also bid a respectful and affectionate farewell to Kaikeyi, the cruel author of their unmerited banishment, Rama remarking that it was not her own heart, but “Destiny alone that had made her press for the prevention of his installation.”

When Rama and his companions appeared in the streets of the capital, in the dress of ascetics, the populace loudly deplored their fate, extolling the virtues of Rama while giving vent to their feelings of disapproval at the king’s weak compliance with his favourite’s whim. Sita came in for her share of popular pity and admiration, since she “whom formerly the very rangers of the sky could not see, was to-day beheld by every passer-by.”

A royal chariot conveyed away to the inhospitable wilderness the two brothers and faithful Sita, torn from stately Ayodhya, their luxurious palaces and the arms of their fond parents. All they carried with them, in the chariot, was their armour and weapons, “a basket bound in hide and a hoe.” Crowds of people, abandoning their homes, followed in the track of the chariot, resolved to share the fate of the exiles. And such was the grief of the people that the dust raised by the wheels of the car occupied by Rama and his companions was laid by the tears of the citizens. They drove at once to the jungles and rested there for the night. During the hours of slumber the exiles considerately gave their followers the slip and hurried off, in the chariot, towards the great forest of Dandhaka. When they arrived at the banks of the sacred and delightful Ganges the charioteer was dismissed with[34] tender messages to the old king from his exiled children. After the departure of the charioteer Rama and his companions began their forest wanderings on foot. Their hermit-life was now to commence in earnest. Before entering the dark forests that lay before them, the brothers resolved to wear “that ornament of ascetics, a head of matted hair,” and, accordingly, produced the desired coiffure with the aid of the glutinous sap of the banyan tree. Thus prepared and clothed in bark like the saints, the brothers, with faithful Sita, entered a boat which chanced to be at the river-side and began the passage of the Ganges. As they crossed the river the pious Sita, with joined hands, addressed the goddess of the sacred stream, praying for a happy return to Ayodhya, when their days of exile should be over. Having arrived on the other bank, the exiles entered the forest in Indian file, Lakshmana leading and Rama bringing up the rear. Passing by Sringavara on the Ganges, they proceeded to Prayaga at the junction of the Ganges and the Jumna. Here they were hospitably entertained by the sage Bharadvaja, who recommended them to seek an asylum on the pleasant slopes of wooded Chitrakuta. On the way thither Sita, ever mindful of her religious duties, adored the Kalindi river—which they crossed on a raft constructed by themselves—and paid her respects to a gigantic banyan tree, near which many ascetics had taken up their abode. On the romantic and picturesque side of Chitrakuta the exiles built themselves a cottage, thatched with leaves, “walled with wood, and furnished with doors.” Game, fruits, and roots abounded in the neighbourhood, so that they need have no anxiety about their supplies. So much did they appreciate the quiet beauties of their sylvan retreat, the cool shade, the perfumed flowers, the sparkling rivulets and the noble river, that they became almost reconciled to their[35] separation from their friends and the lordly palaces of Ayodhya, in which city important things were happening.

The exile of Rama had been too much for the doting old Maharajah.[29] Weighed down by sorrow, he soon succumbed to his troubles, and Bharata, who was still absent at Giri-braja, was hastily summoned to take up the regal office. He, accompanied by his brother Satrughna, hurried to the capital, and finding, on his arrival, how matters really stood, heaped reproaches upon his wicked, ambitious mother, indignantly refusing to benefit by her artful machinations. In a transport of grief Bharata “fell to the earth sighing like an enraged snake,” while Satrughna, on his part, seized the deformed slave-girl Manthara, and literally shook the senses out of her. In Rama’s absence, Bharata performed his father’s obsequies with great pomp. The dead body of the late king, which had been preserved in oil, was carried in procession to the river side and there burnt, together with heaps of boiled rice and sacrificed animals. A few days later the sraddha ceremonies for the welfare of the spirit of the departed king were performed, and, as usual, costly presents,—money, lands, houses, goats and kine, also servant-men and servant-maids were bestowed upon the fortunate Brahmans.

When this pious duty, which occupied thirteen days, had been fulfilled, affairs of State demanded attention. Bharata, although pressed to do so, resolutely declined to accept the sceptre, and resolved to set out, with a vast following, on a visit to Rama in his retreat, hoping to persuade him to abandon his hermit-life and undertake[36] the government of the realm. Great preparations had to be made for this visit to Rama, which was a sort of wholesale exodus of the people of Ayodhya of all ranks and occupations. A grand army was to accompany Bharata, and the court, with all the ladies of the royal family, including the no-doubt-reluctant Kaikeyi, were to swell the procession. A road had to be made for the projected march of this host; streams had to be bridged, ferries provided at the larger rivers, and able guides secured. When the road was ready and the preparations for the journey completed, chariots and horsemen in thousands crowded the way, mingled with a vast multitude of citizens riding in carts. Artificers of every kind attended the royal camp. Armourers, weavers, tailors, potters, glass-makers, goldsmiths and gem-cutters, were there; so also were physicians, actors and shampooers, peacock-dancers and men whose profession it was to provide warm baths for their customers. Of course the Brahman element was strongly represented in this great procession from the flourishing city to the solitudes of the forest. Bharata’s march is described at great length by the poet; but only one incident need be mentioned here. On the way the hermit Bharadvaja, desirous of doing Bharata honour, and probably not unwilling to display his power, invited him and his followers, of whom, as we have seen, there were many thousands, to a feast at his hermitage. At the command of the saint the forest became transformed into lovely gardens, abounding in flowers and fruit. Palaces of matchless beauty sprang into existence. Music filled the cool and perfumed air. Food and drink, including meat and wine, appeared in profusion:—soups and curries are especially mentioned, and the flesh of goats and bears, deer, peacocks and cocks; also rice, milk and sugar. In addition to all this, a host of heavenly nymphs from[37] Swarga descended to indulge in soft dalliance with the ravished warriors of Bharata’s army.

“Then beauteous women, seven or eight,

Stood ready by each man to wait.

Beside the stream his limbs they stripped,

And in the cooling water dipped,

And then the fair ones, sparkling-eyed,

With soft hands rubbed his limbs and dried,

And sitting on the lovely bank

Held up the wine-cup as he drank.”

—Griffith.

For one day and one night the intoxicating enjoyment continued; and then, at the word of command, all the creations of the sage’s power vanished, leaving the forest in its wonted gloom.

Having taken a respectful leave of the mighty ascetic, Bharata and his followers threaded their way through the dense forests towards the Mountain Chitrakuta and the River Mandakini. After a long march they at last found the object of their desire, the high-souled Rama, “seated in a cottage, bearing a head of matted locks, clad in black deerskin and having tattered cloth and bark for his garment.” When Rama heard of his father’s death he was deeply moved and fell insensible upon the ground, “like a blooming tree that hath been hewn by an axe.” The loving Vaidehi (Sita) and the brothers Lakshmana and Bharata sprinkled water on the face of the prostrate man and restored him to animation, when he at once burst into loud and prolonged lamentations. Presently Rama pulled himself together and duly performed the funeral rites, pouring out libations of water and making an offering of ingudi fruits to the spirit of his departed father. These offerings were not worthy of being presented to the manes of so great a man as Dasahratha; but were justifiable, under the circumstances[38] of the case, on the accepted principle that “that which is the fare of an individual is also the fare of his divinities.”[30] Bharata and the rest, respectfully sitting before Rama with joined hands, entreated him, with the greatest humility, to undertake the reins of government; but he was not to be persuaded to do so. He would not break the resolution he had made, nor would he be disloyal to his dead father’s commands. Then Javali, a Brahman atheist, insisting that there was and could be no hereafter, that Dasahratha, once his sire, was now mere nothing, advised the prince to yield to the reasonable wishes of the living and return with them to rule over the kingdom of his ancestors. Rama, however, warmly rebuked the atheist for his impiety, and all that Bharata could accomplish was merely to induce him to put off from his feet a pair of sandals adorned with gold, which he (Bharata) carried back with him in great state to the deserted Ayodhya—now inhabited only by cats and owls—as a visible symbol of his brother Rama, in whose name he undertook to carry on the affairs of the State until the appointed fourteen years of exile should have run their course.

The incidents connected with Rama’s exile to the forests, his life and rambles at Chitrakuta, Bharata’s imposing march through the same wooded country which the exiles had traversed, affords the poet of the “Ramayana” rare opportunities of displaying his love for the picturesque and his strong natural leaning towards the serene, if uneventful, life of the hermit. Often in these early forest rovings, and indeed throughout[39] the fourteen years of exile, does Rama, or some other one, linger to note and admire the beauties of woodland and landscape, and to hold loving communion with the fair things of field and forest. Though he praises the cities, and pictures their grandeur of gold and gems, it is plain throughout that the poet’s heart is in the woods, displaying on his part an appreciation of the charms of nature and scenery, very remarkable, indeed, when we consider how slowly the taste for the beauties of inanimate nature was developed in Europe. After Bharata’s return to Ayodhya, Rama and his companions moved further southwards, in the direction of the great forest of Dandhaka, which extended indeed as far as the Godavari. In their wanderings they came to the abode of a certain ascetic whose wife, having performed severe austerities for ten thousand years, was privileged, during ten years of drought, to create fruits and roots for the sustenance of the people and to divert the course of the river Jumna, so that its waters should flow by the thirsty asylum of the hermits. This ancient dame took a great fancy to Vaidehi, and, woman-like, gave her fair disciple a worthy gift, consisting of fine apparel, of beautiful ornaments, a precious cosmetic for the beautification of her person, and a rare garland of flowers. Nor was the old lady contented until she had seen the effect of her present on Janaka’s charming daughter, who had pleased her much by her good sense in affirming that “the asceticism of woman is ministering unto her husband.”

Wheresoever the exiles turned their steps, in these almost trackless forests, they were told of the evil doings of the Rakshasas, who not only interrupted the sacrifices, but actually carried off and devoured the anchorites. Very curious, too, were the ways in which some of these Rakshasas compassed the destruction of the saints. One of them, the wily Ilwala, well[40] acquainted with Sanskrit, would assume the form of a Brahman and invite the hermits to a sraddha feast. His brother, in the assumed form of a sheep, would be slaughtered and cooked for his guests. When they had enjoyed their repast the cruel Ilwala would command his brother Vatapi to “come forth,” which he would do unreluctantly, and with a vengeance, bleating loudly and rending the bodies of the unhappy guests, of whom thousands were disposed of in this truly Rakshasa fashion. It is noteworthy that those ascetics who had, by long and severe austerities, acquired a goodly store of merit, might easily have made short work of the Rakshasas; but, on the other hand, if they allowed their angry passions to rise, even against such impious beings, they would, while punishing their tormentors, have inevitably lost the entire advantage of their long and painful labours. Hence many of the hermits made a direct appeal to Rama for protection.

Entering the forest of Dandhaka the exiles encountered a huge, terrible and misshapen monster, besmeared with fat and covered with blood, who was roaring horribly with his widely distended mouth, while with his single spear he held transfixed before him quite a menagerie of lions, tigers, leopards and other wild animals. This awful being rushed towards the trio, and, quick as thought, snatched up the gentle Vaidehi in his arms, bellowing out “I am a Rakshasa, Viradha by name. This forest is my fortress. Accoutred in arms I range (here), feeding on the flesh of ascetics. This transcendantly beauteous one shall be my wife. And in battle I shall drink your blood, wretches that ye are.” At this juncture, Rama, as on some other trying occasions, gave way to unseasonable lamentations and tears; but Lakshmana, always practical, bravely recalled him to the necessity of immediate action. The Rakshasa, having ascertained[41] who his opponents were, vauntingly assured them that, having gratified Brahma by his asceticism, he had obtained this boon from him, that no one in the world could slay him with weapons; and he mockingly advised the princes to renounce Sita and go their way. But Rama’s wrath was now kindled, and he began a vigorous attack upon the monster, piercing him with many arrows. A short, though fierce, combat ensued, the result being that the Rakshasa seized and carried off both Rama and Lakshmana on his ample shoulders. His victory now seemed complete, and Sita,—who had apparently been dropped during the combat,—dreading to be left alone in the terrible wilderness, piteously implored the monster (whom she insinuatingly addressed as the “best of Rakshasas”) to take her and to release the noble princes. The sound of her dear voice acted like a charm upon the brothers, and, with a vigorous and simultaneous effort, they broke both the monster’s arms at once, and then attacked him with their fists. They brought him to the ground exhausted, and Rama, planting his foot upon the throat of his prostrate foe, directed Lakshmana to dig a deep pit for his reception, and when it was ready, they flung him into it. The dying monster, thus overcome, though not with weapons, explained that he had been imprisoned in that dreadful form of his by the curse of a famous ascetic, and was destined to be freed from it only by the hand of Rama. With this explanation the spirit of the departed Viradha passed into the celestial regions.

Rama, with his wife and brother, now sought the hermitage of the sage Sarabhanga, and on approaching it, a strange, unexpected and imposing sight presented itself to Rama’s view:—Indra, attended by his court, in conversation with the forest sage! The god of heaven, in clean apparel and adorned with celestial[42] jewels, was seated in a wondrous car drawn by green horses up in the sky. Over him was expanded a spotless umbrella, and two lovely damsels waved gold-handled chowrees above his head. About him were bands of resplendent celestials hymning his praises.

At Rama’s approach the god withdrew and the sage advised the prince to seek the guidance of another ascetic named Sutikshna, adding, “This is thy course, thou best of men. Do thou now, my child, for a space look at me while I leave off my limbs, even as a serpent renounces its slough.” Then kindling a sacrificial fire, and making oblations to it with the appropriate mantras, Sarabhanga entered the flames himself. The fire consumed his old decrepit body, and he was gradually transformed, in the midst of the flames, into a splendid youth of dazzling brightness, and, mounting upwards, ascended to the heaven of Brahma. After Sarabhanga had left the earth in this striking manner, bands of ascetics waited on Rama, reminded him of his duty as a king, and solicited his protection against the Rakshasas. As Rama and his companions wandered on through the forests another wonder soon engaged their attention. Sweet music reached them from beneath the waters of a charming lake covered with lotuses, and on inquiring about the strange phenomenon, a hermit told them that a great ascetic had formed that lake. By his fierce austerities, extending over ten thousand years, he had acquired such a store of merit that the gods, with Agni at their head, began to fear that he desired a position of equality with themselves. To lure him away from such ideas they sent him five lovely Apsaras to try the power of their charms upon him. Sage though he was, he succumbed to their allurements, and now, weaned from his old ambitions, he passed his time in youth and happiness—the reward of his austerities and yoga practices—in the company of the seductive[43] sirens whose sweet voices, blending with the tinklings of their instruments, came softly to the ears of the wandering princes.

Sita, who had confidently followed her husband, like his very shadow, through all these adventurous years in the forest, seems at length to have been somewhat shaken by the very risky encounter with Viradha, of which she had been an unwilling and terrified eye-witness, in which her own person had been the object of contention, and which had threatened, at one critical moment, to end very tragically for her and her loved ones. Under the influence of these recent and impressive experiences, Sita ventured, in her gentle, womanly way, to suggest to her husband the advisability of avoiding all semblance of hostility towards the Rakshasas. There were, she timidly assured her husband, three sins to which desire gave rise: untruthfulness, the coveting of other men’s wives, and the wish to indulge in unnecessary hostilities. Of untruthfulness, and of allowing his thoughts to stray towards other women, Sita unhesitatingly exonerated her lord; but she artfully insinuated that, in his dealings with the Rakshasas, he was giving way to the sin of provoking hostilities without adequate cause, and she advised his laying aside his arms during his wanderings in the forest; since the mere carrying of bows and arrows was enough to kindle the wish to use them. To give point to this contention, Vaidehi related how, in the olden time, there lived in the woods a truthful ascetic whose incessant austerities Indra desired, for some reason or other, to frustrate. For the attainment of his end the king of heaven visited the hermit in the guise of a warrior, and left his sword with him as a trust. Scrupulously regardful of his obligation to his visitor, the ascetic carried the sword with him wherever duty or necessity directed his footsteps, till[44] constant association with the weapon began to engender fierce sentiments, leading eventually to the spiritual downfall of the poor ascetic, whose ultimate portion was hell. Rama received Sita’s advice in the loving spirit in which it was offered, and thanking her for it, explained that it was his duty to protect the saints from the oppression of the evil Rakshasas, and that Kshatriyas carried bows in order that the word “distressed” might not be known on this earth.

Several years of exile slipped away, not unpleasantly, in the shady forests through which the royal brothers roamed from hermitage to hermitage, always accompanied by the lovely and faithful Sita, whose part throughout is one of affectionate, unfaltering and unselfish devotion to her husband. On the banks of the Godavari, Lakshmana, who has to do all the hard work for the party, built them a spacious hut of clay, leaves and bamboos, propped with pillars and furnished with a fine level floor, and there they lived happily near the rushing river. At length the brothers got involved in a contest with a brood of giants who roved about the woods of Dandhaka, delighting, as usual, in the flesh of hermits and the interruption of sacred rites. This time it was a woman who was at the bottom of their troubles. Surpanakha, an ugly giantess and sister of Ravana, charmed with the beauty and grace of Rama, came to him, and, madly in love, offered to be his wife. But Rama in flattering terms put her off, saying he was already married. In sport, apparently, he bid her try her luck with Lakshmana. She took his advice, but Lakshmana does not seem to have been tempted by the offer, and, while artfully addressing her as “supremely charming and superbly beautiful lady,” advised her to become the younger wife of Rama, to whom he referred her again. Enraged by this double rejection, the giantess attempted to kill Sita, as the hated obstacle to the fulfilment of[45] her desires. The brothers, of course, interposed, and Lakshmana, always impetuous, punished the monster by cutting off her nose. Surpanakha fled away to her brother Khara, and roused the giant Rakshasas to avenge her wounds. These terrible giants possessed the power of changing their forms at will; but their numbers and their prowess were alike of little avail against the valour and skill of Rama, who, alone and unaided,—for he sent Lakshmana away with Sita into an inaccessible cave,—destroyed fourteen thousand of them in a single day. The combat, which was witnessed by the gods and Gandharvas, Siddhas and Charanas, is described at great length, and the narrative is copiously interspersed with the boastful speeches of the rival chiefs. In the bewildering conflict of that day his fourteen thousand assailants poured upon Rama showers of arrows, rocks, and trees. Coming to close quarters they attacked him vigorously with clubs, darts, and nooses. Although hard pressed and sorely wounded, the hero maintained the conflict with undaunted courage, sending such thousands of wonderful arrows from his bow that the sun was darkened and the missiles of his enemies warded off by them. Finally Rama succeeded in laying dead upon that awful field of carnage nearly the entire number of his fierce assailants. Khara, the leader of the opposing host, a worthy adversary and possessed of wondrous weapons, still lived. Enraged at, but undaunted by, the wholesale destruction of his followers, Khara boldly continued the fight. In his war-chariot, bright as the sun, he seemed to be the Destroyer himself, as he fiercely assailed the victorious Rama. With one arrow he severed the hero’s bow in his hand; with seven other shafts like thunder-bolts he severed his armour joints, so that the glittering mail fell from his body. He next wounded the prince with a thousand darts. Not[46] yet overcome, however, Rama strung another bow, the mighty bow of Vishnu, and discharging shafts with golden feathers, brought Khara’s standard to the ground. Transported with wrath at this ill-omened event, Khara poured five arrows into Rama’s bosom. The prince responded with six terrible bolts, some of them crescent-headed. One struck the chief in the head, two of the others entered his arms, and the remaining three his chest. Following these up with thirteen of the same kind, Rama destroyed his enemy’s chariot, killed his horses, decapitated his charioteer, and shattered his bow in his grasp. Khara jumped to the ground armed with a mace, ready to renew the conflict. At this juncture Rama paused a moment to read the Rakshasa a homily on his evil doings; the latter replied with fierce boasts, and hurled his mace at Rama, who cut it into two fragments with his arrows as it sped through the air. Khara now uprooted a lofty tree and hurled it at his foe; but, as before, Rama cut it into pieces with his arrow ere it reached him, and with a shaft resembling fire put a period to the life of the gallant Rakshasa. At this conclusion of the conflict the celestials sounded their kettle-drums, and showered down flowers upon the victorious son of Dasahratha. Thus perished the Rakshasa army and its mighty leader:

“But of the host of giants one,

Akampan, from the field had run,

And sped to Lanka to relate

In Ravana’s ear the demon’s fate.”

—Griffith.

This fugitive made his way to the court of Ravana, the king of the giants, and related to him the sad fate of his followers. Close on the heels of Akampan came Surpanakha herself, with her cruelly mutilated face. Transported with rage at the destruction of his[47] armies and at sight of the disfigured countenance of his sister, the terrible Rakshasa chief vowed vengeance on Rama and Lakshmana. But the necessity for great caution in dealing with such valorous foes was apparent, and Ravana did not seem over-anxious to leave his comfortable capital, Lanka, in order to seek out the formidable brothers in the woods of Dandhaka. But Surpanakha, scorned and mutilated, was thirsting for an early and bitter revenge. Reproaching her brother for his unkingly supineness, she artfully gave him a description of Sita’s beauty, far superior to that of any goddess, which served to kindle unlawful desires in his heart. She referred to Vaidehi’s golden complexion, her moon-like face, her lotus eyes, her slender waist, her taper fingers, her swelling bosom, her ample hips and lovely thighs, till the giant was only too willing to assent to her suggestion, that the most effectual and agreeable revenge he could take for the destruction of his hosts, and the cruel insults to his sister, would be to carry off the fair Sita, by stratagem, from the arms of her devoted husband, and thus add the lovely daughter of Janaka to the number, not very small, of the beauties who adorned his palace at Lanka. We shall presently see that the plot was ingeniously contrived and too successfully carried out.