Engᵈ. by E. G. Williams & Bro. N.Y.

| Rare Portrait of Columbus[1]— | Frontispiece. | |

| Explorations of the North American Coast, previous to the Voyage of Henry Hudson. | Benjamin F. De Costa, D. D. | 1 |

| From advance sheets of “The Memorial History of New York.” | ||

| Early American Literature, | T. J. Chapman | 27 |

| The Ohio Society in New York and Ohio in New York, | James Harrison Kennedy | 33 |

| Gen. Thomas Ewing—Col. William F. Strong—Hon. George Hoadly. | ||

| De Soto’s Camps in the Chickasaw Country, 1540-1. | T. H. Lewis | 57 |

| Chicago Pioneers, | Howard Louis Conard | 62 |

| Hon. Isaac N. Arnold. | ||

| Some Ancient Methods of Punishment in Massachusetts, | Hon. F. C. Sessions | 67 |

| Gen. William E. Strong,—A Memorial. | 76 | |

| Mistakes in History; The Pilgrims not Puritans, but Separatists, | D. W. Manchester | 82 |

| Were the Dutch on Manhattan Island in 1598? | Daniel Van Pelt, A.M. | 91 |

| A Famous Political Contest in Illinois, | W. H. Maguire | 97 |

| Hon. Henry H. Evans. | ||

| Editorial and Historical Notes, | 102 | |

| The Change of Name—What it Means—Field of American History—Material for War History—Growth of Historical Societies—Value of Their Papers—Historic Interest in Legend and Tradition—The Memorial History of New York—Preserving the Field of Valley Forge—Monument to Red Jacket—International Pan-Republic Congress—The Washington State Historical Society. | ||

| Notes from the Historical Societies, | 105 | |

| Recent Historical Publications, | 107 | |

| Adam’s Historical Essays—Minnesota Historical Society’s Collections—Beginnings of Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley—J. Freeman Clarke’s Autobiography Diary and Correspondence—Howe’s Historical Collections of Ohio—Ohio Historical Society, Vol. III. | ||

[1] Said by the present Duke of Veragua to be the most representative of the known portraits.

Published Monthly—Entered at New York Post Office as Second Class Mail Matter.

With this NOVEMBER Number, the Magazine of Western History, appears under its new name

THE NATIONAL MAGAZINE.

A Journal devoted to American History.

(See Editorial Notes.)

Engᵈ. by E. G. Williams & Bro. N.Y.

One of the earliest Greek dreams, prominent in the classic literature, was that of a beautiful island in the ocean at the far West. Perhaps, nevertheless, we have been accustomed to think of the conception too much as a dream, a piece of pure imagination; for it is absolutely certain, as Pliny and Strabo prove, that bold Phenician navigators passed far beyond the Pillars of Hercules into the vast Atlantic, discovering and naming the Canary Islands, pushing their observations far and wide. Possibly, like Columbus, as on his first voyage, they sailed over tranquil seas, smooth as the rivers in Spain, and through ambient air, soft as the air of Andalusia in spring, until they reached the Edenic Cuba, and thus furnished the foundation of that Greek conception of an exquisitely fair isle, the home of the immortals, an Elysium on whose happy, fragrant shores the shrilly-breathing Zephyrus was ever piping for the refreshment of weary souls.

In the fifteenth century the islands in the west formed the object of many a voyage, but even in 1306 Marino Sanuto laid down the Canaries anew, while Bethencourt found them in 1402. The Azores and the Madeira Islands appear in the chart of Pizigani in 1367, and the sailors of Prince Henry the Navigator went to the Azores, the Isles of the Hawks, in 1431, as preparatory to those voyages which, beginning with the rediscovery of the Cape Verde Islands in 1460, were destined to prepare the way for the circumnavigation of Africa, and thus open the way to the Indies by the Cape of Good Hope. Long before this, however, the Spaniards were credited with the establishment of colonies in the western ocean, and on[2] the globe of Martin Behaim, in 1482, may be seen the legend crediting Spanish bishops with the founding of seven cities in a distant island in the year 734. In 1498 De Ayala, the Spanish ambassador in England, reported to his sovereign that the city of Bristol had for seven years sent out ships in search of the island of Brazil and the Seven Cities, which were commonly laid down in maps, together with the great island of “Antillia,” by many supposed to refer to the American Continent.

FERDINAND OF SPAIN.

In the time of Columbus enterprise was generally active, and men everywhere were eager to realize the prediction of Seneca, who declared that the Ultima Thule, the extreme bounds of the earth, would in due time be reached. But Columbus would win something more than beautiful islands. He aimed at a continent, and would reach the eastern border of Asia by sailing west, in accordance with the early philosophers, who had accepted the spherical form of the earth, not dreaming that, instead of a few islands, scattered like gems in the ocean, a mighty continent barred the way. Dominated by the antique notions of the classic writers, Columbus, after encountering and overcoming every discouragement, finally sailed towards the golden West, finding the voyage a pleasant excursion, interrupted only by the occasional fears of the sailors, lest the light breeze might prevent their return to Spain, by blowing all the time the one way. At a given point of the voyage Columbus met with an experience, and made a decision, that perhaps determined the destiny of North America. October 7, 1492, Martin Pinson saw flocks of parrots flying southwest, and argued that the birds were returning to land, which must lie in that direction. He accordingly advised the Admiral to change the course of the ship. Columbus realized the force of the argument and knew the significance of the flights of birds, the hawk having piloted the Portuguese to the Azores. He was now sailing straight for the coast of North Carolina, and must inevitably have discovered our continent, but the parrots were accepted as[3] guides, the course was changed to the southwest, and in due time the Island of San Salvador rose before their expectant eyes. All his efforts, therefore, after this memorable voyage, were devoted to the West Indies, and in the fond belief that he had reached fair Cathay. Consequently John Cabot was left to discover North America at least one year before Columbus sighted the southern portion of the western continent. Even then Columbus held that South America was a part of India, and he finally died in ignorance of the fact that he had reached a new world.

His error proved a most fortunate one for the English-speaking people; since, if he had confined on the western course, the Carolinas would have risen to view, and the splendors and riches of the Antilles might have remained unknown long enough for Spanish enterprise to establish itself on the Atlantic coast. This done, the magnificent Hudson would have become the objective point of Spanish enterprise, and a Spanish fortress and castle would to-day look down from the Weehawken Heights, the island of New York yielding itself up as the site of a Spanish city.

The mistake of Columbus, however, was supplemented by what, perhaps, may properly be called a series of blunders, all of them more or less fortunate, or at least in the interest of a type of civilization very unlike that of Spain, especially as expanded and interpreted in Central and South America. It is, therefore, to the series of nautical adventures following the age Columbus, and extending down to the voyage of Henry Hudson, the Englishman, in 1609, that this article is mainly devoted, showing how this entire region was preserved from permanent occupation by Europeans, until it was colonized by the Walloons under the Dutch, who providentially prepared the way for the English.

ISABELLA OF SPAIN.

First, however, it may be interesting to glance at voyages made during the Middle Ages, considering whether they had any possible connection[4] with the region now occupied by the city of New York.

That Northmen visited the shores of North America no reasonable inquirer any longer doubts. Even Mr. George Bancroft, who for about half a century cast grave reflections upon the voyages of the Northmen, and inspired disbelief in many quarters, finally abandoned all allusion to the subject, and subsequently explained that in throwing discredit upon the Icelandic narratives he had fallen into error.[2]

The probability now seems to be that the Irish had become acquainted with a great land at the west, and gave it the name of “Greenland,” which name was simply applied by Eric the Red to a separate region, when he went to the country now known as Greenland in the year 985. The next year Biarne Heriulfsson, following Eric, was blown upon the north Atlantic coast, and in the year 1000-1 Leif, son of Eric, went in quest of the land seen by Biarne, reaching what is generally recognized as New England. Others followed in 1002 and 1005, while from 1006 to 1009 Thorfinn Karlsefne visited the same region, then known as “Vinland the Good,” and made a serious but abortive effort to found a colony. Freydis, daughter of Eric the Red, visited New England in 1010 to 1012. Vague accounts in the Icelandic chronicles tell of a visit of one Are Marson to a region called White Man’s Land (Hvitrammanaland) in 983, ante-dating Eric’s appearance in Greenland. We also hear of Biörn Asbrandson in 999, and of the voyage of Gudlaugson in 1027. Certain geographical fragments refer to Bishop Eric, of Greenland, as searching for Wineland in 1121, while in 1357 a small Icelandic ship visited “Markland,” the present Nova Scotia. The voyages of Asbrandson and of Gudlaugson are generally viewed as standing connected with a region extending from New England to Florida, known as White Man’s Land, or Ireland the Great. In these accounts there is found no definite allusion to the region of the Hudson, though Karlsefne’s explorations may have extended some distance southwesterly from Rhode Island; while later adventurers, who came southward and followed the course of Are Marson, who was discovered in the country by Asbrandson, must have sailed along our shores. Still no record of such a visit now remains, which is not at all singular, since many a voyager went by, both before and afterwards, with the same failure to signalize the event for the information of posterity. “They had no poet and they died.”

Turning to the voyages of the Welsh, who, some think, reached the western continent about the year 1170, led by Madoc, Prince of Wales, there is the same failure to connect them with this region. Catlin, who visited the White or Mandan Indians, supposes that the Welch sailed down[5] the coast to the Bay of Mexico and ascended the Mississippi; although there is just as much reason to hold, if the Mandans were their descendants, that they entered the continent and found their way westward from the region of Massachusetts or New York. The latter, however, might be favored, for the reason that our noble river forms to-day the most popular and certainly the most splendid gateway to the far West.

The voyages of the Zeno brothers, who are believed by most competent critics to have reached America about the close of the fourteenth century, and who left a chart, first published in 1558, show a country called “Drogeo,” a vast region which stretched far to the south, whose inhabitants were clothed in skins, and subsisted by hunting, being armed with bows and arrows, and living in a state of war. The description would apply to our part of the coast. At this period the Red Indians had come from the west, and dispersed the original inhabitants, known to the Northmen as Skraellings. The red man on this coast was an invader and conqueror, not the original proprietor of the land. In a very brief time, however, he forgot his own traditions and indulged in the belief that he was the first holder of this region, which was deeded to him by the Great Father in fee simple; and it was in this belief that, in turn, the simple savage conveyed vast tracts of territory to the white man, in consideration of trinkets and fire-water.

SEBASTIAN CABOT.

So far as can be discovered, the Skraelling was the first proprietor, and by the Skraelling is meant what is called the “Glacial Man,” who appeared on this coast when the great ice-sheet that once covered the highlands of America was melting and sliding into the sea. The evidences of the so-called glacial man are found at the present time in the gravels of the Trenton River, of New Jersey, consisting of stone implements that seem to have been lost while engaged in hunting and fishing. With the disappearance of the ice and the moderation of the climate, these men of the ice-period spread along the Atlantic[6] coast from Labrador to Florida, their descendants being the modern Eskimo and Greenlander, whose ancestors were driven northward by the red man when he conquered the country. The immediate region of the Hudson has thus far afforded none of the stone implements that abound at Trenton yet it may be regarded as beyond question that the first inhabitant of New York was a glacial man, ruder than the rudest red savage, and in appearance resembling the present Eskimo.

VERRAZANO.

We turn, however, to note what, in this immediate connection, may be styled the course of maritime enterprise, the first voyage of interest in connection with our subject being the voyage said to have been made by Sebastian Cabot along the coast from Newfoundland in 1515. Upon this initial voyage many Englishmen based their claim, but in the present state of knowledge the expedition itself is considered debatable by some. That John Sebastian Cabot saw the continent in 1498, or one year before Columbus saw South America, can hardly be doubted; but convincing testimony is required respecting the alleged voyage down this part of the coast in 1515. If we accept the voyage as a fact, this expedition, whose objective point was Newfoundland, may be regarded as the first known English expedition to these shores.

Before this time, however, the Portuguese were very active, and had run the coast from Florida to Cape Breton, evidence of which they left in the “Cantino” Map, and in the Ptolemy of 1513. This was in continuation of the enterprise of the Costas, or “Cortereals,” who made voyages to the north in 1500-1-2. The expedition made a long our coast at this period left no memorials now known, save the maps to which allusion has been made. As early as 1520 the Spaniards began to navigate to the north from the West Indies, and in that year Ayllon reached the coast of Carolina, on an expedition to capture slaves, though Martyr speaks of the country he visited as “near the Baccaloos,” a term applied at that time to the region far south of Newfoundland. Nevertheless, in the year 1524, we reach a voyage of deep interest, for in this year the Bay of[7] New York comes distinctly into view, Europeans being known for the first time to pass the Narrows. Reference is here made to the voyage of the celebrated Italian, Giovanni da Verrazano, in the service of Francis I. of France.

This celebrated navigator is supposed to have been the son of Piero Andrea di Bernardo de Verrazano and Fiametta Capella. He was born at Val di Greve, a little village near Florence, in the year 1485. At one time a portrait of Verrazano adorned the walls of a gallery in Florence. This portrait[3] was engraved for the well-known work entitled, “Uomini Illustri Toscani.” A medal was also struck in his honor, but no copy of it can now be found. The family, nevertheless, appears to have maintained a definite place in local history, the last known Florentine representative being the Cavaliere Andrea da Verrazano, who died in 1819.

Verrazano, the great explorer of the American coast, seems to have had a large experience as a sailor upon the Mediterranean, eventually entering the service of Francis I. of France, as a privateer or corsair, in which calling Columbus and many of the old navigators shone conspicuously, the profession at that time being quite creditable, even though dangerous. In 1523 Verrazano was engaged in capturing Spanish ships that brought the treasures of Montezuma from Mexico. In the following year he made his voyage to America, and one statement makes it appear that, subsequently, he was captured by the Spaniards and executed. Ramusio tells us that on a second voyage he was made a prisoner by the savages, and was roasted and eaten in the sight of his comrades. The light which we have at the present time does not suffice for the settlement of the question relating to the manner of his death, but we have overwhelming evidence of the reality of his voyage in 1524, which is vouched for by invaluable maps and relations contained in a lengthy letter addressed to his employer, Francis I.

This letter is of unique interest, especially for the reason that it contains the first known post-Columbian description of the North Atlantic coast, and the first pen-picture of the Bay and Harbor of New York. In connection with our local annals Giovanni da Verrazano must hold a high place. As might be supposed, the narrative of Verrazano has exerted a commanding influence upon historical literature. For more than three centuries it has furnished quotations. This fact has not prevented one or two occasional writers from questioning the authenticity of the Letter of Verrazano, though the discussion which followed simply resulted in the production of additional proof, especially that found in two maps previously unknown, establishing the authenticity of both voyage and letter, and taking the subject from the field of controversy.

VESPUCIUS.

The voyage of Verrazano was projected in 1523. On April 25th of that[8] year, Silveira, the Portuguese embassador at the Court of Francis I., wrote to his master: “By what I hear, Maestro Joas Verrazano, who is going on the discovery of Cathay, has not left up to date for want of opportunity, and because of differences, I understand, between himself and his men.... I shall continue to doubt unless he takes his departure.” It appears that he first went to sea with four ships, but met a severe gale and was obliged to return to port, apparently with the loss of two ships. After making repairs, he sailed for the Spanish coast alone in the Dolphin, the captain of the remaining ship leaving Verrazano, and giving color to the story of Silveira, that he had quarreled with his men. In the Carli correspondence, there is a reference to one Brunelleschi, “who went with him and unfortunately turned back.”

On January 17, 1524 (old style), Verrazano finally sailed from a barren rocky island, southeast of Madeira, though Carli erroneously says that he departed from the Canaries. The discrepancy is useful, in that it proves an absence of collusion between writers in framing a fictitious voyage. Steering westward until February 14th, he met a severe hurricane, and then veered more to the north, holding the middle course, as he feared to sail southward, by the accustomed route to the West Indies, less he should fall into the hands of the Spaniards,[4] who with the Portuguese, claimed the entire New World, in accordance with the decree of Pope Alexander. Hence the navigator, to avoid the Spanish cruisers, held his course westward in sunshine and storm, until the shores of the American continent appeared above the waves. March 7th he saw land which “never before had been seen by any one either in ancient or modern times,” a statement that he was lead into by the desire to claim something for France. He knew that his statement could not be exactly true, because, like all the navigators of his day, he was familiar with the Ptolemy of 1513, containing a rude map of the coast from Florida to 55° N. Evidently he did not attach any value to the explorations of the Portuguese[9] as represented by the maps, and hence, after sighting land in the neighborhood of 34° N., he sailed southward fifty leagues to make sure of connecting with the actual exploration of the Portuguese, and then began coasting northward in search of a route through the land to Cathay. Columbus died in 1508, believing that he had reached Cathay, but in the day of Verrazano it was understood by many that the land found formed a new continent, though this was not everywhere accepted until the middle of the sixteenth century.

CARTIER.

Navigating northward, Verrazano reached the neighborhood of the present site of Charlestown, South Carolina, describing the country substantially as it appears to-day, bordered with low sand-hills, the sea making inlets, while beyond were beautiful fields, broad plains, and vast forests. On landing they found the natives timid, but by friendly signs the savages became assured, and freely approached the French followers of Verrazano, wondering at their dress and complexion, just as, in 1584, Barlow, in the same locality, said that the natives wondered “at the whiteness of our skins.” The descriptions of Verrazano were so faithful that Barlow, though without credit, employed his language, especially when he says, speaking of the forests before reaching the land, “We smelt so sweet and strong a smell as if we had been in the midst of some delicate garden.” As Verrazano held northward, his descriptions continued to exhibit the same fidelity, being used by Barlow and confirmed by Father White. They were also confirmed by Dermer, who ran the coast in 1619, finding the shores low, without stones, sandy, and, for the most part, harborless. When near Chesapeake Bay, Verrazano found that the people made their canoes of logs, as described by Barlow and Father White. The grapes-vines were also seen trailing from the trees, as indicated by these writers; and, speaking of the fruit, Verrazano says that it was “very sweet and pleasant.” This language, being used early in the season, led to the rather thoughtless objection that Verrazano never made the voyage. The simple explanation is that the natives were accustomed to preserving fruits by drying them; and hence Hudson,[10] in 1609, found dried “currants,” which were sweet and good, meaning by the word, “currant” what all meant at that period, namely, a dried grape. The letter of Verrazano contains exaggerations, like all similar productions. Cortez made Montezuma drink wine from cellars in a country where both wine and cellars were unknown. Cartier caused figs to grow in Canada, and Eric the Red called the ice-clad hills of the land west of Iceland, “Greenland.” Verrazano, however, falls into none of these flat contradictions, and often the objection to the authenticity of the voyage has grown out of the ignorance of the critic of very common things.

Leaving Delaware Bay, Verrazano coasted northward, sailing by day and coming to anchor at night, finally reaching the Bay of New York, which forms the culmination of the interest of the voyage, so far as our present purpose is concerned. After proceeding a distance roughly estimated, on the decimal system, at a hundred leagues, he says: “We found a very pleasant situation among some little steep hills, through which a very large river (grandissima riviera), deep at its mouth, forced its way to the sea,” and he adds: “From the sea to the estuary of the river any ship might pass, with the help of the tide, which rises eight feet.” This is about the average rise at the present time, and the fact is one that could have been learned only from actual observation. It points to the “bar” as then existing, and gives the narrative every appearance of reality. Many things observed were noted in what Verrazano calls a “little book,” and evidently it was from data contained in this book that his brother compiled the map which illustrates the voyage. Verrazano, however, was cautious, as he possessed only one ship, and he says: “As we were riding at anchor in a good berth we would not venture up in our ship without a knowledge of the mouth; therefore,” he says, “we took the boat and entering the river, we found the country on its banks well-peopled, the inhabitants not differing much from the others, being dressed out with feathers of birds of various colors.” The natives, by their action, showed that their faith in human nature had not been spoiled by men leading expeditions like those of Ayllon in 1521, to the Carolinas for slaves. They were still a simple and unaffected people, not spoiled by European contact, as in the time of Hudson, and accordingly, unlike the sly people met where Ayllon’s kidnappers had done their work, “they came towards us with evident admiration, and showing us where we could most securely land with our boat.” Continuing, the narrative says: “We passed up this river about half a league, when we found it formed a most beautiful lake, three leagues in circuit, upon which were rowing thirty or more of their small boats from one shore to the other, filled with multitudes who came to see us.” This “beautiful lake” (bellissimo lago) was,[11] so far as one is able to judge, the Bay of New York.

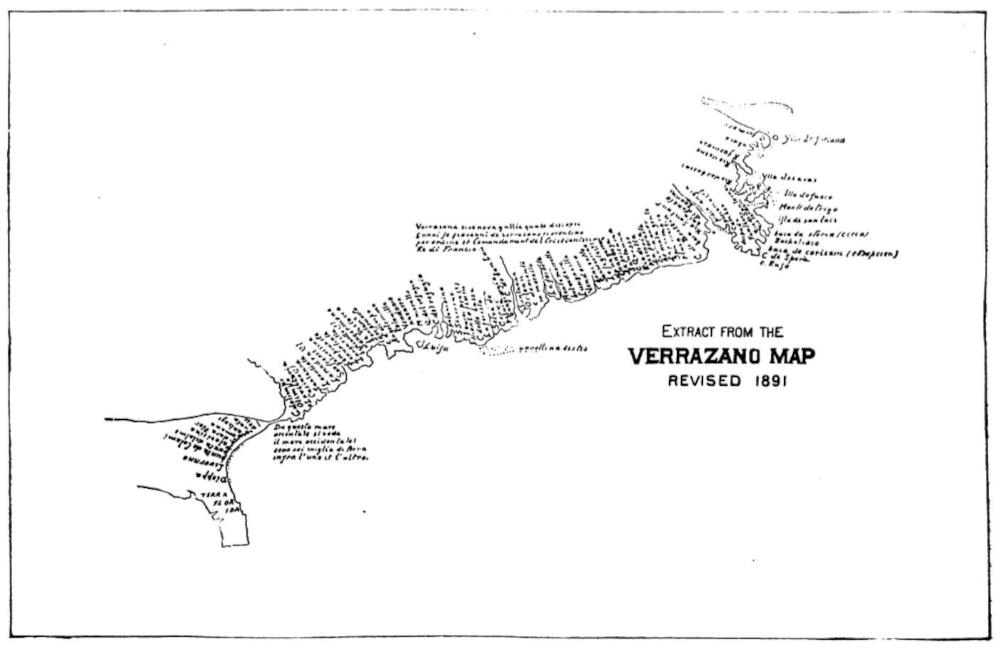

Verrazano passed the bar and anchored at the entrance of the Narrows, the position being defined as between “little steep hills” (infra piccoli colli eminenti), which exactly describes the heights of Staten Island, and the shore of Long Island as far up as Yellow Hook, the present Bay Ridge. Then far and wide the spacious harbor was surrounded by well-wooded shores, upon which Verrazano and his followers, evidently the first of Europeans to enter the port, gazed with admiration. It would appear that they did not cross the harbor, but they probably espied in the distance the island upon which our city now stands, clothed in the dusky brown, touched only here and there with patches of the evergreen pine. Nothing is said of the beauty of the foliage in this region, since in March none could have been apparent, though the population was evidently numerous, and from the shores the smoke of many wigwams was seen by day, with the distant illuminations that filled the eye of the sailor by night. Verrazano little dreamed of the value of the situation. It never occurred to him that on this “beautiful lake” would one day stand a city which in wealth and importance would eclipse the far-famed city of Montezuma. The situation was pleasing, but it did not offer what Verrazano sought, namely, an opening to India. He learned that he was at the mouth of a swift river that poured out a powerful tide from between the hills, and he saw the unreasonableness of continuing his search at this place. What conclusion he might have reached eventually, had his stay been prolonged, we cannot predict, but he was soon hurried away. He says: “All of a sudden, as it is wont to happen to navigators, a violent contrary wind blew in from the sea and forced us to return to our ship, greatly regretting to leave this region, which seemed so commodious and delightful, and which we supposed must contain great riches, as the hills showed many indications of minerals.” By a glance at the chart it will be seen that the ship lay in a position in the lower bay perilous for a stranger, and in case of a gale she would be in danger of being driven upon the shore of either Long Island or Staten Island. Verrazano would not take his ship through the Narrows into the harbor, on account of his ignorance of the situation, and when the wind set upon shore from the sea he at once decided to get out of danger. Accordingly he says: “Weighing anchor we sailed fifty leagues towards the east, the coast stretching in that direction, and always in sight of it.” Thus he coasted along the shores of Long Island, and “discovered an island in triangular form, some ten leagues from the main land, in size about equal to the Island of Rhodes.” This was Block Island, and we mention the circumstance here, in order that the reader may appreciate the fact that Verrazano first visited New York, and[12] that he properly describes the coast. Block Island is distinctly a triangular island. Then he went to a harbor in the main, identified as Newport Harbor.[5] The natives who appeared in the harbor, it will be noticed, had some thirty small boats (barchettes). The word itself does not indicate the manner of their construction, but, when at Newport, Verrazano says distinctly, that these barchettes were hollowed out of single logs of wood (un sole fusto di legno). The Dutch found the natives using the same kind of boats here in the early days, though the bark canoe was also employed. The objections urged against the authenticity of the voyage of Verrazano have simply resulted in fresh investigation and the production of proofs that establish beyond question the truth of the narrative, which is supplemented by a long series of maps. The series begin with the map of Verrazano, drawn in the year 1529, by Hieronimo da Verrazano, brother of the navigator, and the Maijolla map, which also represents the voyage, giving particulars not given in the narrative of Verrazano. The map of Verrazano is now preserved in the museum of the “Propaganda Fide” at Rome,[6] and forms a wonderful advance upon the Ptolemy of 1513, which, after passing Florida, is vague and, upon the whole, quite useless as respects our present purpose, since it shows no knowledge of the Bay and Harbor of New York, and calls for no particular notice here.

It has already been observed that much of that which is wanting in the Letter is furnished by the map of Verrazano, noticeably the Shoals of Cape Cod. The map was constructed by the aid of the “little book,” in which, as Verrazano told Francis I., there were many particulars of the voyage, and it forms the best sixteenth century map of the coast now known to be extant in the original form. After Verrazano the delineation of the coast, as a whole, gradually, in the neglect of cartography, became more and more corrupt, culminating in the monstrous distortions of Mercator.

On the map of Verrazano the Cape of Florida is most unmistakable, though by an error in following Ptolemy, the draftsman placed the cape nine degrees too high, thus vitiating the latitudes, also failing to eliminate the error before reaching Cape Breton. This however, does not prevent us from recognizing the leading points of the coast. At Cape “Olimpo” we strike Cape Hatteras, and near “Santanna” is the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. “Palamsina,” a corruption perhaps of Pallavicino, marks the entrance to the Delaware. “Lamuetto,” possibly Bonivet after the general of that name, distinguishes what apparently was intended for Sandy Hook; while “San Germano” and “La Victoria” stand on the lower Bay of New York. Verrazano did not know enough about the river of “the steep hills” to enable him to give it a pronounced name, though in after times the Hudson, as we shall see, was called “the river of the mountains.” It will be readily recognized that San Germano is a name given out of compliment to his patron by Verrazano, as it recalls the splendid palace of Francis I., at St. Germaine-en-Lay. If circumstances had favored, the name of Francis might have been affixed to a great French metropolis at the mouth of the Hudson.

EXTRACT FROM THE

VERRAZANO MAP

REVISED 1891

The influence of the Verrazano Map upon succeeding charts was most marked down even to 1610, when all obscurity in regard to the position of the Harbor of New York had passed away. The same is true of the exhibition of the relation of New York Bay to Rhode Island and the Island of Luisa. The influence of Verrazano upon the Globe of Vlpius, 1542, was most emphatic, as will be noticed later; though it is to be remembered that Verrazano’s voyage was pictured on the Map of Maijolla before the Verrazano Map was drawn, notes from Verrazano, probably out of the “little book” that he mentions, affording the requisite material. Verrazano evidently furnished an abundance of names for localities, and the various draftsmen seemed to have exercised their judgment to some extent respecting their use. It would, however, prove wearisome to the reader to peruse any minute statements of the contents of the many maps that indicate the Bay of New York; since neither the authenticity nor the influence of the voyage of Verrazano can now be questioned. In directions where it was never suspected, the Letter of Verrazano to Francis I. had a decided influence, as will be noted hereafter, though attention may again be called to the fact that Barlow, in his voyage to North Carolina, 1584, used the Letter without credit, according to the custom of the time; while, when Gosnold visited New England, in 1602, he sailed, as tacitly acknowledged, with the Letter of Verrazano, translated by Hakluyt as his guide.

Next, however, the reader’s attention must be directed to the voyage of Estevan Gomez, who followed Verrazano in 1525. This adventurer was a Portuguese in the service of Spain. While Verrazano was abroad on his voyage, Gomez attended the nautical congress at Badajos, in Spain, when, we are told, Sebastian Cabot was present. At this congress Portugal opposed the plan presented for an expedition to the Indies, being very jealous, as usual, of the power of Spain. The differences of the two powers were nevertheless reconciled, and the king of Spain, with the aid of several merchants, fitted out a caravel and put Gomez in command. Gomez, if he did not stand as high as some men of his time, was a navigator of experience. In 1519 he sailed as chief pilot with Magellan, but incurred much odium by leaving him in the Straits which now bear Magellan’s name, and returning to Spain. Peter Martyr, who gives an account of the congress at Badajos, says: “It is decreed that one Stephanus Gomez, himself a skilful navigator, shall go another way, whereby, between Baccalaos and[15] Florida, long since our countries, he says he will find out a way to Cataia. Only one ship, a caravel, is furnished for him,” and, the chronicler continues, “he will have no other thing in charge than to search out whether any passage to the great Chan from among the various windings and vast compassing of this our ocean is to be found.” Of the voyage out from Spain few particulars are now available, though the account of the return was penned by Martyr subsequently to November 13, 1525, and probably before the close of the year. The voyage was, upon the whole, a short one. Martyr, however, says that he returned at the end of “ten months,” while Navarrete states that he sailed in February. Galvano tells us that, having failed to obtain the command of an expedition to the Moluccas, he went on the coast of the new world in search of a passage to India, observing that “the Earl Don Fernando de Andrada, and the doctor Beltram, and the merchant Christopher de Serro, furnished a galleon for him, and he went from Groine, in Gallicia, to the Island of Cuba, and to the Cape of Florida, sailing by day because he knew not the land.” Galvano tells us, likewise, that he passed the Bay of Angra and the river Enseada, and so “went over to the other side, reaching Cape Razo in 46° N.” This means that he sailed up from Florida past the coast of Maine. Martyr, writing after the return of Gomez, indulges in a strain of ridicule, and says: “He, neither finding the Straight, nor Cataia, which he promised, returned back in ten months after his departure;” and continues: “I always thought and supposed this worthy man’s fancies to be vain and frivolous. Yet he wanted not for suffrages and voices in his favor and defense.” Still, Martyr admits that “he found pleasant and profitable countries agreeable with our parallels and degrees of the pole.”

The results of the voyage along the coast from Florida to Newfoundland are indicated on the Map of Ribeiro, 1529, which represents a new exploration, as nothing seems to have been borrowed from either the voyage of Verrazano or from the voyages made by the Portuguese, with the exception that Ribeiro used old Portuguese maps of Newfoundland, which was the case with Verrazano. We must, however, confine our observations to things that relate to this immediate region, and notice what the accompanying maps so fully exhibit, the difference of the delineation of Sandy Hook and Long Island. On the Ribeiro Map Sandy Hook appears as “Cabo de Arenas,” the Sandy Cape, exaggerated in size, while Long Island is hardly distinguishable, as the coast line runs too close to the north. It is indicated by the section of the coast between two rivers, “Montana Vue,” evidently one of the hills of Long Island that the navigator now views from the sea. On the Verrazano Map, the region of Sandy Hook is “Lamuetto” and “Lungavilla,” while Long Island is indicated as a[16] part of the mainland, bearing the names of “Cabo de Olimpo” and “Angolesme,” the bay of “San Germano” lying between. The delineations of Verrazano exhibit his short stay and hasty departure, while the survey of Gomez must have occupied more time, at least around Sandy Hook. That this map resulted from the voyage of Gomez is evident from the legend, which calls the land “Tierra de Estevan Gomez;” (the country of Stephen Gomez) while eastward, where the coast of Maine is delineated, is the “Arcipelago” of Gomez. On this Map of Ribeiro the lower Bay of New York is indicated by “E. de S. Xpoal,” with several Islands. A river appears between this bay, given in later documents as Bay of “St. Chrispstabel,” and Long Island, but the name of the river is not given. “B. de S. Antonio,” however, is given which indicates the upper bay or harbor, and subsequently we shall see the river itself indicated as the river “San Antonio,” while the place of Sandy Hook in the old cartography will be fully established and identified with Cape de Arenas. Ribeiro evidently had pretty full notes of the calculations and observations of Gomez.

FRA. DRAKE.

As the reverential old navigators were often in the habit of marking their progress in connection with prominent days in the Calendar, it is reasonable to suppose that the Hudson was discovered by Gomez on the festival of St. Anthony, which falls on January 17. Navarrete indeed says that he left Spain in February, but the accounts are more or less confusing. If Martyr, who is more particular, is correct, and Gomez was absent “ten months,” he must have sailed early in December, which would have brought him to our coast on the festival of the celebrated Theban Father. At this time the navigator would have seen the country at its worst. Evidently he made no extended exploration of the river, as in January it is often loaded with ice and snow.

Gomez was laughed at by the courtiers, and had no disposition to return to the American coast. The legend on the Map of Ribeiro proclaiming[17] his discovery, that is, exploration of the coast, declared that here were to be found “many trees and fruits similar to those in Spain,” but Martyr contemptuously exclaims, “What need have we of these things that are common to all the people of Europe? To the South! to the South!” he ejaculates, “for the great and exceeding riches of the Equinoxial,” adding, “They that seek riches must not go to the cold and frozen North.” Gems, spices, and gold were the things coveted by Spain, and our temperate region, with its blustering winters, did not attract natures accustomed to soft Andalusian air.

After the voyage of Gomez, which, failing to find a route to the Indies, excited ridicule, there is nothing of special interest to emphasize in this connection until 1537. In the meanwhile, the English were active, and in 1527 two ships, commanded by Captain John Rut, were in American waters. It has been claimed that he sailed the entire coast, often sending men on land “to search the state of these unknown regions,” and it has been affirmed that this is “the first occasion of which we are distinctly informed that Englishmen landed on the coast.” Also that, “after Cabot, this was the second English expedition which sailed along the entire east coast of the United States, as far as South Carolina.” Granting, however, that the expedition of Rut actually extended down the American coast, there is no proof that he gave any attention to the locality of the Hudson.

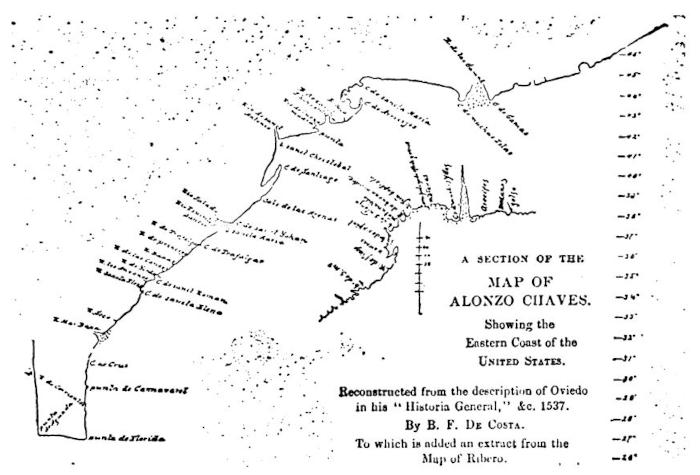

A SECTION OF THE

MAP OF ALONZO CHAVES.

We turn now to the account of our particular locality, as given by Oviedo in 1537, who wrote an account of the coast based largely upon the Map of Alonzo Chaves. It appears that, in 1536, Charles V. ordered that the official charts should “be examined and corrected by experienced men, appointed for that purpose.” Acting under their instructions, Alonzo Chaves drew up a chart, embodying the information that he had been able to collect from maps and narratives. It is evident that he had notes of the voyage of Gomez, and that he used the Ribeiro Map, but he had no information about the voyage of Verrazano or that of Cartier in 1534. His delineation of the coast began in the Bay of Mexico, and extended to Newfoundland. Oviedo, in his “History of the Indies,” used this map, and describes the coast by its aid. The Map of Chaves does not appear to be accessible, but its American features have been reconstructed from the descriptions of Oviedo, and this portion of the Map is given herewith, the latitudes and distances being exactly preserved. From the Cape of Florida, Oviedo moves northward in his descriptions, which are distinctly recognizable. “Cabo de Sanct Johan” stands at the mouth of the Chesapeake, and from this place “Cabo de los Arenas” is thirty leagues to the north-northeast. The latter cape is 38° 20′ N. From “Arenas” the coast runs thirty leagues to “Cabo de Santiago,”[18] which is 39° 20′ N. On this map Sandy Hook appears as Cape Santiago, but generally the name of “Arenas,” the Sandy Cape, is affixed to the Hook[7]. Oviedo, on reaching the end of Sandy Hook, proceeds to give an unmistakable delineation of the Bay and Harbor of New York, and of the river which is now known as the Hudson. “Thence,” continues Oviedo, with his eye on the Map of Chaves, “the coast turns southwest twenty leagues to the Bay of Sanct Christobal, which is in 39°, passes said bay, and goes thirty leagues to Rio de Sanct Antonio, north and south with the bottom of this bay; and the ‘Rio de Sanct Antonio’ is in 41° N.” Dr. Kohl says that “it is impossible to give a more accurate description of the Hudson River,” but this is not quite true. It was an excellent description for that period, considering the material at hand; yet it must be remembered that all the distances are given as general estimates on the decimal system. Besides, the Map of Chaves, like all the maps, was drawn on a small scale, and Sandy Hook and the Lower Bay are both exaggerated, as on the Map of Ribeiro, which will be seen by a comparison of the two maps, placed side by side to facilitate investigation. Both Ribeiro and Chaves had erroneous measurements of distances, and made the Lower Bay quite a large gulf, while the latitude of “Rio Sanct Antonio” is placed one[19] degree too high. Ribeiro, however, gave the Hook its right name, “Arenas.”[8] The size of the Hook is exaggerated on the Maijolla Map, 1527, though not on the Verrazano, 1529. These things show free-hand drawing on the part of the mapmakers, and defective rule-of-thumb measurements by the navigator, who probably viewed the waters behind the Hook when veiled in mist, failing to test his own estimates.

Oviedo says that “from the Rio de Sanct Antonio the coast runs northeast one-fourth east forty leagues to a point (punta), that on the western side it has a river called the Buena Madre, and on the eastern part, in front of (de lante) the point, is the Bay of Sanct Johan Baptista, which point (punta) is 41° 30′ N.”; or, rather, correcting the error of one degree, in 40° 30′ N. This point is Montauk Point, Long Island being taken as a part of the main. The Thames River in Connecticut answers to the River of the Good Mother, and the Bay of John Baptist is evidently the Narragansett. Oviedo then goes on to the region of Cape Cod, varying from the general usage, and calling it “Arrecifes,” or the Reef Cape, instead of “Cabe de Baxos,” which signifies substantially the same thing. Under the circumstances, the description of Long Island is remarkably exact, as its shore trends northward almost exactly half a degree in running to Montauk Point. What, therefore, lies on either side of the River San Antonio fixes beyond question the locality of the Hudson, and proves that it was clearly known from the time of Gomez to 1537.

The next navigator whose work touched our part of the coast was Jehan or Jean Allefonsce, who, in 1542, came to Canada as pilot of Roberval, and gained considerable knowledge of the North Atlantic shores. This hardy sailor was a native of Saintonge, a village of Cognac, France. After following the sea for a period of more than forty years, and escaping many dangers, he finally received a mortal wound while engaged in a naval battle in the harbor of Rochelle. Melin Saint-Gelais wrote a sonnet in his honor during the year 1559. It can hardly be doubted that Allefonsce himself ran down the coast in one of the ships of Roberval, probably when returning to France.

With the aid of Paulin Secalart he wrote a cosmographical description, which included Canada and the West Indies, with the American coast. Very recognizable descriptions are given as far down as Cape Cod and the islands to the southward. The manuscript also possesses interest in connection with the region of the Hudson, though farther south the description becomes still more available.

Allefonsce after disposing of the region of New England, turns southward, and says: “From the Norombega River,” that is, the Penobscot, “the coast runs west-southwest about two hundred and fifty leagues to a large bay (anse) running inland about[20] twenty leagues, and about twenty-nine leagues wide. In this bay there are four islands close together. The entrance to the bay is by 38° N., and the said islands lie in 39° 30′ N. The source of this bay has not been explored, and I do not know whether it extends further on.... The whole coast is thickly populated, but I had no intercourse with them.” Continuing, he says: “From this bay the coast runs west-northwest about forty-six leagues. Here you come upon a great fresh-water river, and at its entrance is a sand island.” What is more, he adds: “Said island is 39° 49′ N.”

From the description of Allefonsce, it is evident that the “great fresh-water river” is the Hudson, described five years before by Oviedo, out of the Map of Chaves, as the River of St. Anthony, while the “island of sand” was Sandy Hook.[9]

Turning from the manuscript of Allefonsce to the printed cosmography, we discover that the latter is only an abridgement, it being simply said that after leaving Norombega, the coast turns to the south-southeast to a cape which is high land (Cape Cod), and has a great island and three or four small isles. New York and the entire coast south have no mention. The manuscript, however, suffices for our purpose and proves that the coast was well known.

It has been already stated that it would be impossible to say when the first Englishman visited this region; yet in the year 1567-8, evidence goes to prove that one David Ingram, an Englishman, set ashore with a number of companions in the Bay of Mexico, journeyed on foot across the country to the river St. John, New Brunswick, and sailed thence for France. Possibly he was half crazed by his sufferings, yet there can be little doubt that he crossed the continent and passed through the State of New York, traveling on the Indian paths and crossing many broad rivers. If the story is true, Ingram is the first Englishman known to have visited these parts.

In April, 1583, Captain Carline wrote out propositions for a voyage “to the latitude of fortie degrees or thereabouts, of that hithermost part of America,” and, in 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert had this region under consideration, Hakluyt observing on the margin of his “Divers Voyages” that this was “the Countrey of Sir H. G. Uoyage.” Hays says in his account of the region, that “God hath reserved the same to be reduced unto Christian civility by the English nation” and, also that “God would raise him up an instrument to effect the same.” All this is very interesting in connection with English claims and enterprise. In the same year the French were active on the coast, and one Stephen Bellinger, of Rouen, sailed to Cape Breton, and thence coasted southwesterly six hundred miles “and had trafique with the people in tenne or twelve places.” Thus the French were moving from both the north and the south towards[21] this central region; but we cannot say how far south Bellinger actually came, as there is nothing to indicate his mode of computation. It is not improbable that he knew and profited by the rich fur-trade of the Hudson.

In 1598 and there about, we find it asserted that the Dutch were upon the ground, for, in the year 1644, the Committee of the Dutch West India Company, known as the General Board of Accounts, to whom numerous documents and papers have been intrusted, made a lengthy report, which they begin as follows: “New Netherland, situated in America, between English Virginia and New England, extending from the South [Delaware] river, lying in 34½ degrees to Cape Malabat, in the latitude of 41½ degrees, was first frequented by the inhabitants of this country in the year 1598, and especially by those of the Greenland Company, but without making any fixed settlements, only as a shelter in winter. For which they built on the North [Hudson] and the South [Delaware] rivers there two little forts against the attacks of the Indians.” Mr. Brodhead says that the statement “needs confirmation.” Still it is somewhat easy to understand why a statement of this kind coming from such a body should require confirmation; but the Committee had no reason for misstating the facts, and ought to have been accurately informed. Yet if confirmation is insisted upon, we are prepared to give it, such as it is, from an English and, in fact, an unexpected source. Our authority is no less a personage than Governor Bradford, of Plymouth Colony, whose office and inclinations led him to challenge all unfounded claims that might be put forth by the Dutch. Nevertheless, writing to Sir Ferdinando Gorges, the father of New England colonization, who likewise was hostile to the pretensions of the Dutch, Bradford says, under date of June 15, 1627, that the Dutch on the Hudson “have used trading there this six-or-seven-and-twenty years, but have begun to plant of later time, and now have reduced their trade to some order.” Bradford lived in Holland in 1608, and had abundant opportunities for knowing everything relating to Dutch enterprise. It is perfectly well known that the Plymouth Colonists of 1620 intended to settle at the Hudson, though circumstances directed them to the spot pointed out by Dermer in 1619, when in the service of Gorges. Thus, about seventeen years before the Committee of 1644 reported, Governor Bradford, an unwilling, but every way competent and candid witness, carried back the Dutch occupancy, under the Greenland Company, to the year 1600. Besides, on the English map of the voyage of Linschoten, 1598, there is a dotted trail from the latitude of the Hudson, 40° N. to the St. Lawrence, showing that the route was one known and traveled at that time. It is evident, from a variety of considerations, that both the Dutch and French resorted to the Hudson at this period to engage in the trade. Linschoten[22] was one of the best informed of Dutch writers, and probably understood the significance of the representation upon his map. The probability is that this route was known a long time before, and that it may be indicated by Cartier, who, when in Canada, 1534, was told of a route by the way of the river Richelieu, to a country a month’s distance southward, supposed to produce cinnamon and cloves, which Cartier thought the route to Florida. Champlain, writing in Canada, says that, in the year previous, certain French who lived on the Hudson were taken prisoners when out on an expedition against the northern Indians, and were liberated, on the ground that they were friends of the French in Canada. This agrees with the report of the Labadists, who taught that a French child, Jean Vigné, was born here in 1614. Evidently the French had been on the ground in force for some years, and were able to make expeditions against the savages. Very likely the French were here quite as early as the Hollanders.

There seems to be, however, another curious piece of confirmation, which comes from the writings of the celebrated Father Isaac Jogues, who was in New Amsterdam during the year 1646. In a letter written on August 3d of that year, he says that the Dutch were here, “about fifty years” before, while they began to settle permanently only about “twenty years” since. The latter statement is sufficiently correct, as 1623 was the year when a permanent colony was established by the Dutch. The former statement carries us back to the date of the “Greenland Company.”

So far as present evidence goes, it is perhaps unnecessary to say anything more in vindication of the statement of the Dutch Committee of 1644, claiming that representatives of the Greenland Company wintered here in 1598. Nevertheless, as a matter of interest, and to show how well the Hudson was known at this time by both Dutch and English, we may quote from the English translation of the Dutch narrative of Linschoten, which clearly describes the coast. He says: “There is a countrey under 44 degrees and a halfe, called Baccalaos.” This country of Baccalaos reached nine hundred miles, that is, from the Cape de Baccalaos [Cape Race] to Florida.

The distances are given approximately, of course, by Linschoten, being on the decimal system, but they distinctly mark the principal divisions of the coast and fix the fact beyond question that the Hudson was perfectly well known.

On the general subject it may be said, that the record of the “Greenland Company” is not satisfactory, yet the word “Greenland” at that time had a very general use, and all that the Committee of Accounts may have meant by the phrase was, that a company or association engaged in the fur and fish trade, which for centuries, even, had been prosecuted at the north, had sent some ships to this region in 1598.[23] There is certainly nothing unreasonable in this supposition, the coast being so well known. Various adventurers of whom we know nothing doubtless came and went unobserved, being in no haste to publish the source from which they derived such a profitable trade in peltries. The Committee of Accounts either falsified deliberately or followed some old tradition. Why may not a tradition be true?

We turn next to examine a map recently brought to notice and which is of unique value. Formerly the map usually pointed out as the oldest seventeenth century map of this region was the Dutch “Figurative” Map, which was found by Mr. Brodhead in the Dutch archives. We have now, however, an earlier map of 1610, which was prepared from English data for James I., a copy finding its way to Philip III., by Velasco, March 22, 1611. Sandy Hook, though without name, is delineated about as it appears in later maps, while Long Island is shown as a part of the main, with no indication of the Sound, though Cape Cod and the neighboring islands are well delineated, and Verrazano’s Island of “Luisa” appears as “Cla[u]dia,” the mother of Francis I. Clearly at this time neither Block nor any other Dutch navigator had passed through Hell Gate into Long Island Sound.

There is nothing whatever in this map relating to explorations by any nation later than 1607. Jamestown appears on the Virginia portion, and Sagadehoc in Maine. It was simply a copy of a map made soon after the voyage to New England and Virginia in 1607. The compiler had not heard of Hudson’s voyage, as that navigator did not reach England until November 7, 1609. If he had received any information from Hudson, he would have shown the river terminating in a shallow, innavigable brook, whereas the river is indicated, in accordance with Captain John Smith’s idea, as a strait, leading to a large body of water. Further, the map contradicts Hudson, who represents the Hoboken side of the river as “Manhatta,” while this map puts the name on both sides, “Manahata,” on the west and “Manahatin” on the east. It is not unlikely that Hudson had with him a copy of the map, for his guidance on the voyage in the Half-Moon.

SIR WALTER RALEIGH.

Though this map bears a date subsequent to Hudson’s voyage, the contents prove that the original could not have been drawn later than 1608. It was evidently one of the various maps of which Smith spoke and which he underrated. Its substance indicates that it was drawn from a source independent of the Dutch and French, showing that the English knew of the Bay of New York and its relation to Sandy Hook, and that they supposed the great river delineated was a broad stream which, in someway, communicated with the Pacific. On the original map of which Velasco’s example was a copy, the land west of the river was colored blue, and the legend says that[24] it is described by information drawn from the Indians. What we need now is the original map, which may still exist in some obscure collection in England or Holland, and quite as likely in the archives of Spain, sent thither by jealous Spanish spies, who lingered, like Velasco, at the court of James I., to learn what they could with respect to English enterprise in America. At all events we have in this English map the first seventeenth century delineation of this region, and one showing that the English knew the form and general character of the country which the crown conveyed to the colonists of North and South Virginia in 1606. So far as now known, it was clearly the English who first became acquainted with the name that the Aborigines applied to the island upon which our great metropolitan city stands. Whether or not this was an aboriginal word or a corruption of a Castilian term future investigators may decide. The unexpected finding of this old English map in the Spanish archives revives our hopes relating to the discovery of new sources of information concerning early voyages to this coast. English enterprise and adventure on the Virginia coast, extending from Raleigh’s expedition, 1584, to Gosnold’s fatal quest, 1603, must have brought Englishmen into the Bay of New York, unless miracle was balanced against curiosity and chance. There are archives yet to be opened that may give the origin of the delineations of this region found in the remarkable map from Samancas, and we need to be cautious in making claims even for the priority of the Dutch in 1598.

The period under consideration was a period of reconnoissance, one that offered some romantic incident, but more of disappointment and mortification. Here was a site for one of the noblest cities in the world, but the voyager was blind. The river offered no route to the gorgeous Indies, and Verrazano had little inclination to test its swift tide. Gomez, in the short January days of 1525, had no desire to ascend, for when his ship met the drift ice tossing on the cold, swirling stream, he thought of Anthony in his desolate[25] retreat on the Red Sea, put the river under his charge, and sailed away in search of happier shores. Sailors of other nationalities, doubtless, ascended the river; but, finding it simply a river, they took what peltries they could get, and, like Gomez, turned the whole region over to the care of the solitary Saint, who for nearly a century stood connected with its neglect. Much remained to be done before steps could be taken with regard to colonization. The initial work, however, was inaugurated by the sturdy Englishman, Henry Hudson, and the proud Spanish caravel disappears, while the curtain rises upon the memorable voyage of the quaint Dutch fly-boat, the Half-Moon.

[2] Letter addressed to the writer in 1890.

[3] The vignette on proceeding page is a faithful representation of the Florentine portrait.

[4] The usual course was to sail southward and reach Florida coasting north, or to sail to Newfoundland and coast southward. It required especial boldness to take the direct course, and, in 1562, when Ribault followed this course, he was proud of the achievement. The fact that Verrazano sailed the direct course at that time proves the authenticity of his voyage, as a forger would not have invented the story.

[5] On the Map of Verrazano, to which attention will be directed, this triangular island is delineated. The voyager approaching the island from the west comes to a point of the triangle where he can look away in the easterly direction, and at a glance take in two sides; while on reaching the eastern limit the third side plainly appears. In sailing past Block Island, as Verrazano did, from west to east, the navigator could not fail to discover its triangular shape. Indeed it is so marked that one is struck by the fact.

[6] The story of this map is curious. The American contents were first given to the public by the writer in the “Magazine of American History,” and afterward reprinted in “Verrazano the Explorer.”

[7] In “Cabo de Arenas,” the coast names taken from a large collection of maps are arranged in parallel columns, illustrating three main divisions of the coast, showing that Cabo de Baxos was the name applied to Cape Cod, and Cabo de Arenas to Sandy Hook. Capo Cod in the early times was not a sandy cape, but a beautiful and well-wooded cape. Sandy Hook ever since it was known has borne its present character.

[8] Those who have fancied that Cape Arenas was Cape Cod, and that the bay behind it was Massachusetts Bay, have the same difficulty as regards dimensions. Students of American cartography understand perfectly well that latitudes in the old maps were often more than two degrees out of the way, the instruments of that period being so defective.

[9] To convince himself of this fact the reader may compare the reconstructed Map of Chaves with the coast surveys, when the main difference will be found to consist in the exaggeration of Sandy Hook. The “Narrative and Critical History of America,” dealing with this point, suppresses all allusion to the fact that Kohl recognizes the cape on the Map of Chaves with the names “Santiago” and “Arenas” as Sandy Hook, which follows, as the river inside of the Hook he identifies with the Hudson. Dr. Kohl, though generally very acute, failed to see that Oviedo’s description of the Map of Chaves was, substantially, the description of Ribeiro, and that in identifying, as he chanced to, the “Arenas” of Ribeiro with Cape Cod, he stultified his own reasoning. Nor did he consider this, that if the great Cape “Arenas” was intended for Cape Cod, there is no representation whatever of Sandy Hook and the Hudson in the old cartography and that all the voyages to this region geographically went for nothing. Credat Judaeus Appellus! This exaggeration of Sandy Hook is conceded, yet the inlets along the New Jersey shore may have been viewed as connected by Gomez; and indeed, so great have been the changes along the coast that no one can well deny that they were connected in 1525, and formed a long bay running down behind Sandy Hook. It will prove more historic to follow the writer, who says, “that the coast of New York and the neighboring district were known to Europeans almost a century before Hudson ascended the ‘Great River of the North,’ and that this knowledge is proved by various maps made in the course of the sixteenth century. Nearly all of them place the mouth of a river between the fortieth and forty-first degrees of latitude, or what should be this latitude, but which imperfect instruments have placed farther north.”—Nar. and Crit. His. of Amer., 4: 432.

Seventy-odd years ago the Rev. Sydney Smith wrote in the Edinburg Review as follows: “Literature, the Americans have none—no native literature, we mean. It is all imported. They had a Franklin, indeed, and may afford to live for half a century on his fame. There is, or was, a Mr. Dwight, who wrote some poems, and his baptismal name was Timothy. There is also a small account of Virginia, by Jefferson, an epic by Joel Barlow, and some pieces of pleasantry by Mr. Irving. But why should the Americans write books, when a six weeks’ passage brings them, in their own tongue, our sense, science and genius in bales and hogsheads?”

Times have changed since Mr. Smith wrote this somewhat sarcastic summary of our native literature; for, while it is true that we still import British “sense, science, and genius in bales and hogsheads,” it is done now on principles of reciprocity, and we return quite as good and perhaps nearly as much as we receive.

Americans do not instance Mr. Dwight, whose “baptismal name was Timothy,” or Mr. Barlow, the author of the epic so sneeringly referred to, as the chiefs of American poesy; yet we need not blush for either of them; for the first was a distinguished scholar the President of Yale College, and the author of the hymn so dear to many pious hearts:

The other, Mr. Barlow, was a well-known man of letters and politician in his day, author of the “Columbiad,” the epic referred to by Mr. Smith, and minister plenipotentiary of the United States to the coast of France at a critical period of our history. As to the “Columbiad,” it has been pronounced by competent critics to be equal in merit to Addison’s “Campaign,” and surely it is no disgrace to have equalled Addison.

It was the fashion in those days for Englishmen to sneer at Americans; and so we find in another review, written by the same gentleman in 1820, this language: “During the thirty or forty years of their independence, they have done absolutely nothing for the sciences, for the arts, for literature, or even for the statesmanlike studies of politics or political economy.... In the four quarters of the globe who[28] reads an American book? or looks at an American picture or statue? What does the world yet owe to American physicians or surgeons? What new substances have their chemists discovered? or what old ones have they analyzed? What new constellations have been discovered by the telescopes of Americans? What have they done in mathematics? Who drinks out of American glasses? or eats from American plates? or wears American coats or gowns? or sleeps in American blankets?” In the very same year that this array of rather insolent queries was propounded by Sydney Smith, the genial Washington Irving, in the advertisement to the first English edition of his Sketch Book, remarks: “The author is aware of the austerity with which the writings of his countrymen have been treated by British critics.” We have not a particle of doubt as to the “austerity” in question. The salvos of Old Ironsides and the roar of Jackson’s guns at New Orleans, were unpleasant facts not yet forgotten by Englishmen.

But Sydney Smith was not quite fair towards our countrymen. It was “during the thirty or forty years of their independence” referred to that Fulton’s steamboat revolutionized navigation, that Rittenhouse developed a mathematical skill second only to that of Newton; that West delighted even royalty itself with the creations of his pencil; while in “the statesmanlike studies of politics or political economy,” it was during this very period that Jefferson, Hamilton, Madison, and their coadjutors did more to develop the true principles of government and politics than had ever been done before in the history of the world. True, we had not much to boast of, but it would have been only just to give us credit for what we were worth. Moreover, in a small way, but to the extent it was possible under the circumstances, the English colonists in America had cultivated letters from the beginning. In 1685, Cotton Mather wrote his Memorable Providences; in 1732, Franklin began to issue his Poor Richard’s Almanac; in 1749, Jonathan Edwards published his Life of David Brainerd, and in 1754, his famous treatise on The Freedom of the Will and Moral Agency. Besides these, which perhaps stand out most conspicuously, there were many minor works of more or less excellence, over most of which the iniquity of oblivion, to use the fine phrase of Sir Thomas Browne, hath scattered her poppy.

The moment that the Edinburg Review was thus dealing our fathers these heavy blows seemed to be the real starting point in our career of literary greatness. William Cullen Bryant, Washington Irving, James K. Paulding, Richard H. Dana, James Fenimore Cooper, Mrs. Sigourney and a host of others were giving direction to that stream of literature that has since flowed broad and free over our land, imparting life and vigor and beauty to our society and institutions. It is, however, anterior to the year 1820, the[29] thirty or forty years of our national independence, during which Mr. Smith says we have done “absolutely nothing” in literature, science or art, to which we must more particularly advert. The literary product of those years was scanty enough, it is true. The student of this period will not find much, and not all of that of the first order, to reward his labor—not much, at least, as compared with other nations at the same time. But may there not have been some sufficient reason for this, outside of any downright intellectual deficiencies on the part of our fathers? Let us for a moment consider the condition of things at that time in this country.

In the first place, at the time referred to, the citizens of the United States were in a daily struggle with the material difficulties of their situation. The country was new. The region west and north of the Ohio and Mississippi was yet an almost unbroken wilderness, while the country east and south of those rivers was but sparsely populated. At the same time the tide of immigration was sweeping into the country, and with it all the rush and turmoil incident to life in a new country was going on. Forests were to be cut down; farms were to be cleared up; houses were to be built; roads were to be made; bridges were to be thrown across the rivers; while a livelihood was to be compelled from the forests, the streams, and the fields. The conditions of a new country are not favorable to the cultivation of the arts, of sciences, or of literature. Why do not Englishmen twit the people of Australia because during the past forty or fifty years in which they have prospered so greatly in material things, they have not produced a Macaulay, a Tennyson, a Gladstone, a Tyndall, or a Huxley? It would be just as fair to do it.

Not only was there this hand to hand contest with their physical environment, but the political conditions were also unfavorable to any general dalliance with the Muses. Only in times of tranquility and ease is it possible.

The country at the period referred to, had just emerged from a long and exhausting war. Society was almost broken up; the arts of peace were well nigh forgotten; the finances were in almost hopeless confusion; the form of government was unsettled, and scarcely yet determined upon. The first thing to do was to evolve some system and some security out of this chaos. Politics alone occupied the moments of leisure. When, finally, authority had crystallized into definite government the people were not allowed to be at rest. Murderous wars with the Indians on the frontiers; the machinations of French emissaries; British oppression of American commerce, and at length another long and bloody war with England, harassed the minds of the people, and prevented them[30] from giving themselves up more generally to the kindly and refining influences of literature and art. When we consider all the circumstances in the case, there seems a degree of severity in Sydney Smith’s sneers and taunts.

But though circumstances were thus unfavorable to the cultivation of letters, yet something was done in this direction nevertheless. Smith refers flippantly enough to Dwight, Jefferson, Barlow and Irving. But besides these there were others, not brilliant luminaries perhaps, yet stars shining in the darkness according to their orders and degrees. We do not design here to enter upon any discussion of their respective merits, but we may mention as a writer of that period no less a character than George Washington, whose greatness in other spheres of life has entirely eclipsed any fame of which he may be worthy as an author, yet whose Farewell Address alone would entitle him to a place among the most accurate writers of English. Among others we may name John Adams, whose pen was scarcely less eloquent than his tongue; Francis Hopkinson, author of The Battle of the Kegs and many other pieces, of which it has been said, that “while they are fully equal to any of Swift’s writings for wit, they have nothing at all in them of Swift’s vulgarity;” Dr. Benjamin Rush, a distinguished writer on medical and social topics; John Trumbull, the author of McFingal and The Progress of Dullness; James Madison, afterward President of the United States, one of the ablest writers in The Federalist; Philip Freneau, a poet of the Revolution and the period immediately following; Alexander Hamilton, a contributor to The Federalist, and one of the clearest of political writers; Joseph Dennie, the author of The Lay Preacher, and editor of The Portfolio; Joseph Hopkinson, author of Hail, Columbia; Charles Brockden Brown, author of Wieland, Arthur Mervyn, and other works, and who was perhaps the first American who wholly devoted his life to literary pursuits; William Wirt, author of the British Spy, the Life of Patrick Henry, and other works; and Lyman Beecher, the author of a work on Political Atheism, anti several volumes of sermons and public addresses. This list might easily be extended, but its length as it now stands, as well as the merits of the writers adduced, is sufficient to contradict effectually the statement that America had “no native literature,” and that during the thirty or forty years immediately subsequent to the Revolution she had done “absolutely nothing” for polite letters. Much of this early literature still remains, and is read; many of these authors are still familiar to this generation, and it is generally admitted that the writer whose fame survives a century is assured of a literary immortality. Sydney Smith was an acute man, a learned man, a great wit, a ready and elegant writer, a trenchant[31] critic, but the names of some of these humble Americans whom he did not deign to mention, or mentioned only to scoff, bid fair to stand as long in the annals of literature as his own.

On the eastern slope of the Andes are a thousand springs from which the slender rills, half hidden at times by the grass, scarcely at any time seen or heard, trickle down the side of the immense mountain range, here and there falling into each other and swelling in volume as they flow, until at length is formed the mighty Amazon, that drains the plateaus and valleys of half a continent. So the beginnings of our literature, like the beginnings of every literature, are small, indistinct, half hidden; but as they proceed, these little rills of thought and expression grow and expand, until the mighty stream is formed that irrigates the whole world of intellectual activity.

This stream, as we have said, first began to assume definite form and direction about the time that Sydney Smith was uttering his tirades against the genius and achievements of our countrymen. In 1817, appeared in the North American Review a remarkable poem called “Thanatopsis.” The author was a young man named William Cullen Bryant, only twenty-three years of age; yet the poem had been written four years before. The annals of literature do not furnish another example of such excellence at so early an age. The poem yet stands as one of the most exquisite in the language. A recent critic has characterized it as “lofty in conception, beautiful in execution, full of chaste language and delicate and striking imagery, and, above all, pervaded by a noble and cheerful religious philosophy.” This first effort on the part of Bryant was succeeded by a long career of eminence in the field of literature. In 1818 appeared a volume of miscellanies called “The Sketch Book,” by Washington Irving, a young man who had already acquired some slight reputation as a dabbler in literature of a trifling or humorous kind. The Sketch Book was almost immediately honored by republication in England. This initial volume was followed by a second series of miscellanies called “Bracebridge Hall,” which was published in London in 1822. In the preliminary chapter the author pleasantly adverts to the general feeling with which American authorship was regarded in England. “It has been a matter of marvel to my European readers,” says he, “that a man from the wilds of America should express himself in tolerable English. I was looked upon as something new and strange in literature; a kind of demi-savage, with a feather in his hand instead of on his head; and there was a curiosity to hear what such a being had to say about civilized society.” In the same year with Irving’s Sketch Book appeared Drake’s Culprit Fay, a poem that has not been surpassed in its kind since Milton’s Comus. In 1821 Percival issued his first volume of[32] poems, Dana his Idle Man, and Cooper, his Precaution. His last named volume was at once followed by a long list of works including such famous titles as The Spy, The Last of the Mohicans, The Pathfinder, and The Deerslayer. It marked the advent of our most distinguished novelist—a man who has been styled the Walter Scott of America. He justly stands in the same rank with the mighty Wizard of the North, and has no other equal. Thus the stream of American literature rolled on its course, and was swelled as it flowed by the contributions of Everett, Prescott, Bancroft, Emerson, Hawthorne, Poe, Willis, Holmes, Whittier, Lowell, and a host of others, whose names the world will not willingly let die.

America has not yet produced a Shakespere or a Milton; but it must be remembered that England has produced but one, each of these in a period of a thousand years. Anywhere below these two great names, American literature of the last seventy years is able to parallel the best work that has been produced by our kinsmen on the other side of the Atlantic. In wealth and elegance of diction, in depth of thought or feeling, in brightness and grace of expression, in any of the thousand forms and flights in which genius seeks to express himself, the current literature of America stands on a level with the current literature of England; and Sydney Smith’s sneers, which must have touched our fathers to the quick, find no response now except the smile of contempt which alone they ever deserved.

T. J. Chapman.