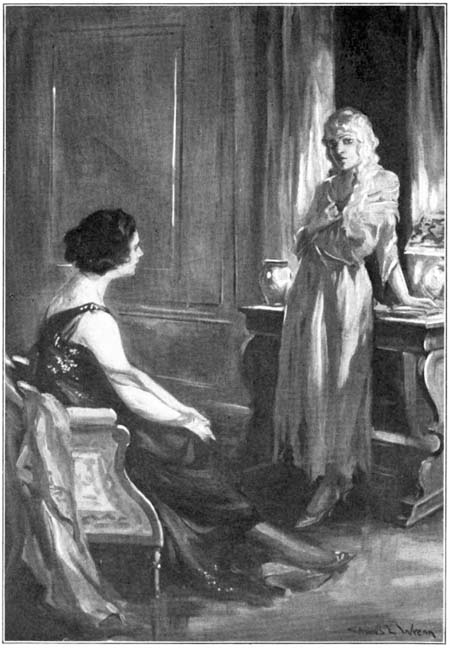

“Hurry, hurry,” she gasped, as a white-robed figure stepped inside her room.

Page 262

THE

THREE STRINGS

BY

NATALIE SUMNER LINCOLN

AUTHOR OF “THE MOVING FINGER,” “I SPY,” “THE NAMELESS MAN,” “C. O. D.,”

“THE TREVOR CASE,” “THE OFFICIAL CHAPERON,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

CHARLES L. WRENN

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

1918

Copyright, 1918, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

TO

Mrs. Theodore Vernon Boynton

OF WASHINGTON, D. C.

Whose Loyal Affection Has Been Mine Since Childhood,

I Send This Problem, in Full Assurance

That She Will Pull the Right “String.”

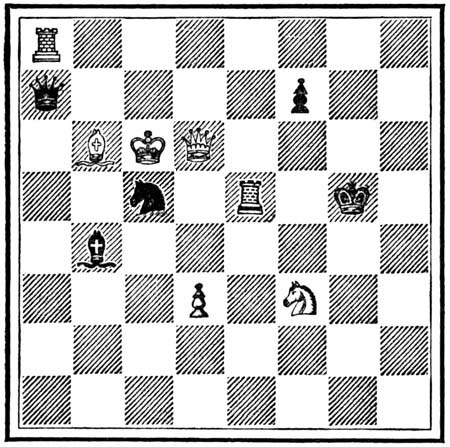

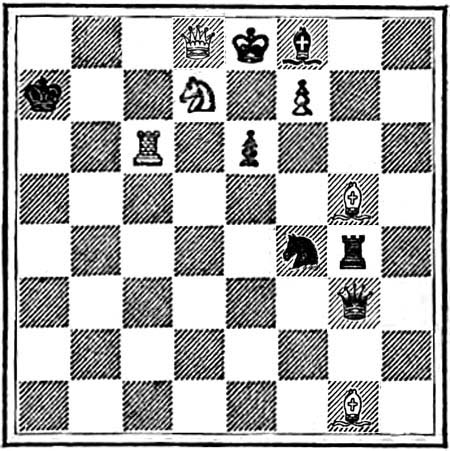

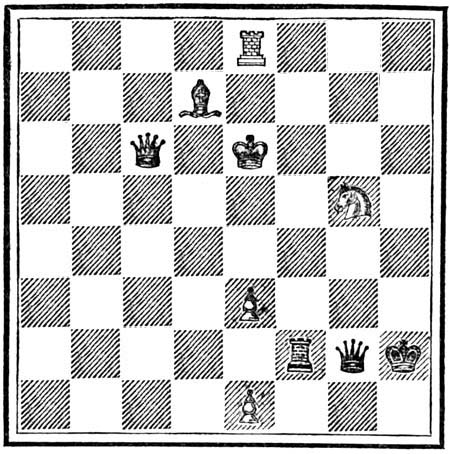

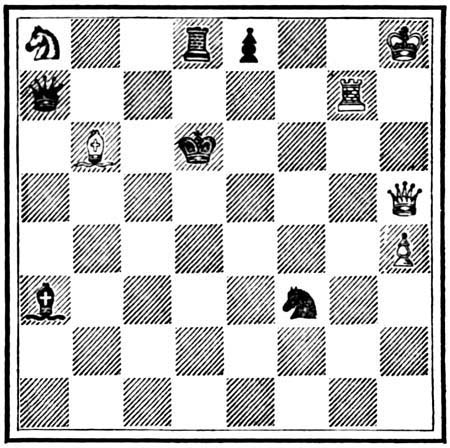

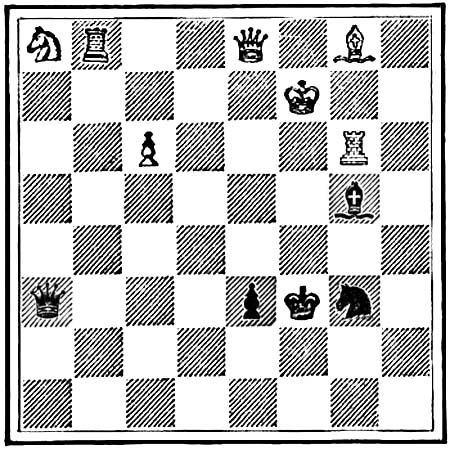

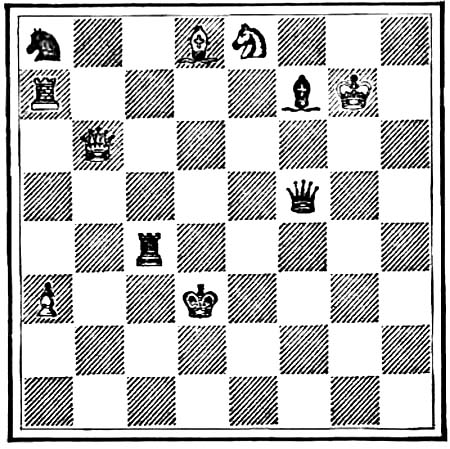

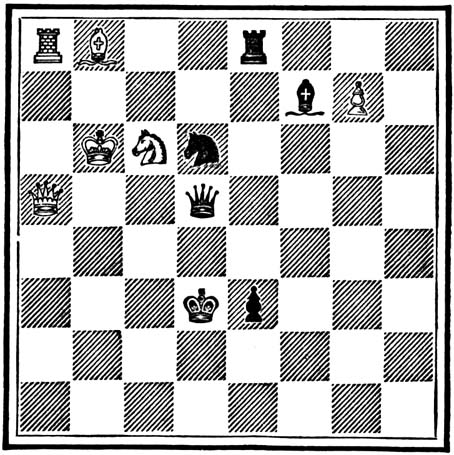

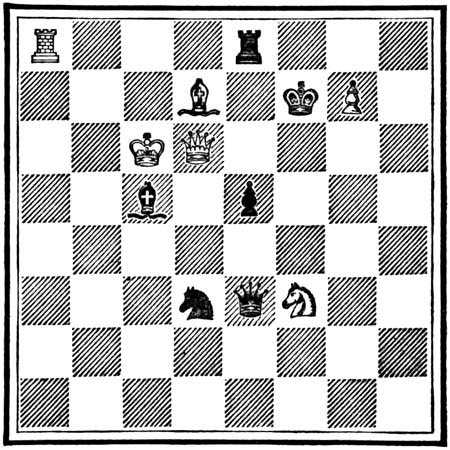

To Alain Campbell White, Esq., of Litchfield, Conn., the Author is indebted for kindly assistance in working out a chess problem which his expert knowledge of chess made feasible.

The Author desires also to express her appreciation of the assistance of Dr. Alexander J. Anderson of Waterbury, Conn., whose help in solving a “knotty” problem was but one of many acts of kindness.

[viii]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The First Move | 1 |

| II. | Complications | 9 |

| III. | Unidentified | 22 |

| IV. | A Question of Time | 39 |

| V. | The “Ace” | 53 |

| VI. | Developments | 70 |

| VII. | The Fifth Man | 85 |

| VIII. | Further Developments | 100 |

| IX. | The Telegram | 113 |

| X. | “Seditious Utterances” | 126 |

| XI. | Conflicting Clues | 143 |

| XII. | The Call | 162 |

| XIII. | The Blotted Page | 177 |

| XIV. | Burnham Prefers Charges | 188 |

| XV. | “The Best Laid Plans” | 204 |

| XVI. | In the Limelight | 220 |

| XVII. | Camouflage | 236 |

| XVIII. | “The Handwriting on the Wall” | 250 |

| XIX. | Bribery | 264 |

| XX. | Identification | 276 |

| XXI. | Unmasked | 284 |

| XXII. | The Missing Diagrams | 297 |

[x]

| FACING PAGE | ||

| “Hurry, hurry,” she gasped, as a white-robed figure stepped inside her room | Frontispiece | |

| Step by step she advanced nearer the dead man | 12 | |

| He took out Marian’s package of papers and placed them in Evelyn’s lap | 80 | |

| “René,” she blushed hotly, “René loves me” | 252 | |

THE THREE STRINGS

EVELYN PRESTON ran lightly up the steps of her home and inserting her latch-key in the vestibule door, pushed it open just as the taxi-driver, following more slowly with many an upward glance at the blind-closed windows, reached her side.

“Put the suit case down,” she directed. “I’ll have the front door opened by the time you get the trunk here.”

The cool if somewhat stale air of the closed house which met Evelyn as she stepped across the threshold of the open door was refreshing after the glare of the asphalt pavements, for Washington was experiencing one of the hot waves which come in late September and make that month one to be avoided in the Capital City.

Evelyn, intent on calling a servant, paused midway[2] in the large hall as the taxi-driver’s bulky figure blocked the light in the front doorway. Without waiting for directions he lowered her motor trunk from his shoulders and stood it against the wall.

“Shall I leave it here, Miss?” he inquired.

Evelyn, busily engaged in searching for change in her purse, nodded affirmatively, and the man propped himself against the door jamb and waited for his pay.

“Thank you, Miss,” he exclaimed a moment later, his politeness stimulated by the generous tip which accompanied Evelyn’s payment of the taxi fare. “Would you like me to carry your trunk upstairs?”

“No; the butler will take it up, thank you.” Evelyn’s gesture of dismissal was unmistakable, and the man hitched uncomfortably at his cap, glanced furtively up the hall and then back at Evelyn who, totally unconscious of his scrutiny, stood impatiently waiting for him to go. He opened his mouth, but if he intended to address her again he thought better of it, and with a mumbled word banged out of the front door.

Evelyn turned at once and sped to the back stairs, but call as she did, no servant responded and the blind-closed windows made the passageway dark and unfriendly. With an impatient exclamation Evelyn returned to the front hall; the[3] servants had evidently not arrived from the seashore to open the house for her.

She stopped only long enough to push her trunk into the billiard room just off the hall and pick up her suit case, then she went rapidly upstairs to her bedroom which, in its summer covered furnishings, looked very inviting to her tired eyes. Four nights in a sleeper and three extra hours added to the tedium of her journey from the west by a hot-box which had delayed her train’s arrival in Washington, had made her long for home comforts.

Going over to the windows Evelyn drew up the blinds and opening the sashes thrust back the shutters, then, tossing off her hat and coat as she moved about her bedroom, she finally jerked open the suit case and tumbled about its contents until she found the garments she sought. In doing so she unearthed a letter from her mother, and she smiled as her eyes caught the words:

“I am sending the servants to the city on the fifteenth, which gives them a day to open the house and have it aired before you get there. Now be sure and reach Washington on the sixteenth. Your Father will be very angry if——”

The remainder of the sentence was on the opposite sheet, but Evelyn did not trouble to read further; instead her slender fingers made mince-meat[4] of the letter and as the torn pieces fluttered to the floor she sighed involuntarily.

Her mother, with her usual inconsistency, had evidently not troubled to study time-tables in deciding that her daughter could not reach Washington by the 15th, and in her own mind Evelyn wondered if the servants would be dispatched from Chelsea in time to reach there before night. The importance of time figured very little in Mrs. Burnham’s indolent sheltered life; her contention that prompt people wasted a great deal of time was frequently borne out by those who waited in impotent wrath for her to keep her engagements.

Evelyn changed into her dressing gown and then, sometimes colliding against furniture in the darkened house, made her way through her mother’s bedroom and boudoir, her step-father’s suite of rooms and into the library which opened from his bedroom, pulling up window shades and letting in fresh air and sunshine as she went. Back once more in her own room she tested the electric lights and was thankful to find the current turned on; apparently Mrs. Ward, her mother’s housekeeper, had attended to some of the details of moving back into their city house.

Encouraged by her success with the electricity, Evelyn tried the water in the bathroom and finding it running, filled the tub and with the aid of an[5] electric plunger, soon luxuriated in a hot bath. But upon emerging she did not immediately complete her toilet, the comfortable lounge exerted too great an appeal to her weary muscles, and taking a silk quilt from a nearby cedar chest she settled down amid soft pillows and was soon in dreamless slumber.

Some hours later Evelyn awoke. It took her several minutes to recall where she was as she sat up rubbing her sleepy eyes. Her windows faced the west and the afternoon sunshine filled every cranny of the room. Evelyn consulted her watch—fifteen minutes past two. With a bound she was on her feet and a second later was dressing in haste, her actions stimulated by pangs of hunger. She had eaten only a modest breakfast on the train, counting upon a hearty luncheon at home. She paused long enough in her dressing to go to the telephone in the library and call up several friends, only to be told by Central that the telephones she wanted had been disconnected for the summer.

A trifle discouraged Evelyn returned to her bedroom and resumed her dressing more slowly. Whom could she get to go out to tea with her?—Marian Van Ness. Evelyn brightened, but paused on her way to the library; what use to telephone, Marian was probably at the State Department and would not leave there until five o’clock. She could[6] get her to dine with her at the Shoreham, but in the meantime she was exceedingly hungry and to wait until seven o’clock—

Evelyn picked up her hat and then laid it down again as an idea occurred to her. Why not forage about the kitchen for eatables? The idea appealed to her the more she considered it. If the servants did not arrive she could go for Marian, whose apartment house was around the corner, and they could dine together; for the present a cup of tea and a few crackers would stay her appetite.

A few seconds later Evelyn was speeding down the staircase on her way to the kitchen. A visit to the butler’s pantry brought to light a package of crackers concealed in a tin box and a canister of her mother’s favorite Orange-Peko tea. Tucking her treasures under her arm Evelyn sought the kitchen and there to her delight found on investigation that she could light the big gas range. It took her but a moment to fill the water kettle, and humming a song she continued her researches in the orderly kitchen. An unopened jar of peanut butter and another of snappy cheese turned up on one of the shelves, and gathering plates and cooking utensils together she was soon enjoying toasted cheese and crackers and a delicious cup of tea.

She was about to refill her cup when the silence of the sunny kitchen was broken by the imperative[7] ringing of the bell. With a joyful exclamation Evelyn rose to her feet—the servants had come at last. As she started for the hall door she came face to face with the room-bell register—the indicator moved slowly downward and stopped at the printed word: “Library.”

Evelyn stared at the indicator in perplexity. Pshaw! the register was out of order; it was the front door bell which had rung. Stopping long enough to turn off the gas burning in the range she hastened upstairs to the front door, only to find the vestibule empty. She stepped out on the doorstep and glanced up and down, but except for a motor vanishing around the corner, the street was deserted.

Considerably perturbed Evelyn reëntered the house, and it was some seconds before she mounted the staircase to the second floor. Her lagging footsteps were accelerated by the sudden thought that perhaps her step-father had returned and gone straight to his room and, supposing from the opened windows that the servants were downstairs, had rung for the butler. He always carried his latch-key; but her mother had mailed her his latch-key!

Evelyn’s hand fell from the portières to her side and she drew back, then, suppressing her growing nervousness, she parted the portières and stepped into the library. She had advanced half across[8] the room before she became aware that a stranger sat half facing her near the great stone fireplace.

Evelyn retreated precipitously; then, gathering her wits, she demanded a trifle breathlessly:

“Who are you?”

No reply.

“How did you get here?”

Silence.

“What do you want?”

Her question remained unanswered; and anger conquering her fright, Evelyn stepped up to the chair and for the first time obtained a full view of the stranger’s ashen face and wide-staring eyes. Instinctively she bent nearer and her hand sought his pulseless wrist; its icy chill struck her with terror. With one horrified look into the dead eyes she fled from the room.

EVELYN never knew how she reached the front door, but as she dashed out into the vestibule she almost fell into the arms of a tall neatly dressed woman standing on the doorstep. For a breathless second she clung to the newcomer in silence.

“Matilda!” Only in moments of stress did Evelyn ever address her mother’s housekeeper by her first name. “Thank God you are here!”

Mrs. Ward gazed at her in alarm. “What’s wrong, Miss Evelyn?” she asked. “Come inside, Miss,” coaxingly, growing conscious that Evelyn was swaying upon her feet. Supporting the half fainting girl, she led her into the billiard room which opened from the hall to the right of the front door. Once in the room Evelyn collapsed on the nearest chair.

“Oh, don’t go,” she begged as Mrs. Ward stepped toward the hall. “Don’t leave me.”

“Only for a moment, Miss; I left my bag outside the house,” and Mrs. Ward, disentangling her[10] skirt from Evelyn’s clutching fingers, disappeared into the hall to return shortly with a glass of water in one hand and her bag in the other. She dropped the latter on Evelyn’s trunk as she entered the room.

“Take a sip of water, Miss Evelyn,” she said, retaining her hold of the glass as Evelyn’s attempts to take it in her shaking hand proved futile. “Are Jones and the cook here?”

“No.” Evelyn was only equal to monosyllables.

“They haven’t come!” Mrs. Ward looked shocked. “All the servants were to leave Atlantic City this morning on the first train. No wonder you were frightened, Miss Evelyn, all alone in this big house.”

“But I was not alone.” Evelyn pushed aside the empty glass; she felt refreshed by the cold water and the presence of Mrs. Ward restored her to some degree of composure. “There’s a dead man upstairs!”

The glass slipped from Mrs. Ward’s hand and broke on the highly polished floor.

“Are you mad?” Mrs. Ward spoke more roughly than she realized, and Evelyn’s angry flush caused her to modify her tone to its customary civility. “Are you in earnest, Miss Evelyn?” Evelyn nodded vigorously, and Mrs. Ward’s comely face paled. “It’s—It’s not Mr. Burnham?”

“No; I have never seen the man before.”

[11]Mrs. Ward stared blankly at Evelyn, then roused herself. “Hadn’t I better go and investigate?” she asked. “You may be mistaken, Miss; perhaps the man’s only asleep.”

Evelyn shivered. “Men don’t sleep with their eyes open,” she said dully, rising. “I’m coming with you,” and she quickened her pace to keep up with Mrs. Ward as the latter led the way upstairs to the library. Mrs. Ward faltered just inside the room as her eyes fell on the quiet figure near the fireplace; then, repressing all emotion, she strode over to the figure and bent, as Evelyn had done, and placed her hand on the dead man’s wrist. When she turned back to Evelyn, who lingered near the doorway, her face rivaled the young girl’s in whiteness.

“I’d better go for Dr. Hayden.” She mumbled the words so that she was forced to repeat them before Evelyn understood her.

“Try the telephone,” the latter suggested, “that’s quicker.”

Mrs. Ward glanced shrinkingly at the telephone stand which stood almost at the dead man’s elbow and shook her head.

“I’d better go,” she reiterated obstinately.

“Nonsense, use the branch telephone in the pantry.” Evelyn’s customary cool-headedness returned as she saw the housekeeper becoming demoralized.[12] “Hurry, don’t waste any more time,” she added, and obedient to the stronger will, Mrs. Ward hastened from the room.

Evelyn stayed by the doorway in indecision, half inclined to accompany the housekeeper downstairs, but an attraction she could not conquer drew her toward the fireplace, and step by step she advanced nearer the dead man until only a chess table separated them. Sinking into a chair in front of the table she stared at the body for a long moment, then hastily averted her eyes. It was the first time she had seen death and its majesty over-awed even her terror.

A clock chiming the quarter aroused her and she mechanically looked at her wrist watch—a quarter of five. Had only two hours and a half passed since she had entered the library to telephone to Marian Van Ness? The time had seemed interminable, and she waited in ever increasing nervousness for the housekeeper’s return, as the clock ticked off minute after minute with maddening regularity.

Finally a murmur of voices coming nearer roused Evelyn and with a subdued exclamation she moved forward to meet Doctor Lewis Hayden, who a second later appeared in the library, Mrs. Ward at his heels.

Step by step she advanced nearer the dead man....

[13]“Has Mrs. Ward explained?” she demanded as Hayden clasped her outstretched hand.

“Only that——” Hayden stopped speaking as his eyes fell on the dead man. Striding forward he made a brief inspection before turning to the silent women. “Tell my chauffeur to go at once for Doctor Penfield, Mrs. Ward,” he directed and there was that in his manner which caused the housekeeper to move with even more than her customary rapidity. As she disappeared between the portières, Lewis Hayden turned his attention to Evelyn.

“A dose of aromatic spirits of ammonia will make you feel better,” he said kindly, noting the girl’s strained expression, and as he spoke he opened his emergency kit and poured the medicine in a glass. “Just add a little water to this,” he supplemented, “and then go and lie down. I’ll wait and see Coroner Penfield and we will take charge of affairs for you.”

Evelyn sighed with relief as she took the medicine. “Oh, thank you, doctor,” she exclaimed, “if you will just——” She stopped speaking as the portières were pulled back and Mrs. Ward, looking very much agitated, ushered in a tall man whose travel-stained appearance did not detract from his air of distinction. Evelyn stared at him as if unable to believe her eyes.

[14]“Mr. Maynard!” she exclaimed. “Dear Mr. Maynard! Where did you come from?”

Dan Maynard clasped her eagerly extended hand in both of his.

“Just back from France,” he explained, and at the sound of his voice Hayden’s memory quickened; its charm across the footlights had lured him often to the theater to see the man whose fame as an actor was international. “I wired Mr. Burnham——”

“Beg pardon,” Mrs. Ward insinuated herself into the little group by the door. “Your telegram was forwarded to Chelsea, Mr. Maynard, and Mrs. Burnham told me to prepare a bedroom for you, sir. It would have been ready but for this——,” and the housekeeper’s gesture toward the tragic figure by the fireplace completed her sentence.

Maynard stared but before Evelyn could offer any explanation the front door bell rang loudly and Mrs. Ward hastened to answer it.

“I imagine that is the coroner,” began Hayden, but an exclamation from Evelyn checked him; in her excitement she had not grasped the use of the word “Coroner” before Penfield’s name.

“A coroner! Good gracious, doctor, why send for him?”

“Because a sudden death cannot be examined[15] without his presence,” Hayden explained. “Go and take your medicine, Evelyn.”

Evelyn’s hesitation was brief; she knew Hayden of old and that he did not permit disobedience from his patients.

“Very well, doctor,” she said submissively. “But first, Mr. Maynard, this is our family physician, Dr. Hayden,” and as the two men silently shook hands, she added as she moved toward the door leading into her step-father’s bedroom, “I’ll be back shortly.”

Hayden’s surmise that Penfield had arrived proved correct, and the coroner, listening attentively to Mrs. Ward’s jumbled remarks as he mounted the staircase, went at once into the library and greeted Hayden.

“Apoplexy, Hayden?” he inquired, going toward the fireplace. “Ah, your aid here——” and Hayden joined him.

Maynard stood an interested spectator by the door, uncertain whether he was expected to go or stay, but as neither physician paid the slightest attention to him, he decided to remain. A sudden movement of the coroner’s toward the windows caused him to step forward and pull the inside Holland shades up to the top. A grunt of approval from Penfield greeted the additional light and Maynard decided to tuck back with the aid of[16] chairs the heavy brocaded curtains which, like the portières, were covered with cretonne to protect them in the summer months, until the large room was filled with the remaining daylight.

The room, wainscoted in Flemish oak with open beams across the high ceiling, was never very bright as its massive furnishings were somber in shade and absorbed the light. It was a very livable room, however, and had the air of being much occupied even with most of its bric-a-bric put away for the summer. The high-backed carved oak chairs and great leather covered lounges all looked comfortable, and the large center table, smoking stands, and card tables gave an added air of hospitality.

Suddenly Coroner Penfield rose from his knees beside the dead man and laid down several instruments on the chess table. He then glanced narrowly up and down the room, his glance resting finally on Dan Maynard, of whose presence he had been until then apparently unaware.

“I must make some inquiries, Hayden,” he said. “Who is this gentleman?”

“Mr. Maynard—I beg your pardon,” Hayden straightened up and faced about. “Didn’t I introduce you?” he added as the actor approached. “Mr. Maynard only arrived here a few minutes before you, Penfield. I’ll call Mrs. Ward, the housekeeper.”

[17]“She doesn’t know anything,” declared Evelyn who, entering unperceived a few minutes before, had overheard the coroner’s request. “I came back to tell you all about everything.”

“Do you feel equal to it?” asked Hayden, pushing forward a chair. “Hadn’t you better wait, Evelyn? You have been under a fearful strain to have your friend die——” He paused in his rapid speech as if at a loss for words and Maynard, with intuitive quickness, detected the physician’s disquietude under his calm professional manner. “—your friend die so suddenly,” Hayden finished.

Evelyn did not heed the concluding remark; but one word had caught her attention.

“Friend! He was no friend of mine,” she declared. “I never saw the man before.”

Penfield bent forward eagerly. “What’s this—a stranger, you say? Are you quite sure, Miss Preston? People’s appearance sometimes alters after death. Please look at him closely.”

Evelyn hesitated and glanced at Hayden who signed to her to approach. Obediently she stepped forward and studied the motionless figure which had been pushed back by Penfield into much the same position it had occupied when Evelyn first discovered it. She judged the man to have been about thirty-six or forty years of age, and noted particularly the brilliant blue of his eyes against the[18] pallor of his skin. He was clean shaven, and his under jaw was thrust forward at an obstinate angle, but whether that was its natural position or the jaw had dropped forward after death Evelyn was incapable of knowing.

“I never saw the man before,” she stated finally.

“Ah! Then how came it that he was admitted to your library?” asked Penfield before Hayden could speak.

“I really don’t know.” Evelyn looked puzzled. “I presume he got in like any other burglar.”

“Burglar!” Penfield started and turning, stared again at the dead man. “Burglars don’t as a rule dress so well; besides, his hands——” He leaned over and held up the man’s limp right hand, turning it over so that all could see the long tapering fingers and well cared for nails.

Maynard studied the hand intently; he had seen its type when traveling among the silent and secretive peoples of the Orient and occasionally met the same type among the deep thinkers and analytical men and women of Europe who rarely forget an injury but are patient with the patience of power conveyed by knowledge and mysticism.

“His finger-prints may give us some clue to his identity,” added Coroner Penfield, laying down the hand. “In the meantime——”

[19]“Why not examine the man’s pockets?” suggested Maynard practically.

Penfield carried out the suggestion with a deftness which won the actor’s admiration, but all he brought to light was a piece of string.

“Every pocket empty,” he announced. “And apparently not even a coat-label—strange!” He cast a penetrating look at Evelyn. “Why did you not notify us sooner, Miss Preston?”

“Sooner?” echoed Evelyn. “I started to go for Dr. Hayden after finding this—this——” Evelyn choked; she was very near to tears and Penfield’s grave manner was beginning to impress her unfavorably. “I met Mrs. Ward, our housekeeper, on the front steps, brought her up here, and then sent her to telephone to Dr. Hayden. That hasn’t been more than an hour ago,” turning for confirmation to Hayden who nodded his agreement. “I only arrived in Washington this morning, Dr. Penfield, and—and—I was all alone in the house. He—he,”—pointing to the dead man—“he might have murdered me if he hadn’t died of apoplexy.”

Hayden, who had followed Evelyn’s statements with ever increasing interest, looked a trifle nonplussed as he glanced at his colleague who was winding the string, taken from the dead man’s pocket, in and out among his fingers.

“You say you arrived at the house this morning,[20] Miss Preston,” began Penfield slowly, “and you did not enter this library until this afternoon.”

“I did, too,” contradicted Evelyn. “I came in here in the morning and opened the blinds; I did the same thing all over this floor so as to air the house, and——” She added as Hayden started to interrupt her, “I came into this room again about half past two——”

“And you sent for us about five o’clock,” commented Penfield dryly. “Your remarks are inconsistent—you previously stated you sent for us at once on finding the body——”

“The body was not here at half past two,” declared Evelyn.

“It wasn’t!” chorused the two physicians, while Maynard looked eagerly at Evelyn and back at them.

“Come, Miss Preston,” began Penfield. “You must be mistaken.”

“I am not,” Evelyn’s foot came down with a stamp. “I used that telephone there, right by the fireplace; do you suppose I could have done so and not become aware that a dead man was sitting by my elbow? I tell you the man wasn’t dead then.”

The silence which followed was broken by Coroner Penfield.

“Miss Preston,” he stated quietly. “That man has been dead at least twelve hours.”

[21]Evelyn stared at him in growing horror. “Dead—twelve hours!” she gasped. “Then who rang the library bell at four o’clock?”

They gazed at each other, but before any one could speak the sound of a heavy fall caused them to wheel about—Mrs. Ward had fainted just inside the portières of the room.

THE Maître d’hôtel, returning from an inspection of the main dining room, paused in Peacock Alley to view with an appraising eye the men and women who promenaded up and down or sat about, some waiting with good grace for their chance to find a disengaged table in one of the dining rooms while others, outwardly rebellious, expressed their candid opinion of Washington in war-time. Suddenly the Frenchman’s air of polite indifference changed to one of alertness as a man pushed his way through the throng and stopped near the door of the Palm Room. The Maître d’hôtel was at his elbow instantly.

“Ah, Monsieur Burnham, welcome, most welcome,” he said. “Have you had a nice summaire?”

“Henri!” Peter Burnham surrendered his hat and cane to a waiting attendant. “The summer has been so-so,” he added, turning back to the Frenchman. “I am waiting for Mr. James Palmer; have you seen him this evening?”

“But yes.” The Maître d’hôtel wormed his way[23] into the Palm Room and beckoned to Burnham to follow. “There, in that corner across the room; this way,” and he darted among the tables and the palms, Burnham following closely, until he reached a small table set for two persons, and pulled out the unoccupied chair.

Palmer looked up from the menu he was studying and greeted Burnham with warmth.

“Have a Martini?” he inquired as their waiter hurried up and the Maître d’hôtel went back to his post in the doorway.

“Yes, and make it dry,” cautioned Burnham to the waiter. “And hurry it along. I am worn out,” he added to his host.

Palmer glanced at him in concern. “You don’t look very fit,” he admitted. “Had a bad trip down?”

“Devilish! Our train was sidetracked for hours waiting to let troop trains pass; nothing to eat——” Burnham paused to empty his glass of ice water. “At our rate of progress I was willing to believe we’d gone back to stage-coach days, but Washington is an eye-opener; I had no idea this place swarmed with people.”

“Washington’s ‘sleepy hollow’ has had a rude awakening,” remarked Palmer cynically. “I don’t mind confessing I am weary of seeing consequential looking people dash about Washington with an air[24] of having arrived just in time to save the Nation. Washington was on the map before Uncle Sam started on this war-path.”

Burnham laughed. “I confess I share your outraged feelings; had to wait interminably at the Union Station before I could telephone you.” He stopped to take the cocktail at that instant placed before him. “Here’s how!”

His host raised his glass in acknowledgment and sipped his Martini with due enjoyment.

“Better have another,” he suggested as Burnham set down his empty glass, “against the time Washington goes dry.”

“I’ve stocked up my wine cellar with that in view,” admitted Burnham and stopped to watch some newcomers who had taken possession of the nearest table. “I suppose I can get a room here for the night in case I find the servants haven’t arrived to open our house.”

“My dear Burnham!” Palmer looked actually shocked. “Empty rooms are unheard of in Washington.”

“How about club chambers?”

“Nothing doing; they are even sleeping in the bathtubs there,” laughed Palmer, and stopped speaking as the orchestra in the mezzanine gallery commenced to play and, dinner arriving at that instant, the two men, except for monosyllabic remarks now[25] and then, completed the meal in silence. As Burnham took one of the cigars proffered him he pushed aside his dessert plate, planted his elbows on the table, and leaned forward.

“I can’t understand why people want an orchestra playing while they eat,” he grumbled. “I don’t enjoy having to shout when I talk.”

“Well, I suggested dining at the club——”

“I know, I know; but I forgot about the beastly orchestra,” he paused to puff abstractedly at his cigar.

“What’s the trouble, Burnham?” asked Palmer quickly. “Is your wife ill?”

“No, no; it’s——” He bent nearer his companion, then paused to shoot a glance over his shoulder and his confidences remained unspoken. “Jove! Evelyn!” he ejaculated. “She wasn’t due here until to-morrow.”

Palmer, but half catching his remark, followed his gaze and saw Evelyn Preston and her friend Marian Van Ness just taking their seats at a table some distance away. Palmer pushed back his chair preparatory to rising.

“Bless my soul, Burnham,” he exclaimed impulsively. “Why didn’t you tell me Evelyn was with you? We could have waited dinner for her and Mrs. Van Ness. Here—” beckoning to their waiter—“tell those ladies——”

[26]“Wait,” broke in Burnham. “We’ve finished, Palmer; suppose we go over and sit at their table, but there’s no hurry, man.”

Burnham’s tone was so petulant that Palmer, curbing his impatience to be with Evelyn, subsided in his seat and gazed at him in speculative silence. What had come over easy-going, absent-minded Peter Burnham? Six weeks had passed since his visit to Burnham Lodge at Chelsea, and that the six weeks had not agreed with Burnham was plain to be seen; his cheeks were a bad color and he seemed to Palmer’s appraising eye to have shrunk in his clothes. A certain nervous tremor in the hand holding his cigar also was noticeable, and Palmer wracked his brain to recall some incident of his stay at Burnham Lodge which might give him the key to Burnham’s altered demeanor. But to the best of his recollection all had been harmonious, and he had been rather a captious guest, for his prediction that the marriage would not turn out a happy one had put him on the alert for matrimonial discords.

Palmer had not been alone in predicting a disastrous ending to the marriage, for all Washington had heard first with incredulity and then laughter of the engagement of the wealthy widow, Lillian Preston, to Peter Burnham, a man considerably her junior, who had been uniformly unfortunate in[27] every business venture he had undertaken. Peter had his good points, his friends contended, and as one of them remarked at the wedding which had followed swiftly upon the announcement of the engagement, his wife could keep him in the style he had been accustomed to before his final financial venture had landed him in bankruptcy.

That Mrs. Burnham was honestly devoted to her husband and admired him, Palmer had come to believe. She was not a woman given to concealing her thoughts, her habit of plain speech frequently landing her in hot water. Peter Burnham was well read, polished in manner, a born raconteur, and a devoted chess player; he cared very little for out-door sports and his greatest hardship was being dragged to horseshows of which his wife was inordinately fond, having inherited her love for horses from her Kentucky ancestors.

Society had speculated as to how Mrs. Burnham’s young daughter and only child would take her mother’s second marriage, but as Evelyn was then away at boarding school, society found little to build gossip upon. Evelyn’s début the winter before had revived interest in the subject, and when she left Washington early in the spring for an indefinite visit in the West, tongues had wagged without, however, getting any satisfaction from Mr. and Mrs. Burnham who went placidly on their way,[28] being entertained and entertaining in their hospitable home in the fashionable Northwest.

The situation had decidedly piqued Palmer’s interest, for as intimate as was his footing in the Burnham home he had never been able to decide Evelyn’s status in the family circle; she was frequently and pleasantly alluded to in conversation, but that was all. He had made no secret of his desire to marry Evelyn, and that both husband and wife favored his courtship he had ample reason to believe, though neither to his knowledge had outwardly espoused his cause to Evelyn.

When called on the telephone about six o’clock that afternoon Burnham had given Palmer to understand that he was alone in Washington; and yet his young step-daughter was also in the city. It was of course possible that Evelyn was visiting Marian Van Ness. Palmer frowned; he disliked few people, but he most heartily disliked brilliant Marian Van Ness; their natures were too utterly foreign for them ever to be congenial.

Palmer transferred his attention from Burnham to the latter’s step-daughter and her companion, both of whom were busily engaged in discussing the menu. Marian Van Ness’ dark beauty was an effectual foil for Evelyn’s curly yellow hair and blue eyes. The entrance of both girls, for Marian appeared little more, in their smart summer costumes[29] had attracted admiring low voiced comment from the other diners in their vicinity, and several friends and acquaintances had looked up to bow or wave their hands to them, for Marian was extremely popular in society. When financial reverses had obliged her to find employment upon her return to her native city after her divorce, she had acted as social secretary for several Cabinet officers’ wives and through their influence had received an appointment in the State Department five years before.

Suddenly Palmer stirred in his chair. “I hardly think Mrs. Van Ness is a staid enough chaperon for Evelyn,” he remarked. “Suppose we join them,” and leaving Burnham no option in the matter he pushed back his chair and rose.

Evelyn, whose healthy young appetite had asserted itself, in spite of the tragic happenings of that afternoon, had been chiefly occupied in selecting the most tempting dishes in the menu, and it was not until an exclamation from Marian drew her attention to her step-father coming toward them, Palmer’s big proportions towering behind him, that she knew of his presence in the dining room. At that moment the diners at an intervening table left their seats, thereby impeding Burnham’s progress, and only Marian caught Evelyn’s low exclamation and noticed her change of color.

[30]“Are you going to faint?” she asked. “Drink some water, dear.”

Instead Evelyn laid trembling fingers on her cool palm.

“Don’t forget your promise,” she pleaded. “Remember, you are going to stay with me....”

“I will.” Marian’s firm hand-clasp was reassuring. “Can’t you tell me more of what took place this afternoon?”

“Not now.” Evelyn straightened up and turned to meet her step-father and, with a poise and air of cordiality which Marian secretly applauded, she held out her hand in greeting to Burnham and then to Palmer. “When did you get here?” she inquired as the men took the chairs proffered by attentive waiters, after first speaking to Marian.

“I might ask the same of you,” retorted Burnham. “You were not due here until to-morrow.”

“I found I could take an earlier train,” responded Evelyn. “Why didn’t you and Mother come up to the house when you arrived?”

“Your mother didn’t come down with me,” answered Burnham, waving away the waiter’s offer of a menu. “She is in New York.”

“Oh!” The ejaculation slipped from Evelyn followed by another: “Oh, waiter, don’t remove that place,” as the servant started to clear away the extra silver and glass. “I am expecting another[31] guest,” she added as Palmer, thinking she did not know that he had dined, imagined she referred to him and started to decline.

“Another guest?” questioned Burnham and his manner sharpened. “Whom do you mean?”

Evelyn shot a half resentful glance at him, then curbing her hot temper which his censorious air and manner invariably aroused, she answered cheerily. “None other than your old friend, Dan Maynard.”

“Maynard in town!” exclaimed Burnham in pleased surprise.

“Not only in town but he is stopping at our house,” rattled on Evelyn, noting with some surprise that Marian had permitted her “Honey-dew” melon to be taken away uneaten. “The servants are putting the house in order.”

“Upon my word!” Burnham polished his eye glasses and looked through them at Evelyn. “Where is Mrs. Ward?”

“Ill,” tersely. “Dr. Hayden is looking after her; and Marian is coming back to help me take care of her.”

Burnham stared at his step-daughter. “Mrs. Ward ill—what next? When did you and she arrive in Washington, Evelyn?”

Palmer, stopping his exchange of small talk with Marian, glanced at Evelyn and her expression[32] caused his interest to quicken. Evelyn was not used to subterfuge and the look she had favored her step-father with was indicative of her feelings.

“We didn’t come together,” she explained. “Mrs. Ward only arrived this afternoon, while I reached the house——” She stopped to help herself to beefsteak and several vegetables.

“Yes,” prompted Burnham, and his restless glance passed from one companion to the other. “You reached——” A hand was laid on his shoulder and Maynard cut into the conversation.

“Found at last,” laughed the actor. “Evelyn, you told me to meet you at the Shoreham and I have been waiting there until it dawned on me to try this hotel. How are you, Burnham, and Palmer, too,” shaking hands as the men rose.

“Marian, have you met Mr. Maynard—Mrs. Van Ness?” asked Evelyn, and Maynard turned to encounter a pair of dark brown eyes raised to him in earnest appeal. The next instant Marian’s hand was taken in a warm clasp and slowly released as Palmer made room for Maynard to sit between them.

“My wife will be delighted to know you have arrived in Washington,” said Burnham. “She was overjoyed when your telegram came stating you might get here any moment. What brings you back to this country, Maynard?”

[33]“War work,” began Maynard. “No, no soup,” he broke off to say to the waiter. “Bring me whatever Miss Preston has ordered. Palmer, I hear you have your hands full with government contracts for erecting temporary office buildings here and at cantonments.”

“All architects are busy these days,” replied Palmer, accepting another cigar from Burnham. “In fact every one is busy; I imagine you have your hands full at the State Department, Mrs. Van Ness.”

Marian, directly addressed, looked up from the bread pellets she was arranging in a neat pile before her. “Well rather, we work night and day.”

“It must be a terrific strain,” acknowledged Maynard. “So much responsibility rests in the State Department.” There was a haunting quality in Maynard’s voice which, no matter how trivial his remark, impressed his listeners, and Marian’s heart beat fast as memory of other scenes rose to torment her, but her manner indicated only polite attention and after a fraction of a second Maynard continued his remarks.

“Washington is a changed city,” he stated. “The Shoreham reminded me particularly of Paris in its military appearance, except that the uniforms are not worn and faded. By the way, Burnham,[34] among the French officers I met there was René La Montagne.”

“René!” The startled exclamation escaped Evelyn before she could check it; and her confusion was so great that she failed to observe the lowered looks of two of her companions. Burnham and Palmer exchanged glances, then their eyes dropped to their cigars and they smoked in silence.

As Evelyn set down her goblet of water a page stopped at her elbow.

“A telephone has just come from your butler, Miss Preston,” he explained, “to ask you to return home. He said Mrs. Ward was quite ill.”

Evelyn pushed aside her plate. “I’ll go at once,” she announced. “But the rest of you need not come until later.”

“I have finished.” As she spoke Marian rose and Maynard also tossed aside his napkin and stood up.

“Wait a minute,” remonstrated Burnham. “We’ll all go with you, Evelyn. Here, waiter, bring me the check, and, Maynard, engage a touring car outside, will you?”

Nodding assent, the actor sped on his errand, leaving the others to follow more slowly. He was fortunate in securing a seven-passenger car, and Burnham bundled his party into it with small ceremony.

[35]“We are right in your neighborhood,” he said as Palmer drew back, “the car can leave you after it has taken us home. There’s plenty of room, Palmer, jump in.”

“Perhaps,” suggested Evelyn, “it would expedite matters to stop for Dr. Hayden.”

“If he is not at your house I can go for him and bring him right over,” answered Palmer, and Burnham agreed.

“Good idea,” he said shortly. “I hope I am not crowding you, Evelyn?” as she shrank against Marian in making room for him on the back seat.

“Oh, no,” she replied and sat silent, grateful for the cool night air which fanned her cheeks. She had tried to forget the mysterious tragedy while in the hotel; had even barely mentioned it to Marian when she picked her up at her apartment to take her out to dinner, but the sudden summons home had brought it vividly before her. Suddenly she caught Maynard’s eyes and his cheery smile gave her a sense of comfort. As the car turned into Connecticut Avenue he leaned forward and addressed Marian Van Ness.

“Are you warm enough?” he asked solicitously. “You have no extra wrap and the night air is chilly.”

Marian looked at him then glanced away. “I am very comfortable,” she murmured.

[36]Palmer, who had chosen to take the vacant seat by the chauffeur in preference to trusting his weight on one of the small pivot chairs in the tonneau of the machine, addressed Burnham several times, but apparently his words were drowned in the rush of wind occasioned by the speed of the car, for Burnham made no response. A short time later the car drew up to the curb, and stopped before the Burnham residence.

Maynard was the first out of the machine and turned at once to help Marian. For a brief second her hand rested lightly on his arm, then was removed as she sprang to the sidewalk. Evelyn was no less quick in getting out and, not waiting to see what became of the others, she caught Marian by the elbow and hurried her into the house and upstairs.

Burnham was slower than the others in leaving the car. “Wait a second, Palmer,” he said, “I’ll send word if we need Dr. Hayden,” and, turning, he accompanied Maynard up the steps. His words were overheard by the anxious faced butler who had been on the outlook for the car and opened the front door when it first drew up to the curb.

“The doctor’s here, sir,” and Maynard was quick to detect the faint, very faint trace of accent in the man’s subdued voice.

Burnham faced about and called to Palmer:[37] “Don’t wait, Palmer, thanks; Hayden is here. See you to-morrow,” and he waved his hand in farewell as the car moved off.

“Come in the billiard room, Maynard,” he said turning to his companion. “We might as well have a game until Hayden comes down——”

“Just a moment, sir,” broke in Jones, the butler. “There’s several gentlemen waiting to see you.”

Burnham halted. “Their names——”

A man standing in the shadow of the drawing room door came forward.

“Detective Mitchell, sir, of the Central Office,” he said politely. “I was sent to investigate the case of the man found dead here this afternoon.”

“A man found dead here!” shouted Burnham, stepping backward and colliding against Maynard. “Who is he?”

“We don’t know,” acknowledged Mitchell. “But we are trying to establish his identity. Your step-daughter found him in the library.”

Burnham stared at the detective wide-eyed. Suddenly he took out his handkerchief and mopped his forehead.

“A dead man here!” he ejaculated feebly. “An unknown man?”

“Perhaps if you will step in here you may be able to help us identify him,” suggested Mitchell.[38] “We have brought the body down into the billiard room preparatory to taking it to the morgue.”

It seemed almost as if Burnham did not comprehend what the detective was saying, and but for Maynard’s guiding hand he would not have found his way into the room. The body lay on the billiard table covered by a sheet. Stepping forward, Mitchell pulled down the sheet, signing to Burnham to step nearer, and both he and Maynard watched Burnham as he bent over the body. After what seemed an interminable time to Maynard, he straightened up.

“I have no idea who he is,” Burnham stated.

TWENTY-FOUR hours had passed since Evelyn Preston’s discovery of the dead man, and the Burnham household had returned somewhat to its normal condition, chiefly through Dr. Hayden’s soothing influence and sound advice which had proved an effectual check to the servants’ inclination to hysteria, Burnham’s temper, and Evelyn’s nervousness. Marian Van Ness, in lieu of a trained nurse, had spent the night with the housekeeper, Mrs. Ward, who had finally quieted down under the influence of bromides and toward morning slept heavily. In the few remaining hours Marian had thrown herself on the couch in the housekeeper’s sitting room and snatched a short nap before going to her work at the State Department.

To Evelyn the day had seemed never ending; she had gone out for part of the morning, returned for luncheon, and afterward had attempted to rest, but she was far too restless to remain long in one place, and about four o’clock in the afternoon she[40] found herself in the drawing room gazing moodily out of the window, her knitting needles for once idle in her lap. The entrance of Jones with the tea roused her from her contemplation of the closed house of her opposite neighbor across the street.

“Not many people are back yet, Jones,” she remarked.

“Not in this section, Miss Evelyn,” answered the butler, wheeling forward the tea-wagon and then going for a nest of tables from which he extracted the smallest. “Every house is closed hereabouts; it’s sort of lonesome, Miss, and strange, too, with the business part and the other streets just packed with people. Has Mr. Burnham returned yet, Miss?”

“I don’t think so.” Evelyn rattled the teacups as she rearranged them. “Are you quite positive, Jones, that no one called me on the telephone while I was out this morning?”

“Quite, Miss. I followed your instructions and stayed where I could hear the telephone bell if it rang; no one called, Miss.”

Jones had made the same answer to the same question at least six times during the day, but he was too well trained a servant to betray his curiosity aroused by Evelyn’s absent-minded harping on the subject. Being of a somewhat morbid tendency he,[41] of all the household, had been the only one to get some entertainment out of the tragedy. The presence of the physicians, morgue attendants, and detectives had thrilled him beyond words; he had never hoped to participate in a humble degree in what promised to be a mystifying and unusual case of sudden death.

“Dr. Hayden went upstairs to see Mrs. Ward just now,” he said, finding that Evelyn asked no more questions. She looked up quickly and set down the tea-pot.

“Is the doctor still here?”

“I think so, Miss.”

“Then run upstairs, Jones, and ask him to stop here for a cup of tea on his way out, and—eh, just see if Mr. Burnham is in his room or the library.”

“Very good, Miss Evelyn,” and the butler departed with alacrity. He had just reached the floor above when he encountered the busy surgeon hurrying downstairs. Hayden paused only long enough to hear his message and then continued on his way to the drawing room. Evelyn greeted his entrance with a warm smile of welcome.

“Thanks, no tea,” he said drawing up a chair. “I will have a glass of water and some sandwiches. Did you lie down as I advised?”

“Yes, but I couldn’t sleep.” Evelyn’s hand shook[42] as she offered him the plate of sandwiches and Hayden scanned her with concern.

“Don’t go too long on your nerves, Evelyn,” he cautioned. “Pull up while you can; rest and quiet are what you need.”

Evelyn moved impatiently. “I’m all right,” she announced obstinately. “Tell me, doctor, what is the matter with Mrs. Ward?”

“Oh, she is suffering from shock and hysteria; in a day or so she will be up and about again.” Dr. Hayden took a tea biscuit. “In the meantime bed is the best place for her.”

“What made her go to pieces?” demanded Evelyn, lowering her voice. “She is a strong healthy woman and in the three years she has been with us I have never known her to have a day’s illness.”

“Shock,” replied Hayden tersely.

“But—but she only saw the body just as I did,” objected Evelyn. “I didn’t faint from shock, and I don’t pretend to be as strong as she is.”

Hayden mentally contrasted her slender, delicate appearance and the housekeeper’s tall angular, raw boned frame and silently agreed with her; the contrast was too great to admit of argument.

“Tell me, Evelyn,” and he, too, sunk his voice. “Exactly when did Mrs. Ward join you here yesterday?”

“I found her standing in the vestibule just after[43] I discovered that poor dead man upstairs; in fact when I was on my way to you. Frankly,” Evelyn smiled apologetically, “my first impulse was to get out of the house.”

“A very natural impulse,” said a voice behind them and wheeling about Hayden saw Maynard approaching. “Sorry to startle you, Evelyn,” the latter added as she spilled her tea in her sudden jump. “I am so accustomed to these rubber heels that I forget others are not. Afternoon, Hayden. How’s your patient?”

“She is much better.” The physician moved back to make room for Maynard who paused long enough to drag forward a large arm chair and seated himself next to Evelyn.

“Good,” he exclaimed in response to Hayden’s statement, and at the sympathetic inflection and the hearty ring in his voice Evelyn brightened. Maynard’s robust personality brought a touch of the out-of-doors into the room and dispelled her morbid thoughts. “Burnham asked me to tell you, Evelyn, that he would not be here for tea. He is greatly concerned about Mrs. Ward,” Maynard continued, addressing Hayden. “Seemed to think last night from her rambling talk that she was in for a long illness, brain fever, or something.”

Hayden smiled. “Nothing like that,” he said.[44] “Mrs. Ward will soon be on her feet again, little the worse for her upset.”

“I hope so truly,” exclaimed Evelyn, handing Maynard his cup and a biscuit. “Not only for her sake, but because Mother is so dependent upon her.”

“Has Mrs. Ward been with you long?” inquired Maynard.

“A little over three years.” Evelyn paused to consider. “She came to us about six months before Mother’s marriage to Mr. Burnham; I was at boarding school that winter.”

“What is Mrs. Ward’s nationality?” asked Hayden. “I ask because last night just before going under the influence of the bromides she used several phrases which——”

A heavy step on the hardwood floor interrupted the physician and Jones appeared at Evelyn’s side.

“Detective Mitchell to see you, Miss Evelyn,” he announced and his low voice held suppressed excitement.

“Oh!” Evelyn gazed at him blankly for a minute, then at her companions; their presence would surely check any undue inquisitiveness which the detective might evince. Her step-father had told her that she might possibly have to appear at the inquest or give her deposition, and he had cautioned her against making any statement to either of the[45] detectives who were then in the house. Evelyn, rather startled by his grave manner, had promptly vanished out of the house by way of the back door while the men from the Central Office were interviewing Burnham.

“Show him in,” she directed, and as the butler retreated, she looked at Hayden. “You were saying; oh, yes, now I remember; you asked about Mrs. Ward—she was born in Switzerland, but I believe has lived in the United States since she was fifteen years old. Is this Mr. Mitchell?” raising her voice as a well dressed, pleasant-faced man appeared in the room.

The detective advanced to the little group and his bow included them all.

“It is, Miss Preston,” he answered. “I was sorry not to see you this morning before you left.” Maynard, who had risen on his entrance, pushed forward his chair for the detective and subsided into one somewhat in the shadow of the grand piano. Mitchell acknowledged the courtesy with a word of thanks, then turned to Dr. Hayden.

“The nurse permitted me to see Mrs. Ward for a moment, doctor,” he began, “but she said she knew nothing of the suicide.”

“Suicide!” ejaculated Evelyn, startled.

“I am quoting Mrs. Ward,” explained Mitchell.[46] “She evidently believes the stranger’s death to have been a case of suicide.”

“But how can she? She heard me tell Coroner Penfield that some one rang the library bell about five or six minutes before I found the body, and according to Coroner Penfield the man had been dead about twelve hours. Yet the body was not in the library when I was in it earlier in the afternoon; some one beside myself was in this house,” declared Evelyn and she came to a breathless and bewildered pause.

“Mrs. Ward heard you make these statements?” asked Mitchell, pencil in hand, and his memorandum pad balanced on one knee.

“Why, I take it for granted that she did,” Evelyn looked puzzled. “She fainted just about then and we found her lying inside the library door, didn’t we, doctor?” Hayden nodded. “Mrs. Ward must have been standing behind the portières and couldn’t help overhearing our conversation.”

“Then you conclude that your remark about the ringing of the library bell caused her to faint,” asked Maynard reflectively.

Evelyn wrinkled her brows and rubbed her forehead vigorously. “I don’t know just what to think,” she acknowledged. “What was there in that statement to shock her?”

Hayden leaned forward. “Could it be——” He[47] began, then broke off abruptly, hesitated, and finally addressed Mitchell. “Did you think to ask Mrs. Ward if she saw any one leave this house as she came up the street?”

“No, doctor. The fact is,” Mitchell completed the entry he was making in his note book, “the fact is the nurse would only let me stay a second in the sick room; she said Mrs. Ward was too ill to be interviewed now.”

“Then I see nothing for it but to wait until Mrs. Ward is better,” commented Maynard. “Will there be an inquest, Mitchell?”

“Oh, yes; but not just now.” Mitchell turned his head so as to face Maynard. “However, our investigation cannot wait; we must sift evidence to present at the inquest and secure expert testimony.”

Maynard thrust his hands in his pockets and leaned back. “Go slow, Mitchell,” he cautioned. “Remember the legal warning: ‘All evidence is made up of testimony, but all testimony is not evidence.’”

“True, sir; but in this case the police have reasonable grounds to suspect a crime has been committed,” protested Mitchell. “Take Miss Preston’s testimony for example; she heard the library bell ring, went upstairs, and found a dead man sitting in the library.”

[48]“Well, he could have rung the bell before drinking the poison,” retorted Maynard.

“Be reasonable, Mr. Maynard.” The detective’s irritation at Maynard’s continued questioning showed in his heightened color. “Coroner Penfield’s testimony proved the man had been dead at least twelve hours.”

“There you go again with your testimony,” Maynard laughed shortly. “Come, doctor, at what moment does rigor mortis appear?”

“In a general way, I should say——” Hayden considered before continuing, “rigor mortis appears from the third to the sixth hour, and it affects the muscles of the jaw first.” Evelyn shuddered as sudden unbidden memory of the dead man’s features returned to her.

“And how long does rigidity continue?” demanded Maynard.

“Oh, its duration may average twenty-four to forty-eight hours; it may, however, last for a few hours only, in other cases it persists for five, six, or seven days,” answered Hayden.

“And you physicians are prepared to swear from rigor mortis as to the exact hour the man died?” persisted Maynard.

“We are prepared to swear to nothing of the sort.” Hayden was commencing to share Mitchell’s irritation at Maynard’s slightly contemptuous manner.[49] “We can say if rigidity is complete, that death is recent. Personally, I believe that rigor mortis can teach us nothing of scientific value in cases of poisoning.”

“But there are other tests to establish the time of death,” broke in the detective. “There’s the cooling of the body.”

“Don’t!” Evelyn held up a protesting hand. “I can’t forget the icy chill of his wrist when I touched him.”

“There!” Mitchell looked triumphantly at Hayden. “Doesn’t the body cool in about twelve hours?”

“It might be said to be quite cold in that time,” replied Hayden. “But the average time taken in cooling is from fifteen to twenty hours.”

“Your first statement will do for me,” Mitchell jotted down some figures. “Let me see, Miss Preston, you found the body about half past three?”

“Yes, or perhaps a few minutes later.”

“Humph! Then it is a safe hypothesis that this man was poisoned between the hours of two thirty and three thirty yesterday (Tuesday) morning.”

Evelyn shivered. “It would seem so,” she admitted. “Yet where was the body all that time?”

“And where the murderer?” Maynard’s light tone struck a jarring note and for once Evelyn ignored him, as she waited for the detective’s answer.

[50]“Is that Mr. Burnham speaking?” questioned Mitchell, rising hurriedly as voices reached them from the hall. Evelyn was saved reply by Burnham walking into the room. He was followed by Coroner Penfield and James Palmer.

“Here are the men you want, Penfield,” he exclaimed on catching sight of Hayden and Maynard. “Come and tell us about the inquest.”

Penfield, directly addressed, bowed gravely to Evelyn, who had risen with the others on their entrance, and then regarded his host with no lenient eye. That Burnham had been drinking or was under some powerful drug was evident, and Penfield wished heartily that Evelyn would retire; he disliked scenes—dead people were one thing, hysterical women another.

“There has been no inquest yet,” he said. “We are waiting for the principals in the case to be in condition to attend it before we hold it.”

“Principals?” Burnham moved nearer and placed an unsteady hand on the back of a chair. “Who d’ye mean?”

“Mrs. Ward, primarily,” responded Penfield politely. “I understand, Hayden, she is ill from shock.”

“Yes, she is; nothing very serious, however.”

“Has she a nurse?”

“Yes. Mrs. Duvall.”

[51]“Excellent,” Penfield rubbed his hands together. “I would like to talk to Nurse Duvall if convenient.”

“Certainly, Penfield,” Hayden made a motion to go but Evelyn was before him.

“I’ll run up and take her place with Mrs. Ward so she can come down to see you,” she volunteered and slipped from the room.

Burnham, who had been brooding over the coroner’s remarks, stopped his restless walk about the room, and thereby collided with James Palmer, whose bulky form dwarfed Mrs. Burnham’s Empire furniture.

“Why’d you tell me in the hall that you held an inquest and then deny it in here?” he asked. “Was it because Evelyn was present?”

“No, Mr. Burnham; you have things mixed,” protested Penfield. “I never mentioned an inquest, but said we had held an autopsy.”

“Ah, and with what results?” asked Hayden. “Or is it not permissible to tell now?”

“Oh, no; it will be in the morning papers, so I am breaking no confidence,” Penfield moved nearer the five men who had grouped themselves about the grand piano. “On submitting the gastric contents to tests we found the presence of a solution of hydrocyanic acid.”

Maynard broke the ensuing silence. “Hydrocyanic[52] acid,” he repeated. “Isn’t that a form of prussic acid?”

“Yes; and in a diluted form sometimes given for stomach disorders,” responded Penfield. At his answer Burnham sat down suddenly as if stricken. His action was only observed by Hayden and Palmer, Penfield’s attention being focused upon Maynard who stood gazing at him across the piano with expressionless face.

“Prussic acid,” he murmured. “Ah, Penfield, that bears out my theory.”

“And what is your theory?” demanded Mitchell quickly, bending forward.

“That the man committed suicide.” Seeing the incredulity with which his statement was received, Maynard added: “Had the man been murdered he would instantly have detected the presence of prussic acid—there is no disguising the taste of bitter almonds.”

“Yes, there is,” retorted Coroner Penfield. “The dose in this instance was administered in a cordial which in itself contains the same bitter flavor—cherry brandy.”

MARIAN VAN NESS detached herself from the stream of people moving slowly up Seventeenth Street and raced to the opposite curb, only arriving in time, however, to see the Mt. Pleasant car sail serenely by. A second, third, and fourth car, their passengers clinging like ants to steps and even fenders, rounded the curve without stopping and continued up Connecticut Avenue. In despair Marian turned about and tucking the papers she carried more securely under her arm, set out for the Burnham house. She had walked but a third of the way when a man fell into step with her and looking around she found René La Montagne by her side.

“Ah! Captain, good afternoon,” she exclaimed. “Did you receive my telephone message?”

“But yes, madame, and I hurried most quickly to the State Department only to find you gone.” The French officer reached over and took her small bundle of papers. “Permit that I carry them,” he said with a quick courtly bow, and taking possession[54] of the papers he slipped them inside the pocket of his blue tunic. “Tell me, madame, you have seen Evelyn,” and Marian read in his eyes the passion even Evelyn’s name kindled in the gallant officer and her heart throbbed with the quick and ready sympathy every woman feels for true romance.

“Yes. I am on my way to join Evelyn now,” she answered. “Frankly, Captain, what has estranged you two?”

La Montagne’s expression grew troubled. “It is not of my making,” he protested. “My letters remain unanswered——”

“Are you quite certain, Captain, that Evelyn received your letters?”

“But yes,” and as she would have spoken he added rapidly: “When I cabled that I would arrive shortly in this country, having been detailed here to instruct in the aviation, and received no reply I questioned in my mind if Evelyn had received it. Getting leave, I went to Chelsea and called upon Mr. and Mrs. Burnham——”

“You did!”

“Of course, madame.” La Montagne emphasized his remarks with gesticulations eminently characteristic of his race. “It was my misfortune that Evelyn was away, and through some inadvertence my cable had not been forwarded to her. I had but a[55] few hours in Chelsea, but upon my return to duty I wrote to Evelyn a letter requiring a reply, and I sent it by what you call ‘registered’ post.”

“And she answered the letter?”

“No.” In spite of his effort to keep his tone expressionless the monosyllable betrayed emotion.

“Then you can take it that Evelyn never received your letter,” exclaimed Marian vehemently.

“You think not!” La Montagne’s face lighted, then fell. “But how is that within the possible? The return card bore her signature of receipt.”

Marian stopped and stared at the Frenchman. “Her signature? Are you quite sure?”

“Oui, madame. I have read her few letters too often to be mistaken,” retorted La Montagne. “She signed the receipt.”

Marian resumed her walk up the street, a puzzled frown creasing her forehead. “Where did you send the letter?” she asked.

“To Burnham Lodge, Chelsea, New Jersey.”

Marian quickened her pace to avoid being run down by a speeding automobile as they crossed Massachusetts Avenue.

“And where was the return receipt card from?” she inquired, a trifle breathless from her exertions.

“From the same place.” La Montagne fumbled in an inside pocket. “But view,” he said, holding up a much battered return registered mail card.[56] Marian took the card and studied the postmark, its date, and Evelyn’s clear and distinct signature in puzzled silence, then handed back the card.

“I can only tell you,” she stated slowly, “that Evelyn spent the entire summer in a convent out West; she has not been at Burnham Lodge for a year.”

The Frenchman stared at her. “What is it you say?” he exclaimed in deep astonishment, and Marian repeated her statement. “But it is not possible!” he ejaculated. “Not possible!”

“Yes it is,” Marian’s face expressed indomitable determination. “And I can’t have Evelyn’s happiness jeopardized by——” She stopped to wave her hand to Dr. Hayden, Dan Maynard, and James Palmer, who whirled by in an automobile. La Montagne, who had raised his hand in salute as the other men lifted their hats, whirled back to Marian, his face alight.

“Evelyn has not lost her affection; she is still true,” he began incoherently. “Ah, you have brought me news the most good—let us hurry to Evelyn.”

“Wait just a moment,” and Marian laid a detaining hand on the impetuous Frenchman’s arm. “We must sift this out a bit first. How were you received at Burnham Lodge and by whom?”

“Most cordially by both Mr. and Mrs. Burnham.”

[57]“Was that the first time you had met them?”

“No, oh, no; we have met before in Paris, and I saw Mrs. Burnham when in New York visiting my American cousins. It was in my cousin’s house that I met Evelyn.”

“So Evelyn told me.” Marian did not think it necessary to add that Evelyn had awakened her from her brief nap after her all night vigil in Mrs. Ward’s room, and poured out her story of love, misunderstanding and lost letters with such pathos that Marian had promptly championed her cause with every impulse of her loyal nature. Having met Captain La Montagne earlier in the summer she had then and there vowed to see him before the twenty-four hours were over, and if, as she had begun to suspect, she found that peculiar methods were being used to estrange the lovers, she decided to try and aid them.

“Captain,” she commenced, “did you see much of Mr. Burnham when he was in Paris?”

“No.” The Frenchman tempered the brief answer with an explanation. “Mr. Burnham is some years older and we are not what you might call”—he paused, searching for a word—“in sympathy.”

“I see.” Marian stared thoughtfully at a passing touring car. “It must have been fully five years ago, but was there not some story about Mr. Burnham when he was in Paris?”

[58]There was a pause, and when he spoke, the Frenchman confined himself to the word: “Yes.”

Marian’s eyes lighted. “My memory sometimes plays me tricks,” she said. “What were the details?”

La Montagne did not answer at once. “It was not so much,” he began. “Count André de Sartiges and Mr. Burnham had a dispute at Longchamps, and the next afternoon André slapped Mr. Burnham’s face in the club.”

“And what happened then?” persisted Marian as he stopped.

“Nothing,” La Montagne shrugged his shoulders. “In France it meant a duel; but as Mr. Burnham was an American who did not believe in dueling, the affair was soon forgotten.”

“All the same Mr. Burnham had to leave Paris,” retorted Marian, “and Mr. Burnham is a man who harbors grievances. I fear, Captain, that he does not favor your engagement to Evelyn.”

La Montagne transferred his regard from Marian to a colored passer-by and the woman happening to catch his eye, started back, alarmed. After he and Marian passed, the woman turned and regarded their backs before continuing on her way.

“I ’spect he looked dat away when he seed a Hun,” she ejaculated. “An’ from de medals he’s awearin’, he musta seen a pile ob Huns, but why[59] fo’ he look at a respectable colored lady like he wanter murder her.”

Totally unaware of the sentiments he had aroused, la Montagne strolled by Marian’s side for some moments in silence.

“Madame Burnham has given me letters of introduction to friends and her husband has invited me to their house,” he said at last. “To question Mr. Burnham’s friendship——”

“Is wise,” supplemented Marian softly. The Frenchman remained silent and she added with vehemence: “Because when Mr. Burnham’s animosity is suppressed it is all the more dangerous. Take a friendly tip from me; do not trust him, and remember, he has great influence over his wife.”

“If Evelyn will but marry me, we need not heed Burnham,” exclaimed La Montagne.

“And what have you to live on if you married without Mrs. Burnham’s consent?” asked Marian dryly. “Ah! forgive me,” as La Montagne colored hotly under his tan. “By the terms of her father’s will Evelyn can only inherit her fortune by marrying to suit her mother. If Mrs. Burnham disapproves, the fortune goes to her instead of to Evelyn.”

“Wills! Bah!” La Montagne’s gestures were expressive. “I adore Evelyn, not her money. If Le Bon Dieu be so good as to spare me through this[60] war Evelyn will not be badly off, as I will eventually inherit my uncle’s estate.” He turned eloquent, appealing eyes to Marian. “Ah, madame, use your kind offices that I may see Evelyn now.”

“Not now, to-morrow.” Marian tempered her refusal with a warm bright smile. “Call it what you will. Captain—a sixth sense, or woman’s intuition—but do not trust Peter Burnham.” She stopped and held out her hand. “I will not let you come further,” she stated positively as he started to remonstrate. “I will telephone you and anything sent in my care will always reach Evelyn. Good by,” and not waiting to hear his hearty thanks she turned down the street and ran up the Burnhams’ steps.

Jones opened the front door for her with gusto.

“Miss Evelyn’s gone to her room,” he confided to her. “And the master’s out. Shall I bring a cup of tea to your room, Mrs. Van Ness?”

“No, thanks, Jones, it is too near dinner time,” and Marian, not glancing inside the drawing room door as she passed down the hall, mounted the staircase to the second floor. She went at once to Evelyn’s room, and to her disappointment found it empty. Pausing undecidedly at the door, she finally crossed the hall to her bedroom and, taking off her hat, wasted no time in dressing for dinner.

It was still lacking fifteen minutes to the dinner[61] hour when she returned to Evelyn’s bedroom; its occupant was still absent, and Marian hesitated whether to go downstairs or into the library. Finally deciding in favor of the latter course she walked down the hall, and parting the portières, stepped into the room. A man bending over an open drawer of the desk straightened up at her approach and she recognized Dan Maynard.

“Good evening,” he exclaimed, and the cordial ring in his voice found its accompaniment in the quick lighting of his eyes as he looked at her. “Don’t go,” as murmuring a polite greeting, she started to leave.

“Am I not disturbing your occupation?” she asked.

Maynard laughed softly. “My occupation consists at the moment in searching for writing paper,” he acknowledged, pushing back a lot of loose papers and some string in the drawer. “Do take this chair,” and he wheeled one forward.

Marian settled down in the depths of the big chair with a sigh of content; she had had no rest the night before, the work at the State Department had been exacting, and while the walk home had for the moment refreshed her, she was more weary than she at first realized.

“I thought I saw you motoring with Dr. Hayden[62] and Jim Palmer,” she remarked, after waiting for Maynard to break the silence.

“He gave me a lift as far as the Connecticut Avenue telegraph office.” Maynard looked down at his business suit and then at her becoming evening dress. “I must apologize for not dressing for dinner,” he said. “The fact is I left England so hurriedly that my luggage is still in London. The clerk in the shipping office, when I went to inquire when the next Cunarder would sail, whispered in my ear that she was leaving that afternoon and I had just time to make the boat but could not go back to collect my belongings.”

“Was your trip across uneventful?” she questioned, noting with inward approval his tall, well-knit form and broad shoulders.

“Yes, except for the search at Quarantine; some report had gotten about that there were suspects aboard and we met with a lot of espionage and were severely cross-examined,” he stepped back to the desk and closed the drawer. “I am glad you like René La Montagne,” he said, and she started at the irrelevant remark. “He’s an ‘ace,’ you know, in the French Flying Corps.”

“Yes.” She looked at him, slightly puzzled. “How do you know I like Captain La Montagne?”

“Because you were walking with him.”

[63]She laughed amusedly. “Is my walking with people a sign that I like them?”

“So I have heard—commented,” he said, and his eyes held hers. “I would very much like to do some sight-seeing; will you not take pity and show me Washington?”

Marian’s fingers were playing with the string of coral which she wore about her neck. “It would be the blind leading the blind,” she said, and her voice sounded strained even to her own ears. “Washington is changed in the last few months. Mr. Burnham would prove a better guide than I.”

“Speaking about me?” inquired their host from the doorway of his room and Marian started; she had not heard the door opened. “Why are you two sitting up here?” he demanded querulously, and Maynard, glancing in his direction, noted that Burnham made a detour of the room which prevented his near approach to the chair where the dead man had been found. “The drawing room is much pleasanter,” he remarked, stopping half way across the room. “Suppose we go there.”

Before Marian could rise, the portières were pushed aside and Detective Mitchell stepped inside the library. He looked with quick displeasure from one to the other.

“You were directed, sir,” he said, addressing[64] Burnham, “by the Chief of Police not to use this room until further notice.”

“Tut, tut!” Burnham reddened angrily. “I don’t take instructions in my own house, and I won’t permit my guests to be dictated to. You can go, Mitchell.”

Instead of complying with his dictatorial order the detective stood his ground. Burnham, his face almost apoplectic in color, advanced threateningly and except for Maynard’s hasty step forward his raised fist would have struck Mitchell.

“Keep cool, Burnham,” he advised, and his voice brought the angry man to his senses. “Mitchell, there is no occasion for this excitement; Mrs. Van Ness and I were sitting here chatting and Mr. Burnham had just joined us. We have moved nothing in this room.”

Mitchell glanced searchingly about; apparently Maynard’s statement was correct; every piece of furniture, even the chess table, apparently stood in its accustomed place. He glanced apologetically at Marian, who had risen and stood with one hand on the back of her chair.

“It’s all right,” he admitted. “But as a precautionary measure the room will have to be sealed.”

Maynard, by an imperative gesture, stopped another explosion from Burnham. “What authority[65] have you, Mitchell, for taking such a step?” he inquired.

“The coroner’s orders,” gruffly. “I’ll get him,” and Mitchell disappeared.

Burnham pounded the nearest table in his wrath. “Do you think I am going to take orders in my own house?” he demanded of Maynard. “Do you?” and his hand continued to punctuate the question.

“Take care, you’ll injure your chess table,” cautioned Maynard. “There is no use in bucking up against the police, Burnham; they are within their rights in asking to have this room set aside for further investigation. It was thoughtless of me to come in.”

“I think we had all better leave,” suggested Marian, who had listened to the argument between Burnham and the detective with a strained attention which had not escaped Maynard’s notice. “I stopped in here expecting to find Evelyn.”

“She is with Mrs. Ward,” grumbled Burnham—his temper was still ruffled. “Hello, what’s that commotion?” as the sound of raised voices reached them. “The police again—I’ll tell Mitchell what I think of him, the interfering idiot!” And taking a hasty step forward he swung his arm upward and back.

But it was not the detective who stepped across[66] the threshold and ran full tilt against Burnham’s outstretched, threatening fist.

“Good gracious, Peter, what are you doing?” demanded his wife, dropping her pet dog to tenderly feel her nose. “Are you mad!” as, ignoring the presence of Marian and Maynard, he embraced her with effusion.

“No,” he retorted. “But I think people will soon make me mad. I sent you a telegram, Lillian, not to return. Didn’t you get it?”