Volume I

Capt. “Tho.” Morris.

Early Western Travels

1748-1846

A Series of Annotated Reprints of some of the best

and rarest contemporary volumes of travel, descriptive

of the Aborigines and Social and

Economic Conditions in the Middle

and Far West, during the Period

of Early American Settlement

Edited with Notes, Introductions, Index, etc., by

Reuben Gold Thwaites

Editor of “The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents,” “Wisconsin

Historical Collections,” “Chronicles of Border Warfare,”

“Hennepin’s New Discovery,” etc.

Volume I

Journals of

Conrad Weiser (1748), George Croghan (1750-1765)

Christian Frederick Post (1758), and

Thomas Morris (1764)

Cleveland, Ohio

The Arthur H. Clark Company

1904

Copyright 1904, by

THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Lakeside Press

R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS COMPANY

CHICAGO

| Preface. The Editor | 11 |

| I | |

| Introductory Note. The Editor | 17 |

| Journal of a Tour to the Ohio; August 11-October 2, 1748. Conrad Weiser | 21 |

| II | |

| Introductory Note. The Editor | 47 |

| A Selection of Letters and Journals relating to Tours into the Western Country. George Croghan | |

| Croghan to the Governor of Pennsylvania; November 16, 1750 | 53 |

| Proceedings of Croghan and Andrew Montour at [the] Ohio; May 18-28, 1751 | 58 |

| Letter of Croghan to the Governor, accompanying the treaty at Logstown; June 10, 1751 | 70 |

| Croghan’s Journal; January 12-February 3, 1754 | 72 |

| Croghan to Charles Swaine, at Shippensburg; October 9, 1755 | 82 |

| Council held at Carlisle; January 13, 1756 | 84 |

| Croghan’s Transactions with the Indians previous to Hostilities on the Ohio; [June, 1757] | 88 |

| Croghan’s Journal; October 21, 1760-January 7, 1761 | 100 |

| Croghan’s Journal; May 15-September 26, 1765 | 126 |

| List of the different Nations and Tribes of Indians in the Northern District of North America, with the number of their fighting men | 167 |

| Croghan to Sir William Johnson; November, 1765 | 170[8] |

| III | |

| Introductory Note. The Editor | 177 |

| Two Journals of Western Tours. Charles Frederick Post | |

| 1. From Philadelphia to the Ohio, on a message from the Government of Pennsylvania to the Delaware, Shawnese, and Mingo Indians; July 15-September 22, 1758 | 185 |

| 2. On a message from the Governor of Pennsylvania to the Indians on the Ohio, in the latter part of the same year; October 25, 1758-January 10, 1759 | 234 |

| IV | |

| Introductory Note. The Editor | 295 |

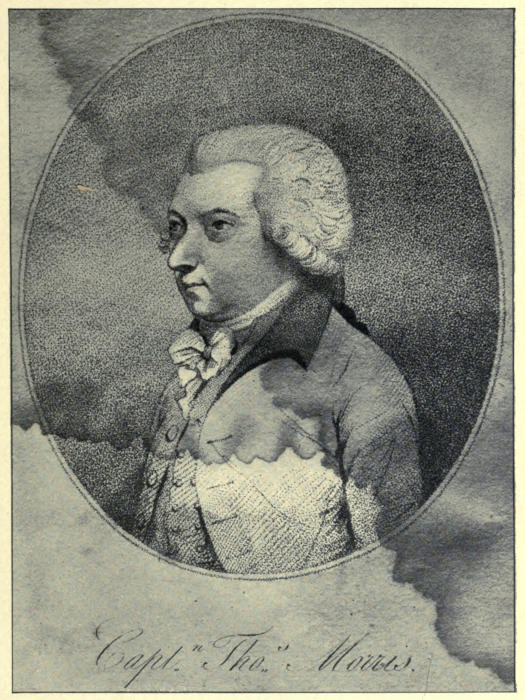

| Journal [of a Tour of the Maumee]; Detroit, September 25, 1764. Captain Thomas Morris, of his Majesty’s XVII Regiment of Infantry | 301 |

| Portrait of Captain Thomas Morris. Photographic facsimile of steel plate in original edition of “Miscellanies in Prose and Verse.” | Frontispiece. |

In planning for this series of reprints of Early Western Travels, we were confronted by an embarrassment of riches. To reissue all of the many excellent works of travel originally published during the formative period of Western settlement, would obviously be impossible. A selection had therefore to be made, both as to period and material. The century commencing with Conrad Weiser’s notable journey to the Western Indians in 1748, set convenient limits to the field in the matter of time. The question of material was much more difficult.

It being unlikely that any two editors would choose the same volumes for reprint, criticism of our list will undoubtedly be made. It should, however, candidly be explained that the matter of selection has in each case necessarily been affected by two important considerations—(1) the intrinsic value of the original from the historical side, and (2) its present rarity and market value. The Editor having selected a list of items worthy of a new lease of life, the Publishers, from their intimate knowledge of the commercial aspect of rare Americana, advised which of these in their opinion were sufficiently in demand by libraries and collectors to render the enterprise financially productive. It is believed that this co-operative method has resulted in an interesting collection, and given point to the descriptive sub-title: “Some of the best and rarest contemporary volumes of travel ... in the Middle and Far West, during the period of early American settlement.”

The first volume of our series is necessarily more varied in composition than any of its successors, it having been deemed important to present herein several typical early tours into the Indian country west of the Alleghenies.

That of Conrad Weiser, occurring in August and September of 1748, was the first official journey undertaken at the instance of the English colonies, to the west of the mountain wall. His purpose was, to carry to the tribesmen on the Ohio a present from the Pennsylvania and Virginia authorities. The results were favorable to an English alliance, but they were partially neutralized by the French expedition headed by Céloron the following year.

The journals of George Croghan (1750-65) are an epitome of the Indian history of the time. The first three documents deal with the period of English progress—in 1750, Croghan was on the Ohio en route to the Shawnee towns and Pickawillany; the next season, he outwitted Joncaire on the Allegheny. The four succeeding documents are concerned with the period of hostility to the English—in 1754 he was on the Ohio after Washington had passed (December, 1753); the letter from Aughwick, in 1755, tells of affairs after Braddock’s defeat; in 1756, we learn particulars of Indian affairs; and in 1757 is given a résumé of past events. The last two journals are the longest and most important—that of 1760-61 is concerned, topographically and otherwise, with the trip to Detroit via Lake Erie, in the company of Rogers’s Rangers, and the return by land to Pittsburg; that of 1765, with a tour down the Ohio towards the Illinois, where the writer is captured and carried to Ouiatanon—in due course making a peace with Pontiac, and returning to Niagara.

The journals of Christian Frederick Post and Thomas[13] Morris are interludes, as to time, in the Croghan diaries. Post’s two journals cover the months of July to September, 1758, and October, 1758 to January, 1759. He was at first sent out, by the northern trail, in midsummer, as an official messenger to the hostiles, among whom he succeeded in securing a kind of neutrality—a venturesome expedition into the neighborhood of Fort Duquesne, whose French commandant offered a price upon his head. The second journey, in the autumn, was undertaken to carry the news of the treaty of Easton (October, 1758), and pave the way for General Forbes’s advance. In the course of his journey he proceeded to the Indian towns on the Ohio and its northern tributaries, and returned to the settlements with Forbes’s army.

Captain Morris accompanied Bradstreet (1764) on the latter’s expedition towards Detroit. Being dispatched from Cedar Point on a mission to the French in the Illinois, Morris was arrested and maltreated at the Ottawa village at Maumee Rapids. He saw Pontiac, went to Fort Miami, narrowly escaped being burned at the stake, and finally made his escape through the woods to Detroit. His journal presents a thrilling episode in Western history.

It is our purpose, in these reprints, accurately to republish the original volumes, with all of their illustrations and other features. While seeking to reproduce the old text as closely as practicable, with its typographic and orthographic peculiarities, it has been found advisable here and there to make a few minor changes; these consist almost wholly of palpable blemishes, the result of negligent proof-reading—such as turned letters, transposed letters, slipped letters, and mis-spacings. Such corrections will be made without specific mention; in some[14] instances, however, the original error has for a reason been retained, and in juxtaposition the correction given within brackets. We indicate, throughout, the pagination of the old edition which we are reprinting, by inclosing within brackets the number of each page at its beginning, e. g. [24]; in the few instances where pages were, as the fruit of carelessness in make-up, misnumbered in the original, we have given the incorrect as well as the correct figure, e. g. [25, i. e. 125]. In two or three instances, where matter foreign to our purpose was introduced in the volume as originally published—such as the journal of a voyage not within our field, or an appendix of irrelevant or unimportant matter—we have taken the liberty of eliminating this; in such cases, however, especial attention will be called to the omission.

An analytical index to the series will appear in the concluding volume.

In the preparation of notes for the present volume, the Editor has been assisted by Louise Phelps Kellogg, Ph.D., of the Division of Maps and Manuscripts in the Wisconsin State Historical Library. He has also been favored with valuable information on various points, from Colonel Reuben T. Durrett of Louisville, Mr. Frank H. Severance of Buffalo, the Western Reserve Historical Society at Cleveland, and Dr. Ernest C. Richardson and Dr. John Rogers Williams of Princeton University.

R. G. T.

Madison, Wis., January, 1904.

Source: Pennsylvania Colonial Records, v, pp. 348-358; with variations from Pennsylvania Historical Collections, i, pp. 23-33.

Conrad Weiser, one of the most prominent agents in the management of Indian affairs during the later French wars, was a native of Würtemberg, being born November 2, 1696. When Conrad was but fourteen years old, his father, John Conrad Weiser, led a party of Palatines to America where they lived four years on the Livingston manor in New York, and in 1714 removed to Schoharie. There young Weiser came in close contact with the Mohawk Indians, was adopted into their tribe, and living among them for some years became master of their language.

In 1729, he and his family, consisting of a wife and five young children, removed to Berks (then Lancaster) County, Pennsylvania, where a number of Weiser’s countrymen had preceded them. The new homestead was a mile east of the present town of Womelsdorf, and became the centre of an extended hospitality both for Pennsylvania Germans and visiting Indians. When Reading was laid out (1748), Weiser was one of the commissioners for that purpose, building therein a house and store that are still standing.

His first employment as an interpreter was in 1731, when forty shillings were allotted him for his services. From this time forward he was official interpreter for Pennsylvania, and for thirty years was employed in every important Indian transaction. The Pennsylvania Council testified in 1736 “that they had found Conrad faithfull and honest, that he is a true good Man & had Spoke[18] their words [the Indians’] & our Words, and not his own.”[1] Again in 1743, the governor of Virginia requested the province of Pennsylvania to send their “honest interpreter,” Conrad Weiser, to adjust a difficulty with the Iroquois Indians; whereupon he proceeded to Onondaga with a present of £100 on the part of Virginia, and made peace for the English colonists.[2] The following year, Weiser was chief interpreter at the important treaty of Lancaster; and throughout King George’s War was occupied with negotiations with the Six Nations, detaching them from the French influence, and keeping the Pennsylvania Delawares quiet “upon their mats.”

After the journey to the Ohio, described in the following diary, Weiser’s Indian transactions were largely confined to the province of Pennsylvania; Montour and Croghan taking over the business with the Ohio Indians until the outbreak of the French and Indian War. Weiser now assumed duties in a military capacity. He raised a company of soldiers for the Canadian expedition (1755), and later was made lieutenant-colonel, with the care of the frontier forts under his charge. At the same time the New York authorities besought his influence with the Mohawks and Western Iroquois; and he assisted in arranging the treaty at Easton, which prepared the way for the success of Forbes’s expedition (1758).

Weiser was the most influential German of his section, possibly of all Pennsylvania; but his religious affiliations and enmities interfered with his political ambitions. Originally a Lutheran, in 1735 he became concerned with the movement of the Seventh Day Baptists, which[19] led to the establishment of the community at Ephrata, where he was known as Brother Enoch, and consecrated to the priesthood. These sectaries charged that the bribe of official position tempted him to forsake his vows; certain it is that in 1741 he was appointed justice of the peace for Berks County, and left Ephrata, later (1743) sending a letter requesting his former brethren to consider him a “stranger.” The opposition of this sect of Germans, the indifference of the Moravians, and the alienation of his earlier Lutheran friends, lost him his coveted election for the assembly; and he afterwards withdrew from politics to remain the trusted adviser of the government upon Indian and local affairs. His sincerity, honesty, and trustworthiness made him greatly respected throughout the entire province, and his death, July 13, 1760, was considered a public calamity.

The journey undertaken to the Ohio, which the accompanying journal chronicles, was the first official embassy to the Indians who lived beyond the Alleghenies, and was undertaken for the following reasons.

The efforts of the English traders to push their connections among the “far Indians” had been increasingly successful, during the decade 1738-48, and the resulting rivalry with the French had reached an intense stage. The firm hold of the latter on the Indian nations of the “upper country” had been shaken by a long series of wars with the Foxes and Chickasaws, accompanied by humiliating defeats. In 1747, the most faithful of the French Indians—those domiciled at Mackinac and Detroit—had risen in revolt; and George Croghan sent word to the council at Philadelphia that some nations along the shore of Lake Erie desired the English alliance, having as an earnest thereof sent a belt of wampum and[20] a French scalp.[3] The Pennsylvania authorities voted them a present of £200, to be sent out by Croghan. About the same time, a deputation of ten Indians from the Ohio arriving in Philadelphia, the council considered this “an extraordinary event in the English favor,” and not only secured a grant of £1,000 from the assembly, but applied to the governors of the Southern provinces to aid in this work; in accordance with which request, Virginia replied with an appropriation of £200.[4] Croghan set off in the spring of 1748, and informed the Allegheny Indians that Weiser, the official interpreter, would be among them during the summer. Meanwhile, the latter was detained by a treaty with the Twigtwee (Miami) Indians, who had come unexpectedly offering to the English the alliance of that powerful nation;[5] so that it was not until August that he was able to start on his mission to the Ohio.

In addition to the delivery of the present, he was also instructed to secure satisfaction for the attack of some Northern Indians upon the Carolina settlements; wherein one Captain Haig, with several others, had been carried off prisoners—supposedly by some Ohio Indians.[6] The success of this mission was most gratifying to the English and the frontier settlers. The Virginia authorities were more active than those of Pennsylvania in following up the advantage thus gained; and under the leadership of the Ohio Company sought to secure the Forks of the Ohio, with the ensuing consequences of the French and Indian War.

R. G. T.

Augˢᵗ 11th. Set out from my House & came to James Galbreath[8] that day, 30 Miles.

12th. Came to George Croghans,[9] 15 Miles.

13th. To Robert Dunnings, 20 Miles.

14th. To the Tuscarroro Path, 30 Miles.

15th and 16th. Lay by on Account of the Men coming back Sick, & some other Affairs hindering us.

17th. Crossed the Tuscarroro Hill & came to the Sleeping Place called the Black Log, 20 Miles.

18th. Had a great rain in the afternoon; came within two Miles of the Standing Stone, 24 Miles.

19th. We travelled but 12 Miles;[10] were obliged to dry our Things in the afternoon.

20th. Came to Franks Town, but saw no Houses or Cabins; here we overtook the Goods,[11] because four of George Croghan’s Hands fell sick, 26 Miles.

21st. Lay by, it raining all Day.

22d. Crossed Alleghany Hill & came to the Clear Fields, 16 Miles.[12]

23d. Came to the Shawonese[13] Cabbins, 34 Miles.

24th. Found a dead Man on the Road who had killed himself by Drinking too much Whisky; the Place being very stony we cou’d not dig a Grave; He smelling very strong we covered him with Stones & Wood & went on our Journey; came to the 10 Mile Lick, 32 Miles.

25th. Crossed Kiskeminetoes Creek & came to Ohio that Day, 26 Miles.[14]

26th. Hired a Cannoe; paid 1,000 Black Wampum for the loan of it to Logs Town. Our Horses being all tyred, we went by Water & came that Night to a Delaware Town; the Indians used us very kindly.[15]

27th. Sett off again in the morning early; Rainy Wheather. We dined in a Seneka Town, where an old Seneka Woman Reigns with great Authority;[16] we dined at her House, & they all used us very well; at this & the last-mentioned Delaware Town they received us by firing a great many Guns; especially at this last Place. We saluted the Town by firing off 4 pair of pistols; arrived that Evening at Logs Town, & Saluted the Town as before; the Indians returned about One hundred Guns;[17] Great Joy appear’d in their Countenances.[25] From the Place where we took Water, i. e. from the old Shawones Town, commonly called Chartier’s Town,[18] to this Place is about 60 Miles by Water & but 35 or 40 by Land.

The Indian Council met this Evening to shake Hands with me & to shew their Satisfaction at my safe arrival; I desired of them to send a Couple of Canoes to fetch down the Goods from Chartier’s old Town, where we had been oblig’d to leave them on account of our Horses being all tyred. I gave them a String of Wampum to enforce my Request.[19]

28th. Lay still.

29th. The Indians sett off in three Canoes to fetch the Goods. I expected the Goods wou’d be all at Chartier’s[26] old Town by the time the Canoes wou’d get there, as we met about twenty Horses of George Croghan’s at the Shawonese Cabbins in order to fetch the Goods that were then lying at Franks Town.

This Day news came to Town that the Six Nations were on the point of declaring War against the French, for reason the French had Imprison’d some of the Indian Deputies. A Council was held & all the Indians acquainted with the News, and it was said the Indian Messenger was by the way to give all the Indians Notice to make ready to fight the French.[20] This Day my Companions went to Coscosky, a large Indian Town about 30 Miles off.[21]

30th. I went to Beaver Creek, an Indian Town about 8 Miles off, chiefly Delawares, the rest Mohocks, to have some Belts of Wampum made.[22] This afternoon Rainy Wheather set in which lasted above a Week. Andrew[27] Montour[23] came back from Coscosky with a Message from the Indians there to desire of me that the ensuing Council might be held at their Town. We both lodged at this Town at George Croghan’s Trading House.

31st. Sent Andrew Montour back to Coscosky with a String of Wampum to let the Indians there know that it was an act of their own that the ensuing Council must be held at Logs Town, they had order’d it do last Spring when George Croghan was up, & at the last Treaty in Lancaster the Shawonese & Twightwees[24] have been told so, & they stayed accordingly for that purpose, & both would be offended if the Council was to be held at Coscosky, besides my instructions binds me to Logs Town, & could not go further without giving offence.

Septʳ. 1. The Indians in Logs Town having heard of[28] the Message from Coscosky sent for me to know what I was resolv’d to do, and told me that the Indians at Coscosky were no more Chiefs than themselves, & that last Spring they had nothing to eat, & expecting that they shou’d have nothing to eat at our arrival, order’d that the Council should be held here; now their Corn is ripe, they want to remove the Council, but they ought to stand by their word; we have kept the Twightwees here & our Brethren the Shawonese from below on that account, as I told them the Message that I had sent by Andrew Montour; they were content.

2d. Rain continued; the Indians brought in a good deal of Venison.

3d. Set up the Union Flagg on a long Pole. Treated all the Company with a Dram of Rum; The King’s Health was drank by Indians & white men. Towards Night a great many Indians arrived to attend the Council. There was great firing on both sides; the Strangers first Saluted the Town at a quarter of a Mile distance, and at their Entry the Town’s People return’d the fire, also the English Traders, of whom there were above twenty. At Night, being very sick of the Cholick, I got bled.

4th. Was oblig’d to keep my bed all Day, being very weak.

5th. I found myself better. Scaiohady[25] came to see me; had some discourse with him about the ensuing Council.

6th. Had a Council with the Wondats, otherways called Ionontady Hagas, they made a fine Speech to[29] me to make me welcome, & appeared in the whole very friendly.[26] Rainy Wheather continued.

7th. Being inform’d that the Wondats had a mind to go back again to the French, & had endeavour’d to take the Delawares with them to recommend them to the French, I sent Andrew Montour to Beaver Creek with a string of Wampum to inform himself of the Truth of the matter; they sent a String in answer to let me know they had no correspondence that way with the Wondats, and that the aforesaid Report was false.

8th. Had a Council with the Chiefs of the Wondats; enquired their number, & what occasion’d them to come away from the French, What Correspondence they had with the Six Nations, & whether or no they had ever had any Correspondence with the Government of New York; they inform’d me their coming away from the French was because of the hard Usage they received from them; That they wou’d always get their Young Men to go to War against their Enemies, and wou’d use them as their own People, that is like Slaves, & their Goods were so dear that they, the Indians, cou’d not buy them; that there was one hundred fighting Men that came over[30] to join the English, seventy were left behind at another Town a good distance off, & they hoped they wou’d follow them; that they had a very good Correspondence with the Six Nations many Years, & were one People with them, that they cou’d wish the Six Nations wou’d act more brisker against the French; That above fifty Years ago they made a Treaty of Friendship with the Governor of New York at Albany, & shewed me a large Belt of Wampum they received there from the said Governor as from the King of Great Britain; the Belt was 25 Grains wide & 265 long, very Curiously wrought, there were seven Images of Men holding one another by the Hand, the 1st signifying the Governor of New York (or rather, as they said, the King of Great Britain), the 2d the Mohawks, the 3d the Oneidos, the 4th the Cajugas, the 5th the Onondagers, the 6th the Senekas, the 7th the Owandaets [Wyandots], the two Rows of black Wampum under their feet thro’ the whole length of the Belt to signify the Road from Albany thro’ the 5 Nations to the Owendaets; That 6 Years ago, they had sent Deputies with the same Belt to Albany to renew the Friendship.

I treated them with a quart of Whiskey & a Roll of Tobacco; they expressed their good Wishes to King George & all his People, & were mightily pleas’d that I look’d upon them as Brethren of the English.

This Day I desir’d the Deputies of all the Nations of Indians settled on the Waters of Ohio to give me a List of their fighting Men, which they promis’d to do. A great many of the Indians went away this Day because the Goods did not come, & the People in the Town cou’d not find Provision enough, the number was so great.

The following is the number of every Nation, given to[31] me by their several Deputies in Council, in so many Sticks tied up in a Bundle:

The Senacas 163, Shawonese 162, Owendaets 100, Tisagechroanu 40; Mohawks 74; Mohickons 15; Onondagers 35; Cajukas 20; Oneidos 15; Delawares 165; in all 789.[27]

9th. I had a Council with the Senakas, & gave them a large String of Wampum, black & White, to acquaint them I had it in Charge from the President & Council in Philadelphia to enquire who it was that lately took the People Prisoners in Carolina, one thereof being a Great man, & that by what discovery I had already made I found it was some of the Senekas did it; I therefore desir’d them to give me their Reasons for doing so, & as they had struck their Hatchet into their Brethren’s Body they cou’d not expect that I could deliver my Message with a good heart before they gave me Satisfaction in that Respect, for they must consider the English, tho’ living in several Provinces, are all one People, & doing Mischeif to one is doing to the other; let me have a plain & direct answer.

10th. A great many of the Indians got drunk; one Henry Noland had brought near 30 Gallons of Whiskey to the Town. This Day I made a Present to the old Shawonese Chief Cackawatcheky, of a Stroud, a Blanket,[32] a Match Coat,[28] a Shirt, a Pair of Stockings, & a large twist of Tobacco, & told him that the President & Council of Philadelphia remember’d their love to him as to their old & true Friend, & wou’d Cloath his Body once more, & wished he might weare them out so as to give them an opportunity to cloath him again. There was a great many Indians present, two of which were the big Hominy & the Pride, those that went off with Chartier, but protested against his proceedings against our Traders. Catchawatcheky return’d thanks, & some of the Six Nations did the same, & express’d their Satisfaction to see a true man taken Notice of, altho’ he was now grown Childish.

11th. George Croghan & myself staved an 8 Gallon Cag of Liquor belonging to the aforesaid Henry Norland, who could not be prevail’d on to hide it in the Woods, but would sell it & get drunk himselfe.

I desir’d some of the Indians in Council to send some of their Young Men to meet our People with the Goods, and not to come back before they heard of or saw them. I begun to be afraid they had fallen into the Hands of the Enemy; so did the Indians.

Ten Warriors came to Town by Water from Niagara; We suspected them very much, & fear’d that some of their Parties went to meet our People by hearing of them.[29]

12th. Two Indians and a white man[30] went out to meet our People, & had Orders not to come back before they saw them, or go to Franks Town, where we left the[33] Goods. The same Day the Indians made answer to my Request concerning the Prisoners taken in Carolina: Thanayieson, a Speaker of the Senekas, spoke to the following purpose in the presence of all the Deputies of the other Nations (We were out of Doors): “Brethren, You came a great way to visit us, & many sorts of Evils might have befallen You by the way which might have been hurtful to your Eyes & your inward parts, for the Woods are full of Evil Spirits. We give You this String of Wampum to clear up your Eyes & Minds & to remove all bitterness of your Spirit, that you may hear us speak in good Chear.” Then the Speaker took his Belt in his Hand & said: “Brethren, when we and you first saw one another at your first arrival at Albany we shook Hands together and became Brethren & we tyed your Ship to the Bushes, and after we had more acquaintance with you we lov’d you more and more, & perceiving that a Bush wou’d not hold your Vessel we then tyed her to a large Tree & ever after good Friendship continued between us; afterwards you, our Brethren, told us that a Tree might happen to fall down and the Rope rot wherewith the Ship was tyed. You then proposed to make a Silver Chain & tye your Ship to the great Mountains in the five Nations’ Country, & that Chain was called the Chain of Friendship; we were all tyed by our Arms together with it, & we the Indians of the five Nations heartily agreed to it, & ever since a very good Correspondence have been kept between us; but we are very sorry that at your coming here we are oblig’d to talk of the Accident that lately befell you in Carolina, where some of our Warriors, by the Instigation of the Evil Spirit, struck their Hatchet into our own Body like, for our Brethren the English & we are of one Body, &[34] what was done we utterly abhor as a thing done by the Evil Spirit himself; we never expected any of our People wou’d ever do so to our Brethren. We therefore remove our Hatchet which, by the influence of the Evil Spirit, was struck into your Body, and we desire that our Brethren the Govʳ. of New York & Onas[31] may use their utmost endeavours that the thing may be buried in the bottomless Pit, that it may never be seen again—that the Chain of Friendship which is of so long standing may be preserv’d bright & unhurt.” Gave a Belt. The Speaker then took up a String of Wampum, mostly black, and said: “Brethren, as we have removed our Hatchet out of your Body, or properly speaking, out of our own, We now desire that the Air may be clear’d up again & the wound given may be healed, & every thing put in good understanding, as it was before, and we desire you will assist us to make up everything with the Govʳ. of Carolina; the Man that has been brought as a Prisoner we now deliver to You, he is yours” (lay’d down the String, and took the Prisoner by the Hand and delivered him to me).[32] By way of discourse, the Speaker said, “the Six Nation Warriors often meet Englishmen trading to the Catawbas, & often found that the Englishmen betrayed them to their Enemy, & some of the English Traders had been spoke to by the Indian Speaker last Year in the Cherrykees[33] Country & were told not to do[35] so; that the Speaker & many others of the Six Nations had been afraid a long time that such a thing wou’d be done by some of their Warriors at one time or other.”

13th. Had a Council with the Senekas and Onontagers about the Wandots, to receive them into our Union. I gave a large Belt of Wampum and the Indians gave two, & everything was agreed upon about what sho’d be said to the Wandots. The same Evening a full Council was appointed & met accordingly, & a Speech was made to the Wandots by Asserhartur, a Seneka, as follows:

“Brethren, the Ionontady Hagas:[34] last Spring you sent this Belt of Wampum to Us (having the Belt then in his hand) to desire us and our Brethren, the Shawonese & our Cousins the Delawares, to come & meet you in your retreat from the French, & we accordingly came to your Assistance & brought you here & received you as our own flesh. We desire you will think you now join us, & our Brethren, the English, & you are become one People with us”—then he lay’d that Belt by & gave them a very large String of Wampum.

The Speaker took up the Belt I gave & said: “Brethren: the English, our Brothers, bid you welcome & are glad you escaped out Captivity like: You have been kept as Slaves by Onontio,[35] notwithstanding he call’d You all along his Children, but now You have broke the Rope wherewith you have been tyed & become Freemen, & we, the united Six Nations, receive you to our Council Fire, & make you Members thereof, and we will secure your dwelling Place to You against all manner of danger.”—Gave the Belt.

“Brethren: We the Six United Nations & all our Indian Allies, with our Brethren the English, look upon you as our Children, tho’ you are our Brethren; we desire you will give no ear to the Evil Spirit that spreads lyes & wickedness, let your mind by easy & clear, & be of the same mind with us whatever you may hear, nothing shall befall you but what of necessity must befall us at the same time.

“Brethren: We are extremely pleased to see you here, as it happened just at the same time when our Brother Onas is with us. We jointly, by this Belt of Wampum, embrace you about your middle, & desire you to be strong in your minds & hearts, let nothing alter your minds, but live & dye with us.” Gave a Belt—the Council broke up.

14th. A full Council was Summon’d & every thing repeated by me to all the Indians of what pass’d in Lancaster at the last Treaty with the Twightwees.

The News was confirm’d by a Belt of Wampum from the Six Nations, that the French had imprisoned some of the Six Nations Deputies, & 30 of the Wandots, including Women & Children.

The Indians that were sent to meet our People with the Goods came back & did not see any thing of them, but they had been no further than the old Shawonese Town.

15th. I let the Indians know that I wou’d deliver my Message to morrow, & the Goods I had, & that they must send Deputies with me on my returning homewards, & wherever we shou’d meet the rest of the Goods I wou’d send them to them if they were not taken by the Enemy, to which they agreed.

The same Day the Delawares made a Speech to me & presented a Beaver Coat & a String of Wampum, &[37] said, “Brother: we let the President & Council of Phila. know that after the Death of our Chief Man, Olomipies, our Grand Children the Shawnese[36] came to our own Town to condole with us over the loss of our good King, your Brother, & they wiped off our Tears & comforted our minds, & as the Delawares are the same People with the Pennsylvanians, & born in one & the same Country, we give some of the Present our Grand Children gave us to the President & Council of Philda. because the Death of their good Friend & Brother must have affected them as well as us.”—Gave the Beaver Coat & a String of Wampum.

The same Day the Wandots sent for me & Andrew & presented us with 7 Beaver Skins about 10 lbs. weight, & said they gave us that to buy some refreshments for us after our arrival in Pennsylvania, wished we might get home safe, & lifted up their Hands & said they wou’d pray God to protect us & guide us the way home. I desir’d to know their names; they behav’d like People of good Sense & Sincerity; the most of them were grey headed; their Names are as follows: Totornihiades, Taganayesy, Sonachqua, Wanduny, Taruchiorus, their Speaker. The Chiefs of the Delawares that made the above Speech are Shawanasson & Achamanatainu.[37]

16th. I made answer to the Delawares & said, “Brethren the Delawares: It is true what you said that the[38] People of Pennsylvania are your Brethren & Countrymen; we are very well pleas’d of what your Children the Shawonese did to you; this is the first time we had publick Notice given us of the Death of our good Friend & Brother Olomipies. I take this opportunity to remove the remainder of your Troubles from your Hearts to enable you to attend in Council at the ensuing Treaty, & I assure you that the President & Council of Pennsylvania condoles with You over the loss of your King our good Friend and Brother.”—Gave them 5 Strouds.

The two aforesaid Chiefs gave a String of Wampum & desir’d me to let their Brethren, the President & Council, know they intended a Journey next Spring to Philadelphia to consult with their Brethren over some Affairs of Moment; since they are now like Orphan Children, they hoped their Brethren wou’d let them have their good Advice and Assistance, as the People of Pennsylvania & the Delawares were like one Family.

The same Day the rest of the Goods arriv’d the Men said they had nine Days’ Rain & the Creeks arose, & that they had been oblig’d to send a sick Man back from Franks Town to the Inhabitants with another to attend him.

The neighboring Indians being sent for again, the Council was appointed to meet to-morrow. It rain’d again.

17th. It rained very hard, but in the Afternoon it held up for about 3 hours; the Deputies of the several Nations met in Council & I delivered them what I had to say from the President & Council of Pennsylvania by Andrew Montour.

“Brethren, you that live on Ohio: I am sent to You by the President & Council of Pennsylvania, & I am now going to Speak to You on their behalf I desire You[39] will take Notice & hear what I shall say.”—Gave a String of Wampum.

“Brethren: Some of You have been in Philadelphia last Fall & acquainted us that You had taken up the English Hatchet, and that You had already made use of it against the French, & that the French had very hard heads, & your Country afforded nothing but Sticks & Hickerys which was not sufficient to break them. You desir’d your Brethren wou’d assist You with some Weapons sufficient to do it. Your Brethren the Presidᵗ. & Council promis’d you then to send something to You next Spring by Tharachiawagon,[38] but as some other Affairs prevented his Journey to Ohio, you receiv’d a Supply by George Croghan sent you by your said Brethren; but before George Croghan came back from Ohio News came from over the Great Lake that the King of Great Britain & the French King had agreed upon a Cessation of Arms for Six Months & that a Peace was very likely to follow. Your Brethren, the President & Council, were then in a manner at a loss what to do. It did not become them to act contrary to the command of the King, and it was out of their Power to encourage you in the War against the French; but as your Brethren never miss’d fulfilling their Promises, they have upon second Consideration thought proper to turn the intended Supply into a Civil & Brotherly Present, and have accordingly sent me with it, and here are the Goods before your Eyes, which I have, by your Brethren’s Order, divided into 5 Shares & layd in 5 different heaps, one heap whereof your Brother Assaraquoa sent to You to remember his Friendship and Unity with You; & as you are all of the same Nations with whom we the English[40] have been in League of Friendship, nothing need be said more than this, that the President & Council & Assaraquoa[39] have sent You this Present to serve to strengthen the Chain of Friendship between us the English & the several Nations of Indians to which You belong. A French Peace is a very uncertain One, they keep it no longer than their Interest permits, then they break it without provocation given them. The French King’s People have been almost starv’d in old France for want of Provision, which made them wish & seek for Peace; but our wise People are of opinion that after their Bellies are full they will quarrel again & raise a War. All nations in Europe know that their Friendship is mix’d with Poison, & many that trusted too much on their Friendship have been ruin’d.

“I now conclude & say, that we the English are your true Brethren at all Events, In token whereof receive this Present.” The Goods being then uncover’d I proceeded. “Brethren: You have of late settled the River of Ohio for the sake of Hunting, & our Traders followed you for the sake of Hunting also. You have invited them yourselves. Your Brethren, the President & Council, desire You will look upon them as your Brethren & see that they have justice done. Some of your Young Men have robbed our Traders, but you will be so honest as to compel them to make Satisfaction. You are now become a People of Note, & are grown very numerous of late Years, & there is no doubt some wise Men among you, it therefore becomes you to Act the part of wise men, & for the future be more regular[41] than You have been for some Years past, when only a few Young Hunters lived here.”—Gave a Belt.

“Brethren: You have of late made frequent Complaints against the Traders bringing so much Rum to your Towns, & desir’d it might be stop’t; & your Brethren the President & Council made an Act accordingly & put a stop to it, & no Trader was to bring any Rum or strong Liquor to your Towns. I have the Act here with me & shall explain it to You before I leave you;[40] But it seems it is out of your Brethren’s Power to stop it entirely. You send down your own Skins by the Traders to buy Rum for you. You go yourselves & fetch Horse loads of strong Liquor. But the other Day an Indian came to this Town out of Maryland with 3 Horse loads of Liquor, so that it appears you love it so well that you cannot be without it. You know very well that the Country near the endless Mountain affords strong Liquor, & the moment the Traders buy it they are gone out of the Inhabitants & are travelling to this Place without being discover’d; besides this, you never agree about it—one will have it, the other won’t (tho’ very few), a third says we will have it cheaper; this last we believe is spoken from your Hearts (here they Laughed). Your Brethren, therefore, have order’d that every cask of Whiskey shall be sold to You for 5 Bucks in your Town, & if a Trader offers to sell Whiskey to You and will not let you have it at that Price, you may take it from him & drink it for nothing.”—Gave a Belt.

“Brethren: Here is one of the Traders who you know to be a very sober & honest Man; he has been robbed of the value of 300 Bucks, & you all know by whom; let,[42] therefore, Satisfaction be made to the Trader.”—Gave a String of Wampum.

“Brethren, I have no more to say.”

I delivered the Goods to them, having first divided them into 5 Shares—a Share to the Senekas, another to the Cajukas, Oneidos, the Onontagers, & Mohawks, another to the Delawares, another to the Owendaets, Tisagechroanu, & Mohickons, and the other to the Shawonese.

The Indians signified great Satisfaction & were well pleased with the Cessation of Arms. The Rainy Wheather hasted them away with the Goods into the Houses.

18th. The Speech was delivered to the Delawares in their own Language, & also to the Shawonese in their’s, by Andrew Montour, in the presence of the Gentlemen that accompanied me.[41] I acquainted the Indians I was determined to leave them to-morrow & return homewards.

19th. Scaiohady, Tannghrishon, Oniadagarehra, with a few more, came to my lodging & spoke as follows:

“Brother Onas, We desire you will hear what we are going to say to You in behalf of all the Indians on Ohio; their Deputies have sent us to You. We have heard what you have said to us, & we return you many thanks for your kindness in informing us of what pass’d between the King of Great Britain & the French King, and in particular we return you many thanks for the large Presents; the same we do to our Brother Assaraquoa, who joined our Brother Onas in making us a Present. Our Brethren have indeed tied our Hearts to their’s. We at present can but return thanks with an empty hand till another opportunity serves to do it sufficiently. We[43] must call a great Council & do every thing regular; in the mean time look upon us as your true Brothers.

“Brother: You said the other Day in Council if any thing befell us from the French we must let you know of it. We will let you know if we hear any thing from the French, be it against us or yourself. You will have Peace, but it’s most certain that the Six Nations & their Allies are upon the point of declaring War against the French. Let us keep up true Corrispondence & always hear of one another.”—They gave a Belt.

Scaiohady & the half King, with two others, had inform’d me that they often must send Messengers to Indian Towns & Nations, & had nothing in their Council Bag, as they were new beginners, either to recompense a Messenger or to get Wampum to do the business, & begged I wou’d assist them with something. I had saved a Piece of Strowd, an half Barrell of Pow[d]er, 100 pounds of Lead, 10 Shirts, 6 Knives, & 1 Pound of Vermillion, & gave it to them for the aforesaid use; they return’d many thanks and were mightily pleased.[42]

The same Day I set out for Pennsylvania in Rainy Weather, and arrived at George Croghan’s on the 28th Instant.[43]

Conrad Weiser.

Pennsbury, Sepᵗ. 29th, 1748.

[1] Pennsylvania Colonial Records (Harrisburg, 1851), iv, p. 88.

[2] Ibid., pp. 660-669, for journal of this tour.

[3] Pennsylvania Colonial Records, v, p. 72.

[4] Ibid., pp. 121, 140, 145-152, 189, 190, 257.

[5] Ibid., pp. 286-290, 307-319.

[6] Ibid., pp. 290-293, 304.

[7] There appear to have been two copies of this journal prepared, one as the official report to the president and council of Pennsylvania, which was published in the Pennsylvania Colonial Records, v, pp. 348-358. A reprint from the same manuscript appeared in Early History of Western Pennsylvania (Pittsburg and Harrisburg, 1846), appendix, pp. 13-23. The other copy seems to have been preserved among the family papers; and was edited and published by a descendant of Weiser—Heister M. Muhlenberg, M.D., of Reading, Pennsylvania—in Pennsylvania Historical Society Collections (Philadelphia, 1851), i, pp. 23-33. We have followed the official copy, indicating by footnotes variations in the other account.—Ed.

[8] Weiser’s house was about one mile east of Womelsdorf, now in Berks County, Pennsylvania. James Galbreath was a prominent Indian trader, one of those licensed by the government of Pennsylvania.—Ed.

[9] Croghan lived at this time just west of Harrisburg in Pennsboro Township, Cumberland County.—Ed.

[10] There were three great Indian paths from east to west through Western Pennsylvania. The southern led from Fort Cumberland on the Potomac, westward through the valleys of Youghiogheny and Monongahela, to the Forks of the Ohio, and was the route taken by Washington in 1753, later by Braddock’s expedition, and was substantially the line of the great Cumberland National Road of the early nineteenth century.

The central trail, passing through Carlisle, Shippensburg, and Bedford, over Laurel Mountain, through Fort Ligonier, over Chestnut Ridge, to Shannopin’s Town at the Forks of the Ohio, was the most direct, and became the basis of General Forbes’s road, and later of the Pennsylvania wagon road to the Ohio. Gist took this trail in 1750.—See Hulbert, Old Glade Road (Cleveland, 1903).

The northern, or Kittanning trail, was the oldest, and that most used by Indian traders. It is this route that Weiser followed. From Croghan’s, he passed over into the valley of Sherman’s Creek (in Perry County), crossed the Tuscarora Mountains at what was later known as Sterritt’s Gap, and reached the Black Log sleeping place near Shade Valley in the southeastern part of Huntingdon County. This was a digression to the south, for in an extract from his journal in Pennsylvania Archives, ii, p. 13, Weiser says: “The Black Log is 8 or 10 miles South East of the Three Springs and Frank’s Town lies to yᵉ North, so that there must be a deduction of at least twenty miles.” From here, following the valley of Aughwick Creek, he crossed the Juniata River, and approached the “Standing Stone.” This was a prominent landmark of the region, and stood on the right bank of a creek of the same name, near the present town of Huntingdon. It was about 14 feet high, and six inches square, and served as a kind of Indian guidepost for that region. From this point, the trail followed the Juniata Valley, coinciding for a short distance with the line of the Pennsylvania Central Railway, but turning off on the Frankstown branch of the Juniata at the present town of Petersburg.

There was also a fourth trail, still farther north, by way of Sunbury and the west branch of the Susquehanna to Venango. This was Post’s route in 1758.—Ed.

[11] Frankstown was an important Indian village in the county of Blair, near Hollidaysburg. The present town of this name lies on the north side of the river, whereas the Indian town appears to have been on the south bank. Remains of the native village were in existence in the early part of the nineteenth century. The Indian name was “Assunepachla,” the title “Frankstown” being given in honor of Stephen Franks, a German trader who lived at this place.—See Jones, History of Juniata Valley (Harrisburg, 1889, 2nd ed.), pp. 298-303. The cause of its desertion when Weiser passed, is not known. The other edition of the journal says, “Here we overtook one half the goods,” which seems more correct in view of the succeeding account.—Ed.

[12] Of the place where the Kittanning trail crosses the Allegheny Range, Jones writes (op. cit.), that the path is still visible, although filled with weeds in the summer. “In some places where the ground was marshy, close to the run, the path is at least twelve inches deep, and the very stones along the road bear the marks of the iron-shod horses of the Indian traders. Two years ago we picked up, at the edge of the run, a mile up the gorge, two gun-flints,—now rated as relics of a past age.” Clear fields was at the head waters of Clearfield Creek, a branch of the Susquehanna River, in Clearfield Township, Cambria County. This is not to be confused with Clearfield (Chinklacamoos), an important Indian town farther north. See Post’s Journal, post.—Ed.

[13] The Shawnees (Fr., Chaouanons), when first known, appear to have been living in Western Kentucky; they were greatly harassed by the Iroquois, and made frequent migrations which are difficult to trace. In 1692, they made peace with the Iroquois and the English, and portions of the tribe settled in the Ohio country and Western Pennsylvania. Intriguing with both English and French, they were treacherous toward both nations. The location of the cabins mentioned here by Weiser is not positively known—it was in the northern part of Indiana County; somewhere on the Kittanning trail.—Ed.

[14] Weiser turned aside from the regular trail that ended at the Delaware Indians’ town of Kittanning, and followed a branch of the path that turned southwest; crossed the Kiskiminitas Creek at the ford where the town of Saltzburg, Indiana County, now stands; and reached the Allegheny River (then called the Ohio) at Chartier’s Old Town, now Chartier’s Station, Westmoreland County. It was at this point that in 1749, the French explorer, Céloron de Blainville, met six traders with fifty horses laden with peltries, by these sending his famous message to the governor of Pennsylvania to keep his traders from that country, which was owned by the French. Weiser calculated the distance of his journey by land as one hundred and seventy miles, and by deducting twenty miles for the detour at Black Log, made the distance from the settlements one hundred and fifty miles.—Ed.

[15] This was the Delaware village known as Shannopin’s Town, from a chief of that name, who died in 1749. It was situated on the Allegheny River in the present city of Pittsburg, and contained about twenty wigwams, and fifty or sixty natives. See Darlington, Gist’s Journals (Pittsburg, 1893), pp. 92, 93.—Ed.

[16] The reference is to Queen Aliquippa, whose town, directly at the Forks of the Ohio, was called by Céloron “the written rock village.” The writings proved on examination to be but names of English traders scrawled in charcoal on the rocks. See Father Bonnécamps’s Relation, Jesuit Relations (Thwaites’s ed., Cleveland, 1896-1902), lxix, p. 175. Céloron says of the Seneca queen: “She regards herself as a sovereign, and is entirely devoted to the English.” Upon the advent of the French, she removed her village to the forks of the Monongahela and Youghiogheny, where she told Gist in 1753 she would never go back to the Allegheny to live, unless the English built a fort. Céloron says of the site of her first village: “This place is one of the most beautiful I have seen on the Beautiful River [la Belle Rivière, the French name for the Ohio].”—Ed.

[17] Logstown (French, Chinnigné, Shenango) was the most important Indian trading village in that part of the country. It was a mixed village composed of Indians of several tribes—chiefly Iroquois, Mohican, and Shawnee. When Céloron visited it a year after Weiser’s sojourn, he spoke of it as “a very bad village, seduced by the desire for the cheap goods of the English.” He was near being attacked here, being saved by discovering the plot, and displaying the strength of his forces. Like Weiser, he was received with a salute of guns, but feared it was more a sign of enmity than amity. Later, the Indians of this village returned to the French alliance, and after the founding of Fort Duquesne, houses were built by the French for its inhabitants. With the restoration of English interest, the importance of the place diminished, and by 1784 it is spoken of as a “former settlement.” The site of Logstown is about eighteen miles down the river from Pittsburg, just below the present town of Economy, Pennsylvania. It was on a high bluff on the north shore. For the history of this place, see Darlington’s Gist, pp. 95-100.—Ed.

[18] There were two Indian towns called by this name—one at the mouth of Chartier’s Creek, Allegheny County, three miles below Pittsburg; the other opposite the mouth of Chartier’s Run, which falls into the Allegheny in Westmoreland County. Weiser refers to the latter of these. Chartier was a French-Shawnee half-breed that had much influence with his tribe. In 1745, he induced most of them to remove to the neighborhood of Detroit, on the orders of the governor of New France. See Croghan’s Journals, post.—Ed.

[19] The other edition of the journal adds, that the horses were “all scalled on their backs.”

The importance of “wampum” in all Indian transactions cannot be overestimated. It was used for money, as a much-prized ornament, to enforce a request (as at this time), to accredit a messenger, to ransom a prisoner, to atone for a crime. No council could be held, no treaty drawn up, without a liberal use of wampum. It was used also to record treaties, as the one described by Weiser between the Wyandots, Iroquois, and governor of New York. Hale—“Indian Wampum Records,” Popular Science Monthly, February, 1897—thinks that it was a comparatively late invention in Indian development, and took its rise among the Iroquois. Weiser’s list of the wampum used and received in this journey is to be found in Pennsylvania Archives, ii, p. 17.—Ed.

[20] The French had retained the Iroquois deputies in order to secure from them the French prisoners in their hands. La Galissonière, the governor wrote to his home government in 1748, that he should persist in retaining their (the Iroquois) people, until he recovered the French. The governor of New York demanded the Mohawks, on the ground of their being British subjects, a claim the French refused to admit. The matter was finally adjusted without an Indian war, although it caused much irritation. See O’Callaghan (ed.), New York Colonial Documents (Albany, 1858), x, p. 185.—Ed.

[21] Kuskuskis was an important centre for the Delaware Indians, on the Mahoning Branch of Beaver Creek, in Lawrence County, Pennsylvania. It consisted of separate villages scattered along the creek, one of which, called “Old Kuskuskis,” was at the forks, where New Castle now stands. See Post’s Journal, post.—Ed.

[22] The Indian town at the mouth of Beaver Creek, where the town of Beaver now stands, was known indifferently as King Beaver’s, or Shingas’s Old Town (from two noted Delaware chiefs), or Sohkon (signifying “at the mouth of a stream”). This was a noted fur-trading station, and after the building of Fort Duquesne, the French erected houses here, for the Indians. It was the starting place for many a border raid, that made Shingas’s name “a terror to the frontier settlements of Pennsylvania.” See Post’s experiences at this place in 1758, post.—Ed.

[23] Andrew Montour was the son of a noted French half-breed, Madame Montour, who being captured by the Iroquois in her youth married an Oneida chief and was a firm adherent of the English. Montour’s services for the English were considerable. He was an expert interpreter, speaking the languages of the various Ohio Indians, as well as Iroquois. First mentioned by Weiser in 1744, when he interpreted Delaware for his Iroquois, he assisted in nearly all the important Indian negotiations from that time until the treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, being employed in turn by the Pennsylvania, Virginia, and New York governments, and the Ohio Company. In 1754, he was with Washington at the surrender of Fort Necessity. Several times he warned the settlements of impending raids, among other services bringing word of Pontiac’s outbreak. He accompanied Major Rogers as captain of the Indian forces, when the latter went to take possession of Detroit; and in 1764 commanded a party against the recalcitrant Delawares. He received for his services several grants of land in Western Pennsylvania, as well as money. For a detailed biography see Darlington’s Gist, pp. 159-175.—Ed.

[24] Twigtwees was the English name for the Miamis, a large nation of Algonquian Indians, that were first met by the seventeenth century explorers in Northern Illinois. But later, they moved eastward into the present state of Indiana, and settled on the Maumee and Wabash rivers, also on St. Josephs River in Michigan. The French had had posts among them for two generations, but from 1723 the English traders had been seeking a foothold in their midst. Their adherence to the English in 1748 was a blow to the French trade.—Ed.

[25] Scarroyahy was an Oneida chief of great influence with the Ohio Indians, especially at Logstown. He remained firm in the English interest, and in 1754 moved to Aughwick Creek, to get away from the French influence, and to protect the settlements. His death the same year, was imputed by his friends to French witchcraft.—Ed.

[26] The Wyandots, or Tobacco Hurons, or Petuns, were of Iroquois stock, but nearly destroyed by that nation in the seventeenth century. Fleeing westward, they placed themselves under French protection, and, after its founding in 1701, were settled chiefly about Detroit. In the early eighteenth century they straggled eastward along the south shore of Lake Erie, and began to open communication with their ancient enemies, the Iroquois. In 1747, occurred the rebellion of their chief Nicholas, who built a fort in the marshes of the Sandusky, and defied the French soldiers. The chiefs whom Weiser met, were deputies from this party of rebels.

The other edition of Weiser’s journal does not mention the “Wondats” until September 7; and has the following entry for September 6: “One canoe with goods arrived, the rest did not come to the river. The Indians that brought the goods found our casks of whiskey hid by some of the traders; they had drunk two and brought two to the town. The Indians all got drunk to-night, and some of the traders along with them. The weather cleared up.”—Ed.

[27] The Tisagechroanu were “a numerous Nation to the North of Lake Frontenac; they don’t come by Niagara in their way to Oswego, but right across the Lake.”—Pennsylvania Colonial Records, v, p. 85. Probably they were a party of the Neutral Hurons.

The other edition adds after the Mohawks, “among whom there were 27 French Mohawks.” The Mohicans were a wandering tribe, whose original home was on the banks of the Hudson, and in the Connecticut Valley. Charlevoix found them in the far West in 1721. These on the Ohio were called “Loups” by the French.—Ed.

[28] Stroud was a kind of coarse, warm cloth made for the use of the Indian trade. A match-coat was a large loose coat worn by the Indians, originally made of skins, later of match-cloth.—Ed.

[29] The other edition adds, “coming down the river.”—Ed.

[30] His name is given in the other edition as Robert Callender. He accompanied Croghan and Gist on their journey to the Ohio in 1750-51.—Ed.

[31] “Onas” was the Indian term for the governor of Pennsylvania—first used for Penn in his treaty with the Delawares, in 1682.—Ed.

[32] Apparently this was a lad named William Brown, whom Croghan sent to the settlements, October 20, 1748.—Pennsylvania Archives, ii, p. 17.—Ed.

[33] The Catawbas were a powerful Indian tribe of South Carolina, thought by Powell—“Indian Linguistic Families of North America,” in U. S. Bureau of Ethnology Report, 1885-86—to be of Siouan stock. They inhabited the western portion of the Carolinas, and were traditional enemies of the Iroquois. The Cherokees were a settled tribe in North Carolina and Tennessee, and at this time in the English interest.—Ed.

[34] “Jonontady Hagas” was the Iroquois phrase for the Wyandot or Huron Indians.—Ed.

[35] “Onontio” was the Indian term for the governor of Canada.—Ed.

[36] Olumpias was principal chief of the Delawares. He had formerly lived in the Schuylkill Valley, and signed the treaty of purchase by which the Germans came into possession of their lands in that region (1732). He died in the autumn of 1747, the president and council of Pennsylvania being asked to name his successor. The Delawares considered themselves the aborigines of Pennsylvania, and spoke of the Shawnees, whom they had permitted to come among them, as “grandchildren.”—Ed.

[37] These names are given in the other edition as “Shawanapon and Achamantama.”—Ed.

[38] This was Weiser’s Indian name.—Ed.

[39] The Virginians were called by the Indians “Long Knives,” or more literally “Big Knives.” Ash-a-le-co-a is the Indian form of this word, which Weiser spells phonetically. He means that the present was sent by both Pennsylvania and Virginia.—Ed.

[40] For this proclamation against the sale of liquor to Indians, see Pennsylvania Colonial Records, v, pp. 194-196.—Ed.

[41] One of those who accompanied Weiser was William, son of Benjamin Franklin, who later became governor of New Jersey. See Pennsylvania Archives, ii, p. 15.—Ed.

[42] Here occurs the following, in the other edition: “The old Sinicker Queen from above, already mentioned, came to inform me some time ago that she had sent a string of wampum of three fathoms to Philadelphia by James Dunnings, to desire her brethren would send her up a cask of powder and some small shot to enable her to send out the Indian boys to kill turkeys and other fowls for her, whilst the men are gone to war against the French, that they may not be starved. I told her I had heard nothing of her message, but if she had told me of it before I had parted with all the powder and lead, I could have let her have some, and promised I would make inquiry; perhaps her messenger had lost it on the way to Philadelphia. I gave her a shirt, a Dutch wooden pipe and some tobacco. She seemed to have taken a little affront because I took not sufficient notice of her in coming down. I told her she acted very imprudently not to let me know by some of her friends who she was, as she knew very well I could not know by myself. She was satisfied, and went away with a deal of kind expressions. The same day I gave a stroud, a shirt, and a pair of stockings to the young Shawano, King Capechque, and a pipe and some tobacco.”—Ed.

[43] The following description of the homeward journey is contained in the other edition:

“The 20th, left a horse behind that we could not find. Came to the river; had a great rain; the river not rideable [fordable].

“The 21st, sent for a canoe about 6 miles up the river to a Delaware town. An Indian brought one, we paid him a blanket, got over the river about 12 o’clock. Crossed Kiskaminity creek, and came that night to the round hole, about twelve miles from the river.

“The 22d, the weather cleared up; we travelled this day about 35 miles, came by the place where we had buried the body of John Quen, but found the bears had pulled him out and left nothing of him but a few naked bones and some old rags.

“The 23rd, crossed the head of the West Branch of the Susquehanna; about noon came to the Cheasts [Chest creek, Cambria County]. This night we had a great frost, our kettle standing about four or five feet from the fire, was frozen over with ice thicker than a brass penny.

“The 24th, got over Allegheny hill, otherwise called mountains, to Frankstown, about 20 miles.

“The 25th, came to the Standing Stone; slept three miles at this side; about 31 miles.

“The 26th, to the forks of the wood about 30 miles; left my man’s horse behind as he was tired.

“The 27th, it rained very fast; travelled in the rain all day; came about 25 miles.

“The 28th, rain continued; came to a place where white people now begin to settle, and arrived at George Croghan’s in Pennsbury, about an hour after dark; came about 35 miles that day, but we left our baggage behind.

“The 29th and 30th, I rested myself at George Croghan’s, in the mean time our baggage was sent for, which arrived.

“The 1st of October reached the heads of the Tulpenhocken.

“The 2nd I arrived safe at my house.”—Ed.

Sources: Pennsylvania Colonial Records, v, pp. 496-498, 530-536, 539, 540, 731-735; vi, pp. 642, 643, 781, 782; vii, pp. 267-271. Massachusetts Historical Collections, 4 series, ix, pp. 362-379. Butler’s History of Kentucky (Cincinnati and Louisville, 1836), appendix, with variations from other sources. New York Colonial Documents, vii, pp. 781-788.

Next to Sir William Johnson, George Croghan was the most prominent figure among British Indian agents during the period of the later French wars, and the conspiracy of Pontiac. A history of his life is therefore an epitome of Indian relations with the whites, especially on the borders of Virginia and Pennsylvania and in the Ohio Valley. A pioneer trader and traveller, and a government agent, no other man of his time better knew the West and the counter currents that went to make up its history. Not even the indefatigable Gist, or the self-sacrificing Post, travelled over so large a portion of the Western country, knew better the different routes, or was more welcome in the Indian villages. Among his own class he was the “mere idol of the Irish traders.” Sir William Johnson appreciated his services, made him his deputy for the Ohio Indians, and entrusted him with the most delicate and difficult negotiations, such as those at Fort Pitt and Detroit in 1758-61; and those in the Illinois (1765) by which Pontiac was brought to terms.

Born in Ireland and educated at Dublin, Croghan emigrated to Pennsylvania at an early age and settled just west of Harris’s Ferry in the township of Pennsboro, then on the border of Western settlement. The opportunities of the Indian trade appealed to his fondness for journeying and sense of adventure. His daring soon carried him beyond the bounds of the province, and among the “far Indians” of Sandusky and the Lake Erie region, where he won adherents for the English among the wavering[48] allies of the French. His abilities and his influence over the Indians soon attracted the attention of the hard-headed German, Conrad Weiser, who in 1747 recommended him to the Council of Pennsylvania. In this manner he entered the public service, and continued therein throughout the active years of his life.

Croghan was first employed by the province in assisting Weiser to convey a present to the Ohio, whither he preceded him in the spring of 1748.[1] The following year he was sent out to report on the French expedition whose passage down the Ohio had alarmed the Allegheny Indians, and arrived at Logstown just after Céloron had passed, thus neutralizing the latter’s influence in that region.[2]

The jealousy of the Indians over the encroachments of the settlers upon their lands west of the mountains on the Juniata, and in the central valleys of Pennsylvania, determined the government to expel the settlers rather than risk a breach with the Indians. In this task, which must have been uncongenial to him, Croghan, as justice of the peace for Cumberland County, was employed during the spring of 1750.[3] The autumn of the same year, found him beginning one of his most extensive journeys throughout the Ohio Valley, as far as the Miamis and Pickawillany, where he made an advantageous treaty with new envoys of the Western tribes who sought his alliance. To Croghan’s annoyance, the Pennsylvania government in an access of caution repudiated this treaty as having been unauthorized.

In 1751 Croghan was again upon the Allegheny, encouraging the Indians in their English alliance, and defeating Joncaire, the shrewdest of the French agents in this region, by means of his own tactics. The next year, he was pursuing his traffic in furs among the Shawnees, but without forgetting the public interest;[4] and the following year finds him assisting the governor and Council at the important negotiations at Carlisle.[5] This same year (1753) Croghan removed his home some distance west, and settled on Aughwick Creek upon land granted him by the Province. His public services were continued early in the next year by a journey with the official present to the Ohio, where he arrived soon after Washington had passed upon the return from the famous embassy to the French officers at Fort Le Bœuf.

The outbreak of the French and Indian War ruined Croghan’s prosperous trading business, and brought him to the verge of bankruptcy. While at the same time a large number of Indian refugees, desiring to remain under British protection, sought his home at Aughwick, where he felt obliged to provision them, with but meagre assistance from the Province. To add to his troubles, the Irish traders, because of their Romanist proclivities, fell under suspicion of acting as French spies, and Croghan was unjustly eyed askance by many in authority.[6] Although he was granted a captain’s commission to command the Indian contingent during Braddock’s campaign, he resigned this office early in 1756, and retired from the Pennsylvania service.

About this time he paid a visit to New York, where his [50]distant relative, Sir William Johnson, appreciating his abilities, chose him deputy Indian agent, and appointed him to manage the Susquehanna and Allegheny tribes.[7] From this time forward he was engaged in important dealings with the natives, swaying them to the British interest, making possible the success of Forbes (1758), and the victory of Prideaux and Johnson (1759). After the capitulation of Montreal, he accompanied Major Rogers to Detroit. All of 1761 and 1762 were occupied with Indian conferences and negotiations, in the course of which he again visited Detroit, meeting Sir William Johnson en route.[8]

Late in 1763, Croghan went to England on private business, and was shipwrecked upon the coast of France;[9] but finally reached London, where he presented to the lords of trade an important memorial on Indian affairs.[10]

Upon his return to America (1765), he was at once dispatched to the Illinois. Proceeding by the Ohio River, he was made prisoner near the mouth of the Wabash, and carried to the Indian towns upon that river, where he not only secured his own release, but conducted negotiations which put an end to Pontiac’s War, and opened the Illinois to the British.

A second journey to the Illinois, in the following year, resulted in his reaching Fort Chartres, and proceeding thence to New Orleans. No journal of this voyage has to our knowledge been preserved.

Croghan’s part in the treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768) was[51] rewarded by a grant of land in Cherry Valley, New York. Previous to this he had purchased a tract on the Allegheny about four miles above Pittsburg, where in 1770 he entertained Washington. At the beginning of the Revolution he appears to have embarked in the patriot cause,[11] but later was an object of suspicion; and in 1778 was proclaimed by Pennsylvania as a public enemy, his place as Indian agent being conferred upon Colonel George Morgan. He continued, however, to reside in Pennsylvania, and died at Passyunk in 1782.[12]

In our selection of material from the large amount of Croghan’s published work, we have chosen that which exemplifies Western conditions under three aspects: First, the period of English ascendency on the Ohio, which is illustrated by three documents of 1750 and 1751. Secondly, the period of French ascendency, hostility toward the English, and war on the frontiers; for this epoch we publish four documents, ranging from 1754 to 1757. The third period, after the downfall of Canada, is concerned with the surrender of the French posts, and the renewed hostility of the Indians; the two journals we publish for this period present interesting material for the study of Western history. Each deals with a pioneer voyage, for Rogers and Croghan were the first Englishmen (except wandering traders or prisoners) to penetrate the Lake Erie region and reach Detroit. The voyage down the Ohio (1765), with its circumstantial account of the appearance of the country, and its description of Indian conditions and relations, is noteworthy.

Croghan was a voluminous writer. In addition to the official reports of his journeys, he evidently had[52] the habit of noting down the events of the day in a simple, straightforward manner, so that many manuscripts of his were long extant, presenting often different versions of the same journey. The earlier antiquaries published these as chance brought them to their notice.[13] The official reports themselves were preserved in the colonial archives, and are published in the Pennsylvania and New York collections. It is believed that this is the first attempt to bring together a selection of Croghan material that in any adequate manner outlines his interesting career. The chronological extent of these journals (from 1750-1765) makes those which follow—Post’s of 1758; and Morris’s of 1764—interludes in the events which Croghan describes, thus throwing additional light upon the same period and the same range of territory.

R. G. T.

Logstown on Ohio, December [November] the 16th, 1750.[15]

Sir: Yesterday Mr. Montour and I got to this Town, where we found thirty Warriors of the Six Nations going[54] to War against the Catawba Indians; they told us that they saw John Coeur about one hundred and fifty miles up this River at an Indian Town, where he intends to build a Fort if he can get Liberty from the Ohio Indians; he has five canoes loaded with Goods, and is very generous in making Presents to all the Chiefs of the Indians that he meets with; he has sent two Messages to this Town desiring the Indians here to go and meet him and clear the Road for him to come down the River, but they have had so little Regard to his Message that they have not thought it worth while to send him an answer as yet.[16] We have seen but very few of the Chiefs of the Indians they being all out a hunting, but those we have seen are of opinion that their Brothers the English ought to have a Fort on this River to secure the Trade, for they think it will be dangerous for the Traders to travel the Roads for fear of being surprised by some of the French and French Indians, as they expect nothing else but a War with the French next Spring. At a Town about three hundred miles down this River, where the Chief of the Shawonese live,[17] a Party of French and French Indians[55] surprised some of the Shawonese and killed a man and took a woman and two children Prisoners; the Shawonese pursued them and took five French Men and some Indians Prisoners; the Twightwees likewise have sent word to the French that if they can find any of their People, either French or French Indians, on their hunting Ground, that they will make them Prisoners, so I expect nothing else but a War this Spring; the Twightwees want to settle themselves some where up this River in order to be nearer their Brothers the English, for they are determined never to hold a Treaty of Peace with the French. Mr. Montour and I intend as soon as we can get the Chiefs of the Six Nations that are Settled here together, to sollicit them to appoint a Piece of Ground up this River to seat the Twightwees on and kindle a Fire for them, and if possible to remove the Shawonese up the River, which we think will be securing those Nations more steady to the English Interest. I hope the Present of Goods that is preparing for those Indians will be at this Town some time in March next, for the Indians, as they are now acquainted that there is a Present coming, will be impatient to receive it, as they intend to meet the French next Spring between this and Fort De Troit, for they are certain the French intend an Expedition against them next Spring from Fort De Troit.[18][56] I hear the Owendaets [Wyandots] are as steady and well attached to the English Interest as ever they were, so that I believe the French will make but a poor hand of those Indians. Mr. Montour takes a great deal of Pains to promote the English Interest amongst those Indians, and has a great sway amongst all those Nations; if your Honour has any Instructions to send to Mr. Montour, Mr. Trent will forward it to me.[19] I will see it delivered to the Indians in the best manner, that your Honour’s Commands may have their full Force with the Indians.

I am, with due respects,

Your Honour’s most humble Servant,

Geo. Croghan.

The Honoble. James Hamilton,[20] Esq.

May the 18th, 1751.—I arrived at the Log’s Town on Ohio with the Provincial Present from the Province of Pennsylvania, where I was received by a great number of the Six Nations, Delawares, and Shawonese, in a very complaisant manner in their way, by firing Guns and Hoisting the English Colours. As soon as I came to the shore their Chiefs met me and took me by the Hand bidding me welcome to their Country.

May the 19th.—One of the Six Nation Kings from the Head of Ohio came to the Logstown to the Council, he immediately came to visit me, and told me he was glad to see a Messenger from his Brother Onas on the waters of the Ohio.

May the 20th.—Forty Warriors of the Six Nations[59] came to Town from the Heads of Ohio, with Mr. Ioncoeur and one Frenchman more in company.

May the 21st, 1751.—Mr. Ioncoeur, the French Interpreter, called a council with all the Indians then present in the Town, and made the following Speech:

“Children: I desire you may now give me an answer from your hearts to the Speech Monsieur Celeron (the Commander of the Party of Two Hundred Frenchmen that went down the River two Years ago) made to you.[22] His Speech was, That their Father the Governor of Canada desired his Children on Ohio to turn away the English Traders from amongst them, and discharge them from ever coming to trade there again, or on any of the Branches, on Pain of incurring his Displeasure, and to enforce that Speech he gave them a very large Belt of Wampum. Immediately one of the Chiefs of the Six Nations get up and made the following answer: