A few paragraphs are so long the position of the illustrations are left as is.

A few words have been left as printed e.g. Rangi-whakaputa Rangiwhakaputa.

OF THE

Port Hills

CANTERBURY, NEW ZEALAND

By

JAMES COWAN

WHITCOMBE & TOMBS LIMITED

Auckland, Christchurch, Dunedin, & Wellington, N.Z. Melbourne and London

1923

E. Cowan, photo

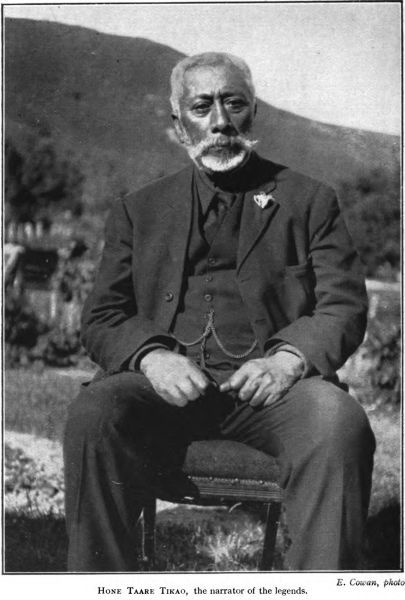

Hone Taare Tikao, the narrator of the legends.

In this little book I have endeavoured to interweave with descriptions of the most picturesque parts of the Canterbury Port Hills some of the Maori poetic legends and historical traditions which belong to the Range, and which have not previously been recorded. These stories, I hope, will invest with a new interest for many Canterbury pakehas the scenic beauties of the Port Hills now opened up from end to end by the Summit Road. Here I desire to record also, with feelings of gratitude, the name of the principal narrator of the legends, Mr. Hone Taare Tikao, of Rapaki, a Ngai-Tahu gentleman whose uncommonly retentive memory is a storehouse of information on local history and who blends in himself the gifts of the folk-lorist and the genealogist. Some of the place-names were supplied by the late Mr. T. E. Green (Tame Kirini), of Tuahiwi, Kaiapoi, one of the last good native authorities on the ancient history of the plains.

For the priceless gift of free access to these grand tops of the Port Range the people are indebted to the efforts and the gifts of a few public spirited residents, but most of all to the exertions of Mr. H. G. Ell, whose enthusiasm, prescience of vision, and singleness of purpose in developing the Summit Road along this mountain park have properly earned him the admiration and the thanks of thousands of his fellow-citizens who daily lift up their eyes to the Hills and who find on those hills their pleasure and their solace for town-tired body and brain. And maybe if Mr. Ell’s name were bestowed, like Tamatea’s of old, upon one of these monumental crags still unchristened, it would but fittingly preserve the memory of a man whose title to such local honour and fame is certainly greater than that of some of his forerunners whose names the landscape bears.

J.C.

| CHAPTER I. The Story of the Rocks. |

|

| The Port Hills and their geological history—The Dead Fire-Cones—“The Fire of Tamatea”—Bold Cliff and Mountain Scenery—Beauties of the Port Range | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. The Port Hills and Their Names. |

|

| Maori Nomenclature of the Port Range—Hills of the Rainbow God—“The Pinnacle of Kahukura”—Crags of the Sounding Footsteps—Ancient Lyttelton: “The Basket of Heads”—Ambuscades in the Bush | 7 |

| CHAPTER III. Round the Sugarloaf. |

|

| The Flanks of Te Heru-o-Kahukura—Tracks on the Mountain Side—At Dyer’s Pass—Maori Name of Marley’s Hill—Exploring the Kahukura Bush—Needles of the Ongaonga—The Valleys and the Small Timber—“Crest of the Rainbow” | 24 |

| CHAPTER IV. Rapaki: A Village by the Sea. |

|

| The Bell on the Ribbonwood Tree—Tikao and his Traditions—The Days of the Ngati-Mamoe—Te Rangiwhakaputa’s Conquests—The Crags of Tamatea—A Sturdy Pagan—Evening Picture at Rapaki | 39 |

| CHAPTER V. The “Ahi-a-Tamatea”: How the Sacred Fire Came to Witch Hill. |

|

| The Giant’s Causeway—A Volcanic Dyke—Tamatea the Polynesian Explorer—A Great March—The Camp at Witch Hill—Tamatea’s Call for Fire—The Tipua Flames from Ngauruhoe—“The Ashes of Tamatea’s Camp Fire” | 52 |

| CHAPTER VI. Hills of Faery: The Little People of the Mist. |

|

| Legends of the Patu-paiarehe —The Fairies of the Port and Peninsula Hills—Mountains of Enchantment—“The Red Cloud’s Rest”—The Fairies and the Mutton-birds—The Maero of the Woods—Mount Pleasant and its Tapu | 61 |

| Map of Lyttelton Harbour and Port Hills-Akaroa, Summit Road | map |

| Hone Taare Tikao, the Narrator of the Legends | Frontispiece |

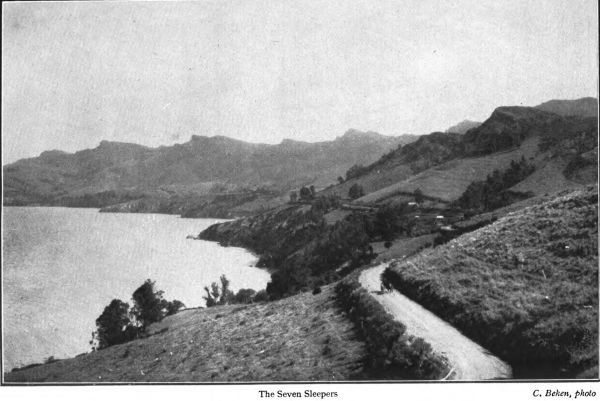

| The Seven Sleepers | 5 |

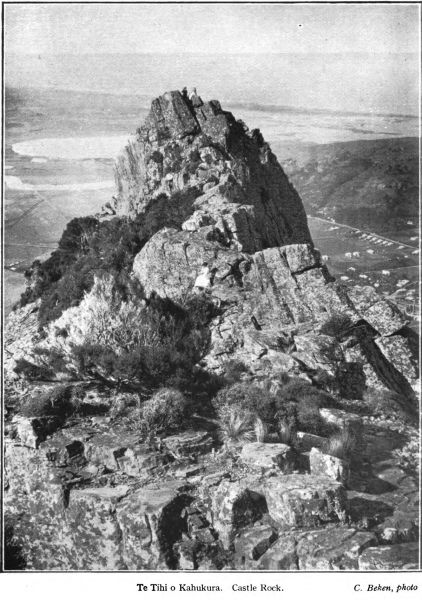

| Te Tihi o Kahukura, Castle Rock | 9 |

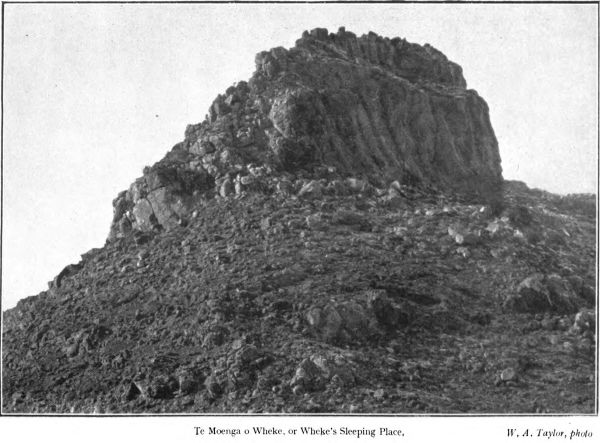

| Te Moenga o Wheke, Giant Tor | 10 |

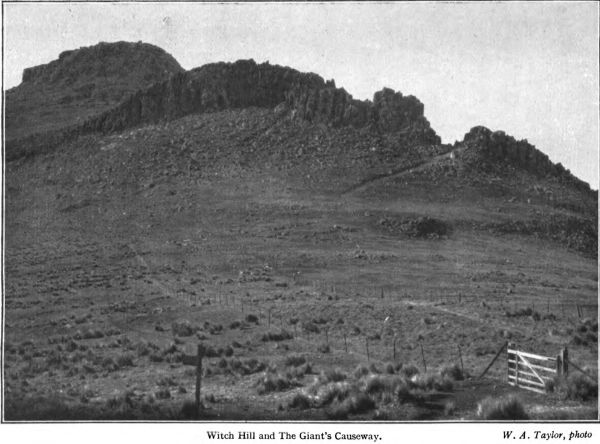

| Witch Hill and the Giant’s Causeway | 13 |

| Orongomai, the Place of the Voices | 15 |

| View from Cass Peak | 17 |

| Whaka-raupo, Lyttelton Harbour and Quail Island | 21 |

| Te Heru o Kahukura, Sugarloaf | 25 |

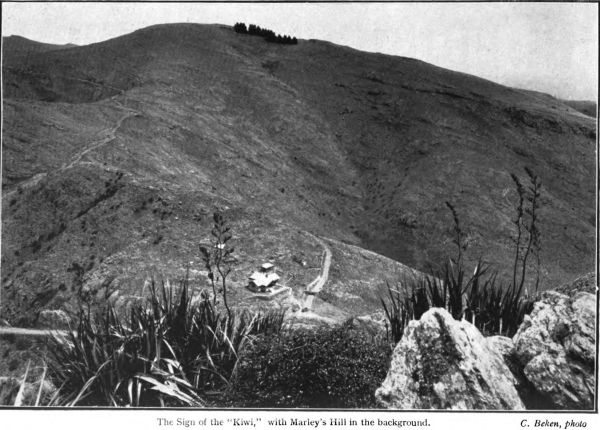

| “The Sign of the Kiwi” Rest House and Marley’s Hill | 27 |

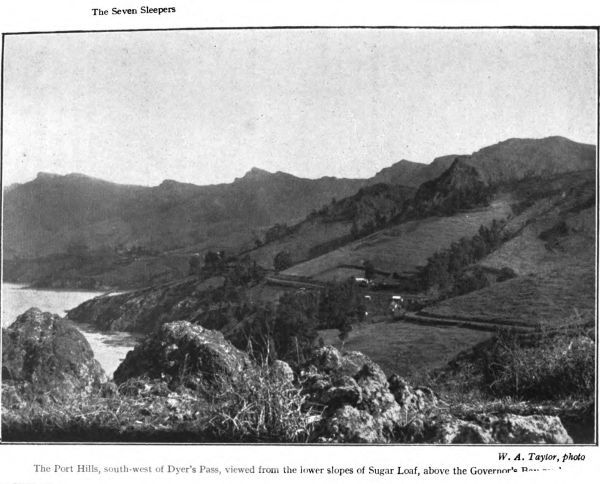

| The Port Hills south-west of Dyer’s Pass | 31 |

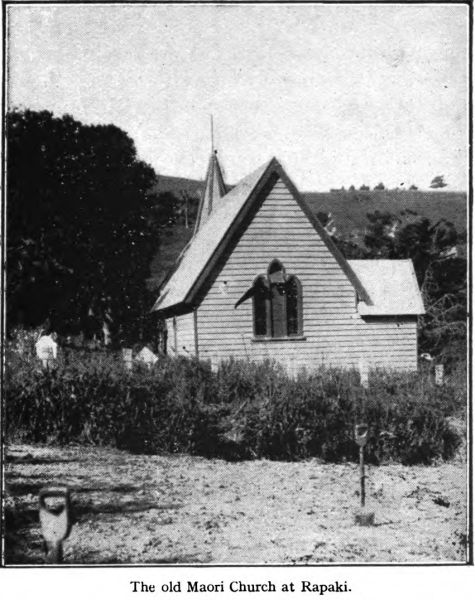

| The Old Maori Church at Rapaki | 33 |

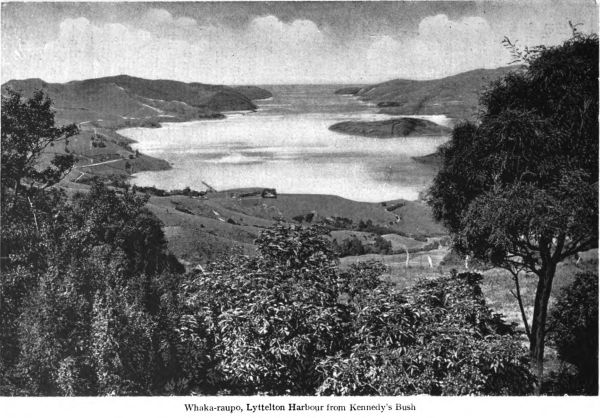

| Whaka-raupo, Lyttelton Harbour from Kennedy’s Bush | 35 |

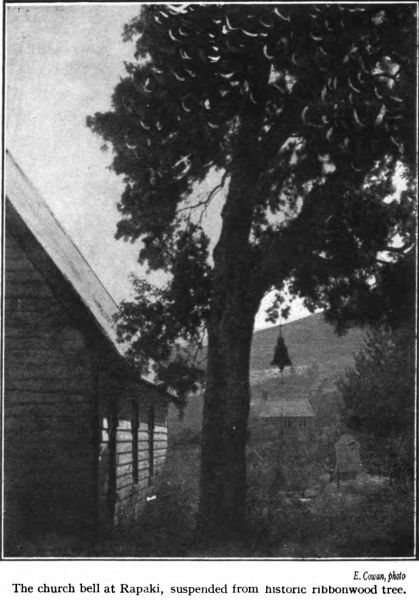

| Old Church Bell at Rapaki | 40 |

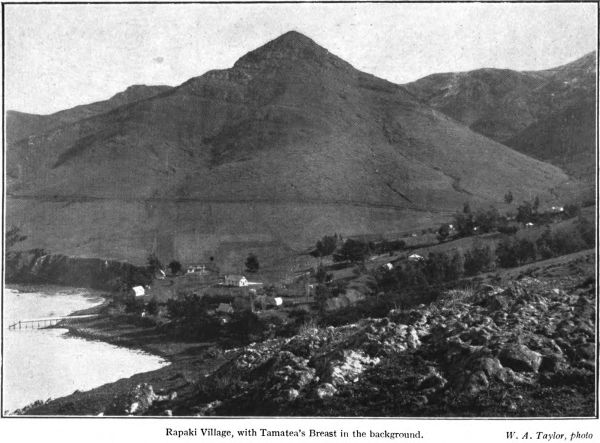

| Rapaki Village and Tamatea’s Breast | 43 |

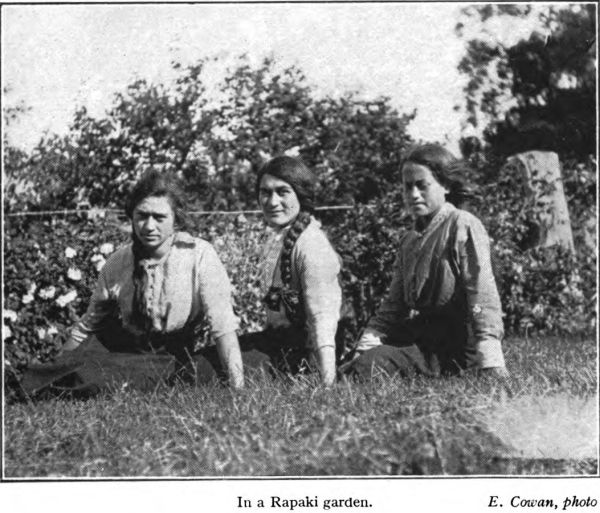

| In a Rapaki Garden | 47 |

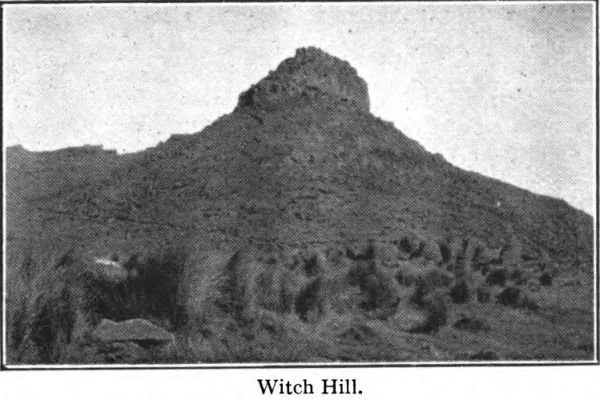

| Witch Hill | 53 |

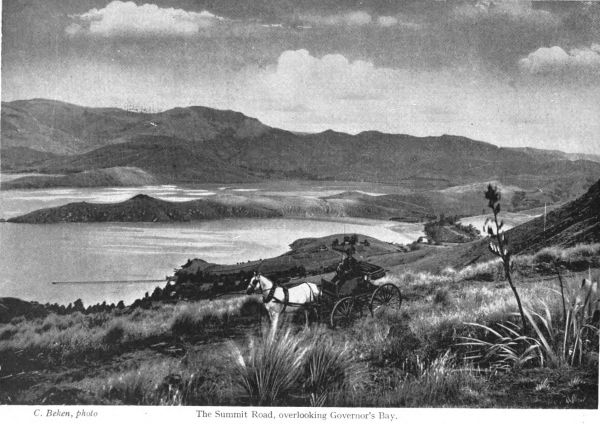

| The Summit Road, overlooking Governor’s Bay | 55 |

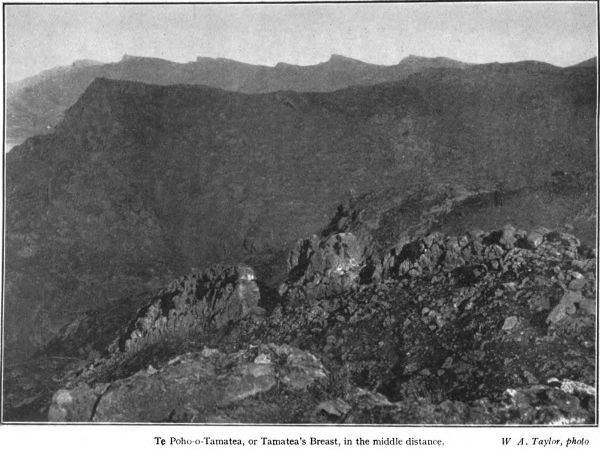

| Te Poho-o-Tamatea, or Tamatea’s Breast | 59 |

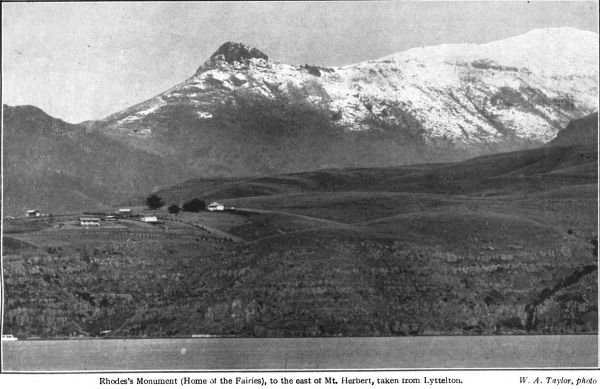

| Rhodes’s Monument, Home of the Fairies | 63 |

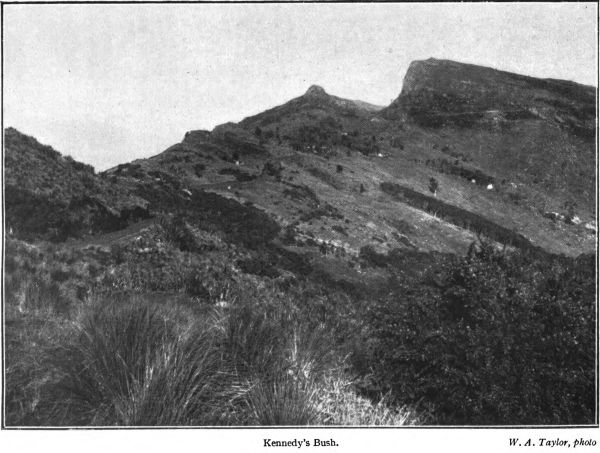

| Kennedy’s Bush, Cockayne’s Cairn, and Cass Peak | 67 |

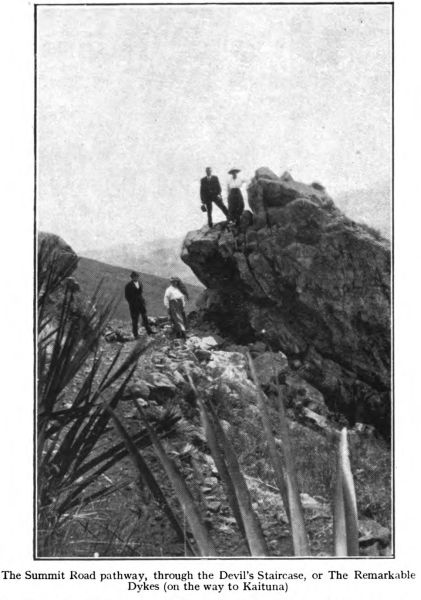

| Through the Devil’s Staircase | 70 |

| Hinekura | 73 |

THE STORY OF THE ROCKS.

With the opening of tracks along the bold range of heights between the Canterbury Plains and Lyttelton Harbour, and the acquisition of new reserves for the public, mainly through the efforts of one tireless worker, Mr. H. G. Ell, Christchurch residents are perhaps coming to a more lively sense of the value of the Port Hills as a place of genuine recreation. The Summit Road has made city people free of the grandest hilltop pleasure place that any New Zealand city possesses within easy distance of its streets, and the worth of this mountain track, so easily accessible and commanding so noble a look-out over sea and plains and Alps, will increase in proportion to the growth of the Christchurch population. The fragments of the native bush which survive in the valleys will be of surpassing botanical interest in another generation or two, but the vegetation of the hills inevitably will suffer many changes, and an exotic growth will for the most part replace the ancient trees. With all the alterations which man’s hand may make in the reserves and along the public tracks, however, the monumental rock-beauty will remain the great and peculiar feature of the hills, their most wonderful and unalterable glory. The Port Range and the Banks Peninsula system of mountains are indeed the most remarkable heights in the whole of the South Island, not excepting the snowy Alps;[2] there is nothing like them outside the northern volcanic regions, and in some aspects they carry a greater scientific and scenic value than even the crater-cones around the city of Auckland. What the Canterbury coast would have been like but for the vast volcanic convulsions which formed these ranges and huge craters is not difficult to imagine. It would have been a uniform billiard-table on an enormous scale, very gently sloping to the sea, with scarcely a break but for the snow rivers and with never a usable natural harbour. Volcanic energy gave us Lyttelton and Akaroa harbours, and shaped for us also the ever-marvellous hills that are at once a grateful relief to the eye from the eternal evenness of the plains and a healthful place of pleasure for our city dwellers.

The passage of untold ages has so little altered these fire-made ranges that build a picture-like ring about Lyttelton Harbour that their origin and history are plainly revealed to the climber and the Summit Road stroller; the story of the rocks can scarcely be mistaken. Geologists from the days of von Haast have written much of the Lyttelton and Akaroa volcanic systems, and in truth it is an ever-new and ever-fascinating subject. There is hardly a more interesting specimen of vulcanism in New Zealand, for example, than the strange wall of grey-white lava rock which Europeans call the Giant’s Causeway and the Maoris “The Fire of Tamatea,” which protrudes from the hilltop just above Rapaki, and which may be seen again on the far side of the harbour, a volcanic dyke that the ancient people—with surely some perception of geological truth—connected in their legends with the internal fires of the North Island. Along the craggy hill faces again, and particularly well in such places as Redcliffs and the Sumner end of the range, it is easy to read the history[3] of the rocks in the alternate strata of solid volcanic rock and the soft rubble that seems almost to glow again with the olden fires. The most wonderful example of this stratified formation is the face of the south head of Akaroa Harbour; but it is possible to study similar pages in the volcanic chapter of Canterbury’s history without going many yards from the Summit Road anywhere from the sea to the hills above the harbour head.

The most perfect local example of an ancient crater perhaps is one that does not seem to have attracted much attention from scientific writers and lecturers, and this may be mentioned as a type of the remarkable places which build up the romantic ruggedness and savageness of our harbour-palisading hills. It is to be studied especially well from the Lyttelton-Governor’s Bay road. Above Corsair Bay and Cass Bay there is a group of bold rocky peaks which, as the traveller passes onward from Lyttelton, is seen to curve inward in a huge half-cup, open to the south, and down this open side are strewn the disorderly remains of the old lava stream which flowed from the core of the volcano and which ran out into the harbour at Cass Bay in a tumbled black reef. It does not require a great effort of imagination to reconstruct that fire-cup as it must have appeared in the era when the fantastic hills were still in the making and shaping. The Maoris, with a quick eye for such significant topographical features, gave the place a name which blends history with legend, “Wheke’s Sleeping Place.” Indeed, that strange hollow in the hills might have made fit cradle for a Finn MacCoul. Like the crater-topped cones of the Tamaki Isthmus, it is softly grassed; a stray ngaio is the one remnant of the bush that once covered the volcanic detritus; but the hugely ramparted and square-hewn rim of[4] the basin stands indomitable and unchangeable, unmistakable memorial of the active volcanic age. Such bold crags are “the eyebrows of the hills”; they give what would otherwise be tame landscapes dignity and force and wildness, and an exploration of these fastnesses of Nature so near our doors, and opened up by the Summit Road, is not merely pleasurable, but is fruitful in an intelligent appreciation of the amazing forces which helped to mould the land in which we live.

All along the fire-fused line of these Summit Peaks from the Lighthouse to the Seven Sleepers and beyond there are amazingly bold bits of rock and cliff scenery—abrupt escarpments like huge redoubt walls, bearded with mountain flax, and flakey from the attack of ages of winter frosts; straight smooth cleavages that seem almost artificial, so sharply and finely are they worked by Nature, the great sculptor; rounded buttresses like enormous pillars shoring up the mountain side; caves here and there, old bubbles in the molten lava, caves that might have sheltered some cannibal highwayman in the days of stone club and face-tattoo; strangely shapen projections of the cliff-edge, some remindful of animal forms; tomahawk faces of grey storm-beaten rhyolite dipping down into the green arms of the little woods where the tui’s rich echoing “bing-bong” and gurgling chuckle are still heard in the shady depths when the bush fruits are ripe. Here and there a little watercourse, its fountain-head waters dripping silently from some cool crevice in the rocks, all arboured over by the matted roofing of kotukutuku, twisty and witchy of branch, and mahoe and glossy-green karaka of the plenteous foliage. Watercourses that fit the bold mountain

[5]

The Seven Sleepers

C. Beken, photo

[Pg 6]

pictures about them; dry in summer, they come down in tumultuous little cataracts in time of heavy rain, plunging over the piled fragments of lava rocks, and filling for a day or two the age-worn pockets and pools and “pot-holes” in the winding valleys all arched over with the close-growing light timber. Deep down in these twisting gullies below the straight cut harbour-facing cliffs, there lingers still a certain quality of primitiveness and a suggestion of the ancient adventure; an atmosphere still in keeping with the legendry of these Hills. Here in the leaf-thatched hollows of Taungahara or the woven thickets that blanket the precipice fronts of the Seven Sleepers still shall you have intimate glimpses of wild nature. Up on the tussock-swarded mountains of the hawk and deep in the sudden valleys still may you, though so near to the City, breathe the mind-refreshing fragrance of the grand out-of-doors, hold healthy commune with[7]

THE PORT HILLS AND THEIR NAMES.

It is the Port Hills’ nomenclature, perhaps, that carries the most poetic suggestions of any of the Canterbury place-names, and here, perhaps, the dwellers on the heights in the days to come when all these Plain-ward-looking slopes are dotted with pretty homes, will seek inspiration in such legendry and history of the soil as we of the present generation have preserved. There are names of dignity and beauty clustered about those old lava-built crags and ruined towers and tors past which the Summit Road goes a thousand feet above the city.

Finest of all is the Maori name of Castle Rock, that from one point in the Heathcote Valley looks like a colossal howitzer threatening the Plains. To the old Maoris it was Te Tihi o Kahukura, “The Citadel of Kahukura,” otherwise “The Pinnacle of the Rainbow.” The explanation brings in a reference to the religion of the tattooed pagan pioneers who explored those hills and plains, and planted their palisaded hamlets by creek-side and in the sheltered folds of the ranges. Kahukura—Uenuku in the North Island—was the principal deity for what may be termed everyday use among the ancient Ngai-Tahu. He was the spirit guardian most frequently invoked by the tohungas , and he was appealed to for auguries and omens in time of war. Each hapu had its image of Kahukura, a small carved wooden figure, which was kept in some tapu place remote from the dwellings, often a secluded flax clump, or on a high, stilt-legged platform or whata. The celestial form of Kahukura was the rainbow; literally the name means[8] “Red Garment.” Omens were drawn in days of war from the situation of the arch of the “Red Garment” when it spanned the heavens. The name is sometimes applied to that phenomenon of days of mist in the mountains, the “sun-dog,” from which auguries were drawn. So when the Natives gave the term to the Castle Rock they were conferring upon it a name of high tapu befitting its bold and commanding appearance.

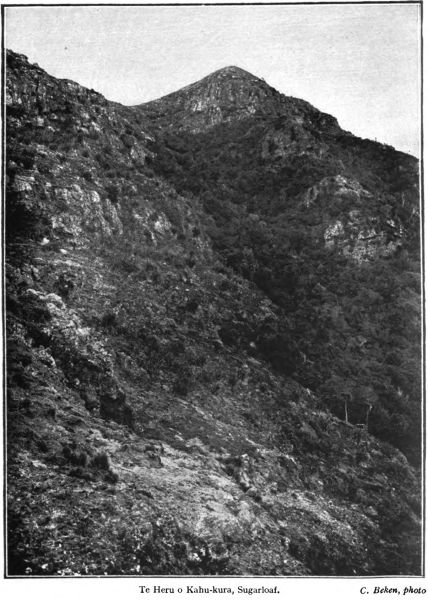

And this is not the only Hills name that holds a memory of the cult of the Rainbow-God. On the tussocky slope where the track goes over from the St. Martins tram terminus to the Summit Road above Rapaki, joining the hill track near Witch Hill, the tohungas kept in a sacred place one of the wooden figures representing Kahukura, for karakia , consultation in time of need, and the spot became known as “Te Irika o Kahukura,” or “The Uplifting of the Rainbow God.” In time the name was applied to the Cashmere Hills generally. And the lofty Sugarloaf peak immediately to the north of Dyer’s Pass, was Te Heru o Kahukura, which being interpreted, is “Kahukura’s Head-Comb.” So the olden folk occasionally displayed a fine taste in names; and although some of those names may be a trifle long for pakeha use it would be well to save them from oblivion.

Otokitoki—“The Place of Axes”—is the name of Godley Head, the lofty cliff upon which the lighthouse stands; its early-days pakeha name was Cachalot Head. Working south from the lighthouse we presently come to the deep bay of Te Awa-parahi, where a little farmstead stands in its well-hidden nest, between the lowering peaks. Nearer Lyttelton, just where the Zigzag Road goes over Evans Pass to Sumner, are the precipitous

[9]

Te Tihi o Kahukura. Castle Rock.

C. Beken, photo

[10]

Te Moenga o Wheke, or Wheke’s Sleeping Place.

W. A. Taylor, photo

[11]

summit rocks of Tapuwaeharuru, “The Resounding Footsteps,” a place-name met with in more than one locality in the volcanic country of the North. Far below is the little indent of Te Awa-toetoe, or “Pampas-grass stream” near the artillery barracks. Mount Pleasant, where a Ngati-Mamoe pa once stood, was known to the Maoris as Tauhinu-Korokio, a combination of two names of shrubs common to the ranges. Passing Castle Rock—Te Tihi o Kahukura—just on the right hand or west as we travel towards Dyer’s Pass, we have on the other hand Te Moenga o Wheke, or “Wheke’s Sleeping Place” and Ota-ranui, or “Big Peak,” the towering rough-hewn crests of the Range looking down on Cass Bay and lying east of the Summit Track. Then comes Witch Hill, with “The Ashes of Tamatea’s Camp Fire,” of which a legend later, and Te Poho o Tamatea, or “Tamatea’s Breast,” overlooking the Rapaki native settlement.Oketeupoko, or, to divide it into its component words, O-kete-upoko, is the Maori name of the rocky heights immediately above the town of Lyttelton. It means “The Place of the Basket of Heads.” A sufficiently grim name this, remindful of the Whanga-raupo’s red and cannibal past, for the heads were human ones. When the olden warrior Te Rangi-whakaputa set out to make the shore of the Raupo Harbour his own, he encountered numerous parties of Ngati-Mamoe, who put up a fight for their homes and hunting-grounds. One of these parties of the tangata-whenua , the people of the land, he met in battle on the rocky beach of Ohinehou where the white man’s breakwaters and wharves now stand. He worsted them, and the heads of the slain he and his followers[12] hacked off with their stone patus and axes. Some, those of the chief men, Te Rangi-whakaputa placed in a flax basket, and, bearing them up to the craggy hill-crest that towered above the beach, he set them down on a lofty pinnacle, an offering to his god of battles. There they were left, say the Maoris, he kai mo te ra, mo te manu —“food for the sun and for the birds.” “O” signifies “the place of,” “kete” basket and “upoko” head, and thus was the place named, to memorise the tattooed brown conqueror of old and the ancient people whom he dispossessed on the shores of the Whangaraupo.

Witch Hill and The Giant’s Causeway.

W.A. Taylor, photo

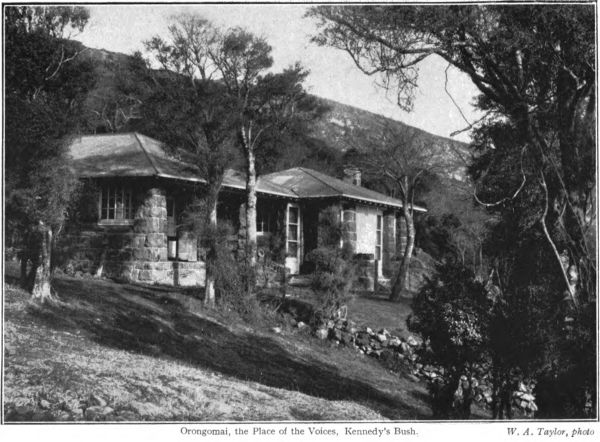

Orongomai, a melodious name when properly pronounced, is the old Ngai-Tahu name of Cass Peak, the rhyolite height which lifts 1780 ft. above the waters of Governor’s Bay, overlooking the remnant of the ancient forest at Kennedy’s Bush. It means “The Place Where Voices are Heard,” or, literally, “Place of Sounding-hitherward.” The name has fittingly enough been given by Mr. Ell to the stone house for visitors which stands under the ribbonwood trees at the head of the Kennedy’s Bush Valley. The story is that when Te Rangi-whakaputa and his followers landed, in their search for the Ngati-Mamoe, after taking the pa at Ohinetahi, in Governor’s Bay, the scouts entered the bush, and at the foot of Cass Peak heard the voices of a party of men in the bush; these men were Ngati-Mamoe, who had come across from their pa at Manuka, on the plains side of the range. Led by the scouts—the torotoro—the invaders rushed upon the Ngati-Mamoe some of whom they killed. The survivors fled over the hills to Manuka, a large pa which it is believed stood on a knoll at the foot of the range not far from Tai Tapu. (Mr. Ell, on being told of this tradition, [14] said that he believed the site of Manuka would be found to be the spur running into an old swamp upon which Mr. Holmes’s homestead is built, on the old coach road south of Lansdowne, and about two miles from Tai Tapu.) The Manuka village, although a strong defensive position, was stormed and taken by Te Rangi-whakaputa. In the vicinity, it is said by the Maoris, there was a shallow cave under the rocky hillside which was used by some of the Ngati-Mamoe as a dwelling-place; it is known in tradition as Te Pohatu-whakairo, or “The Carved Rock.” No doubt it was so called from the natural markings sometimes seen on the faces of these overhanging rock shelters, such as were used as dwelling and camping-places in many parts of the South Island by the ancient people.

Ohinetahi[1] pa , defended with a palisade of split tree-trunks and with ditch and parapet, stood near the shore at the head of Governor’s Bay two hundred years ago. After the place had been captured from the Ngati-Mamoe by Te Rangi-whakaputa, his son Manuwhiri occupied it with a party of Ngai-Tahu. This chief Manuwhiri had many sons, but only one daughter, and he named his pa after his solitary girl, “The Place of the One Daughter.” The Governor’s Bay school now occupies the spot where this long-vanished stockaded hamlet stood.

[1] This name was adopted by the late T. H. Potts for his stone house at Governor’s Bay, directly below Kennedy’s Bush.

[15]

Orongomai, the Place of the Voices, Kennedy’s Bush.

W. A. Taylor, photo

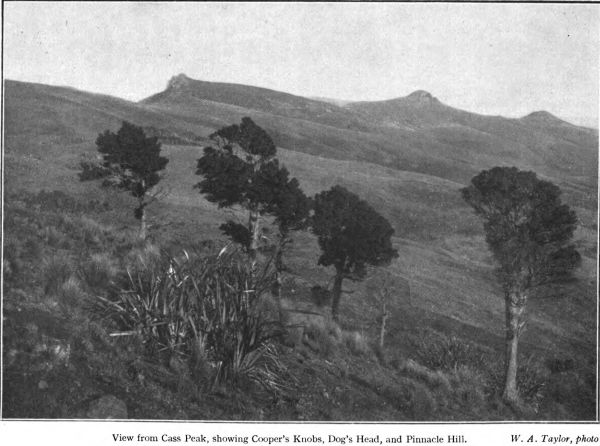

The name of Cooper’s Knobs, the highest of the three tooth-like crags lifting abruptly above the head of Lyttelton Harbour to an altitude of 1880 feet, memorises, like so many others, an incident of the head-hunting cannibal days. After the Rangi-whakaputa and his merry men had conquered the various Ngati-Mamoe pas around the harbour, they

[16] found frequent diversion in hunting out stray members of the fugitive hapus and converting them to a useful purpose through the medium of the oven. Often there were bush skirmishes, and although the Ngati-Mamoe frequently put up a good fight, they usually got the worst of the encounter. Mawete, the chief of Ngati-Mamoe, and a party of men from Manuka pa were on their way across the range to Lyttelton Harbour to fish for sharks when they were ambuscaded in the bush just below Cooper’s Knobs by a band of Ngai-Tahu warriors. The Ngati-Mamoe chief and most of his followers were killed in the skirmish that followed, with the Maori weapons of wood and stone, the spear, the taiaha , and the sharp-edged patu , and their bodies went into the oven, for the Maori’s commissariat in that age was the flesh of his foeman. And the Mamoe leader’s name still clings to that wild craggy spot where he met his death blow, for the peak which the pakeha has named Cooper’s Knobs was called by the Ngai-Tahu conquerors Omawete, meaning the place where Mawete fell.Beyond again are the peaks of Otuhokai and Te Tara o Te Raki-tiaia; below the harbour head curves into the bay of Te Rapu. Next as we go up to meet the hills of Banks Peninsula is the bold precipice of Te Pari-mataa, or “Obsidian Cliff,” with the great volcanic dyke of Otarahaka, and then our present pilgrimage ends, for we are right under the hugely parapeted castle hill of Te Ahu-patiki—Mt. Herbert—with its level top, where a lofty pa of Ngati-Mamoe stood three centuries ago.

[17]

Cooper’s Knobs Dog’s Head Pinnacle Hill

View from Cass Peak, showing Cooper’s Knobs, Dog’s Head, and Pinnacle Hill.

W. A. Taylor, photo

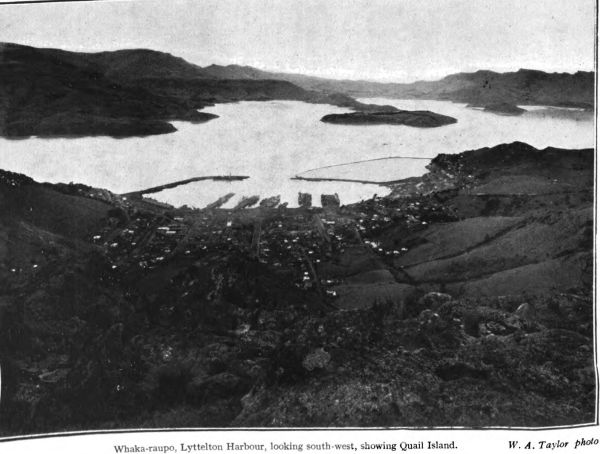

Te Whaka-raupo is the ancient name of Port Cooper or Lyttelton Harbour. The name sometimes has been given as Te Waka-raupo, which means “The Canoe of Raupo reeds,” otherwise a raft or mokihi of the [18] type so often used on the South Island rivers. This, however, is not correct. “Whaka” here is the Ngai-Tahu dialectical form of “Whanga,” which is a harbour or bay, as in Whangaroa and Whanganui. Whaka-raupo, therefore, means “Harbour of the raupo reed.” The tino or exact place from which the harbour takes this name is Governor’s Bay, at the head of which there was a swamp filled with a thick and high growth of these reeds. It was here, at the head of Governor’s Bay, that the stockaded pa Ohinetahi stood; it was occupied by Te Rangi-whakaputa’s son after the dispersal of the Ngati-Mamoe tribe in these parts more than two hundred years ago.

Corsair Bay and Cass Bay, as the Kaumatua of Rapaki tells us, have Maori names which contain a reference not only to the ancient forests which clothed the slopes of the Port Hills and descended to the sandy beachside, but to one of the vanished practices of the native people, fire-making by wood-friction. Corsair Bay was named by Te Rangi-whakaputa, Motu-kauati-iti, meaning “Little Fire-making Tree-grove,” and Cass Bay was Motu-kauati-rahi, or “Great Fire-making Tree-grove.” The bays were so designated because on the shores and the slopes above there were plentiful thickets of the kaikomako (pennantia corymbosa), the small tree into which Mahuika, a Polynesian Prometheus, threw fire from his finger-tips, so that it should not be extinguished by Maui’s deluge. A myth which to the Maori quite satisfactorily accounts for the readiness with which fire can be obtained from the kaikomako by the simple process of taking a dry block of the wood and rubbing a groove in it with a stick of hardwood—with, of course an incantation to give more power to the elbow—until the dust and the shavings become ignited. The kaikomako wood is used as the[19] kauati , the piece which is rubbed; the pointed rubbing stick which the operator works to and fro is the kaurima . Motu in these two names is a tree-clump or grove. There are none of the ancient fire trees on the bay shores nowadays; the pakeha’s pinus insignis and cocksfoot grass have long supplanted them.

Ri-papa is the full and correct name of Ripa Island, in Lyttelton Harbour. It is an historic and appropriate name, carrying one back to the ancient days when the brown sailors hauled their long canoes up on its little shelving beach. Ri means a rope, the painter of flax by which canoes were dragged up on shore, and papa is a flat rock. Ripapa is a white man’s fort these days, but centuries before a British gun was planted there it was a fortified place, though the weapons of its garrison would hardly carry as far as those of the present coast defence force. The Ngati-Mamoe three hundred years ago had a small village on this rocky islet, commanding the harbour-gate; it was defended with a palisade. But when the Rangi-whakaputa conquered the inhabitants of Te Whaka-raupo, he took the island and named it Ripapa—its first name is forgotten—and he built a pa on the spot where the fort of the pakeha artillery-men now stands.

Quail Island, the dark-cliffed isle of the lepers, is known by the Maoris as Otamahua. Herein is a reference to an era when the island was a birding ground of the olden race. Many sea-birds, gulls and puffins and divers, bred in the crannies of its fire-made rocky shores, and the mainland Maoris canoed across on fowling expeditions. The eggs (hua ) of the sea-fowl were esteemed delicacies, especially by the children (tamariki ), who were fond of roasting them on their island expeditions. Manu-huahua , or birds cooked and preserved in their own fat, and[20] done up in sea-kelp receptacles, as is the way in the Stewart Island mutton-bird industry to-day, also formed a large portion of the native supply of winter food in these parts.

Looking out from the Port Hills the olden Maori wayfarer surveyed the far-spreading Plains and the name handed down from the days of the Waitaha tribe, the forerunners of the Ngati-Mamoe, came to his lips: “Nga Pakihi Whakatekateka a Waitaha.” It is a barbed-wire fence, perhaps, to the average pakeha, yet abbreviated it is not inappropriate as a Plains homestead name. In the long ago, before water-races and artesian wells, the trails across the Plains from the Waimakariri to the Selwyn and the Selwyn to the Rakaia and the Ashburton were weary and thirsty tracks, for there were very few springs of drinking water and the Maori disliked the water of the cold glacial torrents. So the tired and thirsting trail-parties, swagging it across the wastes of tussock and cabbage trees, came to call the district “The Deceptive Plains of Waitaha,” for they discovered that it was unwise to rely upon springs and streams on the long tramp. They made water-bags of seaweed, the great bull kelp, which they split and made watertight, and these poha henceforth became as necessary to the kit of a trans-“Pakihi” traveller as a water-bottle is to the soldier in the field to-day.

The Heathcote River, whose native name has been abbreviated to Opawa, was originally the Opaawaho, which means “The outer, or seaward, pa ,” otherwise “An outpost.” A tribe-section or hapu of the Ngai-Tahu, about two hundred years ago, built a village on the left bank of the river, on a spot slightly elevated above the surrounding swampy country; the exact spot must have been

[21]

Whaka-raupo, Lyttelton Harbour, looking south-west, showing Quail Island.

W. A. Taylor photo

[22]

close to the present Opawa Railway Station. The name of the village was Poho-areare, or “pigeon breasted,” after some chief of those days, and it was because of its situation, the outermost Kainga of the Plains and swamp dwellers, commanding the passage down the Heathcote to the sea, that the river became known as the stream of “The Outpost.” Here it may be recalled that the hapus who lived where Christchurch City now stands were given a nickname by the outer tribes at Kaiapoi and elsewhere. They were called “O-Roto-Repo,” or more briefly, “O-Roto-re’,” which means “In the Swamp,” or the “Swamp-Dwellers.” They lived in a marshy region which had its compensations in the way of abundant food, for the swamps and creeks swarmed with eels and wild duck. The upper part of the Heathcote was the O-mokihi or “The Place of Flax-Stalk Rafts.” The tino of the name, the place where it had its origin, was an ancient lagoon-swamp at the foot of the Cashmere Hills, which the river drained. Another version of the Heathcote name is Wai-Mokihi, or “Flax-stalk Raft Creek.” Lower down the Heathcote, where the broad tidal shallows are, the Maoris gave the place an equally appropriate name; they called it O-hikaparuparu, which may be translated as “The spot where So-and-so fell in the mud,” or “Stick-in-the-mud,” which serves equally well to-day. About Redcliffs, where the tramline passes round from the broads and under the great cave-riddled lava precipice, there belongs a rather beautiful name, Rae-Kura, which is more modern than most of the other Native designations. It means “Red-glowing Headland,” or, let us say, “Rosy Point.”Immeasurably more ancient is Rapanui, which is the name of Shag Rock, in the Estuary; a place-name[23] that could very well be appropriated by some of the near-by residents. It is a far-travelled name, for it was brought by the first Maori immigrants from Hawaiki, just as our white settlers brought their Canterburys and Heathcotes and Avons with them. We find it on the map of the Pacific some thousands of miles away; it is one of the Native names of Easter Island, that strange relic of a drowned Polynesian land in Eastern Oceania. And further out still, there is Tuawera, the Cave Rock at Sumner, to which belongs a legend of love and wizardry and revenge, to be narrated at another time, in which the chief figures were a girl from Akaroa named Hine-ao or “Daughter of the Dawn,” the chief Turaki-po, of “The Outpost” village, and Te Ake, the tohunga of Akaroa.

[24]

ROUND THE SUGARLOAF.

“THE CREST OF THE RAINBOW.”

The saying that the best place to see the mountains is from below, not from their summits, may properly be qualified in its application to our Port Hills by the opinion that the finest view of the craggy range of old volcanic upjuts is that to be had from a few hundred feet below the range crest, on the Lyttelton Harbour side. Really to appreciate the special and peculiar beauty of the hills, with their nippled peaks and crags and their age-weathered cliffs, one must travel along the Lyttelton-Governor’s Bay road rather than view the range from the Plains, where the smoothed and settled ridges, like a series of long whalebacks, give little hint of the sudden rocky wildness of the precipitous dip to the harbour slopes. There, on the white road that curves along the hillsides well above the waters of the Whanga-Raupo, it is easy to understand something of the fiery history of these hills, when the hollow that now is Lyttelton Harbour was one terrific nest of volcanoes and when the tremendous forces of confined steam and gases hurled whole mountain-tops skyward and helped to give savage shape to the walls of rhyolite rock that stand to-day little altered by the passage of the untold centuries of years. Better still, truly to understand this most wonderful part of Canterbury, one should make a traverse of the upper parts of the eastern dip by the new tracks, two or three hundred feet below the pinnacles of the ridge. Off

[25]

Te Heru o Kahukura, Sugarloaf.

C. Beken, photo

[26]

the tracks if you care for the exercise there is rock-climbing in plenty and there are scrambles under the low-growing trees and along steep faces hanging on to the flax clumps and the tough-branched koromiko . And at about this level on the Hills side there are aspects of crag scenery, and crag and woodland combined, that are altogether missed by the stroller who keeps to the beaten track. Our Christchurch artists need not go further away than the inner dip of the range, the battered rim of the ancient fire cauldron, for impressions of bold rock faces straightly grand and honeycombed with curious caves, and witchy-looking weathered old trees; pictures that approach grandeur when the storm clouds swirl about the tussock-topped tors of Kahukura, the Rainbow God, giving the dark cores of the olden volcanoes an added height and mystery, or when they drift softly and mistily from the deep gullies between the ridges like steam masses from some hidden geyser.The Mitchell Track that winds along northward between the tumbled rocks and among the hill flax gives the explorer a start on his traverse from Dyer’s Pass. It begins just opposite the picturesque stone-built tea-house with its swinging signboard and its quaint inscriptions in the saddle of the Pass, and it splendidly opens up the seaward face of the Sugarloaf whose rounded summit lifts directly over us yonder more than 1,600 feet above the harbour level. Immediately below us, in the gully that long ago was a channel for lava flow, the rocky depths are softened by the foliage of a fragment of the olden bush, a green covering for the valley floor. The valley is more attractive outside, for almost every vestige of the moss and ferns and underbrush has disappeared before grazing stock and the

[27]

The Sign of the “Kiwi,” with Marley’s Hill in the background.

C. Beken, photo

[28]

sudden torrents that have poured down from the ridge to make the little storm-creek flowing into the harbour beside the grassy mound of Pa-rakiraki. The lava-builded, notched and caverned walls of the Sugarloaf shoot up above us just here like a parapet, in regularly marked layers; tufts of flax and tussock and wiry veronica beard the face of the old fire-cliffs. Looking back at the Pass, just before we round the first bend in the rocky traverse, the cliff makes a terraced halt in its descent, and here on this tussock-grown tiny level, broidered with flax bushes and their honey-sweet korari blossoms, there is an eye-taking prospect of the Dyer’s Pass dip to the soft-blue sunlit harbour and of the black rock-faces and strong folds of the Port Hills southward.Immediately southward of the Pass road the land goes easily swelling up into Marley’s Hill, a little higher than our Sugarloaf, and now a story of old-time explaining the meaning of the Maori name of that airy saddle comes to mind.

The original name of the ridge leading southward from Dyer’s Pass, and including Marley’s Hill, says Hone Taare Tikao of Rapaki, is Otu-Tohu-Kai, which being translated is “The Place Where the Food Was Pointed Out.” The tradition is that nearly two centuries ago, when the Ngai-Tahu from the North conquered this part of the country from the Ngati-Mamoe, a chief named Waitai ascended this height from Ohinetahi (now Governor’s Bay), taking with him Manuwhiri and other of the children of the chief Te Rangi-whakaputa who had taken possession of the harbour shores, in order to point out to them the good things of the great Plains. Waitai had already explored the country, and was able to tell of its worth as a home for Ngai-Tahu.

[29]

When Waitai and his companions emerged from the bush and topped the lofty round of the range, he halted, and bade them look out over the wide, silent country. He pointed to the reedy lagoons and streams that silvered the flax and tussock desert, where Christchurch City and its suburbs now spread out leisurely and shade off into the rural lands, and said: “Yonder the waters are thick with eels and lampreys, and their margins with ducks and other birds; in the plains beyond there are wekas for the catching.” The Plains, as he showed them, were plentifully studded with the ti-palm, from which the sugary kauru could be obtained. Then, turning in the other direction, he spoke of the fish-teeming waters of the harbour, where flounders, shark, and other kai-matai-tai , “food of the salt sea,” were to be had in abundance. Such were the foods of this Wai-pounamu; and so good seemed the land to those conquistadors as they stood there on the windy height surveying the great new country fallen into their hands, that they decided to remain in so promising a place; and it is their descendants who people Rapaki and other kaingas to-day.

Now we turn and, passing a rugged cornice in the lava wall, descend into the gully to examine for ourselves the tree-covering of old Kahukura’s shoulders. There is a thick growth of flax on the little terraces and steep slopes above the bush, and in one place we force our way through a regular jungle of it, growing so thickly as almost to encourage the idea that a flax-mill would find profitable business here. Some of the tall korari stalks are well in flower and bees are busy; on others the long dark-sheathed buds are just unfolding. Flax-flower honey-water makes a[30] pleasant enough drink, and the Boy Scout tastes and pronounces it good. There is a pretty Maori love-lament in which a girl compares her sorrowing self to this blossom of the flax:

“My eyes are like the wind-waved korari blossoms; when the breeze shakes the flowers down fall the honey showers; so flow my tears.”

A little lower and we are in the bush, taking care as we enter it to give a wide berth to the insinuating Maori nettle, the ongaonga , with its unhealthy-looking light-coloured leaves covered with a thick growth of fine spines or hairs. The Boy Scout sidles warily past those bushes of ongaonga when he is told of its poisonous qualities, and of an experience the narrator had with it years ago in the King Country bush. Away up yonder, in the Ohura Valley, between the open lands of the King Country and Taranaki, the ongaonga grew into tall shrubs, ten or twelve feet high, and its virulence apparently was in proportion to its growth. All of our exploring party were more or less badly stung and suffered the effects for a day or two, but the unfortunate horses suffered most. Two of them went mad with the poisonous stings, which swelled their sides and legs, and a pack-horse actually drowned itself by bolting into a creek and lying down in the water in its desperate need of ease from the pain. Really bad ongaonga stings provoke feverish sickness; and so it is prudent to make a detour on these hill slopes rather than encounter over-closely even these insignificant little specimens. If you are on a steep, slippery slope and reach out for a hand-grip, as likely as not instead of a friendly flax or tussock bunch the ongaonga will be there waiting for you with his devilish little stinging hairs. And don’t attempt to apply to our Maori Land nettle the amiable counsel of old Aaron Hill that was given out to us in our school days:— [31]

Don’t, if you value your skin, try that on the ongaonga.

The Seven Sleepers

The Port Hills, south-west of Dyer’s Pass,

viewed from the lower slopes of Sugar Loaf, above the Governor’s Bay road

W. A. Taylor, photo

Lower down, however, the way is clear of this bush plague, and we find ourselves under a shady roof of thick foliage, woven of the cool green leaves of the broadleaf, a small puka , the mahoe and kowhai and other minor trees of the Maori bush with much of the kotukutuku , the native fuchsia, now come into flower, with its masses of slender pendulous blossom giving promise of abundant konini berries for the birds. (Like several other New Zealand trees the fruit of the kotukutuku is given a different name from the plant itself.) The graceful lacebark or ribbonwood, too, is here in plenty; there are some beautiful specimens on these hills and slopes, and finest of all perhaps is the grand old houi that overshades the little Maori Church at Rapaki. Aka vines interlace the close-growing trees and here and there present tangling obstacles to a passage along the gully sides. The place lacks the softness of moss and fern underfoot to which we are accustomed in the real bush; nevertheless it has something of the atmosphere of the olden forest wild; grateful bush scents are in our nostrils, the leaf-covering is close, though the trees are not tall, and the twisting character of growth and the matting of creepers help to make compact the tentage of green.

Making north-east with the general curve of the Sugarloaf slopes we leave the first bush patch and,[33] breasting another wild garden of flax, with here and there a cabbage-tree sweetening the air with its creamy flowers, discover a deep trend to the north-west into the main valley. Here, under a steep-to uplift of the ancient igneous rock, curving out above our heads in savage cornices and rude attempts at gargoyles, we look down upon a picture of surprising beauty, one of the many surprises folded in among these Port Hills.

The old Maori Church at Rapaki.

On this side of the Heru-o-Kahukura the range is deeply bitten into by a cup-shaped valley, with one[34] side of the cup, that facing the harbour, cut away for the passage of the old lava streams and now the rainy season watercourses. The inside of the valley, too, is given the semblance of a fan by the numerous converging tributary gullies, separated by grassy and flax-grown ridges. There are perhaps half a dozen of these subsidiary valleys, and each one is filled with a sweet green mass of light bush similar to that behind us. The higher the little valleys, too, the more bush there is; the gully bottoms are hidden everywhere with many tinted foliage, a taller tree here and there protruding its head above its fellows, and these remnants of the ancient forest climb to the very parapets of dark and grey rock that seem to form the main defences of Kahukura’s citadel. The curving lines converge, the shouldering ridges fall away as the now dry watercourses blend into one hundreds of feet below the rocky elbow of ours.

It is perhaps half a mile across the main gully and we fix a course for the Summit track on the ridge northwards and strike down through the bush. Here in the shadowy depths there is some bird life; the trill of the riroriro , the little grey warbler, is almost constant, and an occasional fantail flits about us; but the thrush is more numerous than any native bird. When the bush bird-foods are ripe the tui sometimes pays this valley a visit from larger woodland tracks. There is a curious wildness in the valley bottom under the thicknesses of the broadleaf and the mahoe and kotukutuku ; it is half-dark in the deepest part, and great rocks lie hurled about, fire-born and water-worn. The floods that sometimes tear down have worn pot-holes here and there, and there are shallow caves obscured by tangles of roots and

[35]

Whaka-raupo, Lyttelton Harbour from Kennedy’s Bush

[36] coiling stems. There is a venerable kotukutuku , a wizard of a tree, its whitened bark hanging in strips like shaggy bits of beard, its trunk all knotted and twisted, standing sentry at the entrance to a little dusky cavern; its misshapen branches, storm-battered, go searching around the broken top of the black and grey rock. Other of the trees take goblin-like shapes, and stretch out their bare roots and feelers, unsoftened by carpet of moss or ferns, to trip the intruder into their dim solitudes. It is but a little bit of a wood, this bush in the gully, but its aloofness and solitariness are made complete by the close-growing habit of the small timber and the great tossed-about rocks that help to seclude it. Totara of some size, we observe, once grew here; there is the tall, smooth barrel of a tree now dead. In the next main gully to the northward, the Taungahara bush, on the Native reserve, there is at least one fine totara , and some big fellows were cut down there not so very long ago by the Rapaki people for fencing posts.

As we make upwards, with care evading the diabolical ongaonga that haunts the bush outskirts, we strike a steep face, with here and there a dripping of water glistening on the moss-crusted rock and on the little flax and koromiko plants that root themselves in tiny crevices. To gain the graded and formed track again, we swarm up the fifty-foot cliff, with koromiko and aka and flax for hand-grips. Above there is a jungle of koromiko , a veronica which here assumes sub-alpine habit, and weaves a wire entanglement, fortunately minus the barbs—the tataramoa or bush-lawyer in the thicket below supplies those in plenty. The butte here is topped by a rock formation so regular and resembling a ruined fortification that the Boy Scout opines it[37] would be a splendid place for a fight, and certainly the old shattered tor of the fire-kings, with its copses of wire-branched koromiko and its thick flax-clumps, suggests itself as a first-rate natural redoubt, where a few riflemen might hold out among their rocks and shrubby cover against a score of times their number.

The little bush on either hand here runs almost to the ridge top, and we come suddenly out of the koromiko thicket on to the great cave-worn ramparts and have a clear track to the Summit Road again. The picture from the breezy ridge is worth the warm scramble up through the matted bit of woodland. The long smooth rolls of hills go down to the Plains on the one hand; on the other the harbour and beyond the cloud-belted heights of the Peninsula. A misty shower is sweeping over the far indigo hills, and a rainbow shines out, grandly spanning a sector of the Peninsula, from the back of Purau to the ocean. And as we turn southward the thought comes, observing the evenly symmetrical round-sweep of the Sugarloaf summit from here, that the Maoris of old-time, who, like the ancient Incas saw in the rainbow the personification of a deity, may very well have caught from the peak’s likeness to the iris arch the poetic fancy that induced them to name it Te Heru-o-Kahukura, “The Comb (or crest) of the Rainbow God.”

By way of the easy return trail, we work back southward under the upper cliffs. Out near the Pass the crannied walls of old Kahukura echo to the voices of a party of girls, a botany class from the city. The instructor is improving the half-holiday with a practical talk on the native flora, and twenty notebooks are out and pencils busy.

[38]

“This,” announces the mentor as the class clusters round, “is a very peculiar plant, Urtica ferox, so called because——”

“Wow!” interrupts one of the earnest learners, as she stoops to rub a plump ankle.“It stings like billy-oh!” She has made the acquaintance of the truculent ongaonga .

—Shakespeare.

[2] Carved above the porch of the Summit Road Rest House on Dyer’s Pass.

[39]

RAPAKI: A VILLAGE BY THE SEA.

In the little Maori kainga of Rapaki, folded away in a valley-fan of Lyttelton harbour-side, there is a tiny, steep-roofed church, of old-fashioned build, and by the side of this church stands a twisty-branched old ribbonwood tree, that in summer showers over porch and steeple its sweet, snowy blossoms, scented like the orange tree. On the lowermost bough of this knotty ribbonwood, the houhi , or houi , of the Natives, that stood here before the church was built, over fifty years ago, hangs the bell that calls the remnant of Ngati-Irakehu to worship; and it is this sylvan belfry that symbolises for me the intermingling of modernism and ancientry in the Rapaki of to-day. Like the other hapus of the Ngai-Tahu tribe, the Ngati-Irakehu and their kin are now half-pakeha in blood; they have intermarried with their European neighbours, and their little township, with its sixty odd souls, is scarcely to be taken at first sight for a Maori settlement. The communal house, of characteristic Native build, with its carved frontal barge-boards and its gargoyle-like tekoteko perched above the entrance, familiar to travellers in the Native districts of the North, is wanting here; but a survey of the village scheme, with its tree-shaded cottages grouped sociably about the central green space, and the hall and school-house and church, soon makes it plain that here stood an old-time Maori kainga , of totara slabs and raupo thatch, with maybe a tall stockade guarding its landward side and stretching from cliff to cliff of the little boulder-beached bay. The plan is the same; the buildings have changed, for Rapaki to-day believes in[40]

The church bell at Rapaki, suspended from historic ribbonwood tree.

E. Cowan, photo

sanitation and modern comforts. Here and there a Maori tree, like our ribbonwood yonder, and a tattered clump of light bush in the gullies or on a rocky cliff-top, to remind us of the different setting when Rapaki was tumultuous with wild Maori life; when tattooed Ngai-Tahu were in fighting flower, and when dense and beautiful forest covered the feet and shoulders of all those dark volcanic crags and tors lifting above us[41] there like so many ruined castles battered by the artillery fire of the gods. A remnant, a morehu , now are tribe and forest; alike they have dwindled to a shadow; “as the woods are swept away,” says the Maori, “so shall the people vanish.” The young people are so Anglicised that they use the pakeha tongue chiefly; the older ones only cling to Maori among themselves. Yet a brave little remnant, with a fighting heart worthy of their warrior ancestry; for of these descendants of fierce old Rangiwhakaputa and Wheke every eligible young man went to the Great War, and some salted with their bones the world’s greatest battlefields. (No Kipling monopoly in the phrase: “Bury me here,” said old Major Pokiha, of the Arawa, a fighting chief of the last generation—“bury me here as salt for the lands of my heroes”). One-eighth of the population of little Rapaki voluntarily enlisted. The well-plucked Ngati-Irakehu and their kinsmen have title to say, as Nelson said of old of his fighting sailors, “We are few, but the right sort.”

The Kaumatua of Rapaki, the pleasant-mannered kindly greybeard, Hone Taare Tikao, a gentleman of true rangatira breeding and demeanour, is the best informed man of his tribe-remnant on the Peninsula and Port Hills history and legends and genealogical recitals—whakapapa in the Maori tongue. Tikao was born at Akaroa over seventy years ago. He is of the Ngati-Irakehu hapu of the Ngai-Tahu tribe, and he is descended by several lines from Te Rangiwhakaputa and other of the warrior chiefs who wrested the Whanga-raupo and the Whanga-roa—Aka-roa is the modernised contraction—from the dusky men of Ngati-Mamoe. From his parents and from Paora Taki, a picturesque old rangatira who once was Native assessor at Rapaki, and kindred people of the[42] generation that has gone, he learned the history and legends of these parts.

The old man tells us first how this village came to be named Rapaki—not Raupaki, as it is erroneously spelled on the maps. The full name of the place is Te Rapaki-a-Te Rangi-whakaputa which means “the waist-mat of Te Rangi-whakaputa,” and to it, obviously, there hangs a story, which when told leads on to the tradition of the conquest of this district from the Ngati-Mamoe a little over two centuries ago. The Rangi-whakaputa’s name in these parts is associated with Homeric exploits with the weapons of old. This long-gone tattooed hero was the Hector of the Whaka-raupo, and this well-hidden valley curving down from the crags was the spot where he settled awhile when the harbour-side fighting was done. He was one of the northern invaders, a kinsman and contemporary of Moki, Tu-rakau-tahi, and other baresark warriors of the end of the seventeenth century. On the beach below the present village he left his waist-garment, a kilt of flax or toi leaves, probably in connection with the act of tapa -ing the place as his possession, and from the fact of this rapaki , which would be a tapu one, being cast there the place received its name. Te Rangi-Whakaputa’s name has been translated as “Day of Daring,” or “Day of Energy.” It suited this enterprising warrior, who is described by his descendant Taare Tikao as a great toa or brave. He was indeed a fine figure of a man, nearer seven feet than six feet high, it is said, very powerful, and a most skilful man in the use of the taiaha , the Maori broadsword of hard tough akeake , and the spear and the stone mere . All these harbour-front villages and camping-grounds he captured from the Ngati-Mamoe who, as Tikao says, were the fourth iwi —race or tribe—to occupy the

[43]

Rapaki Village, with Tamatea’s Breast in the background.

W. A. Taylor, photo

[44]

South Island; the first people were the Hawea, the second the Rapuwai, the third the Waitaha and the fourth the Ngati-Mamoe, whom the Ngai-Tahu dispossessed, in their turn to be supplanted by the white-skins with their bags of gold sovereigns and their land-sale deeds.And this Homeric figure of two centuries ago, great of stature and terrible in fight, had a son whose name is scarcely less famous in the little-written traditions of the conquest of the Whanga-Raupo. His name was Wheke, which means “Octopus,” and like his father he spread terror among the Ngati-Mamoe. With his war parties he scoured all these ranges and tracked the frightened fugitives into their most secret valleys and caves. One of his camping-grounds on a war expedition was yon fort-like nest of basalt towers and upjuts above Cass Bay, overlooking our Lyttelton road; he slept one night near the summit of one of these crags, a wild hard camping place, and it is still known as “Te-Moenga-o-Wheke” or “Wheke’s Bed.” And over the doorway of the large meeting hall in the village of Rapaki you will see the name of Wheke painted, in memory of a brown hero whose bones have been dust these two hundred years.[3]

[3] The following note describing the occupation of these localities after the first conflict between the two great tribes of the South Island was written by Mr. T. E. Green (Tame Kirini) of Tuahiwi, Kaiapoi, who died in 1917, and who was an authority on the history of his mother’s clan:—

“The Ngati-Mamoe were subdued by the Ngai-Tuhaitara section of the Ngai-Tahu tribe under Moki, an account of whose expedition is given in Canon J. W. Stack’s contribution to “Tales of Banks Peninsula.” Te Raki (or Rangi) -whakaputa was of the Ngati-Kurii section of the tribe; Ngati-Kurii carried their conquest no further south than Kaikoura. From there southward is the conquest of Ngai-Tuhai-tara. The second daughter of Te Rakiwhakaputa was the wife of Tu-Rakautahi, the founder of Kaiapoi Pa, so Te Rakiwhakaputa came to Kaiapoi after the settlement of the Ngai-Tuhaitara, here accompanied by other Ngati-Kurii chieftains, namely, Mako, Te Ruahikihiki and others, and dwelt in the vicinity of Kaiapoi for some time. There is a spot on the eastern bank of the Whakahume (the Cam), about half a mile from the Kaiapoi Woollen Mills, named Te Pa o Te Rakiwhakaputa. Some occurrence there enraged Parakiore, youngest son of Tu-Rakautahi and grandson of Te Rakiwhakaputa, and he declared that he would have no interloper in his midst, referring to his grandfather Te Rakiwhakaputa, (to[45] whom, for brevity, I shall now refer by his short name Te Raki) and Mako (Mango) who was married to his aunt (Te Raki’s eldest daughter). As a result of this attitude of his son, Tu-Rakautahi said to Te Raki, ‘You must go out to the Whaka-raupo (Lyttelton Harbour); there are sharks there for us two.’ Mako he sent to Little River, to Wairewa, saying: ‘Yonder are eels for us two.’ To Te Ruahikihiki he said, ‘Go to Taumutu (at Lake Ellesmere); there are patiki (flounders) for us two there.’ Kiri-Mahinahina he sent out to Paanau: ‘Go yonder and catch hapuku for us.’

“Now this is what the present generation living at these places object to, the idea that their ancestors were sent there to procure food supplies for Kaiapoi. As Moki, the younger brother of Tu Rakautahi, headed the Ngai-Tuhaitara clan who conquered the Peninsula, you will readily perceive that no chief would deliberately go and settle on the territory of another, and particularly one so powerful as Tu-Rakautahi, without his permission—which in this case was given—and without tribute being paid annually for the privilege. This was strictly carried out by them until the advent of the pakehas. Of course Kaiapoi gave them kauru generally in return, merely in Maori etiquette; some are now trying to make out that the kauru (the sugar extract of the tii , or cabbage tree) was the payment for their fish.”

When first I went round the high bend in the harbour-side road from Lyttelton and saw Rapaki village a-slumber in the afternoon sun below, all in its green and gold of groves and flowers, grassy fields lapped about it in soft folds, the sea coming up in gentle breathings at the foot of the little cliffs, and the grand old crags above, with one huge taiaha -head of a peak lording it sentry-wise over all, I thought that for beauty of setting very few Maori kaingas even in the romantic bushlands and highlands of the North Island were peers of this hamlet of the Ngai-Tahu, almost jostled off the map by the crowding hordes of the pakeha . Down the bend into the hollow, where the ghost of a mountain stream goes tinkling through the little gully, and the towns that are so near seem a hundred miles away. The mat-kilted conquistador of old who gave his name to the place had an eye for a secure, well-hidden site for his pa . He could scarcely have chosen a spot more snug about these savage Port Hills. The dominating tors and marline-spikes of fire-born rock and the great up-swell of land on all sides but the sea ward off the cold winds. Loftiest of all and nearest is that towering spear-head Te Poho-o-Tamatea,[46] a dark grey triangle of rhyolite, thrusting its naked apex into the warm sky a thousand feet and more above the groves and dwellings of Tikao’s people. It looks what it is, the mountain guardian of Rapaki; its presence, grimly grand on dark lowering days when the mists trail about it and give it added height and dourness, is no less overpowering in the night, when it leans over the deep-cut valley of dreams, a huge rugged blade of blackness etched against the sky. And even in this day of sunshine, when every cave and cranny in the Poho-o-Tamatea were searched by the golden light and when the mystery of its fiery birth stood revealed, the great spear-rock still seemed a place of eeriness and tapu .

That old ribbonwood tree that quite overshadows the little Rapaki church holds memories of the vanished forests that once clothed all these Port Hills and of the “flitting generations of mankind” it has so long outlived. It is a dignified survivor of the woodlands of the Rapaki-a-Te Rangi-whakaputa. Once upon a time the indigenous timbers thickly covered all these now-grassy slopes slanting quickly from the rhyolite hilltop crags to the quiet waters of the Whaka-Raupo. There were big trees—totara , rimu , kahikatea and mataii —but all have gone long ago. Remains there but a remnant from the general slaughter with fire and axe and crosscut saw—a copse on yonder rocky point on the Lyttelton side of the hamlet, where the poetically named ake-rautangi , the ake of the “crying leaves” and a few other shrubs hold their little stony fort; and in Taare Tikao’s garden the kaumatua has some treasured plants, such as the handsome rau-tawhiri shrub, and the flowering hakeke , a variety of ake , the leaves of which when crushed in the hand have a lemon-like perfume; the Natives used[47] to boil them for the hinu kakara , the fragrant oil expressed. But the old ribbonwood, or lacebark, or thousand-jacket, as the bushman variously calls it, is the tree that takes the eye. The Maoris of the north call it whauwhi and houhere , here it is houhi or houi . It takes its pakeha name from the peculiar characteristics of the inner bark, which is tough and strong of fibre and beautifully netted and perforated. The early colonists have been known to use it for the trimming of ladies’ hats and bonnets. I have seen a war-dance party of Taupo Natives, more than a hundred strong, kilted with short rapakis made of this lacebark, deftly twisted and woven by their womenfolk for the ceremonial leaping parade.

In a Rapaki garden.

E. Cowan, photo

[48]

That is the tree that extends its Maori mana tapu and its twisting flowery branches over the village church, with a little spire like an old-time candle extinguisher, and it was under its shade that Tikao told something of the past of these parts. The church itself, as he remembered, was built in 1869 by the Wesleyan Natives, but the Anglicans used it also, for in those days there was no puhaehae , no violent jealousy of sects. And in its very shadow, when the sun westers, is a tangled grassy spot sacred to the memory of a heathen chief who would have none of the white man’s church or the white man’s beliefs. Mahuraki was his name, a shaggy tattooed pagan of the first half of the last century. He was exceedingly tapu , steeped in wizardry and mysticism. Often the missionaries besought him to become a Christian, but the grim old warlock scoffed at the Rongo Pai. “Hu!” he grunted, “what is your Karaiti? Who was he? My god is Kahukura, the god whose sign is the rainbow. As for yours, your Karaiti—he is a poriro , a misbegotten!” And at last the sorely pained missionary abandoned in despair the hopeless task of plucking the ancient man from the burning. Mahuraki died sixty years ago and was buried in a hole dug in the floor of his thatched hut, which was left to decay. As he lived, he died, a sturdy unregenerate pagan, and the faith of Ihu Karaiti prevailed; the bell of the Rongo Pai calls the kainga to prayers within a few paces of Mahuraki’s grave, and the tohunga’s mumblings are a forgotten creed. The tohunga himself is by no means forgotten, for one of the names of yonder lofty arrowhead of a crag that overlords Rapaki is “Mahuraki’s Head.” The original name, as we have seen, is Te Poho-o-Tamatea, which means “Tamatea’s Breast,” so named by this barefooted pioneer of Maori land surveyors by way of claiming[49] the land for his tribespeople. In about 1849-50, when the commander of a British surveying ship made the first survey of Lyttelton Harbour and named the landscape saliencies, his Maori interpreter asked the name of this sharp peak, whereupon our old savage claimed that it was named after himself, “Te Upoko-o-Mahuraki.” It was his way of perpetuating his name and fame. But long-distance pedestrian Tamatea fairly has prior claim.

So by the foot of the greenwood tree was begun the talk of olden days that ended, as the sun declined behind the historic crags of Tamatea, on Taare Tikao’s hospitable verandah, overlooking the little village and the soft blue placid waters of the Whaka-Raupo. It was a rambling korero , wandering deviously from pakeha times into romantic ancientry, when the wild men lived in the woods and when war canoes filled with fierce tattooed eaters of men swept up and down this shining harbour of ours. The Kaumatua , describing the old industrious age of his people, told by way of example of the tribal communistic energies how great flax nets fully a quarter of a mile long used to be made for the catching of the shark in this sea arm. These immensely long seines were six or eight feet deep, and were worked by canoes, which would take one end out into mid harbour, the other being made fast, and sweep the great kupenga round the shoals of fish making their way up the harbour with the flood tide. Huge quantities of sharks and other fish were caught in this manner, a fishing fashion which was only possible under the old tribal system, when the whole strength of the hapu was available for such tasks.

Lest readers should question the dimensions of that quarter of a mile seine, let me say that in quite recent times, up to within the last thirty-five years or so, an[50] old Ngati-Pikiao chief, the late Pokiha Taranui (better known as Major Fox), had a net nearly a mile in length, which was used on special occasions, such as the gathering of food for native meetings; the locality was Maketu village, on the shores of the Bay of Plenty. But those enormous kupengas will never again be hauled through the fish-teeming waters.

From Tikao, too, we hear something of the poetic legend and nature-myth that steep those swart hills above Rapaki. Yon savage Poho of rhyolite, and the peaked and pinnacled cores of old volcanoes that break through the grassy hills for mile after mile, all have their tales of pre-pakeha years, of which we shall chronicle something again. Just now we may content ourselves with the gentler scenes in Rapaki valley, where the kowhai has shed its showers of gold and the pakeha fruit trees in blossom sweeten the soft air deliciously. That patch of ploughed land behind the settlement before long will show the first shoots of kaanga , or maize; there is not much grown in this island except by the Natives. The water-front, in spite of its smart new jetty for the launches, is lonelier than in the old days; for there was a time, long after the war-canoe era, when three long whaleboats were hauled up on the sand where the boulders are piled aside yonder and often these could be seen pulling down to Lyttelton laden with potatoes, corn and fruit. That bit of beach is over-rough; but a little way to the north, under the lee of a wild bit of a rocky headland thick with beautiful light bush, is a gem of a white beach, clean and hard and shining, a sandy alcove that must have been made for picnicking. And from this hillside turn in the road where we get our first glimpse of Rapaki, we may also most fitly take our sunset farewell of the kainga of an artist’s dream.

[51]

The sun is over the range, and Tamatea’s gloomy peak is outlined in sharp symmetry against the burning west. In the deep gullies between the spear-head and the ridge of the Sacred Fire the smoky-blue mists are already forming, and wreathing and creeping around the tangled shrubberies of bush that have escaped the general massacre. The harbour lies a sheet of scarcely moving tender turquoise, just a shade lighter than the face of the famous Tikitapu, inaccurately called the Blue Lake by the pakeha ; high beyond the shark’s-teeth of the peaks that someone has named the Seven Sleepers are drawn in soft blue upon the rose of the heaven above, their feet are bathed in violet, and the purple mists swim wraith-like from their hidden hollows. The sun goes, and the delicacy, the tenderness of colour, the fading of landscape details into a haze like the camp-fire smokes of the legendary Patu-paiarehe , weave a veil of faery over the valley and the darkening sea. The little boys and girls of the settlement are still at play around the meeting-hall, and every call and every laugh come clearly through the velvet soft air. Down in a nearer dwelling, a girl is rehearsing a poi -dance song, and the lilt is familiar, the half-sad chant that begins,

It is the song crooned by the women and the children in every kainga that, like slumbrous little Rapaki down yonder, sent its young men to use rifle and bayonet beside their pakeha brothers-in-arms on the thundering battlefields half a world away.

[52]

THE “AHI-A-TAMATEA.”

HOW THE SACRED FIRE CAME TO WITCH HILL.

As we travel northward along the Summit Track from the Poho-o-Tamatea, observing from this commanding height—a thousand feet above little Rapaki village, lying in its grassy nest below—how that great spearhead of rock has in reality an almost level top, we come to a remarkable broken wall of grey lava moss-crusted and shrub-tufted, protruding from the grassy flanks of the craggy knoll called Witch Hill. It is in fact a huge dyke of once-molten lava, cutting wall-like through the old lava flows and trending southward across the shoulder of its parent hill. From the very crest of the range it shoots in a palisade of frost-shattered rock, towering thirty feet and more in places above the stone-strewn tussocks, and it stretches some distance in irregular cyclopean steps down the steep slope towards Rapaki. There is an old stone quarry on the face of Witch Hill, where this dyke juts out like a broken castle wall of the Patu-paiarehe , the Dim People of long ago, and just there the old waggon track goes down over the smoothed-out hills to the Canterbury Plains and the green banks of the Opaawaho.

Witch Hill.

The Giants’ Causeway some fanciful pakeha has named this wall of lava. To the Maori it is the “Ahi-a-Tamatea” or “the Fire of Tamatea”, and a strange nature legend there is thereto; a folk tale in which fable and geologic myth are curiously blended. It is a volcano myth which closely resembles, and is no doubt[53] a copy of, the North Island legend of Ngatoro-i-Rangi and the origin of the Ngauruhoe volcano. The march downhill of this curious upstanding dyke of lava, grey against the more sombre tints of the range, may be traced in the masses of lava boulders through which the Rapaki water-course has cut its way in its lustier days. And if you turn your face southward and look far across the upper part of the harbour, near the western slopes of Mount Herbert, you will plainly see what seems a continuation of the remarkable wall of lava which welled ages ago white-hot from the cauldrons of Ruaimoko. Those grey-white parapets of fire-made rock are the Ashes of the Fires of Tamatea, and this is the wonderful tale of Tamatea and his magic fire, a tale of old which brings in, too, our great arrowhead peak, towering yonder on Rapaki’s western side, yon huge upjut lording it sentry-wise over the Maori kainga . The peak of “Tamatea’s Breast,” is one of the very few landscape saliencies in these parts which still remain in the hands of the people of Takitimu descent. A venerable name this, for it is quite six hundred years old and is a connecting link with the greatest land-explorer in Maori-Polynesian story, a prototype of the adventurous[54] “Kai-ruri,” the white surveyor of pakeha pioneering days.

Tamatea seems to have been possessed of the true “wander-hunger,” for when he arrived on the shores of the North Island in his ocean-going canoe the Takitimu (or Takitumu) from his Eastern Pacific home—Tahiti or one of the neighbouring islands—via Rarotonga—his restless heart impelled him to more adventure. First making the land in the far north, he voyaged on down the East Coast, sailing and paddling from bay to bay, leaving here and there some of his sea-weary crew, who intermarried with the inhabitants, and he did not cease his sailorly enterprise until he had reached the foggy shore of Murihiku, the “Tail of the Land” which the white man calls Southland. Here the Takitimu was hauled ashore and if one is to accept literally the legend of the Maori, there she is to be seen now, metamorphosed in marvellous fashion into mountain form, the lofty blue range of the Takitimu—mis-spelled “Takitimos” on the maps and locally spoken of as “the Takitimos.” It is curious that this isolated range—fairy-haunted in native legend—lifting abruptly on all sides from the tussocky plains that slope to Lake Manapouri, from more than one point bears a resemblance to the form of a colossal canoe upturned. Legend, too, says that Tamatea settled awhile at the foot of the Canoe Mountains, and that he had a camp village at the lower end of Lake Te Anau, where eels and birds were abundant.

[55]

The Summit Road, overlooking Governor’s Bay.

C. Beken, photo

Then, wearying for the trail and the pikau , he set out on a march which was nothing less than heroic, from Southland to the newly-settled homes of his people in the North. With a number of companions and food bearers the barefooted explorer trudged across country, through the unpeopled tussock prairies of Otago and the plains now known

[56] as Canterbury, fording or swimming the rivers or crossing them on rude rafts (mokihi ) made of bundles of flax-stalks or of dried raupo , until he reached the hills that wall in Lyttelton Harbour. He travelled along the range-top, as was the way of the Maori explorer, until he neared the dip in the sharp ridge at the back of Rapaki, over which the Maoris and the pioneer white men made a track.

Now, Tamatea had carried with him, in a section of a hollow rata log, as was the fashion of the Maori, a smouldering fire for his nightly camps. No common fire this; it was an ahi-tipua , a “magic blaze,” a sacred fire directly kindled from that trebly-tapu fire which Uenuku, the great high priest of far Hawaiki, had sent with his canoe voyagers. The Takitimu, being a tapu canoe, carried no cooked food, and the only plants the people brought in her were ornamental ones, for scent and beauty and sweet flowers. She was a great double canoe, and could carry two hundred people. Her consort was the canoe Arai-te-uru, which carried “Te Ahi-a-Uenuku—Uenuku’s Fire”—and all kinds of food plants, even, says Tikao, a grain which is said to have resembled the pakeha’s wheat. Coming round Te Matau-a-Maui, Hawke’s Bay, the Arai-te-Uru nearly capsized; she went over on her side, and continued in that attitude until she finally overturned at Matakaea Point, near Oamaru, where she still lies—turned to stone! The sacred fire was saved and it was taken by the chiefs up the Waitaki River and placed there in the ground; and there until about forty-five years ago it was still actually burning, issuing from the earth in a little undying flame, and it was called “Te Ahi a Uenuku.” (A seam of lignite is said to have been found burning in the locality by the early settlers and explorers, and this[57] the Maoris identified with the Hawaikian sorcerer’s magic blaze.)

But it seems that Tamatea’s fire so carefully tended by the gods went out as he travelled slowly up the hills from Otago, and none had been kindled again when he reached the Port Hills. And as he and his companions came out of the bush and passed out on to the summit of the mountain above Rapaki, a great storm of wind and rain, followed by hail and snow, burst upon them from the south and they were like to perish from the cold. It was freezing cold, and Tamatea was without fire or the means of making one, for no fire-making timbers grew in that spot. In his extremity he stood upon the tall crag-top yonder—the one that now is called “The Breast of Tamatea”—and called aloud and karakia’d and made incantations for sacred fire to be sent from the North Island, the land of active volcanoes, to save the lives of himself and his companions. He called to his elder relative, Ngatoro-i-Rangi, and to the guardians of the Ahi-Tipua, the volcanic fires.

And the chief’s fervent prayer was answered in a moment. The fire, sent by the gods in the heart of the North Island, burst forth from Tongariro and speeding down the rift of the Wanganui River valley it touched a spot near Nelson, and again it touched Motu-nau—the small island close to the Canterbury Coast—and then it appeared again in a magic blaze on the side of Witch Hill, and the Maori explorers warmed their frozen limbs and were saved. The fire did not stop here in its wonderful flight, for it went on across the harbour, and the white chute of rock, like a huge sheep-dip trough, shining yonder above the bay of Waiaki is the last of the sacred flames of Tamatea.

[58]

And when the chief left the spot next day to continue his journey he said, “Let this place be called The Place where Tamatea’s Fire-Ashes Lie”; and so to-day the rocky wall which the white man has named the Giant’s Causeway is to the Maori “Te Whaka-takanga-o-te-Karehu-a-Tamatea.” And the volcanic fire itself is “Te Ahi-a-Tamatea.”

Such is the story of Tamatea’s Fire as told by Hone Taare Tikao, in reciting the legends learned from the long-dead elders of his tribe. A legend embalming a distinct perception of the geological history of these hills. The Kaumatua truly says that the magical walls of Tamatea’s Fire Ashes are of later origin than the volcanic crags and hills which lie about them, and across which they cut. The Wanganui River, down which the sacred fire came from the crater of Ngauruhoe, was then dry; it was a rift opened for it by the Volcano Gods. Tikao speaks of a time when the lower part of Lyttelton Harbour was not in eruption, but when the upper part was; from the southern side of Quail Island to the head of the bay was a furnace; there was no water in it at that immeasurably distant day. There are lava rocks, he says, like those of the Ahi-a-Tamatea on the shore of Quail Island; and then there are the always wonderful cliff of Pari-mataa and the wall of Otarahaka on the Mount Herbert side of the upper harbour.

Of the lava dykes Professor R. Speight writes in his account of the geology of the Port Hills that they radiate from the harbour as a centre and form, as it were, the ribs of the mountain, holding it firmly together and helping it to resist the enormous strains to which it was exposed before and during eruptions. “Judging from the persistent nature of these dykes,” he adds, “it is clear that the mountain must have been split at times from top to bottom, and the liquid material which welled from the fissures must have looked at night like a red-hot streak across the country.”

[59]

Te Poho-o-Tamatea, or Tamatea’s Breast, in the middle distance.

W. A. Taylor, photo

[60]