BOOKS BY PROF. JOHN C. VAN DYKE

Art for Art’s Sake. University Lectures on the Technical Beauties of Painting. With 24 Illustrations. 12mo.

The Meaning of Pictures. University Lectures at the Metropolitan Museum, New York. With 31 Illustrations. 12mo

Studies in Pictures. An Introduction to the Famous Galleries. With 40 Illustrations. 12mo

What is Art? Studies in the Technique and Criticism of Painting. 12mo

Text Book of the History of Painting. With 110 Illustrations. New Edition. 12mo

Old Dutch and Flemish Masters. With Timothy Cole’s Wood-Engravings. Superroyal 8vo

Old English Masters. With Timothy Cole’s Wood-Engravings. Superroyal 8vo

Modern French Masters. Written by American Artists and Edited by Prof. Van Dyke. With 66 Full-page Illustrations. Superroyal 8vo

New Guides to Old Masters. Critical Notes on the European Galleries, Arranged in Catalogue Order. Frontispieces. 12 volumes. Sold separately

Nature for Its Own Sake. First Studies in Natural Appearances. With Portrait. 12mo

The Desert. Further Studies in Natural Appearances. With Frontispiece. 12mo

The Opal Sea. Continued Studies in Impressions and Appearances. With Frontispiece. 12mo

The Mountain. Renewed Studies in Impressions and Appearances. With Frontispiece. 12mo

The Money God. Chapters of Heresy and Dissent concerning Business Methods and Mercenary Ideals in American Life. 12mo

The New New York. A Commentary on the Place and the People. With 125 Illustrations by Joseph Pennell.

AMERICAN PAINTING

AND ITS TRADITION

AS REPRESENTED BY INNESS, WYANT, MARTIN, HOMER,

LA FARGE, WHISTLER, CHASE, ALEXANDER,

SARGENT

BY

JOHN C. VAN DYKE

Author of “Art for Art’s Sake,” “The Meaning of Pictures,”

“What is Art?” etc.

With Twenty-four Illustrations

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1919

Copyright, 1919, by Charles Scribner’s Sons

Published October, 1919

PREFACE

THE painters about whom these chapters are written helped to make up the period in American painting dating, generally, from about 1878 to, say, 1915. That period has practically closed in the sense that a newer generation with different aims and aspirations has come forward, and the men who broke ground years ago in the Society of American Artists have turned their furrow and had their day. Indeed, those I have chosen to write about herein, with the exception of Sargent, have passed on and passed out. Not only their period but their work has ended. We are now beginning to see them in something like historic perspective. Perhaps, then, the time is opportune for speaking of them as a group and of their influence upon American art.

Not all of the one-time “new movement” originated and died with these nine men. Dozens of painters became identified with American art just after the Centennial, and many of those who came back from Munich and Paris in the late seventies and the early eighties are still living and producing. But while the nine were by no means the whole count they were certainly representative of the movement, and their works speak for almost every phase of it. The value of the movement to American art can be rightly enough judged from them.

During their lives these nine did not lack for praise—some of it wise and some of it otherwise. They were much exploited in print. I myself joined in the chorus. I had more or less acquaintance with all of them, lived through the period with them, and from 1880 on wrote much about them. My opportunities for seeing and hearing were abundant, and perhaps such value as this book may possess comes from my having been a looker-on in Vienna during those years. To personal impressions I am now adding certain conclusions as to what the men on my list, taken as a body, have established. They wrought during a period of great material development—wrought in a common spirit, making an epoch in art history and leaving a tradition. The pathfinders in any period deserve well of their countrymen. And their trail is worth following, for eventually it may become a broad national highway.

J. C. V. D.

Rutgers College,

1919.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | ||

| I. | The Art Tradition in America | 1 |

| II. | George Inness | 19 |

| III. | Alexander H. Wyant | 43 |

| IV. | Homer Martin | 65 |

| V. | Winslow Homer | 89 |

| VI. | John La Farge | 115 |

| VII. | James Abbott McNeill Whistler | 147 |

| VIII. | William Merritt Chase | 185 |

| IX. | John W. Alexander | 217 |

| X. | John S. Sargent | 243 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| FACING PAGE | |

| George Inness, “Evening at Medfield” | 32 |

| George Inness, “Sunset at Montclair” | 34 |

| Reproduced by the courtesy of F. F. Sherman, publisher of “George Inness,” by Elliott Daingerfield |

|

| George Inness, “Hackensack Meadows” | 38 |

| Alexander H. Wyant, “Mohawk Valley” | 52 |

| Alexander H. Wyant, “Broad, Silent Valley” | 58 |

| Homer D. Martin, “View on the Seine” | 78 |

| Homer D. Martin, “Westchester Hills” | 84 |

| Reproduced by the courtesy of F. F. Sherman, publisher of “Homer Martin,” by Frank Jewett Mather |

|

| Winslow Homer, “Undertow” | 102 |

| Winslow Homer, “Marine” | 104 |

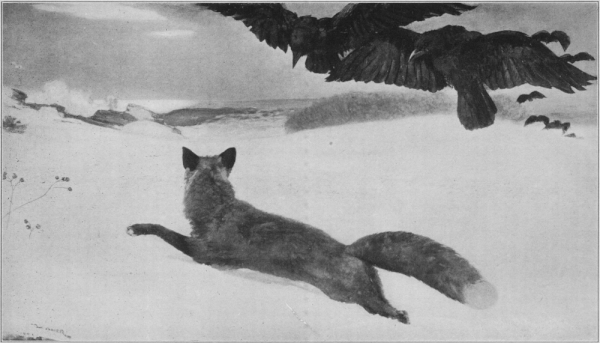

| Winslow Homer, “Fox and Crows” | 108 |

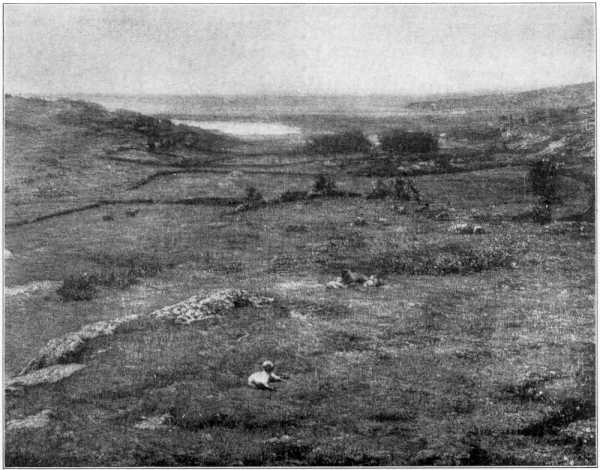

| John La Farge, “Paradise Valley” | 130 |

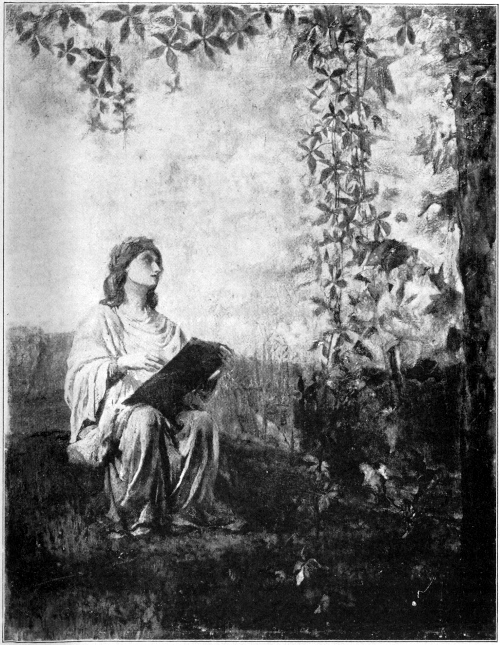

| John La Farge, “The Muse” | 134 |

| John La Farge, “The Three Kings” | 138 |

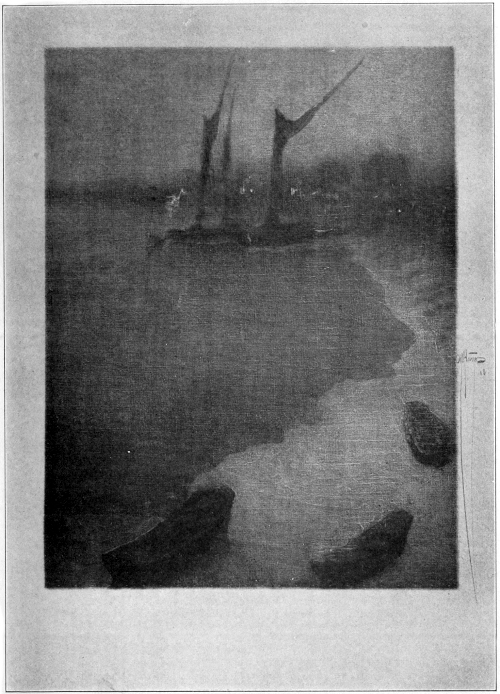

| James A. McNeill Whistler, “Nocturne. Gray and Silver. Chelsea Embankment” |

158 |

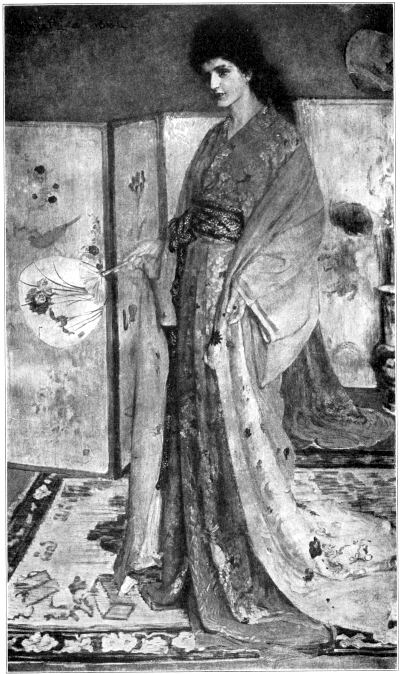

| James A. McNeill Whistler, “The Princesse du Pays de la Porcelaine” |

162 |

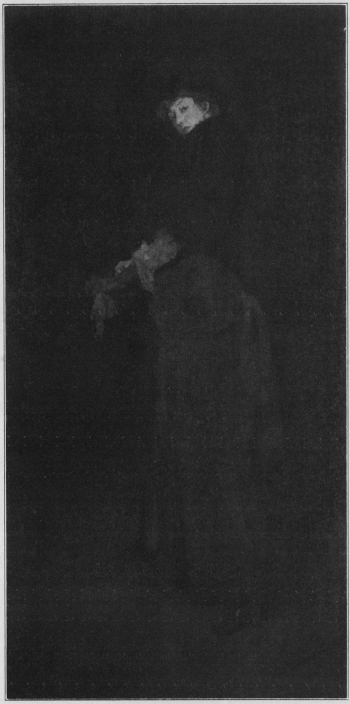

| James A. McNeill Whistler, “The Yellow Buskin” | 168 |

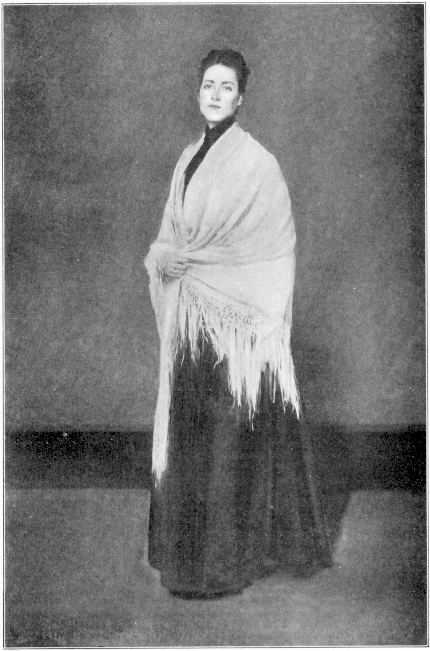

| William Merritt Chase, “The Woman with the White Shawl” |

202 |

| William Merritt Chase, “Afternoon at Peconic” | 204 |

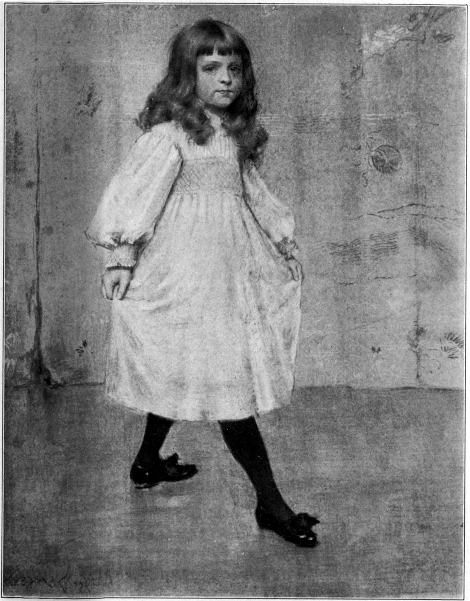

| William Merritt Chase, “Child Dancing” | 212 |

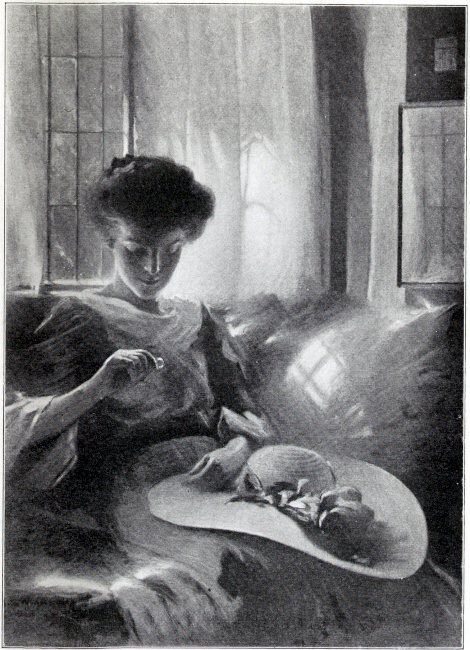

| John W. Alexander, “The Ring” | 230 |

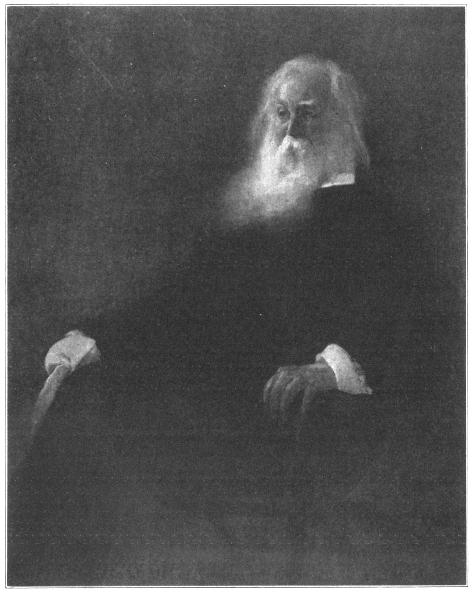

| John W. Alexander, “Walt Whitman” | 236 |

| John S. Sargent, “Mrs. Pulitzer” | 256 |

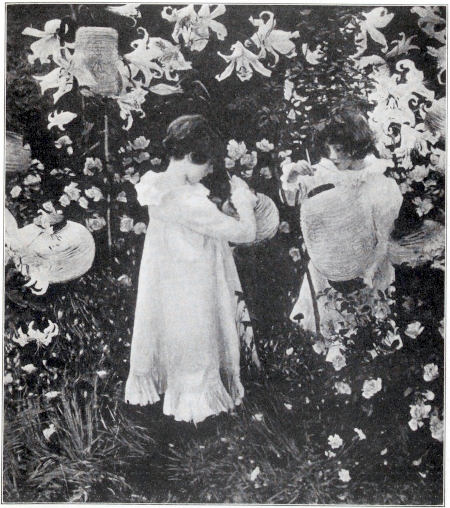

| John S. Sargent, “Carnation Lily, Lily Rose” | 260 |

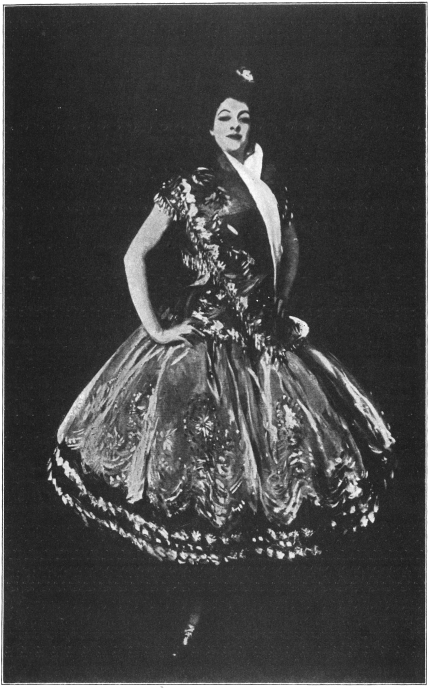

| John S. Sargent, “Carmencita” | 262 |

[Pg 3]

I

During the Revolutionary Period, and immediately thereafter, art in America was something of sporadic growth, something not quite indigenous but rather transplanted from England. Painting was little more than portraiture, and the work was done after the English formula. America had no formula of its own. There was no native school of art, no tradition of the craft, no body of art knowledge handed down from one generation to another. West and Copley started out practically without predecessors. They were the beginners.

With Cole, Durand, and, later on, Kensett, that is about 1825, another kind of painting sprang up on American soil. It was the painting of landscape—landscape of the Hudson River variety—and, whatever its technical shortcomings, at least it had the merit of being original. Apparently nothing of artistic faith or of accumulated knowledge or art usage was handed down to the Hudson River men by the portrait-painters who had preceded them. The leaders worked from nature with little or no instruction. They were self-taught, and if any inkling of how[Pg 4] work was carried on in the painting-rooms of Copley, Stuart, or Vanderlyn was given them, they turned a deaf ear to it or found it inapplicable to their landscape-work. If they knew of a tradition they ignored it.

This matter of tradition—the accumulated point of view and teaching of the craft—is of some importance in our inquiry. It has gone to the making of all the great art of the past. There were several hundred years of sculptors in Greece, with a continuous story, before Scopas and Praxiteles brought their art to final maturity; for centuries painters, with their craftsman-making guilds, had preceded Raphael, Leonardo, and Titian; countless “primitives” and “early men” went to the shades unsung before Velasquez, Rubens, Rembrandt, Holbein came to power. In America the Copley-Stuart contingent caught at, and in large measure grasped, the foreign teaching handed down by Reynolds and his school. Perhaps that accounts in some measure for their success. A generation later Cole and Durand started out to paint landscape without any teaching whatever. Does that account in any degree for their failure? They failed to produce any fine quality of art, but they had pupils and followers in whom the Hudson River school finally culminated. It became a school because Cole and Durand established with themselves a teaching, such as it was, and handed down to their pupils a point of view[Pg 5] and a body of tradition. Perhaps again that explains, to some extent, the varied successes of such followers of the school as Inness, Wyant, Martin, Swain Gifford, Whittredge, McEntee.

But not entirely. Some of these last-named were influenced by European art, outgrew the teaching of their forerunners, and in middle life rather forsook their early love and faith. Yet it would be idle to contend that they had not received an inclination, even an inspiration, from contact with the older men. Short-lived though it was, and shallow as were its teachings, the Hudson River school, nevertheless, had weight with its followers. Even error is often helpful in establishing truth, and a feeble precedent is perhaps better than none at all. Some of the pupils—F. E. Church and Sandford Gifford, for examples—never outgrew their basic teaching. To the end they carried on the Cole-Durand tradition, improving and bettering it. They bettered it because they could add to their own view-point the observation and teaching of their masters. Three generations at least are supposed to be necessary to the making of the thorough gentleman. Is it possible to make the thorough artist in one?

But the Hudson River school was too frail inherently to carry great weight. Men like Inness, Wyant, and Martin soon began to see its weaknesses. Even before they went to Europe they had doubted and after their return to America they were openly heretical. They held allegiance[Pg 6] only in the matter of the Catskill-Adirondack subject, and even that became modified to a virtual disappearance toward the end of their careers. Both aim and method changed with them. They saw deeper and painted freer, until finally they were wholly out of sympathy not only with the thin technique of the school but with its panoramic conception of nature.

So it was that in 1876 when the United States held its first national art exhibition—the Centennial, at Philadelphia—the painting of the country was in something of an anomalous condition. The Hudson River school was practically at the end of its rope. The older portrait-painters had been succeeded by Harding, Alexander, Neagle, Elliott, Inman, Page, Healy—each of them more or less going his own way. The German Leutze had been here and had blazed a brimstone trail of Düsseldorf method, along which some painters followed. Hicks and Hunt at Boston had introduced the French art of Couture and Millet, and they also had a following. Quite apart from all of them stood some independent personalities like La Farge and Winslow Homer, who seemed to say, “a plague on all your houses.” And they, too, went their own ways. There was no school unity.

No wonder then with these conflicting individualities, and with all traditions obsolete or unknown, there was no such thing as an American school of painting at the Centennial Exhibition.[Pg 7] The visitor in Memorial Hall wandered hither and yon among the pictures and vainly strove to grasp a consensus of art opinion or even an art tendency. The exhibition was more or less of a hodgepodge. As a result both painter and public went away in a somewhat bemuddled condition. Perhaps the only thing about the exhibition that impressed one strongly was the general incompetence and inconsequence of it.

Just at this time there entered upon the scene another generation, a younger group of American painters. Many of them had seen the exhibition at the Centennial and had, perhaps, been unwarrantably influenced by it. They brought away from it a longing to paint; but they realized that such art as that at Philadelphia was not what they wished to produce, and if American teaching was responsible for it, so much the worse for the teaching. They would have none of it. Once more there was a sharp break with everything that might resemble a school view or a school method. The younger group left the country and sought instruction in European studios believing that nothing of good could come out of the Nazareth of America.

Some of this later generation had gone abroad for study just before 1876. Shirlaw, Chase, and Duveneck were at Munich; Maynard, Minor, and Millet at Antwerp; Blashfield, Bridgman, Beckwith, Thayer, Alden Weir, Low, Wyatt Eaton at Paris. After 1876 the exodus was greater and[Pg 8] Paris was the goal. A few years later some of these students were homeward bound, having finished a more or less advanced course of instruction under competent masters. They immediately set up studios in New York, and, with the enthusiasm and assurance of youth, began to impart information to the effect that the only painting of importance was that of Europe. As for the native American art, it was not worth reckoning with. The Academy of Design was merely the abiding-place of the ossified, and, of course, it would be surrendered on the demand of the younger men. But the Academy, after a battle of words, declined to give up the fort, and a little later declined even to hang some of the pictures of the gifted. This was regarded as unspeakably outrageous, and swift action followed. In 1877 there was a call for the establishment of a new art body, and out of it came the Society of American Artists, with twenty-two initial members.

The younger men had not invited the academicians as a body to join them, but they had recognized the talent of certain men, who, though members of the Academy, were not in full sympathy with it. In other words, the aloof element of the Academy was elected to membership in the Society. These men—La Farge, Inness, Martin, Moran, Tiffany, Colman, Swain Gifford—joined the new without abandoning the old, and the Society quickly got under way, with its[Pg 9] declaration of independence nailed to the masthead. In ten years the Society had grown in membership to over a hundred, had held yearly exhibitions from 1878 on, and had achieved a substantial success—a success of technique, if nothing more.

It is worth noting just here that this departure was a third violent break in the American art tradition. The young men in the Society practically proclaimed that they would start all over again and build a more worthy mansion than their predecessors. Had they not gone to Europe and received the best of technical training? Did they not know how to draw and paint? For the first time in its history America might congratulate itself upon possessing a body of painters that understood the technique of their craft. American art would now begin.

Lest progressive craftsmanship should die out new students continued to go abroad, and the Art Students League was started for those stopping at home. This new institution was not bound by any conventionalities; its existence was a protest against them. It had no century-old precedents to live up to; it was free to stickle for good workmanship alone. It was the training-school for no peculiar kind of art; it stood ready and eager to adopt any new method or medium or material that was offered. It was progressive to the last degree—progressive to the extent of burning every bridge behind it and starting out[Pg 10] de novo to produce technicians (and consequent art) worthy of the name.

Well, the men, and the institutions, and the movement have been under way for forty years. Much paint has been spread on canvas in that time and hundreds of hands have been busy producing pictures. The “young men” have become old men and many of them have dropped out. The movement itself no longer moves, though some of its best men are still painting. But what is the net result of these forty years? Have the European-trained, after all, succeeded in producing in their one generation, sans tradition, an American art? No one will question for a moment that they have produced many exceptionally good works, even masterpieces; that they are a competent, even learned, body of artists; but has what they have said proclaimed American ideals and reflected American life, or has it repeated the conventions and atelier methods of Europe? Has not the manner of saying with them been more in evidence than the thing said? Is their foreign-based art entirely satisfactory or representative of America?

From a Whistlerian point of view this matter of tradition is, of course, great nonsense. Art just “happens” in Ten O’Clock, and the artist is that one in the multitude whom the gods see fit to strike with divine fire. He is called to service by inspiration as were the prophets of old. All of which no doubt explains the anointing of[Pg 11] Whistler but does not account for the high-priesthood of Velasquez, of Rembrandt, of Raphael, or of Rubens. To say that three centuries of guild-teaching in the best way to grind color, or lay a gesso ground, or draw a figure, or fill a given space, is not better than the intuition of any one man of a period is equivalent to saying that the accumulated knowledge of the world is worthless, and each new generation should discard it and begin all over again. That is substantially what Mr. Whistler advocated. And, further, that the artist should stand aloof and create independently of time, place, or people.

But out of nothing nothing comes, and psychology assures us that there is no such thing as originality save by a combination of things already known. The old is added to and makes the new. The old is the tradition of the craft; the new is the revised point of view and method plus the old. It was so with Whistler notwithstanding his pretty argument around the clock. He was beholden to Gleyre, Ingres, Boucher, Velasquez, Courbet, Albert Moore, Hokusai, and helped himself to them when, where, and how he could. He would have been the last one to deny it. Had there been more continuity and stability in his training, had he followed the teaching of the craft more intently, he would not have been worried all his life as to whether his people stood well upon their feet, and he might have produced[Pg 12] art with the calmness and poise of his great Velasquez. His misfortune was that he had no thorough schooling, inherited no body of taste, and practically stood alone in art. That he succeeded was owing to exceptional genius. That he was never in the class with Velasquez or Titian or Rembrandt was perhaps due to the fact that they had the training and the tradition and he had not.

The Whistler type is not infrequently met in American life—the type that seeks to scale Olympus without the preliminary of antecedent preparation. In art he usually has half a dozen strings to his bow, and paints, lectures, writes, speaks, carries on a business in Wall Street or elsewhere. He is glib in many things, has great facility, is astonishingly clever; but somehow he never gets beyond the superficial. He has not depth or poise or great seriousness. There is no hard training or long tradition or intellectual heritage behind him. He is not to the manner born.

Every writer in America knows that present-day American literature, with some precious exceptions, does not reach up to contemporary English literature; that poetry or romance or criticism with us has not the form, the substance, or the technical accomplishment of the same work in France. Every architect in America must realize that with all the get-learned-quick of his foreign study, with all his appropriations[Pg 13] from the Gothic or the Renaissance or the Georgian, with all his cleverness in solving business needs and doing building stunts under peculiar circumstances, there is something lacking in his productions; that they are not so monumental as he could wish for; that they are not firm set in the ground and do not belong to the soil and remain a part of the land and the people in the sense of contemporary French or even English architecture. Every musician with us must have a similar feeling about our music. As with architecture and painting, there have been some remarkable compositions put forth by our composers. Europe compliments us by playing them and nods approval at the endeavor, but again they do not reach up to corresponding work in Paris or Berlin or Munich. Why not? Have we not as good brains and fiddles in New York as in Vienna? What is it we lack?

Surely we are not wanting in energy, in resource, in materials. Is it perhaps the restraint of these that we need? Time and patience are very necessary factors in all of the arts. Attitude of mind, a sense of proportion—a style, in short—cannot be attained in a few years of schooling. To the training of a lifetime must be added a something that has been more or less inherited. That something handed down from father to son, from master to pupil, from generation to generation, is what I have called tradition. It[Pg 14] is not technique alone, but a mental outlook, added to the body of belief and experience of those who have gone before. The skilled hand of a Kreisler, a Sargent, a MacMonnies is perhaps possible of attainment in a decade, but the mental attitude—its poise and its restraint—is that something which is inherited as taste, and many decades may go to its formation. In this latter respect, perhaps, Kreisler has had the advantage of both Sargent and MacMonnies.

Coming back, therefore, to the men of the Society of American Artists, we cannot say that they failed in skill or were wanting in endeavor, or had no intelligence. They had all of these, but, unfortunately, they were not of artistic descent, and inherited no patrimony of style. Instead they tried to adopt in a few years the long story of French style, and attained only that part of it relating to technique. They were of the third generation in American art, but each one of these generations had denied and forsworn its predecessor, had flung its mess of pottage, such as it was, out of the window, and had left the ancestral roof never to return. The third generation then had nothing by descent, not even a pictorial or a plastic mind that could see the world in images. It went forth empty-handed into the highways and byways of Europe, became proficient in craftsmanship, and relied upon that for success.

This is not merely figure of speech, but statement[Pg 15] of fact. None of the American painters spoken of in these pages, with the exception of La Farge, came from what might be called an artistic family, or had æsthetic antecedents. They were boys on a farm or grew up in the atmosphere of trade or profession, and came to art at twenty or thereabouts. They then learned the technique of painting quickly, and with much facility, but their mental attitude toward art was untrained and remained undetermined. Long after they knew how to paint they knew not what to paint or how to think. Their point of view was superficial or commonplace, or otherwise negligible. I have excepted La Farge, for, as we shall see hereafter, he did have an æsthetic legend behind him. Is that why he is now placed as the one Olympian of the period? I would also partly except Inness, Wyant, and Martin, who did know and follow at one time the rather feeble Hudson River school tradition. I ask again is that why they remain, even to this day, the best of our rather long line of landscape-painters?

Is tradition then synonymous with the academic? Not entirely; though the academies are usually the custodians and conservers of it. Unfortunately, their practice tends to perpetuate a manner that soon becomes a mannerism, and finally the mannerism usurps the place of style. The academic in France or Germany or Italy has of recent years become a term of reproach.[Pg 16] All the rebels in art have been opposed to it. When they rebelled, their rebellion was called by them, or their biographers, “the break with tradition.” Rather was it a break with an indurated method or the tyranny of a hanging committee. For tradition has to do more with the spirit and style of art, while the academic is recognized in a method or a formula which, endlessly repeated, finally becomes trite and even banal.

The art of old Japan ran on for centuries and was excellent art notwithstanding it was academic and based in tradition. It did not run into formalism and never became trite until recent years. Its ruin lies straight ahead of it if it shall abandon its traditions and continue to coquette with Occidental art. But the bulk of painting by the young men of the Society of American Artists became commonplace within a dozen years after their return because they had learned abroad only a manner and reproduced it here in America with the persistence of a mannerism. They never knew the academic in its larger significance; they never felt the spirit and style of the traditional.

That is not to proclaim their work worthless or their movement inconsequent. On the contrary, almost everything that one generation in art could do was done. And well done. They established a foundation in sound technique. It remains to be seen if those who come after will[Pg 17] build upon it or cast it down. Moreover, as an expression of the individual quite apart from the time, place, or people, as a representation of cosmopolitan belief about art, it must be accorded a very high place. Whistler and Sargent happen just now to be the most talked about exponents of the cosmopolitan, but dozens of painters here in America since 1876 belong in the same class and have the same belief. It is all along of a new departure in art, and how it shall work out no one can say, but that it does not entirely satisfy contemporary needs is already manifest. In spite of present practice, and quite apart from Ten O’Clock and other painter extravagances, art is still believed to be in some way an expression of a time, a place, and a people. The world has not yet grown so small that it does not continue to exhibit race characteristics in its art manifestations. That the all-the-world-as-one idea may be farther-reaching, more universal in its scope, and therefore loftier in its art expression than any national or race expression is very possible; nay, probable. Still, even then, with cosmopolitanism in the saddle, there will be the need and the use of tradition—the consensus of opinion and body of belief as to what constitutes style in art.

[Pg 21]

II

1825-1894

A plain man of the business world, knowing nothing of the peculiar manifestations of the artistic mind, would be very apt to wonder over the mental make-up of a George Inness. An artist’s way of looking at things is never quite sensible to the man in the street. It is too temperamental, too impulsive; and Inness was supertemperamental even for an artist. When he expressed himself in paint he was very sane; but when he argued, his auditors thought him erratic. And not without reason. He was easily stirred by controversy, and in the heat of discussion he often discoursed like a mad rhapsodist. His thin hands and cheeks, his black eyes, ragged beard, and long dark hair, the dramatic action of his slight figure as he walked and talked, seemed to complete the picture of the perfervid visionary.

He was always somewhat hectic. As a boy he was delicate, suffered from epilepsy, and was mentally overwrought. His physician had nothing to recommend but fresh air. As a man, one[Pg 22] of his hearers over the dinner-table, after listening to his exposition of the feminine element in landscape, or some allied theme, said: “Mr. Inness, what you need is fresh air.” Inness used to tell this story about himself with a little smile, as though conscious of having appeared extravagant. As for fresh air in the sense of out-of-doors, he knew more about it than all his business acquaintances put together; but in the sense of its clearing the vision so that he could see things in a matter-of-fact light, it was wholly unavailing. He was born with the nervous organization of the enthusiast. That is not the best temperament imaginable for a practical business man.

And yet Inness certainly thought that his views about life, faith, government, and ethics were sound and applicable to all humanity. Art was only a part of the universal plan. In his theory of the unities everything in the scheme entire dropped into its appointed place. He could show this, to his own satisfaction at least, by the symbolism of numbers, just as he could prove immortality by the argument for continuity. All his life he was devoted to mystical speculations. He had his faith in divination, astrology, spiritualism, Swedenborgianism. And he was greatly stirred by social questions. During the Rebellion he volunteered to fight for the freedom of the slave but was rejected as physically unfit; and later he became interested in labor problems, believed in Henry George and the Single Tax,[Pg 23] and had views about a socialistic republic. He never changed. In his seventieth year he was still discoursing on Swedenborg, on love, on truth, on the unities, with unabated enthusiasm. To expect such a man to be “practical” would be little less than an absurdity, and to expect a practical man to understand him would be almost as futile.

But the fever of intensity that burned in Inness and his visionary way of looking at things were the very features that made possible his greatness as an artist. There is something in the abnormal view—one hardly knows what—that makes for art. Certainly the “practical” work of the camera gives only a statement of fact where the less accurate drawing of a Millet gives something that we call “artistic.” The lens of the camera records mechanically and coldly, which may account for the prosaic quality of photography; but the retina of the artist’s eye records an impression enhanced by the imagination, which may account for the poetry of art. Whichever way we put it, it is the human element that makes the art. The painter does not record the facts like a machine; he gives his impression of the facts. Inness, with his exalted way of seeing, was full of impressions and was always insisting upon their vital importance.

“The true purpose of the painter,” Mr. Sheldon reports him as saying, “is simply to reproduce in other minds the impression which a scene has[Pg 24] made upon him. A work of art is not to instruct, not to edify, but to awaken an emotion. Its real greatness consists in the quality and force of this emotion.”

And he practised this preaching. Such nervous manifestations as enthusiasm, emotion, and imagination working together and producing an impression were the means wherewith he constructed pictures in his mind. They made up his point of view, and without them we should perhaps have heard little of George Inness as a painter.

It was no mean or stinted equipment. In fact, Inness had too many impressions, had too much imagination. His diversity of view opposed singleness of aim. While he was trying to record one impression upon the canvas, half a dozen others would rush in. Cleveland Cox, who knew him well, said that he changed his mood and point of view with the weather, and if he started a canvas with a storm piece in the morning, it was likely to end in the evening with a glorious sunset, if the weather corresponded. He was never satisfied with his work; he was always altering it and amending it, painting pictures one on top of another, until a single canvas sometimes held a dozen superimposed landscapes.

The late William H. Fuller used to tell the story of buying a landscape in Inness’s studio one afternoon and going to get the picture the next day, only to find an entirely different[Pg 25] picture on the canvas. To his protests Inness replied:

“It is a good deal better picture than the other.”

“Yes, but I liked the other better.”

“Well, you needn’t take it—needn’t pay for it.”

“It isn’t a question of losing money. I have lost my picture. It is buried under that new one.”

Even when not bothered by many impressions, Inness had great difficulty in contenting himself with his work. It was never quite right. There was a certain fine feeling or sentiment that he had about nature and he wished to express it in his picture; but he found when the sentiment was strong, the picture looked weak in the drawing, had little solidity or substance; and when the solidity was put in with exact lines and precise textures, then the sentiment fared badly. He knew very well where the trouble lay.

“Details in the picture must be elaborated only enough fully to reproduce the impression. When more is done the impression is weakened and lost, and we see simply an array of external things which may be very cleverly painted and may look very real, but which do not make an artistic painting. The effort and the difficulty of an artist is to combine the two; namely, to make the thought clear and to preserve the unity of impression. Meissonier always makes his thought clear; he is most painstaking with details,[Pg 26] but he sometimes loses in sentiment. Corot, on the contrary, is to some minds lacking in objective force. He tried for years to get more objective force, but he found that what he gained in that respect he lost in sentiment.”

This is Inness’s own statement of the case and it enables us to understand why many of his later canvases were vague, indefinite, often vapory. He was seeking to give a sentiment or feeling rather than topographical facts. When the facts looked too weak, he tried to strengthen them here and there by bringing out notes and tones a little sharper with the result of making them look hard or too protruding. After several passings back and forth from strength to weakness, from sentiment to fact, the canvas began to show a kneaded and thumbed appearance. Its freshness was gone and its surface looked tortured and “bready.” He was hardly ever free from this attempt to balance between two stools. It is a plague that bothers all painters, and no doubt many of them would agree with Inness in saying:

“If a painter could unite Meissonier’s careful reproduction of details with Corot’s inspirational power, he would be the very god of art.”

But Inness was much nearer to Corot than to Meissonier. He loved sentiment more than clever technique, and perhaps as a result left many “swampy” canvases behind him. His studio was filled with them. He used to take[Pg 27] them from the floor and work upon them, sometimes half a dozen in a day. He never was “the perfect master of the brush” that we have heard him called, though he was an acceptable, and often a very powerful, technician. He usually began by basing a canvas in a warm gray or a raw umber tint, afterward sketching in with charcoal or pencil the general outline of forms and objects. His pigments at first were thin, and his canvas in its general distribution of masses was little more than stained. Upon that foundation he kept adding stronger notes, glazing his shadows to keep them transparent and push them back, and placing his opaque lights on top of the glaze. In this way he gradually developed the picture, keying up first one part and then another, until finally he drew the whole picture into unity and harmony.

It was most interesting to see Inness at work in this keying-up process. He always painted standing, and would walk backward and forward, putting on dabs here and rubs there with great expertness. He was a painter in oils, seldom employing any other medium, and yet he would use on his canvas almost anything that the impulse of the moment told him might prove effective. One day I watched him for fifteen minutes trying to deepen the shadows in a tree with a lead-pencil. The canvas was dry at the time and he did not want to put any more wet paint upon it. As he painted he talked,[Pg 28] argued, declaimed, glared at you over the top of his glasses with apparently little embarrassment to himself or detriment to his canvas.

Painting he believed he had reduced to a scientific formula, but he kept changing the formula. Rules of procedure, too, he had in abundance, but they also kept shifting. At one time he insisted that a picture should have three planes—the middle plane to contain the centre of interest, the foreground to be a prologue, and the background an epilogue to this central plane. At another time he would spread a half-tone throughout the whole picture, keeping his sky low in key, and upon this neutral ground he would place lights and darks, making them brilliant and sparkling by contrast. Others before him—notably the Fontainebleau-Barbizon men—had worked with similar rules in mind, but Inness was quite original in his application. And he was always moving on to something new and better. Ripley Hitchcock quotes from one of his letters:

“I have changed from the time I commenced because I had never completed my art; and as I do not care about being a cake, I shall remain dough, subject to any impression which I am satisfied comes from the region of truth.”

What Inness was at the time he commenced may be gathered from another quotation from the same authority:

“My early and much of my later life was borne[Pg 29] under the distress of a fearful nervous disease which very much impaired my ability to bear the painstaking in my studies which I could have wished. I began, of course, as most boys do, but without any art surroundings whatever. A boy now would be able to commence almost anywhere under better auspices than I could have had then, even in a city. I was in the barefoot stage, and, although my father was a well-to-do farmer, the boys dressed very much in Joseph’s coat style as to color, the different garments being equally variegated, while schooling consisted of the three R’s, and a ruler, with a rattan by way of change.”

At fourteen Inness received some instruction in drawing from a man named Barker, and at nineteen he was working as a map-engraver with Sherman and Smith in New York. It is said that he engraved several plates, but Inness himself evidently counted this apprenticeship of little value, for he later said:

“When almost twenty I had a month with Regis Gignoux, my health not permitting me to take advantage of study at the Academy in the evening, and this is all the instruction I ever had from any artist.”

He was virtually self-taught as a youth, but his later work was developed and somewhat influenced by the study of other painters at home and abroad. At first he studied Cole and Durand, and his pictures were rather panoramic[Pg 30] in theme and hard in drawing. He worked much over detail, and at this early time must have been acquired a knowledge of form and a store of visual memories which were to serve him thereafter. The brittle landscapes of Inness’s youth are seldom seen to-day. What became of them no one knows. He sold them for any sum that would temporarily keep the wolf from the door, and, passing into the hands of unappreciative people, they have perhaps perished. I never heard him so much as mention his very early work, though in his letter to Ripley Hitchcock he speaks of some of his studies under Gignoux as being “very elaborate.”

In 1850 he was married, and through the assistance of one of his patrons, Mr. Ogden Haggerty, he went to Italy and spent fifteen months there, returning through Paris, seeing the Salon, and the work of Rousseau for the first time.

“Rousseau was just beginning to make a noise. A great many people were grouped about a little picture of his which seemed to me metallic. Our traditions were English; and French art, particularly in landscape, had made but little impression upon us.”

Just when he made this statement is not apparent, but certainly it was not his final estimate of Rousseau and French landscape. He was later on much influenced by Corot, Rousseau, and Daubigny; but with his first long stay in Europe,[Pg 31] chiefly near Rome, it was to be expected that the romance and glamour of the place with such classical painters as Salvator, Claude, and Poussin would sway him.

The second period of his development, dating from about 1853 to 1875, is full of diverse influences. Succeeding trips to Europe and repeated studies of European art rather disturbed his preconceived opinions, and made him doubtful. At one time he would work in one vein; at another time he would reverse himself and go back to his early affinities. It was a period of struggle not only with his art but with the more purely material affair of gaining a livelihood. He lived during this time for four years at Medfield, Massachusetts, then at Eagleswood, New Jersey; and in both places painted some notable canvases, though they were not popular with the buying public.

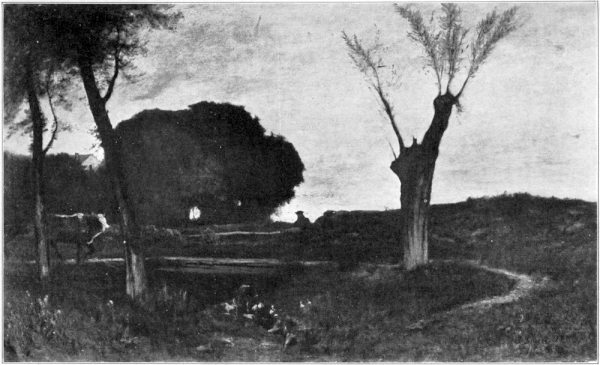

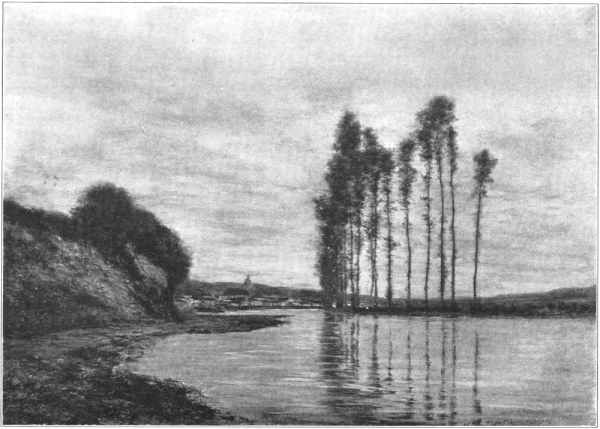

The “Peace and Plenty,” now at the Metropolitan Museum, painted in 1865, is a huge affair, and the wonder is that it was not a huge failure. It is a little too diversified in the lights, and a bit spotty, perhaps, but it is rather broadly handled with a flat brush, and, all told, a remarkable canvas for the time. It represents him under Italian inspiration. The “Evening at Medfield,” also in the Metropolitan, painted in 1875, suggests French influence, perhaps Daubigny. It is broader, freer, thinner in handling, simpler in masses, and has more unity.[Pg 32] None of the pictures at this period are counted his best output, but they are not the less works of decided merit.

It was after four continuous years in Europe (1871-1875) that Inness came into a third style of work (the “Evening at Medfield” indicates it), quite his own, quite American, and quite splendid. It was during this stay abroad that he seemed finally to find himself. His brush broadened, his light grew more subtle, his color became richer and fuller. Corot had taught him how to sacrifice detail to the mass, Rousseau had improved his use of the tree, Daubigny gave him many hints about atmosphere; from Decamps he learned how to drive a light with darks, and Delacroix opened to him a gamut of deep, rich color. He was now in position to graft the French tradition of landscape upon the American stock. And this he did, but in his own manner and with many lapses, even failures, by the way.

All through this third period, and for that matter up to his death, Inness was experimenting with landscape. Every canvas was a new adventure in color, light, and air. In his last period he seemed to see landscape in related masses of color rather than in linear extensions; and so he painted it holding the color patches together with air and illuminating the whole mass by a half-mysterious light. It was not attenuated color—mauves, pinks, and sad grays—but strong reds, blues, greens, and yellows [Pg 33]keyed up oftentimes to a high pitch and fire-hued by sunlight. Nor were they put on the canvas in little dots and dabs, but rather shown in large masses brought together for massed effect and made resonant by contrast.

“Evening at Medfield,” by George Inness.

In the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

(click image to enlarge)

Almost all of his later pictures will be found to hinge upon color, light, and atmosphere. He was very fond of moisture-laden air, rain effects, clouds, rainbows, mists, vapors, fogs, smokes, hazes—all phases of the atmosphere. In the same way he fancied dawns, dusks, twilights, moonlights, sunbursts, flying shadows, clouded lights—all phases of illumination. And again, he loved sunset colors, cloud colors, sky colors, autumn tints, winter blues, spring grays, summer greens—all phases of color. And these not for themselves alone, but rather for the impression or effect that they produced. If he painted a moonlight, it was with a great spread of silvery radiance, a hushed effect in the trees, a still air, and the mystery of things half seen; when he painted an early spring morning, he gave the vapor rising from the ground, with dampness in the air, voyaging clouds, and a warming blue in the sky; with an Indian summer afternoon there was the drowsy hum of nature lost in dreamland and the indefinable regret of things passing away. His “Rainy Day—Montclair” has the bend and droop of foliage heavy with rain, the sense of saturation in earth and air, the suggestion of the[Pg 34] very smell of rain. The “Delaware Water Gap” shows the drive of a storm down the valley, with the sweep of the wind felt in the clouds, the trees, and the water. The “Summer Silence” is well named, for again it gives that feeling of the hushed woods in July, the deep shadows, the dense foliage that seems to sleep and softly breathe.

Always the impression—the feeling which he himself felt in the presence of nature and tried to give back in form and color upon canvas. I remember very well standing beside him before his “Niagara” and hearing him say what interested him in that scene. It was not so much the thundering mass of the waters, the volume and power, the sublimity of the cataract, as the impression of clouds of mist and vapor boiling up from the great caldron and being struck into color-splendor by the sunlight. Only an Inness in the presence of Niagara could have thrown emphasis upon so ethereal a phase as its mists and color. They made the impression and he responded to it.

Every feature of landscape had its peculiar sentiment to him. He said so many times and with no uncertain voice:

“Rivers, streams, the rippling brook, the hillside, the sky, clouds—all things that we see—can convey sentiment if we are in the love of God and the desire of truth. Some persons suppose that landscape has no power of conveying [Pg 35]human sentiment. But this is a great mistake. The civilized landscape peculiarly can; and therefore I love it more and think it more worthy of reproduction than that which is savage and untamed. It is more significant.”

That last statement of his about the civilized landscape is well worth noting, because that was the landscape he painted. His subjects are related to human life, and some of our interest in his pictures is due to the fact that he gives us thoughts, emotions, and sensations that are comprehensible by all. He tells things that every one may have thought but no one before him so well expressed. In other words, he brings our own familiar landscape home to us with new truth and beauty. This, it may be presumed, is the function of the poet and the painter in any land. It was the quality that made Burns and Wordsworth great and may account in measure for the fame of Rembrandt, Hobbema, Constable—yes, and Inness.

When he was young there were traditions of the Hudson River school in the air. The “mappy” landscape with its crude color and theatrical composition held the place of honor. Inness was probably captivated by it at first sight, but he soon discovered its emptiness. It had no basis in nature; it was not the landscape we see and know. The “Course of Empire” and the “Voyage of Youth” were only names for studio fabrications. The truly poetic landscape[Pg 36] lay nearer home. This was what Inness called the “civilized landscape,” the familiar landscape, the paysage intime, the one we all see and know because it has always been before us—its very nearness perhaps blinding us to its beauty.

How hard it is to believe that the true poetry of the world lies close about us! We keep fancying that romance is not in our native village, but in Rome or Constantinople or Cairo; and that the poetic landscape is not that of the wood-lot behind the house, but that of Arden Forest or some Hesperidian garden far removed from us. Emerson has noted that at sea every ship looks romantic but the one we sail in. Yet there is plenty of romance in our ship if we have the eyes to see it; and there is abundance of beauty in the wood-lot if we have the intentness of purpose to study it out and understand it. Any one can admire the “view” from a mountain-top, but it takes some imagination to see beauty in the quiet meadow. And after you have seen it it requires a great deal of labor and skill to tell what you have seen. Wordsworth and Constable made more failures with it than successes. Just so with Inness. He shot wide of the mark innumerable times, but when he hit, it was with very decided effect.

A love of the familiar landscape would seem to have always been with Inness. After a period of following the Hudson River panorama of nature undefiled by man, he gave it up. While[Pg 37] in Rome he produced some semiclassic landscapes, but he gave them up, too. Not so with the Fontainebleau-Barbizon landscape. Rousseau and his band had broken with the classic and were producing the paysage intime to which Hobbema (not Constable, of whom they knew nothing) had called their attention through his pictures in the Louvre. They had done in France just what Inness had sought to do in America: they had abandoned the grandiloquent and put in its place the familiar. Inness was in sympathy with them almost from the moment he first saw their work. Had he been born in France, no doubt he would have been a member of the Rousseau-Dupré group.

Again it is worth noticing in passing that all of the so-called “men of 1830” were really provincial in what they produced. Corot painted Ville d’Avray, Rousseau, Dupré, and Diaz the Fontainebleau forest, Daubigny the Seine and the Marne. None of their work represents the south or the east of France, and none of it carries beyond France. It is localized about Paris. Just so with the work of Inness. It is emphatically American, but limited to the North Atlantic States. The appearances which he portrayed are peculiar to the region lying east of the Alleghanies. In his pictures the light and coloring, the forms and drift of clouds, the mists and hazes, the trees and hills, the swamps and meadows may be recognized as belonging to New[Pg 38] Jersey or New York or New England, but none of them belongs to Minnesota or Louisiana or California. He pictured the American landscape perhaps more completely than any other painter before or since his time; but his “civilized landscape” was nevertheless limited as regards its geographical range.

Nor would we have it otherwise. All the masters of art have been provincial so far as subject goes. Titian, Velasquez, and Rembrandt never cared to go beyond their own bailiwicks for material. And Inness—though he may not rank with those just mentioned—found all the material he needed within fifty miles of New York. It was the discovery of this material, his point of view regarding it, what he did with it, and what he made us see in it, that perhaps gives him his high rank in American art.

The man and his impulsive nature never changed, though he kept shifting his methods and his point of view from year to year. He went his own pace and was always something of a recluse. The art movements about him interested him in only a slight way. The Academy of Design honored him with membership, but he cared little about it. The Society of American Artists elected him a member also, but he cared even less for the brilliant painting of the young men than for the weak performances of the academicians. He kept very much to himself and painted on in his own absorbed, impulsive fashion. [Pg 39]His studio was only a bare barn of a room with a few crazy chairs in it. Wall-hangings, stuffs, screens, brass pots, shields, spears—the artistic plunder which one usually finds in a painter’s apartment—he regarded as so much trumpery. In his later days he came and went to his studio from Montclair, seeing landscapes out of the car-window, and in his mind’s eye seeing them upon his canvases. His art swayed him completely.

He had no pupils, though he corrected, advised, and instructed many young painters after his own method. It was a decidedly arbitrary teaching. Elliott Daingerfield tells a story of one of his own landscapes in which a rail fence was running down into the foreground. When Inness was asked in to criticise the canvas, he objected to the fence and said it should be taken out.

“Why can’t I have the fence there if I want it?” Daingerfield protested. To which Inness replied:

“You can if you want to be an idiot.”

His criticism of older painters and pictures was just as unqualified. And in matters outside of art, where he spoke with no peculiar authority, his vehemence was no less. Crossing on the Arizona in 1887, he talked every one out of the smoking-room on the Single Tax question, so a friend informs me. In 1894, when I happened to be crossing with him, he was as positive as ever about his religious, socialistic, and political[Pg 40] convictions. His interest and enthusiasm were in no degree abated. In the mornings he sat on deck wrapped up in rugs under the lee of a life-boat, and amused himself doing examples in vulgar fractions out of an ordinary school arithmetic; but in the afternoon he liked to talk, and I was a willing listener, though I had heard him discourse many times.

Every one remembers his caustic criticism of Turner’s “Slave Ship.” He always had a kick for Turner, though at heart he admired him, and in many respects his own methods were very like that master. They both worked from visual memory, Turner putting in what pleased him in architecture, people, and boats; and Inness putting in cows or bridges or wagons, as pleased him. Neither painter resorted to the model or to a sketch for these accessories. They painted them out of their heads, and sometimes they were vague in drawing or false in lighting. The only difference was that Turner took more liberties with his text than Inness, and often lost truth of tone. This gave Inness his chance to say that Turner was a painter of claptrap—his detail was spotty, he could paint figures in a boat, but he couldn’t paint a boat with figures.

For Gainsborough he had some admiration, and in his early days rather followed him, but he outgrew the brown-fiddle tone of Gainsborough’s foliage and came to think his work lacking[Pg 41] in color. Constable, too, he admired, perhaps because he painted the greens of foliage very frankly; but his light and color were cold. Turner’s heat and Constable’s cold he did not believe could both come out of England, except through subjective distortion. The pictures of Watts, he insisted, looked as though dipped in a sewer, so unhealthy and morbid were they in color. This referred to the later pictures of Watts which Inness had seen in a loan collection exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum. He was fond of brilliant color himself, and evidently he had never studied the earlier and middle-period pictures of Watts. Wilson he liked, though recognizing that he was merely a reviser of the old classic formula of landscape. But Wilson knew how to handle his sky and could tie things together with atmosphere.

Corot was a very pretty painter—and by “pretty,” Inness meant clever. He wagged his head in saying it and smiled as though the statement were incontestable. The sentiment of light and air with Corot was something that Inness thoroughly understood. And he greatly fancied Corot’s composition. At one time he painted pictures that have a Corotesque arrangement—notably the “Wood Gatherers,” formerly in the Clarke Collection. What he did not understand was Corot’s monotony of color, or, as other painters expressed it, Corot’s refinement of color. Millet was wonderful, especially in his landscape-work,[Pg 42] which had attracted so little attention. Delacroix was one of the great gods for his wonderful gamut of color, if nothing else. And so on.

The steamer trip in 1894 was the last one that Inness made. He died that summer at the Bridge of Allan in Scotland. His funeral was held in the National Academy of Design in New York, and the Swedenborgian minister who officiated, in the course of his eulogy, said: “Those of you who knew George Inness knew how intense a man he was.” “Intense” is exactly descriptive of the man. He was keyed up all his life and worked with feverish intensity. But the word does not describe his art, for that has no feeling of stress or strain about it. Sometimes one is conscious of its vagueness, as though the painter were groping a way out toward the light—a vagueness that holds the mystery of things half seen, a beautiful glimpse of half-revealed impressions. But usually his pictures are serene, hushed, and yet radiant with the glow of eternal sun-fires from sky or cloud.

They were lofty and poetic impressions, and the loftier they were the more intense the painter’s effort to reveal them. The heights of Parnassus are very calm, but they are not reached without a struggle. The great ones—those who scale the upper peaks—are perhaps the most intensive strugglers of all. Inness was one of them.

[Pg 43]

[Pg 45]

III

It was Corot who declared that in art Rousseau was an eagle and he himself was merely a lark singing a song from the meadow-grasses. The contrast and the comparison are not inapplicable to two of our own painters. Wyant never possessed the wide range or the far-seeing eye of Inness, but he had something about him of Corot’s mood and charm. He, too, was a lark, or should we say a wood-thrush singing along the edge of an American forest? He had only a few mellow notes, yet we would not be without them. They still charm us. And it is not certain that in the long account of time the direct and simple utterances of Corot and Wyant may not outlive the wide truth of Rousseau and the vision splendid of Inness. More than once in æsthetic story the songs of a Burns have been held more precious than the tumults of a Milton.

The wonder of Wyant’s success is greater than that of Inness, for his boyhood surroundings, if anything, were less stimulating and his pictorial education far more restricted. Besides, Inness lived on to seventy years, but Wyant died at fifty-six, having endured ill-health, and for[Pg 46] the last ten years of his life—his best working years—been paralyzed in his right arm and hand. Living much to himself, something of a hermit in his mountain home, weighed down by misfortunes and disappointments, the wonder grows that he not only kept up and improved his technique to the end, but that he preserved his serenity of mood and purity of outlook through it all. He must have been a man with fortitude of soul beyond the average. It is not every painter that can turn stumbling-blocks into stepping-stones.

Wyant was the typical barefoot boy of the near West in the days before the Civil War. He was born in 1836 at Evans Creek, Tuscarawas County, Ohio, and his boyhood and early youth were far removed from anything like the madding crowd. His parents were Americans of the soil, his father being a farmer and carpenter of Pennsylvania extraction, and his mother of Dutch-Irish descent. They were nomadic, after the manner of border people, and soon left Evans Creek to live in or near Defiance, where Wyant learned his three R’s in the village school. There were less than one thousand people in the town at that time, and what Wyant got out of it by way of enlightenment or encouragement must have been meagre. As a boy he, no doubt, roamed the woods, fished the streams, and trailed along the Ohio hilltops; and at this time, unconsciously perhaps, he was storing up[Pg 47] visual memories of appearances that were to be of service to him later on.

That he had an eye and was an observer from the start comes to us in the tales told of his boyish sketches on the floor made with charcoal from the wood-fire. At least they showed an inclination that was afterward to develop into a passion. But the inclination found no immediate outlet. After leaving school the youth served as an apprentice in a harness-shop, but he did not care for harness-making. He preferred to paint photographs, cards, signs—almost anything that could be done with a brush. At twenty-one he went to Cincinnati and for the first time saw some paintings in oil. Before that his ideas of art had been bounded by book illustration and the omnipresent chromo. It is said that among the pictures he saw at Cincinnati was something by Inness. The young man was impressed by it, or by the reports about Inness, for he took the train to New York to consult that master about art as a vocation.

He found Inness at Eagleswood, near Perth Amboy. How long he stopped there and what was said we do not know, but the master was encouraging, and the young man went back to Cincinnati determined to be a painter. He had a right instinct about art at that early time or he never would have chosen Inness for a counsellor. The famous landscape-painters then were[Pg 48] Kensett and Church. Inness was the most progressive, the most ultra-modern of the time, and had not yet won universal applause. He did not paint enough in detail for the man in the street, and evidently he must have given Wyant his argument for breadth of view over detail, for, as we shall presently see, Wyant had it almost from the start. But perhaps the most and the best that he got from Inness was inspiration.

Back in Cincinnati and painting pictures after his own formula, Wyant found a purchaser and a patron in Nicholas Longworth. It became possible for him shortly thereafter to move to New York. There, in 1863, he saw a large exhibition of Düsseldorf pictures that probably stirred his imagination. Pictures in America at that time were rather scarce, and any exhibition of foreign work would be more impressive then than now. The next year he exhibited at the National Academy of Design for the first time, and in 1865 he went to Europe on a Düsseldorf pilgrimage, impelled thereto by a mountain-and-waterfall landscape of Gude which he had seen in New York.

He went straight to Gude at Carlsruhe and put himself under his tutelage. Gude was a Norwegian painter, influenced by Dahl, and imbued with the Düsseldorf method and point of view. The grand landscape—panoramic in extent and mountainous in height, with a hot sun[Pg 49] in the heavens—was then in vogue, and Achenbach was its prophet. From Wyant’s short stay with Gude it seems that his enthusiasm was soon chilled down to zero. In after-life he often referred to the great kindness of Gude and his wife, but he seemed to think that his instruction in art had been fundamentally wrong. His pupil, Bruce Crane, says that he spoke of his art environment there as being “a miserable one,” and Wyant believed that “environment played the greater part in the making of a painter for good or bad.”

He left Gude and started back to America, but stopped on the way in England and Ireland, where he studied pictures and painted some of his own. The old masters in the National Gallery apparently did not make a strong appeal to him. His work shows no sign of Claude, Salvator, Poussin, Ruysdael, Hobbema, or Cuyp. Even Gainsborough and the ascendant Turner seem to have left him cold. But Constable he liked very much. Here at last was a man seeing things in a large way and doing them with breadth of brush. Moreover, he was doing simple transcripts of nature, not the panorama of blazing perspective. In America Wyant had inherited something of the spectacular from his Hudson River predecessors; Düsseldorf had aided the conception, and Turner had abetted it; but Constable seemed to be against it. Wyant was inclined to renounce it. Constable produced[Pg 50] the broad realistic look, and at that time Wyant had probably not arrived at any other conception of art than as a large transcript of nature. Ruskin’s doctrine of fidelity to fact was in the air, and the landscape as emotional expression, or as a symphony, or even as a decorative pattern, was little known either in the studios or the critic’s den. There was, however, plenty of controversy going on. And yet fresh from varying theories and impressions, Wyant went over to Ireland and painted pictures that bore no earmark of any painter or any school.

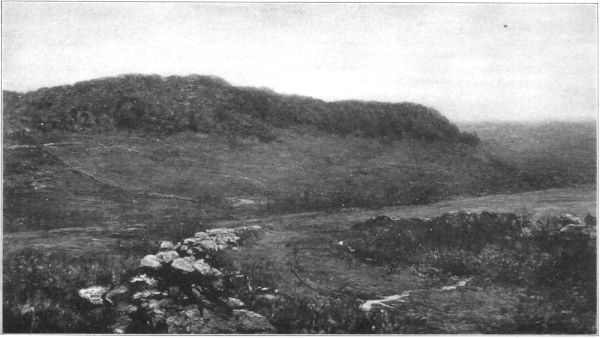

In the Metropolitan Museum there is an Irish landscape by him done in 1866—“View in County Kerry, Ireland.” There are gray mountains at the back, a green foreground with a pool of water, a gray-blue and whitish sky, a gray atmosphere. At the right middle distance is a white cottage. The rest is treeless upland running into mountain heights that are lost in haze and cloud. The picture is not only remarkable for its simplicity of composition but its absence of small objects or distracting details. Though a mountain landscape, it is broadly seen, largely and simply massed, and painted with a broad flat brush. It may have been repainted in later years, but I am willing to believe from the breadth of its composition that it was painted broadly to correspond, and is to-day substantially as when originally done.

This picture is in somewhat violent contrast[Pg 51] with another Wyant landscape hanging in the same gallery and dated in the same year—1866. I refer to the large “Mohawk Valley” landscape—an excellent picture, though evidencing limitations perhaps peculiar to America. It is a huge valley view with a gorge and stream in the foreground running down to a fall from which mist is rising. The stream as a pool is seen again emerging in the middle distance. A half-lighted sky with falling rain at the left and warm grays of clouds and blues of distance make up the background, while in the foreground a tall tree at the left is balanced by a group of lesser trees at the right. The whole color-tone is warm (probably from underbasing), especially in the foreground, which shows in grays and browns. It is a symmetrical composition with a central point of sight, and in its detailed elaboration gives no hint of selection or sacrifice. The trees, the ledges of rock in the foreground, the water, the clouds are all exactly drawn and realized to the last item, each one having quite as much importance as its fellow. As for the painting, it is thin, kept thin to allow the underbasing to show through; but it is flatly painted, not stippled. In the latter respect it is an advance on, say, Church’s panorama, “Heart of the Andes,” in the same gallery, where the stippling with white paint produces a glittering, bedizened surface, and the minute drawing of leaves in the foreground runs into petty niggling.

[Pg 52]

Now, the “Mohawk Valley” was probably completed just before Wyant went to Europe; at least in method it antedates the “County Kerry, Ireland,” landscape of the same year.[1] It is a very important picture and represents the culmination of Wyant’s early style—a beautiful picture for any place or period or painter to have produced. It shows Wyant’s original point of view, with some of the influences that must have come to him from the Hudson River school, from Inness, from various unknown American sources. But the “County Kerry, Ireland,” landscape shows a departure, a widening, and a broadening of both brush and vision which were to increase and expand thereafter into a second style—the style of Wyant’s later and nobler canvases. To this style Wyant was undoubtedly helped at first by what he saw abroad, especially by the pictures of Constable.

[1] “In regard to the two pictures in the Metropolitan Museum, ‘View in County Kerry, Ireland,’ and the ‘Mohawk Valley,’ I never could reconcile myself to the idea that they were both painted in 1866. There is no doubt about the ‘Mohawk Valley’ because its manner is so much like the many canvases of that period which Wyant often showed me and which Mrs. Wyant destroyed after his death. The ‘View in County Kerry, Ireland,’ marks a new period in his art and the widely different handling as well as view-point are too much to have been acquired in one year. There is certainly some mistake in the date—I should say a difference of ten years. At some time that picture has been cleaned and the restorer accidentally destroying the date restored it incorrectly.”—(Bruce Crane in a letter to the writer, December 13, 1917.)

This was a time of rapid production with Wyant and he was always afire with his theme. The recognition of artists was coming to him if not the large patronage of the public. His picture [Pg 53]of a “View on the Susquehanna” resulted in his being elected an associate of the National Academy in 1868, and he was named a full academician in 1869. But ill-health was with him, and in the hope of improving his physical condition and at the same time gathering material for his art, he joined in 1873 a government expedition to New Mexico and Arizona. There were many hardships on the trip, and Wyant’s never very robust constitution broke down under the strain. He was put on the train and sent back East. It is said that on the way East he passed his home town of Defiance, but would not get off. Ill as he was, with few friends and less money, he determined to go on to New York and fight it out. The fine courage of all that becomes more marked when we understand that the illness was so severe that it had resulted at Fort Wingate in paralysis of his right hand and arm. He was never to paint with his right hand again. It was a crippled painter coming back to New York—crippled in a vital spot—but he had determined that his left hand should be trained to service. And it was.

The West not only maimed him physically but apparently taught him nothing artistically. The deserts that he crossed with their red porphyry mountains, dull-yellow sands, and gas-blue air—the most wonderful landscapes in the world in their definition of form and their quality of color—seem to have made no impression[Pg 54] whatever upon him. This is understandable only by considering the inheritance of tradition and environment. In Wyant’s time a handsome landscape meant a mountain-valley with forests, rocks, waterfalls, and the variegated foliage of summer or autumn. The desert was unknown and remained for a later generation of painters to discover; the plains were unpainted and thought unpaintable; even the marsh and the meadow, which Corot loved, were considered too slight for art. The grand-view conception in landscape-painting died hard. In Wyant’s time it was very much alive. Naturally enough, he was impressed by it, and though in later life he did many small intimate bits of nature, he never got away entirely from the wide mountain-valley theme.

He was, in fact, always a mountain lover. After his return to New York he spent much of his summer-time in the Adirondacks. He was then deeply interested in the pictures of the Barbizon-Fontainebleau painters which were coming into the United States. So outspoken was his admiration for Rousseau that he sent a picture to the Academy with the title “In the Spirit of Rousseau.” His own style was growing broader and simpler each year, and, strange enough, the public was buying his pictures. He became measurably prosperous, had a studio in the Y.M.C.A. Building in Twenty-third Street, and received a number of pupils. One of his pupils, a Miss Locke, he married in 1880.

[Pg 55]

After his marriage much time was spent in the Keene Valley, and in 1889 he moved to Arkville in the Catskills, where with a fine sweeping outlook from his porch upon woods, valleys, and hills he found enough material to last him the rest of his life. He saw little of the town thereafter. He had never mingled freely with his fellow man. The Society of American Artists had honored him with membership in 1878, he was a founder of the American Water-Color Society, and a member of the Century Association, but he always held somewhat aloof from them. Friendly enough with painters and people who sought him, he was, nevertheless, a little shy, which perhaps gave him the reputation of being gruff. He seemed less fitted to the city street than the aisle of the forest. It was in his mountain home on the forest edge that he died in 1892, having suffered much physical pain before his going.[2]

[2] “I met Wyant in 1876; his right arm was then practically useless. Later on his right side was affected, and the last six years he was compelled to walk sideways. Yet through all these years of suffering he worked day and night, and during the last six years, when his suffering was the worst, he recorded on canvas some of the beautiful things that survive him.”—(Bruce Crane, ibid.)

Like many another painter, Wyant doubtless knew infinite regrets that he could not live to complete his art. For he never believed in his having reached a final goal, and was always changing, experimenting, trying to better his work. My first meeting with him must have been in 1882. I seem to remember him seated before[Pg 56] a picture with his palette fastened to the easel, his right arm hanging rather limp, and his left hand holding a brush. There was nothing noteworthy about the meeting except that his first words were a request that I should tell him what was wrong with the picture on the easel. He was so anxious to get a new view-point that he was quite willing to listen to a stranger, whether he spoke with authority or not. Of course I did not venture to say anything other than in praise of the canvas, though as I now remember it the picture was bothering him and looked a little tortured in its surface.

He worried a good deal over many of his pictures. When Inness came in to see him he relieved the strain in his impetuous way by taking up Wyant’s palette and brushes to add a touch here and there. The result usually was that the canvas grew into an Inness before the acquiescent Wyant’s eyes. There was so much of this that Mrs. Wyant finally forbade Inness her husband’s studio—at least that is the story told by the Inness family. But Wyant would do anything, submit to anything, for the love of painting. Bruce Crane writes me:

“How that man did love to paint! I often thought he worked too hard, sometimes failing to get his breath between canvases. He wished always to be alone so that he could paint, paint, not for praise nor emolument; never with the thought of reward. I recall Z. visiting the studio[Pg 57] one day and remarking that he, Z, would like to be considered the best landscape-painter in America. After he left, Wyant said: “What a h—— of an ambition!”

Loving the mountains and the forests as he did, it was to be expected that he would use them in art. It was his earliest inheritance and his latest love. Any one at all familiar with the Adirondacks or the Catskills will recognize in Wyant’s landscapes not their topography, perhaps, but their characteristics. The valleys, the side-hills with outcropping rock, the pines, beeches, and birches, the little streams and pools, the clearings with their brush-edgings, are all there. Wyant arranged them in his pictures with the skill of a Japanese placing flowers in a pot. He made not so much of a bouquet as an arabesque of trees and foliage, illuminated by sunlight filtered through thin clouds at the back and warmed with golden-gray colors. Atmosphere—the silvery-blue air of the mountains—held the pattern together, lent it sentiment, sometimes (with shadow masses) gave it mystery.

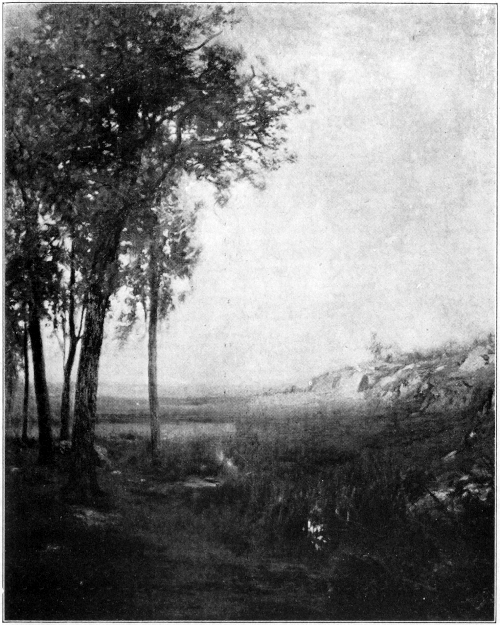

Perhaps the best illustration of this in any public gallery is the “Broad Silent Valley” in the Metropolitan Museum. It is doubtful if Wyant ever expressed himself better or more completely than in this picture. It is a large upright canvas, the very shape of which adds to the dignity and loftiness of the composition placed upon it. At the left are half a dozen large[Pg 58] trees, at the right a rocky hillside, in the central plane a reflecting pool of water, at the back a high, clouded sky, radiant with the light beyond it. Simple in materials, not brilliant in color but rather sombre in tones of golden gray, devoid of any classic or romantic interest, it is nevertheless profoundly impressive in its fine sentiment of light, air, and color. It is as strong almost as a Rousseau in its foreground and trees, and as charming as a Corot in its light and air. But you cannot detect either Corot or Rousseau in it. When it was painted, Wyant was greatly taken with those painters, but he did not imitate or follow them. His pictures were always his own—the “Broad Silent Valley” not excepted.

The beauty and charm of its sentiment with the wonder of its strong mental grasp are paralleled by the workmanship displayed. Looking closely at the canvas, one finds it not heavily loaded, but dragged broadly and laid flatly with pigment. The ground has been underbased in warm browns, the shadows kept transparent and distant by glazes, the lights put in with opaque pigments. The handling is very broad if thin, and there has been little or no kneading or emendation or fumbling. It is straightforward flat painting of a masterful kind. And this was done with that late-trained left hand!

“Broad, Silent Valley,” by Alexander H. Wyant.

In the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As for the drawing, it does not bother with the edges of objects, but concentrates force on the body and bulk—the color mass. Wyant had [Pg 59]learned linear drawing with the exactness of a Durand and used it in his early pictures, but he soon outgrew the fancy for photographic detail. It was not effective. And he could give the solidity of a ledge of rock or the lightness of a floating cloud much better with a broader brush. As he grew in art his brush continued to broaden. His work became more sketchy, his brush freer and fuller, and possibly before he died he may have heard his work referred to as “impressionistic”—heaven save the word!

The general public usually regards any breadth of brush-work whatever as a sign of impressionism. The term in its present meaning, or lack of meaning, covers a multitude of stupidities. Every one who paints gives an impression because he cannot give anything else. Realism is a misnomer. The real is nature itself, and art is the report about the real made by the painter. If it is a minute report of surface detail that can be seen through a magnifying-glass the public immediately dubs it realistic; if it is a broad report that ignores the surface detail for bulk, mass, and body, it is called impressionistic. But the difference is merely between the smallness and the largeness of the view-point. The great landscapists have usually regarded a tree as more important in its shadow masses and volume than in its leaves, a rock as more impressive in its weight than its veins or stains, a bar of sunlight more striking in its luminosity than in its[Pg 60] sharp-cut edges. Seeing and painting that way it is easy to comprehend how they should be set down as impressionists when in a large sense they are making more faithful record than the men who see only the surface glitter. Such men were Corot, Constable, Inness, Wyant, not to mention Manet or Monet.