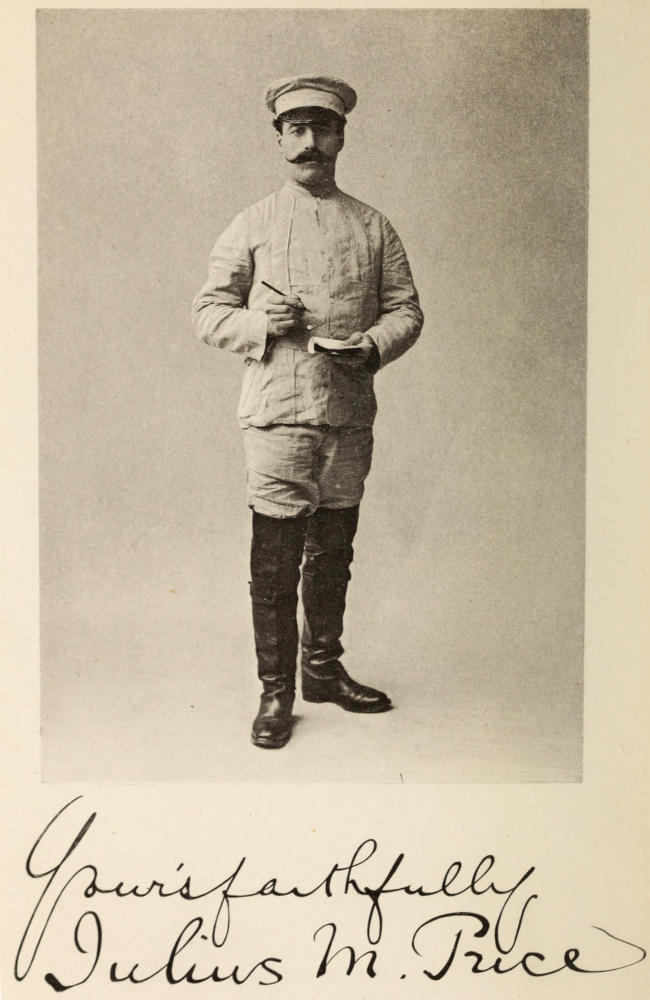

Your’s faithfully

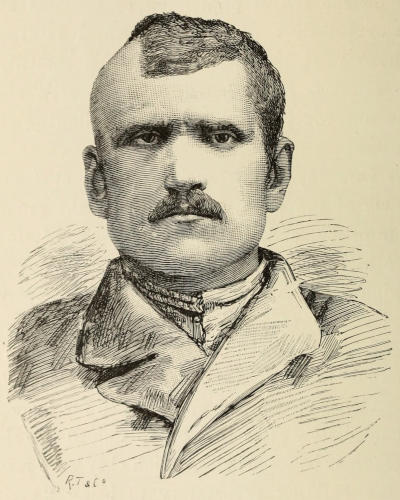

Julius M. Price

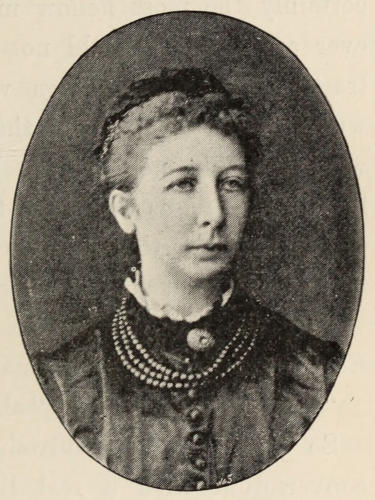

From a photograph by Alfred Ellis. Sampson Low, Marston & Co. Ltd. Héliog Lemercier & Cie Paris.

I am indebted to the proprietors of the Illustrated London News for their kind permission to reproduce in this work the sketches and drawings I made for them whilst on my journey, a great many of which have already appeared in that paper; and also for the use of the text accompanying them, which has formed the basis of this work.

Your’s faithfully

Julius M. Price

From a photograph by Alfred Ellis. Sampson Low, Marston & Co. Ltd. Héliog Lemercier & Cie Paris.

FROM THE ARCTIC OCEAN

TO THE YELLOW SEA.

THE NARRATIVE OF A JOURNEY,

IN 1890 AND 1891, ACROSS SIBERIA, MONGOLIA,

THE GOBI DESERT, AND NORTH CHINA.

BY

JULIUS M. PRICE, F.R.G.S.,

Special Artist of the “Illustrated London News.”

WITH ONE HUNDRED AND FORTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS

FROM SKETCHES BY THE AUTHOR.

NEW YORK:

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS,

743 AND 745, BROADWAY.

1892.

Before leaving Siberia, probably for ever, I am desirous of recording my gratitude for the assistance afforded me and the many kindnesses I received during the winter I spent there. From the highest officials to the humblest employé, the courtesy I was shown on all occasions was so great, that in all my varied experiences of travel I remember nothing to equal it; and if it is the same all over this mighty empire, I trust that my wanderings will lead me some day into Greater Russia itself. Amongst the many gentlemen to whom I owe a special debt of gratitude. I may mention Mr. E. Wostrotine, in Yeniseisk; General Telakoffsky, Dr. Peacock, and Messrs. Cheripanoff, Matwieff, and Kusnitsoff, in Krasnoiarsk; General Grimiken, M. Soukatchoff, and Mr. Charles Lee, in Irkutsk; and M. Feodroff and M. Shollingen, in Ourga.

J. M. P.

A few introductory remarks are, I feel, necessary, if only to give the raison d’être of my journey, and as a sort of apology for adding to the already formidable array of books of Asiatic travel.

The celebrated voyage of Captain Wiggins in 1887, when he successfully accomplished the feat of navigating a steamer (the Phœnix) across the Kara Sea and up the river Yenisei to the city of Yeniseisk, is too well remembered for it to be necessary for me to recapitulate an exploit which is destined to become historic, solving as it did the much-vexed question of the practicability of establishing commercial relations between England and Siberia viâ the Arctic Ocean and the Kara Sea.

This successful expedition, opening up such immense possibilities, naturally encouraged its financial promoters to follow it up by another and much more important one. Towards the end of July in the following year, therefore, the Labrador, a powerful[viii] wooden steamer specially built for Arctic work, was despatched to the mouth of the Yenisei with a cargo of “all sorts,” with which to try the Siberian market; the Phœnix, which had been laid up for the winter at Yeniseisk, being commissioned to proceed down the river and fetch back the cargo brought out by the Labrador, the latter vessel being too large to be able to get such a distance from the estuary. For all this, special permission had naturally to be got from the Russian Government; but so far from making any objections or putting any obstacles in the way of the scheme, the officials, advised of course from head-quarters, lent every assistance in their power and showed a most friendly spirit. Through a diversity of causes, into which it is not necessary to enter here, the expedition failed to accomplish its purpose, and the Labrador returned to England without having crossed the Kara Sea at all. An ordinary man would have been discouraged, at any rate for a time, by such a failure; but Wiggins is not of that stuff. Nothing daunted, he at once began trying to raise “the sinews of war” for a fresh expedition, and was so successful (such confidence had his friends in him), that the following year the Labrador once again started for the far North-East—but only to meet with another failure, though this[ix] time the failure, it was proved afterwards, could have been easily averted. In fact, so conclusively was this proved, that, emboldened with the knowledge of how near it had been to being a success, a syndicate of rich and influential London men was without difficulty got together, and it was at once decided that two ships should be sent out the following year, and that everything possible should be done to ensure success. This time there were no half-hearted measures; money was forthcoming, and with it a renewed enthusiasm in the scheme, which, I may add parenthetically, helped not a little to bring about its eventually satisfactory result; this notwithstanding the fact that the expedition started handicapped by the untoward absence (owing to his having met with shipwreck on his way to join us) of Captain Wiggins, the leading spirit of the project.

Talking about Russia one morning with Mr. Ingram at the office of the Illustrated London News, he suddenly suggested my going out as their “special artist” with this expedition. The love of travel and the spirit of adventure are so strong in me, that without the slightest hesitation I eagerly caught at the idea; in fact, had he suggested my riding across the Sahara on a bicycle I should probably have jumped at it with just as much alacrity.

Well, to cut a long story short, after a lot of correspondence had passed between us, the “Anglo-Siberian Trading Syndicate” agreed to take me, subject to certain restrictions as to publication of sketches and matter relating to the expedition, and to land me eventually, if all went well, at the city of Yeniseisk, in the heart of Siberia. On my taking a map of the route down to the office, and asking Mr. Ingram where I was to go if I ever found myself there, “You can go wherever you like, so long as you send us plenty of interesting sketches for the paper,” was his generous reply. With liberty, therefore, to roam all over the world, so to speak, and with unlimited time and plenty of means at my disposal, I started on a journey, the narrative of which I now venture to put in print, in the hope that at any rate some parts of it may give a few fresh facts about the vast continent I traversed from north to south.

In conclusion, I must candidly confess I arrived in Siberia with foregone conclusions derived from the unreliable information and exaggerated stories so current in England about this part of the world. How far my subsequent experiences dispelled the prejudices with which I started, the reader of my narrative may judge for himself. I have touched but en passant on the exile and prison system, for nothing[xi] was further from my thoughts, when I undertook the journey, than to make a profound study of this question. Efforts in this direction have been made both by prejudiced and unprejudiced writers, all of whom, however, are agreed on the main point, that the system is an anachronism and unsuitable to the present age. What I felt was that in Siberia, that vast country with such immense natural resources, there must be much which would be novel and interesting to study in its social aspect, apart from the actual prison life and hardships with which the name of Siberia has always been associated; so I determined to devote my chief attention to phases of life which are still, in general, so little known that to many readers, probably, much that I have attempted to describe in these pages will come, as it did to me, in the light of a revelation.

JULIUS M. PRICE.

Savage Club, London,

March, 1892.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. FROM BLACKWALL TO SIBERIA. |

|

| The object of the expedition—The steamer Biscaya and its passengers and cargo—Across the North Sea—Uncomfortable experiences—First glimpse of Norway—Aalesund—The Lofoden Islands—The midnight sun—A foretaste of the Arctic regions—“Cape Flyaway”—Our ice-master, Captain Crowther—We sight the coast of Siberia—The village of Kharbarova—The entrance to the Kara Sea | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. THE KARA SEA. |

|

| In the midst of the ice-floes—Tedious work—Weird effects at twilight—A strange meeting—We pay a visit to the home of the walrus-hunter—Curio-hunting—A summer morning in the ice—Delightful experience—The Arctic mirage—We part from our new friends—An uncertain post-office—Ice-bound—Novel experiences—Seal-hunting | 16 |

| CHAPTER III. THE KARA SEA—continued. |

|

| Further impressions of the Arctic regions—The awful silence—Average thickness of the ice—On the move[xiv] once more—A fresh danger—A funny practical joke—The estuary of the River Yenisei—Golchika—A visit from its inhabitants—From Golchika to Karaoul | 27 |

| CHAPTER IV. THE PORT OF KARAOUL AND ITS INHABITANTS. |

|

| The tundras of Northern Siberia—The Samoyedes—Arrival of the Phœnix—My first Russian meal—Vodka and tea—Our departure for Kasanskoi | 36 |

| CHAPTER V. KASANSKOI. |

|

| Our Russian customs officer—A shooting-excursion—Visit to the settlement of Kasanskoi—The house of a Siberian trader—Interesting people—First experience of Russian hospitality—The return of the Phœnix—Departure of the Biscaya | 48 |

| CHAPTER VI. THE RIVER VOYAGE OF THE PHŒNIX UP TO YENISEISK. |

|

| The Yenisei river—Its noble proportions—Scenery along the banks—The first tree—Our first mishap—The return of the tug—An exciting incident | 60 |

| CHAPTER VII. THE RIVER VOYAGE—continued. |

|

| An awful fatality—Misfortune follows misfortune—M. Sotnikoff—Selivanaka, the settlement of the Skopti—A visit from the village “elder” | 70[xv] |

| CHAPTER VIII. TURUCHANSK. |

|

| Visit to the monastery—Werchneimbackskoi—Our first visit from official Russia—The police officer of the district—The village priest | 80 |

| CHAPTER IX. THE KAMIN RAPIDS. |

|

| A whole chapter of accidents—First touch of winter—Arrival at Yeniseisk | 88 |

| CHAPTER X. THE CITY OF YENISEISK. |

|

| Custom-house officials—Novel sights in market-place and streets—My lodgings—Siberian idea of “board and lodging”—Society in Yeniseisk— A gentleman criminal exile | 97 |

| CHAPTER XI. THE CITY OF YENISEISK—continued. |

|

| A visit to the prison—First impressions of the Siberian system | 107 |

| CHAPTER XII. YENISEISK—continued. |

|

| The hospital—Siberian houses—Their comfort—The streets of the city | 117[xvi] |

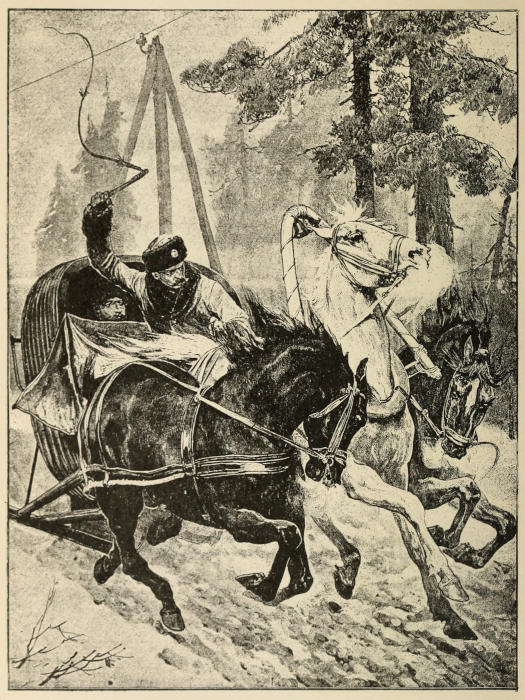

| CHAPTER XIII. FROM YENISEISK TO KRASNOIARSK. |

|

| My first experience of sledging—A delightful adventure—Krasnoiarsk—The market-place—The High Street | 123 |

| CHAPTER XIV. KRASNOIARSK—continued. |

|

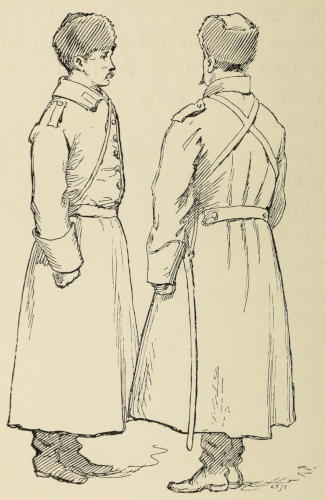

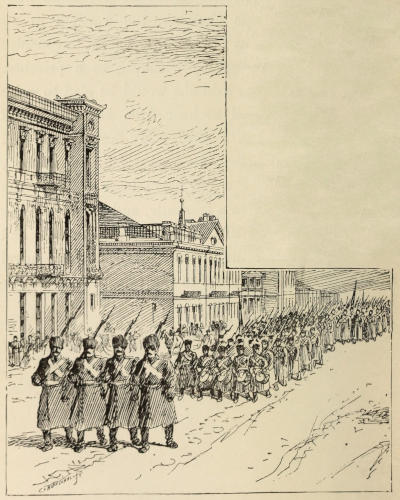

| Privileged criminal exiles—Ordinary criminals—A marching convoy on the road—Convoy soldiers—The convoy—Proceedings on arrival at the Perasilny of Krasnoiarsk—The staroster of the gang—A stroll round the Perasilny—The married prisoners’ quarters—A “privileged” prisoner in his cell—Scene outside the prison—Prison labour—I give it a trial—Details as to outside employment of prisoners | 134 |

| CHAPTER XV. MY JOURNEY FROM KRASNOIARSK TO IRKUTSK. |

|

| My servant Matwieff—The Great Post Road—The post-houses—Tea caravans—Curious effect of road—Siberian lynch law—Runaway convicts—A curious incident—The post courier—An awkward accident—Arrival at Irkutsk | 156 |

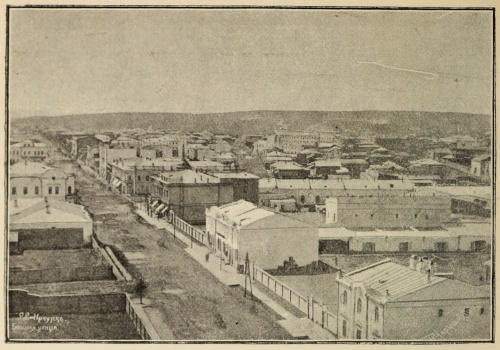

| CHAPTER XVI. IRKUTSK. |

|

| Unpleasant experiences at hotel—Hospitality of Mr. Charles Lee—First impressions of the city | 180[xvii] |

| CHAPTER XVII. PRISON LIFE IN SIBERIA—continued. |

|

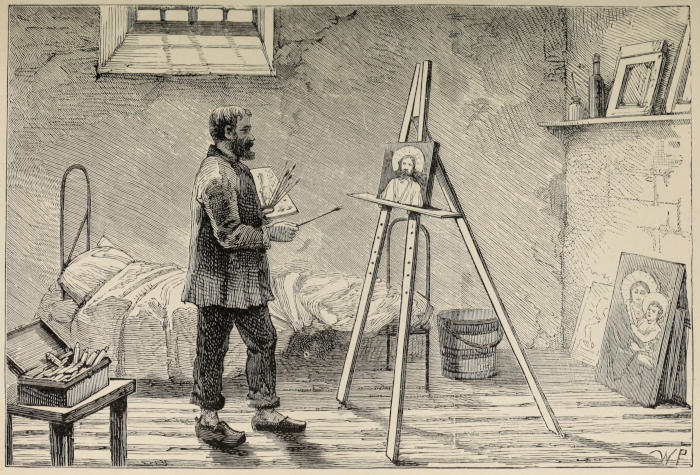

| The Irkutsk prison—Comparative liberty of prisoners—Incongruities of prison life—The “shops”—Prison artists | 192 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. PRISON LIFE IN SIBERIA—continued. |

|

| Outdoor employment of prisoners—A chat with an employer of convict labour—The “convict’s word”—An interview with a celebrated murderess—The criminal madhouse—Political prisoners in solitary confinement—I get permission to paint a picture in one of the cells—End of my visits to the prison | 198 |

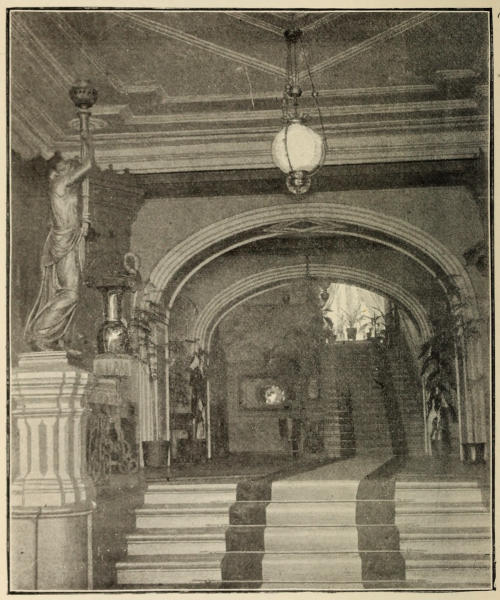

| CHAPTER XIX. IRKUTSK—continued. |

|

| A gold-caravan—Particulars as to the gold-mining industry of Siberia—The Foundling Hospital—The fire-brigade—Celebration of the Czar’s birthday—Living in Irkutsk | 208 |

| CHAPTER XX. FROM IRKUTSK TO THE MONGOL CHINESE FRONTIER. |

|

| My journey to Kiakhta, the city of the tea princes—Across Lake Baikal on the ice—Interesting experiences | 221[xviii] |

| CHAPTER XXI. FROM IRKUTSK TO THE MONGOL CHINESE FRONTIER—continued. |

|

| The road from Lake Baikal to Kiakhta—The “Kupetski track”—Incidents on the way—I change my sledge for a tarantass—Exciting adventures—Arrival at Troitzkosavsk, the business suburb of Kiakhta | 235 |

| CHAPTER XXII. ACROSS MONGOLIA. |

|

| The Russo-Chinese frontier—Maimachin—The Mongols of to-day—Curious customs—Hair-dressing extraordinary—A pestilent farmyard—Exciting incidents—A forced encampment—An awful night’s experiences—The Manhati Pass—Magnificent scenery—I pull off a successful “bluff”—“Angliski Boxe” in the wilds of Mongolia—Arrival at Ourga | 249 |

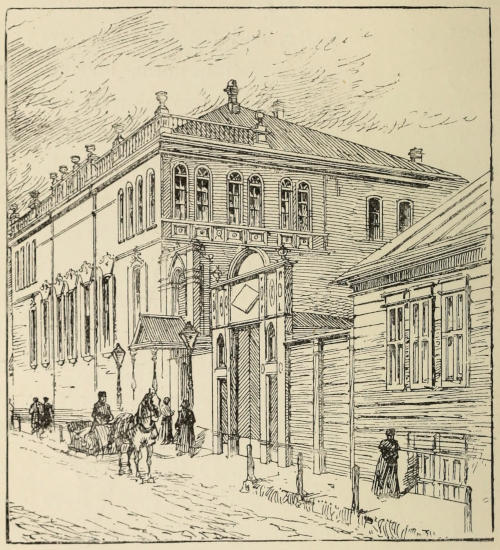

| CHAPTER XXIII. THE SACRED CITY OF OURGA. |

|

| The Russian consul, M. Feodroff—Hospitality of the Consulate—The “lions” of Ourga—The colossal statue of the “Maidha”—The “Bogdor of Kurene”—An impromptu interview—Prayer-wheels—Praying-boards—Religious fervour of the Mongols | 272 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. FROM OURGA TO THE GREAT WALL. |

|

| My preparations for the journey across the Gobi Desert—The Russian Heavy Mail—My camel-cart—Good-bye to Ourga—The first few days out—Discomforts of the journey—The homeward-bound mail—The desert settlement of Tcho-Iyr | 301[xix] |

| CHAPTER XXV. THE GOBI DESERT—continued. |

|

| Sport in the desert—The “post-station” at Oud-en—The last of the desert—Saham-Balhousar—First impressions of China—Chinese women—Returning to sea-level—Curious experience—The eclipse of the moon—Arrival at Kalgan | 318 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. KALGAN TO PEKING. |

|

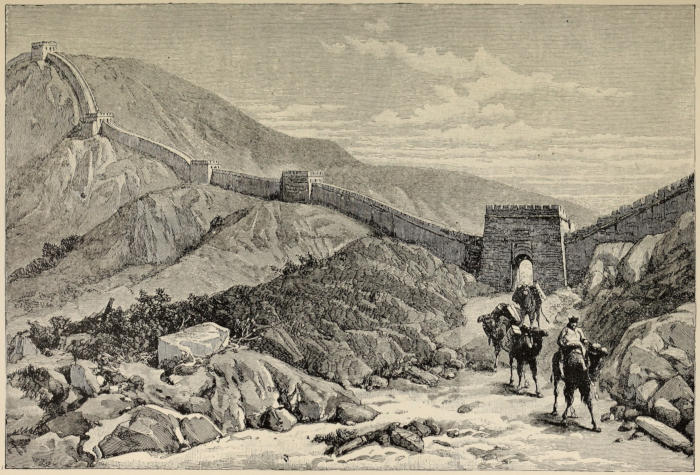

| A hearty welcome—Yambooshan—The Great Wall of China—American missionaries—My mule-litter—From Kalgan to Peking—Scenery on the road—Chinese inn—First experience of a Chinese dinner—Amusing rencontre—The Nankaou Pass—The Second Parallel of the Great Wall—First impressions of Peking—The entrance to the city | 331 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. PEKING. |

|

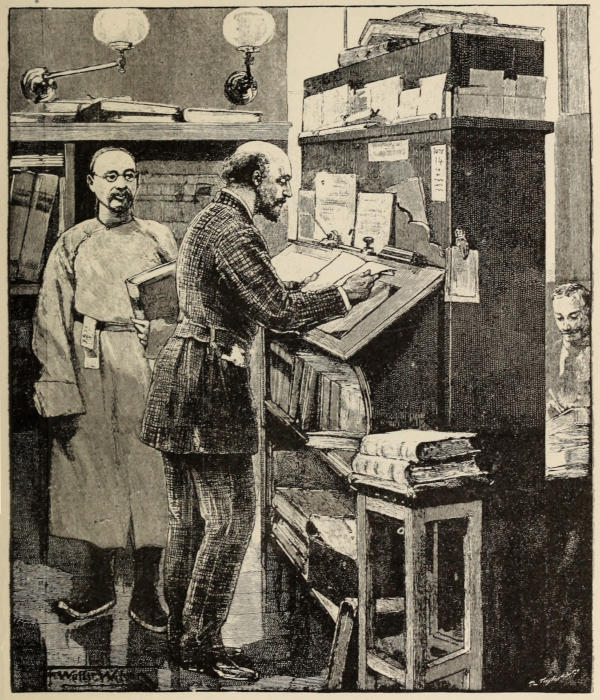

| Exciting times—A chat with Sir John Walsham—The Chinese city—Horrible scenes—Social life at the Legations in Peking—Lady Walsham’s “At homes”—The hardest-worked man in the East—Interesting evening with Sir Robert Hart—His account of his life | 353 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. PEKING (continued)—AND HOME. |

|

| Difficulty of sketching in the streets—My journey from Peking to Tientsin—A Chinese house-boat—The Peiho River—Tientsin—From Tientsin to Shanghai—And home | 371 |

| PAGE | |

| The “Biscaya” leaving Blackwall | 1 |

| Preparations for the Arctic Regions | To face 8 |

| A “Dead Reckoning” in the Kara Sea | 10 |

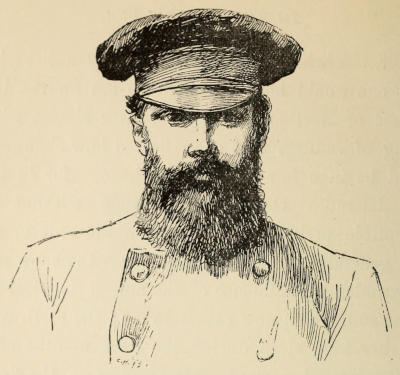

| Our Ice-master, Captain Crowther | 13 |

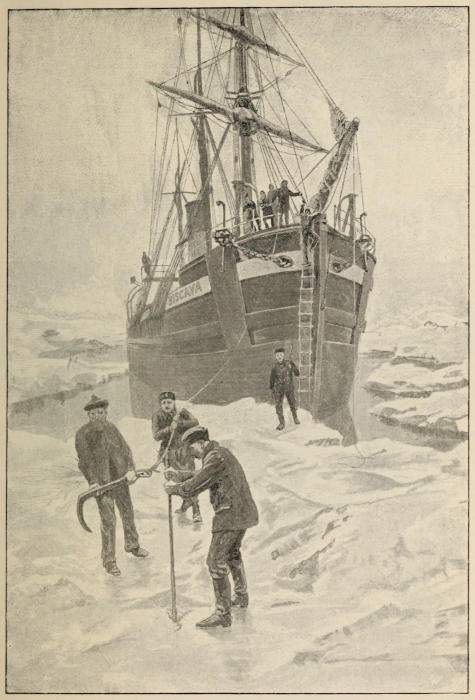

| Clearing the Drift Ice from the Propeller | 16 |

| The Home of the Walrus-hunter | 20 |

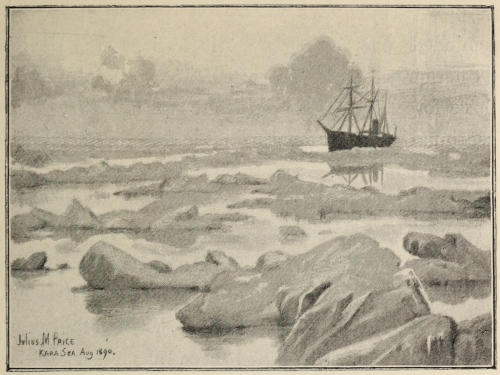

| The “Biscaya” Ice-bound in the Kara Sea | To face 24 |

| After Seals | 25 |

| “One Speck of Life in the Ice-bound Waste” | 27 |

| The Handsomest Member of his Family | 33 |

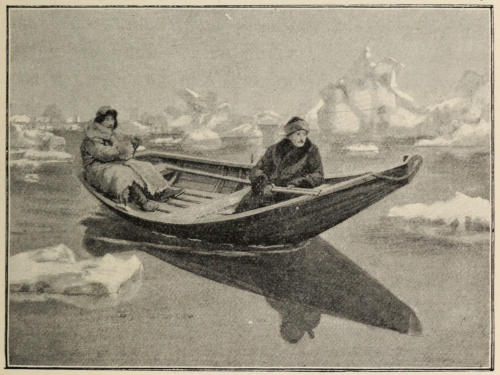

| Samoyede Boatmen | To face 34 |

| Karaoul | 36 |

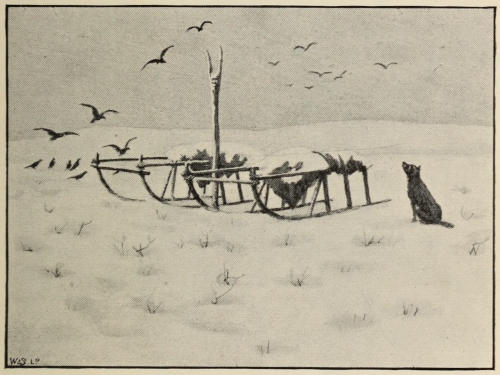

| The Samoyede’s Grave | 39 |

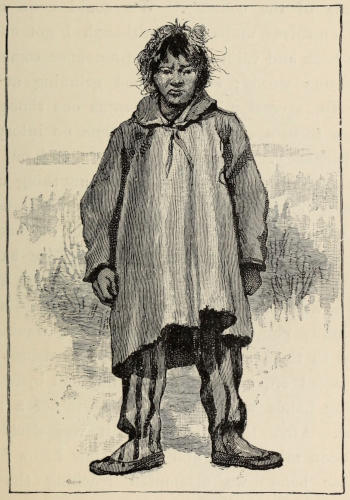

| A Samoyede Lady | 40 |

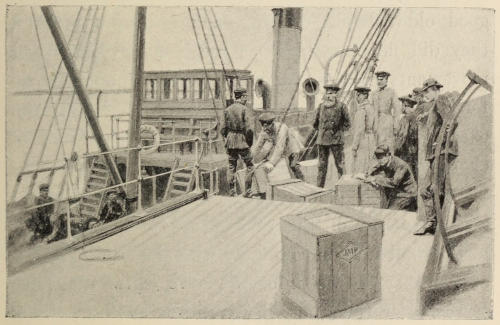

| Transhipment of our Cargo to the “Phœnix” | 43 |

| Our Custom-House Officer | 48 |

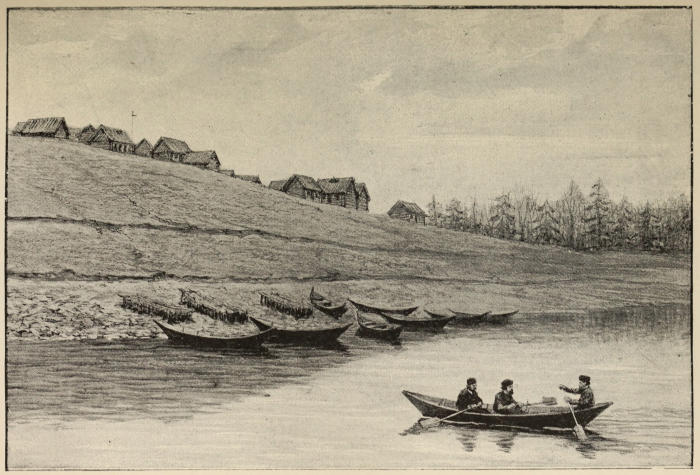

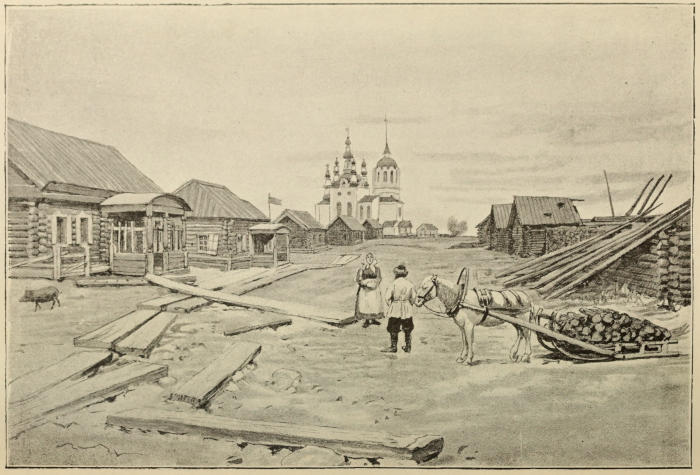

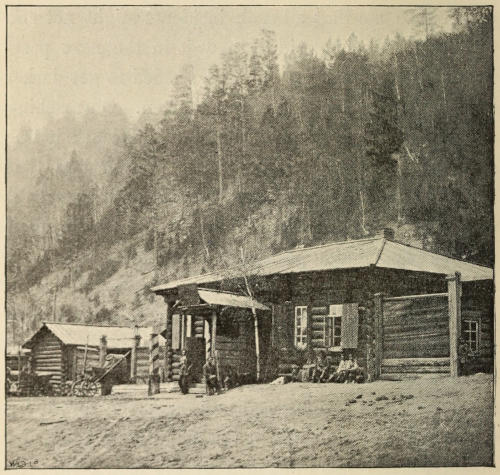

| Kasanskoi | 50 |

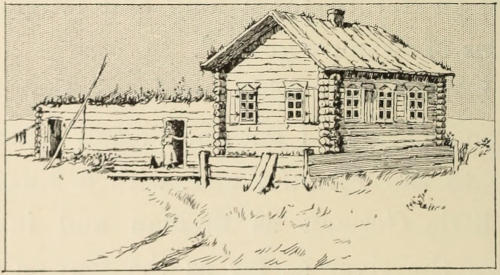

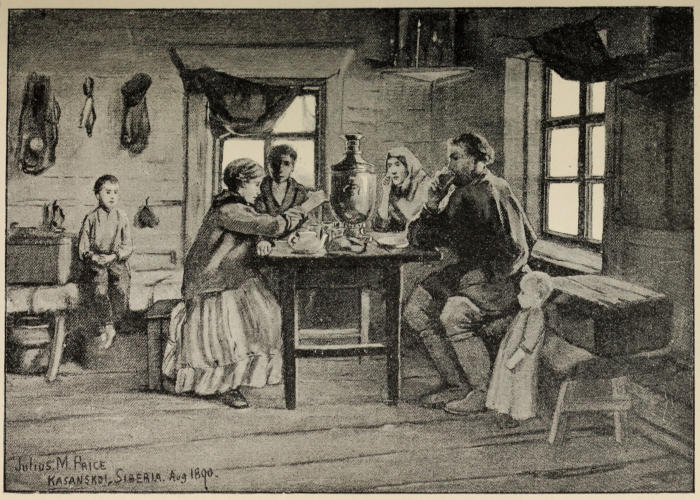

| Trader’s House at Kasanskoi | 50 |

| Mine Host at Kasanskoi | 51 |

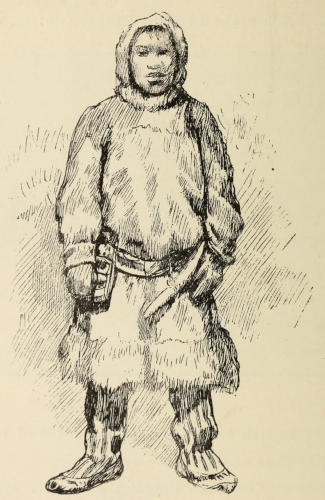

| Sweet Seventeen | 53 |

| A Home in Northern Siberia: The Morning Meal | To face 54 |

| Materfamilias | 55 |

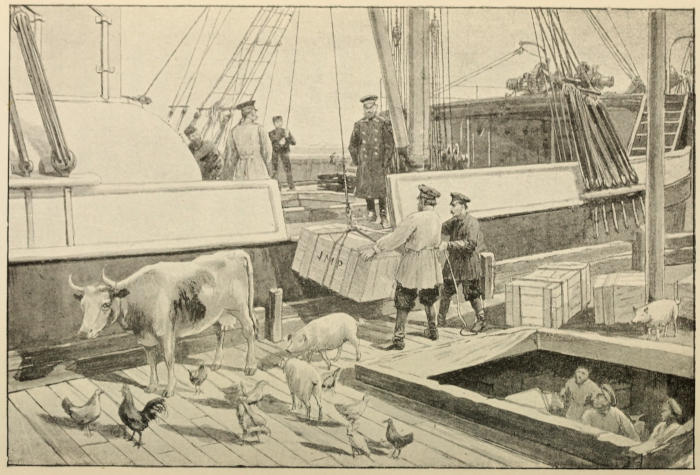

| Temporary Farmyard on one of the Barges | To face 57 |

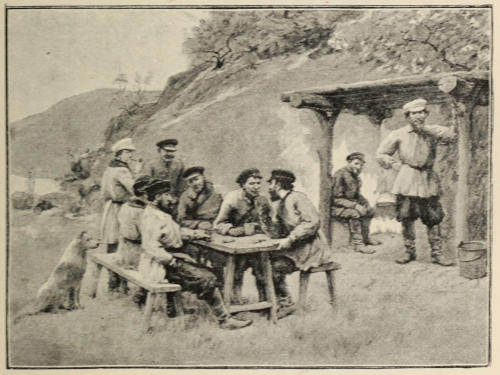

| Tea-time at the Men’s Quarters on Shore | 57 |

| Cossacks | 58 |

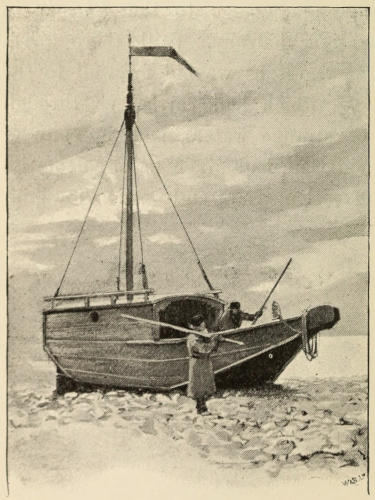

| A House-boat | 60 |

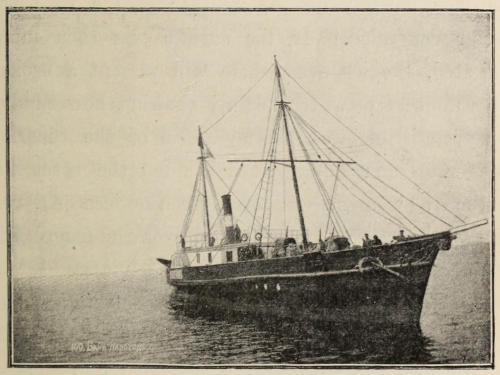

| The “Phœnix” | To face 61 |

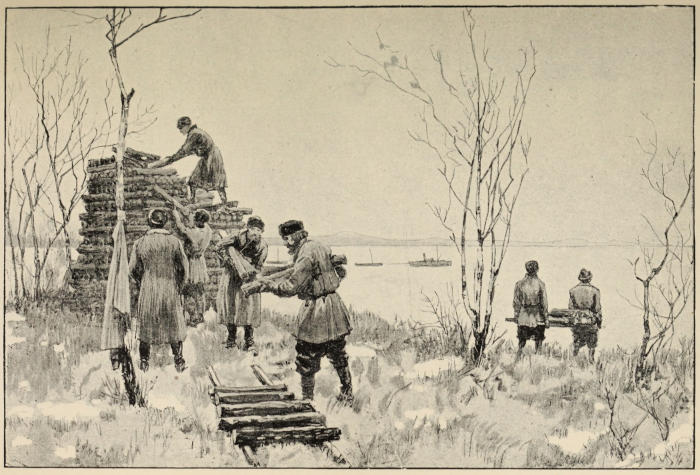

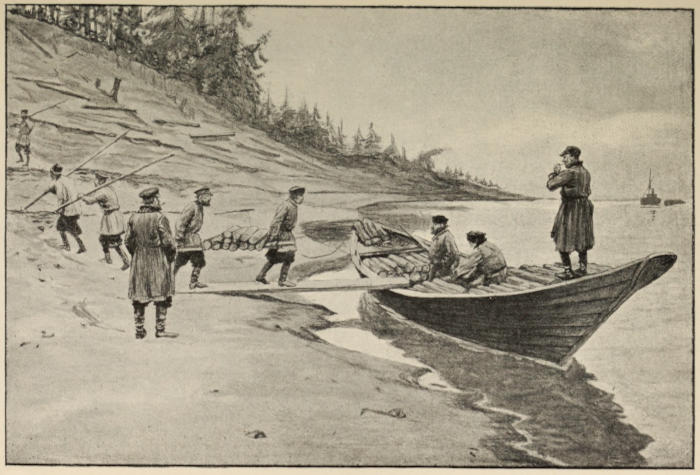

| Loading Wood for the “Phœnix” | ” 66 |

| Difficult Navigation | 70 |

| Selivanaka | To face 78 |

| The Principal Thoroughfare, Turuchansk | 80 |

| Our First Visit from Official Russia | To face 83 |

| Werchneimbackskoi | ”83 |

| Interested Observers | 83 |

| The Russian Police Officer | To face 84 |

| The Village Priest | 85 |

| A Village Boat | 88[xxii] |

| A River Pilot | 89 |

| The River Yenisei at Worogoro | To face 90 |

| Storing the Winter Forage: a Village Scene on the Yenisei | To face 96 |

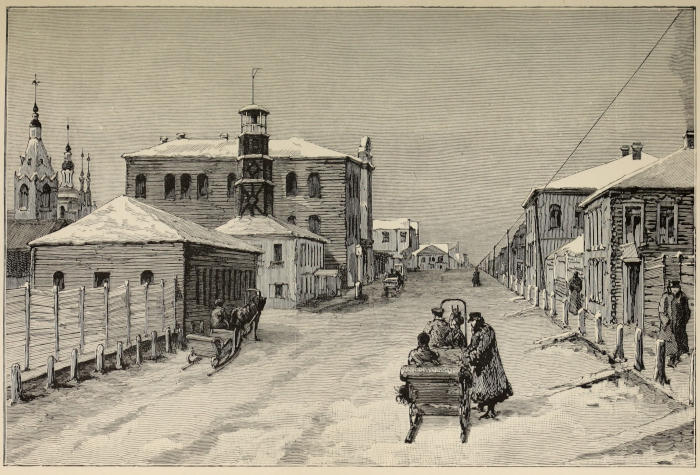

| Yeniseisk | 97 |

| Peasant Woman | 101 |

| In the Market-place, Yeniseisk | To face 101 |

| A Prison Beauty | 107 |

| The Governor visiting the Men’s Prison, Yeniseisk | To face 109 |

| The Murderers’ Department, Yeniseisk Prison | 111 |

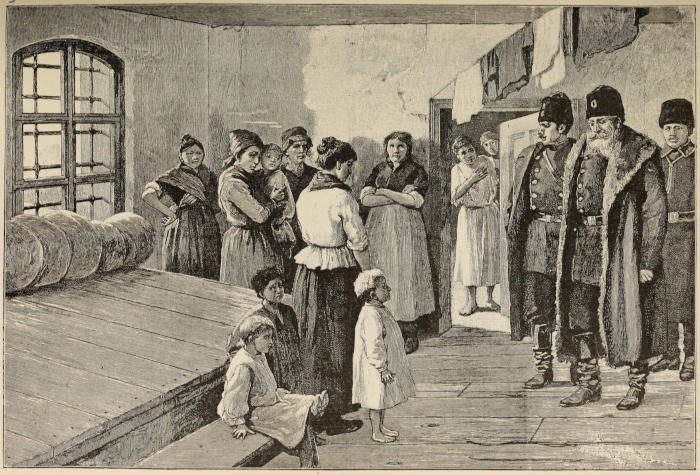

| The Governor visiting the Women’s Prison, Yeniseisk | To face 112 |

| Criminal Prisoners waiting at Yeniseisk for Convoy to start for Krasnoiarsk | To face 113 |

| Street Scene, Yeniseisk | 117 |

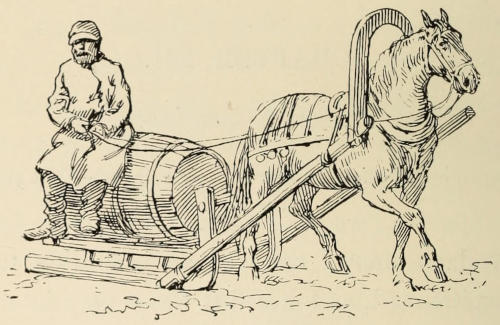

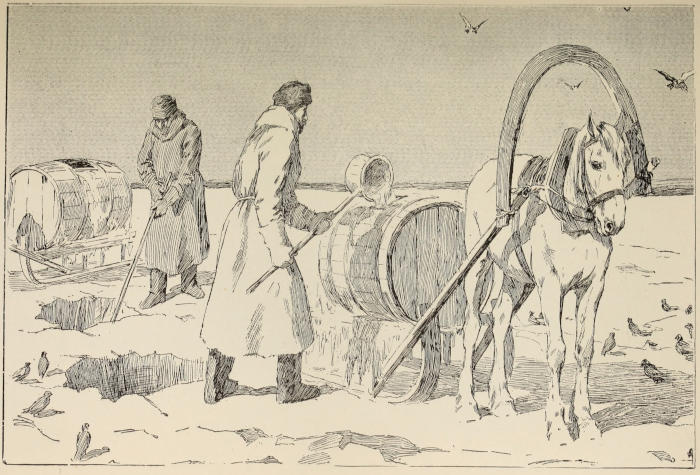

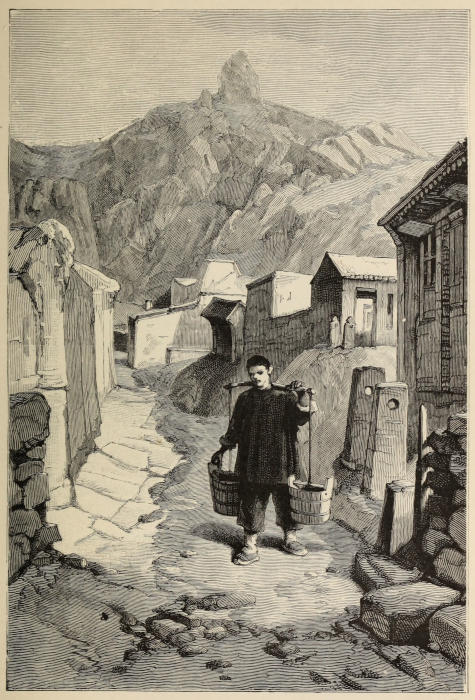

| A Water-carrier | 118 |

| Getting Water from the Frozen River Yenisei | To face 118 |

| The High Street, Yeniseisk | ”118 |

| A Swell | 119 |

| The Two Collegiate Schools, Yeniseisk | To face 120 |

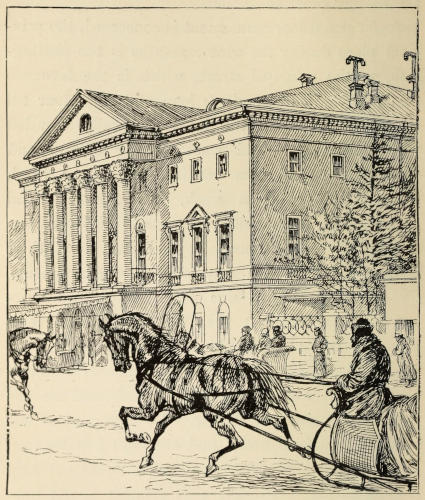

| Life in Siberia: An Afternoon Drive in Yeniseisk | ”121 |

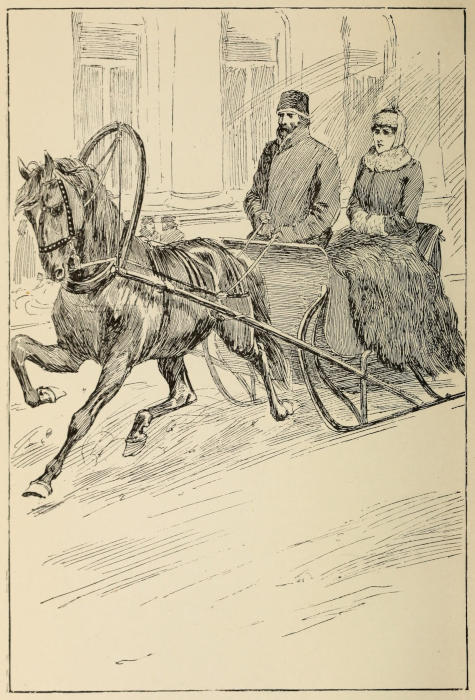

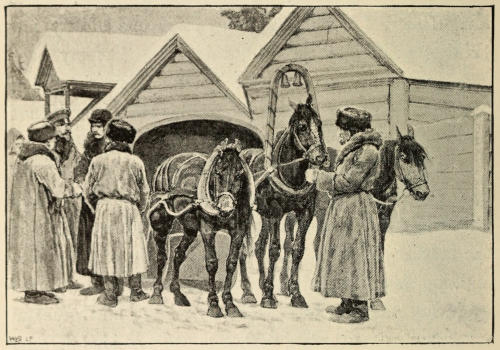

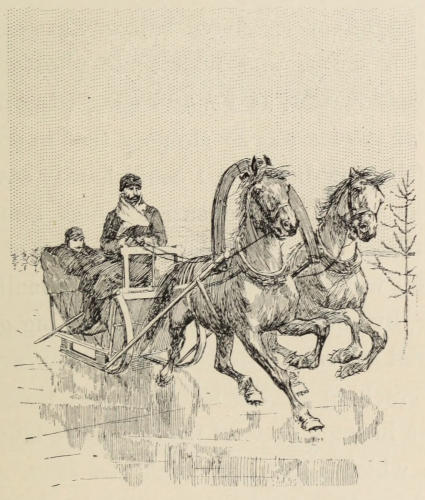

| Ready to Start | 123 |

| “Good-bye” | 126 |

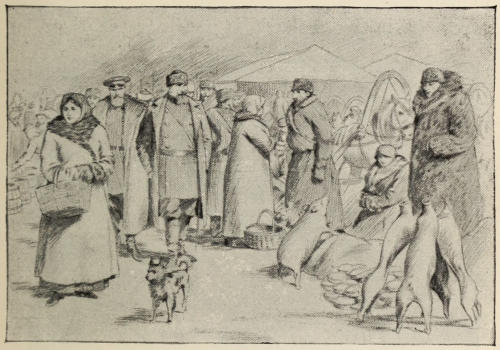

| In the Meat Market, Krasnoiarsk | 131 |

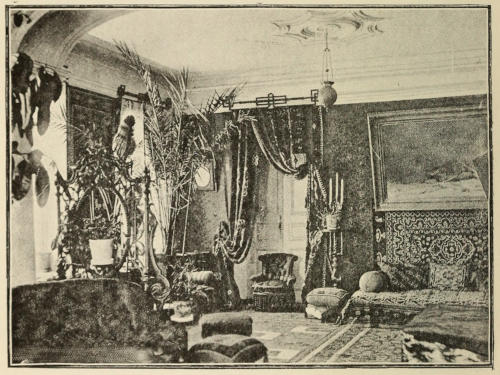

| A Typical Siberian Interior, Krasnoiarsk | 132 |

| Snow Scavenger, Krasnoiarsk | To face 133 |

| The Cathedral, Krasnoiarsk | 134 |

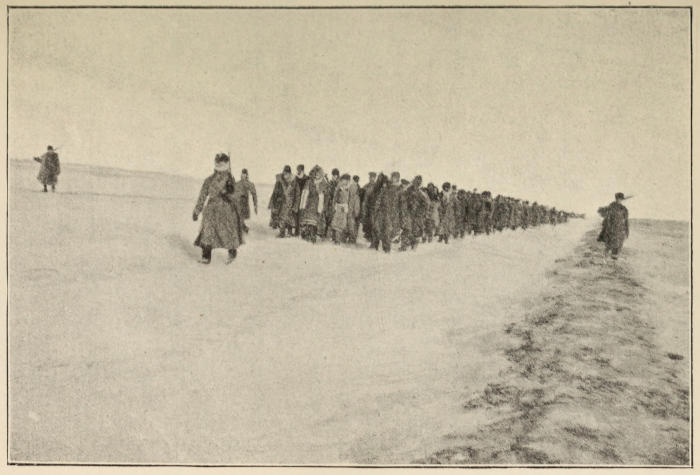

| A Convoy of Prisoners on the March (Enlargement from an Instantaneous Kodak Photo) | To face 138 |

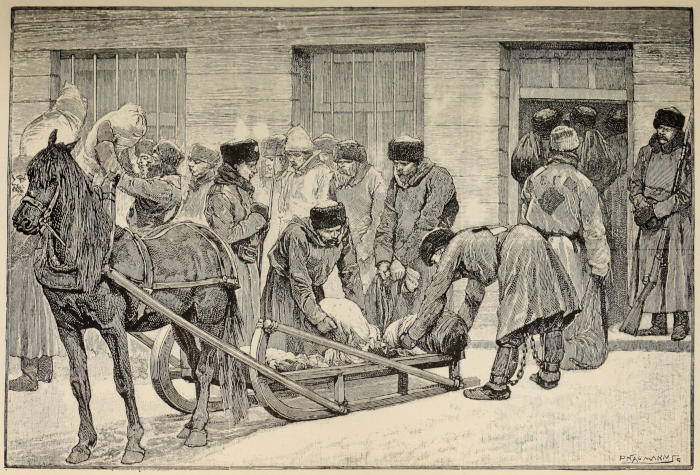

| Prisoners unloading Sledges on Arrival at Perasilny, Krasnoiarsk | To face 140 |

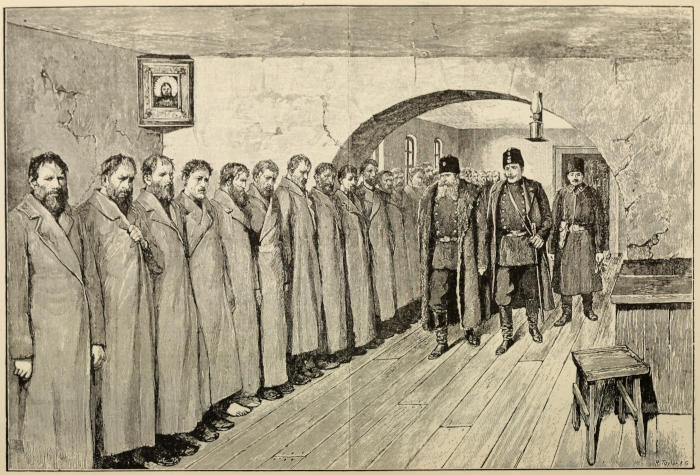

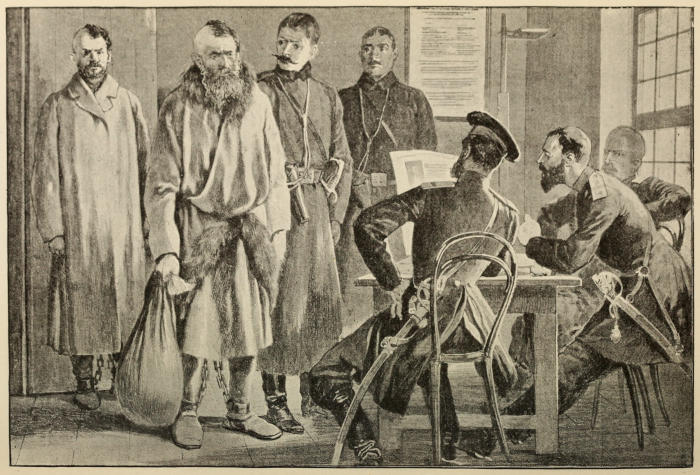

| Verification of Prisoners on Arrival at Perasilny, Krasnoiarsk | To face 141 |

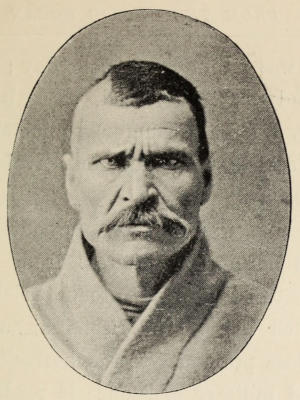

| The Staroster of the Gang | 142 |

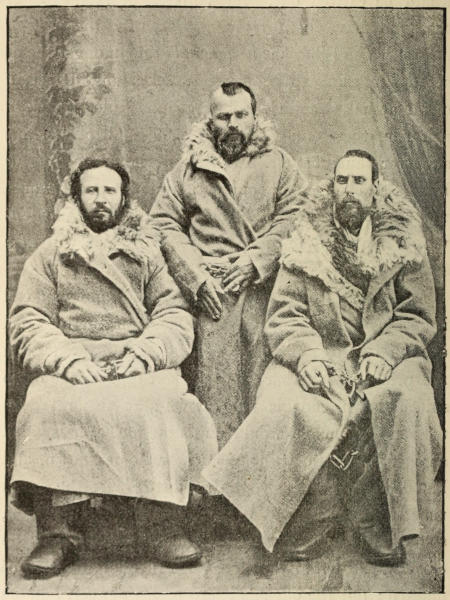

| Group of Prisoners (from a Government Photo) | 144 |

| A “Priviligiert,” or Privileged Prisoner | 148 |

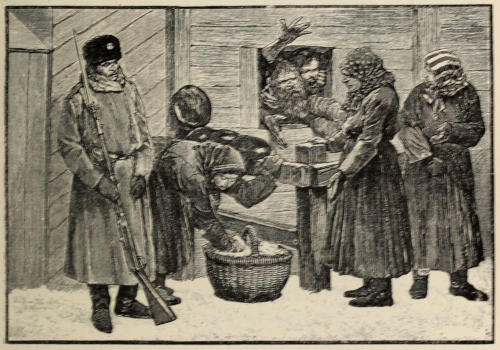

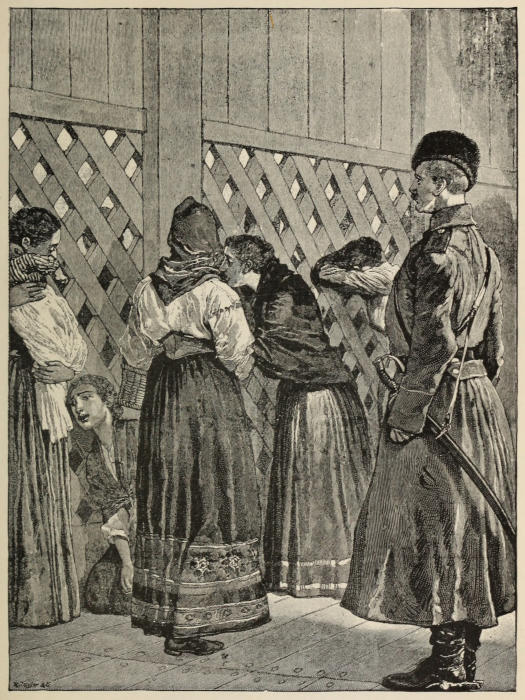

| Peasant Women selling Provisions to Prisoners | 149 |

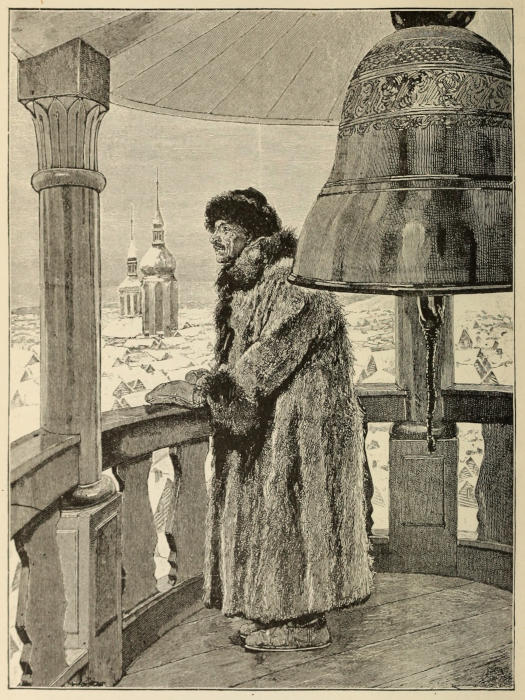

| Watchman on Duty in Fire Tower, Krasnoiarsk | To face 155 |

| My Servant | 156 |

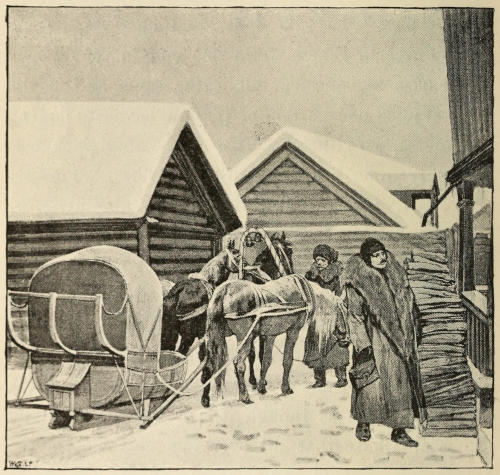

| Arrival at a Post Station | 164 |

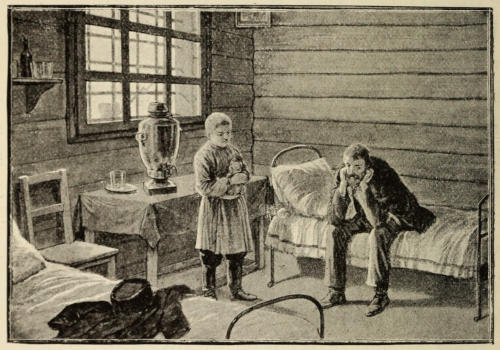

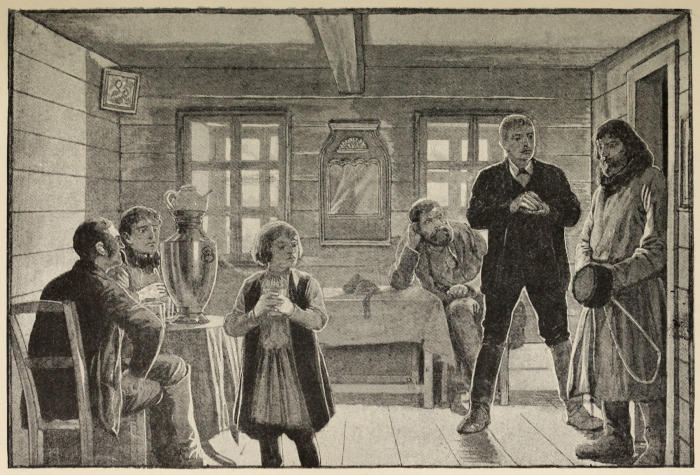

| Interior of a Post-house | To face 166 |

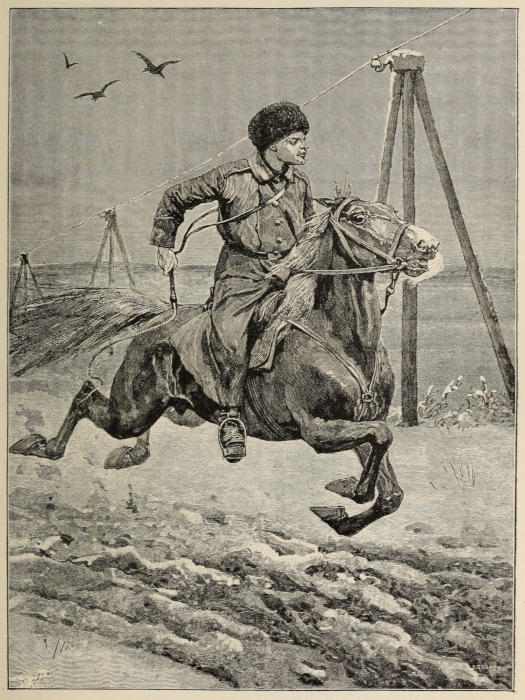

| The Imperial Mail | ”173[xxiii] |

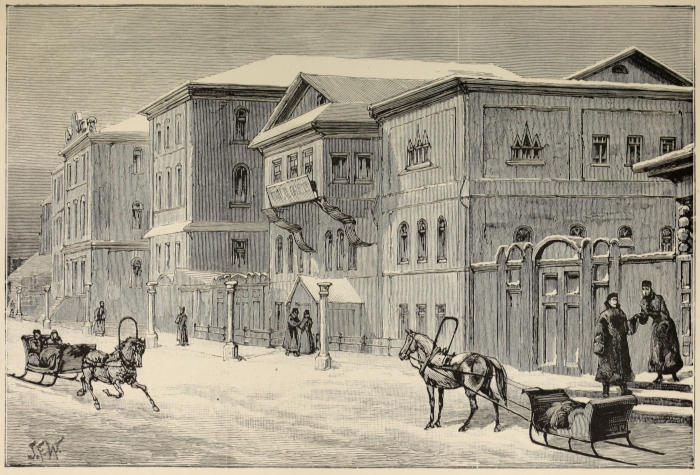

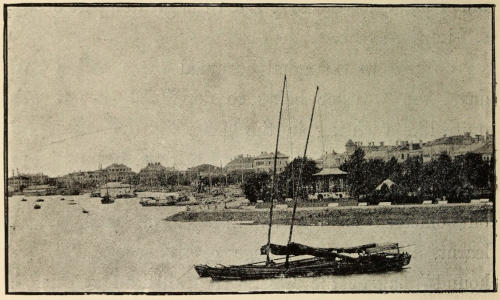

| Irkutsk | 180 |

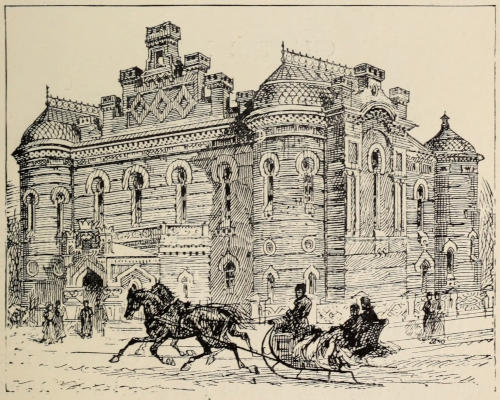

| The Moskovskaia Podvorié, Irkutsk | To face 180 |

| An Irkutsk Beauty | 185 |

| Entrance Hall of Millionaire Gold-mine Owner’s House, Irkutsk | 186 |

| Street Scene, Irkutsk | 188 |

| A Cossack | To face 190 |

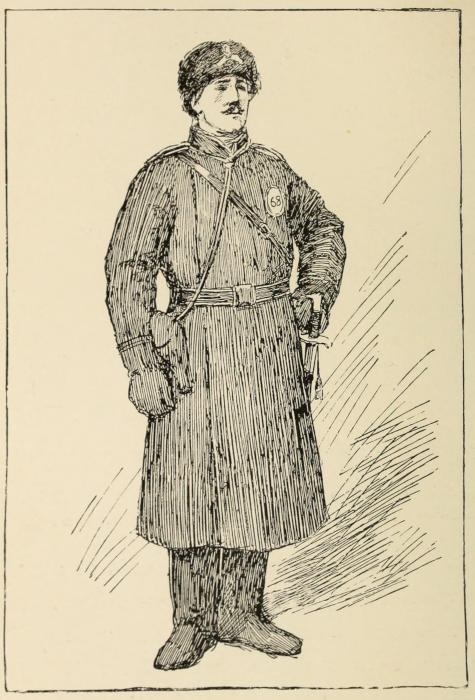

| An Irkutsk Policeman | ”191 |

| The Museum, Irkutsk | 191 |

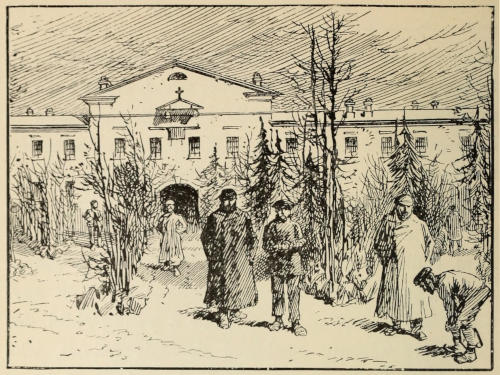

| The Recreation Ground, Irkutsk Prison | 192 |

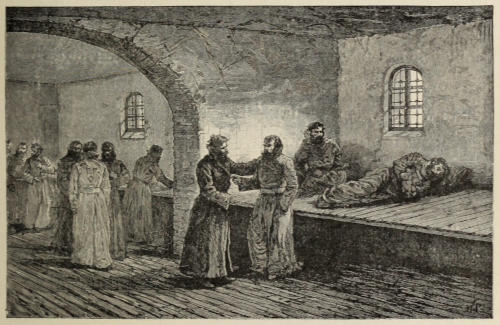

| Married Prisoners waiting to be served with New Clothes on Arrival at Prison, Irkutsk | To face 193 |

| The Prison Artist | ”196 |

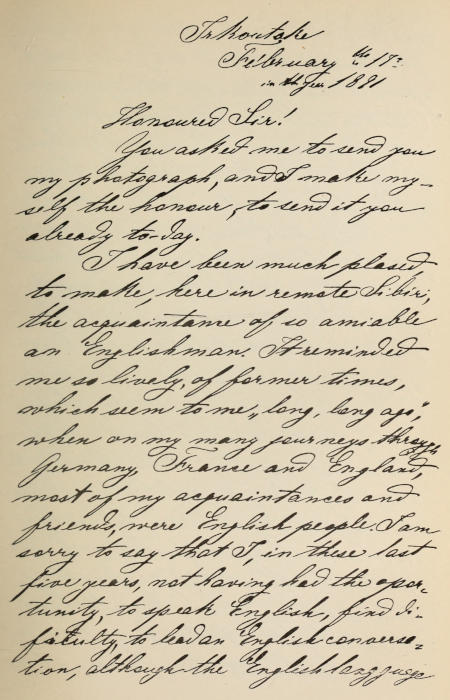

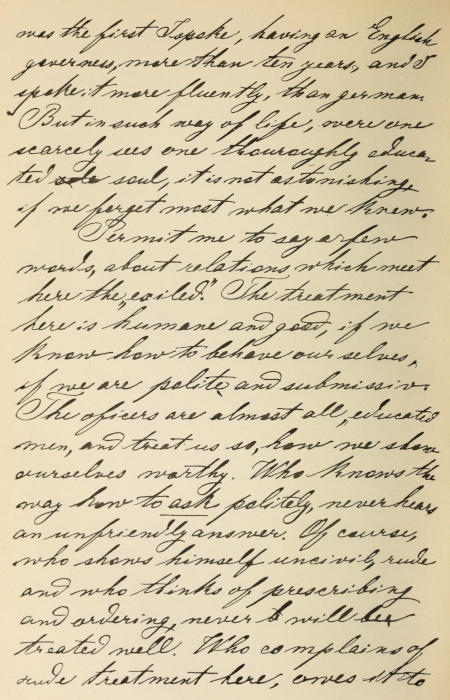

| The Baroness | 201 |

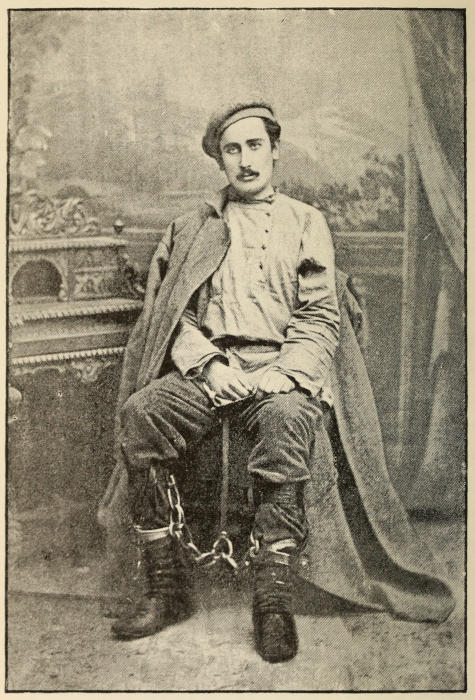

| A “Political” (from a Government Photo) | To face 205 |

| “Sweethearts and Wives:” Visiting-Day in the Irkutsk Prison | To face 206 |

| Autograph Letter from the Baroness | ”207 |

| The High Street, Irkutsk | 208 |

| In the Courtyard of a Fire Station, Irkutsk | 215 |

| The Governor-General’s House, Irkutsk | 218 |

| Street Scene, Irkutsk | 220 |

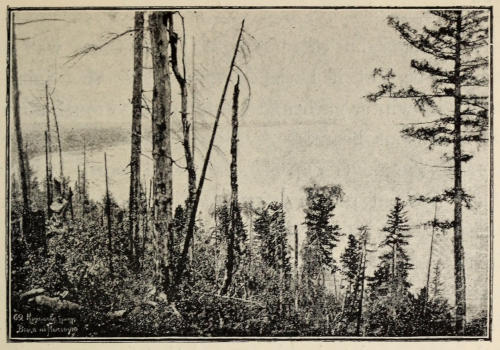

| A Bit on the Road to Lake Baikal | 221 |

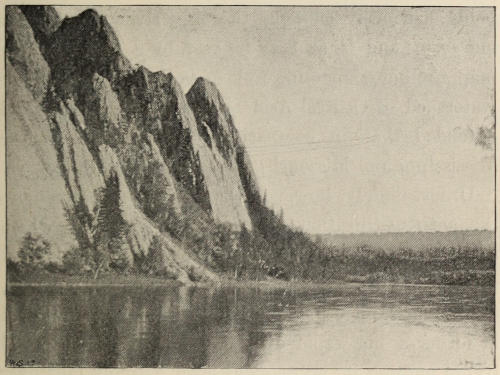

| The River Angara near Lake Baikal | 225 |

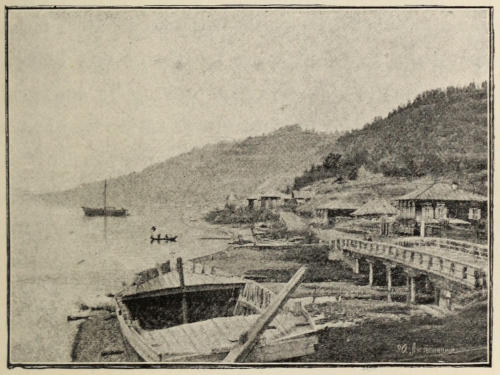

| Liestvinitz, on Lake Baikal | 229 |

| A Lake Baikal Steamer | 231 |

| Crossing Lake Baikal | 233 |

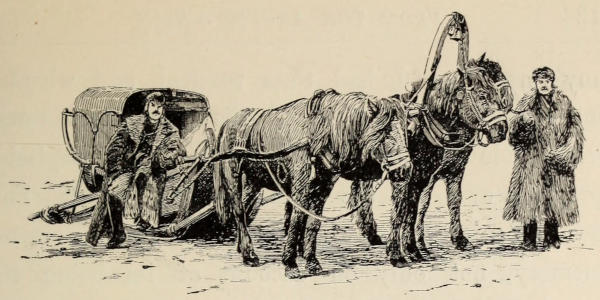

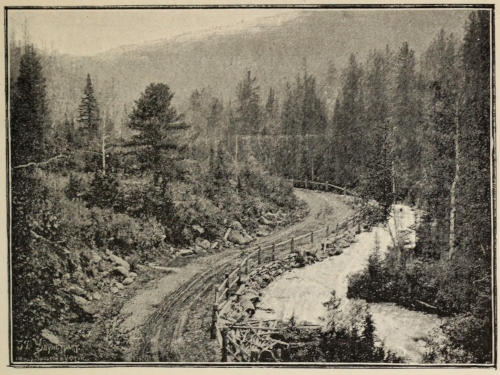

| The Kupetski Track | 235 |

| A Post-house on the Kupetski Track | 238 |

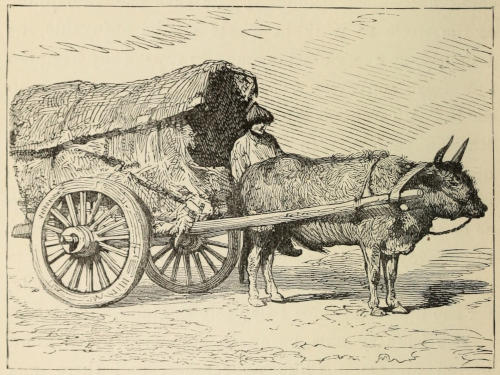

| A Tea Cart | 240 |

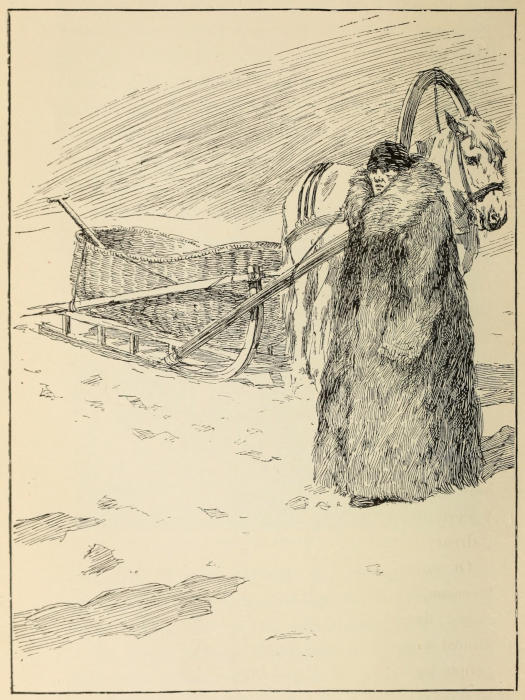

| Day-dreams: A Sketch in the Trans-Baikal | To face 242 |

| The High Street, Troitzkosavsk | ”245 |

| My First Glimpse of Mongolia | ”246 |

| A Bourriate Lady | 247 |

| Sketch by a Political Prisoner, made whilst on the March across Siberia (the Original is in Sepia and White) | To face 248 |

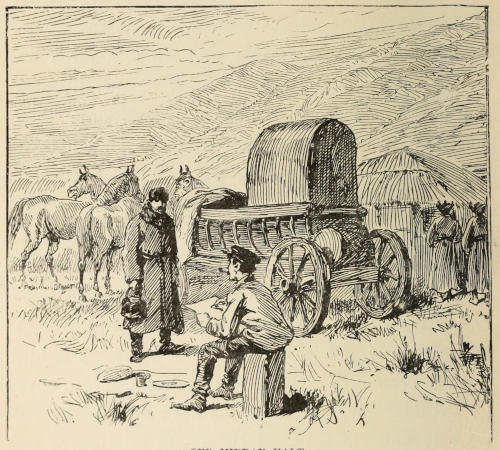

| On the Road to Ourga | 249 |

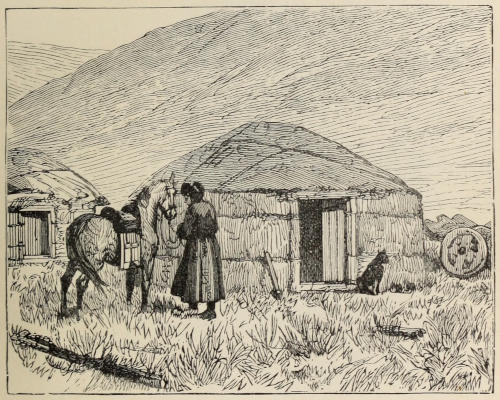

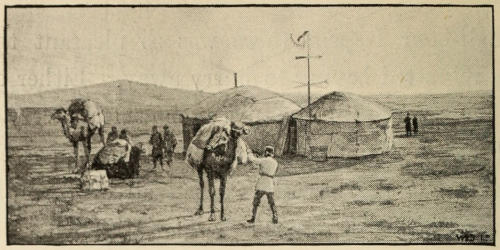

| A Mongol Yourt | 253 |

| A Mongol | 254 |

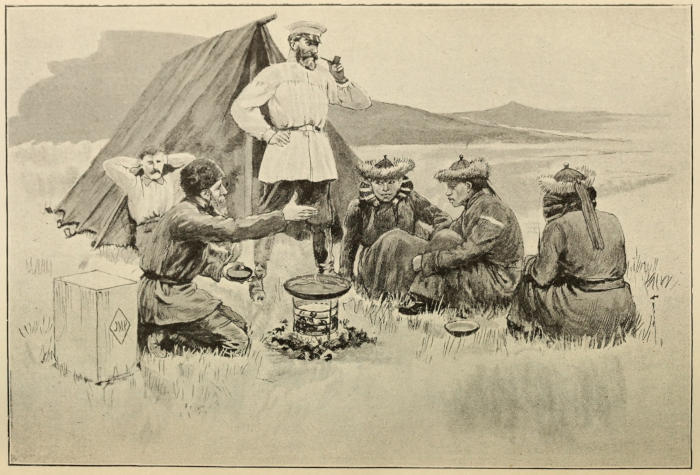

| Our Midday Halt | 260 |

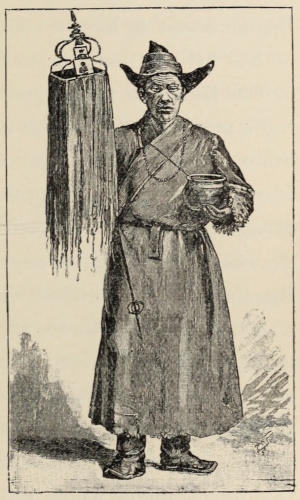

| A Street Musician, Ourga | 272 |

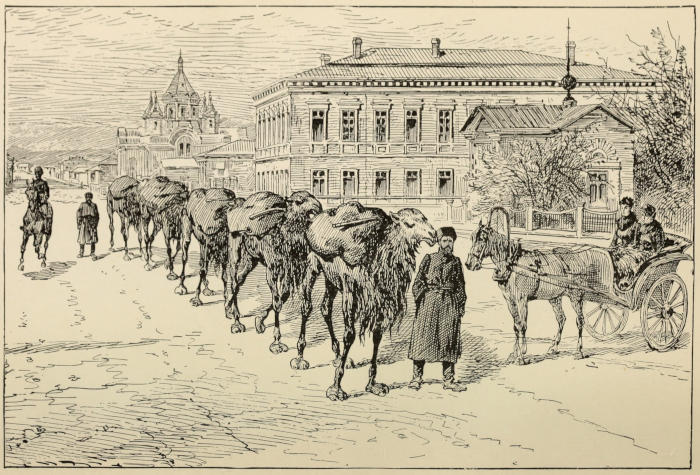

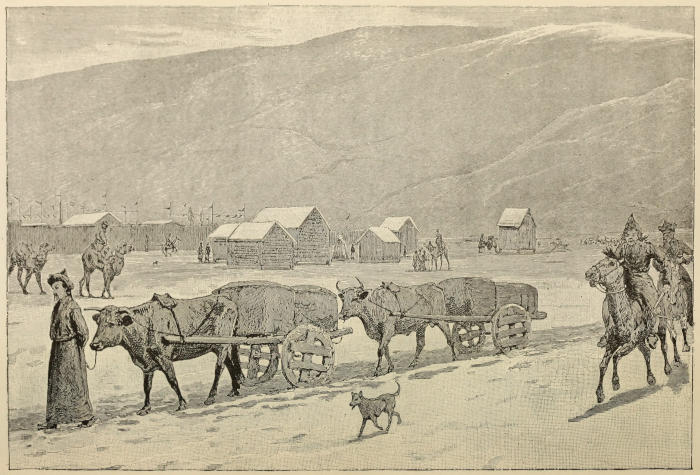

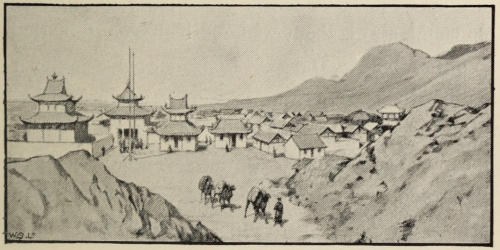

| The Principal Thoroughfare, Ourga | To face 273[xxiv] |

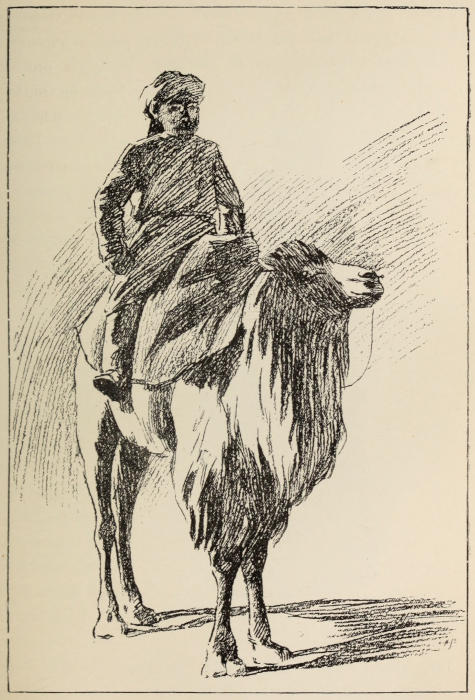

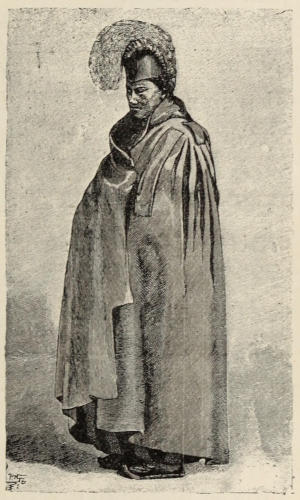

| A Pilgrim from Thibet | 277 |

| A Lama | 281 |

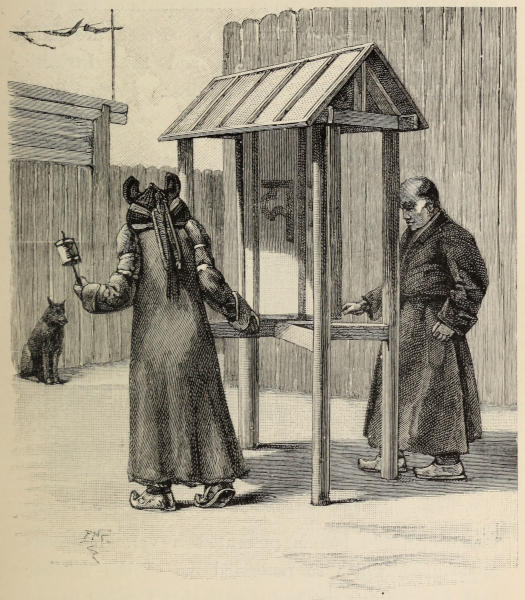

| A Prayer-wheel, Ourga | 283 |

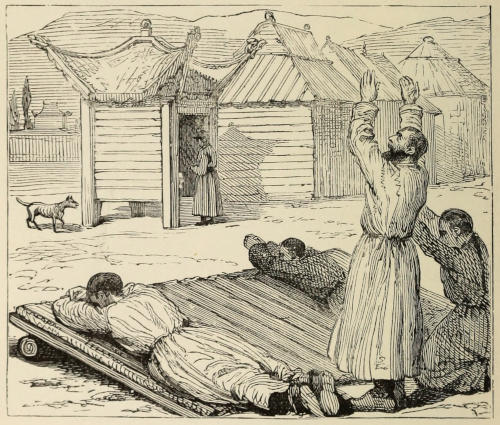

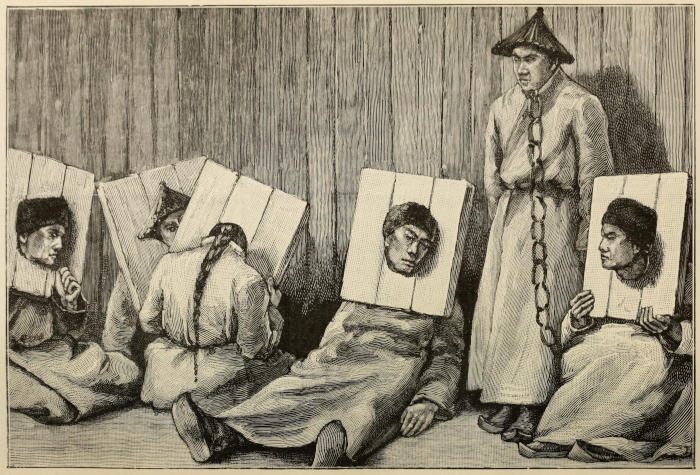

| Prayer-boards, Ourga | 284 |

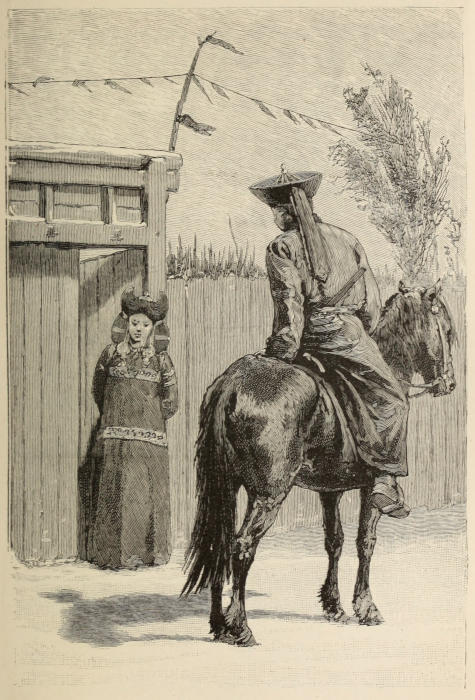

| “The Old, Old Story all the World over” | To face 286 |

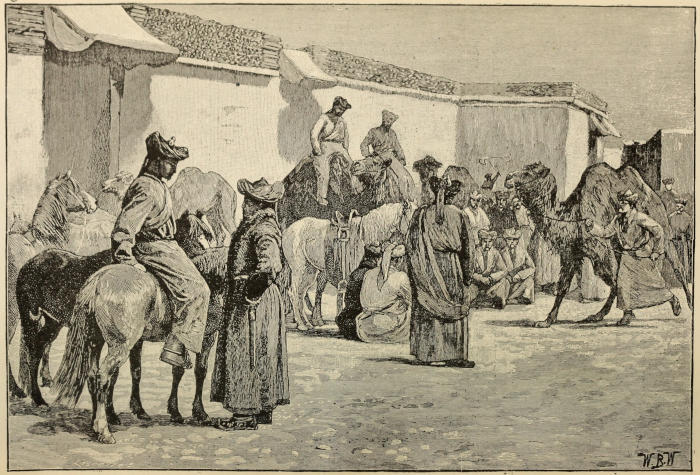

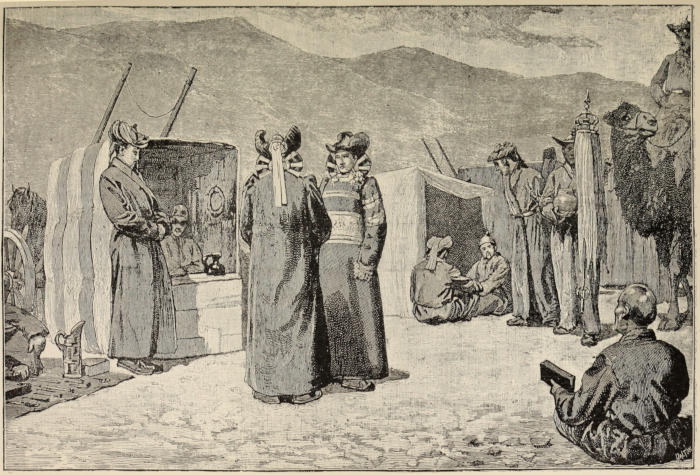

| In the Camel and Pony Bazaar, Ourga | ”293 |

| In the Bazaar, Ourga | ”294 |

| The Punishment of the “Cargue:” A Sketch outside the Prison, Ourga | To face 295 |

| An Ourga Beauty | ”299 |

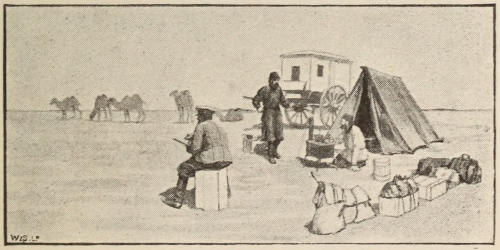

| In the Gobi Desert | 301 |

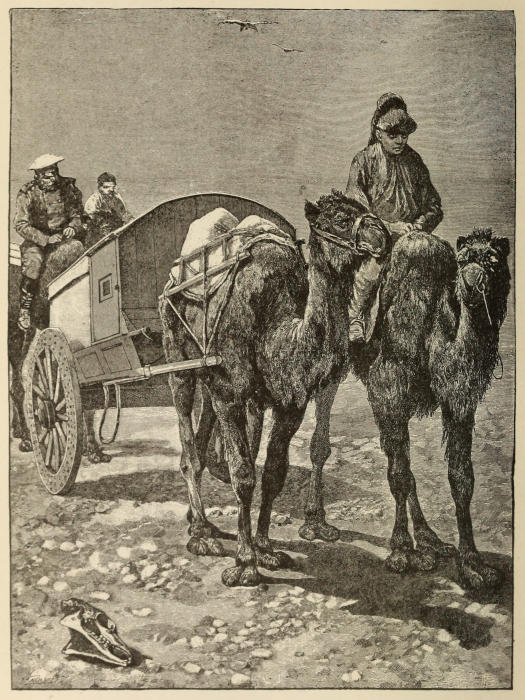

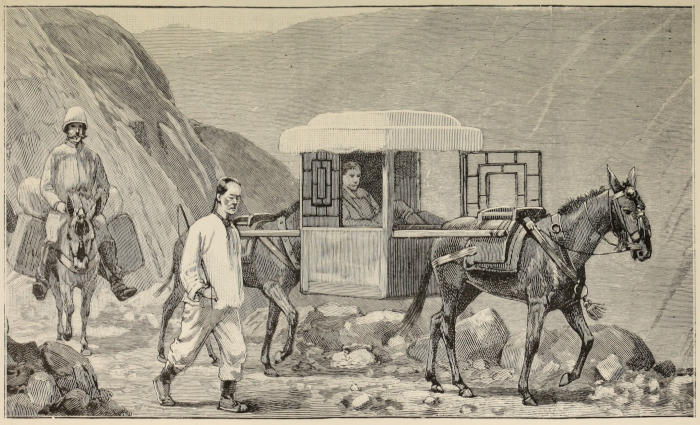

| My Camel-cart | To face 303 |

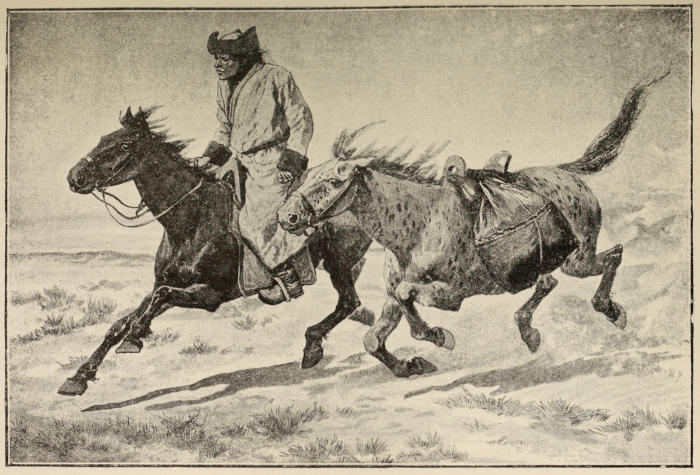

| Mongol conveying the Russian Light Mail across the Gobi Desert | To face 306 |

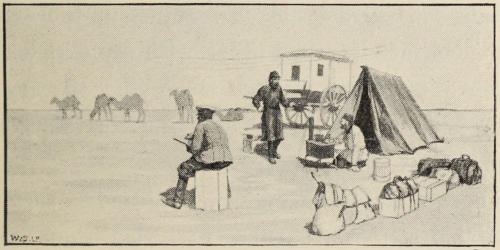

| The Midday Halt in the Desert | 309 |

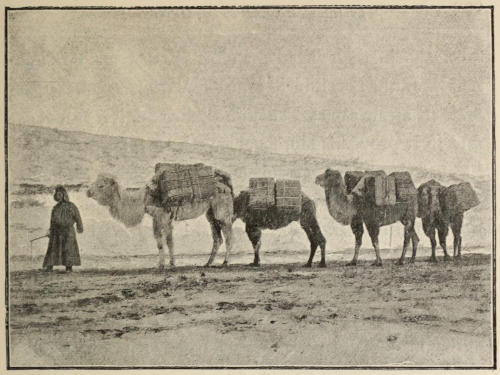

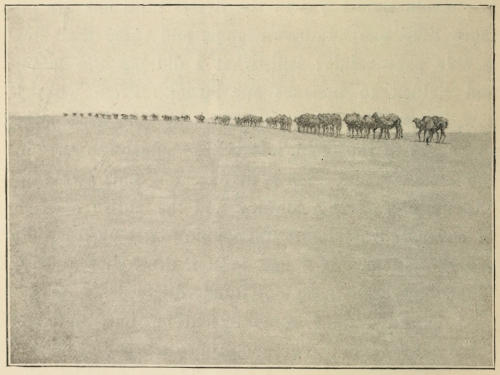

| My Caravan in the Desert (from a Kodak Photo) | 313 |

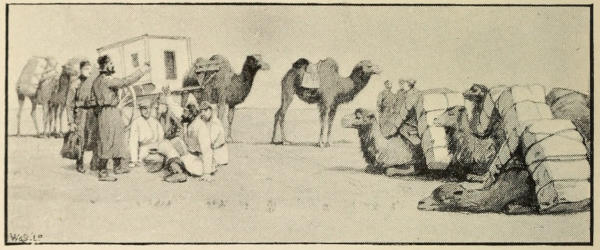

| We meet the Homeward-bound Mail | 314 |

| The Lama Settlement of Tcho-Iyr in the Gobi Desert | 315 |

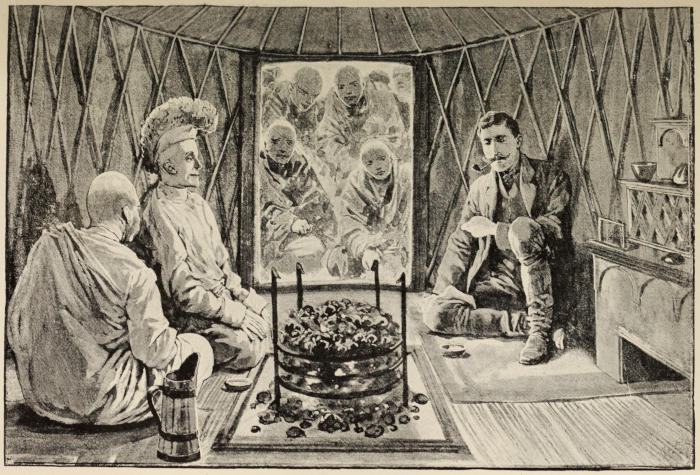

| I take Tea with a Lama in the Gobi Desert | To face 316 |

| The Russian Post-station in Mid-desert | 318 |

| In the Gobi Desert: A Tea Caravan on its Way to Siberia (from a Kodak Photo) | 320 |

| In the Gobi Desert: Lady Visitors to our Encampment | To face 323 |

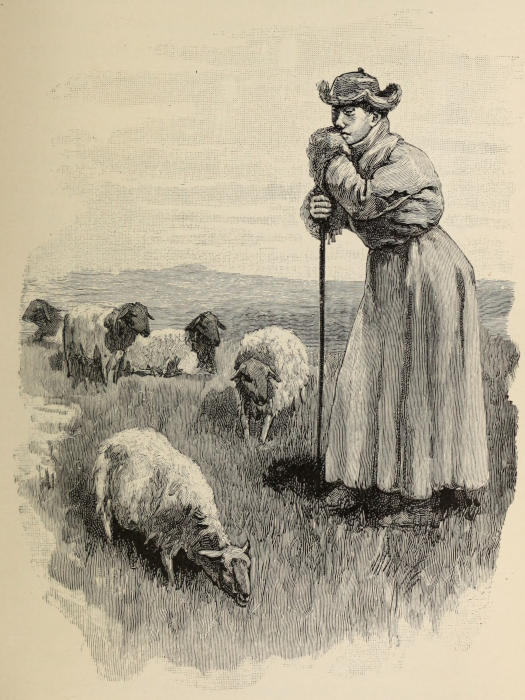

| “Ye Gentle Shepherdess of ye Steppe” | ”324 |

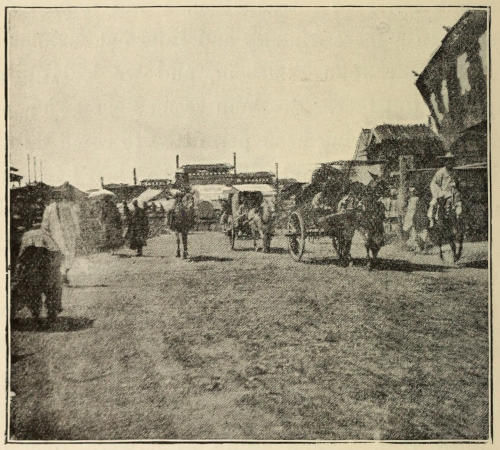

| Street Scene, Yambooshan (showing the “Great Wall” on Mountain in Background) | To face 332 |

| My Mule-litter | ”338 |

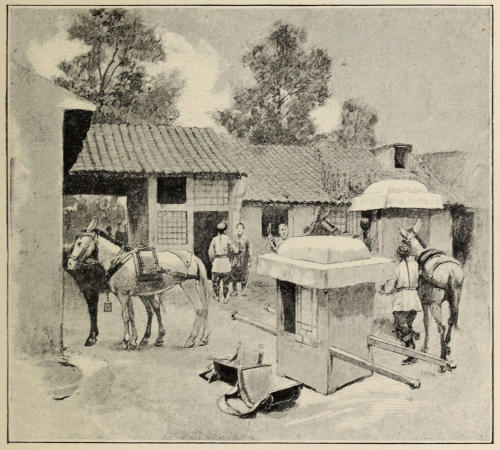

| The Courtyard of a Chinese Inn | 341 |

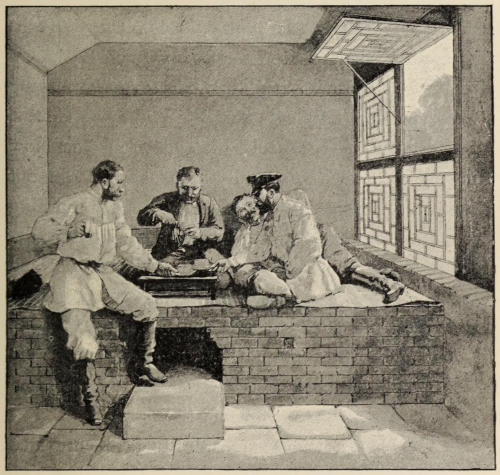

| A “Room” in a Chinese Inn | 343 |

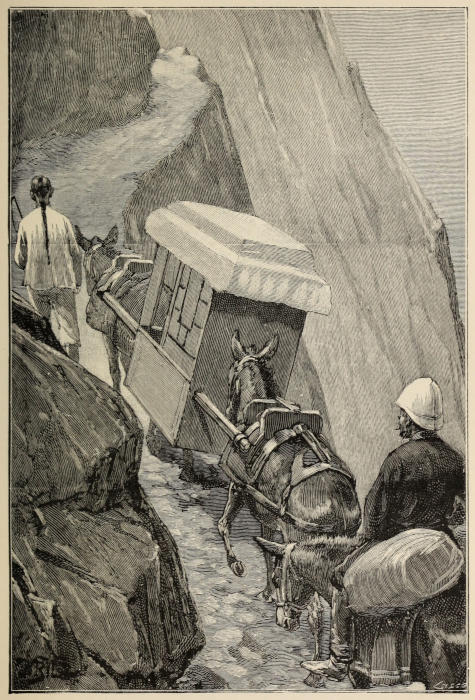

| A Nasty Bit of Road | To face 346 |

| The Great Wall of China at the entrance to Nankaou Pass | To face 348 |

| Street Scene, Tartar City, Peking | 356 |

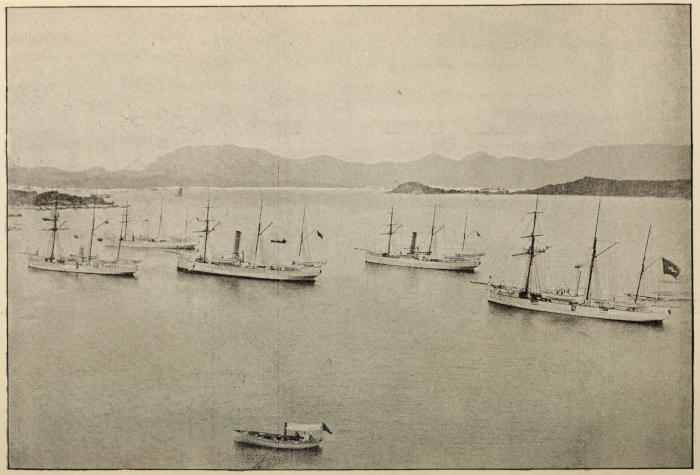

| Chinese Revenue Cruisers in Hong Kong Roadstead (from a Photo given by Sir Robert Hart) | To face 363 |

| Sir Robert Hart, G.C.M.G., in his “Den” at Peking | To face 366 |

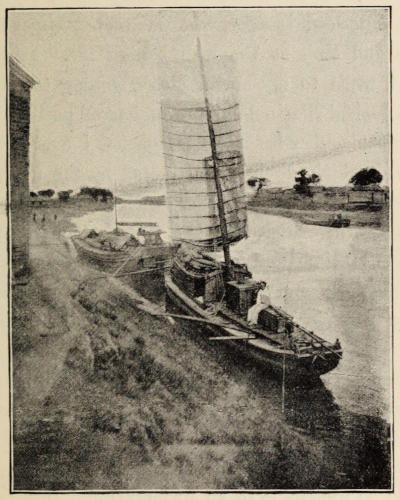

| My House-boat | 375 |

| Shanghai | 380 |

The object of the expedition—The steamer Biscaya and its passengers and cargo—Across the North Sea—Uncomfortable experiences—First glimpse of Norway—Aalesund—The Lofoden Islands—The midnight sun—A foretaste of the Arctic regions—“Cape Flyaway”—Our ice-master, Captain Crowther—We sight the coast of Siberia—The village of Kharbarova—The entrance to the Kara Sea.

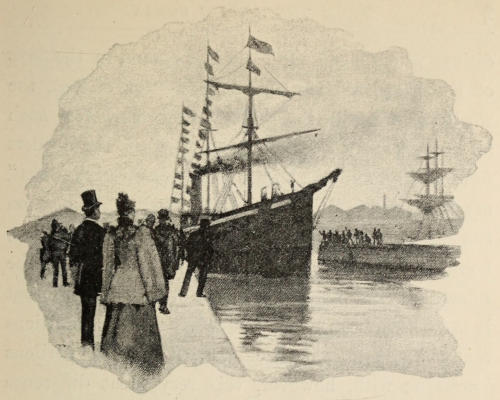

THE “BISCAYA” LEAVING BLACKWALL.

In these prosaic days of the nineteenth century one hardly expects a revival of the adventurous expeditions[2] which made the fame of England in the days of Frobisher and Drake. As a matter of fact, the world is almost too well known now for such adventures to be possible, even were the leaders forthcoming, and the “good old buccaneering days” are long past. Still, I could not help thinking, on the day we left Gravesend for the far North-East, bound for a region but little known, and with the uncertainty of ever reaching our destination, that it must have been under somewhat similar conditions that the adventurers of old started on their perilous journeys; with, however, this very great difference—ours was not a filibustering expedition, but a commonplace commercial enterprise, backed up by several well-to-do Englishmen, with absolutely nothing of the romantic about it beyond the fact of its having to traverse these wild and comparatively unknown regions before it could be successfully achieved.

We started from the Thames on Friday, July 18, 1890, in the chartered Norwegian steamer Biscaya, eight hundred tons gross, bound for the Yenisei River with a nondescript tentative sort of cargo, consisting of a mixture of all sorts, from a steam sawmill down to the latest toy for children, our ultimate destination being the town of Yeniseisk, which is situated some fifteen hundred miles from the mouth of this mighty river. The object of the expedition was to endeavour to open a trade route between[3] England and Siberia by means of the Kara Sea passage, which was discovered by Nordenskiold in 1875.

Nothing of particular interest occurred during the first few days after we left the Thames. We were so closely packed that it required some careful arrangement to get us all comfortably stowed, so to speak. Imagine seven men jammed into a cabin just about large enough to accommodate four, and each man with the usual amount of superfluous luggage without which Englishmen could not possibly travel, this baggage also stowed in the cabin, and you will guess that we were packed like sardines. As, however, no doubt even sardines get used to being packed, after a time so did we; and, although the passage across the North Sea was about as uncomfortable a one as I ever experienced, we somehow managed to settle into our respective grooves long before we sighted the coast of Norway. Our party consisted of two representatives of the London Syndicate, two engineers, a master stevedore (to unload the ship on arrival), an experienced ice-master, who knew the Kara Sea thoroughly, the captain of the Biscaya, and your humble servant. I don’t think I ever was on board a more crowded ship. Even the decks were packed with all sorts of paraphernalia, including a large steam-launch and several pens of live stock; and, so as to obviate any fear of running short of coal in the outlandish parts we were[4] going to, the fore and upper decks had over seventy tons of loose coal on them. We had a head wind and a heavy sea nearly the whole way after passing Harwich, where we dropped our pilot, thus bidding a last farewell to Old England. Off the Dogger Bank we went right through the fishing fleet which congregates there, and took advantage of the opportunity to get some fresh fish—a matter of no small difficulty, as the men had a preposterous idea of its value: they would not take money for it, but actually had the effrontery to want to swop a couple of small cod, a ling, and a pair of soles for two bottles of whiskey and a pound of tobacco! Fish is evidently dearer on the fishing-ground itself than in London. Whiskey, however, was far more valuable to us than fish, so, when the men saw we were not buyers on their terms, they eventually came down to 1½ lb. of ship tobacco (value 2s. 4d.) for the lot, which was reasonable enough. After passing the Dogger Bank the wind freshened very considerably towards evening, and added much to the discomfort of the crowded ship; in fact, so badly did she roll about that not only was all our party busy “feeding the fishes” most of the time, but our cook was also so ill that he could not attend to his duties, and we all had to lend a hand in the galley as well as we could. I had never been a long voyage in a wooden ship before, so could hardly sleep a wink all night, owing to the (to me) unusual noise caused[5] by the groaning of her timbers as she pitched and tossed about. It sounded not unlike what I should imagine it would be sleeping near a lot of new leather portmanteaus which were being continually shifted. During the whole of the following day it was blowing big guns, and the sea was so heavy that the cabin was almost dangerous to remain in, owing to the sort of cannonade of packages from all sides, many things being damaged. There was absolutely nothing to do but sit down and wait events, and, meanwhile, make one’s self as comfortable as one could under the circumstances. By the next day the gale had moderated considerably, and during the morning we got our first glimpse of Norway—a high, rock-bound coast, with a dim vista of mountains in the background. Shortly after, a small pilot-boat hove in sight, evidently on the chance of a job, probably taking the Biscaya for a tourist steamer wishing to pass inside the islands, which is the most picturesque route, though somewhat longer. We had no time, however, to waste on scenery, so, although one of our party, who was suffering from an attack of dysentery, offered to pay the pilotage (about £15) out of his own pocket if the calm-water channel was followed, it was at once decided to keep outside the whole way up the coast, and thus get on as fast as possible, more especially as the weather showed signs of clearing up.

On the Norway coast we anchored for a short[6] time off the quaint little village of Aalesund, with its pretty wooden houses nestling under the high snow-clad mountains which encircle the beautiful fiord on which it is situated. I was disappointed on a nearer inspection of the village, which looked so quaint as seen from the sea: the houses all appeared to be almost new, doubtless owing to the fact that they are all built entirely of wood. The effect is thoroughly characteristic of Norway, the smell pervading the place especially so, being, as far as I could guess, a mixture of paraffin and pickled fish, with just a soupçon of burnt wood thrown in here and there. Everything looked as clean as a new pin, but, as each house is exactly like its neighbour, the effect is certainly monotonous. Nevertheless, there were several pretty bits which I should have liked to sketch had I had time. What, if anything, struck me most was the entire absence of any national or picturesque costume, which gives such local colour to most Continental villages. At Aalesund the inhabitants looked for all the world like English people, and their fair hair and blue eyes added to this resemblance. I was told, however, that on fête days there are some quaint costumes to be seen here and there.

No time was lost in getting away, and shortly after we had lost sight of the quiet little village, where we had spent a few lazy hours, and were heading it once more for the far-distant Arctic[7] regions. The days after this date began to lengthen considerably, and, although we had hardly noticed it at first, it astonished us very much when we suddenly found that it was eleven o’clock at night, and yet the sun was shining as brightly as during the afternoon. When the novelty had worn off, as it naturally did after a few days, the amount of daylight almost palled on one. It seemed too absurd turning in while the sun was up; still, like everything else, one gets used to it after a time. The next few days were uneventful, as we were out of sight of land, and the usual monotony of shipboard life was only broken by the usual skylarking, without which no sea voyage would be complete.

On July 28 we sighted the Lofoden Islands, about fourteen miles off on our starboard quarter. It was a lovely morning, and the lofty snow-capped mountains towering against the calm eastern sky presented a grand and impressive sight. The effect was almost that of a colossal painting, so still was everything in the bright sunshine. I was so impressed by the quiet grandeur of the scene that I got out my paint-box and started a sketch, but only succeeded in making a sort of caricature of my impressions. Late the next evening we came across a fleet of small fishing-boats—about the quaintest lot of craft I ever saw: they looked as if they had been copied from the frontispiece of the Argosy. We got some coarse sort of fish from them in[8] exchange for tobacco, biscuits, and the inevitable rum. The men were a very fine-looking set of fellows, very much like Englishmen (as, in fact, most Norwegians are), and seemed quite comfortable in their ramshackle-looking boats. After leaving them we saw for the first time the curious phenomenon of the sun above the horizon at midnight. It was so bright, and the atmosphere so clear, that I took an instantaneous photograph of a group on deck, and it came out very well.

The next morning we arrived off the North Cape, and passed it close in to the shore. We were now well inside the Arctic Circle, but perceived no difference whatever in the temperature, except that perhaps it was warmer than it had been previously. As a matter of fact, we had out the hose and took a most enjoyable bath on deck in the warm sunshine. In the afternoon, however, we had our first taste of the Arctic regions, as a dense fog came on, and lasted till late in the evening. Everything seemed saturated with moisture; the very rigging was dripping as under a heavy shower.

PREPARATIONS FOR THE ARCTIC REGIONS.

[To face p. 8.

For the next few days nothing of interest occurred, when suddenly one morning, as we were nearing Kolguier Island, we were aroused by the news that there was a steamer in sight, and soon we were all on deck eagerly scanning the horizon. Considering how far we were from the ordinary track of vessels, our excitement was natural; for what was a ship[9] doing in these outlandish parts? We soon made out that it was a large steamer, coming from due north straight towards us. She was coming at such a spanking rate that very soon we could see she was flying the Russian flag; and shortly after she passed round our stern, and we dipped our colours to each other as she did so. She then brought up, and stopped not far from us, while our captain hailed her in English, and asked if they would take some letters ashore for us. With difficulty, we understood their reply to be “Yes.” When, however, in their turn, they asked us where we were bound for, and got the reply “Siberia,” they seemed somewhat astonished, as well they might, for “Siberia” is vague. We then lowered a boat, and sent them our packet of letters; after which, bidding each other farewell by means of our fog-horns, we continued our way. We subsequently learnt from the mate, who had been in the boat, that it was a steamer which had been sent to Nova Zemla to try and discover a Russian ship, which had been lost there some months back.

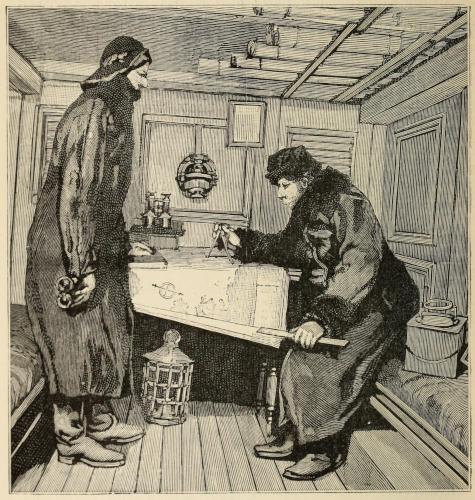

A “DEAD RECKONING” IN THE KARA SEA.

During the remainder of that day our course was again obscured by thick fog, which prevented us from sighting Kolguier Island in the afternoon as we had expected. When, however, we came on deck after tea, a curious incident occurred. Our ice-master, who had been intently looking through his glasses at something which had attracted his attention,[10] suddenly declared that he saw land on the horizon behind us. We were all naturally somewhat startled at this intelligence, as we hardly expected to see it in so distant a quarter, for even had we passed Kolguier in the fog, at the rate we were going it could not possibly have been so far away from us in the time. But what land was it, then? for on looking through our glasses we certainly did see high[11] mountains capped here and there with snow, their base lost in the surrounding mist. On consulting the chart we were not a bit the wiser, for it seemed as doubtful as ourselves. I give, as a proof, the following “caution,” which is printed on the “Map of the Coast of Russia included between Cape Kanin and Waygatch Island” (Imray, 1883): “As the sea comprised within the limits of this chart is very imperfectly known, no survey of any portion of it having been made, it should be navigated with more than ordinary care. The geographical positions of headlands and islands are all, without exception, uncertain, and their general delineation is only approximately accurate.” (This is from the map we were then consulting.) After a while, however, the mysterious land gradually disappeared in the distance; and, as we shortly after sighted the looked-for Kolguier Island ahead of us, there can be very little doubt that the mountains we thought we saw were part of what the sailors call “Cape Flyaway.” It was a most realistic effect, and, even seen through powerful glasses, was exactly like land.

The sunset that evening was magnificent; in fact, I never remember seeing such glorious sky effects anywhere else as I have observed in these latitudes, the most wonderful part of them being their extraordinary stillness. For at least an hour I have frequently noticed masses of cumuli absolutely unchanged either in shape or position.

The days were now beginning to get shorter again, although it was still broad daylight all night (if such an expression is English), the sun remaining below the horizon a few minutes longer every day. By the way, I believe we were fortunate in getting in the neighbourhood of the North Cape exactly on the last day in the year, when the sun is visible above the horizon at midnight. All of us were now anxiously looking forward to getting a glimpse of the coast of Siberia, and yet the weather was so warm and the sea so calm and blue that it was more like yachting in the Mediterranean than a voyage through the dreary Arctic regions; in fact, on August 4, when we at length sighted the land, the sun was simply broiling. Lovely, however, as the day was, it seemed to have very little effect on the dreary-looking coast-line, for a more dismal and uninviting country I never saw, flat and uninteresting right down to the very water’s edge, and with a striking absence of any colour, except a dingy muddy brown. This, of course, is easily accounted for, as it is only for two or three short months that the ground is free from snow, and there is no vegetation in these regions.

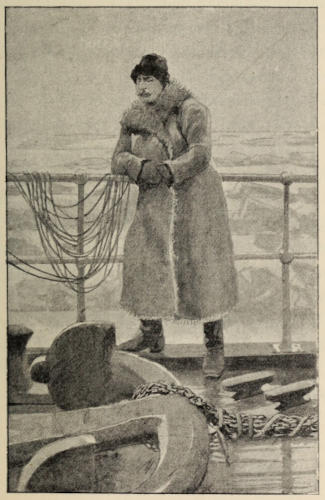

OUR ICE-MASTER, CAPTAIN CROWTHER.

Captain Crowther, our ice-master, a veteran Arctic traveller, who was out with the Eira expedition in 1881-2, and is the only man on board who knows these parts, now assumed the command of the ship, and took up his position on the bridge. We were[13] about to enter the Kara Sea by the Waygatch Straits, and it was uncertain as yet if the navigation was open, as this remote sea is never entirely free from ice. It was to be an exciting time for the next hour or so, for, if our passage through the Straits was blocked, we should have to return and try and get round by the coast of Nova Zemla, a much[14] longer and still more doubtful route. Sailing as we were, on a summer sea and in the warm sunshine, one could hardly realize that, perhaps a mile or so ahead, we might find our passage blocked by impenetrable ice; it seemed so utterly improbable as to be hardly worth the thought. But we did not know the Arctic regions yet.

We soon reached the entrance to the Straits, which are formed by the Island of Waygatch on one side and Siberia on the other, and are only about one and a half mile across, passing so close to the shore that we could plainly distinguish the battered wreck of a small vessel lying on the beach near a primitive sort of wooden beacon, which seemed strangely out of place in so melancholy a spot. Some distance farther, on the Siberian side, we could see the small hamlet of Khabarova, consisting of about a dozen wooden huts or cottages clustered round a little church, with a few fishing-coracles drawn up on the shingle in front, while a short distance away were several Polar bear skins hanging up to dry. It looked unutterably sad, this poor little outpost of humanity so far away from the busy world. One could not help wondering what inducement this dreary Arctic waste could possibly offer for any one to wish to dwell in it. I hear, however, that a few Russian merchants live there, carrying on a sort of trade with the Samoyede natives in return for furs, walrus tusks, etc.

Up till now we had been having real summer weather, with rippling waves sparkling in the brilliant sunshine. Suddenly the scene changed, and, with barely any warning, a drenching shower came down, and with it the wind veered round to the north-east, dark clouds obscured the sky, and as we entered the Kara Sea the effect was indescribably weird. It was like going from daylight into a horrid, uncanny sort of twilight. Behind us we could still see the lovely sunshine we had just left, while ahead the scene was Arctic in the extreme, and thoroughly realized my wildest expectations. All was cold and wretched, with a wintry sky overhead. Under the low cliffs which encircled the dreary shore one could see huge drifts of snow which the sunshine of the short Arctic summer had been powerless to disperse, while for miles round the sea simply bristled with drift ice in all sorts of uncouth shapes. I felt that it would require the pencil of a Doré or the pen of a Jules Verne to convey any adequate idea of the weird scene in all its desolate grandeur.

In the midst of the ice-floes—Tedious work—Weird effects at twilight—A strange meeting—We pay a visit to the home of the walrus-hunter—Curio-hunting—A summer morning in the ice—Delightful experience—The Arctic mirage—We part from our new friends—An uncertain post-office—Ice-bound—Novel experiences—Seal-hunting.

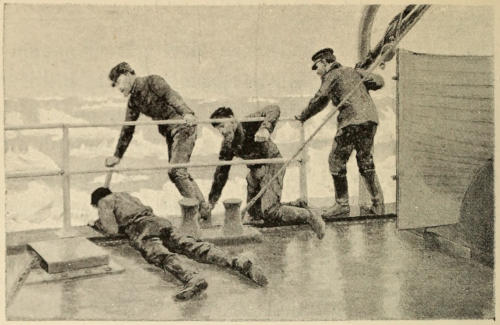

CLEARING THE DRIFT ICE FROM THE PROPELLER.

Notwithstanding its unpromising aspect, our plucky ice-master put the Biscaya straight for the icy obstacles, and soon we were surrounded on all sides by ghostly shapes, which appeared to be hurrying past us like so many uneasy spirits under the leaden sky. Although the ship was well and skillfully handled, in a very short time we were actually blocked in on all sides by huge masses of ice, and remained so for several hours. Then the floes drifted sufficiently[17] to allow of our gradually wedging our way through, which we did with considerable difficulty and not without several severe bumps; in fact, it was a wonder to me how we managed to get through at all, still more without serious damage. Curiously enough, all the ice for the moment seemed to be gathered in one spot, for the sea beyond was clear for several miles ahead after this; then more drifts appeared, and during the night we were again hemmed in on all sides.

The next morning the sun was shining in a cloudless sky once more, a great contrast to our previous evening’s experience, and the effect of the snow-white drift-ice floating on the blue sea was very beautiful and novel. This time the water was sufficiently clear ahead to allow of our passage without much difficulty, and we proceeded without any special incident for several hours. Towards the afternoon, however, we observed a curious effect on the horizon before us: it was a sort of white reflection in the sky. Our experienced ice-master, who had been up to the mast-head with his glasses, however, did not look at it in the same light as we did; to him it was neither novel nor interesting. He told us that it was the reflection in the sky of enormous fields of ice, which it would be impossible to get through, unless we found a passage in some part of it. For the moment he could see nothing for it but to turn back and try another course, as the[18] sea ahead was blocked on either side as far as he could see. This did not sound cheerful, as it immediately raised visions of wintering in the Arctic regions, if, indeed, our ship was not smashed up before then. Without any delay the Biscaya’s head was immediately turned right round to the southeast, in the hope of finding a clear passage, and creeping north again under the shelter of the land. It was wearisome work going right back again over the old ground, but this was but a forerunner of what we had to do for some time afterwards, and by the time we had done with the Kara Sea we had all learnt a good lesson in patience. So as to economize the coal, we only steamed half-speed ahead all the time. After several hours on this course, it was decided once more to try our luck and get northward again, and all that night we went steadily on without meeting with any ice.

The next morning, when we got up on deck, a most provoking sight awaited us. We were steaming very slowly, for a few miles ahead of us was the wall of ice we had been trying in vain to avoid. There it lay, stretched out as far as the eyes could reach on either side in the bright sunshine, a ghostly barrier between us and our route. Our ice-master was pacing the deck in a very restless manner, and evidently did not like the look of affairs at all. At last he told us that it was no good humbugging about it: we were fairly in for it. As far as he could judge, the Kara[19] Sea was full of ice to the north, so that the only thing we could do was to dodge about on the chance of finding a weak spot to try and get through. If we did not succeed in finding a passage, he thought “it would be a very long job before we got out of the ice.” His language was forcible enough to carry weight with it, even if his experience had not, so once more the ship’s course was altered, and we started on a fresh voyage of discovery, westward this time. All that day we were pounding along the fringe of the interminable fields of ice, when, towards evening, it was decided to try what appeared to be a sort of opening some few miles ahead, although it did not look a very hopeful undertaking. For an hour or so, however, before making the attempt, the engines were slowed down as much as possible, in order to give our captains an opportunity of taking a little rest, as they knew that, once inside the ice, there would be no time for sleeping. At eight o’clock the ship’s head was turned due north again, and in a very short time we were entirely surrounded by ice, which seemed to get more and more compact as we advanced, if advance it could be called; for at times we barely moved at the rate of a mile an hour, with continual stoppages to enable the men to clear away the drift-ice from the propeller. Round us was an extraordinary scene, and one which I hardly know how to describe. There was not a breath of air stirring; in the growing twilight the sea looked[20] like polished glass, and on it the floating ice, which was rapidly melting, took all sorts of weird and grotesque shapes, conjuring up visions of low tide on some immense shore in antediluvian days, with uncouth monsters disporting themselves in the shallow water. We were so much impressed by our surroundings that we remained on deck watching the slowly moving panorama all night, or, rather, during the hours which are usually night, for it was but a sort of mysterious twilight all the time, which considerably added to the effect.

THE HOME OF THE WALRUS-HUNTER.

Towards morning we got into somewhat clearer water, when, to our great surprise, we sighted some vessels ahead of us in the ice. They turned out to be walrus-hunters, and, on our getting up to the nearest one, a sort of sloop with a crow’s-nest at the mast-head, with a man in it on the look-out, they[21] sent a boat over to us, and we then learnt that they were all in the same fix as ourselves, and had been blocked in for some days past, as they also wanted to get north. They hailed from Hammerfest, and had been in the Kara Sea since April, but hoped to be able to get out and on their way back to Norway towards the end of August. One of our party, an enthusiastic curio-hunter (without which no party could be complete), immediately “scented” his prey, and on inquiry found that the men had on board a Polar bear’s skin they could sell him, also some sealskins and walrus tusks; so we jumped into their boat, and they took us across to have a look at them while their captain and ours hobnobbed together and talked Norwegian to their heart’s content in the Biscaya’s cabin. On nearer inspection, the sloop proved larger than we had imagined it, and certainly dirtier. In a few minutes a cask was hauled up out of the hold, and a large yellowy-brown bundle, covered thickly with wet salt, pulled out of it and spread on the greasy deck. This was the Polar bear’s skin we had come to see. Our curio-hunter’s enthusiasm went down to zero at once, for it was as unlike the snowy-white rugs one sees in London drawing-rooms as chalk is to cheese; still, they actually asked the modest sum of £5 for it in this dirty state. The sealskins were also very disappointing, and we were about to return to the boat, when one of the crew produced a lot of Samoyede costumes and walrus[22] tusks, which we all made a rush for, as, at any rate, they were interesting—and clean. Of such there were enough to satisfy us all, and they were soon bought up. I got off cheapest, as I managed to get some very curious articles in return for my Waterbury watch, which took the man’s fancy. On returning to the Biscaya we found that it had been arranged to tow the sloop a short distance, as its captain said he knew the coast, and thought he could pilot us through the ice part of the way. The ships therefore got under way in company, and most of us then turned in for a few hours, after a most fatiguing day.

In the morning we were at a standstill, fairly blocked in on all sides by the ice, which glistened and sparkled round us till one’s eyes ached from the glare. The sea was as calm as a mill-pond, the sun was shining in a cloudless sky, and it was so warm that had it not been for the ice around I should have suggested having the hose out and a bath on deck, for the thermometer marked fifty degrees in the shade. It was simply delightful, and made one feel quite pleased to be alive, so to speak. I could not help thinking, as I breathed the exhilarating air, how few Londoners have ever experienced such delight, as inhaling this sort of air seems to impart to one a kind of desire to jump about and give vent to one’s animal spirits in quite a schoolboyish fashion, reminding one of one’s youthful days before the cares of manhood were upon us, when on the weekly half-holiday[23] the rush was made for the cricket-ground. Owing to the purity of the atmosphere, the refraction or mirage along the horizon was so great that the ice seemed to be literally standing straight up, thus producing the impression of our being surrounded by a high white wall or cliff—an almost indescribable effect, and which, when seen through the glasses, reminded one of a transformation scene at a theatre, when the background is formed of painted gauze which is gradually lifted to disclose further surprises behind. A long and wearisome delay now occurred, as it was manifestly absurd even to try and advance any farther in the direction we were in. At last it was decided that the Biscaya should get out again into the open sea as soon as possible, as our ice-master did not like the look of the huge masses of ice which were pressing tightly on her sides. The walrus-hunter expressed his intention of remaining where he was for a few days, to try and get some seals. Before parting company we entrusted to his care a packet of letters which he promised to post at the first port he touched at—rather a vague promise on his part, as he was uncertain when he would return to civilization. However, it was worth chancing, as he might possibly get back before we reached the end of our long journey. I could not help wondering how long my letter would take to reach the Strand, and felt certain I should never find a more uncertain post-office than this one.

THE “BISCAYA” ICE-BOUND IN THE KARA SEA.

[To face p. 24.

For the next few days we were dodging the ice in all directions. North, south, east, and west, everywhere it seemed to be closing in on us, till at last, during a futile effort to break through, we got so hemmed in that it was deemed advisable to anchor to a floe for a time, and see if there was any chance of the drifts breaking up with the advancing season. So we brought up at a huge field of hummocky ice, and some men were sent down with the ice-anchor. Most of us then enjoyed our first bit of exercise for a fortnight. It was a novel experience being on one of these floating islands. Though not very slippery, one had to be careful. Along the edges the water deepened gradually, as upon a shore, for a couple of yards or so, till where the ice ended, when it suddenly went off into hundreds of fathoms, which looked like a black abyss beneath us. There was very little to see, however, and, although we took our rifles with us, we did not meet with a single living object, still less a bear or a walrus, as we had fondly hoped we might.

AFTER SEALS.

The next few days passed quietly. I managed to do a little sketching, although it was chilly work for one’s feet on the ice. Then the weather changed, and it came on to rain, with a thick fog accompanying it, so we found the close and stuffy cabin very cosy after being in the bleak wind outside, and, if singing (or, rather, making an infernal row) could help to pass away the time, we certainly[25] did our best to lose no opportunity, our only drawback being that we had not a single musical instrument among us. However, as it generally only was a question who could invent the most unearthly noise to accompany the “songs,” the result can be more easily imagined than described. Sometimes we managed to get a shot at a stray seal which was rash enough to come within range, but, as they invariably dived down immediately we had fired, we could never tell if they had been hit or not, still less get them. One brute, with a face like that of an old man, was particularly “cheeky.” He would come up alongside and almost stand up in the water and have a good look at us, as much as to say,[26] “Here I am, you fellows! Why don’t you try and get me? But you know you can’t!” Then, by the time we had got our rifles and ammunition ready, he would disappear suddenly, and a few seconds after come up on the other side of the ship. After a little of this sort of thing we simply got mad, and at last there was quite a battery waiting for him when he did appear. The ice-master, who was up at the mast-head, and could, from that elevated position, see him quite plainly under the water, directed our movements, and when at last we got a shot at him grew awfully excited, yelling out, “That’s it! Hit him again in the same place, and you’ll get him!” We did not get him, however, for the poor brute dived down, leaving a track of blood in the water, and did not reappear. We then got out a boat, and went on a sort of hunting-expedition round about, but without finding anything; in fact, we came to the conclusion, after paddling about for half an hour, that there was nothing to find, so we gave it up as a bad job.

At last it was decided to up anchor and once more try our luck, as our captains, and, in fact, all of us, were getting impatient at the delay, unavoidable though it was. The rain appeared to have loosened the floes considerably, so we were a bit more hopeful.

Further impressions of the Arctic regions—The awful silence—Average thickness of the ice—On the move once more—A fresh danger—A funny practical joke—The estuary of the River Yenisei—Golchika—A visit from its inhabitants—From Golchika to Karaoul.

“ONE SPECK OF LIFE IN THE ICE-BOUND WASTE.”

The novelty of being blocked in on all sides by fields of ice soon wears off. Even the chance of a shot at a seal now and again fails to enliven one. The silence of the surroundings is too oppressive; all seems dead, and it seems like some hideous dream to row about on these motionless waters, with the ghostly frozen monstrosities floating around. It[28] reminded one of Doré’s illustrations to Dante’s “Inferno.” One can realize how awful it must be to be forced to pass a winter in the far North, where continual night is added to the horrors of the death-like surroundings. The silence of the great forest Stanley tells us of in his book must be almost noisy (if one can use the expression) compared with it; at any rate, he had living nature around him, whereas in the Arctic regions all is gloom and eternal silence, without even vegetation to enliven it. Before leaving the floe to which we had been anchored, out of curiosity I ascertained the thickness of the ice, and to my astonishment I found it averaged seventeen feet, some pieces being even as much as twenty-five feet in thickness, and this after several weeks of continuous thaw.

It would take too long to describe the wearisome attempts we made during the next few days while trying to break through the immense barrier which lay between us and the mouth of the Yenisei River, and during all this time we experienced every variety of Arctic climate, from hot sunshine to sudden and icy cold fogs. This delay was trying to our patience, for time was precious, as we had to get up the river, discharge cargo, and get the ship off again on her return journey to England before the winter ice set in, otherwise it meant her being fixed in the Kara Sea till the late spring of next year. At length from the mast-head one[29] evening came the long-expected and joyful intelligence that there was clear water visible ahead, and our ice-master reported having discovered what he thought looked like a passage to it. This was good news indeed, as the monotony of the last few days was beginning to pall on us, and we were none of us grieved when, after a few more hours of slow steaming, the intelligence proved correct, and we at last saw a clear horizon before us. Even then a new and unexpected danger presented itself. A gale had been blowing, and, although inside the ice-floes all was calm as in a lagoon, outside a heavy sea was running, and the enormous masses of loose ice were being tossed about like corks. It was an awful sight, and one of the utmost danger to the Biscaya, as it was most difficult to steer clear of the huge heaving masses which threatened at any moment to smash into us. Fortunately, however, we managed to pass through them without the slightest injury to the ship, and we gave a hearty cheer for our skipper when we found ourselves once more out in the open sea, and the order was given, for the first time for many days, “Full speed ahead!”

Before quite leaving the ice behind, I must tell you of a very funny practical joke our captain played on us while we were at anchor. One morning, at about three o’clock, when we were all fast asleep, we were aroused by the captain rushing into our cabin in a state of great excitement, and calling out[30] to us that there was a bear on the ice close by. To jump out of one’s bunk and make for one’s rifle was the work of a moment, while the captain, who appeared to be in a frantic state of excitement at the chance of such capital sport, was rushing about looking for his ammunition. In a few seconds, and without waiting to put on coat or slippers, I was out on the deck, with nothing on but my pyjamas, in order to get the first shot if possible. I found all the crew looking over the bulwarks. It was broad daylight, a cold, raw sort of morning, with a dense fog enveloping everything a few yards ahead. About a hundred yards away, on a huge piece of ice which was slowly drifting towards us, was a large animal looming out through the mist. It was too far away to be distinctly made out, but there it was undoubtedly—a Polar bear. It would make for the water before I could get a shot, so without the slightest hesitation I commenced blazing away. It was so cold standing out in the frosty air, with scarcely anything on and coming straight from one’s warm bed, that I could scarcely hold my rifle, still less distinguish the dim outline in the distance at which I fired four rounds in rapid succession, as I expected every minute the other fellows would turn up before I could hit it. All at once, the mass of ice having by this time drifted nearer, the animal turned slowly round towards us, and started a plaintive bleating. “Why, it’s only a sheep!” I[31] fairly yelled, as I now made out its form quite distinctly. Immediately there rose from all sides such shrieks of laughter as were never heard before in the Arctic regions, I imagine; the crew simply rolled about the deck in convulsions. As to the captain and the others, they nearly went into fits. To my astonishment, I then saw one of the ship’s boats which had been waiting on the other side put off to fetch back the pseudo-bear—which was only one of our own sheep, after all, and which the captain, as a joke, had himself put on the ice, rightly guessing that in our half-awakened state none of us would hit it. The others, however, did not turn out quickly enough, so I was the sole beneficiary of what was one of the funniest practical jokes I ever heard of, and I laughed as heartily as any of them when I “twigged” it all. It was no use going back to bed again directly, so, to show I could appreciate a good bit of fun, and to keep out the cold, we opened a bottle of whiskey, and spent a pleasant hour, while laughing again and again at the description of how I looked, rushing out on deck in my pyjamas, half asleep, and firing wildly over the side of the ship. The sheep (which had been condemned for mutton), in recognition of its valour while under fire, was reserved as our very last victim for the flesh-pot.

We were once more fairly on our way towards the Yenisei, and, although we sighted a great deal[32] more ice, we encountered none which formed any serious obstacle; we evidently had passed the worst. On August 11 we got as far north as it was necessary for us to go (our position being at the time 75 deg. north), and probably very few of us will ever get so near the North Pole again. It was a real Arctic day, as I take it, wretchedly cold, with heavy rain and a dense fog, so there was nothing for it but to remain in the cabin all day. In the afternoon we crossed the estuary to the river Ob, and—curious phenomenon—passed through fresh water for some hours. We got some on deck, and found it drinkable though brackish.

It was now only a question of making up for lost time, as it had been arranged that the river steamer, the Phœnix, should come from Yeniseisk and meet us at the mouth of the river about August 12, which would give us ample time to get out from England, allowing for delays. We reached our place of rendezvous on the 13th—wonderful time, all things considered—and brought up opposite the little station of Golchika, without seeing anything of the ship which ought to have been waiting for us. The river here was about ten miles wide, and the coast on either side was as bare and desolate as that we had seen when passing through the Waygatch Straits. It was profanely though graphically described by one of our party, who remarked that it looked as if it were “the last[33] place God had made, and He had forgotten to finish it!”

THE HANDSOMEST MEMBER OF HIS FAMILY.

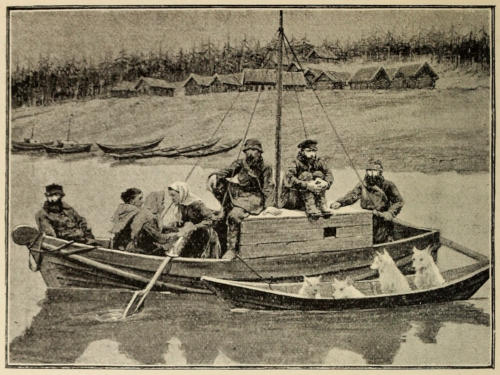

In reply to our gun, which we fired as a signal, a boatful of men put off from the land, and soon reached the ship, and then we had before us our first visitors from the kingdom of the White Czar. There were six of them—two Russians, and the rest Samoyede natives. Good specimens of the Mongolian[34] race, they were dressed in what looked like undressed sheepskin of great age, judging from its colour, the fur being worn inside next their bodies. The two Russians were dressed in the usual peasant costume of the country. We could none of us make ourselves understood, although I got out my guide-book and vainly tried to pronounce some jaw-dislocating words; so we stood grinning at each other for several minutes, till some one thought of offering them a cigarette. This time no interpreter was necessary. What we wanted to find out from them was whether they had seen anything of the Phœnix, but could not make them understand; in fact, our difficulty now was to get rid of them—to let them know we were pleased to have had the pleasure of meeting them, but that “enough was as good as a feast.” As they did not understand a hint, we simply pointed down to their boat, waving our hands to them as a sign for them to depart; this they acted on, but not before they had insisted on shaking hands with us all round—rather a trying ordeal. After their departure, it was decided to anchor in mid-stream and wait a few hours for the Phœnix before we attempted reaching the next station without a pilot.

SAMOYEDE BOATMEN.

[To face p. 34.

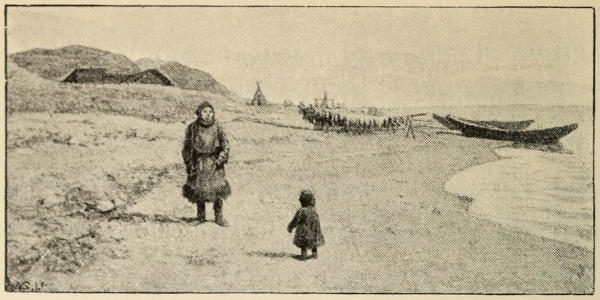

In the mean time, the steam-launch we had on board was got out and put in readiness. The following day, there still being no signs of the Phœnix, it was decided to attempt to reach the next station,[35] Karaoul, a distance of about a hundred and sixty miles, without her, as it was thought she might have met with an accident on her way down with so many lighters in tow; so, with the launch a few hundred yards ahead taking soundings, the Biscaya left Golchika, and started up the river in the hope of seeing the missing ship. We made slow but sure progress, considering we had no pilot, and how imperfect our only chart was, and it certainly was a bit of luck that we got on so well as we did, as the river is full of sandbanks. No incident worthy of note occurred. It was blowing a nasty head wind all the time, so those in the launch had a rough and wet time of it, as the river averaged three miles wide the whole way, and there was no shelter whatever; yet they stuck to their work manfully, although they were nearly swamped several times by the heavy seas. Towards evening the next day we came in sight of a solitary log-cabin on the dreary shore, with a dilapidated sort of storehouse next to it; close to the water’s edge stood a Samoyede tent with a lot of native dogs lying round it; all about were empty casks and other miscellaneous rubbish. Not a human being was in sight. We had safely accomplished the risky voyage from Golchika without a pilot; for this wretched little station off which we dropped anchor, with all our colours flying, was Karaoul, the goal of the Biscaya’s voyage.

The tundras of Northern Siberia—The Samoyedes—Arrival of the Phœnix—My first Russian meal—Vodka and tea—Our departure for Kasanskoi.

KARAOUL.

In my last chapter I told you how we had safely reached Karaoul, the destination of the Biscaya, and that, to our great disappointment, the ship which ought to have been there to meet us was not at the rendezvous. What could have happened to her? Naturally, the first idea that suggested itself was that she had run aground and was unable to get off, encumbered as she was with the heavy barges that she was towing down from Yeniseisk to take back our cargo in. It was manifestly out of the question attempting to proceed any farther without a pilot, so it was decided to wait where we were, in the hope of the Phœnix turning up during the next day or two.

In the evening we all went ashore to have a look round, and were received on landing by quite a pack of native dogs, which, however, only offered a mild protest against an invasion by barking at us from a distance. A limp-looking individual, dressed in the usual Russian costume, with the inevitable top-boots, strolled listlessly down towards the beach with his hands in his pockets, and stared at us in an aimless sort of fashion. The dismal loneliness of the surroundings had evidently had their effect on him, and he was incapable of arousing himself to anything requiring a mental effort, for he did not evince the slightest interest in our arrival, strange and unusual though it certainly must have been to him in this out-of-the-way sort of place. We found, however, that he still retained the use of his tongue, and my slight knowledge of German then proved very useful, as it turned out he was not a Russian, but hailed from the “Vaterland.” He informed us that he was the only white man in the place (which, by the way, only contained as many inhabitants as there are letters in its name), and usually spent the summer months there looking after the Samoyede fishermen who were working for the merchant who owned the dilapidated wooden buildings. In the winter he was employed as a butcher at Yeniseisk, and very glad he was to get back again there, as he said he had a fearfully dull time of it here, with not a soul to speak to except the Samoyedes, and very little work to do[38] even when fish was brought in to salt. One could not help pitying a man who was so down on his luck as to be obliged to bury himself alive so far from his native land in order to earn his daily bread.

There was not much to see on the beach, so we started for a walk over the hills, and had a very pleasant ramble through country which reminded one not a little of the Scottish Highlands. Everywhere we were knee-deep in luxuriant grasses and moss, while all around flowers were growing in wild profusion—it was almost like being in a huge deserted garden. I noticed no end of old friends, such as the wild thyme, campanella, and mountain daisy. It was hard to realize that the ground is eternally frost-bound a foot or so beneath the surface, and that all this wonderful vegetation only comes up during the few months when the ground is not covered with snow; for during the greater part of the year there is absolutely nothing to relieve the white vista of the endless rolling plains, which are then deserted by even the aborigines themselves. We came across a solitary Samoyede grave on the hillside, the spot being marked by two sledges standing ready packed as for a journey. The Samoyedes thus leave their dead, and the custom is almost touching in its simplicity. All the earthly belongings of the deceased are placed on the sledges, covered with a reindeer skin, and abandoned to the mercy of the elements, with no other protection than[39] a rudely carved forked stick stuck in the ground close by to frighten away evil spirits. They have no fear of robbers, as they know that their own people would not desecrate a grave, and to strangers the few primitive articles on the sledges would not offer much temptation; still, I must confess, it rather made my mouth water to see such a lot of tempting curiosities thus abandoned.

THE SAMOYEDE’S GRAVE.

On our way back to the ship we had a look in at the loghouse, and one look was almost enough for most of us, as the heat inside was simply stifling; for, although it was quite a warm summer evening, all the windows appeared to be hermetically closed, and the large stove was in full blaze. There was nothing particularly striking about the interior,[40] which was but a poor Russian home. I could not help remarking the extreme order in which the place was kept; everything seemed to have its place, to which it was scrupulously returned when moved.

A SAMOYEDE LADY.

We then paid a visit en passant to the Samoyede hut, or tent, or whatever they call the bundle of dirty rags that serves them for a sort of shelter. Inside we saw an old man, two women, and four or five half-naked children huddled together, in an indescribable state of filth, round a few smoking[41] embers which were intended to represent a fire. The stench was so great that it seemed more like looking at a den of wild beasts than at human beings. The river might have been ten miles away, instead of only as many yards, for all the use they ever made of it.

It had been decided that the next day our steam launch should be sent on a voyage of discovery up the unknown reaches of the mighty river, in search of the missing Phœnix. The launch had already been thoroughly overhauled, so without delay a supply of provisions, sufficient to last at least three months, was put on board of her, and three of our party told off for the expedition. At eight o’clock the next morning all was in readiness, and the little launch, packed absolutely to the gunwale and towing a boat full of coal for her engine, started on her venturesome journey, her crew looking very uncomfortable in their cramped quarters: still, as it was a lovely day, the sun shining brilliantly, it almost made one envy them their trip, if they had such weather all the time. There was just a slight mist on the river, so they were not long getting out of sight, blowing us a final good-bye with their steam whistle, to which we replied by firing a volley with our rifles. Our now reduced party then returned to the cabin to finish breakfast, wondering how long we were doomed to wait at Karaoul in glorious inactivity.

At the end of the meal, as we were getting up from table, we were startled by hearing the launch’s whistle blowing with great vigour close at hand. We all rushed on deck, fearing some accident had befallen her, when, to our astonishment, we saw her returning at full speed, while close behind her, towering above the mist and with all her colours flying, was the ship she had gone in search of. We were simply dumbfounded, as the situation was almost too absurd; for, had the mist only lifted, or the launch been detained only a quarter of an hour, we must have seen her before her pursuer could have started, and thus saved ourselves a lot of trouble. As may be imagined, the gallant crew of the launch came in for a lot of good-humoured chaff, and we were able to congratulate them on the successful result of their mission and their safe return. In a very short time the Phœnix was alongside, and we then learnt that she had been delayed by the number of barges she had had to tow—so much so, in fact, that, in order to save time, it had been decided to leave most of them some twenty miles behind, at a convenient spot, and come on with only one, so as to commence the transhipment without any more unnecessary delay, and then return for the rest. No time was lost, therefore; and in less than an hour after we had shaken hands with those on board the steamer, our hatches were off, the steam winches going merrily, and the cargo being rapidly taken[43] out of the hold, under the supervision of a stately Russian custom-house officer, who was attended by two Cossacks.

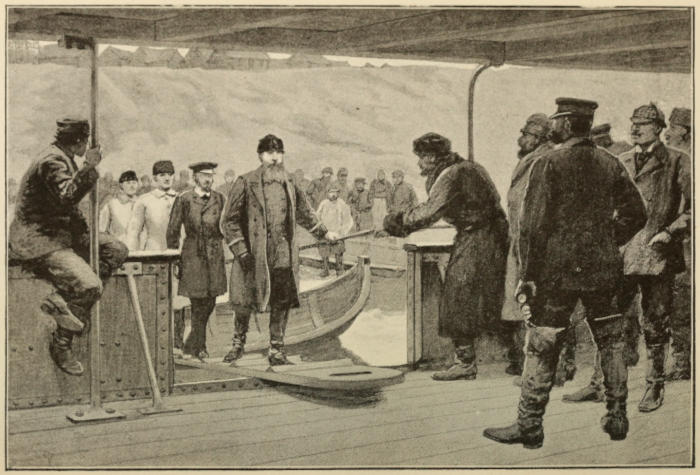

TRANSHIPMENT OF OUR CARGO TO THE “PHŒNIX.”

The Phœnix appeared to be crowded with men, as compared with our small crew of twelve. I learnt afterwards that no less than forty-five men had been brought down from Yeniseisk to work the barges and get in the cargo, and that among this big crowd there was a baker, a butcher, and a man specially told off to attend to the live stock, of which they had quite a farmyard, on one of the barges. They evidently knew how to make themselves comfortable while they were about it. I spent an hour in watching the men working at the cargo, and could not help coming to the conclusion that with a little less talk a good deal more work[44] could have been accomplished in the time; there seemed to be too many foremen, and all seemed to differ in their orders at any critical moment, and so helped to increase the confusion which was already caused by the jabbering of the men. It was, however, a picturesque and interesting sight, this crowd of rough, unkempt men, with their coloured blouses and their loose trousers, tucked into high boots, reminding one not a little of bold buccaneers in the good old Adelphi dramas; and although, perhaps, they did not put quite as much energy into their movements as they might have done, they made up for it in “effect,” from an artistic point of view—an effect which was heightened by a quaint sort of chorus they sang at intervals. They struck me as being a much better-looking lot of men than an average crowd of the same class in England, and looked well fed and contented with their lot. A few among them, I was informed, were exiles who have served their time, but who prefer to continue living in Siberia, where, from what I can gather, the general opinion is that one is better off as an exile than as a free man in Russia itself.

We had our first taste of Russian cooking that morning, as we all lunched on board the Phœnix—and a very good lunch it was, although it certainly was very trying to have to eat without drinking, as is the Russian custom, and I mentally decided to live à la Française while in Holy Russia. At the end of[45] the meal a hissing samovar was brought in, tea was brewed, and a decanter of vodka passed round, and we all agreed that vodka makes a very good substitute for whiskey, but that weak tea without milk, drunk boiling hot out of tumblers, would take some getting used to, as it evidently is an acquired taste, and wants educating up to by a prolonged stay in Russia. The cabin of the Phœnix, though small, was so clean and cosy that it seemed quite a treat to have a decently served meal after all the “pigging” we had had to put up with on the Biscaya; it made us almost wish for the time to come when we should transfer our quarters to her for the river journey. Everything looked as prim as on a yacht, from the white paint on the deck-house to the deck itself, which was kept perfectly clean. I feel sure that were the Phœnix to return once more to her native port of Newcastle, her old owners would not recognize, in the smart-looking river boat, their quondam steamer, so thoroughly has she been altered and Russianized. The next day it was decided to go back to where the other barges had been left by the Phœnix, so our anchors were weighed, and both vessels started.