1. “El Embarque: Himno á la Flota de Magellanes.” (The Departure: Hymn to Magellan’s Fleet.)

This poem seems to have been dated December 5, 1875, but according to Rizal’s friends, Vicente Elio and Mariano Ponce, it was written in 1874. It was first published in

“La Patria,” Manila, December 30, 1899.

2. “Y Es Espanol: Elcano, el Primero en Dar la Vuelta al Mundo.” (And He Is Spanish: Elcano, the First to Go Around the World.)

A poem in couplets. Dated December 5, 1875.

3. “El Combate: Urbistondo, Terror de Jolo.” (The Battle: Urbistondo, the Terror of Jolo.)

A romance, dated December 5, 1875.

4. “Un Diálogo Alusivo á la Despedida de los Colegiales.” (A Dialogue Embodying His Farewell to the Collegians.)

Rizal mentions this poem as having been delivered toward the end of his course at

the Ateneo, which would mean March, 1876.

5. “Al Niño Jesús.” (To the Child Jesus.)

A poem dated Manila, November 14, but the year is not given. Supposed to have been

written in 1876.

6. “Un Recuerdo á Mi Pueblo.” (A Remembrance to My Town.)

Poem offered by the author at one of the sessions of the Academy of Literature of

the Ateneo. First published in “La Patria,” December 30, 1899. Written about 1876.

7. “Alianza Intima entre la Religión y la Buena Educación.” (Intimate Bond between Religion and Good Education.)

Dated April 1, 1876.

8. “Por la Educación Recibe Lustre la Patria.” (Through Education the Country Receives Light.)

Poem written about April 1, 1876. First published in “El Renacimiento,” January 2, 1906.

9. “El Cautiverio y el Triunfo: Batalla de Lucena y Prisión de Boabdil.” (The Captivity and the Triumph: Battle of Lucena and the Imprisonment of Boabdil.)

Poem dated Manila, December 3, 1876.

10. “La Conquista de Granada: Abre la Ciudad sus Puertas á los Vencedores.” (The Conquest of Granada: Let the City Open Its Gates to the Conquerors.)

Legend in verse; dated December 3, 1876.

11. “En Año de 1876 á 1877.”

Written by Rizal between 1876 and 1877. A sketch of the history of Spanish literature.

12. “Cuaderno de Varias Preguntas Escritas por J. R. Mercado.” (Copy-book of various questions written by J. R. Mercado.)

[372]

Notes on history.

13. “Colón y Juan II.” (Columbus and John II.)

Lyric poem composed at the Ateneo.

14. “El Heróismo de Colón.” (The Heroism of Columbus.)

Epic canto, dated December 8, 1877.

15. “Leyenda, Gran Consuelo en la Mayor Desdicha.” (Reading, the Great Consolation in the Worst Misfortune.)

Poem written at the Ateneo, probably 1877.

16. “A la Juventud Filipina.” (To the Philippine Youth.)

The ode that contains the oblation, “My Fatherland.” First published in the “Revista del Liceo de Manila, 1879.”

16 b. “A la Juventud Filipina.” (To the Philippine Youth.)

Translation of the foregoing into Tagalog verse by Honorio Lopez, in the booklet “Ang Buhay ni Dr. José Rizal,” of which Lopez was the author.

17. “Abd-el-Azis y Mahoma.” (Abd-el-Azis and Mohammed.)

Historical romance, read at the Ateneo by Manuel Fernández y Maniung, December 8,

1879, at the meeting in honor of the Ateneo’s patron saint.

18. “A Filipinas.” (To the Philippines.)

A sonnet dated February, 1880, and written in the album of the Society of Sculptors,

now extinct. First published in the “Independencia,” December 29, 1898.

19. “El Consejo de los Dioses.” (The Council of the Gods.)

An allegory written in praise of Cervantes and for the celebration of his anniversary.

First published in the “Revista del Liceo,” 1880.

19 b. “El Consejo de los Dioses.”

The foregoing translated into Tagalog by Pascual H. Poblete, 1905.

20. “Junto al Pasig.” (Beside the Pasig.)

Melodrama in verse. First published in “La Patria,” December 30, 1902.

20 b. “Junto al Pasig.”

Part of the first scene of the foregoing as sung by students in a religious procession,

November 27, 1904. The music was composed by Blas de Echegoyen.

20 c. “Sa Virgen ng Antipolo.”

Translation into Tagalog verse of the children’s chorus in “Junta al Pasig,” by Honorio Lopez.

21. “Al M. R. P. Pablo Ramon, Rector del Ateneo, en sus Dias.” (To his Reverence Pablo Ramon, Rector of the Ateneo.)

An ode dated January 25, 1881.

22. “A la Virgen Maria.” (To the Virgin Mary.)

A sonnet first published by “La Alborada,” Manila, December 30, 1901.

23. “Memorias Intimas.” (Intimate Memories.)

Impressions since leaving Calamba, May 1, 1882, and until May 3, 1883.

24. “El Amor Patrio.” (Love for the Fatherland.)

Article published under the pseudonym “Laong Laan” in the “Diariong Tagalog,” Manila, August 20, 1882—the first article he wrote in Europe.

[373]

24 a. “Ang Pag Ibig sa Tinubuang Lupa.”

Tagalog translation of the foregoing and printed at the same time.

25. “Los Viajes.” (The Voyages.)

Article in “Diariong Tagalog,” 1882.

25 b. “Ang Pangingibang Lupa.”

Tagalog translation of the foregoing and printed at the same time.

26. “Me Piden Versos!” (You Ask Me for Verses.)

Poem, for which see Appendix. Dated Madrid, Oct 7, 1882. First printed in “La Solidaridad.”

26 b. “Pinatutula Ako!”

Tagalog translation of foregoing.

27. “Las Dudas.” (Doubts.)

Article published under the pseudonym “Laong Laan” in Madrid, November 7, 1882.

28. “Revista de Madrid.” (Review of Madrid.)

An article dated Madrid, November 29, 1882, written under the name “Laong Laan” for

the “Diariong Tagalog” and returned because that journal had ceased to exist.

29. “P. Jacinto: Memorias de un Estudiante de Manila.” (P. Jacinto: Memories of a Student of Manila.)

Refers to himself. Written after his arrival in Madrid, 1882.

30. “La Instrucción.” (Instruction.)

Probably written after his arrival in Madrid in 1882.

31. “Apuntes de Obstetricia.” (Notes on Obstetrics.)

Found in a copy-book.

32. “Apuntes clínicos.” (Clinical Notes.)

Madrid, not dated.

33. “Lecciones de Clínica Médica.” (Lessons in Medical Clinical Procedure.)

Madrid, October 4, 1883, to May 29, 1884.

34. “Filipinas Desgraciada.” (The Unfortunate Philippines.)

Article describing the calamities of 1880–82. Written in Madrid.

35. “Discurso-Brindis.” (Reply to a Toast.)

Speech at the Café de Madrid night of December 31, 1883.

36. A historical novel, unfinished.

Five chapters. He began to write it in Madrid while a student there. It has no title.

37. “A la Señorita C. O. y R.” (To Miss Consuelo Ortiga y Rey.)

Poem written in Madrid, August 22, 1883, first published in “El Renacimiento,” December 29, 1904.

38. “Sobre el Teatro Tagalo.” (On the Tagalog Theater.)

Written May 6, 1884, refuting an attack made by Manuel Lorenzo d’ Ayot. Published

in Madrid.

39. “Discurso-Brindis.” (Reply to a Toast.)

Speech made in Madrid, June 25, 1884, which received great newspaper notoriety.

40. “Costumbres Filipinas: un Recuerdo.” (Philippine Customs: a Memory.)

An incomplete article, written in Madrid, 1884 or 1885.

41. “La Fête de Saint Isidro.”

Not dated. Written in French.

[374]

42. “Notes on Field Fortifications.”

Written in English about 1885. Found in a clinic note-book.

43. “Llanto y Risas.”

An uncompleted article, written in Madrid between 1884 and 1886.

44. “Memorias de un Gallo.” (Memories of a cock.)

Incomplete. Mutilated.

45. “Apuntes de Literatura Española, de Hebreo, y de Arabe.” (Notes on Spanish, Hebrew, and Arabian Literature.)

Not dated. Notes in a copy-book.

46. “Semblanzas de Algunos Filipinos Compañeros en Europa.”

Closely Noted Observations on Certain Filipinos Then Residing in Europe.

47. “Estado de Religiosidad de los Pueblos en Filipinas.” (Religious State of the Towns in the Philippines.)

Unpublished.

48. “Pensamiento de un Filipino.” (Thoughts of a Filipino.)

An unpublished article, date unknown.

49. “Un Librepensador.” (A Free-Thinker.)

An unpublished article. Probably written in Madrid.

50. “Los Animales de Juan.” (John’s Animals.)

An unpublished story.

51. “A S.…” (To S——)

Poem dated November 6, ——.

52. “A.…” (To ——)

Poem, not dated; rough draft.

53. “Mi Primer Recuerdo: Fragmento de Mis Memorias.” (My First Recollection: Fragments of My Memories.)

All these last few works seem to have been written while Rizal was a student in Madrid.

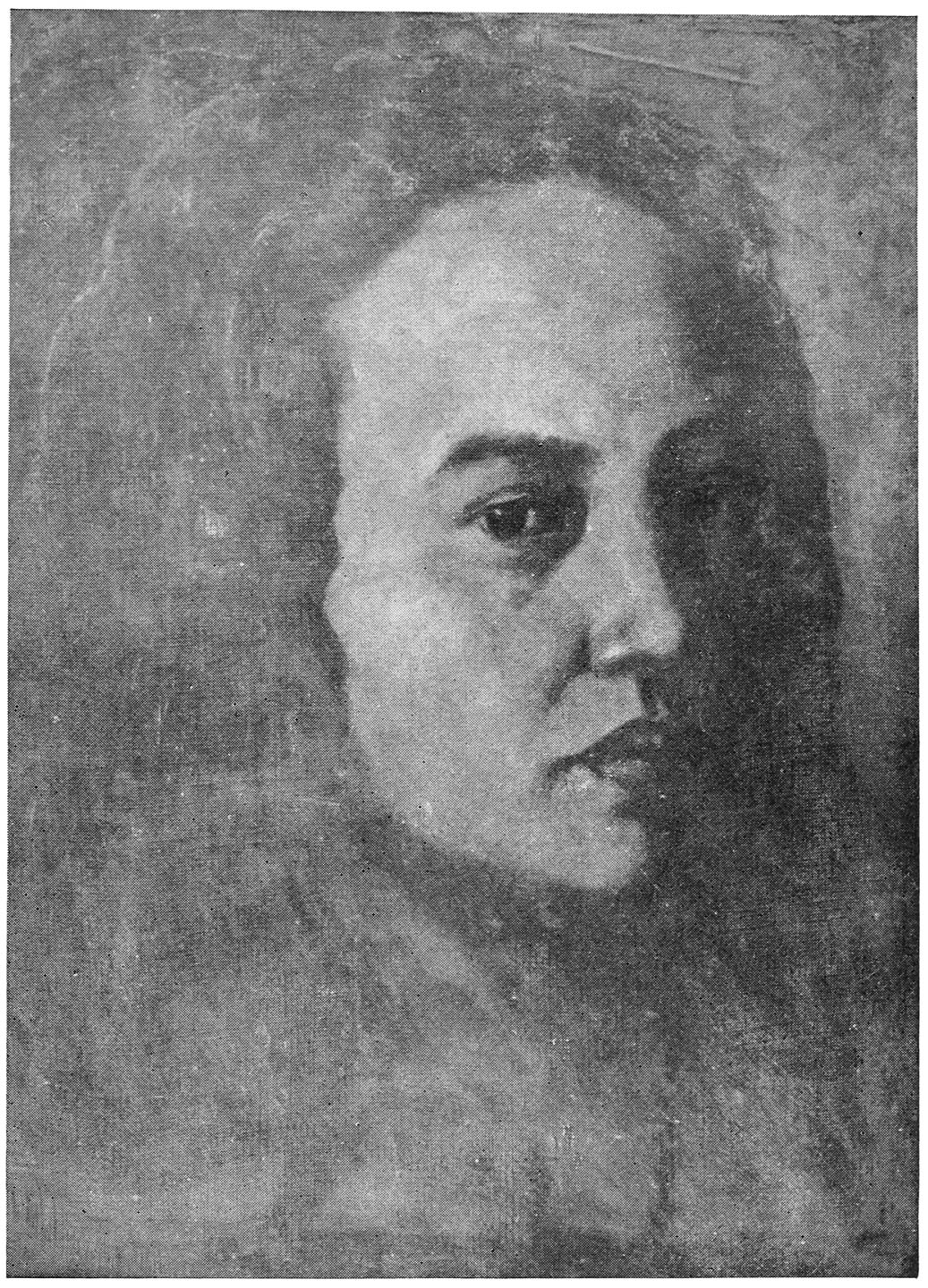

54. “Juan Luna.”

Article, published in the “Revista Hispano-Americana,” of Barcelona, February 28, 1886, carrying a front-page portrait of the great Filipino

painter.

55. “A las Flores de Heidelberg.” (To the Flowers of Heidelberg.) Poem dated Heidelberg, April 22, 1886. Signed “Laong

Laan,” first published in “La Solidaridad.”

56. “Madrid.”

An epistolary chronicle, written in French from Germany in 1886. First published in

“Nuestro Tiempo” in February, 1905.

57. “Crítica Literaria.”

Not dated. Criticisms in French on “Tartarin sur les Alpes” and “Le Pistolet de la Petit Baronne.” Germany, 1886.

58. “Essai sur Pierre Corneille.”

In French. Germany, 1886.

59. “Tinipong Karunungan ng Kaibigan Ng mga Taga Rhin.”

Beginning of a translation of a book by Hebel into Tagalog.

60. “Une Soirée chez M. B.…”

Written in Berlin, in French. Unpublished sketch. No date.

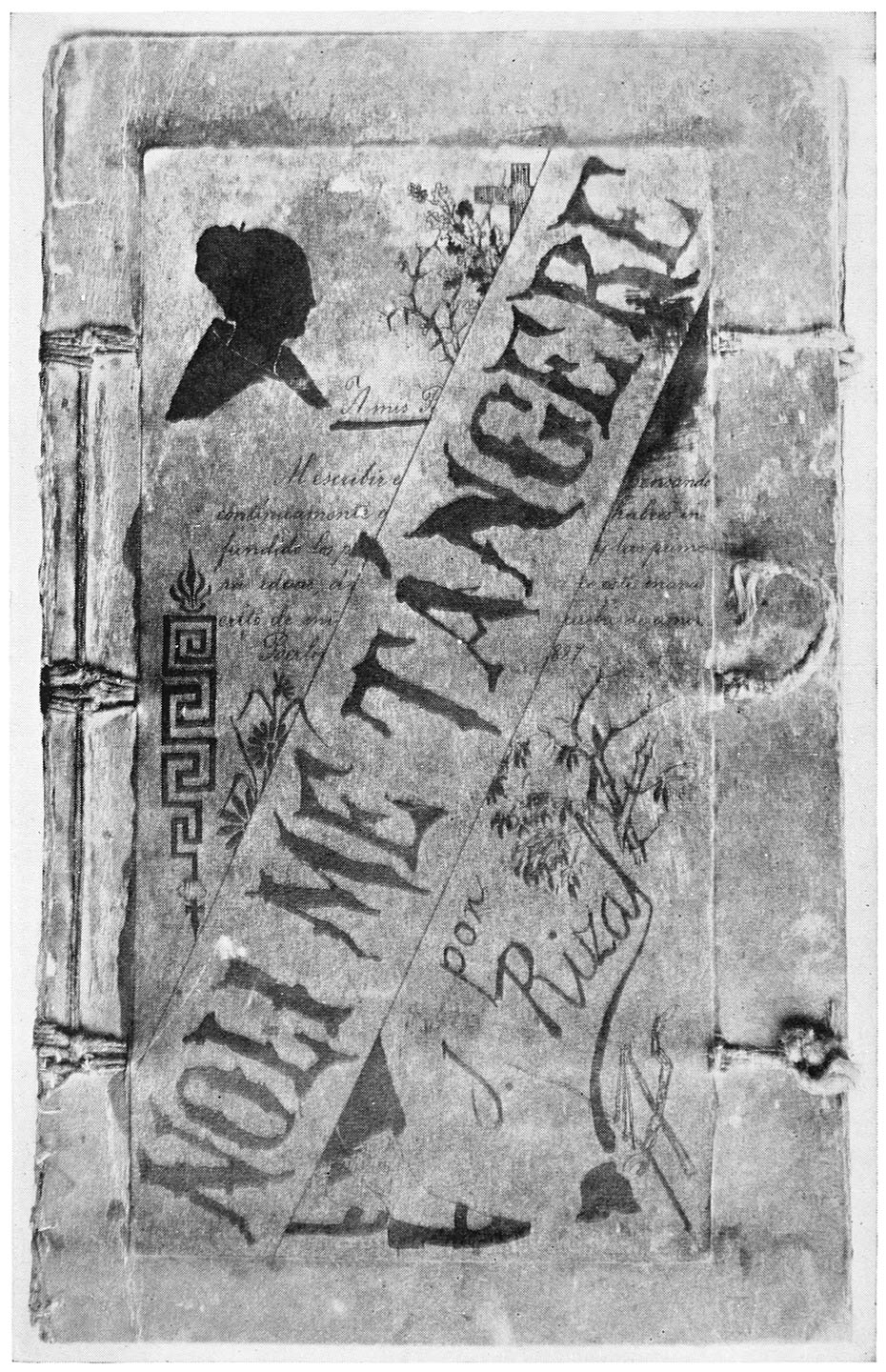

61. “Noli Me Tangere.” Berlin, March, 1887.

His first complete novel.

61 b. “Noli Me Tangere.”

[375]

Second edition, Manila, Chofre & Co., 1899.

61 c. “Noli Me Tangere.”

Third edition, Valencia, Sempere, 1902. Somewhat shortened and with mutilations.

61 d. “Noli Me Tangere.”

Fourth edition, Barcelona, Maucci, 1903. With a short prologue by Ramon Sempau.

61 e. “Au Pays des Moines.”

French translation of 61 by Henri Lucas and Ramon Sempau. Paris, 1899. With a few

notes.

61 f. “An Eagle’s Flight.”

Abbreviated English translation. New York: McClure, Phillips & Co., 1900.

61 g. “Friars and Filipinos.”

Another English translation, somewhat fuller than 61 f, by F. E. Gannet. New York,

1907.

61 h. German translation of “Noli Me Tangere.”

Never finished, by Dr. Blumentritt.

61 i. “Noli Me Tangere.”

Tagalog translation by Paciano Rizal, brother of the author. Rizal himself revised

and corrected the sheets.

61 j. “Noli Me Tangere.”

Tagalog translation by P. H. Poblete.

61 k. “Noli Me Tangere.”

Cebuana translation by Vicente Sotto.

61 l. “Tulang na sa ‘Noli.’”

The song from Chap. XXIII translated into Tagalog by M. H. del Pilar. 1888.

61 m. “Noli Me Tangere” (Extracts).

Translations of chapters, paragraphs, and sentences into many dialects in broadside

form for general distribution in the islands.

61 n. “Ang ‘Noli Me Tangere.’”

Playlet performed on Rizal’s birthday. Mentioned in “El Renacimiento,” Manila, 1905.

61 o. “The Social Cancer.”

A complete English Version of “Noli Me Tangere,” from the Spanish of José Rizal by Charles Derbyshire (with a life of Rizal), Manila,

Philippine Education Company, 1912.

62. “Histoire d’ une Mère.”

A Tale of Andersen’s. Translation from German to French. Berlin, March 5, 1887.

63. “Tagalische Verskunst.”

Work read before the Ethnographical Society of Berlin, April, 1887, and published

the same year, by that society.

63 b. “Arte Métrica del Tagalog.” (Metrical Art of the Tagalogs.)

Spanish translation, made by Rizal, of the foregoing work. Amplified.

64. “Autocrítica de ‘Noli Me Tangere.’” (Self-Criticism of “Noli Me Tangere.”)

An unpublished article in French.

65. “An Account of the Life and Writings of Mr. James Thompson.” By Patrick Murdoch.

A study in English literature. 1887. Unpublished.

[376]

66. “Deducciones. El, segun El, Por un Pigmeo.” (Deductions, by himself, a pigmy.)

Published in “España en Filipinas,” Madrid, April, 1887.

67. “Dudas.” (Doubts.)

Madrid, May 28, 1887. Published in “España en Filipinas.”

68. “En las Montañas.” (In the Mountains.)

Poem written in Germany in 1887.

69. “El Historiador de Filipinas Fernando Blumentritt.” (The Historian of the Philippines, Fernando Blumentritt.)

July 7, 1887. “España en Filipinas.”

70. “De Heidelberg á Leipzig, Pasando por el Rhin.” (From Heidelberg to Leipzig, along the Rhine.)

Notes of travel.

71. “De Marsella á Manila.” (From Marseilles to Manila.)

Notes of travel.

72. “Traducción de Poesías Alemanes al Tagalo.” (Translation of German Poems into Tagalog.)

Done in Calamba about 1887 or 1888. Unpublished.

73. “Guillermo Tell: Trahediang Tinula ni Schiller sa Wikang Aleman.” (William Tell.)

Tagalog translation in which he used the new method of spelling.

74. “Informe al Administrador de Hacienda pública de la Laguna acerca de la Hacienda de

los PP. Dominicos en Calamba.” (Report to the Administrator of Public Finance of La Laguna about the Estate of

the Dominican Friars in Calamba.)

Rizal’s report in the tax fight. It was signed by the justice of the peace, the board

of officers, and seventy leading men of the Calamba district. Mr. Ponce describes

it as the first stone thrown in the bitter contest that ensued between the village

and the powerful religious corporation. It was published as an appendix to “La Soberanía Monacal,” by M. H. del Pilar. The date was early in 1888.

75. “Diario de Viaje a Través de Norte-America.” (Diary of Trip across North America.)

April–May of 1888. See Appendix.

76. “Notas, en Colaboración con el Dr. A. B. Meyer y el Dr. F. Blumentritt, á un Códice

Chino de la Edad Media, Traducido al Aleman por el Dr. Hirth.” (Notes, Collaborated with Dr. A. B. Meyer and Dr. F. Blumentritt, on an old Chinese

Manuscript of the Middle Ages, Translated into German by Dr. Hirth.)

Published in “La Solidaridad,” April 30, 1889.

77. “Specimens of Tagal Folk-Lore.”

London, May, 1889. “Trübner’s Record.” Composed of three parts: proverbial sayings,

puzzles, verses.

78. “La Verdad para Todos.” (The Truth for All.)

Article. Barcelona, May 31, 1889. Published in “La Solidaridad.”

79. “Barrantes y el Teatro Tagalo.” (Barrantes and the Tagalog Theater.)

Article, published in “La Solaridad,” Barcelona, June, 1889.

80. “Two Eastern Fables.”

In “Trübner’s Record,” London, June, 1889. English.

81. “La Visión de Fr. Rodríguez.” (The Vision of Friar Rodriguez.)

[377]

Barcelona, 1889. Under the pseudonym “Dimas Alang,” a booklet published surreptitiously.

81 b. “The Vision of Friar Rodriguez.”

English version made by F. M. de Rivas and published in the book “The Story of the Philippine Islands” by Murat Halstead, Chicago, 1898.

82. A novel in Spanish.

No title. Rizal began it in 1889, left unfinished.

83. “Por Teléfono.” (By Telephone.)

Under the pseudonym “Dimas Alang,” a handbill published surreptitiously.

84. “Verdades Nuevas.” (New Truths.)

Article in “La Solidaridad,” Barcelona, July 31, 1889.

85. “Una Profanación.” (A profanation.)

Anonymous article. “La Solaridad,” July 31, 1889. In this he told of the disinterring by the friars of the body of

Herbosa.

86. “Diferencias.” (Differences.)

An article in “La Solidaridad,” Barcelona, September 15, 1889.

87. “Filipinas dentro de Cien Años.” (The Philippines a Century Hence.)

Four articles in “La Solidaridad,” 1889 and 1890.

88. “A Nuestra Querida Madre Patria!!! España!!!” (To Our Beloved Mother-Country!!! Spain!!!)

Proclamation in sheet form, three columns. Paris, 1889. Ironical.

89. “A La Patria.” (To the Home-Land.)

Article in “La Solidaridad,” Madrid, November 15, 1889.

90. “Inconsecuencias.” (Inconsequences.)

Article against “El Pueblo Soberano” of Barcelona. Madrid, November 30, 1889.

91. “En la Ausencia.” (Absence.)

A poem written in Paris, 1889.

92. “Sa Mga Kababay-ang Dalaga sa Malolos.”

A letter headed “Europe, 1889.”

93. “Notas a la Obra, Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, por el Dr. Antonio de Morga.” (Notes to Happenings in the Philippines by Dr. Antonio de Morga.)

Prologue by Professor Blumentritt. December, 1889.

94. “Ingratitudes.” (Ingratitudes.)

Article in “La Solidaridad,” January 15, 1890.

95. “Al Excmo. Sr. D. Vicente Barrantes.” (To his Excellency Sr. D. Vicente Barrantes.)

Article in “La Solidaridad,” Madrid, February 15, 1890.

96. “Sin Nombre.” (Without Name.)

Article in “La Solidaridad,” Madrid, February 28, 1890.

97. “Filipinos en el Congreso.” (Filipinos in the Assembly.)

“La Solidaridad,” March 31, 1890.

98. “Seamos Justos.” (Let Us Be Just.)

Article in “La Solidaridad,” Madrid, April 15, 1890.

99. “Sobre la Nueva Ortografia de la Lengua Tagalog.” (On the new spelling of the Tagalog language.)

“La Solidaridad,” April 15, 1890.

[378]

99 b. “Die Transcription des Tagalog von Dr. José Rizal.”

Translated into German by F. Blumentritt with comments.

100. “Cosas de Filipinas.” (Things Philippine.)

Article in “La Solidaridad,” Madrid, April 30, 1890.

100 b. “Más sobre el Asunto de Negros.” (More Concerning the Affair in Negros.)

Second part of the above article appearing May 15, 1890.

101. “Una Esperanza.” (A Hope.)

Article in “La Solidaridad,” Madrid, July 15, 1890.

102. “Sobre la Indolencia de los Filipinos.” (Filipino Indolence.)

“La Solidaridad,” Madrid, July–September 15, 1890.

103. “Venganzas Cobardes.” (Cowardly Vengeance.)

Anonymous article. “La Solidaridad,” August 31, 1890.

104. “A la memoria de José Maria Panganiban.” (To the Memory of José Maria Panganiban.)

A meditation in “La Solidaridad,” Madrid, September 30, 1890.

105. “Una Contestación á Isabelo de los Reyes.” (An Answer to Isabelo de los Reyes.)

Article in “La Solidaridad,” Madrid, October, 1890.

106. “Las Luchas de Nuestros Días.” (The strifes of Our Day.)

Two criticisms of the work “Pi y Margall” appearing in “La Solidaridad,” Madrid, November 30, 1890.

107. “Como Se Gobiernan las Filipinas.” (How the Philippines Are Governed.)

“La Solidaridad,” December 15, 1890.

108. “A Mi Musa.” (To My Muse.)

Poem under the pseudonym “Laong Laan,” published in “La Solidaridad,” Madrid, December 31, 1890.

109. “Mariang Makiling.”

Legend. Under the pseudonym “Laong Laan,” published in “La Solidaridad,” December 31, 1890.

109 b. “Mariang Makiling.”

Tagalog translation of the foregoing. This was the last work that Rizal did for “La Solidaridad.”

110. “Discurso en el Banquete de la Colonia Filipina de Madrid en la Noche del 31 de Diciembre

de 1890.” (Speech at the Banquet of the Philippine Colony of Madrid, held in that city on

the Evening of December 31, 1890.)

111. “El Filibusterismo: Novela Filipina.” (Filibusterism.)

Ghent, 1891. First edition, rare. Fragments were published by papers in Spain in 1891.

111 b. “El Filibusterismo.”

Second edition. Manila, Chofre & Co., 1900.

111 c. “El Filibusterismo.”

Tagalog translation by P. H. Poblete, 1904.

111 d. “El Filibusterismo: Novela Filipina.”

Third edition. Prologada y anotada por W. E. Retana. Barcelona, de Henrich and Company. 1908.

111 e. “The Reign of Greed.”

A complete English version of “El Filibusterismo,” from the Spanish of José Rizal by Charles Derbyshire. Manila, Philippine Education

Company, 1912.

[379]

112. “Diario de Viaje de Marsella a Hong-Kong.” (Diary of a Voyage from Marseilles to Hong-Kong.)

Unpublished. Written in 1891.

113. “Ang Mga Karapatan Nang Tao.”

Tagalog translation of the Rights of Man proclaimed by the French revolutionists of

1789. This was probably done during his stay in Hong-Kong and is what the Filipinos

call a “proclamation.”

114. “A la Nación Española.” (To the Spanish Nation.)

Hong-Kong, 1891. An undated proclamation, written in Hong-Kong about November, 1891.

Refers to the land question in Calamba.

115. “Sa Mga Kababayan.”

Sheet printed in Hong-Kong in December, 1891. It deals with the land question of Calamba.

116. “La Exportación del Azucar Filipino.” (Exportation of Philippine Sugar.)

An article printed in Hong-Kong about 1892.

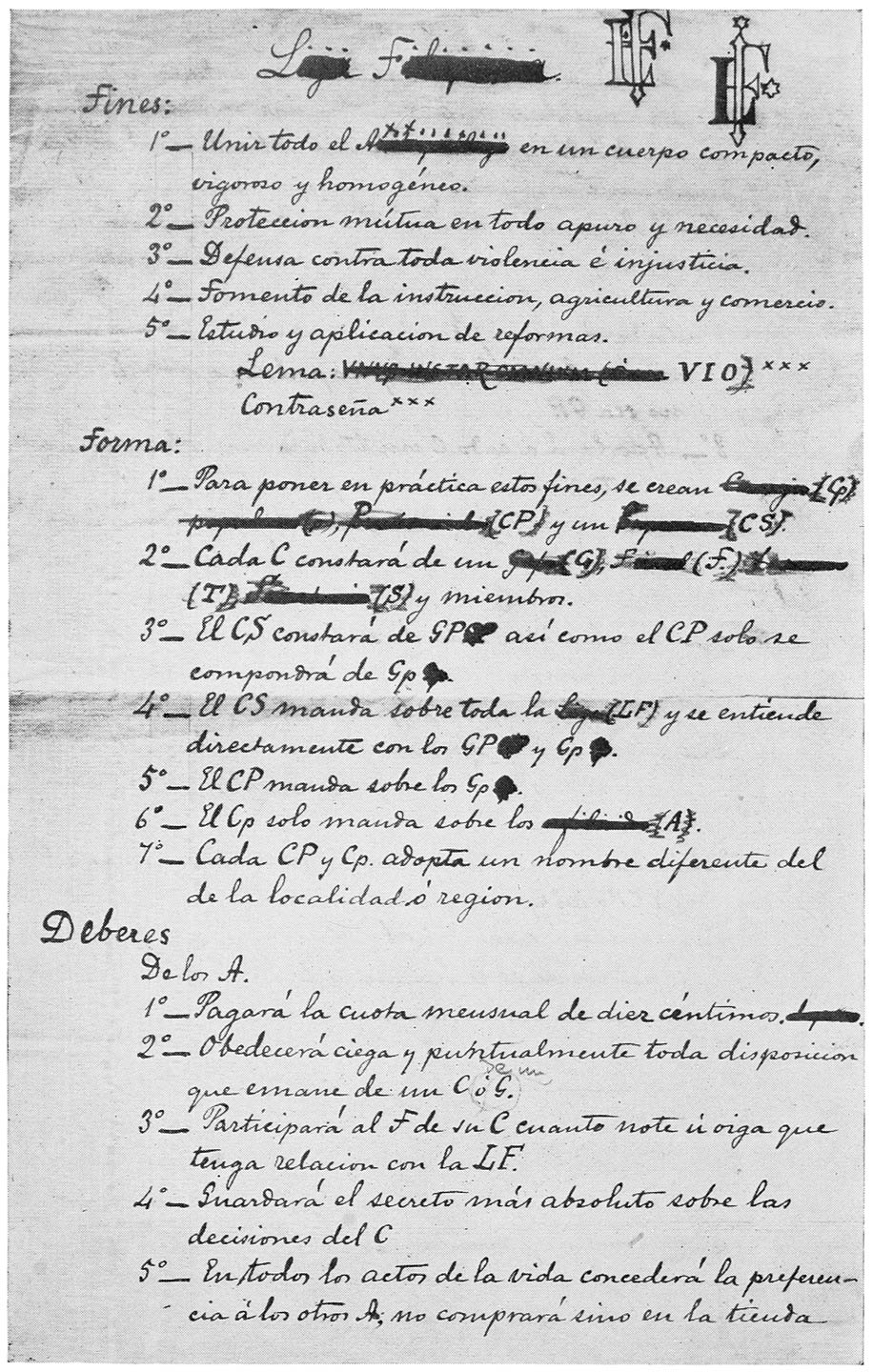

117. “Estatutos y Reglamentos de la Liga Filipina.” (Statutes and Rules of the Philippine League.)

Written in Hong-Kong, 1892.

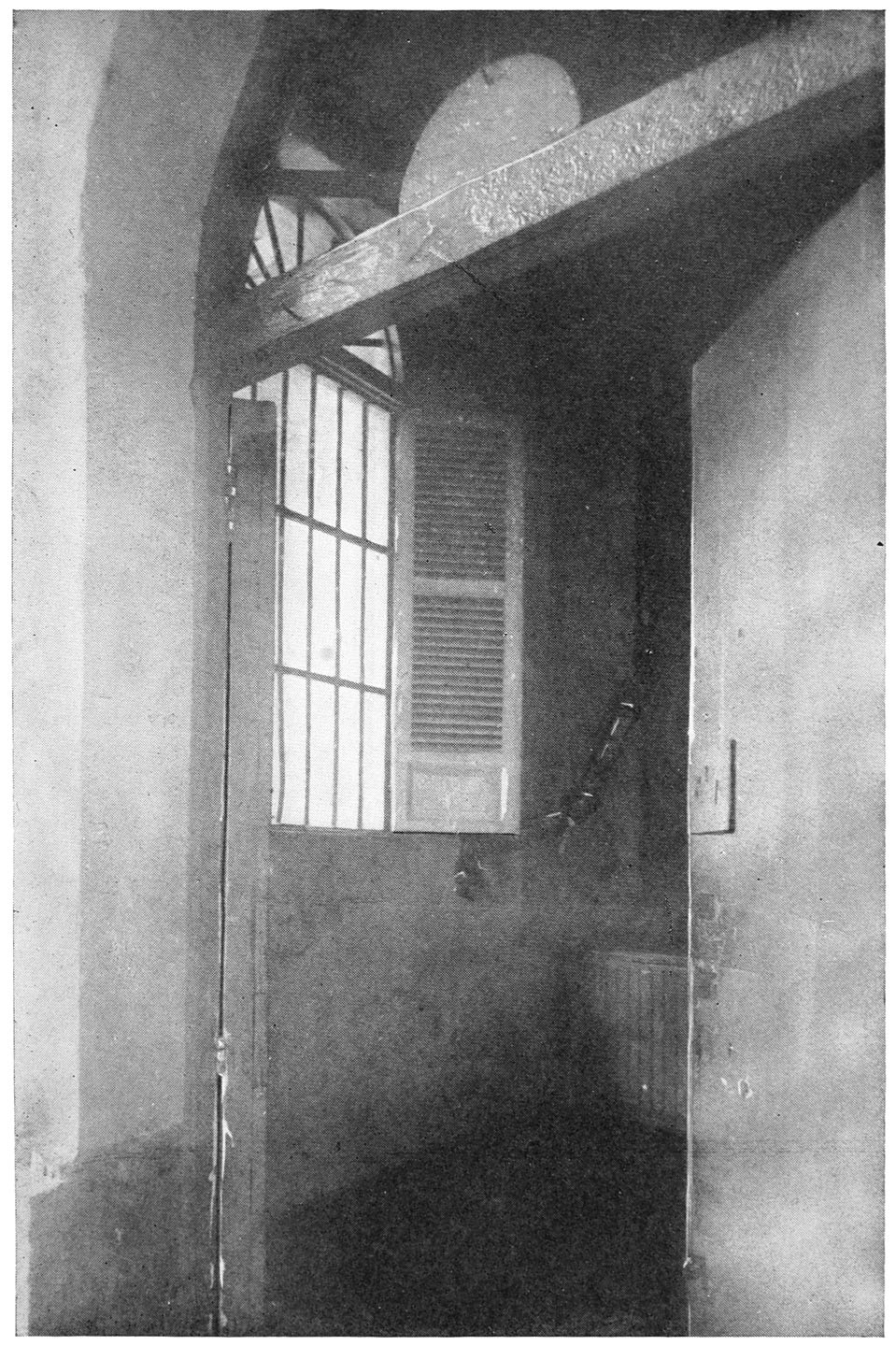

118. “Una Visita a la Victoria Gaol.” (A Visit to Victoria Jail.)

Written in Hong-Kong in March, 1892, describing his visit to the city jail.

119. “Colonisation du British North Borneo, par des Families des Iles Philippines.” (Colonization of British North Borneo by families from the Philippine Islands.)

He also did this work in Spanish.

119 b. “Proyecto de Colonización del British North Borneo por Filipinos.”

An elaboration of the same idea. No date, but it is known that he wrote this at about

the time of his trip to Borneo in April, 1892.

120. “La Mano Roja.” (The Red Hand.)

Sheet printed in Hong-Kong, June, 1892, calling attention to the number of fires started

intentionally in Manila.

120 b. “Ang Mapulang Kamay.”

Translation of above, published in 1894.

121. “A los Filipinos! (Testamento público.)” (To the Filipinos.)

Dated at Hong-Kong, June 20, 1892. Published in various newspapers of the country.

The address to his countrymen to be made public in case of his death.

122. “Notas de Sucesos desde su Desembarco en Manila, Procedente de Hong-Kong, hasta su

Deportación y Llegada a Dapitan. 1892.” (Notes of Events from his Landing in Manila Arriving from Hong-Kong up to his Deportation

and Arrival at Dapitan, 1892.)

123. “Cartas Filosofico-Religiosas de Controversia con el P. Pablo Pastells, S. J.” (Letters of His Philosophical-Religious Controversy with P. Pablo Pastells, S. J.)

124. “Etnografia de la Isla de Mindanao.” (Ethnography of the Island of Mindanao.)

Translated from the German of F. Blumentritt.

125. “Ampliación a Mi Mapa.” (Enlargement of My Map.)

Map of the Island of Mindanao, translated into Spanish by Rizal and dedicated to F.

Blumentritt.

[380]

126. “Estudios sobre la Lengua Tagala.” (Studies on the Tagalog Tongue.)

Written in Dapitan in 1893 and first published in “La Patria” of Manila in 1899.

126 b. “Manga Pag-Aaral sa Wikang Tagalog na Sinulat ni Dr. José Rizal.”

Tagalog translation of the foregoing by Honorio Lopez.

127. “Canto del Viajero.” (Song of the Traveler.)

Poem written in Dapitan. First published in 1903.

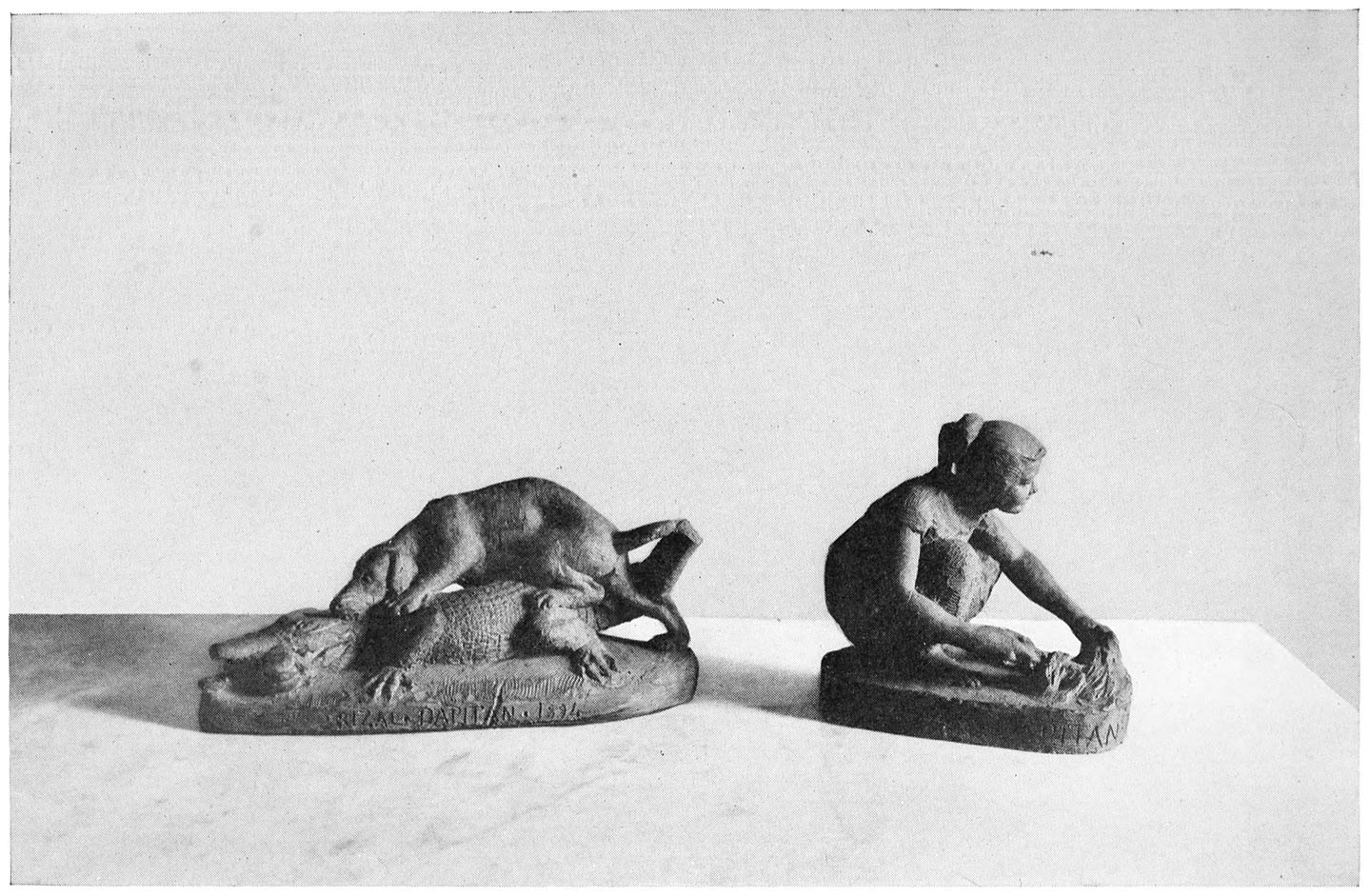

128. “Dapitan.”

Introduction to a work which was never followed up.

129. “Avesta: Vendidad.”

An uncompleted Spanish translation.

130. “Fragmentos de una Novela Inédita y sin Concluir.” (Fragments of an Incomplete and Unpublished Novel.)

Written in Dapitan. Fragments of a novel.

131. “Makamisa.”

Verses beginning a novel in Tagalog. Never completed.

132. “Sociedad de Agricultores Dapitanos.” (Society of Dapitan Farmers.)

Statutes and by-laws, Dapitan, 1895.

133. “Mi Retiro: A Mi Madre.” (My Retirement: To My Mother.)

Poem written in Dapitan, 1895. First published in “República Filipina” in 1898.

133 b. “Ang Ligpit Kong Pamumuhay: Sa Aking Ina.”

Tagalog translation of the above by Honorio Lopez.

134. “Himno a Talisay.” (Hymn to Talisay.)

Composed in Dapitan, October 13, 1895.

135. “La Curación de los Hechizados.” (The Cure for the Bewitched.)

An article believed to be unpublished.

136. “Comparative Tagalog Grammar.”

Written in English. Incomplete.

137. “Datos para Mi Defensa.” (Points for My Defense.)

Written in Santiago Prison, December 12, 1896.

138. “Manifiesto—a Algunos Filipinos.” (Manifesto—To Certain Filipinos.)

Manila, Santiago Prison, December 15, 1896. This was published by many newspapers

in the country.

139. “Adiciones a Mi Defensa.” (Additions to My Defense.)

Manila, December 26, 1896.

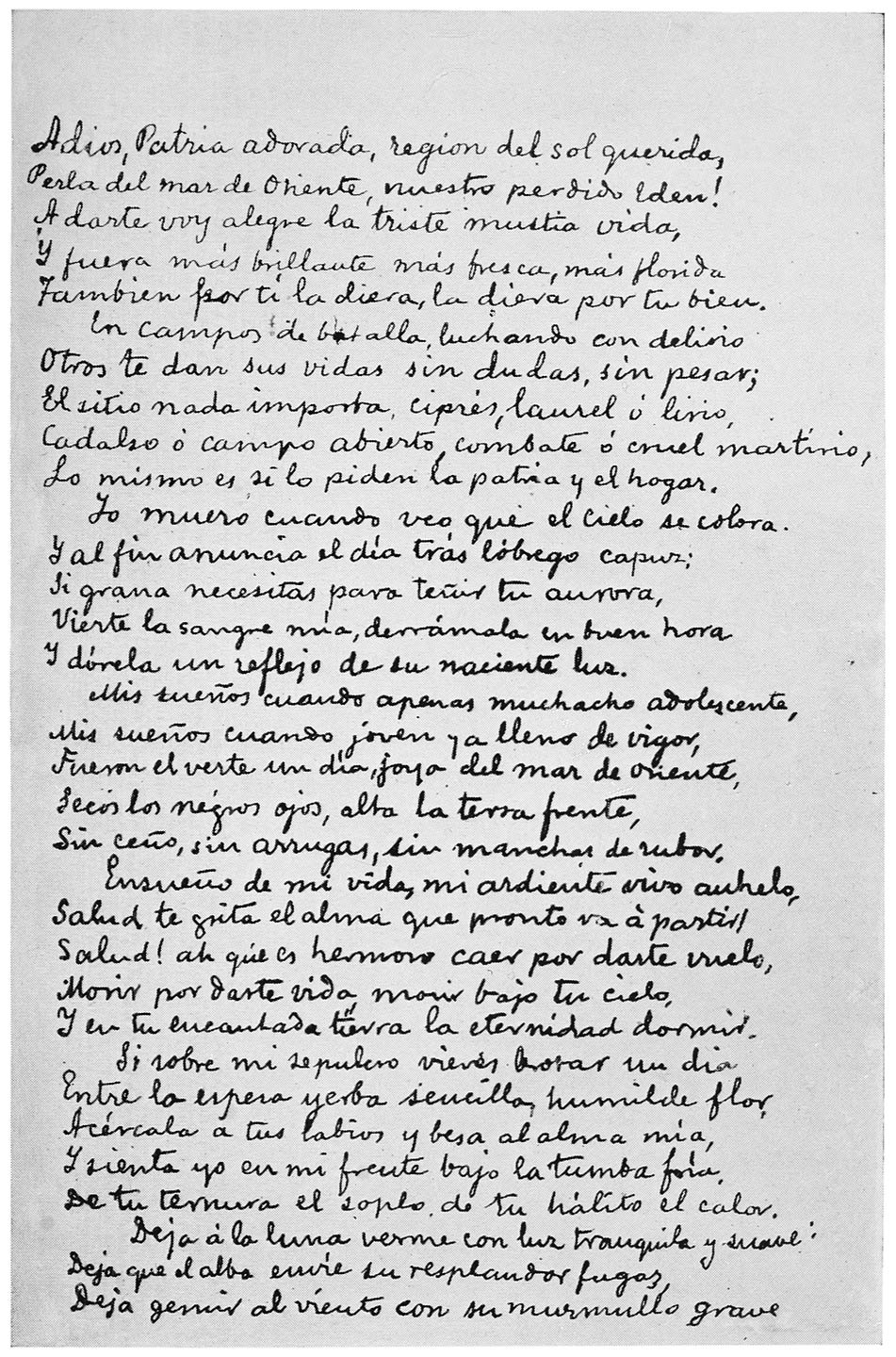

140. “Ultimo pensamiento.” (Last Thoughts.)

The poem written in the chapel, a few nights before his death. The original manuscript

was unsigned and written on ordinary ruled paper. Alcohol stains (from the lamp) can

still be seen on the original where it blurred the ink. The above title was given

to the poem by Mr. Ponce.

Under the title “Ultimo Adiós” (My Last Farewell) it was published in “La Independencia,” September 25, 1898.

It has been translated into many languages, including the island dialects, French,

English, German, Chinese, and Japanese.

141. “French Composition Exercises,” by José Rizal, B. A., Ph. M., [381]L. C. M. (Madrid), Postgraduate student in Paris, Leipzig, Heidelberg, Berlin and

London. Manila, 1912. Philippine Education Company.

142. “The Indolence of the Filipino,” by José Rizal, translated by Charles Derbyshire, edited by Austin Craig, Manila,

1913.

143. “Rizal’s Own Story of His Life.” National Book Company, 1918.

Contains also “Rizal’s First Reading Lesson,” “Rizal’s Childhood Impressions,” “The

Spanish Schools of Rizal’s Boyhood,” “The Turkey That Caused the Calamba Land Trouble,”

“Mariang Makiling,” and other short pieces.

144. “Manila en 1872.”

An article by Rizal discovered after his death and published in the Manila “Citizen,”

January 9, 1919.

145. “Cartas á un Jesuita.”

Another posthumous article, published in the Manila “Citizen,” February 7, 1919.

The following books and articles relating to Rizal may also be noted:

“The Story of Rizal,” Hugh Clifford, “Blackwood’s,” November, 1902.

“Rizal’s Views on Race Differences,” “Popular Science Monthly,” July, 1902.

“The Future of the Philippines,” M. F. Steele, “The Nation,” March 27, 1902.

“A Filipino That Died for His Country,” “Literary Digest,” July 26, 1919.

“Rizal’s Picture of the Philippines under Spain,” “Review of Reviews,” May, 1913.

“The Martyred Novelist of the Philippines,” “Current Opinion,” April, 1913.

“The Malay Novelist,” “The Nation,” January 9, 1913.

“The Composite Rizal,” “The Nation,” April 10, 1913.

“The Life of José Rizal, a Chronology by Austin Craig,” “The Manila Independent,”

December 31, 1921.

“Autógrafos de Rizal,” Fernando Canon, “The Manila Independent,” December 31, 1921.

“Páginas Inéditas de Rizal” (Dapitan), “Dia Filipino,” Manila, June 19, 1918.

“Rizal en Hong-Kong,” by Vicente Sotto, in “Renacimiento Filipino,” Manila, July 7, 1913.

“Rizal’s Story of His Life,” the Manila “Citizen,” August and September, 1918.

“Rizal and Philippine Nationalism,” by José Melencio, the Manila “Citizen,” February

21, 1919.

“Rizal as a Historian,” by Austin Craig, “Philippine Herald,” Manila, July 10, 1921.

“The Song of the Wanderer,” translated by Arthur Ferguson, “Dia Filipino,” June, 1918.

“The Song of the Wanderer,” translated by Charles Derbyshire, “Philippine Journal

of Education,” Manila, December, 1919.

“To My Muse,” translated by Charles Derbyshire, “Philippine Journal of Education,”

December, 1919.

[382]

“To the Flowers of Heidelberg,” translated by Charles Derbyshire, “Philippine Journal

of Education,” December, 1919.

“Rizal as a Poet,” by Eliseo Hervas, “Philippine Journal of Education,” 1919.

“Inspiring Traits of Rizal’s Character,” by Ignacio Villamor, “Philippine Journal

of Education,” December, 1919.

“Rizal as a Patriot, Author, and Scientist,” by former Governor-General Francis Burton

Harrison, “Philippine Journal of Education,” December, 1919.

“Rizal as a Scientist,” Benito Soliven, “Philippine Journal of Education,” December,

1919.

“Rizal’s Character,” by T. H. Pardo de Tavera, published by the Manila Filatélica,

1918.

“The Story of José Rizal,” by Austin Craig, published by the Philippine Education

Publishing Company, 1909.

“Revista Filipina,” Manila, December, 1916, a Rizal number, with articles by Mariano Ponce, Epifanio

de los Santos, and others.

“Murió el Doctor Rizal Cristianamente? Reconstitución de las Ultimas Horas de Su Vida.” Estudio Histórico por Gonzalo M. Piñana, Barcelona, 1920.

[383]