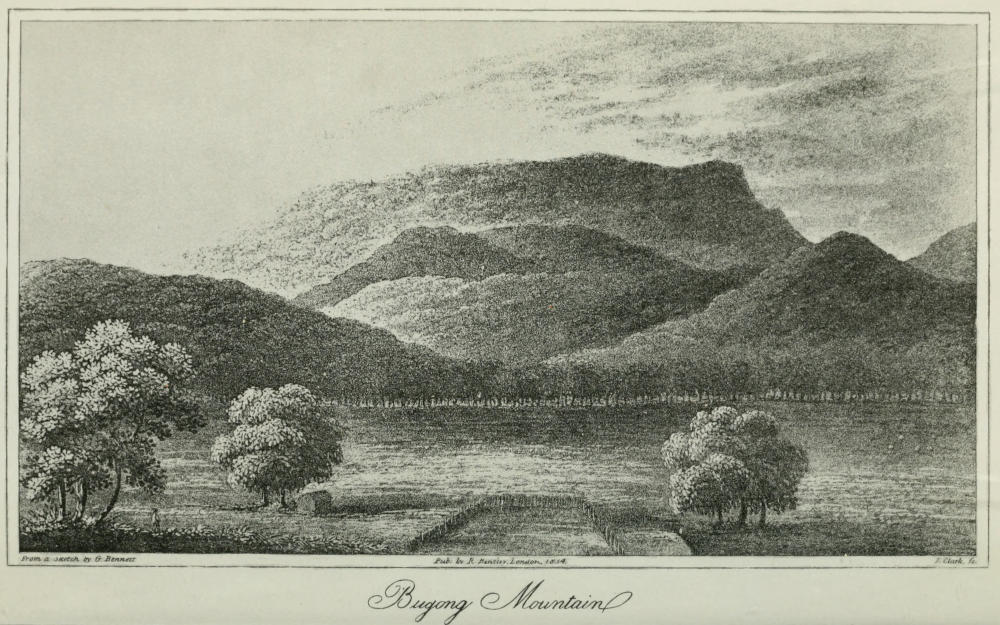

From a Sketch by G. Bennett. Pub: by R. Bentley, London, 1834. T. Clark, sc.

Bugong Mountain

From a Sketch by G. Bennett. Pub: by R. Bentley, London, 1834. T. Clark, sc.

Bugong Mountain

WANDERINGS

IN

NEW SOUTH WALES,

BATAVIA, PEDIR COAST, SINGAPORE,

AND CHINA;

BEING

THE JOURNAL OF A NATURALIST

IN THOSE COUNTRIES, DURING 1832, 1833, AND 1834.

BY

GEORGE BENNETT, Esq. F.L.S.

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF SURGEONS, &c.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET.

Publisher in Ordinary to his Majesty.

1834.

LONDON:

IBOTSON AND PALMER, PRINTERS, SAVOY STREET, STRAND.

The Work now given to the Public is the result of a series of recent excursions into the interior of the Colony of New South Wales, at intervals of disengagement from professional duties, and at periods of the year best calculated for observations in natural history. To this are added a detail of such incidents as appeared to the Author worthy of notice, while visiting Batavia, Singapore, China, &c. on his return to England.

The writer in his narrative has limited himself principally, if not entirely, to the notes taken at the instant of observation, his object being to relate facts in the order they occurred; and, without regard to studied composition, to impart the information he has been enabled to collect in simple and unadorned language, avoiding, as much as possible, the technicalities of science.

London, June, 1834.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Island of Porto Santo—Madeira—The Desertas Islands—Town of Funchal—The Physalia, or Portuguese man of war—Description of that animal—An experiment—Effects of the Physalia’s sting—Method of preserving the animal—Land in sight—Approach to the Cape Verd Islands—Islands of Mayo and St. Jago—Anchor at Porto Praya—The town—Famine—Novel method of Fishing—Tropical trees and other plants—Valley of St. Trinidad—The monkey bread-tree—Springs of water—Severe drought—Negro Huts—Plantations—The gigantic boabab-tree—Residence of Don F. Melo—The Orchilla weed—Date palms—Leave the island | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Enter the tropics—Flying fish—Luminosity of the ocean—Magnificent scene—Phosphoric light—Interesting facts in elucidation of that phenomenon—Albicores and Bonitos—A colossal whale—Sea birds—Gigantic species of Albatross—Description of those birds—Their manner of flight | 28[viii] |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Sombre appearance of the Australian coast—Feelings of an emigrant on approaching it—Improvement of Sydney—Fruits produced in the colony—Extent of the town—Cultivation of flowers and culinary vegetables—House-rent—The streets—Parrots—Shops—Impolicy of continuing the colony as a penal settlement—The theatre—Aspect of the country in the vicinity of Sydney—The grass tree—Floral beauties—Larva of a curious insect—The colonial museum—Visit to Elizabeth Bay—Valuable botanical specimens in the garden of the Honourable Alexander Macleay—New Zealand flax—Articles manufactured from that vegetable—Leave Sydney—Residence of Mr. M’Arthur—Forest flowers—Acacias—Paramatta—Swallows | 50 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Road from Paramatta to Liverpool—Arrival at Raby Farm—The opossum—Prisoners and free men—Advantage of being sentenced to an iron gang—London pickpockets converted into Shepherds—Suggestion with regard to the convicts—Leave Raby—Mr. Jones’s farm—Cultivation of the vine—Sameness of the forest scenery in Australia—Lose our way—Journey resumed—Gloomy appearance of the Australian vegetation—The tea tree—Colonial farms—Emu-ford—Blue Mountain range—The Pilgrim Inn—View from Lapstone Hill—Variety of flowering shrubs—A beautiful garden—Road over the Blue Mountains—Picturesque prospects—A mountain station—Bleak air of the place—Our supper | 84[ix] |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Our journey resumed—The new road—Road-side flowers—Blackheath—The pass through Mount Vittoria—Talent and perseverance of Major Mitchell, the surveyor-general—Appearance of an iron gang—Leave the Blue Mountain range—Arrive at Collet’s Inn—Resume our journey towards Dabee—New line of road—Aspect of the country—Arrival at Mr. Walker’s farm—Residence of Mr. Dalhunty—Huge mounds of clay—Blackman’s Crown—Gum-trees—Bush travelling—Encamp for the night—Caution to travellers—Cherry-tree Hill—A deserted station—Encampment of Aborigines—The musk duck—Produce of Mr. Cox’s dairy-farm—Mount Brace—Infanticide—Custom of native women relative to their dead offspring—Native practice of midwifery—Animal called the Cola—Belief in the doctrine of metempsychosis | 104 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Cross the country to Goulbourn Plains—A road-gang stockade—Splendid view—The old Bathurst road—Sidmouth valley—Brisbane valley—Squash field—Bolam Creek—Turril, turril—Gum resin—Swampy country—Mr. Cowper’s farm—Anecdotes—Distant view of Goulburn Plains—Mr. Bradley’s estate—Cross the plains—Hospitable reception at Cardross—The Manna tree—Failure in rearing the tulip tree | 132[x] |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Appearance among the natives of a disease resembling the small-pox—Origin and progress of that malady among the aborigines—Medical investigations—Plan of treatment—Variety of forms assumed by the disease—Its duration—The critical period—Dr. Mair’s report | 148 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Bredalbane Plains—Forest country—Cockatoos and parrots—Peculiar species of the lizard tribe—Medicinal trees—Bark of the wattle trees—Mr. Manton’s farm—Picturesque view—Yas Plains—Encampment of natives—Stringy bark, or box tree—Use of that tree—Native method of cooking—The Australian negro—Game—The flying squirrel—Human chimney ornaments—Cloaks of opossum or kangaroo skins—Barbarous ceremonies—Women not admitted to the confidence of the males | 162 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Perch, and other fish—An elegant couple—Kangaroo dogs—Black and white cockatoos—Vegetable productions—Mr. O’Brien’s farm—Herds of cattle—Bush life—Proceed towards the Murrumbidgee river—A bush track—Romantic country—Arrive on the banks of the Murrumbidgee—Cross the river—Swamp oaks, and other trees—Remarkable caves—Return to Yas—Superstitious ceremonies—Crystal used in the cure of diseases—Mode of employing it | 179[xi] |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Leave Yas Plains for Sydney—Mr. Shelley’s farm—Splendid new road—Mr. Barber’s farm—Shoalhaven gullies—Interesting spot—Mr. Campbell’s farm—Journey resumed—Settlement of Bong, Bong—Bargo Brush—Profusion of flowering shrubs—View from the summit of Mount Prudhoe—The cow pasture road—Farms of Mr. M’Arthur, and Captain Coghill—Flowers—The white cedar—Government hospital at Liverpool | 195 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Second Journey into the interior commenced—Land of roses—The grape-vine—Foreign grain—Missionary rewards—Bargo brush—Small species of Lobster—Another species—Snakes—Leeches—Mr. Button’s farm—Proceed on the journey to Gudarigby—Native plants—Magnificent mountain view—Our repast—The laughing jackass—A spacious cavern—Its interior—Black swans and other birds | 208 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

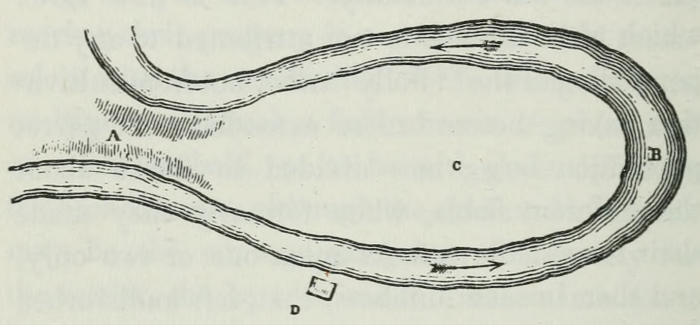

| Native dogs—Their tenacity of life—Return to Yas Plains—The Australian raspberry—Native cherry-tree—The summer season—Tree hoppers—Their clamour—Gannets—Country about the Tumat river—Bugolong—The Black range—A storm—Vicinity of rivers—Native blacks—Their costume and weapons—Wheat-fields—Destructive birds—Winding course of the Murrumbidgee | 231[xii] |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

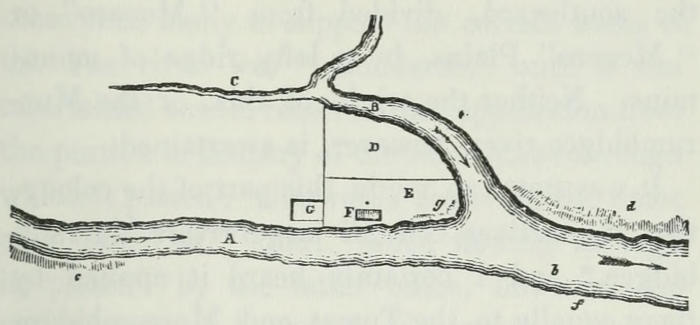

| Devoted attachment of Women—Remarkable instance of this, exemplified in the tale of an Australian savage—Journey resumed—Botanical productions—The Munne-munne range—Luxuriant Plain—Mr. Warby’s farm—The bell bird—Junction of the Murrumbidgee and Tumat rivers—Native names of rivers—Soil—River cod—Aquatic fowl—The Tumat country—Fertility of the plains—Assigned servants—A mountainous range—The Murrumbidgee Pine—Geological character of the vicinity—Mr. Rose’s cattle station | 247 |

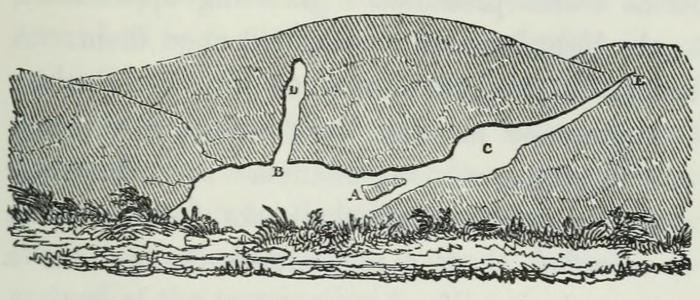

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Wooded hills—Base of the Bugong mountains—Multitudes of the Bugong moths—Timber trees and granite rocks—Snow mountains—Method of collecting the moths—Use of these insects—Crows—Height of the Bugong mountains—The aborigines—Dread of ridicule in the females—Native fine arts—Lyre-bird of the colonists—Destruction of kangaroos and emus—The station of Been—Sanguinary skirmishes—A fertile plain—Cattle paths—Shrubs on the banks of the Tumat | 265 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Kangaroo hunt—Ferocity of that animal—Use of its tendons—The culinary parts—Haunts of the kangaroo—A death struggle—Dissection of a kangaroo—Preservation of human[xiii] fat—Ascent of trees in pursuit of game—Parrots and cockatoos—The emu—The native porcupine—Species of ophthalmia, termed the blight—Leave the Tumat country—Banks of the Murrumbidgee—Aborigines—Water gum-tree—Kangaroo-rat—The fly-catcher—The satin bird—Sheep stations—Colonial industry | 283 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Flocks of pelicans and grey parrots—Arrive at Jugiong—A busy scene—The harvest—Quails and Hawks—Mr. Hume’s farm—Domestic life among the settlers—Miss my way in the forest—Mr. Reddal’s farm—Disease called the Black Leg—Mr. Bradley’s residence at Lansdowne Park—Drooping manna trees—Christmas festival—Mr. F. M’Arthur’s farm—Aboriginal tribes—Native costume—Noisy revelry—Wild ducks and pigeons—Spiders | 310 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Arrive at Wombat Brush—Animals called Wombat—Parched country—Road-side houses—Colonial English—Column to the memory of La Perouse—Death of Le Receveur—Sydney police-office—The Bustard—Botanic garden—The aborigines—King Bungaree—The castor-oil shrub—Diseases of Australia—New Zealanders—Australian ladies—Prejudice against travellers from Botany Bay—Anecdote—A fishing excursion—Cephalopodous animals—Conclusion of the author’s researches in this colony | 329[xiv] |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Leave Sydney—Rottenest Island—Colonial prospects—Voyage to Batavia—Prince’s Island—The Java coast—Anchor in Batavia roads—The river—Alligators—Streets of Batavia—M. Choulan’s tavern—Forests—Java ponies—A veterinary monkey—Public buildings—The traveller’s tree—Celebrated Javanese chief—Sketch of his life and actions—Exactions of the Dutch government—The orang-utan—Society in Batavia—Animals of Java—Doves—Dried specimen of the hippocampus | 346 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Leave Batavia and anchor off Hoorn Island—Islands about the Bengal Passage—Gingiong roads—Lofty aspect of the land—The coast—The golden mountain—Island of Sumatra—Aspect of the country—The lover’s leap—Village of Pedir—Ships of the Acheenese Rajah—Visit to the Rajah—Dense vegetation—Buffaloes—Ba Assan trees—Hall of reception—Interview with his Highness—Commercial negociations—Curiosity of the natives—The Areka or Betel-nut—Flowering shrubs and plants—Rice-planting—Return to the ship—A prohibition | 375 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Visit from the young Rajah—Native weapons—Costume—The “trading minister” and his boy—Inspection of the ship by the natives—Population of the Pedir district—Rambles[xv] on the coast—King Crabs—Land crabs—Ova of fish—Soldier crabs—Their food—The Rajah’s house—Cocoa-nut water—Habitations in the Rajah’s inclosure—The fort—The bazaar—Banks of the river—Plants—Native fishing—Fruits—The country farther inland—Vegetation—The Eju Palm—A fine plain | 395 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Country about Pedir—“White Lions”—The rajah’s habits—A decision—Ornaments for the ear—Female curiosity—The rajah’s horses—War between the rajah of Acheen and the rajah of Trumong—A native’s account of the quarrel—Purchase of betel-nut—The Areka-nut—Trade in that article—Anecdote—A Chittagong brig—Dried fish—Beautiful appearance of the Golden Mountain—Assemblage of the mountains—Tornados—The fire king and his demons—Yamora—Burial-ground—Large tree—Small crabs—Game called Mein Achu—Leprosy—Party of natives—The Viverra musanga—Applications for medicine—Rajah of Putu—His retinue—Object of his visit | 416 |

Island of Porto Santo—Madeira—The Desertas Islands—Town of Funchal—The Physalia, or Portuguese man of war—Description of that animal—An experiment—Effects of the Physalia’s sting—Method of preserving the animal—Land in sight—Approach to the Cape Verd Islands—Islands of Mayo and St. Jago—Anchor at Porto Praya—The town—Famine—Novel method of Fishing—Tropical trees and other plants—Valley of St. Trinidad—The monkey bread-tree—Springs of water—Severe drought—Negro Huts—Plantations—The gigantic boabab-tree—Residence of Don F. Melo—The Orchilla weed—Date palms—Leave the island.

On the 15th of May 1832, the island of Porto Santo, in latitude 35° 5′ north, longitude 16° 5′ west, was seen bearing south-west, half-south, at the distance of forty miles from the ship “Brothers,” Captain Towns, bound to New South[2] Wales, eleven days having elapsed since leaving Plymouth, from whence we had taken our departure. The appearance of the island, when we had reached to within seven or eight miles of it, was generally barren, varied by an occasional verdant patch scattered over the rugged rocks, which terminated in steep cliffs to the water’s edge.

On the following morning at daylight, the dark towering land of Madeira[1] was visible, rising like a huge black mass from the blue water. By eight A.M. we were in the passage between the south-east side of Madeira and the group of islands known as the Desertas, sailing, with a light and agreeable breeze, from the eastward, which enabled us to have an excellent view both of the former islands and Madeira; and as our progress seemed to be quicker than would have been expected from our gentle zephyrs, we were probably also aided by a current.[2]

The passage between the Desertas and Madeira is considered to be about eleven miles across. The Desertas stretch nearly north-north-west and south-south-east, and may be five leagues in extent; they have an abrupt, barren appearance, with steep, rugged, perpendicular rocks descending to the sea; on the largest island there was some appearance of cultivation, and the tufa, or red volcanic ash, imparts that colour to several parts of the island; there is a high pyramidal rock, resembling a needle or pillar, situated about the north-west part of the group, which at a distance is like a ship under sail.

By eight A.M. the heat of the sun had dissipated the gloomy mist which had previously been pending over and concealing the beautiful features of the island of Madeira, and caused it to burst forth in all its luxuriance and beauty; the northern part of the island had a very sombre, barren aspect, when compared with the fertility of the southern; the plantations, glowing in varied tints, interspersed with neat white villas and small villages, gave much animation and picturesque beauty to the scene.

Early in the morning is the time best calculated to view the island clearly, as the sun, gradually emerging from the dense masses of clouds which have previously enveloped[4] the towering mountains, gilds their summits, and, gradually spreading its rays over the fertile declivities, enlivens and renders distinct the splendid prospect afforded to the voyager. As the sun, however, acquires a stronger power, its proximity to a wide expanse of waters soon causes a mist to arise by which the clearness of the view from the sea is much obstructed.

As we approached, the town of Funchal opened to our view, the white habitations rising like an amphitheatre, and the hills around, covered by the variegated tints of a luxuriant vegetation: the whole appearance of the island was such, as to be well calculated to excite the most agreeable sensations of delight at any time, but more especially after the eye has enjoyed for a time only the prospect of sea and sky.

As it was not our intention to touch at this island, in the course of the day we had passed and left it far in the distance. We spoke off the island one of Don Pedro’s blockading squadron; it was a brig mounting eighteen guns, filled with such a motley crew as one may expect to see in a piratical craft. The spokesman informed us that Don Pedro was with Admiral Sartorius, in a large ship off the north side of the island: we then parted; they wishing us “un bon voyage,” and we, in return, hoped they might obtain[5] abundance of prize money, but which we hardly supposed would ever be realized.

There are various objects well calculated to excite interest to a naturalist during a long voyage, and to furnish both amusement and instruction. The splendid Physalia, or “Portuguese man of war,”[3] is often seen floating by the ship; the inflated, or bladder portion of this molluscous animal, glowing in delicate crimson tints, floats upon the waves, whilst the long tentaculæ of a deep purple colour extend beneath, as snares to capture its prey. It is oftentimes amusing to see persons eager to secure the gaudy prize; but they find, by painful experience, that, like many other beautiful objects of the creation, they possess hidden torments; for no sooner have they grasped the tinted and curious animal, than, encircling its long filiform appendages over the hands and fingers of its capturer, it inflicts such pungent pain by means of an acrid fluid discharged from them, as to cause him to drop the prize, and attend to the smarting occasioned by it.

This beautiful molluscous animal inhabits the[6] tropical seas, and is also seen in high latitudes during the summer months[4] of the year. When first removed from the water, it excites the admiration of the spectators by the elegant and vivid colours with which it is adorned. These tints, however, are as evanescent as they are brilliant; and soon after this animal is taken from its native element, the crest sinks; the bright crimson, green, and purple tints lose their brilliancy, and the beauty which had previously excited so much admiration fades, and at last totally vanishes. There are a number of species of the genus;[5] but the one most commonly seen is the Physalia pelagica of Lamarck, (Holothuria physalis of Linn.) They are known to our seamen as the “Portuguese men of war,” and[7] galére or frégate among the French, from having some resemblance to a small vessel resting tranquilly on the surface of the water during a calm, at which time they are more readily discerned than during strong breezes: they have also been confounded by many persons unacquainted with natural history with the Nautilus.

The figure of this species is somewhat ovate; the upper portion resembles an inflated bladder, rounded at one extremity, and with a beak-like termination at the other. On the summit or back is a crest or ridge, slightly elevated, sulcated, and fringed at the edges: the whole of this part of the animal is of a light blue, with occasional streaks of delicate sea-green, and tinged with brilliant crimson: this portion of the animal is filled with air, and, although I have heard it frequently asserted that the animal has the voluntary power of collapsing the bladder on the approach of tempestuous, or inflating it on a return of fine weather, yet I do not credit the remark, considering it is more probably a seaman’s tale than the result of a naturalist’s observation. On examination, no apparatus is found by which such an effect could be produced; and if it actually possesses such a power, why is it not exercised in every moment of peril?—for, when we approach the animal to capture it, or[8] when it is taken from the water, no such change occurs; the bladder still remains inflated, and can be preserved thus distended either in a dried state or by placing it in alcohol. During strong breezes, I have seen them floating on the waves; but, from the ship passing at that time rapidly through the water, they are then more rarely observed. I have also seen them thrown in tempestuous weather on the beach at New South Wales, the bladder portion of the animal still remaining inflated. From these, and other reasons which might be adduced, the assertion cannot be considered as the result of actual observation. Situated at the under portion of the animal is a mass of tentaculæ, some short and thick, others long, filiform, and extending to several yards in length: these seem to consist of a chain of globules, filled with an extremely acrid fluid: in colour, they are of a beautiful purple, with an admixture of crimson; and they are covered by a glutinous substance, having a peculiar odour. The inflated membrane is probably intended to keep the animal buoyant on the water, by which it is readily enabled to extend its long tentaculæ in search of prey, or it may be designed as a locomotive agent, aiding the animal in its progress over the “vast bosom of the ocean,”—thus serving the purpose[9] of a sail. It is said that the appearance of the Physalia near to the sea-coast is the indication of an approaching tempest.[6]

Having captured a very fine specimen of this animal on a former voyage in latitude 9° 0′ south, and longitude 12° 59′ west, and being aware of the pungent property residing in the tentaculæ, I was desirous of trying its effects on myself, for the purpose of ascertaining from personal experience the constitutional irritative effects resulting from it. On taking hold of the animal it raised its tentaculæ, and stung me on the second and ring fingers. The sensation was[10] similar at first to that produced by the nettle; but before a few minutes had elapsed, a violent aching pain succeeded, affecting more severely the joints of the fingers, the stinging sensation at the same time continuing at the part first touched by the acrid fluid. On cold water being applied, with the intention of removing or lessening the pain, it was found rather to increase than diminish the effects. The irritation resulting from the poisonous fluid emitted by the animal extended upwards, increasing in extent and severity, (apparently acting along the course of the nerves,) and in the space of a quarter of an hour, the effect in the fore-arm (more particularly felt at the inner part) was very violent, and at the elbow-joint still more so. It may be worthy of remark, that when the joints became affected the pain always increased. It became at last almost unbearable, and was much heightened on the affected arm being moved; the pulse of that arm was also much accelerated, and an unnatural heat was felt over its whole surface. The pain extended to the shoulder-joint; and on the pectoral muscle becoming attacked by the same painful sensation, an oppression of breathing was occasioned, which we find similarly produced by rheumatism, when it attacks that muscle; and it proved very distressing[11] during the time it remained. The continuance of the pain was very severe for nearly half an hour, after which it gradually abated, but the after effects were felt during the remainder of the day in a slight degree of numbness and increased temperature of the arm.

About two hours after I had been stung, I perceived that a vesicle had arisen on the spot; and when children have been stung, I observed that numerous small vesicles arose, similar to those produced by the nettle. The intensity of the effects produced depends on the size and consequent power of the animal; and after it has been for some time removed from the water, it is found that the stinging property has diminished. This irritative property, unattended, however, by any of the constitutional effects, remains for a long time in the tentaculæ, even after they have been removed from the animal; for on touching a handkerchief some weeks after it had been used in wiping off some portions of the tentaculæ, the stinging property was found to have remained, although it had lost that virulent quality, which produced on a recent application such violent constitutional irritation.

This irritative secretion does not, however, exist solely in this species of mollusca; several of the medusæ have similar properties, which[12] may perhaps be considered as both offensive and defensive; and it has been, and no doubt correctly, supposed to be given to these animals as a means of procuring their food, the benumbing principle existing in the tentaculæ rendering their prey when touched unable to escape. For what purpose this acrid property is found existing in the vegetable kingdom, it is difficult to decide, and all that has yet been said on the subject may be considered as merely hypothetical. For instance, at the island of Singapore there is a remarkable species of the order Fuci, usually found growing in isolated patches upon coral banks. Finlayson thus mentions it: “It is pinnated, plumose, elegant, about a foot and a half in length, and of a whitish colour. It is endued with a property of stinging like nettles; the sensation produced is more acute and more penetrating, more instantaneous, but somewhat more permanent. The hand is scarcely brought into contact with it, before the wound is inflicted. A small corrugated granular bag, filled with a transparent fluid, would seem to be the organ by which it produces this effect. These are no sooner touched than they discharge the fluid they contain. The plant soon loses this power after being removed from the water.” This plant seems, therefore, to possess an offensive[13] or defensive property analogous to that of the Physalia, but for what purpose it would be difficult to form an opinion.

The usual method adopted for the preservation of this curious and beautiful mollusca is by placing it in spirits; the form is thus well preserved; but its vivid tints, the subject of so much admiration, are totally lost. As it is with the beautiful but evanescent colour of flowers, no method has been discovered by which their natural brilliancy can be preserved, and it is impossible to retain that peculiar brightness given only by life and health. I have preserved the animal by detaching the tentacute from the bladder; (on account of their being too soft and perishable to enable them to be dried, en masse, with any chance of success; their form only being preserved well in spirits;) then permitting the air to escape from the bladder, dried, pressed, and afterwards gummed on paper, it produces a good lateral view of the form of this mollusca; the colours being afterwards artificially renewed by the pencil, and the tentaculæ underneath drawn and coloured, the tout ensemble conveys an idea of the brilliant appearance of the animal, as far as can be produced by art. I have also kept the animal with the bladder inflated, dried it in that state, and, by[14] afterwards colouring it, the appearance produced is very excellent; but, it is only by repeated trials that the best and most accurate methods of preserving objects of natural history can be discovered—the greatest difficulty existing, being that of preserving them accurately in their natural appearance.

We had the N. E. trade in lat. 28° N. and long. 18° 11′ W. and at three P.M. of the 25th made the “Northern Saddle Hill,” (N. W. hill,) on the island of Sal, (Cape Verd group,) bearing S. E. about six leagues distant.

The announcement of “land in sight,” and the delightful sensations produced by it, can only be appreciated by those who have for some length of time been tossed about on the “deep, deep sea,” for many a weary day, with nothing but sea and sky to gaze upon. All hasten on deck as soon as the land is stated to be visible; at first its rather indistinct form, as it rises from the horizon, does not excite so much interest; but, on a nearer approach, the variously tinted strata of the lofty mountains become visible, and plantations, trees, shrubs, and neat habitations cheer the eye; and, on landing, a profusion of the floral beauties of the vegetable kingdom, with butterflies vieing with them in splendour of tints, or several species of the coleoptera tribe[15] decked in golden armour, meet the eye. But the approach to the Cape Verd islands does not possess these beauties in any profusion—barren volcanic mountains, contrasted occasionally only by a few others of a verdant character are seen instead; even these become an agreeable prospect, being a change from the monotony of a ship, but a departure from them, after a few days’ sojourn, is attended with but little if any regret.

On the 26th, at daylight, we sailed with a pleasant breeze between the island of Mayo and that of St. Jago; the former distant about ten, the latter about eighteen miles; the western side of Mayo had a very sterile appearance; there was not a tree or speck of verdure to be seen. The lofty mountain of St. Antonio, on the island of St. Jago, was visible; its declivities verdant, but the peaked summit was for the most part hidden by clouds. As we coasted along the latter island, the feature of the coast was very barren, although it was occasionally relieved by a small verdant valley, diversified by some miserable huts and a few stunted cocoa-nut trees. In the afternoon we anchored at Porto Praya,[7] about a quarter of a mile distant from the shore.

After dinner we paid a visit to the shore; the landing-place is very inconvenient, and often dangerous, from the surf, which at this time was fortunately not high. After landing we had to walk over a soft sandy road, varied only by large stones coming in contact with our feet, and assuring us of their presence by the pain they occasioned. Several miserable date palms and dusty plants of Aloe perfoliata (a few of the latter being in flower) grew by the road side. Then by a winding and steep ascent, covered by loose stones, we arrived at the town, which is built upon a table land of moderate elevation, and on this side of the approach there is a battery mounting twenty-one guns. From the descriptions I had previously perused, the town appears to have been much improved since they had been written, but still it has nothing of interest to recommend it; but the view of the bay and shipping from the elevated site is very pretty. The Plaza (in which the American consul resides, and where there is a small church, which as yet cannot boast of a steeple,) contains the best houses and stores, where almost any supplies of foreign manufacture can be purchased, but at exorbitant prices.

At the period of our visit, this, together with the whole of the islands of the group were suffering from a severe and long drought; this one,[17] from its fertility, and the irrigation that is capable of being produced, as well as from imports, is in a better condition than the others. At the island of Fuego, more particularly, the inhabitants were said to be dying daily in great numbers, from famine. The island of St. Jago alone is stated to have a population of 27,000 inhabitants.

I observed several boats engaged in fishing near the ship, previous to our landing, and their mode of capturing the finny tribe appeared to me novel; they sprinkled something over the water, like crumbs of bread, that attracted the fish (which were five or six inches long) to the surface in shoals; the fishermen then swept amongst them a stick to which a number of short lines and hooks were attached, and by aid of this they usually brought up several fish at a time. After the fish were caught, some women, who were in the boat, were engaged in cleansing and salting them.

Tired of the dull village, we descended from the elevated site to a garden in which the well was situated whence the supply of water of excellent quality is procured for shipping. At this spot the plantain, date, papaw, and cocoa-nut trees, attracted the attention of those of our party who had never before seen these magnificent[18] tropical trees. The sides of the paths were adorned with the gay and handsome flowers of the Poinciana pulcherrima, and the more elevated lilac tree (Melia azedarack) profusely covered with its long panicles of fragrant flowers. As we rambled further into the scrubby parts beyond this cultivated spot, cotton shrubs, (Gossypium herbaceum,) the thorny Zizyphus and mimosas were abundant. The Jatropha curcas was used for hedges, and a handsome asclepias (procera?) called bombadero by the Portuguese, was abundant about this waste land, both in fruit and flower: the flowers are succeeded by a large somewhat oval fruit, containing a quantity of pretty feathered seeds; the whole plant (like all the family to which this belongs) abounds in a viscid milky juice; the capsule of the pod is elegantly veined, reminding the anatomist of the veins displayed on the exterior of the heart.

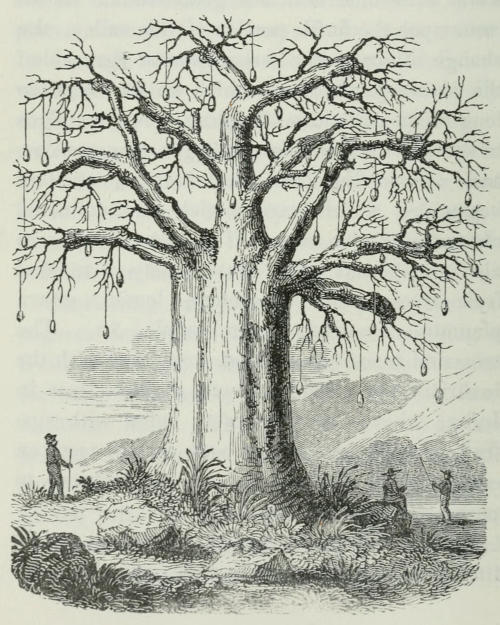

On the following morning a small party was formed for an excursion to the valley of St. Trinidad, to gain some idea, if possible, of the fertile portions of this apparently very sterile island. This valley, it may be said, commences soon after descending the table land on which the town is situated. We diverged from the direct road, for the purpose of visiting a plantation about a mile and a half distant from[19] the town. The road was stony, and there was nothing in the aspect of the country around to relieve the eye; a few stunted Mimosæ, (occasionally varied by a few of the same species of large dimensions and great age,) some stunted Zizyphi, and a few trailing plants of Convolvulus soldanella, which, by its dark green leaves and purplish flowers, contrasted in a beautiful manner with the sterile brown soil of the scorched plains. The plantation we visited was not yet in order; it contained some flourishing coffee plants, with cocoa, plantain, cashew-nut, and other tropical trees; but the principal object of my visit was to view a specimen of the Adansonia digitata, or monkey bread tree, and its very peculiar appearance and growth imparted much gratification; it was about eighteen or twenty feet high, and twenty-one feet in circumference. This tree was in full foliage, and its bright green digitated leaves imparted much animation to it. The tree is surrounded to some depth by a spongy sap. As subsequently at the valley I saw a much larger specimen of this gigantic tree, but destitute of foliage, I shall then return to its description, and add a sketch. From this part of the island I collected but few plants; Momordica senegalensis grew wild about the fertile parts, as well as Lotus jacobæus, Tribulus cistoides, Asclepias, (procera?)[20] and a very pretty convolvulus, with lilac flowers, climbed over rocks and trees in good soil.

From this place we proceeded to our destination. The sun was fervent, but the inconvenience was in some degree mitigated by a delightful north-east trade breeze. We passed over scorched plains, about which a few stunted bushes of mimosa were scattered, and at other places some wretched trees of Jatropha curcas. In a small vale we passed a rivulet of delicious water, at which several negresses were busily engaged in washing linen. The springs of water appear excellent, and there seems to be no deficiency of it in the valleys; but the want of rain is often severely felt: it was stated to me, that during the previous twenty months only half an inch has fallen on this island.

Continuing our journey, we passed several negroes conveying their produce, consisting of fruit, vegetables, orchilla weed, &c. to the town for sale, upon asses, with panniers made from bullocks’ hides. The animals seemed in excellent condition, at which we were not a little surprised, from what we had seen of the sterility of the soil. A few cattle were also seen wandering over the plains, where barely a speck of verdure tinged the barren volcanic rocks, still[21] the animals were sleek, and in tolerable condition; we therefore came to the conclusion that they were turned out to feed, or, what was much more likely, to view the country and fast during the day, and driven home to feed at night.

We pursued our dreary path, occasionally passing a few negro huts, and refreshing ourselves with some delicious goats’ milk. As we came upon the fertile portion of this valley, the change of scene was certainly most agreeable; the brown-parched soil which we had been so long previously alone regarding, now gave place to the verdant plantations of sugar-cane, manioc, and various European and tropical esculent vegetables, which gave a rich and animated character to the scene. The plantations were also interspersed with a great variety of tropical fruit trees, such as orange, lemon, guava plantain, tamarind, custard apple, &c. The tamarind trees were stunted, compared with the luxuriant and elegant growth of those trees in India; they were, however, laden with ripe fruit, whose powerful acid soon set the teeth on edge of such of our party as were induced to partake of them.

Several trees of the Boabab, or monkey bread-tree, (Adansonia digitata,) were now seen, and[22] among them one was particularly conspicuous from its size, as also from a resemblance to the union of three trees. This tree was destitute of foliage, but that loss was compensated by the curious character it assumed, being covered with fruit pending from a long, twisted, spongy stalk, varying in length from one to two feet.[23] This tree measured forty feet in circumference, and was about sixty feet high; the bark was smooth, and of a greyish colour; the termination of its larger branches is remarkable, from being abruptly rounded, and from these rounded extremities the smaller branches are given off, as may be seen in the accompanying drawing; this forms a very characteristic feature in the tree. The fruit, on the outer shell being broken, contained not the yellow pulp usually mentioned, but a white farinaceous substance enveloping the dark brown seeds, of an agreeable acidulated taste. This may proceed from the fruit being old. The fruit is of an oval form, usually six inches in length, and three or four in diameter; rough externally, and, when mature, of a brownish yellow colour; a dark red gum exuded from the outer part of the fruit.[8]

Some of the farms and plantations were in very fine and luxuriant condition, and this was an enjoyment to us after the arid country we had before seen, destitute almost of vegetation, and covered with loose stones. Of the feathered tribe, although not very numerous, a few were shot by one of the party, among which were two specimens of Halcyon senegalensis, and a fine hawk; quails and Guinea fowls (Numida meleagris, Linn.) were abundant, and several of the former were also shot; the crow and several species of Fringillæ were likewise seen. In the afternoon we returned to the town. The population consists for the most part of mulattos and negroes: fruit, including plantains, bananas, oranges, and pine-apples, was abundant, but not yet fully in season.

Among the very few decent houses in this paltry town, was one, the residence of a Don[25] F. Melo, (who speculates in orchilla weed,) situated in the Plaza, which displays taste and neatness both in the exterior and interior of its arrangement: on the lower land, behind the house, he has laid out with much labour an extensive garden, well irrigated, and in which European and tropical vegetables, fruits, and elegant flowering plants, were thriving in luxuriance, and sufficiently proved that even in that sterile spot, industry and perseverance could surmount almost any difficulty. At the house of this gentleman, I had an opportunity of seeing some excellent specimens of the orchilla weed; this valuable production of the vegetable kingdom is indigenous to this and other islands of the group, as well as to Madeira, the Canaries, and the coast of Barbary; it is the Roccella tinctoria of botanists,[9] and is held in high estimation for the purplish dye it yields, and I believe, excepting the cochineal, is the only dye that possesses a mordant in itself. This[26] lichen is of a gray colour, and those plants which are of the darkest hue, long and strong, are considered the best; it grows to a great length, but is rarely obtained so, as the natives gather it before it comes to any size, on account of its high value.

The quantity collected in one year, among the whole of this group of islands, was 537,600 lbs.; but sometimes a larger quantity is obtained, when, not having much work upon the plantations, the negroes can be employed for the purpose.[10] It is found on the steep rocks in the interior of the islands, and growing in the crevices; the finest orchilla is collected at the island of St. Antonio, where it grows in some places so inaccessible as to be only procured by lowering the gatherer down the cliffs by ropes. This lichen is exported only to Lisbon, there being an order from the Portuguese government to that effect, but quantities were often smuggled direct to some foreign port.[11]

Date palms were very numerous in the vicinity of the town, but did not appear to attain any high degree of perfection, or bear fruit, and were used, for what they alone seemed fit, as firewood.

The troops were decently clad, and consisted of about five hundred, principally negroes and mulattoes, officered by Europeans.

All arrangements having been completed, we left the island in the evening, with a fine north-east trade breeze.

Enter the tropics—Flying fish—Luminosity of the ocean—Magnificent scene—Phosphoric light—Interesting facts in elucidation of that phenomenon—Albicores and Bonitos—A colossal whale—Sea birds—Gigantic species of albatross—Description of those birds—Their manner of flight.

On the 31st of May we lost the north-east trade, in 8° 40′ north, and longitude 23° west, after which we experienced variable winds with torrents of rain, until the 4th of June, when we had the south-east trade in latitude 4° 38′ north, and longitude 22° 49′ west, and crossed the equator early on the morning of the 7th, in longitude 27° 5′ west, being altogether only thirty-two days from Plymouth, including our delay at St. Jago.

On entering the tropics many animate objects excite attention, among others the flying-fish;[29] it is surprising how many different opinions have been formed on the subject of this fish; some considering it seeks the air for sport or pastime, whilst others regard it as only taking flight when pursued, and thus decide its existence to be a continued series of troubles and persecutions. Between such opposite opinions, we can only form our judgment from actual observation, and there is one circumstance without any doubt resting upon it; that the supposed war of extermination exercised against them has not diminished their numbers, for they are observed in as large “flocks” at the present day, as navigators have related of them former days; they must also have had a long cessation of hostilities from the time of birth, to enable them to arrive at maturity. To say that these fish undergo persecution more than any other living animals of the creation, is absurd, for we may observe the same principle throughout the whole of the animated kingdom of nature.

On arriving in tropical regions, this curious fish is seen, and affords some variety to the tedium of a ship; the passengers amusing themselves by watching its flight, and sometimes its “persecution,” when pursued by bonitos, dolphins, albicores, among the finny, and tropic birds, boobies, gannets, &c. among the feathered tribe.[30] I have frequently derived both information and amusement by watching the flight of these fish; to observe them skim the surface of the water for a great distance, sometimes before, and at other times against the direction of the wind, elevating themselves either to a short height from the surface, or to five or six feet, and then, diverging a little from their course, drop suddenly into their proper element; sometimes when their flight was not high above the water, and it blew fresh, they would meet with an elevated wave, which invariably buried them beneath it, but they would often again start from it and renew their flight.

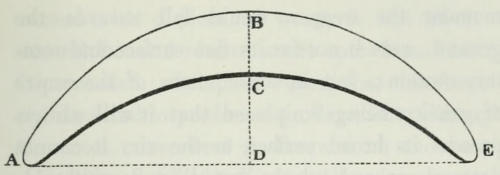

I have never yet been able to see any percussion of the pectoral fins during flight, although such a high authority as Cuvier says, “the animal beats the air during the leap, that is, it alternately expands and closes its pectoral fins;” and Dr. Abel also supports this opinion, and says that it agrees with his experience; he has repeatedly seen the motion of the fins during flight, and as flight is only “swimming in air,” it appears natural that those organs should be used in the same manner in both elements. But the structure of a fin is not that of a wing; the pectoral fins or wings of the flying fish are simply enlarged fins, capable of supporting,[31] perhaps, but not of propelling the animal in its flight.[12]

In fish, the organ of motion for propelling them through the water is the tail, and the fins direct their course; in birds, on the contrary, the wings are the organs of motion, and the tail the rudder. The only use of the extended pectoral fins in the fish is for the purpose of supporting the animal in the air, like a parachute, after it has leaped from the water by some power, which is possessed by fish of much larger size, even the whale. From the structure of the fin, I cannot consider it at all calculated for repeated percussions out of the water, although while in that fluid it continues its natural action uninjured, as it soon dries when brought into contact with the air, and the delicacy of the membrane between the rays would very readily become injured, were the organ similarly exerted in that medium.

The greatest length of time that I have seen these volatile fish on the fin, has been thirty seconds by the watch, and their longest flight, mentioned by Captain Hall, has been two hundred yards; but he thinks that subsequent observation has extended the space. The most[32] usual height of flight, as seen above the surface of the water, is from two to three feet; but I have known them come on board at a height of fourteen feet and upwards; and they have been well-ascertained to come into the channels of a line of battle ship, which is considered as high as twenty feet and upwards.[13]

But it must not be supposed they have the power of elevating themselves in the air, after having left their native element; for on watching them I have often seen them fall much below the elevation at which they first rose from the water, but never in any one instance could I observe them raise themselves from the height at which they first sprang, for I regard the elevation they take to depend on the power of the first spring or leap they make on leaving their native element.

On the 6th of June, in latitude 1° 50′ north, and longitude 25° 14′ west, a flying-fish was brought me by one of the steerage passengers, which had just “flown” on board over his head, as he was standing near the fore-part of the ship; being still alive when he brought it to me, I hastened to place it in a bucket of water, to ascertain whether it would attempt[33] to spring from it, and “take flight;” however, I found it was too late, for after floating about with its long pectoral fins half expanded, as it remained near the surface of the water, it continued alive for about the space of a minute, and then died. They usually, from the violence with which they come on board, receive some injury against the spars, boats, or chains, sufficient to destroy them; and therefore it will be difficult to observe their true actions as when performed in full vigour in their native element. This specimen measured nine inches in length. What excited my attention in this fish was a species of anatifa attached by its peduncle to the thorax. I regard as a very unusual circumstance, the existence of an anatifa attached to a living animal, particularly one of such rapidity of motion as this fish is usually supposed to be. The height at which this fish came on board could not have been less than fourteen feet from the surface of the water, and on the windward side of the vessel.

The “flight” of these fish has been compared to that of birds, so as to deceive the observer; however, I cannot perceive any comparison, one being an elegant, fearless, and independent motion, whilst that of the fish is hurried, stiff, and awkward, more like a creature requiring[34] support for a short period, and then its repeated flights are merely another term for leaps. The fish make a rustling noise, very audible when they are near the ship, dart forward, or sometimes take a curve to bring themselves before the wind, and when fatigued fall suddenly into the water. It is not uncommon to see them, when pursued, drop exhausted, rise again almost instantly, proceed a little further, again dipping into the ocean, so continuing for some distance until they are out of sight, so that we remain in ignorance whether they have been captured or have eluded pursuit.

The flying-fish swim in shoals, for on one day they are seen rising about, and in the vicinity of the ship, in great numbers; and on the day following, or latter part of the same day, only a few stragglers are seen. When disturbed by the passage of the ship through the shoal, they rise in numbers near the bows of the ship, and the consternation seems to spread among those far distant: the same may be observed when dolphins and albicores are pursuing them. On passing between the islands of Fuego and St. Jago, (Cape Verd group,) in December, 1828, I witnessed a number of bonito in pursuit of flying-fish; the former springing several yards out of the water, in eager chase, whilst large[35] shoals of the latter arose with an audible rustling noise before their pursuers, and the chase continued as far as we could see, a number of victims no doubt being sacrificed to the voracity of their hunters. Besides the finny enemies, they had to encounter, as they rose from the water, boobies, gannets, and tropic birds, which hovered about, and in our view secured very many as they sought refuge in the air. It was a novel sight, and one not often witnessed during repeated voyages, and afforded much amusement and interest to those who beheld it.[14]

Occasionally our attention was excited during the voyage, by the remarkable luminosity assumed by the ocean in every direction, like rolling masses of liquid fire, as the waves broke and exhibited an appearance inconceivably grand and beautiful. The phosphoric light, given out by the ocean, exists to a more extensive and brilliant degree in tropical regions,[36] although in high latitudes it is occasionally visible, more especially during the warm months of the year. The cause of it has excited much speculation among naturalists; and although many of the marine molluscous and crustaceous animals, such as salpa, pyrosoma, cancer, several medusæ have been found to occasion it, yet no doubt debris, from dead animal matter, with which sea water is usually loaded, is also often one of the exciting causes.

As the ship sails with a strong breeze through a luminous sea on a dark night, the effect produced is then seen to the greatest advantage. The wake of the vessel is one broad sheet of phosphoric matter, so brilliant as to cast a dull, pale light over the after-part of the ship; the foaming surges, as they gracefully curl on each side of the vessel’s prow, are similar to rolling masses of liquid phosphorus; whilst in the distance, even to the horizon, it seems an ocean of fire, and the distant waves breaking, give out a light of an inconceivable beauty and brilliancy: in the combination, the effect produces sensations of wonder and awe, and causes a reflection to arise on the reason of its appearance, as to which as yet no correct judgment has been formed, the whole being overwhelmed with mere hypothesis.

Sometimes the luminosity is very visible without[37] any disturbance of the water, its surface remaining smooth, unruffled even by a passing zephyr; whilst on other occasions no light is emitted unless the water is agitated by the winds, or by the passage of some heavy body through it. Perhaps the beauty of this luminous effect is seen to the greatest advantage when the ship, lying in a bay or harbour in tropical climates, the water around has the resemblance of a sea of milk. An opportunity was afforded me when at Cavité, near Manilla, in 1830, of witnessing for the first time this beautiful scene: as far as the eye could reach over the extensive bay of Manilla, the surface of the tranquil water was one sheet of this dull, pale, phosphorescence; and brilliant flashes were emitted instantly on any heavy body being cast into the water, or when fish sprang from it or swam about; the ship seemed, on looking over its side, to be anchored in a sea of liquid phosphorus, whilst in the distance the resemblance was that of an ocean of milk.

The night to which I allude, when this magnificent appearance presented itself to my observation, was exceedingly dark, which, by the contrast, gave an increased sublimity to the scene; the canopy of the heavens was dark and gloomy; not even the glimmering of a star was to be[38] seen; while the sea of liquid fire cast a deadly pale light over every part of the vessel, her masts, yards, and hull; the fish meanwhile sporting about in numbers, varying the scene by the brilliant flashes they occasioned. It would have formed, I thought at the time, a sublime and beautiful subject for an artist, like Martin, to execute with his judgment and pencil, that is, if any artist could give the true effect of such a scene, on which I must express some doubts.

It must not be for a moment conceived that the light described as brilliant, and like to a sea of “liquid fire,” is of the same character as the flashes produced by the volcano, or by lightning, or meteors. No: it is the light of phosphorus, as the matter truly is, pale, dull, approaching to a white or very pale yellow, casting a melancholy light on objects around, only emitting flashes by collision. To read by it is possible, but not agreeable; and, on an attempt being made, it is almost always found that the eyes will not endure the peculiar light for any length of time, as headaches and sickness are often occasioned by it. I have frequently observed at Singapore, that, although the tranquil water exhibits no particular luminosity, yet when disturbed by the passage of a[39] boat, it gives out phosphoric matter, leaving a brilliant line in the boat’s wake, and the blades of the oars when raised from the water seem to be dripping with liquid phosphorus.

Even between the tropics, the phosphoric light is increased or diminished in its degree of brilliancy, in a very slight difference of latitude; on one day it would be seen to a most magnificent extent, on the next it would be perhaps merely a few luminous flashes. It might proceed from the shoals of marine animals, that caused the brilliancy to be less extensively distributed over one part of the ocean than another. That I am correct in asserting that some of the animals which occasion the phosphoric light, emitted by the ocean, do travel in shoals, and are distributed in some latitudes only in a very limited range, I insert two facts which occurred during this voyage, and which will no doubt be regarded as interesting.

On the 8th of June, being then in latitude 00° 30′ south, and longitude 27° 5′ west, having fine weather and a fresh south-easterly trade wind, and range of the thermometer being from 78° to 84°, late at night the mate of the watch came and called me to witness a very unusual appearance in the water, which he, on first seeing, considered to be breakers. On arriving upon the deck, this was found to be a very broad and[40] extensive sheet of phosphorescence, extending in a direction from east to west as far as the eye could reach; the luminosity was confined to the range of animals in this shoal, for there was no similar light in any other direction. I immediately cast the towing net over the stern of the ship as we approached nearer the luminous streak, to ascertain the cause of this extraordinary and so limited a phenomenon. The ship soon cleaved through the brilliant mass, from which, by the disturbance, strong flashes of light were emitted; and the shoal (judging from the time the vessel took in passing through the mass) may have been a mile in breadth: the passage of the vessel through them, increased the light around to a far stronger degree, illuminating the ship. On taking in the towing net, it was found half filled with pyrosoma, (atlanticum?) which shone with a beautiful pale greenish light, and there was also a few small fish in the net at the same time; after the mass had been passed through, the light was still seen astern until it became invisible in the distance, and the whole of the ocean then became hidden in darkness as before this took place. The scene was as novel as it was beautiful and interesting, more so from having ascertained, by capturing the luminous animals, the cause of the phenomenon.

The second was not exactly similar to the preceding;[41] but, although also limited, was curious, as occurring in a high latitude during the winter season. It was on the 19th of August,[15] the weather dark and gloomy, with light breezes from north-north-east, in latitude 40° 30′ south, and longitude 138° 3′ east, being then distant about three hundred and sixty-eight miles from King’s Island, (at the western entrance of Bass’s Straits). It was about eight o’clock, P.M. when the ship’s wake was perceived to be luminous, and scintillations of the same light were also abundant around. As this was unusual and had not been seen before, and it occasionally also appeared in larger or smaller detached masses giving out a high degree of brilliancy: to ascertain the cause, so unusual in high latitudes during the winter season, I threw the towing net overboard, and in twenty minutes succeeded in capturing several pyrosoma, giving out their usual pale green light; and it was no doubt detached groups of these animals, that were the occasion of the light in question. The beautiful light given out by these molluscous animals soon subsided, (being seen emitted from every part of[42] their bodies,) but by moving them about it could be reproduced for some length of time after. As long as the luminosity of the ocean was visible, (which continued most part of the night,) a number of Pyrosoma atlanticum, two species of Phyllosoma, an animal apparently allied to Leptocephalus, as well as several crustaceous animals, all of which I had before considered as inter-tropical species, were caught and preserved. At half-past ten, P.M. the temperature of the atmosphere on deck was 52°, and that of the water 51½°. The luminosity of the water gradually decreased during the night, and towards morning was no longer seen, nor on any subsequent night.[16]

Albicores,[17] bonitos, and even a colossal whale[43] close under the stern, beguiled a tedious hour, until we arrived in latitudes where the various species of albatross, cape petrel, and other oceanic birds afforded a change from the “finny” to the “feathered” tribe. We lost the south-east trade on the 13th of June, in about 14° 30′ south, and long. 32° 14′. west. In lat. 30° 0′ south, and long. 24° 18′ west, on the 25th of June, cape petrels[18] were first seen, and increased in numbers as we proceeded, continuing about the ship, in greater or less numbers, even to Port Jackson; albatrosses were not seen until we arrived in lat. 36° south, long. 5° 18′ west, when several species of this bird were often about the vessel.

Besides the sight of flying fish, sharks, dolphins, and other deep-water fish; cape petrels, albatrosses, and other oceanic birds, serve to banish the sameness of a sea voyage, and that ennui which lays its benumbing hand upon those who have but few resources in themselves, and looking for it in objects around, too often feel disappointed. It is usually about the 29° of latitude, and 26° of west longitude, that the gigantic[44] species of albatross is usually first seen, as well as the smaller but not less elegant species of the same bird. At first but few are seen, but they increase in numbers as the vessel gets into more southern latitudes; at some seasons of the year they appear more numerous than at others, which may be attributed to the pairing time, which may keep them, at certain seasons, nearer the rocky islets upon which they breed or rear their young. The large white or wandering albatross,[19] (Diomedia exulans,) the type of the genus, excites much interest by its majestic appearance, either when almost sweeping the sides of the vessel with its huge pinions, or when beheld a prisoner on the ship’s deck, realizing the idea of the famed roc (allowing for the brilliant and exaggerated descriptions usual in all eastern nations) mentioned in the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments.[20]

It is pleasing to observe this superb bird sailing in the air in graceful and elegant movements, seemingly excited by some invisible power, for there is rarely any movement of the wings seen, after the first and frequent impulses given, when the creature elevates itself in the air; rising and falling as if some concealed power guided its various motions, without any muscular exertion of its own; and then descending sweeps the air close to the stern of the ship, with an independence of manner, as if it were “monarch of all it surveyed.” It is from the very little muscular exertion used by these birds, that they are capable of sustaining such long nights without repose.

When these elegant birds are captured, and brought on board, their sleek, delicate and clean plumage is a subject of much admiration; and the fine snow-white down which remains after the removal of the outer feathers, is in requisition among ladies for muffs, tippets, &c. The large species of albatross measures from eight to fourteen feet. I have even heard it asserted, that specimens have been shot of this species, the expanded wings of which measured twenty feet across; but the greatest spread I have seen, has been fourteen feet.[21] The immense distance these birds[46] are capable of flying, seems almost incredible, although often ascertained by birds having been caught, marked, and again set at liberty. When seizing an object floating on the water, they gradually descend with expanded or upraised wings, or sometimes alight, and float like a duck on the water, while devouring their food; then, elevating themselves, they skim the surface of the ocean with expanded wings, giving frequent impulses, (as the great length of their wings prevents their rising with facility from a level surface,) as they run along for some distance, until they again soar in mid-air, and recommence their erratic flights. It is interesting to view them during boisterous weather, flying with, and even against, the wind, seeming the “gayest of the gay” in the midst of howling winds and foaming waves.

To watch the flight of these birds used to afford me much amusement;—commencing with the difficulty experienced by them in elevating themselves from the water. To effect this object, they spread their long pinions to the utmost, giving them repeated impulses as they run along the surface of the water for some distance. Having, by these exertions, raised themselves above the wave, they ascend and descend, and cleave the atmosphere in various directions, without[47] any apparent muscular exertion. How then, it may be asked, do these birds execute such movements? The whole surface of the body in this, as well as, I believe, most, if not all, the oceanic tribes, is covered by numerous air-cells, capable of a voluntary inflation or diminution, by means of a beautiful muscular apparatus. By this power, the birds can raise or depress themselves at will, and the tail, and great length of the wing, enable them to steer in any direction. Indeed, without some provision of this kind, to save muscular exertion, it would be impossible for these birds to undergo such long flights without repose, as they have been known to do; for the muscles appertaining to the organs of flight, although large in these birds, are evidently inadequate in power to the long distances they have been known to fly, and the immense length of time they remain on the wing, without scarcely a moment’s cessation.

When several species of the albatross, as well as petrels and other oceanic birds, are about the ship at the same time, no combats have been seen to take place between them; but on the death of one, the others soon fall upon and devour it. When one of this tribe of birds is captured and brought upon the deck, it appears to be a very[48] muscular bird,—judging from its external form. This deception is occasioned by the quantity of down and feathers, with a very dense integument, and the air-cells being often inflated in a slight degree. When these are removed, the body of the bird is found to be of a smaller size than would have been supposed, and, comparatively speaking, does not possess the muscular power, which, from its long flights, our ideas might lead us to suppose. I remarked that the albatross would lower himself even to the water’s edge, and elevate himself again without any apparent impulse; nor could I observe any percussion of the wings when the flight was directed against the wind,—but then, of course, its progress was tardy. Many, however, have differed with me in considering that the birds never fly “dead against the wind,” but in that manner, which sailors term, “close to the wind,” and thus make progress, aided by, when seemingly flying against, the wind.[22]

The different species or varieties of the albatross,[49] are but little understood; in the course of a long voyage but few opportunities occur to any person acquainted with natural history to examine specimens, and consequently our knowledge respecting them is limited to a very few facts. It is not in many instances that a new species can be defined; age and sex often producing differences which are frequently regarded as specific characters. If persons, who may feel an interest, or have studied this interesting science, would note down the differences of plumage, size, and sex, &c. of the birds captured, in course of time a mass of information might be collected, which would serve, in some degree, to determine the different changes of plumage undergone by the various species.[23]

On the 21st of August, the south end of King’s Island was seen, bearing east-north-east, by compass, at a distance of thirty miles. We entered Bass’s Straits on the same night, and anchored in Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, on the morning of the 25th of August.

Sombre appearance of the Australian coast—Feelings of an emigrant on approaching it—Improvement of Sydney—Fruits produced in the colony—Extent of the town—Cultivation of flowers and culinary vegetables—House-rent—The streets—Parrots—Shops—Impolicy of continuing the colony as a penal settlement—The theatre—Aspect of the country in the vicinity of Sydney—The grass tree—Floral beauties—Larva of a curious insect—The colonial museum—Visit to Elizabeth Bay—Valuable botanical specimens in the garden of the Honourable Alexander Macleay—New Zealand flax—Articles manufactured from that vegetable—Leave Sydney—Residence of Mr. M’Arthur—Forest flowers—Acacias—Paramatta—Swallows.

As we sailed by the Australian coast, its barren aspect neither cheered or invited the stranger’s eye; even where vegetation grew upon its shores, it displayed so sombre an appearance as to impart no animation to the scenery of the coast. To an emigrant, one who has left the land of his fathers, to rear his family and lay his bones in a distant soil, the first view of this, his adopted[51] country, cannot excite in his bosom any emotions of pleasurable gratification; despondency succeeds the bright rays of hope, and he compares with heartfelt regret the arid land before him with the fertile country he has forsaken, because it afforded not sustenance for himself and family, and thus reluctantly caused him to sever the affectionate ties that united him to dear friends in his native land—the place of his birth—the soil and habitation of his forefathers for centuries.

One does not behold the graceful waving of the cocoa palm, the broad and vivid green foliage of the plantain, nor the beautiful luxuriance of a tropical vegetation, which delight the vision of the wearied voyager on a first approach to a tropical region, where the soil teems with cultivation, or a profuse natural vegetation extending from the loftiest mountains even to the ocean’s brink. But on landing and viewing the interior of Australia, the wanderer, although seeing much to confirm his first impressions, will also view many parts of the country recalling to his memory features resembling the land he has left; and as industry gives him wealth and independence, and he finds his family easily maintained, he becomes reconciled to his choice, and remains comparatively if not entirely happy.

Sydney was much improved and enlarged since my last visit in 1829; provisions were abundant and exceedingly cheap, the shipping being supplied with fresh beef at one penny a pound, and even less; vegetables are also very abundant, except in the most arid of the summer months; and fruit is, during the summer months, plentiful, and a great portion of excellent quality, consisting of several varieties of peaches, apricots, apples, pears, water-melons, loquats, grapes, plums, and strawberries, &c. Fruit of a superior kind obtains a high price, but the common kinds are very cheap; peaches for preserves or tarts being hawked about the streets at a penny a dozen. Gooseberries will not succeed in the vicinity of Sydney, but this fruit has been produced in the Argyle and Bathurst districts. Grapes have lately been perfected in the colony in great abundance, both as to size and flavour; and much attention is now devoted by the colonists to the cultivation of the vine; for which, from its prolific and early bearing, the Australian soil seems to be exceedingly well calculated.

Several enterprising individuals have introduced the different species and varieties of vines from Spain, France, Portugal, &c. &c. producing grapes, valuable in the manufacture of wine, as[53] also for the dessert; and we may hope that the time is not distant when grapes will abound in Australia as they at present do at the Cape, and that wine both for home-consumption and exportation will be made from them. The immense increase of grapes in the colony during the last two or three years, leads one to suppose that the above opinion will speedily be confirmed.

On making a circuit around the town of Sydney, the metropolis of the Australian colony, the extent of ground it occupies, the number of buildings completed, as well as those erecting for the increased and still increasing population, the variety and neatness of the shops, excite the surprise of a stranger, and still more of a person who revisits the town after a brief absence, at the rapid improvements that have taken place in this distant colony in so short a period of time. The humble wooden dwellings are fast giving place to neat houses and cottages constructed of brick or sandstone; but, as may be expected in all recently established towns, there is much want of symmetry in the construction of the buildings; and on perambulating the streets, specimens of several unknown orders of architecture are seen; the cottage style, with neat verandas, is one much adopted for private dwellings, and has a neatness of external appearance, with which the[54] interior usually corresponds. Many have neat gardens attached to them, in which, during the summer season, the blooming rose, as well as the pink, the stock, and other European flowers, impart a beauty, and remind one of home; or, in lieu of these gay vegetable productions, the industrious housekeeper has caused the plot of ground to be planted with peas, beans, cabbages, and other culinary vegetables. The tree cabbage, common on the European continent, but rarely seen in England, I observed introduced in the gardens; it thrives well in the colony.

House-rent is excessively high in the colony, being one of the greatest expenses to a resident in Sydney; it varies from sixty to two hundred and fifty pounds annually. The streets being of sandstone, the constant attrition of it by vehicles, &c. produces, from its friability, much dust, which occasions, during windy days, much annoyance; from the same cause, the streets are often out of repair, and the best material for repairing them is a kind of flinty stone, brought by ships from Hobart Town as ballast.

Parrots are, perhaps, of all the feathered tribe, the most numerous in the colony; and different species are lauded for speaking, whistling, and other noisy accomplishments. No one can walk the streets of Sydney or any of the villages of[55] the colony, or enter an inn or dwelling-house, without seeing this class of birds hung about in cages, and having his ears assailed by the screeching, babbling, and whistling noises which issue from their vocal organs: it is the street music of the colony, and “pretty polly,” “sweet polly,” are tender sounds which issue from the exterior as well as interior of every dwelling. These birds are evidently gifted with the bump of talkativeness. It was once asserted, that ladies kept the birds to converse with when alone, which served a double purpose—that of being to them both practice and amusement.

The best view of the town, shipping, and adjacent country is that seen from the “rocks,” and the prospect afforded from this elevated situation is very fine. Shops of all kinds are rapidly multiplying; and lately there have been extensive emigrations of artisans of all descriptions from every part of the united kingdom; butchers, bakers, pastrycooks, provision merchants, shoemakers, apothecaries, fancy-bread bakers, booksellers, &c. &c. are numerous, and have neat, and some even elegant shops; the press sends forth their cards and circulars, and large posting bills, printed in a neat and even superior manner, equal to any similar production in our country towns in England. Circulating[56] libraries and literary reading rooms are now becoming numerous, for the Australians are desirous of being a reading as well as a thinking people, and are anxious to have the permission of legislating for themselves; but whilst the free and emancipist parties are each desirous of gaining an ascendancy in colonial affairs, it would certainly not be advisable to grant the boon; both have their interests at home, and the emancipists are a wealthy and powerful body; and although I am not anxious to enter into the political affairs of the colony, I would, while on this subject, merely wish to suggest the expediency, from the wealth and importance of this part of the Australian colony, to no longer use it as a penal settlement, but encourage free emigration of labourers, and send the convicts to a new colony, which might be founded at the northern portion of the extensive Australian territory; then there can be no doubt that party spirit will in some degree subside, and the colony will increase still more in prosperity, being undivided by any party feeling.

It is well known that free emigration is detested by most of the convict party, and a wealthy individual of this class once remarked, “What have the free emigrants to do here? the[57] colony was founded for us, they have no right here;” and that individual, from his wealth, would probably be elected a member of a future House of Assembly. The emigration of wealthy settlers has been much retarded by the government order, that no grants of land are to be given, but only purchased; until that order is repealed, no great increase of settlers for agricultural purposes will take place; one grant—but one grant only—ought to be given to the emigrant on his arrival in the colony as before; and those who may be desirous of having an additional grant, may then be able to effect it by purchase; the land sold since the new order has been in operation, has been principally, if not entirely, purchased by those among the settlers who were desirous of increasing the extent of their property, and from the vicinity of the “selection” to their former grant, can afford to give a higher price for it, than the newly arrived settler, ignorant of the quality of the land, and the district in which it may be situated.

A theatre having been licensed by the governor, and lately opened by a select company of performers, I visited it one night to ascertain the actual state of the drama in the colony, as also to see the mingled society[58] which would be brought together by such a novel place of amusement. On the night mentioned, I visited it with a party of friends; the evening’s entertainment was the “Heir at Law,” and “Bombastes Furioso.” The interior of the theatre (which was fitted up as a temporary measure, in a large room of the Royal Hotel[24]) is small, and is used only until one more complete can be erected: considering the disadvantages under which theatrical exhibitions must labour in so young a colony, the “tout ensemble” far exceeded what I had expected. The pit and boxes (for there was no gallery) might probably contain one hundred and fifty persons. To speak of the performance of Colman’s celebrated comedy, would be to say it was beneath criticism; and the actors seemed determined to “play the comedy” after a manner of their own, substituting passages of their own for those of the author, in defiance of all dramatic rules.

The greatest novelty of the evening was a young Australian actress, to whom the drama was as much a novelty as she became to us this evening; and consequently she had no medium of comparison by which her judgment could be directed. Her predominant fault was a want of feeling. In the very affecting scene, where poor Henry, long supposed to be lost, returns to his beloved and disconsolate Caroline—he was in ranting raptures, while she received him in the most hard-hearted manner that can be conceived, uttered the expressions placed by the author into her mouth as a mere matter of course; and, as the unfeeling creature evidently showed that she neither felt nor understood the sentiments uttered, it proved no affecting scene either to actors or auditors. However, “Advance Australia;” the lady and the colony, we thought, are both young. As for the rest of the corps, they too often mistook indecency for wit, and probably by so doing they pleased the majority of their audience; if so, both parties would be satisfied. The pit contained those usually seen in the galleries of the theatre at home; and squabbles, threats, and actual combats, served to amuse some, and discipline others; and the various scenes and expressions in both pit and boxes excited in our[60] minds any thing but an idea of the sublime and beautiful. It may also be worthy of remark, as a proof of the increasing morality of the colony, that no one was stationed at the doors, as in our depraved metropolis, warning you to “take care of your pockets;” and that neither myself, or any gentlemen in company, either in our ingress or egress, had our pockets picked.