HERMAN CARRYING TYNDALE TOWARDS THE RIVER BANK. (See page 7.)

HERMAN CARRYING TYNDALE TOWARDS THE RIVER BANK. (See page 7.)

A STORY OF

THE DAYS OF WILLIAM TYNDALE

BY

ALBERT LEE

AUTHOR OF

"THE KEY OF THE HOLY HOUSE" "THE KING'S TREACHERY"

"THE FROWN OF MAJESTY" "A THIEF IN THE NIGHT"

"THE EARL'S SIGNATURE" ETC. ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

JOHN F. CAMPBELL

MORGAN & SCOTT LTD.

12, PATERNOSTER BUILDINGS

LONDON ENGLAND

CONTENTS

CHAP.

I. THE MAN IN THE MEADOW

II. THE MAN ON THE STAIRS

III. THE PICTURE IN THE FIRE

IV. THE COMING OF THE GUARD

V. THE MAN IN THE ARCHWAY

VI. THE SEARCH

VII. THE PASSAGE

VIII. THE PRINTER'S WORKSHOP

IX. THE MAN BY THE RIVER

X. ROYE AND THE INQUISITORS

XI. ALONE IN THE CAVERN

XII. THE NIGHT RIDE

XIII. THE PRISONER

XIV. THE FOREST RANGER

XV. A DARING DECISION

XVI. WITHIN THE CASTLE

XVII. THE MAN IN THE DUNGEON

XVIII. IN THE CELL

XIX. SPOILING THE EGYPTIANS

XX. THE FLIGHT FROM THE HOLY HOUSE

XXI. THE MILL IN THE FOREST

XXII. HERMAN'S RETURN

XXIII. IN THE LION'S MOUTH

XXIV. THE GREAT ALTERNATIVE

XXV. THE COMING OF THE FORESTER

XXVI. THE PURCHASE OF THE VAULT

XXVII. THE HOUSE ON THE WALL

XXVIII. THE NIGHT RIDE IN THE FOREST

XXIX. THE NIGHT RIDER'S CALL

XXX. THE ELEVENTH HOUR

ILLUSTRATIONS

HERMAN CARRYING TYNDALE TOWARDS THE RIVER BANK ...... Frontispiece

MARGARET LEADING THE WAY THROUGH THE CAVERN (missing from source book)

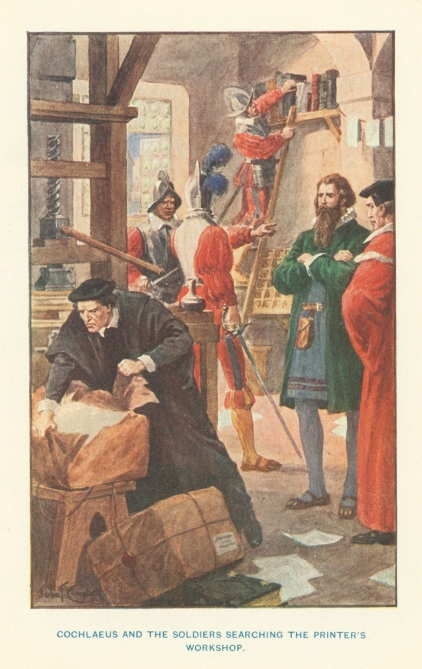

COCHLAEUS AND THE SOLDIERS SEARCHING THE PRINTER'S WORKSHOP

"THE FAMILIAR FELL LIKE A LOG ON THE STONES AT MY FEET"

"HERMAN DUG IN HIS HEELS, AND THE HORSE GALLOPED PAST"

"MY LORD, THERE IS A SHIP COMING ROUND THE BEND!" THE MAN CRIED BREATHLESSLY

SHE SAW A MAN'S FINGERS CLOSING ROUND THE BARS

"HALT!" CAME THE CRY ON THE NIGHT AIR

THE CALL OF THE NIGHT RIDER

As she walked across the meadow, carrying a basket in one hand, and swinging a a dainty blue hood in the other, Margaret Byrckmann made a picture that was pleasing to behold. She looked up as she moved along, but her eyes went down again before the dazzling sun which was setting in a blaze of red splendour, silhouetting the battlemented walls of the city.

She gave this evening beauty scanty attention, for her dark eyes were watching the meadow. Then a cry of pleasure broke from her lips, and she hastened forward; but before she had gone far her face filled with disappointment, and she stopped abruptly.

"I thought it was Herman!" she exclaimed, almost petulantly.

She watched a man who was walking wearily. He looked dusty and wayworn, and the movement on the beaten path seemed to be toilsome and painful. She thought he must have travelled far, for he carried a heavy-looking wallet on his back, and the staff in his hand was used as though it was real labour to go forward.

"He is tired to death, poor man!" she muttered, her sympathy getting the better of her disappointment, and she crossed the meadow to intercept him.

Until he halted, in sheer weariness, to look around for some spot—a tree, or a bush—anything that would screen him from the glare of the sun, the man in the meadow did not see her; but the moment he spoke, Margaret knew that he was not one of her countrymen.

"Mistress, how far is it to the city?" he asked, in a foreign accent.

"That is it," she answered softly, and full of concern, for the stranger's limbs trembled, and his hand shook when he raised it to set his cap straight. With the other he gripped his staff tightly, lest he should fall.

"Yonder?" he exclaimed, gazing beneath his hand. "I did not see it in the blaze of the sunset. It seems a long way off."

"More than two miles," said Margaret.

"Two miles!" was the dismayed response; "so far as that?"

"Yes, sir. But how will you think to enter the city, since 'tis but a few minutes to sundown? They close the gates the moment the sunset bell has stopped."

"Is it so?" came the discouraged response. "I forgot that it is not here as it is in England, where our walled cities are so few. Then I must lie in the meadow till sunrise."

"You could enter if you had a pass," said Margaret, who was concerned for the stranger; for, in spite of his wallet and the travel stains, she saw that he was no common wanderer.

"But I have no pass."

The stranger and the girl, standing in silence, while the slanting sunlight was sending long shadows over the grass, looked around for some place—a hut, or a barn, or anything where a man who was tired could lie down and sleep; but there was nothing of that sort in view; no village, far or near.

"There is no place that I can see," said Margaret, who had never noticed how empty the fields were of houses until now, when they were so badly needed.

"Ah, well! I may not complain," the stranger muttered. "Why should I? Even the dear Lord saw many a sun go down, and had nowhere to lay His head."

He spoke more to himself, as if forgetful that the girl was near, until she moved.

"I will sit down under the chestnut tree, and take my chance, unless your home is anywhere outside the city walls."

"I live in the city, sir, but they know me, and I have a permit to get in after the gates are shut," said Margaret. "And yet I am so sorry for you," she went on softly.

"If I only knew where I might find some food I would not care," the stranger said, gazing around him, his hand above his eyes.

A low call came while he was speaking, like the sweet note of the last evening bird. It travelled over the meadow from the river, and Margaret looked up quickly. Her dark eyes flashed, and her lips parted with pleasure; then she sent back an answering cry, full of soft, rich music. The stranger, watching her pale face, saw the flush of colour darken it, and, worn out though he was, he marvelled at her beauty, and smiled to himself.

"Pardon me for a moment, sir," she exclaimed, when her answer ended. "I will come back again."

While she spoke she moved away with hurried steps to meet a young man who had appeared on the bank of the broad river. He had been bending low to fasten his boat to the root of one of the willows, but when he saw her coming he came to meet her, and, throwing his arms about her, he kissed her till she asked for breathing time.

"There's a stranger yonder, Herman, and he will see us," she exclaimed, her face burning at the thought.

"A stranger?" Herman cried, flushing at being caught like that, and the girl's laugh rang out when she held back, still in his arms, and saw the colour of his browned face deepen.

"'Tis what I have told you, Herman, again and again," she said roguishly. "You ought to look before you love."

"Look before I love!" the young fellow blurted. "I looked, and saw a girl so sweet and lovely that I lost my heart at once. That's looking before you love, is it not? But where's the stranger? I can't see anyone."

Her lover's arm was still about her when Margaret turned to point to the man she left standing near the chestnut tree.

"He's gone!" she exclaimed, in real surprise, and, breaking away from Herman, she ran to the spot where she and the stranger had been standing. Then a cry of dismay broke from her lips. The man lay in a heap in the hollow, and, leaping into it, she dropped on her knees, and gazed at him with startled eyes.

"Is he dead?" cried Herman, who had come at her heels, and now was in the hollow by her side.

"God forbid!" the girl exclaimed, beginning to chafe the unconscious man's hands.

"He came here while I was waiting for you, Herman. He wanted to know how far it was to the city, and he seemed so distressed when I told him the gates would soon be shut—long before he could reach them. We cannot leave him here, poor man!"

She broke off almost abruptly at a thought that came.

"I might have known! He asked if there was any place where he could buy some food, but when your call came I left him to go to you. It was so thoughtless of me!" she added reproachfully.

"You couldn't come to anyone better," said Herman, with a laugh, but only in jest, for he fully appreciated her regret.

"He must be hungry," the girl exclaimed. "He shall have some of this to help him on till he can get a good meal."

She drew her basket closer, and gave it to her lover, bidding him open a jar that was there. Then she put her arms around the shoulders of the helpless one, who was crouching in a bundled heap, and drew him to her, so that his head rested on her bosom. Putting out her hand for the jar, she gently poured some of the cordial between his lips.

The man swallowed it slowly, and presently his eyes opened.

"Ah, I remember!" he exclaimed weakly. "I have travelled far to-day, and, not being well, the heat and hunger have been too much for me."

"Drink more of this," urged Margaret, and when she held the jar once more to the parched lips the stranger drank the cool draught almost eagerly.

"Now eat this," said Margaret, with a pleasing peremptoriness, when, with one of her hands, she drew a parcel from her basket, and deftly unfolded the spotless cloth which wrapped round something. It was food, and she placed it so that he might help himself while she still held him close to her bosom. He seemed too weak otherwise to sit up.

The sun was now gone down, and the heavens were glowing with many-coloured splendour. Away to the west lay the emerald sea, whose silver-crested waves rolled against the sapphire shores, while purple islands dotted the waters and rested there in stately stillness, and the snowclad mountains on the mainland caught the changing glory. Some of that last beauty of the summer's evening entered the little hollow where these three were grouped together, one helpless in his weariness, the others wondering what they should do with him.

"I am another man," said the stranger presently, sitting up, while Margaret sat back on her heels, watching his face keenly. "Whoever you may be, may the Lord reward you both, for dealing so kindly towards me."

He attempted to rise, but failed completely. Not until Herman lifted him in his strong arms could he feel his feet, and even then he swayed, and flung his arm about the young man's shoulder.

"That does not look like walking two miles," said Herman seriously. "Do you know anyone in the city with whom you thought to stay?"

The stranger shook his head.

"No. I started on my way this morning, and, from what they told me, I expected to arrive in good time to look for a lodging; but the heat was so overpowering that I was forced to go slowly, and here I am, outside, and the city gates are closed."

Herman, still with the man's weight on his shoulder, wondered what he could do for this helpless one, whose face had won his confidence. Presently his perplexity passed.

"I have it!" he exclaimed. "I was to bring in that man whom the Burgomaster sent me to meet, and my permit was to admit both him and me by the water-gate. 'Tis the very thing, since Manton has proved a laggard, and word has come that he won't be here for a week or more. I will take you to my mother's house, master," he exclaimed. "Margaret, unstrap the wallet, and carry it, while I take him to the boat."

The girl's fingers moved about the buckles, and in a little while they were on the move, Herman giving the worn-out man the help of his strong arm. He stopped before they had gone far.

"We can't go on like this," he said decisively; and, taking the stranger in his arms bodily, he went forward with strong, swift strides, but as gently as he knew how, towards the river. The boat was there, and laying his burden in the stern, and bidding Margaret sit beside him, Herman pulled the little craft down the darkening stream, not pausing till he reached the water-gate.

He answered the challenge. What he said satisfied the sergeant of the gate, and, mounting the green-stained steps, now once more with the stranger in his arms, and Margaret following anxiously, lest her lover's feet should slip, he stood on the topmost step of all, and waited for her. Passing along the dark and narrow streets, they paused at last at the door of Herman's home.

Margaret threw the door open and waited for him to pass in.

"Mother," he cried, when, at the end of the passage, he stood in an open doorway, "I have brought you a lodger!"

The woman who sat at the table looked up, her needle half-drawn through the cloth, and her blue eyes opened so wide that Herman laughed at his mother's surprise.

Mistress Bengel started to her feet in wonder at seeing her son so burdened.

"Who is it?" she exclaimed. "Is he ill?" she asked, before there was time to answer her first question.

"Nay, not ill, but worn out. I will take him upstairs to the empty chamber."

He turned as he spoke, and mounted the stairs. At the top, before he thrust the door open with his foot, he called down to the others:

"Mother, you will find that I have brought home an angel unawares."

He laughed again. Yet he felt that it was no jest. He had watched the stranger, and something told him he was above the common run of men.

When the stranger lay quiet on the bed, sighing contentedly to find himself at rest, and clasping his hands for silent prayer before he slept, Herman turned away and crept down the stairs softly.

"Mother," he said, in little more than a whisper, when he entered the living-room and closed the door behind him noiselessly, "do you guess who that man is?"

The woman watched her son's face, and marvelled at the kindling of his eyes.

"No, my boy, I cannot. I did not so much as see his face."

Herman gazed around the room before he spoke again. His eyes turned to the window, as if he thought someone might be peering in. He went to the passage and looked along it. He did more than that, for he went to the street door and, opening it, looked into the dark street, but it was silent, and he saw no one. There was not so much as a footstep to be heard anywhere.

"Margaret," he asked, when he came back to the two wondering women, "did anyone, think you, see us enter the house?"

"No, Herman," the girl responded, in a whisper, awed by this mystery Herman had brought downstairs with him. "I looked about, but I cannot tell you why, and I saw no one. It was so dark. But what of it?"

The question came eagerly.

"What of it?"

Herman's voice sank to a scarcely audible whisper. "The man upstairs, mother, is a friend of Doctor Martin Luther. He is the Englishman for whom such tireless search is being made, and his name is William Tyndale! What would the Familiars of the Holy House say if they knew that he was here!"

Margaret stood at the door of her home in the Merdenstrasse, and looked in all directions anxiously before she stepped into the street and closed the door behind her. Her face, lit up dimly by the lantern which hung over the shallow portico, would have shown anyone who saw it that the errand on which her father had sent her was distasteful; for it was dark, and the rain was coming down in an uncomfortable drizzle.

It was not any unwillingness which made her hesitate. It was this going at night, when all that was of ill repute came out of hiding—the scum, one might call it, of the city—and made the streets dangerous.

The Merdenstrasse was empty, but there were sounds which made the delicately nurtured girl shrink. Among them was the clash of steel somewhere, which meant a savage onslaught on a wayfarer who had drawn his sword and was fighting desperately in self-defence. The scream of a woman was heard. The ribald jests and foul songs sung by men who were leaving the taverns where they had spent hours in heavy drinking and gambling came on the night air. At times she heard the tramp of horses' hoofs, and the clink of chain and armour, reminding her that the mounted watch were on their rounds, to make some sort of show of maintaining law and order. But largely it was mere pretence, and it brought no assurance to Margaret.

Whenever she heard the approach of some drunken roysterers, hooting, and shouting out their songs, she drew into the shadow of a portico to hide herself, and once or twice, when the sounds were more than usually startling, she ventured in at some stable door, and waited in the darkness till the way was clear again.

Constantly in that night journey through the drizzle she thought of the stranger whom she and Herman had brought into the city some time before. She did not know how he spent his days, closeted in his room in Herman's home, where he sat from early morning until sundown. What his task was, neither she nor Herman nor his mother knew. Yet they felt that what he did was of the first importance in the man's estimation, and secret. There was no doubt as to the secrecy, for whenever he left his chamber for meals, or, after darkness had set in, went into the streets for air and exercise, he locked his papers in a strong oaken chest that was in the room. He had asked for the use of it when he saw it there, and never left the place without turning the key, and bringing it away with him.

What was that work which so absorbed him? There was never any trace of it when Mistress Bengel put his room tidy in his occasional absence for the night walk in the streets; nothing on the table but an odd scrap or two of paper without a mark to indicate what he had been doing, and the pens with which he wrote.

Surely there was nothing wrong in this task in which he was engaged! Such a man, the friend of Martin Luther, would not stoop to what was ignoble and unworthy!

Margaret had the feeling whenever she thought of him, and more this night than usual, that Master Tyndale's deep thoughts were at work, and that he was bent on holy purposes.

Something had made Herman and his mother, as well as Margaret, lock up in their hearts that secret fact, that such a man was in the house; for, while he never asked them to be silent, they had the idea that trouble would come, disaster, indeed, if it were whispered abroad that William Tyndale was inside the walls of the city.

She was thinking of this, and forgetful of the drizzling rain, when a man's arms were flung around her, the cold hands passing over her eyes.

"Who am I?" was the laughing question.

Her alarm was gone in an instant, and her laughter burst out on the night air. She drew down the hands and kissed them; then, swinging round, she held up her lips for the man to kiss.

"Why is my sweetheart out alone and at this time?" asked Herman, seriously now, for it was never well for a woman, and much less his own darling, to be alone in the dark streets at so late an hour.

"My father asked me to carry a message to his foreman," Margaret answered, as they walked on, hand in hand. "He had no help for it but to send me to Gropper."

Talking quietly, they came to a house in the Wendenstrasse, behind the cathedral, and, leaving Herman in the street, Margaret opened the door, moved along the dark passage, and, finding the stairs, groped her way up them, counting the doors until she came to the room she was seeking.

She gave her message, and turned to go.

"I'll see you to the door, and part way home, Mistress Margaret," said the man, standing, and reaching for his cap.

"There is no need, John. Herman Bengel is outside, waiting for me," the girl said, her pretty face flushing.

"To the door, then, for the stairs are awkward," said Gropper, with a smile, for he had known the girl from her babyhood, and they moved down the stairs together.

They had not gone more than a few steps when they halted, for a man was ascending, carrying a candle which he shielded with his hand, and the light falling on his face showed it plainly. A moment later he had passed into a room on the landing below. Margaret heard Gropper gasp, and it sounded so much like a suppressed cry of dismay that she turned involuntarily, but could not see the man's face at all, not even his form in the darkness.

"What does that man want here?" Gropper muttered, putting out his hand, and holding the girl by the sleeve to stay her from going farther.

"Who is he?" she asked, in a startled whisper, for something was surely wrong, or a strong-minded man like Gropper would not be so put out.

"Who is he?" the answer followed, and the words were whispered in her ear, in trembling tones. "He is that Argus-eyed heresy hunter who goes by the name of Cochlaeus. Surely, mistress, you have heard of him? He is a Deacon of the Church of the Blessed Virgin in Frankfort, and when he ever comes to our city there is trouble for some poor soul who has dared to have anything to do with the Reformation doctrines."

Margaret had not lost a word, and she shivered, for the man's reputation was wide, and thrilled so many with a sense of dread.

They moved on almost unwillingly, going down the stairs with stealth, afraid lest they should attract the attention of this man who had disappeared into the room below. They had to pass the door, and to their alarm it stood slightly ajar.

Neither of them had any wish to play the part of eavesdropper, and were passing on, but as they moved they caught sight of a man who sat at a table in the room, as well as of the other who was in the act of blowing out the candle. But what they heard held them both spellbound.

Cochlaeus either did not notice that the door was partly open, or he was careless as to whether his words were overheard.

"Buchsel," he exclaimed, in a jubilant tone, "I have made a discovery—a wonderful one!"

"Ha!" was the response of the man who was gazing at Cochlaeus questioningly, but in a tone of perplexity. It was plain that he was wondering why the Deacon of the Blessed Virgin was in the city, and coming to his room of all others.

"Yes. I have made a discovery! That accursed English heretic—that limb of Satan!—William Tyndale—is here, within the city walls, and I can give a broad guess as to what he is doing. You remember how he started the translation of the Bible in England?"

He paused, but Buchsel's only response was a nod, for he was waiting for Cochlaeus to tell his story, which he did, not knowing of those two who were standing outside and heard every word with growing dismay.

"He must be here at his old work—that devil's work, I call it!—translating the Scriptures, meaning to scatter his pestilential stuff far and wide, seducing the people who read it to heresy."

The man at the table stared at Cochlaeus incredulously.

"William Tyndale, that arch-heretic, here, in this city, did you say?" he asked, in an amazed tone.

"Yes, I said 'here.' Where could that mean but in this city?"

Margaret's heart beat so wildly that she held her hands to her bosom as if to still it; but she waited eagerly for what would follow. There was no thought about eavesdropping now, much as she abhorred it, for she was asking herself what this would mean for the man who was lodging in Herman's home.

"Where does he lodge?" asked Buchsel, standing up so suddenly that the chair fell to the floor noisily. He was staring hard at the heresy hunter.

Margaret felt faint with fear of what the answer might be.

"Where? I've got to find out. He is here in the city. I know that much. But he shall be found, and then—ah, me!—I will hand him over to the tormentors. He shall be lodged in the dungeon of the Holy House, and the Familiars shall deal with him!"

He paused, and there was silence for a few moments—silence so intense to Margaret that she could hear her heart-beats and the quick breathing of the startled man at her side.

Cochlaeus broke the silence.

"Only to-day I heard it, not an hour since, in fact. I was passing the Gurzenich, where two men were talking in whispers, but my sharp ears—— Buchsel," he broke off, "if ever you go on the hunt for heretics, be sure to thank God if He has given you a quick ear! He has given me that, and I praise Him! My sharp ears caught the words, for I was going softly, my noiseless shoes giving no token of my passing in the dense darkness, so I halted, scarcely daring to breathe lest I should betray my presence."

"And the man—what did he say?" interposed the other, for Cochlaeus went so slowly with his story, lingering over it as though he enjoyed it.

"Ah yes! He said that William Tyndale was inside the walls, somewhere, that he had spoken with him, and had been told that he was prospering with his translation here, because England had become too hot to hold him. And that was not all. He was on the look out for a printer who would put his vile sheets through the press! This accursed printing!" Cochlaeus burst forth, in savage anger. "It will be the ruin of the Church! It will render the whole world Lutheran, unless we find the fellow and crush him!"

Silence followed again, and those who stood on the landing could not move on. They seemed compelled to take the risk of discovery rather than miss what was to follow.

"What do you propose to do?" asked Buchsel, presently.

"Burn the printing-press, and the printer, if I can induce the authorities of the city to display sufficient spirit. And if I can lay my hand on that fellow, Tyndale, he, too, shall burn, and all the papers he has shall go to the flames with him. God help me, and give me the joy of doing it!"

Suddenly the speaker crossed the floor, and slammed the door, leaving Margaret and her companion in the darkness.

When Margaret stepped into the street she was trembling with anxiety. Herman, who was waiting for her, saw by the light of one of the swinging oil lamps that her face was white, and he marked the startled look in her eyes, as well as her trembling hands when she put one out for him to lead her.

"What's wrong, little woman?" he asked in some concern, dropping her hand and putting an arm around her shoulder, walking with her thus along the uneven and slippery pavement.

"I dare not tell you here, in the street," she answered in a frightened whisper, looking up at her lover's face. "Oh, the very stones of the city have ears. Let us talk of something else until we get to your home. Then I will tell you all."

She shivered as she spoke, and looked behind her, gripping one of Herman's hands, for she seemed to feel the approach of that man Cochlaeus, or, still worse, the coming of one of the cloaked and hooded Familiars of the Inquisition. Herman felt her shudder, and tightened his arm about her to give her confidence. Scarcely a word passed between them until they reached his home.

When they stepped into the dark passage, and Herman closed the door, Margaret turned and thrust the bolt into its socket.

"What's that for?" asked Herman, surprised at the movement.

"It will keep out all intruders," she exclaimed, and moved on to the door of the room in which Mistress Bengel was busy with her sewing at the table.

The woman looked up with a smile, but when she saw the girl's face the smile vanished.

"Has anything frightened you, my child?" she asked, dropping her work from her hand and looking at Margaret with great concern.

"Yes," the girl answered, going forward, but halting part way to look behind her. "I bolted the street door, Herman, so I suppose none can hear what I am going to say?"

"It's safe, my love, and no one can come in," said Herman, wondering still more; for he had never known her like this before.

They sat before the fire, but Margaret would only sit where she could see the door. Then the story of the man upon the stairs was told, and what she and Gropper had heard as they listened.

The faces of her listeners blenched, for the penalties of heresy were many and fearful.

"They talk in that manner of that godly man who is under our roof," exclaimed the elder woman in tremulous tones. "Herman, do you realise Master Tyndale's danger?"

"I do, mother, but we must contrive to save him," Herman answered, wiping his face, which had gone damp with the horror of these possibilities. "That man, Cochlaeus, must not find him!"

"He must not!" cried the mother, in suppressed emotion. "No, he must not! Please God, they shall not take him! And yet," she added, with a shudder, "what can we do? What has anyone ever done, when those wolf-hounds of the Inquisition were on the trail? Oh, why did the poor man come here, into the very jaws of danger?"

She buried her face in her hands, and sobbed, for her memory was busy in those moments, and she had in mind the penalty that had been levied on one who was so dear to her, and who would never come home again.

The others watched her, their own eyes blurred with tears, for they guessed what her sorrow was, and what her memory was telling her. They sat in silence, speechless, because they saw that words would be of no avail. They thought, as well, while Herman's mother rested her elbows on the table and wept in silence, of their own helplessness, to say nothing of their own danger, if William Tyndale were to be found in this home of theirs. The only way to escape punishment was by betrayal, but that could never be; and Herman clenched his hands and closed his teeth tightly in keeping with his resolution.

"Mother," he said, breaking the stillness, "we shall not betray Master Tyndale?"

"Betray him?" his mother cried, looking up, her face, tear-wet though it was, almost indignant at the bare suggestion. "God helping us, never, my son! God sent him here for some wise purpose, and we must do our solemn best, my boy, to save him. He's doing God's work, although I wot not what it is. But what did he say yesterday, when I expostulated with him about working so strenuously? 'Wist ye not, mistress, that I must be about my Father's business? I must—I can do no other!—I must work the work of Him that sent me!' I can't forget that, Herman."

"Then you will never give him up? Oh, I am so glad," exclaimed Margaret, leaning forward and laying her own soft hand on the other woman's.

"Give him up? God do so to me, and more, if I betray the saintly man!" the widow said, in tones that left no doubt.

It was growing late, and Margaret got up to go, knowing that they would be anxious at home. Herman stood up to go with her, and they went into the passage. When they walked softly past the door of the front room where Master Tyndale worked it was slightly ajar, and a streak of light fell across the floor of the passage and on the wall. They saw him seated at the table, the candle light shining on his face, and his elbows on the table, and near by a pile of manuscript. His hands were clasped, and his eyes closed. He was speaking, and the low-spoken words came to them plainly.

"Dear Lord, did I not solemnly vow, long years ago, that if my life were long enough, I would cause the boy who driveth the plough to know the Scriptures?"

There was a pause in the prayer, and they watched his face, which for a moment he covered with his hands; but he lifted it again, since the prayer was not yet ended. There was more to hear, and this time the words came even more earnestly.

"O God, the task set for me is great. The burden is almost too heavy for me! And I am compassed about with dangers. I tremble lest something should come to bring ruin to my endeavours. Yet, Lord, it is not the thought of threatening death that troubles me. My fear is, lest my enemies should compass my destruction before I have done my work, and placed the Word of God within the reach of the people at home. Spare me until I have fulfilled my task, and then I will say, 'Lord, now lettest Thou Thy servant depart in peace.'"

They watched him. They were unable to tear themselves away. It was something to hear this holy man pleading with God, asking for nothing for himself, but only for time to complete his work, and ready after that to live or die, as God would say it should be.

Tyndale unclasped his hands and, taking up his pen, began to write as a man would whose time for work was limited, and whose salvation depended on the completion of the task set for him.

Herman and Margaret went along the passage in silence, almost in stealth, and, closing the street door after them softly, they hurried towards the girl's home in haste. When they stopped at her father's door, Margaret gripped her lover's arm tightly.

"Look, Herman," she whispered. She did not point with her finger, but he saw in what direction Margaret was gazing. On the other side of the street were two men, both looking at her father's house, and Margaret gasped when the lantern, swinging in the night breeze, cast a light on their faces. One was Cochlaeus, but Herman did not know him, nor had he ever seen the other; but the girl knew him for the man she had seen at the table while she and John Gropper listened on the stairs.

"The man on the right," she whispered, shuddering, "is Cochlaeus. The other is the man he was talking to in Gropper's house. Why should they be watching our home?"

The answer seemed to come in natural sequence with the question, for her memory recalled what Cochlaeus had said concerning the fate of the printer who should be so daring as to print Tyndale's translation of the Bible.

Surely, oh, surely, her father had nothing to do with that work?

The men passed on. It was a relief to see them going; a greater relief still when they had gone out of sight. And Margaret put up her lips for Herman's kiss. But even while her lips met his she gasped.

"Herman," she said, keeping her lips near his, "they have come back."

The young man looked up and saw them. The men were at the corner of the street, just visible in the lantern light, and it seemed to him and Margaret, as they watched, that they were gazing at the house once more.

But what could he do?

He was asking that question when the men again passed out of sight.

"Good-night, beloved," said Margaret, throwing her arms around her lover's neck, as he gathered her closer to himself. A fear had come that something tragic and terrible might happen before they met again—if ever they did meet. That presentiment of coming trouble made her kiss Herman as, in spite of her whole-hearted love, she had never done before.

"You are late, my child, and I was growing anxious," said her father when she had lifted the latch and entered the room where he was sitting before an open book which contained the account of his sales in the printing-shop.

"I have been hindered, but I will tell you all," the girl exclaimed, going to his side to give him the answer from John Cropper.

"Father," she went on, when he had made a note of her message in the book that was in front of him, "do you know Master William Tyndale?"

The printer's face paled at the unexpected question, and the pen dropped from his fingers on to the open page. The impulse came to prevaricate, but after some hesitation the answer came slowly.

"Yes, my child; I know him."

"Do you know a man named Cochlaeus, father?" she asked, when that answer came, and almost before she had ended her question Byrckmann sprang to his feet, with a cry.

"God be our helper! Why do you mention that man's name?"

His face betrayed the intensity of his fear.

"Sit down, dear, and I will tell you," said Margaret, dropping on a stool at the hearth, where, when he should sit, she could see his face.

The printer sank into his chair, when he had turned it to face the fire, looking down at his daughter with eyes that were filled with terror. She saw that his body trembled as an aspen leaf shivers on its tree, when she told him what she had seen and heard in Cropper's house. When her story ended he rested his elbows on his knees and buried his face in his hands, and for some time not a word was spoken. Margaret's hand lay gently on his knee, and sitting thus in silence, wondering, yet almost afraid to speak, she gazed into the fire, save when for a brief moment now and again she watched her father furtively.

Horror gathered about her in those waiting moments, for her imagination revealed some terrible pictures in the fire. She saw a dungeon there, and in it were some dark-robed Familiars. Around were all the instruments of torture, and a red fire glowed in which were thrust the implements that were to do some deadly work. And presently into the chamber came two men, their hands chained, and about them were four Familiars. But it was these two chained ones to whom she looked, for she knew them. One was William Tyndale—the other was her father!

Her father's voice helped her to smother her cry of anguish at a picture which seemed so real.

"My child, if Cochlaeus were to come to this house it would mean ruin for us all, and death for me."

Her lips parted, but she was speechless. It flashed upon her that the printer of Tyndale's sheets was her own father, and if Cochlaeus came he would find them in the house, somewhere, she could not think where; but in that case the terrible picture in the fire was not imagination, but something too real—too fearful—and the day might not be far away when her father and William Tyndale would actually walk into the dungeon to face the tormentors.

"Come with me, my child," said Byrckmann, standing up and staring before him with a face so full of pain that she was alarmed more than she already had been.

He said no more, but went out of the room, carrying the lamp with him. She followed him into the workshop where the printing-presses were; then going to a room beyond, he walked to a corner where piles of paper stood. Giving her the lamp to hold, he cleared a space on the floor, and to her surprise she saw him go on his knees. Had trouble so overwhelmed him that he meant to pray?

But it was not that. He drew a key from his pocket and inserted it in a hole from which he carefully scraped the dust. Standing up, he bade her drop back to the doorway, and, bending low, raised a portion of the floor, making it lean back against one of the printing machines. What she saw brought a cry of surprise to her lips, for she was gazing into a dark cellar. A printing-press stood in the centre of the stone floor below, and close by it was a great pile of paper.

Following her father down the ladder, carrying the lantern with her, she looked around. Thrust up against the walls were other piles, and, going to one of them, she saw that they were printed folios. She picked up the top sheet and read it, and trembled, for it was a printed sheet of a part of the New Testament in English, which she was able to read; and now she understood why her father spoke of ruin being possible. She was realising the far-reaching consequences when she recalled what Cochlaeus had said.

She almost whispered her words when she had looked around to be assured that they were alone.

"Father, is it not perilous for these to be here?"

She pointed to the pile on which she replaced the sheet she had been reading. "I only ask because of what that heretic hunter said, and especially after I have seen him and that other man in the street gazing at our home."

There was silence. No sound came until a few moments later the cathedral bell boomed out the hour with slow and heavy strokes.

"Can we not destroy all this, father?" Margaret asked, when the last sound of the bell came; and she crossed the floor to where her father stood in dumb perplexity. She laid her hand on his shoulder and looked into his face with glistening eyes.

"Destroy God's Word, my child?" he asked. "That were cowardice. It would be like a man throwing down his cross because the crowd was threatening. The Word of God is far too precious; but if you are ready to help, we can make these papers fit for removal, so that if Cochlaeus came he would not find them."

"If I am ready, father?" she asked reproachfully. "How could you question it? I am more than ready. Tell me what to do."

She set the lamp down on the printing-press, and waited to be told.

For long hours, on through the dark night, she toiled with him, putting the precious sheets in bundles, and covering them with strong paper, that none might see their contents. The great bell of the cathedral boomed out twelve slow and heavy strokes at midnight, and the task had barely begun. They never thought of time, and scarcely heard the strokes, for here was a matter of life and death—an endeavour to hide these folios from the hunters of heresy, and, as Margaret felt while she toiled on feverishly, to save her father from the torments of the Inquisition.

The bell boomed out a solitary note and the work was not yet done. Again and again Margaret paused to listen. She thought she heard footsteps—the rattle of steel, the sharp word of command, and then a noise on the street door; but it was her fancy, and her father assured her so when she spoke about it.

Again the strokes boomed on the night air—two. They came an hour later—three. But not until the fourth stroke sounded and the city settled again into silence was the work ended.

"What next, father?" Margaret asked, sitting down on one of the bundles, too weary to stand after the long night of strain.

"That, my child, the Lord must decide. Let us make sure of His guidance, for everything touching on our safety lies with Him."

The printer went on his knees, and Margaret knelt beside him on the stones, her hands clasped and her eyes closed, while her father prayed that the work of sending forth the Truth for the enlightenment of men might not be hindered. Margaret listened in wonder, for there was not one word in the prayer for his own escape. He was centring his thought on the safety of these precious sheets on which he had been working night after night for many weeks, and as well on the safeguarding of the man of God who dwelt in her lover's home.

The day was breaking when they rose from their knees. Climbing out of this unsuspected cellar and lowering the floor into its place again, they piled great bundles of paper round the shop on that side, leaving everything as it had been before.

The long day passed, and every hour was filled with intolerable anxiety for Margaret. She went about the household duties in her home with a heart that was heavy with dread. Every unusual sound had menace in it, for her. Had anyone noticed her they would have wondered why, again and again, she glanced around with startled eyes, while her parted lips went far to betray her distress.

Her mother was ill at the time, and again and again Margaret had to go into her room to see to her comfort; but when the girl's hand was on the latch she was careful to throw aside all traces of anxiety, and she went in with a loving smile and a happy-looking face, not wishing to add to her mother's care or to set her thinking that something was wrong. It was a hard task, but her eyes glanced about the room merrily, and she stood at the bedside and chatted pleasantly about little things that made for laughter.

But God knew how the poor girl's heart and mind were on the strain, and how, when she heard some measured footsteps in the street, she listened with an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, lest it should be some of the City Guard, coming to the house to search in her father's printing-shop for what some esteemed tenfold worse than treachery.

Once, while her mother was asking a question as to some petty household matter, she heard the sound for which she had been listening ever since she had got out of bed in the early morning. She gave an answer which made her mother wonder what she was thinking of, and then hurried to the window and looked into the street below.

Her hands clasped in dread, and she almost cried out in her terror, for the thing had come that might well mean ruin. Below were half a score of soldiers of the City Guard, with their halberds gleaming in the watery sun, and the soldiers' eyes were carelessly scanning the houses around them as they stood at ease, or were nodding to some acquaintance who went by. She had seen the men do this many a time, and thought nothing of it; but now she gazed into the street with frightened eyes, and her clasped hands rested on her bosom to still the beating of her heart.

"Father!" she murmured noiselessly, for she thought of that picture she had seen in the fire.

The officer of the Guard was carelessly looking at some papers in his hand, turning one over the other, as if searching for one in particular. Never had she gazed as she was gazing now, her breath coming and going in gasps.

"Why are you breathing in that way, my dear?" the sick woman asked, looking at the girl at the window.

"Was I breathing differently than usual, mother?" Margaret asked, turning for a moment, careful to hide the look of dread, and with a forced smile for her mother's sake. "Perhaps I was!" she added lightly. "Ha! there's Targon, the butcher. I must go down and give him an order for to-morrow's dinner."

She moved to the bedside, and, bending over to give her mother a kiss, she hurried down the stairs.

What did it mean? For when the Captain of the Guard had found the paper he wanted, and had thrust the others back into his belt, he moved straight to her father's door, as if to enter the shop. As she descended the steps of the staircase at a dangerous speed her mind was as quick as her feet. Startling visions of possibilities rose before her. It was that horrible picture again which she had seen in the fire. There was more in it now than before. There was the stake, with its flames fanned by the breeze, and her father chained in the midst of them all. There was that wheel of torture on which he was to be broken. There was the dark cell, with its slime, and horrors, and blackness, all made more intolerable because there would be no more glimpse of the daylight for him, if they did not decide to burn him. Or there might be no death, but the galley to which her father would be chained, with his back bared to the sun and wind, while the whip of the galley captain would come down on the flesh, and leave its streaks of blood.

It was there in those few moments.

She stood in the doorway of the parlour, in the shadow, from whence she could see what was passing in the shop.

The Captain of the Guard was there, and the paper was in his hand.

"Master Byrckmann," she heard the soldier say, with a disconcerting lack of cordiality, "the Burgomaster bade me bring you this."

Almost rudely he tossed the paper on the counter, among the printed sheets and other things that lay there.

"See to that without fail," he added curtly.

Without another word he stamped his way to the door, and, with a rattle of steel as his armour moved on his body, strode into the street, and left the shop door to slam after him. The noise of the slamming sounded very much like a death-knell to Margaret.

"What is it, father?" she cried, hurrying to the printer's side behind the counter when a customer was served, and was gone, and they were alone together.

She glanced into his face, and, although he had appeared unperturbed while the soldier and the customer were in the shop, it was white now, and when her father's fingers were put forward to take up the paper they trembled so that he could scarcely close them on it.

"Something from the Burgomaster, my dear," Byrckmann answered, trying to appear at ease, but completely failing.

He broke the city seal, smoothing out the paper on the counter. They read it with their heads close together, their cheeks almost touching. It was written in the ill-formed characters which were so noticeable in everything which came from the Chief Magistrate's hand.

It told its own story. Word had reached him that a notable and troublesome heretic had come from England, whose name was William Tyndale. How it had happened no one knew, but this fellow, so it was said, had contrived to get into the city. Possibly he had come in disguise, a man with a godless heart, and a mind bent on spreading his scandalous heresy. He was hiding somewhere, but no one knew where, and was supposed to be translating the Scriptures into English. It was suspected, as well, that, if he had not already done so, he would be trying to induce one of the printers to run his wicked sheets through the printing-press.

"I charge you, Master Byrckmann, as I am charging all the printers within my jurisdiction," the paper ran, "to abstain from having anything to do with this scandalous fellow who, like Doctor Martin Luther, is working out the devil's wicked will, and seeking to wean away the people from His Holiness the Pope and Mother Church.

"For bethink you, Master Byrckmann, what can happen more calamitous to the credit of our famous city than that this man, Tyndale, should be sheltering in a house inside our walls, and daring, in his insolence, to interpret Divine Law, the statutes of our Fathers, and those decrees which have received the consent of so many ages, in a manner totally at variance with the opinion of the learned priests of the Church! Yet this fellow has dared to do this thing! He has done what Luther dared! and now, like him, he is tampering so wickedly with the Word of God.

"I demand of you, Master Byrckmann, that if you come across him you shall take his work with a subtle readiness. Pretend to applaud his endeavours. Make him all sorts of promises. Make him believe that it is a joy to you to be of service in his cause; but when he is gone, send me instant word as soon as you have traced him to the house wherein he is lodging."

"Father," said Margaret, whose arm stole about his neck while they still bent over the counter.

He looked at her and saw the colour coming back to her face, and her lips were now relaxed to their usual softness after this intolerable strain.

"What is it, my dear?" Byrckmann asked.

"The Captain of the Guard had other papers in his belt, so he must be going the round of the printers. Do you not think so?"

"That must be it, my child. I thank God," he murmured, clasping his hands like one in prayer as they rested on the counter. "None knows but God, and Master Tyndale and you and I——"

"And Herman, father, and his mother," said Margaret softly. "They know."

"Ah yes! I had forgotten. Now may God send the good man safe deliverance."

He unclasped his hands and stood upright, and gazed out of the window with eyes that gleamed with tears which blurred the forms of those who walked along the street. None of the passers-by suspected what nearness to tragedy there had been in the printer's shop.

"Kiss me, father," said Margaret, and the printer, turning, put his arms about her, and kissed her almost passionately. He had always loved his daughter, but here was an even closer bond; something that was linking them to other things; things that were sacred, and beyond the matters that came in the common round of daily life.

Margaret went back to her mother, singing softly as she went from place to place in the bedroom, putting things right, and making the chamber look more cosy. When she moved it was with a tender grace. When she spoke it was with a gladness and a smile that were restful to the sick mother on the bed.

Who could wonder? That string of visions was passed at all events for the present. Her father, so far, was safe. But at odd times, when she moved about the house, she stopped to say a prayer, pleading that the dear Lord would keep the secret from that ignoble Cochlaeus, and all others who were scenting heresy, and striving to find Master Tyndale and all who had dealings with him. Their success meant so much. Ruin for her father! Ah!—and she went pale at the thought—ruin for Herman!

As the day went on the relief gave place to anxiety.

Her heart grew more and more heavy, for after the first revulsion from that deadly fear her memory served her with a cruelty that was hard to bear. It brought back all that happened the night before. That coming of the man on the stairs of Cropper's home; the enforced but unintentioned eavesdropping outside the door on the landing, and hearing what Cochlaeus knew; and, later still, the watchers in the street just opposite her father's house. It was terrible to contemplate the possibilities, for who could tell whether that paper from the Burgomaster was a blind—something to throw her father off his guard? She shivered at the thought; then she went so hot that she drew her dainty kerchief from her bosom to wipe the dampness from her face.

A change came over her father which greatly puzzled her. She could not understand how he could move among the workmen, and be so cheerful, and smile so comfortably at the customers who bought things over the counter of the shop. Not one among them would have suspected that he had been faced with death, and even now might see the Captain of the Guard enter, and take him away.

She did what under other circumstances she would have despised herself for, but she could not help it now. She felt she must do it, or she would die of anxiety. She stood where she could hear what was said when all the workmen had gone save Gropper, who closed the street door, so that no one should enter the shop, and break in on their conversation without it being known.

"What say you, Gropper, now that you know as much as I do?" her father asked, when the foreman stood before him at the counter.

"Get Master Tyndale and everything belonging to him out of the way," came the answer, in decisive tones.

"Out of the way?" the printer interrupted. "What do you mean by that?"

"I mean, get him out of the city; but where, I cannot say for the moment. We'll think about it, Master Byrckmann. We'll pray over it, and God will show us which way the path lies," the man said quietly.

He was going to say more, but a customer came in noisily, and the foreman stood back, and waited until the man was served and went away.

As if she came out of the house casually, Margaret crossed the shop, and, going to the door, called to the customer, who was their butcher, and gave him an order for the next morning. Her face was aflame with having played that mean part of listener, but so much was at stake. It was a matter of life or death. And Herman was involved; for if Cochlaeus or the Burgomaster found him harbouring that arch-heretic there was no other end but death.

In her confusion she gave Targon an order which made the butcher stare at her in surprise.

"Haven't you made a mistake, Mistress Margaret?" the man asked, wondering at her paleness; for now her face had changed.

"What did I say?" she asked, and when he repeated the order her face crimsoned. "It must be this thunder in the air," she answered, by way of exculpation, and with an effort she told Targon what she really required.

She wanted to get away, to see Herman and tell him all she knew. If she could talk the matter over with him he might suggest something, and she could tell her father of the plan. But she was hindered. Her father went back to the workshop with Gropper, and left her to look after the customers, who came in one after another, some for the merest trifles, and some on matters of importance.

Two or three stopped to talk of what was being said in the city. First and foremost Cochlaeus was there, and that suggested heresy. Then a special body of the Guard had been out most of the day, halting at every printer's shop to leave a letter which, of course, was from the Burgomaster. But what was of more importance still was this—that it was declared that William Tyndale was somewhere in the city, and that to-morrow a great reward was to be offered as the price upon his head, and a price, also, on the head of any who harboured him.

Margaret thought she would choke when they talked on in that strain, little knowing what she knew, and what it meant to her beloved if the reward were to be claimed. Her Herman! the man who was all the world to her! Once again, while the customers were standing at the counter, talking on in that strain, she did not see them, for she was gazing afresh at that picture in the fire, and she shuddered because it seemed so real that her father and Herman alike were being broken on the wheel.

One by one the customers dropped off, and then none came at all, and the shop was empty when her father came in with a sealed letter in his hand, which trembled as he held it out to her.

"Take this to Master Tyndale," he whispered. "Put it into your bosom so that none may see it, and wait to hear what he says concerning it. Go warily. But there! None will suspect, because Herman and you are shortly to be wedded."

She went to her room for her cloak and hood, and standing at the window she gazed into the street, which was shadowing into dark twilight, earlier than usual because it was raining, and black clouds were sweeping up from the river and spreading over the city. Preparing for bad weather, she went out into the street, after first showing her father where she had hidden the letter.

The rain was coming down steadily, but presently it came pelting, and the wind rushing along between the houses of the narrow streets blew into her face. But she scarcely noticed it. She was absorbed with the thought that she was going to see Herman, to whom she would tell all she knew. Perhaps he would propose that William Tyndale should get away at once, lest to-morrow should be too late.

The rain came down so heavily that the streets were almost empty, although it was not late. It was one of those storms which no one would face if it could be avoided.

At the corner of the street in which Herman lived she paused, not for the wind, although it was sweeping along with the force of a tempest now, but because of what was happening. Out of a narrow passage, where some wayfarers sheltered, there swung out, two by two, some of the City Guard, and at their head the Captain who had left the Burgomaster's letter with her father.

If they had turned her way she would have been relieved, and the fear would have passed which shook her terribly; but they went the other way. Was it possible that they were going to Herman's home?

Margaret hurried into the archway, where others were sheltering, and a man who was standing near shifted to make room for her. As she stepped in the raindrops came down so heavily that they leapt up from the stones. The water ran from the edge of her hood in little streams which trickled down her face; but it was relief rather than otherwise, for the coolness revived her.

Heavily as the rain was pouring, she bent forward to see whether the Guard were going to Herman's house, but the man, putting a hand on her shoulder, drew her back. They were alone now, for the other people, believing that the rain had set in for the night, hurried away.

"The water is falling down on you, mistress," he said, civilly enough; and he pointed to the gargoyle over the archway, where the water came as from a pipe, and spread out like a fan.

"I was anxious to see where the Guard were going in all this rain," she explained, looking round at him; and the man, catching a glimpse of her face by the light of a lamp which a stableman had just hung up in the arch, saw the look of dread upon it.

"Stand here, then, and you will not get that shower bath," said the stranger, drawing her forward almost roughly, although he had no thought of rudeness. He wondered whether this dainty little damsel, whose pretty face looked so startled, had any reason to dread the City Guard.

Margaret gazed from her new standing-place unrestrainedly, and with her eyes glued on that moving company of men, she noted every step they took. It appeared to her, in her anxiety, that their movements were relentless. They were even cruel, she thought. They passed the greater buildings, looking neither to right nor left, each man resting his chin tightly down on his muffling collar, so that the water which streamed from his helmet should not find its way down his neck.

Even that indifference to what was on either side of the soldiers of the Guard seemed sinister to Margaret. It left everything in such uncertainty. The shock would be so much greater if, after all, the Captain called a halt at Herman's door.

She wished she could see the officer who showed the way, but she could only obtain an occasional glance at the streaming helmet whenever he passed a swinging lantern. She thought that if she could see him she might judge his purpose by his bearing, whether he meant to pass on or slow down to a pace which would enable him to find the house.

The man in the archway became infected with her eagerness, for he, too, stared down the street despite the pouring of the water from the ugly gargoyle's mouth. But she was scarcely aware of his presence. At another time she would have stood out in the drenching rain, in the midst of it, where it poured its heaviest, rather than trust herself in the gloomy archway with an unknown stranger whose presence might well be intolerable to a defenceless girl. But her mind was altogether on Herman, and all other considerations receded. The man near by was an incident in her night's experiences, while the absorbing thought was the disastrous consequences if the Guard went to Herman's house and found Master William Tyndale there!

The Guard moved on and on, going more and more slowly, she thought. Were they doing it deliberately so that the Captain might not miss her lover's home? The thought made her feel sick at heart, and for a moment she reeled. She would have fallen had not the man put out his hand and caught at her arm.

"Dear heart!" he muttered. "I know it all. They stopped at my door one night—just such a night as this!"

The words came unexpectedly, and Margaret turned quickly, looking into his face inquiringly, for she could not miss the pain that was in that almost whispered exclamation.

"'Tis all right, little one," the man said tremulously. "The memory came like a flood upon me, of a night like this, when a City Guard came to my door and took away my darling, just such a girl as yourself."

He held his hands to his face for a few moments, and his body shook with sobs, as it can only do with a strong man in his agony.

Margaret gazed at him. He spoke with a foreign accent, and something reminded her of Master Tyndale.

Brushing his hands across his face, and without another word, the man stepped to and fro in the narrow archway, and then went into the storm and walked away with bent head, while the pelting rain beat on him. Margaret marked how his hands clenched while he passed along in a direction opposite to that which the armed Guard had taken.

His going after those unexpected words made her heart palpitate the more, for if the Guard took that man's daughter, would they hesitate to take a man, and that man her lover?

"No! They would not!"

The words were cried out on the night, but the wind beat them down, and perhaps no one heard them.

The thought that obsessed Margaret was that the Guard were going for Herman. They must have discovered that it was Tyndale whom he had carried up the steps at the Water-Gate. It must be so! Five hundred golden pieces were to be the reward of the man or men who found him who harboured William Tyndale. Five hundred! It meant wealth. Who would care for rain, or pity, when so much gold was to be had?

Lower down the street, which was a very long one, there was a bend, and from the archway Margaret could not see Herman's house. She must see for herself whether the Guard passed it by, in spite of the pelting rain and the boisterous wind.

She left the archway and ran along the causeway with a light, swift tread, careless as to the beating of her soddened dress against her knees. Herman's home lay beyond the bend, but not very far, and they must be very near to it by this time. In her haste she did not see a man standing in the way, with his arms outstretched to stop her.

"My dainty darling!" he cried drunkenly, but she endeavoured to evade him. She failed, and his arms closed about her, and he drew her to him and set his wet and hairy cheek against hers.

"Kiss me, my sweet!" he exclaimed; but her courage served her, and, losing sight of the Guard, she drew up her hands and rained her blows on his face. She hammered at him with her small fists, beating at his eyes until he was fain to let her go to save himself.

"The vicious little minx!" he cried, staggering, and tumbling into the gutter, as she darted away.

She was soon close up to the Guard, but was careful to keep well out of sight, walking as near to the doors of the houses as the projecting steps would allow. Not far away was Herman's home. She saw it, and wondered what would happen, whether the soldiers would halt there.

Her heart almost stood still, and she sank on a doorstep near by, for the Guard had halted opposite Herman's door. The thought of the inevitable discovery, now, was overwhelming. There was no hiding-place there, for Herman had never spoken of one. And William Tyndale was in that house!

Her eyes were riveted on the men whose halting spelt ruin to her own hopes, to her lover's destiny, and to William Tyndale's splendid endeavours to set the Truth before the world. Ruin! Yes, nothing less than that!

She saw the men turn half-way round so that they formed a double line in the middle of the road, the ends of their halberds resting on the ground, and the steel end of each gleaming in the lantern rays.

The Captain of the Guard went to the door which she prayed he might pass by—to Herman's! He mounted the steps—one, two, three! There could be no mistake. It was Herman's home, for, as she knew, and he had often boasted, no other house in that street had that number of steps. There were houses with four, with two, with one, with none, but only Herman's had three.

The soldier struck on the door with his sword handle, and the sounding blows reached her ears, loud, even in the swishing rain.

No answer came, and the summons was repeated.

The heavy shutter opened at one of the windows, and a head appeared, but it was too dark to see whose it was.

"What is your will?" came the question, and Margaret's heart leapt at the sound of Herman's voice.

"I must come in to search your house, Master Bengel."

"To search my house?" interrupted Herman, who did not betray any perturbation in his voice in spite of the sight of a double row of soldiers in the street. "For what? For whom?"

"For one named William Tyndale," answered the Captain, who was taken by surprise at this show of ease—the absence of confusion and fear.

Margaret could scarce believe her ears when a laugh came through the rain; a laugh she would have known if all the men in the city had been there.

"For one named William Tyndale?" Herman cried, after the laugh, and in such a tone of incredulity that Margaret was amazed at his courage, and his ease in carrying it, when he must have known that he was faced with the prospect of the wheel, or prison, or the stake, with torture preceding it. "Who told you such a mad thing that the Englishman should be here in my house, of all houses in the city?"

"Never mind that," was the impatient answer. "Open this door, and let me enter."

"I protest that you will find no William Tyndale here, if you mean the so-called Reformer who, they say, came over from England some time since," said Herman, as he leisurely pulled the shutter into its place.

It astonished Margaret that he should play this part; and yet she admired his effrontery, and was taken with his boldness in meeting the inevitable disaster. That inevitable thing was ruin. It was death! But her heart bounded with a certain pride at her lover's fortitude. Better die a bold man than a craven. And he was bound to die, because William Tyndale was in the house!

She heard the bolt being drawn. She heard the clinking of the falling chain. She caught the sound of the screaming key in the lock, and then the dull grumble of the opening door.

"Come in," she heard Herman say in an easy tone.

The Captain called to three men to step forward, and the four soldiers entered the house.

Margaret asked herself the question—What should she do? But what was it possible to do? Her presence or her absence could in no way serve Herman; and yet she wanted to be near him in his trouble, to throw her arms about him ere they took him away to those horrible dungeons in the Holy House—the headquarters of the Inquisition—and whisper in his ear that whatever came she was his, for life or for death, just as God willed.

The thought decided her. She sprang up from the step on which she had been sitting in the shadow, around which, unknown to her, the water had gathered and soaked into her dress, and hurried across the road. Disregarding the soldiers lined up in the middle of the street, standing still in the pelting rain, she was moving up the steps, feeling the water squashing in her shoes as she moved.

The soldiers inside the house were standing about; one in the front room with the Captain—in the very place where she had last spoken to William Tyndale—and two others near the foot of the staircase, and in such a position as to look up the stairs, or into the room where Herman's mother usually sat.

Margaret's lips parted in wonder, for Mistress Bengel, who was there, was perfectly self-possessed, her hands idle, it is true, and her usual sewing lying untouched on the table. Whether her ease was real or assumed it was difficult to say, but Margaret was puzzled.

When the girl entered the room, white faced and startled, she looked up and smiled.

"I have visitors, my dear," she said, in her pleasant way.

It was mysterious. Was William Tyndale gone away from the house, so that Herman and his mother could afford to be at ease even with the Captain of the Guard paying this unwelcome visit? Or—and the thought came over her with startling force—was the poor man dead, and, being so, was it of no consequence if the soldier should find his dead body lying in his bedroom?

But dead!

The bare thought of it was a troubling one; for a few hours before she had seen the dear man in the attitude of prayer, with his hands clasped, his face full of fervent entreaty, and she had heard him plead in an earnestness that was indescribable:

"Spare me, O God, until my work is ended."

The prayer was surely heard; but had it been answered? Or was Tyndale dead after all, before his work was done? Was it to be as she had heard her father say, more than once, that God buries His workmen, but carries on His work?

From where she stood, undecided as to what she should do—whether to go into the room and stay with Mistress Bengel, or follow her lover with her watchful eye, and perhaps be of some sort of service, if the opportunity came—she could hear Herman's voice. Shifting a little, she saw what was going on, since the door was partly open. Herman was holding a lighted lamp in one hand, and making a gesture with the other; but his face bore no trace of anxiety as to the issue of the search.

"The room is at your service, Captain Berndorf, but there is no William Tyndale in it. Nor is he anywhere in the house."

The soldier was looking round searchingly. Margaret marked his eager glances, and saw how he passed round the room. He opened a cupboard, and ran his hand round the sides; he shifted pieces of furniture, and pulled down some of the pictures if they suggested space sufficient for a man to go into hiding.

The search in that room was a vain one.

The Captain, with the soldier, came out of it, and not seeing Margaret he brushed against her. When he saw her he was not surprised at the startled look on her face, for such looks were usual in his experience, when he went hunting for rogues and rascals, and honest men and women whose crime was heresy. What was more, he knew her to be Herman Bengal's sweetheart, so that he merely asked her pardon for blundering up against her, and did not inquire why she should be in the house. It seemed to him the most natural thing in all the world that she should be there, and for a moment a sympathetic thought came that the poor girl should witness the arrest of her lover.

"I must go through the house," the Captain exclaimed, turning his back on Margaret, but he had more to say, which plainly showed that he had no sense of certainty as to this errand on which he had come.

"Why it should be suggested that a fellow of Tyndale's stamp should be lodging under your roof," he went on, "I cannot imagine. It was mentioned, probably, by someone who owed you a grudge. Still, here's my warrant to search for the man, and I may not leave you until I have thoroughly satisfied myself that he is not here."

He walked into the room where Herman's mother sat, and Margaret entered that one where the search had been just made. The lamp stood on the sconce, and she looked around. There was nothing on the table where Tyndale had so often sat to write. Nothing was in the place to suggest his presence; not a sheet of paper, no clothing, no traveller's wallet, nothing that could in any way be connected with the stranger whom she and Herman had brought within the city.

Would Master Tyndale be in hiding elsewhere in the house? There lay the question, the tarrying of the answer adding to her heart-beats and her despair. This inexplicable indifference on Herman's and his mother's part would go dead against them when discovery came.

She went sick with dread. Her knees so trembled that she sank into a chair close by, regardless of the soddened clothes which clung to her. She could only bury her face in her hands, and hope, and pray. There was plenty of scope for prayer; so little for hope.

When she felt she could stand again and move about, feeble compared with the sound of loud beating in her heart, she heard the Captain's voice once more.

"He is not here; but he may be upstairs. Men, see that none pass you to go into the street. I will go up and make sure for myself."

He began the tramp up the stairs while he was speaking, and other heavy footsteps followed his.

Margaret's heart quailed when she hurried out of the room and followed the men up the stairs. Now, for a certainty, Herman's protégé would fall into the hands of his enemies, and escape seemed impossible. Her pulse beat high, and despair swept over her, to think how she was to witness the undoing of one who was striving for the triumph of the right.

To be caught in a trap like a rat! It was unbearable to think of.

The dulled sound of the footsteps on the carpeted boards of the stairs seemed to call up a vision of a scene which would ere long be real—the vision of a prisoner on his trial; condemned in effect by his judges before he had made his defence, just because he was William Tyndale. And then the attitude of the crowd that thronged the market-place where the stake was standing, and Tyndale chained to it. She could imagine it all, and she could almost hear the babel of execration against him.

To think of it! A man of such noble mien to be browbeaten and battered by the screaming mob, cursed, reviled, mud-covered. She shuddered at the thought, and while the impulse came to follow the others up the stairs, she hid her face while doing so, and sobbed.

She stood at the top of the stairs and looked around. Here, on her right hand, was the room into which Herman carried the tired stranger that night they brought him into the city. On the left was Herman's chamber. Just beyond it, again, was his mother's. Master Tyndale must be in one of them.

Captain Berndorf went into Herman's room, followed by the others, and in a few moments Margaret heard the soldier say roughly:

"Are you here? Come out of it, if you are!"

Resistance would be unavailing, for the Captain's sword was drawn and ready, gleaming in the lamp-light.

Margaret went into Tyndale's chamber. It was lighted by the lantern in the street, for the rays came through the rain-splashed window, and as she stepped in she almost expected to see him sitting somewhere, or lying on the bed, waiting for the inevitable. Yet, when she stood well within the place there was a sense of emptiness. William Tyndale was neither in the bed, nor at the table near the window.

Was he really gone?

While her keen eyes ranged around she saw a square of whiteness on the floor, by the table, and went to it quickly, with an instinctive feeling that it was something which would betray Tyndale, or Herman. When she bent down and caught it up she knew that it was a printed sheet. Under it lay another; under that, again, a third. By the dim light she saw that they were printed folios, and one glance was sufficient to show her that they were proofs of the New Testament, such as she had seen in her father's hidden cellar.

She glanced towards the door, wondering whether the soldiers were there, and had seen that she had some papers in her hand, but the doorway was clear. Bending her head a little, she saw that the passage was empty. The men were still in Herman's room.

She thought of the way out of this very real danger with her swift woman wit, and hastily unbuttoning her dress, she pushed the sheets into her bosom. It was nothing that they were crumpled. What were three sheets of printed paper compared to the lives of two men?

To her, as she thrust them in, the papers seemed to make enough noise to be heard all over the house, for they crinkled in her hands, and the dampness came on her face lest she had been heard, and they should ask her what she had been doing.

While she was rapidly buttoning her dress she turned her face to the window, where the rain came against the glass in heavy gusts, just as the wind drove it. Below were the soldiers of the City Guard, as when she saw them last, two lines of silent, unmoving men, with their halberds gleaming.

The hope sprang in her heart that William Tyndale was really gone. He was not in Herman's room, or they would have found him. They were now going into Mistress Bengel's bedroom, and would they find him there? If not, he could not be in the house, for he was not in this chamber. Her woman mind showed her what a man might not have noticed. The bed was not made as if waiting for a sleeper. It was surprising. Herman's mother had taken away the sheets from the bed, and it looked as though the room had not been used for a long time past.