Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

In your ordinary use of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, you give your attention to the one article that will answer the one question you have in your mind. The aim of this Guide is to enable you to use the Britannica for an altogether different purpose, namely, for systematic study or occasional reading on any subject.

The volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica contain forty-four million words—as much matter as 440 books of the ordinary octavo size. And the subjects treated—in other words, the whole sum of human knowledge—may be divided into 289 separate classes, each one completely covering the field of some one art, science, industry or other department of knowledge. By the mere use of scissors and paste the alphabetical arrangement of the articles could be done away with, and the Britannica could be reshaped into 289 different books containing, on the average, about half as much again as an ordinary octavo volume. It would misrepresent the Britannica to say that you would then have 289 text-books, because there is an essential difference in tone and purpose. A text-book is really a book intended to be used under the direction and with the assistance of a teacher, who explains it and comments upon it. The Britannica, on the other hand, owes the position it has enjoyed since the first edition appeared in 1768 to the fact that it has succeeded, as no other book has succeeded, in teaching without the interposition of a teacher.

It is not, of course, claimed that the idea of reading certain groups of Britannica articles in the order in which they will combine themselves into complete books is a novel invention. Thousands of men owe the greater part of their educational equipment to a previous edition of the Britannica. And not only did they lay out their own courses of reading without the aid of such a Guide as this, but the material at their disposal was by no means so complete as is the 11th Edition. Every edition of the Britannica before this one, and every other book of comparable size previously published, appeared volume by volume. In the case of the last complete edition before the present, no less than 14 years elapsed between the publication of the first volume and the last. It is obvious that when editors have to deal with one volume at a time, and are unable to deal with the work as a whole, there cannot be that exact fitting of the edges of one article to the edges of another which is so conspicuously a merit of the 11th iiEdition. All the articles in this edition were completed before a single volume was printed, and the work stood, at one stage of its preparation, in precisely the form which, as has already been said, might be given to it by merely rearranging the articles according to their subjects.

In this Guide, the principal articles dealing with the subject of each chapter are named in the order in which you may most profitably study them, and the summaries of the larger articles afford such a preliminary survey as may assist you in making your choice among the courses. Besides, where it seems necessary, there is added to the chapter a fairly complete list of all articles in the Britannica on the subject, so that the reader may make his study exhaustive.

A brief review of the six parts into which the Guide is divided will show the general features of its plan, of which a more detailed analysis is given in the Table of Contents.

Part 1 contains 30 chapters, each designed for readers engaged in, or preparing for, some specific occupation. To the beginner, who still has everything to learn, the advantages derived from such a course of study may well be so great as to make the difference between success and failure in life, and to those who have already overcome the first difficulties, to whom the only question is how marked a success awaits them, the Britannica can render invaluable service of another kind. No amount of technical training and of actual experience will lead a man of sound judgment to believe that he alone knows everything that all his competitors put together know; or that his knowledge and theirs is all that ever will be known. The 1500 contributors in 21 different countries who wrote the articles in the Britannica include the men who have made the latest advances in every department of knowledge, and who can forecast most authoritatively the results to be expected from the new methods which are now being experimentally applied in every field of activity. The experienced merchant, manufacturer, or engineer, or the man who is already firmly established in any other profession or business, will naturally find in some of the articles facts and figures which are not new to him, but he can profit by the opportunity to review, confirm, reconsider and “brush up” his previous knowledge.

Part 2 contains 30 chapters, each devoted to a course of systematic study designed to supplement, or to take the place of, some part of the usual school and college curriculum. The educational articles in the Britannica are the work of 704 professors in 146 universities and iiicolleges in 21 different countries. No institution of learning in the world has a faculty so numerous, so authoritative, or so highly specialized. Nor has any system of home study ever been devised by which the student is brought into contact with teachers so trustworthy and so stimulating. The fascination of first-hand knowledge and the pleasure of studying pages intended not for reluctant drudges submitting themselves to a routine, but for students eager to make rapid progress, are factors in the educational value of the Britannica that cannot be overestimated, and the elasticity with which any selected course of study can be enlarged and varied is in full accordance with the modern theories of higher education.

Part 3 is devoted to the interests of children. The first of its chapters describes Britannica articles of the utmost practical value to parents, dealing with the care of children’s health, with their mental and bodily training, and with the intelligent direction of their pastimes. The second chapter indicates varied readings in the Britannica for children themselves, showing how their work at school can be made more interesting and profitable to them by entertaining reading on subjects allied to those included in their studies. The third chapter in this Part gives a number of specific questions such as children are prone to ask, as well as questions which may be put to them in order to guide their natural inquisitiveness to good purpose. The references to pages in the Britannica show where these questions are clearly and instructively answered.

Part 4 suggests readings on questions of the day which relate to American citizenship and to current politics. A study of the articles indicated in this section of the Guide will aid the reader not only to form sound opinions for himself, but also to exercise in private or public life the influence for good which arises from a clear view of the arguments on both sides of controverted questions. It is no exaggeration to say that the Britannica is the only existing work in which such subjects as tariffs, trusts, immigration, labour and the relation between legislative and judiciary powers are treated without partisan bias and with adequate fulness.

Part 5, especially for women, deals with their legal and political status in various parts of the world, their achievements in scholarship, art and science, as well as with home-making, domestic science and kindred subjects. The important part which women, both among the contributors and on the editorial staff of the Britannica, took in the preparation of the work sufficiently indicates that the editor-in-chief made ample provision for the subjects peculiarly within their sphere.

ivPart 6 is an analysis of the many departments of the Britannica which relate to recreation and vacations, travel at home and abroad, photography, motoring, out-door and indoor games and other forms of relaxation and of exercise. The extent to which the work can be used in planning motoring tours, and the superiority, in such a connection, of its articles to the scant information found in ordinary guide books, are shown in the extracts, included in this Part 6, relating to a trip from New York through the Berkshire Hills to the White Mountains.

It will be seen from this brief survey of the field covered by the Guide that provision has been made for every purpose which can dictate the choice of a course of reading. But as you proceed to examine its contents for yourself, you should remember that the lists it gives name only a fraction of the articles in the Britannica, and that for a fuller summary of the work as a whole you should turn to the Table on pp. 881–947 of Vol. 29.

Finally, the form in which this Guide is printed may call for a word of justification. It is inevitable that chapters, of an analytical character, bespattered with references to the numbers of volumes and of pages, and terminating with lists of the titles of articles, should bear a certain air of formality. There is no danger that the possessor of the Britannica, familiar with the fascination of its pages and the beauty of the illustrations which enhance their charm would permit his impression of the work itself to be affected by the bleak appearance of the Guide. But he may feel that because a list has a forbidding aspect the pleasure he has derived from browsing at will in the Britannica would give place to a sense of constraint if he rigidly pursued a course of reading. It may easily be shown that such a fear would be groundless, for the Britannica articles are all the better reading when one carries forward the interest which one of them has excited to others of related attraction. But to anyone who is firmly determined that he shall not be persuaded to read systematically, the Guide will none the less be useful, for he may flit from one chapter to another, selecting here and there an article merely because the account which is given of it pleases him. Or, better yet, he may find, in one portion only of a selected course, a series of only three or four articles which will, in combination, make the best of occasional reading.

| Part I | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Courses of Reading Especially Useful to Those Engaged in Certain Occupations, or Preparing for Them | ||||

| Page | ||||

| Chapter | 1. | For Farmers | 3 | |

| „ | 2. | For Stock-Raisers | 10 | |

| „ | 3. | For Dairy Farmers | 14 | |

| „ | 4. | For Merchants and Manufacturers, General and Introductory | 19 | |

| „ | 5. | Textiles | 21 | |

| „ | 6. | Machinery | 28 | |

| „ | 7. | Metals, Hardware, Glass and China | 33 | |

| „ | 8. | Furniture | 39 | |

| „ | 9. | Leather and Leather Goods | 44 | |

| „ | 10. | Jewelry, Clocks and Watches | 48 | |

| „ | 11. | Electrical Machinery and Supplies | 55 | |

| „ | 12. | Chemicals and Drugs | 58 | |

| „ | 13. | Food Products | 63 | |

| „ | 14. | For Insurance Men | 69 | |

| „ | 15. | For Architects | 71 | |

| „ | 16. | For Builders and Contractors | 79 | |

| „ | 17. | For Decorators and Designers | 83 | |

| „ | 18. | For Railroad Men | 90 | |

| „ | 19. | For Marine Transportation Men | 94 | |

| „ | 20. | For Engineers | 100 | |

| „ | 21. | For Printers, Binders, Paper-makers and All who Love Books | 109 | |

| „ | 22. | For Journalists and Authors | 117 | |

| „ | 23. | For Teachers | 122 | |

| „ | 24. | For Ministers | 127 | |

| „ | 25. | For Physicians, Surgeons and Dentists | 135 | |

| „ | 26. | For Lawyers | 143 | |

| „ | 27. | For Bankers and Financiers | 151 | |

| „ | 28. | For Civil Service Men | 156 | |

| „ | 29. | For Army Officers | 158 | |

| „ | 30. | For Naval Officers | 168 | |

| vi | ||||

| Part II | ||||

| Courses of Educational Reading to Supplement or Take the Place of School or University Studies | ||||

| Chapter | 31. | Music | 175 | |

| „ | 32. | The Fine Arts, Introductory and General | 187 | |

| „ | 33. | Painting, Drawing, Etc. | 189 | |

| „ | 34. | Sculpture | 198 | |

| „ | 35. | Language and Writing | 207 | |

| „ | 36. | Literature, Introductory and General | 214 | |

| „ | 37. | American | 218 | |

| „ | 38. | English | 224 | |

| „ | 39. | German | 230 | |

| „ | 40. | Greek | 234 | |

| „ | 41. | Bible Study | 237 | |

| „ | 42. | History, Introductory and General | 246 | |

| „ | 43. | American | 248 | |

| „ | 44. | Canadian | 270 | |

| „ | 45. | English, Scotch and Irish | 272 | |

| „ | 46. | French | 278 | |

| „ | 47. | The Far East: India, China, Japan | 281 | |

| „ | 48. | Economics and Social Science | 288 | |

| „ | 49. | Health and Disease | 294 | |

| „ | 50. | Geography and Exploration | 300 | |

| „ | 51. | Anthropology and Ethnology | 308 | |

| „ | 52. | Mathematics | 316 | |

| „ | 53. | Astronomy | 322 | |

| „ | 54. | Physics | 329 | |

| „ | 55. | Chemistry | 334 | |

| „ | 56. | Geology | 338 | |

| „ | 57. | Biology, General and Introductory | 344 | |

| „ | 58. | Botany | 347 | |

| „ | 59. | Zoology | 353 | |

| „ | 60. | Philosophy and Psychology | 361 | |

| Part III | ||||

| Devoted to the Interests of Children | ||||

| Chapter | 61. | Readings for Parents | 371 | |

| „ | 62. | Readings for School Children | 379 | |

| „ | 63. | Questions Children sometimes ask, and Some Questions to ask Children | 387 | |

| vii | ||||

| Part IV | ||||

| Readings on Questions of the Day | ||||

| Chapter | 64. | 393 | ||

| Education, Training of Defectives, Psychology | ||||

| Crime, Juvenile Courts, Alcoholism | ||||

| Heredity and Eugenics | ||||

| Wages and Labour, Labour Organization | ||||

| Immigration, The Negro Problem | ||||

| Trusts, Finance, Tariff, Banking, Insurance | ||||

| Socialism and its Tendencies | ||||

| Initiative, Referendum and Recall, Government by Commission | ||||

| Suffrage and the Suffrage Question | ||||

| International Relations, Peace Arbitration | ||||

| The Greater United States | ||||

| Part V | ||||

| For Women | ||||

| Chapter | 65. | 411 | ||

| The many subjects on which Women contributed to the Britannica | ||||

| Accomplishments of Women in Scholarship, Art and Science | ||||

| Women’s Legal Position in the United States and elsewhere | ||||

| Their Disabilities in Great Britain | ||||

| Home-making, Domestic Science, the Table | ||||

| Food Preservation and Food Values | ||||

| Costume and Ornament | ||||

| Women famous in History and Literature, and on the Stage | ||||

| Part VI | ||||

| Readings for Recreation and Vacation | ||||

| Chapter | 66. | 425 | ||

| Motoring, a Specimen Trip: New York to the White Mountains | ||||

| Photography | ||||

| Out-door Games and Athletic Sports | ||||

| Hunting, Fishing and Taxidermy | ||||

| Sailing, Canoeing and Boating | ||||

| Mountaineering and Winter Sports | ||||

| Driving, Riding, Polo and Horse-racing | ||||

| Gardening and Plants | ||||

| In-door Games and Pastimes, Bridge, Needlework | ||||

| Dancing, the Stage | ||||

| Travel at Home and Abroad | ||||

Every farmer in the United States knows that farming is to-day an industry which calls for study of the world’s agricultural products, processes, and markets as well as for scientific knowledge of soils, crops, and animals. Fifty years ago the farmer sold for consumption in his immediate neighborhood the small surplus of his crops that was not needed for his own household and live stock. To-day he competes, in all the world’s great markets, with all the world’s farmers, and is the chief among American exporters. The Russian wheat fields and the Argentine cattle ranches are really nearer to him than a farm in the next township was to his grandfather. He lives better, does more for his children and pays higher wages than do farmers in other parts of the world, and yet he can successfully compete with them, because, as the article on Agriculture in the Encyclopædia Britannica says, in speaking of the United States, “there is no other considerable country where as much mental activity and alertness has been applied to the cultivation of the soil as to trade and manufactures.” American farmers “have been the same kind of men, out of precisely the same houses, generally with the same training, as those who filled the learned professions or who were engaged in manufacturing or commercial pursuits”; and their competitors abroad have been, for the most part, ignorant peasants. The course of reading indicated here is designed for wide-awake farmers who intend to be large farmers—by whom the latest information and the broadest outlook are recognized as essential to their calling. If you think the articles named here cover a great deal of ground, remember that the Massachusetts Agricultural College provides no less than sixty-four distinct courses of instruction, and that the subjects included in all the sixty-four are treated in the Britannica.

You may think, as you look at the titles of articles mentioned in these pages, that there are some which you need not read because you have already read bulletins of the United States Department of Agriculture or of your State Experiment Station. These official publications are most valuable, but naturally, they do not attempt to cover the whole range of agricultural subjects as the Britannica does—they are not intended for that purpose. Their arrangement and the way in which they are issued shows that they are designed to meet only certain special needs, not to give a general view of all the branches of farming. One subject may for example be discussed in three different bulletins, published in three different years, and the first may be out of print before the third appears. In the Britannica you get information that forms the very foundation of a thorough knowledge of farming and that also extends over the widest field. Of course it would be absurd to say that merely reading these articles will make 4any man a successful farmer as to say that a medical student who works hard at his books will always develop the tact and the sound judgment that a doctor needs. But unless the medical student has studied those text books he will never make a successful doctor; and similarly the information in the Britannica will give the farmer new advantages, no matter how much practical experience and special training he has had.

There are in the Encyclopædia Britannica 1,186 articles dealing with animal and vegetable life; and among the 11,341 geographical articles a great many give important information about the production, distribution and consumption of farm products. Those upon continents, countries, states and provinces describe the local crops and any local methods of farming that are of special interest. There are some 600 articles on individual plants, of which a list will be found on pp. 889 and 890 of Vol. 29 (the index volume). If any one of these thousands of articles were not in the Britannica, it would not be quite so valuable as it is to you, for you may, any day, want to find out about any plant that grows, or about farming in any part of the world. A professor in an agricultural college would of course be glad to study the whole series. But in this Course of Reading only the articles which are of most immediate use to all practical farmers are mentioned, and the contents of each of these is described, so that you can omit any article that goes into details which you think you do not want. If you do skip any of them, it will, however, be a good plan to mark their titles in this list, for you may like to come back to them later when you realize how practical and understandable all the Britannica articles are—even those with dullsounding names.

Of course you will begin by reading the article Agriculture (Vol. 1, p. 338), by Dr. Fream and Roland Truslove, which is the key to the whole subject. And remember that this chapter of the Readers’ Guide mentions only those subjects that are treated more fully in other parts of the Britannica than in that article, so that the chapter does not attempt to tell the whole story.

The first thing a farmer has to deal with is the ground from which his crops are to come. The whole surface of the earth was originally hard rock. The article on Petrology, the science of rocks (Vol. 21, p. 323), by J. S. Flett, and the second part (Vol. 11, p. 659) of the article Geology, by Sir Archibald Geikie, deal with the “weathering” of rock, which has in great part broken it down into the small particles of stone that, mixed with decayed roots and plants, form the soil or subsoil. It may seem that it is going very far back into the origin of things for a farmer to read about the sources from which soil comes, but the nature of the mineral substances in it has a great deal to do with its power to nourish plants, and you cannot know too much about the material on which your principal work is done. The article which should next be read, Soil (Vol. 25, p. 345), continues the story of these particles of rock and shows how sand and clay must be combined with decaying vegetable or animal matter in order to make the best soil. This mixture is in turn “weathered” by air, heat, frost, and moisture; and not only the size of the grains in which it lies, but also their shape—which makes them pack more or less tightly—affect the pores, or spaces between the grains, through which the roots of the plants must push their way, and through which air and water must reach these roots. The article Earthworm (Vol. 8, p. 825) describes the useful part that worms play in stirring the mixture, while the natural and artificial fertilizers, which supply 5whatever ingredients the soil lacks, are discussed in the article Manures and Manuring (Vol. 17, p. 610). An important part of this article deals with the best methods of keeping farm yard manure in such a way that it does not lose its value before it is spread over the fields, and with the use, in this connection, of the liquid-manure tank. The microbes in the soil render the farmer an enormous service by changing crude nitrogen, which plants cannot digest, into the forms in which it is indispensable to them, and this process is described in the article Bacteriology (Vol. 3, p. 164), by Professor Marshall Ward, Professor Blackman, and Professor Muir.

The action of light, the supply of which is just as necessary in causing growth as the warmth the sun gives, and the action of water and of heat and cold, are explained in the section “Physiology” (Vol. 21, p. 745) of the article on Plants. The proper method of working each farm, with a view to using these four in the right proportions, is influenced by the latitude in which it lies, its height above sea level, the protection that mountains give it, the slope at which the fields face the sun or turn away from it, the rain-fall, the relative dampness or dryness of the air when it is not raining, and the moisture of the soil. Every one of these subjects is vital to the farmer, and the Britannica brings to its readers the latest information regarding them in articles written by the leaders of progress. You will find the latest scientific guidance, in the most practical shape, in the articles Climate (Vol. 6, p. 509), by Professor R. de C. Ward, of Harvard, Meteorology (Vol. 18, p. 264), by Professor Cleveland Abbe, of the United States Weather Bureau, and Acclimatization (Vol. 1, p. 114). The distribution of heat in the soil is described in the article Conduction of Heat (Vol. 6, p. 893), where the diagram showing variations of temperature at different depths in the soil should be carefully studied.

The brackish water that troubles farmers near tidal creeks, the alkali water that often occurs West of the Mississippi, and the stagnant water that never does the farm any good, are all as bad in their way as the river-floods or the merely sodden soil in which nothing will grow but coarse grass that is always unsafe pasturage. Drains and embankments need very careful planning, and sound information will be found in the articles Drainage of Land (Vol. 8, p. 471), Reclamation of Land (Vol. 22, p. 954), and River Engineering (Vol. 23, p. 374), the latter by Professor L. F. Vernon H. Harcourt, the leading authority on such subjects the world over.

The saving of water and the method of bringing it to the farm and distributing it over the fields are authoritatively discussed in the articles Irrigation (Vol. 14, p. 841), Water Supply (Vol. 28, p. 387), by G. F. Deacon, Windmill (Vol. 28, p. 710), Pump (Vol. 22, p. 645), and in the section headed “Utility of Forests” (Vol. 10, p. 646) of the article Forests and Forestry, by Gifford Pinchot, formerly U. S. Chief Forester. The other parts of this article, dealing with the timber industry, are of course important to farmers whose land includes any lumber. Water Rights (Vol. 28, p. 385) explains the laws which regulate the taking of water from streams and lakes, and the article Lake (Vol. 16, p. 86) is also of interest in connection with irrigation.

When the farmer, who has to be everything by turns, has been an engineer long enough to get the water off his farm or on his farm—and perhaps he has to do both in different parts of the 6same farm—he must next take on the builder’s job. He will be reminded of a good many precautions and economies that are often overlooked, and may find, too, some hints that are quite new to him, in the excellent series of articles, all by experts in the building trade: Farm Buildings (Vol. 10, p. 180), Building (Vol. 4, p. 762), Foundations (Vol. 10, p. 738), Brickwork (Vol. 4, p. 521), Stone (Vol. 25, p. 958), Masonry (Vol. 17, p. 841), Timber (Vol. 26, p. 978), Carpentry (Vol. 5, p. 386), and Roofs (Vol. 23, p. 697). The use of concrete for buildings, tanks, irrigation works, etc., has proved so successful, and is so rapidly increasing, that you will be especially interested by the article Concrete (Vol. 6, p. 835). Barbed Wire (Vol. 3, p. 384), in which the meshed field fencing, of late increasing in favor, is also dealt with, is another practical article.

Advertisers no doubt supply you with more literature about farm machinery than you find time to read, but that makes it all the more essential to get sound information that has no trade bias. The Britannica goes into the principles of construction and helps you to see the good and bad points in the new models you are constantly offered. You can learn a great deal from the articles Plough (Vol. 21, p. 850), Harrow (Vol. 13, p. 27), Cultivator (Vol. 7, p. 618), Hoe (Vol. 13, p. 559), and the sections on machines in the articles Hay (Vol. 13, p. 106), Reaping (Vol. 22, p. 944), Sowing (Vol. 25, p. 523) and Thrashing (Vol. 26, p. 887). Oil Engine (Vol. 20, p. 35), Water Motors (Vol. 28, p. 382) and Traction (Vol. 27, p. 118) are also of importance.

Farm horses and the other live-stock required in general farming fall under Chapter II of this Guide.

You cannot read the articles already mentioned, and consider all that has to be done in merely getting a farm ready to be worked, without realizing how grossly unfair it is that the American farmer should be hampered, as he is, by the want of proper banking facilities when he is making a start. And after he has bought and prepared his land and equipped and stocked his farm he needs, each year, money to finance his crops. For any loan used in the purchase of land and in permanent improvements such as buildings, drainage, irrigation, a mortgage is the natural security; but the short-term farm mortgages—five years at most—customary in the United States, do not give the farmer as much time as he needs for repayment, no matter how successful he may be. The average farm offers quite as good a certainty of continued earning power as does the average railroad, and farm mortgages should be—in fairness—regarded not as opportunities for short loans, but as sound standing investments, just as suitable as railroad bonds for conservative investors. The farmer’s position is even worse when he needs a short loan that he will be able to repay as soon as his crops have been sold, for he is then expected either to give a mortgage as security or to pay exorbitant interest.

Notwithstanding the prosperous conditions of farming in the United States, the country as a whole produces only half as much grain for every acre of farm land as is produced in Europe, and the only reason is that most of our farmers lack the capital needed in order to get the fullest yield from their land. In the chief European countries, the system of banking facilities for farmers, described in the article Co-operation (Vol. 7, p. 86), by Aneurin Williams, shows what can be done, and sooner or later will be done, in the United States. This article fully describes the admirable 7Raiffeisen banks in Germany, which are based upon the idea that a society of farmers (restricted to the neighborhood, so that each member’s honesty and capability are known to the other members) make themselves jointly responsible for loans to the members. A promissory note is the only security required. The French, Italian, Austrian, and other systems are also discussed in the Britannica, but the German plan is that which offers the best example to America.

This course of reading has now covered the conditions and the material required for farming, and it is time to get down to something that grows. In the old books everything about the life of a plant was treated as a part of the science of botany, and if you remember the botany you were taught at school, you remember a string of long names and very little else. There is of course an article on botany in the Britannica, but it deals chiefly with the history of botanical science, and the life of the plant is treated under another heading, and in a novel, interesting, and practical way. The article Plants (Vol. 21, p. 728) is indeed one of the most important and unusual in the Encyclopædia, giving the results of recent investigation which you could not find in any other book. It is written by eight contributors, all men who have done a great deal of original work. The section on classes of plants is by Dr. Rendle, that on the anatomy of plants by A. G. Tansley, that on the healthy life of plants by Professor J. Reynolds Green, that on their diseases by Professor H. Marshall Ward, that on the relation between plants and their surroundings by Dr. C. E. Moss, that on plant cells by Harold Wager, that on the forms and organs of plants by Professor S. H. Vines, and that on the distribution of plants in various parts of the world by Sir. W. Thiselton-Dyer. Special accounts of the chief parts of the plant are given in the articles Leaf (Vol. 16, p. 322), Stem (Vol. 25, p. 875), and Root (Vol. 23, p. 712). The success of artificial fertilization or impregnation is explained (Vol. 13, p. 744) in the article Horticulture.

Apart from the diseases described in the section, already mentioned, of the article Plants, the greatest danger to which crops are exposed is that of insect pests, and the special article Economic Entomology, dealing with them (Vol. 8, p. 896), gives a full account of each of the remedies that have proved useful. The cotton boll weevil is the subject of a most interesting section of the article Cotton (Vol. 7, p. 261). Separate articles are devoted to individual pests, such as Locust (Vol. 16, p. 857), and—turning to a larger enemy—Rabbit (Vol. 22, p. 767). There is no bird that troubles the farmer, or helps him by killing insects, upon which there is not an article, for more than 200 distinct bird articles are listed under the heading “Birds” on p. 891 of Vol. 29 (the index volume), in addition to the information in the article Bird (Vol. 3, p. 959), and the article on families of birds (Vol. 20, p. 299).

The crops of all climates are treated in general in the article Agriculture, and in particular under their individual names, all of which are so familiar, and indeed so fully listed on p. 889 of Vol. 29 (the index volume), that they need not be repeated here. Naturally you will include in this course of reading the crops with which you are personally concerned, and in any case you ought to read Grass and Grassland (Vol. 12, p. 367), and Grasses (Vol. 12, p. 369).

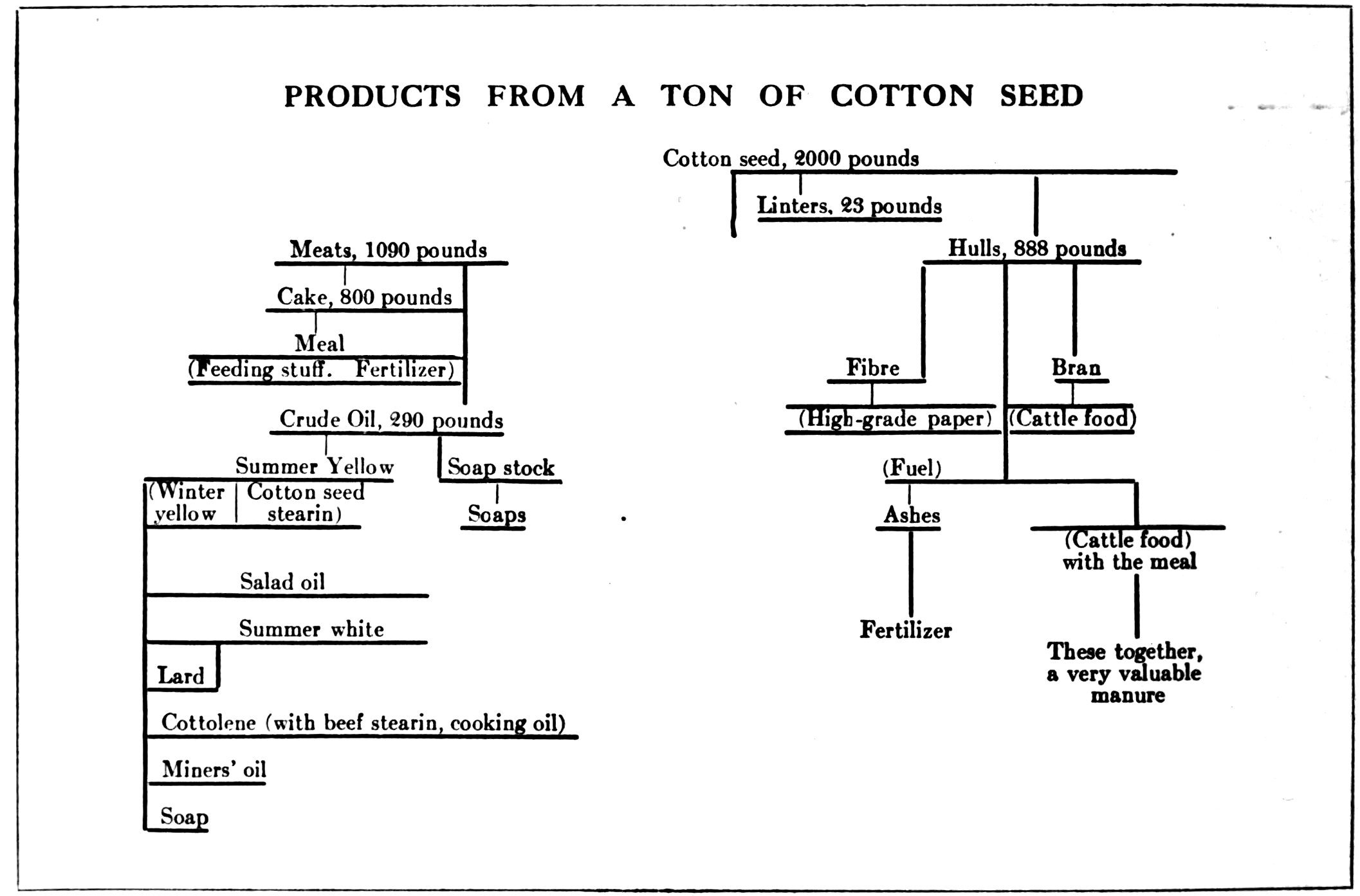

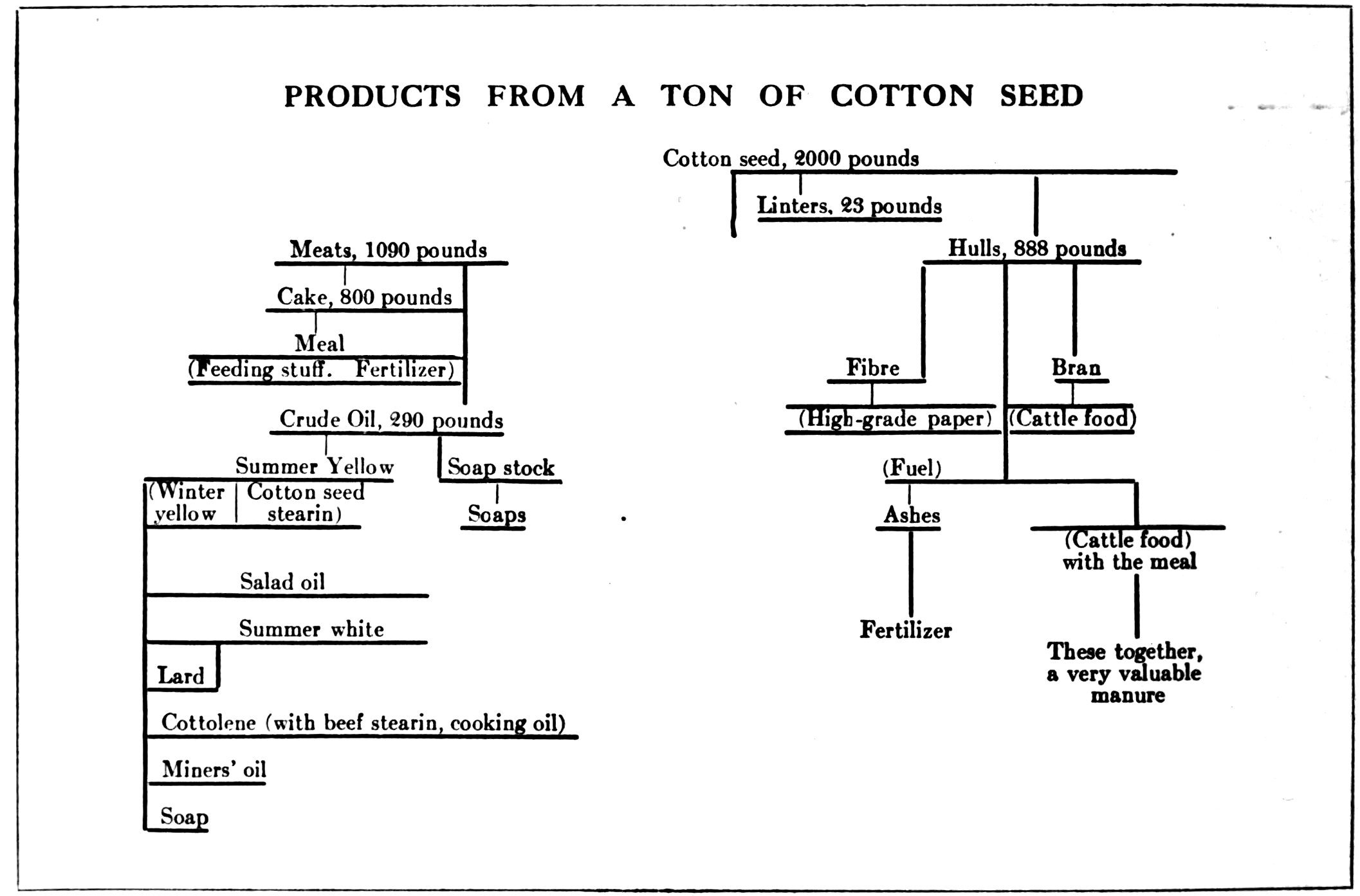

The article Wheat (Vol. 28, p. 576) deals with one of the chief products of “the greatest cereal producing region of the world.” It begins the story of a wheat crop with the burning of the old straw of the previous year, then takes up ploughing, harrowing, 8seeding, thrashing, labor in connection with all these operations, and transportation and marketing. At this point, the article Flour and Flour Manufacture (Vol. 10, p. 548), by G. F. Zimmer, takes up the later history of wheat. It may surprise you to learn from the Britannica that wheat first found its way to America through a few grains being accidentally mixed with some rice. Barley (Vol. 3, p. 405) is an interesting article on the grain that is the oldest cereal food of the human race, and that is also remarkable for its power to grow over a greater range of latitude than any other grain. Cotton (Vol. 7, p. 256), by Professor Chapman, is an article of which the vast importance may be judged by the following table taken from page 261:

Every one of the other cereal and general crops produced in any part of the world is treated in the Britannica with the same fullness of information and with the same practical detail which characterizes these articles on wheat, barley and cotton.

Some of the principal articles on the routine of farming such as sowing, reaping, and the like, have already been mentioned in connection with agricultural machinery. The articles on individual countries contain sections on the crops of each of them, and you will find Canada (Vol. 5, p. 152), and Germany (Vol. 11, p. 810), of special interest. The special features of tropical farming are described in the articles on tropical crops.

The article Fruit and Flower Farming (Vol. 11, p. 260) covers fruit culture in general, and, in the section of it which deals with the United States (Vol. 11, p. 268), the American fruit crops. This section describes the wonderful development of the fruit industry since cold transportation and cold storage enabled consumers in every part of the 9country, and in Europe as well, to purchase fruit grown in whatever state most advantageously produces any one variety. You should select, from the twenty separate articles on individual fruits, not only those on the varieties which you are already growing, but those on any others that are possible in the part of the country where your land lies. The section on fruit in the article on Horticulture (Vol. 13, p. 775) is devoted to growing on a smaller scale, in gardens. It contains (Vol. 13, p. 780) a practical calendar to show each month’s work.

Flower culture is the subject of special sections in both the articles above named and there is a descriptive list (Vol. 13, p. 766) of more than three hundred hardy annuals, biennials, and perennials, full of practical information. The calendar already mentioned indicates the dates for indoor and out-door operations. From the many articles on individual flower plants listed at the end of Part 3 of this chapter you can make your own choice.

Poultry and their rearing are dealt with in the articles Poultry and Poultry Farming (Vol. 22, p. 213), Fowl (Vol. 10, p. 760), Turkey (Vol. 27, p. 467), Guinea Fowl (Vol. 12, p. 697), Duck (Vol. 8, p. 630), Goose (Vol. 12, p. 241), and Incubation and Incubators (Vol. 14, p. 359). Bee-keeping and the honey industry are treated in the articles Bee (Vol. 3, p. 625) and Honey (Vol. 13, p. 653). Truck farming is treated in the section dealing with vegetables (Vol. 13, p. 776), of the article Horticulture. Apart from the law as to water rights already mentioned the legal doctrine most particularly affecting farmers is that of Emblements (Vol. 9, p. 308). Grain Trade (Vol. 12, p. 322), and Granaries (Vol. 12, p. 336), the latter describing the latest type of grain elevators, are articles of great interest to farmers who specialize in cereal crops.

The new system of purchase of grain by the government, which is working admirably in Western Canada, protects the farmer against the speculators who buy standing crops for less than a fair price, and it is to be hoped that some similar plan may be adopted in the United States.

Economics (Vol. 8, p. 899), by Professor Hewins, Co-operation (Vol. 7, p. 82), and Tariff (Vol. 26, p. 422), deal with topics related to the marketing of all agricultural products. The articles on learned societies have an extensive section (Vol. 25, p. 317) on the agricultural societies of all countries.

Agricultural history is, naturally, based upon the history of vegetable life, and the fossil plants described in the article Palæobotany (Vol. 20, p. 524), long as their appearance preceded that of man, greatly affected the nature of the earth’s crust which he was to occupy.

The earliest of all known writings, the Code of Khammurabi, described in the article on Babylonian Law, shows (Vol. 3, p. 117) that agriculture was the subject of careful legislation under the oldest government of which a contemporary record has survived; and the provisions as to the working of land on the “metayer” system, under which the landowner received from the landholder a share of the crops, and as to irrigation, are most explicit and practical. Ancient Egyptian implements of agriculture are fully described (Vol. 9, p. 69) in the article Egypt, and pictures of them appear on page 72 of the same volume. If the ancient history of farming interests you, it is only necessary for you to turn to the heading “Agriculture,” in the Index (Vol. 29), where you will find references to a number of other articles on the early civilizations.

From these articles, as from the historical section of the guiding article Agriculture, and the passages relating 10to agriculture in many of the 6,292 articles on the histories of races and countries, the reader may learn that agriculture has been the key to all history. The earliest migrations of the human race, as definitely as the comparatively recent development of America, Australasia and the interior of Africa, were based upon an agricultural impetus. And his reading upon other subjects in the Encyclopædia Britannica will often remind him that the wool and cotton and linen and leather that we wear, the carpets and blankets and sheets in our houses, all originated in farming of one kind or another; while every food that nourishes us, save fish and game, is directly an agricultural product. All the bustle of the great cities, all the wheels that turn in the mills, all the intricate mechanism of industry and commerce, all the world’s work and thought and happiness, depend upon the mysterious and inimitable processes by which the brown soil yields green growth. For all the progress science has made, we are no nearer to replacing these processes by any short cut of chemistry than were the first farmers whose husbandry is recorded in history. If all the little roots ceased for one year to do their work in the dark, the human race would hopelessly starve to death.

The alphabetical list of articles at the end of Chapter III of this Guide will make it easy for you to add to this course of reading, choosing for yourself the line that will be most attractive to you. In making your choice, do not forget that plant-life is a subject you cannot study too closely. No matter what crop you make your specialty, you have to educate the plants that produce it to do their work, just as carefully as a teacher trains children. Another fact to keep in mind is that just as a doctor is dealing with organs in the human body which he cannot see, so you are particularly concerned with the roots down in the soil, and the more you know about the way they eat and drink, the better for your farm.

The names of many of the writers of these articles are given in the table of the 1,500 Contributors to the Britannica, beginning at page 949 of Vol. 29 (the index volume); a glance will show you what authoritative positions they occupy and how thoroughly they command your confidence.

[See list of articles on subjects connected with farming, at the end of Chapter III of this Guide.]

Stock-raising in the United States was, until quite recent years, under the evil influence of the careless methods which had been handed down from the old days of the range-cattle industry. Chicago men still tell the story of the Chicago banker, afterwards Secretary of the Treasury, who declared, in reply to a request for a loan on the security of range-cattle, that he “would as soon lend money on a shoal of mackerel in the Atlantic Ocean.” The vague possession and the vague methods of breeding and marketing which suggested this comparison did not form the habits of close observation and incessant care which became necessary when land and food began to cost money. The lesson has been learned, and the present conditions of the industry are infinitely better for the country at large. It has been proved that fattening as well as breeding can be successfully undertaken in almost every part of the United 11States. Even in the North West, the tendency to-day is to turn from exclusive grain growing to a combination of cropping and feeding. Cattle, and also work horses of the right type, for which the demand is always greater than the supply, are yielding fair profits on many of the New England farms which had been neglected for years.

One of the most encouraging features of the present situation is that the broader distribution of the live-stock industry encourages farm-bred boys to remain at home. It has long been a popular belief that the attraction of the cities lies largely in the facilities for amusement which they offer; but the best class of young men who have left the farms have done so because they did not believe that plowing and sowing and reaping gave enough scope for their intelligence and their initiative. When stock-raising is combined with tillage, there is not only a greater interest in farm life and a greater chance to make general knowledge effective, but there are also better opportunities for a young man to make a small venture of his own while he is still a farm hand. It is certainly true that stock-raising needs the young man who is determined to know something about everything and all there is to know about one thing. To him the articles in the Britannica which are indicated in this chapter should be of the greatest value, for they cover a broad range, and they are written by specialists of the highest authority. They do not profess to teach what can only be learnt in the course of practical experience, but they will make each day’s work more interesting and more effective.

You cannot do better than to begin your reading with the article (Vol. 4, p. 337) on the family of animals to which cattle belong, a family so varied that it includes so small a creature as the hare, and so large a one as the rhinoceros. The article Cattle (Vol. 5, p. 359), by Professor Wallace and Dr. Fream, begins by reminding you that the idea of cattle owning has always been so closely associated with the idea of wealth that the two words “capital” and “cattle” have the same root, and that our word “pecuniary” is taken from the Latin term for cattle. This article, illustrated with photographs of the best specimens of bulls and cows of different breeds, deals with Shorthorns, Herefords, Devons, Holsteins, Dutch Belteds, Sussexes, Longhorns, Aberdeen-Angus, Red Polleds, Galloways, Highlands, Kerry’s, Dexters, Jerseys and Guernseys, and has a section on the rearing of calves. Ox (Vol. 20, p. 398) is chiefly about the origin of domestic cattle. Agriculture (Vol. 1, p. 388) contains information of a more general kind as to practical stock-raising. The best methods of mating are described fully in Breeds and Breeding (Vol. 4, p. 487), Variation and Selection (Vol. 27, p. 906), and Heredity (Vol. 13, p. 350), by Dr. Chalmers Mitchell. Mendelism (Vol. 18, p. 115) will tell you all about the theory which is nowadays the great subject of discussion among experts in breeding. Embryology (Vol. 9, p. 314), by Dr. Hans Driesch, and Reproduction (Vol. 23, p. 116), by Professor Vines, contain the results of the latest investigations, and the article Sex (Vol. 24, p. 747) describes the recent experiments undertaken with the hope that breeders may at some future time be enabled to vary at will the proportion of males and females. Telegony (Vol. 26, p. 509) gives you the evidence for and against the belief that offspring are influenced by a previous mate of the dam. Food Preservation (Vol. 10, p. 612) and Refrigerating (Vol. 23, p. 30) cover the cold shipping and cold storage of beef. Leather (Vol. 16, p. 330), by Dr. J. G. Parker, one of the foremost 12technical experts on this subject, follows hides through the market to their final distribution and industrial uses.

Notwithstanding the harm that trolley cars and automobiles and mechanically propelled agricultural machines have done to important branches of the horse business, and notwithstanding the competition which American exporters find in Europe from the Argentine ranches, there is still an active market for farm horses and for stock suited to trucking and light delivery work in cities. You no doubt find, in whatever part of the United States your interests lie, that you need to watch the market very closely, and that you must always be ready to change your plans at short notice. But it is to the quick-witted man who is always prepared to vary his methods that the Britannica offers the greatest practical services. The article on the horse family in general (Vol. 9, p. 720) is very interesting, but you will give more time to the elaborate article Horse (Vol. 13, p. 712), by Richard Lyddeker, E. D. Brickwood, Sir William Flower, and Professor Wallace. The illustrations are unusually valuable, for instead of following the usual custom of making all the photographs the same size, the Editors of the Britannica showed good sense and originality by making each one to scale. The breeds are separately described, and the sections on feeding and breaking are full of useful hints. The history of the thoroughbred strain is carefully traced, the pedigree of one famous type being shown in a table naming more than one hundred ancestors. The article Horse-Racing (Vol. 13, p. 726), by Alfred Watson, shows how the sport has influenced breeding, and the description of American trotting goes back to the day when “Boston Blue,” in 1818, trotted a mile in three minutes, “a feat deemed impossible” at that period! The English race meetings, in which American owners and jockeys now play so conspicuous a part, are described in special sections, as well as the training at Newmarket. Riding (Vol. 23, p. 317), and Driving (Vol. 8, p. 585), are by practical experts, and Traction (Vol. 27, p. 118) contains an interesting table analyzing the draft power of the horse. The section on Arab horses in the article Arabia (Vol. 2, p. 261) should be read, for it adds to the information, in the articles already named, on the breed that has influenced every variety of horse. Mule (Vol. 18, p. 959) will tell you about the varieties not only in the United States and Mexico, but also in France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, Algeria and North China. The section on Hybrids (Vol. 13, p. 713) of the article Horse deals with all the attempts that have been made to get a perfect type of mule by introducing various strains of blood.

Sheep (Vol. 24, p. 817) contains separate descriptions of the 28 best breeds, discussing their values both for wool and for the meat trade. Breeding, feeding, dipping and lambing are fully treated. Sheepdogs and other breeds useful to the stock-raiser fall under the article Dog (Vol. 8, p. 374). Wool (Vol. 28, p. 805), by Professor Aldred Barker, is an article in which you will at once be impressed by the splendid thoroughness that is characteristic of the Britannica. It goes to the very foundation of the subject by giving you microscopic photographs, on a scale of 320 to 1, of each of the six great varieties of wool, and explaining the structure of the fibres. The article Fibres (Vol. 10, p. 309) will enable you to compare another microscopic photograph of wool fibre with similar pictures of silk, flax, cotton, jute, and other textile materials. The article wool deals next with wool-yolk and wool-fat, and then goes on to show why greasy wool is better than 13wool washed before shearing. Wool classing and sorting are next described, and then scouring. From this point the treatment of wool hardly comes within the jurisdiction of the sheep-man, although he cannot know too much about the qualities of the yarns obtained from different kinds of wool. It is interesting to note in this article that the first fulling mill in America was built at Rowley, Mass., in 1643, only thirty-four years after the first sheep was brought to America, and only twenty-three years after the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock.

The article Swine (Vol. 26, p. 236) deals with the swine family in general, and the article Pig (Vol. 21, p. 594), containing a fine full-page plate, gives a detailed account of the breeds most profitable on the farm, including the Poland-China, the Berkshire, the Duroc, and the Chester White. Eleven breeds in all are particularized. The breeding and fattening of hogs, although it is now successfully followed as a distinct branch of the live-stock industry, must always remain in great part a mere branch of general farming; for the pig’s power of thriving on many kinds of food, enables the farmer to utilize produce that cannot advantageously be shipped, and to keep his pigs following his cattle over the fields. Much information will be found all through the article Agriculture (Vol. 1, p. 388). Trichinosis (Vol. 27, p. 266) deals with a disease that has sometimes seriously affected the pork market, and been made the excuse, too, for some very harsh restrictions on American exportation.

You will find in the Britannica (Vol. 28, p. 6) a very full and clear account of the diseases of all domestic animals, by Dr. Fleming and Professor McQueen, with special sections on the maladies of the horse, of cattle, of sheep, and of pigs, and on the parasites that infest them. Tuberculosis (Vol. 27, p. 354) calls for special study, for it is a “disease of civilization” almost unknown among wild animals in their natural state and among the uncivilized races of mankind. The connection between the disease in cattle and its spread among human beings is fully explained in this article. Pleuro Pneumonia (Vol. 21, p. 838) deals with the lung disease from which cattle are the only sufferers, Rinderpest (Vol. 23, p. 348), with the infectious fever which affects both cattle and sheep, and Anthrax (Vol. 2, p. 106), with the terribly infectious carbuncles communicated from cattle and sheep to man by the microbes carried in wool and hides. Glanders (Vol. 12, p. 76) describes the form in which this disease of horses and mules afflicts human beings, the symptoms and course of which, in the animals themselves, fall under the subject of horse diseases (Vol. 28, p. 8). The microbe by which this disease is carried is shown in the plate facing one of the pages (Vol. 20, p. 770) of the article Parasitic Diseases. Foot and Mouth Disease (Vol. 10, p. 617) afflicts cattle, sheep, and pigs, and occasionally human beings.

Among the articles on continents and countries which contain special information on stock-raising, you should not miss the interesting general review of the European live-stock industry in the article Europe (Vol. 9, p. 914), the section on live-stock in Canada (Vol. 5, p. 153), that in Argentina (Vol. 2, p. 465), in Australia (Vol. 2, p. 950), and in New Zealand (Vol. 19, p. 627) The history of stock-raising is fully treated at the beginning of the article Agriculture (Vol. 1, p. 388).

When you have read the articles mentioned in the three parts of this chapter on Farming, do not turn away with the idea that you have got from the 14Britannica all that it can give you to help you in your business. Remember that you have to judge men, as well as live-stock, in order to succeed, and that general knowledge is of the greatest use in doing that. The one sure sign of the kind of man you cannot rely upon is that he talks confidently about subjects of which he really knows little, and the more you yourself know, the more readily you can detect the pretentious people who might make you think too well of them.

If you turn over the pages of this guide, and ask yourself, as you glance at the chapters, in what departments of general knowledge you are weakest, you will see what courses of reading will do most to make you an “evened up” man, without any weak threads in your intellectual texture. And, whatever you read, do not forget that the Britannica is a book of reference as well as for reading: that you are debasing your mind every time you leave unanswered any question that comes up in the course of the day’s work or talk, or while you are reading your newspaper. A vigorous mind wants an answer whenever it becomes conscious of a question or of a doubt, and if you fail to feed it with the information it asks for, it loses health. Now that you have the Britannica, the food is in the store-room, do not leave it there!

[See list of articles on subjects connected with stock-raising and other branches of farming, at the end of Chapter III of this Guide.]

The admirable set of rules for dairy farmers issued by the United States Department of Agriculture begins by telling you to “read current literature and keep posted on new ideas.” And you can easily see that the information on dairy-farming and the many subjects connected with it, supplied by the Britannica, must cover a much broader field of new ideas than can be included in any periodical or dairying manual. The branches of science in which the greatest advance has been made since the beginning of the present century happen to be those that have most to do with dairying; and the industry itself has been completely revolutionized since the days when cities got their milk from ramshackle cow-sheds in their suburbs, and when butter-making was regarded as one of the “chores” to be done at odd times.

The key article in the Britannica, Dairy and Dairy Farming (Vol. 7, p. 737), deals with the best milking breeds, the installation, equipment, and management of a dairy farm, the values of various kinds of pasturage and fodder; with the milk trade, with butter-making and cheese-making, with condensed milk, skim milk, and milk powder and with the organization and operation of creameries, cheeseries, and dairy factories in general. Such subjects as soil, grass, hay and other fodder crops fall under Part I of this chapter, and the articles dealing with the breeding and rearing of dairy cattle are mentioned in Part II, “For Stock-Raisers.”

15Cattle diseases in general are also covered by the course of reading suggested in Part II; but the dairy farmer has a special interest in contagious mammitis, milk fever, contagious abortion, and cowpox, all of which are described (Vol. 28, p. 10) in the article on Veterinary Science. You cannot study too carefully the article on Tuberculosis (Vol. 27, p. 354), for this terrible infection is not only a standing danger to your herd, but also affects the transportation and marketing of milk. Dr. Hennessy, who wrote the article, is an expert of the first rank and, like most other great authorities, is not inclined to encourage the popular exaggeration of the dangers for which newspaper “sensations” are responsible.

You get to the very foundation of the supply of milk in Professor Parson’s and Dr. Edmund Owen’s article Mammary Gland (Vol. 17, p. 528), in which the comparative anatomy of the milk yielding organ is fully treated. The article Milk (Vol. 18, p. 451) discusses the chemistry of many kinds of milk and the diseases carried by milk, and deals with the gravest problems of the industry: the difficulty of sterilizing milk, so that tuberculosis and typhoid cannot be carried by it, and the difficulty of sterilizing cream, so that butter may be quite safe, without making the milk less nutritious and the butter less delicate in flavor. The article Bacteriology (Vol. 3, p. 156), by Professor H. Marshall Ward and Professor Blackman, goes to the root of this whole question of infection. Milk is, on the other hand, used to convey into the human system the “friendly microbes,” and the use of soured milk and cheese for this purpose is explained in the articles Therapeutics (Vol. 26, p. 800) and Longevity (Vol. 16, p. 977), which deal with Metchnikoff’s system of treatment. Pepsin (Vol. 21, p. 130) describes the process by which milk is rendered more digestible, and Infancy (Vol. 14, p. 513) deals with the preparation of milk to be sold for the use of young children. There is so general a demand for prepared milk which is from every point of view wholesome that you will find it worth while to read, in this connection, Food (Vol. 10, p. 611), Nutrition (Vol. 19, p. 920) and Dietetics (Vol. 8, p. 214).

Butter (Vol. 4, p. 889,) and Cheese (Vol. 6, p. 22) are brief articles which you should not overlook, although they refer you to the key and article on dairying for details; and Oils contains (Vol. 20, p. 47) an interesting analytical table in which butter is compared with other animal fats. Food Preservation (Vol. 10, p. 612) deals with the cold storage of butter, cheese, condensed milk and milk powder; and Refrigerating (Vol. 23, p. 30) with the processes and machinery employed. Koumiss (Vol. 15, p. 920) describes the milk-wine or milk-brandy prepared by fermenting mare’s milk, and the similar product “kerif” made from cow’s milk. Although the special developments of dairying in various parts of the world are discussed in the article Dairy and Dairy-Farming, the articles on individual countries also contain information of value. The section on dairying (Vol. 5, p. 154) in the article Canada, and the account of co-operative dairying (Vol. 7, p. 87) in Denmark should not be overlooked.

In reading these articles in Britannica, and thinking of the present conditions of this great business, you will be reminded that dairying is an industry of peculiar importance to the whole people of the United States, not only because of the money made out of it, and not only because it gives hundreds of thousands of men employment on the land instead of in crowded cities, but also because it 16promises to develop the co-operative action which harmonizes with the best ideals of democracy. The co-operative plants which are beginning to be established by dairy farmers are the only institutions our modern civilization has created in which you find the neighborly spirit that the first American settlers showed in the days when they joined to defend themselves against the Indians. At political meetings, in machine shops and cotton mills and shoe factories, you hear unhappy talk about the relations of capital and labor, about strikes and trusts, about the man on top and the man underneath. But where the farmer’s wagons clatter up to the separator platform, there is combination in the best sense of the word. The Britannica article on co-operation says that the word “in its widest usage, means the creed that life may best be ordered not by the competition of individuals, where each seeks the interest of himself and his family, but by mutual help, by each individual consciously striving for the good of the social body of which he forms part, and the social body in return caring for each individual; ‘each for all, and all for each’ is its accepted motto. Thus it proposes to replace among rational and moral things the struggle for existence by voluntary combination for life.”

The article on Technical Education in the new (Eleventh) Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (Vol. 26, p. 487), written by Philip Magnus, one of the greatest educational authorities in the world, says that:

“The widespread appreciation of the advantages of the higher education among all classes of the American people, and the general recognition among manufacturers, engineers and employers of labour, of the value to them in their own work, of the services of college-trained men, has largely helped to increase the number of students in attendance at the universities and technical institutions.”

A still broader truth is that the men who have learned to think clearly, by whatever study or reading they may have developed that power, possess the greatest of all advantages. As the Britannica article on Education indicates, the true value of education (not simply school education, but all education) lies as much in the influence which intelligently directed study exerts upon the mind as in the immediate usefulness of the information acquired, and the articles in the Britannica not only supply the most recent and authoritative information, but are so logically arranged, one dove-tailing into another, that they give the reader precisely that orderly view of knowledge which is the foundation of all mental training.

Since all of the series of chapters which immediately follow and which are intended for merchants and manufacturers, deal with commerce and manufactures, it will be for the reader’s convenience to begin by dealing with those two subjects in general. But certain branches of industrial and manufacturing knowledge are dealt with in special chapters. The articles on banking and finance are described fully in this Guide in the chapter For Bankers and Financiers, those on insurance in the chapter For Insurance Men, and those on law in the chapter For Lawyers. Three of the legal articles should, however, be mentioned here, as they are on especially important subjects: Sale of Goods (Vol. 24, p. 63), Company (Vol. 6, p. 795), which deals with the laws in various countries regulating corporations, and Employers’ Liability (Vol. 9, p. 356), on this topic so important in modern industrial law and in the relations between capital and labour.

The broad questions of commercial and industrial policy are discussed in Economics (Vol. 8, p. 899), by Prof. Hewins; Commerce (Vol. 6, p. 766); Trusts (Vol. 27, p. 334); Monopoly (Vol. 18, p. 733), and Trade Organization (Vol. 27, p. 335), which describes commercial associations in the United States, the work of the consular service, and the organizations in Germany, France, Great 20Britain and other countries. Book-keeping (Vol. 4, p. 225), with its up-to-date account of modern accounting methods, card ledgers and loose leaf systems; Advertisement (Vol. 1, p. 235), and Mercantile Agencies (Vol. 18, p. 148) may be named as specimens of the many practical articles on business methods which need not all be enumerated here.

Much of what you read and hear about the tariff systems of the United States and various other countries and about their influence upon trade is so vague and confusing that you will be delighted with the group of clear, common-sense articles in the Britannica. Tariff (Vol. 26, p. 422) is by one of the most famous American economists, Prof. Taussig of Harvard, and is a very full and fair discussion of the points in controversy. Protection (Vol. 22, p. 464) is by Prof. James of the University of Illinois, and Free Trade (Vol. 11, p. 89) by William Cunningham. You should read with care Customs Duties (Vol. 7, p. 669); Free Ports (Vol. 11, p. 88), and Bounty (Vol. 4, p. 324). Balance of Trade (Vol. 3, p. 235) and Taxation (Vol. 26, p. 458) are both by Sir Robert Giffen. Exchange (Vol. 10, p. 50), by E. M. Harvey, a partner in one of the largest firms of bullion brokers in the world, deals with the movement of gold. Commercial Treaties (Vol. 6, p. 771) is by Sir C. M. Kennedy. Freights are discussed in Affreightment (Vol. 1, p. 302) by Sir Joseph Walton. Lien (Vol. 16, p. 594), with its section on “Stoppage in transitu,” is by F. W. Raikes; Salvage (Vol. 24, p. 97), by T. G. Carver, and Blockade (Vol. 4, p. 72), by Sir Thomas Barclay, the great international lawyer in Paris. Marine insurance, indemnity, Lloyds, and other insurance subjects fall under the chapter of this Guide For Insurance Men to which you should refer. Cargo-carrying and merchant shipping are further covered by Shipping (Vol. 24, p. 983). This article is by Douglas Owen, honorary secretary and treasurer of the Society of National Research, and author of Ports and Docks; it contains information about the great freight carrying lines of the world that can be found in no other book. Railroad freighting is covered by the article Railways (Vol. 22, p. 819), in which there is a special section (p. 854b) on the new models of American freight cars.

In the article United States, which contains more matter than a whole book of ordinary size and more information than a dozen ordinary books, the sections (Vol. 27, p. 639) on manufactures and on foreign and domestic commerce, are by F. S. Philbrick, Ph.D. The internal commerce of the United States, as this article states, is in itself greater than the total international commerce of the world, and is so far from exhausting the country’s power of production and consumption, that even when coastwise traffic is disregarded, New York is the most active port in the world. A section (Vol. 9, p. 916) of the article Europe deals with European commerce in general. The articles on the great manufacturing towns of Europe contain much information as to industries. Great Britain’s industries are dealt with in the article United Kingdom (Vol. 27, p. 691). The industries of England alone are separately treated in a section (Vol. 9, p. 426) of the article England. Germany’s industries are the subject of sections (Vol. 11, p. 811) of the article Germany; and it is interesting to note that although Germany has outranked France in cotton manufactures since Mülhausen, Colmar and other important milling centres of Alsace became German, France has retorted by 21overtaking and passing Germany in the production of linen. The sections (Vol. 10, p. 785) on foreign commerce in the article France show her position as in the main a self-supporting country, though only a fourth of the cargoes loaded and discharged in French ports are carried under the French flag. It would be a waste of space to enumerate here the articles on Belgium, Switzerland, Italy and other countries, which you will consult in relation to those of their exports in which you are especially interested; but you should not overlook the article on Japan. The Britannica has done commerce a great service in giving to the world at last a good account of this extraordinary country.

The body of the article Japan (Vol. 15, p. 156) is by Capt. Brinkley, long editor of the Japan Mail, whose opportunities of seeing Japanese life from the inside have been greater than those of any other foreign observer. Baron Dairoku Kikuchi, President of the Imperial University of Kyoto, a statesman of great experience and authority, contributes to the article a section (Vol. 15, p. 273) dealing with Japan’s international position. His remarks upon the commercial morality of the Japanese are so ingenuous and so candid that an extract from them cannot be omitted:

Now when foreign trade was first opened, it was naturally not firms with long-established credit and methods that first ventured upon the new field of business—some few that did failed owing to their want of experience—it was rather enterprising and adventurous spirits with little capital or credit who eagerly flocked to the newly opened ports to try their fortune. It was not to be expected that all or most of those should be very scrupulous in their dealings with the foreigners; the majority of those adventurers failed, while a few of the abler men, generally those who believed in and practised honesty as the best policy, succeeded and came to occupy an honourable position as business men.... Commerce and trade are now regarded as highly honourable professions, merchants and business men occupy the highest social positions, several of them having been lately raised to the peerage, and are as honourable a set of men as can be met anywhere. It is, however, to be regretted that in introducing Western business methods, it has not been quite possible to exclude some of their evils, such as promotion of swindling companies, tampering with members of legislature, and so forth.

The account (Vol. 15, p. 201) by Capt. Brinkley of the curious system of creating branches of Japanese business houses is another part of this article which should not be overlooked.

The proportion of labour cost to the total cost of production is in most industries so great that you cannot study too carefully every aspect of the labour question. The chief articles are Labour Legislation (Vol. 16, p. 7), jointly written by the late Dr. Carroll D. Wright, the great American authority on the subject, and Miss A. M. Anderson, Principal Lady Inspector of Factories to the British government; Trades Union (Vol. 27, p. 140); Strikes and Lockouts (Vol. 25, p. 1024); Wages (Vol. 28, p. 229), by Prof. J. S. Nicholson; Profit Sharing (Vol. 22, p. 423), by Aneurin Williams and Apprenticeship (Vol. 2, p. 228), by J. S. Ballin. The article Employers’ Liability (Vol. 9, p. 356), has already been mentioned.

The Course of Reading outlined in this chapter will help anyone who has to do with the making or with the buying and selling of textiles, in three ways, at least, each of the greatest importance to him—and possibly in many more. Taking up these three:—In the first place, it will teach him many facts about manufacturing and merchandizing in general, and about dry goods in particular, that he could learn nowhere else, because the scope of the Britannica is broader than that of any other book—or, for that matter, than the scope of any collegiate course can well be. In the second place, the number of distinguished men who have devoted their exclusive attention to the subjects upon which they write, and have given to the Britannica the results of their research and of their experience as practical experts—in many cases, indeed, as successful business men—is far greater than the number of men who form the faculty of any university in the world. The fifteen hundred contributors in fact include no less than 704 connected with the staffs of 151 different universities, technological and commercial institutes and colleges in twenty countries. The reader thus gets the benefit of contact with the thought of many, of varied, and always of authoritative, personalities. In the third place, the textile trade is peculiarly an international trade, the raw materials often traveling from one end of the world to the other before manufacture, and making as long a journey in the finished form, before they reach the consumer, and the international character of the Britannica gives equal weight to the articles which deal with the textiles and with the markets of all countries—a statement which it would certainly not be safe to make about any other book.

The article Fibers (Vol. 10, p. 309), by C. F. Cross, whose name has been much before the public in connection with the recent scientific investigation of the subject, compares the fibres yielded by all the vegetable and animal substances used in textiles. The 18 microscopic photographs on the full page plates (facing pp. 310 and 311) and the table of vegetable fibres (p. 311) should be carefully studied. Cellulose (Vol. 5, p. 606) deals with the “body” of cotton, flax, hemp and jute fibres. Carding (Vol. 5, p. 324) deals with the brushing and combing of fibres. Spinning (Vol. 25, p. 685) covers both cotton and linen, and it is curious to note from this article that in preparing yarns for the exquisite Dacca muslins one pound of cotton has been spun into a thread 252 miles long; while the article Dacca says that a piece 15 feet by 3 was once woven that weighed only 900 grains. Yarn (Vol. 28, p. 906) deals with cotton, 23woollen and silk yarns. Weaving (Vol. 28, p. 440), by Prof. T. W. Fox, author of Mechanics of Weaving, and Alan Cole, is the first article you should read in a group dealing with processes applied to more than one material. The first section is on the various combinations of warp and weft, and contains 23 illustrations showing the chief weaving “schemes.” A section on weaving machinery follows, and then one on weaving as an art, illustrated with a number of reproductions of famous specimens of hand-loom work. The whole article is full of practical every-day information of the kind the merchant and manufacturer wants to know. Bleaching (Vol. 4, p. 49) describes the chemical processes which have expedited the bleaching of cotton, wool, linen and silk, which it used to take all summer to complete. Dyeing (Vol. 8, p. 744), by Prof. Hummel, author of The Dyeing of Textile Fabrics, and Prof. Knecht, author of A Manual of Dyeing, is another of the thorough articles which entitle the Britannica to rank as a great original work on textiles. Every dye is separately treated, and the latest models of dyeing machinery are carefully described. Finishing (Vol. 10, p. 378) deals with the processes used for cotton, woollens, worsteds, pile fabrics, silks and yarns. Textile-Printing (Vol. 26, p. 694) is by Prof. Knecht and Alan Cole, author of Ornament in European Silks, and not only describes all the styles of printing, but gives sixty recipes for various shades of colour. The full page plates reproduce fine specimens of early printing. The art of textile-printing “is very ancient, probably originating in the East. It has been practised in China and India from time immemorial, and the Chinese, at least, are known to have made use of engraved wood-blocks many centuries before any kind of printing was known in Europe.”

The elaborate article Cotton (Vol. 7, p. 256) begins by discussing the peculiar twist of the hairs on the cotton seed which by facilitating spinning gives cotton its predominant position as a textile material. The section on cultivation, by W. G. Freeman, deals with the soils, bedding, planting, hoeing and picking, then with ginning and baling. A section on diseases and pests of the cotton plant follows, then a discussion of the improvement of yield by seed selection. The section on marketing and supply is by Prof. Chapman, and his practical study of “futures,” “options,” and “straddles” shows how greatly the movement of prices is affected by speculation and often by artificial manipulation.

Cotton Manufacturing (Vol. 7, p. 281) describes the industry in England, that of the United States, with a special section on the recent developments in the two Carolinas, Georgia and Alabama, and also the mills in Germany, France, Russia, Switzerland, Italy and in other countries, including India, China and Japan. It is interesting to note (p. 293) that “Americans were making vast strides in industrial efficiency even before the period when American theories and American enterprise were monopolizing in a wonderful degree the attention of the business world” abroad. As far back as 1875 progress in the United States was so rapid that the production for each operative had increased during the ten years 1865–75, by 100% in Massachusetts as against only 23% in England. One explanation of American success is that the American employer “tries to save in labour but not in wages, if a generalization may be ventured. The good workman gets high pay, but he is kept at tasks requiring his powers and is not suffered to waste his time doing the work of unskilled or boy labour.”

Cotton Spinning Machinery (Vol. 7, p. 301) describes all the machines in great detail and contains a number of 24full-page plates and other illustrations. Mercerizing (Vol. 18, p. 150) is another important article.

Wool, Worsted and Woollen Manufactures (Vol. 28, p. 805) is by Prof. Aldred F. Barker. The development in wool production of various countries is first described and then the wool fibre is studied and microscopic photographs reproduced to show the structure of different varieties. A diagram of a fleece shows the qualities obtained from various parts of the animal, ranging from the shoulders, where the finest is found, to the hind quarters. Lamb, hogg and wether wools are compared and the article discusses shearing, classing, sorting, scouring, drying, teasing, burring, mule spinning, combing, drawing and spinning. The centres of the industry are then compared, with details as to the special products of each. The article contains illustrations of a number of machines. Articles dealing with certain sources of wool or of the wool-like hair used in textiles, and with the finished products, are: Alpaca (Vol. 1, p. 721), the history of its manufacture being “one of the romances of commerce;” Mohair (Vol. 18, p. 647), which deals with the hair of the Angora goat, familiar from discussions of the Underwood Tariff bill, and dealing with its weaving and the imitations of the cloth; Llama (Vol. 16, p. 827); and the articles Guanaco (Vol. 12, p. 649) and Vicugna (Vol. 28, p. 47), on the two wild animals from whose hair high priced materials, extraordinarily warm and light, are woven.

Flax (Vol. 10, p. 484) describes the cultivation of the crops which are harvested by being “pulled,” roots and all, instead of being cut, the process of separating the capsules from the branches, and the subsequent stages of preparation. Linen and Linen Manufactures (Vol. 16, p. 724), by Thomas Woodhouse, takes up the story where the flax fibre is ready for market and carries it to the point where the yarn is delivered for weaving. The winding, warping, dressing and beaming, and the looms employed, are virtually the same processes and machines that are used for cotton. The article states that the finest linen threads used for lace are produced by Belgian hand spinners who can only get the desired results by working in damp cellars, the spinner being guided by touch alone, as the filament is too fine for him to see. This thread is said to have been sold for as much as $72 an ounce.

Jute (Vol. 15, p. 603) deals with the vegetable fibre which ranks, in its industrial importance, next after cotton and flax and with the processes employed in its manufacture.