By the same author:

Buddhist Parables. Translated from the original Pāli. One volume. xxix + 348 pages. With photogravure of a Bodhisattva head from Gandhāra, from original in the Pennsylvania Museum. Octavo. Cloth. Yale University Press, 1922. $5.00.

Buddhist Legends. Translated from the original Pāli text of the Dhammapada Commentary. Three volumes. Harvard Oriental Series, 28, 29, 30. 1114 pages. Octavo. Cloth. Harvard University Press, 1921. $15.00 a set.

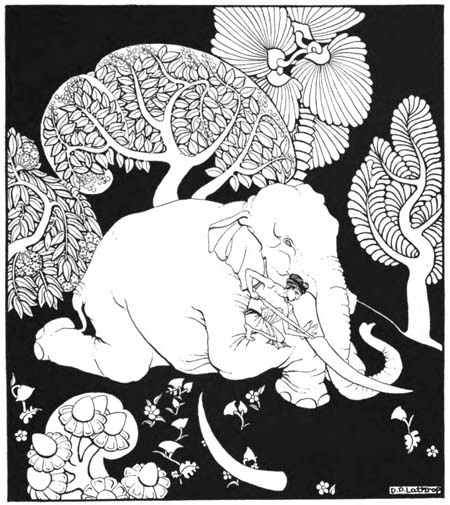

Then the elephant with his trunk caressed the Future Buddha and lifted him up.

The Grateful Elephant

And Other Stories Translated from the Pāli

By Eugene Watson Burlingame

with Illustrations by Dorothy Lathrop

New Haven, Yale University Press

London, Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press

Mcmxxiii

Copyright 1923 by Yale University Press.

Printed in the United States of America.

To my nephew Westcott

This book contains twenty-six stories selected from the author’s larger work Buddhist Parables, Yale University Press, 1922. The translation is a close, idiomatic rendering of the original Pāli text. In a few cases, words and phrases have been softened, and sentences have been omitted. In Story 1, two whole paragraphs which interrupt the progress of the story have been omitted. The author has not, however, “written down” any of the stories in order to remove such difficulties as the original translation may present to the child.

The quantity of vowels is marked throughout. Short a is pronounced like u in but, long ā like a in father, long ī like ee in see, long ū like oo in too, short i and short u differing from the corresponding long vowels not in sound but in length. The u in Buddha, for example, is short. Simple consonants are pronounced as in English, except that c is pronounced like ch in church, g as in get, and j as in judge. Combinations like th and dh should be pronounced as in hothouse and madhouse. Names containing underdotted letters have been eliminated. A syllable is said to be long if it contains either a long vowel, or a short vowel followed by two consonants (except a consonant followed by h). Words of three or more syllables are accented on the second syllable from the last, provided the next to the last syllable is short, as Gótama, Mállika. If the next to the last syllable is long, it receives the accent, as Brahmadátta, Nibbāna.

| PAGE | ||

| Note on pronunciation of Pāli names | viii | |

| List of illustrations | xiii | |

| Introduction | xv | |

| Note on the illustrations | xxix | |

| 1. The grateful elephant | Jā. 156: ii. 17 | 1 |

| Where there’s a will, there’s a way | ||

| 2. Grateful animals and ungrateful man | Jā. 73: i. 322 | 9 |

| Driftwood is worth more than some men | ||

| 3. Elephant and ungrateful forester | Jā. 72: i. 319 | 19 |

| The whole earth will not satisfy an ungrateful man | ||

| 4. Quail, crow, fly, frog, and elephants | Jā. 357: iii. 174 | 26 |

| The biter bit | ||

| 5. Quails and fowler | Jā. 33: i. 208 | 30 |

| In union there is strength | ||

| 6. Brahmadatta and the prince | Vin. i. 342 | 33 |

| Love your enemies | ||

| 7. Antelope, woodpecker, tortoise, and hunter | Jā. 206: ii. 152 | 48 |

| In union there is strength | ||

| 8. Brahmadatta and Mallika | Jā. 151: ii. 1 | 52[x] |

| Overcome evil with good | ||

| 9. A Buddhist Tar-baby | Jā. 55: i. 272 | 58 |

| Keep the Precepts | ||

| 10. Vedabbha and the thieves | Jā. 48: i. 252 | 64 |

| Cupidity is the root of ruin | ||

| 11. The anger-eating ogre | S. i. 237 | 72 |

| Refrain from anger | ||

| 12. The patient woman | M. 21: i. 125 | 75 |

| Patient is as patient does | ||

| 13. Blind men and elephant | Udāna, 66 | 79 |

| Avoid vain wrangling | ||

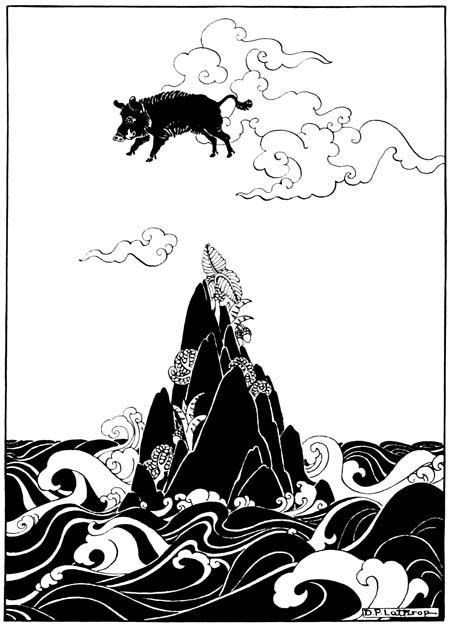

| 14. King and boar | 83 | |

| Evil communications corrupt good manners | ||

| Part 1. Gem, hatchet, drum, and bowl | Jā. 186: ii. 101 | |

| Part 2. Corrupt fruit from a good tree | Jā. 186: ii. 104 | |

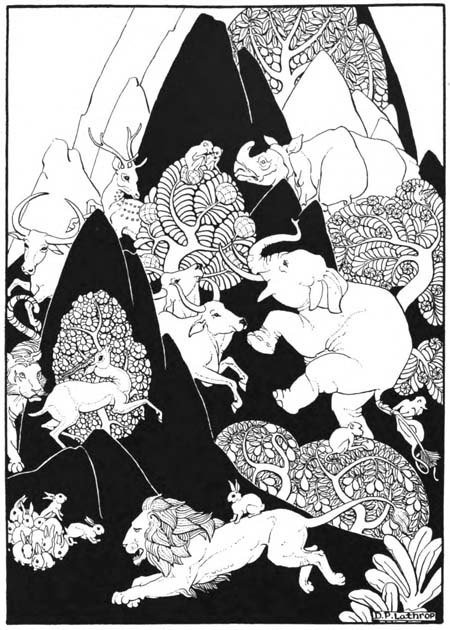

| 15. A Buddhist Henny-Penny | Jā. 322: iii. 74 | 92 |

| Much ado about nothing | ||

| 16. The birds (cf. 17) | Vin. iii. 147 | 97 |

| Nobody loves a beggar | ||

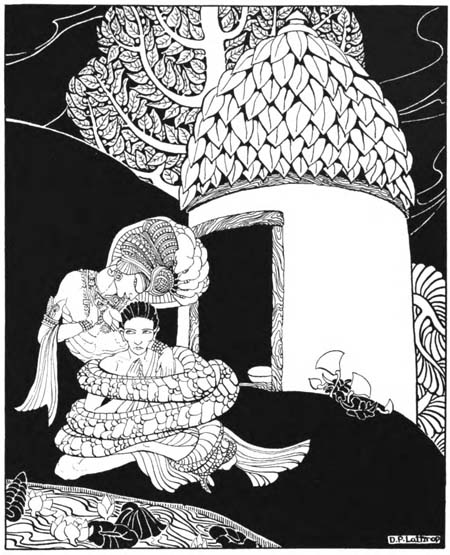

| 17. Dragon Jewel-neck | 99[xi] | |

| Nobody loves a beggar | ||

| A. Canonical version | Vin. iii. 145 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | Jā. 253: ii. 283 | |

| 18. Snake-charm | 107 | |

| A blessing upon all living beings! | ||

| A. Canonical version | Vin. ii. 109 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | Jā. 203: ii. 144 | |

| 19. Partridge, monkey, and elephant | 114 | |

| Reverence your elders | ||

| A. Canonical version | Vin. ii. 161 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | Jā. 37: i. 217 | |

| 20. The hawk | 119 | |

| Walk not in forbidden ground | ||

| A. Canonical version | S. v. 146 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | Jā. 168: ii. 58 | |

| 21. How not to hit an insect | 124 | |

| Better an enemy with sense than a friend without it | ||

| A. Boy and mosquito | Jā. 44: i. 246 | |

| B. Girl and fly | Jā. 45: i. 248 | |

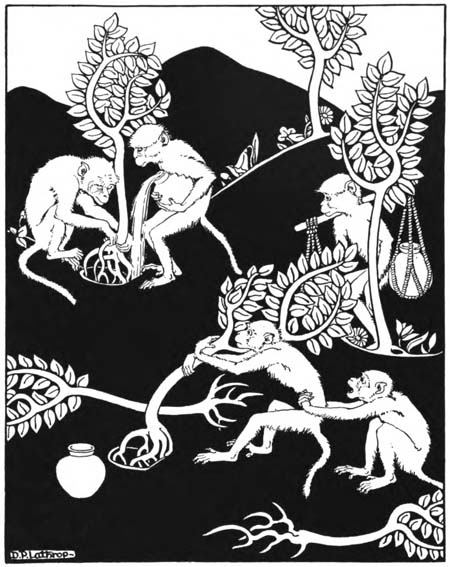

| 22. Monkey-gardeners | 129 | |

| Misdirected effort spells failure | ||

| A. One-stanza version | Jā. 46: i. 249 | |

| B. Three-stanza version | Jā. 268: ii. 345 | |

| 23. Two dicers | 135[xii] | |

| Take care! | ||

| A. Canonical version | D. ii. 348 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | Jā. 91: i. 379 | |

| 24. Two caravan-leaders | 138 | |

| Be prudent! | ||

| A. Canonical version | D. ii. 342 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | Jā. 1: i. 95 | |

| 25. Boar and lion | Kathāsaritsāgara, 72 | 154 |

| Eat me, O lion! | ||

| 26. Fairy-prince and griffin | Kathāsaritsāgara, 22 and 90 | 157 |

| Eat me, O griffin! | ||

| Glossary | 169 | |

| Story | Facing |

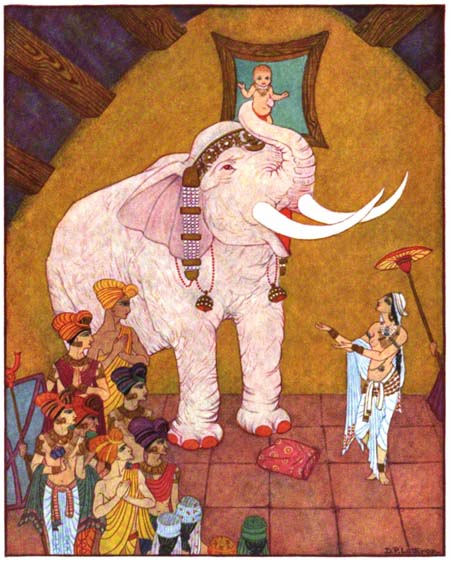

| 1. The grateful elephant | Title-page |

| Then the elephant with his trunk caressed the Future Buddha and lifted him up | |

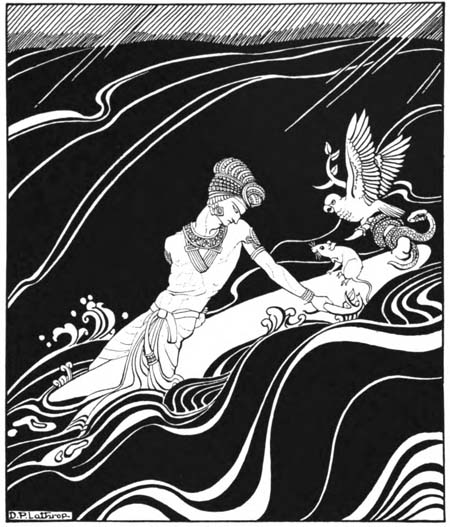

| 2. Grateful animals and ungrateful man | 12 |

| Thus did those four persons travel together, swept along by the river | |

| 3. Elephant and ungrateful forester | 22 |

| The man actually cut off his two principal tusks! | |

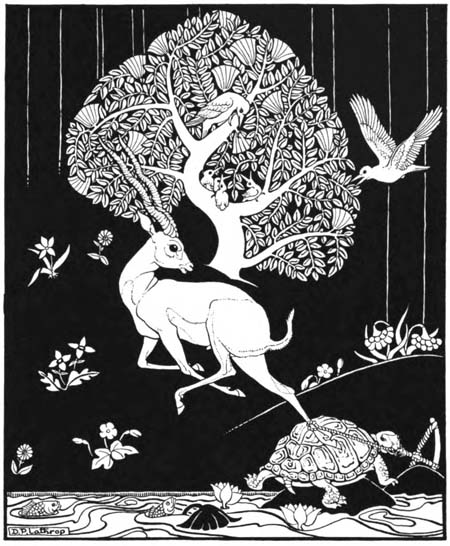

| 7. Antelope, woodpecker, tortoise, and hunter | 50 |

| At that moment the tortoise had chewed all of the strips except just one strap | |

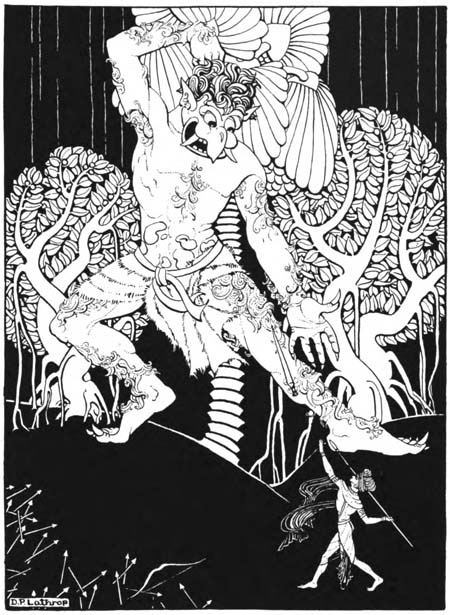

| 9. A Buddhist Tar-baby | 60 |

| Then he hit him with a spear | |

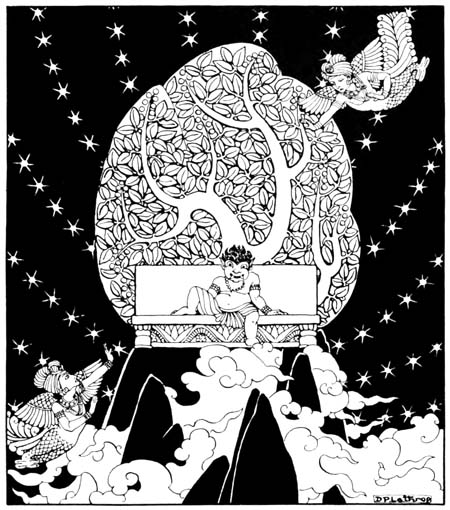

| 11. The anger-eating ogre | 72 |

| “Here, Sire, a certain ogre, ill-favored, dwarfish, sits in your seat” | |

| 14. King and boar | 86 |

| He bit the gem, and by its magical power rose into the air | |

| 15. A Buddhist Henny-Penny | 96 |

| So taking the little hare on his back, he sprang forward with the speed of a lion | |

| 17. Dragon Jewel-neck | 104[xiv] |

| Every day Jewel-neck the dragon-king would encircle him with his coils | |

| 22. Monkey-gardeners | 130 |

| “When you water the young trees, pull them up by the roots, every one” |

THESE stories are said to have been related by Gotama Buddha for the purpose of conveying to his hearers moral and religious lessons and the lessons of common sense.

Gotama Buddha was born nearly twenty-five centuries ago in the city of Kapila, in Northeast India. Kapila was the principal city of the Sakya tribe, and his father was king of the tribe. Gotama was his family name. Buddha means Awakened or Enlightened, that is to say, awakened or enlightened to the cause and the cure of human suffering.

The Buddhist Scriptures tell us that when Gotama was born, the angels rejoiced and sang. An aged wise man inquired: “Why doth the company of angels rejoice?” They replied: “He that shall become Buddha is born in the village of the Sakyas for the welfare and happiness of mankind; therefore are we joyful and exceeding glad.”

The wise man hastened to the king’s house, and said: “Where is the child? I, too, wish to see him.” They showed him the child. When he saw the child, he rejoiced and was exceeding glad. And he took him in his arms, and said: “Without an equal is he! foremost among men!” Then, because he was an old[xvi] man, and knew that he was soon to die, he became sorrowful and wept tears.

Said the Sakyas: “Will any harm come to the child?” “No,” replied the wise man, “this child shall one day become Buddha; out of love and pity for mankind he shall set in motion the Wheel of Religion; far and wide shall his religion be spread. But as for me, I have not long to live; before these things shall come to pass, death will be upon me. Therefore am I stricken with woe, overwhelmed with sorrow, afflicted with grief.”

Seven days after Gotama was born, his mother died, and he was brought up by his aunt and step-mother. When he was nineteen years old, he married his own cousin. For ten years he lived a life of ease, in the enjoyment of all the comforts and luxuries which riches and high position could give him. When he was twenty-nine years old, a change came over him.

For many centuries, it has been a common belief in India that when a human being dies, he is at once born again. If he has lived a good life, he will be born again on earth as the child of a king or of a rich man, or in one of the heavens as a god. If he has lived an evil life, he will be born again as a ghost, or as an animal, or in some place of torment.

[xvii]According to this belief, every person has been born and has lived and died so many times that it would be impossible to count the number. Indeed, so far back into the past does this series of lives extend that it is impossible even to imagine a beginning of the series. What is more to the point, in each of these lives every person has endured much suffering and misery.

Said the Buddha: “In weeping over the death of sons and daughters and other dear ones, every person, in the course of his past lives, has shed tears more abundant than all the water contained in the four great oceans.”

And again: “The bones left by a single person in the course of his past lives would form a pile so huge that were all the mountains to be gathered up and piled in a heap, that heap of mountains would appear as nothing beside it.”

And again: “The head of every person has been cut off so many times in the course of his past lives, either as a human being or as an animal, as to cause him to shed blood more abundant than all the water contained in the four great oceans.”

Nothing more terrible than this can be imagined. Yet for many centuries it has been a common belief in India. Wise men taught that there was a way of[xviii] escape, a way of salvation. If a person wished to avoid repeated lives of suffering and misery, he must leave home and family and friends, become a monk, and devote himself to fasting, bodily torture, and meditation.

The Buddhist Scriptures tell us that when Gotama was twenty-nine years old, he saw for the first time an Old Man, a Sick Man, a Dead Man, and a Monk. The thought that in the course of his past lives he had endured old age, sickness, and death, times without number, terrified him, and he resolved to become a monk.

Leaving home and wife and son, he devoted himself for six years to fasting, bodily torture, and meditation. Finally he became convinced that fasting and bodily torture were not the way of salvation, and abandoned the struggle. One night he had a wonderful experience. First he saw the entire course of his past lives. Next he saw the fate after death of all living beings. Finally he came to understand the cause of human suffering and the cure for it.

Thus it was that he became Buddha, the Awakened, the Enlightened. He saw that the cause of rebirth and suffering was craving for worldly pleasures and life and riches. He saw that if this craving were uprooted, rebirth and suffering would come to[xix] an end. He saw that this craving could be uprooted by right belief, right living, and meditation.

For forty-five years the Buddha journeyed from place to place, preaching and teaching. He founded an order of monks and nuns, and won many converts. He lived to be eighty years old. Missionaries carried his teachings from India to Ceylon and Burma and China and Tibet and Japan. In a few hundred years the religion of the Buddha had spread over the whole of Asia. Hundreds of millions of human beings have accepted his teachings.

In at least two respects, the teachings of the Buddha were quite remarkable. In the first place, he insisted on the virtue of moderation. He urged upon his hearers to avoid the two extremes of a life devoted to fasting and self-torture, and a life of self-indulgence. In the second place, he taught that a man must love his neighbor as himself, returning good for evil and love for hatred. But this was not all. He taught men to love all living creatures without respect of kind or person. He taught men not to injure or kill any living creature, whether a human being or an animal, even in self-defense. All war, according to the teaching of the Buddha, is unholy.

In the course of time it came to be believed that[xx] Gotama had become Buddha as the fruit of good deeds performed in countless previous states of existence, especially deeds of generosity. At any time, had he so desired, he might have uprooted craving for worldly pleasures and life and riches by meditation, and thus have escaped the sufferings of repeated states of existence. But this he deemed an unworthy course. Out of pity and compassion and friendliness for living creatures, he preferred to be reborn again and again, to suffer and to die again and again, in order that, by the accumulated merit of good works, he might himself become enlightened and thus be able to enlighten others.

In comparison with the career of the Future Buddha, devoted to the performance of good works, unselfish, generous to the point of sacrificing his own body and blood,—the career of the monk, isolated from the world, selfish, seeking by meditation to uproot craving for worldly pleasures and life and riches, seemed low and mean. The disciple began to imitate his Master. Thus began the Higher Career or Vehicle of Mahāyāna or Catholic Buddhism, as distinguished from the Lower Career or Vehicle of the more primitive Hīnayāna Buddhism of the Pāli texts. Thus did the quest of Buddhahood supplant the quest of Nibbāna. This development took place long before the beginning of the Christian era.

[xxi]Gotama Buddha made frequent use of similes, allegories, parables, fables, and other stories, to illustrate his teachings. His example was imitated by his followers, and in the course of time hundreds and hundreds of stories were attributed to him on general principles. Most of these stories were, in their original form, nothing but simple folk-tales, many of them of great antiquity. Parallels and variants are found in the Mahābhārata, the Panchatantra, Bidpai’s Fables, the Hitopadesha, the Kathāsaritsāgara, and other fiction-collections, especially those of the Jains.

Of the twenty-six stories contained in this book, of eight of which two versions are given, eleven stories or versions of stories (6, 11, 12, 13, 16, 17 a, 18 a, 19 a, 20 a, 23 a, 24 a) are taken from the oldest canonical texts of the Buddhist Sacred Scriptures. Of these eleven stories, the first nine are said to have been related by Gotama himself, the last two being attributed to the Buddhist sage Kumāra Kassapa. It is highly probable that the tradition embodied in the texts regarding these eleven stories is correct. We may therefore feel quite certain that such remarkable parables as Brahmadatta and the prince (6), Blind men and elephant (13), and The birds (16) were actually related by Gotama himself, in[xxii] substantially the same form as that in which we now have them. It is not at all unlikely that such a parable as Brahmadatta and Mallika (8) was also related by Gotama, but of this we cannot be certain.

The approximate date of these old canonical texts is now well established. Numerous references to the Buddhist Scriptures in the Bhābrā edict of Asoka, about 250 B.C., and in the canonical work Kathāvatthu, of about the same date, amply justify the statement that the texts from which these eleven stories are taken are, in their present form, at least three or four centuries anterior to the Christian era. It may interest the reader to know that these texts, originating in North India in the lifetime of Gotama, were handed down by oral tradition for many generations, were reduced to canonical form within a century or two of the death of Gotama, were carried to Ceylon in the third century B.C., were written down for the first time in the first century B.C., and were copied and recopied on palm-leaves by successive generations of scribes until comparatively recent times.

The rest of the stories (except 25 and 26) are taken from the Book of the Buddha’s Previous Existences or Jātaka Book. This remarkable work, which also originated in North India, relates in[xxiii] mixed prose and verse the experiences of the Future Buddha in each of 550 states of existence previous to his rebirth as Gotama. The received text of this work represents a recension made in Ceylon early in the fifth century A.D., but much of the material is demonstrably many centuries older. For example, the stanzas rank as canonical Scripture, older versions of some of the stories occur in the canonical texts, and many of the stories (including 4 and 7 and 22) are illustrated by Bharahat sculptures of the third century B.C. Stories 25 and 26 are also Jātaka tales, adapted from C. H. Tawney’s translation of the Kathāsaritsāgara.

For the most part, the Jātaka stories purport to relate incidents in Gotama’s previous states of existence as a human being. For example, as Prince Noble-heart (1), he triumphs over his enemies and succeeds to the throne of his father through the kindly offices of a grateful elephant. As a Brahman’s son (2), he befriends in turn a pampered prince, a snake, a rat, and a parrot, with the result that he is basely betrayed by the prince, but treated with profound gratitude by the three animals.

As King Brahmadatta (8), he overcomes anger with kindness, evil with good, the stingy with gifts, and the liar with truth. As Prince Five-weapons[xxiv] (9), he overcomes the giant ogre Sticky-hair with the Weapon of Knowledge. As a Brahman’s son (17 b), he frees his younger brother from the power of Jewel-neck, the dragon-king. As a Brahman’s son (18 b), he teaches friendliness for all living beings. As a caravan-leader (24 b), he protects his companions from a troop of man-eating ogres. As Jīmūta-vāhana, prince of the fairies (26), he offers the sacrifice of his body and blood for the welfare of all living beings.

Several of the stories purport to relate incidents in Gotama’s previous states of existence as an animal. For example, as a generous elephant (3), he gives his tusks to an ungrateful forester who has betrayed him. As a merciful elephant (4), he spares the life of a tiny quail. As a wise quail (5), he avoids the snares of a fowler. As a brave lion (15), he averts the destruction of a host of frightened animals. As a wise partridge (19 b), he serves as the preceptor of a monkey and an elephant. As a wise quail (20 b), he outwits a hawk. As a wise boar (25), he offers the sacrifice of his body and blood.

How did the Future Buddha come to be identified with the hero of each of these stories? The stories themselves give us the answer. For example, in the[xxv] story of Brahmadatta and the prince (6), we read that a high-minded prince generously forgave the murderer of his father and mother, returning good for evil and love for hatred. In this, the oldest form of the story, the Future Buddha is not even mentioned. But in a later form of the story, Jātaka 371, we are expressly told that the generous prince was none other than the Future Buddha.

Stories 17, 18, 19, 20, 23, and 24 illustrate the same process in a very striking way. Of each of these stories we have two versions, an earlier version from a canonical source, and a later version from an uncanonical source. It will be observed that in the older versions the Future Buddha is not mentioned at all. But in the later versions he is identified in turn with a wise ascetic (17 b, 18 b), a wise partridge (19 b), a wise quail (20 b), an honest dicer (23 b), and a wise caravan-leader (24 b).

Originally a simple folk-tale, each of these stories has been converted into a birth-story by the simple literary device of identifying the highest and noblest character in the story with the Future Buddha. This, of course, was a comparatively easy matter, for the Future Buddha, in his previous states of existence, was believed to have exhibited the qualities of wisdom, courage, and generosity,[xxvi] and there are few of the stories in which at least one of the characters does not exhibit one or another of these qualities.

The attempt to introduce the Future Buddha into the stories is not always carried out in a way to satisfy or convince the reader. Thus, as an honest dicer (23 b), he violates Buddhist teaching by administering deadly poison to his companion, a dishonest dicer. The latter must not, of course, be allowed to die. The honest dicer is therefore made to administer an emetic to his companion and to admonish him. As a wise quail (20 b), he again violates Buddhist teaching by saving his own life at the expense of his enemy’s life. Here the inconsistency is allowed to stand, and the story is used to illustrate the folly of walking in forbidden ground.

In the case of some of the stories, the figure of the Future Buddha is, so to speak, lugged in by the heels. For example, little or nothing is gained by identifying the antelope caught in a trap (7) with the Future Buddha. As a Brahman’s pupil (10), and as a king’s counsellor (14), the Future Buddha offers only a word of advice. As a trader (21), and as a wise man (22), he is merely a spectator, and contents himself with remarking on the folly of misdirected effort. It is quite clear that in the case of[xxvii] these stories also we are dealing with simple folk-tales which have undergone only slight modification.

Some of the stories have traveled all over the world. In the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries, many of them found their way into the highways and byways of European literature. With Story 1, The grateful elephant, compare the story of Androclus and the lion, Aesop’s fable of the Lion and the Shepherd, and Gesta Romanorum 104. With Story 2, Grateful animals and ungrateful man, compare R. Schmidt, Panchatantra i. 9; C. H. Tawney, Kathāsaritsāgara ii. 103; E. Chavannes, Cinq Cents Contes 25; A. Schiefner, Tibetan Tales 26; Gesta Romanorum 119; and the following stories in Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen: 17 Die weisse Schlange, 60 Die zwei Brüder, 62 Die Bienenkönigin, 85 Die Goldkinder, 107 Die beiden Wanderer, 126 Ferenand getrü und Ferenand ungetrü, 191 Das Meerhäschen. For additional parallels, see J. Bolte und G. Polivka, Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- und Hausmärchen der Brüder Grimm, Märchen 17, 62, 191.

With Story 3, Elephant and ungrateful forester, compare E. Chavannes, Cinq Cents Contes 28. With Story 4, Quail, crow, fly, frog, and elephants, compare R. Schmidt, Panchatantra i. 18. Variants[xxviii] of Stories 5 and 7 form the frame-story of Panchatantra ii. With Story 5, Quails and fowler, compare C. H. Tawney, Kathāsaritsāgara ii. 48; J. Hertel, Tantrākhyāyika iii. 11; also Aesop’s fable of the Falconer and the Birds. With Story 7, Antelope, woodpecker, tortoise, and hunter, compare Mahābhārata xii. 138; C. H. Tawney, Kathāsaritsāgara i. 296; also Aesop’s fable of the Lion and the Mouse. With Story 6, Brahmadatta and the prince, compare E. Chavannes, Cinq Cents Contes 10; also Jātaka 371. With Story 8, Brahmadatta and Mallika, compare Mahābhārata iii. 194.

With Story 9, A Buddhist Tar-baby, compare E. Chavannes, Cinq Cents Contes 89 and 410; also the well-known story in Joel Chandler Harris, Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings. Story 10, Vedabbha and the thieves, is the original of Chaucer’s Pardoner’s Tale; compare also A. Schiefner, Tibetan Tales 19. With Story 13, Blind men and elephant, compare E. Chavannes, Cinq Cents Contes 86. With Story 14, Part 1, Gem, hatchet, drum, and bowl, compare Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen: 36 Tischchen deck dich, Goldesel, und Knüppel aus dem Sack; 54 Der Ranzen, das Hütlein, und das Hörnlein. For additional parallels, see Bolte-Polivka.

[xxix]With Story 15, A Buddhist Henny-Penny, compare A. Schiefner, Tibetan Tales 22; also the well-known children’s story of the same name. With Story 19, Partridge, monkey, and elephant, compare A. Schiefner, Tibetan Tales 24. With Story 21, How not to kill an insect, compare Aesop’s fable of the Bald Man and the Fly. For an interesting account of the history of some of the stories, see W. A. Clouston, Popular Tales and Fictions, as follows: Story 2: i. 223-241. Story 9: i. 133-154. Story 10: ii. 379-407. Story 14: i. 110-122. Story 15: i. 289-313. Story 21: i. 55-57.

Just fifty years ago Sir Alexander Cunningham discovered among the ruins of a memorial mound or stūpa near the village of Bharahat, 120 miles southwest of Allahabad, a series of sculptures of the third century B.C., illustrating the legendary life of the Buddha and stories from the Book of the Buddha’s Previous Existences or Jātaka Book. Photographs of these sculptures, together with a detailed description of each, will be found in the explorer’s monumental work Stūpa of Bharhut.

It is from these Bharahat sculptures that the[xxx] artist has taken most of the materials for the illustrations to the present volume. From these sculptures have been taken, not only three entire scenes, but animals, costumes, trees, plants, fruits, flowers, and other objects. In the case of two scenes, where the sculptured objects differ materially from the objects described in the text, the artist has followed the sculptures rather than the text. In the matter of details, the illustrations are believed to be correct in every particular.

The design which appears on the cover, and again on the title-page, Elephant and children, is taken from Cunningham, Plate xxxiii. 2, Elephant and monkeys. The Bharahat sculpture represents an elephant being driven along by a troop of monkeys. The artist has substituted children for monkeys, but has preserved the spirit of the scene. It may as well be said here as anywhere else that the saffron yellow of the cover is the exact color of the robes of a Buddhist monk. The color is therefore symbolic.

The frontispiece, illustrating Story 1, The grateful elephant, represents the scene in the elephant-stable. A pure white elephant is shown in the act of raising the young prince, the Future Buddha, to his shoulders. On the right stands the queen, under a parasol held by an attendant. On the left stand[xxxi] ministers of state, ladies-in-waiting, and slaves. The open window, through which the blue sky is seen, forms an effective panel for the portrait of the young prince. The saffron yellow of the background is again symbolic.

The illustration to Story 2, Grateful animals and ungrateful man, represents the pampered prince astride of a tree-trunk, accompanied by his three companions, a snake, a rat, and a parrot, swept along by the river amid storm and darkness.

The illustration to Story 3, Elephant and forester, shows the Future Buddha, in the form of a pure white elephant, reclining like a cow, and willingly permitting the ungrateful forester to cut off his two tusks. Trees.—Left middle: Pātali-tree, Trumpet Flower, Bignonia Suaveolens, the Bo-tree of the Buddha Vipassi. See Cunningham, Plates xxiii. 3 and xxix. 1. Centre over elephant: Probably the Sāl-tree, Shorea Robusta, the Bo-tree of the Buddha Vessabhu. The mother of Gotama is said to have stood upright at his birth and to have supported herself by a branch of a Sāl-tree. See Cunningham, Plate xxix. 2 and 5. Over elephant’s head: Fan-palm, Borassus Flabelliformis. See Cunningham, Plate xxx. 4. Right middle: Probably a Sandalwood-tree, Candana. See Cunningham,[xxxii] Plate lvii. Lower left: Magnolia. See Cunningham, Plate xxv. 1 (above archer).

The illustration to Story 7, Antelope, woodpecker, tortoise, and hunter, is taken from Cunningham, Plate xxvii. 9. As the hunter approaches, the tortoise releases the antelope from the trap, and the antelope springs to a place of safety. In drawing the trap, the artist has followed the sculptured model, rather than the description in the text. The tree in the background is the Sirīsa-tree, Acacia Sirisa, more properly, Albizzia Lebbek, the Bo-tree of the Buddha Kakusandha. See Cunningham, Plate xxix. 3.

The illustration to Story 9, A Buddhist Tar-baby, represents the Future Buddha in the person of Prince Five-weapons casting a spear at the giant ogre Sticky-hair. The drawing of the ogre follows closely the description given in the text. The tree in the background is the Fan-palm, represented in Cunningham, Plate xxx. 4. The trees to the right and left are specimens of the Banyan-tree, the Nyagrodha, Ficus Indica, the Bo-tree of the Buddha Kassapa. Note the down-growing roots. See Cunningham, Plates xv. 3, xxvi. 6, xxx. 1 and 2.

The illustration to Story 11, The anger-eating ogre, represents the ogre seated on the Yellowstone[xxxiii] throne of Sakka (Indra), king of the gods, in the heaven of the Thirty-three gods, thereby arousing the indignation and anger of the gods, of whom two are shown in the drawing. The tree in the background is probably the Sāl-tree. See note on illustration to Story 3.

The illustration to Story 14, King and boar, represents the boar flying through the air by the magical power of the gem which he has just bitten. The power of flying through the air is mentioned in the oldest texts as one of the several varieties of magical power which may be acquired by the Practice of Meditation.

The illustration to Story 15, A Buddhist Henny-Penny, shows the Future Buddha, in the form of a lion, setting out with the little hare on his back to discover the cause of the flight of the animals. The artist has introduced representatives of the various animals mentioned in the story, and a few monkeys for good measure. Trees.—Left: Magnolia. See Cunningham, Plate xxv. 1 (above archer). Centre: Jack-tree. See Cunningham, Plate xiv. 1 (extreme left), xli. 4, xlii. 8, and xliii. 1. Top: Udumbara-tree, Ficus Glomerata, the Bo-tree of the Buddha Kanakamuni. See Cunningham, Plate xxix. 4. Right middle: Sirīsa-tree, Acacia Sirisa, more properly,[xxxiv] Albizzia Lebbek, the Bo-tree of the Buddha Kakusandha. See Cunningham, Plate xiv. 3. In the illustration to Story 7, the tree is represented in flower. Compare Cunningham, Plate xxix. 3. Lower right: Rose-apple, Jambu-tree. See Cunningham, Plate xliv. 8. India is frequently called the Land of the Rose-apple.

The illustration to Story 17, Dragon Jewel-neck, represents the king of the dragons encircling the ascetic with his coils. The ascetic is seated at the door of his leaf-hut on the bank of the Ganges. The tree in the background is the Sacred Fig-tree, the Pipphala, Ficus Religiosa. It was under a tree of this species that Gotama sat on the night of his Enlightenment. Accordingly, this tree has a symbolic value for Buddhists corresponding to that which the Cross has for Christians, and is frequently sculptured on the monuments. See Cunningham, Plates xiii. 1, xxx. 3. The tree to the right of the hut may be a Sandalwood-tree. See note on illustration to Story 3.

The illustration to Story 22, Monkey-gardeners, is taken from Cunningham, Plate xlv. 5. The monkeys, in obedience to the instructions of their leader, are pulling up the young fig-trees by the roots, examining the roots, watering plentifully the trees[xxxv] with long roots, but sparingly the trees with short roots, and planting them again. In drawing the water-pots, the artist has followed the Bharahat sculpture rather than the description given in the text.

Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

Jātaka 156: ii. 17-23.

Relying on Noble-heart. This parable was related by the Teacher while he was in residence at Jetavana with reference to a certain monk who relaxed effort. Said the Teacher to him: “Of a truth, monk, did you not, in a previous state of existence, by exerting yourself, get and give to a young prince no bigger than a piece of meat, dominion over the city of Benāres, a city twelve leagues in measure?” So saying, he related the following Story of the Past:

In times past, when Brahmadatta ruled at Benāres, there was a carpenters’ settlement not far from Benāres. In this settlement lived five hundred carpenters. They would go up-stream in a boat, cut timber for building materials for houses in the forest, and prepare houses of one or more stories on the spot. Then, marking all of the timbers, beginning with the pillars, they would carry them to the river-bank, load them on a boat, return to the city with the current, and for a price build for any particular person any particular kind of house he desired to have built. Then they would go back to the forest and get building materials once more. Thus they made their living.

[2]One day, not far from the camp where they were fashioning timbers, a certain elephant trod on an acacia splinter, and the splinter pierced his foot. He suffered intense pain, and his foot became swollen and festered. Maddened with pain, hearing the sound of those carpenters fashioning timbers, thinking to himself, “With the help of these carpenters I can get relief,” he went to them on three feet and lay down not far off. The carpenters saw that his foot was swollen, and on drawing closer, saw the splinter in his foot. So making incisions all round the splinter with a sharp knife, they tied a cord to the splinter, removed the splinter with a pull, let out the pus, washed the wound with hot water, and by applying proper remedies, in no very long time made the wound comfortable.

When the elephant was well, he thought: “I owe my life to these carpenters; now I ought to do something for them.” From that time on he helped the carpenters remove trees, rolled them over and held them for the carpenters while they were fashioning them, brought them their tools, and held the measuring-cord, taking it by the end and wrapping his trunk about it. As for the carpenters, when it was time to eat, each one of them gave the elephant a morsel of food; thus in all they gave him five hundred morsels of food.

[3]Now that elephant had a son, and he was pure white, a noble son of a noble sire. So the following thought occurred to the elephant: “I am now old. I ought therefore to give my son to these carpenters to help them in their work, and myself go away.” Without saying a word to the carpenters, he entered the forest, and leading his son to the carpenters, said: “This young elephant is my son. You gave me my life; I give you this elephant by way of paying the fee which I owe to my physicians. Henceforth he will work for you.”

Then he admonished his son: “Henceforth you are to do whatever it was my duty to do.” Having so said, he gave his son to the carpenters and himself entered the forest. From that time on the young elephant obeyed the commands of the carpenters, was patient of admonition, performed all of the duties. They fed him also with five hundred morsels of food. After doing his work, he would descend into the river and play, and then come back. And the carpenters’ children used to take hold of him by the trunk and play with him, both in the water and on dry land.

The elephant-trainers reported that incident to the king, remarking: “That noble elephant should be sought out and brought to you, your majesty.” The king made haste up the river with boats and[4] rafts; with rafts bound up-stream he reached the place of abode of the carpenters. The young elephant, playing in the river, on hearing the sound of the drum, went and stood by the carpenters. The carpenters went forth to meet the king, and said: “Your majesty, if you have need of timber, why did you yourself come? why shouldn’t you have sent men to get it?” “I didn’t come for timber, I assure you, but I came for this elephant.” “Take him and go, your majesty.”

The young elephant would not go. “What, pray, will you have done, elephant?” “Have the carpenters paid for my keeping, your majesty.” “Very well, I will,” said the king. He had a hundred thousand pieces of money laid near each of the elephant’s four feet, near his trunk, and near his tail. But for all that the elephant would not go. When, however, pairs of cloths had been given to all of the carpenters, when under-garments had been given to the carpenters’ wives, and when the proper attentions had been paid to the children he had played with, then the elephant turned around, and eyeing the carpenters and their wives and their children as he went, accompanied the king.

The king took the elephant, went to the city, and caused both city and elephant-stable to be adorned.[5] He caused the elephant to make rightwise circuit of the city and to be taken into the elephant-stable. He adorned the elephant with all the adornments, sprinkled him, made him his riding-animal, elevated him to the dignity of a friend, gave him half his kingdom, and had him treated as himself. From the day when the elephant arrived, the king obtained complete mastery over all the Land of the Rose-apple.

As time thus went on, the Future Buddha received a new existence as the child of the chief consort of that king. But before the child was born, the king died. Now if the elephant had known that the king was dead, it would have broken his heart then and there. So they said not a word to the elephant about the king’s death, but waited on him just as if nothing had happened.

But when the king of Kosala, who ruled over the country immediately adjoining, heard that the king was dead, he reflected: “The kingdom, they say, is empty;” and came with a large army and surrounded the city. The citizens closed the gates of the city and sent the following message to the king of Kosala: “The chief consort of our king is about to give birth to a child. The soothsayers have told us: ‘Seven days hence she will give birth to a son.’[6] If, on the seventh day, she gives birth to a son, we will give battle,—not the kingdom. Wait that long.” “Very well,” said the king in assent. On the seventh day the queen gave birth to a son. On the day when he received his name, because, as they said, “He is born extending a noble heart to the multitude,” they gave him the name Noble-heart, Alīnacitta.

Now from the day he was born, the citizens fought with the king of Kosala. But because they had no man to lead them in battle, the force, large as it was, gave way little by little in the conflict. Ministers reported this fact to the queen, saying: “We fear that if the force continues thus to give way, we shall lose the battle. But the state elephant, the king’s friend, does not know that the king is dead, that his son is born, and that the king of Kosala has come to fight.” And they asked her: “Shall we let him know?” “Yes,” said the queen, assenting. She adorned the boy, laid him in a head-coil of fine cloth, came down from the terrace, and accompanied by a retinue of ministers, went to the elephant-stable, and laid the Future Buddha at the feet of the elephant. Said she: “Master, your friend is dead. We didn’t tell you because we were afraid it would break your heart. Here is the son of your friend. The king of Kosala has come and has surrounded the city and[7] is fighting with your son. The force is giving way. Do you either kill your son or get and give him the kingdom.”

Then the elephant with his trunk caressed the Future Buddha and lifted him up and put him on his shoulders and cried and wept. Then he lowered the Future Buddha and laid him in the arms of the queen, and with the words, “I will capture the king of Kosala!” went out of the elephant-stable. Then the ministers clad him with armor and adorned him, and unlocking the city-gate, went out in his train.

As the elephant went out of the city, he trumpeted the Heron’s Call, making the multitude tremble and quake, and frightening them away. He broke down the stockade, seized the king of Kosala by the top-knot, and carried him and laid him at the Future Buddha’s feet. And when men rose to kill him, he would not let them, but set the king free with the admonition: “Henceforth be careful; do not presume on the youth of the prince.”

Thenceforth the Future Buddha had complete mastery over all the Land of the Rose-apple. No other adversary dared to stand up against him. When the Future Buddha was seven years old, he received the ceremonial sprinkling and became known as King Noble-heart. He ruled with righteousness,[8] and when his life was come to an end, departed, fulfilling the Path to Heaven.

When the Teacher had related this parable, he uttered, as Supreme Buddha, the following stanza:

Driftwood is worth more than some men.

Jātaka 78: i. 322-327.

True is this saying of some men of the world. This parable was related by the Teacher while he was in residence at Bamboo Grove with reference to Devadatta’s going about for the purpose of killing him. For while the Congregation of Monks, sitting in the Hall of Truth, were discussing Devadatta’s wickedness, saying, “Brethren, Devadatta knows not the Teacher’s virtues, but is going about for the sole purpose of killing him,” the Teacher drew near and asked: “Monks, what is the subject that engages your attention now as you sit here all gathered together?” “Such-and-such,” was the reply. “Monks,” said the Teacher, “not only in his present state of existence has Devadatta gone about for the purpose of killing me; in a previous state of existence also he went about for the purpose of killing me in the very same way.” Then, in response to a request of the monks, he related the following Story of the Past:

In times past Brahmadatta ruled at Benāres. He had a son named Prince Wicked, and Prince Wicked was as tough and hard as a beaten snake. He never spoke to anybody without either reviling him or striking him. The result was that both by[10] indoor-folk and by outdoor-folk he was disliked and detested as much as dust lodged in the eye or as a demon come to eat.

One day, desiring to sport in the water, he went to the river-bank with a large retinue. At that moment a great cloud arose. The directions became dark. He said to his slaves and servants: “Come, fellows! take me and conduct me to mid-stream and bathe me and bring me back.” They led him there and took counsel together, saying: “What can the king do to us! Let’s kill this wicked fellow right here!” So saying, they plunged him into the water, made their way out of the water again, and stood on the bank.

As the courtiers returned to the king, they reflected: “In case we are asked, ‘Where is the prince?’ we will say, ‘We have not seen the prince; it must be that upon seeing a cloud arise he plunged into the water and went on ahead of us.’” The king asked: “Where is my son?” “We do not know, your majesty. A cloud arose. We returned, supposing: ‘He must have gone on ahead of us.’” The king caused the gates to be flung open, went to the river-bank, and caused them to search here and there. “Search!” said he. Nobody saw the prince.

As a matter of fact, in the darkness caused by the cloud, while the god was raining, the prince, swept[11] along by the river, seeing a certain tree-trunk, clambered on it, and sitting astride of it, traveled along, terrified with the fear of death, lamenting.

Now at that time a resident of Benāres, a certain treasurer, who had buried forty crores of wealth by the river-bank, by reason of his craving for that wealth, had been reborn on top of that wealth as a snake. Yet another had buried thirty crores of wealth in that very spot, and by reason of his craving for that wealth, had been reborn on the spot as a rat. The water entered their place of abode. They went out by the very path by which the water came in, cleft the stream, and went until they reached the tree-trunk bestridden by the royal prince. Thereupon one climbed up on one end, the other on the other, and both lay down right there on top of the tree-trunk.

Moreover, on the bank of that very river there was a certain silk-cotton tree, and in it lived a certain young parrot. That tree also, its roots washed by the water, fell on top of the river. The young parrot, unable to make headway by flying while the god was raining, went and perched on one side of that very tree-trunk. Thus did those four persons travel together, swept along by the river.

[12]

Now at that time the Future Buddha was reborn in the kingdom of Kāsi in the household of a Brahman of high station. When he reached manhood, he retired from the world and adopted the life of an ascetic, and building a leaf-hut at a certain bend in the river, took up his abode there. At midnight, as he was walking up and down, he heard the sound of the profound lamentation of that royal prince. Thought he: “It is not fitting that that man should die in sight of an ascetic like me, endowed with friendliness and compassion. I will pull him out of the water and grant him the boon of life.” He calmed the man’s fears with the words, “Fear not! fear not!” Then, cleaving the stream of water, he went and laid hold of that tree-trunk by one end, and pulled it. Powerful as an elephant, endowed with mighty strength, with a single pull he reached the bank, and lifting the prince in his arms, set him ashore.

Thus did those four persons travel together, swept along by the river.

Seeing the snake, the rat, and the parrot, he picked them up also, carried them to his hermitage, and lighted a fire. “The animals are weaker,” thought he. So first he warmed the bodies of the animals; then afterwards he warmed the body of the royal prince and made him well too. When he[13] brought food also, he first gave it to those same animals, and afterwards offered fruits and other edibles to the prince. Thought the royal prince: “This false ascetic does not take it into his reckoning that I am a royal prince, but does honor to animals.” And he conceived a grudge against the Future Buddha.

A few days after that, when all four had recovered their strength and vigor and the river-freshet had ceased, the snake bowed to the ascetic and said: “Reverend Sir, it is a great service you have done me. Now I am no pauper. In such-and-such a place I have buried forty crores of gold. If you have need of money, I can give you all that money. Come to that place and call me out, saying: ‘Longfellow!’” So saying, he departed. Likewise also the rat addressed the ascetic: “Stand in such-and-such a place and call me out, saying: ‘Rat!’” So saying, he departed.

But when the parrot bowed to the ascetic, he said: “Reverend Sir, I have no money; but if you have need of ruddy rice,—such-and-such is my place of abode,—go there and call me out, saying: ‘Parrot!’ I’ll tell my kinsfolk, have them fetch ruddy rice by the cart-load, and give it to you. That’s what I can do!” So saying, he departed.

But that other, the man, because it was his custom[14] to betray his friends, said not so much as a word according to custom. Thought he: “If you come to me, I’ll kill you!” But he said: “Reverend Sir, when I am established in my kingdom, be good enough to come and see me; I’ll furnish you with the Four Requisites.” So saying, he departed. And in no very long time after he had gone, he was established in his kingdom.

Thought the Future Buddha: “I’ll just put them to the test!” First he went to the snake, and standing not far off, called him out, saying, “Longfellow!” At the mere word the snake came out, bowed to the Future Buddha, and said: “Reverend Sir, in this place are forty crores of gold; carry them all out and take them with you!” Said the Future Buddha: “Let be as it is; if occasion arises, I’ll think about it.” So saying, he let the snake go back.

Then he went to the rat and made a noise. The rat also behaved just as had the snake. The Future Buddha let him also go back. Then he went to the parrot and called him out, saying: “Parrot!” The parrot also, at the mere word, came down from the top of the tree, and bowing to the Future Buddha, asked: “Tell me, Reverend Sir, shall I speak to my kinsfolk and have them fetch you self-sown rice[15] from the region of Himavat?” Said the Future Buddha: “If I have need, I’ll think about it.” So saying, he let the parrot also go back.

“Now,” thought the Future Buddha, “I’ll test the king!” He went and passed the night in the king’s garden, and on the following day, having put on beautiful garments, entered the city on his round for alms. At that moment that king, that betrayer of friends, seated on the back of his gloriously adorned state elephant, accompanied by a large retinue, was making a rightwise circuit of the city. Seeing the Future Buddha even from afar, he thought: “Here’s that false ascetic, come to live with me and eat his fill! That he may not make known in the midst of this company the service he has rendered me, I’ll straightway have his head cut off!”

He looked at his men. Said they: “What shall we do, your majesty?” Said the king: “Here’s a false ascetic, come to ask me for something or other, I suppose. Without so much as giving that false ascetic, that bird of evil omen, a chance to look at me, take that fellow, bind his arms behind his back, conduct him out of the city, beating him at every cross-roads, cut off his head in the place of execution,[16] and impale his body on a stake!” “Very well,” said the king’s men in assent. They bound the Great Being, guiltless as he was, and started to conduct him to the place of execution, beating him at every cross-roads. The Future Buddha, wherever they beat him, uttered no lament, “Women! men!” but unperturbed, uttered the following stanza:

[Native gloss: A stick of wood washed up on dry land is of some use: it will cook food; it will warm those who are shivering with the cold; it will remove dangerous objects. But an ingrate is worse than useless.]

Thus, wherever they beat him, did he utter this stanza. Hearing this, wise men who stood by said: “But, monk, what is the trouble between you and our king? have you done him some good turn?” Then the Future Buddha told them the whole story, saying: “I alone, by pulling this man out of a mighty flood, have brought suffering upon myself. I speak as I do because I keep thinking: ‘Alas! I have not heeded the words of wise men of old!’”

Hearing this, Warriors and Brahmans and others, residents of the city, became enraged. Said they: “This king here, this betrayer of friends, has not the slightest conception of the virtues of this[17] embodiment of the virtues, this man who has granted him the boon of his own life! What have we to gain through him! Capture him!” And rising in all quarters, they slew him, even as he sat on the back of the elephant, by hitting him with arrows and spears and rocks and clubs. And laying hold of his feet, they dragged him and threw him back of the moat. And conferring the ceremonial sprinkling on the Future Buddha, they established him in the kingdom. The Future Buddha ruled righteously.

Again one day, desiring to test the snake, the rat, and the parrot, he went with a large retinue to the place of abode of the snake and called him out, saying: “Longfellow!” The snake came, bowed to him, and said: “Here’s your money, master; take it.” The king entrusted to his ministers wealth amounting to forty crores of gold. Then he went to the rat and called him out, saying: “Rat!” The rat also came, and with a bow handed over to him wealth amounting to thirty crores. The king entrusted that also to his ministers. Then he went to the place of abode of the parrot and called him out, saying: “Parrot!” The parrot also came, and reverencing his feet, said: “Master, shall I fetch rice?” Said the king: “When there is need of rice, you may fetch it; come, let’s go.”

With the seventy crores of gold, causing those[18] three animals also to be carried along, he went to the city. And ascending to the grand floor of his magnificent palace, he caused that wealth to be stored and guarded. For the snake to live in, he caused a golden tube to be made; for the rat, a crystal cave; for the parrot, a golden cage. For the snake and the parrot to eat, he caused every day sweet parched grain to be given in a vessel of gold purified with fire; for the rat, grains of perfumed rice; he gave alms and performed the other works of merit. Thus those four persons, one and all, dwelt together in unity and concord all their days, and when their days were come to an end, passed away according to their deeds.

Said the Teacher: “Monks, not only in his present state of existence has Devadatta gone about for the purpose of killing me; in a previous state of existence also he went about for the purpose of killing me in the very same way.”

The whole earth will not satisfy an ungrateful man.

Jātaka 72: i. 319-322.

To an ungrateful man. This parable was related by the Teacher while he was in residence at Bamboo Grove with reference to Devadatta. The monks, seated in the Hall of Truth, were saying: “Brethren, Devadatta the ungrateful knows not the virtues of the Teacher.” The Teacher drew near and asked: “Monks, what is the subject that engages your attention now, as you sit here all gathered together?” “Such-and-such,” was the reply. “Monks,” said the Teacher, “not only in his present state of existence has Devadatta proved to be ungrateful; in a previous state of existence also he was ungrateful just the same. At no time soever has he known my virtues.” Then, in response to a request of the monks, he related the following Story of the Past:

In times past, when Brahmadatta ruled at Benāres, the Future Buddha was reborn in the region of Himavat as an elephant. When he was born, he was pure white, like a mass of silver; moreover his eyes were like globules of jewels, and from them shone forth the Five Brightnesses; his mouth was like a crimson blanket; his trunk was like a rope of silver, ornamented with spots of ruddy gold; his four feet were as if rubbed with lac. Thus his person, adorned[20] with the Ten Perfections, attained the pinnacle of beauty.

Now when he reached the age of reason, elephants from all over Himavat assembled and formed his retinue. Thus did he make his home in the region of Himavat, with a retinue of eighty thousand elephants. After a time, perceiving that there was contamination in the herd, he isolated himself from the herd and made his home quite alone in the forest. Moreover, by reason of his goodness, he became known as Good King Elephant.

Now a certain resident of Benāres, a forester, entered the forest, seeking wares whereby to make his living. Unable to distinguish the directions, he lost his way, and terrified with the fear of death, went about with outstretched arms lamenting. The Future Buddha, hearing those profound lamentations of his, thought: “I will free this man from his suffering.” And impelled by compassion, he went to him.

The instant that man saw the Future Buddha, he fled in fright. The Future Buddha, seeing him in flight, halted right where he was. The man, seeing that the Future Buddha had halted, himself halted. The Future Buddha came back. The man fled a second time, but halting when the Future Buddha halted, thought: “This elephant halts when I flee,[21] and approaches when I halt. He has no desire to do me harm, but without a doubt desires only to free me from this suffering.” And summoning up his courage, he halted.

The Future Buddha approached him and asked: “Why, Master man, do you go about lamenting?” “Master, because I couldn’t distinguish the directions, lost my way, and was afraid of death.” Then the Future Buddha conducted him to his own place of abode, and for a few days gladdened him with fruits and other edibles. Then said the Future Buddha: “Master man, don’t be afraid: I’ll conduct you to the path of man.” And seating him on his back, he proceeded to the path of men.

But that man, that betrayer of friends, even as he sat on the back of the Future Buddha, thought: “If anybody asks me, I must be able to tell him where this elephant lives.” So as he went along, he noted carefully the landmarks of tree and mountain. Now the Future Buddha, having conducted that man out of the forest, set him down on the highway leading to Benāres, and said to him: “Master man, go by this road; but as for my place of abode, whether you are asked or not, say nothing to anybody about it.” So saying, he took leave of him and went back to his own place of abode.

Now that man went to Benāres, and in the course[22] of his walks came to the street of the ivory-carvers. And seeing the ivory-carvers making various kinds of ivory products, he asked: “But, sirs, how much would you make if you could get the tusk of a real live elephant?” “What are you saying, sir! The tusk of a live elephant is far more valuable than the tusk of a dead elephant.” “Very well! I’ll fetch you the tusk of a live elephant.” Accordingly, obtaining provisions for the journey and taking a sharp saw, he went to the place of abode of the Future Buddha.

When the Future Buddha saw him, he asked: “For what purpose have you come?” “I, sir, am a poor man, a pauper, unable to make a living. I came with this thought in my mind: ‘I will ask you for a fragment of one of your tusks; if you will give it to me, I will take it and go and sell it and with the money it brings make a living.’” “Let be, sir! I’ll give you tusks, if you have a sharp saw to cut them off with.” “I brought a saw with me, sir.” “Very well, sever the tusks with your saw and take them and go your way.” So saying, the Future Buddha bowed his knees together and sat down like a cow. The man actually cut off his two principal tusks!

The man actually cut off his two principal tusks!

The Future Buddha, taking those tusks in his trunk, said: “Master man, not with the thought, ‘These tusks are not dear to me, not pleasing to me,’ do I give you these tusks. But dearer to me than[23] these a thousand times,—a hundred thousand times,—are the Tusks of Omniscience, which avail to the comprehension of all things. May this gift of tusks which I here bestow enable me to attain Omniscience!” So saying, as it were sowing the Seed of Omniscience, he gave him the pair of tusks.

The man took them and went and sold them. When the money they brought was gone, he went to the Future Buddha again and said: “Master, the money I got by selling you tusks turned out to be no more than enough to pay off my debts. Give me the rest of your tusks!” “Very well,” said the Future Buddha, consenting. And ordering all things precisely as before, he gave him the rest of his tusks.

Those also did that man sell, and then came back again. “Master,” said he. “I cannot make a living. Give me the stumps of your tusks!” “Very well,” said the Future Buddha, and sat down precisely as before. That wicked man trod on the Great Being’s trunk,—that trunk which was like unto a rope of silver; climbed up on the Great Being’s temples,—those temples which were like unto the snow-clad peaks of Kelāsa, with his heel kicking the tips of the tusks and loosening the flesh; and having mounted the temples, with a sharp saw severed the stumps of the tusks, and went his way.

But even as that wicked man receded from the[24] vision of the Future Buddha, the solid earth, which extends for a distance of two hundred thousand leagues and four Inconceivables more, which is able to endure such mighty burdens as Sineru and Yugandhara, and all manner of foul-smelling and repulsive objects,—even the solid earth, as if unable to endure the wickedness he had piled upon it, burst asunder and yawned. Instantly from the Great Waveless Hell flames of fire shot forth, enveloped that man, that betrayer of friends, wrapping him, as it were, in a blanket proper for death and laid hold of him.

When that wicked man thus entered the earth, the tree-spirit resident in that forest-grove thought: “An ungrateful man, a man who will betray his friends, cannot be satisfied, even if he be given the kingdom of a Universal Monarch.” And making the forest ring, proclaiming the Truth, the tree-spirit uttered the following stanza:

Thus did that tree-spirit, making the forest ring, proclaim the Truth. The Future Buddha, having remained on earth during the term of life allotted to him, passed away according to his deeds.

[25]Said the Teacher: “Monks, not only in his present state of existence has Devadatta proved ungrateful; in a previous state of existence also he was ungrateful just the same.” Having completed the parable, he identified the personages in the Birth-story as follows: “At that time the man who betrayed his friend was Devadatta, the tree-spirit was one of my disciples, but Good King Elephant was I myself.”

The biter bit.

Jātaka 357: iii. 174-177.

Hearing that the monks of Kosambi were quarreling, the Exalted One went to them and said: “Enough, monks! No quarreling! No brawling! No contending! No wrangling!” Then he said: “Monks, quarrels, brawls, contentions, wrangles,—all these are unprofitable. For because of a quarrel even a tiny quail brought about the destruction of a noble elephant.”

In times past, when Brahmadatta ruled at Benāres, the Future Buddha was reborn as an elephant. He grew up to be a fine big animal, acquired a retinue of eighty thousand elephants, and becoming the leader of a herd, made his home in the Himālaya region. At that time a tiny female quail laid her eggs in the elephants’ stamping-ground. When the eggs were hatched, the fledglings broke the shells and came out. Before their wings had grown and while they were yet unable to fly, the Great Being came to that spot with his retinue of eighty thousand elephants in search of food.

When the tiny quail saw him, she thought: “This elephant-king will crush my fledglings and kill them. Well, I will ask of him righteous protection for the defense of my little ones.” So folding her[27] wings and standing before him, she uttered the first stanza:

Said the Great Being: “Do not worry, tiny quail; I will protect your little ones.” And he stood over the fledglings, and the eighty thousand elephants passed by. Then he addressed the tiny quail: “Behind us comes a single solitary elephant; he will not obey our command. If you ask him also when he comes, you may obtain safety for your little ones.” So saying, he went his way.

The tiny quail went forth to meet the solitary elephant, did homage to him with her wings, and uttered the second stanza:

The solitary elephant, hearing her words, uttered the third stanza:

[28]So saying, he pulverized her little ones with his foot, and went his way trumpeting. The tiny quail perched on the branch of a tree and thought: “Just now you go your way trumpeting. In only a few days you will see what I can do! You do not understand that the mind is stronger than the body. Ah, but I will make you understand!” And threatening him, she uttered the fourth stanza:

Thus spoke the tiny quail. For a few days she ministered to a crow. The crow was pleased and said: “What can I do for you?” Said the tiny quail: “Master, there is only one thing I want done. I expect you to peck out the eyes of that solitary elephant.” “Very well,” assented the crow. The tiny quail then ministered to a green fly. The fly also said, “What can I do for you?” Said the tiny quail: “When this crow has put out the eyes of the solitary elephant, I wish you would drop a nit on them.” “Very well,” assented the fly also. The tiny quail then ministered to a frog. Said the frog: “What can I do?” Said the tiny quail: “When this solitary elephant has gone blind and seeks water to drink, then[29] please squat on the mountain-top and croak; and when he has climbed to the top of the mountain, then please hop down and croak at the bottom. This is all I expect of you.” The frog also, hearing her words, assented, saying, “Very well.”

Now one day the crow pecked out both of the elephant’s eyes, and the fly let a nit drop on them. The elephant, eaten up by maggots, maddened with pain, overcome with thirst, wandered about seeking water to drink. At that moment the frog, squatting on the mountain-top, let out a croak. The elephant thought: “There must be water there;” and climbed the mountain. Then the frog hopped down, and squatting at the bottom, let out a croak. The elephant thought: “There must be water there.” And going to the brink of the precipice, he tumbled and fell to the foot of the mountain, and met destruction.

When the tiny quail realized that he was dead, she cried out: “I have seen the back of my enemy!” And pleased and delighted, she strutted over his shoulders, and passed away according to her deeds.

In union there is strength.

Jātaka 33: i. 208-210.

Then said the Exalted One to those monks: “Monks, be united; do not wrangle. For because of a wrangle many thousand quails lost their lives.”

In times past, when Brahmadatta ruled at Benāres, the Future Buddha was reborn as a quail, and lived in the forest with a retinue of many thousand quails. At that time a certain quail-hunter used to go to the haunt of the quails and attract them by imitating a quail’s whistle. When he perceived that they had assembled, he would throw a net over them and huddle them all together by trampling the edges. Then he would fill his basket, go home, and sell them. Thus he made his living.

Now one day the Future Buddha said to those quails: “This fowler is bringing our kinsfolk to destruction. I know a way by which he shall not be able to catch us. From this time on, the moment he throws the net over you, let each quail stick his head through a single mesh, lift the net, and carrying it wherever you will, let it down on some thorn-brake. This done, we can escape each through his own mesh.” They all assented, saying, “Very well!”

[31]When the net was thrown over them on the following day, they raised the net precisely as the Future Buddha had told them to, dropped it on a certain thorn-brake, and themselves escaped from under. Twilight came on with the fowler still busy disentangling the net from the brake, and he went away absolutely empty-handed. On the next day, and thereafter also, the quails did the very same thing. The fowler also, busy every moment until sunset disentangling the net, got nothing, and went home absolutely empty-handed.

Now his wife got angry and said: “Day after day you return empty-handed; I suppose there is some other household outside you have to provide for too.” Said the fowler: “My dear, there is no other household I have to provide for. The fact is, these quails are acting in unison. The moment I throw the net, they depart with it and drop it on a thorn-brake. But they will not live in unity forever. Do not worry. When they fall to wrangling, I will return with them all and bring a smile to your lips.” And he recited the following stanza to his wife:

Now after only a few days had passed, one quail, lighting on the feeding-ground, accidentally trod on the head of another. The other was offended and[32] said: “Who trod on my head?” “I did, but accidentally; do not be offended.” But the other was offended just the same. They bandied words and wrangled with each other, saying, “You alone, I suppose, lift the net!”

While they wrangled, the Future Buddha thought: “There is no safety for a wrangler. From this moment they will not lift the net. Then they will come to a sorry end. The fowler will get his chance. It is impossible for me to live in this place.” And he went elsewhere with his own retinue.

As for the fowler, he came back after a few days, imitated a quail’s whistle, and when the quails had assembled, threw the net over them. Then said one quail: “They say that in the very act of lifting the net, you lost the down on your head. Now lift!” Said another: “They say that in the very act of lifting the net, you lost your wing-feathers. Now lift!”

Even as they said: “You lift!” “You lift!” the fowler tossed the net. And huddling them all together, he filled his basket, and went home and brought a smile to the lips of his wife.

And for the second time the Exalted One said this to those monks: “Enough, monks! No quarreling! No brawling! No contending! No wrangling!”

But in spite of this, they paid no attention to his words. Thereupon the Exalted One related the following Story of the Past:

Love your enemies.

Vinaya i. 342-349.

In olden times at Benāres, Brahmadatta king of Kāsi was rich, possessed of great wealth, ample means of enjoyment, a mighty army, many vehicles, an extensive kingdom, and well filled treasuries and storehouses. Dīghīti king of Kosala was poor, possessed of meagre wealth, scanty means of enjoyment, a small army, few vehicles, a little kingdom, and unfilled treasuries and storehouses.

Now Brahmadatta king of Kāsi drew up his fourfold army and went up against Dīghīti king of Kosala. And Dīghīti king of Kosala heard: “Brahmadatta king of Kāsi, they say, has drawn up his fourfold army, and is come up against me.” Then to Dīghīti king of Kosala occurred the following thought: “Brahmadatta king of Kāsi is rich, possessed of great wealth, ample means of enjoyment, a mighty army, many vehicles, an extensive kingdom, and well filled treasuries and storehouses. But I am poor, possessed of meagre wealth, scanty means of enjoyment, a small army, few vehicles, a little kingdom, and unfilled treasuries and storehouses.[34] I am not strong enough to withstand even a single clash with Brahmadatta king of Kāsi. Suppose I were merely to countermarch and slip out of the city!”

Accordingly Dīghīti king of Kosala took his consort, merely countermarched, and slipped out of the city. Thereupon Brahmadatta king of Kāsi conquered the army and vehicles and territory and treasuries and storehouses of Dīghīti king of Kosala, and took possession. And Dīghīti king of Kosala with his consort set out for Benāres, and in due course arrived at Benāres. And there, in a certain place on the outskirts of Benāres, Dīghīti king of Kosala resided with his consort, in a potter’s dwelling, in disguise, in the guise of a wandering ascetic.

Now in no very long time the consort of Dīghīti king of Kosala was with child. And this was her craving: She desired at sunrise to see a fourfold army drawn up, clad in armor, standing in a pleasant place, and to drink the rinsings of swords. Accordingly the consort of Dīghīti king of Kosala said this to Dīghīti king of Kosala: “I am with child, O king. And this craving has arisen within me: I desire at sunrise to see a fourfold army drawn up, clad in armor, standing in a pleasant place, and to drink the rinsings of swords.” “Whence are we, wretched[35] folk, to obtain a fourfold army drawn up, clad in armor, standing in a pleasant place, and the rinsings of swords?” “If, O king, I do not obtain my desire, I shall die.”

Now at that time the Brahman who was the house-priest of Brahmadatta king of Kāsi was a friend of Dīghīti king of Kosala. Accordingly Dīghīti king of Kosala approached the Brahman who was the house-priest of Brahmadatta king of Kāsi. And having approached, he said this to the Brahman who was the house-priest of Brahmadatta king of Kāsi: “Sir, your female friend is with child. And this craving has arisen within her: She desires at sunrise to see a fourfold army drawn up, clad in armor, standing in a pleasant place, and to drink the rinsings of swords.” “Very well, O king, we also will see the queen.”

Now the consort of Dīghīti king of Kosala approached the Brahman who was the house-priest of Brahmadatta king of Kāsi. The Brahman who was the house-priest of Brahmadatta king of Kāsi saw the consort of Dīghīti king of Kosala approaching even from afar. And seeing her, he rose from his seat, adjusted his upper robe so as to cover one shoulder only, and bending his joined hands in reverent salutation before the consort of Dīghīti king of Kosala, thrice breathed forth the utterance:[36] “All hail! A king of Kosala shall be born of thee! All hail! A king of Kosala shall be born of thee!” Then he said: “Be not distressed, O queen. You shall obtain your desire to see at sunrise a fourfold army drawn up, clad in armor, standing in a pleasant place, and to drink the rinsings of swords.”

Thereupon the Brahman who was the house-priest of Brahmadatta king of Kāsi approached Brahmadatta king of Kāsi. And having approached, he said this to Brahmadatta king of Kāsi: “Thus, O king, the signs appear: To-morrow at sunrise let the fourfold army be drawn up, clad in armor, standing in a pleasant place, and let the swords be washed.” Accordingly Brahmadatta king of Kāsi ordered his men: “Do as the Brahman who is my house-priest has said.” Thus the consort of Dīghīti king of Kosala obtained her desire to see at sunrise a fourfold army drawn up, clad in armor, standing in a pleasant place, and to drink the rinsings of swords. And when that unborn child had reached maturity, the consort of Dīghīti king of Kosala brought forth a son, and they called his name Dīghāvu. And in no very long time Prince Dīghāvu reached the age of reason.

Now to Dīghīti king of Kosala occurred the following thought: “This Brahmadatta king of Kāsi has done us much injury. He has robbed us of army[37] and vehicles and territory and treasuries and storehouses. If he recognizes us, he will cause all three of us to be put to death. Suppose I were to cause Prince Dīghāvu to dwell outside of the city!” Accordingly Dīghīti king of Kosala caused Prince Dīghāvu to dwell outside of the city. And Prince Dīghāvu, residing outside of the city, in no very long time acquired all the arts and crafts.

Now at that time the barber of Dīghīti king of Kosala resided at the court of Brahmadatta king of Kāsi. The barber of Dīghīti king of Kosala saw Dīghīti king of Kosala residing with his consort in a certain place on the outskirts of Benāres, in a potter’s dwelling, in disguise, in the guise of a wandering ascetic. When he saw him, he approached Brahmadatta king of Kāsi. And having approached, he said this to Brahmadatta king of Kāsi: “O king, Dīghīti king of Kosala is residing with his consort in a certain place on the outskirts of Benāres, in a potter’s dwelling, in disguise, in the guise of a wandering ascetic.”

Thereupon Brahmadatta king of Kāsi ordered his men: “Now then, bring Dīghīti king of Kosala with his consort before me.” “Yes, your majesty,” said those men to Brahmadatta king of Kāsi; and in obedience to his command brought Dīghīti king of Kosala with his consort before him. Then Brahmadatta[38] king of Kāsi ordered his men: “Now then, take Dīghīti king of Kosala with his consort, bind their arms tight behind their backs with a stout rope, shave their heads, and to the loud beating of a drum lead them about from street to street, from crossing to crossing, conduct them out of the South gate, hack their bodies into four pieces south of the city, and throw the pieces in the four directions.”

“Yes, your majesty,” said those men to Brahmadatta king of Kāsi; and in obedience to his command took Dīghīti king of Kosala with his consort, bound their arms tight behind their backs with a stout rope, shaved their heads, and to the loud beating of a drum led them about from street to street, from crossing to crossing.

Now to Prince Dīghāvu occurred the following thought: “It is a long time since I have seen my mother and father. Suppose I were to see my mother and father!” Accordingly Prince Dīghāvu entered Benāres, and saw his mother and father, their arms bound tight behind their backs, their heads shaven, being led about, to the loud beating of a drum, from street to street, from crossing to crossing. When he saw this, he approached his mother and father.

Dīghīti king of Kosala saw Prince Dīghāvu approaching even from afar. When he saw him, he said this to Prince Dīghāvu: “Dear Dīghāvu, do not[39] look long! Do not look short! For, dear Dīghāvu, hatreds are not quenched by hatred. Nay rather, dear Dīghāvu, hatreds are quenched by love.”

At these words those men said this to Dīghīti king of Kosala: “This Dīghīti king of Kosala is stark mad, and talks gibberish. Who is Dīghāvu to him? To whom did he speak thus: ‘Dear Dīghāvu, do not look long! Do not look short! For, dear Dīghāvu, hatreds are not quenched by hatred. Nay rather, dear Dīghāvu, hatreds are quenched by love’?” “I am not stark mad, I assure you, nor do I talk gibberish. However, he that is intelligent will understand clearly.” For the second and the third time Dīghīti king of Kosala spoke thus to Prince Dīghāvu, and those men spoke thus to Dīghīti king of Kosala.

Then those men led Dīghīti king of Kosala with his consort about from street to street, from crossing to crossing, conducted them out of the South gate, hacked their bodies into four pieces south of the city, threw the pieces in the four directions, posted a guard of soldiers, and departed.

Thereupon Prince Dīghāvu entered Benāres, procured liquor, and gave it to the soldiers to drink. When they were drunk and had fallen, he gathered sticks of wood, built a pyre, placed the bodies of his mother and father on the pyre, lighted it, and with[40] joined hands upraised in reverent salutation thrice made sunwise circuit of the pyre.

Now at that time Brahmadatta king of Kāsi was on an upper floor of his splendid palace. And Brahmadatta king of Kāsi saw Prince Dīghāvu, with joined hands upraised in reverent salutation, thrice making sunwise circuit of the pyre. When he saw this, the following thought occurred to him: “Without doubt that man is a kinsman or blood-relative of Dīghīti king of Kosala. Alas, my wretched misfortune, for no one will tell me the facts!”

Now Prince Dīghāvu went to the forest, wailed and wept his fill, and wiped his tears away. Then he entered Benāres, went to the elephant-stable adjoining the royal palace, and said this to the elephant-trainer: “Trainer, I wish to learn your art.” “Very well, young man, learn it.” Accordingly Prince Dīghāvu rose at night, at time of dawn, and sang and played the lute with charming voice in the elephant-stable.