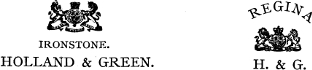

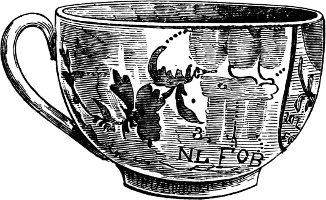

with, sometimes, the

initial of the house for whom they are made, as for “Keiller,” and so

on.

with, sometimes, the

initial of the house for whom they are made, as for “Keiller,” and so

on.

FROM PRE-HISTORIC TIMES DOWN TO THE PRESENT DAY

BEING A HISTORY OF THE ANCIENT AND MODERN

POTTERY AND PORCELAIN WORKS

OF THE KINGDOM

AND OF THEIR PRODUCTIONS OF EVERY CLASS

BY

LLEWELLYNN JEWITT, F.S.A.

LOCAL SECRETARY OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF LONDON;

HON. AND ACTUAL MEMBER OF THE RUSSIAN IMPERIAL ARCHÆOLOGICAL COMMISSION, AND STATISTICAL

COMMITTEE, PSKOV;

MEMBER OF THE ROYAL ARCHÆOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND;

ASSOCIATE OF THE BRITISH ARCHÆOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION;

HON. MEMBER OF THE ESSEX ARCHÆOLOGICAL SOCIETY AND OF THE MANX SOCIETY, ETC.;

COR. MEMBER OF THE ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY,

ETC. ETC. ETC.

ILLUSTRATED WITH NEARLY TWO THOUSAND ENGRAVINGS

IN TWO VOLUMES.—II.

LONDON

VIRTUE AND CO., Limited, 26, IVY LANE

PATERNOSTER ROW

1878

[All rights reserved.]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY VIRTUE AND CO., LIMITED,

CITY ROAD.

[All rights reserved.]

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| Potteries of the Tyne, Tees, and Wear—Newcastle-on-Tyne—Warburton Pottery—Newcastle Pottery or Forth Banks Pottery—Stepney Bank Pottery—Ouseburn Bridge Pottery—Ouseburn Ford Pottery—Ouseburn Potteries—Low Pottery—South Shore Pottery—Phœnix Pottery—St. Peter’s Pottery—Gateshead—Carr’s Hill Pottery—St. Anthony’s Pottery—Sherriff Hill Pottery—Tyne Main Pottery—North Shields—Low Light Pottery—South Shields—Tyne or Shields Pottery—North Hylton—South Hylton or Ford—Southwick Pottery—Wear Pottery—High Southwick Pottery—Deptford Pottery—Monkwearmouth—Sheepfold Pottery—Sunderland Pottery and the Garrison Pottery—Seaham Harbour—Newbottle—Bishop Auckland—New Moor Pottery—Stockton-on-Tees—Stafford Pottery—North Shore Pottery—Middlesborough-on-Tees—Wolviston Pottery—Coxhoe Pottery—Alnwick | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Liverpool Pottery—Shaw’s Delft Ware—Shaw’s Brow—Zachariah Barnes—Sadler and Green—Transfer Printing—Wedgwood’s Printed Ware—Drinkwater’s Works—Spencer’s Pottery—Richard Chaffers—Reid and Co.’s Works—The Penningtons—Patrick’s Hill Works—The Flint Pottery—Herculaneum Works—Warrington Pottery and China—Runcorn—Prescot—St. Helen’s—Seacombe | 18 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

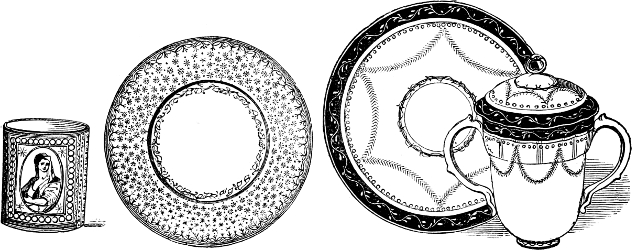

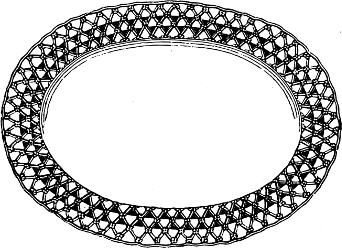

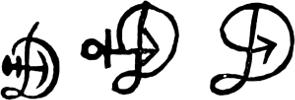

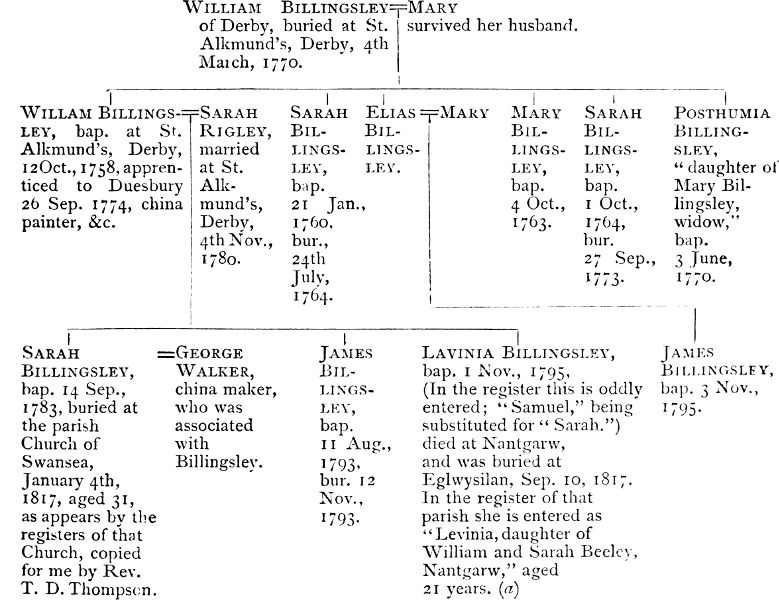

| Derby—Cock-pit Hill—Mayer—Heath—Derby China—Andrew Planche—Duesbury and Heath—William Duesbury—Purchase of the Chelsea Works—Weekly Bills—Show Rooms in London—Sales by Candle—Changes in Proprietorship—Bloor—Locker—Stevenson & Co.—Hancock—Painters and Modellers—Spengler—Coffee—Askew—Billingsley—Pinxton—Nantgarw—Swansea—Other Artists employed at Derby—Cocker and Whitaker’s China Works, &c., &c. | 56 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

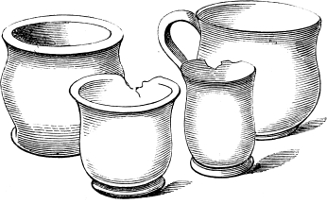

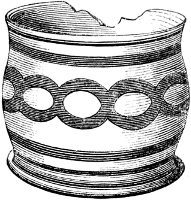

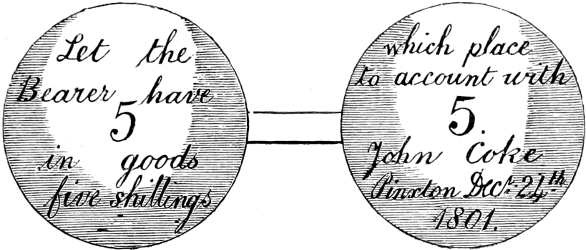

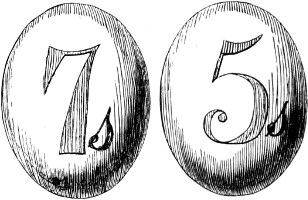

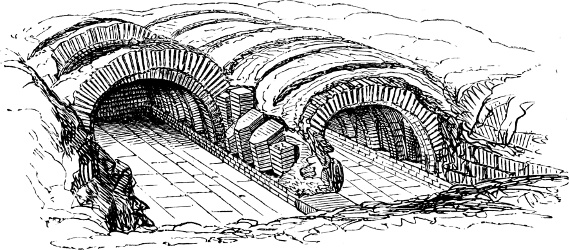

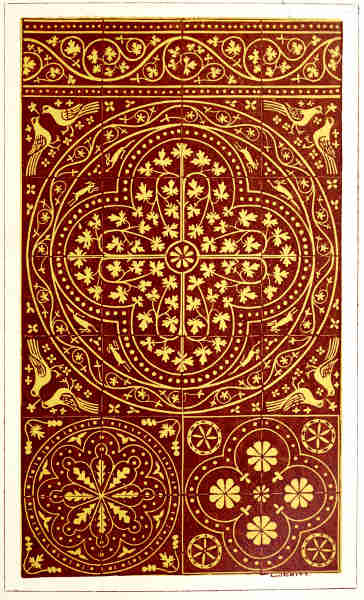

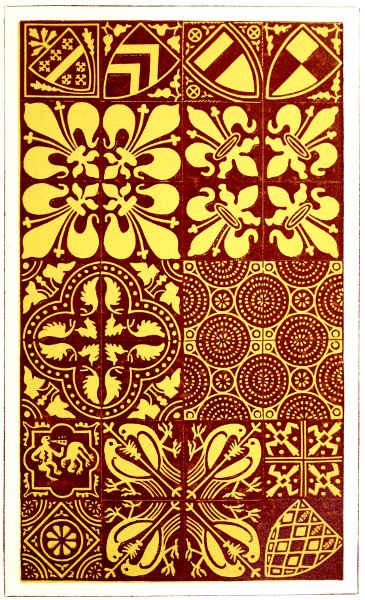

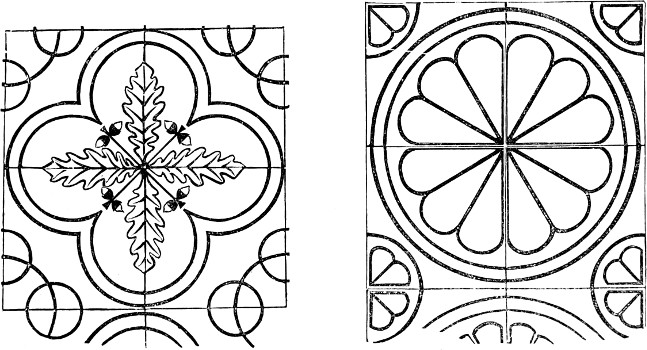

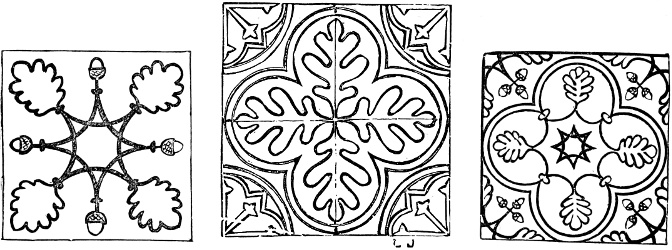

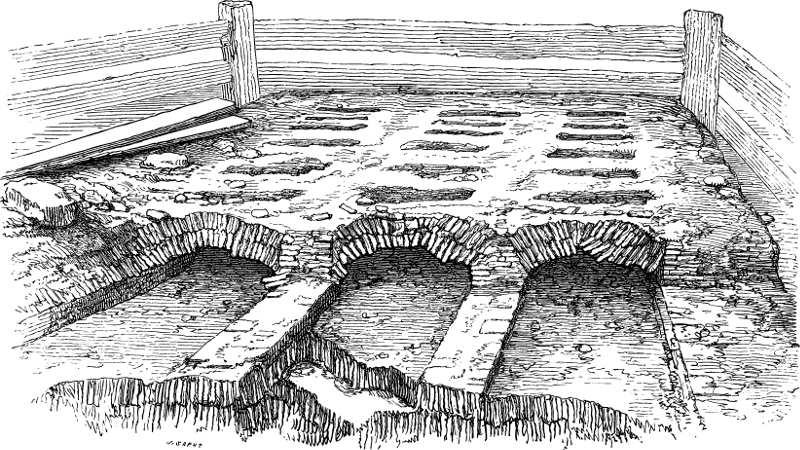

| Chesterfield—Caskon—Heathcote—Brampton—Posset Pots—Puzzle Jugs—Welshpool and Payne Potteries—The Pottery—Walton Pottery—Wheatbridge Pottery—Alma, Barker, and London Potteries—Whittington—Bromley—Jewitt—Newbold—Eckington—Belper—Codnor Park—Denby—Bournes Pottery—Shipley—Alfreton—Langley Mills—Ilkeston—Pinxton—Pinxton China—China Tokens—Wirksworth—Dale Abbey—Repton—Encaustic Tiles—Tile Kilns, London—Tickenhall—Kings Newton—Burton-on-Trent—Swadlincote Potteries—Church Gresley Potteries—Gresley Common—Woodville—Hartshorne, &c.—Wooden Box—Rawdon Works—Pool Works—Coleorton—&c., &c. | 115 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

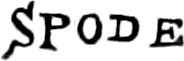

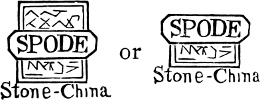

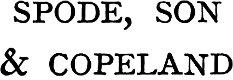

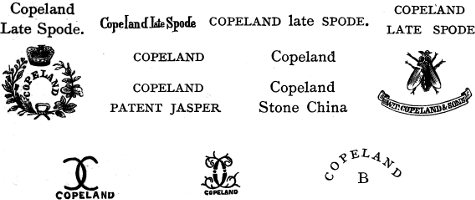

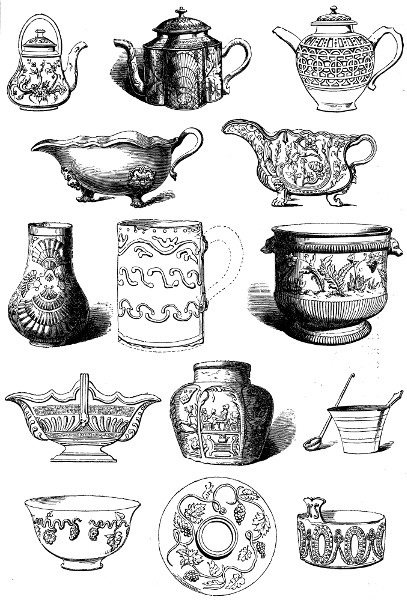

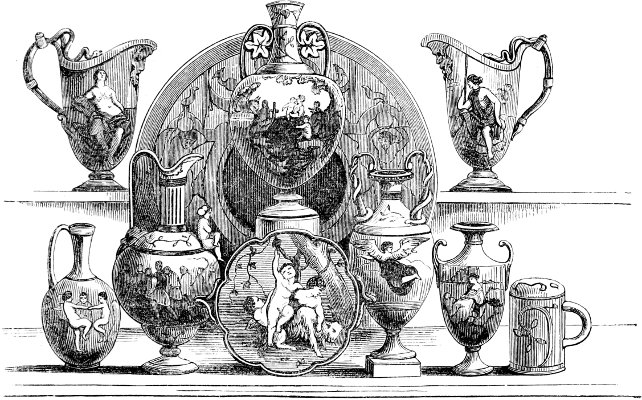

| Stoke-upon-Trent—Josiah Spode—Copeland and Garrett—Copeland and Sons—Mintons—Hollins—Trent Pottery; Jones—Albert Street Works—Copeland Street Works—Glebe Street and Wharf Street Works—Copeland Street—Bridge Works—London Road; Goss—Kirkham—Campbell Brick and Tile Company—Harrison and Wedgwood—Bankes—Hugh Booth—Ephraim Booth—Wolf—Bird—Adams and Son—H. and R. Daniel—Boyle—Reade—Lowndes and Hall | 167 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

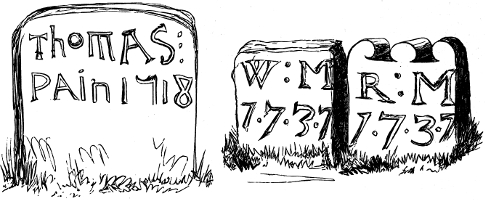

| Burslem—Early Potters—Earthenware Gravestones—Toft—Talor—Sans—Turnor—Shawe—Mitchell—Cartwright—Rich—Wood—Wood & Caldwell—Churchyard Works—Bell Works—Red Lion Works—Big House—Ivy House—Lakin & Poole—Waterloo Works—Boote & Co.—Washington Works—Nile Street Works—Newport Pottery—Dale Hall—Stubbs—Bates—Walker & Co.—Mayer & Co.—Dale Hall Pottery—Rogers—Edwards & Son—Dale Hall Tile Company—Albert Street Works—Mersey Pottery—Steel—Maddock & Son—New Wharf Pottery—Over House Works—Swan Bank Pottery—Hill Top Pottery—Hill Pottery China Works—Crown Works—Scotia Works—Queen Street Works—Hill Works—Ralph Wood—Sylvester Pottery—High Street Pottery—Sneyd Pottery—Hadderidge Pottery—Navigation Works—Sytch Pottery—Kiln Croft Works—Albert Pottery—Waterloo Works—Central Pottery—Longport—Davenports—Terra Cotta—Brownhills—Wood—Littler—Marsh and Heywood—Brownhills Pottery Company—Cobridge—Cobridge Works, Brownfields—Clews—Furnivals—Bates & Bennett—Abbey Pottery—Villa Pottery—Cockson & Seddon—Alcock & Co.—Elder Road Works—Warburton—Daniel, &c. | 236 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Hanley and Shelton—Miles—Phillips—Astbury—Baddeley—Edwards—Voyez—Palmer—Neale—Wilson—New Hall Works—Hollins—Keeling—Turner—Warburton—Clowes—Bagnall—New Hall Company—Richard Champion—Glass—Twyford—Mare—Twemlow—Old Hall Works—Meigh—Broad Street Works—Mason—Ashworth—Cauldon Place—Ridgways—Browne-Westhead & Co.—Trent Pottery—Keeling—Booth & Co.—Stafford Street Works—Church Works—Waterloo Works—Kensington Works—Burton Place Works—Clarence Street Works—Nelson Place—Phœnix and Bell Works—Bedford Works—Mayer Street—Cannon Street Works—Brewery Street—Percy Street Works—Taylor, Tunnicliffe & Co.—Biller & Co.—Albion Works—Eastwood Vale—Eastwood Works—Dental Manufacturing Company—Trent Pottery—James Dudson—Victoria Works—Charles Street Works—High Street—Eagle Works—Brook Street Works—Cannon Street—William Stubbs—Norfolk Street Works—Broad Street—Albert Works—Ranelagh Works—Swan Works—Mayer Street Works—Brook Street Works—Dresden Works—Bath Street Works—Waterloo Works—New Street Pottery—Castle Field Pottery—Henry Venables | 298 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

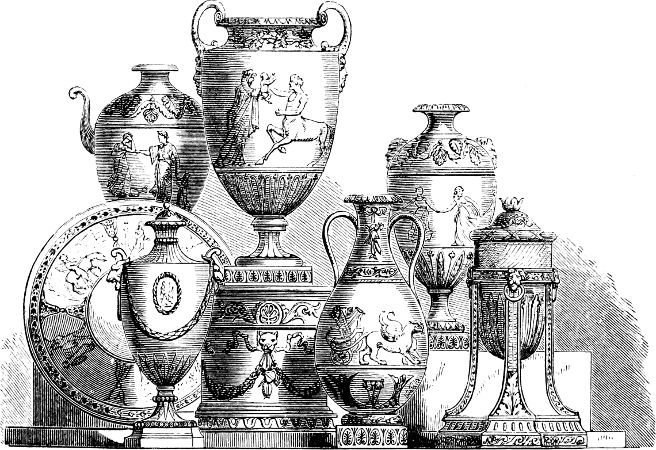

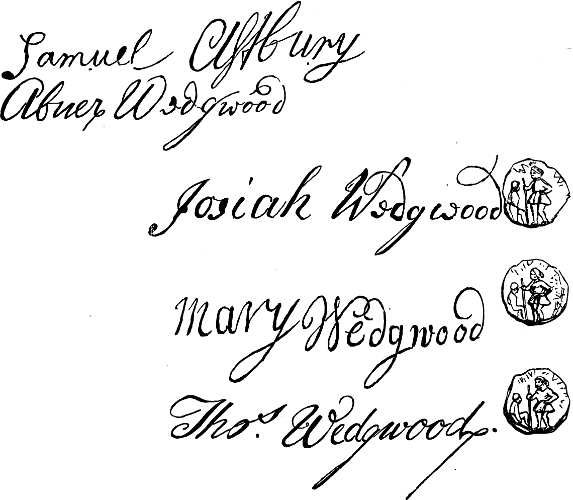

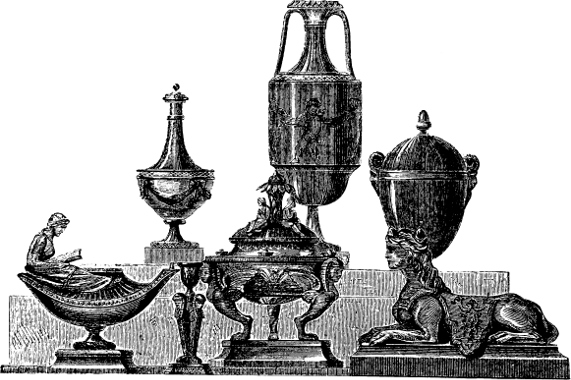

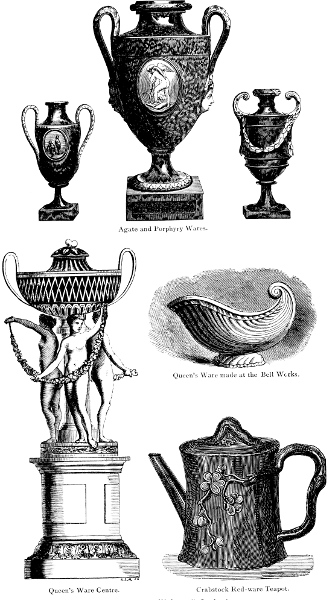

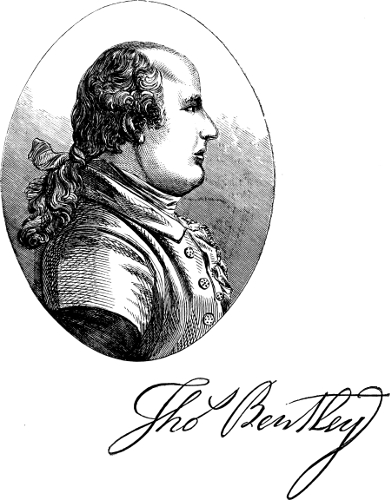

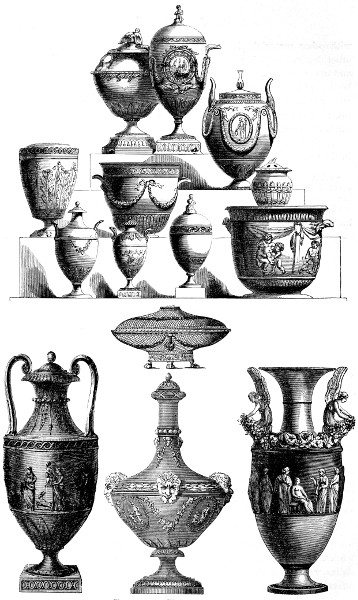

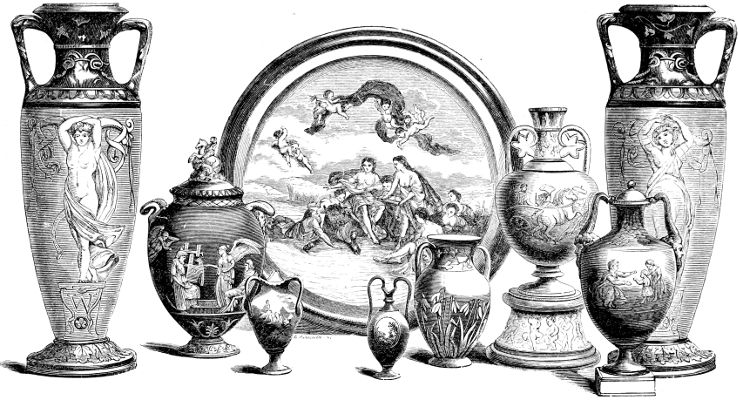

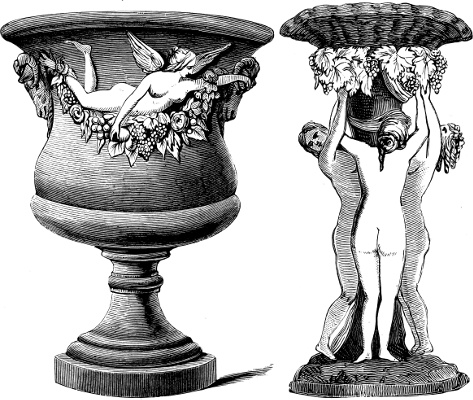

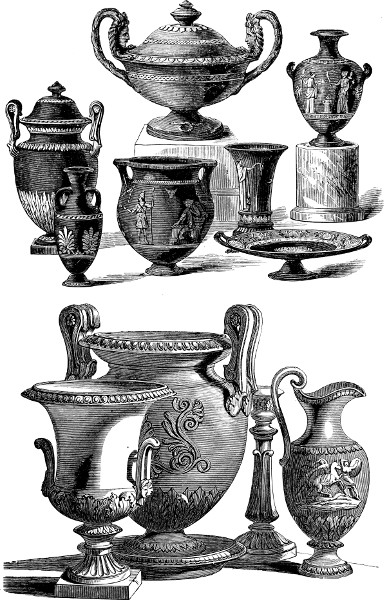

| Etruria—Josiah Wedgwood—The Wedgwood Family—Indenture of Apprenticeship—Ridge House Estate—Etruria Works founded—Thomas Bentley—Flaxman—Catalogues of Goods—Jasper and other Wares—Portland Vase—Monument to Josiah Wedgwood—Marks—Various productions of the Works—M. Lessore | 345 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Longton—Sutherland Road Works—Market Street Works—High Street Works—Park Works—Sheridan Works—Commerce Street Works—Crown Works—Stafford Street Works—Peel Pottery—King Street Works—Chancery Lane Works—St. Mary’s Works—Commerce Street—New Town Pottery—Borough Pottery—High Street—New Street—Prince of Wales Pottery—High Street Works—Alma Works—Market Street—Victoria Works—Stafford Street—Russell Street—Mount Pleasant Works—High Street—British Anchor Works—Royal Porcelain Works—Stafford Street—St. Gregory’s Pottery—Gold Street Works—Wellington Works—St. Martin’s Lane—Heathcote Works—Green Dock Works—Chadwick Street—Baddeley—Waterloo Works—Heathcote Road Pottery—Sutherland Potteries—Church Street—Cornhill Works—Sutherland Works—St. James’s Place—Daisy Bank—Park Hall Street—Viaduct Works—Beech, King Street—Anchor Pottery—Dresden Works—Palissy Works—Fenton, Minerva Works—Victoria Works—Fenton Potteries—Fenton Pottery—Foley—Old Foley Pottery—Anchor Works—Fenton Potteries—Lane Delph Pottery—Grosvenor Works—Park Works—Foley Pottery—Foley Potteries—Foley China Works—King Street Works—Heath—Bacchus—Meir—Harrison—Martin—Miles Mason—Whieldon—Wedgwood & Harrison—Turner—Garner—Edwards—Johnson—Phillips—Bridgwood—Greatbach—Greenwood—Heathcote, &c. | 386 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Tunstall—Early Potters—Enoch Booth—Child—Winter—Unicorn and Pinnox Works—Greenfield Works—Newfield Works—George Street Pottery—Phœnix Works—Sandyford—Lion Works—Victoria Works—Swan Bank Works—Church Bank Works—Well Street Works—Old Works—Black Bank—High Street Works—Woodland Pottery—Greengate Pottery—Sandyford Works—Tunstall Works—Highgate Pottery—Clay Hill Pottery—Royal Albert Works—Soho Works—Marshall & Co.—Walton—Stevenson—Birch—Eastwood—Shorthose & Co.—Heath & Son—Newcastle-under-Lyme—Tobacco-pipes—Charles Riggs—Garden Edgings—Thomas Wood—Terra Cotta Works—Armitage—Lichfield—Penkhull, &c. | 423 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

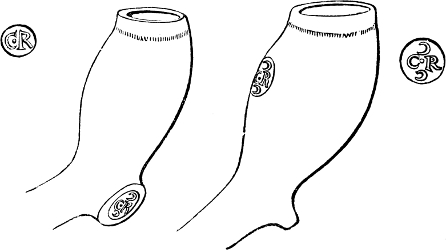

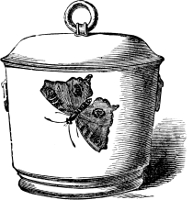

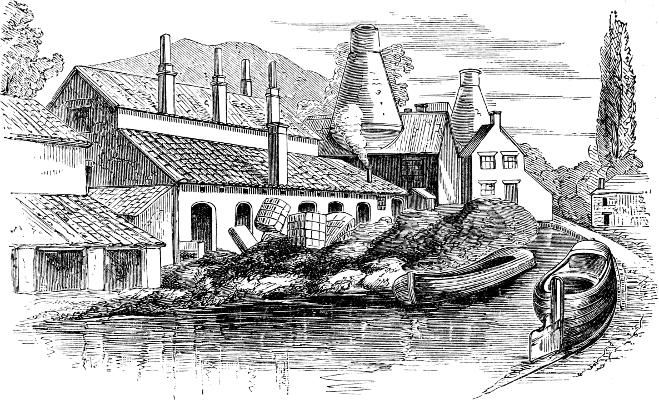

| Swansea—Cambrian Pottery—Dillwyn’s Etruscan Ware—Swansea China—Glamorgan Pottery—Rickard’s Pottery—Landore Pottery—Llanelly—South Wales Pottery—Ynisymudw—Terra Cotta Works—Nantgarw—Billingsley—Nantgarw China—Brown and Stoneware Potteries—Cardigan—Cardigan Potteries—Hereford—Lugwardine Tile Works—Torquay—Terra Cotta Works—Alderholt—Smethwick—Reading—Coley Avenue Works—Wakefield Moor—Houghton’s Table of Clays—Ditchling Pottery, &c.—Amblecote—Leicester—Spinney Hill Works—Wednesbury—Winchester—Aylesford—Exeter—Lincoln | 435 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Irish Ceramics—Early Pottery of Ireland—The Cairns—The Crannogs—Mediæval Pottery of Ireland—Dublin—Delamain—Stringfellow—Grants by Irish Parliament—Donovan—Delft Ware—Brown Ware Manufactories—Belfast—Leathes and Smith—Delft Ware—Coates’ Pottery—China Works—Florence Court Pottery—Coal Island Pottery—Youghal Pottery—Captain Beauclerc’s Terra Cotta—Larne Pottery Works—Castle Espie Pottery—Belleek China and Earthenware Works, &c. | 459 |

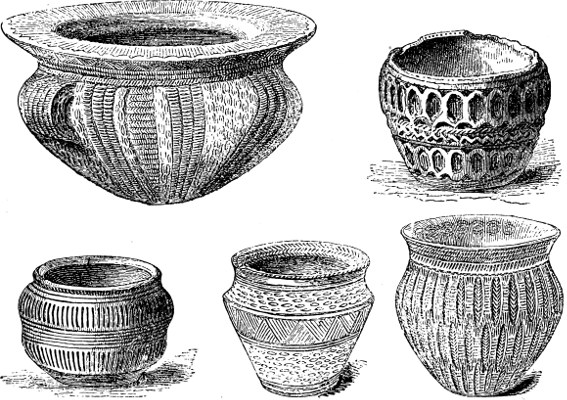

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

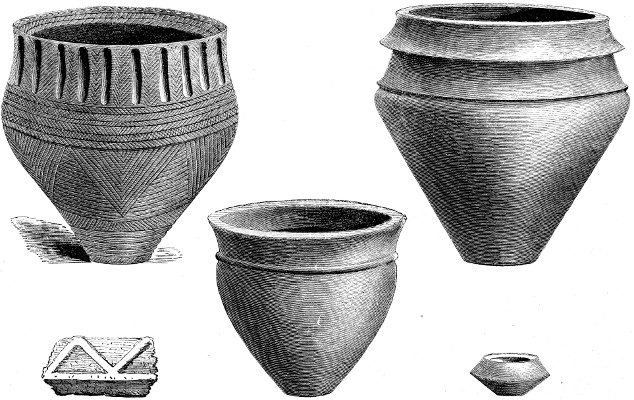

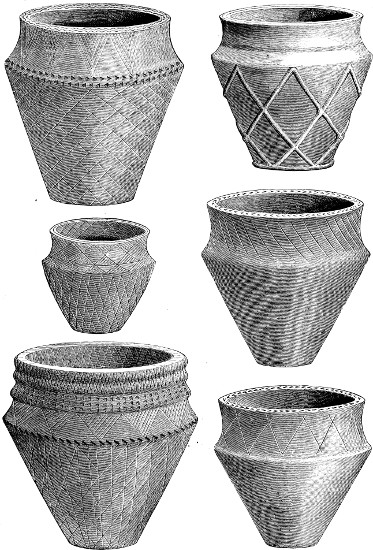

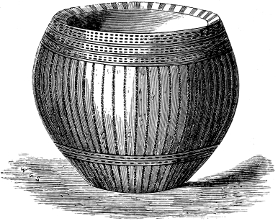

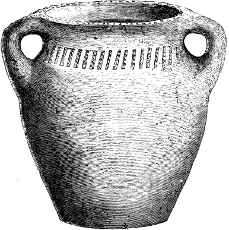

| Early Pottery of Scotland—Cinerary Urns—Mediæval Pottery—Glasgow—Delft Ware—Verreville Pottery—Garnkirk Works—Gartcosh Works—Heathfield Pottery—Glasgow Pottery—North British Pottery—Saracen Pottery—Port Dundas Pottery Company—Hyde Park Potteries—Britannia Pottery—Annfield Pottery—Bridgeton Pottery—Barrowfield Pottery—Coatbridge—Glenboig Star Works—Glenboig Fire-Clay Works—Cardowan and Heathfield Works—Paisley—Ferguslie Works—Shortroods and Caledonia Works—Paisley Earthenware Works—Crown Works—Grangemouth—Fire-brick Works—Greenock—Clyde Pottery—Dumbarton—Rutherglen—Caledonia Pottery—Portobello—Midlothian Potteries—Portobello Pottery—Kirkcaldy—Sinclairtown Pottery—Kirkcaldy Pottery—Gallatown Pottery—Boness—Boness Pottery—Prestonpans Pottery—Alloa—Alloa Pottery—The Hebrides | 499 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| A List of Patents relating to Ceramics from 1626 to 1877 | 524 |

[1]

CERAMIC ART IN GREAT BRITAIN.

Potteries of the Tyne, Tees, and Wear—Newcastle-on-Tyne—Warburton Pottery—Newcastle Pottery or Forth Banks Pottery—Stepney Bank Pottery—Ouseburn Bridge Pottery—Ouseburn Ford Pottery—Ouseburn Potteries—Low Pottery—South Shore Pottery—Phœnix Pottery—St. Peter’s Pottery—Gateshead—Carr’s Hill Pottery—St. Anthony’s Pottery—Sherriff Hill Pottery—Tyne Main Pottery—North Shields—Low Light Pottery—South Shields—Tyne or Shields Pottery—North Hylton—South Hylton or Ford—Southwick Pottery—Wear Pottery—High Southwick Pottery—Deptford Pottery—Monkwearmouth—Sheepfold Pottery—Sunderland Pottery and the Garrison Pottery—Seaham Harbour—Newbottle—Bishop Auckland—New Moor Pottery—Stockton-on-Tees—Stafford Pottery—North Shore Pottery—Middlesborough-on-Tees—Wolviston Pottery—Coxhoe Pottery—Alnwick.

The following brief account of the earthenware works of Newcastle-upon-Tyne and its district, drawn up for the British Association, in 1863, by Mr. C. T. Maling, one of the manufacturers, may serve as an introduction to this chapter. “The manufacture of white earthenware was introduced into this district by Mr. Warburton, at Carr’s Hill Pottery, near Gateshead, about 1730 or 1740. Those works were very successfully carried on for seventy years, when they gradually declined, and in 1817 were closed. A small portion of the building is still used as a brown ware pottery. The next manufactory was built by Mr. Byers, at Newbottle, in the county of Durham, about 1755, where brown and white earthenware still continues to be made. In 1762, Messrs. Christopher Thompson and John Maling erected works at North Hilton, in the county of Durham; their successor, Mr. Robert Maling, in 1817 transferred his operations to the Tyne, where his descendants still continue the manufacture. St. Anthony’s, Stepney Bank, and Ouseburn Old Potteries were commenced about the year 1780 or 1790. Messrs. A. Scott & Co. and Messrs. Samuel Moore & Co. erected potteries at Southwick, near Sunderland, the former in the year 1789, the latter in 1803. The pottery carried on by Messrs. John Dawson & Co., at South Hylton, was built by them in 1800. The works of Messrs. John Carr & Sons, at North, Shields, were[2] erected in 1814. Messrs. Thomas Fell & Co. built St. Peter’s Pottery in 1817. The establishment of Messrs. Skinner & Co., Stockton-on-Tees, dates from 1824. There are now about twenty-five potteries in this district, of which, on the Tyne, six manufacture white and printed wares, four white, printed, and brown wares, and three brown ware only, employing 1,200 people, and manufacturing yearly about 12,000 tons of white clay and 3,000 tons of brown clay, and consuming in the process of manufacture about 34,000 tons of coals. On the Wear there are two potteries manufacturing white and printed wares, two white, printed, and brown wares, and two brown ware only, employing about 500 people, manufacturing yearly about 4,000 tons of white clay, 1,500 tons of brown clay, and consuming in the manufacture about 14,000 tons of coals. On the Tees there are four potteries manufacturing white and printed wares, employing 500 people, manufacturing 5,000 tons of white clay and consuming 13,000 tons of coals. Two potteries at Norton manufacture brown wares; the particulars of their operations the author has not been able to obtain. The potteries in this district, being situated upon navigable rivers, have great advantages over their inland competitors, Staffordshire and Yorkshire. The expenses on clay from sea freight and inland carriage average 13s. per ton to Staffordshire, and 5s. per ton to this district; and in flints the advantage is still greater, in Staffordshire the average being 19s. per ton against 4s. 6d. per ton here. Coals, although a little dearer here per ton, are so much superior in quality that 80 tons of Newcastle coals are equal to 100 tons of Yorkshire or Staffordshire coals. About 1858 Messrs. Skinner & Co., of Stockton-on-Tees, first applied Needham & Kite’s patent filtering press for expelling the surplus water from the slip, which had formerly been done by evaporation. This is a much cleaner and better process than the old system, and is now adopted by thirty or forty potteries in England and Scotland. With the exception of three potteries in this district and at Glasgow, machinery has been very little applied to the manufacture of earthenware, and even at these works not nearly to the extent to which it is capable of being profitably adopted. One manufactory on the Tyne, Ford Pottery, having the best machinery, supplies at least 80 per cent. of the jars used by confectioners for marmalade and jam, &c., in England and Scotland. The description of goods manufactured in this district is that used by the middle and working classes, no first class goods being made here. The principal markets,[3] in addition to the local trade, are the Danish, Norwegian, German, Mediterranean, and London, for exportation to the colonies. The trade to the United States being so very small from here, the American war has affected this district less than any other.”

The potteries of the Tyne are:—

Warburton Pottery was established about 1730; its site was on Pandon Dean, Newcastle-on-Tyne. Coarse ware was, I believe, its only product. It was removed between 1740 and 1750 to Carr’s Hill, Gateshead (which see).

Newcastle Pottery, or Forth Banks Pottery, commenced operations about 1800, by Messrs. Addison and Falconer. Some years after it passed into the occupation of Messrs. Redhead, Wilson, and Co., then Messrs. Wallace and Co., who now make only brown ware, but formerly manufactured white and printed ware also.

The Stepney Bank Pottery was established about 1780 or 1790, for the production of the common earthenware. In 1801 it was occupied by Messrs. Head and Dalton; in 1816 by Messrs. Dryden, Coxon, and Basket; in 1822 by Messrs. Davies, Coxon, and Wilson; in 1833 by Messrs. Dalton and Burn, who were succeeded by Mr. G. R. Turnbull, by whom the character of the ware was considerably improved. About 1872 the works passed into the hands of Mr. John Wood, who produces both white and brown ware.

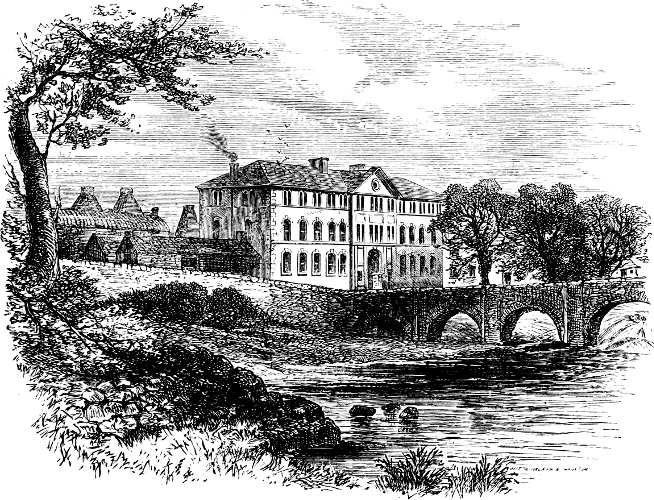

Ouseburn Bridge Pottery was commenced in 1817, by Mr. Robert Maling (see North Hylton Pottery), who manufactured white and printed ware chiefly for the Dutch market. He was succeeded, in 1853, by his son, C. T. Maling, who in 1859 built Ford Pottery, and discontinued his old works. They were re-opened under the name of the Albion Pottery, by Bell Brothers, about 1863; next by Atkinson and Galloway, and lastly by Mr. W. Morris, and were finally closed in 1872.

[4]

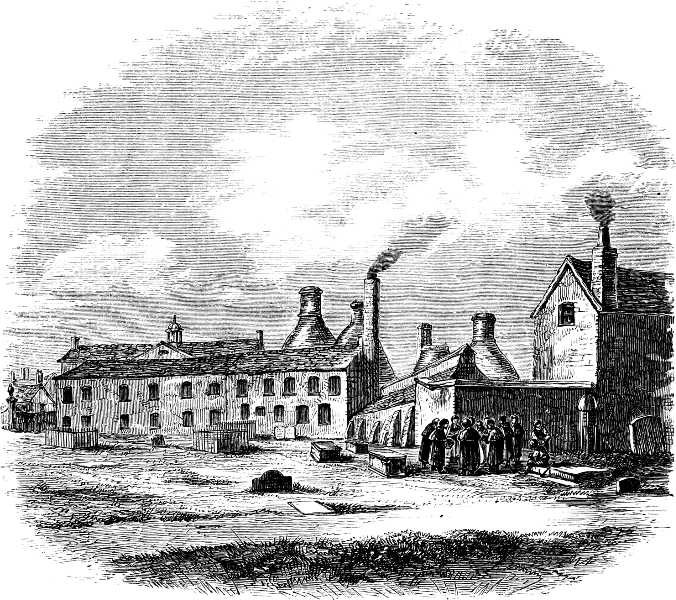

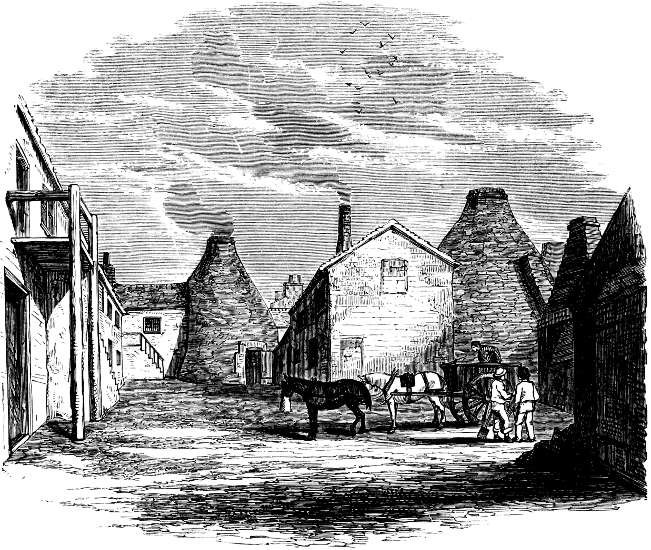

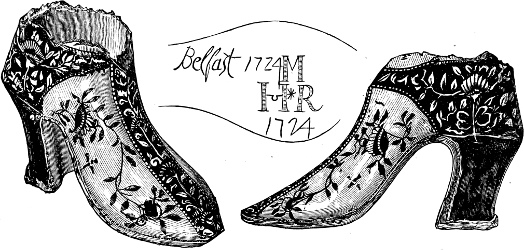

Ford Pottery.—This pottery was built in 1859 by Mr. Christopher

T. Maling, son of Mr. Robert Maling, who, in 1817, had removed the

Hylton pottery[1] to Newcastle. The works were erected for the purpose

of manufacturing by machinery the various goods produced by Mr. Maling,

the main bulk of which are marmalade, jam, and extract-of-beef pots.

These are of a very fine and compact white body, with an excellent

glaze made from borax without any lead; and it is said that at least

95 per cent. of these pots used by wholesale manufacturers in Great

Britain are made at this establishment. The pots being entirely made

by machinery are necessarily much more uniform in size and weight and

thickness than those produced by any other process, and these, as

well as the excellence of body and glaze, are advantages which have

been appreciated. The mark used is simply the name or MALING

impressed in the clay,

with, sometimes, the

initial of the house for whom they are made, as for “Keiller,” and so

on.

with, sometimes, the

initial of the house for whom they are made, as for “Keiller,” and so

on.

Ouseburn Pottery was built about the same date as Stepney Bank Pottery, by Mr. Yellowley, who was succeeded by Messrs. T. and J. Thompson, then by Mr. I. Maling; it was finally closed about 1864. White, printed, and brown ware were its productions.

Another “Ouseburn Pottery” was established, at the latter end of last or the early part of the present century, by Mr. Ralph Charlton, who carried on the business on a small scale for the manufacture of brown ware. On his death he was succeeded by his son, John Charlton, who after a few years gave up the business, and was succeeded by Mr. George Gray who, or his predecessor, enlarged the kilns, &c. Mr. Gray was succeeded in the business by Messrs. Morrow and Parker, from whose hands it passed into those of Mr. Rogers, who erected another kiln and otherwise extended the buildings. It was next worked by Mr. William Blakey, who held it until 1860, when it passed into the hands of Messrs. Robert Martin and Co., who still continue the business. The goods made are brown ware, and brown ware lined with white, in all the usual classes of domestic vessels.

Another “Ouseburn Pottery,” established some years ago, passed[5] in 1860 into the hands of Mr. John Hedley Walker. Its productions are plain and ornamented flower-pots, chimney-pots, and horticultural vessels of various kinds, as well as the lead-pots and lead-dishes which are so extensively used in the lead works of the district.

The Low Pottery, identical with the Ouseburn Pottery, now discontinued, was carried on by Messrs. Thompson Brothers, for the manufacture of white and Sunderland wares.

South Shore Pottery.—Now discontinued.

The Phœnix Pottery was built by John Dryden and Co., about 1821, for the manufacture of brown ware. White and printed ware were made afterwards. About 1844, it passed into the hands of Messrs. Isaac Bell and Co. for a short time; it was afterwards purchased and carried on by Messrs. Carr and Patton (who at same time had North Shields Pottery); it was then carried on by Mr. John Patton; next by Messrs. Cook Brothers, who discontinued manufacturing earthenware in 1860, and converted the premises into a Chemical Factory.

Mr. John Charlton had also a small manufactory in the Ouseburn.

St. Peter’s Pottery was established in 1817 by Messrs. Thomas

Fell and Thomas Bell under the style of “Thomas Fell & Co.,” by whom

it was carried on until 1869, when it became a limited liability

company under the same title; the shareholders being the descendants

of the original proprietors. The productions are still, as they have

always been, the ordinary classes of common earthenware, in white,

printed, and sponged varieties. The mark was formerly an anchor with

the letter F  (for “Fell”) on one side,

and the workman’s mark or number on the other, impressed in the body

of the ware. Later on this mark was discontinued, and the name FELL

substituted. Under the company only printed ware is marked, and that

bears the name FELL & Co.

(for “Fell”) on one side,

and the workman’s mark or number on the other, impressed in the body

of the ware. Later on this mark was discontinued, and the name FELL

substituted. Under the company only printed ware is marked, and that

bears the name FELL & Co.

St. Anthony’s Pottery.—This is one of the oldest potteries for fine ware on the Tyne, being established about 1780, but nothing is known as to its earlier history. In 1803 or 1804 it passed into the[6] hands of a Mr. Sewell, in whose family it has continued to the present day, under the styles of “Sewell & Donkin,” and “Sewell & Co.” The following particulars were furnished to me by the aged manager of the works, Mr. T. T. Stevenson:—

“I cannot go back to say when first begun as a Small White and Common Brown Ware Works, but about 1803 or 1804 it was taken by the Sewells, and gradually extended by them for Home trade until 1814 or 1815, when a considerable addition was made to manufacture entirely for exportation, chiefly C.C. or Cream Coloured, Painted, and Blue Printed, and when I came to the Works in 1819, the description of ware then produced say about five Gloss Ovens and two or three Enamel Kilns per week, say C.C. and best Cream Colour to imitate Wedgwood’s Table Ware then made in considerable quantities for Holland and other Continental markets, all kinds of Biscuit Painted, Printed very dark engraved patterns, also Stamping with Glue, and Printing on the Glaze from Wood Engravings, also with Glue, I believe the first that was done in this way, Gold and Silver lustre, &c. So it has been continued up to the present period by the Sewell family; but latterly not doing so much business, owing to a change of partnership, and is at present in the market for sale since the death of Mr. Henry Sewell, the natural son of the late Joseph Sewell, who was the Potter for nearly sixty years, and was a noble specimen of a good master and the old English gentleman.”

The fact of printing on pottery from wood engravings, being practised at these works, is highly interesting, as I have been enabled to ascertain that engravings by Bewick were thus brought into use; specimens are, however, very rare. In the Museum of Practical Geology are examples of St. Anthony’s ware; they bear the marks—

SEWELL SEWELL & DONKIN SEWELLS & DONKIN SEWELLS & CO.

The Carr’s Hill Pottery was the first manufactory for white ware in the North of England. Painted, enamelled, and brown ware was also made. It was established about 1750, by a Mr. Warburton, who removed to this place from Newcastle (see Warburton Pottery), and was successfully carried on by him and his successors until 1817, when it was closed. A part of the premises was afterwards carried on by Messrs. Kendall and Walker, and later still by Messrs. Isaac Fell and Co.

Sherriff Hill Pottery.—These works are carried on by Mr. George Patterson, as the successor of the firm of Jackson and Patterson. His chief productions are white ware, which are supplied largely to the Norwegian Markets.

[7]

Messrs. Lewins and Parsons are also stated to have had a pottery here for the manufacture of the common kinds of earthenware.

Tyne Main Pottery, on the opposite side of the river to St. Peter’s, was built by Messrs. R. Davies and Co., in the year 1833, and carried on by them, manufacturing white, printed, and lustre ware, chiefly for the Norwegian market. It was closed in 1851. Mr. R. C. Wilson, the managing partner, then commenced manufacturing at Seaham Harbour.

There was also a pottery at Heworth Shore, carried on by Patterson, Fordy, and Co. It was closed about 1835.

There was also a pottery at Jarrow for a few years, which manufactured brown ware only.

The “Low Light Pottery” was established in 1814, by Mr. Nicholas Bird, and afterwards passed from him, in or about 1829, to Messrs. Cornfoot, Colville, and Co. The firm was afterwards changed to Cornfoot, Patton, and Co., and on the withdrawal of Mr. Cornfoot, and the addition of Mr. John Carr, the style was changed to that of “Carr and Patten.” Next the firm was “John Carr and Co.,” and when the concern became the property of the first of these partners, the late Mr. John Carr, he and his sons carried it on under the style of “John Carr and Sons.” It is still continued by the same family under that style. Originally brown and black wares of the usual common kinds were made, in addition to the ordinary earthenware, but in 1856 these were discontinued, and the ordinary white earthenware in cream coloured, printed, painted, and lustred varieties substituted; these are the only productions of the firm. These goods are exported principally to the Mediterranean ports and to Alexandria, for transport to Cairo, and by the Red Sea to Bombay, &c. It is for these markets that the goods are mainly manufactured. In brown ware, common mugs, butter-jars, pancheons, milk-pans, &c., were produced; and in black ware, Egyptian black and smeared tea-pots, cream ewers, and other articles were produced. The mark, which, however, has been but seldom used, is a stag’s head.

The Tyne or Shields Pottery was established about 1830, by a Mr. Robertson, from whom, about 1845, it passed into the hands of Mr.[8] John Armstrong; by whom the works were considerably enlarged. In 1871 the concern was purchased by Messrs. Isaac Fell and George Shields Young, by whom it is still carried on under the style of “Isaac Fell and Co.” The goods manufactured are “Sunderland” and “brown” wares, of which large quantities are shipped for the Continent, as well as supplied to the London, Scottish, and other home markets. The goods are, as usual, made from the common brick clay, and after drying are lined inside with white slip; and they are glazed with lead glaze. The “Tyne Pottery” is, with the exception of the works of Messrs. Harwood, at Stockton-on-Tees, the largest in the district for this kind of pottery.

The Potteries of the Wear are:—

A pottery was established here in 1762, by Messrs. Christopher Thompson and John Maling, for the manufacture of the ordinary brown and white earthenware for the home trade, and also for France: the first printed ware made in the North of England was manufactured here. The works were also celebrated for their enamel and lustre wares. In 1817 their successor, Mr. Robert Maling, removed his works from Hylton to the neighbourhood of Newcastle-on-Tyne, where he manufactured principally for the Dutch markets. They were afterwards carried on by Dixon, Austin, Phillips, and Co., who at the same time carried on the Sunderland Pottery (which see).

In the Mayer Museum is an excellent example of this lustre ware. It is a large jug, of creamy-white earthenware, very light, ornamented with purple lustre in wavy lines, &c. On one side of the jug is an engraved and coloured view of the iron bridge over the river Wear, and underneath it (engraved and transferred from the same plate) in three small ovals, with borders, &c., are the inscriptions:—“A South-East View of the Iron Bridge over the Wear, near Sunderland. Foundation-stone laid by R. Burdon, Esq., September 24th, 1795. Opened, August 9th, 1796. Nil Desperandum. Auspice Deo.” “Cast Iron, 214 tons; Wrought do., 40.” “Height, 100 feet; Span, 256.” “J. Phillips, Hylton Pottery.” On the other side of the jug is another engraving, having in its centre a tree, on one side of which, in the distance, is a ship, and on the other a public-house. In the foreground of the ship side of the tree is a sailor; and on the other a woman with hat and feathers, an[9] umbrella, and a little dog. Underneath are the words—“Jack on a Cruise. ‘Avast there! Back your maintopsail.’” In front of the jug, beneath the spout, in an oval, occurs the verse:—

In my own collection is another example of this white ware with purple “lustre-splash” ornament. On one side is an engraving, in an oval, of the same bridge; and around the oval the inscription—“A West View of the Cast Iron Bridge over the River Wear; built by R. Burdon, Esq. Span, 236 feet; height, 100 feet. Begun, 24 Sept., 1795. Opened, 9 Aug., 1796.” On the other side, a ship in full sail. Another example is a punch-bowl. Like the others, it is decorated with purple lustre, and with views, ships, and verses in transfer-printing. On the bottom, inside, is a similar view of the Wear bridge to the one just described, in an oval, with the same inscription. The inside is divided into three compartments, in one of which is a ship in full sail, with the words—

in another, in a border of flowers, surmounted by a small ship, is this verse:—

and on the third, is a similar border:—

[10]

On the outside, are also three engravings. The first is a ship in full sail; the next a border of flowers with a small “world” at top, with the verse:—

and the third has a border of flowers and the verse:—

The works of Messrs. John Dawson & Co. were erected by them in 1800, and were carried on by the firm until 1864, when, on the death of the last of the family, Mr. Charles Dawson, they were closed and converted into bottle houses; these were destroyed by fire. The flint mill was taken by Mr. Ball, of the Deptford Pottery, who grinds large quantities of flint for both home consumption and export. The mark was simply the name “DAWSON” impressed in the ware. A part of the premises were, several years afterwards, used as a brown ware manufactory, and later still by Messrs. Isaac Fell and Co.

The Southwick Pottery was built in 1788, by Mr. Anthony Scott, who had, previously to that time, carried on a small potwork at Newbottle, and it is still the property of one of his descendants, Mr. Anthony Scott, and is carried on by that family, under the style of “Scott Brothers and Co.” At these works, which are among the most successful in the district, and where especial care is taken as to quality of the productions, the usual classes of white, coloured and brown earthenware are produced. In these works upwards of 150 “hands” are employed. The goods are made for foreign markets, the greater part being exported to Denmark and Germany. Messrs. Scott Brothers and Co., of these works, stand—and deservedly so—high in the scale of manufacturers, and their goods,[11] whether of the finer or of the commoner classes, are in good repute, and are well calculated for an extensive home trade.

The Wear Pottery, founded by Messrs. Brunton & Co., in 1803, and soon after carried on by Messrs. Samuel Moore & Co., passed, about 1861, into the hands of its present proprietor, Mr. Robert Thomas Wilkinson, by whom it is carried on under the style of “Samuel Moore & Co.” The goods manufactured are the ordinary descriptions of white, sponged, and printed earthenware, and also brown ware, for the English, German, and Danish markets.

The High Southwick Pottery, for Sunderland ware, is carried on by Mr. Thomas Snowball.

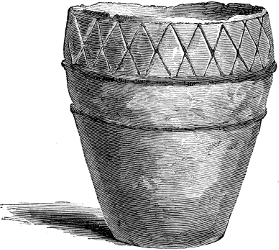

Deptford Pottery.—These works were established at Diamond Hall, in 1857, by Mr. Wm. Ball for the manufacture of flower-pots, in which he effected many important improvements, one of the principal of which is the “making them hollow footed, or with concave bottoms, with apertures for drainage and air, and kept free from the attacks of worms. This gives them a superiority over most, and has gained an extensive patronage.” In 1863 the manufacture of “Sunderland Ware”—glazed brown earthenware lined with white—was introduced, and is carried on very largely for the London and Scottish markets. At these works, too, suspenders, highly decorated, and other flower vases, seed-boxes, &c., are extensively made. Machinery has lately been introduced which very much facilitates the manufacture of the ware.

The Sheepfold Pottery, for Sunderland ware, is carried on by Messrs. T. J. Rickaby & Co.

The Sunderland Pottery or the Garrison Pottery, also established by Mr. Phillips, and carried on by Dixon, Austin, Phillips, and Co., produced white and Queen’s ware, in all the usual variety of articles. Sponged, printed, painted, and lustred earthenware were also produced. The works are now discontinued. The marks were

PHILLIPS & CO. PHILLIPS & CO.

Phillips & Co. SUNDERLAND, 1813

PHILLIPS & CO.

SUNDERLAND POTTERY.

[12]

In the Mayer collection is a well-painted quart mug, with allegorical group of the arts, with the name “W. DIXON, 1811,” pencilled on the bottom. Among other examples in the Jermyn Street Museum are a printed coloured and lustred jug, bearing on one side the common view of the bridge over the Wear, and on the other the Farmers’ Arms, while in front are the words—“Forget me not,” within a wreath. It bears the name DIXON AUSTIN & CO., SUNDERLAND. Figures were also produced, and marked examples may be seen in the same museum. The name occurs in various ways beyond those just given. Thus, among others, are “W. Dixon,” “Dixon & Co.,” “Dixon & Co., Sunderland Pottery,”

DIXON AUSTIN & CO

Sunderland Pottery

DIXON & CO

Sunderland Pottery

DIXON & CO

SUNDERLAND

A manufactory was built here about the year 1836 for the manufacture of brown ware by Captain Plowright, of Lynn, and in 1838 it was altered into a white and printed ware manufactory, by a number of workmen from Messrs. Dawson and Co., of Hylton; it was closed about the year 1841, and re-opened in 1851, by Mr. R. C. Wilson, and finally closed in 1852.

These works were founded about 1755, by Mr. Byers, and he manufactured both brown and white wares. They passed into the hands of Mr. Anthony Scott, who carried them on until 1788 (see “Southwick”). They are now discontinued. A pottery for the manufacture of common brown ware, and flower-pots, &c., was also carried on by Messrs. Broderick, but is now discontinued.

New Moor Pottery, at Evenwood, carried on by Mr. George Snowdon for the manufacture of brown ware.

The potteries of the Tees are:—

Stafford Pottery.—Several earthenware manufactories have been carried on at this place, and, at the present day, there are four pot-works in operation, at each of which a considerable number of[13] hands are employed. The largest, called the “Stafford Pottery,” at South Stockton, or Thornaby, was established, in 1825, by Mr. William Smith, a builder of Stockton, for the manufacture of the ordinary brown ware. Determining shortly afterwards to add the general earthenware to its productions, he visited Staffordshire, and engaged and ultimately took into partnership Mr. John Whalley, a Staffordshire potter of considerable skill, to carry on the work. The firm commenced, under the style of “William Smith & Co.” in January, 1826. In 1829, in order further to extend the concern and increase its capital, a partnership was entered into with Messrs. William and George Skinner, sons of Mr. Skinner, banker, of Stockton, and continued for some years, when Mr. George Skinner having purchased the interest of his brother, and of Mr. William Smith, changed the name of the firm to that of “George Skinner & Co.” By Mr. George Skinner and Mr. Whalley it was carried on for some years, when the latter retired, and the management devolved on Mr. Ambrose Walker, who, shortly after the death of Mr. Skinner in April, 1870, succeeded to the business, and still carries it on in connection with the executors of Mr. Skinner under the style of “Skinner and Walker.” Mr. Walker is a native of Hanley, and in 1837, when a boy, came to Stockton with his father, who at that time entered the service of Messrs. Smith & Co. In 1843 he became junior clerk, and was instructed in the art of potting by Mr. Whalley, who subsequently transferred to him his valuable receipts.

It is worthy of remark that at these works for many years past, no thrower is employed; this important branch of the art being entirely superseded by machinery, for the application of which to potting the firm has acquired a high reputation.

The goods manufactured were principally “Queen’s ware;” a fine white earthenware; and a fine brown ware, which were shipped in large quantities for Belgium, Holland, and some parts of Germany. I am also informed that the firm at one time established a branch pottery at Genappes, near Mons, in Belgium, sending workmen from Stockton; and that the manufactory there was carried on under the style, of “Capperman & Co.” One mark is—

W. S. & CO.

QUEEN’S WARE.

STOCKTON.

[14]

impressed in the body. Other examples have simply the words

STOCKTON.

or

S. & W.

QUEEN’S WARE.

STOCKTON.

or the same, without the initials impressed upon them.

In 1848 the firm consisted of William Smith, John Whalley, George Skinner, and Henry Cowap, and in that year an injunction was granted restraining them from using, as they had illegally done, the name of “Wedgwood & Co.” or “Wedgewood,” stamped or otherwise marked on goods produced by them. The following is the official notification of this matter, which I here reprint from my “Life of Wedgwood:”

“Vice-Chancellor of England’s Court,

“Lincoln’s Inn, 8th August, 1848.

“In Chancery.

“Wedgwood and others against Smith and others.

“Mr. Bethell on behalf of the Plaintiffs, Francis Wedgwood and Robert Brown (who carry on the business of Potters, at Etruria, in the Staffordshire Potteries, under the Firm of ‘Josiah Wedgwood and Sons’), moved for an Injunction against the defendants, William Smith, John Whalley, George Skinner, and Henry Cowap (who also carry on the business of Potters, at Stockton, in the County of Durham, under the firm of ‘William Smith and Company’), to restrain them and every of them, their Agents, Workmen, or Servants, from stamping, or engraving, or marking, or in any way putting or placing on the Ware manufactured by them, the Defendants, the name ‘Wedgwood’ or ‘Wedgewood,’ and from in any manner imitating or counterfeiting such name on the Ware manufactured by the Defendants since the month of December, 1846, or hereafter to be manufactured by the Defendants, with the name ‘Wedgwood’ or ‘Wedgewood,’ stamped, engraved, or otherwise marked or placed thereon. M‘r. Bethell stated that the trade mark ‘Wedgwood’ had been used by the family of the Wedgwoods for centuries; he would not, however, go further into the matter at present, because Mr. Parker appeared for the Defendants, and it might become necessary—with whom, and himself, it had been arranged by consent on Mr. Parker’s application on behalf of the Defendants, for time to answer the Plaintiffs’ Affidavits—that the Motion should stand over until the Second Seal in Michaelmas Term next; and that in the meantime the Defendants should be restrained as above stated; except that for the words, ‘since the month of December, 1846,’ the words, ‘since the month of July, 1847,’ should be substituted. Mr. J. Parker said he appeared for the Defendants, and consented without prejudice; and on his application for time to answer the Plaintiff’s Affidavits, the Court made an order accordingly.

“On the 9th day of November, being the Second Seal in Michaelmas term, 1848, Mr. E. Younge, as counsel for the above-named Plaintiffs, moved for, and obtained, a perpetual Injunction against the Defendants in the Terms of Mr. Bethell’s Motion, substituting for the words, ‘since the month of December, 1846,’ the words, ‘since the month of July, 1874;’ the Defendants consenting to pay to the Plaintiffs their costs.

“Solicitor for the Plaintiffs,

“Samuel King,

“Furnival’s Inn, Middlesex.”

In 1845, Messrs. George Skinner and John Whalley took out a[15] patent for “certain improvements in the manufacture of earthenware pastes and vitreous bodies, and also a new composition and material for the same, with certain new modes of combination thereof, which improvements, compositions, and combinations are applicable to the manufacture of earthenware pastes, vitreous bodies, slabs, tiles, and pavement, and various other useful and ornamental purposes, and is especially adapted for grave indicators, hydrant indicators, etc., as it is impervious to all weather and unaffected by change of atmosphere.” This consists in “combining chalk or carbonate of lime in union with silica, flint, or silex.” In the specification seven compositions are given, five of which are for ware and the other two for glaze. The compositions for ware are various “combinations of the above substances, and they contain besides, some or all of the following substances, namely, Cornwall stone, china clay, ball clay, felspar, helspar, or sulphate of barytes.” The wares may be tinted with the oxides generally used. Nos. 1 and 2 compositions do not require glazing; Nos. 3, 4, and 5 can be glazed with glazes which either do or do not contain lead. In this patent two glazes without lead are claimed. One of these is made of felspar and chalk, and the other of chalk, silica, flint, or silex, Cornwall stone, china clay, ball clay, and felspar, mixed in certain proportions.

The “North Shore Pottery” was established about 1840, by Mr. James Smith, afterwards of Danby Grange, near Yarm, in Yorkshire, and was carried on by his nephew, Mr. William Smith, Jun. (son of the William Smith to whom I have alluded as the founder of the “Stafford Pottery”), under the style of “William Smith, Jun., and Co.” Subsequently to this the business was carried on successively under the styles of “G. F. Smith and Co.” and “G. and W. Smith.” A few years ago the senior partner, Mr. S. P. Smith, retired from the concern, and since then it has been continued solely by Mr. William Smith, son of the founder and still present owner of the works.

The classes of goods made at this pottery were both in white and cream-coloured wares, and some of the examples of the first productions are of excellent quality. The markets for which, principally, the “North Shore Pottery” goods were and are made, are, besides the home trade—which is principally confined to London and the South of England—Holland, Germany, and Denmark. Large quantities of wares are also exported to Constantinople, and other[16] Mediterranean markets. The goods now made are the usual classes of white earthenware, and printed and coloured goods, in dinner, teas, toilet, and other services; bread, cheese, and other trays of good design; mugs, jugs, basins, and all the usual varieties of domestic vessels. In quality they equal the ordinary classes of Staffordshire ware, and many of the printed patterns (notably, perhaps, the “Danby”) are of a superior kind. The “sponge patterns” for foreign markets are extensively used, and green-glazed ware in flower-pots, &c., are also made.

The impressed mark at the present time is

W. S.

Stockton.

The printed marks, besides an ornamental border and the name of the pattern, bear simply the initials W. S.

Other potteries are Mr. Ainsworth’s, at North Stockton, for white and printed wares; Mr. Thomas Harwood “The Norton Pottery,” at Norton, for Sunderland and yellow wares; and Messrs. Harwood Brothers, “Clarence Pottery,” for Sunderland ware.

The Middlesborough Pottery was established in 1831; the first oven being fired in April of that year, and the first order shipped to Gibraltar in September. They were the first public works established in Middlesborough. From 1831 to 1844 the firm traded under the style of “The Middlesborough Pottery Company,” and from that year until 1852 as “The Middlesborough Earthenware Company.” From 1852 to the present time the firm has traded under the name of the proprietors as “Messrs. Isaac Wilson & Co.” The works, with wharf, occupy an area of about 9,702 square yards.

At the first commencement of the works the proprietors directed their attention to the production of the better classes of ordinary earthenware for the continental trade, and in the same year in which the works were started, their present extensive warehouse at Roding’s Mart, Hamburg, was established. The goods produced are the ordinary “opaque china,” cream-coloured ware, and lustre enamelled ware in dinner, tea, and toilet services, and all the general classes of domestic vessels, enamelled flower pots, bread trays, &c. Some of these are of very good quality, and the printed services are equal to the more ordinary Staffordshire goods. The principal impressed marks, used are the following—

The printed marks indicating the pattern have, in addition to the[17] name of the pattern (“Convolvulus,” “Trent,” “Nunthorpe,” &c.) the initials of the firm, as “M. P. & Co.” for “Middlesborough Pottery Company,” and “I. W. & Co.” for “Isaac Wilson & Co.”

Wolviston Pottery, now discontinued, formerly produced yellow ware.

Coxhoe Pottery, also discontinued, produced Sunderland ware.

There were formerly pot-works here; but no trace of them is now left, save the name of the street, “Potter Gate,” where they existed. The former name of this street was, in 1567, “Barresdale Street,” but potters having there located themselves, it became gradually changed. Another old street in this town now known as “Clayport,” was formerly called “Clay-peth,” peth being a provincialism for a steep road, and clay the nature of the soil; probably it was this clay that the Alnwick potters turned to good account.

[18]

Liverpool Pottery—Shaw’s Delft Ware—Shaw’s Brow—Zachariah Barnes—Sadler and Green—Transfer Printing—Wedgwood’s Printed Ware—Drinkwater’s Works—Spencer’s Pottery—Richard Chaffers—Reid and Co.’s Works—The Penningtons—Patrick’s Hill Works—The Flint Pottery—Herculaneum Works—Warrington Pottery and China—Runcorn—Prescot—St. Helen’s—Seacombe.

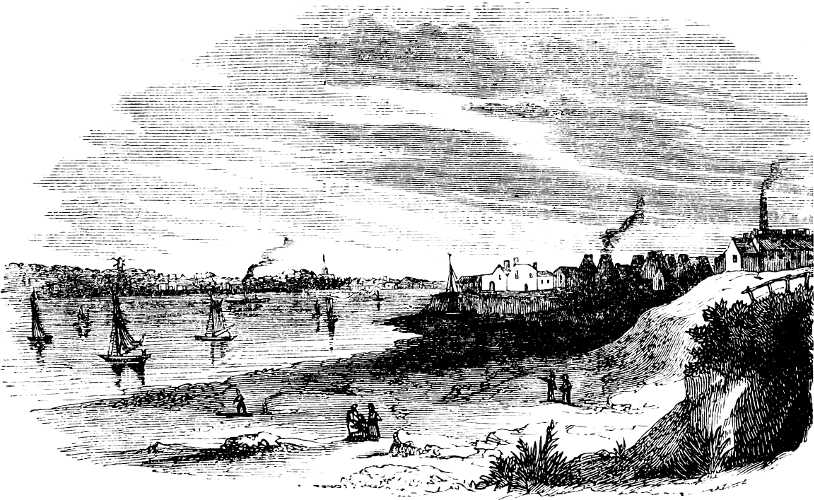

It would, perhaps, scarcely be expected that in such a busy, bustling, and gigantic place of enterprise and commercial activity as Liverpool—in the midst of shipping of every description, and surrounded by the most enormous and busy undertakings of one kind or other—we should successfully look for the full and perfect accomplishment of so quiet, so unostentatious, so peaceful, and so delicate an art as that of the potter. But thus it is; and Liverpool, which counts its docks by tens, its wharves and stores by hundreds, its shipping by thousands, and its wealth by millions—which can boast its half-million inhabitants, its overground and under-ground railways, and every appliance which skill and enterprise can give or trade and commerce possibly require—which has undertaken the accomplishment of some of the most wonderful and gigantic schemes the world ever knew, and has carried them out in that spirit of commendable and boundless energy that invariably characterises all its actions—has not been behindhand with its more inland and more modest neighbours in the manufacture of delicate porcelain, and of pottery of the most fragile nature.

It is more than probable that in mediæval times the coarse ware of the period—the pitchers, porringers, dishes, &c.—was made on the banks of the Mersey. The first mention of pottery, however, occurs in 1674, when the following items appear in the list of town dues:—

“For every cart-load of muggs (shipped) into foreign ports, 6d. For every cart-load of muggs along the coasts, 4d. For every crate of cupps or pipes into foreign ports, 2d. For every crate of cupps or pipes along the coast, 1d.”

[19]

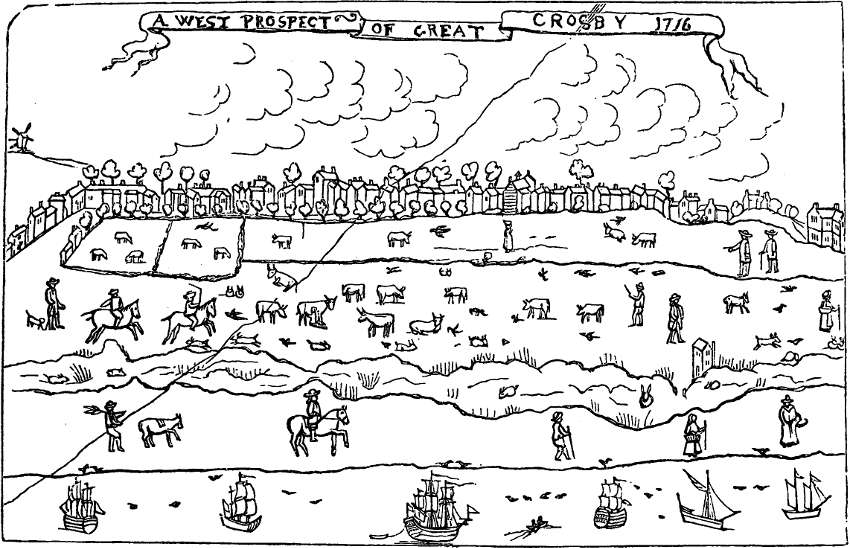

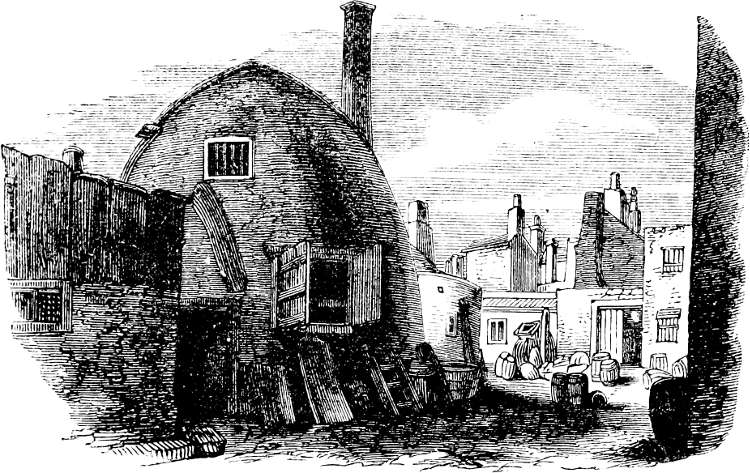

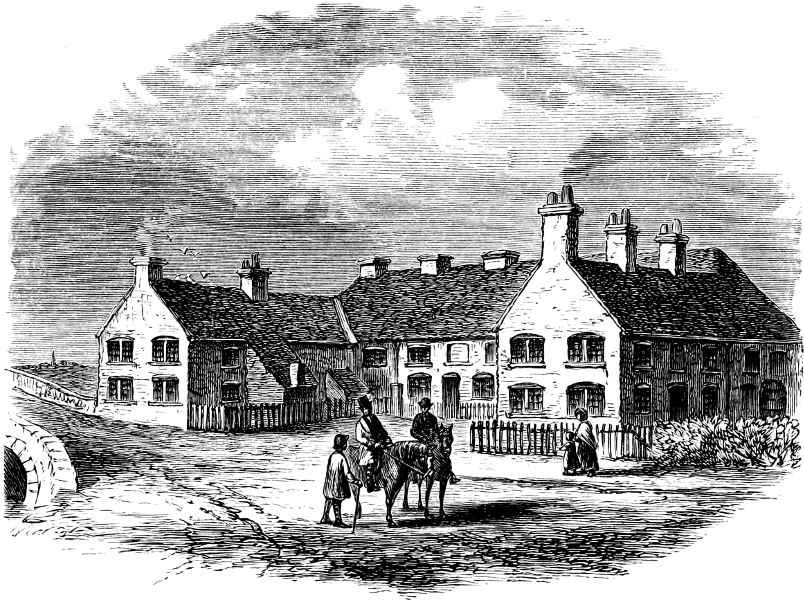

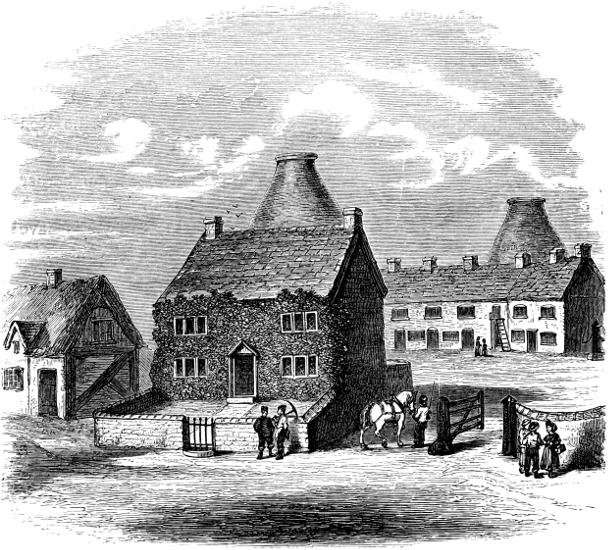

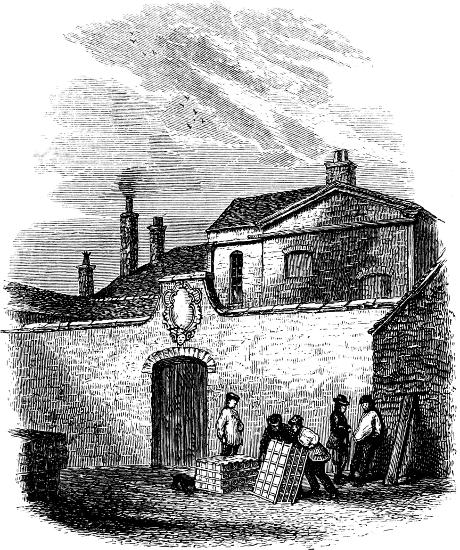

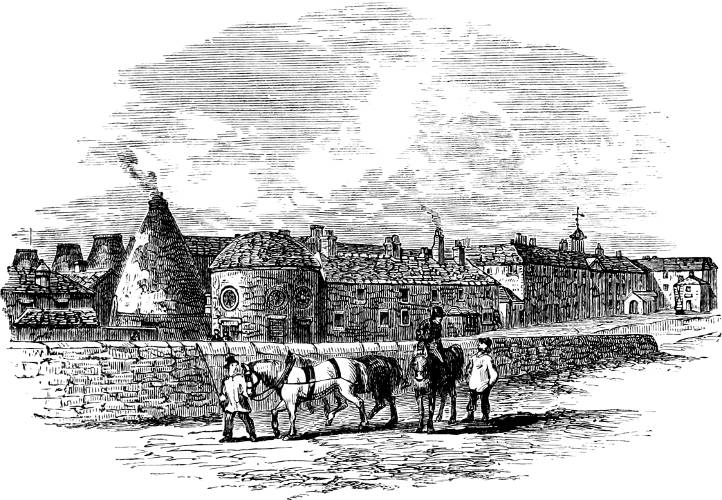

A WEST PROSPECT OF GREAT CROSBY 1716

Fig. 1.

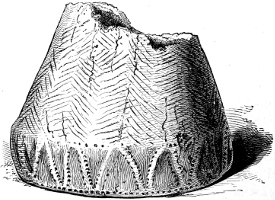

Shaw’s Delft Ware Works.—The earliest potwork of which there is any reliable information, appears to have been that of Alderman Shaw, situated at Shaw’s Brow, which afterwards became a complete nest of pot-works belonging to different individuals. At these works was most probably made the earliest known dated example of Liverpool delft ware. This is a large oblong-square plaque, unique in its size and decoration, which is preserved in the Mayer museum, and is shown on Fig. 1. It is of fine delft ware, flat in surface, and measures 2 feet 7 inches in length, by 1 foot 8 inches in depth, and is nearly three quarters of an inch in thickness. The body is composed of the ordinary buff-coloured clay, smeared, like what are usually called “Dutch tiles,” on the face with a fine white clay, on which the design is drawn in blue, and then glazed. The plaque represents the village of Great Crosby as seen from the river Mersey, and bears the name and date, “A west prospect of Great Crosby, 1716,” on a ribbon at the top. In the foreground is the river Mersey, with ships and brigs, and a sloop and a schooner. The large ship in the centre of the picture has a boat attached to her stern, and another boat containing two men is seen rowing towards her, while on the water around them are a number of gulls and other sea-birds. On the sandy banks of the river are several figures,[20] consisting of a woman with a basket on her arm, apparently looking across the river; another woman, also with a basket on her arm, walking with a long stick; a man also walking with a stick; a gentleman on horseback; and a man driving an ass before him. Beyond these figures rise the sandbanks, covered with long grass and heather, in which is a rabbit warren. The warren keeper’s house is shown, as are also numbers of rabbits. Beyond this again, in the open space, are a number of figures: men are seen galloping on horseback; women are carrying baskets; men are walking about, some with dogs, others without; and the intermediate space is pretty well studded with cattle, rabbits, and birds; a milkmaid milking one of the cows. Behind this, again, the ground is divided by hedgerows into fields, in which are cattle, people walking to and fro, and a milkmaid carrying a milkpail on her head. In the background is the town of Great Crosby, including the school-house and numerous other buildings, with long rows of trees, palings, gates, and other objects incidental to the scene. To the left of the spectator is Crosby windmill, still standing; and those[21] who are best acquainted with the aspect of the place, as seen from the river at the present day, say that little alteration has taken place in the village; that this view, taken a hundred and fifty years ago, might well pass for one just executed.

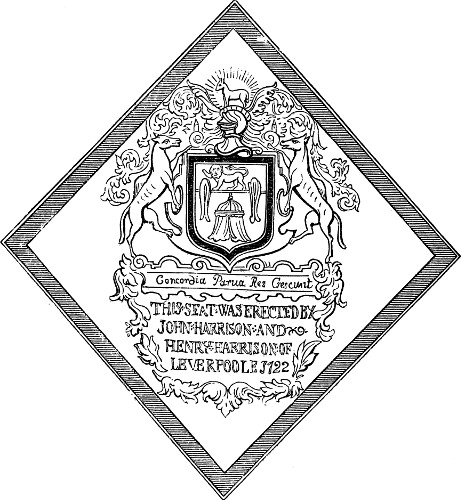

Concordia Parua Res Crescunt

THIS SEAT WAS ERECTED BY

JOHN HARRISON AND

HENRY HARRISON OF

LEVERPOOLE 1722

Fig. 2.

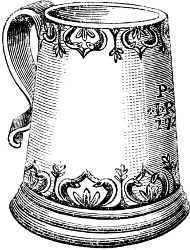

Another plaque, Fig. 2, is of a few years later date, 1722. It is affixed to the wall over one of the seats of old Crosby Church, and bears the arms of the Merchant Taylors’ Company, viz., argent, a royal tent between two parliament robes, gules, lined ermine; on a chief azure, a lion of England; crest, a Holy Lamb in glory, proper; supporters, two camels, or; motto, “Concordia parvæ res crescunt.” Below is the inscription—“THIS SEAT WAS ERECTED BY JOHN HARRISON AND HENRY HARRISON, OF LEVERPOOLE, 1722.” This plaque measures sixteen inches on each side, and is nearly an inch and a half in thickness. It is of precisely the same kind of ware as the view of Crosby, and was doubtless the production of the same establishment. John and Henry Harrison are said to have been natives of Crosby, the grammar school of which village they erected and endowed, after having made large fortunes as merchants in London, the trust being held by the Company of Merchant Taylors. Mr. Mayer mentions that another of these curious plaques, or slabs, was attached to the front of a house at Newton-cum-Larten. It was circular, and bore the arms of Johnson and Anton impaled, with the date 1753. The Mr. Johnson whose armorial bearings it represents, was afterwards Mayor of Liverpool, and formed St. James’s Walk. He married Miss Anton, an heiress, and built the house where the slab was affixed, and which is believed to have been made and presented to him for that purpose by his brother alderman, Mr. Shaw, the potter. Another dated example is a mug in the Mayer museum shown on the accompanying engraving. It is decorated with borders in blue and black, and bears on its front the initials and date

P

I · R

1728

Fig. 3.

There were, it appears, two potters, at least, of the name of Shaw—Samuel Shaw, who died in October, 1775, and Thomas Shaw, who,[22] I believe, was his son. The works were, as I have stated, at a place which, from that circumstance, took the name of Shaw’s Brow, a rising piece of ground on the east side of the rivulet that ran at the bottom of Dale Street. Here the early pot-works were established, and here in after years they increased, until the whole “Brow” became one mass of potter’s banks, with houses for the workmen on both sides of the street; and so numerous were they that, according to the census taken in 1790, there were as many as 74 houses, occupied by 374 persons, the whole of whom were connected with the potteries. At these works, Richard Chaffers, to whom credit is due for the advances he made in the manufacture of porcelain, was apprenticed to Shaw, and on the Brow he established his own manufactory. In 1754 the following very interesting little notice of these pot-works occurs in “The Liverpool Memorandum Book:”—

“The chief manufactures carried on here are blue and white earthenware, which at present almost vie with China. Large quantities are exported for the colonies abroad.”

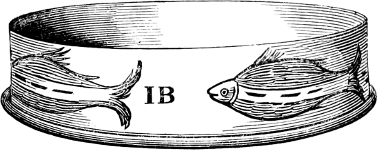

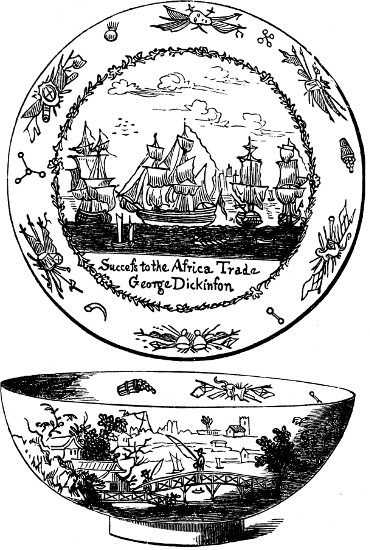

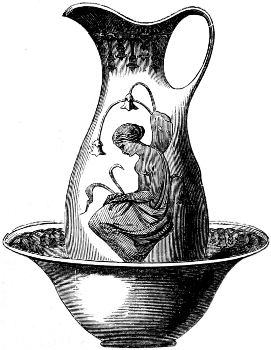

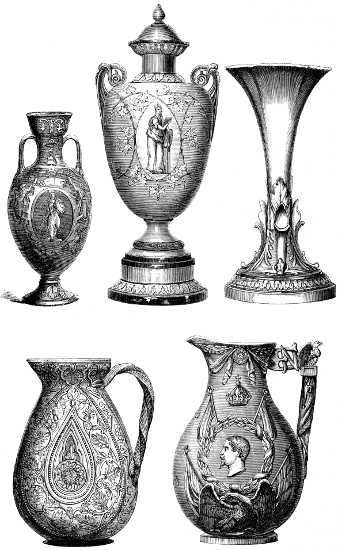

Fig. 4.

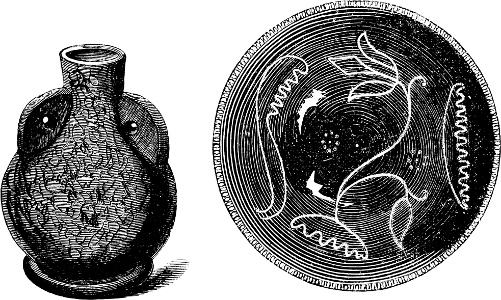

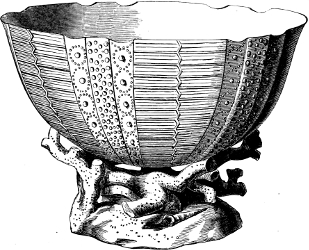

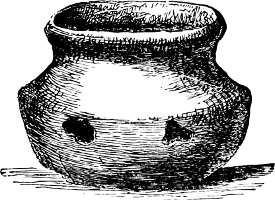

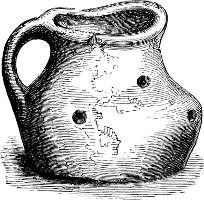

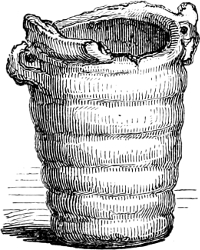

Of about this period are some examples in the Mayer museum. Fig. 4 is a magnificent punch-bowl, measuring 17½ inches in diameter, and of proportionate depth. It is of the ordinary Delft ware; its decorations painted in blue. At the bottom of the bowl, inside, is a fine painting of a three-masted ship, in full sail, with streamer flying at the mast-head, the Union Jack at the jib, and a[23] lion for a figure-head. This bowl was “made for Captain Metcalfe, who commanded the Golden Lion, which was the first vessel that sailed out of Liverpool on the whale fishery and Greenland trade, and was presented to him on his return from his second voyage, by his employers, who were a company composed of the principal merchants of Liverpool, in the year 1753.” The size of the bowl, and the excellence of its decorations and workmanship, show to what perfection Shaw had arrived in this manufacture. Among other articles besides mugs and punch-bowls, were char-pots; these, like the rest, are of Delft ware, and usually decorated with fishes around their outsides. One (Fig. 5) bears the initials I. B. Figs. 6 and 7 are two mugs, of the same body and glaze as the plaques already described. The larger one, a quart mug, is ornamented with flowers, painted in blue, green, and black, and bears the initials and date T. F. 1757, the initials being those of Thomas Fazackerley, to whom it was presented by its maker, a workman at Shaw’s pottery. In 1758, Mr. Fazackerley having married, his friend made the smaller of the two mugs, a pint one, on which he placed the initials of the lady, Catherine Fazackerley, and the date C. F. 1758 within an oval on its front. This mug is decorated with flowers, painted in green, yellow, and blue. Fig. 8 is one of a pair of cows, 4¾ inches in height; the upper half of each lifts off. They are excellently modelled, and painted in flowers, evidently by the same artist as the Fazackerley mugs, in yellow, blue, and green. Fragments of figures were, I believe, found in excavating on the site of Shaw’s pottery.

Fig. 5.

Figs. 6 and 7.

Another dated example of about this period is a fine Delft ware bowl, on the outside of which are painted birds, butterflies, and flowers, and on the inside a man-of-war, painted in blue and colours, with the inscription, “Success to the Monmouth, 1760.”

[24]

Fig. 8.

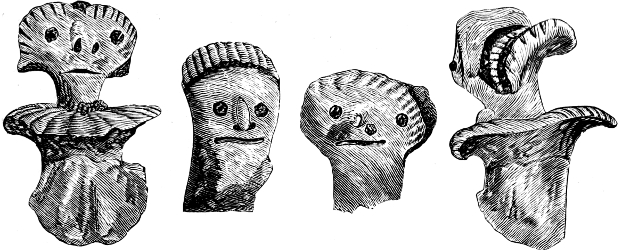

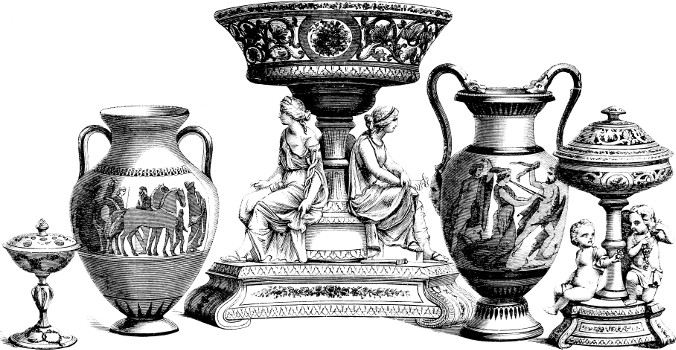

Figs. 9 to 12.

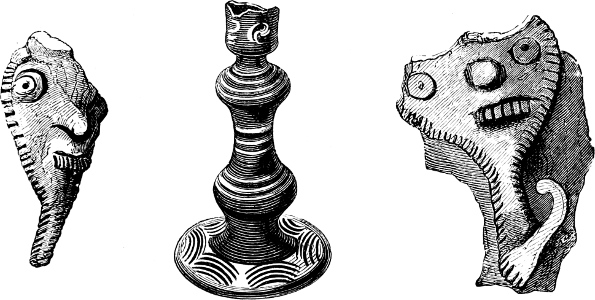

A most interesting matter in connection with the Delft ware works at Shaw’s Brow is the fact of a number of broken vessels being discovered on its site during excavations for building the Liverpool Free Library and Museum, in 1857. On that occasion an old slip-vat was found containing clay, which might probably have been prepared as early as 1680. The clay was of the common coarse kind, the same as the general body of Delft ware. Of this clay so discovered Mr. Mayer had a vase thrown and fired. Some of the Delft cups, &c., exhumed are shown on Figs. 9 to 14. These are all of a pinkish white; one only having a pattern painted in blue. Another example of Delft ware (Fig. 15), said to be of Liverpool make, in Mr. Mayer’s collection, is one of a pair of flower vases, of good design, with heads at the sides, and elaborately painted in blue. It is marked on the bottom—

W

D A

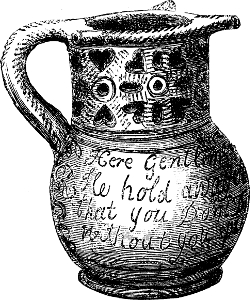

in blue. Another example (Fig. 16), said to be of Liverpool make, is the puzzle jug, and bears the very appropriate motto, painted in blue—

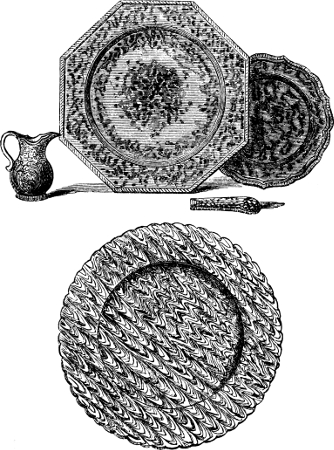

Zachariah Barnes.—another maker of Delft ware in Liverpool—was a native of Warrington, and brother to Dr. Barnes, of Manchester.[25] He was born in 1743, and having learned the “art, mystery, and occupation” of throwing, &c., commenced business as a potter in the old Haymarket, at the left-hand side in going to Byrom Street. He is said to have first made China, but afterwards turned his attention to Delft ware, and soon became proficient in the art. The principal varieties of goods made by him were jars and pots for druggists; large dishes, octagonal plates and dishes for dinner services; “Dutch tiles;” labels for liquors; potted-fish pots, &c., &c. Of the druggist’s jars, of which he made considerable quantities, it is said that the labelling in his time underwent no less than three changes from alterations in the pharmacopæia.

Fig. 13.

Fig. 14.

Fig. 15.

Fig. 16.

The large round dishes made by Barnes were chiefly sent into Wales, where the simple habits of their forefathers remained unchanged among the people long after their alteration in England; and the master of the house and his guest dipped their spoons[26] into the mess and helped themselves from the dish placed in the middle of the table. Quantities of this ware were sent to the great border fairs, held at Chester, whither the inhabitants of the more remote and inaccessible parts of the mountain districts of Wales assembled to buy their stores for the year. The quality of this ware was very coarse, without flint, with the usual Delft-like thick tin glaze. But Barnes’s principal forte lay in the manufacture of square tiles, then much in vogue. When these tiles were required to be printed, that part of the work was done by Messrs. Sadler and Green. So large was the sale of this article, that Mr. Barnes has been heard to say he made a profit of £300 per annum by his tiles alone, he having a monopoly of the trade. He also made large quantities of pots for potting char, which were sent to the lakes. The ovens were fired with turf brought from the bogs at Kirkley, and on the night of firing, the men were always allowed potatoes to roast at the kiln fires, and a certain quantity of ale to drink.

WORMWOOD

Fig. 17.

The labels for different kinds of liquors, to which I have just alluded as being largely made by Barnes, were of various sizes, but generally of one uniform shape; the one engraved (Fig. 17) being five a and half inches long. Examples in the Mayer Museum are respectively lettered for Rum, Cyder, Tent, Brandy, Lisbon, Peppermint, Wormwood, Aniseed, Geneva, Claret, Spruce, Perry, Orange, Burgundy, Port, Raisin, and other liquors. They are of the usual common clay in body, faced with fine white slip and glazed.

Fig. 18.

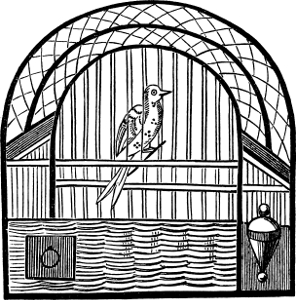

The tiles made by Zachariah Barnes were usually five inches square, and about a quarter of an inch in thickness, and were used for lining fire-places, forming chimney-pieces, and other domestic purposes. Originally, the tiles were painted in the ordinary Delft style, with[27] patterns of various kinds—flowers, landscapes, ships, groups, &c.—usually in blue, but sometimes in colours. A plaque of Liverpool Delft, painted in two or three colours (in the possession of Mr. Benson Rathbone), is shown on Fig. 18; it represents a bird in a cage, the perspective of which is more curious than accurate.

Sadler and Green.—The tiles to which I have alluded bring me to a very interesting part of the subject of this chapter. I mean the introduction of printing on earthenware, an invention which has been attributed to, and claimed by, several places, and which will yet require further research to entirely determine. At Worcester it is believed the invention was applied in the year 1756, and it is an undoubted fact that the art was practised there in the following year, a dated example of the year 1757 being, happily, in existence.[2] At Caughley transfer-printing was, as I have already shown, practised at about the same period. At Battersea, printing on enamels was, it would seem, carried on at about the same date, or probably somewhat earlier. At Liverpool it is certain that the art was known at an earlier period than can with safety be ascribed to Worcester. A fine and exquisitely sharp specimen of transfer-printing on enamel, dated 1756, is in Mr. Mayer’s possession. It is curious that these two earliest dated exemplars of these two candidates for the honour of the invention of printing on enamels and earthenware, Liverpool and Worcester, should be portraits of the same individual—Frederick the Great of Prussia. But so it is. The Worcester example is a mug, bearing the royal portrait with trophies, &c., and the date 1757; the Liverpool one an oval enamel (and a much finer work of art), with the name, “J. Saddler, Liverpl. Enaml.”

The art is said to have been invented by this John Sadler, of Liverpool, in 1752. In Moss’s “Liverpool Guide,” published in 1790, it is stated:—“Copper-plate printing upon china and earthenware originated here in 1752, and remained some time a secret with the inventors, Messrs. Sadler and Green, the latter of whom still continues the business in Harrington Street. It appeared unaccountable how uneven surfaces could receive impressions from copper-plates. It could not, however, long remain undiscovered that the impression from the plate is first taken upon paper, and thence communicated to the ware after it is glazed. The manner in which this continues to be done here remains still unrivalled in perfection.”

[28]

John Sadler, the inventor of this important art, was the son of Adam Sadler, a favourite soldier of the great Duke of Marlborough, and was out with that general in the war in the Low Countries. While there, he lodged in the house of a printer, and thus obtained an insight into the art of printing. On returning to England, on the accession of George I., he left the army in disgust and retired to Ulverstone, where he married a Miss Bibby, who numbered among her acquaintance the daughters of the Earl of Sefton. Through the influence of these ladies he removed to Melling, and afterwards leased a house at Aintree. In this lease he is styled “Adam Sadler, of Melling, gentleman.” The taste he had acquired in the Low Countries abiding with him, he shortly afterwards, however, removed to the New Market, Liverpool, where he printed a great number of books—among which, being himself an excellent musician, one called “The Muses’ Delight” was with him an especial favourite. His son, John Sadler, having learned the art of engraving, on the termination of his apprenticeship bought a house from his father, in Harrington Street, for the nominal sum of five shillings, and in that house, in 1748, commenced business on his own account. Here he married a Miss Elizabeth Parker, daughter of Mr. Parker, watchmaker, of Seel Street, and soon afterwards became engaged in litigation. Having got together a good business, his fellow townsmen became jealous of his success, and the corporation attempted to remove him as not being a freeman of Liverpool, and therefore having no right to keep a shop within its boundaries. Disregarding the order of removal, the corporation commenced an action against him, which he successfully defended, and showed that the authorities possessed no power of ejection. This decision was one of great importance to the trading community, and opened the door to numberless people who commenced business in the town.

Mr. John Sadler was, according to Mr. Mayer, the first person who applied the art of printing to the ornamentation of pottery, and the story of his discovery is thus told:—Sadler had been in the habit of giving waste and spoiled impressions from his engraved plates to little children, and these they frequently stuck upon pieces of broken pot from the pot-works at Shaw’s Brow, for their own amusement, and for building dolls’ houses. This circumstance gave him the idea of ornamenting pottery with printed pictures, and, keeping the idea secret, he experimentalised until he had nearly succeeded, when he mentioned the circumstance to Guy Green, who had then recently[29] succeeded Mr. Adam Sadler in his business. Guy Green was a poor boy, but spent what halfpence he could get in buying ballads at the shop of Adam Sadler. Sadler liking the lad, who was intelligent beyond his age or his companions, took him into his service and encouraged him in all that was honourable. John Sadler having, as I have said, mentioned his discovery to Guy Green, the two “laid their heads together,” conducted joint experiments, and having ultimately succeeded, at length entered into partnership. This done, they determined to apply to the king for a patent; which, however, under the advice of friends, was not done.

The art was first of all turned to good account in the decoration of tiles—“Dutch tiles,” as they are usually called—and the following highly interesting documents relating to them, which are in the possession of Mr. Mayer, and to whom the antiquarian world is indebted for first making them public, will be read with interest:—

“I, John Sadler, of Liverpoole, in the county of Lancaster, printer, and Guy Green, of Liverpoole, aforesaid, printer, severally maketh oath that on Tuesday, the 27th day of July instant, they, these deponents, without the aid or assistance of any other person or persons, did within the space of six hours, to wit, between the hours of nine in the morning and three in the afternoon of the same day, print upwards of twelve hundred Earthenware tiles of different patterns, at Liverpoole aforesaid, and which, as these deponents have heard and believe, were more in number and better and neater than one hundred skilful pot-painters could have painted in the like space of time, in the common and usual way of painting with a pencil; and these deponents say that they have been upwards of seven years in finding out the method of printing tiles, and in making tryals and experiments for that purpose, which they have now through great pains and expence brought to perfection.

“Taken and sworn at Liverpoole, in the county of Lancaster, the second day of August, one thousand seven hundred and fifty-six, before William Statham, a Master Extraordinary in Chancery.”

“We, Alderman Thomas Shaw and Samuel Gilbody, both of Liverpoole, in the county of Lancaster, clay potters, whose names are hereunto subscribed, do hereby humbly certifye that we are well assured that John Sadler and Guy Green did, at Liverpoole aforesaid, on Tuesday, the 27th day of July last past, within the space of six hours, print upwards of 1,200 earthenware tiles of different colours and patterns, which is upon a moderate computation more than 100 good workmen could have done of the same patterns in the same space of time by the usual painting with the pencil. That we have since burnt the above tiles, and that they are considerably neater than any we have seen pencilled, and may be sold at little more than half the price. We are also assured the said John Sadler and Guy Green have been several years in bringing the art of printing on earthenware to perfection, and we never heard it was done by any other person or persons but themselves. We are also assured that as the Dutch (who import large quantities of tiles into England, Ireland, &c.) may by this improvement be considerably undersold, it cannot fail to be of great advantage to the nation, and to the town of Liverpoole in particular, where the earthenware manufacture is more extensively carried on than in any other town in the kingdom; and for which reasons we hope and do not doubt the above persons will be indulged in their request for a patent, to secure to them the profits that may arise from the above useful and advantageous improvement.

[30]

“Liverpoole, August 13th, 1756.

“Sir,

“John Sadler, the bearer, and Guy Green, both of this town, have invented a method of printing potters’ earthenware tyles for chimneys with surprising expedition. We have seen several of their printed tyles, and are of opinion that they are superior to any done by the pencil, and that this invention will be highly advantageous to the kingdom in generall, and to the town of Liverpoole in particular.

“In consequence of which, and for the encouragement of so useful and ingenious an improvement, we desire the favour of your interest in procuring for them his Majesty’s letters patent.

“Addressed to Charles Pole, Esq., in London.”

In the Mayer museum are found, among other invaluable treasures, some enamels on copper bearing impressions from copper-plates transferred to them, and having the name of “J. Sadler, Liverpl, Enaml,” and other examples of enamels and of earthenware with the names of “Sadler, Sculp.,” or of “Green.” Messrs. Sadler and Green appear to have done a very profitable and excellent business in the printing on pottery. The process was soon found to be as applicable to services and other descriptions of goods as to tiles; and these two enterprising men produced many fine examples of their art, some of which, bearing their names as engravers or enamellers, are still in existence. Josiah Wedgwood, always alive to everything which could tend to improve or render more commercial the productions of his manufactory, although at first opposed to the introduction of this invention, as being, in his opinion, an unsatisfactory and unprofitable substitute for painting, eventually determined to adopt the new style of ornamentation, and arranged with the inventors to decorate such of his Queen’s ware as it would be applicable to, by their process. The work was a troublesome one, and in the then state of the roads—for it must be remembered that this was before the time even of canals in the district, much less of railroads—the communication between Burslem and Liverpool was one of great difficulty. Wedgwood, however, overcame it, and having made the plain body at his works in Staffordshire, packed it in waggons and carts, and even in the panniers of pack-horses, and sent it to Liverpool, where it was printed by Sadler and Green, and returned to him by the same kind of conveyance. The works of Sadler and Green were in Harrington Street, at the back of Lord Street, Liverpool, and here they not only carried on their engraving and transfer-printing for other potters, but made their own wares,[31] and carried on an extensive business. It was here that they printed ware for Josiah Wedgwood. Of this connection of Wedgwood with the Liverpool works, Mr. Mayer thus writes:—

“About this time Josiah Wedgwood was making a complete revolution in the art of pottery; and four years after Messrs. Sadler and Green’s invention was announced to the world, Wedgwood brought out his celebrated Queen’s ware. Dr. Gagerly seizing upon the new style of ornamentation invented in Liverpool, he immediately made arrangements with the proprietors for decorating his hitherto cream-coloured Queen’s ware by their process; and accordingly I find him making the plain body at Burslem, and sending it in that state to Liverpool by waggon, where it was printed, and again returned to him by the same conveyance, except in the case of those orders that must go by sea, fit for the market. This he continued to do until near the time of his death, when we find by invoices in my possession that ware was sent to Liverpool and printed by Mr. Guy Green as late as 1794. A little before this time, his manufactory at Etruria having been made complete in all other branches of the art, and the manufacture at Liverpool being much decayed, he engaged many of the hands formerly employed there: amongst the indentures is the name of John Pennington, son of James Pennington, manufacturer of china, dated 1784, to be taught the art of engraving in aquatint, and thus he was enabled to execute the printing on his own premises in Staffordshire, thereby saving the expense of transport to and fro. In proof that Mr. Wedgwood did this, I may quote a few passages from letters to his partner, Mr. Bentley, in London. He says:—

“‘1776.—We wrote to Mr. Green in consequence of your letter, acquainting that a foreign gentleman wanted a series of ware printed with different landskips, but that he would not confirm the order without knowing how many different designs of landskips we could put upon them.’

“Mr. Green’s answer is:—

“‘The patterns for landskips are for every dish a different landskip view, &c.; about 30 different designs for table, soup, and dessert plates, and a great variety for various purposes of tureens, sauce boats, &c.’

“‘1768.—The cards (address) I intend to have engraved in Liverpool, &c.’

“‘1769.—One crate of printed tea-ware.’

“On the other hand I find letters from Mr. Green to Mr. Wedgwood:—

“‘1776.—Your Mr. Haywood desires the invoice of a box of pattern tiles sent some time ago. As I did not intend to make any charge for them, I have no account of the contents. The prices I sell them for to the shops are as follows:—For black printed tile, 5s. per dozen; green vase tile, 4s. ditto; green ground, 4s. ditto; half tiles for borders, 2s. 9d. ditto; rose or spotted tiles, 3s. 6d. ditto, &c.’

“‘1783.—I have put the tile plate to be engraved as soon as I received your order for doing it; but by the neglect of the engraver it is not yet finished, but expect it will be completed tomorrow.’

“‘1783.—Our enamel kiln being down prevented us sending the goods forward as usual.’

“‘1783.—The plate with cypher was done here. I think it would be best to print the cypher in black, as I am much afraid the brown purple that the pattern was done in would not stand an up and down heat, as it would change in being long in heating.’

“‘1783.—For printing a table and tea-service of 250 pieces (D. G.) for David Garrick, £8 6s. 1½d.

“‘1783.—Twenty-five dozen half-tiles printing and colouring, £1 5s.’

“The last invoice I find from Mr. Green is dated

“‘1793.—I am sorry I cannot make out the invoice you request of goods forwarded you, April 4, for want of having received your charge of them to me. Only directions for printing these came enclosed in the package.’

“‘1798.—To printing two fruit baskets, 1s.’

“This last item, of course, does not imply that Mr. Wedgwood had the chief of his work done here, but no doubt the articles were required to match some service previously sold, of[32] which Mr. Green had possession of the copper plates. In the following year Mr. Green retired from business to enjoy the fruits of his long and successful labours. The following memorandum, in the handwriting of Mr. Sadler (from Mr. Sadler’s receipt-book in my possession, date 1776), will give an idea of the extent of their business:—

“J. Sadler and G. Green would be willing to take a young man about 18 into partnership for a third of their concern, in the printing and enamelling china, earthenware, tile, &c., business, on the following conditions:—1st, That he advances his £200 for the third part of the engravings and other materials necessary for the business (N.B.—The engravings alone have cost above £800). 2nd. That he should give his labour and attendance for twelve months without any share of the profits, in consideration of being instructed completely in the business. 3rd. After the expiration of twelve months, the stock in ware should be valued as low as is common in such cases, and he should immediately enter as a partner into the profits of the whole concern throughout, either paying the value for his third share of such stock, or paying interest for it till it is cleared off. The value of the stock is uncertain, being sometimes £200 more than other time; but reckon it at the least may be about £600. The sole reason of taking a partner is, J. Sadler not choosing to confine himself to business as much as heretofore.”

Specimens of these early printed goods, bearing Wedgwood’s mark, are rare. The curious teapot (Fig. 19) will serve as an example. It bears on one side a well-engraved and sharply printed representation of the quaint subject of the mill to grind old people young again—the kind of curious machine which one recollects in our boyish days were taken about from fair to fair by strolling mountebanks—and on the other an oval border of foliage, containing the ballad belonging to the subject, called “The Miller’s Maid grinding Old Men Young again.” It begins—

Fig. 19.

The teapot is marked WEDGWOOD. In the possession of Mr. Beard, of Manchester, is a fine dinner service of the printed “Queen’s ware,” and other pieces of interest. In the Museum of Practical Geology is an example of this printing, the design on one side of which is a group at tea—a lady pouring out tea for a gentleman, and on the opposite side the verse:—

Examples of Liverpool made pottery, printed by Sadler and Green, are also of uncommon occurrence. In the Mayer Museum the[33] best, and indeed only series worthy the name in existence, is to be found, and to these wares I direct the attention of all who are interested in the subject.