Transcriber’s Note: This ebook makes extensive use of Greek metrical symbols, for example ⏑ (U+23D1 METRICAL BREVE), ⏘ (U+23D8 METRICAL TETRASEME). If these do not display for you, you’ll need to install a font which can handle these characters. Everson Mono is one such font.

GREEK TRAGEDY

BY

GILBERT NORWOOD, M.A.

FORMERLY FELLOW OF ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

PROFESSOR OF GREEK IN THE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, CARDIFF

METHUEN & CO. LTD.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

First Published in 1920

This book is an attempt to cover the whole field of Greek Tragedy. My purpose throughout has been twofold. Firstly, I have sought to provide classical students with definite facts and with help towards a personal appreciation of the plays they read. My other intention has been to interest and in some degree to satisfy those “general readers” who have little or no knowledge of Greek. This second function is to-day at least as important as the first. Apart from the admirable progress shown in Europe and the English-speaking world by many works of first-rate Greek scholarship, in the forefront of which stand Jebb’s monumental Sophocles, Verrall’s achievements in dramatic criticism, and the unrivalled Einleitung of Wilamowitz-Moellendorff,—the magnificent verse-translations of Professor Gilbert Murray, springing from a rare union of poetic genius with consummate scholarship, have introduced in this country a new epoch of interest in Greek drama among many thousands who are unacquainted with the language. Even more momentous is the fact that the feeling of educated people about drama in general has been revolutionized and reanimated by the creative genius of Ibsen, whose penetrating influence is the chief cause of the present dramatic renaissance in Great Britain.

Two important topics have been given more prominence than is usual in books of this kind: dramatic structure and the scansion of lyrics.

It might have been supposed self-evident that the former of these is a vital part, indeed the foundation, of the subject, but it has suffered remarkable neglect or still more remarkable superficiality of treatment: criticism of the Greek tragedians has been vitiated time and again by a tendency to ignore the very existence of dramatic form. It is a strange reflection that the world of scholarship waited till 1887 for the mere revelation of grave difficulties in the plot of the Agamemnon. Examining boards still prescribe “Ajax vv. 1-865,” on the naïve assumption that they know better than Sophocles where the play ought to end. Euripides has been discussed with a perversity which one would scarcely surpass if one applied to Anatole France the standards appropriate to Clarendon. Throughout I have attempted to follow the working of each playwright’s mind, to realize what he meant his work to “feel like”. This includes much besides structure, but the plot is still, as in Aristotle’s day, “the soul of the drama”.

Chapter VI, on metre and rhythm, will, I hope, be found useful. Greek lyrics are so difficult that most students treat them as prose. I have done my best to be accurate, clear, and simple, with the purpose of enabling the sixth-form boy or undergraduate to read his “chorus” with a sense of metrical and rhythmical form. With regard to this chapter, even more than the others, I shall welcome criticism and advice.

I have to thank my wife for much help, and my friend Mr. Cyril Brett, M.A., who kindly offered to make the Index.

GILBERT NORWOOD

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Literary History of Greek Tragedy | 1 |

| II. | The Greek Theatre and the Production of Plays | 49 |

| III. | The Works of Æschylus | 84 |

| IV. | The Works of Sophocles | 132 |

| V. | The Works of Euripides | 186 |

| VI. | Metre and Rhythm in Greek Tragedy | 327 |

| Index | 365 |

All the types of dramatic poetry known in Greece, tragic, satyric, and comic, originated in the worship of Dionysus, the deity of wild vegetation, fruits, and especially the vine. In his honour, at the opening of spring, were performed dithyrambs, hymns rendered by a chorus, who, dressed like satyrs, the legendary followers of Dionysus, presented by song and mimic dance stories from the adventurous life of the god while on earth. It is from these dithyrambs that tragedy and satyric drama both sprang. The celebrated Arion, who raised the dithyramb to a splendid art-form, did much[1] incidentally to aid this development. His main achievement in this regard is the insertion of spoken lines in the course of the lyrical performance; it seems, further, that these verses consisted of a dialogue between the chorus and the chorus-leader, who mounted upon the sacrificial table. Such interludes, no doubt, referred to incidents in the sacred story, and the early name for an actor (ὑποκριτής, “one who answers”) suggests that members of the chorus asked their leader to explain features in the ritual or the narrative.

At this point drama begins to diverge from the dithyramb. With comedy we are not here concerned.[2][2] The drama of the spring festival may be called “tragedy,” but it was in a quite rudimentary state. Its lyrics, sung by fifty “satyrs,” would altogether outshine in importance the dialogue-interludes between chorus-leader and individual singers; the theme, moreover, would be always some event connected with Dionysus. Two great changes were necessary before drama could enter on free development: the use of impersonation in the interludes and the admission of any subject at will of the poet. The first was introduced by Thespis, who is said to have “invented one actor”. The second was perhaps later, but at least as early as Phrynichus we find plays on subjects taken from other than Dionysiac legends. It is said that the audience complained of this innovation: “What has this to do with Dionysus?”[3]

Another great development is attributed to Pratinas—the invention of satyric drama. The more stately, graver features and the frolicsome, often gross, elements being separated, the way was clear for the free development of tragedy and satyric into the forms we know. But satyric work, though always showing playful characteristics and a touch of obscenity, was never confounded with comedy. Stately figures of legend or theology regularly appeared in it—Odysseus in the Cyclops, Apollo in the Ichneutæ—and it was a regular feature at the presentations of tragedy; each tragic poet competed with three tragedies followed by one satyric play. When the latter form changed its tone slightly, as in the work of the Alexandrian Pleiad,[4] it approximated not to comedy but to satire.[5]

The Dorians claimed the credit of having invented both tragedy and comedy.[6] There seems little doubt that they provided the germ, though the glories of Greek drama belong to Athens. Arion, whose contribution has been described, if not himself a Dorian, worked among Dorians at Corinth, which Pindar,[7] for example, recognized as the birthplace of the dithyramb. Moreover the lyrics of purely Attic tragedy show in their language what is generally regarded as a slight Doric colouring.[8]

Aristotle[9] sums up the rise of tragedy as follows:[4] “Tragedy ... was at first mere improvization ... originating with the leaders of the dithyramb. It advanced by slow degrees; each new element that showed itself was in turn developed. Having passed through many stages, it found its natural form, and there it stopped. Æschylus first introduced a second actor; he diminished the importance of the chorus, and assigned the leading part to the dialogue. Sophocles raised the number of actors to three, and added scene-painting. It was not till late that the short plot was discarded for one of greater compass, and the grotesque diction of the earlier satyric form for the stately manner of tragedy. The iambic measure then replaced the trochaic tetrameter, which was originally employed when the poetry was of the satyric order, and had greater affinities with dancing.... The number of ‘episodes’ or acts was also increased, and the other embellishments added, of which tradition tells.”

We have but meagre knowledge of the drama before Æschylus, whose vast achievement so overshadowed his predecessors that their works were little read and have in consequence practically vanished. Tragedy was born at the moment when, as tradition relates, Thespis of Icaria in Attica introduced the actor. Arion, as we saw, had already caused one of the chorus to mount upon the sacrificial table or the step of the altar and deliver a narrative, or converse with his fellow-choristers, concerning Dionysus, using not lyrical metre, but the trochaic tetrameter.[10] Thespis’ great advance was to introduce a person who should actually present the character to whom Arion’s chorister had merely[5] made allusion: the action, instead of being reported, went on before the eyes of the audience. This change clearly at once begets the possibility of drama, however rudimentary. By retiring to the booth while the singers perform their lyric, he can change his mask and costume and reappear as another person; by learning and discussing what has been said by his supposed predecessor, he can exhibit the play of emotion or the construction of a plan.

If this was done by Thespis, he was the founder of European drama. His floruit may be assigned to the year 535 B.C., the date of the first dramatic competition at Athens. But little is known of him. Aristotle in his Poetic[11] does not mention his name. Far later we have the remarks of Horace, “Diogenes Laertius,”[12] and Suidas. Horace tells[13] that Thespis discovered tragic poetry, and conveyed from place to place on waggons a company of players who sang and acted his pieces, their faces smeared with lees of wine: “Diogenes Laertius” says that Thespis “discovered one actor”. Suidas gives us the names of several plays, Phorbas or The Trials (ἆθλα) of Pelias, The Priests, The Youths, Pentheus. We possess four fragments alleged to belong to these, but they are spurious. Aristotle,[14] moreover, affirms that Tragedy was in the first place a matter of improvization. The conclusion seems to be that Thespis did not “write plays” in the modern sense of the phrase. He was much more like those Elizabethan dramatists who provided “the words” for their actors, and for whom printing and publication were only thought of if the play had achieved success upon the boards. He stood midway between Æschylus and the unknown actor-poets before Arion who improvized as they played.

The next name of importance is that of Chœrilus[6] the Athenian, who competed in tragedy for the first time during the 64th Olympiad (524-1 B.C.) and continued writing for the stage during forty years. He produced one hundred and sixty plays, and obtained the first prize thirteen times. Later generations regarded him as especially excellent in the satyric drama[15] invented by his younger contemporary Pratinas. To him were attributed the invention of masks, as a substitute for the wine-lees of Thespis, and more majestic costume. We know by name only one of his works, the Alope, which is concerned with the Attic hero Triptolemus. A fragment or two reveal an unexpected preciosity of style; he called stones and rivers “the bones and veins of the earth”.

Pratinas of Phlius, in the north of the Peloponnese, is said to have competed with Æschylus and Chœrilus in the 70th Olympiad (500-497 B.C.). His great achievement, as we have said, was the invention of satyric drama. Fifty plays are attributed to him, of which thirty-two were satyric. Hardly any fragments of these are extant, but we get some conception of the man from a hyporchema in which he complains that music is encroaching upon poetry: “let the flute follow the dancing revel of the song—it is but an attendant”. With boundless gusto and polysyllabic energy he consigns the flute to flames and derision.

At length we reach a poet who seems to have been really great, a dramatist whose works, even to a generation which knew and reverenced Æschylus, seemed unworthy to be let die—Phrynichus of Athens, son of Polyphradmon, whose first victory occurred 512-509 B.C. It is said that he was the first to bring female characters upon the stage (always, however, played by men). The following dramas are known by name: Egyptians; Alcestis; Antæus or The Libyans; The Daughters of Danaus; The Capture of Miletus; Phœnician Women (Phœnissæ); The Women of Pleuron; Tantalus;[7] Troilus. The Egyptians seems to have dealt with the same subject as the Supplices of Æschylus; so does the Danaides; these two dramas may have formed part of a trilogy. The Alcestis followed the same lines as the Euripidean play; it is probable, indeed, that the apparition of Death with a sword was borrowed by Euripides from Phrynichus. The Antæus related the wrestling-match between Heracles and his earth-born foe. The manner in which Aristophanes[16] refers to the play shows that the description of the wrestling-bout was still celebrated after the lapse of a century. The Pleuroniæ treated of Meleager and the fateful log which was preserved, and then burnt in anger, by his mother Althæa.

Two plays were specially important. The Phœnissæ (produced in 476), celebrated the victory of Salamis, had Themistocles himself for choregus, and won the prize; its popularity never waned throughout the fifth century. We are told that the prologue was spoken by an eunuch while he placed the cushions for the Persian counsellors; further—an important fact—that this person, at the beginning of the play, announced the defeat of Xerxes. The Capture of Miletus, less popular in later days—no fragments at all are to be found—created even more stir at the moment. Miletus had been captured by Darius in 494 B.C., Athens having failed to give effective support to the Ionian revolt. While the distress and shame excited by the fall of the proudest city in Asiatic Greece were still strong in Athenian minds, Phrynichus ventured to dramatize the disaster. Herodotus tells how “the theatre burst into tears; they fined him a thousand drachmæ for reminding them of their own misfortunes, and gave command that no man should ever use that play again”.[17]

Few lost works are so sorely to be regretted as those of Phrynichus. The collection of fragments merely hints at a genius who commanded the affection of an age which knew his great successors, a master whose dignity was not utterly overborne by Æschylus, and whose tenderness could still charm hearts which had thrilled to the agonies of Medea and the romance of Andromeda. The chief witness to his popularity is Aristophanes, who paints for us a delightful picture[18] of the old men in the dark before the dawn, trudging by lantern-light through the mud to the law-court, and humming as they go the “charming old-world honeyed ditties” from the Phœnissæ. In another play[19] the birds assert that it is from their song that “Phrynichus, like his own bee, took his feast, food of the gods, the fruit of song, and found unfailingly a song full sweet”. One or two snatches survive from these lyrics, lines from the Phœnissæ in the “greater Asclepiad” metre which is the form of some of Sappho’s loveliest work, and a verse[20] from the Troilus which Sophocles himself quoted: “the light of love on rosy cheeks is beaming”.

It is clear that for most Athenians the spell of Phrynichus lay in his songs; succeeding poets he impressed almost equally as a playwright. It has already been mentioned that Euripides seems to have borrowed from the Alcestis. Æschylus, especially, was influenced by his style, and in the Persæ followed the older poet closely. Indeed the relation between the Persæ and the Phœnissæ is puzzling, but ancient authority did not hesitate to say that the later work was “modelled on” the earlier.[21] It is no question of a réchauffé to suit the[9] taste of a later age, like the revisions of Shakespeare by Davenant and Cibber, for the two tragedies are separated at the utmost by only seven years; rather we appear to have a problem like the connexion between Macbeth and Middleton’s Witch. Perhaps the soundest opinion is that the younger playwright wished to demonstrate his own method of writing and his theory of dramatic composition in the most striking way possible—by choosing a famous drama of the more rudimentary type and rewriting it as it ought to be written. Two features in the Phœnissæ seem to lend support to this view. Firstly, the prologue was delivered by a slave who was preparing the seats of the Persian counsellors. The Persæ expunges the man and his speech, presenting us at once with the elders in deliberation. Nothing is more characteristic of the architectonic power in literature than the instinct to sweep away everything but the minimum of mere machinery; at the first instant we are in the midst of the plot. Secondly, the prologue at once announced the disaster. Nothing was left but the amplification of sorrow, a quasi-operatic presentation by the Phœnician women who formed the chorus. Here again the Persæ provides a most instructive contrast.

From the fragments, from ancient testimony, and from the recasting of the Phœnissæ which appeared instinctive or necessary to Æschylus, we gain some clear conception of Phrynichus. A lyrist of sweetness and pellucid dignity, he has been compared[22] to his contemporary Simonides; the graceful phrases in which Aristophanes declared that Phrynichus drew his inspiration from the birds recall to us the “native wood-notes wild” of Shakespeare’s earlier achievement. As a playwright in the strict sense he is, for us, the first effective master, but still swayed by the age of pure lyrists which was just reaching its culmination and its close in Pindar—so greatly swayed[10] that the “episodes” were still little more than interruptions of lyrics which gave but a static expression to feeling.

Æschylus, the son of Euphorion, was born at Eleusis in 525 B.C. At the age of twenty-five he began to exhibit plays, but did not win the prize until the year 485. The Persian invasions swept down upon Athens when Æschylus had come to the maturity of his powers. He served as a hoplite at Marathon[23] and his brother Cynegirus distinguished himself even on that day of heroes by his desperate courage in attempting to thwart the flight of the invaders. That the poet was present at Salamis also may be regarded as certain from the celebrated description in the Persæ. He twice visited Sicily. On the first occasion, soon after 470 B.C., he accepted the invitation of Hiero, King of Syracuse, and composed The Women of Etna to celebrate the city which Hiero was founding on the slope of that mountain. Various stories to explain his retirement from Athens were circulated in antiquity. Some relate that he was unnerved by a collapse of the wooden benches during a performance of one of his plays. Others said that he was defeated by Simonides in a competition: the task was to write an epitaph on those who fell at Marathon. According to others he was chagrined by a dramatic defeat which he sustained at the hands of the youthful Sophocles in 468. A fourth story declared that he was accused of divulging the Eleusinian Mysteries in one of his plays, and was in danger of his life until he proved that he had himself never been initiated. These stories are hard to accept. Possibly he wrote something which offended against[11] Eleusinian rule, and was condemned to banishment or possibly to death, which (as often occurred) he was allowed to escape by voluntary exile. We cannot suppose that he pleaded ignorance[24] seriously; a man of his genuinely devout temperament, and a native of Eleusis, must assuredly have been initiated. A second visit to Sicily was taken after he had again won the prize with the Oresteia. He never returned. Story tells how he was sitting on the hillside near the city of Gela when an eagle, flying with a tortoise in its claws in quest of a stone whereon to crush it, dropped its prey upon the bald head of the poet and killed him. He left two sons, Euphorion and Bion, who also pursued the tragic art—a tradition which persisted in the family for generations.

Æschylus is too great a dramatist to receive detailed treatment in the course of a general discussion; a separate chapter must be allotted to this. At present we shall consider only his position in the history of tragedy.

The great technical change introduced by Æschylus was that he “first introduced a second actor; he diminished the importance of the chorus, and assigned the leading part to the dialogue”.[25] The two last statements are corollaries of the first, which describe a deeply important advance. It has been said above that the drama was founded by the man who “invented one actor”; at the same time it is easy to realize how primitive such drama must have been. The addition of another actor did not double the resources of tragedy, rather it increased them fifty-fold. To bring two opposed or sympathetic characters face to face, to exhibit the clash of principles by means of the clash of personalities, this is a step forward into a new world, a change so great that to call Æschylus the very inventor of tragedy is[12] not unreasonable. This meagre equipment of two actors was found sufficient by two of the fifth-century masters for work[26] of the highest value. The further remark of Aristotle that Æschylus “diminished the importance of the chorus” follows naturally from the vast increase in the importance of the “episodes”.

Revolutionary as Æschylus was, he did not attain at a bound to a characteristic dramatic form of his own and then advance no farther. In his earliest extant play, the Supplices, the alterations mentioned above are certainly in operation, but their use is tentative. The chorus is no doubt less dominant than it had been, but it is the most important feature, even to a modern reader. To an ancient spectator it must have appeared of even greater moment. The number of singers was still fifty, and the lyrics, accompanied by music and the dance of this great company, occupy more than half of our present text. We have left Phrynichus behind, but he is not out of sight.

It is necessary at this point to give some account of the life of Sophocles and his position in dramatic history, though a detailed discussion of his extant work must be reserved for a separate chapter. He was born about 496 B.C., the son of a well-to-do citizen named Sophillus, and received, in addition to the usual education, more advanced training in music from the celebrated Lampros. The youth’s physical beauty was remarkable, and at the age of sixteen he was chosen to lead the choir of boys who performed the pæan celebrating the victory of Salamis. Nothing more is known of his life till the year 468, when he produced his first tragedy. One of his fellow-competitors was Æschylus, and we are told[27] that feeling ran so high that the Archon, instead of choosing the judges by[13] lot as usual, entrusted the decision to the board of generals; they awarded the victory to the youthful Sophocles. For sixty years he produced a steady stream of dramatic work with continuous success. He at first performed in his own plays—his skill in the Nausicaa gained great applause—but was compelled to give this up owing to the failure of his voice. The number of his plays was well over a hundred, performed in groups of four, and he won eighteen victories at the City Dionysia; even when he failed of the first prize, he was never lower than the second place.[28] His genius seems even to have increased with advancing age; he was about ninety when he wrote the Œdipus Coloneus. Sophocles took a satisfactory if not prominent part in public life,[29] being twice elected general, once with Pericles and later with Nicias. He served also as Hellenotamias—a member, that is, of the Treasury Board which administered the funds of the Delian Confederacy. It is an interesting comment on the early part of the Œdipus Coloneus that the poet acted as priest of two heroes, Asclepius and Alcon. He had several sons, the most celebrated of whom was Iophon, himself a tragedian of repute. A famous story relates that Iophon, being jealous of his illegitimate brother, brought a suit to prove his father’s insanity, with the intent to become administrator of his estate. The aged poet’s defence consisted in a recitation of the Œdipus Coloneus which he had just completed, and the jury most naturally dismissed Iophon’s petition. He died late in 406 B.C., fully ninety years old, a few months later than Euripides, and not long before the disaster of Ægospotami. The Athenian people mourned him as a hero under the name of Dexion, “The Entertainer,” or “Host,” and brought yearly sacrifice to his shrine.

The personality of Sophocles stands out more[14] definitely before the modern eye than that of perhaps any other fifth-century Greek. His social talent made him a noted figure whose good sayings were repeated, and of whom the gossips as well as the critics loved to circulate illustrative stories. He seemed the embodiment of all that man can ask. Genius, good health, industry, long life, personal beauty, affluence, popularity, and the sense of power—all were his, and enjoyed in that very epoch which, beyond all others, seems to have combined stimulus with satisfaction. Salamis was fought and won just as he had left childhood behind. His adolescence and maturity coincided with the rise and establishment of the Athenian Empire; he listened to Pericles, saw the Parthenon and Propylæa rise upon the Acropolis, associated with Æschylus, Euripides, Aristophanes, and Thucydides, watched the work of Phidias and Polygnotus grow to life under their fingers. Though he carried into the years of Nestor the genius of Shakespeare, he was yet so blessed that he died before the fall of Athens. Phrynichus, the comic poet, wrote: “Blessed was Sophocles, who passed so many years before his death, a happy man and brilliant, who wrote many beautiful tragedies and made a fair end of a life which knew no misfortune”.[30] Sophocles’ own words[31] come as a significant comment:—

“Best of all fates—when a man weighs everything—is not to be born, and second-best beyond doubt is, once born, to depart with all speed to that place whence we came.”

Of his social charm there are many evidences. He gathered round him a kind of literary club or salon.[15] Some hint of the talk in this circle may be gathered from the fragment of Ion’s Memoirs which tells how when the poet came to Chios he engaged in critical battle with the local schoolmaster concerning poetical adjectives, and quoted with approbation Phrynichus’ line λάμπει δ’ ἐπὶ πορφυρέαις παρῇσι φῶς ἔρωτος. He was a friend of Herodotus, from whom he quotes more than once, and to whom he addressed certain elegiac verses. With regard to his own art, we possess two remarks of deep interest. The first is reported by Aristotle:[32] “I depict men as they ought to be, Euripides depicts them as they are”. It is excellent Attic for “he is a realist, I am an idealist”. Nevertheless, he esteemed his rival; when he led forth his chorus for the first time after the news of Euripides’ death in Macedonia had reached Athens, he and his singers wore the dress of mourning. The second remark is a brief account[33] of his own development: “My dramatic wild oats were imitation of Æschylus’ pomp; then I evolved my own harsh mannerism; finally I embraced that style which is best, as most adapted to the portrayal of human nature”. All that we now possess would seem to belong to his third period, though certain characteristics of the Antigone may put us in mind of the second.[34]

Apart altogether from his glorious achievement in actual composition, Sophocles is highly important as an innovator in technique. The changes which he introduced are: (i) the number of actors was raised from two to three;[35] (ii) scene-painting was invented[35]; (iii) the plays of a tetralogy were, sometimes at any rate, no longer part of a great whole, but quite distinct in subject;[36] (iv) it is said[37] that he raised the number of the[16] chorus from twelve to fifteen, was the first tragedian to use Phrygian music and to give his actors the bent staff and white shoe which they sometimes used.

The points named under (iv) are of small importance save the change in the number of choreutæ, but that is a detail which can scarcely be accepted, Æschylus during part of his career employed fifty choreutæ, and it is extremely improbable that the number sank as low as twelve, only to rise slightly again at once. The invention of scene-painting is clearly momentous; it became easy to fix the action at any spot desired, and a change of scene also became possible. Æschylus, of course, in his later years made use of this development. The other two points are vital.

Though the stage gained immensely by the introduction of a third actor, little perhaps need be said on the point. An examination of the early Æschylean plays, and even of the Choephorœ or Agamemnon, side by side with the Philoctetes or Œdipus Coloneus, will make the facts abundantly clear. In the crisis of Œdipus Tyrannus (for example) the presence of Jocasta,[38] while her husband hears the tidings brought by the Corinthian, does not merely add to the poignancy of the scene; it may almost be said to create it.

The last change, that of breaking up the tetralogy into four disconnected tragedies, is equally fundamental. The older poet was a man of simple ideas and gigantic grasp. His conceptions demanded the vast scope of a trilogy, and perhaps the most astonishing feature of his work is the fact that, while each drama is a splendid and self-intelligible whole, it gains its full import only from the significance of the complete organism. Sophocles realized that he possessed a narrower, if more subtle, genius, and moulded his technique to suit his powers. Each of his works, however spacious and statuesque it may seem beside Macbeth, Lear, or even Hippolytus,[17] shows, as compared with Æschylus, a closeness of texture in characterization and a delicate stippling of language, which mark nothing less than a revolution.

Tradition tells that Euripides was born at Salamis on the very day of the great victory (480 B.C.); the Parian marble puts the date five years earlier. He was thus a dozen or more years younger than Sophocles. His father’s name was Mnesarchus; his mother Clito is ridiculed by Aristophanes as a petty green-grocer, but all other evidence suggests that they were well-to-do; Euripides was able to devote himself to drama, from which little financial reward could be expected, and to collect a library—a remarkable possession for those days. He lived almost entirely for his art, though he must, like other citizens, have seen military service. His public activities seem to have included nothing more extraordinary than a single “embassy” to Syracuse. Unlike Sophocles, he cared little for society save that of a few intimates, and wrote much in a cave on Salamis which he had fitted up as a study. The great philosopher Anaxagoras was his friend and teacher; several passages[39] in the extant plays point plainly to his influence. It was in Euripides’ house that Protagoras read for the first time his treatise on the gods which brought about the sophist’s expulsion from Athens. Socrates himself is traditionally regarded as the poet’s friend. Aulus Gellius[40] says that he began to write tragedy at the age of eighteen; but it was not till 455 B.C. (when he was perhaps thirty) that he “obtained a chorus”—that is, had his work accepted for performance. One of these pieces was the Peliades; he obtained only the third place. By the end of his life he had written nearly a hundred dramas, including satyric works, but obtained the first prize only four times: his fifth victory was won by the tetralogy which included the Bacchæ, performed after his death. His influence[18] was far out of proportion to these scanty rewards.[41] On any given occasion he might be defeated by some talented mediocrity who hit the taste of the moment. When he offered the Medea itself he was overcome, not only by Sophocles, but by Euphorion; yet his vast powers were recognized by all Athens. Euripides was married—twice it is said—and had three sons. Late in his life he accepted an invitation from Archelaus, King of Macedonia; after living there a short time in high favour and writing his latest plays, he died in 406 B.C. He was buried in Macedonia and a cenotaph was erected to his memory in Attica.

Further light both on the career and works of Euripides has recently been provided by an interesting discovery. In 1912 Dr. Arthur S. Hunt published[42] extensive fragments of a life of the poet by Satyrus, from portions of a papyrus-roll found at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt by Dr. Grenfell and Dr. Hunt. Satyrus lived in the third century before Christ: our MS. itself is dated by its discoverers “from the middle or latter part of the second century” after Christ. The most striking points are (i) Satyrus quotes the fragment of the Pirithous dealt with below,[43] attributing it, as was often done, to Euripides, and saying that the poet “has accurately embraced the whole cosmogony of Anaxagoras in three periods”;[44] (ii) there are new fragments, on the vain pursuit of wealth; (iii) the poet was prosecuted for impiety by the statesman Cleon; (iv) we read that Euripides wrote the proem for the Persæ composed by his friend the musician Timotheus; (v) Satyrus, in discussing peripeteia, mentions “ravishings, supposititious infants, and recognitions by means of rings and necklaces—for these, as you know, are the back-bone[19] of the New Comedy, and were perfected by Euripides”.

A discussion of Euripides’ surviving work will be found in a separate chapter. Our business here is to indicate his position in the development of technique. Though he is for ever handling his material and the resources of the stage in an original and experimental manner, the definite changes which he introduced are few. That many of his dramas are not tragedies at all but tragicomedies, is a development of the first importance. Another fact of this kind is his musical innovations. The lyrics of his plays tend to become less important as literature and to subserve the music, in which he introduced fashions not employed before, such as the “mixed Lydian”; it is impossible to criticize some of his later odes without knowledge, which we do not possess, of the music which he composed for them and the manner in which he caused them to be rendered. Hence the loose syntax, the polysyllabic vagueness of expression, and the repeated words—features which irritated Aristophanes and many later students.

Another novelty is his use of the prologue. Since this is properly nothing but “that part of the play which precedes the first song of the whole chorus,”[45] prologues are of course found in Æschylus and Sophocles. The peculiarity of the Euripidean prologue is that it tends to be non-dramatic, a narrative enabling the spectator to understand at what point in a legend the action is to begin. It is from Euripides’ use of the prologue that the modern meaning of the word is derived.

Aristophanes in his Frogs makes a famous attack upon most[46] sides of Euripides’ art as contrasted with that of Æschylus. But it is often forgotten that, damned utterly as the younger tragedian is, Æschylus by no means[20] escapes criticism. Many of the censures put into Euripides’ mouth are just and important; it seems likely that Aristophanes is practically quoting his victim’s conversation; the remark[47] about Æschylus that “he was obscure in his prologues,” is no mere rubbish attributed to a dullard. That Euripides did criticize his elder is a fact. The Supplices[48] contains a severe remark on the catalogue of chieftains in the Septem; the elaborate sarcasm directed in the Electra[49] against the Recognition-scene of the Choephorœ is even more startling. Besides this, Aristophanes seems to quote remarks of Euripides on himself and his work: “When I first took over the art from you, I found it swollen with braggadocio and tiresome words; so the first thing I did was to train down its fat and reduce its weight”.[50] His comment on dialogue is no less pertinent: “With you Niobe and Achilles never said a word, but I left no personage idle; women, slaves, and hags all spoke”.[51] Finally, there is the perfect description of his own realism[52]: οἰκεῖα πράγματ’ εἰσάγων, οἷς χρώμεθ’, οἷς σύνεσμεν, “I introduced life as we live it, the things of our everyday experience”. Such sentences as these reflect unmistakably the conversation of a playwright who was jealous for the dignity and the progress of his art.

Though during his own time Euripides was hardly equal in repute to his two companions, scarcely had his Macedonian grave closed over him than his popularity began to overshadow theirs. Æschylus became a dim antique giant; Sophocles, though always admired, was too definitely Attic and Periclean to retain all his prestige in the Hellenistic world. It was the more cosmopolitan poet who won posthumous applause from one end of the civilized earth to the other. From 400 B.C. to the downfall of the ancient world he was[21] unquestionably better known and admired than any other dramatist. This is shown by the much larger collection of his work which has survived, by the imitation of later playwrights, and by innumerable passages of citation, praise, and comment in writers of every kind. He shared with Homer, Vergil, and Horace the equivocal distinction of becoming a schoolbook even in ancient times. Nine of our nineteen plays were selected for this purpose: Alcestis, Andromache, Hecuba, Hippolytus, Medea, Orestes, Phœnissæ, Rhesus, and Troades. It is not easy to see what principle of selection prompted the educationists of the day: Andromache and Hippolytus do not strike a modern reader as specially “suitable”. Owing to their use in schools they were annotated; these scholia are still extant and are often of great value. In the Byzantine age the number was reduced to three: Hecuba, Orestes, Phœnissæ.

Among the numerous lesser tragedians of the fifth century five hold a distinguished place: Neophron of Sicyon, Aristarchus of Tegea, Ion of Chios, Achæus of Eretria, Agathon of Athens.

Neophron is an enigmatic figure. It would seem that he was an important forerunner of Euripides. Not only do we learn that he wrote one hundred and twenty tragedies and that he was the first to bring upon the stage “pædagogi” and the examination of slaves under torture; it is said also that his Medea was the original of Euripides’ tragedy so-named.[53] “Pædagogi” or elderly male attendants of children are familiar in Euripides, and the “questioning” of slaves is shown (though not to the audience) in the Ion.[54] As for the third point, we have three fragments which clearly recall the extant play—a few lines in which Ægeus requests[22] Medea to explain the oracle, a few more in which she tells Jason how he shall die, and the celebrated passage which reads like a shorter version of her great soliloquy when deciding to slay her children. There is the same anguish, the same vacillation, the same address to her “passion” (θυμός). Such a writer is plainly epoch-making: he adds a new feature to tragedy in the life-time of Sophocles. The realism of everyday life and the pangs of conscience battling with temptation—these we are wont to call Euripidean. But some have denied the very existence of Neophron as a dramatist: the fragments are fourth-century forgeries, or Euripides brought out a first edition[55] of his play under Neophron’s name. Against these views is the great authority of Aristotle,[56] who, however, may have been deceived by the name “Neophron” in official records. An argument natural to modern students, that a poet of Euripides’ calibre would not have borrowed and worked up another’s play, is of doubtful strength. Æschylus, as we have seen, probably acted so towards Phrynichus. The best view is probably that of antiquity. We may note that Sicyon is close to Corinth, and that a legend domestic to the latter city might naturally find its first treatment in a playwright of Sicyon.

Aristarchus of Tegea, whose début is to be dated about 453 B.C., is said by Suidas to have lived for over a hundred years, to have written seventy tragedies, two of which won the first prize, and one of which was called Asclepius (a thank-offering for the poet’s recovery from an illness), and to have “initiated the present length of plays”.[57] This latter point sounds important, but it is difficult to understand precisely what Suidas means. For though the average Sophoclean or Euripidean tragedy is longer than the Æschylean,[23] Aristarchus began work later than Sophocles and no earlier than Euripides. It has been thought that Suidas refers to the length of dramas in post-Euripidean times, but of these we have perhaps no examples.[58] Aristarchus’ reputation was slight but enduring. Ennius two and a half centuries later translated his Achilles into Latin; the same work is quoted in the prologue of Plautus’ Pœnulus. A phrase[59] from another play became proverbial.

A more distinguished but probably less important writer was Ion of Chios, son of Orthomenes, who lived between 484 and 421 B.C. A highly accomplished man of ample means, he travelled rather widely. In Athens he must have spent considerable time, for he was intimate with Cimon and his circle, and produced plays the number of which is by one authority put at forty. Besides tragedy and satyric drama, he wrote comedies, dithyrambs, hymns, pæans, elegies, epigrams, and scolia. He was, moreover, distinguished in prose writing: we hear of a book on the Founding of Chios, of a philosophic work, and of certain memoirs.[60] This latter work must be a real loss to us, if we may judge from its fragments. In the fifth century B.C. no one but a facile Ionian would have thought it worth while to record mere gossip even about the great; for us there is great charm in an anecdote like that of the literary discussion between Sophocles and the schoolmaster, or the exclamation of Æschylus at the Isthmian Games.[61] Ion would seem to have been less a great[24] poet than a delightful belletrist; the quality is well shown in his remark[62] that life, like a tragic tetralogy, should have a satyric element. One year he obtained a sensational success by winning the first prize both for tragedy and for a dithyramb; to commemorate this he presented to each Athenian citizen a cask of Chian wine. He died before 421, the date of Aristophanes’ Peace,[63] wherein he is spoken of as transformed into a star, in allusion to a charming lyric passage of his:—

“We awaited the star that wanders through the dawn-lit sky, pale-winged courier of the sun.”

His tragedies,[64] though they do not appear to have had much effect on the progress of technique or on public opinion, were popular. Aristophanes, for instance, nearly twenty years after his death, quotes a phrase from his Sentinels[65] as proverbial, and centuries later the author of the treatise On the Sublime[66] wrote his celebrated verdict: “In lyric poetry would you prefer to be Bacchylides rather than Pindar? And in tragedy to be Ion of Chios rather than—Sophocles? It is true that Bacchylides and Ion are faultless and entirely elegant writers of the polished school, while Pindar and Sophocles, although at times they burn everything before them as it were in their swift career, are often extinguished unaccountably and fail most lamentably. But would anyone in his senses regard all the compositions of Ion put together as an equivalent for the single play of the Œdipus?”

Achæus of Eretria was born in 484 B.C., and exhibited his first play at Athens in 447. He won only one first prize though we hear that he composed over forty plays, nearly half of which are known by name. That he was second only to Æschylus in satyric drama was the opinion held by that delightful philosopher Menedemus[67] the minor Socratic, the seat of whose school was Eretria itself, Achæus’ birthplace.

It has been suggested that the apparent disproportion of satyric plays written by Achæus is to be accounted for by his having written them for other poets.[68] He is once copied by Euripides and parodied twice by Aristophanes.[69] Athenæus makes an interesting comment on his style: “Achæus of Eretria, though an elegant poet in the structure of his plots, occasionally blackens his phrasing and produces many cryptic expressions”.[70] The instance which he gives is significant:—

“the cruse of alloyed silver, filled with ointment, swung beside the Spartan tablet, double wood inscribed”. That is, “he carried an oil-flask and a Spartan general’s bâton”. Aiming at dignified originality of diction Achæus has merely fallen into queerness. On the other side, when he seeks vigorous realism he becomes quaintly prosaic. In the Philoctetes, for instance, Agamemnon utters the war-cry ἐλελελεῦ in the middle of an iambic line.

A far more noteworthy dramatist was Agathon the Athenian, who seems to have impressed his contemporaries, and even the exacting Aristotle, as coming next in merit to the three masters. Born about 446 B.C., he[26] won his first victory in 416 and retired to the Court of the Macedonian prince Archelaus some time before the death of Euripides (406). From contemporary evidence we gather that he was popular as a writer and as a social figure, handsome, and given to voluptuous living.

Three striking innovations are credited to him:—

(i) He produced at least one play of which both the plot and the characters were invented by himself.[71] The name of this “attractive” drama is uncertain: it may have been The Flower (Anthos) or Antheus. Agathon, here as elsewhere, shows himself a follower of Euripides. The master had employed recognized myths as a framework for a thoroughly “modern” treatment of ordinary human interests; his disciple finally throws aside the convention of antiquity.

(ii) Another post-Euripidean feature is the use of musical interludes. Aristotle tells us: “As for the later poets, their choral songs pertain as little to the subject of the piece as to that of any other tragedy. They are therefore sung as mere interludes—a practice first begun by Agathon.”[72] Our poet then is once more found completing a process which his friend had carried far. Sophocles had diminished the length and dramatic importance of the lyrics, but with him they were still entirely relevant. Euripides shows a strong tendency to write his odes as separable songs, but complete irrelevance is hardly found. Plays such as Agathon’s could obviously be performed, if necessary, without the trouble and expense of a chorus, which in process of time altogether disappeared. His interludes served, it seems, more as divisions between “acts” than as an integral part of the play. In this connexion should be mentioned his innovation in the accompaniment—the use of “chromatic” or coloured style.[73] His florid music is laughed at by Aristophanes as “ants’ bye-paths”.[74]

(iii) Occasionally he took a great extent of legend as the topic of a single drama, and it seems likely[75] that he composed a Fall of Troy, taking the whole epic subject instead of an episode. Agathon is trying yet another experiment—it was necessary for a writer of his powers to vary in some way from Euripides, but this attempt was unsatisfactory.[76]

In the Thesmophoriazusæ Aristophanes pays Agathon the honour of elaborate parody. Euripides comes to beg his friend to plead for him before an assembly of Athenian women, and the scene in which Agathon amid much pomp explains the principles of his art, contains definite and valuable criticism under the usual guise of burlesque; that Aristophanes valued him is shown by the affectionate pun on his name which he introduces into the Frogs (v. 84):—

“a good poet, sorely missed by his friends”. Plato lays the scene of his Symposium in the house of Agathon, who is celebrating his first tragic victory; the poet is depicted as a charming host, and, when the conversation turns to a series of panegyrics upon the god of Love, offers a contribution to which we shall return.

From these sources we learn as usual little about the poet’s dramatic skill, much as to his literary style. But under the first head falls a vital remark of Aristotle: “in his reversals of the action (i.e. the peripeteia), however, he shows a marvellous skill in the effort to hit the popular taste—to produce a tragic effect that satisfies the moral sense. This effect is produced when the clever rogue, like Sisyphus, is outwitted, or the brave villain defeated. Such an event is, moreover, probable in Agathon’s sense of the word: ‘it is probable,’ he says, ‘that many things should happen contrary to probability’.”[77] Agathon belongs to the class of playwrights who win popularity by bringing down to the customary theatrical level the methods and ideas of a genius who is[28] himself too undiluted and strange for his contemporaries. Agathon’s relation to Euripides resembles that of (let us say) Mr. St. John Hankin, in his later work, to Ibsen. Of his literary style much the same may be said. He loves to moralize on chance and probability and the queer twists of human nature, with Euripides’ knack of neatness but without his insight. Such things as

“this alone is beyond the power even of God, to make undone that which has been done,” and even the celebrated τέχνη τύχην ἔστερξε καὶ τύχη τέχνην, “skill loves luck, and luck skill,” give the measure of his power over epigram. His easy way of expressing simple ideas with admirable neatness may remind us of a much greater dramatist—Terence, or, in later times, of Marivaux.[78]

Plato tells us that he was a pupil both of Prodicus[79] and of Gorgias,[80] the renowned sophists, and we may trace their teaching in the fragments and in the remarkable speech which the greatest stylist of all time puts into his mouth in the Symposium—the rhymes, antitheses, quibbles, and verbal trickiness of argument. The parody, both brilliant and careful, which Aristophanes presents at the opening of his Thesmophoriazusæ is directed chiefly perhaps against his music, whereof we have no trace. The blunt auditor, Mnesilochus, describes it as lascivious.[81] The words set to it read like a feeble copy of Euripides—fluent, copious, nerveless, in spite of the “lathe,” the “glue,” the “melting-pot,” and the “moulds”[82] over which his satirist makes merry.

Agathon, then, marks unmistakably the beginning of decadence. The three masters had exhausted the possibilities of the art open to that age. A new impulse from without or the social emancipation of women might have opened new paths of achievement. But no great external influence was to come till Alexander, and then the result for Greece itself was loss of independence and vigour. And the little that could be done with women still in the harem or the slave-market was left to be performed by Menander and his fellow-comedians.[83] Agathon made a valiant effort to carry tragedy into new channels, but lacked the genius to leave more than clever experiments.

On a lower plane of achievement stands Critias, the famous leader of the “Thirty Tyrants”. Two tragedies from his pen are known to us, Pirithous[84] and Sisyphus, both at one time attributed to Euripides; but he is too doctrinaire, too deficient in brilliant idiomatic ease, for such a mistake to endure. The Pirithous deals with Heracles’ descent into Hades to rescue Theseus and to demand of Pluto Persephone’s hand for Pirithous. Of this astounding story we find little trace in the fragments, which are mostly quasi-philosophical dicta. For instance:—

In strong contrast to these prosaic lines is Critias’ superb apostrophe to the Creator, which may be paraphrased thus:—

From all time, O Lord, is thy being; neither is there any that saith, This is my son.

All that is created, lo, thou hast woven the firmament about it; the heavens revolve, and all that is therein spinneth like a wheel.

Thou hast girded thyself with light; the gloom of dusk is about thee, even as a garment of netted fire.

Stars without number dance around thee; they cease not, they move in a measure through thy high places.

From the same hymn probably comes the majestic passage which tells of “unwearied Time that in full flood ever begets himself, and the Great Bear and the Less....”

In apparent contrast to this tone is the remarkable passage, of forty-two lines, from the Sisyphus. It is a purely rationalistic account of religion. First human life was utterly brutish: there were no rewards for righteousness, no punishment of evil-doers. Then law was set up, that justice might be sovereign; but this device only added furtiveness to sin. Finally, “some man of shrewdness and wisdom ... introduced religion” (or “the conception of God,” τὸ θεῖον), so that even in secret the wicked might be restrained by fear. The contradiction between these two plays is illusory: Critias combines with disbelief in the personal Greek gods belief in an impersonal First Cause. It is too often forgotten that among the “Thirty Tyrants” were men of strong religious principles. The democratic writers of Athens loved to depict them as mercenary butchers, but it is plain from the casual testimony of Lysias[85] that they looked upon themselves as moral reformers. “They said that it was their business to purge the city of wicked men, and turn the rest of the citizens to righteousness and self-restraint.” Such passages read like quotations from men who would inaugurate a “rule of the saints,” and if their severities surpassed those of the English Puritans, they were themselves outdone by the cruelty which sternly moral leaders of the French Revolution not only condoned but initiated. Critias was the Athenian Robespierre. But the one revolution was the reverse of the other. The régime of the Thirty was a last violent effort of the Athenian oligarchs to stem the tide of ochlocracy, to[31] induce some self-discipline into the freedom of Athens. They failed, and Critias was justified on the field of Chæronea.

The most successful tragic playwright of the fourth century was Astydamas, whose history furnishes good evidence that after the disappearance of Euripides and Sophocles the Greek genius was incapable of carrying tragedy into new developments. While prose could boast such names as Plato and Demosthenes, the tragic art found no greater exponent than this Astydamas, of whose numerous plays nothing is left save nine odd lines. There were, moreover, two Astydamantes, father and son, whose works (scarcely known save by name) it is difficult to distinguish. But it seems that it was the son whose popularity was so great as to win him fifteen first prizes and an honour before unknown. His Parthenopæus won such applause in 340 B.C. that the Athenians set up a brazen statue of the playwright in the theatre; it was not till ten years later that the orator Lycurgus persuaded them to accord a like honour to the three Masters. We learn from Aristotle[86] that Astydamas altered the story of Alcmæon, causing him to slay his mother in ignorance; and Plutarch[87] alludes to his Hector as one of the greatest plays. He was nothing more than a capable writer who caught the taste of his time, and probably owed much of his popularity to the excellence of his actors.

Only one fact is known about Polyidus “the sophist,” but that is sufficiently impressive. Aristotle twice[88] takes the Recognition-scene in his Iphigenia as an example, and in the second instance actually compares the work of Polyidus with one of Euripides’ most wonderful successes—the Recognition-scene in the Iphigenia in Tauris. It appears that as Orestes was led away to slaughter he exclaimed: “Ah! So I was fated, like my sister, to be sacrificed.” This[32] catches the attention of Iphigenia and saves his life. Polyidus here undoubtedly executed a brilliant coup de théâtre.

During the fourth century many tragedians wrote not for public performance but for readers. Of these ἀναγνωστικοί[89] the most celebrated was Chæremon, of whom sufficient fragments and notices survive to give a distinct literary portrait. Comic poets ridiculed his preciosity: he called water “river’s body,” ivy “the year’s child,” and loved word-play: πρὶν γὰρ φρονεῖν εὖ καταφρονεῖν ἐπίστασαι.[90] But though a sophisticated attention to style led him into such frigid mannerisms, he can express ideas with a brief Euripidean cogency: perhaps nothing outside the work of the great masters was more often quoted in antiquity than his dictum “Human life is luck, not discretion”—τύχη τὰ θνητῶν πράγματ’, οὐκ εὐβουλία.

The only technical peculiarity attributed to him is the play Centaur, if play it was. Athenæus calls it a “drama in many metres,”[91] while Aristotle[92] uses the word “rhapsody,” implying epic quality. It may be that the epic or narrative manner was used side by side with the dramatic in the manner of Bunyan. Here is another proof that by the time of Euripides tragedy had really attained its full development. Attempts at new departures in technique are all abortive after his day.

A delightful point which emerges again and again is Chæremon’s passion for flowers. From Thyestes come two phrases—“the sheen of roses mingled with silver lilies,” and “strewing around the children of flowering spring”—which indicate, as do many others, Chæremon’s love of colour and sensuous loveliness. It was his desire to express all the details of what pleased[33] his eye that led him into preciosity—a laboured embroidery which recalls Keats’ less happy efforts. But he can go beyond mere mannerism. A splendid fragment of his Œneus shows Chæremon at his best: it describes the half-nude beauty of girls sleeping in the moonlight. One can hardly believe that Chæremon belonged to the fourth century and was studied by Aristotle. In this passage, despite its voluptuous dilettantism, there is a sense of physical beauty, above all of colour and sensuous detail, which was unknown since Pindar, and is not to be found again, even in Theocritus, till we come to the Greek novelists. In one marvellous sentence, too, he passes beyond mere prettiness to poetry, expressing with perfect mastery the truth that the sight of beauty is the surest incentive to chastity: κἀξεπεσφραγίζετο ὥρας γελώσης χωρὶς ἐλπίδων ἔρως:—

It is the idea which Meredith has voiced so magically in Love in the Valley:—

That Greek literature has progressed far towards the self-conscious Alexandrian search for charm can nevertheless be observed if we compare this passage from Chæremon with the analogous description in Euripides’ Bacchæ[93] (which no doubt suggested it). There the same general impression, and far more “atmosphere,” is given with no voluptuous details: θαῦμ’ ἰδεῖν εὐκοσμίας—“a marvel of grace for the eye to behold”—is his nearest approach to Chæremon’s elaboration. If, as has been well said,[94] one may compare the three Masters to Giotto, Raffaelle, and Correggio respectively, then Chæremon finds his parallel among the French painters; he reminds one not so much of the handsome[34] sensuality of Boucher as of that more seductive simplesse in which Greuze excelled.

A curious figure in this history is Dionysius the Elder, tyrant of Syracuse from 405-367 B.C. Like Frederick the Great of Prussia, not satisfied with political and military glory, he aspired to literary triumphs. With a pathetic hero-worship he purchased and treasured the desk of Æschylus, and similar objects which had belonged to Euripides, hoping (says Lucian[95]) to gain inspiration from them. The prince frequently tried his fortune at the dramatic contests in Athens, but for long without success, and naturally became a butt of the Attic wits, who particularly relished his moral aphorisms (such as “tyranny is the mother of injustice”!); Eubulus devoted a whole comedy to his tragic confrère. In 367 B.C. he heard with joy that at last the first prize had fallen to him at the Lenæa for Hector’s Ransom; gossip said that his death in the same year was due to the paroxysms of gratified vanity. Little is known about the contents of his dramas, but we hear that one play was an attack upon the philosopher Plato. In other works, too, he appears to have discussed his personal interests. Lucian preserves the bald verse:—

and the astonishing remark:—

But one may be misjudging him. Perhaps by “useful” (χρησίμην) he meant “good” (χρηστήν); Dionysius had a curious fad for using words, not in their accepted sense, but according to real or fancied etymology.[96]

Ancient critics set great store by Carcinus, the most distinguished of a family long connected with the theatre. One hundred and sixty plays are attributed to him, and eleven victories. He spent some time at the court of[35] the younger Dionysius, the Syracusan tyrant, and his longest fragment deals with the Sicilian worship of Demeter and Persephone. We possess certain interesting facts about his plots. Aristotle[97] as an instance of the first type of Recognition—that by signs—mentions among those which are congenital “the stars introduced by Carcinus in his Thyestes” (evidently birthmarks). More striking is a later paragraph:[98] “In constructing the plot and working it out with the proper diction, the poet should place the scene, as far as possible, before his eyes.... The need of such a rule is shown by the fault found in Carcinus. Amphiaraus was on his way from the temple. This fact escaped the observation of one who did not see the situation. On the stage, however, the piece failed, the audience being offended at the oversight.” This shows incidentally how little assistance an ancient dramatist obtained from that now vital collaborator, the rehearsal. In the Medea[99] of Carcinus the heroine, unlike the Euripidean, did not slay her children but sent them away. Their disappearance caused the Corinthians to accuse her of their murder, and she defended herself by an ingenious piece of rhetorical logic: “Suppose that I had killed them. Then it would have been a blunder not to slay their father Jason also. This you know I have not done. Hence I have not murdered my children either.” Just as Carcinus there smoothed away what was felt to be too dreadful in Euripides, so in Œdipus he appears[100] to have dealt with the improbabilities which cling to Œdipus Tyrannus. He excelled, moreover, in the portrayal of passion: Cercyon, struggling with horrified grief in Carcinus’ Alope, is cited by Aristotle.[101] The Ærope too had sensational success. That bloodthirsty savage Alexander, tyrant of Pheræ, was so moved by the emotion wherewith the actor Theodorus performed his part, that he burst into tears.[102]

Two points in his actual fragments strike a modern[36] reader. The first is a curious flatness of style noticeable in the one fairly long passage; every word seems to be a second-best. The opening lines will be sufficient:—

To turn from this dingy verbiage to his amazing brilliance in epigram is like passing from an auctioneer’s showroom into a lighthouse. (The difference, we note, is between narrative and “rhetoric”.) Such a sentence as οὐδεὶς ἔπαινον ἡδοναῖς ἐκτήσατο (“no man ever won praise by his pleasures”) positively bewilders by its glitter. It is perhaps not absolutely perfect: its miraculous ease might allow a careless reader to pass it by; but that is a defect which Carcinus shares with most masters of epigram, notably with Terence and Congreve. More substantial is the wit of this fragment:—

“I rejoice to see that you harbour spite, for I know that of all its effects there is one that is just—it straightway stings those who cherish it.” One notices the exquisite skill which has inserted the second line, serving admirably to prepare for and throw into relief the vigorous third verse.

Theodectes of Phaselis enjoyed a brilliant career. During his forty-one years he was a pupil of Plato, Isocrates, and Aristotle, obtained great distinction as an orator (Cicero[103] praises him), produced fifty plays, and obtained the first prize at eight of the thirteen contests in which he competed. Alexander the Great decked his statue with garlands in memory of the days when they had studied together under Aristotle. That philosopher quotes him several times, and in particular pays Theodectes the high honour of coupling him with[37] Sophocles; the examples which he gives[104] of peripeteia are the Œdipus Tyrannus and the Lynceus of Theodectes. The same drama is used[105] to exemplify another vital point, the difference between Complication and Dénouement.

He was doubtless a brilliantly able man and a popular dramatist with a notable talent for concocting plots. But all that we can now see in his remains is a feeble copy of Euripides, though he was, to be sure, audacious enough to place Philoctetes’ wound in the hand instead of the foot—for the sake of gracefulness, one may imagine. For the rest, we possess a curious speech made by some one ignorant of letters, who describes[106] as a picture the name “Theseus”—this idea is taken bodily from Euripides—and sundry sententious remarks, one of which surely deserves immortality as reaching the limit of pompous common-place:—

Mention should be made of Diogenes and Crates the philosophers, who wrote plays not for production, but for the study, as propagandist pamphlets. They may none the less have been excellent plays, like the Justice of Mr. Galsworthy. Very little remains on which an opinion can be founded. One vigorous line of Diogenes catches the attention: “I would rather have a drop of luck than a barrel of brains”.[107]

A more remarkable dramatist was Moschion, whose precise importance it is hard to estimate, though he is deeply interesting to the historian of tragedy. For on the one hand, he was probably not popular—nothing is known of his life,[108] and Stobæus is practically the only writer who quotes him. On the other hand, he is the[38] one Greek poet known to have practised definitely the historical type of drama. Moschion is of course not alone in selecting actual events for his theme. Long before his day Phrynichus had produced his Phœnissæ and The Capture of Miletus, Æschylus his Persæ; and his contemporary Theodectes composed a tragedy Mausolus in glorification of the deceased king of Caria. But all four were pièces d’occasion. Moschion alone practised genuine historical drama: he went according to custom into the past for his material, but chose great events of real history, not legend.[109] His Themistocles dealt with the battle of Salamis; we possess one brief remnant thereof, in which (as it seems) a messenger compares the victory of the small Greek force to the devastation wrought by a small axe in a great pine-forest. The Men of Pheræ appears[110] to have depicted the brutality of Alexander, prince of Pheræ, who refused burial to Polyphron.

These “burial-passages” include Moschion’s most remarkable fragment, a fine description in thirty-three lines describing the rise of civilization. The versification is undesirably smooth—throughout there is not a single resolved foot. Like a circumspect rationalist, Moschion offers three alternative reasons, favouring none, for the progress made by man: some great teacher such as Prometheus, the Law of Nature (ἀνάγκη), the long slow experience (τριβή) of the whole race. His style here is vigorous but uneven; after dignified lines which somewhat recall Æschylus we find a sudden drop to bald prose: ὁ δ’ ἀσθενὴς ἦν τῶν ἀμεινόνων βορά:[111] “the weak were the food of the strong”.

It is convenient to mention here a remarkable satyric drama, produced about 324 B.C., the Agen,[112] of[39] which seventeen consecutive lines survive. This play was produced during the Dionysiac festival in the camp of Alexander on the banks of the Hydaspes or Jhelum, in the Punjaub. Its subject was the escapades of Harpalus, who had revolted from Alexander and fled to Athens. The author is said[113] to have been either Python of Catana or Byzantium, or the Great Alexander himself. No doubt it was an elaborate “squib” full of racy topical allusions. Were it not that Athenæus calls it a “satyric playlet”[114] we might take the fragment as part of a comedy. But about this time satyric drama tended to become a form of personal attack—a dramatic “satire”. Thus one Mimnermus, whose date is unknown, wrote a play against doctors[115]; Lycophron and Sositheus, both members of the Alexandrian “Pleiad,” attacked individual philosophers, the former writing a Menedemus which satirized the gluttony and drunkenness of the amiable founder of the Eretrian school, the latter ridiculing the disciples whom the “folly of Cleanthes” drove like cattle—an insult which the audience resented and damned the play.[116]

The third century saw a great efflorescence of theatrical activity in Alexandria. Under Ptolemy II (285-247 B.C.), that city became the centre of world-culture as it already was of commerce. All artistic forms were protected and rewarded with imperial liberality. The great library became one of the wonders of the world, and the Dionysiac festivals were performed with sedulous magnificence. Among the many writers of tragedy seven were looked on as forming a class by themselves—the famous Pleiad (“The Constellation of Seven”). Only five names of these are certain—Philiscus, Homerus, Alexander, Lycophron, and Sositheus; for the other two “chairs” various[40] names are found in our authorities: Sosiphanes, Dionysiades, Æantides, Euphronius. Nor can we be sure that all these men worked at Alexandria.[117] That the splendour of the city and Ptolemy’s magnificent patronage should have drawn the leading men of art, letters, and science to the world’s centre, is a natural assumption and indeed the fact: Theocritus the idyllist, Euclid the geometer, Callimachus the poet and scholar, certainly lived there. Of the Pleiad, only three are known to have worked in Alexandria: Lycophron, to whom Ptolemy entrusted that section of the royal library which embraced Comedy, Alexander, who superintended Tragedy, and Philiscus the priest of Dionysus. Homerus may have passed all his career in Byzantium, which later possessed a statue of him, and Sositheus was apparently active at Athens.

Lycophron’s Menedemus has already been mentioned. His fame now rests upon the extant poem Alexandra, in high repute both in ancient and in modern times for its obscurity. But Sositheus is the most interesting of the galaxy. We may still read twenty-one lines from his satyric drama Daphnis or Lityerses, describing with grim vigour the ghoulish harvester Lityerses who made his visitors reap with him, finally beheading them and binding up the corpses in sheaves. Sositheus made his mark, indeed, less in tragedy than in satyric writing: he turned from the tendency of his day which made this genre a form of satire, and went back to the antique manner. Sosiphanes, finally, deserves mention for a remarkable fragment:—

“O mortal men, whose misery is so manifold, whose joys so few, why plume yourselves on power which one day[41] gives and one day destroys? If ye find prosperity, straightway, though ye are naught, your pride rises high as heaven, and ye see not your master death at your elbow”—a curiously close parallel with the celebrated outburst in Measure for Measure. We observe the Euripidean versification, though Sosiphanes “flourished” two centuries[118] after the master’s birth, and though between the two, in men like Moschion, Carcinus, and Chæremon, we find distinct flatness of versification. The fourth-century poets, however second-rate, were still working with originality of style: Sosiphanes belongs to an age which has begun not so much to respect as to worship the great models. He sets himself to copy Euripides, and his iambics are naturally “better” than Moschion’s, as are those written by numerous able scholars of our own day.

After the era of the Pleiad, Greek tragedy for us to all intents and purposes comes to an end. New dramas seem to have been produced down to the time of Hadrian, who died in A.D. 138, and theatrical entertainments were immensely popular throughout later antiquity, as vase-paintings show, besides countless allusions in literature. But our fragments are exceedingly meagre. One tragedy has been preserved by its subject—the famous Christus Patiens (Χριστὸς Πάσχων), which portrayed the Passion. It is the longest and the worst of all Greek plays, and consists largely of a repellent cento—snippets from Euripides pieced together and eked out by bad iambics of the author’s own. The result is traditionally, but wrongly, attributed to Gregory of Nazianzus (born probably in A.D. 330). Its only value is that it is often useful in determining the text of Euripides. It would be useless to enumerate all the poetasters of these later centuries whose names are recorded.

In this chapter we have constantly referred to the Poetic of Aristotle, and it will be well at this point to[42] summarize his view of the nature, parts, and aim of tragedy. Before doing so, however, we must be clear upon two points: the standpoint of his criticism and the value of his evidence. It was long the habit to take this work as a kind of Bible of poetical criticism, to accept with blind devotion any statements made therein, or even alleged[119] to be made therein, as constituting rules for all playwrights for ever. Now, as to the former point, the nature of his criticism, it is simply to explain how good tragedies were as a fact written. He takes the work of contemporary and earlier playwrights, and in the light of this, together with his own strong common sense, æsthetic sensibility, and private temperament, tells how he himself (for example) would write a tragedy. On the one hand, could he have read Macbeth then, he would have condemned it; on the other, could he read it now as a modern man, he would approve it. As to the second point, the value of his evidence, we must distinguish carefully between the facts which he reports and his comment thereon. The latter we should study with the respect due to his vast merits; but he is not infallible. When, for instance, he writes that “even a woman may be good, and also a slave; though the woman may be said to be an inferior being, and the slave quite worthless,”[120] and blames Euripides because “Iphigenia the suppliant in no way resembles her later self,”[121] we shall regard him less as helping us than as dating himself. But as to the objective facts which he records he must be looked on as for us infallible.[122] He[43] lived in or close to the periods of which he writes; he commanded a vast array of documents now lost to us; he was strongly desirous of ascertaining the facts; his temperament and method were keenly scientific, his industry prodigious. We may, and should, discuss his opinions; his facts we cannot dispute. The reader will be able to appreciate for himself the statement which follows.

Aristotle’s definition of tragedy runs thus: “Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play; in the form of action, not of narrative; through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions”.[123] Adequate discussion of this celebrated passage is here impossible; only two points can be made. Firstly, the definition plainly applies to Greek Tragedy alone and as understood by Aristotle: we observe the omission of what seems to us vital—the fact that tragedy depicts the collision of opposing principles as conveyed by the collision of personalities—and the insertion of Greek peculiarities since, as he goes on to explain, by “language embellished” he means language which includes song. Secondly, the famous dictum concerning “purgation” (catharsis) is now generally understood as meaning, not “purification” or “edification” of our pity and fear, but as a medical metaphor signifying that these emotions are purged out of our spirit.

Further light on the nature of tragedy he gives by comparing it with three other classes of literature. “Comedy aims at representing men as worse, Tragedy as better than in actual life.”[124] In another place he contrasts tragedy with history: “It is not the function[44] of the poet to relate what has happened, but what may happen—what is possible according to the law of probability or necessity. The poet and the historian differ not by writing in verse or in prose.... The true difference is that one relates what has happened, the other what may happen. Poetry, therefore, is a more philosophical and a higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular.”[125] Our imperfect text of the treatise ends with a more elaborate comparison between Tragedy and Epic, wherein Aristotle combats the contemporary view[126] that “epic poetry is addressed to a cultivated audience, who do not need gesture; Tragedy to an inferior public. Being then unrefined, it is evidently the lower of the two.” His own verdict is that, since tragedy has all the epic elements, adds to these music and scenic effects, shows vividness in reading as well as in representation, attains its end within narrower limits, and shows greater unity of effect, it is the higher art.[127]

In various portions of the Poetic he gives us the features of Tragedy, following three independent lines of analysis:—

§ I. On the æsthetic line he discusses the elements of a tragedy: plot, character, thought, diction, scenery, and song. Of the last three he has little to say. But on one of them he makes an interesting remark. “Third in order is Thought—that is, the faculty of saying what is possible and pertinent in given circumstances.... The older poets made their characters speak the language of civic life; the poets of our time, the language of the rhetoricians.”[128] This prophesies from afar of Seneca and his like. As for character, it must be good, appropriate, true to life, and consistent.

Concerning Plot, which he rightly calls “the soul of a tragedy,”[129] Aristotle is of course far more copious. The salient points alone can be set down here:—

(a) “The proper magnitude is comprised within such limits, that the sequence of events, according to the law of probability or necessity, will admit of a change from bad fortune to good, or from good fortune to bad.”[130]

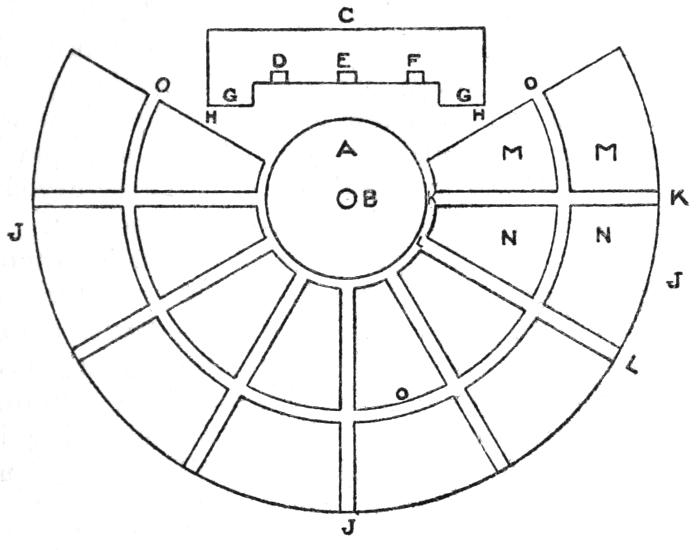

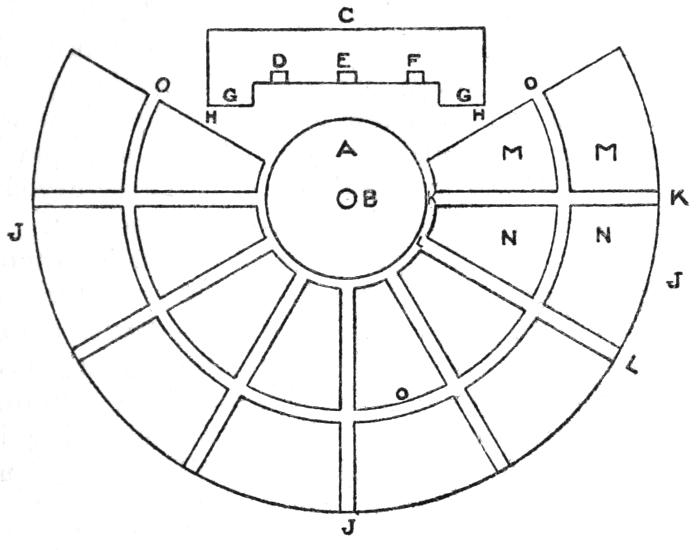

(b) “The plot ... must imitate one action and that a whole, the structural union of the parts being such that if anyone of them is displaced or removed, the whole will be disjointed and disturbed.”[131] A tragedy must be an organism. It therefore follows that “of all plots and actions the episodic are the worst ... in which the episodes or acts succeed one another without probable or necessary sequence”.[132] He is recommending the “Unity of Action”.