Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

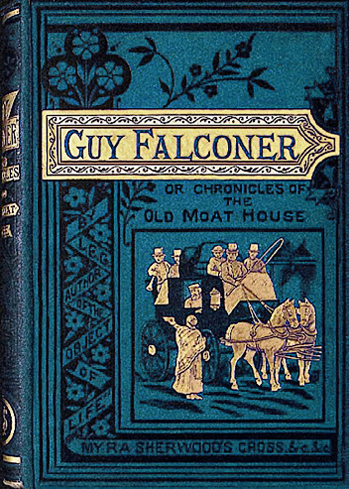

THE OLD MOAT HOUSE.

OR,

The Chronicles of the Old Moat House.

————————

A BATTLE OF FORTUNE.

————————

BY

L. E. G.

AUTHOR OF "THE OBJECT OF LIFE," "MYRA SHERWOOD'S CROSS,"

"HOMES MADE AND MARRED," ETC., ETC.

THIRD THOUSAND.

London:

SUNDAY SCHOOL UNION, 56, OLD BAILEY, E.C.

Hazell, Watson, and Viney, Printers, London and Aylesbury.

CONTENTS.

——————

CHAPTER I. ONLY A STROKE OF THE PEN

CHAPTER III. STILL UNDER THE ELM TREES

CHAPTER IV. THE TOMB BENEATH THE CEDARS

CHAPTER V. A LADY OF THE OLDEN TIME

CHAPTER VIII. THE PLACE OF THE BEAUTIFUL

CHAPTER XV. UNDER THE ELMS AGAIN

CHAPTER XVI. CLOUDS WITH SILVER LININGS

——————

ILLUSTRATIONS.

FRONTISPIECE-THE OLD MOAT HOUSE

GUY FALCONER:

A BATTLE OF FORTUNE.

ONLY A STROKE OF THE PEN.

"THE papers have arrived, sir, and the witnesses are ready. Only a stroke of the pen, and the thing is done. It will not fatigue you much."

The old gentleman to whom this was spoken in a tone of gentle entreaty turned himself with difficulty on his bed, and looked earnestly at the speaker.

"You have decided, then, Geoffry," he said; "you are sure you don't mind? You won't regret it by-and-by? I had thought that perhaps you had given it up."

"I have quite decided; I shall not regret it; and I never thought of giving it up, but it was of no use to talk about it until the requisite documents were prepared. Penacre has not been in a hurry, but what he does is well and safely done. Shall I read over the particulars to you?"

"No, no, I must trust to you. My debts will all be paid, as well as yours, and there will be no stain upon my name, that's one comfort," and he groaned as if other comforts just then were not many.

"Phœbe, Phœbe," said he as his son left the room; "what are you doing there?"

"Tinking, sar," and a dark face, trimmed round with white and yellow muslin, instantly appeared at the bed-side with the next cordial for the patient. "Thinking, eh? What are you thinking about pray?"

"Tinking about one bery bad debt, sar. Wondering if it's going to be paid along de rest."

"What do you mean, woman? How dare you think about my concerns, or listen to what I say to my son?"

"Couldn't help it, sar. 'Sides, if dat 'ar debt ain't paid, him leab a bery big stain dat never come out nohows."

"What debt, woman? You shall be paid well, for you've been a faithful nurse to me, Phœbe."

"Dat's noting, sar; Phœbe not tinking about pay down here, but de big bill up dere," and she pointed upward, "must be paid by somebody, sar. By de good Lord on His cross all blot out in His precious blood, or—don't disb'lieve it 'cause poor old Phœbe say it—or by massa his own self in de eberlasting prison, whar de poor debtors neber reach de end ob der 'count."

"Stuff and nonsense, woman," said the old man angrily.

"True as de Bible, sar. How's massa going to do 'bout it?" persisted the nurse.

"Do! Why I've nothing to do with it. I shall take my chance with you, I suppose."

"Phœbe havn't noting to do with chance, sar. De kind good Lord find poor lost sheep, an' He say, 'Come unto Me.' Den I say, 'What for poor Phœbe come?' He say, 'You know you a sinner,' and 'De wages ob sin is death,' but 'God so lub de world dat He gabe His only begotten Son, dat whosoever b'lieveth in Him should not perish, but hab eberlasting life."

"Ah, yes; I heard that years ago, Phœbe, when I was a child."

"Why you not mind it, den? Phœbe neber hear it till she got old, and she come, and she b'lieve, and now noting to do but go up to be eber wid de Lord one ob dese days; all her sins washed away, and sing hallelujah! No chance 'bout it."

"Well, you foolish old woman, if you like it so, have it so, but it doesn't suit me."

"Phœbe like it very much; just suit poor old sinner like Phœbe; suit eberybody dat wants to go to hebben white and clean. Better tink 'bout it, sar, 'fore you feels de grip ob Satan on yer soul; too late den, he'll neber leave go."

"There, go away; here's another sort of sermon coming, and I'm very tired. Oh, for some rest!" And the old man groaned wearily.

"'Come unto Me all ye dat are weary and heby-laden, and I will gib you rest,'" said the old nurse, as she straightened the pillows, and made way for the party just entering the room.

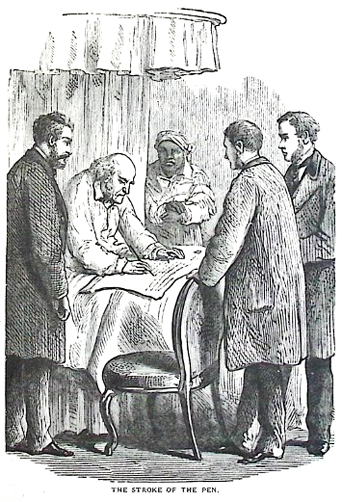

The parchments were spread, and the right place indicated. The old man, after a moment's bewilderment, did what he had to do with dignity and calmness. He signed his name legibly; his son followed; then the witnesses, two respectable clerks from the Government offices, and the business was settled to the satisfaction of, at least, one person concerned.

"Geoffry," said the old gentleman, when they were again alone, "you will not forget some provision for poor Guy's widow and children? You see, I spent all Guy's money that came of his mother's property; he had nothing but his commission out of it, poor lad, and it ought to be refunded to his family out of the estate; in fact, I think there's some deed or document to that effect somewhere."

"Very well, sir; it shall be sought and acted on."

"Very good, all right; for you see, Geoffry, what with debts at home, and the expenses of my establishment here, I have saved nothing; you understand, Geoffry, saved nothing."

"I must be stupid, indeed, if I do not, sir, for you have told me so fifty times this week."

"Have I? Well, but it's important to be remembered when you are settling things for them. They must remain there, you know, until you pay that money, due to Guy, out of the proceeds."

"You did not mention it until to-day, sir."

"No, I believe I didn't; but that old fool, Phœbe, reminded me somehow, with her talk of some bad debt, and I'm glad I've mentioned it, for they may want it, you know. Now let me rest."

As the son retired, the nurse stole softly in.

"Rest, poor massa; no rest 'cept you come to de dear Lord Jesus," said she softly. "'No rest,' saith my God, 'to de wicked;' and who's dey? Why, old Phœbe and eberybody, 'cause 'All hab sinned and come short de glory ob God,' but bless de Lord, for 'Behold de Lamb of God dat taketh away de sin ob de world.' 'Though your sins be scarlet, dey shall be white as snow.' Only b'lieve; dere's de blessed rest, dere's de peace ob God for Phœbe and eberybody who come; no more wicked den, but de Lord's own dear children welcome home! Poor massa! Hope him go dat way 'fore he die."

In the night there came a cry from the bed, "Mother, mother!"

Phœbe moved forward and knelt down.

"Oh, massa, goin' to be a child again, and listen to de words ob Jesus: ''Cept ye be as a little child ye shall not enter de kingdom ob hebben.'"

THE STROKE OF THE PEN.

"You are right, Phœbe; she says so, and the proud old man is wrong—lost, lost!"

"De dear Lord Jesus can save to de uttermost: him dat cometh He will in nowise cast out. Oh, come, dear massa! Look to Him."

"Too late—call Geoffry. I'm dying. I've lived without God, and now I must die without Him. It is just, and it is perdition. But let me tell my son."

They watched and ministered, and Phœbe wept and prayed unchecked for some hours while the mortal struggle lasted, and then there was rest,—for the body at least. The poor neglected soul was gone to its own experiences—somewhere, and the "stroke of the pen" that morning was to leave no pleasant experience of the last act on earth. For wonderful things a stroke of the pen can do. It can sign away an estate of hundreds of years of entailed possession; it can exile the widow and disinherit the orphan, and lay broad acres and stately oaks under the salesman's hammer. It can set idle clerks to work in attorneys' chambers, and make land agents and appraisers speak and look like "monarchs of all they survey."

But that stroke of the pen did a great deal more.

VILLAGE POLITICS.

ONLY a signature! Nothing more, and only occupying two or three moments, but, nevertheless, it roused the scattered population of a certain quiet district in an island thousands of miles away, and caused more eyes to open in amazement, and more heads to be scratched in perplexity, than had been known within the memory of the oldest inhabitant.

The loyalty of England's people, and the stability of her government presented a happy contrast to the restless experiments which agitated all classes in a neighbouring country; the law of primogeniture still upheld the dignity of rank, while constitutional rights secured the liberty of all. Landowners and tenants mutually sympathised for the common welfare, and this exception on one side excited general surprise and indignation.

For there suddenly sprang up, at all points of the doomed estate that skirted a thoroughfare, huge boards, either hung to trees or mounted on poles, bearing large printed advertisements, which also placarded barn doors and wayside gateposts for miles in every direction, while newspapers echoed the eloquent praises of,—

"All that valuable, desirable, and fertile estate known as the Falcon

Range, comprising every charm, indulgence, and delight that human

taste, desire, or imagination could conceive or covet. Game for the

sportsman, fish for the angler, views for the artist, and traditions

for the poet; relics for the antiquary, and specimens for the

naturalist."

In fact, an Eden of bliss for the happy purchaser, were he either of these accomplished amateurs, or all in one.

Even the dull wits of the villagers could not avoid connecting these strange advertisements with the appearance of a gentleman in a gig, with his clerk and a blue bag, who drove through the village street without stopping at the Falconer's Arms (as all respectable travellers invariably did), and up the avenue to the Moat House without favouring anyone with an idea of his business there.

It was a dismal day; the wind in the east, and provoking in the extreme that gentlemen with blue bags should presume to excite curiosity without satisfying it, especially when people felt out of sorts and had nothing particular to do.

So when towards evening the great placards began to appear, the cat had jumped out of the blue bag, and an endless theme of wonder and remark was provided.

"TO BE SOLD"

First caught the eyes of Mr. Spadeley, the village clerk and sexton, as he came past the gates of the principal entrance to the park.

He stopped, stared, put on his spectacles, and read carefully again, "To be Sold." Yes, there it was and no mistake.

"Why sure the old master must be mad, and Mr. Geoffry, too," said he to himself. "To be sold, indeed! How can they? How dare they?" And the very spade in his hand seemed to share his indignation as it bounced down upon the road with a cutting remark upon the hardness of the world and its ways.

Still more disgusted was he, as he approached his own peculiar province, to find one of the obnoxious placards stuck upon the churchyard gate without his leave asked or cared for! And an assembly of village urchins spelling out the whole particulars and slowly apprehending their meaning.

"Well," said Mr. Spadeley, clerk and sexton of Falcon Range, before whom the rising generation were not wont to play pranks, but on whose countenance there was something they construed sympathetically just now.—"Well, what do you think about it?" he asked.

"Do it mean selling her house over her head?" asked a sharp-looking lad at his elbow, and pointing towards the Moat.

"Yes, that's what it means, seemingly."

"Then here goes! I say, stand out of my way, will ye?"

And, with sudden inspiration in his legs, the boy clambered up the gate-post, balanced one foot on an iron spike, and tore down the great placard in shreds. The little rabble shouted and jumped about with energy and triumph, and dared some other presumptuous feats before Mr. Spadeley's eyes, while instead of clutching the hero by the hair, as had happened more than once, the sexton only patted him on the shoulder, quietly dropped a halfpenny into his dirty cap, and edged himself out of the noisy demonstration.

* * * * * *

The errand of the gentleman in the gig to the lady at the Moat House was not a pleasant one. He knew that he must look very like a deputy tyrant, and she like an innocent victim, and it required a wonderful amount of coolness and self-possession to face the gaze of pained inquiry which met the first unfolding of his mission.

"How lovely she is still," thought Mr. Penacre; "I wish my client had written direct, instead of thrusting his ugly errand upon me."

But, to his credit, he executed it with as much courtesy as it permitted, trying to veil the abominations of pride, malice, and covetousness, beneath professional technicalities, providential circumstances, and naturalization in a foreign land.

But threading her way through the maze and gloss of an eloquent peroration, Mrs. Falconer traced at last the real core of its meaning.

"Then I am to understand," said she calmly, "that the Moat House is to pass into other hands, and is no longer my home, or that of my children?"

"I regret to say that your view of the matter is correct, madam," replied the attorney bowing.

"But my son is presumptive heir, unless Mr. Geoffry Falconer were to have a son," said she thoughtfully.

"Not now, madam. I thought I had explained that the entail is cut off by a deed legally executed by the owner and his heir, old Mr. Falconer and his son Mr. Geoffry. This enables them to sell the estate."

"And is there no charge upon it on my late husband's behalf, sir?" asked the lady. "His father had appropriated a large sum due to him, and now of course due to his widow and children."

"I am instructed to say, madam,—hem!—a—it is difficult to explain these things to ladies unused to business; but my client's idea is this: that having had the benefit of a home at the Moat so long—somewhere about ten years, I think—any debt on the proprietor's part is cancelled by that tenancy, for which no rent has ever been paid. Moreover, the house is greatly dilapidated, and must be sold at a loss in consideration of repairs, which would have been exacted from any other occupant."

The lady seemed to comprehend at last, and her pale face became paler still, as some of the consequences of this cruel act began to loom into view.

"One thing more I have to add," said Mr. Penacre; "that you are at liberty to remove any articles of the family plate which bear Mr. Guy Falconer's initials. The rest will be sold with anything else that the purchaser of the estate may wish to dispense with, and a valuation is to be made immediately—that is, at your convenience, madam."

"Whenever you please," said the widow; "we shall not waste any time in opposition to this unexpected change, for armed with the authority you represent, it would be useless to remonstrate. I had thought, however, that during the life of my father-in-law—"

"Pardon me, madam, for interrupting you, but though the fact was not positively announced by the mail which brought my instructions, I have reason to believe that Mr. Falconer died even before the ship sailed. So that you perceive there is no redress—no hope, I mean, of any alteration of purpose."

"I will give orders that every attention is paid to you here, in the execution of your business, Mr. Penacre. Of course you will remain at the Moat until you have settled everything."

"If it is no intrusion, it would certainly convenience me much, and I shall be grateful for the hospitality."

"And in the meantime you will, I am sure, kindly excuse me."

Whereupon Mr. Penacre rose, and bowed solemnly.

The lady rose also, curtsied, and left the room, no more to re-enter it as the mistress of Moat House. The last item in the information conveyed that day was for a time first in her thoughts. Her husband's father was, probably, no more on earth, and what that fact might involve to him was a matter of trembling apprehension. Probably she would never know more until "the day should declare it." And now, in her worldly circumstances, she seemed at the mercy of one who knew little of sympathy or liberality, who disliked her with the mortified vanity of a selfish unforgiving spirit, because a younger brother had many years before been preferred to himself.

* * * * * *

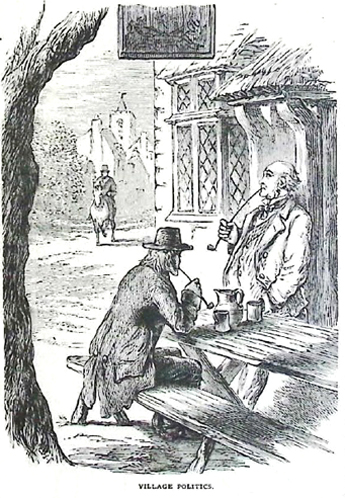

Passing events had many commentators beside the demonstrative heroes of the rising generation, and Mr. Spadeley's meditations led him as usual to the society of his intimate friend, the landlord of the Falconer's Arms, whose sympathies had been born and grown up in, and were limited like his own to the region of the Falcon Range.

"Who'd have thought of him quartering himself on the Moat House with his mean pitiful business?" said Timothy Turnbull, shaking the ashes from his pipe, and replenishing his own and his companion's tankards with his best "own brewed." "It's just like her to allow it though."

"Just like her, as you say; but I reckon she don't understand all about it yet. You see it's a hard, shameful crush for the poor young gentleman, and they say, leastways the housekeeper told Mrs. Tribe, who told my daughter, and she told me, that he went into an awful rage when he heard it."

And Mr. Spadeley sipped his ale to drown his decided approbation of this particular rage, though known to advise people in general to keep their tempers under all provocation; for he made it a rule to confirm the opinions expressed in the pulpit as decidedly as those from the desk, more especially since the fact that the young minister who succeeded the old one not long deceased, had entirely hindered his little nap in his little den during the sermon, thus enabling him to follow up the exhortations with more practical impressiveness.

"Ah, yes, poor boy! I'm right sorry for them all," said Timothy.

And the two gossips shook their grey heads, and looked gloomily at each other, and up to the interlacing branches of the grand old elms that overshadowed their bench and table, the comfortable trysting-place where they had discussed the affairs and fortunes of their neighbours for more than a quarter of a century.

"We all hoped poor Mr. Guy's son was born to the honours as well as the name of his ancient house," he continued, glancing round at the sign of "The Falconer's Arms," which swung over the porch of the village inn behind him.

"You see," said the sexton, "when men can bring themselves to cutting off entails, there ain't much hope of the family hanging together. It's who's the highest bidder after that. I wonder who's to be highest bidder here?"

"There's one coming along who could tell us, if he'd a mind," said Timothy, lowering his voice, as a gentleman on horseback approached along the road, and stopping before the inn, permitted his horse to accept the refreshment ready in a moment from the ostler's pail.

It was the owner of the blue bag returning from a ride over the estate, and his authority would certainly be trustworthy in such a matter.

"Good evening, friends." said he pleasantly. "This is a pretty spot, this Falcon Range; some fine timber left yet; rich meadows, quite justifying the description given of it."

The landlord could never resist a cheery voice, or a civil speech, so he felt bound to speak.

"True, sir; more's the pity that it's got to change hands. I suppose nobody's offered yet—it would take all the county by surprise."

"It is a pity, and I'm very sorry for the family," said the stranger, rising instantaneously in the estimation of at least one of his hearers; "but if we get Mr. Hazelwood here, there will be nothing to regret in the matter of the landlord."

"Mr. Hazelwood! Squire Hazelwood of Hazel Copse! You don't say so!" said Timothy.

"Yes I do; he is anxious to purchase, seeing that the lease of Hazel Copse is running out, and he can't agree to terms of renewal."

"Well, he's a fine man, they do say. I've heard of him many a time, for I've a friend as come from his parts."

The sexton began to feel impatient of this praise of a purchaser of the Falcon Range, and put in a word.

"Whoever and whatever he be, sir, it's a shame to blot out a good old family from their neighbourhood and inheritance. So Squire Hazelwood, if he was my lord mayor himself, needn't think to come in triumphant here. Money won't buy no hearts in Falcon Range."

"No, no," cried Timothy, shaking his fist at the singular animals, of species unknown, which represented the Falconer's Arms; "there hangs the old sign put up by my great grandfather, when his honoured master set him going in business in this very house, and no other shall swing there while Timothy Turnbull can hold his own."

"It is a very ancient painting apparently," said the lawyer, looking at it as respectfully as if it had been a Rembrandt, or a Holbein; "time-worn and weather-beaten."

"Aye, sir, that's true enough, but we do brighten it up a bit now and then; I've a nephew in the oil ana colour trade, and he puts a fresh coat on it beautiful; the feathers and claws looks ready to fly and clutch the game, I'll warrant you, after that!"

"No doubt of it, Mr. Turnbull; you stand up for the old families, I see, and the Falconers seem to be of a venerable stock."

"Aye, sir. Find a venerabler one in the three kingdoms, if you can," exclaimed the sexton proudly. "Why, they came in with the Conqueror, the Falconers did!" And he gave a complacent puff to the tobacco, as if to say, "There, you are annihilated now!"

"Well," said Mr. Penacre undauntedly, "it is nevertheless a fact that Mr. Hazelwood's family can trace back to the time of King Alfred and the old Saxon parliament, with certain grants then made to an ancestor for service rendered to the king. What do you say to that?"

"You don't go for to set a Saxon churl before a Norman knight, I hope, sir," said Mr. Spadeley, with great disdain.

"Put earl for churl, and adventurer for knight, and give each his due," said the lawyer good-humouredly. "You know it was Saxon plenty that attracted lackland knights, and since they've shaken so well together, and bygones are bygones, it doesn't much matter whether we quarter arms with a Saxon bow or a Norman lance. For my part, I'm content to trace back to Noah, with whom your progenitor and mine, good friends, outrode the storm that swept away all landmarks. Good evening to you, and don't despise Squire Hazelwood himself, whatever you may think of his bluff ancestors."

And dropping a silver coin into the ostler's empty pail, he trotted away, raising his hat smilingly to the village parson, who just then came up and heard his concluding remarks.

VILLAGE POLITICS.

STILL UNDER THE ELM TREES.

"RATHER a pleasant sort of gentleman after all," remarked Timothy Turnbull, looking after the stranger, and rising respectfully to greet the new-comer, who, begging both the gossips to keep their seats, sat down on the opposite bench to rest, and leaning forward, began to trace lines in the dust at his feet with his walking stick, and to speak as if musing on the lawyer's parting words.

"Yes, quite true; our ancestors survived that storm, and it will be well for us if we are lodged in a better ark with a greater than he, and safe to outride the more awful storm which will some day sweep away the usurper's frail barriers and false distinctions, and restore the lost inheritance to its rightful heir."

"Sir!" said the landlord, taking out his pipe and gazing curiously at the speaker.

"Eh!" said the sexton, rubbing his forehead with a puzzled air. "Surely you think that poor Master Guy may come to his own again, sir?"

"I fear not, friends; but I hope he will come to something better—'an inheritance that fadeth not away,' and if his name and ours are 'written in heaven' in the Book of Life, it will matter very little where they stand in the pedigrees of men, and the title deeds of earth. So let us all see that we hold our own by the safe and lasting title."

"And what may that be, sir, to your way of thinking?" asked Timothy, feeling that he must say something to break an awkward pause.

"By faith in the Son of God; 'whosoever believeth,' that is the deed of transfer which makes eternal life and glory ours. And if we do cast in our lot with Him who gave Himself to be 'made sin for us, that we might be made the righteousness of God in Him,' we shall share the triumph of that hour for which all creation groans, when the once rejected King and Saviour shall come to assert His blood-bought rights, and receive His redeemed inheritance."

"Amen," said the clerk solemnly. "But, sir, we should like to hear what you think about this bad business of selling the property away from its right owners, for the whole village is downhearted about it."

"And justly so," said the young clergyman; "I am of the same mind in the matter, and it would do no good to attempt to excuse such a cruel, selfish act."

"I'm right glad to hear you say that, sir!" exclaimed Timothy, throwing down his pipe, and slapping his knees with both hands. "It's no true religion that makes black anything but black, is it Spadeley?"

"It does me good to hear things called by their right names," said Spadeley; "I thought you'd begin to preach about resignation and the like of that, and make it out somehow to be the right thing after all."

"But you see there are two aspects of the case, friends," said Mr. Herbert, determined to set himself right with the downhearted villagers in the matter, and aware that what he said would be repeated in many forms amongst them. "There is the side of the human actors in the circumstances which have occurred, and before God and man a great wrong is done, and the widow and the fatherless are oppressed. God is displeased, and will make it felt at the right time and way, so far as the oppressor is concerned; and He does not require us to close our eyes and hearts, and not see and feel with indignation and disgust, as honest, true men should. But as He has not seen it good to interfere and hinder their doings, we are constrained by the knowledge of His word and ways to the conclusion, that in His providence He has something better in view—some yet unseen benefit to work out for His troubled children, which shall far exceed and outvalue all they are losing now. And in this aspect we are bound to cultivate resignation and exercise patience. We are to trust God in fact, and be sure that He will never fail them that trust in Him."

"Amen," said Mr. Spadeley; "and is that the way the poor lady feels about it, sir?"

"Yes, I am glad to say that I have quoted nearly her own words, and what I am sure she wishes all her friends to feel. And it is the right view to take of all the disagreeable things of life when once we take our stand upon the 'Rock of Ages,'—eh, my friends?"

"Very good, sir," said the landlord; "and if one turns to making the best of it, it do seem as if the old place might have fallen into worse hands than Squire Hazelwood's."

"That is true, Mr. Turnbull; he will not let things go to ruin, and perhaps may help forward some of our little plans among his tenantry, so let us hold by God's promises and hope for the best. You know where to find them, for I saw the good old book upon your parlour table the other day. Ana you, Mr. Spadeley, must have much knowledge of them from your position and duties among us."

"Well, sir," said Mr. Spadeley graciously, "I do have to look out for pretty texts for the tombstones often, for you see when the country folk bring no verses of their own composing, and not boasting much of a gift that ways myself, I fall back upon the Bible, and we're sure to come at something comfortable. But that reminds me of poor old Hayes. Have you seen him lately, sir?"

"The gardener at the Moat? Yes, I see him every day, and a more true, simple-hearted believer in our Lord Jesus Christ does not lie ready for the summons home."

"Amen, and right, sir. Well, you see when I knew he wasn't going to get better, I thought I would ask him about his epitaph, for he must have a head-stone, and it shall be a good one, and I naturally wanted something nice to carve on it. And what do you think he chose, sir? It do downright get over me. None of the pretty verses I told him of would do."

"'Chief of sinners,'" suggested Mr. Herbert. "I know he feels like that."

"Well, he did name it, and I said out flat, No, I wouldn't put it; I'd have more words to make my work worth while. So he thought a bit, and then he said, 'Few and evil have the days of the years of my life been,' and there he's stuck ever since, and I can't move him, so I shall have to do it, I s'pose, for I wouldn't rile a passing spirit."

"And," said the clergyman, "since you don't mind the work, my kind friend, you shall add something to it at my expense whenever the time comes, and it shall be this, 'Blessed is he whose transgression is forgiven, whose sin is covered.' 'Unto Him that loved us, and washed us from our sins in His own blood, be glory and dominion for ever.' I feel sure our dear old brother will not object to that addition."

"Well, he's a real gentleman, our young parson is, though I say it, that's part of the profession in a way," said the clerk and sexton, resuming his pipe, as the clergyman bade them good-night and walked away.

"A real Christian, too, I should say," added Mr. Turnbull; "though they did say he'd been among the Methodies. Never mind that; he's the right sort to comfort the poor lady and her children in their troubles."

"Ah! Poor, dear lady!" ejaculated the sexton. "I mean to beg a last favour of her before she goes, that she'll be sure to come back to be buried in the old vault under the cedars,—for I shouldn't like anybody to do it for her but me, nor for her to lie anywhere but amongst her own kin, and I dare say our parson would like to read the service over her his own self. Good-night, and thank you, landlord; I shall just call in and see how Hayes does to-night, and tell him about the epitaph, and cheer him up a bit."

* * * * * *

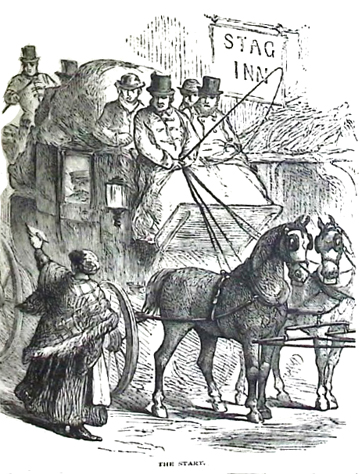

"Joe," said the landlord of the Falconer's Arms a few days after to his ostler and factotum,—"Joe, we've got to horse the carriage that's to carry away the family from the Moat, d'ye hear?"

"Yes, sir."

"Well, Joe, somebody must drive;" and the landlord smoothed his grey hair, and rubbed it up again, and looked perplexed, while Joe looked stolid.

"Joe, my lad, you must drive them," at last said the landlord, well knowing how hard a task he was setting to one whose whole family and lifetime had been comforted and helped by the kind lady at the Moat.

"Sir, master, don't ye now; I can't do it, indeed I can't. I'd sooner be thrashed." And poor Joe looked almost tearfully earnest.

"So would I, Joe, but I can't do it myself; and after all, it will be better for a friend to do it; they'll feel it less themselves than if I got a stranger, and they always like your driving, Joe; yes, you must do it, that's all about it."

After a pause, during which Joe might have been cogitating the possible consequences of a flat refusal,—

"Which 'osses, master?" said he gloomily.

"The black ones, Joe—black harness and all—just like a funeral. I shan't let my spanking bays go on no such an errand. And if Squire Hazelwood should be here, he'll see mourning, that's all."

"Mourning enough," thought Joe, walking off, and grumbling to himself. "The beautifullest, nicest, best lady in all the country round, and as good a pair of children as ever was set eyes on! What will us do to show our love and our trouble all at once, I wonder? Why, if ever poor Joe gets to heaven, it's cause she taught me the way. And I'm to drive her away from the only home she's got on earth! I wish I could take her straight to paradise among the angels she's like; wouldn't I! And never come back no more. Well, don't be a fool, Joe, but do your duty as she's bid you; that's the best way to show gratitude and love to her. But if we goes with them old black 'osses' funeral paces, we'll have all the village sobbing round us, and none of us can't stand that. I must drive and whip and shout my best for all sakes, and so you old 'osses must just step out for once."

"It's quite true, Joe," said his particular friend, Jane Spadeley, whom he met quite by accident as he went to look after the black horses in the lower meadow; "Squire Hazelwood has ended the bargain, and they say he's coming as soon as possible, so missus will be off in a day or two."

"But you are going with 'em, I suppose, Jane. As for Squire Hazelwood, I don't want to hear nought about him, but what about the missus, and poor Miss Maude, and Master Guy?"

"Why, Joe, they won't let me go with them, that's my trouble," and Jane's tears began to struggle into her eyes, though all through a trying interview with her mistress she had bravely bidden them back.

"Won't let you go?" said Joe in amazement; for the thing seemed incredible. He would have let her do anything she wished.

"No; and why they won't breaks my very heart to think of. They can't afford to keep a maid to wait upon them now. I've begged and begged, and I've offered to go without any wages, and eat next to nothing, but it's of no use; and missus cried, and took my poor hand as if I'd been a lady, and dear Miss Maude put her arms round me and kissed me, and we were all in a pretty state, when in burst Master Guy. He looked round for a moment, and though he seemed choking, he said,—

"'Cheer up, mother, cheer up all of you! We'll all come back to the old place some day when I'm a man,' and with a great stamp of his foot, he rushed away again. But it brought us to, and did us good, even to think of such a thing."

"Poor Master Guy! Poor dear lady!" said Joe. "What can we do for them?"

"Why, Joe, she says we can do the very best thing for them all—we can pray for them, and ask that they may say truly and honestly, 'Thy will be done.'"

"It's very hard," said Joe, slashing the grass with his whip, "and goes right agin the grain."

"It's part of the victory, she says," continued Jane, "and must be fought for, and won."

"Gee up, whoa," said Joe, throwing his halter over the neck of one of the calm black horses as he came up with the creature, out of which all frolicsome spirits had long departed. "Thee's got a bit of ugly work to do, so see thee does it kindly."

It was a bit of ugly work, enough to displease all the animal creation of the Falcon Range.

Captain Guy Falconer, the younger son of the late owner of the Moat, had come home from active service with his regiment abroad, to die in the prime of manhood of a neglected wound.

But not before having, both by precept and example, impressed all around him with the conviction that to him "to die was gain," and that his triumphant faith had enfolded the young wife and children whom he must leave behind, and placed them in his heavenly Father's arms, to be cared for, and brought to Him in due time.

And this treasured remembrance now soothed the pain of an uprooting from home and its associations, such as neither she nor her husband had ever contemplated. For the elder Mr. Falconer had long held a lucrative and honourable appointment abroad, and only used his inheritance at home to drain its resources, and to supply his own and his elder son's extravagances, leaving the mansion and grounds to the tenancy of Captain Falconer's family with the impression that the estate must one day follow its long antecedent history by descent in the male line to the lawful heir-presumptive, the only son of Guy and Blanche Falconer.

Mr. Geoffry, the elder son of the now deceased proprietor, had neither inclination nor health for the English climate, hated the responsibilities of a landlord, was childless, and devoid of affection or sympathy for the brother whose interests he did not scruple to set aside, and whose admired and devoted wife he rejoiced to humble and oppress.

The late turn of affairs had revealed something of this to the boy, who had hitherto considered himself born to a respectable though encumbered inheritance, and the tumult of feeling roused within taught him an unexpected lesson upon the very unsatisfactory foundation of earthly hope, and the treacherous failure of human character unsustained by Christian principle.

For Master Guy had found himself in several violent passions, had indulged in more unbecoming language concerning his uncle and grandfather than had ever been heard from his lips before, had flung his lesson books into a corner, trampled down the flowers in his own particular garden, shaken his young fist at the aggravating birds that sang on cheerily among the trees, and exhausted himself in a flood of tears, with his arms clasped round the neck of a sympathising pony.

The ferment of feeling among tenants and dependents did not serve to lessen his disgust and indignation; wherever he went, kind hearts resented, and thoughtless tongues commented, until poor Guy regarded himself as the most injured of mortals, and his own the most blighted of prospects, to say nothing of those of his mother and sister.

In a state of utter self-abandonment, dreading the event of the morrow, hating to think of the last night in the dear old home, the boy had wandered from spot to spot endeared by happy childish memories, until he could bear no more, and as if the tomb would be a desirable end to all his troubles, went last to the quiet resting-place beneath the cedars.

THE TOMB BENEATH THE CEDARS.

THE last evening before the removal of the family from the Moat, the moon shone out brightly at intervals from a cloudy sky, touching with silvery light the gables and turrets of the mansion, the old church tower, and the edges of the tombstones that nestled amidst the grass and shrubs. Beneath three fine old cedars which wrapped one spot in the churchyard in gloom, was the family vault of the Falconers, and thither from her last visit to the cottage of the dying gardener, Mrs. Falconer directed her steps.

It was not with any superstitious or fanciful idea of communing with her husband's spirit that she sought the place where his dust reposed, but, with the natural tenderness of a bereaved heart for the hiding-place of something it has loved and lost, she liked to associate her farewell to the home in which he had left her, with the remembrance of that separation which had made her life a lonely pilgrimage, and her heart for a long time a mere storm-swept wreck.

But she did not now forget that he whom she so deeply loved and truly mourned was "absent from the body," and because of his faith in a crucified Redeemer was "present with the Lord."

And though the tomb that enclosed the mortal part was to her a consecrated memorial place, yet she could calmly leave that behind, in the knowledge that the Saviour and His heaven, where the hosts of the blessed are, cannot be limited by time or space, and would be as real and near in the crowded haunts of busy life as in the moonlighted solitude of the grave beneath the cedars.

There the gentle voice of the much-tried mother soothed her excited boy, and her loving arm encircled him as they leaned together over the marble slab that bore the record of so many honoured names.

"Guy, my son," she whispered, "here let all your wrong feelings be laid aside, and your young life be consecrated to new and noble purposes."

"Oh, mother, it is so hard," murmured the boy.

"I know it, Guy; but I never felt it so hard as to-day, because it has revealed to me the weakness and cowardliness of your heart, which fails at the first touch of adversity. A sorry protector for us indeed, if Maude and I had no other."

"Oh, mother!"

"I see at least one good reason for the reverse which has come to us, Guy. You would have become the ruined child of ease and selfishness, and you may now be something better, if you choose."

"But, mother, suppose it is good for me, it is not good or right for you—it is cruel, wicked, unpardonable for you."

"My dear child, it is as good and right for me. And here by your dear father's grave I am able to forgive fully and freely, as I hope to be forgiven, all whose conduct may have seemed to injure us, and I charge you solemnly before God to do the same. No peace, no rest can help the unforgiving spirit, and so long as you encourage hate and anger, you will be the unhappy slave of unspeakable wretchedness.

"Moreover I deny your right to associate me with your sinful murmurings against God and His ways, and I forbid it. I know that all is wise and well. 'Whom the Lord loveth, He chasteneth.' 'They that trust in Him shall not want for any good thing,' and there I find reason and assurance enough to bear me through everything.

"Guy, my darling, try to tread with me this peaceful path, renounce this angry, bitter, troublesome old self, and be a new creature by God's grace, forgiving, submissive, patient, Christ's dear servant, your mother's faithful prop and help, and the worthy son of him whose life and example is echoed in the instruction I have tried to give. Oh, let it be seen that I am faithful to my trust from God and him."

"Oh, mother, mother," sobbed the boy; "I see, I know I am wrong—I will try—"

"To forgive, and to ask forgiveness, dear child. Oh, what a load will roll off your heart as you feel the soothing sweetness of God's pardoning love, and the godlike power to forgive as you are forgiven! Guy, my son, I shall feel that I am the happy mother of the truest hero of your race, for 'greater is he who conquereth his own spirit than he that taketh a city.'"

They stood awhile in silence, the mother and her son; what prayers and thoughts rose out of full hearts there were no words mighty enough to tell, but at last drawing her gently away,—

"Come, mother," he said softly, "perhaps the angels may note to-night, and so shall I."

And it was a night to be remembered, though not chiefly for its trying farewells. There was a cloud, and no need to ignore it, but there was light behind it, and it began to fringe the cloud and to illumine life's future with touches of beauty and hope, which a few hours before seemed impossible to the despairing spirit of Guy Falconer.

* * * * * *

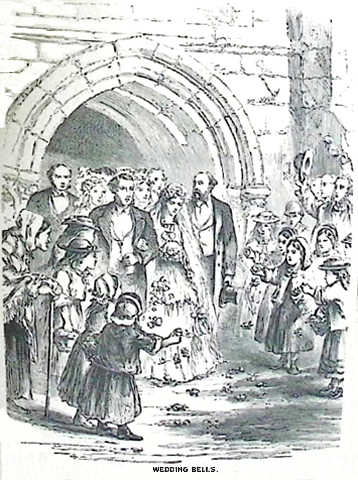

Early the next morning, all the inhabitants of the Falconer Range were astir; groups of people well-to-do, and groups of poor people, and of children innumerable, gathered about the park gates and along the village street, and when Joe and the black horses emerged from the park with the much loved exiles behind them, there was a rush to the carriage windows, hands were shaken and kissed, and murmured benedictions burst from many lips. Old men uncovered their grey heads, women sobbed, and children for once moved quietly.

In vain the occupants of the carriage strove to smile or seem calm; in vain Joe made hideous grimaces to keep up his dignity; in vain Mr. Herbert, who had mounted escort for a part of the way, rode gently amongst the people, and entreated them to restrain their feelings for the sake of the dear, tried lady from whom they had to part; in vain Guy impatiently called out his orders to Joe to "drive on;" the solemn black horses, perfectly self-possessed, were masters of the position, and all poor Joe's struggles failed to move them beyond their own conceptions of the occasion.

Before the Falconer's Arms they nearly came to a stand, as if there were something special to be noted there. And perhaps there was, for the worthy landlord and the dame his wife had made decided demonstration. Blinds were down, and shutters closed, a black crape scarf was thrown over the far-famed sign, and the whole family stood bare-headed under the beautiful elms in solemn silence.

At the village school, the children stood in silent array, and the tallest of them presented a basket filled with little pin-cushions, needle-books, and such like tokens of loving handiwork. And a boy, gentle and modest-looking, handed up a little carving in wood of the front of the Moat House, which he had privately executed in his leisure time.

All this, with an occasional "God bless you," "May you come back to your own again," marked the progress through the village. And then Joe, exasperated beyond endurance with his self-sufficient steeds, commenced a most unusual belabouring of their shining coats. Mr. Herbert, equally out of patience, adding the stimulus of the riding whip, so that the stately march was at last urged into a brisk walk, such as they usually assumed for a funeral at a distant church when wayside observers were neither numerous nor mournful.

Joe's foresight had provided for the occasion, though he had not dared to controvert his master's orders, so far as the first three miles were concerned. There however, he had soothed his own feelings, and obliged his passengers by securing a relay, and joyfully began the acceptable exchange.

While this was proceeding, a carriage-and-four drove briskly up to the inn door.

The gentleman who was driving threw the reins to his servant, and dismounted, noticed the dignified black horses, asked a question or two of the ostler, held a short parley at the window of his carriage, where appeared the pleasant faces of a middle-aged lady and a young girl, and finally bidding Joe "hold in," advanced to the chaise door, and hastily opened it.

"I beg your pardon, madam," he said, "but we cannot let you pass us on the road without a word. We meant to have put up at the Falcon Range last night, hoping to have stopped your journey this morning, but the horses were too tired. Is it too late? Cannot you return now? But I forgot—you don't know me. Roger Hazelwood, madam—at your service. Here! Dorothy, Evelyn! Come and speak to Mrs. Falconer, the lady from the Moat."

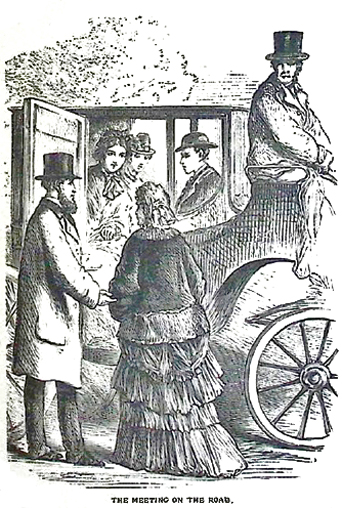

THE MEETING ON THE ROAD.

Guy and his sister hereupon resisted the strong desire to see again the bright face of the girl as she peeped round from her corner in the carriage, and utterly amazed and confounded, saw the elder lady alight and advance to their mother. Her countenance was sweet and fair, with a mingled expression of sympathy, respect, and humility, and in the most winning of voices she entreated Mrs. Falconer to delay her journey at least for a time, and return with them to the Moat, echoing her husband's regret that they had not arrived in time to make their request more opportunely.

"Dear sir, dear madam," said Mrs. Falconer warmly, "I can but attempt to express my thanks; I could not have anticipated such kindness, but our arrangements are made, and we are proceeding at once to London."

"Well, I'm very sorry," said Squire Hazelwood; "it can't be helped then, I suppose, but I'm a bad hand at writing; I let the lawyers settle everything, and I did not know how matters stood, else I would have said my say in proper time."

"It is indeed too late now," said the lady, taking Mrs. Falconer's hand with a gentle pressure; "but we may perhaps meet again under happier circumstances." And drawing back with a curtsey, she re-entered her carriage.

"The sooner the better," said the Squire; "Evelyn is shy, but she means well, silly child. Good-bye, madam; your hand, young sir—we must be friends you know, though the Moat is between us. I hate feuds, and would rather carry your God-speed with us among the people who may be pardoned for feeling that we can't supply your place."

"May God-speed you, sir, I pray so with all my heart," said Mrs. Falconer earnestly, giving her hand into that which her son had scarcely touched.

And so they parted on life's highway with its "changes and chances," unexpected and unknown, but all appointed and ordered in the omniscient love that links together only what works "for good," and drops out of the chain all that we mistake and mismanage for ourselves.

The carriage-and-four rolled deliberately through Falcon Range, where, notwithstanding the novelty of a private equipage in mail coach style, doors were suddenly banged, and surly faces peered from cottage windows; the crape yet hung over the Falconer's Arms, and its landlord stood with his hands in his pockets, and his hat on his head, not deigning to salute the purchaser of the estate of the Falconers, even though his pedigree dated back to the Saxon instead of the Norman Conquest.

But the generous-hearted English gentleman was more touched by the evident sympathy of the villagers for the late occupants of the Moat than disturbed by the slight to himself.

"Poor things," he remarked afterwards to his wife, "I like them for it; who wins their hearts will keep them, and I hate weather-cock friends. However we'll wait our time, Dorothy, and if you don't find your way within those noisy doors that said so plainly, 'You shan't come here,' I shall be more surprised than ever I was in my life yet. So I'll bid you welcome to the Moat, if nobody else does."

And gallantly kissing his wife and daughter, he left them to explore their new abode.

There had not been very much to regret in the removal from Hazel Copse, which had been a long contemplated event, and where many circumstances had estranged them for some time. All that they particularly valued in the form of servants, pet ponies, horses, dogs, and other delights, accompanied them, and Squire Hazelwood of the Falcon Range would be a more important personage in the world's history than the Squire of Hazel Copse. At least so thought the little spoiled heiress of his house and fortune, as she flew about exclaiming with rapture over all she saw.

"Such a dear old place, mother," "Come here," and "Go there," was the frequent interruption to the work of the lady in newly arranging her household, as Evelyn lighted on a terrace walk, or penetrated some dark corner, or, best of all, explored her way into a real "tapestried chamber," haunted of course, ever since Judge Jeffries, of evil renown, tarried there for a night in the civil wars, and was reported to have left some token of ill, like an ancient leper, in the walls of the house that sheltered him.

Evelyn declared herself bold enough to face any wig and gown that might venture from behind the arras, but beyond a saucy rat of venerable lineage, and a few hungry spiders on the search for flies, she never discovered anything to test her boasted courage.

The mansion itself might have served as an illustration of the varieties of English architecture since the first Falconer planted his lance on the sunny slope where his castle was to stand.

There was a tower, ivy-clad and crumbling, remnant of feudal times; there were gables and turretted roofs, porches and pilasters, oriel windows, lattices, arches, and griffins, in fact tokens of all tastes and fashions—Plantagenet, Tudor, Stuart, and Hanoverian, with carvings and heraldic devices blending the armorial bearings of all the family alliances of the ancient House innumerable.

There were huge fire-places, oak parlours, and deep bay window seats; a hall decorated with the old armour of knights, and the antlers of hunted stags, the crusader's sword and the palmer's staff, the banners of rival Roses, the doublet of a cavalier, and the buff coat of a Round-head, the falconer's glove, and the sportsman's fowling-piece, all named and dated with aristocratic pride, harmless and pardonable.

The gardens and grounds were even more attractive, with quaint borders, straight walks, and clipped trees in my lady's pleasaunce, winding paths to wild dingles and dells, accommodation for every kind of the animal creation of the British Isles, from stables and kennels for my lord to covers for foxes, and nests for hornets; there was a lake for fish, a rookery for birds, and far-spreading meads for cattle.

Of the original "Moat," there remained no precise indication, unless the dingles which terminated the shrubbery, and a river which divided some meadows, had once done guardian duty in that capacity,—a reasonable surmise, from the fact of a broken arch in near neighbourhood, where resolute antiquarians discovered symptoms of portcullis pretensions, though a portly bailiff had left on record his belief that it was merely a remnant of modern masonic skill, erected of material cleared away from a fallen tower of the old castle, and in which sheep used to be penned on washing days!

There was no auction at the Moat House. Things were to stand as in past time, with the addition of a few valued possessions from Hazel Copse, for which there was ample space in chambers long disused, and which were now opened, renovated, and made to partake somewhat of the sunny spirt of the new owners of the mansion.

The Squire was busy with lands and live stock, the lady with domestic improvements, and Miss Evelyn, as long accustomed, ran wild over everything, including the stiff prejudices of dependants and villagers.

A LADY OF THE OLDEN TIME.

A RETROSPECTIVE glance at the antecedents of fair Mistress Hazelwood peeps into her old-fashioned, hospitable home at Daisy-Meade, where she fulfilled the mission of one of the bright spirits that seem sent into the world to round off sharp corners, pad rough edges, fit in curious angles, and sheath drawn swords. Quick to observe without seeming to detect, prompt to act without attracting notice, her influence worked just where it was wanted, and her word was spoken just when it would have weight.

People often wondered how certain good things came about, and possibly congratulated themselves on their own wisdom and foresight, when, if truth had appeared from behind the scenes, it was Miss Dorothy's wise suggestion, or gentle hint, or kindly act, or invisible influence that wrought round the circumstances, and shaped them into acceptable form.

Her father was "a fine old English gentleman of the olden time;" a little obstinate, perhaps, as such old gentlemen are said to have been, but having excellent common sense, devout belief in God and the Bible, and whether or not he read "the whole duty of man," he did it, so far as he saw it, with consistency and decision. He had the usual country tastes and occupations, with unusual refinement of mind and tenderness of feeling, which were invaluable to his children when bereft of their mother's care.

His notions of female character and duty and position were derived partly from their illustration in the life of his own much loved wife, and also from an old record of principles which they studied together, in one of the books of their scanty library. It is to be found in most libraries still; but in modern book-seeking days, when people are more interested about wrong roots of things speculative and imaginary, than right ones real and trustworthy, it is left to be regarded more as a curious relic which has seen its best days, than an authority that "lives and abides for ever."

Howbeit the Squire of Daisy-Meade thought and said, and endeavoured to enforce his idea, that woman's endowments, both by nature and grace, are to be exercised in private life, and felt in the blessedness of home; not armed to the teeth for strife and debate, or fussy and famous before the world, which mocks while it applauds, and sneers while it submits to the intrusion of things out of place.

And Miss Dorothy had so wonderfully impersonated his views, that he inconsistently shrank from one of their consequences, and petulantly denounced the covetous spirit of certain young squires who hovered about the sweetest flower in Daisy-Mead, wanting to transplant it for the home "help-meet" it had bloomed to be.

"Dorothy, my dear," he said one day as he was settling himself in the great chair for his afternoon nap, "can't you be a little more disagreeable? Talk loud and fast, be self-willed, or extravagant, or something; perhaps if you would make a dash on Silvertail at a five-barred gate, or be in at the death at the next hunt, or appear at church in some fantastical mopsey gear, it might do. Nobody shall send you to Bedlam for it."

Dorothy opened her merry eyes at her father and laughed.

"Aye, you may laugh, you puss, but I really am at my wits' end. Here's another thief come reconnoitering my unfortunate premises, and I don't know what to do."

"Let him know there is nothing worth stealing here, father," said the young lady, carelessly.

"But you see, he is not of that opinion, Dorothy, and doesn't regard mine, being evidently desirous to manage his own affairs."

"Then say there is nothing that will allow of a theft, your property is too well guarded."

"So be it, my dear. What should I do without thee?"

"You can't part with me, father, and until you can, I shall never go; so please take your nap. And, father, I'll practise for the five-barred gate, and surprise the hunt next opportunity."

The Squire smiled, and drew a silk handkerchief over his face, and dozed; while Dorothy went on with her work, kept the dogs quiet on the rug, and prevented the logs from scuttling down with crackle and thump on the hearth as they burned away.

Suddenly the silk handkerchief was withdrawn, and the Squire awoke from a dream about thieves and good little daughters.

"But, Dorothy," said he, doubtfully, "if you wanted to go, if some booby that you liked came prowling, what then?"

"Dear father, I shan't like a booby," said Dorothy, with her silvery little laugh; "you are very complimentary in the anticipation of such a monstrous choice."

"Well, well, there's no wisdom in meeting trouble half way; only, my girl, I couldn't tell what you might say to young Hazelwood, if he should dare to tell you what he told me this morning; but I'm glad it's all right, and now I'll finish my nap;" and the handkerchief was drawn over his head again.

Poor Miss Dorothy! The needle had dropped from her fingers, the merry light faded from her eyes, the colour came and went on her cheek. What! Could it be possible?—The handsome, gallant young squire of Hazel Copse, the admired of all the ladies round, the generous, warm-hearted, pitiful young master who excused old Wilks his rent when he fell ill and couldn't work; forgave poor Slade for poaching, and refused to prosecute; saved Widow Crane's boy from drowning, and took care of them all, until Wilks got well, and Slade got honest employment, and the boy came through the fever;—the best huntsman in the field, Captain in the Militia, and the possible choice of the county at the next election;—and more and better than all, the most regular and apparently sincere worshipper in the parish church, and the best helper the vicar had in whatever good he proposed to do. Amazing!

Could this gentleman really have thought of her, the little daisy of the Meade, as some of the silly old people called her? And her father had called him a booby, and she had coolly assented! What a miserable mistake!

But, after all, what did it matter? She could not and would not leave her dear, kind father for any squire in Christendom, so there was an end of that. And Miss Dorothy calmed down, and picked up her fallen needle, and a very soft little sigh escaped as she resumed her work.

The kind old gentleman was not so sleepy as he seemed, and out of the corner of an eye, and a convenient little hole in his India-silk handkerchief, he had carefully watched his child; noting the start, the colour, the expressive mouth as she sat thinking, and his quick ear caught the little sigh. So, after a suitable make-believe sleep, he pretended to awake, shook himself, whistled to his dogs, and went out, thinking hard about what he would have to do next. The simple fatherly heart had no thought of hindering the happiness of others for his own; and feeling in a strange maze upon the subject, he stumbled against the cause of his disquietude.

"Ah, I thought so, sir; you couldn't wait a whole day, it seems, before coming to know whether you may rob an old man of his best and sweetest. Look you, sir, ask my best horse, my finest field, or biggest barn with all its fresh-gathered store, and you shall be welcome; but Dorothy, my singing-bird, my home-sunshine, I don't know how to part with her yet."

"Well, sir," said Mr. Hazelwood, frankly, "I do feel very like some house-breaker in your presence, and my dismissal will pain no one but myself; but I have strictly obeyed your command of a week ago to abstain from any attempt to plead my own cause, and now you must give me your decision."

"All fair and straightforward for a thief, I admit," said Dorothy's father. "I honestly tell you that I took the week since you broached the subject to make searching inquiries about you, and I took the last few hours to fathom my Daisy's mind, if I could. If you won't give me any more time, you must just find it out for yourself."

"Sir, if your daughter cannot willingly and happily become my wife after I have convinced her of my affection, I will never again distress you with my suit."

"Well, well, likely story; you don't believe in disappointment, not you," thought the old man; "it's all up if I give him the chance he asks. I wish he'd broke—no, no I don't,—selfish old fool!

"Well, sir, I can't help myself, it seems; wherever she goes, her father's heart and blessing go with her. She's in there at some woman's work you may be sure," pointing back through the hall: "but I'm just going down to look at the hop-ground; you can come too if you care for the crops this year," he added, drily.

Mr. Hazelwood seized his hand with a right earnest grasp.

"The hops must wait this time, sir, and I thank you with all my heart." And darting away, he left the good father to contemplate the painful loneliness of his closing years.

It was not a cheerful walk, and so prolonged that Dorothy was anxiously watching for him in the path from the hop-grounds.

"Well, my child, is it settled?" he asked, drawing her within his arm.

"Yes, sir," said Dorothy, demurely, "if you please."

"Humph, you have forgotten that you don't like boobies. How soon must I give you up?"

"Not before seven years, father, and another seven to that if it would make you sad to do it."

"Ah! A Jacob and Rachel sort of business, is it? But they say Hazel Copse wants a mistress now."

"I can't help that, father. Daisy-Meade wants a mistress too, and I am queen here until you choose to dethrone me."

"Well, well, my child, who knows but I may be—"

Dorothy's hand was on his lips, before what might be, could be spoken.

And if Mr. Hazelwood could have seen the mingled love and pain that were depicted on each face for the moment, he ought to have felt some compunction for the disturbance he had made.

"But what must be must, and should be faced manfully," the old Squire said. And he set about plans for furthering the hopes of his son-in-law elect, who had rashly quoted the patient patriarch in deference to the filial affection of his ladye love.

Before a year expired, he resigned his farm and its business into the hands of his son, who had qualified himself for the responsibility, and at the earnest desire of Mr. Hazelwood, took up his chief residence at Hazel Copse, where he could watch and be tended by his transplanted flower, and see her bloom into matronly beauty, the light of another home.

Such was the lady who paid her momentary visit to Mrs. Falconer at the carriage door, and whose thoughts as she moved about in her new and spacious home continually reverted to the banished ones, possibly shut up in some dingy house of the city street.

Everywhere she traced the graceful tastes of the late mistress of the Moat, everywhere she heard regrets for her departure, and praises of her character; and the desire grew strong within her to prove sympathy and respect in some substantial manner.

But Mistress Hazelwood's instinctive practise was to hide her own loving impulses behind her husband's actions, and to claim for him the tribute, while she shared with him the pure pleasure of generous and useful deeds.

She knew well how a little suggestion expanded in his mind, and often went beyond all her expectations. Presently he would certainly perceive some way to benefit those who had been suddenly deprived of so much that he and his were now enjoying.

In the meantime, there must be no grasping at a shadow and losing the substance; no craving for future usefulness in some congenial form, while duty ready to her heart and hand lay before her in God's appointment.

Those closed doors in the village had chilled her, and must be opened somehow; she must try to supply Mrs. Falconer's place. Her devout and humble manner as she took her place in the great family pew at church on Sunday was particularly approved by the clerk, who commented thereon to the good old gardener, who had not yet required the epitaph.

But of Miss Hazelwood, he could not so favourably report; for she had looked about her, and stared in a peculiar manner at him when he delivered his first "Amen," which he had meant to render unusually impressive, and she did not seem impressed at all,—at least, not respectfully so.

"But she is but a young thing, and must be taught better. Hazel Copse was but an outlandish sort of place, and maybe young Miss had never heard before an 'Amen' as it should be. As for the Squire, he was certainly a pleasant gentleman enough, and not too proud to shake hands with an honest poor man. He had himself looked in at the gardener's cottage with a bunch of grapes for the invalid, which was a good sign; and he would have power to do a deal more than Mrs. Falconer could do in the way of gifts; so perhaps when they came to be known, and the pert little Miss had mended her manners, things might not go so badly after all."

Mr. Herbert heard opinions and remarks, and wisely left matters to take their course. The turn of feeling in the village would be all the stronger when resulting from personal experience, than if constrained by any pressure of advice or suggestion from him.

In honourable sympathy with the general feeling which attended the transfer by purchase of an old family estate, there were no rejoicings at the Moat; and the chief changes to be noticed were the presence of a master and manager of his own affairs, with a bright cheerful little lady for his help-mate, instead of the calm pale face of the widow in her suit of undeviating black, and instead of the poor young heir and his graceful sister, only the one radiant presence of the butterfly heiress, whom nobody could ever resolve to correct or punish. She bounded about like a ball, dived into things serious and comic, resolutely refused to mount the black pony, which she learned had been Guy's, and most irreverently mimicked Mr. Spadeley's impressive "Amen" in his own place of dignity, when exploring the church.

But in the churchyard, she conquered him quite; listened to his tales of the heroes of the Falconers' line; gleaned wonders of village lore from names and dates and epitaphs; trod softly round the tomb beneath the cedars; made him lift her high enough to read the record on the marble slab, and before tripping away,—

"Thank you," she said, gravely. "I wish Mrs. Falconer and the children had not gone away from the Moat; there is plenty of room for us all, and I can't see why they should go; can you, Mr. Spadeley?"

Mr. Spadeley pushed back his hat and rubbed his shining head meditatively.

"Well, Miss, you see, people don't like staying in their troubles where they've seen better days; and the Moat's bought from right over their heads you know."

"Is it? I didn't know; I thought they sold it to my father because they wanted some money."

"Aye, more shame for them that did it that's in a foreign land; but there's no blame for it to them, or to your father, little Miss, so don't put the cap on the wrong head; it's got a thorn or two in it, depend upon that."

"I see," said Miss Evelyn, looking very profound. "And tell you what, Mr. Spadeley, they shall come back again and be happy here, or else I'm not Evelyn Hazelwood; you'll see, Mr. Spadeley; good morning to you, you'll see." And shaking her little head as she looked back at him, she darted off with a new light in her mind.

"I'll see!" repeated Mr. Spadeley in immense admiration. "I shan't see anything prettier nor you one while. Bless your little heart, it's a pity you can't do all you'd like to."

And leaning over the handle of his spade, the worthy sexton made a long meditation. Then suddenly lifting himself up, he struck it vigorously under a weed.

"I have it!" he exclaimed. "That 'll do! And, my little lady, as you say, we'll see,—yes, yes, we'll see what we shall see, and be right glad and satisfied, after all's said and done!"

What vision brightened the end of the vista through which he had been mentally looking, possibly his daughter Jane and the landlord of the "Falconers' Arms" might know soon, but there was no one near to whom to tell it at that moment.

DAILY BREAD.

AFTER many a weary walk in search of apartments cheap enough to suit her altered circumstances, and wholesome enough for her country plants, so suddenly transferred to a new atmosphere, Mrs. Falconer at last engaged three rooms within easy distance from one of the parks, and then began to consider how best to augment her income, and complete the education of her children. Its object now was changed; the routine which before was pursued in preparation for adorning the station in which they were born, and fitting them for its duties and responsibilities, must now be directed to some special kind of occupation for emolument, and the choice was difficult.

Hitherto Guy had enjoyed the benefit of a good school, and the advantage of assistance from the young pastor of Falcon Range, who was not only a faithful minister of Christ, but also an accomplished scholar; and Maude had not yet passed beyond the hitherto sufficient instruction of her mother.

To enter her son at a public school, and to obtain professional help for Maude with a view to earning a livelihood, seemed the only course to pursue at present; and in order to do this, some unusual effort must be made by herself.

Chief among the attainments of earlier days was great skill, added to the natural taste of an artist; and Mrs. Falconer found encouragement from certain patrons of the Fine Arts, of which she was not slow to avail herself.

To conceal this plan from her children was next to impossible, so she resolved not to attempt it, but rather to claim their gratitude to God for such a graceful and congenial means of assistance. But to poor Guy's unsubdued spirit, the idea was intolerable, and he refused to attend any school or incur any expense to be provided for on such terms.

"I mean to work myself, mother. I have given up all thought of being a gentleman," he urged.

"My son must be a gentleman, whatever else he may be," said his mother, smiling. "I only want you to fit yourself for work, dear Guy, and when that is done, I will not refuse to profit by your labours. You do not yet recognise God's will and providence in our lot, as I had begun to hope."

"Oh, mother, it will drive me mad to see you obliged to work! I cannot bear it!" exclaimed the boy.

"Then, Guy, I must follow the troubled father to kneel at the feet of Jesus, until He in pity casts out the evil spirit that torments my child, my only son; you cannot see and sympathise until this is done. I have no desire to over-tax my strength, or grieve my children; I am only trying to follow, as nearly as I can see it, the loving Hand that beckons in what only our own wilfulness and discontent can prevent from being a 'way of pleasantness' and a 'path of peace.'"

Maude drew closer to her mother and tenderly kissed her brow.

"Oh, Guy," said she, "why do you add to our sorrow by your naughty anger against God? Do you think He does not love this dear mother better than we do? And couldn't He have prevented all that has happened if He thought it right? Take care, dear brother, or we shall have the hard pain of finding out that she has to suffer for our sakes, because we are rebellious and proud, and must be humbled and proved, and made good somehow."

"People can be good, I suppose, without having such miserable things happening to them," said Guy.

"A trial, to be such, must strike where we feel it," said Mrs. Falconer. "Many things might have happened, and have produced no effect. This, which has altered the whole tenor of our lives, must produce some effect. Our Heavenly Father chastens only for our profit; therefore I feel He has sent us a blessing in disguise. Let us penetrate the disguise to find the blessing, and so honour Him in adversity as we should not have been able to do in our late comparative prosperity. And, Guy, if ever we should have the means of helping others, how much wiser and more tender will be our sympathy with those whom God brings low. Oh, let us be assured that He knows best the kind of discipline His people need."

"Hark! What is that for?" said Maude, as the solemn toll of a minute bell struck from the tower of a neighbouring church, soon re-echoed by others at a greater distance.

"Perhaps," said Mrs. Falconer, softly, "some whom no such trial as ours could have touched, Death has stricken. May it be in mercy to the mourners."

In a few minutes, the landlady, pale and breathless, burst into the room.

"Oh, ladies! Oh, Mrs. Falconer!" she gasped, "Have you heard? Oh, such a sorrow, such a dreadful blow!" And regardless of everything but this great sorrow, she sank into a chair and sobbed aloud.

Alas! Her news, when she could tell it, was indeed a sorrow. It thrilled the heart of England as no such event had ever done before, and from the palace to the cottage there was mourning, lamentation, and woe. * Death had stricken suddenly where no other kind of blow could have fallen with such mighty weight of trouble. And as the children each clasped the hands of their mother, and gazed in her pale sweet face, they both felt that the loss of property, position, anything they had possessed, was as nothing compared with the anguish it would have been to lose her, their tender, true, best earthly friend.

* Death of the Princess Charlotte.

Then she turned their thoughts to the suffering that no regal state could evade, no lofty titles resist; and they knelt together to pray for God's pitiful help for the stricken mourners around the lifeless form of their most deeply, dearly loved.

That afternoon, Mrs. Falconer was glad to send Guy and his sister to walk in the park and to be alone. Her heart was very full, and she needed time to think and pray, even also to weep; for the news of the morning had touched her deeply, and knew something of the agony of a separation that only death could inflict. Tears of sympathy are like a spring shower, refreshing the parched ground, to be followed by new verdure and fragrance; and in loving prayer for others, the widow almost forgot for the time her own anxieties.

One friend had sought her out, and obtained a ready welcome whenever she chose to come; for she brought in her own large heart much of the Spirit of her Master. And if it were not always manifested in the gentlest, meekest way, it was not because or any self-sufficiency or conceit of her own opinions, but rather from the quick, vigorous grasp which her mind took of things that she deemed worth thinking about. She was, moreover, a woman of business, and went straight to her point, whatever it might be, with very little courtly preface or circumlocution.

Such persons are not very common, and the world rather objects to them; but when natural quickness and decision are softened by Christian love and ruled by Christian principle, they become valuable leaders of thought and action.

God's gracious plan is not to crush out the individualism of human character, but to consecrate and utilize all that is susceptible of sanctifying influence. His gifts are manifold in natural things, and when the supernatural takes possession, it is like a new steersman taking his place at the helm of an ill-directed ship, when she is constrained to yield to a master's hand, and to stand for the destined haven. It is the same ship, the same masts, sails, and tackling, but a new will controls; her course is altered, and all her appliances are made to serve their proper purpose. Some chains may rattle more than others, some timbers creak and strain, but they are doing their duty for all that, and the trifling jar upon sensitive ears is forgotten in their indispensable usefulness.

It is a pity when useful people do not try to be lovable also, because "God is love," and whoever belongs to Him and desires to do His work ought to imitate in his heart as well as his hand. Real kindness and positive service may lose their value in an uncouth manner or ungracious tone, and in a moment turn gratitude to gall.

But whatever might be the estimate of the Honourable Mrs. W— in committees of management (for she never gave her name where she did not intend to work), she knew well how to appreciate character, and the kind of sympathy and aid to render; and if she found some whom she was extremely disposed to snub, she knew full well when across her path came those whom her Lord and Saviour would have to be cherished and comforted.

On that day of national grief, the committee meeting of a certain institution supported by public subscription broke up in surprise and concern. And Mrs. W—, with plans maturing in her hands, and on which no decisive sentence had been passed, made her way to Mrs. Falconer's lodgings, and using the freedom of friendship, walked up unannounced. To her gentle knock, no answer was returned, and she pushed the door open. Mrs. Falconer lay asleep on a couch, tears yet undried on her cheek, and a smile of peace and tranquility on her lips.

The visitor glanced round the apartment. There was an easel bearing an unfinished picture of some lovely spot, an open portfolio of designs and copies, brushes and paints and chalks, a few books, a delicate piece of ladies' fancy work, on which Maude was sometimes employed; and from the hand of the sleeper, a little Testament had slipped.

From these surroundings, Mrs. W—'s gaze returned to that still beautiful face, and she almost shuddered to see how very worn it looked, how delicate and thin the cheek, how care-lined the brow.