EDWARD STRATEMEYER’S BOOKS

Old Glory Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.25.

The Bound to Succeed Series

Three volumes. Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.00.

The Ship and Shore Series

Three volumes. Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.00.

War and Adventure Stories

Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.25.

Colonial Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.25.

American Boys’ Biographical Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.25.

OR

The Young Miller of Torrent Bend

BY

AUTHOR OF “UNDER DEWEY AT MANILA,” “A YOUNG VOLUNTEER IN CUBA,”

“FIGHTING IN CUBAN WATERS,” “THE LAST CRUISE OF THE SPITFIRE,”

“RICHARD DARE’S VENTURE,” “OLIVER BRIGHT’S SEARCH,”

ETC., ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON

Copyright, 1895,

By THE MERRIAM COMPANY.

Copyright, 1900, by Lee and Shepard.

All Rights Reserved.

Reuben Stone’s Discovery.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith

Norwood Mass. U.S.A.

“Reuben Stone’s Discovery” forms the second volume in the “Ship and Shore” Series. It tells, in a matter-of-fact way, of the exploits of a young miller who is left in charge of his father’s property while the parent goes West to seek a more promising field for business. A great number of things happen while the youth is thus left to himself, and he is made to believe several stories concerning his absent parent and the mill property which cause him great uneasiness in mind. Suspicious at last that all is not right, Reuben starts out on a tour of investigation which places him in more than one position of peril. But the lad never falters, knowing he is doing what is right, and his triumph at the end is fairly earned.

Reuben tells his own story, and does it in his own peculiar way. Perhaps this method may not be altogether satisfactory to older heads; but the success of the first edition of the book had demonstrated the fact that it is satisfactory to the boys, and it was for these that the story was set to paper. If Reuben does some[iv] astonishing things throughout the course of the story, it must be remembered that the lad was acting largely in his father’s place, and that the world moves and boys of to-day are full of energy.

EDWARD STRATEMEYER.

Newark, N.J.,

June 1, 1899.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The Young Miller | 7 |

| II. | At the Bank | 16 |

| III. | Bad News | 26 |

| IV. | Mr. Enos Norton | 33 |

| V. | Hot Words | 42 |

| VI. | At Rock Island | 51 |

| VII. | A Pitched Battle | 62 |

| VIII. | A Blow from Behind | 69 |

| IX. | The Two Strangers | 77 |

| X. | A Surprise | 85 |

| XI. | Mr. Norton’s Move | 93 |

| XII. | A Midnight Crime | 100 |

| XIII. | At Squire Slocum’s House | 108 |

| XIV. | Mr. Norton’s Statement | 116 |

| XV. | Some Facts in the Case | 124 |

| XVI. | A Friend in Need | 133 |

| XVII. | Back to the Mill | 140 |

| XVIII. | A Moment of Excitement | 149 |

| XIX.[6] | Lively Work | 157 |

| XX. | We make a Prisoner | 165 |

| XXI. | A Storm on the Lake | 173 |

| XXII. | An Interesting Conversation | 182 |

| XXIII. | Captured | 190 |

| XXIV. | In the Woods | 198 |

| XXV. | A Miraculous Escape | 204 |

| XXVI. | The Chase | 212 |

| XXVII. | At the Depot | 218 |

| XXVIII. | The Pursuit becomes Perilous | 224 |

| XXIX. | Mr. Norton’s Accusation | 230 |

| XXX. | Norton Bixby | 237 |

| XXXI. | A Lucky Find | 243 |

| XXXII. | A Welcome Arrival | 249 |

| XXXIII. | A Happy Ending | 254 |

“It ain’t no use to talk, Rube, that bill has got to be paid.” Mr. James Jackson brought his fist down on the little desk in one corner of the mill with such force that everything jumped. “I’ve waited for it till I’m all out of patience, and now I want my money.”

“I’m sorry, Mr. Jackson,” I replied, “very sorry indeed to keep you waiting; but it cannot be helped. Business has been backward this summer, as you know, and money is tight.”

“It never was tight when your father was here,” growled the principal storekeeper of Torrent Bend, as he strode up and down the whitened floor. “Every bill was paid on the spot.”

“That is true, sir; but father knew the business was getting poorer every day, and that is the reason he[8] left to see if he couldn’t locate in some place in the West.”

“Might better have stayed here and tended to this place, and not let his son run it into the ground.”

“I am not running the business into the ground,” I cried, with some show of spirit, because I thought the assertion an unfair one. “I do all the grinding that comes in, and even go over to Bayport and down to Sander’s Point in the boat to get it.”

“Pooh! don’t tell me! Young men around here don’t amount to much! But that ain’t here or there. I came for that money.”

“I will see if I can pay it to-day. I have a load of middlings to take over to Mr. Carnet this morning, and if he pays me I will come right down to the Bend and settle up.”

“And if he don’t pay?”

“I trust he does.”

“Well, pay or not, I’ve got to have my money, and that’s all there is to it. You can’t have any more goods till you square accounts.”

And having thus delivered himself, Mr. Jackson stamped out of the mill, jumped into his buckboard, and drove off for the village.

He did not leave me in a very happy state of mind. I was in sole charge of the mill, and I was finding it hard work to make everything run smoothly.

Two months before, my father had departed for the West, with a view to locating a new mill in any spot that might promise well. Affairs in Torrent Bend were nearly at a standstill, with no prospect of improving.

I was but sixteen years old, but I had been born and raised in the mill, and I understood the business fully as well as the average miller.

I ground out all the wheat, corn, rye, and buckwheat that came to hand, took my portion of the same and disposed of it to the best advantage. In addition to this I used up all my spare time in drumming up trade; and what more could any one do?

With the exception of my father, and an uncle whom I had never seen, I was alone in the world. My mother had died four years before, while I was still attending the district school, and two years later my twin sisters had followed her.

These deaths had been a severe blow to both my father and myself. To me my mother had been all that such a kind and loving parent can be, and my sisters had been my only playmates.

My father and I were not left long to mourn. There were heavy bills to be met, and we worked night and day to get out of debt.

At length came the time when all was free and clear, and we were nearly two hundred dollars ahead.[10] Then my father got it into his mind that he could do better in some new Western place; and he left to be gone at least three months.

For a time all worked smoothly. I had for a helper a young man named Daniel Ford, a hearty, whole-souled fellow, and we got along splendidly together; but one night an accident happened.

The raceway to the mill was an old one, and a heavy rain-storm increased the volume of water to such an extent that it was partly carried away. I had the damage repaired at once; but the cost was such that it threw us once more into debt, and made it necessary for me to purchase groceries from Mr. Jackson on credit.

This I hated to do, knowing well the mean spirit of the man. But his store was the only one on this side of Rock Island Lake where my father was in the habit of purchasing, and I had to submit.

“Humph! seems to me old Jackson is mighty sharp after his money,” observed Ford, who was at work in the mill, and had overheard our conversation.

“If Mr. Carnet pays up I won’t keep him waiting.” I replied. “I suppose he’s entitled to his money.”

“If I was in your place I’d make him wait. I wouldn’t take any such talk without making him suffer for it. Do you want to load these bags on the boat now?”

“Yes; sixteen of them.”

Getting out the wheelbarrow, the young fellow piled it high with the bags of middlings, and carted them down to the sloop that was tied to the wharf that jutted out into the lake. It was only a short distance, and the job was soon finished.

“Now I’m off,” I said, as I prepared to leave. “You know what to do if anything comes in while I’m gone.”

“Oh, yes.”

“And in the meanwhile you can get that flour ready for Jerry Moore.”

“I will.”

I jumped aboard the sloop, unfastened the painter, hoisted the mainsail, and stood out for the other shore. A stiff breeze was blowing, and I was soon well underway.

Rock Island Lake was a beautiful sheet of water, four miles wide by twelve long. Near its upper end was a large island covered with rough rocks, bushes, and immense pine-trees. On one side of it was the thriving town of Bayport; and opposite, the village of Bend Center, situated a mile below the Torrent Bend River, which emptied into the lake at the spot where my father had located his mill.

The two resident places were in sharp contrast to each other. Bend Center was a sleepy spot that had not increased in population for twenty years, while[12] Bayport, which had been settled but fifteen years, was all life and activity.

Among the attractions at the latter place were three large summer hotels, now crowded with boarders. The hotels were built upon the edge of the lake, and boats on fishing and pleasure trips were to be seen in all directions.

On this bright morning in midsummer the scene was a pretty one, and had I felt in the humor I could have enjoyed it thoroughly.

But I was out of sorts. As I have said, I was doing my best to pay off what bills were due; and to have Mr. Jackson, or, in fact, any one, insinuate that I didn’t amount to much, and that my father had made a mistake in trusting the business to me, cut me to the heart.

I was but a boy, yet I was doing a man’s work, and doing it as manfully as I knew how. I arose every morning at five o’clock, and sometimes worked until long after sundown.

I kept a strict account of what came in and went out; and looking at the account-book now, I am satisfied that I did as well as any one could have done under the circumstances.

The work around the mill was hard, but I never complained. I did fully as much as Ford, and if at night my back ached as it never had before, no[13] one ever heard me mention it, and I was always ready for work on the following morning.

During the two months that had passed I had received but three letters from my father. He was out in South Dakota, and had not yet been able to locate to his satisfaction. In his last communication he had written that he was about to take a journey to the north, and that I need not expect to hear from him for two weeks or more.

This was somewhat of a disappointment; yet I trusted the trip he was about to undertake would be a fruitful one. The whole West was booming, and why could we not participate in the fortunes to be made?

As the sloop sped on its way I revolved the matter over in my mind. So busy did I become with my thoughts, I did not notice the freshening of the wind until a sudden puff caught the mainsail, and nearly threw the craft over on her side.

Springing up, I lowered the sheet, and then looked to see if the cargo was still safe.

Luckily Ford had placed the bags tight up near the cuddy, and not one had shifted. Seeing this, I ran the sail up again, trimmed it, and stood on my course.

As I did so I saw a large sloop not a great distance ahead of me. It had all sails set, and was bowling along at a lively rate.

I became interested in the large sloop at once. By the manner in which she moved along I was certain those in charge of her did not understand the handling of such a craft. The mainsail and jib were set full, and the boom of the former was sweeping violently in the puffs of wind.

“On board the sloop!” I called out. “Why don’t you take in some sail?”

“We can’t!” came back the answer. “The ropes are all stuck fast.”

By this time I had come up to starboard of them. I saw that there were two men, a woman, and a little boy on board.

The two men were trying in vain to lower the sails. They had evidently knotted the ropes when tying them, and now they were so taut nothing could be undone.

“What shall we do?” called the elder of the two men.

“If you can’t untie the knots, cut the rope,” I called back, “and don’t lose any time about it.”

One of the men immediately started to follow out my suggestion. I saw him draw out his pocket-knife, open the blade, and begin to saw on the rope.

The next instant another puff of wind, stronger than any of the others, came sweeping down the lake. I was prepared for it, and sheered off to windward.

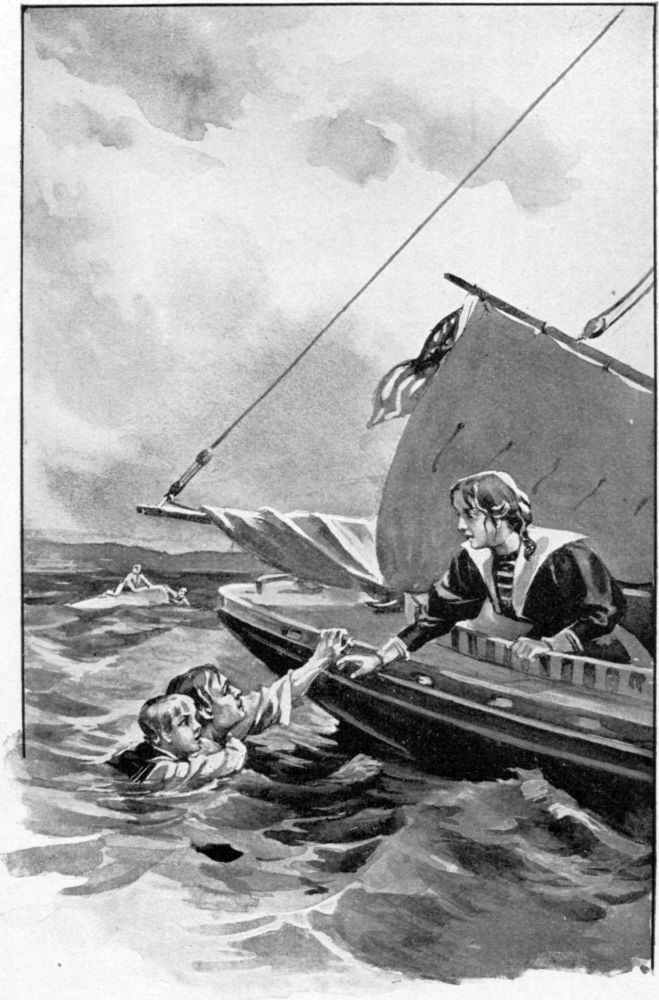

But the puff caught the large sloop directly broadside. The mainsheet and the jib filled, then the craft careened, and before I could realize what was happening, the four occupants were sent tumbling out into the waters of the lake.

I was both astonished and dismayed to see the large sloop go over and precipitate its passengers into the water. The catastrophe happened so quickly that for a moment I knew not what to do.

Then my presence of mind came back, and I set promptly to work to rescue those who had gone overboard. In a moment I had the woman on board of my own craft. She was insensible.

“Save my boy!” cried one of the men. “Don’t mind us; we can both swim.”

“All right; I’ll do what I can,” was my reply.

Looking about, I discovered the body of the little fellow some distance back. I tried to tack, but it could not be done, the wind being too strong from the opposite direction.

“He is going down!” went on the father in agonized tones that pierced my heart. “Oh, save him! save him!” And he made a strong effort to reach the spot himself; but the weight of his clothes was against him, and I knew he could not cover the distance before[17] it would be too late. I was a first-class swimmer, and in a second had decided what to do.

With a bang I allowed the mainsail to drop, and threw over the anchor, which I knew would catch on the rocky bottom twelve or fifteen feet below.

Then I kicked off my boots, ripped off my vest and coat, and sprang to the stern. A single glance showed me where the boy had just gone down, and for this spot I dived head first.

I passed under the water some ten or a dozen feet. When I came to the surface I found the little fellow close beside me. He was kicking at a terrible rate, and I could see he had swallowed considerable of the fresh liquid of which the lake was constituted.

“Don’t kick any more,” I said; “I will save you. Here, put your arms around my neck.”

“I want papa and mamma,” he cried, spitting out some of the water.

“I’ll take you to them if you’ll do as I tell you.”

Thus reassured, the little fellow put his arms around my neck. I at once struck out for the sloop, and reaching it, clambered on deck. As I did so the woman I had saved seemed to come to her senses, and rising to her feet she clasped the boy in her arms.

“My Willie! my darling Willie!” she cried. “Thank God you are saved!”

“Yes, mamma; that big boy saved me. Wasn’t it good of him?”

“Yes, indeed, my child!”

Looking around, I discovered that the two men were clinging to the keel of the large sloop, which had now turned bottom upwards. I pulled up the anchor, hoisted the sail again, and was soon alongside.

“Here you are!” I called out, throwing them a rope by which they might come on board.

“Did you save my son?” demanded the elder one anxiously.

“Yes, William; he is safe,” returned the woman.

“All right; then we’ll come aboard too,” said the man. “Here, Brown, you go first. This accident is entirely my fault.”

“No more yours than mine,” returned the man addressed, as he hauled himself up over the stern. “It was I who wanted to go out without a man to manage the boat, Mr. Markham.”

“Yes; but I tied the knots in the ropes,” was the reply, as the elder man also came on board.

They were all well-dressed people, and I rightly guessed that they were boarders at one of the hotels at Bayport.

“Well, young man, it was lucky you came along,” said Mr. Markham, turning to me. “You have saved at least two lives.”

He was still excited, and put the case rather strongly.

“Oh, no, I didn’t!” I protested. “I only picked you up. Any one would have done that.”

“Didn’t you jump overboard and rescue my son?”

“Well, yes; but that wasn’t much to do.”

“I think it was a good deal. If my son had gone down I would never have wanted to go back. All of us owe you a deep debt of gratitude.”

“Yes, indeed!” burst out Mrs. Markham. “What would I have done without my precious Willie?” And she strained the little fellow to her breast.

The situation was both novel and uncomfortable for me. I had but done my duty, and I didn’t see the use of making such a fuss over it.

“Where are you bound?” I asked, by way of changing the subject.

“We started for a trip down the lake about an hour ago,” replied Mr. Markham. “Will you take us back to Bayport?”

“Certainly; that is just where I am bound. But what do you intend to do with your sloop?”

“Leave her adrift. I never want to see the craft again.” And Mr. Markham shuddered.

“She can easily be righted,” I went on.

“If you want her, you may have her. I will pay the present owner what she is worth.”

“Thank you; I’ll accept her gladly,” I cried; “but it won’t cost much to bring her around, and hadn’t you better pay her owner for the damage done, and let him keep her?”

“No; I’ve given her to you, and that’s settled.”

“Then let me thank you again, sir,” I said warmly, greatly pleased at his generosity.

“Humph! it isn’t much. May I ask who you are?”

“I am Reuben Stone. I run my father’s mill over at Torrent Bend River.”

“Indeed! Rather young to run a mill alone.”

“I have a man to help me. I was brought up about the place.”

“I see. My name is William Markham. I am in the dry-goods trade in New York. This is my wife and my son Willie, and this is Mr. Brown, an intimate friend.”

I acknowledged the various introductions as best I could. Every one was wet, and scarcely presentable; but in that particular we were all on a level, and I did not feel abashed.

We were now approaching the Bayport shore, and Mr. Markham asked me to stop at the hotel’s private wharf, which I did.

“Will you come up to the hotel with us?” he asked.

“I’m not in condition,” I laughed. “I had better be about my business.”

“No, no; I want you to stay here,” he returned quickly. “I want to see you just as soon as I can change my clothes.”

“Suppose I come back in half an hour?”

“That will suit me very well.”

After the party had landed I skirted the shore until I came to the business portion of the town. Here I tied up, and made my way at once to Mr. Carnet’s flour and feed store.

“Well, Rube, got that middlings for me?” he exclaimed as I entered.

“Yes, sir; sixteen bags.”

“All right. Just pile them up in the shed on the wharf. I’ll go down with you. How much?”

“I would rather you would see them before I set a price,” I returned. “I am afraid some of the bags are pretty wet.”

“I don’t want wet bags. How did it happen?”

I related what had occurred. By the time I had finished we had reached the wharf.

“My! my!” exclaimed the flour-dealer. “Mr. Markham! I know him. He is one of the richest men at the Grand. So he said you could have the boat. She is worth a couple of hundred dollars.”

“Yes, and a hundred added. He is more than generous.”

“He can afford it, I suppose.”

“Here are the bags,” I went on. “Ten of them are dry.”

“Those I’ll give you regular price for,—dollar and a half.” Mr. Carnet examined the others. “Suppose we make the six a dollar each?”

“Can’t you make it a dollar and a quarter?”

“No; a dollar is all they are worth to me.”

“Very well. When do you want more?”

“Any time next week,” replied the flour-merchant, handing over the twenty-one dollars that were due me.

“All right. I’ll be over Tuesday. Want anything else?”

“Not for the present. Trade is rather slow.”

Putting the money in my pocket-book, I entered my sloop again, and steered for the hotel wharf. I found Mr. Markham already awaiting me.

“Just tie up here and come with me,” he said.

I did so, and we walked along the principal street of Bayport, which at this hour of the day was nearly deserted.

“I am going to the bank on business,” he went on with a twinkle in his eye. “This is my last day here, and I want to draw out the deposit I made for convenience’s sake when I came.”

I did not see what this had to do with me, but said nothing.

We soon reached the bank, which, in contrast with the many fine buildings in the place, was a dilapidated structure. We entered the main office; and here Mr. Markham asked me to wait while he held a brief consultation with the president.

I waited for half an hour. During that time many people came and went; but I knew none of them. The janitor eyed me sharply, and finally asked me what I wanted.

His tone was a rough one, and I replied curtly that I was waiting for a gentleman who had gone in to see the president; then I turned on my heel, and walking outside, stood on the pavement. It was not until some time later that I found out how suspicious my actions had been regarded.

Presently Mr. Markham came down the steps in a hurry. He was pale with anger, and his eyes flashed with indignation.

“It is an outrage! an abominable outrage!” he ejaculated.

I was rather surprised, and could not refrain from asking what was the trouble.

“You would hardly understand it, Reuben,” he replied. “I made a deposit in this bank under rather peculiar circumstances, and now President Webster refuses to allow me to draw the balance due me until certain matters are adjusted.”

“I hope you don’t lose by it.”

“I won’t lose much. But that isn’t the point. I expected to reward you for what you have done for me, and now I am not able to do so.”

“I don’t expect any reward, sir.”

“Nevertheless, I shall do what is right.”

“The sloop is worth several hundred dollars. That is more than I deserved.”

“I don’t think so. Every time I think of what might have happened to my wife and my little son I cannot help but shudder. Brown and I ought never to have ventured out without a man to sail the boat. We have learned a lesson that we shall not forget in a hurry.”

“It was a risky thing to do in this wind, sir.”

“It was. But about this reward—”

“I don’t want any reward, sir. The value of the sloop is more than I deserve.”

“Nevertheless, you shall hear from me in the near future.”

On this point Mr. Markham remained firm, and a quarter of an hour later we parted, I hoping that none of the party would suffer any from the involuntary bath.

I jumped aboard the sloop, feeling on particularly good terms with myself. As I sped away from Bayport I began to calculate on what the large sloop[25] would net me at a sale. Certainly not less than two hundred and fifty dollars; and this would clear off the bill for repairs at the mill, and leave me a hundred dollars ahead. In my present straitened circumstances this amount would be a perfect windfall.

I tried to steer for the overturned craft, and tow her to a safe place, where I might right her and fix her up.

The wind was as fresh as ever, and I had to steer with care, lest the standing-room should get filled with water from the waves that dashed over the bow. To a person not used to the lake the passage would have been a rough one, but I was accustomed to far worse weather, and did not mind it.

At length I reached the spot where the catastrophe had occurred, and looked around.

The large sloop had disappeared.

For a moment I could not believe the evidence of my own eyes. I had fully expected to find the large sloop in the spot I had left her, held there by the anchor that must have fallen from the deck. But she was gone, and a rapid survey of the surrounding water convinced me that she was nowhere within a quarter of a mile.

This discovery was a dismaying one; yet it did not entirely dishearten me.

The sloop had probably drifted to the lower end of the lake, somewhere near the Ponoco River, which was its outlet. I would no doubt find her beached in the vicinity of the south shore.

I at once turned and sped away in that direction. The distance was about two miles, and in half an hour I had covered it, and skirted the shore for a considerable length.

The large sloop was nowhere to be seen.

I was now really worried. Was it possible that some one had found the craft, and towed her off?

It seemed more than probable. The situation was unpleasant, to say the least. The sloop was now my property just the same as if I had purchased her, and I did not like the idea of any one making off with her, and then setting up a claim against me for so doing.

I spent two hours in my search for the craft, but without success. By this time it was well on in the afternoon, and it became necessary for me to return to the mill.

With something like a sigh, I tacked about, and started on the return, resolved to continue the search at daylight on the following day.

In sailing up the lake to the spot where the Torrent Bend emptied, I had to pass Bend Center; and I decided to tie up at the village, and settle up with Mr. Jackson, who was so afraid I was going to cheat him.

There was a trim harbor at this spot, and into this I ran and lowered the mainsail.

“Hullo, Rube!” I suddenly heard some one call; and looking up, I beheld Tom Darrow, an old fisherman that I knew well, seated at the other end of the pier, smoking his pipe.

“Hullo, Tom!” I returned. “Through work for the day?”

“Yes.”

“How’s the catch?”

“Pretty poor, Rube. Too windy for pickerel,” returned Tom, as he arose and knocked some ashes from the top of his pipe-bowl.

“I suppose it is.”

“Where have you been?” he went on, coming to where I was tying up.

“Over to Bayport with a load of middlings.”

“That so? Thought I see you coming up the lake.”

“I’ve been down looking for a sloop that capsized,” I returned. “Did you see anything of her?”

“What kind of a sloop?”

“A large one, painted blue and white, and named the Catch Me. I believe she used to belong to some one in Bayport.”

“No, I didn’t see her; that is, I don’t think I did. I saw some fellows towing something up the lake about an hour ago. But I thought that was a raft.”

I was interested at once.

“Are you sure it was a raft?”

“Oh, no; come to think of it, it didn’t look very much like a raft, either. You see, it was out pretty far, and I wasn’t paying much attention.”

“Who were the fellows?”

“I don’t know. They had a pretty smart-looking craft, but whose it was I couldn’t make out.”

My heart sank at Tom Darrow’s words. I was certain that the supposed raft was nothing less than the Catch Me. The question was, what had the men who found her done with her?

“What makes you so interested in the sloop?” went on Tom curiously.

“She belongs to me, Tom.”

“What! Where did you ever raise money enough to buy her?”

“I didn’t buy her; she was given to me.”

Tom Darrow was more taken aback than ever. I enjoyed his amazement, and told my story.

“I declare, Rube, you’re quite a hero, and no mistake!” cried the fisherman. “So he gave you the sloop for the job? It was money easily earned.”

“It wasn’t earned at all, Tom. But the question is, what has become of the craft? Unless I find her she won’t do me any good.”

“True enough; but you are sure to find her sooner or later. She can’t leave the lake very well, and all you’ve got to do is to keep your eyes open.”

“I don’t know about that,” I replied, shaking my head. “They might change her rigging a bit, and paint her over, and I would have a job recognizing her.”

“So they might if they were sneaks enough to do so; and I reckon some of them north-enders ain’t too good to try it on. Tell you what I’ll do.”

“What?”

“I’ll try to hunt her up for you.”

“Will you? I’ll pay you for your trouble, Tom.”

“Don’t want no pay, Rube. You’ve done me many a good turn, and so did your father when he was here. I’ll take a trip around the lake first thing to-morrow.”

“And so will I. Between the two of us we ought to discover something.”

After this we arranged our plan. Darrow was to start from the Bend, and go up the west shore, while I was to come down from the mill, and investigate along the east shore. At noon we were to meet at Bayport and compare notes.

“By the way,” said he, when this matter was finished, “heard from your father lately?”

“I expect a letter next week,” I replied. “He is out in South Dakota. He hasn’t located yet.”

“Hope he strikes it rich when he does,” concluded Darrow. “No man in these parts deserves it more.”

Leaving the pier, I made my way to Mr. Jackson’s store, which, as I have said, was the largest at the Bend.

I found the merchant behind the counter, weighing out sugar.

“Well, have you come to settle up?” he asked shortly.

“I have come to pay some on account,” I replied.

“How much?”

“Twenty-one dollars.”

“Why don’t you pay the whole bill of twenty-four, and be done?”

“Because I haven’t so much. Some of the middlings I sold Mr. Carnet got wet, and I had to make a reduction.”

“Humph! Well, hand over the money. Every little helps. But I can’t trust out any more goods till the entire amount is settled.”

And Mr. Jackson placed twenty-one dollars in the drawer, and gave me credit on his books.

I walked out somewhat downcast. I had wanted several things in the shape of groceries, and with no money to purchase them what was I to do?

As I walked down the one street of the village, I passed the post-office. Mr. Sandon, the post-master, was at the window, and he tapped for me to come in.

“A letter just came for you,” he said. And he went behind the counter and handed it over.

For an instant my heart gave a bound of pleasure as I thought it must be a letter from my father; then I saw that the handwriting was strange, and I opened the epistle, wondering what it could contain.

It was dated at Huron, South Dakota, and ran as follows:—

My dear Nephew Reuben,—You will no doubt be very much surprised to hear from an uncle whom you have never seen, but circumstances make it necessary that I should address this letter to you. I wish that my first lines to my nephew might be brighter, but our wishes cannot always be fulfilled, and we must bear up bravely under all trials that come to us.

Hear, then, the sad news that your father is dead. He lost his life by falling down a deep ravine on the morning of the 10th instant. We were out prospecting for a good mill location, and he slipped, and, before I could come to his aid, plunged headlong to the bottom. When I reached him he was unconscious, and lived but a short hour after. I am now arranging to have him buried to-morrow, and shall then follow this letter to Bend Center, to take charge of his affairs.

As you perhaps know, I met your father in Chicago. I loaned him quite a sum of money, and we went to South Dakota together. But of this and other important matters we will speak when we meet, which will be shortly after you receive this letter.

Affectionately your uncle,

Enos Norton.

P.S. I would not speak of money matters in such a letter as this, but I cannot afford to lose that which I have advanced. I trust the mill is in good running order.

I could hardly finish the communication. I became so agitated that all the lines seemed to run into each other. Mr. Sandon noticed how I was disturbed.

“Anything wrong, Rube?” he asked kindly.

“My father is dead!” I gasped out, and sank down on a box completely overcome.

For a long time I sat on the box in the little village post-office. I could think of nothing but that my father was dead.

The shock of the news, coming as it did so unexpectedly, completely staggered me. The only parent that had been left to me was gone, and I was left to fight the battle of life alone.

“It’s too bad, Rube; that’s a fact,” said Mr. Sandon, laying his hand on my shoulder. “What ailed him?”

“Nothing. He met with an accident,” I replied, struggling hard with the lump that seemed bound to rise in my throat. “He fell over a ravine while looking for a place to locate a mill. You can read the letter if you wish.”

“I will.”

Mr. Sandon adjusted his spectacles, and read the letter carefully. While he did so I sat with my head buried in my hands, trying to hide the tears that would not stop flowing.

“This is from your Uncle Enos Norton, I see,”[34] he went on. “I thought Enos Norton was dead long ago.”

“I have never seen him,” I replied.

“He used to be around these parts years ago when he was a young man; but he got a sudden notion to go West, and he went. He loaned your father some money, it appears.”

“So he says. I don’t know what for. Father took enough along to pay his expenses,” I returned despondently.

“Maybe he made a venture of some kind or another. A man is apt to risk more when he strikes a new country.”

I made no reply to this remark. My heart was too full for further talk, and leaving the post-office I walked slowly back to my boat.

If the prospect before had been gloomy it was now worse. The pang over the news of my father’s death overshadowed everything else; yet I could not help but remember that my uncle was soon to arrive, and that my father’s estate was indebted to him for money loaned.

Entering my sloop, I was soon on the way to Torrent Bend River. The wind was still fresh, and I skirted the shore rapidly, arriving in sight of the mill at sundown.

Ford stood at the door awaiting me.

“Been a little longer than you expected,” he said. “Anything wrong?”

“Yes, Dan; everything is wrong,” I replied. “Read that letter.”

He did so; and somehow it was a comfort to see his eyes grow moist.

“Dead!” he exclaimed, and then he caught me by the shoulder. “Rube, I can’t say how sorry I am for you; there ain’t words strong enough to tell it.” And without another word he led me into the mill.

We passed a rather silent evening. Ford was in the habit of leaving as soon as the day’s work was over, but that night he remained. He was the first up in the morning, and when I came down I found breakfast already prepared.

“Come, Rube, have a strong cup of coffee,” he said. “I know you haven’t slept a wink. I hardly got a nap myself, thinking matters over. Do you know anything about this uncle that’s coming?”

“Nothing but that he was my mother’s brother.”

“He seems to be mighty anxious about his money,” went on the mill-hand, who was always outspoken in his opinions.

“Well, I suppose he is entitled to what is due him.”

“He might have waited till he got here. Wonder when he will arrive?”

“I’m sure I don’t know.”

I was utterly cast down, and could not do a stroke of work. I took a walk up the river, and sat down on a rock to think the whole matter over.

It was two hours later before I rose to go back. The time had been a bitter one; but now I felt better, and was ready to face whatever was to come.

When I arrived at the mill I found Ford hard at work. Tom Darrow had just tied up at the pier, and my helper had told him the sad news.

“It’s hard, Rube, dreadful hard, and no mistake,” he said.

Later on he told me he had sailed around the lake, and into many of the coves, but had seen no trace of the Catch Me. I was sorry to hear this, but in the light of the greater calamity I hardly gave the matter any attention.

“I suppose you didn’t think to get them things you spoke on?” observed Ford when the fisherman was gone.

“What things?” I asked.

“The groceries you were going to get down to Jackson’s.”

“He wouldn’t let me have them. He said I would have to settle up in full before I could have anything more.”

“The miserly chump!” exclaimed Ford; “and after you paying him hundreds of dollars! I wouldn’t patronize him any more!”

“I don’t intend to.” I paused for a moment. “Dan, I am in a bad fix all around. I haven’t any money, and we need things. I don’t know how I am going to pay you your wages next Saturday.”

“Well, don’t let that worry you, Rube; I can get along.”

“But that’s not the point. It isn’t fair to ask you to wait,” I went on earnestly.

“I ain’t starving,” he laughed. “I’ve got some little saved. Besides, when you find the Catch Me, she’ll be worth at least a couple of hundred dollars to you.”

“That’s so; but I imagine finding her will be a bigger job than I thought it would be. I am satisfied that some one has towed her off, and has got her in hiding.”

There was quite a bit of grinding to do at the mill, and after a dinner of which I hardly ate a mouthful, I started in to help Ford do the work.

It was the best possible thing I could undertake; for it diverted my mind, and that eased my heart, which felt at times like a big lump of lead in my breast.

As I tended to the hoppers and helped fill the bags I began to speculate upon what kind of a man my uncle would prove to be. The tone of his letter, as I read it over again, did not exactly satisfy[38] me. What did he mean by stating that he intended to take charge of affairs?

At five o’clock I heard the sound of a horn coming from the main road that ran from Harborport through the Bend to Kannassee, ten miles distant.

“There’s the horn of the stage-coach,” said Ford. “Bart Pollock must want to see you.”

“Perhaps he’s after some feed,” I replied. “I’ll go down and see.”

Brushing the flour from my face and hands, I left the mill on a run. The main road was fifteen rods away through the bushes. There was a rough path but little used, and this I followed.

When I arrived I found the stage-coach standing in the middle of the road, with Bart Pollock, the driver, sitting contentedly on the front seat along with a tall stranger.

“Here I am, Bart!” I sang out. “What’s wanted?”

“Hullo, Rube! Nothin’s wanted. Here’s a visitor to see you,—your uncle, all the way from Western parts.”

“Oh!”

I stopped short to look at the man as he hopped to the ground. He was slimly built, with a thin, sharp face, and cold gray eyes. He carried a hand-satchel, and this he swung from his right to his left hand as he came forward to greet me.

“So this is my nephew Reuben?” he said in a high voice, as we shook hands. “I suppose you’ve been expecting me?”

“Not quite so soon,” I replied. “I thought you’d come in a day or two, sir.”

“Well, I made first-class time. The train left half an hour after the funeral was over, and I didn’t see no use in hanging around any longer. I settled all the bills beforehand. They were mighty high too. A hundred and twenty-five dollars for the coffin and carriage, and fifty dollars for the ground, besides twenty-five for the undertaker, which brings the whole up to two hundred dollars.”

By this time the stage-coach was on its way again, and we were left standing alone.

“Tell me about my father,” I said. “I want to know all about how the awful thing happened.”

“Now, don’t be so fast, Reuben; there’s lots of time. Wait till I’ve had supper, and got rested up a bit. Traveling don’t seem to agree with me. How are things at the mill?”

“Rather slow, sir.”

“What! you must be fooling!”

“No, I am not. Trade all around has been slack this summer.”

“Humph! That must be because you are only a boy. Just you wait till I get to managing things, then I guess business will hum.”

“I do the best I can,” I replied, not liking to be talked to in this fashion.

“Of course, of course; but then you’re nothing but a boy, and a boy can’t do half as well as a man.”

“I am doing as well as any one in these parts. I go ’way over to Bayport for orders.”

Mr. Norton started slightly.

“Bayport?” he queried.

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, that ain’t very far.”

“It is farther than father used to go.”

“Well, your father wasn’t any great hand for business, I guess.”

“Father was always ready to do his best,” I returned warmly, not liking the manner in which my father’s character had been assailed. “He was not responsible for the dull times here.”

“Maybe; but business is just what a man makes it.”

“Are you a miller, sir?”

“No, I ain’t; but I guess it won’t take a man like me long to learn the business.”

I had my doubts concerning the truth of the last assertion. I had been around a mill all my life, and yet there was hardly a day passed but what some new difficulty presented itself.

“You see, I’m a self-made man,” went on Mr. Norton. “I left home long before my sister Mary had[41] married your father. I went out to Chicago, and all the money I have I made there without help from any one.”

“Are you rich?” I ventured.

“Oh, no; but I’m comfortable,—that is, I will be when I get back the money I loaned your father.”

“Father couldn’t have borrowed much.”

“What?” cried Mr. Norton. “That is all you know about it. He came to me pretty often; and that money, added to the funeral expenses, made a good round sum.”

“How much?” I asked faintly.

“All told, it’s just six hundred and fifty dollars,” was the reply.

I cannot say that my first impression of Mr. Enos Norton was a favorable one. His manner was domineering, and evidently he intended to conduct matters to suit himself.

He knew nothing at all about running a mill, yet he expected to take sole charge. This, to say the least, was peculiar.

His assertion that my father’s estate was indebted to him to the amount of six hundred and fifty dollars astonished and dismayed me. What had my parent done with the greater part of this? and how was I ever to settle up?

The mill property as it now stood was not worth over twelve hundred dollars, and at a forced sale it was not likely that it would bring half that sum. How, then, was his claim to be met? and, when all was settled, what was to become of me?

By the time I had asked myself these questions we had reached the mill. Here I introduced Ford, and the three of us entered.

“Not such a good place as I expected to find,” remarked Mr. Norton, examining first one thing and then another. “You don’t seem to keep things in very good order.”

“We keep them in as good order as possible. Many of the things are worn so much that they cannot be repaired,” I replied.

“And it takes work to fix things up,” he added, with a hard look.

I did not reply, and I saw Ford toss his head.

“Well, let us go into the house part,” went on Mr. Norton. “I’m fearfully hungry. Got anything good?”

“I can give you some fried fish, bread and butter, and some blackberries,” I said, as I led the way into the living-room.

“Ain’t you got no coffee?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then those things will do first rate. I’m fearfully hungry. Didn’t have a mouthful since this morning. Make the coffee good and strong.”

“I will, Mr. Norton.”

“Don’t call me Mr. Norton. I’m your Uncle Enos.”

“All right, Uncle Enos; I’ll try to remember.”

I went into the cook-shed, and began to prepare supper. I did not feel in good-humor, and my face must have shown it, for when Ford came in he remarked,—

“Your uncle ain’t going to play second, fiddle to nobody, is he?”

I shrugged my shoulders without replying. The prospects ahead were not very bright.

Presently I had to go into the living-room to get some spices out of the pantry. I found Mr. Norton in the act of taking a deep pull from a small black flask.

“My blackberry brandy,” he said, by way of an explanation. “I have to take it for a weak stomach.”

“Are you sickly?” I asked.

“Somewhat.”

I went out again; but through the crack of the door I saw him take another pull at the flask, and then put it in his pocket.

This was another action that I did not like. About the Bend were a number of men who spent every cent of their money for drink, and this had led me to become strictly temperate.

At length the meal was ready, and I set it on the table, and called in Ford. We sat down, and Mr. Norton helped himself to a liberal portion.

“Why don’t you take hold?” he asked, seeing that I scarcely touched a thing.

“I don’t feel like eating,” I replied. “I am waiting to hear about my father.”

“Oh, well, then, I’ll give you the whole story. We[45] started out from Hamner’s Gulch one bright morning to go up what is known as the Black Hawk Ravine. Your father had an idea that he could set up a saw-mill there if a grinding-mill didn’t pay.”

“He never said anything about a saw-mill to me,” I put in.

“Your father was a very queer man,” said Mr. Norton. “Did he say anything about me in his letters, or about the money he borrowed?”

“Not a word.”

“I thought so. Guess he was ashamed of the money he let fly, traveling to this place and that, and paying a holding price down on half a dozen spots, and then letting them go.”

“But about the journey?” I said, anxious to get back to the particulars of my father’s death, which just now interested me more than anything else.

“Oh, yes! Well, we started out for the ravine, and we reached it about two o’clock in the afternoon. It was a wild spot, and I was for going back; but your father wanted to go ahead, and he did so, I following.”

“And was that where he lost his life?”

“Exactly. He was ahead, and by six o’clock it was getting dark. I called out to him to be careful, as we were then walking along a narrow ledge, and far below was a mountain torrent, ten times worse than this one you have here.”

“And this was the ledge he fell over?”

Mr. Norton nodded.

I shuddered. In imagination I could see my father going over, and clutching out vainly to save himself. It was a horrible thought.

“Yes, he went over. It was no use to try to save him, though I did spring forward. He went down, and struck on his head.”

“You went after him at once?”

“Of course; as quick as I could. He was alive yet, but he didn’t live very long; just long enough to settle up his private matters, and put me in charge of his affairs.”

“How is that?”

“He made me write it out on a bit of paper, and then he signed it. I didn’t want to do it, but he said I was his only relative, and I must.”

“Then he wanted you to take entire charge of his affairs?” I asked.

“That’s it. In other words, I was to become your guardian, Reuben.”

My heart sank at these words. As I have said, I did not take to my newly arrived relative from the start, and it was not a pleasant thought that in future he was to have full power over me. I heartily wished that my twenty-first birthday was at hand.

“I take it your father wasn’t no great business[47] man,” went on Mr. Norton, helping himself to more fish and another cup of coffee. “The state of affairs here shows that he wasn’t. He would have done better by remaining here than by going West as he did.”

This was not the first time that this man had said things derogatory to my father’s memory, and it made me angry.

“I think my father knew his own business best,” I cried. “He knew all about milling, and you don’t know a thing.”

“Don’t talk to me in this style,” cried Mr. Norton, turning quickly. “What I’ve said I’ll stick to; your father was no business man. He didn’t know how to manage.”

“He certainly made a mistake when he appointed you my guardian,” I replied pointedly.

Mr. Norton turned pale.

“What do you mean by that?” he demanded.

“I mean just what I say.”

“You don’t like the idea of my being set over you, eh?”

“No, I don’t.”

“Well, you’ll have to get used to it.”

“I don’t think I ever shall. I could never like any one who spoke of my father in the style you have done.”

“Hoity-toity! That is all boy’s talk.”

“I mean it.”

“Well, like me or not, you must remember that I am now in charge of everything. I shall expect you hereafter to do as I say.”

To this I did not reply. I looked at Ford, and saw that his lip was curled up. Evidently he did not like Mr. Enos Norton any more than I did.

“You have been having things here your own way too long. You have let the business go to the dogs, and all that sort of thing. Now all this has got to be stopped. I have got to get back my six hundred and fifty dollars, and then I have got to get what remains into shape, and invest it for your future good. How does your bank account stand at present?” and Mr. Norton stopped eating to hear my answer.

I paused before replying.

“Did you hear me?” he added. “How much money have you got in the bank?”

“Not a cent,” I returned. And somehow it gave me pleasure to say so.

“Not a cent! Come, I want the truth.”

“I have told the truth. We have no bank account.”

“Well, then, how much money have you on hand?”

“Not a dollar.”

“You mean that?”

“If I didn’t I wouldn’t say so. Business is bad, and I have all I can do to make both ends meet.[49] I took in twenty-one dollars yesterday, and paid it out on account a few hours afterwards.”

Mr. Norton sank back in his chair. I could see that his hopes had had a great fall. Evidently he had expected me to mention quite a round sum.

“Then how do you expect to pay me my six hundred and fifty dollars?” he demanded after a spell of silence.

“I’m sure I don’t know.”

“I laid out the money, and I expect it back.”

“Well, as you have charge of my father’s affairs, you must get it back the best way you can,” I replied briefly.

“None of your impudence!”

“I am not impudent. I haven’t any money, and there is no money here belonging to father; that’s all there is to it.”

Mr. Norton jumped up from his chair and strode about the room.

“You are lying to me!” he cried passionately.

“I tell the truth.”

“I don’t believe a word of it,” he went on. “Your father had money, and either you have spent it, or else you intend to keep it from me. Now, I am going to know the truth.”

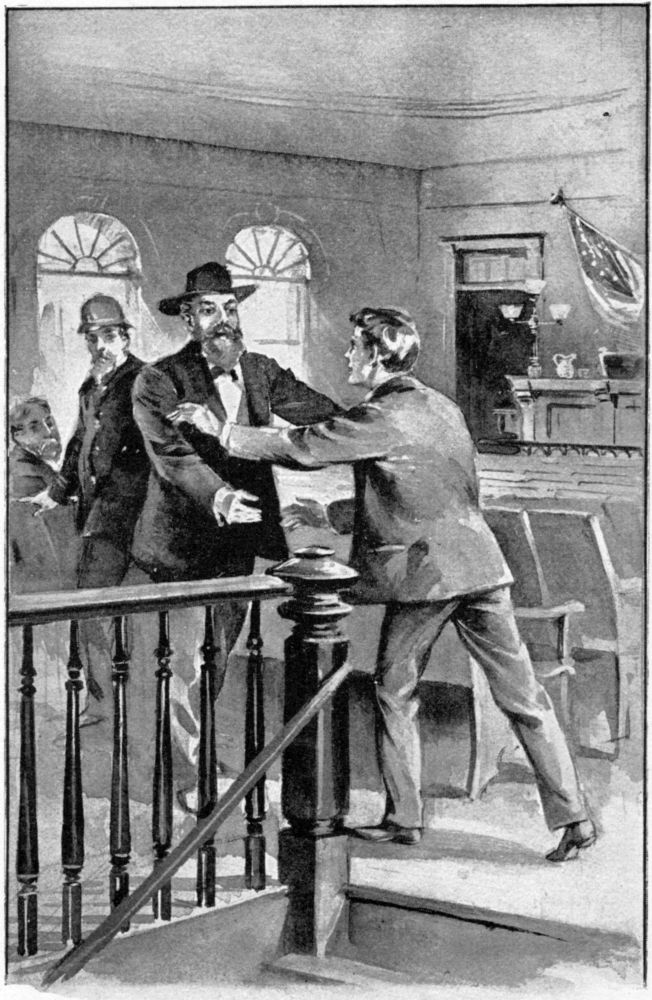

As Mr. Norton concluded he walked over to the corner, and caught up a hickory stick that stood behind the door.

“What do you intend to do?” I cried, as he advanced upon me.

“I am going to give you your first lesson in telling the truth,” he replied.

“You shall not touch me with that stick!”

“I will. You shall learn to mind me, and that the very first thing.”

And with these words Mr. Norton rushed on me, and grabbed me by the collar.

I could hardly believe that Mr. Norton intended to strike me. I had not been struck for a long time; in fact, as far back as I could remember, and I did not intend to submit.

Accordingly, when the man caught me by the collar, I jerked away as quickly as possible, and put the table between us.

This seemed to enrage him still more, and he fairly leaped the distance, caught me again, and bore me to the floor.

“We’ll see if you are going to mind or not!” he cried.

“Let me up!” I screamed.

“Yes, let him up,” put in Ford. “I won’t have you thrashing Rube.”

And he caught Mr. Norton by the arm, and pulled him in such a fashion that he went sprawling on his back.

My tormentor was completely astonished by this movement. He scrambled to his feet, and I lost no time in doing the same.

“What do you mean by interfering?” demanded Mr. Norton, turning a livid face to the mill-hand.

“I won’t stand by and see Rube abused,” retorted Ford.

“It’s none of your business!”

“I’ll make it my business.”

“You’ll do no such a thing!” howled Mr. Norton. “I won’t have such a fellow as you about the place. You are discharged.”

“I am willing. I wouldn’t want to work here if you are to be the boss. But I’m Rube’s friend, and I’m going to stick up for him. Nice kind of a man you are, raising a fight when you haven’t been here but a few hours! You ought to be ashamed of yourself! If I told folks down to the Bend about the way you carry on, they’d ride you on a rail.”

Ford was in for easing his mind, and I let him go on.

“Stop! stop!” cried Mr. Norton. “I won’t listen to a word.”

“Oh, yes, you will,” went on Ford. “Here is Rube just about heard of his father’s death, and you treating him in this fashion! You haven’t got a heart as big as a toad. Besides, the boy has told you the truth.”

“How do you know?” asked the man, somewhat abashed by the fact that Ford did not back down. “His father must have been worth something.”

“Well, he wasn’t; and in these times it’s hard to make a living at anything in Bend Center. I’ve looked around and I know.”

Mr. Norton was silent for a moment; then his manner appeared to change. He threw the stick into the corner, and sat down on a chair.

“Perhaps I was a little hard,” he admitted; “but I was led to believe that Stone was rich, otherwise I would never have loaned him the money I did.”

No one made any reply to this, and he went on,—

“Sit down, Reuben; I won’t touch you. I didn’t think you had just got the bad news. It’s over a week old to me.”

“I got your letter last evening.”

“Yes? I suppose it was enough to upset you. Come, we will let things run along as they have been for a few days. You won’t find me hard to get on with after you once know me.”

I had my doubts about this, but decided to keep them to myself. We finished the meal in silence, and then Ford beckoned me out into the mill-room.

“Do you want me to stay with you to-night?” he asked.

“Won’t it be too much of an inconvenience?”

“Not at all. I’ll go down to the house, and let the folks know, and then come right back.”

“If you do you’ll have to sleep with me, for I’ll have to give the spare bed to Mr. Norton,” I said.

“I won’t mind that if you don’t,” replied the mill-hand.

So the matter was settled. If Mr. Norton heard of it he did not say anything, and for the remainder of the evening things ran smoothly.

Before we retired I had learned many things that are not necessary to repeat here. Mr. Norton told of how he and my father had met in Chicago, how my father had begged of him to advance him money from time to time, and how the two had started together for South Dakota. He was a fluent talker, and I grew quite interested, though I did not exactly believe all that was told me.

We were all up early the next morning, and Ford and I prepared breakfast. Before eating, Mr. Norton applied himself again to the bottle, and asked the mill-hand if there was a good tavern at the Bend; to which Ford replied that there was a tavern, but whether good or bad he did not know, as he had never stopped there.

“Got any grinding to do?”

“Enough to keep us running till noon.”

“And after that?”

“We’ll have to wait for something to come in,” I replied.

“Then, Ford, we can get along without you,” continued Mr. Norton. “In the future Reuben and I will do all the work.”

“All right,” said the mill-hand, seeing that there was nothing else to be done. “How about my wages?” and he winked at me.

“How much is coming to you?”

“Eight dollars.”

“Reuben, have you the money?”

“No, sir; as I said before, I haven’t a dollar.”

Mr. Norton thought for a moment, and then got out his pocket-book.

“Here you are,” he said. “Give me a receipt. I will have to charge the amount against the estate.”

“Then I don’t want it,” said Ford. “I’m not going to rob Rube of what little is coming to him.”

“Take it, Dan,” I said. “You’ve earned it.” And I compelled him to put the money in his pocket.

Then the receipt was written out, and this Mr. Norton placed carefully in his notebook.

“Now we are done with you,” he said. “If I ever need you in the future I will send Reuben for you. I suppose you never thought of buying the mill, did you?”

“I haven’t got the money,” replied Ford.

“The reason I asked is because the place may be up for sale,” went on Mr. Norton; “if so, it ought to be a pretty good investment for you.”

“It might be,” said Ford.

A little later he went off, and Mr. Norton and I[56] were left alone. I set to work with a will, and he stood around watching me.

“That’s easy enough,” he said, as I fed the grain into the hoppers. “I should think almost any one could do that.”

“Feeding is easy enough, but there are a good many other things to learn, as you will soon see.”

A little later Mr. Norton took a walk around the outside of the place. He was gone fully an hour, and when he came back he appeared to be quite uneasy.

“Do you need anything from the village?” he asked.

“We need a number of groceries,” I replied. “I wanted to get them day before yesterday, but Mr. Jackson wouldn’t let me have them until I settled up in full. I owe him three dollars yet.”

“Well, you had better go down and get those groceries now. Let this grinding go till this afternoon or to-morrow. I want you to get me some—some tobacco.”

“I will have to pay for all I get.”

“Well, I will give you the money. Will two dollars do?”

“I need but a dollar.”

“Then here is a dollar and a quarter. Get me a quarter’s worth of plug-cut smoking. You needn’t[57] hurry about getting back. Seeing what you’ve got on your mind you need a rest.”

In ten minutes I was off in the sloop. Mr. Norton seemed to be very anxious to have me go, but for what reason I could not determine.

“And remember you needn’t hurry back,” he called out as I hoisted the mainsail and stood off from the shore; “if any orders come in I will attend to them.”

As I moved down the shore toward the Bend I reviewed my strange situation. How much had happened in the last forty-eight hours!

I was far from satisfied with Mr. Norton—somehow I could not call him my uncle. I had expected my mother’s brother to be a different kind of a man. He would evidently make a hard guardian, and I was sure that for me there were many breakers ahead.

As the sloop skimmed along far enough from the shore to catch the full benefit of the breeze that was blowing, I espied another craft anchored in a little cove a quarter of a mile below the mill.

She was a stranger to me, and I wondered who owned her, and why her master had stopped at the spot, which was a rocky one, full of thorny bushes.

Perhaps he had come for some geological specimens, which the visitors at Bayport were frequently after. The region was full of all kinds of stone, and I knew it was quite a fad to study them.

I passed the craft, and continued on the way to Bend Center, arriving there in the middle of the forenoon.

I found that the news of my father’s death had been widely circulated, and nearly every one I met came forward to extend a sympathy that went straight to my heart.

I did not go to Mr. Jackson’s store, but to the “opposition,” as it is called in such places. This was kept by Mr. Frank Lewis, a young man, and one whom I found very obliging.

It did not take me long to make my purchases. As I turned to go back to the boat I came face to face with Tom Darrow.

“Hullo, Rube!” he exclaimed. “Well, this is lucky! You’re the fellow I want to see.”

“What about?” I asked. “Have you found the sloop?”

“Come with me and I’ll tell you,” he replied.

And he led the way out of the store, and down to the pier.

“I ain’t found the sloop, Rube, but I’ve found out something about her.”

“What have you found out, Tom?” I questioned, as my heart gave a bound.

“I overheard three men talking about some sloop they had picked up,” went on the old fisherman.[59] “They stopped talking as soon as they saw I was around. I reckon they want to scoop the prize for themselves.”

“Who were the men?”

“I didn’t know two of them; the other was Andy Carney. You know him?”

“Yes; he is one of the tough fishermen from the north end. What do you suppose the three have done with the boat?”

“Taken her up to one of the coves at Rock Island. If I was you I’d sail up and take a look around.”

“I will,” I replied.

“I’d go along, only I can’t spare the time,” said Darrow.

Five minutes later I was on board my sloop, and speeding for Rock Island in search of the Catch Me, which I was now certain had been stolen.

The large sloop had become my property, and as the craft was worth at least three hundred dollars it is no wonder that I was anxious to find her. The sum of money represented a good deal to me, especially in my present situation.

Mr. Norton, my newly appointed guardian, had told me to take my time about getting back to the mill, so I considered that I had at least several hours of my own before me. This was long enough, I calculated, to take a run up to Rock Island, make an investigation,[60] and get back to the mouth of the Torrent Bend River.

I let the mainsail out full, and also the jib. This was all the small sloop could carry in the present wind, and even then I found I had a lively time whenever it came to changing the tack.

I stowed away the stuff I had bought in the cuddy, where it would not get wet, and then took things easy in the stern-sheets.

It was a beautiful day, and had my mind been free I would have enjoyed the outing thoroughly. But the clouds of sorrow and perplexity were upon me, and I paid scant attention to the fair blue sky above and the rippling water beneath.

At length I came within a quarter of a mile of the island, and then began to keep my eyes wide open for whatever might come to view.

Rock Island was half a mile wide by nearly a mile long, and on all sides were a number of coves and inlets, some well hidden by the masses of bushes and trees that grew along the shores.

I decided to make my investigation as systematic as possible, knowing that it would be folly to sail about in a haphazard fashion. I ran into the first cove I came to, looked around in every direction, and continued this until I had visited the entire south and east shores.

By this time it was midday. I was hungry, for a breeze on the water is calculated to sharpen up almost any one’s appetite. I had a lunch in the locker, and this I munched as the sloop sped along to the north shore.

Suddenly I saw, or fancied I saw, a speck of white in the bushes some distance ahead. I tacked in the direction, and presently distinguished the mast of some vessel standing out straight among the crooked trees that lined a long and narrow inlet.

Satisfied that I had made a discovery of importance, I lowered the jib and took several reefs in the mainsail. The wind carried me directly into the opening, and here I dropped anchor.

“Hullo, there! What do you want here?”

It was a rough voice that hailed me, and looking around I beheld a rougher-looking man standing on the shore, not ten feet away from me.

It was Andy Carney, the fellow Darrow had mentioned to me. He carried a gun, and his manner was one of astonishment and anger.

I was astonished to find myself face to face with Andy Carney, whom I knew to be one of the toughest characters that infested the north shore of Rock Island Lake.

But if the meeting was unexpected for me, it was equally so for him, for after hailing me he stood still for a moment; and in that space of time I had a chance to recover.

“I say, what do you want here?” he repeated, seeing that I did not answer him.

“I was looking for a sloop that capsized on the lake a couple of days ago,” I returned.

“What kind of a sloop?”

I described the Catch Me as best I could.

“No such craft around this island,” said Carney, after I had finished.

“Are you sure?”

“Certain. I was all around the shore only this morning.”

I did not believe this statement, and I paused, undecided what to do next.

“Was it your sloop?” went on the fisherman.

“Yes. She was given to me the day she was blown over.”

“That so? Why didn’t you see to her at once?”

“I didn’t have time. I was told she was somewhere up here.”

“Who told you?”

“Tom Darrow.”

The instant I uttered the name I was sorry I had done so for I did not wish to get my honest old friend into trouble. The man I addressed scowled.

“Darrow ought to keep his mouth shut,” he muttered. “The sloop ain’t here.”

“What boat is that over yonder?”

“That’s my own craft.”

“You have got her pretty well up the cove,” I added.

The man scowled even deeper than before.

“See here, what business is that of yours?” he demanded. “Reckon I can take my boat where I please.”

“I suppose you can; I only asked. I reckon I can do that.”

“I drew the boat up because I’m busy painting her, and this is a good spot to do it.”

“Do you live here?” I went on, more to gain time to think than for any desire to know.

“Sometimes. I’ve got a sort of a house here, and another over to the shore yonder. I own this island.”

This last assertion I knew to be a falsehood. I had on my good clothes out of respect to my father’s memory, and he evidently took me for one of the summer boarders.

“I should like to see your boat,” I ventured.

“What for?”

“Just to see how a boat is painted. I may want to do such a job myself some day.”

“Well, I’m sorry, but you can’t see her,” replied Carney decidedly.

“Why not?”

“Because I don’t want anybody fooling around. I’ve been mighty particular over the work, and I don’t want it spoilt.”

“I won’t touch a thing.”

“Oh, I know all about that! I ain’t going to have no finger-marks all over the gun’ale and the gold lines.”

I turned and looked at the mast, which was all I could now see of the hidden craft. If my memory served me rightly it was the exact counterpart of the one belonging to the Catch Me. The man was plainly lying, and had my property in his possession.

“Well, I’m coming ashore, anyway,” I returned; and I jumped from the sloop to the rocks.

“What do you mean by disobeying my orders?” cried Carney, rushing over to where I had landed.

“Disobeying your orders?” I repeated.

“Yes. You know well enough I don’t want you to land here.”

“If I want to land I don’t see how you are going to stop me,” I replied as coolly as I could, although I was anxious as to the outcome of the situation.

“You don’t, eh? Didn’t I tell you I owned this island?”

“I don’t believe it. The property has always been in the families of several Bend Center folks.”

“What do you know about Bend Center?”

“I know all about it.”

“You don’t mean to say you live there?” and there was actual wonder in the man’s tone.

“I live near the place. I run the mill over at Torrent Bend River.”

Carney stepped back.

“Are you Reuben Stone?” he cried.

“That’s my name.”

In spite of his bronzed face I saw the fellow turn pale. What impression had the discovery of my identity made upon him?

“I thought you said you owned the boat you are looking for?” he said at length.

“So I do.”

“The Catch Me belonged to Bayport.”

“I thought you didn’t know anything about her?” I returned sharply.

“Well, I—I thought I didn’t,” he stammered; “but what you said put me in mind of her.”

“She was given to me for rescuing the two men and the woman and the boy who were sailing in her.”

“Given to you?”

“Yes.”

“Humph!” Carney tossed his head. “Well, she ain’t here, and you had better look elsewhere for her.”

“I’m going to take a walk around the island.”

I had hardly uttered the words before the man caught me by the shoulder.

“You are going to do nothing of the sort!” he cried. “I want you to clear out at once.”

“Suppose I don’t choose to do so?”

“I’ll make you.”

I looked at the fellow. He was pretty big, and he looked strong; still I stood my ground.

“How are you going to make me go?” I asked.

“Do you see this gun? Well, if you don’t hustle off you may feel it.”

In spite of my efforts to remain calm I shivered. The weapon looked as if it was capable of doing some wicked work.

“You see I’m the boss around Rock Island,” went on Carney, “and I don’t take any talk from any one. I want you to get out at once.”

And saying this, he stepped back and pointed the gun at my head. I did not think he meant to fire it. He thought he would scare me; that was all. But it was not pleasant to have the barrel in line with my head, and I stepped back and out of range.

“Now get on board of your sloop, and pull up anchor,” continued Carney. “I don’t want any more talk.”

While he was speaking I watched my chance, and as he lowered the gun I rushed forward, grasped it with both hands, and pulled it away from him.

“Here! give me back that gun!” he exclaimed, as I retreated.

“Not a bit of it!” I returned. “You’ll find that two can play at that game.”

And I brought up the barrel of the weapon on a level with his breast.

“Don’t shoot!”

“I don’t intend to if you behave yourself. Just you march over to your right.”

“What for?”

“Never mind; do as I tell you.”

With very bad grace Carney did as I had directed.[68] When he had reached a point fully fifteen yards away I told him to halt. The spot was in the midst of a number of barren rocks, and here I felt sure that I could watch him.

“Now I am going to take a look at your boat,” I went on. “Don’t you dare to move while I do so.”

“Won’t do you any good,” he muttered.

Without replying, I made my way through the rough brush and over the rocks to where the mast of the boat could be seen. It was but a short distance, and soon I stood face to face with the hidden craft.

For an instant I did not recognize her. The blue-and-white hull had given way to one of red, and the name had been scratched and covered with several coats of paint; but the general appearance of the deck and rigging had not been changed, and I was certain that the craft was the missing Catch Me.

Had I come a day later, the job of transformation would have been complete, and the sloop might have been lost to me forever. I counted myself lucky at having made the trip of investigation as soon as I had.

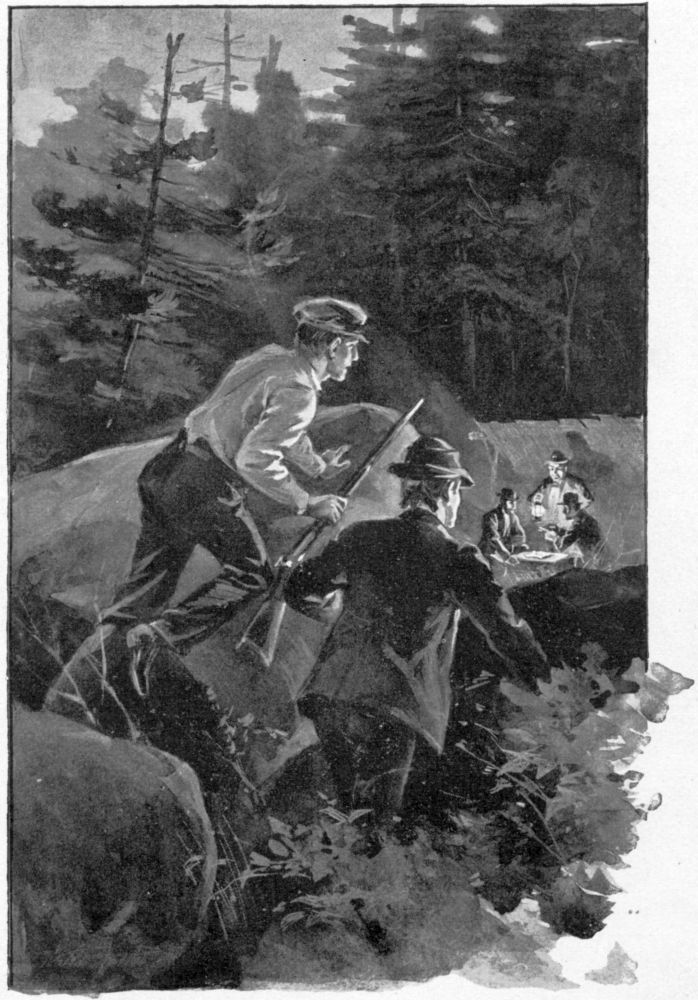

An instant later I looked around to see if Carney was where I left him, and I was chagrined to note that he had disappeared.

For an instant I did not know what to do. Carney had vanished, and that, I was satisfied, boded no good to me.

With my gun ready for use, I picked my way back to the rock nearest to my boat, intending to embark at once. The man was probably not alone on the island, and had gone off for assistance. Perhaps he would soon appear with the other two men Tom Darrow had mentioned.

But as I jumped aboard my boat another surprise awaited me. Carney was hidden under an old sail forward, and I had hardly set foot upon deck when he jumped up and struck me a cruel blow from behind.

“Take that for interfering with me!” he cried.

I caught but a glimpse of him; then came the blow, and I saw millions of stars. I staggered forward, and for a while my senses forsook me.

I think I remained unconscious at least a quarter of an hour. When I came to I found myself lying on the bottom of my sloop.

Somewhat confused from the rough treatment I had received, I raised my head and looked around me. Water was on every hand, and I saw that the craft had been shoved off from the island, and sent drifting down the lake.

As soon as I was able I ran up the mainsail, and then stood over for the west shore. There was no use returning to Rock Island for the present.

Carney had his gun once more, and would not now hesitate to use it. I must get some one to help me before going back for my property.

I turned the matter over in my mind, and then decided to return to the mill, leave the groceries and Mr. Norton’s tobacco, and then sail down to the Bend for Tom Darrow, and perhaps one or two others with whom I was well acquainted, and who I knew would help me.

As I skimmed over the surface of the lake I decided not to tell Mr. Norton of what had happened and of what I intended to do. It was none of his affair, and he would no doubt claim the boat as part of the estate under his charge. Perhaps I was not doing right according to law, but I was no lawyer, and I thought I could run matters quite as well as he could.

The distance to the mill-landing was soon covered, and then I lowered the sail and prepared to tie up.[71] As I did so I saw two strange men walk out of the mill-room, followed by my newly arrived relative.

I knew every man, woman, and child in the region, and I was sure the two men were total strangers in the lake district. They were short, small built, well dressed; and I could not imagine what had brought them to the place.

The spot where I had tied up was partly hidden from the mill by a number of bushes and trees. I saw that the painter was properly fastened, and then walked slowly towards my home.

“Yes, there is no use of waiting any longer,” I overheard one of the men say. “We have made enough mistakes already. Delay will mean more.”

“Then you intend to go ahead to-night?” asked the voice of Mr. Norton anxiously.

“Yes. By the way, how do you get on with the boy?”

“Pretty well. He’s rather high-strung. I expect him back any moment. I sent him over to Bend Center for some tobacco.”

“Good. Come, Bill; let’s be off before he returns.”

“Just as you say, Dick. You are running this deal, not I.”

And with these words the two men passed out of hearing, and made for the boat I had seen anchored in the inlet when I had gone down to the Bend in the morning.

This conversation surprised me not a little. At first I had intended to come forward and show myself, but now I was glad I had not done so.

Who were the two men? and what was their mission to the mill? Plainly they were well known to Mr. Norton; and yet he had just come from the West, and had not been in Bend Center for many years.

Perhaps these men were also from the West, and, knowing Mr. Norton was at the mill, had stopped over, most likely from Bayport, to see him. This was a rather lame explanation, and it by no means satisfied me. As to what was to be “gone ahead with” that night I had not the faintest idea.

Ordinarily I would not have given the entire matter any attention; but, as I have said, Mr. Norton’s way of doing things did not suit me, and I was anxious to find out something about him, and what I was to expect from him in the future.

I waited for several minutes after the men had gone, and then making rather more noise than was necessary, walked up to the mill.

Mr. Norton met me at the door. “Back at last, I see,” he said. “Got that tobacco?”

“Yes, sir;” and I handed it over.

“Good. I’m nearly dead for a smoke. Do you use the weed?”

“No, sir.”

“That’s right. Never start. It’s costly, and does a fellow no good.”

I took the groceries I had brought, and put them in the pantry. Mr. Norton filled his pipe, and began to puff away vigorously.

“Always have to smoke when I’m thinking,” he remarked as he blew a cloud of smoke to the ceiling.

I was on the point of asking him the subject of his thoughts, but checked myself.

“What are you going to do now?” he inquired.

“If I can, I would like to get off for the rest of the day,” I returned.

“Has that grinding got to be done?”

“No, sir; to-morrow will do.”

“Then you can go. I didn’t think about this news of your father’s death being so new to you, or I wouldn’t have asked you to go to work to-day. Fact is, I’m all upset with traveling around. That’s what riled my temper up last night.”

“I’m not used to such treatment,” I could not help remarking.

“I suppose your father was very easy. Well, we’ll let what’s gone alone, and take a new start. What time do you expect to be back?”

“Some time this evening.”

“All right.”

“By the way,” I went on, as I walked towards the door, “weren’t there two men here just before I came?”

Mr. Norton jumped to his feet.

“What’s that?” he exclaimed in surprise.

I repeated my question.

“I didn’t see them,” he answered. “What made you think they were here?”

His reply rather staggered me. I had not expected so deliberate a falsehood.

“I thought I saw them,” I said simply.

“Must have been mistaken. Nobody here since you went away.”

I walked down to the sloop in a thoughtful frame of mind. What did this false statement mean? Surely there was some mystery connected with the visit of the two strangers,—a mystery that Mr. Norton was anxious to conceal.

I was half inclined to turn back and find out what was “in the wind;” but I concluded that for the present it would be useless to do so. No one but my uncle was about, and he would not tell me a word.

When I reached the pier at the Bend I found Tom Darrow at his accustomed place, disposing of a big mess of fish he had caught during the morning. I told him of what had happened at the island, and he agreed to go with me without delay.

“Never mind taking anybody else,” he said. “I know Andy Carney. He is a rough customer, but a regular coward at heart. When he sees that we mean business he’ll cave right in.”

“I trust it is as you say, Tom,” I replied. “He was pretty ugly this noon.”

“We’ll manage him, never fear.”

“If we get the sloop, I wish you would take charge of her for me,” I continued. “I don’t care to take her down to the mill-landing.”

“I will, Rube.”

Tom jumped aboard, and we were off and up the lake. It was now getting well on in the afternoon, and by the time we approached the island the sun was setting.

“We’ll have to be careful,” I said; “Carney may be on the lookout for us.”

“He wouldn’t dare to fire at us,” laughed Darrow.