For a man who never flew before to step from an airplane into space thousands of feet above the earth—that takes nerve! Yet old Beth knew that was the only slim chance for his fire-trapped logging crew

“Slow timed fire bombs started the blaze—we run onto one of them that hadn’t exploded! Whoever done it knew a cross-fire would trap th’ men at the camp—”

Old Beth’s gaunt face worked with a grim tightening around his lips.

“Reckon you boys could fly ’round the fire ’fore it hits th’ camp. I ain’t ever been up in a plane, but I’ve heard you could drop a man anywhere with one of them parachutes—I’ll take a chance. We gotta put an intake valve on that engine, load th’ men an’ make a run for it down th’ mountain.”

Nick Mims, fire patrol pilot, demurred at first, not because he lacked the guts to go, but orders were orders.

According to the old logger, Beth, his camp high on Round Top mountain was cut off by the fire from all the trails leading down. And once the flames sweeping up the slopes had reached the camp, there was no escape.

“But, Nick, we gotta do it.”

Five or six times during old Beth’s recital, Jack Singer, mechanic and relief pilot, had reiterated this. In the back of young Singer’s mind was the thought of his wife, Nellie. She was camping with friends in the Priest Lake vicinity. Last year there had been a bad fire there, too. Supposing Nellie were trapped? Jack kept thinking of that.

“We gotta do it,” he affirmed, impatiently.

“Yeh,” agreed Nick at last, reluctantly. “An’ if we crash, it’s curtains for our jobs—if we get out.”

“Them boys must be facin’ hell up there right now,” said Beth. “They can see the blaze for miles. The dinky-engine will come hell-beltin’ down th’ grade through th’ cutover stuff—she might make it if we could only get her started. But th’ dinky’s settin’ on a mile of level track—gotta have that intake fixed ’fore they could fire ’er.”

“Who’d you think set the fires?” asked Nick, his gray eyes glinting.

“You sort o’ put a crimp in Hinton’s monopoly by gettin’ the rail right o’ way ’cross his cutover land an’ runnin’ logs to the lake, didn’t you?”

“Hinton wouldn’t murder my boys,” said Beth. “He’s my enemy, not theirs.”

“Let’s go,” said the older pilot. “It’s a chance. We’ll fly around an’ volplane down over the mountain top. There ain’t ozone enough in the draft over that fire to keep the motor turnin’.”

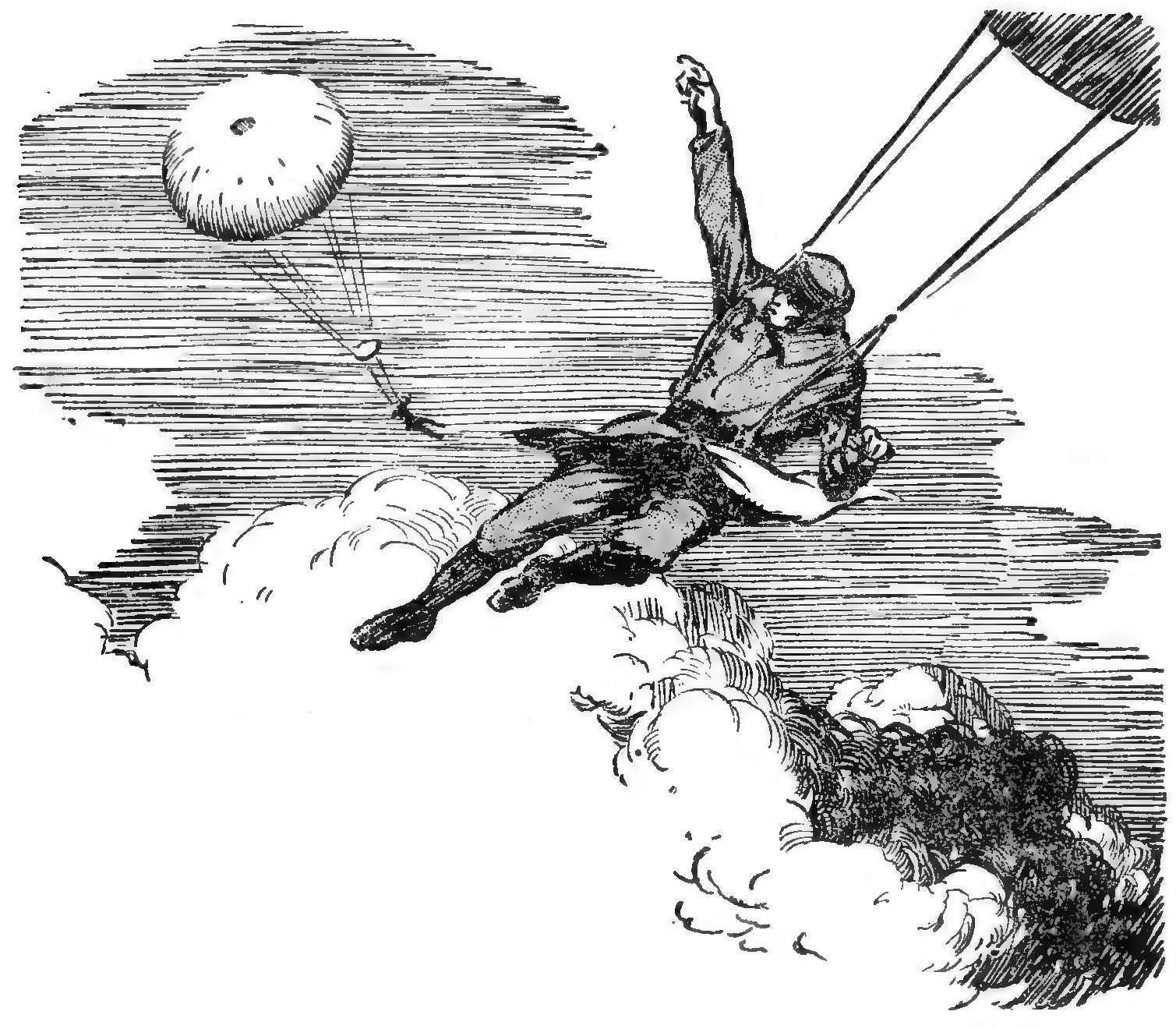

Old man Beth was making his first flight. He had had the parachute strapped on, asking for detailed instructions about its use. He feared the height; and the idea of jumping into two or three thousand feet of space was appalling. But a score of his boys were in the fire-rimmed camp. Old man Beth would give them their one slim chance of escape or he would die with them.

Jack saw there was no shaking his intention.

“Dinky engineer there,” he asked, “to put in the valve and get ’er out?”

“I’ll get ’er patched up,” evaded the old man. “I been ’round dinky engines a lot”

Jack knew then it was as he suspected. The dinky engineer was not in the camp. Probably not a man there was mechanic enough to install and adjust an intake valve properly, let alone drive the dinky down that perilous ten-mile grade to the terminal at the mouth of the St. Joe on the lake. If old Beth were sure the jump meant death, he’d jump out of the plane regardless.

“You’ll likely land in a tree-top,” Nick told Beth. “Don’t try to slip through if you do. The ’chute will hang you up. Grab on, cut your straps an’ climb down if you can. Cut your cord as soon as you jump. I’ll zoom the ship so you’ll be safe enough.”

Nick sent the plane along the Cœur D’Alene lake shore until they were directly opposite the mouth of the St. Joe River and the circling fire on Round Top mountain above it. He banked the Stearman, pulled the control stick hard back and climbed.

Beth groaned when the plane had topped the drifting gray smoke. The flames had been rushing up the mountain at greater speed than he had figured. Less than two miles, as nearly as he could judge, separated the logging camp site from the fire.

Jack watched Beth, and he knew when the old man turned sick. The draft of hot air from the flames, roaring over the mountain top made the going bumpy. The big Stearman rocked, dropped, caught the air cushion and bounced along through the air holes. Jack’s own stomach was not sitting so pretty and he was aware that Beth was having a bad time of it.

This form of air sickness is closely akin to seasickness and it requires all of a man’s nerve to keep a stiff upper lip. But Beth’s mouth was a straight line. He was looking down through the floor windows and he touched Jack’s shoulder.

Jack had a glimpse of white through the trees a mile or so down the mountainside. The camp then was still untouched, but at any moment a drifting brand borne on the wind might jump the fire along for the extra mile or two.

At a point about fifteen hundred feet above the mountainside, where he dared swing no closer to the dangerous updraft from the fire, Nick idled the engine for an instant and called out:

“Close as we can come—get set an’ jump when I swung!”

Although his face was tinged with a grayish pallor, old man Beth arose and stood ready while Jack unlatched the door. Jack saw that Beth did not look down and he knew why. Sheer grit is required to step off into nothingness. The old man was looking only at the door. His right hand was on the ’chute’s rip cord.

Nick gave the motor the gas and tilted the wings sharply.

“Now!” he shouted and waved his hand.

Beth took one firm step toward the door and vanished over the side. Jack turned instantly, touched Nick’s shoulder, and before the older pilot could remonstrate, dropped out the open door after the old man.

Nick was not so surprised as Jack expected he might be. He had known all the time that Jack would take the jump. He had kept silent because he did not want Jack to know that he knew. Nick swung the plane back toward the mountain top.

It was his job to get back to the mouth of the St. Joe and have emergency facilities ready. They would be needed if the desperate attempt at rescue succeeded.

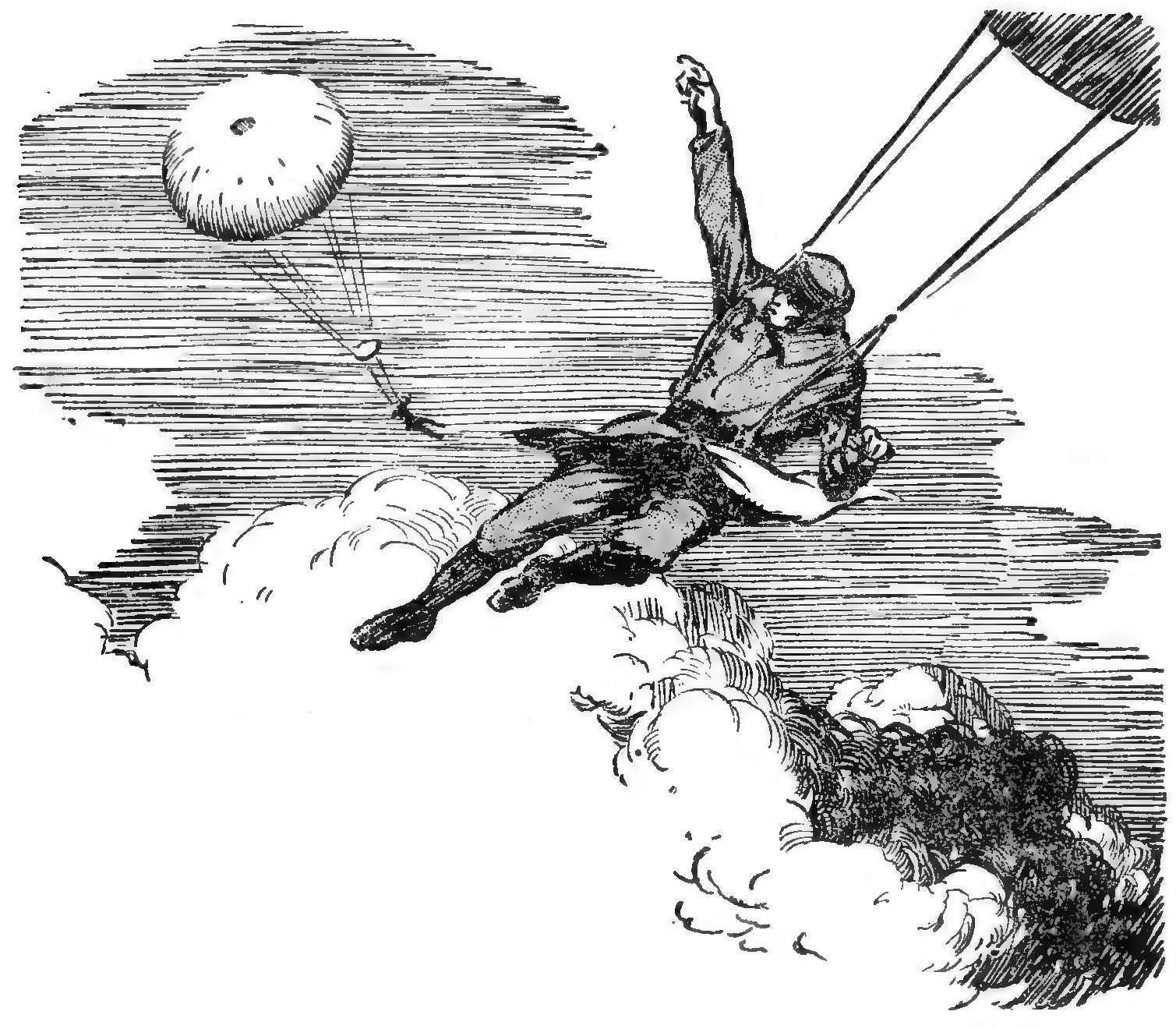

Jack was relieved when he saw that Beth’s ’chute had opened. Two or three hundred feet below him the round top of the ’chute was swinging in the wind. Underneath he caught a glimpse of Beth’s swaying body. He saw all of this in the split seconds it required him to fall head downward past Beth’s ’chute. He wanted Beth to know he was with him, so he did not rip his cord until he was a hundred feet or so under the old man. When his umbrella spread, he waved his hand and shouted. He heard the old man’s voice and knew he was all right.

The wind created by the miles of solid fire front below swept the ’chutes swiftly toward the mountain side. The worst moment of their descent was at hand. Jack had been hung in the spike-topped cedars on previous occasions. But he was the lucky one of the pair this time. The edge of his ’chute twisted off a branching limb, and although Jack landed with a jolt, he was on the ground unhurt. Old man Beth was less fortunate.

Beth’s umbrella was spiked squarely in the top of a slender cedar. Jack, freeing himself from the straps, got under the tree. Beth was fumbling with the cords and Jack saw he was cutting them.

A hard object came hurtling through the air and narrowly missed Jack’s head. Jack smiled grimly. It was the new intake air valve for the dinky.

“Get th’ valve—don’t wait for me—I’ll make it down—”

Despite his own perilous situation, Beth’s mind was fixed on getting the log train engine working. But Jack stayed below until he saw the old man had freed himself and was making his way slowly down the tree. Beth reached the lower limbs of the cedar and was attempting to cling to the trunk when a branch snapped. He fell heavily at Jack’s feet, and Jack grew sick as he saw how the old man’s leg had twisted under him.

Heedless of Beth’s protests, Jack got him to his shoulder and started down the mountain toward the camp. He was making slow progress when he heard a crashing in the bush. Four or five of the logging crew had seen the plane and the ’chutes. They contrived a rough sling for old man Beth, and one of the men hurried ahead with Jack to the camp.

Occasional brands and sparks were falling near by. Jack looked along the twisting log track, with its light, rusted rails, and his heart sank.

Men of the logging crew crowded around, a new hope succeeding the black despair with which they had watched the crawling blaze. Jack had the pipes apart and the intake valve in place when Beth was brought in. His fractured leg did not prevent the old man from thinking.

“Grab down the canvas an’ souse it in the springs,” he directed. “Get the wet canvas an’ all th’ gunny sacks we’ve got onto the cars—when we get goin’, every man wrap himself up—it’ll likely be hotter’n blue hell, but the wet rags’ll help.

“The track doesn’t hit the heavy timber—goes across the cutover land, so it ain’t likely there’ll be any trees blockin’ ’er. The cutover’ll be hot, but we couldn’t go through th’ tall stuff.”

Plenty of willing hands piled wood into the firebox when the valve job was done. Whether they survived or perished, Jack was glad he had come. Inexpert hands, he was sure, could not have installed the intake valve.

Jack’s only twinge of conscience concerned Nellie. But had she known, she would have had him do as he did. She was game, was Nellie.

Jack watched the needle creep up on the steam gauge. The suspense of waiting for power to move was worse than all the rest had been. Jack helped get the dripping tent canvas on the cars to help protect the men. Bearded, silent, overgrown boys they were. Some had the strained look around their eyes that told what the hours of watching the approach of the blazing death had meant.

At last the steam hissed from the safety cock. Beth advised that they haul three of the flat cars. He figured it would give the men more room to fight the blaze, if the wet canvas proved insufficient to safeguard them. With two men stoking the firebox, Jack tested the throttle. The dinky coughed and its four teetering wheels bit into the rails. They were beginning to move.

Some one shouted from the rear car. A brand had fired the woods directly behind them and the blaze was spreading. They were moving in the nick of time. Some of the men shouted again, and Beth called to Jack to stop. Jack could not hear distinctly, but when he had shut off the steam, Beth told him to wait for a minute.

“Three or four campers from up on the mountain just got into the clearin’,” Beth explained across the top of the tender. “They’re gettin’ ’em covered with canvas on our last car. There—they’re all clear—let ’er go.”

The dinky coughed and the wheels spun again. Jack got no reassurance as to the light engine’s stability from the rocking movement over the poorly built track, even at its first slow speed. The track ran for a mile on a level grade around the mountainside. This had been the loading spur. The dinky dragged the flats at a speed of less than ten miles an hour. To Jack, accustomed to the rushing take-off of his planes, they seemed scarcely to move. The acrid tang of the wood smoke drifted into the open cab and stung Jack’s nostrils and throat.

He should have provided himself with one of the wet sacks or a strip of canvas. But old man Beth had thought of that, too. A lumberjack came climbing over the wood on the tender, dragging a wet canvas. Jack wrapped one end around his shoulders and trailed the remainder for the stocky little Irishman who was poking wood into the firebox.

The dinky puffed nobly and its wheels slipped and screamed on the rails as it strove to gather speed, despite the dragging weight of the flat cars. The chuffing exhaust drowned all other sound. The tall cedars and Ponderosa pine trees began to move past more swiftly. It was like riding a smoke-filled tunnel.

Just before the dinky reached the downgrade curve, a vagary of the wind swept the smoke back. Jack had a view of thin rails that dipped suddenly over the brink and corkscrewed down the mountain. He figured he would hold the dinky to low speed until they actually entered the heated zone. But the brakes?

Good Lord! He had not thought of that.

The logging train was not equipped with air appliances. Hand brakes on the flats were used to ease the loads of logs down the mountain. Jack sent his fireman back over the tender to instruct the men about the brakes. And, if they got into fire so hot that the men could not expose themselves, well—Jack refused to think further along that line.

Jack had thought he had taken extreme risks in the planes. But up in the air you could see something. Now the smoke closed in again and he was compelled to draw a corner of the wet canvas across his mouth and nose.

They were on the very brink of the grade. Instead of the dinky pulling the flats, Jack could now feel the shoving weight of the cars. The dinky was leaping ahead and down. If he had only thought of those brakes sooner. But the wheels squealed and grated on the rails. The men of the logging crew knew their stuff. For a mile they eased along, the smoke lifting and dropping, alternately shutting off Jack’s wind and giving him a chance to breathe.

Jack’s fireman crouched under the corner of the damp canvas. The dinky and the flats would run by gravity all the way to the transfer pier on the St. Joe River, if they held the rails.

The smoke lifted. For an instant Jack had a sense of relief. But the reason for the sudden swirling of the smoke wiped that out. A sheeted wall of flame leaped across the track ahead. The men on the cars had seen it, too. Jack felt the dinky lurch forward. The brakes on the flats had been released.

It seemed to Jack that the weight behind must hurl the rolling little engine from the rails. But the drive-wheel flanges were tapered for just that sort of thing. The wheels screeched, but they held.

The flames sent a stinging tongue through the cab window. Jack instinctively jerked the corner of the canvas over his face. The hot wind tore at him like a breath from a furnace. He smelled the hair singeing on the backs of his hands. The little Irishman crawled close to his legs under the canvas. The dinky and the flats had become a blind rocket rushing down the mountainside.

The dinky rocked and lurched. Jack prayed inside that there might be nothing across the rails. He groaned as he thought of what would happen if a burned tree had fallen to block their way. He hoped that if they failed that he might be utterly destroyed. That would be better for Nellie than having him brought home afterward.

Jack risked a look ahead. The corner of the wet canvas was steaming. In front on either side the blaze was leaping and licking at short growth trees. Beth had been right. Only the fact that this was cutover land, small stuff, might save them. In the heavier timber of the virgin forest they would not have had a chance.

Their rushing speed now was more like the swift dash of an airplane. But a plane could go up. The dinky and the flats could only become a twisted mass of wood and iron if they were ditched. A blast, hotter than all the others, scorched Jack’s face. He got his head under the wet canvas again before he breathed, which was well. One draught of that blaze into his lungs and whether they held the track or plunged into the superheated ground would not have mattered to him.

It seemed like an hour or more they had been tearing along, hemmed in by the blaze. Probably it was no more than a minute, for the swathe of the fire was less than a mile in width. A quick cooler draught struck Jack’s face. He pulled away the canvas. For the first time since leaving the upper level he could see the track ahead. Two snaky rails were running toward him and disappearing under the dinky.

Jack heard the wheels squeal again. The men were striving to set the brakes. Their speed did not seem to lessen perceptibly. He heard a loud snap on one of the flats. A brake chain had parted. One of the men came crawling over the top of the tender, clinging to the swaying sides.

“We can’t hold ’er!” he shouted. “Don’t try brakin’ th’ dinky—you’ll pile ’er up.”

Curves where the track disappeared shot up the mountain toward them, and miraculously disappeared under the engine and cars just when Jack was sure they would be catapulted into the wall on one side or over the precipice on the other.

“If she holds we kin check ’er on th’ loadin’ pier—gotta mile run there,” said the lumberjack in Jack’s ear.

A long straight stretch of track, steeply pitched, loomed ahead. They were out of the fire zone now. Bushes and small trees became a weaving wall of green on either side. The dinky plunged into a cut. Jack breathed easier.

“Cross th’ highway just ahead,” yelled the lumberjack. “State road ’round th’ lake.”

Jack had a flash of the road. It wound up alongside the track on one side before it crossed. On the other it disappeared abruptly behind the wall of the cut. Jack thought of his whistle, but the steam was down. The whistle made no sound.

The automobile roadster that shot from behind the wall of the cut almost cleared the rails ahead of the rushing dinky. Jack thought it had, until, in a brief backward glance, he saw the little car turning over and over down the steep bluff below the highway. That same flashing view revealed another car coming down the highway and then the dinky shot around a curve and the scene was shut off.

“God!” cried Jack, “I hope nobody’s killed.”

“Musta heard th’ dinky,” said the lumberjack. “Can’t be helped now—only a mile to go—’round that next bend—I’m goin’ back—we’ll try an’ stop ’er.”

The dinky and the flats, with brakes grinding, stopped on the long level stretch of the transfer tracks. Nick was among the first to reach the dinky. Jack felt strangely light and a confused blur of faces danced before him.

“Jack! Oh, Jack!”

He opened his eyes with warm, moist lips on his own. Nellie? It couldn’t be Nellie down here. She was camping up at Priest Lake.

But it was. She had been with the party that had gone for the trip up Round Top mountain. She was one of the party that had been under the canvas on that last flat.

Jack struggled to his feet despite the protests of Nellie and Nick. He saw old man Beth lying on a stretcher ready to be placed in a car. Beth reached out his hand. He tried to speak, but no words came.

A man came hurrying across the transfer pier from the office. He came straight to Beth.

“Hinton’s killed,” he said. “Just got the phone message from the fire warden. He’d been chasing him. His roadster went off the highway, turned over. Had a case of fire bombs in the back. Some of them exploded—burned up the car—Hinton was caught underneath.”

“The mills of the gods,” said old man Beth in a hushed voice, his fingers tightening on Jack’s hand.

Transcriber’s Note: This story appeared in the October 20, 1928 issue of Argosy All-Story Weekly magazine.