THROUGH UNKNOWN

NIGERIA

LIFE IN AN INDIAN OUTPOST.

By Major Casserly. Fully Illustrated. Demy 8vo. 12s. 6d. net

ALONE IN WEST AFRICA

By Mary Gaunt. 15s. net

CHINA REVOLUTIONISED

By J. S. Thompson. 12s. 6d. net

NEW ZEALAND

By Dr Max Herz. 12s. 6d. net

THE DIARY OF A SOLDIER OF FORTUNE

By Stanley Portal Hyatt. 12s. 6d. net

OFF THE MAIN TRACK

By Stanley Portal Hyatt. 12s. 6d. net

WITH THE LOST LEGION IN NEW ZEALAND

By Colonel G. Hamilton-Browne (“Maori Browne”). 12s. 6d. net

A LOST LEGIONARY IN SOUTH AFRICA

By Colonel G. Hamilton-Browne (“Maori Browne”). 12s. 6d.

MY BOHEMIAN DAYS IN PARIS

By Julius M. Price. 10s. 6d. net

WITH GUN AND GUIDE IN N.B. COLUMBIA

By T. Martindale. 10s. 6d. net

SIAM

By Pierre Loti. 7s. 6d. net

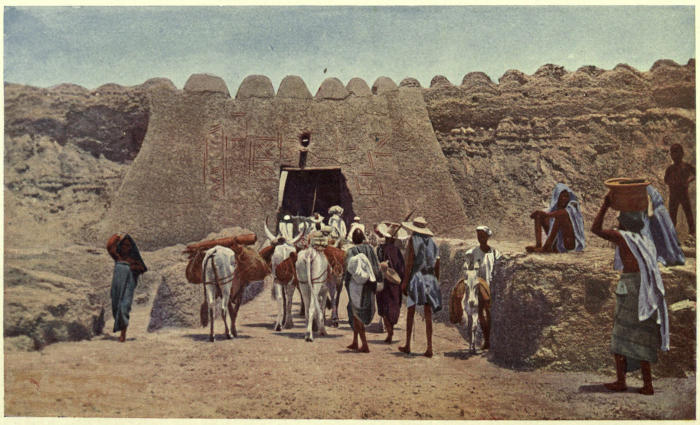

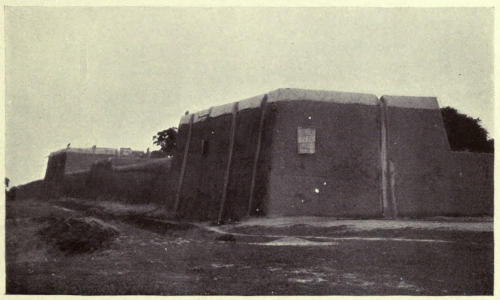

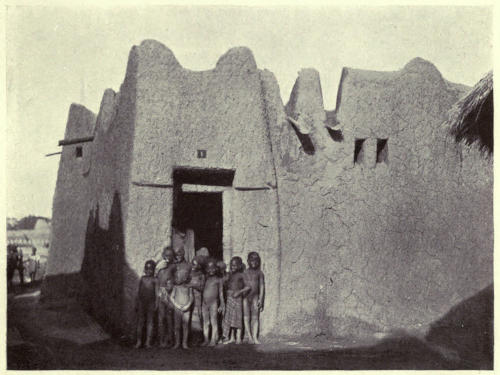

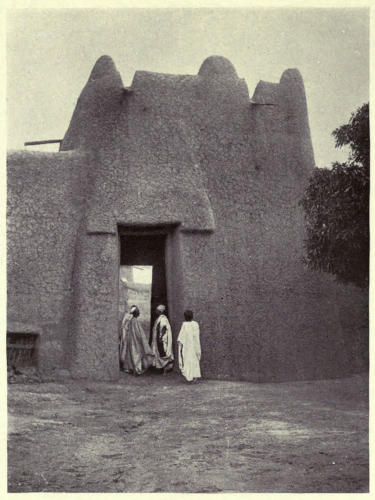

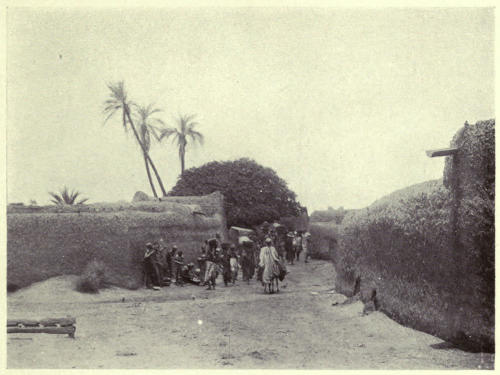

A GATEWAY IN THE WALL OF KANO.

The wall, which is made of mud, is 40 feet in thickness, 50 feet high, and 7 miles in circumference.

Photo by the Author.

THROUGH

UNKNOWN NIGERIA

BY

JOHN R. RAPHAEL

LATE TRAVEL EDITOR OF “THE AFRICAN WORLD”

ILLUSTRATED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHOR

LONDON

T. WERNER LAURIE LTD.

8 ESSEX STREET, STRAND

Nigeria is in process of change, in some places rapid change. Since this book has been written Southern and Northern Nigeria have been amalgamated administratively. The two colonies, or protectorates, whichever title be preferred, are being unified. The public service have been fused. What were the Lagos Government Railway, the Baro-Kano Railway and the Bauchi Light Railway recently received the comprehensive designation of Nigerian Railways. The volume was in too advanced a condition for the alterations to be made; and perhaps use of the old names will give a better idea of the efforts to open up the youngest dependency brought under the Crown.

Linking rich Southern Nigeria with her Northern sister provides money for railway and other development, which is to be pushed on vigorously. Many of the conditions of the country must necessarily alter. The locomotive is to whistle through regions where few white men have trod. Wild areas are to be penetrated by trains. Naturally the character of the inhabitants will be affected: no doubt many superstitious rites and, incidentally, cruelty and inhumanity in social customs be dispelled. Pagans[viii] will catch the passing fashions, or an imitation, and clothe, or at least cover, themselves.

These and other material benedictions are sure to radiate from the emblems of civilisation. Let us hope we shall not also be the means of dispensing many of the blessings taken by Europeans to the Coast towns of West Africa in former centuries and in evidence to-day by the moral and physical degeneration of adult natives, as well as by children saturated with hereditary disease.

Contact with aborigines may be a very fine thing for them. Let care be taken that their second state is not worse than the first. That is likely to be avoided if the policy followed by Sir George Taubman Goldie and Sir Frederick Lugard with the Fulani and the Hausa population of Northern Nigeria be scrupulously continued: that of encouraging and fostering all which is good in tribal life, repressing only those features which violate the principles of human existence.

No attempt has been made in the following pages at an historical survey or at a deep examination of the difficult problems that confront the administration. There are a number of books in which both subjects are treated excellently. Recent ones occurring to mind are Lady Lugard’s, “A Tropical Dependency”; Colonel Mockler-Ferryman’s, “British Nigeria”; Captain Orr’s, “The Making of Northern Nigeria”; Mr E. D. Morel’s, “Nigeria: Its People and Problems”; and the several publications of Major Tremearne.

This volume is no more than impressions taken from a quiver of them gained in the course of a rather long visit, part of it through country not well known. Most chapters were written during the journey, either at the close of a day’s trek or whilst detained at various spots.

My obligations are manifold for the courtesy, kindness and assistance shown in various quarters. If all to whom I feel indebted were stated several pages would be required.

I cannot, however, allow the volume to go to Press without again tendering thanks to my former Editor and present friend, Mr Leo. Weinthal, of The African World, for the opportunity given to carry out the expedition and for allowing me to incorporate in these pages matter printed in his paper; Sir Walter Egerton and Sir Hesketh Bell, ex-Governors respectively of Southern and Northern Nigeria, for the letters of introduction which proved an open sesame to the good-will of the high officials administrating each colony; Mr F. Seton James, C.M.G., and Mr A. G. Boyle, C.M.G., both of whom in the course of my stay were in turn Acting Governors of Southern Nigeria; Mr F. W. Waller, Acting General Manager, Lagos Government Railway; Mr Charles L. Temple, C.M.G., Acting Governor of Northern Nigeria; Captain G. C. Kelly, temporarily in command of the 1st Battalion Northern Nigeria Regiment; Captain C. F. S. Maclaverty, in charge of the Battery; Mr C. Maclean, Agent of the Niger Company at Zungeru; Mr E. M. Bland,[x] Deputy Director of Railways, Northern Nigeria; Mr Joseph E. Trigge, Managing Director of the Niger Company; the late Mr Walter Watts, its Agent General; Mr Robert Lenthall, also Agent General of same Company; Mr W. P. Byrd, and Captain J. J. Brocklebank, D.S.O., of Kano, and also my native friends of that city, Adamu Ch’Kardi and Suly; Mr F. Beckles Gall, Resident at Naragutu; Mr F. D. Bourke, Manager of Naragutu Tin Mine; Mr S. E. M. Stobart, Resident at Bukuru; Mr T. H. Driver, Manager of the Anglo-Continental Mines; Mr A. C. Francis, Acting Resident at Zaria; Major E. M. Baker, temporarily in command of the 2nd Battalion Northern Nigeria Regiment; Mr W. H. Hibbert, of Lokoja; Mr Bertram D. Byfield, Cantonment Magistrate there; and Mr A. E. Price, of Burutu. Although not strictly within the scope of this book, I add Mr J. B. McDowell, Managing Director of the British and Colonial Kinematograph Company, who gave special care and attention to the apparatus and material which enabled me to bring back unique moving pictures of people in whose country no instrument of the kind had ever been taken.

J. R. R.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I OUTWARD BOUND |

|

| Call of the Coast—Mal-de-mer—Coasters afloat—From 78° to 90°—The Kru sailor—His civilised degeneration—Laundryman’s discipline—A dangerous stretch—The skipper—From ship to train | 1 |

| CHAPTER II FROM THE COAST BY TRAIN—THE WEST AFRICAN PULLMAN |

|

| Iddo Wharf—Strange sights and thoughts—Umbrellas—“Niggers”—Train luxuries—Liquor permits—The iron-horse at the Niger—Ferry and bridge—Budget details | 12 |

| CHAPTER III ZUNGERU—THE CAPITAL OF THE PROTECTORATE |

|

| A garden-city Capital—“Ikey” square—Autocracy thorough—Circumscribed accommodation and doubled-up quarters—Young administrators—Strict, stern, severe economy—The Governor’s “Palace”—Job-lot furniture—His Excellency’s 1s.-an-hour, Bank-Holiday motor-car—Pooh-Bah Cantonment Magistrate | 19 |

| CHAPTER IV ZUNGERU—THE CAPITAL OF THE PROTECTORATE—(continued) |

|

| Native settlement—Rents and Treasury—A model prison—Northern Nigeria Constabulary—Mails paid time-work—Sport at the door—Up-country and Coast natives—Selection of Zungeru—The future Capital | 33[xii] |

| CHAPTER V ZUNGERU TO KANO |

|

| Everybody his own porter—Religion and missions—Divining water—Carriages patchy in parts—Native passengers—In the track of the slave-raider—Engine sustenance—Kaduna Bridge—A tight-rope performance—Close cultivation—“The lazy negro”—Two civilisations—At Kano | 43 |

| CHAPTER VI ARRIVAL AT KANO |

|

| Plans and expectations—Small water-famine—The handy man—Change of quarters—Ants as sauce—Niger Company | 57 |

| CHAPTER VII FASHIONS, GOVERNMENT, ADMINISTRATION |

|

| An Empire builder—The country and population—Hausa tribes—Moslem and Pagan—Sartorial distinctions—Ruling through natives—Election of their own rulers—Lugard’s peaceful persuasion—A modern Earl of Warwick—The genius of Taubman Goldie and Lugard—Native administration—Residents—Taxation—Law Courts | 63 |

| CHAPTER VIII KANO PROVINCE AND CITY—BRITISH TRADE PROSPECTS |

|

| Town and country—Officials and traders—Belgravia and Bermondsey—A housekeeping budget—European stores—Buying and selling—A Syrian in the fold | 72 |

| CHAPTER IX A GENTLEMAN ADVENTURER |

|

| The London and Kano Trading Company—The Captain intervenes—Army, Civil Service, Commerce—Discarding appearances—Contrast of mansions—The pleasure of business—“Traders” and others | 80[xiii] |

| CHAPTER X KANO CITY |

|

| The founder—Hunter and prophet, too—The city wall—Warfare and slave hunts—Provocation and defiance to the British—The Emir’s challenge—March on the city—First check—Renewed attempt—Entry—A new ruler | 86 |

| CHAPTER XI KANO CITY—(continued) |

|

| Houses and rents—From 1s. 6d. to £5 a year—Mud mansions—No. 1 Kano—When to build and repair—Advice on building—A contract and a surprise | 93 |

| CHAPTER XII KANO MARKET |

|

| A cosmopolitan rendezvous—Arab merchants—The desert route and the iron-horse—War and commerce—Local industries—Arts and crafts—Skilled workers—Camels, cattle, sheep, horses—Pitiful brute suffering—An appeal | 100 |

| CHAPTER XIII KANO MARKET AND CITY—(continued) |

|

| Deference to the Englishman—A sagacious policy—Administration of justice—An Alkali’s judgment—The native Treasury—Kano municipality—Money matters | 112 |

| CHAPTER XIV SOME ASPECTS OF SOCIAL LIFE |

|

| Wives of the upper-class—Women and the mosques—Polygamy—Its difficulties in the home-circle—How to maintain peace—Hints on management of the feminine character—A domestic diplomat—Slavery—The former and the present position—Status of a slave | 119 |

| CHAPTER XV THE MISSIONARY QUESTION |

|

| Missions and Moslems—Strong comments—Bearings of the situation—Present practice—The British solemn promise—The alternative | 125[xiv] |

| CHAPTER XVI THE BAUCHI LIGHT RAILWAY |

|

| Zaria and other stations—The two gauges—Through new country—Second-hand rails—A new post for Sir Frederick Lugard—A relic of tribal warfare—Sport for the gun—A derailment—Blend of tongues—Smart re-railing work | 130 |

| CHAPTER XVII AT RAHAMA RAILHEAD |

|

| Engaging carriers—How to facilitate getting away—Hausa horse coupers and political economy—Bullock transport—Donkey carriage—The man who belies a fable | 139 |

| CHAPTER XVIII ON TREK—RAHAMA TO JUGA |

|

| Heavyweight and overweight—The white barred—Collective displeasure—Getting off—A doki boy—Tin-mine pilgrims—A scion of royalty—The rest-house—Village elders—Acrobatic horsemanship—The carriers—Headman Hanza—Over the edge of the Pagan belt | 146 |

| CHAPTER XIX RAHAMA TO JUGA—(continued) |

|

| Stopped by a stream—A volunteer—Amadu the carrier—Sun heat—Across the river—“Kow abinshi”—The doki boy’s experiment—The climate and granite—Domestic details on trek—A chilling downpour—Mark Tapleys—Sun and warmth—Hanza’s command—A dignified procession | 156 |

| CHAPTER XX JUGA TO NARAGUTA |

|

| Native feminality and the cavalry spirit—Scarcity and economy—A house of straw—Carriers, professional and other—Diversified panorama—Parting with the first carriers | 169[xv] |

| CHAPTER XXI TWO SHORT JOURNEYS |

|

| Man proposes—A narrow river barrier—Travellers this side of the stream; beds, the other side—Pagan cultivation—A postal description—Headmen and Headmen—Gotum Karo | 175 |

| CHAPTER XXII THE NIGER COMPANY’S JOS CENTRE |

|

| Jos and St Peter’s—A wet and dry object—Fashion in stationery—Smoking and writing materials—The cost of money—Coin in transit—Tin-mine labourers and food—Inception of European transport—Linguistic stimulus and aptitude—Donkey caravans—The animals’ acumen—Double-distilled philosophy | 181 |

| CHAPTER XXIII MINES—MEDICAL |

|

| Tin-mining—First Exclusive Prospecting Licence—Early tin-winning—Mr Law’s work—Health and economics—Feminine nursing—The medical service | 194 |

| CHAPTER XXIV A MURDER TRIAL |

|

| Mining licences and leases—The Government Inspector of Mines—Nine years without doors—Two Residents—Poisoned arrow welcome—A murder trial | 202 |

| CHAPTER XXV TROUBLES OF THE TREK |

|

| Philosophers’ test—At the back of white men’s minds—Human calculations—Blows to plans—Oje leaves—The servant problem—Short, severe rations—Doki boy Kolo—A Pagan pony—Its performances—Injury to insult—Human and equine elements | 209[xvi] |

| CHAPTER XXVI INCIDENTS ON TREK |

|

| The changed seasons—End of the rainy season—Bush fires—Rolling downs and kopjes—A 25-miles march without food or drink—Return journey commenced—Ascent of the escarpment, 2,200 feet—A Hausa and Pagan affray—An ugly situation | 221 |

| CHAPTER XXVII INCIDENTS ON TREK—(continued) |

|

| Information and advice in West Africa—Different men, different manners—Ritz by comparison—A Samaritan by the way—Dried streams—Primitive transport—A visitor from Rhodesia—Omitting anti-fever precautions | 230 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII CLOSE OF THE TREK |

|

| Character of carriers—The only blow given—Native grooms’ monetary transactions—Material for a cause célèbre—Dispensing justice on the road—Headman Dan Sokoto—Dan’s sharp practices—A long march | 237 |

| CHAPTER XXIX TOWARDS THE PAGAN COUNTRY |

|

| Hausa and Pagan—Distinction of dress—Deeper divisions—The price of peace in former days—Public highway—Revenge and brotherhood—Scope of an Assistant Resident | 243 |

| CHAPTER XXX IN A PAGAN TOWN |

|

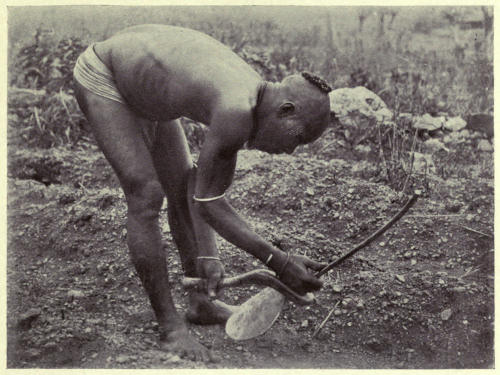

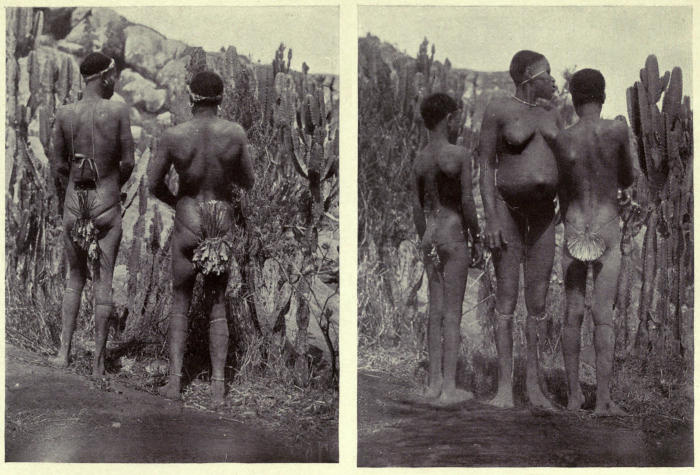

| Bukuru Residency—Bukuru town—Its ingenious defences—Traps for an attacking force—The blacksmith—Musical instruments—Pagan orchestras—A royal male Pavlova—The Court band—A King’s reward—Pagan homesteads—The sleeping apartment—Farming—Incentives[xvii] to obtain, money—Enhancing nature’s charms—Male and female decorations—Bareback and bitless horsemanship—Races—Care of horses—The hunt—Sign language | 247 |

| CHAPTER XXXI ADMINISTERING JUSTICE AND TAXATION |

|

| Direct rule—Cases in a Resident’s Court—Wife and “another man”—Trial by ordeal—Modification of that method—Kidnapping for slaves—“The liberty of the subject”—Extenuating circumstances and even-handed justice—Benefits that are not welcomed—The joy of fighting—Graduated taxation—How to express numerals to people who have no such terms—Two tax collectors—First lessons in administration | 260 |

| CHAPTER XXXII MARRIAGE AND DEATH CUSTOMS |

|

| Fashions—A wedding-ring warning—The former way with undesirables—Succession to a Chief ship—Marriage—Dowries—A perpetual leap-year—Widows—Burial usages—Cannibalism—Eating those who die from natural causes—Etiquette of the practice—A credit and debit account | 269 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII SOLDIERS AND THEIR SPORTS |

|

| British-trained troops—Little-known Mr Atkins—Swearing-in recruits—Hausa and Pagan oaths—Native priests on active service—Number of wives allowed—Artillery on men’s heads—Gun drill—Dipping for toroes—Mounted infantry—Signalling tuition—Teaching the band—Inculcating self-reliance—The military classification of white civilians | 278 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV ZARIA CITY AND PROVINCE |

|

| Prominence of Zaria—As a produce and trading centre—The gold discoveries—Opposite deductions—Model, native town-planning—Various taxes | 291[xviii] |

| CHAPTER XXXV THE BARO-KANO RAILWAY |

|

| Emir’s assent—Compensation for palm trees—A locomotive’s food—Engine whistling preferred to Caruso—Official opening—Natives’ curiosity—A Mallam’s impressions—Horse v. train | 299 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI BARO ON THE NIGER |

|

| Baro port—A Selfridge-Whiteley 400 miles up the Niger—London frock-coats in West Central Africa—Fretwork and ladies’ garments—An untutored eye and its guide—The rat a table delicacy—Oje’s local patriotism—Baro and Jebba; hygienic problems—A superfluous hospital | 306 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII LOKOJA |

|

| First stage down the Niger—Lokoja’s past—The discovery of the brothers Lander—Previous theories—McGregor Laird’s enterprise—Eighty per cent. mortality—The 1841 expedition—Richardson, Barth and Overweg—Laird’s second endeavour—The House of Commons scuttle policy—Its reversal—First Fulani battle—Imperial control—Commerce of Lokoja—Vessels at the beach—Loading boats—Freedom of contract | 312 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII LOKOJA—(continued) |

|

| A cosmopolitan town—A Baron Haussman—The Cantonment Magistrate—Some of his duties—Expenditure and economy—King Abigah—A plea for generosity—The hospitals—A black Bishop’s legacy—The missionary question—Critics and the converse | 324 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX NAVIGATING THE NIGER |

|

| Rise and fall—A tideless stream—Comfort afloat—The uncertain river—Nasaru the Pilot—Altered channels—When aground—Breakdown of machinery and smart repair—Tropical scenery—The crocodiles’ rest—Riverside[xix] villages—Where money is ignored—Estimation for old bottles and tins—Harmattan fog—An island trading station—Hazard and skill to maintain a time-table | 334 |

| CHAPTER XL BURUTU |

|

| A port in a swamp—Training native engineers—A composite village—Social grades—Medical provision—Mr John Burns on a Nigerian river—Back to the sea | 348 |

| A Gateway in the Wall of Kano | Frontispiece | |

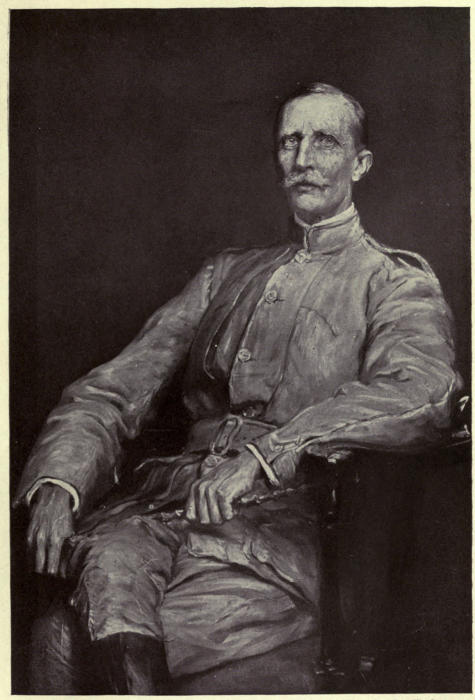

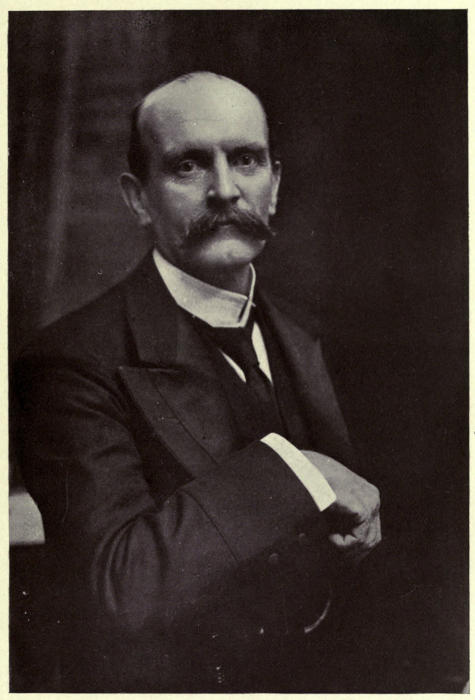

| The Rt. Hon. Sir George Taubman Goldie, Founder of Nigeria | Facing page | 64 |

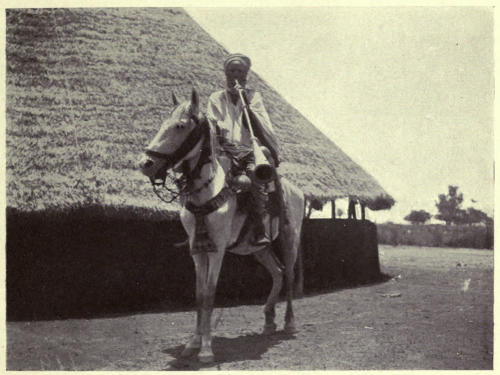

| One of the Emir’s Trumpeters | ” | 78 |

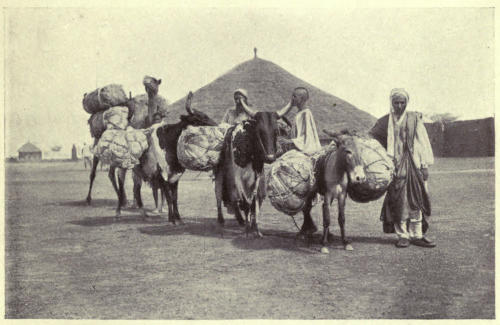

| Native Skin-merchants with Transport, Kano | ” | 78 |

| Captain J. J. Brocklebank, D.S.O. | ” | 82 |

| The Premises of the London and Kano Trading Company at Kano | ” | 82 |

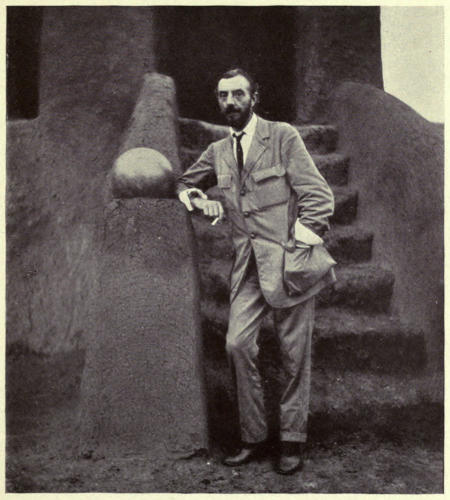

| Sir Frederick Lugard, D.S.O., First Governor of Northern Nigeria | ” | 92 |

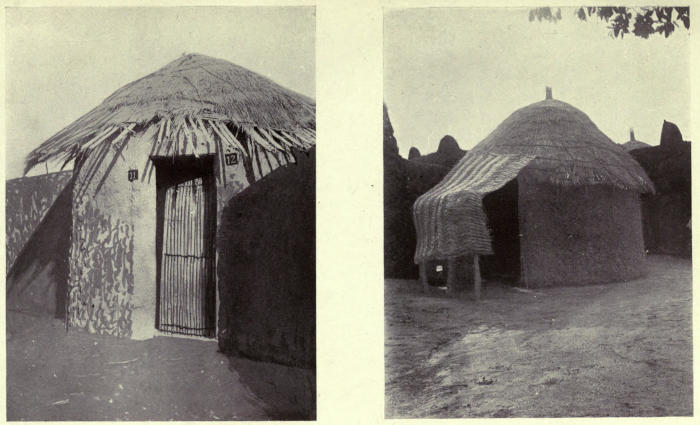

| Houses in Kano City. The cheapest type, rent 1s. 6d. a year | ” | 94 |

| Houses in Kano City. A detached dwelling, rent 1s. 9d. a year | ” | 94 |

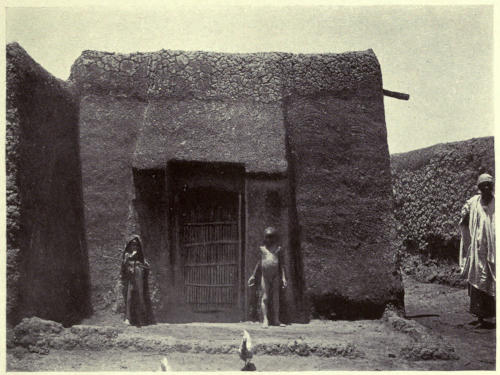

| House in Kano City, rent 2s. 6d. a year | ” | 96 |

| No. 1 Kano. The houses in the city are numbered to facilitate taxation | ” | 96 |

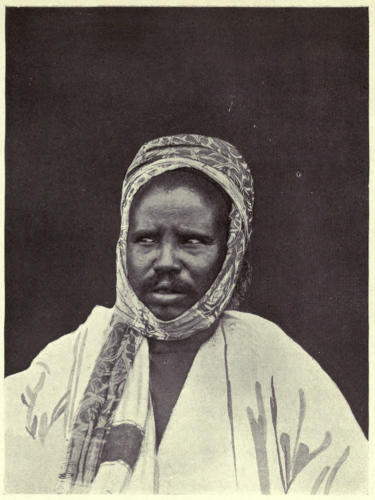

| An Arab Merchant who trades from the Shores of the Mediterranean to Kano | ” | 102 |

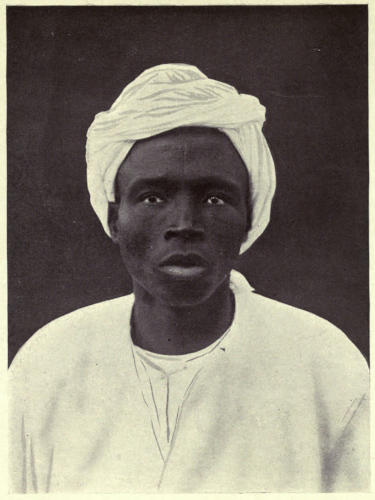

| Ex Sergt.-Major Dowdu, a Beri-Beri from Bornu | ” | 102 |

| The Magistrate’s Court in the Market. His worship is on the steps | ” | 108 |

| A Detachment of the Emir’s Police | ” | 108 |

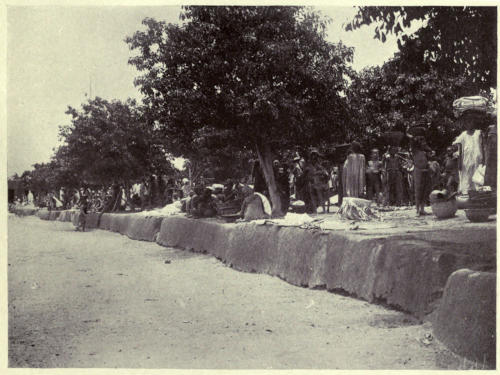

| A Corner of Kano Market. Note the stocks | ” | 112 |

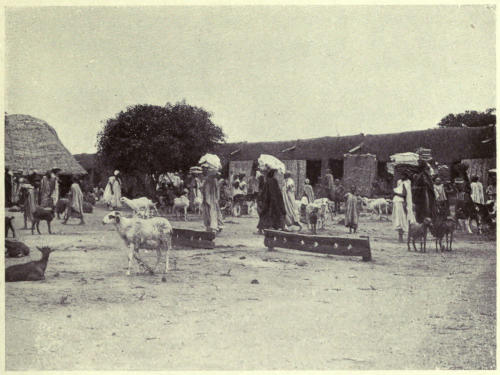

| A Section of the Market with Open-air Stalls | ” | 112 |

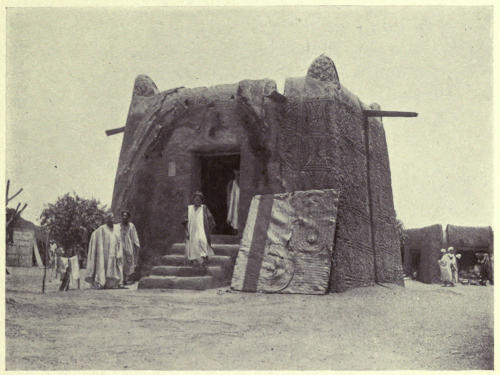

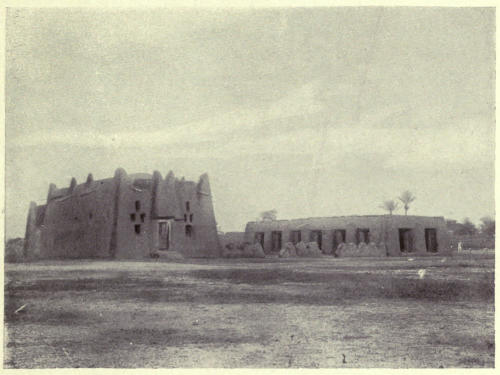

| The Principal Mosque | ” | 114 |

| An Entrance to the Courtyard of the Emir’s Palace | ” | 114 |

| The Royal Courts of Justice | ” | 116 |

| The Native Treasury, known as the Beit-el-Mal | ” | 116 |

| A Street in Kano | ” | 118[xxii] |

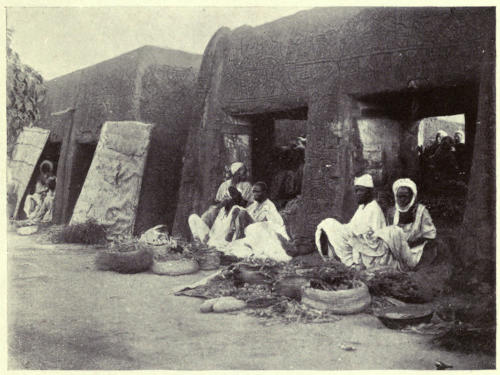

| Doctor’s Shop in the Market | ” | 118 |

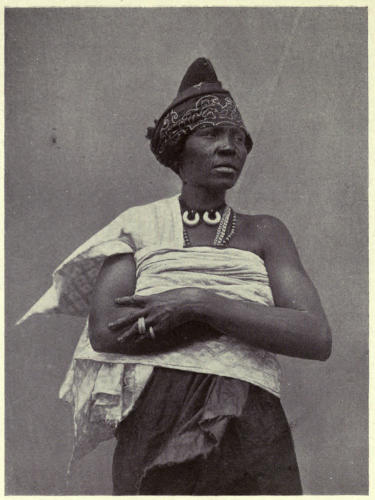

| Hausa Woman-trader. Her clothes are silk and her rings silver | ” | 120 |

| A Hausa Belle | ” | 120 |

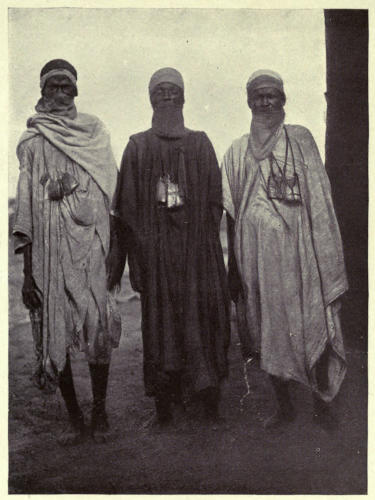

| Tureg Traders from Lake Chad. They are reformed robbers | ” | 122 |

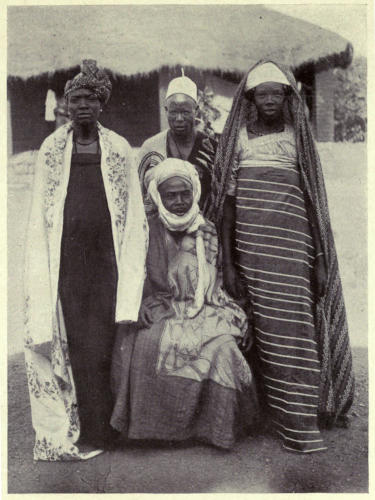

| Abigah (seated) and his Two Wives | ” | 122 |

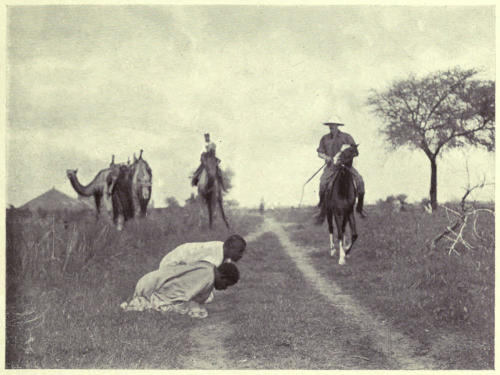

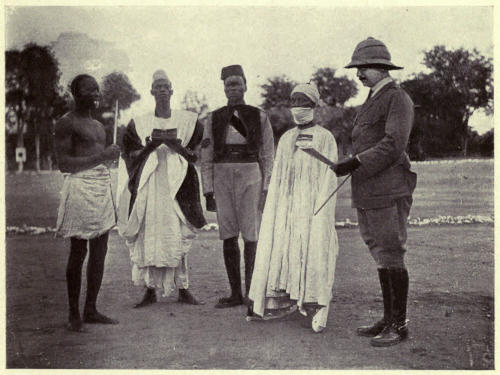

| “Zaki!”—Natives giving the usual salute to a white man | ” | 128 |

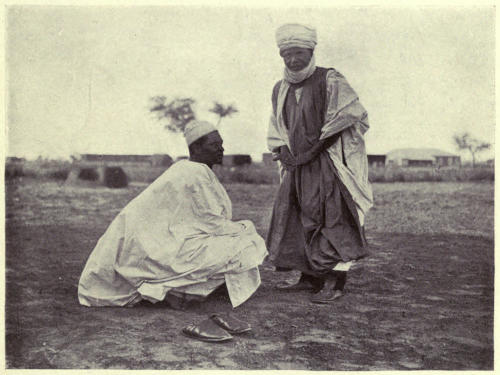

| Respect to the Aged is shown by removing the Shoes and Curtsying | ” | 128 |

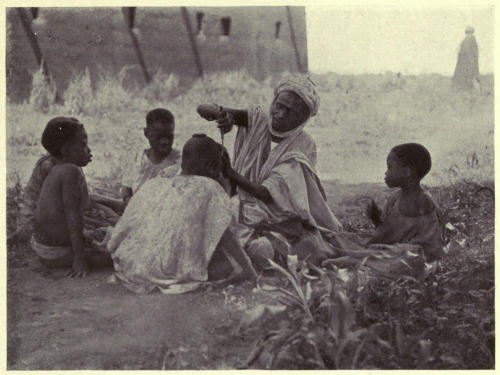

| The Religion of the Mohamedan forbids the use of soap, as it contains fat. Shaving therefore is done with the aid of water only | ” | 138 |

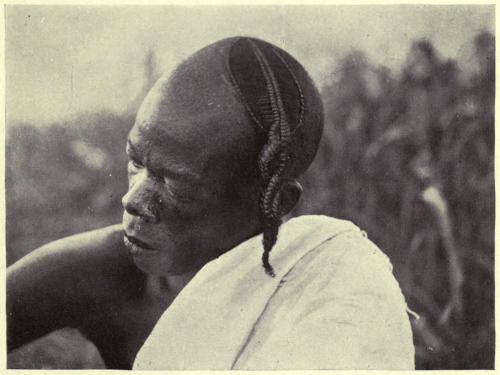

| Specimen of the Barber’s Art | ” | 138 |

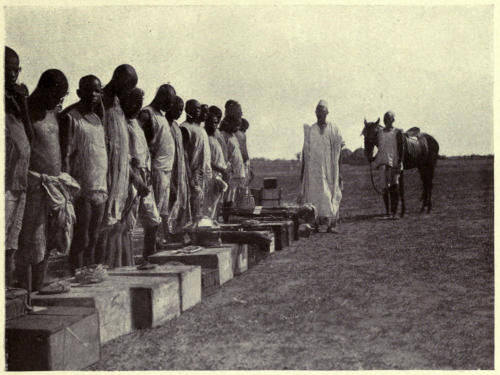

| Carriers ready to start | ” | 168 |

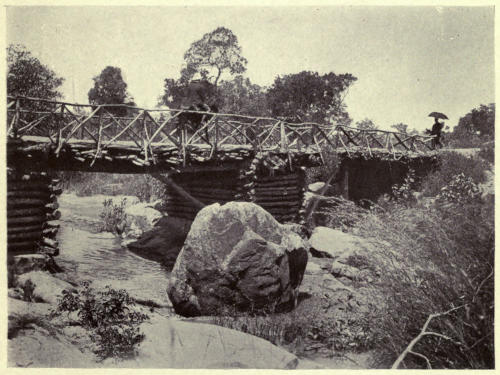

| A Bridge which is swept away by the stream each year during the wet season | ” | 168 |

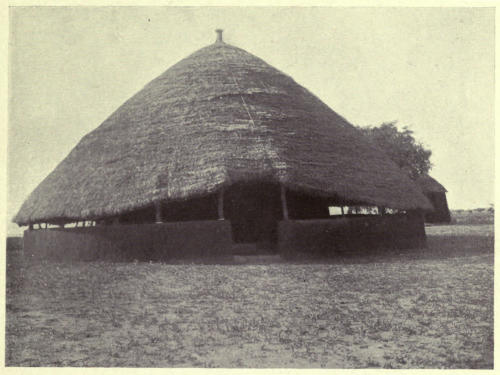

| A Government Rest-house | ” | 174 |

| The Headman’s House at Toro, where the Author slept | ” | 174 |

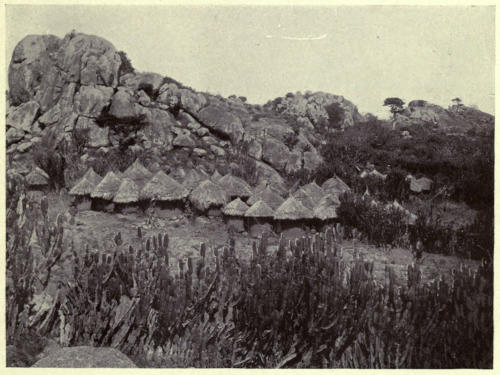

| Approach to a Pagan Town. A maze of impenetrable cactus | ” | 248 |

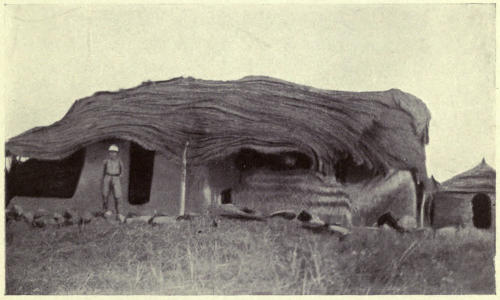

| A Pagan Homestead, built against a rock to prevent rear attacks | ” | 248 |

| Pagan Farmer using his only implement, a spade-hoe | ” | 250 |

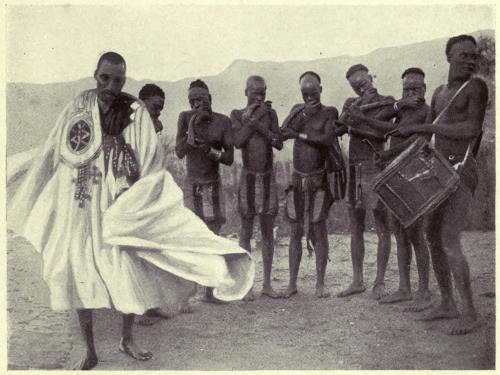

| The King of the Jarawa Pagans dancing in Honour of the Author’s Visit. The accompaniment is by his Court band in State uniform | ” | 250 |

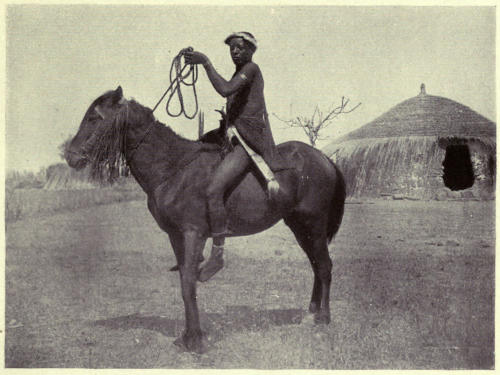

| A Naked Pagan riding his pony barebacked | ” | 256 |

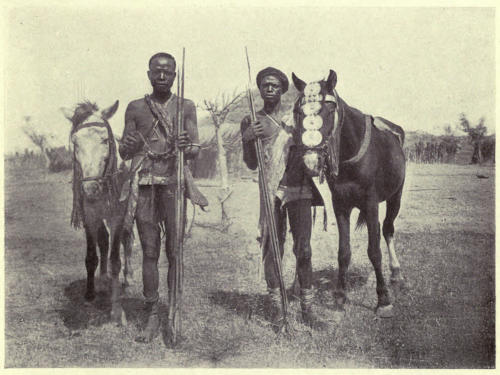

| Pagan Horsemen | ” | 256 |

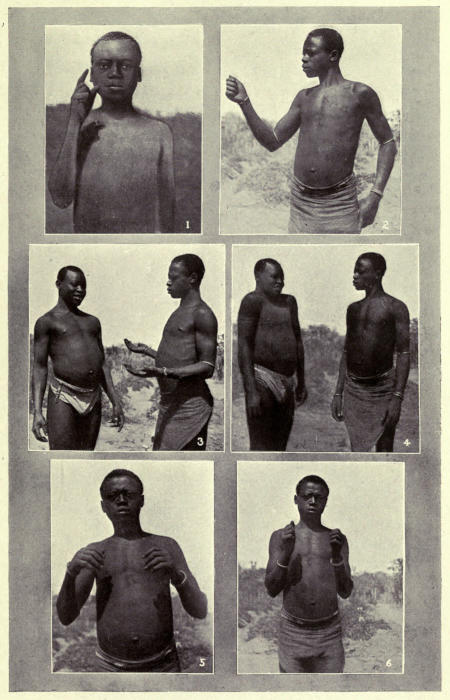

| Bukuru Sign Language | ” | 258 |

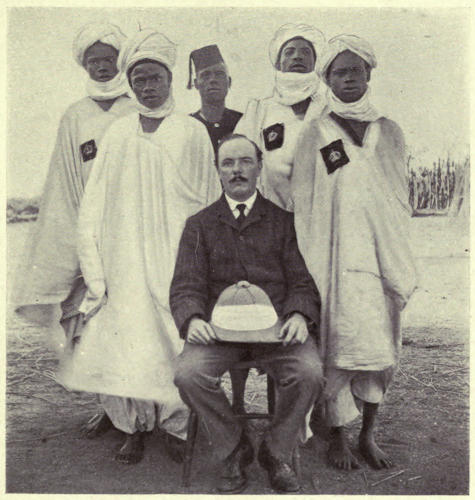

| Mr S. E. M. Stobart, the Resident at Bukuru, and His Staff | ” | 268 |

| Bukuru Residency | ” | 268 |

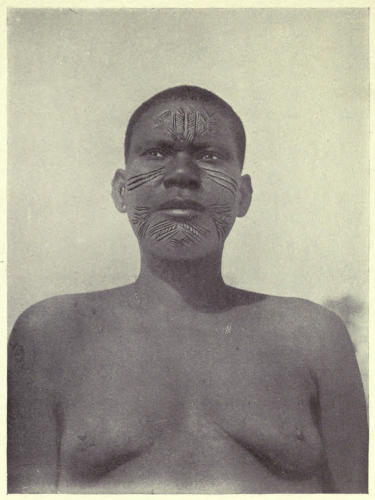

| Pagan Feminine Fashions | ” | 270 |

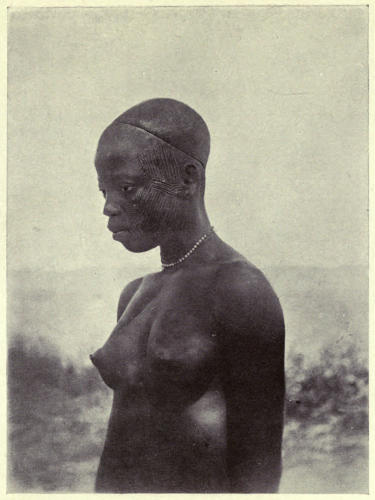

| A Pagan Beauty of the Dass Tribe | ” | 272 |

| A Girl of the Jarawa Tribe. The cuts in the face are made when she reaches the age of puberty | ” | 272[xxiii] |

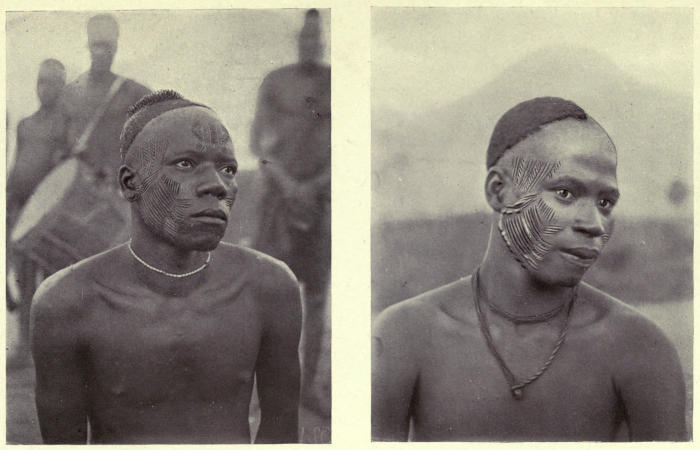

| Jarawa Pagans. The marks are produced by the flesh being cut and charcoal placed in the incision | ” | 276 |

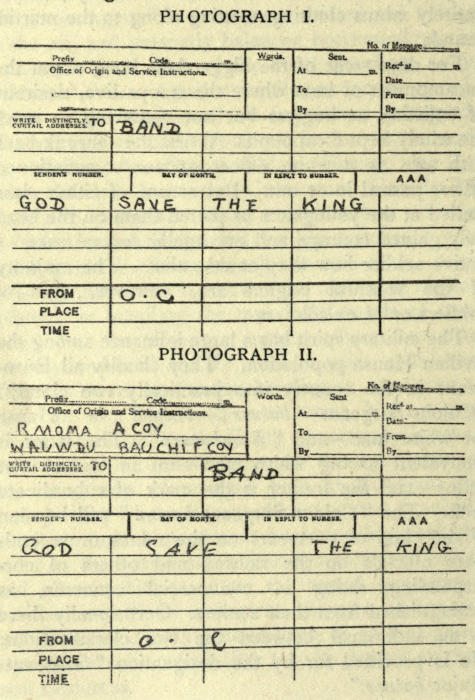

| Signalled message | Page | 290 |

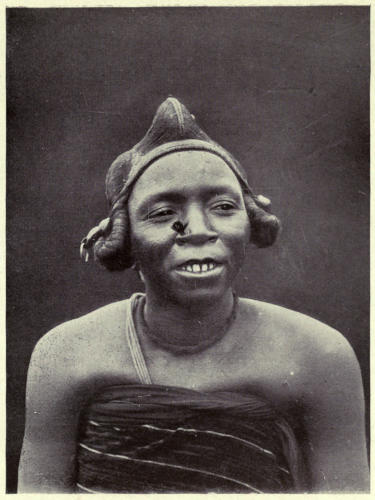

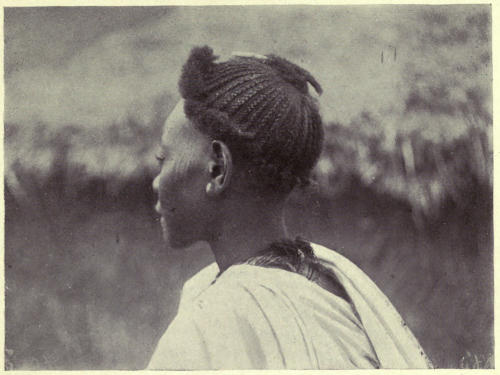

| A Beri-Beri Woman with an elaborate headdress | Facing page | 290 |

| Swearing in a Pagan and a Mohamedan for the Northern Nigeria Regiment | ” | 290 |

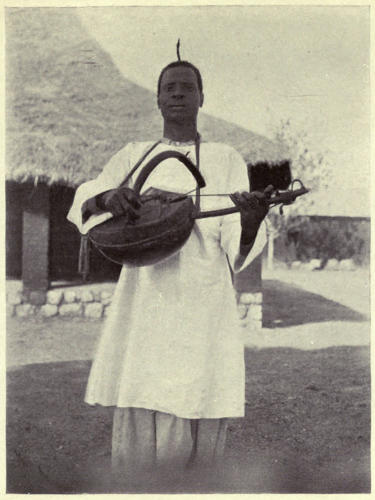

| Hausa Boy playing the molah, a kind of banjo | ” | 298 |

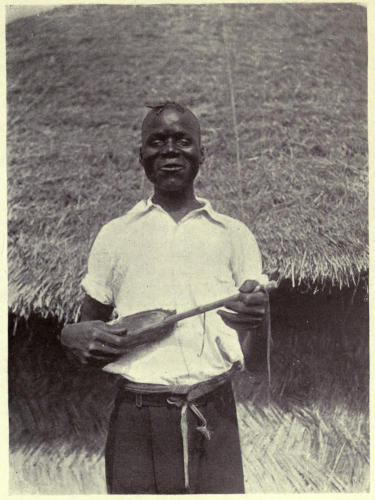

| Fiddle with Strings and Bow of Horse-hair rubbed with Gum | ” | 298 |

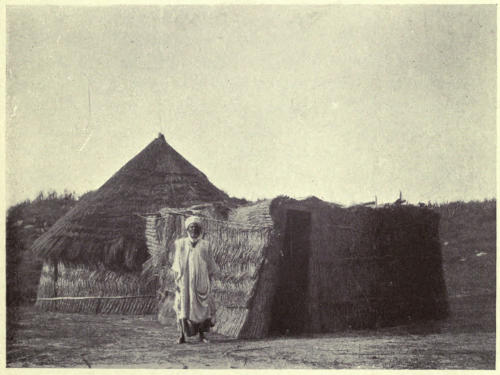

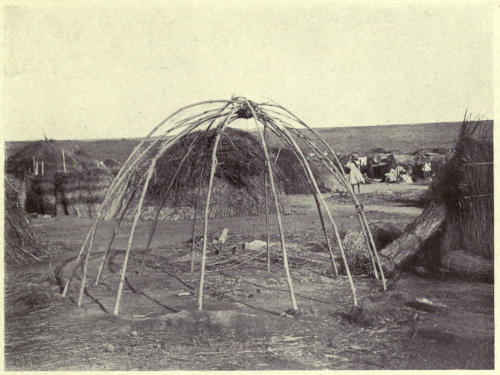

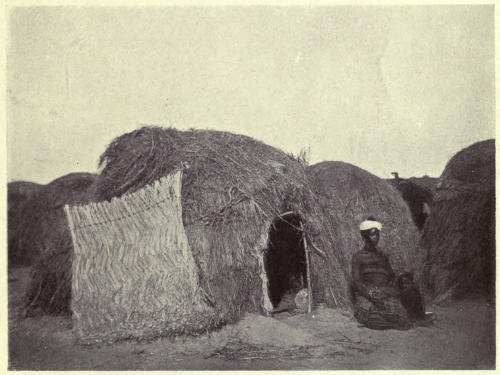

| Hausa House-Building with Grass. The foundation | ” | 310 |

| The Finished Mansion. It is put up, including cutting the grass, in a couple of hours | ” | 310 |

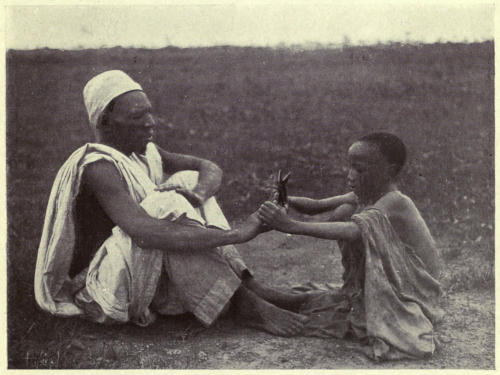

| Manicure. The fee is twenty cowries, i.e., about one-fourteenth of a penny | ” | 338 |

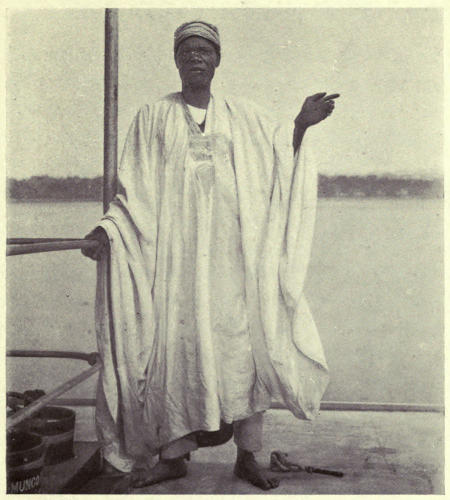

| A Nupé Pilot on the Niger | ” | 338 |

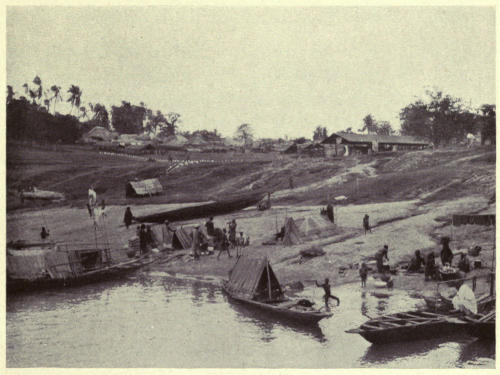

| A European Trading Station on the Niger | ” | 342 |

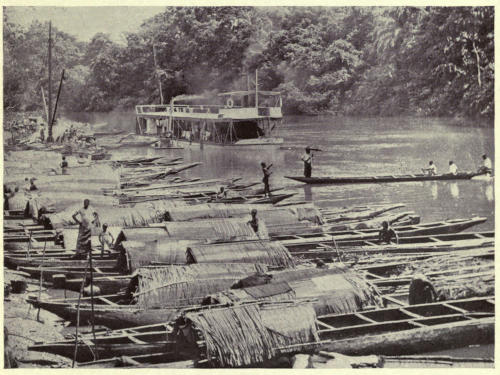

| On a Creek of the Niger | ” | 342 |

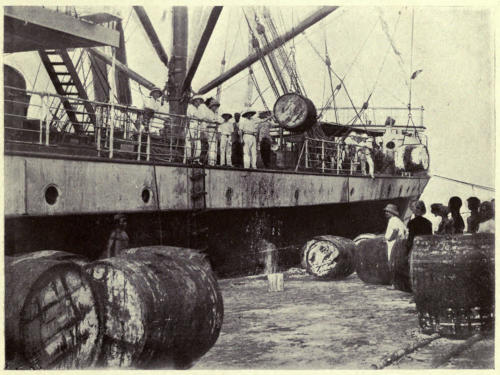

| The Niger Company’s Wharf at Burutu | ” | 348 |

| Shipping Palm-oil for Direct Transit to Liverpool | ” | 348 |

Call of the Coast—Mal-de-mer—Coasters afloat—From 78° to 90°—The Kru sailor—His civilised degeneration—Laundryman’s discipline—A dangerous stretch—The skipper—From ship to train.

What induces that mysterious, elusive “call to the Coast” to which few who have been to West Africa remain unresponsive? None deny its existence, even those who remain unaffected. Yet no conclusive answer has been given for a strange, fascinating attraction to revisit a part of the world which is regarded as uninviting. The “call” cannot be one of mere novelty, for it is only men and women who have lived in West Africa—perhaps suffered there—who are impelled to return, in spite of its drawbacks and talked-of risks, some real, some unduly and unnecessarily magnified.

Whether I felt the “call” strongly, overpoweringly, or merely preferred the country as a change to England has been tested. Not long ago my Editor enquired was I willing for a journey to[2] Egypt, with its splendid climate and the charm of looking on the land of Bible stories; he asked whether I cared for a trip through East Africa, with the delightful flora and fauna of a new colony. Neither attracted me. The mention of each created no eagerness. But when, one Wednesday afternoon, he called me into his room and spoke of West Africa I was all agog.

“You will be there in the rainy season,” he warned.

“I know, though I should prefer another period of the year; but do not ask anybody else if you wish me to go.”

“All right. When would you be ready to start?”

“From London next Tuesday if you urgently desire, but I should like a little longer, to fulfil a special engagement.”

The conversation took place at 2.30 p.m. By 5.30 the following afternoon everything had been settled.

Another prospective journey in West Africa filled me with delight, and no more blithesome soul stepped on the Elder Dempster liner Akabo the morning she left the Princes’ Quay at Liverpool.

A smooth course through the Irish Sea takes us next morning round Land’s End and across the mouth of the English Channel, which is in anything but a friendly mood; and, as usual on the second day out, the chronicler promptly goes into involuntary retirement. In previous similar experiences he had not troubled the ship’s doctor, but on the present occasion a slight trouble not yielding to the applications from his own medicine-case, he thinks it well to utilise skilled, professional treatment.

As promptly as if he were carrying out a three-guinea visit, Dr Hanington appears. A British Columbian with an exceedingly rapid delivery of words, before you have finished your explanation, not a look at tongue nor a touch at the pulse, he has darted out of the cabin and almost instantaneously returns, holding a tube of gelatine in the left hand and a tumbler of water in the other. You cannot gulp down drug and liquid and splutter or stammer your thanks in time for them to catch the swiftly disappearing doctor, who whilst you have been employed in the operation of swallowing has ejaculated, with a delightful Irish brogue, “That will put you right. You will be skipping about the deck to-morrow.”

Three times that day Dr Hanington came unsolicited to see the patient, the two later visits extending to interviews with conversations. They were of the bright, cheery kind, such as, “The Channel is always beastly. I am usually sick there myself. We shall be through the Bay to-morrow noon. It will be smoother than this choppy water”—a glance through the glass of the porthole—“and then you will be running along the promenade deck.” That seems a far-distant vision to the helpless victim of grievous mal-de-mer, though its manifestation is limited to intense headache.

Meanwhile prompt attention is forthcoming from the berth steward, W. Harrison. The measure of your suffering is indexed by your feed. The first morning of being down Harrison enters the cabin and asks tenderly, “What can I get you for breakfast, sir?” holding out a menu-card. “Don’t show me that” is the shuddering reply. The sight[4] certainly the thought, of it provokes an internal protest against food. “My stomach no fit for chop,” as the natives down the Coast would say. Anglise: “I cannot possibly eat.”

Midday Harrison appears in an enquiring attitude, “No, thank you; not now.”

The evening brings him again. The situation is slightly on the mend, for a few grapes are requested and a large bunch is sent in by the chief steward, Mr James Toner. Next morning there is a brighter outlook. Life appears worth living. Dry biscuits and grapes are readily asked for. The doctor makes a call, which is repeated a few hours later, and each time he insists, in his quick manner of expression, that the still-stricken patient is appreciably nearing the stage of tearing about the deck.

Lunch-time the menu-card, which Harrison on his calls has evidently been holding behind him, out of sight, no longer creates the former revulsion, and a little cold meat, mashed potatoes and biscuits are selected. The fulfilment of the doctor’s prophecy still, however, feels a long way off, but he urges the powers of the sea, the fresh air and the breeze, adding that “the close breathing in a cabin gives as much trouble as the rolling waves.”

Two efforts were made to dress. They had to be abandoned. The prone position was the only one endurable. An hour or two and a third endeavour. Very laboured was each stage of the toilet. There were strong indications that internal influences would prevail. Fortunately the perpendicular balance was maintained until the last touch had been given, and then a washed-out looking object crawled upstairs and huddled itself in a deck chair. Dr Hanington’s[5] declaration was not as far removed from justification, after all, for the fresh air proved wonderfully recuperative, and by the following morning the patient was, like Richard, himself again. It was the shortest of his many terms of mal-de-mer, the limited span entirely due to the excellent doctor of the Akabo.

Now there is opportunity to look at one’s surroundings. We have not many trippers aboard. Half-a-dozen for the Canary Islands. The rest are Coasters, the term given to men employed in West Africa, either in the Government service or in commercial concerns. Some are going out for the first time; others have served many years and are returning after the home leave which is given at the close of every twelve months, eighteen months, or two years, according to the agreement. Government men are allowed four months in England, on full pay, for every twelve spent in West Africa. It sounds pleasant and easy, but, although marvels have been wrought in the health statistics by the discoveries of Manson, Ross and Boyce on the transmission of malarial fever; and the splendid medical staff in the colonies, with the hospital Sisters, have multiplied many times the chances of life, still, under the best conditions the climate must remain a trying one, and an unduly long sojourn in it is likely to undermine the constitution of the strongest.

Contact with another civilisation, or years passed in places where there is none, has not made coarse the tender chord of sentiment in these outward-bound Coasters. Look in at their cabins and you will frequently discover the framed photograph of[6] a female figure and perhaps the voyager in front of it, bent, writing. Possibly the original in some English home is similarly occupied towards this direction.

It must not be assumed, however, that people whose days are spent in West Africa have a more serious view of life than the rest of mankind. As a body, they are a happy, light-hearted community, with the colonial spirit of good-fellowship. No fears of the unhealthiness of the climate affect them. If fever or worse is to come, time enough when it puts in an appearance. They are not men to meet trouble half-way. Part of the battle in warding off climatic disease is not to think of it. They act on that principle. Whether as Government officials or those associated with mining or commerce, nearly all are physically above the corresponding class in Europe.

One quickly realises why the men are the few chosen from the many called. They have been selected with care. There is no place for wasters in West Africa, either from the health or the business aspect. A few may get there. They are soon found out. In recruiting their staffs the trading firms select those likely to justify the expense of being sent. The salary to be earned as an “agent”—manager of a store—attracts persons who have not the opportunities in England which present themselves in West Africa. There are drawbacks, but the recompense is not small for a man who can make his way. Everybody must weigh the pros and cons for himself.

A sharp change of temperature occurs as we pass Cape Verde, nine days out. A little beyond this[7] point is the great Gambia River, which comes out heated by the scorching winds of the Sahara Desert, and at the mouth of the river there are also flowing up towards us warm currents from the south. It is not uncommon for hardy voyagers to be weakened and temporarily knocked over by the sudden rise of temperature. These are the figures we experience:

Thursday 10 a.m. 72° off Cape Blanco.

Friday 10 a.m. 78° approaching Cape Verde.

Saturday 10 a.m. 82°.

Saturday 4.40 p.m. 86° in a well-ventilated cabin with an electrical fan running.

Saturday 4.40 p.m. 90° on deck of the ship at full speed, under a stout awning.

At Sierra Leone—eleven days from Liverpool—the ship’s company is augmented by a number of Kru sailors, who proceed to a spring-cleaning with a zest and enjoyment unmistakable.

The Kruman is the seaman of West Africa. His villages are on the seashore. He is put in the water and made to swim from babyhood. He can be seen coming to a ship, on rough, rolling waves, in a frail canoe crudely cut or burnt out from the trunk of a soft-wood tree. A couple of small boys will paddle such a canoe two or three miles out to sea. At certain parts of the Coast the lads dive for coppers thrown from an anchored vessel, and do it as unconcernedly as though they were in a calm river instead of a place frequented by sharks. Yet no fatalities are known, which is probably due to the noise the youngsters make. Should a shark be espied hovering near, several of the boys will even swim towards it, shouting, yelling, and splashing, and the brute, who is a coward, slips away.

At Axim, Gold Coast, three days beyond Sierra Leone, a further complement of Krumen are shipped. Each batch is of a different tribe. That from Sierra Leone consists of Nana Krus; at Axim they have come from the Beri-Beri country, on the French Grain Coast. Some years ago they clandestinely left French territory, where they were compelled to labour on public works, and founded a small settlement near Axim, for the purpose of serving on British ships. At one time the French prevented shipment from their own shore unless at a tax per man, but now there is no objection to enlistment at recognised ports of entry. Krus who have made homes in the British sphere prefer to remain there.

Considerable difference is noticeable between the two tribes mentioned. The Nanas are greatly inferior in physique and stamina. The degeneration is due to evils resulting from the “civilisation” to be found in certain districts of Sierra Leone. The Beri-Beris, who have been freer from these influences, are a much better type. In a set period, fifteen of the latter will do more work, with less effort, than can be carried out by twenty-five of the former in the same time.

Each body of Krus is under its own Headman, who will be either a village Chief or appointed by the Captain of the ship. The Headman can usually be relied upon to keep his folks up to the mark. He receives instructions from the officers as to what is required. They leave him to have it done, and, as a rule, it is sure to be done well. The Headman is given tea and other small luxuries, in addition to the usual rations of rice and fish, and he is allowed[9] to bring a small boy, usually his son, to assist him in cooking.

At Sierra Leone there has also come on board the black laundryman and his “boys,” who deal with passengers’ linen. It is not turned out in the finished style of a first-class establishment in England, but what is lacking in other respects is made up by very liberal starching. A couple of collars feel they could support an anchor.

The laundryman frequently walks round with a broom. The article is not for professional use in connection with the tub; the handle is utilised for gentle persuasion and is applied to the cranium of the delinquent who needs stimulus or correction. When applied, the thwack can be heard many yards distant and is only rivalled in sound by the ship’s siren. A thin skull would be crushed by such a blow. The “boy” who receives one shakes it off as nothing, and sometimes gets a succession of them for laughing at the first. There is “Home Rule all round” for the various black departments of the vessel, and he is a wise man who does not attempt to interfere with local customs and usage.

The night after leaving Sierra Leone we are passing the Kru Coast, Liberia, probably the most uncertain and dangerous four hundred miles stretch along West Africa, because of the outlying rocks and reefs and the irregular insetting currents. Except at Monrovia, Grand Bassa and Cape Palmas, and even there the lights are of minor power, no illuminations or beacons mark the dangers. Often without warning the currents set towards the land. No precautions on the ship are considered[10] superfluous. The deep-sea lead is cast at not longer intervals than every four hours, and anybody who owing to the heat has made his bed on deck and is awake may see the figure of the Captain frequently flit from his cabin during the night to join the officer on watch on the bridge.

When we are in calmer waters and the dark night has shut out surroundings and made us feel we are a little world to ourselves, we are now and again reminded of the vigilance maintained for our safety, as the look-out sings to the officer of the watch, “Light on the starboard bow, sir,” and you see, miles away on your right front, a small gleaming lamp which tells of another ship on these trackless areas. And if the officer of the watch is in light mood you may hear him humming the doggerel of the “rule of the road” at sea:

Skippers of these West African liners become well known to the voyagers who pass backwards and forwards at regular intervals, and it is my good fortune to sail with one of the most popular of them. The manner Captain Pooley is regarded by travellers may be gauged from the fact that three on this journey are making the third voyage designedly on[11] his ship and another had altered the date of starting by a fortnight to again be with him.

Twenty years along the West Coast of Africa and among its native population has not dulled the sympathy of Captain Pooley towards that race. All that can possibly be done for the deck passengers, taken on at the various ports, is effected. Canvas awnings are put up to protect the men “and especially the women and babies,” as he explains, from the downpours of the wet season.

The skipper is a storehouse of stories about the Krumen. He tells a tale related by a fellow Captain against himself. He was carrying two white, Rotterdam hogs to the Oil Rivers and noticed one of his Kru sailors seated on the ground, gazing into the pen where the animals were kept. Placing his hand on the Kruman’s woolly pate, he said, “Hullo, my frien’, you look your brudder, eh?”

Turning his face upwards the Kruman answered, “Massa Capin, he no be my brudder,” adding, with a twinkle, “he be white.”

Secondee, Cape Coast and Accra are the further ports at which stops are made, and at 7 a.m. on the sixteenth day from leaving Liverpool we are at anchor about four miles off Lagos, the capital of Southern Nigeria. Passengers going up-country tranship to a branch steamer of about eight hundred tons which takes them over the sand-bar, which the liner cannot pass, and across the large lagoon, depositing them at Iddo Wharf, the railway terminus.

Iddo Wharf—Strange sights and thoughts—Umbrellas—“Niggers”—Train luxuries—Liquor permits—The iron-horse at the Niger—Ferry and bridge—Budget details.

Passing the length of the lagoon—a mile wide at its broadest point—leaving the town of Lagos, with its busy wharves and crowded streets, on his right, less than an hour’s steaming from the Roads and the traveller is at Iddo Wharf. The train is drawn up near the water, and passengers walk a few steps from marine to land locomotion.

Strange sights appear to the traveller as he stands at Iddo Wharf. The strangest—or the strangest thought—of all is that there should be a train running in West Africa on which there is every reasonable comfort and luxury, and that this train should be in existence—the first of its kind in this part of the world—a few months after the extension of the line had been opened. First, however, a word or two on the surroundings at the terminus.

The train leaves at 9 p.m. on whatever day the ocean ship arrives. The vessel is due in the morning, but people have not the inconvenience of loafing about a strange town for hours. The boat train is an ark, available all day as a resting-place[13] for the sole of the foot. All its resources for meals can at once be utilised.

By nightfall most of the luggage will have been stowed in the vans. A few late arrivals, perhaps persons who have not come by the ship, will be having their belongings attended to. Black wharf labourers, who have been working late and are going home, put their umbrellas on the ground in order to give a hand in packing the vans. These labourers, whose attire is usually like that of the Wandering Minstrel in “The Mikado,” “a thing of shreds and patches,” almost to a man carry an umbrella as they go home o’ nights—bless you! not for protection against rain, but as an article of adornment. It is as much a matter of course with them as the clay pipe and the cloth cap are with their counterpart in Great Britain. Different countries, different customs.

Nearly all the other officials at Iddo Wharf are also indigenous West Africans—clerks, inspectors, foremen, porters. There are as many grades and degrees of education among any one Coast people as there are with our folks in Europe. Were this fact always recognised and remembered, perhaps a little more tact might be exercised by individuals who regard all black men as “niggers” and suit their actions to the word. I stand as no apologist for the smatteringly-educated native, who dressed in uniform takes up an attitude truculent and offensive towards white men. It is British policy and systems of education which are responsible.

There is also at Iddo Wharf at least one first-class, white railway official on duty to attend to any matter requiring his attention.

The train usually consists of eight coaches, some of them fifty feet long, and therefore easy running at the fairly high speed over certain portions of the line. Meals are served en route, and every attention is received from the inspector of restaurant cars, who was formerly a chief steward in the Elder Dempster fleet. In the course of the journey I witnessed his solicitude, and that of the European head guard, Cyril Richards, for passengers who were not well and unable to take the table meals. The inspector, whose name I regret to have mislaid, had light food brought instead, the charge for which was, in instances, less than a quarter that of the regular menu. Perhaps the action does not appear surprising, but it means a deal in a country where a man feels weak and knows he has little margin of strength to withstand the effect of the climate.[1]

The term sleeping saloon means provision of bed, blankets, and linen. Couches are fitted for rest during the day. Electric light is in all compartments, which are provided with electrically-driven fans and have mosquito-proof windows. Shower baths are another luxury for which there is no extra payment. No doubt it all sounds prosaic enough to the trotter across the European continent. Let him “pad the hoof” in the tropics, or so much as be in an ordinary West African train for several days where he is entirely “on his own,” with a temperature ranging from 90 degrees to 112 degrees in the shade, or with the Harmattan winds bringing[15] scorching dust into his ears, nostrils and the pores of his skin, covering every mouthful before it can enter that avenue. Should he have experienced these things, have a memory, and is inclined to gratitude, then he will take off his hat to the Administration of the Lagos Government Railway, if he does not go so far as to be Biblically impelled and rise up and call the work of their hands blessed.

The traveller wakes for early morning tea to find himself traversing the palm belt. There is a continuous line of the tall, thin, bare trunks, surmounted by the graceful, drooping palms beneath which cluster the kernels which are the main wealth of Southern Nigeria. Palm kernels and palm oil are to Southern Nigeria what coal is to England. There are rumours that that mineral has been located on the lower Niger. Possibly I may be able to say something on the subject as I come down the river on the return journey.

Running through at night, several features of interest are unseen, prominent among them the exceptionally pretty view towards the Sacred Hill at Olokemeji and Ibadan, the largest town in West Africa, though not nearly so frequently spoken of as the much smaller ones of Zaria, Bida, Sokoto and Kano. Each has had the advertisement of war.

A short stop for water—not the first—is made at 6.45 a.m. at Oshogbo, 187 miles from Lagos, and still one of the hopes of the British Cotton Growing Association. Little more than an hour later the line enters Northern Nigeria. At Offa, the station over the frontier, permits have to be shown to take[16] wines or spirits into the Mohamedan land, even for personal consumption. We are now 1,500 feet above sea level.

Jebba, 306 miles, is reached at noon, and here one of the stiff difficulties of railway construction which faced the engineers can be seen. The Niger must be crossed. The easiest way of doing so is from the south mainland to a large island, thence to the north mainland. The south channel is 1,100 feet broad, the north one rather less. The latter has been bridged; the former is still under that operation, which will not be finished for two years, making three in all.

The length across the river is the least of the obstacles to be solved. Heavy rises and falls of the water—in a month it may alter from 15 feet to 50 feet—made the work not only hard and hazardous, but impossible at certain periods of the year. But with hundreds of miles of rail completed south and north last November, it would have been an exasperating position to have to wait a further two and a half years for through connection. A civil engineer will tell you that nothing on earth is impossible. It is only a matter of money and time.

Well, the same train which carries you from Lagos to its destination at Minna, 161 miles beyond Jebba, covers its course without the traveller having to leave his carriage. The train goes over the Niger by means of a ferry. That, however, is itself a difficult subject by reason of the varying height of the river. The question at issue was how to transport weights, too heavy to be safely lifted, from a fixed level to an alternating one.

The carriages are run to the head of an inclined plane and a wire rope fastened to each coach, the other end encircling a winding drum. Another rope bound to the further end of the carriage draws it on the slope of the plane, and the winding machine lets it down. The plane carries the carriages to a trolly bridge resting on the river, and rising and falling with it. The trolly bridge fits to a steam ferry which bears four carriages, so that the entire train is taken over in two journeys. At Jebba Island the reverse process is followed, and a freight engine being coupled up the train proceeds over the north channel bridge and thus onwards.

Kooty-Wenji should be made by daylight, and there a halt is made till next morning, as the line has not yet been ballasted, and is therefore not safe to be used at night.

At 6 a.m. the train is again on the move, and in less than an hour-and-a-half we draw up at Zungeru, 430 miles from Lagos. The course has been covered in thirty-six hours. A week later the boat train attained a record by doing the journey in twenty-four hours.

I am making a short stay at Zungeru; but perhaps it will make a better connected narrative if a few additional railway particulars are given now. Midday the train leaves for Minna, which is its destination. A journey straight ahead can be made by ordinary train to Kano, 282 miles from Zungeru. The traveller for the tin fields in the Bauchi and the Nassarawa Provinces will alight at Zaria, 90 miles south of Kano. From Zaria, the Bauchi Light Railway will in seven hours take him the 88½ miles to Rahama railhead.

Appended are the through fares by the boat train, including sleeping accommodation and attendance:

| £ | s. | d. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagos to | Ibadan | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| ” ” | Zungeru | 6 | 7 | 3 |

| ” ” | Zaria | 8 | 12 | 4 |

| ” ” | Rahama | 9 | 14 | 7 |

| ” ” | Kano | 9 | 14 | 10 |

First-class passengers by the boat train are allowed the following weight of luggage, excess of which is placed at heavier rates:

| 2 | cwts. | free. | |||||

| 20 | ” | at | 7s. | 2d. | per cwt. | to Zungeru. | |

| 20 | ” | at | 9s. | 3d. | ” ” | to Zaria. | |

| 20 | ” | at | 9s. | 11d. | ” ” | to Kano. | |

| Additional | 20 | ” | at | 10s. | 6d. | ” ” | to Zungeru. |

| ” | 20 | ” | at | 13s. | 6d. | ” ” | to Zaria. |

| ” | 20 | ” | at | 14s. | 6d. | ” ” | to Kano. |

Meals are charged: early morning tea, 6d.; breakfast, 2s.; lunch, 3s.; afternoon tea, 1s.; dinner, 4s. 6d.

Doubtless very mundane details, but useful to the man who desires to know before setting forth from Europe how he is to fare financially in small matters.

A garden-city Capital—“Ikey” square—Autocracy thorough—Circumscribed accommodation and doubled-up quarters—Young administrators—Strict, stern, severe economy—The Governor’s “Palace”—Job-lot furniture—His Excellency’s 1s.-an-hour, Bank-Holiday motor-car—Pooh-Bah Cantonment magistrate.

I expected to find Zungeru a town more or less roughly divided into official, business and residential quarters, with clearly-defined and named roads and thoroughfares. The Capital of Northern Nigeria—the administrative headquarters—is, however, a city in a garden; and a very small city at that, probably the smallest in existence, much smaller than Monrovia, the Capital of the Republic of Liberia.

Still, power is seated at Zungeru—power strong, clear, absolute. The Governor of Northern Nigeria is given fuller authority over the people and the country than is in the hands of the Kaiser of Germany or the Czar of Russia. Without giving a reason he can decide questions of life and death; cancel a lease held by European or native; deny entry of or expel white or black; make law by simply issuing a Proclamation. He has not even a nominated Legislative Council, as in Crown Colonies. The form of government for natives in Northern Nigeria will be dealt with in a separate chapter.

Zungeru consists of a few bungalows dotted irregularly amidst trees in open grass and bush country. The roads, made by the Public Works Department, are very good: gravel, 10 to 30 feet wide and excellent for cyclists. The thoroughfares are all unnamed. You do not say that you live at such-and-such a house in such-and-such a road, or avenue, or street, but that your address is number one, two, or three, or any other number, as the case may be, Zungeru.

One point must not be included in this generalisation. Leaving out the Secretariat, five of the principal Government buildings face the same centre, and are designated by the natives Aiki—pronounced Ikey—Square. Aiki is the Hausa word for work, and the name therefore means “the place where the work is done.” Gratifying to the persons whose hours are spent there.

Certainly there is an official quarter, but it comprises the whole of the town, with the exception of the Niger Company’s store, and the native village, which is a recent creation. Midway between the two points are the native clerks’ houses. Distinct from all the places stated are the military lines and the police barracks. That, in outline, is the story of Zungeru to-day.

It is ten years old, and previous to the advent of the British, in 1901, was scarcely a “geographical expression,” for few maps gave the place. The population is made up of seventy officials, two hundred native officials, and four white members of the staff of the Niger Company and the Bank of Nigeria.

The extension of the Lagos Railway from Jebba[21] to Kano via Zungeru last January has brought the last-named within two days of the sea, instead of between three and four weeks, according to the state of the rivers. But the character of Zungeru is unchanged, and is likely to remain so. There is no prospect within sight of its becoming a city or even a town, as understood in Europe. More passengers may pass up and down the line, for commercial or other reasons, than formally travelled through, and a number of individuals may consider it necessary to come to Zungeru to see Government officials about mining matters—though the total of these is not likely to be large, as the Government Inspector of Mines, who advises the Governor, is located at Naraguta—but there is nothing at present to indicate an appreciable influx of population to Zungeru.

Let there be no mistake about the accommodation in Zungeru. It is extremely limited. If anybody thinks to arrive by train and “roll off” to an hotel he will be grievously disappointed. Only in one town of Southern and Northern Nigeria—territory 333,300 square miles in extent—is there an hotel. That is at Lagos. Men come without previous notice or inquiry to Zungeru and expect provision to be made in the way of board and lodging. It simply cannot be done. Bungalows are few and nearly all are overcrowded, from Government House down. The Chief Secretary to the Government, the Chief Justice, the Attorney-General, the Commandant, the Treasurer, the Director of Public Works, the Principal Medical Officer, the Chief Transport Officer, the Inspector-General of Police, and the Commissioner of Police alone have separate[22] housing, very circumscribed. The rest of the Government staff are “doubled-up,” i.e., two men to every three-roomed bungalow. As matters stand, there are not sufficient bungalows to go round even on this plan. It is not uncommon for an official to be moved from one to another as a man returns to duty, just finding room where somebody is going on vacation.

Four rest-houses are provided for visitors staying temporarily. The structures are rather primitive, of dried mud walls and thatched roofs. The stranger within the gates must bring all his daily requirements with him: bed, table, chair, cooking utensils, groceries, etc. Fresh meat can be bought in the native market at certain hours of the day.

Happy in the enjoyment of hospitality at a large private house, I felt quite a twinge of unworthiness at going to interview at one of these rest-houses a President of Chamber of Mines, Colonel Judd, who in England probably dines at the Carlton, the Ritz, or the Midland Grand, and who, even in Northern Nigeria, wearing a bush shirt, was still spruce, with a gold-rimmed monocle. A dozen people would have been glad to pay him the compliment of an invitation as guest, but there was simply no room in Zungeru where he could be placed. Colonel Judd was the least concerned of anybody. He expressed himself as quite content, and told me, as we both sat on the arm-rests of the single deck-chair available, that he had had to put up with much worse places in the course of his journey and that I would be fortunate to get as good in the areas I shall shortly cross.

These four rest-houses are frequently all occupied[23] to the fullest extent. The advent of a stranger, perhaps bent on business with a Government department, creates a painful situation.

Everything in Zungeru has been done on the lowest price scale, which is perhaps not the cheapest. From the first, Northern Nigeria has been short of funds. The Imperial grant-in-aid was kept down to a minimum, and that minimum much less than it should be in justice to the men who serve here at great risk to life and health. Not a penny has been spent that could be avoided. With the exception of the railway bungalows, which are of brick, but for which rich Southern Nigeria paid, all the others are of wood which has been exposed to a wasting climate for ten years. Several are in a dilapidated condition. They are occupied by men holding high posts whose work is essential to the administration, the finances, and the peace of the country; yet we make them live in dwellings—there are none other—which are a daily challenge to health and provocation to disease. This is not economy; it is gambling with men’s lives for the sake of a miserable few shillings capital outlay. Sanitary housing—houses of the proper material and with ample air and protection against the insect and accompanying pests of the land—is second only to good food in keeping “fit.” It is high time the necessary measures were carried out.

Excuses have been made for the situation. The future of Zungeru is uncertain as the Capital of the Protectorate. I will deal with that as a separate question. On the ground that the Capital may eventually be located elsewhere, the word went forth five years ago that no further building was to[24] take place beyond what was absolutely necessary. It is only what is absolutely necessary that I advocate.

The high invaliding and death-rate which formerly obtained amongst officials in Northern Nigeria is to be attributed to the bad housing to which they have been subjected. The rate has lowered greatly. But too strong a deduction should not be drawn from the latest figures. An unhealthy station may enjoy long immunity. Tropical illnesses will not always arrange their appearance in the arbitrary terms of twelve months. To facilitate statistical argument, they more frequently rise and fall in a cycle of years. Let the proper steps be taken in Zungeru before the old high percentage of mortality reasserts itself.

Northern Nigeria is a country of and for young men.

The Postmaster-General strikes you as a fair-haired boy of twenty-two. He tells you, with pride, he is “much older than that.” He is thirty-two. The Acting Chief Justice is no “potent, grave, and reverend seigneur,” but is of an age when in England he would probably be fulfilling the rôle of “devil” to a leader in the High Court. The cool, clear-headed, and obviously capable officer temporarily in command of the 1st Battalion (1,314 men) Northern Nigeria Regiment, Captain G. C. Kelly, would, elsewhere, in these days of slow promotion, be lucky to have got his company. His colleague in charge of the battery of four light guns, Captain C. F. S. Maclaverty, could not hope to discharge anything like that responsibility at home. The Deputy Director of Railways, under the famous[25] John Eaglesome, might pass as a youth who had not long finished his articles.

Those at the head of affairs are not much older in years. I do not venture to ask the Acting Governor his age, and there is no “Who’s Who” within reach, but I should judge Mr C. L. Temple, C.M.G., to be on this side of forty; and the next in rank, the Acting Chief Secretary, Mr H. S. Goldsmith, who recently temporarily carried out the duties of the highest position—with absolute rule over a territory containing 10,000,000 inhabitants—is, I learn from a friend, thirty-eight.

He started thirteen years ago, when Northern Nigeria was taken over by the Crown from the Niger Company. He began, as there was urgent demand for getting the administrative machinery into working order, in a very junior post in the Protectorate. In the course of his first year he had to give help wherever it was most pressing, going from one office to another: Stores, Transport, Treasury, and the Marine Department. All his willingness and eagerness were not wasted. Although seemingly unnoticed at the time, it marked out the kind of officer Sir Frederick Lugard wanted. In the last birthday honours list Herbert Symond Goldsmith, Acting Chief Secretary to the Government of Northern Nigeria, received a C.M.G.

Yes, the country has still opportunities for the man who is ready and keen. But it is not the place where “the lotus life” can be lived. The tradition of plenty of work and responsibility which Lugard established still obtains. Government office hours end at 2 p.m., with an hour’s interval from nine to ten for breakfast. But they start early, and you[26] may be startled at first at finding that an appointment for which you asked has been fixed for 7 a.m.

The time for official hours does not mean that it is a case of “down tools” as the clock points. I have found the Chief Secretary still hard at his duties at 5.30 in the afternoon, and one Sunday morning, when I went to see Captain Kelly at his bungalow, I learnt that he was closely engaged at the Brigade Office on a defence scheme.

The Secretariat has only a few constituting the personnel, nothing like the number one might look for at the Capital of such a large and well-populated territory. In Northern Nigeria the Government is greatly decentralised. Wide discretion is left to the Residents, who in some distant and not easily accessible places, such as Bornu and Sokoto, occupy the position of well-nigh sovereign kinglets. Further, actual and daily rule is left to the hereditary Emirs of the Provinces, subject to the advice and guidance, when necessary, of the Residents.

Another cause of the limited staff at the Secretariat is that in Northern Nigeria strict, stern, severe economy remains the order of the hour. There is evidence of it all round. The Secretariat is a poor building indeed. Bare brick whitewashed walls and cement floor crumbling in places, and in others worn into holes. Not a roll-top desk or anything approaching it in the place. Old, plain wooden tables, and, at the farther edge of each, roughly-made pigeon-holes. By way of contrast, the tables are of a light colour and the pigeon-holes have at some time or other been given a single daub of green paint, now faded. The Chief Secretary’s room is just like the others. His table is covered[27] by a bit of threadbare green baize which a messenger at Whitehall would not think fit to wipe his boots upon and for which no Hausa trader would give a handful of cowries.

At present occupied by the Acting Governor, Mr Temple—whose wife shares his “plain living”—the Governor’s “Palace” is a mean shanty. A seven-roomed, wooden bungalow, it has stood “the battle and the breeze” for nine years and shows signs of the ordeal in all directions. It looks as though it could be easily shaken to bits. The dining-room is walled with boards which once received a single dash of brown staining. This apartment, however, is luxurious compared with the Governor’s office adjoining, the plank partition of which has not its ugliness improved by a sparse covering of green paint, of the quality used in England on the garden fences of thirty-pounds-a-year houses. Nor does His Excellency recline on soft velvets or plush cushions, as might be expected of the ruler of Emirs and Kings who turn out in splendour. As I talked with him he sat in a plain chair, the hardness of the seat of which was somewhat relieved by an old horse-blanket folded.

The furniture at Government House is of the same nondescript character. It might have been picked up in job lots at public auction rooms. In order that I might take a group photograph six chairs were brought into the grounds from the drawing-room and I noticed that the six were made up of three different styles. Before the picture could be composed I had to do a temporary repair to one of the chairs.

The motor-car in which he gets about Zungeru,[28] and which is used for traversing distant roads the railway does not cover, is an old shambling machine making as much noise as a traction engine. The motor-cabs of Europe, and even the vehicles of the London General Omnibus Company are smart and ultra-fashionable by comparison. I should say that a suburban shopkeeper would scorn to hire it at a shilling per hour on a Bank Holiday to take his family round Battersea Park or Hampstead Heath. Well-to-do natives in Lagos use better.

These latter things are not written in any mere fault-finding, jeering spirit. They are set out in heartfelt admiration of the manner in which unnecessary hardships are cheerfully accepted by the members of the Government of the Northern Nigeria Protectorate, from the highest to the humblest. Millions have been spent on the country, but the money has gone in building railways, facilitating commerce, bettering the material opportunities of the native population and assuring them protection that they may pursue their ways in peace. The question may fairly be asked whether the time has not come when something should be done for the men who have put this policy into actual operation. John Bull stands to gain a great deal by the acquisition of Northern Nigeria. I am sure he would willingly acquiesce in more liberality on the part of those who act for him.

A figure which pervades Zungeru at every turn is the Cantonment Magistrate. The Governor is a commanding person, of whom everyone, from the visiting Sultans and Emirs to resident and travelling Europeans, stand much in awe. But the Governor is on a pedestal away from the general, daily run[29] of affairs. Excepting on special occasions, when Government House is opened to hospitality, or an audience is sought, the ordinary individual does not come in contact with the Governor.

The Chief Secretary, as the leading member of the administrative staff, is pretty prominent, yet unless a matter is of importance he will not personally appear on the scene, though his name or signature will be used.

But the Cantonment Magistrate! You cannot get away from his authority. His functions seem interminable. He is a dozen individuals rolled into one. He is a veritable “Pooh-Bah” without, as it was darkly hinted to me, the emoluments of that Gilbertian creation.

Here are some of the parts carried out by the Cantonment Magistrate of Zungeru, formerly Captain, now Mr, J. Radcliff:

He is President of the Cantonment Court, and tries small cases at law.

He is Coroner within the area of the Cantonment.

He is an ex-officio Commissioner of the Supreme Court.

He is the Public Trustee, being charged with administration of the estates of all deceased Europeans.

He is the Borough, or Town Council, for to him falls the levying of rates on all houses in the Cantonment, excepting those occupied by Government officials.

He is Public Treasurer, as keeper of the Cantonment Fund.

He is Registrar General, for he must keep a register of all residents.

He is the local London County Council, as he regulates all streets and buildings. You may not cut down a tree without the permission of the Cantonment Magistrate.

He is the Highways Committee of the local London County Council; he constructs the roads.

He is the Local Government Board, for the work of the public department in England in the matter of sanitation is at Zungeru discharged by the Cantonment Magistrate.

He bears another duty of the L.C.C., in issuing licences to domestic servants, who are all males.

He does what is performed over post-office counters in England at certain times, for he gives a licence to keep a dog.

He supervises the native quarter of Zungeru.

He is the outside Master of Ceremonies of Government House, as he arranges communications and interviews between the local native notables and the Governor.

See the Cantonment Magistrate in his own court. Note the side glance of scepticism, scorn, and unbelief as a voluble female pours out her tale of woe. It is just the glance of the stipendiary on the bench at home. Looking at the lady, one would be driven to the conclusion that, after all, human nature is pretty much the same the world over, and that there is no great difference between Bridget or Mary Ann in England and Amina, Fatima, or Rekia in Zungeru.

Every Wednesday morning the local native Council consult with the Cantonment Magistrate. I chanced to be at his office as the four of them and the Chief came up. They salaamed by kneeling and bending their heads to the ground, and then arose and followed the Englishman into the building. Conversation ranged over several subjects. The C.M. lightly reminded the Chief that rents of market pitches were not being collected with that regularity, thoroughness, and completeness which the Governor liked. The Chief responded that people complained of little business, but that he would see to the arrears forthwith, and he improved the occasion by pointing out to the C.M. that certain parts of the market needed repair and money spent on improvements. The C.M. answered that it would be the first thing to be put in hand as soon as the arrears were received.

The talk branched into another channel. The Chief proceeded to say that he had been somewhat troubled in mind of late. The slightest trace of a questioning smile came on the visage of the Cantonment Magistrate. The Chief continued that it was so long since he had paid his respects to the Acting Governor that he was commencing to feel quite uneasy. His Excellency might consider him indifferent to politeness and his obligations.

The Cantonment Magistrate gravely told him to sleep well at nights on that score, as the Acting Governor was thoroughly aware of the Chiefs loyalty. All the same, the C.M. would ascertain His Excellency’s convenience for the audience and would promptly inform the Chief.

Then the visitor asked about the health of the[32] Acting Governor. The C.M. gave satisfactory assurances on that point. The next enquiry was as to the well-being of Mrs Temple. The C.M. rendered an equally gratifying report, and diplomatically remarked that she was looking forward to the pleasure of meeting the Chief, at which his face showed that he rejoiced exceedingly.

With similar ceremony to that at the commencement of the visit it ended.

Native settlement—Rents and Treasury—A model prison—Northern Nigeria Constabulary—Mails paid time-work—Sport at the door—Up-country and Coast natives—Selection of Zungeru—The future Capital.

The only European trading establishment in Zungeru is the store of the Niger Company. It adjoins the Cantonment. With a white population composed entirely of Government officials, all of whom bring their main requirements for a twelve-month’s term, it cannot be said there is room for another firm. The store is a great convenience, as men frequently miscalculate what they will need, or occasionally run out of some article of diet or clothing. The store is comprehensive, and stock is kept of provisions, hardware, men’s wardrobes, and wines.

During one of my purchases over the counter a man who had been up-country for a considerable period, and whose attire was much the worse for what it had undergone, came in to be equipped for a visit to comparatively fashionable Lagos. He was fitted literally from head to foot, if not in Bond Street style, at least in striking contrast to what would pass muster in the bush districts.

The store stands in a compound wherein grow trees bearing paw-paws, limes, oranges, mangoes, cactus and rubber shrubs.

A mile or so from the Cantonment is the native town, which shows in miniature the principle on which the government of the country is carried on, that of ruling the natives through and by natives. At Zungeru a native settlement came as a sequence to the selection of the place as the administrative headquarters. The people were given plots 100 feet by 50 feet. The town has been designed on thoroughly sanitary lines and wells were sunk. A market, with iron roof and concrete floor, is in the centre of the town. For a pitch in it two shillings and sixpence per month is paid. Another market has been put up with thatch-covered stalls, and here ninepence per month is the due.

These market dues go entirely to the native Treasury, which has to render a strict account to the Cantonment Magistrate, and are used for the upkeep and improvement of the native town and for payment of native officials who are appointed by the Chief, including the market and the Alkali’s court officials and the town police.

First-class plots for houses are rented at sixteen shillings a quarter, second-class plots eight shillings a quarter. Half the rent goes to the Government and half to the native Treasury.

Reverting to the direct British administration, Zungeru possesses a model prison, where the inmates have humane treatment without being made so comfortable that they welcome a sojourn within its walls as a place where the tasks are light and regular food is in larger quantities than they[35] would get “on their own.” The prison, which is used for convicts sent from various parts of the country to serve long sentences, is controlled by Captain A. E. Johnson, D.S.O., who is also Inspector-General of the Northern Nigeria Police. He is making good use of his hobby as a skilled amateur gardener. Prison labour has been used to lay out a rubber plantation of 100 acres, started 3½ years ago and added to annually. It promises to yield good results.

He has also had fruit trees set along the left bank of the Dago: orange, lime, mango, guava, banana, covering 30 acres, all of which are doing well; and these at the proper stage will give Zungeru and surrounding districts the luxury of fresh fruit supplies. It may be asked why the step has been left to the Director of Prisons to utilise suitable soil. The answer is that with an 8 months’ severe drought in 12, the necessary watering could never be done by private and paid labour at a remunerative sum.

The interior organisation of the gaol is equally estimable. Whilst a number of prisoners are put to road-making, railway construction—they made the first five miles from Zungeru to Minna—the best behaved are taught trades. There are five workshops—detached structures of brick, put up by delinquents—where carpentry, blacksmithing, tailoring, boot and slipper making, and grass mats (coloured and used as window and door screens) are turned out.

In the blacksmith’s section curios are made. I saw a pair of native stirrups produced from old aluminium water bottles. Used cartridge cases are[36] converted into various articles; they are hammered into one piece and a fancy plate shaped from it. The plan in all these trades is for a long-term man of commendable conduct to be taught a trade, and he teaches others. The system makes honest labour of more monetary value than malpractices to the discharged convict.

The Emirs and Chiefs throughout the Protectorate raise and maintain their own native police, but there is also a force under the central Government, termed the Northern Nigeria Police. It was started in 1900 by Sir Frederick Lugard, with 50 men selected from the Royal Niger Company Constabulary. It now consists of an Inspector-General, the aforesaid Captain A. E. Johnson, a Deputy Inspector-General, 4 Commissioners, 14 Assistant Commissioners, and 838 non-commissioned officers and men, the training being on modified military lines. The Sergeant-Major of the Zungeru detachment is the best-looking negro I had met to the time of visiting the town, and his intelligence is equal to his position. Several times I asked the Commissioner, Captain F. A. E. Godwin, to alter the position of the body paraded to be photographed. In every instance the request was transmitted to the Sergeant-Major, who promptly gave the proper order in military terms, never once failing to bring the 40 men into the required situation.

The force is recruited chiefly from ex-soldiers of the West African Frontier Force. Among the representative races the proportions are: Hausas, 60 per cent.; Yorubas, 30 per cent.; the remainder is comprised principally of Daka-Keri, Kukuruku, and Bauchi Pagans. For night duty the constables[37] carry tell-tale clocks with dials for pricking at certain hours, and there are similar clocks in fixed spots where they must also register. The rank and file live together in lines, each man having his separate house. There are no bachelors in the Zungeru detachment.

The 1st battalion of the Northern Nigeria Regiment and 4 guns of the artillery are quartered at Zungeru. The training and efficiency of the troops are dealt with separately in Chapter XXXIII.

The Postmaster-General of Northern Nigeria, Mr H. M. Woolloy, is located at Zungeru. Mail services are by rail or river, where practicable. In many instances, however, runners have to be employed. Where possible, they are mounted on Bornu ponies. The runners are specially selected and work by contract; the faster they travel the more their pay. This is found more expeditious than providing relays. Thus the road from Zungeru to Sokoto is really a 17 days’ journey. It is covered by the mail runners, afoot, each carrying a 40 lb. to 50 lb. bag, in 11 days. The postal and telegraph services were originally designed solely for administrative and strategical purposes and were not calculated to prove revenue-producing until a remote period. In spite of this, whilst the income in 1901 was £842, last year the value of the work performed amounted to over £20,000, obtained with an expenditure of £16,000. Apart from the Naraguta and the Kano telegraphs, none north of Zungeru can be regarded as of any commercial value.

The little white community of Zungeru try to make life pass pleasantly. The Games Club provides for tennis and golf, and there are similar associations[38] for angling, polo, and races. A horse costs about £8. Sport with the gun abounds, though it must not be indulged within 3 miles of the Cantonment, or, figuratively, the hand of the C.M. would be on your shoulder.

Anybody may walk beyond the limit and easily find plenty of warthog, hartebeest and winged game, and sometimes bigger prizes. These occasionally visit the Cantonment. The other evening a large leopard stood looking contemptuously at the bungalow in which I am staying but elected not to jump the low palings. Had he, no doubt the C.M. would have taken a merciful view of the use of a couple of rifles which were cocked and ready. Nearly every evening at the same distance there is a vocal performance by a company of hyænas.

There is an extremely pleasant aspect in Zungeru, typical of Northern Nigeria, of the respect and good feeling shown by the coloured population to the white, and reciprocated. I say “coloured” instead of “native,” for there are a fair number of “foreigners” from the Gold Coast and from Sierra Leone, imported for routine clerical work. The native Moslems invariably salute a European. The form of salute is generally that of removing sandals, followed by a low bow. The Gold Coast and Sierra Leone clerks are affected by the environment and custom. They scarcely ever fail to raise their hats and utter a “Good morning” or “Good afternoon, sir.” In the Coast towns the prototypes of these young men are too frequently gratuitously arrogant and needlessly insolent towards an Englishman. Problem: Why is the up-country native in all British West African colonies, be he Moslem or Pagan, in[39] nearly every case a gentleman by nature, whilst the output of the Government and missionary schools, with the possible exception of Catholics, too often a creature who makes himself hateful to white men?

The theme could be enlarged by analysis of the proportion contributed by the clerk class in Europeanised towns to the criminal calendar. Elementary education on English lines in West Africa is certainly not a success, decidedly not in the aspect of honesty and morals.

Does the respectful salutation of the Moslem to the English mark the subserviency of one to the other? Emphatically, no. It is a token of respect towards a race standing in the position of a Protectorate Power, exercising its position in the interest of the inhabitants and safeguarding their traditions, their customs, their religion.