Emil Holub

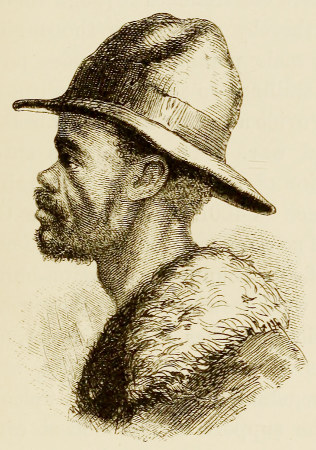

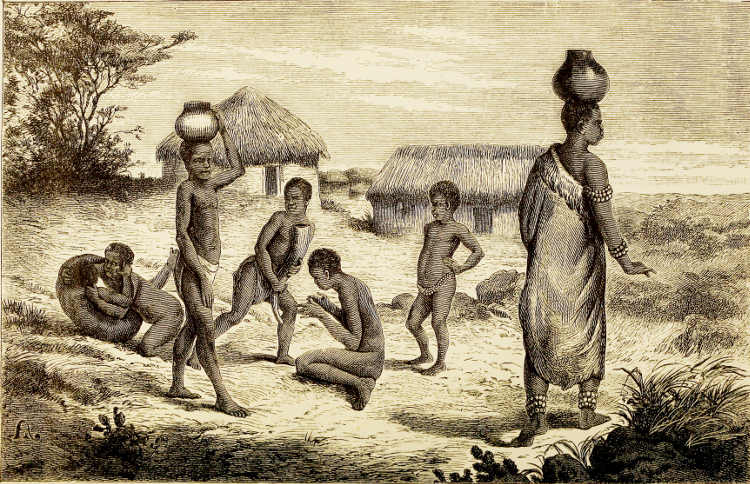

Frontispiece.

Emil Holub

Frontispiece.

TRAVELS, RESEARCHES, AND HUNTING ADVENTURES,

BETWEEN THE DIAMOND-FIELDS AND THE ZAMBESI (1872–79).

BY

Dr. EMIL HOLUB.

TRANSLATED BY ELLEN E. FREWER.

WITH ABOUT TWO HUNDRED ORIGINAL ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

SECOND EDITION.

London:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON,

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET STREET.

1881.

[All rights reserved.]

LONDON:

GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, PRINTERS,

ST. JOHN’S SQUARE.

[iii]

From the days of my boyhood I had been stirred with the desire to devote myself in some way to the exploration of Africa, and whenever I came across the narratives of travellers who had contributed anything towards the opening up of the dark continent, I only read them to find that they gave a more definite shape to my longings.

It was in 1872 that an opportunity was afforded me of gratifying my wish, and I then decided that South Africa should be the field of my researches. For seven years I applied myself to my undertaking with all the energy, and with the best resources that, as a solitary individual, I could command, and was enabled to make the three journeys which are described in the following pages.

[iv]

On my third return to the Diamond-fields I was urged by my South African friends immediately to publish an account of my travels; my time, however, was so engrossed by my medical practice that I had no leisure for the purpose, and contented myself with merely sending a few fragmentary articles to some of the South African newspapers.

But on arriving in London I was again so repeatedly solicited to make public what I had seen, that, on reaching home, I determined to issue these volumes containing an account of the leading incidents in my travelling experiences. To enter into the details of all the scientific observations that I made would occupy me for at least three years, and would interfere altogether with my scheme for returning to Africa as soon as possible, so that I have been satisfied to leave these results of my labours to be worked out by the co-operation of the men of science to whom they may be of interest.

I cherish the hope that these volumes may tend to increase the public interest which is now so powerfully drawn to South Africa, and I trust that the time is not far distant when I may submit to the public some further researches relating to “the continent of the future.”

EMIL HOLUB.

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| Voyage to the Cape—Cape Town—Port Elizabeth | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Journey to the Diamond Fields | 24 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Diamond Fields. | |

| Ups-and-downs of medical practice—Mode of working the diggings—The kopjes—Morning markets—My first baboon-hunt—Preparation for first journey | 53 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| From Dutoitspan to Likatlong. | |

| My travelling-companions—Departure from the Diamond-fields—The Vaal River and valley—Visit to Koranna village—Structure of Koranna huts—Social condition of the Korannas—Klipdrift—Distinction between Bechuanas and Korannas—Interior of a Koranna hut—Fauna of the Vaal valley—A bad road—A charming glen—Cobras and their venom—Ring-neck snakes—The mud in the Harts River | 93 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| From Likatlong to Wonderfontein. | |

| Batlapin life—Weaver-birds and their nests—A Batlapin farmstead—Ant-hills—Travelling Batlapins—An alarming accident—Springbockfontein—Gassibone and his residence—An untempting dish—On the bank of the Vaal—Water lizards—Christiana—Bloemhof—Stormy night—Pastures by the Vaal—Cranes—Dutch hunters—A sportsman’s Eldorado—Surprised by black gnus—Guinea-fowl—Klerksdorp—Potchefstroom—The Mooi River valley—Geological notes—Wonderfontein and its grottoes—Otters, birds, and snakes | 118 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Return Journey to Dutoitspan. | |

| Departure from Wonderfontein—Potchefstroom again—A mistake—Expenses of transport—Rennicke’s Farm—A concourse of birds—Gildenhuis—A lion-hunt—Hallwater Farm and Salt-pan—A Batlapin delicacy—Rough travelling—Hebron—Return to Dutoitspan—The Basutos | 182 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| From Dutoitspan to Musemanyana. | |

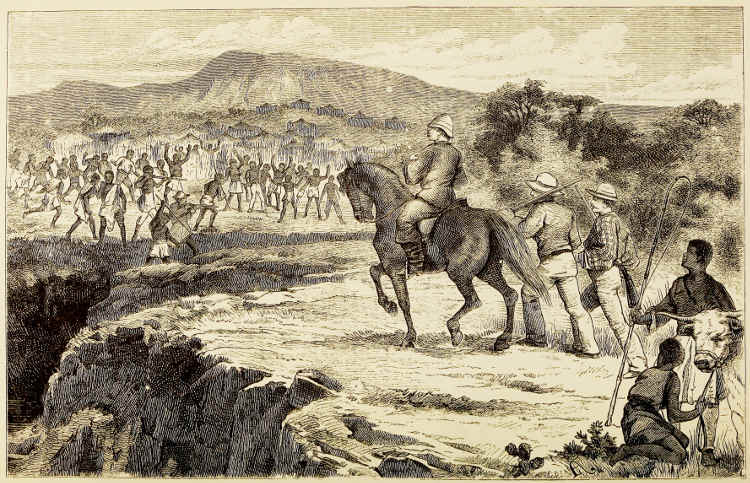

| Preparation for second journey—Travelling-companions—Departure—A diamond—A lovely evening—Want of water—A conflagration—Hartebeests—An expensive draught—Gassibone’s kraal—An adventure with a cobra—A clamorous crowd—A smithy—The mission-station at Taung—Maruma—Thorny places—Cheap diamonds—Pelted by baboons—Reception at Musemanyana | 216 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| From Musemanyana to Moshaneng. | |

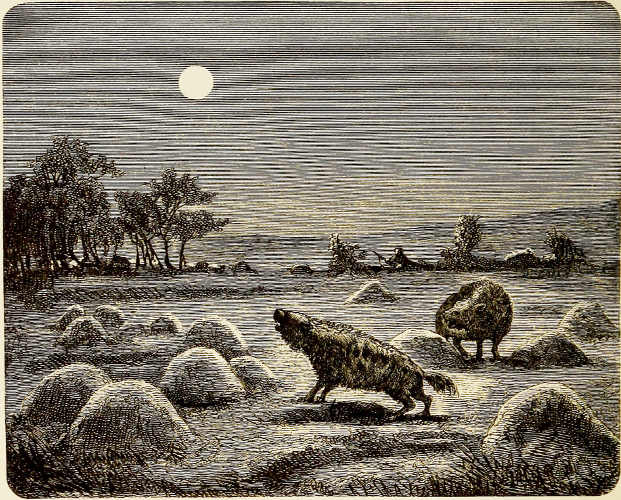

| Departure from Musemanyana—The Quagga Flats—Hyæna-hunt by moonlight—Makalahari horsemanship—Konana—A lion on the Sitlagole—Animal life on the table-land—Gnu-hunt at night—A missing comrade—Piles of bones—Hunting a wild goose—South African spring-time—Molema’s Town—Mr. Webb and the Mission-house—The chief Molema—Huss Hill—Neighbourhood of Moshaneng—Illustrious visitors | 252 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| From Moshaneng to Molopolole. | |

| King Montsua and Christianity—Royal gifts—The Banquaketse highlands—Signs of tropical vegetation—Hyæna-dogs—Ruins of Mosilili’s Town—Rock-rabbits—A thari—Molopolole | 294 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| From Molopolole to Shoshong. | |

| Picturesque situation of Molopolole—Sechele’s territory—Bakuena architecture—Excursion up the glen—The missionaries—Kotlas—My reception by Sechele—A young prince—Environs of Molopolole—Manners and customs of the Bechuanas—Religious ceremonies—Linyakas—Medical practice—Amulets—Moloi—The exorcising of Khame—Rain-doctors—Departure from Molopolole—A painful march—Want of water—The Barwas and Masarwas—Their superstition and mode of hunting—New Year’s Day in the wilderness—Lost in the woods—Saved by a Masarwa—Wild honey—The Bamangwato highlands—Arrival at Shoshong | 312 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| From Shoshong back to the Diamond Fields. | |

| Position and importance of Shoshong—Our entry into the town—Mr. Mackenzie—Visit to Sekhomo—History of the Bamangwato empire—Family feuds—Sekhomo and his council—A panic—Manners and customs of the Bechuanas—Circumcision and the boguera—Departure from Shoshong—The African francolin—Khame’s saltpan—Elephant tracks—Puff-adders—A dorn-veldt—A brilliant scene—My serious illness—Chwene-Chwene—The Dwars mountains—Schweinfurth’s pass—Brackfontein—Linokana—Thomas Jensen, the missionary—Baharutse agriculture—Zeerust and the Marico district—The Hooge-veldt—Quartzite walls at Klip-port—Parting with my companions—Arrival at Dutoitspan | 367 |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

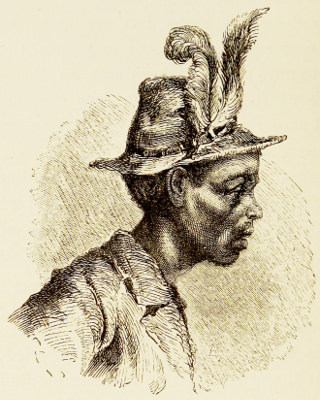

| Emil Holub | Frontispiece. |

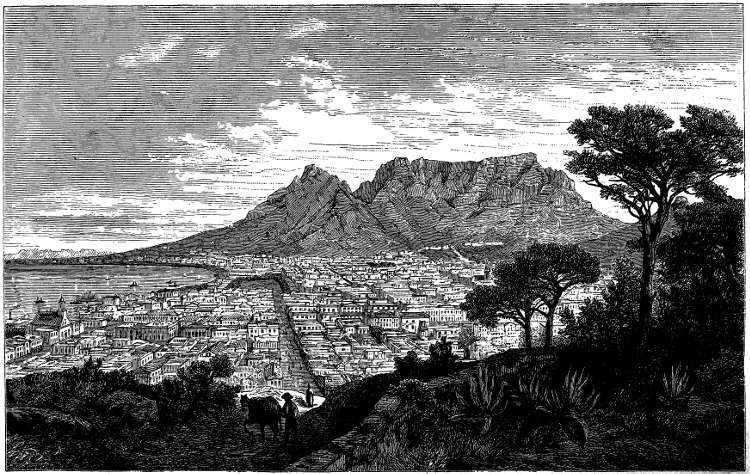

| Cape-Town | 5 |

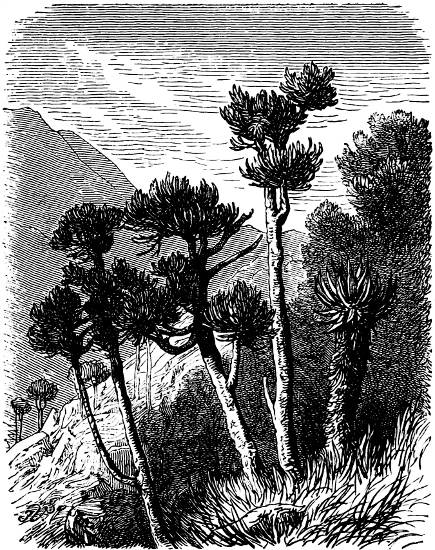

| Euphorbia Trees | 17 |

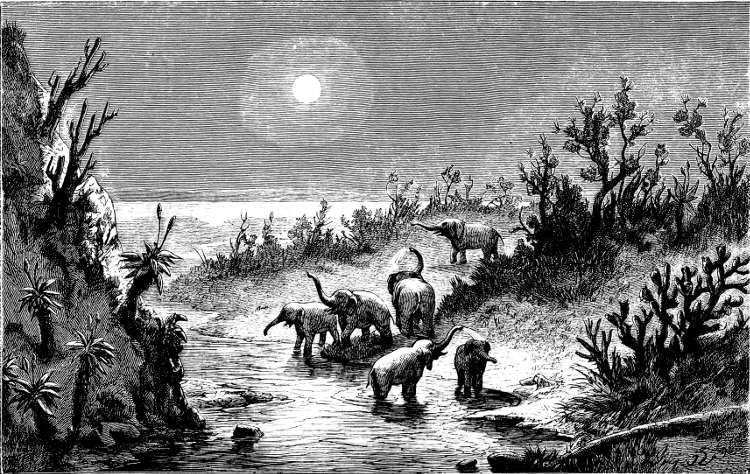

| Elephants on the Zondags River | 28 |

| Springbock Hunting | 33 |

| Antelope Trap | 36 |

| The Country near Cradock | 37 |

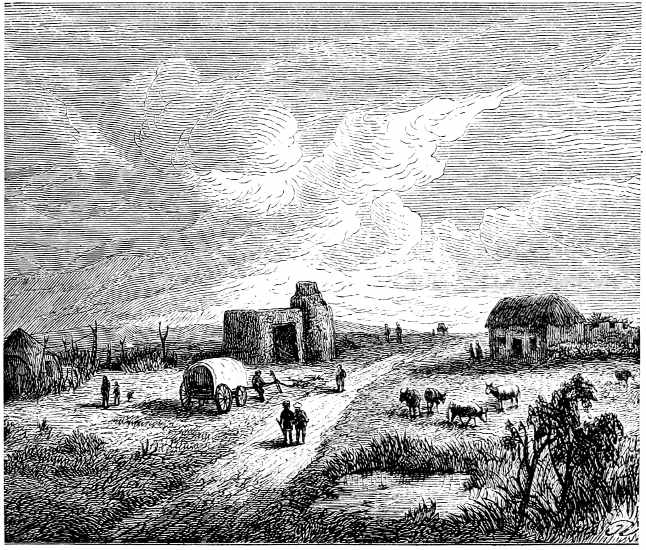

| On the Way to the Diamond-Fields | 40 |

| Hotel on the Riet River | 49 |

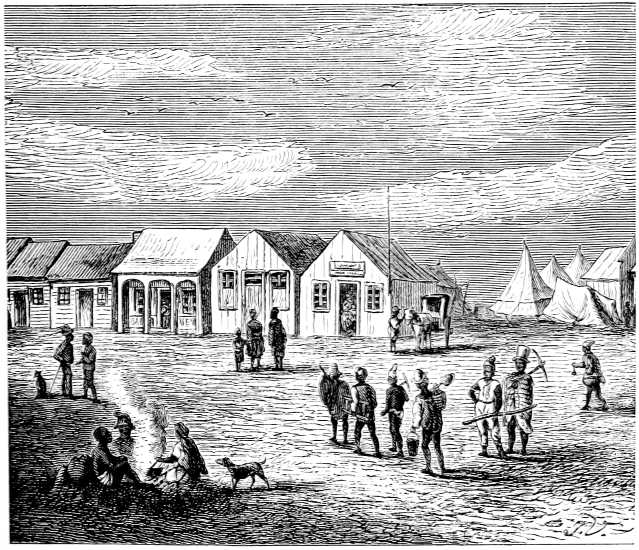

| Square in Dutoitspan | 63 |

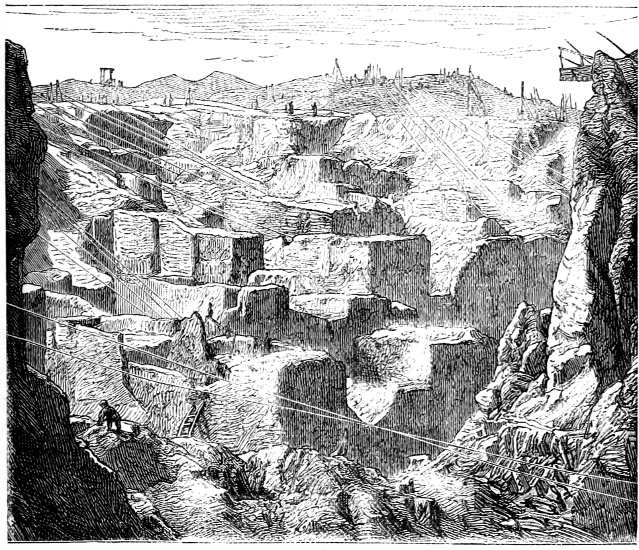

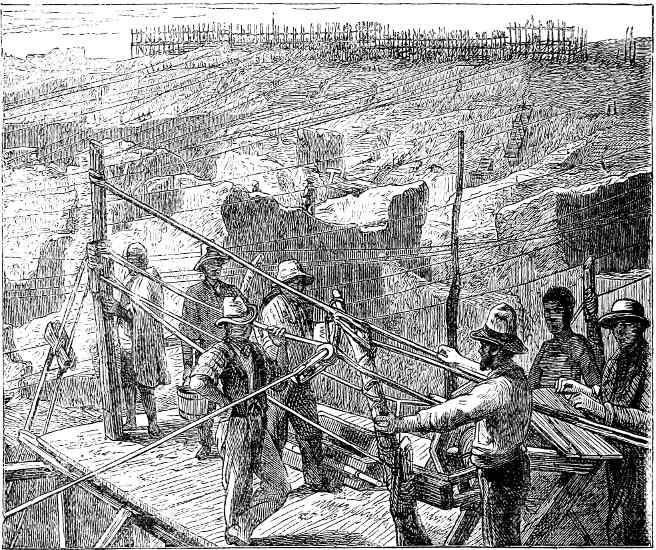

| Kimberley Kopje in 1871 | 67 |

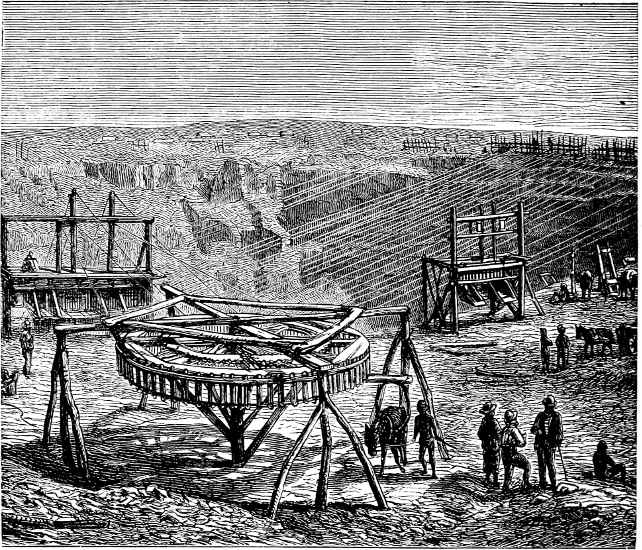

| Horse Whims in the Diamond Quarries | 68 |

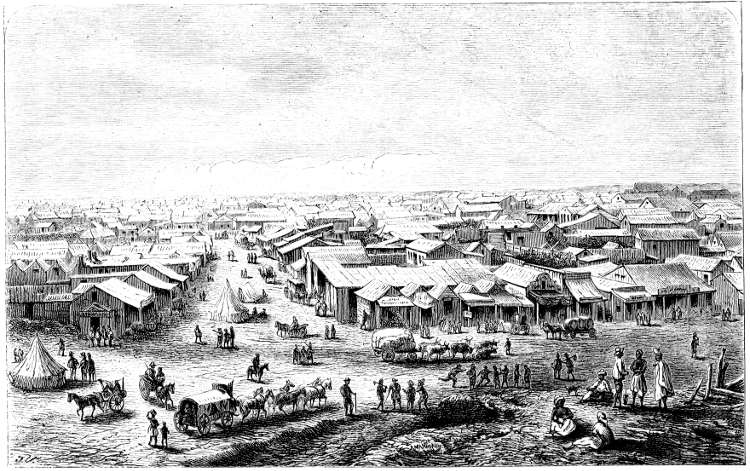

| Kimberley | 69 |

| Kimberley Kopje in 1872 | 70 |

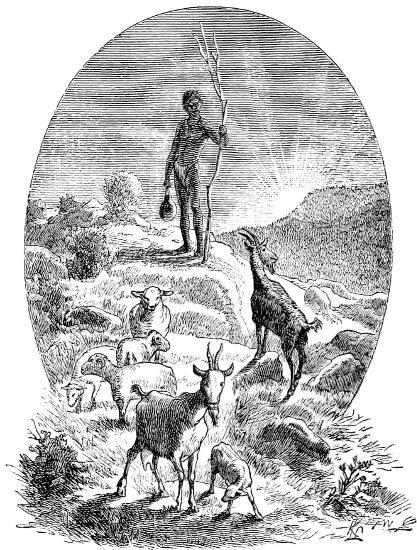

| Kaffir Shepherd | 77 |

| Baboon-hunt | 88 |

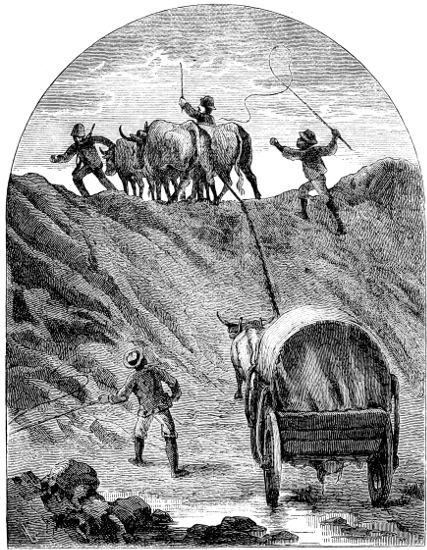

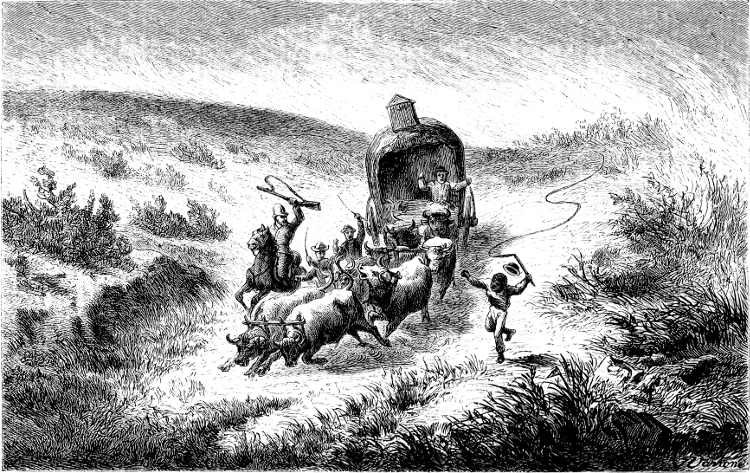

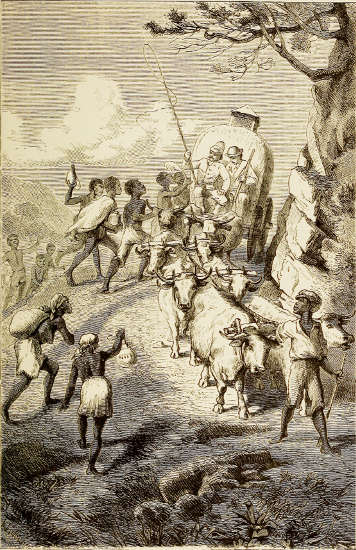

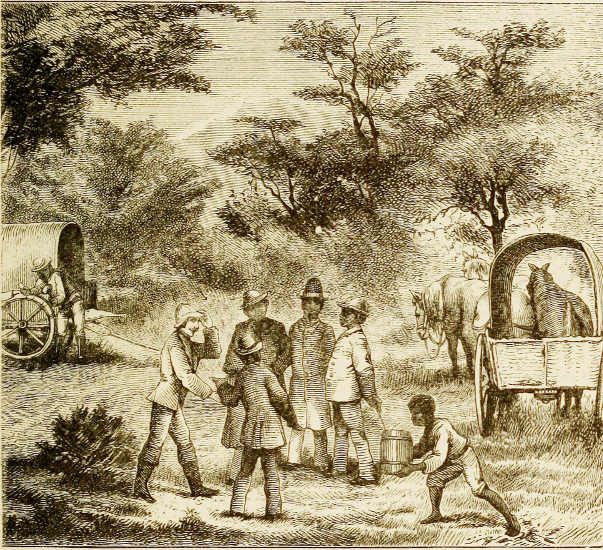

| “Fore-spanning” | 95 |

| Koranna Huts in the Valley of the Harts River | 96 |

| Korannas | 96 |

| Interior of a Koranna Hut | 103 |

| Batlapin Boys throwing the Kiri | 109 |

| Batlapin | 111 |

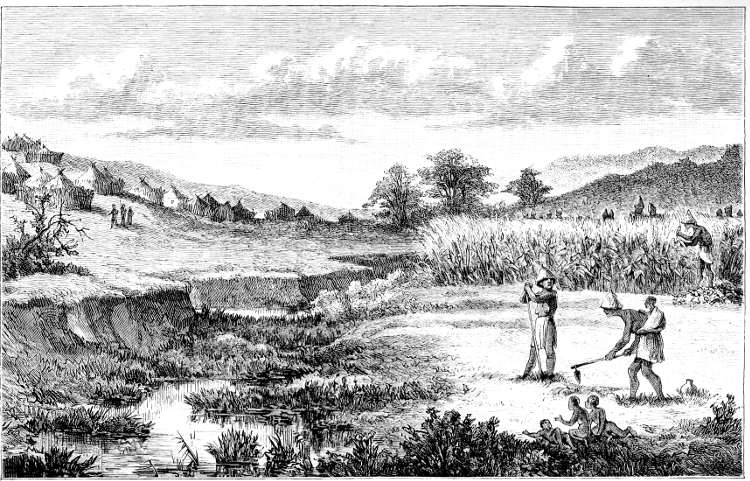

| Batlapin Agriculture | 116 |

| Nests of Weaver-Birds | 123 |

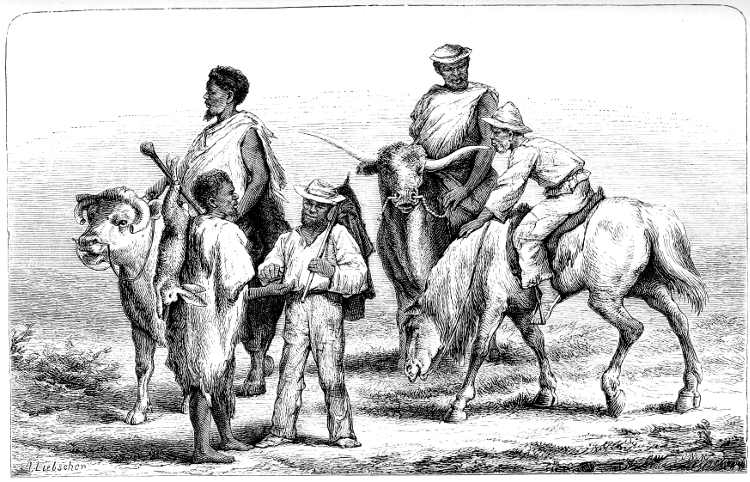

| Batlapins on a Journey | 126 |

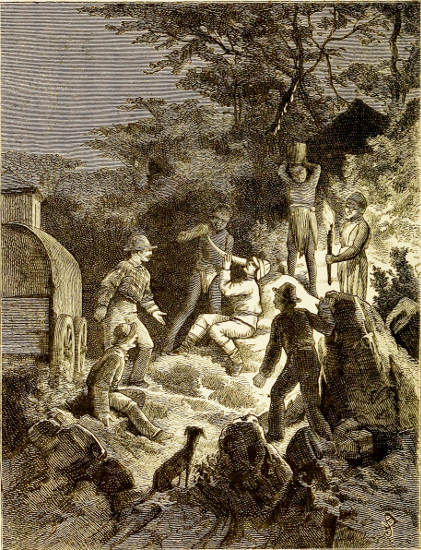

| Accident in the Harts River Valley | 129 |

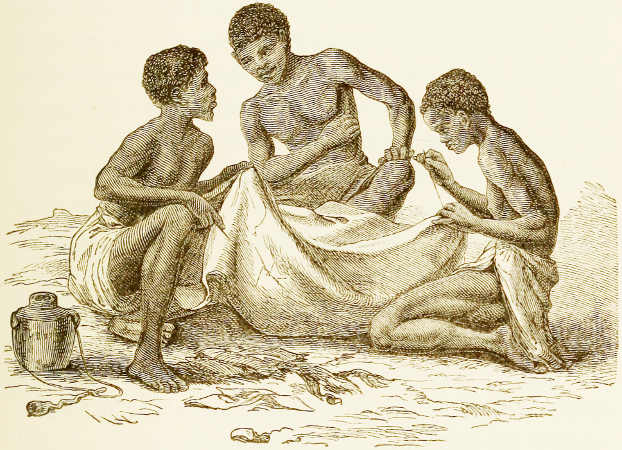

| Batlapins sewing | 133 |

| Camp on Bamboes Spruit | 147 |

| Return from the Gnu Hunt | 155 |

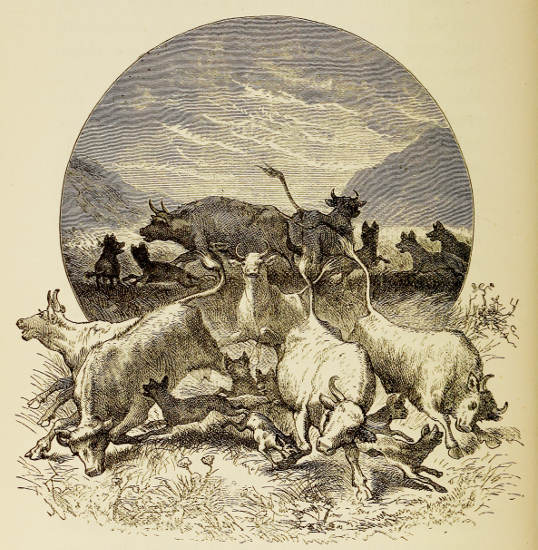

| Startled by a Herd of Black Gnus | 156 |

| Night-Camp | 168 |

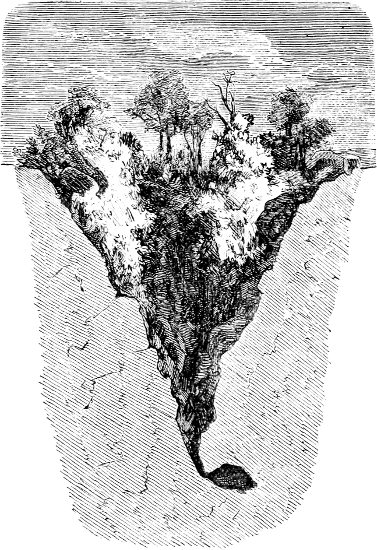

| Funnel-shaped Cavity in Rocks | 170 |

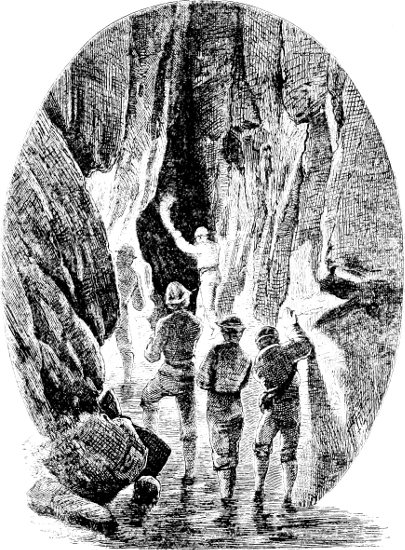

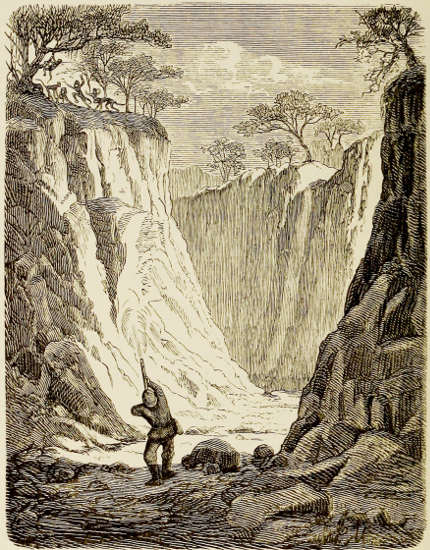

| Grotto of Wonderfontein | 173 |

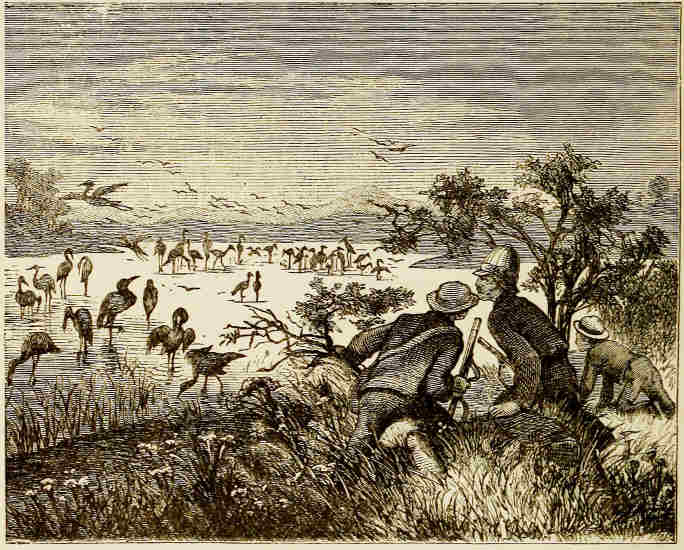

| A Bird Colony | 190 |

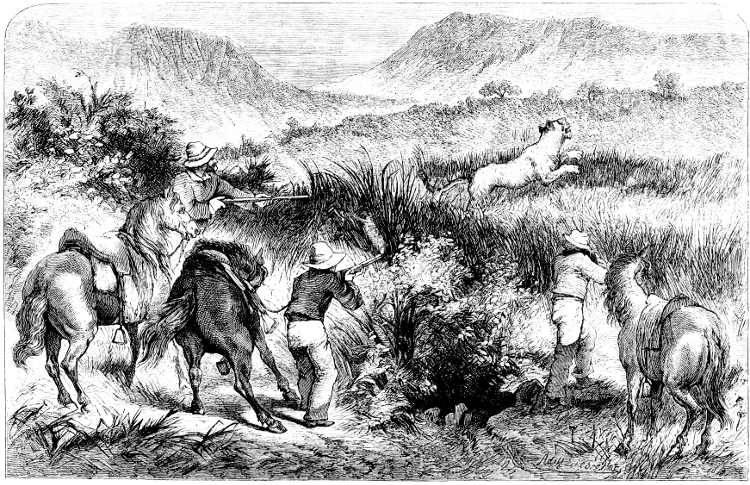

| Lion Hunt in the Maquasi Hills | 193 |

| Hallwater Farm | 195 |

| Koranna | 197 |

| Batlapins returning from Work | 201 |

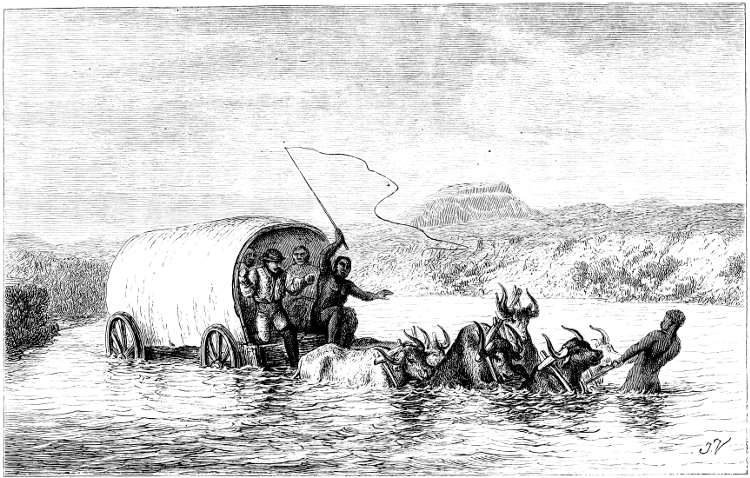

| Easter Sunday in the Vaal River | 208 |

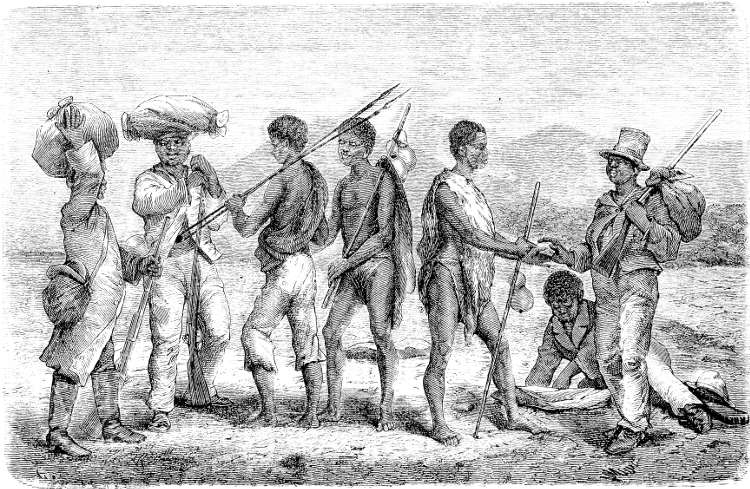

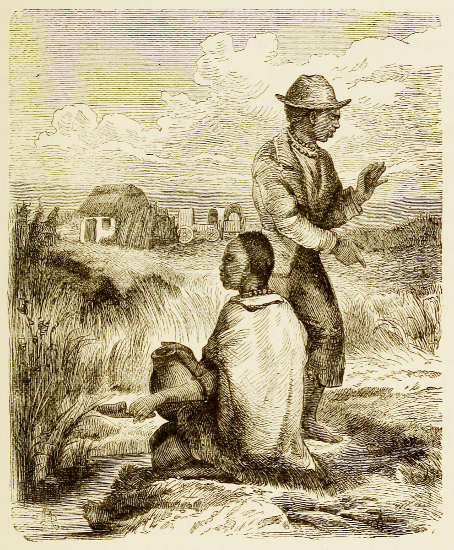

| Meeting between Basutos returning from the Diamond Fields, and others going thither | 213 |

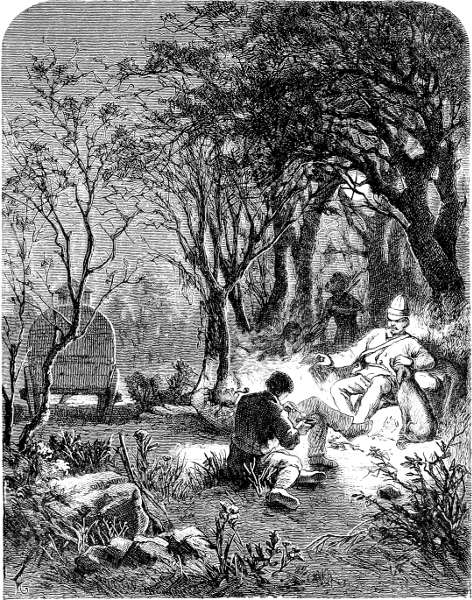

| A Moonlight Evening in the Forest | 216 |

| The Plains on Fire | 225 |

| Hartebeest | 228 |

| Head of the Hartebeest (Antilope Caama) | 229 |

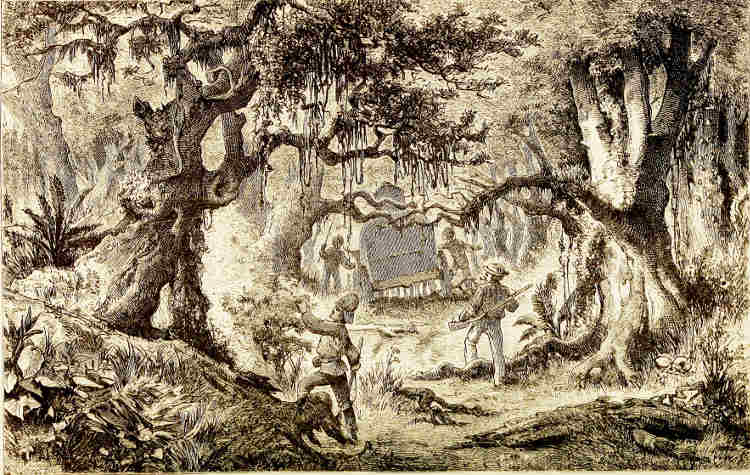

| Woods at the Foot of the Malau Heights | 231 |

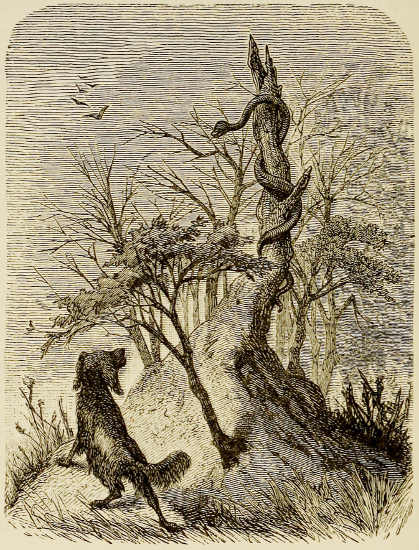

| Niger and the Cobra | 234 |

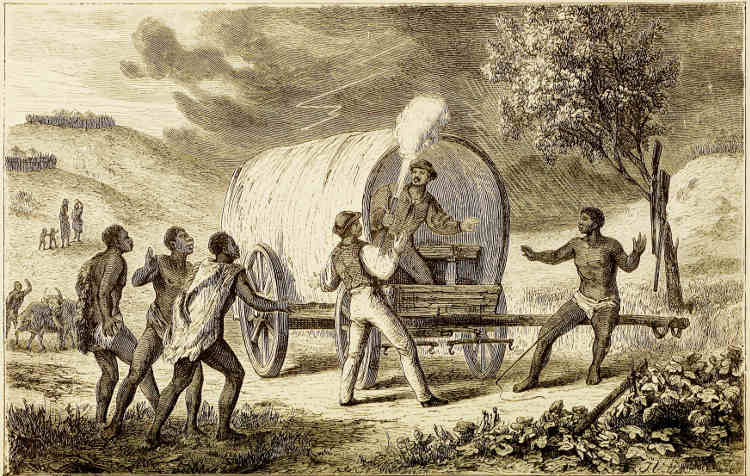

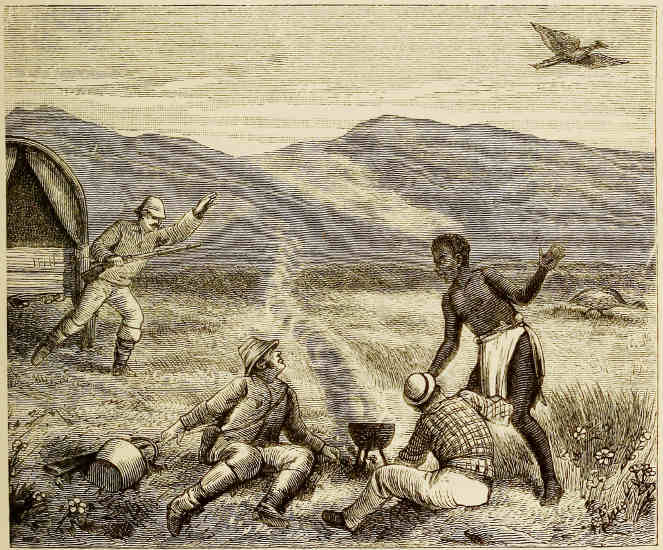

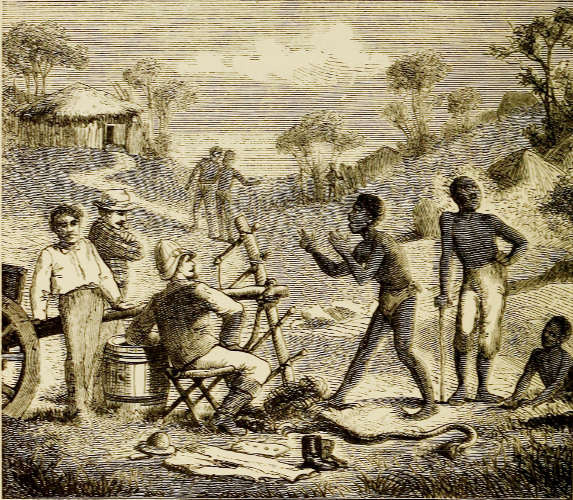

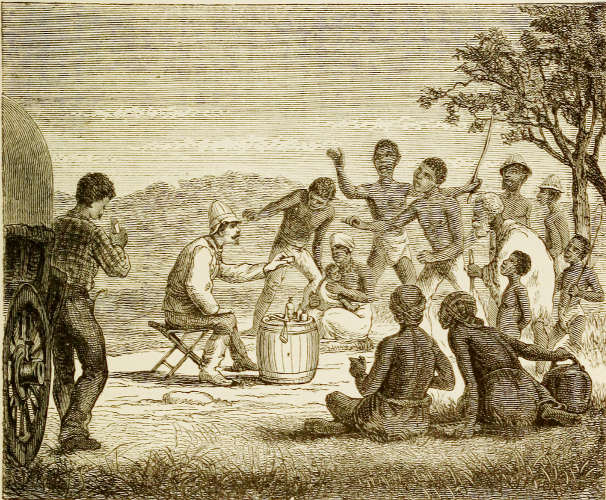

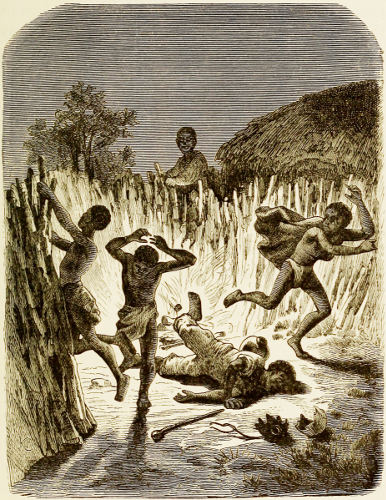

| Mobbed for Spirits | 236 |

| Caught by Thorns | 241 |

| Cheap Diamonds | 242 |

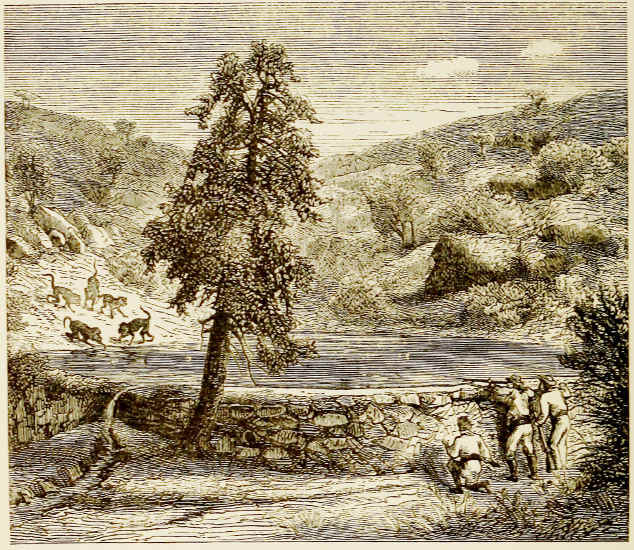

| Surprised by Baboons | 244 |

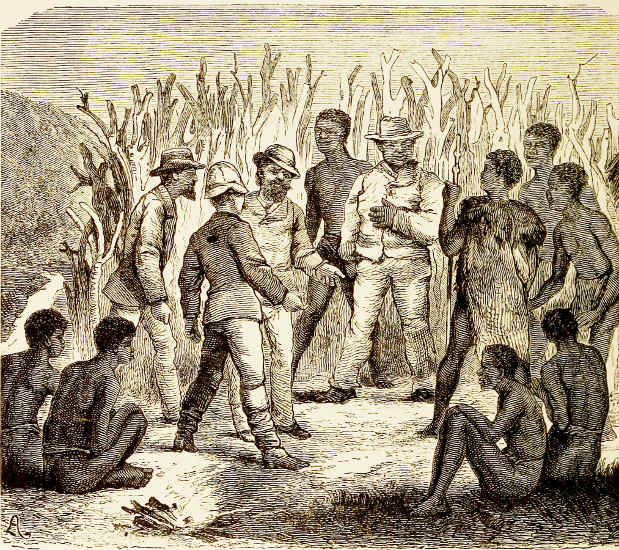

| Reception in Musemanyana | 249 |

| Musemanyana | 251 |

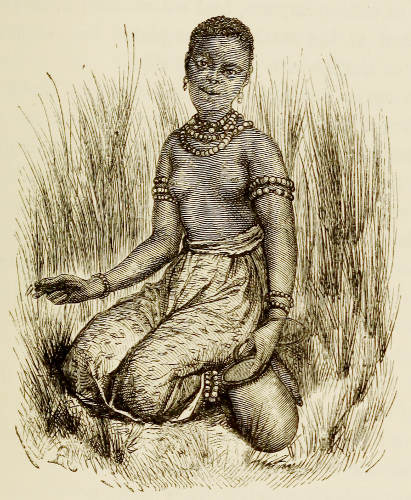

| Barolong Maiden collecting Locusts | 253 |

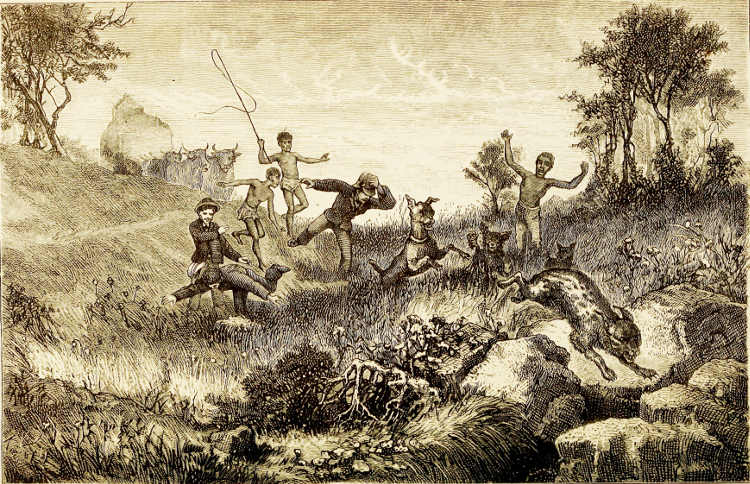

| A Hyæna Hunt | 256 |

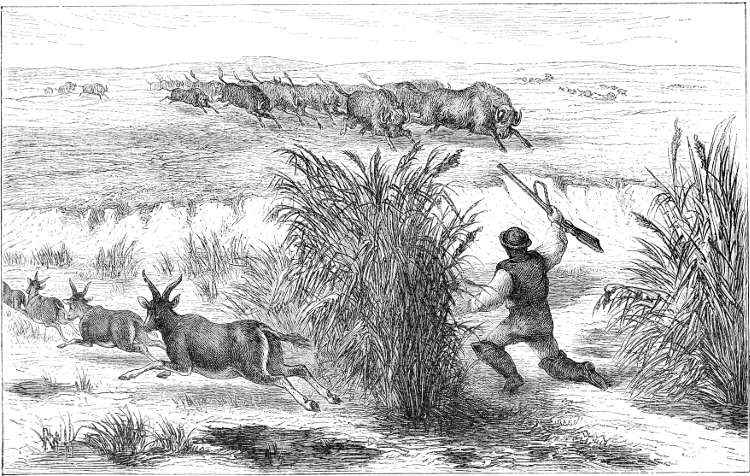

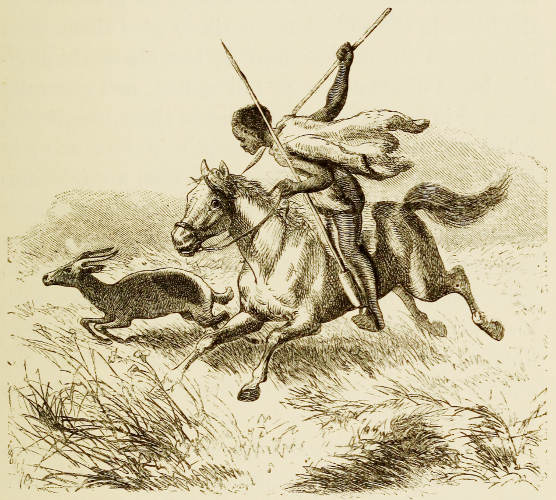

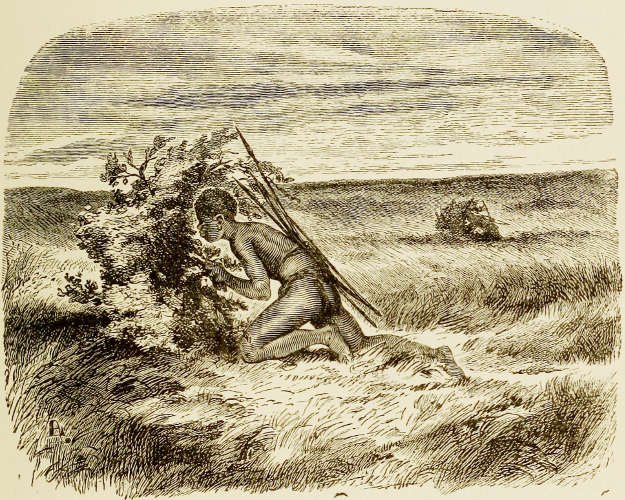

| A Yochom of the Kalahari chasing a Bless-bock | 259 |

| A Barolong Story-teller | 262 |

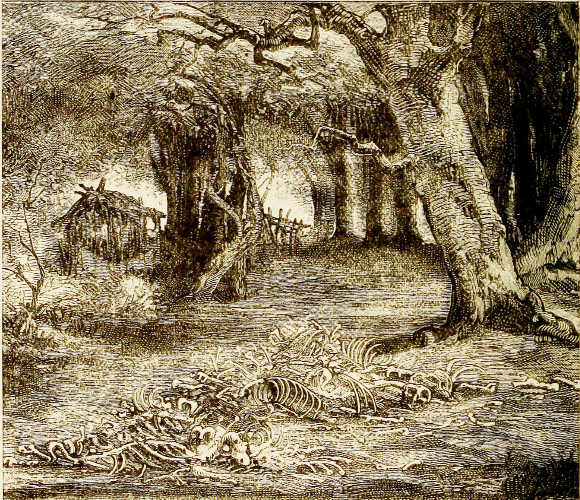

| The Bechuana finds the Remains of his Brother | 265 |

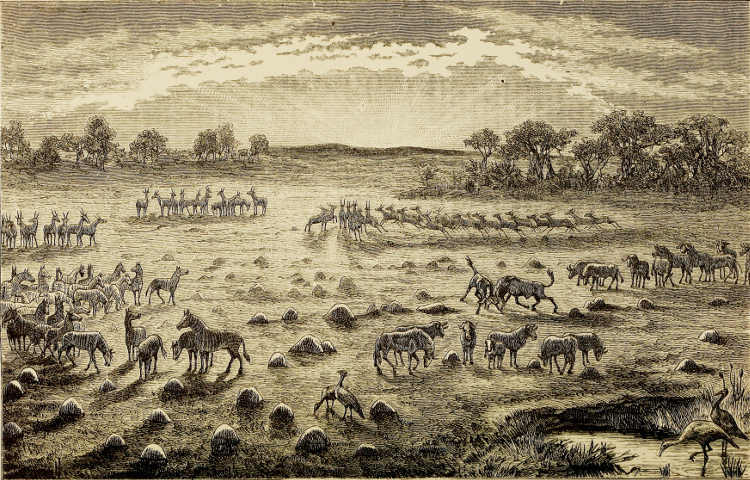

| Wild Animals on the Plains | 267 |

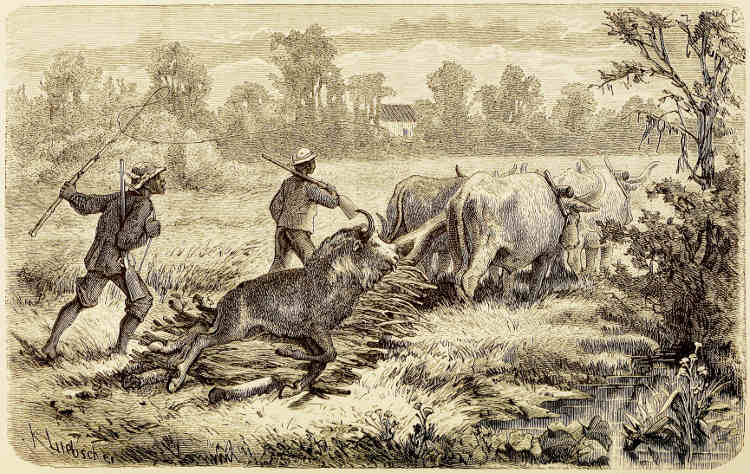

| Barolongs chasing Zebras | 268 |

| Gnu-hunting by Night | 270 |

| Deserted Hunting-place of the Barolongs | 274 |

| Egyptian-goose on Mimosa-tree | 275 |

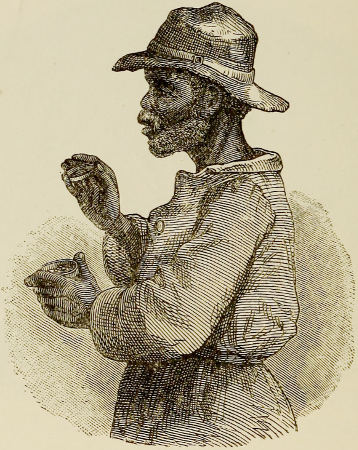

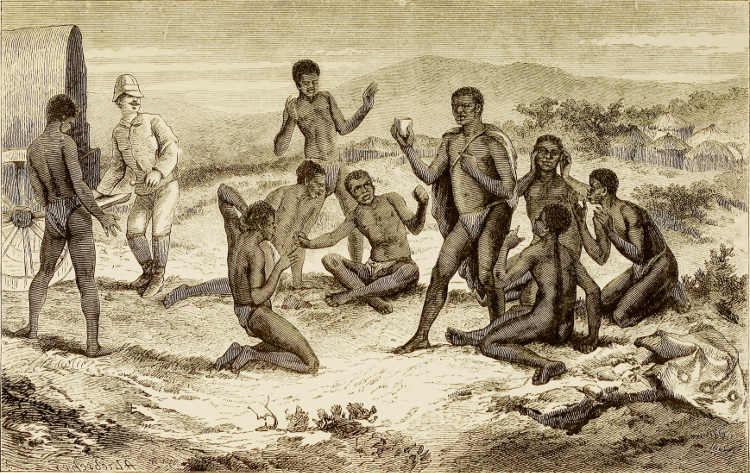

| Dispensing Drugs in the Open | 281 |

| Nest of Weaver-birds | 284 |

| Collecting Rain-water | 287 |

| A Refreshing Draught | 288 |

| Royal Visitors | 289 |

| Barolong Women at Moshaneng | 297 |

| Hyænas among the Cattle | 302 |

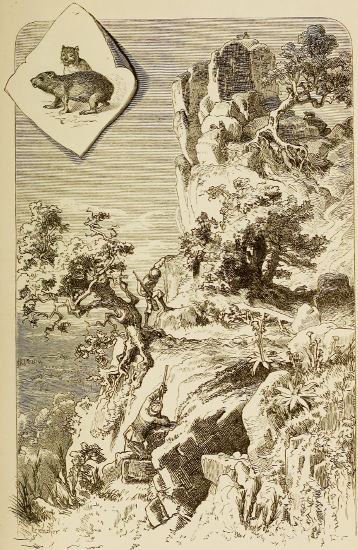

| Hunting the Rock-rabbit | 306 |

| The African Lynx | 309 |

| White-ant Hills | 312 |

| King Sechele | 318 |

| Rain-doctors | 325 |

| Khame’s Magic | 335 |

| Pit, the Griqua, discovers Leopard Tracks | 342 |

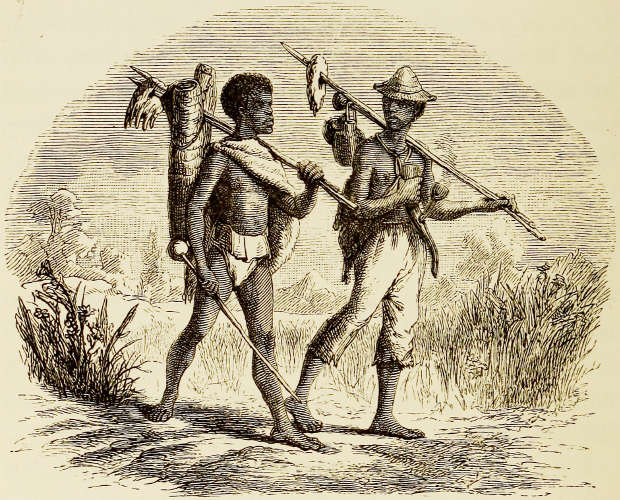

| Native Postmen | 346 |

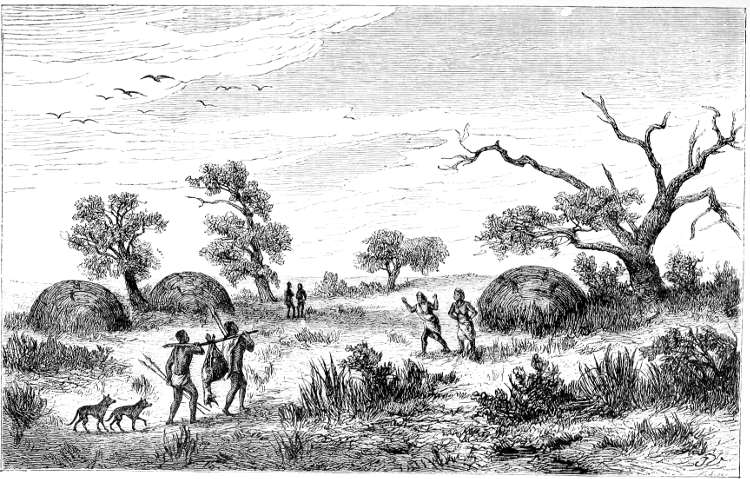

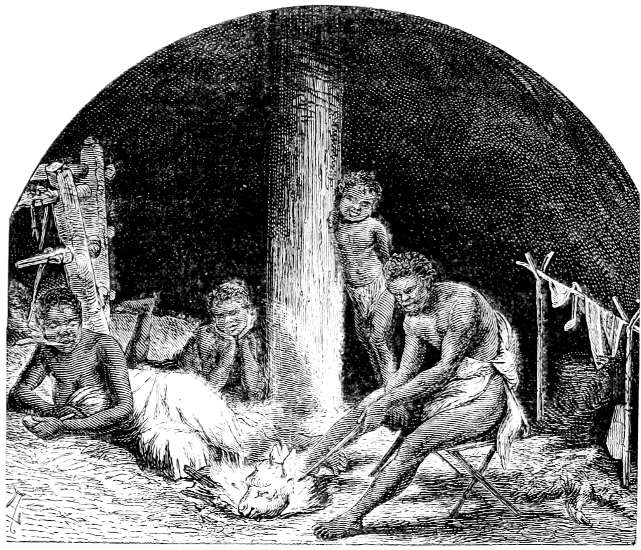

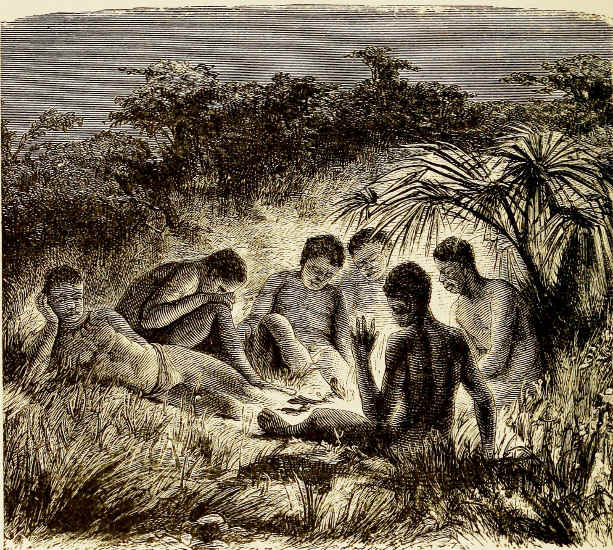

| Masarwas around a Fire | 350 |

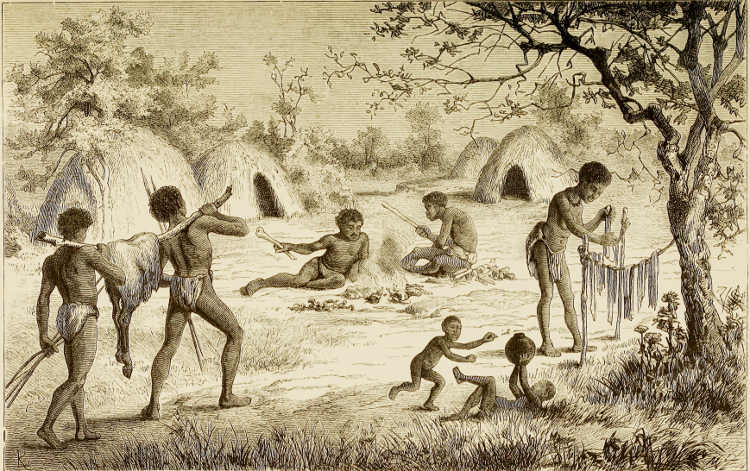

| Masarwas at Home | 352 |

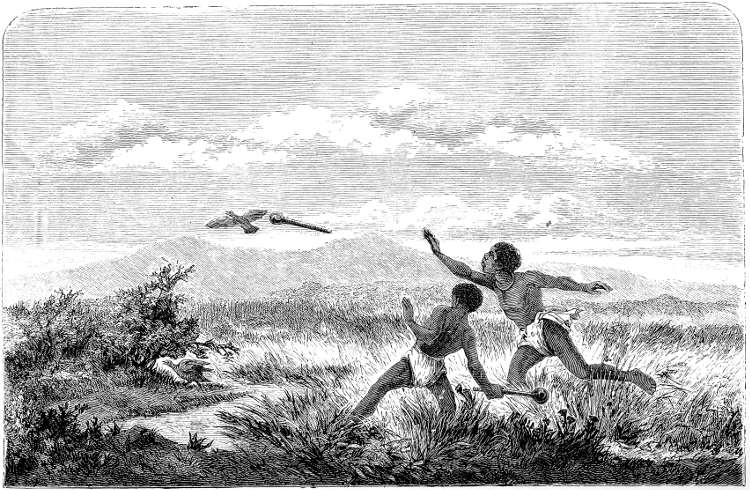

| Mode of Hunting among the Masarwas | 353 |

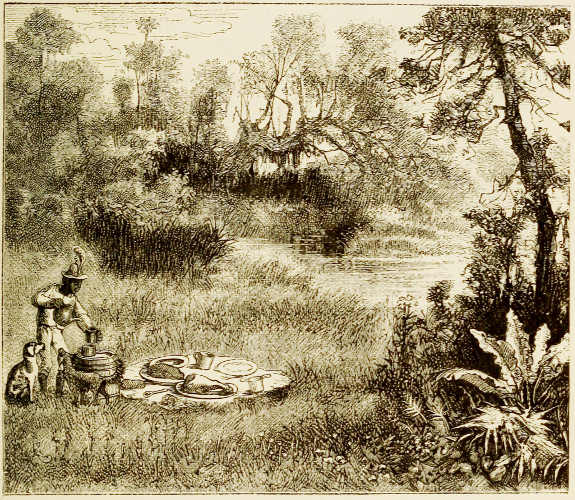

| Preparing the New Year’s Feast in the Forest | 355 |

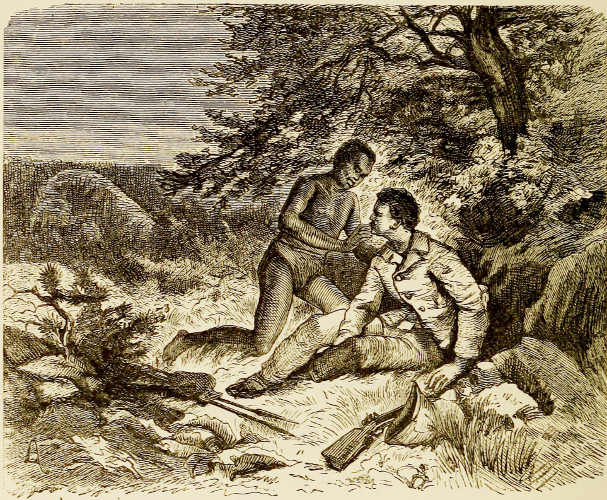

| Succoured by a Masarwa | 360 |

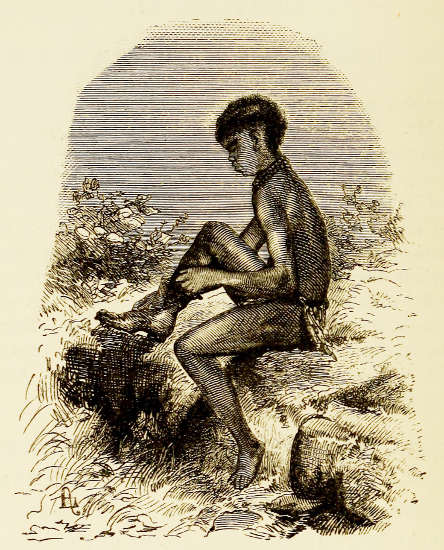

| A Bamangwato Boy | 368 |

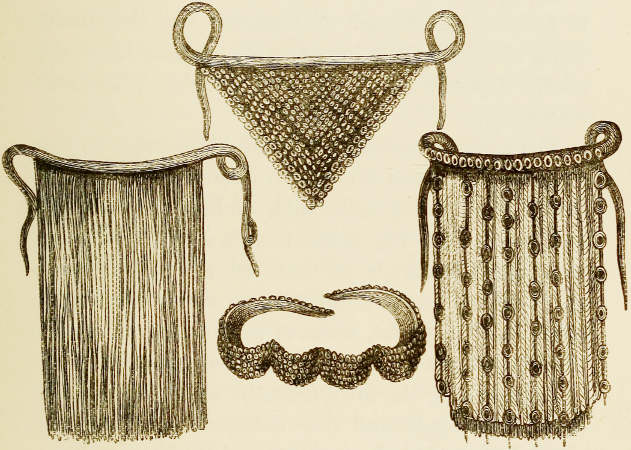

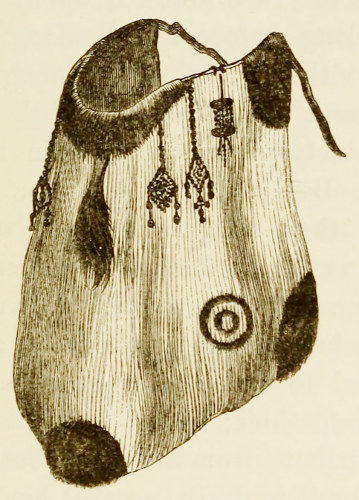

| Aprons worn by Bamangwato Women | 369 |

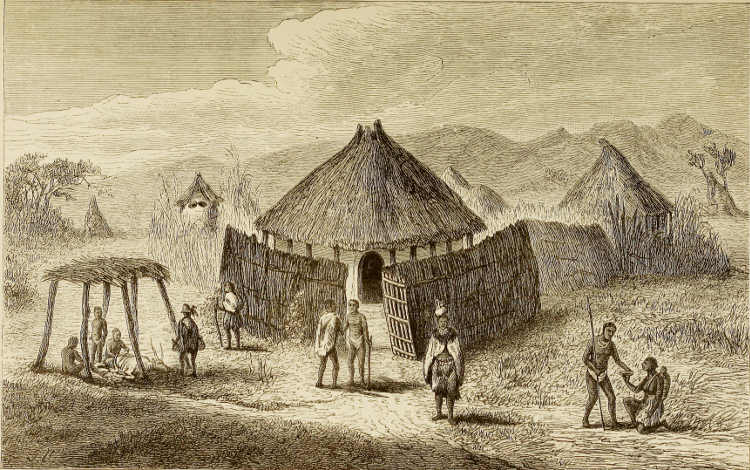

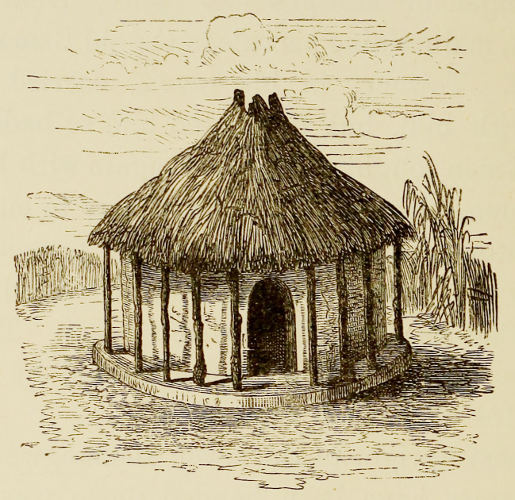

| Bamangwato Huts at Shoshong | 372 |

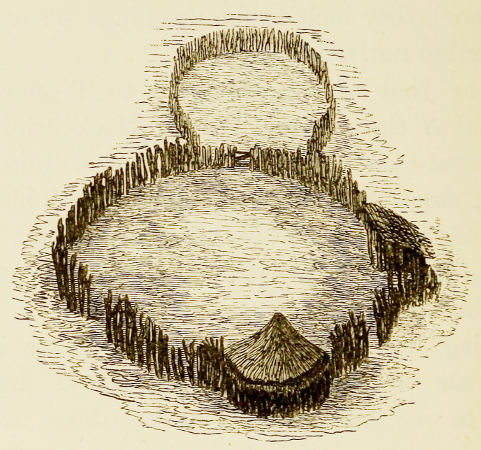

| Kotla at Shoshong | 374 |

| Sekhomo and his Council | 376 |

| Bamangwato House | 378 |

| Court Dress of a Bamangwato | 379 |

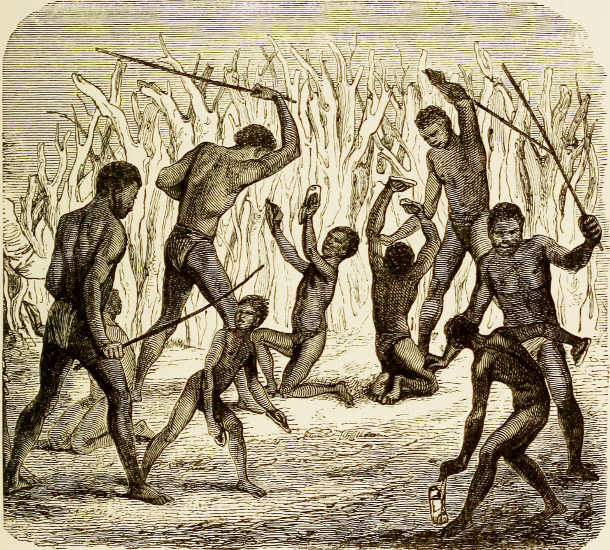

| Training the Boys | 397 |

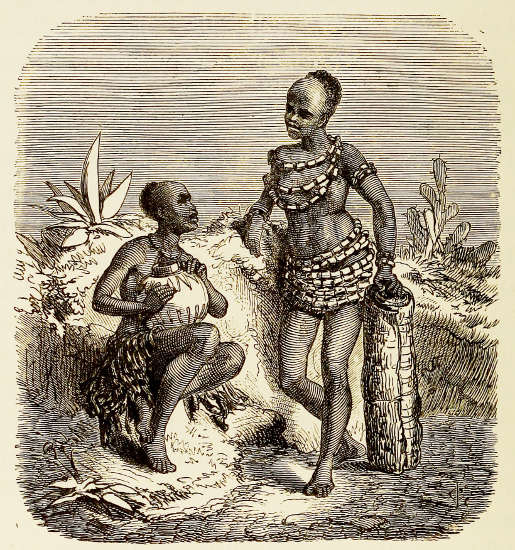

| Bamangwato Girls Dressed for the Boguera | 400 |

| Khame’s Salt-pan | 404 |

| Buisport, Rocky Cleft in the Bushveldt | 413 |

| Baharutse Drawing Water | 415 |

| Chukuru, Chief of the Baharutse | 417 |

| Baharutse Village | 419 |

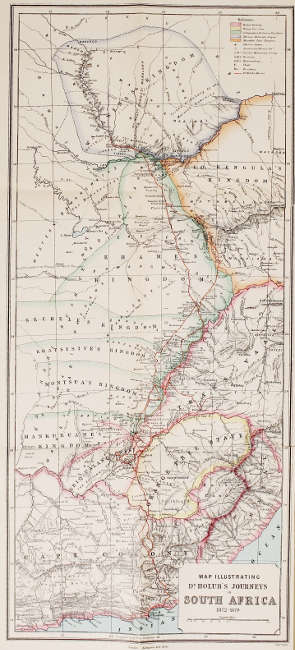

MAP ILLUSTRATING

DR. HOLUB’S JOURNEYS

IN

SOUTH AFRICA

1872–1879

[1]

However fair and favourable the voyage between Southampton and South Africa, a thrill of new life, a sudden shaking off of lethargy, alike physical and mental, ever responds to the crisp, dry announcement of the captain that the long-looked-for land is actually in sight. As the time draws near when the cry of “Land” may any moment be expected from the mast-head, many is the rush that is made from the luxurious cabin to the deck of the splendid steamer, when with straining eyes the passengers eagerly scan the distant horizon; ever and again in their eagerness do they think they descry a mountain summit on the long line that parts sea and sky; but the mountain proves to be merely the topmast of some distant vessel, and disappointment is intensified by the very longing that had prompted the imagination.

[2]

But at last there is no mistake. From a bright light bank of feathery cloud on the south-south-east horizon there is seen a long, blue streak, which every succeeding minute rises obviously more plainly above the ocean. That far-off streak is the crown of an imposing rock, itself a monument of a memorable crisis in the annals of geographical discovery; it is the crest of Africa’s stony beacon, Table Mountain.

[3]

Out of the thirty-six days, from May the 26th to July the 1st, 1872, that I spent on board the “Briton” on her passage from Southampton to Cape Town,[1] thirty were stormy. For four whole weeks I suffered from so severe an attack of dysentery that my strength was utterly prostrated, and I hardly ventured to entertain a hope that I should ever reach the shores of South Africa alive. My readers, therefore, will easily understand how my physical weakness, with its accompanying mental depression, gave me an ardent longing to feel dry land once more beneath my feet, especially as that land was the goal to which I was hastening with the express purpose of there devoting my energies to scientific research. But almost sinking as I felt myself under my prolonged sufferings, the tidings that the shore was actually in sight had no sooner reached my cabin than I was conscious of a new thrill of life in my veins; and my vigour sensibly revived as I watched until not only Table Mountain, with the Lion’s Head on one side and the Devil’s Peak on the other, but also the range of the Twelve Apostles to the south lay outstretched in all their majesty before my eyes.

Before leaving the “Briton” and setting foot upon African soil, I may briefly relate an adventure that befell me, and which seemed a foretaste of the dangers and difficulties with which I was to meet in South Africa itself. On the 20th of June, after three weeks of such boisterous weather that it had been scarcely possible for a passenger to go on deck at all, we found ourselves off St. Helena. By this time not only had my illness seriously reduced my strength, but the weaker I became the more oppressive did I feel the confined atmosphere of my second-class cabin; my means not having sufficed to engage a first-class berth. On the morning in question I experienced an unusual difficulty in breathing; the surgeon was himself seriously ill, and consequently not in a condition to prescribe; accordingly, taking my own advice, I came to the conclusion that I would put my strength to the test and crawl on deck, where I might at least get some fresh air. It was not without much difficulty that I managed to creep as far as the forecastle, splashed repeatedly on the way by the spray from the waves that thundered against the bow; still, so delightful was the relief afforded by the breeze to my lungs, that I was conscious only of enjoyment, and entertained no apprehension of mischief from the recurring shower-baths.

[4]

But my satisfaction only lasted for a few minutes; I soon became convinced of the extreme imprudence of getting so thoroughly soaked, and came to the conclusion that I had better make my way back. While I was thus contemplating my return, I caught sight of a gigantic wave towering on towards the ship, and before I could devise any means for my protection, the vessel, trembling to her very centre, ploughed her way into the billow, where the entire forecastle was quite submerged. My fingers instinctively clutched at the trellis-work of the flooring; but, failing to gain a hold, I was caught up by the retreating flood and carried overboard. Fortunately the lower cross-bar broke my fall, so that instead of being dashed out to sea, I slipped almost perpendicularly down the ship’s side. The massive anchor, emblem of hope, proved my deliverance. Between one of its arms and the timbers of the ship I hung suspended, until the boatswain came just in time to my aid, and rescued me from my perilous position.

CAPE-TOWN.

Page 5.

But to return to Table Mountain, the watchtower of Cape Colony. In few other points of the coast-line of any continent are the mountains more representative of the form of the inland country than here. At the foot of the three contiguous mountains, Table Mountain, Devil’s Peak, and Lion’s Head, and guarded, as it were, by their giant mass, reposing, as it might well appear, in one of the most secure and sheltered nooks in the world, lay Cape Town, the scene of my first landing. It is the metropolis of South Africa, the most populous city south of the Zambesi, and the second in importance of all the trade centres in the Anglo-African colonies. Although, perhaps, in actual beauty of situation it cannot rival Funchal, the capital of Madeira, which, with its tiers of terraces on its sloping hillside, we had had the opportunity of admiring in the course of the voyage, yet there is something about Cape Town which is singularly attractive to the eye of a stranger; he seems at once to experience an involuntary feeling of security as he steams slowly along the shores of Table Bay; and as he gazes on the white buildings (not unfrequently surmounted by slender towers) which rise above the verdure of the streets and gardens, he recognizes what must appear a welcome haven of refuge after the stormy perils of a long sea passage. But appearances here, as often elsewhere, are somewhat deceptive; and as matter of fact, both the town and the bay are at some seasons of the year exposed to violent storms, one consequence of which is that the entire region is filled with frightful clouds of dust. Even in calm weather, the dust raised by the ordinary traffic of the place is so dense and annoying that it is scarcely possible to see a hundred yards ahead; and to escape it as much as possible people of sufficient means only come into the town to transact their business, having their residences in the outskirts at the foot of the adjacent mountains.

[6]

This disadvantage is likely to attach to the town for some time to come; first, because there are no practicable means of arresting the storms that break in on the south-east from Simon’s Bay; and secondly, because no measures have yet been taken in hand for paving the streets. It must be acknowledged, however, that within the last few years, during Sir Bartle Frere’s administration, the large harbour-works that have been erected have done much to protect the town from the ravages of the ocean,—ravages of which the fragments of wreck that lie scattered along the shores of Table Bay are the silent but incontestable witnesses.

[7]

At the time of my arrival, in 1872, our vessel had to be towed very cautiously into the harbour. Mail steamers are now despatched to the colony every week, but at that time they only reached South Africa about twice a month, and it was therefore no wonder that each vessel, as it arrived from the mother-country, should be hailed with delight, and that the signal from the station at the base of the Lion’s Head should attract a considerable crowd to the shore. There were many who were expecting relations or friends; there were the postal officials, with a body of subordinates, waiting to receive the mail; and there were large numbers of the coloured population, Malays, Kaffirs, and Hottentots, as well as many representatives of the cross-breeds of each race, who had come to offer their services as porters. All these had found their way to the water’s edge, and stood in compact line crowded against the pier. In a few minutes the steamer lay to, and the passengers who, after two days, were to go on to Port Elizabeth hurried on shore to make the most of their time in exploring the town.

At a short distance from the shore, we entered Cape Town by the fish-market. Here, every day except Sunday, the Malay fishermen display an immense variety of fish; and lobsters, standing literally in piles, seem especially to find a ready sale. Any visitor who can steel his olfactory nerves against the strong odour that pervades the atmosphere of the place may here find a singularly ample field for ethnographical and other studies. The Malays, who were introduced into the country about ten years since, have remained faithful to their habits and costume. Imported as fishermen, stone-masons, and tailors, they have continued their own lines of handicraft, whilst they have adopted a new pursuit adapted to their new home and have become very successful as horse-breakers.

[8]

Passing along, we were interested in noticing the dusky forms of these men as they busily emptied the contents of their boats into baskets. They were dressed in voluminous linen shirts and trousers; and their conical hats of plaited straw, rushes, or bamboo, were made very large, so as to protect their heads effectually from the sun. Their physiognomy is flat, and not particularly pleasing, but their eyes, especially those of the women, are large and bright, and attest their tropical origin. The women, who wore brilliant handkerchiefs upon their heads, and the fullest of white skirts over such a number of petticoats as gave them all the appearance of indulging in crinoline, were assisting their husbands in their work, laughing with high glee over a haul which evidently satisfied them, and chattering, sometimes in their own language and sometimes in Dutch. A black-headed progeny scrambled about amongst their busy elders, the girls looking like pretty dolls in their white linen frocks, the boys dressed in short jackets and trousers, none of them seeming to consider themselves too young to do their best in helping to lug off the fish to the market.

On leaving the fish-market, we made our way along one of the streets which lie parallel to each other, and came to the parade, a place bordered with pines. Inside the town the eye of a stranger is less struck by the buildings, which for the most part are in the old Dutch style, than by the traffic which is going on in the streets, where the mixed breeds predominate. In every corner, in every house, they swarm in the capacity of porters, drivers, or servants, and Malays, Kaffirs, and half-breeds are perpetually lying in wait for a job, which, when found, they are skilful enough in turning to their own advantage. Much as was done during my seven years’ sojourn in the country to improve the external appearance and general condition of the town, this portion of the population seemed never to gain in refinement, and the sole advance that it appeared to make was in the craftiness and exorbitance of its demands. Exceptions, however, were occasionally to be found amongst some of the Malays and half-breeds, who from special circumstances had had the advantage of a somewhat better education.

[9]

Cape Town is the headquarters of the Chief Commissioner for the British Possessions and Dependencies in South Africa, as well as for his Council and for the Upper and Lower Houses of Assembly. It is also the see of an Anglican bishop. The town contains sixteen churches and chapels, and amongst its population, which is chiefly coloured, are members of almost every known creed. Amongst the white part of the community, the Dutch element decidedly preponderates.

At the head of the present Government is a man who has gained the highest confidence of the colonists, and who is esteemed as the most liberal-minded and far-seeing governor that England has ever entrusted with the administration of the affairs of her South African possessions. It is confidently maintained that many of Sir Bartle Frere’s measures are destined to bear rich fruit in the future.

The public buildings that are most worthy of mention are the Town Hall, the churches, the Government House, the Sailors’ Home, the Railway Station, and especially the Museum, with Sir George Grey’s Monument, and the adjacent Botanical Gardens; but perhaps the structure that may most attract attention is the stone castle commanding the town, where the Commander-in-chief resides, and which has now been appointed as the temporary abode of the captive Zulu king, Cetewayo.

[10]

Whether seen from the sea, or viewed from inland, the environs of Cape Town are equally charming in their aspect. Approached from the shore, the numerous white specks along the foot of the Lion’s Head gradually resolve themselves into villas standing in the midst of luxuriant gardens, sometimes situated on the grassy slopes, and sometimes picturesquely placed upon the summit of a steep bare rock. The well-to-do residents, especially the merchants, are conveyed from this suburb into the town by a horse-tramway, which is in constant use from six in the morning until ten at night. The part lying nearest to the town is called Green Point, the more remote end being known as Sea Point. Between the two are the burial-grounds, the one allotted to Europeans being by no means dissimilar, to the quiet cypress gardens in Madeira. The native cemeteries lie a little higher up the hill, and afford an interesting study in ethnography. That of the Mohammedan Malays cannot fail to claim especial attention—the graves marked by dark slate tablets, distinguished by inscriptions, and adorned with perpetual relays of bright paper-flowers.

[11]

Charming as is the scene at the foot of the Lion’s Head, there is another, still more lovely, on the lower slopes of the Devil’s Mountain. Here, for miles, village after village, garden after garden, make one continuous chain, the various farmsteads being separated and overshadowed by tracts of oaks or pines. Every hundred steps an enchanting picture is opened to the eye, especially in places where the mountain exhibits its own interesting geological formation, or forms a background clothed with woods or blossoming heath. The suburb is connected with the town by the railroad, which runs inland for about a hundred miles.

On this railroad the third station has a peculiar interest as being the one nearest to the Royal Observatory, which is built in some pleasure-grounds near the Salt River. World-wide is the reputation of the Observatory through its association with the labours of Sir John Herschel, astronomical science being at present prosecuted under the superintendence of Professor Gill.

Our two days’ sojourn at Cape Town sped quickly by, and the “Briton” left Table Bay. Rounding the Cape of Good Hope, she proceeded towards Algoa Bay, in order to land the majority of her passengers at Port Elizabeth, the second largest town in the colony, and the most important mercantile seaport in South Africa.

Along the precipitous coast the voyage is ever attended with considerable danger, and many vessels have quite recently been lost upon the hidden reefs with which the sea-bottom is covered.

[12]

Like the other bays upon the coast, Algoa Bay is wide and open, and consequently much exposed to storms; indeed, with the exception of Lime Bay, a side-arm of Simon’s Bay, there is not a single secure harbour throughout the entire south coast of the Cape. This is a most serious disadvantage to trade, export as well as import, not simply from the loss of time involved in conveying goods backwards or forwards from vessels anchored nearly half-a-mile from the shore, but on account of the additional expense that is necessarily incurred. Large sums of money, undoubtedly, would be required for the formation of harbours in these open roadsteads, yet the outlay might be beneficial to the colony in many ways.

Situated on a rocky declivity some 200 feet high, Port Elizabeth extends over an area about two miles in length, and varying from a quarter of a mile to a full mile in breadth. The population is about 20,000. Any lack of natural beauty in the place has been amply compensated by its having acquired a mercantile importance through rising to be the trade metropolis for the whole interior country south of the Zambesi; it has grown to be the harbour not only for the eastern portion of Cape Colony, the Orange Free State, and the Diamond-fields, but also partially for the Transvaal and beyond.

[13]

A small muddy river divides the town into two unequal sections, of which the smaller, which lies to the south, is occupied principally by Malay fishermen. At the end of the main thoroughfare, and at no great distance from Baker River, bounded on the south side by the finest Town Hall in South Africa, lies the market-place; in its centre stands a a pyramid of granite, and as it opens immediately from the pier, a visitor, who may have been struck with the monotonous aspect of the town from off the coast, is agreeably surprised to find himself surrounded by handsome edifices and by offices so luxurious that they would be no disgrace to any European capital. Between the market-place and the sea, as far as the mouth of the Baker River, stand immense warehouses, in which are stored wool ready for export, and all such imported stores as are awaiting conveyance to the interior.

My own first business upon landing was to select an hotel, but it was a business that I could by no means set about with the nonchalance of a well-to-do traveller. For after paying a duty of 1l. for my breech-loader, and 10s. for my revolver, my stock of ready money amounted to just half-a-sovereign; and even this surplus was due to the accidental circumstance of the case of my gun not having been put on board the “Briton.” However, I had my letters of introduction.

A German merchant, Hermann Michaelis, to whom I first betook myself, directed me to Herr Adler, the Austrian Consul, and through the kind exertions of this gentleman in my behalf, Port Elizabeth proved to me a most enjoyable place of residence. He introduced me to the leading gentry of the town, and in a very short time I had the gratification of having several patients placed under my care. I had much leisure, which I spent in making excursions around the neighbourhood, but I had hardly been in Port Elizabeth a fortnight when I received an offer from one of the resident merchants, inviting me to settle down as a physician, with an income of about 600l. a year. The proposal was very flattering, and very enticing; it opened the way to set me free from all pecuniary difficulties, but for reasons which will hereafter be alleged, I was unable to accept it.

[14]

I generally made my excursions in the morning, as soon as I had paid my medical visits, returning late in the afternoon. Sometimes I went along the shore to the south, by a long tongue of land partially clothed with dense tropical brushwood, and partially composed of wide tracts of sand, on the extremity of which, seven miles from the town, stands a lighthouse. Sometimes I chose the northern shore, and walked as far as the mouth of the Zwartkop River. Sometimes, again, I spent the day in exploring the valley of the Baker River, which I invariably found full of interest. Furnished with plenty of appliances for collecting, I always found it a delight to get away from the hotel, and escaping from the warehouses, to gain the bridge over the river; but it generally took the best part of half an hour before I could make my way through the bustle of the wool depôt, which monopolizes the 250 yards of sand between the buildings and the sea.

Towards the south, as far as the lighthouse, the coast is one continuous ledge of rock, sloping in a terrace down to the water, and incrusted in places with the work of various marine animals, especially coral polypes. Sandy tracts of greater or less extent are found along the shore itself, but the sand does not extend far out to sea in the way that it does on the north of the town, towards the mouth of the Zwartkop.

[15]

All the curiosities that I could fish up at low tide from the coral grottoes, and all the remarkable scraps of coral and sea-weed that were cast up by the south-easterly storms, I carried home most carefully; and after my return from the interior, I found opportunity to continue my collections over a still larger area, and met with a still larger success.

Accompanied by four or five hired negroes, and by my little black waiting-maid Bella, I worked for hours together on the shore, and brought back rare and precious booty to the town.

The capture of the nautilus afforded us great amusement. We used to poke about the pools in the rocks with an iron-wire hook, and if the cephalopod happened to be there it would relinquish its hold upon the rock to which it had been clinging, and make a wild clutch upon the hook, thus enabling us to drag it out; of course, it would instantly fall off again; if it chanced to tumble upon a dry place, it would contract its tentacles and straightway make off to the sea; but if it lighted on the loose shingle we were generally able, by the help of some good-sized stones, to pick it up and make it a prisoner. The bodies of the largest of these mollusks are about five inches in length, but their expanded tentacles often reach to a measure of two feet. They are much sought after and relished by the Malays, who call them cat-fish.

[16]

Occasionally we saw young men and women with hammers collecting oysters, cockles, and limpets, to be sold in the town; and every here and there were groups of white boys with little bags, not unlike butterfly-nets, catching a sort of prawns, which some of the residents esteem a great delicacy. Diver-birds and gulls abounded near the shallows, the former rising so sluggishly upon the wing, that several of them allowed themselves to be captured by my dog Spot.

[17]

The coast, as I have already mentioned, here forms a wide tongue of land, half of which is a bare bank, whilst, with the exception of the extreme point, the other part, near the town and towards the lighthouse, is clothed with luxuriant vegetation. At least a thousand different varieties of plants are to be found in the district, and this is all the more surprising because they have their roots in soil which is mere sand. Fig-marigolds of various kinds are especially prominent; here and there citron-coloured trusses of bloom, as large as the palm of one’s hand, stand out in gleaming contrast to the dark finger-like, triangular leaves; a few steps further, and at the foot of a thick shrubbery, appear a second and a third variety, the one with orange-tinted blossoms, the other with red; and while we are stopping to admire these, just a little to the right, below a thicket of rushes, our eye is caught by yet another sort, dark-leaved and with flowers of bright crimson. Another moment, and before we have decided which to gather first, something slippery beneath our feet makes us look down, and we become aware that even another variety, this time having blossoms of pure white, is lurking almost hidden in the grass. In the pursuit of this diversified and attractive flora, the multiplicity of dwarf shrubs, of rushes, and of euphorbias, stands only too good a chance of being completely overlooked.

EUPHORBIA TREES.

For miles this sandy substratum forms shallow, grassy valleys from 10 to 20 feet deep, and varying from 100 to 900 yards in length, running parallel to each other, and alternating with wooded eminences rising 30 to 50 feet above the sea level.

[18]

Westwards from the lighthouse the shore is especially rich in vegetation. Its character is that of a rocky cliff broken by innumerable trickling streams. Several farm-houses are built upon the upper level. The swampy places are overgrown by many sorts of moisture-loving plants, the open pools being adorned with graceful reeds, and not unfrequently with blossoms of brilliant hue. The slope towards the sea is well-nigh covered by these marshes, whilst the low flattened hills that intervene are carpetted with heaths of various species, some so small as to be scarcely perceptible, others growing in bushes and approaching four feet in height. Truly it is a spot where a botanist may revel to his heart’s content. These heaths not only exhibit an endless variety of form in their blossoms, but every tint of colour is to be traced in their delicate petals. The larger sorts are ordinarily white or grey; the smaller most frequently yellow or ochre-coloured; but there are others of all shades, from the faintest pink to the deepest purple.

The heaths that predominate in the southern districts of Cape Colony are characteristic of the South African flora, though they are a type of vegetation that does not extend far inland. The largest number of species is to be found in the immediate neighbourhood of Cape Town and of Port Elizabeth.

[19]

Besides the heaths, lilies (particularly the scarlet and crimson sorts) are to be found in bloom at nearly all seasons of the year. Gladioli, also, of the bright red kind, are not unfrequently to be met with, vividly recalling the red flowering aloe which grows upon the Zuurbergen. Mosses are to be found in abundance on the downs.

A stranger wandering through this paradise of flowers would be tempted to imagine that, with the exception of a few insects and song-birds, animal life was entirely wanting. Such, however, was far from being the case. Lurking in the low, impenetrable bushes are tiny gazelles, not two feet high, hares, jerboas, wild cats, genets, and many other animals that only wait for the approach of nightfall to issue from their hiding-places.

My excursions to the shore, along the tongue of land, were upon the whole, highly successful. During my visit I collected a large variety of fish, crabs, cephalopods, annelids, aphrodites, many genera of of mollusks, corals, sponges, and sea-weeds, as well as several specimens of the eggs of the dog-fish.

[20]

Nor did I confine myself to exploring the south shore. I wandered occasionally in the opposite direction, towards the mouth of the Zwartkop. There the shore for the most part consists of sand, which extends far out to sea, making it a favourable stranding-place for any vessel that has been torn from its anchorage during one of the frequent storms. From the sea I procured many interesting mollusks. Dog-fish abound near the mouth of the stream, while the river itself seems to teem with many kinds of fish. The banks, more especially that on the left, are rich in fossils of the chalk period, and in the alluvial soil are remains of still extant shell-fish, as well as interesting screw-shaped formations of gypsum. The coast is flatter here than it is towards the south, and the large lagoons that stretch inland furnish a fine field for the ornithologist’s enjoyment, as they abound in plovers, sandpipers, and other birds. I observed, also, several species of flowers that were new to me, particularly some aloes, marigolds, and ranunculuses, and a fleshy kind of convolvulus, which, I think, has not been seen elsewhere.

Generally I returned home by way of the saltpan, a small salt lake about 500 yards long by 200 broad, which lies between the town and the river, and is for part of the year full of water. Here I found some more new flowers, besides some beetles and butterflies. The saltpan lies in in a grassy plain, bounded on the west by the slope on which the town is built. Both the plain and the rocky declivity produce a variety of plants, but the majority of them are of quite a dwarf growth; in August and September, the spring months, they abound in lizards, spiders, and scorpions, and of these I secured a large collection. On the slope alone I caught as many as thirty-four snakes. Just at this season, when the winter is departing, the beetles and reptiles begin to emerge from their holes; but, finding the nights and mornings still cold, they are driven by their instinct to take refuge under large stones. Here they will continue sometimes for a week or more in a state of semi-vitality; and, captured in this condition, they may easily be transferred to a bottle of spirits of wine without injury to the specimens.

[21]

My inland excursions, which for the most part took the direction of the valley of Baker River, had likewise their own special charm. In its lower course the river-bed is bounded by steep and rocky walls, rising in huge, towering blocks; but higher up there are tracts of pasturage, where the tall grass is enlivened by a sprinkling of gay blossoms, that indicate the close proximity of the sea. Scattered over the valley are farms and homesteads, and in every spot where there is any moisture a luxuriant growth of tropical shrubs, ferns, and creepers is sure to reveal itself, and in especial abundance upon the ruins of deserted dwellings.

[22]

In one of the recesses of the valley there is an establishment for washing wool by steam. At a very short distance from this I found a couple of vipers rolled up under a stone, in a hole that had probably been made by some great spider. I seized one of them with a pair of pincers, and transferred it with all speed to my flask, which already contained a heterogeneous collection of insects and reptiles. I had caught the male first, and succeeded in catching the female before she had time to realize that her mate was gone. I kept them both in my flask with its neck closed for a time, sufficiently long, as I supposed, to stupefy them thoroughly, and went on my way. Finding other specimens I opened my receptacle and deposited them there, but it did not occur to me that there was any further need to keep the flask shut. I had not gone far before I was conscious of a strange thrill passing over my hand; a glance was sufficient to show me what had happened; one of my captive vipers had made an escape, and was fastening itself upon me; involuntarily I let the flask, contents and all, fall to the ground. I was not disposed, however, to be baulked of my prize, and immediately regaining my presence of mind, I managed once again to secure the fugitive, and was careful this time to fasten it in its imprisonment more effectually.

[23]

One day, Herr Michaelis invited me to accompany him and another friend to the high table-land on a bee-hunt. It was an excursion that would occupy about half a day, and I was most delighted to avail myself of the offer. We started up the hill in a covered, two-wheeled vehicle, and turned eastward across the plain that extends in a north-easterly direction. The plateau was clothed with short grass, and studded with thousands of reddish-brown ant-hills, chiefly conical in form and measuring about three feet in diameter, and something under three feet in height. Those that were still occupied had their surface smooth, the deserted ones appearing rough and perforated. An ant-hill is always forsaken when its queen dies, and our search was directed towards any that we could find thus abandoned, in the hope of securing its supply of honey. In the interior of Africa a honey-bird is used as a guide to the wild bees’ nests; but in our case, we employed a half-naked Fingo, wearing a red woollen cap, who ran by the side of our carriage, and kept a sharp look-out. It was not long before a gesture from him brought us to a standstill. He had made his discovery; he had seen bees flying in and out of a hill, and now was our chance. We lost no time in fastening up our conveyance, lighted a fire as rapidly as we could, and in a very few minutes the bees were all suffocated in the smoke. The ant-hill itself was next cleared away, and in the lower cells were found several combs, lying parallel to each other, and filled partly with fragrant honey, and partly with the young larvæ. I could not resist making a sketch of the structure. The removal of the earth brought to light two more snakes, which were added to my rapidly increasing collection.

With these and similar excursions, four weeks at Port Elizabeth passed pleasantly away. The time came when I must prepare to start for the interior. Tempting as was the offer that had been made to me to remain where I was, there were yet stronger inducements for me to proceed. Not only had a merchant in Fauresmith, in the Orange Free State, held out hopes of my securing a still more lucrative practice, but Fauresmith itself was more than sixty miles further to the north, and thus of immense advantage as a residence for one who, like myself, was eager to obtain all possible information about the interior of the country.

Besides advancing me the expenses of my journey, Herr Hermann Michaelis himself offered to accompany me to Fauresmith.

[24]

I need hardly say with how much regret I left Port Elizabeth, and all the friends who, during my visit, had treated me with such courtesy and consideration.

It was in the beginning of August that I started on my journey from Port Elizabeth to Fauresmith, viâ Grahamstown, Cradock, Colesberg, and Philippolis. My vehicle was a two-wheeled cart, drawn by four small horses, and the distance of eighty-six miles to Grahamstown was accomplished in eleven hours.

The beauty of the scenery and of the vegetation made the drive very attractive. The railway that now runs to Grahamstown also passes through charming country; but, on the whole, I give my preference to the district which was originally traversed by road. For the greater part of the way the route lies beneath the brow of the Zuur Mountains, which, with their wooded clefts and valleys, and their pools enclosed by sloping pastures, must afford unfailing interest both to the artist and to the lover of nature.

[25]

Occasionally the trees stand in dense clumps, quite detached, a form of vegetation which is very characteristic of wide districts in the interior of the continent; but by far the larger portion of this region is covered by an impenetrable bush-forest, consisting partly of shrubby undergrowth, and partly of dwarf trees. Many of these appear to be of immense age, but many others seem to have been attacked by insects, and have so become liable to premature decay.

Every now and then our road led past slopes, where the stems of the trees were covered all over with lichen, which gave them a most peculiar aspect, and it was a pleasant reminiscence of the woods of the north to see a beard-lichen (Usnea) with its thick grey-green tufts a foot long decorating the forked boughs as with a drapery of hoar-frost. In other places, the eye rested on declivities covered for miles with dwarf bushes, of which the most striking were the various species of red-flowering aloes, and the different euphorbias, some large as trees, some low, like shrubs, and others mere weeds, but altogether affording a spectacle at which the heart of a botanist could not but rejoice.

[26]

Numerous varieties, too, of solanum (nightshade) laden with yellow, white, blue, or violet blossoms, climb in and around the trees, and in some parts unite the stems with wreaths that intertwine so as to form almost an impenetrable thicket, where the grasses, the bindweeds, the heaths, and the ranunculuses in the very multiplicity of their form and colour fill the beholder with surprise and admiration. Like a kaleidoscope, the vegetation changes with every variation of scenery; and each bare or grassy flat, each grove or tract of bushwood, each swamp or pool, each slope or plain has ever its own rare examples of liliaceæ, papilionaceæ, and mimosæ to exhibit.

Here and there, in the midst of its own few acres of cultivated land, is to be seen a farm, and at no unfrequent intervals by the wayside are erections of brick or galvanized iron, which, although often consisting of only a couple of rooms and a store, are nevertheless distinguished by the name of hotels.

[27]

Throughout this district the fauna is as varied as the flora, and the species of animals are far more numerous and diversified than in the whole of the next ten degrees further north towards the interior. As I had opportunity in my three subsequent journeys to examine the different animal groups in detail, I shall merely refer here to their names, deferring more minute description for a future page. Ground squirrels and small rodents abound upon the bare levels where there is no grass, associating together in common burrows, which have about twenty holes for ingress and egress, large enough to admit a man’s fist. In places where there is much long grass are found the retreats of moles, jackals, African polecats, jerboas, porcupines, earth-pigs, and short-tailed armadilloes. In the fens there are otters, rats, and a kind of weasel. On the slopes are numerous herds of baboons, black-spotted genets, caracals, jumping mice, a peculiar kind of rabbit, and the rooyebock gazelle; and besides the edentata already mentioned, duykerbock and steinbock gazelles are met with in those districts where the trees are in detached clumps. The tracts of low bushwood, often very extensive, afford shelter to the striped and spotted hyæna, as well as to the strand-wolf (Hyæna brunnea); and there, too, amongst many other rodentia is found a gigantic field-mouse; also two other gazelles, one of them being the lovely little bushbock. The bushes on the slopes and the underwood are the resort of baboons, monkeys, grey wild-cats, foxes, leopards, koodoo-antelopes, bushvarks, blackvarks, buffaloes, and elephants, the elephants being the largest of the three African varieties. A hyrax that is peculiar to the locality, and lives in the trees, ought not to be omitted from the catalogue.

Leopards are more dangerous here than in the uninhabited regions of the interior, where they are less accustomed to the sound of fire-arms, and so desperate do they become when wounded, that it is generally deemed more prudent to destroy them by poison or in traps.

The capture of elephants is forbidden by law; consequently several wild herds, numbering twenty or thirty head, still exist in Cape Colony; whilst in the Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and the Bechuana country the race has been totally annihilated.

[28]

Their immunity from pursuit gives them an overweening assurance that is in striking contrast with the behaviour of the animals of their kind in Central and Northern South Africa. There a shot, even if two or three miles away, is enough to put a herd to speedy flight, and they seldom pause, until they have placed the best part of twenty miles between themselves and the cause of their alarm; and although within the last twenty years 7500 elephants have been killed by Europeans, it is the very rarest occurrence for one of them to make an unprovoked attack upon a human being. Here, on the contrary, between Port Elizabeth and Grahamstown, it is necessary to be on one’s guard against meeting one of the brutes. Just before I returned to Port Elizabeth on my homeward journey, a sad accident had happened in the underwood by the Zondags River, which flows partially through the forest. A black servant had been sent by his master to look for some cattle that had strayed; as the man did not return, a search was made for him, but nothing was found except his mangled corpse. From the marks all around, it was quite evident that a herd of passing elephants had scented him out, and diverging from their path, had trampled the poor fellow to death. It should be mentioned, that although ordinarily living under protection, these ponderous creatures may be slain by consent of the Government.

ELEPHANTS ON THE ZONDAGS RIVER.

Page 28.

To enumerate all the varieties of birds to be seen hereabouts would be impossible; an ornithologist might consume months before he could exhaust the material for his collection; I will only say that a sportsman may, day after day, easily fill more than his own bag with different kinds of bustards, guinea-fowl, partridges, sand-grouse, snipes and plovers, wild ducks and wild geese, divers and other water-fowl. The wonderful and beautiful productions of the vegetable kingdom that excite the admiration of the stranger as he makes his excursions in this district, whether in pursuit of pleasure or of science, derive a double charm from the numerous graceful birds and sparkling insects that hover and flit about them. Here are long-tailed Nectariniæ, or sun-birds, now darting for food into the cup-shaped blossoms of the iris, and now alighting upon the crimson flower-spike of the aloe; and there, though not the faintest breath of air is stirring, the branches of a little shrub are all in agitation; amidst the gleaming dark-green foliage, a flock of tiny green and yellow songsters, not unlike our golden-crested wren, are all feasting busily upon the insects that lie hidden beneath the leaves.

On the tops of the waggon-trees, hawks and shrikes, beautiful in plumage, keep their sharp look-out, each bird presiding over its own domain; and no sooner does a mouse, a blindworm, or a beetle expose itself to view, than the bird pounces down upon its prey; its movement so sudden, that the bough on which it sat rebounds again as though rejoicing in its freedom from its burden.

[30]

The leafy mimosas, too, covered with insects of many hues, attract a large number of birds. Nor are the reedy districts at all deficient in their representatives of the feathered race, but reed-warblers, red and yellow finches, and weaver-birds keep the lank rushes in perpetual motion, and make the valleys resound with their twittering notes.

As representatives of the reptile world, gigantic lizards are to be found near every running water; tortoises of many kinds abound on land, one sort being also met with both in streams and in stagnant pools; there are a good many poisonous snakes, such as buff-adders, cobras, horned vipers, besides coral snakes; likewise a species of green water-snake, which, however, is harmless. Venomous marine serpents also find their way up the rivers from the sea.

[31]

We reached Grahamstown late at night on the same day that we left Port Elizabeth, and started off again early the following morning. During the next two days we had some pleasant travelling in a comfortable American calèche, and arrived at Cradock, a distance of 125 miles. At first the country was full of woods and defiles similar to those we had passed after leaving Port Elizabeth, but afterwards it changed to a high table-land marked by numerous detached hills, some flat and some pointed, and bounded on the extreme north-east and north-west by mountain chains and ridges. The isolated hills rise from 200 to 500 feet above the surrounding plain, and are mostly covered with low bushes, consisting chiefly of the soil-exhausting lard-tree. The valleys display a great profusion of acacias, hedge-thorns and other kinds of mimosa, but the general type of vegetation which is conspicuous hereabouts disappears beyond Cradock, and is not seen again in any distinctness until near the Vaal River, or even farther north.

On our way to Cradock I had my first sight of those vast plains that stretch as far as the eye can reach, and which during the rainy season present an illimitable surface of dark green or light, according as they are covered with bush or grass, but which, throughout all the dry period of the year, are merely an expanse of dull red desert. They abound in the west of Cape Colony, in the Free State, in the Transvaal, and in the Batlapin countries, and are the habitations of the lesser bustard, the springbock, the blessbock, and the black gnu. Where they are not much hunted all these animals literally swarm; but on my route I saw only the springbock, which is found in diminished numbers on the plains to the north. I did not observe one at all beyond the Salt Lake basin in Central South Africa; along the west coast, however, as far as the Portuguese settlements, they are very abundant.

[32]

The springbock (Antilope Euchore) is undeniably one of the handsomest of the whole antelope tribe. Besides all the ordinary characteristics of its genus, it possesses a remarkable strength and elasticity of muscle; and its shapely head is adorned with so fine a pair of lyrate horns that it must rank facile princeps amongst the medium-sized species of its kind. The gracefulness of its movements when it is at play, or when startled into flight, is not adequately to be described, and it might almost seem as if the agile creature were seeking to divert the evil purposes of a pursuer by the very coquetry of its antics. Unfortunately, however, sportsmen are proof against any charms of this sort; and under the ruthless hands of the Dutch farmers, and the unsparing attacks of the natives, it is an animal that is every day becoming more and more rare.

The bounds of the springbock may, perhaps, be best compared to the jerks of a machine set in motion by watch-spring. It will allow any dog except a greyhound to approach it within quite a moderate distance; it will gaze, as if entirely unconcerned, while the dog yelps and howls, apparently waiting for the scene to come to an end, when all at once it will spring with a spasmodic leap into the air, and, alighting for a moment on the ground six feet away, will leap up again, repeating the movement like an indiarubber ball bounding and rebounding from the earth. Coming to a standstill, it will wait awhile for the dog to come close again; but ere long it recommences its springing bounds, and extricates itself once more from the presence of danger. And so, in alternate periods of repose and activity, the chase goes on, till the antelope, wearied out as it were by the sport, makes off completely, and becomes a mere speck on the distant plain.

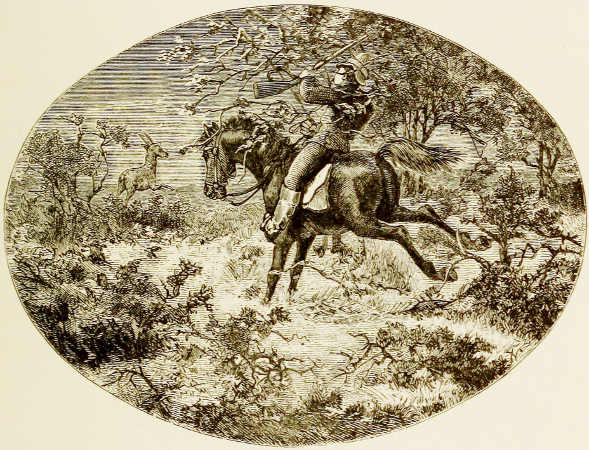

SPRINGBOCK HUNTING.

Page 33.

But the agility of the nimble creature cannot save it from destruction. Since the discovery of the diamond-fields thousands of them, as well as of the allied species, the blessbock and the black gnu, have been slain. The Dutch farmers, who are owners of the districts where the antelopes abound, are excellent shots and their worst enemies. On their periodical visits to the diamond-fields they always carry with them a rich spoil; and whilst I was there, in the winter months, from May to September, I saw whole waggon-loads of gazelles brought to the market. Nevertheless, in spite of the slaughter, it is a kind of game that as yet has by no means become scarce, and it is sold in the daily markets at Kimberley and Dutoitspan at prices varying from three to seven shillings a head.

[34]

Springbock hunting is rather interesting, and is generally done on horseback. The horses, which have been reared on these grassy plains, are well accustomed to the burrow-holes and ant-hills with which they abound, so that they give their rider no concern, and allow him to concentrate all his attention upon his sport. A gallop of about two miles will usually bring the huntsman within a distance of 200 yards of a herd of flying antelopes. A slight pressure of the knees suffices to bring the horse to a standstill, when its rider dismounts and takes a deliberate aim at the victim. Amongst the Dutch Boers the most wonderful feats of skill are performed in this way; and I have known an expert marksman bring down two running antelopes by a single shot from his breech-loader. Other instances I have witnessed, when, both shots having missed, or the second having been fired too late, the herd has scampered off to a distance of 700 yards or more and come to a stand, when a good shot has made a selection of a special victim for his unerring aim. Well do I recollect one of these experts pointing to a particular antelope in one of these fugitive herds, and exclaiming, “Det rechte kantsche bock, Mynheer!” He brought the creature down as he spoke.

There is another method of hunting these springbocks, by digging holes two or three feet deep and three feet wide, in proximity to ponds or pools in half-dried-up river-beds; in these holes the hunter crouches out of sight, and shoots down the animals as they come to drink. This kind of chase, or rather battue, is very common in the dry season, when there are not many places in which the antelopes can quench their thirst, and is especially popular with the most southerly of the Bechuanas, the Batlapins, and the Baralongs, who are, as a rule, by no means skilful as shots.

[35]

On the plains between the Harts River and the Molapo a different plan is often followed. Several men lie down flat on the ground, either behind ant-hills or in some long grass at intervals of from 50 to 200 yards, and at a considerable distance—ordinarily about half a mile—from the herd. A large number of men then form themselves into a sort of semicircle, and, having encompassed the herd, begin to close in so as to drive them within range of the guns of the men who are lying in ambush. As the weapons are only of the commonest kind, often little better than blunderbusses, the success of the movement of course depends entirely on the first shot. When the party is small, they not unfrequently spend a whole day waiting most patiently for the springbocks to be driven sufficiently within range. I have myself on one occasion seen a party of six of these skirmishers, after watching with the sublimest patience for many hours, take their aim at an animal that had been driven within the desired limits; the old muskets went off with a roar that made the very ground tremble; the volume of smoke was immense; six dusky faces of the Bechuanas rose from the grass; every eye was full of expectation; but as the cloud rolled off, it revealed the springbock bounding away merrily in the distance. The six shots had all missed.

I feel bound, however, to confess to a performance of my own, about equally brilliant. After watching one day for several hours, I observed a few springbocks scarcely more than twenty yards away from me. I felt quite ashamed at the thought of doing any injury to the creatures, they were so graceful, but we were really in want of food, and it was only the remembrance of this that made me overcome my scruples. I could not help regarding myself almost as a murderer; but if I wanted to secure our dinner, there was no time to lose. My trembling hand touched the trigger; the mere movement startled the springbocks, and before I could prepare myself to fire, they were far away, totally uninjured.

[36]

The snare called the hopo-trap, described by Livingstone in his account of gazelle-hunting amongst the Bechuanas, I never saw anywhere in use. It would probably be now of no avail, as the game is much wilder and less abundant than it was in his time.

ANTELOPE TRAP

[37]

A still different mode of chasing springbocks has been introduced by the English, who hunt with greyhounds, not using fire-arms at all. Mounted on horses, that in spite of being unaccustomed to the ground, do their work admirably, the pursuers follow on until the gazelles are fairly brought down by the dogs; although it not unfrequently happens that the dogs get so weary and exhausted by the run, that the chase has to be abandoned.

THE COUNTRY NEAR CRADOCK.

[38]

We only remained in Cradock one day. The town is situated on the left bank of Fish River, a stream often dried up for months together, so as to become merely a number of detached pools; but a few hours of heavy rain suffice to overfill the channel with angry waters, that carry ruin and destruction far and wide. The great bridge that spanned the river at the town was in 1874 swept right away by the violence of the flood, the solid ironwork being washed off the piles, which were themselves upheaved. The new bridge was erected at a securer altitude, being about six feet higher.

On the second day after leaving Cradock we reached the town of Colesberg. Our travelling was so rapid that I had scarcely time properly to take in the character of the scenery; but seven years later, on my return in a bullock-waggon, and when progress was especially slow on account of the drought, I had a fairer opportunity of examining, at least partially, the geological structure of the district, and of gaining some interesting information about the adjoining country.

[39]

Towards Colesberg the isolated, flattened eminences gradually decrease both in number and in magnitude, the country becoming a high table-land. One of the prettiest parts is Newport, a pass in which is seen the watershed between the southerly-flowing streams, and the affluents of the Orange River. The heights in the district are haunted by herds of baboons, by several of the smaller kinds of antelopes, and by some of the lesser beasts of prey of the cat kind, principally leopards. On the table-land itself are to be counted upwards of fifty quaggas, belonging to the true species, the only one I believe to be met with in South Africa. I was delighted to find that latterly they had been spared by the farmers; ten years previously their number had been diminished to a total of about fifteen heads.

The town is distinguished by a hill, which has the same name as itself, and which exhibits the stratification of the various rocks of which the district is composed. Colesberg itself is somewhat smaller than Cradock, and is situated in a confined rocky vale. The contiguous heights are for the most part covered with grass and bushwood, of so low a growth that from a distance they have the appearance of being almost destitute of vegetation. In summer-time the radiation of heat from the rocks is so intense that the town becomes like an oven, and is by no means a pleasant place of residence.

[40]

Proceeding northwards, a journey of a couple of hours brought us to the Orange River, the boundary between the Orange Free State and Cape Colony. Two hours later we reached Philippolis. The aspect of this place was most melancholy. The winter drought had parched up all the grass, alike in the valley and on the surrounding hills, leaving the environs everywhere brown and bare. Equally dreary-looking were the square flat-roofed houses, about sixty in number, and nearly all quite unenclosed, that constituted the town; whilst the faded foliage of a few trees near some stagnant pools in the channel of a dried-up brook, did nothing to enliven the depressing scene. The majority of the houses being unoccupied, scarcely a living being was to be seen, so that the barrenness of the spot was only equalled by its stillness.

ON THE WAY TO THE DIAMOND-FIELDS.

[41]

Hence, for the rest of the way to Fauresmith, we had to travel in a mail-cart, a two-wheeled vehicle of most primitive construction. A drive of three hours in such a conveyance over the best paved highway, and in the most genial weather, could hardly have been a matter of any enjoyment; but in the teeth of a piercing cold wind, and along a road covered with huge blocks of stone, and intersected by the deep ruts made by the streams from the highlands, and over which, in order to exhibit the mettle of his horses, our driver persisted in dashing at a break-neck pace, the journey was little better than martyrdom. The seat on which three of us had to balance ourselves was scarcely a yard long and half a yard wide, and in our efforts to preserve the equilibrium of ourselves and our luggage, our hands became perfectly benumbed with cold; and, to crown our discomfort, snow, which is of rare occurrence in these regions, began to fall.

We held out till man and beast were well-nigh exhausted, and had accomplished about three-quarters of the distance, when the barking of a dog, the sure symptom of the proximity of a dwelling-house, fell like music on our ears. The most miserable of Kaffir huts would have been a welcome sight; my friend declared himself ready to give a sovereign for a night’s lodging in a dog-kennel; but we were agreeably surprised at finding ourselves arrive at a comfortable-looking farmhouse, where the lights seemed to beam forth a welcome from the windows. We were most hospitably received, and sitting round the farmer’s bountiful board, soon forgot the troubles of the way.

[42]

After the meal was over we went to the door to ascertain the state of the weather. The snow had ceased almost before our horses were unharnessed, and, except in the south-east, the direction of the departing storm, the sky was comparatively clear, and there was a faint glimmer of moonlight. As I stood listening, I caught again the screeching note of a bird which already I had heard while sitting at the table. My host informed me that it proceeded from “det grote springhan vogl,” and I thought I should like to take my chance at a shot. The bird was really the South African grey crane, to which the residents have given the name of “the great locust bird,” on account of the great service it performs in the destruction of locusts. It is so designated in distinction to the small locust bird, which migrates with the locust-swarms. The great cranes (C. Stanleyi) never leave their accustomed quarters.

[43]

In the prosecution of my design I crept slowly along, but very soon became aware that the birds were not wanting in vigilance. The first rustle made the whole flock screech aloud and mount into the air. I did not want to fire promiscuously among them all, and so abandoned my purpose, and came back again. I afterwards observed that these cranes, together with the crowned cranes (Balearia regulorum), and the herons, as well as several kinds of storks, are accustomed to pass the night in stagnant waters in order that they may rest secure from the attacks of hyænas, jackals, foxes, hyæna-dogs (Canis pictus), and any animals of the cat tribe. As soon as darkness sets in the birds may be observed standing in long rows right in the midst of the pools, and until the break of day they never quit their place of refuge. But not even the security of their position seems to throw them off their guard. I observed during my many hunting excursions, both in the neighbourhood of the salt-water and of the fresh-water lakes, that a certain number of sentinel birds were always kept upon the watch, and that at intervals of about half an hour there was a short chatter, as if the sentries were relieving guard. A similar habit has been noticed both amongst the black storks in the Transvaal, and amongst the various herons in the Molapo river, and in the valleys of the Limpopo and the Zambesi.

The time came only too soon for us to leave our hospitable quarters. We set out afresh, and after a miserable jolt of several hours’ duration, we reached our destination at Fauresmith.

In its general aspect, Fauresmith is very like the other towns in the Free State. Although consisting of not more than eighty houses, it nevertheless covered a considerable area, and the clean white-washed residences, flat-roofed as elsewhere, peeping out from the gardens, looked altogether pleasant enough. The town is the residence of a kind of high sheriff, and must certainly be ranked as one of the most considerable in the republic. The district of the same name, of which it is the only town, is undoubtedly the wealthiest in the Free State, and deserves special notice, both on account of its horse-breeding and of its diamond-field at Jagersfontein.

[44]

Like various other towns in South Africa, Fauresmith is enlivened four times a year by a concourse of Dutch farmers, who meet together for the combined purpose of celebrating their religious rites and making their periodical purchases. At these times the town presents a marked contrast to its normal condition of silence and stagnation; large numbers of the cumbrous South African waggons make their way through the streets, and form a sort of encampment, partially within and partially on the outskirts of the place, the farmers’ sons and the contingent of black servants following in the train. Many of the wealthier farmers have houses of their own in the town, sometimes (where water is to be readily procured) adorned with gardens; but such as have inferior means content themselves with a hired room or two, whilst the poorest make shift for the time with the accommodation afforded by their own waggons. These recurring visits of the farmers are regarded as important events by the towns-people, and are looked for with much interest; in many respects they are like the fairs held in European cities. Especially are they busy seasons to the medical men, as, except for urgent cases, all consultations are reserved for these occasions and the majority of ordinary ailments that befall the rural population abide these opportunities to be submitted to advice.

Here in Fauresmith, just as in similar places with limited population, the sheriff, the minister, the merchant, the notary, and the doctor, form the cream of the society.

[45]

Nothing could exceed the hopefulness of the temper in which I had started for this town. Not only had I satisfied myself that I should be so much farther inland than I was at Port Elizabeth, and consequently that my advantages would be great in ascertaining what outfit would be really requisite for my progress into the interior, but I had been sanguine enough to anticipate that I should be in a position to earn the means that would enable me to carry out my design. So favourably had the prospect been represented to me, that I had accepted the proposition of the Fauresmith merchant in all confidence; perhaps my helplessness and complete want of resources had made me too trusting; I was, perchance, the drowning man catching at a straw.

A very few days of actual experience were enough to dispel any bright anticipation in which I had indulged. I could not conceal from myself that I was a burden upon the very man who had offered to befriend me, and induced me to come; his good offices in my behalf necessarily placed him in a false position with an older friend, a physician already resident in the town, and to whom he was now introducing a rival; it was only to be expected that his long-established friendship with him should prevail over his recent goodwill towards myself; he saw his mistake, and soon took an opportunity of telling me that if I proceeded to the diamond-fields I should find myself the right man in the right place.

I took the counsel into my best consideration, and quickly came to the conclusion that nothing else was to be done. Accordingly, I made arrangements to start.

[46]

But my difficulties were great. I had hardly any clothes to my back, my boots were in holes, and I had no money to replace either. I had no alternative but to get what I required upon credit. I succeeded in this, and set out forthwith, my pride not permitting me to remind my Port Elizabeth friend of the kind offer of assistance which he had made me.

Herr Michaelis once again rendered me the kindest of service; after advancing me money to forward me on my way, he undertook to convey me as his guest to the diamond-fields, which he had himself made up his mind to visit. We were joined by a third traveller, Herr Rabinsvitz, the chief rabbi for South Africa, from whom I received marked courtesy and consideration.

Although for the time I was disappointed, I could not feel otherwise than grateful for the hospitality shown me during my short residence in Fauresmith, by the worthy merchant. I acknowledge my obligation to him by this record, and rejoice to remember how I quitted the place with no ill-will for the past, but with the fullest confidence for the future.

[47]

Very monotonous in its character is the district between Fauresmith and the diamond-fields, the only scenery at all attractive being alongside the Riet River and in the valley of the Modder, which we had to cross. At this spot there seemed to be a chance of getting some sport, and I employed the few minutes during a halt after dinner in exploring the locality. The Riet River, like a fine thread, flowed north-westwards in a deep clear channel to its junction with the Modder, and, as is the case with most of the South African streams in the dry winter season, there were large pools, nine or ten feet deep and full of fish, extending right across the river-bed.

The whole valley is thickly covered with weeping willows (Salix Babylonica), and amongst these I found some very interesting birds. Pushing my way through the brushwood, with the design of making a closer inspection of one of the pools, I was startled by a great rustling, and by a chorus of notes just over my head. I stepped back, and a whole flock of birds rose into the air and settled in a thorn at no great distance. They were the pretty long-tailed Colius leucotis. I afterwards saw two other varieties of the same species. One of the flock that I had disturbed perched itself upon a bough almost close at hand, as if resolved to make a deliberate survey of the strangers who had intruded on its retirement, but all the rest had taken refuge in the bush, and were completely hidden from my view. They are lively little creatures, but very difficult to keep in confinement; the only caged specimens I ever saw were in Grahamstown, in the possession of a bird-fancier, who kept them with several kinds of finches, and fed them with oranges.

[48]

The most common birds in the Riet River valley are doves, and those almost exclusively of two sorts, the South African blue-grey turtle-dove, and the laughing-dove; of these the latter is found even beyond the Zambesi; it is a most attractive little creature, that cannot fail to win the affection of every lover of birds. I had a couple of them, which I had succeeded in catching after slightly wounding them. I kept them for years, and they afforded me much amusement. As early as three o’clock in the morning the male was accustomed to greet his brooding mate with his silvery laughing coo, and she would reply in low and tender notes that were soft and melodious as distant music. I eventually lost them through the negligence of one of my black servants.

[49]

On the plains on either side of the river I found the white-eared bustard, the commonest kind of wild-fowl in all South Africa; its cry, from the first day of my journey through the Orange Free State and the Transvaal to the last, rarely ceased to be heard. It affords a good meal, and may easily be brought down by the most inexperienced marksman. As soon as it becomes aware of the approach of a pursuer, it turns its head with an inquiring look in all directions, and suddenly dives down; just as suddenly it rises again, shrieking harshly, and after an awkward flight of about a couple of hundred yards, sinks slowly to the earth with drooping wings and down-stretched legs. Its upper plumage is of a mixed brown; its head, with the exception of a white streak across the cheeks, is black, as are also the throat and chest; its legs are yellow. Its habitat does not extend beyond the more northerly and wooded districts of South Africa, and, like other birds to which I have referred, it is extremely difficult to keep in confinement.

Our road through the valley led us past Coffeefontein, the second diamond-field in the Free State, where the brilliants, though small, are of a fine white quality. Late in the evening we crossed the river by the ford, spending the night in an hotel on the opposite bank.

HOTEL ON THE RIET RIVER.

[50]